Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Security Challenges and Analysis Tools in Internet of Health Things: A Comprehensive Review

1 Department of Mathematics, College of Science, University of Basrah, Basrah, 61004, Iraq

2 Department of Computer Science, College of Education for Pure Sciences, University of Basrah, Basrah, 61004, Iraq

3 Department of Business Management, Al-Imam University College, Balad, 34011, Iraq

4 Shenzhen Institute, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, 518000, China

5 Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, 40601, Kenya

6 Department of Applied Electronics, Saveetha School of Engineering, SIMATS, Chennai, 602105, Tamil Nadu, India

7 Department of Electrical Engineering and Mechatronics, Faculty of Engineering, University of Debrecen, Otemeto u.4-5, Debrecen, 4028, Hungary

8 College of Engineering, National University of Science and Technology, Dhi Qar, 64001, Iraq

* Corresponding Authors: Ali A. Yassin. Email: ; Zaid Ameen Abduljabbar. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2305-2345. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066579

Received 11 April 2025; Accepted 28 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

The digital revolution era has impacted various domains, including healthcare, where digital technology enables access to and control of medical information, remote patient monitoring, and enhanced clinical support based on the Internet of Health Things (IoHTs). However, data privacy and security, data management, and scalability present challenges to widespread adoption. This paper presents a comprehensive literature review that examines the authentication mechanisms utilized within IoHT, highlighting their critical roles in ensuring secure data exchange and patient privacy. This includes various authentication technologies and strategies, such as biometric and multi-factor authentication, as well as the influence of emerging technologies like blockchain, fog computing, and Artificial Intelligence (AI). The findings indicate that emerging technologies offer hope for the future of IoHT security, promising to address key challenges such as scalability, integrity, privacy and other security requirements. With this systematic review, healthcare providers, decision makers, scientists and researchers are empowered to confidently evaluate the applicability of IoT in healthcare, shaping the future of this field.Keywords

Over the past three decades, the Healthcare System (HCS) has undergone extensive changes and improvements globally [1]. However, the healthcare sector faces numerous challenges, including continuous population growth, behavioral changes, shifting lifestyles, and a range of chronic and infectious diseases. These challenges have necessitated the design of advanced technological implementations and systems that monitor, measure, forward and disseminate health-related data to the relevant stakeholders. This has been demonstrated to help meet the needs of patients, families, and service providers [2].

The HCS framework is a testament to the value of collaboration among diverse group of people, institutions and information communication technology resources to address medical needs and services. While HCSs vary and differ across countries and cultures, they still share fundamental components: the human and physical resources [3]. The human component encompasses various roles, including system supervisors, service providers, and employees responsible for feeding the system with data, analysis, and maintenance, among others. This component also includes users who have the authority to browse, read, modify, and work on data as patients, doctors, or medical technicians [4]. Meanwhile, the physical component comprises peripheral devices, such as sensors, wearable devices, radiology equipment, analytical instruments, and others, which provide feedback to the system regarding the patient’s condition, diagnosis, and medical treatment [5]. Cloud computing represents one such physical resource, where numerous devices support diverse functions such as transferring and controlling data among components [6]. The cloud systems are characterized by local or global servers, peripheral computers for browsing and access, as well as mobile devices for users or doctors to interact with and utilize the system’s functionality [7,8].

The Internet of Things (IoT) has become a crucial component in the success of various services across multiple fields related to networked information systems [9]. IoT comprises physical objects or ‘things’ embedded with sensors, software, and other technologies that enable data exchange and interconnection of entities (people and devices) over the Internet [10]. These connected “things” can be industrial elements, sensors, household items, or mobiles. Basically, IoT components are responsible for collecting and sharing data, allowing smart and highly efficient operations and decision-making across various sectors, such as smart cities, commerce, healthcare and educational systems [11]. As explained in [12], healthcare is one of the common applications of IoT, as healthcare data requires high regulatory and security strategies [12].

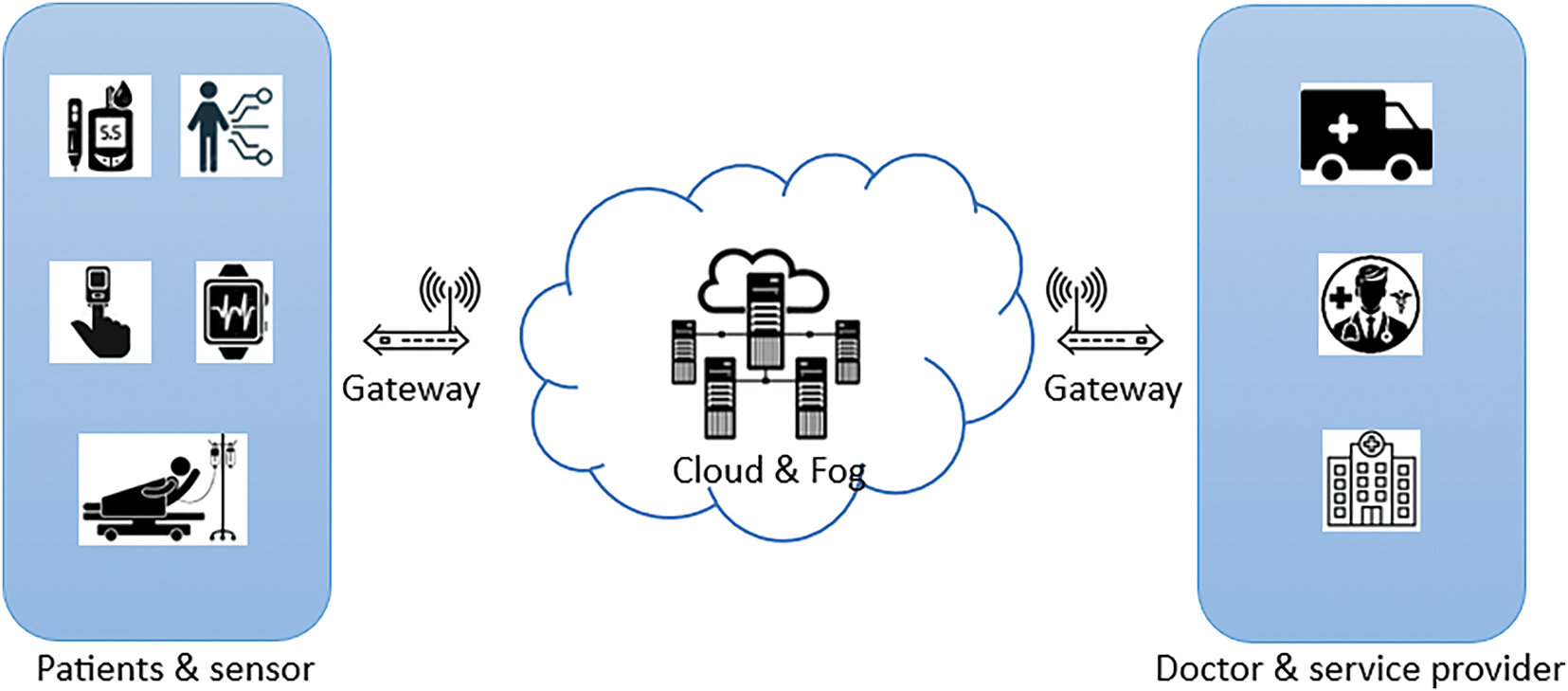

The traditional HCS was built based on the IoT architecture, referred to as the Internet of Health Things (IoHT) [13] or Internet of Medical Things IoMT [6], based on how systems react to data. Basically, IoHT is a system to monitor and alert, while IoMT is a system to monitor and treat [14,15]. Fig. 1 illustrates the main elements of a typical IoHT system.

Figure 1: IoHT system

Medical devices in IoHT are designed to collect and analyze a wide range of data. These devices connect to sensors that track patient physiological data such as blood pressure, sugar, heart rate, and body temperature. Additionally, data on other activities unrelated to diseases, such as sleep patterns or walking can be monitored and collected [12,16]. Furthermore, IoHT devices have implicit algorithms for analysis, decision-making, and writing reports. This helps enhance medical care and support the healthcare systems even in the absence of medical staff [17,18]. This advancement has played a crucial role in managing chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease. As such, IoHT provides assurance about the potential of technology in improving the healthcare sector [19].

With the increasing number of connected devices, systems, and the diversity of data and connected networks, the IoHT continues to evolve and mature. However, this technological development comes with various risks and challenges arising from the amount of data processed and transmitted via different networks. Such risks include healthcare data leakages, modifications, integrity violation, and unauthorized access [20,21]. For instance, a report by Censys reveals that nearly 14,004 unique IP addresses threaten healthcare devices and data systems on the public internet, exposing them to the risk of unauthorized access, with potentially many more devices remaining invisible. Meanwhile, the FBI’s 2023 Internet Crime Report identifies the Healthcare and Public Health sector as the primary targets for ransomware attacks [22]. Another concern in IoHT is data sharing, ownership, and protection from unauthorized access and host–provider intrusion. Therefore, strict regulatory and security strategies are required [12]. As such, researchers and practitioners have been exploring and developing many technologies to mitigate these risks, including cyber and physical attacks [23,24].

In IoHT, authentication is the primary and most critical line of defense for safeguarding exchanged data. In an IoHT environment, effective authentication and access management are essential due to the volume and sensitivity of healthcare data and applications. In addition, robust security protection is required due to the critical role these systems play in patient care, which remains vulnerable to various cyber threats [25]. Some of the well-known malicious attacks in IoHT include Denial of Service (DoS), Man-In-The-Middle (MITM) [26], malware infections, spoofing, replay, phishing, and insider attacks [27]. Therefore, there is need to implement and evaluate robust authentication techniques so as to ensure the secure management of IoT devices [28]. Consequently, numerous security techniques, algorithms, models, frameworks, protocols, and methods have been presented in literature [29].

Ideal authentication systems for IoT must help preserve integrity, privacy, and availability [30]. In addition, other features such as confidentiality, key agreement, scalability, and password change, are required to ensure comprehensive security [31]. Although traditional password-based authentication is simple, cost-effective, and does not require extra devices or tokens, it poses significant security challenges. For instance, passwords are easy to hack, and can be obtained through conventional eavesdropping and fraudulent methods [16,20]. Meanwhile, the hacked account risks differ based on the role played by the authenticated user. For example, a patient exposing data faces a lower risk than a doctor or employee with authority to access and modify that data [32].

Apart from password-based solutions, several biometric authentication methods have been proposed to protect medical information and securely manage data flows [33]. In biometric authentication, unique physical characteristics of individuals are utilized for identification and security [34]. To achieve this, many biometric features are deployed, ranging from fingerprints, facial, voice, iris, to palms [35,36]. These methods are considered highly secure due to the unique traits of the individual entities that cannot be easily cloned [34,37]. In addition, these methods provide user-friendly authentication, reducing the risk of stealing or replicating passwords. As explained in [34], biometric traits enhance security by applying multi-factor authentication. In spite of all the advantages, biometric authentication suffers from privacy concerns since the entities involved give their bio information. In addition, biometric authentication systems are costly and can experience recognition failure, as well as potential inaccuracies such as false positives or false negatives [31].

Artificial intelligence (AI) learning mechanisms play a vital role in developing and implementing advanced authentication systems to detect hacking or attacks. In addition, AI helps create approaches or applications that monitor and evaluate any processes or indicators related to any access by intruders, determine its severity, and establish whether it is acceptable or not [38]. The most well-known AI learning architectures are deep learning (DL) methods and machine learning (ML) algorithms [39]. In a nutshell, AI systems can observe and learn from user behavior over time and repeated attempts, providing continuous real-time authentication, immediately detecting anomalies and suspicious activities [40]. However, it’s crucial to note that AI can also be utilized as an attack vector to enhance the effectiveness and sophistication of cyberattacks. This potential underscores the urgency of developing robust security measures, as AI can leverage its capabilities to deceive targets and manipulate automated phishing attacks [41], malware Development, as well as brute force attacks. This is accomplished by the prediction of likely passwords based on user behavior and common patterns, as well as exploiting network weaknesses more efficiently and effectively [42]. However, these AI systems may suffer from complexity, misidentification, training data quality dependency, and cost-related issues [40,43].

Essentially, IoHT systems must be available anytime and anywhere, ensuring easy accessibility and user-friendliness [44]. To the greatest extent possible, IoHT systems should remain effective even during crises or outages and operate seamlessly across different devices and platforms. To achieve this, it is necessary to adopt decentralization in the design of IoHT [45]. Recently, a decentralized and distributed ledger technology, referred to as Blockchain (BC), has been developed. This technology plays a crucial role in preventing unauthorized access and data breaches through cryptographic techniques [46]. It is utilized in authentication through transaction verification, presenting unalterable and trustable authentication technique [47]. In addition, Blockchain uses cryptography to ensure that only authorized users can access or manipulate authentication information, providing a reassuring layer of security [48].

Another decentralized computing infrastructure is Fog Computing (FC), which increases the utility of network edges by allowing them to implement data operations (process, store, analysis) instead of depending on centralized cloud servers [49]. FC is effective in enhancing authentication for IoHT systems through the reduction of authentication time. It also offers real-time verification with multi-layered security such as local firewalls and intrusion detection systems [50]. Furthermore, FC contributes to scalability by facilitating the addition of nodes and terminals whilst maintaining system consistency and performance. As explained in [51], FC supports Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) through the incorporation of authentication at various system layers [51].

The main contributions of this paper are illustrated as follows:

1. Providing a comprehensive and chronological literature review of authentication techniques to understand the evolution of security in IoHT systems.

2. The analysis of common authentication methods and security requirements, along with the integration of traditional and AI techniques, is a significant aspect of this research. This integration holds the potential for improved threat detection in IoHT systems. Examining how FC and BC are utilized to enhance the security requirements of the IoHT environment, focusing on authentication mechanisms.

3. This paper helps bring out the transformative potential of AI-based tools that offer semantic robustness in addressing security challenges in the IoHT environment.

4. Discussing security vulnerabilities, their detection and corresponding countermeasures using ML and DL algorithms and BC techniques.

5. Providing an overview of the formal tools and testing methodologies for analyzing security protocols.

6. Finally, we discuss several studies that combined various models and methods to strengthen privacy and safety, identifying critical security gaps.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: Section 3 discusses the IoHT system model, including architecture, security requirements, threats and solutions. Sections 4 and 5 describe various IoHT security tools and security analysis tools, respectively. On the other hand, Section 6 provides a review of related works in IoHT. In contrast, Section 8 highlights future concerns that should be considered in the development of IoHT systems, underscoring the need for further research and development in this area. Finally, Section 9 concludes the paper.

A systematic literature search was conducted in Google Scholar, Scopus and IEEE Library, adhering to the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), a widely accepted framework for conducting systematic reviews. To ensure comprehensive coverage of the relevant research landscape, the search terms included “Internet of Things”, “IOT”, “IOHT”, “IOMT”, “IODT”, and to further refine the search, the terms “Blockchain”, “IPFS”, and fog computing were also incorporated in combination with “Healthcare system”. Additionally, inclusion criteria were English language articles published in reputable journals, available in full text, and published in the period (2005–2025) to capture both the early development and more recent advancements in the field. Following the initial search based on the inclusion criteria, a total of 974 articles were swiftly and efficiently filtered by title and abstract with irrelevant papers promptly excluded ensuring a streamlined and time-efficient process.

Duplicate articles were also filtered to finally yield 183 articles, which were deemed the most relevant and comprehensive for the study. Notably, 39 articles of the final chosen articles were IoHT-relevant systematic reviews and survey articles. Fig. 2 shows the PRISMA flowchart outlining search and inclusion criteria.

Figure 2: PRISMA flow chart

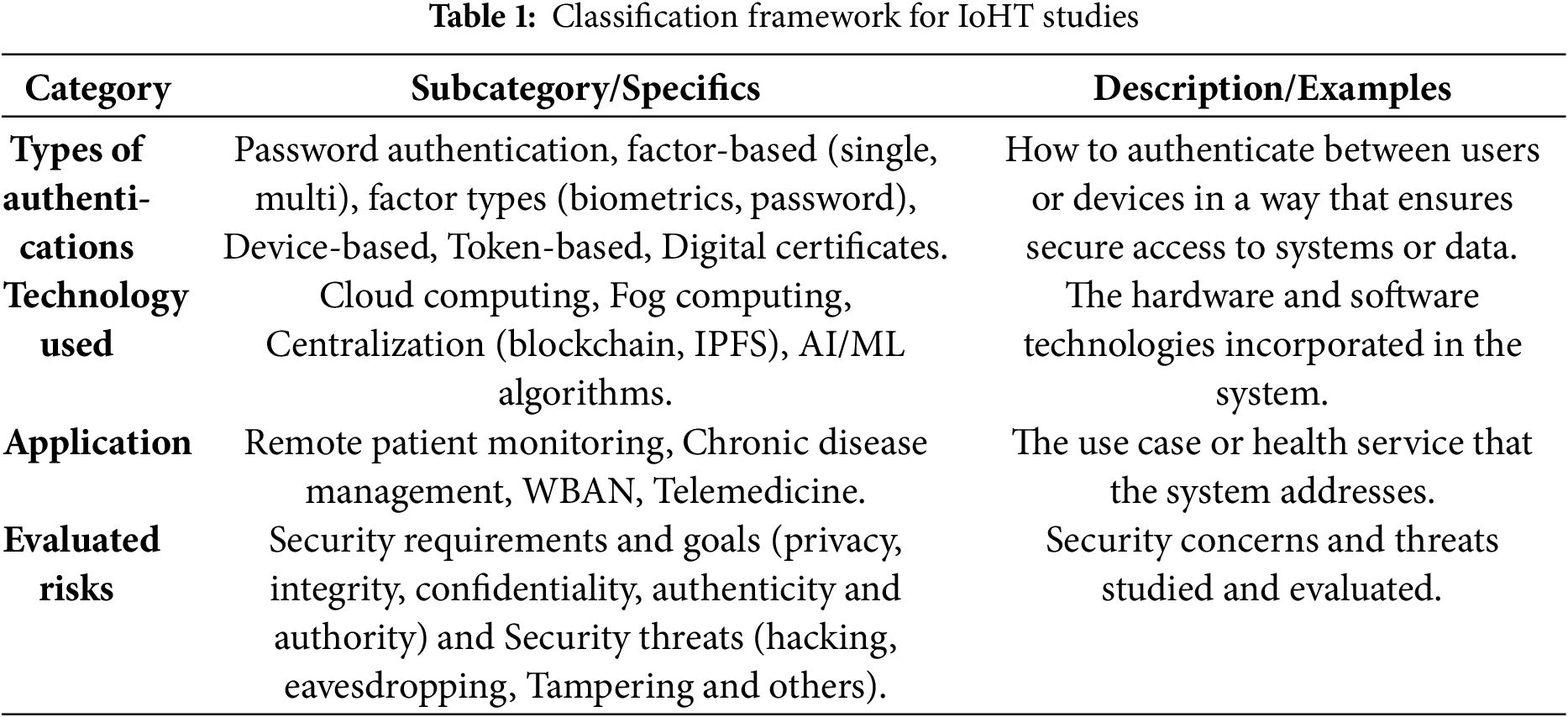

The resulting research articles in this review were selected based on a classification framework that includes the types of authentications, the technology used, the application, and the assessed risks shown in Table 1.

The IoHT system model comprises of a set of interconnected devices and heterogeneous technologies that manage and analyze patient and healthcare data. This ranges from physical components such as measuring devices and sensors, to software components for collection, analysis and monitoring, along with their connective entities to cloud platforms to facilitate the sharing process [52].

System architecture refers to the high-level organization of system elements and the interconnections between them [53]. There are unified standards for the general architecture of the IoTs, consisting of either 3, 4 or 7 layers [54] as described below.

According to [1], the three-layers model is the basic IoHT model consisting of the perception layer (works on sensors, gadgets, and other devices), network layer (maintains the connectivity between IoT contents), and the application (the user interaction interface). On the other hand, the four-layers model [55,56] comprises of the sensing layer (sensors in IoT device), network layer (communication channel), data processing layer (the main data processing unit), and the application layer (user interface). As explained in [57,58], the seven-layers model is made up of the collaboration and processes layer (humans and business processes), application layer (user interface), data abstraction layer (data reconciling, semantics, completeness and integration), data accumulation layer (real-time data formatting for later use), edge (fog) computing layer (data analysis and transformation), connectivity layer (data communication networks), and the physical devices and controllers layer (actuators and gadgets).

Although the terms (IoT) and (IoHT) share the same general architecture, they differ in the applications of connected devices [59]. IoHT specifically focuses on healthcare applications and devices that monitor, sense vital indicators, and improve wellness of the patients. Such devices include wearables, such as smartwatches, and pressure measurement sensors. On the other hand, such applications include fitness and heart monitors [15]. According to [39], IoHT is a model of the internet of things specialized in the healthcare sector. In IoHT, the seven-layered architecture provides a comprehensive framework that enhances the modularity of each layer by replacing or maintaining each layer individually. In addition, it provides adaptability and scalability to a certain extent by integrating new devices or techniques without disrupting existing functionalities, interoperability, and multiple levels of security. This serves to enhance efficiency in data collection and management, user experience, and flexibility, making it superior to simpler architectures [41]. Fig. 3 gives an illustration of this seven-layered architecture. In order to achieve adaptation and scalability, IoHTs are normally integrated with FC, as discussed in Section 4.2.

Figure 3: Seven-layers IoHT architecture

The protection of data in the IoHT systems is a major focus in studies within the healthcare field. This is due to its critical role in upholding healthcare data privacy, reliability of individuals and devices in the healthcare sector, and the overall protection of the system. In most of the conventional IoHT sytems, medical data is stored in centralized storage systems [17]. However, this centralization leads to a single point of failure, privacy [36], and security concerns attributed to the single architecture deployed for storing and processing data [23].

3.3 IoHT Security Requirements

The essential security requirements of IoHT include access control, integrity, confidentiality, non-repudiation, availability, forward secrecy, backward secrecy, and scalability [60]. Here, access control is divided into two concepts: mutual authentication and authorization [61]. As discussed in [62], mutual authentication is the process of reciprocally confirming system entities, users, or devices on both sides, thereby granting permission to access system resources [62]. On the other hand, authorization is a mechanism that regulates access permissions and controls network resources for authorised users or devices only. This authorization is based on various principles such as Role-based access control (RBAC), Attribute-based access control (ABAC), also known as policy-based access control (PBAC) or claims-based access control (CBAC). In RBAC, resource access is restricted based on a person’s role within an organization [63]. It is based on the levels of access that users have to the network. Therefore, access is granted based upon several factors, such as authority, responsibility, and job competency [61]. However, in ABAC, permissions are established and restricted according to specific positions, including department, location, managerial oversight, and time of day [63].

As discussed in [64], data integrity is crucial in ensuring data consistency, reliability, and accuracy, all of which are important for patient safety. In IoHT, several factors, such as human error, system failures and manipulation by cyber threats, can compromise data integrity. Therefore, various processes and controls are implemented to maintain data integrity, such as data validation, access controls, backups, error detection and correction techniques, and audits. On the other hand, non-repudiation ensures that entities cannot deny or dispute the legitimacy of any communication or transaction. It is considered as an important accountability tool in the occurrence of an attack [65]. With regard to confidentiality, its goal is to keep sensitive data secure and protected from unauthorized access [12], while availability guarantees accessibility of the services and data when required [33]. This implies keeping the system operable and usable at all times.

The authors in [66] have defined forward secrecy as the process of ensuring that each session has a unique and invulnerable key which cannot be re-used in the new session. On the other hand, backward secrecy ensures that if a long-time key used for all sessions has been compromised, the attacker cannot utilize it to decrypt previous messages or gain access to current or future communications [67]. Regarding scalability, the components of the system must seamlessly adapt and evolve with the dynamic evolution of communication systems [15]. In terms of key sizes, salability depends on the key block size and increases exponentially with the increase in block size [64]. To support anonymity, an individual’s identity must be concealed and not revealed to others so as to render an individual unidentifiable. It is often sought for various reasons, such as protecting users, safeguarding the privacy of vulnerable individuals or maintaining personal security and safety [68]. On the flipside, anonymity can also be used to conceal illegal or unethical activities, which raises concerns about the potential misuse of anonymity [67].

As discussed in [69], decentralization guarantees that there is no dependency on central authorities, which strengthens the system’s security and functionality by maintaining synchronised transactions. The distributed computational power simplifies the management and operation of the network. In addition, decentralization offers various features, such as data availability, responsibility, scalability, and mitigates single-point failure problems [70]. With regard to attacks prevention, the authors in [71] explain that devoid of security resistance mechanisms in IoHT, attacks will outweigh all the system’s benefits. This can cause network capacity reduction, misrouting, latency, data disclosure, and other problems. The authors in [59] have explained that IoHT is susceptible to various types of attacks, such as spoofing, data altering, replay, Denial of Service (DoS), Sybil, node capture and many more, as discussed in Section 3.4.

The continuous development of the IoHT structure, integration of heterogeneous devices and technologies, and the criticality of healthcare data have made it a target of numerous cyber-attacks and threats. Therefore, they have been concerted efforts in developing security techniques to curb these threats and vulnerabilities, and hence maintain the security of the IoHT system [60]. The authors in [65] explain that the impact of vulnerabilities is more pronounced in authentication models based on centralized and traditional databases. In addition, the decentralized systems have also been subjected to security attacks that damage and breach sensitive data. In this regard, the IoHT system may be susceptible to the following cyber-attacks and threats:

• Brute-force and dictionary attacks: These are considered the simplest attacks on networks, requiring basic computer and software knowledge to gain unauthorized access to systems, accounts, or encrypted data. In healthcare systems, the data includes patient, care and tracking, device management and treatment, and other network data and accounts. The attacker uses sophisticated devices and software to try out many possible combinations of passwords and accounts and try different encryption keys until they obtain the correct choice. Accounts with weak passwords and simple keys are easily hacked in these ways [60]. To withstand these attacks and reduce the likelihood of successful compromise, strong passwords should be combined, multi-factor authentication and secure password storage techniques [27].

• Man-in-the-middle attacks: MITM attacks are remotely carried out by intercepting the communication channel between two entities. In addition, authentication phase can be compromised, allowing snooping on or changing of the data being exchanged [72]. In the IoHT system, the attacker intercepts communication channels between legitimate components in the healthcare system (such as the patient, devices, healthcare service, or medical records) [52]. To face MITM attacks, employ strong encryption with valid certificates, mutual authentication, forward secrecy, and implement secure protocols and channels like HTTP [71].

• An eavesdropping attack: This refers to the unauthorized interception of patients’ and healthcare data transmitted over the communication channels or the cloud. As discussed in [73], one of the facilitating factor for these attacks is the transmission of plain data using non-secure protocols. This attack may be used to collect or alter information, causing system failure. To eliminate such attacks, approaches that focus on detecting unauthorized interception of data are needed. Such approaches utilize ensemble learning methods that combine ML for detection and network breach monitoring [73].

• Spoofing: In this threat, attackers impersonate the identity of an authorized device or account to obtain data. Afterwards, adversaries can use network resources, or steal and sabotage them. This exposes violates the privacy of the patients and can lead to failure of the health system [74]. Several types of spoofing threats exist, including IP address spoofing, manipulation of DNS records, using hidden phones or numbers, or even using Media Access Control (MAC) in the case of local networks. According to [75], spoofing is usually overcome by using multi-factor authentication or secure protocols such as Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP).

• Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks: These threats prevent legitimate IoHT users from accessing network resources by overwhelming the network with excessive requests, making it unavailable. These attacks are implemented by multiple entities trying to block access to a service for legitimate users [76]. Attackers may conceal or manipulate the service’s IP address to prevent access or utilize various sources and devices to target a service provider, distracting it from serving its legitimate users [77]. DDoS defense requires layered strategies: immediate response, resilience, and long-term planning, such as limiting traffic from individual IP addresses sent to the server to prevent overload, blocking malicious traffic, and employing AI techniques to monitor service requests [64].

• Sybil attacks: These attacks aim to steal data using malware that impersonates a legitimate user. The Sybil node assumes multiple identities to simultaneously appear in various locations, which threatens data safety and the utilization of IoHT resources. In a nutshell, Sybil looks like many ordinary users but it is one masquerade node [71]. Cryptographic techniques, including key exchange, digital signatures, and an Asymmetric Proof-of-Work defense algorithm, can mitigate Sybil attacks by authenticating node identities and messages, preventing unauthorized nodes from joining the network [78].

• Physical attacks: These threats are carried out through direct attacks on IoHT devices. They can also destroy the infrastructure of the IoHT systems. These attacks intentionally tamper with the functionality of the devices connected to the network, sabotage them, and make them inoperable. As such, they take them out of service, losing or altering the data, potentially threatening the safety of patients, healthcare systems as well as disrupting its services [5]. Protection from these attacks is achieved by providing physical protection for network devices, encrypting stored data, and integrating protection and tampering detection programs into the devices [71].

• Botnet attacks: It is a group of network devices infected with malware, commonly referred to as zombies. These devices are controlled by the attacker, who performs various activities such as stealing and changing data, launching a DDoS attack, and distributing malicious spam messages on email. These attacks are detected by monitoring traffic, observing abnormal patterns, and securing devices with authentication and strong passwords [79].

• Node capture: This attack gains access to a crucial node or group of nodes in the system to steal data stored on IoHT network devices [80], to protect against these attacks, it is preferable to employ robust encryption algorithms for stored data to prevent its content from being exposed by untrusted nodes [81].

• Timing attack: In this attack, the adversary analyzes the responding time of the devices and attempts to find vulnerabilities to be used in the hack, to eliminate timing attacks, constant-time algorithms should be implemented, utilizing blinding and cryptographic methods, and regular network monitoring and testing [82].

• Malicious code attack: These attacks are carried out by malicious programs called computer viruses, which are intended to damage or ruin internet devices and applications, defending against malicious code involves using security software like firewall, keeping them updated, restricting user permissions, securing networks and maintaining backups [83].

• Impersonation attacks: These threats involve a malicious adversary pretending to be a trusted entity to reveal sensitive information or transactions [67]. To stop impersonation attacks, employ multi-factor authentication and enforce strong, unique passwords, digital certificates, strong access controls, adding strategies of anomaly detection, secure communication, user education, and performing verification processes within the authentication protocol [84].

• Replay attacks: Here, adversaries capture and reuse valid authentication messages to gain unauthorized access, effectively halting replay attacks requires many strategies: exchanged data encryption and timestamping to ensure that each communication is unique and cannot be reused maliciously [85].

• Hijacking attack: In this type of attack, the adversaries try to steal or predict the session key of an authorized user to gain unauthorized access. Active hijacking attacks can manipulate or alter the client’s connection. On the other hand, passive hijackers can only monitor or capture network traffic or information [86]. On the other hand, these attackers can be undermined using strong authentication with MFA, a strong password, and RBAC to restrict unauthorized access, as well as using secure session protocols and system monitoring strategies for anomalies [87].

• 51% attack: Suppose an entity or group of malicious users control (s) over 50% of the BC or decentralized network. In that case, they will have the ability to alter the cryptocurrency blockchain. This can prevent access to new transaction confirmations, obstruct payment, or reverse non-confirmed transactions that were completed [88]. Some implementations may prevent 51% attacks like promoting decentralization, using resistant consensus algorithms (POS), implementing economic penalties, monitoring network distribution, and layer security measures [89].

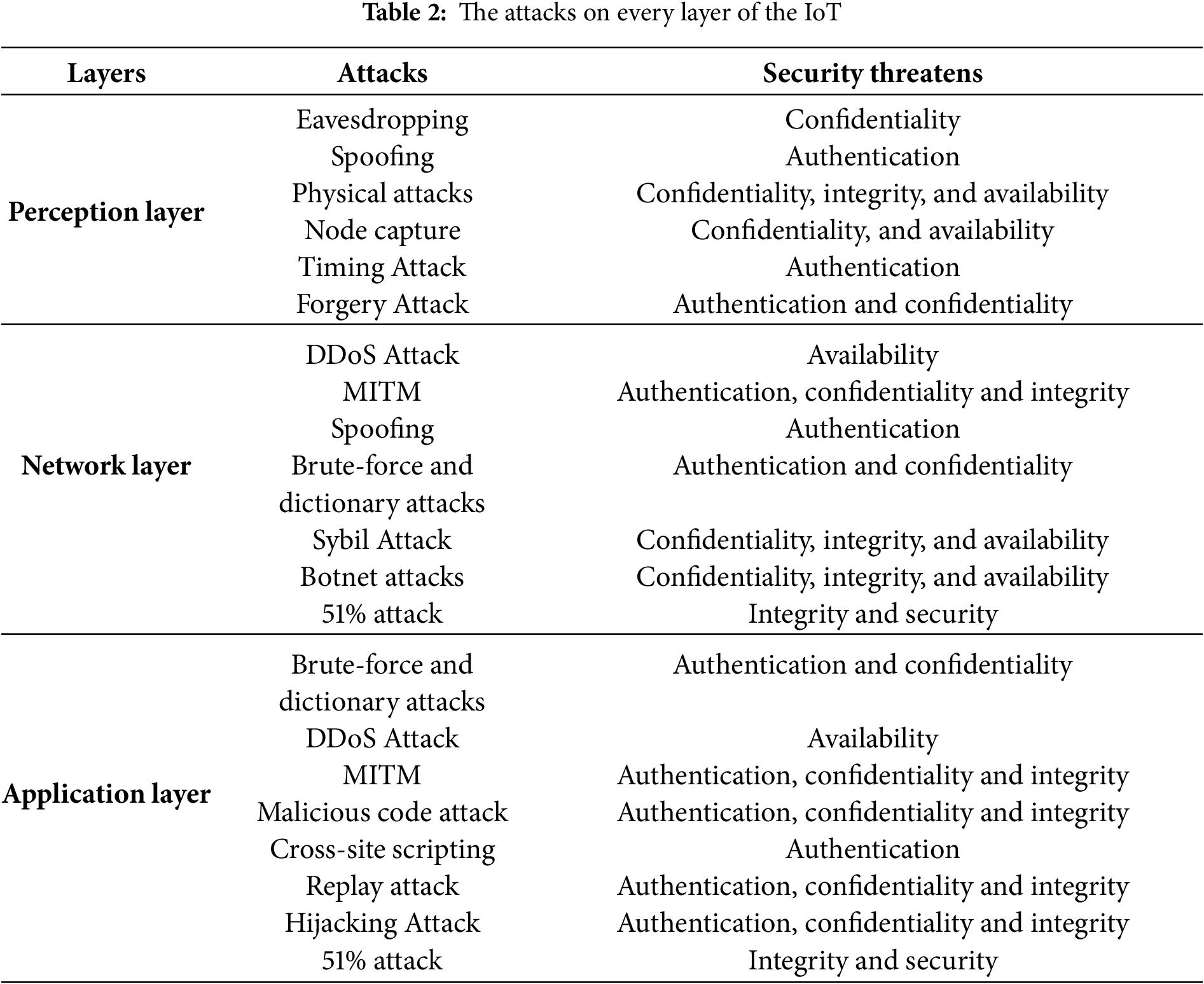

• Forgery attack: In this attack, the adversary impersonates a legitimate entity to gain unauthorized access, allowing access and manipulating data [90]. This attack is typically accomplished through utilizing forged data or employing man-in-the-middle attack techniques. Fortunately, these attacks are often mitigated and thwarted using machine learning techniques [91]. Table 2 shows each layer of attack and the security requirements it violates.

3.5 IoHT Security Requirements Enforcement

Globally, the security, safety and privacy of healthcare systems are supervised by international organizations such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). These organizations establish the necessary laws and technologies to protect and secure data and devices for the entire healthcare system [92], in addition to expanding their roles to include supervision and evaluation of medical products. Moreover, these organizations supervise the development and deployment of health information systems to protect privacy and data security. On the same breadth, they prevent breaches which threaten the safety of the patient and the healthcare system [93].

Over the recent past, traditional solutions have been prevalent in detecting attacks, intrusions, and attempts to maliciously control access [45]. However, the dynamic and evolutionary nature of IoHT networks, coupled with their continuous complexity renders traditional methods such as password and email authentication insufficient [93]. These techniques are unable to handle the complexity, continuous evolution, and expansion of modern attack methods, as well as network complexity [94]. Fortunately, AI-based solutions, such as DL, ML and other technologies, have been presented to support such developments. These solutions are characterized by the ability to collect, analyze data and detect breaches as well as anomalies in real-time. This helps in developing responses to various cyber threats [95]. One of the most important security considerations in IoHT is access control, which is the basic mechanism for regulating who or what is allowed to access network resources. Basically, access control ensures that only authorized entities can access the network and use its applications, data, devices, and other network components [16,96]. The basic tenets of access control include authentication, authorization and integrity.

1. Authentication

Authentication systems incorporate AI techniques to achieve high security standards and enhance privacy [37,97]. One of the common strategies for AI-based authentication is DL due to its ability to collect and analyze large amounts of data with complex patterns such as biometric, facial or behavioral patterns [98]. Another mechanism for access control is based on attributes, using federated deep learning (FDL). This technique allows multiple parties to train a model collaboratively while keeping their data decentralized. This helps get optimal access parameter threshold, producing high data privacy and integrity [20]. In addition, other ML techniques have an important role in IoHT authentication for enhancing security, improving utility and facilitating the management of healthcare devices [99,100]. These methods areas based on neural learning utilizing legitimate and malicious access data for training. The trained models help in detecting suspicious requests in authentication and access control processes [21]. Over the recent past, BC has been used as an authentication tool, owing to its characteristics such as decentralization, smart contracts (SCs), distributed ledgers and two keys crypto instead of traditional passwords [24]. Nevertheless, numerous security challenges have been identified in BC networks. To mitigate BC attacks, DL or ML techniques have been integrated with BC as a hybrid system with high protection features [101].

2. Authorization

Authorization is a process that typically follows authentication and is used to grant an individual or system permission to access network resources or perform actions within a system or network. This is achieved after verifying the identity of the user [102]. Authorization is crucial in specifying which resources a user can access and what actions they can perform. These actions include read, write, or execute files, based on predefined permissions and roles [1]. Some researchers have proposed secure SDN-based frameworks for healthcare systems to provide trusted services for patients using MAC addresses to control authorization for legitimate users [103]. Meanwhile, other researchers have developed access control mechanisms for healthcare data using symptom matching technology. These techniques are based on blind signatures which are used to maintain privacy and ensure that only authorized people engage in data exchange. In addition, some researchers have developed continuous authentication techniques to support access to authorized users [98]. To implement continuous authentication, IoHTs employ biometric factors, behavioral patterns, contextual or multiple factors, as well as ML and anomaly detection. The specific choice of continuous authentication mechanisms depends on the capabilities and security requirements of the system [104].

3. Data integrity

Data integrity in IoHT is important because it directly relates to patient health and the healthcare system. Integrity represents the accuracy, consistency, and reliability of data collected and exchanged across the healthcare system entities [105]. As such, numerous security solutions have emerged to protect data from changes and breaches. In addition to imposing many restrictions, other approaches include limiting IoHT use to authorized users, and providing updated firmware [106].

In spite of the above efforts, a number of attacks have emerged that threaten data integrity. Such risks include tampering, poisoning, and alteration. Consequently, much research efforts have been directed towards AI and decentralized techniques to find effective solutions [5]. For instance, authors in [107] have presented a decentralized AI healthcare system based on FDL to secure patient health record data and maintain its privacy as well as integrity. Other researchers have utilized BC technology to secure and protect data integrity from potential security breaches. The attacks in BC are attributed to its distributed nature, as well as the inclusion of smart contracts and cryptographic technologies [21]. In addition, other researchers have adopted two-step authentication through the integration of BC with the cloud to offer two levels of protection: authentication and integrity [108].

This section presents some of the most common cryptographic primitives frequently deployed to offer protection in an IoHT environment.

• Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC)

ECC is one of the newest, strongest, and most secure encryption techniques compared with most encryption techniques [11]. This technique is also lightweight and hence enhances authentication speeds. It relies on elliptic curve for generation of security tokens. ECC uses standard point multiplication as a mathematical operation for encryption, and is considered a leap from classical encryption to modern encryption [109].

The elliptic curve is mathematically represented by the equation below.

Let G be a point on the curve (generator point), which is used to produce a cyclic group of points [110]. These points lie on that elliptic curve and are generated by multiplying G by an integer k

ECC is based on the difficulty of solving the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP). This problem is very cumbersome and requires powerful computers to break solve. Basically, these computers need to expose k given the value of public key G [59,111]. Mathematically, ECC needs to find a scalar k that helps derive the following.

This multiplication process is used to generate asymmetric encryption keys where P is the public key value, while k represents the private key [112].

• SHA-256

SHA-256 is a cryptographic hash function developed by the National Security Agency (NSA) in the United States. It is designed to withstand various attacks. This function takes any value as input and converts it to a fixed hash length of 256 bits, which makes it resistant to data alteration attacks. As such, it upholds the integrity of the data and prevents it from being exposed. SHA-256 is fast and computationally inexpensive. The algorithm of this function works in several steps: first the data are divided into blocks of 512 bits. This is followed by the hash calculation step in which a series of logical and arithmetic operations are performed to expand and compress the blocks, ultimately producing a hash of 256 bits [113].

• Shamir’s Secret Sharing (SSS) Algorithm

Secret sharing is a cryptographic technique for securely distributing pieces of private information called shares amongst a distributed group or network such that each group member receives only one share without information about the original secret. The SSS algorithm is based on the property of polynomial interpolation over a finite field. The linear polynomial can be reconstructed by two or more points (i.e., shares S1 and S2). Consequently, the secret is disclosed by (0) = Secret. However, if we have only one share (S1), it is impossible to reconstruct the linear polynomial and disclose the secret [114].

In general, any polynomial of degree t − 1 can be obtained only by (sℎares => t) where t is the number of shares required to reconstruct the secret. According to [20], the threshold (t) should be less than or equal to the total number of group members (n) who share the secret.

• Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)

AES is a symmetric encryption mechanism that uses a single key for encryption and decryption. Mathematically, AES encryption is expressed as follows.

where P is the plaintext message and C is the resulting ciphertext. The system’s security relies on the secrecy of the key K [115].

AES encryption involves several cryptographic operations that utilize a symmetric key. These operations include dividing data into 128-bit blocks, repeatedly applying substitution, permutation, and key-dependent operations. As explained in [79,115], the number of rounds varies with key size, with longer keys providing stronger encryption.

• Bilinear Pairing (BP)

This is an asymmetric cryptographic technique that involves using a mathematical principle referred to as bilinear mapping [116]. Mathematically, BP can be expressed as follows.

where G1 is additive, G2 is multiplicative while GT represents a multiplicative group [79].

The function e must satisfy the bilinear condition below:

where P

BP has a wide application in cryptography. For instance, this technique has been deployed in attribute-based encryption (ABE) and short signatures [117].

• Harmonic Cryptography (HC)

HC is a modern cryptographic technique that unlike traditional methods relies on algebraic structures and cryptographic hashes. It offers an efficient alternative by using mathematical waveforms for encryption [118]. HC employs sinusoidal transformations to derive a dynamic keystream a process that is both efficient and effective. HC is designed to be robust with scaling factors derived from the key and a varying frequency per encryption cycle.

where

4.2 Artificial Intelligent Tools

• Machine Learning (ML)

This is an artificial intelligence method that develops algorithms and statistical models which enable computers to analyze patterns and make decisions [21]. ML systems learn from data and make decisions based on their attributes and features [99]. This method relies on an extensive data set for training and learning, significantly enhancing performance. ML-based systems are characterized by their adaptability and self-improvement through feedback and training. Therefore, these systems are used in complex systems, such as image and speech recognition, natural language processing, autonomous vehicles, and detecting security breaches in IoT systems [120,121].

According to [122], there are several types of machine learning methods, some of which are described below.

○ Supervised learning: In this form of learning, the model is trained using labeled data, and data features are extracted to train the model to predict outcomes.

○ Unsupervised learning: In these models, the data is unlabeled and the model works to identify patterns and clusters without pre-specified information.

○ Reinforcement learning: These models interact with the environment for learning, using feedback to strengthen the learning process.

However, it also faces significant limitations. These challenges stem from the unique characteristics of IoT environments, including computational Limitations such as processing power, making it difficult to implement complex ML algorithms effectively, and Energy Consumption, which is critical for battery-operated devices. More aspects like vulnerability to Attacks, such as cloning through Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs) [122]. Inability to withstand newly arising attacks. Additionally, the training data may contain sensitive data that poses a privacy concern [21].

• Deep Learning (DL)

This is a subset of ML used for modeling complex patterns in large data sets. It involves multi-layered neural networks that simulate the human brain and allow incremental learning [123]. DL requires a large amount of labeled data for training and is characterized by its ability to extract attributes from the data automatically. Although it yields highly accurate results, it faces some limitations, such as demanding significant computational resources, consuming time, and often requiring substantial energy, which negatively affect battery-operated devices. Furthermore, it is vulnerable to MITM and replay attacks [124].

• Federated Deep Learning (FDL)

This is an approach within ML that involves decentralized data storage. The training data remains on local devices (such as smartphones, and IoT devices). At the same time, the model is trained across these devices without transferring the data to a central server, which helps enhance privacy [19]. FDL is highly efficient in terms of communication cost because it only exchanges model updates. It is also scalable due to its distributed training nature. All these attributes render FDL suitable for IoHT applications where data privacy is a major concern [125].

However, FDL trust issues are worsened by diverse IoT devices, creating vulnerabilities. Decentralization causes authentication inefficiencies with cross-domain data exchanges, increasing latency and reducing throughput [95].

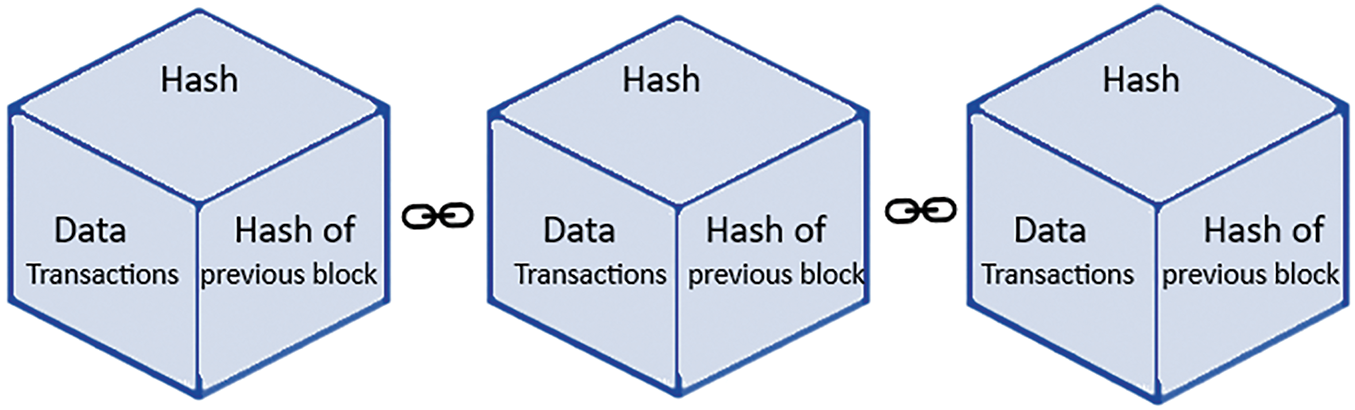

• Blockchain (BC)

This is a new technology consisting of a decentralized distributed ledger used to store data as blocks [125]. These blocks form a digital list of ordered entries collected and arranged in an organized manner so that a cryptographic hash of the previous block is stored in the next block. This makes the blocks interconnected and thus immune to changes since any change in one block affect other connected blocks. Therefore, any node cannot individually manipulate or control data [126]. The records in BC are unchangeable for any type of data such as currency and medical [127]. The distributed architecture nature of BC, coupled with its decentralization protects the system from central point of failure problems [70]. Fig. 4 shows the blockchain connectivity.

Figure 4: The BC connection mechanism

As explained in [69], the BC distributed ledger is a shared database for storing transactions that can only be accessed and modified by authorized team members. Additionally, Smart Contracts (SCs) are pre-defined with conditions (if...then) and are executed automatically when these conditions are met [128]. The BC also utilizes public key cryptography to ensure secure authentication and control access to data [129].

In spite of the several secure authentication schemes in IoHT, unauthorized access remains a threat to healthcare systems due to the human factors. Therefore, there are challenges in preserving confidentiality when dealing with authorized accounts and their transactions [69]. In addition, the decentralized structure of BC requires huge resources in terms of time, storage, and processing resources. This leads to a decrease in scalability, which is considered as one of the critical aspects in healthcare databases [1,130].

As explained in [131], there are three types of BC: public, private and Consortium BC. In public BC, anyone can reach the ledger and make data appending, while in private BC, the access needs to be authorized by the owner organization [131]. The third is Consortium BC, which supports both public and private ledger access. The consensus process can be controlled by multiple organizations rather than one [12,132]. A hybrid BC also exists, combining groups of the three types of BC for more flexibility in managing records and data. In the healthcare industry, the choice of BC type depends on the system requirements, as well as challenges for security, privacy, scalability and regulatory compliance [133].

In BC, a consensus algorithm is a hash-based mechanism used in distributed systems to ensure the effective agreement of all participants for data transmission. This algorithm is crucial for maintaining the integrity and reliability of blockchain networks and other decentralized systems [69]. Many types of consensus algorithms have been developed to determine the consensus propagation for data transactions among untrustworthy network node participants. According to [134], these consensus algorithms can be classified according to their implementations and characteristics.

Proof of Work (PoW): In this algorithm, participants (referred to as miners) need to solve complex mathematical problems to add new blocks to the BC. The first miner to solve the problem gets the right to add the block and is rewarded with cryptocurrency [135]. In this environment, this implementation ensures that 51% attacks are kept at bay [88].

Proof of Stake (PoS): This algorithm allows nodes to create new blocks based on the number of coins they have and are aiming to stake as collateral [69].

Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT): This algorithm is designed to enhance the reliability and security of distributed systems. This is because it can tolerate a certain number of faulty nodes and still execute transactions even in the presence of faulty or malicious nodes [69].

Proof of Stake Velocity (PoSV): This algorithm combines elements of both PoS and the concept of velocity in economics. It aims to promote a more dynamic and engaged network by incentivizing the holding of coins and their active use in transactions [136].

○ Smart Contract (SCs) are self-executing codes with the terms of an agreement for transaction regulation. They are used in blockchain networks to implement automated and trustless transactions without intermediaries when predefined conditions are met [109]. SCs offer transparency, security through cryptographic techniques, and efficiency in reducing transaction time and computational cost. Moreover, SCs are utilized within various applications, such as financial services, supply chain management, and decentralized applications (DApps) [137].

• Fog Computing

The FC is a paradigm for managing resources and data in decentralized and distributed computing environments; it is used to present computing resources over networks such as servers, data, and storage [138]. The general architecture of FC consists of edge devices, local servers, and gateways in addition to the cloud as shown in Fig. 5. This structure consists of three layers:

Figure 5: FC structure

○ Things layer: This layer contains connected devices that act as data inputs. Such devices may include sensors, wearable devices, Arduino, and actuators [138].

○ Fog layer: This is the middle layer whose task is transferring data between data collectors (things layer) and the cloud. This layer includes network devices, internet gateways, local servers, and routers [137].

○ Cloud layer: This is the third layer, which receives incoming data. Through its servers characterized by high processing, and storage capabilities, this layer analyses this data to facilitate decision making [139].

As explained in [140], fog nodes are the basic physical infrastructure in FC. These nodes are categorised into two groups: resource-rich machines, and resource-poor devices. Resource-poor devices include routers, switches, or access points. On the other hand, resource-rich machines include Cloudlets and IOx devices that are located at the edge of the network [141] They closely or directly interact with the user to enhance or provide resources, processing, and manage IoT applications [142].

FC offers unique advantages such as reduced latencies for data processing. This is particularly crucial for time-sensitive applications. Therefore, FC is ideal for the management of IoT systems [9,143]. FC’s scalability, demonstrated by its ability to accommodate more nodes and be operable by multiple cloud and server providers [144], opens up possibilities for growth and expansion.

In healthcare systems, the things layer consists of devices that read vital signs and patient data which is then transferred to the cloud layer. In the cloud, the data can be stored, protected or analyzed to facilitate decision making during important medical and therapeutic emergencies [9]. The main drawback of FC is the complexity it presents during management and deployment. This is mainly due to its decentralized, distributed, and scalable nature [142].

These tools include Interplanetary File System (IPFS), Ethereum, Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), Solidity, Node.js, Node Package Manager (NPM), Ganache, Truffle, and MetaMask. These tools are described in the sub-sections below.

• The Interplanetary File System (IPFS): This is a distributed system for storing files in a peer to peer version. It is based on content-addressing as a guide for requesting files [12]. This is done through its unique hashes generated cryptographically from the content of the file, instead of its address on the server [145]. These hashes can be considered as alternatives to the file contents [19]. The file storage mechanism is shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Storing files in IPFS

• Ethereum: This is an open-source decentralized platform that enables developers to build and deploy SCs and decentralized applications [146]. This platform is also used to execute fee payment, transactions on the network without intermediaries, digital assets management or management of items ownership. These programmable contracts can operate on three kinds of data storage: stack, temporary memory, and permanent storage (which is used for storing contracts after completion of computations) [147]. Any operation such as contract call, memory usage, or data retrieval is paid by Ethereum’s cryptocurrency, ether [12].

• Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM): This is presented by Ethereum on the BC to provide a suitable decentralized execution environment for SCs across all Ethereum nodes. A VM’s essential ability is to encapsulate the entire network and operate as a supercomputer to solve any computational tasks. EVM uses “gas” as currency to account for the computational effort required for executing various operations [148,149].

• Solidity: This is an object-oriented highly effective programming language built for EVM. It is deployed for writing and developing smart contracts. It easily creates contracts for various uses, such as voting, blind auctions, multi-signature wallets, and other functions [150]. Solidity software is based on programming languages such as Python, JavaScript, and C++, with the ability to support libraries, inheritance, and user-defined types [151].

• Node.js: This is an open-source runtime environment built on the JavaScript V8 engine. This tool is used to build high-performance and scalable applications. It efficiently works with heavy I/O applications and can simultaneously handle multiple tasks [152]. Moreover, Node.js is fast and efficient in building real-time applications, which renders it highly popular. As explained in [153], it is flexible and can run on different operating systems such as Windows, Linux, and Mac.

• Node Package Manager (NPM): This tool allows users to install and use different versions of a package whilst running a single execution. Node.js has a vast ecosystem of libraries and frameworks for managing several dependencies. These extensive libraries and functions help developers in building professional applications easily [154]. According to [153], over 2.1 million packages are listed in the NPM registry.

• Ganache: This is an Ethereum development tool that enables developers to deploy, manage, and test SCs [155]. It is used to simulate the Ethereum BC, allowing for complete control during examination and testing. All transactions are instantly mined. This results in not only fast but also efficient testing and development, devoid of confirmation. As explained in [156], Ganache provides pre-funded Ethereum accounts to facilitate the work of developers. Fig. 7 presents Ganache user-interface.

Figure 7: Ganache user-interface

• Truffle: This is a framework that integrates with Ganache to develop, manage, deploy, and scale SCs on Ethereum through its comprehensive environment [157]. Fig. 8 presents the Truffle framework.

Figure 8: Truffle framework

• MetaMask: This is an extension that can be added to the browser to serve as a cryptocurrency wallet and a gateway to the Ethereum BC. This extension enables users to store and manage their Ethereum-based assets. It also facilitates interaction with DApps through a user-friendly interface, as depicted in Fig. 9. This facilitates easy manipulation of accounts and provides a secure environment for transactions [158].

Figure 9: MetaMask cryptocurrency wallet

In this section, various security analysis tools are described. They include Scyther, AVISPA, ProVerif, Burrows-Abadi-Needham (BAN) logic analysis, Real-or-Random (ROR), Interrogator, Naval Research Laboratory NRL protocol analyzer, and Murphy analyzer as detailed in the sub-sections that follow.

• Scyther: This is a tool for large-scale protocol verification tests. As shown in Fig. 10, it offers a user interface, command-line and scripting interfaces functionality [8]. It has numerous salient characteristics and high performance. For instance, it allows termination of correct proof sessions for protocols with unlimited trials. Unlike other tools, Scyther analyzes the protocol, produces its behavior, and describes the class of the attack. Finally, this tool facilitates multi-protocol analysis with parallel composition of sub-protocols [159].

Figure 10: Scyther user-interface

As in [160], Device X’s authentication and voice protocols were modeled using the Scyther Tool with protocol MSC compilation. In authentication, MSA and MSB initiated device registration, while in voice, only MSA initiated communication. Scyther Tool verified Device X’s authentication protocol model. Scyther Tool analysis involves interpreting test results to assess protocol conditions and analyzing attack patterns that violate security claims. Fig. 10 provides a summary of verification results.

• AVISPA: This is a tool designed to validate and verify internet security-sensitive protocols and applications. It enables users to formally define safety properties and specifications. It then uses an extensive set of libraries to perform evaluations. AVISPA employs the High-Level Protocol Specification Language (HLPSL) for specifying protocols, allowing for comprehensive analysis and verification of security measures [161]. Fig. 11 shows the AVISPA tool interface.

Figure 11: AVISPA security verification tool

• ProVerif: This is a formal tool designed to verify and analyze cryptographic protocols. It provides a precise framework to ensure protocols meet various security properties such as confidentiality, authenticity, and integrity. This tool can be modeled to check for potential vulnerabilities devoid of expertise. It has a simple and concise presentation language to represent and analyze complex protocols without the need for manually proving security properties [157]. The tool, shown in Fig. 12, can analyze symmetric and asymmetric cryptographic protocols while providing a vulnerability detection feature to debug and improve the protocol [159].

Figure 12: ProVerif formal verification tool

• Burrows-Abadi-Needham (BAN) Logic Analysis: This is a formal analysis mechanism to prove the security and viability of new protocols. It uses primitives and inference rules to describe crypto-system principles [162]. This mechanism follows three reasoning steps. Firstly, the description of the authentication protocol is logically expressed and initialized. Secondly, the exchanged messages of the authentication protocol are converted into BAN logic language, and unrelated phrases are eliminated. Thirdly, using the inference rules and based on the idealized model, the proposed protocol is traced and proven whether it accomplishes the security goals or not [67].

• Real-or-Random (ROR): This security analysis tool evaluates cryptographic protocol security, especially protocols that establish session keys and mutual authentication. It compares the protocol’s output to a random model. This analysis emphasizes on privacy preservation and the strength of security definitions applied to specific schemes [163]. Moreover, this analysis works on the probability of whether an adversary can distinguish between real protocol messages and random messages. Basically, the protocol is regarded secure if the adversary is unable to carry out this distinction. ROR can define both adversary capabilities and security properties such as mutual authentication or forward secrecy. This helps in the identification of potential vulnerabilities, ensuring the security of the entire system [164].

• Interrogator: This is a Prolog program with a GUI interface designed and controlled by LISP to determine vulnerabilities and observe key distribution flow within text-defined security protocols. The system has a tool that displays a simulation of the attacker’s movement, tracks any changes made, and shows them as pop-up messages [165]. Additionally, the system looks for message modification attacks that undermine the protocol objective [166]. The Interrogator code in Fig. 13 checks for common vulnerabilities based on predefined rules.

Figure 13: Interrogator interface

• Naval Research Laboratory NRL Protocol Analyzer: This tool is developed by the U.S. NRL, and used to analyze and debug network protocols. The analyser is implemented in Prolog programming language, and is designed to run on platforms that support Prolog environments [167]. The NRL supports a wide range of protocols, analyzes communication across different network layers, observes the flow of data and traffic, and is able to identify anomalies or bottlenecks in communication [166].

• Murphy Analyzer: This is a tool for analyzing network protocols and provides performance and reliability assessments. It focuses on error detection and correction, network performance, and efficiency. Moreover, it handles data reliability by evaluating data error and loss [166].

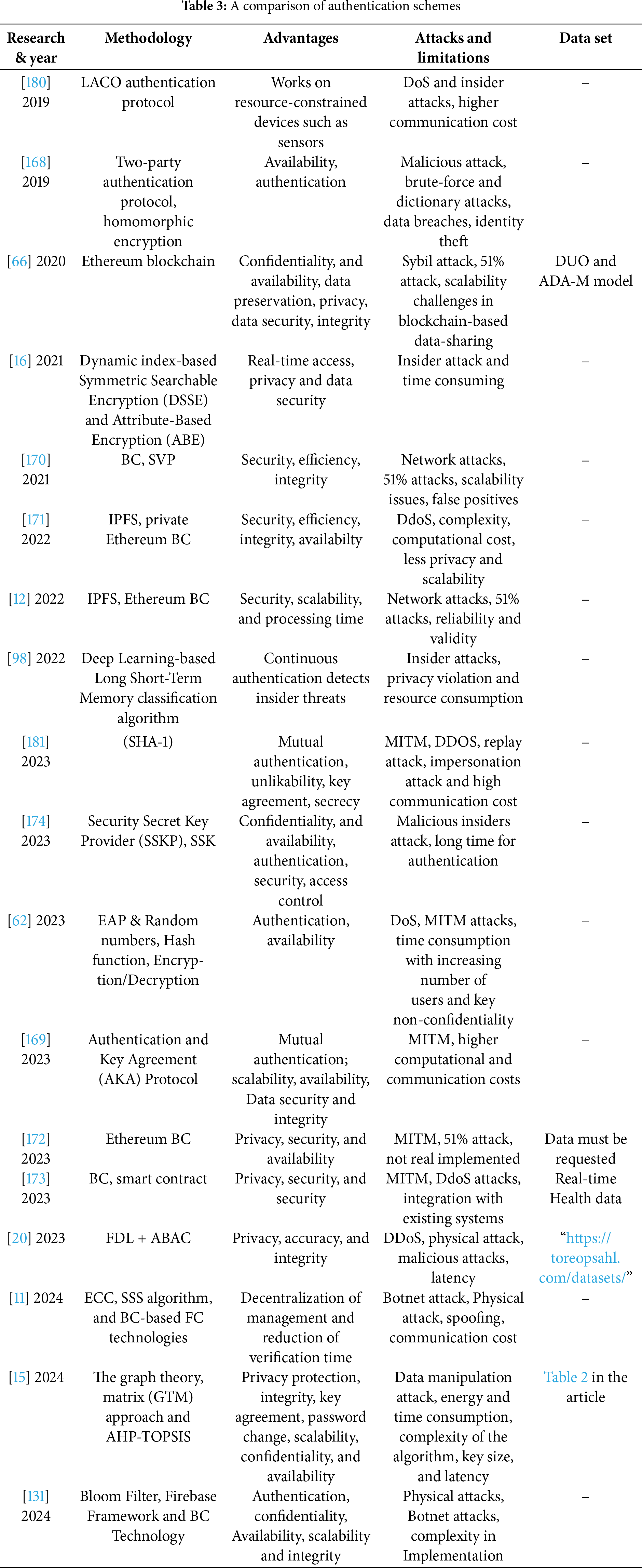

Numerous studies have presented authentication protocols for the IoHT, based on a variety of elements, such as the network server, the encryption algorithm used and the number of authentication factors. These studies focused on both external and internal attacks on the network. According to [108], attackers within the network are more dangerous than external attackers. In this respect, Feng et al. (2019) have proposed a lightweight authentication system that strikes a perfect balance between security and performance in electronic health record (EHR) systems. This protocol is a secure two-party authentication based on holomorphic encryption. It is devoid of a trusted third party to recover the original private key, but guarantees that only authorized users can collaboratively access and manage data. This protocol is shown to enhance security and efficiency [168]. On the other hand, Oliveira et al. (2021) introduced the AC-AC protocol, a dynamic revocable access control system designed for healthcare teams to access encrypted electronic medical records (EMR) during emergencies. This protocol grants real-time access rights during critical care situations while maintaining patient privacy and data security. The system utilizes a hybrid encryption approach combining Dynamic index-based Symmetric Searchable Encryption (DSSE) and Attribute-Based Encryption (ABE) with less time consumption for access operations [16]. Yadav et al. (2023) introduced a lightweight dual-factor authentication protocols for WLAN-connected IoT. Their protocol is built on Extensible Authentication Protocol (EAP) encryption algorithms, random numbers, hash functions, and a combination of symmetric-key, public-key, and hash-based cryptography. The EAP is utilized to boost data security, and the protocol is shown to incur less time consumption and is highly scalable [62]. Wu et al. (2023) proposed a lightweight enhanced authentication and key agreement (AKA) protocol for the IoHT environment that aims to ensure data transmission security and protect user privacy. The proposed protocol facilitates the establishment of session keys between doctors and network nodes [169]. However, it is shown to be vulnerable to threats, such as privileged insider IP attacks. To effectively verify, identify, and authenticate IoT devices in a fog computing environment, Britto et al. (2024) developed a security model that combines machine learning and hybrid mathematical encryption techniques of Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) and Proxy Re-encryption (PR) with Enhanced Salp Swarm Algorithm (ESSA). The proposed model is shown to be capable of detecting and predicting system vulnerabilities in the IoHT environment. In addition, its security and performance analyses demonstrates its effectiveness in improving performance metrics such as energy consumption, throughput, response time, execution time, processing time, packet error rate, reliability, and verification time compared to traditional cryptographic algorithms. However, the system’s formal or informal security analyses are not carried out [121].

To transform patient identification in a healthcare system, Janelle et al. (2020) proposed an authentication technique based on biometrics. This technique combines periocular biometrics and an electronic master patient index during the authentication process. According to [37], this system has the potential to significantly enhance human identification in IoHTs [37]. To authenticate individuals in a healthcare system, Manjula Devi et al. (2022) have introduced a retina-based efficient biometric identification system, named ARBAS (ANFIS-based Retina Biometric Authentication System). The system utilized the VARIA database, which contains retinal images collected from various persons. This scheme comprises two main phases: enrollment and authentication. During the enrollment phase, retinal images are scanned, and the biometric patterns are derived and stored. On the other hand, the authentication involves scanning a user’s retina and comparing the extracted pattern to the stored data. The results showed that it achieved a False Rejection Rate (FRR) of 2.78% and a False Acceptance Rate (FAR) of 2.94%. These results highlight its potential to significantly improve security in the healthcare sector [34].

To maintain authorized access to data, Jaiman et al. (2020) have introduced an Ethereum BC-based consent model designed for health data-sharing platforms. This model introduces the Data Use Ontology (DUO) and Automatable Discovery and Access Matrix (ADA-M). The proposed model enhances accountability, flexibility, and personalization in data access requests through SCs whilst ensuring compliance with GDPR. However, the scalability and data privacy are not considered [66]. On the other hand, Ray (2021) proposed a novel system for an e-healthcare application, which involves a BC-lightweight IoT node-based system with an enhanced Simplified Payment Verification (SPV) process. However, this technique employs the Bloom filter which brings scalability issues. In addition, this system has high false positives, and needed special hardware to be implemented [170]. Alnuaimi et al. (2022) proposed a healthcare model based on private Ethereum that utilized off-chain storage IPFS for image storage. For traceability and trustworthiness, the model used two SCs for registration and approval. Unfortunately, the system is unable to resist DoS attacks. In addition, it incurs high computational costs, and supports limited privacy and scalability [171].

To support remote chronic disease patients who need regular monitoring, Azbeg et al. (2022) proposed a BlockMedCare healthcare system which is based on the Ethereum BC and IPFS [12]. The system considered three main requirements: security, scalability, and processing time. The security is ensured through an encryption proxy, while scalability is achieved by utilizing an off-chain database based on IPFS. In this scheme, Ethereum is used to reduce execution time. However, the data reliability and validity were neglected in this method [12]. Luis et al. (2023) have developed a BC technology-enabled technique for medical records exchange. They utilized the Ethereum BC platform to provide a better healthcare service and minimize costs. In this technique, BC offers privacy, security, and availability. However, this approach cannot withstand 51% attacks [172].

To secure electronic health records (EHRs), enhance data integrity, and improve patient privacy, Agha (2023) has introduced BC technology-based decentralized framework. This system deploys sensors for real-time monitoring and is shown to enhance health information management. In this approach, patients have full control of their personal healthcare data. In addition, the usage of SCs offer more efficiency and reduce costs. However, the system suffers from limited scalability and presents some difficulties during its integration with existing systems. In addition, it fails to withstand DDoS and MITM attacks [173].

Norah et al. (2024) proposed group authentication for the IoMT framework. In addition, they introduced fog computing for maintaining scalability, enhancing efficiency and overcoming high costs associated with the decentralized BC technology. Nonetheless, the framework incurs high communication costs due to the large number of devices that need to be verified by a single entity [11]. To enhance authentication, security and efficiency in IoHT systems, Muwafaq et al. (2024) have developed a system based on the Bloom filter, Firebase framework and BC. In this scheme, the Bloom filter mainly reduces the authentication time, Firebase manages real-time synchronization, while the BC preserves data security and integrity. Despite the widespread use of the Bloom filter, it is costly due to its hardware requirements and the potential for high false positives [131].

On the other hand, Lin et al. (2023) have presented a novel technique for managing large volumes of medical data through an attribute-based secure access control mechanism (SACM) for IoT-enabled healthcare. The proposed mechanism is based on FDL and utilizes graph convolutional networks to establish a relationship between users’ social attributes and their trustworthiness. In so doing, it helps control access to sensitive medical data. The system provided good access control accuracy and maintained data integrity and privacy. However, it has long latencies and malicious participants can manipulate or alter data [20].

Qadir et al. (2023) have presented an authentication and access control model for secure and efficient data sharing among healthcare providers. The proposed framework is based on Security Secret Key Provider (SSKP) technology for access control as well as managing and securing personal health records. However, authentication takes a long time [174]. To solve the problem of third parties-induced vulnerabilities, Ussatova et al. (2023) have developed an enhanced two-step authentication scheme. This approach combines cloud technology and BC to secure medical data access. The practical implementation and analysis demonstrate the efficiency of biometric login. Still, their solution has some limitations as the encryption key generation is not fully defined and the key formation method is limited, and the limited fingerprint database reduces accuracy [108]. On the other hand, Abbas AI et al. (2024) have developed a robust fuzzy-based method for enhancing security in cloud-enabled healthcare systems. This ECC-based technique achieves good results in terms of communication cost, mutual authentication, and data integrity. However, it might not protect against cyber-attacks such as replay attacks, de-synchronization and spoofing [175].

Tance et al. (2023) have presented a review paper evaluating recent solutions in the field of authentication in healthcare systems. In addition, the authors describe the latest technologies integrated into IoHT, the applications of next-generation MFA, as well as the security requirements for these systems and their corresponding solutions [60]. On the other hand, Singla and Verma N (2023) presented a survey of research works published between 2010 and 2022, dealing with authentication techniques used in IoT systems. Their study provided a comprehensive description of three authentication techniques, namely knowledge-based authentication (based on information known by a legitimate-User), inherence-based authentication (based on integrated things to an individual), and possession-based authentication (based on something owned by the legitimate user). In addition, a review of the deployed performance metrics (such as accuracy, EER and FAR) is provided [176]. Similarly, Enrique et al. (2023) reviewed numerous papers dealing with different AI-based schemes that address security issues, withstand specific attacks and threats. They also described how AI techniques, including ML, DL, and reinforcement learning, can be employed to detect intrusion, malicious attacks, or other threats [5].

Khan et al. (2022) carried out extensive literature review on authentication process security. They analyzed the advantages of each type of authentication scheme, concluding it is challenging to design a suitable authentication framework with a complete package of security requirements to withstand hacking problems [177]. Some of these requirements include ward security, mutual authentication, privacy protection, integrity, key agreement, password change, scalability, confidentiality, and availability. On the other hand, Ghaffari et al. (2024) have comprehensively reviewed literature on IoT security based on DL and ML approaches, describing their advantages, and limitations. They identified vulnerabilities in IoT systems, such as eavesdropping, denial of service, unauthorized access to data and snooping threats. They emphasized the critical role of machine learning and deep learning techniques in mitigating these risks.

As explained in [178], ML techniques such as support vector machine (SVM), artificial neural network, and linear modeling are successful on small datasets while DL models have higher accuracies on large dataset. Dargaoui et al. (2024) have presented a comparative study of IoT security researches. They presented an analysis of latest authentication protocols developed in the period between 2018 and 2024. The aim of the authors was to summarize IoT security research, the most prominent vulnerabilities and attacks such as impersonation, reply, node capture, DoS, privileged insiders, and MITM. In addition, a review of appropriate security technologies such as BC, ML, physically unclonable function (PUF) and cryptography is provided. Moreover, the most commonly used formal security analysis tools are presented, such as ProVerif, Scyther, Random Oracle, and AVISPA [179]. Cobrado et al. (2024) have carried out a study that reviewed 24 published research works on the most common methods used for access control. These methods include identification, authentication, authorization, and accountability. The authors concluded that the most common mechanism is Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC) [102].

Mohamed et al. (2024) conducted a literature review to study authentication protocols in an IoT environment. The authors discussed the applications and the appropriate type of authentication, as well as how to choose the key agreement and exchange mechanism. The cryptographic techniques used in this field, and the methods of formal and informal threat analysis and countermeasures to these threats were also discussed. Furthermore, they mentioned using hybrid cryptography and authentication measures such as biometrics and multi-factor authentication to enhance security without compromising usability. However, the authors noted potential drawbacks such as data privacy concerns and new vulnerabilities [79].