Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

SDN-Enabled IoT Based Transport Layer DDoS Attacks Detection Using RNNs

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Yuan Ze University, Taoyuan, 32003, Taiwan

2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Jashore University of Science and Technology, Jashore, 7408, Bangladesh

3 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, State University of Bangladesh, South Purbachal, Kanchan, Dhaka, 1461, Bangladesh

4 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Prime University, Dhaka, 1216, Bangladesh

5 Electrical and Electronic Engineering Department, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, 43600, Malaysia

* Corresponding Authors: Mohammad Nowsin Amin Sheikh. Email: ; I-Shyan Hwang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 4043-4066. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065850

Received 23 March 2025; Accepted 14 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

The rapid advancement of the Internet of Things (IoT) has heightened the importance of security, with a notable increase in Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks targeting IoT devices. Network security specialists face the challenge of producing systems to identify and offset these attacks. This research manages IoT security through the emerging Software-Defined Networking (SDN) standard by developing a unified framework (RNN-RYU). We thoroughly assess multiple deep learning frameworks, including Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Feed-Forward Convolutional Neural Network (FFCNN), and Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), and present the novel usage of Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique (SMOTE) tailored for IoT-SDN contexts to manage class imbalance during training and enhance performance metrics. Our research has significant practical implications as we authenticate the approache using both the self-generated SD_IoT_Smart_City dataset and the publicly available CICIoT23 dataset. The system utilizes only eleven features to identify DDoS attacks efficiently. Results indicate that the RNN can reliably and precisely differentiate between DDoS traffic and benign traffic by easily identifying temporal relationships and sequences in the data.Keywords

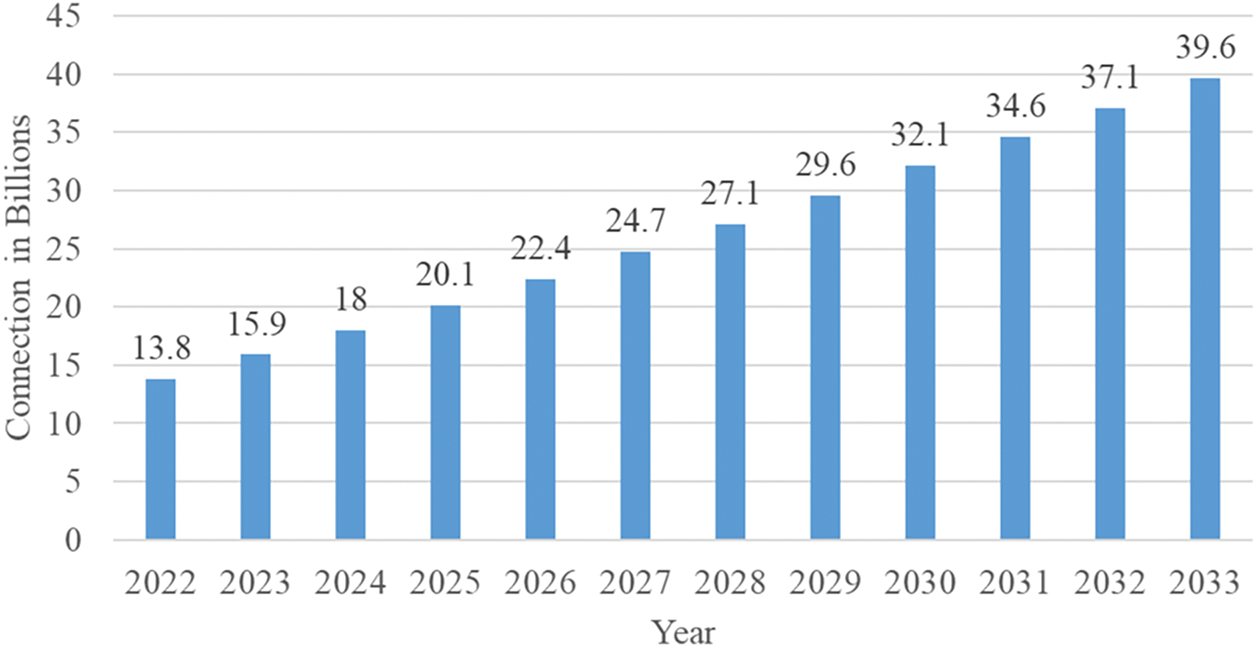

The mechanism behind the Internet of Things (IoT) has evolved to the point where a vast number of people utilize or are involved with smart devices daily. It extends benefits beyond automation, improved production, and practical resource use [1]. Additionally, the range of IoT applications prevalent in areas such as smart grids, residences, healthcare, transportation systems, and more is an outcome of recent developments in research on wireless communications, cloud computing, and data analytics [2]. IoT devices incorporate various types of sensors, cameras, and IP cameras. It is possible to create an innovative environment by integrating millions of smart devices in this manner [3]. Around the globe, a large number of individuals are using IoT devices. There have been significant increases in the use of IoT devices in recent years, with forecasts indicating that the number of IoT devices will exceed 21 billion by the end of 2025 [4] and reach approximately 100 billion by 2030 [5], as shown in Fig. 1.

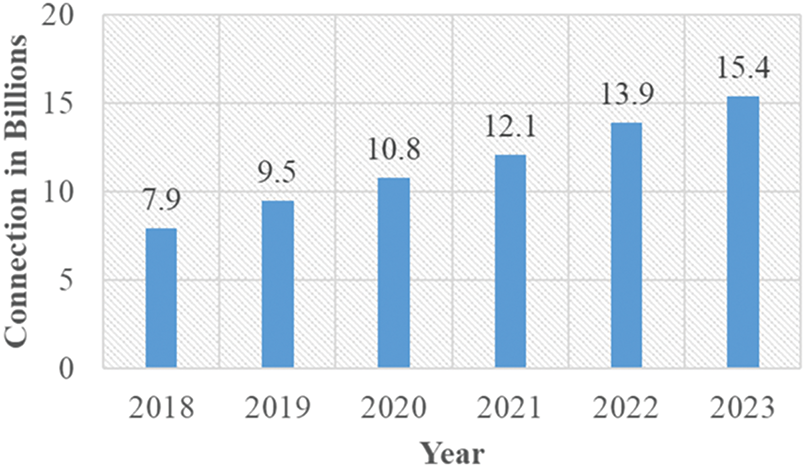

Figure 1: Worldwide IoT connectivity forecasts through 2033

Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks typically occur when multiple systems overburden the bandwidth or system resources of a target, often one or more web servers. Such an attack typically results from several compromised systems overwhelming the targeted system with traffic. Based on the statistics, DDoS attack size will increase by 63% every year, and by 2023, there will be 15.4 million DDoS attacks globally [6], shown in Fig. 2. The DDoS defense and mitigation market, valued at nearly US $4.24 billion in 2022, is projected to reach US $11.21 billion by 2029, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14.89% [7]. Researchers expect Software-Defined Networking (SDN) technology to revolutionize the way existing network companies operate [8]. SDN offers a plethora of new opportunities for IoT management and security [9]. An IoT network differs from a traditional network in several key aspects. One major management challenge for IoT networks is the variation in processing power, scalability, energy consumption, and other features [10]. Network management and configuration are becoming increasingly complicated, and SDN has emerged as a promising paradigm for networks [11]. Through effective network design and operation transformation to increase flexibility, SDN seeks to enhance network functionalities effectively. A versatile, reliable, and secure network is therefore made possible by SDN. Due to the success of SDN in network administration and security maintenance, a growing number of experts and researchers are advocating for the integration of IoT conceptual models with the novel network paradigm of SDN, and they are pushing for the development of a Software-Defined Internet of Things (SD-IoT) platform. Not only can the SDN controller monitor incoming and outgoing traffic, but it can also manage the IoT heterogeneous system. As a result, we have combined the IoT with the SDN paradigm to control traffic and defend against DDoS attacks.

Figure 2: Global DDoS attacks forecast 2018–2023

Most mitigation solutions focus on SDN control planes (20%), smart homes (8%), IoT data centers (4%), industrial IoT (4%), and ship communication systems (4%), with 60% being generic solutions not specific to any IoT scenario [12]. Often using unrealistic topologies (which do not accurately reflect the complexity, diversity, or hierarchical structure found in real-world IoT environments) or traditional datasets that may not be suitable for non-SD-IoT applications, several authors have contributed to SD-IoT DDoS attack detection. No research has specifically addressed practical scenarios in smart cities. This motivation led the author to develop an SDN testbed and generate the SD-IoT traffic dataset. Motivated by the high frequency and disruptive impact of attacks like TCP SYN floods and UDP floods in IoT-based systems, we specifically focus on detecting transport-layer DDoS attacks within SD-IoT environments. Transport-layer characteristics are readily accessible from packet headers, enabling efficient extraction and analysis without the need for deep packet inspection—an advantage that is particularly significant in resource-constrained IoT environments. Additionally, SDN’s centralized control and flow-level visibility align well with transport-layer monitoring, facilitating timely and effective anomaly detection. While we acknowledge that DDoS attacks can occur across all layers of the protocol stack, application-layer attacks typically require complex content-based analysis that is computationally intensive and less suitable for real-time detection in constrained IoT infrastructures. Similarly, network-layer attacks, though relevant, are often less complex and can be mitigated through conventional filtering and rate-limiting techniques. By focusing on the transport-layer, our approach strikes a practical balance between detection effectiveness, system performance, and the architectural constraints of SD-IoT systems.

In our proposed approach, we aim to enhance IoT security by leveraging the emerging SDN standard. We introduce RNN-RYU, which integrates the Ryu controller that manages the data flow between IoT devices and network infrastructure, while the RNN is responsible for detecting anomalies and DDoS attacks within the traffic. The RNN-RYU (DDoS attack detection) framework examines a smart city scenario that contains 14 hosts and 4 OpenFlow switches. We developed an SD-IoT traffic dataset (SD_IoT_Smart_City dataset) using the Ryu SDN controller and Mininet, simulating UDP flood, TCP SYN flood, and TCP PUSH-ACK transport layer DDoS attacks. We validated RNN-RYU on the CICIoT23 dataset [13] and our custom SD_IoT_Smart_City dataset, using metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC. The main contributions of the proposed scheme are summarized as follows:

• We identified and addressed a critical gap in the detection of DDoS attacks in SD-IoT environments, particularly within smart city applications, unlike prior studies that used unrealistic topologies or generalized datasets [14].

• We proposed the RNN-RYU framework for DDoS attack detection, tailored to the unique requirements and challenges of SD-IoT networks.

• In our scheme, we developed the SD_IoT_Smart_City dataset using the Ryu SDN controller and Mininet, which incorporates various transport-layer DDoS attack types, including UDP flood, TCP SYN flood, and TCP PUSH-ACK.

• The effectiveness of the proposed approach is demonstrated through validation with both custom and publicly available datasets, ensuring its applicability across various DDoS attacks at the transport layer.

This research paper organizes its content as follows: Section 2 outlines relevant studies and provides an overview of IoT systems, SDN, and DDoS attacks. Section 3 describes the proposed RNN-RYU framework, including the architecture, dataset generation, data preprocessing, application of RNN for time-dependent DDoS classification, and the training and classification processes of the RNN-RYU model. Section 4 outlines performance evaluation and result analysis (including performance metrics, feature importance, evaluation through SD_IoT_Smart_City and CICIoT23 datasets, comparison with other recent models). Section 5 outlines the conclusions and future research directions of our research.

2 Related Work & Overview of IoT System, SDN and DDoS Attack

This section begins with a review of related work, followed by an overview of the Internet of Things (IoT) and Software-Defined Networking (SDN). It explores how these two technologies are integrated and discusses the role of intermediary technologies in facilitating Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks within the context of SD-IoT. In addition, the section provides a detailed demonstration of transport-layer DDoS attacks in SD-IoT networks.

Numerous studies have explored DDoS attacks and proposed various defense strategies, including traffic separation, attack detection and mitigation, and source tracing. Recent research indicates that IoT networks utilizing Software-Defined mechanisms are vulnerable to DDoS attacks, even with the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) [15].

Ravi and Shalinie [16] utilize SDN and cloud computing to prevent DDoS attacks on IoT systems with their Learning-Driven Detection Mitigation (LEDEM) system, which employs a semi-supervised machine learning algorithm. This algorithm identifies malicious network flows to alert the controller, enabling the implementation of appropriate filtering rules. However, LEDEM lacks flexibility as it can only handle specific DDoS attacks and relies on a single classification algorithm.

Yin et al. [17] proposed an SD-IoT architecture that detects DDoS attacks by analyzing network traffic and using packet rate vectors for cosine similarity near SD-IoT switch borders. If the cosine similarity exceeds the defined threshold, the system detects an attack and discards the malicious packets. However, the approach’s effectiveness is limited by its reliance on a single threshold, which may not be suitable for all cases, and by the absence of advanced ML-based classification algorithms.

Tortonesi et al. [18] have developed an SPF framework utilizing SDN to mitigate data bursting in the IoT. A programmable module augments the data plane by introducing a processing and distribution plane. After classifying user application requests based on the services they require, the processing module confirms a priority for later distribution. SDN controllers make informed judgments based on their knowledge.

Özçelik et al. [19] proposed an Edge-Centric Software-Defined IoT Defence (ECESID) that can detect and mitigate DDoS attacks at the edge of an IoT network. The prediction relies on two key assumptions: benign connections tend to be more successful than malicious ones, and infected hosts typically generate a higher number of connection attempts. The system identifies infected hosts by analyzing attempts to establish connections and failures that occur within a specific time frame. Then, it blocks all traffic from these hosts by updating the SDN controller’s rules.

Sharma et al. [20] propose a machine learning-based solution called OpCloudSec to defend IoT networks from DDoS attacks by integrating cloud networks with wireless SDN. OpCloudSec uses deep network analysis to identify attack flows among new network traffic. The system reports both known and expected attack flows to the controller for further action. The system allows for updates to the attack pattern database, enabling it to recognize new attack types in the future.

Nobakht et al.’s [21] innovative home-based approach, IoT-IDM, utilizes methods employing machine learning to detect intrusions applicable to IoT. IoT-IDM uses the interpacket duration and the overall byte size within both response and command packets as detection metrics. A practical implementation of a logistic regression model, which can be both linear and nonlinear, can provide an accuracy rate above 94%.

Xu et al. [22] highlight the limitations of using a single controller for IoT infrastructures, noting that this centralized approach reduces network flexibility. To address this, they propose the Smart Security Mechanism (SSM), which monitors the mismatched flow rate of each switch over time. The system flags switch with traffic rates below a defined threshold as suspicious and redirect their traffic to the security middleware to block any malicious flows.

A different set of research aimed to prevent DDoS attacks on expansive networks. Researchers proposed these techniques to overcome the centralized limitations encountered during the administration of SDN architecture. The suggestions were proposed by Nguyen et al. [23] and Rathore et al. [24].

Rafique et al. [25] address the controller-to-switch overhead issue in IoT networks with SIESec, an SDIoT-Edge Security architecture. Each cloudlet runs an SIESec instance to reduce processing load and detect DDoS attacks. The collector component monitors switch traffic and sends data to the packet analyzer and feature extractor, which preprocesses flows. The classifier, using the Self-Organizing Maps (SOM) algorithm, categorizes flows as benign or malicious. The status analyzer analyzes malicious flows and the rule generator applies the appropriate filtering rules.

VARMAN, a multi-layered architecture described by Krishnan et al. [26], is intended to identify and mitigate attacks in IoT data centers that rely on SDN. Researchers employed several machine learning techniques during the selection and classification phases to identify harmful flows. Utilizing Network Functions Virtualization (NFV) characteristics, the mitigation procedure enabled the deployment of multiple virtual nodes with filtering capabilities. Furthermore, the VARMAN architecture provided load balancing between SDN controllers.

SDN-Oriented Secure and Agile Architecture (SEAL) was presented by Bawany and Shamsi [27]. The SEAL’s primary goal was to secure data centers used for IoT applications. It can prioritize mitigating DDoS attacks for that application. Another motivation for developing SEAL was to address DDoS attacks targeting the SDN architecture itself.

Nair et al. [28] developed a DDoS prevention system that quickly estimates attack frequency by analyzing the link between IP and MAC addresses. The system identifies potential malicious clients by detecting multiple source IP addresses associated with a single MAC address. It also uses a threshold based on flow table entries, packet delay, and the average time for the controller to receive a packet to determine the occurrence of an attack.

Houda et al. [29] developed Co-IoT, a secure and efficient system utilizing blockchain. It utilizes smart contracts to share attack information between SDN domains securely. Each domain creates a collaboration agreement and establishes a trust network with other domains. During the attack, the affected domain receives a malicious address list from the originating domain to block targeted devices.

Galeano-Brajones et al. [30] investigate OpenState, a protocol based on OpenFlow modification that enables SDN switches to store data regarding previously handled flows, utilizing rules present in the flow tables. As a result, the switches receive a portion of the knowledge on mitigating attacks on the networks, which often lessens the controller burden. They also employed the entropy approach to mitigate the attack and identify malicious traffic caused by the controller.

Chen et al. [31] developed an architecture to detect and mitigate DDoS attacks in smart cities that are very close to their origin. The system collects flow data from base stations and sets a traffic threshold. Devices exceeding this threshold are flagged as doubtful and joined to an anomaly tree. The tree is then analyzed to identify if these devices are malevolent.

On the CIC-IoT 2023 dataset, Jony et al. [32] and Gheni et al. [33] also employed machine learning or deep learning algorithms to identify and counteract DDoS attacks. Researchers have employed various methods to improve the F1-score, recall, accuracy, and precision. These techniques have a drawback in that they have only considered existing datasets; they have not utilized self-generated datasets to evaluate their models.

DDoS attack detection in SD-IoT networks has improved. However, most research depends on publicly available datasets that do not reflect the dynamic and complex nature of real-world IoT environments. Existing models often cover broad attack scenarios and lack adaptability to the evolving characteristics of IoT networks. To overcome this limitation, we introduce the SD_IoT_Smart_City dataset, enabling a more comprehensive evaluation tailored to SD-IoT systems. Our RNN-RYU framework surpasses traditional methods by capturing temporal dependencies and sequential patterns in smart city traffic using Recurrent Neural Networks, thereby enhancing flexibility and adaptability in the complex, ever-changing network environment.

Researchers refer to the integration of SDN technology with IoT technology as SDN-IoT collaboration. They achieve this by employing SDN switches and controllers to centrally and dynamically monitor and control network traffic from connected IoT devices. The initial phases of the process involve defining the network requirements, ensuring compatibility between IoT devices and the SDN architecture, and utilizing the SDN controller to implement traffic management and security regulations. It can accommodate an increasing number of Internet of Things devices. Furthermore, it provides dynamic resource allocation for bandwidth and load balancing in addition to ongoing analytics and network performance monitoring. Integration is made simpler by standards for APIs and interoperability. The linked network must then be continuously managed, tested, and validated in order to ensure its protection and optimization.

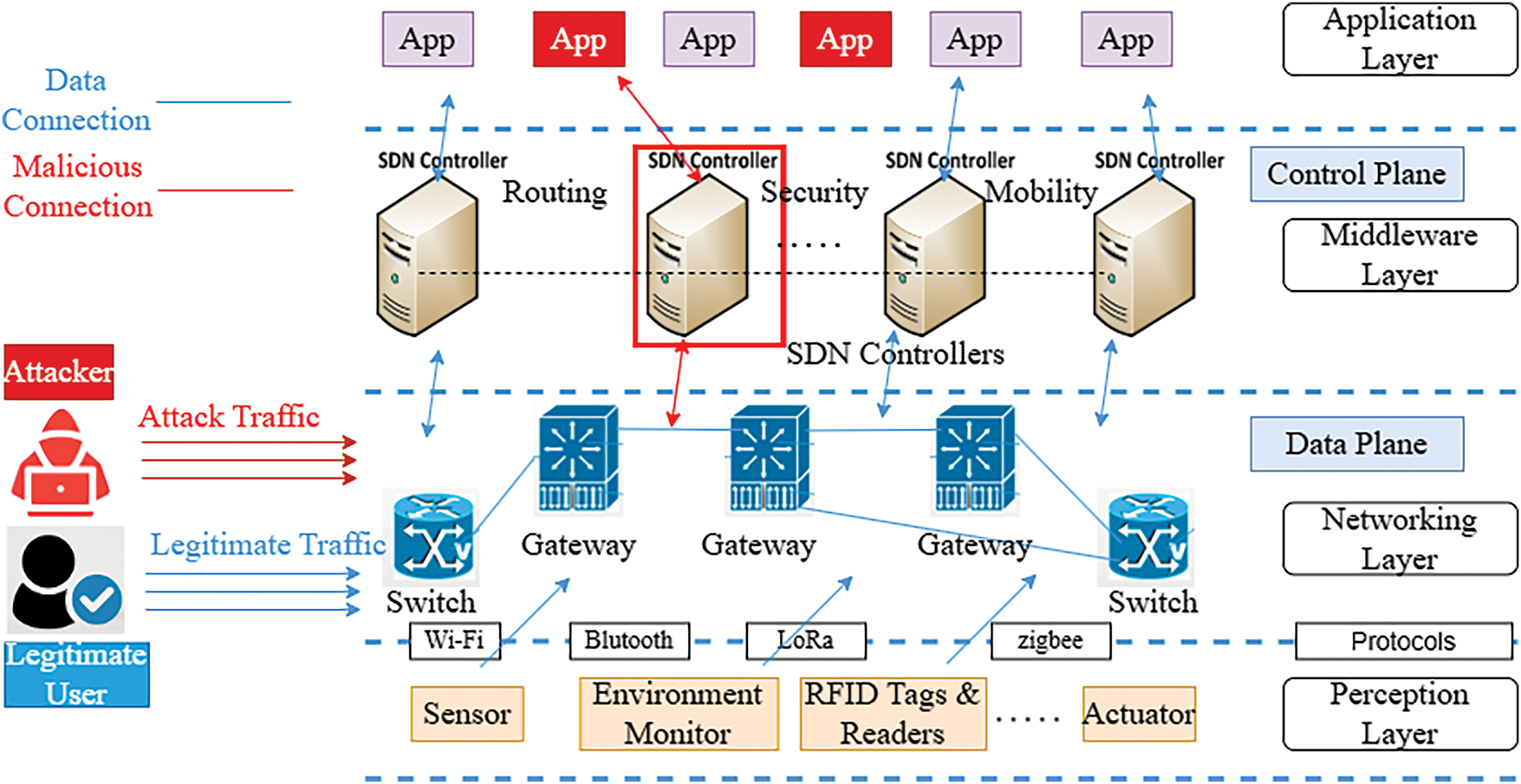

The most popular IoT architecture, based on four layers and modified to fit the SDN paradigm, is illustrated in Fig. 3: the perception layer, networking layer, middleware layer, and application layer [34]. The perception layer collects data through sensors and actuators and transmits it to the networking layer using communication protocols such as Bluetooth, Zigbee, LoRa, and Wi-Fi. The network layer handles data routing and transfer, often managed by SDN controllers for optimized performance and security. The middleware layer processes, stores, and analyzes the data before sending it to the application layer, where end-user applications use it for decision-making and control. SDN enhances this architecture by providing centralized control, optimizing data flow, and ensuring efficient and secure communication across all layers.

Figure 3: Multi-layer SD-IoT architecture & DDoS attack

A DDoS attack overwhelms a network or service with excessive traffic, rendering it unresponsive to legitimate requests. In the context of the four-layer IoT architecture depicted in Fig. 3, this type of attack can significantly disrupt the system’s functionality. Attackers using distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks must maintain their anonymity to evade detection by firewalls or other security measures at the target’s location. Attackers use several intermediary technologies to launch attacks.

In an SD-IoT setting, attackers initiate a DDoS attack by sending malicious packets to a specific SDN-based IoT switch, overloading the entire network with traffic. This high traffic corrupts the flow of data picked up by the SD-IoT controllers, causing the switch to become overloaded, which may lead to packet loss, delays, or poor data management. This anomalous circumstance makes it difficult for the controller to react promptly. Modifying flow tables, rerouting traffic, or evading security measures are some ways an attacker may interfere with the system. These issues cause the performance of different layers to deteriorate, which may result in service failure or unavailability as resources, such as CPU, memory, and bandwidth, become depleted, leading to potential crashes and prolonged downtime.

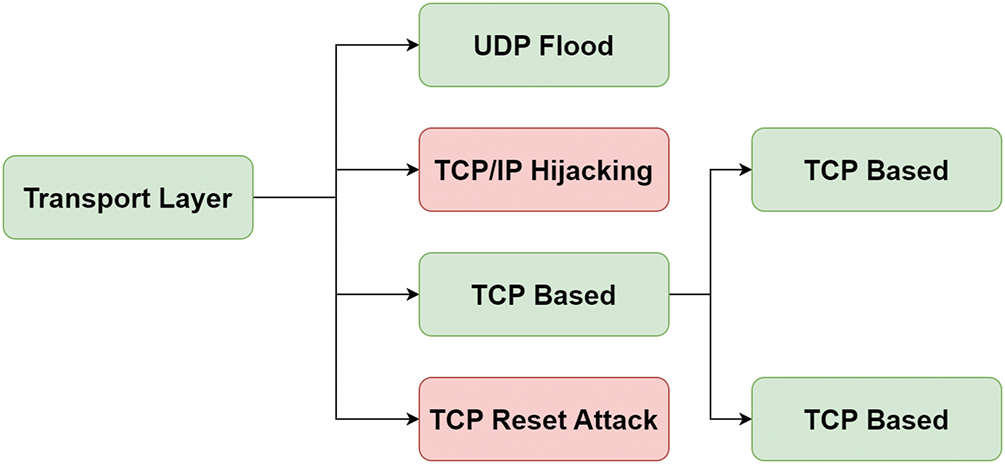

2.4 Transport Layer DDoS Attack in SD-IoT

At the transport-layer, two protocols—TCP and UDP—are employed to provide dependable and effective data delivery between IoT devices. The aim is to hinder legitimate users from accessing the network or to impede regular data transmission. Fig. 4 illustrates a transport-layer DDoS attack in an SD-IoT network.

Figure 4: Transport layer DDoS attack in SD-IoT

• TCP SYN Attack: It is a common type of DDoS attack at the transport-layer. The client and server exchange three handshakes over a TCP connection: ACK (acknowledgment), SYN-ACK (synchronize-acknowledgment), and SYN (synchronize). A SYN flood attack happens when an attacker sends a large amount of SYN requests to the network without acknowledging the server’s SYN-ACK. Consequently, the server forfeits resources that are anticipating the acknowledgment, so limiting the creation of more connections.

• UDP Attack: It is an additional type of transport-layer DDoS attack. If TCP requires a handshake, UDP is a connectionless protocol that does not require to establist the connection. The network’s capacity is overloaded and put to the test when a UDP flood attack sends UDP packets beyond the target’s IP address. High-volume packets can quickly overwhelm the network, causing congestion and obstructing connections between IoT devices, as UDP cannot authenticate or verify that the data reaches its intended recipient.

3 System Overview & Proposed RYU-RNN Framework

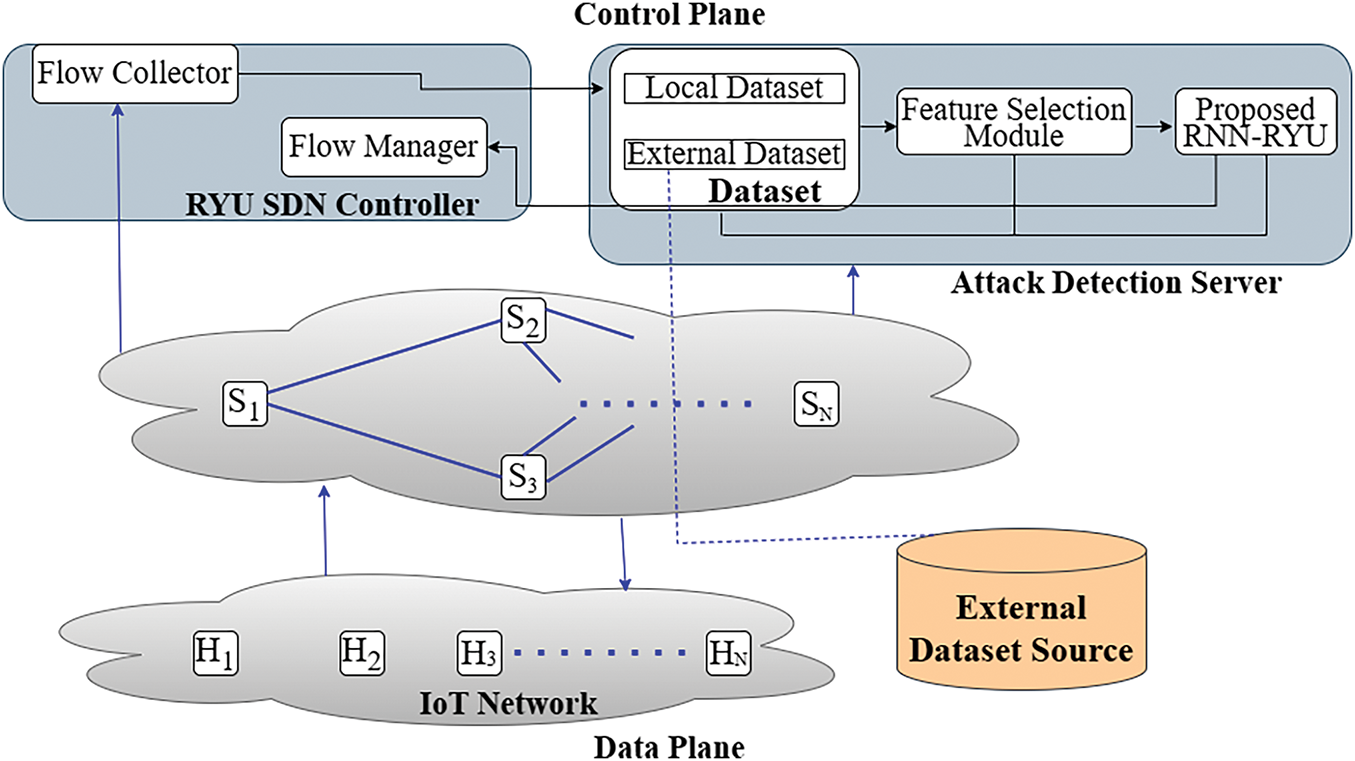

Fig. 5 illustrates the proposed SDN-based DDoS detection architecture for IoT environments, with a clear separation between the control plane and data plane. The data plane consists of IoT hosts (

Figure 5: Proposed system architecture

The attack detection server is responsible for DDoS detection through a batch-mode pipeline, which includes modules for local and external dataset ingestion, a feature selection module [35], and the proposed RNN-RYU model. This structure explicitly identifies the RNN-RYU block as the functional unit responsible for detecting DDoS attacks. The training and evaluation dataset originates from both a local simulation and an external dataset source, as depicted in the lower right corner, with the data flow accurately illustrated as it enters the system.

Overall, this architecture not only models a realistic SD-IoT environment using a software-defined approach, but also integrates all components necessary for detection.

3.1 Proposed RNN-RYU Framework

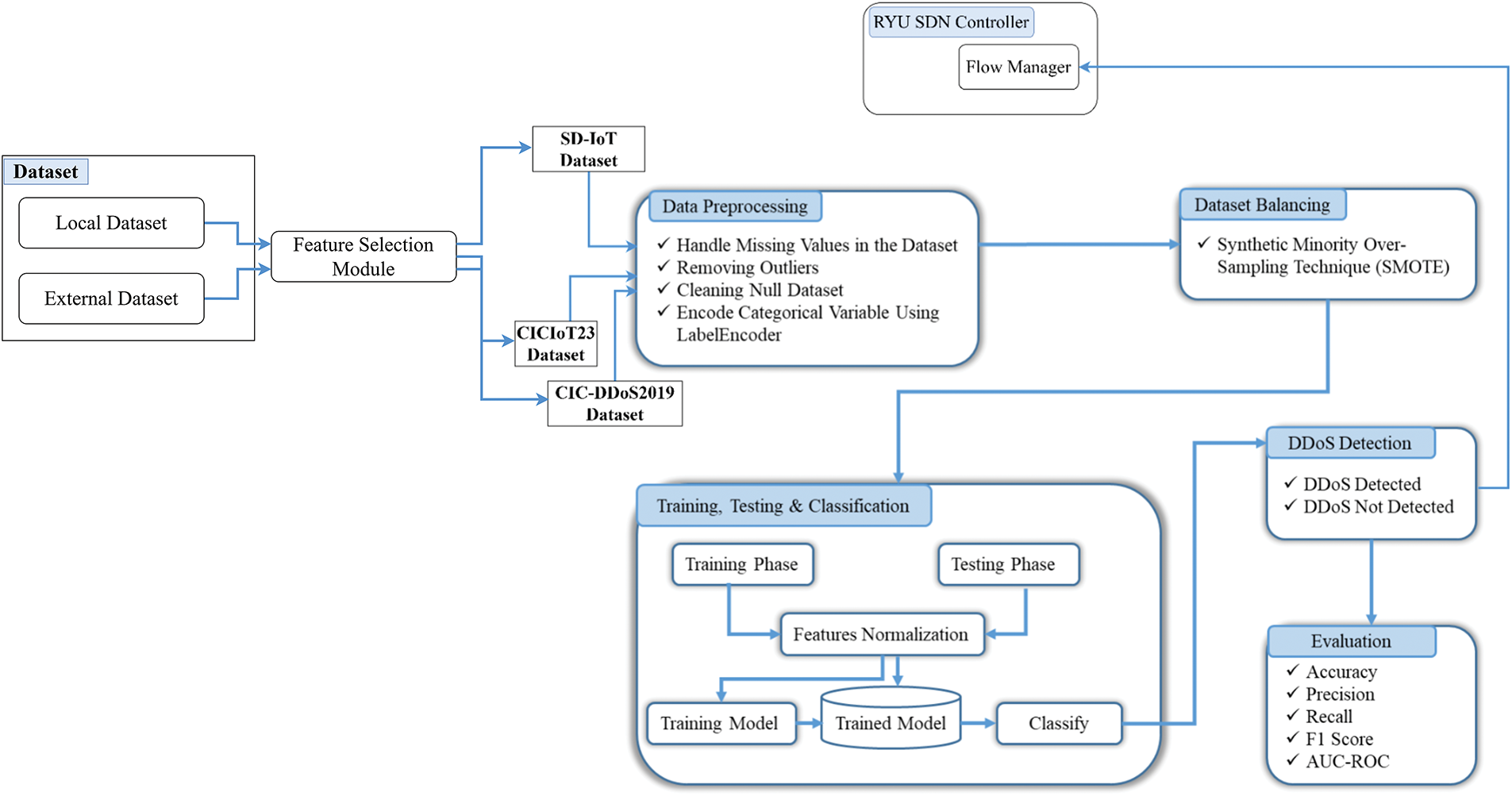

Fig. 6 illustrates the DDoS attack detection framework designed for a simulated SD-IoT environment. The framework consists of three main layers: the perception layer, the control layer, and the application layer. The perception layer is responsible for generating both the regular and attack traffic between IoT devices (mimicked as hosts). The Ryu controller, functioning as the SD-IoT controller, is at the control layer, which centrally manages the data flow between switches and hosts and coordinates network connectivity. At the application layer, the DDoS attack detection model preprocesses the data and uses the balanced and preprocessed characteristics to classify traffic. We evaluate the model’s performance using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC.

Figure 6: Pipeline of the proposed methodology of the detection approach of DDoS attack in SD-IoT

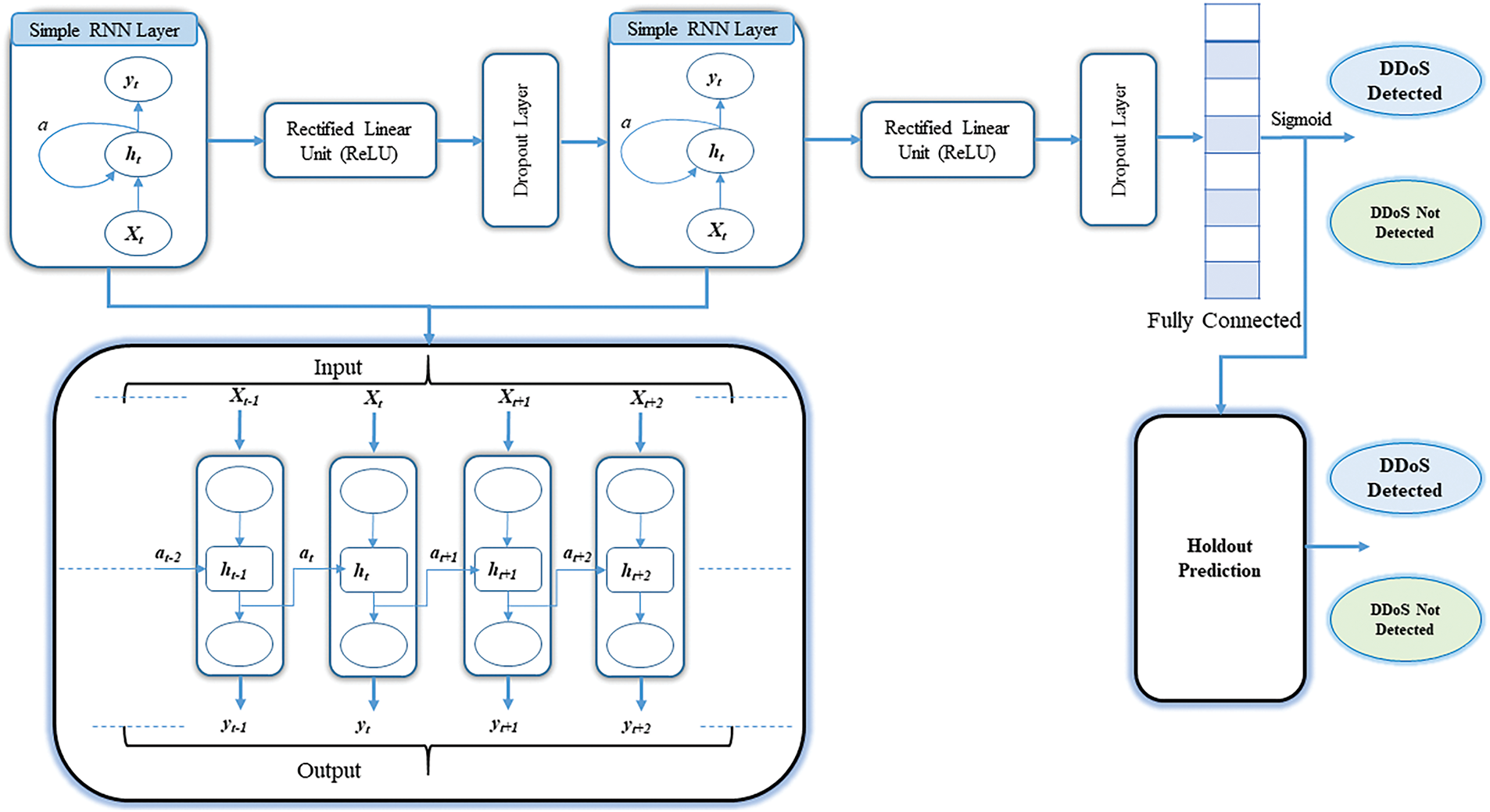

In the framework, the Ryu controller complements the RNN in managing IoT traffic. The Ryu controller manages the data flow between IoT devices and network infrastructure, while the RNN is responsible for detecting anomalies and DDoS attacks within the traffic. Specifically, by identifying temporal relationships in network traffic, the RNN analyzes sequential traffic data from IoT devices. This step is essential for identifying emerging patterns associated with DDoS attacks. The framework’s input features, including ip_src, flow_id, ip_proto, packet_count_per_nsecond, byte_count_per_nsecond, byte_count, timestamp, ip_dst, tp_dst, flow_duration_per_nsec, allow the RNN to model the sequential nature of traffic and learn patterns indicative of attacks. We selected simple RNN for its suitability in handling time-series data and configured the framework with simple RNN layers containing 160 and 64 units to optimize performance for this task. Additionally, dropout layers with a rate of 0.1 are employed to prevent overfitting. Additionally, we tuned hyperparameters using Keras Tuner’s random search, which optimized the network architecture for the given task.

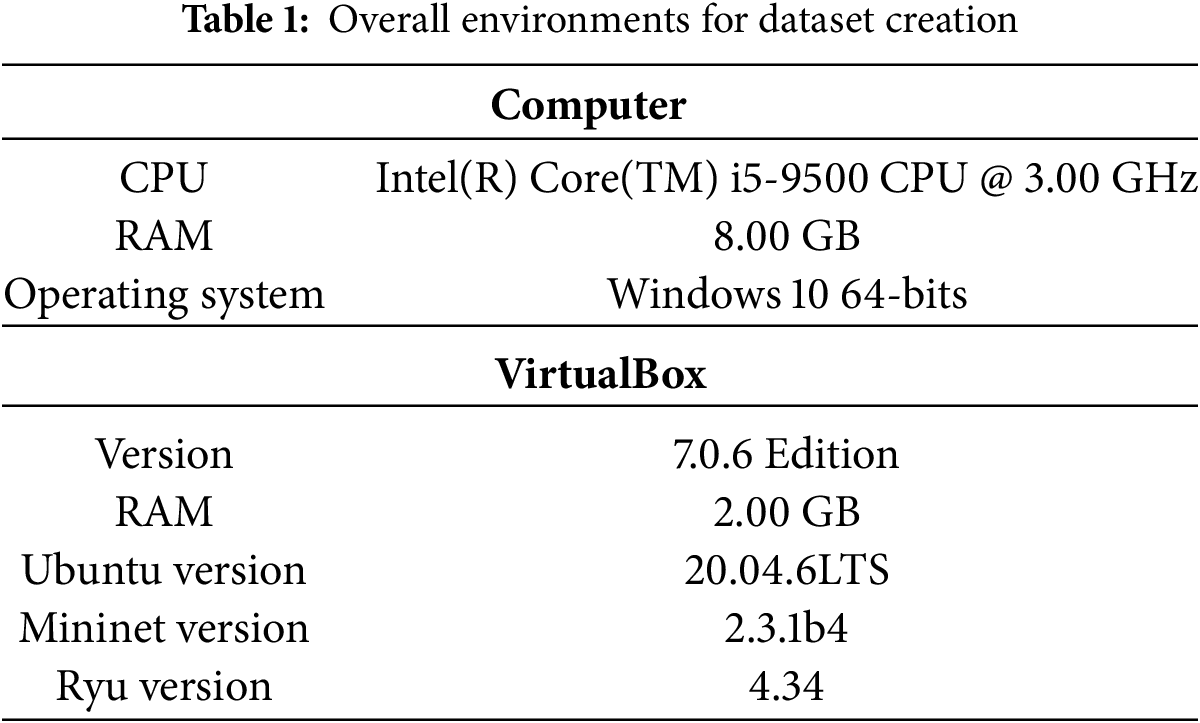

We conducted the dataset generation simulation on an ASUS PC equipped with an Intel® Core™ i5-9500 CPU running at 3.00 GHz, a 64-bit Windows 10 operating system, and 8 GB of RAM. We installed all software on VirtualBox 7.0.6, which runs the Windows 10 operating system as its platform. Ubuntu 20.04.6 LTS, along with 2 GB of RAM, is installed inside the Virtual machine. We have considered the SD-IoT controller as Ryu 4.34 and the SD-IoT switch as OpenvSwitch. We simulated the network topology using Mininet 2.3.1b4 running on Ubuntu 20.04.6 LTS, as presented in Table 1.

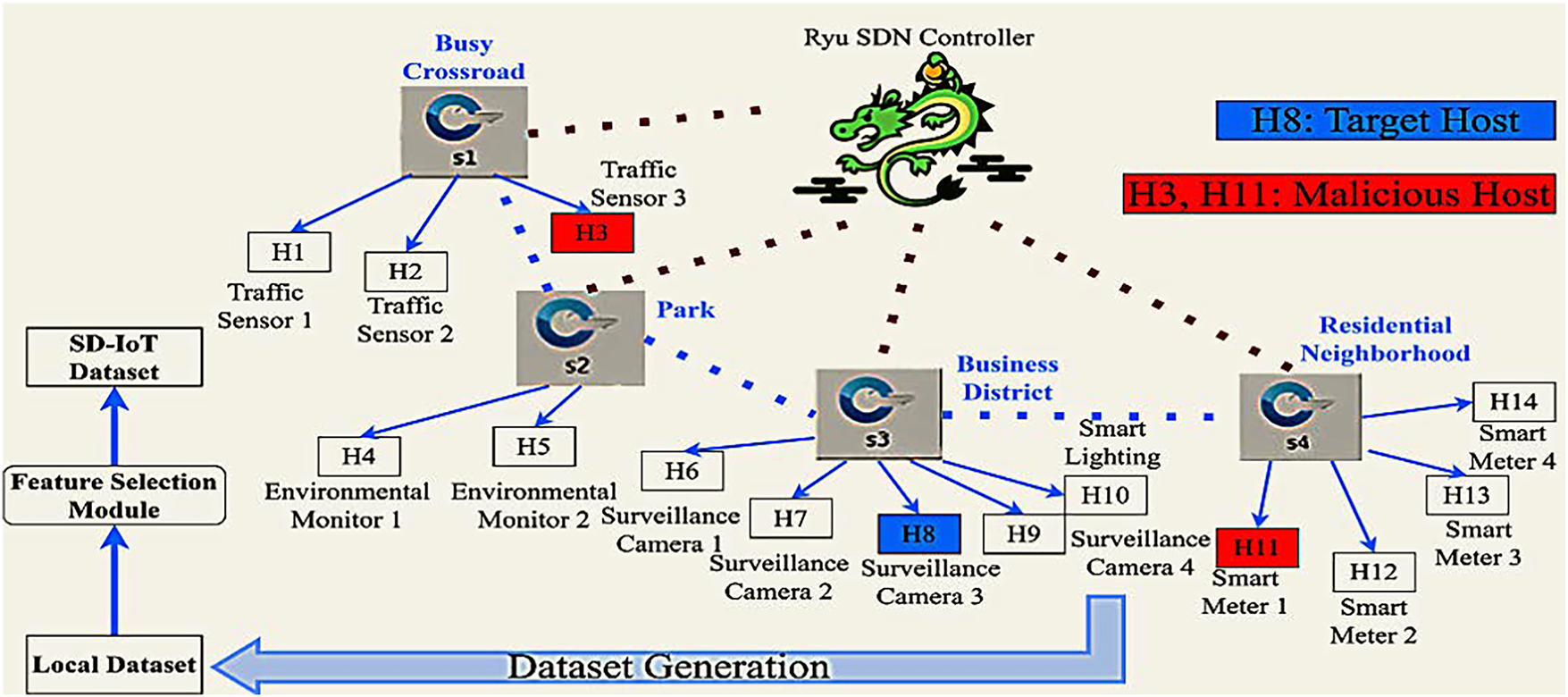

Using 14 hosts and 4 OpenFlow switches, we have presented a simulation of a DDoS attack detection architecture for an SD-IoT environment, as shown in Fig. 7. The network reacts to DDoS attacks under various host-to-switch distributions, including 3, 2, 5, and 4 hosts, to assess its response. This setup represents a small-scale smart-city network. A busy crossroads may have three traffic sensors under Switch 1’s control; a park might have two environmental monitors under Switch 2, a business district could have five surveillance cameras and bright lighting under Switch 3, and a residential neighborhood could have four smart meters under Switch 4’s guidance. The malicious hosts are

Figure 7: SD_IoT_Smart_City dataset creation process

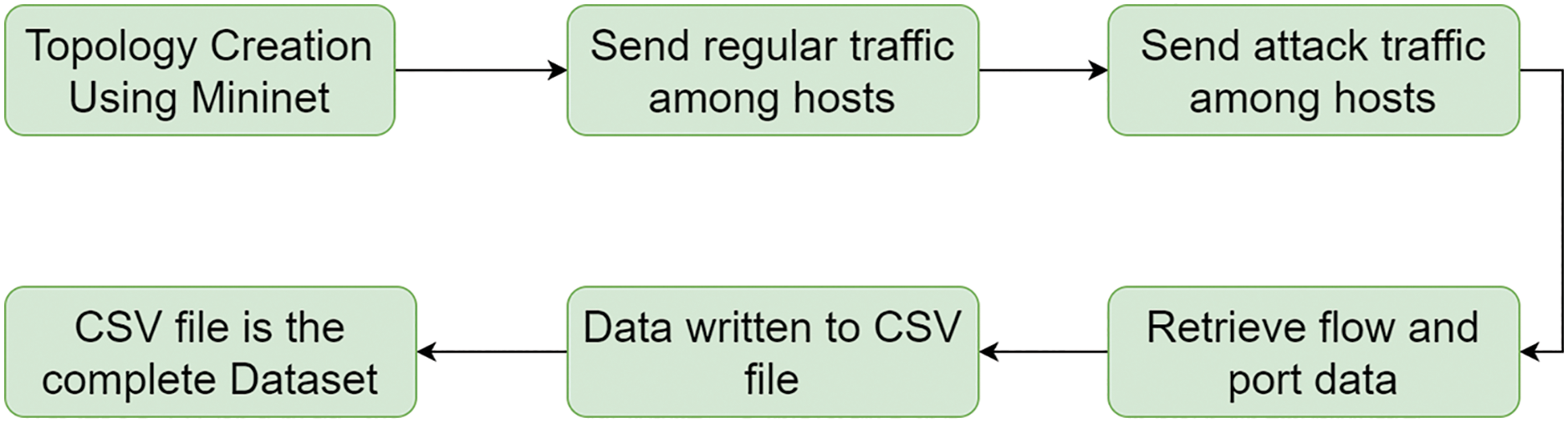

A single Ryu controller connects all hosts and the Open vSwitch. Tools such as ping and iperf generate normal ICMP, UDP, and TCP traffic. In our experiment, we used Hping3 to generate attack traffic targeting the host, simulating attacks such as UDP flood, TCP SYN flood, and TCP PUSH-ACK. The dataset, generated over two hours, includes 184,975 samples with 11 features recorded in a CSV file without missing data, as shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: SD_IoT_Smart_City dataset creation process

It is necessary to convert raw data into a clear and comprehensible format as this processed data is necessary since it significantly improves the precision and effectiveness of machine or deep learning models. A crucial preprocessing step is addressing missing values. It may reduce statistical power, lead to incorrect estimates, or even result in incorrect conclusions. Accurate model training and assessment are made possible by a dataset that is resilient. We have used the method of filling in missing values using the matching column mean to handle missing values. The reason for selecting this approach is its effectiveness and minimal impact on data distribution. We represent it as follows:

Let X be the feature matrix and

where

StandardScaler from Scikit-learn is used next to normalize features that are numeric to obtain a mean value of zero and a standard deviation value of one, thus improving the convergence speed and stability of the model. Normalization using the StandardScaler from Scikit-learn has been applied for standardizing features by removing mean values and scaling to unit variance. If X is the original feature matrix and X′ is the normalized feature matrix, then, for the normalization process, each element

where

For the next step, the categorical features are encoded using LabelEncoder, which assigns each unique category a numerical value. This is crucial for converting categorical data into a numerical format which are been provided to machine learning algorithms to improve predictions. It can be represented as:

where

Balancing the dataset addresses class imbalance by ensuring adequate representation of each class during the training process. This process enhances model performance, robustness, and generalization, particularly in accurately detecting instances of the minority class. This research employs SMOTE to balance the dataset, as referenced in [36]. The dataset is balanced by accomplishing synthetic samples for the minority class. Using the minority class samples and their corresponding k-nearest neighbors and then generating synthetic samples by joining the segments of the samples, this approach also proves helpful.

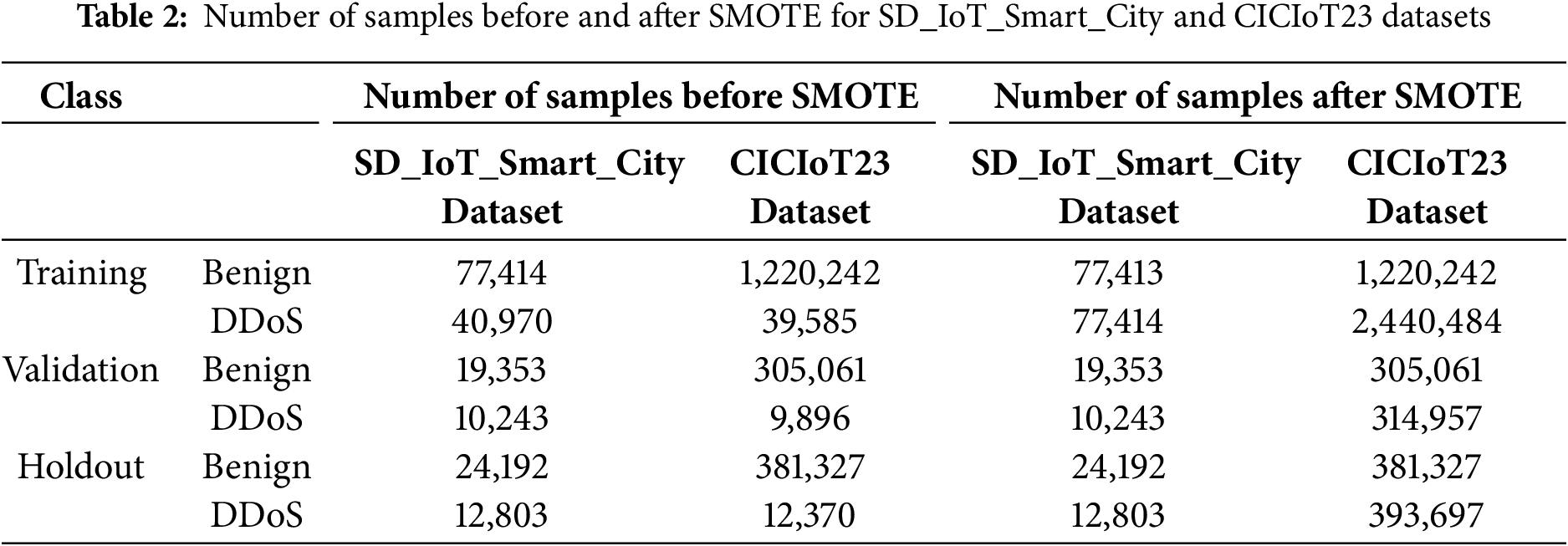

Table 2 illustrates the distribution of our generated SD_IoT_Smart_City dataset, which comprises 1 feature set, alongside the CICIoT23 dataset. We have applied Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling (SMOTE) to balance the dataset during training.

Before applying SMOTE, the SD_IoT_Smart_City dataset consisted of 118,384 training samples, 29,596 validation samples, and 36,995 holdout samples. In the training dataset, we applied SMOTE to balance the dataset, resulting in 154,827 samples. For validation and holdout, the number of samples was 29,596 and 36,995, respectively.

To validate our SD_IoT_Smart_City dataset and novel detection approach, we utilized the CICIoT23 dataset [13], explicitly focusing on parts 00000 to 00010. This dataset initially exhibited a significant imbalance, containing 39,585 instances of DDoS attacks and 1,220,242 instances of regular traffic with 47 features. To address this imbalance and ensure robust model training, we applied SMOTE, resulting in an equal distribution of 1,220,242 instances for both DDoS attacks and regular traffic. This balanced dataset was crucial for enhancing the detection accuracy and generalization capabilities of our model across different traffic scenarios. For validation and holdout, the number of samples was 314,957 (9896 for DDoS attacks and 305,061 for regular traffic) and 393,697 (12,370 for DDoS attacks and 381,327 for regular traffic), respectively.

3.4 RNN Utilization for Time-Dependent DDoS

In various sequential data applications, such as speech recognition and machine translation, RNNs and their variants have demonstrated exceptional performance. IoT device security is another potential application for RNNs. To detect potential network threats, IoT devices generate massive amounts of sequential data from various sources, including network traffic flows. For instance, studies [37–40] investigated the use of RNNs to evaluate network traffic behavior and identify potential attacks. The study found that the RNN successfully categorized network traffic, enabling the precise identification of malicious activity. RNNs are, hence, a good choice in practical contexts. Our feature set includes time-dependent metrics, such as timestamp, flow_duration_per_nsec, packet_count_per_second, byte_count_per_second, and bandwidth, which are crucial for capturing the temporal dynamics of network traffic. These features reflect sequential patterns, such as bursts and trends in traffic, which are characteristic of DDoS attacks. RNNs are particularly well-suited for modeling such time-ordered data, as they can effectively capture dependencies across sequential inputs. The inclusion of these temporal features in the dataset necessitates a model that can leverage these relationships. While Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) demonstrate high effectiveness in pattern recognition tasks, particularly in image processing, they lack the inherent capability to process time-dependent data. Similarly, traditional statistical methods are limited in their capacity to model complex, nonlinear relationships in large-scale IoT traffic data. In contrast, RNNs excel in this domain by maintaining state information across time steps, enabling them to capture and learn the evolving temporal patterns inherent in network traffic. Given the dynamic and continuous nature of traffic in smart city IoT environments, RNNs are uniquely suited for detecting DDoS attacks, as they can effectively recognize patterns such as traffic bursts and trends that characterize these types of attacks. Although advanced architectures like LSTMs, GRUs, and Transformers handle vanishing gradients more effectively and capture long-term dependencies, this study employs standard RNNs, as they offer sufficient temporal resolution with lower computational complexity.

3.5 Training and Classification of RNN

After applying the SMOTE technique to balance the dataset, the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) approach is employed to train and classify DDoS attacks or normal traffic. Here are the detailed steps involved in the RNN-RYU working process.

At first, the balanced dataset is reshaped to fit the input format required by the updated RNN-RYU. The input features are treated as a sequence of timesteps as shown by:

where

In the second phase, the RNN-RYU model initializes multiple layers, including two simple RNN layers with 160 and 64 units, respectively, dropout layers with a 0.1 dropout rate, and a dense output layer followed by a softmax activation function. We calculate the values after completing hyperparameter tuning.

We define the RNN model with tunable hyperparameters, including the number of units in the simple RNN layers, the dropout rate, and the learning rate. We use Keras Tuner’s random search method to explore different combinations of hyperparameters. We search for 10 trials, executing each trial once. An early stopping callback supervises the validation loss val_loss and halts training after observing 10 consecutive epochs without improvement, then restores the best model weights. The tuner searches through the specified hyperparameter space, trains models, and assesses their performance on the validation set. The best hyperparameters are selected based on the highest validation accuracy achieved during the search process.

In the third phase, the forward pass is performed, involving the RNN cell operation and generating the output of the RNN layer at each time step. For each time step

where

where

In the fourth phase, the output from the RNN layer is fed into a dense layer with a softmax activation function for classification.

The softmax activation function for classification can be represented by:

where

The softmax function is defined as:

where

In the fifth phase, the loss calculation is performed. The loss function is the categorical cross-entropy loss, which measures the discrepancy between the predicted probabilities and the true labels.

The loss function can be represented as:

where

In step six, the gradients of the loss function are calculated using backpropagation through time. It is shown by:

where

This method allows the model to adjust the parameters over multiple time steps by calculating gradients for each time step and summing them to update the weights and biases. By propagating the error backward through time, BPTT enables the model to capture how each time step affects the final output, thus ensuring effective learning of sequential patterns in the data.

The parameters of the model can be updated using some optimization algorithm such as Adam which can be represented by:

where

The parameters of the neural network architectures were chosen through a hyperparameter tuning process using Keras Tuner’s random search. The search space included the number of units (32 to 256) in the simple RNN layers, dropout rates (0.1 to 0.5), and learning rates (

The trained RNN-RYU model is evaluated on the holdout dataset using various evaluation metrics described in the Result Analysis section. These metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance. The final step involves using the trained RNN model to classify incoming network traffic as either benign or indicative of a DDoS attack. This classification helps in the timely detection and mitigation of potential DDoS attacks in an SD-IoT environment, shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Training and classification of RNN methodology

4 Performance Evaluation & Result Analysis

We conducted the detection experiments using Google Colab, leveraging key libraries and functions. Pandas and NumPy were used for data manipulation and numerical computations, respectively. Scikit-learn provides tools for feature normalization, label encoding, dataset splitting, and model evaluation metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the Receiver Operating Characteristic-Area Under the Curve (ROC-AUC). We utilized TensorFlow and Keras to build and train deep learning models that incorporated various components, including Sequential, Dense, Dropout, Simple RNN, Conv1D, MaxPooling1D, Flatten, LSTM, Bidirectional, Early Stopping, and categorical processing. These tools enabled a comprehensive setup for developing and evaluating our transport-Layer DDoS attack detection approach in the SD-IoT framework [41].

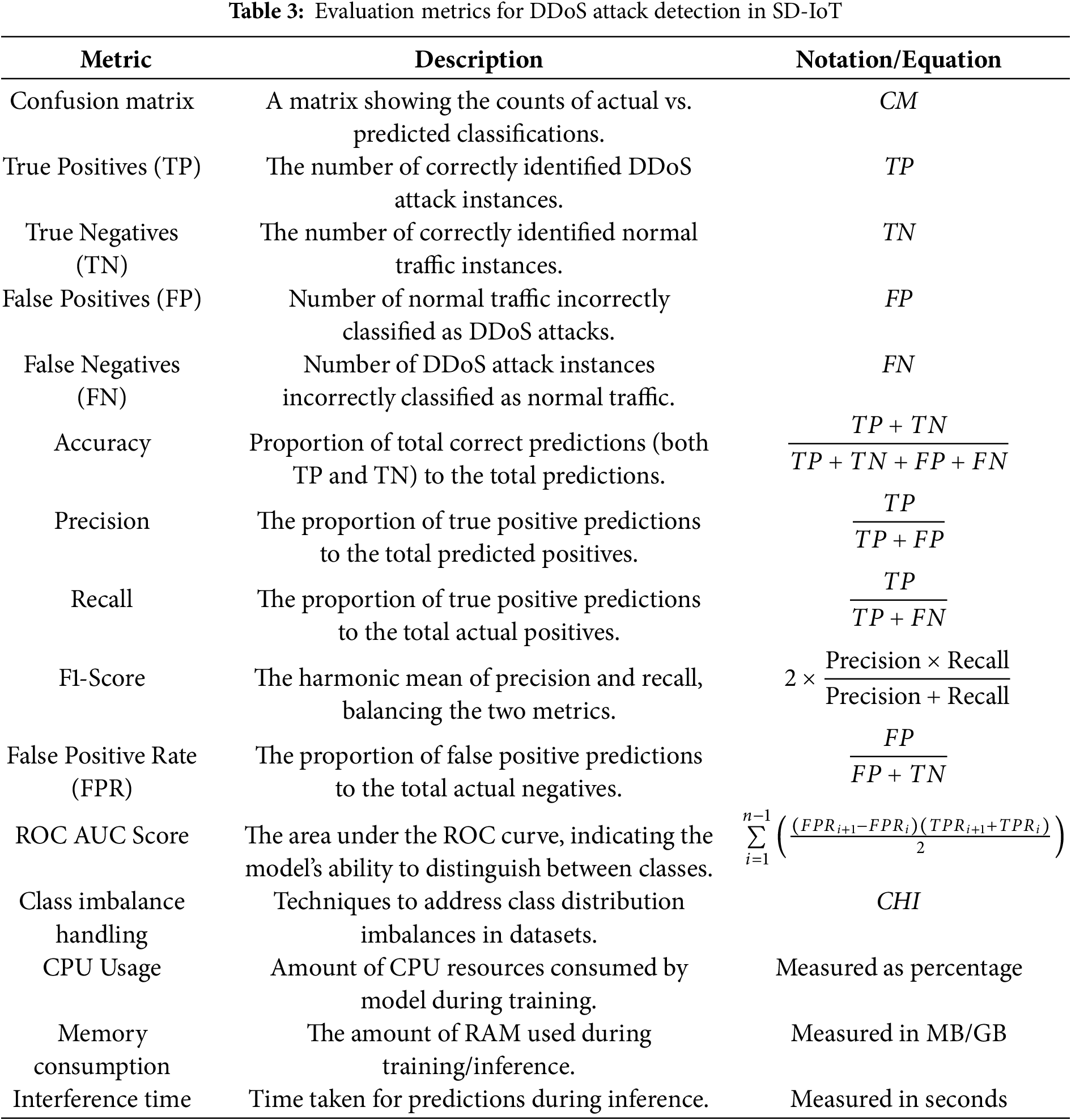

4.1 Performance Metric & Feature Importance

We assessed the model’s performance using several important metrics: ROC AUC score evaluates the model’s capability to distinguish between classes; True Positive Rate (TPR), sometimes called recall or sensitivity, measures the correctly identified positive cases; False Positive Rate (FPR) calculates the proportion of negatives incorrectly classified as positives; accuracy measures the proportion of correct predictions; precision indicates the percentage of correctly predicted positive cases; F1 score combines recall and precision to handle imbalanced datasets. When combined, these metrics offer a complete evaluation of the model’s performance. These metrics represent the comparison between the model’s predictions and the actual results. Table 3 displays the evaluation metrics for the SD-IoT detection approach.

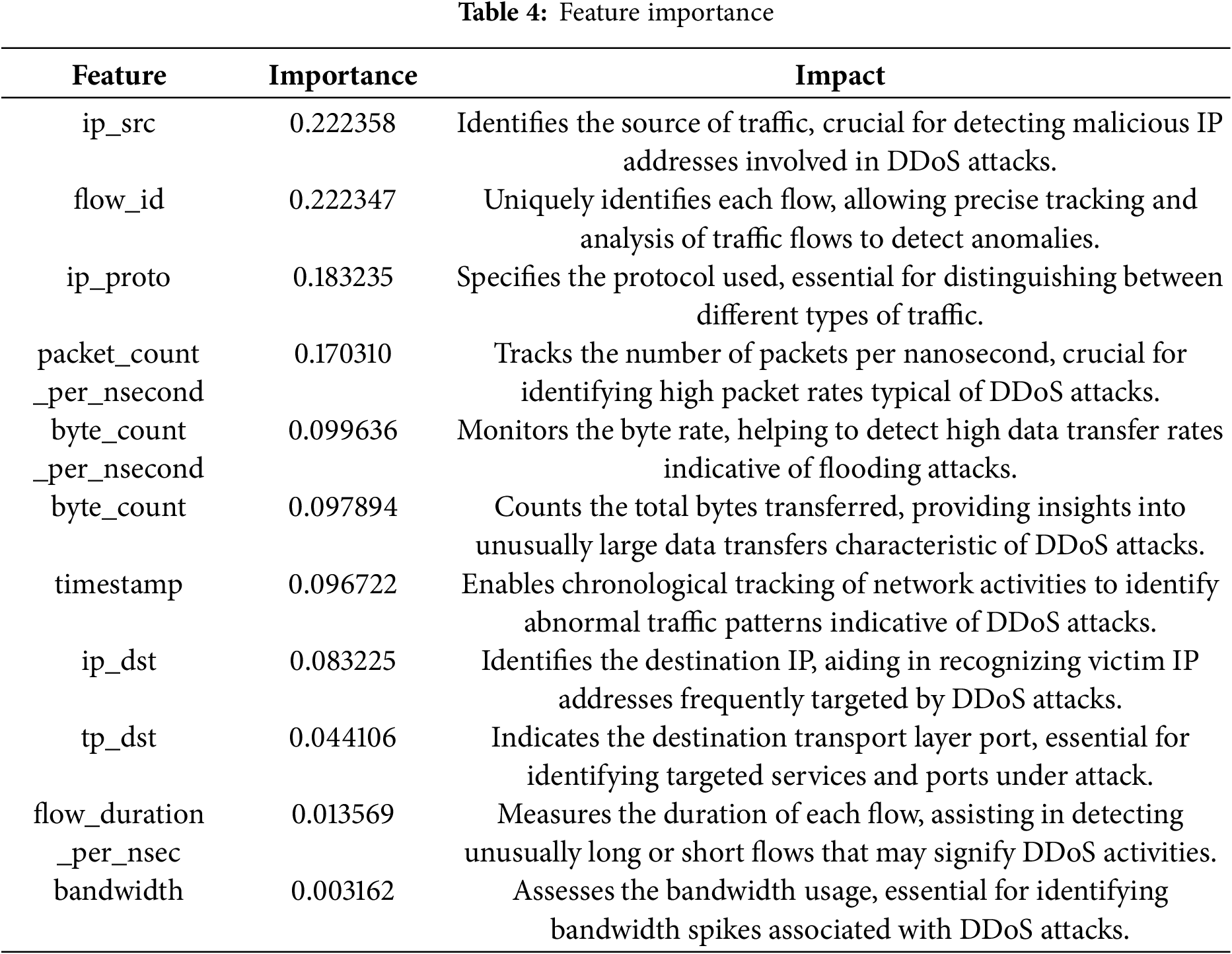

Using permutation importance, Table 4 presents feature importance. The following are important parameters: ip_src (Identifies the source of traffic), flow_id (identifies each flow), ip_proto (protocol used), packet_count_per_nsecond (tracks the number of packets per nanosecond), byte_count_per_nsecond (monitors the byte rate), byte_count (counts the total bytes transferred), timestamp (chronological tracking of network activities to identify abnormal traffic patterns), ip_dst (identifies the destination IP), tp_dst (destination transport layer port), flow_duration_per_nsec (duration of each flow) and bandwidth (assesses the bandwidth usage).

4.2 Evaluation through SD_IoT_Smart_City Dataset

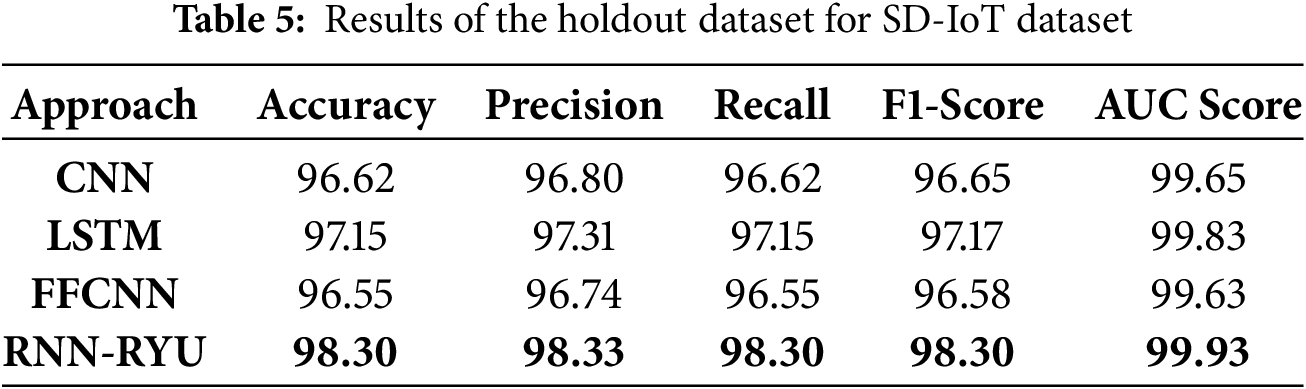

Table 5 presents the comprehensive performance metrics for various deep learning models evaluated on the holdout dataset after balancing the training data with SMOTE. The models compared include CNN, LSTM, FFCNN, and our proposed RNN-RYU. We report key performance indicators—Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and ROC-AUC Score—to assess the efficacy of each model.

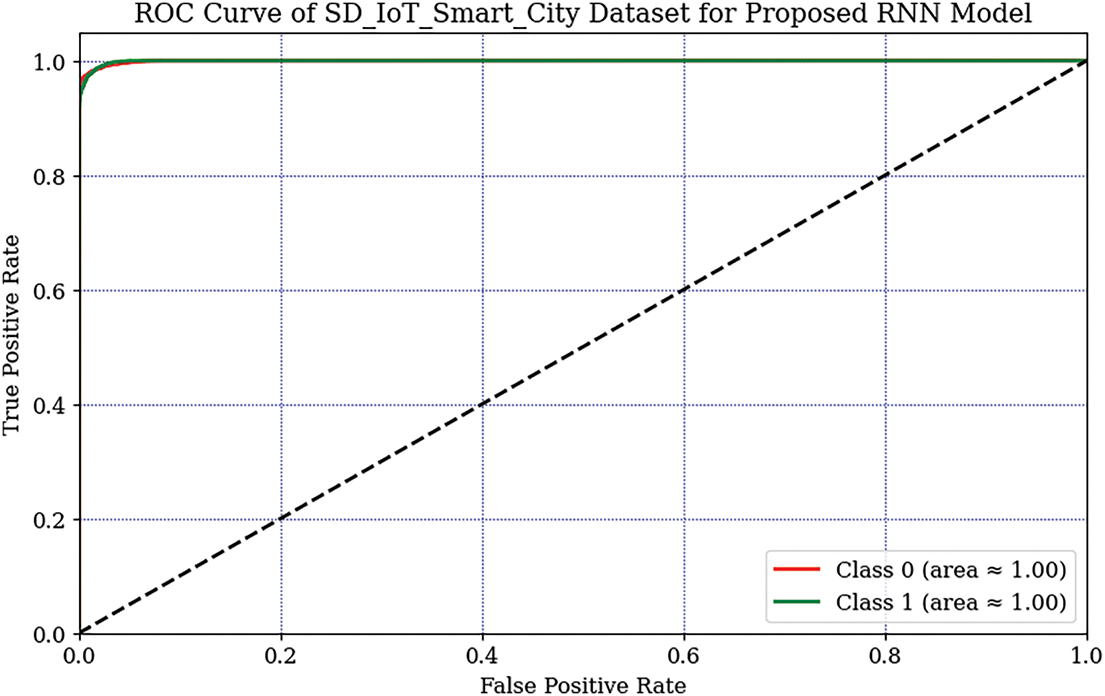

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for our RNN-RYU model on the holdout dataset are shown in Fig. 10, achieving an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of almost 1.00 for each class. This ROC-AUC value demonstrates the model’s exceptional ability to distinguish between regular and attack traffic, with no overlap in predictions.

Figure 10: ROC-AUC curve of proposed RNN-RYU

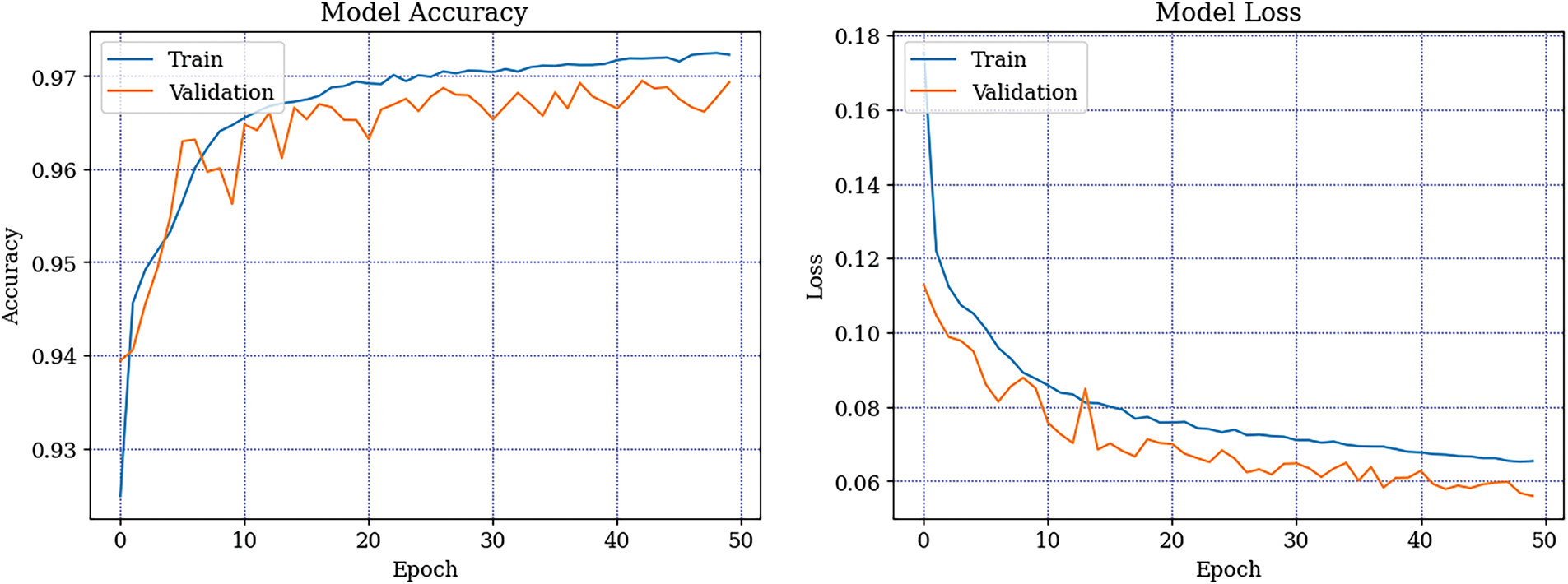

Fig. 11 presents the performance of the proposed Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) model across 50 epochs, illustrated through two subplots: model accuracy and model loss. We demonstrate the training and validation performance of the proposed RYU-RNN model on the SD_IoT_Smart_City dataset using accuracy and loss metrics over 50 epochs. The model accuracy plot (left) illustrates a consistent increase in both training and validation accuracy, with training accuracy attaining about 97.5% and validation accuracy stabilizing at 97%.

Figure 11: Model training and validation performance of the proposed RNN-RYU for SD_IoT_Smart_City Dataset

The model loss plot (right) demonstrates a consistent decline in both training and validation loss, approaching minimal values by the 50th epoch. The training loss decreased rapidly, while the validation loss followed a similar pattern, stabilizing without overfitting. The results highlight the resilience and durability of the RYU-RNN model in capturing intricate patterns and maintaining excellent performance on the SD_IoT_Smart_City Dataset.

4.3 Evaluation through CICIoT23 Dataset

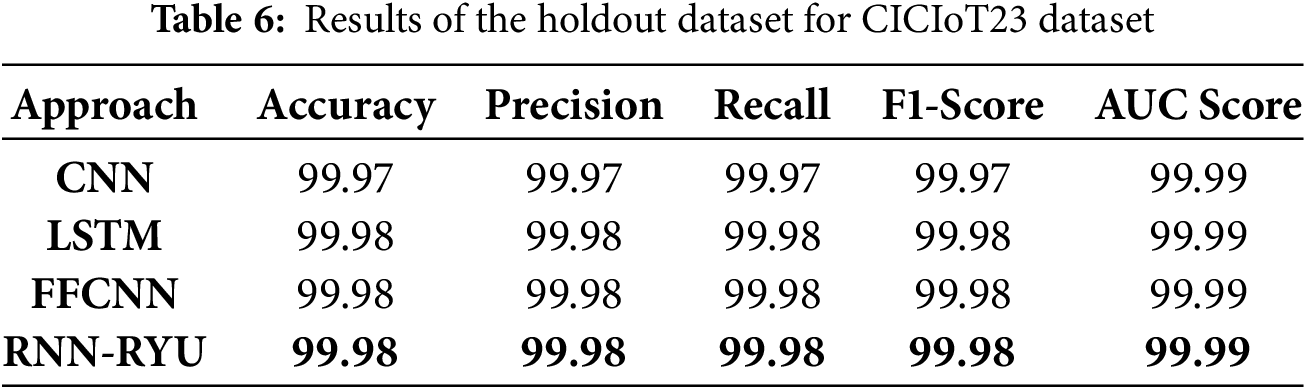

Table 6 presents the performance metrics of the proposed RNN-RYU approach on the holdout dataset from the CICIoT23 Dataset, achieving an almost perfect accuracy of 99.98%, precision of 99.98%, recall of 99.98%, F1-score of 99.98%, and an ROC-AUC score of 99.99%.

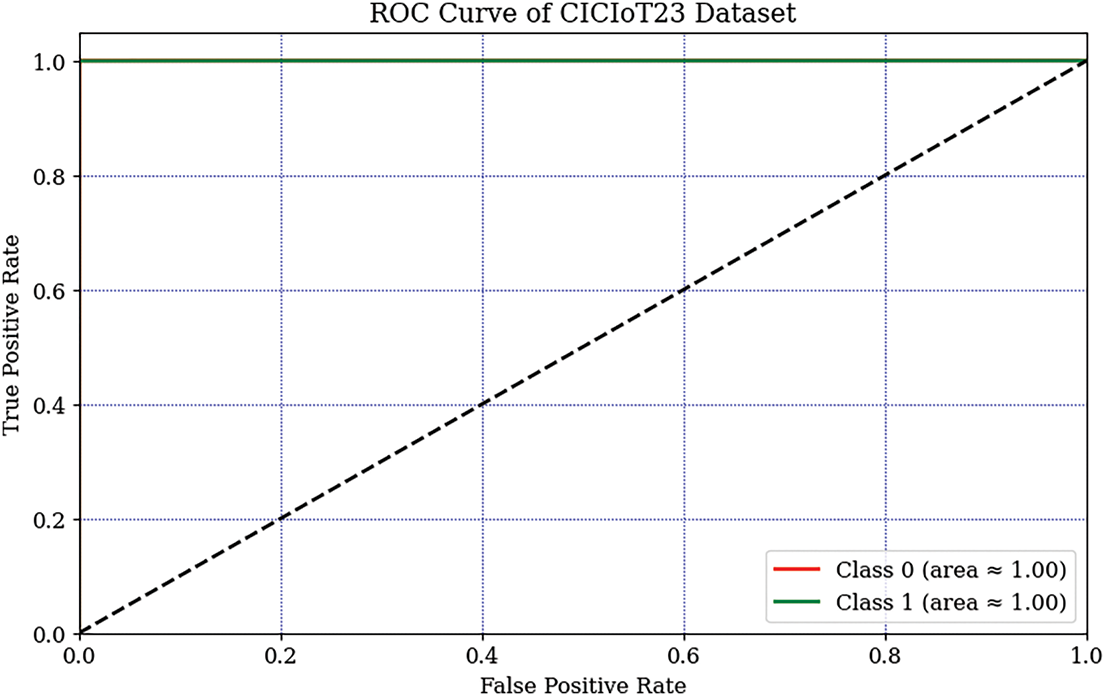

Fig. 12 illustrates the ROC curve for the balanced dataset from the “CICIoT Dataset 2023”. The ROC curve showcases the model’s outstanding performance, with both Class 0 (regular traffic) and Class 1 (DDoS attacks) achieving an ROC-AUC of almost 1.00. This perfect ROC-AUC score indicates that the model has an exceptional ability to distinguish between regular and attack traffic, with no overlap in predictions, affirming the effectiveness and precision of our detection approach.

Figure 12: ROC-AUC curve of proposed RNN-RYU for CICIoT23 dataset

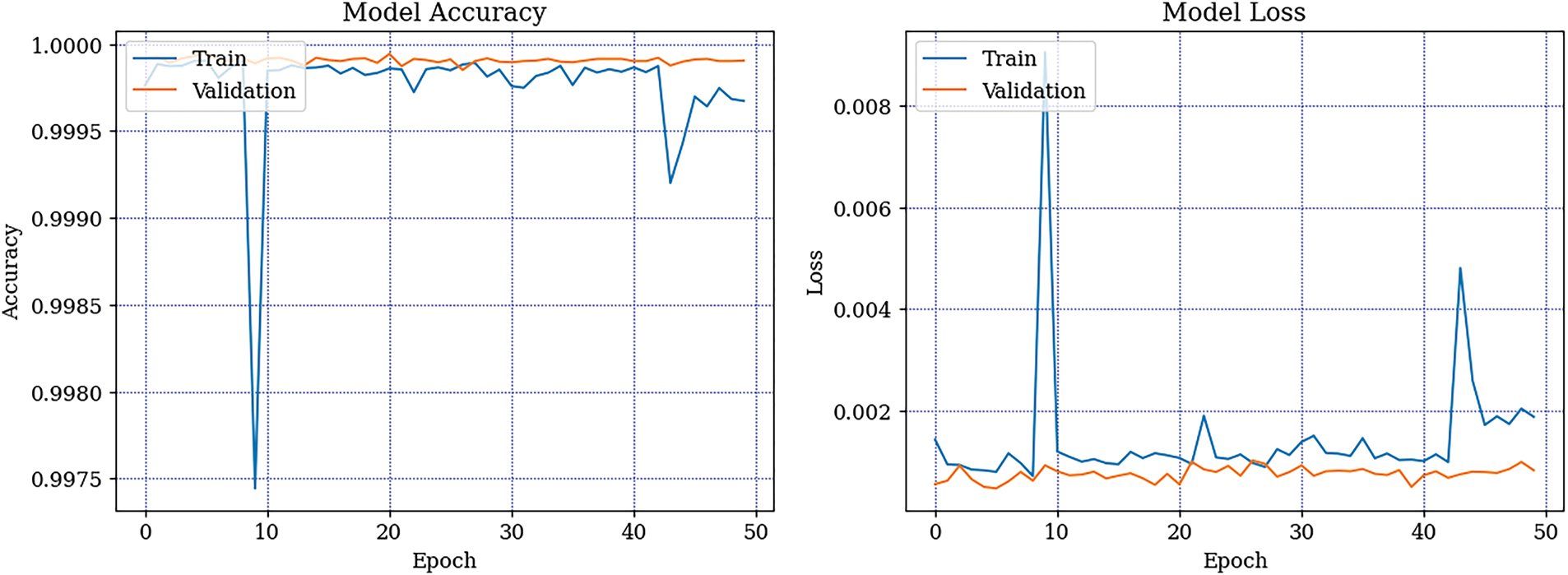

Fig. 13 presents the performance of the proposed RNN-RYU model across 50 epochs, illustrated through two subplots: model accuracy and model loss. We depict the training and validation performance of the proposed RYU-RNN model on the CICIoT23 dataset using accuracy and loss metrics over 50 epochs. The model accuracy graph shows that the training accuracy reaches nearly 100%, with the validation accuracy stabilizing at around 99.98%

Figure 13: Model training and validation performance of the proposed RNN-RYU for CICIoT23 dataset

The model loss graph displays a minimal and stable validation loss, while the training loss remains near zero, with only minor fluctuations. These trends indicate that the model is effectively learning the dataset features while avoiding overfitting. Overall, these results affirm the robustness and reliability of the RYU-RNN model in accurately detecting anomalies and malicious activities in IoT networks.

4.4 Comparison of Our Proposed Approach with Other Recent Models

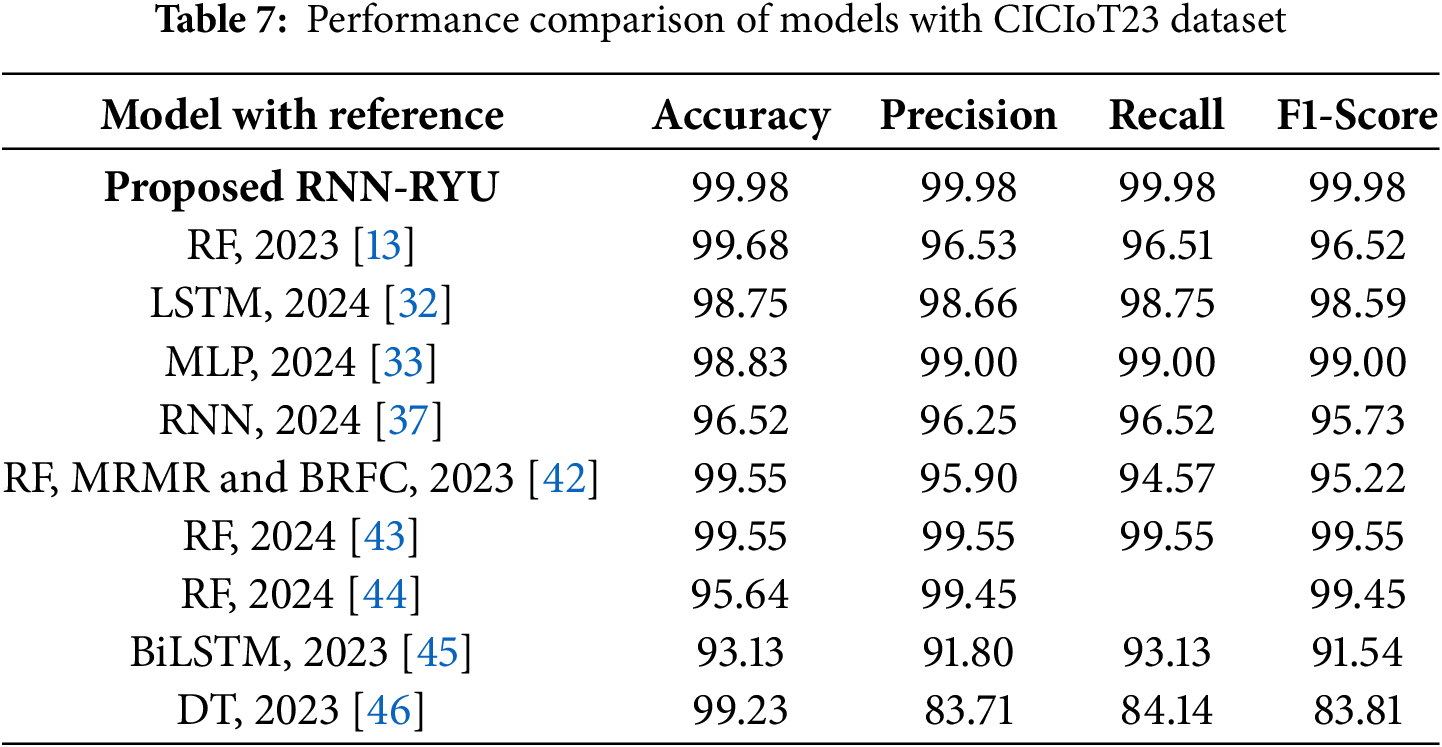

Table 7 presents a comparison between our RNN-RYU-based approach and other existing models. Our RNN-RYU-based proposed framework outperforms other models in terms of accuracy (99.98%), precision (99.98%), recall (99.98%), and F1-score (99.98%). This performance improvement shows the effectiveness of our approach in identifying DDoS attacks within IoT environments.

IoT devices, which offer mobility and service availability, are integral components of the current digital landscape. IoT devices are susceptible to a range of risks, as they are often placed in public areas, run on limited power, and have limited resources. Any IoT system must be able to recognize and mitigate DDoS attacks launched against and through IoT devices. Our proposed RYU-RNN approach demonstrates significant potential for enhancing DDoS detection in IoT environments. Our proposed RYU-RNN produces the best results for both the CICIoT23 and SD_IoT_Smart_City datasets. RYU-RNN obtained 98.30% accuracy, 99.33% precision, 98.30% recall, 98.30% F1-score, and 99.93% AUC concerning the SD_IoT_Smart_City dataset. In contrast, the CICIoT23 dataset yielded nearly perfect accuracy of 99.94%, precision of 99.94%, recall of 99.94%, F1-score of 99.94%, and an ROC-AUC score of 99.99%.

Our proposed solution, although effective, has some limitations. Our approach may face challenges on extremely resource-constrained devices. Moreover, this experiment relies entirely on simulation, limiting the practical insights that the use of physical devices could provide. While the proposed RNN-RYU framework demonstrates promising results, several avenues for future exploration remain. First, the current system operates in batch mode; integrating real-time inference capabilities by embedding the trained RNN model directly into the SDN controller will enable live traffic classification and more responsive mitigation. Additionally, to enhance adaptability in dynamic IoT environments, future work will explore online learning techniques and concept drift detection to ensure sustained performance as traffic patterns evolve. We also aim to extend the detection framework to cover a broader range of DDoS attack types and investigate its applicability across diverse IoT infrastructures. Finally, deploying the system on physical hardware and testing it in real-world smart city scenarios will allow us to validate its effectiveness beyond simulation and further bridge the gap between theoretical design and practical implementation.

Acknowledgement: We wish to acknowledge the anonymous referees who gave precious suggestions to improve the work.

Funding Statement: This project was supported by NSTC 113-2221-E-155-055 and NSTC 113-2222-E-155-007, Taiwan.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Mohammad Nowsin Amin Sheikh, I-Shyan Hwang and Ihsan Ullah; methodology, Mohammad Nowsin Amin Sheikh, Muhammad Saibtain Raza and Md. Alamgir Hossain; software, Mohammad Nowsin Amin Sheikh, Md. Alamgir Hossain and Muhammad Saibtain Raza; validation, Mohammad Nowsin Amin Sheikh, Ihsan Ullah, Tahmid Hasan and Muhammad Saibtain Raza; formal analysis, Mohammad Nowsin Amin Sheikh, Tahmid Hasan and Md. Alamgir Hossain; investigation, Mohammad Nowsin Amin Sheikh and Ihsan Ullah; resources, Mohammad Nowsin Amin Sheikh and Muhammad Saibtain Raza; data curation, Mohammad Nowsin Amin Sheikh and Muhammad Saibtain Raza; writing—original draft preparation, Mohammad Nowsin Amin Sheikh and Ihsan Ullah; writing—review and editing, Ihsan Ullah, I-Shyan Hwang and Mohammad Syuhaimi Ab-Rahman; visualization, Mohammad Nowsin Amin Sheikh and Muhammad Saibtain Raza; supervision, I-Shyan Hwang, Ihsan Ullah and Mohammad Syuhaimi Ab-Rahma; project administration, I-Shyan Hwang, Ihsan Ullah and Mohammad Syuhaimi Ab-Rahman; funding acquisition, I-Shyan Hwang and Ihsan Ullah. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used in this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Maddikunta PKR, Gadekallu TR, Kaluri R, Srivastava G, Parizi RM, Khan MS. Green communication in IoT networks using a hybrid optimization algorithm. Comput Commun. 2020;159(3):97–107. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2020.05.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Alshahrani MM. A secure and intelligent software-defined networking framework for future smart cities to prevent DDoS attack. Appl Sci. 2023;13(17):9822. doi:10.3390/app13179822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Mrabet H, Belguith S, Alhomoud A, Jemai A. A survey of IoT security based on a layered architecture of sensing and data analysis. Sensors. 2020;20(13):3625. doi:10.3390/s20133625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Kalutharage CS, Liu X, Chrysoulas C, Pitropakis N, Papadopoulos P. Explainable AI-based DDOS attack identification method for IoT networks. Computers. 2023;12(2):32. doi:10.3390/computers12020032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Statista. Number of Internet of Things (IoT) connections worldwide from 2022 to 2023, with forecasts from 2024 to 2033 [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Jun 28]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1183457/iot-connected-devices-worldwide. [Google Scholar]

6. Cisco. Cisco Annual Internet Report (2018–2023) [Internet]. White Paper; 2024 [cited 2024 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/solutions/collateral/executive-perspectives/annual-internet-report/white-paper-c11-741490.html. [Google Scholar]

7. Maximize Market Research. Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Protection and Mitigation Market–Global Industry Analysis and Forecast (2023-2029) [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Feb 15]. Available from: https://www.maximizemarketresearch.com/market-report/global-distributed-denial-of-service-ddos-protection-and-mitigation-market/33007. [Google Scholar]

8. Sheikh MNA, Hwang IS, Raza MS, Ab-Rahman MS. A qualitative and comparative performance assessment of logically centralized SDN controllers via mininet emulator. Computers. 2024;13(4):85. doi:10.3390/computers13040085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sheikh MNA, Hwang IS, Ganesan E, Kharga R. Performance assessment for different SDN-Based Controllers. In: 30th Wireless and Optical Communications Conference (WOCC); 2021 Apr; Taipei, Taiwan. p. 24–5. doi:10.1109/WOCC53213.2021.9603050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Siddiqui S, Hameed S, Shah SA, Ahmad I, Aneiba A, Draheim D, et al. Towards software-defined networking-based IoT frameworks: a systematic literature review, taxonomy, open challenges and prospects. IEEE Access. 2022;10(20):70850–901. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3188311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Khalid M, Hameed S, Qadir A, Shah SA, Draheim D. Towards SDN-based smart contract solution for IoT access control. Comput Commun. 2023;198:1–31. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2022.11.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dantas Silva FS, Silva E, Neto EP, Lemos M, Venancio Neto AJ, Esposito F. A taxonomy of DDoS attack mitigation approaches featured by SDN technologies in IoT scenarios. Sensors. 2020;20(11):3078. doi:10.3390/s20113078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Neto ECP, Dadkhah S, Ferreira R, Zohourian A, Lu R, Ghorbani AA. CICIoT2023: a real-time dataset and benchmark for large-scale attacks in IoT environment. Sensors. 2023;23(13):5941. doi:10.3390/s23135941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Ahuja N, Singal G, Mukhopadhyay D, Kumar N. Automated DDoS attack detection in software defined networking. J Netw Comput Appl. 2021;187(6):103108. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2021.103108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yousuf O, Mir RN. DDoS attack detection in Internet of Things using recurrent neural network. Comput Elect Eng. 2022;101(3):108034. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.108034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ravi N, Shalinie SM. Learning-driven detection and mitigation of DDoS attack in IoT via SDN-cloud architecture. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;7(4):3559–70. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2020.2973176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yin D, Zhang L, Yang K. A DDoS attack detection and mitigation with software-defined Internet of Things framework. IEEE Access. 2018;6:24694–705. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2831284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Tortonesi M, Michaelis J, Morelli A, Suri N, Baker MA. SPF: an SDN-based middleware solution to mitigate the IoT information explosion. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communication (ISCC); 2016 Jun 27–30; Messina, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 435–42. [Google Scholar]

19. Özçelik M, Chalabianloo N, Gür G. Software-defined edge defense against IoT-based DDoS. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (CIT); 2017 Aug 21–23; Helsinki, Finland. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 308–13. doi:10.1109/CIT.2017.61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sharma PK, Singh S, Park JH. OpCloudSec: open cloud software defined wireless network security for the Internet of Things. Comput Commun. 2018;122(1):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2018.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Nobakht M, Sivaraman V, Boreli R. A host-based intrusion detection and mitigation framework for smart home IoT using OpenFlow. In: Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES); 2016 Aug 31–Sep 2; Salzburg, Austria. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 147–56. doi:10.1109/ARES.2016.64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Xu T, Gao D, Dong P, Zhang H, Foh CH, Chao H. Defending against new-flow attack in SDN-based internet of things. IEEE Access. 2017;5:3431–43. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2666270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Nguyen TG, Phan TV, Nguyen BT, So-In C, Baig ZA, Sanguanpong S. SeArch: a collaborative and intelligent NIDS architecture for SDN-based cloud IoT networks. IEEE Access. 2019;7:107678–94. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2932438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Rathore S, Kwon BW, Park JH. BlockSecIoTNet: blockchain-based decentralized security architecture for IoT network. J Netw Comput Appl. 2019;143(4):167–77. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2019.06.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Rafique W, Khan M, Sarwar N, Dou W. A security framework to protect edge supported software defined internet of things infrastructure. In: Collaborative Computing: Networking, Applications and Worksharing: 15th EAI International Conference, CollaborateCom 2019; 2019 Aug 19–22; London, UK. p. 71–88. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-30146-0_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Krishnan P, Duttagupta S, Achuthan K. VARMAN: multi-plane security framework for software defined networks. Comput Commun. 2019;148(4):215–39. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2019.09.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bawany NZ, Shamsi JA. SEAL: SDN based secure and agile framework for protecting smart city applications from DDoS attacks. J Netw Comput Appl. 2019;145:102381. doi:10.1016/J.JNCA.2019.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Nair A, Jayapandian N, Jingle D. Distributed denial-of-service detection and mitigation using software-defined network and internet of things. J Adv Res Dyn Control Syst. 2019;11:2778–87. [Google Scholar]

29. Houda ZAE, Hafid A, Khoukhi L. Co-IoT: a collaborative DDoS mitigation scheme in IoT environment based on blockchain using SDN. In: IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM); 2019 Dec 9–13; Waikoloa, HI, USA. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/GLOBECOM38437.2019.9013542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Galeano-Brajones J, Carmona-Murillo J, Valenzuela-Valdés JF, Luna-Valero F. Detection and mitigation of DoS and DDoS attacks in IoT-based stateful SDN: an experimental approach. Sensors. 2020;20(3):816. doi:10.3390/s20030816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Chen W, Xiao S, Liu L, Jiang X, Tang Z. A DDoS attacks traceback scheme for SDN-based smart city. Comput Elect Eng. 2020;81:106503. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2019.106503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Jony AI, Arnob AKB. A long short-term memory based approach for detecting cyber-attacks in IoT using CIC-IoT2023 dataset. J Edge Comput. 2024;3(1):28–42. doi:10.55056/jec.648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Gheni HQ, Al-Yaseen WL. Two-step data clustering for improved intrusion detection system using CIC-IoT2023 dataset. 2024. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4762201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Jmal R, Ghabri W, Guesmi RM, Alshammari BM, Alshammari AS, Alsaif HS. Distributed blockchain-SDN secure IoT system based on ANN to mitigate DDoS attacks. Appl Sci. 2023;13(8):4953. doi:10.3390/app13084953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Raza MS, Sheikh MNA, Hwang IS, Ab-Rahman MS. Feature-selection-based DDoS attack detection using AI algorithms. Telecom. 2024;5(2):333–46. doi:10.3390/telecom5020017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Elreedy D, Atiya AF. A comprehensive analysis of synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) for handling class imbalance. Inf Sci. 2019;505(1):32–64. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2019.07.070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Abbas S, Bouazzi I, Ojo S, Al Hejaili A, Sampedro GA, Almadhor A, et al. Evaluating deep learning variants for cyber-attacks detection and multi-class classification in IoT networks. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2024;10(12):e1793. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.1793. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Torres P, Catania C, Garcia S, Garino CG. An analysis of Recurrent Neural Networks for Botnet detection behavior. In: IEEE Biennial Congress of Argentina (ARGENCON); 2016; Buenos Aires, Argentina. doi:10.1109/ARGENCON.2016.7585247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhong C, Cheng S, Kasoar M, Arcucci R. Reduced-order digital twin and latent data assimilation for global wildfire prediction. Natural Hazards Earth Syst Sci. 2023;5(5):1755–68. doi:10.5194/nhess-23-1755-2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Cheng S, Zhuang Y, Kahouadji L, Liu C, Chen J, Matar OK, et al. Multi-domain encoder–decoder neural networks for latent data assimilation in dynamical systems. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2024;430(7878):117201. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2024.117201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Keras. GitHub [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Apr 10]. Available from: https://github.com/keras-team/keras. [Google Scholar]

42. Narayan KR, Mookherji S, Odelu V, Prasath R, Turlapaty AC, Das AK. IIDS: design of intelligent intrusion detection system for Internet-of-Things applications. In: IEEE 7th Conference on Information and Communication Technology (CICT); 2023; Jabalpur, India. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

43. Khan MM, Alkhathami M. Anomaly detection in IoT-based healthcare: machine learning for enhanced security. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):5872. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-56126-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Parfenov D, Grishina L, Zhigalov A, Parfenov A. Investigation of the impact effectiveness of adversarial data leakage attacks on the machine learning models. ITM Web Conf. 2024;59:04011. doi:10.1051/itmconf/20245904011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Wang Z, Chen H, Yang S, Luo X, Li D, Wang J. A lightweight intrusion detection method for IoT based on deep learning and dynamic quantization. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2023;9(19):e1569. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.1569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Sahin O, Uludag S. Advancing intrusion detection efficiency: a ‘Less is More’ approach via feature selection. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3398752/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools