Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Utility-Driven Edge Caching Optimization with Deep Reinforcement Learning under Uncertain Content Popularity

Department of Computer Engineering, Inha University, Incheon, 22212, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Minseok Song. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 519-537. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066754

Received 16 April 2025; Accepted 21 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Efficient edge caching is essential for maximizing utility in video streaming systems, especially under constraints such as limited storage capacity and dynamically fluctuating content popularity. Utility, defined as the benefit obtained per unit of cache bandwidth usage, degrades when static or greedy caching strategies fail to adapt to changing demand patterns. To address this, we propose a deep reinforcement learning (DRL)-based caching framework built upon the proximal policy optimization (PPO) algorithm. Our approach formulates edge caching as a sequential decision-making problem and introduces a reward model that balances cache hit performance and utility by prioritizing high-demand, high-quality content while penalizing degraded quality delivery. We construct a realistic synthetic dataset that captures both temporal variations and shifting content popularity to validate our model. Experimental results demonstrate that our proposed method improves utility by up to 135.9% and achieves an average improvement of 22.6% compared to traditional greedy algorithms and long short-term memory (LSTM)-based prediction models. Moreover, our method consistently performs well across a variety of utility functions, workload distributions, and storage limitations, underscoring its adaptability and robustness in dynamic video caching environments.Keywords

The explosive growth in video streaming demand has highlighted the critical need for efficient data delivery in modern networks. Video content represents a significant portion of Internet traffic, consuming substantial bandwidth and often leading to network congestion. Edge caching has emerged as a key solution to these challenges, enabling data to be stored closer to users [1,2]. By reducing reliance on core network resources, edge caching minimizes data transmission, reduces latency, and alleviates network bottlenecks. These benefits translate into faster content delivery, improved quality of experience (QoE), and significant reductions in bandwidth usage, making edge caching an essential component of video streaming systems [3].

The rise of short-form video platforms such as Instagram Reels, TikTok, and YouTube Shorts has further amplified the demand for low-latency, high-quality video delivery. These applications rely heavily on real-time responsiveness and personalization, requiring efficient caching strategies that can adapt to fast-changing content popularity. As video continues to dominate everyday mobile usage, intelligent edge caching becomes increasingly vital to sustain user satisfaction and reduce strain on network infrastructure [4].

Edge caching faces significant constraints due to limited storage capacity. These constraints make strategic caching decisions critical, as maximizing the utility of edge resources is essential for balancing user satisfaction and operational efficiency. Utility, in this context, is defined as the overall benefit derived by edge service providers, considering cache bandwidth usage, video quality, and user satisfaction [5]. Importantly, utility is not solely determined by cache hit ratios; it also depends on the ability to deliver high-quality video content.

When the requested bitrate version is unavailable, lower bitrate versions can be provided to maintain service continuity. However, this often results in degraded QoE and reduced utility. To address these challenges, caching strategies must go beyond maximizing hit rates and instead prioritize storing bitrate versions that align with user demand and quality expectations. Effective policies must account for fallback scenarios, where delivering lower-quality alternatives risks degrading QoE and reducing overall utility.

1.2 Motivation and Contributions

Traditional caching methods often model the caching problem as a knapsack problem, using greedy algorithms to prioritize content with high hit ratios [6]. These algorithms are computationally efficient and work well under static content popularity assumptions. However, they struggle to adapt to the dynamic and uncertain nature of real-world video popularity, where user preferences and content demands fluctuate over time [7]. This lack of adaptability leads to suboptimal caching decisions, especially in environments characterized by variable workloads and shifting content popularity. This highlights the pressing need for adaptive caching strategies that can maximize utility under uncertainty and dynamic popularity trends.

In addition, modern VoD systems require caching strategies that go beyond simple content presence and consider which bitrate versions to store. Since delivery cost and user satisfaction vary with quality, caching must balance storage and QoE through version-aware decisions.

To handle the dynamic and uncertain nature of user demand, deep reinforcement learning (DRL) offers a data-driven way to learn adaptive caching policies. By avoiding explicit popularity modeling, DRL is well-suited for utility-driven caching in environments with fluctuating content trends and multi-version video delivery.

The contributions of this study are as follows:

• This study introduces a DRL-based caching algorithm for edge servers, designed to adapt dynamically to changes in video popularity and workload uncertainty. By leveraging DRL, the proposed method addresses the limitations of conventional caching approaches, including those relying on static rules, heuristic policies, and predictive models, thereby providing more robust performance under dynamic content popularity.

• This approach integrates a reward model that combines video quality and utility optimization. The model prioritizes high-quality content delivery while ensuring efficient use of cache resources, balancing user satisfaction and system performance.

• The proposed method demonstrates superior performance compared to traditional greedy algorithms. It achieves greater adaptability to uncertain and variable content popularity, higher utility for edge service providers, and more efficient bandwidth and storage utilization, validating its effectiveness under dynamic conditions.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the related work. Section 3 introduces the system model, and Section 4 provides the process of generating a synthetic dataset. Section 5 formulates the problem. Section 6 describes the proposed algorithms in detail. Section 7 presents the experimental results. Section 8 discusses key findings and implications of this work. Finally, the paper concludes in Section 9.

Several studies have employed DRL to enhance edge caching efficiency. Cui et al. [8] introduced a real-time caching method that integrates DRL with Q-learning techniques to address cooperative edge caching. Their approach improves energy efficiency, adapts caching policies in real time, and minimizes replacement and interruption costs. Similarly, Sun et al. [9] proposed a decentralized framework combining recommendation systems with edge caching to optimize resource utilization via direct and soft cache hits. Leveraging multi-agent Markov decision processes and the soft actor-critic (SAC) algorithm, their method enables edge servers to independently learn and implement optimal caching policies. However, these methods mainly focus on cache hit rates or coordination efficiency, without explicitly modeling video quality or multi-version delivery trade-offs. These methods, however, largely focus on cache hit rates or cooperation, without explicitly addressing multi-version video placement or quality-aware delivery. Wu et al. [10] proposed a DRL-based content update strategy that adapts in real time to dynamic content popularity. Zhong et al. [11] presented a multi-agent DRL framework to coordinate edge caching decisions in wireless networks, showing performance improvements without prior knowledge of popularity distributions. These methods, however, largely focus on cache hit rates or cooperation, without explicitly addressing multi-version video placement or quality-aware delivery. Kwon and Song [12] proposed a deep reinforcement learning-based approach to enhance the cache hit rate by adapting to dynamic file request patterns. Unlike their work, which considered single-version content in general file caching, our approach targets utility-driven caching in video-on-demand systems, supporting multi-version video placement and quality-aware delivery under dynamic popularity.

Research has also focused on video quality optimization under server capacity constraints. Lee et al. developed an algorithm for optimizing caching and transcoding tasks in multi-access edge computing (MEC) environments, adjusting bitrates based on video popularity and retention rates while considering server capacity limitations [13]. Tran et al. proposed a caching and processing framework for video streaming in MEC systems, addressing bitrate optimization through an online iterative greedy-based adaptive algorithm to tackle the NP-hard nature of the problem [14]. These methods rely on pre-defined rules and are less adaptable to dynamically changing multi-version workloads.

Several studies have explored trade-offs among cache hit ratios, content quality, and latency. Dao et al. [15] proposed a dynamic caching and quality level selection policy in adaptive bitrate streaming, modeled as a multidimensional knapsack problem and solved using a transfer learning-based genetic algorithm. Tran et al. [16] examined caching policies for mobile data traffic management, focusing on trade-offs among hit ratios, latency, and storage efficiency, and categorized algorithms into machine learning, deep learning, and game theory-based approaches.

Several recent studies have focused on similarity caching, where an edge cache stores and delivers similar content, such as lower bitrate versions, instead of the exact requested content. Araldo et al. [17] studied optimal content placement in caching systems by selecting appropriate bitrate versions to improve video delivery performance under storage constraints. Zhou et al. [18] proposed adaptive offline and online caching algorithms that jointly optimize content placement and delivery decisions by considering content similarity and user-perceived quality. Garetto et al. [19] investigated content placement strategies in networks of similarity caches, where content placement decisions are made by leveraging content similarity to improve caching efficiency. Wang et al. [20] developed an online similarity caching algorithm based on an adversarial bandit framework to adaptively handle dynamic user requests in cooperative edge networks.

Several studies have addressed content quality adaptation and multi-version caching, where multiple bitrate versions of the same content are considered to enhance user QoE and caching efficiency. Tran et al. [21] proposed a collaborative caching and processing framework in mobile-edge computing networks to support adaptive bitrate video streaming and improve user experience under storage and network constraints. Bayhan et al. [22] proposed EdgeDASH, a network-assisted adaptive video streaming framework that improves edge caching efficiency by dynamically aligning client requests with cached content through quality adaptation.

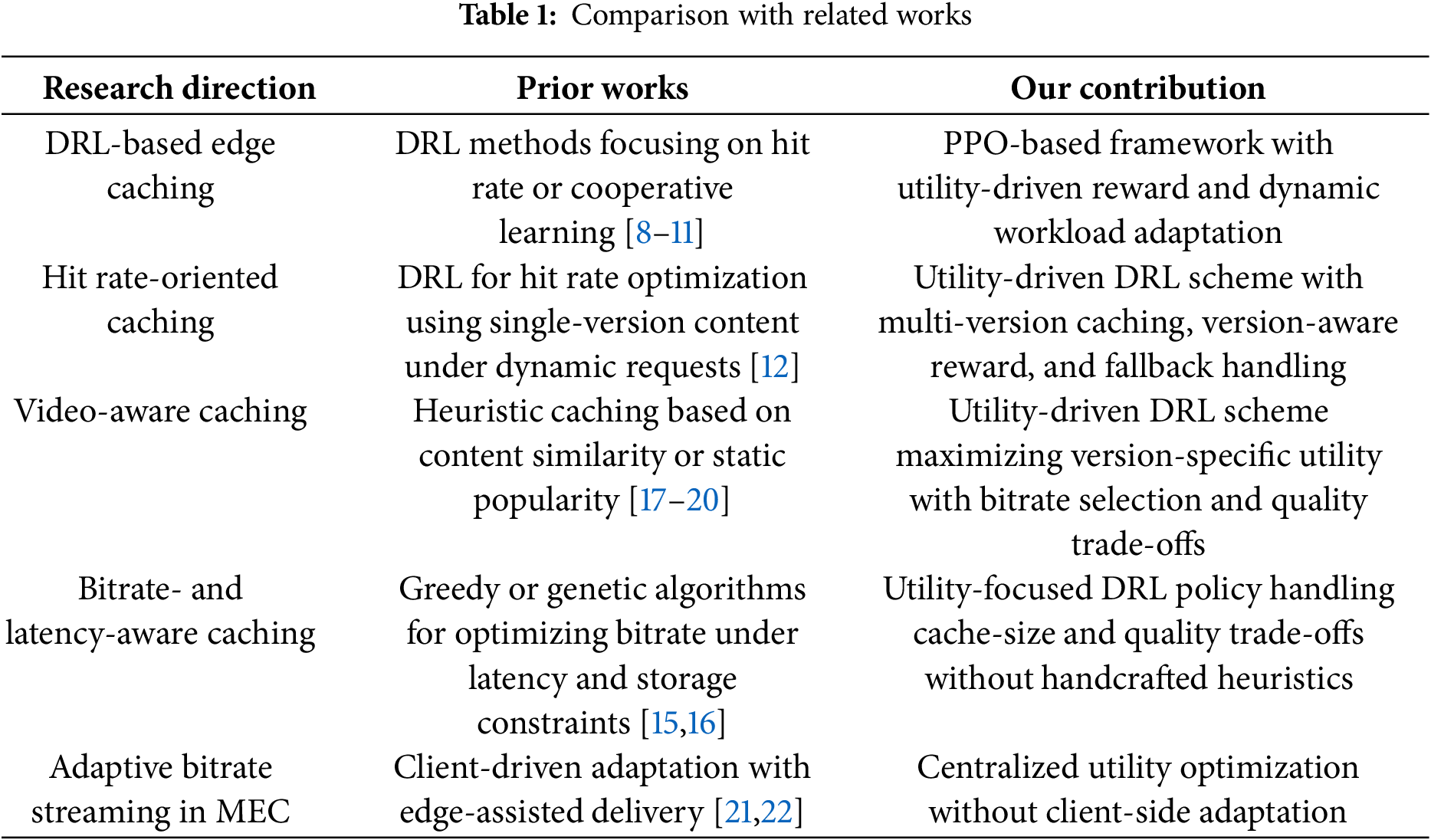

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to address edge cache management in scenarios with dynamically changing content popularity using DRL. By incorporating a utility function that integrates video quality and cache efficiency, our approach provides a robust and adaptable solution for optimizing edge caching under uncertain and variable content popularity conditions. A comparison with representative related works is summarized in Table 1, highlighting the distinctions in objective, granularity, and learning methodology.

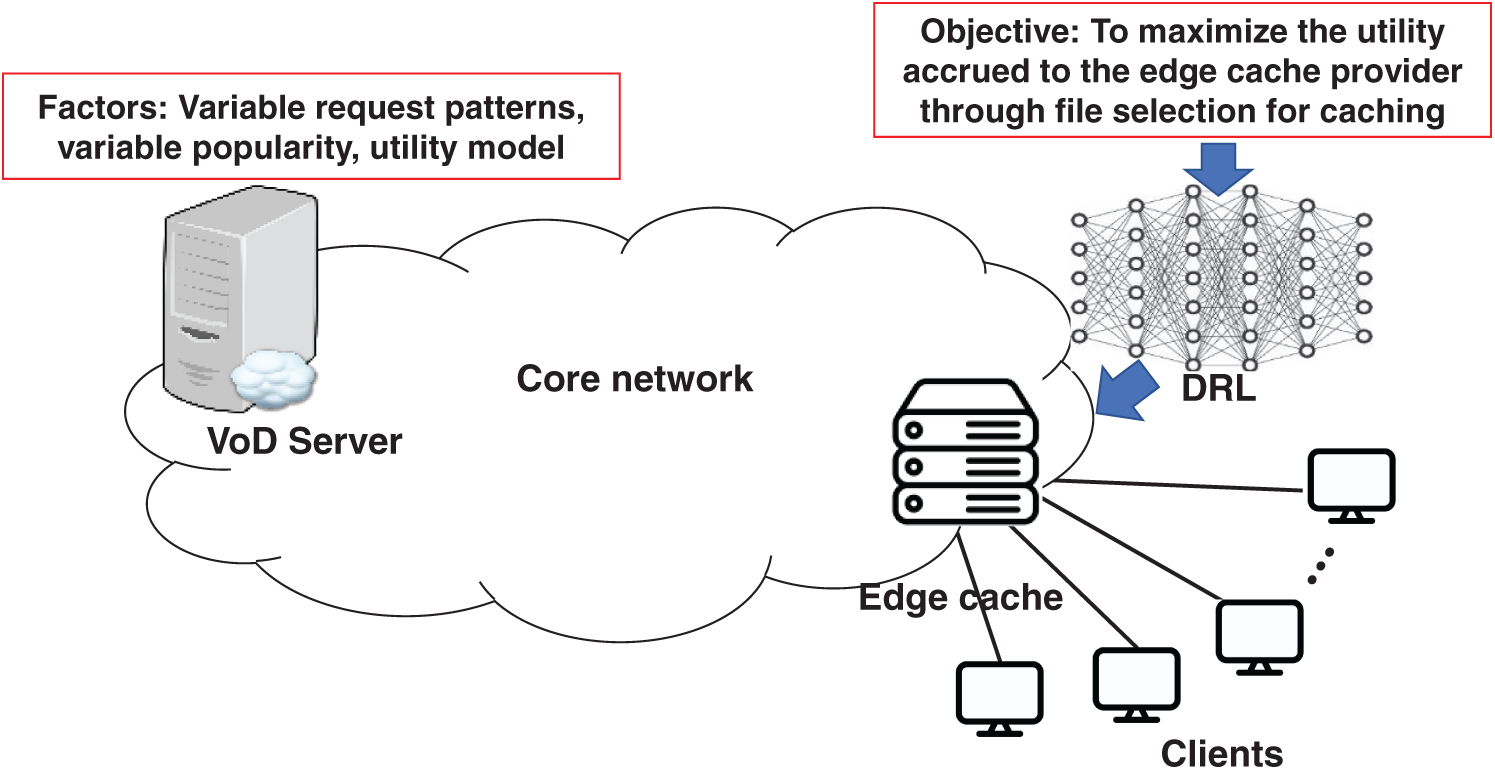

Fig. 1 illustrates the system architecture for caching video content on edge cache. Edge caching reduces network bandwidth consumption by storing popular content closer to end users, thereby decreasing data transmission through core networks, lowering latency, and improving overall network efficiency [23]. From the perspective of the edge cache provider, maximizing the bandwidth utilized by the edge cache is directly linked to the profit generated.

Figure 1: System architecture

In this context, utility is defined as the profit accrued by the edge service provider, which is proportional to the bandwidth provided by the edge server. The edge caching system operates on the principle that higher bandwidth utilization reflects enhanced service delivery capabilities, leading to increased revenue for the provider [24]. The overarching objective is to maximize the total utility generated for the service provider while satisfying the edge cache capacity constraint.

Assume that the VoD server depicted in Fig. 1 stores

The edge server processes user requests based on cached files, with requests handled as follows:

• Cache hit: If the requested video is cached, it is directly served from the edge server. This also includes cases where a lower bitrate version of the requested video is cached and served to minimize bandwidth usage [22].

• Miss: If neither the requested video nor a lower bitrate version is cached, the request cannot be fulfilled.

Let

Here,

We consider three utility models based on the bandwidth provided by the edge cache: proportional (linear growth), convex (accelerating growth), and concave (diminishing growth) relationships. These models enable adaptability to diverse utility requirements and reflect various profit structures [25]. Let

where

4 Synthetic Dataset Generation

In this section, we describe the process of generating a synthetic dataset for evaluating VoD caching systems. The dataset models two key aspects: the total number of requests across time intervals and the dynamic popularity of videos and their versions.

• The normalized number of requests

• Video popularity: Each video

• Version popularity: Within each video, the popularity of its bitrate versions is modeled using a normal distribution,

Using these models, a synthetic dataset is generated with

These modeling components are grounded in prior literature on caching workload simulation [26,27], enhancing the realism and reproducibility of the generated dataset. Furthermore, by varying model parameters such as request skewness and version-level diversity, researchers can customize the dataset to evaluate a broad range of caching algorithms under diverse operational scenarios.

It is worth noting that the dataset is constructed solely from content-level popularity metrics and request distributions, without involving any user identifiers, behavioral traces, or session-level logs. As a result, the training and evaluation processes remain fully compliant with privacy-preserving principles in edge computing.

Let us first define the normalized concurrent request count

where

Next, the weighted utility

For each video

The optimization problem can be formulated to maximize the expected popularity-weighted utility, considering the stochastic nature of video popularity and the number of requests per interval. The storage size of version

1. Objective Function: The objective function computes the expected total request-driven utility over all intervals

2. Constraints:

• The total storage cost of all cached versions must not exceed the available storage

3. Stochastic Parameters:

• Both

This formulation optimizes caching strategies to maximize the expected popularity-weighted utility while adhering to storage capacity constraints. DRL is the most suitable approach for addressing this problem, as it can learn optimal policies that adapt in real-time to highly dynamic environments, effectively handle stochastic elements, and balance both short-term performance and long-term efficiency.

We propose a DRL-based cache determination algorithm (CDA) that uses proximal policy optimization (PPO) due to its ease of implementation, sample efficiency, and reliable convergence [29,30]. PPO stabilizes training through clipped probability ratios, making it particularly suitable for dynamic environments with fluctuating content popularity [29,30].

The algorithm operates in two phases: training and decision. In the training phase, the agent learns its caching policy over

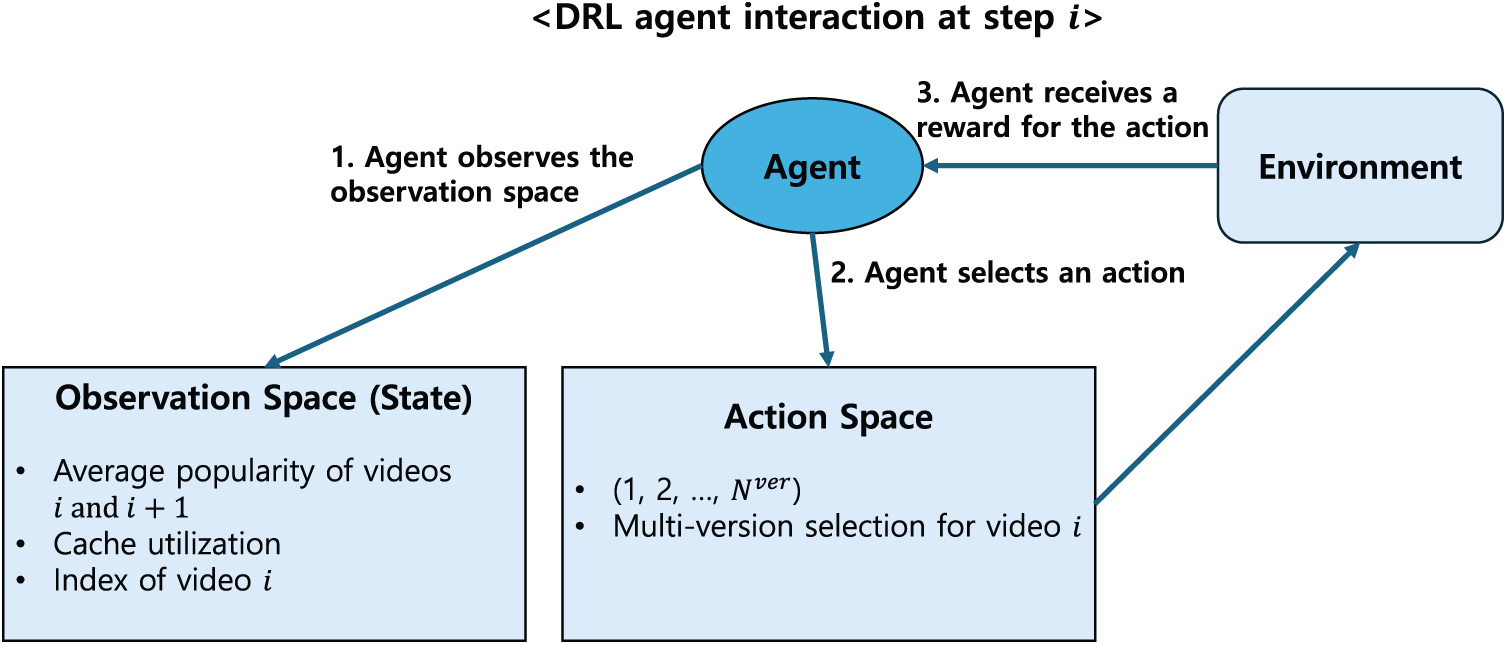

We model the caching process as a sequential decision-making problem, where the agent selects which bitrate versions of a video to cache, processing one video at each decision step. Therefore, the time step in the DRL formulation corresponds directly to the video index, denoted as

At each step

1. The agent observes the current state of the environment, which includes features such as storage usage and popularity estimates for video

2. The agent selects an action

3. The environment updates its state and calculates a reward based on the utility gained and whether minimum caching requirements are met.

The DRL algorithm is built upon three main components:

1. Action space: The action space A is defined as the set of all possible versions an agent can select:

2. Observation space: The observation space represents the current state of the environment. It includes relevant metrics such as video popularity, cache utilization, and system constraints that influence caching decisions.

3. Reward model: The reward model assigns a scalar value to each action, reflecting its immediate benefit or cost. The agent’s objective is to maximize cumulative rewards, which represent the overall performance of the caching policy.

The valid action space

The observation state at each video index

where

The reward function is designed to promote caching decisions that maximize utility while ensuring that at least one version is cached for every video. At each decision step

To penalize scenarios in which no version of a video is cached—thus resulting in zero utility—a penalty term is applied. For each video

The total reward for an episode is then computed by summing the individual rewards

This reward structure encourages the agent to not only prioritize caching versions that yield higher utility but also to ensure that at least one version is cached per video. As a result, the agent learns a balanced policy that improves overall utility.

To visually clarify the agent’s behavior during training, Fig. 2 illustrates the decision-making process at each step

Figure 2: Agent’s decision process at step

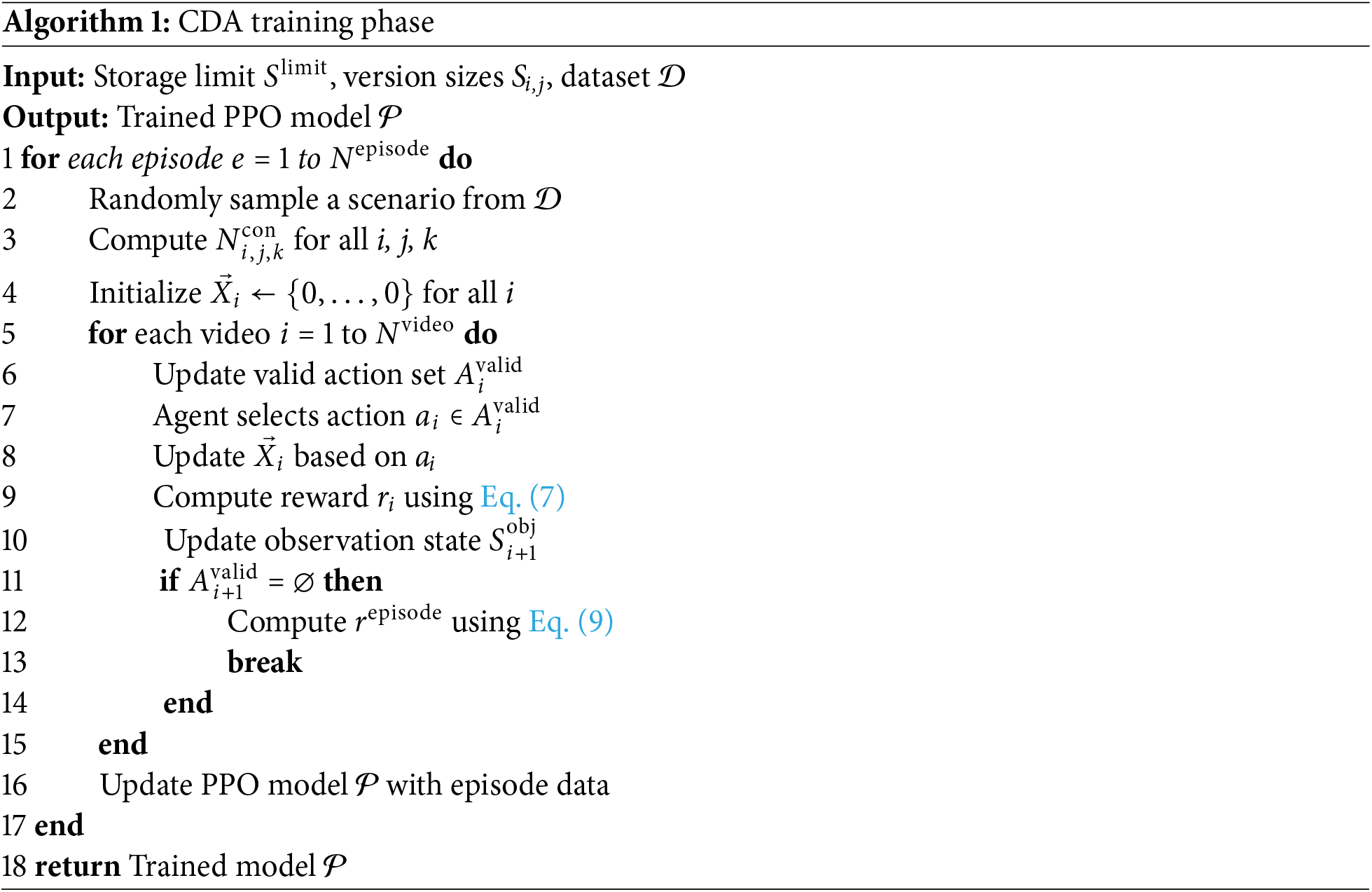

Algorithm 1 describes the training phase of the proposed CDA algorithm. In this phase, the agent learns caching strategies by interacting with a simulated environment over multiple episodes. At the beginning of each episode, a sample scenario is selected from the dataset

The agent processes the videos sequentially. For each video

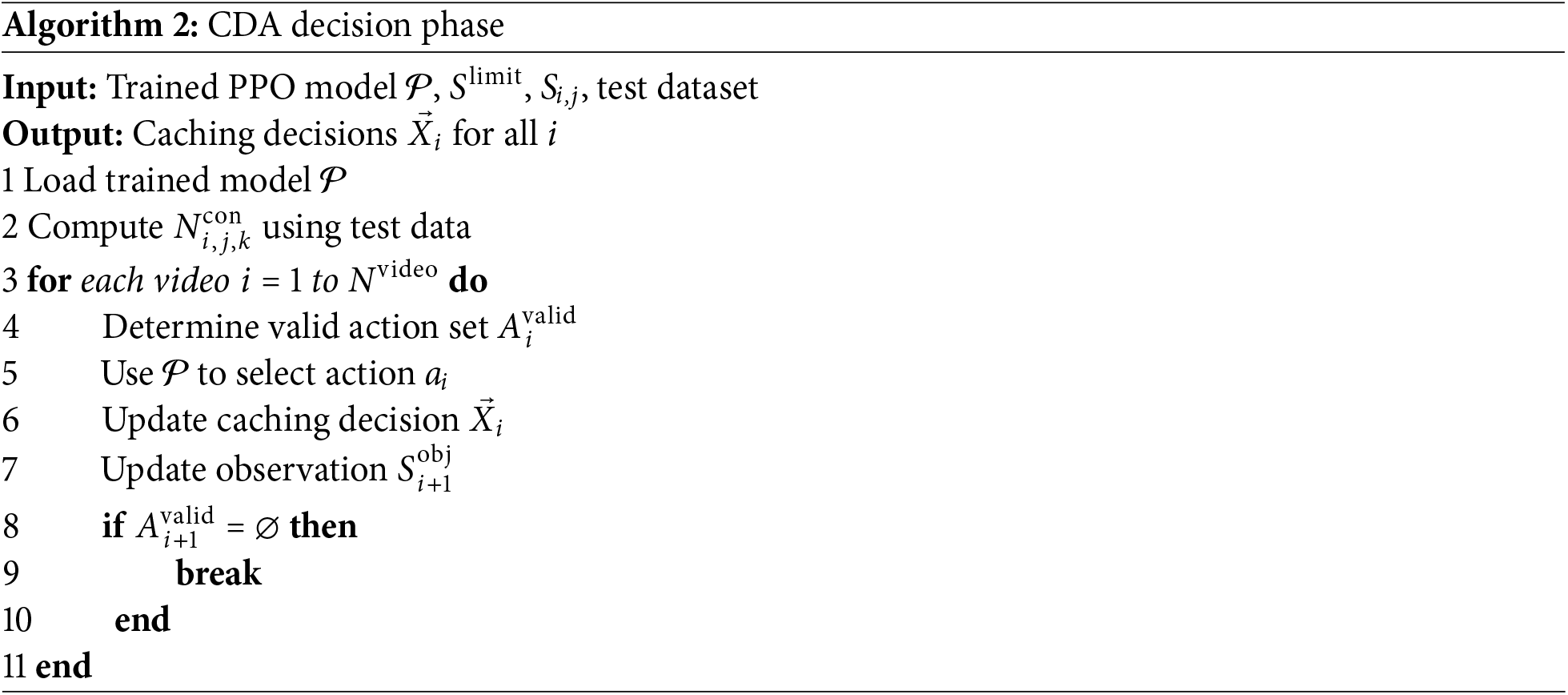

Algorithm 2 presents the decision phase of the CDA algorithm, during which the trained PPO model

Given the trained model and a test dataset, the concurrent request values

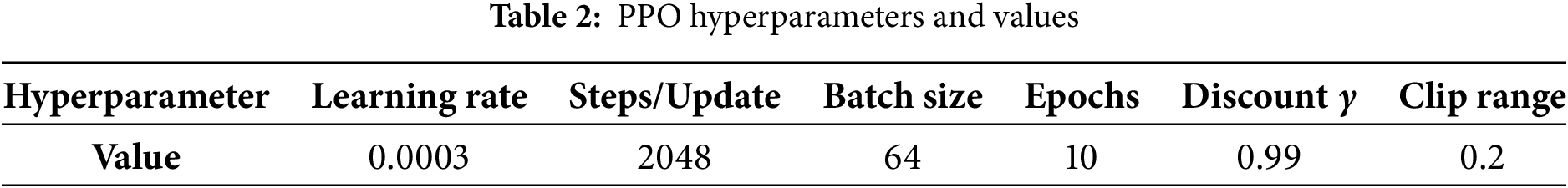

To optimize the performance of the PPO-based caching agent, we employed Optuna [31], a state-of-the-art hyperparameter optimization framework that uses a Bayesian optimization strategy. The objective was to maximize the average episode reward during training by identifying the most effective hyperparameter configurations for the PPO algorithm. The search space was defined over three key hyperparameters: the learning rate, the clipping range, and the value function coefficient.

Specifically, as shown in Table 2, the final PPO hyperparameter settings were as follows. The learning rate was set to 0.0003 to balance convergence speed and policy stability. Each policy update used 2048 steps to collect sufficient experience, and the batch size was set to 64. We trained the model for 10 epochs per update. The discount factor was set to 0.99 to account for long-term rewards, while the clip range was fixed at 0.2 to stabilize the policy updates. Lastly, the value function coefficient was set to 0.5, balancing the optimization of the policy and the accuracy of the value function estimation.

Optuna conducted a total of 100 trials using the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) as the sampling algorithm. Each trial trained the PPO agent for a fixed number of episodes and reported the mean episode reward as the objective metric. The best-performing configuration was selected based on its ability to maximize long-term utility across diverse caching scenarios.

We conducted simulations to evaluate the proposed scheme, with the DRL algorithm implemented using the PyTorch framework. The experimental parameters were configured with

The utility model parameters were set as follows:

To evaluate the performance of CDA, we adopted the total utility—normalized to the utility achieved by CDA—as the primary performance metric. We compared CDA against six baseline caching strategies, including four greedy heuristics and two predictive models based on long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. In all cases, video popularity is quantified by the number of concurrent requests:

1. Initial Popularity-Capacity Ratio (IPCR): Videos are cached based on their initial popularity (i.e., number of concurrent requests) divided by their size, prioritizing those with the highest ratio.

2. Average Popularity-Capacity Ratio (APCR): Similar to IPCR, but uses the average popularity across all dataset samples instead of the initial value.

3. Initial Popularity Greedy (IPG): Videos are cached in descending order of their initial popularity.

4. Average Popularity Greedy (APG): Videos are cached in descending order of their average popularity across all samples.

5. LSTM-based Popularity Predictor (LSTM-P): An LSTM model is trained on the synthetic dataset

6. LSTM-based Popularity-Capacity Ratio Predictor (LSTM-PCR): Another LSTM model is used to estimate the popularity-to-capacity ratio. Caching is performed in descending order of this predicted ratio.

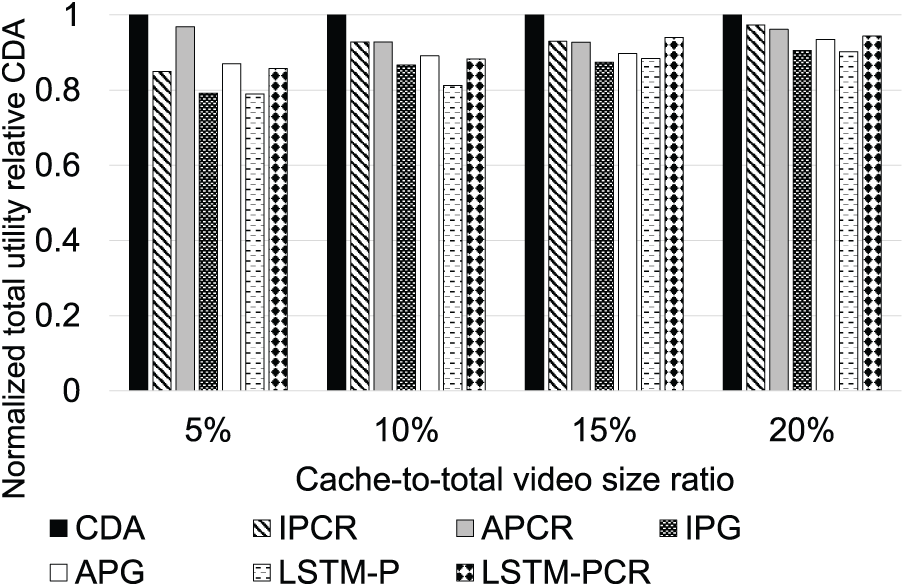

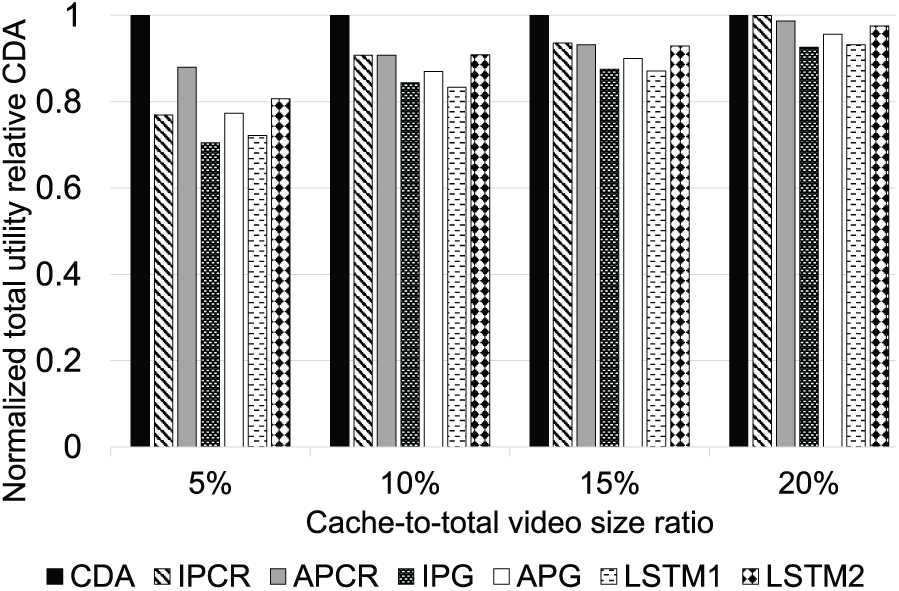

Fig. 3 illustrates the impact of the cache-to-total video size ratio on overall utility. CDA consistently outperforms the benchmark algorithms, achieving utility improvements ranging from

Figure 3: Normalized utility relative to CDA for different cache-to-total video size ratio values

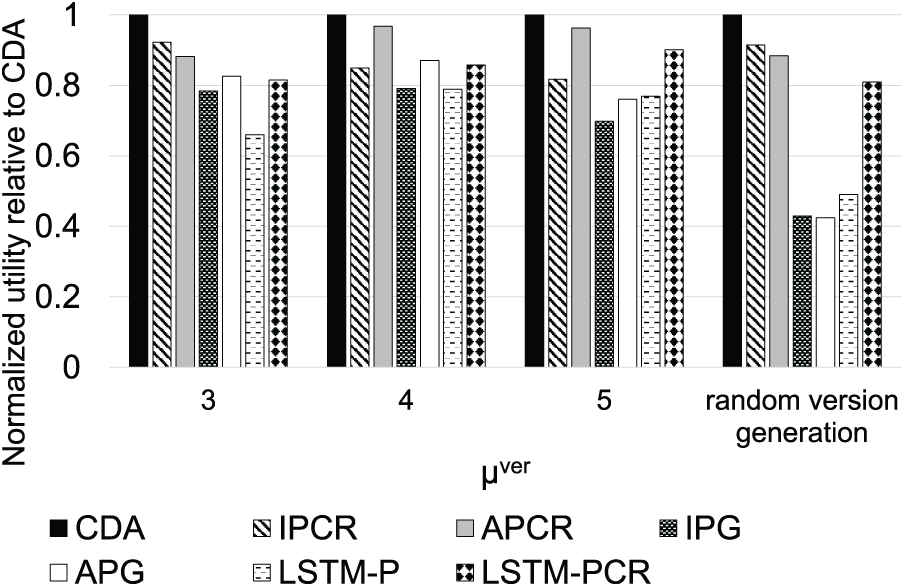

Fig. 4 illustrates the impact of varying

Figure 4: Normalized utility compared to CDA for varying

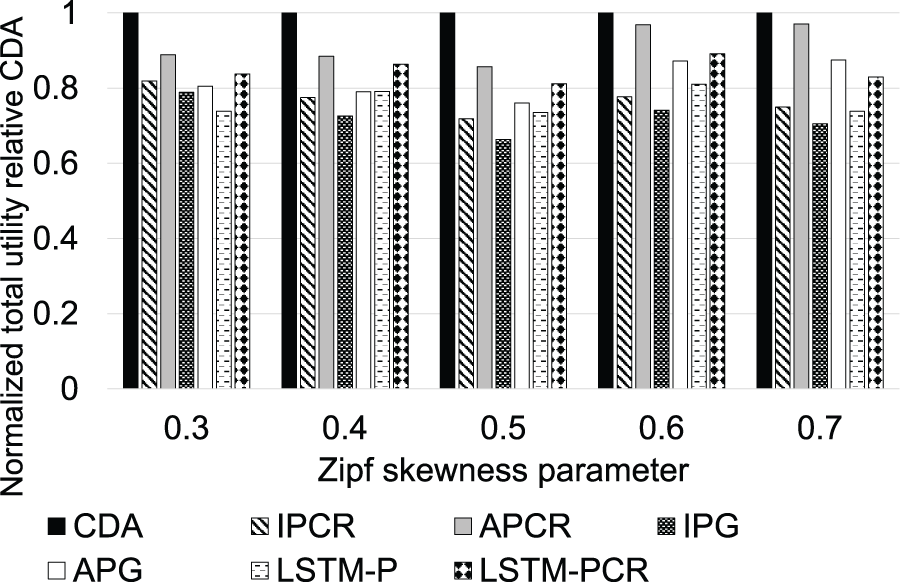

Fig. 5 illustrates the impact of popularity bias on performance, where the Zipf skewness parameter indicates the degree of bias in the popularity distribution. Higher values reflect stronger bias, while lower values represent a more uniform distribution. CDA consistently outperforms the benchmark algorithms, achieving utility improvements ranging from

Figure 5: Normalized utility relative to CDA for varying Zipf parameters

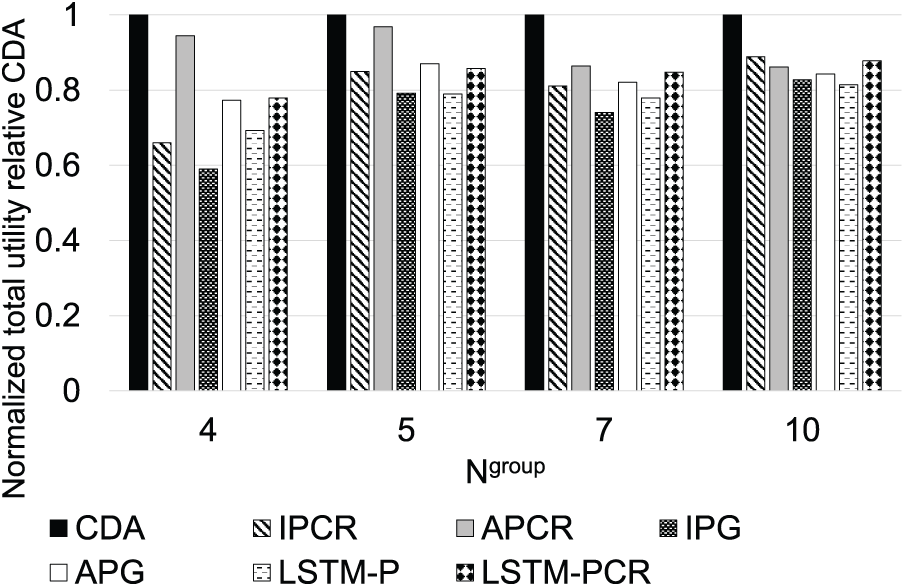

Fig. 6 shows the impact of varying

Figure 6: Normalized utility compared to CDA for varying

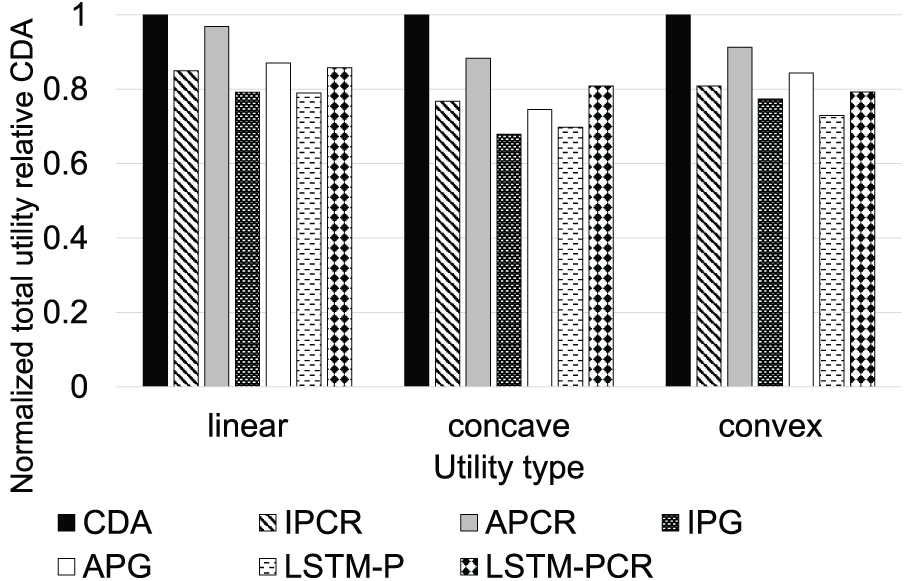

Fig. 7 illustrates the impact of utility types on performance, categorized as linear, convex, or concave. CDA consistently outperforms the benchmark algorithms, with utility improvements ranging from

Figure 7: Normalized utility compared to CDA for different utility models

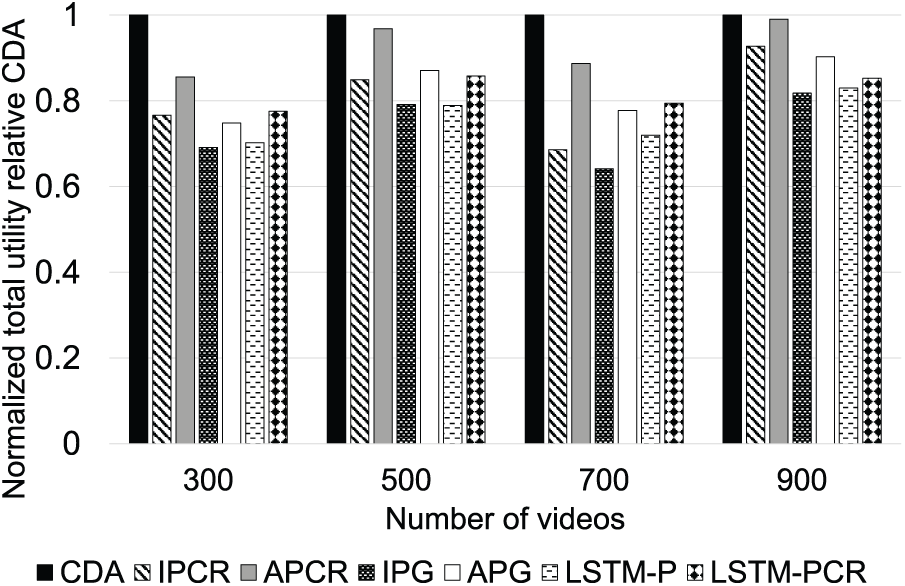

Fig. 8 illustrates the impact of the total number of videos on caching performance. CDA consistently outperforms the benchmark algorithms across all tested video counts, achieving utility improvements ranging from 1.02% to 55.87% (average 23.81%). These results demonstrate that CDA effectively prioritizes high-utility versions even as the content scale increases, highlighting the strong adaptability of the DRL model.

Figure 8: Normalized utility compared to CDA for different number of videos

To assess CDA under realistic conditions, we leveraged video popularity information from a VoD access trace [32], focusing on the top 500 most requested videos. Fig. 9 shows the normalized utility of each method relative to CDA. CDA consistently outperformed all baselines, achieving utility gains ranging from 0.05% to 41.9%, with an average improvement of 14.2%. These results demonstrate the practicality and robustness of our DRL-based caching strategy under realistic content dynamics.

Figure 9: Normalized utility relative to CDA using real-world VoD dataset

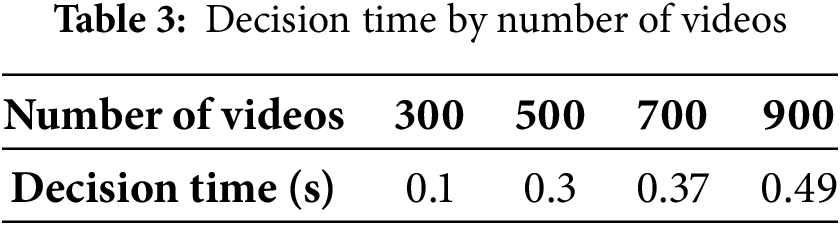

CDA requires an average of 26 min to execute 1 million timesteps during the training phase. In the decision phase, the inference time depends on the total number of videos, as each video corresponds to a single decision step. As shown in Table 3, the overall decision time increases with the number of videos. These results were obtained in an environment with an 8-core CPU running at a clock speed of 4.05 GHz.

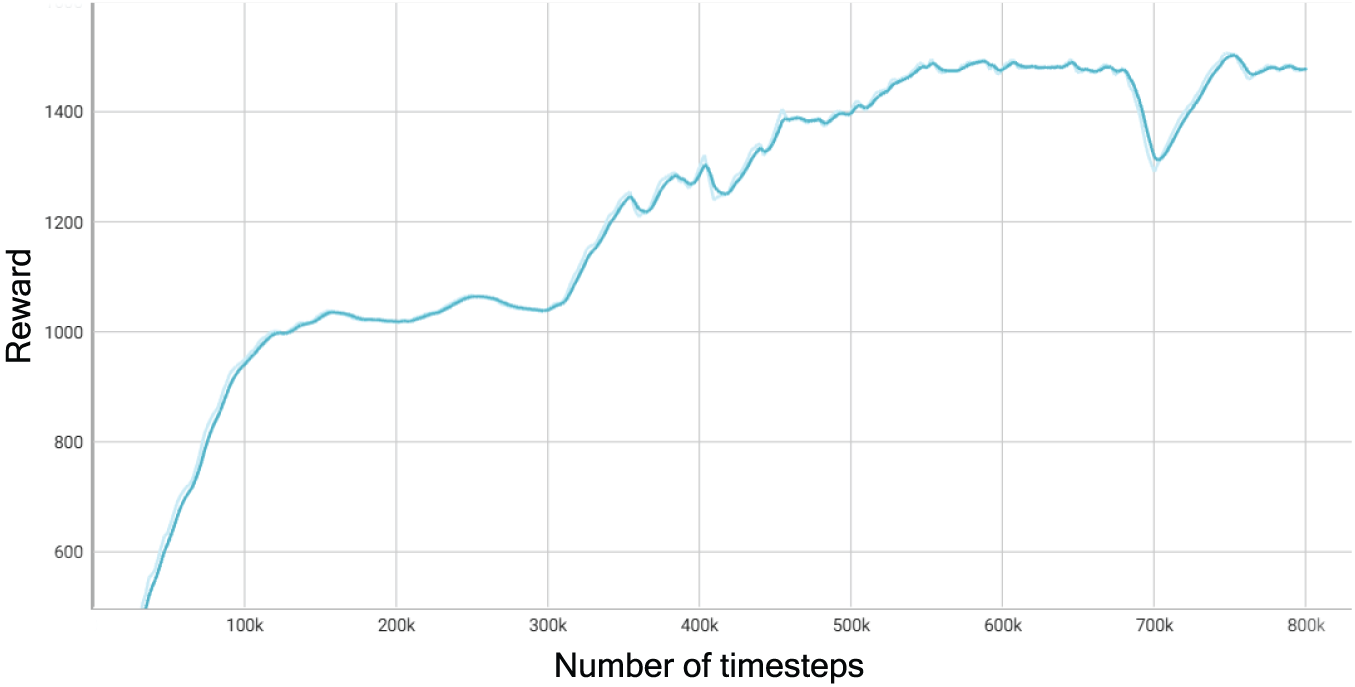

To further validate the learning stability of the proposed DRL model, we plotted the average episode reward across training. As shown in Fig. 10, the learning curve stabilizes after sufficient training episodes, confirming convergence of the PPO-based caching agent.

Figure 10: Learning curve of the PPO-based caching agent during training

We highlight the following major findings:

• The proposed CDA algorithm consistently outperforms both conventional greedy-based algorithms and LSTM-based prediction-driven strategies across various scenarios. It achieves significant utility improvements under limited cache capacity, high popularity of low-bitrate versions, skewed content popularity, and dynamic rank variations. In addition, CDA maintains robust performance across different utility models, demonstrating its adaptability to diverse system environments.

• The relative performance gain of CDA becomes more pronounced as the uncertainty of the environment increases, such as in scenarios with highly dynamic version popularity or rapid changes in content rankings. This indicates that the proposed DRL-based approach effectively learns adaptive caching policies rather than relying on static strategies, thereby ensuring robust performance even in dynamic caching environments.

• We analyzed the proposed approach in terms of optimization. The training process is stable, as the reward converges reliably, and the learned policy consistently outperforms baselines across varying utility models, video set sizes, Zipf parameters, and cache capacities. The trained policy also supports real-time decision-making due to its minimal inference time.

• The proposed DRL-based caching framework is designed to be adaptable to various edge environments, as it learns directly from request patterns and utility definitions. By adjusting these inputs, the framework can generalize to different content types where popularity varies over time, such as live video streams, trending news articles, short-form video clips, or social media posts.

• Although DRL methods are often computationally intensive, our approach is lightweight at inference, making caching decisions in just 0.32 s on average. It requires minimal CPU and memory, as it uses pre-trained parameters without online learning or per-user processing. These features enable practical deployment for real-time or periodic cache updates on resource-constrained edge devices.

• Our framework ensures privacy by relying solely on content-level popularity and aggregate request patterns, without using user identifiers or session-level logs. This design inherently supports privacy-preserving learning and aligns with data protection requirements for deployment in edge environments.

• While collaborative filtering has proven effective for personalized recommendation and, in some cases, caching, such methods depend on identifiable user behavior. Our approach, by contrast, operates solely on aggregate access patterns, enabling robust caching decisions without requiring content semantics.

This paper presented a deep reinforcement learning-based caching algorithm designed to optimize content placement in edge caching systems under dynamic video popularity and resource constraints. Unlike traditional greedy or static strategies, our proposed cache decision algorithm (CDA) leverages the proximal policy optimization (PPO) framework to learn adaptive caching policies through experience-based exploration and feedback. We introduced a novel reward structure that integrates both cache utility and video quality degradation, enabling the agent to make balanced and informed decisions that align with provider-centric utility goals.

To rigorously evaluate the algorithm, we developed a comprehensive synthetic dataset generator that models real-world access behaviors including diurnal variations, Zipf-based popularity dynamics, and probabilistic bitrate version preferences. In addition, we conducted an experiment using the top 500 most popular videos from a real-world VoD trace to validate the algorithm under realistic access patterns.The experimental results confirm that CDA significantly outperforms both greedy baselines and LSTM-based prediction-driven caching strategies across a wide range of scenarios. Notably, CDA exhibits strong performance under severe cache constraints, unpredictable version preferences, and when the utility model reflects diminishing returns, such as in concave cases. The utility gains are most pronounced in highly dynamic environments where traditional and prediction-based methods typically struggle.

In addition to utility performance, we validated the computational efficiency of CDA, showing that the model can be trained within practical timeframes and deployed with minimal inference overhead. This makes our approach suitable for real-time edge deployment on low-power platforms. Future work will extend this model to multi-agent cooperative caching scenarios across federated edge nodes and explore transfer learning techniques to reduce training overhead under non-stationary popularity shifts. In addition, collaborative filtering techniques may be incorporated in environments where user-level data is available to enhance personalized caching.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Inha University Research Grant.

Author Contributions: Concept and design: Mingoo Kwon, Minseok Song; data collection: Mingoo Kwon; analysis of results: Kyeongmin Kim, Minseok Song; manuscript writing: Mingoo Kwon, Kyeongmin Kim, Minseok Song. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sun S, Zhou J, Wen J, Wei Y, Wang X. A DQN-based cache strategy for mobile edge networks. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;71:3277–91. doi:10.32604/cmc.2022.020471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Liu F, Zhang Z, Xing Y. ECC: edge collaborative caching strategy for differentiated services load-balancing. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;69(2):2045–59. doi:10.32604/cmc.2021.018303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Mehrabi A, Siekkinen M, Yla-Jaaski A. QoE-traffic optimization through collaborative edge caching in adaptive mobile video streaming. IEEE Access. 2018;6:52261–76. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2870855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Cisco. Cisco Annual Internet Report (2018–2023); 2020. [cited 2025 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.cisco.com/./annual-internet-report/index.html,. [Google Scholar]

5. Liu W, Zhang H, Ding H, Yu Z, Yuan D. QoE-aware collaborative edge caching and computing for adaptive video streaming. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2023;23(6):6453–66. doi:10.1109/twc.2023.3331724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang S, He P, Suto K, Yang P, Zhao L, Shen X. Cooperative edge caching in user-centric clustered mobile networks. IEEE Trans Multimedia. 2017;17(8):1791–805. doi:10.1109/tmc.2017.2780834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wu J, Zhou Y, Chiu D, Zhu Z. Modeling dynamics of online video popularity. IEEE Trans Multimedia. 2016;18(9):1882–95. doi:10.1109/tmm.2016.2579600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Cui L, Ni E, Zhou Y, Wang Z, Zhang L, Liu J, et al. Towards real-time video caching at edge servers: a cost-aware deep Q-learning solution. IEEE Trans Multimedia. 2021;25:302–14. doi:10.1109/tmm.2021.3125803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sun C, Li X, Wen J, Wang X, Han Z, Leung V. Federated deep reinforcement learning for recommendation-enabled edge caching in mobile edge-cloud computing networks. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2023;41(3):690–705. doi:10.1109/jsac.2023.3235443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wu P, Li J, Shi L, Ding M, Cai K, Yang F. Dynamic content update for wireless edge caching via deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Commun Lett. 2019;23(10):1773–7. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2019.2931688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhong C, Gursoy MC, Velipasalar S. Deep reinforcement learning-based edge caching in wireless networks. IEEE Trans Cogn Commun Netw. 2020;6(1):48–61. doi:10.1109/tccn.2020.2968326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kwon M, Song M. A deep reinforcement learning-based technique for enhancing cache hit rate by adapting to dynamic file request patterns. Korean Instit Smart Media. 2025;14:26–34. doi:10.30693/SMJ.2025.14.1.26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Lee D, Kim Y, Song M. Cost-effective, quality-oriented transcoding of live-streamed video on edge-servers. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2023;16(4):2503–16. doi:10.1109/tsc.2023.3256425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Tran A-T, Dao N-N, Cho S. Bitrate adaptation for video streaming services in edge caching systems. IEEE Access. 2020;8:135844–52. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3011517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Dao N, Ngo D, Dinh N, Phan T, Vo N, Cho S, et al. Hit ratio and content quality tradeoff for adaptive bitrate streaming in edge caching systems. IEEE Syst J. 2023;15(4):5094–7. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2020.3019035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tran A, Lakew D, Nguyen T, Tuong V, Truong T, Dao N, et al. Hit ratio and latency optimization for caching systems: a survey. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Networking; Jeju Island, Republic of Korea; 2021. p. 577–81. [Google Scholar]

17. Araldo A, Martignon F, Rossi D. Representation selection problem: optimizing video delivery through caching. In: Proceedings of the IFIP Networking Conference and Workshops; Vienna, Austria; 2016. p. 323–31. [Google Scholar]

18. Zhou J, Simeone O, Zhang X, Wang W. Adaptive offline and online similarity-based caching. IEEE Netw Lett. 2020;2(4):175–9. doi:10.1109/lnet.2020.3031961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Garetto M, Leonardi E, Neglia G. Content placement in networks of similarity caches. Comput Netw. 2021;201(2):108570. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2021.108570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang L, Wang Y, Yu Z, Xiong F, Ma L, Zhou H, et al. Similarity caching in dynamic cooperative edge networks: an adversarial bandit approach. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;24(4):2769–82. doi:10.1109/tmc.2024.3500132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Tran T, Pompili D. Adaptive bitrate video caching and processing in mobile-edge computing networks. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2018;18(9):1965–78. doi:10.1109/tmc.2018.2871147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bayhan S, Maghsudi S, Zubow A. EdgeDASH: exploiting network-assisted adaptive video streaming for edge caching. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2020;18(2):1732–45. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2020.3037147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li C, Ye T, Zong T, Sun L, Cao H, Liu Y. Coffee: cost-effective edge caching for 360 degree live video streaming. arXiv:2312.13470. 2023. [Google Scholar]

24. Liang Y, Ge J, Zhang S, Wu J, Tang Z, Luo B. A utility-based optimization framework for edge service entity caching. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2019;30(11):2384–95. doi:10.1109/tpds.2019.2915218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mehrabi A, Siekkinen M, Ylä-Jääski A. Cache-aware QoE-traffic optimization in mobile edge assisted adaptive video streaming. arXiv:1805.09255. 2018. [Google Scholar]

26. Lee D, Song M. Quality-aware transcoding task allocation under limited power in live-streaming systems. IEEE Syst J. 2022;16(3):4368–79. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2021.3103526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhou S, Wang Z, Hu C, Mao Y, Yan H, Zhang S, et al. Caching in dynamic environments: a near-optimal online learning approach. IEEE Trans Multimedia. 2021;25:792–804. doi:10.1109/tmm.2021.3132156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Little JDC. A proof for the queuing formula: L = λW. Operat Res. 1961;9(3):383–7. doi:10.1287/opre.9.3.383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Schulman J, Wolski F, Dhariwal P, Radford A, Kimov O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv:1707. 06347. 2017. [Google Scholar]

30. Tang C, Liu C, Chen W, You S. Implementing action mask in proximal policy optimization (PPO) algorithm. ICT Express. 2020;6(3):200–3. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2020.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Akiba T, Sano S, Yanase T, Ohta T, Koyama M. Optuna: a next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In: Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; Anchorage, AK, USA; 2019. p. 2623–31. [Google Scholar]

32. Zink M, Suh K, Gu Y, Kurose J. Characteristics of youtube network traffic at a campus network-measurements, models, and implications. Comput Netw. 2009;53(4):501–14. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2008.09.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools