Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Method for Small Target Detection and Counting of the End of Drill Pipes Based on the Improved YOLO11n

1 School of Energy Science and Engineering, Henan Polytechnic University, Jiaozuo, 454000, China

2 School of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Henan Polytechnic University, Jiaozuo, 454000, China

3 China Henan International Joint Laboratory of Coalmine Ground Control, Jiaozuo, 454000, China

* Corresponding Author: Miao Li. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 1917-1936. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067382

Received 01 May 2025; Accepted 21 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Aiming at problems such as large errors and low efficiency in manual counting of drill pipes during drilling depth measurement, an intelligent detection and counting method for the small targets at the end of drill pipes based on the improved YOLO11n is proposed. This method realizes the high-precision detection of targets at drill pipe ends in the image by optimizing the target detection model, and combines a post-processing correction mechanism to improve the drill pipe counting accuracy. In order to alleviate the low-precision problem of YOLO11n algorithm for small target recognition in the complex underground background, the YOLO11n algorithm is improved. First, the key module C3k2 in the backbone network was improved, and Poly Kernel Inception (PKI) Block was introduced to replace Bottleneck in it to fully integrate the target context information and the model’s capability of feature extraction; Second, within the model’s neck network, a new feature fusion pyramid ISOP (Improved Small Object Pyramid) is proposed, SPDConv is introduced to strengthen the P2 feature, and CSP and OmniKernel are combined to integrate multi-scale features; Finally, the default loss function is substituted with Powerful-IoU (PIoU) to solve the anchor box expansion problem. On the self-built dataset, experimental verification was conducted. The findings showed that the Recall rose by 6.4%, mAP@0.5 increased by 4.5%, and mAP@0.5:0.95 improved by 6% compared with the baseline model, effectively solving the issues of false detection and missed detection problems in small target detection task. Meanwhile, we conducted counting tests on drilling videos from 5 different scenarios, achieving an average accuracy of 97.3%, which meets the accuracy needs for drill pipe recognition and counting in coal mine drilling sites. The research findings offer theoretical basis and technical backing for promoting the intelligent development of coal mine gas extraction drilling sites.Keywords

In the field of coal mine safety production, gas extraction is a key measure to prevent gas disaster [1]. As the core parameter of gas extraction, the accurate quantification of drilling depth is crucial for improving gas extraction efficiency and ensuring coal mine safety production. At present, the statistical method for drilling depth primarily relies on manual labor, which judges by recording the quantity of drill pipes inserted or retracted throughout the drilling operation. However, this video surveillance-based manual counting method heavily depends on workers’ concentration and memory, and long-term work can easily lead to fatigue, resulting in missed records, incorrect tallies, or repeated counting. Furthermore, coal mines’ intricate underground surroundings, marked by noise, dust, and humidity, may affect workers’ operational conditions and visual field, interfere with the counting accuracy, and make overall work efficiency relatively low. Moreover, workers’ quality sometimes may render the manual counting process perfunctory, resulting in a decrease in gas extraction efficiency and affecting coal mine safety production [2]. Therefore, developing an automated and accurate drill pipe counting technology holds significant practical implications and application prospects for advancing intelligent development of coal mines.

With the advancement of intelligent mining system theory and smart mine systems engineering [3], the application research of computer vision in coal mine production activities has developed rapidly, especially visual algorithms based on deep learning frameworks, which have seen extensive application in coal mining scenarios [4–7]. For instance, applying the YOLO algorithm [8–10] in various mining applications, including safety helmet detection [11,12], conveyor belt foreign object detection [13], coal gangue detection [14], and miner location detection [15,16]; Applying tracking algorithms such as StrongSORT to real-time detection and continuous monitoring of critical equipment and miners [17]; Applying U-Net segmentation network to particle size analysis of coal particles [18], and deploying visual algorithms to autonomous mining vehicle detection [19], etc. However, unlike other application scenarios in coal mines, drill pipe counting faces the following problems: (1) The drill sites are frequently replaced and vary greatly. (2) The drill sites have the characteristics of uneven lighting and low target distinguishability. (3) The process of drilling construction is more cumbersome. These problems have led to the current research results having strong limitations. Therefore, based on the actual operational scenarios of gas extraction and drilling processes in coal mine drilling sites and considering the detection accuracy and real-time efficiency of the YOLO algorithms, the research of this paper endeavors to attain precise detection of small drill pipe head objects using an optimized YOLO11 algorithm, subsequently enabling accurate drill pipe counting. Through targeted optimization of the YOLO11 architecture, we enhance its capability for small target feature extraction and recognition. By incorporating the operational characteristics of drill pipes into our counting strategy design, we effectively address limitations inherent in conventional pipe counting methods. The primary contributions of this research are listed below:

(1) The Poly Kernel Inception (PKI) Block, which is used for remote sensing detection task, is introduced to enhance the C3k2 within the backbone network of YOLO11n. The PKI Block mainly consists of PKI Module and Context Anchor Attention (CAA) Module. The former is an inception-style module, emphasizing the extraction of multi-scale local contextual information. The latter is used to capture long-range contextual information. These two components collaborate to promote adaptive feature extraction of both local and global contextual information, thereby enhancing the feature extraction capability of C3k2.

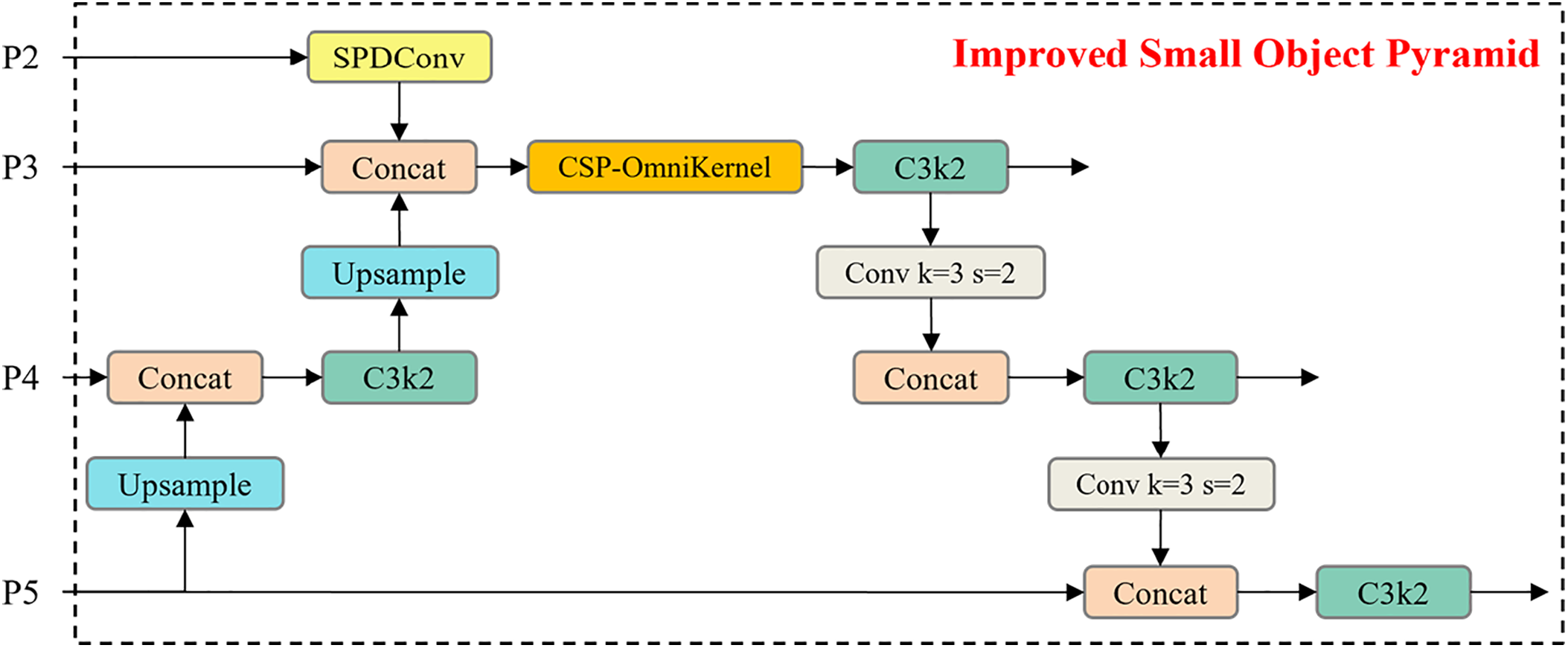

(2) We improved the neck network based on the original Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network (PAFPN) and proposed an Improved Small Object Pyramid (ISOP) for small targets. The P2 feature layer was processed through SPDConv to obtain features abundant in small target information, which were subsequently fused with the P3 feature layer. Following that, we combined CSP and OmniKernel for improvement and developed the CSP-OmniKernel module for feature integration.

(3) We introduced Powerful-IoU (PIoU) to replace the default loss function Complete-IoU(CIoU) of YOLO11n. PIoU proposed a penalty factor that adapts to target size and a gradient-adjusting function based on the quality of anchor box. It can dynamically adjust the gradient weights based on target size, alleviating the problem of unstable gradients for small targets caused by CIoU’s sensitivity to aspect ratios. This significantly enhances the model’s convergence speed and detection accuracy.

(4) A method for intelligent drill pipe counting based on the quantity of detected drill pipe bounding boxes in images is proposed. Additionally, to tackle the problems of false and missed detections in the model, we design a special correction mechanism that leverages the position and area of detected bounding boxes, consequently enhancing the accuracy of drill pipe quantification.

The subsequent sections of this paper are organized in the following manner: Section 2 presents an overview of the relevant work involved in this study, including small target detection techniques and drill pipe counting methods; Section 3 presents the baseline model and the architecture of the improved model, and specifically describes the three proposed improvement strategies; The primary emphasis of Section 4 lies in the experimental design and the subsequent analysis of results; Section 5 mainly introduces the implementation method of drill pipe counting in this paper as well as the corresponding correction mechanism. Section 6 summarizes the research work of this study.

Within the field of computer vision, the detection of small targets has consistently been a significant research challenge [20]. Owing to their minimal pixel coverage and indistinct feature representation in images, traditional object detection algorithms typically struggle to achieve satisfactory performance for small targets. Therefore, the core of small target detection hinges on efficiently and precisely locating and identifying small targets in complex backgrounds, while ensuring the real-time performance and computational efficiency of the algorithm. To enhance small target detection capability, researchers have proposed various improved methodologies. Xu et al. [21] introduced Transformer into small target detection tasks and proposed a new architecture called Dual-Key Transformer Network (DKTNet) [22], which has stronger target feature extraction capabilities and higher detection accuracy. Zhang et al. [23] combined the Feature Enhancement Module (FEM), Feature Fusion Module (FFM), and Spatial Context Aware Module (SCAM) to propose an efficient detector named FFCA-YOLO. It enhances the weak feature representation of small targets and suppresses confusing backgrounds. Tang et al. [24] proposed an optimized YOLOv5 model to resolve the large computational cost of the model, facilitating real-time deployment. Sun and Shen [25] proposed an enhanced YOLOv8 model incorporating multi-scale feature fusion and refined loss function for small target face detection task, and introduced Gaussian noise in the course of training to enhance detection accuracy and operating efficiency. Zhang et al. [26] designed detail-sensitive PAN (DsPAN), a lightweight architecture for multi-scale small target detection of defects and incorporated it into YOLOv8 for industrial real-time defect detection.

2.2 Drill Pipe Counting Methods

Traditional drill pipe counting methods primarily rely on manual operations, where workers visually inspect and tally pipes on-site. Over the past few years, deep learning technology has achieved significant advancements in the domain of object detection, providing more powerful tools for drill pipe counting. Object detection algorithms based on deep learning can automatically learn the features of targets, and have higher detection accuracy and robustness in complex backgrounds. Gao et al. [27] combined learning rate warm-up and Logistic curve to update the learning rate based on the ResNet50 network, improving the classification confidence of the loading and unloading of drill pipes in video frames. Finally, the confidence of the classification action results was filtered using integration method, and the quantity of falling edges was counted to achieve drill pipe counting. Based on the YOLOv8 algorithm, Ran et al. [28] calculated the number of low-light drill pipes in coal mines by detecting the centroid coordinates of the two predicted boxes of the drill chuck and the holder, drawing the spacing curve, and counting the peak values. Cheng et al. [29] introduced an intelligent counting method based on an improved YOLO11 model combined with Savitzky-Golay (SG) smoothing. This approach effectively alleviates the influence of complex underground conditions. Chen et al. [30] proposed a target detection algorithm named YOLOv7-GFCA, which first uses YOLOv7-GFCA to obtain the movement trajectory of the drilling rig target and then achieves drill pipe counting through coordinate signal filtering. Jiang et al. [31] used an improved YOLOv8n algorithm to perform semantic segmentation on drill pipes. Based on the changing pattern of drill pipe mask area increase and decrease, they completed the drill pipe counting task, which also brought a new idea for drill pipe counting. Du et al. [32] used the Alphapose algorithm to construct the skeleton sequence of miners’ drilling actions. Combined with the Multi-Scale Spatial Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (MST-GCN) model, he effectively identified the action categories in the skeleton sequence and completed the drill pipe counting by recording the number of actions.

As a classic algorithm in object detection, the YOLO (You Only Look Once) series stands out for its real-time capabilities, accuracy, and usability. Ultralytics has released YOLO11 based on YOLOv5 and YOLOv8, offering five model scales: n, s, m, l, and x, which can meet requirements in diverse application scenarios. For coal mine application scenarios, where model size and detection speed are crucial, this paper selects YOLO11n—the smallest in volume and fastest in speed—as the baseline model.

The basic structure of YOLO11 comprises three key components: Backbone, Neck, and Head. Specifically, the Backbone focuses on feature extraction, converting the original image into feature maps that encapsulate abundant semantic information. Compared with YOLOv8, YOLO11 improves the C2f module to the C3k2 module and adds the Cross Stage Partial with Pyramid Squeeze Attention (C2PSA) layer after the Spatial Pyramid Pooling-Fast (SPPF). This not only effectively alleviates the computational load but also further boosts the model’s feature extraction ability, providing a foundation for subsequent detection tasks. The Neck processes and fuses multi-level features from the Backbone, then passes them to the Head for object detection. The Head is the model’s output unit. Using feature maps refined by the Backbone and Neck, it executes the final object detection, outputting information such as object classification, localization, and confidence. The head part of YOLO11 draws on the idea of the lightweight architecture of YOLOv10. It uses depth-wise separable convolutions to replace conventional convolutions in the classification head to reduce computational overhead and improve efficiency.

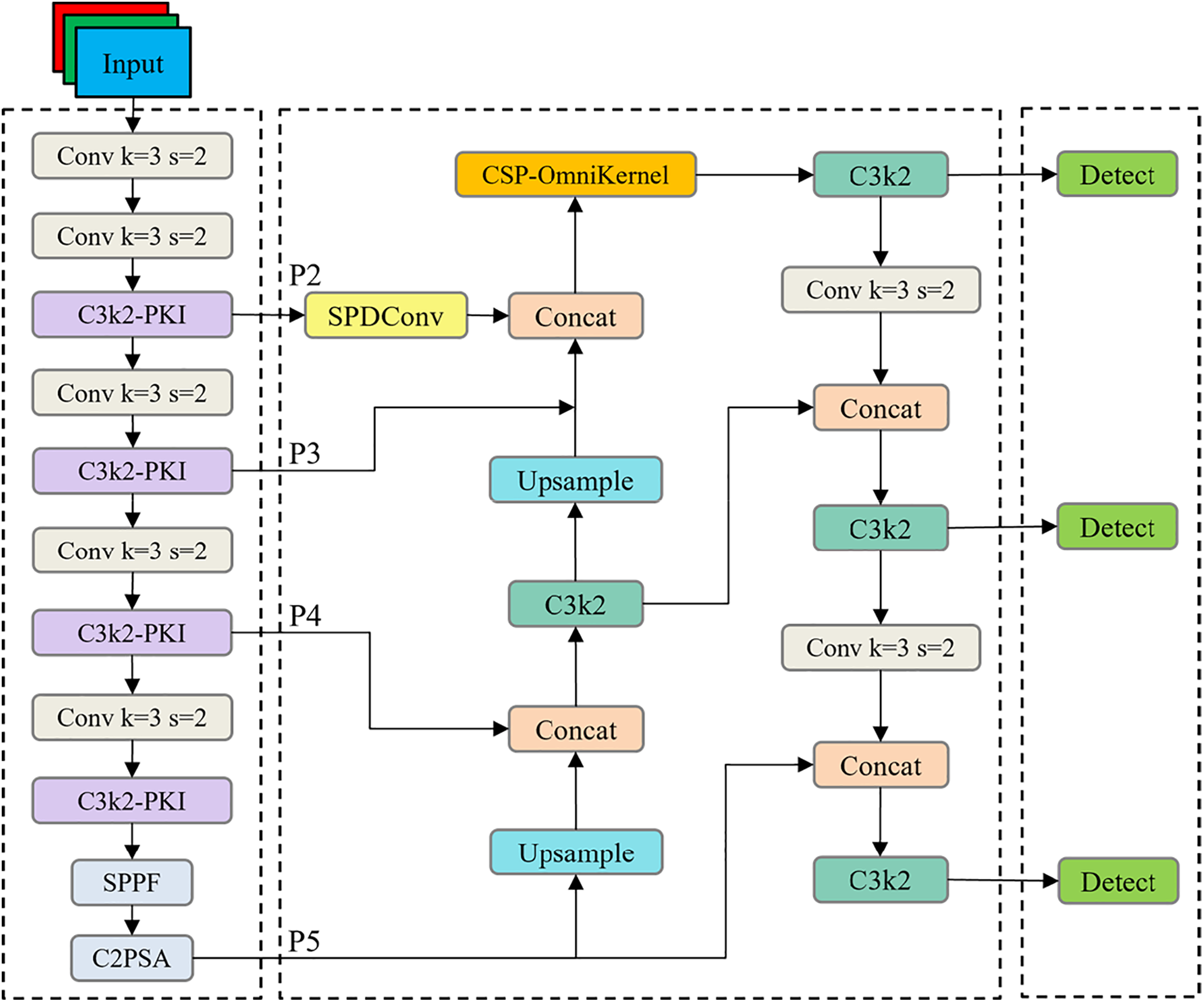

As presented in Fig. 1, the improved model structure introduces three core enhancements: Firstly, introducing the PKI Block to substitute the Bottleneck module of C3k2 in YOLO11n’s Backbone; Secondly, proposing an Improved Small Object Pyramid (ISOP) for small targets in the Neck; Thirdly, replacing YOLO11n’s default loss function CIoU with PIoU.

Figure 1: Improved model structure diagram

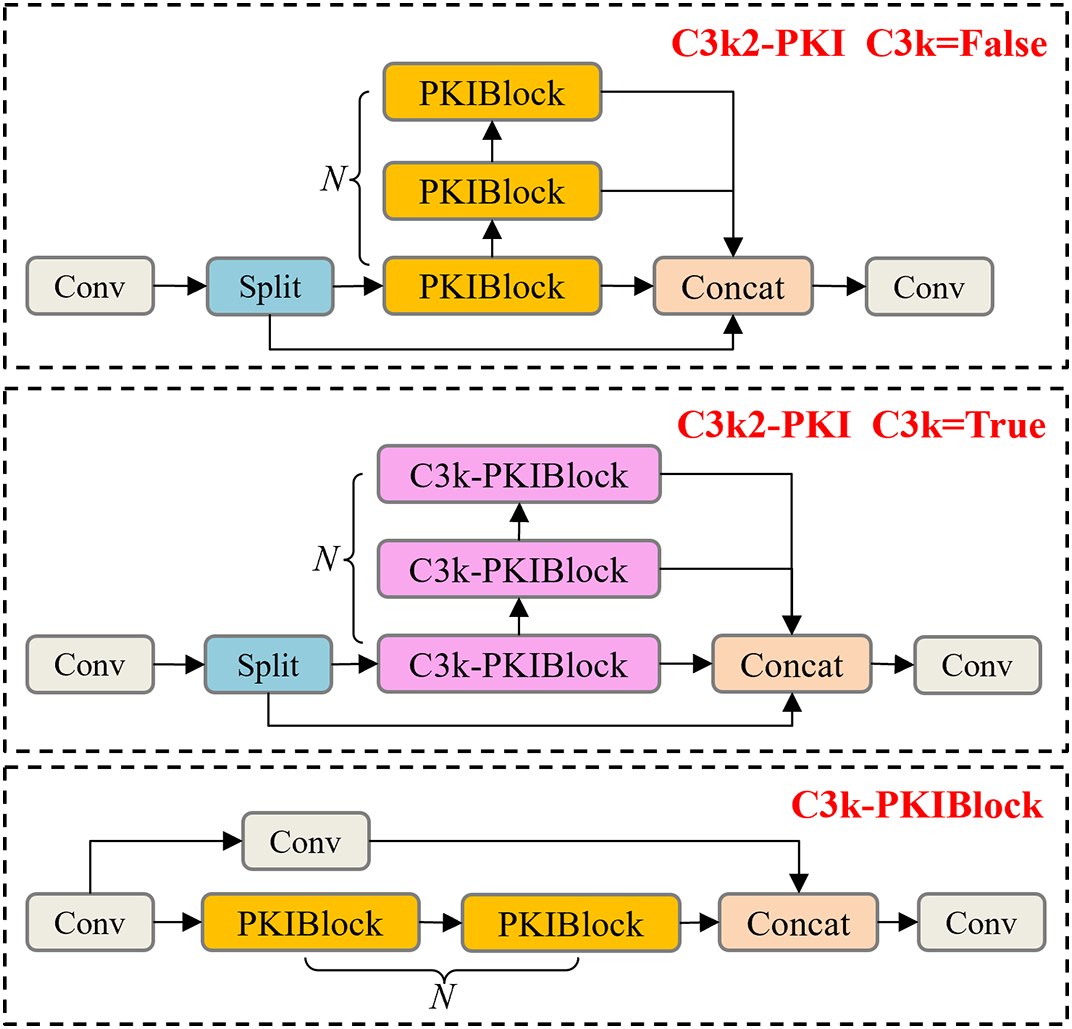

Due to the limited ability of conventional convolution in the Bottleneck to extract only single-scale local features, the C3k2 module struggles with comprehensive contextual integration. To address this, we introduce the PKI Block [33], which is used for processing remote sensing images, as a replacement of Bottleneck in C3k2, thus forming the C3k2-PKI module. The structure of this module is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: C3k2-PKI module structure diagram

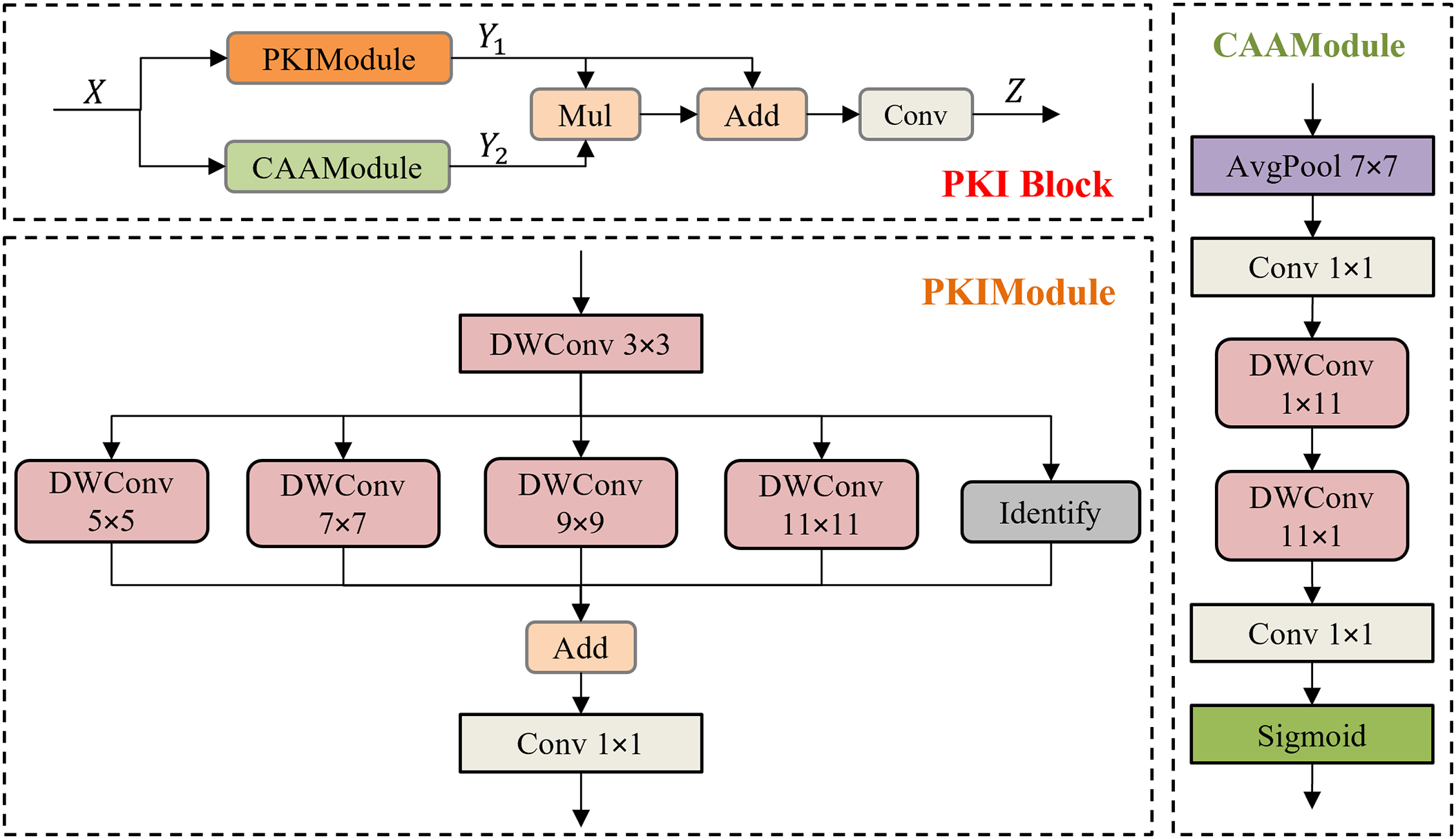

As shown in Fig. 3, the architectural composition of the PKI Block comprises two branches: the PKI Module and CAA Module. The PKI Module employs an inception-style structure, where channel adjustment is first performed through point-wise convolution, followed by 3 × 3 depth-wise convolution for local feature extraction. In order to better capture the contextual information at multiple scales, it uses depth-wise convolutions with kernels of different sizes, namely 5, 7, 9, and 11, to process the input feature maps in parallel. Subsequently, point-wise convolution is employed to fuse the local information and the contextual information at different scales. The CAA Module uses AvgPool and point-wise convolution to obtain local features, a pair of strip depth-wise convolutions extract stripe features in the feature map’s height and width dimensions, and point-wise convolution performs feature fusion and channel adjustment. The sigmoid function is employed to constrain the feature map within the range of (0, 1), generating attention weights for enhancing the output of the PKI Module. Generally speaking, when the input

where

Figure 3: PKI Block and its two components structure diagram

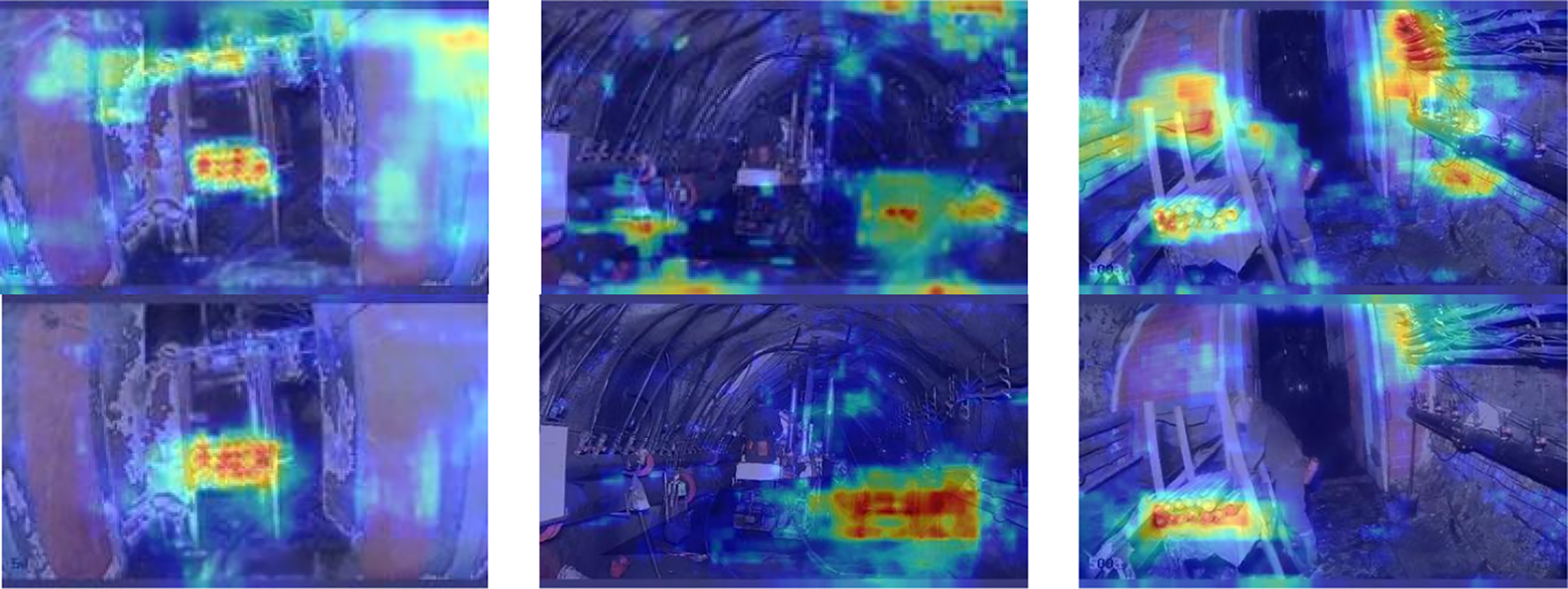

C3k2 has a certain feature extraction capability, while the PKI module uses parallel arranged depth-wise separable convolution kernels of varying sizes to extract multi-scale texture features with diverse receptive fields. Introducing PKI into C3k2 can further enhance its capacity to capture features of targets across diverse scales, which helps to detect small targets more accurately. Moreover, the CAA module in PKI enables C3k2 to better understand the contextual information of targets when extracting small target features, leveraging the surrounding environmental information to assist in small target detection and reducing missed detections caused by inconspicuous small target features. In the domain of small target detection, the PKI Block has exhibited remarkable effectiveness, which has been confirmed in many studies. For example, Reference [34] also introduces the CAA in PKI to enhance the attention to central region features, improving the robustness and accuracy of small object detection. The heatmaps comparison between C3k2 and C3k2-PKI is illustrated in Fig. 4. The red areas represent the positions that the model is interested in. The redder the color, the greater the influence of the features at this position on the detection results. The comparison results show that C3k2-PKI focuses more on the features of the target region, reducing the algorithm’s interest in the background region. This suggests that the model can more effectively learn target features, which in turn enhances detection accuracy. At the same time, the ablation experiment in Section 4.4 of this paper also verifies the efficacy of C3k2-PKI in enhancing the model accuracy.

Figure 4: Comparison of the heatmaps of C3k2 and C3k2-PKI, with C3k2 at the top and C3k2-PKI at the bottom

3.4 Improved Small Objects Pyramid

In detection tasks with smaller target scales, the conventional approach is to introduce an extra P2 layer preceding the P3 layer, using high-resolution shallow features to directly preserve the detailed information of small targets, thereby solving the problem of feature loss in deep networks. However, the cost is the significant increase in the model’s computational complexity and the limited real-time performance caused by post-processing time. To overcome this problem, this paper introduces a new feature pyramid termed ISOP, which is developed from the original PAFPN, as depicted in Fig. 5. We retained the P2 features, introduced Space-to-Depth Convolution (SPDConv) [35] to enhance the P2 features, and then fused them into P3. This compensated for the insufficient representation of small objects in P3 and improved the sensitivity of the detection head to small objects. Afterwards, we embedded OmniKernel [36] into the branch structure of CSP [37] to integrate multi-scale information, dynamically enhancing small target features while maintaining efficient computation.

Figure 5: ISOP structure diagram

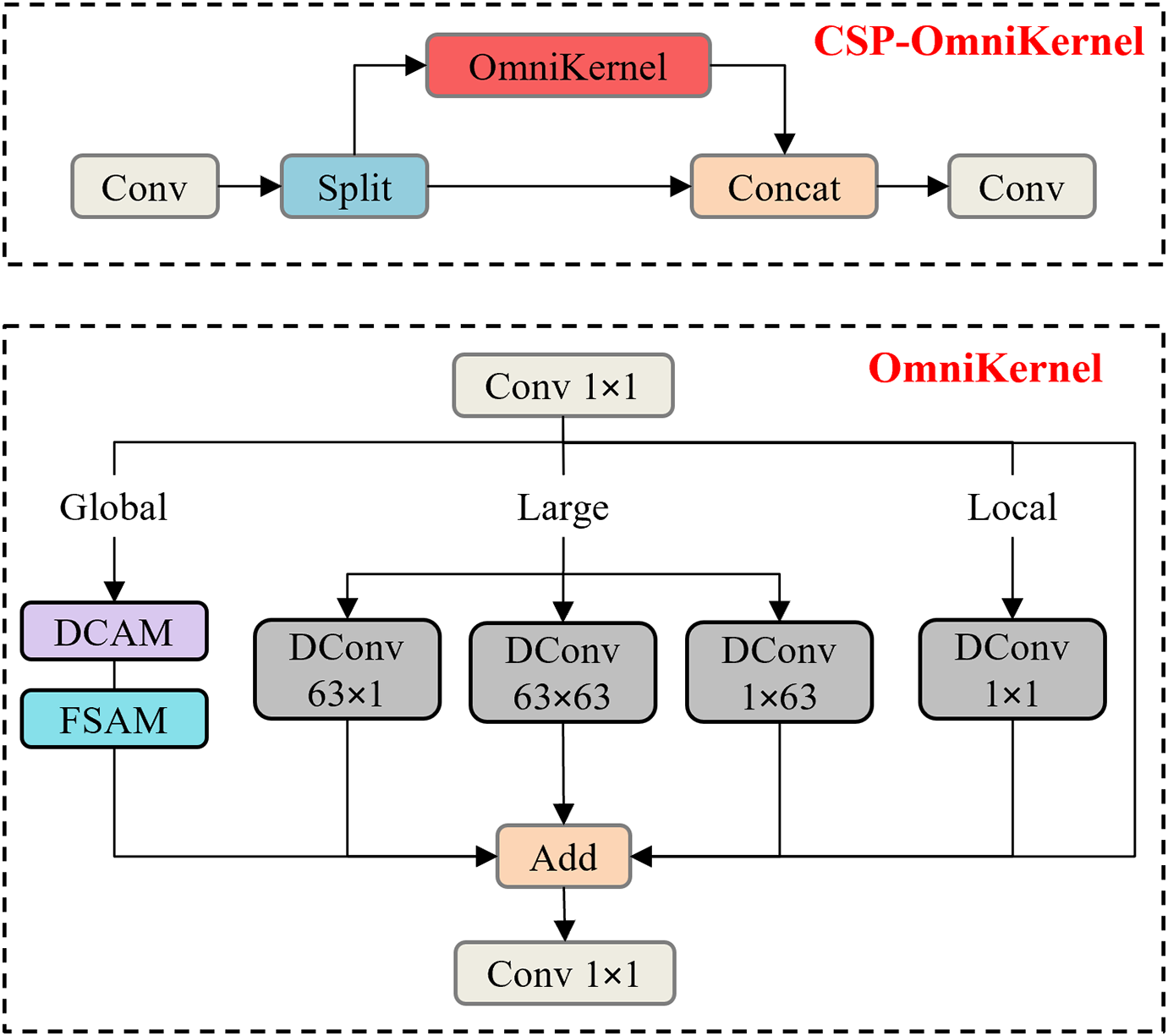

The SPDConv consists of a space-to-depth layer and a non-strided convolution layer (with a stride of 1). The former reorganizes the information of the spatial dimension (H × W) into the channel dimension (C), achieving a reduction in resolution while completely preserving the information. The following non-strided convolution layer is responsible for fusing the channel information and extracting high-order features. The core idea of SPDConv lies in substituting traditional strided convolution and pooling operations, in order to preserve more fine-grained information and improve performance when handling small objects and low-resolution images. Therefore, using SPDConv for processing the P2 layer in YOLO11n can significantly enhance the performance of detecting small objects while maintaining a balance in computational efficiency. The features processed by SPDConv are fed into P3 for fusion, and then input into the CSP-OmniKernel for multi-scale feature fusion. Fig. 6 displays the CSP-OmniKernel’s structure. This block combines the CSP with OmniKernel. Along the channel dimension, the input feature map is split into two branches by CSP, with one branch passes through the dense computation block, while the other branch is directly forwarded to the next stage (shortcut). Then, the two feature map parts are merged together, which addresses the problem of gradient redundancy in traditional deep networks and enhances the efficiency of information flow. The core of OmniKernel lies in efficiently capturing feature representations from global to local through three branches (global, large, and local). The input features initially undergo a 1 × 1 convolution processing, and then the three branches perform feature extraction, respectively. The global branch achieves global perception capabilities through a frequency-based spatial attention module (FSAM) and a dual-domain channel attention module (DCAM). Using large-kernel depth-wise separable convolutions of different shapes, the large branch captures a wide range of contextual information. The local branch, to supplement local information, utilizes 1 × 1 depth-wise separable convolutions. The outputs of the three branches are fused through addition and modulated by additional 1 × 1 convolution. Fig. 6 illustrates the specific structure in detail. With this multi-scale branch design, fine-grained features and contextual information for small targets can be captured simultaneously. When combined with the efficient feature fusion strategy of CSP, it not only improves the detection capability of small targets such as drill pipe heads but also avoids excessive consumption of computational resources.

Figure 6: CSP-OmniKernel structure diagram

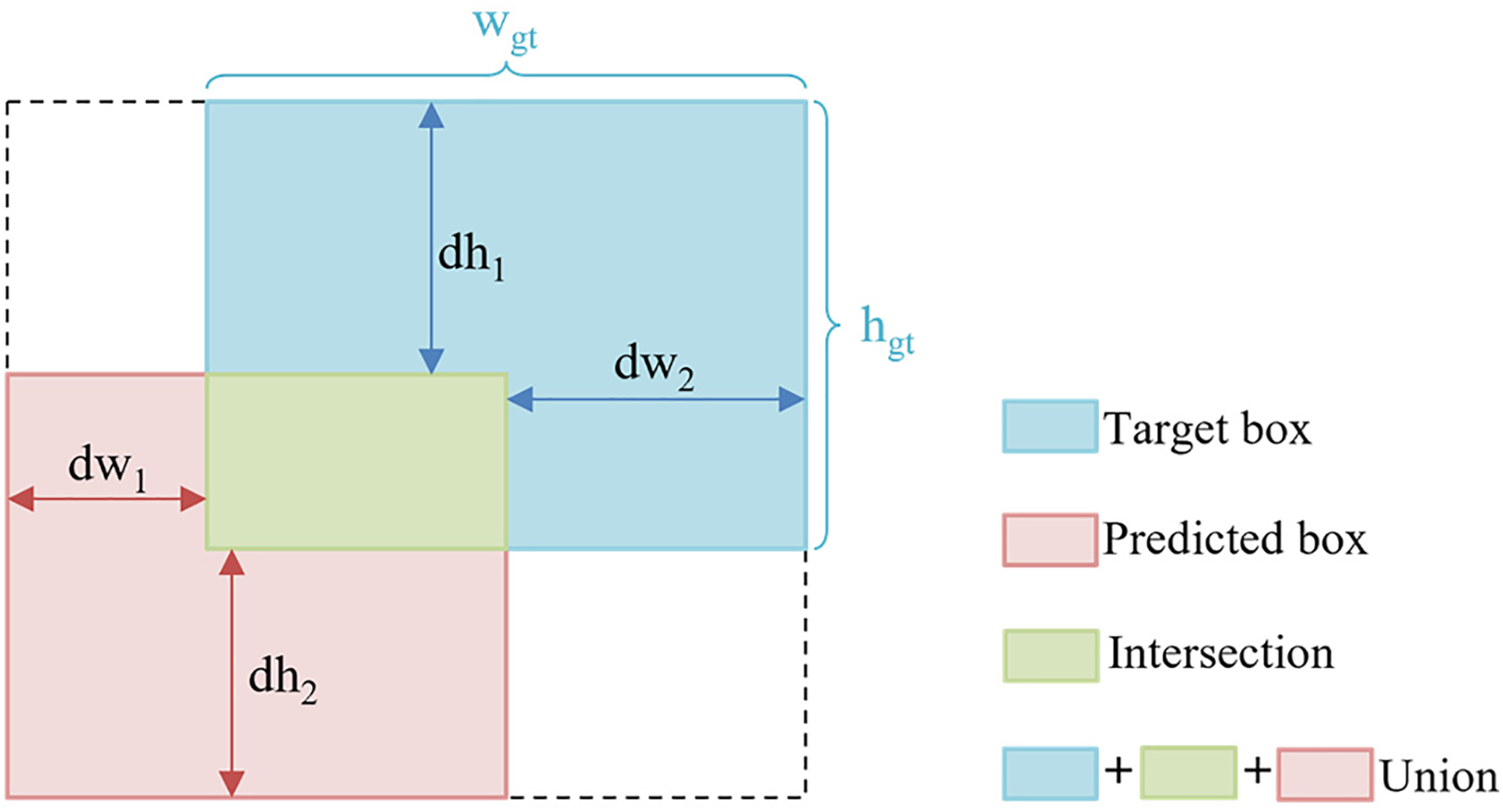

The default loss function of YOLO11 is CIoU [38]. Nevertheless, CIoU has limited adaptability to target scale changes. The aspect ratio penalty term in CIoU can cause gradient optimization imbalance for small targets with slight scale changes, degrading detection accuracy and stability. To overcome this limitation, we propose replacing CIoU with the PIoU loss function [39].

PIoU originates from the problem of anchor box expansion caused by unreasonable penalty factors in existing IoU-based loss functions. For example, the sensitivity of CIoU to the aspect ratio makes the gradient of small targets unstable, because a slight pixel-level change in their size will disproportionately amplify the penalty term. In response to this, PIoU proposes a penalty factor with target size adaptability. This penalty factor is capable of dynamically adjusting the aspect ratio weight in accordance with the actual size of the target box to alleviate this problem. The penalty factor P is defined in the following manner:

where

Figure 7: PIoU schematic diagram

In addition, PIoU proposes a gradient-adjusting function grounded in anchor box quality, which is shown as follows:

By integrating the above formulas, we can obtain:

Overall, by introducing the target size-adaptive penalty factor and the gradient-adjusting function that is grounded in the anchor box quality, PIoU can more efficiently guide the regression of anchor box, avoid the problem of anchor box expansion, and thus achieve a faster convergence speed. It has achieved higher detection accuracy compared to the default loss function CIoU.

4 Experimental Design and Result Analysis

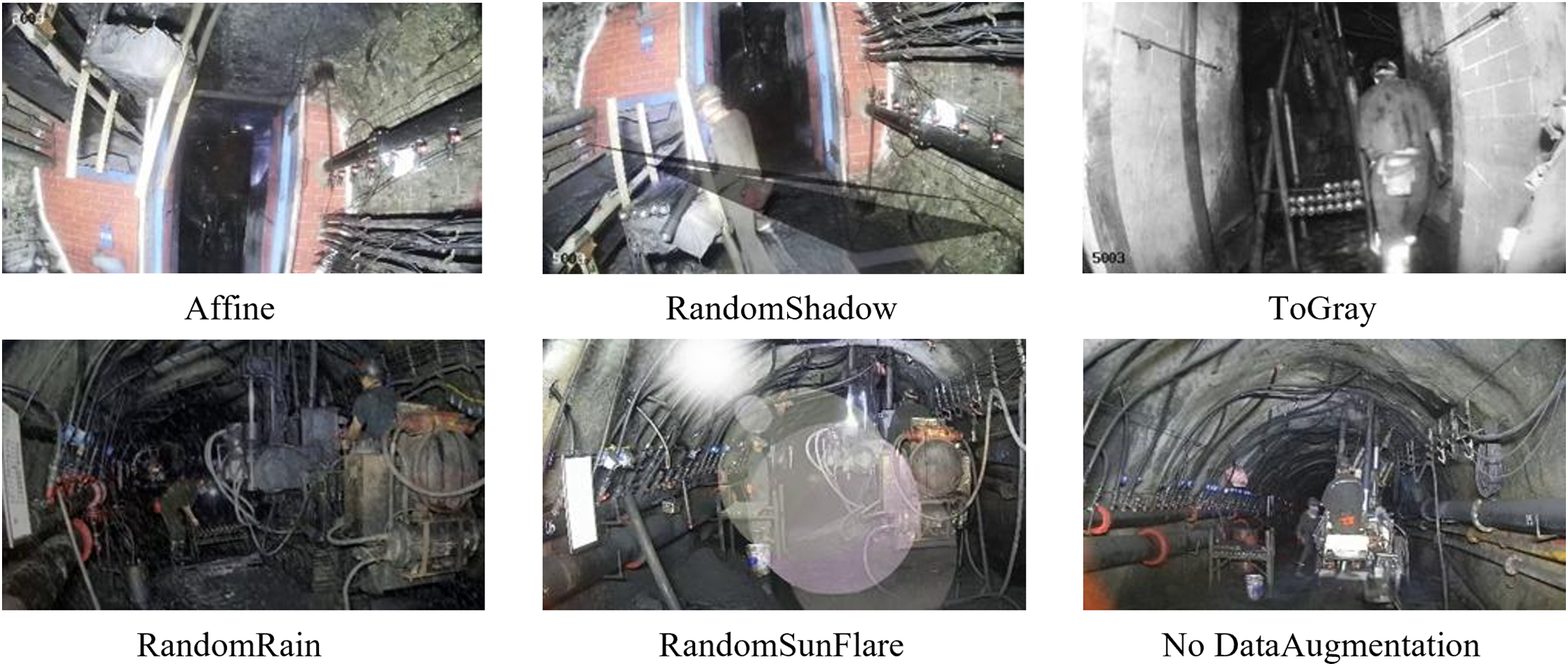

The experimental research adopts self-built dataset in this paper. The original data mainly comes from the drilling monitoring videos recorded on-site at Fengyang Coal Mine. After the completion of the video acquisition, frames are extracted to obtain a total of 2166 target images with a resolution of 1920 × 1080. Subsequently, the labeling tool X-AnyLabeling is employed to annotate the pipe head targets in the images. After the labeling is completed, the image labels in the txt format suitable for the YOLO model are directly exported. In order to further enrich the dataset and prevent overfitting of the model, it is necessary to carry out data augmentation on the original dataset. Data augmentation generates more diverse data by applying various transformation operations to the original data. The common data augmentation strategies in image data mainly include geometric transformation, spatial transformation, color transformation, noise addition, and blur processing. Fig. 8 presents the partially enhanced images and the original images in the dataset, using the following data augmentation methods:

Affine: Affine is a linear transformation that supports operations like scaling, rotation, translation, and cropping without altering the parallelism and proportion of the original image.

RandomShadow: Randomly generate shadow areas in the image to simulate the situation of uneven lighting (such as occlusion and projection) in real-world scenes.

ToGray: Convert the RGB image into a single-channel grayscale image to simulate infrared shooting effects.

RandomRain: Adding randomly distributed raindrop stripes to simulate the visual effect of sometimes blurry water mist in underground mine environment, similar methods include RandomFog and RandomSnow.

RandomSunFlare: Add randomly distributed solar halos to simulate the visual effect of strong light exposure in the underground environment of coal mines.

Data augmentation not only effectively expands the scale of the dataset but also enriches the diversity of the dataset. After data augmentation, the dataset comprises 8664 images in total. These are split into a training set (6931 images) and a validation set (1733 images) in an 8:2 ratio. The training set is utilized for optimization of the model and the validation set is used for evaluating the model’s performance.

Figure 8: Data augmentation examples

4.2 Experimental Environment and Training Parameters

The experimental setup in terms of software and hardware configuration is detailed as follows: The operating system employed is Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS. The deep learning framework uses Pytorch2.0.0. The CUDA version is 11.8. The GPU is NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 24 G and the CPU is Intel® Xeon® Platinum 8352V. For the model’s training parameters, the initial and final learning rates are both 0.01. The SGD optimizer is used, with a weight decay coefficient of 0.005 and a momentum factor of 0.937. The maximum number of training epochs is 300, the batch size is 32, and the workers are set to 16. The input image resolution for the model is 640 × 640 pixels.

To better evaluate the model’s performance, the present study uses commonly-recognized metrics in object detection, including Precision (P), Recall (R), mean Average Precision (mAP), and Frames Per Second (FPS). In the small target detection task of drill pipe head, since the pixel coverage of the target is relatively small, accurate positioning is of vital importance. At the same time, the challenge of missed detection in small target tasks is also quite prominent. Therefore, we take the mAP and Recall as the key indicators for assessing the performance of the object detection algorithm.

Precision (P) refers to the proportion of true positive samples among all the samples predicted as positive by the model. Recall (R) refers to the proportion of positive samples that are correctly predicted as positive by the model among all the actual positive samples. Their calculations are provided below, respectively:

Among them, TP (True Positive) stands for the true positive example, meaning the model correctly predicts an actual target as a target; FP (False Positive) stands for false positive example, meaning the model incorrectly predicts the background or other objects as the target; FN (False Negative) represents false negative example, that is, the model incorrectly predicts the target as the background or other objects.

The mAP is a comprehensive evaluation metric, where mAP@0.5 denotes the average precision when the IoU threshold is 0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95 represents the average precision under multiple thresholds (10 in total) with the IoU threshold ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 (step size of 0.05). The average precision quantifies the area formed by coordinate axes and Precision-Recall curve (PR curve). The calculation is provided below:

FPS denotes the number of image frames processed by the model in one second, which is the best metric to measure the model’s real-time capability. Given that mine monitoring videos have a capture frame rate of 30 frames per second, 30 FPS is taken in this paper as the standard that can satisfy real-time performance demands.

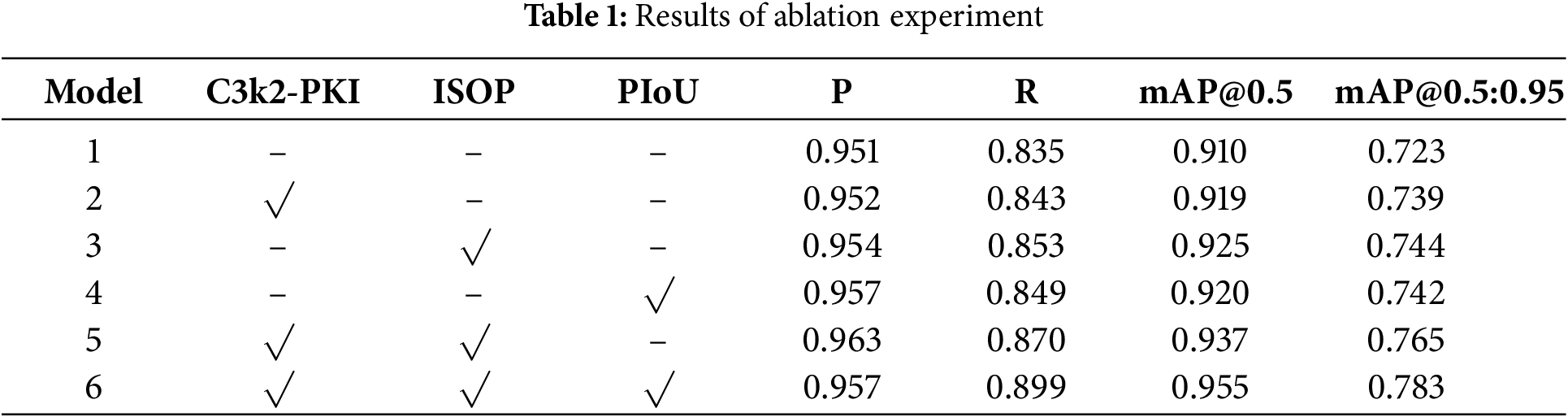

For the purpose of validating the efficacy of each enhancement strategy incorporated into the algorithm, this paper conducts the ablation experiment using YOLO11n as the baseline model. Table 1 presents the experimental results.

In the table, Model 1 represents the baseline model YOLO11n without adding any improvement strategies. Model 2 represents the introduction of the PKI Block on the basis of Model 1, which is used to improve C3k2 to enhance the feature extraction ability. The mAP@0.5:0.95 value has increased by 1.6% compared with the baseline model. Model 3 represents the improvement of the neck network based on Model 1, proposing a feature pyramid ISOP specifically for small targets, introducing SPDConv to enhance P2 layer features, and integrating feature representations more comprehensively based on CSP-OmniKernel. Compared with Model 1, Model 3 exhibits a 1.8% rise in Recall and a 2.1% increase in mAP@0.5:0.95. Model 4 uses PIoU instead of YOLO11n’s default loss function CIoU, resulting in more accurate predicted box localization. Compared with using CIoU, Precision increased by 0.6%, and the mAP@0.5:0.95 value saw a 1.9% rise. Model 5 represents the addition of ISOP on the basis of Model 2, further enhancing the small target features obtained by the backbone network. At this time, the precision reaches 96.3%, a 1.2% improvement over the baseline model, mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 values rise by 2.7% and 4.2%, respectively. Model 6 corresponds to the enhanced algorithm proposed in this study. Relative to Model 5, Model 6 substitutes the loss function with PIoU. Compared with the baseline model, the Recall reaches 89.9%, marking a 6.4 percentage points increase. The mAP@0.5 reaches 95.5%, an increase of 4.5 percentage points, and with a 6 percentage points increase, the mAP@0.5:0.95 reaches 78.3%, which fully demonstrates the effectiveness of each improvement point for the model.

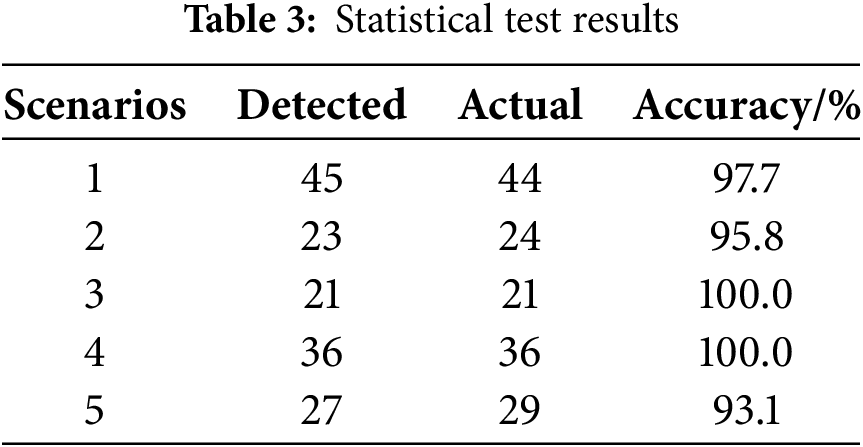

To highlight the performance of the enhanced algorithm, comparative experiments are conducted with other popular object detection algorithms under the same experimental environment. The detection results of each algorithm on the dataset are displayed in Table 2.

According to the table data, regarding the accuracy metrics, mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5, as key metrics for evaluating the model’s overall performance, the improved algorithm reached the highest level among the compared algorithms, with 95.5% and 78.3%, respectively. Compared with the baseline model, they have increased by 4.5% and 6%, respectively. Moreover, the Recall of our algorithm reached 89.9%, which is likewise the highest value among all algorithms under comparison. This indicates that the algorithm proposed significantly alleviates the problem of missed detection. The Precision of the algorithm in this study reaches 95.7%, which is only slightly lower than that of Mamba YOLO at 96.0%. However, with respect to Recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95 metrics, Mamba YOLO fails to match the algorithm proposed in this paper. In terms of FPS, although the inference speed of the algorithm in this study, which is 141 frames per second, is not as fast as that of YOLOv5, YOLOv8n, YOLOv10n, and YOLO11n, according to the acquisition rate of 30 frames per second for coal mine surveillance videos, the algorithm in this paper can still satisfy the demands of real-time detection very well. To summarize, the enhanced algorithm in this study achieves excellent performance with respect to Precision, Recall, mAP and other metrics. In particular, it reaches the highest values among the comparative experiments for the key metrics Recall and mAP. Meanwhile, with an inference speed of 141 FPS, the algorithm in this study can satisfactorily meet real-time detection requirements. Compared with other object detection algorithms, it strikes the best balance between performance and efficiency.

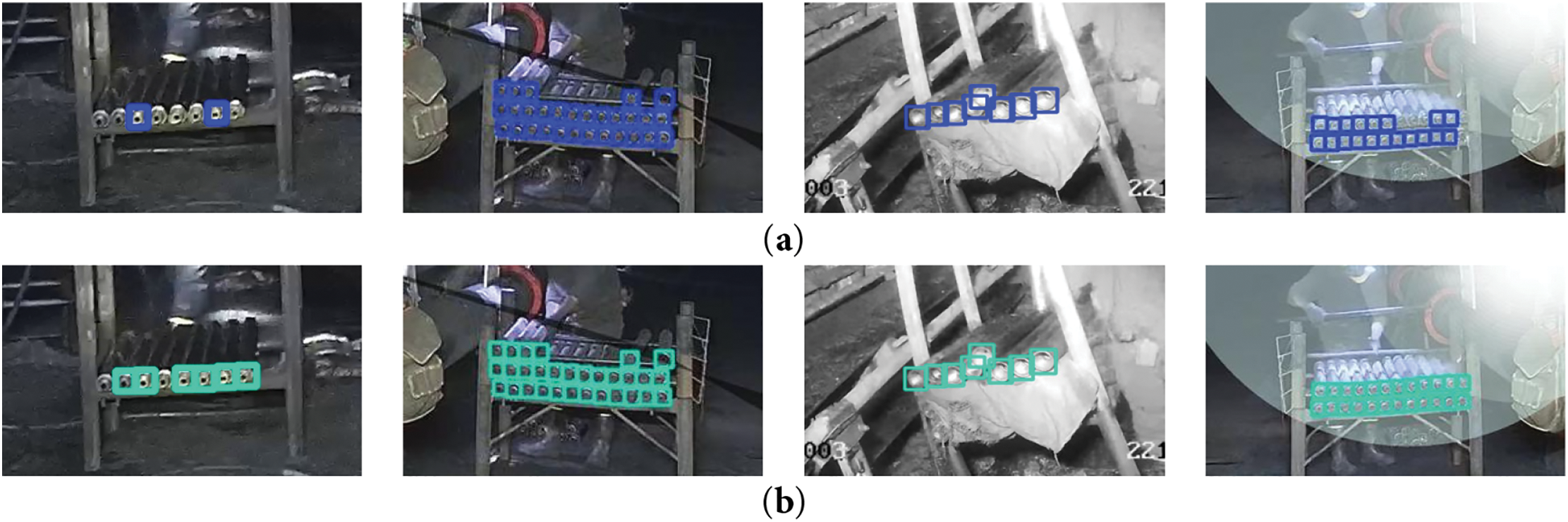

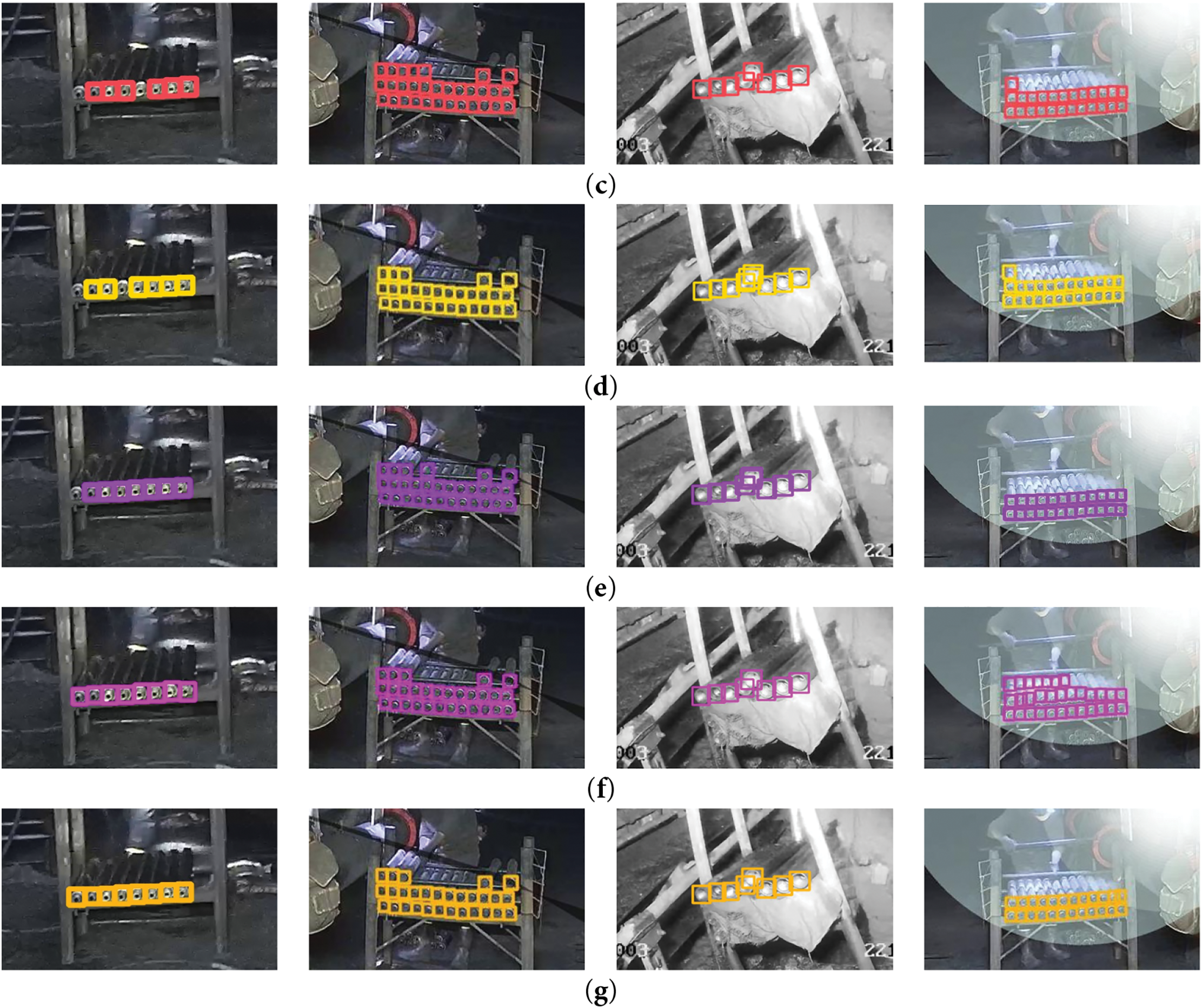

In order to more intuitively showcase the performance of different detection algorithms, Fig. 9 presents visual comparison detection effects of each algorithm in four different scenarios. Due to the target has small scale and concentrated distribution, we crop the images to retain only the detection areas, highlighting the visual comparison effect. Within the first detection scenario, the problem of missed detection is most pronounced in the YOLOv8n algorithm, with a total of 6 targets being missed. YOLOv9t, YOLOv10n, and YOLO11n all miss 2 targets, while YOLOv12n misses 1 target. Mamba YOLO and the algorithm put forward in this paper have the best detection performance, with all targets detected completely; The second scenario adds some random shadows, and YOLOv9t, YOLOv10n, and YOLOv12n have the problem of false detection of irrelevant backgrounds as targets; In the third scenario, data augmentation is used for grayscale processing. Most algorithms perform well in detection. However, YOLO11n and YOLOv12n are affected by grayscale and detected an additional target. The fourth scenario adds a data augmentation method that takes into account the influence of light sources and image mirroring. Mamba YOLO has 7 false positives, which is a relatively prominent issue. YOLOv10n and the baseline model YOLO11n also suffer from the problem of false detection. YOLOv8n, on the other hand, has the phenomenon of missed detection, with 5 targets being missed. YOLOv9t, YOLOv12n, and the algorithm put forward in this paper achieved complete and accurate detection results. Compared comprehensively, the enhanced YOLO11n algorithm proposed shows obvious advantages in accuracy and detection rate alike, fully verifying the effectiveness of algorithm optimization.

Figure 9: Visual comparison of detection results of various algorithms. (a) YOLOv8n; (b) YOLOv9t; (c) YOLOv10n; (d) YOLO11n; (e) YOLO12n; (f) Mamba YOLO; (g) ours

5 The Proposed Counting Method and Correction Mechanism

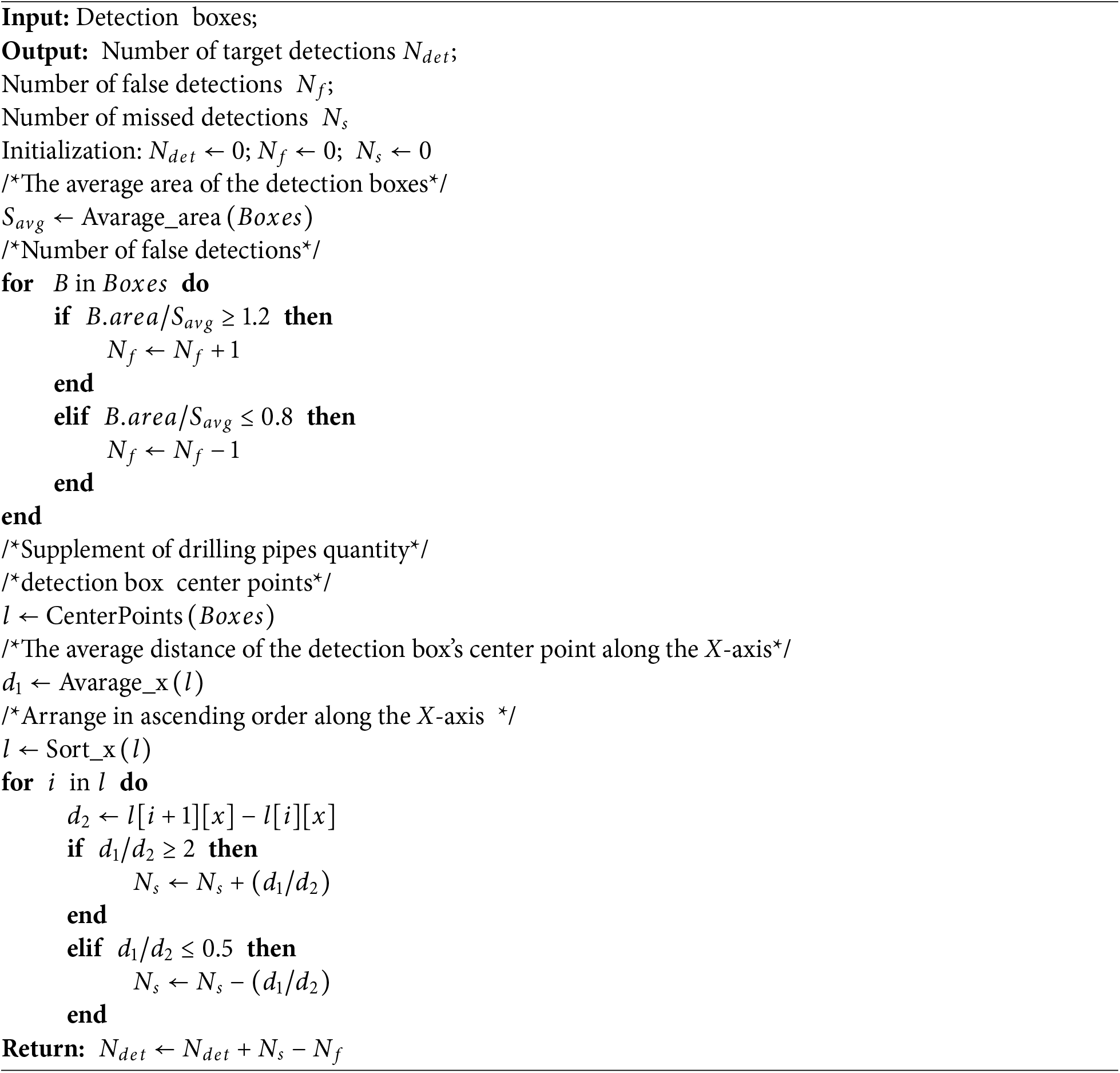

Inspired by the steel bar counting method, our proposed counting method calculates the number of drill pipes by counting detection boxes within a single frame image. However, unlike steel bar counting, changes in lighting conditions and worker occlusion in the drilling site can cause fluctuations in the quantity of detection boxes. The small scale and dense distribution of drill pipe head targets will lead to phenomena of false detection and missed detection. Therefore, in order to increase the accuracy of counting, we have added two optimization measures on the basis of counting the number of detection boxes:

(1) Correct the quantity of drill pipes according to their positional relationship.

(2) Calculate the average area of the detection boxes to eliminate the influence caused by false detection.

For the missed detection problem displayed in Fig. 10a, we define the average distance between all target boxes as d1 and the distance between adjacent target boxes as d2. When

Figure 10: Problems of missed detection and false detection

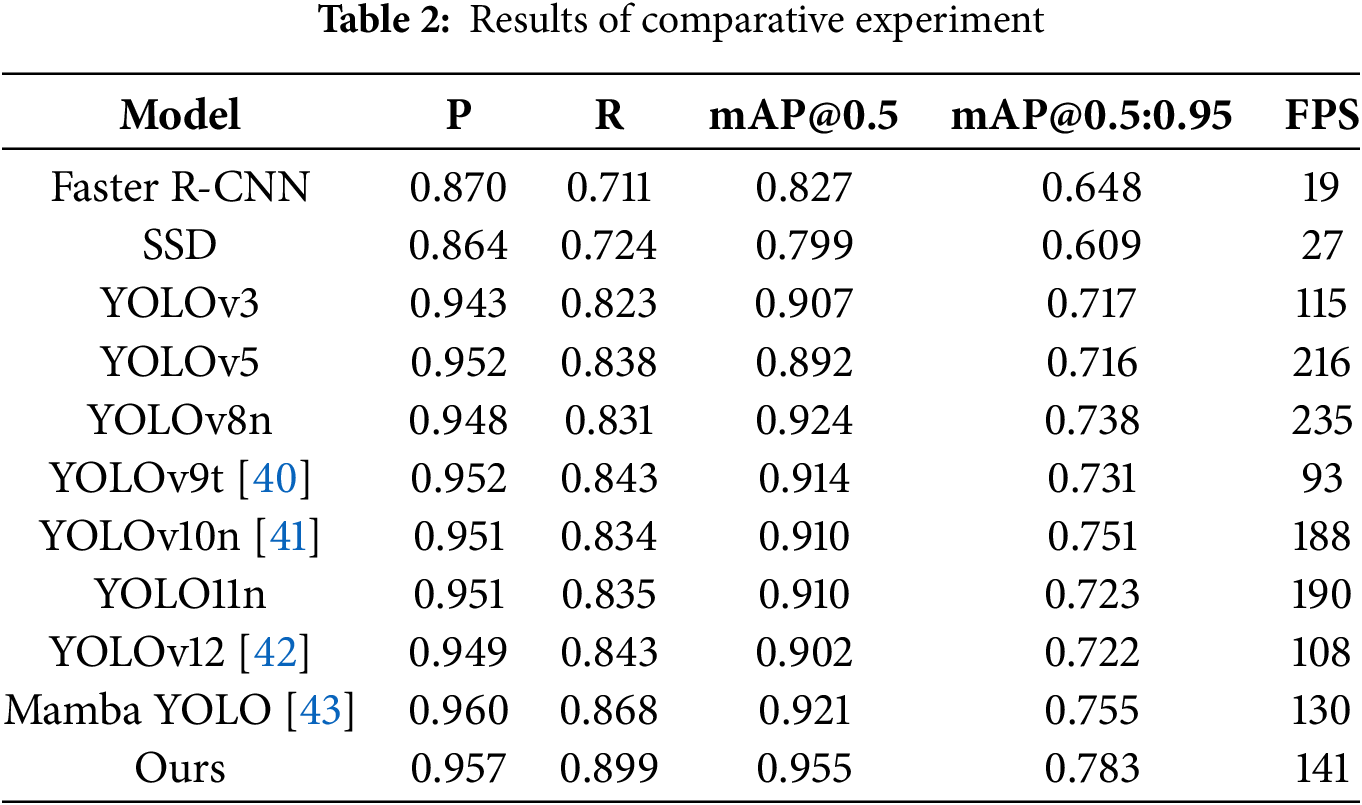

In addition, with the aim of testing the accuracy of the method proposed in this study, we selected drilling site videos from 5 different scenarios for counting. Table 3 illustrates the final test results, and the average accuracy of the method proposed reached 97.3%.

At coal mine drilling sites, manual drill pipe counting is highly susceptible to human error, often resulting in significant inaccuracies, low efficiency, and sometimes becoming merely a perfunctory exercise. To tackle these challenges, a drill pipe counting method based on the YOLO11n model is proposed in this paper. The quantity of drill pipes is determined by tallying the quantity of target boxes detected by the improved model, and a corresponding correction mechanism is designed to increase the accuracy of counting. For the purpose of improving the detection accuracy, we make three improvements to the YOLO11n model. The improvement strategies mainly include: introducing the PKI Block to improve the C3k2 module, capturing local and global context information features, and enhancing the target detection performance; proposing ISOP specifically for small targets, improving the neck network by introducing SPDConv to strengthen the features of the P2 layer, integrating multi-scale features based on CSP and OmniKernel; using PIoU to optimize the loss function and improving the positioning accuracy of the predicted box. The experimental findings demonstrate that the enhanced algorithm achieves superior performance in the challenging coal mine setting, effectively improving detection accuracy and mitigating the prevalent issues of missed and false detections in small target detection. Moreover, it fully satisfies the needs of real-time performance. According to the proposed implementation method and correction mechanism for drill pipe counting, the counting accuracy has reached 97.3% meeting the current accuracy requirements for drill pipe counting in drilling sites.

Although this paper has achieved certain results in the task of realizing intelligent drill pipe counting, there are still some deficiencies. For example, while the model’s accuracy has been improved via effective improvement strategies, its detection speed still leaves room for further enhancement. Going forward, we plan to proceed with pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation, among other aspects, to further increase the speed while ensuring the accuracy, and explore its lightweight edge deployment to be suitable for low computing power embedded devices in the underground mine.

Acknowledgement: We are very grateful to the editorial team as well as the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions on this paper.

Funding Statement: Henan Province University Science and Technology Innovation Team Support Program Project (22IRTSTHN005).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Miao Li and Xiaojun Li; methodology, Miao Li and Mingyang Zhao; data collection, Xiaojun Li and Mingyang Zhao; software and experiment, Miao Li; results analysis, Miao Li and Mingyang Zhao; supervision, Xiaojun Li; writing—original draft preparation, Miao Li; writing—review and editing, Miao Li, Xiaojun Li and Mingyang Zhao; funding acquisition, Xiaojun Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data can be provided upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhou A, Xu Z, Wang K, Wang Y, An J, Shi Z. Coal mine gas migration model establishment and gas extraction technology field application research. Fuel. 2023;349(3):128650. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2023.128650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhang K, Yang X, Xu L, Thé J, Tan Z, Yu H. Enhancing coal-gangue object detection using GAN-based data augmentation strategy with dual attention mechanism. Energy. 2024;287(2):129654. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.129654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang G, Ren H, Zhao G, Zhang D, Wen Z, Meng L, et al. Research and practice of intelligent coal mine technology systems in China. Int J Coal Sci Technol. 2022;9(1):24. doi:10.1007/s40789-022-00491-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mu H, Liu J, Guan Y, Chen W, Xu T, Wang Z. Slim-YOLO-PR_KD: an efficient pose-varied object detection method for underground coal mine. J Real-Time Image Process. 2024;21(5):160. doi:10.1007/s11554-024-01539-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yang T, Guo Y, Li D, Wang S. Vision-based obstacle detection in dangerous region of coal mine driverless rail electric locomotives. Measurement. 2025;239:115514. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li W, Gao Z, Feng G, Hao R, Zhou Y, Chen Y, et al. Damage characteristics and YOLO automated crack detection of fissured rock masses under true-triaxial mining unloading conditions. Eng Fract Mech. 2025;314(1):110790. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2024.110790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Imam M, Baïna K, Tabii Y, Ressami EM, Adlaoui Y, Boufousse S, et al. Integrating real-time pose estimation and PPE detection with cutting-edge deep learning for enhanced safety and rescue operations in the mining industry. Neurocomputing. 2025;618(3):129080. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.129080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 779–88. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Redmon J, Farhadi A. YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 7263–71. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Redmon J, Farhadi A. Yolov3: an incremental improvement. arXiv:1804.02767. 2018. [Google Scholar]

11. Zhang L, Sun Z, Tao H, Wang M, Yi W. Research on mine-personnel helmet detection based on multi-strategy-improved YOLOv11. Sensors. 2024;25(1):170. doi:10.3390/s25010170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Li J, Xie S, Zhou X, Zhang L, Li X. Real-time detection of coal mine safety helmet based on improved YOLOv8. J Real-Time Image Process. 2025;22(1):26. doi:10.1007/s11554-024-01604-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gao H, Zhao P, Yu Z, Xiao T, Li X, Li L. Coal mine conveyor belt foreign object detection based on feature enhancement and transformer. Coal Sci Technol. 2024;52(7):199–208. (In Chinese). doi:10.12438/cst.2023-1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang S, Zhu J, Li Z, Sun X, Wang G. GDPs-YOLO: an improved YOLOv8s for coal gangue detection. Int J Coal Prep Util. 2025;45(4):683–96. doi:10.1080/19392699.2024.2346626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Jin H, Ren S, Li S, Liu W. Research on mine personnel target detection method based on improved YOLOv8. Measurement. 2025;245(2):116624. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.116624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shao X, Liu S, Li X, Lyu Z, Li H. Rep-YOLO: an efficient detection method for mine personnel. J Real-Time Image Process. 2024;21(2):28. doi:10.1007/s11554-023-01407-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhao D, Su G, Cheng G, Wang P, Chen W, Yang Y. Research on real-time perception method of key targets in the comprehensive excavation working face of coal mine. Meas Sci Technol. 2023;35(1):015410. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ad060e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Xu S, Jiang W, Liu Q, Wang H, Zhang J, Li J, et al. Coal-rock interface real-time recognition based on the improved YOLO detection and bilateral segmentation network. Undergr Space. 2025;21(S1):22–43. doi:10.1016/j.undsp.2024.07.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Gu Q, Dong H, Li S, Yin H, Hong Y. Localization and mapping method of unmanned mine trucks on underground inclined slopes based on laser SLAM. Coal Sci Technol. 2024:1–12. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

20. Liu Y, Sun P, Wergeles N, Shang Y. A survey and performance evaluation of deep learning methods for small object detection. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;172(4):114602. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.114602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xu S, Gu J, Zhuang L, Li N, Shi L, Liu Y. Small object detection based on two-stage calculation transformer. J Front Comput Sci Technol. 2023;17(12):2967–83. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

22. Xu S, Gu J, Hua Y, Liu Y. DKTNet: dual-key transformer network for small object detection. Neurocomputing. 2023;525(3):29–41. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.01.055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang Y, Ye M, Zhu G, Liu Y, Guo P, Yan J. FFCA-YOLO for small object detection in remote sensing images. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62:1–15. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2024.3363057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Tang S, Zhang S, Fang Y. HIC-YOLOv5: improved YOLOv5 for small object detection. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2024 May 13–17; Yokohama, Japan. doi:10.1109/ICRA57147.2024.10610273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sun L, Shen Y. Intelligent monitoring of small target detection using YOLOv8. Alex Eng J. 2025;112(9):701–10. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.10.114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang Y, Zhang H, Huang Q, Han Y, Zhao M. DsP-YOLO: an anchor-free network with DsPAN for small object detection of multiscale defects. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;241(13):122669. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Gao R, Hao L, Liu B, Wen J, Chen Y. Research on underground drill pipe counting method based on improved ResNet network. Ind Mine Autom. 2020;46(10):32–7. (In Chinese). doi:10.13272/j.issn.1671-251x.2020040054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ran Q, Dong L, Wen N. Improved YOLOv8 method for counting drill rods in low-light images in coal mines. Electron Meas Technol. 2025;48(11):155–65. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

29. Cheng C, Cheng X, Li D, Zhang J. Drill pipe detection and counting based on improved YOLOv11 and Savitzky-Golay. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):16779. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-01776-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Chen T, Dong L, She X. Research on automatic counting of drill pipes for underground gas drainage in coal mines based on YOLOv7-GFCA model. Appl Sci. 2023;13(18):10240. doi:10.3390/app131810240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Jiang Y, Liu S. A coal mine underground drill pipes counting method based on improved YOLOv8n. J Mine Autom. 2024;50(8):112–9. (In Chinese). doi:10.13272/j.issn.1671-251x.2024040073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Du J, Dang M, Qiao L, Wei M, Hao L. Drill pipe counting method based on improved spatial-temporal graph convolution neural network. J Mine Autom. 2023;49(1):90–8. (In Chinese). doi:10.13272/j.issn.1671-251x.2022030098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Cai X, Lai Q, Wang Y, Wang W, Sun Z, Yao Y. Poly kernel inception network for remote sensing detection. In: 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.02617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chai Z, Zheng T, Lu F. StarCAN-PFD: an efficient and simplified multi-scale feature detection network for small objects in complex scenarios. Electronics. 2024;13(15):3076. doi:10.3390/electronics13153076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Sunkara R, Luo T. No more strided convolutions or pooling: a new CNN building block for low-resolution images and small objects. In: Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases; 2022 Sep 19–23; Grenoble, France. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2022. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-26409-2_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Cui Y, Ren W, Knoll A. Omni-kernel network for image restoration. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2024;38(2):1426–34. doi:10.1609/aaai.v38i2.27907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wang C, Liao H, Wu Y, Chen P, Hsieh J, Yeh I. CSPNet: a new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2020 Jun 14–19; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPRW50498.2020.00203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zhang Z, Wang P, Liu W, Li J, Ye R, Ren D. Distance-IoU loss: faster and better learning for bounding box regression. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(7):12993–3000. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i07.6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Liu C, Wang K, Li Q, Zhao F, Zhao K, Ma H. Powerful-IoU: more straightforward and faster bounding box regression loss with a nonmonotonic focusing mechanism. Neural Netw. 2024;170(2):276–84. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2023.11.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Wang C, Yeh I, Liao H. Yolov9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In: European Conference on Computer Vision; 2024 Sep 29–Oct 4; Milan, Italy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024. p. 1–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-72751-1_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wang A, Chen H, Liu L, Chen K, Lin Z, Han J, et al. Yolov10: real-time end-to-end object detection. In: 38th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2024); 2024 Dec 10–15; Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

42. Tian Y, Ye Q, Doermann D. YOLOv12: attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv:2502.12524. 2025. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2502.12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wang Z, Li C, Xu H, Zhu X, Li H. Mamba YOLO: a simple baseline for object detection with state space model. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2025;39(8):8205–13. doi:10.1609/aaai.v39i8.32885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools