Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

MMIF: Multimodal Medical Image Fusion Network Based on Multi-Scale Hybrid Attention

1 School of Information Science and Engineering, Qingdao Huanghai University, Qingdao, 266427, China

2 College of Computer Science and Engineering, Shandong University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, 266590, China

3 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Tongji University, Shanghai, 201804, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yang Li. Email: ; Xiaoting Sun. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Medical Imaging Techniques Using Generative Artificial Intelligence)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3551-3568. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066864

Received 18 April 2025; Accepted 22 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Multimodal image fusion plays an important role in image analysis and applications. Multimodal medical image fusion helps to combine contrast features from two or more input imaging modalities to represent fused information in a single image. One of the critical clinical applications of medical image fusion is to fuse anatomical and functional modalities for rapid diagnosis of malignant tissues. This paper proposes a multimodal medical image fusion network (MMIF-Net) based on multiscale hybrid attention. The method first decomposes the original image to obtain the low-rank and significant parts. Then, to utilize the features at different scales, we add a multiscale mechanism that uses three filters of different sizes to extract the features in the encoded network. Also, a hybrid attention module is introduced to obtain more image details. Finally, the fused images are reconstructed by decoding the network. We conducted experiments with clinical images from brain computed tomography/magnetic resonance. The experimental results show that the multimodal medical image fusion network method based on multiscale hybrid attention works better than other advanced fusion methods.Keywords

Image fusion has been widely used in computer vision, remote sensing, traffic safety, and other fields. Using appropriate feature extraction methods and fusion strategies, a single image containing important features and complementary information is generated from two or more source images for a more explicit description and easier understanding of the target scene. Since the 1990s, image fusion techniques have been developed and applied in the medical field. Medical image fusion techniques fuse important reference information from different modal images into a single image that can display more visual, comprehensive, and transparent information [1]. It is convenient for doctors to observe and estimate cases, analyze lesions, and diagnose more accurately. Brain injury, cerebrovascular diseases, brain tumors, and other brain diseases account for the largest proportion of diagnoses in the elderly, with the highest incidence of cerebrovascular disease and high mortality. Acute cerebral infarction is a common cerebrovascular disease with a trend of increasing incidence year by year and gradually decreasing the age of onset. Diagnosing and treating these types of brain diseases at an early stage is essential. In general, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET) are often used by physicians to visualize brain disorders. Different medical image modalities have unique characteristics and provide different medical information [2,3]. For example, CT images can clearly show the anatomical structures and skeletal tissues of the brain with high resolution, which can provide a good reference for establishing the extent and location of lesions. In contrast, CT images lack functional information and information about the interior of the lesion. The spatial resolution of MRI images is lower than that of CT images. MRI images also do not show functional information in MRI images. However, they can clearly show the lesion’s soft tissue and internal structure. PET images provide mainly functional metabolic information but poorer anatomical structures and can give sensitive information for detecting early lesions and determining the level of lesions. The critical medical semantic information contained in different medical image modalities and their complementary information are essential references for the diagnosis of brain diseases. Image fusion technology integrates and enhances this information from two source images into one image, enabling physicians to observe, understand and diagnose diseases more efficiently and accurately [4–6]. Therefore, brain CT/MRI/PET image fusion techniques are essential to help physicians diagnose brain diseases. In recent years, many medical image fusion methods have been proposed. These existing methods mainly include two categories: traditional manual fusion methods [7,8] and deep learning-based fusion methods.

Traditional methods are driven by manual cognition [9,10]. Traditional feature extraction methods rely mainly on manual extraction, which requires specialized domain knowledge and complex parameter-tuning processes. In addition, each technique targets a specific application scenario. Therefore, the generalization ability and robustness could be better, and most fusion strategies are based on basic processing techniques without considering high-level abstract information. But traditional methods can capture global and local structural information and point singularities of signals. And deep learning-based methods are data-driven. They can learn a large number of samples to obtain deep abstraction features. The datasets are more efficiently and accurately represented, and the extracted abstract features are more robust and generalizable. Deep learning methods have been successfully applied to many areas of image processing. However, medical image analysis based on deep learning cannot express the singularity of curves in two-dimensional information and is still in the early development stage. Corresponding research is becoming hot and will have many application prospects.

To solve the above problems, a multimodal medical image fusion network based on multiscale hybrid attention is proposed in this paper, which uses multiscale hybrid attention to design a novel feature extraction network to extract the low-rank and significant parts of the input image. The medical image fusion is performed using DenseFuse. We use three filters of different sizes to extract features at the end of the original DenseFuse encoder separately. We use a fusion strategy to fuse them individually to get more feature maps of different scales. Finally, we cascade the fused features of different scales into the decoder to obtain the combined image. The research contributions of this paper are as follows.

a. To preserve the structural information of the images, a multimodal medical image fusion network model based on multiscale hybrid attention is proposed, which uses large-sized extraction frames to extract global structural information for filtered images and small-sized extraction frames to extract local structural information for detail layer images.

b. For feature maps of different scales, this paper proposes a hybrid self-attentive module to further filter the features of different channels in the feature maps to improve the feature representation of key channels and further guide the network to focus its attention on the regions containing key information.

c. Because the background of medical images are mostly similar, and the data of the same class will present large visual differences due to different acquisition objects, thus the sample features between different types are hybrid due to the highly similar background areas and the distance in the feature space is enlarged due to the large visual differences between the data of the same class, therefore, this paper solves the above problem through decoding network reconstruction.

With the development of machine learning technology, image processing techniques have been widely used, among which image fusion techniques are now commonly used in remote sensing, computer vision, and the medical field studied in this paper. Medical image fusion integrates useful human body information in multiple source images obtained from different imaging modalities into a single image by some technical means. Image fusion technology can realize the organic combination of multimodal medical image information, enrich helpful details to assist disease diagnosis, reduce the randomness and redundancy of information, and at the same time, improve the efficiency of diagnosis of certain complex diseases. The existing fusion methods include traditional fusion methods and deep learning-based fusion methods.

2.1 Application of Traditional Manual Methods in Image Fusion

Traditional fusion methods can capture the signal’s global and local structural information and point singularities of the signal. Chen et al. proposed a new noise-containing image fusion strategy that uses the similarity of low-rank components to constrain intra-class consistency and applies it to the coding coefficients to improve the recognition ability of dictionary learning further [11]. Minimum rank regularization is used to estimate the potential subspace for fusion recovery. Gillespie et al. proposed a simple and effective image fusion method based on potential low-rank representation to better retain the useful information in the source images [12]. Using the idea of low-rank clustering, the medical images are divided into low-rank and significant parts. Then the coefficients of the low-rank and significant parts are multiplied by 0.5 and summed up, which is the final fusion result. To solve the problem that multi-exposure low dynamic range images and high dynamic range image fusion methods are sensitive to noise, object motion, etc. Nandi proposed a new method based on low-rank matrix recovery features to fuse consecutive multi-exposure images into images, which improves the ability to resist noise and remove artifacts, as well as the performance of captured images [13]. Ghandour et al. proposed an image fusion method based on low-rank sparse representation [14]. Himanshi et al. used different morphological gradient operators to distinguish the focus, scattered, and focus boundary regions in reconstructing the fused image [15]. Yadav and Yadav proposed a multi-focused noisy image fusion method based on low-rank representation, which is a representation learning method [16]. The source image is decomposed into low-frequency and high-frequency coefficients using a multiscale transform framework. For the low-frequency coefficients, a spatial frequency strategy is used to determine the fused low-frequency coefficients. In contrast, the high-frequency coefficients are fused using an LRR-based fusion strategy. Finally, the fused image is reconstructed by the inverse multiscale transformation of the fused coefficients. To fully exploit the useful information of the image, a low-rank representation algorithm is used in this paper. LRR statistically decomposes the image into a linear correlation between the low-rank and significant parts, which improves the ability to resist noise and eliminate artifacts.

2.2 Application of Deep Learning in Image Fusion

Recently, image fusion methods based on deep learning have been rapidly developed and widely used. He proposed a method based on the deep learning model and DT-CWT image fusion to achieve multi-focus multi-source image fusion [17]. Calhoun and Adali used the depth features of the source images to reconstruct the fused images [18]. Convolutional neural networks are one of the most successful applications of deep learning algorithms and have brought new developments in image fusion [19,20]. Convolutional layers play a crucial role in feature extraction. It can extract a broader and richer range of features than traditional manual feature extractors [21]. In addition, the convolutional layer is also used as a weighted average to generate the output image. Convolutional neural networks have great potential in the field of image fusion. Deep learning-based fusion methods attempt to design an end-to-end network to generate fused images directly [22]. Li et al. studied the problem of pulse-coupled neural networks (abbreviated) and digital image fusion. They proposed a real-time deep-learning model for a two-channel fusion algorithm based on image clarity [23]. Combined with the hyperviscosity syndrome compliant orthogonal color space, the traditional Pulse Coupled Neural Network (PCNN) model was simplified to a parallel two-channel adaptive PCNN structure. Li et al. proposed an unsupervised fusion network based on Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and multilayer features [24]. Kumar et al. designed a new unsupervised end-to-end CNN learning method with a structural similarity metric as a loss function during training [25]. Zhao and Lu proposed a new network (Fusion Generative Adversarial Network) that automatically generates image information using adversarial game theory and has been successfully applied in image fusion tasks [26]. The fusion results of this method can maintain thermal radiation in infrared images and texture in visible images. Wang et al. fused infrared and visible images by multi-scale image decomposition based on wavelet transform [27]. The key issues in image fusion, i.e., the measure of activity and the design of fusion rules, were addressed using continuous convolutional neural networks. The reconstruction results are more sensitive to the human visual system. Zhang et al. proposed a general image fusion framework based on the convolutional neural network (IFCNN) for the fusion of different types of images [28]. Although CNN models have achieved some success in image fusion, the existing models need more generalization capability and can only fuse specific types of images effectively. To obtain more effective fused images, the new generalized fusion network NestFuse uses a network model to optimize existing fusion algorithms such as IFCNN to get more and better depth features [29–31]. However, its network structure is complex. From the experimental results, the method is suitable for infrared and visible images, but relatively poor for medical images. The above techniques are designed for visual, infrared, remote sensing, and photographic images. Even for the standard multiple-image fusion methods, the fusion effect in medical brain images could be better [32–35].

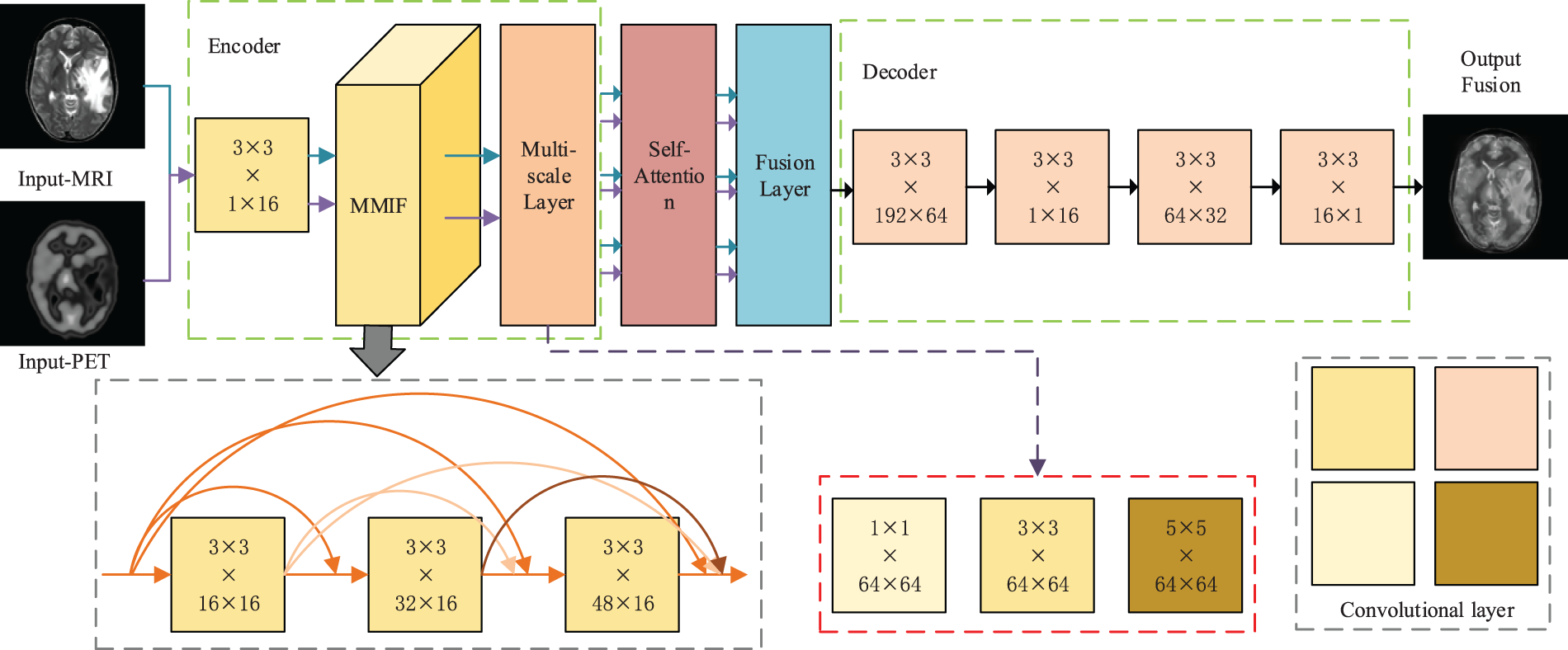

A multimodal medical image fusion method based on multiscale hybrid attention is proposed to obtain the detailed features of multimodal images for the randomness of gene mutation location, heterogeneity of lesion degree, and loss of structural details in brain diseases. The method first proposes a multiscale hybrid attention mechanism to decompose the original image and extract the detail features of the low-rank part and the significant portion of the original image. Then the image fusion is performed by the fusion strategy of the decoder. The MMIF-Net network structure consists of a feature encoder, multiscale, hybrid attention, and decoding, and the network structure diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Multimodal medical image fusion network structure based on multiscale hybrid attention

The core innovation of MMIF is that it is specifically adapted to solve the core challenges of multimodal fusion. Faced with the inherent heterogeneity, redundant complementarity of multi-source information, and the potential cross-modal gradient dissipation and information bottleneck problems in deep networks, MMIF explicitly constructs a cross-layer and cross-modal fusion state feature library by allowing each fusion layer to directly access the output of all previous fusion layers. This mechanism ensures that the original and intermediate fusion features of different abstract levels and modal combinations are retained and reused for a long time, enabling the network to dynamically and flexibly select and integrate the most relevant cross-modal cues, and greatly promotes the effective return of gradients between multimodal paths. At the same time, the dense connection of MMIF is task-oriented, and its design core focuses on deep modeling of complex cross-modal interactions and overcoming the information integration difficulties unique to multimodality, thereby achieving significant performance improvements in specific tasks that exceed traditional stacking or simple fusion methods. Therefore, the innovation of MMIF lies in the first demonstration and realization of the effectiveness and unique advantages of dense connection as a key technology for solving information flow maintenance and interaction efficiency in multimodal deep fusion.

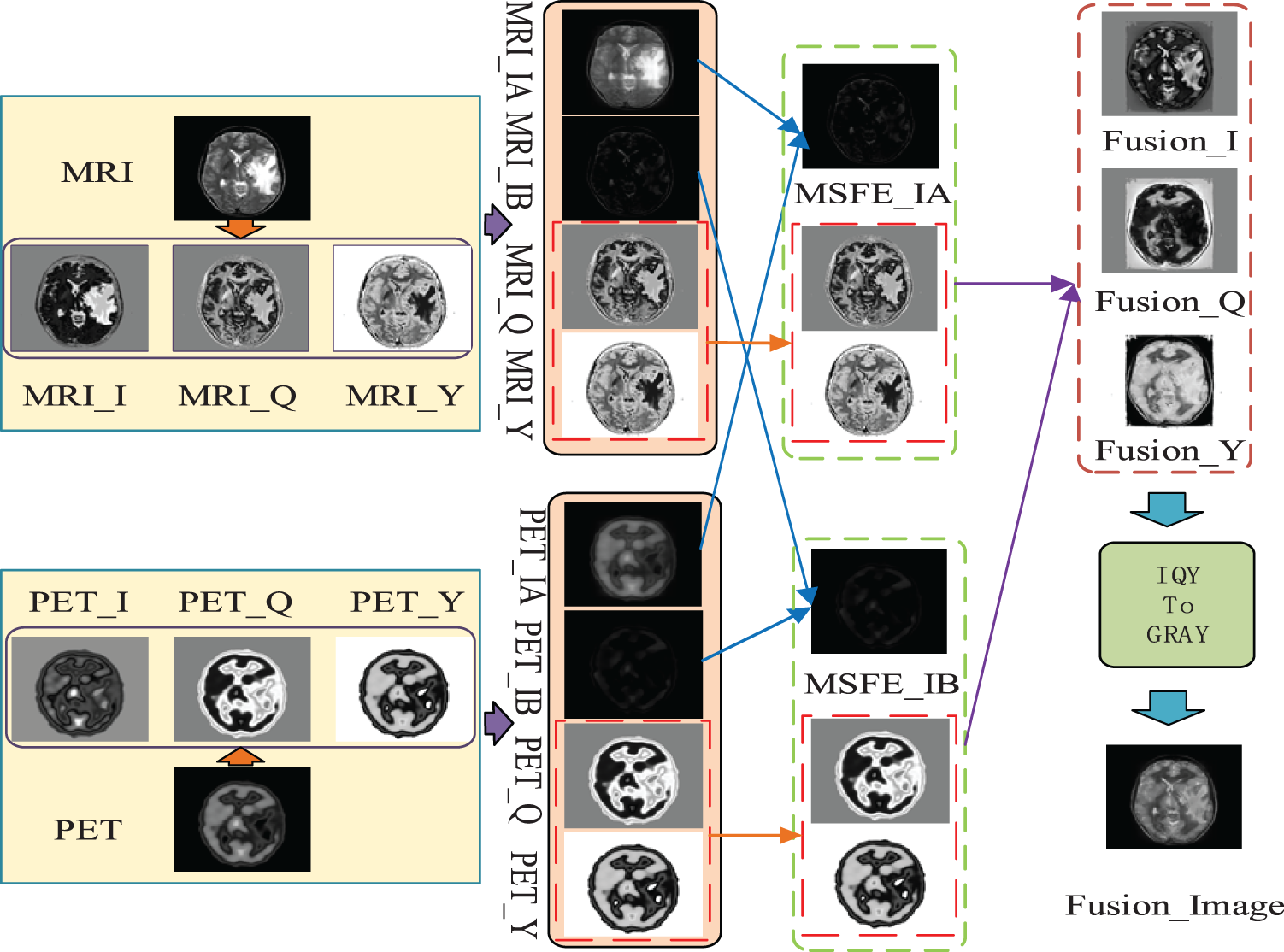

In this paper, MRI and PET images of the brain are fused by the proposed multimodal medical image fusion network (MMIF-Net), and the detailed process is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: The flowchart of the proposed method

As shown in Fig. 2, the first step of this paper is to input MRI and PET images, convert the input images to NTSC color space, and then extract the I, Q, and Y channels of NTSC space, respectively. In the second step, this paper extracts the global and local parts from the I channel of the obtained MRI and PET images, respectively. In the third step, the international and local parts corresponding to the second step are fused by the MMIF-Net method to obtain the I, Q, and Y channels of the reconstructed MRI and PET images. In the fourth step, the MMIF-Net method is used to fuse the I, Q, and Y component maps of the reconstructed MRI and PET images to obtain the I, Q, and Y component maps of the fused image. The fifth step is to convert the I, Q, and Y channels of the fused image into a fused grayscale image.

The backbone network for feature extraction consists of 2 parts, as shown in Fig. 1. The encoder is constructed by a convolutional layer, dense block and a multi-scale layer. We add multi-scale layer whose filters’ size are

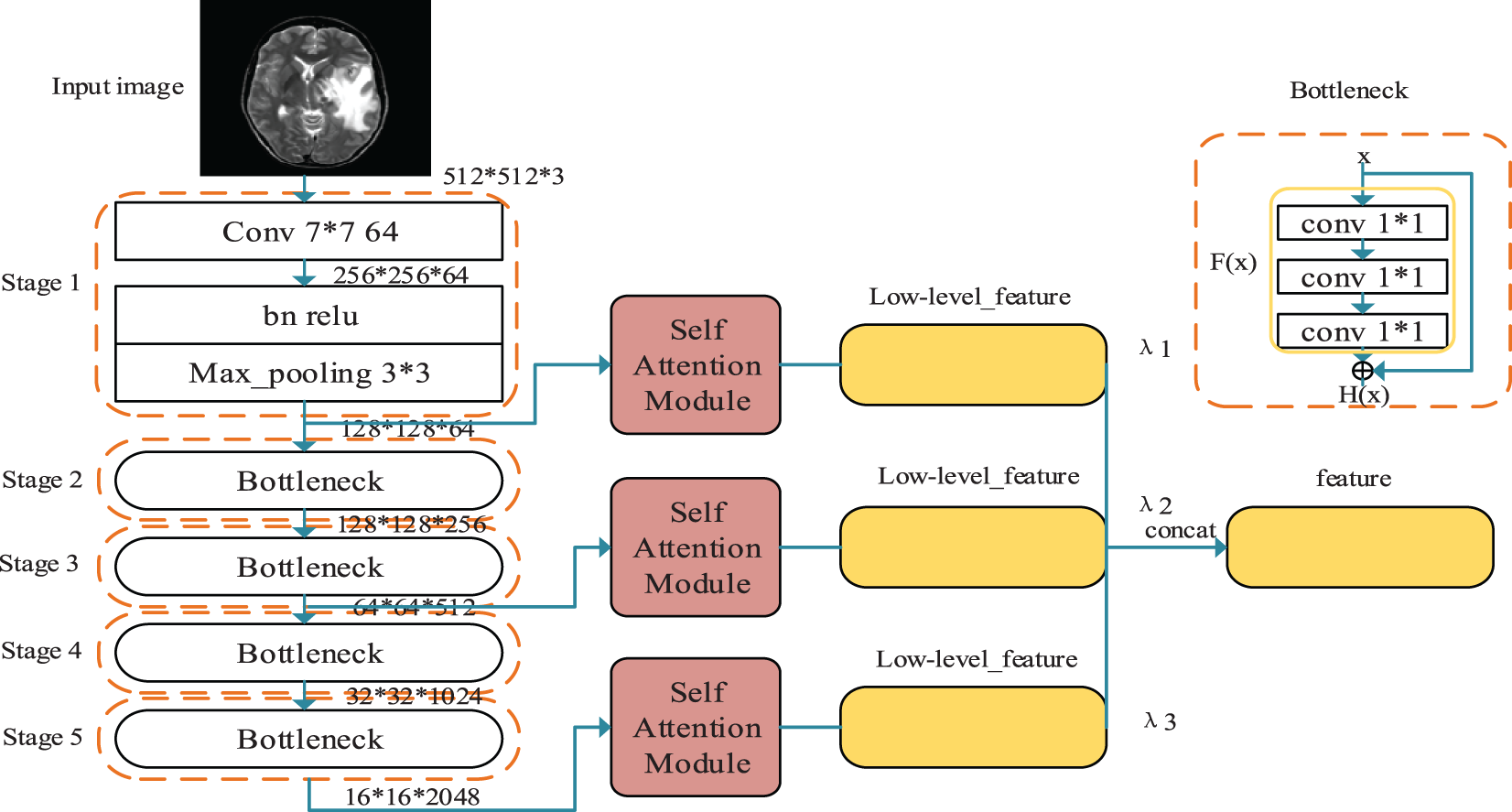

In the feature extraction module, a multi-scale feature structure is proposed in this paper, as shown in Fig. 3, where we hope to obtain deep semantic features in medical images by a deep network. To solve the problem of inadequate learning of the shallow network brought by the deeper network. For this purpose, the ResNet network proposes the classical residual block structure, i.e., the Bottleneck structure in the above figure. On top of the original sequentially stacked three convolutional layers, the input is superimposed on the output by a jump connection. The presence of the jump connection allows passing the gradient obtained near the result to the external network near the input, avoiding the gradient dispersion problem caused by the angle only passing back through the deep network. The residual block in Fig. 3 is the optimized structure. The original residual block consists of two

Figure 3: Multiscale hybrid attention module

Meanwhile, to enable the network to thoroughly learn features of different scales and improve the effectiveness of features, this paper extracts the output feature maps of Stage 1, Stage 3, and Stage 5, respectively, based on the Resnet network, and for the input of

For the feature maps of different scales output by the residual network, this paper designs a self-attentive module to further screen the different channel features in the feature maps. The design idea of this module comes from the non-local mean (NLM) noise reduction algorithm, which suppresses the irrelevant information in the image to express adequate information fully.

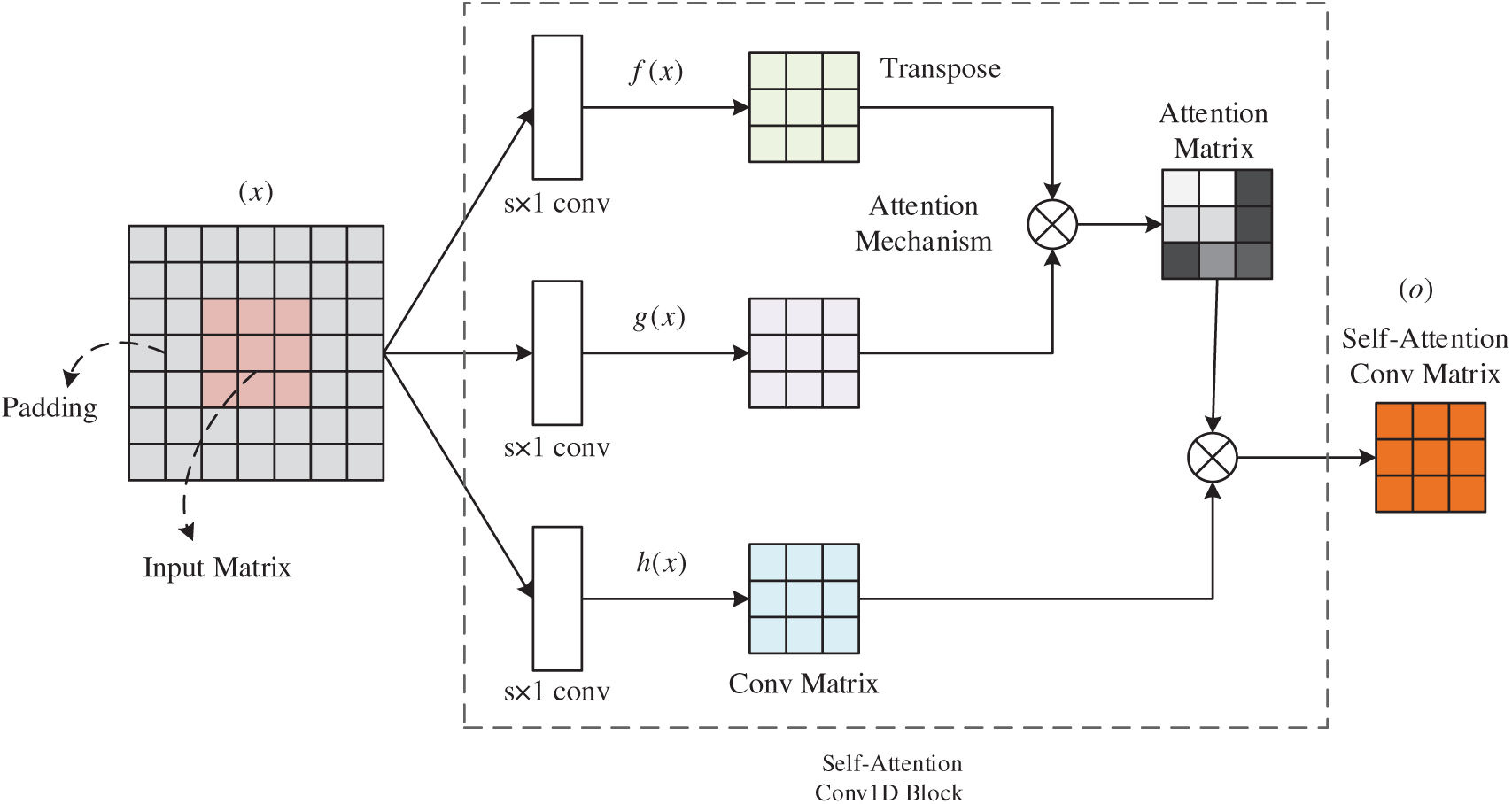

The Self-Attention Convolution Module consists of self-attention convolution layer and global average pooling layer. The input matrix x consisting of word embedding

CNNs perform discrete convolution operations on an input matrix using several different filters to obtain local sentence feature. However, since the length of a sentence is often long and convolution processes information in local neighborhoods, using only the convolutional layer in obtaining the long-distance semantic relationships is inefficient. For the issues, we adapt the non-local model of to introduce self-attention to the CNN network. The proposed convolution block is called Self-Attention Convolution Block (SACB) due to its self-attention module and SACB is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Self-attention block

Given input matrix

where the score

In this paper, we use self-attention convolution block of different sizes to form a self-attention convolution layer so that we can learn the features of multiple granularities. In addition, to make the input and output size consistent, we apply a zero-padding strategy before the self-attentive convolutional layer. Then the output matrices of the three SACBs are concatenated together, which helps to aggregate the semantic features and feed it to the global average pooling layer.

We use global average pooling to extract one feature for each filter using the pooling technique. It also ensure that the information obtained by the SACBs is not lost. In addition, this method can handle variable sentence lengths. These features form the final features obtained by the self-attention convolution module.

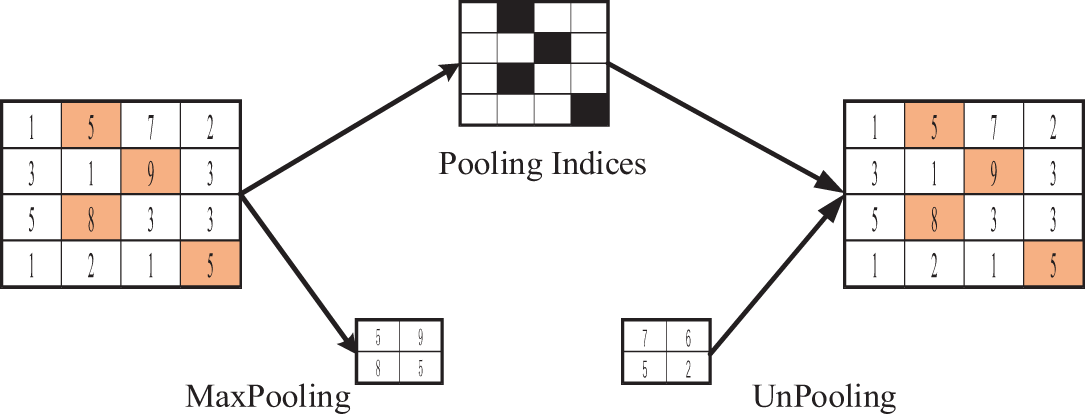

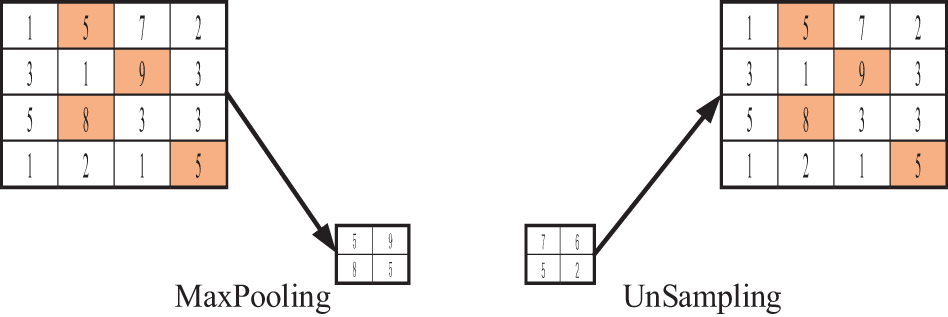

The decoder is a symmetric structure of the encoder. During the construction of the encoder, the spatial size information passed to the following layer decreases as the convolution layers are added. The decoder should adjust the image size and the number of convolution layers to reconstruct the original image. Transpose Convolution can increase the spatial size and convolution, but transpose convolution layers cause artifacts in the final output image. In order to keep more critical information about the original image in the reconstructed image, upsampling techniques are needed in the decoder. The most common upsampling methods are UnPooling and UnSampling.

The process of UnPooling is shown in Fig. 5, where the maximum position information is retained during Max pooling. Then the feature map is expanded with this information during the UnPooling phase, and the rest is complemented by 0. This is the inverse of pooling, and restoring all the original data through the pooling result is impossible. If you want to recover all the information from the pooled primary information, the maximum information integrity can only be achieved through complementary positions.

Figure 5: UnPooling operation procedure

The process of UnSampling is shown in Fig. 6. This operation does not use the location information of Max Pooling and directly copies the maximum expansion feature map.

Figure 6: UnSampling operation procedure

In this paper, different upsampling operations are designed for decoders of different layers according to the characteristics of shallow and deep layer features in the network. Considering the fact that the information extracted from the shallow network structure is coarser and contains more useless information, while the feature maps extracted from the deep network structure are smaller, rich in semantic information, and contain relationships between global contexts, the up-sampling in the deep D4(∙) and D3(∙) layers in the process of designing the decoder uses the UnSampling operation, which directly copies the input feature map content to expand the upsampling layer feature map; and in the shallow D2(∙) and D1(∙) upsampling using the UnPooling operation, which records the location information of the maximum value at the time of maximum pooling, and then uses this information in the upsampling phase to expand The feature map of the upsampling layer is complemented by 0 except for the position of the maximum value. UnSampling preserves the overall data features, and UnPooling preserves features with vital semantic information, typically texture features. These two upsampling methods combine to compensate for the lost spatial feature information while preserving important information in the original feature space.

In this section, we conduct extensive experiments to evaluate medical image fusion methods based on multiscale contextual reasoning.

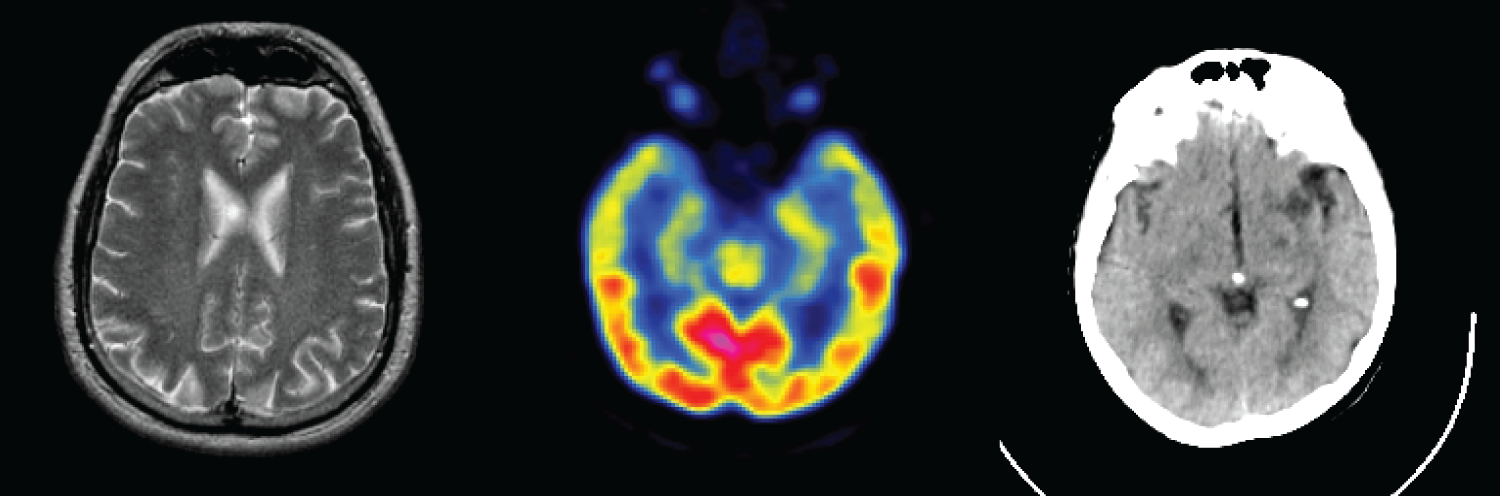

Datasets: To further prove the effectiveness of our proposed fusion method, experiments were carried out on different pairs of brain images (CT-MR/MR-PET). 10000 MRI-PET image pairs as the training set are obtained from the Whole Brain Atlas (http://www.med.harvard.edu/aanlib/ (accessed on 10 July 2025)), and their sizes are 256 × 256. The three medical image categories are shown in Fig. 7. In this paper, 60% of the acquired data are used as the training set, 10% as the test set, and 30% of the data is used as the test set. The fusion experiments results were analyzed with DenseFuse [22], IFCNN [26], NestFuse [27], FusionDN [32] and FusionGAN [35] algorithms.

Figure 7: Multimodal images of the brain

Environment Configuration: All the algorithms are coded using python in PyCharm Community Edition 2020. For each algorithm configuration and each instance, we carry out five independent replications on the same AMD Ryzen 5 3500X 6-Core Processor CPU @ 3.60 GHz with 16.00-GB RAM and NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1660 SUPER GPU in the 64-bit Windows 10 professional Operation System.

Model-Related Parameters: The kernel filter of the fusion network in this paper is initialized to a truncated normal distribution with a standard deviation of 0.01 and a deviation of zero. Each layer has a step size of 1 and no padding during convolution because each downsampling layer removes detailed information from the input image, which is crucial for medical image fusion. We use batch normalization with a slope of 0.2 and ReLU activation to avoid the problem of gradient disappearance. The network is trained for 200 epochs on a single GPU with a batch size of 1 and different

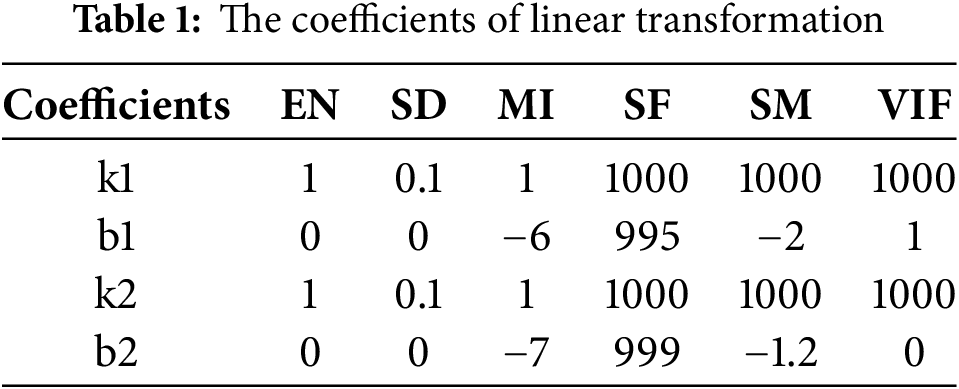

We evaluate MMIF using six evaluation metrics: EN, SD, MI, SF, SM and VIF. EN and SD indicate the information contained in the input image. The larger the value, the better the fusion effect. The larger the MI, the more original information and features of the source image can be preserved. The larger the QM and VIF values, the more structural information of the source image is preserved by the fusion algorithm, and more natural features can be generated. The SF is a measure of spatial frequency, which can be divided into two cases. When

4.3 Experimental Results between the Proposed Method and Existing Methods

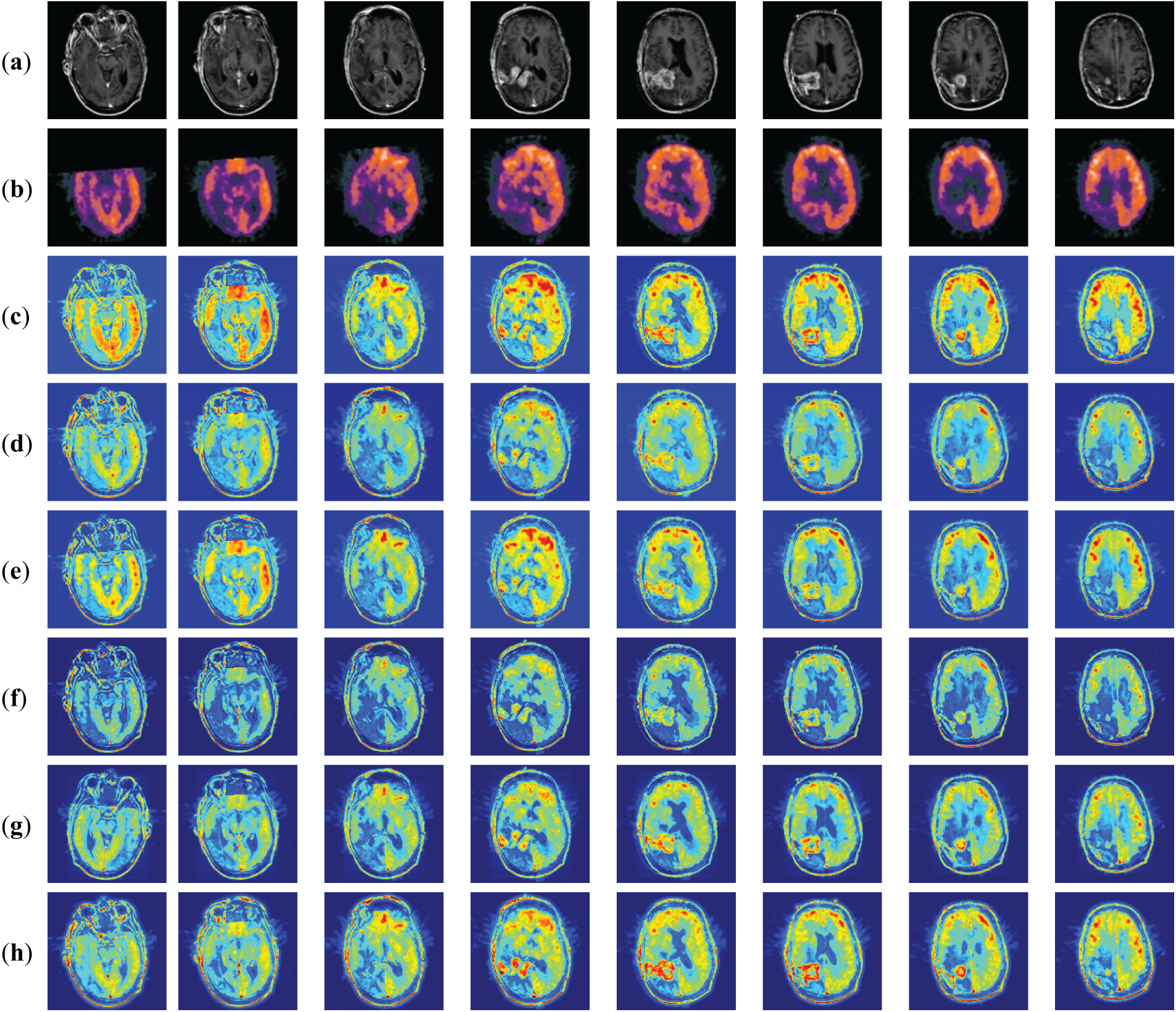

MRI is used to obtain electromagnetic signals based on the different attenuation of energy materials in different structural environments of the body. MRI images have a high resolution and clear soft tissue information to locate lesions better. PET images are obtained by injecting a radioisotope drug into the body, which is metabolized by human tissues to cause the drug to decay and produce gamma photons, which are then converted to light/electricity and processed by a computer into PET images. PET images have a lower resolution and poorer localization ability. However, the fused MRI and PET raw images provide structural and activity information with high spatial resolution. Fig. 8 shows the subjective evaluation of MRI-PET fusion. Where (a) denotes MRI source image, (b) denotes PET source image, (c) denotes FusionDN fusion method, (d) denotes FusionGAN fusion method, (e) denotes IFCNN fusion method, (f) denotes DenseFuse fusion method, (g) denotes NestFuse fusion method, and (h) denotes MMIF fusion method proposed in this paper.

Figure 8: Fused results of MRI-PET medical image fusion

Fig. 8 shows the fusion results of MRI-PET images of patients with brain tumors. We give eight sets of MRI-PET fusion results to facilitate comparative analysis in Fig. 8. From these eight sets of results, we can find that DenseFuse (f) can fuse MRI and PET images better with clear contours, but some artifacts make the resultant images blurred by artificial factors. Texture details in IFCNN (e) are apparent, but more PET information is discarded. The detail in NestFuse (g) is the opposite of that in IFCNN (e). The fusion results of NestFuse (g) contain more information about PET but less about MRI. The fusion results of FusionDN (c) are similar to the method proposed in this paper, which can retain the information of both original images well. The contour information of FusionGAN (d) is clear, but the specific texture details could be clearer.

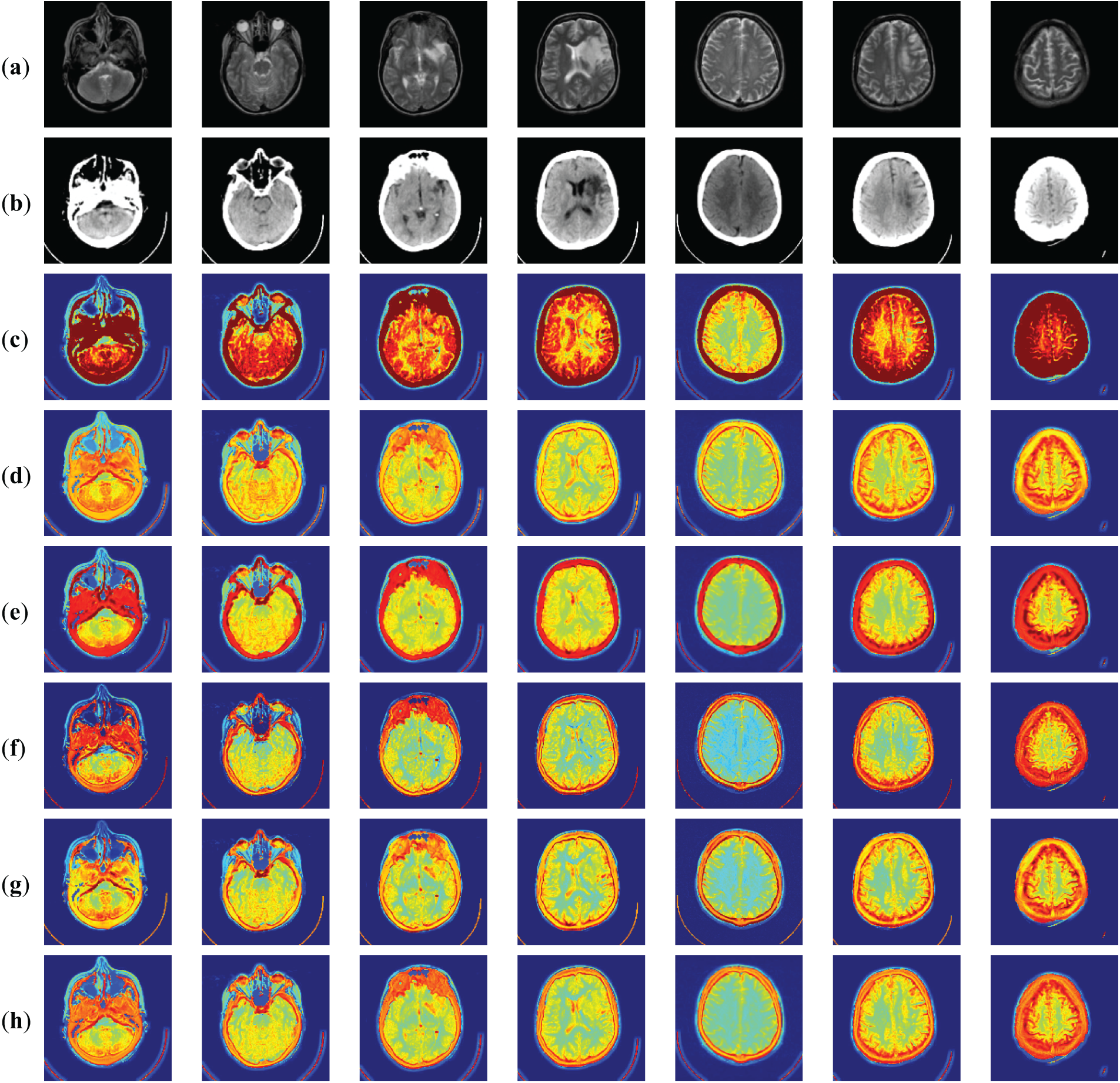

Fig. 9 shows the MRI-CT fusion results. a and b are the original MRI and CT images, and the other rows show the fusion results obtained by different methods. For comparison and analysis, we present the fusion results of 7 groups of MRI-CT in Fig. 9. Fig. 9 shows the subjective evaluation of MRI-CT fusion. Where (a) indicates the MRI source image, (b) indicates the CT source image, c indicates the FusionDN (c) fusion method, d indicates the FusionGAN (d) fusion method, e indicates the IFCNN (e) fusion method, (f) indicates the DenseFuse (f) fusion method, g indicates the NestFuse (g) fusion method and h indicates the MMIF (h) fusion method proposed in this paper. Fig. 9c shows the fusion results obtained by DenseFuse (f). LRR is used to extract the significant and low-rank parts of the image and then combine these two parts to reconstruct the fused image. In Fig. 9c, we can see that some details are lost, the reconstructed image is incomplete, and the brightness of the fused image is lower than that of the original image. Fig. 9d shows the fusion results obtained by IFCNN (e). The fusion strategy can be divided into three cases: the maximum, average, and sum of two feature values. The IFCNN (e) algorithm uses the maximum value when processing medical images. So in the experiment, I only list the results of the maximum fusion. From the visual effect, the edges and internal regions are clear. Fig. 9e shows NestFuse (g) using the maximum fusion strategy. The idea of the NestFuse (g) algorithm is encoding, decoding, and fusion. The encoding includes double convolution and pooling operations, and the decoding includes dual convolution and sampling operations. The network structure is complicated, but deeper features can be obtained. From the results, it is similar to DenseFuse (f) without clear texture details. Fig. 9f shows the fusion results obtained by FusionGAN (d). The fused image has good contrast between light and dark and can retain the structure and luminance information of the two source images well. Fig. 9g shows the fusion results obtained by FusionDN (c) based on a densely connected network. The results of this method show that the brightness is improved, but some details are smoothed out. The last result image is an application of the MMIF (h) method in this paper. Compared to other algorithms, our fusion results have more suitable brightness, sharper contours, and finer textures. In addition, our results preserve and enhance crucial medical information very well.

Figure 9: Fused results of MRI-CT medical image fusion

4.4 Comparison of the Proposed Method with Advanced Method Statistics

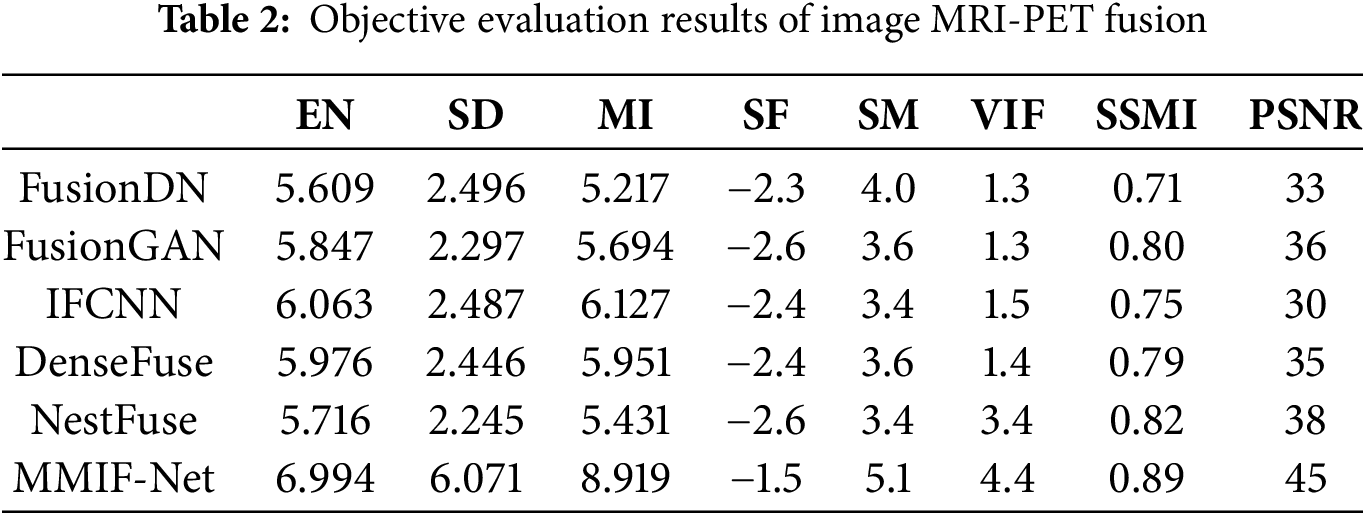

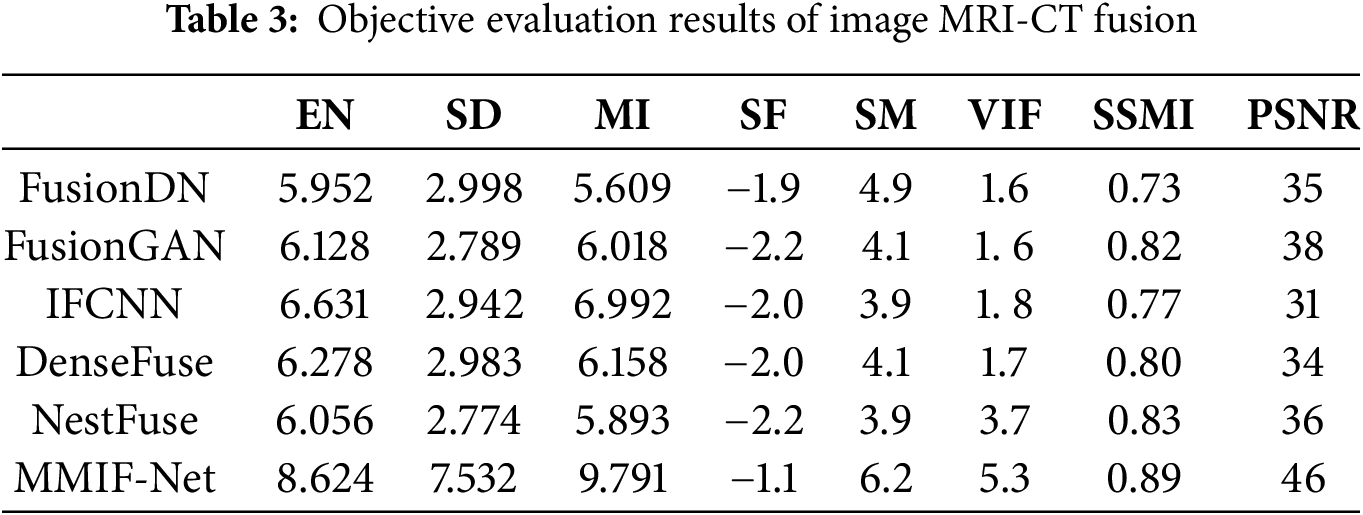

The objective evaluation indexes of MRI-PET image fusion are shown in Table 2. The objective evaluation indexes of MRI-CT image fusion are shown in Table 3.

The quantitative performance comparison of the results in the figure is given in Table 2. From Table 2, it can be seen that the algorithm of this paper achieves the best results in the six objective evaluation indexes of EN, SD, MI, SF, SM, and VIF for MR-PET image fusion. This indicates that the algorithm of this paper has richer fused image information and better edge contour fusion. The MMIF-Net-based image fusion method has significantly improved in these six indexes compared with other methods. Combining the subjective and objective evaluations, the quality of the fused images of this algorithm is better, and the fused images have better fusion quality and better performance indexes when this algorithm is used for MRI and PET image fusion compared with several other comparative algorithms.

Table 3 lists one evaluation metric in each column, where the bold numbers represent the maximum values. Each row lists separately the values of MRI-CT images fused using different fusion methods and evaluated on different metrics. The evaluation values of MMIF-Net fusion methods on EN, SD, MI, SM, and VIF are much larger than those of other fusion methods. The metric values MMIF-Net for SD of the six methods differ significantly from others. Because the SD index is the distance of each data from the mean, it reflects the relationship between the data series and the mean and explains the data set’s dispersion. The larger the value, the higher the measurement accuracy. SF is an image fusion metric based on the spatial frequency error ratio. It is susceptible to small changes in image quality. The higher the absolute value of SF, the better the fusion effect. Because the upper and lower layers can retain the structural features in the spatial structure better but need to avoid the loss of specific details, the value will be relatively small for the method in this paper.

It can be seen from Tables 2 and 3 that the SD of the MMIF network is significantly improved. This is firstly because the multi-scale module can capture the global contextual information of the brain tumor and avoid structural breaks caused by local fusion; secondly, it suppresses the redundant response of the background uniform tissue and highlights the grayscale variation of the brain tumor area; finally, we use a multi-modal complementary optimization strategy in the multi-scale module to produce synergistic enhancement through weight modulation when fusing images of different modalities.

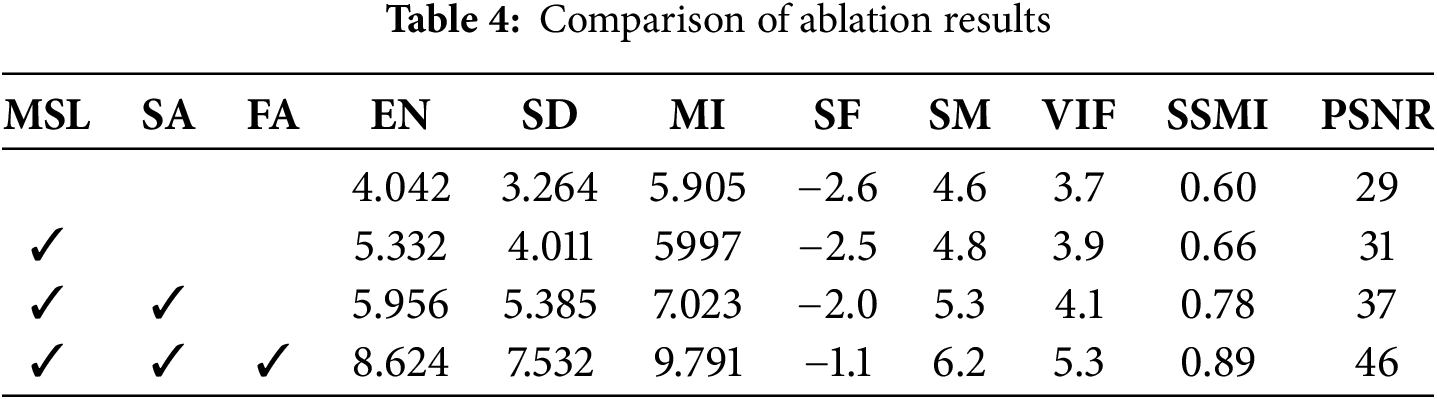

This paper studies the impact of each network module on the overall method and judges its performance based on the fusion results. In addition, this paper lists the scores of each component on each indicator through experimental control methods. MSL is a multi-scale module, SA is a self-attention mechanism module, and FA is a fusion module. The scores of each network module on each indicator are shown in Table 4.

Ablation experiments show that the MSL module integrates multi-scale features through atrous spatial pyramid pooling, significantly improving the EN and SD indicators and enhancing the ability to retain details of small objects; the SA module uses a sparse self-attention mechanism to optimize feature selection, performs outstandingly in the MI and SF indicators, and effectively captures cross-modal associations in key areas; the FA module significantly improves SM and VIF through the synergy of channel attention and deformable convolution, suppresses background noise and enhances texture alignment. The joint action of the three modules improves SSMI and PSNR respectively, among which MSL provides multi-scale context, SA strengthens semantic focus, and FA achieves cross-modal complementary fusion.

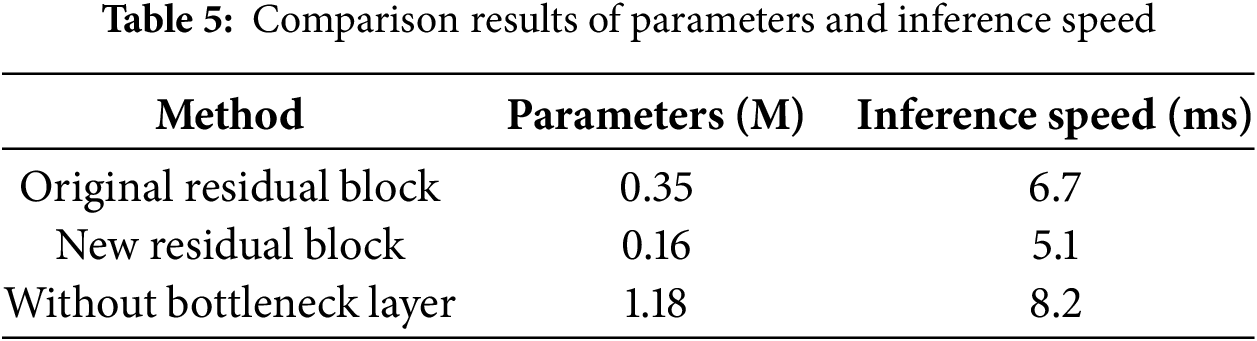

In order to verify the changes in parameters and inference speed in the MMIF-Net network, this paper compares the original residual block (composed of two 3∗3 convolutions) with the new residual block (composed of three 1∗1 convolutions). The comparison results are shown in Table 5.

By comparing the results, we can see that the residual block designed in this paper can compress and expand the feature map channel, which reduces the number of model parameters and speeds up the forward reasoning speed of the network while ensuring the network accuracy.

This paper proposes a multimodal medical image fusion network based on multiscale hybrid attention. The method first decomposes the original image to obtain the low-rank and salient parts. Then, extracting features from different parts using a multiscale mechanism, which uses three filters of different sizes to extract features in the coded network. Also, a hybrid attention module is introduced to obtain more image details. Finally, the fused image is reconstructed by the decoding network. The attention module can not only improve the noise immunity performance of the algorithm and the accuracy of fusion. And it can also enhance the generalization ability of the convolutional network, which can fully reflect the importance of spatial information and ensure the validity of the fusion results. The medical brain images are processed and analyzed, including CT-MR image fusion and MR-PET image fusion. Experiments show that our method has strong generalization and robustness for different types of image pairs compared with existing methods and can achieve high-accuracy reconstruction. In the future, we will consider extending the framework to integrate two or more imaging modalities, such as CT, MR, PET, SPECT, and DTI, and apply them to clinical diagnosis.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank the Qingdao Huanghai University School-level Scientific Research Project, Undergraduate Teaching Reform Research Project of Shandong Provincial Department of Education, National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant and Qingdao Postdoctoral Foundation under Grant.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by Qingdao Huanghai University School-Level Scientific Research Project (2023KJ14), Undergraduate Teaching Reform Research Project of Shandong Provincial Department of Education (M2022328), National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant (42472324) and Qingdao Postdoctoral Foundation under Grant (QDBSH202402049).

Author Contributions: Jianjun Liu provided the main methodological writing and first draft of the paper; Yang Li provided visualization and funding acquisition; Xiaoting Sun provided review and editing; Xiaohui Wang provided format and analysis; Hanjiang Luo provided method validation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data in this article comes from a public dataset. The URL of the public dataset is: http://www.med.harvard.edu/aanlib/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Thomas E, Kumar SN, Midhunchakkaravarthy D. Effect of segmentation of white matter, grey matter and CSF in the prediction of neurological disorders. Int J Neurol Nurs. 2024;10(2):9–14. [Google Scholar]

2. Verclytte S, Lopes R, Lenfant P, Rollin A, Semah F, Leclerc X, et al. Cerebral hypoperfusion and hypometabolism detected by arterial spin labeling MRI and FDG-PET in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroimaging. 2016;26(2):207–12. doi:10.1111/jon.12264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Nguyen MP, Kim H, Chun SY, Fessler JA, Dewaraja YK. Joint spectral image reconstruction for Y-90 SPECT with multi-window acquisition. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference (NSS/MIC); 2015 Oct 31–Nov 7; San Diego, CA, USA. doi:10.1109/NSSMIC.2015.7582110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li H, Yuan M, Li J, Liu Y, Lu G, Xu Y, et al. Focus affinity perception and super-resolution embedding for multifocus image fusion. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025;36(3):4311–25. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2024.3367782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Du J, Fang M, Yu Y, Lu G. An adaptive two-scale biomedical image fusion method with statistical comparisons. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;196(10):105603. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2020.105603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Li H, Wu XJ. DenseFuse: a fusion approach to infrared and visible images. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2018;28(5):2614–23. doi:10.1109/TIP.2018.2887342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Li Y, Chen J, Xue P, Tang C, Chang J, Chu C, et al. Computer-aided cervical cancer diagnosis using time-lapsed colposcopic images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2020;39(11):3403–15. doi:10.1109/TMI.2020.2994778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ganasala P, Kumar V. Feature-motivated simplified adaptive PCNN-based medical image fusion algorithm in NSST domain. J Digit Imaging. 2016;29(1):73–85. doi:10.1007/s10278-015-9806-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Huang C, Tian G, Lan Y, Peng Y, Ng EYK, Hao Y, et al. A new pulse coupled neural network (PCNN) for brain medical image fusion empowered by shuffled frog leaping algorithm. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:210. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.00210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Daneshvar S, Ghassemian H. MRI and PET image fusion by combining IHS and retina-inspired models. Inf Fusion. 2010;11(2):114–23. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2009.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen CI. Fusion of PET and MR brain images based on IHS and log-Gabor transforms. IEEE Sens J. 2017;17(21):6995–7010. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2017.2747220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gillespie AR, Kahle AB, Walker RE. Color enhancement of highly correlated images. II. Channel ratio and chromaticity transformation techniques. Remote Sens Environ. 1987;22(3):343–65. doi:10.1016/0034-4257(87)90088-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nandi D, Ashour AS, Samanta S, Chakraborty S, Salem MAM, Dey N. Principal component analysis in medical image processing: a study. Int J Image Min. 2015;1(1):65. doi:10.1504/ijim.2015.070024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ghandour C, El-Shafai W, El-Rabaie EM, Elshazly EA. Applying medical image fusion based on a simple deep learning principal component analysis network. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(2):5971–6003. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-15856-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Himanshi, Bhateja V, Krishn A, Sahu A. An improved medical image fusion approach using PCA and complex wavelets. In: Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Medical Imaging, m-Health and Emerging Communication Systems (MedCom); 2014 Nov 7–8; Greater Noida, India. doi:10.1109/MedCom.2014.7006049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yadav SP, Yadav S. Image fusion using hybrid methods in multimodality medical images. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2020;58(4):669–87. doi:10.1007/s11517-020-02136-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. He C, Liu Q, Li H, Wang H. Multimodal medical image fusion based on IHS and PCA. Procedia Eng. 2010;7(2):280–5. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2010.11.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Calhoun VD, Adali T. Feature-based fusion of medical imaging data. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2009;13(5):711–20. doi:10.1109/titb.2008.923773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Haribabu M, Guruviah V. An improved multimodal medical image fusion approach using intuitionistic fuzzy set and intuitionistic fuzzy cross-correlation. Diagnostics. 2023;13(14):2330. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13142330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Haribabu M, Guruviah V. Enhanced multimodal medical image fusion based on Pythagorean fuzzy set: an innovative approach. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):16726. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-43873-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Shreyamsha Kumar BK. Image fusion based on pixel significance using cross bilateral filter. Signal Image Video Process. 2015;9(5):1193–204. doi:10.1007/s11760-013-0556-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hu J, Li S. The multiscale directional bilateral filter and its application to multisensor image fusion. Inf Fusion. 2012;13(3):196–206. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2011.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li S, Kang X, Hu J. Image fusion with guided filtering. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2013;22(7):2864–75. doi:10.1109/TIP.2013.2244222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Li W, Jia L, Du J. Multi-modal sensor medical image fusion based on multiple salient features with guided image filter. IEEE Access. 2019;7:173019–33. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2953786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kumar N, Tao Z, Singh J, Li Y, Sun P, Zhao BH, et al. FusionINN: invertible image fusion for brain tumor monitoring. arXiv:2403.15769. 2024. [Google Scholar]

26. Zhao W, Lu H. Medical image fusion and denoising with alternating sequential filter and adaptive fractional order total variation. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2017;66(9):2283–94. doi:10.1109/TIM.2017.2700198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wang Z, Cui Z, Zhu Y. Multi-modal medical image fusion by Laplacian pyramid and adaptive sparse representation. Comput Biol Med. 2020;123(11):103823. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.103823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang X, Yan H. Medical image fusion and noise suppression with fractional-order total variation and multi-scale decomposition. IET Image Process. 2021;15(8):1688–701. doi:10.1049/ipr2.12137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Li X, Zhou F, Tan H, Zhang W, Zhao C. Multimodal medical image fusion based on joint bilateral filter and local gradient energy. Inf Sci. 2021;569(7):302–25. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2021.04.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Tan W, Thitøn W, Xiang P, Zhou H. Multi-modal brain image fusion based on multi-level edge-preserving filtering. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2021;64(11):102280. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2020.102280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zong JJ, Qiu TS. Medical image fusion based on sparse representation of classified image patches. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2017;34(2):195–205. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2017.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wen X. Image fusion based on improved IHS transform with weighted average. In: Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computational and Information Sciences; 2011 Oct 21–23; Chengdu, China. doi:10.1109/ICCIS.2011.162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Pajares G, la Cruz JMD. A wavelet-based image fusion tutorial. Pattern Recognit. 2004;37(9):1855–72. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2004.03.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang S, Fan J, Li H. A self-attention hybrid network for aspect-level sentiment classification. In: Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Frontiers Technology of Information and Computer (ICFTIC); 2022 Dec 2–4; Qingdao, China. doi:10.1109/ICFTIC57696.2022.10075144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Nanavati M, Shah M. Performance comparison of different wavelet based image fusion techniques for lumbar spine images. J Integr Sci Technol. 2024;12(1):703. doi:10.48084/etasr.5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools