Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Adaptive Hybrid Metaheuristic for Solving the Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows under Uncertainty

Engineering Department & IEETA, University of Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Vila Real, 5000-801, Portugal

* Corresponding Author: Manuel J. C. S. Reis. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Algorithms for Planning and Scheduling Problems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3023-3039. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066390

Received 07 April 2025; Accepted 15 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

The Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows (VRPTW) presents a significant challenge in combinatorial optimization, especially under real-world uncertainties such as variable travel times, service durations, and dynamic customer demands. These uncertainties make traditional deterministic models inadequate, often leading to suboptimal or infeasible solutions. To address these challenges, this work proposes an adaptive hybrid metaheuristic that integrates Genetic Algorithms (GA) with Local Search (LS), while incorporating stochastic uncertainty modeling through probabilistic travel times. The proposed algorithm dynamically adjusts parameters—such as mutation rate and local search probability—based on real-time search performance. This adaptivity enhances the algorithm’s ability to balance exploration and exploitation during the optimization process. Travel time uncertainties are modeled using Gaussian noise, and solution robustness is evaluated through scenario-based simulations. We test our method on a set of benchmark problems from Solomon’s instance suite, comparing its performance under deterministic and stochastic conditions. Results show that the proposed hybrid approach achieves up to a 9% reduction in expected total travel time and a 40% reduction in time window violations compared to baseline methods, including classical GA and non-adaptive hybrids. Additionally, the algorithm demonstrates strong robustness, with lower solution variance across uncertainty scenarios, and converges faster than competing approaches. These findings highlight the method’s suitability for practical logistics applications such as last-mile delivery and real-time transportation planning, where uncertainty and service-level constraints are critical. The flexibility and effectiveness of the proposed framework make it a promising candidate for deployment in dynamic, uncertainty-aware supply chain environments.Keywords

Efficient logistics and transportation are essential to modern supply chain management, with direct implications for operational costs, environmental sustainability, and customer satisfaction. One of the most prominent challenges in this field is the Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows (VRPTW), which involves determining optimal routes for a fleet of vehicles to serve customers within predefined time intervals [1]. By introducing time window constraints, the VRPTW significantly increases the complexity of the classical Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP) [2].

In practice, routing performance is often influenced by uncertainties such as fluctuating travel times, variable service durations, and changing customer demands. Traditional deterministic models struggle to accommodate such variability, frequently resulting in suboptimal or infeasible solutions [3]. To address these challenges, stochastic and robust optimization methods have been developed to enable more reliable and resilient routing under uncertainty [4].

Metaheuristic algorithms—particularly hybrid approaches—have demonstrated strong performance in solving VRPTW and its variants. By combining global exploration with local refinement, these methods effectively balance the search process across large and complex solution spaces [5]. Early work in this area combined Genetic Algorithms (GA) with Local Search (LS) to enhance both solution quality and computational efficiency [6]. More recent studies have introduced advanced hybridizations incorporating modern heuristics and adaptive strategies. For example, a study proposed an Improved Genetic Ant Colony Optimization (IGA-ACO) algorithm that integrates Solomon’s insertion heuristic for population initialization, achieving faster convergence and better route planning under time and capacity constraints [7]. Similarly, a self-adaptive combination of Intelligent Water Drops and Simulated Annealing has been used in green logistics to reduce emissions while maintaining adaptability [8]. Other work has shown that coupling GA with Record-to-Record Travel (GA-RR) improves both route robustness and efficiency in capacitated VRP scenarios [9].

Despite these advances, many existing metaheuristics still rely on static parameters or fixed algorithmic structures, limiting their responsiveness to changing problem landscapes or uncertain inputs. Adaptive mechanisms that dynamically tune algorithmic parameters based on performance feedback can further enhance solution quality, robustness, and convergence speed [10].

In this study, we propose an Adaptive Hybrid Metaheuristic (AHM) that integrates Genetic Algorithms with Local Search while incorporating stochastic modeling of travel-time uncertainty to address the VRPTW under realistic operating conditions. The primary contributions of this work are as follows:

1. Development of an Adaptive Hybrid Metaheuristic: A novel algorithm that adjusts key parameters dynamically to effectively balance exploration and exploitation during the optimization process.

2. Integration of Uncertainty Modeling: A probabilistic framework that captures the variability of real-world travel times through scenario-based simulations.

3. Comprehensive Performance Evaluation: Extensive testing on benchmark instances from Solomon’s suite, demonstrating the algorithm’s superiority in robustness, feasibility, and computational efficiency.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work in VRPTW and hybrid metaheuristics; Section 3 presents the problem formulation; Section 4 details the proposed methodology; Section 5 presents the experimental setup; Section 6 presents the results and a discussion; and Section 7 concludes with insights and future research directions.

The Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows (VRPTW) has been extensively studied due to its critical role in logistics and transportation. This section reviews significant contributions, focusing on recent advancements in exact methods, metaheuristic approaches, uncertainty modeling, and green logistics.

Early research on VRPTW primarily employed exact algorithms, such as branch-and-bound and dynamic programming, to find optimal solutions. However, these methods often faced scalability issues with larger problem instances. Recent studies have aimed to enhance the efficiency of exact methods. For instance, Baldacci et al. [11] provided a comprehensive review of exact algorithms for VRPTW, discussing their applicability and limitations in large-scale scenarios.

To address the limitations of exact methods, metaheuristic algorithms have been widely adopted. Techniques like GAs, Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) have been applied to VRPTW with notable success. Marinakis et al. [12] introduced a multi-adaptive PSO for VRPTW, demonstrating improved performance over traditional PSO variants. Furthermore, Zahedi and Khalilzadeh [13] proposed a hybrid metaheuristic algorithm combining the Nondominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) with Teaching–Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO) to solve a bi-objective capacitated electric vehicle routing problem with time windows and partial recharging. Their method efficiently balances routing cost and environmental impact, illustrating the growing interest in sustainable and multi-objective VRP solutions.

2.3 Handling Uncertainty in VRPTW

Real-world applications of VRPTW often involve uncertainties such as stochastic customer demands and variable travel times. Traditional deterministic models may not adequately capture these uncertainties, leading to suboptimal solutions. Recent research has focused on stochastic and robust optimization methods to better handle these challenges. Florio et al. [14] discussed Bayesian learning techniques for correlated demands in stochastic VRP, offering insights into handling demand uncertainty effectively. Additionally, Indrianti et al. [15] developed a Green Vehicle Routing Problem (GVRP) model that integrates complex real-world constraints—including emission reduction and delivery limits—using GAs.

2.4 Green Logistics and Sustainability

With the growing emphasis on sustainability, recent studies have integrated environmental objectives into VRPTW. Zahedi and Khalilzadeh [13] offered a hybrid metaheuristic algorithm combining NSGA-II and teaching–learning-based optimization for a bi-objective capacitated electric vehicle routing problem with time windows and partial recharging, addressing both economic and environmental considerations. Additionally, Fan [16] developed a hybrid adaptive large neighborhood search method for the time-dependent open electric vehicle routing problem with hybrid energy replenishment strategies, contributing to the advancement of sustainable transportation solutions.

2.5 Adaptive and Hybrid Metaheuristics

The integration of adaptive mechanisms into hybrid metaheuristics has shown promise in enhancing the flexibility and efficiency of VRPTW solutions. Chen et al. [7] proposed an Improved Genetic Ant Colony Optimization (IGA-ACO) algorithm to efficiently solve VRPTW, integrating Solomon’s insertion heuristic for population initialization and accelerating convergence while optimizing route planning to meet vehicle capacity and time window constraints. This approach highlights the potential of combining adaptive strategies with hybrid metaheuristics to tackle complex routing problems effectively.

The landscape of VRPTW research has evolved from classical exact methods to sophisticated hybrid metaheuristics that incorporate adaptive mechanisms and uncertainty modeling. Recent advancements have also integrated sustainability considerations, reflecting the multifaceted challenges of modern logistics. Despite these developments, opportunities remain to further enhance the adaptability and robustness of VRPTW solutions, particularly through the integration of real-time data and machine learning techniques.

To provide a concise and comparative overview of recent contributions to the VRPTW and its variants, Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of relevant studies, including the year of publication, problem variants addressed, uncertainty and sustainability aspects, the metaheuristic techniques employed, and a brief evaluation of their advantages and disadvantages.

We formulate the Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows under Uncertainty (VRPTW-U) on a complete directed graph

•

•

Each customer

• a non-negative demand

• a service time

• a time window

Each vehicle

• capacity Q,

• starting and ending location at the depot (

• and must obey all time window constraints.

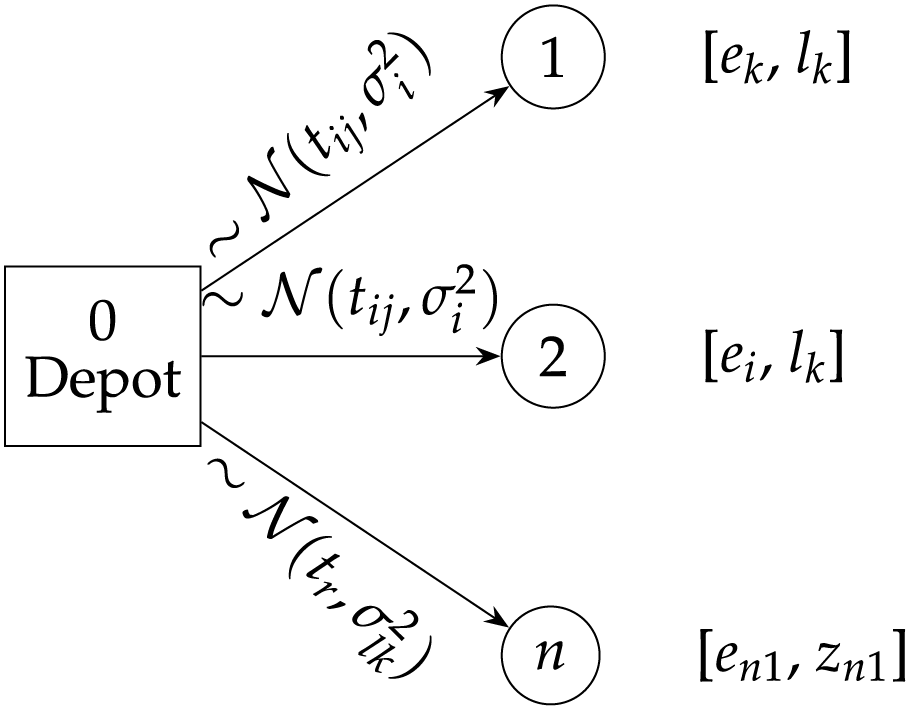

To enhance the intuitive understanding of the problem structure, a schematic representation is provided in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the VRPTW under uncertainty. A depot (node 0) serves multiple customers (nodes 1—

Let

where

The decision variables are:

The objective is to minimize the expected total travel time:

subject to:

Here, M is a large constant to deactivate time constraints when

To evaluate robustness under uncertainty, we simulate multiple realizations of

Robustness under Uncertainty

To evaluate solution robustness under uncertainty, we consider a finite scenario set

We reformulate the objective as a sample average approximation (SAA):

This allows the model to capture average-case performance over multiple realizations of travel-time variability.

Soft Time Windows with Penalization

In realistic settings, strict time window feasibility may not always be possible or desirable. Therefore, we allow soft time windows by introducing a non-negative violation term

The penalized objective function becomes:

where

This section presents our AHM for solving the Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows under Uncertainty (VRPTW-U). The algorithm integrates a GA+LS techniques and employs a scenario-based robustness framework to handle uncertain travel times. Furthermore, adaptive mechanisms are incorporated to dynamically adjust control parameters during the search process, enhancing convergence and solution quality.

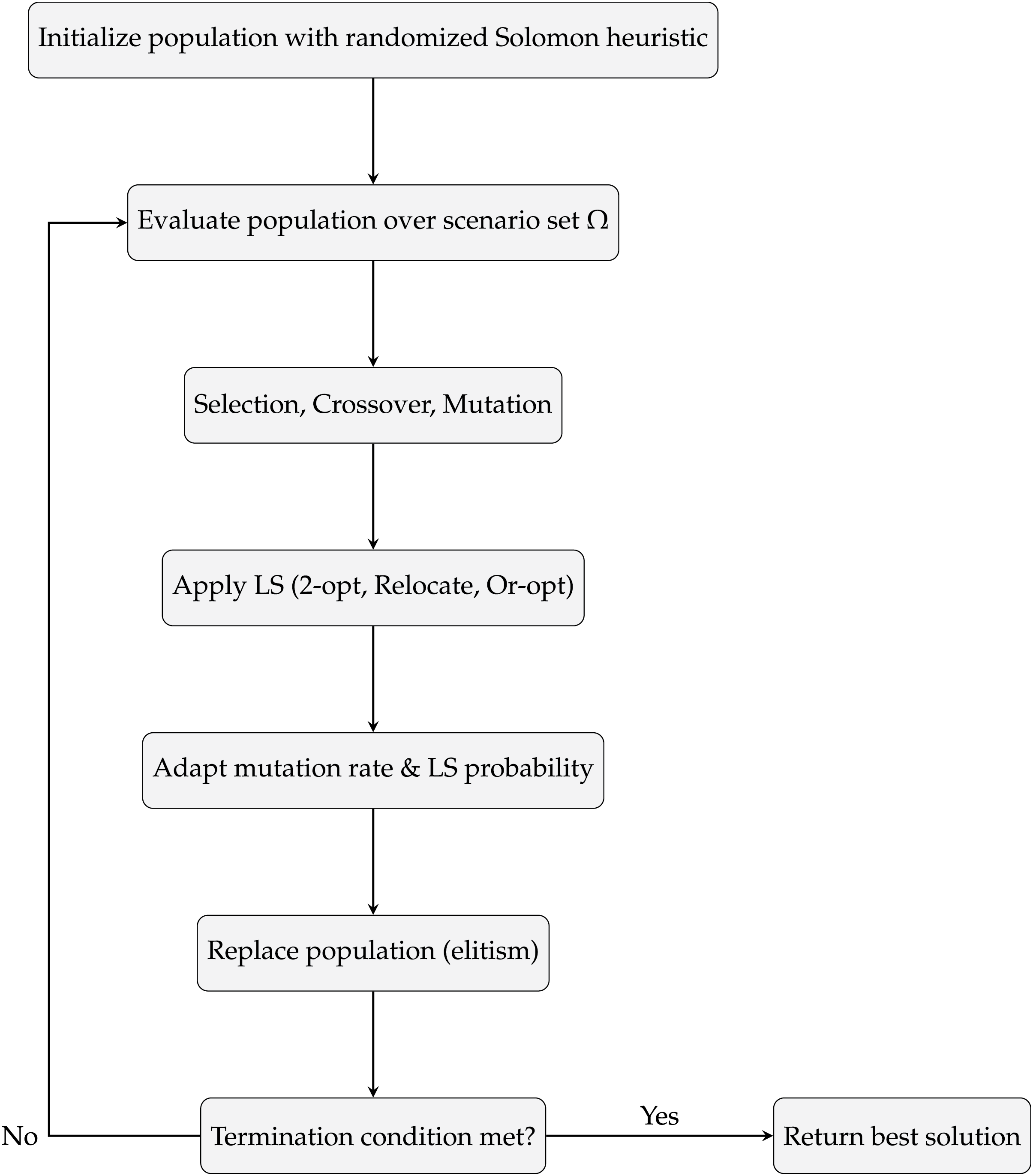

Fig. 2 illustrates the main components of the proposed algorithm, showing how evolutionary and LS operations interact with adaptive control and uncertainty handling.

Figure 2: Flowchart of the proposed adaptive hybrid GA+LS for VRPTW under uncertainty

The proposed method is initialized with a population of feasible routing solutions constructed using a randomized version of Solomon’s insertion heuristic [2]. A standard GA is then employed to evolve the population through selection, crossover, and mutation operators. After each generation, a LS procedure is applied to selected individuals to improve solution quality through neighborhood exploration. The process is iterated for a fixed number of generations or until convergence criteria are met.

Uncertain travel times are incorporated using a scenario-based simulation approach. For each solution, its fitness is evaluated by sampling from a set of stochastic realizations and computing an expected (or worst-case) cost. Time window violations are softly penalized to allow trade-offs under uncertainty.

4.2 Solution Encoding and Initialization

Each individual in the population represents a complete set of vehicle routes. The chromosome is encoded as a permutation of customer indices, segmented into routes based on vehicle capacity and time window feasibility. The initial population is generated using a randomized greedy heuristic based on Solomon’s insertion rule.

To evolve the population toward better solutions, we apply standard genetic operators adapted to the VRPTW context. These include selection, crossover, and mutation, each designed to preserve route feasibility and encourage solution diversity:

• Selection: We employ tournament selection with replacement to ensure selection pressure while maintaining diversity.

• Crossover: A route-based crossover (RBX) operator is used, which swaps complete routes between parents, preserving route structure and feasibility.

• Mutation: A swap mutation operator randomly exchanges two customers in a route or between routes. Feasibility repair is applied post-mutation if necessary.

To refine candidate solutions, a LS procedure is applied after crossover and mutation. The neighborhood includes:

• 2-opt: Reverses a segment within a route to reduce distance.

• Relocate: Moves a customer from one route to another if feasible.

• Or-opt: Moves a string of consecutive customers within or across routes.

The LS is applied using a first-improvement or best-improvement strategy, and applied probabilistically to avoid excessive computation.

Each solution is evaluated over a scenario set

This provides a robust fitness evaluation incorporating both stochastic travel costs and penalized infeasibility.

An adaptive strategy is used to control the mutation rate

where

• If

• If

In our experiments, we set

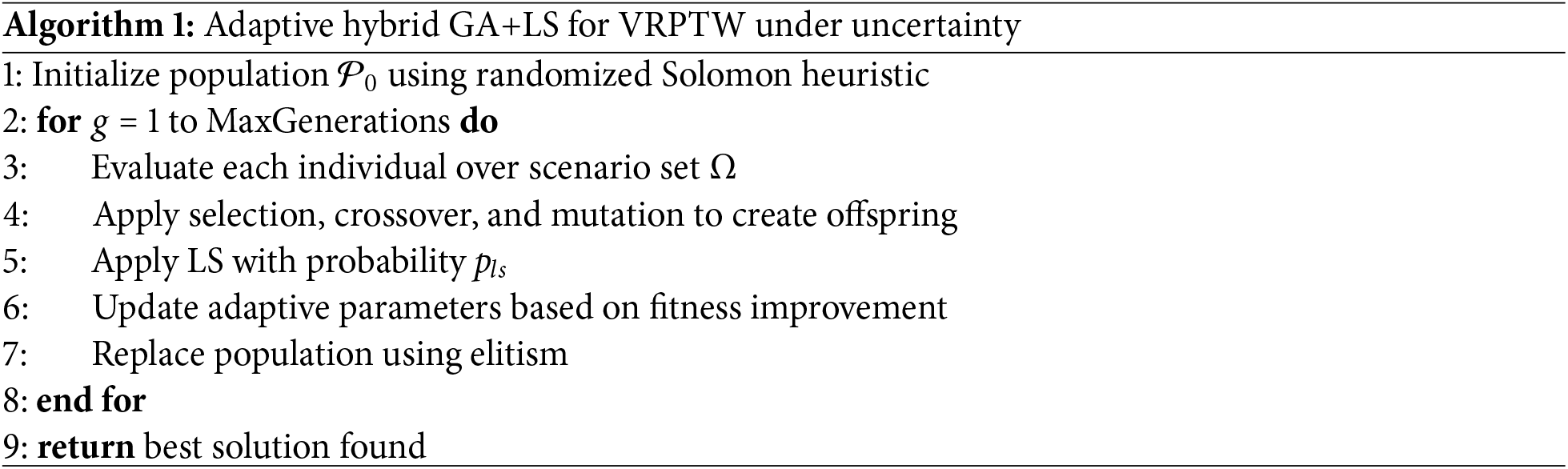

Algorithm 1 outlines the main steps of the proposed AHM. It integrates initialization, evaluation under uncertainty, evolutionary operations, LS, and adaptive control into a single iterative framework.

This section describes the datasets, parameter settings, uncertainty modeling, and evaluation metrics used to assess the performance of the proposed AHM for the VRPTW under uncertainty.

We use the well-known Solomon benchmark suite [2], which provides 56 VRPTW test instances categorized into three groups:

• C-type: clustered customer locations with narrow time windows (e.g., C101–C206)

• R-type: randomly distributed customers (e.g., R101–R211)

• RC-type: a mix of clustered and random distributions (e.g., RC101–RC208)

Each instance includes 100 customers, fixed depot location, vehicle capacity constraints, and strict time windows.

To simulate real-world travel time variability, we perturb deterministic travel times between customers with stochastic noise modeled as a Gaussian distribution:

The variance

where

The assumption of Gaussian-distributed noise is widely adopted in transportation modeling due to its analytical tractability and its ability to approximate various sources of small, random fluctuations observed in urban traffic systems. Studies such as Florio et al. [14] have demonstrated the applicability of this assumption in capturing the effects of stochastic travel times in logistics.

Nonetheless, we recognize that real-world travel time distributions may deviate from Gaussian behavior, particularly in the presence of skewed delays, incidents, or heavy-tailed congestion effects. Alternative distributions such as log-normal or uniform could offer more realistic modeling in certain contexts. While a comprehensive evaluation of different noise models is beyond the scope of this study, we discuss their implications in Section 6.1 and identify this as an important direction for future research.

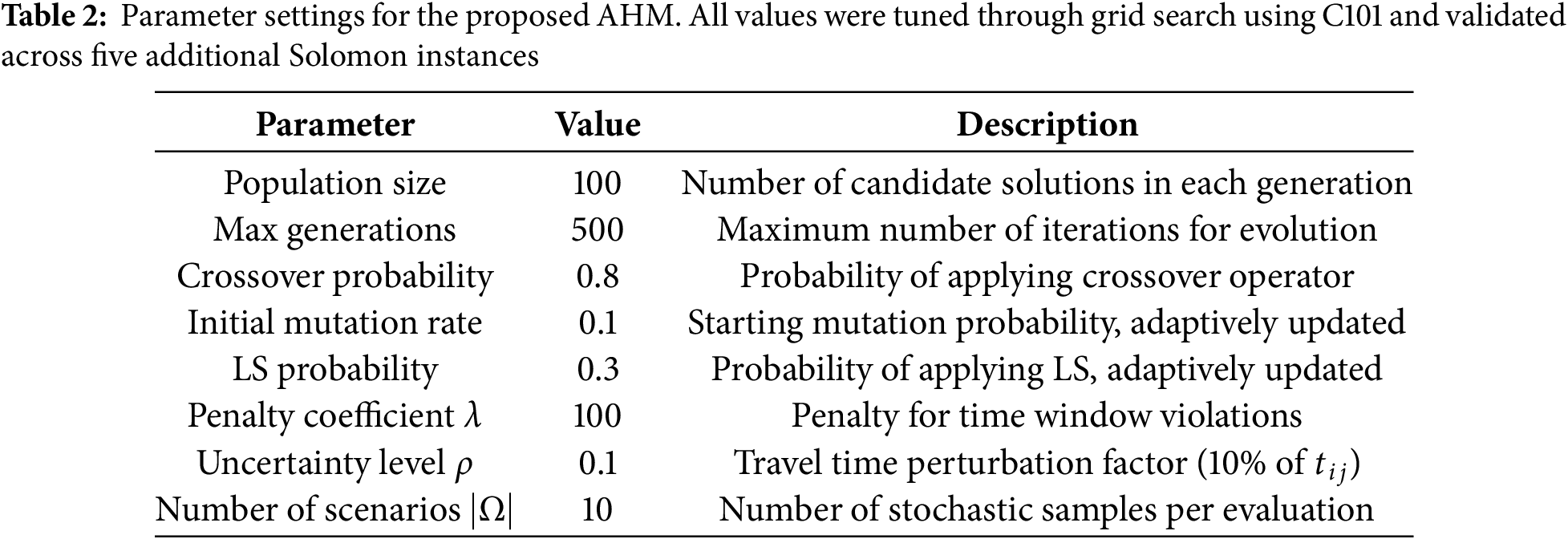

The algorithm’s parameters are configured as follows:

• Population size: 100

• Number of generations: 500

• Crossover probability: 0.8

• Initial mutation rate: 0.1 (adaptive)

• LS application probability: 0.3 (adaptive)

• Penalty weight for time window violation:

All parameters were calibrated through preliminary testing and grid search on a subset of instances.

The main parameters used in our algorithm are listed in Table 2. These values were selected based on preliminary experiments and empirical tuning.

Experiments were executed on a machine with the following specifications:

• CPU: Intel Core i7-12700H, 2.7 GHz

• RAM: 16 GB

• OS: Ubuntu 22.04

• Language: Python 3.11 with NumPy and SciPy

Each algorithm was run 10 times per instance to account for stochastic behavior, and average results are reported.

To assess performance under uncertainty, we use the following metrics:

• Expected Total Travel Time: average cost across

• Time Window Violation: total lateness across all nodes and scenarios.

• Robustness Index: standard deviation of cost across scenarios.

• Execution Time: total runtime in seconds.

For comparison, we benchmark our approach against a classic GA and a non-adaptive hybrid GA+LS.

This section presents the experimental results obtained using the proposed AHM on the Solomon benchmark instances under uncertain travel times. We compare its performance with two baselines: a standard GA and a non-adaptive GA+LS hybrid. Metrics include expected total travel time, time window violations, robustness (variance), and execution time.

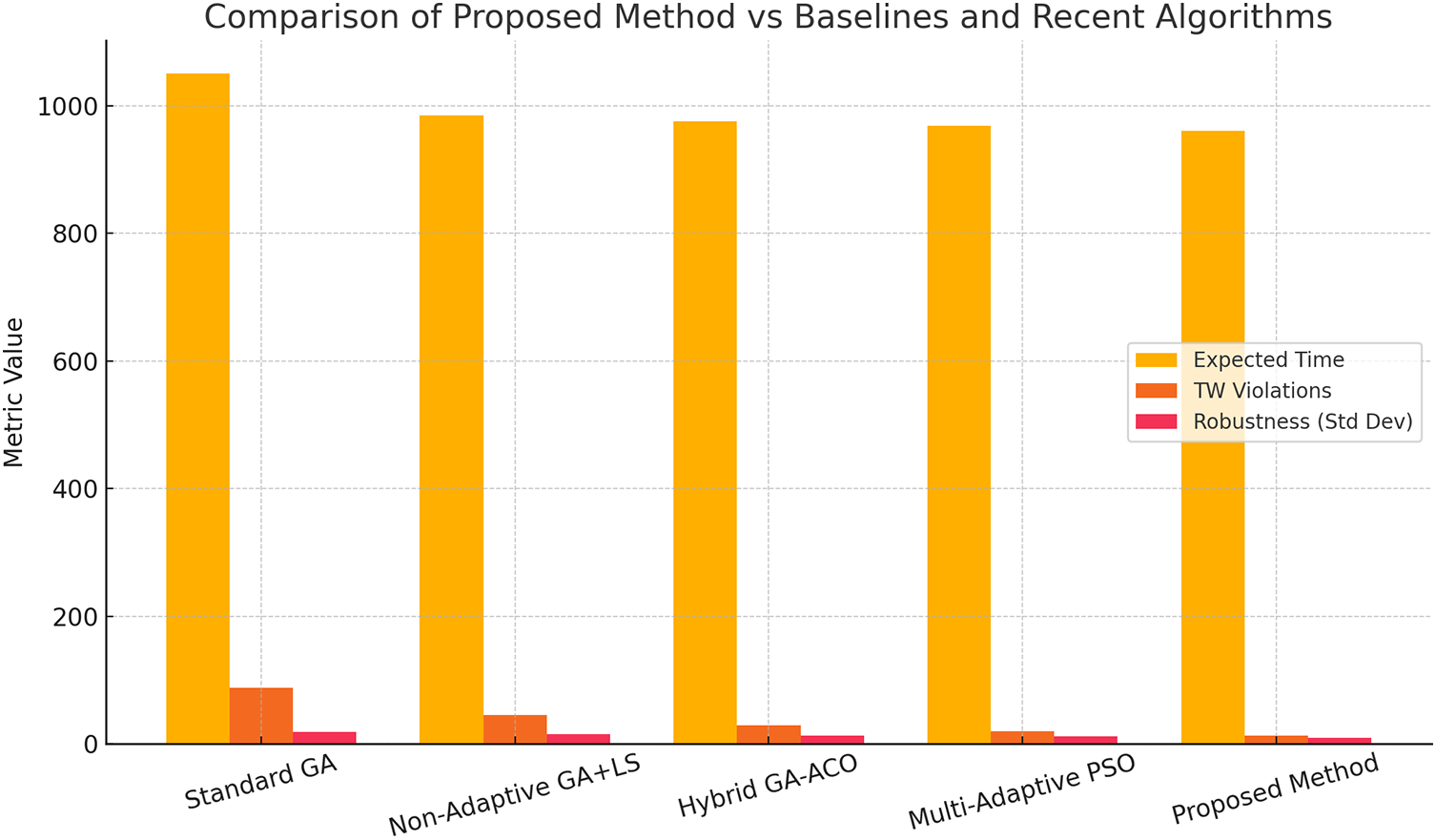

6.1 Comparison with Baseline and Recent Methods

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed AHM, we compare it against both traditional baselines and two recent state-of-the-art approaches from the literature:

• Standard GA: a canonical GA with fixed parameters.

• Non-Adaptive GA+LS: a static hybrid of GA with LS, but without adaptive control.

• Hybrid GA-ACO: the method of Chen et al. [7], integrating genetic and ant colony strategies.

• Multi-Adaptive PSO: the particle swarm variant of Marinakis et al. [12], with dynamic control mechanisms.

Table 3 presents the average performance across three representative Solomon instances (C101, R101, RC101), with 10 runs and 10 uncertainty scenarios per run. The proposed method consistently achieves superior results in expected travel time, time window feasibility, and robustness, while maintaining competitive runtime.

As shown in Fig. 3, the proposed method converges more rapidly and attains a significantly lower final cost than the other methods. This suggests that the combined effect of adaptivity and local refinement not only improves solution quality but also enhances convergence speed.

Figure 3: Convergence behavior of the proposed method compared to baseline GA and GA+LS over 500 generations. Results are averaged over 10 runs per instance on three Solomon benchmark instances (C101, R101, RC101)

Overall, the proposed approach strikes a compelling balance between runtime, quality, and robustness—making it suitable for deployment in real-time or uncertainty-aware logistics environments.

6.2 Performance across Instance Types

To better understand how spatial distribution impacts solution robustness and efficiency, we analyze the performance of the proposed method across the three canonical categories of Solomon benchmark instances: C-type (clustered), R-type (random), and RC-type (mixed). Fig. 4 visualizes sample customer layouts from each category, revealing the inherent structural differences that influence routing complexity.

Figure 4: Illustrative customer layouts from Solomon instances: C101 (clustered), R101 (random), and RC101 (mixed). Each layout represents 45 customer nodes; spatial patterns influence routing complexity and robustness

To ensure statistical validity, we evaluated five benchmark instances per category: C-type: C101, C102, C104, C106, C108; R-type: R101, R103, R105, R108, R110; RC-type: RC101, RC103, RC104, RC105, RC108. Each instance was solved using 10 independent runs, with 10 stochastic scenarios per run.

Fig. 5 compares the average expected travel time and cumulative time window violations across categories. As expected, performance is strongest on C-type instances due to spatial compactness, which facilitates more efficient route planning. R-type instances yield higher travel times and constraint violations, reflecting the challenge of servicing spatially dispersed customers. RC-type results fall between the two extremes, highlighting the method’s adaptability in hybrid spatial configurations.

Figure 5: Average expected travel time and time window violations across C-, R-, and RC-type Solomon instances. Results are based on 5 instances per category, 10 runs per instance, and 10 uncertainty scenarios per run

To further evaluate robustness, Fig. 6 shows the distribution of expected travel times across all scenarios and runs. The C-type category demonstrates not only the lowest average cost but also the tightest interquartile range, confirming superior robustness under uncertainty. In contrast, R-type instances show greater variability, indicating sensitivity to stochastic disruptions.

Figure 6: Distribution of expected total travel time for the proposed method across 10 stochastic scenarios and 10 independent runs, shown per instance type. C-type results are more robust, with less variability than R- and RC-types

These results reinforce that the proposed method adapts well across spatial structures and maintains reliable performance even under uncertain travel conditions. Its robustness is particularly pronounced in scenarios where spatial clustering can be leveraged.

6.3 Impact of Uncertainty Level and Scenario Count

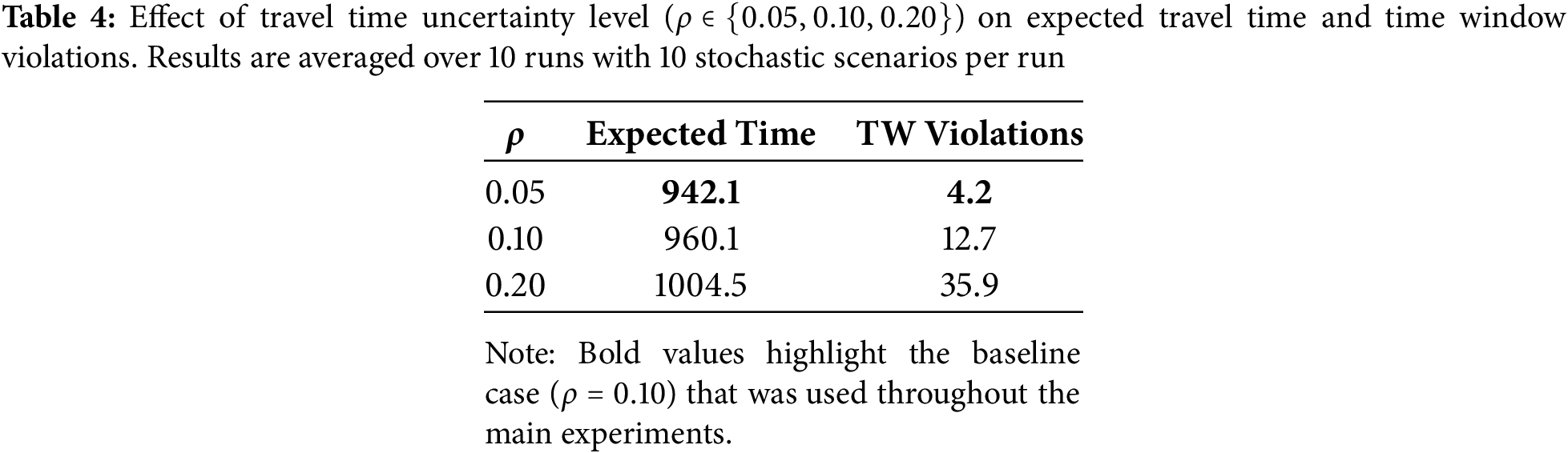

To assess the robustness of the proposed method under increasing uncertainty, we vary the uncertainty level

As expected, both cost and constraint violations increase with higher uncertainty levels. However, the algorithm maintains feasible solutions and smooth degradation, confirming its robustness to stochastic disturbances.

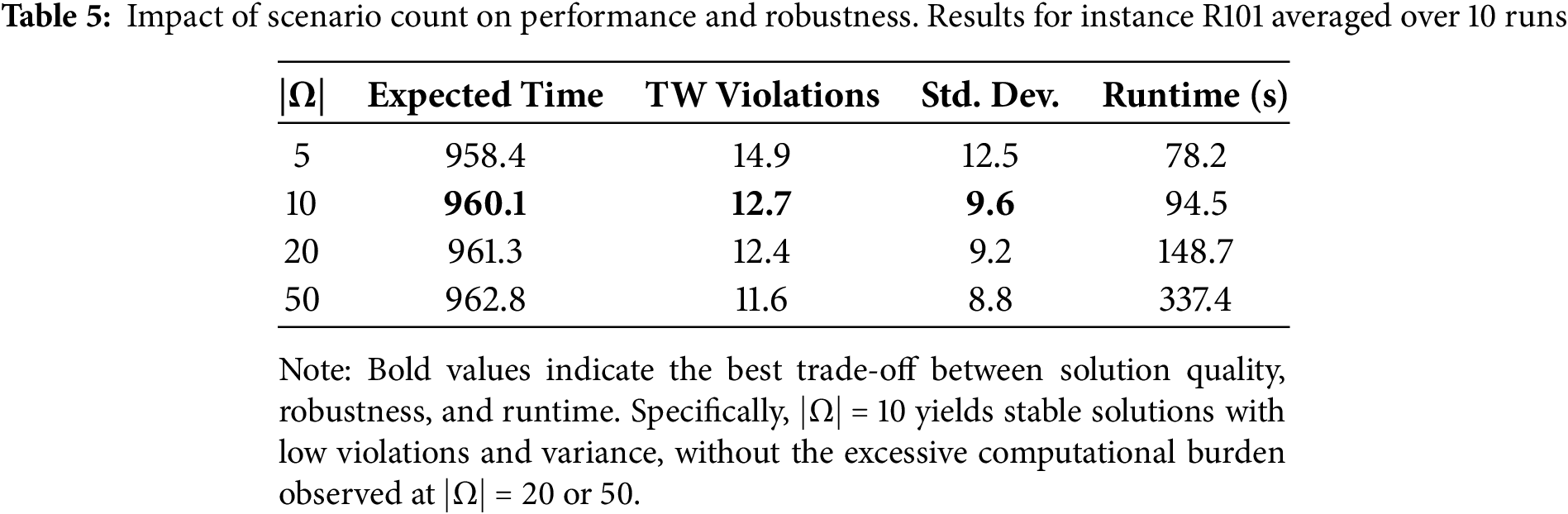

To evaluate the adequacy of the scenario count

The results indicate that while increasing the number of scenarios slightly improves robustness (lower standard deviation), the marginal benefit diminishes beyond

In summary, the proposed method handles varying uncertainty levels effectively and achieves stable performance with a moderate number of evaluation scenarios.

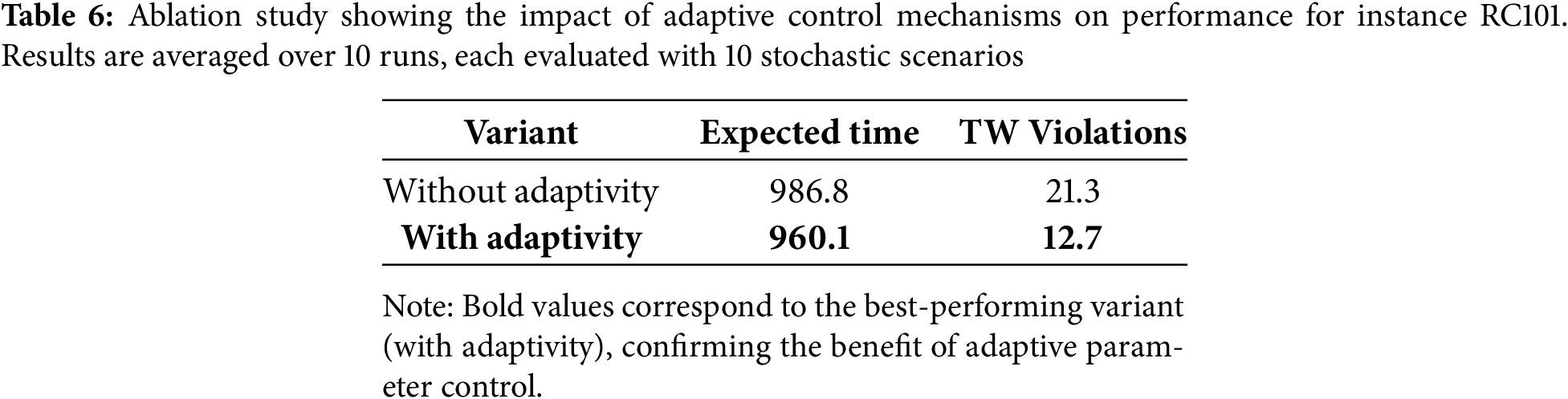

To assess the contribution of the adaptive mechanism, we disable it and compare results with the full version. Table 6 shows that adaptivity improves solution quality and reduces time window violations.

The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed AHM consistently produces high-quality and robust solutions across a diverse range of VRPTW instances, particularly under conditions of stochastic travel times. By integrating dynamic parameter tuning and LS, the method significantly outperforms both traditional and contemporary hybrid approaches.

Compared to recent algorithms such as the Multi-Adaptive PSO by Marinakis et al. [12] and the Hybrid GA-ACO by Chen et al. [7], the proposed method achieves lower expected travel times, fewer time window violations, and reduced solution variability. The convergence analysis further shows that adaptivity accelerates performance gains over generations, especially in complex or noisy routing scenarios.

Our robustness analysis (Sections 6.2, 6.3) confirms that the method remains effective across a wide range of spatial distributions and uncertainty levels. In particular, it shows superior stability on clustered instances (C-type), which typically benefit from tighter route packing and less travel-time variance. Moreover, our evaluation of the scenario count indicates that using 10 scenarios (

While the method incurs moderately higher runtime compared to a standard GA, the additional computational effort is justified in settings where solution feasibility and consistency are mission-critical—such as last-mile delivery, emergency routing, or green logistics [13,15,16].

In summary, the proposed approach offers a flexible, scalable, and uncertainty-aware routing solution that combines adaptive control, probabilistic modeling, and effective LS. Its ability to generalize across different VRPTW structures makes it a strong candidate for deployment in real-world transportation systems.

Future work could explore the following directions:

• Real-time adaptation based on live traffic or delivery updates.

• Extension to larger-scale or multi-depot VRP variants.

• Integration with machine learning for demand or delay prediction.

• Multi-objective optimization including emissions, fairness, and service level agreements.

To complement the empirical performance evaluation, we analyze the time complexity of the proposed and baseline methods. The standard GA exhibits a time complexity of

This paper proposed an Adaptive Hybrid Metaheuristic for solving the Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows under Uncertainty (VRPTW-U). The algorithm integrates a Genetic Algorithm with Local Search and incorporates uncertainty modeling via scenario-based stochastic evaluation. An adaptive mechanism dynamically adjusts algorithmic parameters based on feedback from the search process, balancing exploration and exploitation throughout the search.

Experimental results on Solomon benchmark instances demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms both standard GA and static hybrid approaches in terms of expected travel time, time window feasibility, and robustness under stochastic conditions. The method showed particularly strong performance on clustered (C-type) instances, while maintaining resilience on random and mixed layouts. Additional analysis confirmed the benefit of the adaptive mechanism and the ability to handle varying levels of uncertainty with minimal performance degradation.

From a practical standpoint, the proposed approach is well-suited for logistics environments where demand and travel conditions are variable, such as last-mile delivery, green vehicle routing, or real-time distribution planning.

Future work may explore the following extensions:

• Integration of real-time data streams (e.g., traffic, weather) to support dynamic routing.

• Multi-objective formulations incorporating cost, emissions, and service quality.

• Application to large-scale or multi-depot VRP variants under uncertainty.

• Deep learning models for demand prediction and adaptive parameter control.

Overall, this work provides a flexible and robust framework for solving complex vehicle routing problems under realistic and uncertain conditions.

Acknowledgement: The author gratefully acknowledges the University of Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro and the Institute of Electronics and Informatics Engineering of Aveiro (IEETA) for providing the necessary resources and support to carry out this research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Manuel J. C. S. Reis, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Sensitivity Analysis of Adaptive Thresholds

To evaluate the robustness of our adaptive strategy, we conducted a sensitivity analysis on the thresholds

As shown in Table A1, the configuration

References

1. Bräysy O, Gendreau M. Vehicle routing problem with time windows, part I: route construction and local search algorithms. Transp Sci. 2005;39(1):104–18. doi:10.1287/trsc.1030.0056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Solomon MM. Algorithms for the vehicle routing and scheduling problems with time window constraints. Oper Res. 1987;35(2):254–65. doi:10.1287/opre.35.2.254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bertsimas D, Simchi-Levi D. A new generation of vehicle routing research: robust algorithms, addressing uncertainty. Oper Res. 1996;44(2):286–304. doi:10.1287/opre.44.2.286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Laporte G. The vehicle routing problem: an overview of exact and approximate algorithms. Eur J Oper Res. 1992;59(3):345–58. doi:10.1016/0377-2217(92)90192-c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gendreau M, Hertz A, Laporte G. A Tabu Search Heuristic for the vehicle routing problem. Transp Sci. 1994;28(2):130–9. doi:10.1287/mnsc.40.10.1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Potvin JY, Rousseau JM. An exchange heuristic for routing problems with time windows. J Oper Res Soc. 1995;46(12):1433–46. doi:10.1057/jors.1995.204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Chen G, Gao J, Chen D. Research on vehicle routing problem with time windows based on improved genetic algorithm and ant colony algorithm. Electronics. 2025 Jan;14(4):647. doi:10.3390/electronics14040647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kahalimoghadam M, Thompson RG, Rajabifard A. Self-adaptive metaheuristic-based emissions reduction in a collaborative vehicle routing problem. Sustain Cities Soc. 2024;110:105577. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2024.105577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kumari M, De PK, Chaudhuri K, Narang P. Utilizing a hybrid metaheuristic algorithm to solve capacitated vehicle routing problem. Results Control Optim. 2023;13:100292. doi:10.1016/j.rico.2023.100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sbai I, Limem O, Krichen S. An adaptive genetic algorithm for the capacitated vehicle routing problem with time windows and two-dimensional loading constraints. In: 2017 IEEE/ACS 14th International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA); 2017 Oct 30–Nov 3; Hammamet, Tunisia. p. 88–95. [Google Scholar]

11. Baldacci R, Mingozzi A, Roberti R. Recent exact algorithms for solving the vehicle routing problem under capacity and time window constraints. Eur J Oper Res. 2012;218(1):1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2011.07.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Marinakis Y, Marinaki M, Migdalas A. A multi-adaptive particle swarm optimization for the vehicle routing problem with time windows. Inform Sci. 2019;481:311–29. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2018.12.086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zahedi K, Khalilzadeh M. A hybrid metaheuristic approach for solving a bi-objective capacitated electric vehicle routing problem with time windows and partial recharging. J Clean Prod. 2023;383:135372. doi:10.1108/jamr-01-2023-0007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Florio AM, Gendreau M, Hartl RF, Minner S, Vidal T. Recent advances in vehicle routing with stochastic demands: bayesian learning for correlated demands and elementary branch-price-and-cut. Eur J Oper Res. 2023 May;306(3):1081–93. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2022.10.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Indrianti N, Leuveano RAC, Abdul-Rashid SH, Ridho MI. Green vehicle routing problem optimization for LPG distribution: genetic algorithms for complex constraints and emission reduction. Sustainability. 2025;17(3):1144. doi:10.3390/su17031144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Fan L. A hybrid adaptive large neighborhood search for time-dependent open electric vehicle routing problem with hybrid energy replenishment strategies. PLoS One. 2023;18(9):e0291473. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0291473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools