Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Deep Learning-Based Automated Inspection of Generic Personal Protective Equipment

Department of Computer Science, College of Computer Science and Information Technology, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, P.O. Box 1982, Dammam, 31441, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Atta Rahman. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Computer Vision and Image Processing: Feature Selection, Image Enhancement and Recognition)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3507-3525. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067547

Received 06 May 2025; Accepted 08 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

This study presents an automated system for monitoring Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) compliance using advanced computer vision techniques in industrial settings. Despite strict safety regulations, manual monitoring of PPE compliance remains inefficient and prone to human error, particularly in harsh environmental conditions like in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. The proposed solution leverages the state-of-the-art YOLOv11 deep learning model to detect multiple safety equipment classes, including safety vests, hard hats, safety shoes, gloves, and their absence (no_hardhat, no_safety_vest, no_safety_shoes, no_gloves) along with person detection. The system is designed to perform real-time detection of safety gear while maintaining accuracy despite challenging conditions such as extreme heat, dust, and variable lighting. In this regard, a state-of-the-art augmented and rich dataset obtained from real-life CCTV, warehouse, and smartphone footage has been investigated using YOLOv11, the latest in its family. Preliminary testing indicates the highest detection rate of 98.6% across various environmental conditions, significantly improving workplace safety compliance and reducing the resources required for manual checks. Additionally, a user-friendly administrative interface provides immediate notification upon detection of breaches so that corrective action can be taken immediately. This initiative contributes to Industry 4.0 practice development and reinforces Saudi Vision 2030’s emphasis on workplace safety and technology.Keywords

Most warehouses in Saudi Arabia still rely on manual checks of personal protective equipment (PPE) compliance among the workers [1]. This traditional approach is laborious, time-consuming, and prone to errors. Consequently, it can result in potential accidents harmful to the workers and environmental safety [1]. The situation demands an automated PPE compliance detection system for better workplace safety [1].

According to [2], 70% of the fall incidents were due to workers not wearing proper PPE at the sites. The study exhaustively surveyed the incidents that occurred only in the USA for one and a half decades. Per the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) database, around 21,000 incidents were reported only in the construction industry. The incidents were categorized into four types: fall, struck by, caught in or between, and electrocution. Among them, fall incidents were significant, with a figure of 80% from a height of a building less than 30 feet, out of which only 11% of the fall victims were wearing proper PPE. In the following year, it was found that 85% of the inspected fatal cases were caused by the lack of PPE compliance [3]. That clearly shows an incremental issue in industrial environments.

These indicators are alarming, and a proper PPE compliance detection system is needed for the timely detection and possible prevention of such fatal incidents. Especially in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, logistics, construction, petroleum, and similar industries are widespread; hence, the need for PPE is significant. Moreover, at present, commendable measures have been taken to improve the workers’ safety. This substantially impacts on the reputation of the relevant agencies since wearing PPE could reduce the chances of falling by 30% [4]. One such measure is designing innovative PPE observation systems during working hours [5]. Nonetheless, a few employees may not adhere to wearing the given PPE temporarily for some reason or reject using the safety set because of a lack of awareness, which could result in fatal and nonfatal injuries. Per the study in [6], there are various factors behind PPE noncompliance. The authors conducted a thorough analysis to examine such factors using a fuzzy clustering algorithm. Consequently, sixteen factors were shortlisted. Inadequate safety supervision, poor risk perception, lack of climate adaptation, safety training, and management support were among the most influential factors. The situation demands an innovative system that can constantly watch for missing PPE, such as helmets, gloves, vests and alert supervisors immediately when someone is not following the rules. This would keep workers safer and save money in the long run by preventing accidents before happening.

The current study aims to automate PPE monitoring because it solves several real challenges in today’s industrial settings. First, traditional safety monitoring is just not comprehensive enough. Safety personnel have a limited field of vision and can only check some limited areas during their inspection rounds. On the other hand, an automated system provides continuous coverage across all monitored zones. The Kingdom’s focus on industrial advancement creates an opportunity to integrate cutting-edge safety technology while modernizing operations. Companies investing in these systems now position themselves as industry leaders in technology adoption and worker protection. The financial impact of safety incidents extends far beyond immediate medical expenses. A single serious incident can cost more than implementing an entire monitoring system. Most importantly, automating routine safety monitoring allows your skilled safety professionals to focus on more complex aspects of workplace safety—like training, hazard analysis, and process improvement. This shifts the safety culture from reactive to proactive, with technology handling repetitive monitoring while humans address the higher-level safety challenges.

In this regard, in this study, YOLOv11 is shortlisted for PPE monitoring and compliance detection because it offers the best balance of speed and accuracy for detecting safety equipment in busy work environments. Unlike systems requiring workers to wear special tags or sensors, camera-based monitoring works without changing existing PPE or disrupting workflows. The system efficiently identifies multiple safety items at once—hard hats, vests, shoes, and gloves—and can tell when any of these items are missing. It performs well even in challenging conditions like changing lighting or when workers are partially hidden behind equipment. The shift from periodic safety checks to continuous monitoring sets this approach apart. Instead of finding out about violations during weekly inspections, supervisors receive immediate alerts when someone isn’t wearing proper protection. This changes safety management from “catching problems after they happen” to preventing accidents before they occur.

The potential contributions of the proposed study are as follows:

1. Most of the studies in literature cover a specific PPE type, the proposed study covers generic PPE detection covering various types such as construction, roadside and warehousing.

2. Preparation of a state-of-the-art multi-sourced augmented dataset for generic PPE detection.

3. Investigation of YOLOv11, the latest version of the YOLO family for PPE detection.

4. Implementation of a GUI-based alert system and dashboard for management.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 is dedicated to a systematic review of literature. Section 3 provides materials and methods. Section 4 presents the experimental results, while Section 5 concludes the paper.

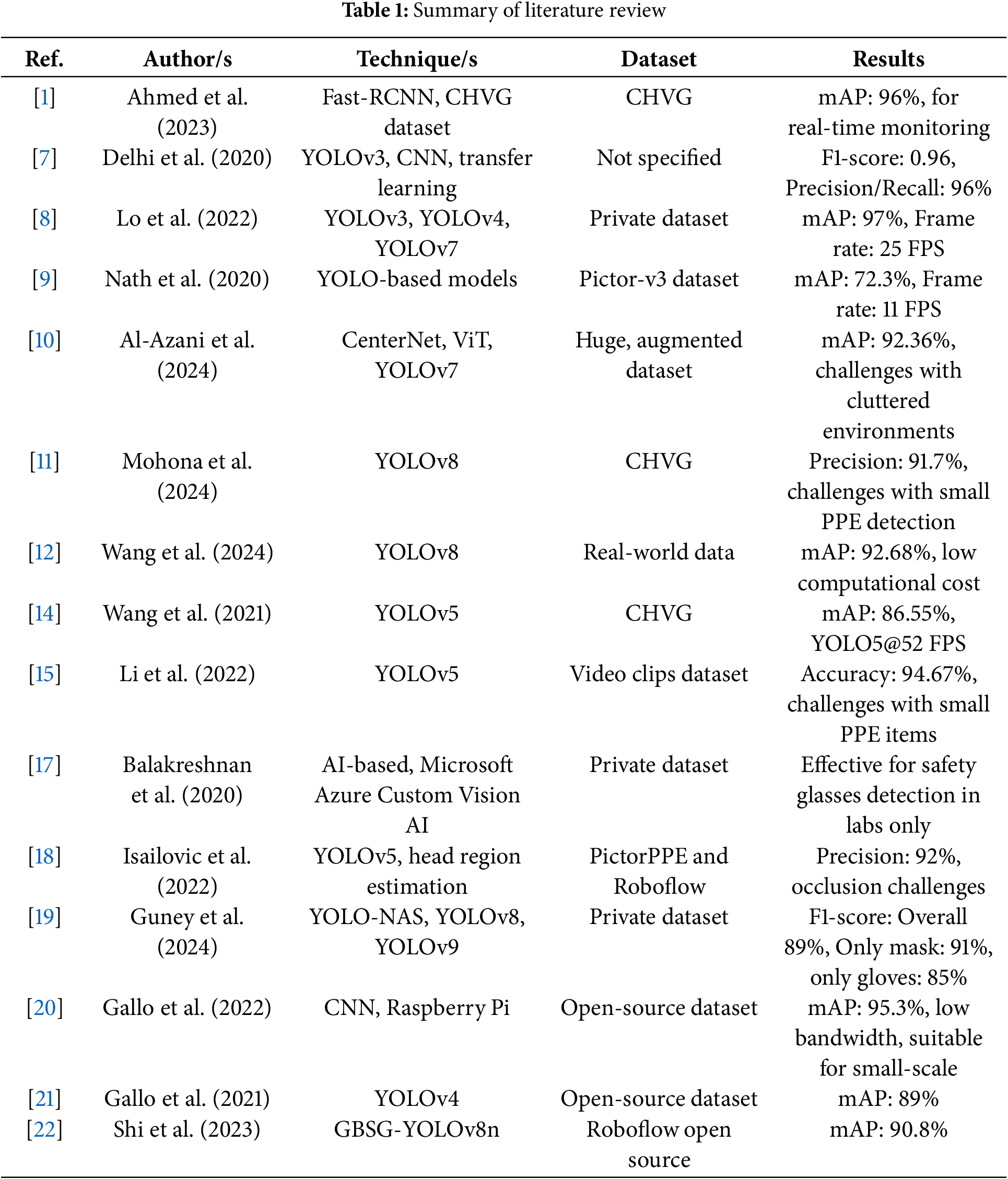

In recent years, significant advancements have been made in developing automated PPE compliance detection systems, with researchers exploring various deep-learning approaches to improve detection accuracy and efficiency. This section reviews key studies in the field to establish the current state of research and identify innovation opportunities.

2.1 Computer Vision Approaches to PPE Detection

Delhi et al. [7] proposed a real-time detection system for PPE adherence on construction sites based on the YOLOv3 structure. The method used in the study was CNN, which has been improved by transfer learning. The dataset comprised 2509 images captured from video recordings at construction sites, and the system classified worker PPE compliance into four categories: SAFE and NOT SAFE, as well as NoHardHat and NoJacket. It was assessed using F1-scores, and the best F1 score was 0.96, with a precision and recall of 96%. It highlighted how real-time detection was possible through the study but also pointed out that future works could endeavor to draw detection for other forms of PPE, and the system could be adapted to handle bigger data sets.

Moreover, in another study [8], YOLOv3, YOLOv4, and YOLOv7 approaches were used to detect helmets and high-visibility vests in real time. The dataset size was much larger than the images used in previous studies, containing 11,000 pictures and 88,725 labels. The methodology was centered on maximizing the domain’s detection rate and efficiency, with the proposed models attaining a mAP of 97% and a frame rate of 25 FPS. It was recommended that apart from achieving high performance, the detection range can be increased to other forms of PPE, like safety glasses, to improve safety observation within warehouses. A subsequent work [9] presented a comparative analysis of three YOLO-based models for PPE detection in construction spaces with a Pictor-v3 dataset of 1500 images. From the real-time worker detection models tested in the study, the focus was to identify those wearing hard hats and vests. The second model, consisting of a single model for worker detection and PPE verification tasks, had the best score of 72.3% in mAP. However, the model had a frame processing rate of 11 FPS, which made real applications challenging as warehouses require high-speed detection.

2.2 Recent Advancements and Comparative Studies

The other huge-scale system [10] ensured proper PPE use in industrial areas through surveillance cameras. This dataset was among the most extensive in the field, containing more than 386,000 video frames. There are several models, CenterNet, Vision Transformer (ViT), and YOLOv7, for object detection, and from all of them, YOLOv7 emerged as the best model with a mAP of 92.36%. However, these findings were still inconsistent and less accurate, especially in detecting PPE from a complex, cluttered environment, so the study recommended future studies to improve detection accuracy.

In [11], the same authors presented YOLOv8 for PPE detection with an average precision of 91.7% on the PPE dataset CHV containing various PPE, including helmets and vests. The study applied technical methods in modelling the challenging environment, including low light and varying distances, characteristics of a warehouse. Nonetheless, it was pointed out that more enhanced results are required to identify small-sized PPE assets like glasses, which is still a drawback in the present models.

Another recent research [12] presented a new model using YOLOv8 along with cross-level path aggregation that can detect PPEs in risky settings like coal mines. We used real-world data, and the system was intended to detect small items such as gloves and safety harnesses. The proposed model delivered a mAP of 92.68% and, simultaneously, was designed with low computational requirements essential for reallocating limited resources. The outcome had positive effects, but a shortcoming discovered from the results was the ability to address occlusions, which could hamper excellent detection in an overcrowded warehouse.

2.3 Edge Computing and Specialized Applications

This topic was accessible, as the World Health Organization (WHO) [13] gave general information regarding lab PPE, assessing laboratory risks, and adherence to standards. While this monograph does not cover topics such as computer vision or deep learning, the conclusions made in this study thus support the relevance of personal protective equipment in high-risk settings. This work shows a lack of real-time compliance detection, which such a system could perform to ensure workers in laboratories are observing biosafety measures.

A research study in [14] engaged eight different YOLO-based networks for identifying PPE, including helmets and vests. For instance, one study employed the CHV dataset containing 1330 images to compare the models. The results revealed that YOLOv5x detected objects with a relatively high mAP of 86.55%, while YOLOv5s was the quickest, with a frame rate/speed of 52 frames per second (FPS). The study highlighted the importance of detecting systems that should be able to monitor workers’ posture and working environments during both day and night. However, as we utilized the blurring effect over the face region, the detection accuracy decreased by 7% for helmet detection on blurred faces, which is the drawback of the model. Another study [15] discussed a deep learning model named YOLOv5 to detect violations of proper wearing of hard hats and safety harnesses, which are essential in avoiding mishaps in construction areas. The dataset was 1200 video clips, and the percentage accuracy of the model was 94.67%. This methodology could be extended to the distributive warehousing contexts to identify violations of the PPE guidelines. Another weakness was the system’s ability to detect other safety items, including gloves and glasses, that could enhance safety in the workplace.

2.4 PPE-Specific Detection Systems

Ahmed et al. [1] presented the method of using Fast-RCNN, trained on the CHVG dataset, to detect eight types of PPE, including hard hats, red, blue, and yellow vests and safety glasses. The model attained a mAP of 96% and is quite suitable for real-time compliance monitoring of employees in hazardous areas such as a warehouse. Nonetheless, further research is recommended since the complexity of the model may not allow it to be implemented in computer systems with modest processing power and in real-time [16].

Another research [17] investigated using AI-based systems for safety glasses detection in learning factory settings with Microsoft Azure’s Custom Vision AI. The study used a hybrid cloud and on-premises AI for live PPE detection, which has the additional advantage of flexibility. The dataset included images obtained from Creative Commons, and the system could identify safety violations in the confined space environment. However, the capacity of the developed system in real environments typical of large warehouses was not discussed in the study.

Authors in [18] proposed a separate study to identify head-mounted PPEs that enclosed helmets by integrating both YOLOv5 and head region estimation approaches. The data set combined images from PictorPPE and Roboflow with twelve types of PPEs. The YOLOv5 model achieved more than other models, attaining a precision of 92%. One issue that arose was that it was logistically challenging to detect PPE under occlusions or when workers are away from the camera, a case of extensive warehousing. Another study in [19] compared YOLO-NAS with YOLOv8 and YOLOv9 to identify PPE in industrial settings. We tested the models on a dataset of 2581 images, and they showed the highest detection accuracy of PPE, such as helmets and vests. However, the study was not comprehensive on safety glasses, an essential component in safety compliance within the warehouse. Future work should enhance the detection rate of small PPE items used on crowded premises.

More studies such as [20] proposed the innovative PPE detection system through edge computing and convolutional neural networks implemented on low-power devices such as Raspberry Pi. Real-time helmets, vests, and gloves were identified with high accuracy and minimized bandwidth utilization due to the absence of processing from the cloud. Large operations should be of special interest in implementing this model due to possible unreliable network conditions in a warehouse. However, it is critical that the study did not consider how the system would extend to more extensive and probably higher-reach industrial settings where the demands for PPE are likely to be more demanding.

The authors in [21] proposed a Real-time PPE monitoring system implemented by YOLOv4, which targeted real-time inference in industrial scenarios. The dataset was open-source, and the system could identify PPE quickly and accurately. The study pointed out that personnel safety should be complemented by fast and reliable detection of PPE in settings where safety is paramount, but the study also pointed out that detection in complex spaces, such as the warehouse, for instance, could be made even better with several optimizations. Table 1 provides a summary of the reviewed literature. In a recent study, Shi et al. [22] proposed a YOLOv8n-based PPE detection approach named GBSG-YOLOv8n in industrial environments. The dataset was considered from the Roboflow source [23]. The study achieved the highest scores of 89.7%, 91%, 90.3% and 90.8% against precision, recall, F1-score and mAP.

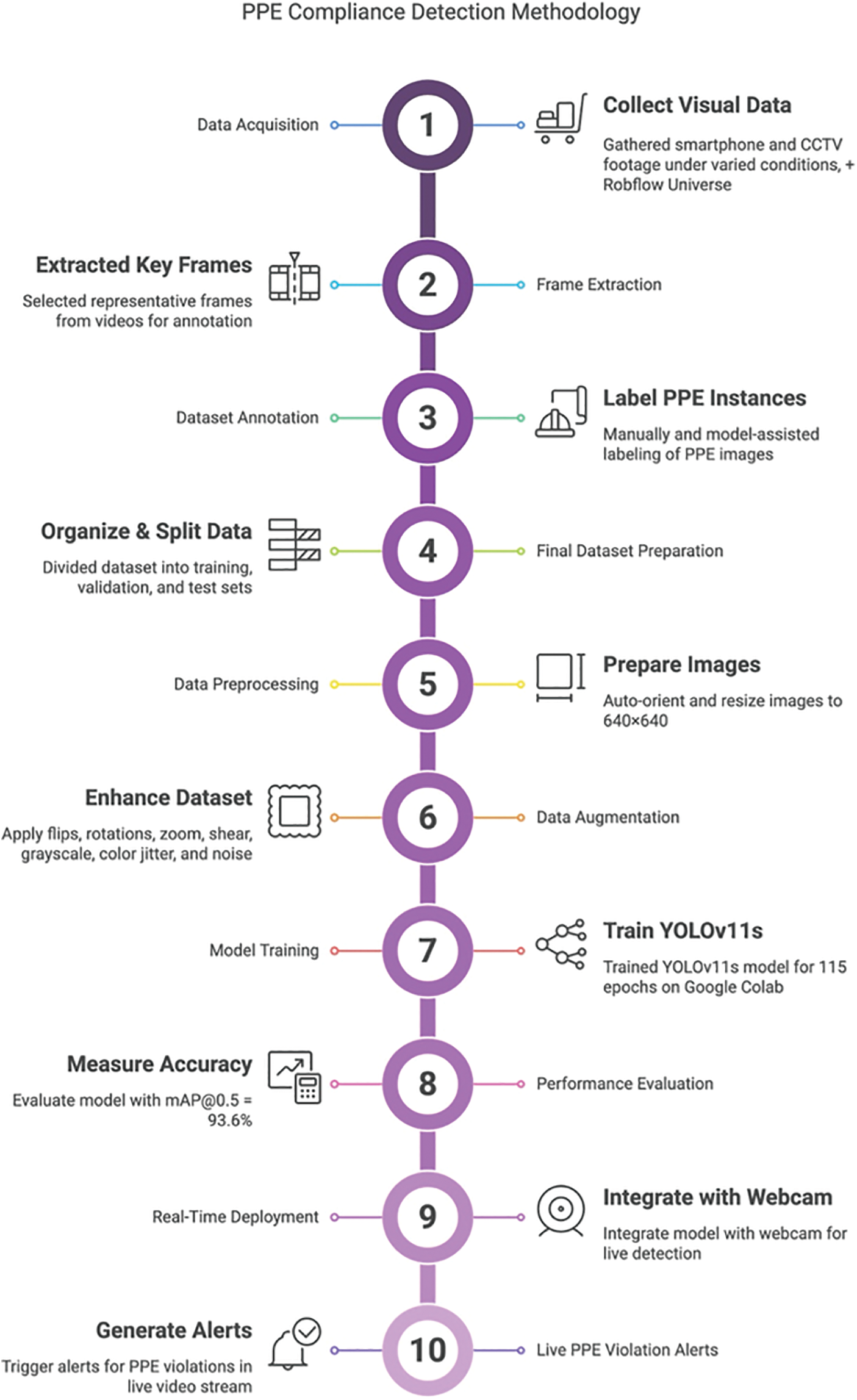

This section outlines the comprehensive methodology for developing our PPE compliance detection model. We follow a structured approach aligned with the project’s objectives and technical requirements. This methodology encompasses data collection and preprocessing, deep learning model training, and systematic performance evaluation. Fig. 1 shows the methodological steps taken in the research, starting from data acquisition/collection, frame extraction, data labeling/annotation, preprocessing and augmentation, model training and fine-tuning, model evaluation, and finally, the integration with a real-time system equipped with alerts.

Figure 1: PPE proposed methodology

3.1 Dataset Sources and Description

The dataset utilized in this project was carefully curated and expanded through multiple stages to comprehensively address variability inherent in PPE compliance scenarios. Initially, images and videos were captured using smartphone cameras across diverse lighting conditions and poses, yielding an initial dataset. Subsequent CCTV camera footage, capturing realistic industrial scenarios, was added to enhance environmental authenticity and relevance. Moreover, this dataset was supplemented by integrating the publicly available annotated dataset, “tml_safety_v3” from Roboflow Universe, which includes professionally annotated images captured by warehouse CCTV setups [23].

As mentioned, the three dataset sources are described, and sample images are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Dataset sources. (a) Smartphone; (b) CCTV; (c) Warehouse Cameras

Smartphone: In the initial phase, we captured images from multiple angles using an iPhone to represent PPE compliance and non-compliance (e.g., hardhat/no hardhat, safety vest/no safety vest, gloves/no gloves, safety shoes/no safety shoes). We then utilized Grounding DINO to automatically generate bounding boxes, followed by manual refinement to ensure accurate annotations.

CCTV: We converted CCTV video footage into individual frames to extend the dataset. Grounding DINO was again employed for bounding box generation, with subsequent manual adjustments for enhanced accuracy. A preliminary model trained on this labelled set provided inference outputs that expedited annotation for additional frames. Since the study uses real footage, the identities are anonymized by blurring faces to comply with the research ethics.

Roboflow: Finally, to prevent overfitting and improve generalizability, we integrated datasets from Roboflow. This introduced a wider range of PPE usage scenarios and environmental conditions in warehouses, ensuring the final model could reliably detect PPE compliance across diverse industrial settings [23].

Building on the previously described data collection and annotation steps, the final PPE compliance dataset comprised 20,001 images before augmentation, each reflecting a range of compliance and non-compliance scenarios comprising nine classes, including person, gloves (with and without), safety vest (with and without), hardhat (with and without), and shoes (with and without). To facilitate rigorous training and evaluation, the dataset was split into a training set of 14,001 images (70%), a test set of 4000 images (20%), and a validation set of 2000 images (10%).

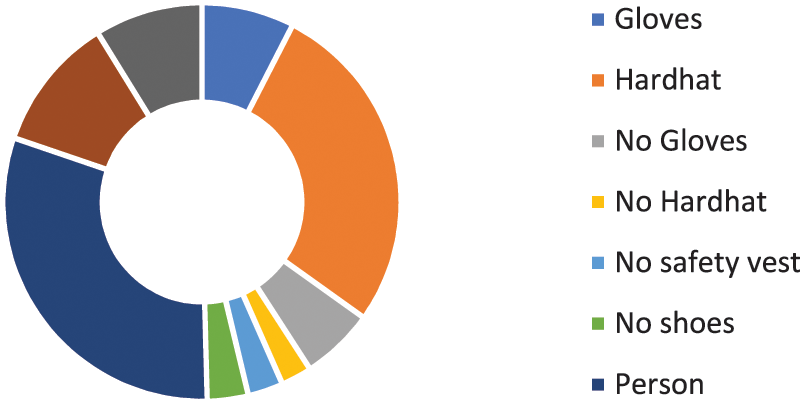

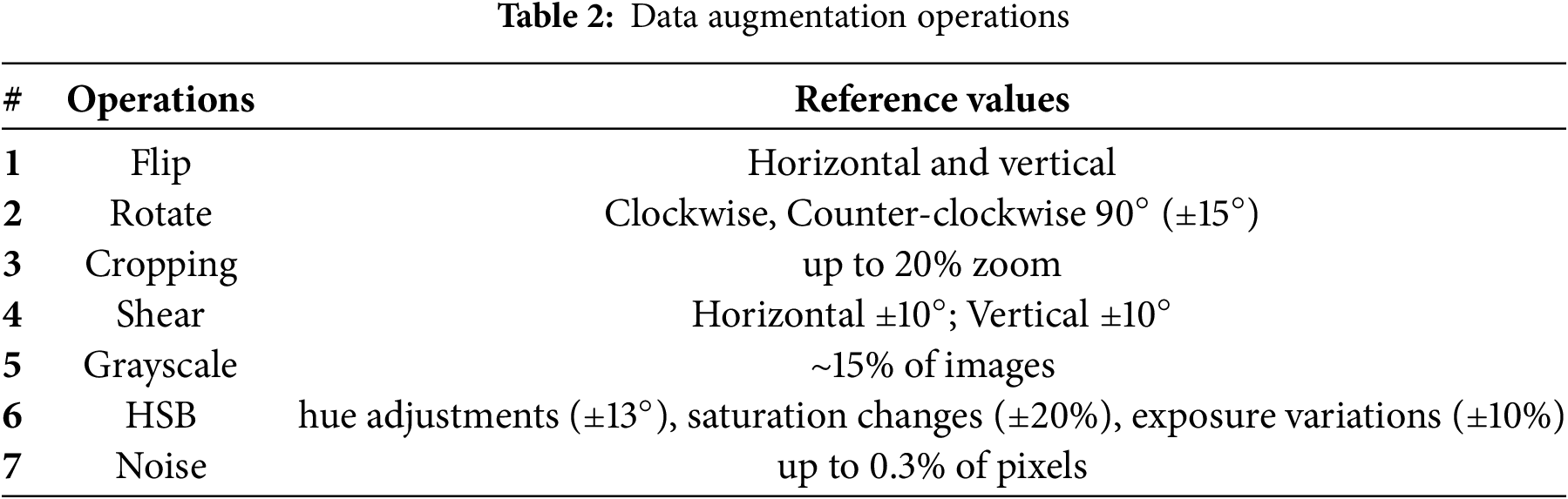

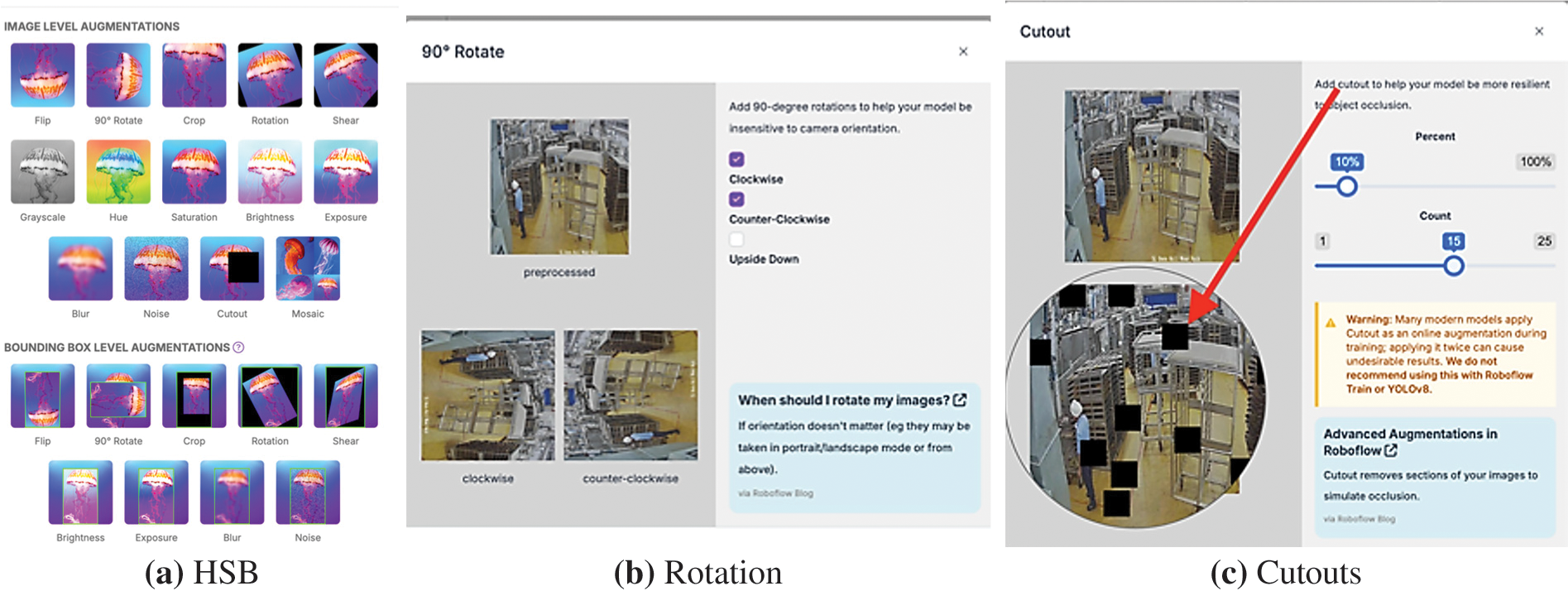

To enhance model robustness and prevent overfitting, each training image underwent a series of augmentations, generating up to ten augmented samples per original image. Here, ‘gloves’ and ‘no-Gloves’ classes contain 6773 images, ‘hardhat’ and ‘no-hardhat’ classes comprise of 14,954 images, ‘shoes’ and ‘no-shoes’ classes contain 6086 images, ‘safety-vest’ and ‘no-safety-vest’ classes contain 6933 images, while ‘person’ class contains 15,350 images forming a comprehensive dataset containing a total of 50,096 images after augmentation. Fig. 2 contains the pie chart depicting class distribution. These transformations included flipping, rotations, zooming, shearing, grayscale, exposure, and noise. Fig. 3 depicts the number of instances per class available in the dataset. Moreover, Table 2 summarizes the data augmentation types and the respective reference range, while Fig. 4 provides some visual evidence of the dataset augmentation process.

Figure 3: Dataset instances distribution per class

Figure 4: Dataset sources. (a) HSB; (b) Rotation; (c) Cutouts

3.1.4 Cleaning, Normalization and Scaling

Pixel values are normalized to improve convergence during training. Whereas scaling ensures consistency in object size representation across the dataset. Furthermore, annotation was conducted using a combination of Grounding DINO and manual labelling (refined via Roboflow), ensuring proper bounding box placement and consistent labelling across all images. Additionally, the following operations were performed on the dataset. Removing irrelevant or unusable images: The images that do not match the intended use case or are of poor quality were discarded. Correcting labels (annotation errors): Although we have used Python scripts and models like Grounding Dino and SAM for automated annotation and segmentation, going through the data manually helped ensure that the dataset is accurate.

The operational framework began with data acquisition, utilizing two primary methods to capture diverse and representative datasets. Initially, images and videos were captured using a smartphone in various lighting conditions and poses, simulating workers both adhering and not adhering to PPE standards. Subsequently, recognizing the operational environment requirements, CCTV cameras were installed to emulate warehouse surveillance setups. The resulting footage was carefully collected, featuring individuals performing tasks with varying PPE compliance in realistic scenarios. All video footage was converted into frames, producing a rich repository of images for subsequent use. The data was then managed via Roboflow, where initial manual annotations were performed. An initial annotated subset served to train a preliminary detection model, enhancing annotation efficiency for subsequent images through model-assisted annotation. Finally, the trained model was deployed and validated through real-time webcam integration tests, ensuring robustness before deployment in an industrial setting. For the final training phase, Google Colab was utilized, leveraging its powerful computing resources. Technical details of the final model include: Ultralytics Version: 8.3.40, Python: 3.11.11, Torch: 2.6.0+cu124, CUDA: 0 (NVIDIA L4, 22693MiB) and YOLOv11s summary (fused): 238 layers, 9,416,283 parameters, 0 gradients, 21.3 GFLOPs.

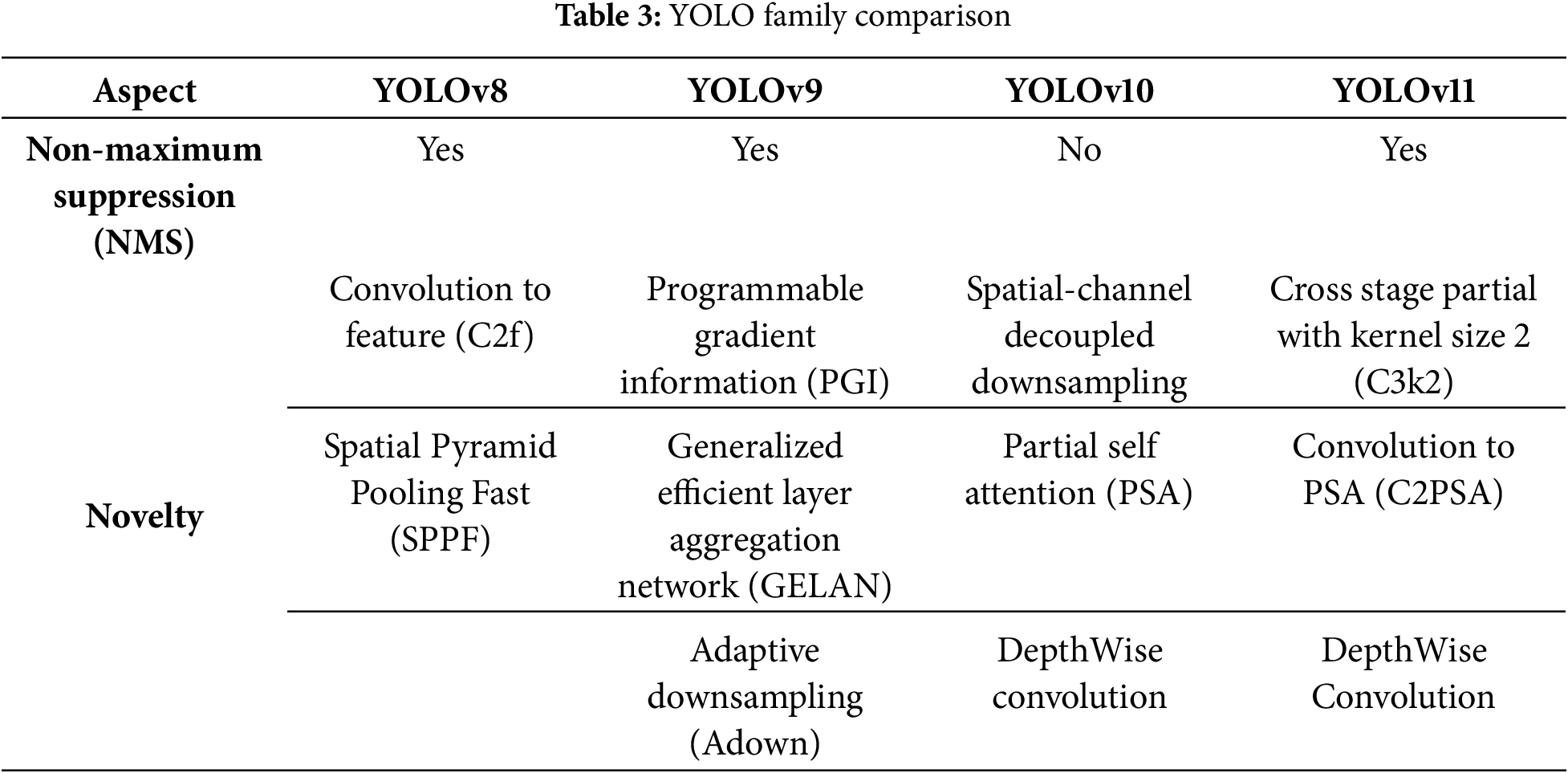

3.3 The Proposed Computational Intelligence Approach

For the research, we implemented the YOLOv11 architecture, recognized for its superior real-time detection capabilities and accuracy in complex environments [24]. To optimize model performance, meticulous hyperparameter tuning was performed, accompanied by strategic preprocessing and augmentation methods. Data preprocessing involved auto-orienting images and resizing them to a consistent resolution of 640 × 640 pixels. Augmentation strategies significantly enriched the dataset variability as mentioned above. This structured augmentation protocol substantially increased the robustness and generalizability of the detection model, addressing potential variability within real-world warehouse conditions. YOLOv11 is undoubtedly a better version in the YOLO family, mainly due to more innovative components (C3k2, C2PSA) that include more intention [24]. A brief comparison of the YOLO family members is given in Table 3.

The primary metric for evaluating the model’s performance was Mean Average Precision (mAP). Specifically, we focused on the commonly used threshold of mAP@0.5 to align with industry standards and benchmark comparisons [23]. The dataset was strategically split into training, testing, and validation subsets to ensure a balanced evaluation framework. Throughout model training, performance metrics were systematically monitored and logged, allowing iterative refinements via further hyperparameter adjustments and dataset balancing as required. The following formula shows how to calculate the mean average precision:

Other than that, the accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score are the most common metrics used for evaluating machine learning and deep learning models as given in Eqs. (1)–(5), respectively [25,26]. Here the values correspond to, True Positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN).

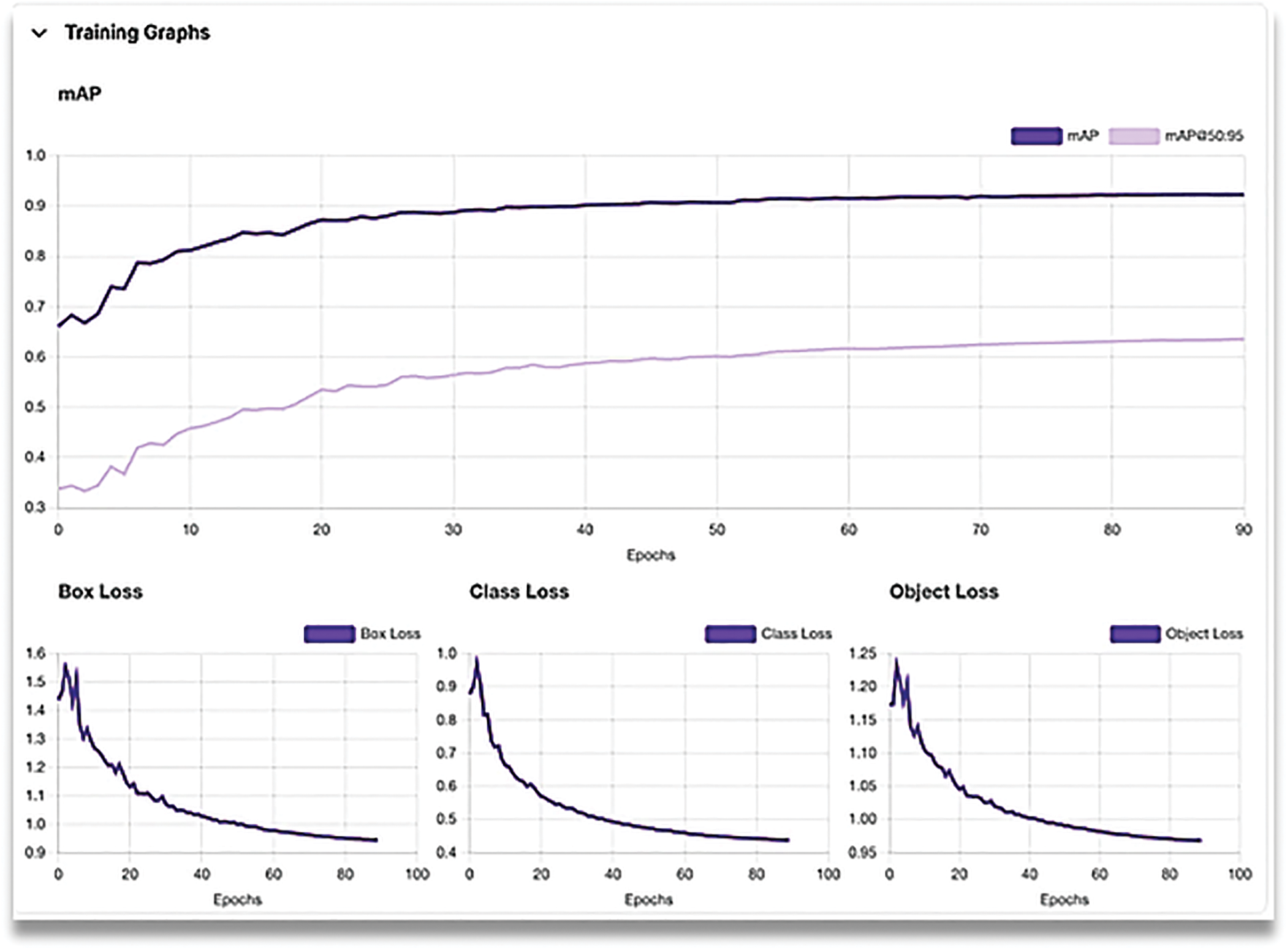

The YOLOv11 model was trained for 90 epochs, with the loss metrics (box, class, and object) consistently decreasing as the model converged. Concurrently, the mAP score is steadily improving over the training period, reflecting the model’s growing ability to distinguish between PPE-compliant and non-compliant classes. It is worth mentioning that the graph was obtained for the Roboflow dataset for the warehouses and industrial environments representing the most practical and real time environments. The highest mAP score was obtained as 93%. Fig. 5 demonstrates the training phase of the proposed model.

Figure 5: Training phase of the proposed model

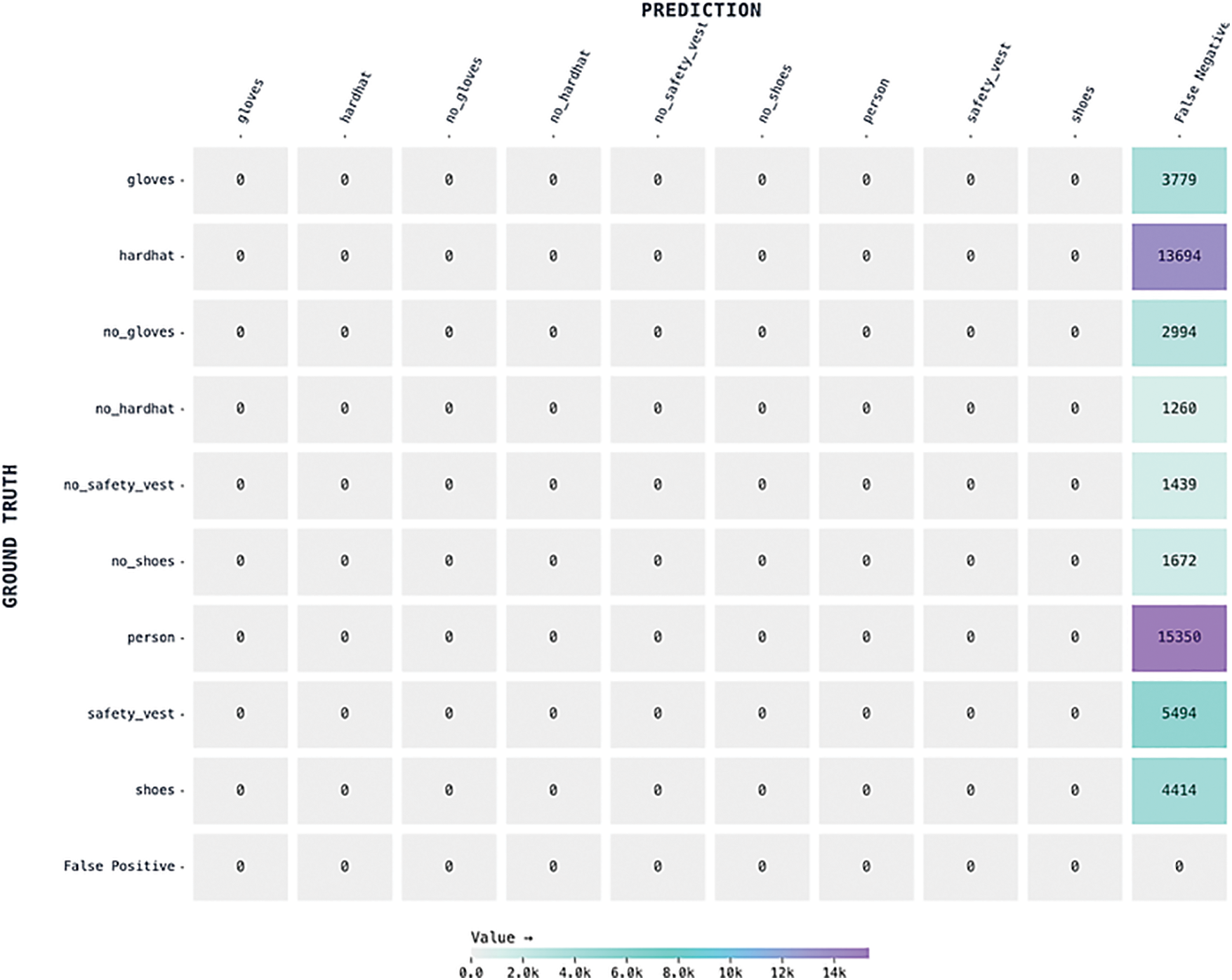

Fig. 6 provides the confusion matrix of the model.

Figure 6: Confusion matrix of the proposed model

4.2 Model Performance Comparison by Dataset Configuration

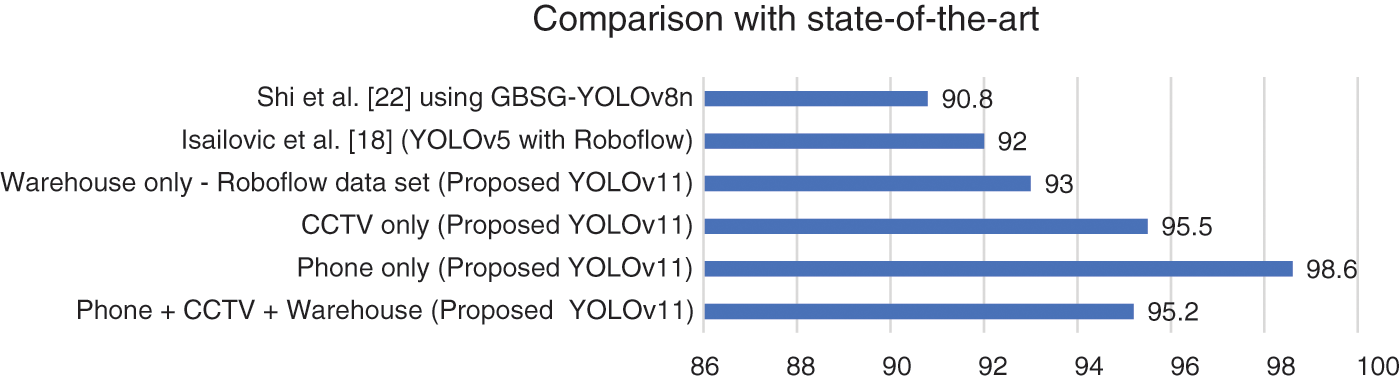

Fig. 7 compares the performance of the PPE compliance detection model using different dataset configurations, measured by the most widely used mAP score in the related studies. Moreover, the comparison has been made with two recent studies in literature employing the same dataset for generic PPE compliance.

Figure 7: Performance comparison for various dataset sources and state-of-the-art [18,22]

Firstly, the “Phone Only” dataset achieved the highest mAP value of 98.6%, which is reasonable and apparent because of the high resolution camera, better lighting conditions and image processing done by the smartphone software. Secondly, the combined comprehensive and augmented dataset (Phone + CCTV + Warehouse) provided a more robust and generalizable performance with a slightly lower mAP value of 95.2%. That is understandable, because the dataset is diverse, augmentation has been employed and joint dataset.

Thirdly, the model trained exclusively on “Warehouse Only (Roboflow dataset)” data yielded 93% performance, underscoring challenges related to the indoor CCTV image quality and environmental complexity, and was duly obtained from real-life warehouse environments. Fourthly, the outdoor CCTV dataset obtained a mAP score of 95.5%. That is closer to the comprehensive dataset, while degraded compared to the Phone only dataset. That is mainly because of the CCTV cameras’ resolution and distance from the moving objects.

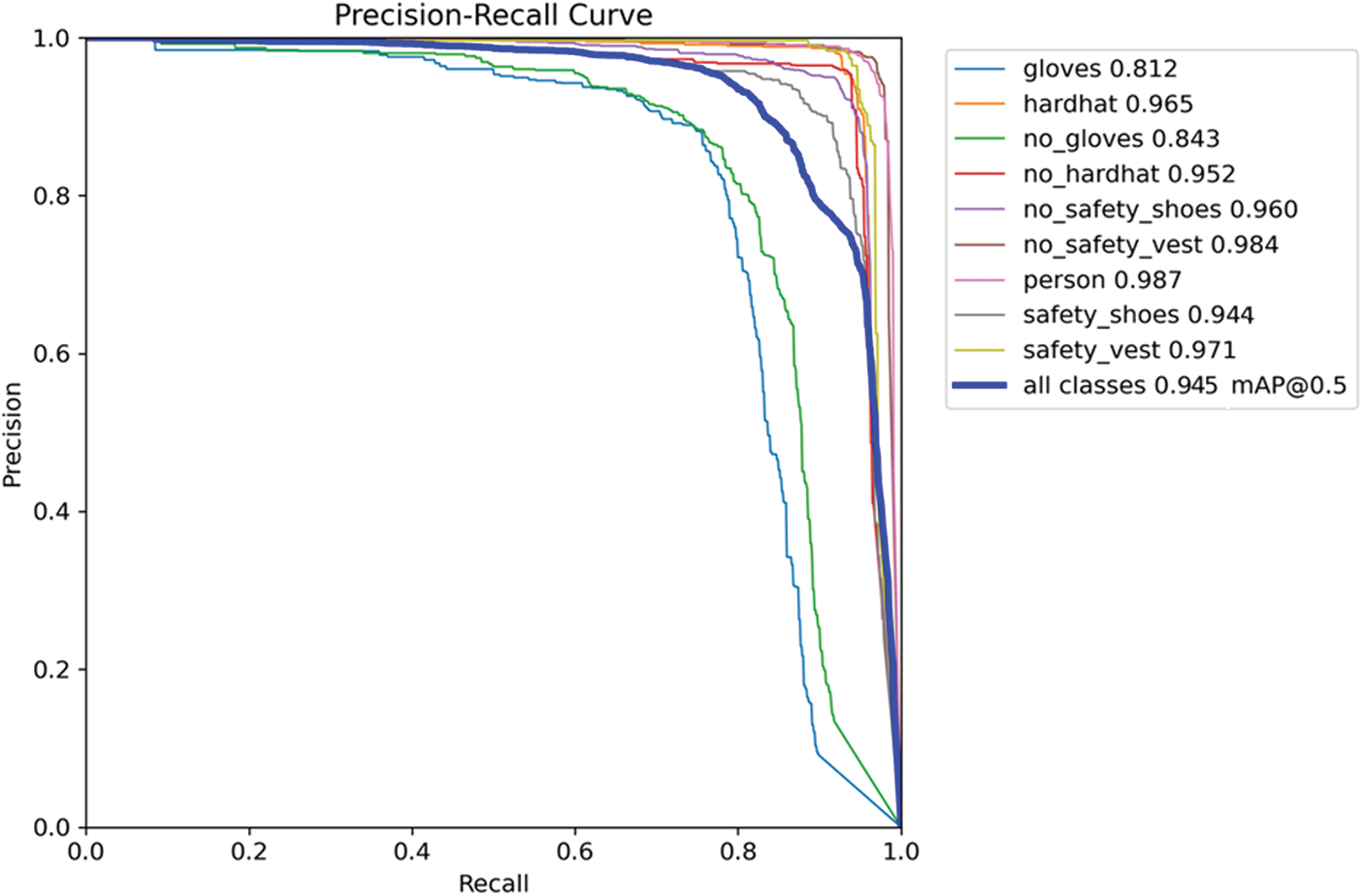

Thus, despite the marginally lower mAP from the phone-only dataset, the comprehensive model that integrates diverse sources demonstrated superior consistency and reliability across varied industrial scenarios. Compared with two techniques employing the same Roboflow dataset, the propose YOLOv11 based approach outperformed YOLOv5 [18] and GBSG-YOLOv8n [23] by 1% and 2.2%, respectively, for the case of same dataset (Roboflow) as explained in the third experiment with Warehouse only dataset. Whereas, in contrast to the comprehensive augmented dataset, the improvement is 3.2% and 4.6% compared to the studies in [18,22], respectively. Additionally, the augmented comprehensive data (including all the sources) analysis yielded the recall, precision, F1-score and accuracy of 92.1%, 93.2%, 92.5% and 94.3%, respectively. Fig. 8 demonstrates the proposed system model’s output with a comprehensive augmented dataset obtained during the implementation phase using a real time setup. It is apparent that the model can accurately detect the PPE compliance in real time environments. Fig. 9 provides the precision-recall curve for the proposed model for the aggregated comprehensive dataset case. It is worth noting that the person class got the highest mAP of 98.4% due to its highest number of instances. While the gloves class underperformed due to the lowest number of instances.

Figure 8: Model’s real-time setup output

Figure 9: Model’s precision-recall curve

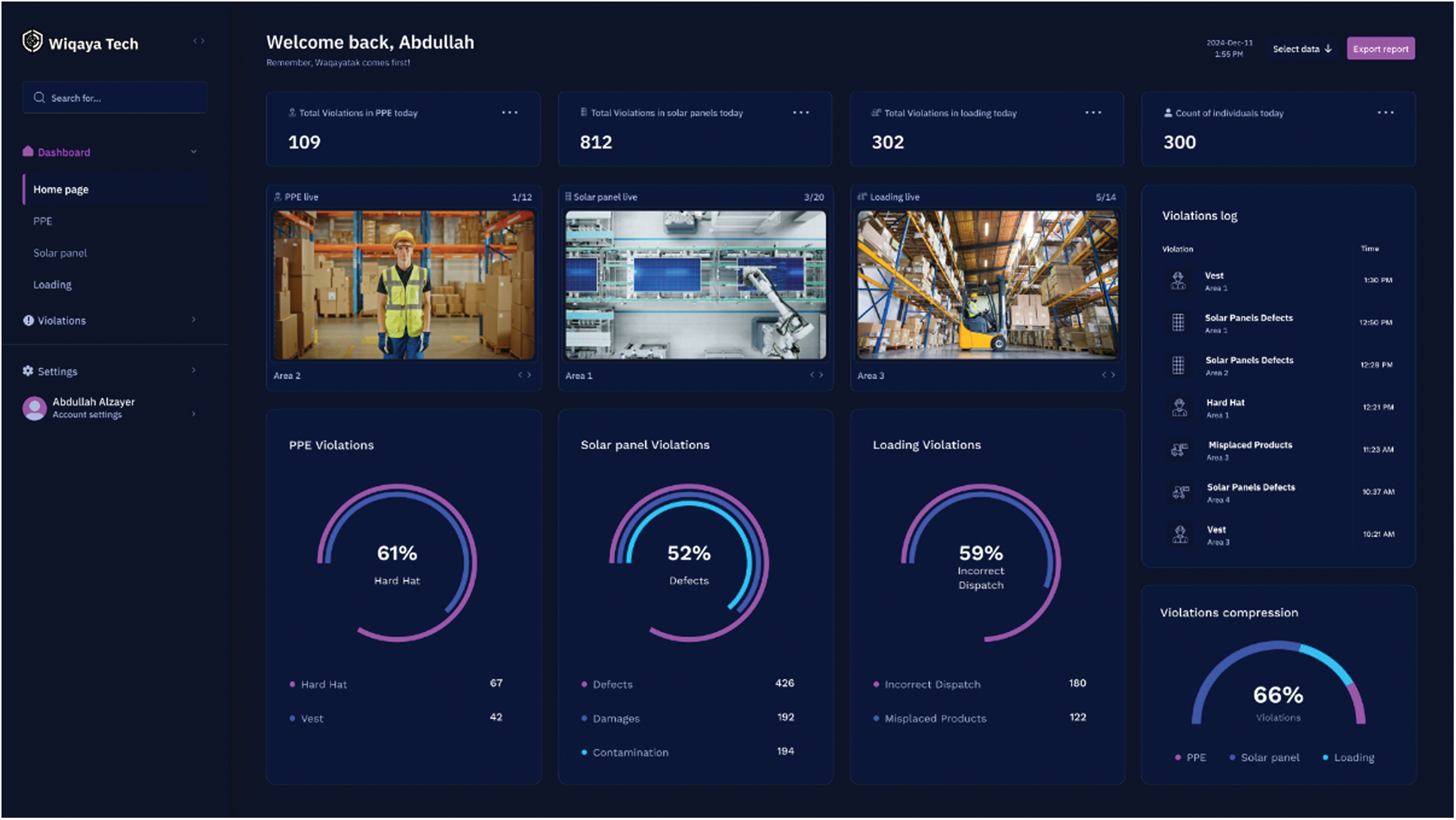

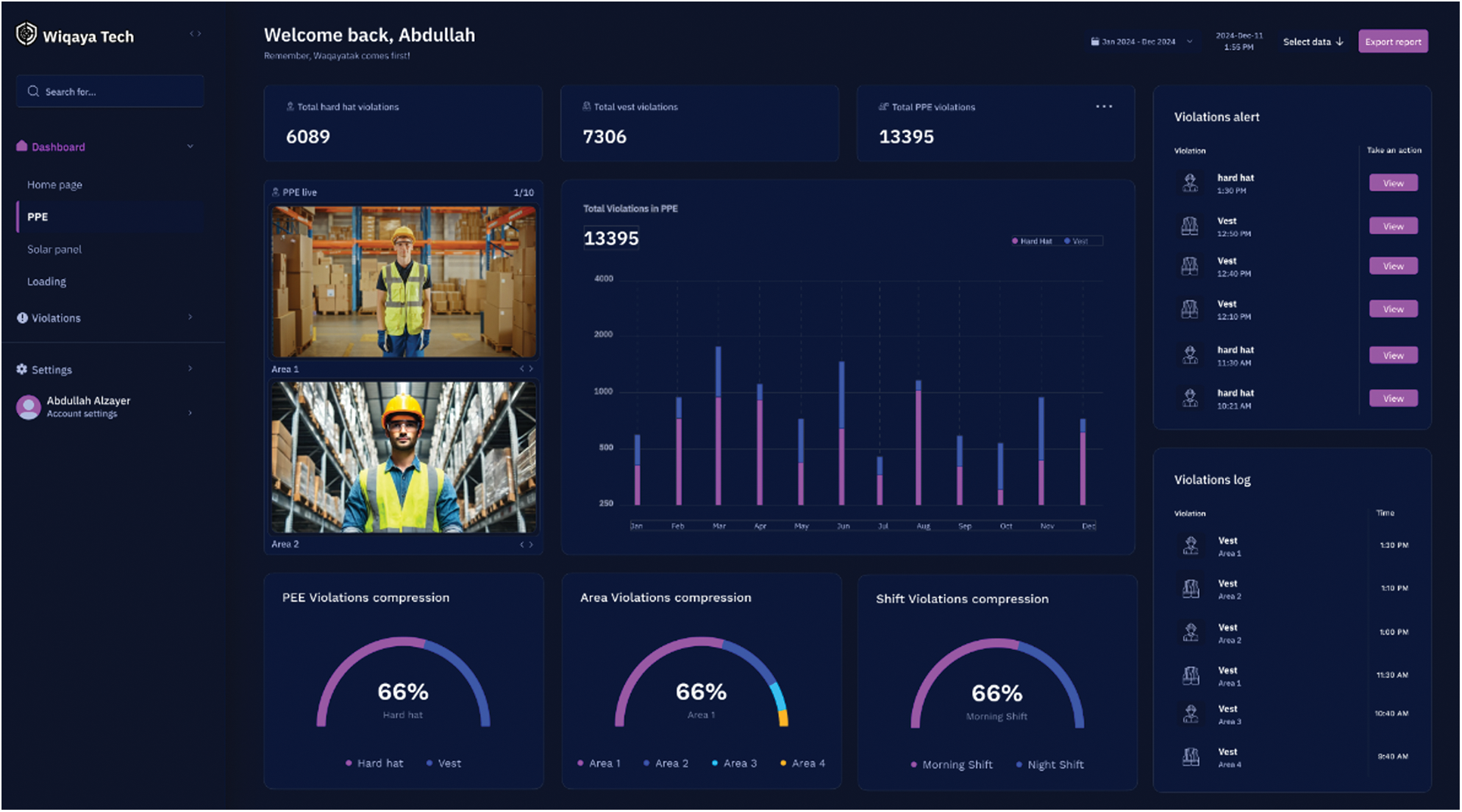

In addition to the model training and evaluation, the system is implemented in the form of a software prototype and tested in a semi-real-time environment from live camera feeds as shown in Figs. 10 and 11. As far as the interface time of the implemented model is concerned, it is recorded as 7.3 ms (on average) on edge devices such as smartphones.

Figure 10: Main dashboard interface

Figure 11: Monitoring dashboard interface

The proposed YOLOv11-based generic PPE detection approach is promising in many ways. The model is built by considering three types of datasets collected by smartphones, CCTV cameras, and available online datasets from Roboflow. Additionally, a complete augmented dataset combining all the sources is available. The highest mAP value obtained for smartphone cameras was captured by manually annotating datasets at 98.6%, which is obvious due to the high resolution of the smartphone camera with more visual details. Next, the best performance was observed with a CCTV-based dataset collected in an outdoor setup. The performance of the proposed scheme over the available Roboflow dataset online was somewhat degraded due to the available image quality and resolution. However, in contrast to the studies employing the same dataset with YOLOv8n, the performance of the proposed model was improved by 2.2%. Finally, the richest and augmented dataset, comprised of all the datasets, resulted in a considerable performance of 95.5%. In contrast to state-of-the-art studies [18,22] with generic PPE compliance detection, the proposed YOLOv11-based model with a comprehensive augmented dataset outperforms by 3.2% and 4.6%, respectively. Another strength of the proposed model is that it incorporates generic PPE conditions encompassing several industries, including warehouses, logistics, construction, and many other indoor/outdoor manufacturing sectors. Additionally, we have investigated YOLOv8 on the augmented comprehensive dataset that resulted in mAP, precision and recall value of 90.3%, 90.4% and 88.9%, respectively, which is lower than the proposed-YOLOv11 based model by 4.9%, 2.8% and 3.2%, respectively.

In terms of detection under occlusion, a typical case of an indoor warehouse environment, the proposed trained model exhibited an mAP score of 93%, which is poorer than the performance observed in the case of the phone-only dataset, CCTV dataset, and comprehensive merged dataset by 2.5%, 5.6%, and 2.2%, respectively. That shows the model’s limitation in indoor warehouse working environments with poor lighting conditions involving plenty of objects. In the future, this limitation may additionally be addressed by means of transfer learning and ensemble learning models [27]. Moreover, the current augmented and comprehensive dataset comprises a huge number of image instances. However, the dataset is potentially imbalanced. In the current study, we go with the idea of ‘let the data speak’ without employing any balancing method. Yet, the model was able to achieve a promising performance for real-time generic PPE detection. However, in the future, the effect of data balancing approaches such as the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) should be investigated in the current setting [28].

Regarding some additional study limitations, the current research only investigates YOLOv11, while other family variants, such as YOLOv11x and the earlier versions, still need to be investigated for the current augmented dataset. Moreover, advanced vision transformers can also be studied to further fine-tune the performance factors [29,30]. As an extension, integrating audio signals or environmental sensors (e.g., heat, noise) with visual data to improve context-aware PPE compliance detection can be investigated.

In conclusion, this study successfully developed and evaluated a robust computer vision system leveraging the YOLOv11 architecture to automate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) compliance monitoring. The custom-built dataset, incorporating diverse image sources such as smartphone captures, realistic CCTV footage, and the integration of publicly available annotated data, effectively addressed the challenges posed by variability in industrial environments. The final trained model achieved an impressive mean average precision (mAP) of 98.6%, demonstrating its potential for accurate real-time deployment in warehouse safety compliance scenarios. However, while the model has shown strong performance, several aspects present opportunities for further improvement and exploration. Future iterations could emphasize deployment optimizations, including edge-computing implementations on devices like NVIDIA Jetson, aiming to reduce latency and computational load for more efficient real-time monitoring. Expanding the dataset to include images from diverse warehouses with different environmental and lighting conditions would further enhance the model’s robustness and applicability across varied industrial scenarios. Integrating IoT-based notification and alert systems could facilitate more immediate intervention during PPE compliance violations, enhancing overall workplace safety management.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge CCSIT for using computing resources during the project.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Atta Rahman and Nasro Min-Allah; methodology, Atta Rahman and Fahad Abdullah Alatallah; software, Fahad Abdullah Alatallah and Younis Zaki Shaaban; validation, Aghiad Bakry, Nasro Min-Allah and Khalid Aloup; formal analysis, Hasan Ali Alzayer; investigation, Atta Rahman and Nasro Min-Allah; resources, Haider Ali Alkhazal; data curation, Younis Zaki Shaaban; writing—original draft preparation, Fahad Abdullah Alatallah, Younis Zaki Shaaban, Abdullah Jafar Almubarak, Haider Ali Alkhazal and Hasan Ali Alzayer; writing—review and editing, Atta Rahman; visualization, Abdullah Jafar Almubarak; supervision, Atta Rahman; project administration, Fahad Abdullah Alatallah; funding acquisition, Hasan Ali Alzayer. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data available at https://universe.roboflow.com/browse/manufacturing/ppe (accessed on 01 January 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ahmed MIB, Saraireh L, Rahman A, Al-Qarawi S, Mhran A, Al-Jalaoud J, et al. Personal protective equipment detection: a deep-learning-based sustainable approach. Sustainability. 2023;15(18):13990. doi:10.3390/su151813990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kang Y, Siddiqui S, Suk SJ, Chi S, Kim C. Trends of fall accidents in the U.S. construction industry. J Constr Eng Manage. 2017;143(8):04017043. doi:10.1061/(asce)co.1943-7862.0001332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Al-Bayati AJ, York DD. Fatal injuries among Hispanic workers in the U.S. construction industry: findings from FACE investigation reports. J Safety Res. 2018;67(2):117–23. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2018.09.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Day O, Khoshgoftaar TM. A survey on heterogeneous transfer learning. J Big Data. 2017;4(1):29. doi:10.1186/s40537-017-0089-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang Y, Li X, Wang F, Wei B, Li L. A comprehensive review of one-stage networks for object detection. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Communications and Computing (ICSPCC); 2021 Aug 17–19; Xi’an, China. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICSPCC52875.2021.9564613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chen S, Demachi K. A vision-based approach for ensuring proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in decommissioning of fukushima daiichi nuclear power station. Appl Sci. 2020;10(15):5129. doi:10.3390/app10155129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Delhi VSK, Sankarlal R, Thomas A. Detection of personal protective equipment (PPE) compliance on construction site using computer vision based deep learning techniques. Front Built Environ. 2020;6:136. doi:10.3389/fbuil.2020.00136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lo JH, Lin LK, Hung CC. Real-time personal protective equipment compliance detection based on deep learning algorithm. Sustainability. 2023;15(1):391. doi:10.3390/su15010391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Nath ND, Behzadan AH, Paal SG. Deep learning for site safety: real-time detection of personal protective equipment. Autom Constr. 2020;112(1–2):103085. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Al-Azani S, Luqman H, Alfarraj M, Sidig AAI, Khan AH, Al-Hamed D. Real-time monitoring of personal protective equipment compliance in surveillance cameras. IEEE Access. 2024;12:121882–95. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3451117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mohona RT, Nawer S, Sakib MSI, Uddin MN. A YOLOv8 approach for personal protective equipment (PPE) detection to ensure workers’ safety. In: 3rd International Conference on Advancement in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (ICAEEE); 2024 Apr 25–27; Gazipur, Bangladesh. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/icaeee62219.2024.10561752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang Z, Zhu Y, Ji Z, Liu S, Zhang Y. An efficient YOLOv8-based model with cross-level path aggregation enabling personal protective equipment detection. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2024;20(11):13003–14. doi:10.1109/TII.2024.3431045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. World Health Organization. Personal protective equipment. Geneva, Switzerlannd: World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

14. Wang Z, Wu Y, Yang L, Thirunavukarasu A, Evison C, Zhao Y. Fast personal protective equipment detection for real construction sites using deep learning approaches. Sensors. 2021;21(10):3478. doi:10.3390/s21103478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Li J, Zhao X, Zhou G, Zhang M. Standardized use inspection of workers’ personal protective equipment based on deep learning. Saf Sci. 2022;150(3):105689. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2022.105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Cabrejos JAL, Roman-Gonzalez A. Artificial intelligence system for detecting the use of personal protective equipment. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2023;14(5):580–5. doi:10.14569/ijacsa.2023.0140561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Balakreshnan B, Richards G, Nanda G, Mao H, Athinarayanan R, Zaccaria J. PPE compliance detection using artificial intelligence in learning factories. Procedia Manuf. 2020;45(1):277–82. doi:10.1016/j.promfg.2020.04.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Isailovic V, Peulic A, Djapan M, Savkovic M, Vukicevic AM. The compliance of head-mounted industrial PPE by using deep learning object detectors. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):16347. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-20282-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Guney E, Altin H, Esra Asci A, Bayilmis OU, Bayilmis C. YOLO-based personal protective equipment monitoring system for workplace safety. J Ilm Teknol Sist Inf. 2024;5(2):77–85. doi:10.62527/jitsi.5.2.238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Gallo G, Di Rienzo F, Garzelli F, Ducange P, Vallati C. A smart system for personal protective equipment detection in industrial environments based on deep learning at the edge. IEEE Access. 2022;10(10):110862–78. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3215148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Gallo G, Di Rienzo F, Ducange P, Ferrari V, Tognetti A, Vallati C. A smart system for personal protective equipment detection in industrial environments based on deep learning. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP); 2021 Aug 23–27; Irvine, CA, USA. p. 222–7. [Google Scholar]

22. Shi C, Zhu D, Shen J, Zheng Y, Zhou C. GBSG-YOLOv8n: a model for enhanced personal protective equipment detection in industrial environments. Electronics. 2023;12(22):4628. doi:10.3390/electronics12224628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. PPE datasets and pre-trained models—Roboflow [Online]. [cited 2024 Dec 12]. Available from: https://universe.roboflow.com/browse/manufacturing/ppe. [Google Scholar]

24. Ultralytics YOLO11 [Online]. [cited 2024 Dec 25]. Available from: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolo11/. [Google Scholar]

25. Vukicevic AM, Djapan M, Isailovic V, Milasinovic D, Savkovic M, Milosevic P. Generic compliance of industrial PPE by using deep learning techniques. Saf Sci. 2022;148(5):105646. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Yang X, Li J, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Dong Z, Zhu G. TMU-GAN: a compliance detection algorithm for protective equipment in power operations. Multimed Syst. 2025;31(3):222. doi:10.1007/s00530-025-01807-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Musleh DA, Olatunji SO, Almajed AA, Alghamdi AS, Alamoudi BK, Almousa FS, et al. Ensemble learning based sustainable approach to carbonate reservoirs permeability prediction. Sustainability. 2023;15(19):14403. doi:10.3390/su151914403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Dablain D, Krawczyk B, Chawla NV. DeepSMOTE: fusing deep learning and SMOTE for imbalanced data. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34(9):6390–404. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2021.3136503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Han K, Wang Y, Chen H, Chen X, Guo J, Liu Z, et al. A survey on vision transformer. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(1):87–110. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2022.3152247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Riaz M, He J, Xie K, Alsagri H, Moqurrab S, Alhakbani H, et al. Enhancing workplace safety: PPE_Swin—a robust swin transformer approach for automated personal protective equipment detection. Electronics. 2023;12(22):4675. doi:10.3390/electronics12224675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools