Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Deep Learning Models for Detecting Cheating in Online Exams

1 Multidisciplinary Faculty of Nador, Mohammed Premier University, Oujda, 60000, Morocco

2 Laboratory LaSTI, ENSAK, Sultan Moulay Slimane University, Khouribga, 54000, Morocco

3 Department of Information Technology, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

4 College of Computer and Information Sciences, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, 11586, Saudi Arabia

5 EIAS Data Science Lab, College of Computer and Information Sciences, and Center of Excellence in Quantum and Intelligent Computing, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, 11586, Saudi Arabia

6 Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Faculty of Science, Menoufia University, Shebin El-Koom, 32511, Egypt

* Corresponding Author: Yassine Maleh. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3151-3183. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067359

Received 01 May 2025; Accepted 16 June 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

The rapid shift to online education has introduced significant challenges to maintaining academic integrity in remote assessments, as traditional proctoring methods fall short in preventing cheating. The increase in cheating during online exams highlights the need for efficient, adaptable detection models to uphold academic credibility. This paper presents a comprehensive analysis of various deep learning models for cheating detection in online proctoring systems, evaluating their accuracy, efficiency, and adaptability. We benchmark several advanced architectures, including EfficientNet, MobileNetV2, ResNet variants and more, using two specialized datasets (OEP and OP) tailored for online proctoring contexts. Our findings reveal that EfficientNetB1 and YOLOv5 achieve top performance on the OP dataset, with EfficientNetB1 attaining a peak accuracy of 94.59% and YOLOv5 reaching a mean average precision (mAP@0.5) of 98.3%. For the OEP dataset, ResNet50-CBAM, YOLOv5 and EfficientNetB0 stand out, with ResNet50-CBAM achieving an accuracy of 93.61% and EfficientNetB0 showing robust detection performance with balanced accuracy and computational efficiency. These results underscore the importance of selecting models that balance accuracy and efficiency, supporting scalable, effective cheating detection in online assessments.Keywords

Examinations serve as a cornerstone of educational assessment, rigorously evaluating students’ comprehension, skills, and abilities across diverse subject areas. Traditionally administered within controlled, in-person settings, exams have been widely recognized as a credible measure of academic achievement, as well as a crucial determinant of students’ academic and professional pathways [1]. With the recent, unprecedented shift to online learning [2], educational institutions worldwide have been compelled to reimagine and adapt these evaluative frameworks. This transition, often to digital assessment platforms, has fundamentally transformed the nature of the assessment process, introducing critical challenges to maintaining fairness, equity, and academic honesty [3–5].

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the widespread adoption of remote examinations, exposing inherent vulnerabilities within the online assessment environment [6,7]. Studies have highlighted a marked increase in cheating behaviors during online exams, underscoring the limitations of remote proctoring in preventing dishonest practices [8,9]. In the absence of physical oversight, combined with the high-stakes nature of assessments, students may be incentivized to exploit digital tools for assistance. The pervasive availability of internet resources, mobile devices, and screen-sharing technologies compounds this issue, posing significant risks to the credibility of exam outcomes and the integrity of academic assessments [10].

Several studies attribute the surge in online exam cheating to a range of factors, including environmental variables, institutional pressures, and the distinct challenges inherent to remote assessments [11]. As online education expands, ensuring the reliability of remote assessments has become a critical priority. However, existing solutions such as browser lockdown tools [12,13], identity verification processes [14], live proctoring [15], and 360 degree monitoring face notable limitations [16]. These methods often suffer from restricted dataset diversity, lack of real-time adaptability, and limited flexibility in addressing the wide array of cheating tactics that students may employ. Additionally, these approaches can be intrusive and challenging to implement consistently, particularly when external environmental factors are difficult to control, thus highlighting persistent gaps in the current strategies for online exam proctoring.

To address these challenges, the present study conducts an in-depth evaluation of various pre-trained deep learning models, leveraging two benchmark datasets specifically tailored for online proctoring contexts. By critically analyzing the performance, accuracy, and real-time adaptability of these models, this research aims to identify optimal approaches that achieve a balance between detection efficacy and computational efficiency. The findings presented herein offer valuable insights into the development of robust, scalable models that are capable of strengthening academic integrity within remote assessment environments.

The contributions of this paper are as follows:

• Comprehensive Comparison of Deep Learning Models for Cheating Detection: This study provides an in-depth comparative analysis of advanced deep learning models, including EfficientNet, MobileNetV2, and ResNet variants, specifically evaluating their effectiveness in detecting cheating behaviors in online exams.

• Evaluation on Diverse Benchmark Datasets: By utilizing two distinct, specialized datasets (OEP and OP), the study ensures robust model assessment across varied online proctoring scenarios, contributing to a more generalized understanding of model performance in real-world online exam environments.

• Guidelines for Model Selection Based on Accuracy and Efficiency: The paper offers valuable insights into model selection by balancing performance metrics like accuracy, F1 score, and computational efficiency, aiding institutions in choosing appropriate models for real-time proctoring systems based on their unique resource constraints.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related works, providing an overview of existing methodologies and their limitations. Section 3 details the datasets and classification methods used in this study. In Section 4, we present evaluation metrics, experimental results, and an analysis of our findings. Then, we discuss the results in Section 5, followed by the presentation of our work’s limitations in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 offers conclusions and suggests directions for future research.

This section provides an overview of recent systems for cheating detection in online examinations, highlighting the application of machine learning, deep learning, and computer vision methodologies for visual analysis and behavioral surveillance.

Liu et al. [8] proposed a framwork named CHEESE for identifying academic dishonesty in online examinations by multiple instance learning (MIL) and spatio-temporal graph analysis. They introduced an innovative weakly supervised method that combines body posture, gaze, head movement, and face data, obtained from OpenFace 2.0 and 3D convolutional networks, to identify spatio-temporal abnormalities in video recordings. Evaluated on the Online Exam Proctoring (OEP) dataset of 65 aberrant and 69 normal videos, CHEESE attained an AUC of 87.58%, surpassing leading methodologies. The model exhibited robust performance on additional anomaly detection datasets, achieving 80.56% AUC on UCF-Crime and 90.79% on ShanghaiTech Dataset.

Ramzan et al. [17] evaluated the efficacy of pre-trained convolutional neural networks in identifying anomalous behaviors during online examinations, specifically cheating behaviors. Key video frames were recovered by motion-based approaches, and deep learning models, including YOLOv5, DenseNet121, and Inception-V3, were utilized to categorize cheating behaviors, such as head movements or the use of external devices. The YOLOv5 model attained superior performance, with a precision of 95.54%, a recall of 93.16%, and a mean average precision (mAP) of 95.40%, outpacing alternative methods in identifying cheating behaviors during online examinations.

Kaddoura and Gumaei [18] suggested a deep learning method for detecting cheating in online examinations using video frames and speech analysis. Their approach incorporates three essential modules: front camera detection, rear camera detection, and speech-based detection, utilizing CNN and Gaussian-based DFT for real-time cheating classification. The system was tested on the OEP dataset, which comprised data from 24 students, achieving an accuracy of 99.83% for front camera recognition and 98.78% for back camera detection.

Nurpeisova et al. [19] created the Proctor SU system, an automated online proctoring technology aimed at improving the integrity of examinations in the higher education sector in Kazakhstan. The system incorporates AI technologies like face detection, facial recognition, and behavioral analysis, employing models such as CNN, R-CNN, and YOLOv3 for real-time surveillance. The system, evaluated at Seifullin Kazakh Agro Technical University, analyzed 5000 photos with a detection rate of 97.12%.

Ozdamli et al. [20] created a facial recognition system to assess student emotions and identify cheating in remote learning settings. Their approach employed computer vision and deep learning technologies, such as CNN, to assess face expressions and actions during online examinations. The system, evaluated using datasets such as FER and FEI Face Database, attained an accuracy of 99.38% for student recognition and 66% for emotion detection. Furthermore, it monitored gaze direction and head motions to identify cheating, achieving a gaze tracking model accuracy of 96.95%.

Hu et al. [21] devoloped a multi-perspective adaptive cheating detection system for online examinations, employing three cameras (overhead, horizontal, and frontal views). The system integrates a gaze recognition model, detects cheating tools, and behavior analysis to enhance monitoring. The system employs datasets of 3000 photos for gaze direction and 7600 overhead and 8899 horizontal perspective images for detecting cheating tools, dynamically adjusting perspectives according to gaze direction. It attained 95% accuracy, providing an efficient and immediate method for mitigating cheating in digital examinations.

Dang et al. [22] developed an AI-driven auto-proctoring system intended for incorporation into MOOCs, emphasizing the identification of dishonest conduct during online assessments. The system integrates facial recognition, mobile device detection, and head posture estimation, employing deep learning models like RetinaFace and YOLOv10 for precise identification. Their system, evaluated on 4311 films from actual examinations, attained a remarkable accuracy of 95.66%, with an average reaction time of 0.517 s.

Potluri et al. [23] presented an automated AI-driven online proctoring system utilizing Attentive-Net to identify student misconduct during tests. The system has four modules: facial detection, multiple individual detection, facial spoofing, and head posture estimation. The authors employed the CIPL dataset alongside a bespoke dataset of over 200 movies exhibiting diverse behaviors to assess their model. Their technique attained an accuracy of 87% utilizing the Attentive-Net in conjunction with the Liveness Net and head position estimation.

Several studies have concentrated on cheating detection systems for online examinations, incorporating facial recognition, object detection, and head and gaze tracking methods. Authors in [24,25] both employed YOLOv3 for object detection in their systems. They introduced a system that combines facial recognition, tracking head movements, identifying objects, gaze and mouth tracking, background analysis, etc. Achieving an accuracy surpassing 80% in gaze tracking, mouth supervision, and object detection. Singh et al. [26] similarly utilized YOLO to detect dishonest activities, including face recognition, mouth tracking, and mobile device detection, to ensure academic integrity during virtual assessments.

Roy and Chanda [27] focused on developing a cost-effective, webcam-based eye-gaze estimation system for human-computer interaction (HCI) using a convolutional neural network (CNN) and Mediapipe for real-time facial identification. Parkhi et al. [28] developed a comprehensive examination monitoring system leveraging deep learning, incorporating face detection, face spoofing detection, object detection (YOLO), eye tracking, and head-pose estimation. Their system achieved a 90% success rate in tracking face and head movements. Gadkar et al. [29] presented an automated proctoring system that incorporates facial recognition, mouth aspect ratio analysis for speech detection, and audio detection to identify suspicious phrases or multiple individuals in the frame, using Haar cascade for face detection.

In terms of anomaly detection, Atabay and Hassanpour [30] proposed a semi-supervised method for online exam proctoring based on skeletal similarity. Their system segments exam videos by evaluating skeletal features and computing the similarity between training and test segments to identify abnormal behavior.

Other approaches focus on human pose estimation. Samir et al. [31] utilized TensorFlow PoseNet to monitor head positions and hand motions in real-time, achieving detection accuracies of 94% for head posture and 97% for hand motions.

This section outlines the proposed benchmarking approaches. To clearly illustrate the implementation flow of our proposed cheating detection framework, we provide the following pseudocode (see Algorithm 1), which outlines the key steps involved—from data preprocessing and annotation to model training and evaluation. The process begins by extracting frames from the input videos, followed by manual annotation of those frames based on observed behaviors. The data is then split into training, validation, and testing subsets. Finally, a selected deep learning model (e.g., EfficientNet, ResNet, or YOLOv5) is trained using the labeled data and evaluated on unseen samples to detect cheating behavior. This structured pipeline ensures a reproducible and transparent methodology.

In this study, we employ two benchmarking datasets, capturing diverse exam behaviors and cheating activities (see Fig. 1). These datasets are crucial for training machine learning models to enhance online examination integrity.

Figure 1: Representative sample images from the OEP and OP datasets

3.1.1 Automated Online Exam Proctoring (OEP)

The OEP dataset [32] from CVLab at Michigan State University consists of video and audio recordings of exam sessions, recorded using webcams from 24 subjects, to replicate diverse testing settings that include both standard exam conduct and particular cheating behaviors. Every recording is meticulously annotated to emphasize key behaviors, including eye movements, head position, auditory signals, and ambient alterations, which are vital for the automatic identification of probable cheating. The dataset is organized to support machine learning applications, including labeled instances for supervised learning and baseline data for unsupervised techniques. This dataset is crucial for the advancement of AI-driven proctoring solutions, improving the integrity of online tests.

3.1.2 Online Proctoring Dataset (OP)

The Proctor-Dataset [33] comprises 200 videos that capture a range of examinee behaviors during online examinations. The dataset contains videos depicting both proper conduct and various forms of cheating behavior. Some videos showcase a combination of misbehavior types, while others specifically capture candidates looking at other screens, using devices for assistance, or conversing with individuals. This annotated dataset, designed for deep learning frameworks, enables ProctorNet to reliably detect a range of suspicious behaviors.

Table 1 presents the main features of online exam proctoring datasets, including data types, duration, annotated behaviors, and application domains.

The datasets employed in this study consist of video files that were systematically converted into individual frames to facilitate their application in model training. Each video was segmented into discrete frames, enabling a precise manual classification of each frame into one of two categories: cheating and not cheating. This classification process was essential in constructing a well-defined labeled dataset, serving as the basis for effective model training and thorough evaluation. Subsequently, the classified frames were allocated into distinct subsets designated for training and validation, ensuring a balanced dataset structure that supports rigorous performance assessment and reliable validation of the models developed in this research.

The classification of samples into “Cheating” and “No Cheating” categories was a critical step in preparing the datasets (OEP and OP) for supervised learning. Initially, each video was decomposed into individual image frames at a fixed sampling rate, ensuring a consistent temporal representation of student behavior. The classification process was conducted manually by domain experts familiar with online proctoring standards, using behavior-based annotation criteria.

For the OEP dataset, classification decisions were based on observable actions such as eye movement irregularities (e.g., repeated glancing away from the screen), unusual head positions, presence of additional auditory signals (e.g., background conversation or device sounds), and environmental changes (e.g., another person entering the frame). Frames depicting these behaviors were labeled as “Cheating,” while those showing the student facing the screen with stable gaze and a quiet, controlled environment were labeled as “No Cheating”.

In the case of the OP dataset, the criteria extended to include more diverse cheating scenarios such as use of mobile phones, visible interaction with unauthorized individuals, and frequent attention shifts toward off-screen devices. Each image frame was visually inspected and categorized accordingly.

To facilitate machine-readable labeling, we used the LabelImg annotation tool to create bounding boxes around suspicious regions (e.g., the student’s face, hands, or surrounding objects) and assign class labels. Each labeled image was stored with its corresponding XML or YOLO-format file, indicating the category (“Cheating” or “No Cheating”) and the location of the observed behavior. In total, 11,581 images from the OEP dataset and 9609 from the OP dataset were annotated.

These annotated samples were then divided into training (70%), validation (20%), and test (10%) sets while preserving the class distribution. This well-structured and behavior-informed classification pipeline enabled the deep learning models to learn fine-grained distinctions between normal and suspicious activities, thereby enhancing the robustness and accuracy of the cheating detection systems.

3.3 Pre-Trained Deep Learning Algorithms

• Convolutional Neural Network [34] is a deep learning model particularly well-suited for image and video analysis due to its capability to automatically learn spatial hierarchies of features. CNNs consist of multiple layers, including convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers, which together capture and combine various visual patterns.

Key Parameters:

– Conv2D Layers: Filters = {32, 64, 128, 256}; Kernel Size = (3, 3); Stride = (1, 1)

– MaxPooling2D: Pool Size = (2, 2); Stride = (2, 2)

– Dense Layers: Units = 512

– Dropout Rate: 0.1

The convolution operation at the core of CNNs involves a sliding kernel applied to the input matrix, computing element-wise multiplications and summing the results. Formally:

where

Max pooling then reduces spatial dimensions, enhancing computational efficiency by retaining only the highest value in each pooling window:

• MobileNetV2 [35] is a lightweight convolutional neural network optimized for mobile and embedded vision applications, utilizing depthwise separable convolutions to significantly reduce the number of parameters while maintaining accuracy. The model applies depthwise convolutions with filters of sizes 32, 64, and 128, where each channel is convolved independently, followed by a pointwise convolution with a (1, 1) kernel size. It incorporates a dropout rate of 0.2 to prevent overfitting. The architecture consists of an input layer of shape (224, 224, 3), a preprocessing layer using MobileNetV2’s preprocess_input function, and a frozen MobileNetV2 base producing an output of shape (7, 7, 1280). A GlobalAveragePooling2D layer is followed by a dropout layer (rate = 0.2) and two dense layers—one with 128 ReLU-activated units and an output layer with a single sigmoid-activated unit. Depthwise convolution applies filters to each input channel individually, while the subsequent pointwise convolution refines feature extraction using a weight matrix.

• ResNet50 and ResNet101 [36] tackle the vanishing gradient problem in deep networks using skip connections, which allow gradients to bypass certain layers, ensuring stable training. ResNet50 and ResNet101 contain 50 and 101 layers, respectively, facilitating deep feature extraction while maintaining efficiency. Each residual block consists of convolutional layers with filters of sizes {64, 128, 256, 512} and a kernel size of (3, 3), followed by batch normalization and ReLU activation. The residual connection is mathematically expressed as:

where

• EfficientNetB0 and EfficientNetB1 [37] achieve optimal accuracy and efficiency through compound scaling, which uniformly increases the depth, width, and resolution. EfficientNetB0 and EfficientNetB1 differ slightly in scale, with B1 having a slightly larger network size and higher accuracy. Each model consists of convolutional layers with filters of sizes {32, 64, 128, 256}, and scaling coefficients

where

• ConvNeXt [38] is a modernized CNN that integrates design principles from transformer architectures, such as layer normalization and residual connections, to enhance performance on computer vision tasks. It consists of convolutional layers with filters of sizes {32, 64, 128, 256}, utilizing GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit) as the activation function and layer normalization for stabilization. Layer normalization ensures stable training by normalizing each layer’s output, expressed mathematically as:

where

• SE-ResNet [39] enhances ResNet by incorporating Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks that recalibrate channel-wise feature responses, allowing the network to focus on the most informative channels. The SE block consists of an excitation layer composed of dense layers with ReLU and sigmoid activations, while a reduction ratio controls the bottleneck in the SE block. The squeeze operation computes global channel-wise statistics as follows:

where H and W denote the height and width of the feature maps. This is followed by an excitation operation that selectively enhances important features:

where

• ResNet50-CBAM enhances ResNet50 by incorporating a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [40], which refines feature learning by focusing on both channel and spatial dimensions to highlight relevant information. The attention module consists of channel and spatial attention blocks, utilizing the Exponential Linear Unit (ELU) activation function. Channel attention emphasizes significant channels and is computed as:

where

where

• Swin Transformer [41] is a vision transformer model tailored for computer vision tasks. It segments images into non-overlapping patches and applies self-attention within these patches, enhancing computational efficiency and scalability. The model hierarchically merges patches across layers, allowing for multi-scale feature representations. Key parameters include a patch size of (4, 4), a window size of 7, and attention heads ranging from 8 to 32. The self-attention mechanism within each window is computed as:

where Q, K, and V represent the query, key, and value matrices, respectively, and

• YOLOv5: YOLO [42] is a family of deep learning models optimized for real-time object detection, striking an effective balance between speed and accuracy. This model utilizes a 640 × 640 pixel image resolution, a batch size of 16, and is trained over 70 epochs to ensure optimal learning. It has been fine-tuned to detect cheating in a binary classification setting, distinguishing between cheating and not cheating.

For each detected instance, the YOLOv5s model outputs:

– Bounding box coordinates

– Confidence score

– Class probabilities

The final score for a class-specific detection is calculated as:

This study examines the effectiveness of various deep learning algorithms—including CNN, MobileNetV2, ResNet50, ResNet101, EfficientNetB0, EfficientNetB1, ConvNeXt, ResNet50_CBAM, SeResNet, Swin Transformer, and YOLOv5—in identifying cheating behaviors during online examinations. Two datasets were utilized in the experiments. Each dataset was divided into 70% for training, 20% for validation, and 10% for testing to ensure optimal training and assessment.

The implementation was carried out using Python version 3.11 on a personal computer using an Intel Core i7-11800H CPU at 2.30 GHz and 16 GB of RAM. To accelerate the training process, the models utilized GPU resources from Google Colaboratory, notably an NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU, which enabled efficient model optimization and faster convergence.

To assess the performance of a machine learning model in the context of cheating detection, a range of metrics are employed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the model’s effectiveness, efficiency, and reliability.

• Accuracy

• Recall

• Precision

• F1-score

• Confusion Matrix

• Mean Average Precision at IoU Threshold 0.5

• Mean Average Precision at IoU Range 0.5 to 0.95

• Inference Time

• Training Time

• Prediction Time

4.3 Result Analysis and Discussion

This section provides an in-depth assessment of the proposed deep learning models aimed at detecting cheating behavior in online examinations. It encompasses a detailed overview of the experimental setup, an in-depth discussion of the evaluation metrics utilized, and a comprehensive presentation of the results obtained.

4.3.1 Performance on OEP Dataset

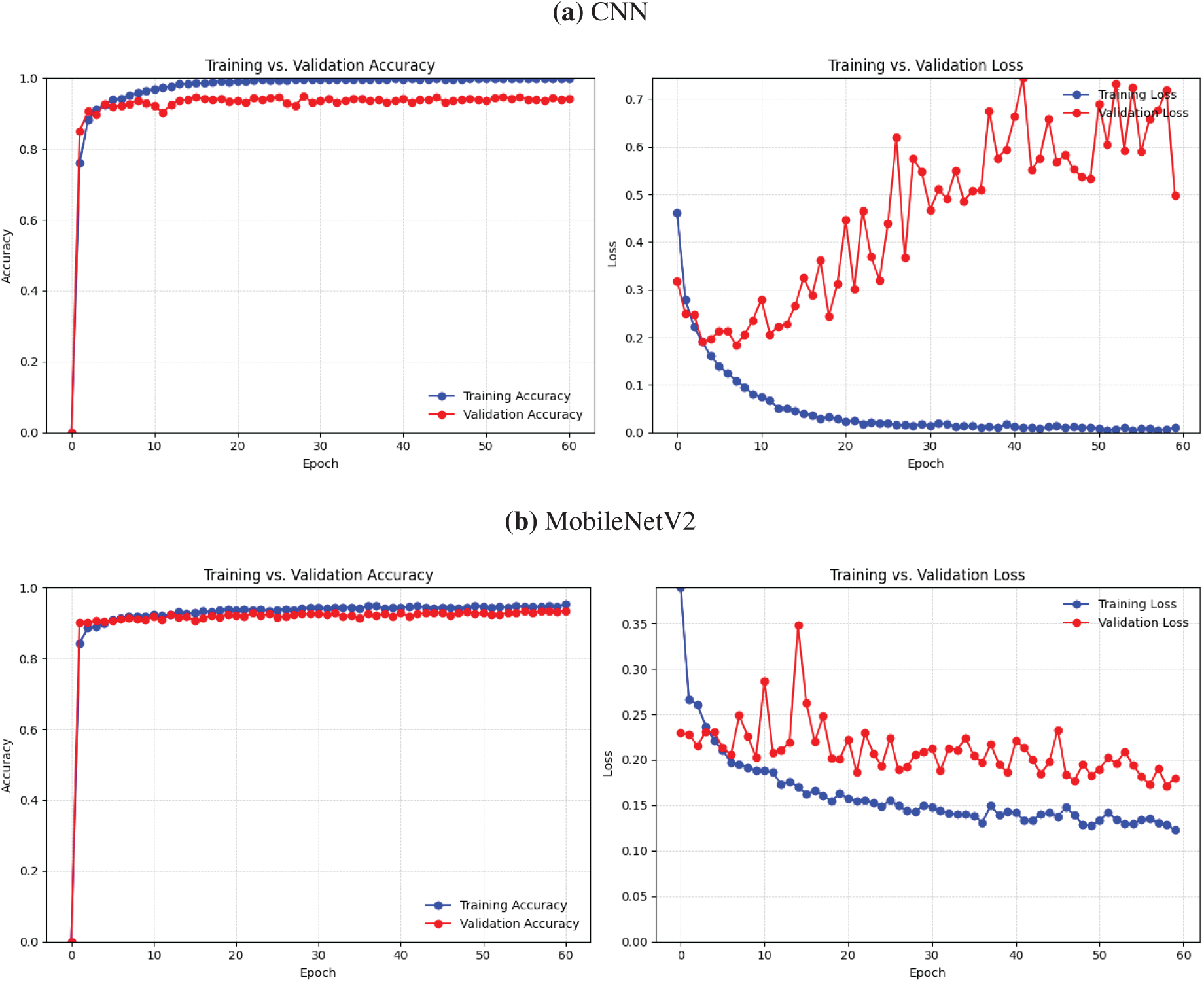

Figs. 2 and 3 display the accuracy and loss metrics for our proposed deep learning models utilizing the OEP dataset, demonstrating considerable variations among the models. The Swin Transformer and EfficientNetB1 models achieved the highest accuracy, indicating superior predictive performance, while models such as MobileNetV2 and ResNet50 demonstrated moderate accuracy but at a lower computational cost. The ConvNext model exhibited computational efficiency; nevertheless, its marginally reduced accuracy indicates possible trade-offs between model complexity and predictive capability.

Figure 2: Accuracy and loss for DL models using OEP dataset (Part 1)

Figure 3: Accuracy and loss for DL models using OEP dataset (Part 2)

Models exhibiting superior accuracy, specifically EfficientNetB1 and the Swin Transformer, attained reduced loss function values, hence confirming their trustworthiness and efficacy in minimizing prediction mistakes. On the other hand, SE-ResNet and ResNet101 had high loss values, which meant that their predictive performance was not as stable as that of models such as ResNet50-CBAM and EfficientNetB0, which had a better balance between accuracy and loss. We identified the Swin Transformer and EfficientNetB1 as the leading models, which demonstrated both superior accuracy and little loss, underscoring their efficacy in trustworthy cheating detection during online examinations.

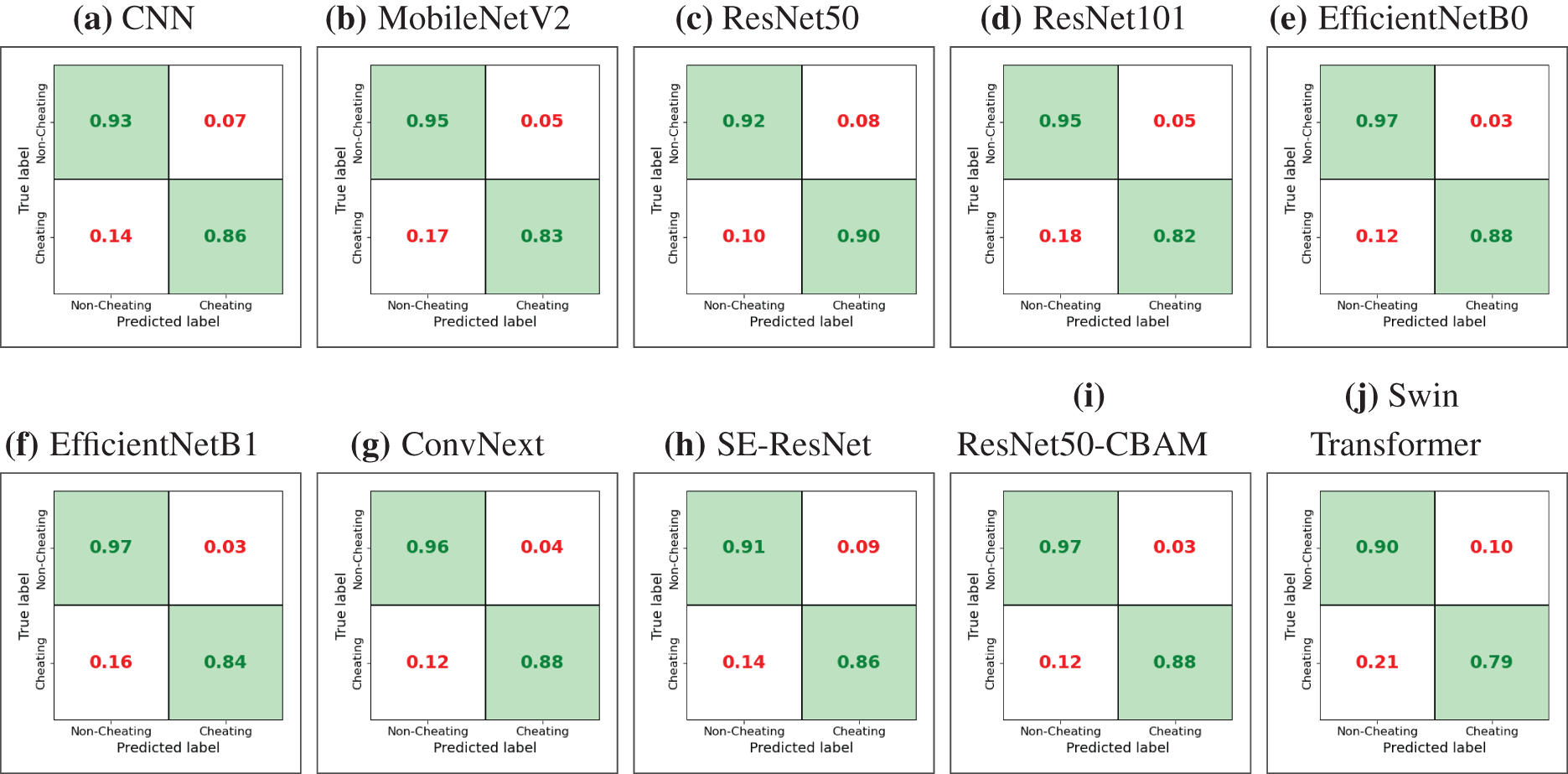

Fig. 4 presents confusion matrices that provide a comparative investigation of several deep learning models for identifying cheating and non-cheating behaviors in online examinations. Each matrix displays the true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN) rates, enabling an evaluation of the accuracy and recall of each model. EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50-CBAM exhibit the best accuracy, each attaining a 97% TN rate and an 88% TP rate, making them the most balanced models. EfficientNetB1 and ConvNext also perform well, with EfficientNetB1 attaining 97% accuracy for non-cheating and 84% for cheating, while ConvNext achieves 96% and 88%, respectively. MobileNetV2 and ResNet101 show moderate results, achieving around 95% accuracy in non-cheating detection but slightly lower cheating detection rates (83% and 82%).

Figure 4: Confusion matrices for DL models using OEP dataset

The Swin Transformer and SE-ResNet exhibit worse performance, with TP rates of 79% and 86%, respectively, and an increased incidence of FPs, suggesting less reliability in detecting instances of cheating. Overall, EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50-CBAM stand out as the optimal choices for precise and equitable cheating detection.

Table 2 presents the performance of our proposed deep learning models on the OEP dataset, with significant metrics emphasized to identify the top-performing models. ResNet50 and ResNet50-CBAM stand out as leading contenders. ResNet50 attains the greatest test accuracy of 93.87%, an exceptional F1-Score of 91.75%, and an AUC of 93.01%. ResNet50-CBAM demonstrates a test accuracy of 93.70%, with a precision of 96.70%, an F1 score of 91.28%, and an AUC of 92.30%. These findings illustrate their equitable and resilient performance.

EfficientNetB0 has commendable performance, with a test accuracy of 93.35%, an AUC of 92.20%, and a robust F1 score of 90.93%. EfficientNetB1 demonstrates competitiveness, achieving a test accuracy of 92.83%, a precision of 94.99%, and an F1 score of 90.13%.

In terms of training efficiency, ResNet50 stands out with the lowest training duration of 1120.02 s while ConvNext attains the test accuracy of 92.75% with F1-score of 90.21%, achieving the quickest test time of 2.08 s, making it efficient for real-time applications. CNN demonstrates high training accuracy (99.83%) with a test accuracy 92.53%.

MobileNetV2 and ResNet101 demonstrate modest performance, achieving test accuracies of 90.76% and 89.81%, respectively; however, they underperform in F1 scores and precision. The Swin Transformer and SE-ResNet exhibit the poorest performance, with the Swin Transformer recording the lowest test accuracy at 86.44% and an AUC of 84.60%, indicating constrained efficacy in this application.

Overall, ResNet50 and ResNet50-CBAM deliver the best outcomes with high accuracy, precision, and F1 scores, while ConvNext excels in test efficiency, making these three models the most appropriate for effective cheating detection on the OEP dataset.

4.3.2 Performance on OP Dataset

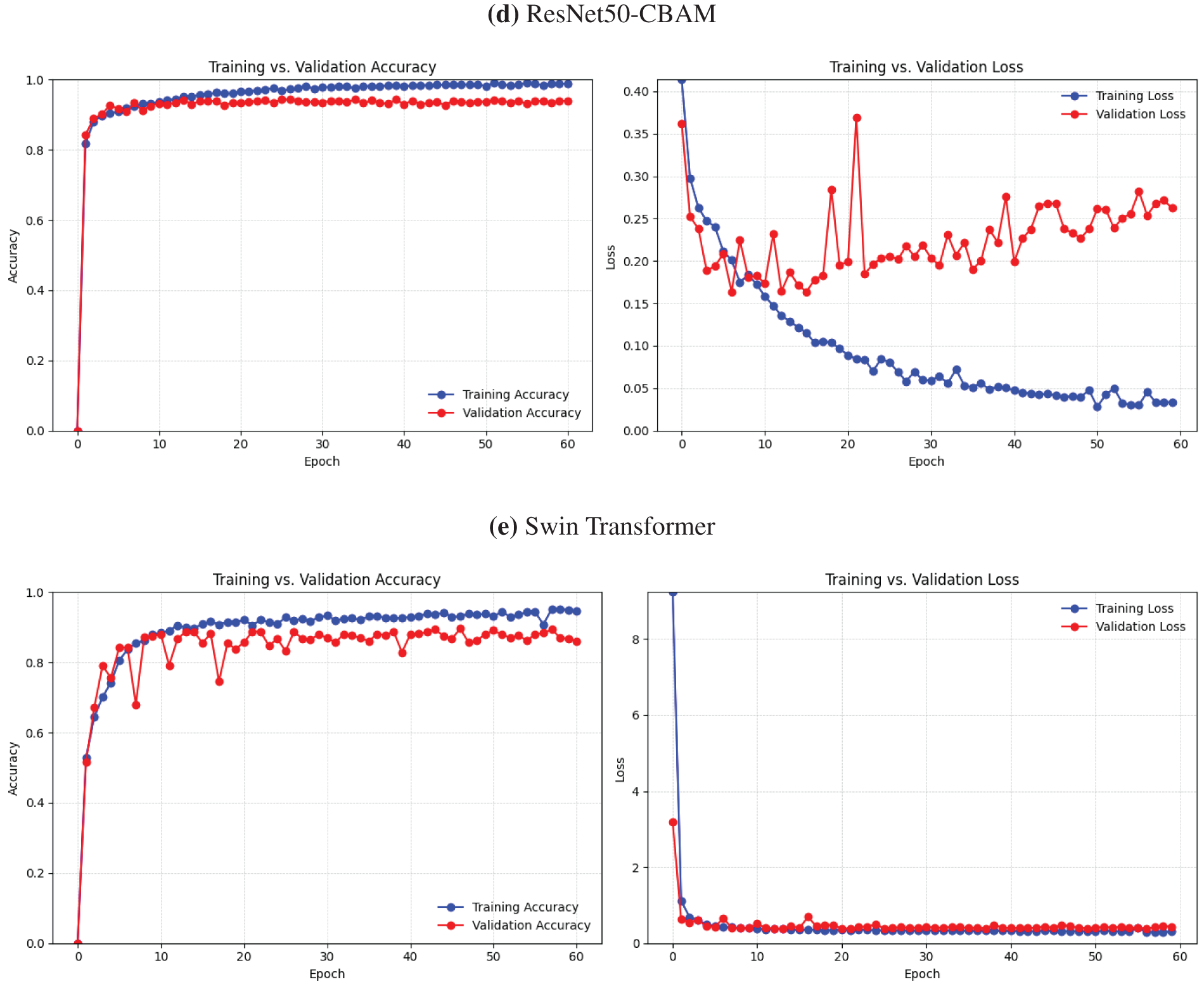

The empirical study evaluates the performance of our proposed deep learning models for online cheating detection through an analysis of their accuracy and loss measures. Each model has distinct strengths and challenges in training dynamics, as seen in Figs. 5 and 6 depicting accuracy and loss graphs.

Figure 5: Accuracy and loss for DL models using OP dataset (Part 1)

Figure 6: Accuracy and loss for DL models using OP dataset (Part 2)

The EfficientNet variations (B0 and B1), SE-ResNet, and the Swin Transformer model demonstrate balanced convergence, attaining high accuracy with minimum loss, signifying strong generalization and stability. These models provide competitive performance while minimizing substantial overfitting, as evidenced by their consistent accuracy and minimal loss over the epochs. Conversely, models like CNN and ResNet101 exhibit more variance in accuracy and a slower convergence rate, potentially due to increased parameter complexity, which may hinder optimization.

ResNet50, ConvNext, and ResNet50-CBAM show distinct performance patterns when compared to the highest-performing models. ResNet50 and ConvNext provide consistent improvements in accuracy, although they display increased variability in loss during first training epochs, suggesting difficulties in achieving optimal convergence. ConvNext, featuring an innovative design influenced by CNN architecture, has somewhat superior accuracy stability compared to ResNet50; nonetheless, both models are slower to converge relative to EfficientNetB1 and SE-ResNet. To enhance accuracy compared to normal ResNet50 by optimizing feature emphasis through attention processes, the ResNet50-CBAM model is augmented with a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM), yet it still falls short of the efficiency of top-performing models.

EfficientNetB1, SE-ResNet, and Swin Transformer are distinguished as the most proficient models, attaining elevated accuracy and little loss while exhibiting consistent learning curves.

The confusion matrices for the 10 deep learning models on the OP dataset offer a detailed assessment of their classification efficacy, shown in percentage format (see Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Confusion matrices for DL models using OP dataset

• Leading Models: The highest-performing models are CNN (a), EfficientNetB1 (f), and ResNet50-CBAM (i), all demonstrating superior accuracy in identifying both categories. CNN achieves a TP rate of 97% and a TN rate of 91%, indicating balanced performance across both classes. EfficientNetB1 attains a high TP rate of 97%, albeit with a slightly lower TN rate of 84%. ResNet50-CBAM demonstrates dependable classification with a TP rate of 94% and a TN rate of 92%.

• Robust Non-Cheating Detectors: Alternative models, including EfficientNetB0 (e), ResNet101 (d), and SE-ResNet (h), have shown efficacy in identifying Non-Cheating occurrences, with TP rates varying from 92% to 96%. Nonetheless, the Cheating detection rates exhibit variability; ResNet101 and EfficientNetB0 achieve commendable performance at about 92%, whilst SE-ResNet declines to 83% for this category, suggesting potential for improvement in achieving balanced detection.

• Moderate Performers: MobileNetV2 (b) and ConvNext (g) exhibit moderate classification performance, each achieving a TP rate of 92%. Nevertheless, their accuracy in Cheating detection is marginally worse, with ConvNext at 90% and MobileNetV2 at 94%. These models exhibit consistent performance but fall short of the top performers in overall accuracy.

• Lower Performing Model: The Swin Transformer (j) demonstrates the poorest overall performance, achieving a TP rate of just 79% in Non-Cheating detection, resulting in an elevated incidence of FP. Although it has a TN rate of 93%, demonstrating effective precision in identifying Cheating situations.

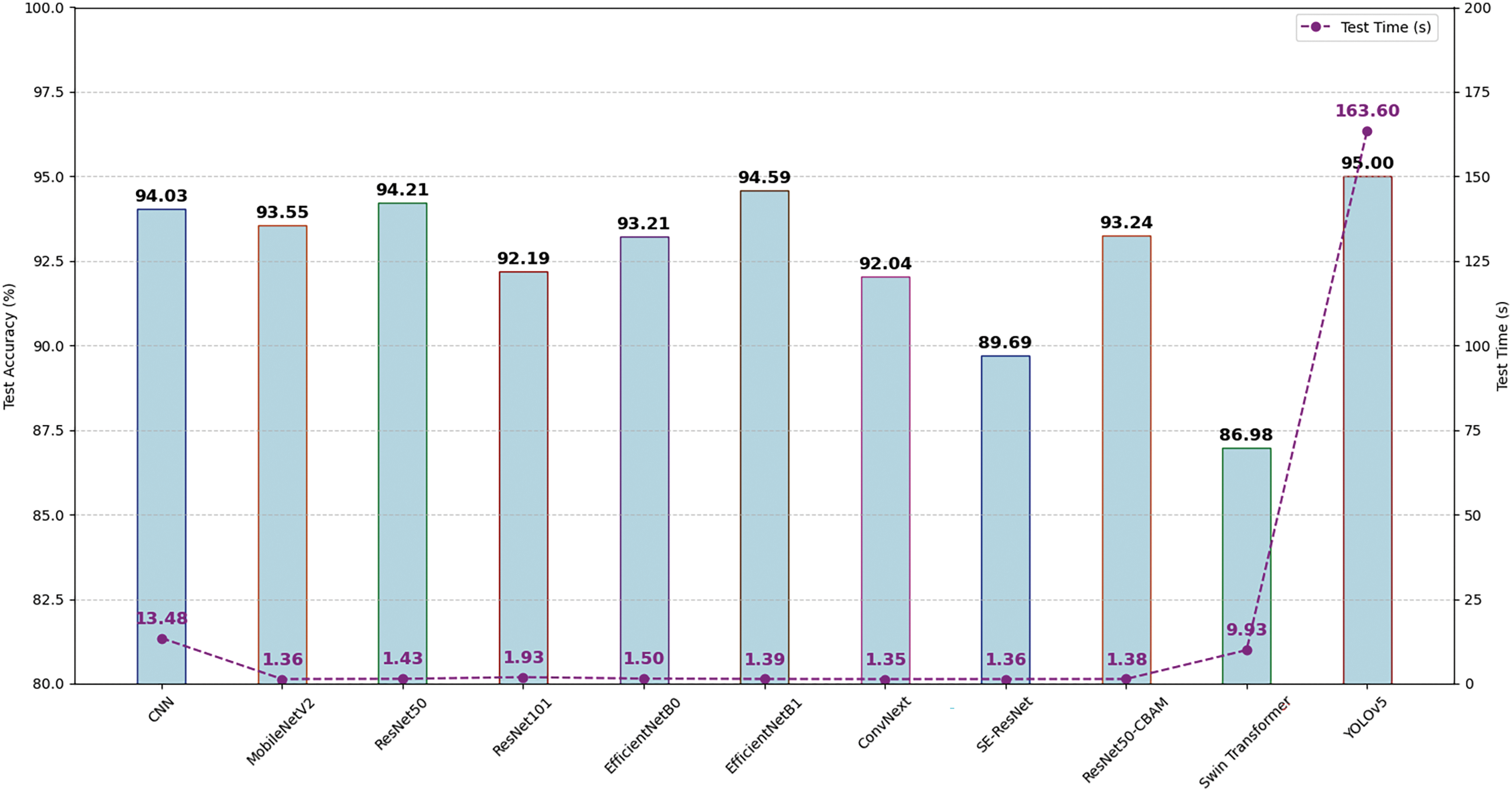

Analyzing the Table 3, we observe distinct variances in performance across several models based on multiple metrics. ResNet50-CBAM attains the greatest train accuracy at 99.90%, while ConvNext follows closely with 99.79%. Test accuracy, which generally offers a better indication of model generalization, peaks with CNN at 97.19%, somewhat surpassing EfficientNetB1 and ResNet50. In terms of train loss, ResNet50-CBAM achieves the lowest score (0.0043), signifying excellent convergence during training, whereas EfficientNetB0 minimizes test loss (0.1436), showing strong performance on unseen data.

In terms of speed, ResNet50 exhibits the least training duration (849.21 s), but ConvNext is the quickest during testing (1.35 s). CNN achieve the highest accuracy at 97.19%, while ResNet50 attains the maximum recall of 96.79%, which is vital for applications that prioritize the identification of true positives. CNN distinguishes itself with the greatest F1 score (97.23%), representing an optimal equilibrium of accuracy and recall, making it appropriate for balanced classification tasks. The AUC score is essential for assessing the discriminative capability of a model, is highest (97.25%) for CNN.

In conclusion, CNN and ResNet50 emerge as top models based on a combination of high test accuracy, balanced F1 score, and competitive AUC. CNN demonstrates superior test accuracy, elevated F1 Score, and little test loss.

4.3.3 Performance on Yolov5 Model

Fig. 8 compares the training accuracy and loss of the YOLOv5 model on two datasets. The model performs strongly on the OEP dataset, showing efficient convergence with all training and validation loss curves decreasing steadily and nearing zero, indicating effective learning and minimal overfitting. Precision and recall quickly stabilize around 0.95, demonstrating high accuracy in object detection and identification. Additionally, the mAP at IoU 0.5 reaches approximately 0.98, while mAP at IoU 0.5:0.95 stabilizes around 0.9, highlighting robust detection performance even under stricter conditions. Overall, the model exhibits high accuracy, efficient loss reduction, and strong generalization on the OEP dataset.

Figure 8: Training accuracy and loss using the YOLOv5 method

In the OP dataset, the YOLOv5 model shows effective training and validation performance with low and consistently decreasing loss values. All loss curves start at higher values but quickly converge towards zero, indicating efficient learning and minimizing overfitting. Validation losses similarly converge near zero, confirming strong generalization to the validation set. The precision and recall metrics stabilize around 0.95, demonstrating high accuracy in detecting and identifying objects. The mAP at IoU 0.5 reaches about 0.95, while mAP at IoU 0.5:0.95 stabilizes around 0.9, reflecting robust performance under varying IoU thresholds. Overall, these results suggest that the OP dataset enables efficient learning and convergence, with the model achieving high accuracy and low loss.

The YOLOv5 model performs excellently on both the OEP and OP datasets, with the best performance observed on the OEP dataset. It achieves high accuracy, efficient loss reduction, and strong generalization, with robust precision, recall, and mAP scores across both datasets.

The confusion matrices for the OEP and OP datasets (see Fig. 9) demonstrate the efficacy of the model in categorizing no_cheating and cheating, emphasizing both strengths and weaknesses within each dataset.

Figure 9: Confusion matrices using the YOLOv5 method

In the OEP dataset (see Fig. 9a), the model demonstrates effective performance in distinguishing between no_cheating and cheating occurrences, achieving 95% accuracy for no_cheating and 93% for cheating. The model faces difficulties with background elements, misclassifying 45% of these cases as either no_cheating or cheating leading to a background accuracy of 55%. This indicates that background characteristics may exhibit similarities with other categories, resulting in misclassifications.

In the OP dataset (see Fig. 9b), the model attains an accuracy of 95% in both the no_cheating and cheating categories. However, it encounters greater difficulty with background components, with a 54% misclassification rate and a 46% effective background accuracy. The somewhat elevated confusion rate relative to the OEP dataset suggests that background components in the OP dataset may be less distinguishable from no_cheating and cheating occurrences.

Both datasets provide a high accuracy of 95% in the no_cheating and cheating categories. The OEP dataset has a marginal superiority in managing background components, achieving an effective accuracy of 55% compared to 46% in the OP dataset, signifying more significant separations between background and labeled occurrences in the OEP dataset.

Fig. 10 presents the precision-recall curves demonstrating the performance of the YOLOv5 model on the OEP and OP datasets for identifying the no_cheating and cheating classes. These graphs provide insights into the balance between accuracy and recall at various choice thresholds, Underscoring the effectiveness of the model in differentiating between these categories.

Figure 10: Precision-recall curve using YOLOv5

In the OEP dataset (see Fig. 10a), the model attains elevated precision and recall metrics, with a precision-recall area of 0.985 for “no_cheating” and 0.978 for “cheating.” The mAP at a threshold of 0.5 across all classes is 0.981, signifying a robust equilibrium between accuracy and recall. The curves for each class are positioned around the upper right corner of the graph, indicating that the model excels in both recognizing TP and reducing FP for this dataset.

In the OP dataset (see Fig. 10b), the model demonstrates robust performance, with a precision-recall area of 0.977 for “no_cheating” and a slightly higher 0.988 for “cheating.” The mAP@0.5 for all classes in the OP dataset is 0.983, just exceeding that of the OEP dataset. Analogous to the OEP results, the curves for each class remain around the optimal top right corner, signifying that the model adeptly balances accuracy and recall.

Both datasets have elevated accuracy and recall, with the OP dataset exhibiting a slightly superior mAP@0.5 (0.983) relative to the OEP dataset (0.981). This indicates that the YOLOv5 model is adept at identifying cheating and non-cheating events in both datasets, with marginally superior overall performance on the OP dataset.

Table 4 compares the performance of YOLOv5 on the OEP and OP datasets across many metrics throughout the training and testing stages.

The YOLOv5 model trained on the OEP dataset outperforms the one trained on the OP dataset in terms of accuracy, achieving 95.7% in training and 94.9% in testing, compared to 94.1% and 93.8% for the OP dataset model. However, the OP dataset model excels in recall, with rates of 96.0% in training and 96.2% in testing, slightly higher than the OEP model achieved 95.9% and 94.2%. This highlights the OP dataset’s strength in identifying all relevant occurrences. Additionally, the OEP model shows a stronger F1 score in training at 95.8%, compared to 95.0% for the OP model, reflecting a more balanced performance between precision and recall.

In terms of mAP, YOLOv5 trained on the OEP dataset excels in mAP@0.5 during both training (98.7% vs. 98.1%) and testing (98.1% vs. 98.3%). However, the YOLOv5 model with the OP dataset outperforms in mAP@0.5:0.95 during testing, achieving 97.5% compared to the OEP model’s 97.0%. Additionally, the OEP model demonstrates a slightly faster inference time during testing (1.7 vs. 1.8 ms), while the OP model significantly reduces the overall training time, completing in 3768.39 s compared to the OEP model’s 4928.86 s, highlighting its greater training efficiency.

Overall, the OEP dataset displays greater accuracy and F1 scores, but the OP dataset excels in recall and efficiency, especially with inference and training length.

The evaluation of deep learning models on the OEP and OP datasets uncovers substantial insights into their efficacy for detecting online test cheating, highlighting the trade-offs among accuracy, computational efficiency, and resilience. EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50-CBAM continuously rank as superior models on the OEP dataset, exhibiting elevated test accuracy alongside balanced precision, F1 scores, and AUC, making them highly reliable choices for accurately detecting cheating behaviors. The ConvNext model, while not achieving the maximum accuracy, exhibits the quickest inference time, indicating its appropriateness for real-time applications. In the OP dataset, EfficientNetB1 excels in accuracy and F1 scores, demonstrating a balanced and effective performance in precision and recall measures, but with increased processing requirements during training and efficient test performance ensures reliable detection with minimal delay, aligning well with the demands of real-time applications (see Figs. 11 and 12).

Figure 11: Test accuracy and test time comparison for DL algorithms using OEP dataset

Figure 12: Test accuracy and test time comparison for DL algorithms using OP dataset

Concerning YOLOv5 on both datasets highlights the disparities in dataset architecture and its impact on model convergence. The OEP dataset seems to promote more efficient model convergence, probably owing to balanced feature patterns and class distributions, leading to consistently reduced test losses. In contrast, models trained on the OP dataset exhibit elevated loss values and variability, suggesting potential issues such as class imbalance or noisy features. Despite these limitations, YOLOv5 attains elevated precision-recall regions and mAP scores across both datasets, confirming its formidable detection capability.

The findings indicate that EfficientNetB0, EfficientNetB1, and ResNet50-CBAM are superior models for achieving a balance between accuracy, computational efficiency, and generalization, whereas YOLOv5 has significant potential for high-stakes cheating detection applications. The findings underscore the significance of choosing the suitable model and dataset, taking into account model convergence, efficiency, and class distribution to get dependable performance in identifying cheating behaviors.

To ensure practical applicability, the models evaluated in this study were specifically chosen and fine-tuned to handle a wide range of real-world cheating tactics, including behaviors involving second devices, behind-the-scenes assistance, and deceptive strategies like imitation. In the OP dataset, for instance, cheating behaviors include the examinee interacting with hidden mobile phones, receiving whispered answers, or mimicking natural behavior to avoid detection—such as looking forward while covertly using peripheral vision to check another screen. Our use of object detection models like YOLOv5 enables direct localization of external devices (e.g., phones or tablets) and subtle cues such as head turns or partial hand gestures, making the system responsive to behind-the-scenes activity.

Furthermore, to simulate practical diversity, the datasets inherently contained variations in environmental conditions—such as differing lighting setups (natural light, artificial overhead, or low-light rooms), background complexity, and camera angles (e.g., slightly above, straight-on, or tilted webcam views). Models like EfficientNetB1 and ResNet50-CBAM demonstrated strong resilience to these conditions due to their ability to learn fine-grained spatial features and adaptively focus on relevant regions through attention mechanisms. CBAM, in particular, improved robustness by dynamically emphasizing spatial and channel-level features, helping detect unusual posture shifts or light-induced image distortions.

The models also addressed imitation behavior—where users attempt to mimic “normal” behavior—through temporal consistency and anomaly detection across frames. For example, even if a student momentarily behaves correctly, sudden or inconsistent gestures, frequent gaze switching, or atypical face orientations across time frames are flagged as suspicious. Additionally, ResNet and ConvNeXt models’ deep feature extraction capabilities helped distinguish genuine from feigned attentiveness.

Together, this model ensemble supports real-time, context-aware classification, accounting for varied cheating strategies and ensuring adaptability across diverse testing environments. These robustness features are essential for deploying reliable proctoring systems in practical academic settings.

Table 5 presents a detailed comparative analysis between our experimental outcomes and prior research on cheating detection in online examination contexts. The results demonstrate that our evaluated models generally exceed or closely align with state-of-the-art findings reported in existing literature. Specifically, our CNN implementation achieved an accuracy of 97.19% on the OP dataset, significantly outperforming the 93% reported in [19]. Similarly, our ResNet50 model achieved 93.87% on the OEP dataset and 93.75% on OP, surpassing the previously documented 87% in [23].

While ConvNext and Swin Transformer have been investigated in earlier works, our study examines them using more comprehensive datasets (OEP and OP), attaining 92.75% and 90.94% accuracy on OP for ConvNext and Swin Transformer, respectively. These results represent an improvement over earlier findings (88.82% for ConvNext [43] and 90.42% for Swin Transformer [44]). Furthermore, YOLOv5 continued to perform among the top models, consistent with prior benchmarks (95.70%), achieving 94.50% and 94.90% accuracy on the OEP and OP datasets, respectively [17].

In addition to revisiting previously studied classifiers, our work introduces and thoroughly assesses several advanced deep learning models not previously explored in the literature, including EfficientNetB0/B1, MobileNetV2, ResNet50-CBAM, and SE-ResNet. These models exhibited strong and dependable performance across both datasets, with EfficientNetB0 and EfficientNetB1 consistently surpassing 93% accuracy. Notably, ResNet50-CBAM reached 93.70% accuracy on OEP and 93.23% on OP, underscoring its effectiveness in balancing accuracy with architectural complexity.

Recent studies such as Automated Smart Artificial Intelligence-Based Proctoring System Using Deep Learning and Smart Artificial Intelligence-Based Online Proctoring System [45] have made significant strides in addressing cheating detection during online exams by developing a multi-modal system with pre-defined behavioral rules or heuristic methods to detect anomalies such as gaze deviation, head pose changes, or presence of multiple faces. While these approaches are effective in controlled environments, they often rely on limited behavior patterns, fixed camera conditions, and constrained datasets, which can reduce adaptability to real-world scenarios with high variability.

In contrast, our approach advances beyond these frameworks in several key ways. First, we introduce a diverse ensemble of advanced models—including EfficientNetB0/B1, ResNet50-CBAM, YOLOv5, ConvNeXt, and Swin Transformer—each offering unique architectural strengths such as compound scaling (EfficientNet) or attention-based refinement (CBAM). This allows our models to capture subtle cheating behaviors such as screen-looking, device use, and background interference with greater sensitivity and generalization.

Second, while previous smart AI-based systems typically focus on single-camera views and assume stable lighting or clean backgrounds, we benchmark our models using two robust, real-world datasets (OEP and OP) that include diverse lighting conditions, multiple angles, background noise, and imitation behaviors, making our evaluation more representative of actual online exam environments.

Third, our approach is deeply comparative and practical—we not only report accuracy and F1-score but also assess each model’s computational cost and inference time, which is crucial for deployability in real-time exam monitoring systems. This comprehensive evaluation makes our framework not only more scalable and accurate but also more adaptable to different institutional needs compared to existing smart AI-based systems.

Overall, the integration of these diverse and contemporary architectures into our study advances the field of deep learning-based cheating detection, providing compelling evidence for the adaptability and scalability of modern models in supporting academic integrity. Our findings underscore the value of examining a broad spectrum of architectures and datasets to identify models that best meet the operational demands of real-world proctoring environments.

The novelty of our proposed approach lies not only in the individual deep learning models used but also in the way we comprehensively benchmark and adapt them to the context of cheating detection under realistic, diverse, and challenging proctoring conditions. While some models like CNN and ResNet have been used in prior studies, our contribution advances the state of the art by introducing and evaluating more recent and powerful architectures—including EfficientNetB0/B1, ResNet50-CBAM, ConvNeXt, and YOLOv5—in a unified framework across two realistic datasets (OEP and OP). EfficientNet models introduce compound scaling, which allows for efficient depth, width, and resolution balancing, improving performance under constrained environments such as remote proctoring. ResNet50-CBAM integrates attention mechanisms at both the channel and spatial level, making it especially effective for detecting subtle and deceptive behaviors that might escape simpler models. YOLOv5, known for real-time object detection, is fine-tuned for binary classification of cheating behavior, providing both speed and high precision in detecting visual cues such as secondary devices or off-screen glances.

Furthermore, our work is novel in how it tests model robustness against variations such as lighting conditions, webcam angles, imitation behavior, and environmental distractions. Most prior works do not systematically evaluate model resilience in such diverse cheating scenarios. The comparative evaluation across architectures also provides practical insights into balancing accuracy and computational efficiency, making this work a step forward toward scalable, real-world deployment of AI-based proctoring systems.

While our study offers a comprehensive evaluation of deep learning models for cheating detection in online examinations, several limitations must be acknowledged. We primarily focused on CNN-based architectures such as EfficientNet, ResNet variants, and YOLOv5, without fully exploring advanced transformer-based models like Vision Transformers (ViT), DeiT, or hybrid CNN-transformer approaches, which have shown promising results in recent computer vision research. Additionally, our evaluation was limited to two datasets (OEP and OP), which, despite being relevant to online proctoring, may not fully capture the diversity of real-world examination settings in terms of behavior, demographics, and environmental context. Another limitation lies in the unimodal nature of our input data, as we relied solely on visual information from video frames. Incorporating multimodal inputs such as audio signals, gaze tracking, or keystroke dynamics could enhance model robustness and improve detection accuracy in complex scenarios.

This paper presents a comprehensive analysis of deep learning models for detecting cheating in online exams, identifying EfficientNetB0, EfficientNetB1, ResNet50-CBAM, and YOLOv5 as top-performing architectures across the OEP and OP datasets. EfficientNet models and ResNet50-CBAM demonstrated balanced accuracy, efficiency, and strong precision-recall performance, making them suitable for real-time proctoring applications, while YOLOv5 excelled in precision and mAP, showcasing potential for high-stakes, real-time detection. Future work should aim to enhance model robustness through hybrid and ensemble approaches, expand datasets to capture diverse cheating behaviors, and develop lightweight, privacy-preserving, multi-modal frameworks that integrate audio, gaze, and other behavioral cues. Addressing ethical concerns, refining adaptive feedback mechanisms, and optimizing for edge devices will support the deployment of scalable, effective, and user-centric cheating detection systems that uphold academic integrity in diverse online education settings.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R752), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This paper also derived from a research grant funded by the Research, Development, and Innovation Authority (RDIA)—Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—with grant number (13325-psu-2023-PSNU-R-3-1-EF). Additionally, the authors would like to thank Prince Sultan University for their support.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R752), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Siham Essahraui and Ismail Lamaakal; data curation, Siham Essahraui and Ismail Lamaakal; formal analysis, Siham Essahraui, Ismail Lamaakal, Khalid El Makkaoui and Yassine Maleh; funding acquisition, May Almousa, Ali Abdullah S. AlQahtani and Ahmed A. Abd El-Latif; methodology, Siham Essahraui, Ismail Lamaakal, Khalid El Makkaoui, Mouncef Filali Bouami, Ibrahim Ouahbi and Yassine Maleh; project administration, Siham Essahraui, Ismail Lamaakal, Khalid El Makkaoui, Yassine Maleh, Ibrahim Ouahbi, May Almousa, Ali Abdullah S. AlQahtani, Ahmed A. Abd El-Latif and Mouncef Filali Bouami; software, Siham Essahraui and Ismail Lamaakal; supervision, Yassine Maleh, Khalid El Makkaoui, Ibrahim Ouahbi, Mouncef Filali Bouami, May Almousa, Ali Abdullah S. AlQahtani and Ahmed A. Abd El-Latif; validation, Siham Essahraui, Ismail Lamaakal, Khalid El Makkaoui, Ibrahim Ouahbi, Mouncef Filali Bouami and Yassine Maleh; visualization, Siham Essahraui and Ismail Lamaakal; writing—original draft, Siham Essahraui and Ismail Lamaakal; writing—review and editing, Yassine Maleh, Khalid El Makkaoui, Ibrahim Ouahbi, May Almousa, Mouncef Filali Bouami, Ali Abdullah S. AlQahtani and Ahmed A. Abd El-Latif. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data are contained within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. French S, Dickerson A, Mulder RA. A review of the benefits and drawbacks of high-stakes final examinations in higher education. Higher Educ. 2024;88(3):893–918. doi:10.1007/s10734-023-01148-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Cui X, Du C, Shen J, Zhang S, Xu J. Impact of gamified learning experience on online learning effectiveness. IEEE Trans Learn Technol. 2024;17(2):2076–85. doi:10.1109/TLT.2024.3462892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ortiz-Lopez A, Olmos-Miguelanez S, Sanchez-Prieto JC. Toward a new educational reality: a mapping review of the role of e-assessment in the new digital context. Educ Inf Technol. 2024;29(6):7053–80. doi:10.1007/s10639-023-12117-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Okoye K, Daruich SDN, De La OJFE, Castaño R, Escamilla J, Hosseini S. A text mining and statistical approach for assessment of pedagogical impact of students’ evaluation of teaching and learning outcome in education. IEEE Access. 2023;11(2):9577–96. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3239779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Pongchaikul P, Vivithanaporn P, Somboon N, Tantasiri J, Suwanlikit T, Sukkul A, et al. Remote online-exam dishonesty in medical school during COVID-19 pandemic: a real-world case with a multi-method approach. J Acad Ethics. 2024;22(3):539–59. doi:10.1007/s10805-024-09571-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Rodríguez-Paz MX, González-Mendivil JA, Zárate-García JA, Zamora-Hernández I, Nolazco-Flores JA. A hybrid teaching model for engineering courses suitable for pandemic conditions. IEEE Rev Iberoam Tecnol Aprendiz. 2021;16(3):267–75. doi:10.1109/RITA.2021.3122893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Newton PM, Essex K. How common is cheating in online exams and did it increase during the COVID-19 pandemic? A systematic review. J Acad Ethics. 2024;22(2):323–43. doi:10.1007/s10805-023-09485-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Liu Y, Ren J, Xu J, Bai X, Kaur R, Xia F. Multiple instance learning for cheating detection and localization in online examinations. IEEE Trans Cogn Dev Syst. 2024;16(4):1315–26. doi:10.1109/TCDS.2024.3349705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ryu R, Yeom S, Herbert D, Dermoudy J. A comprehensive survey of context-aware continuous implicit authentication in online learning environments. IEEE Access. 2023;11(1):24561–73. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3253484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Susnjak T, McIntosh TR. ChatGPT: the end of online exam integrity? Educ Sci. 2024;14(6):656. doi:10.3390/educsci14060656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Taherkhani R, Aref S. Students’ online cheating reasons and strategies: EFL teachers’ strategies to abolish cheating in online examinations. J Acad Ethics. 2024;22(22):539–59. doi:10.1007/s10805-024-09502-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dilini N, Senaratne A, Yasarathna T, Warnajith N, Seneviratne L. Cheating detection in browser-based online exams through eye gaze tracking. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Technology Research (ICITR); 2021 Dec 1–2; Colombo, Sri Lanka. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2021. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/ICITR54349.2021.9657277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Khabbachi I, Mdaghri-Alaoui G, Zouhair A, Mahboub A. A cheating detection system in online exams through real-time facial emotion recognition of students. In: Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computer, Internet of Things and Microwave Systems (ICCIMS); 2024 Jul 29–31; Gatineau, QC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ICCIMS61672.2024.10690812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mellar H, Peytcheva-Forsyth R, Kocdar S, Karadeniz A, Yovkova B. Addressing cheating in e-assessment using student authentication and authorship checking systems: teachers’ perspectives. Int J Educ Integr. 2018;14(1):1–21. doi:10.1007/s40979-018-0025-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Verma P, Malhotra N, Suri R, Kumar R. Automated smart artificial intelligence-based proctoring system using deep learning. Soft Comput. 2024;28(4):3479–89. doi:10.1007/s00500-023-08696-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chatterjee P, Dansana J, Swain S, Gourisaria MK, Bandyopadhyay A. Identity verification in real-time proctoring: an integrated approach with face recognition and eye tracking. In: Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Algorithms and Computational Intelligence Systems (IACIS); 2024 Aug 23–24; Hassan, India. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/IACIS61494.2024.10721819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ramzan M, Abid A, Bilal M, Aamir KM, Memon SA, Chung TS. Effectiveness of pre-trained CNN networks for detecting abnormal activities in online exams. IEEE Access. 2024;81(17):1–6. doi:10.1109/IACIS61494.2024.10721819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kaddoura S, Gumaei A. Towards effective and efficient online exam systems using deep learning-based cheating detection approach. Intell Syst Appl. 2022;16:200153. doi:10.1016/j.iswa.2022.200153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Nurpeisova A, Shaushenova A, Mutalova Z, Ongarbayeva M, Niyazbekova S, Bekenova A, et al. Research on the development of a proctoring system for conducting online exams in Kazakhstan. Computation. 2023;11(6):120. doi:10.3390/computation11060120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ozdamli F, Aljarrah A, Karagozlu D, Ababneh M. Facial recognition system to detect student emotions and cheating in distance learning. Sustainability. 2022;14(20):13230. doi:10.3390/su142013230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hu Z, Jing Y, Wu G, Wang H. Multi-perspective adaptive paperless examination cheating detection system based on image recognition. Appl Sci. 2024;14(10):4048. doi:10.3390/app14104048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Dang TL, Hoang NMN, Nguyen TV, Nguyen HV, Dang QM, Tran QH, et al. Auto-proctoring using computer vision in MOOCs system. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;1(7):1–27. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-20099-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Potluri T, Venkatramaphanikumar S, Kolli VKK. An automated online proctoring system using Attentive-Net to assess student mischievous behavior. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(20):30375–404. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-14604-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Wang H, Yan X, Li H, Xu F. Double-frame rate-based cheat detection. In: Third International Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Analysis (ICCPA 2023); Hangzhou, China: SPIE; 2023. Vol. 12754. p. 529–35. doi:10.1117/12.2684283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Thampan N, Arumugam S. Smart online exam invigilation using AI-based facial detection and recognition algorithms. In: Proceedings of the 2022 2nd Asian Conference on Innovation in Technology (ASIANCON); 2022 Aug 26–28; Ravet, India. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ASIANCON55314.2022.9908748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Singh T, Nair RR, Babu T, Duraisamy P. Enhancing academic integrity in online assessments: introducing an effective online exam proctoring model using YOLO. Procedia Comput Sci. 2024;235(12):1399–408. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2024.04.131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Roy K, Chanda D. A robust webcam-based eye gaze estimation system for human-computer interaction. In: Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Innovation in Science and Engineering Technology (ICISET); 2022 Feb 26–27; Chittagong, Bangladesh. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2022. p. 146–51. doi:10.1109/ICISET54810.2022.9775896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Parkhi PN, Patel A, Solanki D, Ganwani H, Anandani M. Proficient exam monitoring system using deep learning techniques. In: International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for Competitive Strategies; Singapore: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 31–49. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-0744-7_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Gadkar S, Vora B, Chotai K, Lakhani S, Katudia P. Online examination auto-proctoring system. In: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Advanced Computing Technologies and Applications (ICACTA); 2023 Oct 6–7; Mumbai, India. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/ICACTA58201.2023.10392679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Atabay HA, Hassanpour H. Semi-supervised anomaly detection in electronic-exam proctoring based on skeleton similarity. In: Proceedings of the 2023 11th European Workshop on Visual Information Processing (EUVIP); 2023 Sep 11–14; Gjovik, Norway. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/EUVIP58404.2023.10323052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Samir MA, Maged Y, Atia A. Exam cheating detection system with multiple-human pose estimation. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Computing (ICOCO); 2021 Nov 17–19; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2021. p. 236–40. doi:10.1109/ICOCO53166.2021.9673534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Atoum Y, Chen L, Liu AX, Hsu SDH, Liu X. Automated online exam proctoring. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2017;19(7):1609–24. doi:10.1109/TMM.2017.2656064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Tejaswi P, Venkatramaphanikumar S, Kishore KVK. Proctor Net: an AI framework for suspicious activity detection in online proctored examinations. Measurement. 2023;206(1):112266. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2022.112266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. LeCun Y, Bengio Y. Convolutional networks for images, speech, and time series. In: Arbib MA, editor. The handbook of brain theory and neural networks. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 1995. p. 3361–70. doi:10.5555/303568.303704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Howard AG. MobileNets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications.arXiv:1704.04861. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016. p. 770–8. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1512.03385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Tan M, Le Q. EfficientNet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 6105–14. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1905.11946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Liu Z, Mao H, Wu CY, Feichtenhofer C, Darrell T, Xie S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2022. p. 11976–86. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2201.03545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018 Jun 18–22; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2018. p. 7132–41. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1709.01507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Woo S, Park J, Lee JY, Kweon IS. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. In: Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. Cham: Springer; 2018. p. 3–19. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1807.06521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin Transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2021. p. 10012–22. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2103.14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Redmon J. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2016. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Hu Z, Jing Y, Wu G. Research on remote intelligent monitoring system for online examination based on gaze direction classification. Proc 9th Int Conf Comput Artif Intell. 2023;535–40. doi:10.1145/3594315.3594369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Huang B, Yin C, Wang C, Chen H, Chai Y, Ouyang Y. Video-based recognition of online learning behaviors using attention mechanisms. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Teaching, Assessment and Learning for Engineering (TALE); Bengaluru, India; 2024. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/TALE62452.2024.10834376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Malhotra N, Suri R, Verma P, Kumar R. Smart artificial intelligence based online proctoring system. In: 2022 IEEE Delhi section conference (DELCON 2022); New Delhi, India: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/DELCON54057.2022.9753313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools