Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

MNTSCC: A VMamba-Based Nonlinear Joint Source-Channel Coding for Semantic Communications

1 School of Computer Science, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, 430068, China

2 School of Computer and Information Science, Hubei Engineering University, Xiaogan, 432000, China

3 Hubei Provincial Key Laboratory of Green Intelligent Computing Power Network, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, 430068, China

* Corresponding Author: Caichang Ding. Email:

#These authors contributed equally to this work

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3129-3149. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067440

Received 03 May 2025; Accepted 10 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Deep learning-based semantic communication has achieved remarkable progress with CNNs and Transformers. However, CNNs exhibit constrained performance in high-resolution image transmission, while Transformers incur high computational cost due to quadratic complexity. Recently, VMamba, a novel state space model with linear complexity and exceptional long-range dependency modeling capabilities, has shown great potential in computer vision tasks. Inspired by this, we propose MNTSCC, an efficient VMamba-based nonlinear joint source-channel coding (JSCC) model for wireless image transmission. Specifically, MNTSCC comprises a VMamba-based nonlinear transform module, an MCAM entropy model, and a JSCC module. In the encoding stage, the input image is first encoded into a latent representation via the nonlinear transformation module, which is then processed by the MCAM for source distribution modeling. The JSCC module then optimizes transmission efficiency by adaptively assigning transmission rate to the latent representation according to the estimated entropy values. The proposed MCAM enhances the channel-wise autoregressive entropy model with attention mechanisms, which enables the entropy model to effectively capture both global and local information within latent features, thereby enabling more accurate entropy estimation and improved rate-distortion performance. Additionally, to further enhance the robustness of the system under varying signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions, we incorporate SNR adaptive net (SAnet) into the JSCC module, which dynamically adjusts the encoding strategy by integrating SNR information with latent features, thereby improving SNR adaptability. Experimental results across diverse resolution datasets demonstrate that the proposed method achieves superior image transmission performance compared to existing CNN- and Transformer-based semantic communication models, while maintaining competitive computational efficiency. In particular, under an Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN) channel with SNR = 10 dB and a channel bandwidth ratio (CBR) of 1/16, MNTSCC consistently outperforms NTSCC, achieving a 1.72 dB Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) gain on the Kodak24 dataset, 0.79 dB on CLIC2022, and 2.54 dB on CIFAR-10, while reducing computational cost by 32.23%. The code is available at (accessed on 09 July 2025).Keywords

The large-scale commercialization of 5G technology has catalyzed rapid advancements in domains including autonomous driving, the Internet of Things (IoT), and artificial intelligence (AI) [1,2]. However, these advancements impose more stringent requirements on data transmission, particularly in terms of achieving ultra-low latency and supporting high-capacity communication. According to Shannon’s information theory [3], the channel capacity of modern communication systems is already approaching its theoretical limit, making further improvements in communication efficiency increasingly challenging. In this context, semantic communication has emerged as a novel paradigm that focuses on transmitting task-relevant information, thereby significantly reducing bandwidth consumption.

First introduced by Weaver, semantic communication differs fundamentally from traditional communication systems, which primarily emphasize the accurate transmission of data or signals. In contrast, semantic communication aims to ensure that the intended meaning of the transmitted information is effectively understood by both the sender and the receiver. By selectively extracting task-relevant semantic information, compressing it, and transmitting it over communication channels, semantic communication systems can significantly reduce data volume and bandwidth requirements. This novel approach increases transmission efficiency while maintaining task relevance and is regarded as a key technological solution to break through current communication bottlenecks.

Recent research on semantic communication systems is increasingly focused on end-to-end training models based on Joint Source-Channel Coding (JSCC) [4], which optimizes both source and channel coding simultaneously. By integrating the coding processes, JSCC can effectively improve system transmission efficiency and performance. Most existing JSCC systems rely on CNNs or Transformers as backbone architectures. For example, DeepJSCC [5] employs CNNs for image transmission and effectively mitigates the “cliff effect” [6] in communication systems. SwinJSCC [7] employs Swin-Transformer (Swin-T) as its backbone network, improving the model’s transmission performance in high-resolution scenarios.

Despite their impressive performance, both CNN- and Transformer-based models (including Swin-T) have limitations. CNNs, for example, struggle with capturing global dependencies, which hinders their effectiveness in high-resolution image processing. In contrast, Transformer-based models excel at modeling global dependencies, but their quadratic complexity requires substantial computational resources during both training and inference [8–10]. The Swin-T model effectively reduces computational complexity while enhancing local information capture capability by incorporating a window-shifting attention mechanism [11,12]. Especially when dealing with high-resolution images, it substantially decreases the required computing resources. Nevertheless, compared to models with linear complexity, Swin-T still demands relatively high computational overhead.

To address these limitations, some researchers have begun exploring optimization schemes for semantic communication systems based on the novel VMamba [13] model. As a pioneering work in this field, the authors of [14] were the first to successfully apply the VMamba architecture to semantic communication systems, proposing the MambaJSCC model. MambaJSCC not only reduces computational complexity but also maintains highly competitive performance. Unlike CNN and Transformer architectures, VMamba is an innovative state-space model and an important extension of Mamba [15] in the field of computer vision. Through a novel 2D selective scanning mechanism, it transforms 2D image data into 1D sequences, effectively aggregating contextual information from different directions of the image. Combined with Mamba’s unique data-dependent selection mechanism, it can dynamically enhance critical features while effectively suppressing noise interference. These characteristics enable VMamba to achieve excellent performance in tasks involving long-range dependency modeling.

Motivated by the success of VMamba in computer vision tasks, we propose a VMamba-based nonlinear adaptive joint source-channel coding model, named MNTSCC. MNTSCC comprises three core components: a nonlinear transform coding (NTC) module, an entropy model and a joint source-channel coding (JSCC) module. Specifically, the NTC module extracts latent feature maps from input images, which are subsequently encoded by the JSCC module into channel input signals. The entropy model is employed to estimate the transmission rate by approximating the joint distribution of the latent features and capturing source dependencies, thereby enhancing the model’s rate-distortion performance. To enable the entropy model to capture more accurate entropy distribution parameters, we propose MCAM, a channel-wise auto-regressive entropy model with attention module. MCAM extends the channel-wise autoregressive entropy model (ChARM) [16] by incorporating an attention mechanism, which helps the entropy model capture both global and local information of latent features, thereby yielding more accurate entropy estimation parameters. In addition, we incorporate the SNR adaptive module (SAnet) into the JSCC module, which allows the model to dynamically adjust its transmission strategy according to varying signal-to-noise ratio(SNR) levels during the encoding phase. As a result, the model can maintain stable image transmission performance at various SNR levels.

The contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

• Building upon the VMamba architecture as the backbone network, we propose MNTSCC, a nonlinear adaptive joint source-channel coding model. Capitalizing on VMamba’s dual strengths in efficient long-range dependency modeling and lightweight computation, the proposed method outperforms NTSCC, which adopts a similar nonlinear architecture, and achieves Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio(PSNR) gains across CIFAR-10 (2.54 dB), Kodak24 (1.72 dB), and CLIC2022 (0.79 dB) under an Additive White Gaussian Noise(AWGN) channel with SNR = 10 dB and channel bandwidth ratio(CBR) = 1/16, while reducing computational cost by 20.92 GFLOPs.

• We introduce a channel-wise auto-regressive entropy model with attention mechanism (MCAM). Building on ChARM, MCAM incorporates an attention mechanism that enables the entropy model to simultaneously focus on both global and local information of latent features, thereby generating more accurate entropy estimation parameters and improved rate-distortion performance.

• To help the model maintain stable performance under different channel conditions, we introduce SAnet. By combining SNR with feature maps, the model is able to sense the channel conditions and adjust the coding strategy according to varying SNR levels.

2.1 Joint Source-Channel Coding

JSCC has emerged as a promising approach for semantic communication, fundamentally differing from conventional systems by integrating source coding, channel coding, and modulation into a unified neural framework. In this paradigm, the encoder directly transforms source data into channel symbols for transmission, while the decoder reconstructs the original information from channel outputs.

Existing JSCC methods can be broadly categorized into linear and nonlinear structural models:

(1) Linear Structure models: DeepJSCC [5] represents the first deep learning-based JSCC framework specifically designed for wireless image transmission. By simultaneously employing CNNs in both the encoder and decoder, it effectively mitigates the “cliff effect” [6] commonly observed in traditional communication systems under deteriorating channel conditions. Building upon this foundation, numerous studies have proposed enhancements. For example, Wang et al. [17] introduced reinforcement learning to improve system robustness under varying channel environments. WITT [18] and SwinJSCC [7] adopt Swin Transformers (Swin-T) as backbone architectures, leveraging their powerful contextual modeling capabilities to achieve superior performance in high-resolution image transmission tasks. MambaJSCC [14] employs VMamba as its backbone, delivering excellent performance while significantly reducing computational costs.

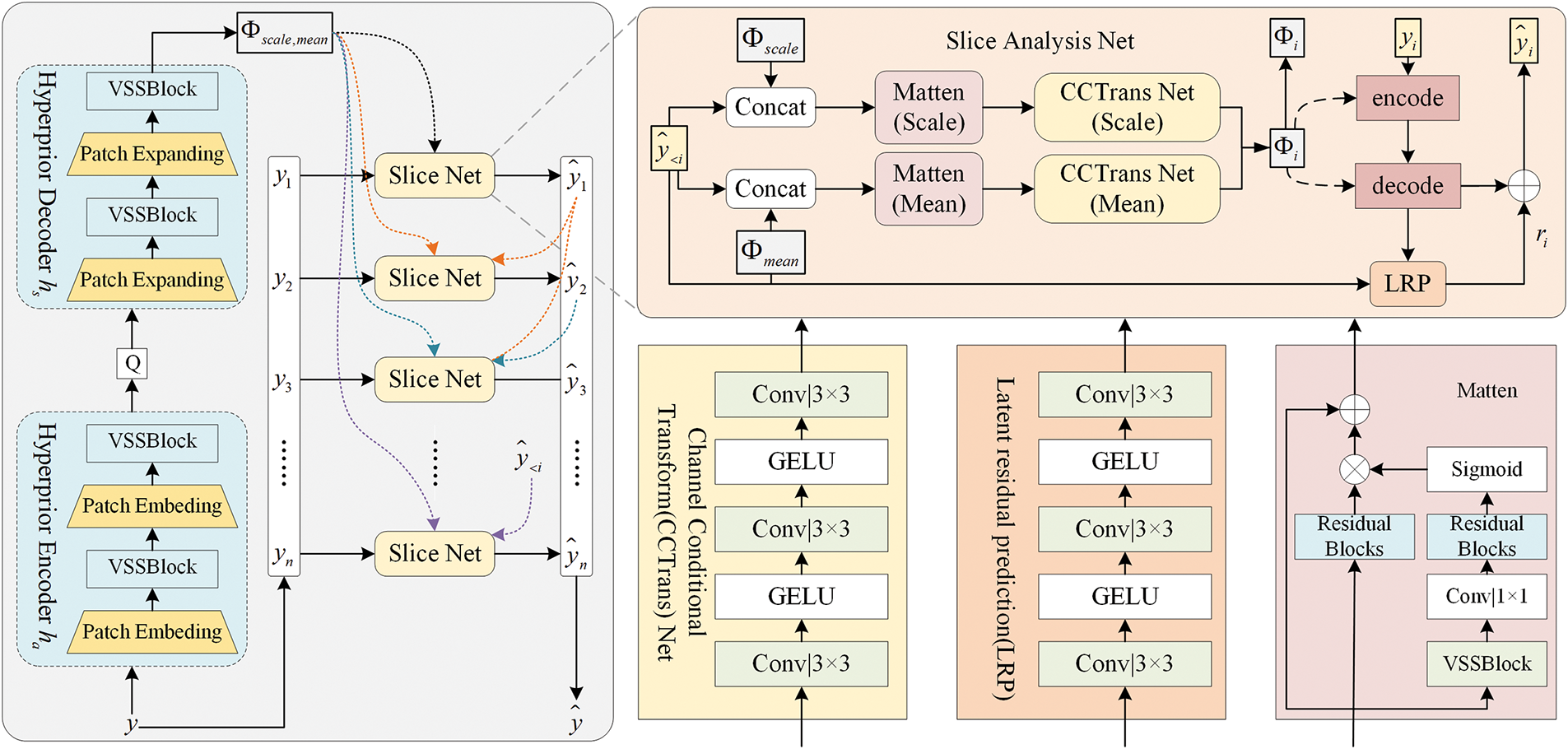

(2) Nonlinear Structure models: Dai et al. [19] pioneered the incorporation of nonlinear transformation encoding into the DeepJSCC framework, subsequently proposing the NTSCC. As shown in Fig. 1, the NTSCC architecture consists of three key components: a nonlinear transform module, an entropy model, and a JSCC module. The nonlinear transform enables the model to obtain compact feature representations of the original data in the latent space. Additionally, the model employs a modern entropy model, commonly used in image codecs, to estimate the probability distribution parameters of latent features. These parameters are then utilized as hyperpriors for the latent representation, providing critical guidance for the JSCC module. Guided by the entropy model, the JSCC encoder-decoder allocates more channel bandwidth resources to the most important content, which is essential for reconstructing the source signal. By dynamically assigning more bandwidth to semantically important regions, the model significantly improves rate-distortion performance. Experimental results demonstrate that NTSCC achieves excellent results in image transmission tasks and provides a new paradigm for applying nonlinear structures in semantic communication.

Figure 1: The overall architecture of NTSCC model

Entropy models, serving as a core component of nonlinear transformations, have extensive applications and research in the field of learned image compression. The pioneering work by Ballé et al. [20] introduced a hyperprior entropy model for learned image compression, substantially improving compression efficiency and reconstruction fidelity. Building upon this foundation, subsequent research has proposed various improvements to entropy modeling. For instance, ChARM [16] incorporates a channel-wise autoregressive context model along with a slicing strategy to more accurately model inter-channel dependencies, thereby enhancing the precision of entropy estimation. Koyuncu et al. [21] proposed a Transformer-based efficient context modeling module, which significantly improves the performance and efficiency of the entropy model by introducing the Spatio-Channel Window Attention(SCAW) mechanism. MLIC [22] proposed a multi-reference entropy model that effectively captures statistical dependencies in latent representations by jointly leveraging channel-wise, local spatial, and global contexts, overcoming the limitations of traditional 1D context modeling. Moreover, Chen et al. [23] developed a 3D CNN-based context prediction model that integrates non-local operations with attention mechanisms, effectively enhancing feature representation while accelerating inference speed.

State-space models (SSMs), including representative architectures like LSSL [24] and HiPPO [25], originate from the theoretical framework of linear dynamical systems in control theory [26]. The core concept of SSM is to represent the internal state of a system using state variables and to describe the evolution of this state over time through linear equations [27]:

where

Inspired by Mamba’s success in NLP tasks, the authors of [28] and [13] extend Mamba into the field of computer vision, respectively, proposing Vim and VMamba. Vim employs a bidirectional state-space model to capture global visual context and incorporates position embeddings to enable location-aware visual understanding. In contrast, VMamba retains Mamba’s data selection mechanism and introduces a cross-scanning strategy to build the 2D Selective Scanning (2DSS) and Visual State Space (VSS) blocks. By scanning the image from different directions, VMamba effectively captures global contextual information from images, significantly enhancing the model’s performance in visual tasks. Currently, both Vim and VMamba have achieved outstanding results across a wide range of computer vision tasks. For instance, Ruan et al. [29] used VMamba as the backbone network to construct VM-Unet with a U-Net architecture, which has demonstrated outstanding performance in medical image segmentation tasks; Wang et al. [30] combined Mamba with YOLO-World [31] to propose Mamba-YOLO-World, significantly reducing the computational complexity of YOLO-World while achieving excellent performance.

The proposed MNTSCC framework, depicted in Fig. 2, is composed of two main components: the NTC module and the JSCC module. The NTC module is composed of an analysis transform module and an entropy model MCAM. During the encoding phase, the analysis transform encoder

Figure 2: Architecture of MNTSCC. The input image is first transformed into a latent representation

This latent feature map

3.1.1 Visual State Space Block

The VSS block derived from VMamaba [13] serves as the backbone network of MNTSCC, with each VSS block consisting of multiple VSS layers. Fig. 3 illustrates the detailed structure of a single VSS layer. As depicted, the VSS layer employs a gated structure with two branches after the normalization stage. For the input feature map

Figure 3: The structure of a single VSS layer

where LN denotes the layer normalization, 2DSS denotes the 2D Selective Scanning module, SiLU denotes the SiLU activation function, DWConv denotes the depth-wise separable convolution layer, and Linear denotes a learnable linear projection layer. Similarly, the gating branch computes the weight vector by:

Finally, the VSS layer’s final output is generated through the fusion of both branch outputs, and the process can be expressed as:

By incorporating a gated structure and the 2DSS module, the VSSBlock effectively captures latent features from the input image while suppressing redundancy. This facilitates the NTC module in generating more compact and informative representations, thereby enhancing the efficiency of downstream probability modeling and transmission.

Vanilla Mamba [15] was initially designed to handle one-dimensional data and was not directly applicable to two-dimensional image data. To effectively capture spatial context in images, VMamba proposed the 2DSS block, which generates unfolded sequences by scanning the input image along multiple directions. The 2DSS block consists of three components: cross-scanning operation, S6 blocks, and cross-merging operation. Given an input image, the 2DSS transforms image patches into sequences by applying four distinct scanning patterns. Each sequence is then processed independently using a dedicated S6 block in parallel. Finally, the outputs are fused through a cross-merging operation to produce the final output.

The S6 block, serving as the foundational component of Mamba, extends the S4 [32] architecture by incorporating a data-dependent selection mechanism that dynamically discriminates between relevant and irrelevant information. This innovation allows the model to retain critical features while suppressing noise.

As shown in Fig. 4, the Analysis Transform module consists of the analysis transform encoder

Figure 4: Network architecture of analysis transform module

3.3 Channel-Wise Auto-Regressive Entropy Model of Attention Mechanism

The entropy model serves as a critical component of the NTC module, tasked with capturing the statistical characteristics of the latent feature map. Specifically, the latent feature map

To address this limitation, we propose MCAM, a channel-wise auto-regressive entropy model with attention mechanism. Building upon the channel-wise autoregressive entropy model (ChARM) [16], MCAM introduces an attention module specifically designed for entropy analysis. This attention module primarily consists of VSS blocks and residual blocks. The VSS blocks enable the model to capture global contextual dependencies within the latent feature map

The overall structure of MCAM is illustrated in Fig. 5, and the pseudo code is provided in Algorithm 1. Specifically, for the input latent representation

Figure 5: The overall architecture of MCAM consists of a superprior codec (right) and a slice network (left). The former processes the latent features to predict global distribution parameters, while the latter performs slice-wise analysis to further refine entropy estimation

where

Afterward, the latent representation

where

The adaptive JSCC module consists of two components: the JSCC encoder

Figure 6: The overall architecture of JSCC module

(1) Rate adaptive allocation: By virtue of the advantage of rate allocation in the NTSCC [19], in the MNTSCC model, the latent feature map

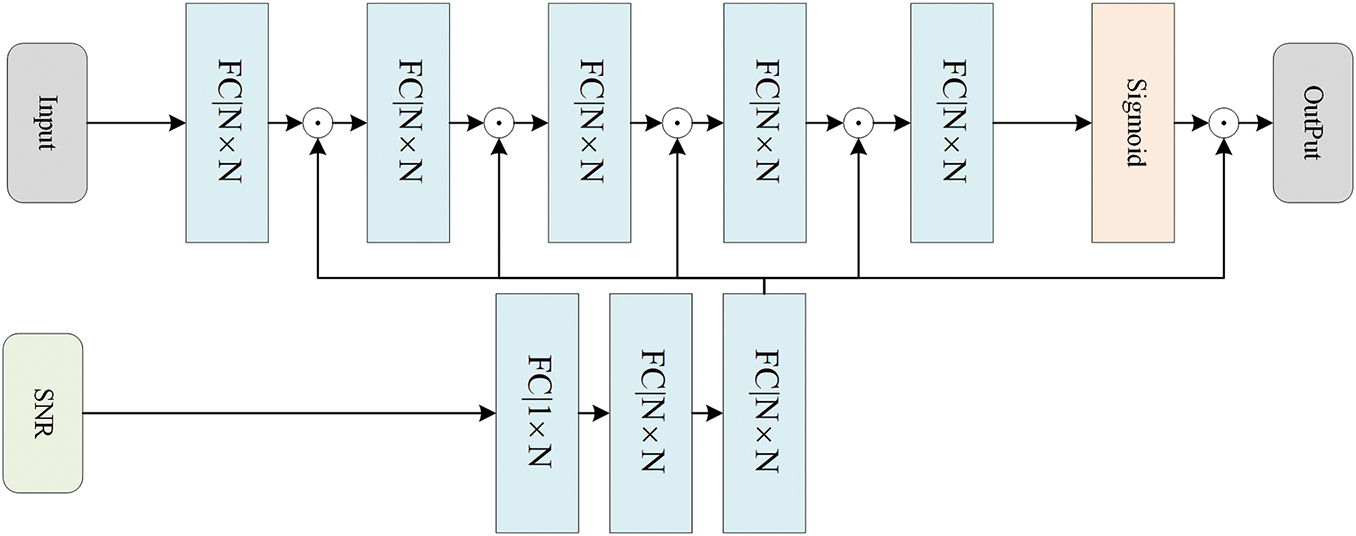

(2) SNR adaptive: Channel conditions, particularly SNR, have a substantial impact on the transmission quality in wireless communication systems [36]. To mitigate this issue, most semantic communication models often adopt a strategy of training separate models for different SNR levels. Although such specialization enables optimal performance under specific conditions, it incurs significant computational and storage overhead due to the necessity of multiple training and deployment pipelines. To overcome these limitations, we propose SNR adaptive net (SAnet), a lightweight and effective SNR-adaptive module which facilitates the model’s adaptation to different SNRs. As shown in Fig. 7, SAnet receives the rate-adaptive encoded semantic feature maps alongside the SNR value. The SNR scalar is first processed through a series of three fully connected (FC) layers and projected into an N-dimensional vector. This vector is then multiplied with the semantic feature maps to modulate the semantic features. The modulated features are subsequently passed to the next FC layer for further processing. SAnet allows the network to effectively perceive channel conditions and adaptively adjust its encoding strategy. This integration enhances the robustness of the transmission process and supports optimal resource allocation under diverse channel environments.

Figure 7: The overall architecture of SAnet

To optimize the image transmission performance of MNTSCC, we employ a loss function based on the rate-distortion trade-off during training. The loss function is defined as follows:

where

To evaluate the performance of the proposed method in image transmission tasks, this section compares it with models such as NTSCC, SwinJSCC, and DeepJSCC. The specific experimental configurations are as follows:

1. Dataset: To validate the efficacy of the proposed method across varying image resolutions, we conducted experiments on different resolution datasets. For the low-resolution image dataset, we used the CIFAR-10 dataset, consisting of 60,000 images (50,000 for training, 10,000 for testing) of size

2. Comparison Methods: To assess performance, we compare our method with NTSCC [19], SwinJSCC [7], and DeepJSCC [5] under varying channel bandwidth ratios (CBR) and SNRs. First, at SNR = 10, models are evaluated across multiple CBRs, where CBR =

3. Evaluation Metrics: To rigorously assess the quality of image transmission, we adopt two widely recognized metrics: PSNR [38] and Multi-Scale Structural Similarity (MS-SSIM) [39]. PSNR offers an objective evaluation of signal fidelity by quantifying the pixel-wise reconstruction error via the MSE [37] between the original and reconstructed images. Although effective for capturing low-level discrepancies, PSNR may not always align with perceptual quality. To address this, MS-SSIM is employed to provide a perceptually meaningful assessment by jointly considering luminance, contrast, and structural similarity across multiple spatial scales, thereby aligning more closely with the characteristics of the human visual system.

4. Model Training Details: In the proposed method, the VSS blocks for the analytical and synthesis transform module vary depending on the image resolution. For the low-resolution CIFAR-10 dataset, only two VSS blocks are used with parameters

4.2 PSNR Performance under Different CBRs

Fig. 8 illustrates the PSNR performance of various semantic communication methods on different resolution datasets and under different CBR conditions, all tested in an AWGN channel with SNR = 10. Specifically, Fig. 8a,b shows the results on high-resolution datasets Kodak and CLIC2022, while Fig. 8c presents the results for the low-resolution dataset CIFAR-10.

Figure 8: The PSNR performance vs. the different CBRs over the AWGN channel at SNR = 10dB. (a)–(c) represent the PSNR performance on the Kodak24, Clic2022, and Cifar10 dataset, respectively

Results demonstrate that compared to the CNN-based DeepJSCC and the SwinT-based NTSCC and SwinJSCC, MNTSCC achieves superior performance on both low-resolution and high-resolution datasets. Different from the linear structure adopted by DeepJSCC and SwinJSCC, our method, along with NTSCC, utilizes a non-linear architecture to extract potential features more effectively and reduce redundant information in the transmitted representations. Therefore, under the same CBR conditions, our method can transmit more features crucial for image reconstruction, thereby achieving better PSNR performance. Furthermore, compared with NTSCC, MNTSCC benefits from the powerful modeling capability of the MCAM entropy model, which enables it to more accurately estimate the information density distribution in the source data. As a result, it achieves simultaneous improvement in compression efficiency and reconstruction quality. Specifically, when CBR = 1/16, the PSNR of MNTSCC on the Kodak dataset is approximately 1.59 dB higher than that of NTSCC. Additionally, compared to DeepJSCC which is based on CNN, this method incorporates the VMamba network, which significantly enhances the model capacity and the ability to model long-range dependencies, thereby further improving the reconstruction performance.

4.3 PSNR Performance under Different SNRs

This section presents a comparative analysis of the PSNR performance of various semantic communication models across different resolution datasets under AWGN channels with varying SNRs. Fig. 9a shows the results for the Kodak dataset, while Fig. 9b presents the results for the Clic2022 dataset, and Fig. 9c presents the results for the Cifar-10 dataset. For both our scheme and the NTSCC scheme, the CBR does not easily settle down to a predetermined value. Therefore, for the high-resolution dataset, we set the maximum CBR to 1/16. For the Cifar dataset, the maximum CBR is set to 1/3. Additionally, since our method and SwinJSCC can adapt to different SNR conditions, we randomly selected SNR values in the range of 2–12 during training, while NTSCC and DeepJSCC were trained under a fixed SNR = 10 condition.

Figure 9: The PSNR performance of different resolution image datasets under varying SNR levels over the AWGN channel, with CBR constrained to 1/16 for the high-resolution dataset and 1/3 for the low-resolution dataset. (a)–(c) represent the PSNR performance on the Kodak24, Clic2022, and Cifar10 dataset, respectively

The experimental results indicate that MNTSCC delivers superior PSNR performance across various SNR levels. As the SNR decreases, the interference from channel noise intensifies, resulting in the degradation of potential features in transmission and the accumulation of decoding errors. Consequently, all methods suffer from different performance degradation under low SNR conditions. However, by incorporating SAnet into MNTSCC, our method can dynamically adjust its coding strategy according to actual channel conditions, thereby effectively adapting to different SNR variations. As a result, our method maintains minimal performance degradation even when the SNR falls below 10. In contrast, NTSCC and DeepJSCC are trained only under an SNR of 10 and lack adaptability to channel variations, leading to a significant decline in PSNR performance under low SNR scenarios.

4.4 MS-SSIM Performance under Different SNRs and CBRs

In this subsection, we compared the MS-SSIM performance of MNTSCC with other methods across different SNR and CBR levels. Since the MS-SSIM values range from 0 to 1, and most of the results exceed 0.9, to enhance readability, we convert the MS-SSIM values to dB units for improved readability. The conversion formula is as follows:

The MS-SSIM results are presented in Fig. 10. Specifically, Fig. 10a,b illustrates the performance under varying CBR conditions, while Fig. 10c,d displays the results under different SNR conditions. The experimental results demonstrate that MNTSCC consistently achieves the highest MS-SSIM performance across various SNR and CBR levels. Notably, in low SNR conditions, the performance gap between our method and the others becomes even more pronounced.

Figure 10: The MS-SSIM performance on the Kodak24 and Clic2022 dataset in AWGN channel: (a)–(b) show the MS-SSIM performance under different CBRs. (c)–(d) show the MS-SSIM performance under different SNRs

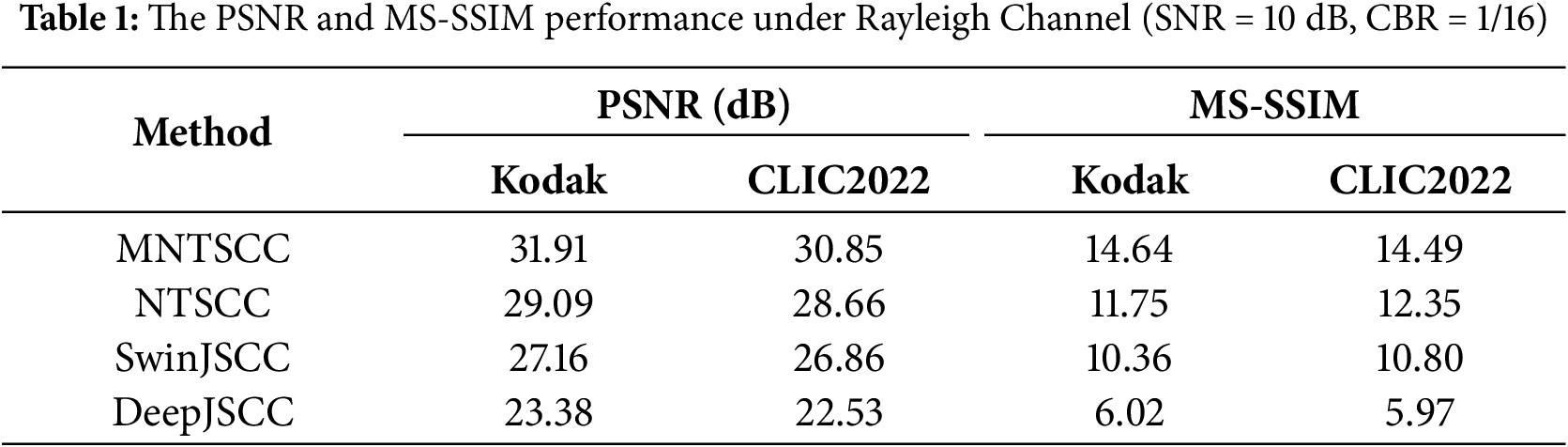

4.5 PSNR and MS-SSIM Performance under Rayleigh Fading Channel

To further analyze the performance of MNTSCC across different channel conditions, we evaluated and compared the PSNR and MS-SSIM metrics of four methods under Rayleigh fading channels with an SNR of 10 dB and a CBR of 1/16. As shown in Table 1, although all methods experience performance degradation compared to their AWGN channel counterparts, the proposed MNTSCC consistently outperforms the others, achieving the highest PSNR and MS-SSIM scores.

4.6 Ablation Study and Efficiency Comparison

This section evaluates the contribution of each module in the MNTSCC model to PSNR performance through ablation experiments. Specifically, under an AWGN channel with a maximum CBR constraint of 1/16, we assessed the PSNR performance by systematically removing different modules. In the experiment, MNTSCC represents the entire model; MNTSCC_w/o_MCAM removes MCAM and replaces it with HEM; MNTSCC_w/o_SAnet refers to the removal of the SAnet module in the JSCC framework, with results trained separately for each SNR, and MNTSCC_w/o_SAnet (train_SNR = 10) represents the model trained with SNR = 10 while removing the SAnet. All models were trained for 500 epochs on the DIV2K dataset and evaluated for PSNR performance on the Kodak dataset.

Fig. 11 presents the results of the ablation experiments. It can be observed that compared to MNTSCC_w/o_MCAM using HEM, MNTSCC shows improved PSNR performance across various SNR conditions. This indicates that the MCAM employed by MNTSCC can generate more accurate entropy estimates, thereby enhancing the rate-distortion performance of the model. When compared to MNTSCC_w/o_SAnet(train_SNR = 10), MNTSCC exhibits superior PSNR performance at SNRs below 10, with the performance gap widening as the SNR decreases. This suggests that SAnet effectively helps the model adapt to varying SNR levels, ensuring more stable performance across different channel conditions. Additionally, while MNTSCC shows a slight PSNR decrease compared to MNTSCC_w/o_SAnet, which was trained with a single fixed SNR, the performance remains within an acceptable range.

Figure 11: The PSNR performance of ablation study under varying SNR levels (AWGN channel, CBR = 1/16)

Fig. 12 compares the computational and memory resource consumption of various models on the Kodak dataset (AWGN channel, SNR 10, CBR 1/16). In terms of memory consumption, since SwinJSCC is a standard deep learning-based JSCC architecture without the NTC module, it has the fewest parameters. However, its PSNR performance is also lower as a result. Among the three models incorporating the NTC architecture, MNTSCC, which employs the more sophisticated MCAM, has a higher parameter count compared to MNTSCC_w/o_MCAM and NTSCC, but it also delivers superior performance. The Vamba-based MNTSCC_w/o_MCAM, which uses the HEM entropy model, not only has fewer parameters than NTSCC but also demonstrates competitive performance. This indicates that using VMamba as the backbone network effectively reduces memory overhead. Additionally, science NTSCC can only be trained for a single SNR and requires separate copies for each SNR, it incurs additional storage costs in practical applications. In contrast, MNTSCC’s SAnet allows the model to adapt to varying SNRs, eliminating the need for multiple training sessions.

Figure 12: The PSNR performance vs computational cost, with the bubble size representing the number of parameters

In terms of computational resource consumption, the linear complexity advantage of VMamba contributes to a lower GFLOPs for both MNTSCC and MNTSCC_w/o_MCAM compared to the Swin-t-based NTSCC. Specifically, MNTSCC_w/o_MCAM equipped with the HEM reduces GFLOPs by 45.614%, and MNTSCC reduces GFLOPs by 32.23%, both relative to NTSCC.

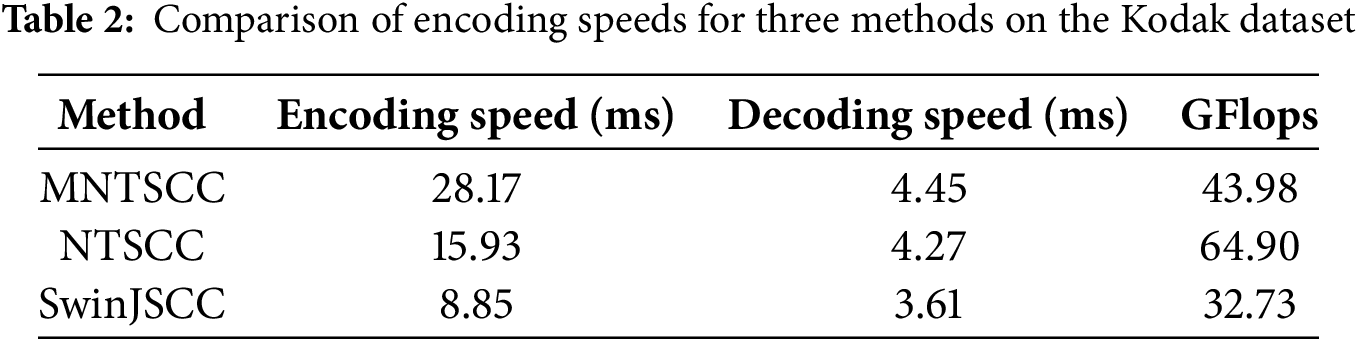

Table 2 compares the encoding speed and GFLOPs of the three methods. The results show that SwinJSCC achieves the fastest encoding speed and the lowest GFLOPs, attributed to its simpler architecture. In contrast, MNTSCC is significantly slower than NTSCC, primarily due to its more complex network design and the adoption of VMamba as the backbone. Although VMamba substantially reduces computational complexity, its inherently sequential state-space modeling, combined with the use of cross-scan mechanisms, limits parallelization and ultimately results in slower processing speed compared to Swin-T.

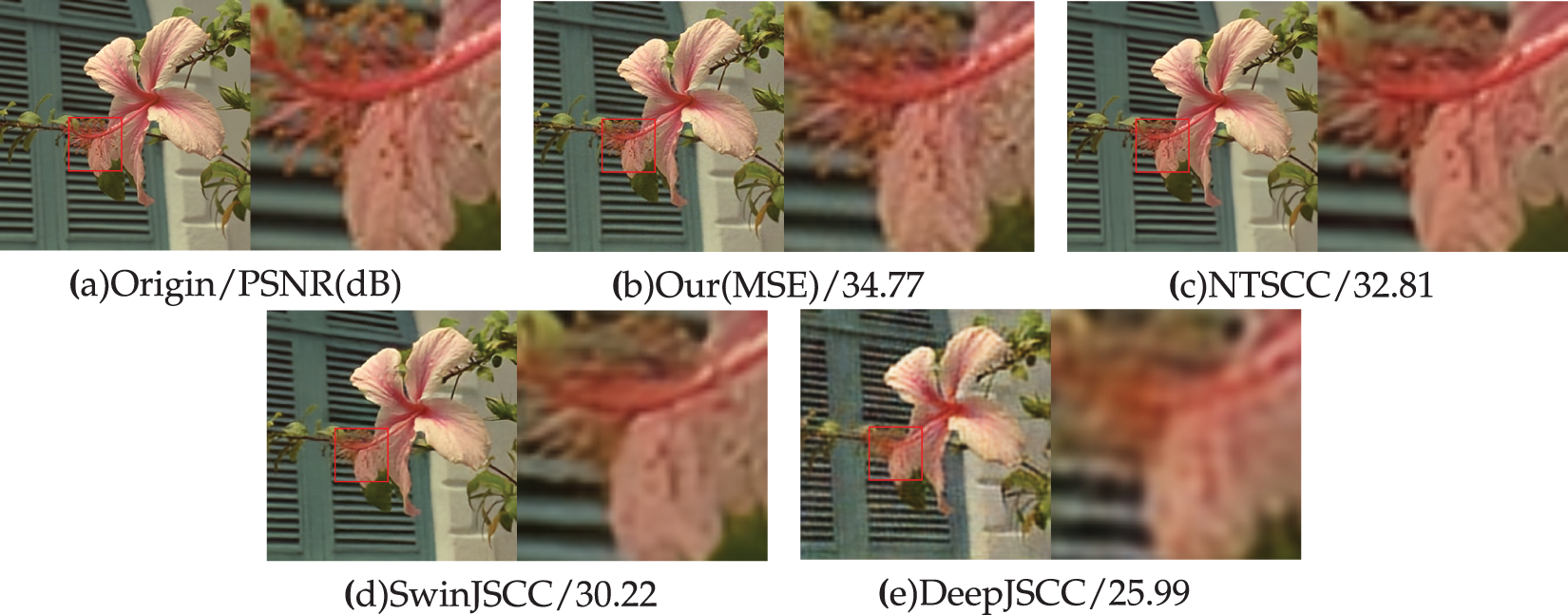

Fig. 13 presents comparative visualizations of four methods. As can be seen from the visual results, our method shows better image recovery performance. Compared to the NTSCC model using the HEM, MNTSCC has a clear advantage in processing image details. This advantage reflects the fact that MCAM can generate a more accurate entropy estimate of the latent representation, thereby refining the latent feature representation.

Figure 13: Examples of visual comparison. When the SNR = 10 dB and CBR = 1/16, the physical channel is AWGN channel

In this study, we propose MNTSCC, a VMamba-based nonlinear joint source-channel coding model for wireless image transmission. The model employs a nonlinear transform module to capture latent features, and then utilizes an entropy model to approximate the joint distribution of latent features and capture source dependence. The JSCC system adaptively allocates transmission rates based on entropy information, significantly enhancing transmission efficiency. By incorporating an attention mechanism into ChARM, we developed the MCAM, which effectively captures both global and local characteristics of the latent features, leading to more accurate entropy estimation and improved rate-distortion performance. Moreover, to address channel condition variations, we design the SAnet module which dynamically adjusts the coding strategy based on SNR information, thereby mitigating performance degradation caused by SNR mismatch. Experimental results demonstrate that our proposed model achieves superior PSNR performance compared to existing approaches, including NTSCC and SwinJSCC. Additionally, by leveraging VMamba’s inherent linear computational complexity, MNTSCC maintains significantly lower computational overhead while delivering these performance gains.

Benefiting from its superior transmission performance, low computational complexity, and end-to-end optimization capability, MNTSCC demonstrates strong potential for practical applications in scenarios with limited computing resources, such as edge computing, remote sensing image transmission, and bandwidth-constrained IoT networks. However, the model still suffers from relatively slow inference speed and a large number of parameters. Future research could focus on lightweight model design through techniques such as knowledge distillation and model pruning to reduce model size and improve inference efficiency. Furthermore, the model’s inference speed could be enhanced by incorporating more efficient VMamba variants such as MambaTree [40] and EfficientVMamba [41]. Moreover, the method proposed is currently designed primarily for high-quality image transmission tasks and can be further extended to communication scenarios associated with downstream tasks dominated by machine vision.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Hubei University of Technology for providing the experimental facilities and resources necessary for this research. We also wish to thank all the faculty and students who offered their assistance and insights throughout the course of this work.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the Key Research and Development Program of Hubei Province under Grant No. 2023BEB024 and the Young and Middle-Aged Scientificand Technological Innovation Team Plan in Higher Education Institutions in Hubei Province under Grant No. T2023007.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Chao Li; writing—review and editing, Chao Li and Yonghao Liao; model building, Chen Wang; methodology, Chen Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Chen Wang; formal analysis, Caichang Ding; investigation, Caichang Ding; funding acquisition, Zhiwei Ye. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The implementation code for this work is openly available in MNTSCC at https://github.com/WanChen10/MNTSCC (accessed on 09 July 2025). The datasets used in this study are publicly available from the following sources: Kodak24 dataset: http://r0k.us/graphics/kodak/ (accessed on 09 July 2025); Clic2022 dataset: https://compression.cc/ (accessed on 09 July 2025); DIV2K dataset: https://data.vision.ee.ethz.ch/cvl/DIV2K/ (accessed on 09 July 2025); Cifar10 dataset: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html (accessed on 09 July 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| CBR | Channel Bandwidth Ratio |

| AWGN | Additive White Gaussian Noise |

| JSCC | Joint Source-Channel Coding |

| SSM | State Space Model |

| VSSBlock | Visual State Space Block |

| 2DSS | 2D Selective Scan |

| NTC | Nonlinear Transform Coding |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| GFLOPs | Giga Floating-Point Operations Per Second |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| MS-SSIM | Multi-Scale Structural Similarity |

References

1. Al-Fuqaha A, Guizani M, Mohammadi M, Aledhari M, Ayyash M. Internet of things: a survey on enabling technologies, protocols, and applications. IEEE Commun Surv Tut. 2015;17(4):2347–76. doi:10.1109/COMST.2015.2444095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Deng D, Wang C, Xu L, Jiang F, Guo K, Zhang Z, et al. Semantic communication empowered NTN for IoT: benefits and challenges. IEEE Netw. 2024;38(4):32–9. doi:10.1109/MNET.2024.3383604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Shannon CE. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Tech J. 1948;27(3):379–423. [Google Scholar]

4. Fresia M, Peréz-Cruz F, Poor HV, Verdú S. Joint source and channel coding. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2010;27(6):104–13. doi:10.1109/MSP.2010.938080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Bourtsoulatze E, Kurka DB, Gündüz D. Deep joint source-channel coding for wireless image transmission. IEEE Trans Cogn Commun Netw. 2019;5(3):567–79. doi:10.1109/TCCN.2019.2919300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kokalj-Filipović S, Soljanin E. Suppressing the cliff effect in video reproduction quality. Bell Labs Tech J. 2012;16(4):171–85. [Google Scholar]

7. Yang K, Wang S, Dai J, Qin X, Niu K, Zhang P. SwinJSCC: taming swin transformer for deep joint source-channel coding. IEEE Trans Cogn Commun Netw. 2025;11(1):90–104. doi:10.1109/TCCN.2024.3424842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. In: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2021 May 3–7; Virtual. p. 611–31. [Google Scholar]

9. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2017. p. 6000–10. [Google Scholar]

10. Lin T, Wang Y, Liu X, Qiu X. A survey of transformers. AI Open. 2022;3(120):111–32. doi:10.1016/j.aiopen.2022.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin Transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar]

12. Liu Z, Hu H, Lin Y, Yao Z, Xie Z, Wei Y, et al. Swin Transformer V2: scaling up capacity and resolution. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 19–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 11999–12009. [Google Scholar]

13. Liu Y, Tian Y, Zhao Y, Yu H, Xie L, Wang Y, et al. VMamba: visual state space model. In: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2024 Dec 9–14; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2025. p. 103031–63. [Google Scholar]

14. Wu T, Chen Z, Tao M, Sun Y, Xu X, Zhang W, et al. MambaJSCC: adaptive deep joint source-channel coding with generalized state space model. arXiv:2409.16592. 2024. [Google Scholar]

15. Gu A, Dao T. Mamba: linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv:2312.00752. 2023. [Google Scholar]

16. Minnen D, Singh S. Channel-wise autoregressive entropy models for learned image compression. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2020 Oct 25–28; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 3339–43. [Google Scholar]

17. Wang L, Wu W, Zhou F, Yang Z, Qin Z, Wu Q. Adaptive resource allocation for semantic communication networks. IEEE Trans Commun. 2024;72(11):6900–16. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2024.3405355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yang K, Wang S, Dai J, Tan K, Niu K, Zhang P. WITT: a wireless image transmission transformer for semantic communications. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2023 Jun 4–9; Rhodes Island, Greece. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

19. Dai J, Wang S, Tan K, Si Z, Qin X, Niu K, et al. Nonlinear transform source-channel coding for semantic communications. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2022;40(9):2300–16. doi:10.1109/JSAC.2022.3180802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ballé J, Minnen D, Singh S, Hwang SJ, Johnston N. Variational image compression with a scale hyperprior. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2018 Apr 30–May 3; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 4961–5007. [Google Scholar]

21. Koyuncu AB, Jia P, Boev A, Alshina E, Steinbach E. Efficient Contextformer: spatio-channel window attention for fast context modeling in learned image compression. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2024;34(8):7498–511. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2024.3371686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Jiang W, Yang J, Zhai Y, Ning P, Gao F, Wang R. MLIC: multi-reference entropy model for learned image compression. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM); 2023 Oct 29–Nov 3; Ottawa, ON, Canada: Association for Computing Machinery; 2023. p. 7618–27. [Google Scholar]

23. Chen T, Liu H, Ma Z, Shen Q, Cao X, Wang Y. End-to-end learnt image compression via non-local attention optimization and improved context modeling. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2021;30:3179–91. doi:10.1109/TIP.2021.3058615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Gu A, Johnson I, Goel K, Saab K, Dao T, Rudra A, et al. Combining recurrent, convolutional, and continuous-time models with linear state-space layers. In: Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2021 Dec 6–14; Virtual Event. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2021. p. 572–85. [Google Scholar]

25. Gu A, Dao T, Ermon S, Rudra A, Ré C. HiPPO: recurrent memory with optimal polynomial projections. In: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2020 Dec 6–12; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2020. p. 1474–87. [Google Scholar]

26. Somvanshi S, Islam MM, Mimi MS, Polock SB, Chhetri G, Das S. A survey on structured state space sequence (S4) models. arXiv:2503.18970. 2025. [Google Scholar]

27. Patro BN, Agneeswaran VS. Mamba-360: survey of state space models as transformer alternative for long sequence modelling: methods, applications, and challenges. arXiv:2404.16112. 2024. [Google Scholar]

28. Zhu L, Liao B, Zhang Q, Wang X, Liu W, Wang X. Vision Mamba: efficient visual representation learning with bidirectional state space model. In: Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning(ICML); 2024 Jul 21–27; Vienna, Austria. p. 62429–42. [Google Scholar]

29. Ruan J, Li J, Xiang S. VM-UNet: vision Mamba UNet for medical image segmentation. arXiv:2402.02491. 2024. [Google Scholar]

30. Wang H, He Q, Peng J, Yang H, Chi M, Wang Y. Mamba-YOLO-World: marrying YOLO-world with Mamba for open-vocabulary detection. In: ICASSP 2025—2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2025 Apr 6–11; Hyderabad, India. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

31. Cheng T, Song L, Ge Y, Liu W, Wang X, Shan Y. YOLO-World: real-time open-vocabulary object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 16901–11. [Google Scholar]

32. Gu A, Goel K, Ré C. Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces. In: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2022 Apr 25–29; Virtual Event. p. 14323–49. [Google Scholar]

33. Babiloni F, Tanay T, Deng J, Maggioni M, Zafeiriou S. Factorized dynamic fully-connected layers for neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW); 2023 Oct 2–6; Paris, France. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1366–75. [Google Scholar]

34. Han Y, Huang G, Song S, Yang L, Wang H, Wang Y. Dynamic neural networks: a survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;44(11):7436–56. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3117837. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Xu BC, Zhang YY. An improved gravitational search algorithm for dynamic neural network identification. Int J Autom Comput. 2014;11(4):434–40. doi:10.1007/s11633-014-0810-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Pauluzzi DR, Beaulieu NC. A comparison of SNR estimation techniques for the AWGN channel. IEEE Trans Commun. 2000;48(10):1681–91. doi:10.1109/26.871393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wang Z, Bovik AC. Mean squared error: love it or leave it? A new look at signal fidelity measures. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2009;26(1):98–117. doi:10.1109/MSP.2008.930649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Horé A, Ziou D. Image quality metrics: PSNR vs. SSIM. In: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition; 2010 Aug 23–26; Istanbul, Turkey: IEEE. p. 2366–9. doi:10.1109/ICPR.2010.579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wang Z, Simoncelli EP, Bovik AC. Multiscale structural similarity for image quality assessment. In: The Thirty-Seventh Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems & Computers; 2003 Nov 2–5; Pacific Grove, CA, USA: IEEE. p. 1398–402. [Google Scholar]

40. Xiao Y, Song L, Huang S, Wang J, Song S, Ge Y, et al. MambaTree: tree topology is all you need in state space model. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2024 Dec 9–14; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 75329–54. [Google Scholar]

41. Pei X, Huang T, Xu C. EfficientVMamba: atrous selective scan for light weight visual Mamba. In: Proceedings of the 39th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI); 2025 Feb 25–Mar 4; Philadelphia, PA, USA. p. 6443–51. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools