Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

CGB-Net: A Novel Convolutional Gated Bidirectional Network for Enhanced Sleep Posture Classification

1 Faculty of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Phenikaa School of Engineering, Phenikaa University, Yen Nghia, Hanoi, 12116, Vietnam

2 Graduate University of Sciences and Technology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

3 Institute of Information Technology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Hanoi, 10072, Vietnam

4 International School, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, 10000, Vietnam

* Corresponding Authors: Ngoc-Linh Nguyen. Email: ; Duc-Tan Tran. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2819-2835. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068355

Received 26 May 2025; Accepted 29 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

This study presents CGB-Net, a novel deep learning architecture specifically developed for classifying twelve distinct sleep positions using a single abdominal accelerometer, with direct applicability to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) monitoring. Unlike conventional approaches limited to four basic postures, CGB-Net enables fine-grained classification of twelve clinically relevant sleep positions, providing enhanced resolution for personalized health assessment. The architecture introduces a unique integration of three complementary components: 1D Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-CNN) for efficient local spatial feature extraction, Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) to capture short-term temporal dependencies with reduced computational complexity, and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) networks for modeling long-term temporal context in both forward and backward directions. This complementary integration allows the model to better represent dynamic and contextual information inherent in the sensor data, surpassing the performance of simpler or previously published hybrid models. Experiments were conducted on a benchmark dataset consisting of 18 volunteers (age range: 19–24 years, mean 20.56 1.1 years; height 164.78 8.18 cm; weight 55.39 8.30 kg; BMI 20.24 2.04), monitored via a single abdominal accelerometer. A subject-independent evaluation protocol with multiple random splits was employed to ensure robustness and generalizability. The proposed model achieves an average Accuracy of 87.60% and F1-score of 83.38%, both reported with standard deviations over multiple runs, outperforming several baseline and state-of-the-art methods. By releasing the dataset publicly and detailing the model design, this work aims to facilitate reproducibility and advance research in sleep posture classification for clinical applications.Keywords

Young adults increasingly face lifestyle challenges that elevate stress, disrupt sleep, and heighten the risk of disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [1]. Positional therapy [2] has emerged as a promising, non-invasive intervention aimed at mitigating these issues by optimizing sleep positions.

Three main sensing approaches have been widely explored for sleep posture monitoring: vision-based, pressure-based, and wearable-device-based systems [3]. Vision-based techniques leverage thermal, depth, or fusion cameras [4–7], and also include alternative modalities such as UWB radar [8–10] and wireless sensors [11,12]. While effective, these systems often raise concerns related to privacy [13], environmental sensitivity, high deployment cost, and infrastructure complexity [14,15]. Pressure-based solutions [16–20] offer enhanced privacy and comfort, yet typically require high-resolution sensor mats, which limit portability and scalability.

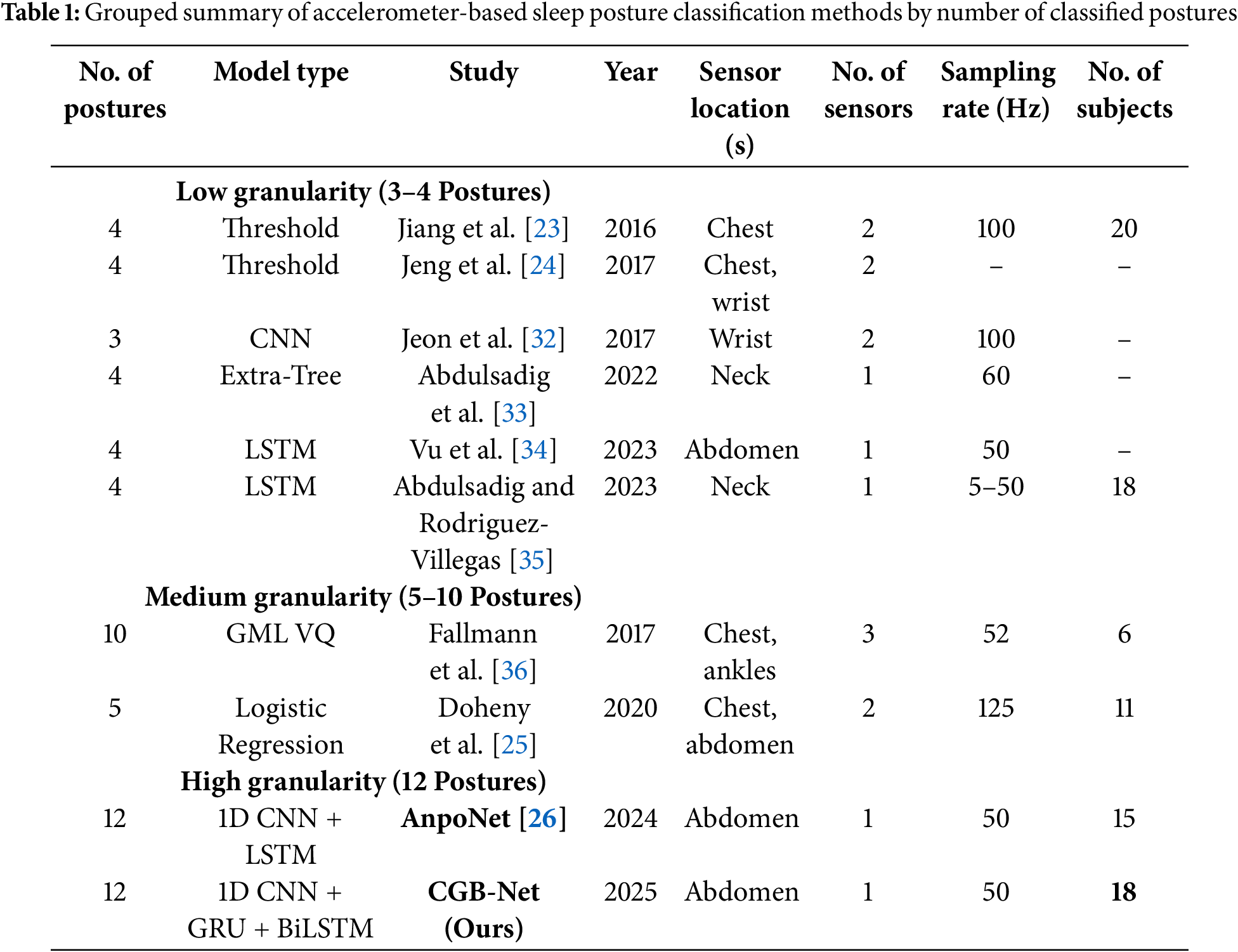

Recently, several studies have employed wearable devices equipped with accelerometers [21,22] to monitor activity and sleep posture. These wearable-based systems are increasingly favored for their unobtrusiveness, affordability, and ease of use. In particular, accelerometer-based approaches have shown strong potential in posture recognition tasks, including sleep monitoring. A comparative overview of recent accelerometer-based sleep posture classification systems is provided in Table 1, highlighting their sensor configurations, model architectures, and classification capabilities.

However, most existing systems still exhibit significant limitations in model design and classification granularity. Many rely on multiple sensors [23] or traditional machine learning techniques such as thresholding [24], and logistic regression [25], typically constrained to 3–5 coarse posture classes as in Table 1. Even recent efforts such as AnpoNet [26], which supports 12-class classification with a single abdominal sensor, utilize relatively simple model architectures—often limited to a cascade of 1D CNN and LSTM layers—thereby lacking the capacity to fully capture complex spatiotemporal patterns inherent in posture transitions. Specifically, these models often fail to leverage bidirectional temporal context and suffer from limited capacity to generalize across subjects.

While most GERD-related sleep posture studies [27] focus only on basic directions such as supine, prone, left, and right lateral positions, we aim to develop a more detailed classification system with 12 postures. This finer granularity not only improves overall model robustness but also enables deeper clinical analysis—for example, distinguishing among different left-lateral subtypes (e.g., LD vs. LU) may help validate or refine medical recommendations that suggest sleeping on the left side to alleviate reflux symptoms. To our knowledge, no prior work has systematically examined how different variants within a single directional class affect GERD outcomes. Similarly, for other directions, posture-specific variations might differentially influence reflux severity or frequency.

To address these goals, the model must learn from subtle yet clinically relevant variations in time-series signals. At the same time, addressing the challenges of modeling such detailed temporal sequences requires consideration of recent progress in time-series learning. In parallel, significant advances have emerged in time-series modeling, including temporal convolutional networks (TCNs) [28], lightweight attention-based architectures like Informer [29] and Linformer [30], and self-supervised learning strategies [31] such as contrastive learning and masked prediction frameworks. However, while powerful, many of these methods remain computationally expensive and rely on large-scale pretraining—limiting their practicality in sleep monitoring applications that require on-device inference, operate under strict energy constraints, and deal with limited annotated data.

To address the aforementioned limitations, this study proposes CGB-Net, a novel deep learning architecture that, for the first time in this domain, integrates 1D CNN, GRU, and BiLSTM in a unified framework. Compared to existing methods such as AnpoNet [26], CGB-Net introduces a more expressive architecture with enhanced temporal modeling capability, while maintaining a manageable model size and efficient training requirements. This work also contributes a comprehensive experimental evaluation across 12 posture classes using single-sensor wearable data, demonstrating the feasibility of fine-grained classification under constrained, clinically-relevant settings.

The key contributions of this work are summarized as follows: (1) Development of a 12-class sleep posture classification system (12-SPCS) using a single abdominal accelerometer; (2) Design of CGB-Net, a novel hybrid neural architecture combining 1D CNN, GRU, and BiLSTM layers—demonstrated to outperform existing approaches; (3) Implementation of a subject-independent evaluation protocol with a more diverse and rigorous participant cohort compared to prior work; (4) Release of a publicly available benchmark dataset to encourage further advancements in fine-grained, sensor-based sleep posture classification.

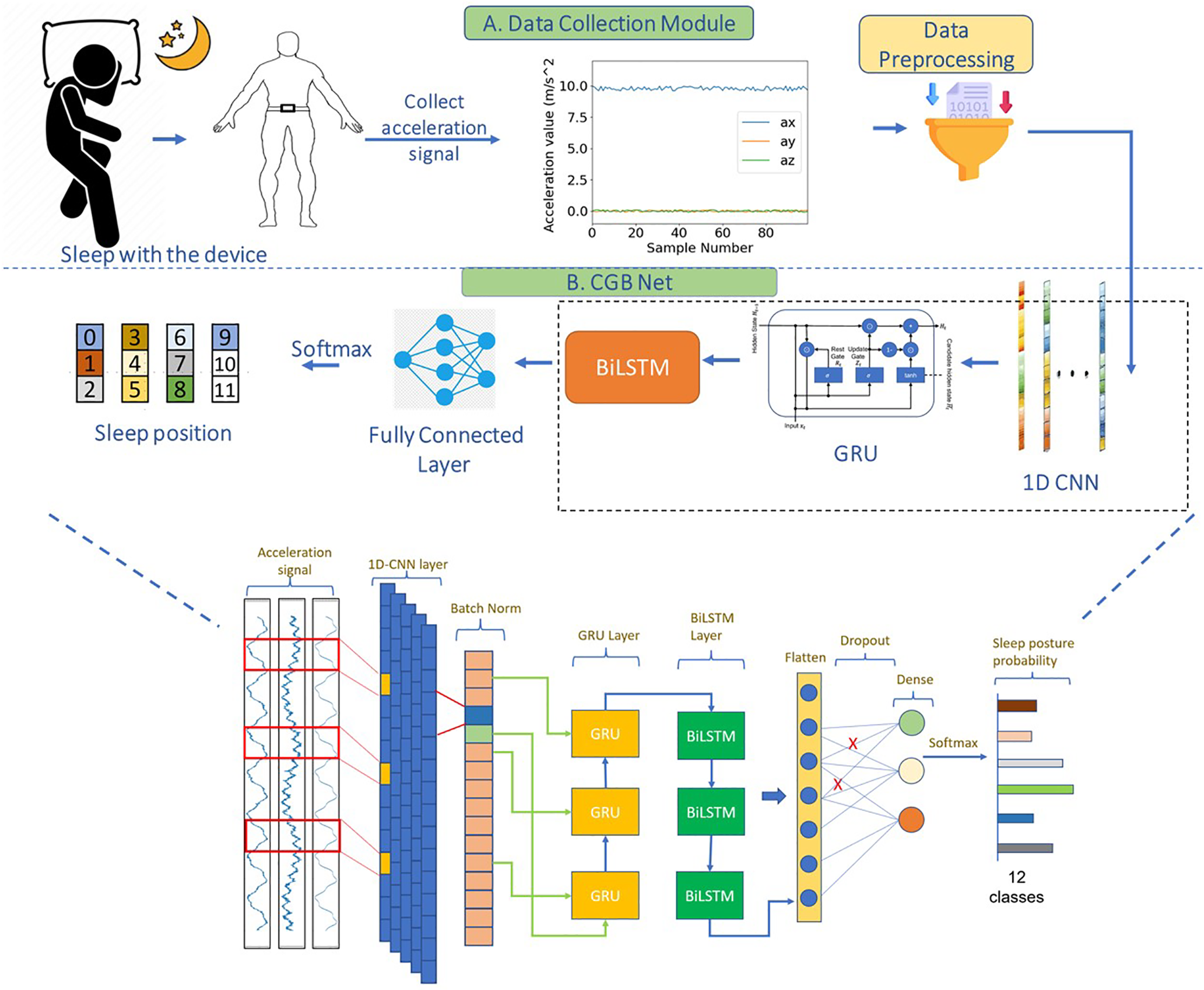

The proposed system aims to recognize a comprehensive set of 12 distinct sleeping postures based on accelerometer signals. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the system comprises two core modules: a data acquisition module and a classification module. In the data acquisition phase, a wearable sensor is employed to continuously capture tri-axial acceleration signals as participants assume each of the predefined sleep postures under controlled conditions.

Figure 1: Two-module system: (A) Data collection and preprocessing module utilizing a wearable accelerometer placed on the abdomen. (B) Classification module architecture—CGB-Net—combining 1D CNN, GRU, and BiLSTM layers for accurate sleep posture recognition

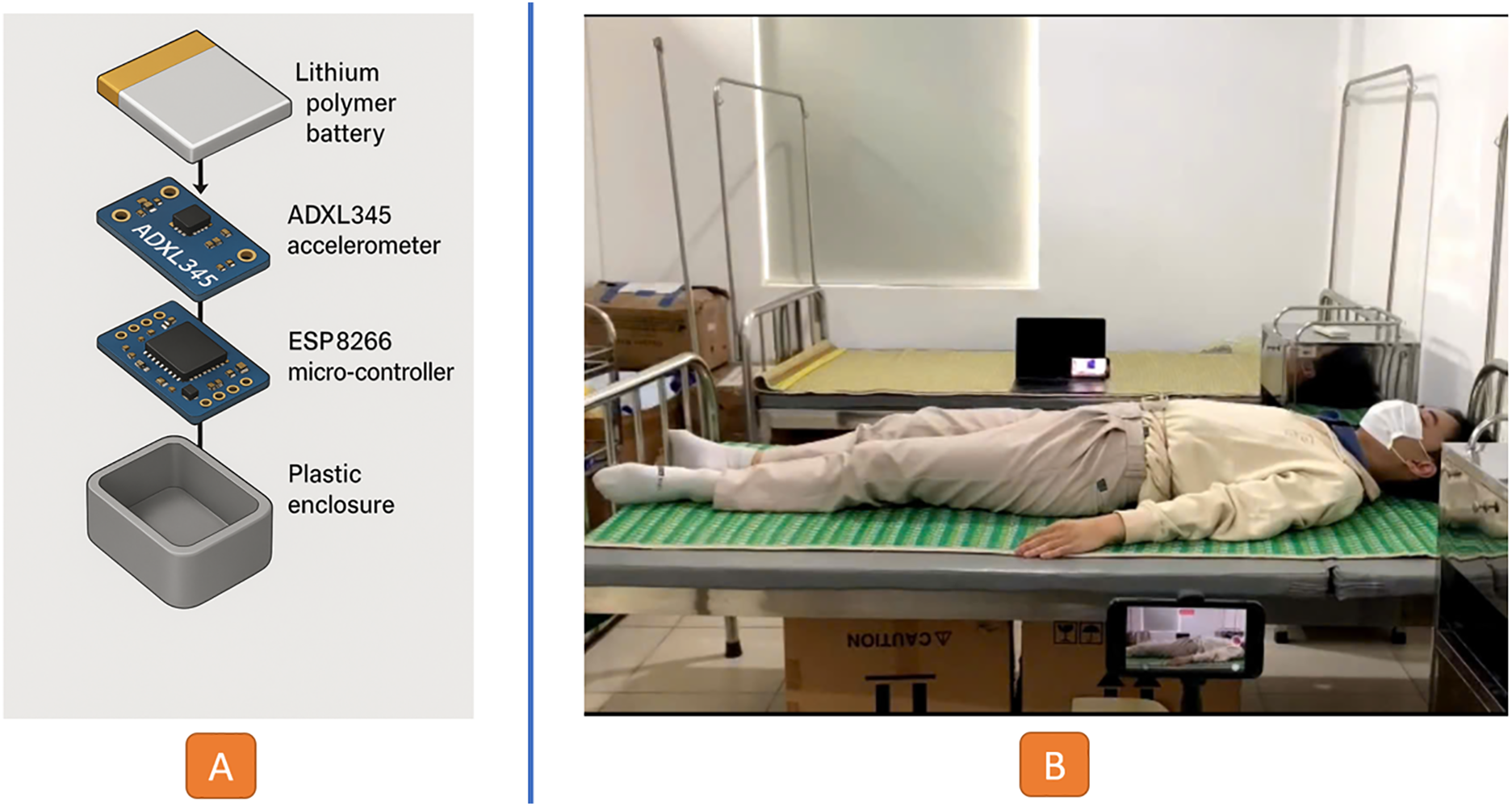

Our custom-built wearable device (Fig. 2A), designed to be worn on the abdomen, continuously captures tri-axial acceleration signals at a sampling rate of 50 Hz. The device operates using a rechargeable Li-ion power source and incorporates a motion-sensing unit based on a digital 3-axis accelerometer (ADXL345), interfaced with an ESP8266 microcontroller responsible for collecting sensor data and enabling wireless communication. To ensure uninterrupted recording, especially during network outages, a microSD card is included for local data buffering. The entire assembly is enclosed in a durable plastic casing to protect the internal components.

Figure 2: (A) Hardware components of the wearable sensing system used in the study; (B) experimental setup illustrating the data collection environment for sleep posture monitoring

The ESP8266 is a low-cost and efficient Wi-Fi chip packed with features, making it ideal for IoT applications. It supports Wi-Fi 802.11 b/g/n with data rates up to 460,800 bps, features a 32-bit Tensilica Xtensa LX106 processor, and offers 4.0 MB of flash memory and 80 KB of SRAM. With 17 GPIO pins, support for various peripheral interfaces, low power consumption, a compact size, and support for a variety of antennas, the ESP8266 is a versatile choice for this work.

The ADXL345: The ADXL345 is a high-performance 3-axis accelerometer that excels in low-power applications. Its ultra-low power consumption of 23

18 volunteers were recruited (age range: 19–24 years, mean: 20.56

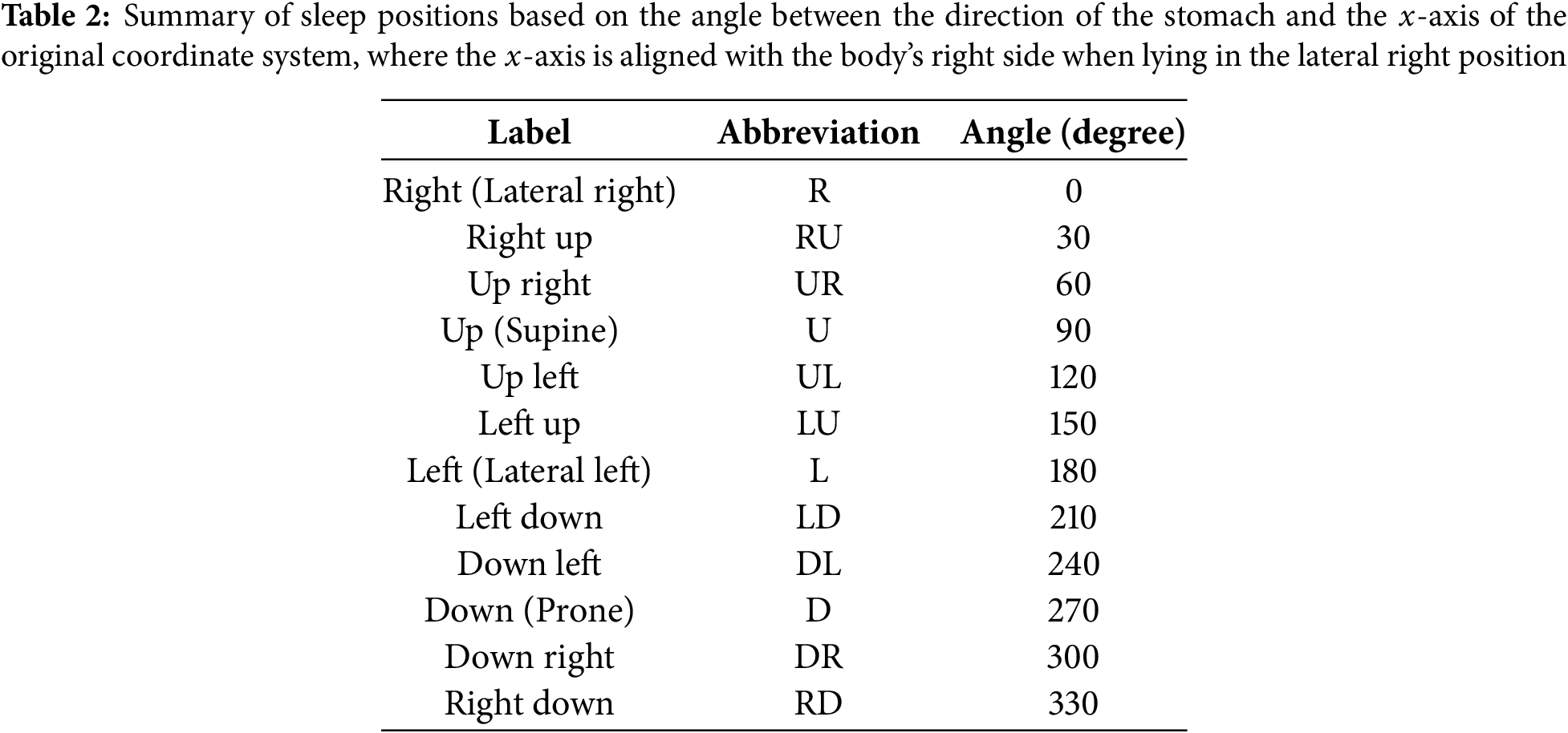

All participants were instructed on how to measure sleeping positions. There are a total of 12 sleep positions as in Table 2: that need to be measured. Each candidate lies on a bed and wears a device on their abdomen to measure pose data from positions as Fig. 2B. Each of these positions corresponds to specific angles: 0 degrees (Right), 90 degrees (Up), 180 degrees (Left), and 270 degrees (Down). Additionally, beyond these standard positions, we also measure with various other angles. Throughout these measurements, the coordinate origin and the initial x-axis remain fixed. These angles are defined by the original x-axis and a vector perpendicular to the body, extending from the back to the abdomen.

Data acquisition was conducted in a structured manner, with each sleeping posture recorded for a duration of one minute. Individual data files were systematically labeled using a consistent naming convention that included both the participant identifier and the corresponding sleep position. In total, 216 files were collected, with each file comprising 3000 samples, corresponding to the 50 Hz sampling rate over 60 s.

2.2 Accelerometer Signal Preprocessing and Deep Learning-Based Classification

The accelerometer signals (ax, ay, az) collected from participants undergo a structured preprocessing pipeline to enhance their suitability for classification tasks. Initially, the dataset is partitioned into training and testing subsets. A sliding window approach is then applied to segment the continuous signal into overlapping frames, facilitating temporal pattern recognition. To suppress high-frequency noise and motion-induced artifacts, a low-pass filter is employed, emphasizing the low-frequency components typically associated with static postures during sleep. This filtering strategy not only enhances signal quality but also retains the temporal continuity between successive segments.

The refined signals are subsequently fed into the proposed CGB-Net model, as depicted in Fig. 1. This architecture comprises three main stages: a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), a GRU, and a BiLSTM network. The CNN module is responsible for learning short-term temporal features that are indicative of distinct sleeping positions. To compensate for the CNN’s limited temporal range, the GRU layer is introduced to efficiently capture longer-term dependencies with lower computational overhead. The BiLSTM layer further enhances temporal modeling by analyzing the input sequences bidirectionally, thereby capturing contextual cues and subtle transitions between sleep postures. Batch Normalization (BN) layers are integrated after the CNN blocks to promote stable and faster convergence during training.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed CGB-Net, comparisons were made against several baseline models, including recent state-of-the-art methods and commonly used neural network architectures for time-series classification tasks. These baselines fall into two categories: (1) established models from the literature, and (2) canonical deep learning architectures adapted to the 12-class sleep posture classification task.

• Abdulsadig and Rodriguez-Villegas LSTM model [35]: Abdulsadig and Rodriguez-Villegas (2023) employed an LSTM network to classify sleep positions using time-series sensor data. This model serves as a representative example of pure recurrent architectures for temporal modeling in posture recognition.

• AnpoNet [26]: Proposed by Vu et al., AnpoNet integrates a 1D CNN with an LSTM layer, complemented by BN after the convolutional operation. The architecture is designed to capture both local temporal patterns and long-range dependencies in accelerometer signals.

3.1.2 Canonical Architectures and Implicit Ablation Variants of CGB-Net

Several models evaluated in this work can be understood as implicit ablation variants of CGB-Net. These architectures help assess the individual contributions of key components such as 1D CNN layer, recurrent layers (GRU and BiLSTM). All models share the same input-output structure and training procedure for consistency and fair comparison.

1D CNN: This model corresponds to the version of CGB-Net with both the GRU and BiLSTM layers removed. It consists of two 1D convolutional layers with 8 and 16 filters, each followed by Batch Normalization and Dropout (rate = 0.4). A dense layer with 16 units and a 12-class softmax output completes the model. This baseline captures only spatial features, without modeling temporal dependencies.

1D CNN + GRU: This variant reintroduces temporal modeling via a GRU layer but omits the BiLSTM block from CGB-Net. It starts with a 1D convolutional layer (8 filters), followed by Batch Normalization, MaxPooling, and Global Average Pooling (GAP). The temporal sequence is processed using a GRU, and classification is performed by a dense layer with 12 output units. This design helps isolate the impact of GRU-based unidirectional temporal modeling.

1D CNN + BiLSTM: This model includes both the 1D CNN and a BiLSTM layers but excludes the GRU layer. It begins with a 1D convolutional layer (8 filters), followed by two stacked BiLSTM layers to model bidirectional temporal dependencies. Batch Normalization, MaxPooling, and GAP are applied before the final dense classifier.

MLP: The MLP model serves as a minimalistic baseline that omits all convolutional and recurrent modules. It consists of two hidden layers (64 and 32 units), each followed by Batch Normalization and Dropout (rate = 0.4). The model directly maps flattened input windows to class probabilities via a softmax output layer.

Transformer: This model represents an alternative temporal modeling approach using self-attention. The encoder includes six Transformer layers with four multi-head attention heads each. Outputs are passed through a multilayer perceptron and a final dense layer for 12-class prediction.

In this study, two evaluation strategies were adopted to assess model performance. The first approach involved a cross-validation scheme, in which the dataset collected from 18 participants was partitioned into training, validation, and test subsets. For each split, data from 15 participants (approximately 83%) were allocated for training and validation, while the remaining 3 participants (around 17%) were reserved for testing. Within the training set, an internal split was performed in an 80:20 ratio to create the validation set.

The second strategy consisted of four independent experiments. In each experiment, three participants were randomly selected as the test set, while the remaining 15 participants were used for training and validation. Final performance was reported as the average result across the three test subjects in each experiment, providing a robust and representative evaluation of the model’s generalization capability.

To optimize the temporal parameters for windowing, a sliding window approach based on time durations rather than raw sample counts was applied. Given a sampling frequency of 50 Hz, window lengths ranging from 0.5 to 4.0 s—corresponding to 25, 50, 75,

In addition, the effect of varying overlap ratios between consecutive windows was examined, with values ranging from 0.2 to 0.8 in increments of 0.2 (i.e., 20%, 40%, 60%, and 80% overlap). Smaller window lengths combined with higher overlaps can enhance model responsiveness and temporal resolution, which is particularly beneficial for real-time applications requiring low latency and fine-grained detection.

To mitigate overfitting, CGB-Net incorporates several regularization strategies, including L1 and L2 penalties, as well as Dropout layers distributed throughout the architecture.

Optimizer. All deep learning models were trained using the Adam optimizer [37], initialized with a learning rate of 0.001. Training was conducted over 300 epochs with a batch size of 512.

Random Seed Selection. We conducted five independent runs using randomly selected seeds to account for performance variability. The reported results represent the mean and standard deviation across these five runs. No seed selection based on performance was applied.

Detail Architecture. The proposed CGB-Net consists of a 1D CNN layer with 8 filters and a kernel size of 3 (80 parameters), followed by Batch Normalization (32 parameters) to stabilize learning. A GRU layer with 16 units (2496 parameters) captures forward temporal dependencies in the sequence. This is followed by a Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) layer with 16 units per direction (6272 parameters), enabling the model to incorporate contextual information from both past and future time steps. Additional Batch Normalization and MaxPooling layers further refine the features. The network ends with global average pooling, a Dropout layer (rate = 0.4), and a Dense output layer for 12-class classification (396 parameters). The total number of trainable parameters is 9532.

The performance of the classification models is primarily evaluated using Accuracy and F1-score, as presented in Eqs. (1) and (4).

where TP represents True Positive, FP represents False Positive, and FN represents False Negative.

Model evaluation and comparison are conducted using both accuracy and F1-score, alongside the confusion matrix for a more detailed performance breakdown. To assess computational efficiency, key indicators such as processing time, inference latency, FLOPS, and memory footprint are considered. In addition, the stability and reliability of each model are analyzed by reporting statistical metrics—namely, the mean and variance—across multiple training iterations.

This section summarizes the key results obtained from the experiments, focusing on model accuracy, F1-score, and efficiency metrics.

4.1 Model Performance and Efficiency

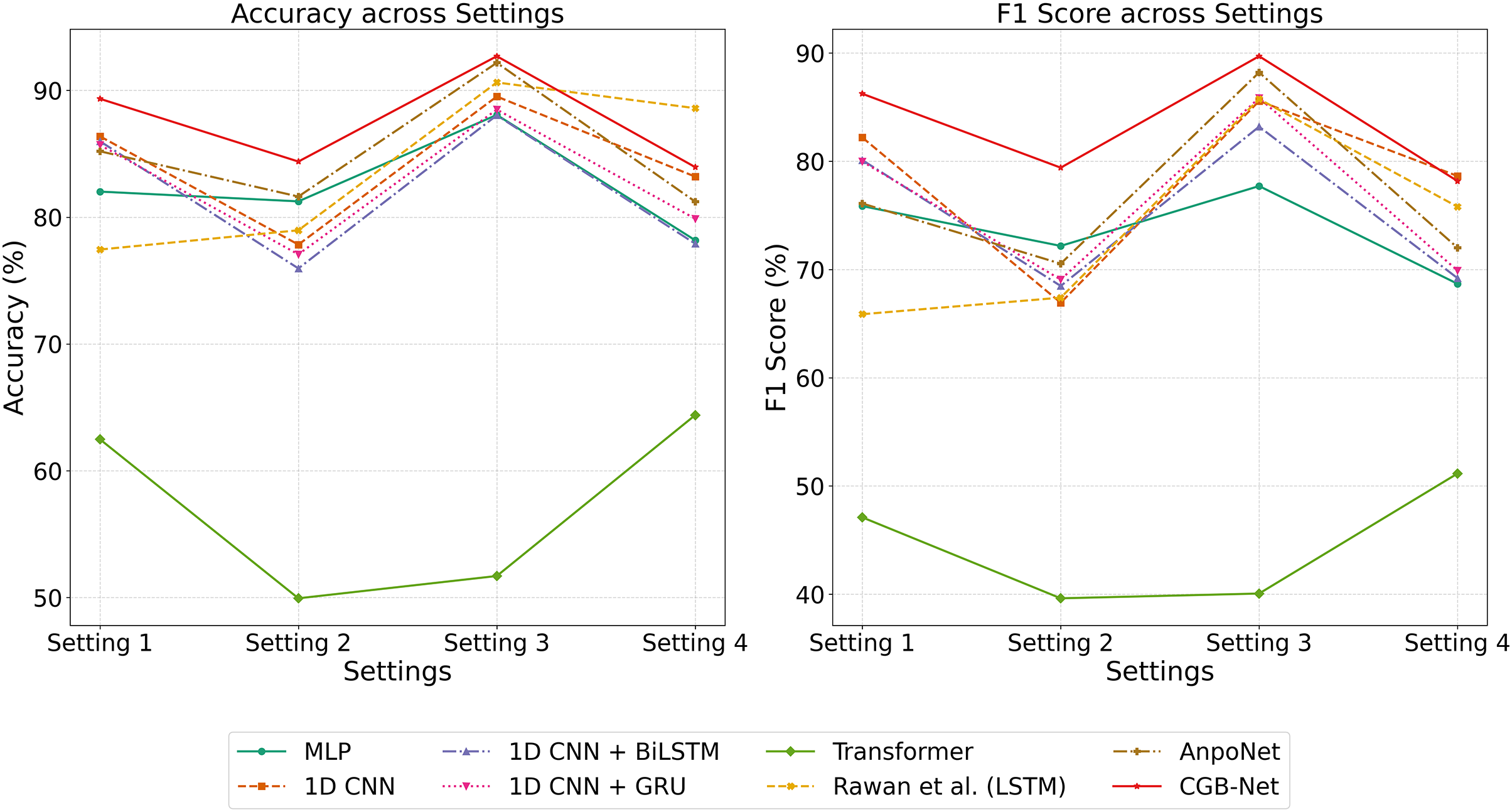

To evaluate the performance of various deep learning models across different experimental settings, we conducted a comparative analysis of eight architectures, including MLP, 1D CNN, 1D CNN + BiLSTM, 1D CNN + GRU, Transformer, the method by Rawan et al. (2023) (LSTM), AnpoNet, and our proposed model, CGB-Net. The results are summarized in terms of both Accuracy and F1 Score in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Accuracy and F1-score of all evaluated models under different experimental settings

Across all four settings, CGB-Net consistently outperformed all baseline models, achieving the highest Accuracy and F1 Score in each configuration. In particular, under Setting 3, CGB-Net reached peak performance with an Accuracy of approximately 92% and an F1 Score of around 90%, demonstrating its robustness and effectiveness.

Other models such as AnpoNet and Rawan et al. (2023) (LSTM) also showed relatively stable performance, especially in Setting 3, where they recorded high accuracy values (around 90%). However, their performance dropped more significantly in Settings 1, 2, and 4 compared to CGB-Net.

The Transformer-based model yielded the poorest results among all tested models, with Accuracy and F1 Score falling below 65% and 50% respectively across all settings, indicating its limited suitability for the given task.

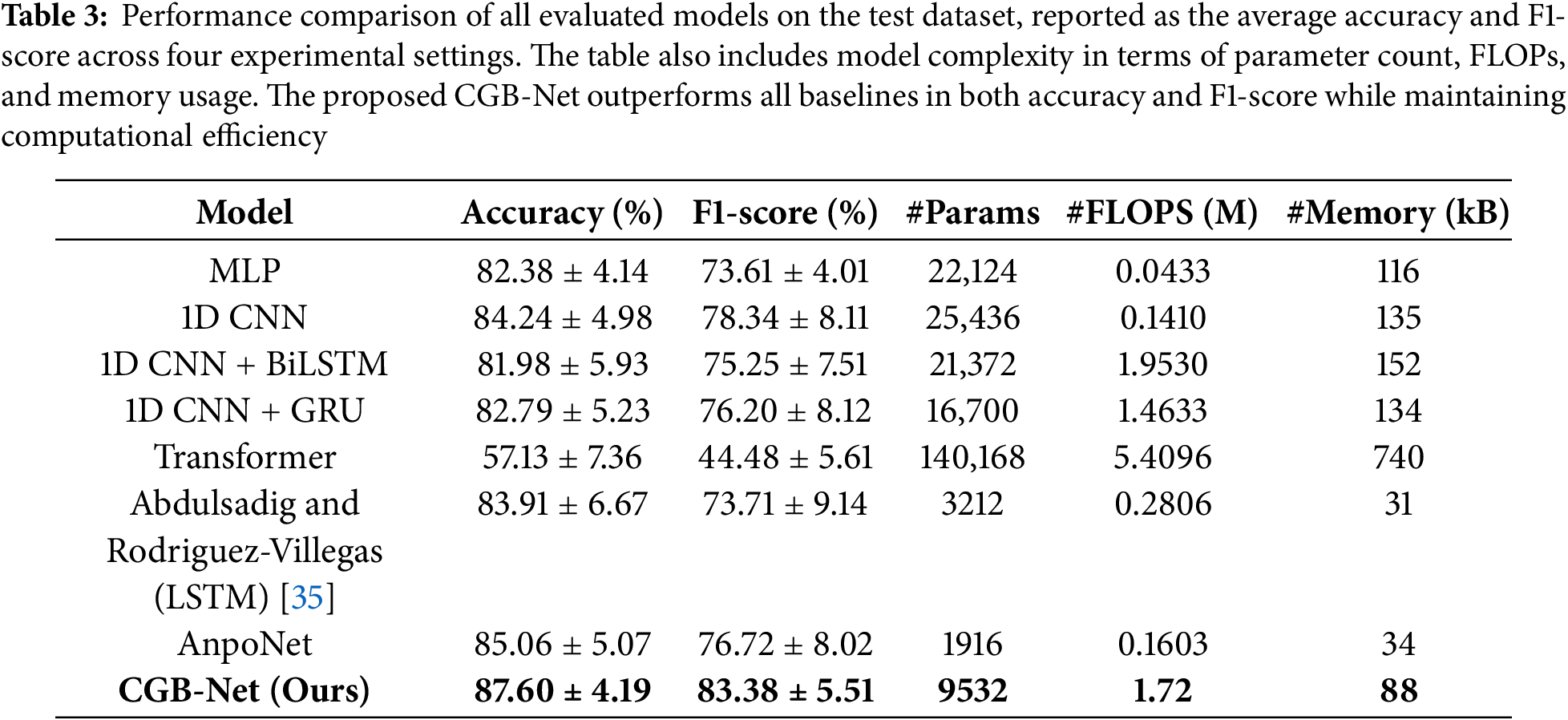

Table 3 presents a comprehensive comparison of different models evaluated on the test dataset using cross-validation, considering both performance metrics (Accuracy and F1-Score) and computational efficiency (number of parameters, FLOPs, and memory usage).

Our proposed model, CGB-Net, clearly outperforms all baseline methods, achieving the highest accuracy (87.60%

Among the baseline models, AnpoNet and Rawan et al. (2023) (LSTM) demonstrate strong trade-offs between performance and efficiency. AnpoNet achieves competitive performance (85.06% accuracy, 76.72% F1-score) with the smallest parameter count (1916) and low memory footprint (34 kB), while Rawan et al.’s (2023) model also performs well with minimal resource consumption. However, both fall short of CGB-Net in terms of prediction quality.

Traditional deep learning models like MLP, 1D CNN, and recurrent-enhanced CNNs (BiLSTM, GRU) yield moderate results, with accuracies ranging from approximately 82% to 84% and F1-scores in the low-to-mid 70% range. While their parameter sizes are manageable, they generally underperform compared to the top models.

In contrast, the Transformer model shows the weakest performance, with an accuracy of only 57.13% and F1-score of 44.48%, despite having the largest number of parameters (140,168) and highest computational cost (5.41 MFLOPs). This suggests that vanilla Transformer architectures may not be well-suited for the specific characteristics of this task without further adaptation or regularization.

Overall, CGB-Net offers the best balance between performance and computational efficiency, confirming its effectiveness and practicality for real-world applications involving limited hardware resources.

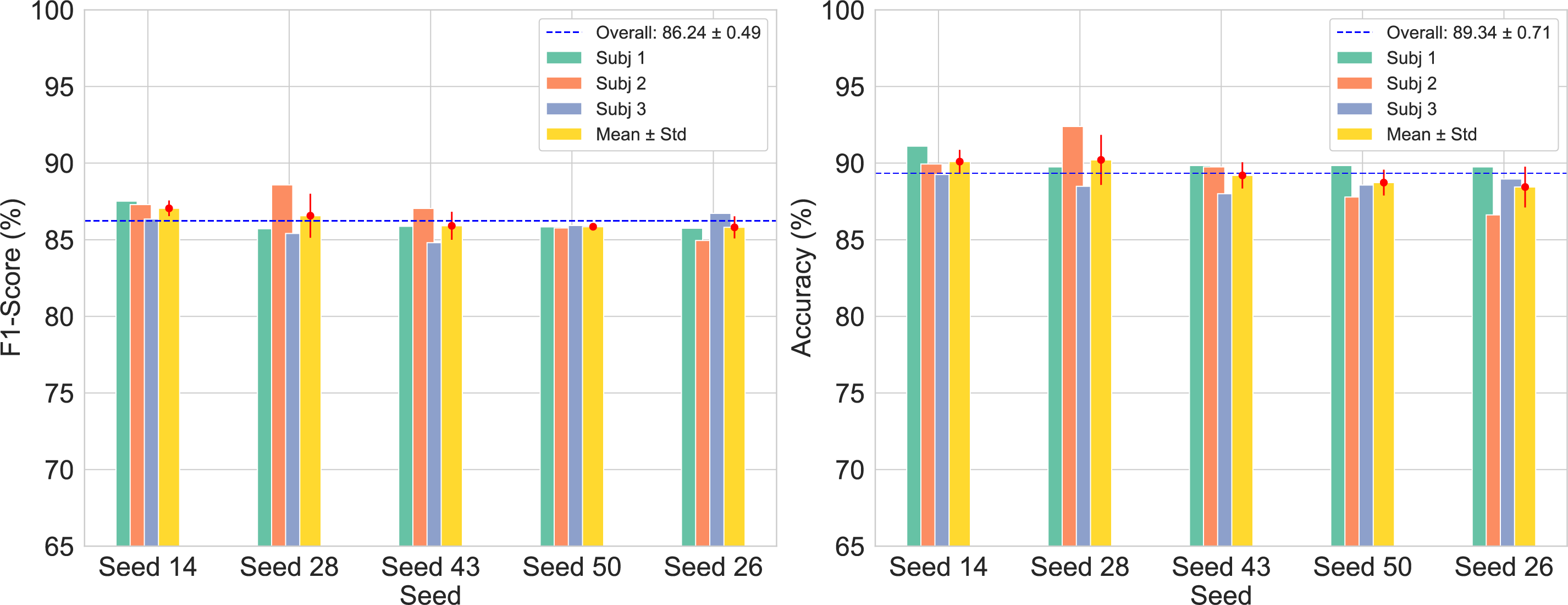

4.2 Evaluation under Random Subject Splits and Seed Variability (Setting 1)

To evaluate the generalization ability of the proposed model, we conducted experiments under Setting 1, where 3 subjects were randomly selected for testing while the remaining 15 were used for training and validation. This process was repeated across five different random seeds (14, 28, 43, 50, and 26), ensuring robust assessment across varying data splits.

The performance of CGB-Net in this setting is illustrated in Fig. 4. The left subplot reports the F1-Score, while the right shows the Accuracy for each test subject and seed. The yellow bars represent the mean

Figure 4: Evaluation of accuracy and F1-score for three test subjects across multiple random seed initializations

CGB-Net achieved a mean F1-Score of 86.24%

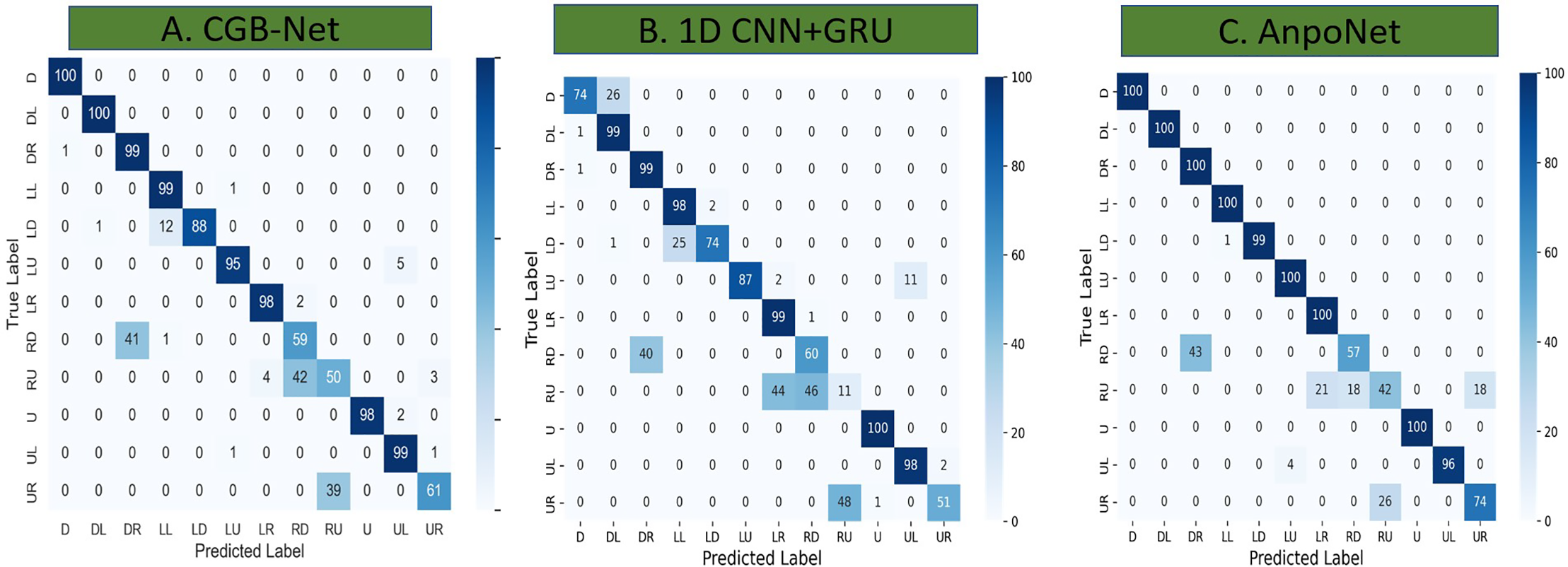

The confusion matrices for the three evaluated models (CGB-Net, 1D CNN+GRU, and AnpoNet) are illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Confusion matrices of CGB-Net, 1D CNN + GRU, and AnpoNet on the test dataset

CGB-Net demonstrates strong overall performance, with perfect accuracy in D and DL, and very high accuracy in DR (99%), LL (99%), UL (99%), U (98%), LR (98%), LU (95%), and LD (88%). However, performance drops in RD (59%), RU (50%), and UR (61%), primarily due to confusion between RU and RD caused by their opposing directions and similar sensor patterns as in Fig. 5A.

Despite these challenges, CGB-Net outperforms both 1D CNN+GRU and AnpoNet in these edge-case classes. For example, RU accuracy in 1D CNN+GRU is only 11%, with 46% misclassified as RD and 44% as LR; AnpoNet performs better at 42%, but still shows misclassification into LR (21%), RD (18%), and UR (18%) as in Fig. 5B,C.

For RD, CGB-Net achieves 59% with 41% misclassified as DR. In comparison, 1D CNN+GRU achieves 60% with 40% misclassified as DR, and AnpoNet reaches 57%, with 43% misclassified as DR. The similar confusion patterns across all three models are understandable, as DR (300°) and RD (330°) are neighboring postures with minimal angular separation.

Interestingly, RU consistently emerges as a difficult class across all models. CGB-Net classifies it correctly 50% of the time, with 42% misclassified as RD. In 1D CNN+GRU, RU is classified correctly only 11%, with 46% misclassified as RD. Similarly, AnpoNet achieves 42% accuracy on RU, with 18% misclassified as RD. These consistent misclassification rates between RU and RD highlight a shared confusion trend toward RD across architectures. Although RU and RD are separated by approximately 60 degrees, both are right-sided postures, which may contribute to their perceptual similarity from the perspective of a single accelerometer. These results highlight CGB-Net’s superior handling of fine-grained posture differentiation, even under challenging leave-one-subject-out conditions. This is particularly evident in the RU–RD scenario, where the confusion is substantial but still consistently lower than in the other models.

Most studies on sleep posture related to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) typically focus on four basic positions (D, U, L, R). This study expands that scope by proposing a more detailed 12-class classification, which can better support targeted therapeutic strategies. GERD patients, for instance, are often advised to sleep on their left side to reduce reflux. The ability to distinguish between specific left-side positions (e.g., LD, LU)—where our model performs very strongly—may help validate and refine such clinical recommendations.

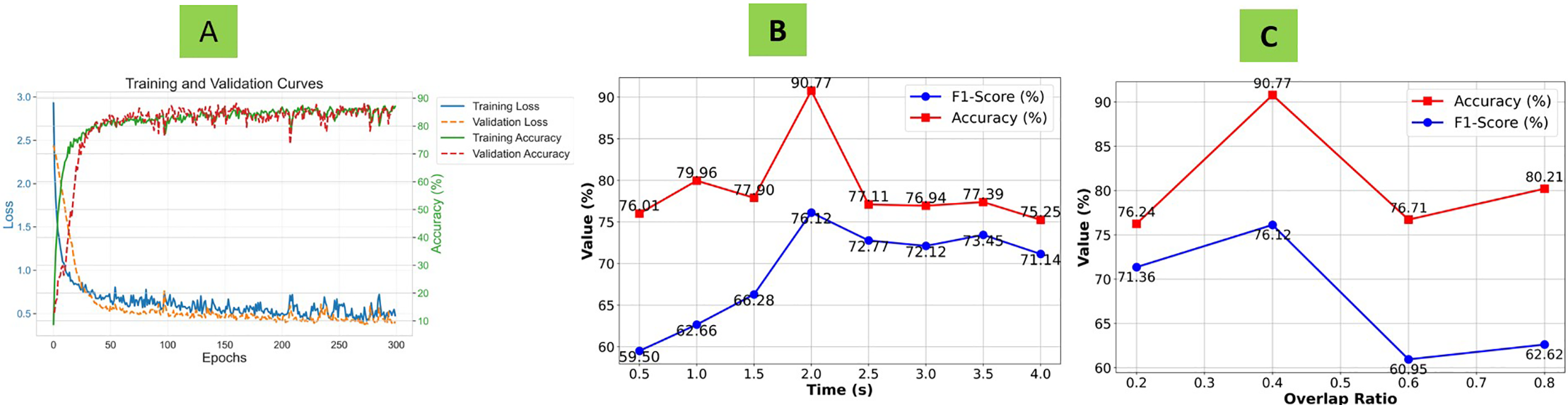

4.4 Training Processs, Effect of Sequence Length, Overlap Ratio

Fig. 6A illustrates the training and validation curves for both loss and accuracy over epochs. The training loss sharply decreases and stabilizes early, while the validation loss follows a similar trend with minimal fluctuation, indicating good convergence. Both training and validation accuracy steadily increase and plateau at high values (90%–95%), without signs of overfitting. This indicates that the model generalizes well to unseen data.

Figure 6: (A) Training and validation curves showing loss and accuracy during CGB-Net training; (B) Accuracy and F1-score of CGB-Net with varying window sizes; (C) Accuracy and F1-score of CGB-Net with different overlap ratios

Fig. 6B illustrates the impact of varying window durations from 0.5 to 4.0 s on model performance, evaluated using Accuracy (%) and F1-Score (%). The results presented here correspond to a single seed under one specific setting, and serve to provide a detailed case-level insight into the behavior of the model.

As the window duration increases, both metrics exhibit a general upward trend, reaching their peak at 2.0 s, where Accuracy reaches 90.77% and F1-Score peaks at 76.12%. This suggests that moderately long windows allow the model to capture sufficient temporal context, thereby enhancing its classification capability.

At shorter durations—specifically 0.5 and 1.0 s—the model only achieves 76.00% and 79.96% Accuracy, with corresponding F1-Scores of 59.50% and 62.66%, indicating underfitting due to limited temporal information. A slight improvement is seen at 1.5 s (Accuracy: 77.90%, F1: 66.28%), but the most significant performance boost occurs when increasing the window to 2.0 s.

Beyond this optimal point, performance begins to deteriorate. At 2.5 s, Accuracy drops to 77.11%, while F1-Score decreases to 72.77%. This trend continues across longer windows: Accuracy fluctuates around 76.94%, 77.39%, and 75.25% at 3.0, 3.5, and 4.0 s, respectively, while F1-Scores are 72.12%, 73.45%, and 71.14%. These results suggest that overly long windows may incorporate redundant or noisy information, which can blur relevant temporal patterns and lead to reduced performance, potentially due to overfitting.

In summary, the results from this individual case highlight 2.0 s as an optimal window duration—balancing temporal resolution and contextual richness—for this specific configuration. While broader generalization would require aggregation across multiple seeds and settings, this instance underscores the model’s sensitivity to window length and the importance of selecting an appropriate temporal resolution.

Fig. 6C presents the performance of the model under varying overlap ratios of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8. The highest accuracy is achieved at an overlap ratio of 0.4, indicating that a moderate level of overlap offers the best trade-off between temporal continuity and data redundancy.

The F1-Score also varies with the overlap ratio, showing a sharp decrease at an overlap of 0.6, which may be attributed to over-redundancy in the data. At lower overlaps (e.g., 0.2), temporal discontinuities could hinder the model’s ability to recognize transitions or patterns effectively. These results emphasize the importance of selecting an appropriate overlap ratio to ensure robust performance without sacrificing data efficiency or introducing excessive correlation between samples.

CGB-Net, in conjunction with the 12-SPCS system, presents a powerful tool for enhancing the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) through intelligent sleep posture monitoring. Rather than diagnosing GERD directly, the system focuses on minimizing positional triggers that exacerbate symptoms during sleep. Leveraging high-precision classification of 12 sleeping positions, CGB-Net enables real-time detection of risk-inducing postures commonly associated with reflux events. This capability allows for timely feedback and posture correction, significantly reducing the likelihood of nocturnal acid reflux. Such a system is particularly advantageous in outpatient care settings, where non-invasive, continuous monitoring can empower patients to manage their condition proactively, reducing dependence on pharmacological treatments and improving long-term outcomes.

5.2 Limitations and Future Work

Although CGB-Net demonstrates promising performance under controlled experimental conditions, several limitations should be acknowledged to better contextualize its potential for real-world and clinical deployment.

First, the evaluation was conducted exclusively on healthy participants within a laboratory setting. While this setup ensures safety and consistency—particularly important during early-stage research where the device is used during unconscious sleep—it does not capture the full range of variability present in actual sleeping environments. External factors such as different bed types, bedding configurations, room conditions, and motion disturbances (e.g., bed-sharing or nearby activity) were not explored. Furthermore, the recordings were limited to relatively short sessions and did not include overnight or multi-night monitoring, which limits the assessment of long-term reproducibility.

To improve ecological validity, future experiments should consider incorporating more realistic conditions, such as prolonged nighttime recordings, varied environmental setups, and diverse participant groups including those with sleep disorders or clinical needs like GERD. These directions will be important for better understanding the generalizability and robustness of the model, although practical and ethical considerations may constrain their immediate implementation.

Second, the current system functions in an offline mode and lacks real-time inference capabilities, which may limit its responsiveness in dynamic scenarios. In addition, long-term usability aspects, such as user comfort over extended periods, have not been formally evaluated and will require ergonomic considerations in future system designs.

Third, the current approach relies solely on accelerometer data. While this single-sensor setup simplifies deployment and enhances user comfort, it also imposes inherent limitations in distinguishing between anatomically similar postures. This is particularly evident in classes such as RD and RU, where significant misclassification persists across all evaluated models. To address this, future versions of the system may consider incorporating gyroscopic data. Gyroscopes provide rotational velocity measurements that can complement linear acceleration data, offering a more complete representation of body orientation. Prior research in wearable sensing has shown that combining accelerometer and gyroscope signals can significantly improve classification accuracy, particularly for angular discrimination tasks. Thus, integrating a low-power gyroscope could be a valuable enhancement with minimal impact on user comfort.

Additionally, incorporating complementary data sources, such as respiratory or cardiac signals, could also be considered to further improve classification performance and enable broader diagnostic applications.

In summary, although CGB-Net serves as a foundational step in sleep posture classification using a single abdominal accelerometer, further work is required to examine its robustness, real-world applicability, and clinical relevance across a wider range of conditions. Enhancements such as gyroscope integration and real-world deployment testing will be crucial steps toward a deployable and clinically reliable system.

In this study, we proposed CGB-Net, a novel deep learning architecture tailored for the fine-grained classification of twelve sleep positions using data from a single abdominal accelerometer. Unlike conventional approaches that typically focused on coarse four-class posture detection, our model enabled the classification of twelve clinically meaningful sleep positions, offering enhanced utility for applications such as GERD monitoring.

CGB-Net combined three complementary deep learning modules: an 1D-CNN layer for local feature extraction, a GRU layer for modeling short-term temporal dependencies, and a BiLSTM network for capturing contextual information in both temporal directions. This hybrid design effectively learned both short- and long-term patterns from raw sensor data.

We evaluated the model using a subject-independent protocol, where data from randomly selected participants were held out entirely for testing in each of four experimental runs. The results showed that CGB-Net achieved a mean classification accuracy of 87.60% and an average F1-score of 83.38%, consistently outperforming several strong baseline models. To support reproducibility and future research, we also released a benchmark dataset for 12-class sleep position classification.

Overall, this work demonstrated the effectiveness of CGB-Net in enabling robust, fine-grained posture classification, and laid a strong foundation for future developments in real-time and clinically oriented sleep monitoring systems.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to the Institute of Information Technology (IoIT-VAST) for allowing us to use the “IoT and Robot Intensive Laboratory” equipment. Thanks to SSA-Lab (Phenikaa University) for supporting us in data collection and hardware development.

Funding Statement: This research is funded by Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) under grant number: NCUD.02-2024.11.

Author Contributions: Hoang-Dieu Vu and Duc-Nghia Tran were responsible for data analysis, machine learning implementation, and manuscript writing. Quang-Tu Pham contributed to data collection, preprocessing, and model development. Hoang-Dieu Vu performed model experimentation and scenario-based evaluations. Duc-Tan Tran and Ngoc-Linh Nguyen, the corresponding authors, conceived and coordinated the study, and provided supervision throughout the research. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the results of this research are accessible by contacting the corresponding author, Duc-Tan Tran.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Local Research Ethics Committee of Phenikaa University (LREC reference number: 024-03.08/DHP-HDDD).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1

References

1. Dave P. Factors contributing to sleep disorders among young adults. Asian J Dent Health Sci. 2024 Jun;4(2):26–31. doi:10.22270/ajdhs.v4i2.76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Srijithesh PR, Aghoram R, Goel A, Dhanya J. Positional therapy for obstructive sleep apnoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;5(5):CD010990. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010990.pub2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Li Z, Zhou Y, Zhou G. A dual fusion recognition model for sleep posture based on air mattress pressure detection. Sci Rep. 2024 May;14(1):11084. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-61267-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Schätz M, Procházka A, Kuchyňka J, Vyšata O. Sleep apnea detection with polysomnography and depth sensors. Sensors. 2020 Mar;20(5):1360. doi:10.3390/s20051360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Li YY, Wang SJ, Hung YP. A vision-based system for in-sleep upper-body and head pose classification. Sensors. 2022 Mar;22(5):2014. doi:10.3390/s22052014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Tam AYC, So BPH, Chan TTC, Cheung AKY, Wong DWC, Cheung JCW. A blanket accommodative sleep posture classification system using an infrared depth camera: a deep learning approach with synthetic augmentation of blanket conditions. Sensors. 2021 Aug;21(16):5553. doi:10.3390/s21165553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Alinia P, Samadani A, Milosevic M, Ghasemzadeh H, Parvaneh S. Pervasive lying posture tracking. Sensors. 2020 Oct;20(20):5953. doi:10.3390/s20205953. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Piriyajitakonkij M, Warin P, Lakhan P, Leelaarporn P, Kumchaiseemak N, Suwajanakorn S, et al. Sleepposenet: multi-view learning for sleep postural transition recognition using UWB. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2021 Apr;25(4):1305–14. doi:10.1109/jbhi.2020.3025900. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Lai DKH, Zha LW, Leung TYN, Tam AYC, So BPH, Lim HJ, et al. Dual ultra-wideband (UWB) radar-based sleep posture recognition system: towards ubiquitous sleep monitoring. Eng Regen. 2023 Mar;4(1):36–43. doi:10.1016/j.engreg.2022.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu X, Jiang W, Chen S, Xie X, Liu H, Cai Q, et al. Posmonitor: fine-grained sleep posture recognition with Mmwave radar. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024 Apr;11(7):11175–89. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3328866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Roshini A, Kiran KVD. An enhanced posture prediction-bayesian network algorithm for sleep posture recognition in wireless body area networks. Int J Telemed Appl. 2022 May;2022(7):1–11. doi:10.1155/2022/3102545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Yue S, Yang Y, Wang H, Rahul H, Katabi D. Bodycompass: monitoring sleep posture with wireless signals. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2020 Jun;4(2):1–25. doi:10.1145/3397311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chaaraoui A, Padilla-López J, Ferrández-Pastor F, Nieto-Hidalgo M, Flórez-Revuelta F. A vision-based system for intelligent monitoring: human behaviour analysis and privacy by context. Sensors. 2014 May;14(5):8895. doi:10.3390/s140508895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Haider A, Hel-Or H. What can we learn from depth camera sensor noise? Sensors. 2022 Jul;22(14):5448. doi:10.3390/s22145448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Plangger J, Govindasamy Ravichandran H, Rodin SC, Atia M. System design and performance analysis of indoor real-time localization using UWB infrastructure. In: 2023 IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon). Vancouver, BC, Canada; 2023 Apr. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/syscon53073.2023.10131059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Liu S, Huang X, Fu N, Li C, Su Z, Ostadabbas S. Simultaneously-collected multimodal lying pose dataset: enabling in-bed human pose monitoring. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023 Jan;45(1):1106–18. doi:10.1109/tpami.2022.3155712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Kau LJ, Wang MY, Zhou H. Pressure-sensor-based sleep status and quality evaluation system. IEEE Sens J. 2023 May;23(9):9739–54. doi:10.1109/jsen.2023.3262747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wan Q, Zhao H, Li J, Xu P. Human sleeping posture recognition based on sleeping pressure image. IEEE Sens J. 2023 Feb;23(4):4069–77. doi:10.1109/jsen.2022.3225290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang Z, Sui Z, Wang R, Zhang A, Zhang Z, Lin F, et al. A piezoresistive array-based force sensing technique for sleeping posture and respiratory rate detection for sas patients. IEEE Sens J. 2023 Oct;23(20):24060–9. doi:10.1109/jsen.2021.3134823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hu Q, Tang X, Tang W. A real-time patient-specific sleeping posture recognition system using pressure sensitive conductive sheet and transfer learning. IEEE Sens J. 2021 Mar;21(5):6869–79. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2020.3043416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Vi MT, Tran DN, Thuong VT, Linh NN, Tran DT. Efficient real-time devices based on accelerometer using machine learning for HAR on low-performance microcontrollers. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;81(1):1729–56. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.055511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhao Y, Wang X, Luo Y, Aslam MS. Research on human activity recognition algorithm based on LSTM-1DCNN. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;77(3):3325–47. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.040528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jiang P, Zhu R. Dual tri-axis accelerometers for monitoring physiological parameters of human body in sleep. In: 2016 IEEE Sensors. Orlando, FL, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 1–3. doi:10.1109/icsens.2016.7808735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Jeng P, Wang LC. An accurate, low-cost, easy-to-use sleep posture monitoring system. In: 2017 International Conference on Applied System Innovation (ICASI). Sapporo, Japan; 2017 May. p. 903–5. doi:10.1109/icasi.2017.7988585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Doheny EP, Lowery MM, Russell A, Ryan S. Estimation of respiration rate and sleeping position using a wearable accelerometer. In: 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society EMBC. Montreal, QC, Canada; 2020 Jul. p. 4668–71. doi:10.1109/embc44109.2020.9176573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Vu HD, Tran DN, Pham HH, Pham DD, Can KL, Dao TH, et al. Human sleep position classification using a lightweight model and acceleration data. Sleep Breathing. 2025 Feb;29(1):258. doi:10.1007/s11325-025-03247-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Schuitenmaker JM, Kuipers T, Smout AJPM, Fockens P, Bredenoord AJ. Systematic review: clinical effectiveness of interventions for the treatment of nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;34(12):e14385. doi:10.1111/nmo.14385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Wei X, Wang Z. TCN-attention-HAR: human activity recognition based on attention mechanism time convolutional network. Sci Rep. 2024 Mar;14(1):7414. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-57912-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Zhou H, Zhang S, Peng J, Zhang S, Li J, Xiong H, et al. Informer: beyond efficient transformer for long sequence time-series forecasting. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021 May;35(12):11106–15. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i12.17325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang S, Li BZ, Khabsa M, Fang H, Linformer Ma H. Linformer: self-attention with linear complexity. arXiv:2006.04768. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2006.04768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Eldele E, Ragab M, Chen Z, Wu M, Kwoh CK, Li X, et al. Time-series representation learning via temporal and contextual contrasting. In: Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-21. Montreal, QC, Canada: International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization; 2021. p. 2352–9. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2021/324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Jeon S, Paul A, Lee H, Bun Y, Son SH. Sleeps: sleep position tracking system for screening sleep quality by wristbands. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC). Banff, AB, Canada; 2017. p. 3141–6. doi:10.1109/smc.2017.8123110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Abdulsadig RS, Singh S, Patel Z, Rodriguez-Villegas E. Sleep posture detection using an accelerometer placed on the neck. In: 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). Glasgow, Scotland, UK; 2022 Jul. p. 2430–3. doi:10.1109/embc48229.2022.9871300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Vu HD, Tran DN, Can KL, Dao TH, Pham DD, Tran DT. Enhancing sleep postures classification by incorporating acceleration sensor and Lstm model. In: 2023 IEEE Statistical Signal Processing Workshop (SSP). Hanoi, Vietnam; 2023 Jul. p. 661–5. doi:10.1109/ssp53291.2023.10208083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Abdulsadig RS, Rodriguez-Villegas E. Sleep posture monitoring using a single neck-situated accelerometer: a proof-of-concept. IEEE Access. 2023 Jan;11:17693–706. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3246266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Fallmann S, van Veen R, Chen L, Walker D, Chen F, Pan C. Wearable accelerometer based extended sleep position recognition. In: 2017 IEEE 19th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom). Dalian, China; 2017 Oct. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/healthcom.2017.8210806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. arXiv:1412.6980. 2014. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools