Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhanced Plant Species Identification through Metadata Fusion and Vision Transformer Integration

1 Department of Computer Science, National University of Computer & Emerging Sciences, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

2 Department of Computer Science, Air University, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

3 Department of Computer Science and Information, College of Science in Zulfi, Majmaah University, Al-Majmaah, 11952, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Syed Fahad Tahir. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3981-3996. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.064359

Received 13 February 2025; Accepted 29 May 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Accurate plant species classification is essential for many applications, such as biodiversity conservation, ecological research, and sustainable agricultural practices. Traditional morphological classification methods are inherently slow, labour-intensive, and prone to inaccuracies, especially when distinguishing between species exhibiting visual similarities or high intra-species variability. To address these limitations and to overcome the constraints of image-only approaches, we introduce a novel Artificial Intelligence-driven framework. This approach integrates robust Vision Transformer (ViT) models for advanced visual analysis with a multi-modal data fusion strategy, incorporating contextual metadata such as precise environmental conditions, geographic location, and phenological traits. This combination of visual and ecological cues significantly enhances classification accuracy and robustness, proving especially vital in complex, heterogeneous real-world environments. The proposed model achieves an impressive 97.27% of test accuracy, and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) of 0.9842 that demonstrates strong generalization capabilities. Furthermore, efficient utilization of high-performance GPU resources (RTX 3090, 18 GB memory) ensures scalable processing of high-dimensional data. Comparative analysis consistently confirms that our metadata fusion approach substantially improves classification performance, particularly for morphologically similar species, and through principled self-supervised and transfer learning from ImageNet, the model adapts efficiently to new species, ensuring enhanced generalization. This comprehensive approach holds profound practical implications for precise conservation initiatives, rigorous ecological monitoring, and advanced agricultural management.Keywords

Plants are crucial in maintaining ecological balance and supporting life on Earth [1]. More than 390,000 species exist [2]. The taxonomic diversity of flora is essential to global biodiversity that can help in understanding the key ecological processes such as primary production, carbon sequestration, and oxygen generation [3–5]. Accurate and efficient plant-species identification is essential for biodiversity conservation, ecological research, and sustainable resource management [6]. In agriculture, plant species identification helps in crop optimization and pest control, while in environmental monitoring, it may serve as bioindicators of ecosystem health and responses to stressors [7]. Plant-species identification becomes a challenging task because of morphological complexity, inter-species similarity, and the presence of closely related or hybrid species. For example, subtle differences between species in the Quercus or Populus genera, or variations within a species due to environmental factors, often result in misidentification [8].

Conventional taxonomy relies on manual analysis of morphological traits such as leaf shape and flower structure, often aided by herbarium specimens and expert-driven diagnostics [9,10]. While effective, these methods are time-consuming, subjective, and sensitive to phenotypic plasticity, which limits scalability and accessibility [6]. Traditional systems also tend to analyze individual plant organs in isolation, while overlook complementary features across multiple organs that could improve identification accuracy [11].

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been widely used for image-based plant-species identification. CNN shows high accuracy on datasets such as PlantVillage and in apps like Flora Incognita [6,12]. Transfer learning further enhances performance on rare or underrepresented species [13]. More recently, Vision Transformers (ViTs) have emerged as powerful tools that are capable of capturing both local and global visual relationships through self-attention mechanisms, thus surpassing CNNs in some visual identification tasks [14]. Hybrid and ensemble models combining CNNs and ViTs such as Plant CNN-ViT have shown even greater robustness by exploiting complementary strengths [15,16].

However, AI-based methods also have some limitations, such as requiring diverse training data, and still difficulty in handling morphologically similar species, thus have reduced reliability in field conditions with varied lighting, occlusion, or seasonal changes [17,18]. Intra-species variability and environmental factors further result in misclassifications.

To address the limitations of image-only plant species identification, we propose a novel multi-modal framework that integrates Vision Transformer (ViT)-based image analysis with contextual metadata, including environmental conditions, geographic location, and phenological traits. This fusion enhances classification accuracy in real-world, heterogeneous environments by exploiting both visual and ecological cues. Our approach specifically targets challenges such as morphological similarity, cryptic species, and intra-species variability, which often hinder traditional and image-only methods. Scalability is another major advantage, as the model is designed to efficiently process large-scale datasets spanning diverse ecosystems. Additionally, through self-supervised learning and transfer learning from ImageNet, the model adapts to new plant species with minimal retraining, ensuring improved generalization across different datasets and real-world environments. Experimental results show that the integration of deep visual embeddings with structured metadata improves species classification, under diverse environmental and phenotypic conditions.

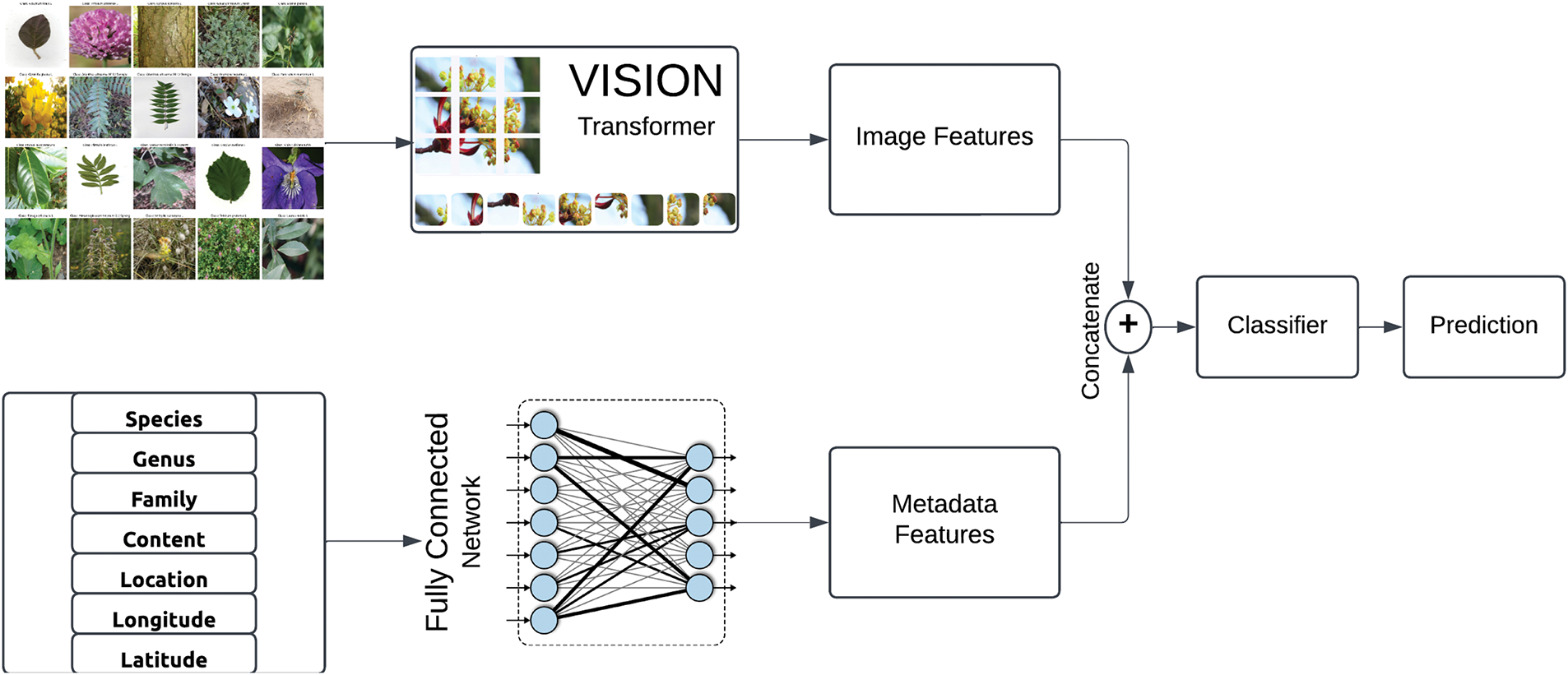

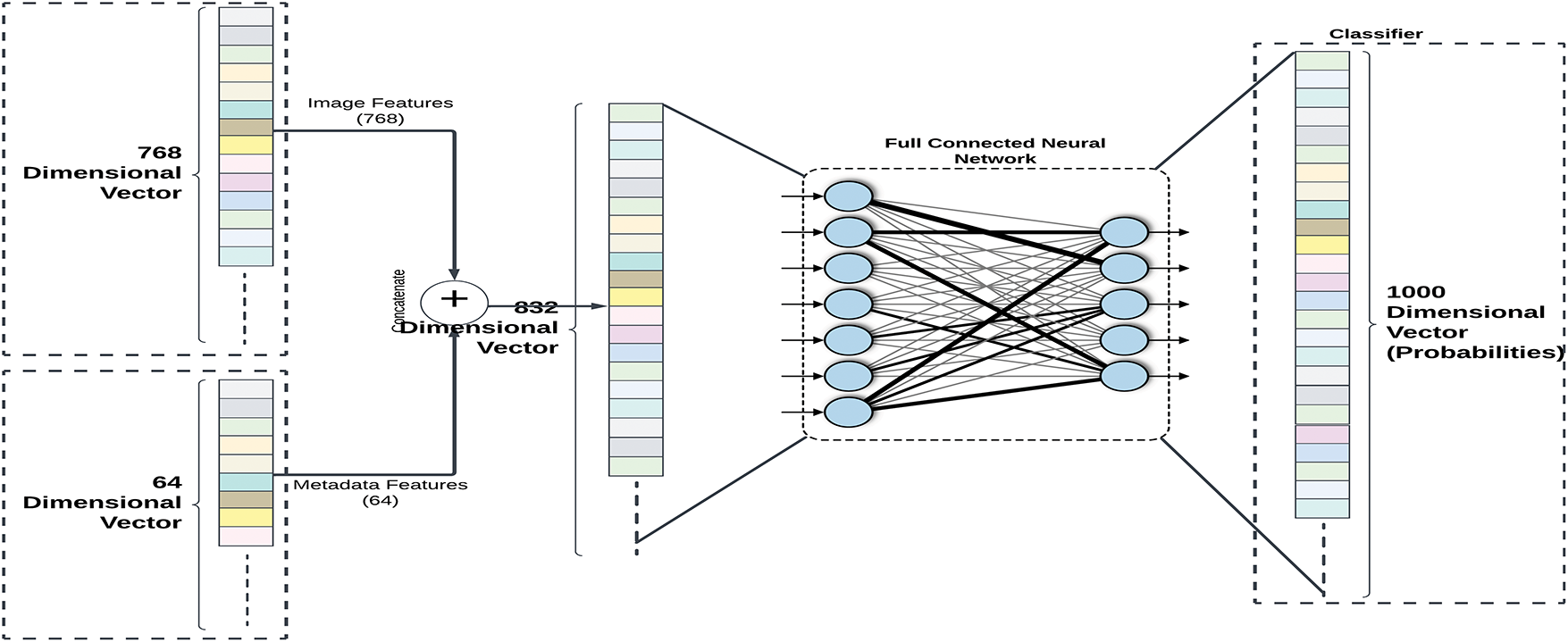

We propose a deep learning-based framework for plant species classification by integrating contextual metadata with visual features extracted from images. The proposed methodology follows a systematic pipeline (Fig. 1), comprising of data preprocessing, feature extraction, feature fusion, model training, and evaluation, ensuring a scalable and robust approach for automated plant species classification. A pre-trained ViT [19] is utilized for image feature extraction that exploits self-attention mechanisms to model long-range dependencies. Meanwhile, structured metadata, including geographical and taxonomic information, is processed through a fully connected neural network (FCNN) [20]. This joined feature vector is then passed through a classification pipeline for the generation of probabilistic predictions across species classes. The feature fusion approach has been shown to significantly improve fine-grained classification accuracy by integrating diverse data modalities.

Figure 1: Block diagram of proposed classification approach that exploits contextual and visual information

To ensure the robustness of the proposed model, the current study utilized diverse and representative publicly available datasets, each with unique contributions, incorporating multi-organ plant images from various geographical regions. The selected datasets provide complementary information essential for hierarchical classification, covering plant morphology at different taxonomic levels. To ensure diversity and representativeness, below publicly available datasets were utilized, each with unique contributions:

• PlantCLEF [3]: A dataset encompassing annotated images of plant organs (e.g., leaves, flowers, fruits) collected from diverse geographical regions. This dataset provides robust taxonomic information for multi-organ classification.

• iNaturalist [4]: To enhance contextual understanding this dataset includes metadata like geolocation and timestamps contributed by global citizen scientists.

• LeafSnap [21]: Primarily focused on high-resolution leaf morphology images, this dataset offers detailed annotations essential for species-level classification.

These datasets (Table 1) collectively offer a wide-ranging spectrum of plant species, ensuring that the model generalizes well across various ecosystems. This integrated approach covers the acquisition of images, validation of annotations, and integration of taxonomic information, resulting in a cohesive dataset suitable for both training and evaluation.

2.2 Dataset Distribution Analysis

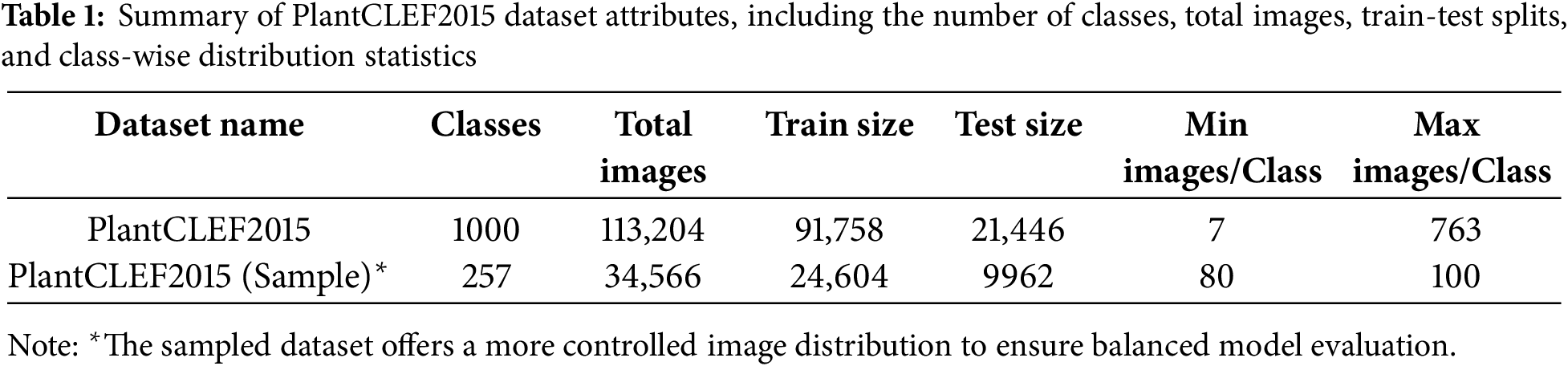

The PlantCLEF training dataset comprises 24,604 images representing 257 distinct plant species from diverse geographical regions and environmental conditions, ensuring broad representation across habitat types, climate zones, and morphological traits [22]. For data distribution analysis, we perform multi-panel visualization, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and geographic distribution analysis. A multi-panel visualization (Fig. 2) illustrates the distribution characteristics, revealing that the dataset is highly balanced. Most classes contain between 80 and 100 images, with both the mean (95.7) and median (100) confirming this consistency. The percentile bar chart shows that 50% of the classes have exactly 100 images. Furthermore, statistical indicators such as a low Gini Coefficient (0.03) and a Max/Min Ratio of 1.25 highlight minimal class imbalance. These factors collectively demonstrate the dataset’s uniformity, which is crucial for training unbiased machine learning models.

Figure 2: PlantCLEF dataset class distribution: The 24,604 images are distributed in 257 different plant species within a range of 80–100 images per class (Max/Min Ratio: 1.25, Gini Coefficient: 0.03)

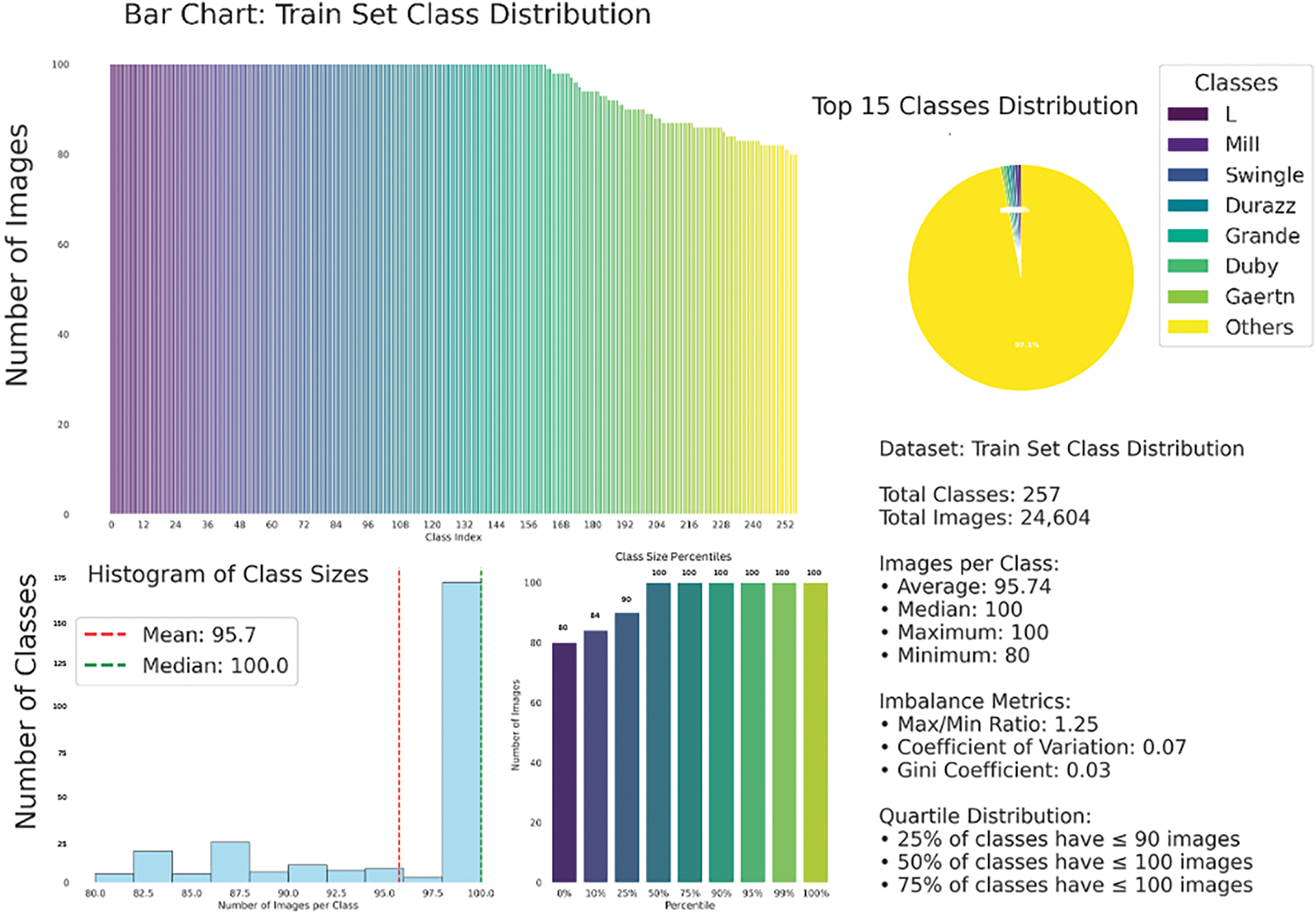

PCA visualization (Fig. 3) reduces the high-dimensional image features to two principal components, capturing 74.81% of the total variance. The resulting plots reveal significant intra-class variation and substantial overlap between different species clusters, indicating that many species share similar visual traits. In Fig. 3b, PCA of the top 20 species is depicted using confidence ellipses, further emphasizing the visual similarity across species and the lack of clear class boundaries. This overlap highlights the inherent difficulty of fine-grained plant species classification based solely on low-level visual features.

Figure 3: The PCA visualizations illustrate substantial intra-class variability and inter-species feature overlap in the PlantCLEF dataset. Plot (a) shows the overall feature distribution across all species. Plot (b) shows the top 20 species using confidence ellipses to highlight overlapping feature spaces. These patterns highlight the challenge of species identification using visual features alone

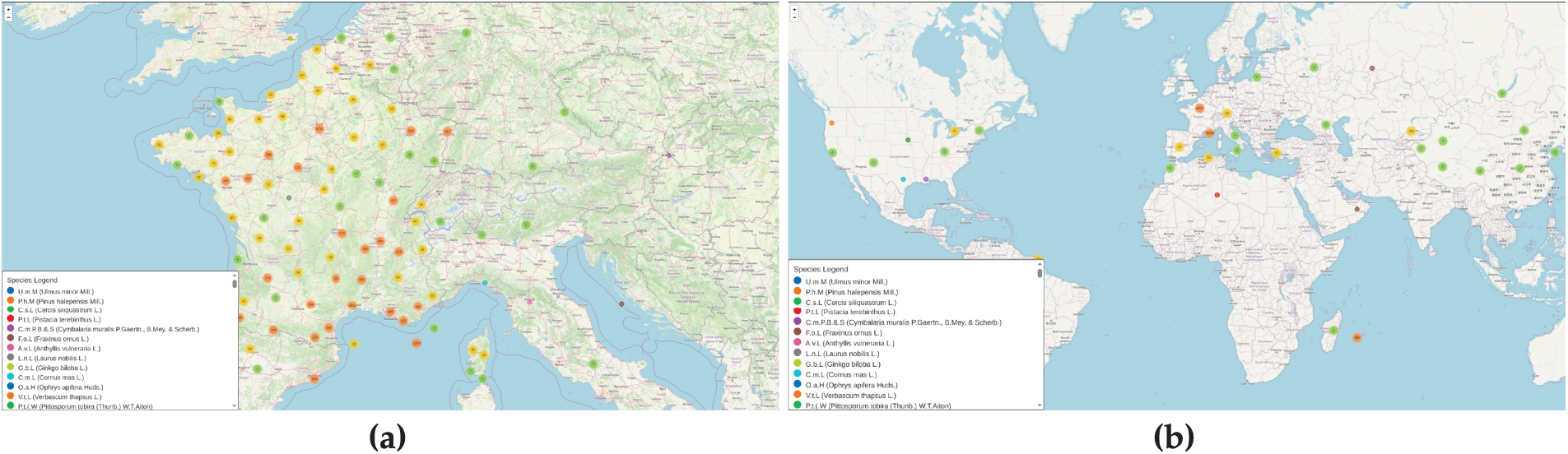

A geographic analysis (Fig. 4) illustrates the spatial distribution of plant observations within the dataset. The visualization highlights wide geographic coverage, representing a variety of ecological and climatic regions. It also reveals disparities in sampling density, from well-documented biodiversity hotspots to underrepresented regions. These insights are valuable for understanding potential geographic biases and ensuring ecological relevance in species recognition models.

Figure 4: Plant biodiversity patterns around the world: (a) shows biodiversity hotspots in France, Germany, and the UK, as well as extensive sampling coverage throughout Europe. (b) Intercontinental sampling with significant representation in North America, Asia, and a few places in Africa and South America

2.3 Metadata Validation and Standardization

A comprehensive validation and standardization process was put in place to guarantee the consistency and dependability of metadata across the various datasets used (PlantCLEF, LeafSnap, and iNaturalist). In order to make sure that geographical coordinates (latitude and longitude) fell within acceptable ranges, field-level validation was applied to numerical characteristics [23].

Additionally, to enable reliable model training, coordinate values were standardized to a consistent scale using min-max normalization:

To find anomalous coordinate entries, we employ inter-quartile range (IQR) based statistical technique [23]. A coordinate value was flagged as an outlier if:

Similarly, we applied IQR for longitude values, where

To remove inconsistencies because of typographical errors or different naming methods, we compared and matched the taxonomic fields such as species, genus, and family to a curated lexicon. To ensure consistency, all entries in textual metadata fields were converted to lowercase and special characters were eliminated. We also removed duplication of photos or metadata information across species classifications during the initial dataset examination. The consistency auditing and metadata validation processes greatly increased the dependability of the contextual data that was entered into the model.

We addressed the conflicting metadata entries through a priority-based field trust mechanism, where taxonomic labels (e.g., species, genus) were assigned higher confidence than auxiliary attributes such as geographic coordinates. We computed a metadata consistency score via cross-validation of taxonomic and spatial information to facilitate the identification of anomalous samples. Training data exhibiting severe inconsistencies such as records of regionally endemic species associated with ecologically inconsistent geographic locations were removed. This preprocessing step reduced the potential for model misinterpretation arising from contradictory metadata signals [5].

Multimodal fusion models are also sensitive to missing metadata. To address this, a two-tiered strategy was adopted. Samples missing essential fields (e.g., species name, genus, latitude, longitude) were excluded to preserve semantic integrity and prevent erroneous contextual inferences. For non-essential fields, missing categorical values were marked as “unknown”, while missing numerical fields were imputed using dataset-level means [24]. To further enhance robustness, we introduced a binary flag to indicate the presence of metadata. Thus, the model to adjusts its reliance on auxiliary inputs dynamically. Additionally, during training, approximately 10% of metadata entries were randomly masked using a metadata dropout strategy. This technique simulated partial metadata availability at inference time and improved generalization under real-world conditions.

To enhance data quality and to ensure consistent input for model training, a comprehensive preprocessing pipeline was implemented. Despite efforts to maintain dataset balance, certain underrepresented species exhibited lower classification confidence, emphasizing the impact of class imbalance. To address this, a combination of oversampling and undersampling techniques was applied. Oversampling enhanced the representation of minority classes through synthetic sample generation and duplication [25], while undersampling reduced the influence of majority classes by selectively removing excess samples. This strategy helped mitigate model bias and ensured that rare species were fairly represented during training.

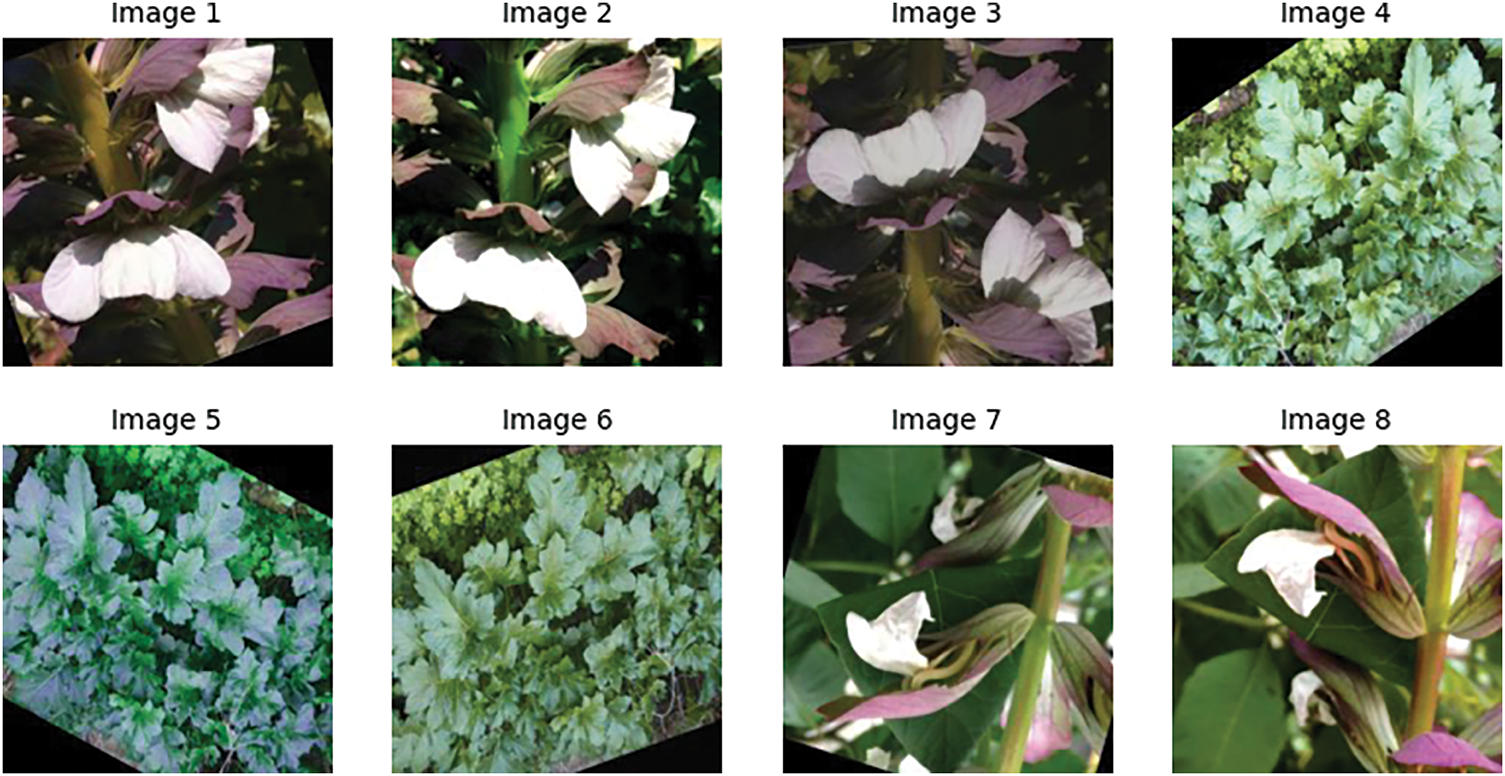

Data augmentation techniques were employed to prevent overfitting and enhance generalization. Geometric transformations such as rotation, flipping, scaling, and cropping simulated diverse viewing perspectives, as shown in Fig. 5. Color jittering introduced, controlled, variations in brightness, contrast, saturation, and hue, while random erasing and occlusion methods increased the model’s resilience to visual obstructions and partial damage [16].

Figure 5: Examples of data augmentation applied to PlantCLEF 2015 dataset

Data cleaning was performed using perceptual hashing to eliminate duplicate images [26], reducing redundancy and potential bias. Additionally, low-quality or corrupted images were filtered out to preserve dataset integrity. Standardization steps followed, including resizing all images to 224

Noise reduction techniques were applied to further improve image clarity. Background segmentation methods were used to isolate plant organs from complex scenes, while denoising filters (e.g., Gaussian blur and median filtering) reduced sensor noise and visual artifacts. These steps ensured that the model received cleaner, more representative inputs, improving its ability to learn discriminative features and effectively classify plant species.

The proposed model employs a multi-modal deep learning approach by integrating ViT for visual feature extraction and a fully connected neural network (FCNN) for metadata processing. These two components collectively enhanced the model’s ability to classify plant species with high accuracy, particularly in cases where visual features alone may be insufficient.

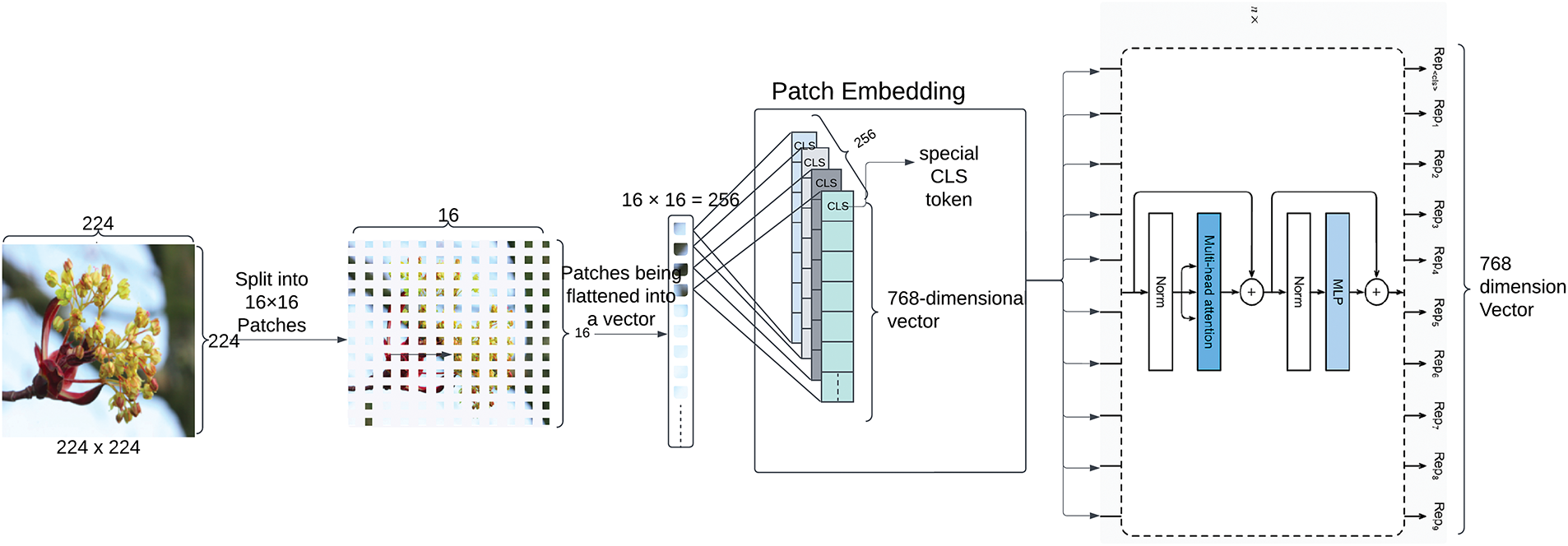

ViT, specifically the ViT-Base-Patch16-224 architecture, is pre-trained on ImageNet-21k [19] and fine-tuned for plant species classification. Resized images were divided into non-overlapping 16

Figure 6: ViT’s architecture for features extraction features from images. Each input is downsized to 224

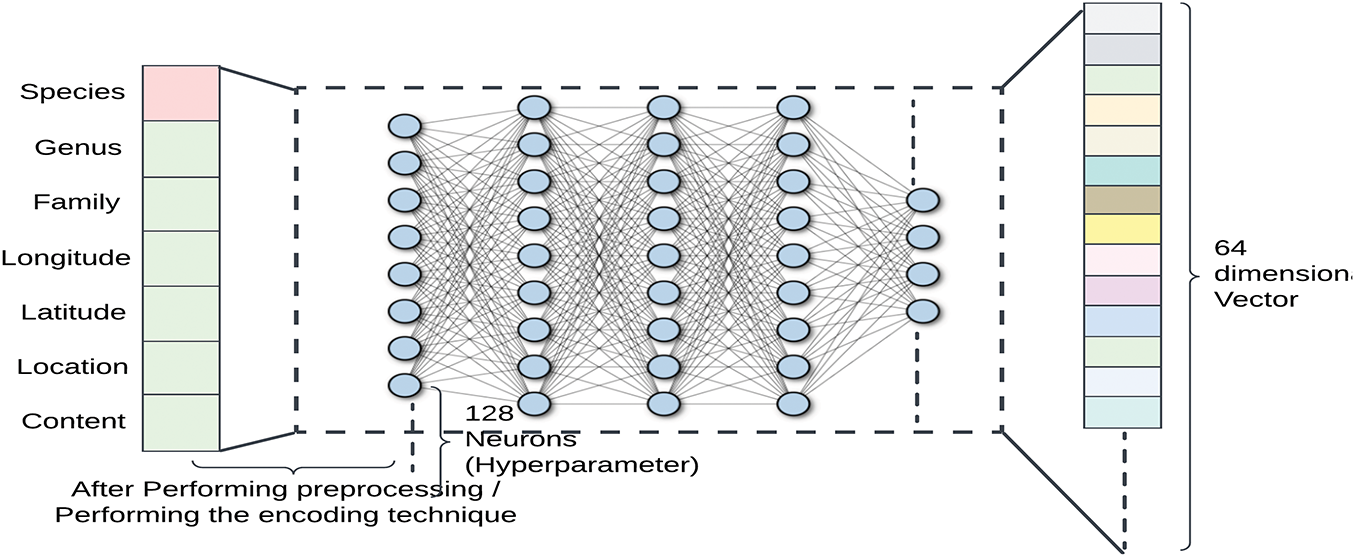

Complementing the visual processing, metadata—including normalized spatial coordinates (latitude, longitude) and taxonomic information (species, genus, family) is processed through a compact FCNN (Fig. 7). The input layer encodes the metadata, which then passes through a hidden layer of 128 neurons with ReLU activation, followed by an output layer that reduces the metadata into a 64-dimensional feature vector. This compact representation enhances classification by providing contextual information, especially for cases where visual similarities make species differentiation challenging [20].

Figure 7: Metadata processing using a fully connected network. The network receives metadata, which is made up of seven features (normalized spatial coordinates and encoded taxonomic designations). ReLU activation comes after the first layer translates the input to 128 neurons. The data is transformed and condensed into a 64-dimensional vector by the hidden layer. In the later phases of the model, this condensed representation is used as the metadata feature output, prepared for fusion with image features

To generate the final predictions, feature fusion is applied by concatenating the 768-dimensional visual feature vector from ViT with the 64-dimensional metadata feature vector from the FNN, forming an 832-dimensional composite representation Fig. 8. This unified feature vector is then passed through a classification head, which consists of A fully connected layer with 128 neurons and ReLU activation, and a softmax output layer, producing probability distributions across species classes. This fusion approach significantly improves classification accuracy by utilizing complementary data sources, combining deep visual representations with contextual metadata to enhance fine-grained species differentiation.

Figure 8: Features from the ViT (768-dimensional CLS token) and metadata (64-dimensional vector) are combined to create an 832-dimensional vector in the concatenation block. Species classification probabilities are generated by processing the concatenated vector through a softmax output layer and a classifier head with 128 neurons (ReLU)

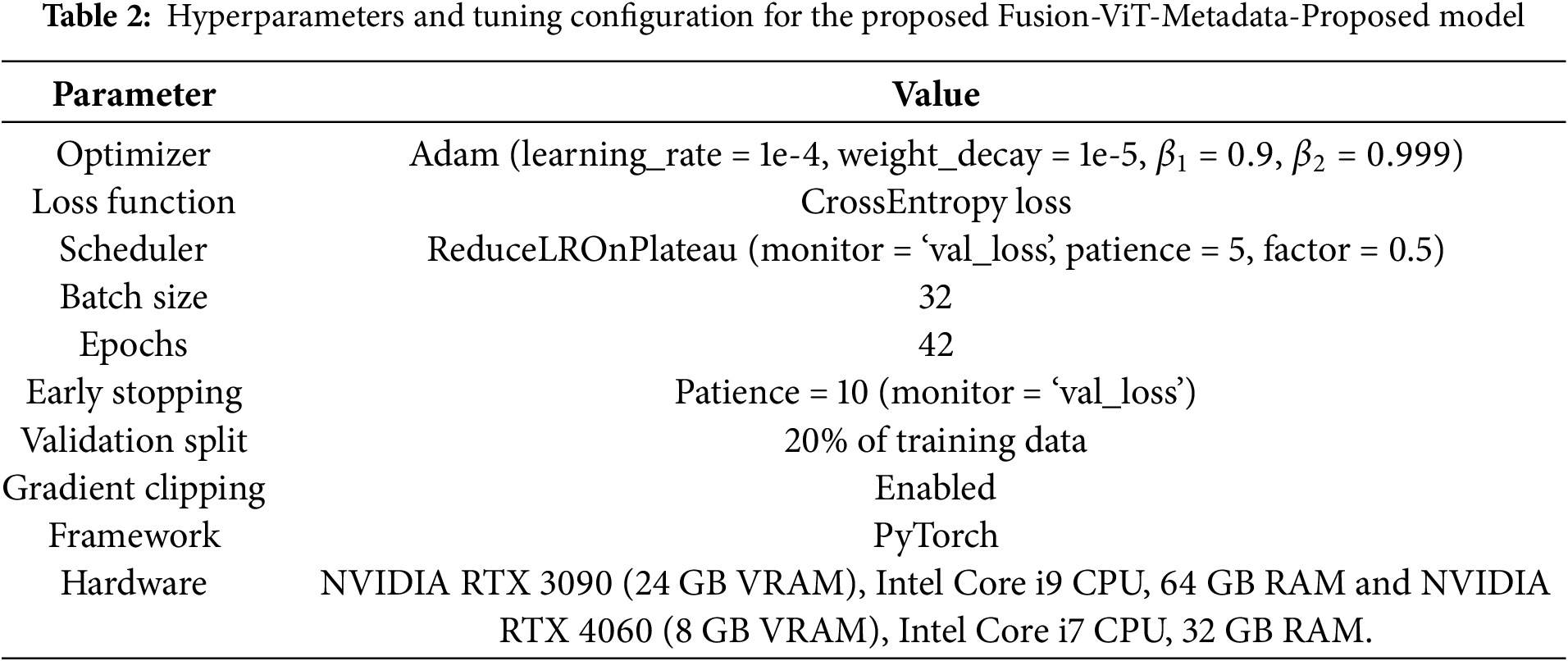

The training and optimization process was designed to ensure efficient learning, robust generalization, and stability in convergence. This section outlines the loss function, optimization strategy, learning rate scheduling, and hardware configuration used in the model training. Table 2 shows the parameters and tuning configurations used in the training of proposed approach.

The model was optimized using Cross-Entropy Loss function, a widely used objective function for multi-class classification problems [28]. This function measures the difference between the predicted probability distribution and the true class labels, ensuring that the model assigns higher confidence to correct classifications while penalizing incorrect predictions given as:

where N represents the batch size, C denotes the number of classes,

The Adam optimizer [30] was chosen for its adaptive learning rate capabilities and to efficiently handle sparse gradients, making it well-suited for deep learning models. Adam combines the advantages of momentum-based optimization and adaptive gradient scaling, ensuring stable training and faster convergence. The initial learning rate was set to

The ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler was employed to dynamically adjust the learning rate based on model performance, ensuring efficient convergence. If the validation loss exhibited stagnation over five consecutive epochs, the learning rate underwent a reduction by a factor of 0.5. This adjustment facilitated the model’s egress from regions of minimal gradient within the loss landscape, thereby enabling continued effective optimization. This adaptive learning rate modulation strategy augments the model’s capacity for robust generalization to unseen data [21]. Additionally, gradient clipping was applied to prevent exploding gradients, maintaining numerical stability and ensuring smooth parameter updates during training.

The model was trained for 50 epochs, with early stopping to prevent overfitting if the validation loss did not improve for 10 consecutive epochs, which also optimized training efficiency and stability. A batch size of 32 was chosen to maintain a balance between gradient stability and computational efficiency. Additionally, 20% of the dataset was allocated for validation to ensure an unbiased evaluation of the model’s performance. To improve model generalization, weight decay was applied to constrain large weight updates, ensuring smoother decision boundaries. Additionally, dropout regularization was used in the fully connected layers, randomly deactivating neurons to improve model robustness in unseen conditions. Finally, gradient clipping was applied to mitigate exploding gradients, ensuring numerical stability, particularly in deeper network layers.

Some post-processing techniques were applied to further refine classification outputs and enhance prediction reliability. Unlike object detection models that rely on bounding box refinement and non-maximum suppression, the current approach focuses on enhancing classification confidence through structured methods.

To reduce low-confidence misclassifications, a confidence threshold was applied, ensuring that only high-confidence predictions were retained. Any prediction below the threshold was excluded from the final classification, thus reducing noise and improving accuracy. In cases where multiple images or metadata records were associated with the same species, an aggregation strategy was employed. This ensemble-like approach improved prediction stability by integrating multiple observations into a unified classification decision, reducing inconsistency in predictions.

2.8 Software and Hardware Configuration

The training pipeline was implemented using the PyTorch framework, chosen for its flexibility in defining deep learning architectures and its support for efficient GPU acceleration. Model training and evaluation were conducted on two computational setups. Initial experimentation was performed on a system with an Intel Core i7 processor, 32 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 4060 GPU with 8 GB memory. For large-scale training and fine-tuning, a more powerful setup featuring an Intel Core i9 processor, 64 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU with 24 GB memory was used.

The proposed approach was evaluated using a comprehensive set of evaluation metrics. In addition, we conducted a detailed statistical analysis of the results and examined the limitations of the method under various scenarios. Finally, we assessed the computational efficiency of the model to highlight its practicality. The dataset was split into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets to ensure unbiased evaluation.

We use a multi-metric evaluation framework that takes into account both overall and class-specific performances. Following Metrics were used for the evaluation of proposed approach:

Accuracy is used to determine the overall percentage of accurate predictions across all species classes. Accuracy in botanical classification offers a clear and understandable indicator of the overall effectiveness of the model [31]. However, because of inherint biasing in accuracy in the case of imbalanced datasets. Precision and recall metrics are employed to assess species-specific classification performance: Precision (positive predictive value) quantifies the proportion of correctly predicted positive instances among all predicted positives. It reflects the model’s ability to avoid false positives when identifying specific plant species. Recall (sensitivity) measures the proportion of actual positives that are correctly identified. It evaluates the model’s ability to detect all instances of a target species.

The F1-score, defined as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, provides a balanced evaluation metric particularly useful for class imbalanced botanical datasets, where species often differ in abundance and ease of collection, leading to naturally skewed distributions. The F1-score reduces the risk of evaluation bias and provides a more reliable measure than accuracy alone [31]. Finally, Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) is chosen especially to assess our model’s ranking performance, which is important in plant identification systems when the user may be provided with several candidate species. MRR evaluates how highly the correct species is rated in the model’s predictions, giving information about the model’s confidence in its accurate classifications. In practical applications, where users may assess several proposed identifications, this statistic is especially useful, given as

where N is the total number of samples and

3.2 Training and Statistical Analysis

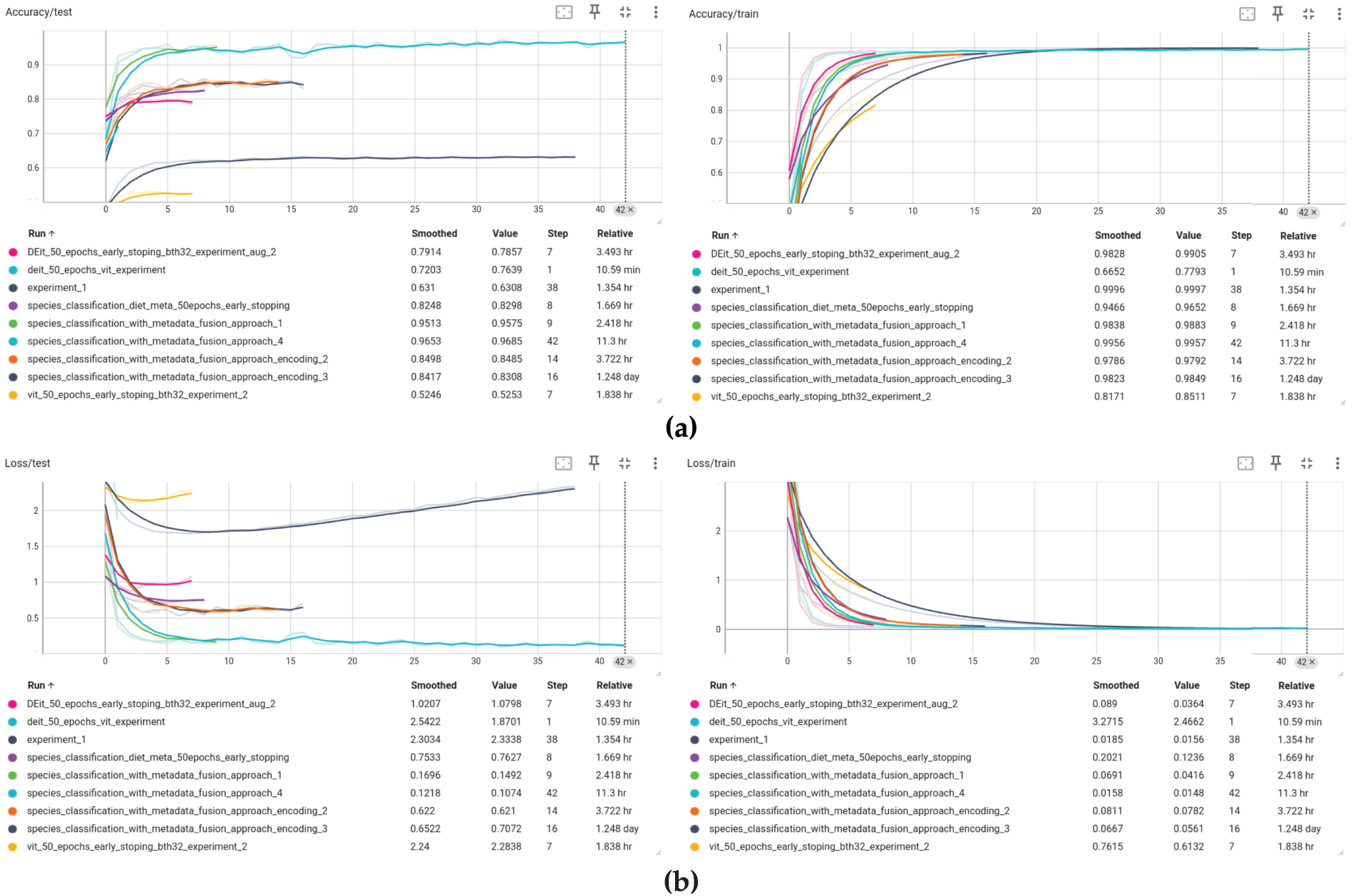

The proposed hybrid model, which combines Vision Transformer (ViT) features with structured metadata, demonstrated strong learning dynamics and stability during training. Fig. 9 shows training and validation curves, demonstrating faster convergence and improved stability when using multi-modal inputs. After 43 training epochs, the model achieved a training accuracy of 99.16% and a validation accuracy of 97.27%, with corresponding training and validation losses of 0.0264 and 0.0986, respectively. These values indicate good generalization with minimal overfitting.

Figure 9: Train and test curves (a) accuracy and (b) loss

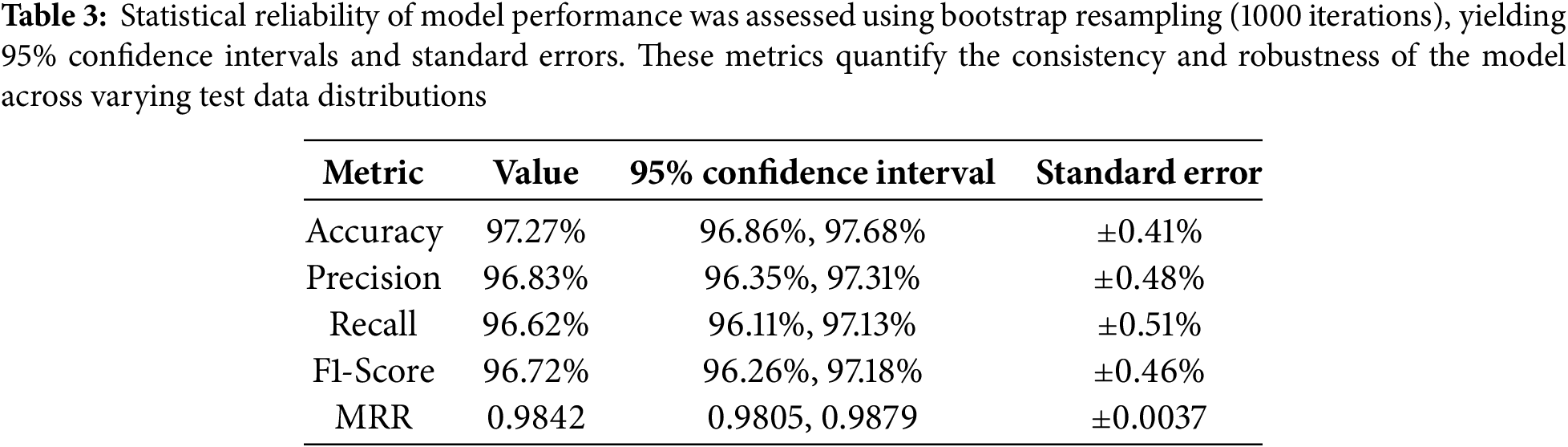

Beyond overall accuracy, the model was evaluated using a comprehensive suite of performance metrics. It achieved a precision of 0.973, recall of 0.974, and an F1-score of 0.973, demonstrating both high sensitivity and specificity (Table 3). These metrics remained consistent across multiple training runs, with a validation accuracy standard deviation of

To evaluate statistical robustness, we conducted 1000-iteration bootstrap resampling to compute 95% confidence intervals for key metrics (Table 3). The resulting narrow intervals confirm the model’s repeatability. Furthermore, McNemar’s test was used to compare our model to baselines, yielding

3.3 Comparison with Baseline Models

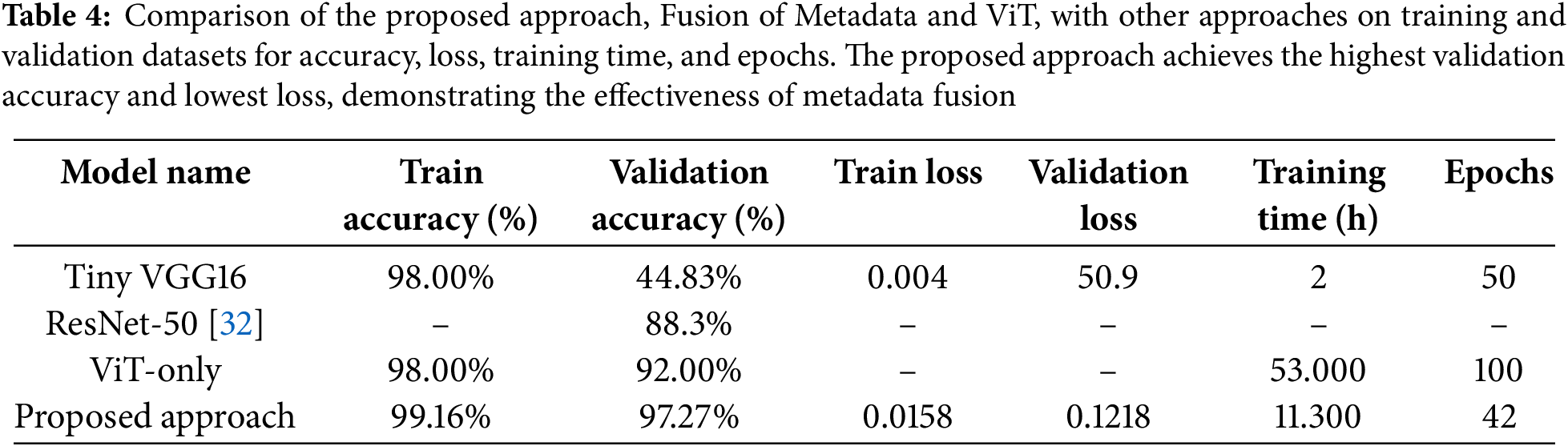

To assess the effectiveness of our fusion strategy, we compared our model with standard CNN architectures (AlexNet, VGG-16, ResNet-50) and a standalone ViT. For instance, ResNet-50 trained on PlantCLEF data achieved 88.3% accuracy [32], whereas our fusion model reached 97.27%. ViT-Base alone yielded 92.00% accuracy, but integrating metadata reduced the validation loss to 0.1218 and significantly improved classification consistency. Table 4 summarizes these comparisons.

Class-level evaluation revealed a median F1-score of 0.97, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 0.94–0.99. Morphologically similar genera such as Ajuga and Acer exhibited slightly lower F1-scores (0.91–0.93) due to inter-species visual overlap. Nevertheless, 16 of the top 20 genera surpassed 96% accuracy, and highly distinctive species like Alcea achieved accuracy up to 99.33%.

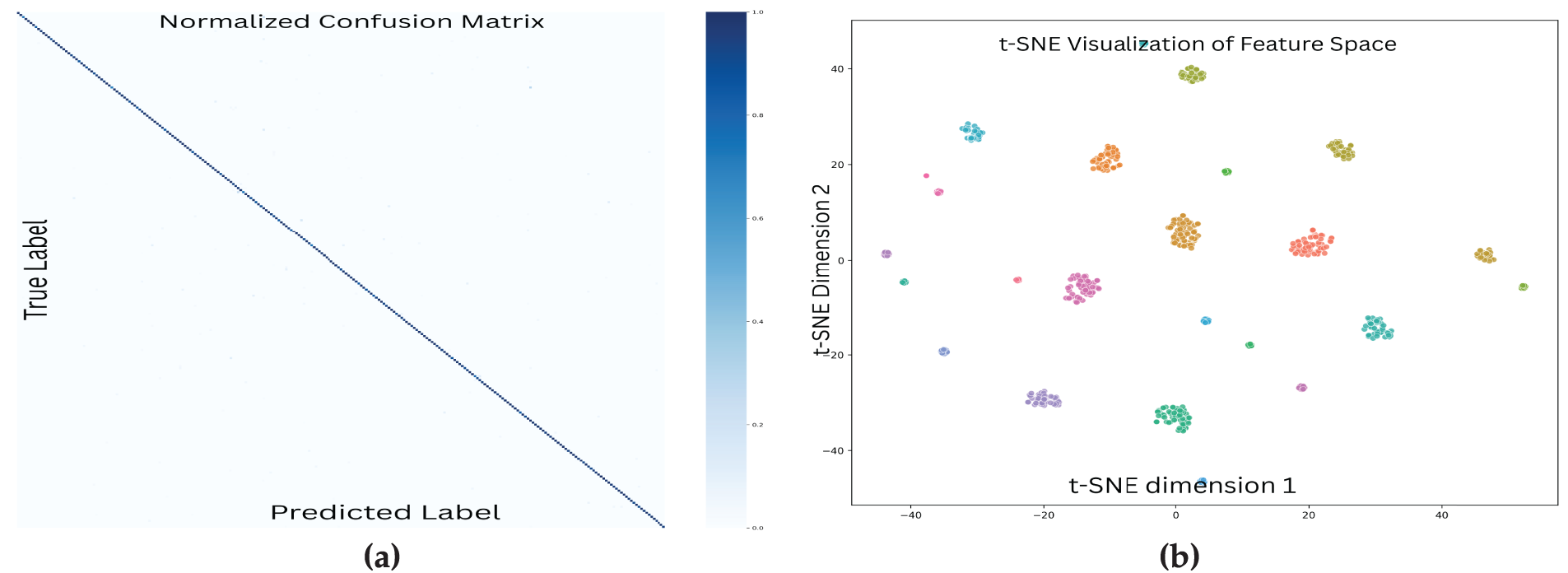

Confusion matrices (Fig. 10a) showed strong diagonal dominance, with most misclassifications occurring within the same genus—indicating taxonomically plausible errors. Additionally, t-SNE projections (Fig. 10b) illustrated clearly separated feature clusters aligned with genus-level taxonomy, suggesting that the model captures semantically meaningful representations.

Figure 10: Visualization of model performance and learned feature representations. (a) The normalized confusion matrix shows strong diagonal dominance, indicating high classification accuracy across plant species. Most misclassifications occur among taxonomically similar species, as reflected by sparse off-diagonal values. (b) The t-SNE plot illustrates the model’s learned feature space, with points colored by genus. Clear, well-separated clusters highlight the model’s ability to learn taxonomically meaningful representations, preserving proximity among morphologically similar genera. These visual patterns align with the high accuracy observed in quantitative evaluations

3.5 Model Applicability and Reliability

The proposed Vision Transformer (ViT) with metadata fusion achieved high classification accuracy (97.27%) at the species level and 99.31% at the genus level. However, practical deployment requires awareness of its limitations and reliability across diverse scenarios. Misclassifications primarily occurred among visually similar species within the same genus, such as Acer, which exhibited a 3.2% within-genus confusion rate. This was particularly evident in morphologically similar leaf specimens. Developmental variability in species like Acanthus mollis also contributed to misclassification, especially during early growth stages [33]. Seasonal transitions increased the misinterpretation rate for deciduous species by 2.7

Multimodal fusion, while beneficial, introduced new technical risks. Incomplete or missing metadata, especially taxonomic and geographic fields, reduced accuracy by 2.9%. Incorrect metadata entries, such as mislabeled locations or species, introduced noise and biased predictions. Under representation of certain geographic regions in the training data resulted in a 4.8%–7.2% accuracy loss for samples from those areas, indicating generalization limitations. The model also exhibited overfitting tendencies when strong correlations existed between visual and contextual metadata, particularly for closely related species. Overreliance on location or seasonal context reduced the model’s ability to generalize and increased susceptibility to contextual bias.

Reliability analysis showed that predictions with confidence scores above 0.85 had strong calibration and low error rates (below 2%), whereas lower-confidence predictions were less dependable. To mitigate these risks, we recommend incorporating metadata quality assessment and assigning dynamic reliability weights to metadata during training. Furthermore, metadata dropout regularization—randomly masking metadata fields during training—can improve robustness by simulating real-world conditions where metadata may be partially missing [15]. While multimodal fusion enhances predictive performance, its effectiveness depends on the quality, completeness, and contextual balance of the metadata used.

On the RTX 3090, the model achieved 100% GPU utilization with peak memory usage of 18 GB, and training required approximately 45 to 48 h (1.5 to 2 days), underscoring the computational cost of fine-tuning the Vision Transformer with metadata fusion. Training times were significantly longer on the RTX 4060, illustrating the impact of hardware capability on convergence speed. Each forward pass involved approximately 12 GFLOPs, demonstrating efficient processing of high-dimensional inputs. Despite the resource demands, optimized memory management and full GPU utilization enabled stable convergence and high predictive performance, justifying the computational investment for large-scale deployment.

The proposed approach advances plant species identification by integrating hierarchical modeling and multi-organ analysis with ViTs and metadata fusion. The approach improves accuracy, achieving 97.27% species-level and 99.31% genus-level classification accuracy, though challenges remain in cross-environmental generalization, metadata quality, and computational efficiency. While the model is highly reliable for confident predictions, its performance declines for underrepresented environmental conditions and developmental stages. Future work aims to enhance efficiency, expand datasets, and improve generalization through multi-modal data integration and uncertainty estimation, reinforcing AI’s role in plant science, conservation, and ecological monitoring.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors did not receive funding from any organization for this research.

Author Contributions: Study conception, design and methodology: Hassan Javed, Labiba Gillani Fahad; manuscript preparation and editing: Syed Fahad Tahir, Hassan Javed, Labiba Gillani Fahad; investigation, analysis and interpretation of results: Mehdi Hassan, Hani Alquhayz. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used in this study is publicly available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Anderson E. Plants, man, and life. Chelmsford, MA, USA: Courier Corporation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

2. Solaiman Z, Akerman K. The diversity of plant life: a comprehensive exploration of plant classification, taxonomy, and their roles in ecological balance. Aust Herb Insight. 2022;5(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

3. Jones R, Brown S, Patel K. PlantCLEF: a large-scale plant identification dataset for biodiversity research. Proc IEEE Conf Comput Vis Pattern Rec. 2021;23(1):12–20. [Google Scholar]

4. Johnson M, Culverhouse P, Cao L. iNaturalist: citizen science and AI for biodiversity research. Biodivers Inf. 2020;15(1):45–56. [Google Scholar]

5. Chapman AD. Principles of data quality. In: Global biodiversity information facility. København, Denmark: GBIF Secretariat; 2005. doi:10.15468/doc.jrgg-a190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wäldchen J, Rzanny M, Seeland M, Mäder P. Automated plant species identification—trends and future directions. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018;14(4):e1005993. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Fränzle O. Complex bioindication and environmental stress assessment. Environ Ind. 2006;6(1):114–36. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2005.08.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Fiorani F, Schurr U. Future scenarios for plant phenotyping. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2013;64(1):267–91. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Nualart N, Ibáñez N, Soriano I, López-Pujol J. Assessing the relevance of herbarium collections as tools for conservation biology. Bot Rev. 2017;83(3):303–25. doi:10.1007/s12229-017-9188-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Haider N. Identification of plant species using traditional and molecular-based methods. In: Davis RE, editor. Wild plants: identification, uses and conservation. New York, NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2011. p. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

11. Campos-Leal JA, Yee-Rendón A, Vega-López IF. Simplifying VGG-16 for plant species identification. IEEE Lat Am Trans. 2022;20(11):2330–8. doi:10.1109/tla.2022.9904757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mohanty SP, Hughes DP, Salathé M. Using deep learning for image-based plant disease detection. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1419. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.01419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Tambe UY, Shanthini A, Hsiung P-A. Integrated leaf disease recognition across diverse crops through transfer learning. Procedia Comput Sci. 2024;233(3):22–34. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2024.03.192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kanade P, Prasad J. Machine learning techniques in plant conditions classification and observation. In: Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Computing Methodologies and Communication; 2021 Apr 8–10; Erode, India. [Google Scholar]

15. Zhang S, Han S, Bi D, Yang J, Ge W, Ye Y, et al. Intraspecific and intrageneric genomic variation across three Sedum species (Crassulaceaea plastomic perspective. Genomics. 2024;15(4):444. doi:10.3390/genes15040444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhong Z, Zheng L, Kang G, Li S, Yang Y. Random erasing data augmentation. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(7):13001–8. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i07.7000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sadeghi-Tehran P, Virlet N, Sabermanesh K, Hawkesford MJ. Multi-feature machine learning model for automatic segmentation of green fractional vegetation cover for high-throughput field phenotyping. Plant Methods. 2017;13(1):103. doi:10.1186/s13007-017-0253-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Schiller C, Schmidtlein S, Boonman C, Moreno-Martínez A, Kattenborn T. Deep learning and citizen science enable automated plant trait predictions from photographs. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):16395. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-95616-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2021 May; Virtual. [cited 2025 Apr 1]. Available from: https://openreview.net/pdf?id=YicbFdNTTy. [Google Scholar]

20. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

21. Smith J, Miller T, Wang R. LeafSnap: a leaf image dataset for automatic plant identification. J Ecol Inf. 2019;50:234–42. [Google Scholar]

22. Goëau H, Bonnet P, Joly A. LifeCLEF plant identification task 2015. Vol. 1391. Toulouse, France: CLEF Working Notes; 2015. [Google Scholar]

23. Han J, Kamber M, Pei J. Data mining (Third Edition). In: The morgan kaufmann series in data management systems. 3rd ed. Boston, MA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann; 2012. p. 633–71. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4831-8404-3.50019-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Rubin DB. Inference and missing data. Biometrika. 1976;63(3):581–92. doi:10.1093/biomet/63.3.581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chawla NV, Bowyer KW, Hall LO, Kegelmeyer WP. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J Artif Intell Res. 2002;16:321–57. doi:10.1613/jair.953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zauner C. Implementation and benchmarking of perceptual image hash functions [master’s thesis]. Austria: Upper Austria University of Applied Sciences, Hagenberg Campus; 2010. [Google Scholar]

27. Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS'12). Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2012. p. 1097–105. [Google Scholar]

28. Botchkarev A. A new typology design of performance metrics to measure errors in machine learning regression algorithms. Interdiscip J Inf Knowl Manag. 2019;14:45–79. doi:10.28945/4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Goodfellow I, Bengio Y, Courville A. Deep learning. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

30. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. In: Proceedings of International Conference on Learning Representations; 2015 May; San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

31. Sokolova M, Lapalme G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Inf Proc Manag. 2009;45(4):427–37. [Google Scholar]

32. Goëau H, Bonnet P, Joly A. Overview of PlantCLEF 2021: cross-domain plant identification. In: Proceedings of the CLEF (Working Notes); 2021 Sep 21–24; Bucharest, Romania. [Google Scholar]

33. Halladin-Dabrowska A, Kania A, Kopeć D. The t-SNE algorithm as a tool to improve the quality of reference data used in accurate mapping of heterogeneous non-forest vegetation. Remote Sens. 2020;12(1):39. doi:10.3390/rs12010039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools