Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

CMACF-Net: Cross-Multiscale Adaptive Collaborative and Fusion Grasp Detection Network

1 School of Electrical and Information Engineering, Wuhan Institute of Technology, Wuhan, 430205, China

2 College of Information and Artificial Intelligence, Nanchang Institute of Science and Technology, Nanchang, 330108, China

* Corresponding Author: Runpu Nie. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2959-2984. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066740

Received 16 April 2025; Accepted 03 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

With the rapid development of robotics, grasp prediction has become fundamental to achieving intelligent physical interactions. To enhance grasp detection accuracy in unstructured environments, we propose a novel Cross-Multiscale Adaptive Collaborative and Fusion Grasp Detection Network (CMACF-Net). Addressing the limitations of conventional methods in capturing multi-scale spatial features, CMACF-Net introduces the Quantized Multi-scale Global Attention Module (QMGAM), which enables precise multi-scale spatial calibration and adaptive spatial-channel interaction, ultimately yielding a more robust and discriminative feature representation. To reduce the degradation of local features and the loss of high-frequency information, the Cross-scale Context Integration Module (CCI) is employed to facilitate the effective fusion and alignment of global context and local details. Furthermore, an Efficient Up-Convolution Block (EUCB) is integrated into a U-Net architecture to effectively restore spatial details lost during the downsampling process, while simultaneously preserving computational efficiency. Extensive evaluations demonstrate that CMACF-Net achieves state-of-the-art detection accuracies of 98.9% and 95.9% on the Cornell and Jacquard datasets, respectively. Additionally, real-time grasping experiments on the RM65-B robotic platform validate the framework’s robustness and generalization capability, underscoring its applicability to real-world robotic manipulation scenarios.Keywords

With the rapid development of the field of artificial intelligence [1,2], robotic grasping has emerged as a fundamental task in intelligent robotic manipulation. Its application has expanded from structured industrial environments to complex, unstructured settings [3]. In structured environments, object poses, categories, and spatial distributions typically follow predictable patterns. However, in unstructured environments, the diversity of objects and background complexity pose significant challenges to the generalization capability of robotic grasping systems.

The integration of vision-guided robot grasping technology is crucial for enabling robots to effectively interact with the real world [4]. Robotic grasp detection aims to determine the optimal grasp pose of a target object, enabling the robot to achieve a stable grasp through controlled finger closure [5,6]. Existing methodologies can be broadly categorized into physics-based analytical approaches and data-driven approaches.

1. Physics-Based Analytical Approaches: Analytical grasping approaches compute optimal grasp poses by mathematically modeling an object’s physical properties, geometry and mechanics under kinematic and dynamic constraints [7]. First, a complete 3D model of the target is acquired and used to generate candidate grasp poses, which are stored in a precomputed database. Once the object is recognized, the system retrieves the most suitable pose and refines it through collision detection and inverse-kinematics planning [8]. Several studies have explored different modeling techniques to enhance grasp detection accuracy: Suzuki et al. [9] identified grasp points by computing the geometric center and principal axis of the object. Moreover, Li et al. [10] redefined grasp detection as a shape-matching task, identifying graspable regions by comparing model features. Herzog et al. [11] developed a grasp template library, incorporating local shape descriptors and optimizing grasp configurations through human demonstration. Despite their theoretical robustness, analytical methods are highly dependent on precise 3D object models, making them extremely susceptible to sensor noise. This dependence significantly limits their applicability to non-rigid objects or targets with complex and unknown geometries.

2. Data-Driven Approaches: Data-driven grasp detection methods focus on extracting abstract features from perceptual data to capture an object’s geometric structure, texture, and other latent grasp-related cues. These extracted features are then mapped to grasp pose scores within the grasp space [12]. Conventional data-driven approaches typically employ a two-stage framework: first, handcrafted features are extracted from images, followed by the application of machine learning models for grasp classification or regression. However, this approach increases system complexity and reduces detection efficiency. For example: Guo et al. [13] integrated visual and tactile information to classify discrete grasp rotation angles, optimizing detection performance. Zhou et al. [14] introduced a fully convolutional network with oriented anchor boxes, enhancing feature extraction for grasp detection. Despite their advancements, traditional data-driven approaches are highly susceptible to noise, especially when dealing with objects of complex shapes. Additionally, handcrafted feature extraction often fails to effectively process multimodal data or capture higher-order nonlinear relationships within images, limiting the model’s generalization capability.

To reduce reliance on high-precision models, recent research has shifted toward model-free grasp detection [15,16]. Jiang et al. [12] introduced a 2D planar grasp rectangle representation, which enables direct grasp configuration prediction from images. Based on this, Lenz et al. [17] proposed a cascaded sparse autoencoder net. Realizing end-to-end optimization of grasp pose prediction. This work laid the foundation for subsequent approaches based on Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). Early research in this domain was often limited by the computational overhead of generating candidate grasp poses. To overcome this, researchers adopted the Region of Interest (ROI) mechanism from object detection [18–20], significantly improving both efficiency and grasping success rates. In recent years, deep learning-based grasp detection has emerged as a dominant research focus both domestically and internationally [21,22]. These methods use large-scale grasp datasets to autonomously learn high-level feature representations from raw perceptual data, enabling the extraction of object characteristics and effective grasping strategies. Notable contributions include: Morrison et al. [23] proposed the Generative Grasp Convolutional Neural Network (GG-CNN), that bypasses the need for candidate box generation by directly outputting pixel-level grasp predictions, thereby significantly improving real-time performance. Kumra et al. [24] introduced Generative Residual Convolutional Neural Network (GR-ConvNet), which integrates deep residual convolutional modules to enhance feature representation. This design effectively mitigates the vanishing gradient problem while improving network depth and generalization capability. Yu et al. [25] incorporated a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) attention module into a residual network to improve key feature extraction. Kuang et al. [26] introduced Omni-dimensional Dynamic Convolution, improving graspable region feature extraction. Fu et al. [27] developed an adaptive filtering strategy to optimize grasp configuration and proposed a generative neural network for quantifying grasp quality. Yu et al. [28] designed a dual-branch SE residual network and introduced a position-focused loss function to improve detection accuracy. Li et al. [29] integrated multi-scale dilated convolutions with BiFPN [30] to optimize feature fusion and information flow across layers, and Zhong et al. [31] proposed a Feature Fusion Pyramid Module (FFPM) between the encoder and decoder to mitigate feature loss during deep encoding. Fang et al. [32] introduced LGAR-Net2, which combines attention blocks with spatial pyramid blocks to enhance the attention to important regions of the image. Zhai et al. [33] integrated the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) into GR-CNN to emphasize critical features and reduce model complexity by compressing channel dimensions. Tong et al. [34] introduced a novel cross-modal complementary information fusion strategy, integrated with geometric constraints for oriented bounding box optimization, resulting in notable improvements in detection performance. However, the fixed receptive fields of CNNs limit the capture of multi-scale information and global spatial correlations. This limitation disrupts the consistent fusion of spatial features, thereby complicating the distinction between target objects of varying sizes and the background.

Recent research has introduced Transformer architectures that use self-attention mechanisms to model long-range dependencies effectively [35,36]. Wang et al. [37] pioneered the application of Vision Transformers to grasp detection, where an adaptive self-attention mechanism effectively captures cross-region feature correlations, significantly enhancing global representation capability. Guo et al. [38] combined CNN-extracted local features with Transformer-based global representations, proposing the MDETR grasp detection network. Yang et al. [39] developed positional encodings for RGB and depth images using sinusoidal and Gaussian functions, effectively capturing object geometry and spatial information. Yu et al. [6] introduced the Pushing and Grasping method based on Vision Transformer and Convolution (PGTC), which models global spatiotemporal features, improving grasp location prediction accuracy. Zhang et al. [40] introduced bidirectional bridges with cross-attention mechanisms to alleviate the perceptual conflict between CNN and Transformer. Although these techniques enhance global representation, they inadvertently suppress local details, leading to the loss of high-frequency features and discontinuities along object boundaries. Consequently, when dealing with objects of irregular or complex geometry, the prediction accuracy of key grasp parameters—such as angle and gripper width—is significantly reduced, thereby compromising grasp precision and overall capture effectiveness.

Furthermore, encoder-decoder architectures reduce spatial resolution, and ordinary deconvolution limits the recovery of fine-grained spatial details during decoding. This degradation may induce artifacts such as the checkerboard effect [41], further impacting grasp detection accuracy. These challenges significantly affect the generalization capability of grasp detection models, thereby constraining their deployment in diverse and complex environments.

To address these limitations, we propose the Cross-Multiscale Adaptive Collaborative and Fusion Grasp Detection Network (CMACF-Net). Unlike existing methods, CMACF-Net integrates a Quantized Multi-scale Global Attention Module (QMGAM) during feature extraction, which employs a dual-path parallel architecture combining multi-scale convolutional operations with attention mechanisms. This architecture enables accurate multi-scale spatial alignment and dynamic coordination between spatial and channel dimensions, enabling effective utilization of multi-scale target features while minimizing background noise, thus improving object-background distinction across diverse settings. In addition, the Cross-scale Context Integration Module (CCI) is placed between the encoder and decoder to strengthen feature transitions. By integrating Local-Global Collaborative Representation (LGCR) Unit and Multi-scale Adaptive Calibration and Fusion (MSACF) Unit in parallel, the CCI module effectively bridges local details and global semantics, ensuring accurate alignment and reducing the loss of fine-grained information during deep propagation. Finally, a U-Net architecture incorporating Efficient Up-Convolution Blocks (EUCBs) is employed to recover spatial details lost during downsampling, thereby enhancing both computational efficiency and overall grasp detection accuracy, while effectively preventing checkerboard artifacts.

The primary contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

1. We propose the Quantized Multi-scale Global Attention Module (QMGAM), that integrates multi-scale spatial alignment and dynamic spatial-channel coordination to optimize multi-scale spatial positional feature extraction.

2. A Cross-scale Context Integration Module (CCI) is proposed to mitigate local detail loss during global modeling, thereby enhancing the prediction accuracy of key geometric parameters relevant to robotic grasping.

3. A U-Net architecture equipped with Efficient Up-Convolution Blocks (EUCBs) is designed to restore spatial resolution lost during downsampling, thereby improving detection precision and robustness while effectively mitigating checkerboard artifacts.

4. CMACF-Net achieves state-of-the-art performance on benchmark datasets, with detection accuracies of 98.9% and 95.9% on the Cornell and Jacquard datasets, respectively, thereby surpassing existing methods. Furthermore, real-world grasping experiments on the RM65-B robotic platform validate its real-time performance and generalization capability in complex environments, underscoring its strong potential for practical deployment.

This section defines the grasp representation for objects of varying shapes and configurations. First, the RGB-D image captured by the depth camera is processed and fed into the grasp detection network, which subsequently outputs a grasp representation comprising five parameters [17]:

where

where

where

where

To independently evaluate grasp quality, grasping sets are defined as follows, to represent grasp candidates in image space:

where

3 Cross-Multiscale Adaptive Collaborative and Fusion Grasp Detection Network

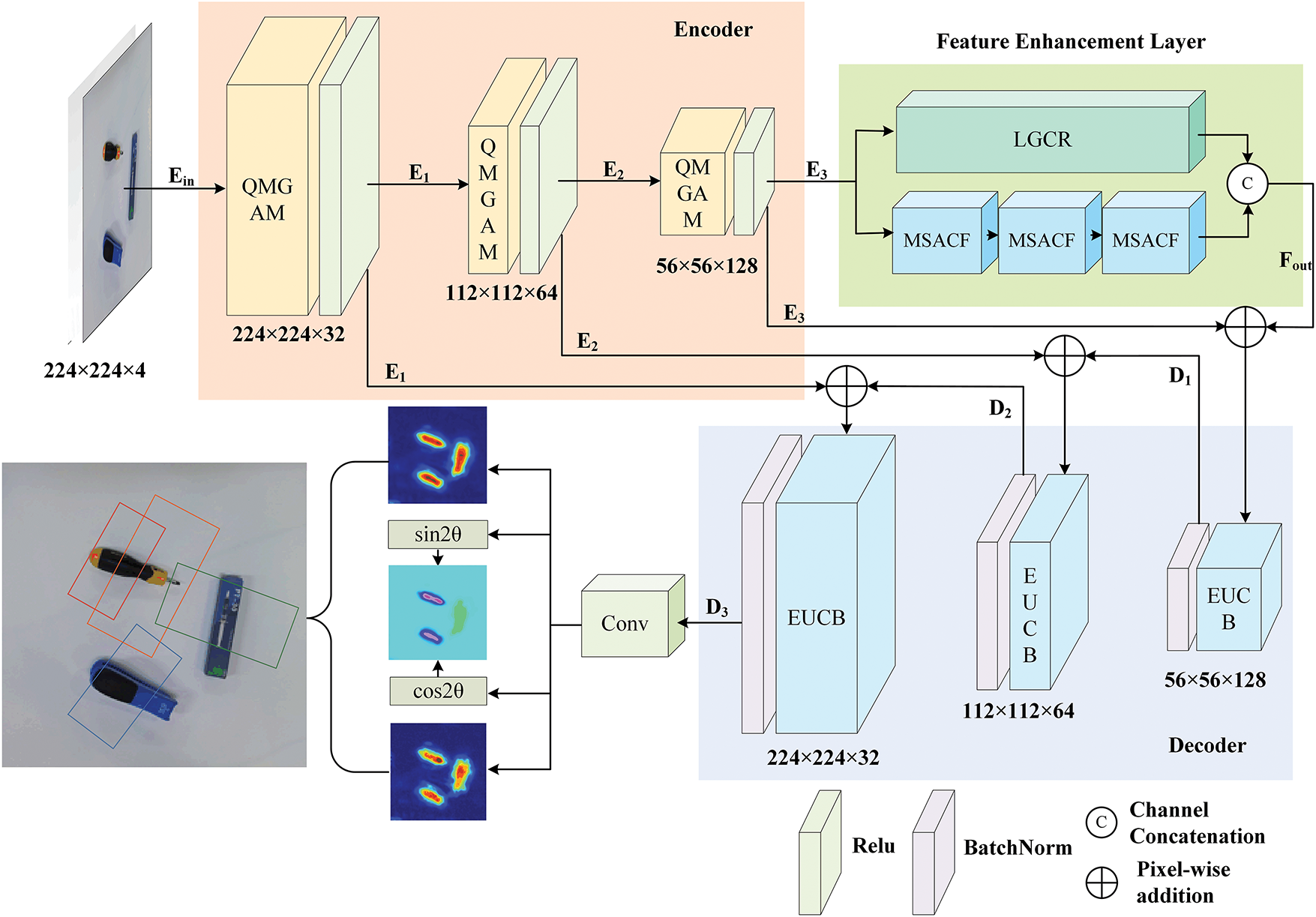

We propose CMACF-Net, a novel grasp detection architecture that enables multi-scale spatial feature calibration, enhances spatial-channel interaction in unstructured environments, and effectively aligns local and global features. Fig. 1 presents the overall framework of the proposed grasp detection network, which consists of five core components: an input layer, an encoder, a feature enhancement layer, a decoder, and an output layer.

Figure 1: Overall architecture of CMACF-Net

Specifically, an RGB image and a depth image are concatenated along the channel dimension to form a 224 × 224 × 4 RGB-D input. Enhanced multi-scale adaptation and global spatial information consistency through QMGAM. After the first QMGAM module, the channel dimension expands from 4 to 32. Subsequently, each additional QMGAM module halves the spatial resolution of the feature map while progressively increasing the number of channels, culminating in a 56 × 56 × 128 output that provides abundant multi-scale semantic information for subsequent processing. The feature enhancement layer integrates a CCI module with a dual-branch design: the MSACF chain focuses on multi-scale extraction and adaptive fusion of local features, while LGCR fosters deeper coupling between local and global information. The two feature streams are then concatenated along the channel dimension and fused via a 1 × 1 convolution for channel adjustment, thereby aligning local and global features more effectively and mitigating local information dilution. To preserve spatial details during feature reconstruction and prevent checkerboard artifacts [41] associated with conventional upsampling techniques, we adopt the EUCB. The output layer provides grasp confidence

3.1 Quantized Multi-Scale Global Attention Module

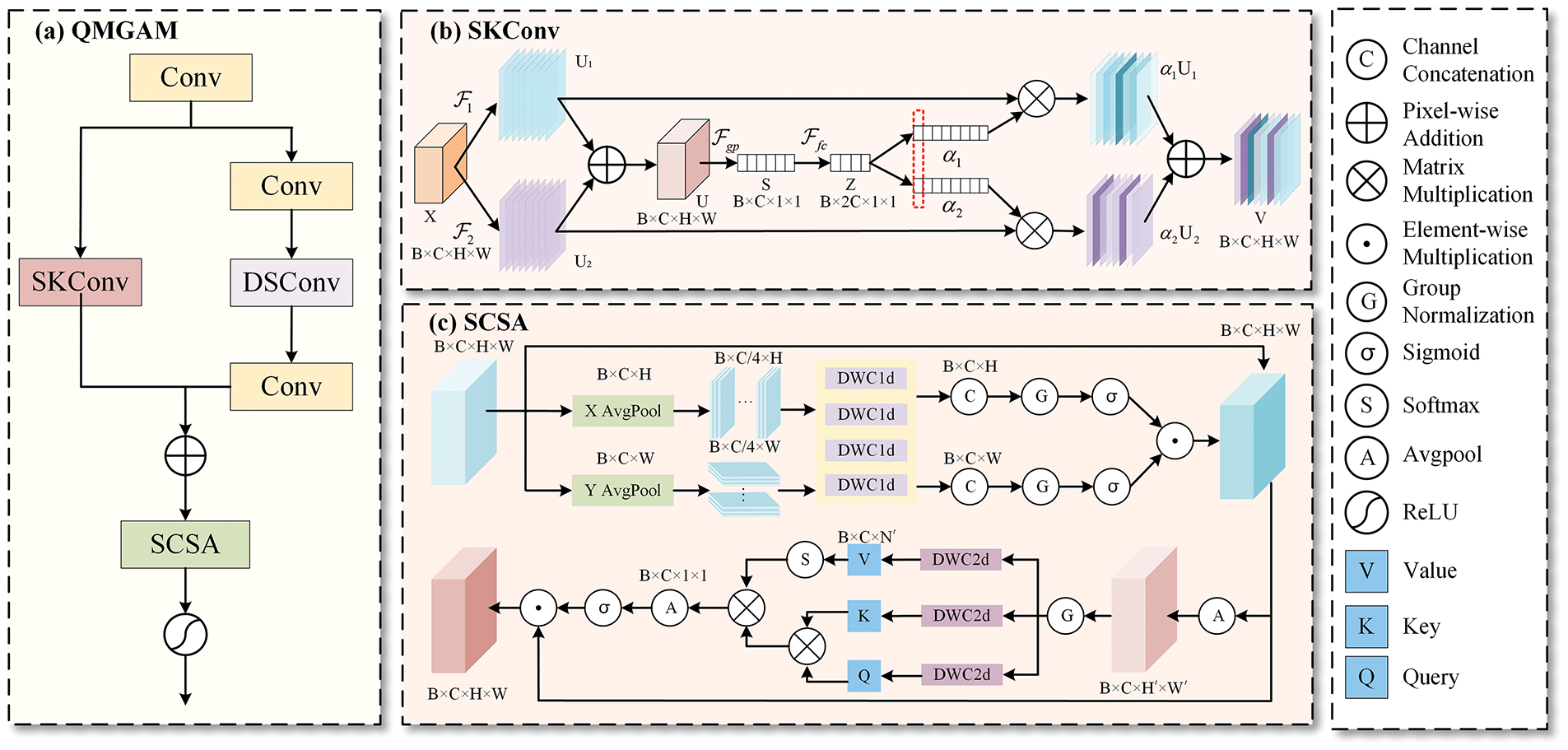

The QMGAM module as depicted in Fig. 2a, integral to the CMACF-Net framework, employs a dual-path architecture integrating multi-scale convolutions with a Spatial-Channel Self-Attention (SCSA) mechanism [42]. It comprises three stages: initial feature extraction, dual-branch parallel processing, and SCSA. One branch focuses on capturing fine-grained details, while the other employs multi-kernel adaptive convolutions to dynamically adjust the receptive field, enhancing spatial adaptability to objects of varying scales. Spatial attention is guided by statistical mean representations along spatial axes, with multi-scale convolution enhancing adaptability and generating attention maps for salient region emphasis. Channel attention involves average pooling, normalization, and grouped 1 × 1 convolutions to produce query

Figure 2: (a) QMGAM; (b) Selective Kernel Convolution (SKConv), where

The input tensor

To enhance the network’s adaptability to objects of varying scales, SKConv [44] is incorporated into the second pathway to dynamically adjust the receptive field, as illustrated in Fig. 2b. Given an input feature map

Subsequently, the aggregated feature representation

where

where

Finally, the weighted fusion of each branch feature is carried out according to the weight:

This mechanism allows convolutional kernels to dynamically adjust their receptive fields in response to varying input conditions. By enabling adaptive multi-scale information capture, it enhances the model’s ability to extract rich hierarchical features, effectively mitigating information loss caused by fixed receptive fields. Finally, the outputs from both pathways are weighted and fused element-wise. Traditional methods are constrained by fixed convolutional kernels and single-path architectures, making it challenging to simultaneously capture fine details of small objects and structural information of large objects. QMGAM employs a dual-path parallel architecture: one path is designed to focus on the fine-grained features of small objects, while the other leverages multi-kernel adaptive convolution to dynamically adjust the receptive field, thereby achieving self-adaptive multi-scale object representation. When dealing with non-uniform geometries such as spoons, the above process not only enhances multi-scale feature representation, but also helps to achieve more comprehensive and consistent spatial information modeling.

The feature map is then fed into the SCSA mechanism [42], as illustrated in Fig. 2c. During the spatial modeling process, the global mean of the fused feature map is computed along both the horizontal and vertical directions to generate the statistical feature representation:

This operation leverages the contrast between the target object’s concentrated distribution and elevated mean characteristics and the background’s homogeneous distribution and diminished mean characteristics to preliminarily distinguish the object from its background. Multiple 1D Depthwise Convolution (DWConv) [43] layers with varying kernel sizes are employed to enhance the spatial adaptability of features across different scales. In particular, the kernels with small receptive fields capture short-range spatial dependencies, while the larger kernels extract long-range spatial patterns, ensuring the coherence of global spatial features. After concatenation, normalization, and Sigmoid activation, spatial attention maps are generated in multiple directions to enable the adaptive regulation of spatial features. These attention maps assign higher weights to target regions.

where

Subsequently, we perform element-wise multiplication on the original feature maps to establish multi-scale spatial dependencies. This operation selectively enhances discriminative regional features while suppressing irrelevant background information, thereby improving the representational capacity for target objects. Such a mechanism further refines the feature discriminability of salient regions, facilitating more effective processing in downstream modules.

where X represents the original feature map.

For channel modeling, average pooling is first applied to downsample the spatially modulated features, reducing computational complexity while preserving essential feature information. Next, normalization is applied to stabilize training and enhance convergence. The feature map channels are then processed through 1 × 1 grouped convolution, generating the query

where

Spatial paths apply multi-scale convolution to generate attention maps, which are spatially reweighted to suppress background and highlight targets. The channel path employs grouped convolution and multi-head attention to enhance inter-channel correlation and dynamically amplify discriminative features. Their coordination achieves accurate multi-scale target and background separation through joint spatial channel optimization.

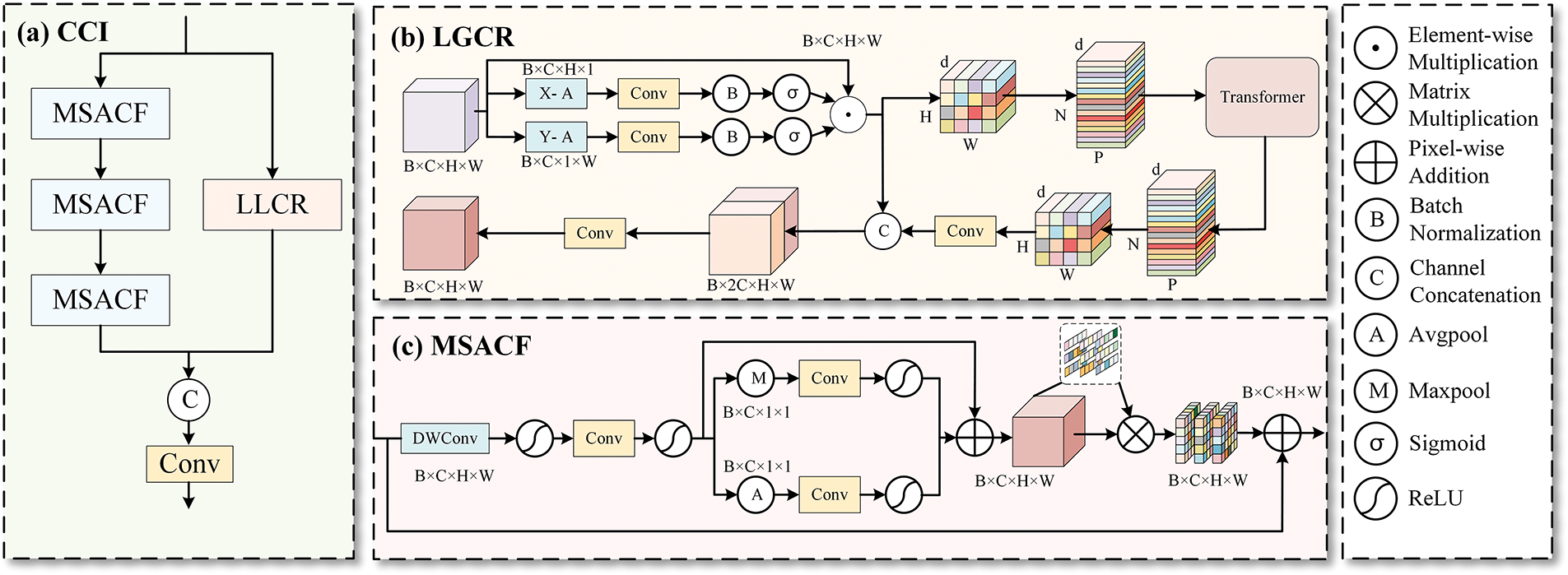

3.2 Cross-Scale Context Integration Module

The CCI module, situated between the encoder and decoder, integrates the LGCR and MSACF mechanisms in parallel, as shown in Fig. 3a. The module not only significantly enhances global semantic perception in grasp detection, reducing the degradation of local features during deep propagation, but also enables the integration and calibration of complementary cross-scale features. Consequently, it not only enhances the network’s performance in complex, unstructured environments but also improves the prediction accuracy of the grasping angle and width.

Figure 3: (a) Cross-scale Context Integration (CCI); (b) Local-Global Collaboative Representation Module (LGCR); (c) Multi-scale Adaptive Calibration and Fusion Module (MSACF)

3.2.1 Local-Global Collaborative Representation Module

The LGCR module establishes a “local filtering-global interaction” cascade structure to enhance feature integrity and robustness. The overall architecture is illustrated in Fig. 3b.

To begin, the Efficient Local Attention (ELA) mechanism [45] is applied to extract fine-grained local spatial features from the input feature map, reinforcing local representation capability through cross-dimensional information interaction. Specifically, the input feature map undergoes pooling along both vertical and horizontal directions to generate 1D feature encodings

where

To further enhance the spatial encoding capability of local features, a 1D convolution is applied, generating new feature representations denoted as

where

This operation effectively reduces the attenuation of local features during depth propagation, thus minimizing the loss of small features such as target internal structural connection points and contour that are related to the grasping angle.

The enhanced feature representations are then fed into MobileViTBlock [46], which uses a global self-attention reconstruction mechanism to facilitate local-global feature interaction. The previous operation ensures that local features are adequately encoded prior to entering the global modeling module. Next, the feature map is partitioned into multiple patches, and the Transformer module extracts global features to enable global context modeling:

where

The LGCR module facilitates the interaction between local and global features through a two-stage process. In the first stage, it preserves high-frequency details by preventing the attenuation of local textures and edge information before integration with global features. In the second stage, a Transformer-based module introduces long-range contextual information, enabling the network to capture the overall shape and orientation of objects and enrich the global perspective. Through multi-level residual fusion, shallow local features and deep global representations are jointly refined and mutually reinforced. This comprehensive fusion allows the model to consider object contours, relative positions, and orientations in a holistic manner, thereby enhancing the accuracy of grasp angle prediction.

3.2.2 Multi-Scale Adaptive Calibration and Fusion Module

To mitigate scale mismatches and weight imbalances during feature fusion, we propose the MSACF module. This module adopts a multi-branch architecture to extract local geometric shape information of grasping points, integrates the Simple Parameter-Free Attention Module (SimAM) [47] based on statistical feature computation, and facilitates fine-grained feature integration via residual connections. These mechanisms enable efficient feature calibration and multi-scale information alignment. The overall structure of the MSACF module is illustrated in Fig. 3c.

Initially, a 3 × 3 DWConv [43] extracts spatial features and captures local neighborhood information, fully preserving details such as object edges and textures. This is followed by a 1 × 1 convolution to adjust channel dimensions, integrating channel-wise information. The nonlinear feature representation is enhanced using the ReLU activation function and normalization. Global max pooling is then applied along the channel dimension to preserve prominent features while emphasizing the local details of key areas of the object. Simultaneously, global average pooling is employed to capture low-frequency global information, thereby improving the model’s comprehension of the background. A 1 × 1 convolution further facilitates weighted feature allocation.

After these operations, residual connectivity is applied between the fused features and the initial inputs so that the model retains the low-level features while combining the multiscale representation, thus mitigating information loss and gradient vanishing. However, multi-scale feature fusion may still introduce scale mismatches or uneven weight distribution, necessitating additional feature calibration. To address this, MSACF integrates SimAM [47] for dynamic calibration, leveraging global statistical perception to adaptively adjust feature responses across spatial and channel dimensions. This process further optimizes feature representation and ensures a more balanced and effective feature fusion mechanism. SimAM [47] first computes the mean

where

To quantify the contrast between a given feature point and its surrounding features, the energy value

A higher energy value indicates greater contrast between the neuron and its neighboring features, signifying that this feature point should receive greater importance in the model. The weight

where

The MSACF module enhances multi-scale feature integration to prevent the information of small objects from being overwhelmed by large-scale features, exhibiting notable performance particularly in preserving fine internal connections and edge continuity of objects. By incorporating SimAM for dynamic calibration, the module assigns higher attention weights to regions with significant geometric variations, while effectively suppressing background noise and redundant texture information. This mechanism improves the channel-wise representation of detailed features, emphasizing the extraction of relevant edges and internal structures. Consequently, it enhances the perception of geometric features across varying scales and strengthens the expression of dimensional attributes such as grasping width and thickness.

The LGCR and MSACF modules are designed to be highly complementary. The former focuses on preserving high-frequency local structures during global modeling to ensure geometric consistency, while the latter dynamically adjusts features in the scale space to compensate for the potential loss of high-frequency information caused by the patch-unfold process in Transformers. Operating in parallel at the same feature scale, these two modules enable collaborative modeling of both local and global information. This design not only retains fine-grained details but also enhances global perception, significantly improving the model’s ability to predict key geometric parameters such as grasp angle and width in complex scenarios. It demonstrates stronger robustness and generalization, especially when dealing with objects of varying sizes or cluttered backgrounds.

3.3 Efficient Up-Sampling Block

After processing through QMGAM and CCI, the feature map resolution is reduced to 56 × 56 × 128. To maintain interpretability and preserve the spatial integrity of the features, an upsampling step is essential. Conventional grasp detection networks typically employ deconvolution for feature restoration; however, if the kernel-to-stride ratio is not appropriately configured, the deconvolution process can introduce periodic artifacts, commonly known as the checkerboard effect [41].

To mitigate this issue, our network incorporates two key optimizations. First, the output features of QMGAM are skip-connected with subsequent features to preserve as much original feature information from the encoder as possible. Second, we introduce the EUCB [48] to achieve artifact-free upsampling and to bolster cross-channel information exchange. Unlike transposed convolutions, EUCB initially employs deterministic, non-parametric interpolation (e.g., bilinear or nearest-neighbor) to elevate spatial resolution, effectively circumventing aliasing-induced checkerboard artifacts. Subsequently, DSConv refine spatial detail with minimal computational overhead. The channel-shuffle operation facilitates cross-channel information exchange and offsets DSConv’s limited inter-channel interaction. Finally, a 1 × 1 convolution realigns the feature dimensions. By blending interpolation with streamlined convolutional operations, EUCB weaken the structural noise typical of deconvolutions, while simultaneously optimizing computational efficiency and inter-channel communication, resulting in a more effective and stable upsampling mechanism.

In the grasp detection task, the loss function is used to optimize the difference between the model’s prediction and the ground truth label. After extensive experimental evaluation, Smooth L1 Loss demonstrates superior performance, effectively addressing the gradient explosion problem while maintaining strong training stability. For a given set of input images

Smooth L1 losses are:

where

where

In this section, we conduct a systematic training and evaluation of CMACF-Net on two well-established grasp detection datasets, comparing its performance with state-of-the-art algorithms. Additionally, real-world grasping experiments are performed using the Realman RM65-B robotic arm to validate the network’s applicability.

4.1 Experimental Device and Index

(1) Dataset: This study focuses on the Cornell Grasping Dataset [49] and the Jacquard Dataset [50], both widely utilized due to their structured data format and precise annotations. The Cornell dataset consists of 885 RGB images with a resolution of 640 × 480, each paired with a corresponding depth image. It covers 224 object categories and provides 5119 labeled grasp rectangles, including grasp position, angle, and width information. In contrast, the Jacquard dataset is significantly larger, containing 54,000 scenes and 1,100,000 target objects, with over 1,000,000 labeled grasp rectangles.

(2) Evaluation Metrics: Grasp detection is evaluated based on the Intersection over Union (IoU) between predicted and ground-truth grasp rectangles, as well as the orientation error. A grasp is considered valid if it meets the following criteria [25]:

IoU: The ratio of the intersection to the union of the predicted and ground-truth grasp rectangles must exceed 0.25 to ensure sufficient overlap:

Orientation Error: The angular deviation between the predicted and ground-truth grasp rectangles must be less than 30°, ensuring accurate grasp direction prediction:

where

(3) Network Training: The CMACF-Net model is implemented using PyTorch 1.10.1 and CUDA 11.1 on an Ubuntu 18.04 system. Training was conducted on an NVIDIA A100-PCIE 40 GB GPU and the training batch size is 32. The network was optimized using the Adam optimizer [51], initialized with a learning rate of 1 × 10−3, which was progressively decayed over time. Training spanned a total of 200 epochs, each consisting of 1000 batches. To prevent overfitting, an early stopping criterion with a patience of 20 epochs was applied. The model takes a 224 × 224 RGB-D image as input and generates three heatmaps of identical spatial resolution as output.

4.2 Analysis of Cornell Dataset Experimental Results

Owing to the relatively small size of the Cornell dataset [49], extensive data augmentation—including random cropping, rotation, and scaling—are applied to increase the diversity of the training samples. To ensure a thorough evaluation of model performance, five-fold cross-validation is also conducted. To improve dataset reliability, we adopt two dataset partitioning strategies: the Image-wise split (IW) [52] and Object-wise split (OW) [52]. The IW method tests the model’s ability to detect grasp positions and poses of objects at different locations. In contrast, the OW method evaluates the model’s generalization ability to unfamiliar objects by dividing the dataset by object category.

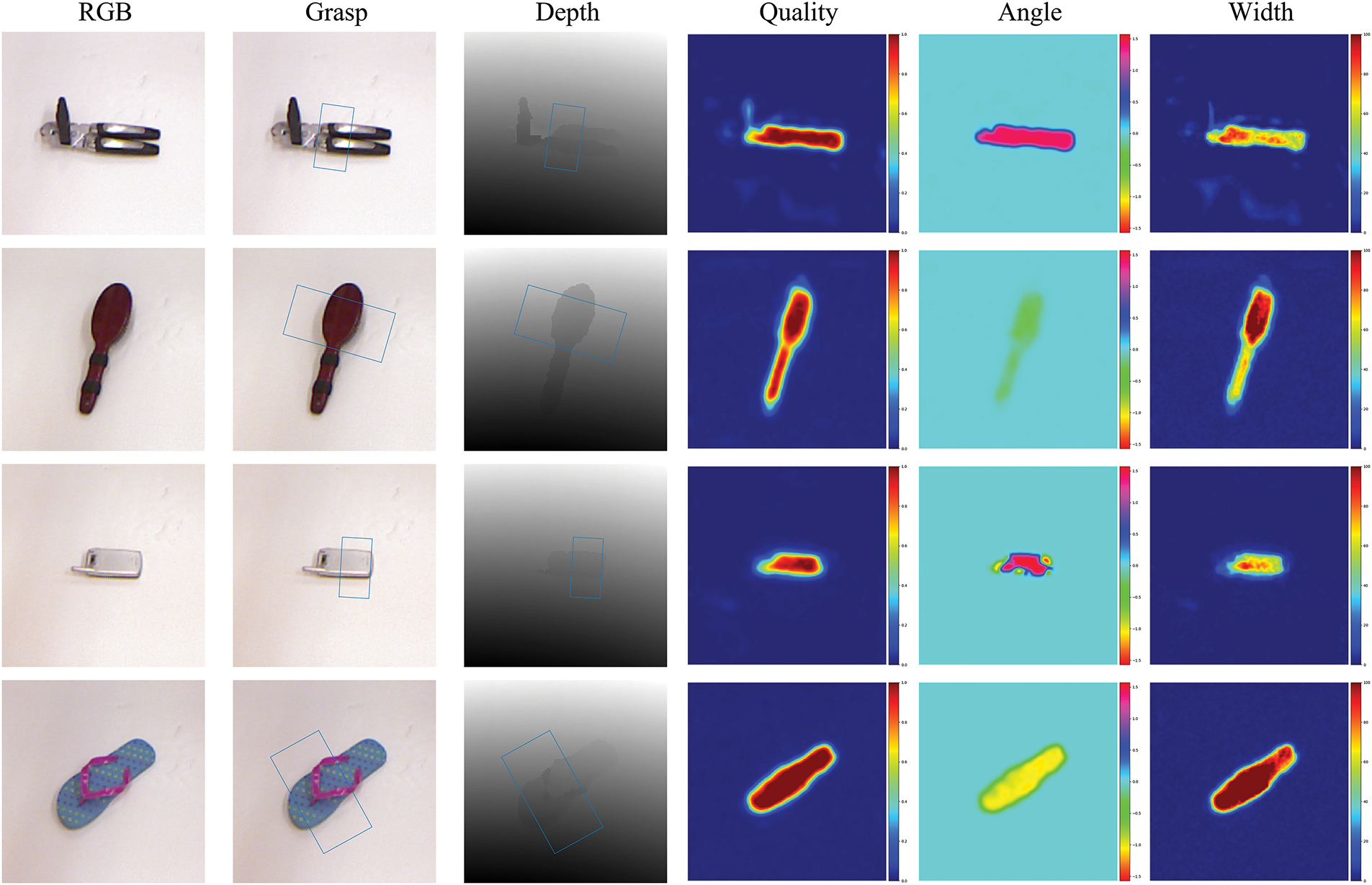

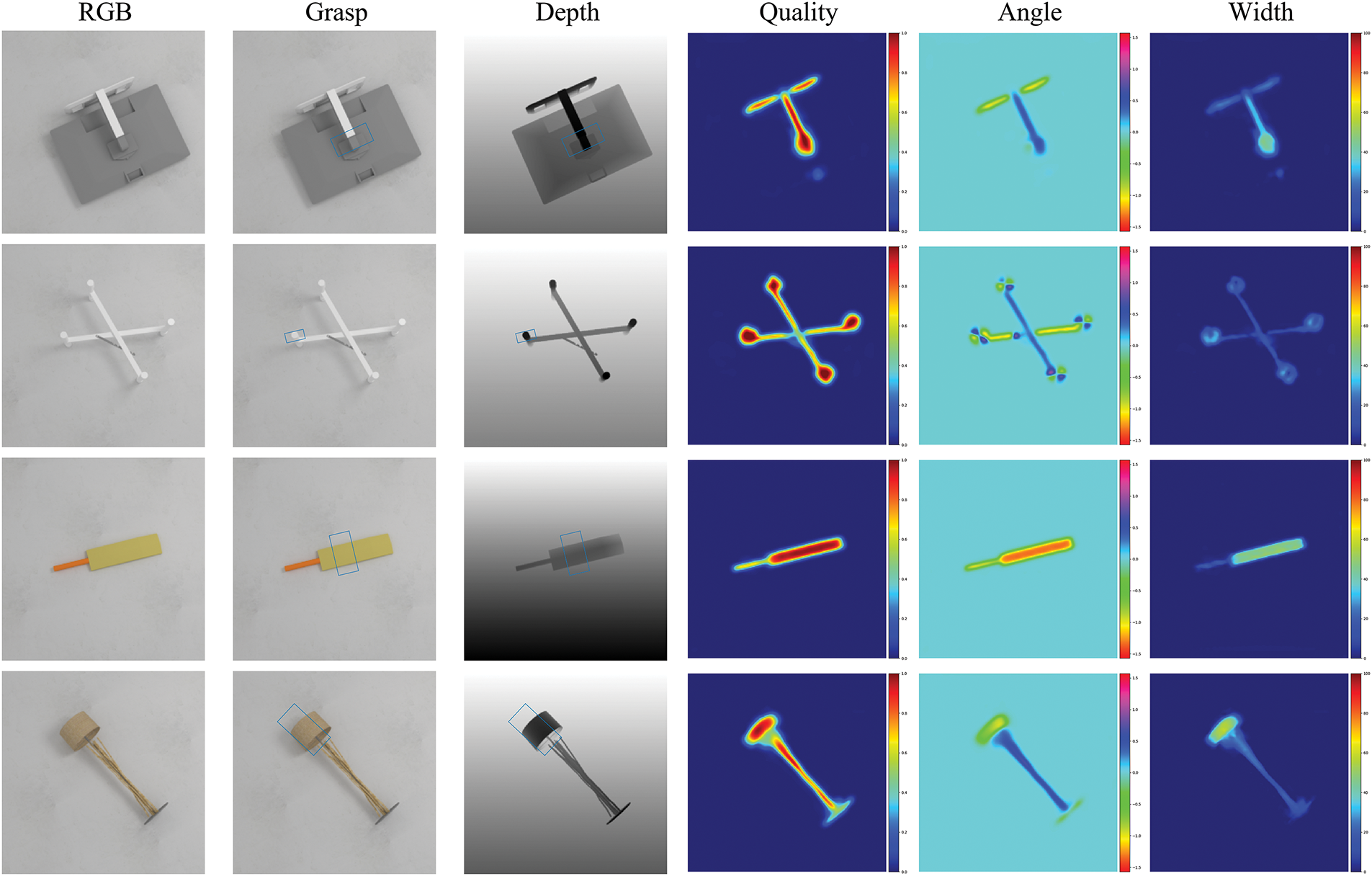

The grasp detection results on the Cornell dataset are illustrated in Fig. 4. The first column shows the raw input images; the second column displays the grasp rectangles predicted on the original images; the third column presents the corresponding depth images; and the fourth, fifth, and sixth columns show the grasp quality map, angle heatmap, and width heatmap, respectively, as generated by CMACF-Net. The grasp quality heatmap generated by CMACF-Net exhibits distinct peak values (scores close to 1.0) in target regions, while maintaining scores near in background areas. This indicates that QMGAM and CCI effectively separate graspable regions from the background, ensuring precise grasp localization.

Figure 4: Grasp detection results with the Cornell dataset

As shown in Table 1, we conduct a comprehensive evaluation and comparative analysis of various grasp detection models, with results from other methods taken from their original publications. CMACF-Net achieves an accuracy of 98.9% under IW [52] and 97.8% under OW [52], surpassing other algorithms in detection performance. It maintains inference speed while being only slightly lower than TF-Grasp [37] and SE-ResNet [25].

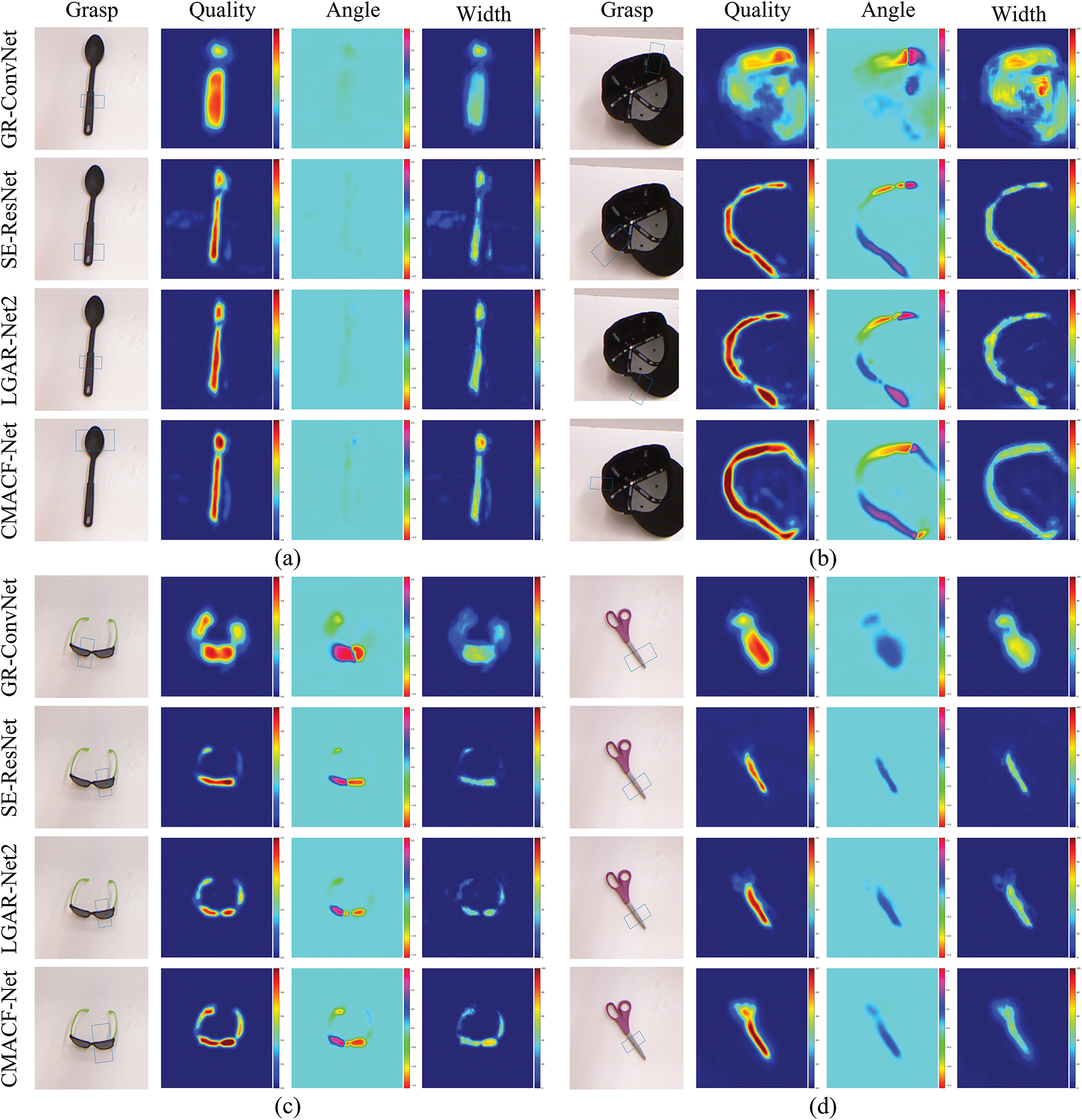

Furthermore, we compare CMACF-Net with three representative models [24,25,37] under identical conditions to evaluate the performance in grasp detection. As shown in Fig. 5, the grasp quality heatmaps reveal several key differences:

Figure 5: Comparison of grasp detection results on the Cornell dataset. (a–d) Respectively corresponding to the comparative test of different networks for the same capture target

GR-ConvNet [24] achieves reasonable grasp detection but lacks focus on the target object, leading to scattered grasp confidence. As depicted in Fig. 5a, the grasp region for the spoon is poorly defined, resulting in imprecise localization of candidate grasp points.

SE-ResNet [25] improves upon GR-ConvNet [24] by introducing an attention mechanism that refines the grasp prediction. Nonetheless, it lacks effective multi-scale feature fusion, limiting its ability to accurately localize grasp points on smaller objects. This shortcoming is evident in Fig. 5c, where the prediction neglects key endpoints of the eyeglass frame, indicating weaknesses in fine-grained grasp localization and in fully leveraging spatial information across scales.

Although TF-Grasp [37] can capture global semantics and detailed features through local window attention and cross-window attention, many local details are lost, leading to discontinuities in the grasp heatmap. This is demonstrated in Fig. 5b, where the connection between the hat and its brim is inadequately captured.

In contrast, CMACF-Net enhances multi-scale spatial calibration and spatial-channel interaction, addressing scale mismatches and feature fusion imbalances. It also improves local-global feature alignment and enables precise grasp detection across objects of varying sizes, especially at complex junctions.

To comprehensively evaluate the stability of CMACF-Net, we employ the Jaccard Index as an evaluation metric and conduct experiments at threshold values of 0.25, 0.30, 0.35, and 0.40, comparing its performance with TF-Grasp [37] and GR-ConvNet [24]. The experimental results are presented in Table 2. As the evaluation criterion becomes more stringent, CMACF-Net exhibits minimal accuracy degradation. When the Jaccard Index threshold reaches 0.40, CMACF-Net achieves an accuracy rate of 92.3% under IW and 91.2% under OW, outperforming both TF-Grasp [37] and GR-ConvNet [24]. These results confirm the stability and robustness of our method across various Jaccard Index thresholds, further validating its generalization capability in grasp detection tasks.

4.3 Analysis of Jacquard Dataset Experimental Results

We select 90% the images for training and the remaining 10% for testing on the Jacquard dataset [50] (see Table 3). The experimental results demonstrate that our approach outperforms other methods, achieving an accuracy of 95.9%, further validating its robustness across diverse grasping scenarios.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, CMACF-Net enhances object contours and geometric differentiation through reinforced spatial-channel collaborative attention. For irregular objects, it performs cross-scale fusion by integrating shallow local features (e.g., edges) with deep global features (e.g., shapes). The CCI module is essential for preserving fine details and mitigating feature dilution in deeper layers.

Figure 6: Grasp detection results with the Jacquard dataset

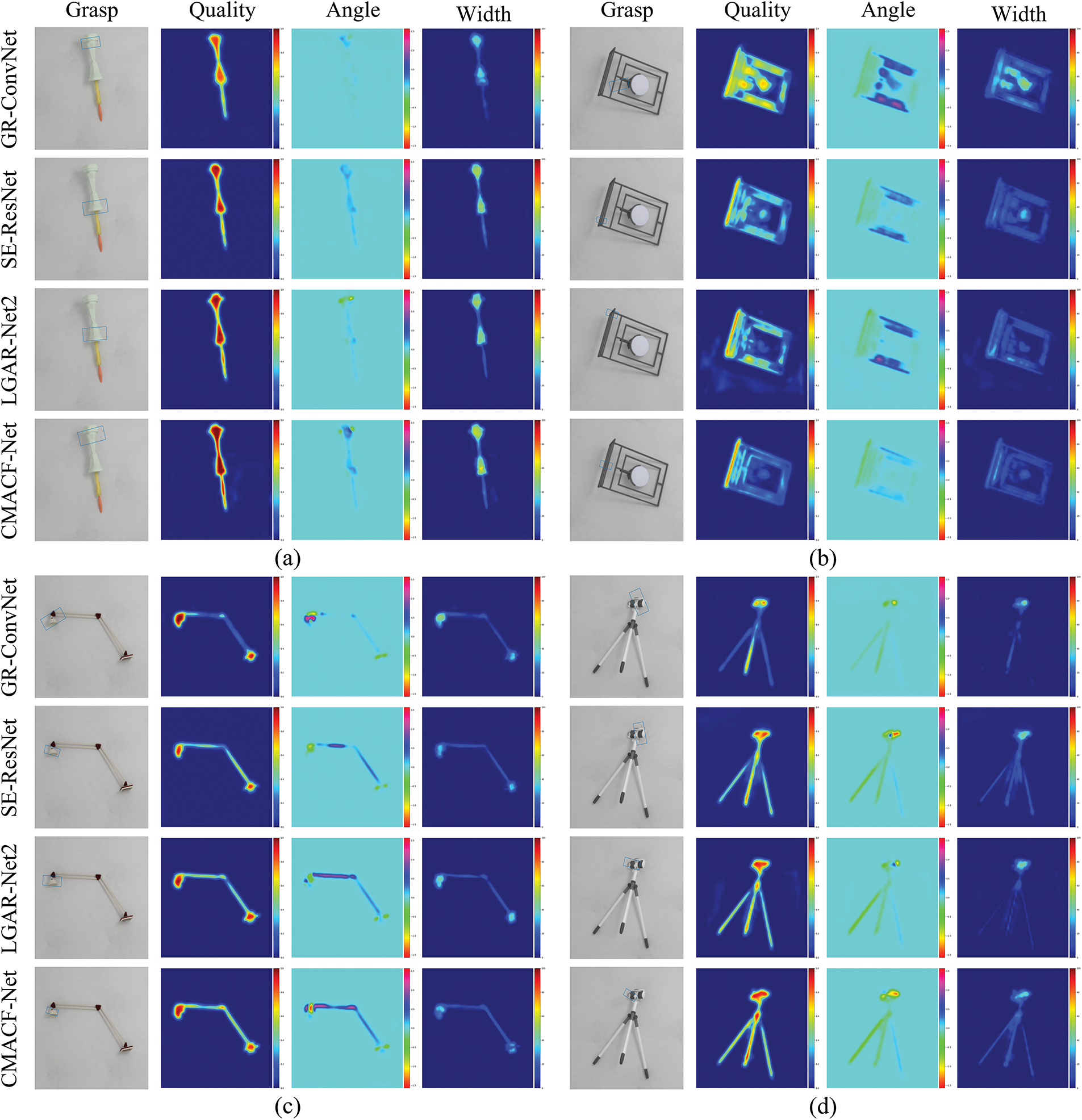

Furthermore, we compare CMACF-Net with three state-of-the-art algorithms [24,25,37] on the Jacquard dataset [50] under identical conditions. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the first column presents the RGB inputs, while the second to fourth columns visualize grasp quality, angle, and width, respectively, enabling a comprehensive comparison of detection performance across models.

Figure 7: Comparison of grasp detection results on the Jacquard dataset. (a–d) Respectively corresponding to the comparative test of different networks for the same capture target

When handling objects with complex shapes, as depicted in Fig. 7b, the GR-ConvNet [24] model is limited to predicting a coarse grasp region, thereby missing the finer structural details needed for accurate grasp positioning.

The SE-ResNet [25] uses a attention mechanism to optimize feature weight distribution, thus enhancing the overall coherence of global grasp predictions. However, its lack of multi-scale feature fusion renders the model insensitive to small-scale key points. For instance, as illustrated in Fig. 7c, the central metal connection point of the table lamp is inadequately detected.

Furthermore, TF-Grasp [37] exhibits inefficiencies in the interaction between local features and global context. This is evident in Fig. 7d, where the thermogram response at the junction between the top and the support is fragmented, leading to a discontinuous distribution of grasp confidence.

In contrast, CMACF-Net effectively captures the continuity relationships between target components and generates high confidence heatmaps in key areas such as connection points and rotation joints. This capability underscores its significant advantages in fine-grained grasp detection for complex structural objects, effectively addressing the primary limitations of traditional models in feature fusion and spatial alignment.

We also adopt the Jaccard index as the evaluation metric and conduct experiments on the Jacquard dataset under four different threshold values. The experimental results are shown in Table 4. On the Jacquard dataset, which features a greater variety of objects and more complex shapes, CMACF-Net still achieves the highest accuracy when the Jaccard index threshold reaches 0.40. These results confirm the stability and robustness of our method across various Jaccard thresholds, further validating its generalization ability in grasp detection tasks.

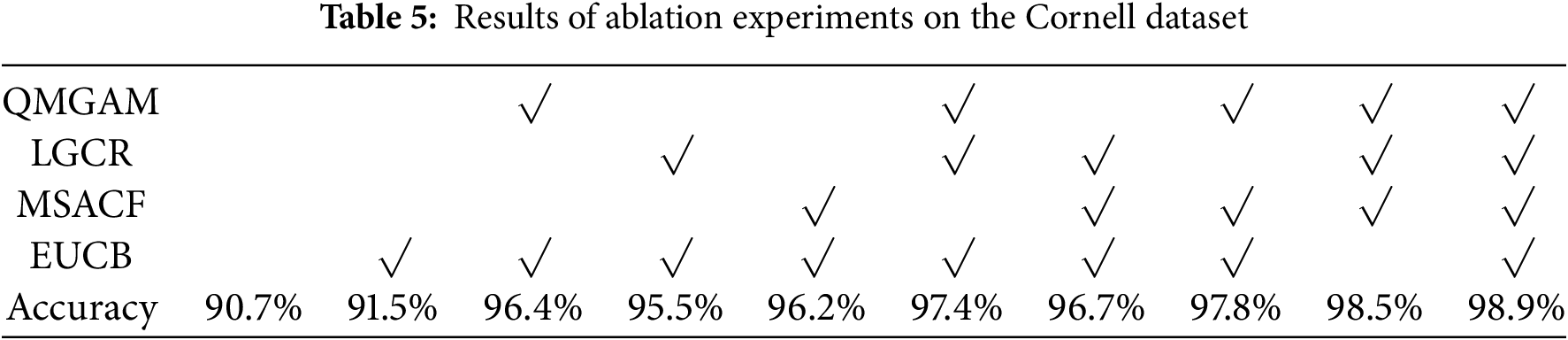

In this section, we conduct an ablation study on the Cornell dataset [49] to evaluate the efficiency of QMGAM and the submodules within CCI. As shown in Table 5, the ablation study consists of replacing QMGAM with standard convolution, substituting LGCR or MSACF in CCI with a shortcut module and replacing EUCB with deconvolution. Among them, a check mark indicates that no replacement has been made. The results confirm that both QMGAM, LGCR, MSACF and EUCB are essential components in improving the performance of CMACF-Net, demonstrating their significance in grasp detection accuracy and feature representation.

To assess the appropriateness of the chosen hyperparameters, we performed multiple experiments using the Cornell dataset. The results are presented in Table 6. Based on these results, we determined an optimal hyperparameter configuration: a learning rate of 0.001 and a batch size of 32.

4.5 Grasping Experiments in the Real World

This section presents a comparative analysis of three grasp detection algorithms [24,25,37] for real-world grasp prediction, with experimental results illustrated in Fig. 8. The findings indicate that CMACF-Net achieves precise grasp pose estimation in both single-object and multi-object scenarios, showcasing its robust generalization ability. In contrast, the grasp detection performance of the other three networks is inferior to that of CMACF-Net, highlighting the advantages of our multi-scale spatial feature alignment and cross-scale feature fusion mechanisms in challenging grasping tasks.

Figure 8: Comparison of grasp detection results in the Real world. (a–d) Respectively corresponding to the comparative test of different networks for the same capture target

We construct a grasping experiment platform comprising a RealMan RM65-B six-DoF high-precision robotic arm and a Microsoft Azure Kinect DK depth camera. Multi-threaded cooperative control is implemented based on the ROS distributed framework. The vision thread employs CMACF-Net for real-time RGB-D processing and publishes grasp positions, while the motion planning thread integrates an enhanced trajectory optimization algorithm to generate motion paths. Grasp parameters are transformed via camera-to-robot coordinate mapping to enable high-precision grasping. Experimental results demonstrate that the system’s modular design enables rapid cross-platform deployment, while millisecond-level response and multi-sensor fusion ensure stable grasping in complex environments. The hardware architecture is illustrated in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Screenshots of grasping in real-world scenarios

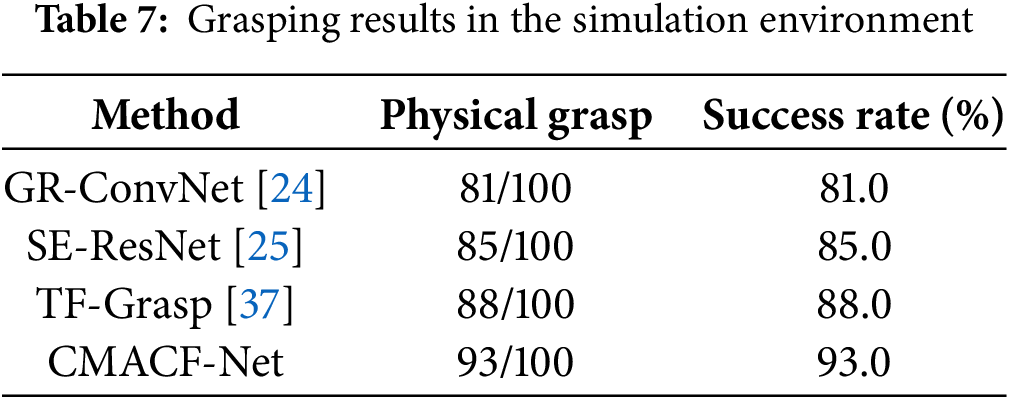

To further evaluate the practical effectiveness of our method, we conducted real-world comparative experiments by constructing a multi-object test scenario that included previously unseen objects such as pliers, screwdrivers, and staplers. A total of 100 grasping trials were performed, during which the grasp candidate with the highest predicted quality score was selected as the optimal grasp. A trial was deemed successful if the robot was able to lift the object without slippage or drop throughout the process. Table 7 summarizes the grasp success rates. Out of 100 attempts to grasp different objects, CMACF-Net achieved a success rate of 93.0%, outperforming all baseline methods. These results demonstrate the superior grasp detection capabilities of CMACF-Net and further validate its robustness and applicability in real-world robotic manipulation tasks.

Despite the promising results of CMACF-Net, current evaluations are primarily conducted in static settings, limiting its demonstrated robustness in dynamic environments. In scenarios involving moving objects, slight deviations in predicted grasp positions and angles can lead to reduced accuracy. Moreover, abrupt changes in lighting conditions significantly increase the rate of false detections. These limitations highlight the need for further investigation and enhancement of the model.

In this study, we propose CMACF-Net, an advanced grasp detection framework designed to tackle critical challenges in unstructured environments through synergistic multi-scale feature alignment and cross-scale semantic fusion. Experimental results demonstrate state-of-the-art performance, with grasp detection accuracies of 98.9% and 95.9% on the Cornell and Jacquard datasets, respectively. Real-world validation on the RM65-B robotic platform further confirms its real-time efficiency, robustness, and generalization capability in clutter scenarios.

Despite the promising performance of CMACF-Net, its relatively higher inference time compared to some lightweight counterparts may lead to response delays in grasping tasks that demand stringent real-time responsiveness. In dynamic scenarios involving moving objects, even minor inaccuracies in the predicted grasp position or orientation can significantly reduce the overall grasp success rate. Addressing these challenges will require the incorporation of temporal modeling strategies and real-time visual tracking to ensure robust and reliable grasp planning under conditions of motion and uncertainty.

Future work will focus on improving the adaptability and reliability of CMACF Net in complex and dynamic conditions, including object motion, variable lighting, occlusions, and the challenges posed by reflective or transparent surfaces. In addition, we plan to integrate dexterous robotic hands to enable more sophisticated manipulation tasks. Efforts will also be directed toward optimizing computational efficiency to facilitate real-time deployment on resource-constrained edge devices, thereby advancing the framework’s practical applicability in real-world robotic systems.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their gratitude for the valuable feedback and suggestions provided by all the anonymous reviewers and the editorial team.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 20232BAB202027), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62367006) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China (No. 2022CFB536).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Xi Li and Runpu Nie; Methodology, Runpu Nie; Software, Zhaoyong Fan; Validation, Xi Li, Runpu Nie, and Lianying Zou; Formal Analysis, Zhaoyong Fan; Investigation, Zhenhua Xiao; Resources, Zhaoyong Fan; Data Curation, Xi Li; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Zhaoyong Fan; Writing—Review and Editing, Lianying Zou and Zhenhua Xiao; Visualization, Kaile Dong; Project Administration, Xi Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Data are not publicly available due to privacy considerations.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cheng B, Sun L. FGNet: faster robotic grasp detection network. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA); 2024 Aug 4–7; Tianjin, China. doi:10.1109/ICMA61710.2024.10632914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Huang Z, Lin C, Xu B, Xia M, Li Q, Li Y, et al. T2EA: target-aware Taylor expansion approximation network for infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2025;35(5):4831–45. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2024.3524794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zou M, Li X, Yuan Q, Xiong T, Zhang Y, Han J, et al. Robotic grasp detection network based on improved deformable convolution and spatial feature center mechanism. Biomimetics. 2023;8(5):403. doi:10.3390/biomimetics8050403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Li C, Zhou P, Chong NY. Safety-optimized strategy for grasp detection in high-clutter scenarios. In: Proceedings of the 2024 21st International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots (UR); 2024 Jun 24–27; New York, NY, USA. doi:10.1109/UR61395.2024.10597484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ding D, Lee YH, Wang S. Computation of 3-D form-closure grasps. IEEE Trans Robot Autom. 2001;17(4):515–22. doi:10.1109/70.954765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yu S, Zhai DH, Xia Y. A novel robotic pushing and grasping method based on vision transformer and convolution. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2024;35(8):10832–45. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3244186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Huang Y, Bianchi M, Liarokapis M, Sun Y. Recent data sets on object manipulation: a survey. Big Data. 2016;4(4):197–216. doi:10.1089/big.2016.0042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ji J, Zou A, Liu J, Yang C, Zhang X, Song Y. A survey on brain effective connectivity network learning. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34(4):1879–99. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2021.3106299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Suzuki T, Oka T. Grasping of unknown objects on a planar surface using a single depth image. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM); 2016 Jul 12–15; Banff, AB, Canada. doi:10.1109/AIM.2016.7576829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li Y, Pollard NS. A shape matching algorithm for synthesizing humanlike enveloping grasps. In: Proceedings of the 5th IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots, 2005; 2005 Dec 5; Tsukuba, Japan. doi:10.1109/ICHR.2005.1573607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Herzog A, Pastor P, Kalakrishnan M, Righetti L, Asfour T, Schaal S. Template-based learning of grasp selection. In: Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation; 2012 May 14–18; Saint Paul, MN, USA. doi:10.1109/ICRA.2012.6225271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Jiang Y, Moseson S, Saxena A. Efficient grasping from RGBD images: learning using a new rectangle representation. In: Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation; 2011 May 9–13; Shanghai, China. doi:10.1109/ICRA.2011.5980145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Guo D, Sun F, Liu H, Kong T, Fang B, Xi N. A hybrid deep architecture for robotic grasp detection. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2017 May 29–Jun 3; Singapore. doi:10.1109/ICRA.2017.7989191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhou X, Lan X, Zhang H, Tian Z, Zhang Y, Zheng N. Fully convolutional grasp detection network with oriented anchor box. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2018 Oct 1–5; Madrid, Spain. doi:10.1109/IROS.2018.8594116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Bohg J, Morales A, Asfour T, Kragic D. Data-driven grasp synthesis—a survey. IEEE Trans Robot. 2014;30(2):289–309. doi:10.1109/TRO.2013.2289018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chen L, Niu M, Yang J, Qian Y, Li Z, Wang K, et al. Robotic grasp detection using structure prior attention and multiscale features. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2024;54(11):7039–53. doi:10.1109/TSMC.2024.3446841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lenz I, Lee H, Saxena A. Deep learning for detecting robotic grasps. Int J Robot Res. 2015;34(4–5):705–24. doi:10.1177/0278364914549607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Cao H, Chen G, Li Z, Lin J, Knoll A. Lightweight convolutional neural network with Gaussian-based grasping representation for robotic grasping detection. arXiv:2101.10226. 2021. [Google Scholar]

20. Geng W, Cao Z, Guan P, Jing F, Tan M, Yu J. Grasp detection with hierarchical multi-scale feature fusion and inverted shuffle residual. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2024;29(1):244–56. doi:10.26599/tst.2023.9010003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Grassucci E, Zhang A, Comminiello D. PHNNs: lightweight neural networks via parameterized hyper complex convolutions. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2022;35(6):8293–305. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2022.3226772. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Marchand E, Uchiyama H, Spindler F. Pose estimation for augmented reality: a hands-on survey. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2016;22(12):2633–51. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2015.2513408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Morrison D, Corke P, Leitner J. Learning robust, real-time, reactive robotic grasping. Int J Robot Res. 2020;39(2–3):183–201. doi:10.1177/0278364919859066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kumra S, Joshi S, Sahin F. Antipodal robotic grasping using generative residual convolutional neural network. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2021 Oct 24–Jan 24; Las Vegas, NV, USA. doi:10.1109/IROS45743.2020.9340777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yu S, Zhai DH, Xia Y, Wu H, Liao J. SE-ResUNet: a novel robotic grasp detection method. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2022;7(2):5238–45. doi:10.1109/LRA.2022.3145064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kuang X, Tao B. ODGNet: robotic grasp detection network based on omni-dimensional dynamic convolution. Appl Sci. 2024;14(11):4653. doi:10.3390/app14114653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Fu K, Dang X. Light-weight convolutional neural networks for generative robotic grasping. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2024;20(4):6696–707. doi:10.1109/TII.2024.3353841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yu S, Zhai DH, Xia Y. CGNet: robotic grasp detection in heavily cluttered scenes. IEEE/ASME Trans Mechatron. 2023;28(2):884–94. doi:10.1109/TMECH.2022.3209488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Li H, Zheng L. Cascaded feature fusion grasping network for real-time robotic systems. Sensors. 2024;24(24):7958. doi:10.3390/s24247958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Tan M, Pang R, Le QV. EfficientDet: scalable and efficient object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhong X, Liu X, Gong T, Sun Y, Hu H, Liu Q. FAGD-net: feature-augmented grasp detection network based on efficient multi-scale attention and fusion mechanisms. Appl Sci. 2024;14(12):5097. doi:10.3390/app14125097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Fang H, Wang C, Chen Y. Robot grasp detection with loss-guided collaborative attention mechanism and multi-scale feature fusion. Appl Sci. 2024;14(12):5193. doi:10.3390/app14125193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhai C, Zhang Z, Dai M, Xia Z, Wen H, Shi Z. Grasp detection method based on grasp center and key features. In: Proceedings of the 2024 30th International Conference on Mechatronics and Machine Vision in Practice (M2VIP); 2024 Oct 3–5; Leeds, UK. doi:10.1109/M2VIP62491.2024.10746036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Tong L, Qian K. HFNet: high-precision robotic grasp detection in unstructured environments using hierarchical RGB-D feature fusion and fine-grained pose alignment. Measurement. 2025;253(2–3):117775. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2025.117775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ren L, Kang Y, Jia H, Wang S, Zhong R. A lightweight detection model without convolutions for complex stacked grasping tasks. Electronics. 2025;14(3):437. doi:10.3390/electronics14030437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Huang Z, Yang Y, Yu H, Li Q, Shi Y, Zhang Y, et al. RCST: residual context-sharing transformer cascade to approximate Taylor expansion for remote sensing image denoising. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2025;63(8):5609615. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2025.3534199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wang S, Zhou Z, Kan Z. When transformer meets robotic grasping: exploits context for efficient grasp detection. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2022;7(3):8170–7. doi:10.1109/LRA.2022.3187261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Guo C, Zhu C, Liu Y, Huang R, Cao B, Zhu Q, et al. End-to-end lightweight transformer-based neural network for grasp detection towards fruit robotic handling. Comput Electron Agric. 2024;221(3):109014. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2024.109014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yang G, Jia T, Liu Y, Liu Z, Zhang K, Du Z. MCT-grasp: a novel grasp detection using multimodal embedding and convolutional modulation transformer. IEEE Sens J. 2024;24(23):39206–17. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2024.3449946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang Y, Qin X, Dong T, Li Y, Song H, Liu Y, et al. DSNet: double strand robotic grasp detection network based on cross attention. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2024;9(5):4702–9. doi:10.1109/LRA.2024.3381091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Odena A, Dumoulin V, Olah C. Deconvolution and checkerboard artifacts. Distill. 2016;1(10):e3. doi:10.23915/distill.00003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Si Y, Xu H, Zhu X, Zhang W, Dong Y, Chen Y, et al. SCSA: exploring the synergistic effects between spatial and channel attention. Neurocomputing. 2025;634(6):129866. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2025.129866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Chollet F. Xception: deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li X, Wang W, Hu X, Yang J. Selective kernel networks. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2019.00060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Xu W, Wan Y. ELA: efficient local attention for deep convolutional neural networks. arXiv:2403.01123. 2024. [Google Scholar]

46. Mehta S, Rastegari M. Mobilevit: light-weight, general-purpose, and mobile-friendly vision transformer. arXiv:2110.02178. 2021. [Google Scholar]

47. Yang L, Zhang RY, Li L, Xie X. SimAM: a simple, parameter-free attention module for convolutional neural networks. Proc Mach Learn Res. 2021;139:11863–74. [Google Scholar]

48. Rahman MM, Munir M, Marculescu R. EMCAD: efficient multi-scale convolutional attention decoding for medical image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Huang Z, Wang L, An Q, Zhou Q, Hong H. Learning a contrast enhancer for intensity correction of remotely sensed images. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2021;29(3):394–8. doi:10.1109/LSP.2021.3138351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Depierre A, Dellandréa E, Chen L. Jacquard: a large scale dataset for robotic grasp detection. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2018 Oct 1–5; Madrid, Spain. doi:10.1109/IROS.2018.8593950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. arXiv:1412.6980. 2014. [Google Scholar]

52. Kumra S, Joshi S, Sahin F. GR-ConvNet v2: a real-time multi-grasp detection network for robotic grasping. Sensors. 2022;22(16):6208. doi:10.3390/s22166208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Song Y, Wen J, Liu D, Yu C. Deep robotic grasping prediction with hierarchical RGB-D fusion. Int J Control Autom Syst. 2022;20(1):243–54. doi:10.1007/s12555-020-0197-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools