Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

VMHPE: Human Pose Estimation for Virtual Maintenance Tasks

School of Electromechanical Engineering, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou Higher Education Mega Center, Guangzhou, 510006, China

* Corresponding Author: Yueming Wu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 801-826. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066540

Received 10 April 2025; Accepted 18 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Virtual maintenance, as an important means of industrial training and education, places strict requirements on the accuracy of participant pose perception and assessment of motion standardization. However, existing research mainly focuses on human pose estimation in general scenarios, lacking specialized solutions for maintenance scenarios. This paper proposes a virtual maintenance human pose estimation method based on multi-scale feature enhancement (VMHPE), which integrates adaptive input feature enhancement, multi-scale feature correction for improved expression of fine movements and complex poses, and multi-scale feature fusion to enhance keypoint localization accuracy. Meanwhile, this study constructs the first virtual maintenance-specific human keypoint dataset (VMHKP), which records standard action sequences of professional maintenance personnel in five typical maintenance tasks and provides a reliable benchmark for evaluating operator motion standardization. The dataset is publicly available at . Using high-precision keypoint prediction results, an action assessment system utilizing topological structure similarity was established. Experiments show that our method achieves significant performance improvements: average precision (AP) reaches 94.4%, an increase of 2.3 percentage points over baseline methods; average recall (AR) reaches 95.6%, an increase of 1.3 percentage points. This research establishes a scientific four-level evaluation standard based on comparative motion analysis and provides a reliable solution for standardizing industrial maintenance training.Keywords

Virtual maintenance is an innovative approach that utilizes Virtual Reality (VR) or Augmented Reality (AR) technologies to simulate real maintenance environments and processes. It enables users to perform equipment maintenance, fault diagnosis, and operational training in virtual environments without interacting with actual equipment, thereby reducing training costs and safety risks [1–3]. By providing immersive, interactive learning experiences, virtual maintenance technology significantly enhances maintenance personnel’s skill levels and work efficiency [4].

As a significant application of VR and AR, virtual maintenance technology is becoming a research hotspot in industries such as industrial manufacturing, healthcare, and education [5]. This technology constructs virtual maintenance environments that enable real-time interaction and operation among multiple users, thereby significantly improving maintenance task efficiency and safety [6]. However, achieving high-quality virtual maintenance faces a key challenge: how to accurately perceive and precisely reproduce participants’ movements [7]. In virtual maintenance, high-precision reproduction of human poses is crucial. Not only does it provide authentic interactive experiences, but more importantly, it can be used to correct improper operational behaviors and guide participants to perform correct maintenance actions [8]. For example, in complex mechanical maintenance tasks, the system can detect and correct incorrect operating postures in real-time by comparing the poses of experts and learners, thereby avoiding potential safety hazards and improving maintenance quality [9]. Human keypoint detection is the first and most critical step in achieving high-precision pose reproduction. In the field of general human keypoint detection, numerous studies have achieved significant results. For instance, OpenPose proposed by Cao et al. [10] and HRNet by Sun et al. [11] have shown excellent performance in multi-person pose estimation. Although human pose estimation is currently a research hotspot, existing studies mostly focus on general scenarios, lacking specialized research for maintenance tasks [12]. Furthermore, the field also lacks relevant professional datasets, which to some extent limits the depth of research development.

To address these issues, this paper proposes a multi-scale feature enhancement-based human pose estimation method for virtual maintenance, VMHPE. This method significantly improves pose estimation performance in complex maintenance scenarios through the organic combination of multi-scale feature correction and fusion attention mechanisms. To support related research development, we have constructed and open-sourced the virtual maintenance-specific dataset VMHKP, which covers five typical maintenance task scenarios and adopts the standard Common Objects in Context (COCO) keypoint annotation scheme, thus providing a reliable evaluation benchmark for research in this field. Through systematic experimental validation, our method demonstrates significant performance advantages in virtual maintenance scenarios, achieving notable improvements in key metrics compared to existing methods. This provides strong support for the further development of virtual maintenance technology.

2 Theoretical Background and Problem Analysis

Human pose estimation is the crucial first step in virtual maintenance, where the accuracy of operators’ movements directly affects training effectiveness and operation quality. Accurate detection and correction of postures requires high-precision human keypoint detection technology supported by large-scale annotated datasets. In this field, researchers have developed several influential datasets including the representative COCO dataset [13], which covers various tasks such as object segmentation and human keypoint annotation. As research progressed, enhanced datasets emerged including COCO-WholeBody [14] with 133 keypoints, Halpe dataset [15,16] with improved keypoint quantity and annotation format, DensePose-Posetrack dataset [17] focusing on multi-person video sequences, DAVIS dataset [18] containing challenging poses, and EPIC-KITCHENS dataset [19] with egocentric perspectives.

However, these public datasets show apparent limitations in the virtual maintenance domain. First, virtual maintenance tasks typically involve specific operation poses and tool usage inadequately represented in general datasets. Second, maintenance tasks may require operators to adopt uncommon or complex poses, which have limited representation in existing datasets. Additionally, virtual maintenance environments may include special lighting conditions, occlusions, and backgrounds not fully considered in general datasets. Most critically, the attention requirements for specific keypoints in maintenance tasks differ significantly from the annotation focus of general datasets. Based on this analysis, constructing a dataset specifically for virtual maintenance scenarios becomes essential to provide samples closely aligned with actual application scenarios, cover key poses and actions in specific tasks, and ultimately improve the accuracy and training effectiveness of virtual maintenance systems. Such a specialized dataset would enable more precise detection of operators’ actions and provide timely correction and guidance.

Beyond dataset support, algorithm design and optimization are equally crucial for improving human pose estimation performance in virtual maintenance. While deep learning has brought revolutionary progress to this field, existing algorithms still face unique challenges in specific domains like virtual maintenance. The following section will analyze the development history and technical characteristics of existing algorithms, as well as their potential and limitations in virtual maintenance scenarios.

The development of deep learning technology has revolutionized human pose estimation, with DeepPose [20] by Toshev and Szegedy pioneering the use of convolutional neural networks for direct regression of human joint positions. Subsequent research has evolved along two major technical approaches: bottom-up and top-down methods.

Bottom-up methods have shown significant progress with OpenPose [10] by Cao et al. achieving efficient multi-person pose estimation through multi-stage Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Part Affinity Fields. This approach was further developed in HigherHRNet [21] by Cheng et al., which improved accuracy through multi-resolution feature fusion, and Jin et al.’s Whole-Body Human Pose Estimation [14] that expanded to simultaneous detection of body, face, and hand keypoints. Concurrently, top-down methods have achieved remarkable results, with HRNet [11] by Sun et al. maintaining high-resolution feature maps for precise pose estimation. This approach was enhanced in HRNetV2-W48 within MMPose for comprehensive detection of body, hand, and facial keypoints, while AlphaPose [22] incorporated object tracking capabilities along with efficient pose estimation. Recent innovations have further advanced keypoint detection accuracy and robustness. ViTPose [23] by Xu et al. leveraged Vision Transformer structures, FCPose [24] by Zeng et al. enhanced efficiency using fully convolutional networks, and Sun et al.’s SimCC model [25] improved computational efficiency through one-dimensional vector representation. For temporal stability, SmoothNet [26] by Zeng et al. improved coherence through temporal modeling. Specialized solutions have emerged for specific applications, such as MediaPipe Hands [27] and InterHand2.6M [28] for hand pose estimation, and the Real-Time Multi-Object (RTMO) model [29] by Lu et al. for multi-person pose estimation.

Despite these advancements, general-purpose algorithms face significant challenges in virtual maintenance scenarios. First, maintenance tasks often require unconventional poses rarely represented in training datasets. Second, virtual maintenance demands higher precision, as small errors can lead to operational mistakes. Third, real-time performance is essential for effective feedback in training systems. These domain-specific requirements necessitate specialized approaches that can better address the unique characteristics of maintenance operations [30–32].

Following this research trajectory, the CID (Contextual Instance Decoupling) [33] architecture has advanced general-purpose pose estimation by decoupling instance features from global context, yet it shows limitations in specialized domains like virtual maintenance that demand higher precision. Building upon these advances, this paper proposes the VMHPE model with three key contributions: 1) a multi-scale feature enhancement framework specifically designed for maintenance contexts to capture complex poses and fine movements; 2) two novel modules-MultiscaleFeatureRectifyModule and MultiscaleFusedAttention-that enhance model performance through adaptive feature correction and multi-perspective feature fusion; and 3) the first virtual maintenance-specific human keypoint dataset (VMHKP) as a standardized benchmark. The VMHPE model effectively addresses the unique challenges of virtual maintenance through targeted multi-scale processing strategies, demonstrating significant advantages in both accuracy and robustness for specialized maintenance operations.

3.1 Virtual Maintenance Specialized Dataset (VMHKP) Definition

3.1.1 Dataset Construction Process

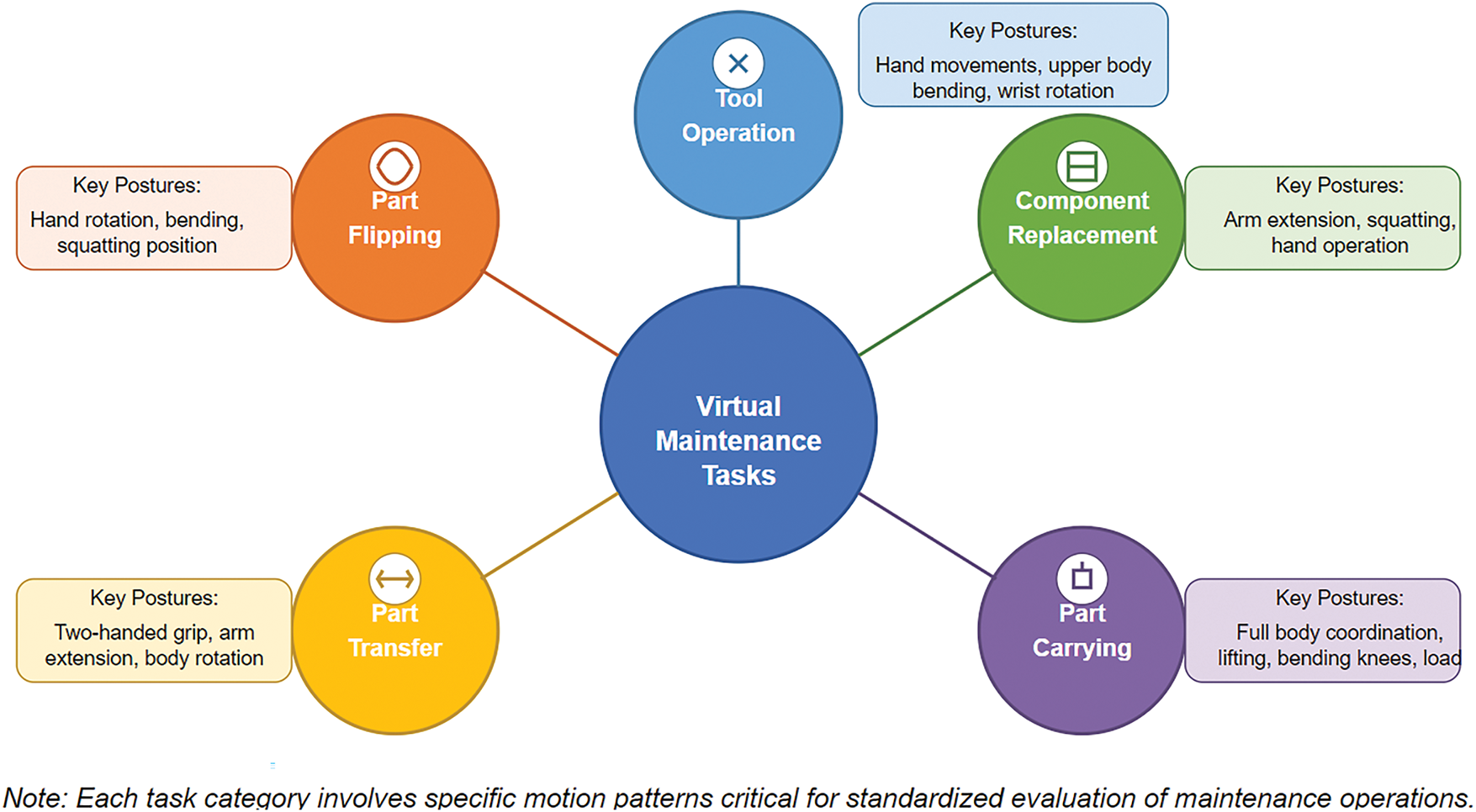

To address limitations in existing datasets, we constructed the Virtual Maintenance Human Keypoint Dataset (VMHKP) through a systematic three-phase process: task design, data collection, and annotation. The dataset includes 1100 RGB images from 11 technicians performing standardized maintenance procedures. These technicians have different body types (lean, medium, and heavy builds) and wear various work clothing (lightweight work attire, standard long-sleeve work uniforms, short-sleeve work uniforms, and work uniforms in different colors). This diversity design significantly enhances the representativeness of the dataset and effectively reduces potential body characteristic bias. Data collection employs a Microsoft Kinect Azure Developer Kit (DK) depth camera integrated with a 12-megapixel RGB camera, fixed at a position 2.5 meters away from the operation area to ensure complete capture of the technicians’ full-body movement range. To ensure data quality and operational smoothness, an image acquisition strategy of collecting one frame every 10 frames is adopted, with 20 most representative images carefully selected from continuous maintenance operation video sequences, covering the preparation, execution, and completion phases of operations. The annotation process uses the COCO-Annotator tool, following the COCO dataset’s 17 keypoint standard for 2D coordinate annotation. The annotation team consists of 3 researchers who received professional training in keypoint localization under the guidance of medical professionals. A dual verification mechanism is employed: after initial annotation, another annotator conducts independent review, and for keypoints with position differences exceeding 5 pixels, consensus is reached through discussion. During the annotation process, consistency checks are implemented by regularly sampling 10% of images for cross-annotator evaluation, ensuring the average error in keypoint localization is controlled within 3 pixels. After all annotations are completed, maintenance technicians with over 5 years of experience are invited to verify the standardization of action postures, ensuring that the annotated actions comply with actual maintenance operation standards. The final dataset passes integrity checks, providing high-quality standard data for model training and evaluation. capturing complete action sequences that embody professional characteristics such as wrist-elbow-shoulder coordination during tool operation and trunk-hip-knee support during component transport. These data provide a reliable foundation for establishing maintenance action evaluation standards. Based on industrial maintenance field investigation, we selected five representative maintenance tasks (Fig. 1). Each task was designed according to actual maintenance manuals to cover operational difficulty, tool usage, and body movement range across different scenarios, ensuring comprehensive coverage and a complete evaluation benchmark for algorithm research.

Figure 1: Virtual maintenance task categories

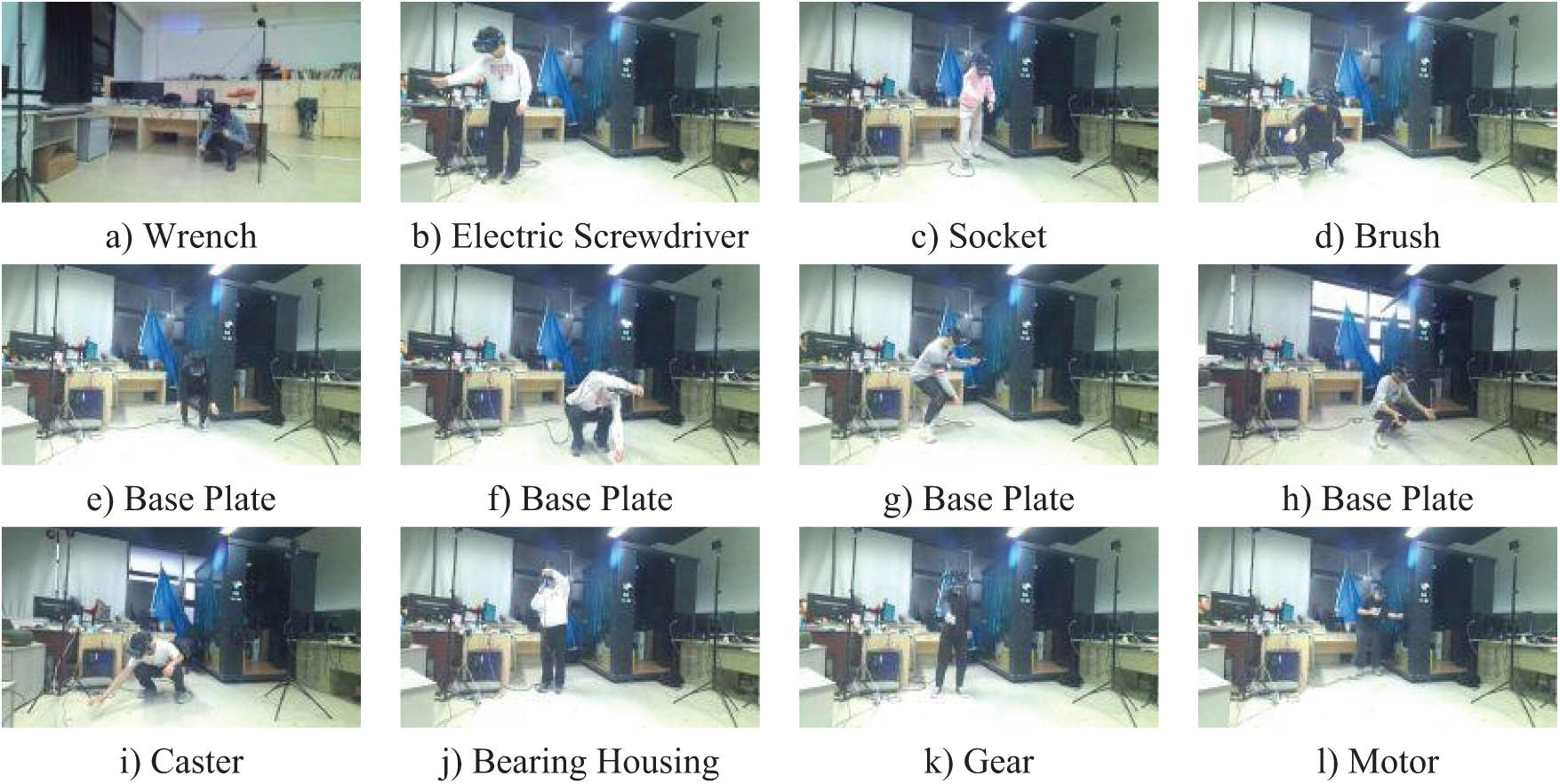

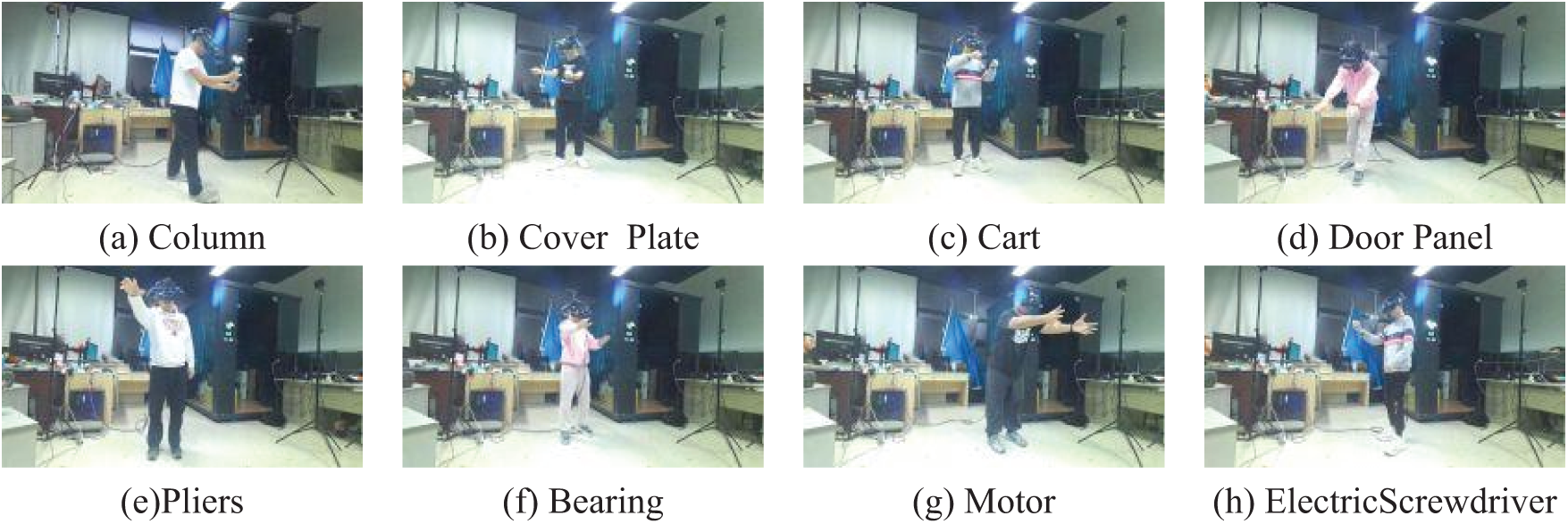

Figs. 2 and 3 demonstrate typical operation scenarios across various maintenance tasks.

Figure 2: Task Action illustrations. (a–d) Tool Operation (TO), (e–h) Part Flipping (PF), (i–l) Component Replacement (CR)

Figure 3: Task Action Illustrations (Part 2). (a–d) PC (Part Carrying), (e–h) Part Transfer (CT)

This systematic construction process ensures data quality and standardization while providing reliable training and evaluation data for the human pose estimation method proposed in Section 3.2.

3.1.2 Dataset Characteristics and Advantages

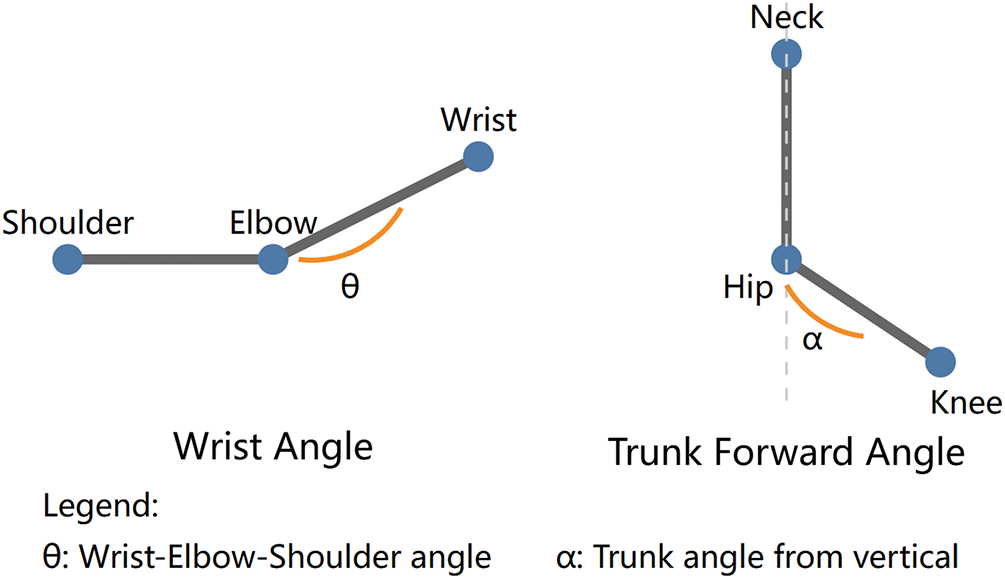

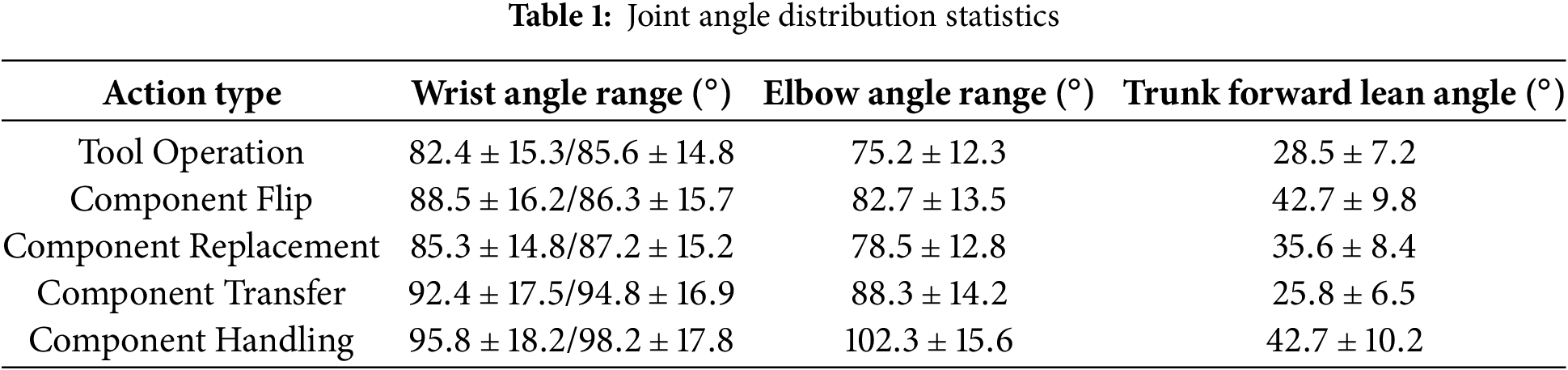

The VMHKP dataset demonstrates unique advantages in three dimensions: data distribution, pose characteristics, and action continuity. Data are evenly distributed across five maintenance tasks, with 220 images per category. Each task includes rich operational scenario variations, such as the common tool application task covering operation poses for 8 maintenance tools including wrenches, electric screwdrivers, and sockets. To quantitatively analyze maintenance pose characteristics, we defined three key angle parameters (Fig. 4): wrist angle, elbow angle, and trunk forward lean angle. The wrist angle is defined as the angle formed by the wrist-elbow-shoulder line, calculated separately for left and right wrists to describe the degree of arm bending. The elbow angle adopts a similar definition. Trunk forward lean angle is defined as the angle between the trunk midline and vertical direction, characterizing the degree of body forward lean.

Figure 4: Schematic diagram of key angle calculation

Statistical analysis of these angles revealed significant differences in joint angle distributions across maintenance tasks (Table 1). Component transfer and transport tasks exhibited larger elbow angles (

Another important VMHKP characteristic is action continuity. By analyzing keypoint displacement changes between adjacent frames, we quantified the continuity characteristics of maintenance actions (Table 2). Different tasks show distinct motion amplitude differences. Tool operation tasks have relatively smaller average inter-frame displacements (

In summary, VMHKP provides a comprehensive foundation for human pose estimation research in virtual maintenance scenarios through balanced task distribution, rich pose characteristics, and complete action sequences. These characteristics enhance model adaptability to maintenance scenarios and provide an important basis for subsequent algorithm optimization.

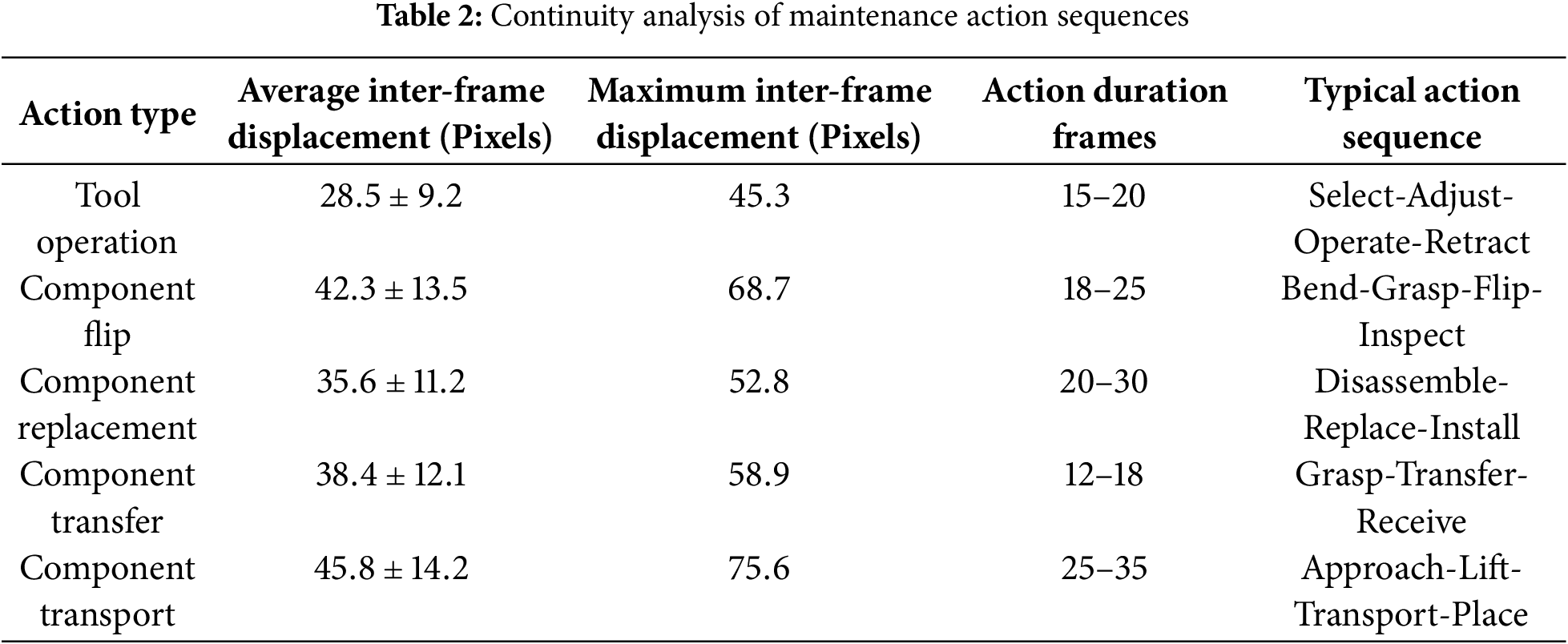

3.2.1 Overall Architecture Design

The VMHPE method is specifically designed to enhance pose estimation performance in virtual maintenance scenarios through multi-scale feature processing and adaptive attention mechanisms. Fig. 5 illustrates the comprehensive architecture of our proposed approach.

Figure 5: Overall architecture design

The framework consists of four integrated modules working in sequence: the backbone network extracts initial features from input images, the Individual Representation Learning (IRL) module generates discriminative individual features, the Multi-scale Feature Correction (MFC) module enhances feature robustness across different scales, and finally the Keypoint Estimation (KE) module produces precise keypoint heatmaps. This sequential design progressively refines features from coarse to fine, enabling accurate pose estimation even under the challenging conditions typical in maintenance operations.

The MFC module performs adaptive correction on multi-scale feature maps F extracted by the backbone network under the guidance of individual representation. This module employs a Multi-scale Feature Correction Module (MFCM), enhancing feature robustness to pose variations and occlusions in both spatial and channel dimensions through adaptive scale weights and enhanced feature correction operations.

After obtaining individual feature correction results, VMHPE aggregates global features at different scales through the Multi-scale Feature Fusion Module (MFFM). This module combines cross-attention and channel embedding mechanisms, introducing multi-scale convolution to fuse local and global context information from multiple perspectives. The fused features, together with individual enhanced features, provide input for keypoint estimation.

Finally, the KE module adopts an encoder-decoder structure, comprehensively utilizing individual enhanced features and fused features to generate K keypoint heatmaps for each individual. During training, VMHPE jointly optimizes the entire framework in an end-to-end manner. The loss functions include heatmap loss, contrastive loss, and regularization terms. These are used to optimize keypoint localization accuracy, feature discrimination ability, and model generalization performance.

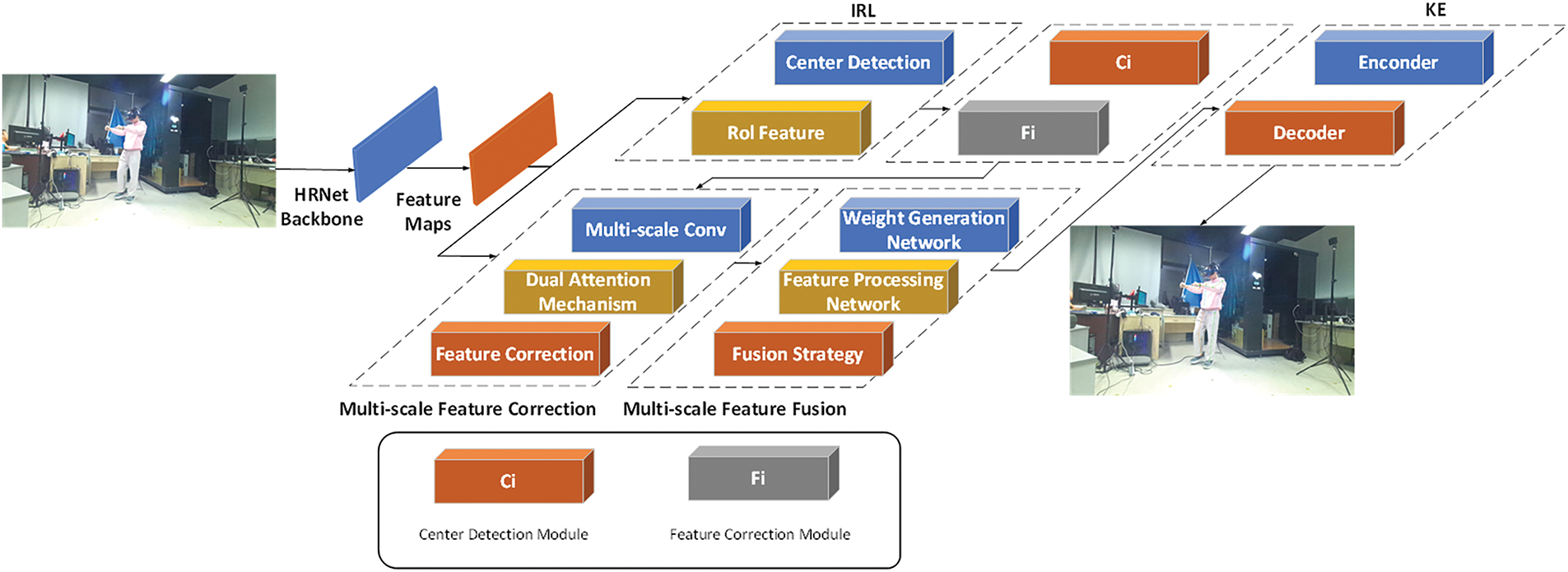

3.2.2 Basic Attention Module Design

This section first introduces two core attention modules in the VMHPE model: Channel Attention and Spatial Attention (Fig. 6). As basic units for feature enhancement, these two modules achieve adaptive enhancement of input features through different feature interaction methods. In the subsequent multi-scale feature processing, these two modules will be used for correction and fusion of features at different scales.

Figure 6: Basic attention module

The Channel Attention module aims to capture dependencies between feature channels and adaptively adjust the importance of each channel. This module takes global features

where

To extract channel correlations, the module applies both global average pooling and max pooling operations to

These descriptors are further concatenated and processed through a multi-layer perceptron (MLP), as shown in Eq. (4):

where the MLP consists of two fully connected layers with ReLU activation in between and Sigmoid activation

The Spatial Attention module focuses on spatial dimension information of feature maps and, in addition to processing global and instance features, optionally accepts instance coordinate information

When instance coordinates are provided, the module computes relative position encoding according to Eqs. (7) and (8):

After concatenating the spatial attention map with relative position encoding, a series of convolution operations generate the final spatial attention weights:

The final output is computed through a similar residual mechanism, as described in Eq. (10):

where the pad operation ensures consistent output dimensions with the input. Through this design, the spatial attention module effectively captures spatial dependencies in the features.

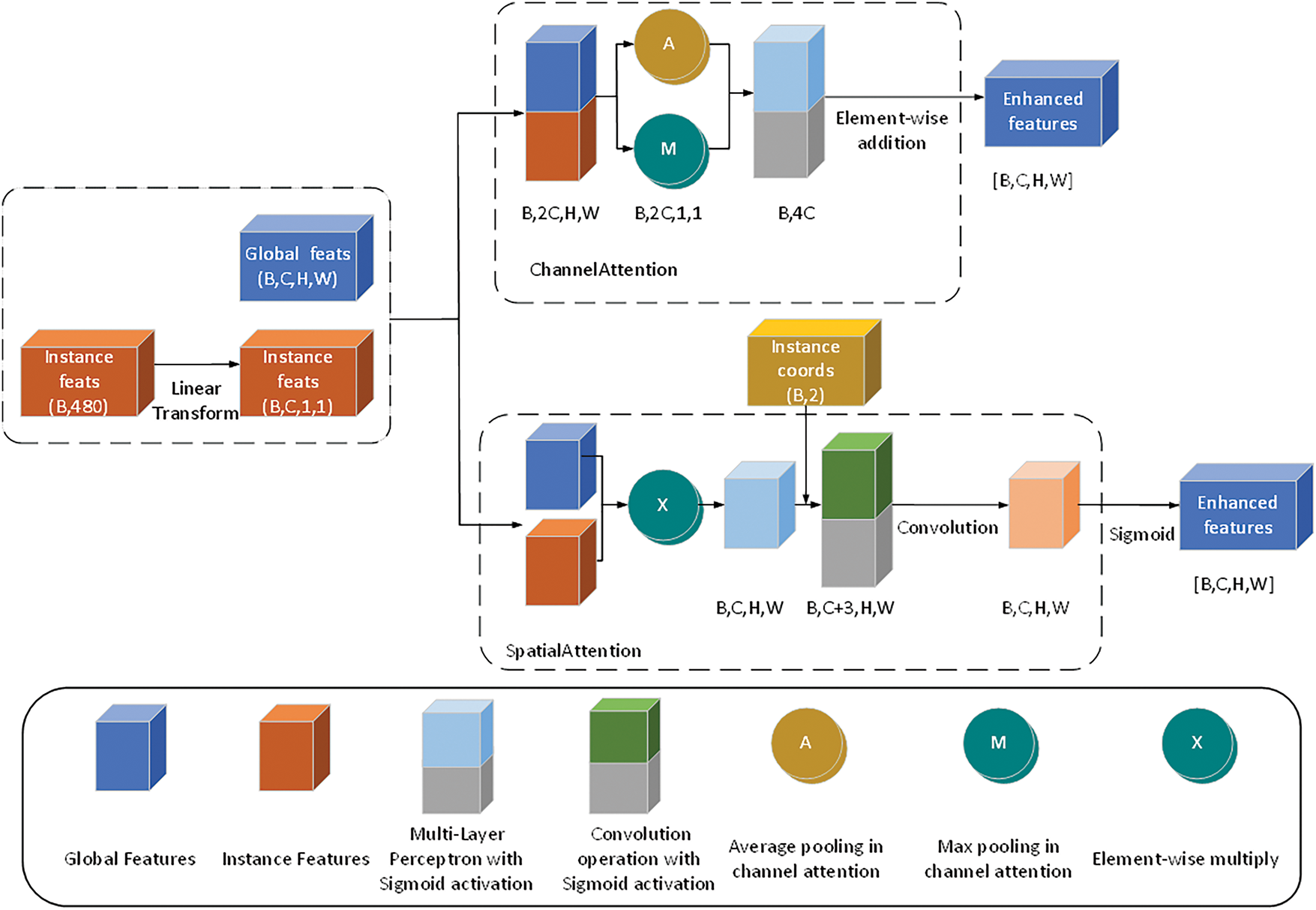

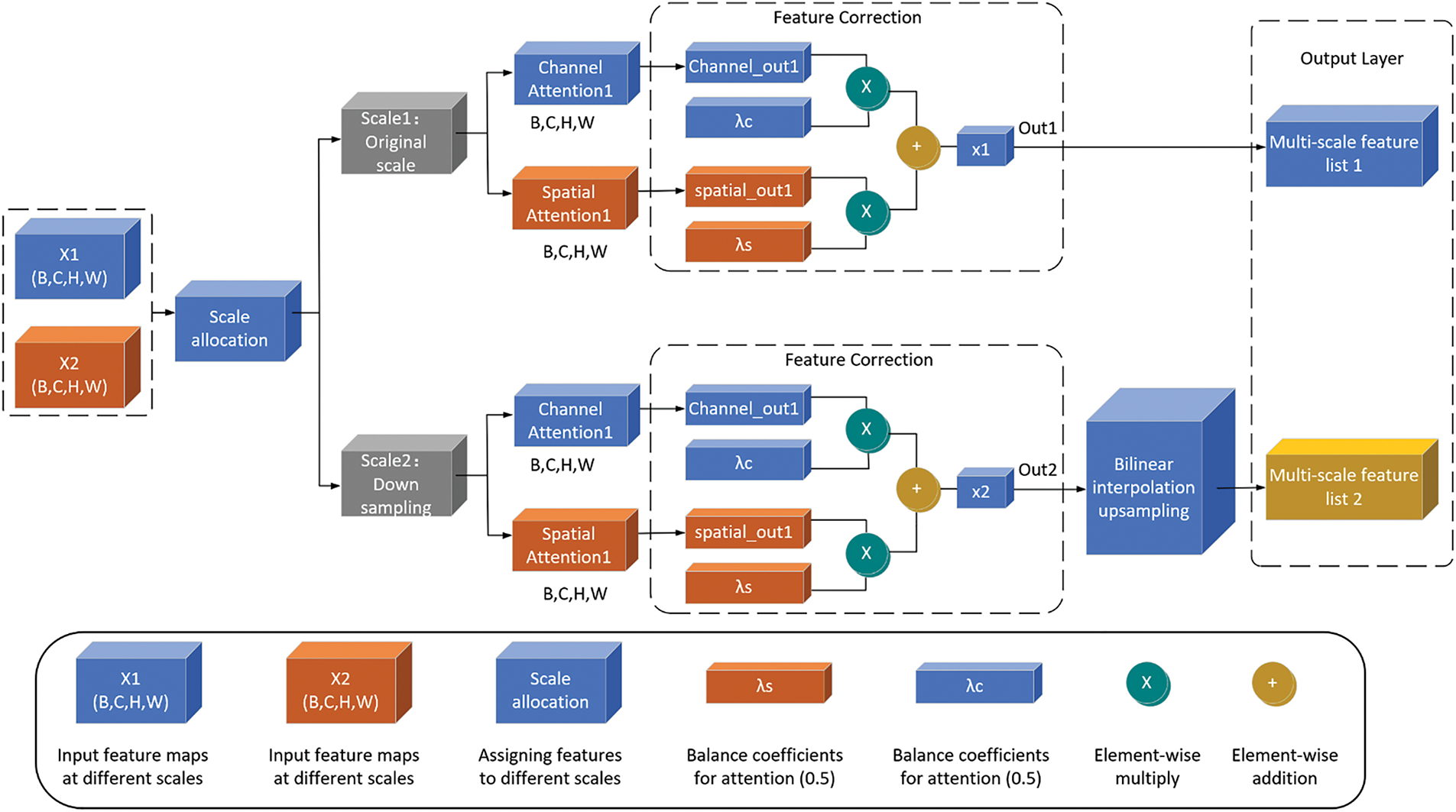

3.2.3 Multi-Scale Feature Correction

The Multiscale Feature Correction Module (MFCM) is a feature enhancement component specifically designed for human pose estimation tasks in virtual maintenance scenarios (Fig. 7). Through adaptive multiscale processing and dual attention mechanisms, this module significantly enhances feature representation capabilities and adaptability to complex scenarios.

Figure 7: Multi-scale feature correction module

At the implementation level, MFCM first constructs a multiscale feature pyramid. The input global feature map F undergoes multiscale sampling, with sampling coefficients scales typically set to [1,2], corresponding to original scale and 1/2 scale. The sampling process is implemented using bilinear interpolation, which can be expressed as:

where

Then channel attention weights are computed through two fully connected layers with nonlinear activations:

where

The spatial attention module focuses on the spatial information distribution of feature maps. It processes the feature map through parallel average pooling and max pooling branches:

These pooled features are concatenated and processed by a convolution layer to generate spatial attention weights:

where [;] represents channel-wise concatenation, and

where

Then scale weights are generated through the softmax function:

where

To maintain feature consistency, features at all scales are upsampled to the original resolution before fusion. This design ensures that the final enhanced features retain both fine-grained details from the original scale and contextual information from larger scales.

Given the specificity of virtual maintenance scenarios, we designed key hyperparameters based on theoretical and practical experience. The setting of the dimensionality reduction ratio

To improve the model’s generalization capability and reduce overfitting risks, we designed multi-level data augmentation strategies: geometric transformation augmentation simulates different observation angles and operational postures through random rotation, scaling transformation, and horizontal flipping; photometric augmentation adapts to different lighting environments through color jittering, brightness and contrast adjustment; spatial perturbation includes random cropping and moderate perturbation of keypoint positions to enhance the model’s adaptability to spatial variations. The design of these augmentation strategies fully considers the characteristics and challenges of virtual maintenance scenarios.

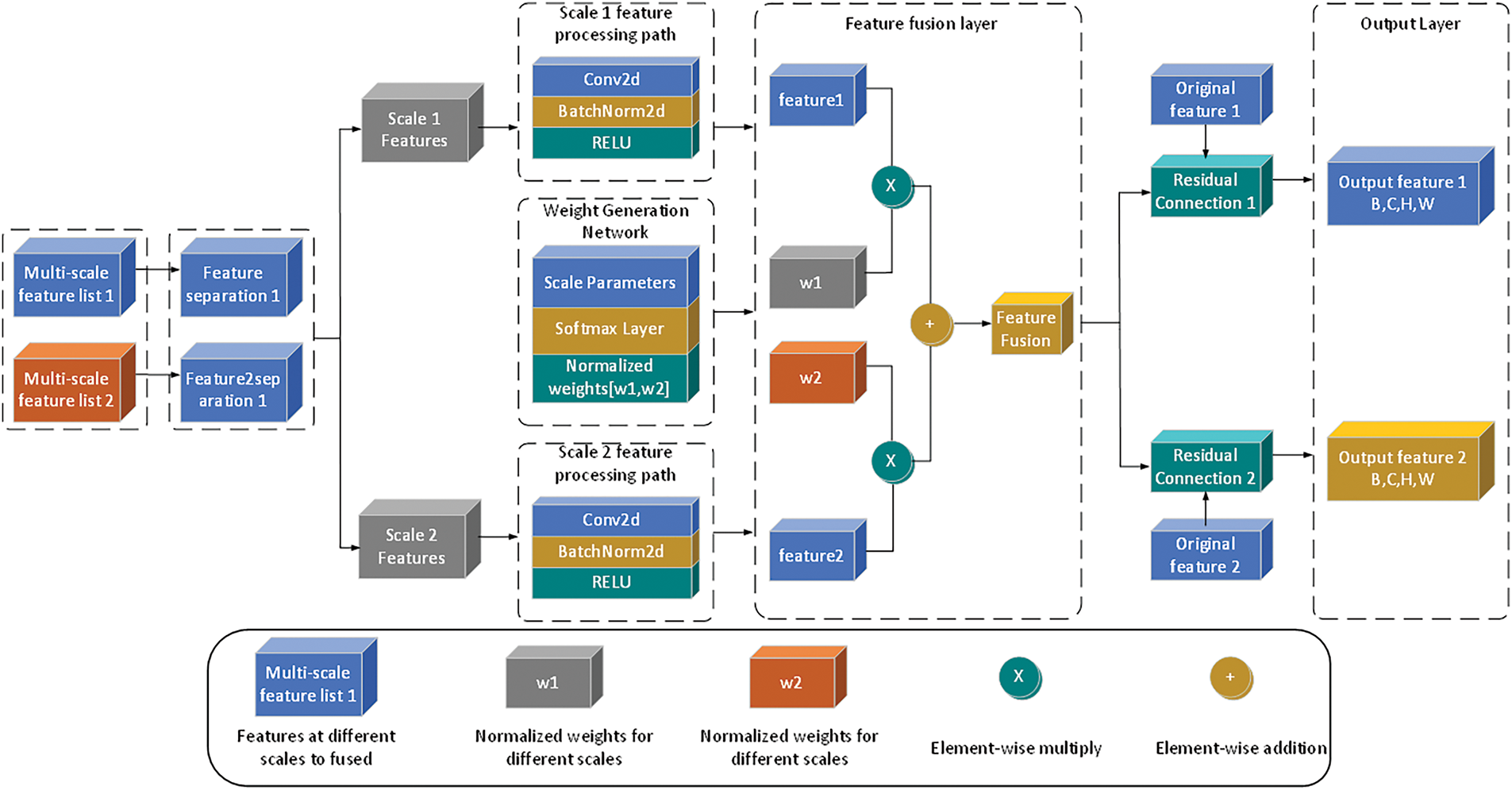

3.2.4 Multi-Scale Feature Fusion

The Multiscale Feature Fusion Module (MFFM) significantly enhances traditional feature fusion approaches through its innovative multi-level interaction and fusion strategies (Fig. 8). Unlike conventional methods, MFFM addresses the unique challenges of virtual maintenance scenarios, particularly the critical requirement for fine motion recognition. This targeted design enables more effective feature integration across different scales.

Figure 8: Multi-scale feature fusion module

The first key component of MFFM is the cross-attention mechanism. Unlike traditional self-attention, cross-attention enables information exchange between features at different scales. The implementation begins with linear transformations of input features to generate queries, keys, and values:

where

where

where

The reduced features are then processed through spatial and channel branches:

where

The multiscale convolution module captures context information at multiple scales through parallel convolutions with different kernel sizes:

where

The training process employs an end-to-end approach with a comprehensive loss function. The keypoint detection loss uses Mean Square Error (MSE) to measure the difference between predicted and ground truth heatmaps:

where N is the number of samples, K is the number of keypoints, H and

where

where

This multi-level, multi-angle feature processing approach enables MFCM and MFFM to effectively handle various challenges in virtual maintenance scenarios, providing robust feature support for subsequent keypoint estimation. The comprehensive design of attention mechanisms, feature fusion strategies, and training objectives ensures effective learning of pose-relevant features while maintaining computational efficiency through the use of depthwise separable convolutions and residual connections.

Using individual enhanced features

Specifically, the encoder part of the KE module consists of several convolutional blocks, with each block containing two

where H and W represent the height and width of the input image, respectively. During training, VMHPE optimizes the entire framework in an end-to-end manner, with a loss function comprising heatmap loss

The contrastive loss

where

where

The final loss function is a weighted sum of the three components:

where

This section first verified the accuracy of the VMHPE algorithm in human keypoint prediction, and then established a maintenance action assessment system based on high-precision prediction results. The experiments were implemented based on the PyTorch framework and conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. The model used ImageNet pre-trained HRNet-W32 as the backbone network. To ensure evaluation reliability, input images were uniformly adjusted to 512 pixels on the short side while maintaining the original aspect ratio. Average Precision (AP) and Average Recall (AR) were used as basic metrics for evaluation.

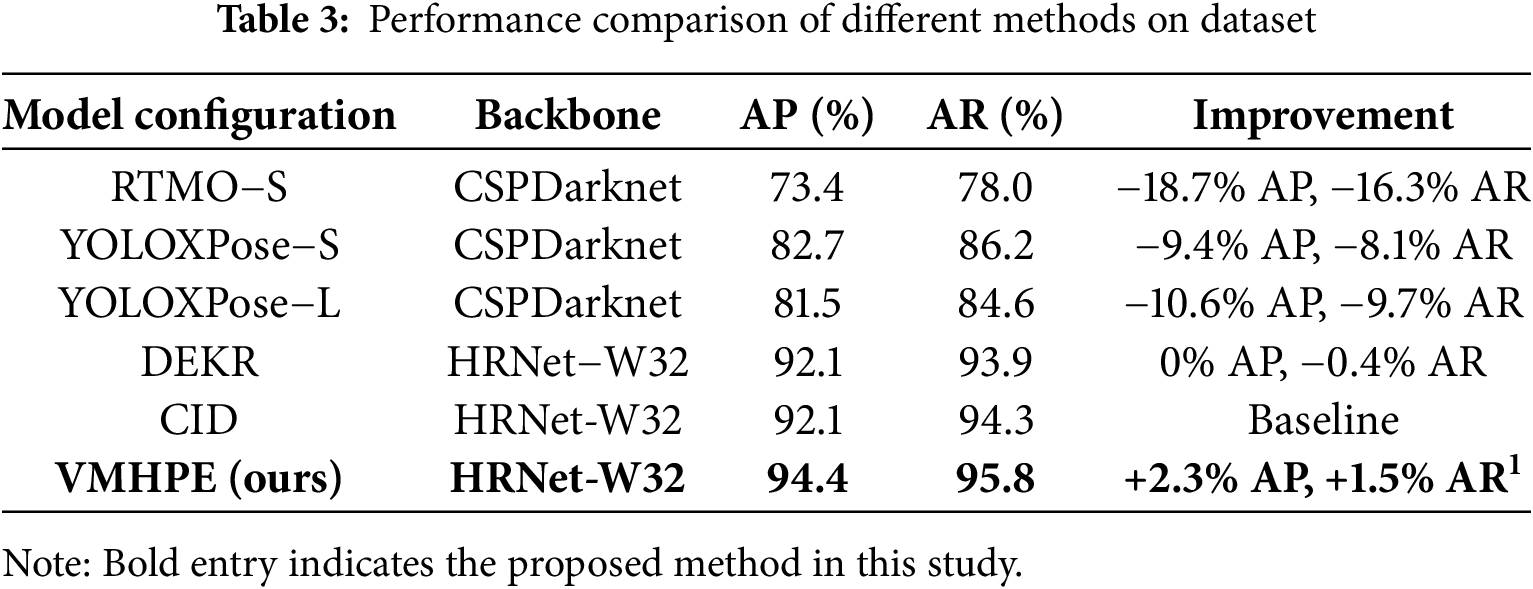

4.2 Comparison with Existing Methods

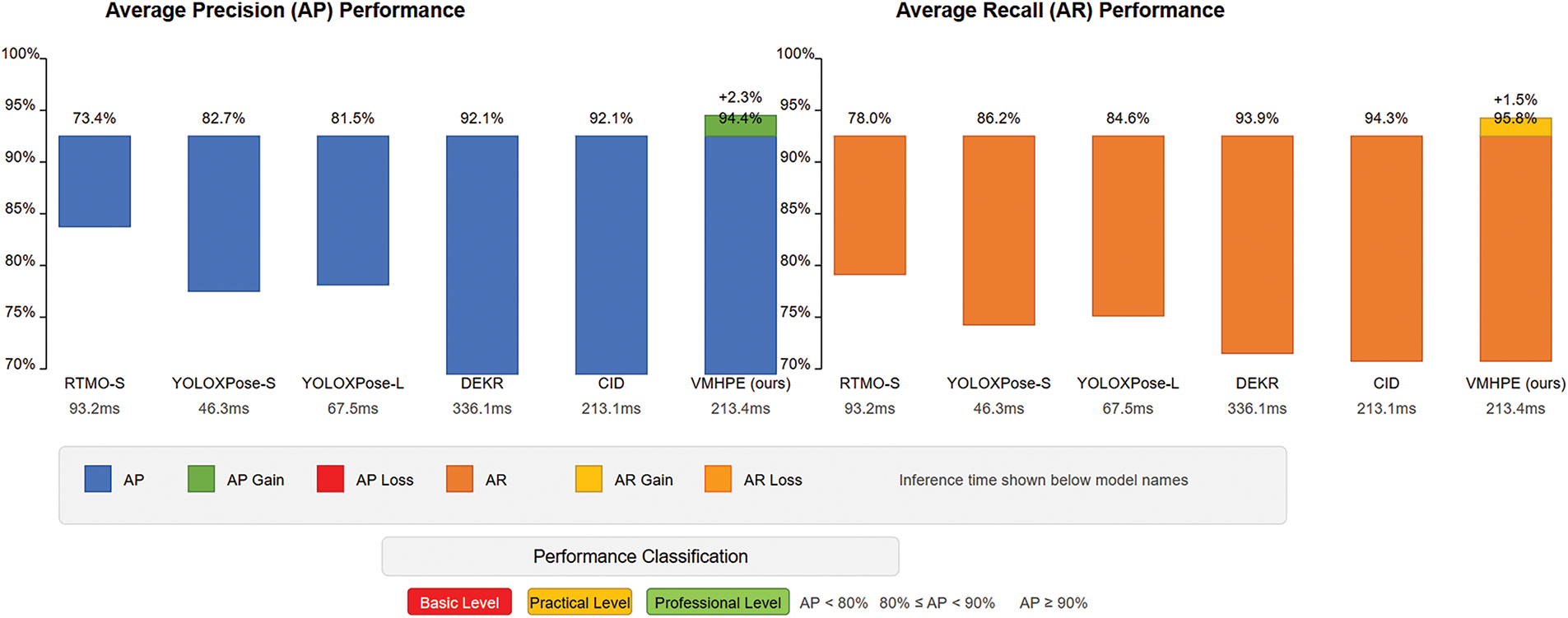

We compared VMHPE with mainstream human pose estimation methods. Table 3 shows our method significantly outperforms existing approaches. Compared to RTMO-S, we achieved a 21.0 percentage point improvement in AP. Against YOLOXPose models, our method improved AP by 11.7–12.9 percentage points. Using the same HRNet-W32 backbone as Disentangled Keypoint Regression (DEKR) and CID, VMHPE improved AP by 2.3 percentage points and AR by 1.3–1.5 percentage points.

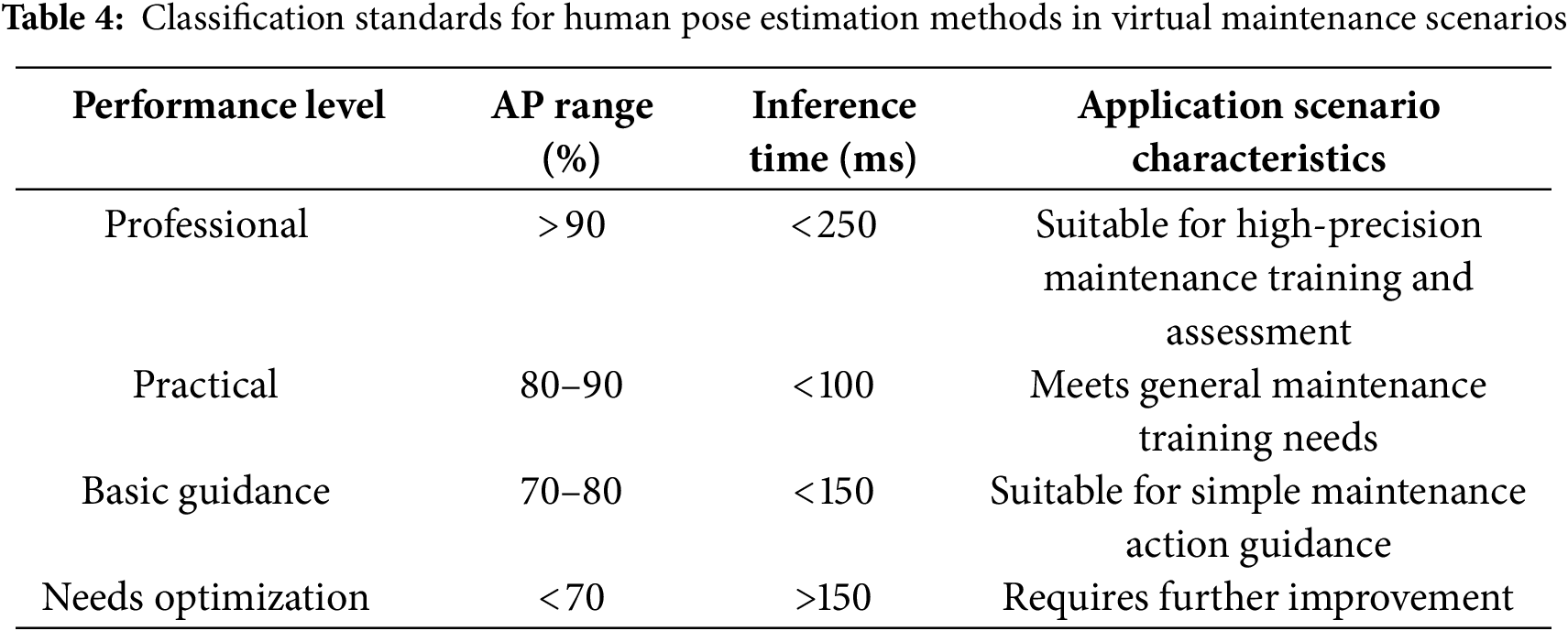

Considering the dual requirements of accuracy and real-time performance in virtual maintenance scenarios, we further evaluated the practicality of different methods. Based on accuracy and inference time metrics, existing methods are divided into four levels (as shown in Table 4).

Experimental results demonstrate that VMHPE achieves professional-level performance (AP = 94.4%, inference time 213.4 ms), meeting both accuracy and real-time requirements for virtual maintenance. As shown in Fig. 9, VMHPE successfully breaks through the performance bottleneck that appears when AP and AR exceed 90%, demonstrating highly balanced characteristics with an AP/AR ratio of 0.985. In contrast, YOLOXPose models offer faster inference (46.3–67.5 ms) but only reach practical-level accuracy (AP

Figure 9: Performance distribution of human pose estimation methods

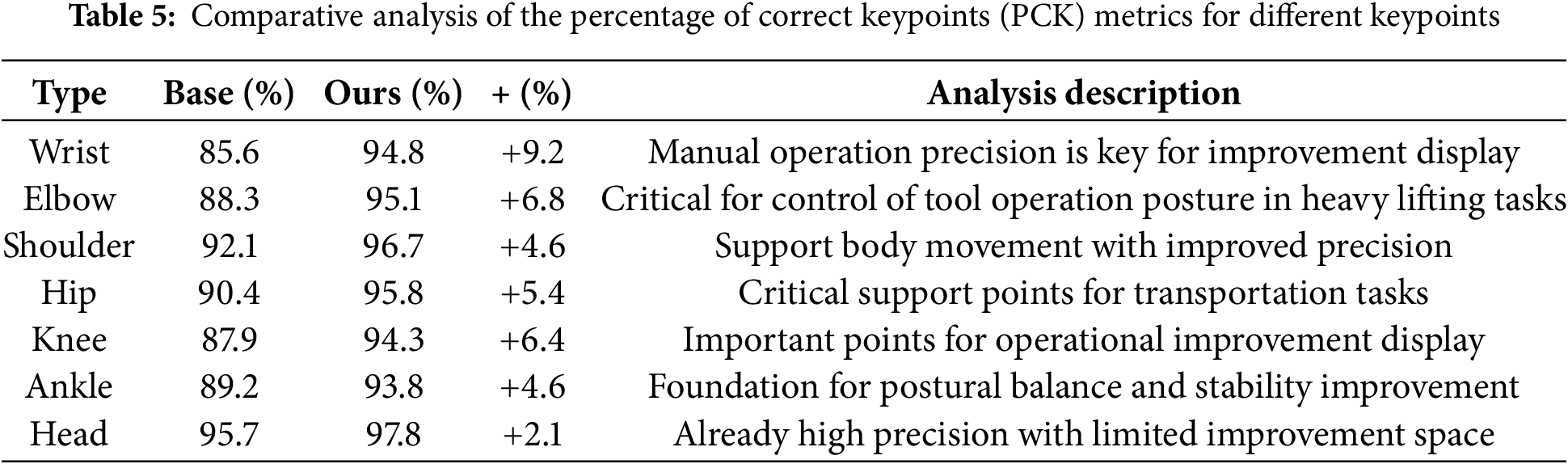

To gain an in-depth understanding of the improvement effects of VMHKD-HPE in maintenance scenarios, we conducted detailed analysis on the prediction accuracy of various key points. As shown in Table 5, our method demonstrates differentiated improvement effects on different types of key points.

From the data, it can be seen that VMHKD-HPE achieved the most significant improvements in wrist and elbow key points (9.2% and 6.8% improvement, respectively). This is highly consistent with the characteristics of maintenance tasks: tool operation and component installation primarily depend on precise control of hands and elbows, which is exactly the strength of our method. In comparison, the improvement for head and other relatively stable key points is smaller (only 2.1%). Further analysis of different maintenance task scenarios reveals that in precision tool operation scenarios, the prediction stability of wrist key points (return position change standard deviation) decreased from the baseline 15.3 (pixel units) to 8.7 (pixels); in heavy component transportation scenarios, the prediction accuracy of hip-knee-ankle support chain angles improved by 7.8%. This targeted improvement validates the advantages of multi-scale feature extraction mechanisms in fine-grained maintenance action details.

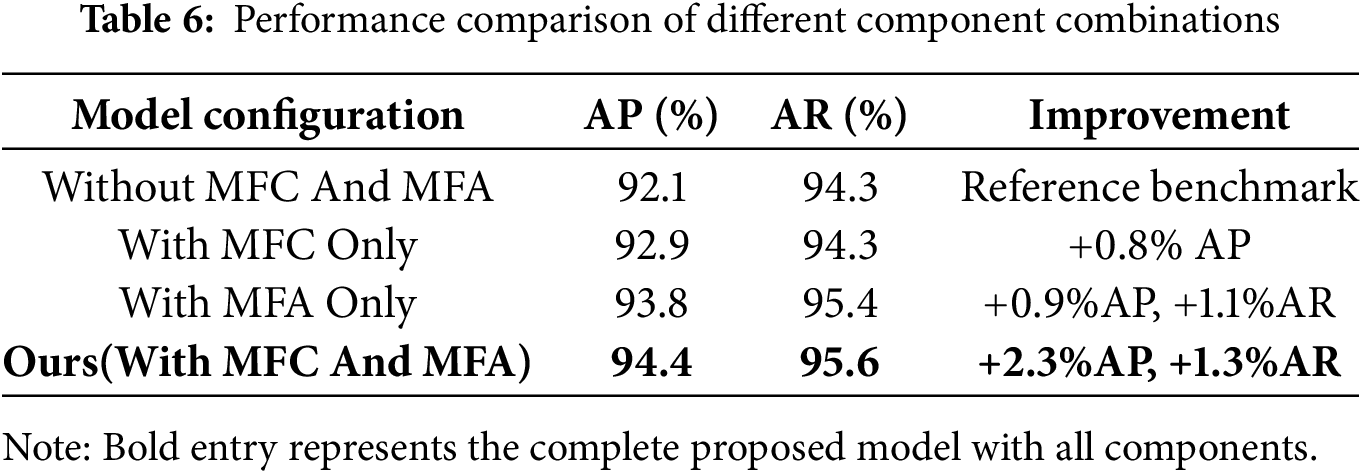

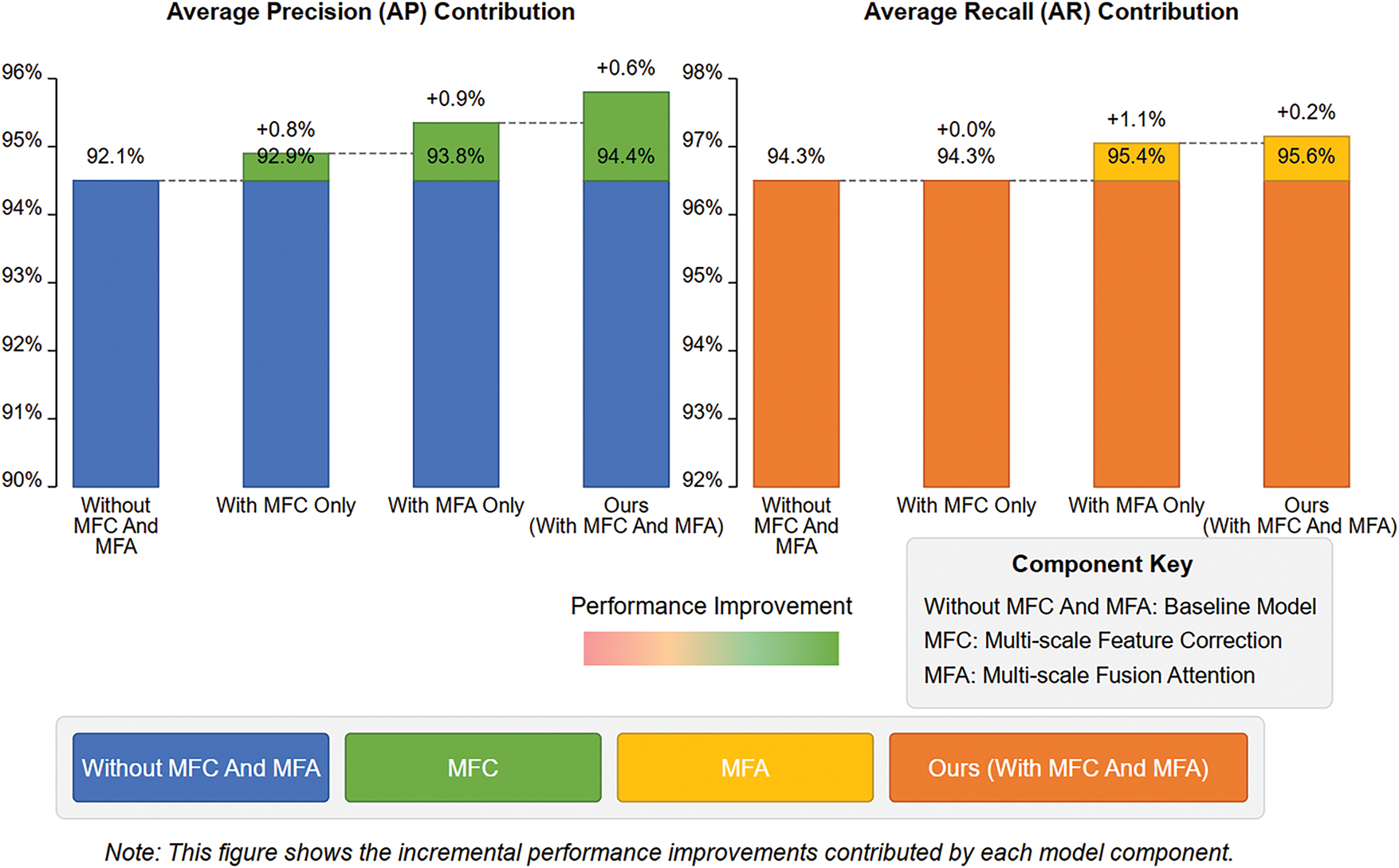

To verify VMHPE’s core components, we performed progressive addition of modules to the CID baseline. As shown in Table 6, adding the multi-scale feature correction module (MFC) improves AP by 0.8% while maintaining AR. Further introducing the multi-scale fusion attention mechanism (MFA) improves AP and AR by 0.9% and 1.1%, respectively. The complete model (MFC+MFA) achieves a total improvement of 2.3% in AP and 1.3% in AR compared to baseline.

Fig. 10 shows the performance change trend across components. Model improvement exhibits nonlinear characteristics, with MFA playing a crucial role in feature integration. AR increases significantly after adding fusion attention, from 94.3% to 95.4%, indicating enhanced detection capability across different scales. AP shows continuous improvement, reflecting the cumulative effect of components in enhancing localization accuracy.

Figure 10: Performance comparison of different component combinations in VMHPE model

4.3.2 Embedding Dimension Analysis

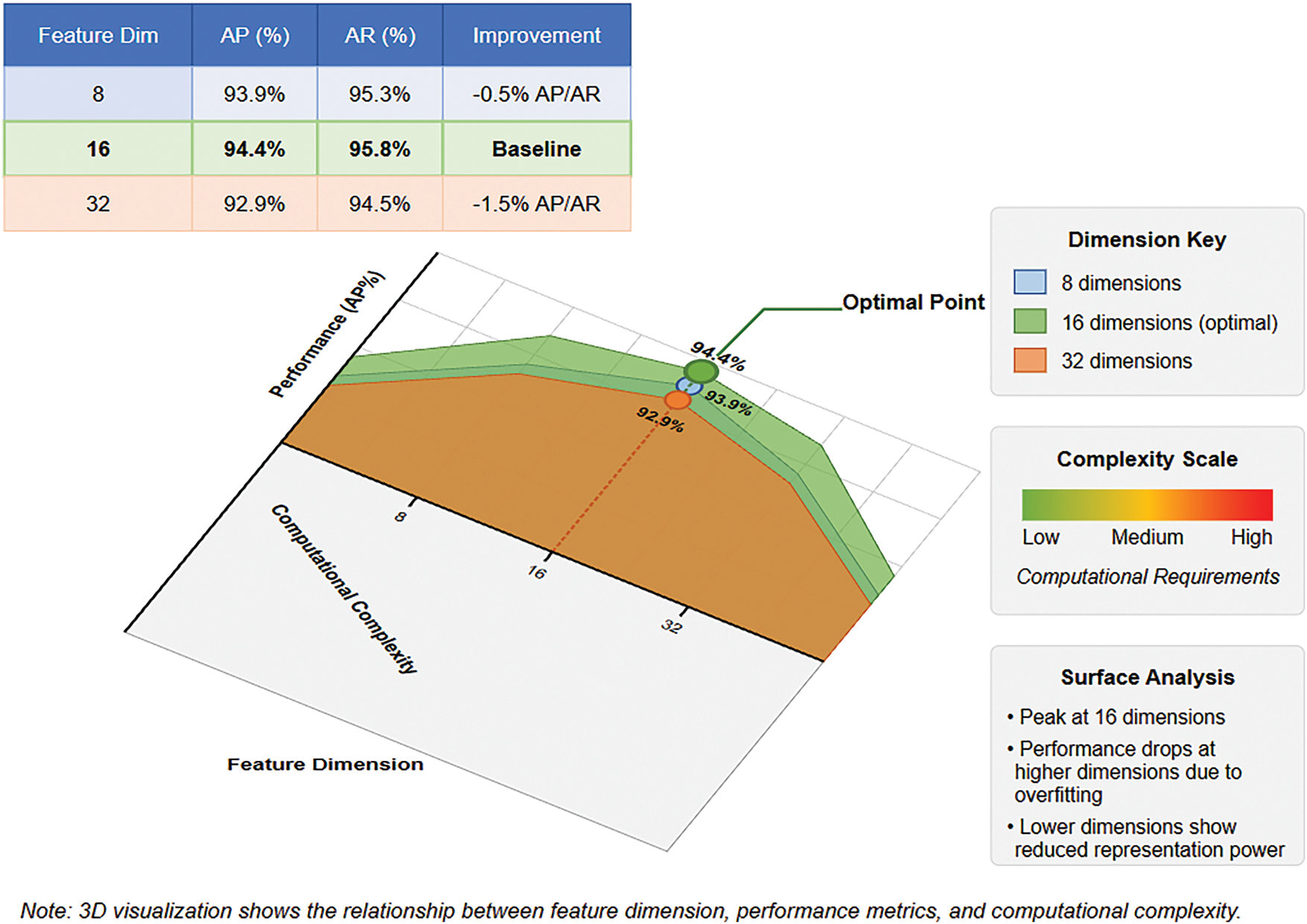

As shown in Fig. 11, feature embedding dimensions significantly impact model performance. The model demonstrates good results with 8-dimensional features (AP = 93.9%, AR = 95.3%), reaches optimal performance at 16 dimensions (AP = 94.4%, AR = 95.8%), but shows performance degradation at 32 dimensions (AP = 92.9%, AR = 94.5%). This asymmetric performance curve indicates that excessive dimensions have a stronger negative impact than insufficient dimensions, likely due to overfitting in high-dimensional feature spaces. The 16-dimension configuration achieves an optimal balance between performance and computational efficiency.

Figure 11: 3D performance surface analysis of feature embedding dimensions

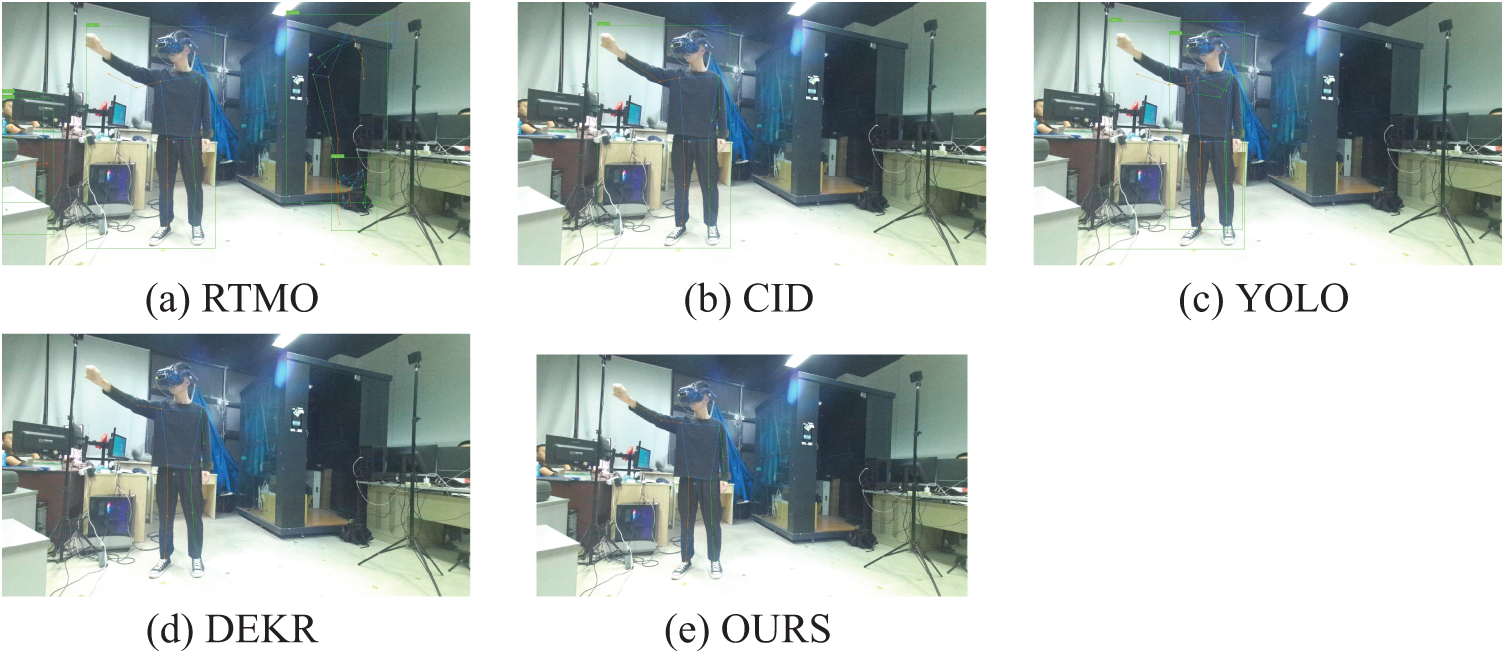

As shown in Fig. 12, there are significant differences in keypoint localization accuracy among different pose estimation methods in virtual maintenance scenarios. The VMHPE model significantly improves keypoint prediction accuracy through multi-scale feature processing mechanisms, especially in key maintenance areas such as hand operations and torso support. In comparison, RTMO-S and YOLOXPose series lack precision in capturing fine movements, while DEKR performs well but still has errors in complex postures. This advantage in accuracy lays a reliable foundation for subsequent maintenance action evaluation based on keypoints.

Figure 12: Comparison of pose estimation performance across different models (a–e) in Virtual maintenance scenarios

4.4 Maintenance Action Assessment

4.4.1 Assessment Standard Establishment

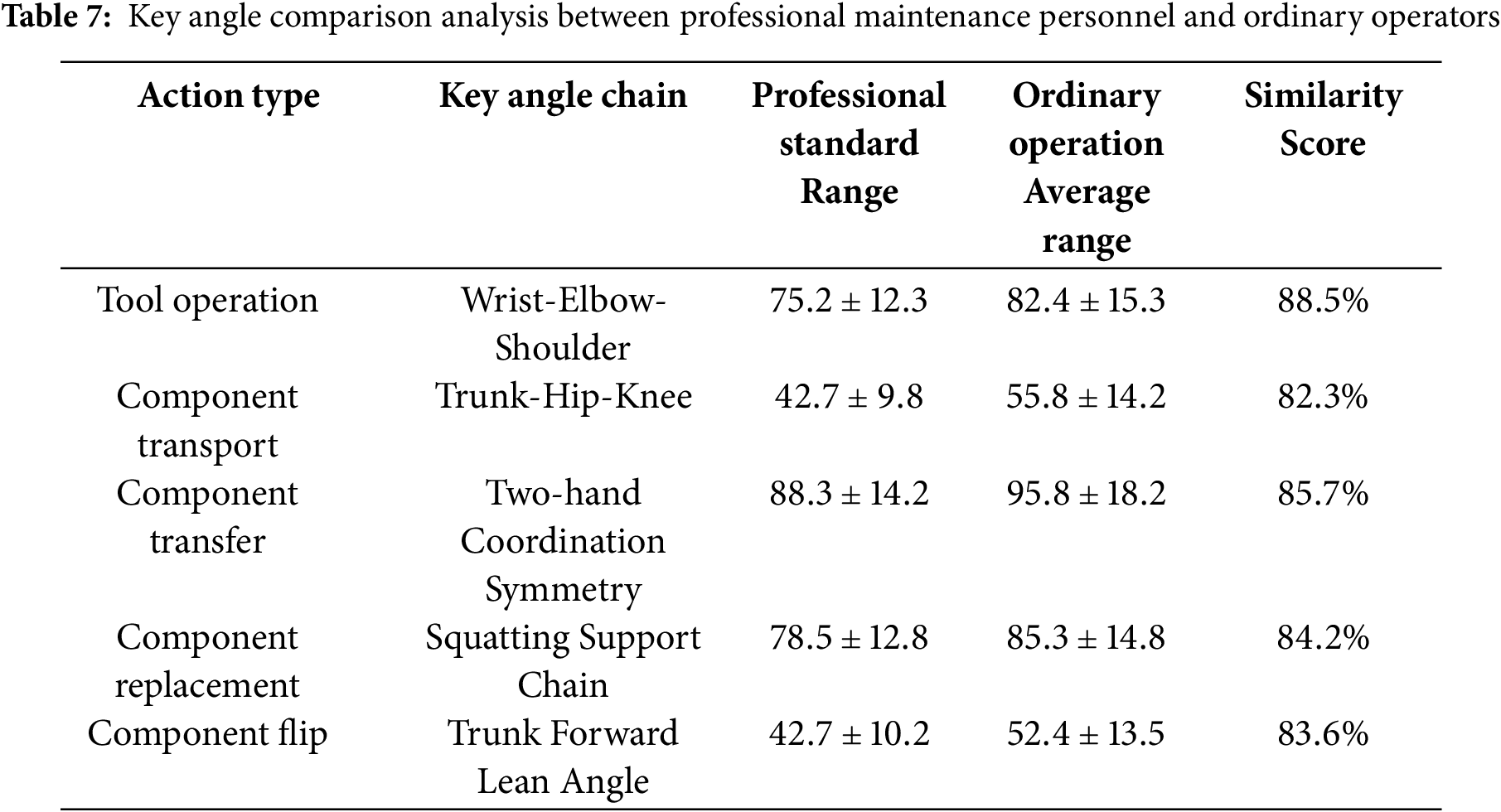

Based on high-precision keypoint prediction results, we calculated similarity between operators’ actions and professional standards by comparing topological structure similarity between keypoint sequences. Professional personnel’s standard actions exhibited clear pattern characteristics-with stable wrist-elbow-shoulder angles during tool operation and specific trunk-hip-knee support angles during transport-forming reliable benchmarks for evaluation. Table 7 presents a quantitative comparison analysis of key angle chains between professional maintenance personnel and ordinary operators, highlighting the differences in posture precision across different action types.

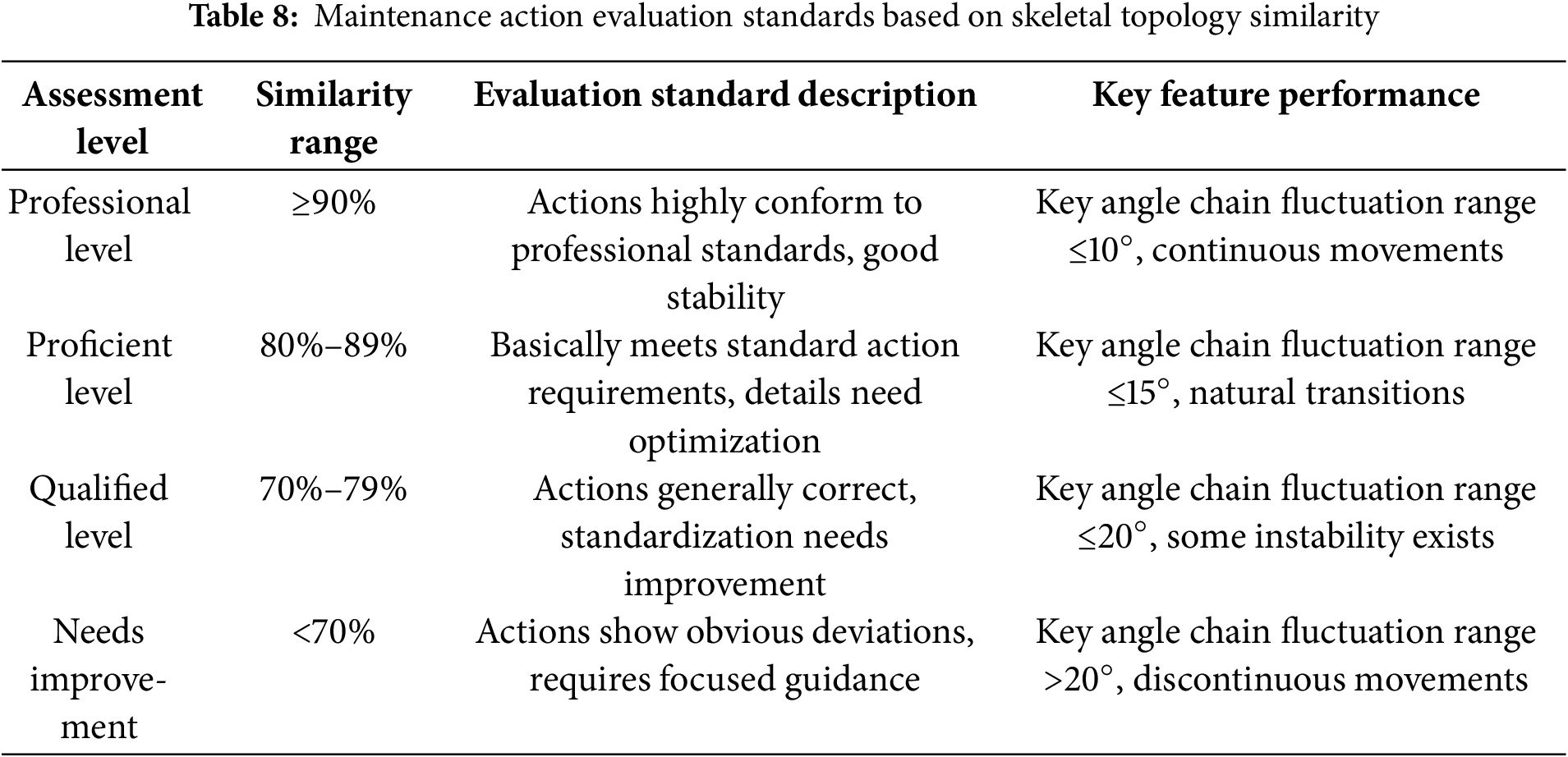

Through experimental validation, we established a four-level assessment standard as shown in Table 8:

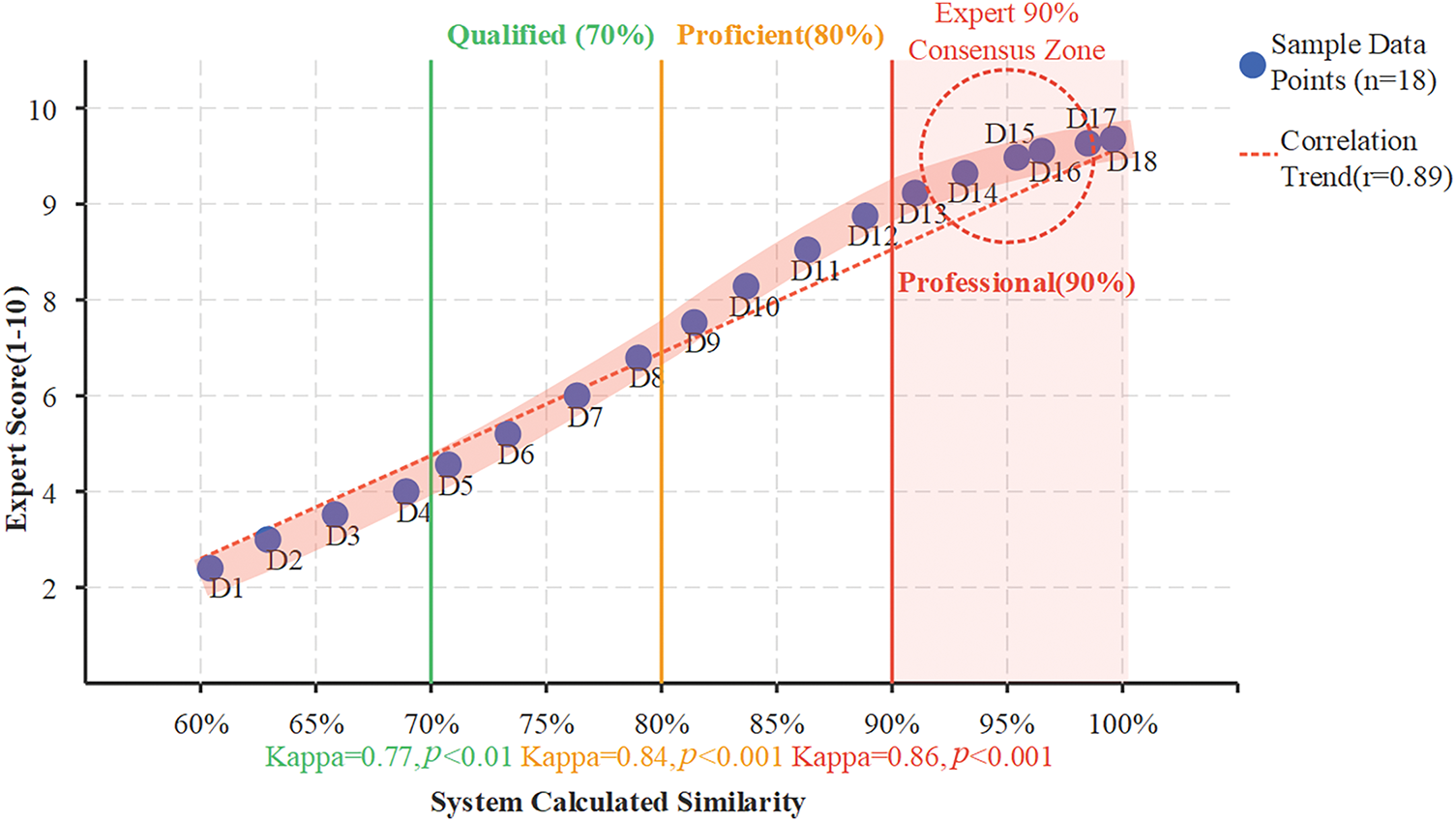

To ensure the scientific validity and practicality of the similarity assessment standards, we conducted rigorous statistical validation through expert evaluation experiments and field application verification. First, we invited 6 experienced maintenance trainers to provide professional ratings (1–10 scale) for 20 operators of different skill levels, and compared these ratings with the system-calculated similarity scores through comparative analysis. As shown in Fig. 13, expert ratings and system similarity demonstrate a high positive correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.89, p < 0.001). Particularly around the 90% similarity threshold, expert rating consistency reached its highest level (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.86), providing strong support for our professional level threshold setting.

Figure 13: Correlation analysis between expert scores and system similarity

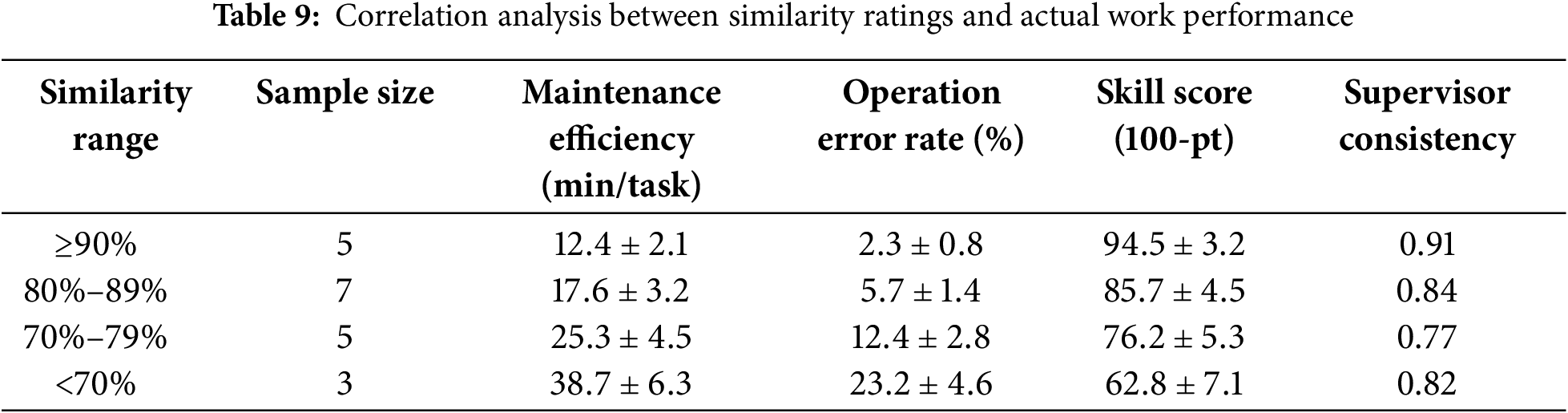

Second, we conducted detailed recording and analysis of the actual work performance of these 20 operators. As shown in Table 9, operators in different similarity intervals exhibited significant differences in work efficiency, operational accuracy, and skill levels.

The data shows that operators with similarity

It is noteworthy that we discovered an important phenomenon in our data analysis: the relationship between skill level and similarity exhibits distinct performance jumps at critical threshold points. Particularly at the 90% similarity point, the operational error rate significantly decreased from 5.7% to 2.3%, and similar ‘step effects’ were observed at 80% and 70% thresholds. This nonlinear relationship further confirms the rationality and practical value of our similarity threshold settings.

4.4.2 Application Value Analysis

VMHPE’s high-precision prediction performance provides important support for virtual maintenance training systems. The system can collect trainees’ operation videos in real-time and extract skeletal keypoints through the algorithm. It then compares them with professional personnel’s standard actions to provide objective evaluation results. This evaluation method based on precise keypoint prediction achieves standardization and regularization of maintenance training, providing technical guarantee for improving training quality.

Based on Section 4’s experimental results, we analyze how VMHPE’s core mechanisms address virtual maintenance challenges. The multi-scale feature correction mechanism improves model AP from 92.1% to 92.9% through adaptive processing of features at different scales. This improvement stems from the feature correction unit’s adaptive capability, enhancing local detail features during fine operations while strengthening global structure information during large-scale movements, effectively addressing pose diversity and occlusion challenges. The multi-scale fusion attention mechanism further enhances feature expression and integration capabilities through spatial and channel dimension attention computation, improving AP and AR to 93.8% and 95.4%, respectively. Spatial attention effectively solves pose interference in multi-person scenarios, while channel attention enhances understanding of complex poses. This performance improvement has significant implications for maintenance action assessment, as high-precision keypoint prediction ensures reliability when comparing with standard actions. In terms of real-time performance, VMHPE achieves a good balance between accuracy and speed, with minimal computational overhead (inference time increased by only 0.3 ms) while significantly improving performance (AP increased by 2.3%). This efficient architecture design makes the model particularly suitable for real-time applications like virtual maintenance.

5.2 Parameter Configuration Analysis

Regarding feature dimension selection, experiments find that 16-dimensional feature configuration (AP = 94.4%, AR = 95.8%) achieves optimal performance. This result indicates that under our proposed feature correction and fusion mechanisms, medium-scale feature space is sufficient to capture key information in virtual maintenance scenarios. Lower dimensions might lead to information loss, while higher dimensions introduce redundant information that affects feature discrimination capability. The 16-dimensional configuration achieves a good balance between performance and computational overhead, providing an important reference for system deployment. The complete VMHPE achieves significant performance improvements with AP and AR reaching 94.4% and 95.6% respectively through the organic combination of multi-scale feature correction and fusion attention mechanisms. This improvement validates our technical solution’s rationality, particularly in complex maintenance scenarios, where these mechanisms provide strong support for accurate pose estimation.

5.3 Dataset Validation Analysis

The maintenance action assessment system established in this research has two key characteristics. First, the assessment benchmark derives from professional maintenance personnel’s standard action data, ensuring evaluation standard authority. Second, high-precision skeletal keypoint prediction ensures the reliability of action similarity calculation.

Analysis of action characteristic differences between professional personnel and ordinary operators reveals that key angle chain distribution patterns effectively reflect operation skill levels. Professional personnel show significantly smaller angle fluctuations in hand key chains during fine operations compared to ordinary operators, providing a basis for establishing quantitative evaluation standards.

Different maintenance tasks have varying action precision requirements. Tool operation tasks emphasize hand movement precision, while component transport focuses on overall posture coordination. Our assessment system adapts to these differences by setting task-related weight coefficients, achieving flexible evaluation standard adaptation.

5.4 Integration with Pose Optimization Methods

The VMHPE method achieves accurate single-frame pose estimation in virtual maintenance scenarios, but constructing a complete training system requires addressing temporal consistency issues. Continuous operation sequences in virtual maintenance training demand natural smoothness of actions in the temporal dimension, yet existing pose estimators often suffer from jittering problems. SmoothNet models the natural smoothness characteristics of body motion by learning long-term temporal relationships of joints [33]. Integration with VMHPE can significantly improve temporal smoothness, which is of great significance for ensuring continuity and standardization in maintenance operation evaluation. From an application development perspective, the expansion of virtual maintenance systems toward three-dimensional evaluation is an inevitable trend. By combining the VMHKP dataset constructed in this study with multi-scale feature fusion strategies, integrating 3D pose optimization methods such as Filter with Learned Kinematics (FLK) [34] can provide spatial constraint capabilities for the system. This expansion not only leverages VMHPE’s accuracy advantages in 2D pose estimation but also ensures the rationality of poses in three-dimensional space through biomechanical constraints, making it particularly suitable for safety evaluation requirements in complex maintenance environments. Based on the four-level motion standardization evaluation system proposed in this paper, integrating pose optimization methods can further enhance the reliability and practicality of evaluation. VMHPE’s multi-scale feature correction mechanism provides accuracy assurance for basic detection, temporal smoothing algorithms ensure coherence of action sequences, and spatial constraint methods guarantee physiological reasonableness of poses. This multi-level integrated architecture not only improves technical indicators but, more importantly, establishes a complete technical chain from accurate detection to standardized evaluation for virtual maintenance training systems, making professional-level (

This paper proposes the VMHPE method for human pose estimation in virtual maintenance scenarios, effectively addressing challenges of pose diversity and occlusions through multi-scale feature correction and fusion attention mechanisms. The VMHKP dataset we constructed provides an important benchmark for this field. Experimental results confirm our method’s superior performance in virtual maintenance contexts. Nevertheless, optimization opportunities remain, particularly in inference time for complex scenarios. As a 2D pose estimation approach, it has limitations in handling complex rotations and occlusions, while 3D pose information is crucial for accurate assessment in virtual maintenance. Future work will focus on dataset extension and technical innovation, including increasing maintenance scenario types, introducing 3D annotations, exploring 2D to 3D pose estimation methods, and researching multi-modal feature fusion strategies. Through continuous innovation, we aim to achieve high-quality, standardized, and intelligent development of virtual maintenance training.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the School of Electromechanical Engineering at Guangdong University of Technology and the Virtual Reality and Visualization Laboratory for providing the research platform and facilities, Pharmapack Technologies Corporation for their support in the joint development project, the technical personnel who participated in the dataset collection and maintenance, and the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Joint Development Project with Pharmapack Technologies Corporation: Open Multi-Person Collaborative Virtual Assembly/Disassembly Training and Virtual Engineering Visualization Platform, Grant Number 23HK0101.

Author Contributions: Research conception and design: Shuo Zhang, Hanwu He, and Yueming Wu. Data collection: Shuo Zhang and Yueming Wu. Results analysis and interpretation: Shuo Zhang, Hanwu He, and Yueming Wu. Manuscript draft preparation: Shuo Zhang and Yueming Wu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The Virtual Maintenance Human Keypoint Dataset (VMHKP) constructed in this study is publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15525037. Additional experimental data and code will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the present study.

References

1. He Q, Cheng X, Cheng Z. A VR-based complex equipment maintenance training system. In: 2019 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC); 2019 Nov 22–24; Hangzhou, China. p. 1741–6. doi:10.1109/cac48633.2019.8996496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Dubey S, Dixit M. A comprehensive survey on human pose estimation approaches. Multimed Syst. 2023;29(1):167–95. doi:10.1007/s00530-022-00980-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Dong C, Du G. An enhanced real-time human pose estimation method based on modified YOLOv8 framework. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):8012. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-58146-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Du Y, Wang Y, Shang X, Zhang J, Duan M. A distributed virtual reality system based on real-time dynamic calculation and multi-person collaborative operation applied to the development of subsea production systems. Int J Maritime Eng. 2021;163(A3). doi:10.5750/ijme.v163ia3.798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Numfu M, Riel A, Noel F. Virtual reality based digital chain for maintenance training. Procedia CIRP. 2019;84(7):1069–74. doi:10.1016/j.procir.2019.04.268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Guo Z, Zhou D, Chen J, Geng J, Lv C, Zeng S. Using virtual reality to support the productś maintainability design: immersive maintainability verification and evaluation system. Comput Ind. 2018;101:41–50. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2018.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang Z, Wang C, Qin W, Zeng W. Fusing wearable IMUs with multi-view images for human pose estimation: a geometric approach. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 2200–9. [Google Scholar]

8. Masood T, Egger J. Augmented reality in support of Industry 4.0—Implementation challenges and success factors. Robot Comput-Integr Manuf. 2019;58(2):181–95. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2019.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Bhattacharya B, Winer EH. Augmented reality via expert demonstration authoring (AREDA). Comput Ind. 2019;105:61–79. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2018.04.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Cao Z, Hidalgo G, Simon T, Wei SE, Sheikh Y. OpenPose: realtime multi-person 2D pose estimation using part affinity fields. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;43:172–86. [Google Scholar]

11. Sun K, Xiao B, Liu D, Wang J. Deep high-resolution representation learning for human pose estimation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 5686–96. [Google Scholar]

12. Jiang W, Kolotouros N, Pavlakos G, Zhou X, Daniilidis K. Coherent reconstruction of multiple humans from a single image. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 5578–87. [Google Scholar]

13. Lin TY, Maire M, Belongie S, Hays J, Perona P, Ramanan D, et al. Microsoft COCO: common objects in context. In: Fleet D, Pajdla T, Schiele B, Tuytelaars T, editors. Computer Vision—ECCV 2014. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2014. p. 740–55. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10602-1_48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jin S, Xu L, Xu J, Wang C, Liu W, Qian C, et al. Whole-body human pose estimation in the wild. In: Vedaldi A, Bischof H, Brox T, Frahm JM, editors. Computer Vision—ECCV 2020. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 196–214. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58545-7_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Fang HS, Xie S, Tai YW, Lu C. RMPE: regional multi-person pose estimation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2353–62. [Google Scholar]

16. Li J, Wang C, Zhu H, Mao Y, Fang HS, Lu C. CrowdPose: efficient crowded scenes pose estimation and a new benchmark. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 10855–64. [Google Scholar]

17. Güler RA, Neverova N, Kokkinos I. DensePose: dense human pose estimation in the wild. arXiv:1802.00434. 2018. [Google Scholar]

18. Perazzi F, Pont-Tuset J, McWilliams B, Van Gool L, Gross M, Sorkine-Hornung A. A Benchmark dataset and evaluation methodology for video object segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 724–32. [Google Scholar]

19. Damen D, Doughty H, Farinella GM, Fidler S, Furnari A, Kazakos E, et al. Scaling egocentric vision: the EPIC-KITCHENS dataset. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. p. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

20. Toshev A, Szegedy C. Human pose estimation via deep neural networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2014 Jun 23–28; Columbus, OH, USA. p. 1653–60. [Google Scholar]

21. Cheng B, Xiao B, Wang J, Shi H, Huang TS, Zhang L. Scale-aware representation learning for bottom-up human pose estimation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 5385–94. [Google Scholar]

22. Fang HS, Li J, Tang H, Xu C, Zhu H, Xiu Y, et al. AlphaPose: whole-body regional multi-person pose estimation and tracking in real-time. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(6):7157–73. doi:10.1109/tpami.2022.3222784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Xu Y, Zhang J, Zhang Q, Tao D. Simple vision transformer baselines for human pose estimation. In: Koyejo S, Mohamed S, Agarwal A, Belgrave D, Cho K, Oh A, editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 35. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2022. p. 38571–84. [Google Scholar]

24. Mao W, Tian Z, Wang X, Shen C. FCPose: fully convolutional multi-person pose estimation with dynamic instance-aware convolutions. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 9034–43. [Google Scholar]

25. Li Y, Yang S, Liu P, Zhang S, Wang Y, Wang Z, et al. SimCC: a simple coordinate classification perspective for human pose estimation. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

26. Zeng A, Yang L, Ju X, Li J, Wang J, Xu Q. SmoothNet: a plug-and-play network for refining human poses in videos. In: Avidan S, Brostow G, Cissé M, Farinella GM, Hassner T, editors. Computer Vision—ECCV 2022. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 625–42. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-20065-6_36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang F, Bazarevsky V, Vakunov A, Tkachenka A, Sung G, Chang C, et al. MediaPipe hands: on-device real-time hand tracking. arXiv:2006.10214. 2020. [Google Scholar]

28. Moon G, Yu SI, Wen H, Shiratori T, Lee KM. InterHand2.6M: a dataset and baseline for 3D interacting hand pose estimation from a single RGB image. In: Vedaldi A, Bischof H, Brox T, Frahm JM, editors. Computer Vision—ECCV 2020. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 548–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58565-5_33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lu P, Jiang T, Li Y, Li X, Chen K, Yang W. RTMO: towards high-performance one-stage real-time multi-person pose estimation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22. Seattle, WA, USA. p. 1491–500. [Google Scholar]

30. Yang X, Huang F, Jiang J, Chen Z. A virtual-reality spatial matching algorithm and its application on equipment maintenance support: system design and user study. Signal Process Image Commun. 2024;129:117188. doi:10.1016/j.image.2024.117188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Rane M, Date A, Deshmukh V, Deshpande P, Dharmadhikari A. Virtual gym tracker: AI pose estimation. In: 2024 Second International Conference on Advances in Information Technology (ICAIT); 2024 Jul 27–27; Chikkamagaluru, India. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

32. Urgo M, Berardinucci F, Zheng P, Wang L. AI-based pose estimation of human operators in manufacturing environments. In: CIRP novel topics in production engineering. Vol. 1. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 3–38. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-54034-9_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang D, Zhang S. Contextual instance decoupling for robust multi-person pose estimation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognitionn; 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 11060–8. [Google Scholar]

34. Martini E, Boldo M, Bombieri N. FLK: a filter with learned kinematics for real-time 3D human pose estimation. Signal Process. 2024;224(1):109598. doi:10.1016/j.sigpro.2024.109598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools