Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Research Progress and Applications of Carbon Nanotubes, Black Phosphorus, and Graphene-Based Nanomaterials: Insights from Computational Simulations

Institute of Advanced Interdisciplinary Technology, Shenzhen MSU-BIT University, Shenzhen, 518172, China

* Corresponding Author: Qinghua Qin. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 1-39. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067293

Received 29 April 2025; Accepted 07 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), black phosphorus nanotubes (BPNTs), and graphene derivatives exhibit significant promise for applications in nano-electromechanical systems (NEMS), energy storage, and sensing technologies due to their exceptional mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties. This review summarizes recent advances in understanding the dynamic behaviors of these nanomaterials, with a particular focus on insights gained from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Key areas discussed include the oscillatory and rotational dynamics of double-walled CNTs, fabrication and stability challenges associated with BPNTs, and the emerging potential of graphyne nanotubes (GNTs). The review also outlines design strategies for enhancing nanodevice performance and underscores the importance of future efforts in experimental validation, multi-scale coupling analyses, and the development of novel nanocomposites to accelerate practical deployment.Keywords

The rapid advancement of technology has heightened the demand for materials with diverse and superior properties, driving the emergence of carbon-based nanomaterials. Materials such as CNTs, graphene, graphyne, and black phosphorus exhibit unique microstructures and outstanding mechanical (tensile strength up to 130 GPa), electrical (carrier mobility exceeding 2 × 105 cm2/V·s), and thermal (thermal conductivity up to 5000 W/m·K) properties. Their atomically precise architectures and tunable characteristics enable exceptional physicochemical behaviors at the nanoscale, facilitating cutting-edge applications in NEMS, energy storage and conversion, biomedicine, and environmental science. For instance, CNTs have enabled high-frequency rotational motion up to 59.5 GHz [1], while BPNT-based materials offer a high theoretical capacity of 2596 mAh/g for lithium-ion battery anodes [2]. Fig. 1 provides a schematic overview of these carbon-based nanomaterials, highlighting their structural attributes, key advantages, and broad application potential across multiple technological domains.

Figure 1: Schematic overview of carbon-based nanomaterials

1.1 Innovative Applications in NEMS

CNTs and BPNTs, with their ultrahigh mechanical strength (approximately 100 times that of steel) and exceptional dynamic responsiveness, have emerged as foundational materials for NEMS. For instance, BPNT-based materials exhibit a high theoretical lithium-ion battery anode capacity of 2596 mAh/g—nearly seven times that of conventional graphite anodes [2,3], a typical nanotube-based NEMS is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: A typical nanotube-based NEMS

(1) High-Frequency Oscillation and Transmission: As mentioned, double-walled CNTs (DWCNTs) have demonstrated rotational frequencies reaching up to 59.5 GHz under temperature gradient-driven conditions [1]. Additionally, triple-walled C@BN@C heterostructured nanotubes exhibit stable transmission performance over a wide temperature range (100–600 K), making them promising candidates for high-speed NEMS actuators and nanotransmission lines [4]

(2) Electronic Device Innovation: Graphene/graphyne heterojunctions, enabled by lattice compatibility, exhibit outstanding spin-charge transport characteristics, including magnetoresistance up to 104% and spin filtering efficiency up to 99%, highlighting their potential for next-generation spintronic devices [5]. Furthermore, one-dimensional nanoribbons derived from 6,6,18-graphdiyne show significantly enlarged band gaps and carrier mobilities surpassing those of armchair graphene nanoribbons, making them suitable for high-speed complementary electronic circuits [6]

(3) Energy Storage Breakthroughs: BPNTs, due to rapid interlayer lithium-ion diffusion, offer a remarkable theoretical capacity of 2596 mAh/g for lithium-ion batteries—substantially outperforming traditional graphite anodes. This positions BPNTs as promising materials for high-capacity, next-generation energy storage devices [2].

1.2 Performance Breakthroughs in Energy Storage and Conversion

Through functional modifications and heterostructure design, carbon-based nanomaterials have significantly enhanced the performance of energy storage and conversion devices. Notable advancements include:

(1) High-Capacity Lithium Storage Systems: The BP/CNT@PPy core–shell structure, stabilized A BP/CNT@PPy core–shell structure, stabilized by chemical bonding at P–C/PPy interfaces, effectively suppresses volume expansion and achieves a high reversible capacity of 1376.3 mAh/g [7]. In contrast, a BP/CNT electrode without the protective shell shows rapid capacity decay, retaining only 530.1 mAh/g after 200 cycles [7].

(2) Metal-Free Catalytic Innovation: γ-GNTs, with their conjugated carbon frameworks and edge-active sites, have shown excellent potential as low-cost, metal-free electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). Density functional theory reveals a high limiting potential of 0.80 V and abundant active sites (16.7%), attributed to curvature-induced enhancement of p-electron exposure [8].

(3) Industrial Advancements and Commercial Viability: Recent breakthroughs underscore the commercial potential of nanocarbon-based battery materials. Sila Nano Technologies developed silicon-carbon composite anodes that deliver a 20% increase in volumetric energy density compared to traditional graphite-based systems [9]. Tareq and Rudra [10] further outlined the operational mechanisms and remaining challenges for silicon anodes in alkali metal-ion batteries. Meanwhile, Nanotech Energy has scaled up production of graphene-based materials for flexible batteries and electromagnetic interference shielding, demonstrating the successful transition of nanomaterials from laboratory research to industrial deployment [11].

Despite substantial research progress, carbon-based nanomaterials continue to face three critical challenges:

(1) Stability Limitations: Black phosphorus (BP) is highly susceptible to oxidation, with a half-life ranging from minutes to ~1 h for monolayers, ~2–24 h for few-layer structures, and several days for bulk forms. Additionally, functional groups on CNTs undergo thermal desorption—e.g., –COOH groups desorb at 200°C–400°C with an activation energy of ~1.2–1.6 eV—limiting their stability in practical environments.

(2) Synthesis Bottlenecks: Chirality control in single-walled CNT (SWCNT) synthesis remains a major hurdle, with selectivity typically below 60%. Although some progress has been made (e.g., preferential synthesis of (6,5) SWCNTs), achieving consistent high-selectivity production remains elusive. Moreover, graphyne synthesis remains confined to gram-scale batches, presenting scalability challenges.

(3) Characterization and Mechanism Gaps: The failure mechanisms of these nanomaterials under coupled mechanical, thermal, electrical, and chemical fields are still not fully understood. Standardized performance evaluation protocols, such as for assessing nanomotor lifespans, are currently lacking.

This review synthesizes insights from over 180 recent studies to systematically explore advances in structural design, performance optimization, and cross-disciplinary applications of carbon-based nanomaterials:

(1) Structural Design: Chirality modulation, heterostructure integration, and stability enhancement strategies.

(2) Performance Optimization: Reinforcement of mechanical strength, catalytic activity tuning, and interfacial charge transport improvement.

(3) Cross-Disciplinary Applications: Cutting-edge implementations in NEMS, next-generation energy systems, and biomedical technologies.

Over the past five years, carbon-based nanomaterials have seen remarkable advancements, pushing beyond traditional performance limits and unlocking novel applications. Key breakthroughs include innovative heterostructures such as CNT@MoS2 nanotubes (CNT@MST), which exhibit superior oscillatory performance—reaching up to 20 GHz for CNT@MoS2 nanotubes and 59.5 GHz for thermally driven DWCNT motors—with enhanced frequency and stability compared to conventional DWCNTs, as demonstrated by Jiang et al. [12]. Similarly, BP/CNT@polypyrrole (PPy) core–shell structures have achieved a high capacity of 1376 mAh/g after 200 cycles, far surpassing conventional graphite anodes in lithium-ion batteries [7].

Advanced approaches have significantly advanced the field. Density functional theories can calculate the curvature effect on ORR activity of γ-graphyne. For example, γ-GNTs have demonstrated a high limiting potential of 0.80 V and abundant active sites (16.7%) [8], comparable to commercial Pt/C catalysts. Cuba-Supanta et al. [13] investigated how structural properties, thermal stability, and temperature affect the rotational frequency of multi-walled BPNTs (MW-BPNTs), revealing that outer wall rota-tion doesn’t impact structural stability but enables thermal-driven rotation up to 16.7 GHz.

Performance improvements continue to drive the momentum of carbon-based nanomaterials. For example, the tensile mechanical properties and fracture mechanisms of γ-graphyne and γ-graphdiyne nanotubes have been investigated using AIREBO and ReaxFF potentials in MD simulations, revealing detailed insights into stress–strain behavior, bond length variation, and structural evolution [14]. In parallel, a novel two-dimensional metallic sp2-bonded carbon allotrope featuring linearly arranged hexagons and bipentagon–octagon rings has been proposed [15], showing promising energetic stability, tunable electronic and magnetic properties in nanoribbon forms, and reduced thermal conductivity—highlighting its potential for thermoelectric applications.

These advancements underscore the rapid evolution and broadening scope of carbon-based nanomaterials across multiple domains. By addressing key scientific challenges and technological limitations, this review aims to establish a systematic theoretical framework and practical roadmap to accelerate their transition from fundamental research to engineering implementation. Notably, industrial breakthroughs such as Sila Nano Technologies’ silicon–carbon composite anodes demonstrate the commercial viability of such materials in high-performance energy storage systems [9].

2 Dynamic Behaviors and Applications of Carbon Nanotubes

Since their discovery, CNTs have offered a solid physical basis for advancing next-generation nanoscale rotational systems and energy conversion devices, owing to their unique hollow structure, outstanding mechanical strength, ultralow friction, and tunable chirality. In particular, DWCNTs and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) demonstrate notable advantages in thermally driven nanomotors, high-frequency oscillators, and nanoscale transmission systems. This section provides a systematic review of MD simulation studies to clarify the fundamental operating mechanisms and performance limits of carbon-based nanotube materials in NEMS, thereby establishing a theoretical foundation and technical pathway for future investigations in this domain.

2.1 Nano-Oscillators and Rotational Motors

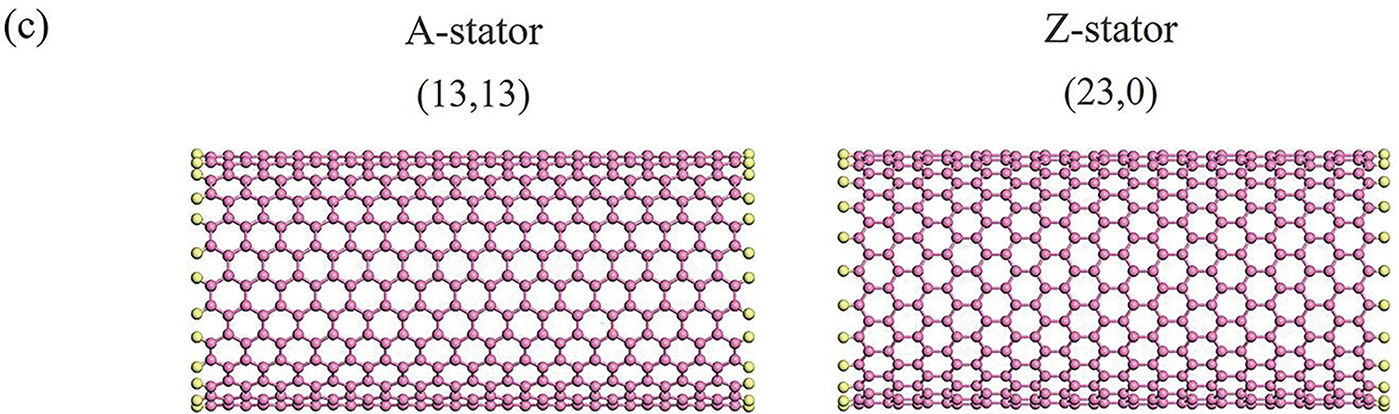

DWCNTs, owing to their tunable interwall spacing and interlayer van der Waals interactions, are ideal candidates for constructing nano-oscillators and rotational nanomotors. Studies have demonstrated a range of dynamic behaviors in DWCNTs, including self-excited oscillations [16], temperature-driven rotation [1,17], and energy transfer and rotation transmission [18]. These structures also enable universal joint-like motion [19] and rotational transmission [20]. While structural defects such as vacancies can degrade performance, chirality-matched configurations significantly improve the efficiency of sliding-to-rotational motion [12,21]. Additionally, edge configurations influence rotor stability [22]. Notable progress in DWCNT-based nanomotor systems has been made by researchers such as [23,24], alongside parallel advances in light- and magnetically driven micro/nanomotors by various groups [25–27]. As an illustrative example, Fig. 3a shows a typical model of a coaxial rotation transmission system (RTS). Each component of RTS is formed with CNT. The orange part is supposed as a rotating motor with constant frequency that can drive the rotating motion of adjacent shaft (green) in the static sleeve (pink). Those two parts in the rotating bearing are also named as rotor and stator in this work. The corresponding heterogeneous structure of rotor (H-rotor) is shown in Fig. 3b. Fig. 3c shows an armchair stator (A-stator) and a zigzag stator (Z-stator) of each chirality [22].

Figure 3: Physical model and components of coaxial rotation transmission system (RTS based on CNTs). (a) Sketch map of RTS. (b) Side view of heterogeneous structure of rotor combining armchair (7, 7) and zigzag (14, 0) chirality with pentagonal and heptagonal C—C layout. (c) Side view of armchair-Stator (13, 13) and zigzag-Stator (23, 0) [22]

2.1.1 Thermally Driven Rotational Motors

CNTs have been extensively applied in thermally driven rotational nanomotors. In particular, the inner tube of DWCNTs has been the subject of numerous studies examining its rotational behavior under thermal gradients [1] and sudden stopping mechanisms [28]. These investigations reveal that environmental temperature, interwall spacing, and geometric deviations significantly influence rotational speed. Directional control of rotor motion can be precisely achieved by adjusting the radial atomic deviations at the stator ends [29].

Building upon the foundational work by Cai et al. [28], subsequent studies [30,31] have examined motion regulation in various nanomotor configurations, emphasizing the roles of interfacial interactions and structural defects. Notably, Cai et al. [32] demonstrated that the rotation frequency of thermally driven DWCNT rotors peaks at thermal equilibrium and can be tuned by modifying the system temperature.

In summary, thermally driven DWCNT-based nanomotors offer tunable rotational frequencies (up to 59.5 GHz) and directional control via geometric modulation, laying a theoretical foundation for the design of high-performance nanoscale actuators. The next section extends these principles to composite-based nanomotor systems.

Nanomotors based on CNTs represent a leading frontier in nanoscale research. Novel nanomotor models have been proposed, accompanied by systematic analyses of how factors such as temperature, rotor–stator interaction energy, and radial deviations of carbon atoms at the stator ends influence rotational behavior, providing a theoretical basis for designing controllable thermally driven nanomotors [28,29]. MD simulations have further elucidated the motion characteristics of CNT-based nanomotors [33,34], the effects of interlayer and edge coupling on the dynamic response of rotational transmission systems [22], and the development of novel nanoconverters capable of multi-signal outputs [35].

Rotational transmission systems composed of C@BN@C hetero-triple-walled nanotubes have demonstrated stable performance across various temperatures [4], while rotors in triple-walled CNT nanomotors exhibit distinct dynamic behaviors depending on temperature and atomic configuration [36]. The incorporation of boron and phosphorus compounds into CNTs has also been shown to enhance thermal stability and field emission properties, offering promising potential for applications such as X-ray tube technology [37].

Defects—including vacancies, Stone-Wales transformations, and heteroatom substitutions—play a crucial role in determining the electronic properties of carbon-based nanotubes. In CNTs, vacancy defects typically introduce localized states within the bandgap, acting as scattering centers that lower carrier mobility and degrade nanoelectronic device performance. Conversely, controlled doping (e.g., with B or N) can engineer bandgaps and enable rectifying behavior, making these materials suitable for transistors and diodes [38]. In GNTs and GDYNTs, the porous architecture amplifies the impact of edge defects, where structural irregularities can localize π-electrons and modulate charge transport. Similarly, in BPNTs, vacancy and substitutional defects can reduce electrical conductivity by up to 60% by disrupting the continuous P–P bonding network essential for carrier transport. These defect-induced variations present both opportunities for tunability and challenges for achieving reliable device performance.

Recent advancements in CNT-based nanomotor design have led to significant performance improvements. For example, CNT@MoS2 nanotube (CNT@MST) heterostructures have demonstrated superior oscillatory behavior compared to DWCNTs, achieving frequencies up to 20 GHz [12]. These heterostructures exhibit enhanced stability and higher operational frequencies, making them promising candidates for high-performance nanoscale devices.

2.2 Dynamic Responses of Bent and Composite Structures

In bent DWCNTs, the curvature of the outer tube significantly increases interlayer friction, leading to reduced rotational frequencies of the inner tube and accelerated energy dissipation [18]. Bent DWCNT-based designs, such as nanoscale universal joints [19] and rotational-to-translational converters [39], demonstrate strong potential for flexible nanodevice applications. Key findings include:

• CNT@MST hetero-nanotube oscillators achieving frequencies up to 20 GHz [12];

• BPNT/CNT composite systems exhibiting enhanced thermal stability [40,41];

• GNTs synthesized via self-assembly or self-folding processes [42]. In functional device applications:

• Nanostrain sensors have achieved significantly improved precision [43–45];

• Nanoejectors have reached ejection velocities up to 700 m/s [46];

• Gas adsorption–desorption systems have attained efficiencies as high as 98% [47].

2.3 Research on Novel Structures

Triple-walled carbon nanotube (TWCNT) oscillators have shown stable performance at low temperatures [48], although high-speed rotors may risk detachment from the stator. Kang et al. [49] studied TWCNT resonators with shortened middle and outer walls using classical molecular dynamics simulations. Ansari et al. [50] explored various motion patterns of TWCNT oscillators. Concurrently, novel structural designs have been proposed, including graphene origami-based structures [51] and self-assembled nanoscroll architecture [52,53]. Current research on these emerging systems primarily centers on several key aspects:

(1) Nanorings Fabrication: Cai et al. [54] proposed a CNT bundle-assisted approach to produce ideal nanorings from rectangular BP nanoribbons;

(2) Hetero-Nanotube Oscillators: Jiang et al. [12] investigated CNT@MoS2 nanotube (CNT@MST) heterostructure oscillators, demonstrating superior oscillatory performance compared to DWCNT counterparts;

(3) Graphyne Nanotube Synthesis: Song et al. [42] introduced a self-assembly method wherein monolayer graphyne (GY) nanoribbons wrap around CNT surfaces, providing theoretical guidance for experimental fabrication of single-walled GNTs;

(4) Diverse Nanodevice Design: Various studies have explored the design and performance of universal joints [19] and continuously variable transmission system [55], contributing to the growing diversity of nanodevice applications.

Notable examples include:

(1) Nanomotors and Transmission Systems: Cai et al. [56] studied the dynamic behavior of CNT-based rotary nanomotors in argon environments. Song et al. [39] introduced a CNT-based rotational-to-translational nanoconverter, elucidating its dynamic mechanisms via MD simulations. Yang et al. [57] combined MD simulations with Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis to investigate the nonlinear dynamic behavior of boron–nitrogen–carbon (BNC) nanotube-based fixed-fixed nanobeams under high-speed C60 fullerene impacts.

(2) Biomedical and Drug Screening Applications: A CNT-based 3D neuromuscular junction biosensing platform was developed to evaluate drugs for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), significantly enhancing neuromuscular junction formation and muscle contraction [58]. Additionally, titanium dioxide nanotube arrays (TNTs) integrated with BP hydrogels enable near-infrared-responsive drug release and antibacterial functionality [59].

(3) Energy and Thermal Management Applications: CNT-reinforced materials have shown substantial improvements in energy and thermal management applications. Examples include solid rocket motor insulation materials [60], cyclotriphosphazene-coated MWCNT-reinforced polydiaryloxyphosphazene composites [61], and MWCNT-enhanced ethylene–propylene–diene monomer (EPDM) composites [62], all exhibiting enhanced ablation resistance and mechanical properties. Furthermore, a predictive model for hybrid nanofluids containing CNT/ZnO nanoparticles in engine oil achieved a prediction deviation below 1% [63].

2.4 Other Nanomaterials and Related Research

The research topics span a diverse range of novel nanomaterials, including boron–nitrogen–carbon (BNC) structures, diamondene, and others. For example, Ren et al. [64] demonstrated a facile approach for fabricating high-performance supercapacitor electrodes using bioderived carbon from poplar and acid-treated carbon nanotubes, yielding a multistage porous structure with a high specific surface area (1500.5 m2/g), excellent capacitance (>432.31 F/g), and outstanding cycling stability (88.3% retention after 5000 cycles). Cai et al. [65] investigated the capture capabilities of BNC nanobeams for high-speed fullerenes and analyzed key influencing factors. Hu et al. [66] focused on the phase change reversibility and thermal stability of Continuous diamond-carbon nanotube foams.

In addition, several studies have addressed self-assembly behaviors of nanomaterials, such as the self-assembly of one-side hydrogenated diamondene nanoribbons and partially hydrogenated graphene ribbons [52,53], as well as nanofluidic devices (e.g., Thermo-hydraulic performance of concentric tube heat exchangers with turbulent flow [67]), nanoparticle manipulation (e.g., nanoejectors [46]), and gas adsorption–desorption systems [47], broadening the application prospects of these nanomaterials. Yang et al. [68] introduced a two-dimensional, three-directional equidistant knitted structure (“nanotexture”) woven from graphene nanoribbons (GNRs) and investigated its thermal stability at finite temperatures. Based on one-side hydrogenated graphene ribbons (H1GRs), Savin and Dmitriev [69] proposed a nanospring model with possibility of creating graphene nanosprings that deform over a wide range of strain with a constant tensile force. Song et al. [70] presented a nanostructure model capable of converting rotational input into oscillatory output, in which the rotor incorporates two identical internally hydrogenated deformable parts (HDPs) to achieve rotational–oscillatory conversion at the nanoscale. Cai et al. [71] further proposed a nanotexture membrane model based on the orthogonal and diagonal weaving of graphene ribbons, detailing its fabrication process. Finally, Song et al. [72] investigated the self-rolling behavior of α-graphyne (α-GY) nanoribbons approaching CNTs under a multiphysical field environment—including temperature, electric field, and argon atmosphere—through MD simulations.

2.5 Dynamic Behaviors and Interface Effects

This section highlights the unique principles governing nanoscale dynamic behaviors and interfacial interactions, focusing on three key areas:

(1) Ultrahigh-Speed Rotation and Directional Control: CNT-based nanomotors operating in aqueous environments have achieved rotational speeds exceeding 1011 revolutions per minute (rpm) [73]. Moreover, carbon hoop structures enable precise directional control of nanomotor motion under temperature gradients [74].

(2) Interfacial Adsorption Optimization: Graphdiyne nanotubes (GDYNTs), with their porous architectures, exhibit significantly enhanced adsorption capacities for ionic liquids, outperforming conventional CNTs [75].

(3) Van der Waals Interactions and Motor Design: MD simulations in Ref. [76] have elucidated van der Waals interaction mechanisms between C20 fullerenes and flagellum-like nanomotors (FLAs) inside single-walled CNTs. Hamdi et al. [31] proposed a novel rotary nanomotor design based on axially aligned, chirality-mismatched CNT shuttle configurations, overcoming conventional structural limitations. Additionally, Chen et al. [30] explored the effects of structural defects on mass transport efficiency in thermally driven CNT-based nanomotors through MD simulations.

2.6 Doping Modification and Structural Property Studies

Research on doping modifications and structural properties spans several key areas:

(1) Doping and Modification Effects: Boron/nitrogen (B/N)-doped single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) can form rectifying junctions [77]. Systematic variations in doping concentrations and distributions have been employed to study their influence on the I–V characteristics of SWCNTs of varying lengths, providing a basis for optimizing doping strategies in future nanoelectronic applications. In addition, amino (NH2) functionalization disrupts the charge symmetry of DWCNTs, making them better suited for nanomotor functional requirements [78,79].

(2) Expansion into Periodic Table Elements: Shahnazari et al. [80] investigated the compressive mechanical behavior of zigzag phosphorene nanotubes, while Karttunen et al. [81] systematically analyzed the structural and electronic properties of single-walled nanotubes composed of Group 15 elements (phosphorus, arsenic, antimony, and bismuth) using quantum chemical methods.

(3) Mechanical Behavior of Novel 2D Material Nanotubes: Faria et al. [14] employed MD simulations to examine the tensile mechanical responses of γ-GNTs and γ-graphdiyne nanotubes (GDYNTs). Liu et al. [82] studied atomic configurations and vibrational modes of GNTs with varying chiralities and radii, while Zhao and Wang [83] provided a comparative analysis of the mechanical performance between armchair and zigzag single-layer X-graphene and Y-graphene structures, as well as multi-walled nanotubes with different stacking sequences.

(4) Performance Comparisons and Breakthroughs: GNTs exhibit a torsional fracture angle 35 times greater than that of conventional CNTs [84], underscoring their exceptional torsional resistance.

The presence of defects during synthesis significantly affects both yield and structural uniformity. For example, in chemical vapor deposition (CVD) growth of SWCNTs, high-temperature fluctuations and uncontrolled catalyst activity frequently introduce defects that impede chirality-specific growth, limiting chirality selectivity to below 60%. In BPNT synthesis, defects generated during self-assembly or low-temperature winding compromise tubular stability, resulting in fragmentation or unrolling under ambient conditions. Similarly, high concentrations of vacancy defects in GNTs during self-assembly from graphyne ribbons reduce crystallinity and yield, posing challenges for large-scale production and application deployment.

2.7 Synthesis and Manipulation Techniques of Nanomaterials

This section highlights recent advancements in novel synthesis methods for nanomaterials and the realization of their precise manipulation and assembly. Key developments include:

(1) Innovative Synthesis Approaches: CNTs have been fabricated using semiconductor nanowire templates combined with electron beam-induced deposition (EBID) and Joule heating techniques [85]. Nitrogen-doped CNTs (N-CNTs) were synthesized via spray pyrolysis chemical vapor deposition (CVD) [86]. Two-dimensional CoP nanosheet/one-dimensional CNT (CoP NS/CNT) heterostructures were constructed using a two-step hydrothermal–phosphidation process [87]. Additionally, PANI/(BP-CNT) composites were prepared through ball milling followed by in-situ polymerization, addressing volume expansion and structural collapse of BP during lithiation/delithiation cycles in lithium-ion battery anodes [88].

(2) Precise Manipulation and Composite Techniques: Nanoscale robotic systems have been developed to enable precise manipulation of CNTs within an electron microscope [89]. Furthermore, hydrogen-substituted graphyne oxide (O-HsGY) and graphene oxide (GO) were modified using deep eutectic solvents (DESs) and ionic liquids (ILs), and subsequently hybridized with oxidized multi-walled CNTs (O-MWCNTs), allowing comparative studies of their adsorption properties and electrochemical performance [90].

These advancements provide a critical foundation for both fundamental research and practical applications of nanomaterials

2.8 Industrial Adoption of CNTs and Graphene Products

The commercialization of CNTs and graphene-based products has advanced significantly in recent years, with multiple applications transitioning from laboratory research to industrial deployment. A prominent example is their use in battery anodes, where companies like Sila Nano have successfully commercialized silicon–carbon composites for lithium-ion batteries, achieving notable improvements in energy density and cycle life [9]. These developments underscore the potential of CNTs and graphene in enhancing the performance of next-generation energy storage devices.

Beyond battery technology, CNTs and graphene have found applications across diverse industrial sectors. For example, Nanotech Energy has developed scalable, cost-effective production methods for high-quality graphene, facilitating its integration into electronics, composite materials, and protective coatings [11]:

(1) Scalability Challenges and Solutions: Despite these promising advancements, the widespread industrial adoption of CNTs and graphene remains hindered by several challenges, with scalability being the most significant. The high cost of production and the difficulty of achieving high yields without compromising material quality remain major barriers.

(2) Cost and Yield Challenges: One of the core obstacles is the expense associated with conventional synthesis techniques. Methods such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD) for CNTs and mechanical or chemical exfoliation for graphene are energy-intensive and require specialized equipment, resulting in high production costs. To address this, researchers and industry players are actively investigating alternative, more economical synthesis approaches. For instance, a scalable process for producing silicon–carbon composites has been developed, significantly reducing production costs while retaining high performance [91].

(3) Scalable Production Methods: Recent progress in scalable production methods offers promising solutions. Levchenko et al. [92], for example, have introduced a proprietary technique based on chemical exfoliation, which enables high-yield, cost-effective production of graphene while preserving material quality. Such approaches mark a key step toward economically viable, large-scale manufacturing of 2D materials.

(4) Future Directions: To accelerate the industrial adoption of CNTs and graphene, future research should prioritize the development of even more scalable and cost-efficient manufacturing technologies. Simultaneously, tailoring material properties to suit specific applications—such as high-capacity energy storage and mechanically robust composites—remains essential. Strong collaboration among academia, industry, and government agencies will be critical to overcoming current limitations and advancing the commercialization of CNT- and graphene-based innovations.

(5) Stability of BPNTs: Historically, the instability of BPNTs under ambient conditions has hindered their practical use. However, recent technological advances have significantly improved their durability. Notably, Zhu et al. and Wu et al. [93,94] demonstrated that encapsulating BPNTs with ultrathin Al2O3 films via atomic layer deposition (ALD) effectively preserves their structural integrity during extended operation. This breakthrough in real-time passivation has marked a turning point in the practical use of BPNTs. A comprehensive review by Mishra et al. [95] further discusses these efforts, highlighting a range of encapsulation strategies designed to maintain the functional properties of BP materials under ambient conditions.

3 Advances in Applications of BPNTs

Having established the dynamic versatility of CNTs, we now turn to BPNTs, which face distinct challenges in stability but offer unique advantages in energy storage. The synthesis, stability, and application of BPNTs in nanodevices have become major research focuses. Key developments are summarized below.

3.1 Synthesis Methods and Structural Stability

3.1.1 Recent Developments in BPNT Synthesis and Stability

Recent advancements in BPNT fabrication have focused on diverse synthesis techniques, including directed assembly [96], fullerene-induced assembly [97], CNT-assisted self-assembly [54], and low-temperature winding methods. Recent studies have also proposed innovative synthesis strategies [98–100], emphasizing improvements in BPNT stability and scalability [101–103].

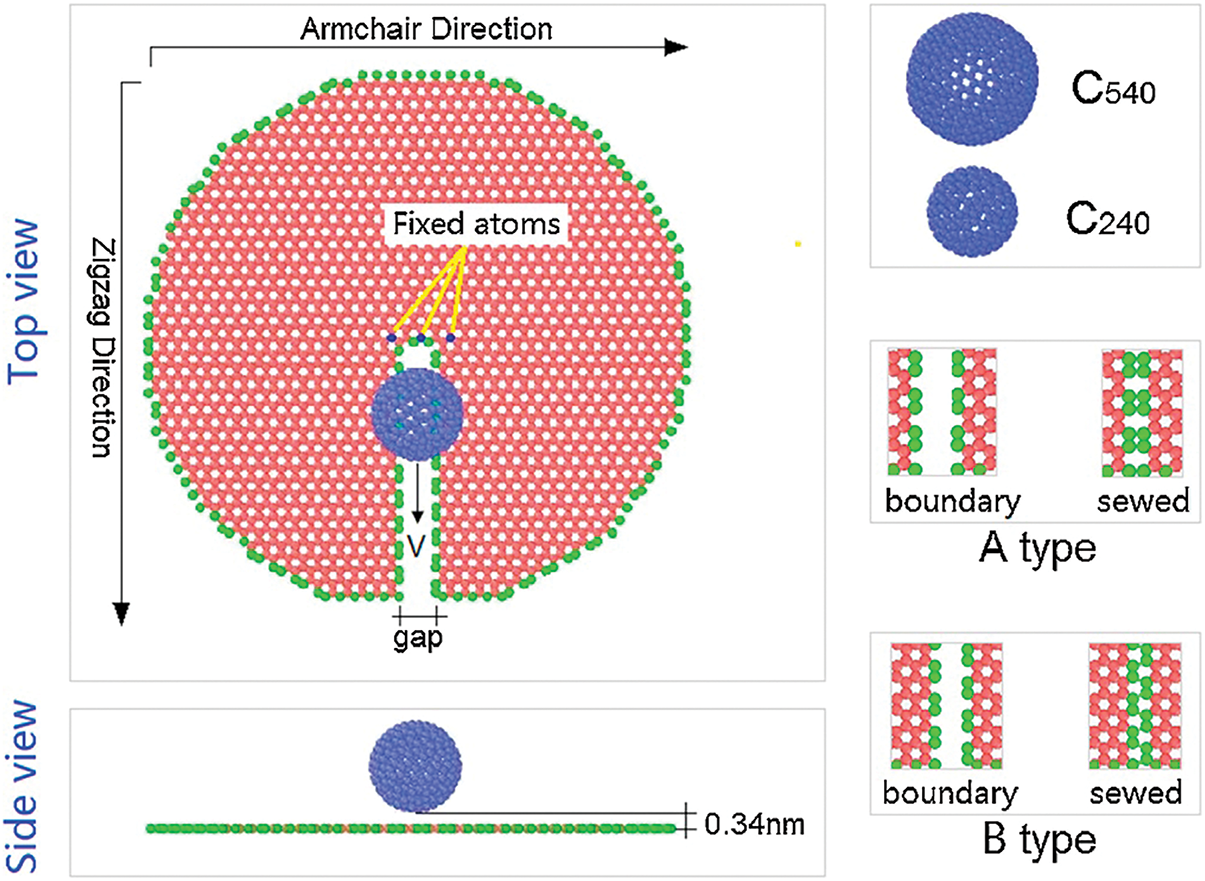

Fig. 4 presents a MD simulation of a nano-welding configuration in which a fullerene molecule is employed to repair a defect gap in a graphene sheet [97].

Figure 4: The circular graphene with radius of ∼4.5 nm has a rectangular gap along the zigzag direction, and the inner side of the gap crosses the center of the sheet. A fullerene of either a C240 or a C540 buckyball is placed over the gap, the normal distance between the ball and the circular sheet being 0.34 nm [97]

3.1.2 Structural Stability Mechanisms

BPNTs are known to exhibit significant structural instability under high-temperature conditions [104]. Factors such as thickness, lateral size, and light exposure can influence stability and few-layer BP flakes (<10 nm) can be effectively preserved for months using ionic liquids, offering a promising route for BP-based device development [104].

Recent in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) experiments have begun to validate the thermal and structural degradation mechanisms of phosphorene-based nanostructures. For example, Zhang and Zhang [100] reviewed key advances in the synthesis and properties of BP, along with its applications in transistors, photodetectors, energy storage, biomedicine, and biosensing. Complementing this, Mishra et al. [95] comprehensively examined encapsulation techniques—such as polymer coatings, metal oxide shells, and hybrid multilayer barriers—that effectively preserve BP’s structural integrity in ambient environments. These findings support earlier MD simulations, which indicate that BPNTs are prone to rapid degradation when exposed to elevated temperatures or oxygen-rich conditions [105].

3.1.3 Challenges in Device Applications

Although thermally driven rotary nanomotors based on hybrid BPNT–CNT architectures have shown promise in theoretical studies, the poor thermal and oxidative stability of BPNTs remains a critical limitation, significantly constraining their practical integration into nanoscale devices [40].

3.2 Mechanical Properties and Composite Reinforcement

Current research on the mechanical properties and composite reinforcement of nanomaterials focuses on three key areas:

(1) Performance Enhancement in Composite Systems: Integrating BPNTs Integrating BPNTs with CNTs to form BPNT@CNT composites has been shown to significantly enhance buckling resistance, thereby improving axial deformation capacity under compressive loading [41].

(2) Key Challenges: Despite improvements in mechanical performance, maintaining structural stability at elevated temperatures remains a critical challenge, necessitating further material optimization and design strategies [40].

(3) Fundamental Property Studies: Studies on the mechanical behavior, vibrational properties, and anisotropic thermal conductivity of phosphorene [106,107] offer valuable theoretical insights that support the development and refinement of nanocomposite structures.

3.3 Recent Studies on BPNT Composite Structures

Recent investigations into BPNT-based composite structures have yielded valuable insights:

(1) Rotary Nanomotors and Thermal Stability: Shi et al. [40] developed a DWNT system comprising BPNTs and CNTs, applying it to thermally driven rotary nanomotors. Their findings demonstrated that BPNTs exhibit distinct dynamic behaviors—particularly during rotational acceleration—although their structural stability deteriorates significantly under high-temperature conditions.

(2) Buckling and Thermal Behavior: While Cai et al. [41] proposed an innovative DWNT composite framework, follow-up studies by Shahnazari et al. [80] and Zhu et al. [106] expanded the understanding of buckling and thermal responses in phosphorene-based systems.

Additional noteworthy studies include:

(1) Interface Effects and Catalytic Activity: Enhanced electron transfer at BP/CNT interfaces significantly boosts oxygen evolution reaction (OER) performance, achieving an overpotential as low as 306 mV—surpassing that of traditional RuO2 catalysts [108].

(2) Triple-Component Aerogels: A ternary MoS2/graphyne/MXene (MGMX) aerogel system demonstrated outstanding hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) activity with an overpotential of just 109 mV, attributed to synergistic interfacial effects [109].

(3) Defect Engineering: Vacancy defects have been shown to reduce the buckling strength of phosphorene nanotubes by approximately 30% [110]. Conversely, in CNT systems, strategically introduced defects can be harnessed to control and initiate rotational motion [111].

(4) Electron Transport in Nanotubes: A comparative analysis of pristine and defective α-GNTs (Z-α-GNTs) revealed significant differences in electron transport characteristics, highlighting the role of structural integrity in electronic performance [112].

3.4 Energy Storage and Conversion Applications

Research into BPNTs for energy storage and conversion has primarily focused on the following key areas:

(1) High-Stability Anode Materials: The BP–TiS2–graphene (BP–TiS2–G) composite anode, utilizing the synergistic bonding of P–C and P–S, delivers excellent cycling stability, retaining a high capacity of 906.2 mAh/g after 1300 cycles at 1.0 A·g−1 [113].

(2) Photocatalytic Performance Enhancement: BP-based composites exhibit broad light absorption and tunable band gaps. For example, BP-doped TiO2 nanotube arrays (BP–TNTA) achieve a 4.4-fold increase in photocurrent density and demonstrate strong performance in both hydrogen evolution reactions (HER) and CO2 reduction [114,115].

(3) Multifunctional Drug Delivery Platforms: Hybrid systems combining BP hydrogels with TiO2 nanotube arrays enable near-infrared-triggered drug release, alongside excellent antibacterial activity, offering multifunctional solutions for theranostic applications [59].

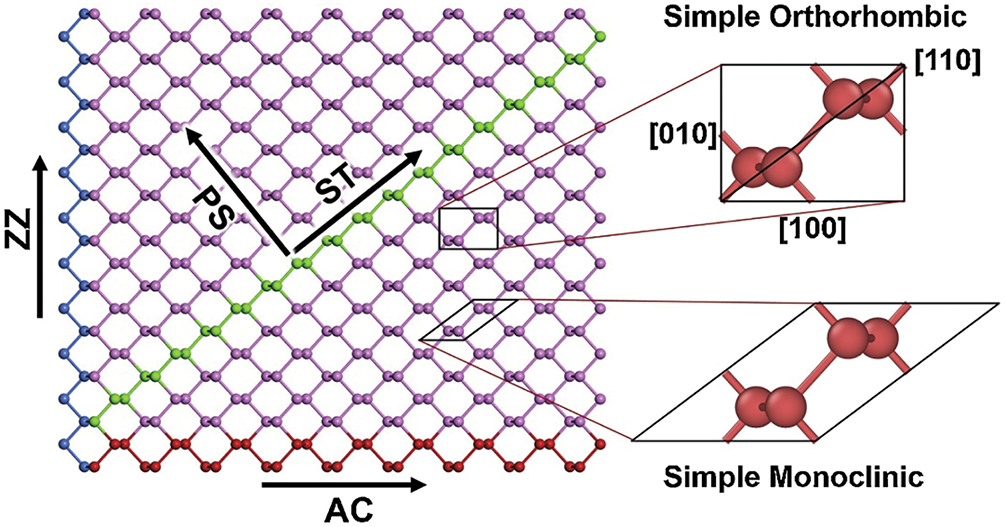

(4) Heterostructure Engineering: Integrating BP nanosheets with CNTs significantly enhances oxygen evolution reaction (OER) activity. Fig. 5 shows a unit cell of phosphorene, represented as a simple orthorhombic lattice. The [100] or [010] direction are named as armchair (AC) or zigzag (ZZ) direction according to the configuration of crystal boundary [106].

Figure 5: Top view of phosphorene with the arrows indicating armchair (AC), zigzag (ZZ) and stair (ST) directions parallel to [100], [010] and [110] directions respectively in simple orthorhombic lattice. PS is representing for the direction perpendicular to stair. Simple monoclinic lattice of 2D phosphorene based on AC and ST directions is also shown with insert map [106]

Energy Storage Breakthroughs: Comparative Performance Analysis

BPNTs are recognized as high-performance anode materials due to their rapid interlayer lithium-ion diffusion and high theoretical capacity. They deliver a specific capacity of 1120 mAh/g—approximately three times that of traditional graphite anodes (372 mAh/g)—and maintain 80% capacity retention after 200 cycles, outperforming graphite, which typically loses 30%–40% capacity over similar conditions.

In comparison, BP/CNT@PPy core–shell hybrid structures further boost storage capacity to 1376 mAh/g by combining BP with conductive polymers. This design effectively mitigates volume expansion during cycling, significantly improving structural integrity and long-term stability [7].

Meanwhile, γ-GNTs present promising catalytic and storage capabilities. Although their energy storage capacity is lower than that of BPNTs, they exhibit strong electrocatalytic performance, including an ORR onset potential of 0.80 V and a current density of 5.2 mA/cm2, rivaling Pt/C catalysts. These findings underscore the potential of BP-based and graphyne-derived materials in high-performance energy systems. A performance comparison of BPNTs and related materials is provided in Table 1.

3.5 Biocompatibility and Safety Challenges

BPNTs have shown significant promise in biomedical applications such as bone regeneration, drug delivery, and biosensing. Recent advances in 3D-printed biopolymer/BPNT composite scaffolds have demonstrated enhanced bone tissue formation, attributed to the synergistic effects of photothermal therapy and osteogenic stimulation. Moreover, in vitro studies report relatively low cytotoxicity of BPNTs, underscoring their suitability for integration into implantable biomedical devices.

(1) Biocompatibility and In Vivo Performance: BPNTs have shown significant promise in biomedical applications such as bone regeneration, drug delivery, and biosensing. Recent advances in 3D-printed biopolymer/BPNT composite scaffolds have demonstrated enhanced bone tissue formation, attributed to the synergistic effects of photothermal therapy and osteogenic stimulation. Moreover, in vitro studies report relatively low cytotoxicity of BPNTs, underscoring their suitability for integration into implantable biomedical devices.

(2) Regulatory and Production Challenges: Despite their biomedical potential, BPNT-based technologies face substantial regulatory and translational hurdles. Regulatory bodies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) require comprehensive evidence of biocompatibility, degradation behavior, and long-term safety prior to clinical approval. Given BP’s degradation sensitivity, particular attention must be paid to its oxidative byproducts and their interactions with biological systems.

Additionally, current BPNT synthesis remains largely confined to laboratory-scale protocols, lacking the throughput, consistency, and cost-efficiency required for commercial or clinical deployment. Scaling up production without compromising material integrity or biocompatibility is an active area of research. Emerging approaches focus on sustainable synthesis, encapsulation with inert or functional biopolymers, and hybrid composites that enhance both mechanical and biochemical performance under physiological conditions.

3.6 Biomedical and Sensor Applications

Recent research underscores the significant potential of BPNT structures in biomedical and sensor applications. Key studies and reviews have collectively explored diverse functionalities, ranging from bone regeneration to environmental sensing:

Wu et al. [116] comprehensively reviewed the development of 3D-printed biopolymer/BP nanocomposite scaffolds for bone implantation. This work highlights suitable biopolymer matrices, characterization methodologies, and the comparative advantages of ink-based and laser-assisted 3D printing techniques. The review also explores the synergistic integration of photothermal therapy with bone regeneration and the role of implant–immune system interactions in modulating biological outcomes.

Complementary review articles [95,100,115,117] provide an in-depth analysis of BP’s crystal structure, synthesis strategies, and physicochemical properties, alongside its applications in transistors, energy storage, sensing, environmental remediation, and biomedicine. Notable findings include:

(1) Bone Implantation and Regeneration: 3D-printed BP/biopolymer scaffolds integrated with photothermal therapy significantly promote osteogenesis and tissue repair [116].

(2) Energy Storage: BP-based materials have been demonstrated as high-capacity, high-stability anodes for lithium-ion batteries [113].

(3) Environmental Remediation: BP-based composites show excellent catalytic selectivity and sensitivity in pollutant degradation and toxic gas detection [115,117].

(4) Sensing Applications: Surface-modified BP structures exhibit enhanced gas and biosensing capabilities due to improved charge transfer and analyte interaction mechanisms [117].

(5) Photoelectronic Performance: Coupled BP surface plasmon modes (BPSP and BPLSP) lead to Rabi splitting phenomena around 8.7 THz, enabling next-generation optoelectronic devices [118].

3.6.1 AI-Driven Nanodevice Design

Artificial intelligence has emerged as a transformative tool in nanomaterials research. Recent applications include machine learning-guided screening of oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) catalysts and ultra-hard materials, drastically accelerating discovery while reducing experimental costs. AI models trained on structural and electronic descriptors are increasingly capable of predicting catalytic activity and optimizing heterostructures, including doping strategies and interfacial interactions.

3.6.2 Roadmap for Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Bridging the divide between theoretical predictions, laboratory experimentation, and industrial application remains a critical challenge. Discrepancies between computational predictions and experimental validation, coupled with scalability and cost barriers in commercialization, hinder progress. A structured collaborative roadmap is essential—one that fosters early-stage cooperation among computational scientists, experimentalists, and industry partners. This includes the creation of open-access data platforms, standardized performance protocols, and cross-sector research hubs to accelerate development and ensure reproducibility. Proven collaborative frameworks from related disciplines serve as a strong model for advancing BP-based technologies from bench to real-world implementation.

4 Innovative Applications of Graphene Derivatives in Nanodevices

Since its discovery in 2004, graphene—a two-dimensional material composed of a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb lattice—has remained a cornerstone of materials science research. Its atomic-scale architecture confers extraordinary properties, including ultrahigh carrier mobility (>2 × 105 cm2/V·s), exceptional thermal conductivity (up to 5000 W/m·K), and remarkable tensile strength (~130 GPa). Building upon these characteristics, graphene derivatives such as graphene nanoribbons (GNRs) and graphynes introduce structural versatility through features like edge hydrogenation, chirality control, and porous topologies. These modifications significantly enhance the electronic, optical, and mechanical performance of the base material, opening new frontiers in the design and functionality of next-generation nanodevices.

4.1 Electronic Properties and Applications

Unilaterally hydrogenated graphene nanoribbons (GNRs) can spontaneously self-assemble into nanoscrolls or helical structures through van der Waals interactions [52]. Subsequent studies [119–121] have confirmed this behavior and explored their promising applications in energy storage. Additionally, the influence of edge hydrogenation on the electronic properties of GNRs has been systematically investigated [122,123], providing valuable guidance for the design of nanoscale electronic devices.

Moreover, orthogonal-diagonal woven GNR membranes, characterized by precisely engineered weaving angles and porosity, exhibit remarkable thermal stability and excellent gas separation capabilities. These properties make them strong candidates for high-temperature nanofiltration applications [71].

4.2 Energy Storage and Conversion

Recent advancements in carbon-based nanomaterials have significantly enhanced the development of efficient energy storage and conversion technologies. Key innovations are outlined below:

γ-Graphyne (γ-GY) nanoribbons have demonstrated the ability to self-scroll onto CNT surfaces, forming helical nanoscrolls with an impressive energy storage density of 300 meV/bond—surpassing traditional carbon nanostructures by over 50% [124]. A precision-controlled two-step thermal treatment process has been developed to fabricate graphdiyne nanotubes (GNTs) via the temperature-induced self-scrolling of graphdiyne nanoribbons, followed by the formation of stable interlayer covalent bonds.

4.2.2 High-Performance Battery Materials

Tri-boron-doped armchair graphene nanoribbons (3B-AGNRs) serve as highly efficient catalysts for CO oxidation, following the Langmuir-Hinshelwood (LH) mechanism with a turnover frequency (TOF) of 2.47 s−1—outperforming many conventional noble metal-based catalysts [125].

Quasi-one-dimensional graphyne and graphdiyne nanoribbons (GYNRs and GDYNRs), owing to quantum confinement and edge effects, exhibit unique physical and electronic properties distinct from their two-dimensional analogs. Despite current challenges in scalable synthesis and structural characterization, these nanoribbons show promise as cathode materials in lithium-ion and sodium-ion batteries, demonstrating enhanced cycling stability and improved charge–discharge performance [126].

4.2.3 Catalytic Performance Optimization

Nitrogen-doped graphene nanoribbons improve oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) activity by modulating adsorption energies of reaction intermediates (*OOH, *OH) under strain conditions [127]. Additionally, boron-doped graphene nanoribbons exhibit excellent metal-free catalytic performance with a TOF of 2.47 s−1, offering cost-effective and environmentally friendly alternatives to metal-based catalysts [125].

4.2.4 Optoelectronic Devices and Energy Conversion

Eighteen-atom-wide graphdiyne nanoribbons (GDY18) have demonstrated exceptional hole mobility of up to 2.0 × 105 cm2/V·s, making them highly suitable for next-generation high-speed optoelectronic devices [6]. Nawaz et al. [128] provided a comprehensive review of graphene derivatives—including graphyne, graphdiyne, and their doped or functionalized variants—highlighting their synthesis techniques, defect engineering strategies, and applications across biosensing, artificial intelligence, energy systems, and water purification.

Furthermore, studies on graphene-based anodes for lithium-ion and other metal-ion batteries [129,130], as well as hydrogen storage, emphasize the role of surface functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl) in optimizing ion transport and hydrogen adsorption capacity. These findings lay the theoretical groundwork for the development of next-generation, high-efficiency energy storage systems.

4.3 Structural and Property Studies of Nanomaterials

4.3.1 Thermal Conductivity Tuning Mechanisms

Graphyne and graphdiyne possess significantly lower thermal conductivity compared to graphene, primarily due to vibrational mismatches introduced by acetylene linkages. This thermal suppression makes them promising candidates for thermoelectric applications. For instance, graphyne exhibits thermal conductivity values that are 2–3 orders of magnitude lower than those of graphenee [131]. Similarly, polycyclic carbon networks demonstrate reduced heat conduction due to their intrinsic phonon bandgap characteristics [132]. Structural modifications—such as varying the number of acetylene bonds or adjusting the composition ratio between graphyne and graphdiyne—further enable the fine-tuning of thermal conductivity in graphene allotrope nanoribbons [133].

4.3.2 Mechanical Behavior Analysis

Carbon-based nanomaterials display a wide range of mechanical behaviors. GNTs exhibit greater resilience to torsional fracture than CNTs, with torsional stiffness increasing exponentially with tube diameter [84]. Density functional theory (DFT) and beam-element-based finite element modeling have been employed to evaluate the elastic properties of zigzag phosphorene nanotubes, revealing that larger-radius nanotubes exhibit higher Young’s modulus [134], Multi-walled BPNTs (MW-BPNTs) have demonstrated thermally driven rotational behavior with frequencies reaching up to 16.7 GHz, while maintaining structural stability across broad temperature ranges—making them attractive candidates for room-temperature nanomotor applications [13].

4.3.3 Electrical Property Modulation

Doping plays a pivotal role in modulating the electrical characteristics of carbon-based nanostructures. Boron and nitrogen-doped CNTs can form rectifying junctions with precise control over conductivity type under chirality modulation [77]. First-principles calculations show that B/N-doped armchair and zigzag GNTs exhibit tunable bandgaps, anisotropic optical responses, and strong ultraviolet absorption, making them promising for next-generation optoelectronic and UV-protective devices [135]. Chemical doping—such as fluorine incorporation—shifts the Fermi level of graphene upward, enhancing carrier concentration and modifying its electrical conductivity [136]. Additionally, chiral BPNTs offer excellent thermal stability and exhibit diameter-independent, tunable direct bandgaps, rendering them suitable for optical and electronic applications requiring precise bandgap engineering [137].

4.4 Thermal Properties and Heat Management

4.4.1 Thermal Transport Mechanisms

MD simulations reveal that phosphorene exhibits intrinsic anisotropic thermal transport, with thermal conductivity following the order: zigzag > perpendicular > [110] > armchair directions. Uniaxial tensile strain enhances thermal conductivity along specific axes, while the formation of nanotubes slightly reduces it, confirming the material’s directional sensitivity and validating MD simulations as a robust analytical tool [106]. For β- and γ-graphdiyne nanotubes (GDYNTs), larger tube diameters correspond to higher carrier mobilities, with values reaching up to 105–107 cm2 V−1 s−1 [138].

4.4.2 Structural Design and Device-Level Simulation

Faceted phosphorene nanotubes and fullerenes, formed by laterally connecting various phosphorene phases, exhibit exceptional stability and tunable electronic properties, including strain- and wall number–induced metal-insulator transitions—offering a new design paradigm for polymorphic nanostructures [139]. Similarly, three-dimensional carbon allotropes such as net-Y and h-carbon exhibit intrinsic metallicity and high carrier velocities (~106 m/s), rivaling graphene [129,140]. BPNTs also display anisotropic thermal and mechanical behavior: armchair BPNTs exhibit higher strength, whereas [110] and perpendicular directions offer greater deformability, supporting their potential in deformable nanodevices [141]. Blue phosphorus nanotubes (βPNTs) exhibit a puckered, non-planar structure and possess an inherent bandgap of ~0.9–1.0 eV in monolayer form [142].

4.4.3 Deformation Dynamics and Functional Behavior

Simulations show that triple-walled C@BN@C nanotubes can function reliably across a wide temperature range (100–600 K) [4]. Graphene/graphyne heterojunctions exhibit high spin polarization with spin-filtering efficiencies exceeding 92% under specific bias ranges [5], δ-Graphyne nanoribbons with zigzag edges demonstrate spin-polarized ferromagnetic edge states and antiferromagnetic coupling between edges, supporting potential spintronic applications [143].

4.4.4 Thermoelectric Conversion Potential

Multiphysics simulations have shown that wrinkled arsenene nanotubes under strain exhibit direct bandgaps near 1 eV, enhancing their thermoelectric performance [144]. Graphenylene nanotubes effectively absorb visible light, offering applications in electromagnetic radiation sensing [145]. A structure–property correlation framework has been developed through integrated atomic-level characterization and multiscale modeling, guiding the precision design of nanodevices—such as high-frequency transistors, heat spreaders, and quantum systems.

4.4.5 Synthesis Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their exceptional properties, large-scale synthesis of materials like GNTs and h-carbon remains a challenge. For example, rotary nanomotors constructed from opposing-chirality armchair nanotube shuttles—capable of intershell, screw-like rotation driven by electrostatic forces—show great potential in NEMS and nanorobotics [37], but current yields are limited to milligram–gram scales.

Similarly, h-carbon—a superhard carbon allotrope with interpenetrating CNT and graphene nanoribbon frameworks—remains theoretically predicted, as atomic-level fabrication has not yet been realized. Techniques such as electron-beam lithography, bottom-up polymerization, and field-assisted self-folding are being explored, though still at proof-of-concept stages.

To accelerate industrial deployment, future efforts should prioritize:

• Development of low-energy, catalyst-free synthesis pathways;

• Integration with additive manufacturing technologies;

• Establishment of standardized performance metrics (e.g., cost per gram, thermal/electrical stability, and scalability).

These directions align with green manufacturing initiatives and ongoing efforts to create robust standards for evaluating NEMS-scale devices and functional composites.

4.4.6 Emerging Thermoelectric Materials

Recent advances highlight the thermoelectric potential of 2D/1D nanomaterials. Lu et al. [146] achieved a peak ZT value of 1.66 in graphenylene-based monolayers—surpassing most graphene-like 2D materials. These findings underscore the viability of next-generation thermoelectric materials for efficient energy harvesting.

4.5 Structural Innovation and Stability

4.5.1 Experimental Synthesis Methods

Recent progress in the synthesis of carbon-based nanomaterials has prioritized scalable, cost-effective, and high-performance fabrication techniques. One notable approach is spray pyrolysis chemical vapor deposition (CVD) for producing nitrogen-doped CNTs (N-CNTs) [86]. This method utilizes high-temperature decomposition of gaseous precursors, with nitrogen introduced into the reactor to incorporate heteroatoms into the carbon lattice. The resulting N-CNTs exhibit improved electrical conductivity and enhanced thermal stability, broadening their utility in electronic and energy-related applications.

Another significant technique is the hydrothermal–phosphidation synthesis of CoP nanosheet/one-dimensional CNT (CoP NS/CNT) heterostructures [87]. This two-step method first forms Co-based nanosheets via hydrothermal treatment, followed by phosphidation to create a robust heterostructure. The CoP NS/CNT composites demonstrate superior electrochemical activity, rendering them highly suitable for high-performance energy storage systems such as batteries and supercapacitors.

4.5.2 Structural Stability and Material Performance

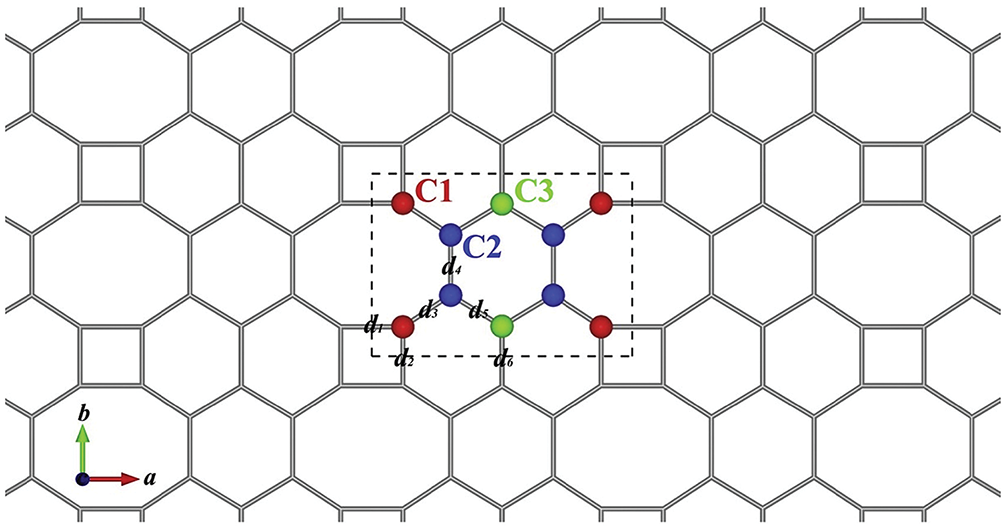

Emerging carbon allotropes such as h-carbon and net-Y are at the forefront of structural innovation due to their unique bonding arrangements and outstanding mechanical and electronic characteristics. h-Carbon features a 3D sp2/sp3 hybrid framework that delivers high hardness while maintaining a moderate bandgap, making it a candidate for multifunctional applications ranging from protective coatings to semiconductor components [129]. In parallel, net-Y—composed of interlinked tetragonal, hexagonal, and octagonal rings—exhibits a distinctive Pmmm (D12h) symmetry and anisotropic mechanical properties, along with intrinsic metallicity [140]. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the structure can be conceptualized as a periodic embedding of fused 4- and 8-membered rings into a graphene lattice. This architecture opens new directions for designing two-dimensional materials with tailored directional properties and conductivity.

Figure 6: Optimized structure of net-Y with a unit cell indicated by the dashed lines. The C1, C2, and C3 with different colors stand for inequivalent atoms [140]

Together, these advancements in synthesis methods and structural designs highlight the growing potential of carbon-based nanomaterials to meet the demands of next-generation devices, combining high stability, customizable properties, and compatibility with scalable manufacturing platforms.

Recent studies also emphasize the structure–property relationships of graphene nanoribbons and graphdiyne, particularly investigating the effects of nitrogen doping and metal atom decoration on their electronic structures and overall performance characteristics [147,148]. Three-dimensional carbon architectures, such as carbon honeycomb frameworks (CHFs) derived from graphyne and integrated with graphene nanoribbons, offer atomically precise edge configurations and enhanced electronic tunability [147]. Additionally, 3D graphyne-based polymers—such as Tri-C18—demonstrate a promising balance between high porosity and mechanical stiffness, making them attractive for multifunctional applications [149].

4.6 Electronic and Spin Property Modulation

Sensing and Catalytic Enhancements

Density functional theory (DFT) studies have evaluated the performance of nitrogen-doped graphene nanoribbons (GNRs) for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), emphasizing the influence of mechanical strain on their electronic structures and catalytic activity [150]. These results offer theoretical guidance for the rational design of high-performance catalysts, particularly for energy conversion and environmental remediation.

These results offer theoretical guidance for the rational design of high-performance catalysts, particularly for energy conversion and environmental remediation.

(1) Zigzag δ-graphyne nanoribbons (ZδGYNRs) exhibit spin filtering efficiencies up to 99% due to intrinsic spin polarization effects [151].

(2) Edge hydrogenated [38] and metal atom adsorption (e.g., Au, Cu, Fe) [148] enable metal–semiconductor transitions and controlled n-type doping.

(3) Concave-edged GNRs functionalized with benzene rings demonstrate enhanced carrier mobility through molecular engineering [152].

(4) Graphdiyne (GDY) display high switching ratios, bandgaps exceeding 0.4 eV, and ultrahigh carrier mobilities, making them suitable for high-speed electronics [6].

(5) ZGYNR molecular junctions show nearly 100% spin filtering efficiency over a wide bias range and exhibit a maximum rectification ratio of 1.5 × 104 [153].

(6) Mechanically strained GNRs (Me-GNRs) exhibit a negative differential resistance (NDR) effect, making them promising candidates for resonant tunneling diode applications [38].

(7) Graphyne’s intrinsically low thermal conductivity (as low as 8 W/m·K at room temperature) [131] and the directionally anisotropic properties of γ-carbon foams (γ-CFs) [154] suggest great potential for thermoelectric energy harvesting.

To support these findings, Table 2 provides a comparative summary of key mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties of CNTs, BPNTs, and graphene-based nanomaterials, offering a concise reference for evaluating their relative advantages across application domains.

4.7 Experimental Validation and Future Directions

The convergence of experimental synthesis techniques and theoretical modeling is essential for advancing the practical application of carbon-based nanomaterials. Scalable methods such as spray pyrolysis chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and hydrothermal phosphidation not only enable mass production but also offer control over material composition and morphology.

To further accelerate progress in this field, future research should prioritize:

(1) Scalable Fabrication: Developing cost-effective, high-throughput methods for producing carbon-based nanomaterials while preserving their structural and functional integrity.

(2) Structural Precision: Refining doping strategies and heterostructure integration to optimize electronic, thermal, and mechanical performance for targeted applications.

(3) Experimental Validation: Undertaking systematic experimental studies to corroborate theoretical predictions, ensuring reliable performance under real-world operational conditions.

By advancing these areas, the transition from laboratory research to industrial application will be significantly expedited, unlocking the full potential of carbon-based nanomaterials for next-generation technologies in energy storage, electronics, and biomedical engineering.

5 Technical Contributions of MD Simulation

MD simulations have been instrumental in elucidating the dynamic behaviors and performance mechanisms of nanomaterials. For example, parameter sensitivity analyses have revealed the influence of temperature fluctuations and geometric deviations on the rotational frequency of nanotube-based rotors [17], while studies have also examined how variations in argon gas density affect the speed of nanomotors [56]. Complementary investigations by [155–157] have reviewed broader factors impacting nanomotor performance, and works by [27,158], have refined simulation parameters to enhance predictive accuracy.

In the context of multiphysics coupling, recent research has explored the combined effects of electric fields, temperature gradients, and argon environments on the self-scrolling behavior of α-graphyne nanoribbons near CNTs [72]. These simulations provide detailed insights into the interplay between external stimuli and nanoscale motion.

Overall, MD simulations serve as a powerful predictive tool for optimizing nanodevice behavior, offering a theoretical foundation that reduces experimental trial-and-error and accelerates the development of advanced nanomaterials and devices.

5.1 Limitations of MD Simulations and Experimental Correlations

MD simulations provide powerful insights into the dynamic behavior of nanomaterials; however, several inherent limitations must be acknowledged. Due to computational constraints, MD simulations are typically restricted to small system sizes and short timescales—on the order of nanoseconds to microseconds. Furthermore, the use of idealized models with periodic boundary conditions often fails to fully replicate real-world experimental conditions.

For instance, MD simulations predict that BPNTs can operate with high structural stability as rotors at rotational frequencies of ~20 GHz at 250 K [40]. However, complementary three-dimensional finite element models show that while diameter has minimal impact on the first natural frequency, it significantly affects higher vibrational modes. Additionally, structures with larger aspect ratios exhibit reduced vibrational frequencies [80,159]. These discrepancies underscore the importance of integrating MD with in situ techniques, such as environmental transmission electron microscopy (TEM), to better capture effects like oxidation and thermal degradation.

In contrast, some MD results show strong alignment with experimental observations. For example, simulations predicting temperature-driven rotational frequencies of up to 59.5 GHz for DWCNTs [1] are consistent with experimental findings from nanoscale rotors. Similarly, the simulated instability of BPNTs at elevated temperatures matches the experimentally observed degradation of BP due to oxidation and thermal stress [160]. Simulated mechanical anisotropy and strain responses in BPNTs also align with experimental data, although parameter refinement is still needed for precise quantitative agreement.

Nonetheless, certain MD-predicted behaviors—such as pendulum or motor-like motion in systems where both the shaft and sleeve are free to move [34], or the self-assembly of GNTs [37]—remain unverified due to fabrication limitations and challenges in nanoscale characterization. Moreover, the accuracy of MD simulations is highly dependent on the choice of interatomic potentials or force fields. Many commonly used potentials struggle to capture complex interactions, such as defect formation, chemical reactions, or electron–phonon coupling, limiting their applicability in highly reactive or multifunctional environments.

To bridge the simulation–experiment gap, it is essential to validate MD results using in situ experimental techniques such as TEM, atomic force microscopy (AFM), and Raman spectroscopy. Continued integration of these approaches will enhance the predictive value of MD, accelerate the discovery of new functional nanomaterials, and support the design of robust, high-performance nanoscale devices.

5.2 Emerging Solutions to Enhance Stability: Encapsulation and Doping Strategies

Stability challenges—such as oxidation sensitivity and thermal degradation—remain major barriers to the practical deployment of BPNTs and related nanomaterials. To address these limitations, recent research has focused on encapsulation and doping strategies as two promising approaches to enhance environmental robustness and material longevity.

5.2.1 Encapsulation Techniques

Encapsulation has proven particularly effective in mitigating oxidative degradation of BPNTs. Encasing BPNTs within protective shells—such as CNTs, graphene oxide, or other impermeable materials—significantly slows oxidation and improves structural integrity under ambient and elevated temperature conditions. Notably, atomic layer deposition (ALD) of ultrathin oxide films (e.g., Al2O3) has emerged as a precise and conformal method for coating BP, dramatically improving its stability in air. These encapsulated structures preserve the electrical and mechanical performance of BPNTs while extending their operational lifespan, making them viable for deployment in harsh or biomedical environments.

Doping BPNTs with heteroatoms such as nitrogen or boron is another effective strategy for improving thermal and oxidative stability. Doping modifies the local electronic environment and enhances bonding strength within the lattice, thereby increasing resistance to structural degradation. For example, nitrogen- or boron-doped BPNTs exhibit enhanced mechanical robustness, reduced reactivity with oxygen, and greater electronic stability under stress. Additionally, doping can tailor the electronic band structure, enabling improved semiconducting behavior and application-specific performance optimization.

Together, encapsulation and doping represent complementary approaches for stabilizing BPNTs and other sensitive nanomaterials. By combining external protection with internal structural reinforcement, these methods provide a robust pathway toward the reliable integration of BPNTs into next-generation energy, sensing, and biomedical devices.

6 Design and Performance Breakthroughs in Novel Nanodevices

With the rapid advancement of nanotechnology, breakthroughs in the design and performance of novel nanodevices have become a key driver of innovation across energy, electronics, materials science, and related fields. Recent years have seen transformative progress in functional integration, energy conversion efficiency, electromechanical systems, and photothermal management. These advancements are driven by strategies such as structural modulation, multi-material hybridization, and cross-scale computational simulations.

6.1 Functional Device Innovations

Researchers have developed a nanoscale continuously variable transmission (CVT) system by controlling rotor eccentricity [55], and designed a microscale precision strain sensor based on the Raman response of carbon nanotubes [43–45].

6.2 Energy Conversion and Storage

Partially hydrogenated graphene ribbons (H-GR) exhibit efficient CO2 adsorption/desorption behavior under mechanical deformation [53]. Studies on nanosprings [161] and mechanical models converting input rotation to output oscillation [70] underscore their promise in energy storage. Notable material developments include:

• r-P@MWCNTs: Ring-shaped phosphorus encapsulated in multi-walled CNTs, achieving a capacity of 444 mAh/g after 500 cycles [162].

• BP/CNT@PPy Core–Shell Structures: Deliver 1376 mAh/g after 200 cycles, with enhanced structural integrity and cycling performance [7].

• PP@MWCNTs: Phosphorus encapsulated in MWCNTs via a solution-based method, showing promise as a high-performance lithium-ion battery (LIB) anode [163].

• MWCNT–SiP2 Composites: Fabricated by ball milling, these are applicable for both LIBs and sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) [164].

• Yttrium-Modified Graphdiyne Nanotubes: Demonstrated enhanced hydrogen storage capacity [165]

• P–O–C Bonded Nanocomposites: Improved cycling stability for energy storage systems [166].

These efforts highlight the potential of nanomaterials across three key domains:

• Anode Materials: CNTs, BPNTs, and phosphocarbon composites have demonstrated high capacities for Li, Na, and K-ion storage [166–168].

• Electrocatalysts: Engineered nanostructures have improved catalytic activity for hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions (HER/OER) [108,109].

• Supercapacitors: High-performance nanocomposite electrodes present strong potential for next-generation energy storage technologies [169].

AI-driven discovery has further accelerated progress. Machine learning algorithms have enabled rapid screening of oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) catalysts, predicting their catalytic activity with high accuracy and minimizing experimental effort [8]. Concurrently, studies of multi-walled black phosphorene nanotubes (MW-BPNTs) reveal that outer-wall rotation does not compromise structural stability. Molecular dynamics simulations confirm that these structures can operate as thermally driven rotors with GHz-range frequencies, indicating strong potential for room-temperature nanomotor applications [13].

6.3 Design of Nanomotors and Nanodevices

Studies on temperature-sensitive rotary nanomotors composed of wedged diamond tips and triple-walled carbon nanotubes demonstrate that their stable rotational frequency and direction are influenced by both temperature and wedge geometry, offering valuable insights for nanoscale machinery design [170]. Electromigration effects have also been shown to induce telescoping motion in CNTs, where the motion velocity exhibits an exponential dependence on load mass [171]. Zhang et al. [172] used molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to reveal that the speed of a linear nanomotor on a stretched CNT substrate can be effectively regulated by temperature gradients, substrate strain, and nanomotor size, with thermophoretic force identified as the primary driving mechanism. Researchers have further developed a range of nanomotor designs and functional nanodevices based on carbon nanomaterials, including:

• Nanomotors: Both rotational and linear nanomotors utilizing CNTs have been extensively studied, with emphasis on their actuation mechanisms, resonance behavior, and frequency control [170,173,174].

• Nanodevices: Designs such as nanorockets and ring-shaped nanomotors have been proposed and analyzed [175,176], providing theoretical foundations and design strategies for advancing nanoelectromechanical systems (NEMS).

6.4 Photoelectric and Thermal Management

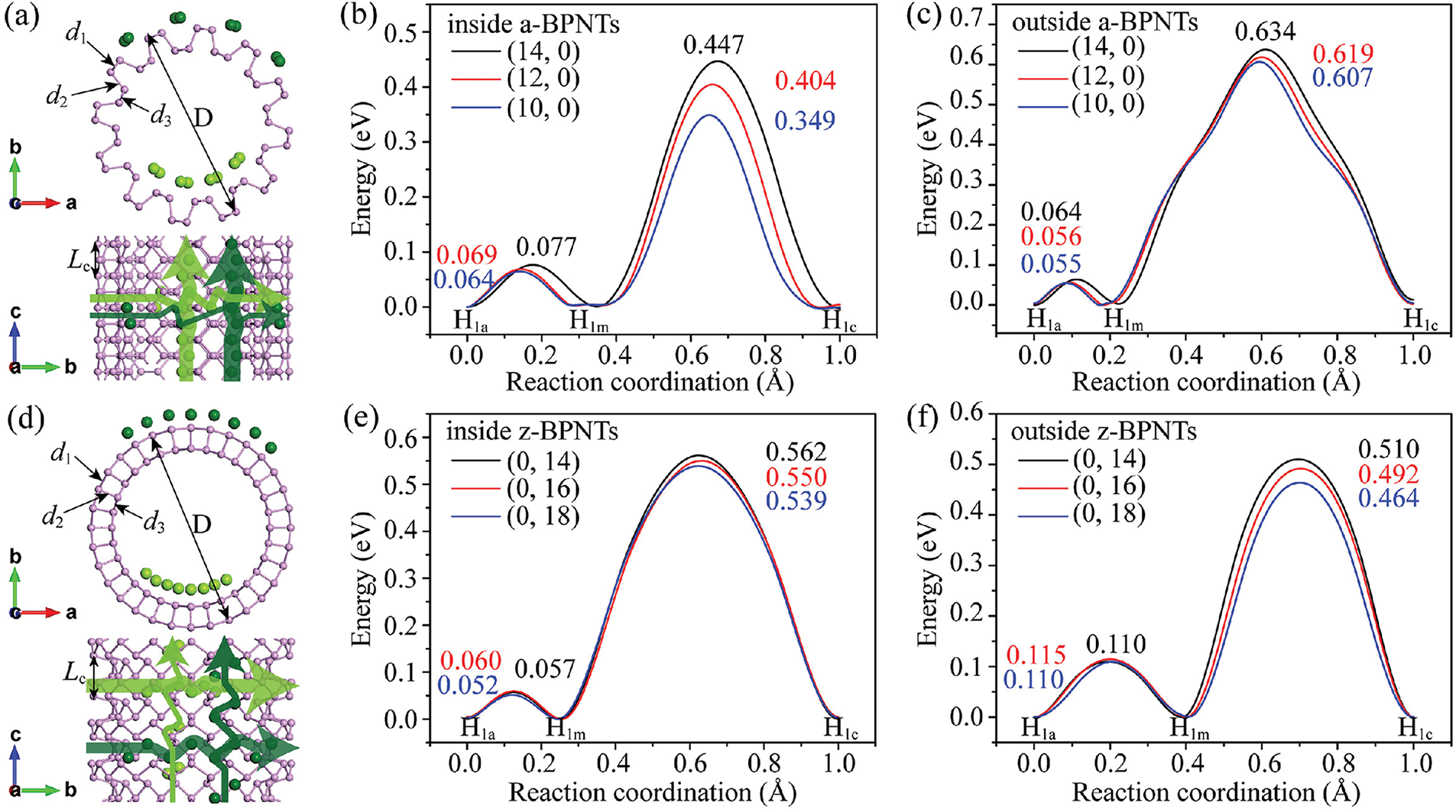

For photoelectric devices, black phosphorus nanotubes (BPNTs) offer tunable bandgap properties. Amorphous BPNTs (a-BPNTs) are well-suited for fast-charging battery applications, while zigzag BPNTs (z-BPNTs) are ideal for high-energy-density storage systems [2]. Fig. 7 illustrates the structural distinctions between a-BPNTs and z-BPNTs. In the realm of electronic materials, Majidi [177] reviewed the structure and electronic properties of graphyne-based nanotubes. Graphdiyne—a two-dimensional carbon allotrope composed of both sp- and sp2-hybridized carbon atoms—features a hexagonal lattice akin to graphene, but with additional carbon–carbon triple bonds that confer distinctive physicochemical characteristics.

Figure 7: The top view and side view of (a) a-BPNTs and (d) z-BPNTs, and corresponding migration trajectories of some Li atoms on the surface. The energy barriers for Li diffusion on (b,c) a-BPNTs and (e,f) z-BPNTs with different diameters [2]

While molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have provided valuable insights into the dynamic behavior, structural stability, and functional performance of nanomaterials, several critical challenges persist:

(1) Experimental Validation Deficits: Many simulation-based findings lack experimental confirmation. For example, thermal degradation of BPNTs observed in simulations aligns with in situ TEM studies of phosphorene oxidation and breakdown. Encapsulation techniques—such as atomic layer deposition (ALD) with Al2O3 and polymer integration—have shown promise in bridging simulation with real-world stabilization strategies [95,100].

(2) Multiscale Coupling Complexities: Interactions between nanodevices and their macroscopic environments (e.g., fluid dynamics, electric field distributions) remain poorly understood. More integrative modeling is needed to accurately predict device performance under practical operating conditions.

(3) Durability and Dissipation: Energy loss due to friction and high-temperature operation is a major hurdle for long-term stability in nanodevice applications.

Key Technical Challenges:

• Composite Material Design: Optimizing CNT-based hybrids for multifunctional applications (e.g., energy storage, sensing) remains an active area requiring innovations in interfacial engineering and hierarchical structuring.

• Multifunctional Integration: Seamless integration of CNTs and their composites with other nanomaterials or smart technologies (e.g., flexible electronics, wearable sensors) is vital for enabling intelligent nanosystems.

• Green and Scalable Synthesis: Environmentally friendly, energy-efficient, and scalable methods for producing CNTs and related nanomaterials are urgently needed to meet industrial demand.