Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Online Optimization of Prediction-Enhanced Digital Twin Migration over Edge Computing with Adaptive Information Updating

1 School of Computer Science and Technology, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Nanjing, 211106, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Massive Personalized Customization System and Technology, Qingdao, 266100, China

3 COSMOPlat Institute of Industrial Intelligence (Qingdao) Co., Ltd., Qingdao, 266100, China

4 COSMOPlat IoT Technology Co., Ltd., Qingdao, 266103, China

5 College of Electrical Engineering and Control Science, Nanjing Tech University, Nanjing, 211816, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xiaoping Lu. Email: ; You Shi. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3231-3252. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066975

Received 22 April 2025; Accepted 11 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

This paper investigates mobility-aware online optimization for digital twin (DT)-assisted task execution in edge computing environments. In such systems, DTs, hosted on edge servers (ESs), require proactive migration to maintain proximity to their mobile physical twin (PT) counterparts. To minimize task response latency under a stringent energy consumption constraint, we jointly optimize three key components: the status data uploading frequency from the PT, the DT migration decisions, and the allocation of computational and communication resources. To address the asynchronous nature of these decisions, we propose a novel two-timescale mobility-aware online optimization (TMO) framework. The TMO scheme leverages an extended two-timescale Lyapunov optimization framework to decompose the long-term problem into sequential subproblems. At the larger timescale, a multi-armed bandit (MAB) algorithm is employed to dynamically learn the optimal status data uploading frequency. Within each shorter timescale, we first employ a gated recurrent unit (GRU)-based predictor to forecast the PT’s trajectory. Based on this prediction, an alternate minimization (AM) algorithm is then utilized to solve for the DT migration and resource allocation variables. Theoretical analysis confirms that the proposed TMO scheme is asymptotically optimal. Furthermore, simulation results demonstrate its significant performance gains over existing benchmark methods.Keywords

The digital twin (DT) is a promising paradigm for creating a virtual representation of a physical entity. By enabling simulation and behavior analysis in the digital space, a DT functions as a virtual sandbox to facilitate fine-grained monitoring and intelligent decision-making for complex tasks originating from its physical counterpart [1]. For instance, in the domain of autonomous driving, DTs support realistic testing by virtualizing vehicle behavior and complex road environments, thereby enabling safe and efficient validation of driving tasks via edge communication technologies [2]. In other applications, DTs and multi-agent systems are leveraged to model and coordinate warehouse robots for cargo handling tasks in a smart cyber-physical environment [3]. Similarly, Lv et al. [4] studied a DT-assisted framework for medical delivery tasks using an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Consequently, owing to its capability to address complex real-world challenges, the DT is recognized as a key enabling technology for applications such as Industry 4.0, the metaverse, and smart cities, garnering significant research attention [5].

A DT-enabled task processing framework typically involves numerous DTs and their associated PTs. In this context, PTs represent real-world entities such as humans, vehicles, or devices, with DTs functioning as their virtual counterparts [6]. Ensuring energy-efficient, low-latency task execution for a PT necessitates the meticulous construction and management of its corresponding DT. These requirements motivate the use of edge computing [7], where DTs are deployed on ESs at the network periphery to execute tasks for their PTs. While recent studies have explored related topics, such as industrial DTs and service deployment on ESs, implementing mobile DT-assisted task execution presents unique challenges. First, unlike stationary entities in industrial plants, the high mobility of PTs results in unstable PT-DT connectivity. Second, in contrast to a limited number of shared service applications, a large number of exclusive DTs must concurrently execute complex tasks for their associated PTs. This intensive computation relies on the limited resources of the host ESs [8], leading to potentially high task response latency and energy consumption. Therefore, to maintain seamless PT-DT connectivity while ensuring low-latency, energy-efficient task execution, the dynamic migration of DTs among ESs becomes essential [9].

However, addressing the aforementioned issues is challenging due to several underlying reasons:

1) Since the transmission of PT status information for mobility prediction is energy-intensive, these updates should occur at a lower frequency. In contrast, the constant movement and task generation of PTs demand that DT migration and resource allocation be optimized more frequently. This suggests that the overall optimization must be handled asynchronously across different timescales.

2) The frequency of uploading PT status data governs a trade-off between task response latency and energy consumption. Shorter upload intervals can reduce task latency but concurrently increase energy usage, whereas longer intervals have the opposite effect. This implies that the upload frequency must be determined adaptively based on feedback regarding system performance.

3) The high mobility of PTs, coupled with the need for frequent DT migrations, means that conventional reactive strategies can lead to severe task response latency and even service interruptions. Therefore, it is necessary to proactively migrate DTs by employing a predictive mobility model [10].

To tackle these challenges, we introduce a novel two-timescale online optimization scheme for a DT-assisted task execution system in an edge computing environment. Specifically, we consider a scenario where each PT has an exclusive DT deployed on an ES to execute its complex tasks. To account for PT mobility, the corresponding DTs are proactively migrated among ESs. These migration decisions are based on the PTs’ future trajectories, which are forecast by a predictive model hosted in a cloud center. To support this model, PTs must upload their status information (e.g., moving speed, direction) as predictive inputs. Our primary objective is to minimize the long-term average task response latency of all DTs, subject to a stringent energy consumption constraint and inherent system uncertainties such as unpredictable PT mobility. To this end, we formulate the problem as a two-timescale online optimization problem. This problem involves dynamically optimizing two sets of decisions. The first set, decided at the larger timescale, is the status information uploading frequency for each PT. The second set, decided at the smaller timescale, includes the DT migration strategy and the allocation of computational and communication resources at the ES. To solve this problem, we develop a novel two-timescale mobility-aware online optimization approach based on extended Lyapunov optimization theory. This approach first decomposes the long-term problem into a sequence of subproblems corresponding to the different timescales. An online learning method is then incorporated to adaptively determine the status information update frequency. Subsequently, for each subproblem within the smaller timescale, we first employ a GRU-based scheme to predict the PT’s trajectory. Based on this prediction, an AM-based algorithm is proposed to optimize the small-timescale decisions.

The key contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

• We address the problem of proactive DT migration at the network edge for executing complex PT tasks. To this end, we formulate a two-timescale mobility-aware online optimization problem that jointly optimizes three key decisions, including the adaptive status update frequency of PTs, the proactive DT migration decision, and the allocation of computational and communication resources on the ESs.

• We propose a novel solution framework, termed TMO, which first decomposes the long-term problem into a sequence of subproblems. To solve these subproblems across their different timescales, the TMO framework integrates two main components. An online learning method is employed to address the large-timescale problem, while an AM algorithm, augmented by a GRU-based prediction scheme, is utilized for the small-timescale problems.

• We conduct both theoretical analysis and extensive simulations to validate the performance of our proposed approach. The results demonstrate that the TMO scheme significantly outperforms existing benchmark methods in reducing both task response latency and overall system energy consumption.

The following section provides a review of related work. The system model and the corresponding problem formulation are detailed in Section 3. Section 4 presents our proposed two-timescale mobility-aware online optimization approach and its theoretical analysis. Section 5 discusses the simulation results, and Section 6 concludes the paper.

As an accurate digital representation of physical entities, the deployment of DTs enables real-time interaction and shows significant potential for supporting emerging 6G applications. For example, Wang et al. [11] propose a DT-based method for attack detection in the internet of things by fusing spatio-temporal features to enhance identification accuracy within dynamic network environments. Similarly, Zhao et al. [12] designed a DT-based application system to improve the accuracy and efficiency of network management. Jyeniskhan et al. [13] proposed a framework for DT systems in additive manufacturing that incorporates machine learning techniques. However, these studies did not fully consider the impact of a dynamic network environment or varying user status on the quality of the PT-DT interaction.

Edge computing is a crucial technology for delivering latency-sensitive services in wireless networks by offloading computation and storage tasks to the network edge. Recently, research efforts have increasingly focused on DT management within edge environments. For instance, Wen et al. [14] proposed an improved artificial potential field method for edge computing environments to achieve cooperative control and DT monitoring of multi-AUG. Lu et al. [15] proposed a DT-assisted wireless edge network framework designed to facilitate low-latency computation and seamless connectivity. In another study, Zhang et al. [16] proposed a framework for DT systems within wireless-powered communication networks, examining adaptive placement and transfer schemes for the DTs. However, these studies typically assume that DTs are either stationary or designed for a single, specific purpose. This assumption makes their approaches inadequate for supporting mobile PTs that have diverse service demands. Beyond DT-specific management, another stream of relevant research focuses on general service migration at the edge. For instance, He et al. [17] presented an efficient planning and scheduling framework for edge service migration that handles live migrations while ensuring low latency for mobile users. Mustafa et al. [18] proposed a hybrid SQ-DDTO algorithm within a three-layer vehicular edge computing framework to optimize task offloading and resource allocation. The same authors [19] also proposed a PPO-based task offloading algorithm for vehicular edge computing. Their approach addresses task dependencies and dynamic network conditions, aiming to enhance policy stability while minimizing delays and the task drop ratio. Nevertheless, these general migration studies assume a limited set of service entity (SE) types, where a single SE can serve multiple users. This contrasts with the inherent exclusivity of a DT, which is dedicated to handling tasks for only its specific PT.

Lyapunov-based optimization is a widely utilized tool for online optimization problems characterized by system uncertainties, as it can guarantee long-term performance stability without requiring future information [20–22]. However, most existing works in this area focus on decisions made within a single timescale. More recently, some studies have employed a two-timescale Lyapunov method [7,23], where the original problem is decomposed and decisions are subsequently made across different timescales. In a different approach, Huang et al. [24] combined the multi-armed bandit (MAB) method with Lyapunov optimization to schedule queueing systems without prior knowledge of instantaneous network conditions. Nevertheless, these schemes cannot be directly applied to our problem. This is primarily due to two factors. First, our model incorporates a flexible duration for the large timescale. Second, it features a complex coupling of decision variables within both the objective function and the problem constraints.

In contrast to previous works, this paper proposes a novel mobility-aware, two-timescale online optimization approach for edge computing environments. This approach is designed to jointly optimize three coupled decisions, i.e., the uploading frequency of PT status information, the DT migration decision, and the allocation of computational and communication resources.

3 System Model and Problem Formulation

To begin with, an overview on the DT-assisted task execution system is provided. After that, the DT proactive migration together with PT task execution are described more specifically.

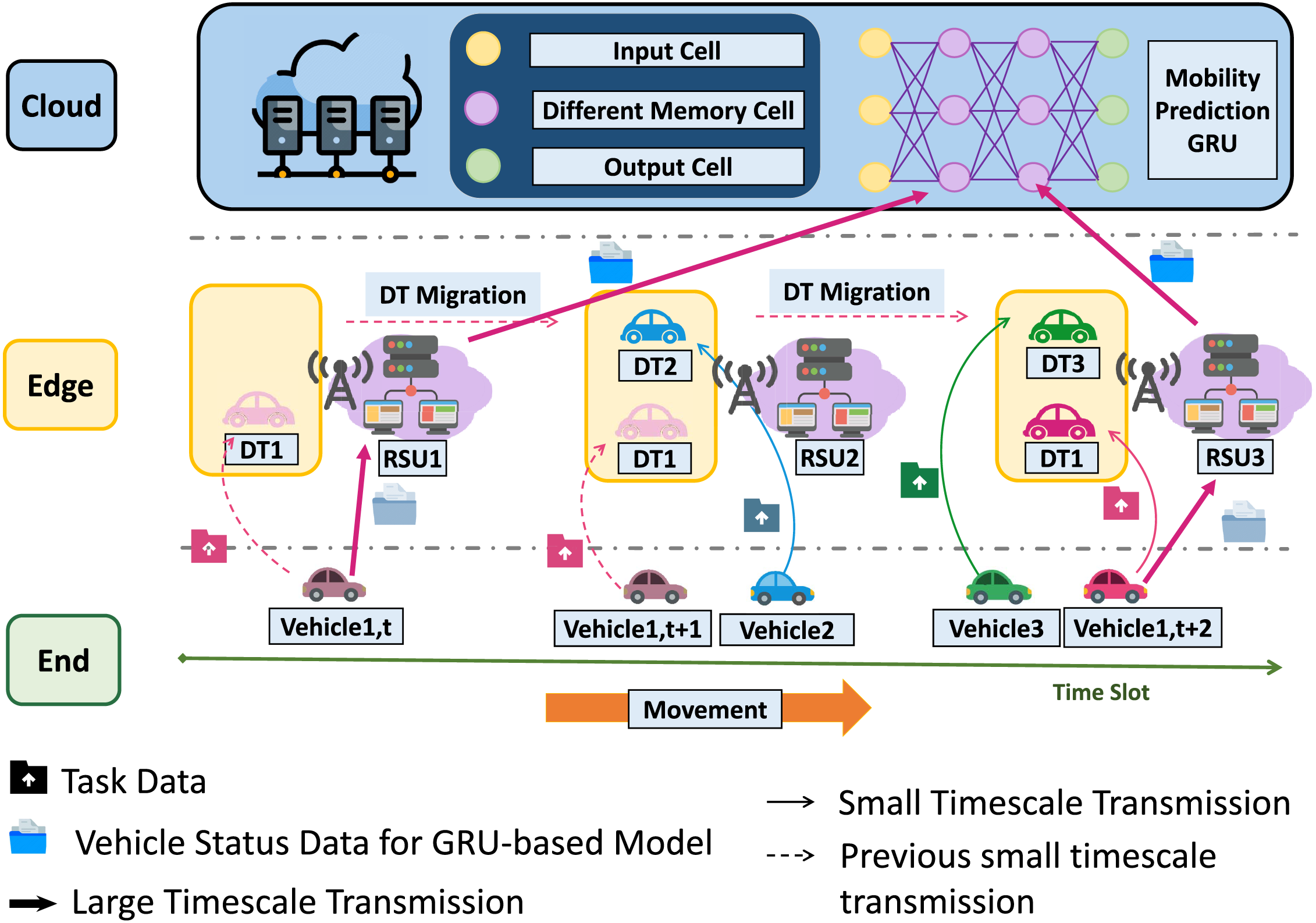

As presented in Fig. 1, we present a DT-assisted task execution system built on edge computing. The system comprises a set of I PTs, denoted as

Figure 1: An illustration of DT-assisted task execution system

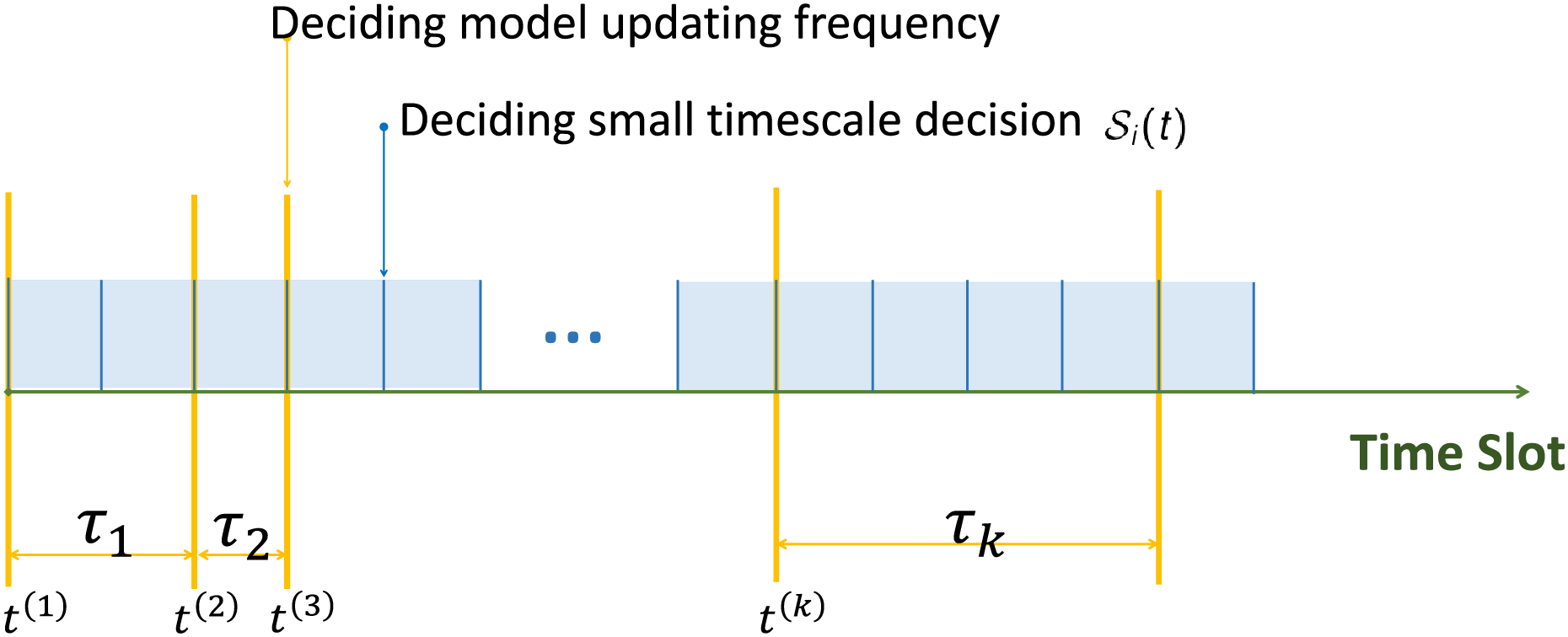

In practice, due to the frequent mobility and task dynamics of PTs, DT migration and the corresponding resource allocation need to be performed more often than the energy-intensive status information uploading. Therefore, as shown in Fig. 2, in the proposed online optimization problem, we consider that the status update frequency of each PT is determined on a large timescale, while DT migration and the associated communication and computation resource allocation on each ES are handled on a small timescale. To be specific, we first segment the timeline into

Figure 2: Design of the online two-timescale approach

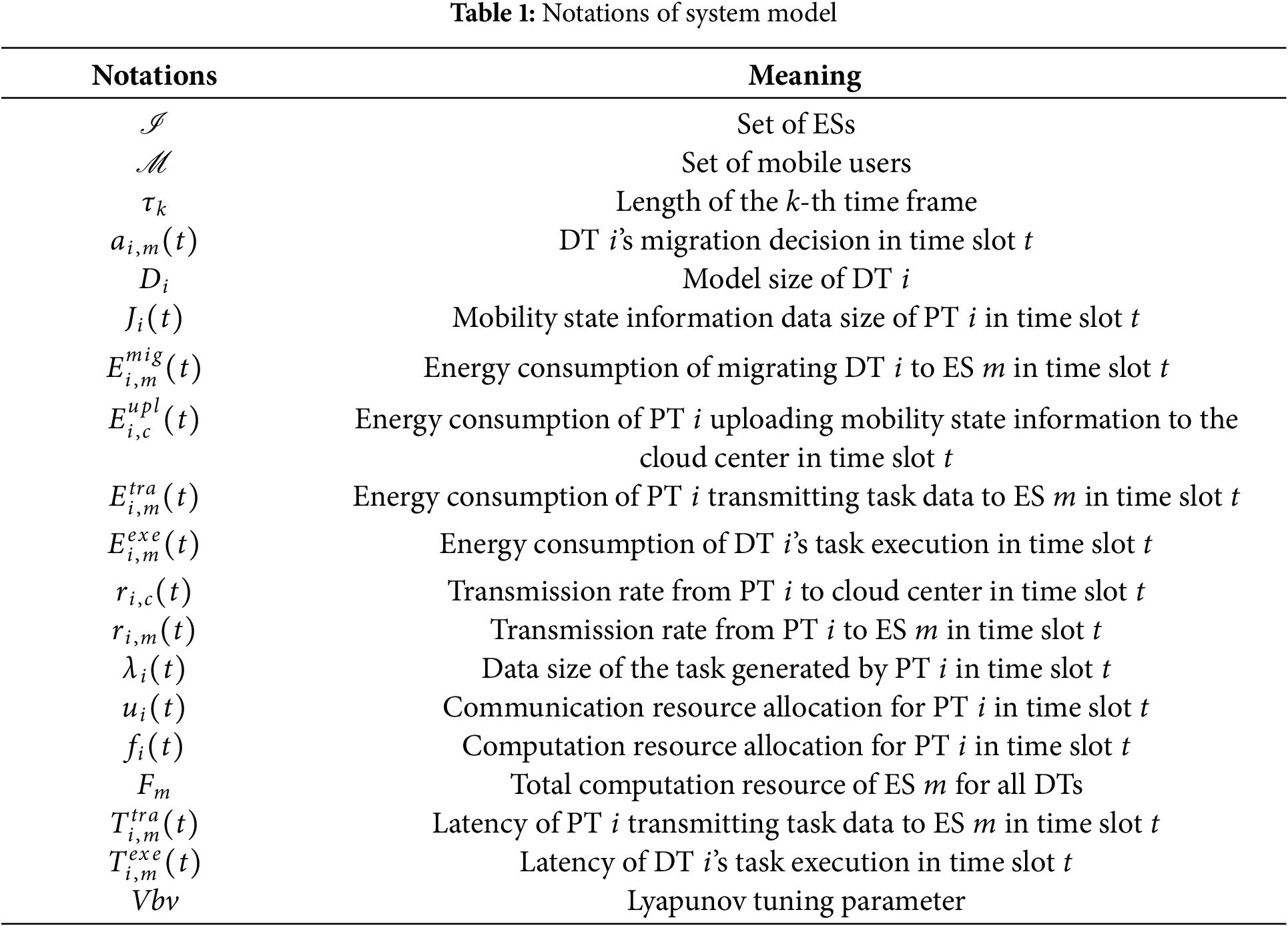

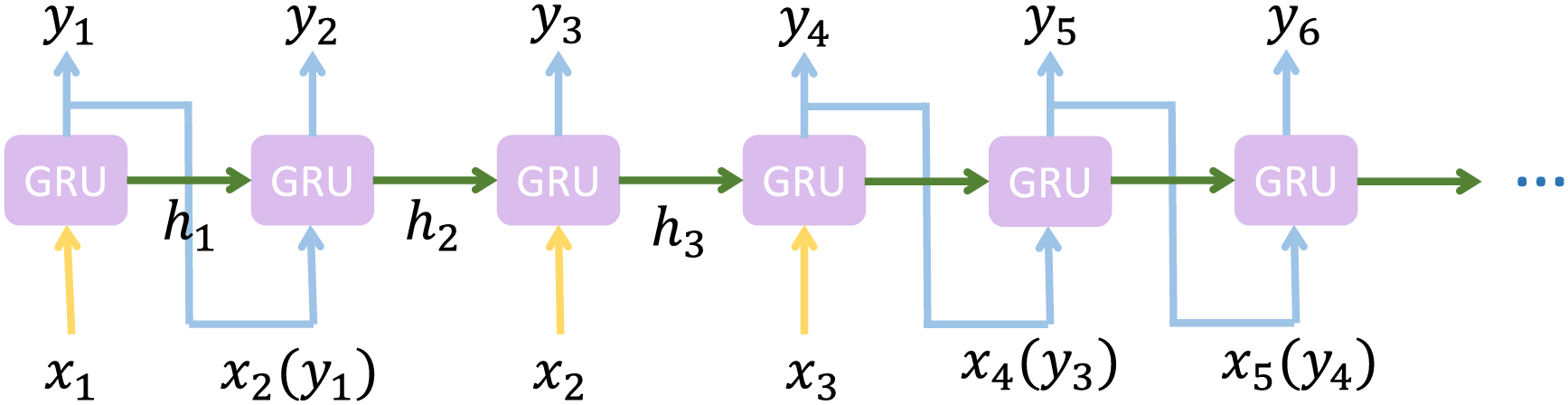

In general, we aim to optimize the task response latency under the stringent energy consumption constraint by addressing: i) How to adjust the real-time PT status updating of the mobility prediction model. ii) Within every time slot, which ES should be the migration target of each DT and how to allocate the communication and computation resource among the deployed DTs. The detailed system model is described as follows, and Table 1 lists the important notations employed in this paper.

To achieve seamless DT-assisted task execution for PTs, each DT should be timely migrated to the new ES in each time slot

where

To achieve proactive DT migration, it is required to obtain the movement trajectories of mobile PTs in the future. Therefore, we construct a GRU-based model at the cloud center for mobility prediction, which is described in detail in Section 4. To make predictions of PTs’ mobile trajectories, the GRU-based model needs to receive status information transmitted from PTs to ES and subsequently uploaded to the cloud. We denote

in which

3.3 DT-Assisted Task Execution

During each time slot

Let

where

where

The small-timescale and large-timescale energy consumption is derived as

To assess the fundamental performance of the DT-assisted task execution system deployed over edge computing, we adopt the long-term average service response latency across all time slots as the evaluation metric, which is computed as

We construct a two-timescale online optimization problem that jointly determines i) the adaptive status information updating frequency

where

Obviously, solving

4 A Two-Timescale Online Optimization Algorithm

In this section, we proposed a novel two-timescale mobility-aware optimization approach, namely TMO, to jointly optimize the uploading frequency of PT status information, DT migration decision and corresponding resource allocation on ESs over edge computing. Specifically, in particular, we begin by breaking down the long-term optimization task into multiple short-term subproblems using an enhanced Lyapunov-based strategy. Next, we apply an online learning algorithm to adaptively adjust the status information updating frequency based on historical feedback in large-timescal. After that, we design a GRU-based prediction network to predict the location of PT and develop an AM-based method to solve for the remaining small-timescale decisions.

We begin by defining the energy deficit queue

Traditional Lyapunov optimization requires fixed constraints to ensure a bounded performance gap. However, since the PT status information updating only occurs when each time frame starts, e.g., at

Subsequently, the Lyapunov function is defined as

Correspondingly, we defined

Theorem 1. Let

where

Proof. Please see Appendix A.

Theorem 1 demonstrates the upper bound of the drift-plus-penalty in each time slot

Therefore,

Note that although problem

4.2 Solution for Large-Timescale Decision

Due to the fact that the future network dynamics including channel conditions, DT migration together with resource allocation decisions in each time slot have not been revealed when we need to determine

Next, to solve the MAB problem

Then, let

Considering both the average reward and an exploration term that grow with time, the optimal

4.3 Solution for Small-Timescale Decisions

4.3.1 GRU-Based Mobility Prediction Network

After the status information uploading frequency is determined, in each time slot, to optimize small-timescale decisions, the location of mobile PTs to support proactive DT migration is required. Different from traditional time series prediction with input available in each time step, since the PTs only upload their status information at the beginning of each time frame, we need to predict their locations in each time slot regardless of whether PTs’ status information is uploaded. To this end, we extend the conventional GRU model into an input-autoregressive PT mobility prediction model, and its state update equations are designed as:

In this model, W and

Figure 3: Workflow of the auto-regressive GRU-based model

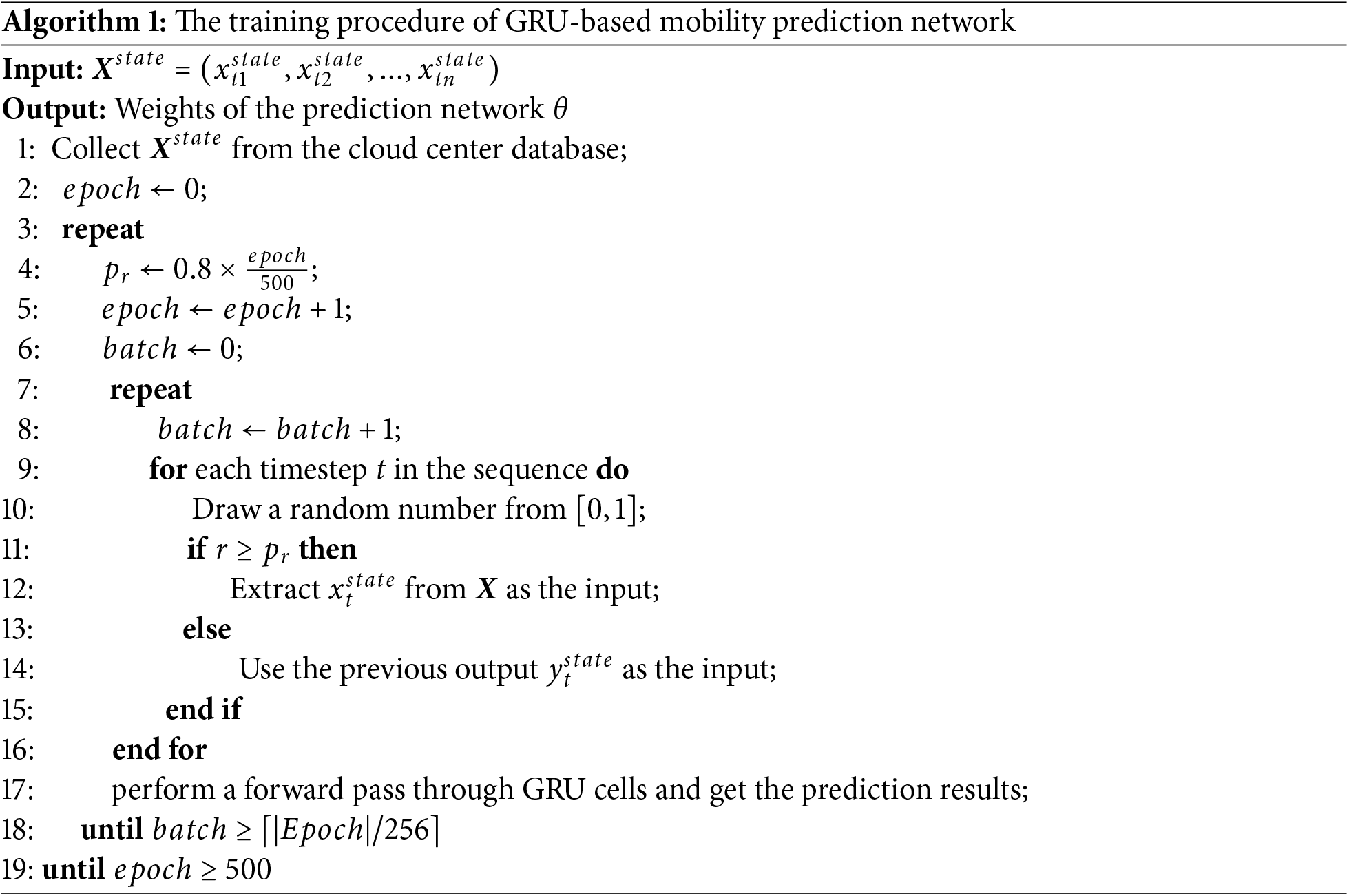

To train the above-designed GRU-based model for PT mobility prediction, we increase the auto-regressive inference capability during the training phase to address the issue of unavailable ground truth data at each time step. Specifically, we replace the real input data with the model’s previous output based on a probability

At the beginning of each epoch, batches of trajectory samples are fetched from the dataset. For each time step, a random number

4.3.2 Algorithm for Small-Timescale Decisions

Given

The subproblem

DT Migration Decision: Fix

Communication and Computation Resource Allocation: Fix

Following the decomposition of

Theorem 2. Problem

Proof. Details can be found in Appendix B.

Building on Theorem 2, we can slove problems

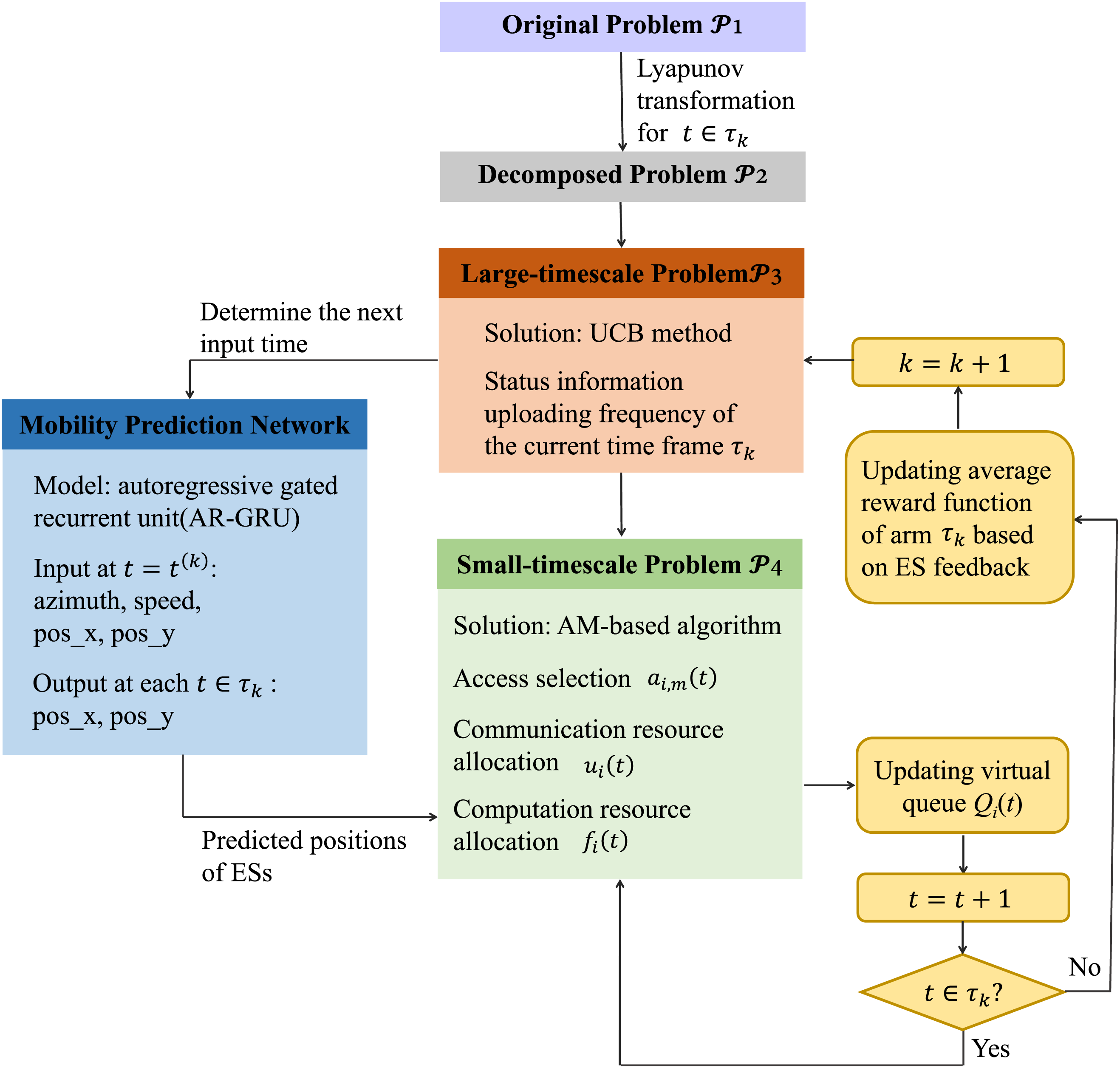

4.4 Analyses of Proposed TMO Scheme

In our proposed two-timescale mobility-aware optimization framework (TMO), we begin by utilizing an extended Lyapunov technique to divide the problem in the long term into a sequence of short-term subproblems. We then incorporate an online learning algorithm to dynamically adjust the update frequency for status information in the large timescale, guided by historical feedback. Subsequently, a GRU-based prediction model is employed to predict the location of each PT, and an alternating minimization (AM) strategy is used to determine the remaining decisions in the small timescale. The overall structure of TMO is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Flowchart of the proposed TMO approach

Theorem 3. Our proposed TMO approach can achieve convergence after finite iterations.

Proof. Since the alternation process is only applied in solving small-timescale problem

It is evident that the gradient in (22) is constant, while (23) and (24) exhibit bounded first-order derivatives under the constraints of the original problem. This implies that all relevant components are L-Lipschitz continuous. Accordingly, the proposed method converges within finite iterations.

Theorem 4. The proposed TMO scheme’s computational complexity is expressed as

Proof. The computationa complexity of the TMO approach mainly determined by the contributions of both UCB method in large timescale and the AM-based algorithm in small timescale. For a standard UCB method, the computational complexity of selecting a arm is

In summary, the TMO algorithm has a computational complexity of

Theorem 5. Given Lyapunov control parameter V and UCB arms number K, the performance gap between the TMO approach and the theoretical optimum to problem

where

Proof. The upper-bound of the performance gap (e.g., regret) between our TMO approach and the optimum can be decomposed into two gaps, respectively. The first gap is bounded by UCB algorithm under feedbacks of choosing

To analyze the gap bounded by Lyapunov optimization theory, inequality (14) can be intuitively expanded and rewritten as

Then, by aggregating (26) over T time slots, we obtain

By rearranging inequality (27), i.e., subtracting

We then analyze the optimal gap

In this section, we conducted extensive simulations to verify the advantages of our proposed TMO scheme for optimizing the PT state information uploading frequency and the DT migration decision together with allocation of computation and communication resource over edge computing. All simulations are conducted based on the real-world traffic scenario dataset, and the results are averaged more than 1000 independent runs with varying parameter setting.

Consider a DT-assisted task execution system in a 15 km

• SO [30]: Single-timescale optimization. This approach optimizes service migration and task routing to balance the online system performance and service migration cost, yet executed synchronously in a single timescale

• FTO [31]: Fixed two-timescale optimization. This method optimizes service migration, as well as computing and communication resource allocation asynchronously in different timescales. However, the length of each time frame is fixed.

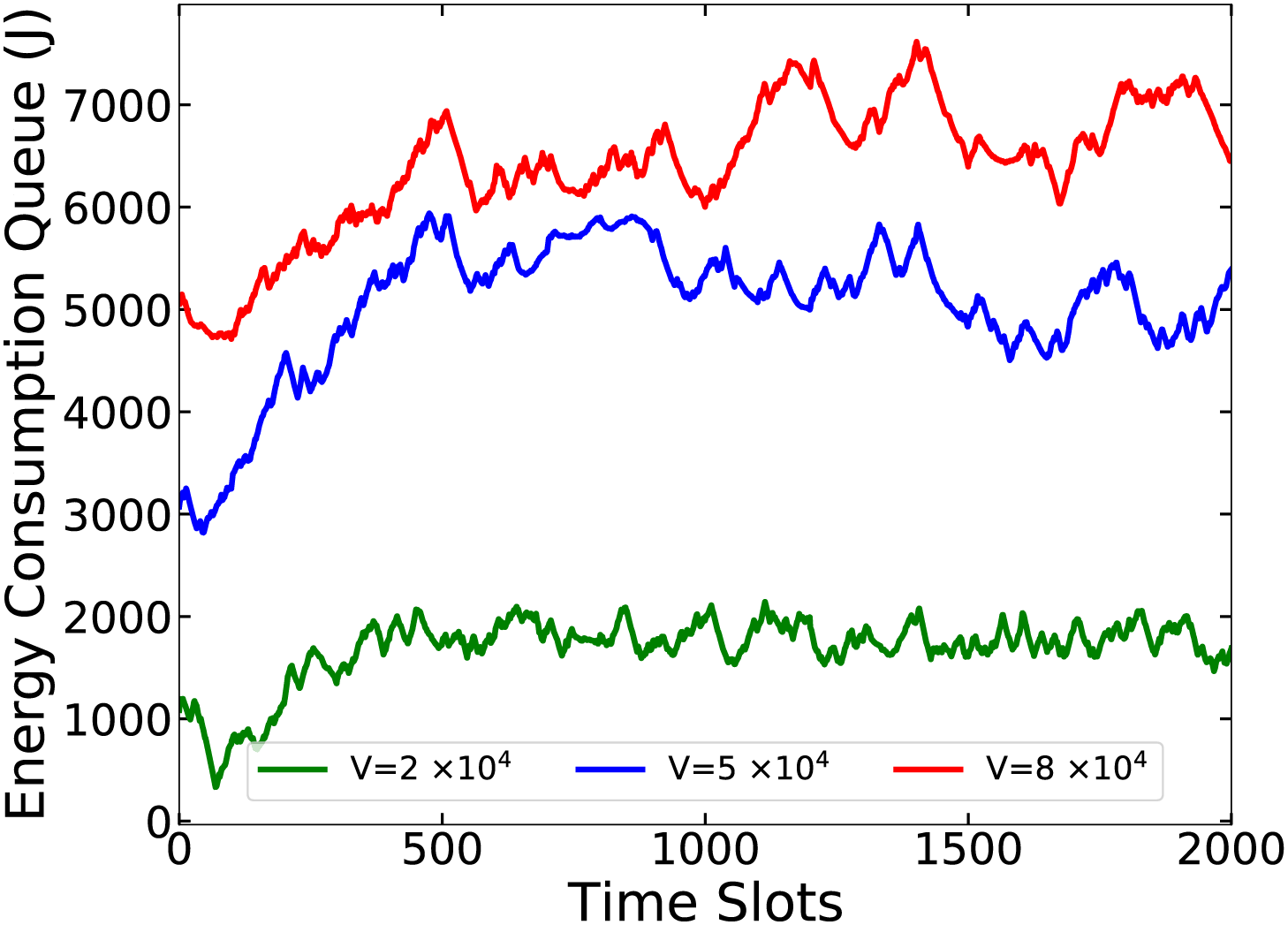

Fig. 5 illustrates the stability of our TMO approach by showcasing the energy consumption queue backlog

Figure 5: Queue backlogs w.r.t. V

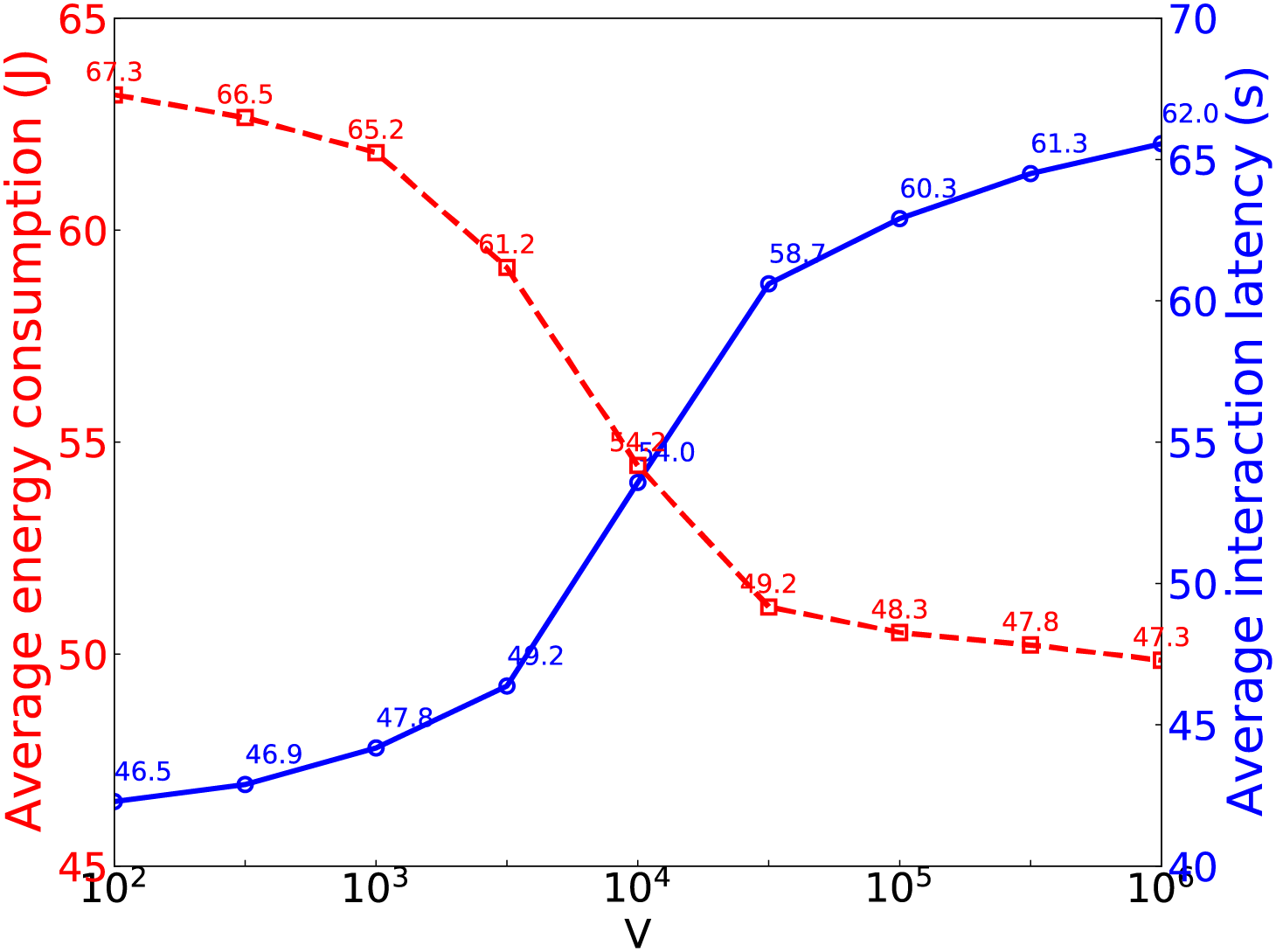

Fig. 6 shows the impact of V’s value on average task reponse latency (i.e.,

Figure 6: The impact of V on average task response latency and energy consumption

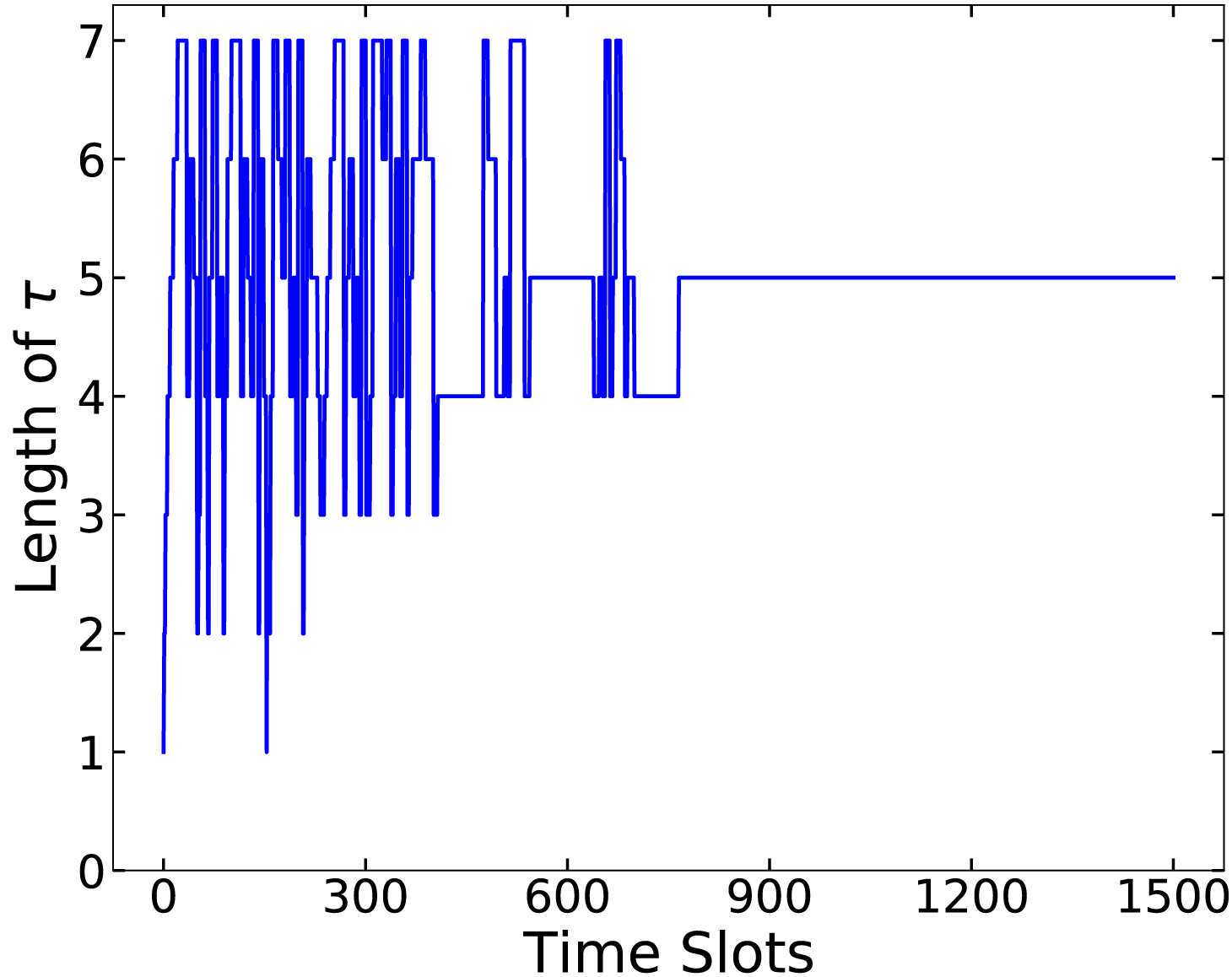

Fig. 7 illustrates the exploration process of

Figure 7: Decisions of

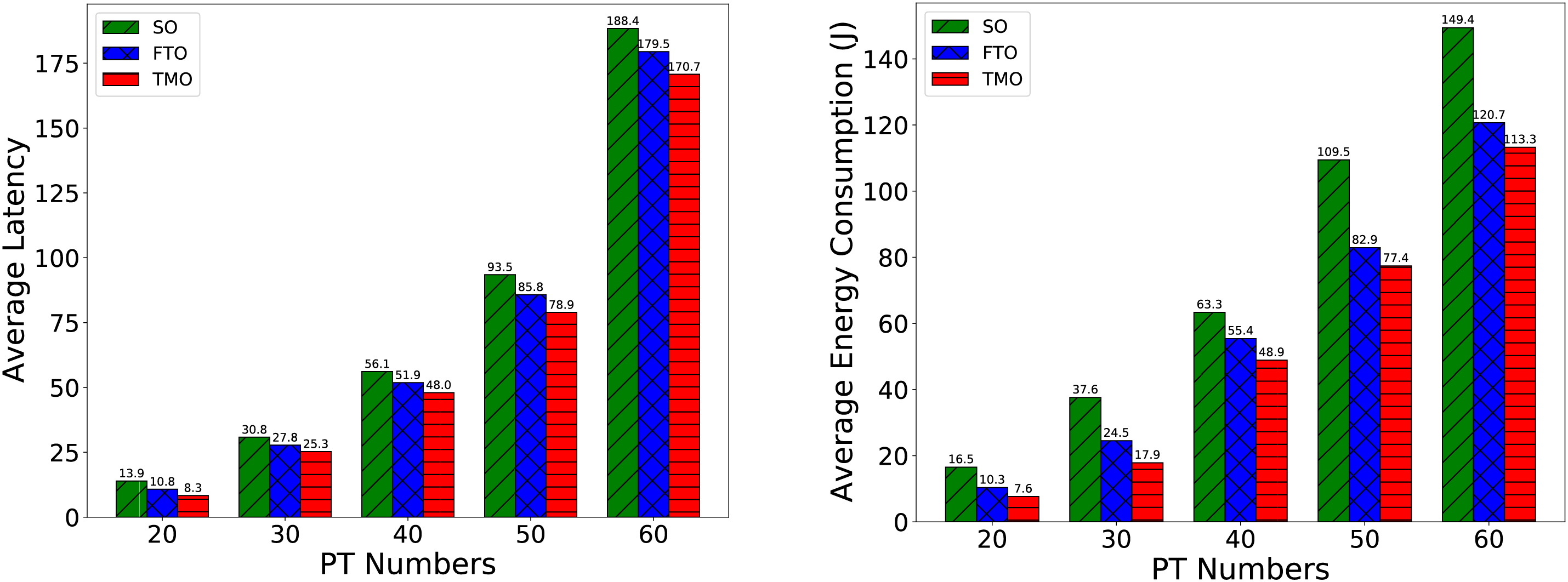

Fig. 8 examines the impact of PT numbers on the average response latency and energy consumption for SO, FTO, and the proposed TMO approach. Both figures demonstrate an exponential increase in response latency and energy consumption for all approaches as I grows, because larger I means more task requests and competition for edge resources. We can tell from the pictures that SO has the worst performance, while FTO and TMO have better performance of both task response latency and average energy consumption than SO because of the less frequent data uploading. Besides, TMO has the best performance on account of more flexible and adjustable data uploading frequency, which can reduce the cost of data transmission mostly.

Figure 8: Comparison on average task response latency and energy consumption with varying PT numbers

In our work, we explore proactive DT migration over edge computing. Specifically, aiming to minimize the average task response latency of PTs under system uncertainties (e.g., PT mobility), we construct a two-timescale online optimization problem to jointly optimize the PT status information updating frequency, DT migration, and the allocation of communication and computation resources. We introduce a novel solution approach, termed TMO, which first break down the long-term online optimization problem into a sequence of instant subproblems. Additionally, we develop an online learning approach and an AM-based algorithm supported by a GRU-based mobility prediction model, to solve the two subproblems at different timescales. Both theoretical analysis and extensive simulations demonstrate that TMO outperforms existing approaches in minimizing task response latency and reducing total system energy consumption.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the State Key Laboratory of Massive Personalized Customization System and Technology, grant No. H&C-MPC-2023-04-01.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Lucheng Chen and Xingzhi Feng; methodology, Xinyu Yu and You Shi; validation, Xinyu Yu, Xiaoping Lu and Yuye Yang; formal analysis, Xinyu Yu and Lucheng Chen; investigation, Lucheng Chen and Xiaoping Lu; writing—original draft preparation, Xinyu Yu; writing—review and editing, Xinyu Yu and Yuye Yang; supervision, Xiaoping Lu and You Shi; project administration, Xingzhi Feng and You Shi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| TMO | Two-timescale mobility-aware optimization algorithm |

| UCB | Upper Confidence Bound |

| MAB | Multi-Armed Bandit |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| AM | Alternate Minimization |

Squaring both expressions in Eq. (13) describing the energy queue yields

By subtracting

Lastly, by adding

For subproblem

Since

For subproblem

Taking the first-order and second-order derivatives yields

Obviously, when

References

1. Lin X, Kundu L, Dick C, Obiodu E, Mostak T, Flaxman M. 6G digital twin networks: from theory to practice. IEEE Commun Mag. 2023;61(11):72–8. doi:10.1109/mcom.001.2200830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Niaz A, Shoukat MU, Jia Y, Khan S, Niaz F, Raza MU. Autonomous driving test method based on digital twin: a survey. In: 2021 International Conference on Computing, Electronic and Electrical Engineering (ICE Cube); 2021 Oct 26–27; Quetta, Pakistan: IEEE; 2021. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

3. Marah H, Challenger M. Madtwin: a framework for multi-agent digital twin development: smart warehouse case study. Ann Math Artif Intell. 2024;92(4):975–1005. doi:10.1007/s10472-023-09872-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lv Z, Chen D, Feng H, Zhu H, Lv H. Digital twins in unmanned aerial vehicles for rapid medical resource delivery in epidemics. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(12):25106–14. doi:10.1109/tits.2021.3113787. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Khan LU, Saad W, Niyato D, Han Z, Hong CS. Digital-twin-enabled 6G: vision, architectural trends, and future directions. IEEE Commun Mag. 2022 Jan;60(1):74–80. doi:10.1109/mcom.001.21143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chen R, Yi C, Zhou F, Kang J, Wu Y, Niyato D. Federated digital twin construction via distributed sensing: a game-theoretic online optimization with overlapping coalitions. arXiv:2503.16823. 2025. [Google Scholar]

7. Yang Y, Shi Y, Yi C, Cai J, Kang J, Niyato D, et al. Dynamic human digital twin deployment at the edge for task execution: a two-timescale accuracy-aware online optimization. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;23(12):12262–79. doi:10.1109/tmc.2024.3406607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chen J, Yi C, Okegbile SD, Cai J, Shen X. Networking architecture and key supporting technologies for human digital twin in personalized healthcare: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun Sur Tutor. 2024;26(1):706–46. doi:10.1109/comst.2023.3308717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Okegbile SD, Cai J, Wu J, Chen J, Yi C. A prediction-enhanced physical-to-virtual twin connectivity framework for human digital twin. IEEE Trans Cogn Commun Netw. 2024;PP(99):1–1. doi:10.1109/tccn.2024.3519331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang C, Peng J, Cai L, Peng H, Liu W, Gu X, et al. AI-enabled spatial-temporal mobility awareness service migration for connected vehicles. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;23(4):3274–90. doi:10.1109/tmc.2023.3271655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang H, Di X, Wang Y, Ren B, Gao G, Deng J. An intelligent digital twin method based on spatio-temporal feature fusion for iot attack behavior identification. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2023;41(11):3561–72. doi:10.1109/jsac.2023.3310091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhao J, Xiong X, Chen Y. Design and application of a network planning system based on digital twin network. IEEE J Radio Freq Identif. 2022;6:900–4. doi:10.1109/jrfid.2022.3210750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jyeniskhan N, Keutayeva A, Kazbek G, Ali MH, Shehab E. Integrating machine learning model and digital twin system for additive manufacturing. IEEE Access. 2023;11:71113–26. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3294486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wen J, Yang J, Li Y, He J, Li Z, Song H. Behavior-based formation control digital twin for multi-AUG in edge computing. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2023;10(5):2791–801. doi:10.1109/tnse.2022.3198818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lu Y, Maharjan S, Zhang Y. Adaptive edge association for wireless digital twin networks in 6G. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(22):16219–30. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3098508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang Y, Zhang H, Lu Y, Sun W, Wei L, Zhang Y, et al. Adaptive digital twin placement and transfer in wireless computing power network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(6):10924–36. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3328380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. He T, Toosi AN, Buyya R. Efficient large-scale multiple migration planning and scheduling in SDN-enabled edge computing. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;23(6):6667–80. doi:10.1109/tmc.2023.3326610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mustafa E, Shuja J, Rehman F, Namoun A, Bilal M, Bilal K. Deep reinforcement learning and SQP-driven task offloading decisions in vehicular edge computing networks. Comput Netw. 2025;262:111180. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2025.111180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Mustafa E, Shuja J, Rehman F, Namoun A, Bilal M, Iqbal A. Computation offloading in vehicular communications using PPO-based deep reinforcement learning. J Supercomput. 2025;81(4):1–24. doi:10.1007/s11227-025-07009-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shi Y, Yi C, Chen B, Yang C, Zhu K, Cai J. Joint online optimization of data sampling rate and preprocessing mode for edge–cloud collaboration-enabled industrial IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(17):16402–17. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3150386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Jia Y, Zhang C, Huang Y, Zhang W. Lyapunov optimization based mobile edge computing for internet of vehicles systems. IEEE Trans Commun. 2022;70(11):7418–33. doi:10.1109/tcomm.2022.3206885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lin X, Wu J, Li J, Yang W, Guizani M. Stochastic digital-twin service demand with edge response: an incentive-based congestion control approach. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2023;22(4):2402–16. doi:10.1109/tmc.2021.3122013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. He Y, Ren Y, Zhou Z, Mumtaz S, Al-Rubaye S, Tsourdos A, et al. Two-timescale resource allocation for automated networks in IIoT. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2022;21(10):7881–96. doi:10.1109/twc.2022.3162722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Huang J, Golubchik L, Huang L. When lyapunov drift based queue scheduling meets adversarial bandit learning. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2024;32(4):3034–44. doi:10.1109/tnet.2024.3374755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mohammadi M, Suraweera HA, Tellambura C. Uplink/Downlink rate analysis and impact of power allocation for full-duplex cloud-RANs. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2018;17(9):5774–88. doi:10.1109/twc.2018.2849698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Georgiadis L, Neely MJ, Tassiulas L. Resource allocation and cross-layer control in wireless networks. Found Trends® Netw. 2006;1(1):1–144. doi:10.1561/1300000001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Auer P, Cesa-Bianchi N, Fischer P. Finite-time analysis of the multiarmed bandit problem. Machine Learning. 2002;47(2):235–56. [Google Scholar]

28. Bieker-Walz L, Krajzewicz D, Morra A, Michelacci C, Cartolano F. Traffic simulation for all: a real world traffic scenario from the city of bologna. In: Modeling mobility with open data. Cham: Springer; 2015. p. 47–60. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-15024-6_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ouyang T, Zhou Z, Chen X. Follow me at the edge: mobility-aware dynamic service placement for mobile edge computing. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2018;36(10):2333–45. doi:10.1109/iwqos.2018.8624174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chen X, Bi Y, Chen X, Zhao H, Cheng N, Li F, et al. Dynamic service migration and request routing for microservice in multicell mobile-edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(15):13126–43. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3140183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Shi Y, Yi C, Wang R, Wu Q, Chen B, Cai J. Service migration or task rerouting: a two-timescale online resource optimization for MEC. IEEE Trans Wireless Commun. 2024;23(2):1503–19. doi:10.1109/twc.2023.3290005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools