Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Efficient and Verifiable Data Aggregation Protocol with Enhanced Privacy Protection

1 School of Cryptography Engineering, Engineering University of PAP, Xi’an, 710086, China

2 Key Laboratory of People’s Armed Police for Cryptology and Information Security, Xi’an, 710086, China

3 School of Data and Target Engineering, Information Engineering University, Zhengzhou, 450000, China

* Corresponding Author: Wei Zhang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3185-3211. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067563

Received 06 May 2025; Accepted 09 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Distributed data fusion is essential for numerous applications, yet faces significant privacy security challenges. Federated learning (FL), as a distributed machine learning paradigm, offers enhanced data privacy protection and has attracted widespread attention. Consequently, research increasingly focuses on developing more secure FL techniques. However, in real-world scenarios involving malicious entities, the accuracy of FL results is often compromised, particularly due to the threat of collusion between two servers. To address this challenge, this paper proposes an efficient and verifiable data aggregation protocol with enhanced privacy protection. After analyzing attack methods against prior schemes, we implement key improvements. Specifically, by incorporating cascaded random numbers and perturbation terms into gradients, we strengthen the privacy protection afforded by polynomial masking, effectively preventing information leakage. Furthermore, our protocol features an enhanced verification mechanism capable of detecting collusive behaviors between two servers. Accuracy testing on the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets demonstrates that our protocol maintains accuracy comparable to the Federated Averaging Algorithm. In scheme efficiency comparisons, while incurring only a marginal increase in verification overhead relative to the baseline scheme, our protocol achieves an average improvement of 93.13% in privacy protection and verification overhead compared to the state-of-the-art scheme. This result highlights its optimal balance between overall overhead and functionality. A current limitation is that the verification mechanism cannot precisely pinpoint the source of anomalies within aggregated results when server-side malicious behavior occurs. Addressing this limitation will be a focus of future research.Keywords

In the era of big data today, the contribution of data has become a crucial factor for the rapid development of industries. Effectively centralizing relevant data is a key step in leveraging data advantages. Federated learning, as a distributed machine learning method, enables cross-institutional data collaboration while effectively protecting data privacy during transmission. Specifically, users do not need to aggregate raw data with other nodes; instead, they use locally trained model parameters. Once these parameters are uploaded to a central server, the server aggregates and updates the data to obtain global model parameters, which are then returned to the collaborating users, completing one iteration of federated learning. This process ensures the privacy security of the user’s data while allowing all users to benefit from collaborative training [1]. Depending on the type of user intersection data, federated learning is categorized into horizontal federated learning, vertical federated learning, and federated transfer learning. In the context of collaborative training for specific tasks in real-world scenarios, research on horizontal federated learning is the most extensive. Conversely, vertical federated learning and federated transfer learning impose higher requirements for handling data heterogeneity, thereby limiting their application scenarios. Federated learning is widely applied in many IoT scenarios today, such as smart homes and intelligent transportation. Additionally, federated learning performs well in areas such as loan status prediction, health assessment, and next-word prediction [2–4]. However, research indicates that the central server can infer private data from the parameters uploaded by users, leading to privacy breaches [5–7], and even enabling the analysis of when and how to recover raw data through recursive gradient attack methods [8].

In order to address the critical issue of privacy leakage in federated learning, researchers have proposed many methods. Google’s secure aggregation based on pairwise additive masking, presented at CCS’17, employs a clever masking offset strategy. Participants need to negotiate pairwise additive masks to protect their own data. During the data aggregation phase, these masks can be offset by addition in pairs without affecting the accuracy of the model, and the resulting computational overhead is small. However, the biggest problem with this method is participant dropout. Once there is a dropout user, it means that the final data aggregation result cannot offset the masks in pairs, resulting in bias in data accuracy. In order to recover the data of dropout users, researchers typically introduce Shamir’s secret sharing, but the additional communication overhead is a critical issue. To avoid the issues of data bias and overhead associated with pairwise additive masking, researchers have innovated masking strategies, increasingly adopting methods such as single masking, double masking, and polynomial masking in subsequent schemes. The ESVFL: Efficient and Secure Verifiable Federated Learning with Privacy-Preserving [9] is a scheme based on a dual-server architecture. It employs polynomial masking to protect privacy and utilizes Lagrange interpolation to achieve low computational overhead for encryption on the client side. Furthermore, the encryption calculation and communication overhead are independent of the number of users, so even if there are dropout users, online users will not incur additional computational and communication overhead. However, this scheme exhibits privacy vulnerabilities when both servers collude; any user collaborating with a server can obtain the same number of equations as the unknowns, thereby reconstructing the system of equations to steal private information.

In addition to the need for privacy protection, users also hope to obtain accurate results through federated learning. The main factors causing inaccurate results include: first, the fraudulent behavior of malicious servers, which do not comply with the protocol requirements for aggregation operations and instead fabricate results at will; second, the lazy behavior of malicious servers, which perform aggregation operations normally but do not aggregate all user data; third, the dropout of some users, which affects the recovery of the final correct result; fourth, the poisoning behavior of Byzantine users undermines the overall distribution characteristics of the data. To avoid the above situations, verifiability has become an important part of improving the effectiveness of federated learning. As shown in Fig. 1, verifiability primarily refers to the client’s ability to verify whether the server has correctly and completely executed the aggregation computation. Existing verifiable data aggregation (VDA) schemes are mainly categorized into two types: those based on cryptography and those based on trusted execution environments. The most commonly used methods are cryptographic-based approaches, which primarily include verification techniques such as commitments, homomorphic signatures, and zero-knowledge proofs. As a VDA scheme based on dual servers, ESVFL [9] employs the simplest form of data consistency verification. It validates the aggregated results returned by the servers through cross-verification between the two servers and user comparison. However, this verification method is only effective in scenarios where a single server is malicious. When the two servers collude, the cross-verification becomes essentially meaningless. Although the threat model of the scheme excludes the possibility of colluding servers forging aggregation results, such a scenario still exists in real-world applications.

Figure 1: Verifiability in federated learning

To address the dual requirements of privacy security and verifiability of aggregated results in federated learning, this work makes the following key contributions:

• Identification and Exploitation of an ESVFL Vulnerability: We propose a novel attack method targeting user privacy in ESVFL. Under the threat model where users are honest-but-curious and dual servers are malicious, we demonstrate how a user conspiring with either server can compromise others’ privacy. Crucially, when the dual servers collude with a user, they can directly reconstruct the target user’s gradients by synthesizing known information. We successfully executed this active privacy attack, exposing a critical vulnerability.

• Protocol Resilient to Dual-Server Collusion: To mitigate ESVFL’s vulnerabilities to privacy leakage and forged aggregated results caused by dual-server collusion, and to effectively deter exhaustive attacks by adversaries, we construct a robust protocol. We enhance the privacy protection strength of polynomial masking by introducing cascaded random numbers and perturbation terms into gradients, significantly increasing the difficulty of privacy theft. Furthermore, we implement a dual-layer verification mechanism capable of detecting collusive behaviors where dual servers jointly slack or forge aggregated results, empowering users to independently identify incorrect results.

• Comprehensive Validation of Protocol Efficiency: We rigorously validate the protocol’s efficiency. Experimental results demonstrate that, compared to prior dual-server architectures, our protocol achieves superior computational efficiency for privacy protection and result verification. Crucially, this enhanced efficiency is attained without compromising test accuracy and while strengthening verifiability functions.

The following is the structure of the article. Section 2 introduces related work on validation methods and privacy protection methods in federated learning and proposes an attack method targeting user privacy in ESVFL. Section 3 defines the system model and threat model of our protocol. Section 4 describes the content of our protocol in detail. Section 5 theoretically analyzes the system in terms of privacy security, verifiability, and fault tolerance. Section 6 evaluates the system performance based on experimental results. Section 7 summarizes the entire article.

2 Related Work and Attack Method

2.1 Verifiable Federated Learning

According to the different architectures of federated learning, verifiable federated learning can be divided into two types. One is centralized, including two verifications of the server and the user, and the other is decentralized, including two verifications of the miner and the trainer [10]. Most current federated learning solutions are based on the Client-Server architecture, and are more aimed at the aggregation behavior of the central server that may forge or omit data, and seek a supervision or verification mechanism to prevent it.

Ghodsi et al. [11] proposed an interactive proof protocol in which users send a randomly selected challenge to the cloud server to prove its correctness through the response of the cloud server. Although this protocol is not applicable to the federated learning scenario, it has guided the direction of subsequent research. In VerifyNet: Secure and verifiable federated learning [12], users use homomorphic hash functions integrated with pseudo-random functions to verify the proof information returned by the server, but users need to upload additional parameters based on the uploaded model parameters. Similar methods are used in [13] and [14], where homomorphic hash functions are applied to gradient information. This approach incurs significant computational costs, and as the dimensionality of the gradients increases, the communication costs also rise accordingly. In order to reduce communication costs, Zhang et al. [15] introduced bilinear aggregate signature technology and used the Chinese Remainder Theorem to reduce communication costs. In addition, VFL: A Verifiable Federated Learning With Privacy-Preserving for Big Data in Industrial IoT [16] uses pseudo-random generators, Lagrange interpolation, and the Chinese Remainder Theorem to encrypt and package data, and users can judge their correctness through the aggregated results obtained by unpacking. Another study [17] stores the server’s proof in the blockchain, and users implement verification through a variant of ElGamal encryption. Versa: Verifiable secure aggregation for cross-device federated learning [18] uses lightweight pseudo-random generators to verify aggregated models, which has significant advantages in terms of computational costs. However, due to the use of pairwise additive masking to encrypt gradients, in order to ensure the correctness of the aggregated results, it is necessary to recover the information of dropout users, which will increase the computational and communication costs. Similar problems are also faced by [12] and [19]. Vcd-fl: Verifiable, collusion-resistant, and dynamic federated learning [20] considers the situation of user dropout, but requires additional overhead to recover the parameters required for verification through online users. Eltaras et al. [21] rely on auxiliary nodes to achieve single-mask protection and verification of aggregated results, and the verification process is not affected by dropout users. Non-interactive verifiable privacy-preserving federated learning based on dual-servers (NIVP-DS) [22] and ESVFL [9] both adopt a cross-verification method with two servers, adding an extra layer of verification protection in the intermediate process, but there are risks of privacy leakage in terms of user data security. RVFL: Rational Verifiable Federated Learning Secure Aggregation Protocol [23] also used a dual-server architecture, one for data aggregation and the other for result verification. The problem with this protocol is that it needs to consider not only dropout users but also dropout auxiliary points, resulting in higher communication costs during the aggregation phase.

2.2 Privacy Protection in Federated Learning

Unlike traditional distributed machine learning, federated learning focuses more on the privacy of collaborative user data. Currently, there are three main privacy protection methods: homomorphic encryption, differential privacy, and masking.

Privacy protection schemes based on homomorphic encryption initially involve users collaboratively encrypting uploaded parameters with a shared secret key through negotiation, enabling secure aggregation on the server. Homomorphic encryption allows operations performed on ciphertexts to produce decrypted results equivalent to operations on the plaintext. Phong et al. [24] employed two encryption algorithms, LWE and Paillier, to encrypt users’ local gradients. By leveraging the additive homomorphic property, they achieved model weight updates on the server. Subsequently, to prevent malicious users from stealing sensitive information, many studies adopted multi-key approaches, where different users encrypt data with distinct public keys. In this scheme, no single user can decrypt the aggregated result independently; only through joint decryption by all users can the result be obtained. However, this approach introduces significant computational complexity. Ma et al. [25] proposed the xMK-CKKS scheme, a multi-key variant of MK-CKKS, which, based on the RLWE assumption, utilizes additive operations to generate the aggregation result. This scheme offers a concise and secure decryption process. While it performs well against privacy attacks and collusion, it is ineffective in handling user dropouts. Overcoming this limitation typically requires increased communication overhead.

Differential privacy-based privacy protection schemes are built on the principle of introducing noise into raw data. Gao et al. [26] proposed a dynamic contribution broadcast encryption supporting user participation and withdrawal, combined with local differential privacy to safeguard data privacy. Jiang et al. [27] employed hybrid differential privacy and adaptive compression methods to protect gradient transmission in industrial environments, effectively preventing inference attacks. Although differential privacy demonstrates strong resistance to collusion and user dropout, it has inherent drawbacks. Increasing the magnitude of noise enhances data privacy but reduces the accuracy of results. Conversely, decreasing noise improves accuracy but compromises privacy. All these schemes involve a trade-off between data accuracy and privacy preservation.

Masking is a lightweight method that does not compromise data accuracy. The core of the masking involves perturbing the original data through additive methods, thereby providing privacy protection during the propagation phase. In the aggregation stage, a carefully designed algorithm is employed to effectively eliminate the perturbations. At present, masks are mainly divided into single masks and double masks. Assuming there are N users in federated learning,

Here, the M mostly uses a pseudo-random number generator (PRG) to generate a result that is indistinguishable from a randomly and uniformly selected element in the output space. The input seed is a fixed-length random uniform value, ensuring unpredictability between users.

To eliminate the mask M, two methods can be adopted. One is in the absence of a trusted third party, where users

When the server performs data aggregation, the calculation results are obtained:

Another approach is to introduce a trusted third party to collect all users’ masks M, and then send the sum of the users’ masks to the server during the aggregation phase, thereby eliminating the masks and obtaining the correct aggregated result.

Bonawitz et al. [28] first proposed the paired additive masking technology, using an interactive Diffie-Hellman(DH) key negotiation to generate the masking seed. Both References [16] and [18] proposed solutions based on this technology. In order to improve efficiency and reduce communication costs, many schemes have been improved. Schlegel et al. [29] introduced coding technology on this basis, while So et al. [30] grouped users and performed aggregation operations through multiple loop structures. Jahani-Nezhad et al. [31] also featured a similar grouping structure, but it requires additional communication to defend against collusion attacks. In Communication-computation efficient secure aggregation for federated learning [32], each pair of users is connected with probability P, running a partial DH key exchange protocol to reduce communication overhead. In addition, another improvement direction is to use a non-interactive method instead of DH key exchange. Reference [33] relies on a trusted third party to distribute users’ seeds, with the sum of the seeds being zero. References [34] and [35] eliminated secret shared seeds in SecAgg, improving overall efficiency but greatly increasing communication costs when users drop out. Later, to adapt to large-scale federated learning applications, a more efficient single masking method replaced the interactive paired additive masking. In Hyfed: A hybrid federated framework for privacy-preserving machine learning [36], each user adds a single mask to the uploaded data, which is then aggregated by a trusted third party to obtain the sum of all users’ masks. When the server aggregates, it is provided with this sum of masks to obtain an accurate aggregation result. For the generation of single masking, reference [37] uses the homomorphic PRG (HPRG) method, and the server can obtain the seed to cancel the mask through Shamir secret sharing and the additive homomorphic property of HPRG. There are also some schemes [38,39] that are based on a chain structure to generate masks, but this method is not secure when the server is untrusted or colludes with users.

2.3 An Attack Method Targeting Privacy in ESVFL

ESVFL is a federated learning scheme that employs masked polynomials for privacy protection. The system utilizes a dual-server architecture, where users split their secret information into two parts and upload them separately to the two servers. The threat model assumes that users are honest but curious, while the dual servers are malicious and may collude with each other. Consequently, it can be inferred that a curious user might conspire with either one of the servers to access other users’ private information. Since collusion between the servers could enable mutual information sharing, this assumption facilitates the execution of the following attacks.

When a user uploads encrypted gradients (

In conclusion, ensuring the security of privacy data while providing efficient and verifiable functionality is challenging. Table 1 compares the differences between our protocol and the above-mentioned schemes in various attributes. The results show that our protocol can maximize the protection of user privacy and achieve verifiable functionality with lower cost and higher rigor.

3 System Model and Threat Model

Before introducing the overall system, we listed the main symbols involved in the system, as shown in Table 2.

The system consists of three entities: an honest manager, two servers

• Honest manager: It is responsible for the initialization and aggregation phases of the system. Before the first round of training, set two points

• Servers: They are responsible for aggregating and mutual verification. Both servers aggregate different information about user gradients and mutually verify by exchanging partial aggregation results. After successful verification, they calculate intermediate information

• User: They are responsible for uploading masked gradients and verifying and calculating the global gradient. Train the local model to obtain the local model gradient

The specific system process is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: The system model of our protocol

Assuming that two servers in the system are malicious.

• Malicious servers may attack masked gradients in order to obtain user privacy, such as through exhaustive attacks or by conspiring with the other server to infer user privacy through information sharing.

• Malicious servers may engage in lazy behavior, aggregating a random selection of masked gradients, but broadcasting the correct set of online users, causing the aggregated password sent by the manager to the user to not produce the correct aggregated gradient.

• Malicious servers may also engage in destructive behavior, sending incorrect verification information to the other server during the mutual verification phase, or providing users with forged intermediate data and aggregation results.

The users in the system are honest and curious, following the protocol requirements to train the model, but attempting to obtain the privacy information of other users.

• Curious users may infer privacy by stealing information transmitted by other users during the process.

• Curious users may also conspire with other users or servers to have the server forge the set of online users without actively revealing their own privacy, and obtain the attacked user’s password by the difference between the aggregation passwords of the two rounds, and then have the conspiring user calculate the user’s gradient privacy, provided that the sets of online users in the two rounds are the same.

It is important to note that our protocol is designed to address attacks targeting privacy information by curious users and malicious servers, as well as deceptive behaviors by malicious servers that compromise the correctness of aggregation results. However, it does not consider data poisoning by malicious users in the context of Byzantine generals, as implementing such defenses would require the introduction of data feature-based verification mechanisms, which are not aligned with our design objectives.

Our protocol is based on the classic FederatedAveraging (FedAvg) [40] algorithm framework, which aggregates model parameters through weighted averaging. The system is a dual-server architecture, with the introduction of a trusted third party, namely the system administrator. The privacy protection method employed in the protocol is polynomial masking. Gradients, one-time passwords, and pseudorandom numbers serve as coefficients for polynomial masking, where cascading random numbers and perturbation terms are introduced to the gradients to enhance protection. The verification mechanism in the protocol is based on cryptographic indirect verification, which does not validate the aggregated gradients themselves but instead verifies other aggregation results related to the aggregated gradients. This ensures the verifiability of the aggregation results through server cross-validation and user validation.

The goals of this proposed protocol can be summarized as follows:

• Ensure Robust Privacy Security: The employed privacy protection mechanism ensures resilience against all user privacy attacks defined within the threat model, even when facing honest-but-curious users and malicious server entities.

• Provide Effective Verifiability: The protocol incorporates a dual-layer verification mechanism: (1) cross-verification between the dual servers to deter malicious actions by a single server, and (2) user verification of results returned by the dual servers to detect and prevent collusive behavior.

• Offer Seamless Fault Tolerance: Addressing the inherent instability of user devices in practical federated learning deployments, our protocol supports dynamic participation, allowing users to join or drop out of training flexibly at any stage while seamlessly maintaining operation.

4.2 Description of Our Protocol

At the beginning of the system, N users participate in the training,

Here,

Figure 3: The principle of cascade random number generation

Name them

The

4.2.4 Double Server Mutual Verification

and sends

and sends

Subsequently,

both of which are sent to the user. The user first checks whether

After two types of verification, the user computes:

Given

In this section, we will analyze our protocol in terms of privacy security, verifiability, and fault tolerance.

Definition 1 (perfect security [41]): Let

then we say that

Theorem 1: Malicious servers cannot obtain privacy through uploaded masked gradients.

Proof of Theorem 1: Its security depends on Shannon’s perfect security. In the masked structure, the one-time password

Although in theory we have increased the difficulty for attackers to obtain privacy, for simple definitions and small value ranges of random numbers, it is still relatively easy to crack privacy data through exhaustive attacks. Suppose a curious user wants to obtain the gradient of another user by colluding with the server, and has obtained four masked gradients. Since the curious user knows the structure of the masked gradients, with five unknowns, it is only necessary to crack any one unknown to obtain the gradient. It is worth noting that in this, in addition to the gradients trained locally by the user being undetermined, the other four random variables must change in each iteration, so attackers cannot obtain any help from information from two iterations. When an attacker wants to crack a one-time password

Theorem 2: When curious users conspire with malicious servers, they cannot obtain other user’s privacy.

Proof of Theorem 2: If a curious user wants to obtain privacy through exhaustive attacks, it must first conspire with two servers simultaneously. Secondly, it requires the ability to decrypt any arbitrary random variable. However, the defense mechanisms we employ are cryptographically secure. Specifically, by expanding the generation space of one-time passwords, perturbations, pseudorandom numbers, and cascaded random numbers, we ensure that the computational complexity for an attacker performing brute-force searches grows exponentially. This renders the decryption infeasible within polynomial time, thereby probabilistically guaranteeing the privacy and security of the data.

Considering an extreme case, when

This protocol includes two layers of verification processes. One layer is the cross-validation between the two servers, used to detect malicious behavior of a single server, such as intentional forgery of information by a malicious server during information exchange between the two servers. The other layer is the user’s verification of the two servers, used to detect lazy behavior of a single server or collusion between the two servers, such as the malicious server may not aggregate all online users’ mask gradients during the aggregation phase, or both servers jointly forge intermediate information and aggregation results.

Theorem 3: If one of the servers forges

Proof of Theorem 3: Before cross-validation,

Results are inconsistent, so verification cannot be passed. Assuming

Theorem 4: When a single server engages in lazy behavior or forges

Proof of Theorem 4:

and send

and send

Since both have parts that have been changed,

When the user receives

This can prove that there are incorrect aggregation results in

Theorem 5: When the two servers collude to engage in lazy behavior or jointly falsify

Proof of Theorem 5: Suppose the two servers collude to aggregate the masked gradients of the users in the set

When the user receives

So far, users cannot detect lazy behavior, so they continue to verify. Due to

It is concluded that the number of aggregated masked gradients in

The fault tolerance in federated learning mainly involves the impact of user dropout on the overall training process. Many privacy protection schemes in federated learning in the past have adopted the Shamir secret sharing method to reconstruct the decryption information of dropout users in order to avoid the impact on the final privacy data recovery. Although this method can tolerate the dropout of any user, the additional communication and computation overhead is obvious. Our approach allows for the addition and withdrawal of any user, and during the training process, the withdrawal of any user at any stage will not affect the generation of the final global parameters. When a new user wants to join the training, they only need to comply with the protocol requirements and provide a one-time password to the honest manager before the start of a new iteration.

Theorem 6: The dropout of users at any stage will not affect the final recovery process of privacy information.

Proof of Theorem 6: We analyze the timing of user dropout from three perspectives:

• When a user disconnects after the end of a round of iteration and before the start of a new round of iteration, since the user did not provide the honest manager with a new one-time password

• When a user disconnects before uploading the masked gradient to the server, since the user’s masked gradient did not participate in the aggregation process, the set

• When a user disconnects after uploading the masked gradient to the server, since the user has already provided the one-time password

In obtaining training loss and test accuracy, we selected two datasets, MNIST and CIFAR-10, and to adapt to the practical scenarios of federated learning, the data chosen is non-IID (non-independent and identically distributed).

• MNIST is a handwritten digit dataset from 0 to 9, which contains 60,000 training samples and 10,000 test samples, with each sample being a 28

• CIFAR-10 is a dataset of RGB format color images containing 100 different objects, with 50,000 training samples and 10,000 test samples, and each sample has a size of 32

6.1.2 Model and Parameter Settings

We chose two models, multilayer perceptron (MLP) and convolutional neural network (CNN). The dimension of the hidden layer in the MLP is set to 200, and ReLU activation function is used. Before training the CNN model, different datasets will undergo different data preprocessing processes. The default number of users in the experiment is 100, the local training rounds are 5, the local batch size is 10, the test batch size is 128, the learning rate is 0.01, and the momentum of stochastic gradient descent (SGD) is 0.5.

6.1.3 Experimental Environment

The experiment is performed on a 64-bit Windows 11 Professional operating system, with an 12th Gen Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-12600KF 3.70 GHz processor, 32 GB memory, and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 Ti graphics card. We run the code using python 3.11 on PyCharm 2022.1.1.

6.2 Model Training Loss and Test Accuracy

As our approach is based on the FedAvg algorithm framework, in this section, we compare this algorithm with our protocol in terms of training loss and testing accuracy to evaluate the performance of our protocol in terms of accuracy.

Firstly, the classic FedAvg algorithm does not involve data encryption process, but rather focuses on the aggregation of data. Our algorithm adds protection to the data, which is equivalent to aggregating encrypted data. From the perspective of training loss, the difference in loss values between the two is not significant in the presence of fluctuations. This indicates that the data protection operation of our protocol does not increase the loss value, and also does not affect the efficiency of model convergence. Furthermore, since users have non-independent and identically distributed data, theoretically the convergence speed of the model is slower than that of independently and identically distributed data. As shown in Figs. 4 and 5, with the increase in the number of epochs, the model’s training loss gradually converges and stabilizes around 100. Lastly, through comparing the experimental results of the two models, whether it is the range of fluctuations or the convergence rate, the training effect of CNN is superior to MLP.

Figure 4: Model training loss with MNIST dataset

Figure 5: Model training loss with CIFAR-10 dataset

In the training of the test set, we compared the accuracy in four different scenarios. As shown in Fig. 6, due to the use of non-independent and identically distributed data, the accuracy is reduced to varying degrees. Among them, the grayscale images of the MNIST dataset performed better in testing than the color RGB images of the CIFAR-10 dataset. Furthermore, through comparison with FedAvg, we found that the testing accuracy of our protocol did not show significant changes. In other words, our protocol maintained good testing accuracy while enhancing data security.

Figure 6: Comparison of the accuracy between FedAvg and our protocol with non-IID dataset

In this section, we analyze the computational complexity and communication complexity of entities in the system, and list the complexity of users and servers in our protocol and the previous three schemes in Table 3. The entity selection is divided into users and servers. In the following analysis, we assume that there are N users online, the gradient size is V, and in the scheme with auxiliary nodes, the number of auxiliary nodes is set to M. It is assumed that the cost of the initialization process can be ignored.

From a macro perspective, all four schemes use the privacy protection method of masking and achieve the correctness verification of the aggregated results. Except for the classical Verifynet, there is no third-party entity involved in the aggregation process. The other three schemes all introduce a third-party entity, and Reference [21] and RVFL both use auxiliary nodes. The difference is that Reference [21] defaults the auxiliary nodes to be online throughout the process, while RVFL considers the problem of users and auxiliary nodes dropping out, so the additional computation and communication overhead are reflected in the complexity. In addition, our protocol and RVFL are both dual-server architectures. RVFL sets up aggregation servers and verification servers separately, while our protocol aggregates and verifies functions on each server. From the comparison of complexity with RVFL, this does not increase the complexity of our protocol. Whether it is on the user side or the server side, the complexity of our protocol is the lowest. In terms of both user’s computational and communication complexity, our protocol is not limited by third-party entities and the number of users, but only determined by the gradient size, which undoubtedly helps to increase user trust and participation. For the server, the computational and communication complexity in our protocol is still not limited by third-party entities, but only affected by the number of users. Compared with the other three schemes, the complexity has not increased, and it has an advantage in communication. For the characteristics of high communication cost in federated learning, our protocol can better adapt to efficient demands. Next, we will introduce the specific complexity of this protocol.

6.3.1 Performance Analysis for User

• Computation Cost: The user needs to calculate a one-time password

• Communication Cost: The user’s communication overhead includes two types: one is to transmit the one-time password of size V for this round to the manager, and the other is to upload four masked gradients of size V to the server. Therefore, the user’s communication complexity is

6.3.2 Performance Analysis for Server

• Computation Cost: Both servers in the are aggregation servers. First, they need to aggregate the masked gradients of all online users, with a complexity overhead of

• Communication Cost: The communication overhead of the two servers includes three aspects. After completing the aggregation, the two servers need to broadcast the online user set

6.3.3 Performance Analysis for Manager

• Computation Cost: The manager only needs to aggregate the one-time passwords sent by this part of the users after receiving the online user set broadcasted by the two servers, so the manager’s computational complexity is

• Communication Cost: The manager’s only communication overhead is to broadcast P used to recover the final aggregated gradient, so the manager’s communication complexity is

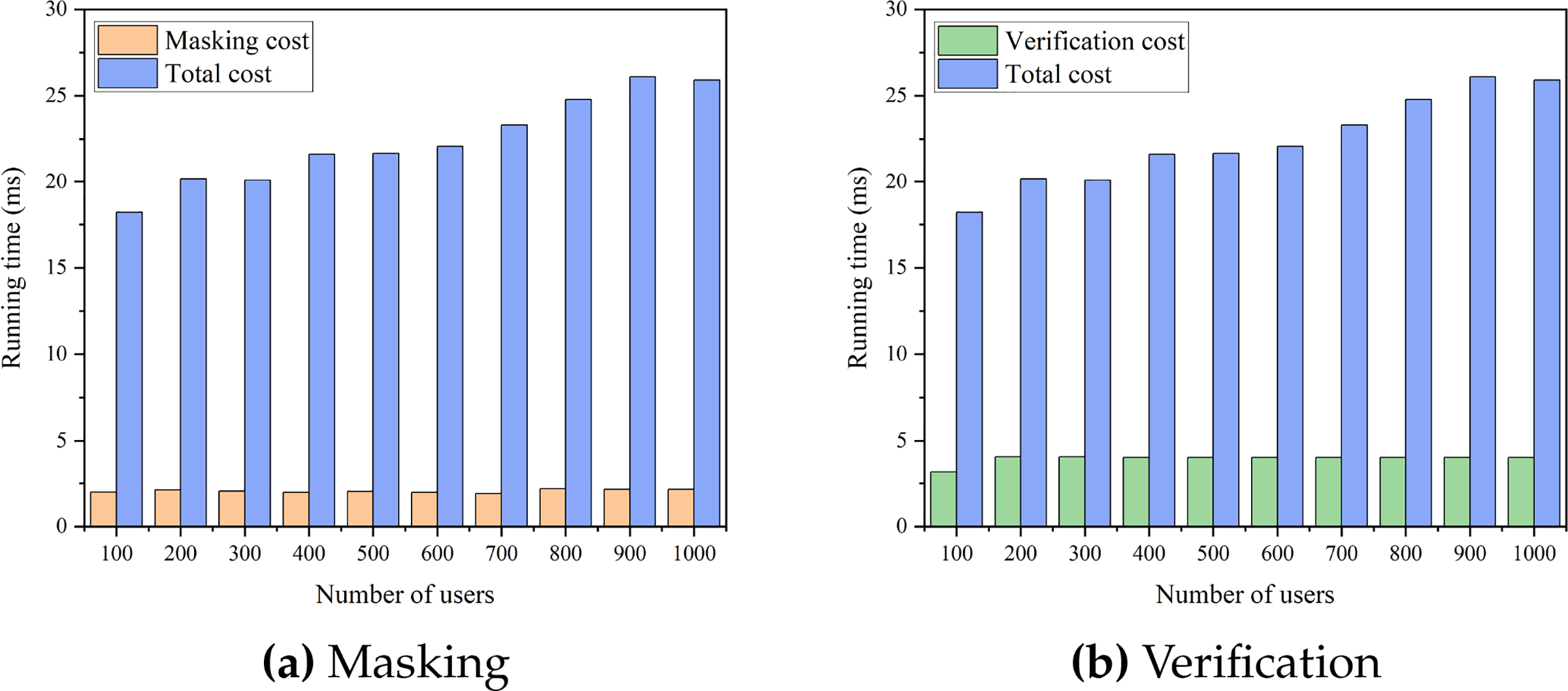

In this section, we compare and analyze the running time of the masking, validation, and aggregation processes in the proposed protocol to assess its practical efficiency. The gradient dimension of the user is set to 1000. The number of users was selected at intervals of 100, ranging from 100 to 1000. As shown in Fig. 7, due to the lightweight nature of masking, the time consumption is very low. The verification mainly involves communication and computation between the two servers and local computation on the user side, so the time consumption is not affected by the number of users. However, aggregation is mainly affected by the number of users and the dimension of gradients, so as the number of users increases, the time consumption will also increase. Overall, the time overhead of adding a mask for a single user accounts for approximately 3.1% to 23.5% of the average time overhead of aggregation.

Figure 7: Comparison of computational overheads at different number of users

Fig. 8 shows the proportion of masking and validation processes in the runtime of a round of iteration as the number of users changes. The time cost of adding masks accounts for approximately 8.3% to 10.9% of the total time, while the time cost of validation accounts for approximately 15.4% to 17.3% of the total time. Therefore, in a round of iterative training, the reduction in the number of users due to user dropouts does not affect the implementation of privacy protection and result correctness verification in federated learning, and it actually promotes overall operational efficiency.

Figure 8: Comparison of partial computational overhead to total overhead

In addition, we set the number of users to 500, and observe the changes in the running time of each stage by changing the gradient dimension of each user. The dimensions of the gradient are selected at intervals of 1000, ranging from 1000 to 10,000. From Figs. 9 and 10, it can be concluded that the time consumption of adding masks, validation, and aggregation processes all increases to varying degrees with the increase of gradient dimensions. In comparison, the time variation of the aggregation process is the most significant, and it accounts for the largest proportion of the overall running time, while the time variation of the validation process is the most stable. Combining Figs. 7 and 9, it can be seen that the changes in the number of users and gradient dimensions have little impact on the validation process of the protocol, indicating that the performance of the validation function in adapting to different conditions is stable.

Figure 9: Comparison of computational overheads at different dimensionality of gradient

Figure 10: Comparison of computational overhead for masking, verification and aggregation with the total overhead

The communication overhead of the user mainly includes providing one-time passwords to the manager and uploading gradients to the dual servers, while the communication overhead of the dual servers includes cross-validation information transmission, broadcasting the online user set, and returning aggregated results to the user. As shown in Fig. 11, the communication overhead of the user and the dual servers is proportional to the dimension of the gradient, because both of their main communication overheads contain parameters that are the same dimension as the gradient.

Figure 11: Communication overhead between users and dual servers at different dimensionality of gradient

To better analyze the effectiveness of the protocol, we chose to compare RVFL, NIVP-DS, and ESVFL, all of which have the same dual-server architecture, with our protocol. We controlled the number of users in all solutions to be 500, with 50 auxiliary nodes in RVFL. Fig. 12a shows the calculation overhead of data protection. Compared to RVFL, our protocol has an average increase of 93.28% in calculation overhead. Similarly using the masking method, ESVFL and our protocol have comparable calculation overhead and are the lowest among the four schemes, indicating the minimal cost of implementing data protection. In addition, our protocol has added more random numbers to address the privacy leakage caused by dual-server communication in ESVFL, but without generating significant computational cost, achieving the desired experimental effect. Fig. 12b shows the computational cost of verification. RVFL measures the interests of each entity from the perspective of game theory, reducing the possibility of collusion between the two servers. However, the verification mechanism itself cannot resist the collusion behavior of the two servers, and the verification process has a high computational cost due to the involvement of auxiliary nodes. Compared with RVFL, our protocol has achieved an average improvement of 92.98% on this basis. NIVP-DS effectively resists the malicious behavior of a single server by using the digital envelope method, and in terms of computational cost, it is similar to our protocol. However, with the increase in gradient dimensions, the stability of our protocol in verification becomes more prominent. Furthermore, our verification mechanism not only resists the malicious behavior of a single server but also prevents collusion between the two servers. Therefore, with a small increase in computational cost, our functionality is stronger than NIVP-DS and ESVFL.

Figure 12: Comparison of computational overhead for masking and verification at different dimensionality of gradient

This paper presents an efficient and verifiable data aggregation protocol with enhanced privacy protection, built upon a dual-server architecture as an improvement to the ESVFL scheme. Our protocol effectively mitigates the privacy leakage vulnerability inherent in ESVFL’s dual-server communication at minimal cost, while simultaneously increasing the difficulty for adversaries to successfully execute exhaustive privacy attacks. Furthermore, the protocol incorporates enhanced verifiability capabilities, enabling the effective detection of collusion between the two servers. The protocol’s privacy security, verifiability, and fault tolerance were rigorously established through six formal proofs. Experimental results demonstrate that our protocol: maintains testing accuracy under non-IID data conditions; enhances privacy security without increasing privacy protection costs; strengthens verifiability without compromising overall efficiency; and exhibits increasingly significant efficiency gains as data dimensionality grows. A current limitation is the protocol’s inability to achieve traceability for anomalous aggregated results. This stems from the indirect verification mechanism and the collaborative nature of the aggregation task performed by the dual servers. Future research will focus on achieving breakthroughs in the separability of digital watermarks and the design of novel incentive mechanisms to address this limitation.

Acknowledgement: The authors wish to express their appreciation to the reviewers and editors for their helpful suggestions which greatly improved the presentation of this paper.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFB3106100), National Natural Science Foundation of China (62102452, 62172436), Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (2023-JC-YB-584).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yiming Zhang and Wei Zhang; methodology, Yiming Zhang and Cong Shen; formal analysis, Yiming Zhang and Cong Shen; writing—original draft preparation, Yiming Zhang; writing—review and editing, Wei Zhang; supervision, Wei Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Konečný J, McMahan HB, Yu FX, Richtárik P, Suresh AT, Bacon D. Federated learning: strategies for improving communication efficiency. In: Proceedings of the 29th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2016 Dec 5–10; Barcelona, Spain. p. 5–10. [Google Scholar]

2. Hard A, Rao K, Mathews R, Ramaswamy Beaufays F, Augenstein S, Eichner H, et al. Federated learning for mobile keyboard prediction. arXiv:1811.03604. 2018. [Google Scholar]

3. Yang T, Andrew G, Eichner H, Sun H, Li W, Kong N. Applied federated learning: improving google keyboard query suggestions. arXiv:1812.02903. 2018. [Google Scholar]

4. Yang Q, Liu Y, Chen TJ, Tong YX. Federated machine learning: concept and applications. ACM Transact Intell Syst Technol (TIST). 2019;10(2):1–19. doi:10.1145/3298981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhu L, Liu Z, Han S. Deep leakage from gradients. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32. 2019. [cited 2025 Jul 8]. Available from: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2019/file/60a6c4002cc7b29142def8871531281a-Paper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

6. Hitaj B, Ateniese G, Perez-Cruz F. Deep models under the GAN: information leakage from collaborative deep learning. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2017 Oct 30–Nov 3; Dallas, TX, USA. p. 603–18. doi:10.1145/3133956.3134012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang Z, Song M, Zhang Z, Song Y, Wang Q, Qi H. Beyond inferring class representatives: user-level privacy leakage from federated learning. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2019-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2019 Apr 29–May 2; Paris, France. p. 2512–20. [Google Scholar]

8. Zhu J, Blaschko M. R-gap: recursive gradient attack on privacy. arXiv:2010.07733. 2020. [Google Scholar]

9. Cai J, Shen W, Qin J. ESVFL: efficient and secure verifiable federated learning with privacy-preserving. Inf Fusion. 2024;109(1):102420. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang Y, Yu H. Towards verifiable federated learning. arXiv:2202.08310. 2022. [Google Scholar]

11. Ghodsi Z, Gu T, Garg S. Safetynets: verifiable execution of deep neural networks on an untrusted cloud. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017;30. [cited 2025 Jul 8]. Available from: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/file/6048ff4e8cb07aa60b6777b6f7384d52-Paper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

12. Xu G, Li H, Liu S, Yang K, Lin X. VerifyNet: secure and verifiable federated learning. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2019;15:911–26. doi:10.1109/tifs.2019.2929409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mou W, Fu C, Lei Y, Hu C. A verifiable federated learning based on secure multiparty computation. In: Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Wireless Algorithms, Systems, and Applications (WASA’21); 2021 Jun 25–27; Nanjing, China. p. 198–209. [Google Scholar]

14. Han G, Zhang T, Zhang Y, Xu G, Sun J, Cao J. Verifiable and privacy preserving federated learning without fully trusted centers. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2022;13(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

15. Zhang X, Fu A, Wang H, Zhou C, Chen Z. A privacy-preserving and verifiable federated learning scheme. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC’20); 2020 Jun 7–11; Dublin, Ireland. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

16. Fu A, Zhang X, Xiong N, Gao Y, Wang H, Zhang J. VFL: a verifiable federated learning with privacy-preserving for big data in industrial IoT. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2022;18(5):3316–26. doi:10.1109/tii.2020.3036166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Jiang C, Xu C, Zhang Y. PFLM: privacy-preserving federated learning with membership proof. Inf Sci. 2021;576(4):288–311. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2021.05.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hahn C, Kim H, Kim M, Hur J. Versa: verifiable secure aggregation for cross-device federated learning. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2021;20(1):36–52. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2021.3126323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Guo X, Liu Z, Li J, Gao J, Hou B, Dong C, Baker T. Verifl: communication-efficient and fast verifiable aggregation for federated learning. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2020;16:1736–51. doi:10.1109/tifs.2020.3043139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Gao S, Luo J, Zhu J, Dong X, Shi W. Vcd-fl: verifiable, collusion-resistant, and dynamic federated learning. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2023;18:3760–73. doi:10.1109/tifs.2023.3271268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Eltaras T, Sabry F, Labda W, Alzoubi K, Ahmedeltaras Q. Efficient verifiable protocol for privacy-preserving aggregation in federated learning. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2023;18:2977–90. doi:10.1109/tifs.2023.3273914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Xu Y, Peng C, Tan W, Tian Y, Ma M, Niu K. Non-interactive verifiable privacy-preserving federated learning. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2022;128(2):365–80. doi:10.1016/j.future.2021.10.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mu X, Tian Y, Zhou Z, Wang S, Xiong J. RVFL: rational verifiable federated learning secure aggregation protocol. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(14):25147–61. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3390545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Phong LT, Aono Y, Hayashi T, Wang L, Moriai S. Privacy-preserving deep learning via additively homomorphic encryption. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2018;13(5):1333–45. doi:10.1109/tifs.2017.2787987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ma J, Naas S‐A, Sigg S, Lyu X. Privacy-preserving federated learning based on multi-key homomorphic encryption. Int J Intell Syst. 2022;37(9):5880–901. doi:10.1002/int.22818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Gao Y, Zhang L, Wang L, Choo K-KR, Zhang R. Privacy-preserving and reliable decentralized federated learning. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2023;16(4):2879–91. doi:10.1109/tsc.2023.3250705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jiang B, Li J, Wang H, Song H. Privacy-preserving federated learning for industrial edge computing via hybrid differential privacy and adaptive compression. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2023;19(2):1136–44. doi:10.1109/tii.2021.3131175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Bonawitz K, Ivanov V, Kreuter B, Marcedone A, McMahan HB, Patel S, et al. Practical secure aggregation for privacy-preserving machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2017 Oct 30–Nov 3; Dallas, TX, USA. p. 1175–91. doi:10.1145/3133956.3133982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Schlegel R, Kumar S, Rosnes E, Amat AGI. Codedpaddedfl and codedsecagg: straggler mitigation and secure aggregation in federated learning. IEEE Trans Commun. 2021;71(4):2013–27. doi:10.1109/tcomm.2023.3244243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. So J, Guler B, Avestimehr AS. Turbo-aggregate: breaking the quadratic aggregation barrier in secure federated learning. IEEE J Selec Areas Inform Theory. 2021;2(1):479–89. doi:10.1109/jsait.2021.3054610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Jahani-Nezhad T, Maddah-Ali MA, Li S, Caire G. Swiftagg: communication-efficient and dropout-resistant secure aggregation for federated learning with worst-case security guarantees. In: 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT); 2022 Jun 26–Jul 1; Espoo, Finland. p. 103–8. [Google Scholar]

32. Choi B, Sohn J-Y, Han D-J, Moon J. Communication-computation efficient secure aggregation for federated learning. arXiv:2012.05433. 2020. [Google Scholar]

33. Shi E, Chan HTH, Rieffel E, Chow R, Song D. Privacy-preserving aggregation of time-series data. In: Annual Network & Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS) 2011; 2011 Feb 6–9; San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

34. Zheng Y, Lai S, Liu Y, Yuan X, Yi X, Wang C. Aggregation service for federated learning: an efficient, secure, and more resilient realization. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2022;20(2):988–1001. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2022.3146448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wang R, Ersoy O, Zhu H, Jin Y, Liang K. Feverless: fast and secure vertical federated learning based on xgboost for decentralized labels. IEEE Trans Big Data. 2022;10(6):1001–15. doi:10.1109/tbdata.2022.3227326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Nasirigerdeh R, Torkzadehmahani R, Matschinske J, Baumbach J, Rueckert D, Kaissis G. Hyfed: a hybrid federated framework for privacy-preserving machine learning. arXiv:2105.10545. 2021. [Google Scholar]

37. Liu Z, Guo J, Lam K-Y, Zhao J. Efficient dropout-resilient aggregation for privacy-preserving machine learning. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2022;18:1839–54. doi:10.1109/tifs.2022.3163592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Li Y, Zhou Y, Jolfaei A, Yu D, Xu G, Zheng X. Privacy-preserving federated learning framework based on chained secure multiparty computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;8(8):6178–86. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2020.3022911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ge L, He X, Wang G, Yu J. Chain-aafl: Chained adversarial-aware federated learning framework. In: Web Information Systems and Applications: 18th International Conference, WISA 2021. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. Vol. 18, p. 237–48. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-87571-8_21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Arcas BA. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS) 2017; 2017 Apr 20–22; Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA. p. 1273–82. [Google Scholar]

41. Boneh D, Shoup V. A graduate course in applied cryptography. Version 0.5; 2020 [Book]. [cited 2025 Jul 8]. Available from: https://dlib.hust.edu.vn/bitstream/HUST/18098/3/OER000000253.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools