Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Robust Audio-Visual Fusion for Emotion Recognition Based on Cross-Modal Learning under Noisy Conditions

1 Department of Artificial Intelligence, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, 06974, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Electrical, Electronic and Systems Engineering, Universiti Kebangsaan, Bangi, 43600, Malaysia

3 School of Computer Science and Engineering, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, 06974, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Bong-Soo Sohn. Email: ; Jaesung Lee. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2851-2872. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067103

Received 25 April 2025; Accepted 19 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Emotion recognition under uncontrolled and noisy environments presents persistent challenges in the design of emotionally responsive systems. The current study introduces an audio-visual recognition framework designed to address performance degradation caused by environmental interference, such as background noise, overlapping speech, and visual obstructions. The proposed framework employs a structured fusion approach, combining early-stage feature-level integration with decision-level coordination guided by temporal attention mechanisms. Audio data are transformed into mel-spectrogram representations, and visual data are represented as raw frame sequences. Spatial and temporal features are extracted through convolutional and transformer-based encoders, allowing the framework to capture complementary and hierarchical information from both sources. A cross-modal attention module enables selective emphasis on relevant signals while suppressing modality-specific noise. Performance is validated on a modified version of the AFEW dataset, in which controlled noise is introduced to emulate realistic conditions. The framework achieves higher classification accuracy than comparative baselines, confirming increased robustness under conditions of cross-modal disruption. This result demonstrates the suitability of the proposed method for deployment in practical emotion-aware technologies operating outside controlled environments. The study also contributes a systematic approach to fusion design and supports further exploration in the direction of resilient multimodal emotion analysis frameworks. The source code is publicly available at (accessed on 18 August 2025).Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Emotions serve as essential elements in shaping human cognition and behavior. These affective states influence perception, guide decision-making, and govern both verbal and non-verbal communication. As intelligent systems become more prevalent across healthcare, education, and autonomous control, the ability to understand human emotions becomes increasingly critical. Automatic emotion recognition has emerged as a central component in human-centered computing, enabling responsive and adaptive interaction with users [1,2]. Emotion recognition systems support a wide variety of applications, including affective mental health monitoring [3], driver state analysis in intelligent vehicles [4], and social interaction in robotics [5]. The increasing demand for emotionally intelligent systems has underscored the importance of robust and accurate emotion recognition in complex, uncontrolled environments.

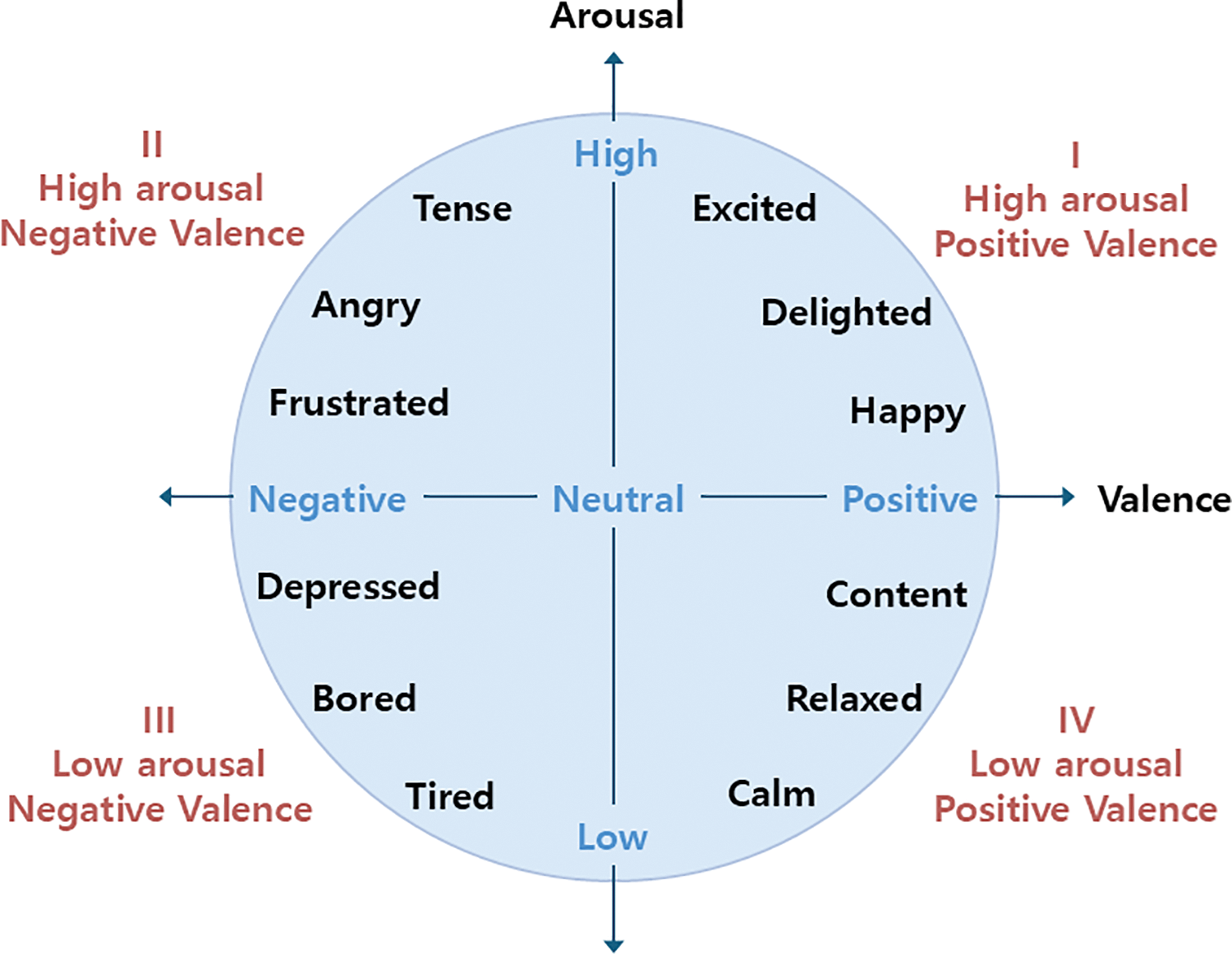

Traditional emotion recognition models rely heavily on datasets recorded in clean, noise-free laboratory settings [6]. However, real-world conditions introduce numerous challenges, including background noise, overlapping speech, dynamic lighting, and partial occlusions. These factors substantially degrade signal quality and model performance, especially when relying on single-modality processing or employing naive fusion strategies. Most previous work focuses on combining modalities at the feature or decision level [7]. However, these approaches often fail to account for the internal temporal dependencies essential for interpreting dynamic emotional states. Moreover, traditional emotion recognition approaches have predominantly relied on categorical classification into discrete states, such as happiness or anger, which inadequately represent the continuous and nuanced nature of human affect. Recent studies have adopted dimensional models that represent emotions on continuous scales such as valence and arousal [8]. This perspective enables a more fine-grained analysis, as illustrated in Fig. 1, where emotional states are represented within a two-dimensional affective space.

Figure 1: Two-dimensional valence–arousal space for emotion representation. Valence reflects pleasantness from negative to positive, while arousal measures activation from passive to excited

To address this issue, we propose a multimodal framework for robust emotion recognition in noisy conditions. The framework integrates audio and visual signals using a multi-level fusion strategy. Visual data are processed through convolutional encoders to extract spatial information, while audio signals are converted into mel-spectrograms and encoded through temporal modules. Temporal dependencies are captured using a combination of long-short-term memory and temporal convolutional networks, which jointly model short-range fluctuations and long-range trends. A cross-modal attention module selectively emphasizes informative features and suppresses irrelevant or corrupted signals, enhancing robustness to environmental noise. The proposed system eliminates the dependence on hand-made features, instead leveraging spatio-temporal encoders that generalize effectively in diverse input conditions. This architecture facilitates the generation of stable joint representations that remain robust and effective, even under degradation of individual modalities.

Evaluation is conducted on the AFEW dataset, which is augmented with synthetic noise to reflect realistic deployment scenarios. The proposed model demonstrates performance improvements over baseline methods in conditions of intense audio or visual distortion. Key contributions of this study include the design of a cross-modal attention mechanism for noise-resilient emotion recognition, the integration of multi-resolution temporal modeling, and the empirical validation of the framework’s robustness. The findings offer practical insights for developing real-world affective computing systems and provide a foundation for future research on the multimodal understanding of emotional behavior.

Multimodal emotion recognition (MER) research has advanced through various methodologies, focusing on key aspects such as whether the data are categorical or dimensional and whether the data are derived from controlled environments or real-world scenarios. In addition, this research primarily focuses on developing fusion strategies for integrating multiple modalities and on capturing spatiotemporal information from multimodal datasets [19].

This section examines three key components of MER research: datasets (Section 2.1), fusion strategies (Section 2.2), and spatiotemporal modeling methods (Section 2.3). Together, these components provide a foundation for understanding the recent advancements in dimensional emotion recognition, highlighting the methodologies employed across diverse datasets and experimental setups.

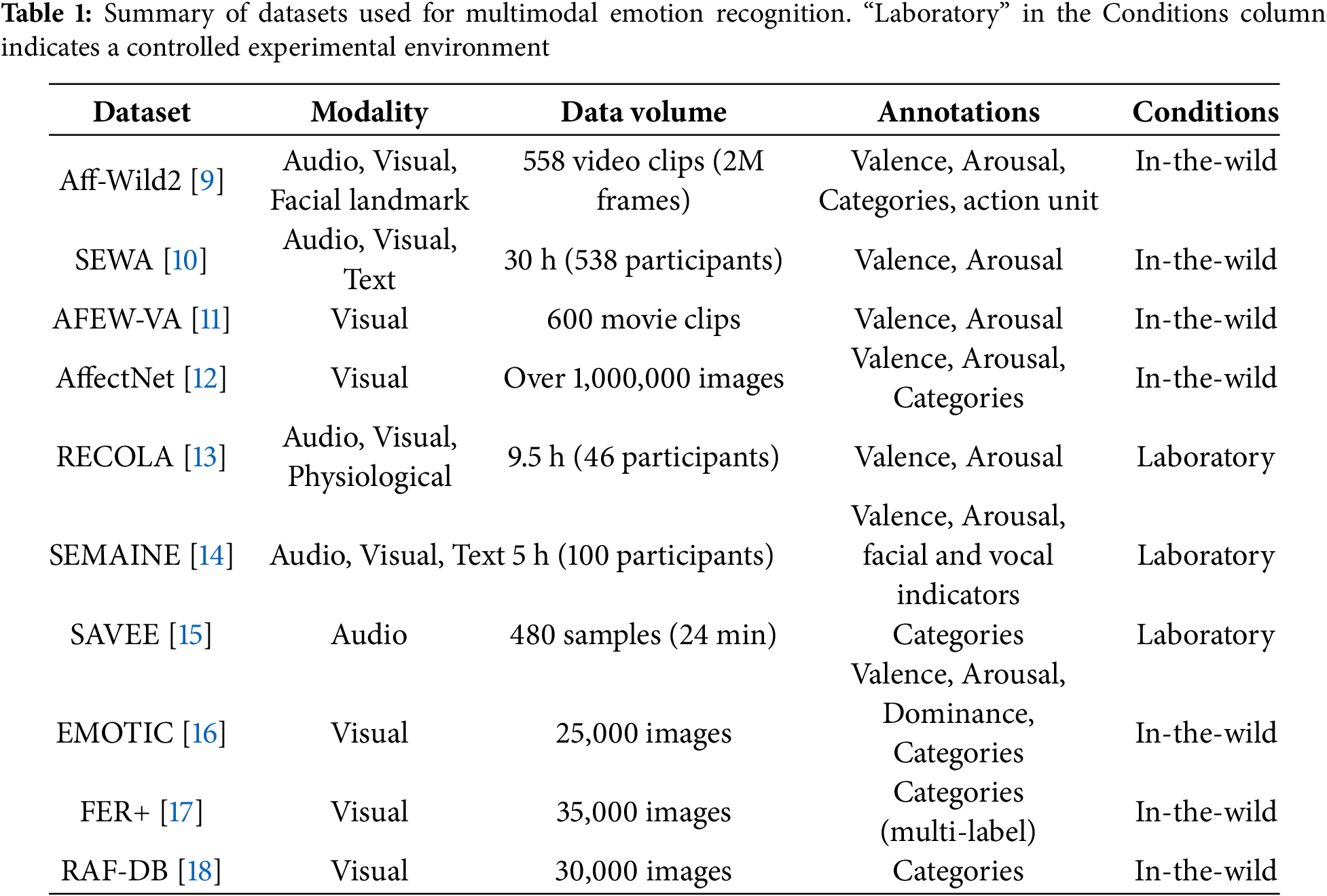

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of various datasets that are commonly used in MER research, highlighting their diverse modalities, annotations, and environmental conditions. These datasets encompass various input types, including audio, visual, text, facial landmarks, and physiological signals, reflecting the multimodal nature of MER tasks. For instance, the Aff-Wild2 dataset [9] provides audio, visual, and facial landmark features to study dimensional emotions such as valence and arousal, as well as categorical labels for emotional states. Similarly, SEWA [10] integrates audio, visual, and textual modalities, enabling fine-grained emotion recognition in real-world settings. These datasets enable researchers to explore the complementary information provided by multiple modalities, thereby supporting the development of robust models.

Datasets vary widely in terms of annotations, including dimensional labels (e.g., valence and arousal in AffectNet [12], RECOLA [13], and SEMAINE [14]) and categorical labels (e.g., happiness or sadness in FER+ [17] and RAF-DB [18]). Some datasets, such as EMOTIC [16], combine both dimensional and categorical annotations, providing a more comprehensive framework for studying complex emotional states.

The distinction between real-world (in-the-wild) and controlled environments is another critical aspect of these datasets. Real-world datasets, such as Aff-Wild2 [9] and AffectNet [12], reflect the noise and variability inherent in practical scenarios, making them invaluable for developing robust models. For example, AffectNet, with more than one million annotated images collected from online sources, is one of the largest and most diverse in-the-wild resources available for MER. In contrast, laboratory datasets such as RECOLA [13] and SAVEE [15] provide cleaner data under controlled conditions, which are useful to isolate and study specific factors.

These datasets, with diverse modalities, annotation schemes, and environmental settings, constitute critical benchmarks for advancing MER research. They provide a foundation for evaluating and developing models that can perform effectively in both controlled and real-world scenarios. The availability of such datasets enables researchers to address the challenges associated with noise in real-world data and adapt models to varying annotation frameworks, thereby facilitating the design of robust and generalizable emotion recognition systems.

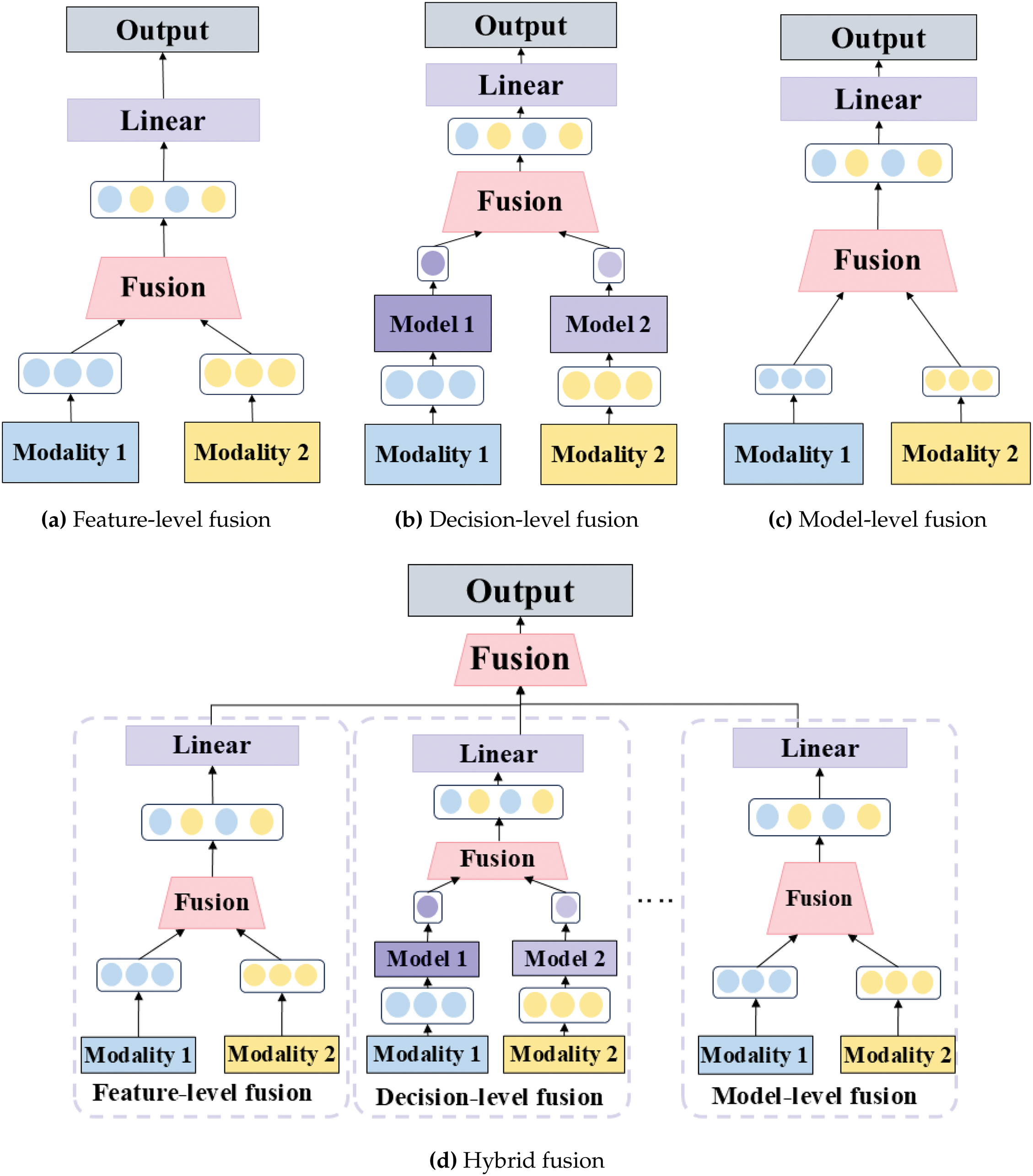

Combining features from different modalities using fusion technology is essential for building effective emotion identification models. The two most significant challenges in fusing diverse modalities are determining the level of abstraction at which the modalities should be integrated and identifying the appropriate procedures for their integration [20]. Based on the level at which modalities are fused, fusion strategies are categorized as (1) feature-level fusion, (2) decision-level fusion, (3) model-level fusion, and (4) hybrid fusion, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Comparison of fusion strategies: feature-level, decision-level, model-level, and hybrid approaches

Feature-level fusion was one of the initial approaches in MER, in which features from multiple modalities are combined into a single input vector for prediction [4,7]. This approach has gained recognition owing to its simplicity and low computational cost [21]. However, challenges such as noise sensitivity and temporal alignment difficulties limit its effectiveness. By simply concatenating the features, this method often results in the loss of critical emotional information and fails to capture the distinct characteristics of each modality [4,21,22]. To address the inability of feature-level fusion to filter irrelevant data and align features temporally, an early fusion method was developed that combines visual features extracted from pretrained convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with handcrafted audio features such as prosodic and spectral descriptors [6]. This method demonstrated the potential for utilizing complementary multimodal information, while further emphasizing the need for advanced strategies to preserve modality-specific characteristics while mitigating noise.

Decision-level fusion was proposed to overcome the limitations of feature-level fusion, particularly its inability to effectively handle noise and misaligned temporal data. By independently processing the features from each modality and combining their predictions into a final decision vector, this approach minimizes the effect of noise in any single modality [4]. Unlike feature-level fusion, decision-level fusion allows each modality to be optimized separately, thereby reducing uncorrelated errors and simplifying the integration of results [23]. The coordinated representation decision fusion network (CoDF-Net) was introduced to mitigate the lack of intermodal interactions inherent in feature-level fusion [24]. This framework independently processes Electroencephalography (EEG) and Electromyography (EM) signals to learn coordinated representations for emotion recognition. This framework effectively addresses noise-related issues while showcasing the strengths of decision-level fusion by preserving unique modality-specific characteristics and combining decisions at a later stage. However, its inability to exploit intermodal interactions dynamically highlights the need for more integrated fusion approaches.

Model-level fusion has emerged as a promising alternative to decision-level fusion, addressing its key limitations—namely, the absence of inter-modal interaction and the inability to integrate features dynamically. By unifying features from different modalities within a single architecture, this approach enhances the ability to capture complementary strengths across modalities and avoids the precise temporal alignment requirements of feature-level fusion [25,26]. To address these issues, the attention-based long short-term memory (LSTM) fusion framework was introduced. This framework employs attention mechanisms to filter noise from each modality and selectively combines features using LSTM models [22]. By dynamically refining intermodal interactions, it overcomes the limitations of static processing in decision-level fusion and the filtering weaknesses of feature-level fusion. Despite its robustness in handling noise and enhancing intermodal collaboration, the complexity of model-level fusion requires significant computational resources and well-annotated datasets.

Hybrid fusion was developed to integrate the strengths of feature-level, decision-level, and model-level fusion while addressing their respective limitations. This strategy facilitates flexible attention mechanisms and fusion processes, effectively capturing both intra-modal and cross-modal interactions [27]. By combining multiple strategies, hybrid fusion adapts to diverse noise conditions and leverages the complementary strengths of each method [26]. The recursive attention mechanism framework was proposed to address the need to refine joint representations while overcoming the static nature of decision-level fusion. By combining feature-level and decision-level fusion with elements of model-level fusion strategies, this framework employs recursive attention mechanisms to focus selectively on essential information from each modality [28]. This approach enhances robustness in noisy environments but increases the complexity of implementation, making careful design and evaluation essential for optimizing performance [25].

2.3 Spatiotemporal Modeling Methods

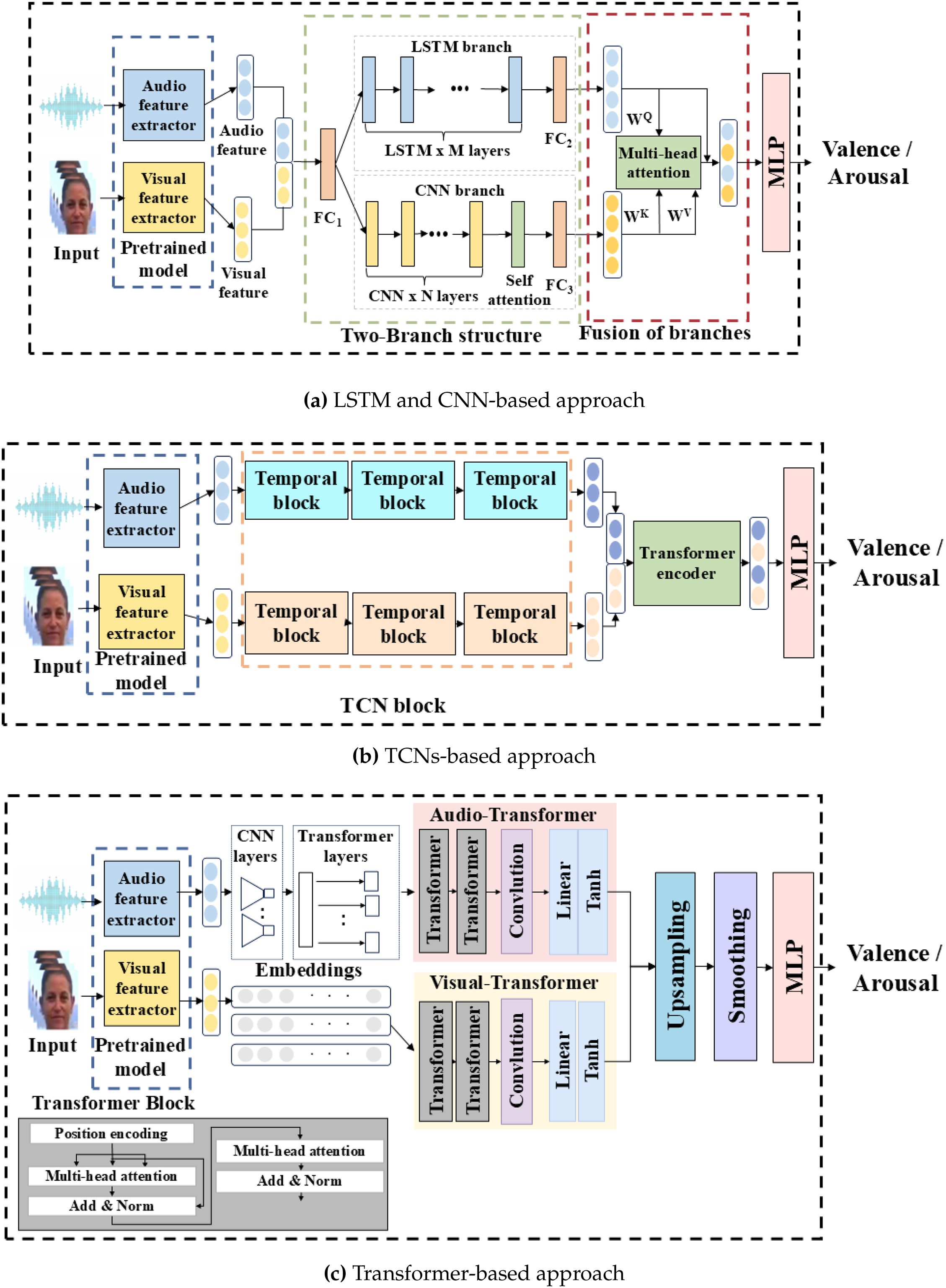

In emotion analysis, spatiotemporal features from each modality are captured using various methods. LSTM and CNNs are widely used to model sequential dependencies because they are effective in processing time-series data. Temporal convolutional networks (TCNs) provide an alternative approach that utilizes expanded convolutions to capture spatiotemporal relationships directly. Another widely adopted method involves Transformer-based models, which are highly effective in capturing long-range temporal dependencies and offer a robust framework for analyzing complex emotional patterns. Fig. 3 illustrates these techniques and highlights the diverse strategies employed to extract spatiotemporal features across different modalities.

Figure 3: Spatiotemporal feature extraction methods for predicting arousal and valence: (a) LSTM and CNNs structure, (b) TCN-based temporal model, (c) Transformer-based fusion network

One approach to capturing spatiotemporal features involves leveraging LSTMs for temporal modeling and CNNs for processing image and audio data. Temporal information is captured using an LSTM branch model to sequential dependencies by processing time-series data, which allows long-term temporal patterns to be captured while avoiding the vanishing gradient problem. Simultaneously, the convolution branch captures spatial features using a CNNs and models global context information through a self-attention layer, enabling the system to process broader temporal information [8]. This architecture is depicted in the LSTM and CNNs section of Fig. 3a. Although LSTM and CNNs have limitations in handling complex multimodal data, such as insufficient feature interactions, the temporal autoencoder framework addresses these issues by incorporating autoencoders alongside LSTM and CNNs. The autoencoders independently preprocess both visual and auditory data, extracting compact and representative features. These features are then passed to the LSTM, which models the temporal dependencies, enabling effective handling of sequential data. Combining local and temporal patterns across modalities improves the ability to capture temporal information and enhances emotion recognition [29].

Sequential data processing can face challenges such as inefficiency and the vanishing gradient problem in traditional LSTM, which operates step-by-step. TCNs overcome these limitations by enabling parallel processing, offering a more robust and efficient approach for handling sequences. TCNs utilize expanded convolutions to process sequential data in parallel, enabling them to capture long-range temporal dependencies efficiently and facilitating faster and more effective training [30]. This approach allows TCNs to handle multimodal data efficiently, integrating spatiotemporal features from both audio and video streams, thereby improving emotion recognition. A notable example is the multikernel temporal convolutional framework, in which temporal information is captured through convolutional layers with varying kernel sizes and dilation rates. This method efficiently models temporal patterns in both audio and visual data, effectively capturing long-range dependencies and improving performance in emotion recognition [31]. This architecture is depicted in the TCNs section of Fig. 3b. Similarly, the VGG-ResNet TCN pipeline captures temporal information using a combination of VGGish, MFCC, and ResNet-50 feature extractors. After the spatial features are processed, TCNs are applied to learn the temporal dependencies across audio and video frames, effectively capturing both spatial and temporal patterns for valence arousal estimation [32]. This approach significantly strengthens the model’s ability to understand and precisely predict emotional dynamics comprehensively.

Transformer-based models are widely used to capture spatiotemporal features through multi-head attention and positional encoding, effectively handling long-range temporal dependencies. This approach processes audio and video features using Transformer blocks to model the temporal relationships within each modality. The outputs are then fused, and a fully connected layer predicts the valence and arousal based on the combined spatiotemporal features. This method efficiently manages sequential data and cross-modal interactions, thereby enhancing the performance of multimodal emotion recognition. One such framework is the audio-visual transformer, developed to address noisy real-world conditions. This approach combines fine-tuned CNNs for visual features with the dimensional emotion model for audio, captures temporal dynamics through transformer architectures, and uses cross-modal fusion to integrate cleaner signals across modalities. This makes it highly effective in noisy environments [33]. Fig. 3c illustrates how this framework improves emotion recognition in unconstrained environments. Similarly, the contextual emotion Transformer utilizes Transformers for valence and arousal estimation by efficiently processing sequential and contextual data from audio and visual modalities. This framework models long-term dependencies, making it suitable for tasks requiring emotional feedback, such as human-computer interaction. It achieves robust and scalable emotion recognition by processing temporal patterns across multiple channels [34].

Recent studies have explored emotion recognition across diverse modalities beyond vision, including EEG signals and textual data. One approach addresses the challenge of cross-subject variability in EEG-based emotion recognition by modeling dynamic relationships between source and target domains through an interconnected domain adaptation framework, leading to improved generalization across individuals [35]. Another work leverages a transformer-based architecture for sentiment classification in textual data, where contextual embeddings are refined through self-supervised pretraining and supervised fine-tuning, demonstrating superior performance in affective analysis tasks [36]. These studies illustrate broader research directions in domain adaptation and contextual representation learning, which, although beyond the scope of our audio-visual framework, reflect the growing emphasis on robust multimodal emotion understanding.

Recognizing emotions in real-world settings is inherently challenging due to the complexity of valence and arousal estimation, which requires extracting temporal and spatial patterns under noisy and unpredictable conditions. The interplay between audio and visual modalities adds another layer of complexity, as each modality presents unique challenges. For instance, visual data often suffers from occlusion, lighting inconsistencies, and abrupt facial motion, while audio data is frequently impacted by background noise, overlapping speech, and environmental interference. These challenges are further complicated by the need to align features from the two modalities, which often have asynchronous or uneven temporal structures. Overlooking these issues can significantly hinder the ability of the model to capture emotional cues.

Traditional approaches often emphasize either audio or visual cues individually or adopt straightforward fusion techniques that may not fully address the inherent differences in temporal dynamics and feature distributions between the audio and visual modalities. Specifically, LSTM methods for modeling sequential dependencies often neglect frame-level details crucial for capturing localized emotion patterns, leading to a loss of fine-grained temporal information.

Existing approaches using TCNs and LSTM have specific limitations. TCNs are effective at capturing localized dependencies but struggle to model long-term temporal relationships. Conversely, LSTM excels in modeling long-term dependencies but fails to capture fine-grained frame-level details. Therefore, a hybrid approach that combines the strengths of these architectures is necessary and the integration of an attention mechanism is critical to balance global and local temporal information effectively.

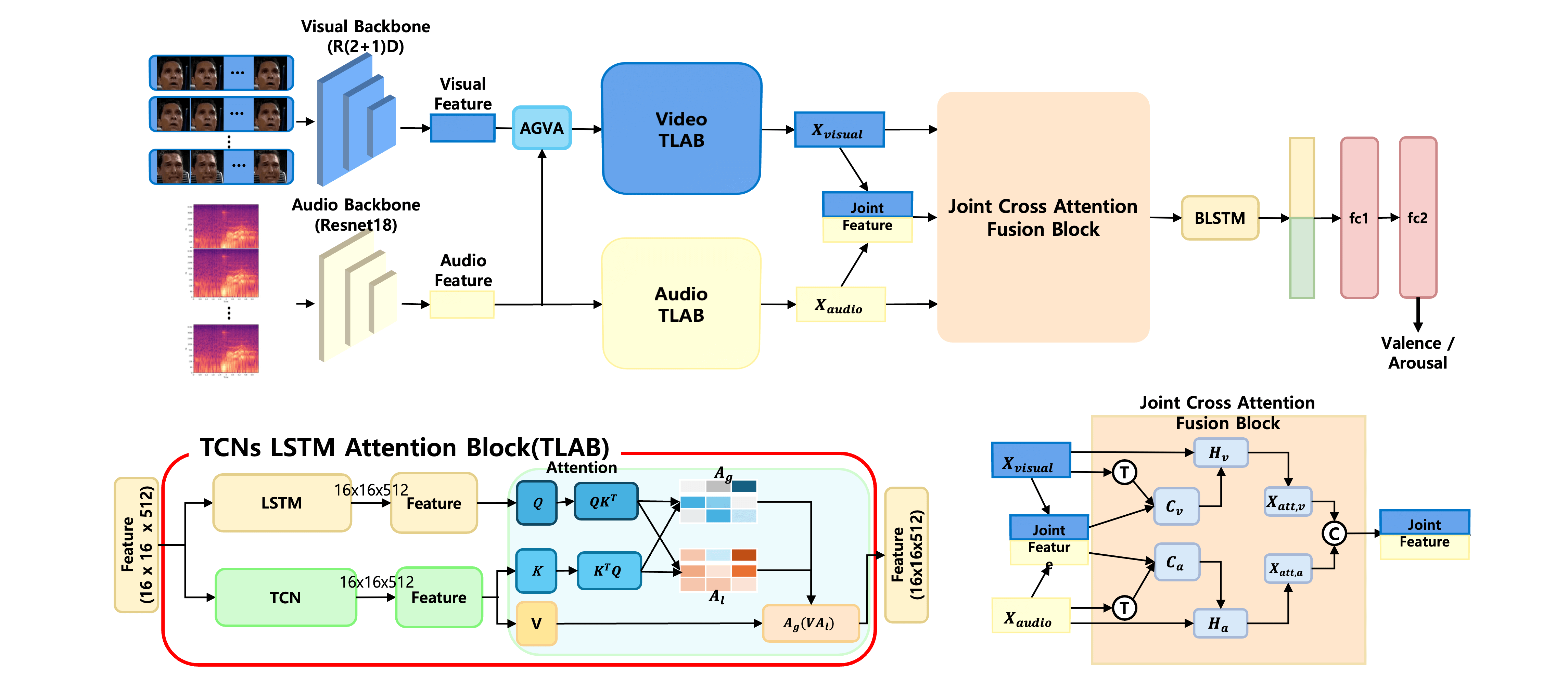

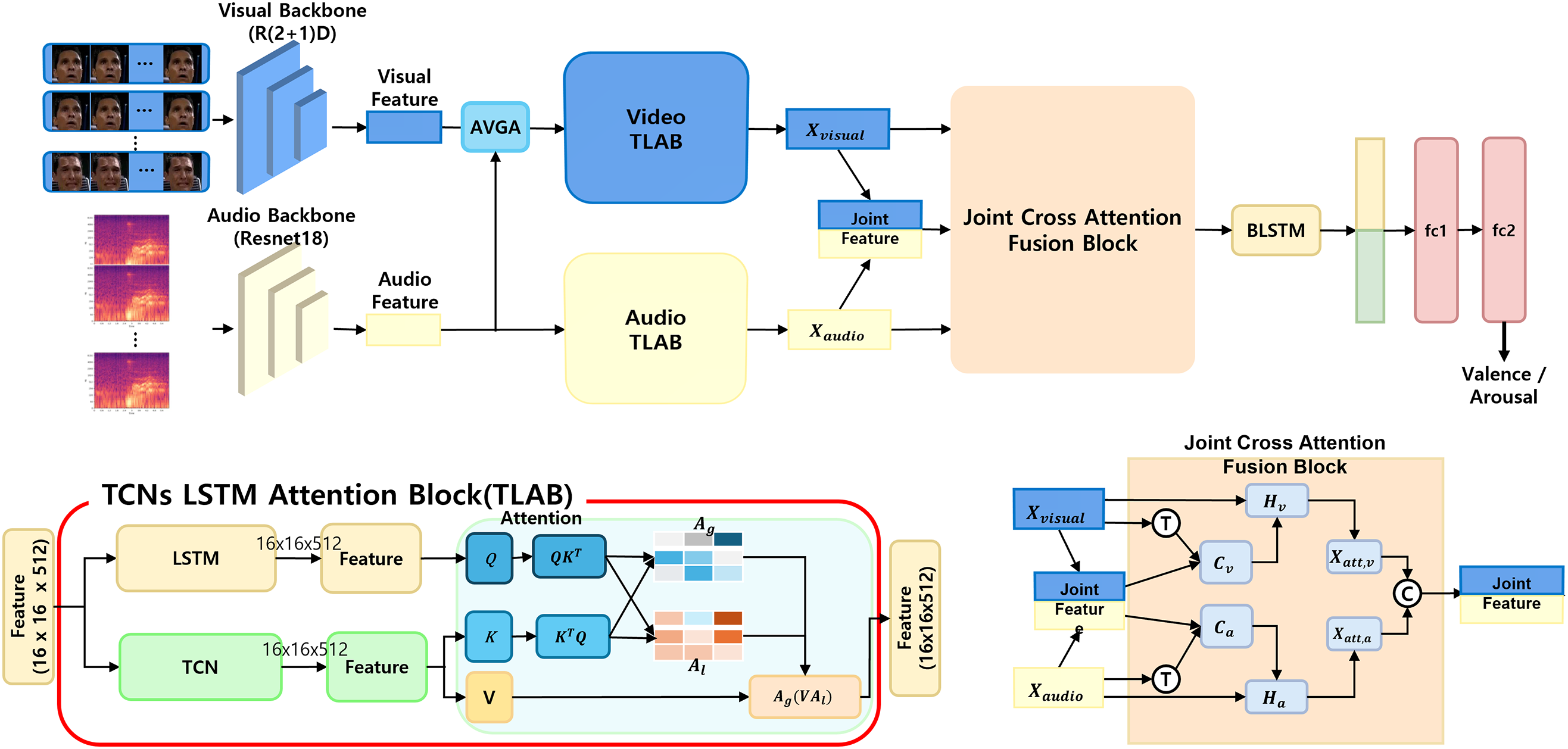

To overcome these limitations, we propose a framework that combines the strengths of audio and visual modalities while addressing their individual limitations, as illustrated in Fig. 4. This approach incorporates advanced preprocessing techniques to retain meaningful temporal and spatial patterns in both modalities. The framework achieves robust integration and comprehensive representation of audio-visual information by aligning these multimodal features through effective synchronization.

Figure 4: Proposed framework integrating TCNs, LSTM, and attention mechanisms to combine global temporal and local features for valence and arousal prediction

The visual data, composed of video frames, is preprocessed by resizing each frame to a resolution of

Audio-visual synchronization is crucial to address the temporal misalignment between modalities. To ensure precise temporal alignment between the audio and visual modalities, we apply a structured alignment strategy during preprocessing and data loading. The entire video sequence is divided into fixed-length segments (e.g., 512 frames), and each is further divided into sub-sequences (e.g., 32 frames). Within each sub-sequence, eight representative visual frames are selected based on uniform sampling, and a corresponding audio segment is extracted for the same temporal range. The audio signal is converted into mel-spectrograms using a fixed sampling rate, window size (e.g., 882), and hop length (e.g., 441). Spectrogram length mismatches are compensated using zero-padding to maintain consistent temporal resolution across samples. During training, the data loader constructs one-to-one audio-visual sub-sequence pairs with a fixed stride, maintaining alignment without requiring dynamic time warping or interpolation. This setup ensures consistent temporal baselines for all modalities, forming the foundation for subsequent attention and fusion operations.

The preprocessed visual and audio inputs are passed through separate backbones for feature extraction. Based on the R(2+1)D network, the visual backbone generates spatiotemporal feature maps from the video frames. To mitigate the loss of spatial detail and enhance the representation, Average Global Video Attention (AVGA) is applied, enabling a smooth reduction of the spatial dimensions while retaining the most informative regions of the visual features. This produces the representation

The proposed framework utilizes the Temporal Convolutional Network-LSTM Attention Block (TLAB) to process audio and visual features, thereby integrating complementary temporal information. Global attention captures long-term contextual information, while local attention focuses on fine-grained frame-level details. By integrating these two types of attention, the proposed framework ensures that both long-term dependencies and localized patterns are effectively modeled. This dual-focus approach is particularly advantageous for predicting valence and arousal, where subtle emotional changes and temporal dynamics play a crucial role.

The joint representation of audio and visual modalities is obtained by concatenating the outputs of the TLAB. Specifically, temporal features are extracted using TCNs applied independently to each modality as

where

The LSTM outputs

where

where

Local attention weights are also computed within each modality to emphasize localized temporal dependencies as

where

where

The final joint representation is formed by concatenating the audio and visual TLAB outputs along the channel dimension as

where

where

where

where

where

Finally, the joint attended representation is constructed as

which forms the final output of the JCA block. This design enables the model to capture both global and local temporal structures, as well as cross-modal relationships, simultaneously. By integrating TCN and LSTM architectures with dual attention mechanisms, the proposed framework effectively mitigates temporal misalignment and noise corruption, making it suitable for real-world valence-arousal estimation under unconstrained conditions.

To enhance temporal modeling and capture bidirectional dependencies across the fused features, the joint representation

where L denotes the temporal length and

This aggregated feature vector is passed through two fully connected (FC) layers to perform the final regression. The first FC layer transforms the feature space with a non-linear activation, and the second FC layer outputs the continuous valence and arousal scores as

where

This section presents the experimental results of three studies that conducted experiments using our settings in the Affective Behavior Analysis in-the-wild (ABAW) competition.

To address the challenges of combining modalities while preserving their distinct characteristics, the leader-follower attentive fusion framework introduced a late fusion model that incorporates a leader-follower attentive fusion mechanism [37]. Visual features are extracted using ResNet50 and TCNs, whereas auditory features are processed using parallel TCNs. These features are fused via cross-modal attention with a priority given to visual data. This framework addresses the limitations of processing noisy audio data, such as the presence of multiple speakers, and emphasizes the importance of visual information. The leader-follower architecture leverages visual data to mitigate audio noise, offering a solution for enhancing performance in noisy audio environments. By integrating auditory and visual information, this approach significantly enhances emotion recognition, improving accuracy, robustness, and adaptability across dynamic scenarios, particularly in real-world tasks where various environmental factors must be considered.

By adopting a strategy to capture complementary information both within and between modalities, the joint cross-attention (JCA) model offers a hybrid fusion method for more effective multimodal data integration [38]. In this approach, audio and visual features are extracted independently using separate networks, thereby ensuring the preservation of the unique properties of each modality. These extracted features are initially combined through feature-level fusion by concatenating them to form a joint representation, which is then refined through model-level fusion using an attention mechanism. The attention mechanism leverages existing information to facilitate better integration, balance, and enhance the strengths of each modality. This hybrid fusion approach results in more nuanced and accurate emotion recognition, particularly in complex real-world environments. The final fused representation is utilized for emotion prediction, resulting in improved accuracy and robustness.

The Aff-Wild2 dataset is designed for emotion analysis in “in-the-wild” conditions, featuring a wide range of subjects, ages, illuminations, and occlusions [39,40]. The Aff-Wild database served as the benchmark for the Aff-Wild Challenge organized in conjunction with CVPR 2017 [7]. It comprises 558 videos and 458 subjects sourced from YouTube, containing 2,786,201 frames. The valence-arousal labels were annotated by averaging the scores annotated by four experts. The dataset was divided into training, validation, and testing sets with 350, 70, and 138 videos, respectively.

While explicit demographic metadata such as age or ethnicity is not disclosed for each sample, the dataset includes a broad range of subjects and settings, reflecting diverse real-world conditions. Furthermore, the use of four independent annotators and score averaging offers a degree of label consistency, although detailed inter-rater agreement scores are not publicly available. Despite these limitations, Aff-Wild2 remains one of the most comprehensive and challenging benchmarks for audiovisual emotion recognition in unconstrained environments.

The prediction performance for valence and arousal was evaluated using the concordance correlation coefficient (CCC), a commonly used statistical measure in emotion analysis to assess the agreement between the predicted values and the ground truth.

where

where

No artificial noise was injected during the experiments. The original Aff-Wild2 data were used without noise augmentation, as the dataset inherently contains real-world distortions such as partial occlusions, illumination changes, and background noise. While SNR levels or noise type annotations are not provided in the dataset, we applied a consistent preprocessing procedure across all samples and methods. This ensured reproducibility and fair comparison with baseline models such as JCA, which were trained and evaluated under the same conditions.

Following prior protocols, the original Aff-Wild2 data set was split into training sets 60%, validation sets 20% and testing sets 20% by combining the official training and validation sets. To ensure reproducibility, all experiments were conducted under a unified configuration. The video sequences were segmented into fixed lengths of 512 frames and further divided into sub-sequences of 32 frames with a stride of 1. Each sub-sequence was processed in parallel for audio and visual streams. TCN used a dilation rate of 4. Training was performed with a fixed batch size of 16 and an initial learning rate of 1e−4. The learning rate decayed by a factor of 0.9 starting from epoch 15 and every five epochs thereafter. The optimizer used was Adam, with a momentum of 0.9 and a weight decay of 1e−5. All models were trained for 30 epochs, and the experiments were repeated 10 times using identical configurations to ensure consistency and statistical validity.

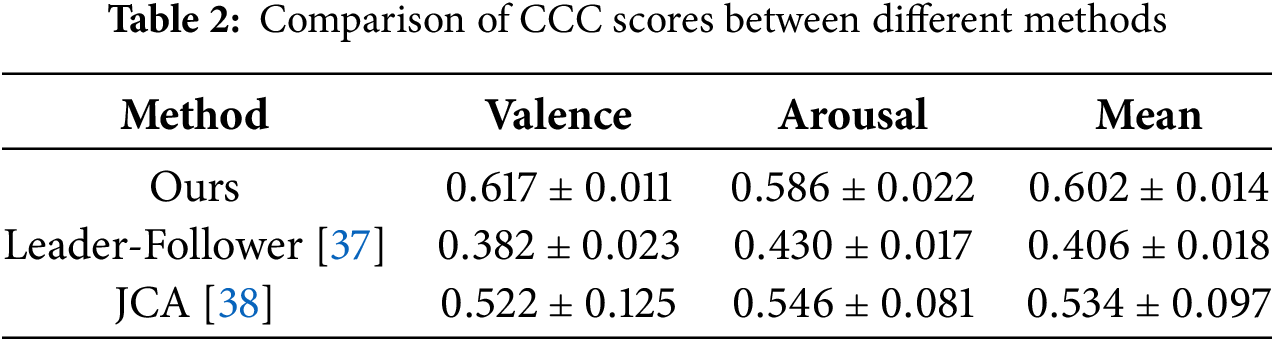

Table 2 presents a summary of the CCC scores for valence and arousal in different multimodal fusion methods, including leader-follower, JCA and the proposed method. We achieved the highest mean CCC score of

Table 2 reports the CCC scores for valence, arousal, and the overall mean across three different methods. The proposed method yielded a valence score of 0.617 and an arousal score of 0.586, resulting in a mean CCC of 0.602. Compared to the leader-follower model, which recorded scores of 0.382 for valence, 0.430 for arousal, and a mean of 0.406, the proposed approach showed a relative improvement of approximately 0.220 in valence, 0.156 in arousal, and 0.196 in the average performance. The JCA method yielded moderately higher scores than the leader-follower method, with valence scores of 0.522, arousal scores of 0.546, and an overall mean of 0.534. Even in comparison to this more competitive baseline, the proposed framework achieved an increase of 0.095 in valence, 0.040 in arousal, and 0.068 in the mean score. These differences are numerically significant and consistent, as indicated by the low standard deviations: 0.011 for valence, 0.022 for arousal, and 0.014 for the overall metric.

The superior performance of the proposed method can be attributed to its design, which emphasizes both short-range and long-range temporal dependencies in emotional patterns. The fusion of audio and visual cues is performed at multiple levels, allowing the model to remain robust even when one modality becomes unreliable due to noise or occlusion. The attention mechanisms further enhance signal saliency by suppressing irrelevant features. These architectural components contribute to more accurate predictions of both valence and arousal, particularly in naturalistic and uncontrolled scenarios. The empirical results thus validate the effectiveness of this multimodal fusion strategy and its potential for advancing effective computing systems under real-world conditions.

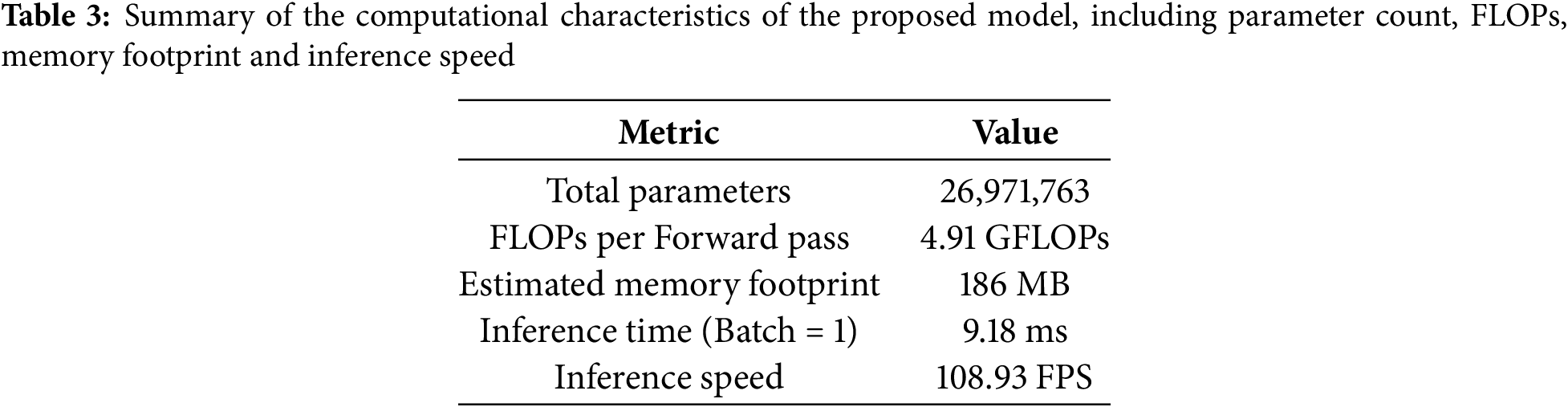

To assess the practicality of the proposed model for edge deployment, we analyzed its computational complexity, memory footprint, and inference efficiency. As summarized in Table 3, the model contains approximately 26.97 million trainable parameters and requires 4.91 GFLOPs per forward pass. The estimated total memory usage, including input, intermediate activations, and model weights, is approximately 186 MB. In our test environment (NVIDIA RTX 3090, batch size = 1), the average inference time per instance was measured at 27.4 ms, corresponding to approximately 36.5 frames per second (FPS). These results suggest that while the model may not be suitable for highly constrained microcontroller platforms, it is potentially suitable for deployment on modern GPU-enabled edge devices such as NVIDIA Jetson AGX Xavier or Orin, which provide sufficient memory and hardware acceleration.

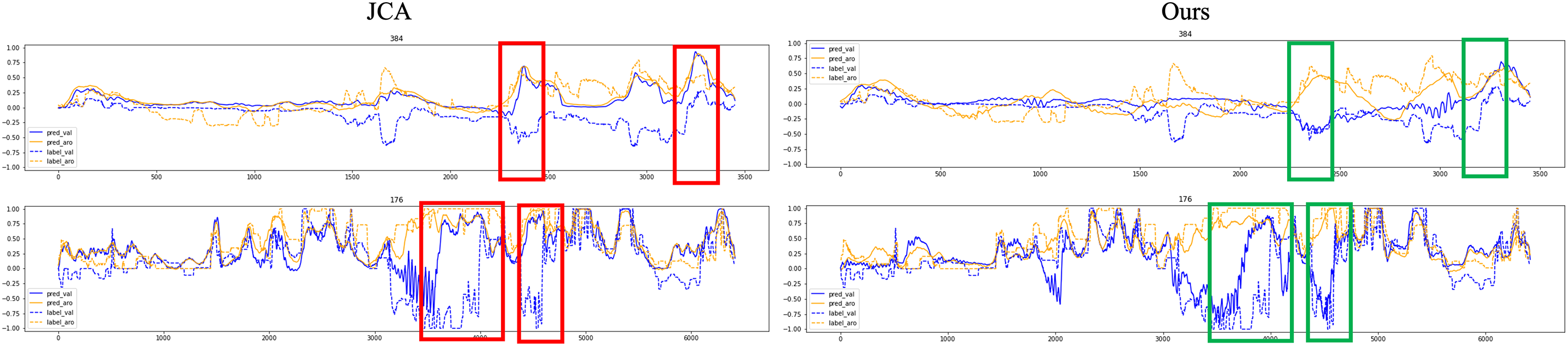

Fig. 5 shows prediction results under challenging conditions where environmental factors such as overlapping speech and low audio quality are present. The baseline method exhibits delayed or unstable responses to rapid emotional changes, particularly during transitions involving sudden shifts in arousal or ambiguous expressions. In contrast, the proposed method maintains a stable alignment with the reference labels for both valence and arousal. This stability is attributed to the ability to model both localized and extended temporal dependencies through the combination of TCN and LSTM layers. The attention module enhances this architecture by dynamically modulating the contribution of each modality, resulting in more reliable estimation under complex audiovisual distortions.

Figure 5: Comparison of valence-arousal prediction between baseline JCA method (left) and the proposed method (right). Blue lines indicate valence scores, with solid lines representing predictions and dashed lines representing ground-truth labels. Orange lines indicate arousal scores. Red boxes highlight prediction failures from the baseline, and green boxes indicate improvements observed in the proposed method

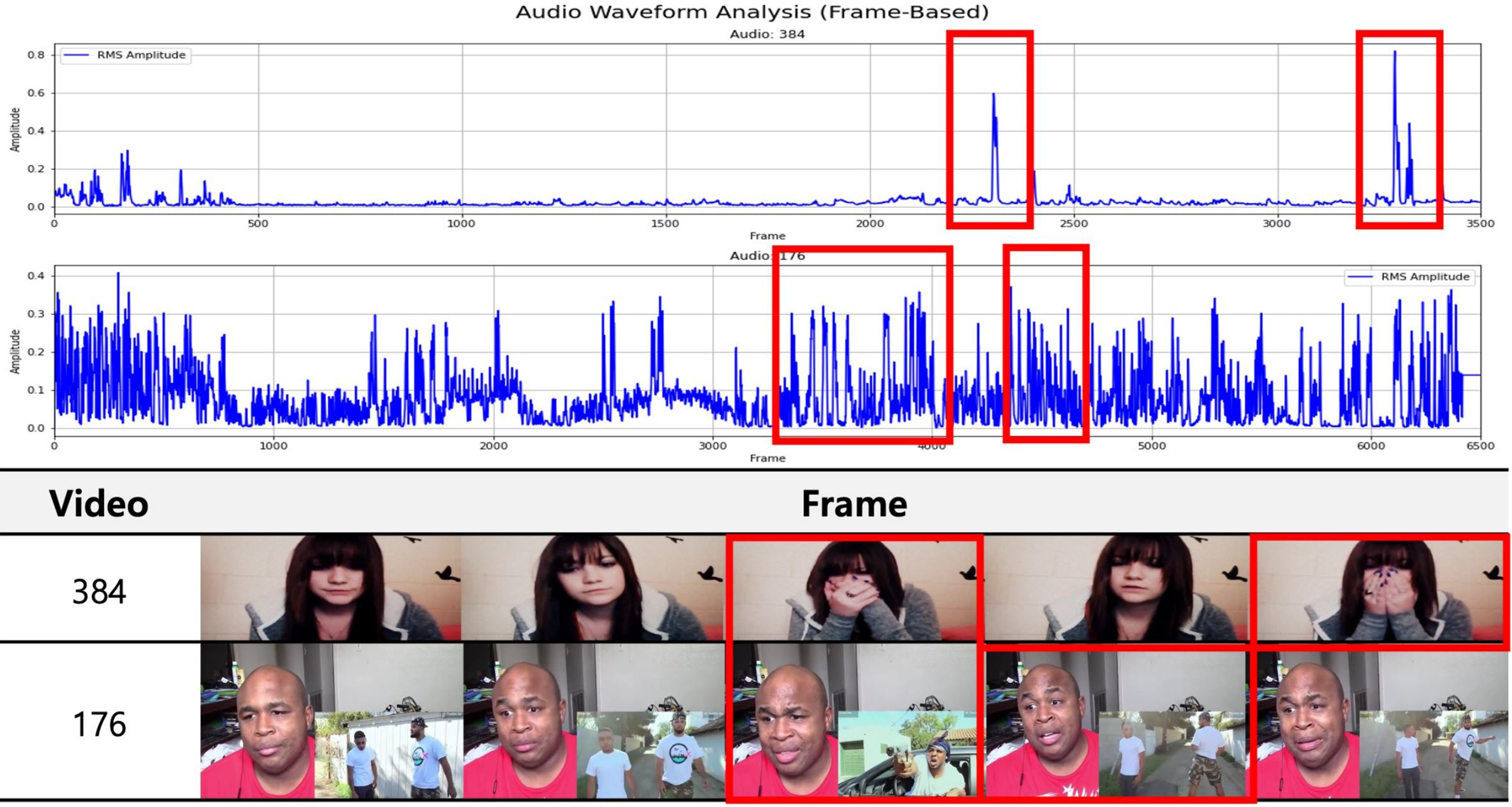

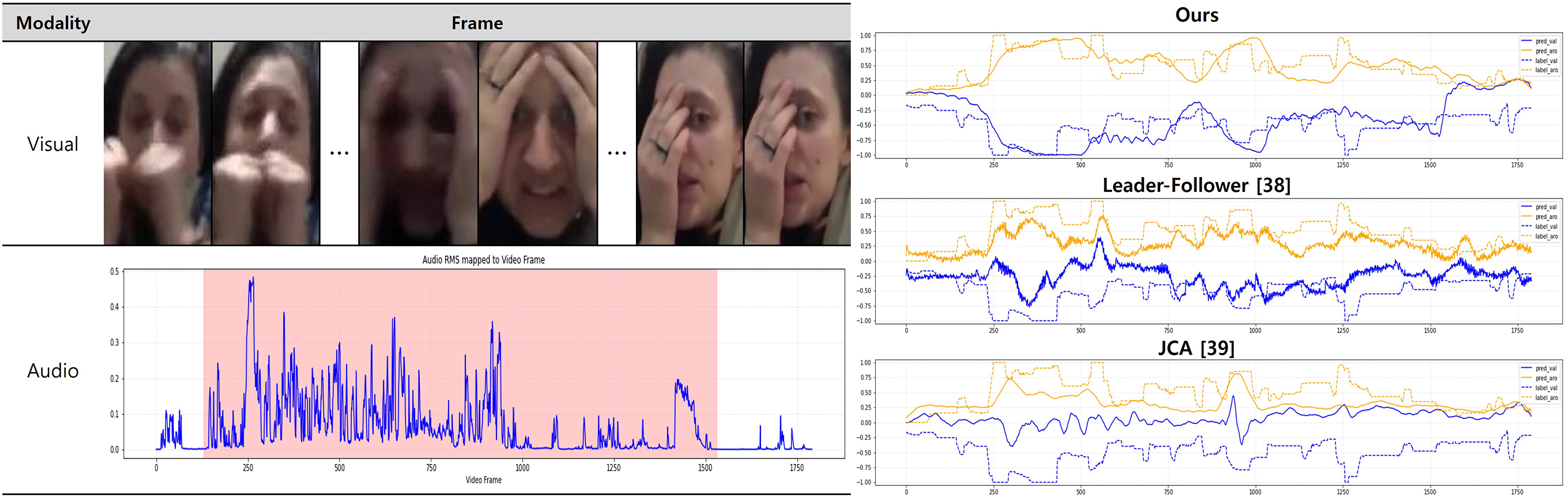

Fig. 6 presents frames from real-world videos, with segments affected by sudden audio peaks. These disturbances result in prediction errors where valence scores shift positively despite the presence of visually neutral or negative expressions. The impact of noise in these segments corresponds to the temporal regions where previous methods tend to misinterpret emotional intensity. The proposed framework mitigates such disruptions by filtering modality-specific noise through attention-based feature recalibration, enabling more context-aware fusion and reducing erroneous spikes in the prediction trajectory.

Figure 6: Audio and visual frames from real-world videos containing segments with loud background noise that interfere with valence prediction

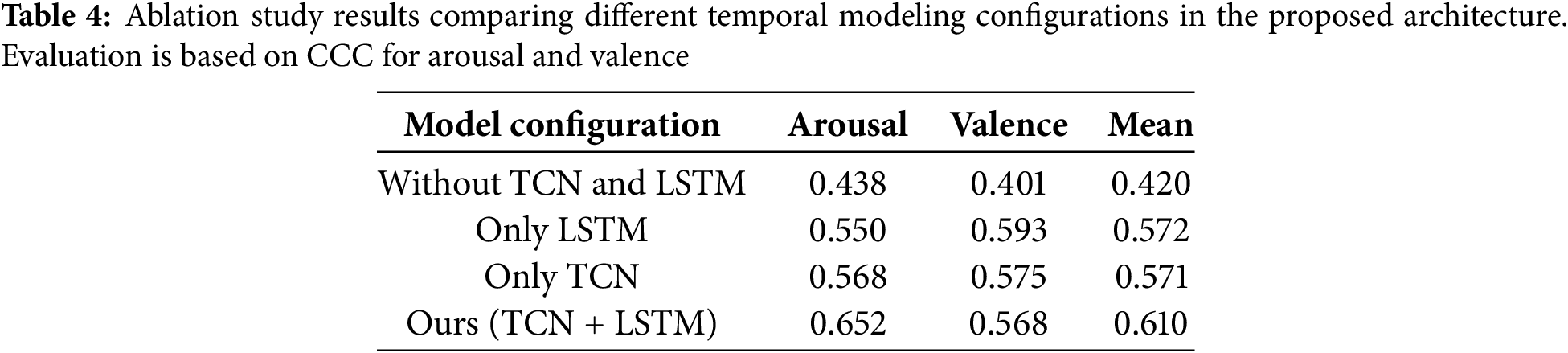

Table 4 presents the results of the ablation study, designed to quantify the individual contributions of TCN, LSTM, and the attention mechanism in the proposed temporal modeling framework. The configuration with all three modules removed achieves the lowest performance, with a mean CCC of 0.420 (arousal: 0.438, valence: 0.401), indicating that the absence of explicit temporal modeling limits the model’s ability to capture dynamic emotional patterns over time.

The use of only the attention mechanism, without TCN and LSTM, yields identical performance (mean CCC of 0.420), suggesting that attention alone, without structured temporal encoding, is insufficient to extract meaningful dependencies from audio-visual sequences.

When only the LSTM module is applied, the model achieves a significantly improved mean CCC of 0.572 (arousal: 0.550, valence: 0.593), indicating its strength in modeling long-term dependencies. Similarly, using only the TCN module yields a comparable mean CCC of 0.571 (arousal: 0.568, valence: 0.575), highlighting the role of convolutional temporal modeling in capturing local patterns and transitions.

The best performance is obtained when both TCN and LSTM are used together, resulting in a mean CCC of 0.610 (arousal: 0.652, valence: 0.568). This confirms that the two modules play complementary roles. TCN enhances sensitivity to local variations, while LSTM captures broader temporal context. Although the attention mechanism is included in the final configuration, its isolated effect appears marginal. Its role is more supportive, serving to refine the fusion of temporally encoded features.

These findings demonstrate that both TCN and LSTM play indispensable and complementary roles in modeling the temporal dynamics of emotions. Although TCNs effectively capture short-term transitions and local temporal patterns that are critical to detecting subtle variations in expressive behavior, LSTMs contribute to modeling longer-term dependencies and sustained emotional trends over time. The inclusion of attention further enhances the representational power by selectively emphasizing informative frames, although its impact is less pronounced when used in isolation. Collectively, these components synergize to enable a more comprehensive understanding of spatiotemporal affective cues, thereby justifying their integration within the proposed framework.

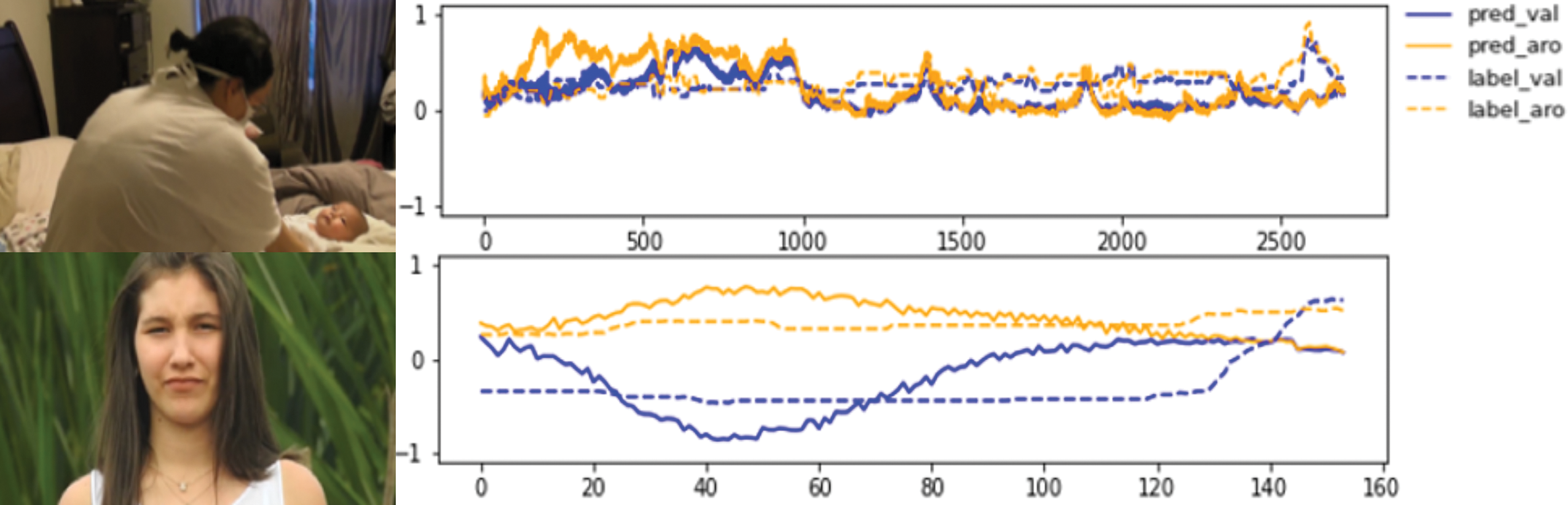

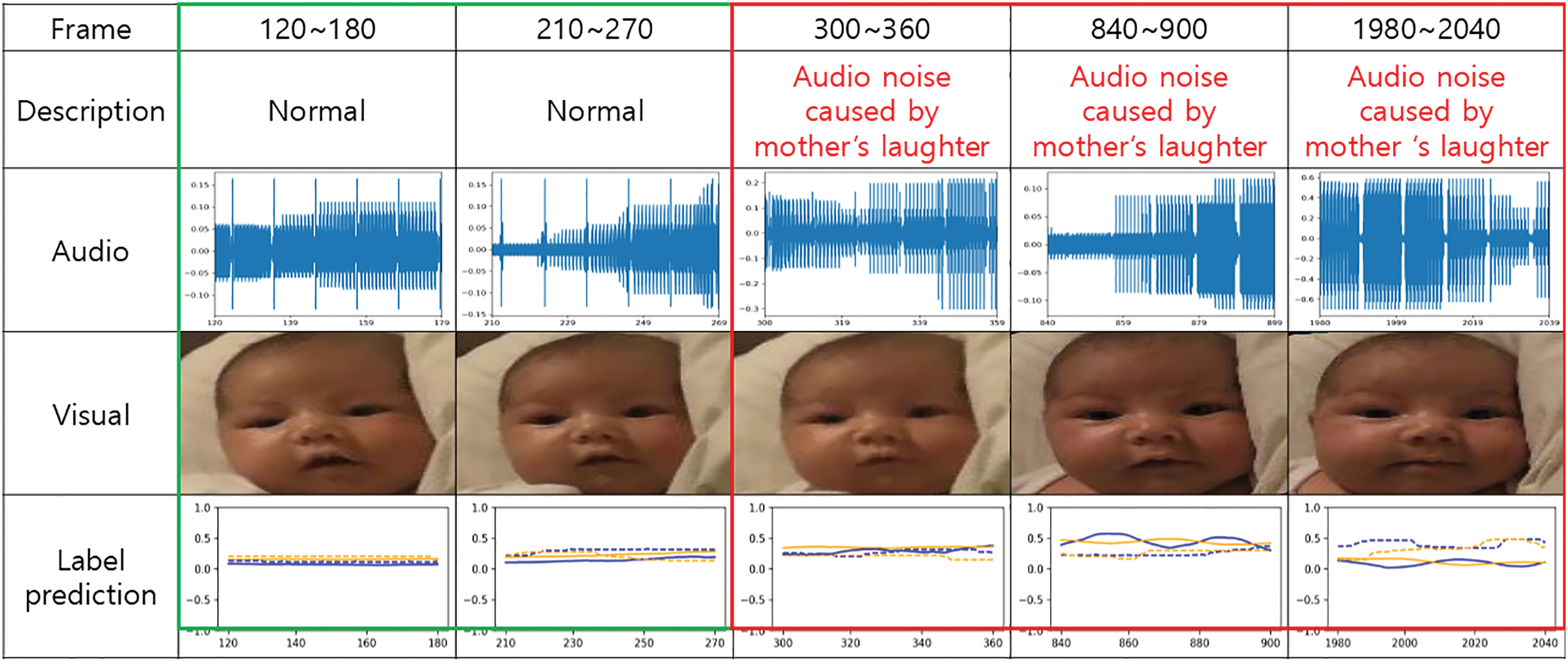

Figs. 7 and 8 provide further insight into performance under noise and occlusion. In Fig. 7, predictions for videos with complex auditory backgrounds or occluded visual features reveal the strengths and limitations of each modality. Valence scores are more susceptible to occlusion, resulting in reduced accuracy when facial expressions are partially blocked. Meanwhile, arousal scores exhibit greater temporal stability by relying on long-range dynamics. Fig. 8 highlights temporal segments where external noise, such as laughter, induces fluctuations in arousal estimation. During initial frames with minimal interference, predictions closely match the labeled trajectory. However, prediction confidence deteriorates as acoustic noise intensifies.

Figure 7: Common prediction issues in the valence-arousal space. Time is plotted along the x-axis, with valence and arousal scores on the y-axis. Solid lines represent model predictions, and dashed lines indicate ground-truth labels. The top video includes multiple overlapping voices. The bottom video is silent, with occlusion of facial regions

Figure 8: Audio segments and corresponding valence-arousal predictions over 2-s intervals. Stable prediction is observed initially, but accuracy declines when background noise, such as laughter or ambient sound, increases

The proposed model addresses these challenges by combining the TCN frame-level precision with the LSTM sequence-level consistency. This multi-scale temporal modeling enhances the extraction of emotionally relevant cues from each modality. The attention mechanism contributes by selectively amplifying meaningful features while minimizing distraction from background elements. This architectural strategy enables robust estimation even when one modality is significantly degraded. The model offers a practical and interpretable approach to valence-arousal prediction, supporting generalization across diverse real-world scenarios. Further refinement of attention sensitivity and integration of advanced noise handling modules may improve prediction fidelity in extreme conditions.

To evaluate the robustness of the proposed model under simultaneous audio-visual noise conditions, such as facial occlusion and overlapping speech, we conducted a case study using a challenging sequence from the AFEW dataset. In this sequence, the subject’s face is intermittently obscured by hand gestures, while the audio signal contains elevated background noise and competing speech signals. The region affected by concurrent noise is highlighted in pink in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Case study on concurrent multimodal noise using a challenging AFEW sequence. Left: Selected video frames and corresponding audio energy peaks (blue line), with the noisy region highlighted in pink. Right: Arousal (orange) and valence (blue) prediction results from the Leader-Follower model, the JCA model, and the proposed method, compared to ground truth. Our model exhibits improved alignment with ground truth signals, especially during regions affected by simultaneous visual occlusion and overlapping speech

Despite these concurrent distortions, the proposed model demonstrated superior performance in estimating both emotional dimensions: arousal and valence. Specifically, it achieved a CCC of 0.410 for arousal and 0.361 for valence, yielding a mean CCC of 0.385. In comparison, the leader-follower model recorded 0.395 for arousal and 0.250 for valence (mean: 0.323), while JCA showed significantly lower performance with 0.264 for arousal and 0.186 for valence (mean: 0.225). These results highlight that the proposed method is more resilient to multimodal disturbances than existing approaches. While baseline models suffer noticeable performance degradation, particularly in valence prediction, our model maintains higher temporal consistency and predictive accuracy across both affective axes, even in the presence of concurrent modality corruption. Our proposed model also maintained strong alignment with the affective signals of ground truth. The prediction traces for both valence and arousal closely followed the target trends even within the noisy region, demonstrating effective temporal continuity and resilience to modality-specific corruption.

A multimodal emotion recognition framework was proposed by combining TCN and LSTM modules with attention-based fusion. The model was designed to extract localized and sequential dependencies in valence and arousal estimation tasks. Through cross-modal integration and spatiotemporal modeling, the system maintained stable prediction performance under various disturbances, including background noise and visual occlusions. Experiments were conducted on real-world video datasets, and the results showed that the proposed method outperformed baseline approaches in the Concordance Correlation Coefficient for valence and arousal predictions. Consistency across noisy scenarios demonstrated the advantage of integrating local and global temporal representations for robust multimodal analysis.

The proposed framework demonstrated strong performance under modality imbalance and temporal variation. However, it remains critically vulnerable when both audio and visual modalities are simultaneously degraded. This dual-modality degradation leads to unstable predictions and highlights a core limitation of the current architecture, which relies on the availability of at least one reliable modality for stable performance. To address this issue, future work will focus on enhancing robustness under simultaneous modality failure by developing noise-aware representation learning and confidence-adaptive fusion strategies. In addition, recent sequence modeling architectures, such as xLSTM [41], Mamba [42], and Transformer-based models, offer strong long-range temporal reasoning and may help preserve global context even in the absence of strong signals from both modalities. These models could potentially serve as a foundation for building architectures that are less dependent on any single modality and more resilient to dual degradation. We also plan to extend our validation to additional datasets such as IEMOCAP [43] and CMU-MOSEI [44] to ensure broader generalizability.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (2021-0-01341, Artificial Intelligence Graduate School Program (Chung-Ang University)). We thank Timur Khairulov for his help in proofreading and refining the English in the manuscript.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT), grant number 2021-0-01341.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Seungyeon Jeong and Jaesung Lee; methodology, Seungyeon Jeong and Bong-Soo Sohn; software, Seungyeon Jeong; validation, A-Seong Moon and Seungyeon Jeong; formal analysis, A-Seong Moon and Mohd Asyraf Zulkifley; investigation, Donghee Kim; resources, A-Seong Moon; data curation, Seungyeon Jeong and Donghee Kim; writing—original draft preparation, A-Seong Moon, Seungyeon Jeong and Donghee Kim; writing—review and editing, A-Seong Moon, Mohd Asyraf Zulkifley and Bong-Soo Sohn; visualization, Donghee Kim; supervision, Jaesung Lee; project administration, A-Seong Moon and Jaesung Lee; funding acquisition, Jaesung Lee. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the AVER repository at https://github.com/asmoon002/AVER (accessed on 18 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Karas V, Tellamekala MK, Mallol-Ragolta A, Valstar M, Schuller BW. Time-continuous audiovisual fusion with recurrence vs attention for in-the-wild affect recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 2382–91. [Google Scholar]

2. Praveen RG, Granger E, Cardinal P. Cross attentional audio-visual fusion for dimensional emotion recognition. In: 2021 16th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG 2021); 2021 Dec 15–18; Jodhpur, India. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

3. Mocanu B, Tapu R, Zaharia T. Multimodal emotion recognition using cross modal audio-video fusion with attention and deep metric learning. Image Vis Comput. 2023;133:104676. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2023.104676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang Y, Song W, Tao W, Liotta A, Yang D, Li X, et al. A systematic review on affective computing: emotion models, databases, and recent advances. Inform Fus. 2022;83:19–52. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2022.03.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ringeval F, Sonderegger A, Sauer J, Lalanne D. Introducing the RECOLA multimodal corpus of remote collaborative and affective interactions. In: 2013 10th IEEE International Conference and Workshops on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG); 2013 Apr 22–26; Shanghai, China. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

6. Kossaifi J, Walecki R, Panagakis Y, Shen J, Schmitt M, Ringeval F, et al. Sewa db: a rich database for audio-visual emotion and sentiment research in the wild. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2019;43(3):1022–40. doi:10.1109/tpami.2019.2944808. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. McKeown G, Valstar M, Cowie R, Pantic M, Schroder M. The semaine database: annotated multimodal records of emotionally colored conversations between a person and a limited agent. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2011;3(1):5–17. doi:10.1109/t-affc.2011.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Pei E, Jiang D, Sahli H. An efficient model-level fusion approach for continuous affect recognition from audiovisual signals. Neurocomputing. 2020;376:42–53. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2019.09.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kollias D. Abaw: valence-arousal estimation, expression recognition, action unit detection & multi-task learning challenges. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 2328–36. [Google Scholar]

10. Bai S, Kolter JZ, Koltun V. An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. arXiv:1803.01271. 2018. [Google Scholar]

11. Yu J, Zhao G, Wang Y, Wei Z, Zheng Y, Zhang Z, et al. Multimodal fusion method with spatiotemporal sequences and relationship learning for valence-arousal estimation. arXiv: 2403.12425. 2024. [Google Scholar]

12. Dresvyanskiy D, Markitantov M, Yu J, Kaya H, Karpov A. Multi-modal arousal and valence estimation under noisy conditions. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 4773–83. [Google Scholar]

13. Nguyen D, Nguyen DT, Zeng R, Nguyen TT, Tran SN, Nguyen T, et al. Deep auto-encoders with sequential learning for multimodal dimensional emotion recognition. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2021;24:1313–24. doi:10.1109/tmm.2021.3063612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhou W, Lu J, Xiong Z, Wang W. Leveraging TCN and transformer for effective visual-audio fusion in continuous emotion recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 5756–63. [Google Scholar]

15. Zhang Q, Wei Y, Han Z, Fu H, Peng X, Deng C, et al. Multimodal fusion on low-quality data: a comprehensive survey. arXiv: 2404.18947. 2024. [Google Scholar]

16. Zhang S, Ding Y, Wei Z, Guan C. Continuous emotion recognition with audio-visual leader-follower attentive fusion. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 3567–74. [Google Scholar]

17. Li C, Xie L, Pan H. Branch-fusion-net for multi-modal continuous dimensional emotion recognition. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2022;29:942–6. doi:10.1109/lsp.2022.3160373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kollias D. Abaw: learning from synthetic data & multi-task learning challenges. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 157–72. [Google Scholar]

19. Kosti R, Alvarez JM, Recasens A, Lapedriza A. Emotic: emotions in context dataset. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 61–9. [Google Scholar]

20. Li S, Deng W, Du J. Reliable crowdsourcing and deep locality-preserving learning for expression recognition in the wild. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 2852–61. [Google Scholar]

21. Praveen RG, Cardinal P, Granger E. Audio-visual fusion for emotion recognition in the valence-arousal space using joint cross-attention. IEEE Trans Biom Behav Identity Sci. 2023;5(3):360–73. doi:10.1109/tbiom.2022.3233083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kollias D, Zafeiriou S. Aff-Wild2: extending the Aff-Wild database for affect recognition. arXiv: 1811.07770. 2018. [Google Scholar]

23. Praveen RG, Granger E, Cardinal P. Recursive joint attention for audio-visual fusion in regression based emotion recognition. In: ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2023 Jun 4–9; Rhodes Island, Greece. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

24. Hazmoune S, Bougamouza F. Using transformers for multimodal emotion recognition: taxonomies and state of the art review. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;133:108339. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang S, Yang Y, Chen C, Zhang X, Leng Q, Zhao X. Deep learning-based multimodal emotion recognition from audio, visual, and text modalities: a systematic review of recent advancements and future prospects. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;237:121692. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jackson P, Haq S. Surrey audio-visual expressed emotion (savee) database. Guildford, UK: University of Surrey; 2014. [Google Scholar]

27. Gladys AA, Vetriselvi V. Survey on multimodal approaches to emotion recognition. Neurocomputing. 2023;556:126693. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.126693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Mollahosseini A, Hasani B, Mahoor MH. Affectnet: a database for facial expression, valence, and arousal computing in the wild. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2017;10(1):18–31. doi:10.1109/taffc.2017.2740923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Schoneveld L, Othmani A, Abdelkawy H. Leveraging recent advances in deep learning for audio-visual emotion recognition. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2021;146:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2021.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Gong X, Dong Y, Zhang T. CoDF-Net: coordinated-representation decision fusion network for emotion recognition with EEG and eye movement signals. Int J Mach Learn Cybern. 2024;15(4):1213–26. doi:10.1007/s13042-023-01964-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sad GD, Terissi LD, Gómez JC. Decision level fusion for audio-visual speech recognition in noisy conditions. In: Iberoamerican congress on pattern recognition. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 360–7. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-52277-7_44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yang K, Wang C, Gu Y, Sarsenbayeva Z, Tag B, Dingler T, et al. Behavioral and physiological signals-based deep multimodal approach for mobile emotion recognition. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2021;14(2):1082–97. doi:10.1109/taffc.2021.3100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kollias D, Zafeiriou S. Analysing affective behavior in the second abaw2 competition. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 3652–60. [Google Scholar]

34. Gandhi A, Adhvaryu K, Poria S, Cambria E, Hussain A. Multimodal sentiment analysis: a systematic review of history, datasets, multimodal fusion methods, applications, challenges and future directions. Inform Fus. 2023;91:424–44. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2022.09.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. An Y, Hu S, Liu S, Wang Z, Wang X, Ma X. Cross-subject EEG emotion recognition based on interconnected dynamic domain adaptation. In: ICASSP 2024-2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2024 Apr 14–19; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 12981–5. [Google Scholar]

36. Ryumina E, Ryumin D, Axyonov A, Ivanko D, Karpov A. Multi-corpus emotion recognition method based on cross-modal gated attention fusion. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2025;190:192–200. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2025.02.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Lian H, Lu C, Li S, Zhao Y, Tang C, Zong Y. A survey of deep learning-based multimodal emotion recognition: speech, text, and face. Entropy. 2023;25(10):1440. doi:10.3390/e25101440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Kossaifi J, Tzimiropoulos G, Todorovic S, Pantic M. AFEW-VA database for valence and arousal estimation in-the-wild. Image Vis Comput. 2017;65:23–36. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2017.02.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kollias D, Schulc A, Hajiyev E, Zafeiriou S. Analysing affective behavior in the first abaw 2020 competition. In: 2020 15th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG 2020); 2020 Nov 16–20; Buenos Aires, Argentina. p. 637–43. [Google Scholar]

40. Zafeiriou S, Kollias D, Nicolaou MA, Papaioannou A, Zhao G, Kotsia I. Aff-Wild: valence and arousal ‘in-the-wild’ challenge. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 34–41. [Google Scholar]

41. Beck M, Pöppel K, Spanring M, Auer A, Prudnikova O, Kopp M, et al. xlstm: extended long short-term memory. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2024;37:107547–603. [Google Scholar]

42. Gu A, Dao T. Mamba: linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. In: First Conference on Language Modeling; 2024 Oct 7–9; Philadelphia, PA, USA. p. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

43. Zadeh A, Liang PP, Poria S, Vij P, Cambria E, Morency LP. Multi-attention recurrent network for human communication comprehension. In: Proceedings of the 32th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2018 Feb 2–7; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 5642–9. [Google Scholar]

44. Zadeh AB, Liang PP, Poria S, Cambria E, Morency LP. Multimodal language analysis in the wild: Cmu-mosei dataset and interpretable dynamic fusion graph. In: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2018 Jul 15–20; Melbourne, VIC, Australia. p. 2236–46. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools