Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Effective Adversarial Defense Framework: From Robust Feature Perspective

1 Information Engineering University, Zhengzhou, 450000, China

2 Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Security, Ministry of Education of China, Zhengzhou, 450000, China

3 National Key Laboratory of Advanced Communication Networks, Zhengzhou, 450000, China

* Corresponding Author: Tao Hu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 2141-2155. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066370

Received 07 April 2025; Accepted 24 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Deep neural networks are known to be vulnerable to adversarial attacks. Unfortunately, the underlying mechanisms remain insufficiently understood, leading to empirical defenses that often fail against new attacks. In this paper, we explain adversarial attacks from the perspective of robust features, and propose a novel Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based Robust Feature Disentanglement framework (GRFD) for adversarial defense. The core of GRFD is an adversarial disentanglement structure comprising a generator and a discriminator. For the generator, we introduce a novel Latent Variable Constrained Variational Auto-Encoder (LVCVAE), which enhances the typical beta-VAE with a constrained rectification module to enforce explicit clustering of latent variables. To supervise the disentanglement of robust features, we design a Robust Supervisory Model (RSM) as the discriminator, sharing architectural alignment with the target model. The key innovation of RSM is our proposed Feature Robustness Metric (FRM), which serves as part of the training loss and synthesizes the classification ability of features as well as their resistance to perturbations. Extensive experiments on three benchmark datasets demonstrate the superiority of GRFD: it achieves 93.69% adversarial accuracy on MNIST, 77.21% on CIFAR10, and 58.91% on CIFAR100 with minimal degradation in clean accuracy. Codes are available at: (accessed on 23 July 2025).Keywords

Deep neural networks (DNNs) provide an excellent end-to-end solution for face recognition [1], automatic driving [2], image segmentation [3], etc. However, DNN-based models are vulnerable to adversarial attacks, causing incorrect high-confidence predictions on modified inputs [4]. In particular, when applying DNNs in blockchain, adversarial attacks amplify the risks such as malicious transactions, loss of control in data ownership management, and damage to intelligent recommendation systems. Due to the black-box property [5] of DNNs, researchers have not yet clearly elucidated the underlying mechanism of adversarial attacks. As a result, adversarial attacks and defenses have become a crucial concern in the applications of DNN-based target models.

The usual methods of adversarial defense are empirical and lack researches on the internal mechanism of adversarial attacks. Therefore, they can only defend against specific attacks, resulting in a lack of generalization, and they can be easily compromised by well-designed adversarial attacks. Meanwhile, there are a few certificated defenses, such as Jacobian norm defense [6] and Random Smoothing [7]. However, these techniques are generally less effective compared to the former approaches. The problem must be addressed at its root; therefore, we should design an adversarial defense based on the internal mechanism of adversarial attacks.

The causes of adversarial attacks have been examined through various hypotheses, including the linear hypothesis [8], the low flexibility hypothesis [9], the high pixel hypothesis [10], and the inherent uncertainty hypothesis [11]. However, all of these explanations have certain limitations. In 2019, Andrew Ilyas proposed the robust feature hypothesis [12] to explain the generation of adversarial samples. He demonstrated that the vulnerability of target models to adversarial attacks can be directly attributed to their learning of non-robust features: features (patterns in the data distribution) that are highly predictive yet vulnerable to perturbations. Since the standard training process of DNN-based target models involves minimizing classification loss, the features learned by the model primarily focus on classification ability, which are referred to as useful features. Consequently, the features that are not learned by the model are termed redundant features. Furthermore, the useful features consist of both robust and non-robust features, with the latter being the source of vulnerability to adversarial attacks. If target models are trained on the robust features directly, they would exhibit high robustness. There has been some research on disentangling features such as [13], but this work has only disentangled the useful features. Therefore, an intuitive problem is:

How can we disentangle the robust features from the training data for adversarial defense?

It is obvious that robust and non-robust features are often intertwined in data distributions, lacking clear mathematical definitions or quantifiable separation criteria. Moreover, the extremely high dimensionality of real-world image data contains numerous redundant features that may obscure robust features, making disentanglement challenging. Previous theories have shown that feature disentangling cannot be achieved solely through unsupervised models or without inductive bias on the data [14]. Hence, we propose GRFD, a new Robust Feature Disentanglement framework based on Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) [15]. GRFD comprises a generator and a discriminator. The key advantage of our proposed GRFD defense method over other GAN-based approaches lies in its explainability-driven design. Without requiring any prior knowledge of adversarial attacks, GRFD can directly extract robust features from samples to train the robust model. In contrast, most comparable methods adopt denoising-based strategies that typically require pre-collected adversarial samples as training data throughout the defense process. For the generator in GRFD, inspired by disentangled representation learning and image translation [16], the beta Variational Auto-Encoder (beta-VAE) [17] is well suited as an image generation model for feature disentanglement. However, considering that the distribution of latent variables in typical beta-VAE is disorderly and scattered, which does not align with the expectation of its design, we improve it and propose the Latent Variable Constrained VAE (LVCVAE) to serve as the generator in GRFD. In LVCVAE, latent variables of samples within the same class are clustered together by adding a constrained rectification module. To supervise the disentanglement of robust features, we design a Robust Supervisory Model (RSM) as the discriminator. Since the target model can learn the features in the dataset well, the architecture of RSM is consistent with that of the target model. It is important to note that the robust features we disentangle are independent of the target model. The key innovation of RSM is its Feature Robustness Metric (FRM), which serves as the training loss and directly determines the defense effectiveness of GRFD. Motivated by the theory of robust features [12], FRM jointly optimizes two key properties: (1) classification performance through standard classification loss, and (2) perturbation resistance through local perturbation gradient similarity—implemented via a finite-difference approximation of loss surface curvature. During the training stage, LVCVAE and RSM learn against each other. Upon convergence, LVCVAE acquires the ability to disentangle the images and generate their robust features. Then the robust features training set disentangled by GRFD will be input into the target model for training, resulting in a robust target model capable of resisting adversarial attacks.

Therefore, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

• We propose GRFD, a novel GAN-based Robust Feature Disentanglement framework for adversarial defense. The GAN architecture plays an important role in providing robust supervision to address the issue that feature disentanglement cannot be achieved solely by unsupervised models or without an inductive bias.

• By adding a constrained rectification module to the typical beta-VAE, we propose the LVCVAE to serve as the generator. Meanwhile, we design the Robust Supervisory Model (RSM) to play as the discriminator. The key component of RSM is the Feature Robustness Metric (FRM), which quantitatively evaluates feature robustness and serves as the training loss.

• We have conducted several convincing experiments on three benchmark datasets: MNIST, CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100. The results show that GRFD effectively disentangles robust features, and achieves higher adversarial accuracy of 93.69% on MNIST, 77.21% on CIFAR10, and 58.91% on CIFAR100 with minimal degradation in clean accuracy compared with other state-of-the-art adversarial defenses.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. Preliminaries and related works are presented in Section 2. In Section 3, our proposed framework GRFD and its detailed composition are introduced. Experiments are presented in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes this article.

2 Preliminaries and Related Work

The vulnerability of DNNs to adversarial attacks was first systematically demonstrated by Szegedy et al. [4], who showed that imperceptible perturbations could cause misclassification in otherwise high-accuracy models. The general paradigm of adversarial attacks is

where

In white-box attacks, the attacker can usually obtain the parameter gradient and other information of the model. For example, FGSM [8] uses single step gradient as the image perturbation in adversarial attacks. After that, many gradient-based attacks have been derived. BIM [18] introduces multi-step iteration, RFGSM [19] proposes random initialization noise, and PGD [20] is a combination of the two. Since then, there have been many researches based on PGD, such as EOTPGD [21] which studies the generation of adversarial examples under different input transformations, APGD [22] which introduces adaptive strategy adjustment. Meanwhile, VMIFGSM [23] enhances the stability by reducing the gradient variance. HMCAM [24] is also a gradient-based method, but it incorporates stochastic sampling techniques to generate a distribution of adversarial examples. Besides, there are also optimization-based adversarial attacks, such as CW [25]. Generating adversarial samples using generative networks is also a promising approach, such as SEAdvGAN [26]. For black-box attacks, attackers cannot obtain the parameter information and can only get the output of the model. Pixle [27] rearranges a small number of pixels within the images, and Square [28] selects localized square at random positions to generate adversarial samples. There are also attacks which integrate a few methods, such as AA [22] which combines APGD and Square, etc. This integration results in a parameter-free, computationally affordable and user-independent combination of attacks. AA becomes a common attack benchmark for DNN robustness testing.

Adversarial defense aims to protect DNN models against perturbation interference while maintaining task performance. Current approaches fall into two main categories: data-based defenses and model-based defenses. For data-based adversarial defenses, defenders achieve model robustness on the data level including the training set and test set. Goodfellow et al. [8] first proposed the adversarial training which was an effective defense method, and then there are many defenses based on adversarial training with different generation methods of adversarial samples, such as the method [29] of Zhang et al. Another approach involves removing adversarial perturbations during the inference stage, such as feature squeezing [30], input transformation (such as JPEG Composing, Bit-depth Reduction [31]), etc. Defenders can also achieve this by denoising (e.g., HGD [32]) and images reconstruction methods that earn clean data distributions through generative models (e.g., APE-GAN [33], DiffPure [34]). For model-based adversarial defenses, they focus on intrinsic model properties. These defenses increase the model robustness not only at the macro level (model classification boundaries), but also at the micro structure (model architecture components). For macro level, most of the defenses are based on defense distillation [35] and gradient regularization [6]. Random Smoothing [7] is also a good idea based on classification boundaries. There are also some robustness analyses based on Bayesian neural networks, such as the argument by Bortolussi et al [36]. Meanwhile, there are also lots of researches to achieve the adversarial defense by adopting the robustness component [37]. Beyond individual model improvements, ensemble methods like TRS [38] combine multiple models for enhanced defense. While feature disentanglement approaches like CD-VAE [13] share conceptual similarities with our work, they focus on useful feature separation whereas our GRFD specifically targets robust feature extraction, representing a critical advancement in defense strategy.

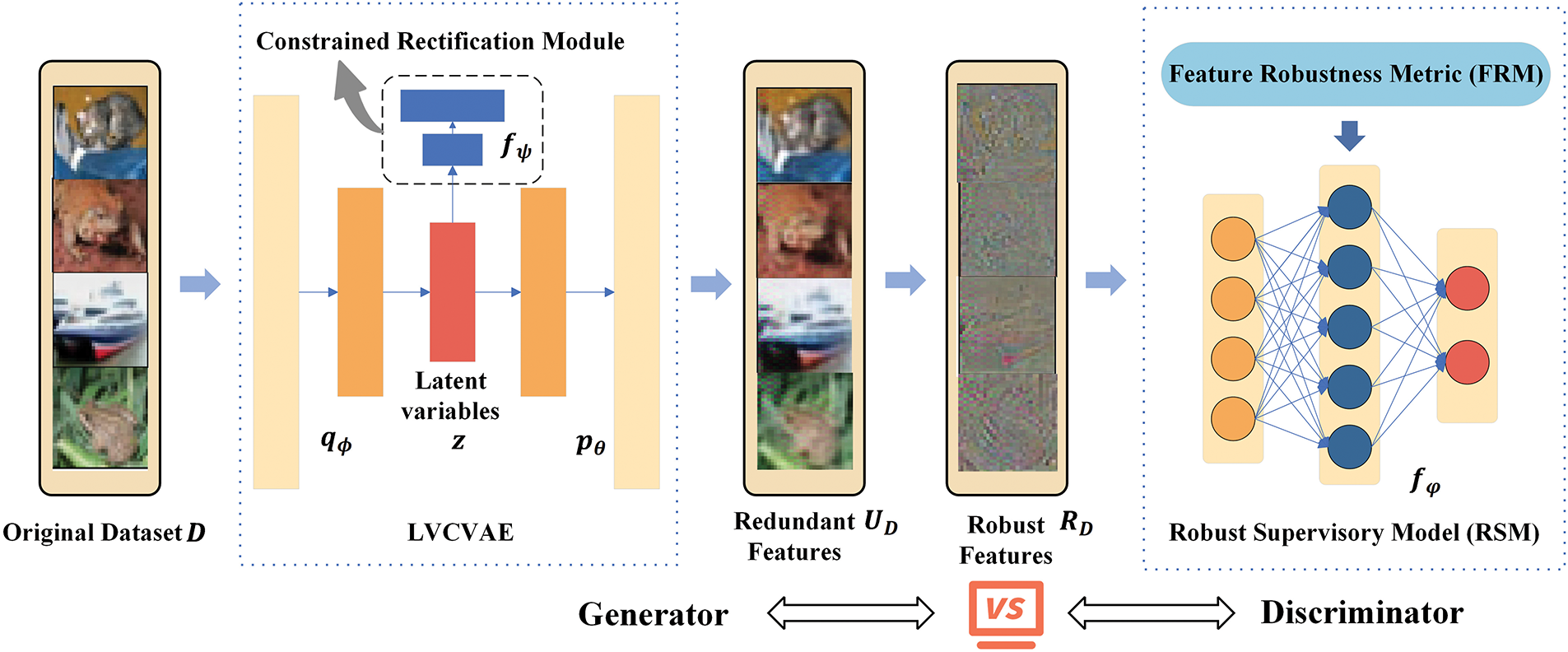

Previous theories have shown that feature disentanglement cannot be realized simply through unsupervised models or without inductive bias on the data. Building upon this theoretical limitations, we propose GRFD (Fig. 1)—a novel GAN-based framework for robust feature disentanglement and adversarial defense. The core of GRFD lies in its adversarial disentanglement architecture, comprising two key components: (1) a Latent Variable Constrained VAE (LVCVAE) generator that explicitly extracts robust features, and (2) a Robust Supervisory Model (RSM) discriminator that guides this process through our proposed Feature Robustness Metric (FRM).

Figure 1: Architecture of our GRFD: a GAN-based robust feature disentanglement framework

During training, GRFD processes the original dataset D through competitive optimization between LVCVAE and RSM, with the complete loss function detailed in Section 3.4. After training, LVCVAE will have the ability to disentangle robust features from the original dataset. In the actual implementation, we set the output of LVCVAE as redundant features

3.2 Latent Variable Constrained VAE

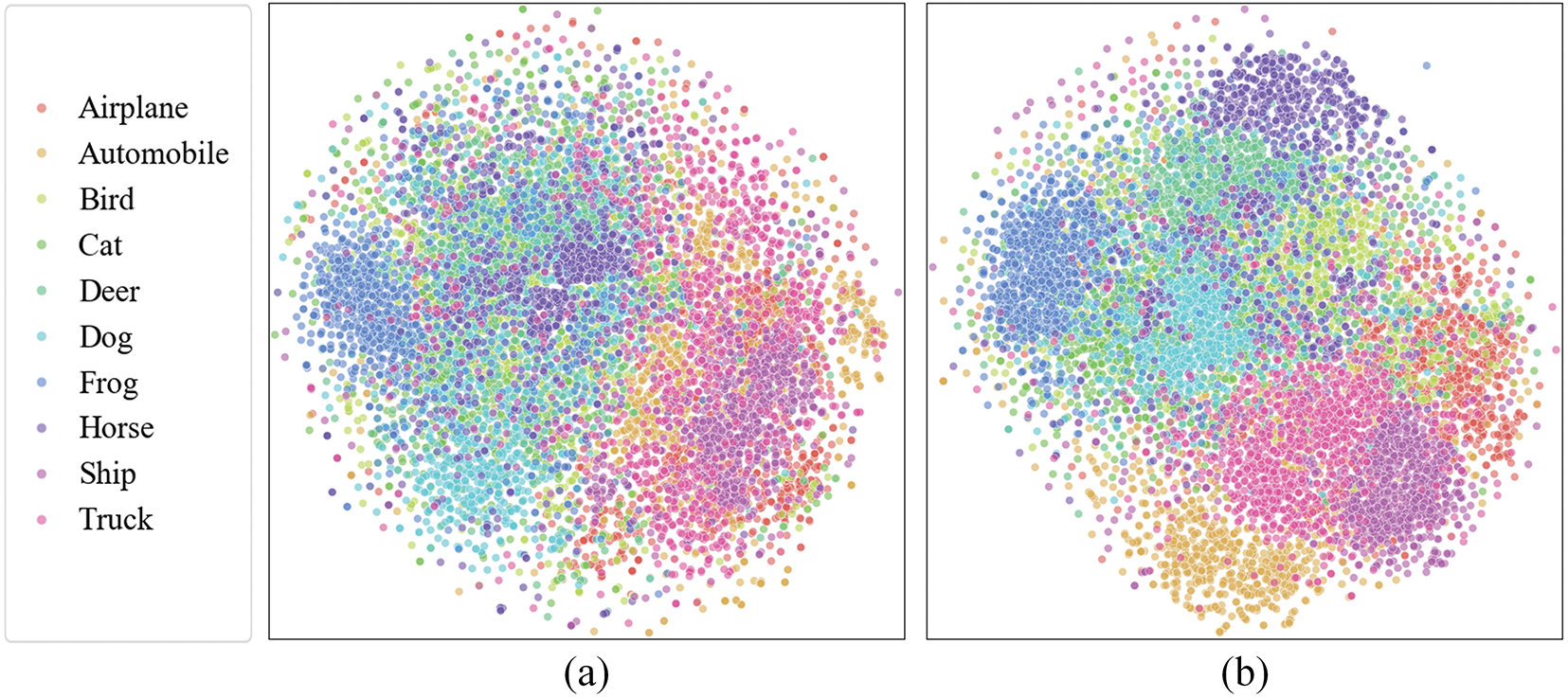

Preliminary experiments showed that the distribution of latent variables in typical beta-VAE was scattered, as shown in Fig. 2a. This is not in line with its design intent and negatively affects the feature disentanglement process. To address this limitation, we introduce a constrained rectification module that explicitly enforces latent space clustering, yielding our proposed Latent Variable Constrained VAE (LVCVAE). The LVCVAE serves as the generator in GRFD. After training, the latent variables of samples with the same labels are clustered together, as shown in Fig. 2b. Meanwhile, we also provide the ablation analysis in Section 4.3, and LVCVAE is described in detail below.

Figure 2: This is the distribution of latent variables, and (a) (left) is the case without the constrained rectification module, and (b) (right) is the case with the constrained rectification module

The typical beta-VAE is composed of an encoder with parameters

Here the first term

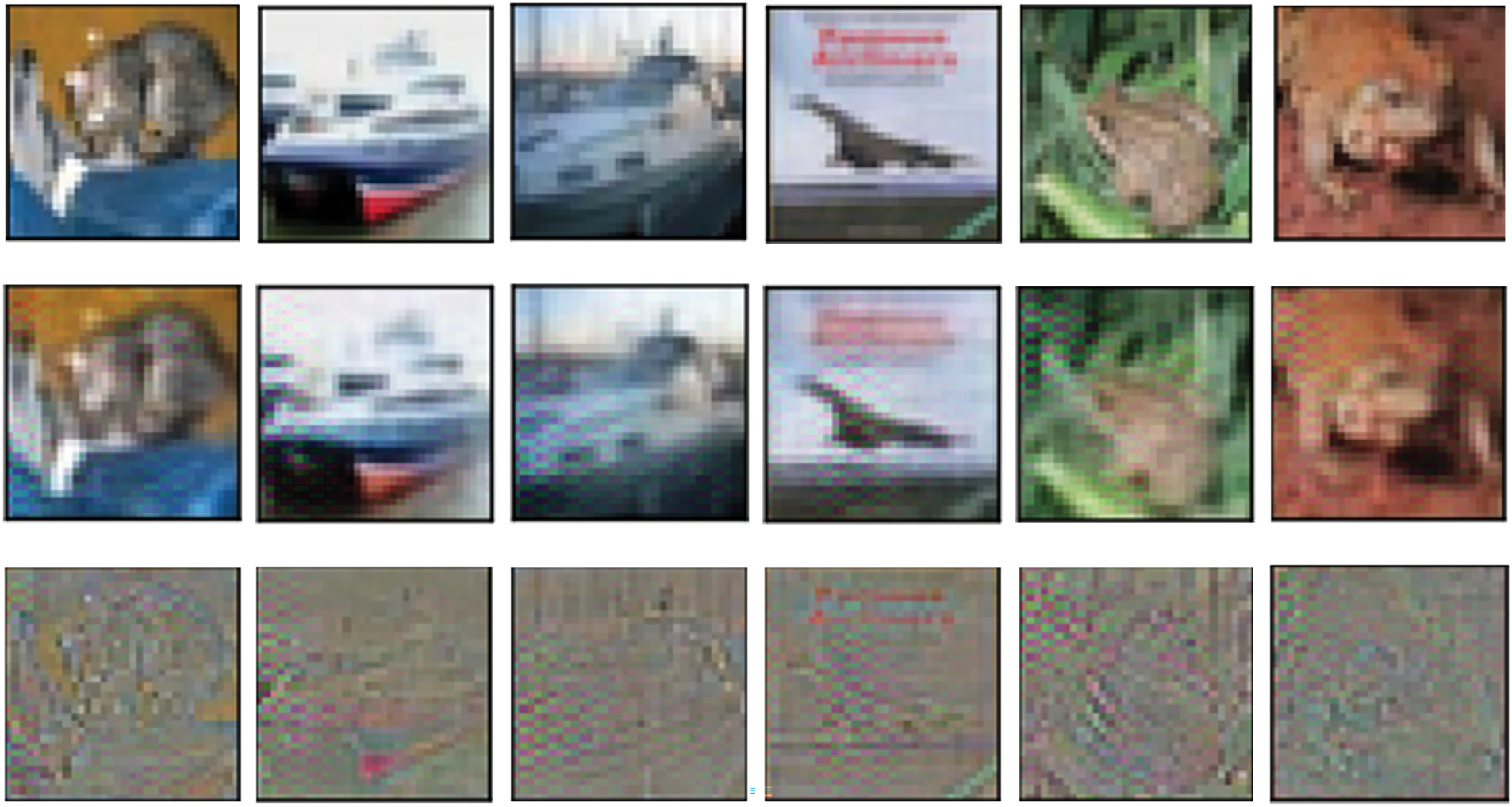

According to the information bottleneck theory, the training process of a DNN involves minimizing mutual information. Recent research has shown that image classification relies more on the sparse part of the image. Therefore, in our feature disentanglement task, assuming the intermediate feature is

Figure 3: Examples of original images (the first row), their redundant features (the second row) and robust features (the third row) on CIFAR10 dataset

The discriminator in GRFD is our proposed Robust Supervisory Model (RSM) (denoted by

Motivated by robust feature hypothesis, the robust features require both the ability of samples classification and the tolerance to perturbations. Therefore, we proposed the Feature Robustness Metric (FRM)

Previous studies have shown a strong relationship between model robustness and the curvature of the loss surface [39], which corresponds to the set of eigenvalues of the hesse matrix H to the loss function. However, in practice, the calculation of H is very resource-consuming, so the finite difference approximation method [40] is usually used to evaluate H in the actual experiment, shown as follows:

where

In feature disentanglement, the robustness metric needs to be taken as a condition for implicit supervision to backpropagate. So the robustness metric needs to be a scalar and the sum of the eigenvalues of hesse matrix

From the perspective of similarity, this is a

The process of our adversarial defense is illustrated in Algorithm 1, our goal is to obtain a robust target model

where

In this section, experiments are conducted to verify the effectiveness of GRFD proposed in this paper. It should be noted that the main work of this paper is to conduct the adversarial defense based on the robust feature hypothesis which can explain adversarial attacks to some extent, not just the empirical adversarial defense. The experiments are implemented based on the package TorchAttacks [41] and PyTorch2.0.0.

Datasets and Models. We conducted experiments on three benchmark datasets: MNIST [42], CIFAR10 [43], CIFAR100 [43], and our target models are Lenet5 [42], WideResNet28(

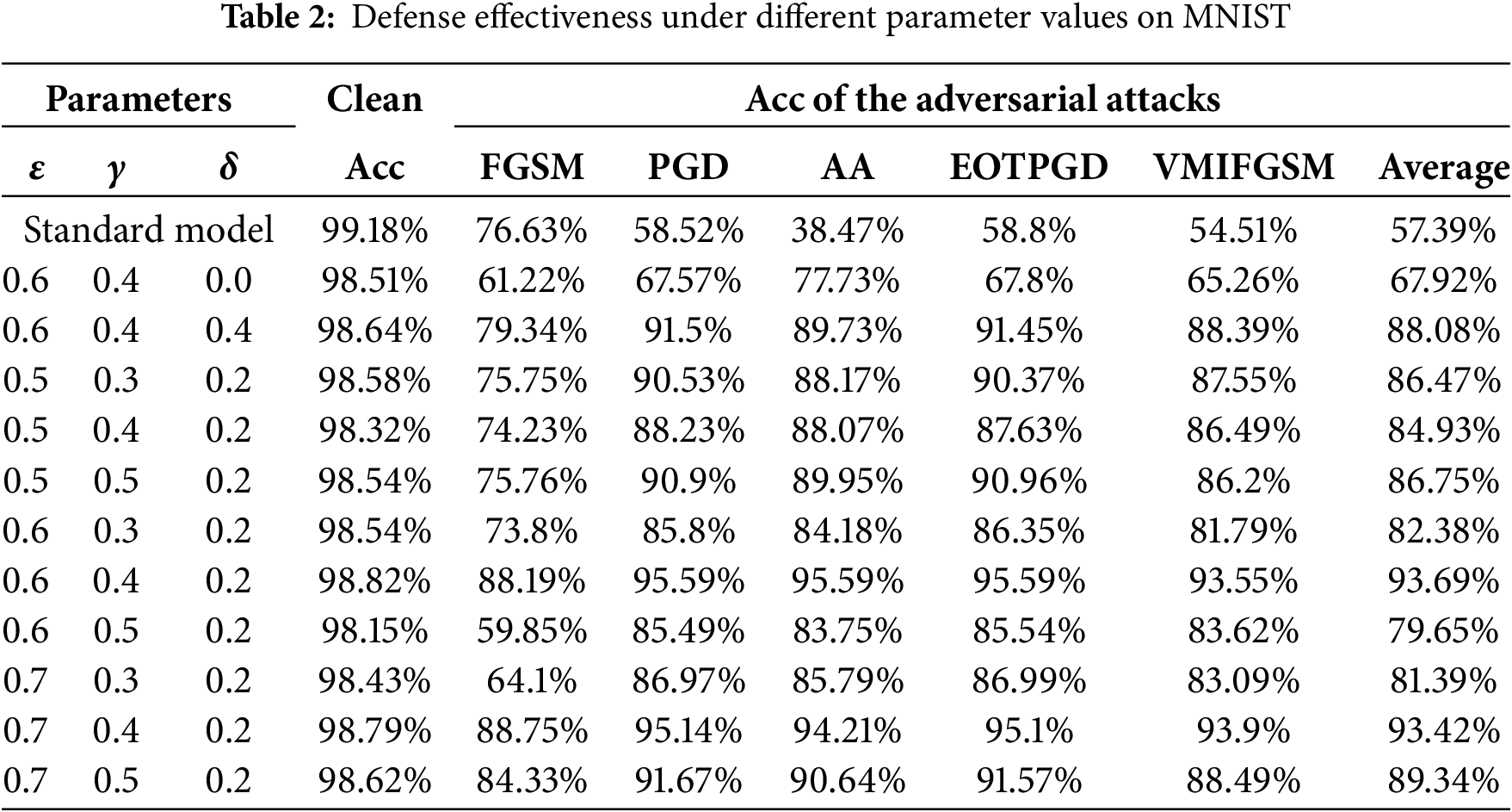

Parameter Settings. We set the drop rate in WideResNet28(

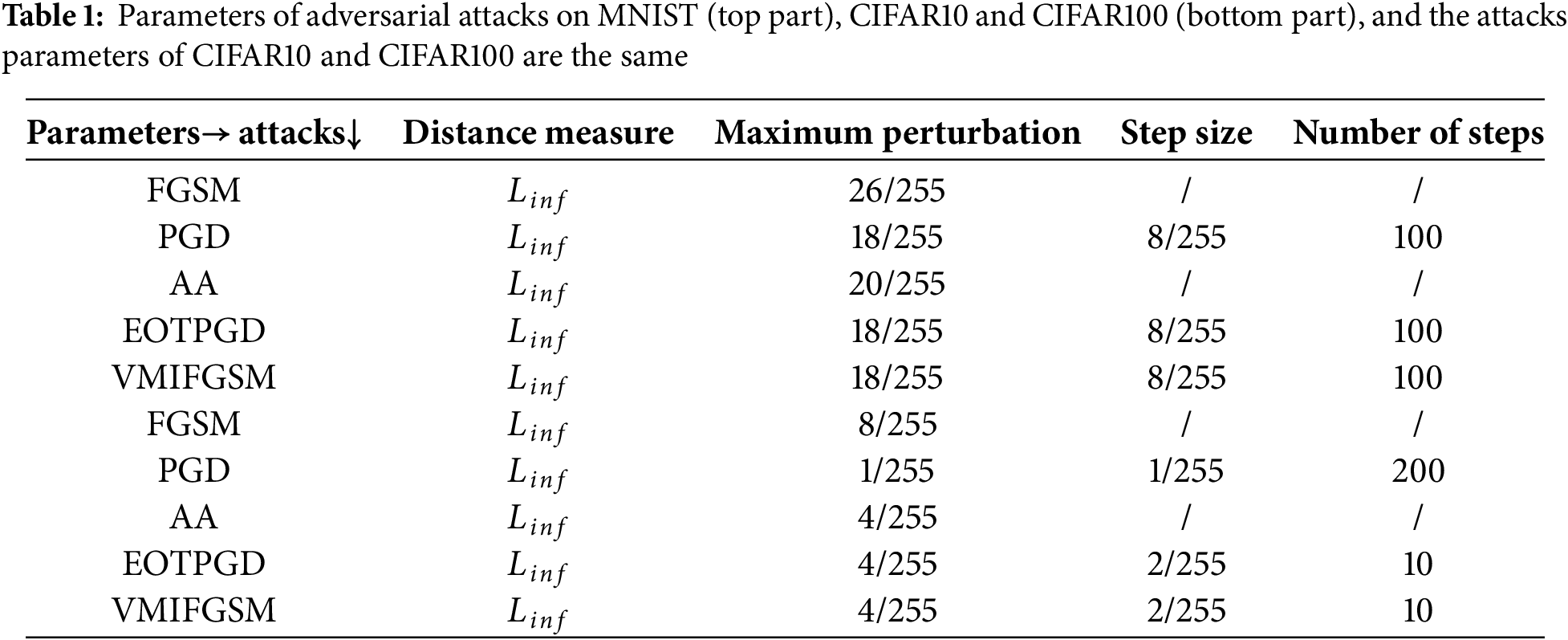

Adversarial Attack Methods. The adversarial attack methods in the experiments are FGSM [8], PGD [21], AA [22], EOTPGD [21], and VMIFGSM [23], which are implemented using the TorchAttacks [41] library. The specific parameters of different attacks are different, and the parameters are shown in Table 1.

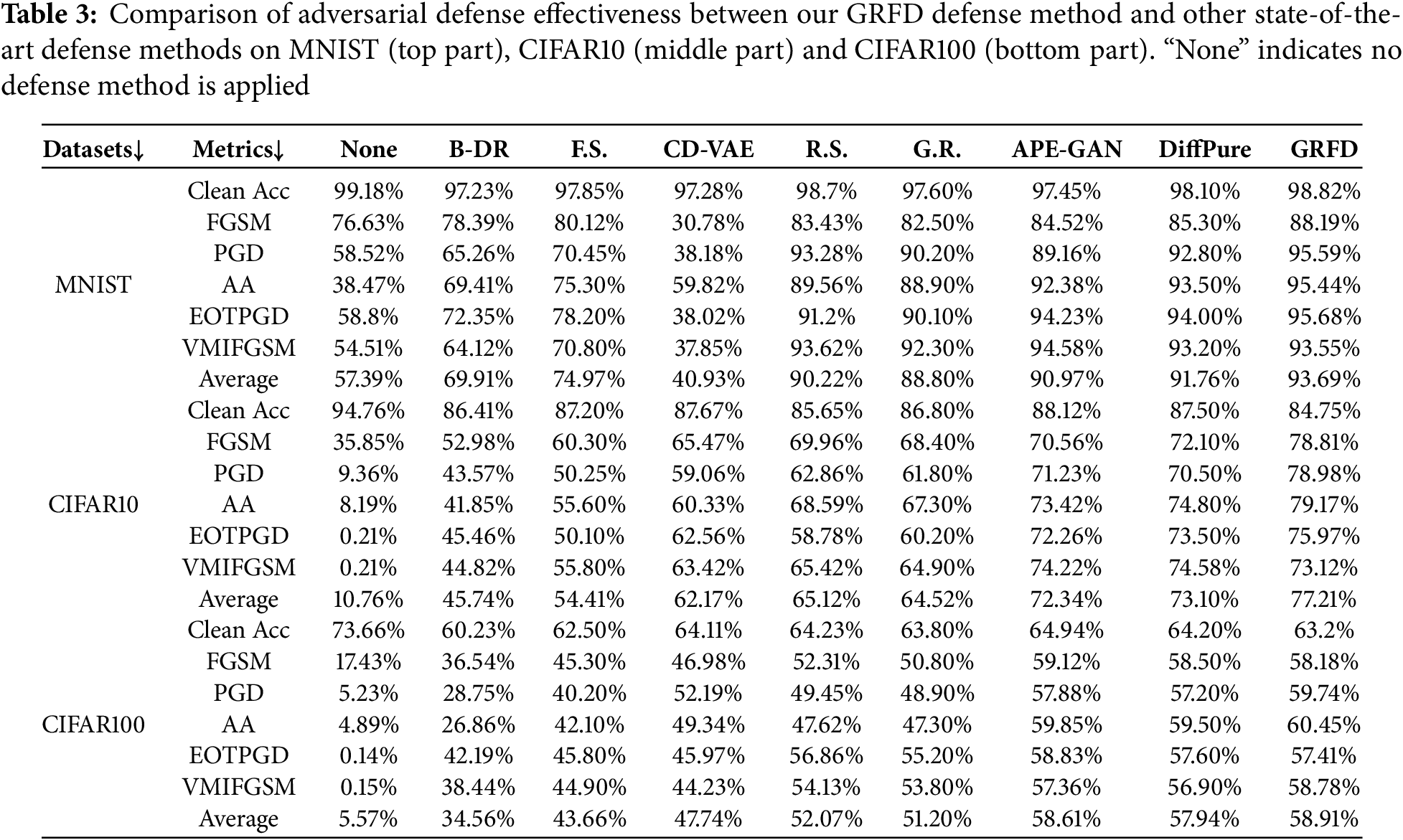

Adversarial Defense Baselines. We compare the effectiveness of our adversarial defense method with other state-of-the-art adversarial defenses: Bit-depth Reduction (B-DR) [31], Feature Squeezing (F.S.) [30], CD-VAE [13], Random Smoothing (R.S.) [7], Gradient Regularization (G.R.) [6], APE-GAN [33] and DiffPure [34]. B-DR and F.S. are methods based on image preprocessing, which can effectively remove adversarial perturbations in images. CD-VAE is also an adversarial defense method based on feature disentanglement. R.S. and G.R. both are certified adversarial defenses. APE-GAN and DiffPure are defense methods based on the reconstruction of images.

Metrics. Both clean and adversarial samples are input into the model, and the experiment result is evaluated by the model prediction accuracy for both types of the data. The metric is simple and intuitive, and is calculated by

In this paper, we have three important parameters:

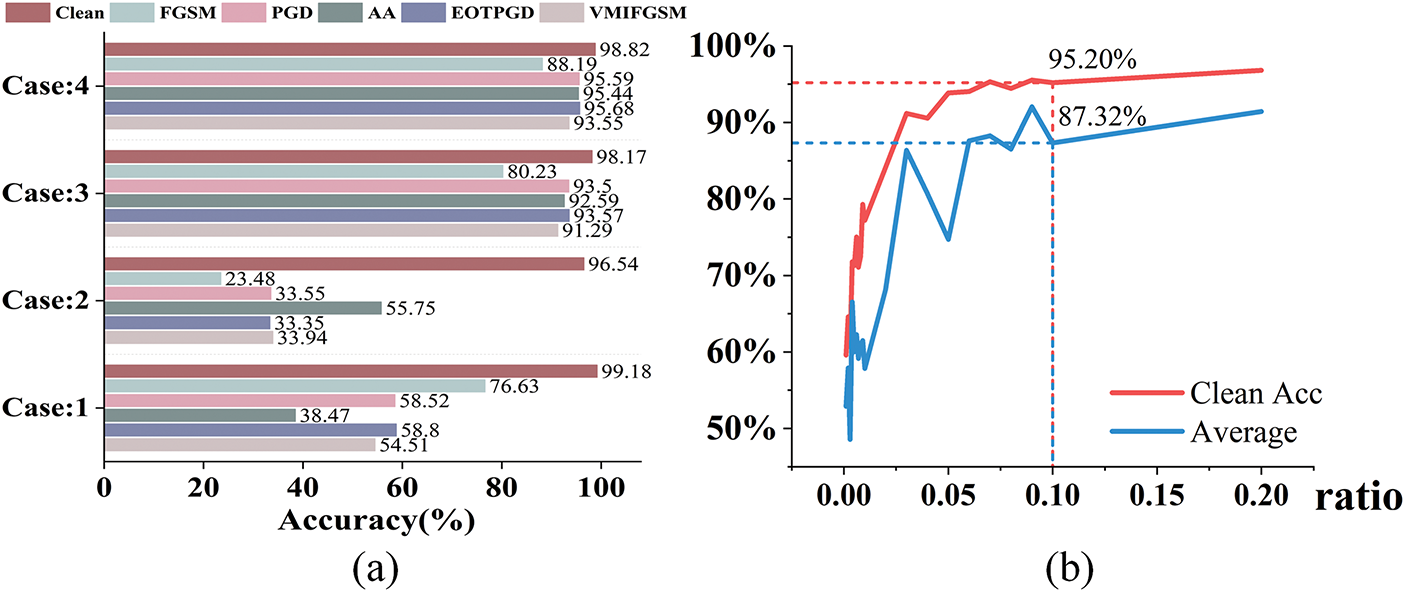

In order to verify the effectiveness of the distinct modules designed in this paper, a series of ablation experiments are conducted. We select MNIST as an example and the ablation experiments are divided into four cases: Case 1: without any defense, Case 2: Only the LVCVAE without RSM (

Figure 4: (a) is the accuracy of ablation experiments on MNIST. (b) illustrates the effect of using different proportions of training data on the disentangling of robust features by GRFD in the MNIST dataset, where “Average” represents the mean adversarial accuracy

In real-world, defenders may not have access to the full training dataset as in the lab environment. In practice, they might only possess a small portion of the training data. Therefore, it is worth exploring whether GRFD can still be effective under such limited-data conditions.

To investigate this, we conducted additional experiments using the MNIST dataset to evaluate GRFD’s defensive capability with limited data, and the results are shown in Fig. 4b. The results show that even with only 10% of the training data (6000 samples, compared to the full 60,000 in MNIST), GRFD achieves a relatively high clean accuracy, just 3.62% lower than when using the full dataset. Meanwhile, the adversarial accuracy only drops by 6.37% (Full data: Clean Acc—98.82%, Average adversarial acc—93.69%; 10% data: Clean Acc—95.20%, Average adversarial acc—87.32%).

4.5 Defense Compared with Other Methods

We compared the effectiveness of our adversarial defense method with other state-of-the-art adversarial defenses: B-DR, F.S., CD-VAE, R.S., G.R. APE-GAN, and DiffPure on three benchmark datasets and five advanced adversarial attacks, the results are shown in Table 3. Additionally, the “None” method in Table 3 serves as a baseline to better evaluate the trade-off between clean accuracy and adversarial accuracy. In general, The improvement of the robustness of the model is accompanied with the decrease of the accuracy of the model for clean samples. Compared with the other seven typical and state-of-the-art defense methods, our methods achieve higher adversarial accuracy (MNIST: 93.69%, CIFAR10: 77.21%, CIFAR100: 58.91%) with smaller accuracy degradation on clean accuracy (MNIST: 98.82%, CIFAR10: 84.75%, CIFAR100: 63.2%). It should be noted that, on the CIFAR10 and CIFAR100 datasets, while APE-GAN achieves slightly higher clean accuracy than our method (CIFAR10: APE-GAN 88.12% vs. GRFD 84.75%; CIFAR100: APE-GAN 64.94% vs. GRFD 63.2%), GRFD demonstrates a clear advantage in adversarial accuracy (CIFAR10: APE-GAN 72.34% vs. GRFD 77.21%; CIFAR100: APE-GAN 58.61% vs. GRFD 58.91%). Notably, on CIFAR10, GRFD shows a significant lead under various attacks, including FGSM, PGD, AA, and EOTPGD. Moreover, compared to no defense (None), our method achieves a significant 67% improvement in adversarial accuracy at the cost of only a 10% drop in clean accuracy on CIFAR10, which is an acceptable trade-off.

4.6 An In-Depth Analysis of Clean and Adversarial Accuracy in GRFD

When using the GRFD method for adversarial defense, a slight drop in clean accuracy is often sacrificed in exchange for a significant improvement in adversarial accuracy. We have conducted a deeper analysis of the reasons behind this accuracy decline, which lies in the extraction of robust features. According to the robust feature hypothesis, DNN models rely on features useful for classification (useful features) when classifying samples, where these features are associated with minimizing the Cross-Entropy between labels and samples. However, a significant portion of these useful features consists of non-robust features, which are the primary cause of adversarial vulnerability. During the process of disentangling robust features, in addition to minimizing the Cross-Entropy between labels and samples, there is also a robust term—local linear gradient similarity. This leads to the removal of some non-robust features, even if they are useful for classification. As a result, adversarial accuracy increases while clean accuracy decreases.

To mitigate the vulnerability of DNNs to adversarial attacks, motivated by the feature hypothesis that the non-robust features is the reason for adversarial attacks, we propose a GAN-based robust feature disentanglement framework GRFD. GRFD is composed of a generator which adopt our improved latent Variable Constrained VAE (LVCVAE), and a discriminator which is carefully designed with a Robust Supervision Model (RSM). For LVCVAE, we add a constraint rectification module to the classical beta-VAE, which successfully solves the problem of scattered distribution of latent variables. Meanwhile, the structure RSM is the same as target model, and the key of RSM is our proposed Feature Robustness Metric (FRM). It combines the classification ability and the resistance to perturbations to measure the robustness of the features, and it is used as part of the loss in the GRFD training process. Extensive experiments validate our effectiveness relative to other state-of-the-art adversarial defense methods.

Acknowledgement: The authors are thankful to researchers in Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Security, Ministry of Education of China for the helpful discussion.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Project “Research on Intelligent Detection Techniques of Encrypted Malicious Traffic for Large-Scale Networks” (Grant No. 62176264).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Baolin Li and Tao Hu; methodology, Baolin Li; software, Baolin Li and Xinlei Liu; validation, Baolin Li and Tao Hu; formal analysis, Baolin Li; investigation, Baolin Li and Jichao Xie; resources, Baolin Li; data curation, Baolin Li; writing—original draft preparation, Baolin Li; writing—review and editing, Baolin Li and Tao Hu; visualization, Baolin Li; supervision, Baolin Li; project administration, Jichao Xie; funding acquisition, Peng Yi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [Github] at [https://github.com/brother2cat/GRFD] (accessed on 23 July 2025). More data of this study that is not on [https://github.com/brother2cat/GRFD] (accessed on 23 July 2025) is available from the Corresponding Author, [Tao Hu], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sun Z, Feng C, Patras I, Tzimiropoulos G. LAFS: landmark-based facial self-supervised learning for face recognition. In: 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 1639–49. [Google Scholar]

2. Hu Y, Yang J, Chen L, Li K, Sima C, Zhu X, et al. Planning-oriented autonomous driving. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 17853–62. [Google Scholar]

3. Lee C, Lee SH, Kim C.S. MFP: making full use of probability maps for interactive image segmentation. In: 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 4051–9. [Google Scholar]

4. Szegedy C, Zaremba W, Sutskever I, Bruna J, Erhan D, Goodfellow I, et al. Intriguing properties of neural networks.arXiv:1312.6199. 2014. [Google Scholar]

5. Khan Z, Fu Y. Consistency and uncertainty: identifying unreliable responses from black-box vision-language models for selective visual question answering. In: 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 10854–63. [Google Scholar]

6. Liu D, Wu LY, Li B, Boussaid F, Bennamoun M, Xie X, et al. Jacobian norm with selective input gradient regularization for interpretable adversarial defense. Pattern Recognit. 2024;145:109902. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2023.109902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cohen J, Rosenfeld E, Kolter JZ. Certified adversarial robustness via randomized smoothing. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 1310–20. [Google Scholar]

8. Goodfellow IJ, Shlens J, Szegedy C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv:1412.6572. 2015. [Google Scholar]

9. Fawzi A, Fawzi O, Frossard P. Fundamental limits on adversarial robustness. In: Proceedings of the ICML, 2015 Workshop on Deep Learning; 2015 Jul 6–11; Lille, France. 55 p. [Google Scholar]

10. Tabacof P, Valle E. Exploring the space of adversarial images. In: 2016 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2016 Jul 24–29; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 426–33. [Google Scholar]

11. Cubuk ED, Zoph B, Schoenholz SS, Le QV. Intriguing properties of adversarial examples. arXiv:1711.02846. 2018. [Google Scholar]

12. Ilyas A, Santurkar S, Tsipras D, Engstrom L, Tran B, Madry A. Adversarial examples are not bugs, they are features. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2019); 2019 Dec 8–14; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 125–36. [Google Scholar]

13. Yang K, Zhou T, Zhang Y, Tian X, Tao D. Class-disentanglement and applications in adversarial detection and defense. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2021); 2021 Dec 6-14; Online. p. 16051–63. [Google Scholar]

14. Locatello F, Bauer S, Lucic M, Raetsch G, Gelly S, Schölkopf B, et al. Challenging common assumptions in the unsupervised learning of disentangled representations. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. Vol. 97, p. 4114–24. [Google Scholar]

15. Goodfellow I, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial networks. Commun ACM. 2020;63(11):139–44. doi:10.1145/3422622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Xu L, Zeng X, Li W, Xie Y. BH2I-GAN: bidirectional hash_code-to-image translation using multi-generative multi-adversarial nets. Pattern Recognit. 2023;133(4):109010. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2022.109010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Higgins I, Matthey L, Pal A, Burgess CP, Glorot X, Botvinick MM, et al. beta-VAE: learning basic visual concepts with a constrained variational framework. In: The 5th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2017 Apr 24–26; Toulon, France. p. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

18. Kurakin A, Goodfellow IJ, Bengio S. Adversarial examples in the physical world. In: The 5th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2017 Apr 24–26; Toulon, France. p. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

19. Tramèr F, Kurakin A, Papernot N, Goodfellow IJ, Boneh D, McDaniel PD. Ensemble adversarial training: attacks and defenses. In: The 6th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2018 Apr 30–May 3; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

20. Madry A, Makelov A, Schmidt L, Tsipras D, Vladu A. Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks. In: The 6th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2018 Apr–May 3; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

21. Athalye A, Engstrom L, Ilyas A, Kwok K. Synthesizing robust adversarial examples. In: Dy JG, Krause A, editors. Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2018. Vol. 80, p. 284–93. [Google Scholar]

22. Croce F, Hein M. Reliable evaluation of adversarial robustness with an ensemble of diverse parameter-free attacks. In: Proceedings of The 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2020 Jul 13–18; Online. Vol. 119, p. 2206–16. [Google Scholar]

23. Wang X, He K. Enhancing the transferability of adversarial attacks through variance tuning. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 1924–33. [Google Scholar]

24. Wang H, Li G, Liu X, Lin L. A hamiltonian monte carlo method for probabilistic adversarial attack and learning. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;44(4):1725–37. doi:10.1109/tpami.2020.3032061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Carlini N, Wagner DA. Towards evaluating the robustness of neural networks. In: 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2017 May 22–26; San Jose, CA, USA. p. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

26. Su L, Chen J, Jiang P. Generating adversarial examples for white-box attacks based on GAN. In: 2023 China Automation Congress (CAC); 2023 Nov 17–19; Chongqing, China. p. 910–5. doi:10.1109/cac59555.2023.10450537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Pomponi J, Scardapane S, Uncini A. Pixle: a fast and effective black-box attack based on rearranging pixels. In: 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2022 Jul 18–23; Padua, Italy. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

28. Andriushchenko M, Croce F, Flammarion N, Hein M. A query-efficient black-box adversarial attack via random search. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2020—16th European Conference. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 484–501. [Google Scholar]

29. Zhang H, Wang J. Defense against adversarial attacks using feature scattering-based adversarial training. In: Wallach HM, Larochelle H, Beygelzimer A, d’Alché-Buc F, Fox EB, Garnett R, editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2019); Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2019. p. 1829–39. [Google Scholar]

30. Xu W, Evans D, Qi Y. Feature squeezing: detecting adversarial examples in deep neural networks. In: 25th Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS); 2018 Feb 18–21; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

31. Guo C, Rana M, Cissé M, van der Maaten L. Countering adversarial images using input transformations. In: The 6th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2018 Apr 30–May 3; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

32. Liao F, Liang M, Dong Y, Pang T, Hu X, Zhu J. Defense against adversarial attacks using high-level representation guided denoiser. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 1778–87. [Google Scholar]

33. Jin G, Shen S, Zhang D, Dai F, Zhang Y. APE-GAN: adversarial perturbation elimination with GAN. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2019 May 12–17; Brighton, UK. p. 3842–6. [Google Scholar]

34. Nie W, Guo B, Huang Y, Xiao C, Vahdat A, Anandkumar A. Diffusion models for adversarial purification. In: Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2022 Jul 17–23; Baltimore, MD, USA. Vol. 162, p. 16805–27. [Google Scholar]

35. Papernot N, McDaniel PD, Wu X, Jha S, Swami A. Distillation as a defense to adversarial perturbations against deep neural networks. In: 2016 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2016 May 22–26; San Jose, CA, USA. p. 582–97. [Google Scholar]

36. Bortolussi L, Carbone G, Laurenti L, Patane A, Sanguinetti G, Wicker M. On the robustness of bayesian neural networks to adversarial attacks. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025;36(4):6679–92. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2024.3386642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Peng S, Xu W, Cornelius C, Hull M, Li K, Duggal R, et al. Robust principles: architectural design principles for adversarially robust CNNs. In: The 34th British Machine Vision Conference 2023 (BMVC); 2023 Nov 20–24; Aberdeen, UK. p. 739–40. [Google Scholar]

38. Yang Z, Li L, Xu X, Zuo S, Chen Q, Zhou P, et al. TRS: transferability reduced ensemble via promoting gradient diversity and model smoothness. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2021); Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2021. p. 17642–55. [Google Scholar]

39. Moosavi-Dezfooli S, Fawzi A, Uesato J, Frossard P. Robustness via curvature regularization, and vice versa. In: 2019 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 9078–86. [Google Scholar]

40. Zhang C, Benz P, Imtiaz T, Kweon IS. Understanding adversarial examples from the mutual influence of images and perturbations. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 14509–18. [Google Scholar]

41. Kim H. Torchattacks: a pytorch repository for adversarial attacks. arXiv:2010.01950. 2020. [Google Scholar]

42. Lecun Y, Bottou L, Bengio Y, Haffner P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc IEEE. 1998;86(11):2278–324. doi:10.1109/5.726791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Krizhevsky A, Hinton G. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. In: Technical report. Toronto, ON, Canada: University of Toronto; 2009. [Google Scholar]

44. Zagoruyko S, Komodakis N. Wide residual networks. In: Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC); 2016 Sep 19–22; York, UK. p. 87.1–12. [Google Scholar]

45. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools