Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

ELDE-Net: Efficient Light-Weight Depth Estimation Network for Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Mobile Robot Path Planning

1 Department of Mechatronics, School of Mechanical Engineering, Hanoi University of Science and Technology, Hanoi, 10000, Vietnam

2 College of Engineering, Shibaura Institute of Technology, Tokyo, 135-8548, Japan

* Corresponding Authors: Thai-Viet Dang. Email: ; Phan Xuan Tan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Computer Vision and Image Processing: Feature Selection, Image Enhancement and Recognition)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2651-2680. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067500

Received 05 May 2025; Accepted 23 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Precise and robust three-dimensional object detection (3DOD) presents a promising opportunity in the field of mobile robot (MR) navigation. Monocular 3DOD techniques typically involve extending existing two-dimensional object detection (2DOD) frameworks to predict the three-dimensional bounding box (3DBB) of objects captured in 2D RGB images. However, these methods often require multiple images, making them less feasible for various real-time scenarios. To address these challenges, the emergence of agile convolutional neural networks (CNNs) capable of inferring depth from a single image opens a new avenue for investigation. The paper proposes a novel ELDE-Net network designed to produce cost-effective 3D Bounding Box Estimation (3D-BBE) from a single image. This novel framework comprises the PP-LCNet as the encoder and a fast convolutional decoder. Additionally, this integration includes a Squeeze-Exploit (SE) module utilizing the Math Kernel Library for Deep Neural Networks (MKLDNN) optimizer to enhance convolutional efficiency and streamline model size during effective training. Meanwhile, the proposed multi-scale sub-pixel decoder generates high-quality depth maps while maintaining a compact structure. Furthermore, the generated depth maps provide a clear perspective with distance details of objects in the environment. These depth insights are combined with 2DOD for precise evaluation of 3D Bounding Boxes (3DBB), facilitating scene understanding and optimal route planning for mobile robots. Based on the estimated object center of the 3DBB, the Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL)-based obstacle avoidance strategy for MRs is developed. Experimental results demonstrate that our model achieves state-of-the-art performance across three datasets: NYU-V2, KITTI, and Cityscapes. Overall, this framework shows significant potential for adaptation in intelligent mechatronic systems, particularly in developing knowledge-driven systems for mobile robot navigation.Keywords

Autonomous navigation primarily seeks to achieve precise and efficient obstacle avoidance [1]. The presence of complex environments imposes considerable processing demands, which can render navigation systems prohibitively expensive [2]. The utilization of cameras, characterized by their compact size, cost-effectiveness, and substantial computational capabilities, offers rich scene information that aligns with system requirements while simultaneously minimizing expenses [3]. Environmental perception tasks, particularly those focused on the identification of 3D objects, are essential for the advancement of autonomous driving technologies [4]. These tasks enable MRs to accurately ascertain the location of objects within a defined range. The capabilities for depth perception and understanding are enhanced through the integration of various sensors, including Lidar, cameras, and depth sensors, which collectively facilitate safe and efficient navigation. As MRs track a predetermined path, sophisticated algorithms are employed to automatically detect objects and obstacles [5]. Presently, methods for 3D object identification methods can be classified into two primary categories: Lidar-based and vision-based techniques [6]. While Lidar-based 3DOD systems are recognized for their high accuracy and effectiveness, their elevated costs and complex computational resource requirements restrict their applicability across diverse industries [7,8]. Conversely, vision-based approaches can be further divided into two distinct types: monocular [9] and binocular vision [10]. Vision-based perception systems are frequently adopted due to their affordability and extensive capabilities. A notable limitation of monocular vision is its inability to directly determine depth from image data, which may result in inaccuracies when estimating the 3D position during monocular object detection [4]. Although binocular vision entails a higher cost relative to monocular vision, it offers more precise depth information. However, this approach also presents a more restricted field of view, which may prove insufficient for certain operational contexts [11].

Monocular 3DOD methods typically build upon established 2DOD networks to predict the 3DBB of objects within 2D RGB images [12]. A significant challenge associated with monocular 3DOD lies in the estimation of missing 3D data from 2D images. A single 2D image can correspond to an infinite array of 3D scenarios due to the nature of projection. The characteristics of the objects present in the scene are extracted and represented, including the estimated distance of each pixel within the field of view. These distance estimations are critical for accurately determining the 3DBB of objects. To effectively estimate the depth of a single 2D scene, a model must analyze and comprehend both the specific details within the image and the broader context of the scene. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNNs) have been extensively employed in recent studies for monocular depth estimation due to their capacity to learn from both local and global contexts. Gao et al. proposed an unsupervised learning approach that simultaneously predicts monocular depth and ego-motion trajectory [13]. Following this, Yin and Shi introduced an adaptive geometric relationship among monocular depth, optical flow, and ego-motion estimation to enhance the robustness of jointly unsupervised learning [14]. Furthermore, Ranjan et al. [15] integrated depth prediction, motion estimation, segmentation, and optical flow through geometric constraints, effectively addressing both static and moving regions while excluding dynamic zones. Additionally, Xiong et al. [16] proposed robust geometric losses to ensure the consistency of depth and pose estimation, thereby stabilizing self-supervised monocular depth estimation through the incorporation of scale-consistent geometric constraints into the loss functions. Subsequently, He et al. [17] utilized deep residual learning to facilitate training based on the ImageNet dataset. However, the implementation of such extensive networks, characterized by numerous parameters, poses practical challenges due to substantial computational costs and significant memory requirements. The down-sampling procedure within the encoder network often results in the loss of small details in lower-resolution layers. Godard et al. [18] generated disparity images by employing reconstruction loss for depth prediction in low-quality depth images. Consequently, the distortion of depth information near edges significantly diminishes the accuracy of subsequent tasks, such as 3D reconstruction [10]. Therefore, the primary objective of the 3D perception system is to retrieve the 3DBB, which is defined within the coordinate frame of the 3D environment, as well as its bird’s eye view (BEV) representation [5]. The orientation of the BEV is determined by omitting the vertical dimension of the object.

The core technology that supports MR’s vision navigation is the recognition of objects within a 3D environment [19,20]. Xie et al. [21] introduced a detection methodology that employs deep CNNs to improve detection speed in intricate scenarios. DRL merges the perceptual strengths of deep learning with the strategic benefits of reinforcement learning, thereby enabling a variety of applications across multiple industries [22]. Mnih et al. [23] identified that traditional RL struggles with tasks featuring large state spaces and continuous action spaces that resemble real-world complexities. Conversely, DQL utilizes neural networks to predict the Q-value to enhance scalability. Lei et al. utilized to explore the dynamic and uncertain obstacles in unknown environments [24]. Khlifi et al. introduced double Deep-Q-Network (DQN) to estimate the value process and enhance the model’s efficacy in complex navigating tasks [25]. The DQN framework, which integrates Q-learning with deep learning for reconfiguring the state-action value function into a format amenable to neural network analysis. This reconfiguration facilitates the calculation of action values pertinent to the current state, thus aiding in the determination of an optimal navigation strategy [26]. Based on vision-based perception systems, DRL has played an important role in path planning, where it demonstrates remarkable capability in navigating complex and unknown environments and executing challenging tasks with notable efficiency.

The paper proposes the lightweight ELDE-Net, which is built on the PP-LCNet backbone and utilizes a fast convolution block as the decoder model. PP-LCNet is a lightweight CPU network that leverages the MKLDNN acceleration strategy. The proposed backbone enhances the network’s performance across multiple tasks. The fast convolution block decodes information from the backbone and generates a depth map. By utilizing only the current data, a new transformation eliminates redundant computations without requiring the overall overlapping data. Data processing speed is significantly improved through arithmetic analysis, indicating that the reduced transformation size provides additional advantages in data manipulation. In summary, the prediction layer employs synthesis to produce the final segment map. Based on the estimated object center of the 3DBB, the DRL-based obstacle avoidance strategy for MRs is developed.

The primary contributions are as follows:

• The authors present the ELDE-Net model, which combines the decoder of a fast convolutional block with a lightweight PP-LCNet backbone leveraging the MKLDNN optimizer to achieve efficient depth estimation in resource-limited systems.

• By applying the SE module to model inter-channel dependencies, along with the flexibility of the two-loss function ratio, the feature representation of the CNN is enhanced.

• Based on the combination of rapid depth estimation and 2DOD by YoloV9, 3D-BBE has been implemented.

• Based on experiments conducted on the NYU-V2, Cityscapes, and KITTI datasets, the proposed model demonstrates superior performance compared to state-of-the-art monocular camera-based depth estimation methods.

• Based on the estimated object center of the 3DBB, the DRL-based obstacle avoidance strategy for the MR has been fully developed.

• Experimental findings confirm the feasibility of DRL-based path planning in real-world scenarios. Furthermore, the obtained 3DBB and 3DOD enhance the operational efficiency and safety of MR systems.

Continue with the following sections of the paper. Related works are shown in Section 2. Section 3 presents the architecture of the proposed ELDE-Net. Section 4 contains experimental results and comparisons. Section 5 presents the final conclusions and future works.

Precise and robust 3DOD is one of the promising applications of MR’s navigation. State-of-the-art methods have facilitated the integration of MR’s diverse perception systems, including cameras, ultrasonic sensors, LiDAR, and radar. In practical applications, LiDAR and cameras are preferred due to their significant advantages, which include the ability to incorporate intelligent tasks into the system, range assurance, and high precision. The focus of this research is to deploy deep neural network models to estimate depth with optimal speed and efficiency, thereby enhancing the rapid and effective construction of 3DBBs.

2.1 LiDAR-Based 3D Object Detection

LiDAR sensors furnish the system with data pertaining to the point clouds derived from the surrounding environment. These signals undergo conversion and processing to produce a comprehensive predictive map that encapsulates both the semantic content and the depths of objects. Generally, algorithms that utilize LiDAR can be categorized into three distinct types: point-based methods [27], projection map-based methods [28], and voxel-based methods [29]. Point-based methods leverage unordered point cloud data as input and employ permutation-invariant operators to extract key features, thereby yielding promising outcomes in three-dimensional detection [30]. However, these methods often place excessive emphasis on the overall perspective of the point cloud, which can result in inadequate differentiation of complex characteristics. In contrast, projection map-based methods address this limitation by converting sparse point clouds into a 2D-BEV format, which aids in the preservation of object attributes [31]. Nonetheless, this transformation frequently leads to a substantial loss of information, negatively impacting detection accuracy. Voxel-based methods, on the other hand, organize sparse point cloud data into volumetric grids and subsequently process this data using efficient convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [32]. With a relatively low computational overhead, approaches such as PointPillars [33] and Second [34] utilize BEV projection to achieve competitive detection performance. In summary, depth estimation through LiDAR presents significant advantages, including high accuracy and remarkable adaptability to varying environmental conditions. However, the primary challenges associated with this technology include the high costs and the intricate nature of processing LiDAR signals.

2.2 Monocular-Based 3D Object Detection

The contemporary monocular 3DOD approaches can be primarily classified into two categories: pseudo-LiDAR-based methodologies and image-based methodologies. Wang et al. [35] employed pseudo-LiDAR techniques to transform image-based depth maps for 3DOD applications. Following this, Chen et al. [36] proposed a method that integrates RGB images with pseudo point cloud data to generate an augmented input for object category prediction. Although this model entails a more complex computational process, it produces a fixed direction 3DBB. Subsequently, AM3D [37] combined 2D image depth with pseudo-LiDAR point clouds to enhance the 3D-BBE by utilizing an attention mechanism based on a gating function. Ye et al. [38] introduced DA-3Ddet to improve the performance of real LiDAR data while addressing a previously neglected issue. Weng and Kitani [39] innovatively fused 3D and 2D sensing using a pseudo-LiDAR point cloud to advance 3D detection methods [40]. While this integration enhances efficiency, the conversion from 2D data to 3D point clouds may introduce errors, potentially resulting in inaccuracies in subsequent detection stages. Although this approach enhances performance and increases efficiency, the transition from 2D data to a 3D point cloud dataset may lead to erroneous data, which could ultimately result in flawed assessments during later detection processes.

Monocular images inherently lack the comprehensive 3D information that is available through LiDAR or stereo vision systems. As a result, many contemporary image-based methodologies enhance detection accuracy by utilizing prior knowledge, geometric constraints, and additional supplementary data. Ji et al. [41] developed a lightweight 3D-BBE to effectively formulate 3D object localization. Similarly, Mousavian et al. introduced the Deep3DBox [42] for 3DOD and pose estimation. The integration of the 3D-BBE with 2D geometric constraints facilitated the precise determination of the 3D object’s pose. To directly predict depth from the center of the 3D bounding box, Qin et al. employed MonoGRNet [43], a model that achieves 3D localization using a monocular RGB image. Shi et al. presented MonoRCNN [44], which incorporates a novel geometry-based distance decomposition algorithm to infer distances. In the study conducted by Chen et al. [45], the MonoPair framework was utilized to investigate paired sample relationships, thereby enhancing monocular 3DOD. Ma et al. [46] successfully estimated the size of 3D objects by addressing localization errors inherent in monocular 3D detection. Brazil and Liu employed the M3D-RPN [47] to ensure the effective functioning of both BEV and 3DOD. However, the coarse and fixed spatial partitioning employed in these models leads to deviations that hinder the accurate capture of object scale and local structure. Additionally, challenges persist in establishing supplementary 3D-to-2D geometric constraints, which significantly impact the resolution of the ambiguous depth inference problem [48]. Overall, while the models introduced provide certain advantages, they also exhibit numerous limitations related to resource constraints, parameter optimization, and data loss.

2.3 Monocular Depth Estimation

Depth estimation from perspective images has attracted considerable attention over the past decade, particularly through the application of deep learning-based monocular depth estimation techniques [49]. To enhance the accuracy of depth map predictions, Eigen and Fergus [50] introduced an innovative multi-dimensional monocular depth estimation method that integrates both global and local perspectives. Acknowledging the inherently ordered nature of depth values, Cao et al. [51] proposed a fully convolutional deep residual network for depth estimation that employs depth classification rather than regression. Zhou et al. [52] developed a novel approach to reduce reliance on ground truth data by simultaneously improving the accuracy of both depth estimation and pose estimation, utilizing images from monocular video sequences. Godard et al. [53] advanced the field with MonoDepth2, a state-of-the-art model designed to effectively address occluded pixels. This model minimizes reprojection loss at a per-pixel level through an auto-masking loss architecture, achieved by filtering out unsuitable training pixels based on camera motion. To facilitate precise depth estimation across extensive areas with varying gradients, Lyu et al. [54] developed HR-Depth, an innovative model based on DepthNet [55]. Its standout features include a reconfigured arrangement of skip connections and the integration of relevant characteristics to produce exceptional high-resolution outputs. In response to the increasing demand for immediate functionalities on cutting-edge devices, several researchers have developed a range of agile monocular depth prediction systems rooted in efficient CNN frameworks such as ESPNet [56], MobileNets [57], and ShuffleNet [58]. Wofk et al. [59] introduced FastDepth, a proficient and lightweight encoder-decoder network that reduces computational complexity and latency. However, challenges remain, including the loss of intricate details and the blurring of edges in predicted depth maps. Rudolph et al. [60] reconstructed high-resolution depth maps using guided upsampling blocks within the decoder, while Zhou et al. [61] progressively refined depth maps through recurrent multi-scale feature modulation. To encompass global contexts, Zhang et al. [62] presented the Lite-Mono architecture, which combines a lightweight CNN with a transformer, thereby reducing model size while maintaining accuracy. Nevertheless, as data processing demands in 3D image reconstruction continue to escalate, these lightweight methodologies must address the limitations of representation capacity and computational resources. Drawing inspiration from Conditional Convolutions (CondConv), Yang et al. [63] replaced standard convolutions with CondConv to enhance the scale and capability of the network while preserving performance and inference costs. By utilizing CondConv to dynamically adapt the convolution kernel based on various inputs and incorporating sub-pixel convolution, the authors introduced a spatially aware dynamic lightweight depth estimation network.

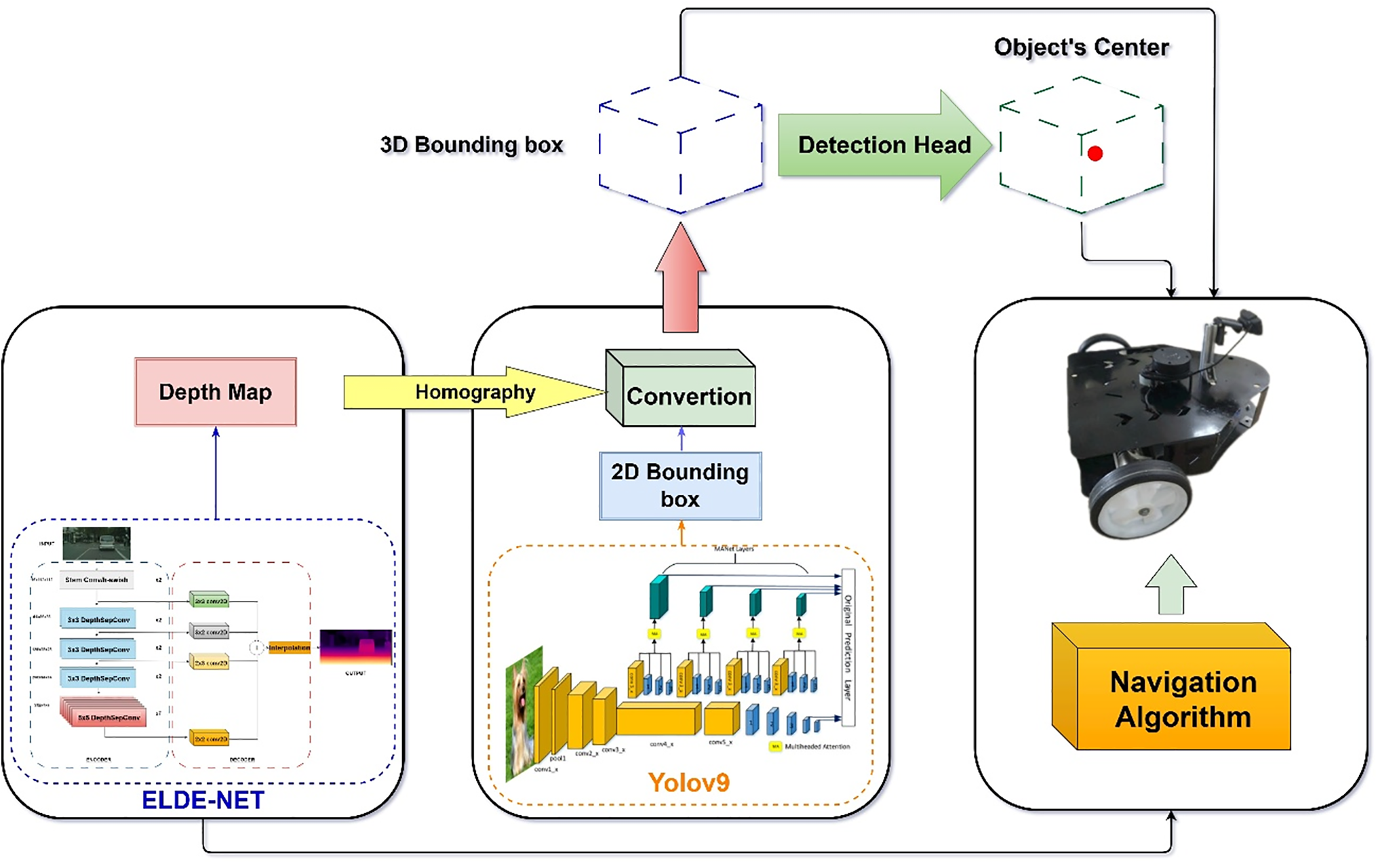

In this section, we present the detailed architecture of the proposed model. The foundation of ELDE-Net is based on depth estimation from 2D images. The depth information for each pixel is predicted and encoded, then transformed into real-world coordinates using a transformation matrix. This initial contextual information is represented in BEV. In the second processing stream, the architecture of YOLOv9 is integrated to generate predictions of 2DBB for prioritized detected objects. A computation head is established to combine the bounding boxes with the depth information of the pixels in the detected region, resulting in an effective estimation of 3DBB. Additionally, the authors introduce a detection head to calculate the center of the bounding boxes, which corresponds to the center of the object. This coordinate value is determined by averaging the coordinates of the 3DBB. Consequently, the information about the objects in the environment is synthesized as input for the navigation algorithm. Finally, the navigation strategy for the MR is designed using the identified centers of objects within the movement environment, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The flowchart of the MR’s strategy of path planning based proposed ELDE-Net model

The authors propose the ELDE-Net architecture, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The methods previously introduced have demonstrated significant effectiveness in estimating depth for each pixel of a single image. However, these methods come with a high computational cost and limited compatibility with resource-constrained embedded systems and devices. Additionally, the complexity of training and deploying two separate models poses further challenges. To address these issues, this study focuses on minimizing the network size and the number of computational parameters, thereby overcoming the aforementioned drawbacks while ensuring accuracy. Our approach involves leveraging features through the PP-LCNet structure [64] to enhance the processing speed of the depth estimation model. By utilizing DepthSepConv, the model can deliver precise outcomes across various CPU and GPU platforms. The integration of the SE module aims to improve convolutional efficiency by effectively separating filters for individual channels. However, PP-LCNet’s lack of extracted features leads to limited computational parameters, resulting in suboptimal performance. Consequently, the authors designed an appropriate decoder to effectively utilize the convolutional layers and adjusted the loss function during the model training process.

Figure 2: Proposed depth estimation model with light convolution layers

CNNs have achieved significant progress in computer vision tasks in recent years. These networks can be trained and utilized across a diverse array of applications, including depth estimation. However, achieving rapid inference speeds on mobile device-oriented ARM architecture or CPU-based x86 architecture poses a significant challenge. The primary factors contributing to this challenge include the excessive generation of parameters and the complex architecture of the models. A notable limitation is the restricted compatibility with the MKLDNN accelerator. The authors advocate for the use of the PP-LCNet model for feature extraction to enhance the processing speed of the depth estimation model. The PP-LCNet model is optimized by employing Depthwise Separable Convolution (DepthSepConv), which facilitates high accuracy when operating on CPU or GPU devices. Each convolutional block comprises multiple convolutional layers arranged sequentially. These layers utilize filters to extract features from the input image, with the filter size and quantity determined by the network architecture. Typically, smaller filters, such as 3 × 3 or 5 × 5, are preferred to minimize the number of parameters while improving computational efficiency. Given the necessity for high per-pixel accuracy in single-camera depth estimation tasks (e.g., obstacle avoidance or object centering), it is crucial to aggregate features at various scales for the decoder to accurately interpret these features. To improve the understanding of image semantics at different scales, we propose the incorporation of convolutional layers with distinct kernel sizes directly associated with the model outputs at dimensions of 112 × 112, 56 × 56, 28 × 28, and 7 × 7. Subsequently, the decoded segments are merged to produce the final output of the model. Initializing the convolutional layers for each encoder output size facilitates the detailed representation of the decoded segments.

3.3 DepthSepConv with Squeeze-Exploit Module

Traditional convolution operations typically utilize the entirety of the image data within the input channel, resulting in a substantial number of parameters and significant computational demands. To mitigate these challenges, DepthSepConv is employed, as illustrated in Fig. 3. This approach fundamentally separates the convolution operation into two distinct stages: depthwise convolution (DW) and pointwise convolution (PW). Additionally, global average pooling (GAP) is incorporated into the architecture. The H-wish activation function is selected for its efficiency and adaptability, particularly in scenarios characterized by data imbalance or interference. The SE module is positioned near the end of the network to enhance balance and accuracy. This configuration is designed to leverage higher-level features effectively. Furthermore, the inclusion of the SE module contributes to the optimization of inference time. The activation functions employed in this framework are ReLU and Sigmoid, respectively. In summary, DepthSepConv presents several key advantages: a reduced number of parameters, optimized computational requirements, improved performance through the separation of filters for each channel, and the utilization of the SE module.

Figure 3: The architecture of DepthSepConv in which the Squeeze-Exploit (SE) module

The decoder holds the key to unraveling and combining the unique attributes derived from the code maker. Hence, this block produces a prediction map with depth information for each pixel. The innovative approach employs 2D convolutional strata (conv2D) with an array of kernel dimensions. The functionality of these convolutional strata is illustrated in Fig. 4. These core elements are meticulously crafted to unearth characteristics across various scopes and proportions. Every stratum analyzes input from its corresponding DepthSepConv unit. The insights from each stratum are consolidated and channeled into the subsequent stratum. Decoders featuring diverse kernel sizes infuse richness into the ultimate insights. The distinctive dimensions and functions of the decoder strata are expounded as follows:

• 3 × 3 Conv2D: Extracts global-scale features from the Stem conv/h-swish layer.

• 3 × 2 Conv2D: Extracts horizontal direction features from the first DepthSepConv layer.

• 2 × 3 Conv2D: Similar to the previous decoder layer, but a 2 × 3 kernel is used to capture vertical information.

• 2 × 2 Conv2D: Employs a small kernel to extract detailed features from the last DepthSepConv layer.

Figure 4: Basic operation of Conv2D layer in the decoder block

The decoder comprises of four upconvolution modules featuring a reduction in the number of channels alongside an increase in the size of the feature map. Within each module, the sequence of blocks unfolds as follows: Unpool, convolution, batch normalization, and Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU). Diverse information can be gathered across various scales and merged through a concatenation block to reintegrate the details into a unified prediction map. Here, the authors utilize the bilateral filter [65] to demarcate the outline of the object in the depth map with the outline of the actual object, which reduces noise in prediction. Ultimately, the deciphered data undergoes interpolation to produce a comprehensive depth estimation. The depth measurement for every pixel is provided and serves either for visualization or for computing the 3DBB at a later stage. The overall architecture for depth estimation proposed brings two main contributions: Using a lightweight backbone that operates quickly for the task of extracting input features, the decoder is designed flexibly across convolutional dimensions to efficiently utilize the parameter count, leveraging data from a monocular camera, which is inherently low-cost, for the depth estimation task in the environment.

3.5 3D Bounding Box Estimation

Drawing upon the depth information estimated for each pixel, the authors seamlessly collaborate with a 2D object detector. Consequently, a comprehensive computation of the 3DBB is derived from the initial image. Primarily, it is crucial to grasp the complexity involved in estimating 3DBBs, particularly when dealing with a solitary 2D image. Numerous existing methods encounter various constraints and demand intricate computational resources. This proves instrumental in constructing cognitive systems for real-time environmental operations. The overall architecture is illustrated in the visual representation presented in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: The 3D-BBE’s architecture

The proposed 3D-BBE is divided into two following stages.

• Stage 1: 2D object detection

The proposed model utilizes YOLOv9 [66] to generate preliminary bounding boxes. By incorporating PGI and the adaptive GELAN architecture capability, YOLOv9 not only enhances the model’s learning ability but also ensures the preservation of critical information throughout the detection process. Specifically, it preserves information during computation and gradient propagation. Ultimately, the outcome is complete 2DBB information on single images. The bounding box size along with the label of the detected object will be further utilized downstream.

• Stage 2: Combine with depth map to calculate the 3DBB

During this stage, the ELDE-Net model generates depth information for each pixel in the image. These values are normalized using a homography matrix H [2,3] to transform them from the image plane to the real-world environment. Specifically, the depth values of each pixel (hij) are normalized according to perspective projection. The transformation formula is shown in the following (1):

where H is a homography matrix; hij is the depth values of each pixel according to perspective projection.

The normalized depth values will be combined with the 2DBB (estimated in Stage 1) to calculate the size and position of the 3DBB, in the following (2):

where

Object tracking in real-world environments relies on maintaining object identity and position over time as it moves through a scene. For collision detection and avoidance in autonomous vehicles and obstacle avoidance systems, accurate object center estimation (OCE) is essential. By utilizing OCE, the observer can pinpoint the precise location of an object within their frame of reference. These systems can predict potential collisions and execute evasive maneuvers to ensure safe navigation by monitoring the centers of surrounding objects. OCE provides valuable insights into spatial arrangement and relationships between objects in an image. This information can be utilized for tasks such as object enumeration, scene understanding, and image segmentation. Moreover, aligning the object’s central point with the monitored path allows for an initial prediction of the trajectory and speed of obstacles that must be avoided by the MR. The determination of the object’s centroid, based on depth data, along with the 3DBB enclosure, supports navigational tasks (see Fig. 1). Therefore, the 3D-BBE will be estimated on the original 2D images. The coordinate values of the 3DBB’s vertices are stored to calculate the center position. The center is calculated by taking the average of the coordinates at the vertices of the upper bounding box in the following (3):

where n is the total number of samples when considering the coordinates of the vertices per bounding box.

4 Experiment Results and Discussion

The proposed model was trained on three datasets (see Fig. 6), which include NYU-V2 of 7560 images [67], Cityscapes of 5000 images [68] and KITTI of 400 images [67]. We implemented the Adam optimization algorithm [69], incorporating a learning rate of 0.001, weight decay set at 0.9, and a batch size of 32. Our choice of framework was Pytorch, and the model underwent training on a server boasting a CPU with an Intel Core i9 11900k, 64 GB of RAM, and an RTX3070 for enhanced performance.

Figure 6: Raw images from three datasets of (a): NYU-V2 [67]; (b): CitySpaces [68]; and (c): KITTI [67] dataset

Then, the loss and accuracy values of the training and testing processes are continuously monitored to show the learning rate of information from the training and testing data. The loss function is set up flexibly to adjust the effectiveness of feature extraction from the convolutional layers. Specifically, the total_loss function is established by the authors using the SSIM and L1 loss functions in following (4):

In particular, the

where

The standard loss function L1 is the sum of the absolute difference between the target value and the estimated value. Hence, the L1 loss is illustrated in the following (6):

Advantages of the total loss function proposed such as follows:

• Two distinct loss functions are utilized in the calculation process, enhancing the versatility of assessing the model’s training and testing efficacy.

• SSIM exhibits a keen sensitivity towards pixel discrepancies in images while deriving the conversion value gradients.

• L1 loss displays a heightened sensitivity towards erroneous predictions, hence expediting enhancements in the model’s training efficiency. This leads to a faster convergence of predicted values towards the true ground values.

• The scale of the two component functions can be adjusted for different dataset cases, ensuring a balance in training that captures features through network layers.

The simultaneous use of two loss functions according to the ratio allows for flexible exploitation of their functional effectiveness. L1 helps quickly penalize values that deviate from the labels. SSIM maintains and improves predictions close to the ground truth value. With each different training scenario, the component ratio between the two loss functions can be flexibly adjusted to quickly adapt, resulting in significant training effectiveness.

The dataset known as NYU Depth V2, which has been meticulously curated by the NYU Depth Lab situated at New York University, plays a crucial role as a fundamental asset in the realm of computer vision research, with a specific focus on tasks related to depth estimation and scene comprehension. This dataset was captured through the utilization of a Microsoft Kinect RGB-D camera, encompassing a wide array of indoor environments, providing RGB images with a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels, corresponding depth maps, and semantic labels for various elements within the scenes. In our experimentation, a total of approximately 43,000 images were utilized for the training phase, while 7560 images were reserved for testing purposes. The original frames, initially of a certain size, have been systematically down-sampled to half of their original resolution and subsequently center-cropped to dimensions of 304 by 228 pixels.

The datasets from Kitti comprise depth maps derived from projected LiDAR point clouds that underwent a comparison with the depth estimation originating from the stereo cameras. Characterized by a high level of sparsity, the depth images exhibit a mere 5% of accessible pixels, leaving the majority as absent. Within this research endeavor, approximately 2000 images were utilized for model training purposes, while 500 images were allocated for model testing. Initially, initially possessed dimensions of 1216 × 352, the original images underwent a down-sampling process to 912 × 228.

Cityscapes dataset acts as an asset within the realm of visual responsibilities related to understanding street scenes. The collection consists of more than five thousand pictures, each with a size of 1024 × 2048 pixels. These datasets feature images sized 128 × 256, accompanied by segmentation labels for 19 different classes and depth labels. Enhancements such as flipping images randomly, tweaking RGB values, standardizing images using color channel statistics, and converting images into torch tensors from Numpy arrays are all enhancements applied to this dataset.

Furthermore, several data augmentation techniques of Random Brightness Contrast [70], Color Jitter [71], Shift Scale Rotate [72], and Hue Saturation Value [73] were implemented to enhance the generalizability of the model based all three datasets.

Mean Squared Error (MSE): is defined as a measure of the average error between the predicted depth

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): is like MSE, less sensitive to larger errors than MSE. Besides, the predictive performance is more demonstrated. RMSE is calculated as the following (8):

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): is a common loss function for many deep learning-based methods. The author uses this metric to represent the pixel difference between basic reality and predicted depth. Then, averaging the results of the evaluation of pixels on the photo. MAE is calculated using the following (9):

Accuracy: determines whether a prediction is considered accurate based on a specific threshold. The threshold values we used were 1.25, 1.252, and 1.253. Accuracy under threshold is calculated as the following (10):

Absolute Relative Error (Abs_Rel): measures the average of the absolute relative difference between predicted depth values and actual ground depth values, normalized by the average of actual ground depth values. Abs_Rel is calculated as the following (11):

Based on the outcomes observed during the training phase, ELDE-Net demonstrates a competitive advantage due to its superior attributes. The proposed approach, which integrates ResNet18 with Upconv, achieved minimal values for both train_loss and val_loss. However, ELDE-Net exhibits a faster rate of convergence and reduced fluctuations in these metrics. Both models yield comparable SSIM_train results on the training set. In contrast, ELDE-Net outperforms ResNet18 combined with Upconv in SSIM_val results on the test set, highlighting its enhanced accuracy in handling objects with slight deviations from the training data. This underscores the superior adaptability of the proposed approach to both training and evaluation datasets. The MSE results from both training and test data confirm ELDE-Net’s stability and its ability to capture objects more efficiently than ResNet18 combined with Upconv. In essence, the comparisons underscore the proposed approach’s superiority in quickly grasping data characteristics. The focal point of this evaluation is ELDE-Net, a fusion of the ResNet18 architecture with localized decoder components for pixel depth estimation (ResNet18+Upconv). Initially, an analysis is conducted on the fluctuation of loss values throughout the training phases of these two models, in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Experimental knowledge distillation results [74] including (a): Traning Loss; (b): Validation Loss; (c): Training SSIM; (d): Validation SSIM; (e): Training MSE; and (f): Validation MSE from ResNet152 for Resnet18 training

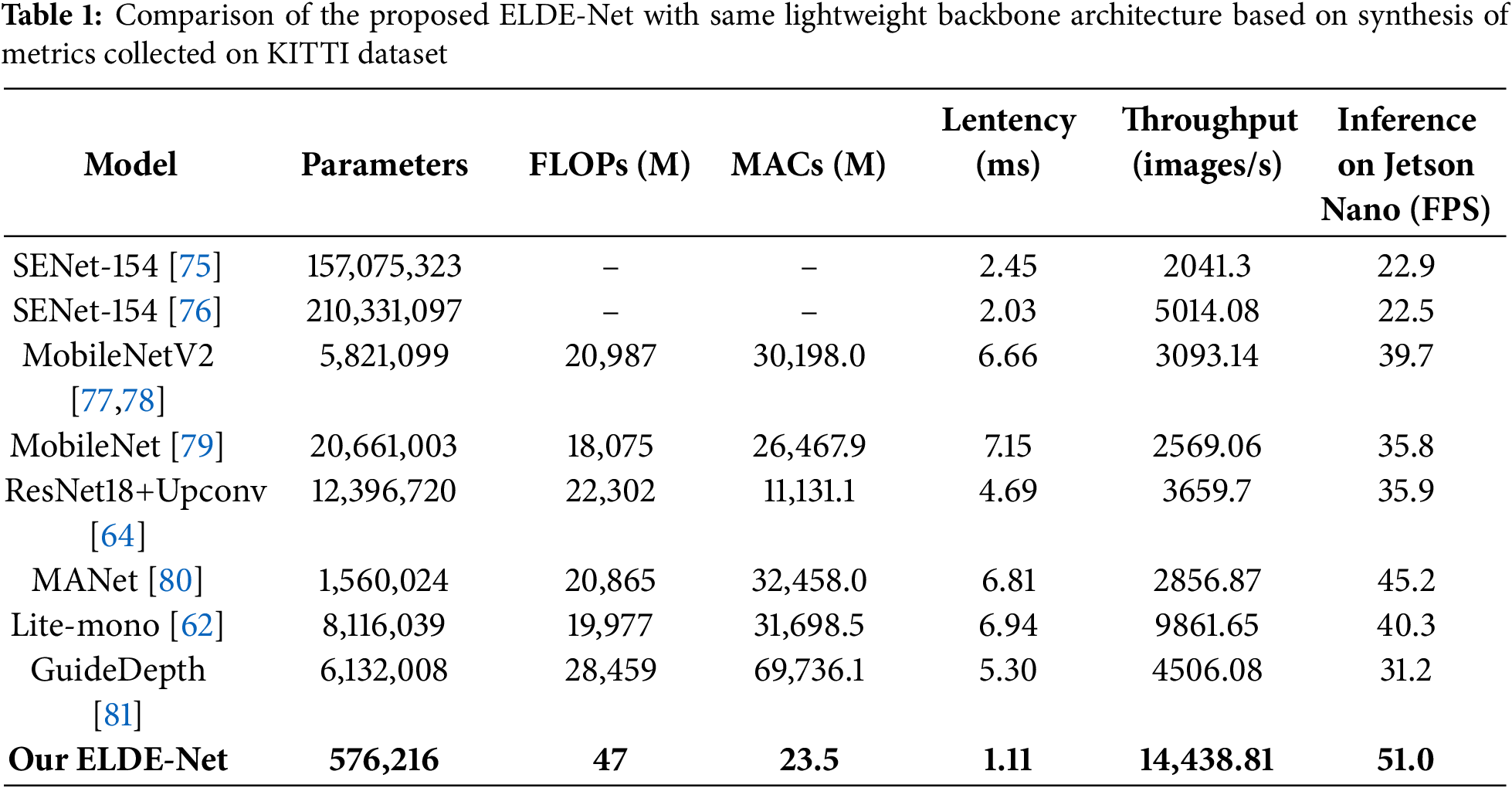

Furthermore, ELDE-Net has been crafted with a size and resource cost that are just right. By harnessing the benefits of DepthSepConv layers, the model effectively utilizes the trained parameters. The performance of ELDE-Net and ResNet18+Upconv is scrutinized by the authors based on various metrics such as number of parameters, FLOPs, MACs, Latency, and Throughput, with the outcomes laid out in Table 1. Remarkably, ELDE-Net uses only 0.04 times the number of parameters in ResNet+Upconv. FLOPs and MAC demonstrate a much more efficient computation in comparison to the alternative model. The latency of ELDE-Net is notably 4.2 times smaller, while the throughput has surged by 3.9 times when contrasted with ResNet18-Upconv. Finally, To evaluate the smoothness and quality of the animation on the Jetson Nano embedded computer based on FPS (frames-per-second), the ELDE-Net model also obtained outstanding results when compared to ultra-lightweight models such as about more than 2.2 times compared to the SENet family; 1.42 times compared to MobileNet; 1.28 times compared to MobileNetV2 and 2.1 times compared to ResNet18+Upconv.

Similar to the other methods compared, the proposed model demonstrates superior agility and operational speed by significantly reducing computational volume. The remaining models are based on lightweight feature extraction blocks, particularly SENet [75,76], MobileNetV2 [77,78], and MobileNet [79] which were tested in this study. The evaluation metrics clearly indicate the advantages of the proposed method in minimizing the number of computational parameters. Consequently, both latency and throughput achieved significantly better results compared to previous approaches. Specifically, throughput is approximately 4.6 times higher, while latency is only 15% to 51% of that of the compared MobileNet family models. Furthermore, the proposed model also shows outstanding superiority not only in training parameters but also in FPS specifications when tested on a Jetson nano embedded computer when compared with current state-of-the-art models such as MANet [80], Lite-mono [81], and GuideDepth [82]. ELDE-Net ultilizes effectivelya small parameter to reduce computational and storage costs for embedded or edge devices, thereby significantly enhancing computational performance and data flow.

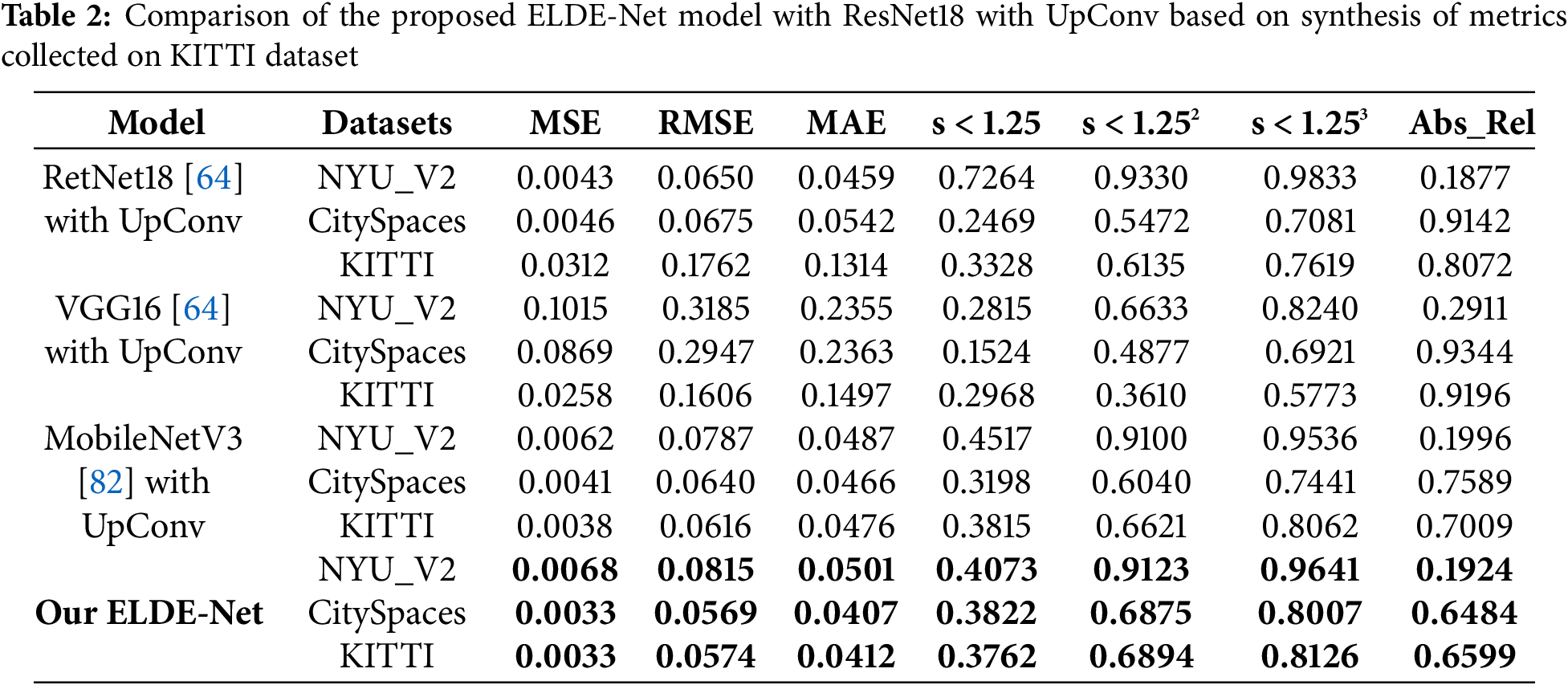

Moreover, the authors draw inferences from three datasets: NYU-V2, Cityscapes, and KITTI. The evaluation metrics used for evaluation were MSE, RMSE, MAE, Accuracy under threshold, and Abs_Rel. Experiments demonstrate that ELDE-Net yields promising results across all metrics. The two datasets, Cityscapes and KITTI, which encompass various elements found in a self-driving car’s operational environment, indicate that the proposed strategy outperforms others, as shown in Table 2. When compared to Res-Net18 [64] with Upconv, VGG16 [64] with Upconv, and MobileNetV3 [82] with UpConv all metrics illustrate the model’s ability to capture object attributes, with MSE, RMSE, and MAE exhibiting higher values. Additionally, the accuracy below the threshold is at a reliable level. As indicated by Abs_Rel, the model surpasses more conventional approaches by narrowing the gap between its predictions and actual outcomes.

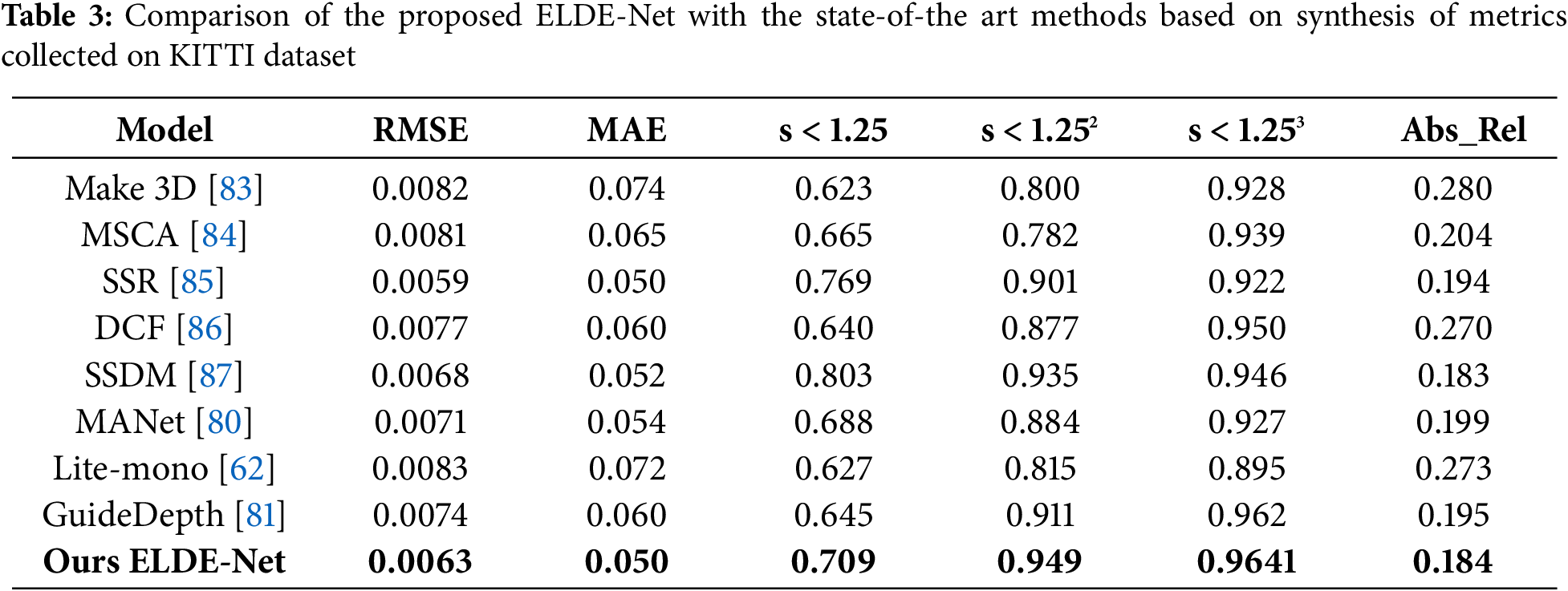

To compare the ELDE-Net with the state-of-the art methods and demonstrate its remarkable competitiveness, the evaluation parameters illustrated in Table 3 highlight its effectiveness in predicting environmental depth maps. Alongside a comprehensive comparison of the presented datasets, the authors assert that the proposed method has the potential to enhance the system’s ability to capture environmental characteristics effectively. In summary, ELDE-Net achieves exceptional inference accuracy while maintaining a compact model size and weight. The results indicate that, compared to current best practices, the proposed strategy performs admirably in experiments.

4.5 3D Bounding Box Estimation

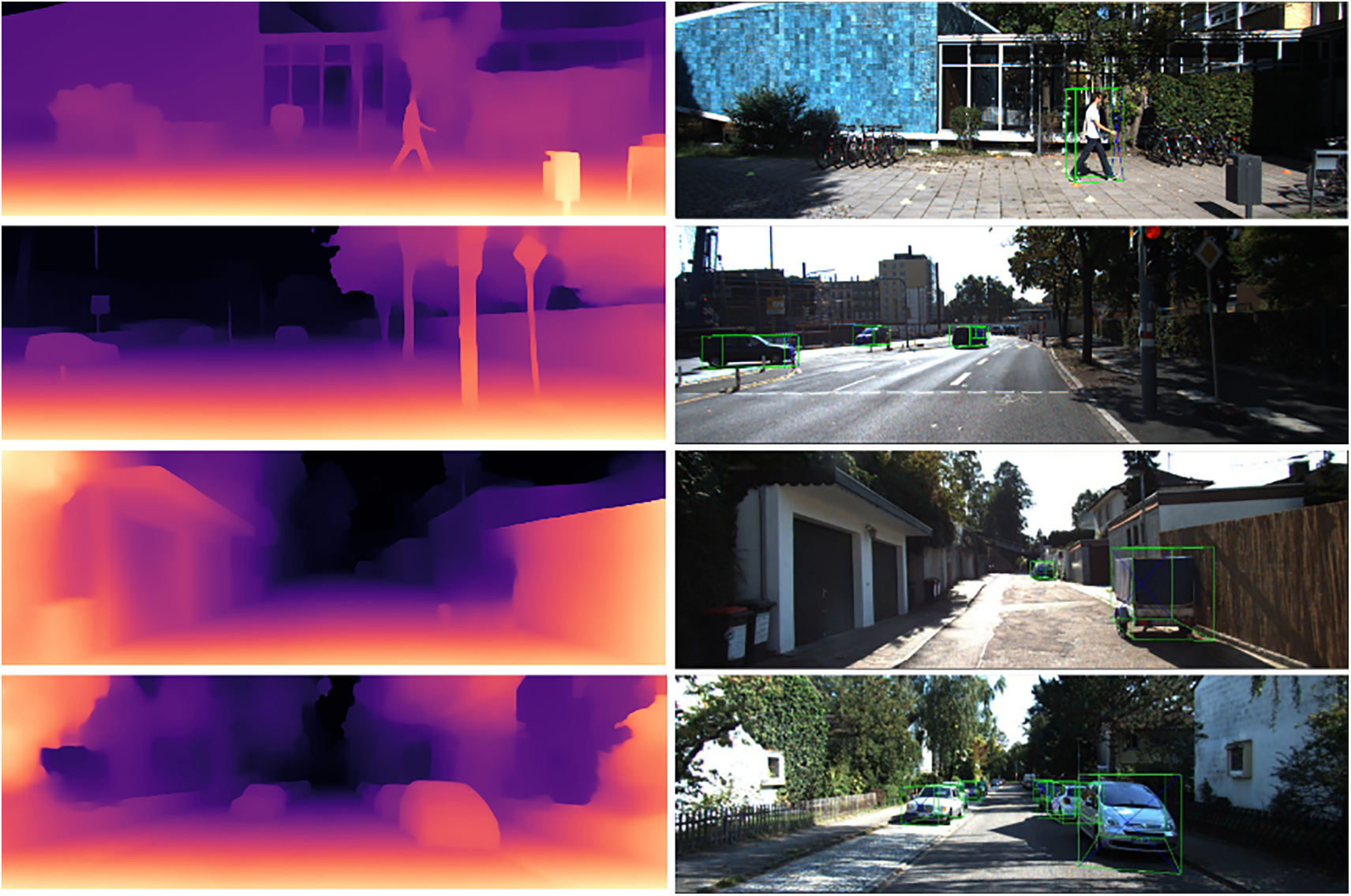

Based on the proposed ELDE-Net, the authors conducted training and inference on the evaluated datasets. The results demonstrate the model’s stability and performance. Notably, rapid training and prediction times are attributed to the use of PPLC-Net as the backbone. Some estimated results are illustrated in Fig. 8, which includes depth data and the 3DBB estimates derived from the KITTI dataset.

Figure 8: Depth and 3DBB are estimated on the KITTI dataset

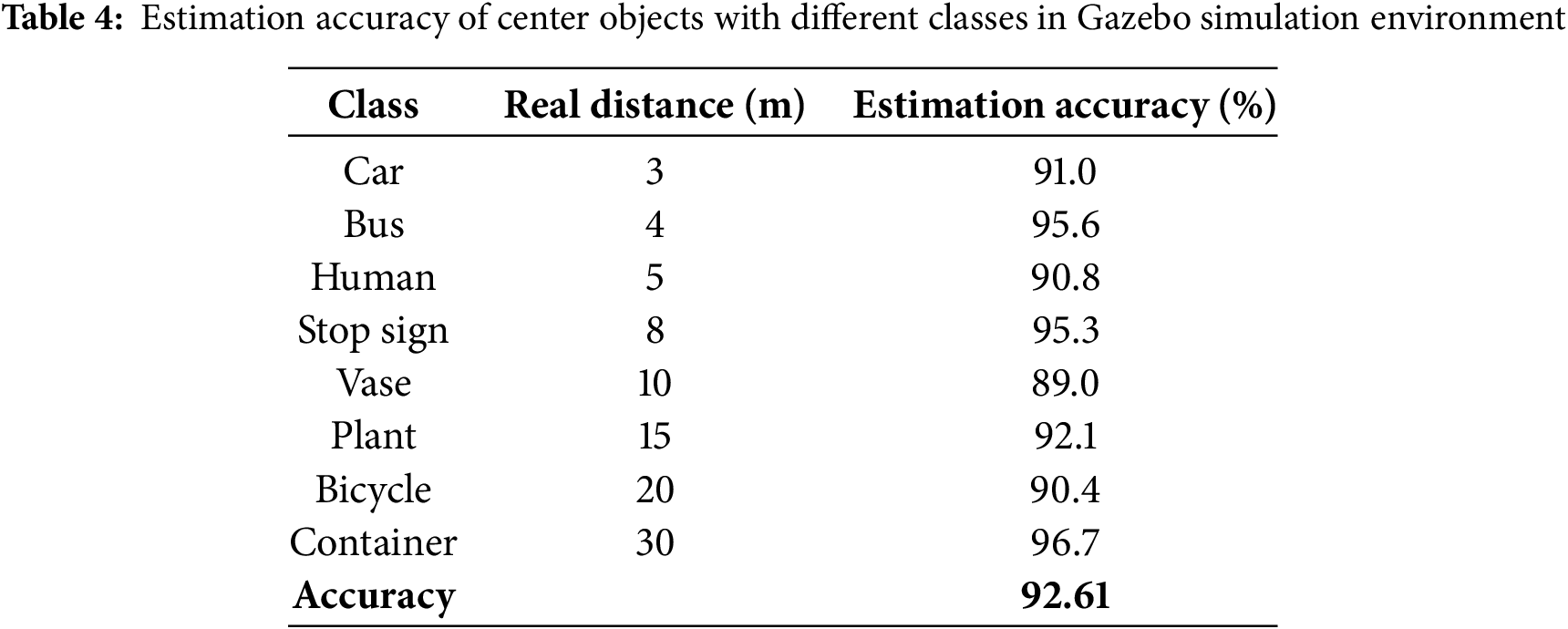

The authors conduct experiments and evaluate the results obtained from the proposed method. The primary focus is on the characteristic objects within the operational environment. The 3DBB is computed with remarkable precision, as illustrated previously. The inferred values delineate the limitations of the coordinates and the distance to the identified objects. Hence, the high accuracy in estimating the center suggests that the 3DBB predictions are reliable. Our experiments are illustrated in Fig. 9. The simulations were conducted on the Gazebo platform, considering a variety of objects, including people, vehicles, and other items. As the results are collected, object center estimation yields result with relative accuracy for objects within the monocular camera’s field of view. Simultaneously, the distance information from the viewpoint to the object center, as provided by ELDE-Net, is accurately verified. The match rate of the object predictions exceeded 65%. Furthermore, Table 4 indicates that the accuracy of the estimated centers is 92.61%. Overall, the evaluation indicators demonstrate remarkable effectiveness in determining the characteristics of objects within the environment.

Figure 9: Center estimation and object classification, testing on a Gazebo simulation environment

4.6 MR’s Strategy of Navigation

In this section, we present the MR navigation mode. Navigation is closely linked to the development of the vision system within the framework [88]. The proposed method focuses on several key factors, including external objects, actions, and the state of the MR environment. Specifically, these data are detected by the ELDE-Net model and utilized as training and inference parameters for the navigation model. A DRL framework is employed to process these parameters and estimate the optimal actions. The architecture and operational process of the RL network are illustrated in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Deep reinforcement leaning architecture for MR navigation

In this section, we present the MR navigation mode. Navigation is closely linked to the development of the vision system within the framework. The proposed method focuses on several key factors, including external objects, actions, and the state of the MR environment. Specifically, these data are detected by the ELDE-Net model and utilized as training and inference parameters for the navigation model. A DRL framework is employed to process these parameters and estimate the optimal actions. The architecture and operational process of the RL network are illustrated in Fig. 10.

• State

Distance measurements between MR and obstacles are derived by calculating the distance to the centers of pixels. To optimize the process, the MR frame is divided into five segments, facilitating the identification of the closest object in each segment.

The state of the MR’s position is determined in (13):

where d: the distance to the goal point and

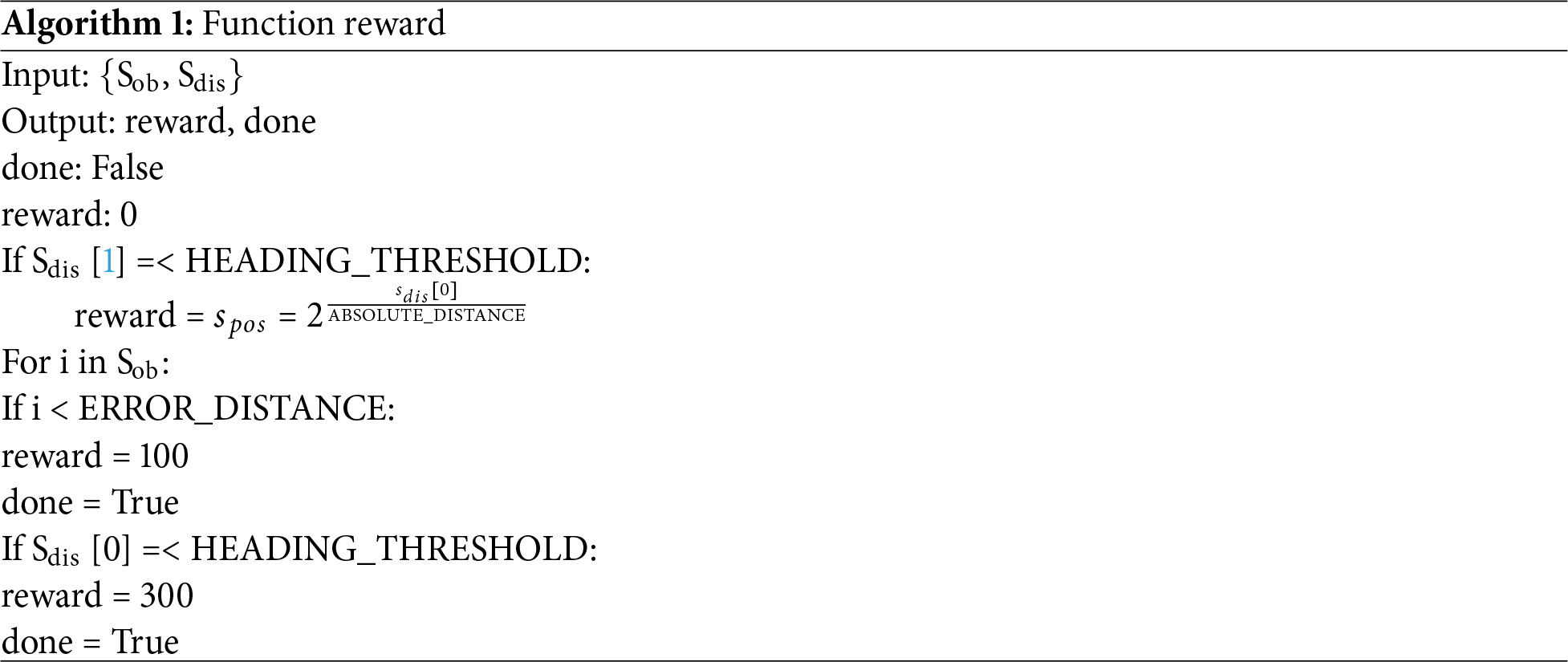

• Reward

The MR’s navigation must guarantee that it successfully reaches its destination while circumventing all obstacles present along the navigation path. We assess and analyze the MR’s sequential actions within the environment to ensure their alignment with the documented environmental conditions. This assessment serves as the foundation for the reward calculation process. Any movement by the MR that minimizes the distance to the destination will be rewarded accordingly. Achieving the destination will result in the maximum reward value. Conversely, the loss function will impose penalties on trajectory values that result in collisions with obstacles. The reward function is constructed utilizing the pseudocode outlined in Algorithm 1.

• Action

The MR is determined by its linear velocity

The MR will be equipped with five predefined angular velocities in two directions to allow for rapid or gradual rotation as required, as illustrated in Fig. 11. Meanwhile, the linear velocity will be directly related to the reward it receives in (15).

Figure 11: The MR’s movement: (a) in Gazebo simulation environment and (b) with wn driving angles set

Next, combine (14) with (15) to yield (16):

Consequently, the MR initiates its search at an elevated velocity, progressively diminishes it, and ultimately ceases upon arriving at the goal point.

• Q-values

The policies (policy_dqn) and targets (target_dqn) in deep Q-Network (DQN) are set up with similar structures but provide distinct functions. The policy_dqn network serves as the main network for action selection during both the training and execution phases within the environment. Therefore, the policy_dqn is continuously refined to predict the Q values for state-dependent actions and to determine the next action. The target_dqn network stabilizes the training process and provides target Q values to calculate the loss function during the training of policy_dqn. The optimization function will calculate the current Q values and the target Q values for each state and action in the minibatch. The MSE function is applied to calculate the loss between the two values to adjust the parameters of the DQN model, using the Adam optimizer [69] to minimize the value of the loss function (see Algorithm 2).

The information about detected objects is encoded into values that represent the correlation between the MR and its environment. A neural network is employed to compute the weights of actions corresponding to the input parameters. In this context, the actions denote the optimal steering angles in relation to the obstacles present in the environment. Furthermore, the MR’s mobility is assessed based on its linear and angular velocities. Based on the proposed navigation algorithm training framework, the authors conducted experiments in both simulated and real environments. Initially, they tested the ELDE-Net architecture for MR navigation using the Gazebo simulator integrated with ROS2. The MR system was equipped with a depth camera D435, which served as the input for the ELDE-Net model.

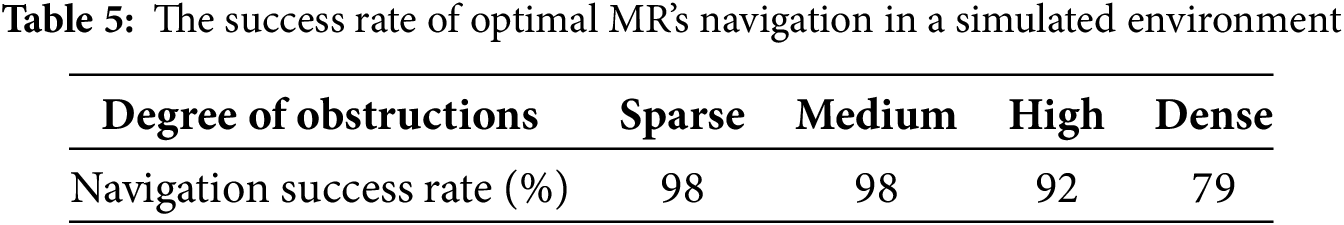

The proposed navigation structure was assessed in various specific scenarios. The authors evaluated the accuracy of pathfinding based on the completion rates of navigation scenarios under different environmental conditions. The tested scenarios included sparse, medium, high, and dense obstacles, with the number of obstacles in each case being 5, 20, 40, and 80, respectively, within a simulated area of 400 square meters. The success rate of finding the path to the destination is detailed in Table 5.

The cases identified as representative of effective navigation adhere to two primary criteria: the MR successfully arrives at the specified destination, and the movement process is executed without colliding with obstacles. The results demonstrate that the implementation of a reinforcement learning framework within navigation algorithms is entirely viable. Subsequently, the authors quantified the duration required for the MR to reach its destination to evaluate the efficiency of its navigation. Comprehensive results are provided in Table 6. In this study, a navigation framework for the MR that employs the A* algorithm and the DWA [78,89] is implemented in conjunction with the proposed model. The proposed architecture exhibits a high degree of feasibility, particularly in stabilizing the navigation time of the MR across the various tested environments. It can be concluded that the integration of bounding box information and object depth information in MR navigation is effective in terms of both accuracy and compatibility with system resources. Consequently, these experiments demonstrate that the proposed pipeline for detecting 3D obstacles can function reliably with any navigation system.

The environment is designed with various objects that obstruct the MR’s path, including pedestrians, vehicles, and boxes. The navigation outcomes and optimal trajectory configurations are depicted in Fig. 12, which comprises twelve snapshots labeled from (a) to (m). The yellow circles denote the MR’s position within the environment, while the dashed lines illustrate the recorded movement logs. The trajectory of movement is documented and assessed, indicating that safe steering angles are developed over time and in relation to the MR’s positions. The MR effectively identifies the shortest path while successfully avoiding collisions with obstacles. The accuracy and stability of the proposed model have been rigorously validated. Additionally, the optimization of computational resources and the aforementioned parameters are fully utilized. In practical experiments, the three-wheeled MR, measuring 60 cm × 50 cm, is equipped with two 24V, 90W servo DC motors, an Intel® RealSense™ Depth Camera D435, and a Jetson Nano, as illustrated in Fig. 13, to confirm its practical applicability.

Figure 12: Navigation results in the Gazebo simulation environment (The trajectory of movement over time is described in the order of subtraction to genealogy and from top to bottom)

Figure 13: The experimental three-wheeled MR: (a) MR fully equipped, and (b) Intel® RealSense™ Depth Camera D435

From the acquired OCE data in a 3D environment reconstruction, MR’s obstacle avoidance strategy effectively tracks the triangular trajectory ABC, exhibiting minimal alterations in the steering angle from the initial position O to the destination (as illustrated in the six snapshots labeled (a) to (f) in Fig. 14). Notably, the MR does not employ an obstacle sensor; rather, it relies exclusively on visual input from its camera for obstacle avoidance. In the outlined scenario, the MR computes the requisite angle and distance to navigate around encountered obstacles, subsequently adjusting its position accordingly. In addition to conforming to the drivable path, the MR strategically avoids restricted turning points and angles that present a high likelihood of collision with obstacles, thereby determining the most appropriate path orientation. The implemented MR model generates outcomes based on environmental images captured under varying lighting conditions, serving as an assessment of the MR’s accuracy in real-world settings. The safe path angle is established through a field marker depicted in the obscured image, which is derived from images obtained by the MR from multiple vantage points. This marker also determines the optimal angle for the MR’s navigational movement within a specified area. The developed methodology for trajectory determination enhances the identification of a suitable trajectory in the context of autonomous navigation.

Figure 14: MR’s obstacle avoidance strategy is constructed by the obtained OCE of 3DBB

The paper proposes a novel real-time navigation method for mixed reality environments, which features extraction from monocular camera images. The proposed ELDE-Net model employs a lightweight PP-LCNet backbone integrated with the SE module effectively retrieving depth information while maintaining minimal computational costs. This efficiency is further enhanced through the incorporation of Depth SepConv, alongside optimization techniques for the SE model and the MKLDNN optimizer. Consequently, depth information is utilized in conjunction with object detection via the Yolov9 model. Experiments conducted across three datasets of Cityscapes, KITTI, and NYU-V2 demonstrate exceptional evaluation results. When assessing processing speed on the same dataset with a lightweight backbone, ELDE-Net exhibits remarkable performance in comparison to the MobileNet and SENet families, as evidenced by a combination of FLOPs, MACs, latency, and throughput metrics. Specifically, the throughput of ELDE-Net is approximately 4.6 times greater, while its latency ranges from 15% to 51% of that observed in the MobileNet family models. Notably, the ELDE-Net model utilizes only 0.04 times the number of parameters required by ResNet-Upconv. Furthermore, the proposed model achieves outstanding performance in RMSE and MAE metrics when compared to state-of-the-art methods, including Make3D, MSCA, SSR, DCF, SSDM, MANet, Lite-mono, and GuideDepth. Moreover, the assessment of the animation’s smoothness and quality on the Jetson Nano embedded computer, measured in frames per second (FPS), indicates that the ELDE-Net model achieved remarkable performance. Specifically, it outperformed ultra-lightweight models by approximately 2.2 times in comparison to the SENet family, 1.42 times relative to MobileNet, 1.28 times when compared to MobileNetV2, and 2.1 times in relation to ResNet18 with Upconv. Based on the estimated object center of the 3DBB, a DRL-based obstacle avoidance strategy for mobile robots has been developed. Finally, the robustness and high performance of the proposed ELDE-Net, as demonstrated through comparative simulations and real-world data, underscore its potential for practical applications.

Acknowledgement: Lab: 821M-C7: Computer Vision and Autonomous Mobile Robot (CVMR), SME, HUST; iRobot Lab, SMAE, HaUI, Vietnam; and Mobile Multimedia Communications Laboratory (MMC), SIT, Japan is gratefully acknowledged for providing work location, guidance, and expertise.

Funding Statement: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Dinh-Manh-Cuong Tran, Phan Xuan Tan and Thai-Viet Dang; Methodology, Nhu-Nghia Bui and Thai-Viet Dang; Software, Nhu-Nghia Bui and Dinh-Manh-Cuong Tran; Formal analysis, Thai-Viet Dang; Investigation, Nhu-Nghia Bui; Resources, Nhu-Nghia Bui and Thai-Viet Dang; Data curation, Nhu-Nghia Bui and Dinh-Manh-Cuong Tran; Writing—original draft, Phan Xuan Tan and Thai-Viet Dang; Writing—review & editing, Phan Xuan Tan and Thai-Viet Dang; Visualization, Nhu-Nghia Bui; Funding, Phan Xuan Tan; Supervision, Thai-Viet Dang; Project administration, Thai-Viet Dang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Thai-Viet Dang.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| BEV | Bird’s Eye View |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| DW | Depth-wise convolution |

| DWA | Dynamic Window Approach |

| GAP | Global Average Pooling |

| MKLDNN | Math Kernel Library for Deep Neural Networks |

| mIoU | Mean Intersection over Union |

| MRs | Mobile Robots |

| OCE | Object Center Estimation |

| PW | Point-wise convolution |

| PSP | Pyramid Scene Parsing |

| 3DBB | Three-Dimensional Bounding Boxes |

| 3D-BBE | Three-Dimensional Bounding Boxes Estimation |

| 3DOD | Three-Dimensional Object Detection |

| 2DOD | Two-Dimensional Object Detection |

| GPU | Graphic Process Unit |

| SE | Squeeze-Exploit |

References

1. Liu Y, Wang S, Xie Y, Xiong T, Wu M. A review of sensing technologies for indoor autonomous mobile robots. Sensors. 2024;24(4):1222. doi:10.3390/s24041222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Dang TV, Bui NT. Multi-scale fully convolutional network-based semantic segmentation for mobile robot navigation. Electronics. 2023;12(3):533. doi:10.3390/electronics12030533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Dang TV, Bui NT. Obstacle avoidance strategy for mobile robot based on monocular camera. Electronics. 2023;12(8):1932. doi:10.3390/electronics12081932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ahmed ED, Amr EZ, Mohamed EH. MonoGhost: lightweight monocular GhostNet 3D object properties estimation for autonomous driving. Robotics. 2023;12(6):155. doi:10.3390/robotics12060155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Dang TV, Tran DMC, Tan PX. IRDC-Net: lightweight semantic segmentation network based on monocular camera for mobile robot navigation. Sensors. 2023;23(15):6907. doi:10.3390/s23156907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Liang Q, Wang Z, Yin Y, Xiong W, Zhang J, Yang Z. Autonomous aerial obstacle avoidance using LiDAR sensor fusion. PLoS One. 2023;18(6):e0287177. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0287177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Huang KC, Wu TH, Su HT, Hsu WH. MonoDTR: monocular 3D object detection with depth-aware transformer. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA: IEEE. p. 4002–11. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Qu S, Yang X, Gao Y, Liang S, Xiang S. MonoDCN: monocular 3D object detection based on dynamic convolution. PLoS One. 2022;17(10):e0275438. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Wu J, Yin D, Chen J, Wu Y, Si H, Lin K. A survey on monocular 3D object detection algorithms based on deep learning. J Phys Conf Ser. 2020;1518(1):012049. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1518/1/012049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Qian R, Lai X, Li X. 3D object detection for autonomous driving: a survey. Pattern Recognit. 2020;30(2):108796. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2022.108796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Nguyen VT, Do CD, Dang TV, Bui TL, Tan PX. A comprehensive RGB-D dataset for 6D pose estimation for industrial robots pick and place: creation and real-world validation. Res Eng. 2024;24(4):103459. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ali U, Bayramli B, Alsarhan T, Lu H. A lightweight network for monocular depth estimation with decoupled body and edge supervision. Image Vis Comput. 2021;113:104261. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2021.104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gao R, Xiao X, Xing W, Li C, Liu L. Unsupervised learning of monocular depth and ego-motion in outdoor/indoor environments. IEEE Int Things J. 2022;9(17):16247–58. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2022.3151629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yin Z, Shi J. GeoNet: unsupervised learning of dense depth, optical flow and camera pose. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Salt Lake City, UT, USA; 2018. p. 1983–92. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ranjan A, Jampani V, Balles L, Kim K, Sun D, Wulff J, et al. Competitive collaboration: joint unsupervised learning of depth, camera motion, optical flow and motion segmentation. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Long Beach, CA, USA; 2019. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.01252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Xiong M, Zhang Z, Zhong W, Ji J, Liu J, Xiong H. Self-supervised monocular depth and visual odometry learning with scale-consistent geometric constraints. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; Yokohama, Japan; 2020. p. 963–9. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2020/134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Las Vegas, NV, USA; 2016. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Godard C, Aodha OM, Brostow GJ. Unsupervised monocular depth estimation with left-right consistency. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Honolulu, HI, USA; 2017. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Nguyen CH, Vu QA, Phung CKK, Dang TV. Optimal obstacle avoidance strategy using deep reinforcement learning based on stereo camera. MM Sci J. 2024;10(4):7556–61. doi:10.17973/MMSJ.2024_10_2024078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nguyen VT, Duong DN, Dang TV. Optimal two-wheeled self-balancing mobile robot strategy of navigation using adaptive fuzzy controller-based KD-SegNet. Intell Serv Robot. 2025;18(3):661–85. doi:10.1007/s11370-025-00606-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xie Q, Zhou D, Tang R, Feng H. A deep CNN-based detection method for multi-scale fine-grained objects in remote sensing images. IEEE Access. 2024;12(12):15622–30. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3356716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Nguyen AD, Vu TD, Vu QA, Dang TV. Research on modeling and object tracking for robot arm based on deep reinforcement learning. MM Sci J. 2025;6(2):8459–63. doi:10.17973/MMSJ.2025_06_2025059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mnih V, Kavukcuoglu K, Silver D, Rusu AA, Veness J, Bellemare MG, et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature. 2015;518(7540):529–33. doi:10.1038/nature14236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lei X, Zhang Z, Dong P. Dynamic path planning of unknown environment based on deep reinforcement learning. J Robot. 2018;12(12):1–10. doi:10.1155/2018/5781591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Khlifi A, Othmani M, Kherallah M. A novel approach to autonomous driving using double deep Q-network-bsed deep reinforcement learning. World Elect Veh J (WEVJ). 2025;16(3):138. doi:10.3390/wevj16030138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Das P, Behera H, Panigrahi B. Intelligent-based multi-robot path planning inspired by improved classical q-learning and improved particle swarm optimization with perturbed velocity. Eng Sci Technol Int J. 2016;19(1):651–69. doi:10.1016/j.jestch.2015.09.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Qian ZM, Chen YQ. Feature point-based 3D tracking of multiple fish from multi-view images. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0180254. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ku J, Mozifian M, Lee J, Harakeh A, Waslander SL. Joint 3D proposal generation and object detection from view aggregation. In: 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); Madrid, Spain; 2018. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/IROS.2018.8594049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Shi S, Wang X, Li H. PointRCNN: 3D object proposal generation and detection from point cloud. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Long Beach, CA, USA; 2019. p. 770–9. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhou Q, Cao J, Leng H, Yin Y, Kun Y, Zimmermann R. SOGDet: semantic-occupancy guided multi-view 3D object detection. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2024;38(7):7668–76. doi:10.1609/aaai.v38i7.28600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhou Y, Tuzel Q. VoxelNet: end-to-end learning for point cloud-based 3D object detection. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Salt Lake City, UT, USA; 2018. p. 4490–9. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Deng J, Shi S, Li P, Zhou W, Zhang Y, Li H. Voxel R-CNN: towards high performance voxel-based 3D object detection. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(2):1201–9. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i2.16207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Lang AH. PointPillars: fast encoders for object detection from point clouds. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Long Beach, CA, USA; 2019. p. 12689–97. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.01298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yan Y, Mao Y, Li B. SECOND: sparsely embedded convolutional detection. Sensors. 2018;18(10):3337. doi:10.3390/s18103337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Wang Y, Chao WL, Garg D, Hariharan B, Campbell M, Weinberger KQ. Pseudo-lidar from visual depth estimation: bridging the gap in 3D object detection for autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; Long Beach, CA, USA; 2019. p. 8445–53. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1812.07179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chen X, Ma H, Wan J, Li B, Xia T. Multi-view 3D object detection network for autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; Honolulu, HI, USA; 2017. p. 1907–15. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1611.07759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ma X, Wang Z, Li H, Zhang P, Ouyang W, Fan X. Accurate monocular 3D object detection via color-embedded 3d reconstruction for autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2019. p. 6851–60. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1903.11444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ye X, Du L, Shi YF, Li YY, Tan X, Feng JF, et al. Monocular 3D object detection via feature domain adaptation. In: European Conference on Computer Vision; ECCV 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 17–34. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58545-7_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Weng X, Kitani K. Monocular 3D object detection with pseudo-lidar point cloud. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops; Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2019. p. 1–10. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1903.09847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. You Y, Wang Y, Chao WL, Garg D, Pleiss G, Hariharan B, et al. Pseudo-lidar++: accurate depth for 3d object detection in autonomous driving. arXiv:1906.06310. 2019. [Google Scholar]

41. Ji C, Liu G, Zhao D. Monocular 3D object detection via estimation of paired keypoints for autonomous driving. Multimed Tools Appl. 2016;81(5):2147–56. doi:10.1007/s11042-021-11801-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Mousavian A, Anguelov D, Flynn J, Kosecka J. 3D bounding box estimation using deep learning and geometry. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA: IEEE. p. 7074–82. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1612.00496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Qin Z, Wang J, Lu Y. MonoGRNet: a geometric reasoning network for monocular 3D object localization. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2019;33(1):8851–8. doi:10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33018851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Shi X, Ye Q, Chen X, Chen C, Chen Z, Kim TK. Geometry-based distance decomposition for monocular 3D object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; Montreal, QC, Canada; 2021. p. 15172–81. [Google Scholar]

45. Chen Y, Tai L, Sun K, Li M. MonoPair: monocular 3D object detection using pairwise spatial relationships. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA: IEEE. p. 12093–102. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2003.00504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ma X, Zhang Y, Xu D, Zhou D, Yi S, Li H, et al. Delving into localization errors for monocular 3D object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Nashville, TN, USA; 2021. p. 4721–30. [Google Scholar]

47. Brazil G, Liu X. M3D-RPN: monocular 3D region proposal network for object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2019. p. 9287–96. [Google Scholar]

48. Xia C, Zhao W, Han H, Tao Z, Ge B, Gao X, et al. MonoSAID: monocular 3D object detection based on scene-level adaptive instance depth estimation. J Intell Robo Syst. 2024;110(1):2. doi:10.1007/s10846-023-02027-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Nguyen VT, Bui NN, Tran DMC, Tan PX, Dang TV. FDE-Net: lightweight depth estimation for monocular cameras. In: The 13th International Symposium on Information and Communication Technology (SOICT 2024); 2024 Dec 13–15; Danang, Vietnam. p. 3–13. doi:10.1007/978-981-96-4282-3_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Eigen D, Fergus R. Predicting depth, surface normal and semantic labels with a common multi-scale convolutional architecture. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); Santiago, Chile; 2015. p. 2650–8. [Google Scholar]

51. Cao Y, Wu Z, Shen C. Estimating depth from monocular images as classification using deep fully convolutional residual networks. IEEE Transact Circ Syst Video Technol. 2018;28(11):3174–82. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2017.2740321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zhou T, Brown MA, Snavely N, Lowe DG. Unsupervised learning of depth and ego-motion from video. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Honolulu, HI, USA; 2017. p. 6612–9. [Google Scholar]

53. Godard C, Aodha OM, Firman M, Brostow GJ. Digging into self-supervised monocular depth estimation. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2019. p. 3827–37. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2019.00393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Lyu X, Liu L, Wang M, Kong X, Liu L, Liu Y, et al. HR-depth: high resolution self-supervised monocular depth estimation. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(3):2294–301. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i3.16329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Zováthi Ö., Pálffy B, Jankó Z, Benedek C. ST-DepthNet: a spatio-temporal deep network for depth completion using a single non-repetitive circular scanning lidar. IEEE Robot Automat Lett. 2023;8(6):3270–7. doi:10.1109/LRA.2023.3266670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Abdelrahman A, Viriri S. EfficientNet family U-Net models for deep learning semantic segmentation of kidney tumors on CT images. Front Comput Sci. 2023;5:1–14. doi:10.3389/fcomp.2023.1235622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Rybczak M, Kozakiewicz K. Deep machine learning of mobilenet, efficient, and inception models. Algorithms. 2024;17(3):96. doi:10.1109/JBHI.2022.3182722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Zhang X, Zhou X, Lin M, Sun J. Shuffenet: an extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile devices. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Salt Lake City, UT, USA; 2018. p. 6848–56. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Wofk D, Ma F, Yang TJ, Karaman S, Sze V. FastDepth: fast monocular depth estimation on embedded systems. In: 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2019 May 20–24; Montreal, QC, Canada: IEEE. p. 6101–8. doi:10.1109/ICRA.2019.8794182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Rudolph M, Dawoud Y, Güldenring R, Nalpantidis L, Belagiannis V. Lightweight monocular depth estimation through guided decoding. In: 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2022 May 23–27; Philadelphia, PA, USA: IEEE. p. 2344–50. doi:10.1109/ICRA46639.2022.9812220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Zhou Z, Fan X, Shi P, Xin Y. R-MSFM: recurrent multi-scale feature modulation for monocular depth estimating. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); Montreal, QC, Canada: IEEE; 2021. p. 12757–66. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.01254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Zhang N, Nex F, Vosselman G, Kerle N. Lite-Mono: a lightweight CNN and transformer architecture for self-supervised monocular depth estimation. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Vancouver, BC, Canada: IEEE; 2023. p. 18537–46. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Yang B, Bender G, Le QV, Ngiam J. CondConv: conditionally parameterized convolutions for efficient inference. In: 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019); 2019 Dec 8–14; Vancouver, Canada. p. 1305–16. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1904.04971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Cheng C, Gao T, Wei S, Du Y, Guo R, Dong S, et al. PP-LCNet: a lightweight CPU convolutional neural network. arXiv:2109.15099. 2021. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2109.15099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Matsuo T, Fukushima N, Ishibashi Y. Weighted joint bilateral filter with slope depth compensation filter for depth maprefinement. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications (VISAPP); Barcelona, Spain; 2013. p. 300–9. [Google Scholar]

66. Li J, Feng Y, Shao Y, Liu F. IDP-YOLOV9: improvement of object detection model in severe weather scenarios from drone perspective. Appl Sci. 2024;14(12):5277. doi:10.3390/app14125277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Choi YH, Kee SC. Monocular depth estimation using a laplacian image pyramid with local planar guidance layers. Sensors. 2023;23(2):845. doi:10.3390/s23020845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Cordts M, Omran M, Ramos S, Rehfeld T, Enzweiler M, Benenson R, et al. The cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Las Vegas, NV, USA; 2016. p. 3213–23. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Liu M, Yao D, Liu Z, Guo J, Chen J. An improved adam optimization algorithm combining adaptive coefficients and composite gradients based on randomized block coordinate descent. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2023;5(1):4765891. doi:10.1155/2023/4765891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Barkan Y, Spitze H, Einav S. Brightness contrast-contrast induction model predicts assimilation and inverted assimilation effects. J Vision. 2008;8(7):1–26. doi:10.1167/8.7.27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Zini S, Gomez-Villa A, Buzzelli M, Twardowski B, Bagdanov AD, Van de Weijer J. Planckian Jitter: countering the color-crippling effects of color jitter on self-supervised training. arXiv:2202.07993. 2022. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2202.07993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Mengu D, Rivenson Y, Ozcan A. Scale-, shift- and rotation-invariant diffractive optical networks. ACS Photonics. 2021;8(1):324–34. doi:10.1021/acsphotonics.0c01583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Kadhim HJ, Abbas AH. Detect lane line for self-driving car using hue saturation lightness and hue saturation value color transformation. Int J Online Biomed Eng (iJOE). 2023;19(16):4–19. doi:10.3991/ijoe.v19i16.43359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Dang TV, Phan XT, Bui NN. KD-SegNet: efficient semantic segmentation network with knowledge distillation based on monocular camera. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(2):2001–26. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.060605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Hu J, Ozay M, Zhang Y, Okatani T. Revisiting single image depth estimation: toward higher resolution maps with accurate object boundaries. In: 2019 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2019 Jan 07–11; Waikoloa, HI, USA: IEEE. p. 1043–51. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1803.08673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Chen X, Chen X, Zha ZJ. Structure-aware residual pyramid network for monocular depth estimation. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-19); 2019 Aug 10–16; Macao, China. [Google Scholar]

77. Tu X, Xu C, Liu S, Li R, Xie G, Huang J, et al. Efficient monocular depth estimation for edge devices in internet of things. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2020;17(4):2821–32. doi:10.1109/TII.2020.3020583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]