Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Phase Field Simulation of Fracture Behavior in Shape Memory Alloys and Shape Memory Ceramics: A Review

1 Failure Mechanics and Engineering Disaster Prevention Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, Sichuan University, Chengdu, 610065, China

2 Sichuan Province Key Laboratory of Advanced Structural Materials Mechanical Behavior and Service Safety, School of Mechanics and Aerospace Engineering, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, 610031, China

* Corresponding Author: Bo Xu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Computational Modeling of Mechanical Behavior of Advanced Materials)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 65-88. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068226

Received 23 May 2025; Accepted 11 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Shape memory alloys (SMAs) and shape memory ceramics (SMCs) exhibit high recovery ability due to the martensitic transformation, which complicates the fracture mechanism of SMAs and SMCs. The phase field method, as a powerful numerical simulation tool, can efficiently resolve the microstructural evolution, multi-field coupling effects, and fracture behavior of SMAs and SMCs. This review begins by presenting the fundamental theoretical framework of the fracture phase field method as applied to SMAs and SMCs, covering key aspects such as the phase field modeling of martensitic transformation and brittle fracture. Subsequently, it systematically examines the phase field simulations of fracture behaviors in SMAs and SMCs, with particular emphasis on how crystallographic orientation, grain size, and grain boundary properties influence the crack propagation. Additionally, the interplay between martensite transformation and fracture mechanisms is analyzed to provide deeper insights into the material responses under mechanical loading. Finally, the review explores future prospects and emerging trends in phase field simulations of SMA and SMC fracture behavior, along with potential advancements in the fracture phase field method itself, including multi-physics coupling and enhanced computational efficiency for large-scale simulations.Keywords

Fracture mechanics, which originated during the intense post-World War II era, has remained vigorous vitality and dynamic development [1]. This field focuses on investigating crack initiation, propagation, and eventual material/structural failure under the combined effects of external stress, temperature, defects, and other factors [2–4]. Its fundamental objective is to characterize and predict fracture behavior to enhance structural safety and operational reliability [5].

To address complex fracture challenges, a multi-dimensional analytical framework has been developed. The linear elastic fracture mechanics establishes quantitative models for crack propagation in elastic materials [6,7], while elastic-plastic fracture mechanics accurately characterizes fracture behavior in materials exhibiting plastic deformation [8]. Based on the fatigue fracture analysis methods, the failure mechanisms, crack growth rates, and fatigue life predictions can be revealed through cyclic loading experiments [9]. Through the probabilistic models based on statistical mechanics, the influence of microstructural defect distributions on crack propagation paths can be effectively quantified [10]. Additionally, multi-scale and multi-physics numerical approaches (e.g., the extended finite element method) provide high-precision simulation platforms for engineering fracture prediction [11–13]. These methods synergize to complement one another, i.e., the combined application of linear elastic fracture mechanics and elastic-plastic fracture mechanics comprehensively resolves fracture dynamics under high strain rates and complex stress states [14], while integrating fatigue analysis with statistical methods significantly improves reliability assessments of structural failure risks under cyclic loading [15].

Despite the success of traditional fracture mechanics in certain applications, its limitations become evident when addressing the phase interface effects, i.e., it is difficult to accurately describe stress redistribution induced by phase transformation and its impact on fracture behavior. Furthermore, uncertainties in material parameter determination and calibration hinder the accuracy and stability of the models. In this context, the phase field method overcomes the shortcomings of traditional approaches in crack path tracking and tip singularity handling by introducing continuous damage variables (fracture order parameters) [16–18]. This method not only efficiently resolves dynamic fracture problems but also demonstrates superior computational accuracy and efficiency in aerospace [19,20], energy [21,22], civil engineering [23,24], and biomedical applications [25]. Compared to conventional methods, the phase field method for fracture offers enhanced adaptability, naturally describing crack nucleation, propagation, and bifurcation without predefined crack paths or supplementary fracture criteria.

Shape memory alloys (SMAs) and shape memory ceramics (SMCs) can experience solid-to-solid phase transformations within specific temperature ranges, accompanied by significant latent heat absorption/release, and stress redistribution. In the phase transformation processes, the crack initiation and propagation can generally occur at phase interfaces [26–28]. The participation of martensitic transformation (MT) leads to a more complex fracture mechanism of SMAs and SMCs compared to general brittle and elastoplastic materials, and it is difficult to reflect the microstructure-dependent fracture mechanism through traditional fracture mechanics methods. Owing to abovementioned advantages of phase field method, it holds exceptional promise for the fracture behavior of SMAs and SMCs.

This review summarizes the application of the phase field method for fracture in SMAs and SMCs, with a focus on utilizing this method to predict and analyze crack initiation and propagation under mechanical loading. Firstly, the fundamentals of phase field theory for the fracture of SMAs and SMCs are introduced (Section 2); then, the phase field simulations of the fracture behaviors in SMAs and SMCs are reviewed by addressing the effects of crystallographic orientation, grain size, grain boundary, etc. (Sections 3 and 4); finally, the prospects and potential trends for phase field simulations of the fracture behavior of SMAs and SMCs, as well as future development direction of the fracture phase field method are discussed (Section 5).

2 Fundamentals of Phase Field Theory for the Fracture of SMAs and SMCs

The phase field method for the fracture of SMAs and SMCs is a multi-physics simulation framework constructed by coupling the phase field models of MT and fracture. Its core feature lies in introducing an order parameter to describe the continuous evolution from intact to fractured material states and some other order parameters to describe the MT. The phase field model coupling MT and fracture can effectively describe complex fracture behaviors in the presence of MT.

The application of phase field method to fracture analysis in SMAs and SMCs emerged relatively late. In 2018, Zhao et al. [29] first developed a coupled phase field model to investigate the fracture behavior accompanied by MT in a single-crystal zirconia. By unifying the description of MT and crack propagation through different order parameters, this pioneering work established the theoretical foundation for subsequent researches. In 2020, Zhu and Luo [30] improved the model of Zhao et al. [29], proposing a simplified phase field framework based on the energy minimization principle. This refined model enhanced the computational efficiency by appropriately decoupling the interactions between MT potential functions and fracture energy while preserving physical consistency in MT and fracture processes. The phase field models that describe MT and fracture, as well as their coupling will be briefly introduced in the following sections.

2.1 Phase Field Model for Martensitic Transformation (MT)

In phase field modeling of MT, the non-conserved order parameters

The chemical free energy term

where

The elastic strain energy

where

where

2.2 Phase Field Model for Fracture

Based on the fracture phase field theoretical framework developed by Hou et al. [37], a double-well order parameter

The gradient energy density

The local free energy density

where

Coupled with the order parameter, the elastic energy density is defined as:

where

To eliminate unphysical compressive fracture behavior, Hou et al. [37] incorporate the strain decomposition concept from Amor et al. [40], splitting the elastic energy density into two components:

where

where

2.3 Phase Field Model Coupling Martensitic Transformation and Fracture

The coupling between MT and crack propagation, as critical microscopic mechanisms of fracture in the materials with MT, has been experimentally and numerically validated. To quantitatively characterize the coupling mechanism between MT and fracture, Zhu and Luo [30] established the coupled phase field model integrating MT and fracture, describing their interactions through a unified free energy functional:

The specific forms of the energy terms are as follows:

Phase transformation chemical free energy (inherited from Eq. (2)):

Crack gradient energy (modified from Eq. (6)):

Crack local energy (inherited from Eq. (7)):

Elastic energy (improved from Eq. (9)):

The evolution of order parameters are governed via the time-dependent Ginzburg-Landau (TDGL) equations:

where L and M are the kinetic coefficients.

The mechanical equilibrium condition is written as:

The Cauchy stress tensor

where

2.4 Recent Developments in Fracture Phase Field Models for SMAs and SMCs

Considering the coupling characteristics and energy equation definitions of phase field method, this method can be adapted to construct application-specific phase field models through appropriate modifications. Leveraging this flexibility, researchers have focused on enhancing simulation accuracy by integrating advanced theories and technologies to optimize and innovate the phase field models coupling MT and fracture, thereby advancing the development of phase field method.

The advancement of fracture phase field method has consistently aimed at simulating and predicting crack propagation in complex environments. Schmitt et al. [41] developed a MT-damage coupled phase field model to address tension-compression asymmetry induced by transformation-induced eigenstrain during MT [42]. This model successfully revealed the dynamic interactions between microcrack propagation and martensite formation. A damage variable

where

Kavvadias and Baxevanis [44] developed a thermo-mechanical fracture phase field model for single-crystal NiTi alloys under quasi-static loading (neglecting latent heat), slow thermal loading (assuming uniform temperature distribution), and metastable austenite temperature constraints. Two critical mechanisms were introduced into the model, i.e., a rule-of-mixtures-based coupling of reversible MT and a constitutive law of austenite plasticity formulated via kinematic decomposition of strains [45]. To improve the coupling accuracy, an interaction term was incorporated into the free energy expression derived from Mori-Tanaka and Kröner’s micromechanical assumptions [46]:

where

The phase field method provides an effective approach for modeling the fatigue crack propagation behavior. Simoes and Martínez-Pañeda [47] developed a phase field framework incorporating elastic strain energy and transformation strain energy, based on an SMA constitutive model that considers both constant fracture energy and the fracture energy dependent on the martensitic volume fraction (via a rule of mixtures). By implementing an efficient implicit time integration scheme, Simoes and Martínez-Pañeda [47] successfully addressed the fatigue fracture problems under complex boundary conditions. Numerical validation demonstrated the model’s exceptional capability in simulating multi-crack propagation in SMAs. Hasan et al. [48] proposed two innovative models: In the first one, a fatigue history variable was introduced to modify the fracture toughness parameters, accurately reproducing the characteristics of experimental Wöhler curve [49]; in the second one, a finite-strain formulation that coupled reversible MT, martensite reorientation, temperature- and load-dependent hysteresis width, as well as asymmetry between forward and reverse MT was developed, enabling precise predictions of complex MT-fracture interactions.

Recently, the phase field model in fatigue fracture modeling have been further advanced. Simoes et al. [50] established a generalized numerical framework combining phase-field fracture theory, a Drucker-Prager-based constitutive model for SMAs, and fatigue degradation functions. They incorporated AT1 and AT2 phase field methods [51,52], establishing a universal methodology. The bulk energy density and surface energy density were introduced into the governing equations, along with a fatigue degradation function, enabling multi-physics coupling analysis. For the fatigue degradation, the asymptotic analysis of Carrara et al. [53] inspired the adoption of a piecewise function:

where the fatigue threshold parameter

From an energy evolution perspective, Abdollahi and Arias [54] developed a phase field model for the crack propagation in ferroelectric anisotropic polycrystalline BaTiO3. A modified fracture surface energy

Expanding the energy framework, Zhen et al. [56] developed a thermodynamically consistent non-isothermal fracture phase field model through rigorous derivation of the Helmholtz free energy function and dissipation inequalities from non-equilibrium thermodynamics. The intricate coupling effects among crack propagation, MT and thermal conduction was well reflected by such a model. This approach provides a comprehensive framework for probing spatiotemporal evolution of multi-physics interactions under thermo-mechanical coupling. Zhu et al. [57] advanced the models of Zhao et al. [29] and Zhu and Luo [30] with four key enhancements, i.e., a temperature-dependent free energy functional, the differentiation of interfacial energy between different phases, an extra GB constraint energy terms, and a single-well potential phase field method, ultimately constructing a multi-mechanism coupled fracture phase field model for tetragonal zirconia polycrystals (TZPs).

Moshkelgosha and Mamivand [58] unified the Ginzburg-Landau theory of MT with variational principles of brittle fracture, establishing a multiphysics fracture phase field model for TZPs. This model accurately captured two dominant fracture mechanisms, i.e., secondary crack nucleation and propagation before main crack propagation, and crack branching. Significantly, Lotfolahpour et al. [59] modified the chemical free energy term in the fracture phase field model to ensure physically consistent elastic responses before the MT onset, enabling predictions of realistic mechanical behavior and experimentally observed microstructures. Pang et al. [60] developed a multiphase phase field model for thermal-shock fracture in multilayered ceramics, incorporating temperature-dependent material properties and the residual stresses caused by MT. The simulations accurately replicated the crack deflection induced by compressive stress redistribution during thermal shock, establishing a reference standard for ceramic thermal shock failure analysis. Xiong et al. [61] pioneered the coupling of crystal plasticity theory (encompassing dislocation slip, deformation twinning, and GB plasticity) with the fracture phase field model to dynamically capture the interplay between crack propagation and microstructural evolution in the NiTi SMAs under cyclic loading. They further formulated the non-isothermal thermo-mechanical coupling equations to simulate the latent heat effect on the dynamic crack propagation [61]. By introducing a GB energy function, they quantitatively characterized the GB suppression of MT and elucidated the role of grain refinement in modulating crack propagation rates and fracture modes (transgranular → intergranular) [61].

The groundbreaking progress in three-dimensional (3D) fracture modeling has been achieved through the phase field method. Moshkelgosha and Mamivand [62] integrated variational principles for brittle fracture with MT dynamics governed by Ginzburg-Landau equations, establishing a 3D phase field model that successfully revealed the microscopic fracture mechanisms of SMCs. Clayton and Knap [63] derived the governing equations for quasi-static loading using variational methods and incorporated the anisotropic fracture surface energy within a 3D framework, enabling directional crack propagation along low-energy cleavage planes. Their simulations demonstrated that the fracture velocity increased when the fracture energy equaled twin boundary energy, while the twin-induced crack propagation decelerated when the fracture energy significantly exceeds the twin boundary energy. Xiong et al. [64] developed a 3D non-isothermal fracture phase field model for polycrystalline NiTi SMAs, which could reflect the crack propagation-MT interaction mechanisms. Numerical results verified the model’s capability to reasonably predict the MT evolution, temperature distribution, and multi-field coupling during crack propagation under varying grain sizes (GSs) and loading rates, providing critical theoretical guidance for SMA engineering applications.

The variational principles for multi-physics coupling have been continued to refine. Moshkelgosha and Mamivand [65] developed a coupled variational framework for MT and brittle fracture, analyzing the tetragonal-to-monoclinic MT during the crack propagation in single-crystal zirconia. Their follow-up work [66] optimized the computational efficiency of the fracture phase field model, enhancing the predictions of crack initiation and propagation. These studies demonstrated the critical role of MT in fracture toughening and crack path selection. The validation of unconventional crack trajectories reinforced the importance of MT mechanisms in brittle fracture analysis. Moshkelgosha and Mamivand [58] coupled MT dynamics with brittle fracture variational theory, constructing a multi-physics model for TZPs. By introducing a GB energy dissipation tensor, the model resolved the competition between MT-induced microcracks and main crack propagation. Farahani et al. [67] developed a strongly coupled system of TDGL equations and mechanical equilibrium from micro-elasticity theory. The innovation lies in introducing a damage tensor as a mesoscale link between MT and fracture, enabling direct observation of energy dissipation mechanisms during MT.

In finite-strain modeling, Hasan et al. [68] innovatively integrated Hencky strain measures with objective rate tensors to develop an advanced fracture phase field model for the thermomechanical fracture in SMAs. This model could reflect the MT and reorientation of martensite variants initiating from a self-accommodated state. However, it is currently limited to quasi-static mechanical loading (neglecting latent heat effects) and slow thermal conduction (with weakened thermal gradient assumptions), highlighting critical directions for future research. In the future, the phase field models for the fracture behaviors of SMAs and SMCs still needs to be further improved and developed.

3 Phase Field Simulations of Fracture Behavior in SMAs

The unique MT characteristics of SMAs have demonstrated significant application potential in civil engineering [69], aerospace [70,71] and biomedical applications [72,73]. However, the complex mechanical behaviors during the MT pose critical challenges to material performance [74,75]. Recent investigations have revealed that the MT regions often develop residual stress fields and microstructural defects due to incomplete MT and multi-variant martensite coexistence [76]. These microstructural defects not only deteriorate mechanical properties but also act as nucleation sites for macrocracks, leading to premature failure.

To overcome these limitations, the phase field method has emerged as a powerful numerical tool for studying the fracture behavior of SMAs, owing to its inherent advantages in multi-physics coupling. This section will systematically review recent advances in phase field applications for the fracture behavior of SMAs, focusing on the factors affecting crack extension, including crystallographic orientation and grain size, as well as the fatigue fracture.

3.1 Fracture Behavior of Single-Crystal SMAs: Effect of Crystallographic Orientation

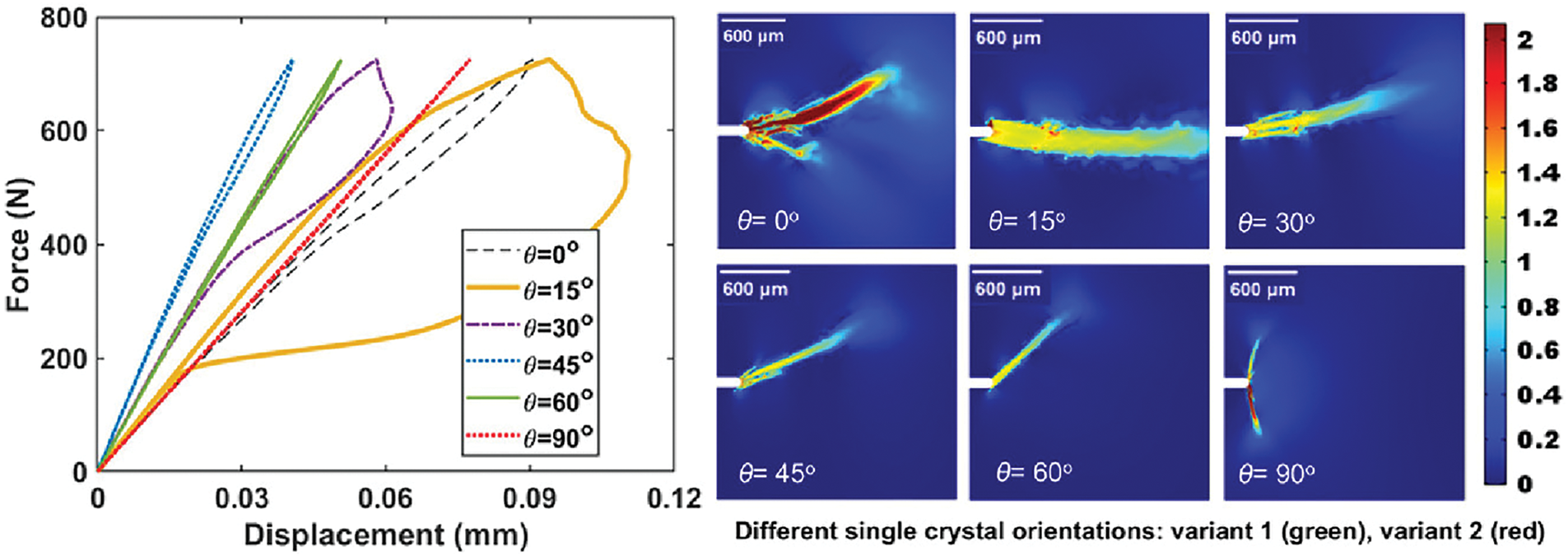

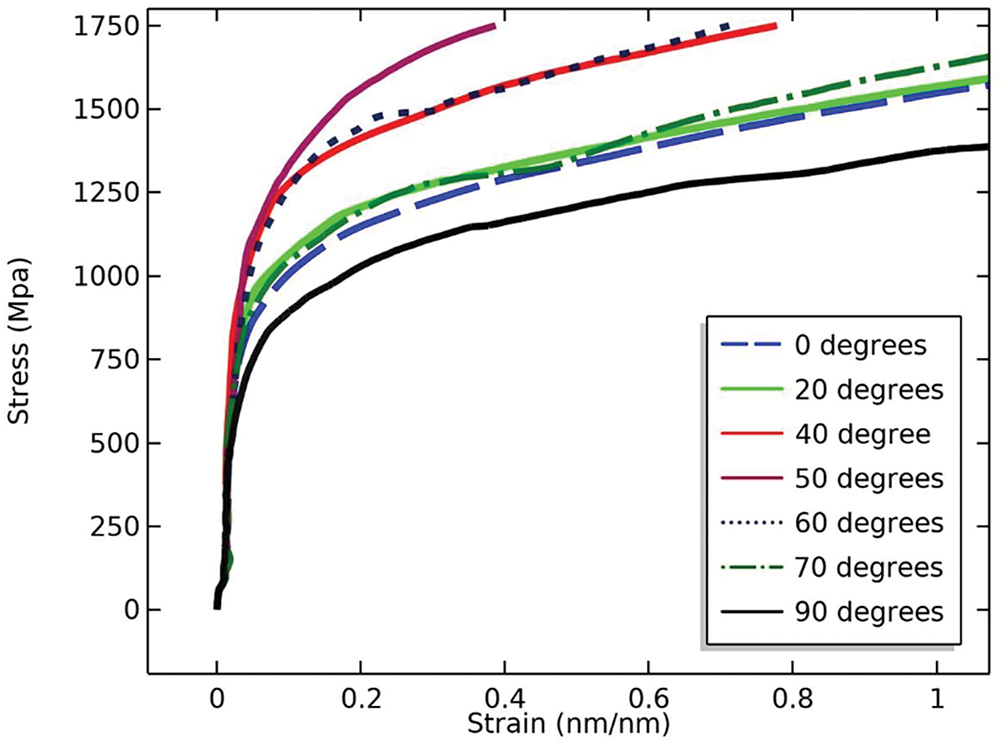

The fracture behavior single crystal SMAs that is relatively easy to handle has attracted attention first. Relevant phase field studies have discussed the influence law of crystallographic orientation on the fracture behavior and the underlying mechanism. Cissé and Zaeem [77] investigated the influence of crystallographic orientation on the crack tip toughening in CuAlBe SMAs through phase field simulations. Their study revealed a strong correlation between MT-induced toughening and the orientation angle of single-crystal SMAs (i.e.,

Figure 1: Load-displacement curves for varying crystallographic orientations in CuAlBe SMAs (Cited from Cissé and Zaeem [77]). Right panels show the martensite microstructures (

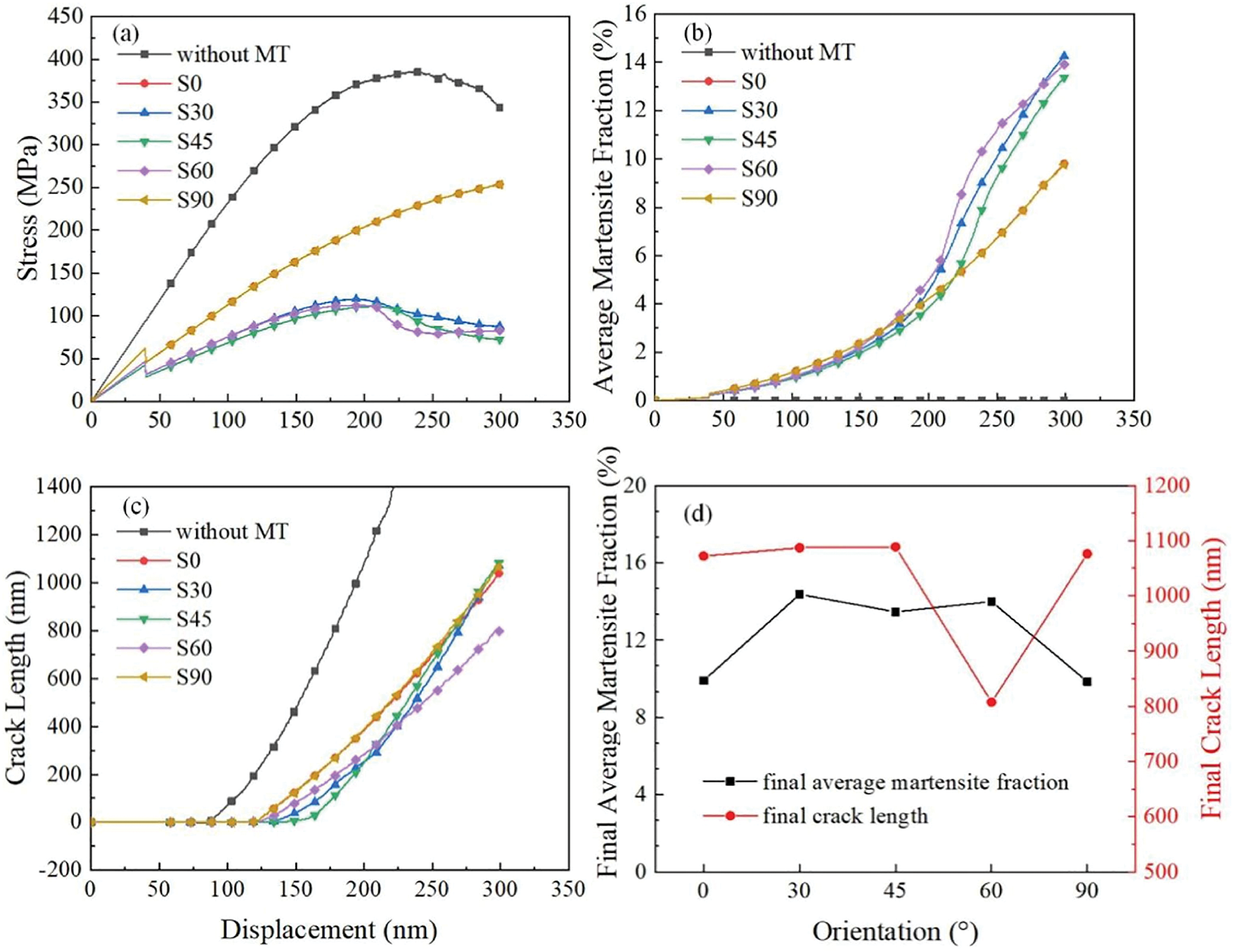

Xiong et al. [78] employed phase field simulations to study the crack propagation and MT-induced toughening in the single-crystal NiTi SMAs with varying crystallographic orientations (S0, S30, S45, S60, S90) and temperatures. The key findings include that: when the temperature exceeded the chemical equilibrium temperature (

Figure 2: Comparative simulation results for the single-crystal NiTi SMAs with different crystallographic orientations (Cited from Xiong et al. [78]): (a) Stress-displacement curves; (b) average martensite fraction vs. displacement; (c) crack length vs. displacement (excluding initial crack length, and full curves for non-MT systems omitted to highlight MT effects); (d) final martensite fraction and crack length post-loading

3.2 Fracture Behavior of Polycrystalline SMAs: Effect of Grain Size

Although the influence of crystallographic orientation on the fracture behavior of single-crystal SMAs has been simulated and discussed via phase field method (Section 3.1), the SMAs in practical applications are almost all polycrystalline materials, whose fracture behaviors are quite different from those of single crystals and more complex. Therefore, the fracture behavior of polycrystalline SMAs has been addressed, and the effect of grain size has been given key consideration.

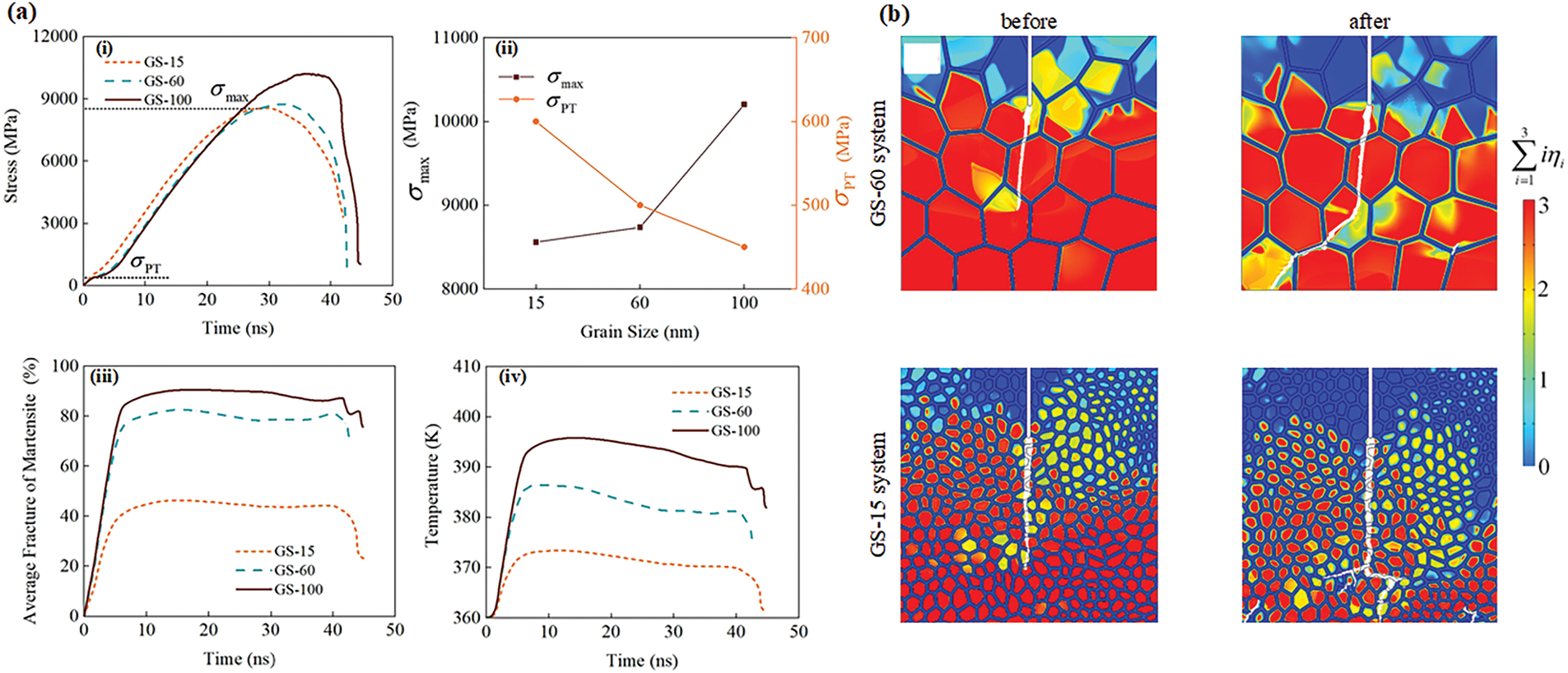

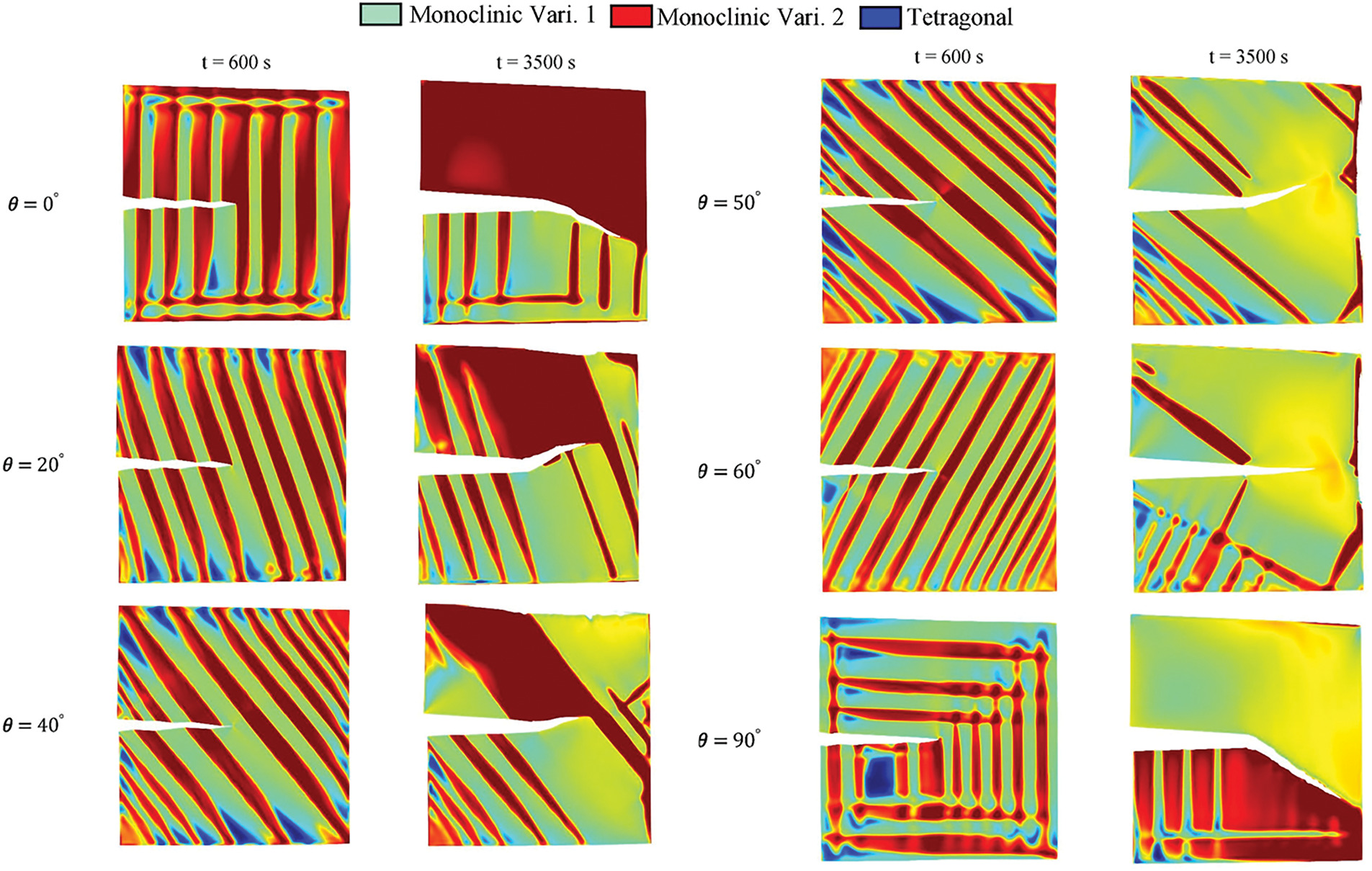

Using a 3D non-isothermal fracture phase field model, Xiong et al. [64] systematically investigated the synergistic effects of GS and loading rate on the crack propagation in polycrystalline NiTi SMAs. The study revealed that increasing GS significantly improves the peak stress (Fig. 3a(i)) and fracture toughness while reducing the MT initiation stress (i.e.,

Figure 3: Simulated crack propagation in polycrystalline NiTi SMAs with varying GSs under a loading rate of

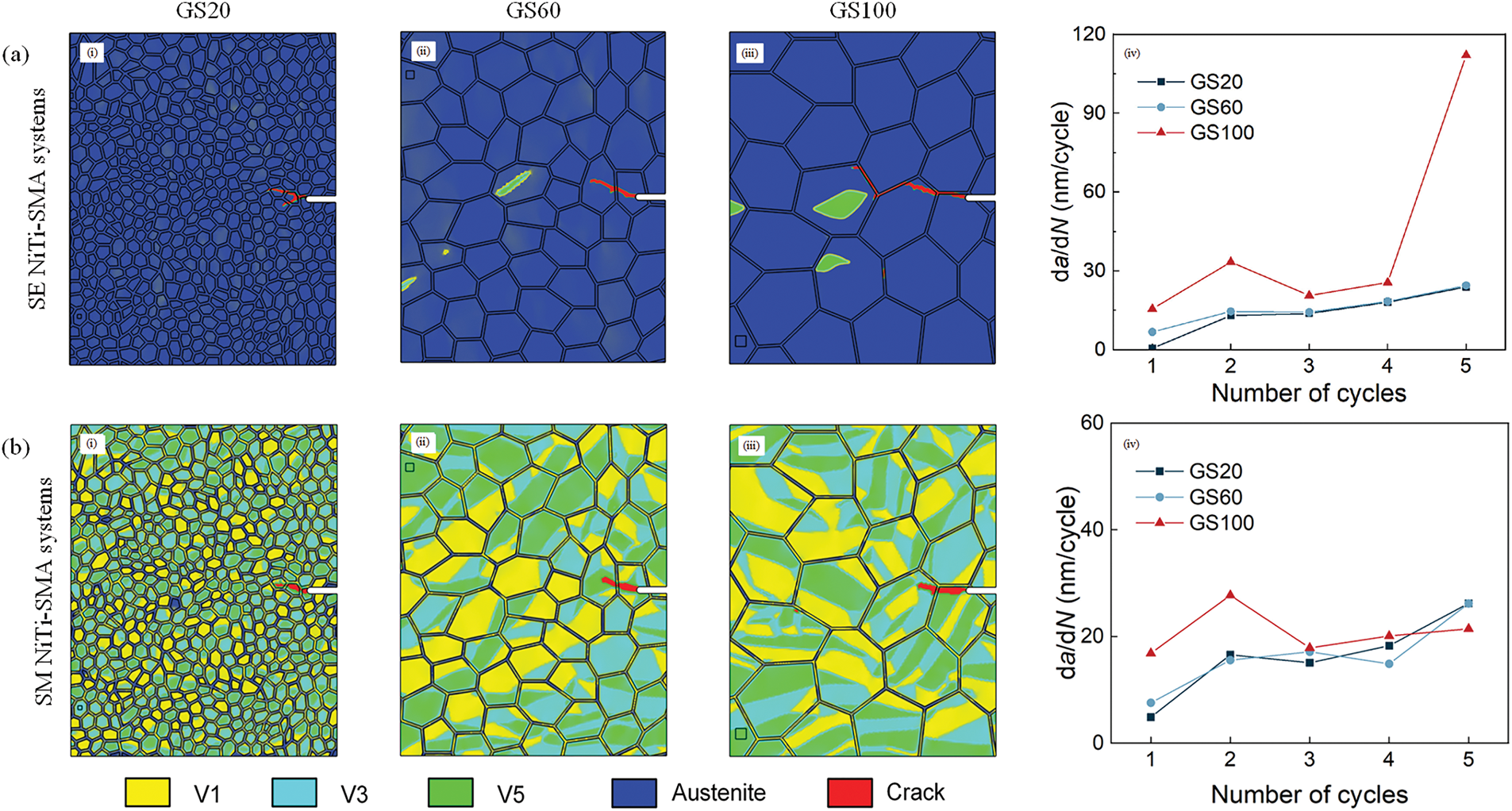

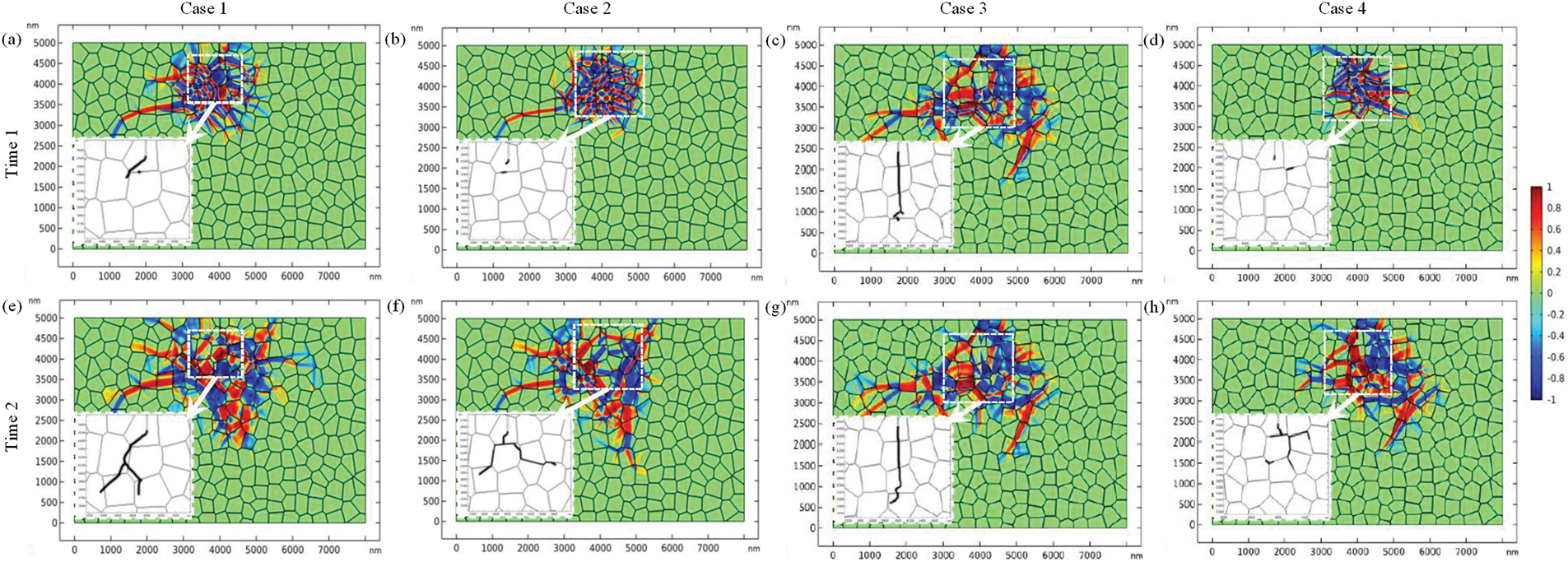

Xiong et al. [61] further quantified the GS effects on the dislocation resistance, elucidating how grain refinement reduces the crack propagation rates and shifts fracture modes from intergranular to transgranular. For superelastic (SE) NiTi SMA (Fig. 4a), increasing GS markedly elevates crack propagation rates (i.e.,

Figure 4: Crack propagation behavior and growth rates (da/dN) in superelastic (SE) and shape memory (SM) NiTi SMAs after five loading cycles (Cited from Xiong et al. [61]). (a) SE system: (i–iii) crack microstructures for GS20, GS60, and GS100; (b) SM system: (i–iii) crack microstructures for GS20, GS60, and GS100. V1, V3, and V5 denote martensite variants 1, 3, and 5.

Fracture behavior in SMAs occurs not only under short-term overload conditions but also poses significant risks in high-cycle and ultrahigh-cycle fatigue regimes. As an advanced fracture mechanics methodology, the phase field method provides a multiscale computational framework for fatigue damage evolution analysis. By coupling the MT thermodynamic principle with continuum damage theory, the phase field method enables accurate simulations of crack propagation under cyclic loading, establishing a theoretical foundation for fatigue life prediction and structural optimization in engineering components.

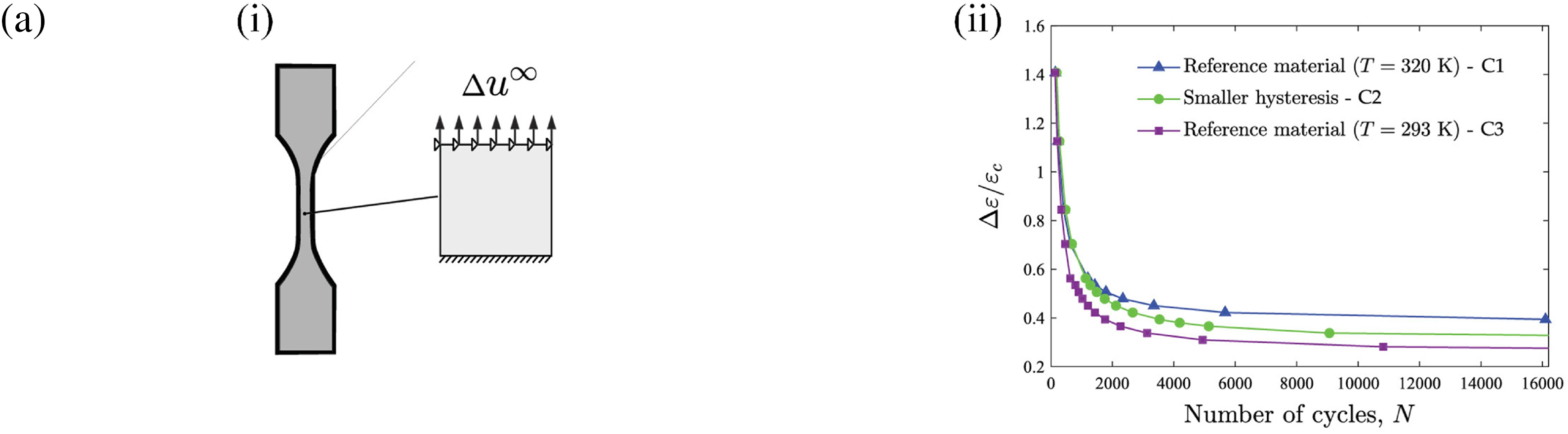

Simoes et al. [50] systematically investigated the key characteristics of fatigue fracture through phase field method across four representative cases: (i) the relationship between uniaxial tensile strain amplitude (

Figure 5: Phase field case studies on the fatigue fracture behavior of SMAs (Cited from Simoes et al. [50]): (a) Virtual

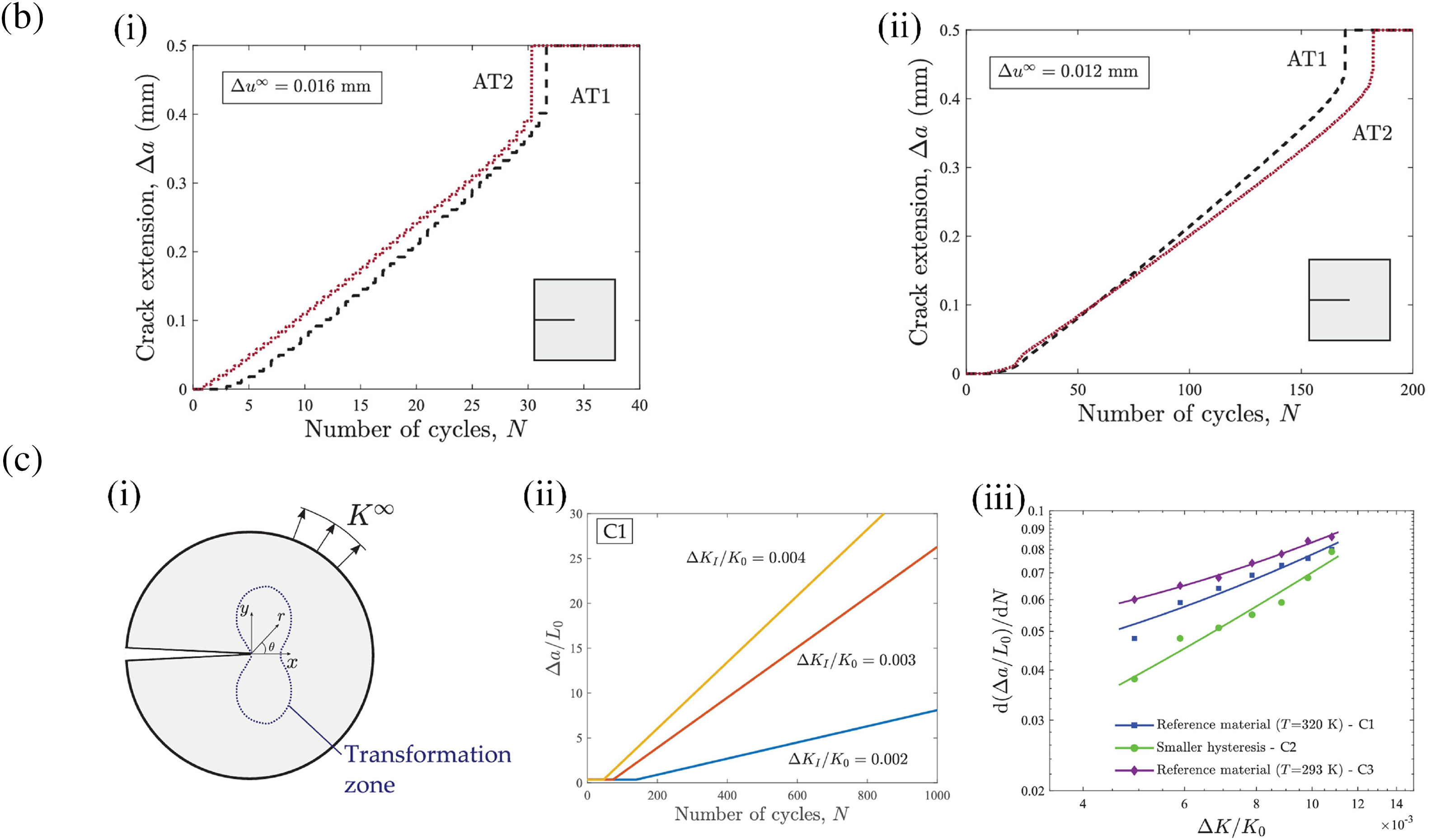

In engineering applications, the multiscale phase field framework developed by Simoes and Martínez-Pañeda [47] constitutes a significant advancement. This framework establishes a cross-scale coupling mechanism linking microscopic transformation to macroscopic damage mechanics, enabling full-domain fatigue life prediction for complex component geometries, multi-field boundary conditions, and nonlinear material parameters. This model has been validated by successfully simulating the fatigue fracture in biomedical stents (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Contours of phase field parameter

4 Phase Field Simulations of Fracture Behavior in SMCs

SMCs have shown great potential for application in the field of automotive [80,81], additive manufacturing [82,83] and aerospace [84] with their unique MT appeal. Similarly, facing the influence of complex mechanical behavior on material properties during MT, it is still necessary to use the phase-field method, which has advantages in multi-physical field coupling. In the following section, a systematic review of recent advances in phase field simulation to the fracture behavior of SMCs is presented, focusing on the factors affecting the crack extension, including crystallographic orientation and grain boundary properties.

4.1 Fracture Behavior of Single-Crystal SMCs: Effect of Crystallographic Orientation

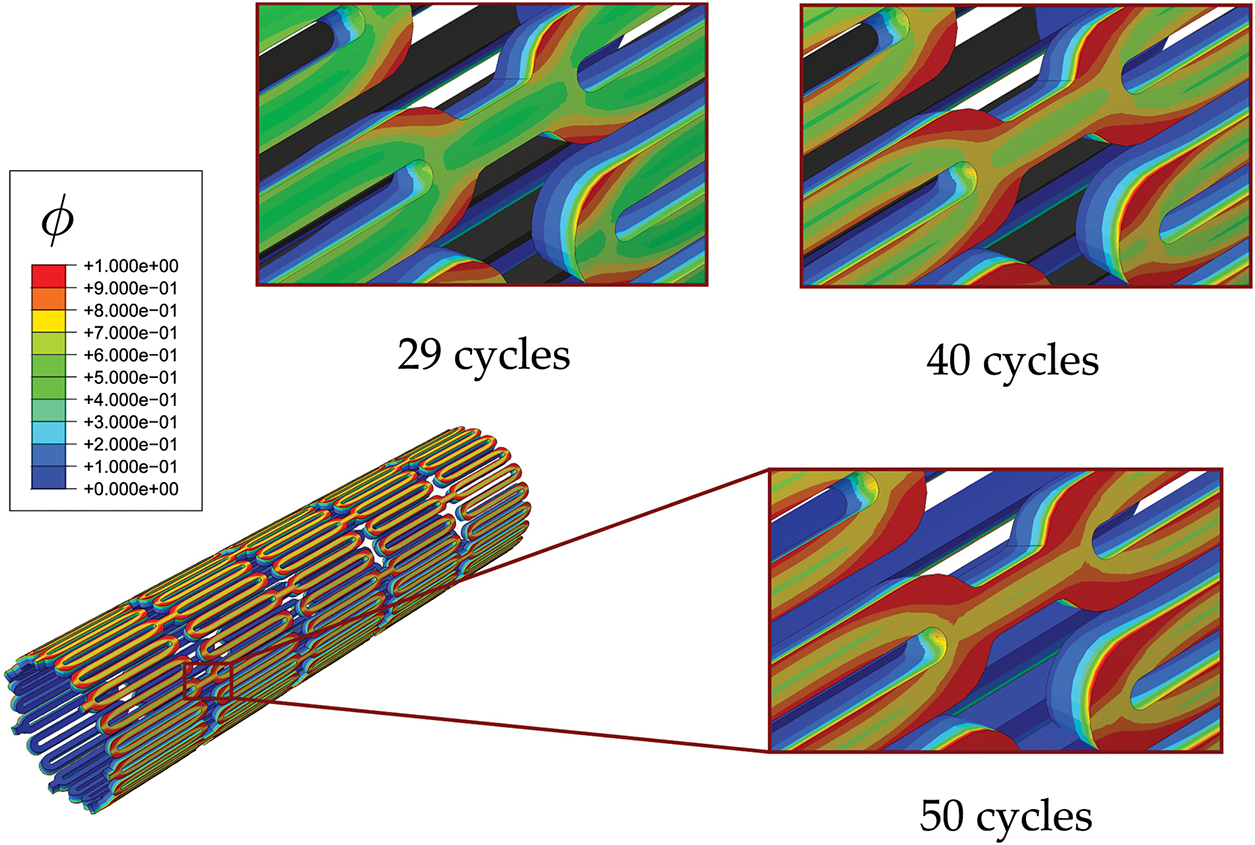

Similar to SMAs, the fracture behavior single crystal SMAs that is relatively easy to handle has attracted attention first. The influence law of crystallographic orientation on the fracture behavior and the underlying mechanism have been discussed. Moshkelgosha and Mamivand [65] investigated the fracture mechanisms in the single-crystal tetragonal zirconia using an MT-coupled fracture phase field model. Their work demonstrated that the MT inhibited the crack propagation through energy dissipation processes, with crystallographic orientation playing a determinative role in crack path evolution and toughening. Comparative analyses of crack paths (Fig. 7) and stress-strain curves (Fig. 8) across orientations (

Figure 7: Effect of crystallographic orientation on crack propagation in a single-crystal tetragonal zirconia under Mode-I loading (Cited from Moshkelgosha and Mamivand [65]). Left and right columns show synchronized MT and crack evolution at 600 s and 3500 s, respectively

Figure 8: Stress-strain curves during the crack propagation in the single-crystal tetragonal zirconia with varying crystallographic orientations (Cited from Moshkelgosha and Mamivand [65]). The loading rates and simulation times were consistent. The maximum and minimum toughening occurred at

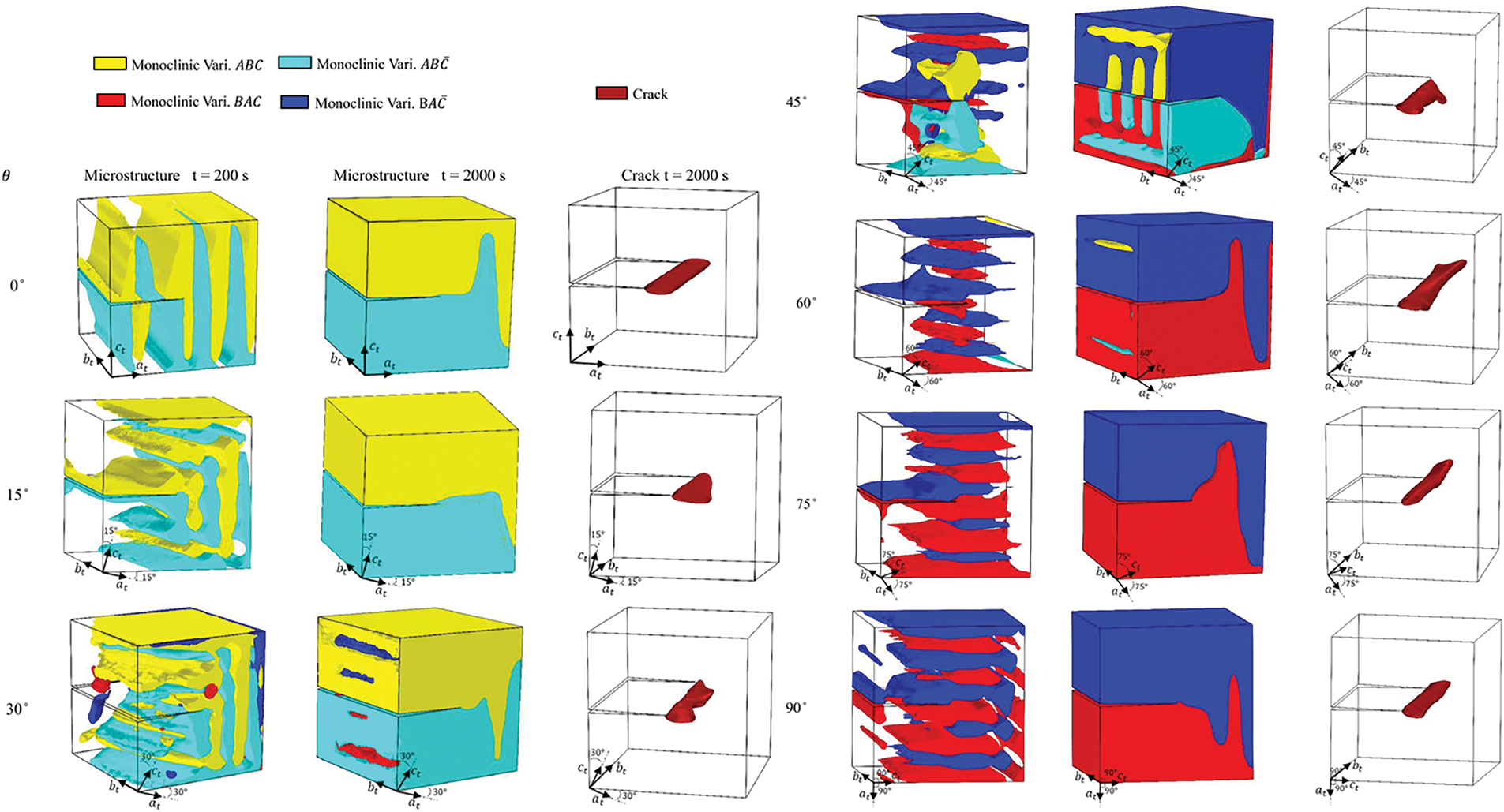

Moshkelgosha and Mamivand [62] systematically investigated the MT behavior of tetragonal zirconia under mechanical loading and its influence on the fracture behavior by incorporating 12 monoclinic martensite variants into a fracture phase field model. The numerical simulations successfully replicated the experimentally observed features, including surface morphology uplift, formation of self-accommodated martensite pairs, and phase zone fragmentation. A systematic analysis of crystallographic orientation effect (Fig. 9) revealed that different crystallographic orientations critically regulate monoclinic variant evolution and crack propagation modes. At

Figure 9: Martensite microstructures and crack patterns at

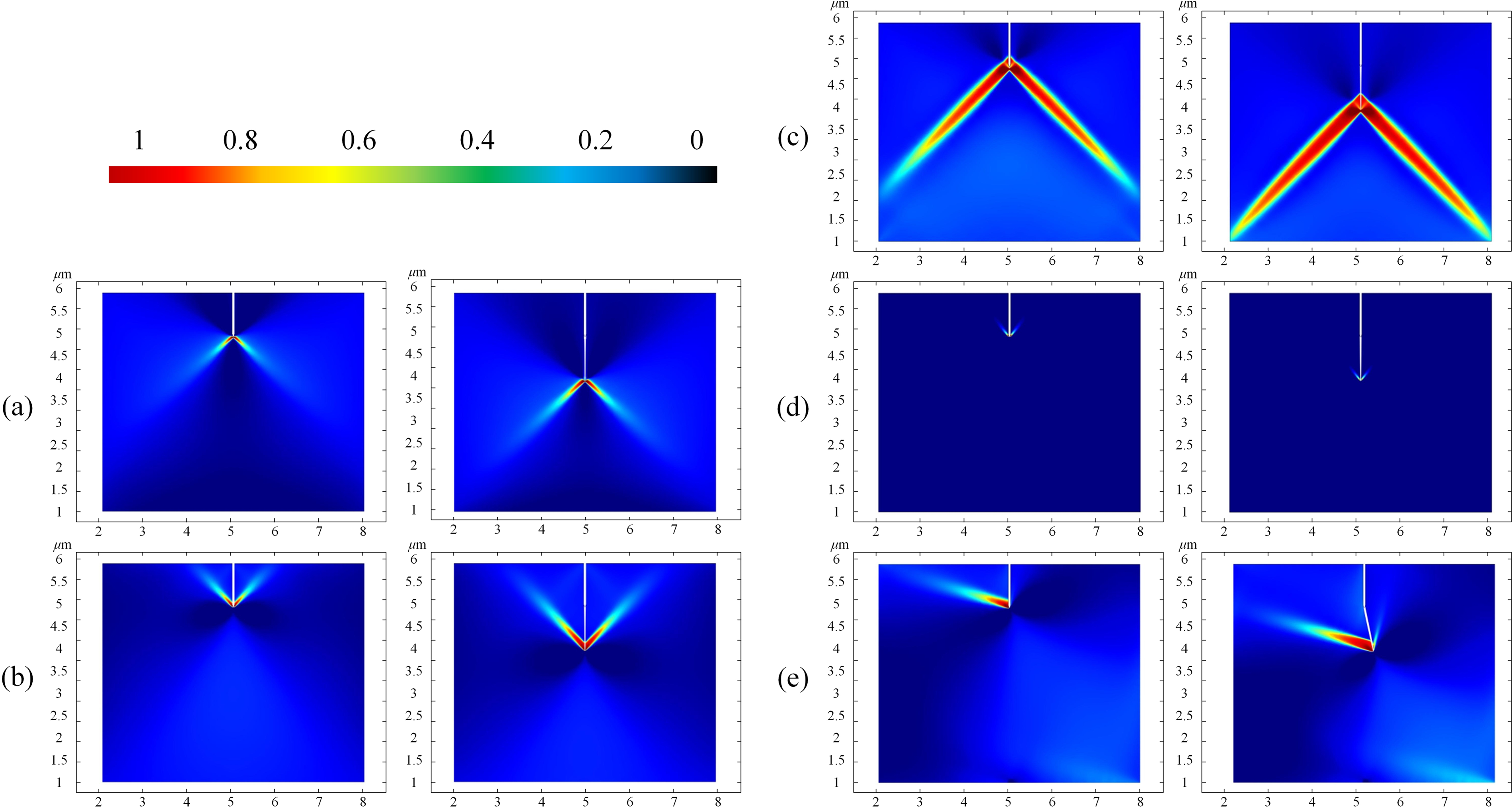

Sun et al. [85] investigated the ferroelastic toughening mechanisms in yttria-stabilized zirconia single crystals under varying crystallographic orientations using a coupled fracture phase field model. The study revealed that at

Figure 10: Ferroelastic domain evolution in yttria-stabilized zirconia single crystals under varying crystallographic orientations and loading modes (Cited from Sun et al. [85]): (a) Domain switching under Load I at

At

4.2 Fracture Behavior of Polycrystalline SMCs: Effect of Grain Boundary Properties

Compared with the single-crystal system, there are a large number of grain boundaries in the polycrystalline system, which may affect the fracture behavior of SMCs. Therefore, some researchers have studied the influence of grain boundary properties on the fracture behavior of SMCs through phase field simulation. Zhu and Luo [30] investigated the low-temperature degradation phenomena in yttria-stabilized TZPs under humid environments using a fracture phase field model to simulate the tetragonal-to-monoclinic MT and GB-induced microcrack evolution. The study focused on the influence of martensite variant width and incidence angles on the microcrack nucleation. The simulation results demonstrated that varying incidence angles could significantly influence the crack initiation/propagation modes and govern the microstructure of monoclinic variant and intergranular microcrack distributions. In the subsequent work, Zhu et al. [57] revealed how relative fracture toughness differences between GBs and the matrix influence the crack paths and toughening mechanisms (Fig. 11). For the “strong GBs” (the fracture toughness = 1.2 MPa·m1/2, matching the matrix), the cracks required higher external loads (180 MPa) to propagate (Fig. 11a). For the “weak GBs” (the fracture toughness = 0.5 MPa·m1/2), the cracks propagated along the GBs under 150–170 MPa (Fig. 11b,f). The stress concentration at monoclinic variant-GB interfaces triggered intergranular microcrack nucleation (Fig. 11b), while the interactions between main cracks and microcracks led to crack deflection along GBs via a healing-reinitiation dynamic process (Fig. 11f). The GB orientation effects were further elucidated through polycrystalline orientation adjustments (Orientation II, Fig. 11c,d,g,h). The “strong GBs” promoted near-linear crack growth under specific orientations (Fig. 11c,g), whereas the “weak GBs” induced the interactions between main cracks and intergranular microcracks at triple junctions (Fig. 11h), highlighting the role of GB topology in fracture mode regulation. Experimental validation confirmed that crack bifurcation (Fig. 11f), intergranular microcracks (Fig. 11b), and healing phenomena (Fig. 11f) align with observations in [88–91], corroborating the reliability of the model.

Figure 11: MT and crack propagation in TZPs under varying GB strengths (fracture toughness), crystal properties, and orientations at Time 1 (onset of intergranular microcracks or significant crack path changes) and Time 2 (simulation termination) (Cited from Zhu et al. [57]). Order parameters (

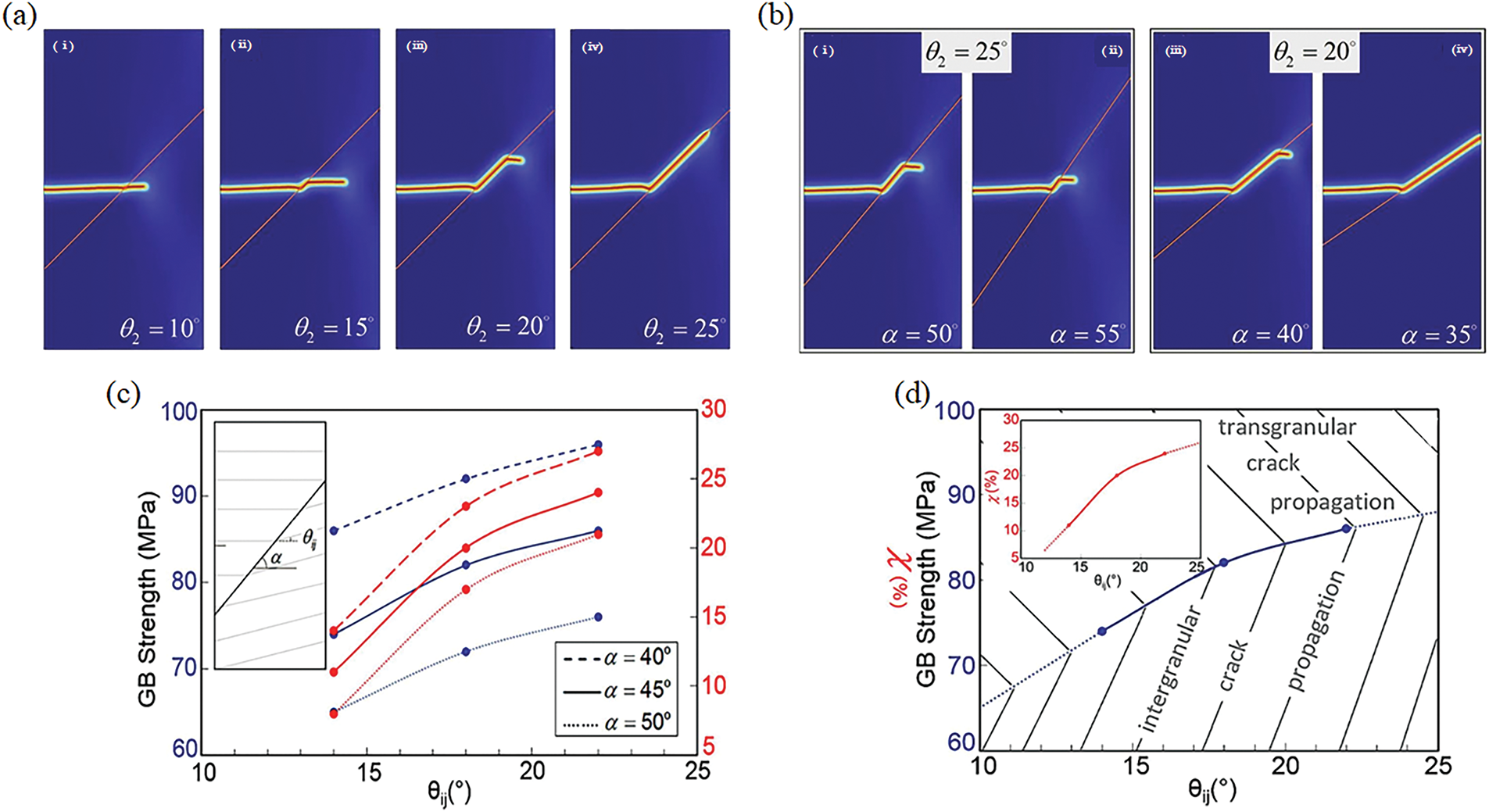

Emdadi and Zaeem [55] investigated the fracture behavior in ZrB2 bicrystals using a modified fracture phase field model. As shown in Fig. 12a,b, increasing misorientation angle

Figure 12: Relationships between crack propagation, grain misorientation, GB angle, and GB strength (Cited from Emdadi and Zaeem [55]). (a,b) Crack propagation in the bicrystal under varying grain misorientation angles (

The fracture phase field method, an advanced simulation approach integrating phase transformation theory and fracture mechanics, has demonstrated extensive applicability and powerful characterization capabilities in materials science. Based on energy variational principles, the fracture phase field method naturally incorporates crack initiation and propagation into material energy evolution, circumventing the challenges of crack interface tracking inherent in conventional models. By introducing continuous order parameters, the fracture phase field method simultaneously accounts for chemical free energy, elastic strain energy, and crack gradient energy, enabling effective simulation of coupled damage evolution, MT, and mechanical responses under external loads. This provides a reliable theoretical framework for elucidating intrinsic relationships between microstructures and macroscopic material properties.

Current fracture phase field studies on SMAs and SMCs mainly concentrate on two primary directions as follows:

(1) Theoretical advancements, including multi-physics coupling mechanisms, and the incorporation of various fracture criteria in the fracture phase field models for SMAs and SMCs.

(2) The revelation of microscopic mechanisms, including the effects of crystallographic orientation, grain size, grain boundary, etc, on the fracture behaviors of SMAs and SMCs.

With advancements in computational capabilities, the fracture phase field method has become a fundamental tool in basic research and increasingly critical for failure prediction, high-performance material design, and engineering safety assessment of SMAs and SMCs.

5.2 Limitations and Challenges

So far, the literatures of phase field modeling of the fracture behaviors of SMAs and SMCs are very limited, and the related research direction is still in the early stage of progress. The phase field researches focusing on the fracture behaviors of SMAs and SMCs are not systematic enough, and their goals are relatively scattered. Therefore, it is difficult to compare the simulation results or research goals by discussing the roles of material parameters (e.g., fracture toughness, elastic anisotropy) taken from different literatures. Moreover, the setting of some empirical parameters (e.g., interface energy coefficient) in different literatures is not unified (this does not affect the rationality of qualitatively analyzing the simulation results and the conclusions drawn), which can lead to different mesh size settings (even several orders of magnitude different). The computational cost has not been mentioned in most of the relevant literatures. This makes it very difficult to evaluate the computational costs and mesh dependencies of different models through comparison.

Despite significant progress in the fracture behaviors of SMAs and SMCs, the fracture phase field method encounters several limitations in complex service environments. For example, systematic frameworks are lacking for modeling magnetic field-induced MT, hygrothermal effects, and corrosion/oxidation influences on crack evolution in SMAs or SMCs. Moreover, the existing fracture phase field models for SMAs and SMCs rely on quasi-static assumptions, failing to accurately capture dynamic fracture processes under high-velocity impacts. The predictive capability remains constrained for complex fracture modes, including mixed-mode II/III crack growth, multi-crack interactions, bifurcation, and self-healing. Modeling GB effects in polycrystalline SMAs and SMCs faces challenges in parameter selection and experimental validation, and the introducing of microstructural defects (e.g., interfaces, dislocations, vacancies) are insufficiently resolved. High computational costs and low numerical efficiency further hinder large-scale applications. Fatigue crack evolution modeling remains underdeveloped, with phase field frameworks of fatigue fracture of SMAs and SMCs requiring substantial refinement.

In the future, the fracture phase field research should focus on multi-physics coupled model development, scale-bridging innovations, and enhanced adaptability to complex environments. These advancements will address critical challenges in fracture toughness enhancement, structural performance optimization, and durability extension, particularly in aerospace and biomedical applications where model reliability directly impacts application performance. Critical research directions include development of fatigue-phase field, integration of macro-micro mechanisms, and practical engineering applications with improved computational efficiency. Only by achieving these goals can fracture phase field method transition from a research tool to an industry-reliable solution for addressing practical material failure challenges.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12202294) and the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2024NSFSC1346).

Author Contributions: Junhui Hua: Writing—original draft, Investigation; Junyuan Xiong: Writing—review & editing; Bo Xu: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition; Chong Wang: Validation, Supervision; Qingyuan Wang: Validation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rougier E, Hunter A. Fracture mechanics—theory, modeling and applications. Appl Sci. 2021;11(16):7371. doi:10.3390/app11167371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang C, Feng J. Fracture criteria and rheological fracture mechanism of brittle materials based on Eshelby stress. Acta Mech. 2024;235(7):4789–810. doi:10.1007/s00707-024-03979-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Nguyen H, Zhang X, Wen J, Zhang X, Ajayan PM, Espinosa HD. Engineering the fracture resistance of 2H-transition metal dichalcogenides using vacancies: an in-silico investigation based on HRTEM images. Mater Today. 2023;70(6):17–32. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2023.10.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang R, Wang S, Li D, Li W, Zhang C. Temperature dependence of the fracture strength of porous ceramic materials. Ceram Int. 2020;46(8):11311–6. [Google Scholar]

5. Goldstein R. 19th European conference on fracture (ECF19) fracture mechanics for durability, reliability and safety. Eng Fail Anal. 2013;29:180–1. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2012.11.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Torabi AR, Hamidi K, Shahbazian B, Cicero S, Berto F. Extension of the equivalent material concept to compressive loading: combination with LEFM criteria for fracture prediction of keyhole notched polymeric samples. Appl Sci. 2021;11(9):4138. doi:10.3390/app11094138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Barcelos BL, Palma ES. Fatigue analysis of a bucket wheel by using linear elastic fracture mechanics. Eng Fail Anal. 2020;118(5):104824. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2020.104824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang GS. An EPFM analysis of crack initiation, stable growth and instability. Eng Fract Mech. 1995;50(2):261–82. doi:10.1016/0013-7944(94)00189-o. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhou X, Cao R, Zhang S, Ma J, Yan Y, Dong H. Study on fatigue failure behavior of 316L/2Cr13 multilayered steel: fracture mechanism and a new method for fatigue strength prediction. Eng Fail Anal. 2025;172:109420. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2025.109420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Shockey DA, Seaman L, Curran DR. The micro-statistical fracture mechanics approach to dynamic fracture problems. In: Williams ML, Knauss WG, editors. Dynamic fracture. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 1985. p. 19–31. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-5123-5_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang P, Li J, Zhao Y, Li J. Numerical simulation and experimental verification of fatigue crack propagation in high-strength bolts based on fracture mechanics. Sci Prog. 2023;106(4):00368504231211660. doi:10.1177/00368504231211660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tang K, Cui C, Liu JW, Ma Y, Zhang QH, Lao WL. Multiscale and multifield coupled fatigue crack initiation and propagation of orthotropic steel decks. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024;199(1):111843. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2024.111843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Khan SM, Li K, Mehmani Y. Order reduction of fracture mechanics in porous microstructures: a multiscale computing framework. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2024;420(10):116706. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2023.116706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Poapongsakorn P, Wiangkham A, Aengchuan P, Noraphaiphipaksa N, Kanchanomai C. Time-dependent fracture of epoxy resin under mixed-mode I/III loading. Theor Appl Fract Mech. 2020;106(4):102445. doi:10.1016/j.tafmec.2019.102445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Xing XS. Nonequilibrium statistical theory of fatigue fracture. Eng Fract Mech. 1987;26(3):393–419. doi:10.1016/0013-7944(87)90021-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Liu G, Li Q, Msekh MA, Zuo Z. Abaqus implementation of monolithic and staggered schemes for quasi-static and dynamic fracture phase-field model. Comput Mater Sci. 2016;121(4):35–47. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2016.04.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Shi Z, Kou S. Analysis of quality defects in the fracture surface of fracture splitting connecting rod based on three-dimensional crack growth. Results Phys. 2018;10(9):1022–9. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2018.08.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Schlüter A, Willenbücher A, Kuhn C, Müller R. Phase field approximation of dynamic brittle fracture. Comput Mech. 2014;54(5):1141–61. doi:10.1007/s00466-014-1045-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hu C, Qi H, Li S, Yang X, Shi D. A phase-field fatigue fracture model considering the thickness effect. Eng Fract Mech. 2024;296:109855. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2024.109855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Xie Q, Qi H, Li S, Yang X, Shi D. A phase-field model for mixed-mode elastoplastic fatigue crack. Eng Fract Mech. 2023;282(1):109176. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2023.109176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Si Z, Hirshikesh, Yu T, Natarajan, S. An adaptive phase-field simulation for hydrogen embrittlement fracture with multi-patch isogeometric method. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2024;418(3):116539. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2023.116539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhao Y, Zou B, Zhang T, Jiang Z, Ding J, Ding Y. A comprehensive review of composite phase change material based thermal management system for lithium-ion batteries. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2022;167:112667. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Guo J, Lin W, Qin X, Xu Y, Dong K. Mesoscopic study on fracture behavior of fully graded concrete under uniaxial tension by using the phase-field method. Eng Fract Mech. 2022;272(7–8):108678. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2022.108678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kurdi A, Almoatham N, Mirza M, Ballweg T, Alkahlan B. Potential phase change materials in building wall construction—a review. Materials. 2021;14(18):5328. doi:10.3390/ma14185328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wu C, Fang J, Zhang Z, Entezari A, Sun G, Swain MV, et al. Fracture modeling of brittle biomaterials by the phase-field method. Eng Fract Mech. 2020;224(3):106752. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2019.106752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Abbassi Y, Baniasadi E, Ahmadikia H. Transient energy storage in phase change materials, development and simulation of a new TRNSYS component. J Build Eng. 2022;50(5):104188. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Fu X, Wu J, Zhou Z, Tan MJ, Huang Y, Sun J, et al. Interfacial strain concentration and relaxation along crystalline-amorphous boundaries of B2-reinforced bulk-metallic-glass-composites during loading. Acta Mater. 2025;287(4):120787. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2025.120787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ziębowicz A, Oßwald B, Kern F, Schwan W. Effect of simulated mastication on structural stability of prosthetic zirconia material after thermocycling aging. Materials. 2023;16(3):1171. doi:10.3390/ma16031171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhao T, Zhu J, Luo J. Study of crack propagation behavior in single crystalline tetragonal zirconia with the phase field method. Eng Fract Mech. 2016;159(9):155–73. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2016.03.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhu J, Luo J. Study of transformation induced intergranular microcracking in tetragonal zirconia polycrystals with the phase field method. Mater Sci Eng. 2017;701(5):69–84. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2017.06.060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Xu B, Xiao X, Zhang Q, Yu C, Song D, Kan Q, et al. Enhanced cyclic stability of NiTi shape memory alloy elastocaloric materials with Ni4Ti3 nanoprecipitates: experiment and phase field modeling. J Mech Phys Solids. 2025;196(1):106011. doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2024.106011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xu B, Yu C, Xiong J, Hu J, Kan Q, Wang C, et al. Progress in phase field modeling of functional properties and fracture behavior of shape memory alloys. Prog Mater Sci. 2025;148(6469):101364. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2024.101364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang Y, Khachaturyan AG. Three-dimensional field model and computer modeling of martensitic transformations. Acta Mater. 1997;45(2):759–73. doi:10.1016/s1359-6454(96)00180-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhu J, Wu HH, Wu Y, Wang H, Zhang T, Xiao H, et al. Influence of Ni4Ti3 precipitation on martensitic transformations in NiTi shape memory alloy: R phase transformation. Acta Mater. 2021;207(17):116665. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2021.116665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhu J, Wu H, Wang D, Gao Y, Wang H, Hao Y, et al. Crystallographic analysis and phase field simulation of transformation plasticity in a multifunctional β-Ti alloy. Int J Plast. 2017;89:110–29. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2016.11.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Mamivand M, Asle Zaeem M, El Kadiri H, Chen LQ. Phase field modeling of the tetragonal-to-monoclinic phase transformation in zirconia. Acta Mater. 2013;61(14):5223–35. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2013.05.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Hou Y, Wang L, Yue P, Sun W. Fracture failure in crack interaction of asphalt binder by using a phase field approach. Mater Struct. 2015;48(9):2997–3008. doi:10.1617/s11527-014-0372-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Borden MJ, Verhoosel CV, Scott MA, Hughes TJR, Landis CM. A phase-field description of dynamic brittle fracture. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2012;217(8):77–95. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2012.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hou Y, Wang LB, Yue PT, Pauli T, Sun WJ. Modeling Mode I cracking failure in asphalt binder by using nonconserved phase-field model. J Mater Civ Eng. 2014;26(4):684–91. doi:10.1061/(asce)mt.1943-5533.0000874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Amor H, Marigo JJ, Maurini C. Regularized formulation of the variational brittle fracture with unilateral contact: numerical experiments. J Mech Phys Solids. 2009;57(8):1209–29. doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2009.04.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Schmitt R, Kuhn C, Skorupski R, Smaga M, Eifler D, Müller R. A combined phase field approach for martensitic transformations and damage. Arch Appl Mech. 2015;85(9–10):1459–68. doi:10.1007/s00419-014-0945-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kan Q, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Kang G, Yu C. Tension-compression asymmetric functional degeneration of super-elastic NiTi shape memory alloy: experimental observation and multiscale constitutive model. Int J Solids Struct. 2023;280(17):112384. doi:10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2023.112384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Bourdin B. Numerical implementation of the variational formulation for quasi-static brittle fracture. Interfaces Free Boundaries Math Anal Comput Appl. 2007;9(3):411–30. doi:10.4171/ifb/171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kavvadias D, Baxevanis T. Phase-field description of fracture in NiTi single crystals. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2024;419(1):116677. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2023.116677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Yu C, Kang G, Kan Q. Crystal plasticity based constitutive model of NiTi shape memory alloy considering different mechanisms of inelastic deformation. Int J Plast. 2014;54:132–62. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2013.08.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Cherkaoui M, Berveiller M, Sabar H. Micromechanical modeling of martensitic transformation induced plasticity (TRIP) in austenitic single crystals. Int J Plast. 1998;14(7):597–626. doi:10.1016/s0749-6419(99)80000-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Simoes M, Martínez-Pañeda E. Phase field modelling of fracture and fatigue in shape memory alloys. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2021;373(96):113504. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2020.113504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Hasan M. Phase-field Approaches to fatigue fracture in brittle materials and overload fracture in shape memory alloys [dissertation]. Houston, TX, USA: University of Houston; 2023. [Google Scholar]

49. Alessi R, Vidoli S, De Lorenzis L. A phenomenological approach to fatigue with a variational phase-field model: the one-dimensional case. Eng Fract Mech. 2018;190(10):53–73. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2017.11.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Simoes M, Braithwaite C, Makaya A, Martínez-Pañeda E. Modelling fatigue crack growth in shape memory alloys. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 2022;45(4):1243–57. doi:10.1111/ffe.13638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Pham K, Amor H, Marigo JJ, Maurini C. Gradient damage models and their use to approximate brittle fracture. Int J Damage Mech. 2011;20(4):618–52. doi:10.1177/1056789510386852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Bourdin B, Francfort GA, Marigo JJ. Numerical experiments in revisited brittle fracture. J Mech Phys Solids. 2000;48(4):797–826. doi:10.1016/s0022-5096(99)00028-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Carrara P, Ambati M, Alessi R, De Lorenzis L. A framework to model the fatigue behavior of brittle materials based on a variational phase-field approach. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2020;361(5–6):112731. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2019.112731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Abdollahi A, Arias I. Numerical simulation of intergranular and transgranular crack propagation in ferroelectric polycrystals. Int J Fract. 2012;174(1):3–15. doi:10.1007/s10704-011-9664-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Emdadi A, Asle Zaeem M. Phase-field modeling of crack propagation in polycrystalline materials. Comput Mater Sci. 2021;186(20–22):110057. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2020.110057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Zhen Y, Wu K, Lu Y, Liu M, He L, Ni Y. A thermodynamically-consistent non-isothermal phase-field model for probing evolution of crack propagation and phase transformation. Int J Mech Sci. 2024;270:109122. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2024.109122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Zhu J, Luo J, Sun Y. Study of the fracture behavior of tetragonal zirconia polycrystal with a modified phase field model. Materials. 2020;13(19):4430. doi:10.3390/ma13194430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Moshkelgosha E, Mamivand M. Concurrent modeling of martensitic transformation and crack growth in polycrystalline shape memory ceramics. Eng Fract Mech. 2021;241:107403. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2020.107403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Lotfolahpour A, Huber W, Asle Zaeem M. A phase-field model for interactive evolution of phase transformation and cracking in superelastic shape memory ceramics. Comput Mater Sci. 2023;216(15):111844. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2022.111844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Pang Y, Li D, Li X, Wang R, Ao X. Phase-field simulation of temperature-dependent thermal shock fracture of Al2O3/ZrO2 multilayer ceramics with phase transition residual stress. Materials. 2023;16(2):734. doi:10.3390/ma16020734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Xiong J, Xu B, Hu J, Kang G. Phase-field simulation on grain-size dependent fracture of cyclically loaded NiTi-SMA. Int J Mech Sci. 2025;289:110041. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2025.110041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Moshkelgosha E, Mamivand M. Three-dimensional phase field modeling of fracture in shape memory ceramics. Int J Mech Sci. 2021;204(3):106550. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2021.106550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Clayton JD, Knap J. Phase field modeling and simulation of coupled fracture and twinning in single crystals and polycrystals. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2016;312:447–67. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2016.01.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Xiong J, Xu B, Kang G. Phase field simulations on the rate- and grain-size-dependent crack propagation of polycrystalline NiTi shape memory alloy. Fatigue Fract Eng Mat Struct. 2024;47(6):2174–94. doi:10.1111/ffe.14296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Moshkelgosha E, Mamivand M. Phase field modeling of crack propagation in shape memory ceramics—application to zirconia. Comput Mater Sci. 2020;174:109509. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2019.109509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Moshkelgosha E, Mamivand M. Anisotropic phase-field modeling of crack growth in shape memory ceramics: application to zirconia. In: Proceedings of the ASME 2019 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition; 2019 Nov 11–14; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. doi:10.1115/IMECE2019-11695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Borzabadi Farahani E, Sobhani Aragh B, Voges J, Juhre D. On the crack onset and growth in martensitic micro-structures; a phase-field approach. Int J Mech Sci. 2021;194(13):106187. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2020.106187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Hasan MM, Zhang M, Baxevanis T. A finite-strain phase-field description of thermomechanically induced fracture in shape memory alloys. Shap Mem Superelast. 2022;8(4):356–72. doi:10.1007/s40830-022-00393-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Fang C, Zheng Y, Chen J, Yam MCH, Wang W. Superelastic NiTi SMA cables: thermal-mechanical behavior, hysteretic modelling and seismic application. Eng Struct. 2019;183(2):533–49. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2019.01.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Chen Z. Application of SMA materials in aerospace. Appl Comput Eng. 2023;25(1):22–9. [Google Scholar]

71. Hartl DJ, Lagoudas DC. Aerospace applications of shape memory alloys. Proc Inst Mech Eng. 2007;221(4):535–52. [Google Scholar]

72. Du H, Li G, Sun J, Zhang Y, Bai Y, Qian C, et al. A review of shape memory alloy artificial muscles in bionic applications. Smart Mater Struct. 2023;32(10):103001. doi:10.1088/1361-665x/acf1e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Mansour NA, Fath El-Bab AMR, Assal SFM, Tabata O. Design, characterization and control of SMA springs-based multi-modal tactile display device for biomedical applications. Mechatronics. 2015;31:255–63. doi:10.1016/j.mechatronics.2015.08.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Yu C, Kang G, Kan Q, Zhu Y. Rate-dependent cyclic deformation of super-elastic NiTi shape memory alloy: thermo-mechanical coupled and physical mechanism-based constitutive model. Int J Plast. 2015;72:60–90. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2015.05.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Yu C, Kang G, Kan Q. A micromechanical constitutive model for anisotropic cyclic deformation of super-elastic NiTi shape memory alloy single crystals. J Mech Phys Solids. 2015;82:97–136. doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2015.05.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Yu C, Kang G, Song D, Kan Q. Effect of martensite reorientation and reorientation-induced plasticity on multiaxial transformation ratchetting of super-elastic NiTi shape memory alloy: new consideration in constitutive model. Int J Plast. 2015;67(6):69–101. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2014.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Cissé C, Asle Zaeem M. Transformation-induced fracture toughening in CuAlBe shape memory alloys: a phase-field study. Int J Mech Sci. 2021;192(10):106144. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2020.106144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Xiong J, Xu B, Kang G. Phase field simulation on the martensite transformation and reorientation toughening behaviors of single crystal NiTi shape memory alloy: effects of crystalline orientation and temperature. Eng Fract Mech. 2022;270(11):108585. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2022.108585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Ahadi A, Sun Q. Grain size dependence of fracture toughness and crack-growth resistance of superelastic NiTi. Scr Mater. 2016;113:171–5. doi:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2015.10.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Shreekrishna S, Nachimuthu R, Nair VS. A review on shape memory alloys and their prominence in automotive technology. J Intell Mater Syst Struct. 2023;34(5):499–524. doi:10.1177/1045389x221111547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Battaglia M, Sellitto A, Giamundo A, Visone M, Riccio A. Shape memory alloys applied to automotive adaptive aerodynamics. Materials. 2023;16(13):4832. doi:10.3390/ma16134832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Wu J, Guo A, Wu H, Ma J, Qu P, Wang S, et al. Programmable polylactic acid-ceramics 4D printing with shape memory function. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2025;20(1):e2505621. doi:10.1080/17452759.2025.2505621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Uchino K. Antiferroelectric shape memory ceramics. Actuators. 2016;5(2):11. doi:10.3390/act5020011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Gantz F, Stroud H, Fuller JC, Adams K, Caltagirone PE, Ozcan H, et al. Aerospace, energy recovery, and medical applications: shape memory alloy case studies for CASMART 3rd student design challenge. Shap Mem Superelasticity. 2022;8(2):150–67. doi:10.1007/s40830-022-00368-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Sun Y, Luo J, Zhu J. Ferroelastic toughening of single crystalline yttria-stabilized t’ zirconia: a phase field study. Eng Fract Mech. 2020;233:107077. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2020.107077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Wang J, Zhang TY. Phase field simulations of polarization switching-induced toughening in ferroelectric ceramics. Acta Mater. 2007;55(7):2465–77. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2006.11.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Sluka T, Webber KG, Colla E, Damjanovic D. Phase field simulations of ferroelastic toughening: the influence of phase boundaries and domain structures. Acta Mater. 2012;60(13–14):5172–81. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2012.06.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Alcalá J, Anglada M. High-temperature crack growth in Y-TZP. Mater Sci Eng. 1997;232(1):103–9. [Google Scholar]

89. Attaoui HE, Saâdaoui M, Chevalier J, Fantozzi G. Static and cyclic crack propagation in Ce-TZP ceramics with different amounts of transformation toughening. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2007;27(2):483–6. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2006.04.108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Chevallier J, Olagnon C, Gremillard L, Fantozzi G. Crack propagation in TZP ceramics. Key Eng Mater. 1999;161:563–8. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/kem.161-163.563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Lee JK, Kim H. Surface crack initiation in 2Y-TZP ceramics by low temperature aging. Ceram Int. 1994;20(6):413–8. doi:10.1016/0272-8842(94)90028-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Emdadi A, Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE, Asle Zaeem M. A modified phase-field model for quantitative simulation of crack propagation in single-phase and multi-phase materials. Eng Fract Mech. 2018;200:339–54. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2018.07.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools