Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

TGICP: A Text-Gated Interaction Network with Inter-Sample Commonality Perception for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis

1 School of Computer Science and Technology, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Zhengzhou, 450002, China

2 School of Software, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Zhengzhou, 450002, China

3 Department of Computing, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, 215123, China

4 Department of Computer Science, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 7ZX, UK

* Corresponding Author: Shuai Zhao. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 1427-1456. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066476

Received 09 April 2025; Accepted 03 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

With the increasing importance of multimodal data in emotional expression on social media, mainstream methods for sentiment analysis have shifted from unimodal to multimodal approaches. However, the challenges of extracting high-quality emotional features and achieving effective interaction between different modalities remain two major obstacles in multimodal sentiment analysis. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a Text-Gated Interaction Network with Inter-Sample Commonality Perception (TGICP). Specifically, we utilize a Inter-sample Commonality Perception (ICP) module to extract common features from similar samples within the same modality, and use these common features to enhance the original features of each modality, thereby obtaining a richer and more complete multimodal sentiment representation. Subsequently, in the cross-modal interaction stage, we design a Text-Gated Interaction (TGI) module, which is text-driven. By calculating the mutual information difference between the text modality and nonverbal modalities, the TGI module dynamically adjusts the influence of emotional information from the text modality on nonverbal modalities. This helps to reduce modality information asymmetry while enabling full cross-modal interaction. Experimental results show that the proposed model achieves outstanding performance on both the CMU-MOSI and CMU-MOSEI baseline multimodal sentiment analysis datasets, validating its effectiveness in emotion recognition tasks.Keywords

With the rapid development of social media and multimedia content, users not only rely on text for emotional expression but also extensively use voice, images, and videos, among other modalities. This multimodal form of emotional expression presents significant challenges to traditional unimodal sentiment analysis methods, creating an urgent need for the development of new technologies to comprehensively capture and understand human emotions [1]. As a result, Multimodal Sentiment Analysis (MSA) has emerged. MSA integrates information from multiple perceptual channels, such as voice, facial expressions, gestures, and text, enabling AI systems to better understand and analyze human emotions. With MSA, AI systems can more accurately recognize, comprehend, express, and regulate emotions, providing a more intelligent and natural emotional experience in fields such as human-computer interaction, mental health, and social robotics. However, current multimodal sentiment analysis still faces several challenges, such as how to effectively extract high-quality emotional features and achieve efficient fusion of information from multiple modalities to fully leverage the emotional data from each modality, thereby enhancing model performance.

To obtain high-quality emotional features that are more comprehensive and rich in emotional information, a commonly used approach is to enhance the unimodal or fused multimodal representations by leveraging common features between modalities. MulT [2] uses a Transformer network for cross-sample translation to learn the commonalities between modalities, thereby refining unimodal features and effectively addressing the information disparity between modalities. MISA [3] constructs modality-invariant and modality-specific subspace representations separately, using the modality-invariant representation as a guiding signal to effectively learn the common features and individual differences between multimodal data. TCSP [4] and SWRM [5] design text-centered private-shared information extraction networks, utilizing information from the text modality to improve multimodal feature representation. Although these methods enhance modality features through invariant emotional feature commonality between modalities, they generally overlook the utilization of emotional commonalities within similar samples in each modality. This results in a certain degree of missing emotional information within modalities, thereby affecting the model’s ability to capture common features within each modality.

In terms of multimodal fusion, existing multimodal sentiment analysis frameworks can generally be divided into two types based on the operational strategy: early fusion and late fusion [6]. In early fusion, methods such as TFN [7], MARN [8], and LMF [9] integrate the input features from various modalities through concatenation, summation, or similar techniques to obtain multimodal features. However, due to the differing parameter spaces of each modality’s data, leading to modality information asymmetry, early fusion may limit the model’s ability to learn modality-specific unique information. In late fusion, models like Self-MM [10], MKL [11], and MFN [12] process unimodal data independently and then concatenate the outputs at the final layer to form multimodal features for prediction. Although late fusion strategies avoid the issue of inconsistencies in the multimodal parameter space, their inherent drawback lies in the difficulty of capturing underlying interaction features between modalities, and they may weaken or overlook cross-modal semantic correlations. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a fusion approach that takes into account both the parameter space differences between modalities and the semantic relationships between them to some extent.

We propose a Text-Gated Interaction Network with Inter-Sample Commonality Perception (TGICP). The TGICP model consists of two main components: the Inter-sample Commonality Perception (ICP) module and the Text-Gated Interaction (TGI) module. In the ICP module, we enhance the original sample features by extracting common emotional features from similar samples within the same modality, thereby improving the expressive power of modality-specific features. The enhanced sample features are then input into the TGI module, which dynamically adjusts the cross-modal interaction process by calculating the information disparity between the text modality and nonverbal modalities. This mechanism dynamically perceives the emotional correlation levels between modalities and adaptively adjusts the multimodal interaction process, thereby effectively alleviating the issue of cross-modal information imbalance. Ultimately, the model fuses the multimodal representations and performs sentiment prediction, significantly improving the accuracy and robustness of sentiment analysis.

To evaluate the performance advantages of the TGICP model, we conducted experimental validation using two multimodal sentiment analysis benchmark datasets: CMU-MOSI and CMU-MOSEI. Compared to existing state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods, TGICP demonstrates significant performance improvements on both datasets, validating its technical innovation and effectiveness.

The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

• We propose a Text-Gated Interaction Network with Inter-Sample Commonality Perception (TGICP) for multimodal sentiment analysis. This model enhances feature representation by extracting common information from intra-modality similar samples and utilizes a text-guided gating mechanism to dynamically regulate cross-modal feature fusion.

• We designed a Inter-sample Commonality Perception (ICP) module. This module extracts the emotional commonalities between similar samples within each modality and uses this common information to supplement and enhance the original samples, thereby enriching their unimodal emotional feature space and helping the model learn more comprehensive and richer unimodal emotional features.

• We introduce the Text Gated Interaction (TGI) module, which quantifies the information disparity between textual and non-textual modalities and dynamically adjusts the cross-modal interaction process. This mechanism enables the text modality to adaptively provide emotional context, effectively enhancing the emotional expression capability of non-textual modalities and significantly alleviating the issue of information asymmetry between modalities, thereby improving the model’s predictive performance.

• We conducted comprehensive experiments on the CMU-MOSI and CMU-MOSEI datasets to evaluate the proposed model. The experimental results demonstrate that our model performs exceptionally well on the majority of evaluation metrics, thoroughly validating its effectiveness and superiority.

2.1 Multimodal Sentiment Analysis

The core objective of multimodal sentiment analysis is to integrate multiple modalities of information (such as text, visual, and auditory data) from the same data sample and deeply explore and assess the emotional components it contains. The challenge in this process lies in the fact that different modalities perceive and interpret the same event from their unique perspectives. For example, text can provide emotional expression through words, the visual modality may convey emotion through facial expressions or body language, while the auditory modality reflects emotional changes through features like tone, volume, and speech rate. Therefore, the key challenge is how to effectively extract useful features from different modalities, enable information interaction and collaboration between modalities, and ultimately fuse these heterogeneous features effectively. This has been a long-standing research focus in the field of multimodal sentiment analysis.

In early research, Zadeh et al. [7] innovatively proposed the Tensor Fusion Network (TFN), which generates feature representations containing unimodal, bimodal, and trimodal combinations through Cartesian product operations. To further enhance the feature extraction capability, they also designed an architecture that combines the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) structure with a memory fusion mechanism, aimed at constructing comprehensive intra-modal and cross-modal feature views. Majumder et al. [13] used GRU to model two modalities layer by layer, enabling sufficient interaction between the two modalities and extracting information. With the development of the Transformer [14] model proposed by Google in various fields, methods using Transformers to process multimodal information have also emerged in the field of multimodal sentiment analysis. Lv et al. [15] proposed a Progressive Modality Reinforcement (PMR) method, which introduces an information center and progressive reinforcement strategy to address the issue of asynchronous data fusion in multimodal sentiment recognition. They also use cross-modal attention to reinforce features from different modalities and gradually enhance information flow. Rahman et al. [16] enhanced the encoding capabilities for different modalities by adding their designed Multimodal Adaptive Gate (MAG) to Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) and XLNET. Han et al. [17] effectively reduced information loss in key task processes by combining mutual information maximization theory with modality interaction theory, significantly improving model performance. Hou et al. [18] proposed a multimodal sentiment analysis method named TF-BERT, which gradually enhances information complementarity between different modalities by introducing Tensor-based Cross-modal Fusion (TCF) modules and Tensor-based Cross-modal Transformer (TCT) modules, enabling the simultaneous fusion of three modalities.

In previous multimodal sentiment analysis models, researchers typically strengthened the joint representation of each modality or multimodal features by extracting common characteristics between different modalities, which, to some extent, supplemented the emotional space of the samples and enhanced the sample features. However, these models generally overlook a key issue: the features of each modality are not always complete. Relying on these incomplete features for sentiment prediction may cause the model to overlook subtle emotional signals within modalities, leading to biased prediction results. Therefore, in our research, we enhance and supplement the original features by learning the commonality information between similar samples within each modality, thereby optimizing the feature quality of each modality and ultimately improving the overall performance of the model.

2.2 Inter-Sample Feature Enhancement

With the growing demand for multimodal data processing, cross-sample feature enhancement techniques have rapidly developed and have now become an important research direction in the field of feature engineering. These techniques have achieved significant success in various cross-modal applications. In multimodal sentiment analysis, this method can effectively enhance the model’s learning capability in unimodal or multimodal sentiment analysis tasks by extracting emotional commonalities between similar samples. Traditional multimodal sentiment analysis methods typically focus on integrating information from different modalities (e.g., text, speech, vision) to improve the accuracy of sentiment prediction. However, these methods often overlook the emotional commonalities between similar samples within the same modality, which actually provide rich latent information that helps the model better understand and capture emotional features. As a result, researchers have begun to explore modeling the relationships between samples and leveraging the similarity between samples to strengthen feature representation.

In the early stages of cross-sample feature enhancement, Chen et al. [19] proposed an innovative knowledge transfer method—cross-sample similarity, which is derived from deep metric learning models. By passing the similarity information between different samples as “dark knowledge” to smaller student models, this method enhances their performance while reducing computational complexity. With the widespread application of multimodal data, more and more researchers began to introduce this method into the processing of multimodal data. Huang and Lin [20] focused on modeling the relationships between samples, considering the interrelationships among multiple samples, and designed the AttnMixup strategy to perform weighted mixing of several samples, thereby enhancing data features and improving the model’s generalization ability. Li et al. [21] proposed a strategy combining within-sample and between-sample contrastive learning, aiming to model the relationships between samples, enabling the model to effectively capture similarities between similar samples and differences between dissimilar samples. Recently, researchers have also started applying cross-sample feature enhancement methods to multimodal sentiment analysis. Zhang et al. [22] designed a dynamic sample selection strategy based on neighborhood density, selecting nearby samples with higher density to identify representative and distinguishable samples, thus effectively focusing on high-quality samples in the cross-sample feature enhancement process. Huang et al. [23] proposed a new cross-sample fusion strategy by merging the modality information of different samples and incorporating adversarial training, pairwise prediction tasks, and two-stage text-centered contrastive learning, which effectively enhances the retention and fusion of specific modality information.

In previous cross-sample feature enhancement methods, the extraction of common features between samples primarily relied on autoencoders to decompose the feature space. However, since autoencoders are optimized based on global loss functions to a certain extent, they focus on the global representation of features and overlook the potential complex and nonlinear local relationships between samples (such as the similarity between neighboring samples). Although autoencoders learn complex mappings by stacking network layers, they still rely on a fixed network structure for data mapping and cannot dynamically adjust weights and topological structures based on graph structures, as graph convolutional networks can, to adapt to different data distributions. Moreover, in previous works, feature enhancement using common features between samples typically employed concatenation or weighted summation, methods that often introduce redundant information, leading to a more complicated feature space. To better leverage the common information between similar samples for feature enhancement, we propose a method based on mutual information constraints using graph neural networks to learn the common information between similar samples. Additionally, we design a Commonality Embedding Optimization Module to achieve multidimensional enhancement of the original features.

In Multimodal Sentiment Analysis (MSA), each modality provides a different emotional interpretation of the same event or behavior through its unique perceptual approach. This multi-perspective analysis enables a more comprehensive and in-depth capture and understanding of the diversity of emotions. Compared to visual and auditory modalities, the text modality typically responds most directly and instinctively to emotional information. This is because language, as a carrier of emotional expression, carries rich emotional content in everyday communication. Humans can precisely convey their emotional world through the combination of vocabulary, sentence structure, and context. Therefore, the text modality not only provides high accuracy in expressing emotions but also reflects subtle emotional changes in greater detail. This has led many researchers to view the text modality as the foundational modality for multimodal sentiment analysis, often relying first on textual data for emotion recognition, and then using data from other modalities for supplementary validation and enhancement.

Sun et al. [24] achieved efficient feature learning by constraining the outer product matrix of text and optimizing with canonical correlation analysis loss. Mai et al. [25] focused on improving the LSTM structure by designing a special gating mechanism to enhance text representation and perform information correction, while also applying auxiliary methods for text information calibration. Meanwhile, with the widespread application of attention-based methods in Natural Language Processing (NLP), Computer Vision (CV), and multimodal domains, new approaches and more advanced text encoders, such as BERT [26] and RoBERTa [27], have been introduced to the field of multimodal sentiment analysis. With the support of these stronger text encoders, researchers are increasingly using the text modality as the core modality for multimodal sentiment analysis. Wu et al. [4] studied the shared and private semantics in nonverbal modalities through a cross-modal prediction task. Wang et al. [28] injected information from the text modality into nonverbal modalities using a text-guided attention mechanism and a cross-modal Transformer, enhancing their representational power. Huang et al. [29] associated three-modal data using a text-centered unimodal and multimodal cross-modal Transformer. Li et al. [30] designed a semantic enhancement framework based on a cross-modal Transformer, which effectively strengthens the emotional representation capability of the text modality by coordinating the interaction mechanisms between the textual and nonverbal modalities.

Based on the previous work, it is clear that current text-centered approaches predominantly rely on cross-modal Transformers for cross-modal translation. However, in multimodal sentiment analysis, the emotional expressions in the text and nonverbal modalities may be asymmetric. Some emotional information may be more prominent in the text, while others are more prominent in nonverbal modalities. Direct cross-modal translation might miss out on the potential emotional information within each modality. Therefore, in order to achieve a more balanced interaction between modality information, we first quantify the information correlation between the text modality and nonverbal modality before performing cross-modal translation. Based on different levels of mutual information, we selectively incorporate text information into nonverbal information, compensating for the information asymmetry and improving the accuracy of sentiment analysis.

In this section, we will provide a detailed introduction to the Text-Gated Interaction Network with Inter-Sample Commonality Perception (TGICP) proposed in this paper. The core objective of TGICP is to extract the common emotional features between each sample and its similar samples using a graph convolutional network, and enhance the original sample features with these common features, thereby enriching the emotional feature space of the sample across different modalities. At the same time, during the cross-modal interaction and fusion process, TGICP uses the strong explicit emotional information in the text modality as a gating mechanism to dynamically regulate the information interaction between modalities, thereby improving the model’s efficiency in utilizing information from each modality.

Multimodal Sentiment Analysis (MSA) aims to predict the emotional tendency and intensity of the speaker in a video by simultaneously utilizing information from multiple modalities. In existing MSA research, this task can be modeled as either a classification problem or a regression problem. In our work, we choose to model and analyze it as a regression task. MSA typically involves three modalities: text (

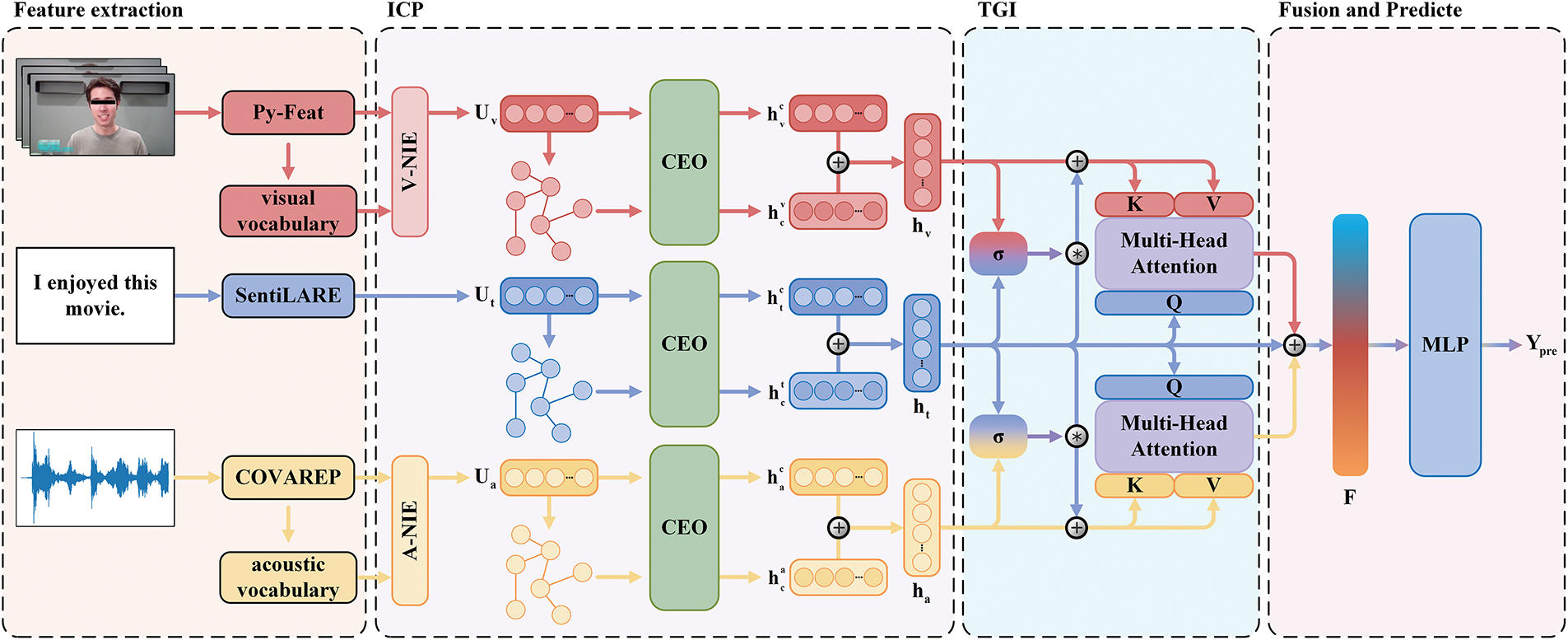

As shown in Fig. 1, TGICP mainly consists of four components: feature extraction, Inter-sample Commonality Perception, Text-Gated Interaction (TGI), and sentiment prediction. The feature extraction component transforms the raw multimodal data into vector representations. The Inter-sample Commonality Perception (ICP) part extracts the common emotional features between the sample and its emotionally similar samples, injecting these common features back into the original sample to enrich the emotional feature space of the sample across different modalities. The Text-Gated Interaction (TGI) component dynamically controls the cross-modal interaction of the sample’s multimodal representation by calculating the information disparity between the text and nonverbal modalities. Finally, the sentiment prediction component analyzes and predicts the fused sample features, providing the final emotional intensity score. In this section, we will provide a detailed introduction to these components.

Figure 1: The overall structure of TGICP primarily consists of four components: feature extraction, Inter-sample Commonality Perception (ICP), Text-Gated Interaction (TGI), and fusion and sentiment prediction

For the text modality, we use the pre-trained language model SentiLARE [31] to obtain text features. SentiLARE is a novel pre-trained language model that, compared to the previous BERT [26] model, enhances text feature representation by incorporating word-level linguistic knowledge through the addition of part-of-speech embeddings and sentence-level word polarity embeddings. The part-of-speech embeddings are derived using the Stanford Log-Linear Part-of-Speech Tagger [32], while the sentiment polarity labels come from SentiWordNet [33]. After passing the text through SentiLARE, we obtain the word embeddings of all the words in the text, denoted as

where

For the visual and auditory modalities, we use the pre-trained open-source tools Py-Feat [34] and COVAREP [35] to extract features

3.4 Inter-Sample Commonality Perception

To more fully utilize the emotional commonalities between samples and enrich their unimodal emotional feature space, we designed a Inter-sample Commonality Perception (ICP) module. This module consists of three components: Nonverbal Modality Information Enhancement (NIE), Inter-sample Commonality Mining (ICM), and Commonality Embedding Optimization (CEO). The following section provides a detailed description of each of these components.

3.4.1 Nonverbal Modality Information Enhancement

In the feature extraction section, we obtained the initial feature representations

Figure 2: Schematic of nonverbal modality information enhancement (NIE)

After obtaining the index features

where

Additionally, to capture the contextual temporal features of these two modalities, we use two independent Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory networks (BiLSTM) to further process the extracted nonverbal modality features

where

Finally, as shown in Eq. (8), the high-level feature representation of each modality is mapped to a shared space through independent encoders

where

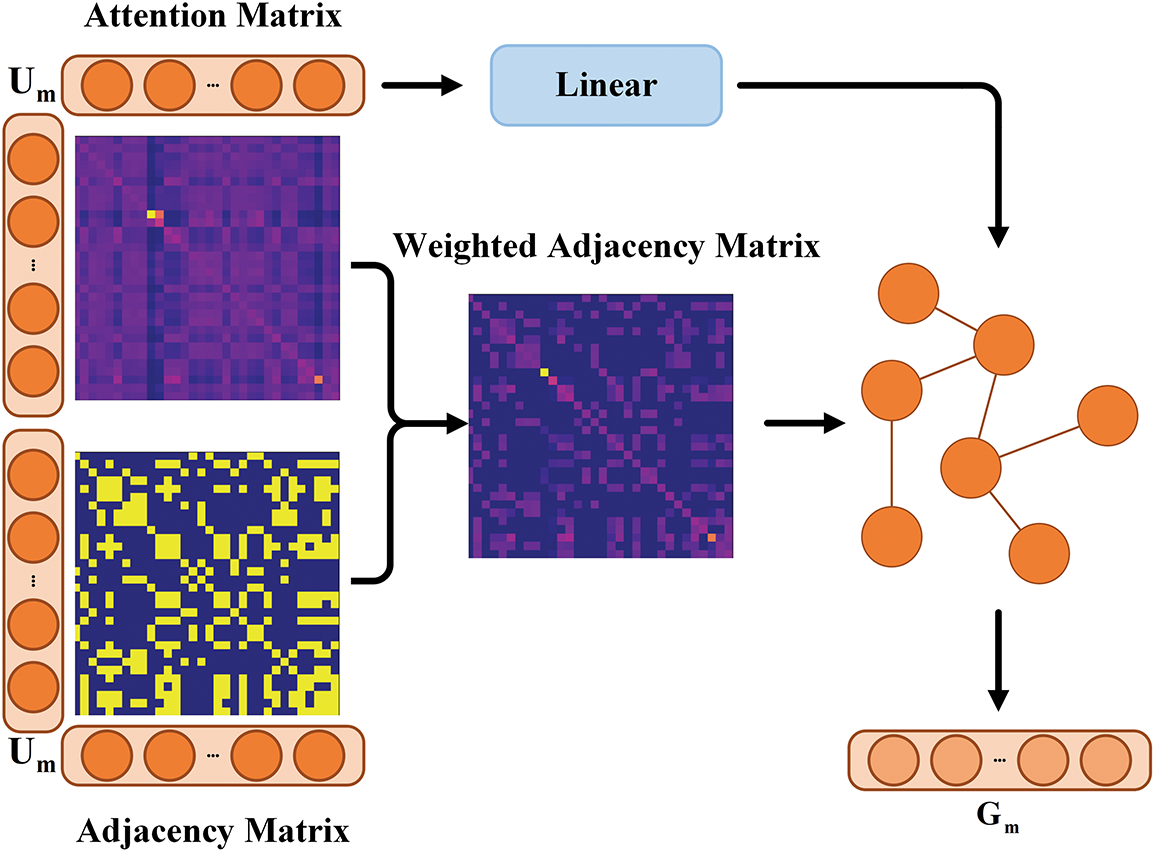

3.4.2 Inter-Sample Commonality Mining

In the work of Mai et al. [37], the problem of multimodal sequence analysis was transformed into a graph learning problem, where Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) were used to process the feature data of each modality. In this approach, an adjacency matrix is constructed within the graph structure by calculating the similarity between samples, and node features are propagated through graph convolution, thereby capturing both intra-modal and cross-modal feature dependencies. Specifically, Mai et al. proposed several methods to define the adjacency matrix, including non-parametric approaches (such as the generalized diagonal matrix) and learnable methods (where the adjacency matrix is learned through gradient descent). These methods, through effective feature propagation, capture the commonalities between intra-modal samples as well as the complex relationships between modalities. Inspired by this, to adaptively extract the emotional commonalities between similar samples based on their structure, we employ a similar graph construction method to design a weighted undirected graph

Figure 3: Schematic of inter-sample commonality mining (ICM)

Graph Construction: As shown in Eq. (9), we first calculate the cosine similarity between pairs of samples for each modality to obtain the feature similarity matrix

where

In order to allow the model to dynamically adjust the weights for extracting commonalities between different samples, we compute the attention weight matrix

where

After obtaining the adjacency matrix

Graph Convolution: After the graph construction described above, we obtain the weighted adjacency matrix

where

Subsequently, we use

where

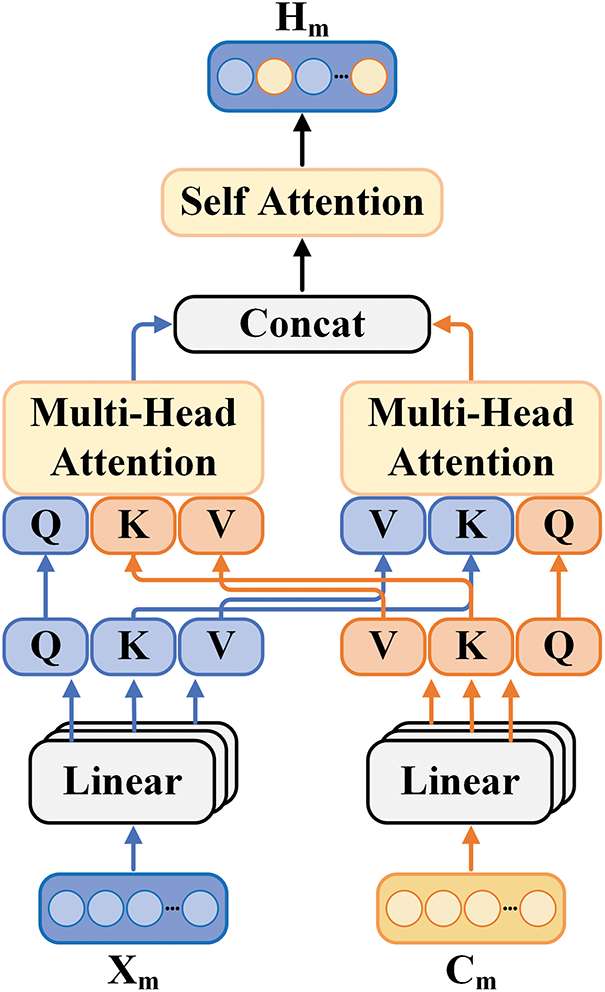

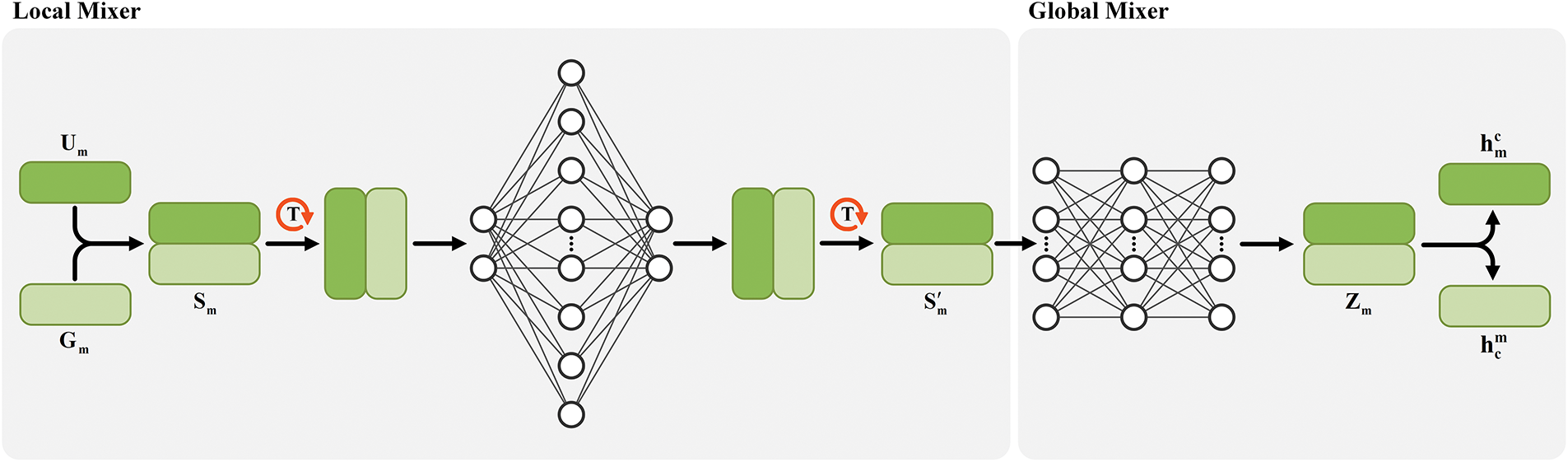

3.4.3 Commonality Embedding Optimization

Through the above steps, we have obtained the inter-sample commonality features

As shown in Fig. 4, the designed CEO consists of two components: the Local Mixer and the Global Mixer. Each component is composed of two linear layers and a Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) activation function, with residual connections incorporated. As described in Eq. (16), we first stack the high-level feature

Figure 4: Schematic of commonality embedding optimization (CEO)

Subsequently, as shown in Eq. (17), the stacked

where

After the local-level interaction and communication, as shown in Eq. (18), the locally interacted feature vector

where

where

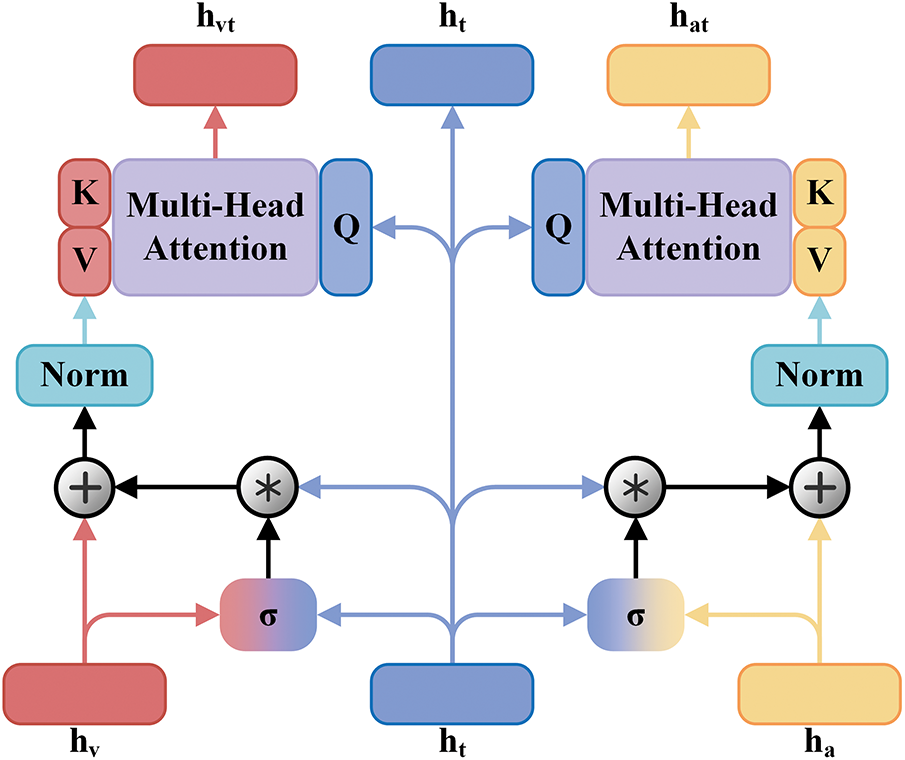

Compared to nonverbal modalities, the text modality is better suited to directly express rich emotional information, with its semantic content being more precise and detailed. In contrast, the emotional information conveyed by nonverbal modalities tends to be more abstract and implicit (e.g., micro-expressions, tone variations), and although the relationship between these signals and text is more indirect, they remain important signals in emotional analysis. However, in existing cross-modal interactions based on relevance, these potentially crucial emotional signals are often overlooked or lost. To address this issue and compensate for the emotional information loss caused by modality information asymmetry during cross-modal interactions, we have designed a text-gated interaction module, as shown in Fig. 5. This module aims to leverage the accurate emotional information in text to dynamically compensate for the information asymmetry between modalities, thereby improving the accuracy and comprehensiveness of emotional analysis.

Figure 5: Schematic of text-gated interaction (TGI)

To provide a concise and intuitive introduction to this part of the method, we use the text-visual modality interaction as an example. To effectively integrate the emotional information from both text and video modalities, it is essential to assess the correlation and complementarity between the two modalities, thereby guiding the feature fusion process. In this context, mutual information is employed to quantify and optimize the emotional information sharing between the modalities, helping to avoid redundancy and address the informational discrepancies between them. First, we calculate the level of mutual information between the two modalities using the CPC method [40], as shown in Eq. (21):

When the information correlation level between two modalities is low, it indicates that the degree of information dependence between the features of the two modalities is also low, with a smaller intersection of emotional information. In this case, we assign a higher weight to the textual modality, enabling it to provide more accurate emotional information to the visual modality, thus helping the visual modality better understand and express emotions. Conversely, if the information correlation level is high, the weight of the textual modality is reduced to avoid the convergence of multimodal data due to the excessive involvement of the textual modality. Therefore, after calculating the mutual information level between the two modalities, we first compute the information complementarity weight

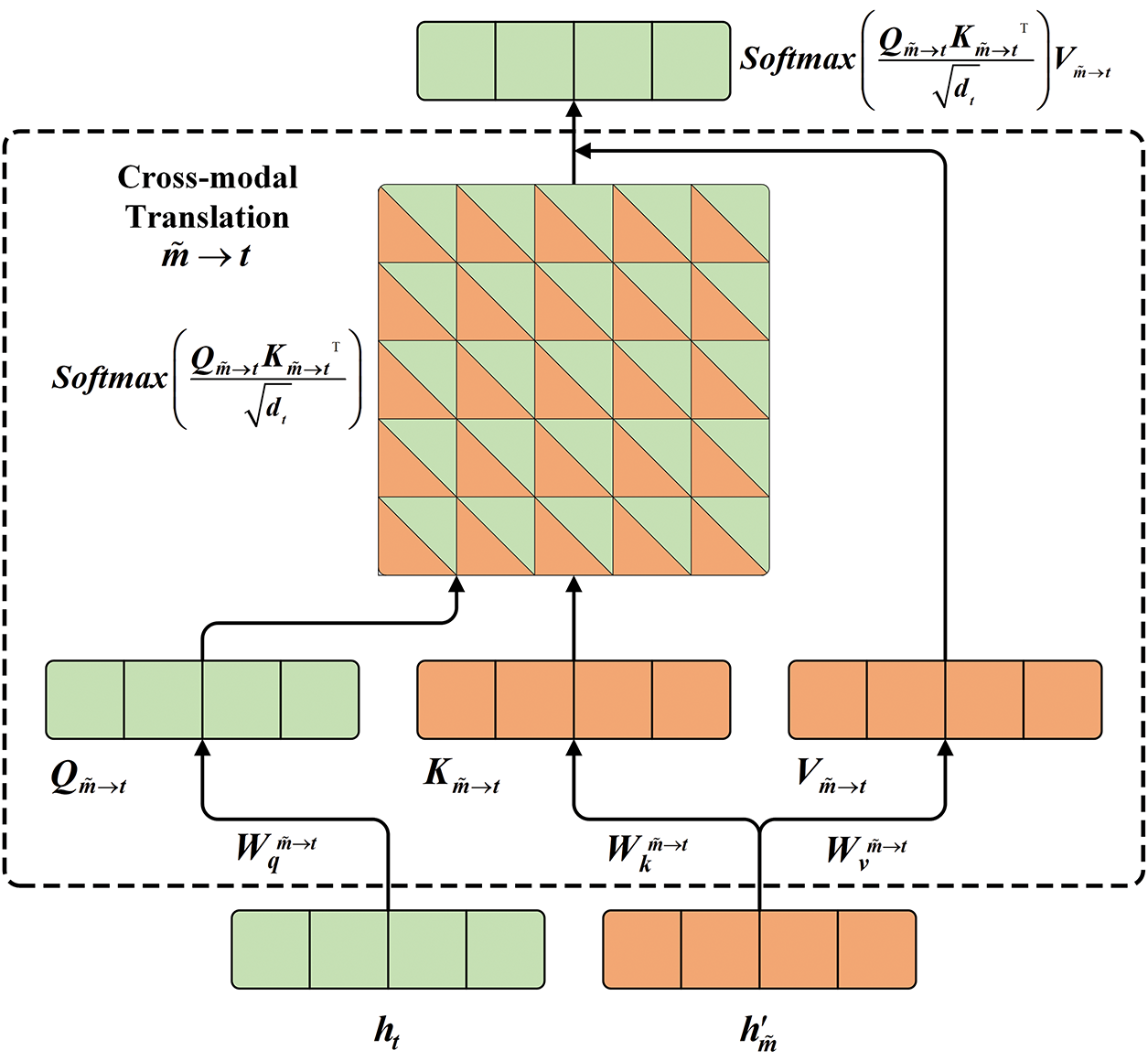

After the gated interaction, to further promote the integration and understanding of cross-modal emotional information, as shown in Fig. 6, we employ a cross-modal translation approach to achieve deep interaction between modalities. First, we treat the text as the query in the cross-modal translation, with the nonverbal modality serving as the key and value, and perform the computation as per Eq. (24). Subsequently, based on the modality pair, the query, key, and value required for the cross-modal translation are calculated using Eq. (25), thereby mapping the information from the nonverbal modality into the text modality, resulting in the feature

where

Figure 6: Schematic of text-centered cross-modal translation

After the inter-sample interaction fusion, we concatenate the three modal features according to the method outlined in Eq. (26), resulting in a multimodal joint representation F.

Subsequently, as shown in Eq. (27), we pass the representation through the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) layer for sentiment prediction, obtaining the model’s sentiment prediction result

where

In our model, the loss function consists of two components: the task loss

For the mutual information loss, we use the calculation method defined in Eq. (20). For the task loss, considering the wide applicability of mean squared error (MSE) in regression tasks, its sensitivity to errors, and its good differentiability, we select MSE as the task loss function to guide model optimization. Therefore, the overall loss function of the model can be expressed in the form of Eq. (28).

where

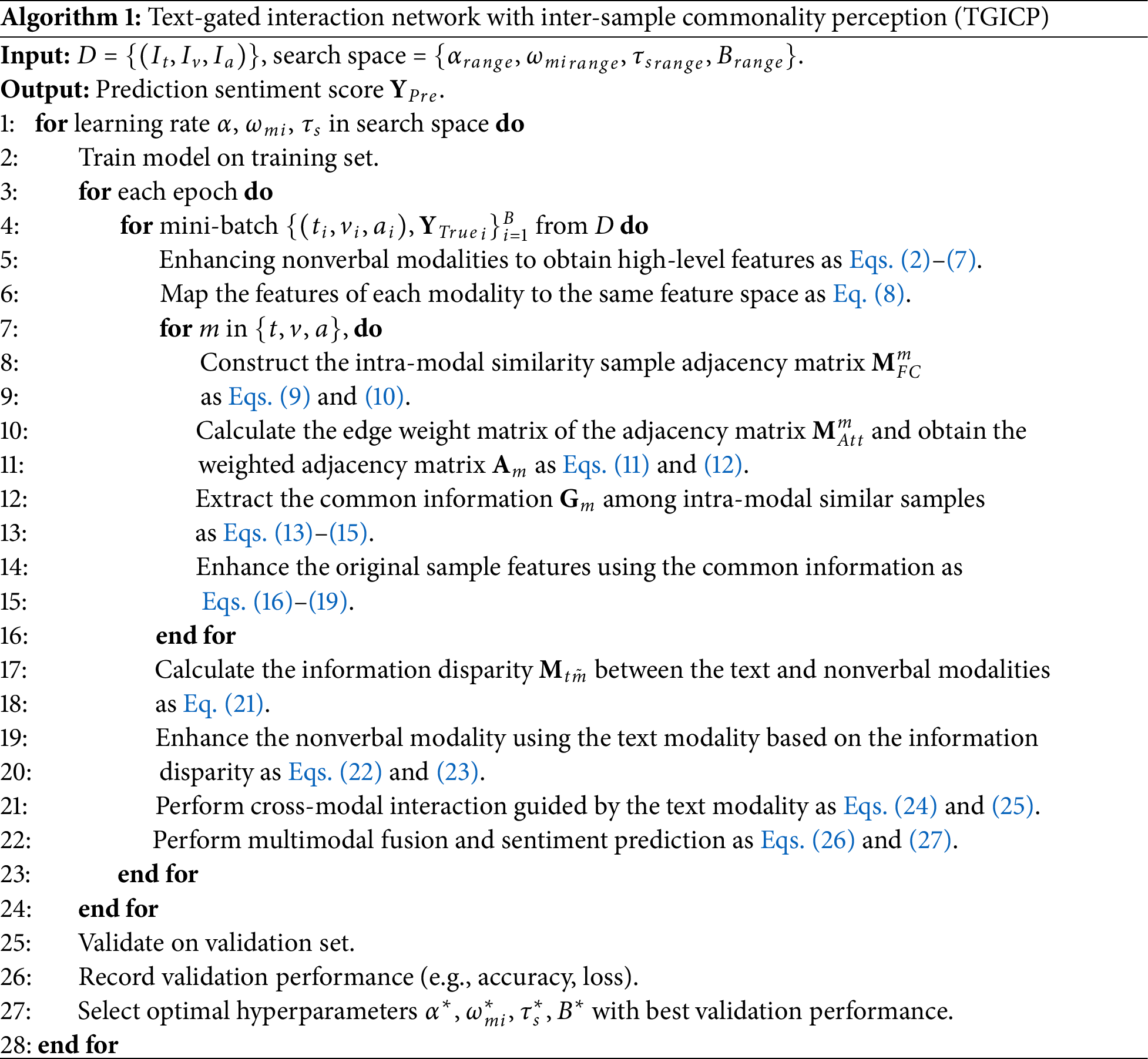

Finally, to present a clearer overview of the complete workflow of the TGICP model, we provide a systematic summary of its key steps in Algorithm 1.

We provide a detailed description of the experimental setup and conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed TGICP model on several mainstream publicly available datasets, validating its performance in the multimodal sentiment analysis task. Additionally, through a series of well-designed ablation experiments, we thoroughly analyze the effectiveness of each key module in the model and assess their contributions to the overall performance.

Our study is conducted on two important multimodal sentiment analysis benchmark datasets: CMU-MOSI [41] and CMU-MOSEI [42].

CMU-MOSI is one of the most commonly used datasets in the field of multimodal sentiment analysis, containing data from three modalities. The dataset includes 93 videos, with each video divided into up to 62 video segments. Each video segment contains a spoken sentence, and the emotional intensity ranges from [−3, +3], where −3 represents the most negative sentiment, and +3 represents the most positive sentiment.

CMU-MOSEI is an extended version of CMU-MOSI, featuring greater speaker diversity and a broader range of topics. This dataset contains 23,453 video segments, with emotional intensity labels identical to those in CMU-MOSI, ranging from [−3, +3] to represent emotional intensity. The video segments are sourced from 5000 videos, covering 1000 different speakers and 250 topics.

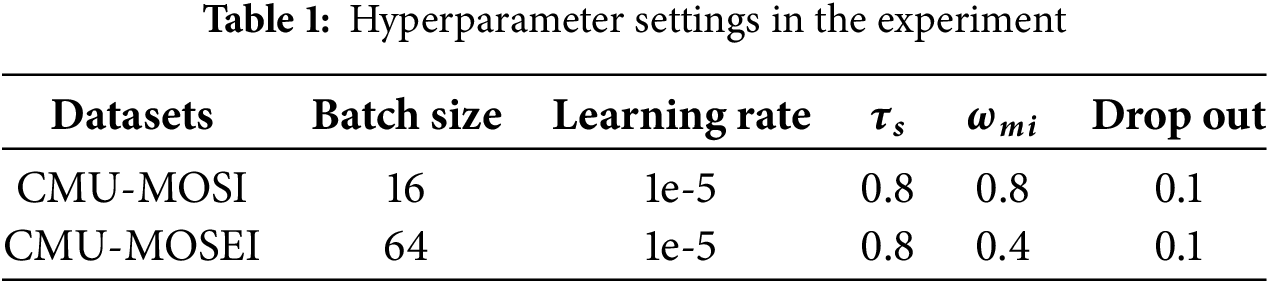

The proposed TGICP model is trained using the Adam optimizer. The model incorporates an early stopping mechanism, with a maximum of 4 training epochs and a patience value of 6. This means that if there is no performance improvement over 6 consecutive epochs, early stopping will be triggered. If no improvement occurs after 4 consecutive early stops, the training process will halt. Each time early stopping is triggered, the learning rate is halved, and the best model from the previous training epoch is restored to ensure the stability and effectiveness of the training process. Detailed hyperparameter settings are provided in Table 1, where

At the same time, to comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance, we conducted a statistical analysis of the model’s parameter size and computational efficiency. The total number of parameters in the model is 125.606 million, of which approximately 110 million parameters come from the pre-trained text feature extraction model SentiLARE, while the remaining parameters (excluding SentiLARE) amount to around 15 million. The test results on an RTX 3080 GPU show that the model’s computational complexity is 4.867 G Floating Point Operations (FLOPs). The training time on the CMU-MOSI dataset is approximately 34 min, with a GPU memory usage of 6 GB during training.

To facilitate comparison with other studies, we adopted the evaluation methods used in previous research and employed the same performance metrics to assess the model’s performance. Specifically, we used Mean Absolute Error (MAE) to measure the error between the predicted and true values, and the Pearson correlation coefficient (Corr) to evaluate the linear correlation between the predicted and true values. In the sentiment analysis task, we first used binary classification accuracy (Acc-2) to measure the accuracy of coarse-grained sentiment analysis, followed by seven-class accuracy (Acc-7) to evaluate the accuracy of fine-grained sentiment analysis. Additionally, we employed the weighted F1 score (F1-Score) to provide a comprehensive assessment of the model’s precision and recall, offering a holistic view of the model’s performance.

We compared the performance of the proposed model with several classic and state-of-the-art MSA models across multiple metrics. The models compared and their brief descriptions are as follows:

TFN [7] generates a multidimensional tensor by computing the Cartesian product between modalities, enabling explicit capture of the interactions between single-modal, bi-modal, and tri-modal features.

LMF [9] improves upon TFN by using low-rank tensors for efficient multimodal fusion, significantly reducing computational complexity.

MulT [2] is based on an attention mechanism that maps the features of one modality to those of another, focusing on cross-modal interactions across time steps.

MISA [3] projects each modality into a modality-invariant subspace, aiming to learn the shared representation of each modality within that subspace.

Self-MM [10] generates unimodal labels through self-supervised tasks, thereby learning the similarities and differences between modalities.

TETFN [28] achieves consistent representations between modalities through a text-enhanced Transformer fusion network and maintains modality-specific differences through the generated unimodal labels.

SGIR [43] significantly reduces computational complexity and enhances noise resistance by facilitating indirect interactions between the central hub features and the modality-specific private features.

TMBL [44] processes multimodal data by introducing a bimodal and trimodal binding mechanism. It leverages an improved Transformer architecture to promote cross-modal interactions when extracting modality-invariant and modality-specific features, and enhances feature interactions through a fine-grained convolutional module.

FNENet [45] reduces the granularity gap between linguistic and non-linguistic modalities by vectorizing the non-linguistic modality. It then integrates non-linguistic information into a pre-trained language model using a sequence fusion mechanism.

SIMSUF [46] dynamically selects the dominant modality and performs feature enhancement and fusion based on this modality, thereby obtaining an effective multimodal fusion representation.

MCL-MCF [47] gradually reduces the representational differences between different modalities through multi-level contrastive learning, and enhances high-level semantic features by utilizing multi-layer convolutional fusion, thereby alleviating the heterogeneity issue in multimodal data.

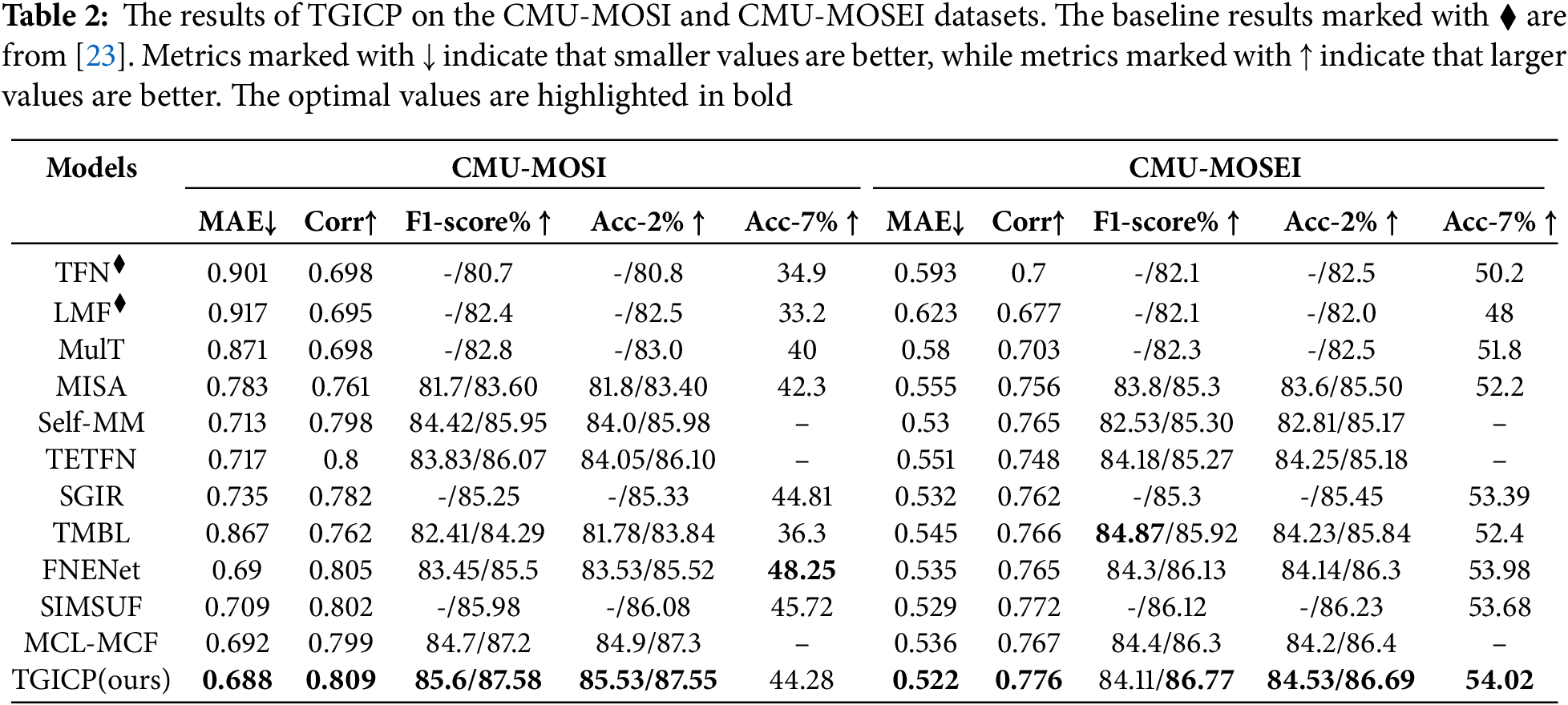

We compared the proposed TGICP model with various classical and state-of-the-art baseline methods on the core datasets for multimodal sentiment analysis, namely CMU-MOSI and CMU-MOSEI. The experimental results are shown in Table 2.

CMU-MOSI: The experimental results on the CMU-MOSI dataset demonstrate that our model outperforms traditional models and existing state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods across key metrics, including MAE, Corr, Acc-2, and F1. Specifically, compared to TETFN, which also performs cross-modal fusion based on text, our model improves by 0.029 in MAE (0.688 vs. 0.717) and 1.45

CMU-MOSEI: The experimental results on the CMU-MOSEI dataset demonstrate that the TGICP model performs exceptionally well in multimodal sentiment analysis tasks. Specifically, it outperforms the state-of-the-art method SIMSUF in both MAE (0.522 vs. 0.529) and Corr (0.776 vs. 0.772), while also improving Acc-2 and F1 scores by 0.29

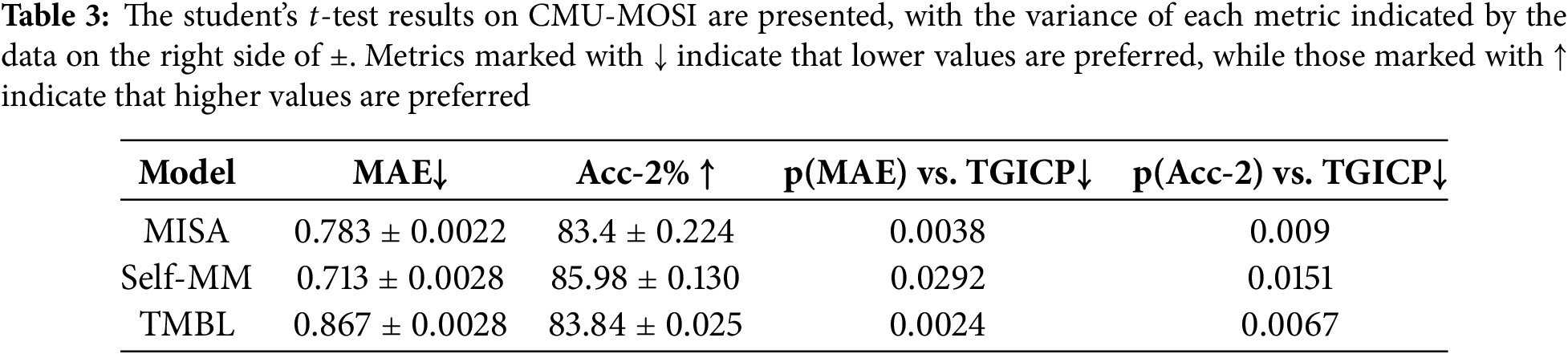

In addition, to verify the reliability of the performance improvement of the proposed TGICP model, we conducted a Student’s

As can be seen from the experimental results, in terms of the MAE metric, the

Regarding the Acc-2 metric, the

Overall, TGICP demonstrates a significant performance advantage over models such as MISA, Self-MM, and TMBL in both MAE and Acc-2 metrics. This indicates that our work has achieved a significant performance improvement in the multimodal sentiment analysis task compared to important and state-of-the-art models.

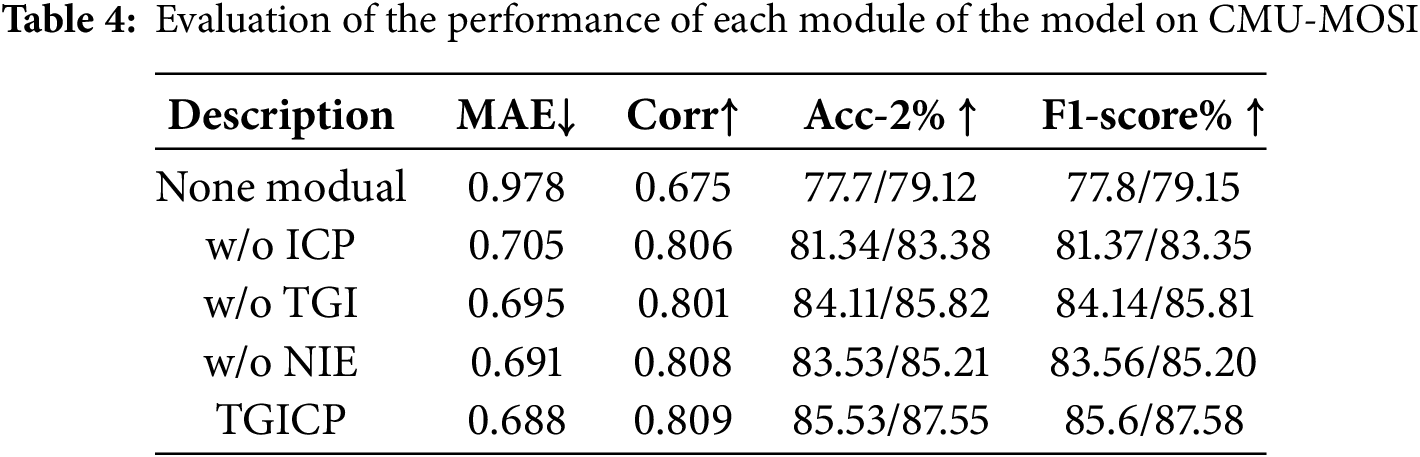

1) Evaluation on components in TGICP: We conducted a detailed performance evaluation of the two main modules and their submodules in the TGICP model on the CMU-MOSI dataset, with the experimental results shown in Table 4. The experiments revealed that removing the ICP module led to the model being unable to obtain a more refined multimodal representation, while removing the TGI module resulted in the model’s inability to fully leverage emotional information from nonverbal modalities during cross-modal interactions. The removal of any module or submodule significantly degraded the overall performance of the model. These results underscore the importance and indispensability of these modules within the entire model. Further analysis showed that the ICP module had the greatest overall impact on model performance, as its key role was to provide the model with more emotionally rich and complete sample features.

To gain a deeper understanding of the contribution of the ICP module, we also conducted separate evaluations of the two submodules within the ICP module: NIE and CEO. The experimental results show that removing the NIE module led to the loss of the commonality relationship between frames in nonverbal modalities. This loss resulted in insufficient capture of potential commonality information during the common feature extraction process, leading to a significant decline in model performance. A detailed analysis of the CEO module and its role in the model will be further discussed below.

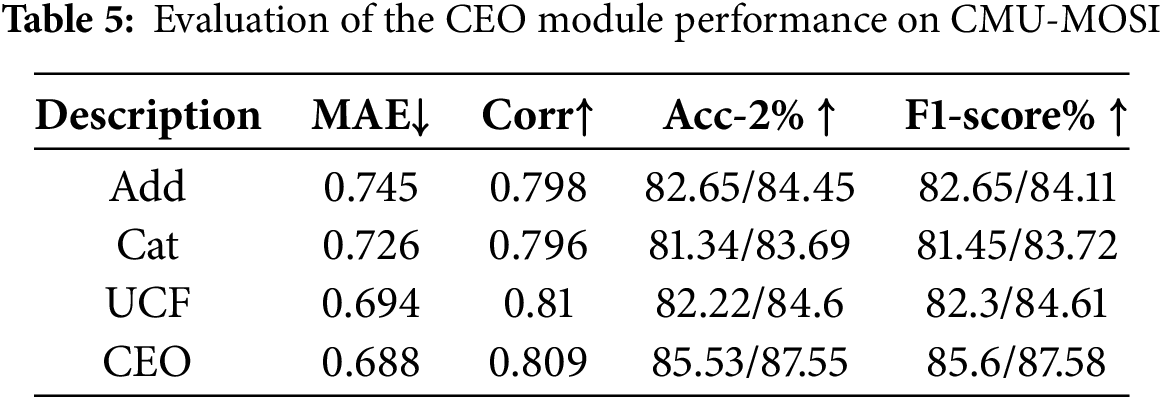

2) Evaluation on CEO: In order to better leverage the common features extracted from the data, we conducted experimental evaluations on several commonly used methods from previous research using the CMU-MOSI dataset. The experimental methods include: adding common features to the original features (Add), concatenating the common features with the original features (Cat), and directly use common features (UCF) to replace original features for subsequent operations. The experimental results of these methods are shown in Table 5.

The experimental results indicate that among the three common methods for utilizing common features, directly use common features (UCF) to replace original features achieved the best performance. Specifically, replacing the original features with common features significantly improves the model’s performance in sentiment analysis tasks, as this method allows for a more direct utilization of common information, thereby optimizing feature representation. However, despite the excellent performance of the UCF method, there remains a noticeable gap compared to the results obtained using our proposed CEO module. By integrating a contextual sentiment optimization strategy, the CEO module can more efficiently consolidate the common features, further enhancing model performance. These experimental findings fully demonstrate the innovation and advancement of the CEO module in utilizing common features. Compared to traditional feature fusion methods, the CEO module can more accurately extract and leverage common features, significantly improving the model’s sentiment recognition ability, and providing an effective direction for further research in this field.

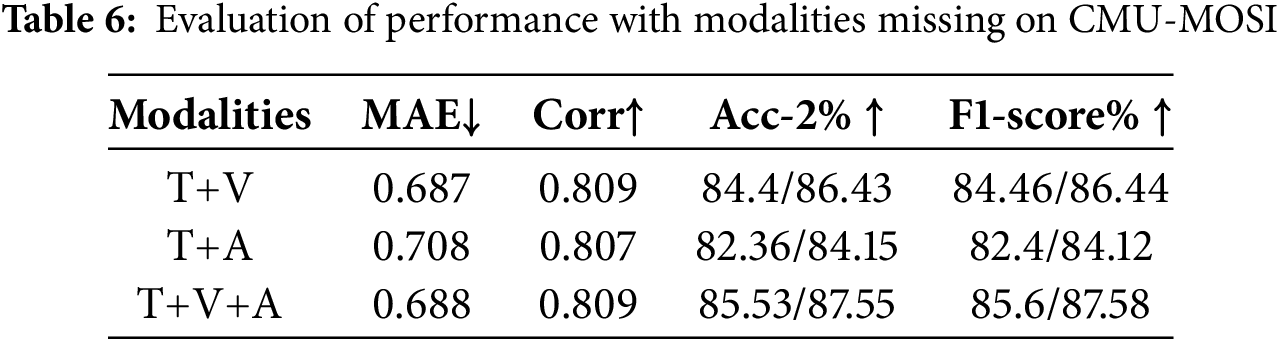

3) Evaluation on missing modality: To assess the contribution of different nonverbal modalities to the model and the effectiveness of cross-modal information extraction in the presence of multimodal data, we conducted ablation experiments on the CMU-MOSI dataset, analyzing the model’s performance under different input modality combinations. The experimental results are shown in Table 6. Since we employed a text-centered cross-modal interaction approach, the experiments considered only combinations of text and nonverbal modalities.

The results indicate that, compared to the auditory modality, the visual modality contributes more significantly to the model’s predictions. This suggests that visual information plays an essential role in sentiment recognition tasks, providing the model with more contextual cues to help capture emotional features more accurately. On the other hand, the three-modal combination (i.e., text, visual, and auditory modalities) outperforms the two-modal combinations (such as text and visual or text and auditory). This result further demonstrates that our proposed model can effectively extract cross-modal information in a multimodal data environment, integrating the strengths of each modality to improve the accuracy of sentiment analysis.

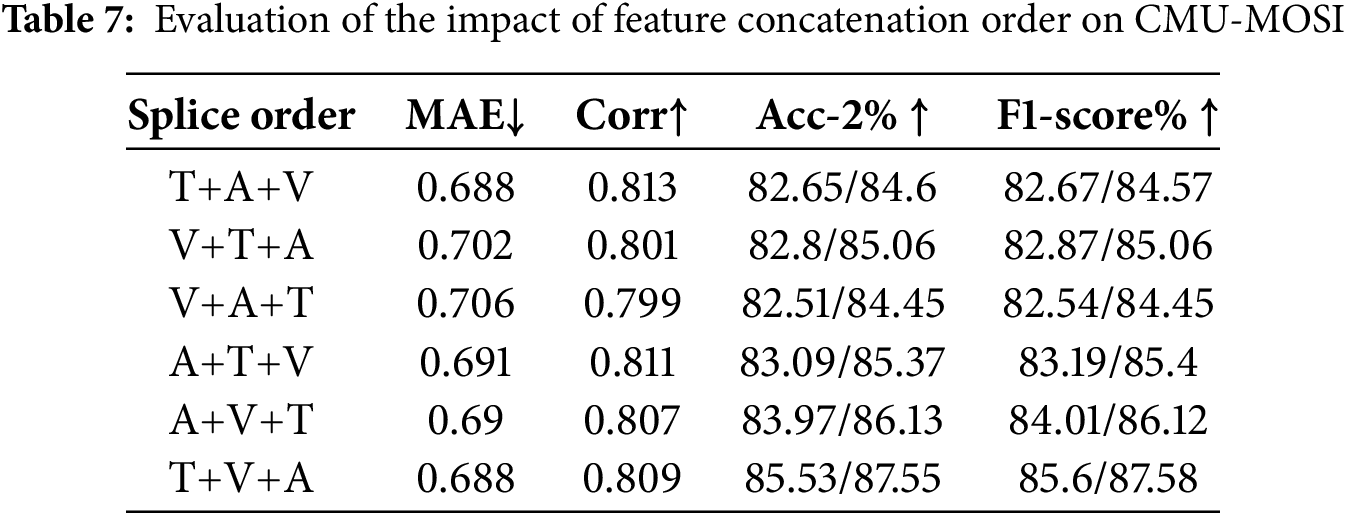

4) Evaluation on different modalities’ splice order: To evaluate the impact of modality concatenation order during the feature fusion phase on model performance, we conducted experiments with different concatenation orders on the CMU-MOSI dataset. The experimental results are shown in Table 7. The results indicate that the T+V+A (Text + Visual + Auditory) order performed the best among all concatenation orders, achieving optimal performance across multiple evaluation metrics.

Specifically, the T+V+A order maximizes the retention of each modality’s strengths during the fusion of features, while simultaneously enhancing the efficiency of cross-modal interaction. Textual information, as the core modality, provides the semantic foundation, while the visual and auditory modalities complement it by enriching the multi-dimensional expression of emotional information. This concatenation order effectively improves the model’s ability to recognize complex emotional patterns and significantly outperforms other concatenation orders across multiple performance metrics. This result validates that the concatenation order chosen at the feature fusion stage is both reasonable and effective.

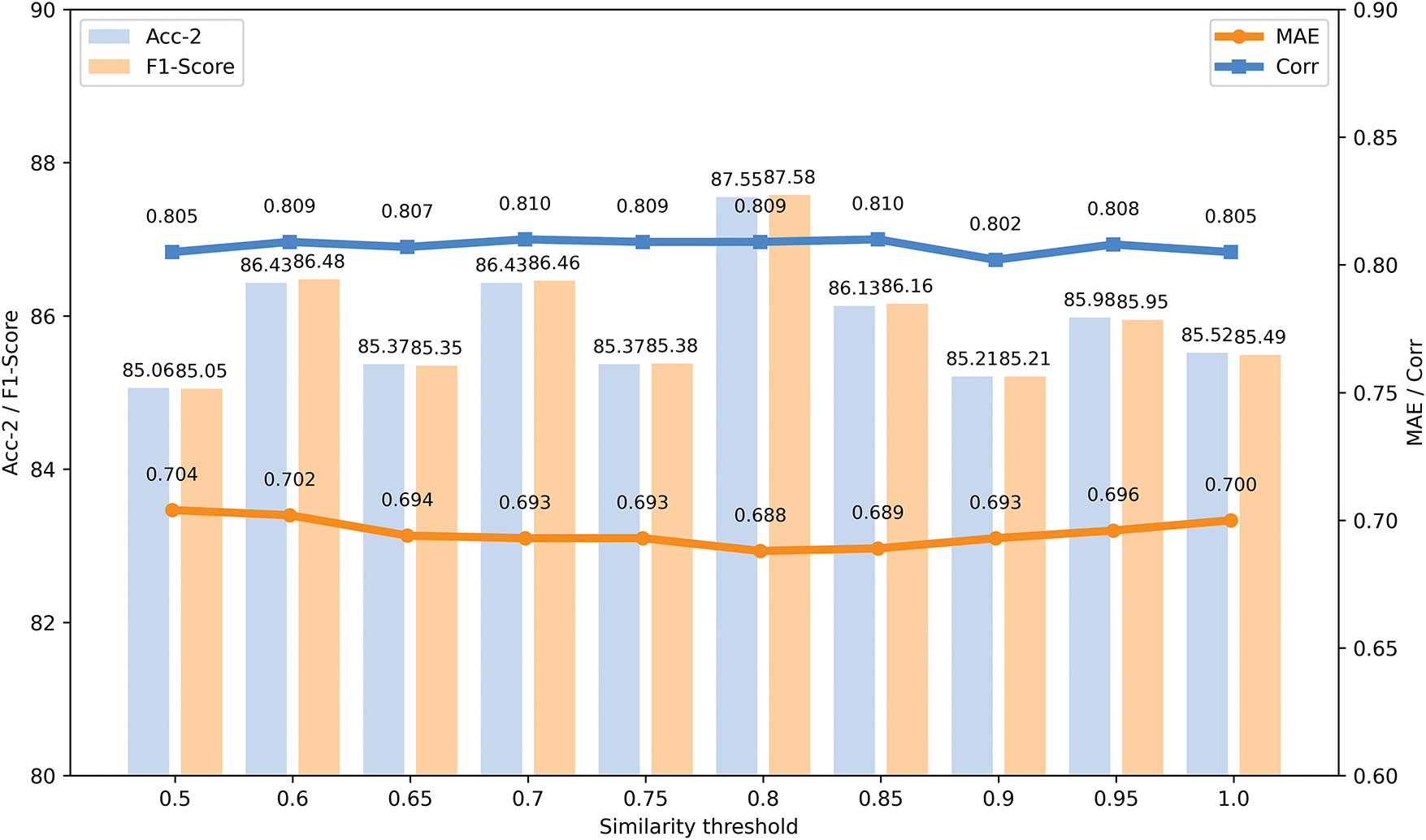

5) Evaluation on similarity threshold: During the selection of similar samples, we set the feature similarity threshold hyperparameter to control which samples can be selected as similar samples. To assess the impact of different thresholds on model performance, we conducted detailed experiments on the CMU-MOSI dataset. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 7. When the feature similarity threshold was set to 0.8, all evaluation metrics, except for the correlation (Corr) metric, achieved their optimal values, and the Corr value was also very close to the optimal value of 0.81.

Figure 7: The impact of different feature similarity thresholds on model performance

The experimental results show that when the feature similarity threshold is set to 0.8, the model is able to select similar samples while minimizing the introduction of noise, thereby improving model performance. Both excessively high and low thresholds lead to inaccurate selection of similar samples, which negatively impacts the model’s training effectiveness. A higher threshold may result in overly stringent filtering, limiting the number of valid samples, while a lower threshold could introduce excessive irrelevant noise, leading to instability in model training. Overall, selecting 0.8 as the feature similarity threshold is the most appropriate choice, as it effectively reduces noise while selecting similar samples within the modality, thus enhancing the model’s performance in multimodal sentiment analysis tasks.

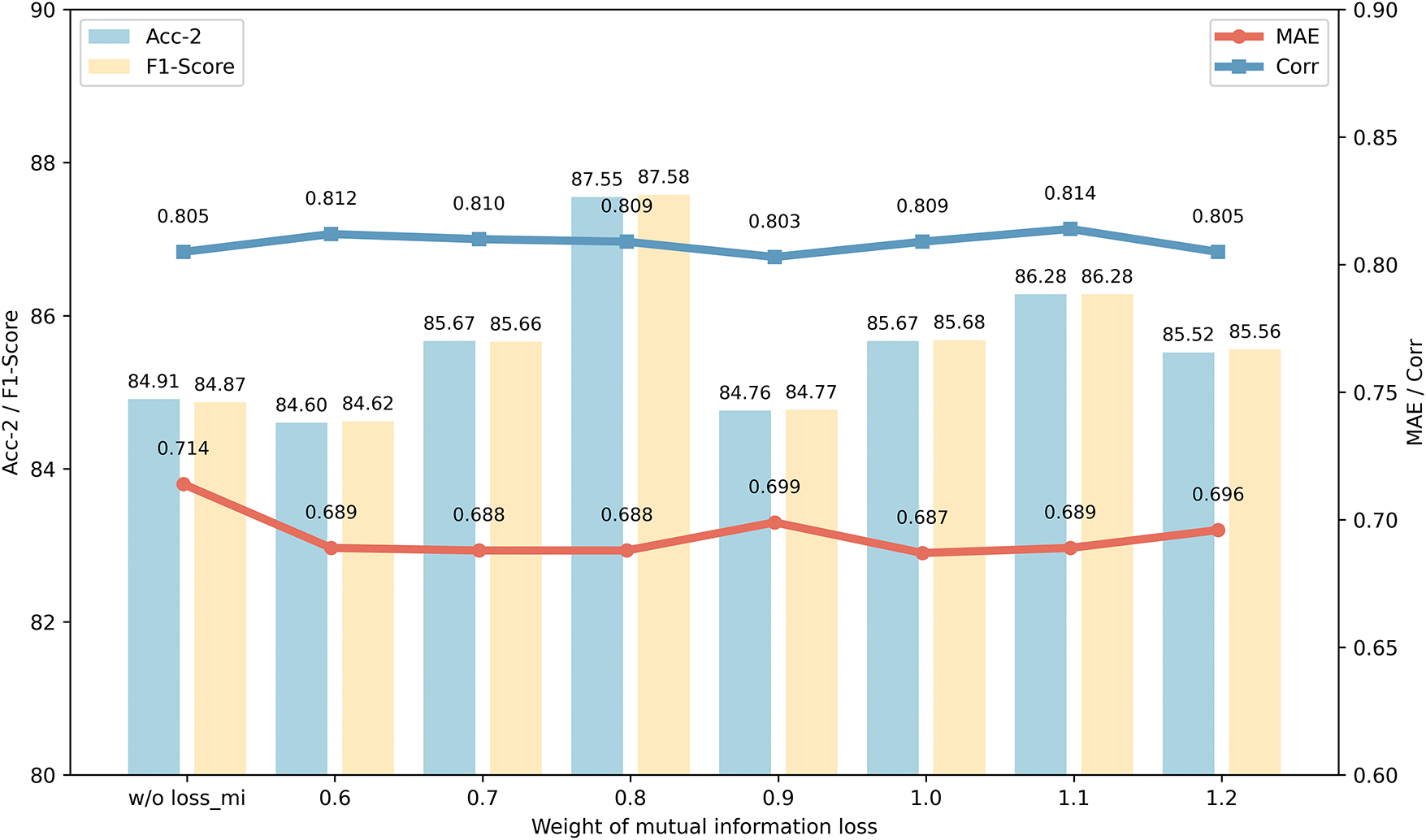

6) Evaluation on mutual information loss weight

Figure 8: The impact of different mutual information loss weights

These results indicate that the setting of the mutual information loss weight has a significant impact on model performance. An appropriate weight can balance the dependencies between features within the modality and the extraction of common features, thus enhancing the model’s performance in multimodal sentiment analysis. Specifically, when the weight is 0.8, the model effectively reduces the dependencies between common features of modality-specific samples and the original samples, thereby enhancing the independence of common features and allowing them to more accurately represent the shared information between modalities. Additionally, the experiment further demonstrates that introducing mutual information loss as a regularization method helps better extract common features, suppress irrelevant features, and significantly improve model performance.

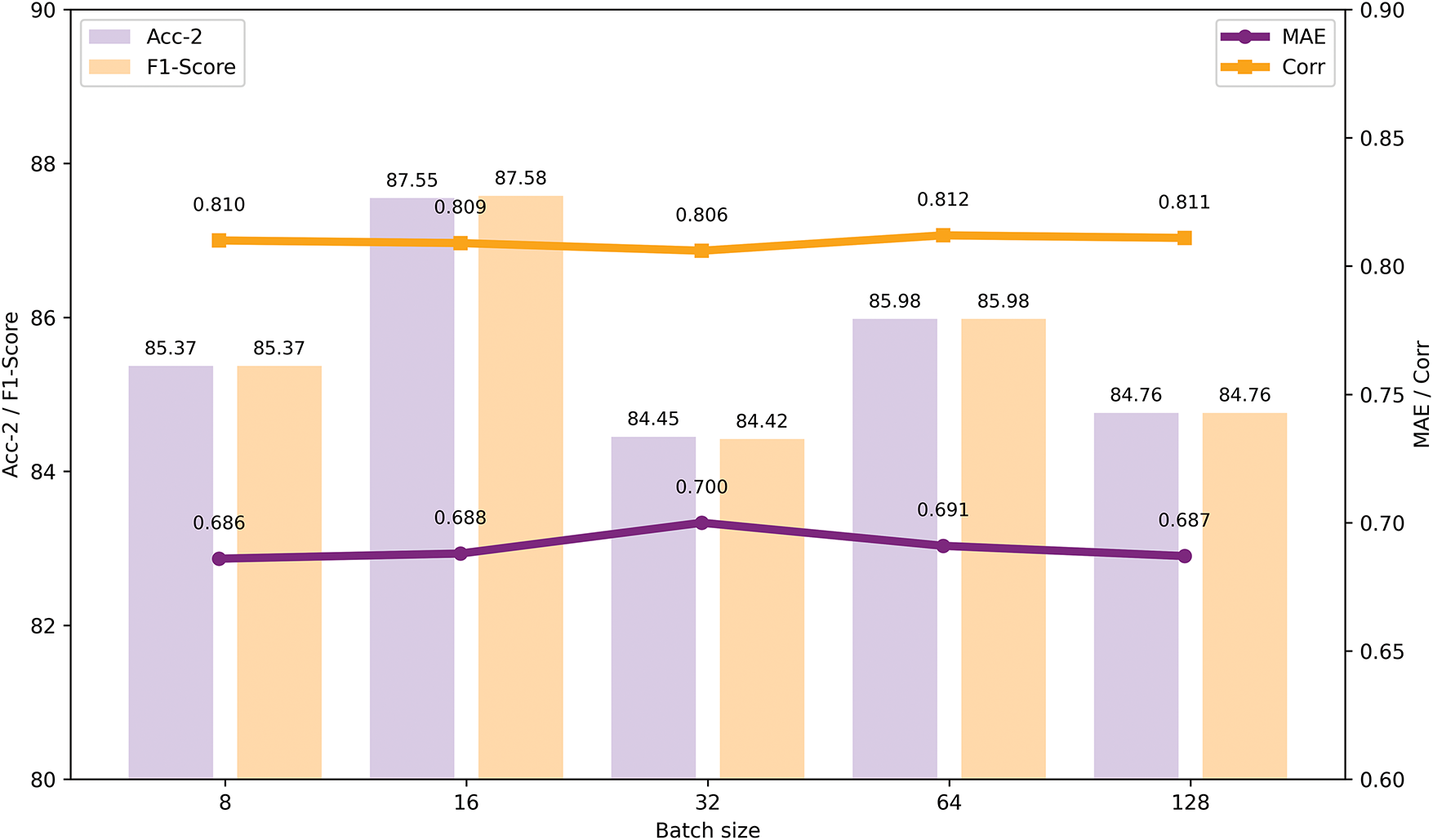

7) Evaluation on batch size: During the model training process, we employed Mini-Batch Gradient Descent for training. To evaluate the impact of different batch sizes on model training effectiveness, we conducted experiments on the CMU-MOSI dataset. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 9. After comparing five common batch sizes, we found that when the batch size was set to 16, the model achieved the best overall performance, with outstanding results across multiple key metrics.

Figure 9: The impact of different batch sizes on model performance

Specifically, when the batch size is set to 16, the model’s Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Correlation (Corr) are close to their optimal values, while Accuracy (Acc-2) and F1 score achieve their best performance. This indicates that a batch size of 16 provides a balanced training effect, ensuring high model precision while effectively capturing subtle differences in the data, particularly in sentiment analysis tasks. Additionally, smaller batch sizes may lead to unstable gradient updates during training, introducing noise and oscillation, which in turn affects convergence speed. On the other hand, larger batch sizes, while reducing such fluctuations, may slow down the training process and increase the risk of getting stuck in local optima. Therefore, choosing 16 as the batch size not only helps the model converge more stably during training but also improves its performance in sentiment analysis tasks.

In conclusion, a batch size of 16 is a suitable choice for the CMU-MOSI dataset, as it ensures high training accuracy while minimizing significant training oscillations, thereby accelerating model convergence and enhancing its overall performance.

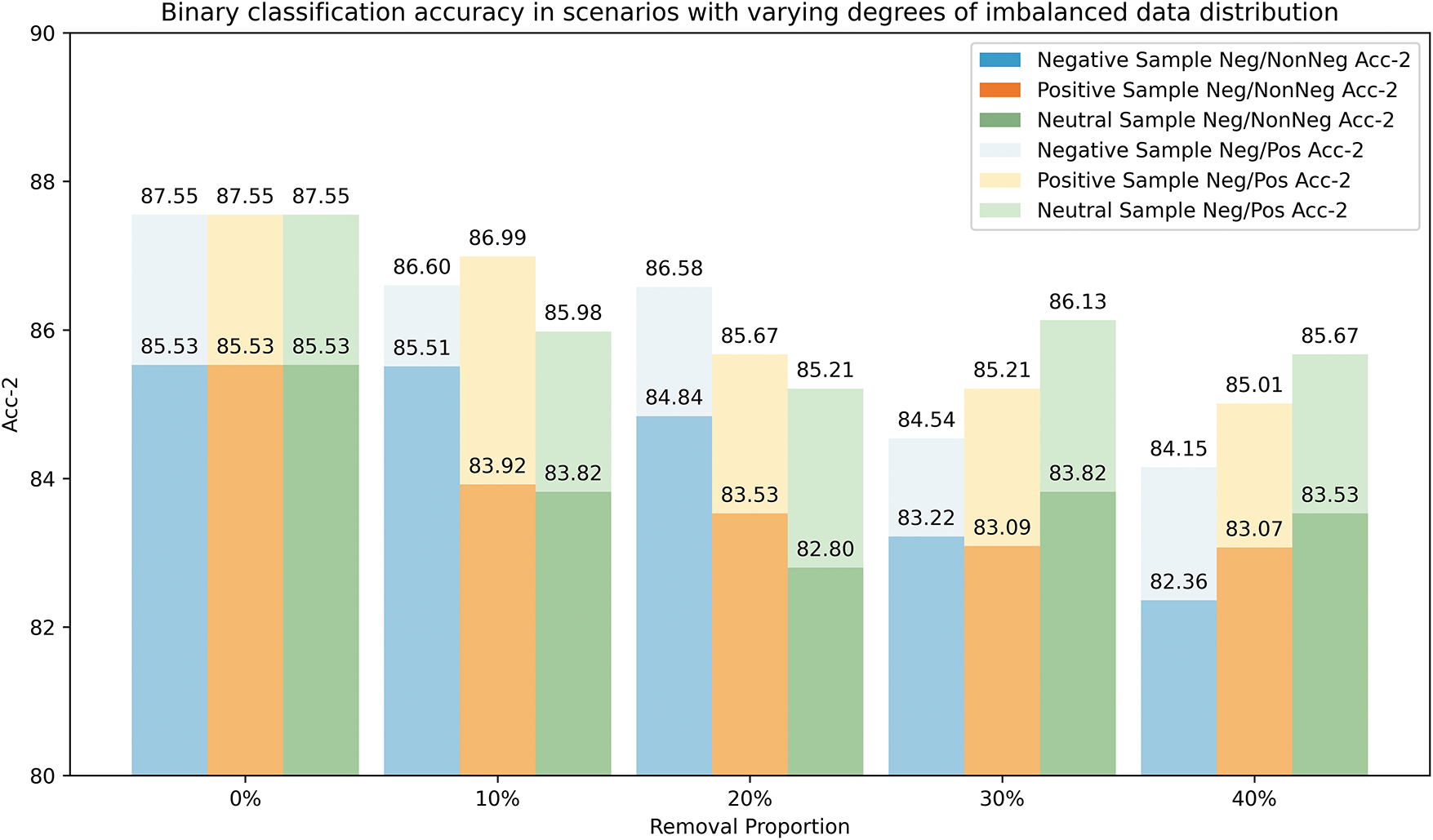

8) Evaluation on imbalance dataset: To evaluate the model’s robustness under imbalanced data distributions, we tested the model’s binary classification accuracy by randomly removing varying proportions of negative, neutral, and positive samples from the CMU-MOSI training set. The results are shown in Fig. 10. The experimental results indicate that as the proportion of randomly removed samples from one class increases (from 0

Figure 10: The model’s binary classification accuracy under different levels of data distribution imbalance

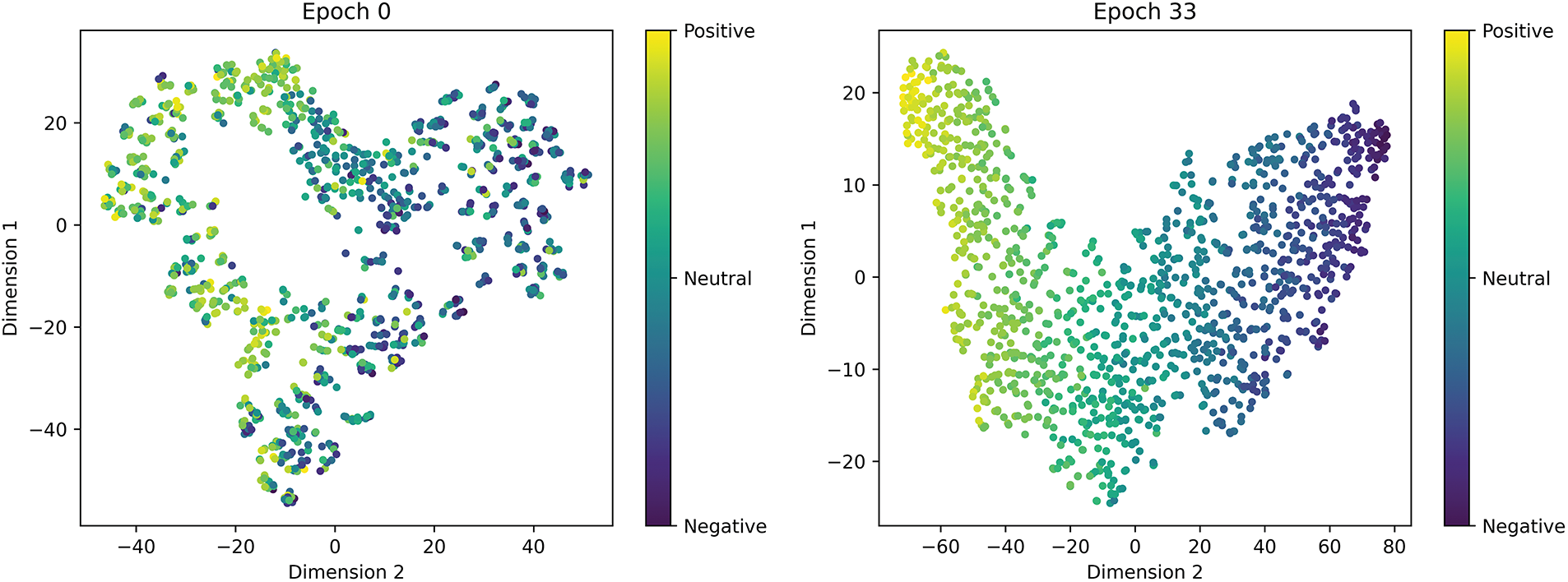

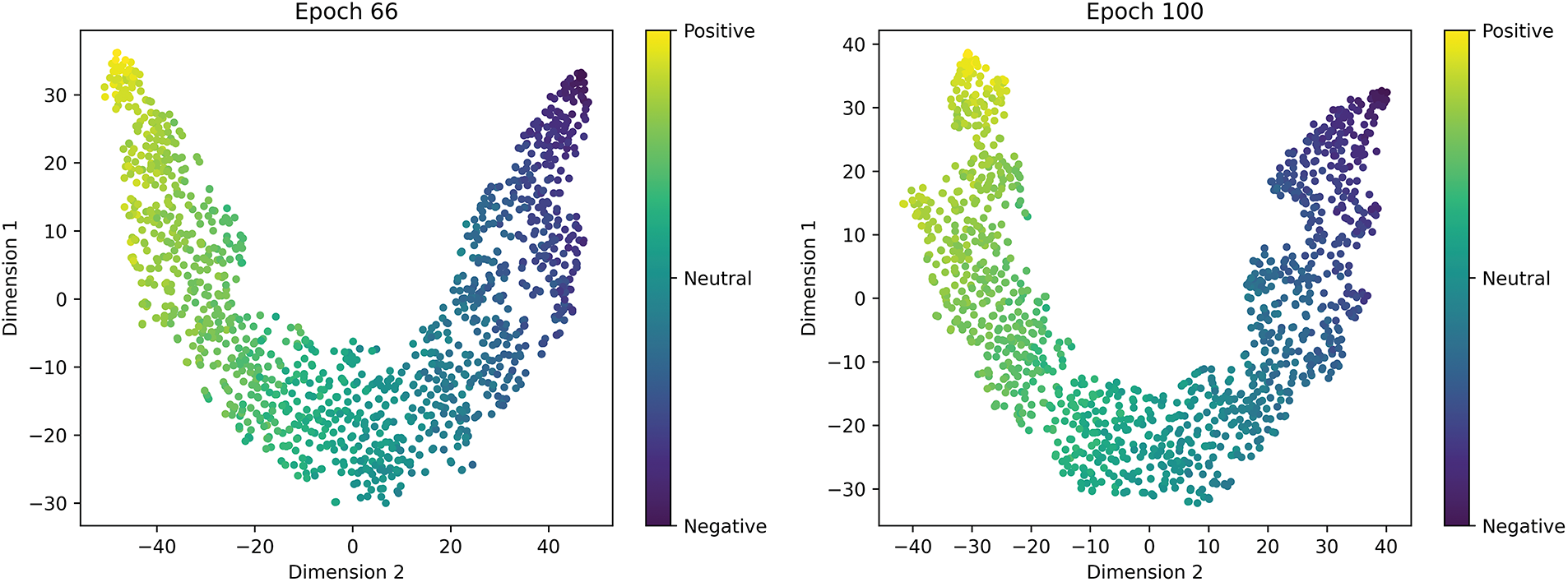

4.7 Results of t-SNE Analysis for Sentiment Clustering

To demonstrate the model’s ability to learn emotional features at different training optimization stages, we present the multimodal joint feature emotion clustering t-SNE plots for four training stages in Fig. 11. Points in the figure that are close to yellow represent a positive emotional bias, while points near purple indicate a negative emotional bias, and the green region represents neutral emotions. By mapping the joint features of the samples to colors, we can visually observe the model’s representation distribution across different emotional polarities, thereby illustrating the model’s learning effectiveness with respect to emotional features at different stages.

Figure 11: Results of t-SNE analysis for sentiment clustering at different learning stages: With the optimization of model training, the emotion clustering performance significantly improved. The distribution of emotional samples became more organized, and the overlap between categories was notably reduced

At the initial stage (Epoch 0), the feature space is chaotic, with high overlap among samples of different emotions, indicating that the model has not yet developed an effective ability to distinguish emotions. As training progresses (Epoch 33), an initial clustering trend begins to appear, but there is still noticeable confusion in the neutral emotional category, showing that the model has started to capture basic emotional features.

In the later stages of training (Epoch 66), the feature space is significantly optimized, with improved separation between categories and reduced overlap, confirming that the model has acquired a more precise emotional discrimination ability. At the final stage (Epoch 100), an ideal continuous emotional distribution is observed, with tight intra-class cohesion and natural inter-class transitions, which fully validates the model’s outstanding multi-modal emotional understanding and classification performance. These results convincingly demonstrate the model’s capability to accurately capture emotional features and highlight its excellent multi-modal emotional comprehension, providing direct evidence of the model’s effectiveness in emotional classification.

This paper presents an innovative multimodal sentiment analysis model, TGICP. The model mines the common information of modality-specific similar samples through a unimodal inter-sample graph, and introduces a dual-perspective commonality embedding optimization layer. This layer enhances the role of common features while preserving the uniqueness of samples, thereby improving the model’s generalization ability and fully leveraging the advantages of each modality. To address the issue of asymmetric information between modalities, the model incorporates a dynamic gating adjustment mechanism. This mechanism dynamically modulates the interaction process by calculating the information discrepancy between textual and non-textual modalities, thus enhancing the model’s ability to learn from non-textual modalities.

The experiments demonstrate that TGICP significantly improves performance on two mainstream multimodal sentiment analysis datasets, but there is still room for improvement. Currently, the cross-sample graph does not fully consider the spatiotemporal relationships of non-text modalities and the word dependencies within the text modality, which may impact representation learning. Additionally, the common feature enhancement process may lead to excessive smoothing in the feature space, potentially introducing unnecessary errors in multiclass tasks. Moreover, due to the lack of large-scale pre-trained corpora with emotional annotations (similar to the English Yelp Dataset Challenge) and linguistic knowledge resources (similar to the English SentiWordNet) in the Chinese domain, SentiLARE can only be applied to English data, which limits the applicability of our model when dealing with non-English data.

Future work will focus on designing more refined methods for extracting emotional information within each modality to enhance representation learning and optimizing the common feature introduction mechanism to avoid the issue of feature space smoothing. Additionally, ongoing exploration of model optimization directions will aim to improve its robustness and applicability in a wider range of scenarios. Once again, although we have improved the temporal information modeling of non-text modalities by designing the NIE module to address the imperfections caused by BiLSTM, and achieved good performance, this improvement has not fundamentally solved the problem. Therefore, in our follow-up research, we will consider adopting other more sophisticated methods for handling temporal features to further optimize the model’s ability to process temporal information. At the same time, we will actively explore pathways for obtaining and constructing large-scale pre-trained corpora in Chinese, along with targeted fine-tuning of SentiLARE; we will also assess and introduce more versatile language models as alternatives, achieving performance improvements through model fusion and parameter optimization.

Furthermore, given the current study’s limitations in user-generated content privacy protection, subsequent research will employ techniques such as data de-identification and privacy-preserving enhancement algorithms to build a secure and compliant research framework, advancing the work while ensuring user privacy.

Finally, to comprehensively evaluate the performance of TGICP in complex labeling scenarios and real-world application environments, we plan to introduce real-world datasets containing multi-level semantic annotations and fine-grained emotional labels. This will allow us to systematically explore the model’s capabilities in complex semantic understanding and scene adaptability. Additionally, we will simulate real application environments to design experimental setups, combining quantitative evaluation metrics and qualitative analysis methods to thoroughly validate the model’s robustness and generalization ability, providing reliable performance evaluation for practical applications.

Acknowledgement: This paper was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Henan, the Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project, the Jiangsu Provincial Scheme Double Initiative Plan, the XJTLU, the Science and Technology Innovation Project of Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Higher Education Teaching Reform Research and Practice Project of Henan Province.

Funding Statement: This paper was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Henan under Grant 242300421220, the Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project under Grants 252102211047 and 252102211062, the Jiangsu Provincial Scheme Double Initiative Plan JSS-CBS20230474, the XJTLU RDF-21-02-008, the Science and Technology Innovation Project of Zhengzhou University of Light Industry under Grant 23XNKJTD0205, and the Higher Education Teaching Reform Research and Practice Project of Henan Province under Grant 2024SJGLX0126.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Erlin Tian and Zuhe Li; methodology, Shuai Zhao; software, Shuai Zhao; validation, Min Huang and Yushan Pan; formal analysis, Min Huang; resources, Erlin Tian; data curation, Yihong Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Shuai Zhao; writing—review and editing, Zuhe Li and Yushan Pan; visualization, Yihong Wang; project administration, Erlin Tian; funding acquisition, Erlin Tian and Zuhe Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li Z, Huang Z, Pan Y, Yu J, Liu W, Wang H, et al. Hierarchical denoising representation disentanglement and dual-channel cross-modal-context interaction for multimodal sentiment analysis. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;252(5):124236. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tsai Y-HH, Bai S, Liang PP, Kolter JZ, Morency L-P, Salakhutdinov R. Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences. In: Korhonen A, Traum D, Màrquez L, editors. Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019 Jul; Florence, Italy. Florence, Italy: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 6558–69. [Google Scholar]

3. Hazarika D, Zimmermann R, Poria S. MISA: modality-invariant and -specific representations for multimodal sentiment analysis. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2020 Oct; Seattle, WA, USA. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2020. p. 1122–31. [Google Scholar]

4. Wu Y, Lin Z, Zhao Y, Qin B, Zhu L-N. A text-centered shared-private framework via cross-modal prediction for multimodal sentiment analysis. In: Zong C, Xia F, Li W, Navigli R, editors. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021; 2021 Aug; Online. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. p. 4730–8. [Google Scholar]

5. Liu Z, Cai L, Yang W, Liu J. Sentiment analysis based on text information enhancement and multimodal feature fusion. Pattern Recognit. 2024;156(11):110847. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2024.110847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Baltrušaitis T, Ahuja C, Morency L-P. Multimodal machine learning: a survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2019;41(2):423–43. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2798607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Zadeh A, Chen M, Poria S, Cambria E, Morency L-P. Tensor fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis. In: Palmer M, Hwa R, Riedel S, editors. Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2017 Sep; Copenhagen, Denmark. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2017. p. 1103–14. [Google Scholar]

8. Zadeh A, Liang PP, Poria S, Vij P, Cambria E, Morency L-P. Multi-attention recurrent network for human communication comprehension. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirtieth Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Eighth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence; 2018 Apr; New Orleans, LA, USA. Menlo Park, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2018. 692 p. [Google Scholar]

9. Liu Z, Shen Y, Lakshminarasimhan VB, Liang PP, Zadeh BA, Morency L-P. Efficient low-rank multimodal fusion with modality-specific factors. In: Gurevych I, Miyao Y, editors. Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2018 Jul; Melbourne, VIC, Australia. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2018. p. 2247–56. [Google Scholar]

10. Yu W, Xu H, Yuan Z, Wu J. Learning modality-specific representations with self-supervised multi-task learning for multimodal sentiment analysis. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021 May;35(12):10790–7. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i12.17289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Poria S, Chaturvedi I, Cambria E, Hussain A. Convolutional MKL based multimodal emotion recognition and sentiment analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM); 2016 Dec 12–15; Barcelona, Spain. p. 439–48. [Google Scholar]

12. Zadeh A, Liang PP, Mazumder N, Poria S, Cambria E, Morency L-P. Memory fusion network for multi-view sequential learning. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirtieth Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Eighth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence; 2018 Apr 2–7; New Orleans, LA, USA. 691 p. doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.12021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Majumder N, Hazarika D, Gelbukh A, Cambria E, Poria S. Multimodal sentiment analysis using hierarchical fusion with context modeling. Knowl-Based Syst. 2018;161(2):124–33. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2018.07.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2017. p. 6000–10. [Google Scholar]

15. Lv F, Chen X, Huang Y, Duan L, Lin G. Progressive modality reinforcement for human multimodal emotion recognition from unaligned multimodal sequences. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 19–25; Nashville, TN, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 2554–62. [Google Scholar]

16. Rahman W, Hasan MK, Lee S, Bagher Zadeh AA, Mao C, Morency L-P, et al. Integrating multimodal information in large pretrained transformers. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020 Jul; Online. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 2359–69. [Google Scholar]

17. Han W, Chen H, Poria S. Improving multimodal fusion with hierarchical mutual information maximization for multimodal sentiment analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2021 Nov; Online. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. p. 9180–92. [Google Scholar]

18. Hou JM, Omar N, Tiun S, Saad S, He Q. TF-BERT: tensor-based fusion BERT for multimodal sentiment analysis. Neural Netw. 2025;185(6):107222. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2025.107222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Chen Y, Wang N, Zhang Z. DarkRank: accelerating deep metric learning via cross sample similarities transfer. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirtieth Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Eighth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence; 2018; New Orleans, LA, USA. 348 p. doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.11783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Huang Y, Lin Z. I2SRM: intra- and inter-sample relationship modeling for multimodal information extraction. In: Proceedings of the 5th ACM International Conference on Multimedia in Asia; 2024; Tainan, Taiwan. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. 28 p. [Google Scholar]

21. Li M, Wei Y, Zhu Y, Wei S, Wu B. Enhancing multimodal depression detection with intra- and inter-sample contrastive learning. Inf Sci. 2024;684:121282. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.121282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang H, Xu H, Long F, Wang X, Gao K. Unsupervised multimodal clustering for semantics discovery in multimodal utterances. In: Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2024 Aug; Bangkok, Thailand. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. p. 18–35. [Google Scholar]

23. Huang Q, Chen J, Huang C, Huang X, Wang Y. Text-centered cross-sample fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis. Multimed Syst. 2024;30(4):228. doi:10.1007/s00530-024-01421-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sun Z, Sarma P, Sethares W, Liang Y. Learning relationships between text, audio, and video via deep canonical correlation for multimodal language analysis. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(5):8992–9. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i05.6431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mai S, Xing S, Hu H. Analyzing multimodal sentiment via acoustic- and visual-LSTM with channel-aware temporal convolution network. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2021;29:1424–37. doi:10.1109/TASLP.2021.3068598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Devlin J, Chang M-W, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); 2019 Jun; Minneapolis, MN, USA. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

27. Liu Z, Lin W, Shi Y, Zhao J. A robustly optimized BERT pre-training approach with post-training. In: Li S, Sun M, Liu Y, Wu H, Liu K, Che W, et al., editors. Proceedings of the 20th Chinese National Conference on Computational Linguistics; 2021 Aug; Huhhot, China. Beijing, China: Chinese Information Processing Society of China; 2021. p. 1218–27. [Google Scholar]

28. Wang D, Guo X, Tian Y, Liu J, He LH, Luo X. TETFN: a text enhanced transformer fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis. Pattern Recognit. 2023;136(2):109259. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2022.109259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Huang C, Zhang J, Wu X, Wang Y, Li M, Huang X. TeFNA: text-centered fusion network with crossmodal attention for multimodal sentiment analysis. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;269(4):110502. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.110502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Li Z, Liu P, Pan Y, Yu J, Liu W, Chen H, et al. Text-dominant multimodal perception network for sentiment analysis based on cross-modal semantic enhancements. Appl Intell. 2024;55(3):188. doi:10.1007/s10489-024-06150-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ke P, Ji H, Liu S, Zhu X, Huang M. Sentiment-aware language representation learning with linguistic knowledge. In: Webber B, Cohn T, He Y, Liu Y, editors. Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 6975–88. [Google Scholar]

32. Toutanova K, Klein D, Manning CD, Singer Y. Feature-rich part-of-speech tagging with a cyclic dependency network. In: Proceedings of the 2003 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics on Human Language Technology—Volume 1. Edmonton, AB, Canada: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2003. p. 173–80. [Google Scholar]

33. Baccianella S, Esuli A, Sebastiani F. SentiWordNet 3.0: an enhanced lexical resource for sentiment analysis and opinion mining. In: Calzolari N, Choukri K, Maegaard B, Mariani J, Odijk J, Piperidis S, et al., editors. Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’10). Valletta, Malta: European Language Resources Association (ELRA); 2010. [Google Scholar]

34. Cheong JH, Jolly E, Xie T, Byrne S, Kenney M, Chang LJ. Py-feat: python facial expression analysis toolbox. Affect Sci. 2023 Dec 1;4(4):781–96. doi:10.1007/s42761-023-00191-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Degottex G, Kane J, Drugman T, Raitio T, Scherer S. A collaborative voice analysis repository for speech technologies. In: Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2014; Florence, Italy. p. 960–4. [Google Scholar]

36. Wang D, Liu S, Wang Q, Tian Y, He L, Gao X. Cross-modal enhancement network for multimodal sentiment analysis. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2023;25:4909–21. doi:10.1109/TMM.2022.3183830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Mai S, Xing S, He J, Zeng Y, Hu H. Multimodal graph for unaligned multimodal sequence analysis via graph convolution and graph pooling. ACM Trans Multimed Comput Commun Appl. 2023;19(2):54–24. doi:10.1145/3542927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Tishby N, Zaslavsky N. Deep learning and the information bottleneck principle. In: 2015 IEEE Information Theory Workshop (ITW); 2015; Jerusalem, Israel. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ITW.2015.7133169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Lambert J, Sener O, Savarese S. Deep learning under privileged information using heteroscedastic dropout. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 8886–95. [Google Scholar]

40. van Den OA, Li Y, Vinyals O. Representation learning with contrastive predictive coding. arXiv:1807.03748. 2018. [Google Scholar]

41. Zadeh A, Zellers R, Pincus E, Morency L-P. MOSI: multimodal corpus of sentiment intensity and subjectivity analysis in online opinion videos. arXiv:1606.06259. 2016. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1606.06259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zadeh AA, Liang PP, Poria S, Cambria E, Morency L-P. Multimodal language analysis in the wild: CMU-MOSEI dataset and interpretable dynamic fusion graph. In: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2018; Melbourne, VIC, Australia. p. 2236–46. [Google Scholar]

43. Ding Z, Lan G, Song Y, Yang Z. SGIR: star graph-based interaction for efficient and robust multimodal representation. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2024;26:4217–29. doi:10.1109/TMM.2023.3321404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Huang J, Zhou J, Tang Z, Lin J, Chen CY-C. TMBL: transformer-based multimodal binding learning model for multimodal sentiment analysis. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;285(1):111346. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zheng C, Peng J, Wang L, Zhu L, Guo J, Cai Z. Frame-level nonverbal feature enhancement based sentiment analysis. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;258:125148. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Huang J, Ji Y, Qin Z, Yang Y, Shen HT. Dominant single-modal supplementary fusion (SIMSUF) for multimodal sentiment analysis. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2024;26(11):8383–94. doi:10.1109/TMM.2023.3344358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Fan C, Zhu K, Tao J, Yi G, Xue J, Lv Z. Multi-level contrastive learning: hierarchical alleviation of heterogeneity in multimodal sentiment analysis. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2025;16(1):207–22. doi:10.1109/TAFFC.2024.3423671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools