Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Thermodynamic Modeling of the Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta Refractory High Entropy Alloy and Its Application in Analyzing Phase Stability

1 School of Materials Science and Engineering, Hebei University of Technology, Tianjin, 300130, China

2National Industry-Education Platform of Energy Storage, Tianjin University, Tianjin, 300350, China

3 State Key Laboratory of Powder Metallurgy, Central South University, Changsha, 410083, China

* Corresponding Authors: Ying Tang. Email: ; Lijun Zhang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 539-556. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067266

Received 28 April 2025; Accepted 31 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta refractory high-entropy alloys (RHEAs) exhibiting a dual-phase structure resulting from martensitic transformation offer significant ductility enhancement, but their design requires precise control of the phase stability between body-centred cubic (BCC) and hexagonal close-packed (HCP) phases. This study establishes a comprehensive thermodynamic database for the Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta system using the 3rd-generation Calculation of Phase Diagrams (CALPHAD) model. The reliability of the database is validated by the strong agreement between the calculated thermodynamic properties and phase equilibria and the experimental data for pure element, as well as for binary and ternary systems. Utilizing this database, the phase stability of various RHEAs within this system was predicted, showing that all RHEAs exhibit a BCC single phase over a wide temperature range. The HCP phase is stable and coexists with BCC phase in both quaternary and quinary RHEAs at lower temepratures. Calculations of the Gibbs energy difference between the BCC and HCP phases () in TiHfZrTax and TiHfZrNbx alloys reveal that both Nb and Ta stabilize the BCC phase, with Nb exerting a stronger influence. Significantly, a metastable BCC+HCP region in the TiHfZrTax and TiHfZrNbx alloys with ranging from 1786 to 2230 J/mol. Utilizing this finding, the critical Nb composition range (0.0367–0.0712) to achieve the metastable BCC+HCP phase is precisely predicted in TiHfZrTa0.2Nbx alloys, enabling targeted design for martensitic transformation. The predictions show excellent agreement with existing experimental measurements.Keywords

RHEAs have emerged as a promising class of materials, distinguished by their exceptional yield strength and remarkable thermal stability [1–3]. These alloys are characterized by a unique composition that includes four or more principal refractory metal elements, which combine to form a single-phase BCC phase. To enhance the mechanical properties of RHEAs, both experimental and theoretical approaches have been undertaken to develop new types of RHEAs, including those utilizing precipitation strengthening [4,5], multi-phase structures [6,7], and martensitic transformation [8–10]. Notably, martensitic transformation in high-entropy alloys (HEAs) have garnered considerable attention due to their exceptional ductility at room temperature [11,12]. In 2016, a dual-phase FeMnCoCr HEAs were reported with high tensile strength and exceptional ductility by introducing the martensitic phase transformation [13], which was obtained by adjusting the contents of Fe and Mn. After that, martensitic transformation was strategically introduced into the HfZrTiTax RHEAs by decreasing the concentration of Ta. This adjustment aimed to thermodynamically destabilize the BCC phase and form a dual-phase structure with both BCC and HCP [12]. Subsequently, a comparable alloy design strategy was implemented for TiHfZrNb [8,14–16], HfZrNbTa [17], and TiZrHfVNbTa [18] RHEAs to enhance room temperature ductility by regulating the stability of the constituent phases.

It is widely understood that the martensitic transformation in RHEAs is influenced by the stacking fault energy (SFE) [19,20]. For an alloy system with a fixed composition, the SFE is predominantly governed by the free Gibbs energy difference between the phases. Consequently, the martensitic transformation within the TiHfZr-related RHEAs can be activated by adjusting the phase stability between the BCC and HCP. However, the significant compositional diversity inherent in RHEAs presents challenges for phase stability analysis when relying on traditional trial-and-error experimental methods. In addition to experimental methods, computer-aided approaches have gained popularity for predicting material characteristics [21–24]. Currently, there are numerous empirical or theoretical methods to predict the phase stability for RHEAs. For instance, by considering the influences of atomic radius, crystal structure, valence electron concentration, and thermodynamic properties on the solid solution phase, the Hume-Rothery criterion [23] can be employed to predict the phase formation of RHEAs. This empirical model demonstrates strong predictive capability for the formation of simple solid solutions in HEAs. However, its effectiveness in predicting complex multiphase alloys requires further analysis. Furthermore, first-principles calculations (FP) have also demonstrated significant reliability in phase stability predictions [24–26]. However, for HEAs with complex compositions, substantial computational resources are often needed, making it challenging to predict the phase stability efficiently. Additionally, the CALPHAD approach is typically employed to calculate phase equilibrium and thermodynamic properties of multi-component alloys [27–29], facilitating efficient predictions of phase stability in RHEAs. It should be noted that the reliability of phase stability predictions using the CALPHAD method is heavily dependent upon the accuracy of the thermodynamic database, which must include the Gibbs energy of each phase along with the corresponding parameters.

Currently, the thermodynamic database for TiHfZr-related RHEAs remains incomplete, which constrains the application of the CALPHAD approach in accurately predicting phase stability. It is believed that a reliable thermodynamic database serves as the foundation for the CALPHAD method. According to the Redlich-Kister (R-K) theory [30], modeling the Gibbs energy of pure elements is fundamental to develop the thermodynamic database for multicomponent systems. To accurately capture the physical significance of the Gibbs energy expression for pure elements, various research groups [27,28,31] have proposed the development of a 3rd-generation thermodynamic model since 1995. In our recent work, a 3rd-generation thermodynamic model was proposed by incorporating thermodynamic properties at temperatures below 298 K, as well as the thermal vacancy contribution near melting points [27,28]. This model was subsequently applied to develop a highly accurate thermodynamic database for the Mo-Nb-Ta-W-Hf-Zr system [27,28].

Consequently, Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta system was selected for this study. Initially, the thermodynamic database will be established using our previously proposed 3rd-generation thermodynamic model. This database will then be applied to analyze phase formation in RHEAs within this system, focusing on the effects of Nb or Ta addition on the phase stability between BCC and HCP phases in TiHfZr-related RHEAs.

The Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta system exhibits three stable phases: BCC, HCP, and Liquid. In our previous work [27,28], a 3rd-generation thermodynamic model for solid solution phase was proposed, which was utilized to establish a thermodynamic description of these phases within the Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta quinary system. The substitution solid solution model was used for the BCC, HCP, and Liquid phases. It is well known that the concentration of thermal vacancies increases with rising temperature. Thermal vacancy concentration becomes significant when the temperature exceeds 2/3Tm [32]. For pure Ti,

in which

It can be found that the value of

The 3rd-generation of

where

The Gibbs energy expression for a pure element in the Liquid state is formulated with the Two-State model [34],

in which

3 Thermodynamic Modeling for Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta System

The Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta system comprises 5 pure elements, 10 sub-binary and ternary systems. Our recent studies have reported the 3rd-generation thermodynamic descriptions for pure Hf, Zr, Nb, and Ta in the BCC, HCP, and Liquid phases. Additionally, the binary and ternary assessments related to these elements under the 3rd-generation framework have also been reported [27,28]. Thus, the present work will focus on the Ti-related binary and ternary systems, as well as developing a comprehensive thermodynamic database for Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta system. The thermodynamic assessment and calculations were performed using Thermo-Calc software [35].

3.1 The 3rd-Generation Thermodynamic Description for Pure Ti

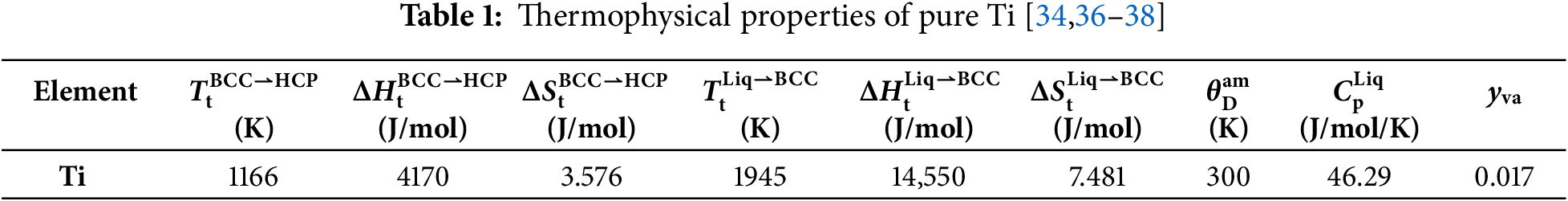

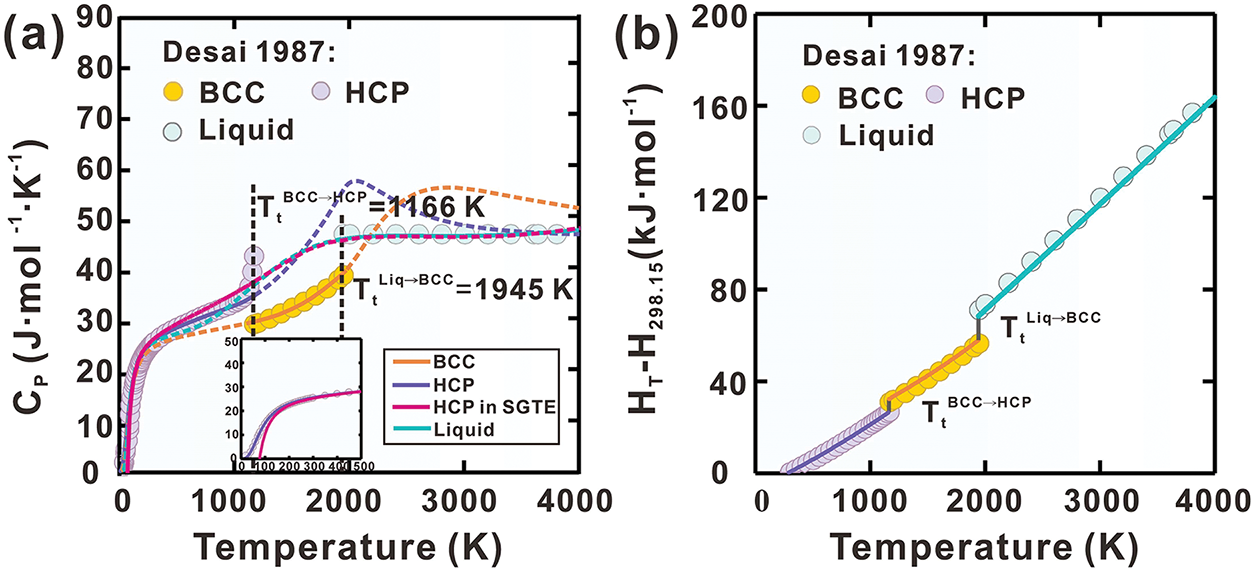

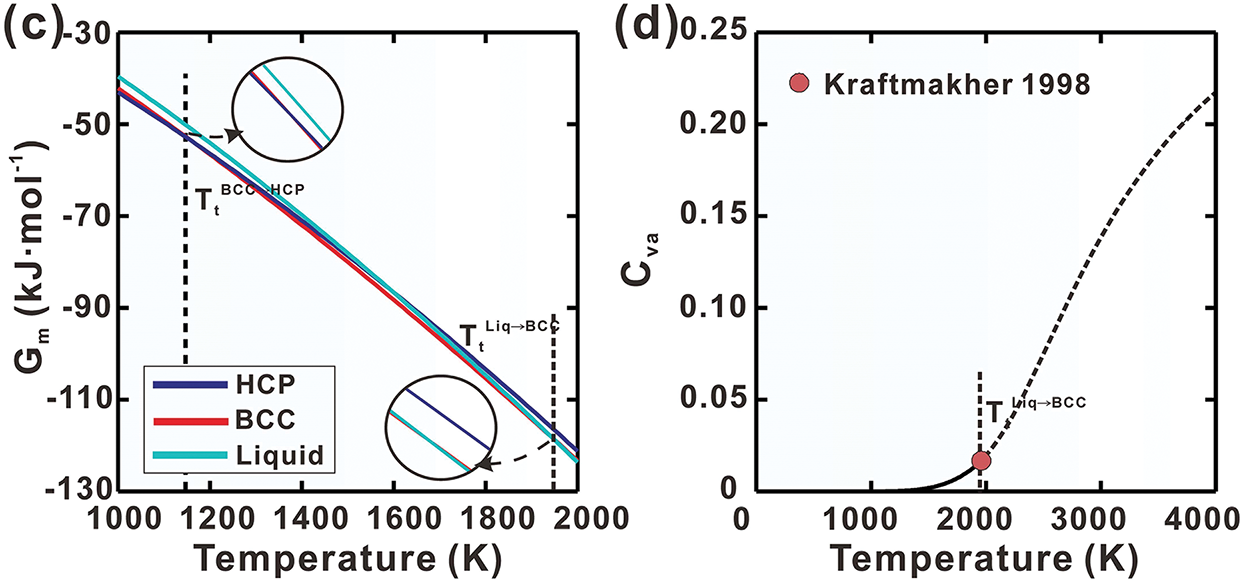

To determine the thermodynamic parameters of HCP, BCC, and the Liquid phases of pure Ti, it is essential to utilize the thermodynamic properties and thermal vacancy concentration as input data. Desai [36] evaluated all thermodynamic properties of pure Ti from 0 to 3800 K based on a comprehensive review of the reported experimental data. The phase transition temperatures, enthalpies, and entropies between the BCC and HCP phases (

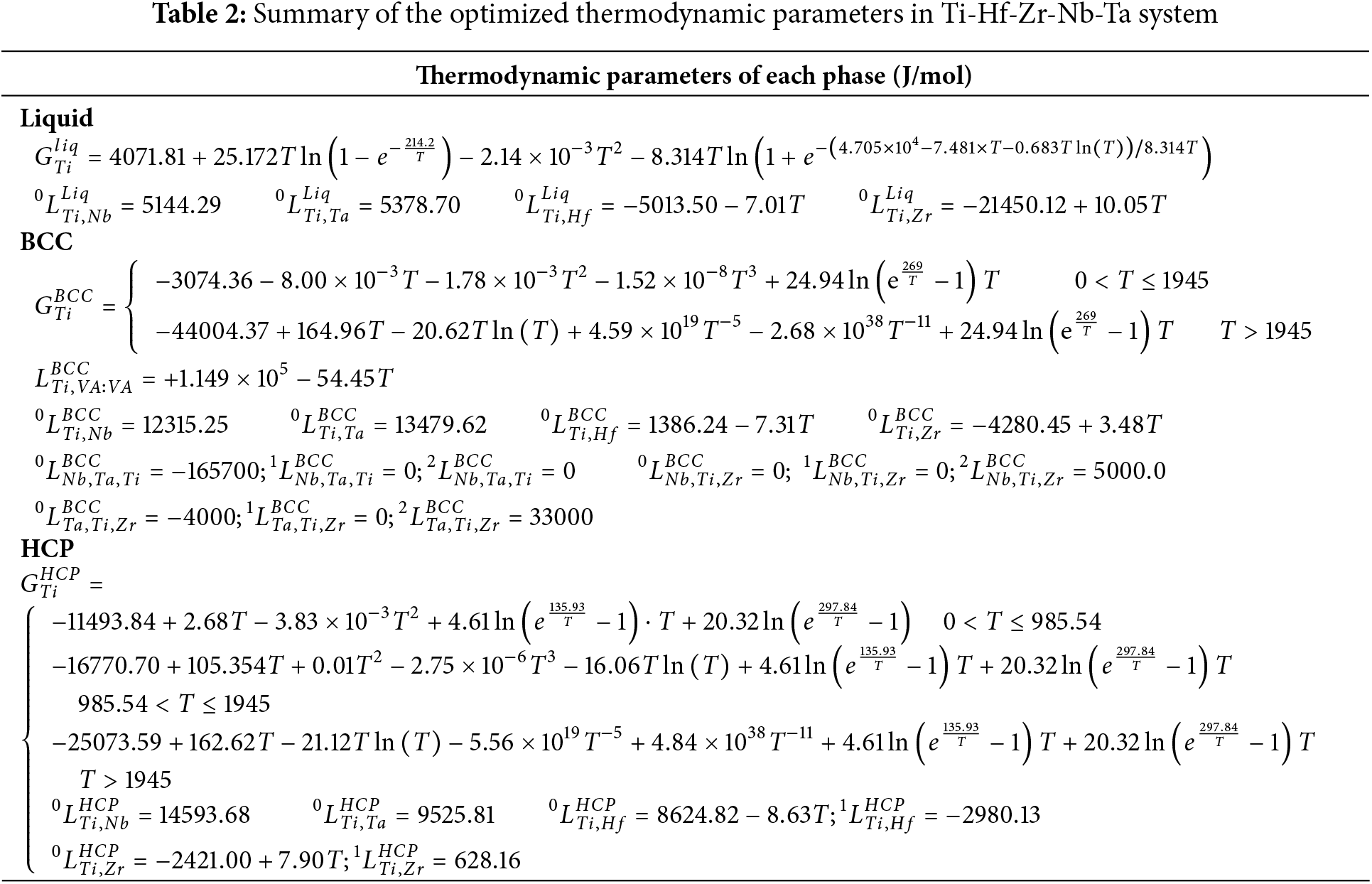

Using the established Gibbs energy expressions, the heat capacity (Cp), heat content (

Figure 1: Calculated curves of pure Ti for (a) heat capacity, (b) heat content, (c) molar Gibbs energy and (d) thermal vacancy concentration in BCC phase, compared with reported data [36,37]

3.2 Thermodynamic Modelling of Sub-Binaries in the Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta System

Various research groups have conducted detailed evaluations of the measured phase diagrams and thermodynamic properties in the Ti-Hf [40], Ti-Zr [41], Ti-Nb [42,43], and Ti-Ta [44] systems. This study focuses exclusively on analyzing the data subsequent to their work. For the Ti-Ta system, Na and Warnes [45] identified the phase boundaries between the BCC and HCP+BCC phase region from 400 to 600°C. Recently, Marker et al. [46] and Uesugi et al. [47] calculated the formation enthalpies of the BCC phase in the Ti-Zr, Ti-Nb, and Ti-Ta systems using FP methods. Considering the experimental data, the binary thermodynamic parameters in the Ti-Hf, Ti-Zr, Ti-Nb, and Ti-Ta systems have been evaluated and are summarized in Table 2.

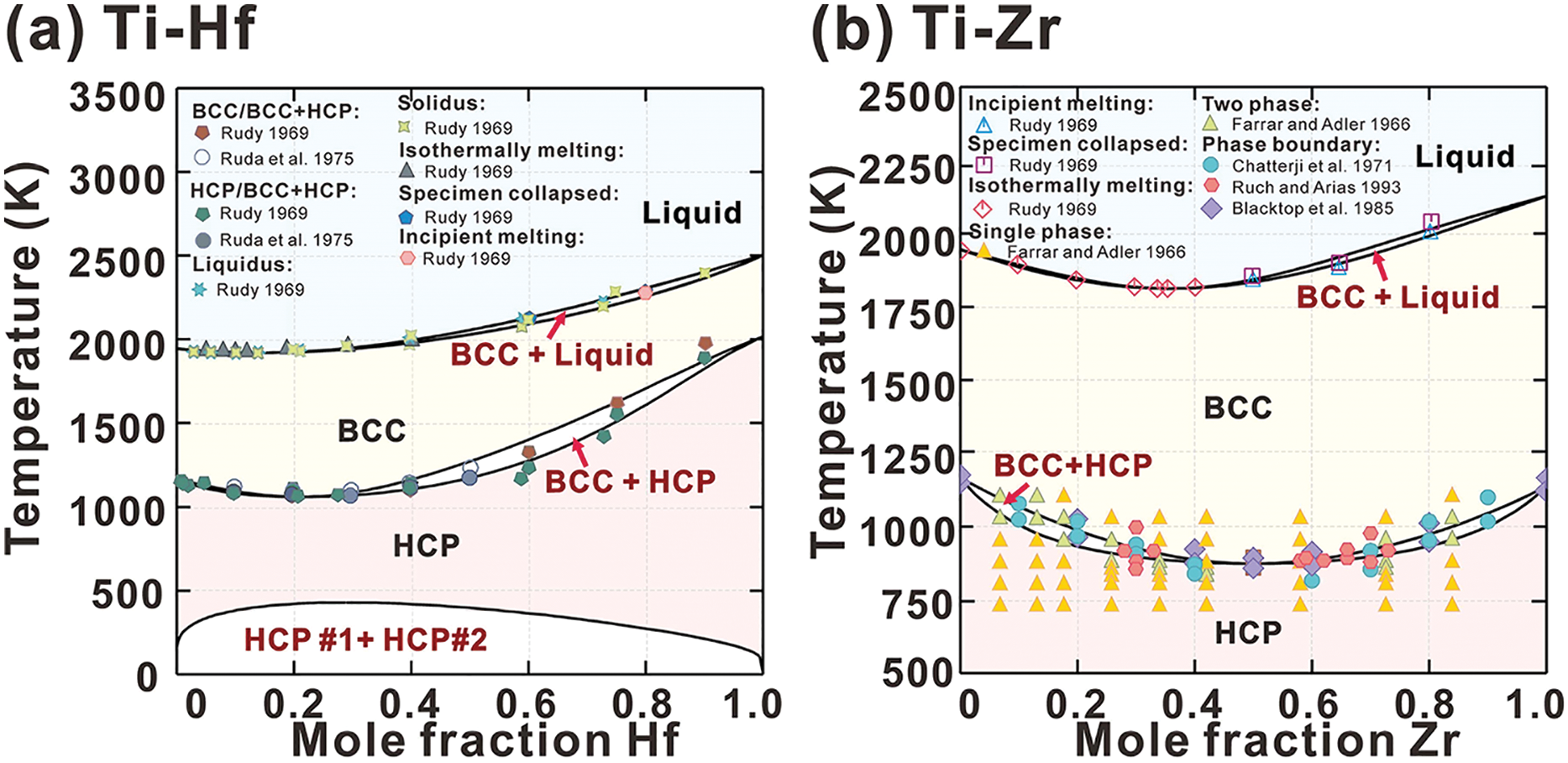

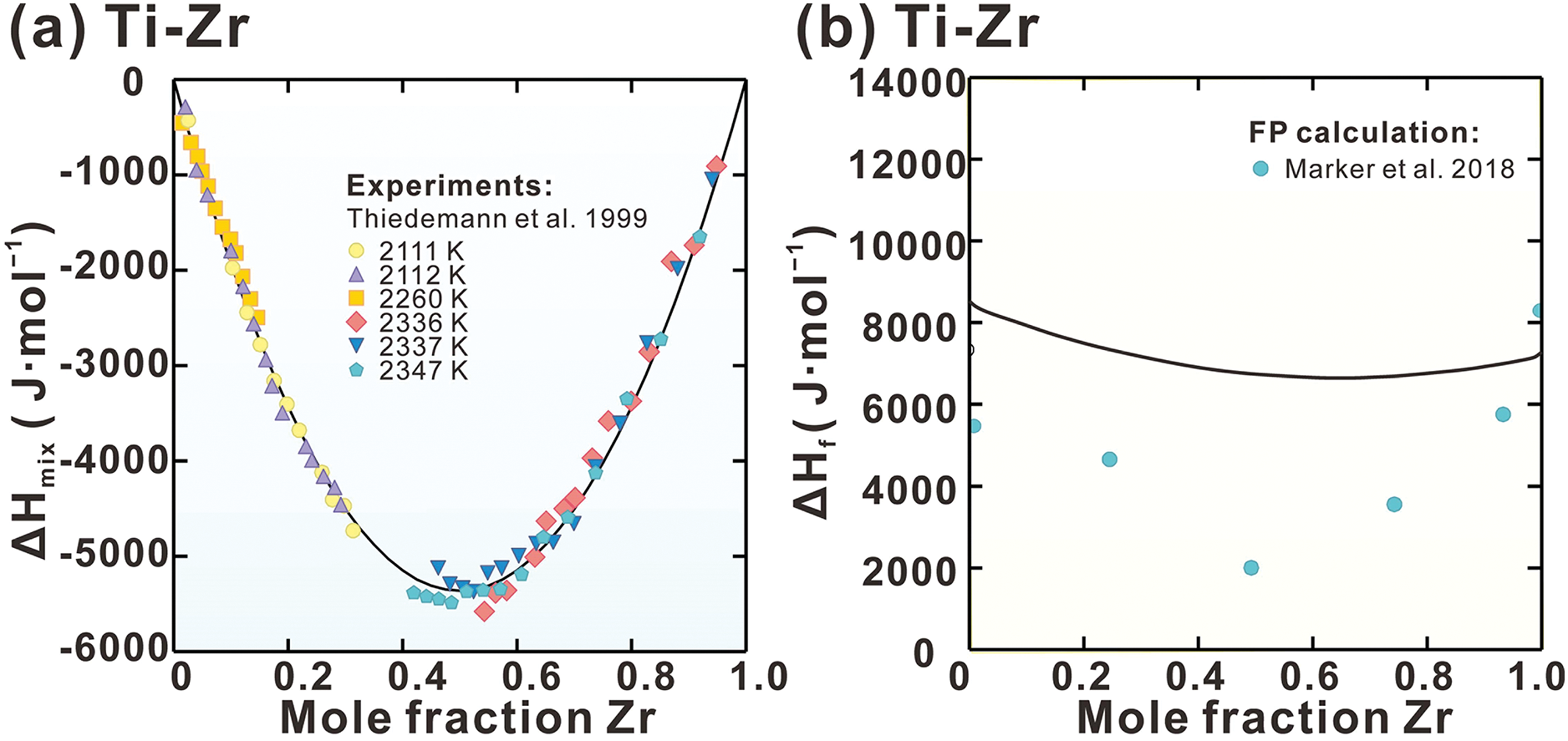

Fig. 2 presents the calculated phase diagrams for the Ti-Hf, Ti-Zr, Ti-Nb, and Ti-Ta binary systems, which agree well with most of the measured data (i.e., for Ti-Hf [48,49], Ti-Zr [48,50–53], Ti-Nb [48,54–57], and Ti-Ta [45,48,58–60]). The calculated phase boundaries of the BCC and BCC+HCP phases in the Ti-Nb binary system align closely with the findings from Zakharov et al. [57], though they show some deviation from the experimental results presented by Hansen et al. [56], as illustrated in Fig. 2c. It has been reported that the diffusion rate of Nb in Ti-Nb alloys significantly decreases with increasing Nb content [42], complicating the attainment of thermodynamic equilibrium, even after extended annealing at temperatures below 1000 K. The deviation may be attributed to the experimental data being obtained under non-equilibrium conditions.

Figure 2: The calculated (a) Ti-Hf, (b) Ti-Zr, (c) Ti-Nb and (d) Ti-Ta phase diagrams compared with experimental data (Ti-Hf [48,49], (b) Ti-Zr [48,50–53], (c) Ti-Nb [48,54–57] and (d) Ti-Ta [45,48,58–60])

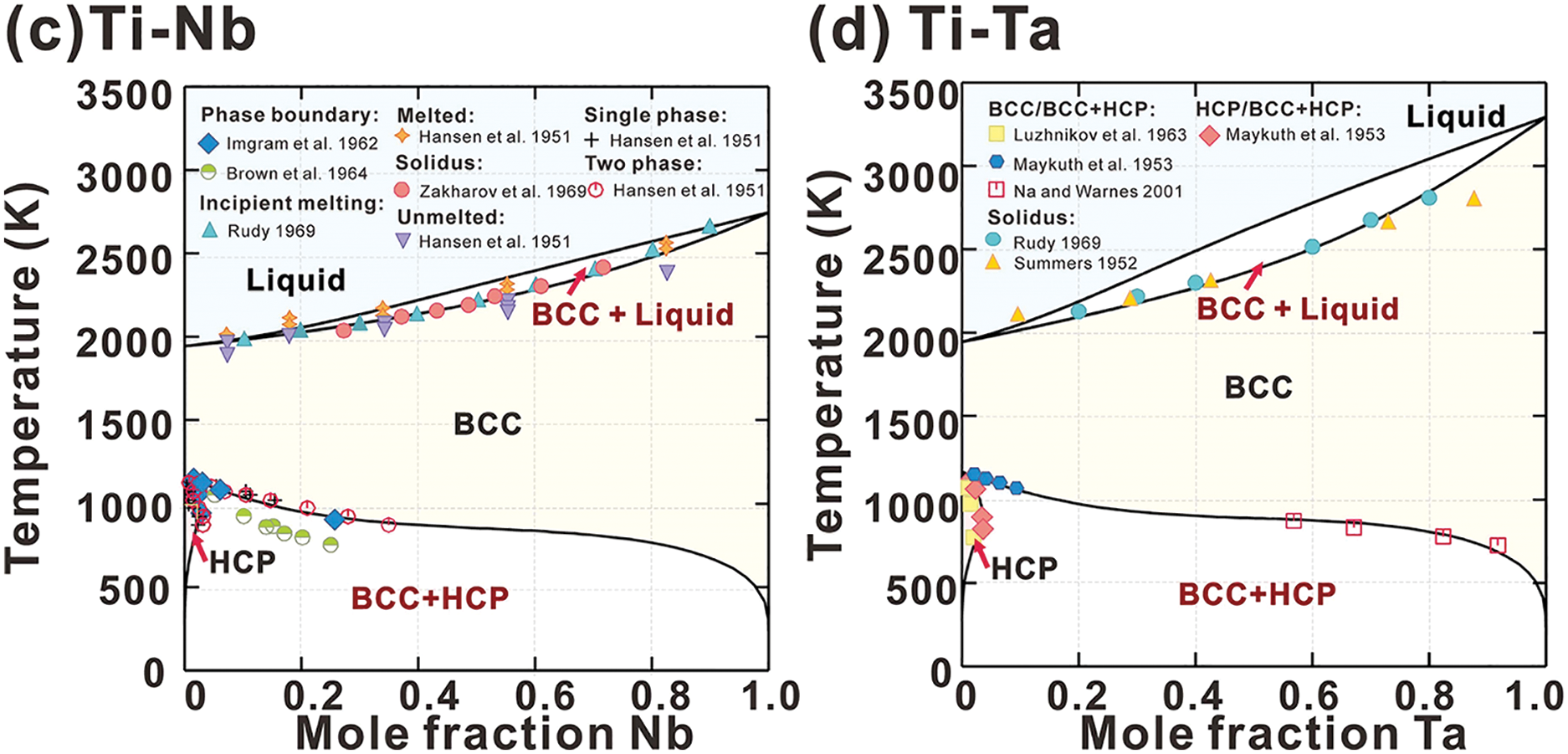

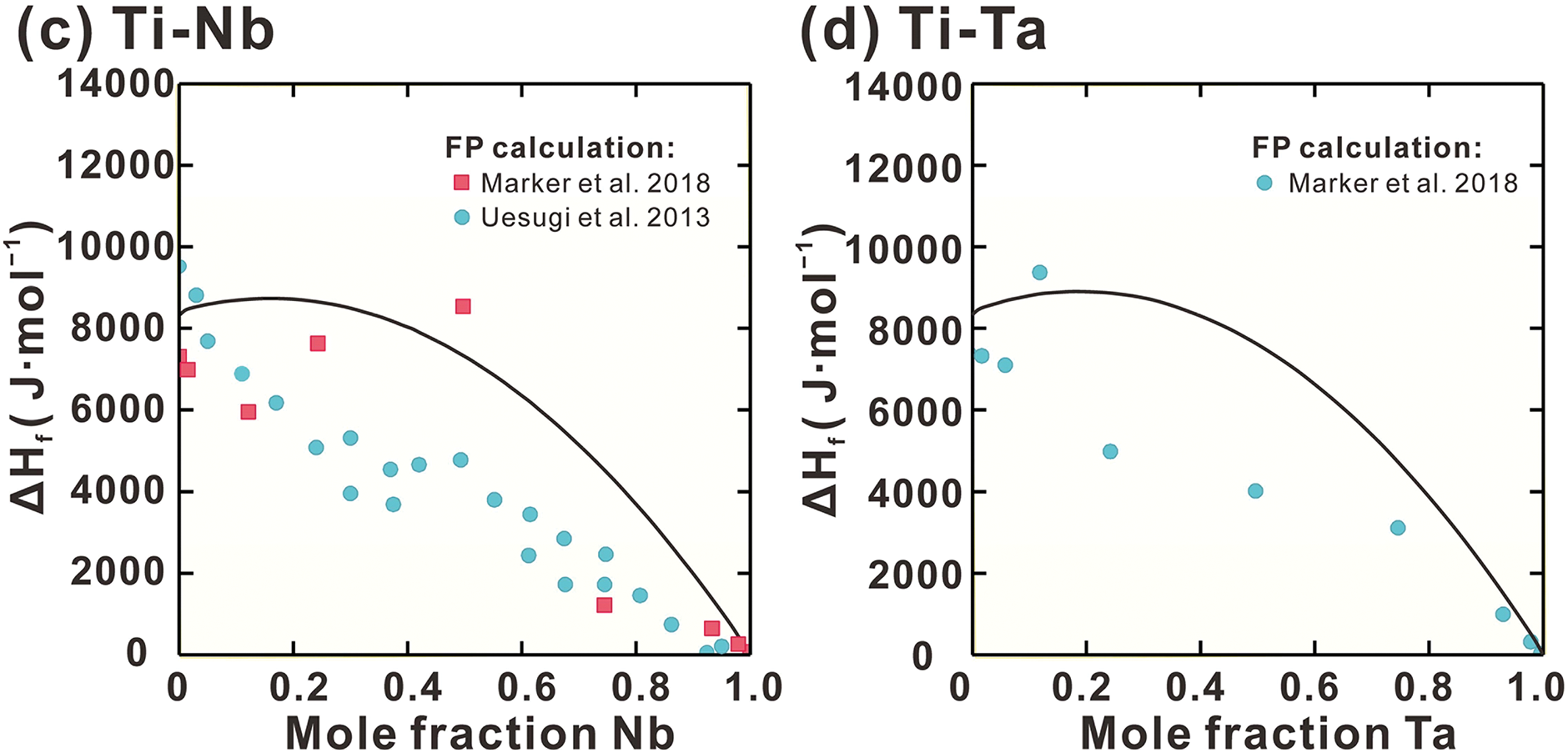

Fig. 3a presents the calculated enthalpy of mixing (Hmix) of Liquid phase in Ti-Zr system, along with the measurements [61]. The measured Hmix at various temperatures between 2111 and 2347 K is consistent. Due to the absence of measured data at other temperatures, the Hmix in Ti-Zr system is regarded as exhibiting a weak correlation with temperature. Consequently, the interaction parameters (a + bT) for Liquid phase in Ti-Zr system are employed. A strong agreement between the measurements and calculations is evident. Fig. 3b–d shows the calculated formation enthalpies of the BCC phase at 0 K for Ti-Zr, Ti-Nb, and Ti-Ta systems, alongside FP results [46,47]. A reasonable agreement is observed at the Ta-rich and Nb-rich sides, however, significant deviations are evident at the Ti-rich and Zr-rich sides. The BCC phase is metastable in pure Ti and Zr at low temperatures. As noted in previous studies [62–66], these BCC phases exhibit mechanical instability under such conditions. The potential energy surface of mechanically unstable phases does not show local minima near the ideal lattice; instead, it presents inflection points or saddle points [66]. However, conventional density functional theory (DFT) calculations tend to anchor energy assessments at non-physically stable states characterized by high symmetry, due to enforced symmetry constraints. This methodology overlooks the natural relaxation paths induced by mechanical instability. As a result, it leads to an overestimation of the energy of unstable phases, ultimately causing deviations in mixing enthalpy predictions.

Figure 3: Calculated (a) mixing enthalpy of the Liquid phase in the Ti-Zr system, (b) BCC phase formation enthalpy of Ti-Zr, (c) Ti-Nb and (d) Ti-Ta systems compared with experimental data [61] and FP calculations [46,47]

3.3 Thermodynamic Modelling of Sub-Ternaries in the Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta System

The measured phase equilibrium data are only available for the Ti-Nb-Ta, Ti-Nb-Zr, and Ti-Ta-Zr ternary systems in the literature [45,67–69], while data for the Ti-Nb-Hf, Ti-Ta-Hf, and Ti-Hf-Zr systems are still lacking. A brief literature review of the reported data for the Ti-Nb-Ta, Ti-Nb-Zr, and Ti-Ta-Zr ternary systems is presented. Na and Warnes [45] determined the phase boundary between (BCC+HCP) and BCC in Ti-Nb-Ta system and constructed isothermal sections at 673 and 823 K. Their findings indicate the presence of a BCC+HCP two-phase region and a BCC single-phase region at these temperatures. Only one research group investigated the phase equilibrium in Ti-Nb-Zr ternary system [67,68]. Their study reveals the existence of BCC#1+BCC#2+HCP three-phase region near the Nb-Zr side at 843 K. Additionally, the BCC and HCP single-phase regions and (BCC#1+BCC#2) and (BCC+HCP) two-phase regions were characterized. Hoch and Butrymowicz [69] reported phase equilibrium data for the Ti-Ta-Zr system at 1273 and 1373 K. Their experimental results revealed a single-phase region (BCC) and a two-phase region (BCC#1+BCC#2). The reported data are subsequently used to evaluate the parameters of the above ternary systems. In contrast, the thermodynamic descriptions for Ti-Nb-Hf, Ti-Ta-Hf, and Ti-Hf-Zr systems are directly extrapolated from their respective sub-binary systems.

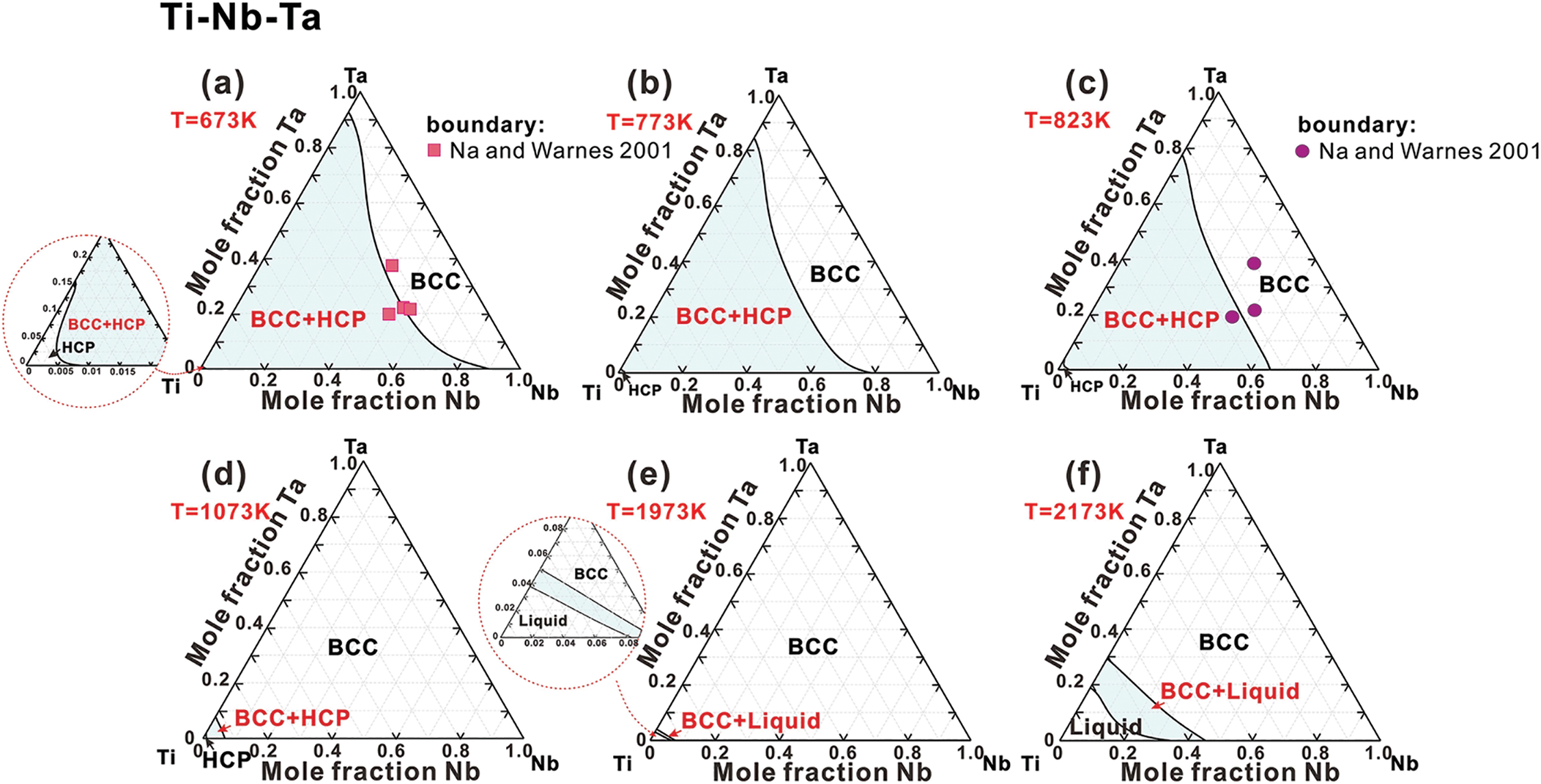

Ti-Nb-Ta system. Fig. 4 illustrates the isothermal sections of the Ti-Nb-Ta system at temperatures of 673, 773, 823, 1073, 1973, and 2173 K. The phase relationships are relatively straightforward, comprising only three stable phases: BCC, HCP, and Liquid. The solubility of the HCP phase is notably limited. As temperature increases, the BCC single-phase region continues to expand. A comparison of the calculated results with experimental data [45] reveals deviations in the isothermal sections at 673 and 823 K, as shown in Fig. 4a,c. As noted in Ref. [45], the Ti-Nb-Ta alloy demonstrates a slow atomic diffusion rate at 673 and 823 K, suggesting that the alloy may not have reached equilibrium. This incomplete equilibration may contribute to the observed discrepancies in phase boundaries.

Figure 4: Isothermal sections of the Ti-Nb-Ta ternary system at (a) 673 K, (b) 773 K, (c) 823 K, (d) 1073 K, (e) 1973 K and (f) 2173 K, compared with experimental data [45]

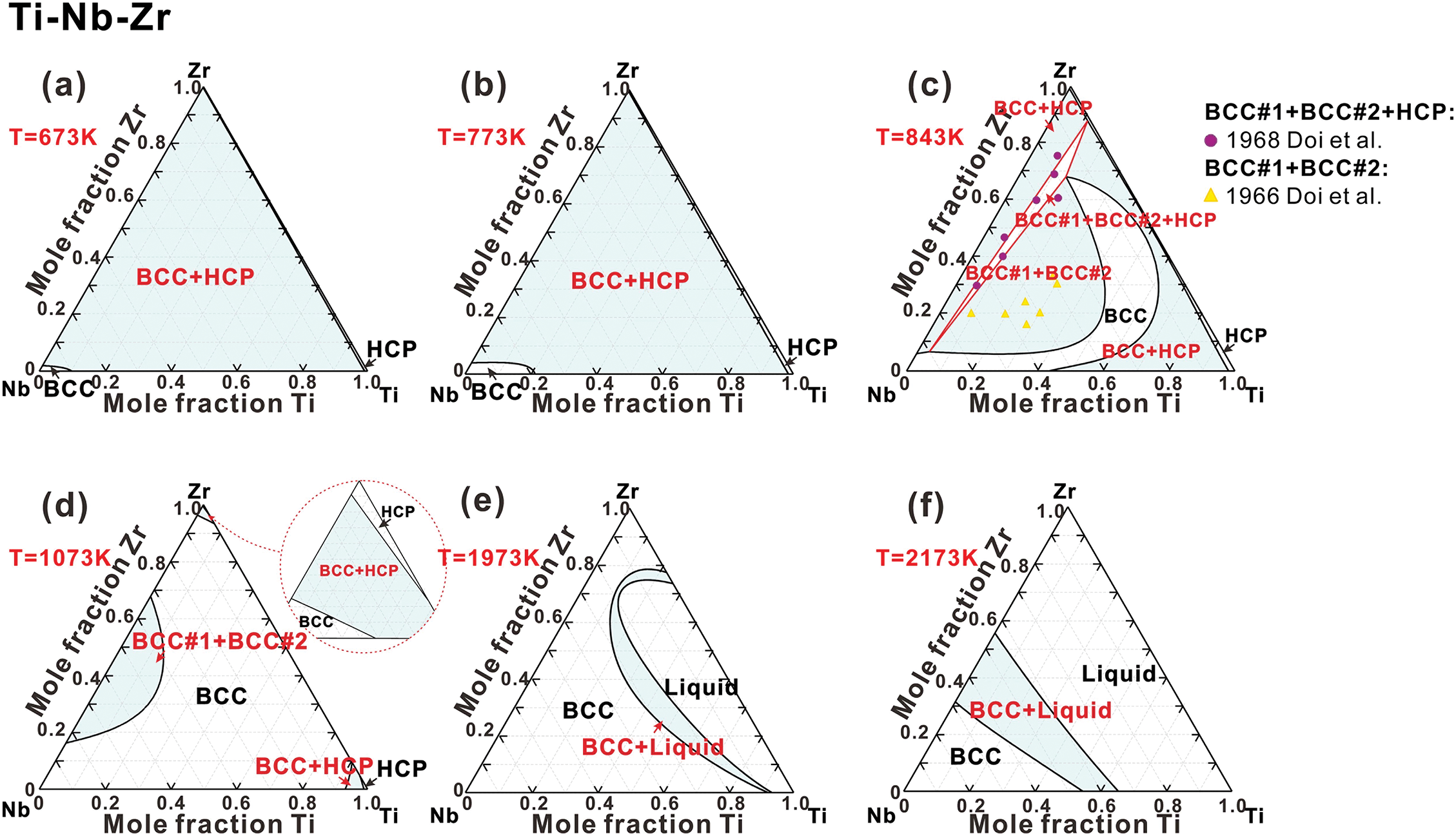

Ti-Nb-Zr system. Fig. 5 illustrates the isothermal sections of Ti-Nb-Zr system at various temperatures. Similar to the Ti-Nb-Ta system, the solubility of HCP phase is very limited. As depicted in Fig. 5a,b, the system exhibits a substantial two-phase region comprising BCC and HCP phases at 673 and 773 K. The decomposition of the BCC phase results in (BCC#1+BCC#2+HCP) region at 843 K, as shown in Fig. 5c. The calculations show a good agreement with the measurements [67,68]. As the temperature increases to 1073 K, BCC phase becomes more stable, resulting in the further expansion of the BCC single-phase region. At 1973 and 2173 K (Fig. 5e,f), the Liquid phase begins to appear, and its corresponding region expands with increasing temperature.

Figure 5: Isothermal sections of the Ti-Nb-Zr ternary system at (a) 673 K, (b) 773 K, (c) 843 K, (d) 1073 K, (e) 1973 K and (f) 2173 K, compared with experimental data [67,68]

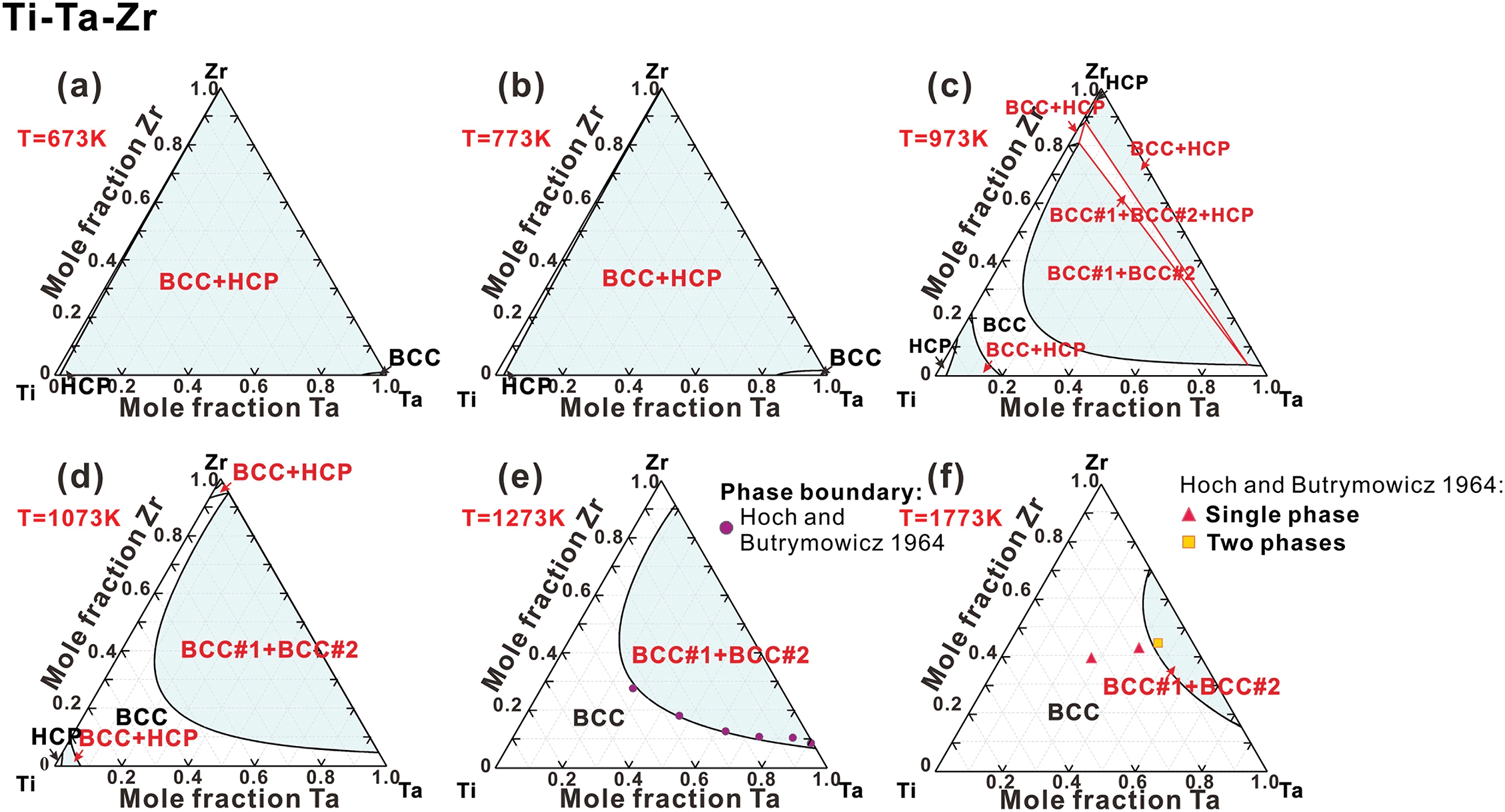

Ti-Ta-Zr system. As demonstrated in Fig. 6a–d, the phase relationships in the Ti-Ta-Zr system exhibit similarities to those in the Ti-Nb-Zr system below 1073 K. Above this temperature, a stable miscibility gap for BCC phase emerges near the Ta-Zr side. The width of this miscibility region diminishes as temperature increases. Additionally, the calculated phase boundaries for the coexistence of BCC#1+BCC#2 phases at 1273 and 1773 K align well with the experimental measurements, as shown in Fig. 6e,f [69].

Figure 6: Isothermal sections of the Ti-Ta-Zr ternary system at (a) 673 K, (b) 773 K, (c) 973 K, (d) 1073 K, (e) 1273 K and (f) 1773 K, compared with experimental data [69]

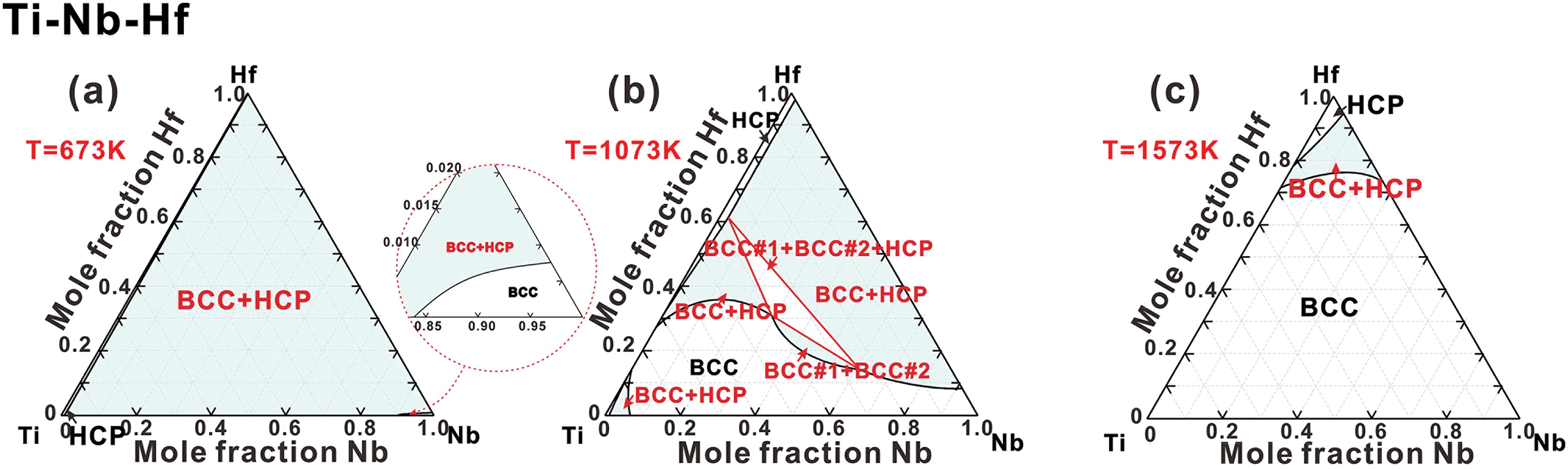

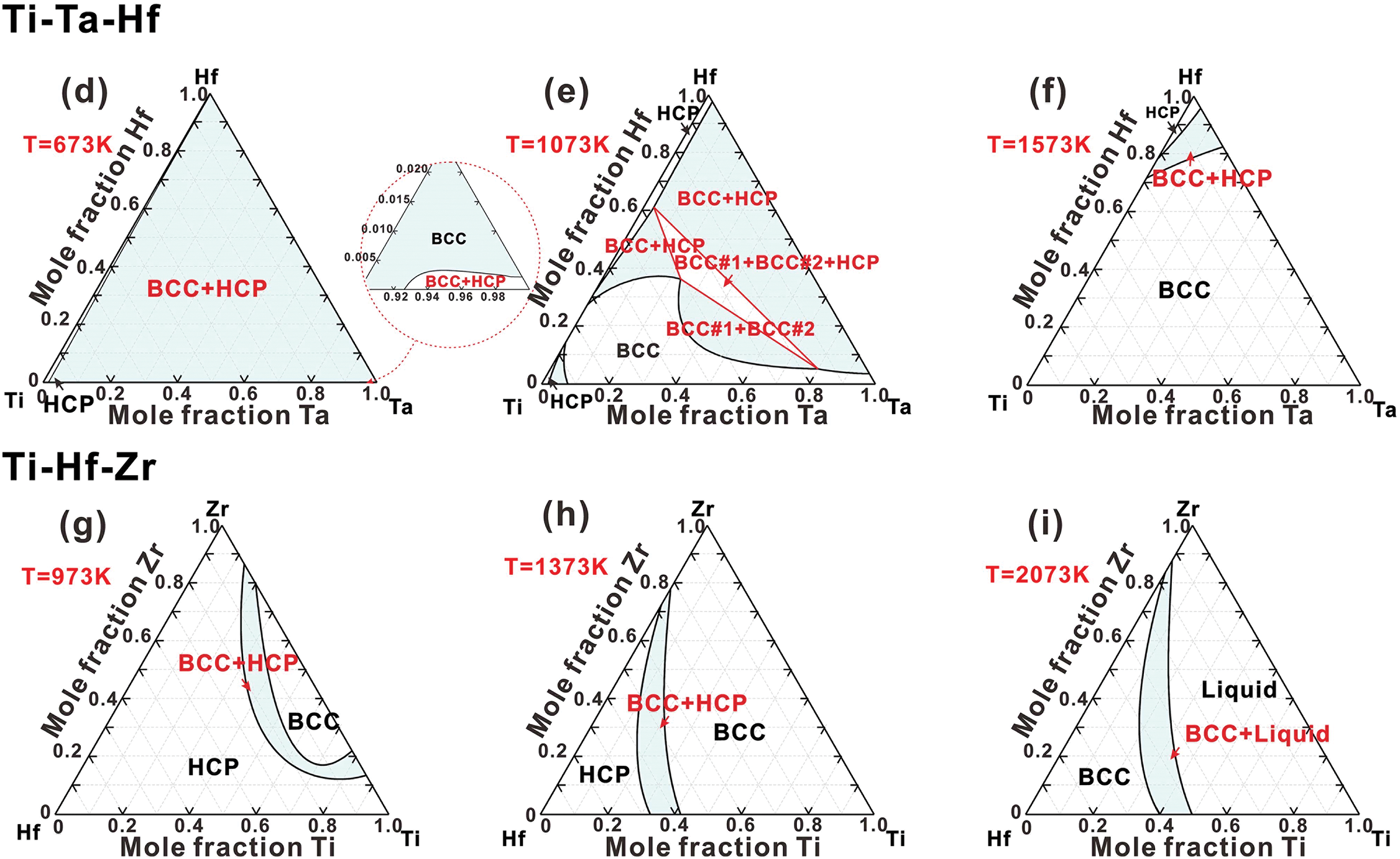

Ti-Nb-Hf, Ti-Ta-Hf and Ti-Hf-Zr systems. Due to the lack of experimental data on the Ti-Nb-Hf, Ti-Ta-Hf, and Ti-Hf-Zr systems, their thermodynamic descriptions are extrapolated from the sub-binary systems. The phase relationships in the Ti-Nb-Hf and Ti-Ta-Hf systems are quite comparable. As illustrated in Fig. 7a,d, both systems feature a substantial two-phase region (BCC+HCP). Fig. 7b,e demonstrates that at a temperature of 1073 K, the BCC phase at the Ti-rich end becomes unstable, resulting in a BCC miscibility gap and (BCC#1+BCC#2+HCP) region. At 1573 K, as shown in Fig. 7c,f, the majority of the composition region consists of the BCC phase, while the HCP phase remains stable in the Hf-rich corner. Fig. 7g–i illustrates the isothermal sections of Ti-Hf-Zr system at temperatures of 973, 1373, and 2073 K, respectively. At 973 K, as shown in Fig. 7g, it contains two single-phase regions (BCC and HCP) along with a narrow (BCC+HCP) region. The BCC phase region gradually expands while the HCP phase region diminishes at higher temperatures, as shown in Fig. 7h. At 2073 K, the HCP phase is completely absent (Fig. 7i), leaving one two-phase region (BCC+Liquid) and two single-phase regions (BCC and Liquid). Given that Ti, Hf, and Zr primarily exhibit HCP structures as their reference states, they can completely dissolve in the HCP phase at lower temperatures, thereby significantly enhancing the stability of the HCP phase.

Figure 7: Isothermal sections in (a–c) Ti-Nb-Hf ternary system at 673, 1073 and 1573 K, (d–f) Ti-Ta-Hf ternary system at 673, 1073 and 1573 K, (g–i) Ti-Hf-Zr ternary system at 973, 1373 and 2073 K

4 Phase Stability Predictions in Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta RHEAs

Due to the high expansibility of the CALPHAD approach, it was employed to establish the 3rd-generation thermodynamic database of the Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta quinary system by extrapolating from the present optimized and reported sub-binary and ternary thermodynamic parameters. Subsequently, a systematic analysis of the phase stability of both quaternary and quinary RHEAs within the Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta system was conducted.

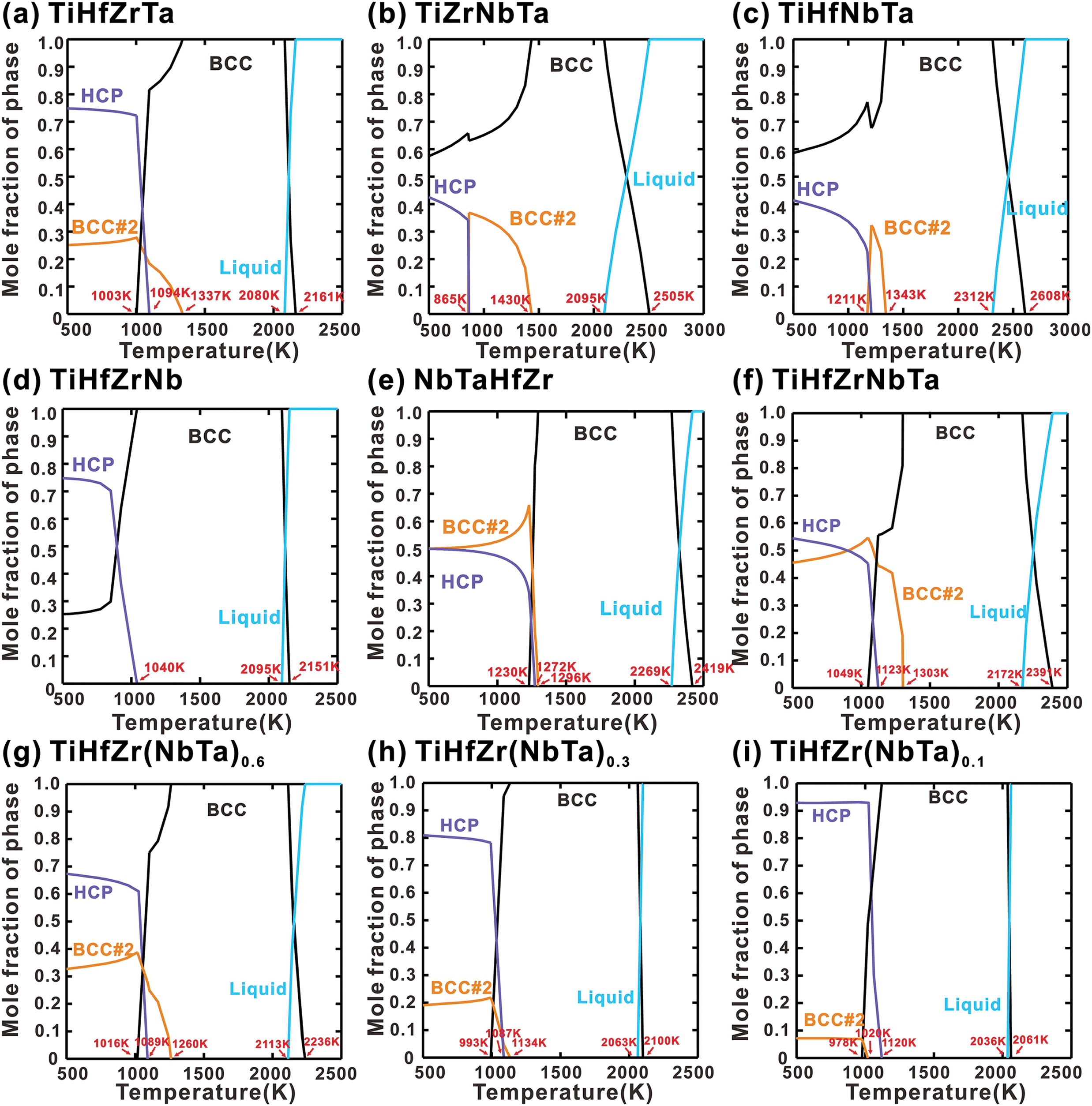

Fig. 8 illustrates the calculated phase fractions of quaternary and quinary RHEAs (TiHfZrTa, TiZrNbTa, TiHfNbTa, TiHfZrNb, NbTaHfZr, TiHfZrNbTa, TiHfZr(NbTa)0.6, TiHfZr(NbTa)0.3 and TiHfZr(NbTa)0.1) from 500 to 3000 K. The results indicate that the BCC phase predominates during the solidification of all these alloys, and all alloys exhibit a wide temperature range in which a single BCC phase is maintained. Notably, the temperature ranges for BCC single-phase stability in TiHfZrTa and TiHfZrNb alloys are 743 and 1055 K, as shown in Fig. 8a,d. This indicates that Nb has a more pronounced effect on expanding the BCC phase region. However, in the TiHfZrTa, TiZrNbTa, TiHfNbTa, HfZrNbTa and TiHfZr(NbTa)x alloys, the BCC phase decomposes into BCC#1 and BCC#2 at temperatures below 1500 K. In the TiHfZrTa and TiHfZr(NbTa)x alloys, the BCC#2 is enriched with Ta, while the TiZrNbTa and TiHfNbTa alloys are enriched with Ti. This decomposition may be attributed to the existing stable BCC miscibility gap in Nb-Zr, Ta-Zr, and Ta-Hf binary alloys, which extends into higher-order systems. Although the TiHfZrNb alloy includes a Nb-Zr binary combination, the incorporation of Hf appears to diminish the compositional range of the miscibility gap within the Nb-Zr system [27]. As the temperature decreases, the HCP precipitates from BCC phase in all these alloys, with its phase fraction increasing correspondingly. This trend indicates that HCP phase becomes more stable at lower temperatures. As illustrated in Fig. 8f–i, as the contents of Nb and Ta decrease, the fraction of the HCP phase gradually increases, while the fraction of the BCC#2 phase declines. This observation indicates that the addition of Nb and Ta has a stabilizing effect on the BCC phase while destabilizing the HCP phase.

Figure 8: Calculated equilibrium phase fractions as a function of temperature for (a) TiHfZrTa, (b) TiZrNbTa, (c) TiHfNbTa, (d) TiHfZrNb, (e) HfZrNbTa, (f) TiHfZrNbTa, (g) TiHfZr(NbTa)0.6, (h) TiHfZr(NbTa)0.3 and (i) TiHfZr(NbTa)0.1 alloys

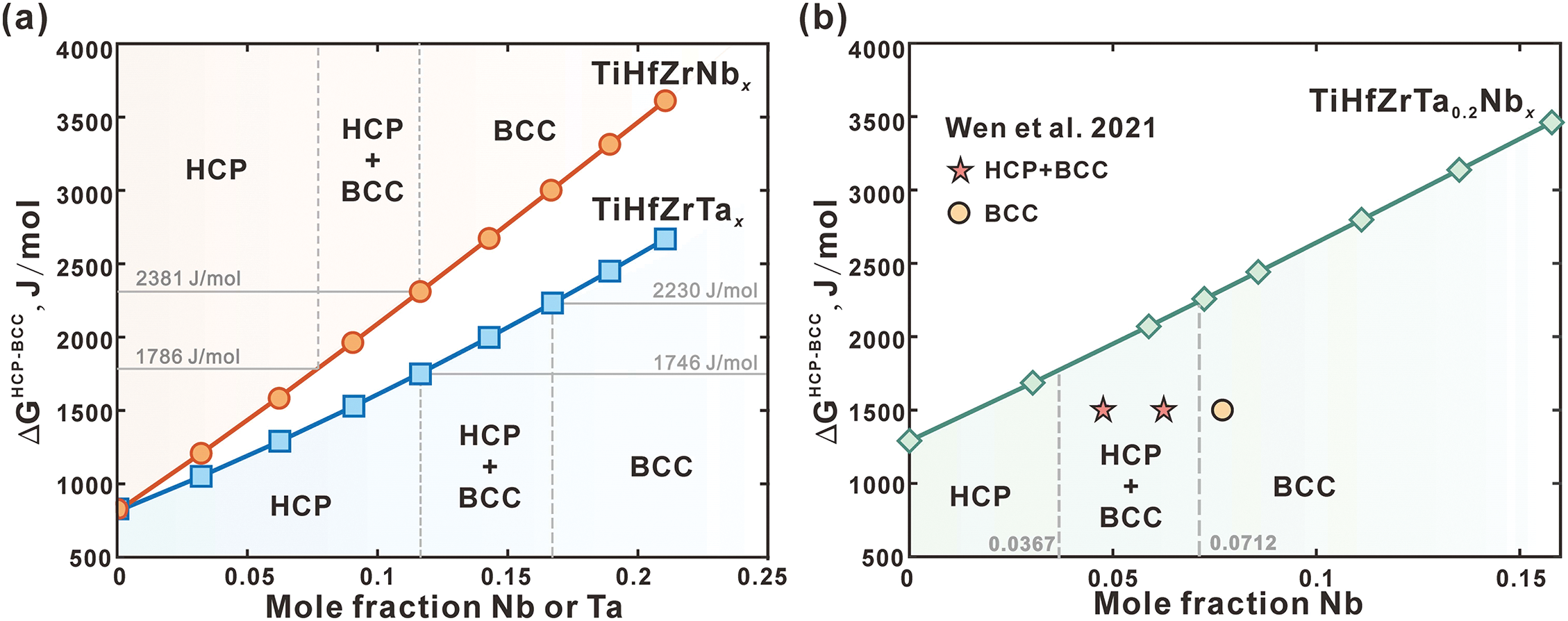

It has been reported that the BCC phase, formed through solidification at elevated temperatures, undergoes a martensitic transformation to form a single metastable HCP phase during the cooling process in TiHfZr alloys [16]. With the addition of Nb or Ta, a metastable dual-phase alloy consisting of BCC and HCP phases can be observed in the TiHfZrTax and TiHfZrNbx alloys [12,14–16]. However, the alloys transition to a single-phase BCC phase with further addition of Nb or Ta. As illustrated in Fig. 9a, the critical concentrations of Nb and Ta required for the transition from the HCP phase to the BCC+HCP phase are 0.077 and 0.116 in the TiHfZrNbx and TiHfZrTax alloys after annealing at 1273 K [16]. Furthermore, the critical concentrations for transitioning from the BCC+HCP phase to the BCC phase are 0.116 and 0.167, respectively. To further analyze the phase stability between the BCC and HCP phases, the Gibbs energy differences between these phases (

Figure 9: The calculated Gibbs energy differences between BCC and HCP phases (

The values of

The CALPHAD methodology has proven to be a practical approach for developing multicomponent databases, primarily due to its unique capability of deriving Gibbs energy calculations from thermodynamic descriptions of binary and ternary subsystems. This characteristic underscores that the accuracy of a multicomponent database is critically dependent on the precision of lower-order system parameters. In the current study, the binary and ternary thermodynamic parameters within the Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta system were systematically evaluated, incorporating thermodynamic and phase diagram information. While additional experimental verification could enhance database reliability, practical limitations arise when studying refractory alloys. The high melting temperatures of the constituent elements necessitate high-temperature treatments for refractory alloys to achieve phase equilibrium. These experimental challenges are especially pronounced in RHEAs, where kinetic limitations from sluggish atomic diffusion further impede the attainment of equilibrium. Consequently, the existing literature reveals a scarcity of experimental phase equilibrium documentation for the Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta system. Addressing this data gap through targeted experimental studies remains a critical objective for future research efforts.

• The expressions of molar Gibbs energy for BCC, HCP, and Liquid phases of Ti were evaluated using a 3rd-generation thermodynamic model. The calculated thermodynamic properties accurately reproduce the measured data, including heat capacity, heat content, and thermal vacancy concentrations. Furthermore, the proposed Gibbs energy expressions can guarantee lattice stability across the entire temperature range.

• By incorporating the 3rd-generation thermodynamic description of pure Ti, the thermodynamic parameters for Ti-related binary and ternary systems within the Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta system were assessed. Utilizing the thermodynamic parameters derived from this work alongside literature reports, a thermodynamic database for Ti-Hf-Zr-Nb-Ta quinary system was constructed with CALPHAD method. The calculated phase equilibria and thermodynamic properties in sub-binary and ternary systems demonstrated good consistency with measured data, thereby confirming its reliability.

• Applying the established thermodynamic database, phase stability for the TiHfZrTa, TiZrNbTa, TiHfNbTa, TiHfZrNb, NbTaHfZr, as well as TiHfZr(NbTa)x RHEAs were predicted. The results indicate that all alloys exhibit a BCC single phase region within a wide temperature range. The HCP phase remains stable and coexists with the BCC phase in both quaternary and quinary RHEAs. In TiHfZr(NbTa)x alloys, the phase fractions of the HCP phase increase as the contents of Nb and Ta decrease, indicating that the addition of Nb and Ta tends to destabilize the HCP phase.

• The Gibbs energy differences between BCC and HCP phases in TiHfZrTax and TiHfZrNbx alloys were calculated, revealing that the addition of Nb and Ta enhances the stability of the BCC phase, with Nb exerting a more significant influence than Ta. Furthermore, values

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province, China (No. E202302154).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Writing—original draft, software, data curation: Jinghan Gao. Visualization, validation: Enkuan Zhang. Writing—review & editing, supervision, methodology, funding acquisition: Ying Tang. Writing—review & editing, methodology: Lijun Zhang. Writing—review & editing, supervision: Jian Ding. Writing—review & editing: Xingchuan Xia. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Pacchioni G. Designing ductile refractory high-entropy alloys. Nat Rev Mater. 2024;10(1):1. doi:10.1038/s41578-024-00763-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Abdullah MR, Peng Z. Review and perspective on additive manufacturing of refractory high entropy alloys. Mater Today Adv. 2024;22(15):100497. doi:10.1016/j.mtadv.2024.100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Li G, Wu Z, Dong Y, Hu Z, Jia Y, Wu S, et al. Microstructures, properties and preparations of lightweight refractory high-entropy alloys: a review. J Mater Res Technol. 2025;35:3183–4. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2025.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kumar P, Kim SJ, Yu Q, Ell J, Zhang M, Yang Y, et al. Compressive vs. tensile yield and fracture toughness behavior of a body-centered cubic refractory high-entropy superalloy Al0.5Nb1.25Ta1.25TiZr at temperatures from ambient to 1200°C. Acta Mater. 2023;245:118620. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2022.118620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yang L, Sen S, Schliephake D, Laube S, Pramanik A, Chauhan A, et al. Creep behavior of a precipitation-strengthened A2-B2 refractory high entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 2025;288:120827. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2025.120827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang P, Sun D, Ibrahim SA, Su Z, Shi T, Li Y, et al. Influence of multiphase microstructure on the strength and ductility of Nb-Zr-Ti-V refractory high entropy alloys. Mater Sci Eng A. 2024;912(9):146954. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2024.146954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Duan C, Kostka A, Li X, Peng Z, Kutlesa P, Pippan R, et al. Deformation-induced homogenization of the multi-phase senary high-entropy alloy MoNbTaTiVZr processed by high-pressure torsion. Mater Sci Eng A. 2023;871(5):144923. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2023.144923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang S, Shu D, Shi P, Zhang X, Mao B, Wang D, et al. TiZrHfNb refractory high-entropy alloys with twinning-induced plasticity. J Mater Sci Technol. 2024;187:72–85. doi:10.1016/j.jmst.2023.11.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang Q, Zhang C, Deng X, Liang L, Xu L, Wang Z. Optimal wear resistance of particle-reinforced heterostructure high-entropy alloy FeMnCoCr by strength-ductility matching and TRIP effect. Wear. 2025;560:205596. doi:10.1016/j.wear.2024.205596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. You Z, Tang Z, Wang B, Zhang H, Li P, Zhao L, et al. Microstructural evolution and deformation behavior of an interstitial TRIP high-entropy alloy under dynamic loading. Mater Sci Eng A. 2024;891(5):145931. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2023.145931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. You Z, Tang Z, Li J, Chu F, Ding H, Misra R. Effect of grain boundary engineering on grain boundary character distribution and deformation behavior of a TRIP-assisted high-entropy alloy. Mater Charact. 2023;205(5):113294. doi:10.1016/j.matchar.2023.113294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Huang H, Wu Y, He J, Wang H, Liu X, An K, et al. Phase-transformation ductilization of brittle high-entropy alloys via metastability engineering. Adv Mater. 2017;29(30):1701678. doi:10.1002/adma.201701678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Li Z, Pradeep KG, Deng Y, Raabe D, Tasan CC. Metastable high-entropy dual-phase alloys overcome the strength-ductility trade-off. Nature. 2016;534(7606):227–30. doi:10.1038/nature17981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Li T, Wang S, Fan W, Lu Y, Wang T, Li T, et al. CALPHAD-aided design for superior thermal stability and mechanical behavior in a TiZrHfNb refractory high-entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 2023;246(19):118728. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2023.118728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang L, Fu H, Ge S, Zhu Z, Li H, Zhang H, et al. Phase transformations in body-centered cubic NbxHfZrTi high-entropy alloys. Mater Charact. 2018;142:443–8. doi:10.1016/j.matchar.2018.06.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Huang HL. Manipulation of microstructure and mechanical property of HfZrTi-based high-entropy alloys via metastability engineering [dissertation]. Beijing, China: University of Science and Technology Beijing; 2022. [Google Scholar]

17. Wen X, Wu Y, Huang H, Jiang S, Wang H, Liu X, et al. Effects of Nb on deformation-induced transformation and mechanical properties of HfNbxTa0.2TiZr high entropy alloys. Mater Sci Eng A. 2021;805:140798. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2021.140798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jung Y, Lee K, Hong SJ, Lee JK, Han J, Kim KB, et al. Investigation of phase-transformation path in TiZrHf (VNbTa)x refractory high-entropy alloys and its effect on mechanical property. J Alloys Compd. 2021;886:161187. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.161187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Xu L, Jia Y, Ma Y, Jia Y, Wu S, Chen C, et al. Slip-band-driven dynamic recrystallization mediated strain hardening in HfNbTaTiZr refractory high entropy alloy. J Mater Sci Technol. 2025;209:240–50. doi:10.1016/j.jmst.2024.04.078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang X, de Vecchis RR, Li C, Zhang H, Hu X, Sridar S, et al. Design metastability in high-entropy alloys by tailoring unstable fault energies. Sci Adv. 2022;8(36):7333. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abo733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhao YH. Understanding and design of metallic alloys guided by phase-field simulations. npj Comput Mater. 2023;9(1):94. doi:10.1038/s41524-023-01038-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chen LQ, Zhao YH. From classical thermodynamics to phase-field method. Prog Mater Sci. 2022;124(2):1–34. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2021.100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mizutani U, Sato H, Massalski TB. The original concepts of the Hume-Rothery rule extended to alloys and compounds whose bonding is metallic, ionic, or covalent, or a changing mixture of these. Prog Mater Sci. 2021;120:100719. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Woodgate CD, Marchant GA, Pártay LB, Staunton JB. Structure, short-range order, and phase stability of the AlxCrFeCoNi high-entropy alloy: insights from a perturbative, DFT-based analysis. npj Comput Mater. 2024;10(1):271. doi:10.1038/s41524-024-01445-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sharma A, Dasari S, Soni V, Kloenne Z, Couzinié JP, Senkov ON, et al. B2 to ordered omega transformation during isothermal annealing of refractory high entropy alloys: implications for high temperature phase stability. J Alloys Compd. 2023;953:170065. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.170065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang M, Lu Y, Lan J, Wang T, Zhang C, Cao Z, et al. Lightweight, ultrastrong and high thermal-stable eutectic high-entropy alloys for elevated-temperature applications. Acta Mater. 2023;248:118806. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2023.118806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Gao JH, Zhang EK, Tang Y, Zhang LJ, Ding J, Xia XC. Third-generation thermodynamic descriptions of MoNbTaWHfZr refractory high entropy alloys and their phase stability. Tungsten. 2025;7(3):582–600. doi:10.1007/s42864-024-00311-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang EK, Tang Y, Wen MW, Obaied A, Roslyakova I, Zhang LJ. On phase stability of Mo-Nb-Ta-W refractory high entropy alloys. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater. 2022;103:105780. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2022.105780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhu S, Sarıtürk D, Arróyave R. Accelerating CALPHAD-based phase diagram predictions in complex alloys using universal machine learning potentials: opportunities and challenges. Acta Mater. 2025;286(2):120747. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2025.120747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Redlich O, Kister AJI, Chemistry E. Thermodynamics of nonelectrolyte solutions-xyt relations in a binary system. Ind Eng Chem. 1948;40(2):341–5. doi:10.1021/ie50458a035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Abe T, Hashimoto K, Shimono M. Description of thermal vacancies in the CALPHAD method. Mater Trans. 2018;59(4):580–4. doi:10.2320/matertrans.M2017328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Tang Y, Zhang LJM. Effect of thermal vacancy on thermodynamic behaviors in BCC W close to melting point: a thermodynamic study. Materials. 2018;11(9):1648. doi:10.3390/ma11091648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Roslyakova I, Sundman B, Dette H, Zhang L, Steinbach I. Modeling of Gibbs energies of pure elements down to 0 K using segmented regression. Calphad. 2016;55(4):165–80. doi:10.1016/j.calphad.2016.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chen Q, Sundman B. Modeling of thermodynamic properties for Bcc, Fcc, liquid, and amorphous iron. J Phase Equilib. 2001;22(6):631–44. doi:10.1007/s11669-001-0027-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Andersson JO, Helander T, Höglund L, Shi P, Sundman B. Thermo-Calc & DICTRA, computational tools for materials science. Calphad. 2002;26(2):273–312. doi:10.1016/S0364-5916(02)00037-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Desai P. Thermodynamic properties of titanium. Int J Thermophys. 1987;8(6):781–94. doi:10.1007/BF00500794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kraftmakher Y. Equilibrium vacancies and thermophysical properties of metals. Phys Rep. 1998;299(2–3):79–188. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(97)00082-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ristić R, Babić E, Stubičar M, Kuršumović A, Cooper JR, Figueroa IA, et al. Simple correlation between mechanical and thermal properties in TE-TL (TE = Ti, Zr, Hf; TL = Ni, Cu) amorphous alloys. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2011;357(15):2949–53. doi:10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2011.03.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Dinsdale AT. SGTE data for pure elements. Calphad. 1991;15(4):317–425. doi:10.1016/0364-5916(91)90030-N. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Bittermann H, Rogl P. Critical assessment and thermodynamic calculation of the ternary system boron-hafnium-titanium (B-Hf-Ti). J Phase Equilib. 1997;18(1):24–47. doi:10.1007/BF02646757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Turchanin MA, Agraval PG, Abdulov AR. Thermodynamic assessment of the Cu-Ti-Zr system. II. Cu-Zr and Ti-Zr systems. Powder Metall Met Ceram. 2008;47(7–8):428–46. doi:10.1007/s11106-008-9039-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhang YL, Liu HS, Jin ZP. Thermodynamic assessment of the Nb-Ti system. Calphad. 2001;25(2):305–17. doi:10.1016/S0364-5916(01)00051-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Thakur AK, Pandey VK, Jindal V. Calculation of existence domains and optimized phase diagram for the Nb-Ti binary alloy system using computational methods. J Phase Equilib Diffus. 2020;41(6):846–58. doi:10.1007/s11669-020-00843-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Murray JL. The Ta-Ti (Tantalum-Titanium) system. Bull Alloy Phase Diagrams. 1981;2(2):62–7. doi:10.1007/BF02873705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Na L, Warnes WH. Estimation of the Nb-Ti-Ta phase diagram. IEEE Trans Appl Supercond. 2001;11(1):3800–3. doi:10.1109/77.919892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Marker C, Shang SL, Zhao JC, Liu ZK. Thermodynamic description of the Ti-Mo-Nb-Ta-Zr system and its implications for phase stability of Ti bio-implant materials. Calphad. 2018;61:72–84. doi:10.1016/j.calphad.2018.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Uesugi T, Miyamae S, Higashi K. Enthalpies of solution in Ti-X (X = Mo, Nb, V and W) alloys from first-principles calculations. Mater Trans. 2013;54(4):484–92. doi:10.2320/matertrans.MC201209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Rudy E. Compendium of phase diagram data. Dayton, OH, USA: Air Force Materials Laboratory, Metals and Ceramics Division; 1969. [Google Scholar]

49. Ruda G, Kornilov I, Vavilova V. Influence of hafnium on polymorphic transformation temperature of titanium. Russ Metall. 1975;5:160–2. [Google Scholar]

50. Farrar PA, Adler S. On the system titanium-zirconium. AIME Met Soc Trans. 1966;236(7):1061–4. [Google Scholar]

51. Chatterji D, Hepworth M, Hruska S. On the system Ti-Zr. Metall Trans. 1971;2(4):1271–2. doi:10.1007/BF02664271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Ruch M, Arias D. Comments on the equilibrium diagram of the Ti-Zr system.Scripta. Metall Mater. 1993;29(4):533–8. doi:10.1016/0956-716X(93)90160-T. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Blacktop J, Crangle J, Argent B. The α→β transformation in the Ti-Zr system and the influence of additions of up to 50 at.% Hf. J Less Common Met. 1985;109(2):375–80. doi:10.1016/0022-5088(85)90070-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Imgram AG, Williams DN, Ogden HR. Tensile properties of binary Titanium-Zirconium and Titanium-Hafnium alloys. J Less Common Met. 1962;4(3):217–225. doi:10.1016/0022-5088(62)90068-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Brown A, Clark D, Eastabrook J, Jepson K. The titanium-niobium system. Nature. 1964;201(4922):914–5. doi:10.1038/201914a0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Hansen M, Kamen E, Kessler HD, McPherson D. Systems titanium-molybdenum and titanium-columbium. JOM. 1951;3(10):881–8. doi:10.1007/BF03397396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Zakharov A, Pshokin V, Baikov A. On the existence of the compound niobium titanide in the niobium-titanium system. Tsvet Met. 1969;6:104. [Google Scholar]

58. Luzhnikov L, Novikova V, Mareev A. Solubility of β-stabilizers in α-titanium. Met Sci Heat Treat. 1963;5(2):78–81. doi:10.1007/BF00650694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Maykuth D, Ogden H, Jaffee R. Titanium-tungsten and titanium-tantalum systems. Tran AIME. 1953;197(2):231–7. [Google Scholar]

60. Summers Smith D. The constitution of tantalum-titanium alloys. J Jpn Inst Met. 1952;81. [Google Scholar]

61. Thiedemann U, Rösner-Kuhn M, Drewes K, Kuppermann G, Frohberg MG. Mixing enthalpy measurements of liquid Ti-Zr, Fe-Ti-Zr and Fe-Ni-Zr alloys. Steel Res Int. 1999;70(1):3–8. doi:10.1002/srin.199905593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Petry W, Heiming A, Trampenau J, Alba M, Herzig C, Schober H, et al. Phonon dispersion of the bcc phase of group-IV metals. I. bcc titanium. Phys Rev B. 1991;43(13):10933–47. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.43.10933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Chinnappan R, Panigrahi B, van de Walle A. First-principles study of phase equilibrium in Ti-V, Ti-Nb, and Ti-Ta alloys. Calphad. 2016;54:125–33. doi:10.1016/j.calphad.2016.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Bhattacharya J, van der Ven A. Mechanical instabilities and structural phase transitions: the cubic to tetragonal transformation. Acta Mater. 2008;56(16):4226–32. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2008.04.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Kadkhodaei S, Hong QJ, van de Walle A. Free energy calculation of mechanically unstable but dynamically stabilized bcc titanium. Phys Rev B. 2017;95(6):064101. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.95.064101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. van de Walle A, Hong Q, Kadkhodaei S, Sun R. The free energy of mechanically unstable phases. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):7559. doi:10.1038/ncomms8559. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Doi T, Ishida H, Umezawa T. Study of Nb-Zr-Ti phase diagram. J Jpn Inst Met. 1966;30(2):139–45. [Google Scholar]

68. Doi T, Kitada M, Ishida F. Isothermal phase diagram of the Nb-Zr-Ti ternary system at 570°C (supplement). J Jpn Inst Met. 1968;32(7):684–5. doi:10.2320/jinstmet1952.32.7_684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Hoch M, Butrymowicz D. The system tantalum-titanium-zirconium-oxygen at 1500°C. Trans Metall Soc AIME. 1964:230. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools