Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Deep Learning-Based Faulty Wood Detection with Area Attention

Faculty of Information Technology, Ho Chi Minh City Open University, 35-37 Ho Hao Hon Street, Ward Co Giang, District 1, Ho Chi Minh City, 700000, Vietnam

* Corresponding Author: Vinh Truong Hoang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine Vision Detection and Intelligent Recognition, 2nd Edition)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 1495-1514. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066506

Received 10 April 2025; Accepted 02 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Improving consumer satisfaction with the appearance and surface quality of wood-based products requires inspection methods that are both accurate and efficient. The adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) for surface evaluation has emerged as a promising solution. Since the visual appeal of wooden products directly impacts their market value and overall business success, effective quality control is crucial. However, conventional inspection techniques often fail to meet performance requirements due to limited accuracy and slow processing times. To address these shortcomings, the authors propose a real-time deep learning-based system for evaluating surface appearance quality. The method integrates object detection and classification within an area attention framework and leverages R-ELAN for advanced fine-tuning. This architecture supports precise identification and classification of multiple objects, even under ambiguous or visually complex conditions. Furthermore, the model is computationally efficient and well-suited to moderate or domain-specific datasets commonly found in industrial inspection tasks. Experimental validation on the Zenodo dataset shows that the model achieves an average precision (AP) of 60.6%, outperforming the current state-of-the-art YOLOv12 model (55.3%), with a fast inference time of approximately 70 milliseconds. These results underscore the potential of AI-powered methods to enhance surface quality inspection in the wood manufacturing sector.Keywords

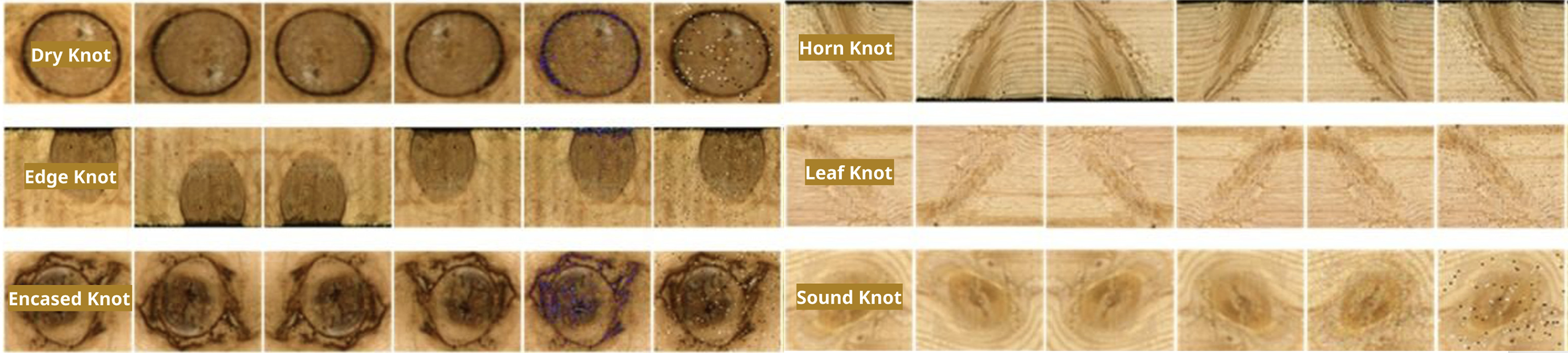

The surface quality of wood-based products plays a vital role in determining user satisfaction and improving the overall aesthetic appeal. A smooth and well-finished surface significantly increases product value, allows manufacturers to command higher selling prices, and bolsters competitiveness in the market. However, various factors during production and transportation can lead to surface defects, including cracks, wormholes, knots, uneven grain patterns, and other imperfections that compromise product quality and visual appeal (as illustrated in Fig. 1) [1]. Historically, manufacturers relied on conventional inspection methods such as visual assessments, tactile evaluations, and rudimentary measurement tools. Recent advancements have introduced more sophisticated techniques, including 3D scanning, camera-based image processing, roughness measurement devices, and hardness testers [2]. These methods must align with international quality standards, such as ISO (International Organization for Standardization) 4287 for surface roughness evaluation, ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) D1666 for defect identification, ASTM D143 for hardness measurements, and ASTM D2244 for assessing wood grain characteristics, ensuring global compliance and reliability [3].

Figure 1: Wood defects

Modern image processing techniques have become integral to surface inspection workflows. Essential approaches include surface feature analysis through histogram evaluations of color and brightness distributions, texture assessment using the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM), spatial frequency analysis via Fourier transforms, and mathematical operations such as gradient and Laplacian methods for noise detection [4]. Advanced techniques like wavelet transform and Fourier analysis enhance roughness evaluation, while dimensional measurement relies on edge detection algorithms, including Canny and Sobel methods, complemented by geometric transformations for precision [5]. Automated defect detection further benefits from thresholding methods such as the Otsu algorithm and machine learning models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which provide scalable solutions for identifying defects with high accuracy [6].

Deep learning techniques have revolutionized wood surface quality inspections by offering robust solutions for defect detection and classification. CNNs effectively handle defect detection tasks, while transfer learning enhances classification capabilities, and regression neural networks support roughness estimation [7]. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as a promising avenue, with applications ranging from defect classification using Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) to roughness estimation via Graph Neural Regression Networks and surface damage pattern detection with Graph Attention Networks (GATs) [8]. Innovations such as the Graph Attention Convolution Network (GACN) [9] leverage attention mechanisms and graph structures to emphasize critical features, further refining defect detection and classification.

Object detection models are central to visual quality inspections and include single-stage approaches like YOLO (versions 1 through 12), SSD, RetinaNet, and CenterNet. These models offer rapid processing suitable for real-time applications but face scalability and optimization challenges. On the other hand, two-stage models like R-CNN, Fast R-CNN, Faster R-CNN, Mask R-CNN, Cascade R-CNN, and HTC deliver higher accuracy for detecting small or densely packed defects but are computationally intensive and less suited for real-time deployment [10]. Research in this area emphasizes addressing these limitations by integrating multiple detection approaches, including GNNs, GATs, and CNNs, to improve accuracy, facilitate multidimensional data collection, and ensure flexibility across diverse manufacturing environments [11]. The variability and complexity of wooden product surfaces, including unclear shapes and dynamic characteristics, remain a persistent challenge. By incorporating Graph Attention Networks (GATs) into Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), researchers aim to enhance recognition performance, particularly in uncertain and variable conditions [12].

The primary research objectives center on enhancing defect detection accuracy and classification performance, with a focus on improving the modeling of spatial relationships within wood surface patterns. This involves leveraging advanced methodologies to expand generalization capabilities through the development of diverse and representative benchmark datasets. Additionally, the study emphasizes the importance of adopting innovative techniques for detailed classification, aiming to address challenges such as varying defect sizes, orientations, and patterns [13].

The proposed model integrates a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) backbone for robust and hierarchical feature extraction, effectively capturing both low-level textures and high-level abstractions critical for defect identification. This is further complemented by region proposal techniques that prioritize high-probability regions of interest, streamlining the detection process. The model employs a multi-headed architecture, incorporating classification, bounding box regression, and segmentation outputs to provide a holistic understanding of wood surface defects. Within this framework, an area attention mechanism is integrated, enhancing the model’s ability to focus on critical features and regions, thereby improving robustness to noise and irrelevant background information. A key innovation is the inclusion of the Residual Enhanced Linear Aggregation Network (R-ELAN), which optimizes detection performance through advanced fine-tuning and multi-scale feature aggregation. This ensures the model remains effective across a diverse range of defect types and manufacturing conditions, addressing challenges such as complex defect shapes and overlapping imperfections [14].

This research tackles key limitations in current wood surface inspection systems, including low accuracy, slow processing, and difficulty handling complex grain patterns or overlapping defects. Existing high-precision models are often too computationally intensive for real-time industrial use, and the integration of attention mechanisms, multi-scale learning, and hybrid CNN–GNN architectures remains limited. Additionally, there is a lack of diverse benchmark datasets tailored to the wood inspection domain. To address these challenges, the study proposes a hybrid CNN-based model that unifies classification, segmentation, and localization tasks. Enhanced with area attention and the R-ELAN module, the model achieves an average precision (AP) of 60.6%, outperforming YOLOv12 (55.3%), and runs at approximately 70 ms per inference, making it suitable for real-time deployment.

The paper is organized to present a comprehensive view of the research. Section 2 reviews related work and existing limitations, while Section 3 details the proposed architecture and innovations. Section 4 reports experimental results, highlighting the model’s accuracy, speed, and robustness. Sections 5 conclude with a discussion on current limitations and future directions, emphasizing the potential for lightweight models, dataset expansion, and broader industrial application. Through these contributions, the study advances automated, precise, and scalable wood defect inspection, supporting higher manufacturing efficiency and reduced material waste.

Common surface defects in wood products include wood rays, ambrosia discoloration, sapwood, ingrown bark, knots, and cracks from drying or stress [15]. These typically result from material flaws, production issues, mishandling, or rarely, customer actions. While consumer-induced defects are uncommon, strict production standards help protect brand value and minimize waste [16]. Traditionally, surface inspection relies on manual methods such as visual and tactile assessments, along with instruments like profilometers and gloss meters [17]. However, these approaches are labor-intensive, subjective, and often fail to detect subtle or hidden defects.

With recent technological advancements, surface inspection has shifted toward automated, AI-driven methodologies that offer significant improvements in accuracy and efficiency. Emerging studies [18] have proposed integrating Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) with models such as CenterNet for detecting wood defects, SSD (Single Shot MultiBox Detector) [19] for real-time image classification, and YOLO [20] for high-speed, precision-based recognition. Optimization algorithms like Battle Royale Optimization (BRO) have been employed to further enhance neural network performance, while Graph Attention Networks (GATs) [9] aid in extracting relevant features for classification [21]. Additionally, Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) serve as core components in deep learning-based classification architectures [22]. Collectively, these models address the limitations of traditional approaches by offering enhanced precision, scalability, and adaptability.

Nonetheless, constructing reliable datasets for defect detection remains a considerable challenge, particularly in dynamic production environments characterized by inconsistent lighting, variable conveyor speeds, and differing camera resolutions [23]. Visual interferences such as shadows, reflections, motion blur, and low image resolution further complicate accurate detection. Although some research focuses on controlled settings, practical, real-time quality inspection in industrial scenarios is still underdeveloped. Addressing these constraints requires careful image acquisition strategies, including high-resolution cameras, calibrated lighting, and optimized camera placement to generate dependable datasets for AI training [24].

This study addresses critical gaps in the current landscape of wood surface quality inspection. Existing manual and automated systems often lack the speed and accuracy required to manage complex and highly variable wood grain patterns. High-performance object detection models tend to be computationally intensive, limiting their deployment in real-time settings. Furthermore, ambiguity and overlap in defect types remain difficult to detect due to the absence of attention mechanisms and multi-scale learning capabilities. The integration of GNNs and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) is underexplored, particularly in modeling spatial relationships and the diverse nature of wood defects. Compounding these challenges is the lack of benchmark datasets specifically tailored for wood inspection. To address these limitations, the study proposes a hybrid CNN-based architecture that combines classification, segmentation, and bounding box regression for comprehensive defect analysis. This model incorporates an area attention mechanism to enhance focus on relevant defect regions and suppress background noise, and leverages the Residual Enhanced Linear Aggregation Network (R-ELAN) to improve multi-scale feature aggregation and overall accuracy.

The proposed system offers a robust AI-based framework for detecting and classifying wood surface defects. It begins with image preprocessing, including noise reduction, contrast enhancement, and data augmentation to improve model robustness. Model training incorporates area attention and R-ELAN for enhanced feature extraction and accurate detection of complex, overlapping defects [22,23]. For real-time industrial deployment, the system employs region proposals and multi-headed strategies to maintain accuracy under varying conditions [24]. This ensures reliable performance in high-throughput manufacturing environments.

Although the study demonstrates the strong potential of AI-driven inspection systems, several areas warrant further research. These include improving computational efficiency for real-time applications in large-scale settings, developing adaptive learning algorithms to accommodate evolving defect patterns, and integrating multi-sensor data (e.g., infrared or ultrasonic) for more comprehensive analyses. Customizing AI models to suit industry-specific requirements remains a critical goal, as does the development of energy-efficient systems aligned with sustainable manufacturing practices.

Ultimately, the outcomes of this research contribute to the advancement of intelligent inspection systems that can transform quality assurance in the wood industry. By enhancing defect detection accuracy, improving operational workflows, and reducing material waste, the proposed system bridges the gap between traditional manual inspection and next-generation AI solutions. These innovations pave the way for real-time, automated quality control and provide a competitive advantage in modern manufacturing.

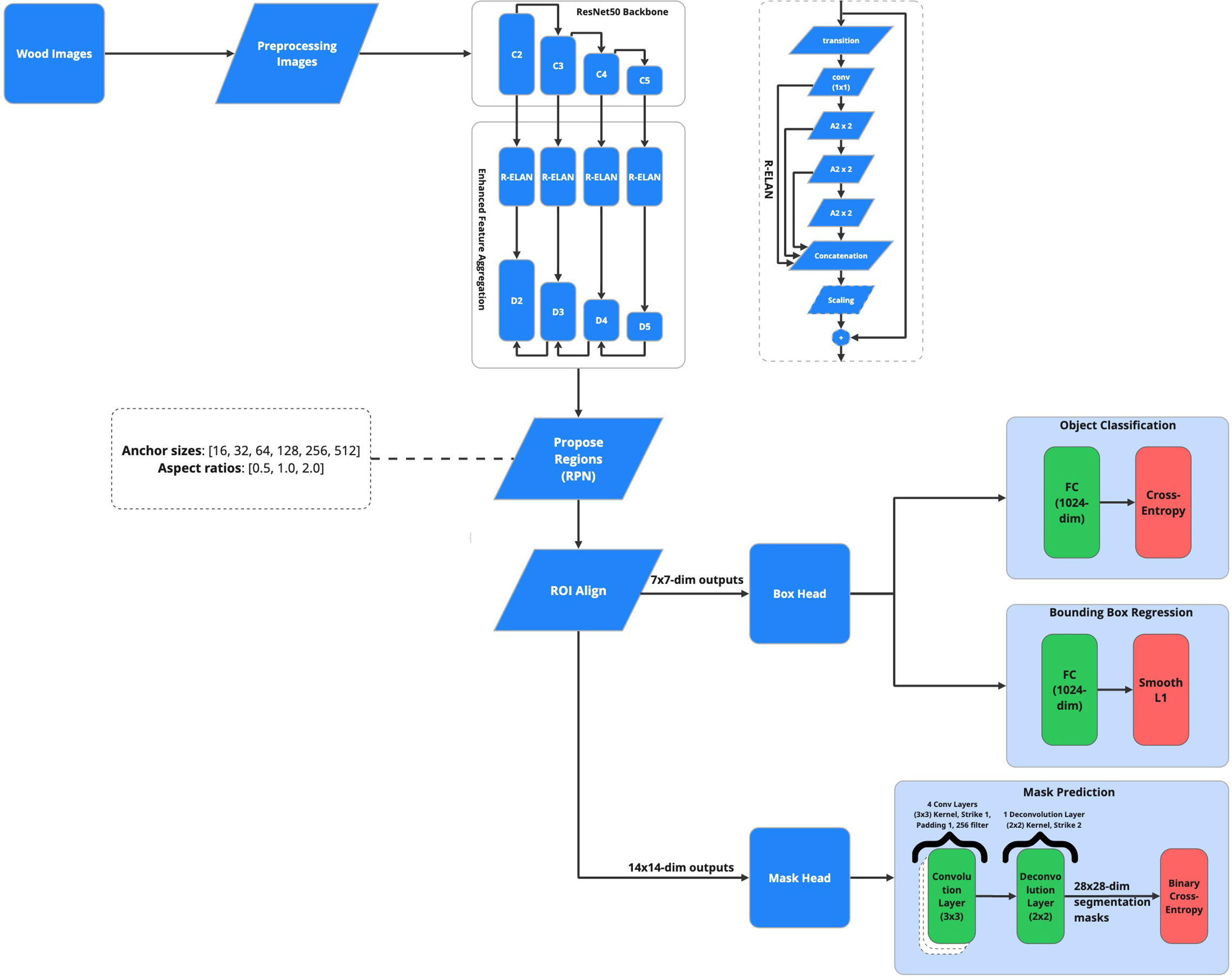

As shown in Fig. 2, the proposed defect detection model is a sophisticated framework designed to significantly enhance both detection accuracy and localization precision. At its core, the model leverages a ResNet50 [25] backbone for robust feature extraction, complemented by region proposal techniques and multi-headed classification and segmentation strategies. By incorporating advanced feature extraction and attention mechanisms, the framework achieves high performance in defect detection, particularly in challenging scenarios with complex or subtle defects [7].

Figure 2: Proposed method

The proposed model architecture is organized into interconnected stages that collectively enhance detection accuracy and efficiency. It begins with image preprocessing normalization, denoising, and resizing to ensure consistency and improve generalization [26]. ResNet50 serves as the backbone for extracting rich spatial features [25], which are further refined by the R-ELAN module to preserve critical defect information [27]. Region proposals guide the model to likely defect areas [28], while a multi-headed structure performs classification, bounding box regression, and mask segmentation simultaneously for detailed analysis [29]. Attention mechanisms, including GAT and Transformer-based modules, improve robustness by focusing on relevant features and filtering out noise [13].

The proposed parameter configuration is meticulously crafted to balance accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency in wood defect detection. At its core, the framework adopts a ResNet-50 backbone integrated with a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [11], both pre-trained on ImageNet, to exploit rich hierarchical features across multiple scales [25]. To further enhance contextual representation, R-ELAN blocks are strategically embedded between feature levels C2 through C5, enabling deeper interactions among spatial and semantic features. The FPN outputs from levels D2 to D5 facilitate effective multi-scale feature aggregation, which is crucial for accurately identifying wood defects of varying sizes and geometries. The Region Proposal Network (RPN) [28] is configured with anchor boxes spanning sizes from 16 to 512 pixels and aspect ratios of 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0, ensuring comprehensive coverage of defect shapes and scales. Anchor strides and Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds are tuned to optimize recall while minimizing false positives. To maintain spatial precision during region pooling, ROI Align is utilized with output resolutions of 7

Overall, this multi-stage framework, with its seamless integration of ResNet50, R-ELAN, and multi-headed detection, represents a cutting-edge approach to defect detection. Its combination of precision, efficiency, and adaptability makes it suitable for a wide range of applications, from industrial quality control to medical imaging.

In this study, wood defect images were sourced from Zenodo [30] to ensure a high-quality, diverse dataset reflecting real-world conditions. Images were categorized into small, medium, and large based on bounding box area to maintain feature integrity and optimize model efficiency (as illustrated in Fig. 3). A curated subset of faulty images was manually annotated into key defect types, with class balancing techniques like oversampling and stratified sampling used to address dataset imbalance. Data augmentation methods including rotation, flipping, noise addition, and contrast adjustment were applied to simulate real-world variations and improve model generalization. Model performance was evaluated using precision, recall, AP, and AR, with 5-fold cross-validation ensuring reliable, robust assessment across different data splits.

Figure 3: Defect sample sizes

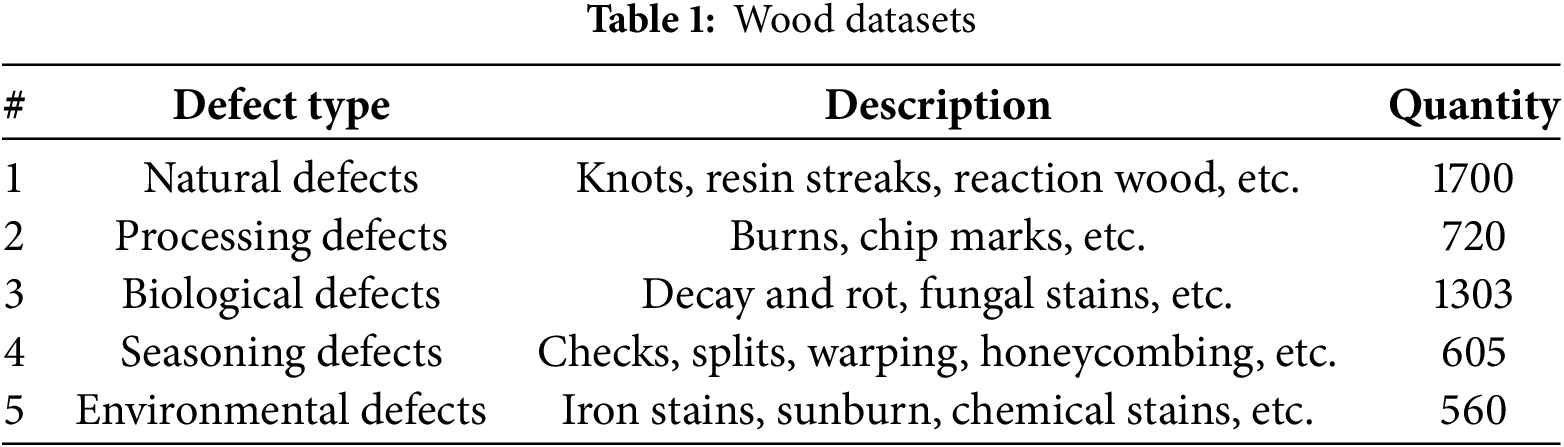

Table 1 summarizes the dataset’s key characteristics, including the number of images, distribution of defect categories. These details reflect the structured and methodical approach taken in dataset preparation, supporting the study’s goals of transparency, reproducibility, and reliability.

Following image acquisition, a comprehensive preprocessing pipeline is implemented to enhance uniformity and optimize the performance of machine learning or computer vision models. Key stages in the preprocessing pipeline include [31]:

Wood defect detection begins with image acquisition, where high-resolution images are captured under controlled lighting to ensure consistent and accurate input data [32]. A structured preprocessing pipeline follows, aimed at enhancing image quality and optimizing model performance. Key steps include: normalization to standardize pixel values [32], noise reduction through filters like Gaussian or median [33], and resizing images to uniform dimensions suitable for neural network input [34]. Contrast enhancement techniques improve defect visibility [35], and optional edge detection methods like Sobel or Canny may be used to emphasize defect boundaries [36]. This pipeline ensures that models receive clean, standardized data for effective defect identification.

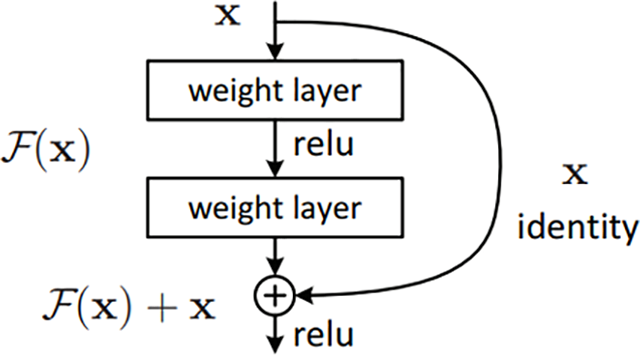

ResNet50 [25] is a deep convolutional neural network designed to extract hierarchical features from images, making it highly effective for complex pattern recognition tasks [7]. Its layered architecture captures information at multiple abstraction levels: early layers (C2) detect basic textures like edges and gradients [26], mid-level layers (C3) extract shapes and object parts [37], and deeper layers (C4 and C5) identify high-level semantic features essential for object detection and classification [38].

Feature extraction is driven by the convolutional operation, structured within the residual architecture depicted in Fig. 4. This approach enhances learning by preserving essential information through shortcut connections, mitigating the vanishing gradient problem, and enabling deeper network training. Mathematically, this process can be represented as:

where:

Figure 4: Residual architecture

The ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) activation function introduces non-linearity, enabling the network to model complex patterns. ReLU is particularly effective because it mitigates the vanishing gradient problem, ensuring that gradients do not shrink to near-zero values during backpropagation [39].

One of the key innovations in ResNet50 [25] is the use of residual connections, which address the challenges of vanishing gradients and degradation in very deep networks. These connections enable the network to bypass certain layers by adding the input feature map directly to the output, forming shortcut connections [7].

By allowing gradients to flow through shortcut connections during backpropagation, residual connections maintain learning stability and ensure that deeper networks can effectively converge without performance degradation [40]. This architecture enables ResNet50 [25] to scale to greater depths while maintaining high efficiency and accuracy, making it one of the most powerful deep learning models for feature extraction in image processing tasks [41].

Additionally, the modular design of ResNet50 facilitates seamless integration with advanced techniques such as attention mechanisms, feature pyramids, and multi-scale feature extraction. This adaptability makes ResNet50 a cornerstone in modern computer vision tasks ranging from image classification to instance segmentation.

3.4 Enhanced Feature Aggregation

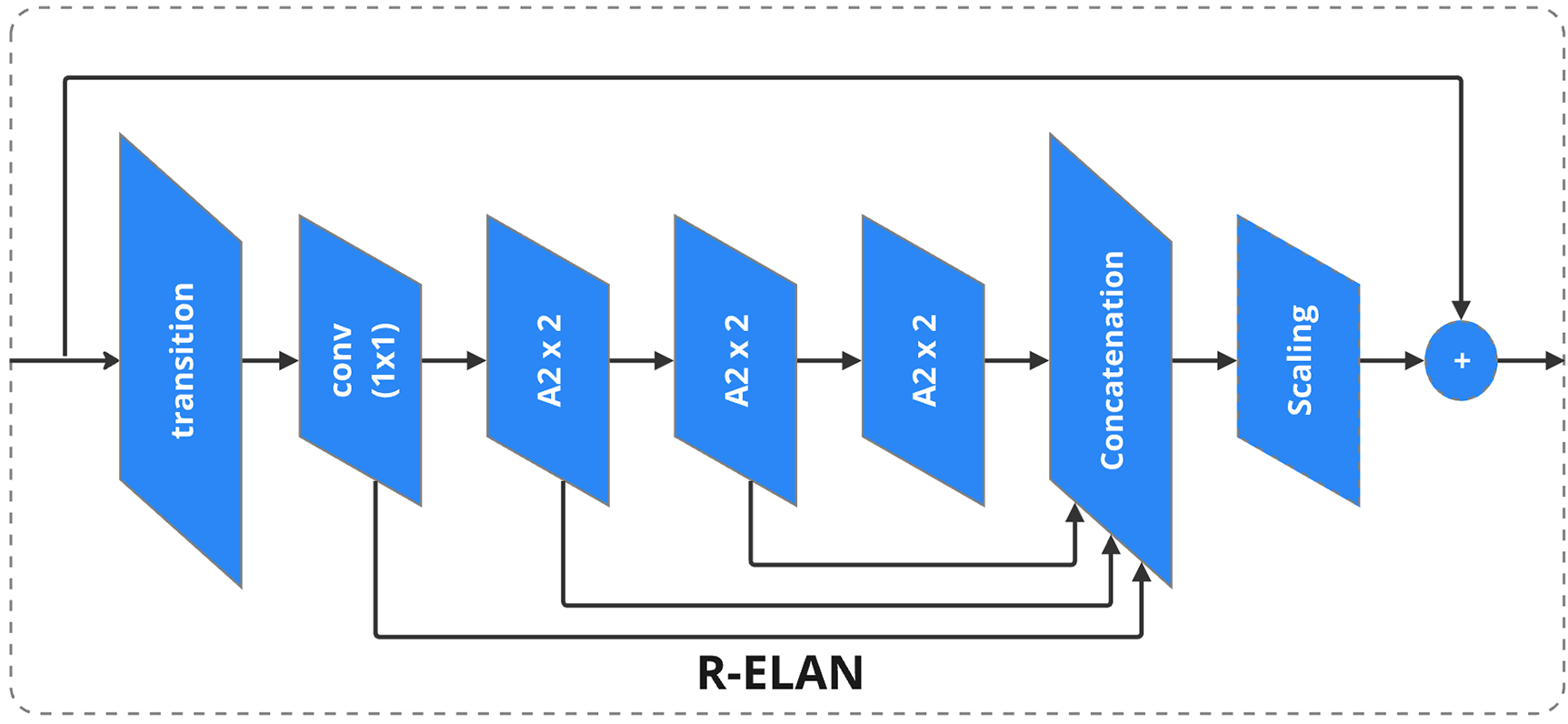

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the Residual ELAN (R-ELAN) module is designed to enhance feature propagation and minimize information loss, making it highly effective in extracting and aggregating features for complex tasks such as defect detection.

Figure 5: R-ELAN

This is achieved through the incorporation of additional residual connections and strategically placed transition layers, which streamline the flow of gradients and preserve crucial information across network layers [42]. By ensuring efficient information retention and reducing redundancy of features, R-ELAN improves the ability of the model to capture fine-grained details while maintaining computational efficiency [43].

A key functionality of R-ELAN lies in its capability to aggregate features from multiple hierarchical levels. This process can be mathematically expressed as

where:

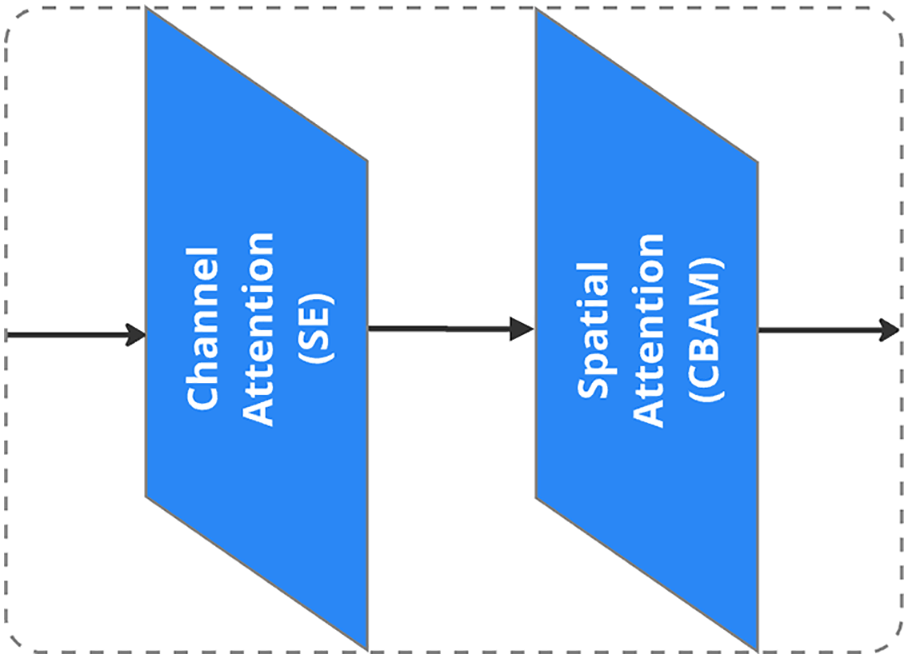

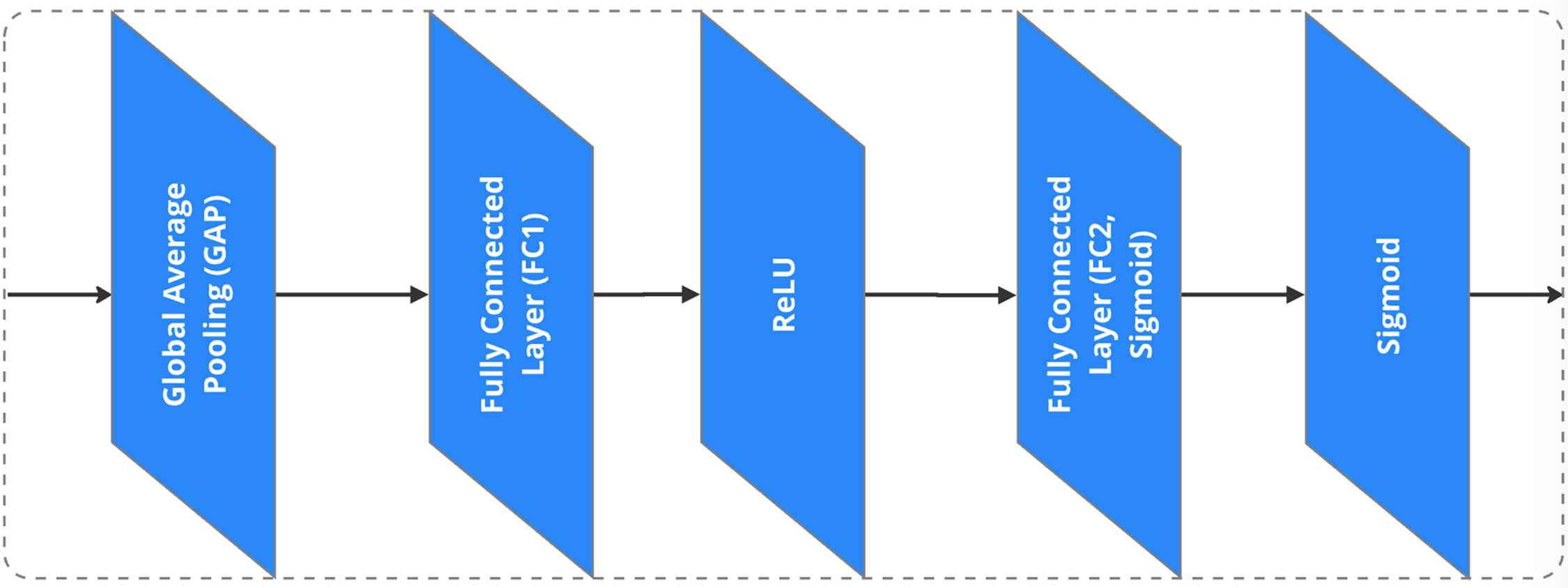

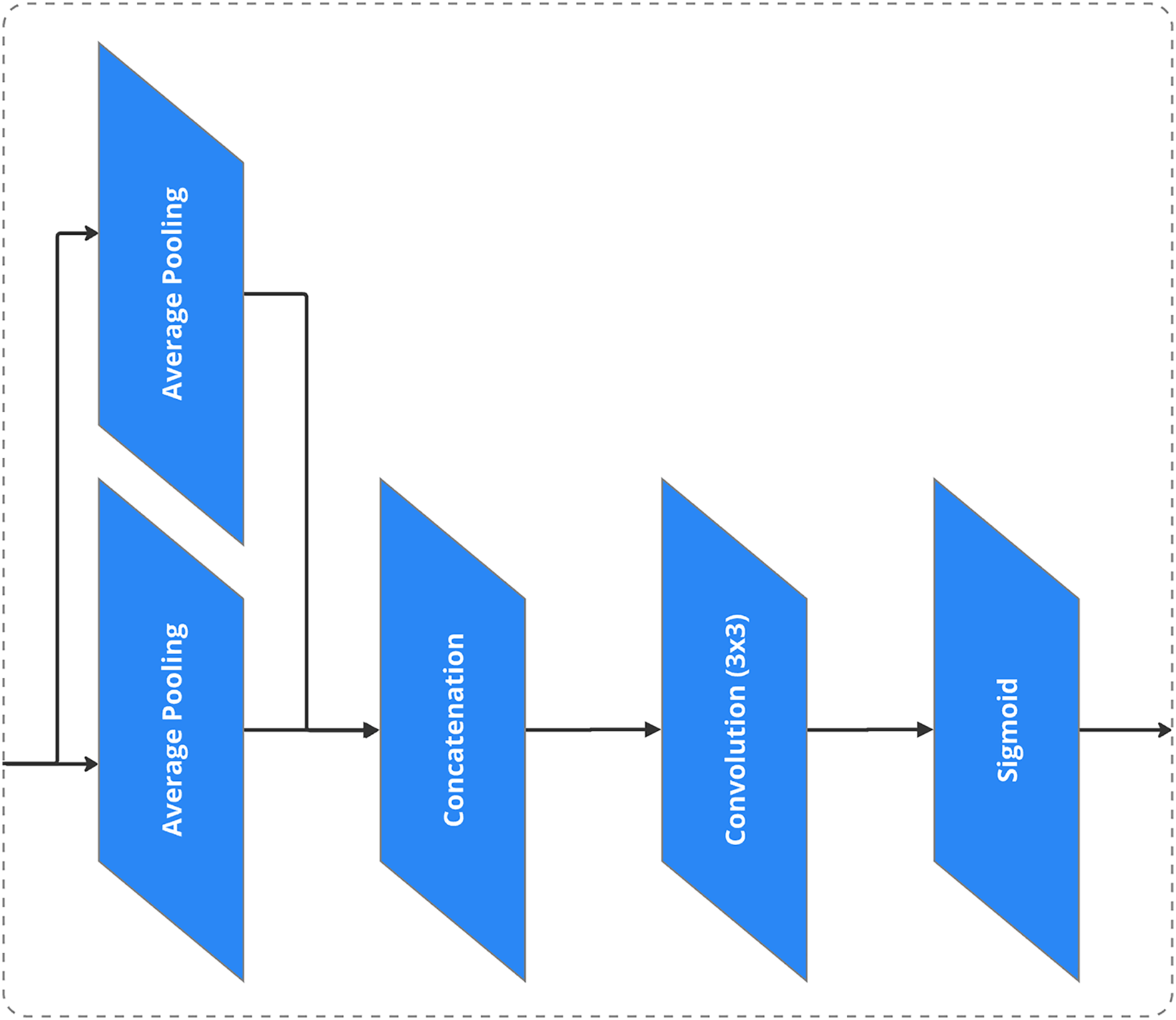

For the attention mechanism, as shown in Fig. 6, the approach applies A2 (Area Attention), while channel attention uses the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) method (Fig. 7), and spatial attention is implemented through the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) (Fig. 8) [44,45].

Figure 6: A2 (Area Attention)

Figure 7: SE channel attention

Figure 8: CBAM spatial attention

R-ELAN consolidates low-level, intermediate, and high-level features by concatenating multi-scale feature maps, particularly from layers D2 to D5, enabling the network to capture both fine-grained details and broader context [46]. This multi-scale fusion significantly enhances detection performance across objects with varying sizes, shapes, and orientations [47].

Residual connections in R-ELAN address the degradation problem in deep networks by allowing information to bypass certain layers, improving learning efficiency and preventing vanishing gradients [7,48]. Transition layers align feature map dimensions for seamless integration [49]. With its combination of feature propagation, residual learning, and multi-scale fusion, R-ELAN plays a vital role in accurate localization and detection in complex vision tasks [50].

3.5 Defect Region Proposal Network

The Region Proposal Network (RPN) [28] is a pivotal component in modern object detection frameworks, including those for defect detection. Its primary function is to efficiently generate candidate regions, or proposals, that are likely to contain objects or defects. These candidate regions serve as input to subsequent stages of the detection pipeline, enabling precise localization and classification.

The RPN operates by estimating the likelihood of a defect being present at a specific region x. This process can be mathematically described as:

where:

To improve feature extraction precision, the framework integrates ROI Align [52], which addresses the misalignment caused by traditional ROI pooling’s coordinate rounding. By applying bilinear interpolation instead, ROI Align ensures accurate alignment between region proposals and feature maps-crucial for pixel-level tasks like defect detection and segmentation [53]. This precise alignment enhances region proposal quality and improves bounding box localization and prediction accuracy.

Combined with a Region Proposal Network (RPN), which efficiently generates proposals focused on likely defect areas, the system avoids exhaustive search and enhances detection speed [54]. Utilizing multi-scale feature maps further enables robust identification of defects across various sizes and orientations. Together, ROI Align and RPN form a powerful foundation for high-accuracy detection, even in cases with subtle or overlapping defects [55].

3.6 Detection and Classification

The loss function used for the classification is the Cross-Entropy Loss, which is designed to handle multi-class problems by comparing the predicted probability distribution to the ground truth labels. The Cross-Entropy Loss can be expressed as:

where:

The regression task refines defect localization by predicting precise bounding boxes around detected regions. This process adjusts the coordinates of the bounding boxes to minimize the discrepancy between the predicted and ground truth locations. It can be formulated as:

where:

The third and final task addresses pixel-wise segmentation of detected defects, providing detailed and granular localization. This is achieved through the binary cross-entropy loss function, mathematically represented as:

where:

The binary cross-entropy loss quantifies the difference between true and predicted mask values, ensuring the model learns fine-grained segmentation. This is crucial for identifying precise defect shapes and boundaries, enabling detailed visual inspection [53].

3.6.4 Integration and Optimization

Key architectural enhancements in the proposed model significantly optimize performance by incorporating advanced components that strengthen feature representation and defect detection accuracy. First, feature pyramids improve multiscale feature extraction, allowing the model to detect defects of varying sizes, shapes, and orientations. This multi-resolution capability supports robust detection of both fine-grained and large-scale anomalies, enhancing generalization across diverse wood textures. Second, attention mechanisms such as A2 (Area Attention), SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation) channel attention, and CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) spatial attention enable the model to focus on the most relevant image regions while suppressing background noise. These mechanisms refine the feature selection process, contributing to higher precision in identifying critical defect areas. Finally, Region Proposal Networks (RPNs) further enhance detection efficiency by intelligently selecting and prioritizing regions of interest. This targeted approach boosts localization accuracy, reduces false positives, and ensures the model can reliably identify subtle or overlapping defects in complex visual contexts.

The optimization of the model involves calculating a total loss as a weighted sum of its key components:

where:

By leveraging deep learning advancements and optimized architectural components, this approach establishes a scalable, efficient, and accurate defect detection pipeline suitable for diverse real-world applications.

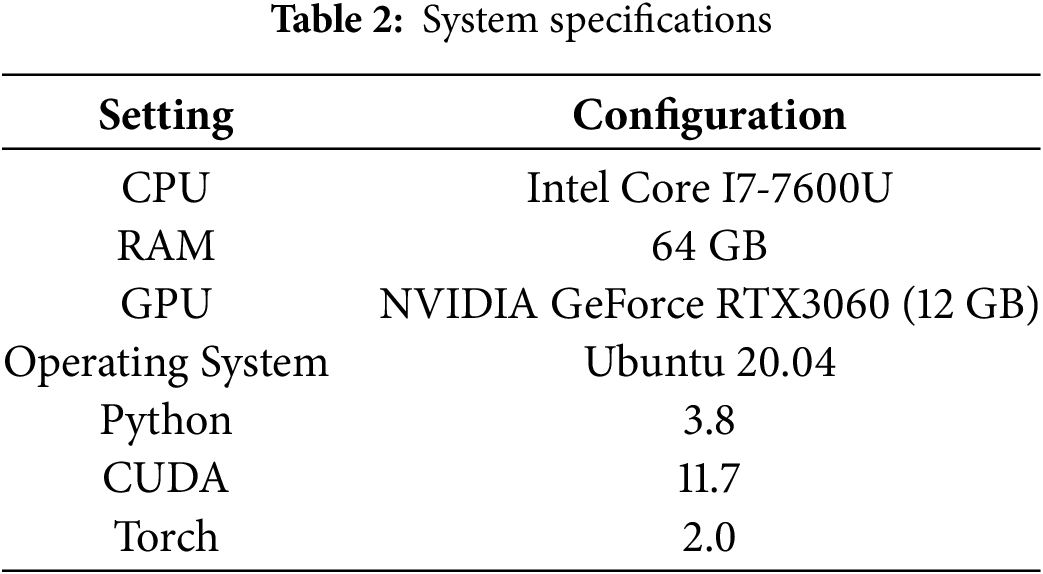

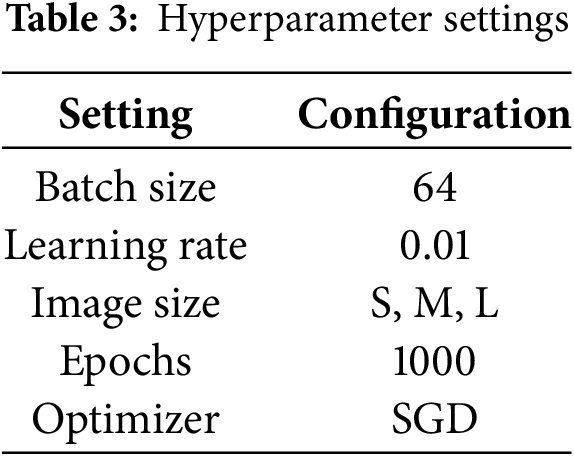

To thoroughly assess the performance and robustness of our proposed model, we implemented a rigorous neural network training and testing regime, utilizing the system specifications and hyperparameter configurations summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. These parameters were meticulously chosen to strike a balance between computational efficiency and predictive accuracy, ensuring optimal performance throughout the experimentation process.

The hardware setup featured an Intel Core i7-7600U CPU, 64 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU with 12 GB of dedicated memory, all running on Ubuntu 20.04. This high-performance configuration enabled seamless execution of complex deep learning tasks, from large-scale data preprocessing to high-throughput model inference. The substantial memory capacity of the GPU played a critical role in the processing of high-resolution images and facilitating parallel computation during training.

Model training was configured with a batch size of 64, a learning rate of 0.01, and a total of 1000 training epochs. The input images were standardized to resolutions of S (small), M (medium), and L (large), providing data for the training process while optimizing GPU memory utilization. To enhance convergence speed and model stability, we employed the SGD optimizer, which dynamically adjusts learning rates for each parameter. This optimization method mitigated common problems such as vanishing or explosive gradients, allowing steady and effective learning throughout the training process [41]. The hyperparameter settings were designed to adhere to best practices in deep learning while addressing the unique challenges posed by our dataset and architecture [42]. The training process was carefully monitored, with periodic evaluations to refine hyperparameters as needed, ensuring consistent improvements in model performance.

By maintaining a well-structured and consistent experimental setup, we established a solid foundation for performance evaluation. This approach not only ensured the reproducibility of the results but also validated the model’s robustness and adaptability to real-world applications. The systematic optimization of hardware, software, and training parameters highlights the potential of the model for scalable deployment in diverse and challenging scenarios, ranging from defect detection in industrial environments to advanced computer vision tasks in other domains [43].

For evaluation, object detection performance is assessed using key metrics such as precision (Pr), recall (Rec), and their averaged forms, including Average Precision (AP) and Average Recall (AR). These metrics offer a comprehensive view of model effectiveness across varied conditions, including imbalanced defect distributions and object sizes. Precision measures the accuracy of positive predictions, while recall assesses the model’s ability to detect all relevant instances; AP and AR variants further refine this evaluation across different IoU thresholds and object scales.

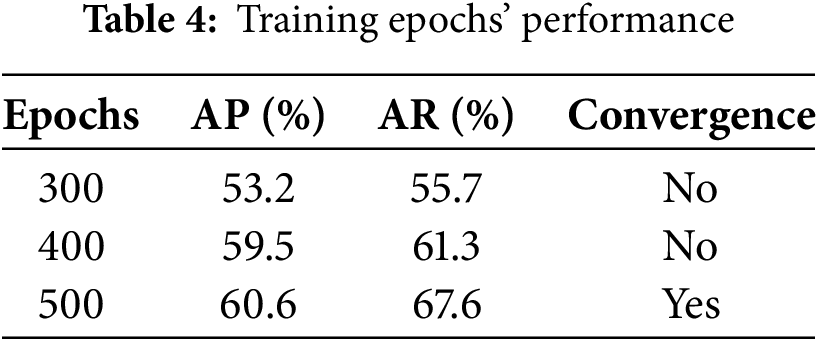

The model’s training dynamics and architectural enhancements were thoroughly evaluated to ensure optimal performance and efficiency. Table 4 analyzes the impact of varying training epochs when training from scratch, revealing that the model achieves peak performance after approximately 500 epochs, striking a balance between convergence and feature learning; fewer epochs lead to underfitting, while excessive training adds computational cost with minimal benefit [28,53].

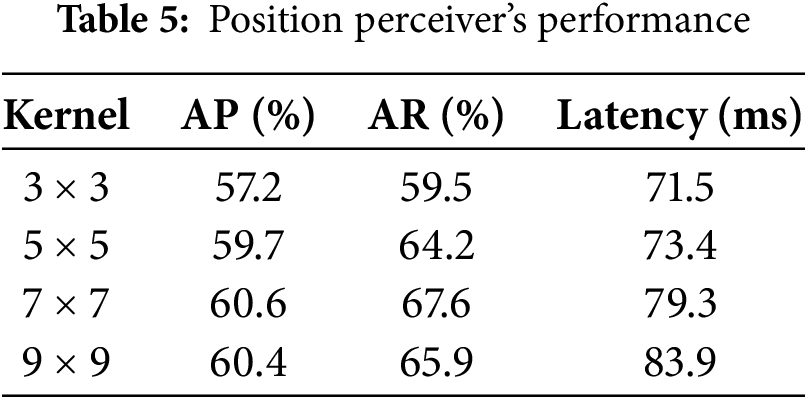

Table 5 explores the effect of the Position Perceiver module, which integrates a separable convolution with a large kernel into the attention mechanism to enhance positional awareness [43]. Applying this convolution directly to attention values preserves spatial structure and improves the model’s ability to capture positional information. Although accuracy increases with larger kernels, such as a 9

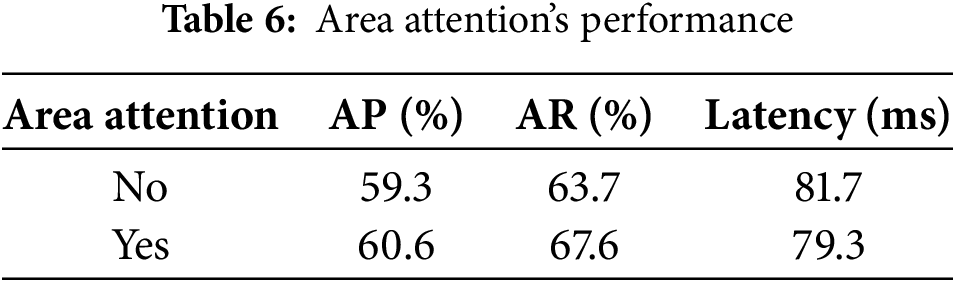

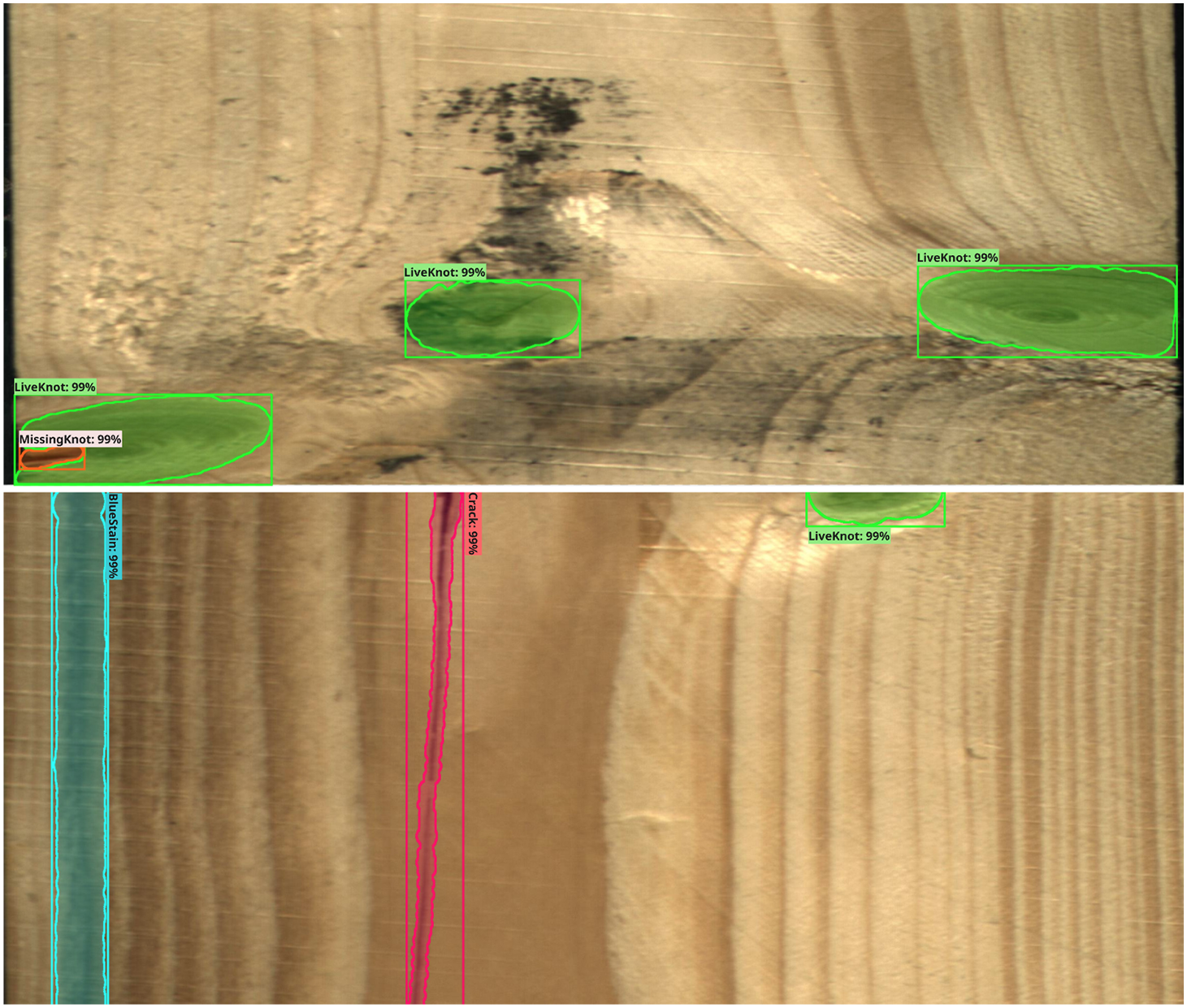

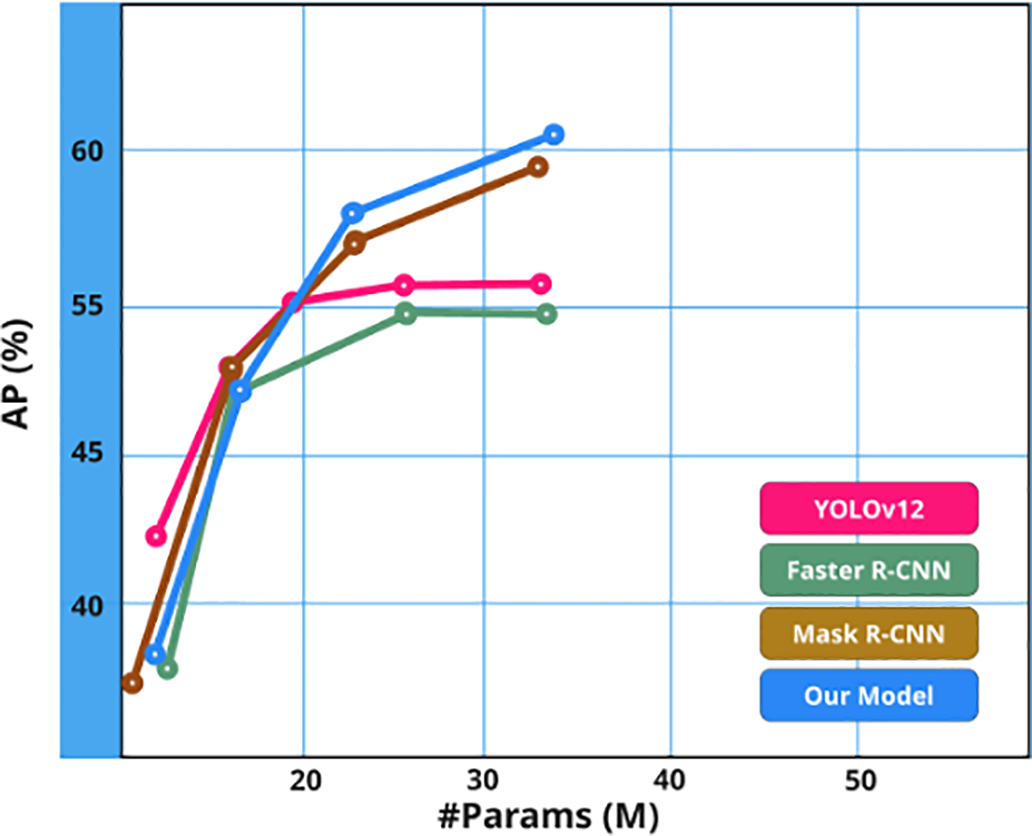

Table 6 focuses on area attention, with FlashAttention used as the implementation of choice. Despite adding computational complexity, area attention significantly improves performance without major slowdowns, demonstrating its effectiveness in directing the model’s focus to critical regions. Fig. 9 presents qualitative detection results, while Fig. 10 illustrates the accuracy-to-parameter trade-off by comparing the proposed model to Mask R-CNN, Faster R-CNN, and YOLOv12. The results confirm the efficiency of the model in achieving high accuracy with fewer parameters [28,54], thanks to its optimized feature extraction and attention modules. This lightweight yet accurate design is particularly advantageous for real-time applications and deployment in edge or resource-constrained environments, where model size and inference speed are critical [43,55]. Furthermore, the proposed model exhibits strong scalability, allowing it to be fine-tuned under different computational limitations while retaining competitive accuracy, thus making it a robust and practical solution for modern object detection tasks.

Figure 9: Detection samples

Figure 10: Accuracy parameter relation

4.2.2 Comparisons with State-of-the-Art Models

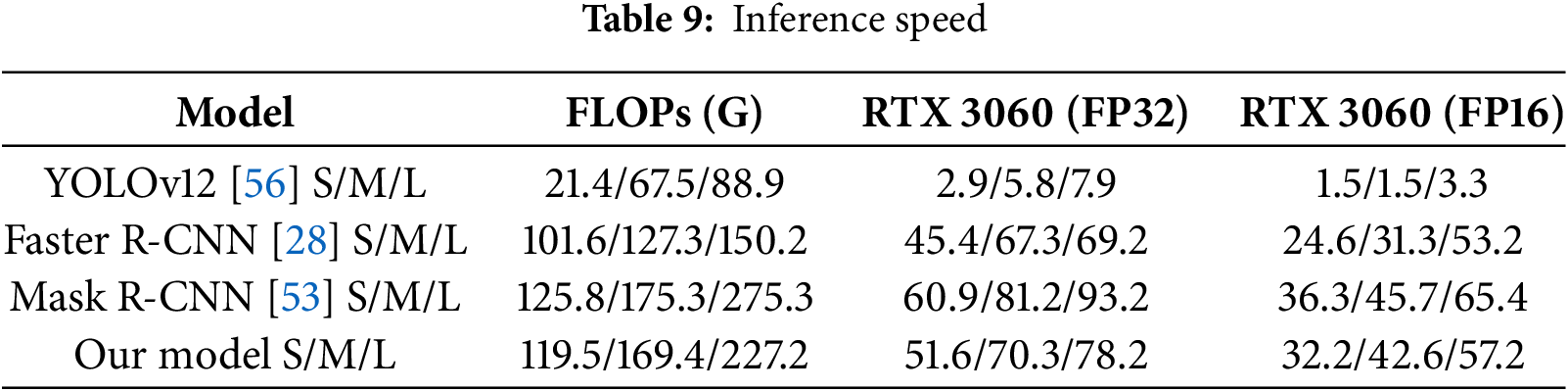

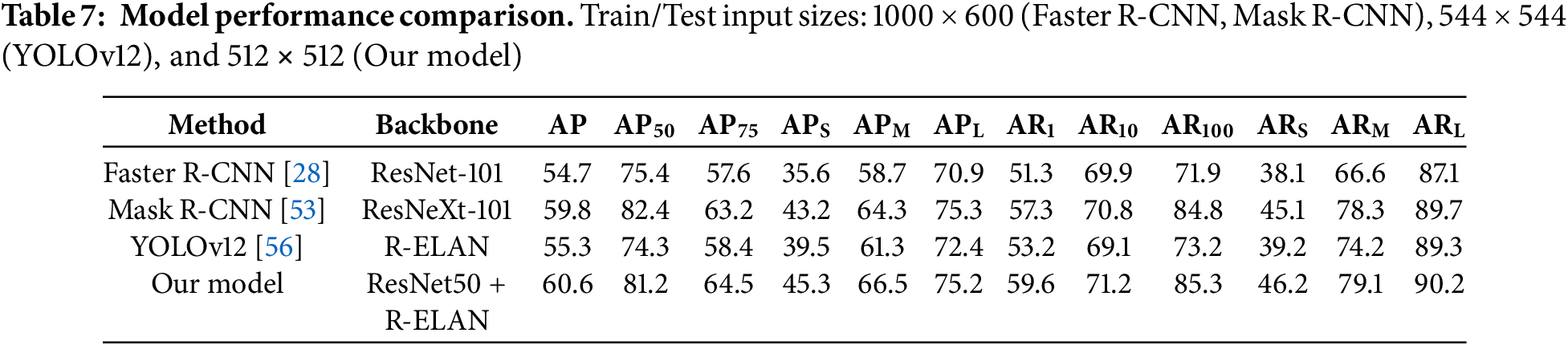

The proposed model exhibits notable advancements in accuracy, computational efficiency, and inference speed over established object detection frameworks, as evidenced by the comparative results presented in Tables 7–9. Evaluated under a standardized setup, with all models implemented within a unified codebase and tested on identical hardware, the model consistently outperforms Mask R-CNN, Faster R-CNN, and YOLOv12 across multiple object scales. It achieves an impressive Average Precision (AP) of 60.6%, with detailed performance metrics indicating 45.3% AP for small objects, 66.5% for medium, and 75.2% for large objects. These results highlight the model’s ability to accurately detect and localize defects regardless of size or complexity, making it highly adaptable to real-world industrial applications. The strong performance in small-object detection is particularly significant, as it demonstrates the model’s sensitivity to fine-grained features that are often missed by conventional architectures. Combined with improved efficiency and faster inference times, the model presents a well-rounded solution optimized for both accuracy and deployment practicality in high-throughput manufacturing environments.

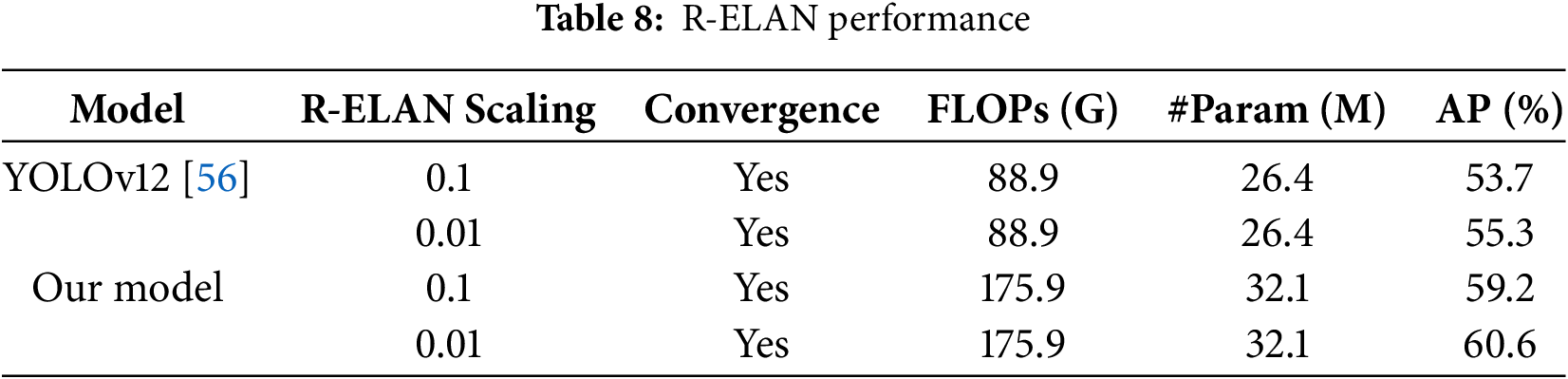

These multiscale detection capabilities emphasize the model’s suitability for real-world applications requiring fine-grained localization. Further architectural contributions are examined in Table 8, where the integration of Residual Efficient Layer Networks (R-ELAN) demonstrates two core benefits: residual connections ensure stable convergence with a low scaling factor of 0.01, enhancing gradient flow and deep feature learning, while R-ELAN effectively reduces computational complexity by lowering FLOPs and parameter count without compromising accuracy. This makes the model well-suited for deployment in environments with limited resources.

Table 9 evaluates inference performance, where the model outpaces Mask R-CNN in speed, rivals Faster R-CNN, and approaches the performance of the highly optimized YOLOv12. Tests conducted on an RTX 3060 GPU using both FP32 and FP16 formats show that while the proposed model is not the fastest, it strikes an effective balance between speed and accuracy, validating its practicality in scenarios requiring real-time inference and computational efficiency. These results collectively affirm that the proposed model not only delivers competitive detection accuracy across scales but also offers architectural and operational efficiency, positioning it as a compelling alternative to conventional frameworks.

The proposed deep learning-based wood defect detection model offers a robust, scalable solution for industrial quality control, effectively handling variations in defect size, shape, and texture through multi-scale feature extraction and ROI Align [57]. Its multitask learning architecture enables accurate classification, localization, and segmentation of defects, making it suitable for stringent production environments. However, the model could be improved by adopting more advanced backbones like Swin Transformers [58] and integrating attention-driven region proposal methods for better sensitivity and localization. To support real-time applications, lightweight architectures and low-precision inference techniques are recommended to reduce latency and resource demands. Additionally, enhancing robustness with attention mechanisms and improving scalability through self-supervised learning and domain adaptation will enable broader industrial deployment.

This study presents a comprehensive AI-driven framework for wood surface defect detection, demonstrating high accuracy, adaptability, and industrial relevance. The model addresses key limitations of traditional and existing automated systems by incorporating multi-task learning, multi-scale feature extraction, and ROI alignment, resulting in a system capable of precise, real-time analysis.

However, to fully address the evolving demands of modern manufacturing environments, future research should prioritize several critical enhancements. These include the integration of advanced attention-based mechanisms to improve robustness against diverse, ambiguous, and fine-grained defect patterns commonly encountered in industrial scenarios. In parallel, computational optimization strategies, such as model pruning, quantization, and the use of lightweight architectures, should be explored to ensure efficient deployment, particularly for real-time applications and resource-constrained edge devices. Scalable deployment frameworks must also be developed, incorporating both cloud-based infrastructures and on-site IoT-compatible platforms to support varying production workflows and operational contexts.

Furthermore, adopting self-supervised learning and domain adaptation techniques will significantly reduce the reliance on extensive annotated datasets, improving flexibility and cost-effectiveness when adapting the system to new environments, materials, or defect types. By addressing these areas, the proposed system stands to revolutionize quality inspection processes in the wood industry, offering a high-precision, sustainable, and cost-effective solution. It promises to not only increase production throughput and minimize material waste but also to promote responsible forestry practices. Ultimately, this advancement bridges the gap between conventional manual inspection and next-generation AI-powered automation, establishing itself as a transformative technology in the future of intelligent wood manufacturing.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: Vinh Truong Hoang supervised the project and revised the manuscript. Nghia Dinh designed the experiments and contributed to writing. Viet-Tuan Le, Kiet Tran-Trung and Bay Nguyen Van supported model development and evaluation. Ha Duong Thi Hong and Thien Ho Huong conducted statistical analysis and contributed to interpretation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yang Y, Zhou X, Liu Y, Hu Z, Ding F. Wood defect detection based on depth extreme learning machine. Appl Sci. 2020;10(21):7488. doi:10.3390/app10217488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang X. Recent advances in nondestructive evaluation of wood: in-forest wood quality assessments. Forests. 2021;12(7):949. doi:10.3390/f12070949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. ISO. ISO 21920-2: 2021 Geometrical product specifications (GPS)—Surface texture: profile [Internet]; 2021 [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.iso.org/standard/72226.html. [Google Scholar]

4. Deotale NT, Sarode TK. Fabric defect detection adopting combined GLCM, Gabor wavelet features and random decision forest. 3D Research. 2019;10(1):5. doi:10.1007/s13319-019-0215-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ganesan P, Sajiv G. A comprehensive study of edge detection for image processing applications. In: 2017 International Conference on Innovations in Information, Embedded and Communication Systems (ICIIECS); 2017 Mar 17–18; Coimbatore, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICIIECS.2017.8275968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yuan X-C, Wu L-S, Peng Q. An improved Otsu method using the weighted object variance for defect detection. Appl Surf Sci. 2015;349:472–84. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.05.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kipf TN, Welling M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv:1609.02907. 2017. [Google Scholar]

9. Liu Z, Zhou J. Graph attention networks. In: Introduction to graph neural networks. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 39–41. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-01587-8_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Redmon J, Farhadi A. YOLOv3: an incremental improvement. arXiv:1804.02767. 2018. [Google Scholar]

11. Lin TY, Dollár P, Girshick R, He K, Hariharan B, Belongie S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 936–44. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wu Z, Pan S, Chen F, Long G, Zhang C, Yu PS. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE Transact Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2021;32(1):4–24. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2020.2978386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Weissenborn D. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv:2010.11929. 2021. [Google Scholar]

14. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HYM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 7464–75. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tsoumis G. Science and technology of wood: structure, properties, utilization. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Chapman & Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

16. Ouis D. On the frequency dependence of the modulus of elasticity of wood. Wood Sci Technol. 2002;36(4):335–46. doi:10.1007/s00226-002-0145-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hendarto B, Shayan E, Ozarska B, Carr R. Analysis of roughness of a sanded wood surface. Int J Adv Manufact Technol. 2006;28(7–8):775–80. doi:10.1007/s00170-004-2414-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Gribanov AA, Mohammed HAA. Automated method recognizing defects in wood. In: 2021 International Conference on Industrial Engineering, Applications and Manufacturing (ICIEAM); 2021 May 17–21; Sochi, Russian. p. 422–7. doi:10.1109/ICIEAM51226.2021.9446355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Teo HC, Hashim UR, Ahmad S. Timber defect identification: enhanced classification with residual networks. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2024;15(4):68. doi:10.14569/IJACSA.2024.0150468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kang J, Cen Y, Cen Y, Wang K, Liu Y. CFIS-YOLO: a lightweight multi-scale fusion network for edge-deployable wood defect detection. arXiv:2504.11305. 2025. [Google Scholar]

21. Goodfellow I, Bengio Y, Courville A. Deep learning. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

22. Chabanet S, Thomas P, Bril El-Haouzi H. MLP based on dissimilarity features: an application to wood sawing simulator metamodeling. SN Comput Sci. 2023;4(4):408. doi:10.1007/s42979-023-01852-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Trampert P, Mantowsky S, Schmidt F, Masiak T, Schneider G. AI-driven toolbox for efficient and transferable visual quality inspection in production. SN Comput Sci. 2025;6(5):1–15. doi:10.1007/s42979-025-03988-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Khanam R, Hussain M, Hill R, Allen P. A comprehensive review of convolutional neural networks for defect detection in industrial applications. IEEE Access. 2024;12(1):94250–95. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3425166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zou X, Wu C, Liu H, Yu Z. Improved ResNet-50 model for identifying defects on wood surfaces. Signal Image Video Process. 2023;17(6):3119–26. doi:10.1007/s11760-023-02533-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Vol. 60. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2017. doi:10.1145/3065386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ge Z, Liu S, Wang F, Li Z, Sun J. Yolox: exceeding yolo series in 2021. arXiv:2107.08430. 2021. [Google Scholar]

28. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Transact Pattern Analy Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kirillov A, He K, Girshick R, Rother C, Dollar P. Panoptic segmentation. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 9396–405. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kodytek P, Bodzas A, Bilik P. Supporting data for deep learning and machine vision based approaches for automated wood defect detection and quality control. Zenodo. 2021. doi:10.5281/zenodo.4694695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Lin TY, Maire M, Belongie S, Hays J, Perona P, Ramanan D, et al. Microsoft COCO: common objects in context. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2014. p. 740–55. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10602-1_48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Atkins CB, Bouman CA, Allebach JP. Optimal image scaling using pixel classification. In: Proceedings 2001 International Conference on Image Processing; 2001 Oct 7–10; Thessaloniki, Greece. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2001.958257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Gonzalez RC, Woods RE. Digital image processing. 4th ed. London, UK: Pearson; 2018. [Google Scholar]

34. Deng J, Dong W, Socher R, Fei-Fei L. ImageNet: a large-scale hierarchical image database. In: 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2009 Jun 20–25; Miami, FL, USA. p. 248–55. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2009.5206848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Pizer SM, Amburn EP, Austin JD, Cromartie R, Geselowitz A, Greer T, et al. Adaptive histogram equalization and its variations. Comput Vis Graph Image Process. 1987;39(3):355–68. doi:10.1016/S0734-189X(87)80186-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Canny J. A computational approach to edge detection. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 1986;PAMI-8(6):679–98. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.1986.4767851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zeiler MD, Fergus R. Visualizing and understanding convolutional networks. In: Computer Vision-ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference; 2014 Sep 6–12; Zurich, Switzerland. p. 818–33. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10590-1_53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv:1409.1556. 2015. [Google Scholar]

39. Nair V, Hinton GE. Rectified linear units improve restricted boltzmann machines. In: Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML’10; 2010 Jun 21–24; Haifa, Israel. p. 807–14. [Google Scholar]

40. Srivastava RK, Greff K, Schmidhuber J. Training very deep networks. In: Cortes C, Lawrence N, Lee D, Sugiyama M, Garnett R, editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 28. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2015. doi:10.5555/2969442.2969505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Huang G, Liu Z, Van Der Maaten L, Weinberger KQ. Densely connected convolutional networks. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 4700–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zagoruyko S, Komodakis N. Wide residual networks. In: Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference; 2016 Sep 19–22; York, UK. p. 87.1–87.12. doi:10.5244/C.30.87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Hu J, Shen L, Albanie S, Sun G, Wu E. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;42(8):2011–23. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2019.2913372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Chen Y, Kalantidis Y, Li J, Yan S, Feng J. A2-Nets: double attention networks. In: 32nd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2018); 2018 Dec 3–8; Montréal, QC, Canada. p. 352–61. [Google Scholar]

45. Woo S, Park J, Lee JY, Kweon IS. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. In: ECCV 2018. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 3–19. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zhao Y, Liu Q, Su H, Zhang J, Ma H, Zou W, et al. Attention-based multiscale feature fusion for efficient surface defect detection. IEEE Transact Instrument Measur. 2024;73:1–10. doi:10.1109/TIM.2024.3372229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Liu S, Qi L, Qin H, Shi J, Jia J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 8759–68. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zhang H, Wu C, Zhang Z, Zhu Y, Lin H, Zhang Z, et al. ResNeSt: split-attention networks. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2022 Jun 19–20; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 2735–45. doi:10.1109/CVPRW56347.2022.00309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Szegedy C, Ioffe S, Vanhoucke V, Alemi A. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet, and the impact of residual connections on learning. In: The 31 AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2017 Feb 4–9; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 4278–84. doi:10.1609/aaai.v31i1.11231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Wong F, Hu H. Adaptive learning feature pyramid for object detection. IET Comput Vis. 2019;13:742–8. doi:10.1049/iet-cvi.2018.5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Girshick R. Fast R-CNN. In: 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 7–13; Santiago, Chile. p. 1440–8. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2015.169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. He K, Gkioxari G, Dollar P, Girshick R. Mask R-CNN. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;42(2):386–97. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2844175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Jiang B, Luo R, Mao J, Xiao T, Jiang Y. Acquisition of localization confidence for accurate object detection. In: Ferrari V, Hebert M, Sminchisescu C, Weiss Y, editors. ECCV 2018. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 816–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01264-9_48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Lin TY, Goyal P, Girshick R, He K, Dollár P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2980–8. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Zhou X, Wang D, Krahenbuhl P. Objects as points. arXiv:1904.07850. 2019. [Google Scholar]

56. Yin X, Zhao Z, Weng L. MAS-YOLO: a lightweight detection algorithm for PCB defect detection based on improved YOLOv12. Appl Sci. 2025;15(11):6238. doi:10.3390/app15116238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Vu T, Jang H, Pham TX, Yoo CD. Cascade RPN: delving into high-quality region proposal network with adaptive convolution. arXiv:1907.07464. 2019. [Google Scholar]

58. Alijani S, Fayyad J, Najjaran H. Vision transformers in domain adaptation and domain generalization: a study of robustness. Neural Comput Applicat. 2024;36(29):17979–8007. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-10353-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools