Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Improving Diagnostic Accuracy in Medical Imaging: A Review

1 Zekelman School of Information Technology, St. Clair College, Windsor, ON N9A 6S4, Canada

2 Cardiff School of Technologies, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, CF5 2YB, UK

* Corresponding Author: Bassam Al-Shargabi. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2443-2486. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066987

Received 22 April 2025; Accepted 08 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

This review comprehensively analyzes advancements in artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning and deep learning, in medical imaging, focusing on their transformative role in enhancing diagnostic accuracy. Our in-depth analysis of 138 selected studies reveals that artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms frequently achieve diagnostic performance comparable to, and often surpassing, that of human experts, excelling in complex pattern recognition. Key findings include earlier detection of conditions like skin cancer and diabetic retinopathy, alongside radiologist-level performance for pneumonia detection on chest X-rays. These technologies profoundly transform imaging by significantly improving processes in classification, segmentation, and sequential analysis across diverse modalities such as X-rays, Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and ultrasound. Specific advancements with Convolutional Neural Networks, Recurrent Neural Networks, and ensemble learning techniques have facilitated more precise diagnosis, prediction, and therapy planning. Notably, Generative Adversarial Networks address limited data through augmentation, while transfer learning efficiently adapts models for scarce labeled datasets, and Reinforcement Learning shows promise in optimizing treatment protocols, collectively advancing patient care. Methodologically, a systematic review (2015–2024) used Scopus and Web of Science databases, yielding 7982 initial records. Of these, 1189 underwent bibliometric analysis using the R package ‘Bibliometrix’, and 138 were comprehensively reviewed for specific findings. Research output surged over the decade, led by Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Access (19.1%). China dominates publication volume (36.1%), while the United States of America (USA) leads total citations (5605), and Hong Kong exhibits the highest average (55.60). Challenges include rigorous validation, regulatory clarity, and fostering clinician trust. This study highlights significant emerging trends and crucial future research directions for successful AI implementation in healthcare.Keywords

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly emerging as a transformative force across the entire healthcare spectrum, offering unprecedented opportunities to enhance clinical efficiency, improve patient outcomes, and redefine medical practice. It has been successfully applied in image analysis within radiology, pathology, and dermatology, achieving diagnostic speeds that surpass and accuracy that parallels those of medical experts. AI has the potential to optimise the care trajectory for chronic disease patients, suggest precision therapies, reduce medical errors, and enhance subject enrolment in clinical trials. Additionally, AI’s application of natural language processing (NLP) to scientific literature and electronic medical records will significantly impact medical practice. Machine learning (ML) from medical data can help mitigate clinical errors caused by human cognitive biases, thereby enhancing patient care. Despite these advancements, physicians will remain essential in cognitive medical practice [1]. In recent years, the integration of AI technologies into medical imaging diagnostics has revolutionised healthcare practices, offering promising avenues for enhanced diagnostic accuracy, patient care, and treatment outcomes [2,3]. This transformative shift emphasises the potential of AI to address enduring challenges in medical imaging, ranging from improving diagnostic precision to streamlining clinical workflows [4–6]. Furthermore, as AI continues to advance, leveraging ML algorithms, deep learning (DL) techniques, and computer vision methodologies, it presents unique opportunities for innovation in medical imaging diagnostics [7]. The convergence of AI and medical imaging holds particular significance in addressing the diagnostic complexities and demands of modern healthcare systems. Medical imaging modalities such as X-ray, Computed Tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound play pivotal roles in disease detection, treatment planning, and therapeutic monitoring [8].

Against this backdrop, the adoption of AI technologies in medical imaging diagnostics offers a paradigm shift, empowering healthcare professionals with advanced computational tools for image analysis, pattern recognition, and decision support [9,10]. AI-driven approaches hold huge potential to augment human capabilities, enabling faster, more accurate diagnoses, personalised treatment strategies, and improved patient outcomes. Moreover, AI algorithms can leverage vast datasets and learn from iterative feedback loops, continuously refining their performance and adaptability to diverse clinical scenarios [4,11]. In this context, medical imaging’s role in diagnosing and predicting various medical conditions is paramount [12]. Traditionally, radiologists have borne the sole responsibility for identifying pathology and predicting outcomes. However, challenges such as fatigue, human perception limitations, and cognitive overload can lead to overlooking subtle details in the images. The integration of AI tools into medical imaging has significantly enhanced diagnostic accuracy and alleviated the workload on human radiologists [13]. AI applications in breast cancer detection and diagnostic imaging have brought about remarkable advancements, promising better patient outcomes in the future. AI aids in the early detection of diseases like COVID-19, precise measurement of tumors and organ volumes, and facilitates the use of AI in smaller medical facilities, reducing the need for specialized expertise [14]. Many prevalent and severe diseases now have the potential for early diagnosis and prognosis using AI alone. The introduction of AI holds the potential to transform healthcare quality, reduce costs, personalize drug therapies, enhance care coordination, and reduce clinical burdens.

However, despite the recognition of AI’s potential, there remain several critical research gaps in the literature on AI applications in medical imaging diagnostics. This review aims to address the research gap by comprehensive evaluation of existing literature on AI applications in medical imaging diagnostics. This review aims to address these gaps by evaluating existing literature comprehensively. Currently, there is a limited synthesis of evidence as individual studies have examined the performance of AI algorithms without integrating findings across studies [10,15,16]. The review will consolidate the evidence to assess the effectiveness and clinical impact of AI-enabled diagnostic tools comprehensively. For a more detailed foundational understanding of AI’s historical development and its specific applications within medical imaging, readers are referred to Section 3: Background and Literature Review.

To this end, the following research questions guide our investigation:

(1) How have ML and DL technologies improved diagnostic accuracy in medical imaging, and what challenges remain for their real-world implementation?

(2) What are the existing gaps in the literature regarding AI applications in medical imaging diagnostics, and how can future research address these gaps?

(3) How has the research output on AI applications in medical imaging diagnostics evolved between 2015 and 2024?

(4) What factors contribute to the decline in citation impact per article, despite the growth in research output on AI and DL applications in medical imaging?

(5) What are the emerging themes and trending topics in the application of AI to medical imaging diagnostics?

By addressing these questions, the review aims to highlight the strengths and limitations of AI, ML, and DL diagnostic tools, provide insights into the current state of research on AI applications in medical imaging diagnostics, and facilitate evidence-based decision-making in clinical practice, healthcare policy, and future research. The primary objectives of this review are to investigate the performance of AI algorithms, ML, and DL methods in medical imaging diagnostics, compare the diagnostic accuracy of AI models with traditional diagnostic methods, and assess the clinical impact and potential benefits of AI-enabled diagnostic tools on patient outcomes and healthcare delivery.

To provide a comprehensive investigation into the literature on ML and DL in medical imaging diagnostics, this review is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines the methodology employed in the review, ensuring a thorough examination of relevant studies; Section 3 provides a detailed background and literature review, setting the context for the research; Section 4 presents the results and analysis, highlighting key findings and trends; and finally, Section 5 offers a discussion of the implications of these findings, drawing meaningful conclusions and suggesting directions for future research.

The investigation into AI applications for improving diagnostic accuracy was carried out using a systematic and structured approach, combining bibliometric methods with recognized review protocols. Notably, we employed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework to guide the search, screening, and selection of relevant studies, ensuring transparency and reproducibility throughout the review process [17,18]. We utilized the R package “Bibliometrix” as the primary analytical tool, given its robust capabilities for evaluating scientific literature across multiple disciplines [19–24]. Additionally, the Biblioshiny web interface, an extension of Bibliometrix, facilitated a more user-friendly environment for conducting detailed bibliometric analysis, including co-citation, keyword co-occurrence, and thematic evolution. Articles were sourced from two major academic databases—Scopus and Web of Science—chosen for their wide coverage and indexing of high-impact journals. We focused on publications from reputable, peer-reviewed sources to ensure the inclusion of high-quality and relevant research. The review process involved a time-interval analysis to examine trends over time and a thematic mapping of research development across geographical regions and disciplines. Bibliometric analysis was employed to identify key research trends, influential publications, emerging themes, and collaboration networks. This method has become increasingly valuable in highlighting the frequency and impact of scholarly output, as well as the evolution of topics within a specific research domain [25–27]. This allows for valuable insights into particular research areas [20]. This dataset was analyzed using bibliometric methods with the R package Biblioshiny, facilitating efficient filtering, organization, and visualization of trends [19,28]. By leveraging this approach, we identified key themes and influential authors that might be overlooked in manual reviews This section is partitioned into two subcategories: Section 2.1, titled “Search Strategy and Study Selection,” outlines the process we used to identify and choose relevant research. Section 2.2, titled “Data Extraction and Analysis,” provides an explanation of how we extracted and processed the data.

To identify relevant studies focusing on the role of AI in improving diagnostic accuracy in medical imaging, we developed a comprehensive search strategy using a combination of keywords. These keywords were selected based on preliminary literature scans and expert consultation to capture the core concepts of the review: “artificial intelligence,” “deep learning,” “machine learning,” “medical imaging,” and “diagnostic accuracy.” We systematically combined these terms using Boolean operators (e.g., AND, OR) to construct search queries. An example of a search string used across databases was: ((“artificial intelligence” OR “deep learning” OR “machine learning”) AND (“medical imaging” OR “radiology” OR “image analysis”) AND (“diagnostic accuracy” OR “diagnosis” OR “detection” OR “prediction”)).

Articles were sourced from two major academic databases: Scopus and Web of Science. These databases were chosen for their extensive coverage of peer-reviewed scientific literature across various disciplines, including medicine, computer science, and engineering, thus ensuring a broad yet high-quality inclusion of relevant research. Our literature search was conducted on 15 September 2024, and was limited to English-language articles and reviews published from 1 January 2015, onwards (up to the search date of 15 September 2024).

The search strategy yielded an initial 7982 records from the Scopus and Web of Science databases. These records were then imported into a reference management tool (e.g., EndNote, Zotero) for deduplication and initial filtering based on publication type. During this initial filtering, 2538 records were excluded as they were identified as books, editors’ notes, conference proceedings, or other non-journal article formats. This process resulted in a refined set of 5444 unique records for subsequent screening.

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Following the initial identification and pre-screening, the remaining 5444 unique records underwent a rigorous screening process based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were included if they were original research articles or review articles published in English between 1 January 2015 and 15 September 2024. A core criterion was their focus on the application of Artificial Intelligence, encompassing ML and DL techniques, specifically in medical imaging for diagnostic purposes. Furthermore, included studies had to report on or directly discuss diagnostic accuracy, performance, or outcomes (such as sensitivity, specificity Area Under Curve(AUC), or overall accuracy) related to medical image analysis, and involve human or animal medical imaging data (including, but not limited to, X-ray, CT, MRI, Ultrasound, Pathology slides, and Fundus images). Conversely, studies were excluded if they were conference abstracts, posters, editorials, letters to the editor, commentaries, or book chapters (as these were largely filtered in an initial step). Unpublished papers, such as preprints not yet peer-reviewed by the time of the search, were also excluded. Other exclusion criteria included studies not primarily focused on diagnostic applications of AI in medical imaging (e.g., those solely on image reconstruction, image segmentation without a diagnostic outcome, or treatment planning without a diagnostic component), studies that did not report diagnostic performance metrics or discuss diagnostic accuracy, and non-English language publications.

The screening process involved two independent reviewers. In the first phase of eligibility screening, titles and abstracts of the 5444 unique records were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. During this step, 163 records were excluded as non-English journal articles, leading to 5281 records proceeding to the next stage.

In the second phase, the titles and abstracts of these 5281 records underwent a more detailed assessment for relevance. 4092 records were excluded at this stage based on their titles, abstracts, or a preliminary full-text review if needed, as they did not meet the core relevance criteria for AI in diagnostic imaging. Any conflicts or disagreements between the two reviewers during these screening phases were resolved through discussion to reach a consensus. If consensus could not be reached, a third senior reviewer was consulted for final arbitration. This comprehensive screening identified 1189 potentially relevant studies for full-text review.

In the final phase of inclusion, the full texts of these 1189 studies were retrieved and meticulously assessed against the complete inclusion and exclusion criteria. Again, two reviewers independently conducted this full-text review, with disagreements resolved by discussion or third-party arbitration. This systematic approach ensured that only the most relevant and methodologically sound studies were selected.

The final dataset for our analysis was then partitioned: all 1189 identified studies formed the basis for the bibliometric analysis, providing a broad overview of publication trends and patterns within the field. From this larger set of 1189 studies, 138 studies were specifically selected for an in-depth “Comprehensive Review.” These 138 studies were chosen based on their direct relevance to diagnostic accuracy outcomes, significant methodological contributions, and representativeness of the diverse AI applications discussed. This allowed for a more focused qualitative synthesis while maintaining the breadth of the bibliometric trends. Fig. 1 illustrates the detailed study screening and selection process, consistent with PRISMA guidelines.

Figure 1: Review process

2.4 Data Extraction and Analysis

Data extraction was performed systematically using a standardized form to gather information on study characteristics (e.g., year of publication, country of origin, type of medical imaging modality, disease area), details of AI models used (e.g., ML/DL technique, architecture), and reported diagnostic performance metrics (e.g., sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, AUC). To maintain accuracy and minimize bias, two reviewers independently conducted this data extraction process [29,30].

The full set of 1189 studies was then analyzed using the Bibliometrix R package, allowing us to summarize publication trends, identify key research themes, influential authors, and collaboration networks within the field. This quantitative bibliometric analysis facilitated efficient filtering, organization, and visualization of trends [19,28]. By leveraging this approach, we identified overarching patterns and influential works that might be overlooked in manual reviews, adding quantitative rigor to our insights into citation trends and key research areas.

Our analysis also included a qualitative synthesis of the diagnostic performance of various AI algorithms across different medical imaging modalities and disease types. This synthesis primarily drew insights from the extracted data of the 138 studies selected for the Comprehensive Review. We considered the potential for meta-analyses and subgroup analyses based on factors like imaging modality, disease type, and AI model architecture, though a formal meta-analysis was beyond the scope of this critical review. Additionally, we examined potential biases within the literature, such as publication and selective reporting biases, to contextualize our findings. As our review synthesized existing published literature, ethical approval was not required. This comprehensive and methodologically sound approach is designed to provide a robust overview of the field, with Fig. 1 illustrating the study screening and selection process.

3 Background and Literature Review

This discussion centres on the fundamental concepts and recent advancements in the application of AI to medical imaging, exploring how ML and DL are transforming diagnostic methods and enhancing patient outcomes. Section 3.1 provides an overview of AI’s role in medical imaging, setting the stage for more specific discussions. Section 3.2 focuses on ML in medical imaging, examining various ML techniques and their contributions to the analysis of medical images. Section 3.3 then shifts to DL in medical imaging, highlighting how advanced DL algorithms are extending the capabilities of image interpretation and increasing diagnostic precision. Together, these sections offer a comprehensive overview of the evolving landscape of AI technologies and their impact on medical diagnostics.

AI has become a game-changer in healthcare, particularly in medical imaging, where it’s making significant strides in diagnostic accuracy and patient care [2,31–33]. There’s been a notable increase in interest in harnessing AI to boost diagnostic precision, enhance patient outcomes, and streamline healthcare processes [5]. This literature review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of research on AI applications in medical imaging diagnostics, focusing on key trends, challenges, and opportunities in this rapidly evolving field.

The integration of AI into medical imaging spans several areas, including radiology, pathology, and ophthalmology. AI-driven methods have shown impressive results in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and efficiency across various imaging modalities. For instance, deep neural networks have achieved dermatologist-level performance in skin cancer classification [12,34], demonstrated dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer using deep neural networks, achieving diagnostic performance comparable to expert clinicians. Similarly, reference [4] developed a DL algorithm for detecting diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs, highlighting AI’s efficacy in ophthalmic diagnostics. AI algorithms, particularly those based on DL techniques, have shown remarkable capabilities in processing, and interpreting complex medical images, such as X-rays, CT scans, MRI, and ultrasound scans [8,35,36]. These AI-powered systems can detect abnormalities, assist in diagnosis, and provide quantitative assessments of disease severity with high accuracy and efficiency. By leveraging large datasets and sophisticated neural networks, AI models can learn intricate patterns and features from medical images, enabling more accurate and consistent diagnostic interpretations in radiology, the advent of DL techniques has revolutionised image interpretation and analysis. Rajpurkar et al. [37] introduced CheXNet, a deep-learning model for pneumonia detection on chest X-rays, achieving radiologist-level performance. Litjens et al. [5] surveyed DL methods in medical image analysis, highlighting its widespread adoption and impact across diverse clinical domains. Pathology has also witnessed significant advancements in AI-enabled diagnostics [38]. Ting et al. [39] developed a DL system for diabetic retinopathy detection in multiethnic populations, demonstrating robust performance across different demographic groups. Hosny et al. [40] reviewed the role of AI in radiology, emphasizing its potential to enhance diagnostic accuracy, workflow efficiency, and patient care. They also applied deep learning techniques to radiomics data for lung cancer prognostication across multiple cohorts [41].

However, the clinical implementation of AI technologies in medical imaging requires rigorous validation, regulatory approval, and ongoing monitoring to ensure their safety, effectiveness, and ethical use in clinical practice. Medical imaging plays a crucial role in disease diagnosis, treatment planning, and monitoring patient response to therapy. However, traditional diagnostic approaches are often subject to limitations, including observer variability, diagnostic errors, and inefficiencies in image interpretation [42–44]. These challenges underscore the need for innovative solutions to enhance diagnostic accuracy and efficiency in medical imaging.

Although AI has shown great progress in medical imaging, a major obstacle to its practical adoption is the lack of transparency in many advanced models—especially DL algorithms—which often operate as “black boxes. While these models can achieve impressive accuracy, their internal decision-making processes are often opaque, making it difficult for medical professionals to understand why a particular diagnosis or prediction was made. This lack of transparency can hinder the adoption of AI in clinical settings, where trust, accountability, and the ability to verify decisions are paramount.

To address this, Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) has emerged as a crucial field of research [45]. XAI aims to make AI models more transparent, interpretable, and understandable to humans. In medical imaging, XAI methodologies are vital for several reasons. First, they enable clinicians to gain insights into the features or patterns an AI model deems most relevant for a diagnosis, fostering trust and confidence in AI’s recommendations. This is particularly important for high-stakes decisions, such as cancer detection or disease progression prediction, where erroneous or unexplainable outputs could have serious consequences for patient care. Significant contributions in this area, notably by Parola et al. [46] and Cimino et al. [47], highlight the development of human-centered XAI solutions for clinical users. Their work introduces methodologies like Informed Deep Learning (IDL) and Case-Based Reasoning (CBR) to effectively integrate medical domain expertise and provide intuitive visual output explanations. This approach not only enhances diagnostic accuracy, even with imperfect images, labeling inaccuracies, and artifacts from low-cost equipment, but also ensures explanations are congruent with clinical user demands and support post-hoc analysis for improved human-AI collaboration in decision-making. Second, XAI can facilitate error detection and model improvement. By understanding the reasoning behind an AI’s misclassification, researchers and developers can identify biases in training data, refine model architectures, or adjust parameters to enhance performance and reliability. Third, XAI supports regulatory compliance and ethical considerations. As AI deployment in healthcare becomes more widespread, there is a growing need for models that can be audited, validated, and justified in accordance with ethical guidelines and legal requirements [48]. XAI techniques, such as data explainability, model explainability, and post-hoc explainability, provide mechanisms to achieve this by offering insights into input data, internal model workings, and justifications for specific outputs, respectively [45]. The ultimate goal of XAI in medical imaging is not merely to provide explanations, but to contribute to the development of trustworthy AI systems that seamlessly integrate with clinical workflows, empower healthcare professionals, and ultimately improve patient outcomes by offering both accuracy and clarity in diagnostic decision-making.

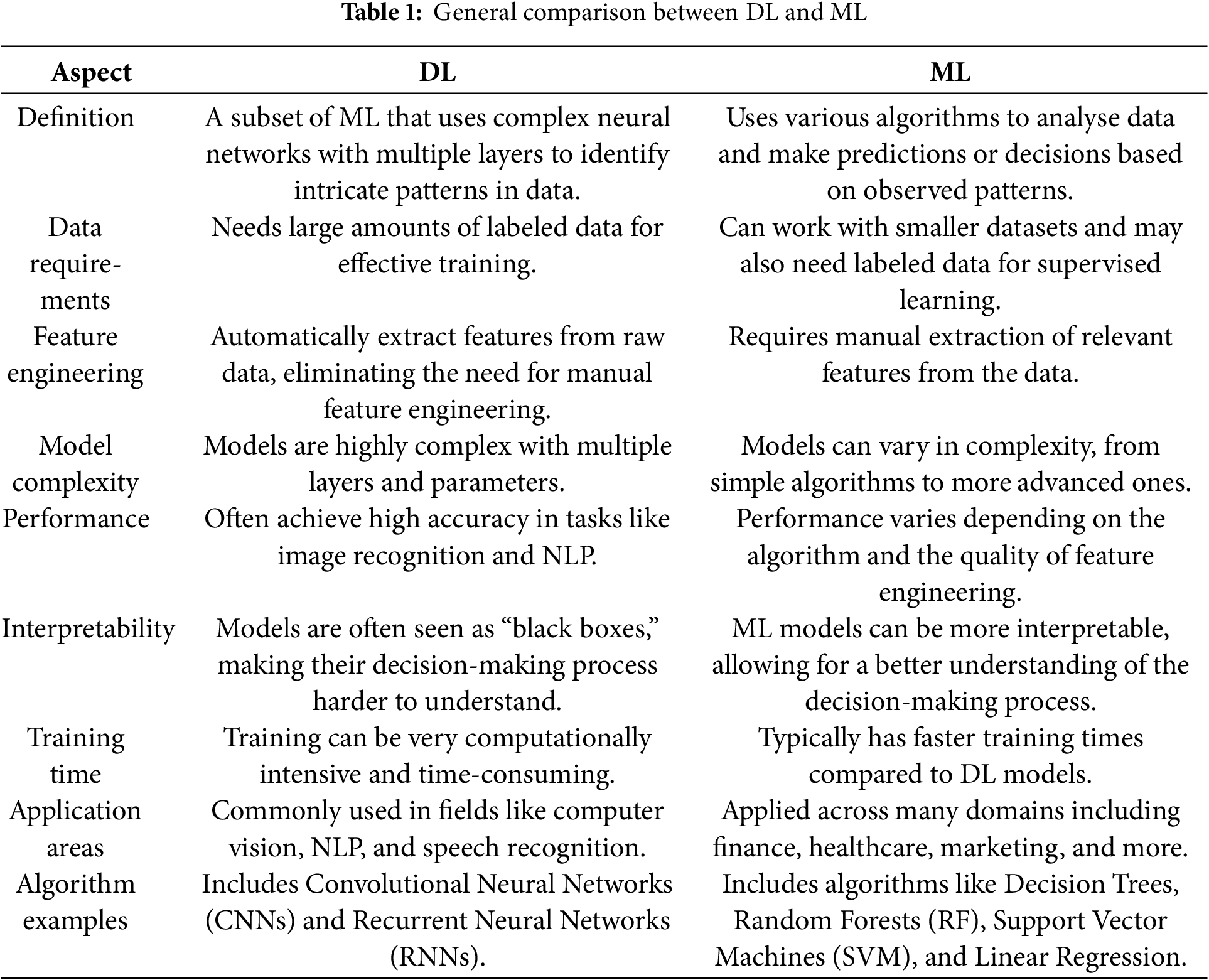

DL and ML are both subsets of AI, but they differ significantly in their approaches to data analysis [35,49,50]. DL, characterized by its use of artificial neural networks with multiple layers, excels at extracting complex patterns from large datasets [38,50]. This makes it particularly well-suited for tasks like image and speech recognition. Conversely, ML algorithms rely on predefined features and rules to make predictions [51–53]. While often interpretable, ML models may be less accurate than DL models for highly complex problems. The authors provide a summary of the general comparison between ML and DL, as shown in Table 1, outlining their differences and strengths.

Understanding these distinctions is crucial for selecting the appropriate approach when addressing specific problems in various domains. In this research, we will cover these comparisons with a focus on their relevance to medical image analysis in healthcare by examining specific studies, algorithms, and applications in the below subsection.

ML algorithms are computational techniques that allow computers to identify patterns, relationships, and rules in data without being explicitly programmed [4,54,55]. These algorithms enable systems to enhance their performance on specific tasks over time by learning from experience, rather than relying solely on direct instructions from programmers. ML is extensively applied across various fields, including finance, healthcare, marketing, and NLP. It powers a range of applications such as recommendation systems, image and speech recognition, autonomous vehicles, and predictive analytics. As technology evolves and data availability increases, ML’s role in fostering innovation and automation continues to expand across different industries [56,57].

In essence, ML algorithms learn from examples and data inputs to make predictions, classifications, or decisions. They analyse large datasets, identify patterns or trends, and use this knowledge to generalize and make predictions on new, unseen data [58]. ML algorithms can be broadly categorised into three types:

1. Supervised Learning: In supervised learning, the algorithm is trained on a labeled dataset, where each data point is associated with a known outcome or target variable. The algorithm learns to make predictions or classifications based on input features and their corresponding labels [58].

2. Unsupervised Learning: Unsupervised learning involves training the algorithm on unlabeled data, where the algorithm must discover patterns or structures within the data on its own. These algorithms are used for tasks such as clustering, dimensionality reduction, and anomaly detection [59].

3. Reinforcement Learning: Reinforcement Learning (RL) is a type of ML where an agent learns to interact with an environment by performing actions and receiving feedback in the form of rewards or penalties. The algorithm learns to maximise cumulative rewards over time by exploring different actions and learning from their outcomes [60].

ML algorithms are widely used for medical imaging [44,55,61]. Sarella and Mangam [62] emphasize that NLP empowers computers to understand human language, crucial for applications like chatbots and machine translation. Lastly, Jayatilake et al. [63] highlight that Unsupervised Learning techniques, such as clustering, aid in discovering patterns in unlabeled data, contributing to tasks like data exploration and anomaly detection. Each technique offers unique strengths, enriching the expansive landscape of AI applications across diverse domains. These algorithms leverage large datasets of medical images to learn patterns and features that aid in the diagnosis and analysis of various diseases and conditions.

The integration of ML in medical imaging has revolutionised the field by providing advanced tools for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment planning. Various ML methodologies, including supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning, have markedly improved the precision, effectiveness, and scalability of medical image analysis. This review consolidates key findings from recent research on ML applications in medical imaging, focusing on the advantages and challenges associated with different methods, as summarized in Table 2.

Supervised learning methods, in particular, have been extensively applied to medical imaging for classification and detection tasks. For instance, probabilistic ensemble methods like RFs have demonstrated significant potential for early detection and categorisation of malignancies. Chudhey et al. [64] utilized RFs for classifying breast cancer based on ultrasound images, integrating traditional imaging features with ML techniques to achieve a high degree of precision. Furthermore, Hawkins et al. [65] applied RFs to predict lung cancer from CT scans, enhancing prediction models by combining conventional imaging metrics with radiomics. Another ML method such as the SVM is extensively employed for the classification of medical images. Akay [66] integrated the SVM with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for the purpose of identifying breast cancer from mammography samples. The PCA was used to reduce the number of dimensions in the data. This not only improved the computing efficiency but also enhanced the classification accuracy by reducing overfitting. Similarly, Wang et al. [67] employed the SVM to categorize prostate cancer based on MRI scans. They use feature extraction methods to enhance the efficacy of the classification model, emphasizing the usefulness of SVM in managing intricate medical imaging data. Gradient Boosting Machines (GBMs), such as XGBoost, have been utilized to improve the precision of disease prediction in medical imaging. In their study, Codella et al. [68] employed XGBoost as a means for detecting skin cancer in dermoscopy images and examined its performance in comparison to other boosting algorithms. This method demonstrated that XGBoost exhibited superior diagnostic accuracy compared to other models, therefore highlighting the benefits of boosting algorithms in effectively managing unbalanced datasets commonly seen in medical imaging. Moreover, the application of XGBoost by Chen and Guestrin [69] to forecast cardiovascular events from clinical imaging data involved the detection of crucial biomarkers linked to risk. This work highlighted the successful integration of imaging data with clinical parameters via XGBoost, resulting in enhanced predictive results.

The unsupervised ML methods also used in medical imaging, as the clustering algorithms, have played a crucial role in the segmentation and analysis of medical images in situations when there is a lack of labeled data. This unsupervised method enabled the distinct identification of several tissue types within the brain, thereby enhancing the precision of tumor boundary detection. Similarly, Mirikharaji et al. [82] employed DBSCAN, an alternative clustering technique, to automatically separate lesions in dermoscopy photograms. This approach successfully identified irregular shapes and boundaries, which are crucial for precise lesion detection and subsequent diagnosis.

Furthermore, dimensionality reduction is a significant unsupervised method employed in medical imaging to handle the enormous number of dimensions exhibited by imaging data. The PCA enhances the effectiveness of subsequent image processing operations by concentrating on the most key features, therefore facilitating the viewing and study of big datasets. Cristian et al. [86] expanded upon this idea by investigating the application of Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) in conjunction with PCA for the analysis of three-dimensional medical images. The remarkable efficacy of UMAP in maintaining local data structures renders it an invaluable instrument for the study of 3D images.

Moreover, the semi-supervised ML methods also exploited in both annotated and unannotated data, which has drawn research interest for its capacity to enhance model performance in situations when annotated data is inadequate. The study conducted by Liu et al. [9] investigated the use of graph-based semi-supervised learning in the diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy using retinal images. By incorporating both annotated and unannotated data, the model attained superior accuracy compared to comprehensively supervised methods, especially in situations with limited annotated data. The presented methodology emphasizes the capacity of semi-supervised learning to improve diagnostic precision while minimising reliance on extensive labeled datasets. Also, using semi-supervised learning methods, Roy et al. [87] identified brain metastases in MRI data, where they demonstrated the efficacy of semi-supervised learning in complicated medical imaging tasks by enhancing model robustness and accuracy through the integration of labeled and unlabeled data. A further investigation of graph-based semi-supervised learning for medical image classification was conducted by Zhu and Goldberg [85], with a focus on the method’s capacity to enhance classification performance by utilising unlabeled data.

The ML paradigm of Reinforcement Learning (RL), which aims to optimise decision-making by trial and error, has demonstrated potential in the fields of individualized treatment planning and real-time surgical guiding. The application of reinforcement learning, particularly multi-agent systems, to optimize customized cancer treatment strategies was investigated by Roy et al. [87]. Utilising patient data and treatment history, the RL model enhanced therapy results, displaying its capacity to customize cancer treatments for each patient.

Within the field of medical imaging, Bahrami et al. [76] employed RL to enhance the efficiency of MRI acquisition procedures. By dynamically modifying imaging parameters in real time, the RL model improved image quality while minimizing scan time, demonstrating its capacity to boost the effectiveness of medical imaging processes. A study conducted by McKinney et al. [88] utilized RL in real-time image-guided surgery to aid surgeons in executing accurate movements during procedures. The reinforcement learning-based system has shown a significant reduction in surgical errors, therefore emphasizing the capacity of reinforcement learning to improve precision and ensure patient safety in intricate surgical operations.

The ensemble Learning methods have been also applied widely in the field of medical imaging, where ensemble learning involves integrating several models to enhance prediction precision and has found extensive application in the field of medical imaging. According to Bron et al. [77], ensemble learning techniques, such as RF and Gradient Boosting, were employed to identify Alzheimer’s disease based on MRI and PET imagery. The ensemble method exhibited superior performance compared to individual models, highlighting its capacity to enhance diagnostic accuracy by combining predictions from several classifiers. In their study, Mienye et al. [84], Sahin [89] utilized ensemble learning to detect colorectal cancer by analysing CT colonography pictures. By integrating RFs and Gradient Boosting, the work attained a superior classification accuracy, highlighting the efficacy of ensemble techniques in enhancing detection rates for intricate medical disorders.

DL, a subset of AI, has emerged as a powerful tool for analysing complex medical images [44,90]. With its ability to automatically learn hierarchical representations from vast amounts of data, DL algorithms, particularly deep CNN, excel in understanding intricate features present in medical images [34]. These networks consist of multiple layers that progressively learn different levels of abstraction, allowing them to capture intricate details and patterns [44]. This hierarchical learning enables DL models to automatically extract meaningful features and make accurate predictions [91]. One of the significant advantages of DL in analysing complex medical images is its ability to handle large and diverse datasets [91]. Medical imaging datasets often contain thousands or even millions of images, making manual feature extraction challenging [91]. DL models can learn directly from these datasets, bypassing the need for manual feature engineering, thus saving time, and increasing the potential for discovering subtle patterns and correlations missed by human experts [34,92]. Moreover, DL models demonstrate remarkable generalization capabilities, effectively analysing new and unseen medical images once trained on a large dataset, providing consistent and reliable results essential for diagnosis, treatment planning, and patient monitoring [49,92,93]. Additionally, DL models can effectively handle the complexities and variabilities present in medical images, including variations in image quality, acquisition parameters, patient demographics, and pathological conditions [34,50]. They can adapt to these variabilities, making them robust and reliable in analysing complex medical images [51]. For further investigation, we summarize and highlight several studies that demonstrate the advantages of DL in medical imaging analysis, as shown in Table 3. These studies reveal that DL methods often perform comparably to or even surpass traditional methods in tasks such as skin cancer classification and brain tumor segmentation [50,94–96].

As shown in Table 4, the DL models and methods applications in medical imaging have resulted in notable improvements in diagnostic precision, image augmentation, and disease prediction. In recent years, a range of DL models such as CNNs, GANs, Autoencoders, and RNNs have been widely employed to tackle intricate problems in medical imaging. This literature review analyses the utilisation of these modelling techniques in many fields of medical imaging, highlighting their efficacy, difficulties, and future prospects.

The CNNs are now foundational in several image-based medical diagnosis systems. Their performance has been especially impressive in challenges that need exceptional precision in picture classification and segmentation. For example, Rajpurkar et al. [37] created CheXNet, a CNN model, with the purpose of categorising pneumonia based on chest ultrasound images. CheXNet, trained on a substantial dataset, attained an AUC of 0.96, exceeding the average performance of radiologists and demonstrating the inherent capabilities of CNNs in aiding clinical diagnosis. Furthermore, Ahn et al. [15] utilised CNNs together with image enhancement methods to diagnose breast cancer at an early stage utilising mammograms. Their methodology greatly enhanced the rates of detection, attaining a precision of 91% and a sensitivity of 90%, thereby accrediting CNNs with their efficacy in enhancing the diagnosis of early-stage cancer. Furthermore, the capacity of CNNs to process intricate volumetric data has been investigated in relation to the prediction of lung cancer. Tseng et al. [106] employed 3D-CNNs to examine CT imagery in order to forecast the occurrence of lung cancer. The model successfully preserved spatial information within the lungs, resulting in an AUC of 0.94, indicating a substantial enhancement compared to conventional approaches. These findings indicate that 3D-CNNs are highly efficient in examining volumetric medical imaging data, such as CT scans, where the spatial connections between voxels are of utmost importance. Zreik et al. [113] employed CNNs for the automated identification of coronary artery disease from cardiac MRI images. They obtained an AUC of 0.91, indicating a high capacity to decrease the need for invasive diagnostic procedures. Furthermore, Spampinato et al. [115] used CNNs to automatically determine bone age from hand radiographs. They achieved a 94% accuracy rate, indicating enhanced diagnostic consistency. Goyal et al. [117] also used CNNs on infrared imaging to enable the early identification of diabetic foot ulcers. The achieved accuracy rate of 91% shows potential in the prevention of ulceration and the reduction of healthcare expenses.

Another crucial use of CNNs is in the early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. A study conducted by Basaia et al. [105] utilized CNNs on MRI scans to extract pertinent characteristics for the categorization of Alzheimer’s patients. Their model attained a classification accuracy of 85%, so emphasizing the capacity of CNNs to detect subtle patterns in MRI scans that are suggestive of early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. This assertion is corroborated by the research conducted by Mehmood et al. [103], who utilised transfer learning with pre-trained CNNs to identify initial indications of Alzheimer’s disease, attaining a classification accuracy of 87%. Transfer learning proved to be especially advantageous in situations when there was a limited amount of labeled data, therefore highlighting its effectiveness in improving the performance of CNN-based models in the field of medical imaging.

The efficacy of RNNs, particularly LSTM networks, in the analysis of sequential data in medical imaging has been demonstrated. Hannun et al. [107] utilized LSTM networks to analyse ECG data in order to forecast cardiovascular illness. By focusing on the temporal patterns in ECG readings, the model obtained an amazing accuracy of 93%, considerably boosting the prediction of cardiovascular events. This study underlines the importance of DL models like LSTM in managing time-series data, which is ubiquitous in different clinical applications, including cardiac monitoring. Moreover, hybrid models integrating CNNs and RNNs have been investigated to use temporal as well as spatial data in medical images. Kawahara and Hamarneh [108] created a hybrid CNN-RNN model specifically designed for segmenting and classifying skin lesions in dermoscopy images. The hybrid method attained a 91% overall accuracy, thus illustrating that the integration of CNNs and RNNs can greatly enhance the accuracy of medical image analysis by effectively capturing both spatial characteristics and temporal relationships.

In medical imaging, GANs have become influential instruments for the production of synthetic data and the process of image augmentation. GANs have proven to be especially useful in situations when labeled data are scarce. Frid-Adar et al. [120] employed GANs to produce artificial medical images, with the explicit purpose of enhancing training datasets for the identification of liver lesions in CT scans. Integrating data generated by a GAN increased the precision of a liver lesion classifier by 5%, illustrating the effectiveness of GANs in overcoming limited data and improving model performance. Another study by Bowles et al. [102] investigated the application of GANs in a semi-supervised learning framework to enhance the classification of medical images. Application of the model to brain MRI data for illness diagnosis resulted in an 89% classification accuracy. The present work emphasises the capacity of GANs to not only produce artificial data but also enhance the accuracy of classification by integrating unlabeled data during the training phase. In addition, GANs applied to under-sampled data in the field of MRI image reconstruction, Yaqub et al. [121] achieved a Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) of 35 dB, lowering scan times without affecting diagnostic quality.

GANs also have been used to improve the quality of radiography pictures, as shown by Albano et al. [42] in their study on detecting dental caries infections. By enhancing image quality, GANs enabled the improved identification of caries lesions, however precise accuracy measures were not expressly given. This application demonstrates the capacity of GANs to enhance the diagnostic usefulness of medical imaging by enriching the images. Furthermore, Shin et al. [122] integrated transfer learning with GANs to enhance the performance of consequential tasks by 7%, highlighting the beneficial impact of synthetic data.

Medical imaging has utilized autoencoders, specifically sparse autoencoders, for the purpose of unsupervised feature learning. A study conducted by Hou et al. [109] employed sparse autoencoders to extract cancer detection characteristics from histopathology photos. The autoencoder-based technique enhanced the performance of subsequent classification tasks, obtaining a 92% accuracy in recognizing malignant tissues. They highlight the capacity of unsupervised learning techniques such as autoencoders for obtaining important features from medical images, hence improving the effectiveness of subsequent classification tasks. Schlegl et al. [119] investigated the use of unsupervised DL with autoencoders for anomaly detection in medical imaging. They successfully attained a sensitivity of 88%, therefore displaying the promising capabilities of unsupervised approaches in the early diagnosis of pathologies.

Moreover, DL has been exploited in prediction of survival rates in cancer patients has been achieved by adding radiomic characteristics into Deep Neural Networks (DNNs). Hosny et al. [40] employed DNNs to forecast the survival of patients with non-small cell lung cancer based on CT scans. The concordance index of 0.75 attained by the model illustrates substantial predictive capability for patient survival, therefore emphasising the promise of DNNs in the realm of individualised cancer therapy. In addition, Suk et al. [112] used DNNs, particularly autoencoders, for feature extraction from functional MRI (fMRI) images to forecast AD. The 95.35% classification accuracy of the model demonstrates the efficacy of DL approaches in capturing intricate patterns in brain imaging data, essential for differentiating between Alzheimer’s patients and healthy controls.

Furthermore, the use of RL is the optimisation of treatment programs in medical imaging. Shen et al. (2017) employed Deep Q Networks (DQN), a variant of RL, to enhance the efficiency of radiotherapy treatment planning. The reinforcement learning model enhanced treatment results by optimising the distribution of radiation, resulting in improved preservation of healthy tissues while efficiently directing the treatment towards tumors. This work emphasises the capacity of RL to customise radiotherapy planning for patients, presenting the adaptability of DL techniques in medical imaging beyond their diagnostic use. The efficacy of Transfer Learning with pre-trained CNNs for the categorization of lung nodules in CT scans was established by Shin et al. [122]. The achievement of an accuracy rate of 86% underscores the usefulness of this approach in improving performance even when there is a scarcity of labeled data. Barnoy et al. [116] investigated RL for real-time image-guided surgery, which exhibited a 20% decrease in surgical tool placement mistakes. This finding suggests that RL has the capability to improve surgical precision.

We can conclude from the literature that a significant gap exists in the first part of research question 2. Specifically, the limited datasets used to train many AI models in medical imaging fail to adequately represent the diversity of patient populations. As a result, this limitation raises concerns about the models’ generalizability and introduces potential biases, which could impact diagnostic accuracy across different demographic groups.

This section presents the comprehensive findings of our review, integrating both bibliometric analysis and a synthesis of evidence on AI applications for improving diagnostic accuracy in medical imaging. We begin by addressing the core objective of the review: the impact of AI on diagnostic accuracy, drawing insights primarily from the subset of studies included in our comprehensive review. Subsequently, we provide a detailed analysis of research trends from 2015 to 2024, including annual scientific production, key research domains, leading journals, most cited and productive countries, annual citation impact, and emerging research themes.

4.1 AI’s Impact on Diagnostic Accuracy in Medical Imaging

Our comprehensive review consistently demonstrates the significant positive impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) technologies, on improving diagnostic accuracy across diverse medical imaging modalities, including radiology, pathology, and ophthalmology. Studies reveal that AI algorithms frequently achieve diagnostic performance comparable to, and in some cases surpassing, that of human experts—exemplified by deep neural networks achieving dermatologist-level skin cancer classification and DL models reaching radiologist-level performance for pneumonia detection on chest X-rays. These systems exhibit remarkable capabilities in processing and interpreting complex images from X-rays, CT, MRI, and ultrasound, enabling improved detection rates for early-stage diseases (e.g., breast cancer, lung nodules, diabetic retinopathy), enhanced precision in lesion characterization, and the rapid, consistent analysis of vast datasets. This ability mitigates human cognitive biases and fatigue, thereby augmenting clinical decision-making. AI’s application further extends to aiding early detection of conditions like COVID-19 and precise tumor measurement, even facilitating use in smaller medical facilities. While the specific details and quantitative metrics of diagnostic performance are elaborated elsewhere in this review, this overarching trend underscores AI’s transformative potential; however, successful clinical implementation necessitates rigorous validation, regulatory approval, and ongoing monitoring to ensure safety, effectiveness, and ethical integration, acknowledging the continued essential role of physicians.

4.2 Annual Scientific Production (2015–2024)

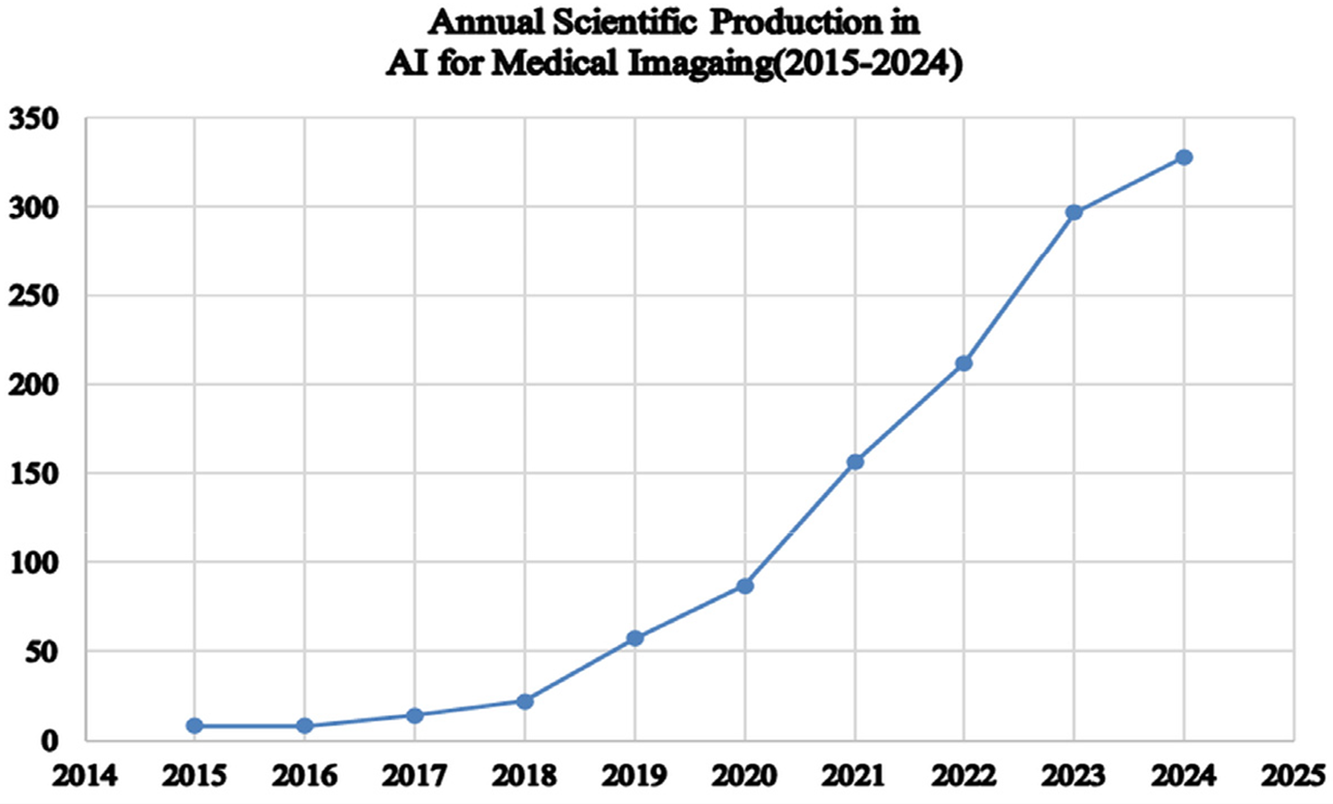

The analysis of annual scientific production in AI applications for medical imaging diagnostics, as shown in Fig. 2, reveals a significant upward trend from 2015 to 2024. Initially, the publication of only 8 articles per year took place in 2015 and 2016. This number began to rise in 2017, reaching 14 articles, and further increased to 22 articles in 2018. Subsequently, the publication rate accelerated, reflecting growing interest and advancements in the field. By 2019, output surged to 57 articles and continued to climb to 87 articles in 2020. This trend persisted, with 156 articles in 2021 and 212 articles in 2022. Notably, in 2023, the number of publications surged further, reaching 297 articles, with a projected peak of 328 articles in 2024. This progressive rise highlights the growing focus and research activity in AI to improve diagnostic accuracy in medical imaging. The substantial growth in publication volume reflects both the increasing importance of AI in healthcare and the ongoing advancements in technology and methodologies. Therefore, this trend highlights the growing recognition of AI’s potential to improve diagnostic precision and the increasing investment in this research area.

Figure 2: Annual scientific production

4.3 Key Research Domains in AI and Medical Imaging

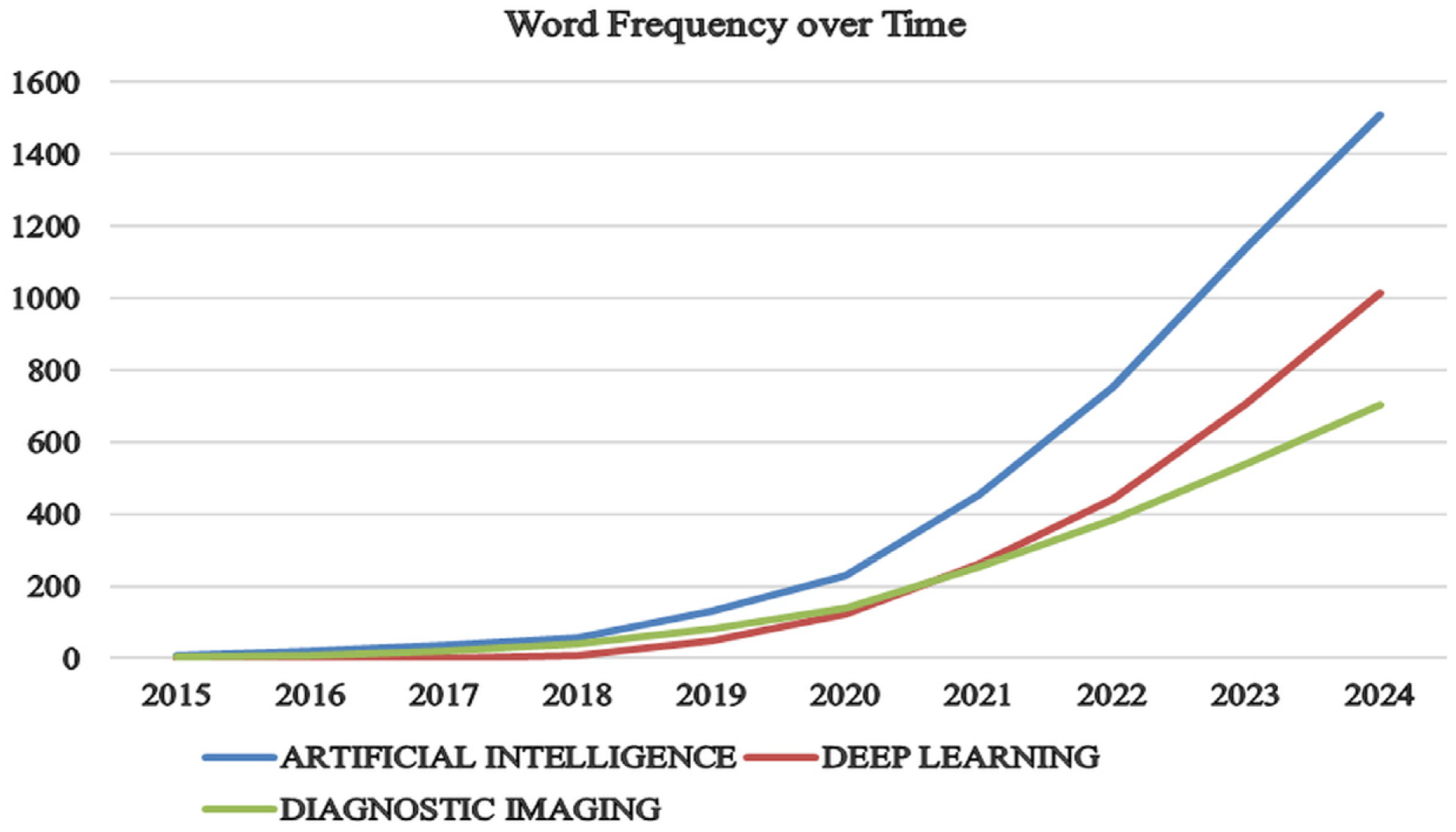

This section explores key research domains by analysing trends in “artificial intelligence,” “deep learning,” and “diagnostic accuracy” over the past decade, based on a sample of 1189 articles, as shown in Fig. 3. The data reveals a significant surge in research activity across these areas. Notably, AI has seen the most substantial growth, with articles increasing dramatically from just 10 in 2015 to an impressive 1508 in 2024. This surge highlights AI’s expanding role in various applications, especially in enhancing diagnostic accuracy in medical imaging. Similarly, DL has experienced remarkable progress, with publications rising from none in 2015 to 1014 in 2024. This rapid increase reflects DL’s transformative impact on both research and practice, driven by advancements in technology and methodology. Furthermore, the field of diagnostic imaging has significantly expanded, with articles increasing from 4 in 2015 to 702 in 2024. This trend underscores the growing importance of diagnostic imaging in medical diagnostics and the broader application of AI technologies to improve precision and outcomes in medical diagnostics, as represented by Kaur et al. [32].

Figure 3: Growth of AI, DL, and diagnostic imaging publications over time

4.4 Leading Journals in AI Applications for Medical Imaging Diagnostics

Section 4.4 explores the leading journals in AI applications for medical imaging diagnostics, focusing on two key aspects: publication volume and journal impact. This section is divided into two parts for clarity: Section 4.4.1 Leading Journals Based on Publication and Section 4.4.2 Leading Journals Based on H-Index. In the first part, we will examine which journals have published the most articles in this field, highlighting their role in advancing research. The second part will assess these journals’ H-Index, reflecting their overall impact and citation frequency. By addressing both publication volume and journal impact, this section aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how different journals contribute to the progress of AI in medical imaging diagnostics.

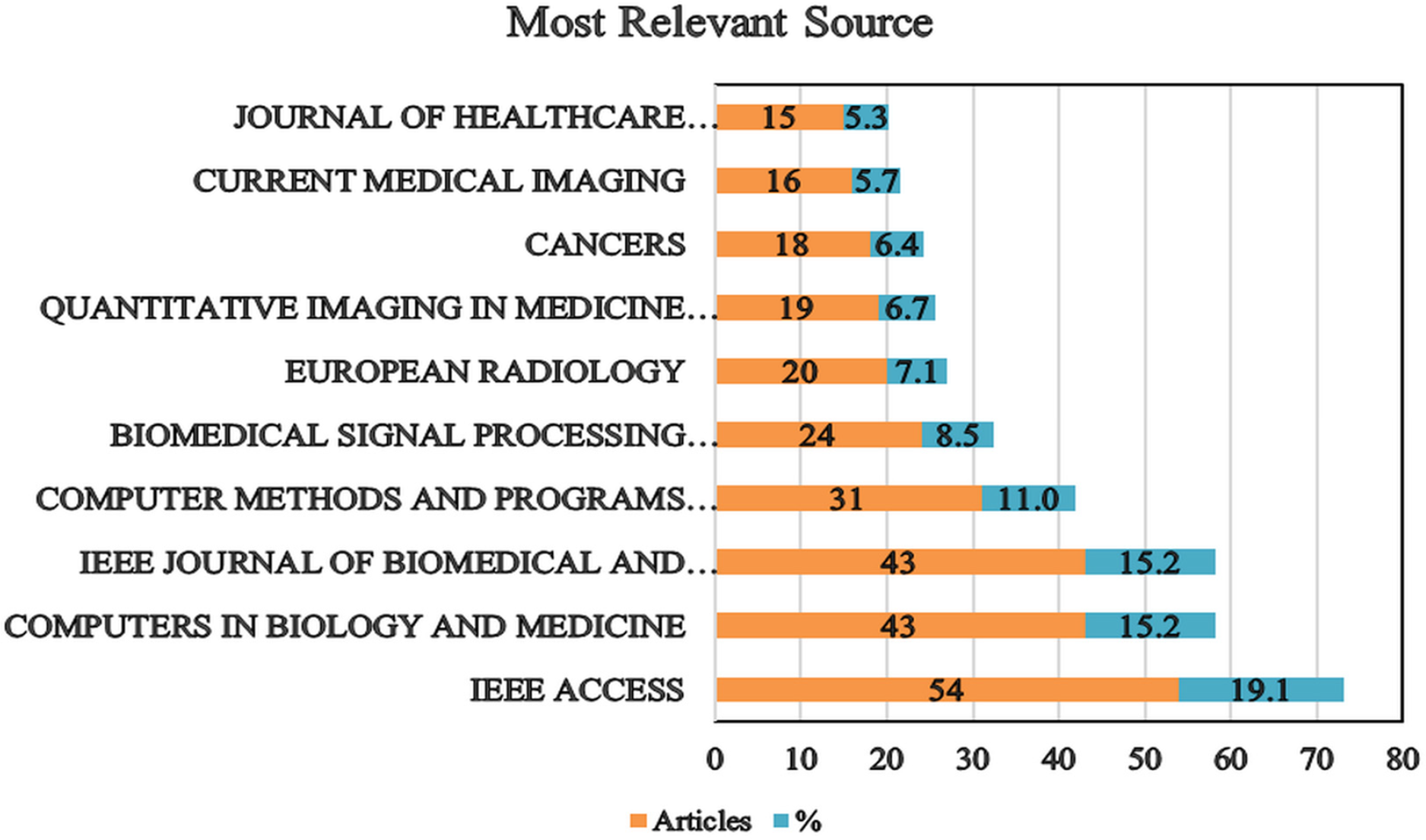

4.4.1 Leading Journal Based on Publication

The chart shown in Fig. 4 highlights the top 10 journals in the field of AI applications for medical imaging diagnostics. “IEEE ACCESS” stands out as the most significant source, publishing 54 articles and accounting for 19.1% of the total publications, thereby underscoring its prominent role in advancing AI research, particularly in diagnostic accuracy and medical imaging. Additionally, “COMPUTERS IN BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE” and the “IEEE JOURNAL OF BIOMEDICAL AND HEALTH INFORMATICS,” each with 43 articles (15.2% of the total), are key contributors, demonstrating their substantial impact on the field. On the other hand, “COMPUTER METHODS AND PROGRAMS IN BIOMEDICINE,” with 31 articles (11%), offers valuable insights into medical informatics and computational methods, though its publication volume is lower compared to the top three journals. “BIOMEDICAL SIGNAL PROCESSING AND CONTROL,” contributing 24 articles (8.5%), emphasizes significant advancements in signal processing techniques that enhance diagnostic systems. “EUROPEAN RADIOLOGY,” with 20 articles (7.1%), highlights its role in integrating advanced research methods with diagnostic imaging. Further down the list, journals such as “QUANTITATIVE IMAGING IN MEDICINE AND SURGERY” and “CANCERS,” with 19 (6.7%) and 18 (6.4%) articles, respectively, focus on specific areas within medical imaging and cancer research. Lastly, “CURRENT MEDICAL IMAGING,” with 16 articles (5.7%), and the “JOURNAL OF HEALTHCARE ENGINEERING,” with 15 articles (5.3%), represent ongoing developments in medical imaging and engineering solutions in healthcare.

Figure 4: A ten-year review of publication trends and journal impact

4.4.2 Leading Journals Based on H-Index

This distribution of publications highlights the varied contributions of these journals, with IEEE ACCESS leading in article count and demonstrating its extensive engagement with AI research in healthcare. The diversity in publication volumes across these journals reflects the broad and multifaceted nature of research output in AI-driven diagnostic accuracy and medical imaging.

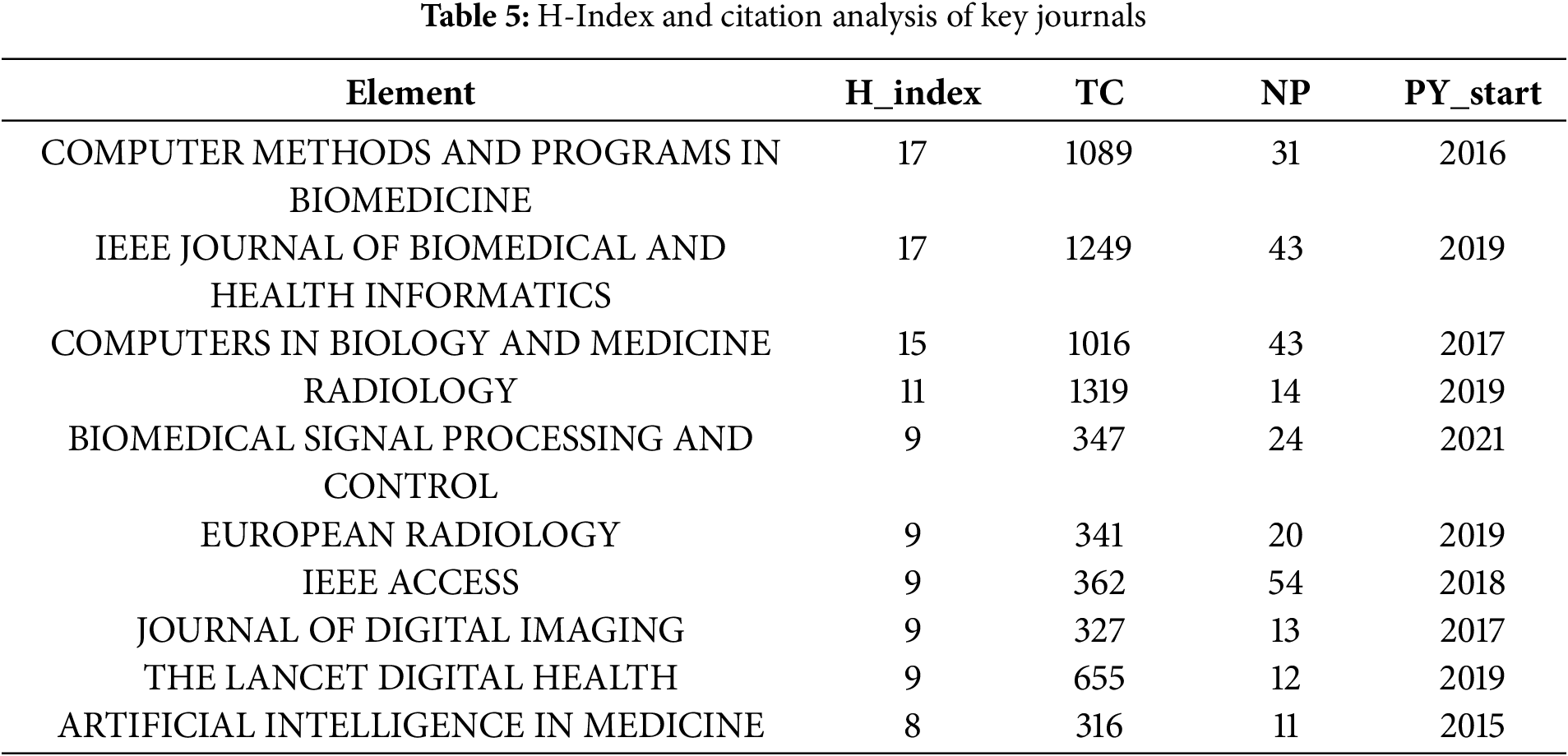

In this section, we analysed the H-index of key journals by examining the terms “artificial intelligence” and “medical imaging” within a sample of 1189 articles from the WoS and Scopus databases. The H-index, or H-factor, quantifies a journal’s impact by representing the number of highly cited papers it has published [123]. As shown in Table 5, “COMPUTER METHODS AND PROGRAMS IN BIOMEDICINE” and “IEEE JOURNAL OF BIOMEDICAL AND HEALTH INFORMATICS” lead the list with an H-index of 17, indicating their high impact and sustained contributions to the literature. Conversely, “RADIOLOGY,” despite having fewer publications (NP = 14), boasts the highest total citations (TC = 1319), illustrating the significant influence of its articles. On the other hand, “IEEE ACCESS” has the largest number of publications (NP = 54) but a moderate H-index of 9, suggesting a high output volume with a relatively lower average citation impact per article. Additionally, journals such as “THE LANCET DIGITAL HEALTH” (H-index = 9, TC = 655) have rapidly gained prominence despite their recent entry into the field, highlighting the dynamic nature of AI research in healthcare. The variation in PY_start (the year of first publication in the field) further illustrates the diversity of journals contributing to the field, from early entrants like “ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN MEDICINE” (PY_start = 2015) to newer ones such as “BIOMEDICAL SIGNAL PROCESSING AND CONTROL” (PY_start = 2021). Overall, Table 5 reflects a broad and evolving landscape of scholarly communication, with both established and emerging journals playing crucial roles in advancing AI-driven medical imaging research.

This means the data indicates that a higher h-index typically reflects a greater local impact. Established journals show robust citation metrics, while newer journals are steadily enhancing their influence as their citation rates grow.

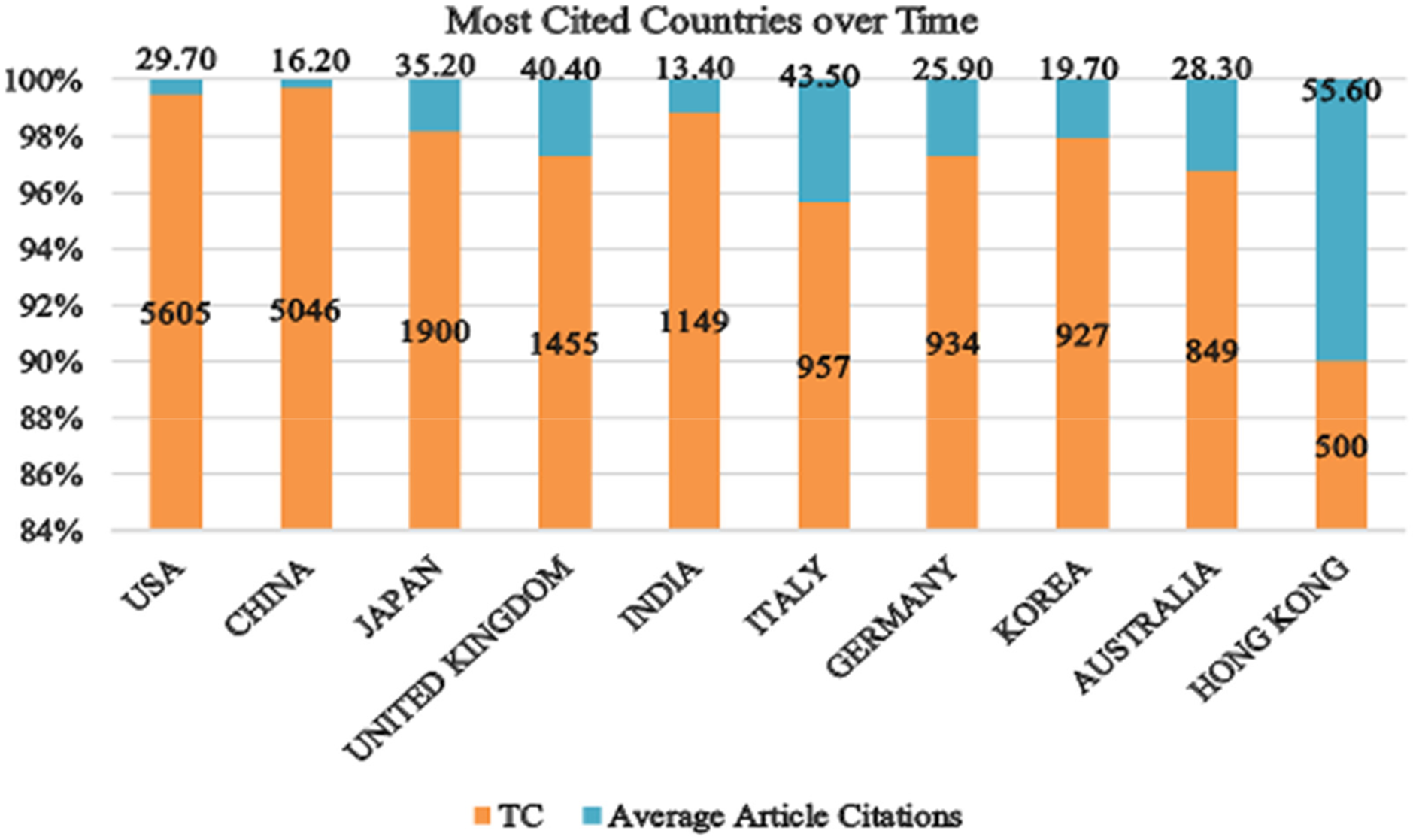

The top 10 most cited countries illustrate a varied landscape of research impact and citation practices in the field of AI in healthcare, particularly in diagnostic imaging. As shown in Fig. 5, publication trends by country over time further emphasise these patterns. The USA leads the list with the highest total citations (TC) of 5605 and an average of 29.70 citations per article, indicating a robust and influential body of research with a significant impact on the field [124]. Following closely, China records a TC of 5046 but has a lower average citation rate of 16.20 per article, suggesting a high volume of publications with fewer frequent citations per individual article. Meanwhile, Japan, despite having a lower total TC of 1900, demonstrates a strong impact per article with an average of 35.20 citations. This highlights the high quality and influence of its research outputs. Similarly, the United Kingdom shows a notable average citation rate of 40.40, with a total TC of 1455, reflecting significant research contributions and impact. Furthermore, Italy, with 957 TC and an impressive average of 43.50 citations per article, demonstrates a high level of influence relative to its total publication count. Additionally, Germany and South Korea, with total citations of 934 and 927, respectively, have average citation rates of 25.90 and 19.70, suggesting solid research impact, though less dominant compared to the leading countries. Moreover, Australia, with 849 TC and an average of 28.30 citations per article, demonstrates a moderate influence in the field. Finally, Hong Kong stands out with the highest average citation per article of 55.60, despite a lower total TC of 500, indicating highly impactful research despite a smaller publication volume.

Figure 5: Top 10 countries with the highest research impact based on citations

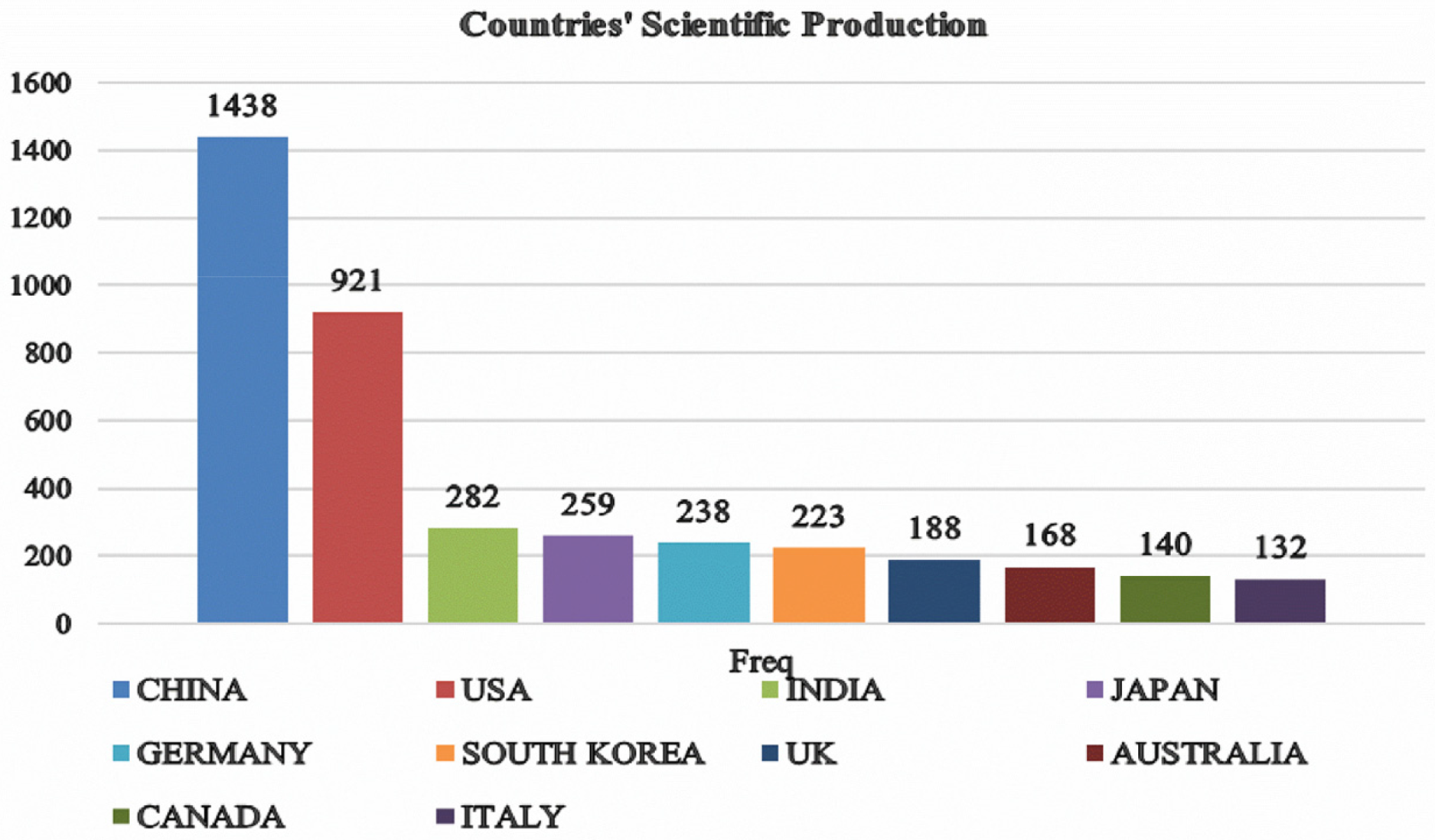

Fig. 6 presents the leading contributing countries and illustrates the scientific production of the top 10 nations over time, offering a detailed overview of their research output in AI for healthcare and diagnostic imaging. Notably, China has the highest production, totalling 1438 articles (36.1%), significantly surpassing other nations and underscoring its dominant role in advancing research and development in these areas. The USA follows with 921 articles (23.1%), reflecting substantial research activity, albeit at a lower volume than China. India and Japan rank next with 282 (7.1%) and 259 (6.5%) articles, respectively, highlighting their growing influence and contributions to the field. Germany, with 238 articles (6.0%), and South Korea, with 223 articles (5.6%), also demonstrate strong research outputs. The UK and Australia contribute 188 (4.7%) and 168 (4.2%) articles, respectively, indicating significant yet comparatively lower contribution levels. Finally, Canada and Italy complete the top 10, with 140 (3.5%) and 132 (3.3%) articles, respectively, marking their notable but smaller roles in the global scientific landscape. This distribution illustrates the varying levels of scientific production among leading nations, with China and the USA as the primary contributors, emphasizing their leading roles in advancing AI in healthcare and improving diagnostic accuracy in medical imaging.

Figure 6: Top 10 countries in AI diagnostic imaging research

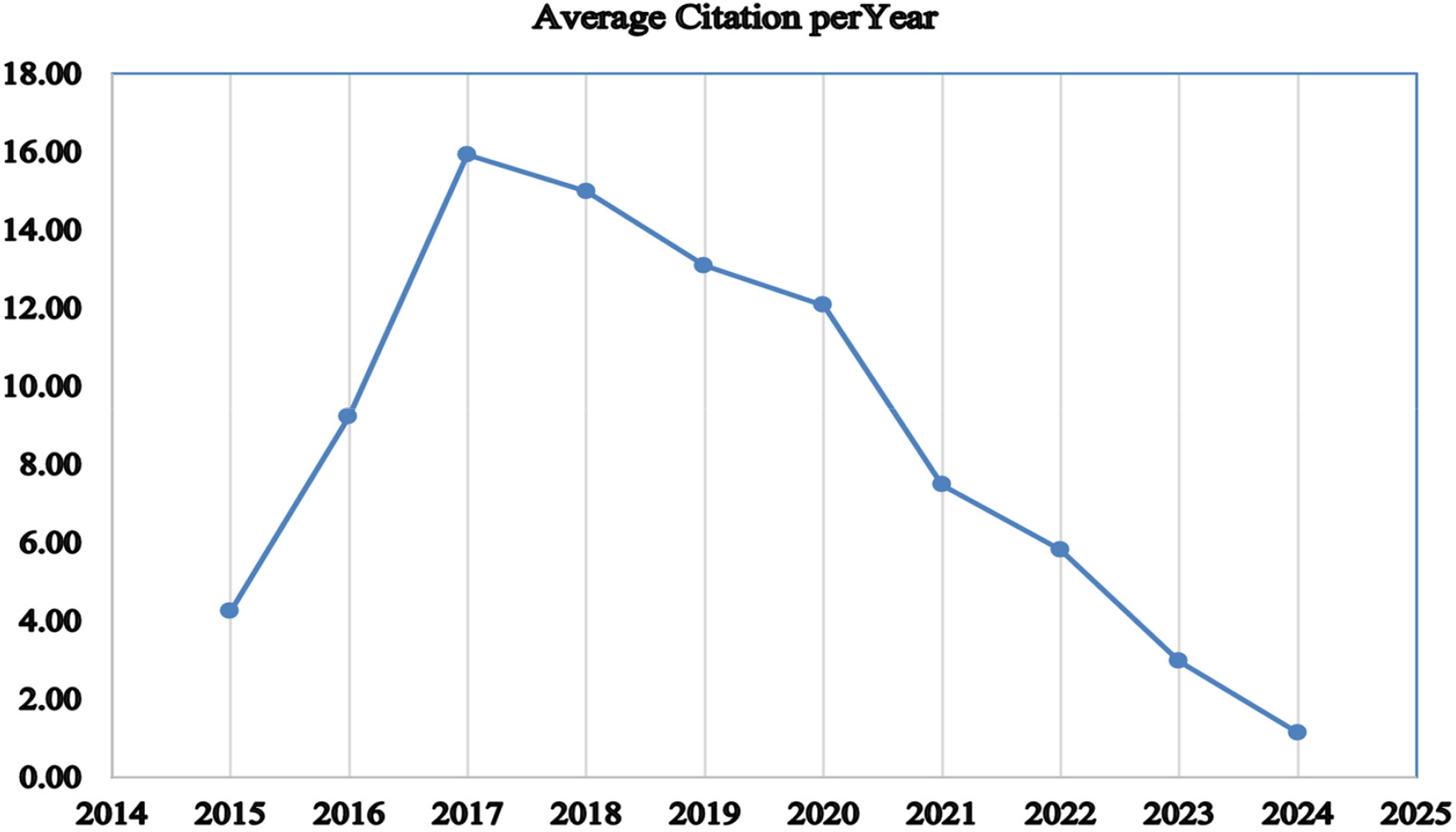

4.7 Annual Citation Analysis of AI in Medical Imaging (2015–2024)

The data shows a clear increase in the number of articles published on AI in healthcare, particularly regarding diagnostic accuracy in medical imaging. This rise reflects a growing interest in how AI can improve diagnostic precision. However, despite the increasing number of publications, the average citations per article have noticeably declined, as shown in Fig. 7. This trend suggests a potential decline in the impact of individual papers, despite the production of more research. One possible explanation for this decline is the rapid growth in the number of similar studies, which may lead to overlap and reduce the novelty of each new paper. As the field evolves, foundational studies may receive fewer citations compared to newer, more specialised topics that attract more attention. Moreover, this decline may suggest that the field is becoming saturated, with new research offering fewer ground-breaking contributions. To counter this trend, there is a need for more innovative and high-quality studies that explore new areas and offer fresh insights, ensuring that research in AI-driven healthcare continues to make a significant impact.

Figure 7: Average total citation per year

4.8 Key Words Co-Occurrence Analysis

The full count method visualises the co-occurrence of authors’ keywords by counting each keyword’s appearance in a document. We selected at least 10 times appearing keywords from a total of 9677, resulting in the grouping of 574 keywords into 7 clusters. The clusters vary in size, with Cluster 1 containing 171 items, Cluster 2 containing 160 items, Cluster 3 containing 74 items, Cluster 4 containing 71 items, Cluster 5 containing 62 items, Cluster 6 containing 35 items, and Cluster 7 containing just 1 item. In this context, the distances between keywords on the diagram signify their associations; shorter distances indicate stronger connections, while the lines connecting the circles represent the relationships between terms. To better understand these connections, we employed keyword co-occurrence analysis. In the network diagram, lines connect circles of various colours and sizes, indicating the strength of associations between keywords. In this visualisation, the colour represents different clusters, while the size of each circle reflects the frequency of keyword use; the larger the circle, the more frequently the keyword appears. For instance, “artificial intelligence” appears 1054 times, accounting for approximately 10.9% of the total occurrences, while “diagnostic imaging” appears 669 times (6.9%), “deep learning” 650 times (6.7%), “diagnostic accuracy” 514 times (5.3%), and “machine learning” 412 times (4.3%). These keywords are central to the research themes, highlighting their importance in the literature. Additionally, the distances between keywords on the diagram signify their associations; shorter distances indicate stronger connections, while the lines connecting the circles represent the relationships between terms [125]. These percentages justify which themes are most central to the field, helping researchers understand where the majority of focus lies. Moreover, this analysis reveals emerging trends and main research areas that receive the most attention in academic literature. Therefore, the keyword co-occurrence analysis helps uncover unique paradigms within the field and identifies key themes in the published literature [126]. As illustrated in Fig. 8, the network diagram shows the interrelationships among research topics in AI and healthcare by clustering frequently co-occurring keywords. Different colours distinguish each cluster, each representing a thematic area. For example, the close grouping of terms like “artificial intelligence,” convolutional neural networks,” and “medical imaging” demonstrates their strong interconnections and frequent use in AI studies, as supported by Jimma [125].

Figure 8: The co-occurrence network created with VOSviewer

By justifying the importance of keyword analysis and cluster formation, we provide a clearer picture of the research landscape. This understanding helps identify major research trends, areas of focus, and potential gaps in the literature, guiding future studies and policy decisions. Furthermore, understanding the connections between different topics can aid in developing more integrated and comprehensive approaches to applying AI in healthcare.

This section is divided into two parts. Section 5.1 will provide a comprehensive review of the literature to address the first research question, focusing on how ML and DL technologies have improved diagnostic accuracy in medical imaging. Section 5.2 will present an analysis of the results and findings through a bibliometric approach, examining trends and patterns revealed by the data.

Within the evolution of AI in cancer diagnosis (2015–2024), supervised learning techniques such as RFs and SVMs have played a foundational role, consistently demonstrating their efficacy in the classification of intricate medical images. For instance, early in this period, studies like those by Hawkins et al. [65] and Chudhey et al. [64] illustrated the effective use of RFs models in the detection of breast and lung malignancies. In these particular studies, RF models notably surpassed conventional diagnostic methods in prediction accuracy, establishing their utility as a robust alternative. Furthermore, the combined use of SVMs with dimensionality reduction methods such as PCA has significantly improved the precision of prostate and breast cancer detection [66,127]. Beyond individual models, the integration of several models using ensemble techniques has proven to be an especially successful approach in enhancing diagnostic accuracy. Studies conducted by Bron et al. [77], Mienye and Sun [128], Lima et al. [8], Schlegl et al. [129], and Zhou et al. [38] demonstrated that ensemble learning approaches, which integrate models such as RF and Gradient Boosting, exhibit superior performance compared to individual models in the detection of intricate diseases like Alzheimer’s disease and colorectal cancer. The widespread implementation of ML and DL techniques in medical imaging has propelled considerable progress across multiple fields, enhancing diagnostic precision, enabling earlier disease detection, and supporting personalized treatment strategies. The analyzed literature strongly indicates that both traditional ML and advanced DL models have become integral components of contemporary medical imaging, providing solutions to previously intractable challenges [35]. Our findings suggest that supervised learning remains the most frequently applied method for medical applications, a trend further supported by Karpov et al. [130].

DL models, specifically CNNs, have completely transformed the process of image classification and segmentation in medical imaging. For example, CheXNet has demonstrated that CNNs can achieve the same or even better performance than human radiologists in detecting pneumonia from chest X-rays [3,94]. Moreover, CNNs show significant potential in identifying diabetic retinopathy, as evidenced by Gulshan et al. [4], who reported a high level of sensitivity and specificity. Additionally, CNNs have shown promise in predicting Alzheimer’s disease; for instance, Basaia et al. [105] demonstrated that models could detect small alterations in MRI images. Furthermore, the use of 3D-CNNs in volumetric data analysis, such as CT scans, has led to notable improvements in lung cancer prediction [51,131,132]. In addition, CNN models have improved the early diagnosis of breast cancer, achieving a high level of accuracy, thereby underscoring their continued significance in the field of medical diagnostics. Meanwhile, RL has demonstrated its advantages in optimising treatment plans and the real-time decision-making process in diagnostic imaging. One study by Shen et al. [91] showed that DQN can make radiotherapy treatment plans more effective. This means that healthy tissues are exposed to less radiation, which leads to better outcomes. Moreover, researchers have utilised RL to enhance MRI acquisition procedures, leading to improved picture quality and shorter scan durations [76,133].

GANs have also effectively addressed the limited availability of labeled data by producing artificial images that augment training datasets. For instance, Frid-Adar et al. [110] showed that data generated by GANs can significantly enhance the performance of a classifier in detecting liver lesions. Furthermore, Sparse Autoencoders, as employed by Hou et al. [109], have contributed significantly to the extraction of unsupervised features, thereby improving the precision of future classification tasks in cancer diagnosis. Studies have demonstrated that GANs enhance the quality of radiographic images, thereby improving the accuracy in identifying dental caries lesions. The work Abbaoui et al. [31] illustrated how image enhancement using GANs can improve diagnostic outcomes, despite the lack of precise accuracy measurements.

Finally, transfer learning has gained popularity, particularly in adapting pre-trained models for novel medical imaging applications. According to Abbaoui et al. [31], the use of transfer learning in precision medicine highlights its ability to reduce dataset size while maintaining accuracy. This approach is especially effective when labeled data is scarce, further demonstrating the adaptability of AI techniques to diverse challenges in medical imaging.

For AI models to truly mature and maintain their efficacy in diverse and evolving clinical environments, a robust and continuous feedback loop from real-world application is indispensable. While initial model development and validation often rely on retrospective datasets, the dynamic nature of patient populations, disease presentations, and imaging protocols necessitates ongoing learning. Integrating AI solutions seamlessly into existing clinical workflows provides an opportunity for real-time performance monitoring and iterative refinement. This feedback allows models to adapt to new data distributions, identify novel patterns, and correct errors that may not have been present in their original training sets. Such a system would enable AI to learn from the discrepancies between its predictions and actual clinical outcomes, continuously improving its generalizability and diagnostic precision over time. However, establishing such a feedback mechanism is complex, involving challenges like ensuring data privacy, standardizing annotation processes, and developing efficient interfaces for clinicians to provide actionable input without disrupting their demanding schedules. Overcoming these hurdles is paramount for AI in medical imaging to transition from a static diagnostic tool to a truly adaptive and ever-improving clinical partner.

Despite the promising advancements of AI in medical imaging, a significant challenge for real-world implementation lies in the limited availability of continuous and structured feedback from clinical environments. AI models often require iterative refinement based on real-world performance data and expert input to maintain and improve their diagnostic accuracy over time. However, several factors impede this crucial feedback loop. Firstly, data privacy regulations and institutional complexities often restrict the easy flow of patient data, which is essential for model validation and re-training. Secondly, many current AI applications are developed and validated using retrospective datasets, which lack the dynamism and real-time variability of clinical practice. Obtaining prospective, real-time annotations and corrections from radiologists and other specialists is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and not yet seamlessly integrated into existing clinical workflows. The absence of standardized mechanisms for collecting diverse and continuous feedback, including instances of model errors or discrepancies, limits the ability of AI systems to adapt and learn from new patient populations or evolving disease patterns. This challenge underscores the need for robust infrastructure and collaborative frameworks that can facilitate the secure and efficient collection of clinical feedback, enabling AI models to truly evolve into reliable and continuously improving diagnostic tools within the healthcare ecosystem.

According to the examined literature, the answer to the first research question, “How have ML and DL technologies improved diagnostic accuracy in medical imaging, and what challenges remain for their real-world implementation?” demonstrates that AI, particularly through ML and DL technologies, has significantly enhanced diagnostic accuracy. For instance, traditional ML methods such as RF and SVMs have proven effective for reliable disease classification. While it is well-established that ensemble ML methods generally show superior performance over single models across various domains, their application in medical imaging is particularly impactful, demonstrably improving prediction precision and robustness in complex diagnostic tasks. Additionally, DL, especially through CNNs, has set new benchmarks in high-accuracy image analysis. The advent of 3D-CNNs has further expanded CNN capabilities to handle complex volumetric data, which is crucial for intricate diagnostic tasks. Beyond these, specialized DL architectures continue to push performance boundaries. For example, innovations like ADMM-Net [1] have significantly improved reconstruction accuracy and computational speed in challenging tasks such as Compressive Sensing MRI. Similarly, Supervised Deep Sparse Coding Networks [2] have demonstrated enhanced discriminative representation learning and efficiency for image classification tasks, particularly in data-constrained scenarios. Furthermore, advanced generative models like GANs and autoencoders have significantly enhanced model performance by addressing challenges related to dataset size and robust feature extraction. RL also holds promise for optimizing treatment plans and enabling real-time clinical decision-making. Selecting the appropriate technique for a given medical imaging challenge requires carefully balancing these diverse methodological strengths to enhance diagnostic accuracy and ultimately improve patient care.

Addressing the challenges for real-world implementation, as part of the first research question, several critical aspects emerge from the literature. These include the “black box” nature of many advanced AI models, which necessitates advancements in XAI to foster trust and enable clinical adoption [45,48]. Furthermore, the limited availability of continuous and structured feedback from dynamic clinical environments, as discussed previously, poses a significant hurdle for ongoing model refinement and adaptation. Other challenges highlighted involve ensuring data diversity and quality, addressing regulatory and ethical considerations, and achieving seamless integration into existing healthcare workflows. These technical and operational barriers are compounded by crucial socio-technical factors. For instance, fostering clinician trust in AI remains a significant hurdle, often stemming from a lack of transparency in AI’s decision-making process and concerns about accountability. Interoperability between various AI systems and existing hospital IT infrastructure also presents a major challenge, hindering seamless data flow and integration into the diagnostic workflow. Regulatory challenges, including the absence of standardized frameworks for AI model approval and post-market surveillance, further complicate widespread adoption. Overcoming these fundamental barriers is crucial for maximizing the clinical impact and widespread adoption of AI in medical imaging.