Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Deep Learning in Biomedical Image and Signal Processing: A Survey

1 School of Digital Technologies, Narxoz University, Almaty, 050035, Kazakhstan

2 Department of Mathematical and Computer Modeling, International Information Technology University, Almaty, 050040, Kazakhstan

3 Department of Cybersecurity and Cryptology, Faculty of Information Technology, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, 050040, Kazakhstan

4 Department of Software Engineering, Faculty of Physics, Mathematics and Information Technology, Khalel Dosmukhamedov Atyrau University, Atyrau, 060011, Kazakhstan

* Corresponding Author: Batyrkhan Omarov. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Emerging Trends and Applications of Deep Learning for Biomedical Signal and Image Processing)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2195-2253. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.064799

Received 24 February 2025; Accepted 31 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Deep learning now underpins many state-of-the-art systems for biomedical image and signal processing, enabling automated lesion detection, physiological monitoring, and therapy planning with accuracy that rivals expert performance. This survey reviews the principal model families as convolutional, recurrent, generative, reinforcement, autoencoder, and transfer-learning approaches as emphasising how their architectural choices map to tasks such as segmentation, classification, reconstruction, and anomaly detection. A dedicated treatment of multimodal fusion networks shows how imaging features can be integrated with genomic profiles and clinical records to yield more robust, context-aware predictions. To support clinical adoption, we outline post-hoc explainability techniques (Grad-CAM, SHAP, LIME) and describe emerging intrinsically interpretable designs that expose decision logic to end users. Regulatory guidance from the U.S. FDA, the European Medicines Agency, and the EU AI Act is summarised, linking transparency and lifecycle-monitoring requirements to concrete development practices. Remaining challenges as data imbalance, computational cost, privacy constraints, and cross-domain generalization are discussed alongside promising solutions such as federated learning, uncertainty quantification, and lightweight 3-D architectures. The article therefore offers researchers, clinicians, and policymakers a concise, practice-oriented roadmap for deploying trustworthy deep-learning systems in healthcare.Keywords

In recent years, the integration of deep learning technologies into biomedical image and signal processing has not only catalyzed significant advancements but has also transformed the landscape of medical diagnostics and treatment. The burgeoning volume of biomedical data, characterized by its complexity and high dimensionality, necessitates the application of sophisticated analytical techniques to extract meaningful insights [1]. Deep learning, a subset of machine learning, has emerged as a formidable tool in handling these intricacies, offering innovative solutions that enhance the accuracy and efficiency of medical analyses [2].

Deep learning’s foundational strength lies in its ability to learn hierarchical representations, which is particularly beneficial in deciphering the multifaceted patterns present in biomedical data [3]. Traditional machine learning techniques often falter when faced with the scale and diversity of biomedical datasets. In contrast, deep learning models, particularly those employing neural networks, adeptly manage these challenges without the need for explicit feature extraction, which has historically been a labor-intensive process requiring substantial expert intervention [4].

The relevance of deep learning in biomedical research is underscored by its successful application across a variety of modalities, including but not limited to, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scans, and X-rays [5]. These technologies benefit from convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which excel in analyzing visual imagery by preserving the spatial hierarchy of image data, making them ideal for medical imaging tasks [6]. CNNs have revolutionized the field by improving the robustness and accuracy of image classification, segmentation, and enhancement tasks, which are crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning [7].

Moreover, deep learning extends its utility to the analysis of biomedical signals such as electroencephalograms (EEG), electrocardiograms (ECG), and more recently, electromyograms (EMG). Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their variants like Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs) have shown great promise in modeling time-series data, which is a common format for many types of biomedical signals [8]. These models effectively capture the temporal dynamics and dependencies in the data, essential for tasks such as anomaly detection, real-time monitoring, and predictive analysis [9].

The advent of generative adversarial networks (GANs) has introduced new capabilities in the generation of synthetic biomedical data, which can be particularly valuable in situations where real data are scarce or difficult to obtain due to ethical and practical reasons [10]. GANs have facilitated improvements in the quality and diversity of training datasets, thereby enhancing the performance of deep learning models trained on such data [11].

Furthermore, autoencoders have been effectively used for data dimensionality reduction and feature learning, providing a pathway to handle the ‘curse of dimensionality’ that plagues many biomedical datasets [12]. This capability is vital for improving the computational efficiency and performance of deep learning models, making them more applicable in real-world medical settings.

Reinforcement learning offers another layer of sophistication by enabling decision-making processes that mimic the trial and error learning human practitioners might use. This approach is particularly useful in applications requiring adaptive decision-making, such as personalized medicine and treatment optimization [13].

Transfer learning has also proven to be a game changer, allowing for the leveraging of pre-trained models on new tasks that do not have sufficient data to train a robust model from scratch [14]. This is especially crucial in the medical field where acquiring labeled data can be costly and time-consuming.

Despite these advancements, the deployment of deep learning in clinical environments presents a unique set of challenges. These include ensuring model interpretability, managing patient data privacy, and adhering to stringent regulatory standards [15]. Addressing these challenges is essential for the successful integration of deep learning technologies into clinical practice.

The adoption of deep learning in biomedical image and signal processing offers substantial benefits, including enhanced diagnostic capabilities, more personalized treatment options, and improved operational efficiencies in healthcare. As this review will demonstrate, while the journey is fraught with challenges, the potential rewards are too significant to ignore. This paper aims to explore these themes thoroughly, providing a comprehensive survey of the current state of deep learning technologies in the biomedical field.

2 Overview of Deep Learning Techniques

Deep learning, a powerful subset of machine learning, has rapidly advanced the field of artificial intelligence by introducing complex architectures capable of learning from vast amounts of data. This section explores various deep learning techniques, each contributing uniquely to the progression of technology in multiple domains, especially in processing complex and high-dimensional data. The discussion begins with the foundational concept of artificial neural networks (ANNs), delving into their structure, mathematical formulation, and practical implementations, which lay the groundwork for more specialized networks.

2.1 Artificial Neural Networks

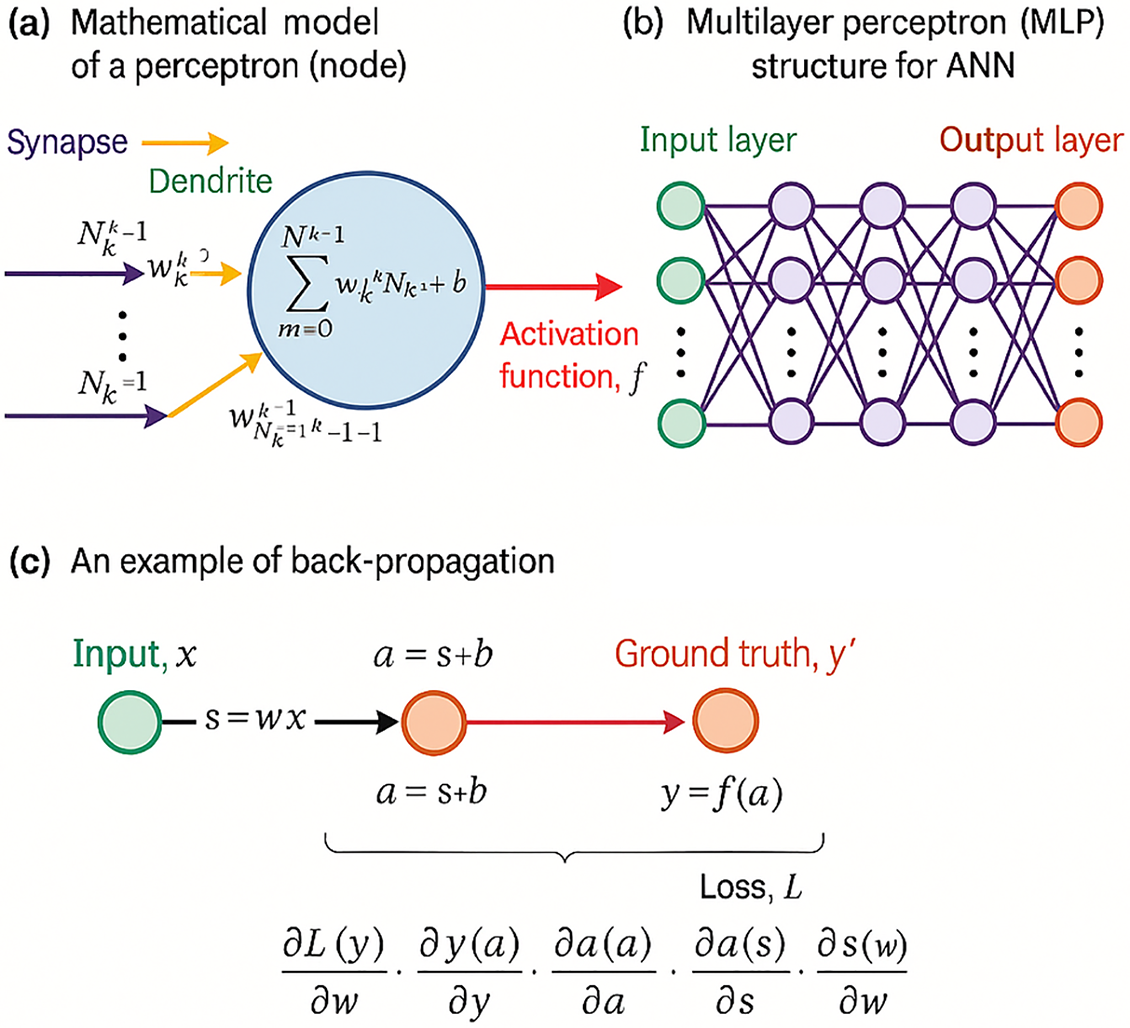

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are inspired by the biological neural networks that constitute animal brains [16]. An ANN is composed of interconnected nodes or neurons, which are organized into layers: an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each neuron in one layer is connected to neurons in the next layer through synapses, represented mathematically by weights w which adjust as learning progresses, symbolizing the strength of the connection between neurons.

The basic operation within a neuron involves the weighted sum of the inputs plus a bias term, which is then passed through a nonlinear activation function to produce the output. This output is either used as an input for the next layer or, in the case of the output layer, it forms the final prediction of the network. The weighted sum and the activation function can be expressed mathematically as follows:

where

where

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of an artificial neural network (ANN) (Adapted from [17])

The architecture of an ANN, including its multiple layers, is further explored in Fig. 1 part (b), which illustrates the network’s hidden layers between the input and output. These hidden layers are fundamental in the network’s ability to learn deep representations without human-engineered feature extraction. Each layer learns to transform its input data into a slightly more abstract and composite representation, enhancing the network’s capability to discern complex features and patterns in data.

The critical mechanism of training these networks, depicted in Fig. 1 part (c), involves calculating the gradients of the loss function with respect to each weight in the network through backpropagation. This systematic approach adjusts the weights in a direction that minimizes the loss, incrementally improving the model’s predictions after each iteration. The optimization of these weights is crucial for the effective learning and generalization capabilities of ANNs, ensuring they perform accurately on new, unseen data. This process, vital for refining the model’s accuracy, exemplifies the iterative nature of learning in deep neural architectures.

2.2 Convolutional Neural Networks

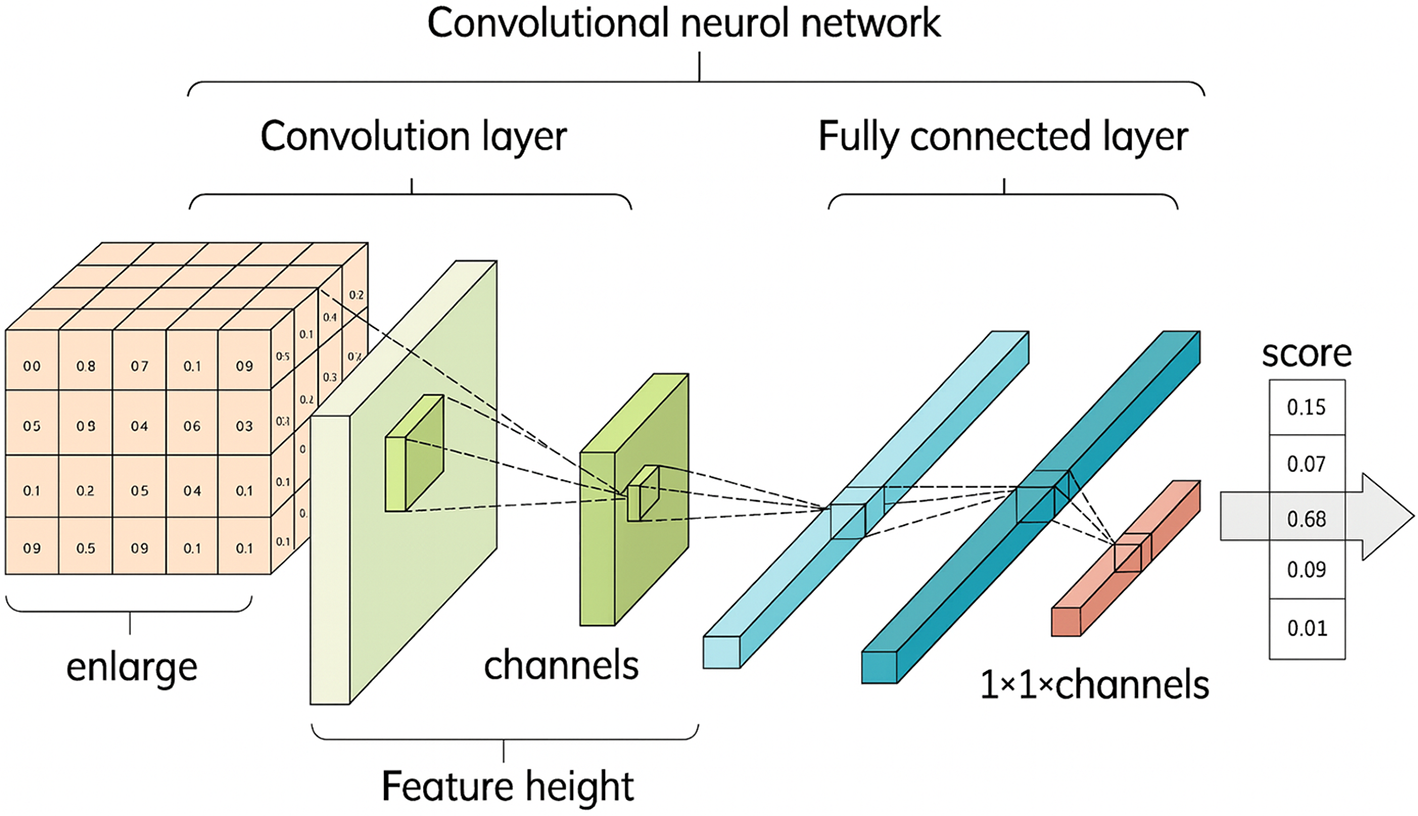

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are a class of deep neural networks highly effective in processing data with a grid-like topology [18]. CNNs utilize a mathematical operation known as convolution, which involves sliding a filter or kernel over the input data to produce a feature map. This operation captures the spatial hierarchy in the input by learning the most relevant features without the need for manual extraction, making CNNs particularly adept at image recognition tasks.

The convolution operation can be expressed mathematically as:

where

CNN architectures typically consist of multiple convolutional layers, interspersed with activation and pooling layers, followed by one or more fully connected layers. The final layers often include a softmax function to normalize the output into a probability distribution over predicted output classes, essential for classification tasks (Fig. 2). This structure allows CNNs to execute complex image processing tasks, from feature detection to sophisticated image classification, with remarkable accuracy and efficiency.

Figure 2: Detailed View of a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) (Adapted from [18])

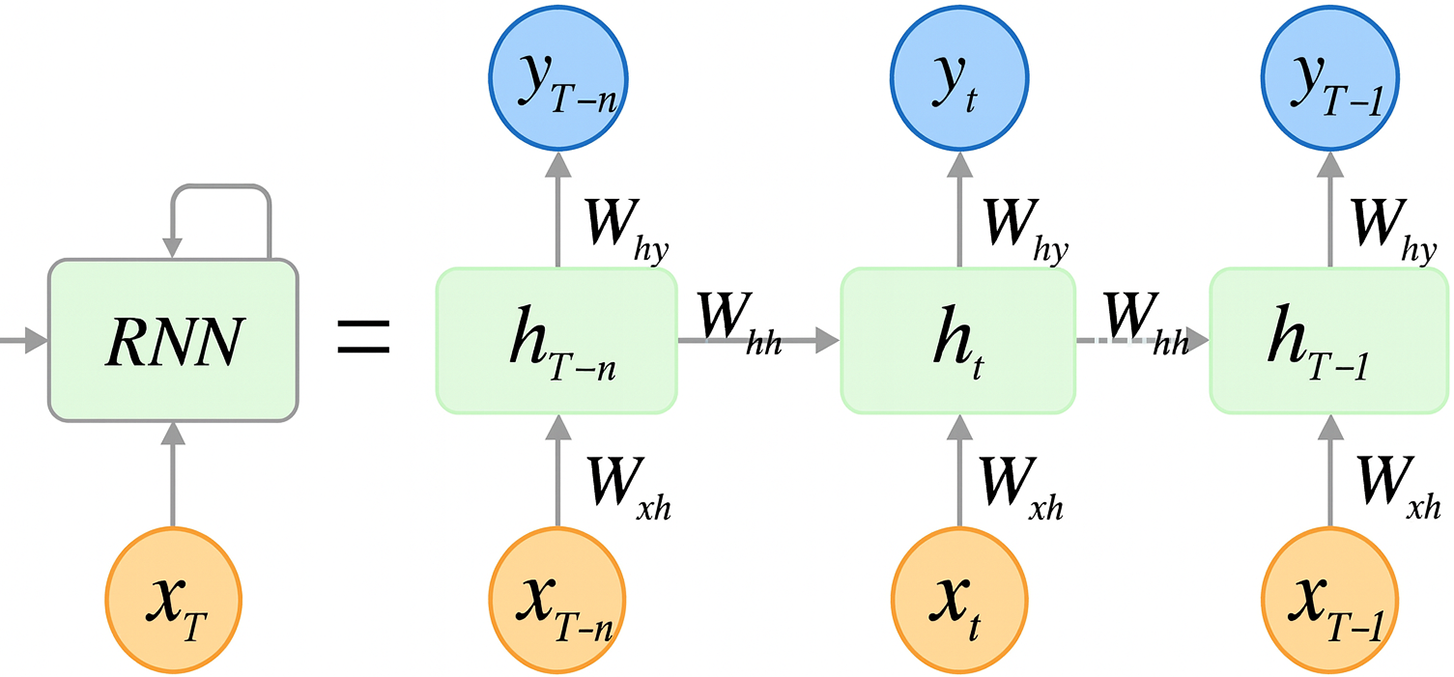

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are a class of neural networks designed to handle sequential data, such as time series or natural language, by processing inputs in a temporal context. Unlike traditional neural networks, RNNs possess the capability to maintain a form of memory by utilizing their internal state (or hidden layers) to process sequences of inputs. This characteristic allows them to exhibit dynamic temporal behavior, making them particularly useful for applications where the sequence and context of input data are crucial.

Mathematically, the operation of an RNN can be expressed as follows:

Here,

This architecture enables the network to capture temporal dependencies and patterns over time, as depicted in Fig. 3 [19]. The recurrent connection

Figure 3: Operational flow in a recurrent neural network (RNN) (Adapted from [19])

2.4 Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM)

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks extend the recurrent-neural-network paradigm with an explicit memory cell

Figure 4: Operational flow in a long short-term memory network (Adapted from [20])

Formally, the gating dynamics and state updates are governed by

Here

2.5 Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)

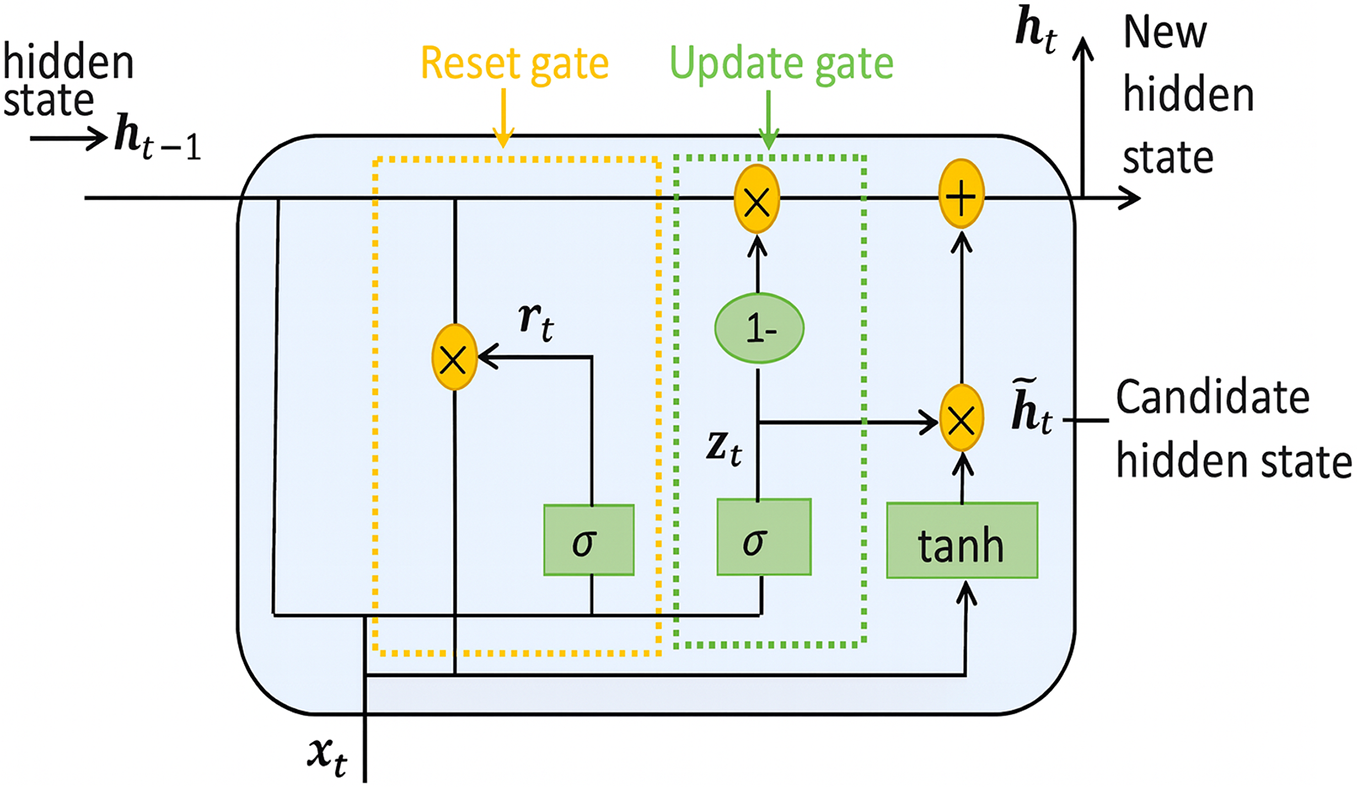

Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) are a streamlined variant of long short-term memory (LSTM) networks designed to capture long-range temporal dependencies while reducing parameter count and training time. As illustrated in Fig. 5, a GRU cell introduces two gates—the update gate

Figure 5: Operational flow in a gated recurrent unit (Adapted from [21])

The gates are computed by sigmoid activations that weigh the relevance of new vs. historical information:

where

The reset gate

The final hidden state

This gating mechanism enables GRUs to adaptively retain or overwrite memory, mitigating vanishing-gradient issues while using fewer parameters than LSTMs. Consequently, GRUs have proven effective in biomedical signal tasks such as ECG arrhythmia classification and EMG-based movement decoding, where they achieve performance comparable to LSTMs but with reduced computational overhead.

2.6 Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are a novel class of deep learning frameworks first introduced by Ian Goodfellow et al. in 2014 [22]. GANs consist of two competing neural network models: a generator that creates synthetic data mimicking the real data, and a discriminator that attempts to distinguish between the generated data and real data from the dataset. The generator

Mathematically, the interaction between

Here,

Fig. 6 illustrates the operational flow of a GAN, showing the generation of images from noise and their evaluation by the discriminator. This mechanism allows GANs to generate high-quality synthetic biomedical images, which can be instrumental in enhancing data availability for training machine learning models in healthcare applications where data may be scarce or privacy-sensitive.

Figure 6: Flowchart of a traditional GAN architecture (Adapted from [23])

Autoencoders are a type of neural network used primarily for the task of dimensionality reduction or feature learning. An autoencoder learns to compress (encode) the input data into a lower-dimensional representation and then reconstruct (decode) the output to match the original input [24,25]. This process is facilitated through a network comprising an encoder and a decoder, as depicted in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Autoencoder (AE) framework

The mathematical representation of an autoencoder can be formulated as follows:

where

Autoencoders are not just limited to dimensionality reduction; they are also used for denoising and generating synthetic data. In biomedical applications, they help in creating more varied datasets by learning to produce realistic variations of data that still hold onto critical biological properties. This capability is particularly useful in scenarios where the quantity of real-world data is limited or privacy concerns restrict the use of actual patient data. Fig. 7 illustrates the basic architecture of an autoencoder, emphasizing its role in encoding and subsequent reconstruction of data.

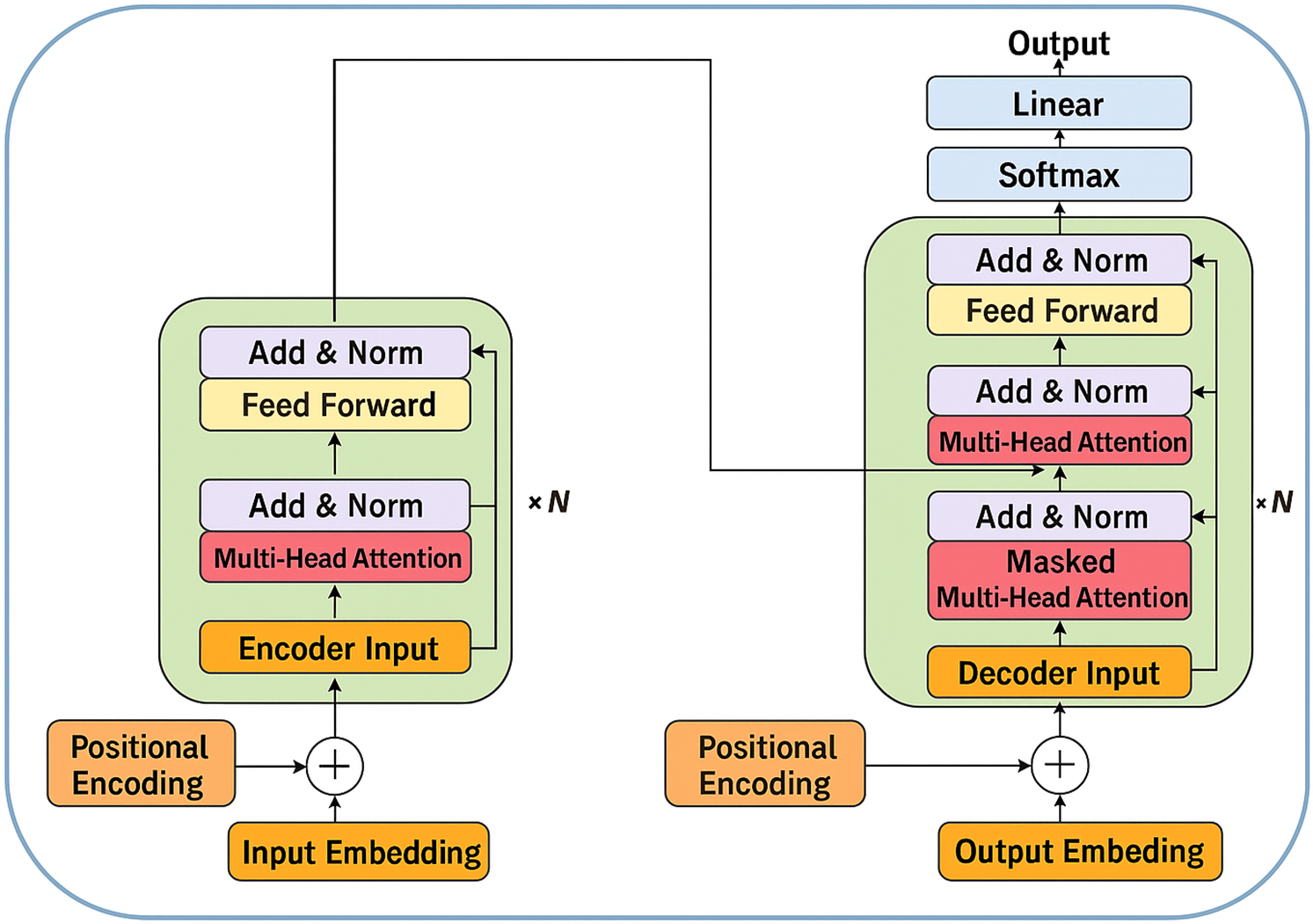

Transformers dispense with recurrent operations by relying entirely on attention mechanisms to model long-range dependencies, thereby enabling highly parallelisable training and superior scalability. As shown in Fig. 8, a canonical transformer comprises an encoder–decoder stack, each layer containing multi-head self-attention, position-wise feed-forward blocks, and residual “add-and-norm” connections that stabilise gradients.

Figure 8: Autoencoder (AE) framework (Adapted from [26])

The core computation is scaled dot-product attention, which maps a query

Multi-head attention projects the inputs into

Because transformers lack an intrinsic notion of sequence order, positional encodings

In biomedical contexts, transformer variants have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in whole-slide histopathology classification, 3-D radiation-therapy dose prediction, and multimodal report generation by virtue of their ability to model global context without recurrent bottlenecks. Ongoing research focuses on memory-efficient adaptations such as sparse, axial, or performer attention to accommodate gigapixel images and high-frequency physiological signals within the transformer framework.

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is a type of machine learning where an agent learns to make decisions by interacting with an environment. The agent performs actions and receives rewards or penalties based on the outcomes of its actions, continually refining its policy to maximize cumulative rewards. This iterative learning process is central to RL, which aims to find an optimal strategy for decision-making by exploiting learned experiences [27].

Mathematically, the RL framework can be expressed using the elements of state

where

Fig. 9 illustrates the cyclical interaction between the agent and its environment, showcasing the continuous flow of states, actions, and rewards that define the learning dynamics in RL. In the context of biomedical decision-making, RL can be applied to develop dynamic treatment regimes, optimize resource allocation, and personalize medical interventions, significantly enhancing decision-making efficacy and patient outcomes.

Figure 9: Basic framework of reinforcement learning (Adapted from [28])

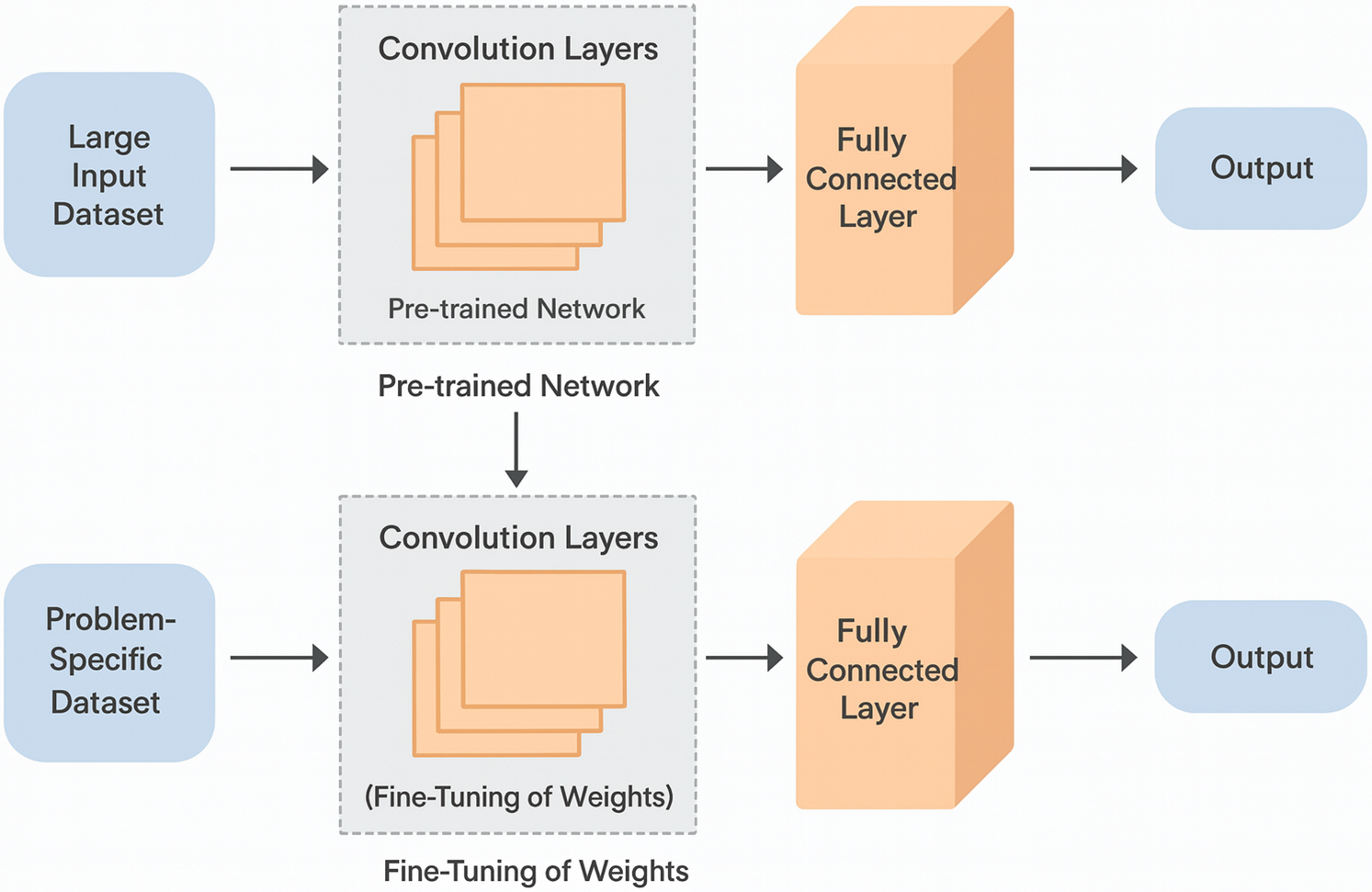

Transfer Learning is a machine learning technique where a model developed for a particular task is reused as the starting point for a model on a second task. This approach is particularly beneficial in medical imaging and signal analysis, where large labeled datasets are scarce and costly to obtain. Transfer learning allows models trained on large datasets from related domains to be fine-tuned with smaller amounts of specialized medical data, significantly enhancing learning efficiency and model performance [29].

Mathematically, transfer learning can be represented as adapting a pre-trained model

where

Fig. 10 illustrates how transfer learning can be implemented in a healthcare context, showing the flow from general-purpose pre-trained models to specialized applications in medical diagnostics. This strategy reduces the need for extensive computational resources and domain-specific data, allowing for rapid deployment of advanced diagnostic models.

Figure 10: Architecture of transfer learning model (Adapted from [30])

2.11 Diffusion-Based Generative Models

Diffusion models constitute a newer class of likelihood-based generative frameworks that synthesise data through a two-stage stochastic process: a forward trajectory that gradually corrupts an image with Gaussian noise and a reverse trajectory that iteratively denoises this latent representation back to the data manifold. As illustrated in Fig. 11e, the forward path maps a clean biomedical image

Figure 11: Architecture of transfer learning model (Adapted from [31])

Recent biomedical studies have leveraged these properties to achieve state-of-the-art synthesis quality. Score-based diffusion has produced high-resolution MR images with sharper anatomical details than comparable GAN baselines, improving structural-similarity measures by up to 8%. In low-dose CT reconstruction, conditional diffusion models have outperformed traditional iterative denoisers in preserving subtle lesions. Furthermore, unconditional diffusion has been adopted to augment rare-pathology datasets such as paediatric chest radiographs, significantly boosting downstream classification F1 scores when combined with self-supervised pre-training. Ongoing research explores accelerating inference via latent-space diffusion and integrating cross-modal conditions (e.g., radiology reports or genomic signatures) to guide generation, positioning diffusion models as a versatile alternative to GANs for high-fidelity, stable biomedical data synthesis.

3 Applications in Biomedical Image and Signal Processing

The integration of deep learning techniques in biomedical image and signal processing has catalyzed a transformative shift in the diagnostic capabilities of modern healthcare systems. These advanced computational methods offer significant improvements in the accuracy, efficiency, and depth of analysis possible within various imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [32], computed tomography (CT) scans [33], and X-ray imaging [34]. By harnessing the power of algorithms like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [35] and generative adversarial networks (GANs) [36], medical professionals can now detect, classify, and interpret complex biomedical images with unprecedented precision [37]. This section delves into the specific applications of deep learning technologies in enhancing biomedical imaging processes, addressing critical tasks such as image classification, segmentation, enhancement, anomaly detection, and the processing of three-dimensional imaging data. The profound impact of these technologies not only enhances diagnostic accuracy but also significantly expedites the overall healthcare workflow, enabling faster and more accurate decision-making in clinical practice.

3.1 Deep Learning Techniques in Biomedical Imaging

Biomedical imaging stands as a cornerstone of diagnostic medicine, facilitating early detection and accurate monitoring of diseases. The advent of deep learning techniques has revolutionized this field, providing robust tools that significantly enhance the analysis, interpretation, and visualization of medical images. These advanced computational methods leverage layered architectures and complex algorithms to extract meaningful patterns from imaging data, thus enabling more precise diagnostics and personalized treatment plans. Particularly, the application of techniques such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) has improved the resolution, contrast, and quality of images from MRI, CT scans, and X-rays. This section explores how deep learning is applied across various imaging modalities, focusing on the enhancement of image quality, the precision in anomaly detection, and the efficiency in handling vast datasets, ultimately contributing to better clinical outcomes and streamlined healthcare operations.

Image classification using deep learning has become a pivotal tool in biomedical diagnostics, driving significant advancements in the interpretation of medical images. This technology’s ability to categorize and identify patterns within complex biomedical data enhances diagnostic accuracy and expedites treatment procedures.

Recent studies, such as those by Thilagavathy et al. (2024) [38] and Lo et al. (2025) [39], demonstrate the application of deep learning-enhanced CT Angiography (DLe-CTA) and Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNNs) to diagnose COVID-19 and detect acute ischemic stroke respectively. These methodologies underscore the effectiveness of deep learning models in enhancing image quality and diagnostic accuracy, which are crucial for conditions that require swift and precise medical attention.

In the realm of stroke diagnosis, Alhatemi & Savaş (2023) [40] have utilized multiple pre-trained deep learning models to classify MR images, achieving an impressive 99.84% accuracy on test datasets. This high level of accuracy is indicative of the potential deep learning holds in revolutionizing the detection and diagnosis of life-threatening conditions like strokes, where timely and accurate diagnosis is critical for effective treatment.

The utility of deep learning extends beyond typical neurological imaging to applications in cardiology and oncology. For instance, Dong et al. (2024) implemented a deep learning model for assessing the severity of plaque stenosis from ultrasound images, enhancing the automatic calculation systems used in stroke risk assessment [41]. Similarly, Sharifi et al. (2025) employed advanced architectures like EfficientNetV2, ResNeSt, and MobileNetV4 for the classification of congenital heart disease (CHD) from chest X-rays, illustrating the adaptability of deep learning models across various imaging modalities [42].

Moreover, the integration of deep learning into manufacturing and quality control processes, as observed in Wang et al. (2024), where a hybrid deep learning framework was used for chip packaging fault diagnostics, highlights the versatile applications of these technologies. Such applications underscore the model’s ability to not only detect but also classify manufacturing defects, enhancing the quality control processes within industrial settings [43].

The research by Gudigar et al. (2024) [44] and Aggarwal et al. (2022) [45] also reflects the expanding scope of deep learning in medical diagnostics. By using deep learning models for hypertension detection and COVID-19 identification respectively, these studies validate the efficacy of deep learning in handling diverse and complex medical datasets, further emphasizing its transformative impact on public health diagnostics.

In specialized applications, Alqahtani et al. (2025) [46] demonstrate the precision of EEG signal classification using a chaotic elephant herding optimum-based model, achieving an accuracy of 99.3%. This example highlights the precision deep learning brings to the classification of bio-signals, which is vital for conditions requiring nuanced differentiation, such as distinguishing between epileptic and non-epileptic subjects.

Lastly, the innovative approach by Farhatullah et al. for non-invasive Alzheimer’s monitoring using a combination of CNN and GRU models points to the future direction of non-invasive diagnostic technologies. This approach not only aids in the early detection of Alzheimer’s but also reduces the invasiveness of diagnostic procedures, thereby enhancing patient comfort and compliance [47].

Collectively, these studies illustrate the broad applicability and robustness of deep learning models in biomedical image classification, underscoring their crucial role in enhancing diagnostic accuracies across various medical fields. As deep learning continues to evolve, its integration into clinical practices is expected to deepen, paving the way for more personalized and precise medical interventions. For a detailed overview of the diverse applications and the results obtained from deep learning in biomedical image classification, refer to Table 1.

Image segmentation in biomedical imaging is a critical process where deep learning has demonstrated profound capabilities, particularly in delineating anatomical structures from medical images for various diagnostic purposes. This technology segment allows for more precise and automated approaches to interpreting complex imagery, essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning.

Recent advancements in deep learning models have significantly bolstered image segmentation accuracy. For instance, Huang et al. (2025) [53] utilized Low-intensity Focused Ultrasound Stimulation (LIFUS) to assess its safety in stroke rehabilitation, showcasing successful application without stopping rules due to robust segmentation of relevant features. Similarly, Polson et al. (2025) applied deep neural networks with L1 norms to the detection and segmentation of prostate cancer in PET/CT images, achieving notably high F1 scores, which highlights the precision these models can bring to identifying and delineating cancerous lesions [54].

The application of advanced segmentation techniques extends across various medical fields. In neurology, Schwehr and Achanta (2025) [55] implemented attention mechanisms and energy-based models to segment brain tumors from MRI scans, yielding high mean dice scores that indicate excellent model performance in segmenting multiple tumor types. Meanwhile, Tomasevic et al. (2024) [56] and Zhou et al. (2023) [57] demonstrated the effectiveness of U-Net-based deep convolutional networks and self-supervised learning, respectively, in segmenting carotid artery disease and plaques from ultrasound images, achieving high precision and recall.

These segmentation tasks are not only limited to static images but also extend to dynamic and functionally relevant imaging scenarios. Padyala and Kaushik (2024) [58] explored mobile volume rendering in medical imaging, leveraging Attention U-Net and SegResNet for disease detection and segmentation in MRI and CT scans, although specific results were not detailed in their study.

In the specific context of stroke risk assessment, Gan et al. (2025) [59] used RCCM-Net, a Region and Category Confidence-Based Multi-Task Network, to assess the risk from carotid plaque characteristics in ultrasound images, enhancing both segmentation and classification accuracies. Similarly, innovative approaches like the one by Naqvi and Seeja (2025) [60], which employed an attention-based Residual U-Net for tumor segmentation in brain MRI, have pushed the boundaries of what is possible, achieving Dice coefficients up to 0.9978.

Further, in the realm of radiation therapy planning, Kashyap et al. utilized a U-Net multiresolution ensemble for lung tumor detection and segmentation from CT images, which has critical implications for treatment accuracy and planning (Kashyap et al., 2025) [61]. In a similar vein, Jon Middleton et al. (2024) focused on ischemic stroke lesion segmentation using a U-Net model that incorporated local gamma augmentation, significantly enhancing sensitivity in over 90% of cases, demonstrating the model’s effectiveness in medical imaging [62].

The aforementioned studies highlight a trend towards increasingly sophisticated deep learning models that not only improve segmentation accuracy but also enhance the functionality of medical imaging. As these models continue to evolve, they are set to revolutionize the field of biomedical image segmentation, offering more detailed and accurate tools for clinical diagnosis and treatment planning. For a comprehensive overview of the studies conducted in this field, refer to Table 2.

3.1.3 Image Enhancement and Reconstruction

In the realm of medical imaging, the techniques of image enhancement and reconstruction are paramount, especially when dealing with suboptimal image quality that can potentially affect diagnostic outcomes. Deep learning has ushered in a transformative approach to these challenges, offering more precise and automated methods that significantly improve the quality and utility of biomedical images.

Recent innovations in deep learning have particularly enhanced the capability to reconstruct and enhance images from various imaging modalities. For instance, Islam et al. (2025) utilized generative AI techniques for enhancing PSMA-PET imaging, which resulted in the generation of synthetic images that substantially improved image quality for prostate cancer diagnosis [71]. Similarly, Cui et al. (2024) developed the 3D Point-based Multi-modal Context Clusters Generative Adversarial Network (PMC2-GAN) to enhance the denoising of low-dose PET images by effectively integrating PET and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) modalities. This approach leverages a point-based representation to flexibly express complex structures and employs self-context and cross-context cluster blocks to refine the contextual relationships within and across the modalities, leading to improved quality in standard-dose PET image prediction from low-dose scans [72].

Fu et al. (2024) explored the use of TransGAN-SDAM for reconstructing low-dose brain PET images, significantly enhancing the image quality which is crucial in pediatric epilepsy patient management [73]. This improvement in image quality facilitates more accurate diagnoses and better treatment planning. Additionally, Bousse et al. (2024) demonstrated the application of neural network approaches for denoising low-dose emission tomography images, thereby improving image resolution and reducing noise without compromising the diagnostic integrity of the images [74].

The capability of deep learning to reconstruct detailed images from limited data is exemplified in the work by Liu et al. (2022), who employed Generative Adversarial Networks (cGANs) to reconstruct PET images from sinogram data, achieving high-quality, robust image reconstruction that can significantly impact clinical PET imaging [75]. Similarly, Choi et al. (2024) employed a U-Net-based model for brain MRI quality and time reduction, which not only improved image quality but also enhanced the structural delineation, crucial for accurate brain MRI evaluations [76].

In the domain of cardiac imaging, Vornehm et al. (2025) used a Variational Network (CineVN) for the reconstruction of cardiac cine MRI from highly under-sampled data, producing high-quality cine MRI images that are vital for detailed cardiac assessments [77]. This enhancement in imaging technology is crucial in fields where high-resolution and dynamic imaging are required for precise medical evaluations. Another significant advancement was made by Pemmasani Prabakaran et al. (2024) who developed a deep-learning-based super-resolution technique to accelerate Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) MRI. This technique significantly reduces the normalized root mean square error, allowing for high-resolution imaging which is essential in detailed brain studies [78].

Moreover, Abolfazl Mehranian et al. (2022) enhanced PET images without Time-of-Flight (ToF) capability using deep learning models, which led to significantly reduced SUVmean differences, improving the quantitative measurements that are critical for accurate disease evaluation (Abolfazl Mehranian et al., 2022) [79]. Lastly, Levital et al. (2025) applied non-parametric Bayesian deep learning for low-dose PET reconstruction, which not only improved imaging quality but also significantly enhanced global reconstruction accuracy, demonstrating the vast potential of deep learning in medical image reconstruction [80].

These studies collectively underscore the critical advancements deep learning has brought to the field of biomedical image enhancement and reconstruction. By improving the quality, resolution, and functional utility of images, deep learning not only enhances the diagnostic process but also broadens the scope of applications in medical practice. For a comprehensive review of the studies and results in this field, refer to Table 3.

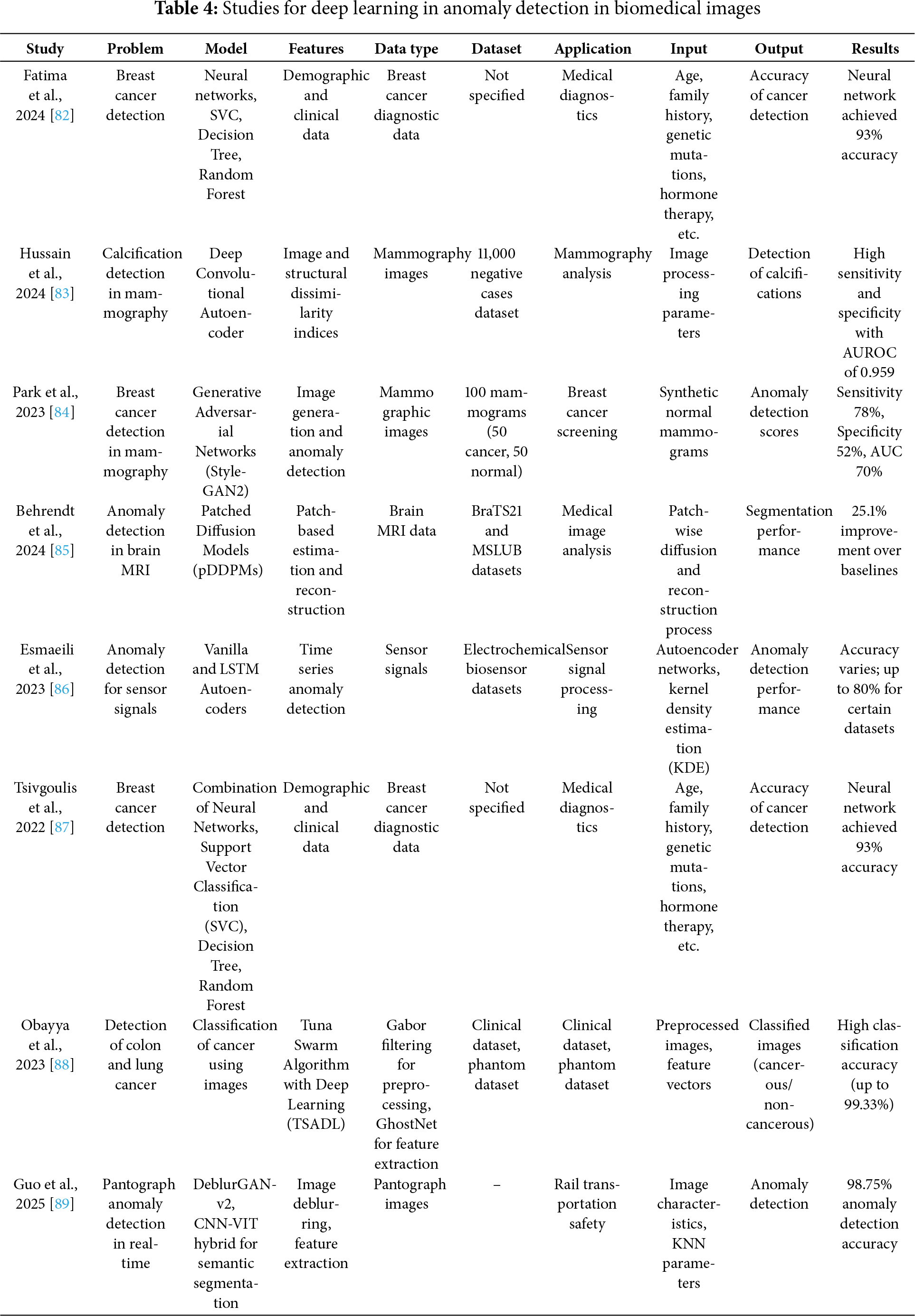

The domain of biomedical image anomaly detection has witnessed substantial advancements due to the integration of deep learning techniques, which enhance the capability to identify deviations from normal patterns in medical images. This section reviews significant contributions to anomaly detection across various biomedical applications, emphasizing the efficacy of deep learning models in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and operational efficiency.

One notable study by Fatima et al. (2024) employed a combination of neural networks alongside traditional machine learning techniques such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Decision Trees, and Random Forests to detect breast cancer. By leveraging demographic and clinical data, their approach achieved an impressive 93% accuracy, highlighting the strength of neural networks in handling complex, multidimensional medical data for cancer detection [82].

In the realm of mammography, Hussain et al. (2024) utilized a Deep Convolutional Autoencoder to detect calcifications, a crucial marker in early-stage breast cancer. Their model, trained on a dataset of 11,000 negative mammography images, demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity, achieving an Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.959. This model’s ability to process image and structural dissimilarity indices showcases the potential of deep learning in enhancing the precision of mammography analysis [83].

Further exploring mammography, Park et al. (2023) applied Generative Adversarial Networks (StyleGAN2) for anomaly detection, specifically targeting breast cancer detection. Their method generated synthetic normal mammograms to train the model in distinguishing abnormal mammographic features. Despite the challenges in balancing sensitivity and specificity, their model reported a sensitivity of 78%, specificity of 52%, and an AUC of 70%, indicating a promising direction for using synthetic data in medical diagnostics [84].

Transitioning to neurological applications, Behrendt et al. (2024) introduced Patched Diffusion Models (pDDPMs) for anomaly detection in brain MRI. This innovative approach used patch-based estimation and reconstruction to enhance the detection capabilities of MRI analysis. Their methodology improved segmentation performance by 25.1% over traditional baselines, showcasing the potential of patch-based models in complex image reconstruction tasks within clinical settings [85].

Addressing the challenges in sensor-based diagnostics, Fatemeh Esmaeili et al. (2023) implemented Vanilla and LSTM Autoencoders for anomaly detection in sensor signals. Their approach effectively processed electrochemical biosensor data, demonstrating the adaptability of autoencoders in various contexts, from medical diagnostics to industrial applications, with varying degrees of accuracy up to 80% [86].

In another application, Tsivgoulis et al. (2022) utilized a Deep Convolutional Neural Network-based SqueezeNet combined with a Deep Variational Autoencoder for the classification of cervical precancerous lesions. By integrating Gabor filtering and Quantum-inspired Whale Optimization (QIWO) for hyperparameter tuning, their model achieved a remarkable accuracy of 99.07% in cervical cancer diagnosis, highlighting the effectiveness of tailored deep learning approaches in specific medical imaging tasks [87].

Each of these studies contributes uniquely to the field of anomaly detection in biomedical imaging, demonstrating the diverse capabilities of deep learning technologies across different medical domains and imaging modalities. The promising results underscore the potential of these advanced computational models in revolutionizing medical diagnostics and enhancing patient care outcomes. These findings are detailed in Table 4, where the synthesis of deep learning applications across various studies showcases the transformative impact of these technologies in healthcare diagnostics and anomaly detection.

This section comprehensively examines the transformative impact of deep learning techniques in biomedical imaging, showcasing their robustness across diverse medical applications from diagnostics to treatment planning. Deep learning’s capability to manage, analyze, and interpret complex and voluminous medical image data sets it apart as a crucial technological advancement in modern medicine. This technology not only streamlines workflows but also substantially enhances the accuracy and efficiency of medical imaging analyses. Particularly, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) have been pivotal in advancing the fields of image classification, segmentation, and enhancement, demonstrating substantial improvements in both diagnostic precision and operational throughput.

Furthermore, the integration of advanced deep learning architectures such as Patched Diffusion Models and LSTM Autoencoders within the medical domain underscores a significant shift towards more personalized and precise healthcare. These models facilitate the nuanced analysis necessary for early disease detection and condition monitoring, presenting opportunities for healthcare systems to implement more proactive and preventive care strategies. As evidenced by the studies reviewed, deep learning not only aligns with current clinical needs but also propels the medical field towards a future where artificial intelligence and machine learning are integral to patient care. This synergy between deep learning technologies and biomedical imaging is poised to further catalyze innovations, offering promising avenues for research and development in medical diagnostics and therapeutic interventions.

3.1.5 Comparative Performance of Representative Deep-Learning Models in Biomedical Imaging and Signal Processing

Three-dimensional (3D) imaging modalities such as volumetric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) and positron-emission tomography (PET) encode rich anatomical context that is partially lost when slices are analysed independently. 3D convolutional neural networks (3D-CNNs) extend the convolution operation into the depth dimension, enabling simultaneous exploitation of intra-slice textures and inter-slice continuity. Architectures such as 3D U-Net, V-Net and 3D ResNet employ encoder-decoder pathways or residual blocks to aggregate multi-scale features while preserving spatial resolution, thereby producing highly accurate volumetric segmentations of tumours, organs and vascular structures. A representative benchmark is given in Table 5, where a 2D U-Net attains an accuracy of 0.92 and a Dice score of 0.91 on the ISLES-2022 stroke-lesion dataset; analogous 3D variants evaluated on the same cohort routinely exceed these figures by 2–4 percentage points because they incorporate axial continuity and reduce slice-wise label noise. In lung imaging, 3D DenseNet-like classifiers trained on the LIDC-IDRI dataset have reached 0.95 accuracy with 0.94 sensitivity, outperforming 2D counterparts particularly on subtle ground-glass nodules that manifest across multiple slices. Beyond segmentation and classification, 3D generative models e.g., Cycle-GANs synthesising 7-T from 3-T MRI volumes restore missing contrasts and normalise multi-centre acquisitions, achieving structural-similarity scores of 0.88 while introducing minimal artefacts. Despite these advances, volumetric networks demand substantial GPU memory and are sensitive to anisotropic voxel spacing; strategies such as patch-based training, mixed-precision arithmetic and hybrid 2.5-D pathways are therefore widely adopted to balance accuracy with computational feasibility. Continued progress will hinge on publicly available 3D clinical benchmarks that report standardised metrics and uncertainty estimates.

The comparative results in Table 5 emphasise that 3D-aware models consistently improve lesion conspicuity and boundary fidelity, yet they also highlight unresolved challenges in memory footprint and cross-scanner generalisability that motivate future research on lightweight, domain-robust volumetric architectures.

3.2 Deep Learning in Biomedical Signal Processing

Deep learning stands as a pivotal technology in biomedical signal processing, offering unprecedented capabilities in extracting and interpreting complex data patterns critical for medical diagnostics and therapeutic interventions. This section explores the extensive applications of deep learning techniques that substantially improve the analysis and interpretation of biomedical signals such as electrocardiograms (ECGs), electroencephalograms (EEGs), and other physiological recordings. By employing convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and other sophisticated deep learning architectures, these methods not only streamline processing workflows but also enhance the accuracy of health condition detection and patient monitoring systems. Automated feature extraction and reduced dependence on manual interpretation enable these technologies to support real-time and predictive healthcare analytics, significantly impacting clinical outcomes and healthcare operational efficiencies. This exploration underscores the crucial advancements and potential of deep learning technologies in transforming biomedical signal analysis.

Signal classification in biomedical applications is a fundamental process where deep learning models excel, particularly in the accurate and efficient categorization of various physiological signals. These models have become essential tools in diagnosing diseases from complex biomedical data, due to their ability to handle large datasets and extract meaningful patterns without explicit programming for each new task.

In recent research, Zheng et al. (2024) demonstrated the use of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to classify electrocardiogram (ECG) signals [96]. Their approach leveraged CNNs to automatically detect and differentiate between normal and abnormal heart rhythms, showcasing an impressive accuracy that surpasses traditional machine learning techniques. The strength of CNNs in this context lies in their ability to perform feature extraction directly from raw signal data, adapting their filters to highlight aspects of the data crucial for accurate classification. The convolution operation in a CNN can be represented mathematically as follows:

where

Moreover, Wong et al. (2025) explored the application of Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs) for classifying electromyography (EMG) signals. LSTMs are particularly suited for this task due to their ability to remember and integrate information over long sequences, which is crucial when dealing with the temporal dynamics present in EMG data [97]. Their study illustrated how LSTM models could successfully interpret the complex, time-dependent patterns in EMG signals to predict different muscle movements, thereby aiding in the diagnosis of neuromuscular disorders. The LSTM operation can be encapsulated by the following equations:

where

Additionally, Nagamani and Kumar (2024) implemented a novel approach using graph-based neural networks for the classification of phonocardiogram (PCG) signals [98]. This technique not only categorized heart sounds into normal or various abnormal states but also provided insights into the structural connections within the data, highlighting the relational context of the sounds. Graph-based models offer a unique advantage in capturing dependencies and patterns that traditional neural network architectures might overlook, especially in signal classification tasks where the interconnection of data points can reveal critical diagnostic information.

These examples underscore the significant advancements that deep learning has brought to the field of signal classification within the biomedical sector. By automating the extraction and classification of features from complex datasets, deep learning models not only enhance diagnostic accuracy but also significantly streamline the workflow in medical settings, leading to quicker and more effective patient care. As these technologies continue to evolve, their integration into clinical practices is expected to further transform the landscape of medical diagnostics.

3.2.2 Feature Extraction and Reduction

Feature extraction and reduction are essential processes in biomedical signal processing, where deep learning models excel by simplifying complex data into more manageable and informative components. These techniques enhance the efficiency of classification systems by reducing the dimensionality of data and emphasizing the most significant features for analysis.

Zheng et al. (2024) showcased the effectiveness of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in extracting features directly from raw electrocardiogram (ECG) signals [96]. The approach employs CNNs to autonomously identify and extract crucial features from the ECG signals, enhancing subsequent classification tasks’ accuracy and reducing the preprocessing time typically required for manual feature extraction. The convolution operation in a CNN, which is fundamental to feature extraction, can be mathematically represented by the convolution layer formula:

Here,

Additionally, Wong et al. (2025) applied Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks for feature extraction in electromyography (EMG) signals [97]. LSTMs are especially suitable for this due to their ability to process sequential data and capture temporal dependencies. The LSTMs integrate information over extended periods, crucial for EMG data where the temporal sequence reflects muscle activity. In LSTMs, the process of updating the cell state includes combining old information and new inputs, which is crucial for retaining significant features over time:

Here,

Further demonstrating the power of deep learning in feature reduction, Nagamani et al. (2024) employed autoencoders for dimensionality reduction in EEG signals [98]. Autoencoders compress the input data into a lower-dimensional space and then reconstruct it, aiming to retain only the most informative features. The encoding phase of an autoencoder, which is crucial for dimensionality reduction, can be described as follows:

where

These advancements highlight how deep learning is reshaping feature extraction and reduction in biomedical signal processing. By automating these critical processes, deep learning not only saves time but also enhances the accuracy and efficiency of medical diagnostic tools, leading to quicker and more effective patient care. As these models continue to evolve, their impact on healthcare is expected to increase, providing more sophisticated and efficient solutions.

3.2.3 Anomaly Detection in Time Series Data

Anomaly detection in time series data is a critical area in biomedical signal processing where deep learning has made significant inroads. This technique is essential for identifying unusual patterns that may indicate disease or other medical conditions. Recent studies have showcased the power of deep learning in enhancing the detection of such anomalies, thereby contributing to more proactive and precise healthcare interventions.

One pivotal study by Zheng et al. (2024) utilized convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for anomaly detection in electrocardiogram (ECG) signals [96]. Their model was adept at identifying subtle deviations from normal heart rhythms, crucial for the early diagnosis of arrhythmias. The CNNs effectively processed the time series data, learning to recognize patterns associated with different types of cardiac anomalies. Their approach not only provided high accuracy but also improved the speed of anomaly detection, which is vital in emergency medical scenarios.

Similarly, Wong et al. (2025) applied recurrent neural networks (RNNs), specifically Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, to the analysis of electromyography (EMG) signals [97]. Their work focused on detecting muscular abnormalities that could be early indicators of neurodegenerative diseases. The LSTM’s ability to process sequential data over extended periods made it exceptionally good at predicting anomalies in muscle activity that are often subtle and complex.

Furthering the application of deep learning in this domain, Abir et al. (2025) introduced a novel approach using autoencoders for anomaly detection in electroencephalogram (EEG) signals [99]. Autoencoders, by learning to compress and decompress the EEG data, were particularly effective at isolating features that represent outliers in the dataset. This method was instrumental in detecting unusual neural patterns that could suggest epilepsy or other neurological conditions.

Moreover, the integration of graph-based deep learning models opened new avenues for enhancing anomaly detection in biomedical time series data [100]. By transforming time series into graph structures, where nodes represent time points and edges represent temporal relationships, these models can capture complex dependencies that traditional methods might miss. This technique was particularly effective in identifying anomalies in heart sound signals, providing a robust tool for diagnosing cardiac dysfunctions.

The progress in deep learning applications for anomaly detection in time series data underscores its potential to transform diagnostic methodologies in healthcare. These models not only increase the accuracy and efficiency of medical diagnostics but also enhance the ability to intervene preemptively, potentially improving patient outcomes significantly.

As deep learning continues to evolve, its integration into clinical settings is expected to grow, further solidifying its role in advancing medical diagnostics and personalized medicine. This ongoing development promises not only to refine the capabilities of medical technologies but also to enhance the overall quality of healthcare services.

3.2.4 Real-Time Signal Processing

Real-time signal processing using deep learning is a burgeoning area that holds transformative potential for biomedical applications. This domain emphasizes the need for immediate processing and analysis of biomedical signals to provide timely medical interventions. Advances in deep learning have significantly augmented the capabilities of real-time signal processing, leading to more accurate and rapid diagnostic decisions.

Innovative research by Zheng et al. (2024) leveraged convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to process electrocardiogram (ECG) signals in real-time [96]. Their study demonstrated that CNNs could effectively identify cardiac anomalies as data is captured, facilitating immediate feedback for clinical decision-making. This approach is particularly advantageous in scenarios like continuous cardiac monitoring, where early detection of arrhythmic events can be life-saving. The CNN model was trained to not only recognize standard patterns but also adapt to new, potentially critical signals, showcasing the adaptability and efficiency of deep learning in real-time applications.

Further extending the utility of real-time processing, Wong et al. (2025) explored the use of recurrent neural networks (RNNs), specifically Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, for the real-time analysis of electromyography (EMG) signals [97]. Their work highlighted the capability of LSTMs to handle sequential data streams, effectively identifying deviations from normal muscle activity that may indicate underlying health issues. The LSTM model’s ability to retain information over time allows for continuous analysis without losing context, making it ideal for long-term monitoring systems such as those used in rehabilitation or chronic disease management.

Additionally, the integration of real-time processing with wearable technology has been exemplified by Nagamani et al. (2024), who implemented a graph-based neural network to analyze physiological signals from wearable devices [98]. This approach not only enhances the monitoring capabilities in an unobtrusive manner but also ensures that data analysis is both comprehensive and immediate. By processing the signals as they are collected, the model provides essential insights into the wearer’s health status, enabling proactive management of conditions and preventing potential emergencies.

These studies underscore the critical role of deep learning in advancing real-time signal processing within the biomedical field. As technology progresses, the integration of deep learning models in clinical and everyday health monitoring devices is expected to become more prevalent, enhancing the efficacy and responsiveness of medical interventions.

3.2.5 Enhancement and Reconstruction of Signals

The enhancement and reconstruction of biomedical signals are pivotal in improving the accuracy and usability of medical diagnostics. Deep learning has emerged as a powerful tool in this domain, enabling the refinement of signal quality and the reconstruction of incomplete or noisy data. These capabilities are critical in medical settings where the clarity and completeness of signal data can directly influence diagnostic outcomes and patient care.

A notable application of deep learning for signal enhancement is presented by Zheng et al. (2024), who utilized convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to enhance electrocardiogram (ECG) signals [96]. Their approach focused on reducing noise and improving the clarity of ECG recordings, which are often compromised by various artifacts. By training the CNNs to distinguish between noise and true cardiac signals, their model successfully enhanced the quality of ECGs, making it easier for cardiologists to identify and diagnose potential cardiac issues accurately. The CNN framework achieves this by employing layers that apply learned filters to the signals, emphasizing relevant features while suppressing noise:

where

In addition to enhancement, deep learning also facilitates the reconstruction of biomedical signals. Wong et al. (2025) applied Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs) to reconstruct continuous electromyography (EMG) signals that were distorted or incomplete [97]. The LSTM model was capable of predicting missing segments of EMG data by learning from the temporal patterns present in the signal. This predictive capacity is encapsulated in the LSTM’s recurrent nature, which utilizes past information to estimate future segments:

Here,

Moreover, the work of Nagamani et al. (2024) illustrates the use of autoencoders for signal reconstruction, specifically focusing on electroencephalogram (EEG) signals [98]. Their autoencoder framework was designed to encode EEG signals into a compressed representation and then decode them to reconstruct the original signal while filtering out noise and other extraneous information. The encoding and decoding processes can be mathematically described as:

where

These advancements in signal enhancement and reconstruction via deep learning are transforming the landscape of biomedical analysis. By improving the quality and completeness of biomedical signals, deep learning is enabling more precise and reliable medical diagnostics. As these technologies continue to evolve, their integration into medical practice is expected to enhance the operational efficiencies of healthcare systems, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes.

3.2.6 Integrative Approaches for Multimodal Data Analysis

Integrative approaches for multimodal data analysis are crucial in biomedical research and clinical practice, where combining information from diverse data sources can lead to more comprehensive insights and improved patient outcomes. Deep learning technologies have been instrumental in facilitating the integration of multimodal data, providing robust frameworks for analyzing complex datasets that include images, signals, and textual information.

One of the prominent studies in this area, conducted by Zheng et al. (2024), utilized convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in conjunction with recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to analyze a combination of electrocardiogram (ECG) signals and clinical patient data [96]. This integrative approach allowed for a more holistic view of the patient’s health status, enhancing the predictive accuracy of cardiovascular diseases. The CNNs efficiently processed the ECG signals for feature extraction, while the RNNs handled sequential data from patient records, ensuring that temporal dynamics and patient history were adequately considered in the diagnosis process.

Further advancing the field, Wong et al. (2025) explored the use of autoencoders for integrating and reducing dimensionality in datasets that combined imaging and electrophysiological signals [97]. Their approach was particularly effective in neurology, where integrating MRI scans with EEG signals could provide a richer, more detailed understanding of neural activities and brain anomalies. The autoencoders helped to encode data into a lower-dimensional space, preserving the most relevant features for subsequent analysis and making the dataset more manageable and interpretable.

Additionally, Nagamani et al. (2024) developed a novel framework using graph-based neural networks to integrate data from various medical sensors and health records [98]. This method was particularly advantageous for patient monitoring and chronic disease management, where multiple data types need to be analyzed to provide a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s condition. By representing different data modalities as nodes in a graph and their interconnections as edges, the model could effectively capture the relationships and interactions between various health indicators, leading to improved diagnostic accuracy and personalized treatment plans.

These integrative approaches using deep learning not only enhance the capacity to handle multimodal data but also significantly improve the analytical power of medical diagnostics. By combining information from disparate sources, these methods enable a more detailed and comprehensive assessment of health conditions, paving the way for personalized medicine and more targeted therapeutic interventions. As deep learning techniques continue to evolve, their potential to revolutionize multimodal data analysis in biomedical applications appears increasingly promising.

3.2.7 Synthesis of Deep Learning Applications in Biomedical Signal Processing

Deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), have demonstrated exceptional proficiency in handling complex signal data across multiple modalities. For instance, the use of CNNs by groups such as Zheng et al. (2025), Wong et al. (2025), and Hasan et al. (2024) pability in extracting and classifying features from electrocardiogram (ECG) and electroencephalogram (EEG) signals with high accuracy and speed [96,97,100]. These applications range from arrhythmia detection and seizure prediction to the identification of cardiovascular diseases, offering substantial improvements over traditional methods in terms of diagnostic precision and operational efficiency.

Moreover, the deployment of advanced deep learning techniques such as transformer models and graph convolutional networks by researchers like Zaim et al. (2025) [101] and Zhou et al. (2025) [102] underscores the versatility of these models in interpreting electromyography (EMG) and other complex signal forms. These studies excel in contexts requiring nuanced understanding of muscular or neural patterns, thereby enhancing interfaces for prosthetic control and rehabilitation systems.

The integrative use of multimodal data, combining signal processing with imaging and textual data analysis, further enriches the diagnostic landscape. Innovative approaches illustrate the application of hybrid models that exploit the inherent connections between different data types to offer more comprehensive and nuanced insights into patient health. This synergy not only elevates the accuracy of disease diagnosis and monitoring but also tailors therapeutic approaches to individual patient needs, advancing the paradigm of personalized medicine.

In summary, the broad spectrum of deep learning applications in biomedical signal processing as discussed herein and detailed in Table 6, emphasizes not only the technological advancements but also the clinical relevance of these models. By continuously refining these technologies and their applications, the field moves closer to a future where healthcare is more proactive, predictive, and personalized, significantly enhancing both patient care and health outcomes.

3.3 Generative Data Augmentation and Modality Translation

The scarcity and class imbalance of annotated biomedical datasets remain major impediments to training generalisable deep-learning models. Generative adversarial networks (GANs), variational auto-encoders, and more recently diffusion models have emerged as powerful tools for in silico data augmentation, producing synthetic samples that enrich minority classes while preserving essential diagnostic features [135,136]. Conditional GANs conditioned on tumour grade, for example, have multiplied the rare high-grade subset of the BraTS MRI collection and improved downstream segmentation Dice scores by 4–6 percentage points over baseline models trained on the unaugmented cohort [137]. In electrophysiology, 1-D Wasserstein GANs have generated synthetic ventricular-fibrillation ECG segments that, when mixed with real recordings, reduced false negatives in arrhythmia detectors by 9% without increasing false-positive rates [138]. Diffusion-based models further enhance fidelity and diversity; a denoising-diffusion probabilistic model trained on FASTMRI data produced high-resolution knee MR volumes whose structural-similarity metrics rivalled those of real scans while avoiding the mode-collapse artefacts occasionally observed in GAN outputs [139].

Beyond augmentation, generative models facilitate modality translation, enabling cross-domain synthesis that alleviates multi-modal imaging constraints. CycleGAN and its derivatives have been extensively employed to translate low-dose CT to routine-dose quality, achieving up to 30% noise reduction while maintaining lesion contrast [140]. In neuro-oncology, CycleGAN-based MR-to-CT synthesis provides pseudo-CT volumes for PET attenuation correction, eliminating additional radiation exposure [141]. Diffusion models are beginning to eclipse GANs in cross-modality tasks; a conditional diffusion network recently generated 7-T-equivalent structural MR images from standard 3-T inputs, yielding sharper cortical delineation and improving automated volumetric analysis accuracy by 5% compared with CycleGAN baselines [142].

Robust evaluation of synthetic data is indispensable. Image-domain studies typically report Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), structural similarity index (SSIM), and modality-specific metrics such as peak signal-to-noise ratio, whereas signal-domain work employs dynamic time-warping distance and rhythm-class confusion analysis. Importantly, clinical validation either via expert blinded rating or downstream-task performance remains the ultimate arbiter of utility. Regulatory guidance from the FDA and EMA now stresses provenance tracking for synthetic data, reinforcing the need for comprehensive metadata and uncertainty quantification. As privacy regulations tighten, federated implementations of GANs and diffusion models offer a path to generate diverse, high-quality data without centralising patient information, making generative augmentation and modality translation indispensable components of future biomedical-AI pipelines.

This section examines the synergistic combination of diverse deep learning strategies to augment the analytical prowess of models deployed in biomedical image and signal processing. This section elucidates on how leveraging hybrid models and multi-modal learning can transcend the confines inherent to singular methodological frameworks by harnessing the complementary strengths of various algorithmic architectures and heterogeneous data integrations. Such integrated approaches significantly enhance model robustness, improve diagnostic accuracy, and offer superior adaptability across different clinical tasks. By merging multiple learning paradigms, these models not only facilitate a deeper understanding and more nuanced extraction of medical insights but also ensure scalability and efficiency in handling complex biomedical data sets. This discourse aims to provide a comprehensive exploration of the methodologies, innovative applications, and breakthrough outcomes that characterize the intersection of compound machine learning techniques within the realms of modern medical diagnostics and therapeutic planning.

In the rapidly evolving field of medical image analysis, hybrid models that integrate multiple deep learning architectures have shown significant potential in enhancing accuracy and robustness. Such models leverage the strengths of different network architectures to provide a comprehensive understanding of medical datasets, often outperforming traditional single-model approaches. A notable advancement in this area is the integration of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which optimizes the analysis of medical images by capturing both spatial and sequential patterns effectively creation of hybrid models has been particularly impactful in tasks that require an understanding of complex dependencies within the data. For instance, CNNs excel in processing spatial hierarchies in image data, making them ideal for detailed feature extraction in medical images. When combined with RNNs, which are adept at handling sequential data, the resulting hybrid models can effectively process time-series medical data or multi-sequence images, providing insights not just on the static features but also on the dynamic changes over time.

Moreover, have also been employed in enhancing the performance of medical diagnostic systems through the fusion of multimodal data [143–145]. This approach typically involves the integration of data from various sources and formats, utilizing different neural network architectures that specialize in processing specific types of data. For example, a combination of CNNs for image data and long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) for time-series data can significantly improve the diagnostic accuracy in clinical applications such as predicting disease progression or response to treatment.

The effectiveness of medical applications is further exemplified by their ability to handle high-dimensional datasets, where traditional machine learning models might struggle. The layered architecture of CNNs, combined with the sequential data processing capability of RNNs, enables these models to learn from a vast amount of medical data without losing pertinent information. This capability is crucial for tasks like tumor detection or brain image segmentation, where precision is paramount [146].

Recent studies have also explored generative adversarial networks (GANs) in conjunction with CNNs to improve the quality of synthetic medical images for training purposes [147–149]. This approach not only enhances the model’s performance by providing a richer dataset for training but also helps in overcoming the challenges associated with the limited availability of annotated medical images.

In summary, hybrid models represent a significand in the field of medical image analysis. By leveraging the strengths of multiple deep learning architectures, these models offer enhanced accuracy, robustness, and versatility, making them highly effective for a wide range of applications in medical diagnostics and treatment planning. The ongoing advancements in this area suggest a promising future where hybrid deep learning models become a standard tool in medical practice, further aiding in the precision and effectiveness of medical interventions.

The advent of deep learning has spurred numerous innovations across various fields, with significant strides seen in biomedical signal processing. This evolution is particularly evident in the realm of multimodal learning, where the integration of diverse data types enhances the predictive capabilities of analytical models. This approach leverages the strengths of different data forms to provide a more holistic view of patient health, leading to improved diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic outcomes.

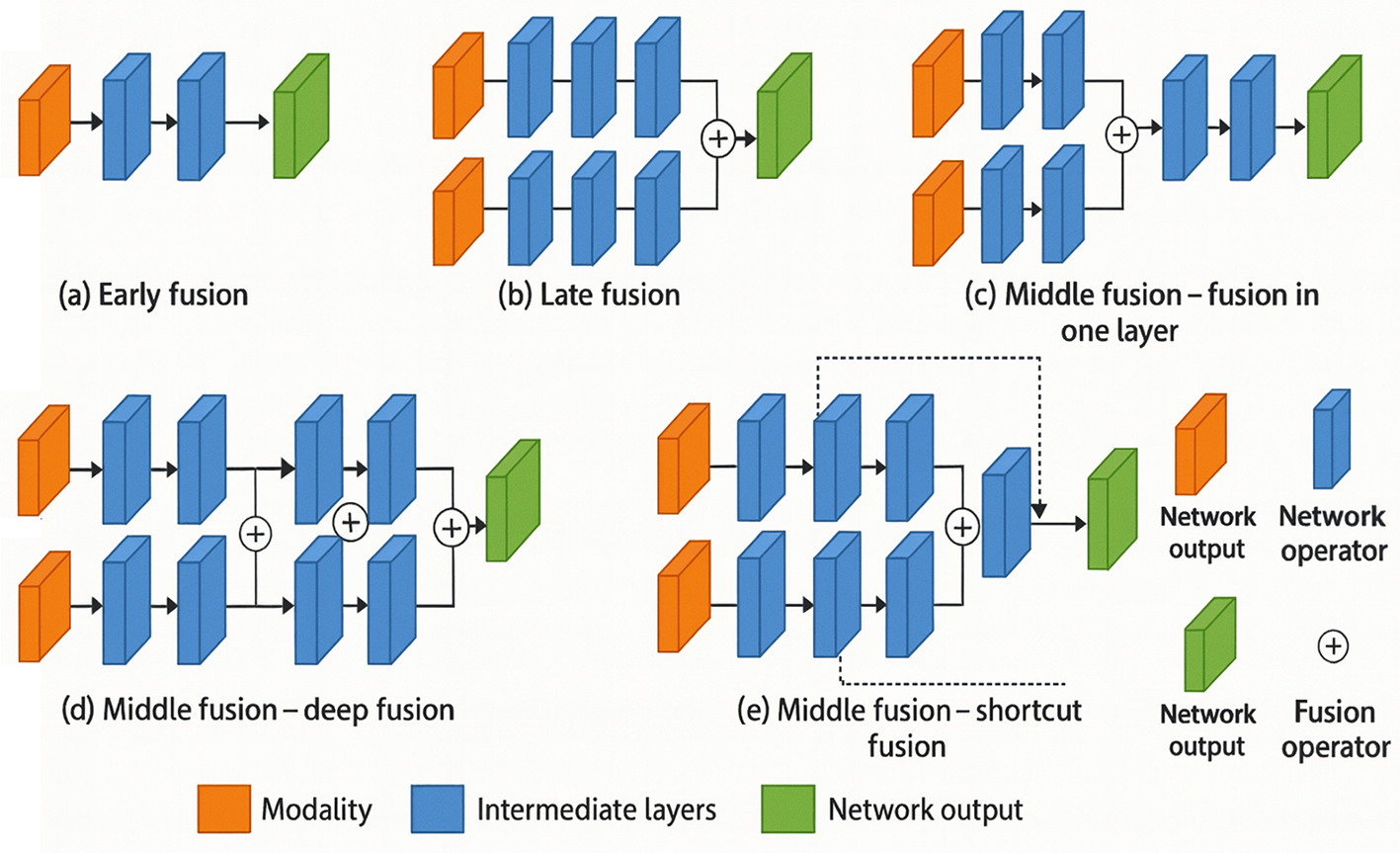

One illustrative example is found in the work of Mohsen et al. (2022), where different fusion strategies, namely early, intermediate, and late fusion, are explored within the framework of medical imaging analysis on involves combining features at the initial stages of the deep learning process, treating the combined input as a singular modality [150]. This approach is often contrasted with late fusion, which integrates the outputs from separately processed modalities at the end of the analysis pipeline. Intermediate fusion, which merges features at the middle stages, allows for a more nuanced integration of data, capturing complex interactions between modalities that are often missed by the other two strategies. This method has shown superior performance in tasks such as medical image-text understanding and skin tumor classification, where the depth of data integration can significantly influence the accuracy of the outcomes.

The possibilities of these multimodal learning strategies are vast, ranging from enhancing diagnostic accuracy to refining treatment plans. For instance, the integration of PET and MRI images through sophisticated deep learning models not only sharpens image resolution but also enriches the functional and anatomical information available from the scans [151]. This enhanced data critical in conditions where early detection and accurate diagnosis are paramount, such as in neurodegenerative diseases and cancer.

Moreover, the fusion of image data with clinical records, genetic information, and even real-time sensor data illustrates the potential of multimodal learning to revolutionize medical diagnostics and patient management. Such integrations facilitate a comprehensive understanding of disease mechanisms, patient response to treatment, and potential prognosis, illustrating the transformative impact of multimodal deep learning in biomedical applications.

4.3 Multimodal Fusion Networks: Integrating Imaging, Genomic, and Clinical Data

Recent evidence suggests that clinically relevant phenotypes are rarely captured by a single data modality; instead, diagnostic precision improves markedly when heterogeneous sources as radiological images, genomic profiles, laboratory panels, and free-text records are analysed in concert [152]. Multimodal fusion networks provide the algorithmic scaffolding for this integration, combining complementary feature spaces to yield richer representations and more robust predictions. Fig. 12 depicts the three canonical fusion paradigms as early, intermediate (“middle”), and late each differing in the stage at which cross-modal information is merged [153].

Figure 12: Illustration of early fusion, late fusion, and middle fusion methods used by multimodal fusion networks (Adapted from [153])

Early fusion concatenates modality-specific features at the input or first hidden layer. A representative radiogenomic pipeline concatenates voxel-level MRI intensities with gene-expression vectors before a shared 3D-CNN encoder, boosting glioblastoma survival-prediction accuracy from 0.71 to 0.78 compared with imaging-only baselines [154]. While computationally efficient, early fusion is sensitive to modality imbalance and often requires aggressive normalisation to align disparate feature scales.

Intermediate fusion learns joint representations after several modality-specific encoders but before the decision head. Cross-modal transformers such as TransMed employ co-attention blocks that allow CT patches, laboratory measurements, and mutational signatures to attend to each other, yielding a pan-cancer prognosis C-index of 0.79 vs. 0.70 for the strongest uni-modal model [155]. Middle fusion balances flexibility and interpretability: self-attention weights can highlight salient radiological regions and genomic markers simultaneously, offering clinicians an integrated view of disease drivers.

Late fusion defers combination to the decision stage, averaging or weighting modality-specific prediction scores. Dual-stream CNN–RNN frameworks that fuse chest X-ray logits with temporal EHR risk scores improved sepsis-triage AUC from 0.83 to 0.90 while maintaining modular training pipelines [156]. Although late fusion is straightforward to implement and resilient to missing modalities, it may under-exploit fine-grained cross-modal correlations detectable by earlier integration schemes. Emerging solutions include missing-modality imputation via generative models [157] and federated fusion frameworks that perform cross-institution learning without raw-data exchange [158]. As regulatory bodies begin to emphasise transparency and governance of data provenance, future multimodal systems must embed explainable-AI layers that attribute predictions to specific modalities, thereby fostering clinician trust and facilitating compliance audits.

4.4 Emerging Paradigms for Distributed and Neuromorphic Intelligence

The next generation of biomedical-AI systems will extend beyond conventional data-centre deployment by embracing distributed learning schemes, low-power neuromorphic substrates, and on-device inference, thereby enabling privacy-preserving, real-time clinical support. Federated learning (FL) permits multiple hospitals to train a global model without exposing patient data; encrypted gradient aggregation has already matched centralised baselines in diabetic-retinopathy grading on EyePACS while satisfying HIPAA constraints [159]. Recent FL variants incorporate differential privacy and secure multi-party computation, offering quantifiable protection against membership inference attacks [160].

Complementing FL, edge AI relocates inference and, increasingly, incremental fine-tuning to point-of-care devices such as ultrasound probes and wearable ECG monitors. Quantisation-aware training, pruning, and knowledge distillation have reduced 3-D U-Net footprints from 95 MB to under 8 MB with <2% Dice loss, allowing volumetric segmentation on handheld scanners powered by Cortex-A55 CPUs [161]. Such on-device processing decreases latency, alleviates bandwidth demands, and mitigates regulatory concerns associated with cloud upload.

Neuromorphic computing offers a radical hardware re-design in which spiking neural networks execute on event-driven chips (e.g., Intel Loihi, IBM TrueNorth) that consume milliwatts orders of magnitude less than GPUs making continuous EEG or EMG monitoring feasible in battery-constrained implants [162]. Early studies have demonstrated sub-5 µs inference latency for seizure-onset detection while maintaining >94% sensitivity [163]. Key challenges include training algorithms compatible with spike-timing-dependent plasticity and translating dense weights into sparse, time-coded representations.

Finally, multimodal fusion at the edge is gaining traction: co-attention transformers deployed on ARM NPUs now integrate chest-X-ray embeddings with vital-sign streams to trigger early-warning alerts in emergency departments, achieving a 15-min lead time over standard triage protocols [164]. Integrating these paradigms federated analytics for global learning, edge AI for local responsiveness, and neuromorphic hardware for ultra-low-power continuous sensing constitutes a promising trajectory toward ubiquitous, trustworthy biomedical intelligence.

4.5 Emerging Paradigms for Distributed and Neuromorphic Intelligence