Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Approximate Homomorphic Encryption for MLaaS by CKKS with Operation-Error-Bound

1 Department of Engineering Science and Ocean Engineering, National Taiwan University, Taipei, 106319, Taiwan

2 Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, Ming Chuan University, Taoyuan City, 33300, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Chia-Hui Wang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 503-518. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068516

Received 30 May 2025; Accepted 22 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

As data analysis often incurs significant communication and computational costs, these tasks are increasingly outsourced to cloud computing platforms. However, this introduces privacy concerns, as sensitive data must be transmitted to and processed by untrusted parties. To address this, fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) has emerged as a promising solution for privacy-preserving Machine-Learning-as-a-Service (MLaaS), enabling computation on encrypted data without revealing the plaintext. Nevertheless, FHE remains computationally expensive. As a result, approximate homomorphic encryption (AHE) schemes, such as CKKS, have attracted attention due to their efficiency. In our previous work, we proposed RP-OKC, a CKKS-based clustering scheme implemented via TenSEAL. However, errors inherent to CKKS operations—termed CKKS-errors—can affect the accuracy of the result after decryption. Since these errors can be mitigated through post-decryption rounding, we propose a data pre-scaling technique to increase the number of significant digits and reduce CKKS-errors. Furthermore, we introduce an Operation-Error-Estimation (OEE) table that quantifies upper-bound error estimates for various CKKS operations. This table enables error-aware decryption correction, ensuring alignment between encrypted and plaintext results. We validate our method on K-means clustering using the Kaggle Customer Segmentation dataset. Experimental results confirm that the proposed scheme enhances the accuracy and reliability of privacy-preserving data analysis in cloud environments.Keywords

As data analysis often involves significant communication and computational overhead, users are increasingly outsourcing these tasks to cloud platforms through Machine-Learning-as-a-Service (MLaaS) [1]. However, such outsourcing introduces privacy concerns, as sensitive data must be transmitted to and processed by untrusted parties.

Fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) [2–4] enables computation on encrypted data without exposing plaintext, making it a promising approach for privacy-preserving cloud analytics. However, the computation cost of FHE is high. To address these challenges, approximate homomorphic encryption (AHE), especially the CKKS scheme [5], has gained attention. CKKS supports efficient fixed-point arithmetic over encrypted data but introduces small errors (CKKS-errors) that can accumulate during multi-step computations. Prior works have applied CKKS to machine learning (ML) tasks but often rely on empirical parameter tuning to manage these errors, limiting reliability and generalizability.

Our previous work [6], RP-OKC, applied CKKS to secure K-means clustering but lacked systematic error estimation, making it hard to ensure output correctness. Without proper error management, ML over encrypted data may yield incorrect results or leak sensitive information through error patterns. This paper proposes a generalizable Operation-Error-Estimation (OEE) framework that quantifies CKKS-errors at each operation. The proposed OEE table facilitates post-decryption result correction through informed rounding, effectively aligning encrypted outputs with their corresponding plaintext results. With this enhancement, our method supports reliable privacy-preserving clustering in encrypted domains and enables better integration of CKKS into MLaaS platforms.

In MLaaS, the data owner (DO) has to delegate control of data privacy well. It is a challenge to make data analysis in cloud computing with protecting data privacy. For privacy-preserving in cloud computing, FHE is proposed as a new direction to solve the data privacy problem in cloud computing. In past years, extensive research on FHE has been conducted extensively [7–11]. Many mainstream FHE algorithms are implemented in open source libraries, including BGV [4], BFV [12,13], and TFHE [14–16]. There are some important applications of FHE focused on training ML models [17–19].

FHE enables untrusted third parties to perform computations on encrypted data without exposing the underlying plaintext. However, due to its considerable computational overhead, AHE, such as CKKS, has become a hot research topic to solve the data privacy problem in cloud computing. CKKS, as an AHE method, supports fixed-point float arithmetic, which will cause extra errors in its results. Our previous paper proposed RP-OKC using CKKS for privacy-preserving K-means clustering. Previous experiments [6] also found that the clustering result will be affected if the range of errors caused by CKKS (called CKKS-errors) are not considered. As CKKS-errors may affect the result of AHE, it is very important to provide a method to ensure that the ciphertext result of CKKS be the same as the direct operation result of plaintext for privacy-preserving AHE.

Recent studies [20] have shown that CKKS-errors behind the significant digits in data can be removed by the rounding process. It motivated us that we may design a data pre-scaling process to extend the significant digits, and thus the CKKS-errors can be reduced. In addition, there may be an upper-bound model of CKKS-errors for each operation in CKKS. Then, the upper-bound model of CKKS-errors for MLaaS can be estimated with its related operations. In this paper, we try to explore the possible model of CKKS-errors for different CKKS operations. Then, we make an OEE table to model the operation-error-bound of CKKS-errors. With this OEE table, a privacy-preserving AHE platform can estimate CKKS-errors in MLaaS and properly round the AHE results after decryption. Based on our previous work [6], we have implemented and evaluated the proposed method for privacy-preserving K-means clustering. Experimental results show that our proposed method can get correct results to improve the privacy-preserving AHE applied in MLaaS.

The proposed scheme provides the following key benefits. Predictability: Developers can now anticipate the error introduced by each operation without trial-and-error experiments. Precision Control: The system can automatically determine appropriate rounding thresholds post-decryption. Scalability: The OEE table can be extended to other CKKS-based ML algorithms beyond K-means. Consistency: By aligning encrypted computation with plaintext results, we increase trust in AHE-based MLaaS.

The CKKS scheme, proposed in 2017 by Cheon et al. [5], is an approximate homomorphic encryption (AHE) method designed to support efficient arithmetic on encrypted real-valued data. CKKS introduces small errors after the significant digits during each homomorphic operation. These CKKS-errors are generally considered acceptable in applications that tolerate slight approximations, especially when the results are rounded post-decryption. As a result, CKKS has become a practical alternative to exact FHE in many privacy-preserving ML scenarios.

In 2018, Kim et al. [21] further discussed the trade-off between precision and efficiency in CKKS, highlighting its potential for real-world deployments. However, subsequent studies [20] identified limitations when applying CKKS in MLaaS systems, particularly due to the accumulation of AHE-induced errors. These studies emphasized the need for rigorous analysis of precision loss and error propagation, especially when homomorphic operations are chained repeatedly, as in ML algorithms.

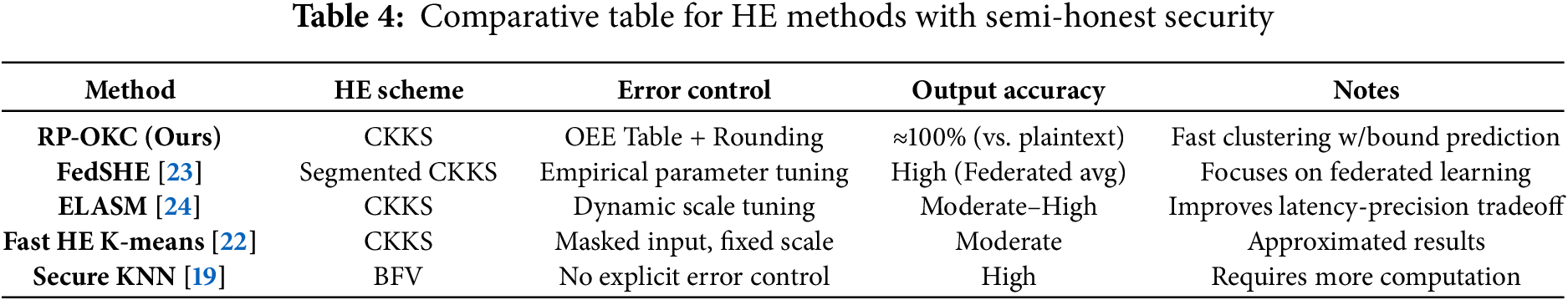

In 2023, Fast Approximate Homomorphic K-means [22] introduced a masked-input strategy to speed up CKKS-based clustering while tolerating approximation errors. FedSHE [23] presented a segmented CKKS encryption framework for federated learning, optimizing communication and computational efficiency. It addresses privacy in distributed ML settings. Both approaches improve speed via algorithmic adjustments but does not quantify or control CKKS-errors.

To address computation inefficiencies, our previous work [6] introduced RP-OKC, a framework that utilizes record packing to reduce the number of time-consuming homomorphic operations in CKKS-based secure protocols. While RP-OKC improved efficiency in privacy-preserving K-means clustering, it lacked a mechanism to quantitatively estimate CKKS-errors. Consequently, even though clustering was performed over encrypted data, the results were not guaranteed to match those of traditional plaintext K-means.

Empirical observations in RP-OKC revealed that rounding the sum of Euclidean squared distances to a specific number of decimal places could sometimes yield results identical to those of plaintext clustering. This suggested the existence of an implicit error threshold, motivating further exploration into modeling and bounding CKKS-errors systematically. However, no formal model or estimation framework was proposed at the time to guide such rounding decisions.

Recent research continues to explore the behavior of CKKS-errors and how to control them effectively. In 2023, ELASM [24] introduced an Error-Latency-Aware Scale Management strategy for CKKS that balances error magnitude and latency by dynamically managing ciphertext scaling. Their work targets general FHE workflows and achieves improvement in efficiency and accuracy. Costache et al. [25] proposed an average-case noise growth model for CKKS that reflects theoretical modeling of the error accumulation.

In contrast to the above, our proposed OEE table provides a unified, operation-specific error estimation framework that enhances the reliability of CKKS-based AHE in MLaaS scenarios. While previous approaches focus on dynamic scale management or average-case modeling to control errors, our work builds a practical OEE Table to estimate the maximum error caused by each CKKS operation for the given data domain. This makes our method more interpretable and easier to apply in deterministic privacy-preserving MLaaS pipelines. It allows developers to anticipate result distortions and to apply post-processing like rounding with confidence, thus enabling more dependable deployment of privacy-preserving data analytics in the cloud.

We categorize the existing literature into three main areas relevant to our work: (1) clustering over encrypted data, (2) privacy-preserving machine learning frameworks, and (3) CKKS-error estimation and control.

(1) Clustering on Encrypted Data:

Traditional clustering algorithms such as K-means require access to plaintext distances, which is infeasible in privacy-preserving settings. Our previous work [6] proposed RP-OKC, which supports encrypted K-means clustering using CKKS. However, it lacked error-bound estimation, leading to potential misclassifications. Other schemes like Fast Approximate Homomorphic K-means [22] and secure KNN classification [19] apply HE to clustering or classification but often rely on empirical adjustments rather than predictable error control.

(2) Privacy-Preserving ML Frameworks:

Frameworks such as FedSHE [23] use adaptive segmented CKKS for federated learning, while ELASM [24] applies scale management strategies to improve the tradeoff between accuracy and latency in FHE. Similarly, secure SVMs [17] and Bayesian classifiers [18] have been implemented with various encryption schemes. Cybersecurity applications also leverage privacy-preserving techniques, as seen in CSKG4APT [10] and ThreatInsight [11], which analyze threats without revealing sensitive source data.

(3) Error Control in Approximate Homomorphic Encryption:

CKKS introduces small errors during each operation, which can accumulate. Costache et al. [25] developed an average-case noise model for CKKS, while ELASM [24] focuses on controlling precision loss via scale-aware mechanisms. However, few works attempt to systematically estimate operation-level error bounds. Our proposed OEE table fills this gap by providing a deterministic way to bound and manage CKKS-errors in ML pipelines.

In summary, while previous efforts have advanced the performance and scalability of CKKS-based privacy-preserving ML, few have addressed operation-level error estimation in a systematic manner. Our work addresses this gap by introducing a deterministic OEE table to improve accuracy and trust in CKKS-powered MLaaS.

The CKKS scheme introduces inherent approximation errors—known as CKKS-errors—due to its support for fixed-point arithmetic over encrypted data. Recent studies [12,20] have shown that these errors, which often appear behind the significant digits of numerical results, can be mitigated by appropriate rounding techniques in post-decryption. This insight inspired us to investigate whether a more systematic and predictive approach could be developed to model, estimate, and manage CKKS-errors during computation, especially in MLaaS scenarios such as K-means clustering.

In additional, we observed that due to CKKS-errors, the decrypted clustering results sometimes diverged from plaintext clustering outputs, especially when the Euclidean distance values were close. In particular, we found that data scaling—that is, multiplying input data by a constant factor to “zoom in” on the significant digits—can improve result accuracy. After homomorphic computation, the results can be “zoomed out” (i.e., rescaled) to restore the original scale. This motivated us to formalize the relationship between data scaling and CKKS-error behavior as the OEE table. With this OEE table, we can estimate CKKS-errors in MLaaS and properly round the AHE results after decryption.

3.1 Operation-Error-Estimation (OEE) Table Construction

To systematically estimate CKKS-errors, we propose the concept of OEE, which captures the upper-bound error magnitudes introduced by different CKKS operations under various data domain of value ranges. The OEE table construction procedure is as follows.

Step 1: Data Domain Sampling.

We define a fixed integer-based value domain and perform sampling of inputs across this domain.

Step 2: Dataset Scaling.

Applying different scale factors to the dataset.

Step 3: Cross-Dataset Analysis.

Using multiple datasets with varying variance and data distance distributions.

Step 4: Operation Evaluation.

We apply core CKKS operations on the sampled encrypted data. For each operation, we decrypt the result and compare it to the corresponding plaintext result to measure the CKKS-error.

Step 5: Bound Estimation and Table Formation.

For each operation, input scale, and data range configuration, we record the maximum observed error, forming a lookup table—the OEE table—that provides the expected CKKS-error bound for a given input configuration.

This table provides a fast estimation framework for evaluating potential error accumulation during encrypted computation without decrypting intermediate results.

3.2 Integration with RP-OKC Framework

We integrate the OEE table into the workflow of our original RP-OKC framework for privacy-preserving data analytics as follows.

Step 1: Preprocessing.

Before encryption, the dataset is scaled to enhance the robustness of significant digits against CKKS-errors.

Step 2: Homomorphic Computation.

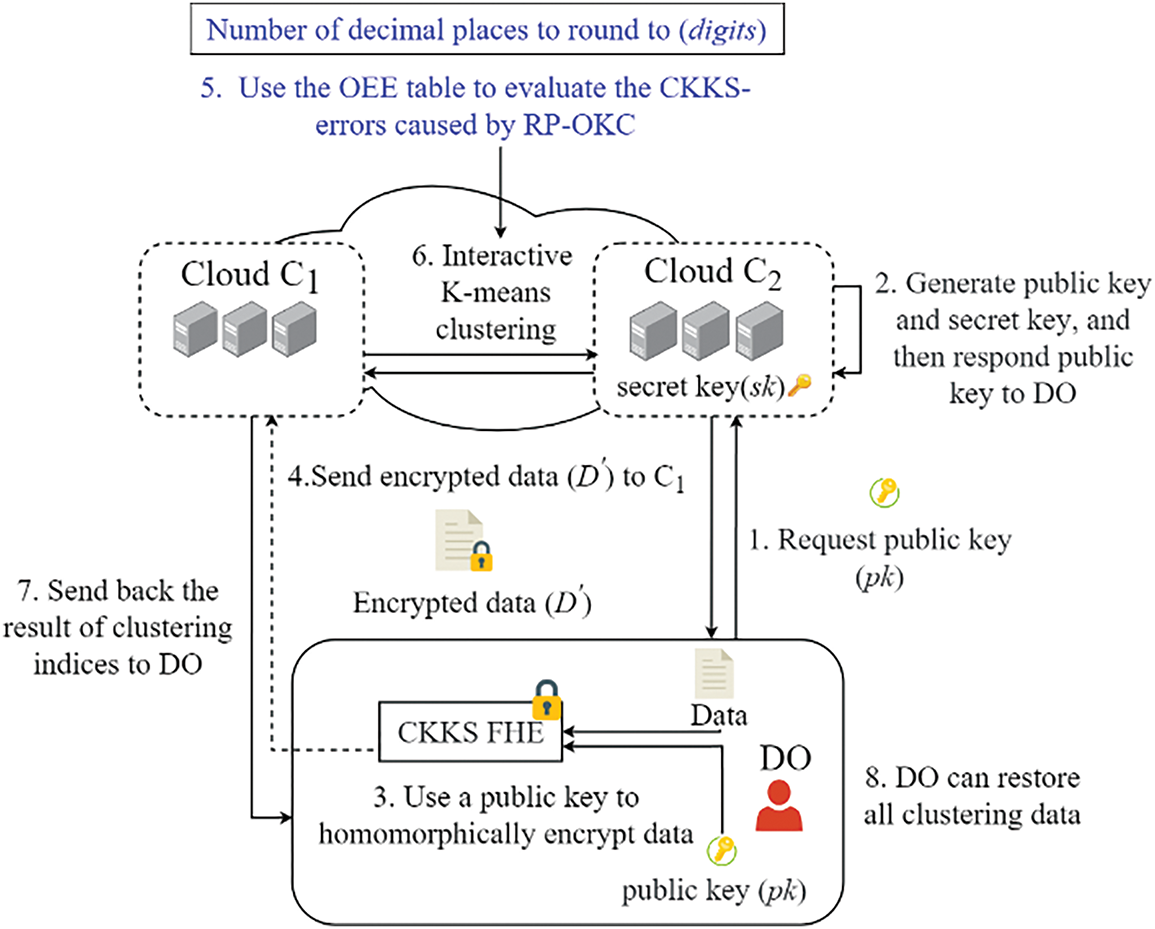

Each operation in data analytics is performed over CKKS-encrypted data using our optimized protocol. CKKS-errors at each stage are estimated using the OEE table, allowing early detection of potential deviations. An example of this homomorphic computation step for K-means clustering is shown in Fig. 1. It integrates the OEE table into the workflow of our original RP-OKC framework.

Figure 1: An example of this homomorphic computation step for K-means clustering. Reprinted from [6]

Step 3: Post-Decryption Correction.

After decryption, results are rounded to an appropriate number of decimal places, determined based on the estimated error range from the OEE table, to align the result with what would be expected from a plaintext operation.

Step 4: Validation.

We compare the final cluster assignments from RP-OKC with those obtained by traditional plaintext data analytics on the same dataset. Matching results validate the correctness of error estimation and the effectiveness of our CKKS-error management method.

In Fig. 1, the RP-OKC protocol assumes two entities:

• C1 (Client/Data owner): generates and encrypts the dataset using CKKS, uploads encrypted data, and decrypts the final clustering result.

• C2 (Cloud/Server): performs all homomorphic computations on encrypted data, including encrypted distance calculations, cluster assignment, and centroid updates.

All intermediate data remains encrypted during computation, and C1 is only responsible for post-decryption result correction using the OEE-based rounding.

CKKS supports approximate fixed-point arithmetic under encryption, including addition, scalar multiplication, and element-wise multiplication. In our protocol, encrypted distances are computed via element-wise operations without decryption. As the privacy preserved, the cloud server never sees plaintext data or cluster assignments, and only the client decrypts the final output.

We assume a semi-honest model where the server follows the protocol but may try to infer information from ciphertexts. The CKKS scheme ensures semantic security under IND-CPA (INDistinguishability under Chosen Plaintext Attack) assumptions and each data vector is encrypted using a unique random key before transmission. Since all computations are performed over ciphertexts, the server cannot learn any intermediate values or final assignments.

4 Experimental Results and Analysis

Our experiments are performed on a Windows 11 system with an AMD Ryzen 7 5800X 8-Core 3.8 GHz CPU and 32 GB of RAM. The RP-OKC protocol uses the CKKS scheme implemented via TenSEAL [26]. The parameters were configured as follows:

– Polynomial modulus degree: 16,384

– Initial scale: 230

– Modulus chain: 5 levels

– Security level: 128-bit (based on standard SEAL recommendations)

These settings balance encryption depth with precision and were chosen to support clustering tasks under real-valued input data while keeping the noise growth manageable. All encrypted operations are approximate, and rounding is applied post-decryption to restore correct class labels.

The experimental dataset will use the Kaggle Customer Segmentation dataset [27], consisting of 2000 samples and 5 numerical features (Age, Income, Spending Score, etc.). Before encryption, all features were normalized to the range [0, 20] using min-max scaling. This scaling ensures compatibility with CKKS encoding and reduces floating-point rounding errors.

4.1 Exploring the Effect of Data Scaling to CKKS-Errors

In [5], it mentioned that CKKS adds noise after the significant digits in data. It motivates us to scale the data to keep away the impact from noisy bits. Then, we can easily remove noisy bits. After these operations are completed, the error-free computation result can be restored. In this sub-section, we explore the effect from data scaling to CKKS-errors by the following three experiments.

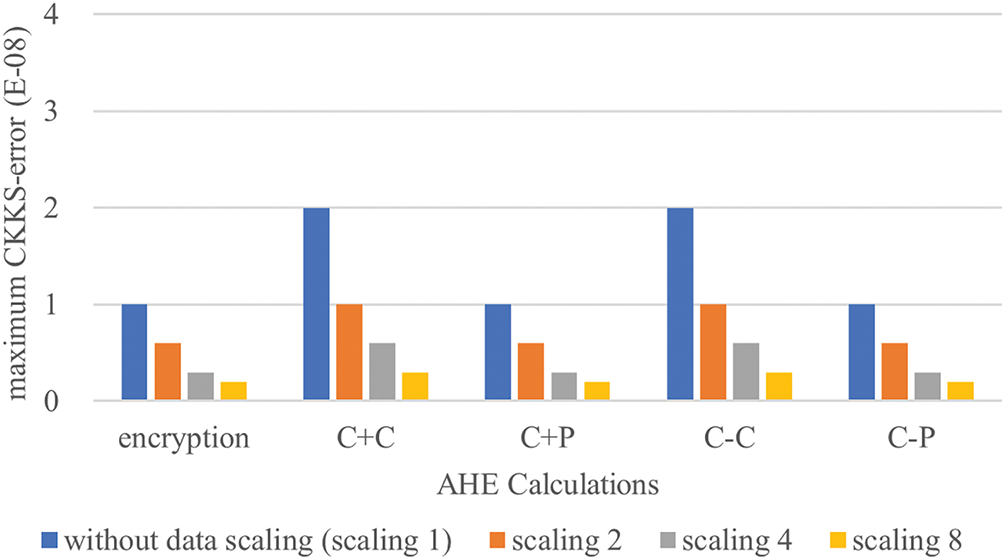

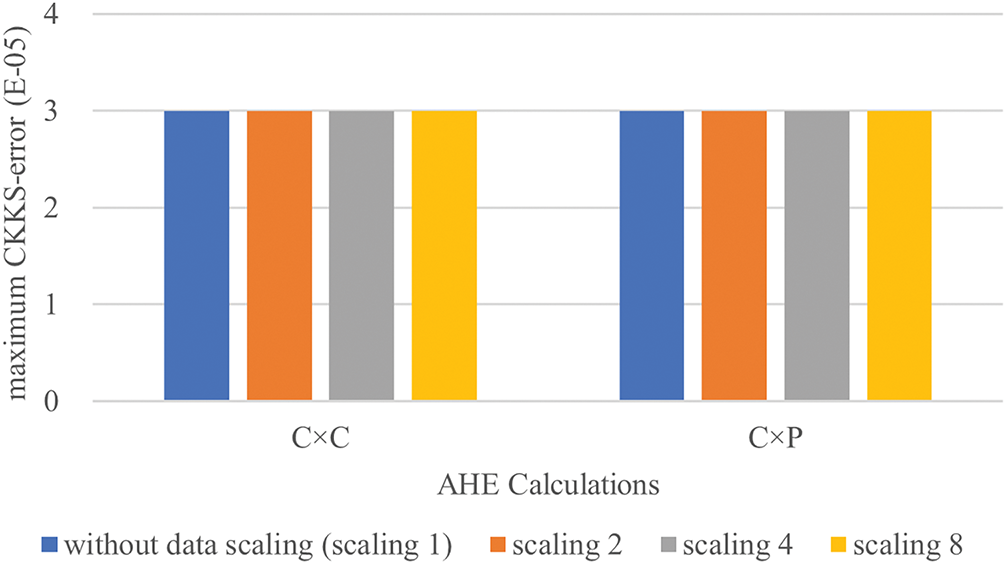

In the first experiment, we compare CKKS-errors with and without data scaling on the same dataset. This experiment uses uniformly distributed dataset in the integer domain [0, 5] (i.e., {x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ x ≤ 5}). This dataset is then scaled this to the integer domain [0, 10] (i.e., {2x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 2x ≤ 10}), [0, 20] (i.e., {4x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 4x ≤ 20}) and [0, 40] (i.e., {8x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 8x ≤ 40}) to compare CKKS-errors caused by without and with data scaling. These results are shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively, where the additive homomorphic operation on ciphertext is expressed as (C + C), additive homomorphic operation on ciphertext-plaintext is expressed as (C + P), subtractive homomorphic operation on ciphertext is expressed as (C − C), subtractive homomorphic operation on ciphertext-plaintext is expressed as (C − P), multiplicative operation on ciphertext is expressed as (C × C) and multiplicative operation on ciphertext-plaintext is expressed as (C × P). (Notably, there is no divisive homomorphic operation “÷” in CKKS). The research was found that in AHE calculation data scaling (zooming in) first, and then restoring after calculations, which can reduce CKKS-errors caused by calculation results. This experiment show that scaling data for AHE calculations, and then restoring the scale in results from AHE calculations, can reduce the CKKS-errors from original data for AHE calculation.

Figure 2: CKKS-error of operations “+” and “−” with different data scalings on the same dataset

Figure 3: CKKS-error of operation “×” with different data scalings on the same dataset

In the second experiment, we observe the CKKS-errors in detailed operations of AHE calculations on different datasets without data scaling. This experiment uses 3 different datasets. The first one is a uniformly distributed dataset in the integer domain [0, 10] (i.e., {x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ x ≤ 10}). The second one is a uniformly distributed dataset in the integer domain [0, 15] (i.e., {x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ x ≤ 15}). The third one is a uniformly distributed dataset in the integer domain [0, 20] (i.e., {x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ x ≤ 20}). By these 3 datasets, we observe CKKS-errors caused by different datasets without data scaling. These results are shown in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. Then, these results indicate that without data scaling, the CKKS-errors caused by homomorphic calculations of encryption, ciphertext/ciphertext-plaintext additive/subtractive operations are the same on different datasets. This experiment shows that, without data scaling, the CKKS-errors caused by the homomorphic calculations of encryption, ciphertext/ciphertext-plaintext additive/subtractive operations on different datasets are the same.

Figure 4: CKKS-error of operations “+” and “−” on different datasets

Figure 5: CKKS-error of operation “×” on different datasets

In the third experiment, we further observe CKKS-errors on different datasets through different data scaling. This experiment performs data scaling on these 3 different datasets. The first is a uniformly distributed dataset in the integer domain [0, 10] (i.e., {x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ x ≤ 10}) scaled to the integer domains [0, 20] (i.e., {2x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 2x ≤ 20}) and [0, 80] (i.e., {8x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 8x ≤ 80}). The second is a uniformly distributed dataset in the integer domain [0, 15] (i.e., {x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ x ≤ 15}) scaled to the integer domains [0, 30] (i.e., {2x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 2x ≤ 30}) and [0, 120] (i.e., {8x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 8x ≤ 120}). The third is a uniformly distributed dataset in the integer domain [0, 20] (i.e., {x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ x ≤ 20}) scaled to the integer domains [0, 40] (i.e., {2x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 2x ≤ 40}) and [0, 160] (i.e., {8x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 8x ≤ 160}). Through these datasets, observe the CKKS-errors caused by different datasets in the case of data scaling. These results are shown in Figs. 6 and 7, respectively. These results indicate that first scaling data on different datasets, and then restoring the results in original scale after calculations, which can reduce CKKS-errors caused by calculation results. This experiment shows that scaling the dataset for AHE calculations, and then restoring the results from AHE calculations to the original scale, which the CKKS-errors can be reduced too.

Figure 6: CKKS-error of operations “+” and “−” with different data scalings on different datasets

Figure 7: CKKS-error of operation “×” with different data scalings on different datasets

4.2 CKKS-Errors for Different Clustering Data Distances

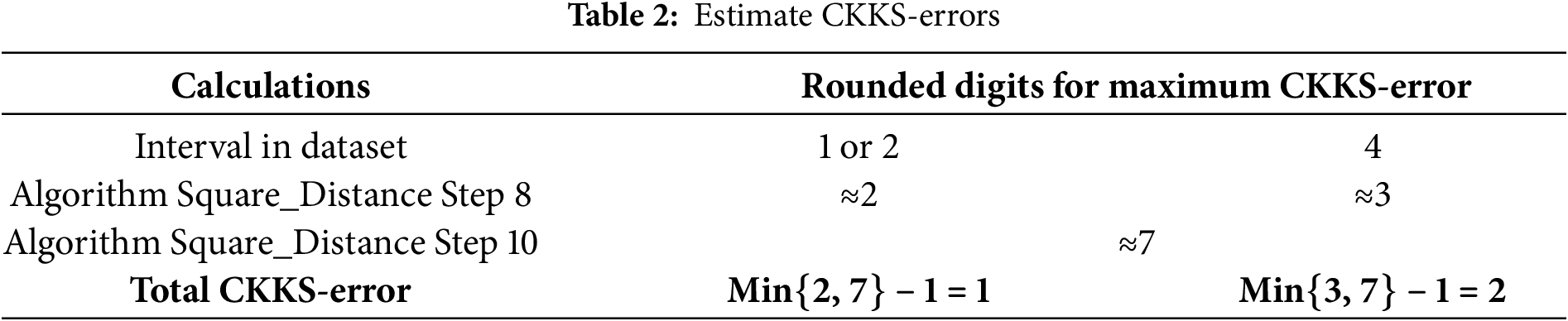

For the convenience of our experiments, we use uniformly distributed dataset and assume that the value domain of the system is the integer domain [0, 20]. The OEE table is the CKKS-errors caused by the AHE calculation for the datasets of all data intervals in this integer domain. For intervals 1, 2, and 4, we consider three datasets {x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ x ≤ 20} (interval is 1), {2x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 2x ≤ 20} (interval is 2), and {4x | x ∈ Z and 0≤ 4x ≤ 20} (interval is 4). These three datasets make the OEE table based on record packing. The experimental results are shown in Table 1. Observe the OEE table, it is found that CKKS-error of multiplicative homomorphism on ciphertext/ciphertext-plaintext is the largest. However, the larger the interval, the smaller CKKS-error. Note that the rounding result of 5E−04 is 1E−03 in rounded digits of 3.

4.3 Estimate of CKKS-Errors from RP-OKC Algorithms

The experiments use the OEE table for different distances in the datasets to estimate CKKS-errors caused by RP-OKC. Then the estimated results are applied to RP-OKC to verify the estimated results. Therefore, we need to estimate CKKS-errors by Algorithm Find_Cluster (Algorithm 1) and Algorithm Square_Distance (Algorithm 2) in RP-OKC [6]. In Algorithm Find_Cluster, k is the number of clusters. Algorithm Find_Cluster needs to decrypt encrypted distance Dis to find cluster to which record belongs (Steps 2 to 6 in Algorithm Find_Cluster). CKKS-errors will directly affect its clustering results, so it is extremely important to remove CKKS-errors as possible as we can in Step 4 of Algorithm Find_Cluster. Encrypted distance Dis is the sum of the Euclidean squared distances from record to each cluster center.

In Algorithm Square_Distance, z is the number of records. m is the number of attributes. Euclidean squared distance is used to calculate the squared distance between the encrypted data and the cluster centers (Step 8 in Algorithm Square_Distance). This step performs subtractive/multiplication homomorphic operation on ciphertext. Sum of the Euclidean squared distances adds up the Euclidean squared distances for each attribute (Step 10 in Algorithm Square_Distance). This step performs an additive homomorphic operation on ciphertext. Finally, find the cluster which record belongs based on the sum of the squared Euclidean distances between the encrypted data and each cluster center (Step 13 in Algorithm Square_Distance). Therefore, CKKS-errors are caused by these different homomorphic operations on ciphertext.

CKKS-errors caused by RP-OCK are estimated using the results in Table 1 and the estimated results are shown in Table 2.

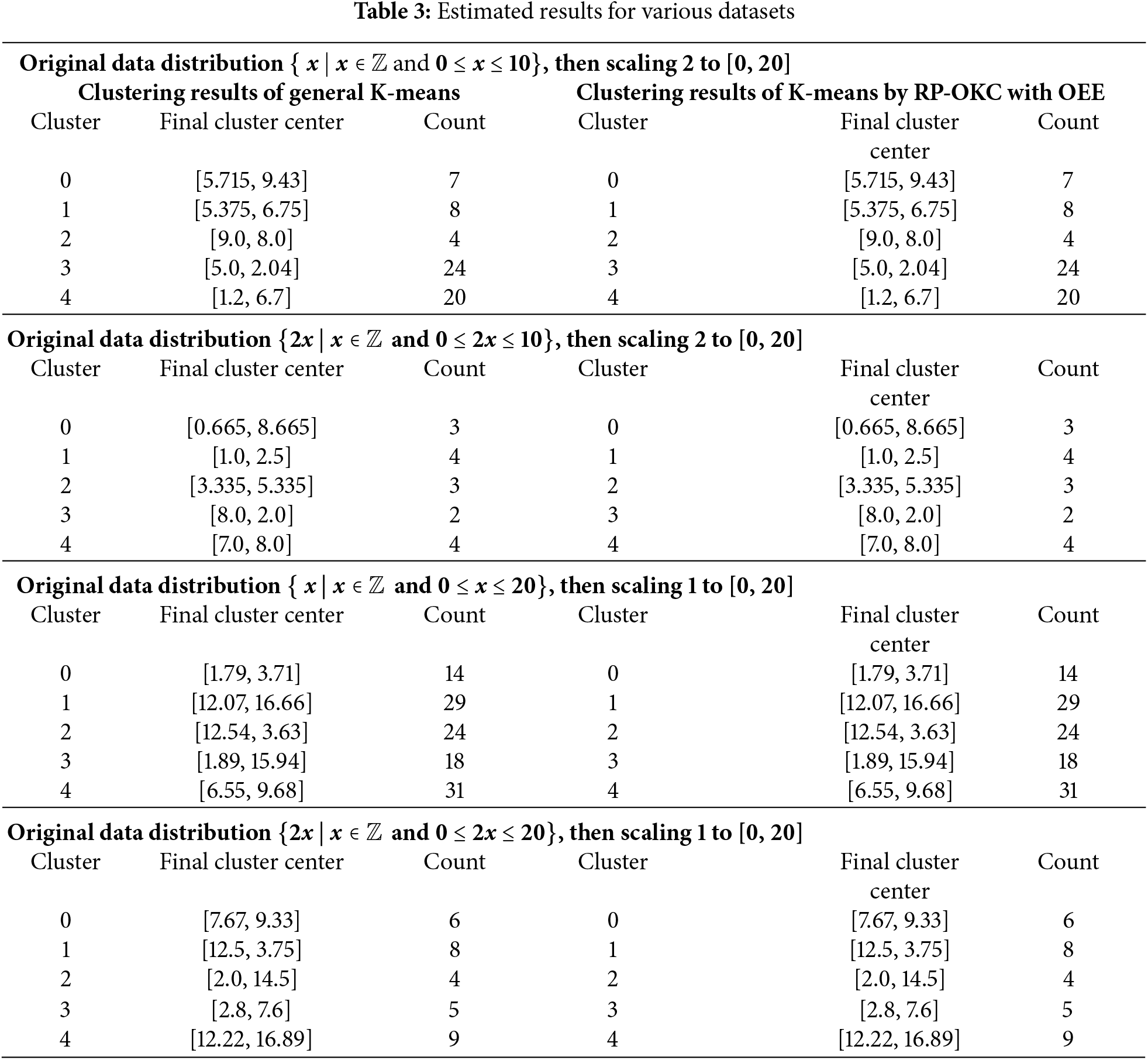

To confirm the accuracy of the estimation results from our proposed OEE table, we further validate the estimated results using the Annual_Income_(k$) and Spending_Score attributes in Kaggle customer data [27]. The data range of Annual_Income_(k$) is [15, 137] and the data range of Spending_Score is [1, 99]. We divided this testing procedure into 4 phases:

In Phase 1, normalize and scale data to the integer interval {x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ x ≤ 10}. It is then scaled to the integer interval [0, 20] (i.e., {2x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 2x ≤ 20}). Thus, the interval of data is 2. After processing data, use the estimated results with interval of 2 in Table 2 for testing.

In Phase 2, normalize and scale data to the integer interval {2x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 2x ≤ 10}. It is then scaled to the integer domain [0, 20] (i.e., {4x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 4x ≤ 20}). Thus, the interval of data is 4. After processing data, use the estimated results with interval of 4 in Table 2 for testing.

In Phase 3, normalize and scale data to the integer domain {x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ x ≤ 20}. Thus, the interval of data is 1. After processing data, use the estimated results with interval of 1 in Table 2 for testing.

In Phase 4, normalize and scale data to the integer domain {2x | x ∈ Z and 0 ≤ 2x ≤ 20}. Thus, the interval of data is 2. After processing data, use the estimated results with interval of 2 in Table 2 for testing.

Finally, perform Step 4 in the Algorithm Find_Cluster of RP-OKC with the estimated result. RP-OKC purpose is to split the data into 5 clusters. The initial cluster centers are generated from random numbers. The random number is fixed using the random number seed. The random seed is from 0 to 99, and then RP-OKC is performed 100 times for each case. That is to say, RP-OKC is performed for privacy-preserving K-means clustering on the same dataset starting from different center in each cluster for each case. The RP-OKC clustering results of each case are the same as the general K-means clustering, as shown in Table 3.

CKKS operations introduce approximate errors that accumulate through chained operations. Additions result in linear error growth, while multiplications increase the noise magnitude multiplicatively. In this study, we estimate total error based on the depth of operations in the clustering protocol. For example, the Square_Distance function performs element-wise subtractions, multiplications, and summations across d dimensions. The estimated error is conservatively modeled as ε_total ≈ d ∗ ε_add + (d − 1) ∗ ε_mul. Although empirical validation was limited to selected configurations, our OEE table provides practical guidance for determining when output correction is necessary.

4.4 Comparisons from RP-OKC Algorithm

In Table 4, we added a comparative table that summarizes key differences between our proposed method and related works with semi-honest security model in terms of security model, error control strategy, output accuracy and notes of computational overhead.

The computational cost of RP-OKC is dominated by homomorphic distance evaluations. Each Square_Distance operation involves two ciphertext-ciphertext subtractions, one ciphertext-plaintext multiplication, and one ciphertext-ciphertext addition per dimension, followed by a summation. For d-dimensional vectors and n data points, the complexity is O(n · d) homomorphic operations per iteration.

The communication overhead consists of:

– Uploading n ciphertexts (one per data point).

– Sending k ciphertexts back for updated centroids.

The ciphertexts are of size ≈ 4–8 KB each (TenSEAL default), resulting in O(n + k) ciphertext transfers per iteration.

Compared to plaintext clustering, this overhead is expected due to FHE costs, but remains practical under the semi-honest model.

While our primary experiments are based on uniformly distributed synthetic data, it is worth noting that CKKS-error behavior can be sensitive to input data variance and distribution. Prior studies [25] have shown that non-uniform distributions—such as Gaussian or skewed data—may result in higher accumulated noise during multiplications, especially when input magnitudes vary significantly. In particular, larger or more dispersed input values increase the risk of precision loss after scaling and rescaling.

Thus, although our current OEE table is based on controlled uniform input, we expect that CKKS-error under non-uniform data may be bounded using the same model but with more conservative parameters. This highlights the need to consider input variance in future OEE table extensions, which we plan to explore in subsequent work.

In order to find a cost-effective way to estimate CKKS-errors. This paper explores the effect of data scaling on CKKS-errors. We propose that data scaling (zoomed in) can move data away from noise bits, thereby reducing CKKS-errors to achieve better data analytics using privacy-preserving AHE. At the same time, in order to better estimate CKKS-errors caused by complex operations. The OEE table, further constructed for RP-OKC, can easily estimate CKKS-errors. Different MLaaS platforms can use the OEE table to estimate CKKS-errors, so that the data owner can get the correct result without a serious impact from CKKS-errors.

With the demonstration from our RP-OKC system for K-means clustering, we make the OEE table, from which we can see CKKS-errors caused by the AHE calculations. From the OEE table, we found that the interval between data will affect the size of CKKS-errors. The larger the interval between the data, the smaller the CKKS-errors. We propose to round CKKS-errors by using the OEE table to estimate CKKS-errors caused by complex operations. Experiments show that rounding the calculated results can make the clustering results of RP-OKC the same as general K-means.

Our future work is to use the OEE table for more algorithms of data analytics and more input variance in future OEE table extensions. The RP-OKC system will be further expanded to add more evaluations for CKKS performance. For example, the time required for encryption, the time required for each AHE operation, the time required for decryption, and the total consumption time for AHE.

We acknowledge that the current method operates under a semi-honest threat model and assumes that system parameters (e.g., scaling factors) are properly chosen. Our approach does not currently defend against malicious adversaries or support dynamic data scenarios. Additionally, while the proposed error estimation is empirically validated, a complete theoretical model of CKKS noise propagation remains an area for future refinement.

In future work, we plan to:

– Extend our approach to support dynamic datasets and streaming clustering;

– Improve real-time performance for low-latency applications;

– Explore the integration of post-quantum secure homomorphic encryption schemes;

– Expand the OEE table to other ML tasks such as logistic regression and decision trees.

These extensions will further improve the practicality and robustness of privacy-preserving analytics over encrypted data in the cloud.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express special thanks to the collaborators for their valuable insights and discussions in completing this article.

Funding Statement: This work is partially funded by National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, grant numbers are 110-2401-H-002-094-MY2 and 112-2221-E-130-001.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Ray-I Chang; methodology, Chia-Hui Wang; software, Yen-Ting Chang; validation, Chia-Hui Wang, Ray-I Chang; formal analysis, Ray-I Chang; investigation, Ray-I Chang; resources, Chia-Hui Wang; data curation, Lien-Chen Wei; writing—original draft preparation, Ray-I Chang, Chia-Hui Wang; writing—review and editing, Chia-Hui Wang, Ray-I Chang, Lien-Chen Wei; visualization, Yen-Ting Chang, Chia-Hui Wang; supervision, Chia-Hui Wang; project administration, Ray-I Chang, Chia-Hui Wang, Lien-Chen Wei; funding acquisition, Chia-Hui Wang, Ray-I Chang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cloud Security Alliance. Top threats to cloud computing: egregious eleven [Internet]; 2019 Aug 9. [cited 2025 Mar 24]. Available from: https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/press-releases/2019/08/09/csa-releases-new-research-top-threats-to-cloud-computing-egregious-eleven/. [Google Scholar]

2. Smart NP, Vercauteren F. Fully homomorphic encryption with relatively small key and ciphertext sizes. In: Proceedings of the International Workshop on Public Key Cryptography; 2010 May 26–28; Paris, France. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2010. p. 420–43. [Google Scholar]

3. Cash D, Jarecki S, Jutla C, Krawczyk H, Roşu MC, Steiner M. Highly-scalable searchable symmetric encryption with support for boolean queries. In: Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2013: 33rd Annual Cryptology Conference; 2013 Aug 18–22; Santa Barbara, CA, USA. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2013. p. 353–73. [Google Scholar]

4. Brakerski Z, Gentry C, Vaikuntanathan V. (Leveled) fully homomorphic encryption without bootstrapping. ACM Trans Comput Theory. 2014;6(3):1–36. doi:10.1145/2633600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Cheon JH, Kim A, Kim M, Song Y. Homomorphic encryption for arithmetic of approximate numbers. In: Lee D, editor. Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2017: 23rd International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptology and Information Security; 2017 Dec 3–7; Hong Kong, China. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017. p. 409–37. [Google Scholar]

6. Chang RI, Chang YT, Wang CH. Outsourced K-means clustering for high-dimensional data analysis based on homomorphic encryption. J Inf Sci Eng. 2023;39(3):525–48. [Google Scholar]

7. Raykova M, Cui A, Vo B, Liu B, Malkin T, Bellovin SM, et al. Usable, secure, private search. IEEE Secur Priv. 2011;10(5):53–60. doi:10.1109/msp.2011.155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Fu Y, Tong Y, Ning Y, Xu T, Li M, Lin J, et al. Swift: fast secure neural network inference with fully homomorphic encryption. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2025;20:2793–806. doi:10.1109/tifs.2025.3547308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wu X, Wang J, Zhang T. Integrating fully homomorphic encryption to enhance the security of blockchain applications. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;161(5):467–77. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.07.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ren Y, Xiao Y, Zhou Y, Zhang Z, Tian Z. CSKG4APT: a cybersecurity knowledge graph for advanced persistent threat organization attribution. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2022;35(6):5695–709. doi:10.1109/tkde.2022.3175719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang Z, Zhou Y, Liu H, Qiu J, Fang B, Tian Z. Threatinsight: innovating early threat detection through threat-intelligence-driven analysis and attribution. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2024;36(12):9388–402. doi:10.1109/tkde.2024.3474792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Brakerski Z. Fully homomorphic encryption without modulus switching from classical GapSVP. In: Annual Cryptology Conference; 2012 Aug 19–23; Santa Barbara, CA, USA. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2012. p. 868–86. [Google Scholar]

13. Fan J, Vercauteren F. Somewhat practical fully homomorphic encryption. IACR Cryptol Eprint Arch. 2012;2012: 144. [Google Scholar]

14. Chillotti I, Gama N, Georgieva M, Izabachene M. Faster fully homomorphic encryption: bootstrapping in less than 0.1 seconds. In: Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2016; 2016 Dec 4–8; Hanoi, Vietnam. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

15. Chillotti I, Gama N, Georgieva M, Izabachène M. Faster packed homomorphic operations and efficient circuit bootstrapping for TFHE. In: International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security; 2017 Dec 3–7; Hong Kong, China. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 377–408. [Google Scholar]

16. Chillotti I, Gama N, Georgieva M, Izabachène M. TFHE: fast fully homomorphic encryption over the torus. J Cryptol. 2020;33(1):34–91. doi:10.1007/s00145-019-09319-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li X, Zhu Y, Wang J, Liu Z, Liu Y, Zhang M. On the soundness and security of privacy-preserving SVM for outsourcing data classification. IEEE Trans Dependable Secur Comput. 2017;15(5):906–12. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2017.2682244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu X, Lu R, Ma J, Chen L, Qin B. Privacy-preserving patient-centric clinical decision support system on naive Bayesian classification. IEEE J Biomed Health Inf. 2015;20(2):655–68. doi:10.1109/jbhi.2015.2407157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Liu J, Wang C, Tu Z, Wang XA, Lin C, Li Z. Secure KNN classification scheme based on homomorphic encryption for cyberspace. Sec Commun Netw. 2021;2021(5):8759922. doi:10.1155/2021/8759922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kim A, Papadimitriou A, Polyakov Y. Approximate homomorphic encryption with reduced approximation error. In: Cryptographers’ Track at the RSA Conference; 2022 Feb 7–10; San Francisco, CA, USA. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 120–44. [Google Scholar]

21. Kim M, Song Y, Wang S, Xia Y, Jiang X. Secure logistic regression based on homomorphic encryption: design and evaluation. JMIR Med Inf. 2018;6(2):e8805. [Google Scholar]

22. Rovida L. Fast but approximate homomorphic k-means based on masking technique. Int J Inf Secur. 2023;22(6):1605–19. doi:10.1007/s10207-023-00708-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yao P, Zheng C, He W, Jing Y, Li HJ, Wang LM. FedSHE: privacy preserving and efficient federated learning with adaptive segmented CKKS homomorphic encryption. Cybersecurity. 2024;7(1):40. doi:10.1186/s42400-024-00232-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lee Y, Cheon S, Kim D, Lee D, Kim H. {ELASM}:{Error-Latency-Aware} scale management for fully homomorphic encryption. In: 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23); 2023 Aug 9–11; Anaheim, CA, USA. p. 4697–714. [Google Scholar]

25. Costache A, Curtis BR, Hales E, Murphy S, Ogilvie T, Player R. On the precision loss in approximate homomorphic encryption. In: International Conference on Selected Areas in Cryptography; 2023 Aug 14–18; Fredericton, NB, Canada. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2023. p. 325–45. [Google Scholar]

26. OpenMined. TenSEAL [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://github.com/OpenMined/TenSEAL. [Google Scholar]

27. Iyyer S. Kaggle customer data [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/shrutimechlearn/customer-data/version/1. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools