Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

From Spatial Domain to Patch-Based Models: A Comprehensive Review and Comparison of Multimodal Medical Image Denoising Algorithms

1 University School of Computing, Sunstone, Rayat Bahra University, Mohali, 140104, Punjab, India

2 Chitkara University Institute of Engineering & Technology, Chitkara University, Rajpura, 140401, Punjab, India

3 Marwadi University Research Centre, Department of Engineering, Marwadi University, Rajkot, 360003, Gujarat, India

* Corresponding Author: Ayush Dogra. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 367-481. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066481

Received 09 April 2025; Accepted 26 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

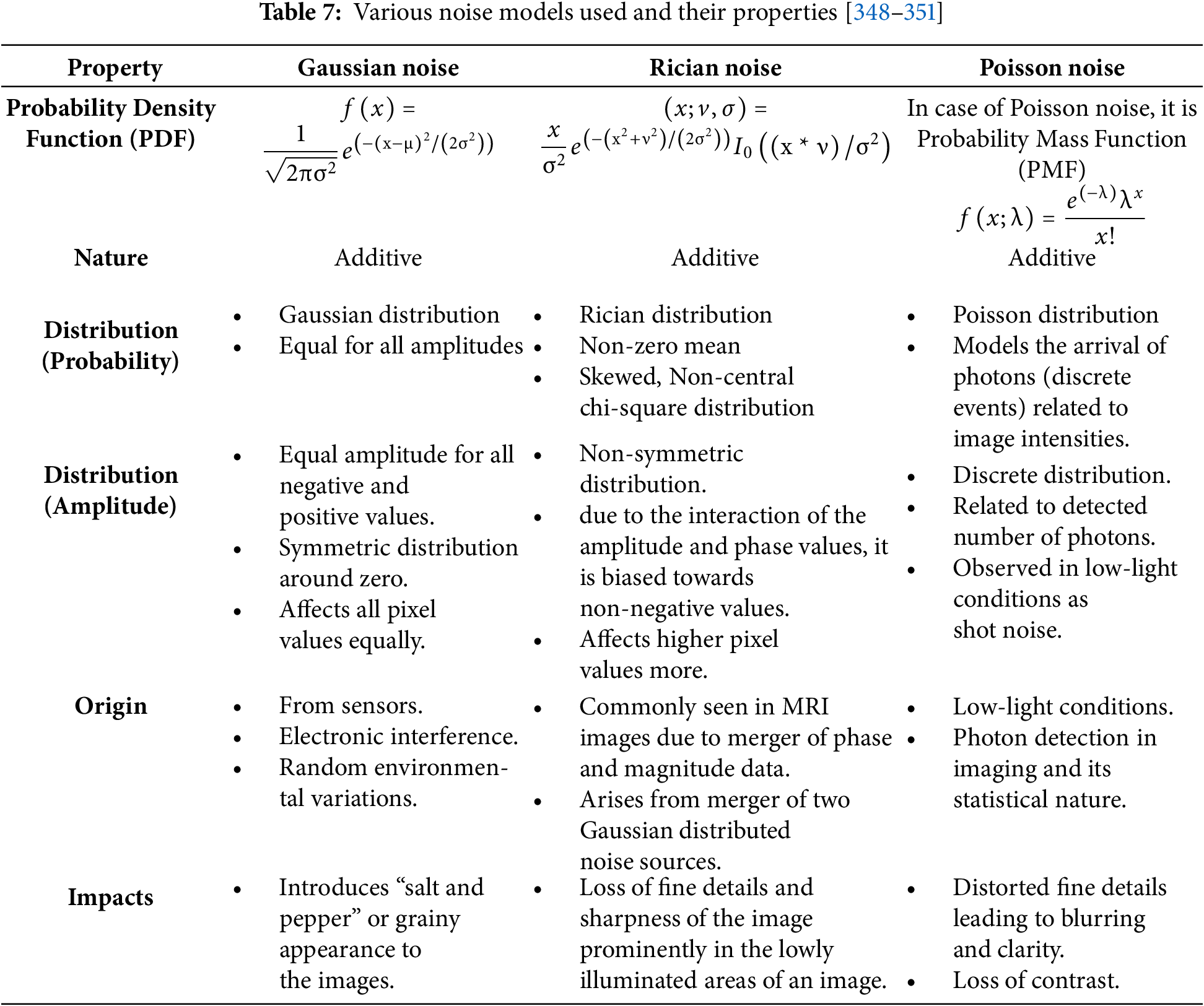

To enable proper diagnosis of a patient, medical images must demonstrate no presence of noise and artifacts. The major hurdle lies in acquiring these images in such a manner that extraneous variables, causing distortions in the form of noise and artifacts, are kept to a bare minimum. The unexpected change realized during the acquisition process specifically attacks the integrity of the image’s quality, while indirectly attacking the effectiveness of the diagnostic process. It is thus crucial that this is attended to with maximum efficiency at the level of pertinent expertise. The solution to these challenges presents a complex dilemma at the acquisition stage, where image processing techniques must be adopted. The necessity of this mandatory image pre-processing step underpins the implementation of traditional state-of-the-art methods to create functional and robust denoising or recovery devices. This article hereby provides an extensive systematic review of the above techniques, with the purpose of presenting a systematic evaluation of their effect on medical images under three different distributions of noise, i.e., Gaussian, Poisson, and Rician. A thorough analysis of these methods is conducted using eight evaluation parameters to highlight the unique features of each method. The covered denoising methods are essential in actual clinical scenarios where the preservation of anatomical details is crucial for accurate and safe diagnosis, such as tumor detection in MRI and vascular imaging in CT.Keywords

A denoising technique’s primary job is to minimize the background noise and, thus, enhance image quality for better visualization and diagnosis via better feature extraction and object recognition. Denoising can be considered a preliminary process before the final image is delivered. However, a significant limitation of denoising is the trade-off between reducing noise and preserving critical anatomical landmarks. In natural images, the noise induced by camera sensors is neither additive nor uniform over different grey levels [1]. The case of medical imaging is different from that of natural imaging in the sense that in medical imaging, the noises are signal-dependent with surfaces that are impossible to miss, making it hard for the conventional denoising techniques to remove them. The aftermaths of applying various spatially variant, direction-sensitive transformations to these images may result in further degradation if the process is not monitored and appropriately controlled. The nature of the image is affected by the nature and proximity of noise, making it very difficult to extract meaningful information, structures, and subtle elements from the debased image, vital for the diagnostic process [2].

Many imaging modalities exist in the medical field, of which CT and MRI imaging are the two most common and most popularly used. As the trend toward laboratory tests faded over time, the diagnosis process through images took over due to its efficiency and effectiveness. Some of the imaging techniques also provide results in real time. However, some challenges remained in the form of sensor noises or other environmental noises, along with artifacts. For the image to be clear, it must have a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and these modalities can provide excellent results if all the prerequisites are achieved with utmost care. Nevertheless, if these pre-requisites are not addressed appropriately, the images may turn out to be noisy and of no use at all [2–6].

Real-world challenges such as time constraints for processing, computational resource limitations, and the need for seamless integration into existing diagnostic processes sometimes constrain the application of denoising techniques in clinical practice. High-throughput environments, e.g., radiology departments or emergency rooms, require fast image processing without compromising diagnostic accuracy. In addition, not every clinical environment will possess the memory and processing power required by some advanced algorithms, deep learning models. These limitations emphasize the importance of developing useful and adaptable denoising methods.

Multimodal denoising methods that combine complementary data from multiple spaces—spatial, frequency, and learned feature spaces—have been increasingly recognized as a response to these challenges. Multimodal techniques can capitalize on numerous strengths to better preserve noise elimination with clinically important features, whereas single-domain approaches may be vulnerable to complex patterns of noise or modality-based distortion. Consequently, this study emphasizes the necessity and growing relevance of hybrid and multimodal denoising models that are tailored to the pragmatic needs of real-world medical imaging environments.

Challenges in Medical Image Denoising:

Medical image denoising has a unique and more challenging problem set than natural image denoising, which has been well researched. Medical images are characterized by highly specific anatomical and pathological features, which have to be preserved with the utmost precision for an effective diagnosis, unlike natural images, which may contain broad and redundant structures at times. Clinical expertise can be compromised if even minor structural features get lost in denoising.

In addition, in comparison to natural image sensors, noise characteristics specific to sensors in medical imaging devices (e.g., CT, MRI, and PET) are often more complex and varied. An example includes the non-stationary, non-Gaussian nature of MRI images, which are prone to Rician noise, and CT scans, which are often affected by Poisson noise.

Because of privacy, ethical, and cost concerns, there is a lack of extensive, annotated training data for medical images, another key difference. The existence of vast datasets in the natural picture domain is the complete opposite. In addition, clinical constraints such as low-dose imaging (to reduce radiation exposure) lead to inherently noisier images, so effective denoising is harder. Because of privacy, ethical, and cost concerns, there is a lack of large, annotated training data for medical images, which is another key difference. The existence of huge datasets in the natural image world is in direct contrast to this. In addition, clinical constraints such as low-dose imaging (to reduce radiation) yield naturally noisier images, rendering effective denoising more difficult.

Finally, the structural preservation and diagnostic integrity need to be taken most seriously in medical image denoising, unlike natural images, where perceptual quality is often sufficient. In a clinical environment, where deceptive features can lead to misdiagnosis, oversmoothing or hallucinating details techniques that are permissible in natural picture improvement are not suitable. Because of such issues, denoising medical images is not merely a technology problem but an area that necessitates a tremendous level of inter-disciplinary perception that combines experience of medical imaging modalities and clinical relevance along with expertise of image processing.

As compared to existing literature, this paper presents a comprehensive and comparative study of 80 denoising algorithms covering the three principal distributions of noise (Gaussian, Poisson, and Rician). This paper is a more practical guide for researchers and industries as it systematically ranks performance based on eight specified evaluation measures, as opposed to existing surveys that only focus on algorithmic concepts. The research also proposes issues specific to every modality and recommends an organization of denoising algorithms based on areas of application (spatial, transform, and sparse). Further, it presents clinical constraints like computational expense and time, and data diversity and angle dependency on PSNR as issues that have often been neglected in past analyses.

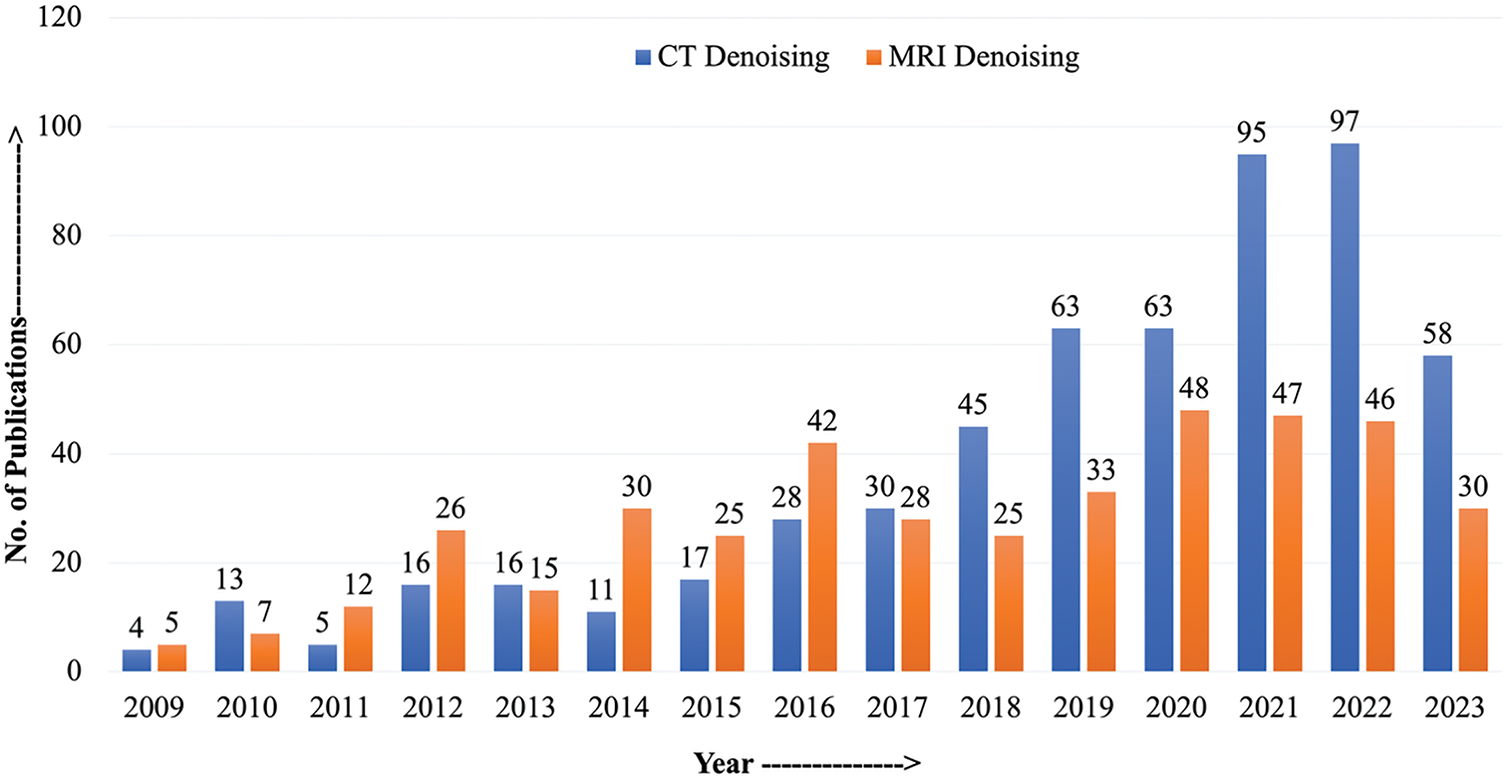

Additionally, imaging through these modalities is expensive, posing another challenge. These reasons push forward the case of the need for image refinement solutions through image processing. Fortunately, due to advancements in image processing, there are plenty of tools available. However, research will improve these techniques and make them suitable specifically for processing medical images. The trend also indicates the rise in popularity of image processing tools for medical images as the number of publications increased drastically in recent years (Fig. 1) [7–10].

Figure 1: Number of publications published with keywords or title CT denoising and MRI denoising from 2009 to 2023 (Source: Google Scholar)

Therefore, putting forth three crucial arguments in favour of the need for a workable denoising technique:

1. A low-resolution (LR) medical image can be converted into a high-resolution (HR) image without repeating the scan with denoising’s help. This is particularly important in cases where rescanning is not feasible or poses a risk to the patient’s health. Additionally, denoising can improve the accuracy of medical image analysis by reducing the impact of noise on image features and patterns. This is especially important in fields such as radiology and pathology, where accurate interpretation of medical images is critical for diagnosis and treatment planning. Finally, denoising can help reduce radiation exposure in medical imaging by allowing for lower-dose scans that still produce high-quality images.

2. By denoising and enhancing a low-radiation image, a high-quality image can be produced, reducing the need for high radiation exposure, as in a CT scan. This is particularly important for patients who require multiple scans over time, as repeated exposure to high levels of radiation can increase the risk of cancer.

3. Denoising brings forth a clearer image, reducing the time for diagnosis by medical professionals. In addition, enhanced images can reveal subtle details that may have been missed in the original scan, leading to more accurate diagnoses and better treatment plans [11,12].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed overview of the medical imaging modalities. Section 3 categorizes and discusses traditional and advanced denoising techniques across spatial, transform, and sparse domains. In Section 4, various Thresholding methods used in denoising have been covered. Section 5 covers the image noise models and artifacts. Section 6 outlines the evaluation metrics used for performance analysis. Section 7 presents the experimental results and comparative assessments. Section 8 discusses limitations, clinical relevance, and future research directions. And concludes the paper with key findings and contributions.

2 Medical Imaging Modalities (CT and MRI)

The new era of technology heralded a revolution in medicine. As we know it today, the practice of medicine results from years of research that went into the development of modern imaging techniques. Since the discovery of the “X-Rays” in 1895, the domain of imaging in medicine has grown by leaps and bounds. As the understanding of these rays grew, it had significant implications for medical imaging. During the period between the discovery of X-rays by Roentgen and the invention of CT scans in 1972 by Hounsfield, the field of medical imaging evolved at a slow pace. The change came with the development of the CT device. It changed how we saw the human body. The X-Ray generated a black-and-white image, in which it was challenging for a clinician to demarcate various body parts. The CT device transmitted the X-Rays simultaneously, measuring the degree of the attenuation coefficient of different tissues to the X-Rays [11]. With the CT came the “Hounsfield Scale,” a quantitative grayscale for describing the human body parts’ radio density. Thus, it increased our potential for visualization of the human body as it was more sensitive than the conventional X-Ray systems. This increased screening, diagnostic, and monitoring capabilities also helped us understand the human anatomy more clearly. However, the recent advances in technology have focused on improving the quality of images produced by these modalities [12]. Medical imaging has made significant progress in giving precise and thorough information about the human body with the development of new technologies. The development of CT scans and MRI devices changed radiology by enabling the study of inside organs and tissues to be seen in greater detail. Healthcare workers may now identify and diagnose illnesses at an earlier stage thanks to these modalities, which have shown to be more sensitive than traditional X-ray systems. Also, they have aided in tracking the development of illnesses and gauging the success of therapies. The quality of the pictures generated by these modalities has been further enhanced by recent technological developments, increasing their usefulness in medical diagnosis and treatment planning. We may anticipate even more advanced imaging technologies as a result of ongoing research and development, which will help us better comprehend the human anatomy and treat patients.

3 Conventional Denoising on Medical Images

As mentioned previously in the introduction, the noise in medical images is signal-dependent, i.e., it varies with the signal’s intensity. The majority of conventional cutting-edge techniques are ineffective in addressing this noise issue. Their inability to adapt to signal-dependent noise characteristics is the primary cause. These techniques frequently presume a fixed statistical model for noise, which may not accurately depict the complex and variable nature of noise in medical images. For instance, Coifman et al. (1995) demonstrated that a widely used denoising technique based on Gaussian assumptions performed inadequately when applied to medical images with non-Gaussian noise distributions [13]. This emphasizes the demand for more sophisticated denoising methods that can manage the various noise patterns present in medical images. For enhancing the accuracy and dependability of medical image analysis, it will be essential to create algorithms that can adapt to signal-dependent noise characteristics.

3.1 Filtering in Spatial Domain

Spatial filtering is performed by convolution of the image with a kernel capable of modifying an image in a particular way on the pixel level. In spatial domain filtering, neighbourhood operations are performed with a fixed-size array (kernel) designed to smooth, sharpen, or extract edges. The low-frequency information includes equal intensity areas. In contrast, the high-frequency information represents the intensity variations within an image. The smoothing process is equivalent to low-pass filtering, and the extraction of edges is equivalent to high-pass filtering of the image. The kernel is used to perform averaging as a neighbourhood operation on the pixels of the image to modify them spatially, i.e., the pixel under consideration is replaced with the weighted average of the pixels in its neighbourhood. This neighbourhood averaging operation can be described mathematically as [14].

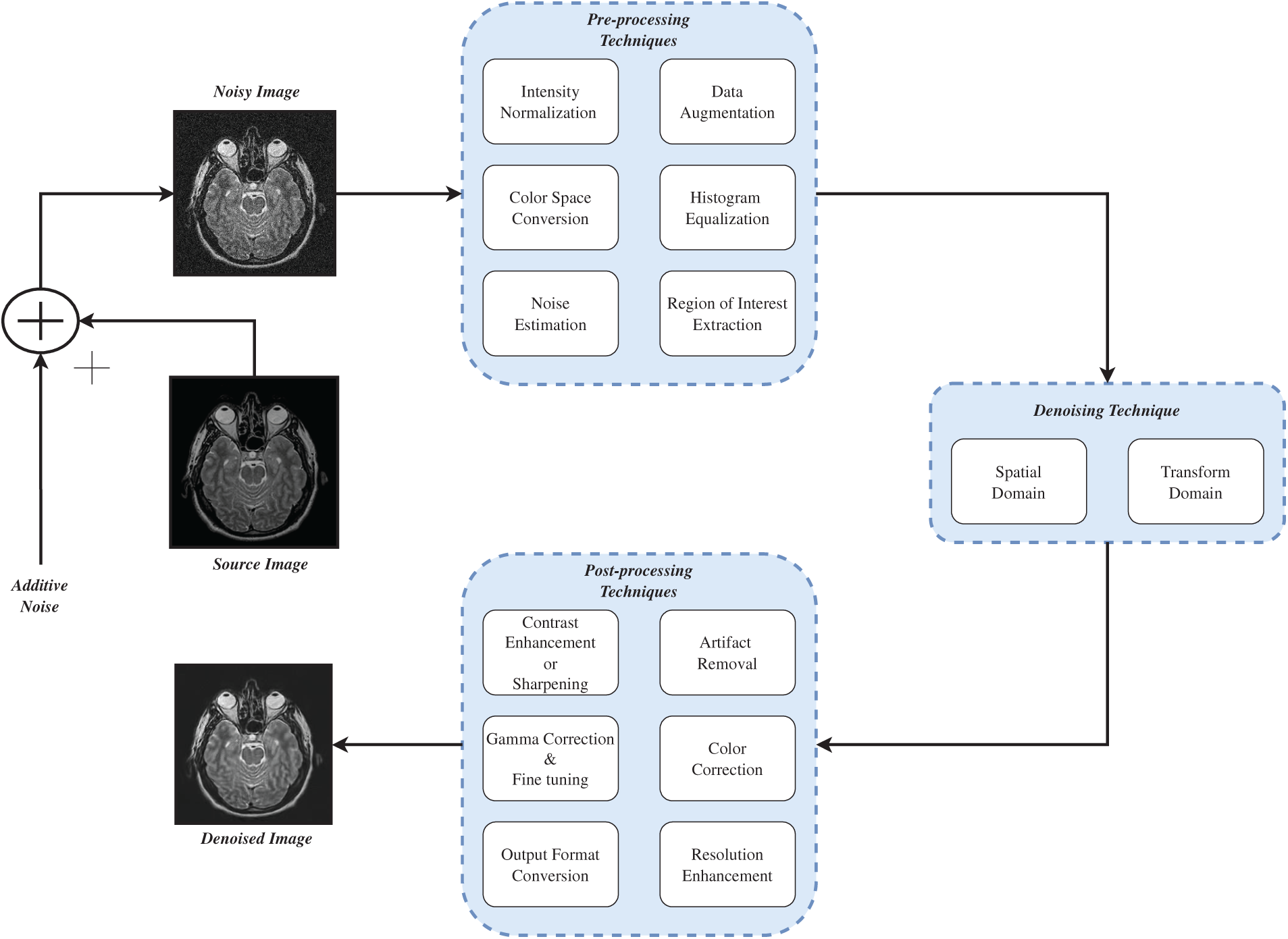

Fig. 2 shows the generic process of image denoising. It shows how denoising process can be carried out. First the noise is added to source image then preprocessing like histogram equalization, noise estimation, etc. is performed on the noisy image. Then image denoising algorithms is applied and at last the denoised image is produced.

Figure 2: A generic image denoising process

Eq. (1) shows that the calculations are performed over a square window of size m

The simplest example of the neighbourhood averaging operation is box filter or mean filter. The name box filter is assigned due to its frequency response resembling a box. A simple 3

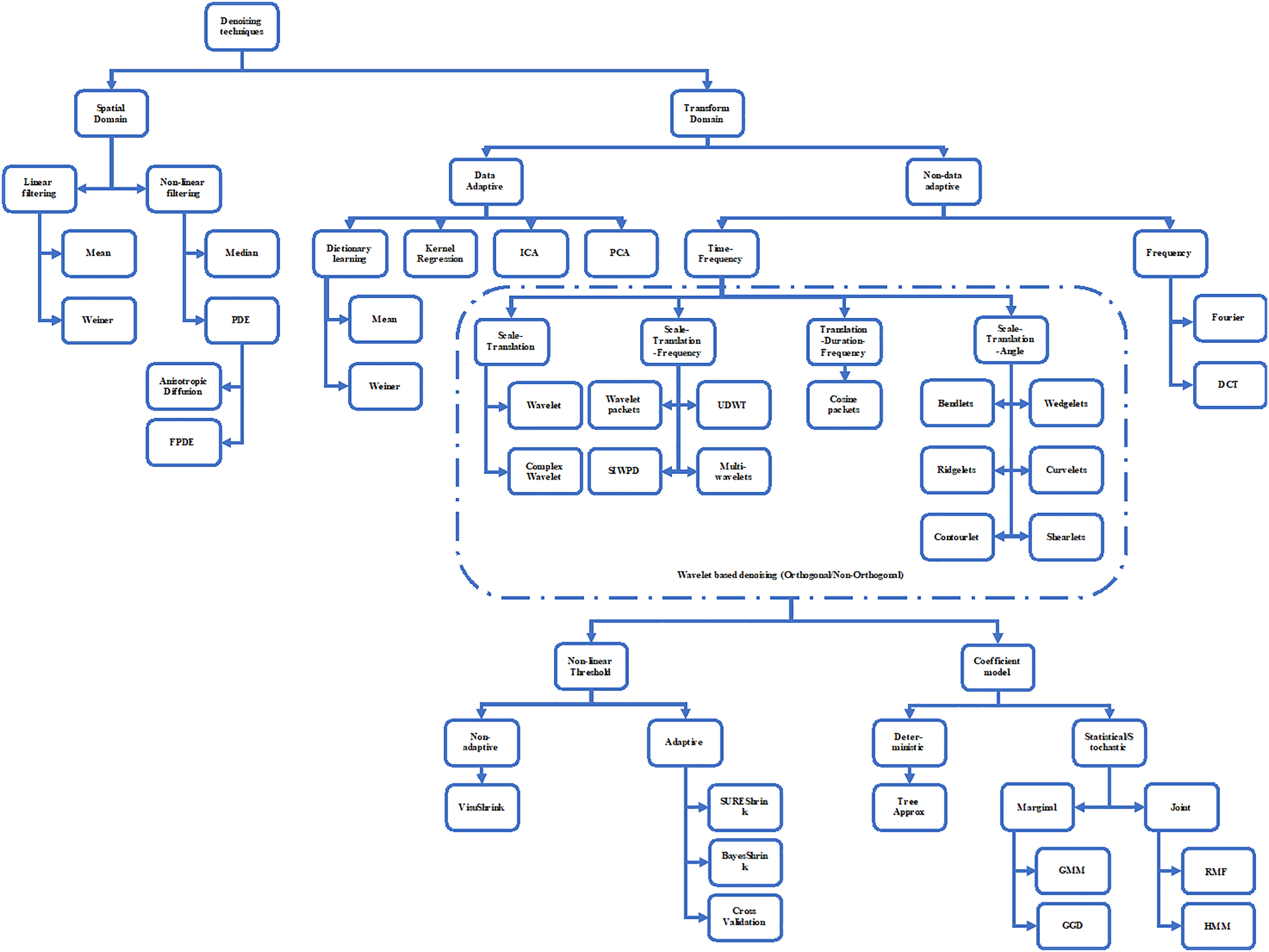

Fig. 3 shows the image denoising techniques and various its classification. The average filter possesses some properties like zero shift, i.e., the object position is not shifted after the operation due to its zero-phase, which implies a symmetric filter mask with a real-valued transfer function. It is well known that the smoothing operator affects the finer scales more than the coarser scales, which means that it should have the monotonically decreasing transfer function so that a particular scale does not get annihilated while simultaneously preserving the smaller scales. Additionally, the smoothing should be the same in all directions, i.e., it should be isotropic. In discrete spaces, this goal is hard to achieve. So, it can be seen as a potential challenge to design kernels that deviates the least from isotropy [16].

Figure 3: Denoising methods classifications

The time-domain representation or the inverse Fourier transform of this box function is a Sinc function. A filter can be represented either in IIR (Infinite Impulse Response) form or FIR (Finite Impulse Response) form. When expressed in FIR form, the time domain’s impulse response needs to be truncated, making the filter perform poorly near the edges. Due to sharp cut-offs in the frequency domain, this filter also introduces ringing near the shapes’ boundaries in the images. Another drawback of the mean filter is that a pixel with the least significance can also influence the average value of pixels in its neighbourhood, affecting the pixels’ values near edges, which leads to the loss of essential details in the image. The filter also deviates from isotropy when the mask size is increased beyond a specific limit, which leads to the decision that the choice of mask size is subjective to the data in hand [18]. In [14], authors presented effective ways in which the mean filter can be used to handle complex images and in [19], non-linear mean filters were used to denoise the medical images and detect edges for effective diagnosis.

It is possible to derive better smoothing filters by knowing the relation between the Fourier transform pairs’ compactness and the smoothness. In the case of mean/box filters where the smaller size of filter masks resulted in degraded transfer functions, the larger mask sizes improved the transfer function at the cost of increased overshoot along with compromised isotropy. The edges or intensity variations are regarded as discontinuities in space, and the Fourier transform’s envelope of a signal having discontinuities in space decays in the frequency domain. This paves the way for the synthesis of efficient filters called the Binomial filters. The 1-D Binomial filter mask can be written as [20,21]

It is the convolution of the elementary binomial smoothing mask,

These masks have values of binomial distribution hence the name Binomial filters. The transfer functions of Binomial filters are monotonically decreasing with zero value at the highest spatial frequency. As the order of the filter is increased, the transfer function tends toward Gaussian distribution. Similarly, in 2-D Binomial filters, when order is increased, the filter loses its isotropic nature. It tends towards an anisotropic character as the transfer function increases in the direction of diagonals. While these linear filters effectively deal with zero-mean Gaussian noise, they cannot appropriately tackle impulse noise [20–23].

Further improvement in mean filters came through Alpha-trimmed mean filters designed for Gaussian noise with underlying impulse noise components. This filter lies on the boundary of mean filters and median filters, where the value of

where

The linear filters are useful in the case of Gaussian noise but perform poorly in the case of binary noise. Additionally, it is generally assumed that every pixel carries information. So, in linear filtering, the information simply gets carried to the neighbouring pixels rather than elimination. The task at hand remains to identify these pixels and eliminate them. The rank-value or median filters do this task [27,28]. The non-linear filters select the medium value of intensity arranged in ascending order based on the array position [29]. As an impulse will be surrounded by the pixels of almost equal intensity, it falls on the sorted array’s extremes; hence it gets replaced with other appropriate pixels. Besides, edges and constant neighbourhoods are also preserved as they are regarded as fixed points. For a single unnecessary discontinuity, lower window sizes are used, whereas larger window sizes are used for the groups of infected pixels [30].

The median filter operation tends to remove thin corners and lines, and its performance is rather unsatisfactory in signal-dependent noise. So, the issue of MRI imaging will not be addressed effectively with this kind of filtering [31]. Later on, other more efficient median filter variants were introduced, trying to solve the associated problems by adaptive measures. The first such evolved variant is Centre Weighted Median Filter (CWMF) [27,32,33], which gives more weight to the window’s central value. It provides a controlling power over the smoothing behaviour of the filter. The CWMG is effective in preserving relatively thinner and sensitive details while removing the white or impulse noise. A similar other example is Neighbourhood Adaptive Median Filter (NAMF) [33], which changes the neighbourhood’s size during filtering operation providing greater flexibility. It has been found that repeated median filtering applied on a sequence of length L converts into a sequence, which becomes invariant to further median filtering. It happens after (L-2)/2 iterations, and it is an advantage in the case of coding but a disadvantage for smoothing a variety of noises. While the median filters are useful in suppressing impulse noise, non-impulsive noise is filtered better by linear average filters. So, a Dual-Window Modified Trimmed Mean (DWMTM) filter was proposed, which blended both linear and median filters’ qualities to remove the impulsive noise the non-impulsive noise simultaneously [34,35]. As linear filters are known for smearing the edges (high-frequency information), a low-order low-pass linear filtering system is used to avoid this [32]. The later improvements in median filtering came in the form of Tristate median filter (TMF) and Decision based median filtering (DBMF) [36,37]. In TMF, the standard median filter is blended with the Centre-Weighted Median Filter (CWMF) to balance the trade-offs between the two. In DBMF, apply a decision map to choose an appropriate substitute value for the central pixel. In DBMF, a decision is made according to the assumption that the corrupted pixel takes minimum and maximum values within the dynamic range (0, 255). If the pixel lies within this range, it is considered a noise-free pixel and is left unaltered otherwise; it is replaced by the median or its neighbouring value [36,38–41].

Extensive research has been carried out for denoising of medical images using median filters and evolution of median filter paved the way. A variety of median filters have been developed over the years to effectively tackle the problem of medical image denoising [42,43]. In [44], median filter and adaptive median filter were studied and used for removing salt and pepper noise from the medical images (MRI and CT) and satisfactory results were obtained. In [45], various parameters influencing the performance of median filter were explored and compared. Various median filter based techniques were reviewed and discussed in detail in [42,37] for denoising of CT and MRI images. The study concluded Adaptive Median Filter (AMF) the most effective in removing salt and pepper noise from CT images. Another manuscript presented a comprehensive performance analysis of the Neutrosophic Set (NS) methodology applied to median filtering for the purpose of eliminating Rician noise from magnetic resonance images. A Neutrosophic Set (NS), an integral component of the theoretical framework of neutrosophy, delves into the examination of the genesis, essence, and extent of neutralities, alongside their intricate interplays with diverse ideational spectra. The experimental findings indicated that the NS median filter exhibits superior denoising efficacy in both qualitative and quantitative assessments when juxtaposed with alternative denoising methodologies [46]. The application of multi-stage directional median filters to MRI images was discussed in [47] and, an improvement was indicated over wavelet method. In the literature mentioned above, the utilization of the median filter technique was observed as a means to address a singular form of noise that pervades medical images. As a result, in the work conducted by Ye Hong Jin et al. [48], the median filter was employed in conjunction with wavelet transform to successfully combat the presence of mixed Gaussian and impulse noise. The experimental findings demonstrated superior efficacy compared to the exclusive utilization of median filtering and wavelet transform based filtering methodology.

Order statistic filters were best suited for impulse noises, which are rarely encountered in medical images. However, the variants of the median filter proposed later on were designed to deal with other noises and impulse noise present in the image; more robust filters are there to explore which are more effective than the median filters. One such example is of Gaussian filter. Gaussian filters are mainly used to eliminate the Gaussian noise present in the image. It is a non-linear, isotropic operator based on Gaussian equation, written as [49–51]

This 2D distribution is used as a “Point Spread Function” (PSF) for Gaussian smoothing. To perform a smoothing operation on an image, this function (equation) is reduced to a discrete approximation. Theoretically, due to its non-zero values, a large size of convolution kernel is required for efficient smoothing but, due to compromised speed of operation, the kernel is truncated above three standard deviations from the means to create a fixed size lower-order mask. When convoluted with the image, this mask produces a resultant image free from Gaussian noise and high-frequency details. The choice of

A smoothing technique’s primary goal is to smooth out intensity variations in an image while preserving meaningful edges and contours. These techniques are called edge-aware smoothing techniques. An edge defining an object in the scene becomes a contour, which means that edges can be detected using local tools, while for contours, some global tools are needed. Applying such tools to an image may boost trivial textures and details and pose serious computer vision problems [54]. To prevent this, images are smoothed first to remove the trivial textures and details, and after that, some more sophisticated tools are applied to boost the relevant details. One such example is the Local Laplacian filter, in which the profile of the discontinuities is maintained. The application of local Laplacian filter may change the magnitude of the variation without losing the shape of the discontinuity (as depicted in graphical representation). This solves the problem of generation of halos, gradient reversal artifacts, and shifted edges. This comes at the price of high computational cost. Many attempts have been made to improve the speed of the operation [55–57].

An image is composed of pixels having individual intensities placed at specific spatial locations. Let us assume that the range of values within the image is between [0, 1], and due to the discrete nature of images, the spatial coordinates will be integers. In Gaussian filtering, only the spatial aspect of images is explored. An improvement in the Gaussian filter was proposed as a Bilateral filter in which both the spatial and the range parameters are considered while filtering. So, the bilateral filter equation is a modification of the Gaussian equation, written as [58,59]

where,

Despite the superior performance of the bilateral filter compared to the Gaussian filter, the denoising capabilities exhibited were still deemed to be below the expected standard. The existing body of literature unambiguously demonstrates that, in order to compensate for the inherent limitations of the bilateral filter, it was conventionally utilized in conjunction with an alternative methodology. For instance, in the works of [63–65], the bilateral filter was implemented on the sub-bands of images derived from the process of multi-resolution decomposition of the original image. In the studies conducted, the image was decomposed using simple and complex wavelets. However, in the research conducted by Vinodhbabu et al. in [66], a different approach known as the Dual-Tree Complex Wavelet Transform (DTCWT) was employed for image decomposition. In a study conducted in [65], the utilization of sub-sampled pyramids and non-subsampled directional filters was observed. Additionally, in another study conducted by K. Thakur, the Shearlets were employed for the purpose of image decomposition [67]. In the study conducted by Tao Wang, the bilateral filter technique is employed for the purpose of decomposing the medical image into sub-bands. Subsequently, the K-SVD algorithm is applied to the high-frequency sub-band in order to generate visually appealing outcomes [68]. In the work conducted by Mohamed Elhoseny, a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is employed in conjunction with a bilateral filter for the purpose of denoising medical images [69]. Furthermore, in [70], the determination of optimal values for space and range parameters was achieved through the utilization of an image-driven approach. This approach demonstrated superiority over conventional bilateral denoising techniques across various benchmarks. In the study conducted in [71], a neural network was employed to enhance the efficacy of the bilateral filter and shows the application of neural networks as an effective system to reduce noise, where a bilateral filter can be used to perform edge-preserved image denoising. The suggested LDA employs statistical functions of mean and median of output pixels results. In [72] the bilateral filter was combined with the Non Local Means (NLM) filter to achieve optimal denoising capabilities.

Later improvements came in the form of Joint/Cross Bilateral filter (CBF) and Guided image filter (GIF). Both of the filters used a guidance image to guide the smoothing towards an edge-aware approach. The guidance image having precise high-frequency details is used as an estimator to evaluate the edge-stopping function

Here,

In literature [80], demonstrates the use of cross- bilateral filter along with PCA (Principal Component Analysis) to denoise medical images where, supplementary image for CBF was generated by applying and PCA to image and then applying preliminary smoothing using wavelet transform on the first principal component generated from the image. Similarly in [81], guided filter was used with DWT to preserve more edges compared to fast guided filter. In [82], iterative guided filter was used to denoise PET-MR (Positron Emission Tomography-Magnetic Resonance) and PET-CT (Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography) and it showed a significant reduction in RMSE (Root Mean Square Error). Finally in [83], a novel guided decimation box filter was introduced along with HPSO (Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization) to effectively denoise medical images. This method was tested on various test retinal, MRI and Ultrasound images and results showed a significant improvement in terms of PSNR, SSIM and FSIM assessment parameters.

Unlike the above-described filters, if the blurring or degrading function of an image is known, the quickest way to restore the image is Inverse filtering. Initially, it is a form of the high-pass filter, so it tends to increase the noise levels of an image but, as the whole idea of Inverse filtering revolves around accurately predicting the blur or the noise model and then filtering the input image through the inverse of that predicted noise model, it can be manipulated to act as an low-pass filter by introducing thresholding in it. So, if the blurred image is modelled as [84]:

where,

In [92], DWT was used parallelly with Wiener filter to denoise MRI and CT images while simultaneously enhancing the images. Similarly, in [93] and [94], the proposed methodology employed a cascaded configuration of the Dual-Tree Complex Wavelet Transform (DTCWT) to generate distinct frequency bands for the purpose of analysis. The outcome exhibited better balance in terms of smoothness and accuracy compared to the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), while also demonstrating reduced redundancy in comparison to the Stationary Wavelet Transform (SWT). N. Jacob and M. Kazubek previously showed the use of the Wiener filter in conjunction with wavelets in [87] and [95] to eliminate Additive White Gausian Noise (AWGN) from general images, and this use was later extended to medical images. In [96], author presented a simple and effective Wiener filtering (WF)-based iterative multistep image denoising method that used the denoised image as input. The denoising process ended when image energy adapted to a circumstance. This technique effectively removed noise while preserving edges. Weiner filter based on Neutroscopic Set approach were also used to denoise MRI images. In this technique Wiener filter was used on True and False membership sets to reduce the indeterminacy and remove Rician noise from MRI images [91].

The domain transform filtering is aimed towards preserving the geodesic distance between curve’s points. The input signal is adaptively warped so that an edge-preserving filtering can be implied in real time. For this an isometry between the curves is defined. It is an fast iterative process applied to original samples of an image, targeted to achieve an optimum trade-off between convergence and operation of smoothing. The domain transform filter is also capable of working on arbitrary scales of an image in real time and its kernel stops operation at firm edges. Despite of these advantages, the domain transform filter was rotationally invariant. So, applications like content matching are not feasible with this kind of filtering. While the domain transforms filter deals with the

An arbitrary noisy signal

where,

In previous works the notion of an edge or an high frequency detail was based on large difference values or large gradients and different contrasts. According to this notion, fine details or textures having fine scale tend to be ignored. The property that differentiates key edges from textural details, called oscillations, were captured by the new multiscale decomposition method based on local extrema [104]. It is a non-linear approach for effectively extracting fine-scale details irrespective of their contrast. According to local extrema based decomposition, the details are defined as fine-scale oscillations between local extrema. So, in this method, smoothing is performed recursively at multiple scales with extrema detection. As a result, high contrast textures are smoothed without affecting salient edges. This makes it an efficient approach for multiscale decomposition [104,105]. The linear and some of the non-linear filtering processes introduced halos in the filtered results. This was due to the inability of the filter to differentiate between fine details because of relative nearness of those details with each other. When filter couldn’t differentiate what to filter and what not to filter, halos are generated at the boundaries of the objects having very fine and closely located details. Weighted Least Square (WLS) filter solves this problem by minimizing the cost function, depicting the difference between the noisy image and its smoothed version. The weighted square error equation which is required to be minimum is given as

In the realm of image denoising, the process of optimization in image processing entails the identification of the most optimal solution to a given problem, as determined by a pre-established objective function. The objective of optimization algorithms is to iteratively adjust model parameters in order to minimize or maximize a given function. Optimization is frequently employed in the field of image processing to identify optimal parameters that result in improved image quality, encompassing the reduction of distortion and the enhancement of details. In contrast, regularization in the field of image processing entails the incorporation of constraints or penalties into optimization problems in order to enhance the quality of outcomes. The utilization of this technique serves the purpose of mitigating overfitting, diminishing noise, and augmenting the visual fidelity of images through the facilitation of specific attributes. Regularization techniques encompass various methods such as L1 regularization (also known as Lasso) [101], L2 regularization (commonly referred to as Ridge) [111–113], Total Variation (TV) regularization, and additional approaches. Complex image processing problems are solved via regularization and optimization. In image deblurring, an optimization method finds the optimal image that minimizes the blurred image’s difference from the predicted sharp image. Regularization terms can be applied to this optimization issue to smooth the sharp image and prevent deblurring artifacts.

One such approach adopted over time to improve the denoising is by regularization of the algorithm called Gradient Descent (GD). Gradient descent is a widely employed optimization algorithm utilized in the process of minimizing a loss function while training machine learning models. The problem is associated with finding a minimum

The regularization function is

The task is to find minimum value of function

The value of

Putting this value in Eq. (15) gives

The linear regression model loses its accuracy when the feature coefficients are reduced. The loss in accuracy is compensated with the “Bias” of model equation. This bias does not depend on feature data. Regularization is one of the ways to tweak the bias according to situation. In this paper, the regularizations explored are Beltrami regularization (BR) [116], regularization with Disc or quadratic priors (QP) [117,118], Huber priors (HP) [119], Log priors (LP), Total Variation (TV) [120,121], etc. All regularization produced different results both visually and parametrically. In total variation (TV), the regularization term is replaced by

And its gradient is given by

All the regularization priors have their own advantages and disadvantages but their operation is totally application dependent.

In the context of medical images, Gradient Descent has been used to match the observation (known as deep image prior) where a randomly initialized convolutional network was used for the reconstruction image’s parametrization [122]. Furthermore, in [123], authors offered a total variation-based edge-preserving denoising algorithm. Their model functional contained a unique edge detector built from fuzzy complement, non-local mean filter, and structure tensor to solve the issues like staircasing effect and detail loss originating from denoising models like Rudin-Osher Fatemi [124].

The Co-occurrence filter (CoF) is based on Bilateral filter. In bilateral filter, a Gaussian is used on the range values to preserve strong edges whereas in CoF, co-occurrence matrix is used [125–127]. The co-occurrence matrix consists weights according to the frequency of co-occurrence of pixels in an image, i.e., frequently occurring pixels have high weight values and vice versa. The filtering process is then carried out according to these weights. CoF is suitable for images with high graphics and differentiable textures but it is not suitable for images with high noise levels [128–130]. Table 1 shows the various regularization techniques that are used for image denoising.

Also, the Haralick feature matrix is large in dimensions, consuming high memory space [159]. There exists a practical relevance of variational solver’s approximations in image processing. While the diffusion or Lagrange equation based solvers are slow and restricted in their performance, the filter based variational energy reduction was an efficient solution. This approach was termed as Curvature filtering. It was based on reduction of regularization with non-increasing energy, applicable to models dominated by regularization with increasing data-fitting energy and decreasing regularization energy. In curvature filtering, discrete filtering is applied to evaluate images with reduced energy for variational models, dominated by regularization with the help of Total variation (TV) or Curvature regularization. This helps in design of faster filters with lesser regularization [160,161]. Despite these pros, this filtering is unstable for certain parameters and may induce artifacts and over-smoothness with lost details. In Savitzky-Golay filters (S-GF), smoothing is achieved when data points adjacent to each other are successively fitted with a polynomial of lower degree with the help of a method called local linear least squares. An analytical solution to the problem of least squares is found when data points are spaced equally. The solution is a set of coefficients which are used to perform convolution with data-sets to provide the estimates of the smoothed signal. Tables of coefficients based on different polynomials were published by Abraham Savitzky and Marcel Golay in 1964 [162–165].

Another filter based on the composition of linear operators and non-linear morphological operators called Bitonic filter was proposed in [166]. This filter was better than median filter in terms of preserving edges and had robustness in its operation because it can be applied to a wide variety of signal with different types of noises. It inherently assumed that signal is bitonic, i.e., having a single maxima or minima in the filter range. The main achievement of this filter was that it was able to reduce noise in different areas of an image containing consistent regions and discontinuities without introducing any additional artifacts and deformities because of independence from data sensitive parameters which helped the filter to locally adapt to noise levels in the image. It also do not require any prior knowledge of the characteristics of the noise present. The tests on various datasets revealed that bitonic filter is efficient in reducing non-uniform noise distributions while preserving edges in a non-iterative way. The filter was faster, stable and not dependent on parameters like anisotropic diffusion, Non-local Means (NLM) and Guided filter, etc. [166,167]. On the other hand, it is sensitive to structuring element’s shape. Three other variants of bitonic filter were proposed later as an improvement over the standard bitonic filter. These variants were the Structurally Varying Bitonic filter (SVB), Multi-resolution Structurally Varying Bitonic filter (MRSVB) and Locally Adaptive Bitonic Filter (LABF) [168]. The LABF was proved to be better than even BM3D filtering for higher levels of Additive White Gussian Noise (AWGN). These evolutions of bitonic filter combined anisotropic Gaussian operator with robust morphological operation. These morphological operations were kept structurally varying to deal with the situation of sensitivity towards structuring element. The multi-resolution framework improved the results even further [168,169].

The Kuwahara filter is an adaptive non-linear filter named after Michiyoshi Kuwahara and developed for processing and analysis of angiocardiographic images. In Kuwahara filter, mean

The Partial Differential Equation (PDE) based smoothing became popular after proposal of Anisotropic diffusion filtering or Perona-Malik diffusion filtering. This filtering was proposed to smooth the images without affecting the “semantically meaningful” edges. PDEs offer several advantages in image processing and computer vision field. PDE based methods help in finding stable algorithms with well-posed scenarios, allowing reinterpretation of classical techniques under a unifying, continuous and rotationally invariant framework [172–176]. PDE based smoothing techniques can also offer more invariance as compared to the classical techniques and, describe new ways of enhancement of line-like, coherent structures, preserving structures and simplifying shapes. The general diffusion equation is given as [173,177]

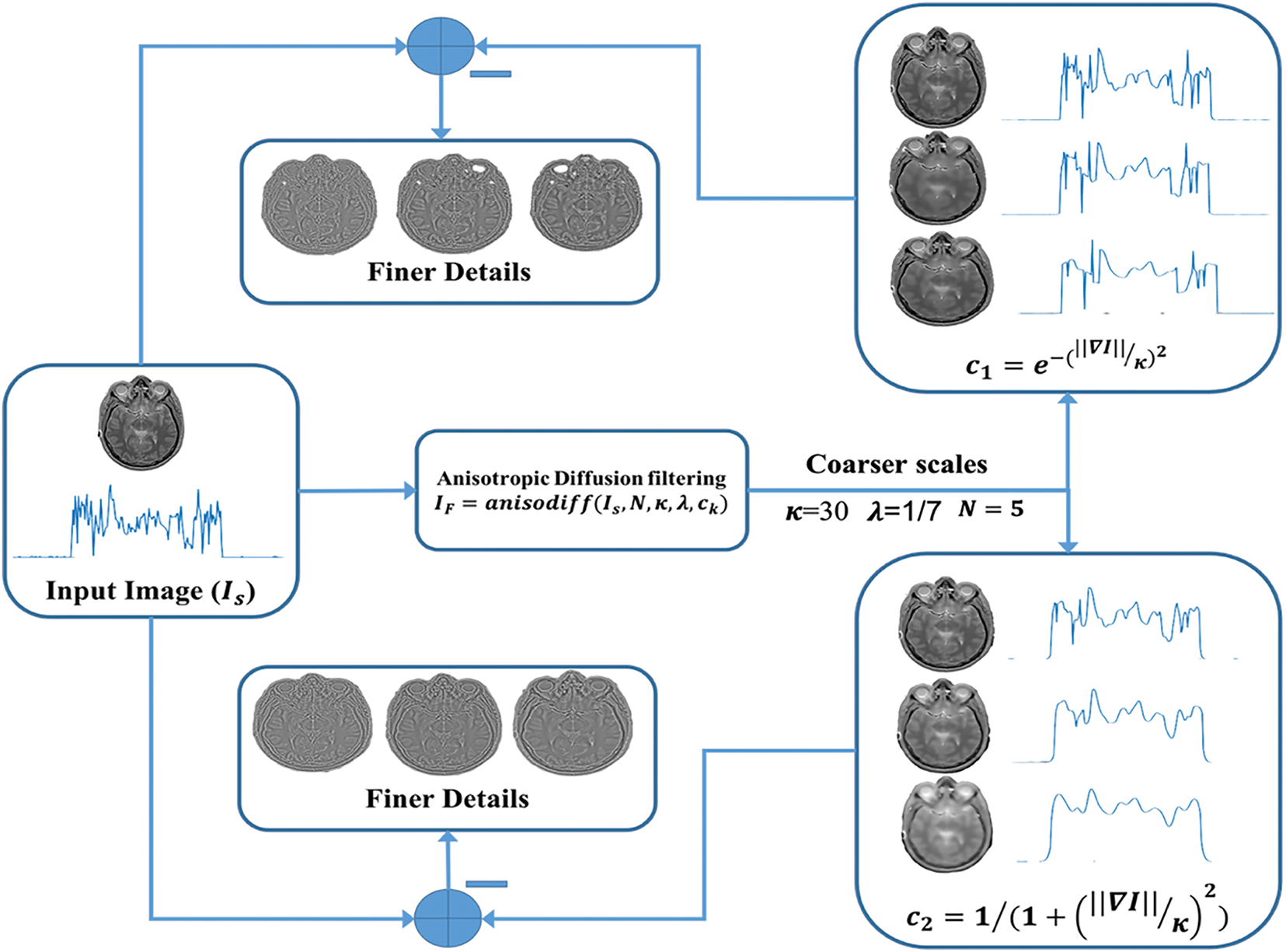

Fig. 4 shows the anisotropic diffusion filtering by using different conduction coefficients. In the context of image filtering, the concentration of grey value at certain locations is considered. Based on the above explanation, the direction of filtering can be taken towards either linear diffusion filtering or non-linear diffusion filtering. The problem associated with linear-diffusion filtering was that, it dislocated edges while moving from finer scale to coarser scale in scale-space representation. So, identified structures did not provide the right location which could be traced back to the original image at coarser scales. Therefore, Perona and Malik proposed a non-linear diffusion technique to prevent localization problems of linear diffusion filtering techniques. The diffusivity is reduced by applying an inhomogeneous process, at locations where there is maximum likelihood of existence of an edge. They introduced a scalar-valued diffusivity instead of a diffusion tensor as

Figure 4: Anisotropic diffusion filtering using different conduction coefficients

Or, as Perona-Malik wrote it

In the above equation,

In local mean filter, mean of the pixels in a fixed sized window is taken to smooth the image. Unlike local mean filter, Non-Local Means (NLM) filter considers the mean of all the pixels in an image. This results in a clear image with less loss of details. The discrete NLM algorithm for an image

where,

Anisotropic diffusion and NLM filtering are two very well researched techniques in the domain of image denoising and restoration due to their robustness and excellent outcomes. In the context of medical images they have been used not only for denoising but for enhancement also. In [183], a Lattice-Boltzmann method based anisotropic diffusion model was proposed to address the instability problem of conventional anisotropic diffusion model. The proposed model was not only faster but more efficient than the model presented by Perona-Malik in [178]. In [184] and [185], anisotropic diffusion filter was used with wavelet transform to eliminate various types of noises from medical images. Additionally, anisotropic diffusion filtering method has been extensively explored for the denoising of Ultrasound images also.

NLM filter has shown promising results in reducing noise while preserving important details in various medical imaging modalities such as MRI, CT scans, and ultrasound. Additionally, the Non-local Means filter has been found to be effective in improving the accuracy of image analysis tasks like segmentation and registration in medical imaging applications. In 2006, faster and optimized version of NLM was used to filter 3D MRI images. The proposed methodology leveraged the inherent redundancy of information within an image to effectively eliminate undesirable noise [186]. An adaptive version of NLM was later used in [187] to denoise medical images. The proposed methodology utilized the singular value decomposition (SVD) algorithm and the K-means clustering technique for the purpose of robustly classifying blocks within images that are affected by noise. In [19] and [188] again, NLM was used to denoise medical images. In [189–191], NLM was used in hybrid with Bilateral filter, PCA and Sparse coding respectively to assist NLM to effectively denoise CT and MRI images. These hybrid techniques were meant to address the limitations and trade-offs between the different denoising techniques employed.

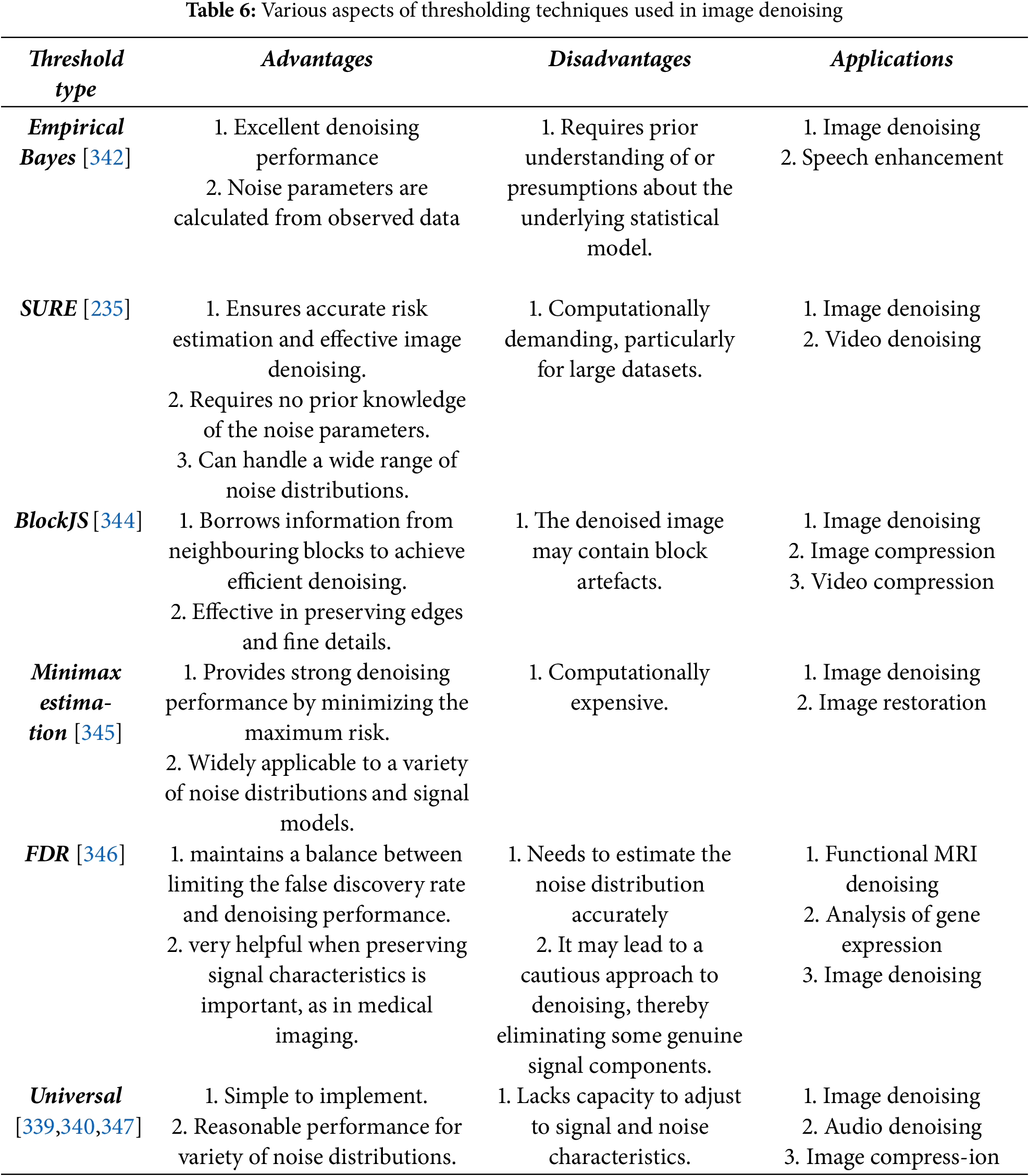

3.3 Frequency Domain Filtering

Frequency domain filtering is based on transforming the image to frequency domain and then applying an appropriate thresholding operation to choose relevant coefficients and then applying inverse transform to bring back the image in spatial domain. The basis of filtering in frequency domain is Multi-Scale Decomposition (MSD), a technique frequently used in image fusion algorithms [192,193]. In all major frequency domain techniques like Wavelets, Shearlets, etc., the image is first decomposed into its low frequency approximate and high frequency detail sub-bands. The approximate sub-band is coarser and high-frequency detail sub-bands and relatively finer. As the noise affects only the finer sub-bands, thresholds are applied to those high-frequency sub-bands, keeping coarser level as it is. Finally, the image is recovered back by applying inverse of the transform initially applied. This type of strategy is very helpful in understanding the dynamics of the noise and often very useful in removing a variety of noises. Some noises like periodic noises are removed efficiently only by frequency domain filtering. In most basic frequency domain operations like Fourier Transform (FT), Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT), images are just transformed and then thresholding operation is applied to the coefficients [194,195]. The various thresholding techniques are discussed in later section.

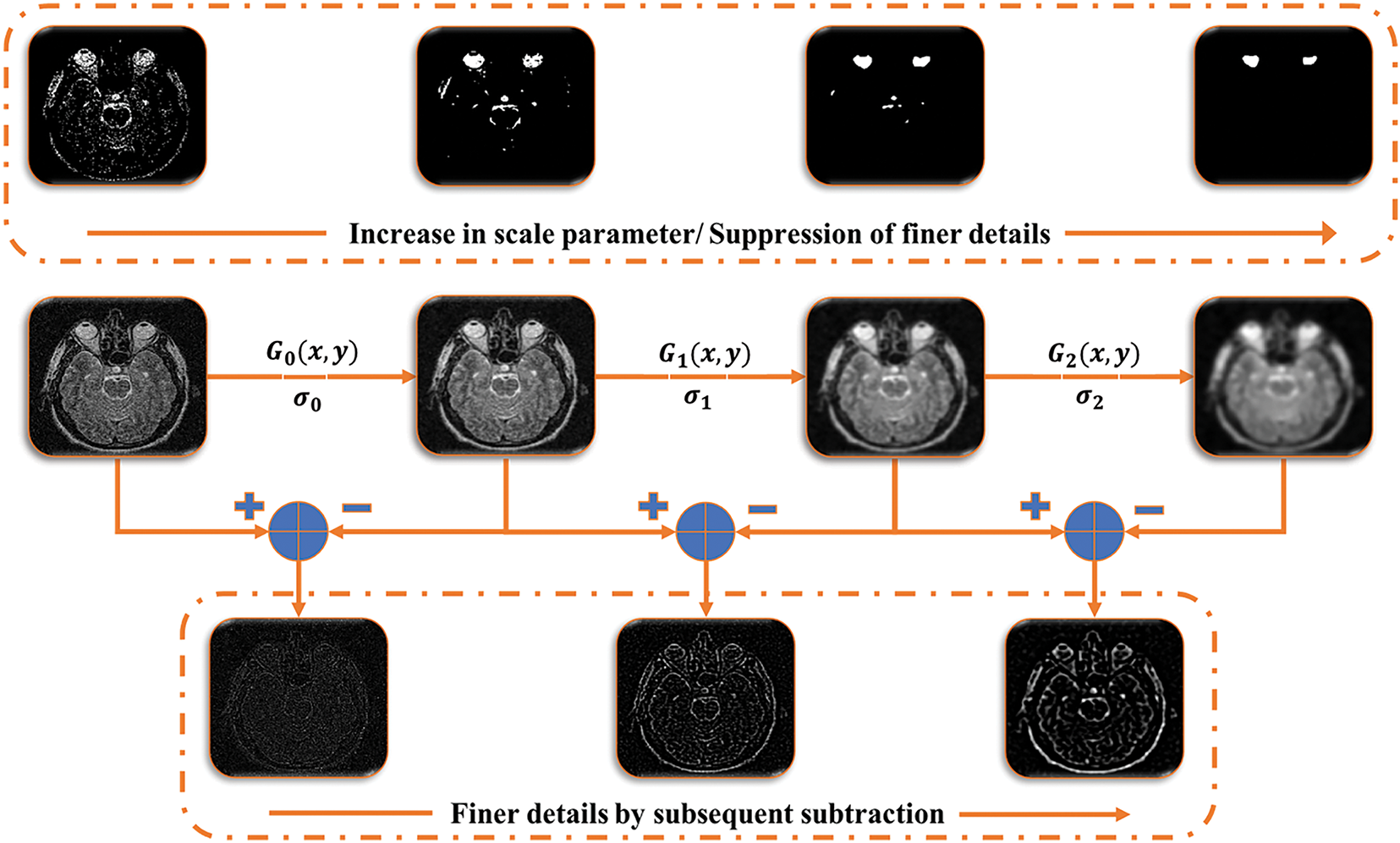

Fig. 5 shows the multi-scale decomposition using spatial filtering. In FFT denoising, the image is first transformed to frequency domain using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), then a fraction is decided for the coefficients which are to be kept. The rest of the coefficients are discarded and after that the image is reconstructed back. The Inverse filtering is explained in earlier sections, K-space filtering and Point Spread Function (PSF) are some of the techniques based on FT [196–198]. The K-space filtering is an extension of the Fourier concept and it is defined by frequency and phase space of data [199]. Similarly, the PSF is used to characterize the distortions in an image caused by the system and then it helps in designing an appropriate image restoration algorithm. This helps in improving the spatial resolution of the image [197]. In Shape Adaptive Discrete Cosine Transform (SADCT), orthonormalization of set of generators constrained to randomly shaped area of interest is considered. These generators act as basis for separable Block-Discrete Cosine Transform (B-DCT), thus forming “Shape Adaptive” Discrete Cosine Transform. Gram-Schmidt procedure is used to perform orthonormalization with support on the region. This method was quite costly in terms of computations hence, more speedy solution were sought and they didn’t require iterative orthogonalizations or costly matrix inversions [200]. In [201], DCT was used with Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) algorithm to effectively denoise medical images.

Figure 5: Multi-scale decomposition using simple spatial filtering

The Fourier transform suffered with the problem of non-sparsity, time-frequency localization and lower speeds. This changed with the introduction of Wavelet Transform. In Fourier transform, sines and cosines are used as basis-functions, for representation of signals. In wavelet transform, fast-decaying, finite length oscillating functions called “mother wavelets” are used as basis-functions. From these, smaller versions called “daughter wavelets” are derived, which are used for the representation of the signal. Mathematically, the continuous wavelet transform can be expressed as [202]

These orthogonal basis functions help in sparsely representing the signal. They follow the principle of orthogonality which says that the inner product of two orthogonal vectors or functions is always zero. Mathematically,

The mother wavelet functions can be defined as:

Scaling function is given as:

And the transformed signal can be reconstructed as

S. Mallat proposed an orthonormal filter bank based multi-scale/multi-resolution representation framework for images in [205,206]. Orthonormal low-pass and high-pass filter banks were used separate the images based on the frequency content present in the images, in that framework. These separated sub-bands are then subjected to thresholding operation to remove the noise present within. The factors that influence the performance of the Wavelet transform are the choice of mother wavelet, levels of decomposition and the type of thresholding applied. Availability of different types of mother wavelets viz. Daubechies (db), Haar (db2), Biorthogonal (bior), Reverse Biorthogonal (rbio), Symlet (sym), Coiflet (coif), Fejer-Korovkin (fk), etc. provide flexibility in terms of operation. A suitable “mother wavelet” can be chosen based on the requirement while choosing an optimum level of decomposition is also very important [204–208]. The wavelet transform evolved over time with introduction of Dual Tree Complex Wavelet Transform (DTCWT) [209], Curvelets [210], Contourlets [211] and Shearlets [212,213]. These transforms tried to achieve more directionality, shift invariance and better artifact mitigation capabilities. In the realm of signal processing, the Dual-Tree Complex Wavelet Transform (DTCWT) overcomes the challenge of shift-variance that plagues conventional wavelet transforms. Conversely, Curvelets, a specialized transform, exhibit remarkable prowess in effectively representing and analyzing curved features within images. Contourlets, conversely, were designed with the primary objective of capturing and representing continuous contours and boundaries within images, thereby rendering them highly advantageous for the execution of intricate operations such as image segmentation and object recognition [203]. Table 2 summarizes the various wavelet based denoising techniques.

In a parallel manner, Shearlets were devised to effectively address the anisotropic characteristics present in images, encompassing edges and textures, through the acquisition of their directional attributes across various scales. The recent progressions in wavelet transforms have significantly enhanced the precision and efficacy of algorithms used in signal and image processing. This has facilitated the ability to conduct more meticulous analysis and manipulation of intricate data. The main type of artifact arousing from X-lets is ringing artifact due to Gibbs phenomena. Ringing artifacts occur at sharp discontinuities in image due to finite approximations. Better noise reduction was also achieved by adopting optimum sets of parameters in Self-Organizing Migration Algorithm (SOMA). In SOMA, parameters like levels of decomposition, type of wavelet, and the type of thresholding were found for wavelet shrinkage denoising to achieve maximum performance [243]. This algorithm is fairly explored in [243–246].

The Wavelet transform successfully encodes the energy of the signal into fewer significant coefficients with remaining insignificant coefficients related to the signal independent noise. In threshold system for denoising, the threshold is required to separate the structural information from the noise. But practically it tends to over-smooth the signal. The efficiency of the denoising algorithm depends on the effective modelling of the inter-scale and intra-scale dependencies between the decomposition levels, presented by the Wavelet transform. Several techniques aimed at exploitation of these dependencies to improve their performance. Additionally, the imposition of down-sampling on Wavelet transform makes it translation variant [13]. As a result of this, visual artifacts in the form of Gibbs phenomena are introduced in the image. To address these issues, in [247], Linear Minimum Mean Square Error (LMMSE) was used for wavelet coefficients in place of soft thresholding. LMMSE scheme achieves efficiency by reducing the statistical estimation error through adaptive spatial classification of Wavelet coefficients. Despite being suitable for the denoising of many images, it proved to be unsuitable for weakly correlated images in the scale space.

Block Matching and 3D filtering method is a state-of-the-art image denoising technique proposed by Dabov et al. in [248]. BM3D is the one of the best techniques for denoising available till now. It is a transform domain technique based on enhanced sparse representation. Grouping of similar 2D image patches (blocks) to form 3D groups is done to achieve enhanced sparsity. After that, collaborative filtering is done on these 3D groups in three steps viz. transformation, shrinkage and inverse transformation. The collaborative filtering outputs revels the finest details shared by the groups, simultaneously preserving unique features present in each block [247]. In [249], BM3D and other state-of-the-art techniques were used and compared on MRI images. It was found that Unbiased Non-Local Means filter and BM3D hyrid with Spatially Adaptive Principal Component Analysis performed better than the other techniques. Pulse Coupled Neural Networks (PCNN) are 2-dimensional neural network, modelled using the cat’s visual cortex system. Its proposition goes back to 1989 when the concept of linking field was explained by Reinhard Eckhorn through which a correlation between attribute linking and perceivable functions could be set up [250,251]. Then after 1994, this neural model was adapted in image processing with name PCNN and till now it has found its application in various fields of image processing and computer vision like motion sensing, feature retrieval, segmentation, enhancement, restoration, fusion, region growth and denoising, etc. What makes this network attractive for computer vision application is its inspiration which comes from the operation of neurons in the primary visual field. So, in context of an image a pixel is represented by a neuron in PCNN. The color information is taken as an outside stimulus and the local stimuli is received from the surrounding neurons by setting up a connection. Then these stimuli are merged in an activation system and an output pulse is generated when the combination reaches a decided threshold. A time series of pulse outputs is generated by iteratively repeating this process. Then different functions are carried out using that time series [251,252].

A simplified version of PCNN known as spiking cortex model was also introduced in 2009. The threshold function for the PCNN is an evolution of neural analog threshold given as

where,

Here,

and

PCNN is a non-linear denoising method with a slow response and parameter dependence [251].

In Total Variation (TV) regularization, it is assumed that the signal with too much irrelevant details have high total variation. This means that absolute gradient’s integral is high. So, minimum total variation is aimed in case of image smoothing by simultaneously preserving relevant edges. A general TV-

where,

Total variation (TV) regularization based image denoising techniques are explored extensively for medical images. In 2006, a new denoising scheme based on TV minimization and wavelets was proposed for medical images [218]. Later in 2011, by examining the needs of medical image characteristics from the perspective of image denoising, a denoising algorithm based on partial differential of total variation was presented [129]. Subsequently, a new technique based on TV was proposed for medical images corrupted by Poisson noise. The study formulated the denoising issue using Bayesian statistics. This was done by establishing a nonnegativity-constrained minimization problem. This problem’s objective function had two terms: the Kullback-Leibler divergence for data fitting and the Total Variation function for regularization. The regularization parameter weighted the term. This paper aimed to propose a powerful computational method for tackling the constraint issue. The Newton projection method resolved the internal system using the Conjugate Gradient approach. This approach was preconditioned and optimized for the application [127].

Later on, many more techniques based on TV were proposed specifically for the denoising of medical images, e.g., [3,120,254,255]. In [120], simple TV regularization was used to denoise medical images whereas in [3] and [255] TV regularization is used along with Curvelet transform and Anscombe transform respectively to carry out the denoising process. These hybrid methods produced excellent result in effectively reducing the Poisson noise problem prevailing in medical images. In [254], Fractional order TV was used with alternating sequential filters to achieve fusion of noisy medical image modalities. Dang NH Thanh in presented an excellent review and a comprehensive analysis of several significant techniques for Poisson noise removal in medical images. These techniques included the modified TV model approach, the adaptive non-local total variation method, the adaptive TV method, the higher-order natural image prior model approach, the PURE-LET method, the Poisson reducing bilateral filter, and the variance stabilizing transform-based methods [7].

Markov properties are the properties, followed by a set of random variables called undirected graphical fields. These fields are also called Markov Random Fields (MRF) [256]. In terms of representation of dependencies, MRF is very similar to Bayesian network. The only difference that exists is that the Bayesian networks are acyclic and directed. A random variable forms an MRF if local Markov properties are satisfied. There are these properties named, Pairwise Markov property, Local Markov property, Global Markov property. In these properties, dependencies of the variables with respect to other variables are declared. The Global Markov property is strongest, followed by Local Markov Property, followed by Pairwise Markov property. Performing a full Maximum-A-Posteriori (MAP) for inference in MRF is very slow [257,258]. To address this problem a suboptimal inference algorithm called Active Random Field (ARF) was proposed by Adrian Barbu in [259]. It is a combination of Markov and Conditional Random Fields. The ARF provides a strong MAP optimum with lower number of iterations and it avoided overfitting by employing a validation sets to detect overfitting. Results showed that the one iteration Active Field of Experts (FOE) was as efficient as 3000 iteration FOE.

The prior modelling of an image is used in many computer vision applications. These prior models are used whenever there is noise and uncertainty in picture. The prior models are also known as depth maps or flow fields. For low level vision problems, methods are developed for learning priors. The priors are then computed for large neighbourhood systems, and for that sparse image patch representations are exploited. One of the important methods for sparse coding is Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) [161,260] and Generalized Gaussian Mixture Models (GGMM) [261]. The models of prior probability are called Fields of Experts (FoE) [262]. In other words, Fields of Experts are used to model natural images for which the standard database of natural images is trained. Due to large dimensions of images and their non-gaussian statistics, modelling of the image priors is a difficult task. A number of attempts have been made to overcome these difficulties and to model the statistics of small image patches as well as of entire images. So, the major goal in this field is to develop a framework for learning generic and expressive prior models for low level vision problems.

Generally, the Field-of-Experts model is defined as

where,

The FoE model share some similarities with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) where, filters banks are applied in a convolutional manner, to the whole image and the filter responses are modelled by using a non-linear function. The only significant difference lies in the training of both models. The convolution networks are trained for specific applications in a discriminative fashion while, the FoE models are trained in a generic manner by learning a generic prior which can be used in different applications. This is because of the probabilistic nature of FoEs [262].

The traditional patch prior based systems for image denoising were computationally complex due to large search windows used to evaluate pairwise similarity. The evaluation of the similarity is needed to generate correlation between the pixels of the target image. As, in natural images, redundancy is primarily presented at a semi-local level. Based on this observation, the patches (local neighbourhood sets) which are used to represent the images are made to collaborate. This collaboration is independent of the spatial position of the pixels. On the prior assumption that the noise infecting the image is additive in nature, the denoising process aims at estimating the an image out of its noisy version. So, a simplified model of the noise is required to effectively denoise the image. To obtain a simplified noise model approximated by a white Gaussian noise, stabilization of the noise variance is done with the help of Anscombe transform. The generalized degradation model for an image is written as

where,

Apart from Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM), Laplacian Mixture Models (LMM) are also used in the image denoising paradigm. The Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) is an appropriate choice for datasets that exhibit clusters resembling the Gaussian distribution. On the other hand, the Laplacian Mixture Model (LMM) demonstrates greater resilience to outliers and data that deviates from the Gaussian distribution. The Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) may encounter challenges when dealing with heavy-tailed data and outliers due to the inherent nature of the Gaussian distribution, which is characterized by light tails. The LMM may exhibit an inclination to overestimate the quantity of clusters when confronted with noise, owing to the heightened susceptibility of the heavy tails of the Laplace distribution to the presence of noise. The Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) exhibits heightened sensitivity towards the covariance structure of the data, whereas the Laplacian Mixture Model (LMM) places comparatively diminished emphasis on the estimation of the covariance matrix owing to the presence of exponential tails. In essence, the selection between Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) and Laplacian Mixture Model (LMM) is contingent upon the inherent attributes and properties of the data that is being subjected to modelling. In [220], Bivariate LMM was used to denoise medical images.

GGMM prior is more flexible and it can model natural images better than GMM prior and Expected Patch Log-Likelihood (EPLL) framework is used often for optimization [263]. EPLL is a classical external patch prior based framework and it is more efficient when compared to internal patch priors, in case of images with higher noise levels [154]. Some other examples of external patch priors based methods include Gradient Histogram Preservation (GHP) [264–266].

Fig. 6 illustrates the patch-prior-based denoising process. It is known that for natural images particularly, Gaussian potential is not suitable. Therefore, filters that fire rarely on natural images are sought out. To identify such filters, a well-known and consistent observation is followed. According to this observation, the power spectrum of natural images tends to decrease with increasing spatial frequency. So, filters with power concentrated in high spatial frequencies are considered for maximum likelihood. The perfect example of such filters is Roth and Black filters, which are frequently used in the case of GSM priors. However, these filters exhibit some drawbacks in lower and upper bounds on the maximum likelihood of the training set. These drawbacks are addressed by considering the possible rotations of basis set (BRFOE) of the filter. To carry out this operation, a basis rotation algorithm is applied to the set of the filters, having power spectrum same as the Roth and Black filters. This results in filters with more structure and extended bounds [267].

Figure 6: Patch-prior based denoising

In comparison to several parametric methods discussed earlier, the nonparametric methods rely on the data to decide the structure of the model. This implicit model is called as regression function and this idea of nonparametric estimation is called as kernel regression. Several concepts related to the general theory of kernel regression has been presented earlier for, e.g., edge-directed interpolation, bilateral filter, moving least squares and normalized convolution. The study of their relation with the general kernel regression theory has been done in [268] and an adapted non-linear kernel regression framework was proposed. In general, this method of filtering is very similar to local linear filtering process and suffers poor reconstruction on edge areas because of its non-adaptiveness near the edges.

Despite the efficacy of the orthonormal bases in sparsely representing the signal, they are inadequate for some specific signals of interest. Instead of orthonormal bases, sparse-based denoising techniques require a trained dictionary to sparsely represent a signal. So, by using an algorithm for sparse approximation a signal

In [279], GSR was used with dictionary learning for the denoising and fusion of CT and MRI images. Sparse coding-based methods has also been explored extensively for multi-modal medical images for, e.g., in [281], a novel global approach based on sparse representation and NLM was adopted to denoise multi-modal medical images. This method effectively denoises images while preserving sensitive tissue details. A sparse coding-based dictionary learning method has also been employed to denoise 3-D medical images [282]. On the same note, a deep learning based framework (unsupervised) was proposed for the denoising of 2-D as well as 3-D medical images [157]. Later on, a combination of medical image denoising and fusion was achieved by hybrid variation sparse representation based on a decomposition model [283] and sparse dictionary learning via discriminative low rank [284].

The fundamental objective of the Weighted Nuclear Norm Minimization (WNNM) technique is to effectively utilize the inherent properties of low-rank and sparse structures that are inherently present within matrices of data. This formulation entails the optimization of a convex objective function that comprises two fundamental components. The first component is the nuclear norm of a matrix with low rank, which quantifies the overall magnitude of the singular values of the matrix. The second component is the weighted ℓ1-norm of a matrix that is sparse, indicating that it contains a significant number of zero or near-zero elements. The utilization of the nuclear norm facilitates the achievement of low-rank approximation by effectively capturing the latent structures that are intricately embedded within the data that is subject to noise. Conversely, the weighted ℓ1-norm is employed to impose sparsity, thereby enabling the representation of noise or outliers in a concise manner [285,286].

The optimization problem linked to Weighted Nuclear Norm Minimization (WNNM) is characterized by its intricate complexity, primarily due to its combinatorial properties and non-convex nature, which stem from the inclusion of the nuclear norm. As a result, the utilization of efficient proximal algorithms, coupled with the incorporation of proximal gradient techniques, is employed to approximate the solution. The aforementioned iterative methodologies employ iterative processes to iteratively modify the low-rank and sparse components, taking into account the weighted regularization factors [287]. In order to guarantee the convergence of a computational algorithm, it is common practice to incorporate adaptive step size selection methodologies and convergence acceleration techniques, such as the renowned Nesterov’s acceleration method [288–290].

The effectiveness of Weighted Nuclear Norm Minimization (WNNM) relies on the prudent choice of the regularization weights, which have a crucial function in achieving a harmonious equilibrium between the low-rank and sparse elements. The weights in question encapsulate a pre-existing understanding of the data and its noise properties, allowing for customization to suit particular applications. The selection of weights that are optimal in nature results in representations that have been denoised or compressed, thereby effectively retaining crucial features while removing any noise or extraneous data components [286].

The fundamental foundation of WNNM resides in its capacity to exploit the concurrent utilization of low-rank approximation and sparse representation. The confluence of these factors results in heightened denoising efficacy, versatility in accommodating diverse noise distributions, and resilience in the face of fluctuating noise intensities. Moreover, the Weighted Nuclear Norm Minimization (WNNM) algorithm can be expanded to incorporate situations that involve the processing of multichannel data, temporal correlations, and heterogeneous noise structures [285]. In [291], the concept of nuclear-norm minimization was used with Rolling guidance filter and CNN to achieve effective multi-modal medical image denoising. In [292], also, WNNM was used to denoise 3-D medical images. Given the inherent complexity of the original problem pertaining to low-rank approximation, the prevailing approach commonly employed involved the utilization of nuclear norm minimization as a means to achieve matrix low-rank approximation. Notwithstanding, the solution derived through the process of nuclear norm minimization typically exhibits a deviation from the solution of the initial problem. A proposition is put forth for the denoising of MR images through the combination of a nonlocal self-similarity scheme with a pioneering low-rank approximation scheme [293].

Adaptive Clustering is a sophisticated computational methodology that effectively tackles the intricacies of unsupervised clustering by employing a dynamic approach to modify cluster attributes in accordance with the specific characteristics of local data. Conventional clustering algorithms frequently encounter difficulties when confronted with data points that manifest diverse densities, shapes, or sizes. The technique known as Adaptive Clustering effectively mitigates the aforementioned limitations by employing a dynamic estimation process to determine the most optimal number of clusters. Additionally, it adapts the parameters of each cluster to more accurately capture the nuanced distribution of the data [294,295].

Progressive PCA Thresholding iteratively captures and retains the most useful features in high-dimensional data, solving its problems. Traditional Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduces dimensionality, but tiny eigenvalues, due to their cumulative effect, can cause information loss in high-dimensional data. A staged eigenvalue thresholding procedure defines Progressive PCA Thresholding. Eigenvalues are ordered in decreasing order of importance and kept above a dynamically defined threshold in each stage. This progressive technique considers just the most impactful eigenvalues and their eigenvectors, resulting in a parsimonious data representation that keeps its intrinsic variance. Progressive PCA Thresholding also uses adaptive regularization to account for data structure differences across dimensions. The approach finds dimensions with low variance and suppresses their contributions to the main components using data-driven sparsity constraints, improving the reduced representation. Progressive PCA Thresholding shines in genomics and hyperspectral imaging, where data dimensionality surpasses sample quantity. Eigenvalue thresholding and sparsity-driven regularization enable adaptive feature extraction while reducing noise and small fluctuations [295].

Similarly, ACVA works on the idea that images have local structures or patches with different noise and image properties. The approach starts with adaptive clustering of related patches. This clustering algorithm groups patches with similar features based on noise levels and structural patterns. After adaptive clustering, ACVA uses variation-adaptive filtering in each cluster. This filter uses local variation data to dynamically alter its settings. ACVA reduces noise while keeping vital characteristics by responding to image patch texture and content fluctuations [296]. Also, Adaptive Soft-Thresholding (AST) Based on Non-Local Samples (NLS) is e technique where adaptive signal modelling is used with adaptive soft thresholding to achieve effective denoising performance [297].

3.4 Deep Learning Based Denoising

In the current scenario, Convolution Neural Networks (CNNs) and Machine learning based image denoising techniques are being rapidly explored and used in medical image denoising [298]. The Denoising Convolutional Neural Network (DnCNN) is an advanced computational framework specifically engineered for the purpose of image denoising. The proposed system utilized a multi-layered convolutional neural network architecture to acquire knowledge of the complex relationship between input images contaminated with noise and their corresponding clean, denoised counterparts. The DnCNN model has been meticulously designed to efficiently eliminate noise from images by capitalizing on its innate capacity to acquire knowledge and depict intricate noise patterns and image structures via the network’s hierarchical feature extraction procedure.