Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Human Motion Prediction Based on Multi-Level Spatial and Temporal Cues Learning

1 School of Software, Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330000, China

2 School of Queen Mary, Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330000, China

3 Department of Information Systems, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O.Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Computer Science and Information Technology, Benazir Bhutto Shaheed University Lyari, Karachi, 75660, Pakistan

5 School of Engineering, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Lausanne, 1015, Switzerland

6 School of Mathematics and Computer Science, Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330000, China

* Corresponding Author: Pengxiang Su. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Action Recognition: Algorithms, Applications, and Emerging Trends)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3689-3707. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066944

Received 21 April 2025; Accepted 24 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Predicting human motion based on historical motion sequences is a fundamental problem in computer vision, which is at the core of many applications. Existing approaches primarily focus on encoding spatial dependencies among human joints while ignoring the temporal cues and the complex relationships across non-consecutive frames. These limitations hinder the model’s ability to generate accurate predictions over longer time horizons and in scenarios with complex motion patterns. To address the above problems, we proposed a novel multi-level spatial and temporal learning model, which consists of a Cross Spatial Dependencies Encoding Module (CSM) and a Dynamic Temporal Connection Encoding Module (DTM). Specifically, the CSM is designed to capture complementary local and global spatial dependent information at both the joint level and the joint pair level. We further present DTM to encode diverse temporal evolution contexts and compress motion features to a deep level, enabling the model to capture both short-term and long-term dependencies efficiently. Extensive experiments conducted on the Human 3.6M and CMU Mocap datasets demonstrate that our model achieves state-of-the-art performance in both short-term and long-term predictions, outperforming existing methods by up to 20.3% in accuracy. Furthermore, ablation studies confirm the significant contributions of the CSM and DTM in enhancing prediction accuracy.Keywords

Human motion prediction, the process of forecasting future pose sequences based on historical data, serves as a cornerstone for enabling intelligent and safe interactions between robots or machines and the physical world. Consequently, human motion prediction has attracted remarkable attention and is at the core of wide applications, such as autonomous driving [1,2], human tracking [3], motion generation [4], and human-robot interactions [5,6].

Early attempts in human motion prediction primarily employed latent variable models, such as the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) [7], Gaussian Processes (GP) [8], and Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM) [9]. These models aimed to establish a correlation between past and future human motions. However, unlike inanimate physical movements governed by deterministic laws, human motion involves intricate dynamic contexts. Consequently, these initial mathematical models faced significant challenges in accurately capturing the complex dynamics of human motion, resulting in suboptimal forecasting outcomes.

Recently, with the improvement of computational power and the availability of large datasets, a large number of deep learning methods have been proposed and show improved results. The general human motion prediction algorithms encompass a sequence-to-sequence model whereby the historical pose sequence is encoded to a hidden temporal dynamic context that is decoded to obtain the future pose sequence. For example, references [10–12] employed recurrent neural networks (RNN), including long short term memory (LSTM), gated recurrent unit (GRU), to capture temporal information via a frame-wise reading method. However, these methods fail to encode long-term temporal dependencies, which only generate accurate predictions at short-term horizons. References [1,13,14] utilized convolutional neural networks (CNN) to encode the input pose sequence into a long-term latent variable, which can capture sufficient short- and long-term temporal correlations. In the aforementioned motion forecasting models, they directly extract motion information only from consecutive frames. Unfortunately, existing methods focus exclusively on consecutive frames and neglect the important temporal cues provided by non-adjacent frames, which are often crucial for accurate long-term predictions. Moreover, existing models treat all frames as equally important, which limits prediction accuracy by ignoring the varying relevance of different frames in the sequence. Embracing the above challenges, we propose a novel Temporal Cues Learning strategy and design a Dynamic Temporal Encoding Module that first utilizes a temporal relation matrix to flexibly establish diverse temporal dependencies from consecutive or non-consecutive frames, and then employs a temporal compression matrix to condense the captured shallow temporal information to deep level for improving information density and smoothness.

Moreover, early approaches only encode the motion information from the temporal dimension, which ignores the complementary motion features from related joints at the spatial dimension. Specifically, in the “Walking” and “Swimming” action, the arms and the legs usually show a mirror symmetry tendency and a side synchronization tendency. Some existing human motion prediction models have demonstrated that extracting the spatial coherence information from related joints and capturing the temporal dynamic context from the whole sequence simultaneously are positive for improving prediction performance. Several studies [15–18] have utilized a spatio-temporal graph to map known spatial dependencies among joints, while others [1,19–21] have employed graph convolutional networks (GCN) to reveal and aggregate intrinsic spatial relationships within a single frame. Nevertheless, these methods often struggle to accurately depict the complex and variable nature of human motion by focusing solely on establishing singular spatial dependencies across different joints. In contrast, transformer-based algorithms have gained prominence due to their ability to encode both local and global features effectively in various computer vision tasks, including human motion prediction [22,23]. Our study introduces a novel Cross Spatial Dependencies Encoding Module leveraging the transformer architecture, which adeptly extracts both local and global spatial dependency information across the entire human body, including joint level and joint pair level.

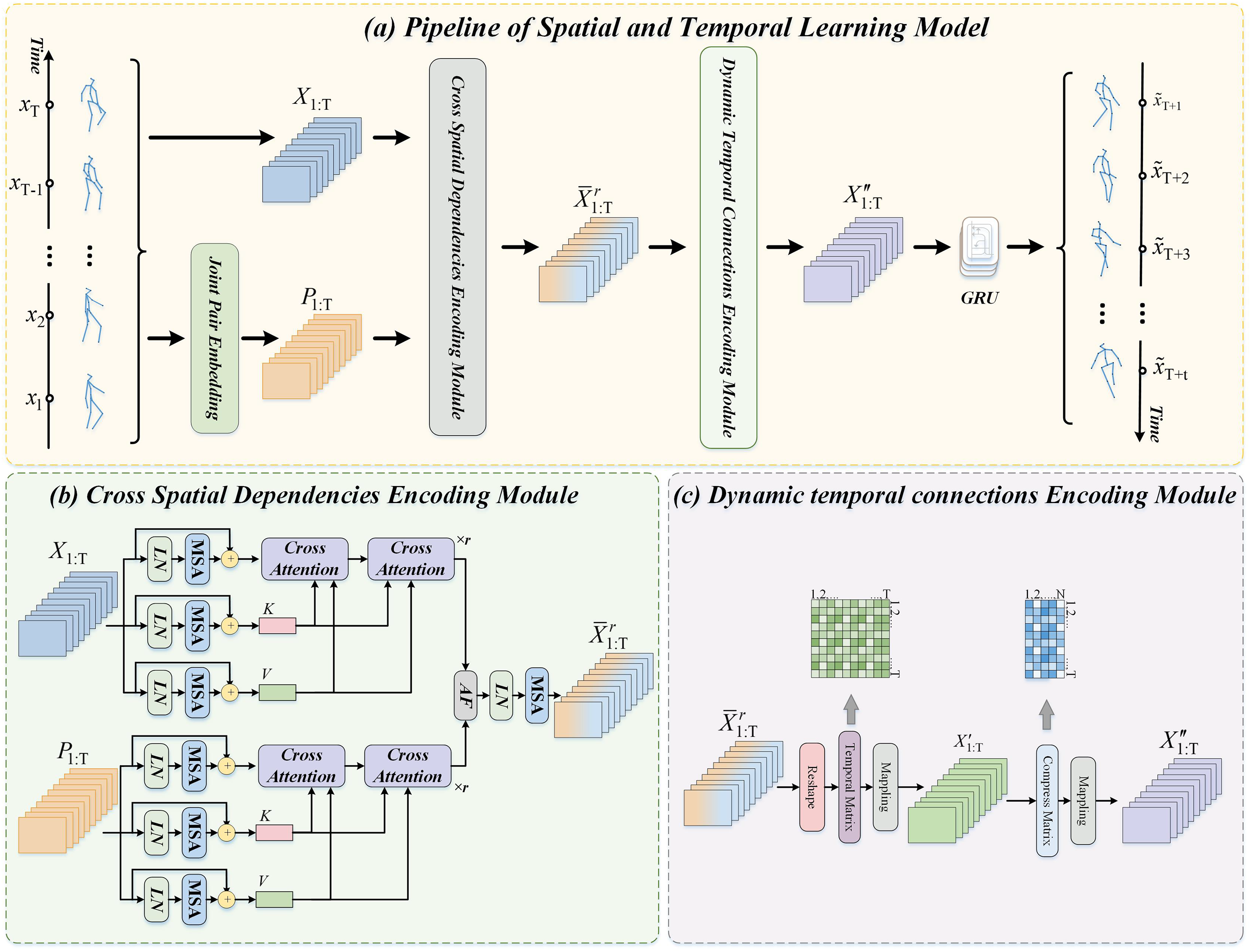

Inspired by the latest advancements in human motion prediction, we are dedicated to mastering the intricate spatial relationships among individual joints or joint pairs within frames, as well as the complex temporal connections spanning any distance within a pose sequence. The model handles the identification and connection of non-consecutive frames in a learned manner. Specifically, the Dynamic Temporal Encoding Module (DTM) employs a temporal relation matrix that is learned during training to capture temporal dependencies not only from consecutive frames but also from non-consecutive frames that are contextually relevant. This matrix enables the model to dynamically learn and establish connections between discontinuous frames based on their temporal relevance to the overall motion sequence. As illustrated in Fig. 1, we have developed an advanced framework called the Multi-level Spatial and Temporal Learning Model (STM). This framework is structured around two fundamental modules: the Cross Spatial Dependencies Encoding Module (CSM) and the Dynamic Temporal Connection Encoding Module (DTM). (1) The CSM dissects each human body frame into distinct joints and joint pairs, which are then simultaneously processed through parallel self-attention layers designed to effectively integrate local and global associated features. This process is further enhanced by employing a multi-head mechanism capable of deriving various motion representations, thereby capturing a comprehensive range of spatial motion features at different spatial levels. (2) In contrast, the DTM treats each joint in every frame as an individual time step. It constructs an adjacency matrix that serves as a foundational tool for establishing temporal correlations between any two frames in the pose sequence. To achieve this goal, a strategic employment of a temporal compression matrix condenses and interprets temporal data efficiently, thus enhancing predictive capabilities.

Figure 1: The architecture of our proposed method. (a) the pipline of multi-level spatial and temporal learning model, (b) the cross spatial dependencies encoding module, (c) the dynamic temporal connection encoding module

Overall, the key contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

• We propose a novel cross spatial dependencies encoding module to simultaneously ensure the local and global spatial coherence from joint level and joint pair level.

• We introduce a dynamic temporal connection encoding module as the key realization of Temporal Cues Learning, which captures diverse and informative temporal evolution patterns, including non-consecutive dependencies, and compresses them to deeper levels to enhance motion smoothness.

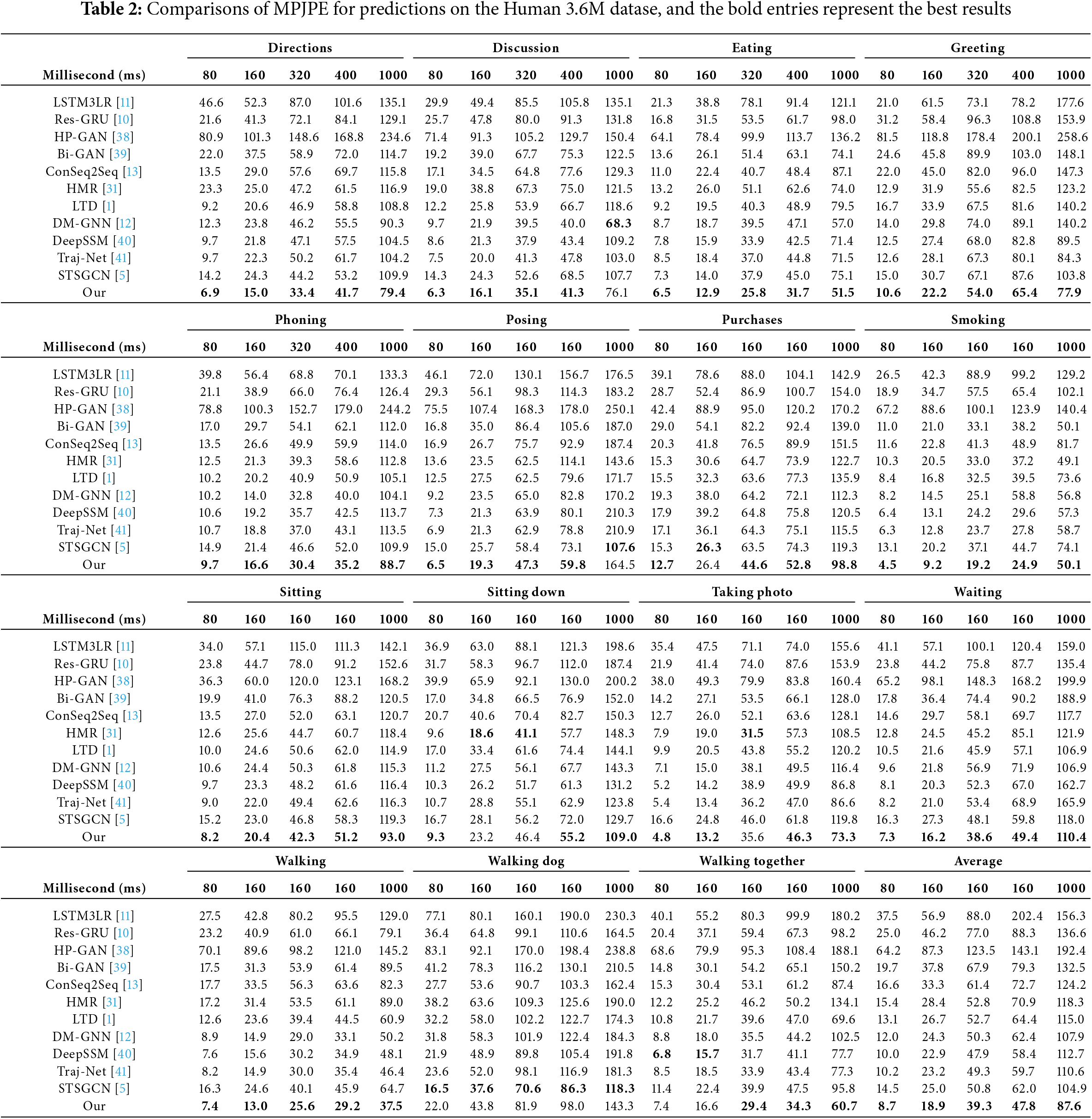

• Our method achieves the state-of-the-art performance on both short- and long-term predictions. On the Human 3.6M dataset, our model improves MPJPE by 17.8% over DeepSSM and 25.3% over STSGCN for long-term predictions. On the CMU Mocap dataset, we achieve 3.9% improvement over STSGCN and 17.9% over TIM for long-term predictions at 1000 ms.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. We review the related works in the field of human motion prediction in Section 2. We then introduce the details of the proposed method in Section 3. Thereafter, Section 4 presents the experimental setup and performance evaluation on the Human 3.6M and CMU Mocap datasets. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines potential future work.

In this section, we review the background of human motion prediction, reviewing key challenges in the field and summarizing relevant prior works that have laid the foundation for our approach.

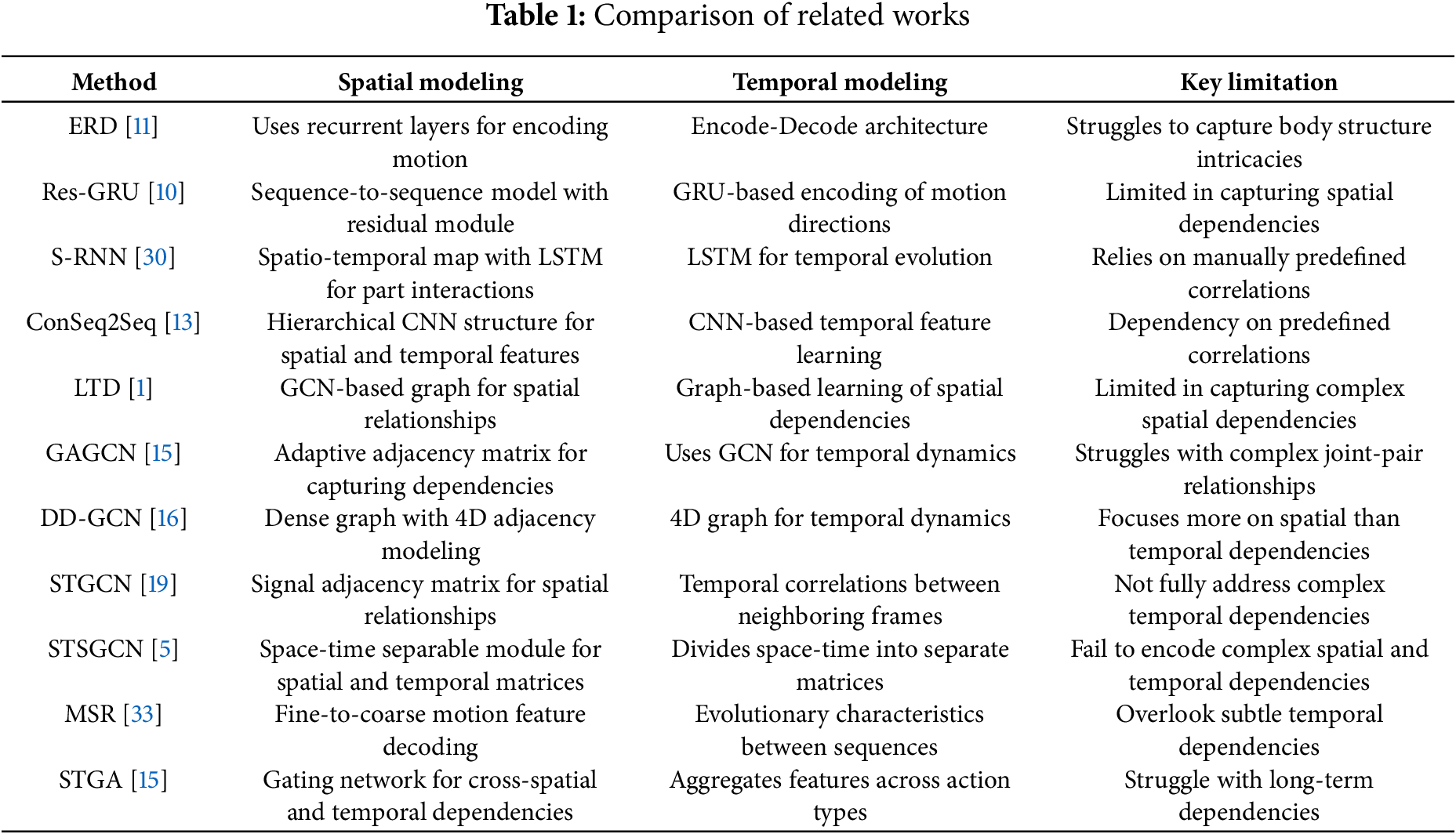

In the field of human motion prediction, initial methodologies were categorized under latent variable models, including the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) [7], Gaussian Processes [8], and the Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM) [9]. The efficacy of deep learning models across a broad spectrum of computer vision tasks has been well-documented [24–26]. In recent years, researchers have developed a variety of deep learning strategies to effectively capture the temporal dynamics present in historical motion sequences [27–29], surpassing the performance of traditional methods in motion prediction. For instance, the ERD framework [11] employs an Encode-Decode architecture with recurrent layers to model motion information and generate future motion predictions. The Res-GRU [10] introduces a sequence-to-sequence model with a residual module before the GRU layer, encoding first-order motion directions. Despite their advancements, these models often fail to fully capture the structural intricacies of the human body, leading to inaccurate or distorted future pose predictions.

Addressing this gap, the S-RNN model [30] creates a spatio-temporal map to represent human structure, using LSTM to extract interactions among body parts. Similarly, the ConSeq2Seq model [13] employs a hierarchical CNN structure to simultaneously construct spatial and temporal correlated features. However, these methods tend to rely on manually predefined correlations, which can limit their robustness and comprehensive characterization. The LTD approach [1] treats the human body as a generic graph via GCN, automating the exploration of graph connections to learn long-range spatial relationships. The GAGCN method [15] utilizes an adaptive adjacency matrix to capture complex dependencies across diverse action types, while the DD-GCN [16] employs a dense graph with 4D adjacency modeling to illustrate temporal dynamics between frames. Nonetheless, these GCN-based approaches primarily focus on individual spatial relationships among joints and often struggle to encapsulate the full spectrum of complex and variable spatial dependencies. To address this, we propose a cross spatial dependencies encoding module, designed to learn both local and global spatial dependency information from a variety of motion representations at the joint and joint-pair levels.

2.2 Spatio-Temporal Dependencies Learning

Human motion is a coordinated movement involving multiple joints, exhibiting pronounced temporal evolution trends. A fundamental challenge in human motion prediction lies in effectively encoding the spatial and temporal contextual information. Previous studies [30,31] have relied on predefined spatial and temporal relationships based on prior knowledge, such as kinematic chains. In contrast, S-RNN proposes a generic and principled spatio-temporal graph combined with an RNN to explicitly capture the interrelationships for accurate motion prediction [30]. This approach defines local spatial relationships among human joints, leading to satisfactory long-term prediction performance. HMR utilize Li algebra based the human global kinematic tree to represent the human spatial connection and utilizes a hierarchical recurrent network for learning temporal evolution [31]. However, this predefined approach for spatio-temporal relations lacks flexibility in modeling motion features effectively. Recently, researchers have proposed various data-driven models to flexibly capture relevant motion features from pose sequences. The STGCN method utilizes a signal adjacent matrix to effectively model the spatial relationships among joints in a pose and the temporal correlations of the same joint across neighboring frames [19]. The MPT method proposes a semi-constrained graph to comprehensively encode the relationships between joints, explicitly encoding prior skeletal connections and adaptively learning implicit dependencies between joints for a more comprehensive representation [32]. The STSGCN designs a signal-graph framework with a space-time separable module to divided the spatio-temporal connectivity into space and time affinity matrices to avoid the space-time cross-talk [5]. The MSR method combines and decodes motion features from fine to coarse scale, as well as from coarse to fine scale, in order to capture the evolutionary characteristics between historical and future pose sequences [33]. The SPGSN approach adopts an adaptive graph scattering between joints and fuses decomposed motion information from both graph spectrum and spatial dimensions [34]. The STGA employs a gating network to learn the cross dependencies of spatial and temporal information, effectively aggregating decoupled features from various action types [15]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated in [1] that compressing time information enhances the smoothness of temporal evolution, thereby assisting in performance improvement. Consequently, we propose a dynamic temporal connection encoding module designed to capture sufficient contextual dynamics from both continuous and discontinuous frames and subsequently compress these features to obtain more concise evolutionary patterns at deep level.

Table 1 shows the comparison of the existing methods, although the existing methods achieving good performance, but there still some problems, including 1) Limited spatial dependency modeling, where many models fail to capture complex relationships between joint pairs; 2) Rigid predefined relationships, restricting flexibility in modeling dynamic motion features; 3) Inadequate handling of non-consecutive temporal dependencies, which impacts long-term prediction accuracy.

To address these challenges, we propose a novel approach that integrates both spatial and temporal dependencies across multiple levels: The Cross Spatial Dependencies Encoding Module (CSM) captures both local and global multi-level spatial dependencies, addressing the limitations of current GCN-based methods; and the Dynamic Temporal Connection Encoding Module (DTM) is designed to learn consecutive and non-consecutive temporal dependencies, enabling our model to perform better on long-term prediction tasks.

In this section, we initially provide a concise overview of our approach, followed by a detailed description of the proposed cross-level spatial dependencies encoding module. Subsequently, we elaborate on the designed dynamic temporal connection encoding module and discuss the employed loss function for training our model.

Problem Formulation The human motion prediction model is to capture the spatial connected information and temporal evolution context to extrapolate the future pose sequence based the historical pose sequence. We denote the historical pose sequence of T frames as

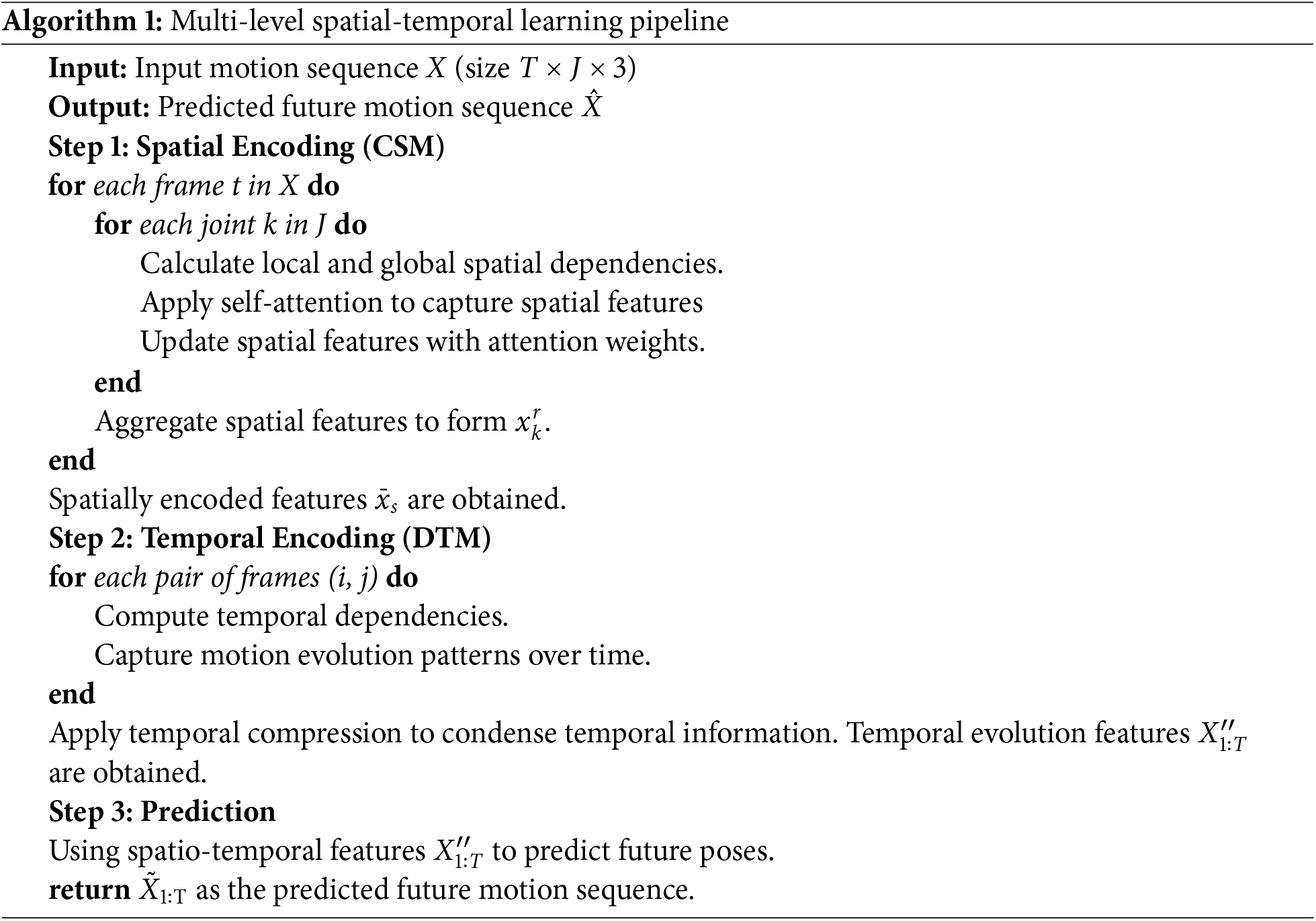

Method Overview The process of Spatial and Temporal Learning Model is shown in Algorithm 1. We can see that the proposed method consists of two key components. (1) A module for encoding cross spatial dependencies is employed to establish local and global spatial correlations from joint level and joint pair level, thereby obtaining complementary and robust spatial related information. (2) These features are fed into a dynamic temporal connection encoding module to adaptively capture the temporal evolution context between any two frames in the entire sequence. Subsequently, the features are compressed to deep level for enhancing compactness and smoothness.

3.2 Cross Spatial Dependencies Encoding Module

For the task of human motion prediction, an efficient model for capturing spatial dependencies is crucial in extracting complementary features that are spatially related, which enhance the performance of prediction. Hence, a multi-level spatial dependencies encoding module are explored to promote the various local-global spatial coherence form joint and joint pair level. The details of our module are presented as follows. Firstly, we constructs an adjacency matrix based on the human body’s anatomical structure. This matrix represents the initial spatial relationships between joint pairs. In particular, we set

where

The formula for SLS is expressed as follows,

where

Finally, we aggregate

where

3.3 Dynamic Temporal Connection Encoding Module

The essence of human motion prediction lies in capturing the underlying temporal evolution relationships to extrapolate motion information. To address this task, it is crucial to consider the temporal evolution by encoding interactions and interdependencies among poses (frames). Traditionally, researchers have employed RNNs and TCNs to capture the temporal evolution from pose sequences. However, these models, which utilize frame-by-frame and sequence-to-sequence methods, are limited in their ability to extract continuous information from rigidly connected adjacent frames and capture implicit patterns of temporal evaluation. Nevertheless, strong connections may also exist between temporally separated poses. For example, in periodic movements such as walking and eating, the hand motion may exhibit high similarity with historical movements. Disregarding these crucial non-consecutive temporal evolution features that are concealed within the inconsecutive pose sequence results in a significant degradation of accuracy. Hence, we propose a dynamic temporal connection encoding module comprising two key components. Firstly, we consider each pose as a time node and disregard the temporal order between poses, which construct a graph structure consisting of a series of time nodes. Consequently, we employ a temporal matrix to enable the model to flexibly encode the temporal relationship between any two time nodes. Formally, given a historical pose sequence which processed by our CSM generate

where

Further, we compresses motion features into a deeper latent representation for promoting the continuation of the temporal information and assist the model in obtaining smoother temporal evolution features. The formula is expressed as,

where

Following existing [32,35], we utilize the weighted position loss and bone length loss as our cost functions. Training aims to minimize the

(1) The weighted position loss ensures the consistency between the forecasted joint position and the ground truth, enhancing the accuracy of our predictions. The formulation of this loss function is as follows:

(2) The weighted loss for bone length is employed to supervise the model in generating consistent predicted bone lengths across different poses, thereby mitigating the occurrence of unnatural movements and inter-frame discontinuities. Formally,

where

In this section, we present the results of our experiments, comparing the performance of our model with existing methods. We analyze the key findings, highlighting the advantages of our approach.

Human 3.6M is the largest available human motion dataset, includes 3.6 million 3D skeleton poses with 15 actions performed by 7 subjects (e.g., “Directions”, “Eating”, “Purchases”, and “Walking”). Each skeleton pose is represented by the 3D coordinates of 32 joints. This dataset was recorded using a Vicon motion capture system. Following the preprocessing protocol employed in previous studies [32,34,36], we downsampled the frame rate from 50 to 25 frames per second (FPS) and eliminated duplicate and constant joints. We employ 5 subjects (S1, S5, S6, S7, S8) for training, S5 and S11 utilized for testing and validation.

CMU Mocap is a challenging and publicly available collection of human motion data, consisting of 6 categories and 23 subcategories (e.g., “Human Interaction”, “Locomotion”). Each human subject is represented by a skeleton comprising 31 joints. Following the methodology employed in previous works [1,12], we select 25 representative joints for each pose and adopt the same training/test split approach. To evaluate our proposed model, we employ a set of 8 actions including “Basketball”, “Directing Traffic”, “Jumping”, and “Washing Window”.

We implemented our model using PyTorch on an Nvidia Tesla A40 GPU. The Adam optimizer was employed for training the model. The learning rate was initialized as 0.001 with a decay of 0.95 every 2 epochs. The batch size was set to 16, and the gradient clipping threshold was set to 5. The model was trained for 50 epochs. During the training stage, we utilized a sequence of historical poses consisting of 10 frames (400 ms) as input to predict future poses comprising of 25 frames (1000 ms). In the MSM module, there were four spatial encode heads incorporated. The adjacent matrix size for the MSM module was

We adopt the Mean Per Joint Position Error (MPJPE) in millimeter to evaluate the performance of all approaches. MPJPE calculates the spatial distance between the ground truth and predicted joint locations. The formula for MPJPE is given by:

where

4.2 Comparison with Existing Methods

We present a comprehensive summary of the Mean Percentage of Joint Position Error (MPJPR) achieved by various methods on 15 human actions using the Human 3.6M dataset, as shown in Table 2. In total, we compare our method with 11 state-of-the-art models, namely LSTM3LR [11], Res-GRU [10], HP-GAN [38], Bi-GAN [39], ConSeq2Seq [13], HMR [31], LTD [1], DM-GNN [12], DeepSSM [40], Traj-Net [41], and STSGCN [5]. Based on empirical evidence, STM outperforms the alternatives, particularly DeepSSM and STSGCN, in terms of performance. Notably, STM demonstrates a significant average accuracy improvement of 19.7% and 21.3% compared to DeepSSM and STSGCN, respectively. For periodic actions such as “Eating” and “Walking”, all algorithms deliver satisfactory prediction results. However, for non-periodic actions like “Photo” and “Purchases”, models that encode spatial relationships (e.g., GCN-based models [1,5]) show significant improvements compared to those that solely rely on temporal context (e.g., [10,11]). Unfortunately, even these GCN-based models [1,5,12] fail to capture sufficient spatial information effectively. In contrast, our proposed CSM focuses on exploring multi-level local and global spatial dependencies which consistently enhance performance in complex and challenging motions. So, the main reasons STM outperforms existing models is its multi-level spatial-temporal learning framework. While many traditional models focus on either spatial dependencies or temporal dependencies, STM integrates both at multiple levels, capturing complex relationships that others miss. The Cross Spatial Dependencies Encoding Module (CSM) enables STM to capture fine-grained spatial dependencies between joint pairs, allowing it to better understand human motion, especially in challenging scenarios like non-periodic actions (e.g., “Photo” and “Purchases”). Additionally, STM’s ability to learn non-consecutive temporal dependencies through the Temporal Cues Learning strategy improves its long-term prediction accuracy. This is particularly useful for motion sequences where dependencies between frames are not strictly sequential.

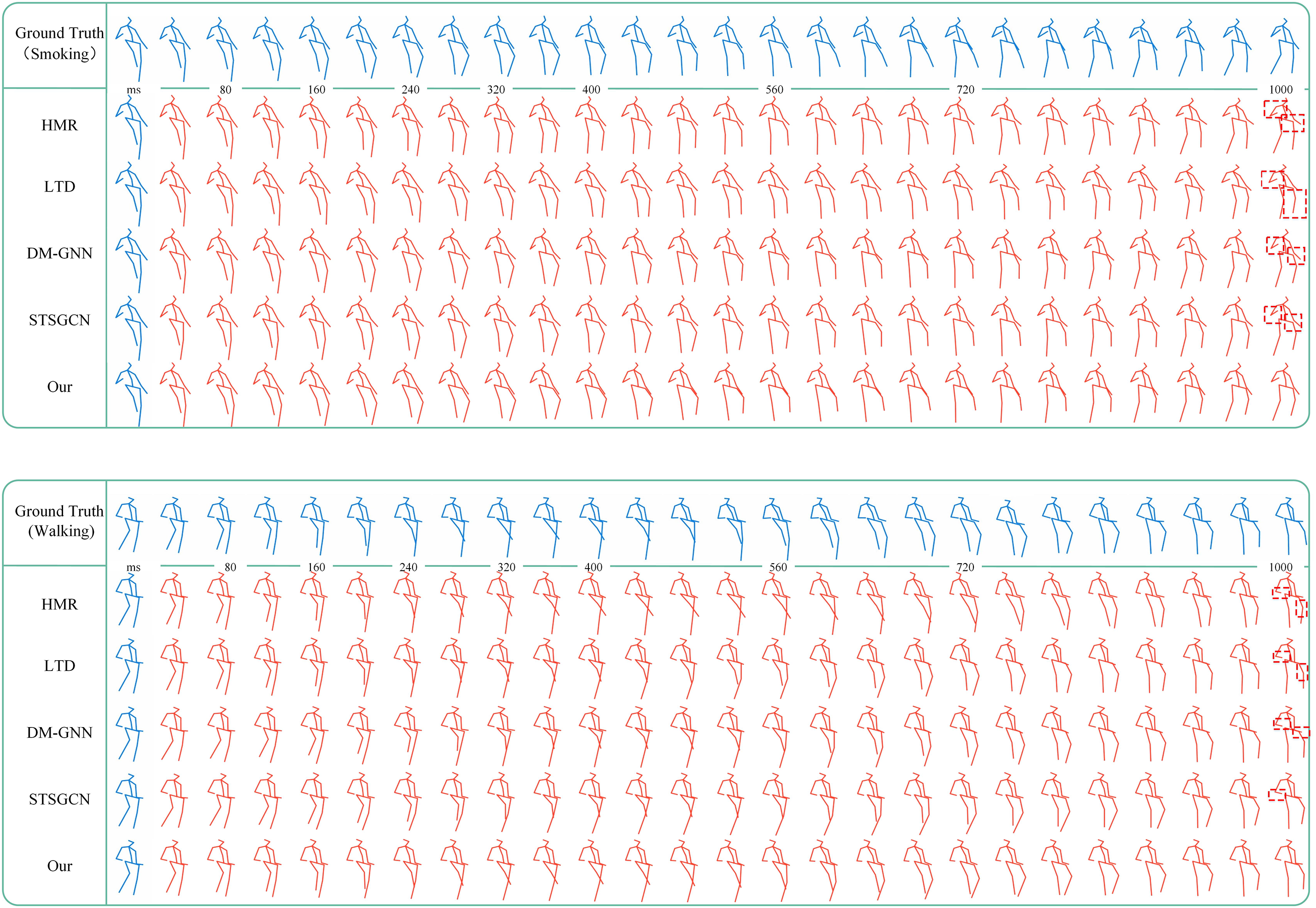

We also present visualizations of the prediction results obtained from HMR [31], LTD [1], DM-GNN [12], STSGCN [5], and our proposed method. Fig. 2 illustrates the forecasted outcomes for the actions “Smoking” and “Walking”. Our model exhibits superior performance compared to existing methods, generating future pose sequences that closely align with ground truth data. Notably, in the case of the “Smoking” action, our model successfully captures both hand movements and stationary leg states, which are not effectively captured by other models. Consequently, these models exhibit significant errors in forecasting leg positions.

Figure 2: The visual results on Human 3.6M dataset

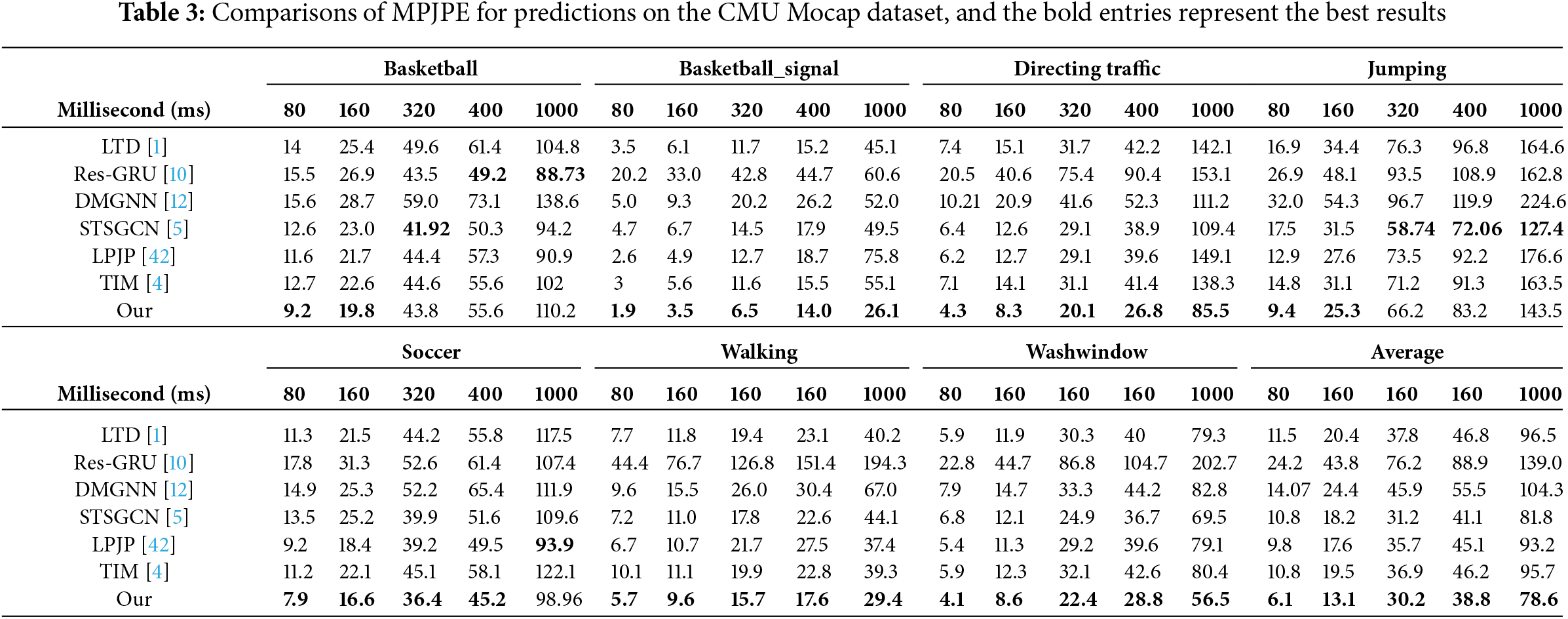

To further evaluate our model, we conducted extensive experiments on the CMU Mocap dataset. Our Spatial and Temporal Learning Model (STM) is compared with six previous methods, namely Res-GRU [10], LTD [1], DM-GNN [12], STSGCN [5], LPJP [42], and TIM [4]. The short-term and long-term prediction performance under the MPJPE metric is presented in Table 3. The proposed STM consistently outperforms the alternatives for both periodic and non-periodic actions. Additionally, our model demonstrates competitive long-term prediction performance with an average improvement of 4.0% over STSGCN and 17.9% over TIM at 1000 ms. These results highlight the benefits of extracting diverse temporal evolution contexts from motion sequences to generate accurate long-term predictions.

The advantage of STM lies in its ability to model both spatial and temporal dependencies across multiple levels. The CSM captures fine-grained spatial dependencies between joint pairs, allowing the model to better handle complex human motion patterns. Unlike models like LTD and DM-GNN, which focus on spatial dependencies but struggle with non-periodic actions, STM excels in these cases due to its integrated temporal learning capabilities. The DTM, through Temporal Cues Learning, captures both consecutive and non-consecutive temporal dependencies, enabling STM to make accurate long-term predictions, especially for non-periodic actions such as “Jumping” and “Direction Traffic.” This ability to capture both short- and long-term dependencies contributes to STM’s superior performance.

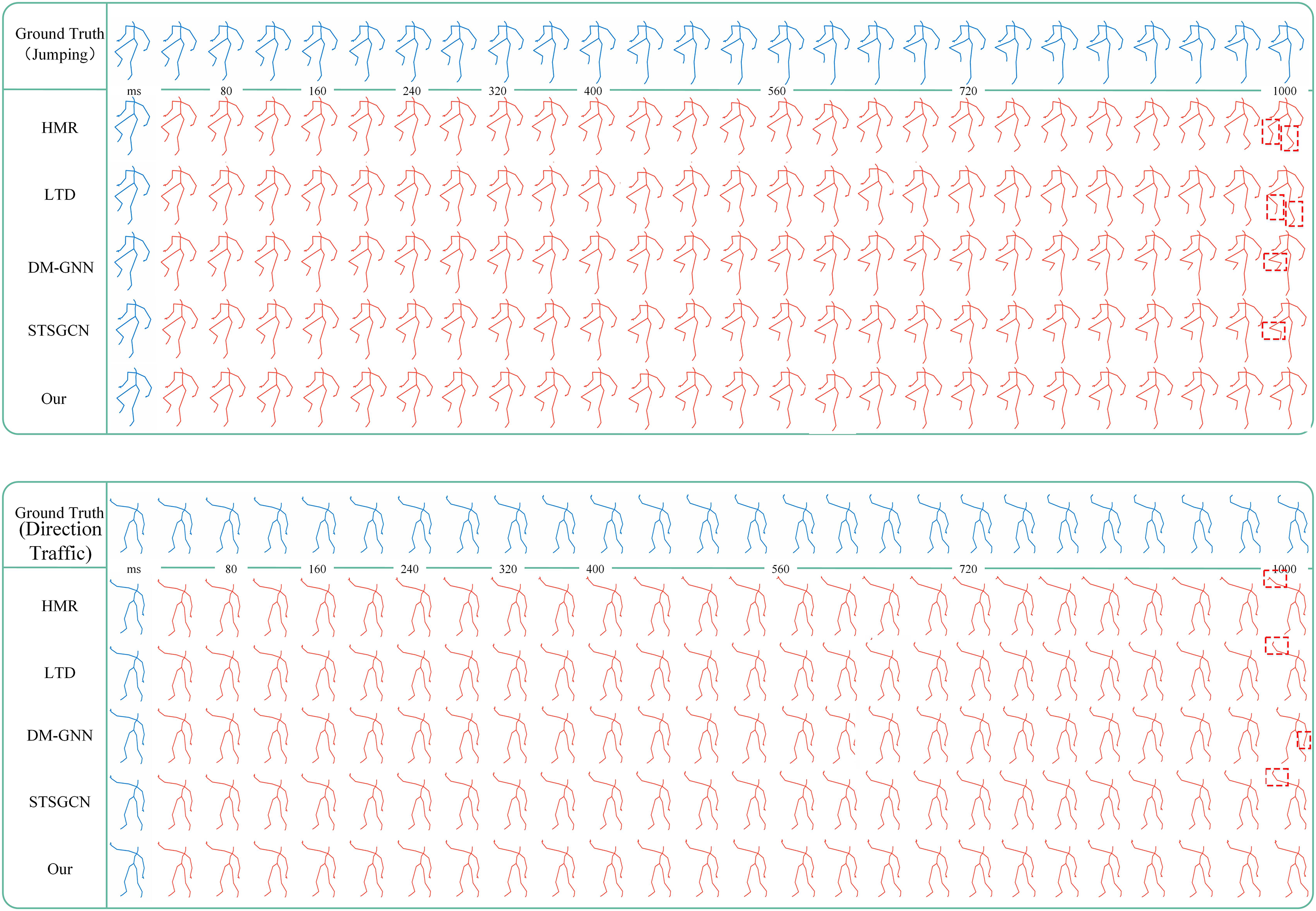

As shown in Fig. 3, we qualitatively compare our STM with HMR [31], LTD [1], DM-GNN [12], and STSGCN [5] on the CMU Mocap dataset. These results demonstrate that our STM produces more authentic future motions for the “Jumping” and “Direction Traffic” actions, exhibiting a higher similarity to the ground truth. In comparison, LTD, DM-GNN, and STSGCN exhibit inaccuracies in certain joints such as the left ankle and right hand during long-term predictions.

Figure 3: The visual results on CMU Mocap dataset

We further investigate the efficacy of individual components comprising the proposed Multi-level Spatial-Temporal Memory (STM) through a series of ablation studies. In this section, we initially analyze the impact of the cross-spatial dependency encoding module and subsequently evaluate the dynamic temporal connection encoding module using Human 3.6M dataset.

4.3.1 Cross Spatial Dependencies Encoding Module

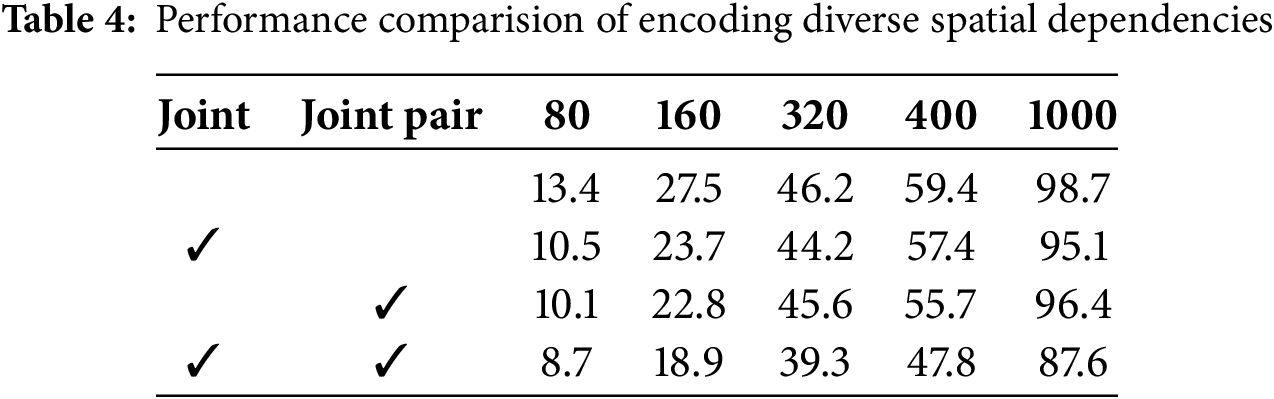

The cross-spatial dependencies encoding block in our model is designed to capture both local and global spatial coherence at joint level and joint pair level. As shown in Table 4, removing this block leads to a significant decrease in short-term prediction accuracy, while only slightly affecting long-term prediction performance. Our focus on capturing spatially correlated features solely from joints or joint pairs results in reduced accuracy, indicating a failure to leverage sufficient and complementary multilevel spatial information.

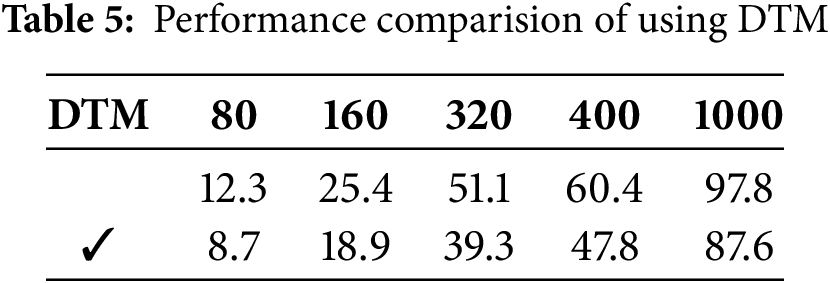

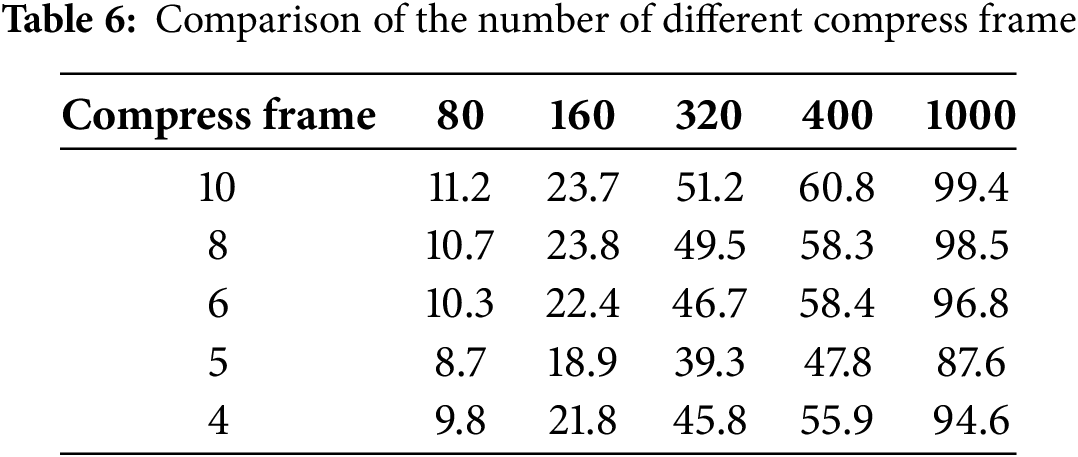

4.3.2 Dynamic Temporal Connection Encoding Module

The module is specifically designed to capture temporal connections from consecutive or inconsecutive frames and condense the motion sequence to deep level, thereby intensifying the temporal context. As demonstrated in Table 5, removing this module leads to a significant degradation in performance. This confirms that solely exploring temporal evolution from connected frames fails to provide sufficient motion contexts. Additionally, as shown in Table 6, we further investigate the effects of capturing diverse temporal correlations and compressing motion sequences separately. It is observed that both approaches result in an improvement in prediction accuracy.

In this paper, we propose a novel algorithm termed Multi-level Spatial and Temporal Learning Model for motion prediction, which consists of a Cross Spatial Dependencies Encoding Module (CSM) and a Dynamic Temporal Connection Encoding Module (DTM). The CSM captures spatial correlation information at the joint level and joint-pair level, respectively, and then adaptively fuses them, especially when extracting correlation information from the original motion features to avoid noise introduced. The DTM encodes temporal context from temporal continuous or discontinuous frames and compresses motion sequences to a deep level that allows the model to acquire supplementary and smooth temporal evolution patterns. Overall, our approach addresses key limitations of existing methods by effectively capturing both spatial and temporal dependencies across diverse frame sequences. The extensive experiments conducted on the Human 3.6M and CMU Mocap datasets demonstrate that our model achieves state-of-the-art performance, outperforming existing methods by up to 20.3% in accuracy. Furthermore, ablation studies confirm the significant contributions of the CSM and DTM in enhancing prediction accuracy. Our approach not only improves motion prediction accuracy but also provides a robust framework for modeling diverse human actions in dynamic environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Urgent Need for Overseas Talent Project of Jiangxi Province (Grant No. 20223BCJ25040), the Thousand Talents Plan of Jiangxi Province (Grant No. jxsg2023101085), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62106093), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi (Grant Nos. 20224BAB212011, 20232BAB212008, 20242BAB25078, and 20232BAB202051), The Youth Talent Cultivation Innovation Fund Project of Nanchang University (Grant No. XX202506030015). This study was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R759), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jiayi Geng and Yuxuan Wu; Methodology, Jiayi Geng and Yuxuan Wu; Software, Wenbo Lu, Di Gai and Amel Ksibi; Validation, Jiayi Geng, Yuxuan Wu and Wei Li; Formal Analysis, Jiayi Geng, Zaffar Ahmed Shaikh and Wei Li; Investigation, Yuxuan Wu and Amel Ksibi; Resources, Amel Ksibi and Wei Li; Data Curation, Yuxuan Wu and Amel Ksibi; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Yuxuan Wu, Di Gai and Wei Li; Writing—Review and Editing, Jiayi Geng; Visualization, Yuxuan Wu and Amel Ksibi; Supervision, Pengxiang Su; Project Administration, Pengxiang Su. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The sources of all datasets are cited in the paper, and can be accessed through the links or GitHub repositories provided in their corresponding papers. Human 3.6M: http://vision.imar.ro/human3.6m (accessed on 23 July 2025), CMU Mocap: http://mocap.cs.cmu.edu (accessed on 23 July 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mao W, Liu M, Salzmann M, Li H. Learning trajectory dependencies for human motion prediction. In: IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2019. Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2019. p. 9488–96. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2019.00958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Xu J, Zhao C, Yang J, Huang Y, Yee L. FDDSGCN: fractional decoupling dynamic spatiotemporal graph convolutional network for traffic forecasting. In: IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing. Hyderabad, India; 2025. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ICASSP49660.2025.10888084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ding R, Qu KH, Tang JKSOF. Leveraging kinematics and spatio-temporal optimal fusion for human motion prediction. Pattern Recognit. 2025;161(8):111206. doi:10.1016/J.PATCOG.2024.111206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lebailly T, Kiciroglu S, Salzmann M, Fua P, Wang W. Motion prediction using temporal inception module. In: Computer Vision-ACCV 2020-15th Asian Conference on Computer Vision. Kyoto, Japan; 2020. p. 651–65. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-69532-3_39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sofianos TS, Sampieri A, Franco L, Galasso F. Space-time-separable graph convolutional network for pose forecasting. In: IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. Montreal, QC, Canada; 2021. p. 11189–98. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.01102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yu T, Lin Y, Yu J, Lou J, Gui Q. Vision-guided action: human motion prediction with gaze-informed affordance in 3D scenes. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference; 2025. p. 12335–46. [Google Scholar]

7. Lehrmann AM, Gehler PV, Nowozin S. Efficient nonlinear markov models for human motion. In: IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Columbus, OH, USA; 2014. p. 1314–21. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2014.171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang JM, Fleet DJ, Hertzmann A. Gaussian process dynamical models. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2005 Dec 5–8; Vancouver, BC, Canada; 2005. p. 1441–8. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2007.1167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Taylor GW, Hinton GE, Roweis ST. Modeling human motion using binary latent variables. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Vancouver, BC, Canada: MIT Press; 2006. p. 1345–52. doi:10.7551/mitpress/7503.003.0173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Martinez J, Black MJ, Romero J. On human motion prediction using recurrent neural networks. In: IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Honolulu, HI, USA; 2017. p. 4674–83. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Fragkiadaki K, Levine S, Felsen P, Malik J. Recurrent network models for human dynamics. In: IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; ICCV 2015. Santiago, Chile; 2015. p. 4346–54. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2015.494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li M, Chen S, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Tian Q. Dynamic multiscale graph neural networks for 3D skeleton based human motion prediction. In: IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Seattle, WA, USA; 2020. p. 211–20. doi:10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li C, Zhang Z, Lee WS, Lee GH. Convolutional sequence to sequence model for human dynamics. In: IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2018). Salt Lake City, UT, USA; 2018. p. 5226–34. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mao W, Liu M, Salzmann M. History repeats itself: human motion prediction via motion attention. In: Computer Vision-ECCV 2020-16th European Conference. Glasgow, UK; 2020. p. 474–89. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58568-6_28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhong C, Hu L, Zhang Z, Ye Y, Xia S. Spatio-temporal gating-adjacency gcn for human motion prediction. In: IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2022). New Orleans, LA, USA; 2022. p. 6437–46. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wang X, Zhang W, Wang C, Gao Y, Liu M. Dynamic dense graph convolutional network for skeleton-based human motion prediction. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2023;33:1–15. doi:10.1109/TIP.2023.3334954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen H, Hu J, Zhang W, Su P. Spatiotemporal consistency learning from momentum cues for human motion prediction. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2023;33(9):4577–87. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2023.3284013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yang J, Tian K, Zhao H, Zheng F, Sami B, Sami D, et al. Wastewater treatment monitoring: fault detection in sensors using transductive learning and improved reinforcement learning. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;264(5):125805. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yan S, Xiong Y, Lin D. Spatial temporal graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. New Orleans, LA, USA; 2018. p. 7444–52. [Google Scholar]

20. Cui Q, Sun H, Yang F. Learning dynamic relationships for 3D human motion prediction. In: IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2020). Seattle, WA, USA; 2020. p. 6518–26. doi:10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yang J, Wu Y, Yuan Y, Xue H, Abdel-Salam M, Prajapat S, et al. Web attack detection using a large language model with autoencoder and multilayer perceptron. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;274(4):126982. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.126982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhao M, Tang H, Xie P, Dai S, Sebe N, Wang W. Bidirectional transformer gan for long-term human motion prediction. ACM Trans Multim Comput Commun Appl. 2023;19(5):1–19. doi:10.1145/3579359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yu H, Fan X, Hou T, Pei W, Ge H, Yang X, et al. Towards realistic 3D human motion prediction with a spatio-temporal cross-transformer approach. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2023;33(10):5707–20. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2023.3255186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhu L, Lu X, Cheng Z, Li J, Zhang H. Deep collaborative multi-view hashing for large-scale image search. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2020;29:4643–55. doi:10.1109/TIP.2020.2974065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Yang X, Zhou P, Wang M. Person reidentification via structural deep metric learning. IEEE Trans Neural Networks Learn Syst. 2019;30(10):2987–98. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2018.2861991. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Feng F, He X, Tang J, Chua T. Graph adversarial training: dynamically regularizing based on graph structure. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2021;33(6):2493–504. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2019.2957786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. You S, Zhou Y. Optimization driven cellular automata for traffic flow prediction at signalized intersections. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2021;40(1):1547–66. doi:10.3233/JIFS-192099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liang C. Prediction and analysis of sphere motion trajectory based on deep learning algorithm optimization. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2019;37(5):6275–85. doi:10.3233/JIFS-179209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. German B, Sergio E, Cristina P. Belfusion: latent diffusion for behavior-driven human motion prediction. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2023). Paris, France; 2023. p. 2317–27. doi:10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.00220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jain A, Zamir AR, Savarese S, Saxena A. Structural-RNN: deep learning on spatio-temporal graphs. In: IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2016). Las Vegas, NV, USA; 2016. p. 5308–17. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu Z, Wu S, Jin S, Liu Q, Lu S, Zimmermann R, et al. Towards natural and accurate future motion prediction of humans and animals. In: IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2019). Long Beach, CA, USA; 2019. p. 10004–12. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.01024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Liu Z, Su P, Wu S, Shen X, Chen H, Hao Y, et al. Motion prediction using trajectory cues. In: IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2021). Montreal, QC, Canada; 2021. p. 13279–88. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.01305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Dang L, Nie Y, Long C, Zhang Q, Li G. MSR-GCN: multi-scale residual graph convolution networks for human motion prediction. In: IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2021). Montreal, QC, Canada; 2021. p. 11447–56. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.01127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Li M, Chen S, Zhang Z, Xie L, Tian Q, Zhang Y. Skeleton-parted graph scattering networks for 3D human motion prediction. In: Computer Vision-ECCV 2022-17th European Conference; 2022 Oct 23–27. Tel Aviv, Israel; 2022. p. 18–36. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-20068-7_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Su P, Shen X, Shi Z, Liu W. Adaptive multi-order graph neural networks for human motion prediction. In: IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME 2022). Taipei, Taiwan; 2022. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICME52920.2022.9859980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Tseng KW, Kawakami R, Ikehata S. CST: character state transformer for object-conditioned human motion prediction. In: Proceedings of the Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision. Tucson, AZ, USA; 2025. p. 63–72. doi:10.1109/WACVW65960.2025.00012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang Y, Kephart JO, Ji Q. Incorporating physics principles for precise human motion prediction. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision. Waikoloa, HI, USA; 2024. p. 6164–74. doi:10.1109/WACV57701.2024.00605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Barsoum E, Kender JR, Liu Z. HP-GAN: probabilistic 3D human motion prediction via GAN. In: IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPR Workshops 2018). Salt Lake City, UT, USA; 2018. p. 1418–27. doi:10.1109/CVPRW.2018.00191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kundu JN, Gor M, Babu RV. BiHMP-GAN: bidirectional 3D human motion prediction GAN. In: AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Honolulu, HI, USA; 2019. p. 8553–60. doi:10.1609/AAAI.V33I01.33018553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Liu X, Yin J, Liu J. AGVNet: attention guided velocity learning for 3D human motion prediction. arxiv:2005.12155. 2020. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2005.12155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Liu X, Yin J, Li J, Ding P, Liu J, Liu H. TrajectoryCNN: a new spatio-temporal feature learning network for human motion prediction. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2021;31(6):2133–46. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2020.3021409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Cai Y, Huang L, Wang Y, Cham T, Cai J, Yuan J, et al. Learning progressive joint propagation for human motion prediction. In: Computer Vision-ECCV 2020-16th European Conference; 2020 Aug 23–28. Glasgow, UK; 2020. p. 226–42. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58571-6_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools