Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mobility-Aware Edge Caching with Transformer-DQN in D2D-Enabled Heterogeneous Networks

School of Electronics and Information Engineering, Liaoning University of Technology, Jinzhou, 121001, China

* Corresponding Author: Hongyu Ma. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3485-3505. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067590

Received 07 May 2025; Accepted 17 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

In dynamic 5G network environments, user mobility and heterogeneous network topologies pose dual challenges to the effort of improving performance of mobile edge caching. Existing studies often overlook the dynamic nature of user locations and the potential of device-to-device (D2D) cooperative caching, limiting the reduction of transmission latency. To address this issue, this paper proposes a joint optimization scheme for edge caching that integrates user mobility prediction with deep reinforcement learning. First, a Transformer-based geolocation prediction model is designed, leveraging multi-head attention mechanisms to capture correlations in historical user trajectories for accurate future location prediction. Then, within a three-tier heterogeneous network, we formulate a latency minimization problem under a D2D cooperative caching architecture and develop a mobility-aware Deep Q-Network (DQN) caching strategy. This strategy takes predicted location information as state input and dynamically adjusts the content distribution across small base stations (SBSs) and mobile users (MUs) to reduce end-to-end delay in multi-hop content retrieval. Simulation results show that the proposed DQN-based method outperforms other baseline strategies across various metrics, achieving a 17.2% reduction in transmission delay compared to DQN methods without mobility integration, thus validating the effectiveness of the joint optimization of location prediction and caching decisions.Keywords

With the rapid development of wireless communication networks and the widespread use of smart devices, mobile network data traffic has experienced exponential growth. According to a report by Cisco, the global mobile data traffic growth rate exceeds 46% annually, with video traffic accounting for more than 80% of this volume [1]. Faced with such immense data demands, traditional centralized data transmission and processing architectures are beginning to show limitations. In centralized architectures, a large amount of computational and storage tasks are concentrated in core data centers, leading to a significant increase in energy consumption, which is not aligned with the direction of green communication development. Moreover, because core networks must handle large-scale backhaul traffic, congestion is likely to occur, reducing the overall Quality of Service (QoS) for users [2]. Additionally, as users’ demands for real-time and high-interactivity services increase, long transmission paths can no longer meet the requirements of real-time video conferencing and cloud gaming scenarios.

To address these challenges, Mobile Edge Caching technology has emerged [3]. Mobile Edge Caching stores the most frequently accessed content at edge nodes, reducing the frequency of user access to core data centers, effectively alleviating the pressure on backhaul links, and reducing content retrieval latency, significantly improving users’ perception of timeliness and service quality [4,5].

At the same time, with the rapid development of deep neural networks (DNN), reinforcement learning (RL) and deep reinforcement learning (DRL) have been widely recognized as effective methods for solving approximate optimal solutions in dynamic environments. RL does not rely on any prior knowledge but instead continuously optimizes decision-making strategies through interaction with the environment, aiming to maximize long-term rewards. This characteristic makes RL widely used in dynamic selection and decision-making problems in Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) environments [6,7].

In this paper, we investigate a mobile edge caching network with unknown geographic locations, design a Transformer-based mobile user location prediction model, and then study the joint optimization problem of content caching and replacement decisions in edge caching based on the predicted future locations of mobile users. To solve this optimization problem, we propose a Deep Q-Network (DQN)-based method that effectively reduces content transmission latency and improves overall system performance.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed review of related work. Section 3 describes the system model and formulates the optimization problem with the objective of minimizing content transmission delay. Section 4 presents a Transformer-based user mobility prediction model. Section 5 proposes a DQN-based edge caching optimization framework. Section 6 conducts simulation experiments and analyzes the performance. Section 7 discusses the methodological implications and implementation challenges. Section 8 presents conclusions and future work.

In current edge caching networks, the limited storage capacity at edge nodes makes it infeasible to cache all available content locally. Consequently, it is essential to design effective caching strategies to optimize overall system performance. Traditional caching research has primarily relied on fixed planning or statistical models, such as Least Recently Used (LRU), Least Frequently Used (LFU), and others [8–11]. Reference [12] maps the content feature time in the LRU strategy to the classical Coupon Collector’s Problem (CCP) to evaluate caching performance. Reference [13] introduces a joint optimization approach for edge caching and computing resources, employing a low-complexity yet high-performance algorithm to reduce network bandwidth consumption. Building on this, Zhang et al. [14] propose a learning-based collaborative caching strategy and develop a novel dynamic programming algorithm that significantly lowers the average content delivery delay. Moreover, some researchers have accounted for the randomness of network environments and signal uncertainty by modeling caching strategies using stochastic geometry. Gao et al. [15] derive an expression for the average transmission cost based on stochastic geometry and apply standard gradient methods to obtain suboptimal solutions. Compared with strategies that merely maximize the probability of successful offloading, their approach achieves a substantial reduction in transmission costs. Emara et al. [16] utilize stochastic geometry to characterize the hit probability of multi-channel support caches in small cell networks and highlight the need for caching strategies that adapt to varying network parameters and functionalities.

However, these methods predominantly focus on single-pattern content access and static optimization, which are insufficient for addressing the complexity and dynamism of real-world user behaviors and network conditions [17,18]. To overcome these limitations, recent studies have introduced deep learning techniques into edge caching research. Li et al. [19] employ Echo State Networks (ESN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to predict user mobility and content popularity. Based on these predictions, they propose a deep reinforcement learning framework that dynamically determines which users should establish D2D links for content transmission, thereby enhancing system performance. Pervej et al. [20] propose an LSTM-based sequential model to capture user content preferences, proactively cache popular content, and develop a collaborative edge caching scheme that minimizes content sharing costs using a greedy algorithm. Sun et al. [21] design a DQN-based intelligent caching strategy aimed at improving energy efficiency in mobile edge networks. Chen et al. [22] apply DQN to optimize caching decisions in wireless networks, focusing on addressing the challenge of caching unknown popular content to support large-scale communications.

In summary, existing research on edge caching exhibits three main limitations: (1) Most studies only consider a single-layer edge node architecture, failing to fully exploit the potential of D2D collaborative caching [23]; (2) Traditional static optimization methods struggle to adapt to dynamic network environments and user mobility variations; (3) Current LSTM-based mobility prediction models demonstrate deficiencies in capturing long-term dependency characteristics. To address these issues, this paper proposes a Transformer-DQN collaborative optimization framework that specifically tackles these challenges by: implementing cross-layer cooperative caching through a three-tier heterogeneous network architecture, employing deep reinforcement learning to handle dynamic environmental challenges, and utilizing multi-head attention mechanisms to enhance mobility prediction accuracy.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

1. We derive the content transmission delay and cache hit rate in a D2D-enabled heterogeneous network, where user mobility is modeled using a grid-based representation. An optimization problem is formulated with the objective of minimizing content transmission delay.

2. A Transformer-based approach is introduced to predict users’ future geographic locations. By employing the self-attention mechanism, this method effectively handles the long-term dependency of user mobility, providing a solid basis for subsequent optimization of caching strategies.

3. We develop a DQN-based approach to solve the optimization problem. The predicted user locations, content popularity distribution, and the cache states of edge nodes are jointly modeled as the state space. Through Q-value iteration, the proposed method achieves optimal cross-layer content distribution, overcoming the limitations of traditional single-layer caching strategies.

3 System Model and Problem Description

This section first introduces the D2D heterogeneous network architecture, followed by the communication model and content popularity model. It also analyzes the overall content download delay and caching hit rate of the system. Finally, a joint optimization problem for content transmission delay is formulated.

As shown in Fig. 1, this paper studies the edge caching system in a three-tier heterogeneous network, which consists of an arbitrary macrocell containing a macro base station (MBS), small base station (SBS), and mobile user (MU). The MBS covers the entire cell’s SBS and MU, and can connect to the cloud server via backhaul links to retrieve requested content. It can also communicate with all SBS through wired connections. The MU can retrieve requested content from the SBS via wireless links, and within a certain region, MU can establish D2D links to access the requested content.

Figure 1: Edge cache system model

In this system, each user in the user set

In the communication process, the transmission types include: MBS to

End-to-End Delay consists of content transmission delay and content request delay. In specific scenarios (such as large data transmission or bandwidth-limited environments), content transmission delay dominates and becomes a key factor in optimizing system performance. Similar to the assumption in [25], we ignore content request delay and only evaluate content transmission delay. Additionally, we assume that each SBS contains multiple subchannels with the same bandwidth, and uses Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDM) for multi-access technology, where interference from D2D communication is negligible. Therefore, the communication rate between

where

where

Based on Eq. (1), the content transmission delay for

Similarly, for D2D communication, the communication rate when

Therefore, the content transmission delay when

Additionally, considering the Quality of Experience, the transmission delay for each user cannot exceed the maximum tolerable threshold

We assume that the content requested by each user follows a Generalized Zipf Distribution, which is an extension of the classic Zipf distribution. By introducing an additional shift parameter

where

3.4 Analysis of Content Download Delay

In time slot

Scenario 1: When the content

Scenario 2: When user

Scenario 3: When neither user

Scenario 4: When the requested content

In summary, the download delay of content

3.5 Cache Hit Rate(CHR) Analysis

The overall CHR of the system is the weighted sum of the hit rates of each layer, with the weights being the probability of a miss in all preceding layers:

where

Based on the content popularity Formula (6), we can obtain:

In summary, the overall cache hit rate of the system can be expressed as:

We investigate the joint optimization problem in mobile edge caching. First, we predict users’ future geographic locations based on their historical mobility data. Then, by incorporating content popularity distribution and the current cache states of edge nodes, we design a dynamic cache replacement strategy. The objective is to minimize the average content download delay across the entire caching system. According to Eq. (7), the average content download delay at time

The optimization problem aims to minimize the total content transmission delay with n time slots

where

To solve the optimization problem in Eq. (14), it is essential to find the optimal decision variables. However, due to the dynamic nature of the system’s state and actions, it is challenging to collect the massive state information of the caching system in real time and formulate an appropriate caching strategy. Moreover, the problem is a mixed-integer programming problem, which has been proven to be NP-hard [28,29]. Additionally, due to the non-convexity of the feasible set, solving the problem through exhaustive or traditional methods is difficult. Therefore, we propose a DQN-based approach to address the above optimization problem, with the detailed solution presented in Section 5.

4 Transformer-Based User Location Prediction Method

The user location prediction model proposed in this paper is based on Transformer and adopts an encoder-decoder architecture [30]. For the mobile edge caching scenario, the model is optimized to a one-step prediction mode by retaining only the encoder [31,32].

The model’s input is a historical trajectory sequence of length

where

Then, to enable the model to recognize the positional information of time steps, we add positional encoding. For this, we use a sine function as the positional encoding, which is represented as:

where

After the positional encoding, to capture the long-term temporal dependencies, the self-attention mechanism is used to calculate the relationships between time steps. Let the input to the

the matrices

Next, the self-attention mechanism is used to compute attention weights, and these weights are applied to compute a weighted sum to obtain the new representation:

To capture diverse features, the Transformer extends the single-head attention to multi-head attention. The formula for the

where

Then, the

Then, it passes through a feedforward neural network with a hidden layer size of

where

Similar to Eq. (21), residual connection and normalization are applied:

By repeating the above steps, after stacking

5 Edge Caching Scheme Based on DQN Algorithm

In this section, we first define the edge caching strategy optimization problem guided by content transmission delay according to the reinforcement learning model, and then provide a caching strategy solution based on the DQN algorithm.

5.1 Reinforcement Learning Formulation

RL, as a branch of machine learning, focuses on how agents learn optimal decisions through interaction with the environment. Its core idea is to guide the agent’s behavior through trial-and-error and reward mechanisms to maximize cumulative rewards. In reinforcement learning, there are three key elements: the state space, the action space, and the reward function. We will construct a reinforcement learning model guided by minimizing content transmission delay based on these three elements.

1. State Space (S)

The state space is used to describe the overall state of the system, including user request features and cache states. At time slot

where we define a matrix

The cache state refers to the set of contents currently cached in the edge server, which can be represented as:

where each element

In summary, the state space of the entire system can be represented as:

2. Action Space (A)

The action space defines the actions that the agent can take at each time step. In the edge caching scenario, the actions mainly include the decision to replace cached content. The action space can be represented as:

where the elements

3. Reward Function (R)

The reward function is used to evaluate the performance of the agent after executing an action. Based on the cache state

where the average transmission delay

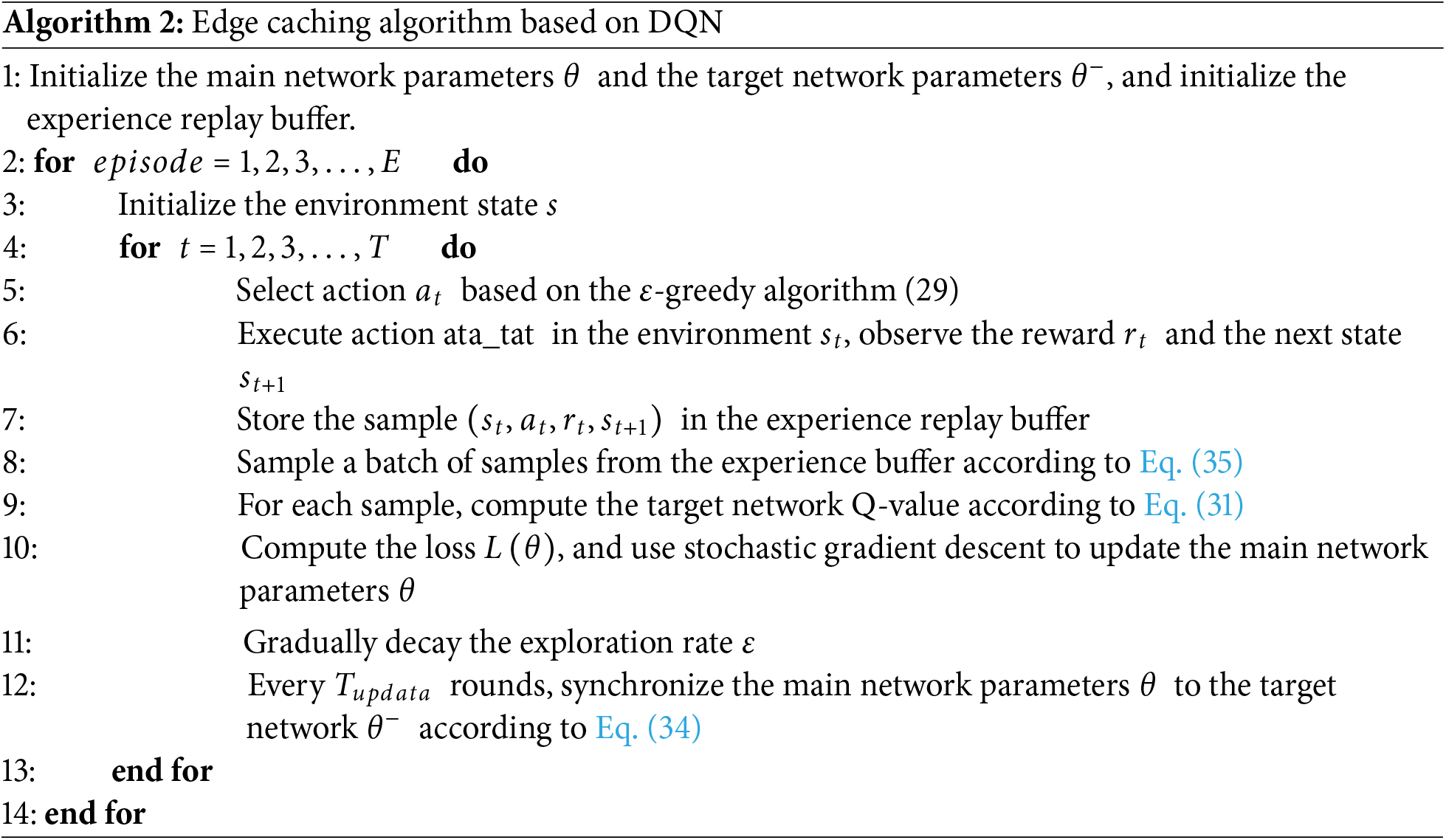

5.2 Design of Edge Caching Scheme Based on DQN

For the edge caching problem we are studying, traditional RL methods can no longer meet the requirements due to the complexity of the state and action spaces. We adopt a model-free reinforcement learning algorithm, DQN, which combines deep neural networks (DNN) with Q-learning to estimate the action-value function in RL.

5.2.1 DQN Adaptability Analysis

DQN has the capability to handle high-dimensional states. In the edge caching scenario, user request features (such as channel gain and content popularity) and cache states (such as multi-content storage conditions) form a high-dimensional state space, which is difficult to efficiently handle with the tabular method of traditional Q-learning. Additionally, DQN utilizes the nonlinear fitting ability of DNN to map high-dimensional states into lower-dimensional feature representations, thus capturing the underlying relationships in complex spaces. Furthermore, user content requests exhibit non-stationarity (e.g., burst traffic, popularity changes), and direct online learning can lead to policy oscillation. However, DQN introduces an experience replay buffer to store experiences

The environment first provides an initial state

During the learning process, there are two types of action decisions: exploration and exploitation. Exploration refers to selecting new or random actions to discover potentially high-reward strategies, while exploitation refers to selecting the action with the highest reward based on the current Q-values. To describe the probabilities of these two decisions, the

where

where

where

Then, the loss between the main network Q-value and the target network Q-value is computed. According to Eqs. (30) and (31), the loss function for the DNN can be expressed as:

By minimizing the loss function

After obtaining the loss function, the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) algorithm is used to update the parameters

where

To further improve stability, the target network is updated using a soft update mechanism. Every

In addition, the experience buffer uses a prioritized experience replay mechanism. The sampling probability is dynamically adjusted based on the temporal difference error

where

This section presents a series of simulations. First, the next user location is predicted based on historical trajectory data using the Transformer algorithm. The predicted location is then used as input to explore the caching strategy using the DQN algorithm. The performance of the DQN-based caching strategy is evaluated by comparing it with other methods.

In this study, experiments are conducted using the real-world GeoLife dataset, which contains GPS trajectory data of 182 users from April 2007 to August 2012 [33], including latitude, longitude, and altitude information. We first preprocess the dataset as follows: (1) Only low-speed scenarios are considered, and points with speeds exceeding 20 km/h are removed, (2) Static points are filtered by removing data points where the user stayed in the same location for more than 30 min, (3) The trajectory is standardized to a fixed time interval of 30 s, with missing values filled using linear interpolation.

We center the MBS and divide a 200 m × 200 m area into a 20 × 20 grid. The input dimension for the Transformer algorithm is set to 64, with 4 encoder layers, 4 attention heads, and a hidden layer size of 128. To evaluate the effectiveness of the algorithm, we compare the position prediction results with those obtained using the LSTM algorithm.

As shown in Fig. 2, the location prediction results for 50 users using different models are presented. It can be observed that, compared to the LSTM-based predictions, the Transformer-based predicted locations align much more closely with the actual locations. This is due to the self-attention mechanism of the Transformer, which can capture relationships at any position within the trajectory simultaneously. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the self-attention mechanism in location prediction. Furthermore, because the self-attention mechanism allows for parallel computation, the training speed of the Transformer is more than twice as fast as that of LSTM, given the same data volume.

Figure 2: User location prediction

6.2 Mobile Edge Caching Strategy Study

After completing the mobility prediction, the next access location and other features are used as inputs to explore the caching strategy. The proposed caching strategy is then evaluated and tested for its performance in mobile edge networks. We focus on evaluating steady-state worst-case scenarios, while future work could incorporate dedicated burst detection modules to further enhance transient robustness. First, a scenario with a three-layer heterogeneous network is set up. The scenario includes one MBS, three SBSs, and 10 users. The coverage radius of the cellular network is set to 200 m, with the MBS positioned at the center and the remaining SBSs evenly distributed. We assume a total of 100 content items, with each SBS able to cache up to 8 files, each user able to cache up to 3 files, and all files are of equal size (10 MB each). The content popularity distribution follows a Zipf distribution. Based on conservative design principles, we assume that popular content undergoes random variations at every moment. The MBS transmission power is set to 50 W, the transmission bandwidth to 50 MHz, the SBS transmission power to 5 W, and the transmission bandwidth to 10 MHz. The MU transmission power is set to 0.25 W, with a transmission bandwidth of 1 MHz. The path loss factor is set to 3.5, and the noise power is fixed at 10−9 W. Additionally, the network parameters for the DQN algorithm are set as shown in Table 1.

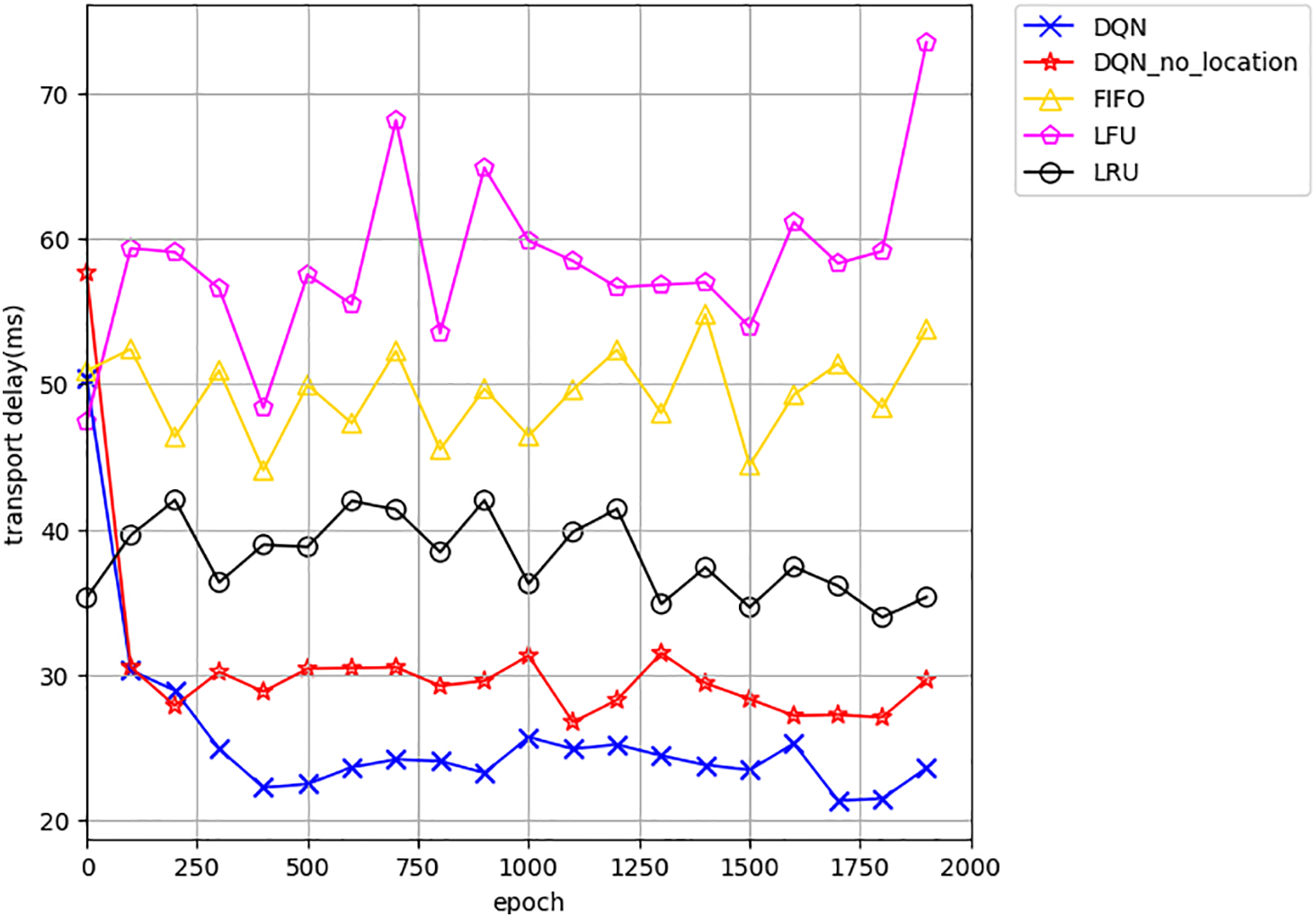

We evaluate the performance of the DQN-based cache strategy by comparing it with other benchmark cache strategies, as follows:

1. FIFO (First In, First Out): When the MU (Mobile User) or SBS (Small Base Station) cache is full, the content that was stored the longest is replaced with the current user’s requested popular content.

2. LFU (Least Frequently Used): When the MU or SBS cache is full, the content that has been used the least over time is replaced with the current user’s requested popular content.

3. LRU (Least Recently Used): When the MU or SBS cache is full, the content that has been requested the fewest times in a given period is replaced with the current user’s requested popular content.

4. DQN without Location Prediction: This method does not consider future user location information and uses the location features from the previous time step as input.

As shown in Fig. 3, we evaluate the content transmission delay under the proposed DQN-based caching strategy compared with other baseline caching methods. It can be observed that, after a certain number of training steps, the transmission delay of the DQN algorithm gradually decreases and eventually converges to approximately 23 ms. Compared to other caching strategies, the proposed method significantly reduces the system’s transmission delay. Moreover, compared to the scenario without considering user mobility, the transmission delay is reduced by approximately 17.2%. This improvement is attributed to the fact that, without mobility awareness, the caching strategy relies on users’ historical location information. However, users’ positions change over time, leading to a mismatch between the input location and the actual location at the next time step, which in turn causes higher transmission delays.

Figure 3: Content transmission delay based on different strategies during training

As shown in Fig. 4, we further evaluate the CHR of the DQN-based caching strategy in comparison with other baseline caching strategies, as well as the CHR of the DQN strategy without location prediction. It can be observed that, after sufficient training, the CHR achieved by the DQN algorithm significantly outperforms that of traditional caching strategies, converging to approximately 55%. In fact, experimental results show that under the same conditions, the optimal caching strategy achieves a CHR of around 61%, indicating that the CHR of the DQN-based method is already close to the optimal performance. Furthermore, considering user mobility improves the CHR by approximately 5%.

Figure 4: CHR based on different strategies during training

Fig. 5 compares the content transmission delay of five caching methods under different numbers of users. With the same number of users, it can be observed that the proposed DQN-based method outperforms the other three caching methods, and the DQN method considering user mobility performs better than the one without mobility consideration. As the number of users increases, the content transmission delay decreases because the user group caches more popular content, and more popular content is transmitted via D2D, reducing reliance on the remote core network, thus significantly lowering the content transmission delay. However, as the number of users continues to increase, a critical point of resource competition is reached, and the content transmission delay begins to rise. This is primarily due to the limited number of available orthogonal subchannels for D2D communications. When excessive concurrent D2D connections occur, co-channel interference emerges, consequently increasing communication latency in D2D links. Moreover, since the DQN-based method dynamically allocates strategies and balances the processing capabilities of edge nodes at different layers, the increase in content transmission delay is slower compared to other caching methods. This indicates that the advantage of the DQN-based method becomes more pronounced when the number of users is large compared to other caching strategies.

Figure 5: Content transmission delay with different numbers of users

Fig. 6 compares the content transmission delay performance of the five methods under different SBS cache capacities. With the same cache capacity, the DQN-based method outperforms the other three methods, and the DQN algorithm considering user mobility performs the best. As the SBS cache capacity increases, the content transmission delay for all algorithms decreases because a larger cache can store more popular content, and user requests are directly served at the edge, without needing to retrieve data from the cloud via the backhaul link. Moreover, when the cache capacity reaches a certain level, the rate of reduction in content transmission delay slows down for all five methods. This is because once the cache covers 90% of the most popular content, further increases in capacity have a minimal impact on content transmission delay.

Figure 6: Content transmission delay with different cache capacities

As shown in Table 2, we evaluated the experimental results of the DQN algorithm under different hyperparameters. The results demonstrate that DQN hyperparameter configurations significantly impact content transmission delay and training efficiency. The initial exploration rate of 0.8 achieved better latency performance compared to the 0.2 scheme, but required 78% more training iterations, revealing a trade-off between exploration capability and computational cost. The exploration rate decay factor of 0.995 reduced performance fluctuations by 17.5% compared to the 0.99 scheme, validating the importance of moderate decay. A learning rate of 0.001 achieved the optimal balance between efficiency and stability, outperforming extreme settings. The target network update interval of 40 steps improved performance by 2.4%, but doubled the training cost. The optimal combination was found to be: initial exploration rate 0.8, decay 0.995, minimum exploration rate 0.01, learning rate 0.001, and update frequency 40, which delivered the best performance despite higher training costs. For scenarios requiring a balance with efficiency, an alternative configuration with an initial exploration rate of 0.2 and update frequency of 10 could be adopted. The study reveals that exploration strategy has the greatest impact on performance, while target network updates and learning rate primarily influence training stability.

This study successfully achieved the established goal of optimizing edge caching performance in dynamic heterogeneous networks. By integrating the Transformer model with the DQN algorithm, we constructed a comprehensive framework capable of simultaneously addressing user mobility prediction and caching decision optimization. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms traditional approaches in key metrics such as content delivery latency and cache hit rate. Specifically, in user location prediction, the Transformer model, leveraging its multi-head attention mechanism, effectively captures long-term dependencies in user movement trajectories. As shown in Fig. 2, its predictions closely align with actual locations, providing reliable input for subsequent caching decisions. In terms of caching strategy optimization, the DQN algorithm successfully reduces content delivery latency to 23 ms and improves the cache hit rate to 55% through continuous interaction-based learning, validating the effectiveness of mobility-aware caching strategies.

However, this study still has several noteworthy limitations. First, the experiments adopted a simplified assumption of synchronous content requests—where all users fetch requested content simultaneously—which differs from real-world asynchronous request scenarios and may lead to overly optimistic evaluations of cache hit rates and delivery latency. Second, regarding content popularity modeling, we assumed user requests follow a Zipf distribution. While this assumption is widely used, it may not be accurate in certain social network scenarios. Additionally, the current Transformer model primarily focuses on global dependencies in trajectory sequences, and its ability to capture local spatial features needs improvement, which somewhat limits its prediction accuracy for short-term user movement patterns.

At the deployment level, the proposed method faces several technical challenges. The limited computational resources of edge nodes pose a primary obstacle, especially when running Transformer and DQN models on resource-constrained devices, necessitating appropriate model compression and optimization. Co-channel interference in D2D communications is another critical issue. As illustrated in Fig. 5, when the number of users exceeds 15, content delivery latency begins to rise due to intensified competition for orthogonal subchannel resources, indicating the need for more refined resource allocation strategies in dense user scenarios. Furthermore, the online model update mechanism in dynamic network environments requires refinement. Achieving incremental learning and rapid adaptation without compromising service quality remains a key challenge for future research. Finally, practical deployment must also account for non-functional requirements such as user privacy protection and security authentication, which may influence overall system performance.

This paper presents a mobility-aware caching strategy based on Transformer-DQN collaborative optimization to address the content distribution mismatch problem in dynamic heterogeneous networks. Through comprehensive theoretical modeling, algorithm design, and experimental validation, we have successfully achieved precise alignment between caching decisions and user mobility patterns in dynamic network environments. Our work establishes a three-tier heterogeneous network optimization framework for transmission delay minimization, which effectively overcomes the limitations of traditional single-layer optimization approaches.

The proposed solution consists of two key components: a Transformer-based geolocation prediction model that effectively captures spatiotemporal dependencies in user trajectories through advanced multi-head attention mechanisms, and a novel mobility-aware DQN algorithm that utilizes predicted locations as state inputs to dynamically optimize cache distributions at both small base stations and mobile users. Extensive experimental results demonstrate significant performance improvements over existing baseline methods across multiple critical metrics. In practical testing scenarios involving 3 small base stations and 10 mobile users, our solution achieves remarkable performance with content transmission latency reduced to 23 ms and cache hit ratio improved to 55%, representing a 17.2% reduction in latency compared to conventional mobility-agnostic strategies. The robustness of our DQN-based approach be-comes particularly evident as user density increases, where it maintains superior performance with more gradual latency degradation compared to other caching methods. This performance advantage in high-density scenarios strongly validates the adaptability and reliability of the Transformer-DQN framework in dynamic network conditions. Our detailed hyperparameter analysis identifies an optimal configuration (initial exploration rate = 0.8, decay = 0.995, min exploration = 0.01, learning rate = 0.001, target update = 40 steps) that delivers the best latency performance, while also suggesting alternative configurations for scenarios requiring different efficiency-performance trade-offs.

The current study employs several simplifying assumptions that point to valuable directions for future research. Our synchronous content request assumption, while useful for initial analysis, may lead to somewhat optimistic estimates of cache hit rates and transmission latency. Future work should investigate more realistic asynchronous scenarios and conduct evaluations at larger scales. Additionally, while we have adopted the Zipf distribution to model content popularity, real-world applications would benefit from more sophisticated approaches that can predict individual user preferences in real time. In terms of location prediction, while our Transformer-based solution effectively handles long-range dependencies, incorporating graph neural network architectures could better capture the local social net-work influences that are often crucial in practical scenarios. These potential enhancements position our work as a foundation for developing next-generation proactive caching systems with improved realism and effectiveness.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the Liaoning Provincial Education Department Fund, grant number JYTZD2023083.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yiming Guo; methodology, Yiming Guo; software, Yiming Guo; validation, Yiming Guo; investigation, Yiming Guo; resources, Yiming Guo; data curation, Yiming Guo; writing—original draft preparation, Yiming Guo and Hongyu Ma; writing—review and editing, Yiming Guo and Hongyu Ma; visualization, Yiming Guo and Hongyu Ma; supervision, Hongyu Ma; project administration, Hongyu Ma. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Microsoft [33].

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rost P, Banchs A, Berberana I, Breitbach M, Doll M, Droste H, et al. Mobile network architecture evolution toward 5G. IEEE Commun Mag. 2016;54(5):84–9. doi:10.1109/MCOM.2016.7470940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Lin F, Zhang ZY, Wang ZF, Xing YT, Wang ZF. ECC: edge collaborative caching strategy for differentiated services. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;69(2):2045–60. doi:10.32604/cmc.2021.018303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang K, Mao YM, Leng SP, He YJ, Zhang Y. Mobile-edge computing for vehicular networks: a promising network paradigm with predictive off-loading. IEEE Veh Technol Mag. 2017;12(2):36–44. doi:10.1109/MVT.2017.2668838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hasslinger G, Okhovatzadeh M, Ntougias K, Hasslinger F, Hohlfeld O. An overview of analysis methods and evaluation results for caching strategies. Comput Netw. 2023;228(4):109583. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2023.109583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kirilin V, Sundarrajan A, Gorinsky S, Sitaraman RK. RL-Cache: learning-based cache admission for content delivery. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2020;38(10):2372–85. doi:10.1109/JSAC.2020.3000415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang XF, Han YM, Leung VCM, Niyato D, Yan XQ, Chen X. Convergence of edge computing and deep learning: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2020;22(2):869–904. doi:10.1109/COMST.2020.2970550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhou H, Wu T, Zhang HJ, Wu J. Incentive-driven deep reinforcement learning for content caching and D2D offloading. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2021;39(8):2445–60. doi:10.1109/JSAC.2021.3087232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Morales K, Byeong KL. Fixed segmented LRU cache replacement scheme with selective caching. In: 2012 IEEE 31st International Performance Computing and Communications Conference (IPCCC); 2012 Dec 1–3; Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

9. Gast N, Van Houdt B. TTL approximations of the cache replacement algorithms LRU(m) and h-LRU. Perform Eval. 2017;117(2):33–57. doi:10.1016/j.peva.2017.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bai S, Bai X, Che XJ. Window-LRFU: a cache replacement policy subsumes the LRU and window-LFU policies. Concurr Comput-Pract Exp. 2016;28(9):2670–84. doi:10.1002/cpe.3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ballabriga C, Chong LK, Roychoudhury A. Cache-related preemption delay analysis for FIFO caches. ACM Sigplan Not. 2014;49(5):33–42. doi:10.1145/2666357.2597814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Poojary P, Moharir S, Jagannathan K. A coupon collector based approximation for LRU cache hits under Zipf requests. In: 2021 19th International Symposium on Modeling and Optimization in Mobile, Ad hoc, and Wireless Networks (WiOpt); 2021 Oct 18–21; Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

13. Sun YP, Chen ZY, Tao MX, Liu H. Bandwidth gain from mobile edge computing and caching in wireless multicast systems. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2020;19(6):3992–4007. doi:10.1109/TWC.2020.2979147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang X, Qi ZN, Min GY, Miao W, Fan QL, Ma Z. Cooperative edge caching based on temporal convolutional networks. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2022;33(9):2093–105. doi:10.1109/TPDS.2021.3135257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gao X, Wang X, Qian ZH, Quek TOS. A stochastic geometry-based cost-efficient caching strategy in device-to-device-enabled multi-layer heterogeneous networks. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2024;73(10):14749–62. doi:10.1109/TVT.2024.3398681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Emara M, Elsawy H, Sorour S, Al-Ghadhban S, Alouini MS, Al-Naffouri TY. Optimal caching in 5G networks with opportunistic spectrum access. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2018;17(7):4447–61. doi:10.1109/TWC.2018.2825351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hazra A, Tummala VMR, Mazumdar N, Sah DK, Adhikari M. Deep reinforcement learning in edge networks: challenges and future directions. Phys Commun. 2024;66(5):102460. doi:10.1016/j.phycom.2024.102460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Li HW, Sun MT, Xia F, Xu XL, Bilal M. A survey of edge caching: key issues and challenges. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2024;29(3):818–42. doi:10.26599/TST.2023.9010051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li LX, Xu Y, Yin JY, Liang W, Li X, Chen W, et al. Deep reinforcement learning approaches for content caching in cache-enabled D2D networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;7(1):544–57. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2019.2951509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Pervej MF, Tan LT, Hu RQ. User preference learning-aided collaborative edge caching for small cell networks. In: GLOBECOM 2020—2020 IEEE Global Communications Conference; 2020 Dec 7–11; Taipei, Taiwan. [Google Scholar]

21. Sun SY, Zhou JH, Wen JX, Wei YF, Wang XJ. A DQN-based cache strategy for mobile edge networks. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;71(2):3277–91. doi:10.32604/cmc.2022.020471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chen QS, Zhou FS, Tang D, Huang GF, Lai SW. Caching popularity-unknown contents for massive communication channels via deep Q-learning. Phys Commun. 2023;58(5):102023. doi:10.1016/j.phycom.2023.102023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Shuja J, Bilal K, Alasmary W, Sinky H, Alanazi E. Applying machine learning techniques for caching in next-generation edge networks: a comprehensive survey. J Netw Comput Appl. 2021;181(11):103005. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2021.103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hazan I, Shabtai A. Dynamic radius and confidence prediction in grid-based location prediction algorithms. Pervasive Mob Comput. 2017;42(6):265–84. doi:10.1016/j.pmcj.2017.10.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chen X, Jiao L, Li WZ, Fu XM. Efficient multi-user computation offloading for mobile-edge cloud computing. ACM Trans Netw. 2016;24(5):2827–40. doi:10.1109/TNET.2015.2487344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Hefeeda M, Saleh O. Traffic modeling and proportional partial caching for peer-to-peer systems. ACM Trans Netw. 2008;16(6):1447–60. doi:10.1109/TNET.2008.918081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li XH, Wang XF, Wang PJ, Han Z, Leung VCM. Hierarchical edge caching in device-to-device aided mobile networks: modeling, optimization, and design. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2018;36(8):1768–85. doi:10.1109/JSAC.2018.2844658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhou H, Zhang ZY, Li DW, Su Z. Joint optimization of computing offloading and service caching in edge computing-based smart grid. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2023;11(2):1122–32. doi:10.1109/TCC.2022.3163750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Saputra YM, Hoang DT, Nguyen DN, Dutkiewicz E. A novel mobile edge network architecture with joint caching-delivering and horizontal cooperation. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2020;20(1):19–31. doi:10.1109/TMC.2019.2938510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

31. Liao JX, Liu ML, Wang JY, Wang YL, Sun HF. Multi-context integrated deep neural network model for next location prediction. IEEE Access. 2018;6:21980–90. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2827422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wang WY, Osaragi T. Learning daily human mobility with a transformer-based model. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf. 2024;13(2):35. doi:10.3390/ijgi13020035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zheng Y, Xie X, Ma WY. Mining interesting locations and travel sequences from GPS trajectories. In: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on World Wide Web; 2009 Apr 20–24; Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools