Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

FedEPC: An Efficient and Privacy-Enhancing Clustering Federated Learning Method for Sensing-Computing Fusion Scenarios

1 State Grid Electric Power Research Institute Co., Ltd., Nanjing, 211100, China

2 Nanjing Nari Information & Communication Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, 211100, China

3 Electric Power Research Institute of State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd., Nanjing, 211103, China

* Corresponding Author: Wang Luo. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 4091-4113. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066241

Received 02 April 2025; Accepted 26 May 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

With the deep integration of edge computing, 5G and Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) technologies, the large-scale deployment of intelligent terminal devices has given rise to data silos and privacy security challenges in sensing-computing fusion scenarios. Traditional federated learning (FL) algorithms face significant limitations in practical applications due to client drift, model bias, and resource constraints under non-independent and identically distributed (Non-IID) data, as well as the computational overhead and utility loss caused by privacy-preserving techniques. To address these issues, this paper proposes an Efficient and Privacy-enhancing Clustering Federated Learning method (FedEPC). This method introduces a dual-round client selection mechanism to optimize training. First, the Sparsity-based Privacy-preserving Representation Extraction Module (SPRE) and Adaptive Isomorphic Devices Clustering Module (AIDC) cluster clients based on privacy-sensitive features. Second, the Context-aware In-cluster Client Selection Module (CICS) dynamically selects representative devices for training, ensuring heterogeneous data distributions are fully represented. By conducting federated training within clusters and aggregating personalized models, FedEPC effectively mitigates weight divergence caused by data heterogeneity, reduces the impact of client drift and straggler issues. Experimental results demonstrate that FedEPC significantly improves test accuracy in highly Non-IID data scenarios compared to FedAvg and existing clustering FL methods. By ensuring privacy security, FedEPC provides an efficient and robust solution for FL in resource-constrained devices within sensing-computing fusion scenarios, offering both theoretical value and engineering practicality.Keywords

With the deep integration of 5G [1] and Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) [2] technologies, intelligent terminal devices are exhibiting a trend of large-scale deployment [3]. Edge nodes such as sensors, smartphones, and wearable devices are exploring the synergy between sensing and computing through the fusion of perception and computation, thereby achieving a new architecture and system characterized by intelligence, integration, low carbon emissions, and high efficiency. This provides unprecedented opportunities for deep learning (DL) [4]. However, in the context of sensing-computing fusion, most data are typically scattered across different locations and exist in isolated forms, creating “data silos” [5]. Relying solely on data from a single device can lead to biased DL models due to insufficiently comprehensive data.

Due to the sensitivity of data and increasing concerns about commercial competition and privacy, countries worldwide are actively updating legal frameworks to enhance data protection. For example, China rolled out the Cybersecurity Law [6] in 2017, followed by the Personal Information Protection Law [7] in 2021. Similarly, the European Union introduced the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [8] in 2018, and other countries have enacted similar legislation. Due to strict data protection requirements, transmitting sensitive user information directly to centralized servers for Artificial Intelligence (AI) training is no longer viable, as it raises substantial risks of unauthorized exposure and exploitation. While conventional distributed learning approaches enable collaborative model development, they still fall short in ensuring robust privacy safeguards [9], creating obstacles for AI advancement. As a result, industries worldwide are increasingly seeking distributed AI systems with enhanced privacy-preserving capabilities.

Google researchers established the theoretical basis for Federated Learning (FL) in their seminal 2016 work [10]. In each communication round of FL, clients train local models using private data and send the trained parameters to a server. The server aggregates these parameters from all clients using the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) algorithm to obtain a new global model, which is then broadcast to all clients for iterative updates. As a distributed machine learning paradigm, FL enables collaborative modeling among multiple parties while protecting data privacy, and it is widely applied in privacy-sensitive fields such as healthcare and finance [11].

However, FL in the real world faces significant challenges of heterogeneity [12] and resource constraints [13], with heterogeneity primarily manifesting as data heterogeneity. The behavioral patterns of end-user devices result in locally generated data that frequently follows a non-independent and identically distributed (Non-IID) pattern, creating significant distributional disparities across clients [14]. When applied to such heterogeneous data, FedAvg demonstrates unstable convergence behavior, particularly for Non-IID datasets where model accuracy degrades considerably [15]. This performance deterioration stems from client drift [16], wherein identically initialized local models diverge after repeated rounds of client-side training and global aggregation on Non-IID data. The resulting inconsistencies introduce systematic biases during model fusion, ultimately compromising the federated model’s accuracy, slowing convergence, and extending the overall training duration.

It is noteworthy that local datasets may not fully represent the complete statistical characteristics of the overall distribution [17], and common FL methods share a single global model across all clients, which cannot adapt to all diverse local data distributions, leading to biased model updates. During federated communication, AIoT devices, due to resource constraints, may experience longer local training times and become stragglers, causing system delays or bottlenecks [18]. Furthermore, differences in client device statuses, including hardware failures or communication interruptions, may degrade system dependability and performance stability.

To enhance the performance of FL in sensing-computing fusion scenarios, researchers have proposed various Personalized FL (PFL) [19] techniques, including Multi-Task Learning (MTL) [20–22], model interpolation [23–25], and clustering, aiming to address the weight divergence resulting from client drift. Nevertheless, these solutions often come with substantial computational and communication burdens or may reveal sensitive data distribution patterns, which deviates from the original intent of FL and could potentially might enable potential breaches of confidential user data. In terms of privacy protection, techniques such as differential privacy [26], secure multi-party computation [27], and homomorphic encryption [28] are commonly employed. While integrating FL with privacy-enhancing technologies improves security, challenges remain. Differential privacy reduces data utility and model accuracy [29], whereas homomorphic encryption and secure multi-party computation incur high computational and communication costs [30], overburdening resource-constrained edge devices. These issues limit the widespread deployment of FL models.

The combined obstacles of data heterogeneity, resource constraints, and privacy protection present significant barriers to implementing FL in sensing-computing fusion applications. Developing FL approaches that maintain both high accuracy and computational efficiency while safeguarding sensitive user information has emerged as a critical challenge in these integrated systems. The refinement of FL system designs and training methodologies to overcome these limitations carries considerable real-world value. By strengthening algorithm resilience to heterogeneous data and constrained resources, we can achieve better predictive accuracy and computational efficiency while maintaining strict privacy protections and preventing unauthorized data exploitation.

In this paper, a method called Efficient and Privacy-enhancing Clustering Federated Learning (FedEPC) is proposed. Unlike traditional FL algorithms and existing clustering FL algorithms, the proposed method includes a dual-round client selection process. The first round of client selection is implemented during data distribution feature extraction and isomorphic device clustering, while the second round selects a subset of devices from each cluster to participate in FL training. This approach captures unique data distributions, ensures that each distribution is fully represented during the training process, mitigates weight divergence caused by data heterogeneity, reduces aggregation bias due to client drift, and alleviates the impact of the straggler problem.

Recent research efforts have focused on addressing the performance issues in FL under Non-IID data environments, particularly those arising from client drift. Compared to traditional algorithms that train a single global FL model, these studies aim to mitigate the effects of client drift and weight divergence by modifying the aggregation process or client selection process in FL, thereby constructing PFL models. Notably, PFL methods based on MTL, model interpolation, and clustering have shown encouraging results when training heterogeneous devices with Non-IID data.

In scenarios where implicit clusters based on domain knowledge exist, clustering can group clients with similar models or data distributions for the FL process, demonstrating significant performance advantages. When dealing with markedly diverse clients or data patterns, the single-model paradigm of traditional client-server FL architectures demonstrates limited effectiveness. Superior results can be achieved by first partitioning clients into meaningful clusters and subsequently training distinct PFL models for each cluster, producing a collection of specialized models that properly address data variability. Additionally, clustering methods are particularly beneficial when dealing with a large number of resource-constrained edge devices, as they prioritize cluster-level relationships rather than pairwise relationship modeling like MTL and model interpolation, helping to reduce the straggler problem during the training phase.

IFCA [31] introduces an iterative federated clustering paradigm where the server constructs multiple global models instead of a single one. Clients are dynamically assigned to distinct clusters, with the server conducting model aggregation separately within each cluster. FedGroup [32] introduces a FL architecture employing static client clustering, complemented by a cold-start approach for newly joined participants. This method utilizes the Euclidean distance for measuring model updates and applies the K-Means++ clustering algorithm to group client contributions. PFA [33] clusters clients with similar data distributions, enabling each client to ultimately obtain a PFL model. HACCS [34], a heterogeneity-aware clustering client selection mechanism, functions by extracting device-side data distribution histograms protected with differential privacy safeguards, which are then transferred to the server to perform the clustering process. CLSM-FL [35] is a clustering-based semantic FL method designed to address FL issues in data-heterogeneous environments. This method uses soft clustering techniques to allocate local models to clusters generated by semantic clustering based on their intrinsic properties, enabling interpretable evaluation of model capabilities. FLACC [36] is a greedy clustering-based FL framework. This method calculates the similarity between gradient updates of clients and gradually merges the most similar clients or client clusters. FLACC does not require pre-specifying the number of clusters, can handle FL with any proportion of client participation, and is robust to hyperparameter tuning.

Federated Prototype Learning (FPL) [37] introduces key innovations in prototype design and optimization strategies. It constructs multi-domain cluster prototypes via unsupervised clustering to preserve domain-specific diversity across clients, while enhancing feature alignment between intra-class samples and their corresponding prototypes through contrastive prototype consistency learning. Furthermore, FPL employs unbiased prototypes as optimization targets under the unbiased prototype consistency regularization framework, effectively balancing gradient directions and improving cross-domain generalization capabilities. FedUC [38] establishes a convergence bounds analysis framework for diverse inter-cluster aggregation patterns in hierarchical aggregation FL, which innovatively integrates data distribution, frequency of clusters’ participation in aggregation, and inter-cluster topology into clustering optimization objectives. By designing an optimal time-sharing scheduling strategy for intra-cluster aggregation, this method achieves significant improvements in both communication efficiency and model convergence speed within heterogeneous edge computing environments. FedCCL [39] achieves significant advancements in addressing non-IID challenges in FL through its innovative dual-clustered feature contrast mechanism. Locally, it employs hierarchical clustering to generate fine-grained intra-class feature clusters, facilitating cross-client knowledge sharing via feature cluster contrast. Globally, it conducts secondary clustering on local feature clusters and aggregates them to produce unbiased guidance signals, which effectively mitigates inter-domain dominance bias issues. This approach demonstrates superior performance in cross-domain heterogeneous scenarios.

Although representing significant advances, existing clustering methods encounter common constraints. The requirement to predefine cluster numbers in IFCA, FedGroup, and PFA creates scalability issues for large edge device networks. Moreover, the exclusive dependence on Euclidean or cosine similarity metrics in IFCA and FedGroup for comparing client updates may yield inadequate model matching and insufficient mitigation of Non-IID data challenges. PFA uses the FedAvg algorithm to aggregate model parameters of clients within a cluster after clustering is completed, without considering the resource constraints of edge devices, which may lead to stragglers during the training process and adversely affect the efficiency of PFL. HACCS directly applies differential privacy to data distribution features, which can significantly reduce data utility and likely lead to suboptimal clustering results, thereby affecting the accuracy of PFL models. FLACC is sensitive to noise, which may result in inaccurate clustering, and its stepwise clustering process may lead to uncertainty in clustering results under complex data distributions. FPL lacks explicit optimization for client scheduling mechanisms, which may exacerbate the straggler problem and constrain model convergence rates in heterogeneous environments. Additionally, while privacy preservation relies on multi-stage prototype averaging to reduce raw data exposure, it does not sufficiently address gradient leakage risks during prototype transmission.

Not only do the aforementioned fundamental clustering methods suffer from optimization bottlenecks, but emerging FL frameworks also face multifaceted challenges in system design and privacy preservation. CLSM-FL has high computational complexity, requiring detailed semantic evaluation and clustering in each global communication round, and the method relies on auxiliary datasets to evaluate the classification capabilities of local models, increasing storage and management complexity. FedUC relies on predefined network topologies or fixed deployment parameters to determine cluster quantities, demonstrating limited adaptability to dynamic edge environments with fluctuating device scales and resource availability. Furthermore, while employing differential privacy techniques for privacy preservation, this approach insufficiently addresses the sensitivity of model accuracy to noise injection under Non-IID data distributions. FedCCL method inadequately addresses the dynamic adaptability of its client selection mechanism to Non-IID data, which may compromise model robustness in dynamic federated environments. Furthermore, its approach of generating low-dimensional signals through local feature clustering and global quadratic averaging fails to provide sufficient privacy guarantees, potentially exposing sensitive information to leakage risks from model inversion attacks or feature correlation analysis.

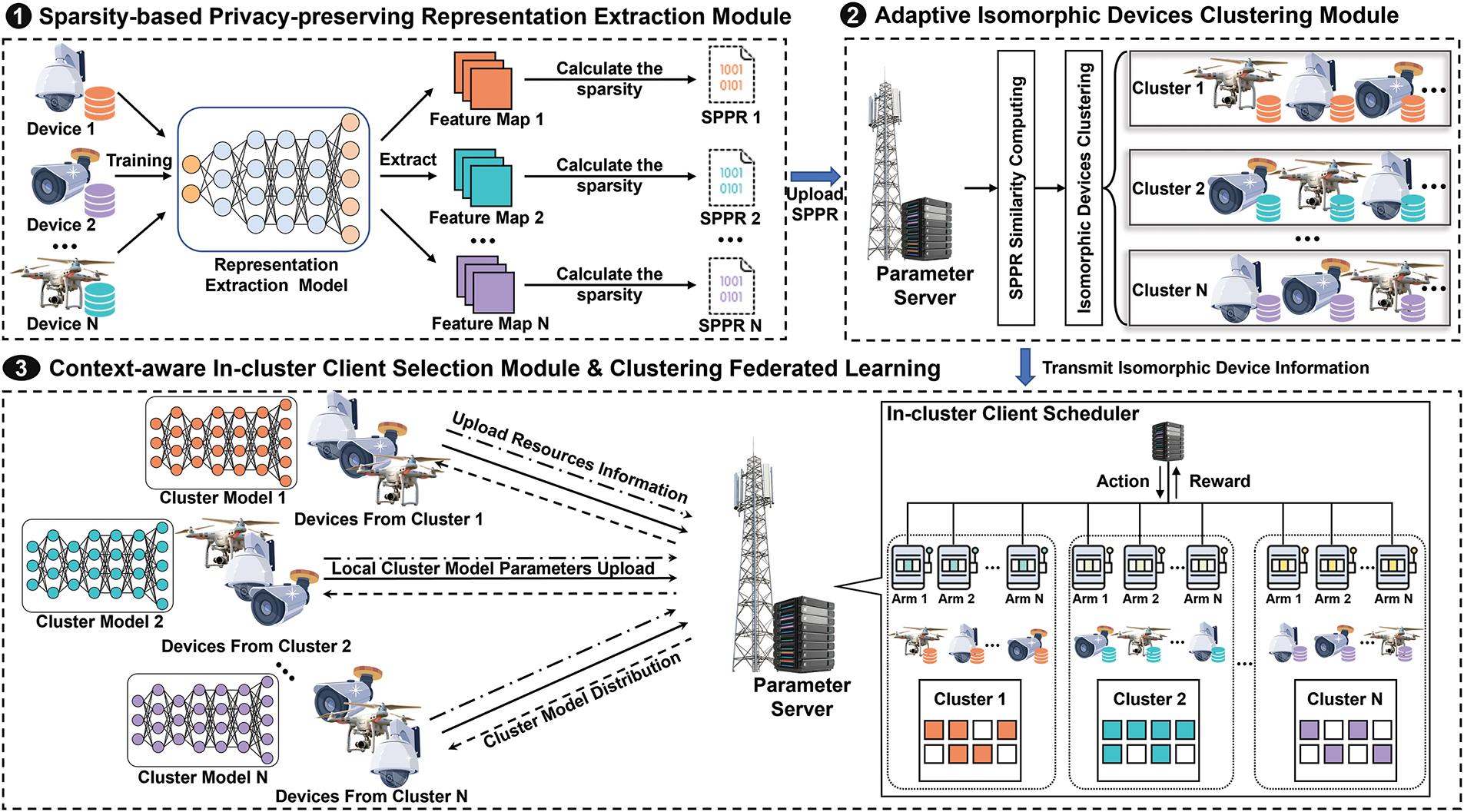

In resource-constrained edge networks, heterogeneous devices typically possess Non-IID data. Therefore, this paper proposes a method called FedEPC. FedEPC designs a framework for implementing PFL through clustering methods. Fig. 1 illustrates the fundamental modules of the FedEPC workflow, including the sparsity-based privacy-preserving representation extraction (SPRE) module, the adaptive isomorphic device clustering (AIDC) module, and the context-aware in-cluster client selection (CICS) module. FedEPC’s core mechanism is a dual-round client selection process. The first round of selection, jointly performed by SPRE and AIDC before formal FL training begins, clusters devices with similar data distribution characteristics into isomorphic clusters. The second round of selection, conducted by CICS, dynamically chooses a subset of devices from each cluster in every FL communication round to participate in training. This approach captures unique data distributions, ensures that each distribution is fully represented during the training process, mitigates weight divergence caused by data heterogeneity, reduces aggregation bias due to client drift, and alleviates the impact of the straggler problem.

Figure 1: The overview of FedEPC

3.2 Sparsity-Based Privacy-Preserving Representation Extraction Module

Effective implementation of PFL in resource-limited edge networks with heterogeneous data distributions necessitates the critical involvement of the SPRE module. Within the developed similarity-based clustered FL architecture, acquisition of representative data distribution features serves as an essential precondition for successful device clustering.

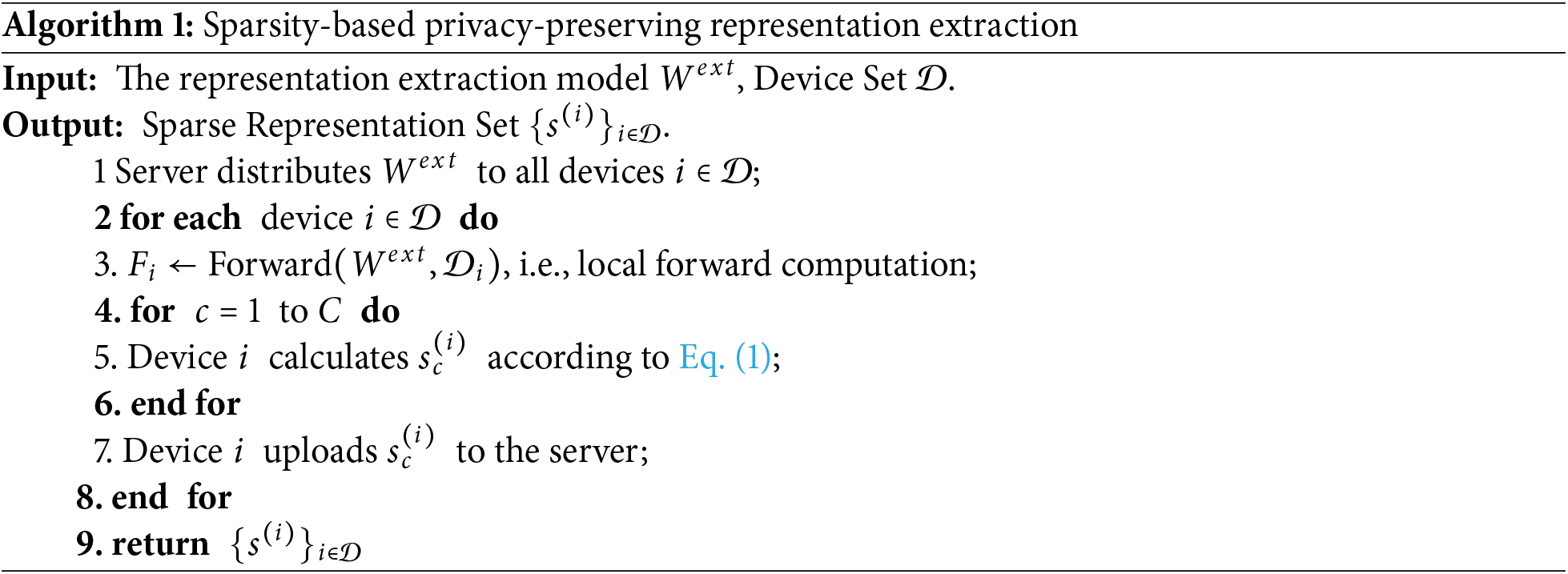

This paper introduces an SPRE module comprising three key stages: server distribution of the representation extraction model, device pre-training and extraction of ReLU layer feature maps in convolutional neural networks (CNN), and sparsity-based privacy-preserving representation feature generation. First, the parameter server located at the edge distributes a pre-trained representation extraction model to all IoT devices within its domain. Then, these devices train the representation extraction model using local data, extract ReLU layer feature maps, sparsify them, and generate privacy-preserving data distribution feature representations, thereby avoiding direct transmission of sensitive data statistics. Unlike explicit data distribution features (e.g., histograms), ReLU sparsity vectors abstractly represent data patterns, minimizing privacy risks. Attackers cannot infer precise class distributions or reconstruct raw images from these sparse features.

Specifically, let the representation extraction model be a CNN structure, and denote the pre-trained parameters of the representation extraction model as

The implementation of the algorithm is described in Algorithm 1. This module reduces the risk of exposing privacy-sensitive information while preserving data distribution features through the sparsification of feature maps. The dimensionality compression characteristic of sparse feature vectors also ensures computational efficiency for subsequent clustering.

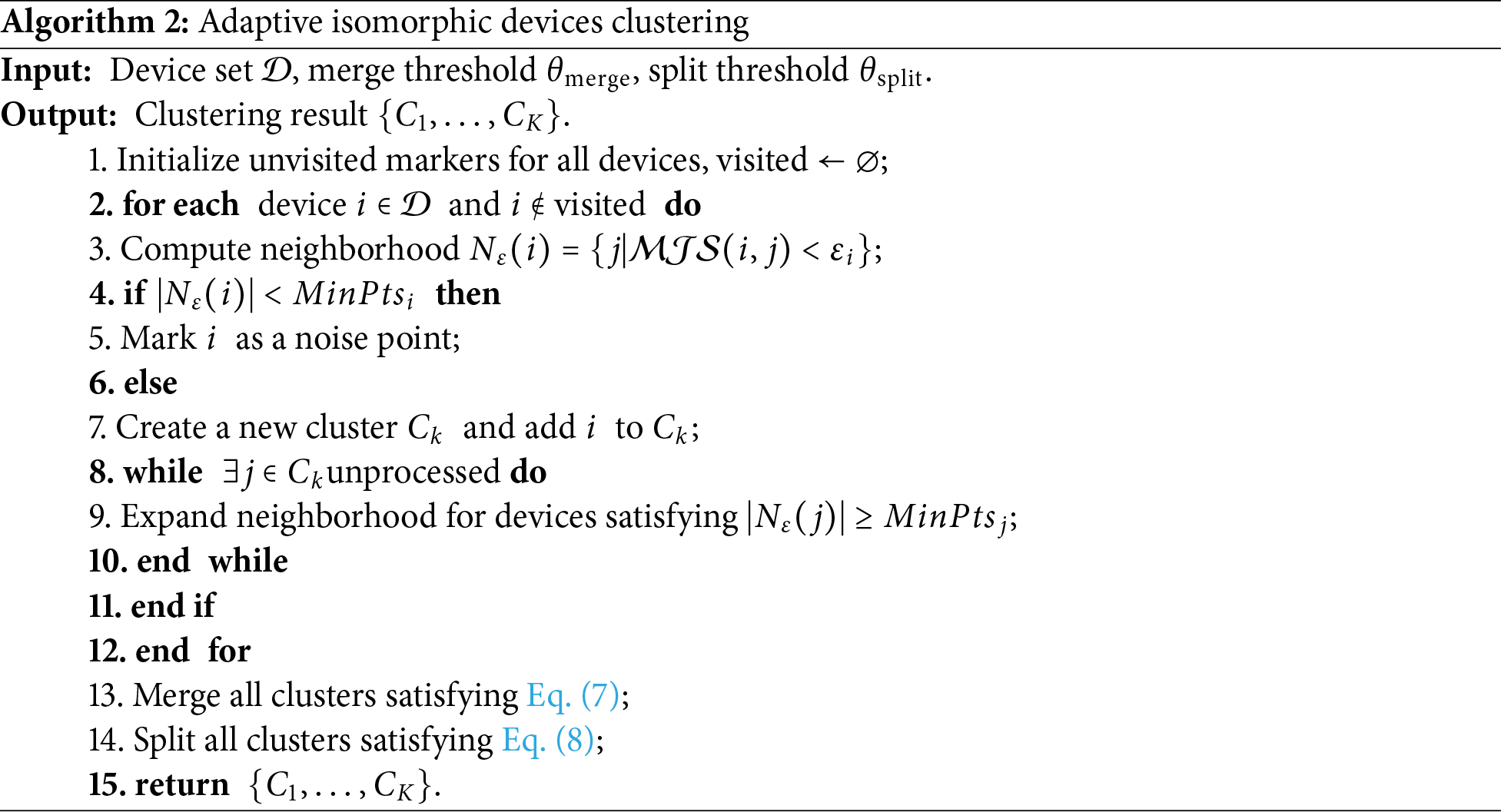

3.3 Adaptive Isomorphic Devices Clustering Module

The substantial data heterogeneity among edge devices, combined with the adverse effects of Non-IID data distributions on FL convergence rates in real-world applications, along with the constrained network connectivity characteristic of resource-limited IoT environments, renders impractical the expectation of simultaneous model updating and aggregation across all participating nodes in FL systems. Therefore, this paper designs the AIDC module, which is specifically designed to group structurally similar devices through data distribution pattern analysis. This component mitigates performance degradation caused by data heterogeneity in FL systems by employing distribution-based clustering techniques.

Specifically, this paper improves and adapts the DBSCAN clustering algorithm to cluster devices based on data distribution similarity metrics. Let the sparsity vectors of devices

Dynamic Neighborhood Radius Calculation: the density radius

Adaptive MinPts Calculation: The minimum number of points is set as shown in Eq. (6), where

The AIDC module dynamically adjusts clusters via merge-split operations. This strategy introduces cluster merging criteria based on data distribution similarity and in-cluster heterogeneity splitting criteria on top of traditional density clustering: merging operations are triggered when the average distribution difference between clusters falls below the merging threshold to enhance global generalization; splitting operations are executed when in-cluster heterogeneity exceeds the splitting threshold to improve local isomorphism. By dynamically balancing the aggregation granularity and distribution consistency of cluster structures, this strategy can maintain stable device clustering under dynamic changes in network topology and data distribution, providing a device grouping foundation for subsequent clustered federated training that combines scalability and distribution homogeneity. Details are as follows:

(1) Cluster Merging Strategy: If two clusters

(2) Cluster Splitting Strategy: If the heterogeneity index of a cluster satisfies Eq. (8), it is divided into two subclusters based on the “maximum heterogeneity pair”.

The algorithm flow is described in Algorithm 2. This module achieves stable clustering through dynamic merging and splitting strategies, providing isomorphic device clusters for subsequent federated training.

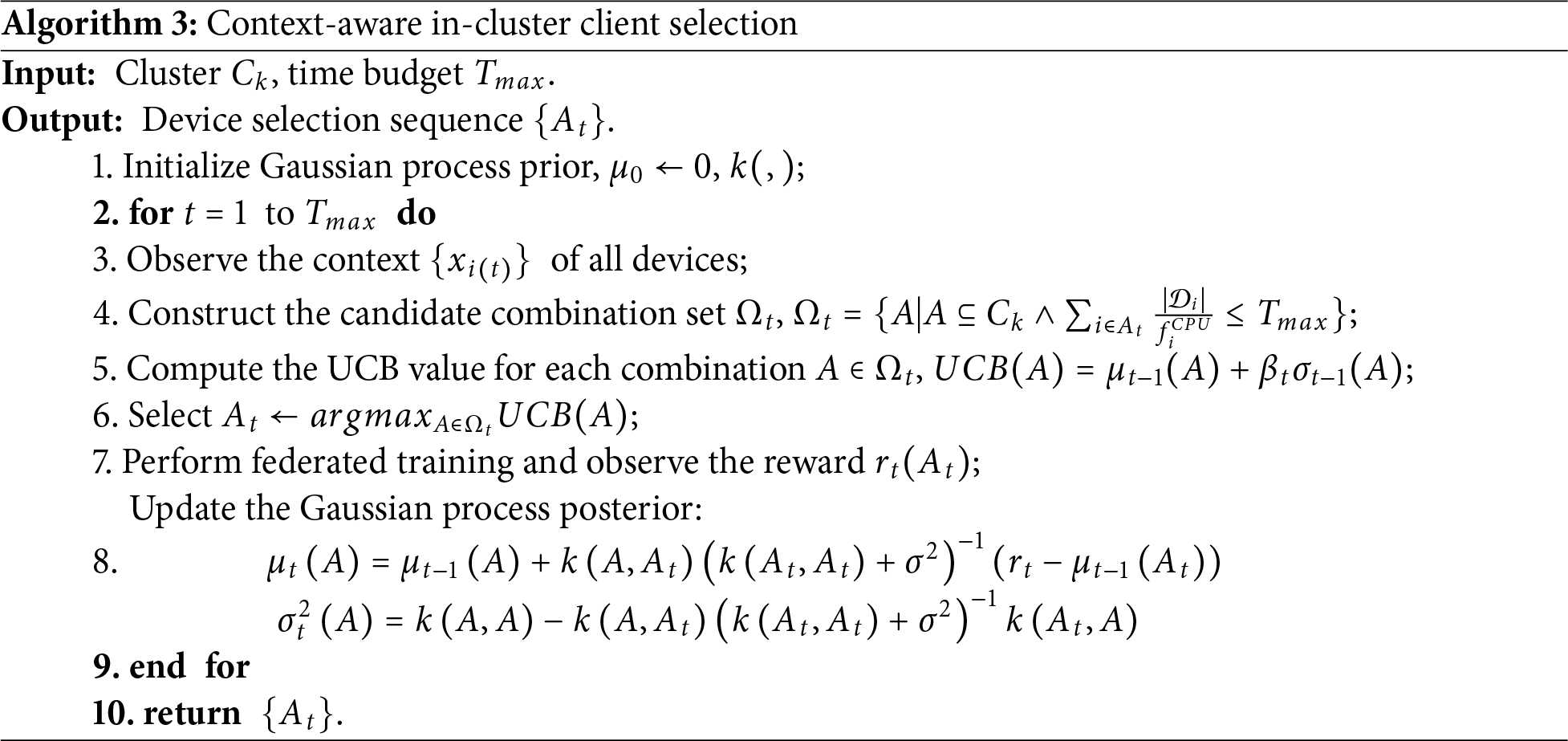

3.4 Context-Aware In-Cluster Client Selection Module

In environments characterized by data heterogeneity, edge servers perform device classification into structurally homogeneous clusters and orchestrate FL processes at the cluster level. Within this architecture, participant devices exclusively exchange gradient updates with cluster members, facilitating the development of cluster-specific global models. Suboptimal scheduling approaches may compromise learning efficiency and exacerbate straggler effects, especially in computationally constrained edge deployments. The efficacy of FL depends fundamentally on representative data distribution sampling rather than exhaustive client participation. Consequently, based on the device clustering results, the CICS module incorporates a contextual combinatorial multi-armed bandit (CCMAB)-based algorithm for client selection. Since clients within the same cluster exhibit similar data characteristics, selecting a subset of clients in each FL communication round suffices to effectively represent the cluster’s overall data distribution. The key to FL model accuracy lies in capturing all unique data distributions rather than merely ensuring coverage across all clients.

Specifically, the context feature vector is first designed. The context

Select a device combination

The optimization objective for selecting the combination is defined as in Eq. (11), where

Dynamic weight updates are performed by introducing an adaptive weight vector

The specific algorithm for the CICS module is described in Algorithm 3. During client selection, if no devices in a cluster can satisfy the time budget constraints due to insufficient computational resources or inadequate data volume, the cluster may remain unselected in that particular round. In such cases, the algorithm temporarily excludes the cluster from aggregation and model updates. The affected cluster will resume participation in subsequent FL rounds once sufficient resources become available.

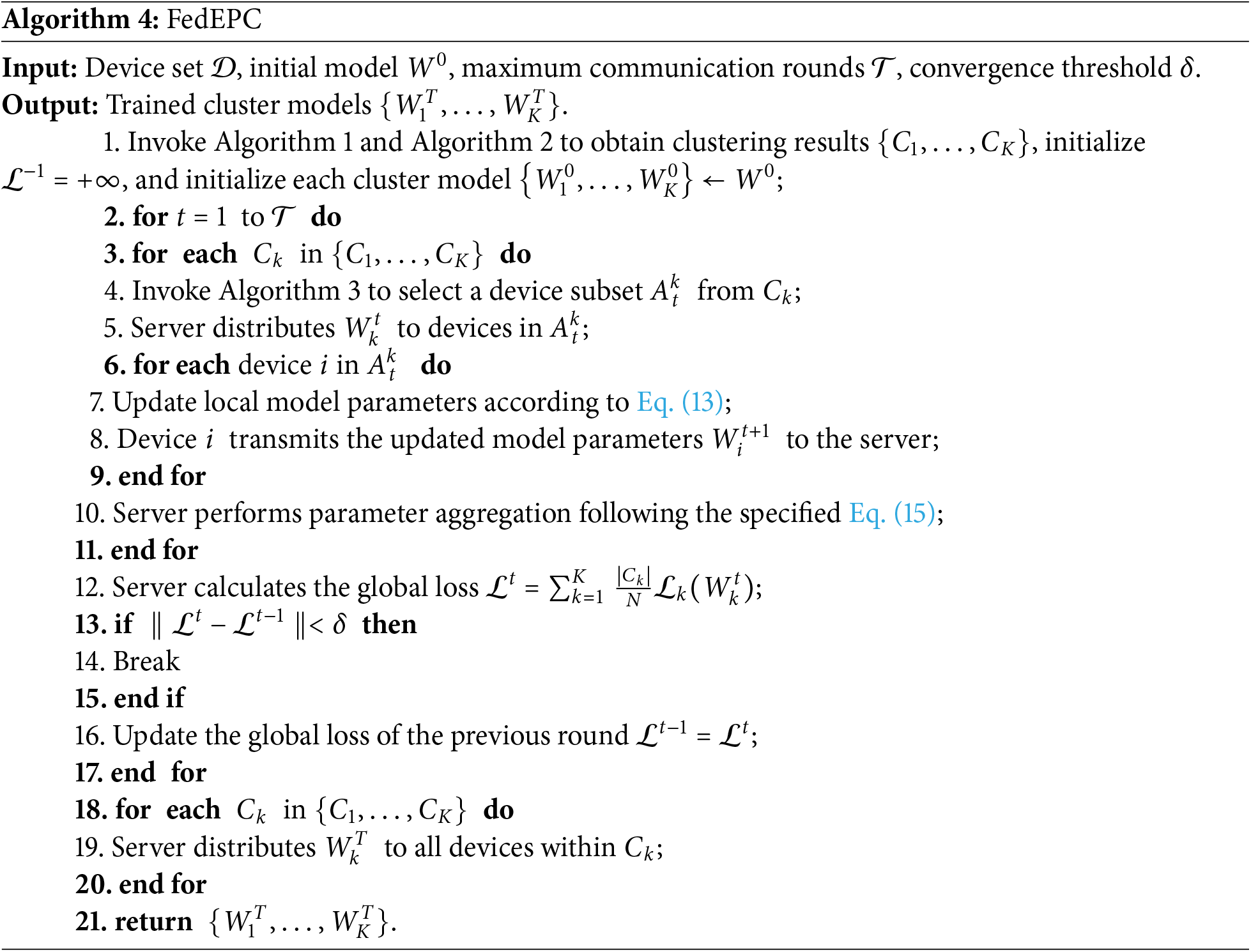

3.5 The Clustering Federated Learning Process of FedEPC

The clustering FL process of FedEPC within isomorphic clusters includes:

(1) In-cluster client selection: the server calls Algorithm 3 to select an appropriate number of devices as clients for FL training.

(2) Cluster model distribution: the server distributes the cluster-specific model to the clients within each cluster.

(3) Local model training: clients receive the cluster model and train it based on their local data, updating the local model parameters. The objective is to obtain the optimal parameters by minimizing the loss function in the

(4) Cluster model aggregation: for each cluster model, the server collects the updated parameters from the corresponding clients and aggregates them, as shown in Eq. (15). The updated cluster model parameters are then distributed to all devices within the cluster to minimize the loss function of each cluster. Subsequently, the personalized model specific to the cluster model is updated.

(5) The server evaluates the updated cluster-specific model to determine whether it has achieved the desired accuracy or convergence. If the cluster model has not yet converged, the process returns to step (1) and continues subsequent FL iterations for that cluster until the loss function of the cluster model in all isomorphic clusters reaches optimal accuracy. Finally, the server distributes the trained cluster model to all edge devices within each cluster.

Specifically, the clustering FL process of FedEPC is described in Algorithm 4.

The convergence of FedEPC under non-IID data is rigorously established through its adaptive clustering mechanism and bounded gradient discrepancy enabled by dynamic client selection.

Assumption 1 (

Assumption 2 (Unbiased Gradient and Bounded Variance): For each cluster

where

Assumption 3 (Cluster Homogeneity): There exists a constant

where

Assumption 4 (Client Selection Stability): The CICS module ensures that the aggregated gradient of selected clients

where

Theorem 1: Under Assumptions 1–4, with learning rate

where

Proof of Theorem 1: The cluster model

Using the

Substituting the update rule and taking expectation over client selection (by Assumption 4), we derive:

Rearranging terms and summing over

where

Substituting

By Assumption 3, the global loss

□

The theoretical analysis presented above validates the feasibility and robustness of FedEPC in efficiently addressing data heterogeneity within resource-constrained edge computing environments, while providing provable convergence guarantees.

The system complexity of FedEPC primarily stems from three newly designed modules:

1. SPRE Module: On the device side, pre-trained federated models perform forward computation to extract ReLU layer feature maps, with per-channel sparsity statistics. The per-device computational complexity is

2. AIDC Module: Device similarity is measured via Euclidean distances between sparsity vectors. To reduce complexity, the proposed method randomly selects a reference client and computes similarities only between other clients and this reference, generating similarity vectors instead of performing full pairwise comparisons. This strategy reduces complexity from

3. CICS Module: The time budget constraint limits the number of candidate combinations

Since sparsity representation extraction operates as a one-time preprocessing step, the overall computational complexity remains

In this section, the performance of the proposed method is evaluated from multiple perspectives through experiments. First, the experimental setup is introduced, including the hardware and software environment, datasets and models, Non-IID simulation methods, and comparative methods. Subsequently, comparative experiments are conducted on three well-known datasets with varying degrees of data distribution heterogeneity, comparing FedEPC with four reference methods. The evaluation focuses on model test accuracy and training latency as core metrics to comprehensively assess the performance of each method.

4.1 Experimental Environment and Setup

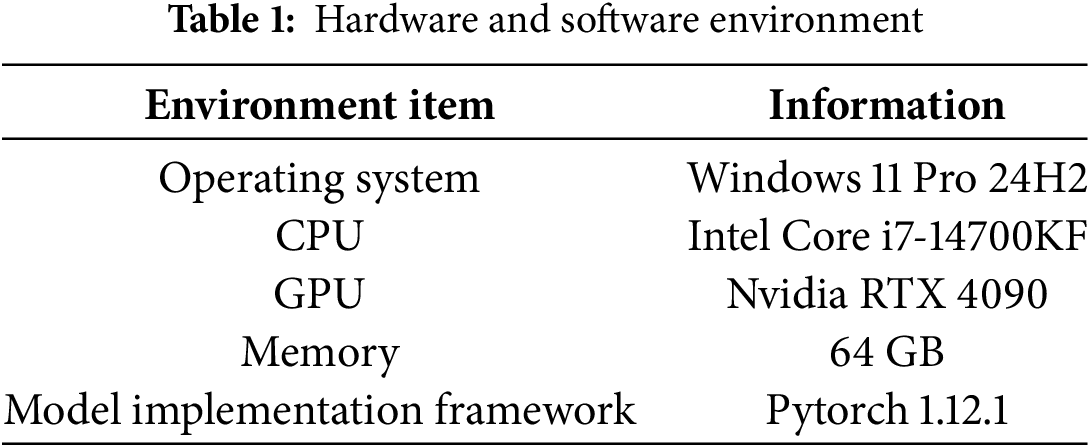

The FL process is simulated on a workstation server for comparative experiments. The hardware and software environment is detailed in Table 1.

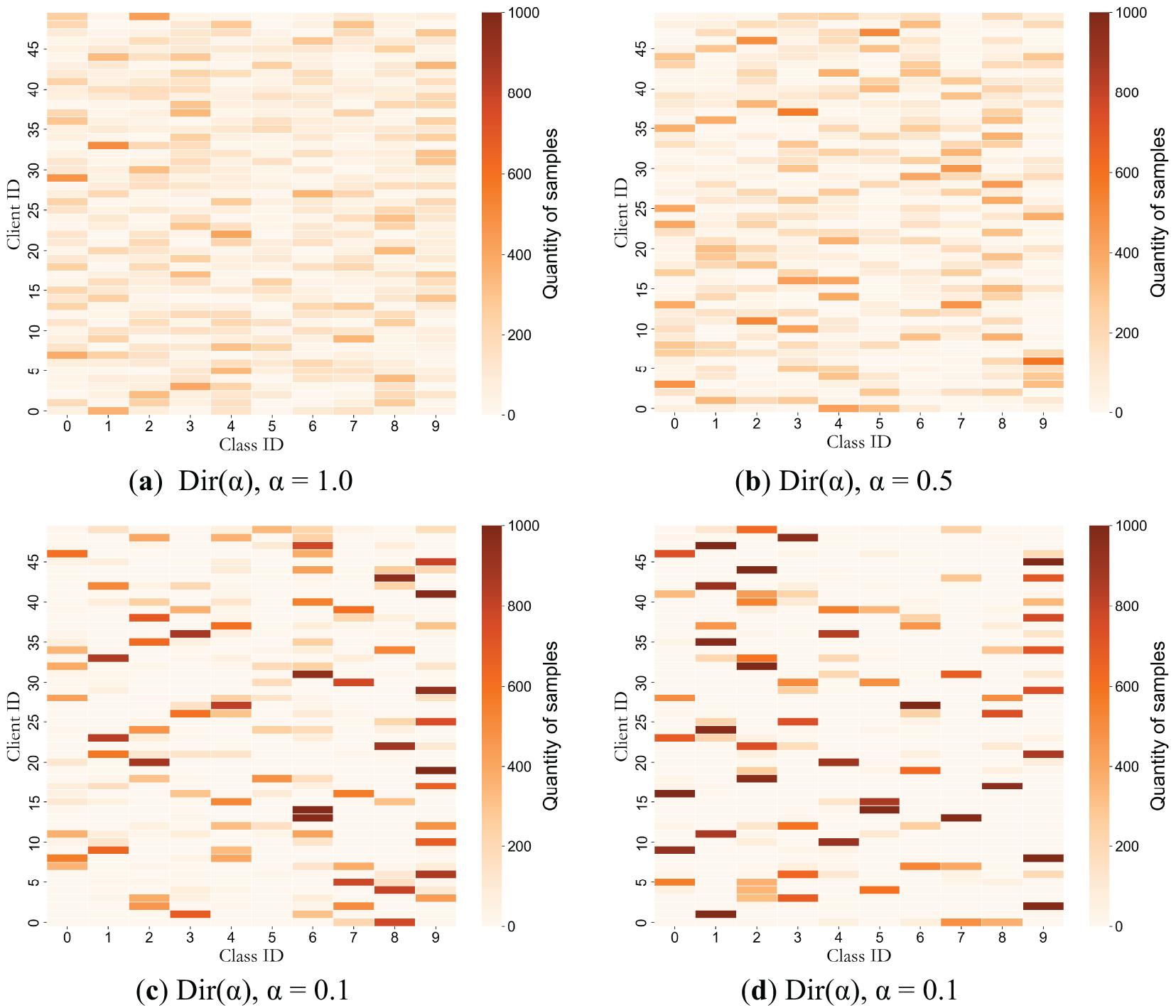

All experiments are conducted on image classification tasks using the MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, and CIFAR-10 datasets, each containing 10 different classes. The proposed method leverages CNN architectures as local models, with ReLU activation layers serving as the basis for privacy-preserving feature extraction. For these datasets, it is assumed that 50 devices participate in FL training. To emulate the characteristic data heterogeneity in Non-IID settings, client-specific datasets are generated through sampling from a Dirichlet distribution Dir(α). Each client generates corresponding class labels based on the proportions of predefined categories. Parameter α serves as a control variable to simulate different levels of data heterogeneity and label distribution imbalance, specifically manifesting as label distribution skew. This configuration maintains consistent conditional distributions

Fig. 2 illustrates the simulation results of client data distribution heterogeneity. Darker squares indicate higher data volumes per class for each client, with color intensity directly proportional to sample counts. Fig. 2a shows a scenario with a larger α, approximating an IID setting, where the color distribution is relatively balanced, and the differences between squares are minimal. From Fig. 2b,d, as α decreases, data heterogeneity increases, resulting in pronounced heterogeneous data distributions. Some squares become significantly darker, while most remain light, visually demonstrating the high imbalance in data distribution across clients.

Figure 2: Visualization of participant data distributions across varying heterogeneity levels

4.2 Experimental Results and Analysis

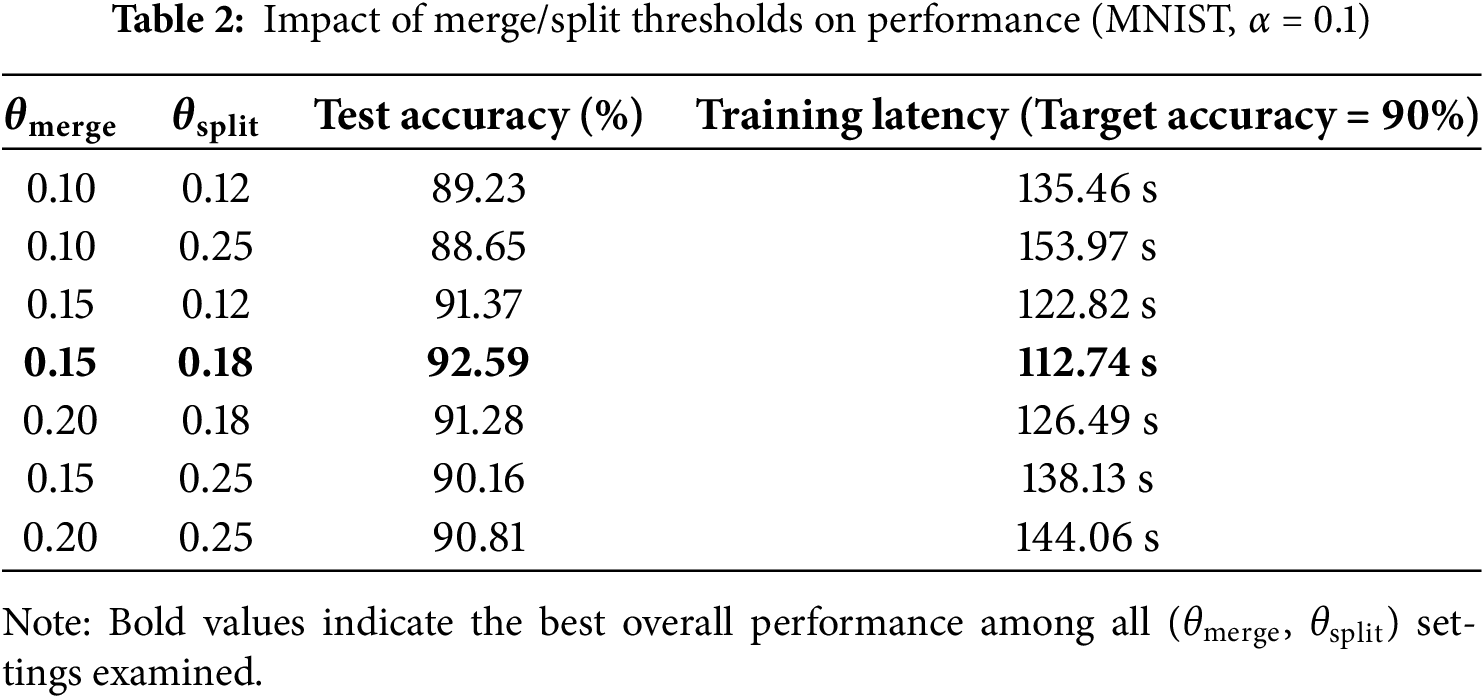

To determine the optimal hyperparameters for the merge and split thresholds, this paper conducted a systematic set of experiments, as summarized in Table 2. The results demonstrate that setting the merge threshold

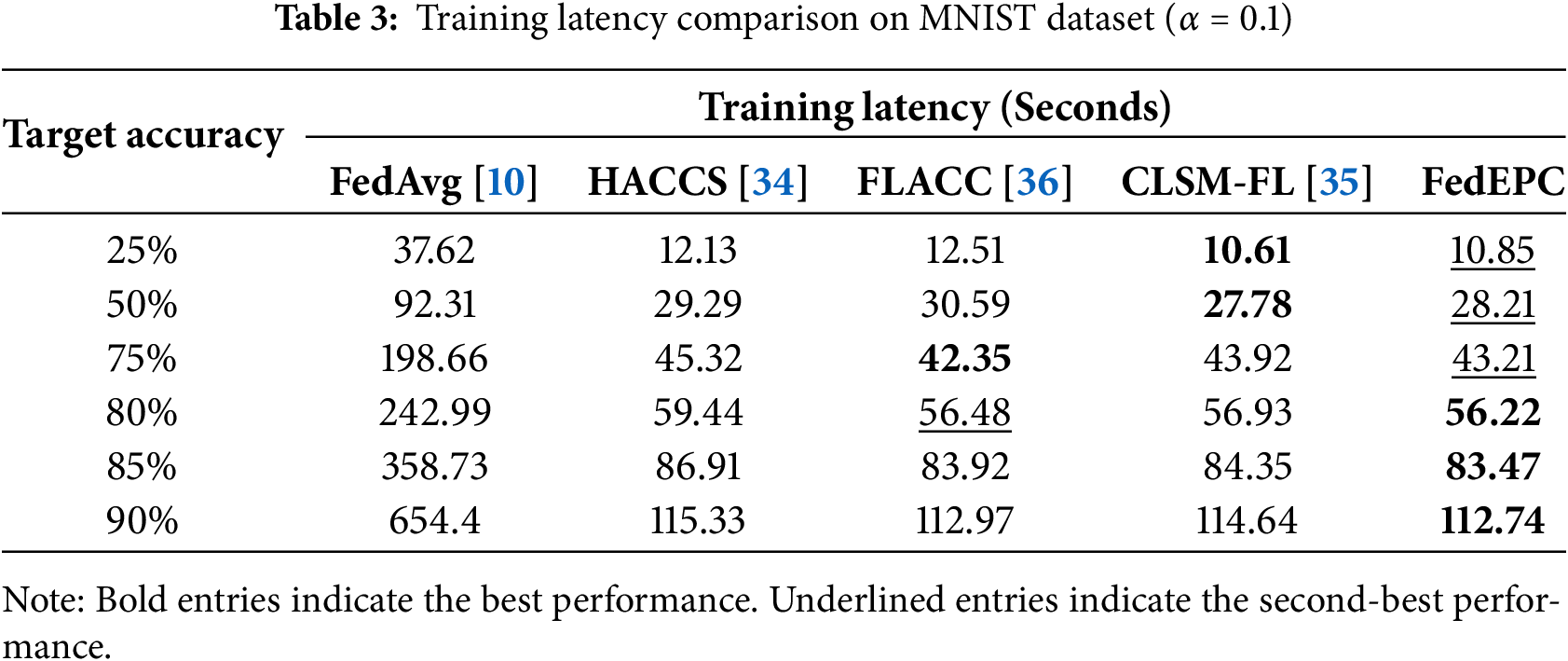

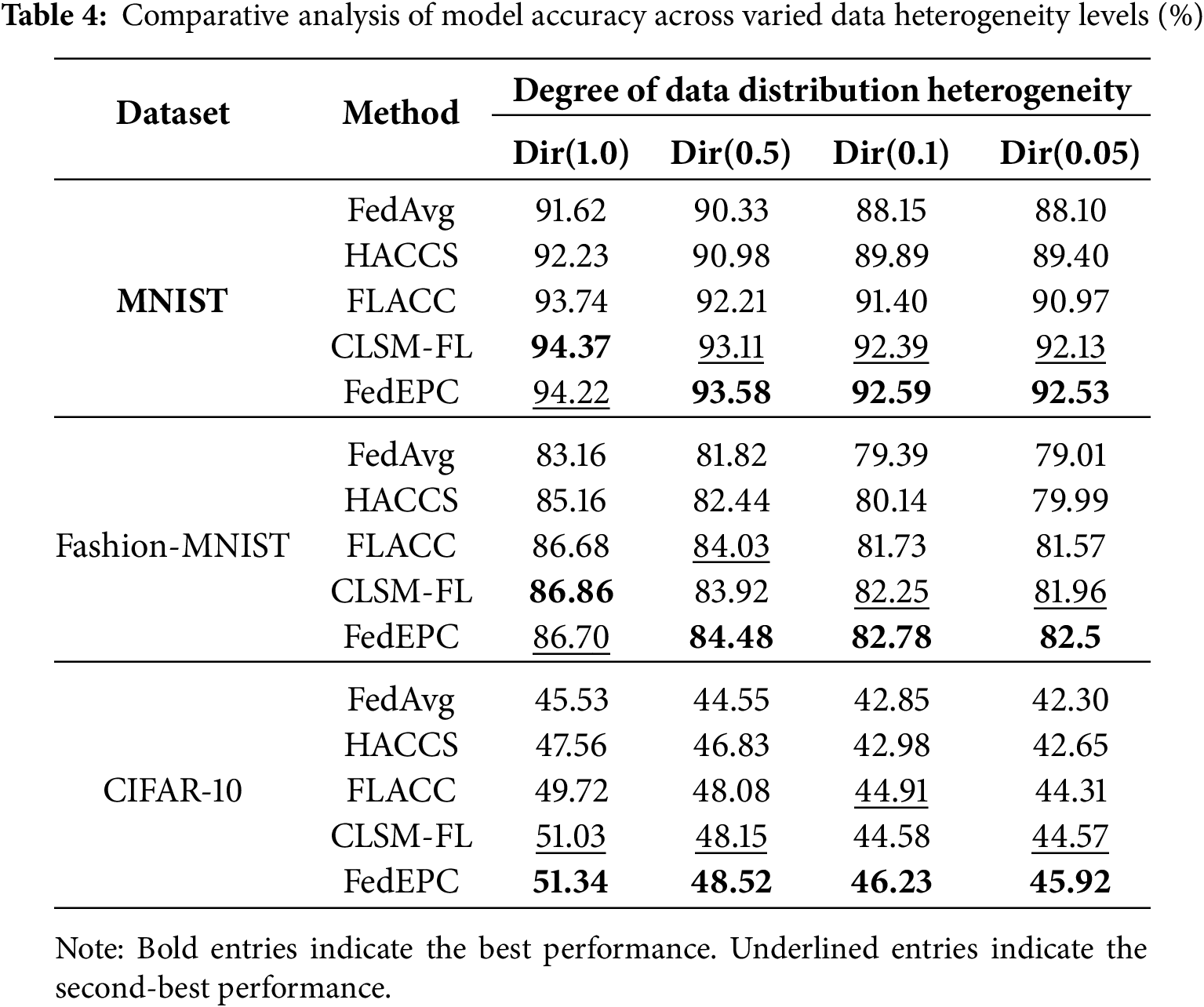

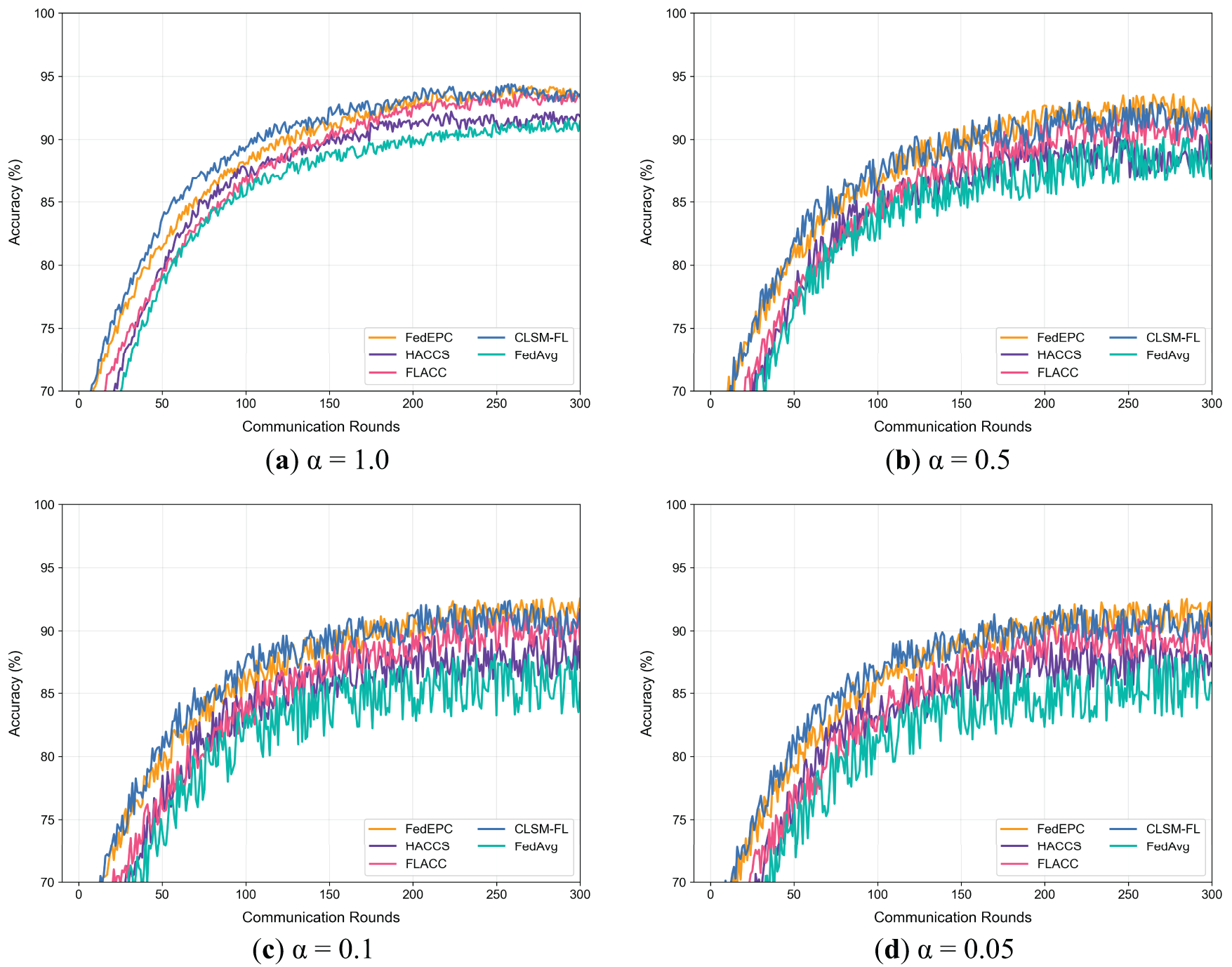

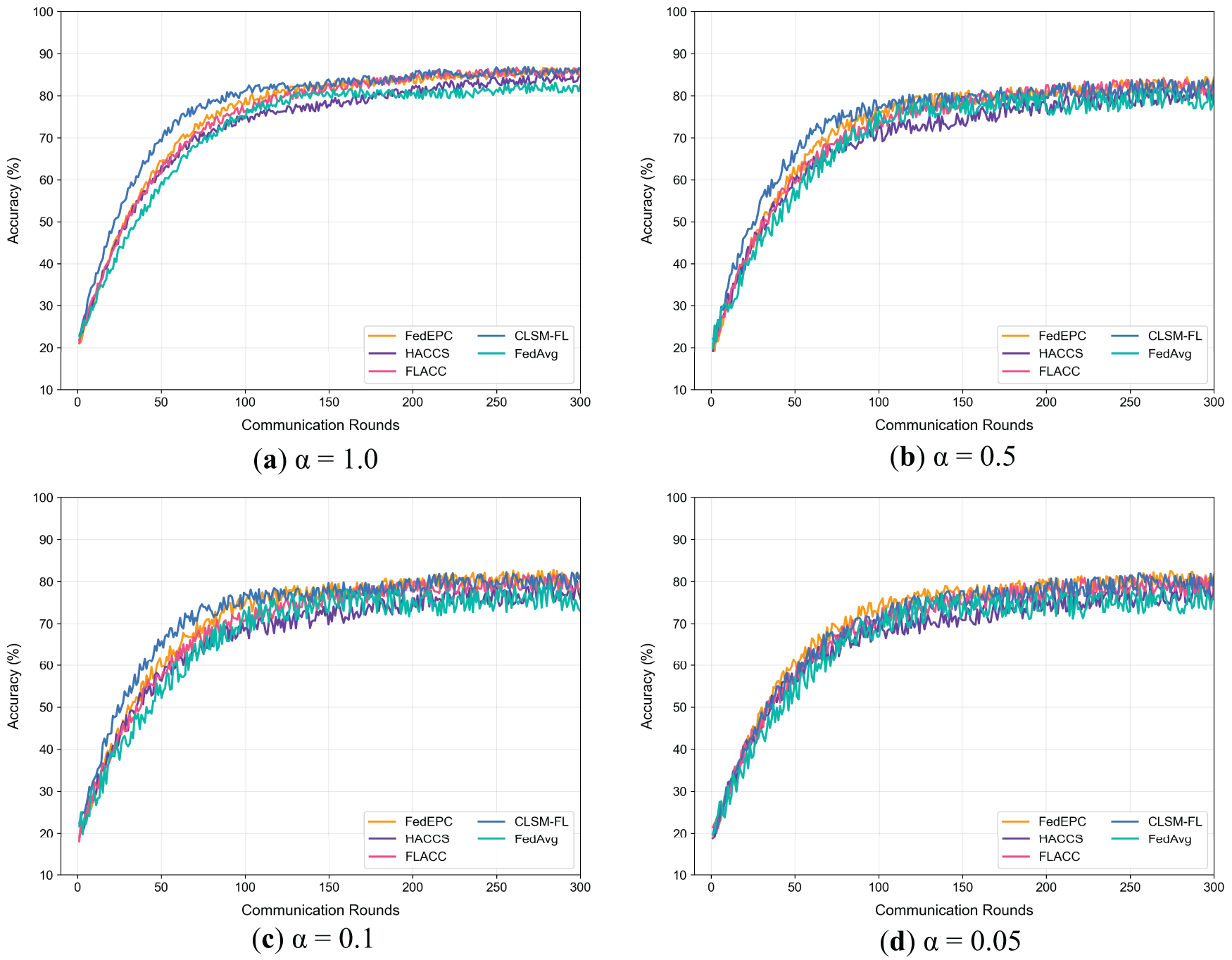

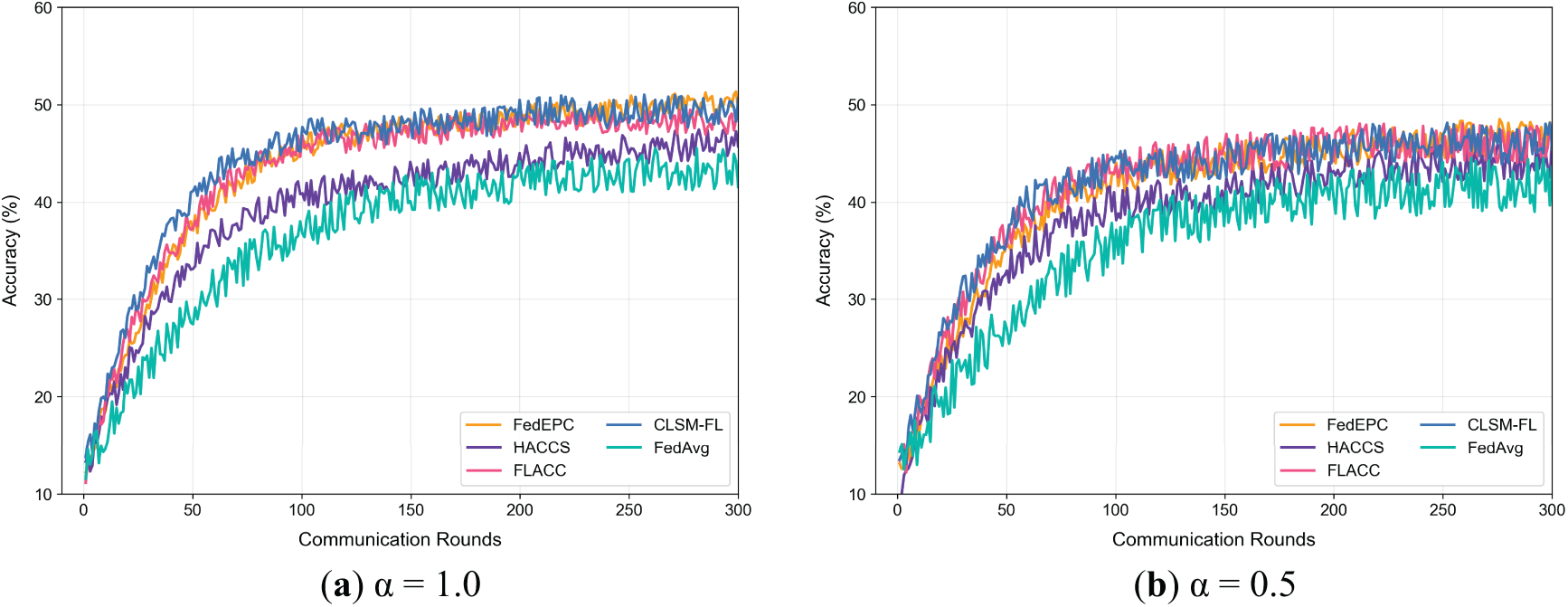

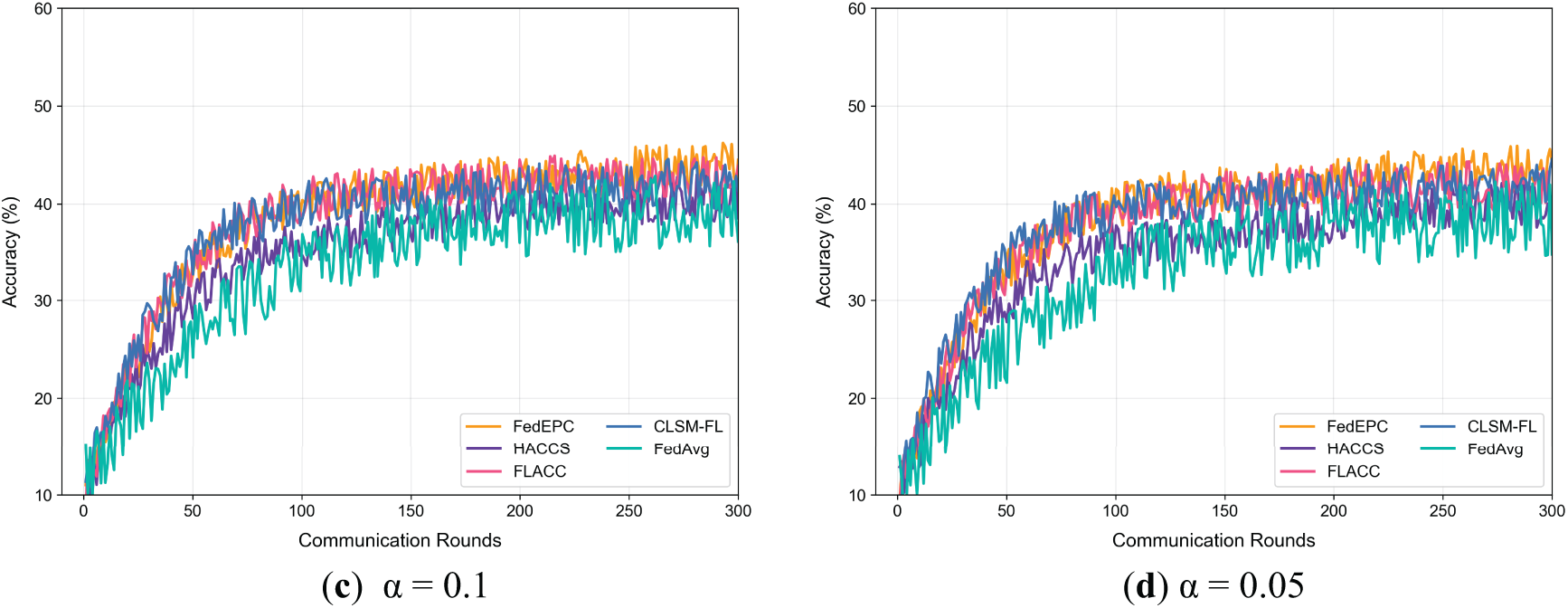

To evaluate the performance of the proposed method, comparative experiments on training latency are conducted on the MNIST dataset, with results shown in Table 3. Additionally, the model test accuracy of different methods on three datasets under varying degrees of data heterogeneity is compared, with numerical results presented in Table 4. Figs. 3–5 illustrate the changes in test accuracy during training.

Figure 3: Test accuracy trends under different degrees of data heterogeneity (MNIST)

Figure 4: Test accuracy trends under different degrees of data heterogeneity (Fashion-MNIST)

Figure 5: Test accuracy trends under different degrees of data heterogeneity (CIFAR-10)

The experimental results presented in Table 3 demonstrate FedEPC’s superior latency performance relative to comparative methods when target accuracy thresholds exceed 80%. Particularly at the 90%, it reduces training time by 82.77% compared to FedAvg. Comparative analysis further reveals substantial latency improvements over HACCS and FLACC, with average training times reduced by 5.09% and 3.37%, respectively. At target accuracies of 25% and 50%, FedEPC does not outperform CLSM-FL but lags by only 2.26% and 1.55%. However, when the target accuracy increases to 75%, FedEPC’s training latency surpasses CLSM-FL, maintaining a lead of 1.04% to 1.66%.

The conventional random client selection mechanism employed by FedAvg induces pronounced straggler issues throughout the FL process, substantially elevating the time required to attain predetermined accuracy thresholds. These straggler problems manifest as operational inefficiencies and extended training durations, adversely affecting both system-wide performance and scalability. FedEPC and alternative benchmark approaches demonstrate varying levels of effectiveness in mitigating such challenges, thereby achieving enhanced latency characteristics and training efficiency. FedEPC demonstrates significant latency advantages at higher target accuracies, substantially reducing training time compared to most reference methods, ensuring the efficient operation of the FL system.

Table 4 presents the experimental results of model test accuracy for the proposed FedEPC method and four comparative methods on the MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, and CIFAR-10 datasets under IID and varying Non-IID scenarios simulated by the Dirichlet distribution. The second row on the right side of the table shows the hyperparameter α values used to simulate data distribution heterogeneity. When α = 0.1, the data distribution approximates IID, while α values of 0.5 to 0.05 result in increasingly severe label skew, with Non-IID degrees escalating.

In the overall model test accuracy comparison, FedEPC achieves the highest accuracy in all cases except for the IID scenarios (α = 1.0) on the MNIST and Fashion-MNIST datasets. For example, on the MNIST dataset with α = 0.05, FedEPC improves test accuracy by 5.03%, 3.50%, 1.71%, and 0.43% compared to FedAvg, HACCS, FLACC, and CLSM-FL, respectively. In the IID scenarios, CLSM-FL, leveraging its soft clustering technique based on model intrinsic properties, effectively integrates different model capabilities. The relatively uniform data distribution in IID scenarios allows CLSM-FL to better utilize the strengths of each model, enhancing its performance in model fusion. Thus, CLSM-FL achieves slightly higher accuracy on the MNIST and Fashion-MNIST datasets, leading by 0.16% and 0.18%, respectively, while FedEPC’s performance improvement in IID scenarios is limited.

However, in Non-IID scenarios, FedEPC’s unique architecture design better adapts to data heterogeneity. By clustering devices, it avoids interference from inter-cluster data feature differences and fully exploits in-cluster data feature commonalities for effective learning. Although CLSM-FL employs semantic-based clustering, its clustering and aggregation strategies struggle to leverage data similarity as effectively as FedEPC in complex Non-IID environments, leading to less pronounced improvements in test accuracy. Consequently, FedEPC demonstrates greater advantages in Non-IID scenarios, with its accuracy improvements becoming increasingly significant as data heterogeneity intensifies (i.e., as α decreases), outperforming CLSM-FL and other methods.

On MNIST and Fashion-MNIST (grayscale datasets with simple features), all methods achieve high accuracy. Consequently, FedEPC’s optimizations show limited improvements here compared to more complex datasets. In contrast, the CIFAR-10 dataset, consisting of RGB three-channel color images, is more complex, with significantly increased data feature complexity leading to lower model accuracy. For example, at α = 0.1, FedEPC improves test accuracy by 7.89%, 7.56%, 2.94%, and 3.70% compared to FedAvg, HACCS, FLACC, and CLSM-FL, respectively. On the complex CIFAR-10 dataset, FedEPC significantly enhances model test accuracy compared to the four reference methods, demonstrating its effectiveness and reliability in real-world applications with more complex data structures and features.

Figs. 3–5 depict the trends of model test accuracy for FedEPC and the four reference methods on the MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, and CIFAR-10 datasets under IID and varying Non-IID scenarios simulated by the Dirichlet distribution. In each subfigure, the x-axis represents FL communication rounds, where one round includes the upload of weight parameters and model distribution between clients and the server, and the y-axis represents model test accuracy.

The figures reveal that, across different datasets and heterogeneity levels, FedEPC achieves the highest test accuracy in all cases except for the IID scenarios where CLSM-FL slightly outperforms on the MNIST and Fashion-MNIST datasets. In terms of convergence, FedEPC is only slightly slower than CLSM-FL in the early and middle stages of training. In all other cases, FedEPC exhibits faster convergence rates compared to all reference methods, with a noticeable upward trend in convergence speed during the later stages of FL training.

FedEPC’s superior performance is primarily attributed to its unique dual-round client selection design, which includes reasonable isomorphic device clustering and effective in-cluster client selection. During FL training, the edge server coordinates the FL process within each isomorphic cluster, and devices share weight parameter updates only with others in the same cluster, generating different in-cluster global models. This reduces interference from inter-cluster data feature differences, enabling the FL model to fully exploit in-cluster data feature commonalities for effective learning. Additionally, during the model aggregation phase, FedEPC collects updated parameters, aggregates them, and minimizes the loss function for each cluster, continuously updating cluster-specific personalized models. This cluster-specific optimization strategy helps the model converge faster and achieve higher accuracy under varying degrees of data heterogeneity.

While the effectiveness of FedEPC has been validated through image classification tasks, its design principles and modular architecture exhibit broad adaptability across diverse domains. In natural language processing (NLP), for instance, FedEPC’s heterogeneous device clustering mechanism can construct personalized models tailored to distinct user groups based on textual features, while protecting user privacy via sparse feature representations. In healthcare data analysis scenarios, where electronic health records from different hospitals exhibit significant distributional discrepancies, FedEPC’s CICS module can dynamically coordinate resource-constrained medical devices to enable cross-institutional collaborative optimization under privacy preservation. Furthermore, in intelligent transportation systems, edge devices often encounter dynamic environments and non-IID data distributions; FedEPC’s dual-round client selection mechanism can effectively capture spatiotemporal heterogeneity in traffic flow patterns, enhancing the robustness of predictive models. Although data modalities and feature extraction methods vary across domains, FedEPC’s core modules (SPRE, AIDC, CICS) can be flexibly adapted by modifying the feature extraction model and similarity metrics, thereby establishing a theoretical foundation for cross-domain generalization.

To address the challenges of data heterogeneity and resource constraints in sensing-computing fusion scenarios, this paper proposes an Efficient and Privacy-enhancing Clustering Federated Learning method, termed FedEPC. The FedEPC method performs the first round of client selection through the SPRE module and the AIDC module, followed by the second round of client selection completed by the CICS module. Within each isomorphic cluster, a certain number of devices are selected for FL training to capture unique data distributions, ensuring that each distribution is fully represented during the training process. This approach addresses three key challenges: weight divergence from data heterogeneity, aggregation bias from client drift, and delays caused by stragglers. Experimental results demonstrate that FedEPC significantly improves the test accuracy and learning efficiency of federated models. Compared to the traditional FL method FedAvg and other clustering FL methods, FedEPC exhibits superior performance in handling highly heterogeneous Non-IID data, effectively addressing the challenges posed by data heterogeneity and resource constraints.

From a practical feasibility perspective, FedEPC’s modular design enables seamless integration with existing multi-access edge computing (MEC) infrastructure, leveraging edge servers to coordinate intra-cluster training tasks and reduce core network load. Its dynamic client selection mechanism further enhances system robustness by adaptively responding to network fluctuations. However, real-world deployment must address challenges such as communication bandwidth constraints and device architecture heterogeneity. Future work could incorporate lightweight model distillation techniques to further compress computational overhead and integrate federated edge caching mechanisms to minimize redundant transmission costs. Additionally, in highly dynamic scenarios, enhancing the AIDC module’s online clustering capability to respond in real-time to device topology changes would improve FedEPC’s adaptability in complex real-world environments. Further research is needed to improve the explainability of privacy protection mechanisms, thereby increasing user confidence in data security.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their gratitude for the valuable feedback and suggestions provided by all the anonymous reviewers and the editorial team.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the State Grid Corporation Science and Technology Project “Research and Application of Key Technologies for Integrated Sensing and Computing for Intelligent Operation of Power Grid” (Grant No. 5700-202318596A-3-2-ZN).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Ning Tang, Wang Luo and Bao Feng; methodology, Wang Luo and Yiwei Wang; software, Ning Tang, Yiwei Wang, Shuang Yang, Daohua Zhu and Wei Liang; validation, Shuang Yang, Jiangtao Xu and Zhechen Huang; formal analysis, Ning Tang, Yiwei Wang and Bao Feng; investigation, Shuang Yang and Jiangtao Xu; resources, Daohua Zhu and Wang Luo; data curation, Jiangtao Xu, Zhechen Huang and Wei Liang; writing—original draft preparation, Ning Tang, Wang Luo, Shuang Yang, Daohua Zhu and Zhechen Huang; writing—review and editing, Yiwei Wang, Bao Feng, Jiangtao Xu, Zhechen Huang and Wei Liang; visualization, Bao Feng, Zhechen Huang and Wei Liang; supervision, Wang Luo and Daohua Zhu; project administration, Wang Luo, Jiangtao Xu and Daohua Zhu; funding acquisition, Wang Luo and Daohua Zhu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Wang Luo, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Siriwardhana Y, Porambage P, Liyanage M, Ylianttila M. A survey on mobile augmented reality with 5G mobile edge computing: architectures, applications, and technical aspects. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2021;23(2):1160–92. doi:10.1109/comst.2021.3061981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Siam SI, Ahn H, Liu L, Alam S, Shen H, Cao Z, et al. Artificial intelligence of things: a survey. ACM Trans Sens Netw. 2025;21(1):1–75. doi:10.1145/3690639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Huang H, Zhan W, Min G, Duan Z, Peng K. Mobility-aware computation offloading with load balancing in smart city networks using MEC federation. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;23(11):10411–28. doi:10.1109/TMC.2024.3376377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wen D, Zhou Y, Li X, Shi Y, Huang K, Letaief KB. A survey on integrated sensing, communication, and computation. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2024. doi: 10.1109/comst.2024.3521498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Qi Z, Meng L, Chen Z, Hu H, Lin H, Meng X. Cross-Silo prototypical calibration for federated learning with non-IID data. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2023 Oct 29–Nov 3; Ottawa ON, Canada; p. 3099–107. doi:10.1145/3581783.3612481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Cybersecurity Law of the People’s Republic of China [Internet]. Beijing, China: National People’s Congress; 2016 [cited 2025 May 25]. Available from: http://www.npc.gov.cn/zgrdw/npc/xinwen/2016-11/07/content_2001605.htm. [Google Scholar]

7. Personal information protection law of the people’s Republic of China [Internet]. Beijing, China: National People’s Congress; 2021 [cited 2025 May 25]. Available from: http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c2/c30834/202108/t20210820_313088.html. [Google Scholar]

8. Voigt P, Von dem Bussche A. The EU general data protection regulation (GDPR). In: A practical guide. 1st ed. Switzerland, Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

9. Liu J, Huang J, Zhou Y, Li X, Ji S, Xiong H, et al. From distributed machine learning to federated learning: a survey. Knowl Inf Syst. 2022;64(4):885–917. doi:10.1007/s10115-022-01664-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Arcas BA. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; 2017 Apr 20–22; Lauderdale, FL, USA. New York, NY, USA: PMLR; 2017. p. 1273–82. [Google Scholar]

11. Li Q, Wen Z, Wu Z, Hu S, Wang N, Li Y, et al. A survey on federated learning systems: vision, hype and reality for data privacy and protection. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2023;35(4):3347–66. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2021.3124599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ye M, Fang X, Du B, Yuen PC, Tao D. Heterogeneous federated learning: state-of-the-art and research challenges. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(3):1–44. doi:10.1145/3625558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Liu J, Zeng Q, Xu H, Xu Y, Wang Z, Huang H. Adaptive block-wise regularization and knowledge distillation for enhancing federated learning. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2024;32(1):791–805. doi:10.1109/TNET.2023.3301972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Luo M, Chen F, Hu D, Zhang Y, Liang J, Feng J. No fear of heterogeneity: classifier calibration for federated learning with Non-IID data. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2021;34:5972–598. [Google Scholar]

15. Luo B, Xiao W, Wang S, Huang J, Tassiulas L. Tackling system and statistical heterogeneity for federated learning with adaptive client sampling. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2022—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2022 May 2–5; London, UK. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 1739–48. doi:10.1109/INFOCOM48880.2022.9796935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li B, Schmidt MN, Alstrøm TS, Stich SU. On the effectiveness of partial variance reduction in federated learning with heterogeneous data. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 3964–73. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Deng Y, Lyu F, Xia T, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Ren J, et al. A communication-efficient hierarchical federated learning framework via shaping data distribution at edge. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2024;32(3):2600–15. doi:10.1109/TNET.2024.3363916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Schlegel R, Kumar S, Rosnes E, Amat AGI. CodedPaddedFL and CodedSecAgg: straggler mitigation and secure aggregation in federated learning. IEEE Trans Commun. 2023;71(4):2013–27. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2023.3244243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Tan AZ, Yu H, Cui L, Yang Q. Towards personalized federated learning. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34(12):9587–603. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3160699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Smith V, Chiang CK, Sanjabi M, Talwalkar AS. Federated multi-task learning. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017;30:4424–34. [Google Scholar]

21. Huang Y, Chu L, Zhou Z, Wang L, Liu J, Pei J, et al. Personalized cross-Silo federated learning on non-IID data. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(9):7865–73. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i9.16960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mills J, Hu J, Min G. Multi-task federated learning for personalised deep neural networks in edge computing. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2022;33(3):630–41. doi:10.1109/TPDS.2021.3098467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hanzely F, Richtárik P. Federated learning of a mixture of global and local models. arXiv:2002.05516. 2020. [Google Scholar]

24. Chen M, Jiang M, Dou Q, Wang Z, Li X. FedSoup: improving generalization and personalization in federated learning via selective model interpolation. In: Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2023; 2023 Oct 8–12; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2023. p. 318–28. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-43895-0_30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yang Z, Liu Y, Zhang S, Zhou K. Personalized federated learning with model interpolation among client clusters and its application in smart home. World Wide Web. 2023;26(4):2175–200. doi:10.1007/s11280-022-01132-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Yang X, Huang W, Ye M. Dynamic personalized federated learning with adaptive differential privacy. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2023;36:72181–92. [Google Scholar]

27. Chen L, Xiao D, Xiao X, Zhang Y. Secure and efficient federated learning via novel authenticable multi-party computation and compressed sensing. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2024;19:10141–56. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2024.3486611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kumar KN, Mitra R, Mohan CK. Revamping federated learning security from a defender’s perspective: a unified defense with homomorphic encrypted data space. In: 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 24387–97. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.02302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Song M, Wang Z, Zhang Z, Song Y, Wang Q, Ren J, et al. Analyzing user-level privacy attack against federated learning. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2020;38(10):2430–44. doi:10.1109/JSAC.2020.3000372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jiang Y, Zhang K, Qian Y, Zhou L. Anonymous and efficient authentication scheme for privacy-preserving distributed learning. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2022;17:2227–40. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2022.3181848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ghosh A, Chung J, Yin D, Ramchandran K. An efficient framework for clustered federated learning. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 2022;68(12):8076–91. doi:10.1109/TIT.2022.3192506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Duan M, Liu D, Ji X, Liu R, Liang L, Chen X, et al. FedGroup: efficient federated learning via decomposed similarity-based clustering. In: 2021 IEEE Intl Conf Parallel Distrib Process Appl Big Data Cloud Comput Sustain Comput Commun Soc Comput Netw (ISPA/BDCloud/SocialCom/SustainCom); 2021 Sep 30–Oct 3; New York, NY, USA; 2021. p. 228–37. [Google Scholar]

33. Liu B, Guo Y, Chen X. PFA: privacy-preserving federated adaptation for effective model personalization. In: Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021; 2021 Apr 19–23; Ljubljana, Slovenia. p. 923–34. doi:10.1145/3442381.3449847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wolfrath J, Sreekumar N, Kumar D, Wang Y, Chandra A. HACCS: heterogeneity-aware clustered client selection for accelerated federated learning. In: 2022 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS); 2022 May 30–Jun 3; Lyon, France. p. 985–95. doi:10.1109/IPDPS53621.2022.00100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lee H, Seo D. CLSM-FL: clustering-based semantic federated learning in non-IID IoT environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(18):29838–51. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3408149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Mehta M, Shao C. A greedy agglomerative framework for clustered federated learning. IEEE Trans Ind Inf. 2023;19(12):11856–67. doi:10.1109/tii.2023.3252599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Huang W, Ye M, Shi Z, Li H, Du B. Rethinking federated learning with domain shift: a prototype view. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 16312–22. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ma Q, Xu Y, Xu H, Liu J, Huang L. FedUC: a unified clustering approach for hierarchical federated learning. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;23(10):9737–56. doi:10.1109/TMC.2024.3366947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Qiao Y, Le HQ, Zhang M, Adhikary A, Zhang C, Hong CS. FedCCL: federated dual-clustered feature contrast under domain heterogeneity. Inf Fusion. 2025;113(3):102645. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools