Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Dung Beetle Optimization Algorithm Based on Bounded Reflection Optimization and Multi-Strategy Fusion for Multi-UAV Trajectory Planning

1 School of Information Engineering, Engineering University of PAP, Xi’an, 710086, China

2 School of Equipment Management and Support, Engineering University of PAP, Xi’an, 710086, China

3 Key laboratory of CTC&IE (Engineering University of PAP), Ministry of Education, Xi’an, 710086, China

* Corresponding Author: Qiwu Wu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Nature-Inspired and Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithms: Theory, Applications, and Emerging Trends)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3621-3652. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068781

Received 06 June 2025; Accepted 28 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

This study introduces a novel algorithm known as the dung beetle optimization algorithm based on bounded reflection optimization and multi-strategy fusion (BFDBO), which is designed to tackle the complexities associated with multi-UAV collaborative trajectory planning in intricate battlefield environments. Initially, a collaborative planning cost function for the multi-UAV system is formulated, thereby converting the trajectory planning challenge into an optimization problem. Building on the foundational dung beetle optimization (DBO) algorithm, BFDBO incorporates three significant innovations: a boundary reflection mechanism, an adaptive mixed exploration strategy, and a dynamic multi-scale mutation strategy. These enhancements are intended to optimize the equilibrium between local exploration and global exploitation, facilitating the discovery of globally optimal trajectories that minimize the cost function. Numerical simulations utilizing the CEC2022 benchmark function indicate that all three enhancements of BFDBO positively influence its performance, resulting in accelerated convergence and improved optimization accuracy relative to leading optimization algorithms. In two battlefield scenarios of varying complexities, BFDBO achieved a minimum of a 39% reduction in total trajectory planning costs when compared to DBO and three other high-performance variants, while also demonstrating superior average runtime. This evidence underscores the effectiveness and applicability of BFDBO in practical, real-world contexts.Keywords

Technological progress in unmanned systems [1] has transformed unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) applications in modern military contexts. By minimizing casualties and optimizing resource allocation—especially in complex battlefields—these platforms execute critical tasks such as reconnaissance, strikes, and electronic jamming [2]. Nonetheless, with the increasing complexity of operational requirements, the limitations of individual UAVs more prominently restrict their effectiveness across diverse scenarios, thereby decreasing task efficiency. In response to these challenges, the research community has increasingly focused on multi-UAV collaborative frameworks [3,4]. Such strategies build on the strengths of individual platforms, enabling the systematic distribution of tasks across fleets to overcome single-vehicle constraints. A central challenge in this domain is cooperative path planning for heterogeneous UAV fleets, which involves designing safe and viable trajectories from specified origins to target destinations. This process requires consideration of both individual UAV limitations and the interdependent dynamics within the fleet. The core difficulty lies in balancing global optimization needs with the demand for timely, high-precision solutions under high-dimensional spatio-temporal constraints. This complexity stems from the interaction between intrinsic operational capabilities, the coupled restrictions of three-dimensional unstructured environments, and multi-objective synergy goals, including collision avoidance and mission scheduling.

To address the multi-UAV trajectory planning challenge, the research community has developed numerous classical approaches, including mathematical planning methods [5,6], graph search algorithms [7,8], spatial sampling techniques [9,10], and potential field methods [11,12]. Mathematical planning methods—such as nonlinear programming and mixed integer linear programming—exhibit theoretical maturity and high accuracy in simple scenarios, though their computational complexity grows exponentially with problem size. The A*, a prevalent graph search algorithm, offers a straightforward implementation; however, in high-dimensional spatial domains, it struggles with inefficiency and multi-constraint trajectory planning. As a representative spatial sampling technique, a rapid-exploring random tree (RRT) eliminates the need for environment discretization and achieves rapid search speeds but lacks optimality in route-finding. The artificial potential field approach provides planning-speed advantages but suffers from local oscillations and minima in high-dimensional spaces, potentially rendering trajectories infeasible. Consequently, traditional algorithms deliver superior results in simple environments but struggle to address autonomous multi-UAV planning in complex, uncertain battlefields.

In recent decades, intelligent optimization algorithms [13–15]—including the genetic algorithm (GA) [16] and particle swarm optimization (PSO) [17]—have emerged as viable solutions. Rooted in evolutionary biology, the GA encodes initial trajectories, formulates fitness functions based on constraints, and evolves optimal solutions through selection, crossover, and mutation. However, GAs exhibit weak late-stage local-search capabilities and premature convergence [18], leading to prolonged planning times and suboptimal routes. Inspired by avian foraging, PSO models particles as potential trajectories, evaluates route quality via fitness functions, and uses inter-particle information sharing to guide convergence. Yet it remains highly susceptible to local optima and demonstrates reduced efficiency in complex environments [19].

Xue and Shen [20] introduced the dung beetle optimizer algorithm in 2023, which offers distinct advantages in complex optimization tasks like trajectory planning, owing to its intra-group differentiation—a feature absent in other swarm intelligence frameworks. The algorithm is divided into four functional subgroups: rolling, foraging, stealing, and breeding, which collectively enhance global search capabilities by enabling rapid convergence to optimal solutions, outperforming single-group approaches. Literature [21] demonstrates the efficacy of the traditional DBO algorithm in trajectory planning for complex mountainous environments, highlighting its generation of higher-quality routes compared to classical PSO and SSA algorithms. Additionally, the improved DBO is developed through the integration of chaotic strategies, exponentially decreasing inertia weights, and adaptive Cauchy mutation, thereby enhancing its trajectory-planning performance.

While the traditional DBO algorithm exhibits robust global exploration capabilities, its position-update mechanisms for rolling and breeding subgroups rely on local optimal positions, leading to overly centralized search directions and limited solution-space exploration. Additionally, its simplistic parameter-tuning strategy fails to dynamically balance global exploration and local exploitation across iteration stages, resulting in suboptimal convergence accuracy, inadequate population synergy, and reduced cooperative efficiency. In the late iterations of the algorithm, population diversity declines rapidly, making the algorithm highly prone to becoming trapped in local optima. Building on these observations, the research community has proposed numerous modifications to the classical DBO framework. Ye et al. [22] introduced the multi-strategy improved dung beetle optimization algorithm (MDBO), which employs Latin hypercube sampling for enhanced population initialization, introduces a novel differential variation strategy to improve local-optimum avoidance, and integrates lens imaging inverse learning with di-mention-wise optimization. This variant demonstrates excellent performance across standard benchmark function test sets and engineering application scenarios. Zhu et al. [23] developed a quantum computing–based multi-strategy hybrid dung beetle search algorithm, incorporating a convergence factor and dynamically balancing the population ratio between egg-laying and foraging subgroups to prioritize global exploration in early iterations and local exploitation in later stages. Experimental results show significant improvements in convergence speed, optimization accuracy, and robustness. Qiao et al. [24] integrated Lévy flight and variable spiral strategies into DBO, enhancing its optimization performance and demonstrating superiority over state-of-the-art metaheuristic algorithms via simulation. Hu et al. [25] proposed a hybrid multi-strategy DBO variant, employing cubic chaos mapping for population initialization, expanding solution-space exploration via a cooperative search framework, incorporating t-distributed mutation and differential evolution strategies, and applying perturbations to maintain diversity. Validation against classical optimization algorithms and their advanced variants on the CEC2017 benchmark suite highlights the algorithm’s robust optimization capabilities. Although these advancements enhance the algorithm’s global exploration to some extent, challenges remain: low computational efficiency, poor performance in high-dimensional problems, insufficient environmental adaptability, and persistent vulnerability to local optima. These limitations hinder the identification of suitable waypoints for planning high-quality routes in complex terrains.

In response to the limitations of existing methodologies, we present a multi-UAV trajectory planning approach that employs the dung beetle optimization algorithm based on bounded reflection optimization and multi-strategy fusion (BFDBO). The key contributions of this study are outlined as follows:

(i) A novel objective function has been formulated that incorporates both the performance constraints of individual UAVs and the coordination dynamics among multiple UAVs, thereby facilitating efficient and safe flight operations. (ii) A new DBO algorithm, referred to as BFDBO, has been introduced, demonstrating the capability to identify optimal solutions across various optimization contexts. (iii) The performance of BFDBO has been benchmarked and compared against other high-performance algorithms. (iv) The BFDBO algorithm has been applied to the trajectory planning of multiple UAVs within complex battlefield scenarios.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the constraints associated with the trajectory planning problem. Section 3 introduces the classic DBO algorithm and proposes the BFDBO algorithm. Section 4 verifies, discusses, and analyzes the performance of the BFDBO algorithm using the CEC2022 test set. Section 5 applies the BFDBO algorithm to solve the multi-UAV cooperative trajectory planning problem in complex battlefield environments. Finally, Section 6 provides a comprehensive summary of the entire study.

Specific trajectory evaluation criteria and quantitative assessment enable rapid identification of optimal/sub-optimal paths, reducing computational waste and enhancing planning efficiency. This study addresses multi-constraint trajectory planning in complex battlefields by formulating it as a multi-objective optimization problem. We define evaluation criteria and construct a comprehensive cost function, where the minimum-cost trajectory is deemed optimal [26].

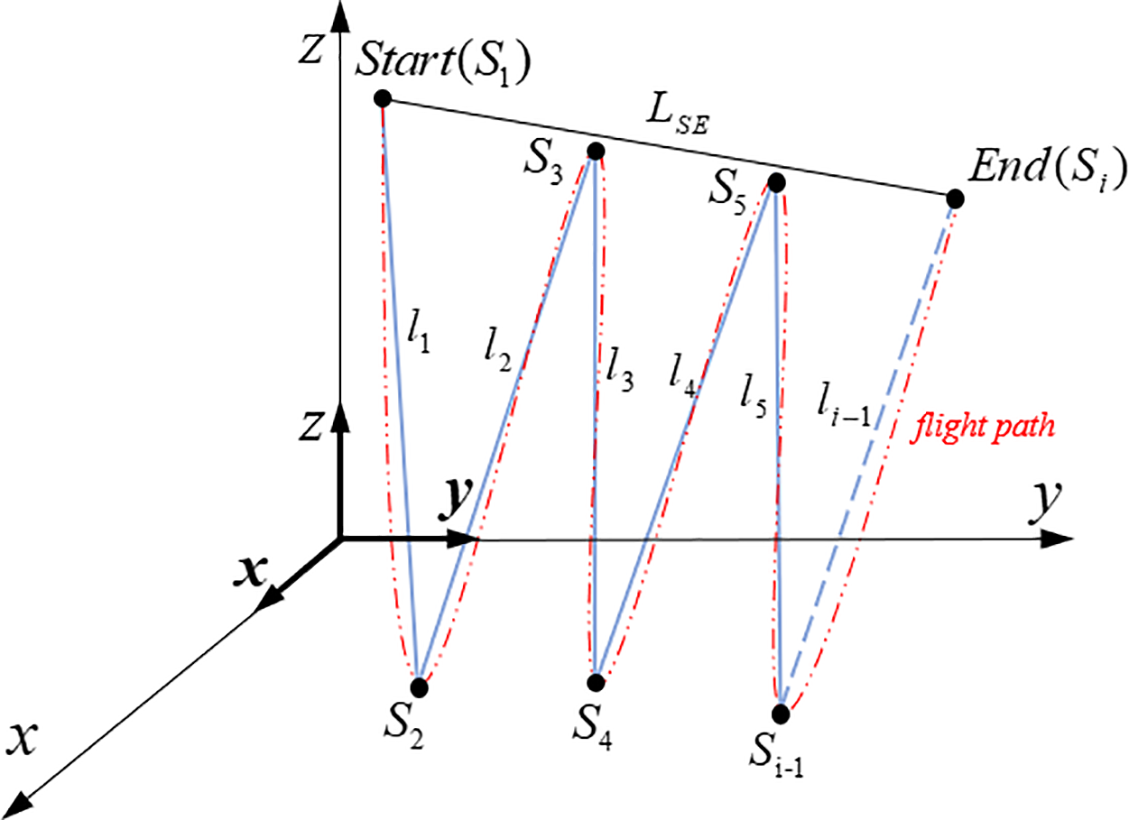

2.1.1 Trajectory Length Constraint

The operational range of UAVs has consistently been a critical factor in their capacity to maintain high-intensity operations. Moreover, a reduction in range can lead to a notable decrease in fuel consumption [27], which in turn contributes to cost savings. As shown in Fig. 1, the voyage length cost

where

Figure 1: Trajectory length cost

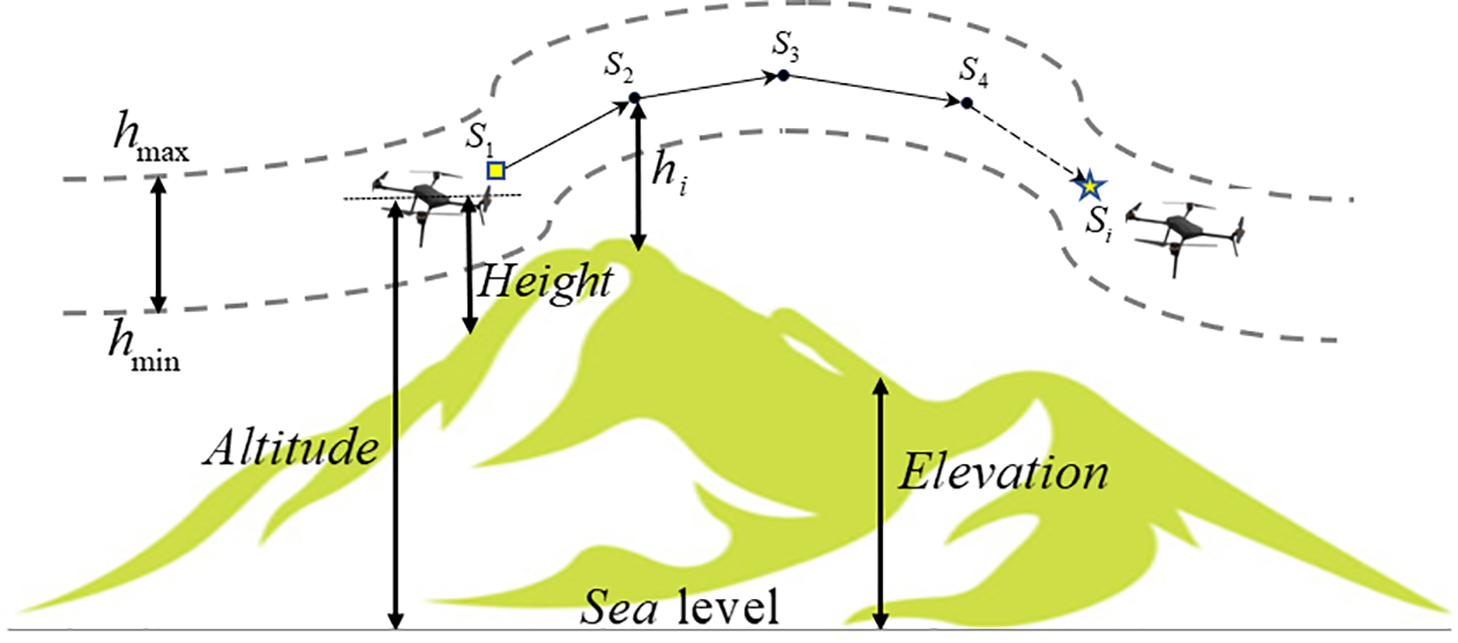

To maintain the safety and stability of UAV operations, it is imperative to regulate the flight altitude within a designated range, as illustrated in Fig. 2. A more stable altitude fluctuation curve correlates with reduced operational stress on the UAV’s flight control system, consequently leading to a significant decrease in fuel consumption during stable flight conditions. Furthermore, when executing combat missions, such as high-altitude reconnaissance and terrain mapping, it is essential to achieve specific resolution and field-of-view parameters, which impose additional constraints on the required flight altitude. The expression for the highly expensive

Figure 2: High cost

where

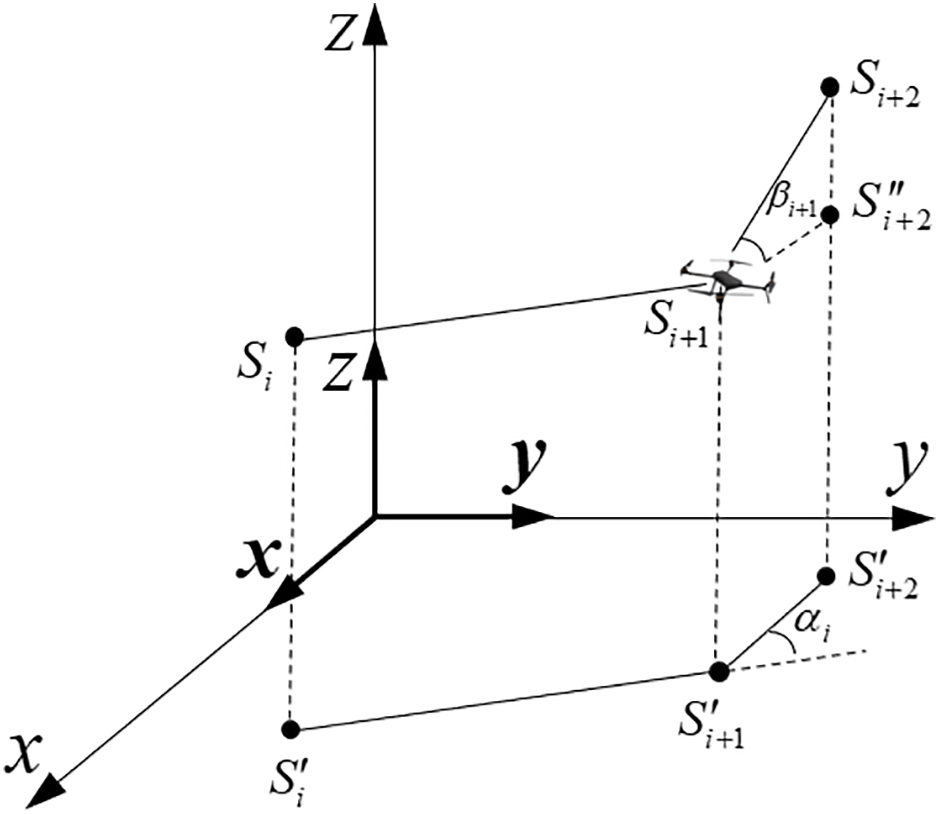

2.1.3 Flight Attitude Constraint

The optimal flight attitude serves as a fundamental element in maintaining the stability of drones. As illustrated in Fig. 3, to ensure safety and control speed, it is essential to restrict the yaw and pitch angles within designated limits. This approach facilitates safe flight operations while preserving a stable attitude. The yaw angle cost is specifically expressed as follows:

Figure 3: Cost of flight attitude

The pitch angle cost is specifically expressed as follows:

2.1.4 Minimum Track Segment Constraint

The alteration of a UAV’s attitude during flight cannot occur instantaneously due to the effects of inertia; rather, it typically involves a gradual process of stabilization. Consequently, establishing the minimum trajectory segment that aligns with the UAV’s performance capabilities and communication delay constraints is essential for the formulation of an effective flight path. The specific representation of the minimum trajectory constraint segment is articulated as follows:

where

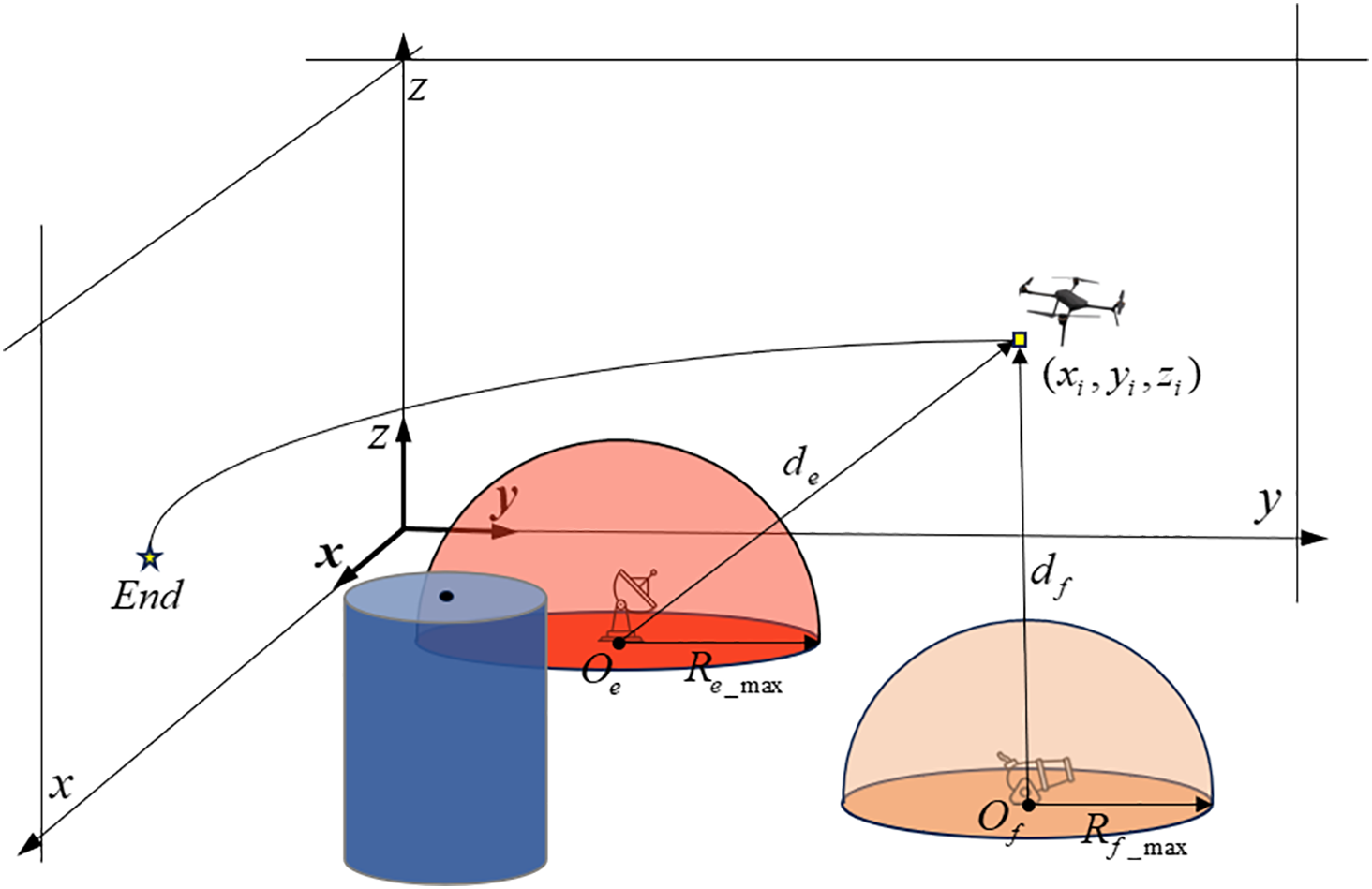

As illustrated in Fig. 4, UAVs are susceptible to numerous adversarial threats, including electronic jamming and direct fire attacks, within an operational context. Such threats have the potential to compromise the success of UAV missions. Consequently, it is imperative to integrate strategies aimed at mitigating these risks during the design of flight paths to guarantee the effective execution of missions [28].

Figure 4: Threat cost

The efficacy of electronic jamming is significantly influenced by the proximity of the UAV to the jamming apparatus; a closer distance to the device’s center correlates with an increased level of threat. The cost of electronic interference is expressed as follows:

where

UAVs are susceptible to destruction from fire strikes, necessitating the avoidance of areas subjected to fire coverage. The associated costs of fire strikes can be delineated as follows:

where

During drone operations, it is imperative to adhere to established regulations to guarantee the safety of both the aircraft and ground personnel. This includes avoiding designated no-fly zones [29], which encompass areas such as airports, high-voltage regions, tall structures, and densely populated locations. The restrictions pertaining to no-fly zones are delineated as follows:

where

2.2 Multi-UAV Cooperative Constraints

To enhance the overall coordination of unmanned aerial clusters and effectively accomplish the designated task, multiple aircraft must adhere to a specific relationship both in terms of time and space while operating collaboratively.

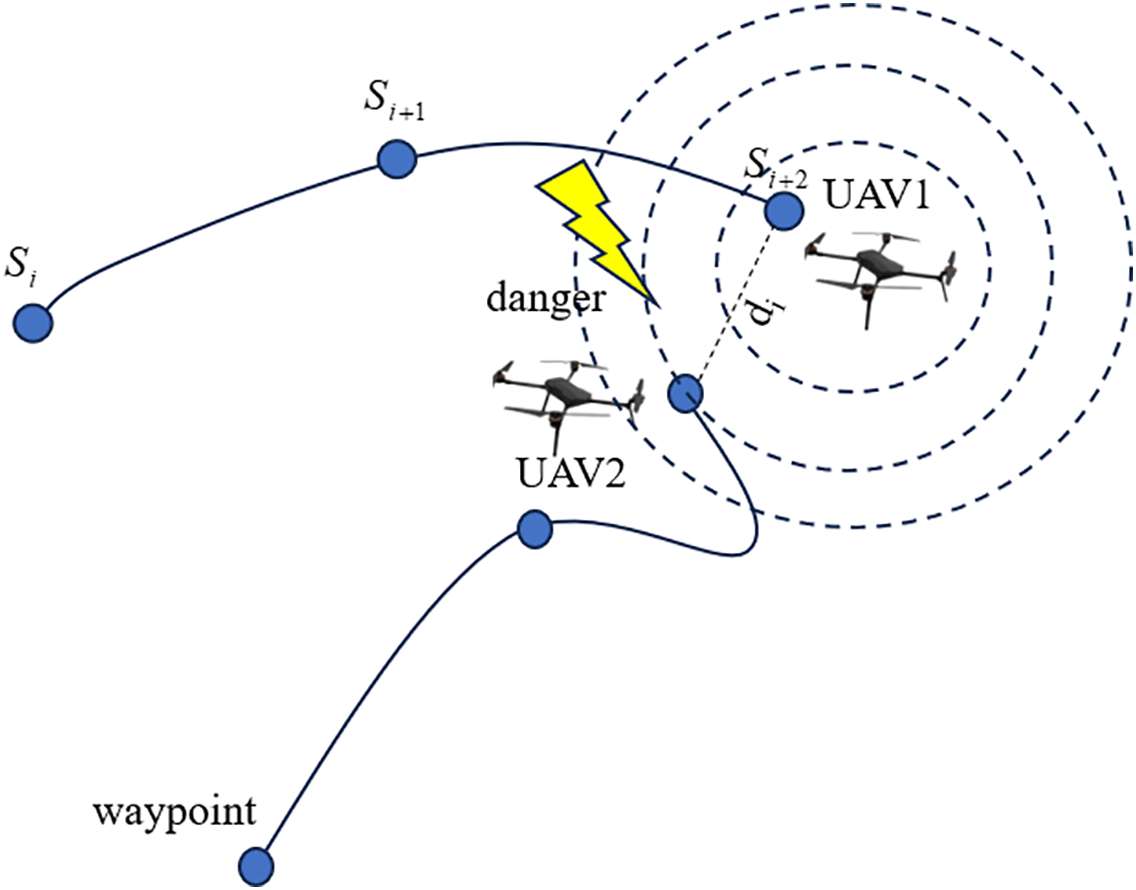

To guarantee the safety of multiple UAVs operating in proximity to one another and to prevent potential collisions, it is essential to monitor their spatial separation while traversing the designated flight path. As illustrated in Fig. 5, by analyzing the coordinates of the nodes along the planned trajectory for each UAV, one can determine if the distance between any two UAVs at a given time falls below the established safety threshold, thereby indicating a risk of collision. The mathematical representation of this condition is as follows:

Figure 5: Collision cost

where

In scenarios where multiple aircraft operate collaboratively, it is typically necessary for each aircraft to reach the designated target simultaneously. However, due to the need to navigate complex terrain obstacles, the flight speeds of UAVs fluctuate within a specified range, making it unfeasible for all aircraft to arrive at the target at precisely the same moment. Consequently, this study posits that if there is an overlap in the time intervals during which each aircraft arrives at the target, it can be assumed that the aircraft have effectively arrived simultaneously. The formal expression of this concept is as follows:

where

The time-constrained cost of construction is as follows:

where

A linear weighting approach is employed to incorporate the constraint cost as a penalty function into the objective function [30], thereby formulating the overall evaluation criterion function represented by the following expression:

where

The BFDBO algorithm has been enhanced through the incorporation of a boundary reflection optimization mechanism, an adaptive hybrid exploration strategy, and a dynamic adaptive multi-scale variation, all within the framework of the DBO algorithm. These improvements aim to address the limitations associated with the DBO algorithm, including its simplistic approach to boundary processing, its propensity to converge on local optima, and its inadequacies in preserving population diversity [31].

3.1 Fundamentals of the DBO Algorithm

The dung beetle optimization algorithm [20] generates an initial population by randomization, and the position of each dung beetle corresponds to a solution to the optimization problem. For the d-dimensional optimization problem, the position of the

The rolling behavior of dung beetles is categorized into two modes: no-obstacle mode and with-obstacle mode. In the absence of obstacles, dung beetles utilize solar navigation to maintain a linear trajectory for the dung ball. The intensity of light influences the beetle’s path, and the position of the dung ball is adjusted according to the methodology outlined in Eq. (19).

In case of an obstacle, the dung beetle uses dancing to reorient itself to a new route; the position update of the dancing behavior is shown in Eq. (20).

where

In the context of reproductive behavior, female dung beetles engage in the practice of rolling dung balls to secure locations that are conducive to egg-laying, subsequently concealing these balls to create appropriate environments for their progeny. Drawing inspiration from this behavior, the original authors introduced a boundary selection strategy aimed at modeling the sites where female dung beetles deposit their eggs, as delineated in Eq. (21).

where,

where

In the context of foraging behavior, certain adult dung beetles excavate the soil in pursuit of nourishment, while the ideal foraging zone for juvenile dung beetles is subject to continuous modification, as illustrated in Eq. (23).

where

The position of the small dung beetle is updated as shown in Eq. (24).

where

Certain species of dung beetles engage in kleptoparasitism by appropriating dung balls from conspecifics. The location of the stealing dung beetle is updated in the manner shown in Eq. (25).

where

While the DBO algorithm demonstrates commendable convergence speed, it is hindered by several limitations, including inadequate maintenance of population diversity throughout the iterative process, a propensity to converge on local optima, and simplistic boundary handling techniques. Consequently, this study proposes three strategies aimed at improving the algorithm’s overall performance.

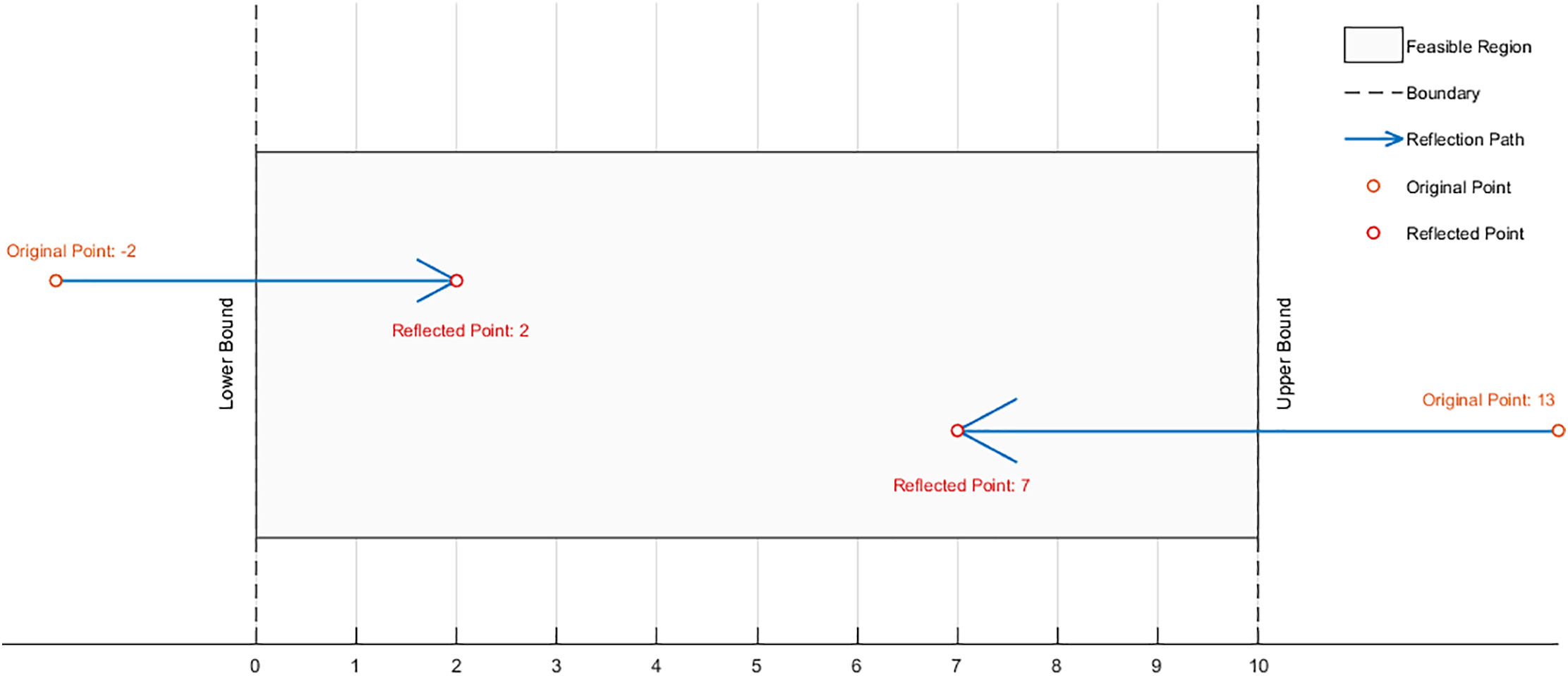

3.2.1 Boundary Reflection Optimization Mechanism

In conventional boundary processing techniques, variables that exceed predefined boundaries are typically truncated to the boundary value. While this approach is straightforward, it results in the loss of the original motion direction and positional information of the variables. Furthermore, by constraining the variables to the boundary, the algorithm is unable to explore regions beyond this limit, which may lead to convergence on a local optimum. Additionally, frequent truncation can disrupt the convergence process, ultimately resulting in a slower convergence rate. To address these issues, a boundary reflection optimization mechanism has been proposed. This mechanism ‘reflects’ variables that exceed the boundary back into the search space, rather than merely assigning them to the boundary value. This strategy enhances the mobility of the variables, thereby improving the algorithm’s global search capabilities and reducing the likelihood of converging to local optima.

The details are as follows:

For

For

Figure 6: Boundary reflection optimization principle

3.2.2 Adaptive Hybrid Exploration Strategies

In the field of optimization algorithms, researchers have consistently concentrated on identifying an optimal equilibrium between global and local search methodologies. Traditional optimization algorithms are particularly susceptible to converging on local optima during the iterative process, especially when confronted with intricate multi-peak optimization challenges. In light of this issue, we introduce an adaptive hybrid exploration strategy designed to augment the global search capabilities of the algorithm. This enhancement is achieved by incorporating a novel update strategy and stochastic mechanism, which simultaneously improves the algorithm’s diversity and stability while preserving the beneficial features of the original dung beetle optimization algorithm. The specific details of this approach are outlined as follows:

For dung beetle individuals in the population that engage in foraging behavior, the original method of position updating was used with a 50% probability, and the new method of position updating was used with a 50% probability. The new position update method is as follows:

A random selection of two to five individuals was conducted, and the mean value of their respective positions was subsequently computed as follows:

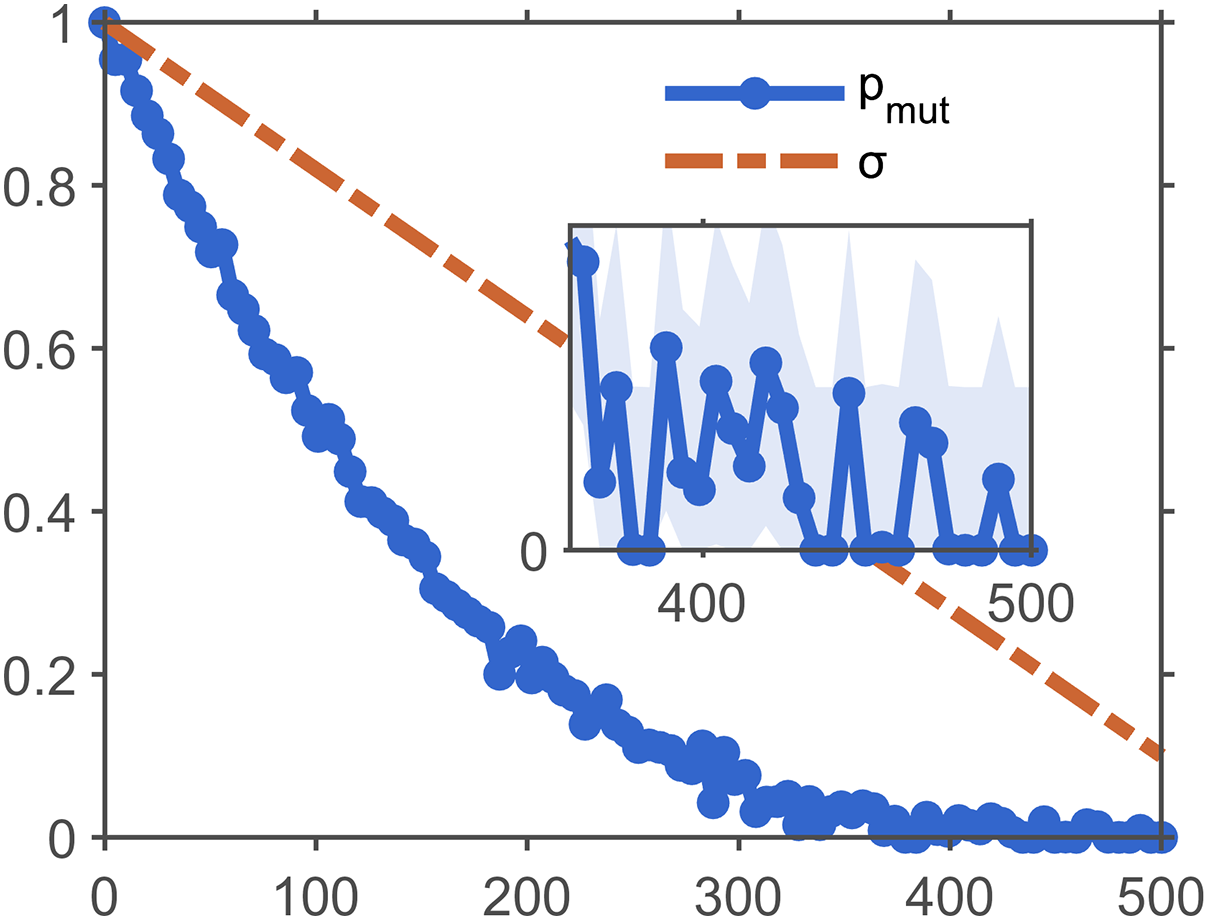

3.2.3 Dynamic Adaptive Multiscale Variational Strategies

While the DBO algorithm demonstrates commendable global search capabilities, it exhibits notable deficiencies in maintaining population diversity throughout the iterative process. As iterations progress, the positions of the individuals within the population tend to converge toward the global optimal solution. This convergence enhances the algorithm’s speed of convergence; however, it concurrently results in a gradual reduction of population diversity. Such a decline in diversity poses a risk of the algorithm becoming trapped in a local optimal solution, particularly when addressing complex multi-peak optimization challenges. Furthermore, the fixed-scale variational strategy employed may inadequately address the need to balance global and local search requirements at various stages of iteration, thereby further constraining the algorithm’s overall performance.

To address these limitations, it is essential to implement a dynamic adaptive multi-scale variation strategy. This approach facilitates the dynamic adjustment of variance probability and variance scale, thereby enhancing the maintenance of population diversity throughout the iterative process. Additionally, it allows for a flexible balance between global and local search capabilities, tailored to the specific stage of iteration and the distribution of the population. The details are as follows:

The positional diversity is obtained from Eqs. (30) and (31):

The fitness diversity is obtained from Eq. (32):

A new global diversity is obtained through Eq. (33):

The adaptive mutation probability is obtained through Eq. (34):

Determine whether

Figure 7: Adaptive parameter changes

Finally, the search enhancement strategy is executed through Eq. (37):

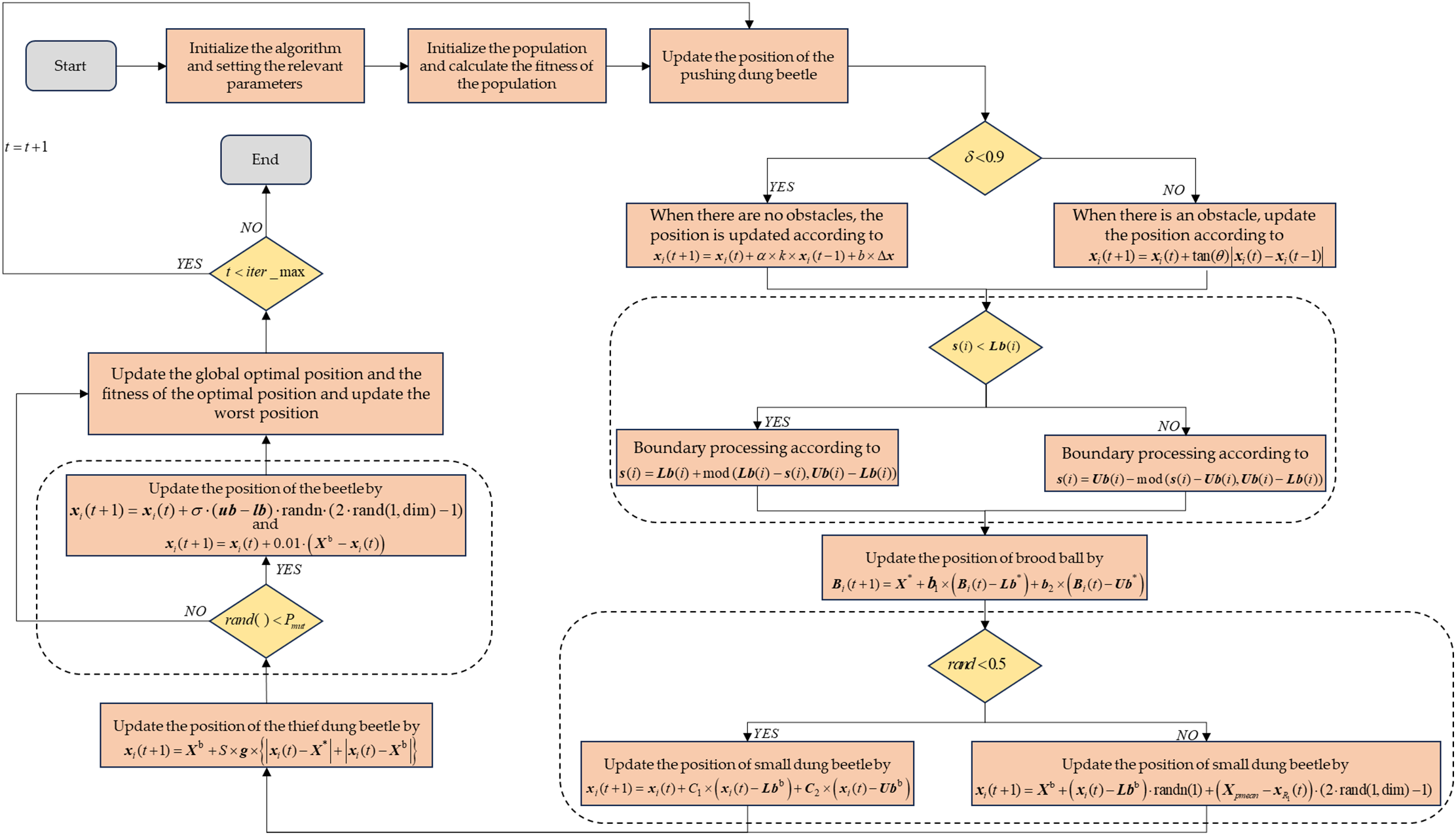

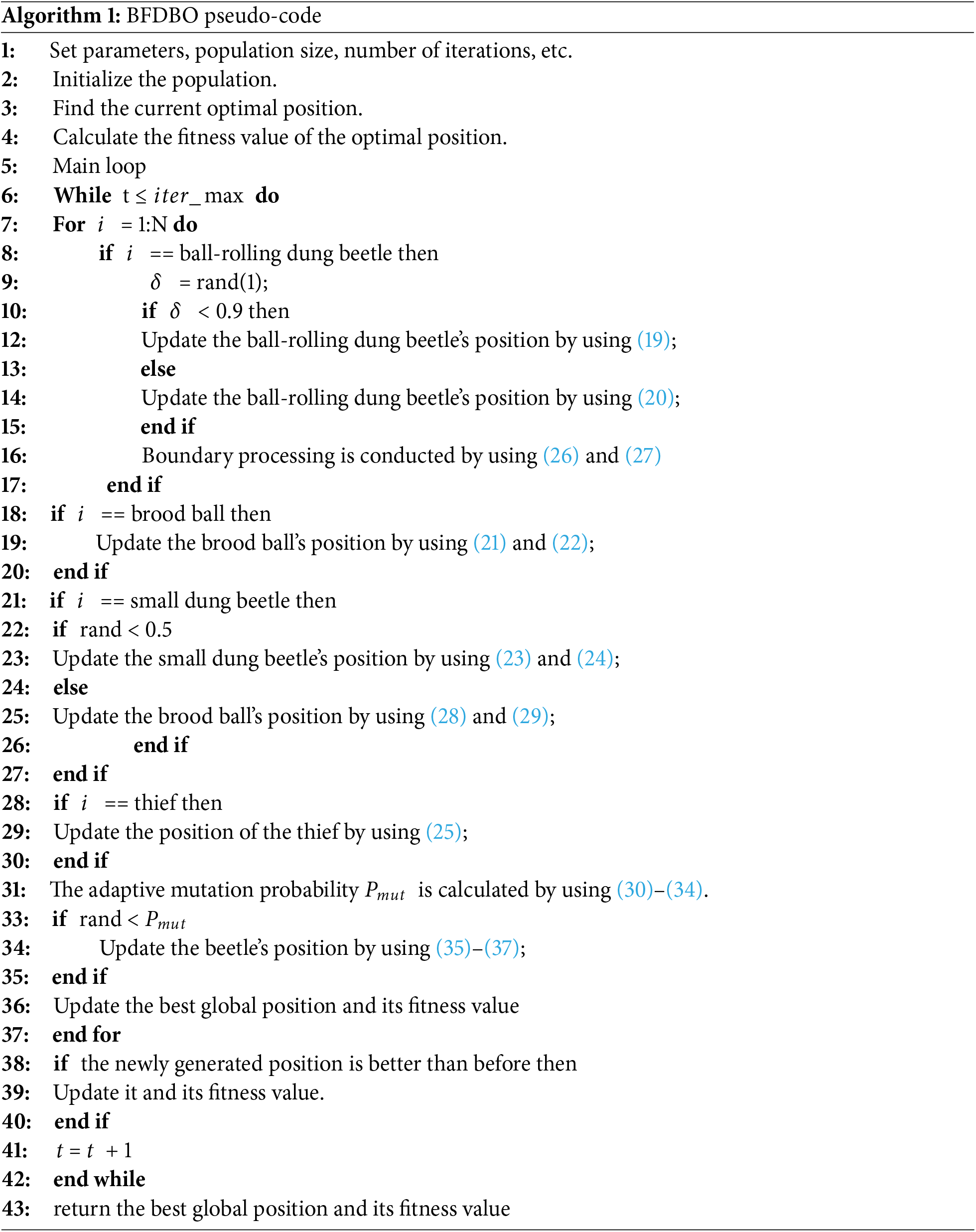

To gain a deeper understanding of how BFDBO operates, Fig. 8 illustrates the process flow, while Algorithm 1 provides its pseudo-code.

Figure 8: Algorithmic process

The BFDBO algorithm is founded on the logical structure of the original DBO algorithm, which has been enhanced through the integration of three distinct strategies. An assessment of the complexity of these strategies is necessary to ascertain the efficacy of the improved algorithm.

Let the quantity of dung beetle populations be denoted as

4 Experimental Results and Discussion

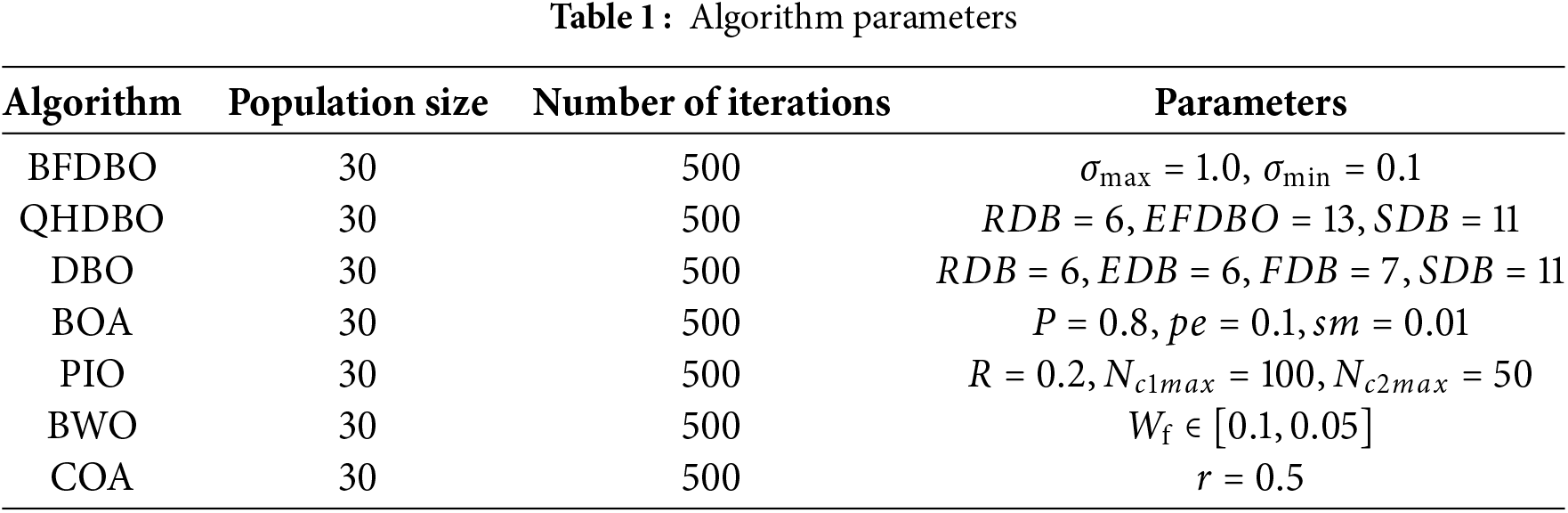

In this research, six representative intelligent optimization algorithms—namely QHDBO [23], DBO [20], BOA [32], PIO [33], BWO [34], and COA [35]—were selected for comparative analysis. The input parameter configurations for these algorithms, as detailed in Table 1, were derived from the original literature in which these algorithms were introduced. To mitigate the influence of stochastic variations inherent in the algorithms, each was executed independently for 30 iterations across test dimensions of 10 and 20. All simulations were conducted on a Windows 11 operating system, utilizing a 13th-generation Intel Core™ i9-13900HX processor operating at 2.20 GHz. Furthermore, MATLAB 2024a software was employed to facilitate the simulations.

4.1 Comparison Test with Other Algorithms

In this research, the evaluation of algorithms was performed utilizing the CEC2022 function test set, which serves as a robust framework for assessing the optimization performance of algorithms and their efficacy in addressing complex problems. The CEC2022 test set comprises four categories of functions: F1 is characterized as a single-peak function with a singular global optimal solution, designed to assess the convergence speed and accuracy of the algorithm; F2 through F5 consist of multi-peak functions featuring multiple local optimal solutions, aimed at evaluating the algorithm’s capacity to circumvent local optima and identify the global optimal solution; F6 to F8 are hybrid functions, constructed by integrating three or more base functions that have undergone rotation or translation to yield more intricate function structures. Each sub-function is assigned a specific weight to assess the algorithm’s overall optimization capability and robustness. Finally, F9 to F12 are composite functions, each derived from the shifting, rotating, and scaling of multiple base functions, followed by the application of weights. Each sub-function is further augmented with an additional bias value to thoroughly evaluate the algorithm’s search capabilities in multi-modal, deceptive, and high-dimensional coupled scenarios.

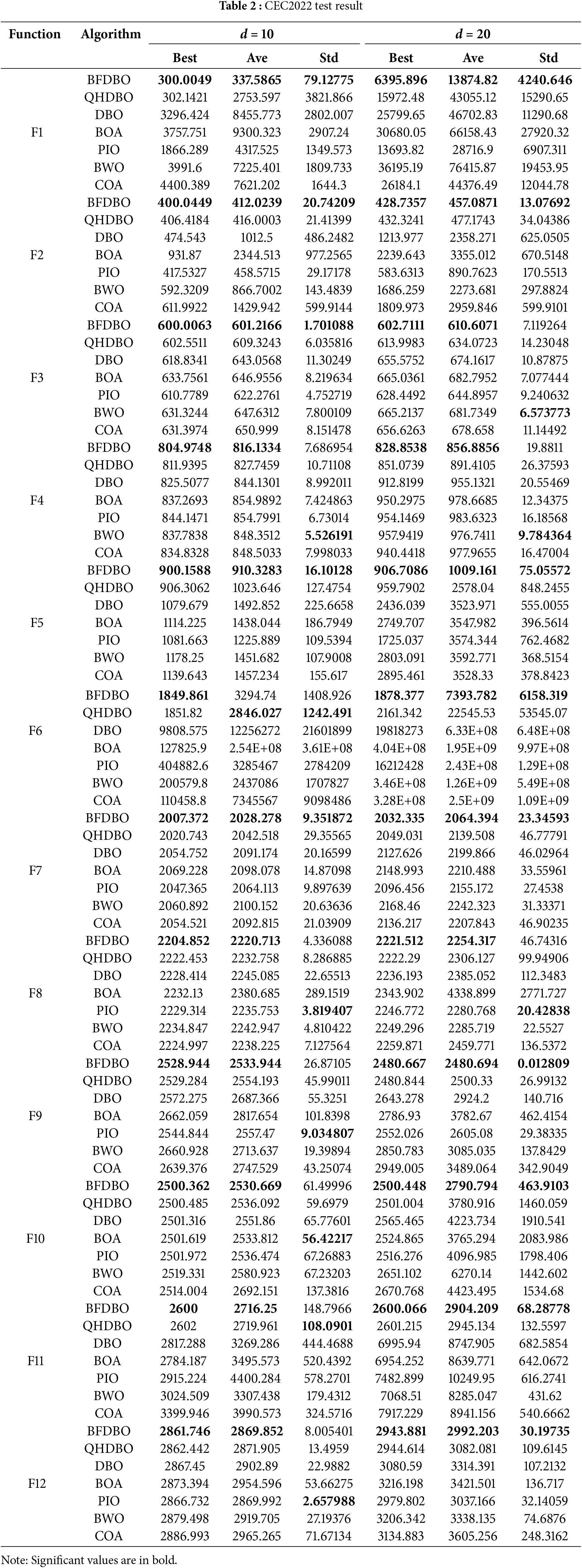

Table 2 delineates the performance outcomes of various algorithms across different test scenarios. In the context of the single-peak problem F1, the BFDBO algorithm exhibits exceptional efficacy in identifying the global optimum, particularly in higher-dimensional settings, where it significantly surpasses other comparative algorithms across all evaluated metrics. In the multi-modal problems F2 to F5, BFDBO continues to demonstrate superior performance regarding both optimal and average value metrics. Although it exhibits slightly less stability than the BWO algorithm in F3 and F4, the overall variance remains relatively low, suggesting that the data is not highly dispersed and that the algorithm possesses commendable robustness. Furthermore, BFDBO shows notable effectiveness in addressing mixed problems F6 to F8, achieving superior optimal and average values in F7 and F8. However, in the lower-dimensional context of F6, its performance is marginally inferior to that of QHDBO; conversely, in higher dimensions, BFDBO outperforms QHDBO, indicating its strong competitive edge. Problems F9 to F12 represent complex combinatorial challenges. In all experiments conducted in a 10-dimensional space, BFDBO consistently outperforms other algorithms in terms of both optimal and average values, albeit with slightly lower stability. This stability issue appears to ameliorate in higher-dimensional experiments, culminating in BFDBO achieving superior performance across all metrics in the 20-dimensional experiment. These results underscore the distinctive advantages and adaptability of BFDBO in tackling composite problems, thereby enhancing its capacity to effectively explore and optimize intricate search spaces.

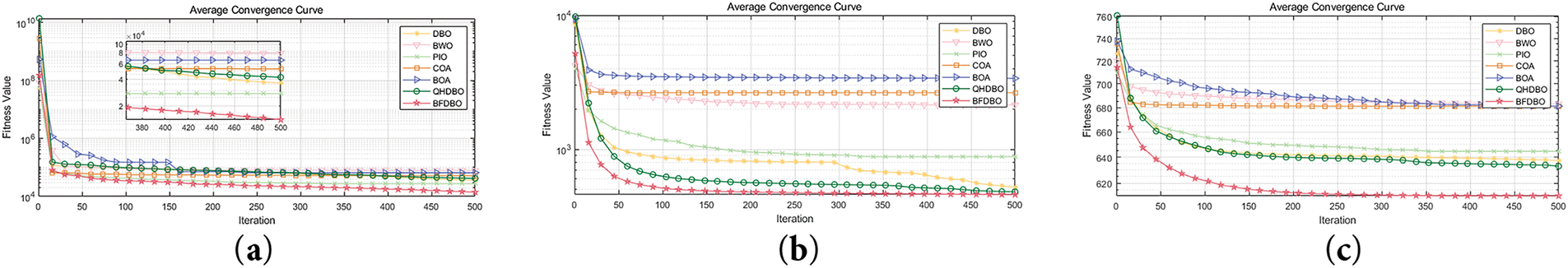

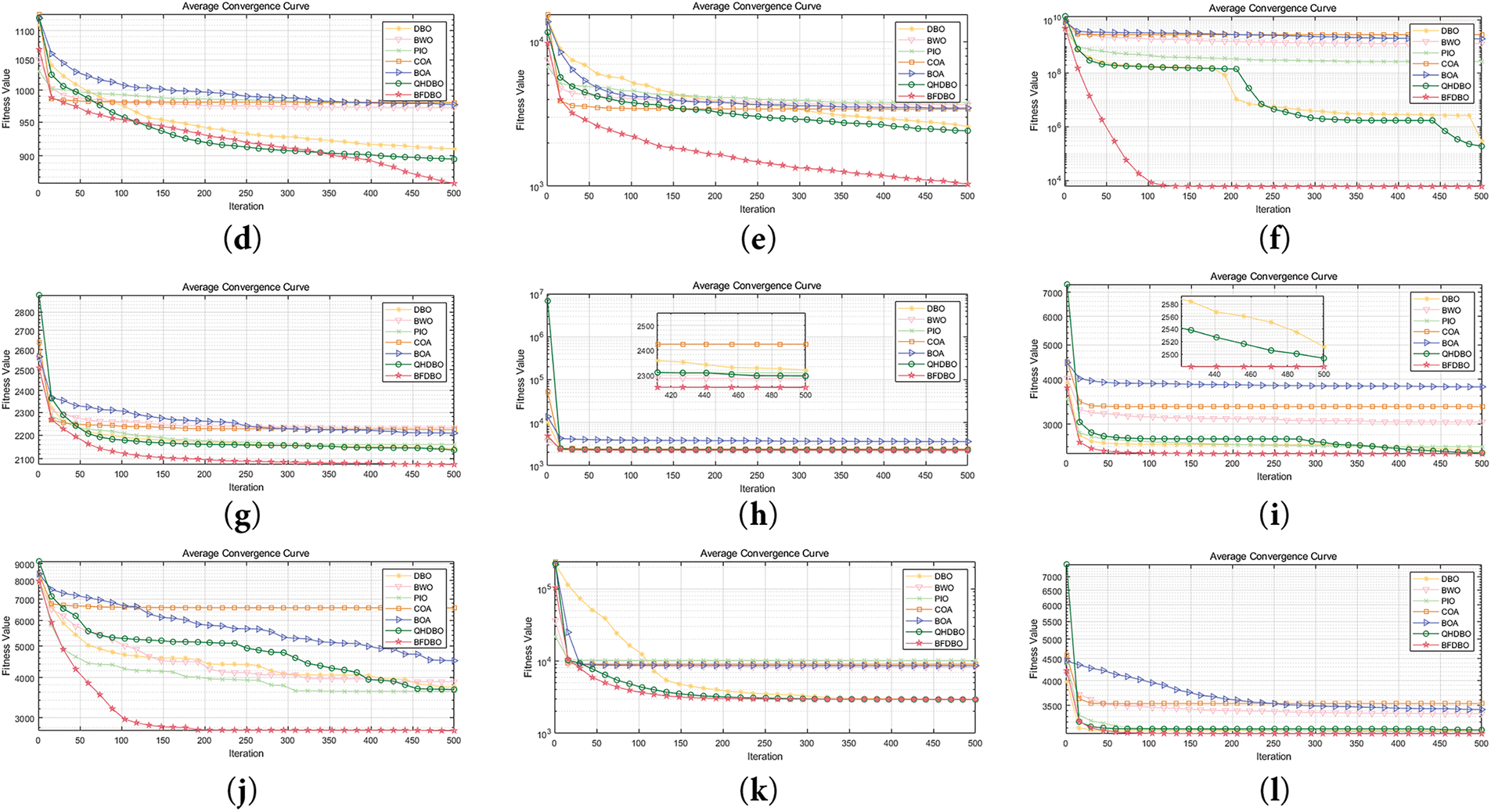

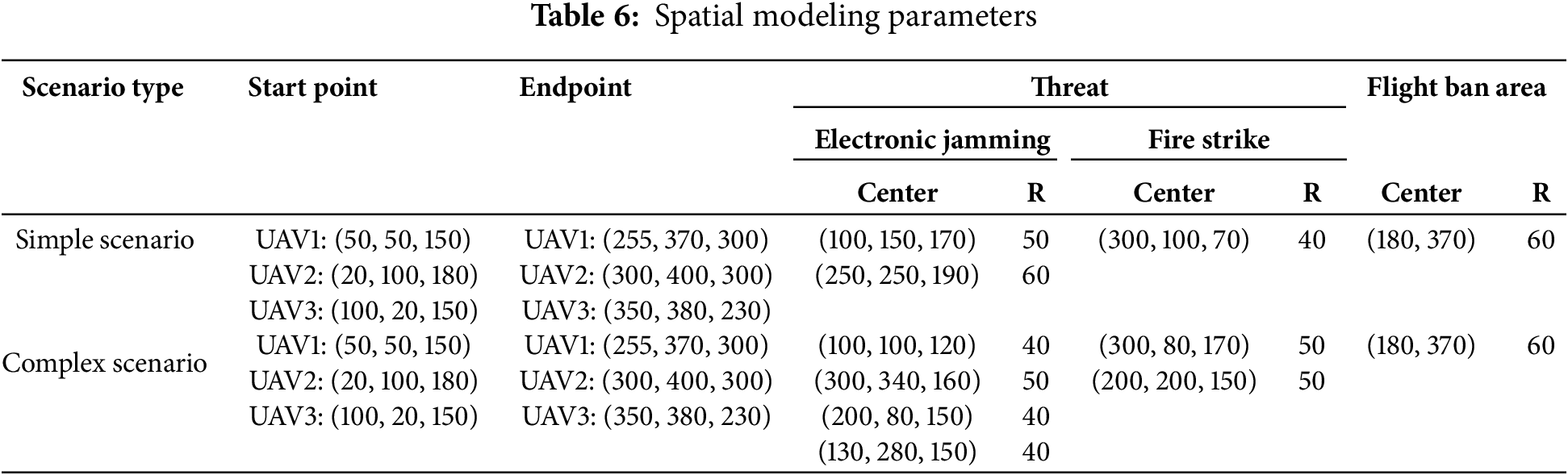

Fig. 9 illustrates the convergence speed and accuracy of seven algorithms evaluated in the CEC2022 benchmark test, specifically at a dimensionality of 20. The findings suggest that the BFDBO algorithm demonstrates a more rapid convergence towards the optimal solution, thereby enhancing problem-solving efficiency and exhibiting superior robustness. In the majority of test scenarios, including functions F3, F5, F6, and F10, BFDBO displays an accelerated convergence trend on the convergence curve, underscoring its significant advantage over competing algorithms. Conversely, in the case of the multi-peak function F4, BFDBO initially underperforms relative to other algorithms during the early iterations. However, as the iterations progress, the implementation of a dynamic adaptive multi-scale variational strategy allows BFDBO to adopt a more refined search approach in the later stages, while simultaneously preserving high population diversity throughout the optimization process. This adaptation enhances the search speed and ultimately results in a higher convergence rate compared to other algorithms, facilitating the identification of superior solutions. A similar trend of progressively improving search capability with increasing iterations is also observable in functions F1 and F5. For functions F8 and F9, BFDBO’s convergence time is comparable to that of other algorithms; however, it achieves greater convergence accuracy within a limited number of iterations. In the case of the composite function F11, BFDBO’s convergence accuracy is on par with that of QHDBO and DBO, while its convergence speed shows slight improvement, further emphasizing BFDBO’s overall superior performance.

Figure 9: Average convergence curve: (a) F1; (b) F2; (c) F3; (d) F4; (e) F5; (f) F6; (g) F7; (h)F8; (i) F9; (j) F10; (k) F11; (l) F12

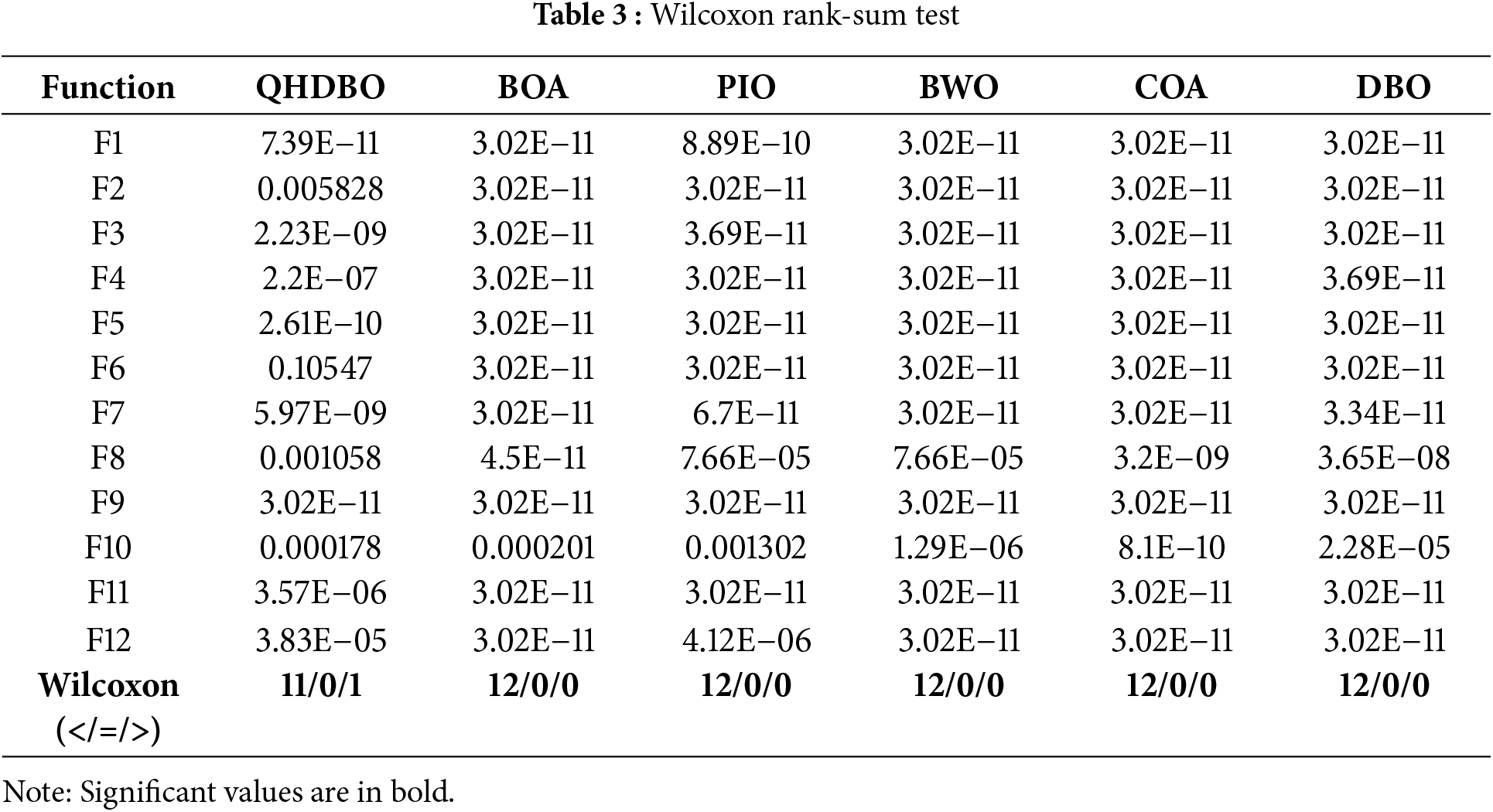

In order to quantitatively assess the performance disparities between BFDBO and other algorithms, we performed a statistical analysis of the experimental data utilizing the Wilcoxon rank-sum test [36,37]. This analysis involved comparing 30 independent executions of BFDBO against 30 executions each of QHDBO, DBO, BOA, PIO, BWO, and COA, maintaining a significance level of 5% and consistent parameter configurations (dimension: 30, population size: 30, maximum iteration count: 500). The performance outcomes are represented by the symbols “<”, “=”, and “>”, which denote superior, equivalent, and inferior performance, respectively. As illustrated in Table 3, with the exception of function F6, where the p-value in comparison to QHDBO exceeded 0.05, the p-values for BFDBO relative to the six benchmark algorithms were below 0.05 for nearly all 12 functions. This finding suggests that BFDBO demonstrates statistically significant superiority over the benchmark algorithms.

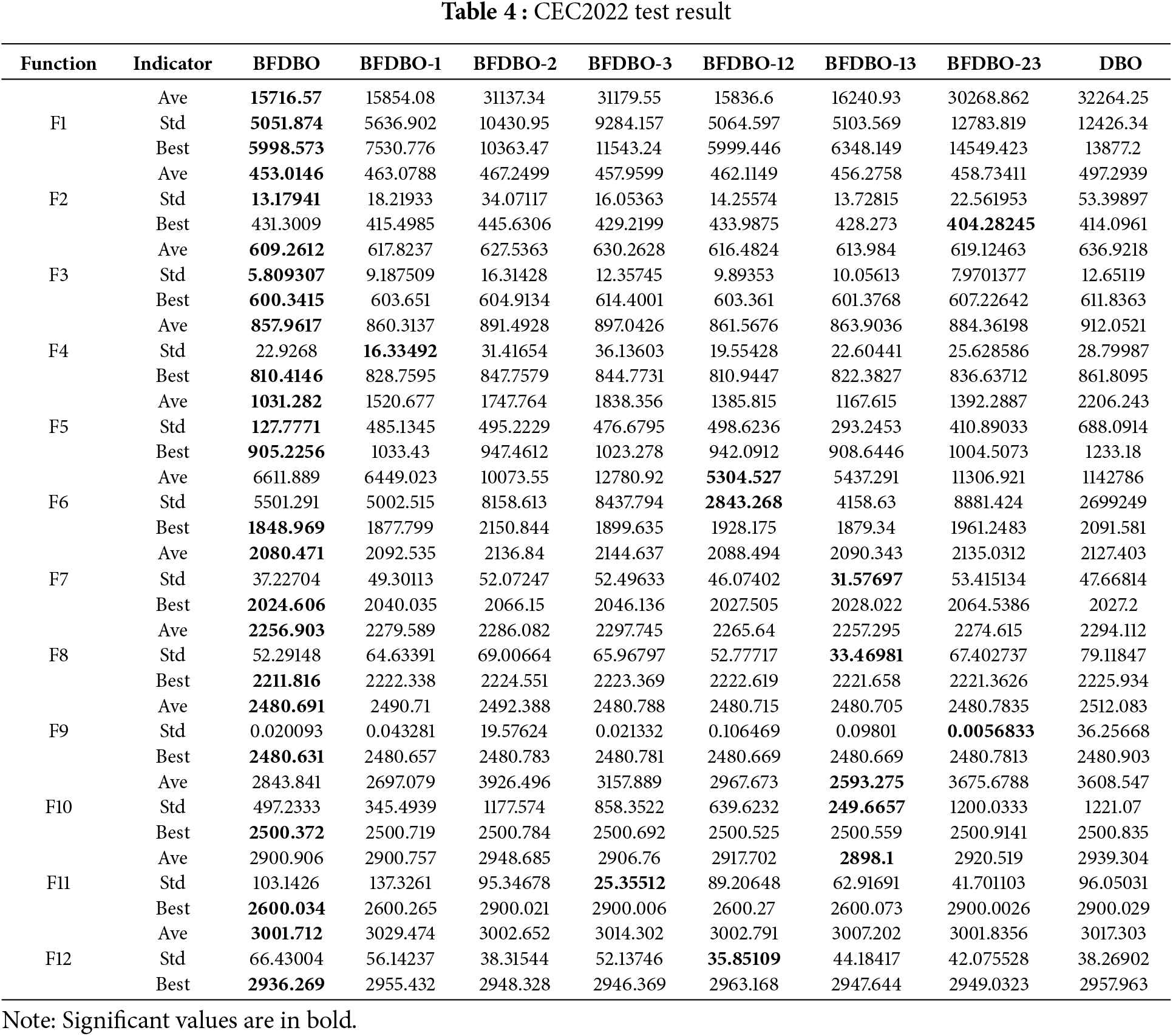

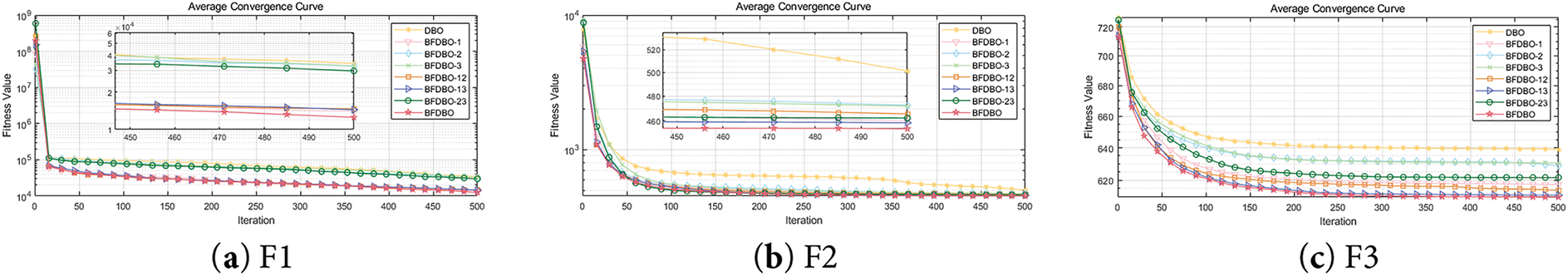

To evaluate the efficacy of the enhancement measures applied to the algorithm, we performed ablation experiments utilizing the same parameter configuration as outlined in the test experiments in Section 4.1. The BFDBO algorithm was augmented through three distinct strategies: BFDBO-1, which incorporates a boundary reflection optimization mechanism; BFDBO-2, which employs an adaptive hybrid exploration strategy; and BFDBO-3, which integrates a dynamic adaptive multi-scale variational strategy. Additionally, BFDBO-12, BFDBO-13, and BFDBO-23 represent variants that combine two of the aforementioned strategies. These six modified versions of BFDBO were assessed using the CEC2022 benchmark function within a 20-dimensional space, with the results presented in Table 4. The findings indicate that each enhancement strategy offers distinct advantages; however, BFDBO consistently outperforms the others across various evaluation metrics, including mean, standard deviation, and optimal value. This suggests that while each individual strategy contributes to performance enhancement, the synergistic effect of the three strategies results in the most significant improvement over the original algorithm.

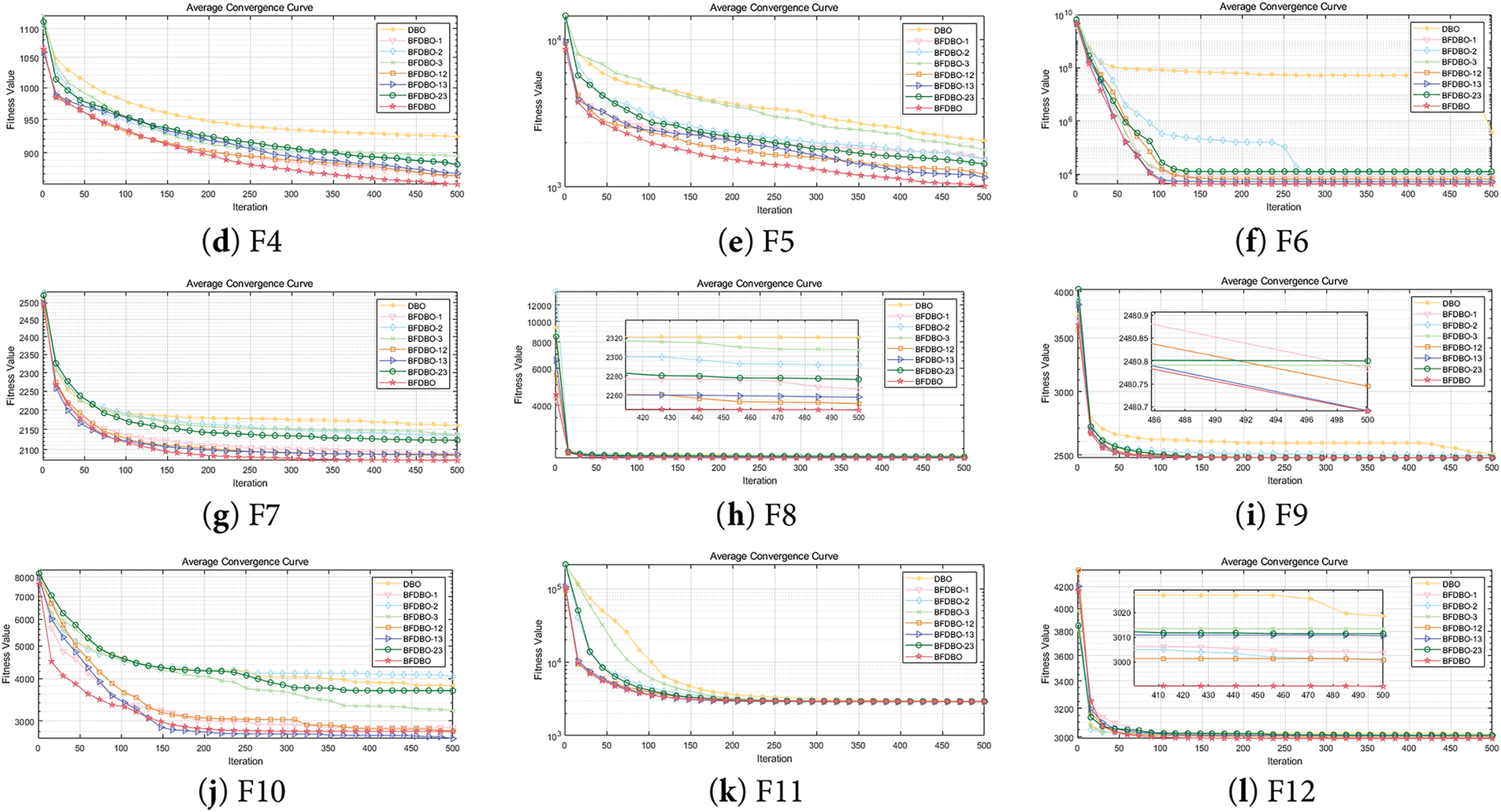

Fig. 10 illustrates the average convergence curves for each algorithm under consideration. A thorough analysis of the effectiveness of the various improvement strategies indicates that BFDBO-1 exhibits the most pronounced performance enhancement, characterized by both superior convergence speed and accuracy when compared to BFDBO-2 and BFDBO-3. This finding suggests that the boundary reflection optimization mechanism effectively retains the movement information of the beetle individuals, thereby enabling the algorithm to demonstrate enhanced optimization capabilities within the feasible space. Regarding comprehensive improvement strategies, BFDBO-13 achieves the highest level of performance enhancement, with its convergence accuracy on the mixed function F10 surpassing that of BFDBO, which incorporates three distinct improvement strategies. In conclusion, all three improvement strategies implemented in BFDBO contribute positively to performance enhancement. Variants employing two improvement strategies generally outperform those utilizing a single strategy, while BFDBO, which amalgamates all three strategies, exhibits the most precise search capability, consistently achieving the highest rankings in terms of convergence accuracy and speed across nearly all test functions.

Figure 10: Average convergence curve: (a) F1; (b) F2; (c) F3; (d) F4; (e) F5; (f) F6; (g) F7; (h)F8; (i) F9; (j) F10; (k) F11; (l) F12

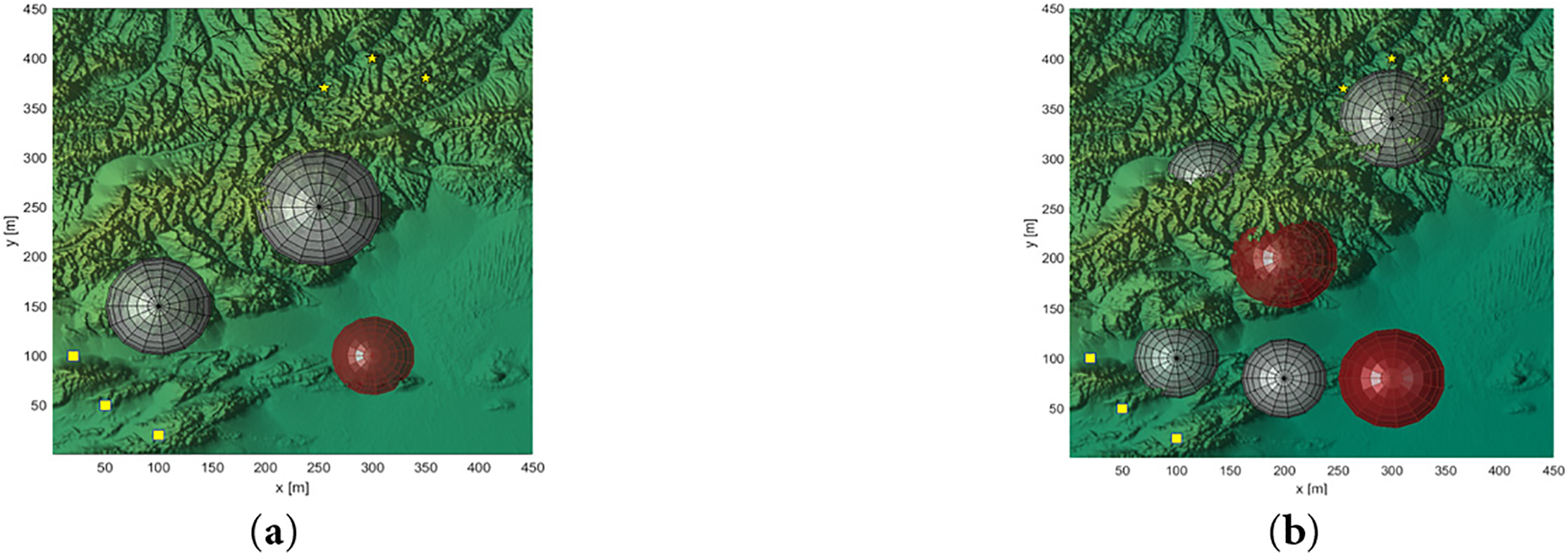

5.1 Parameterisation of Algorithms and UAVs

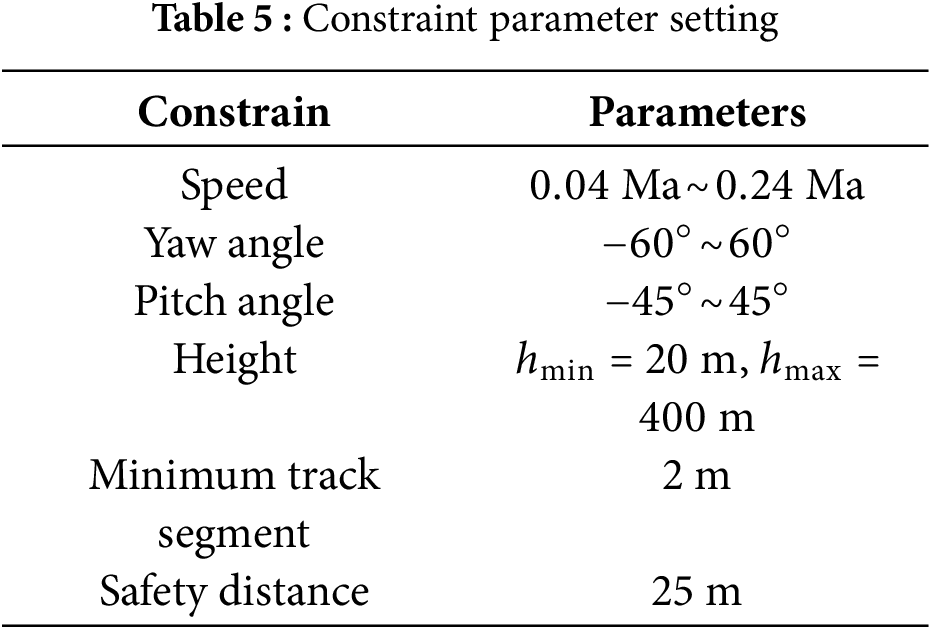

In order to thoroughly assess the efficacy of the proposed algorithm, a comparative analysis was conducted involving DBO, QHDBO, EIDBO [38], and GODBO [39]. Trajectory planning simulations were performed in two environments characterized by varying levels of complexity. For detailed observation, the most representative baseline algorithm, DBO, along with the superior variant QHDBO and the proposed BFDBO, were chosen for trajectory visualization. The detailed statistical outcomes for all other comparative algorithms are systematically presented in tabular format. For each environment, the starting point, target point, and threat distribution were configured independently. The algorithm parameters were configured as follows: population size N = 30, maximum iterations = 200, and waypoints n = 12. To mitigate random effects, each algorithm was independently executed 50 times, with the optimal result retained for analysis. Accounting for UAV performance constraints, realistic flight parameters were adopted (Table 5).

Three UAVs were utilized for collaborative trajectory planning, with mission durations configured as the 60, 40, and 30 s for each UAV, using an optimization weight matrix

5.2 Simulation Environment Construction

During combat missions, including material distribution, reconnaissance strikes, and aerial broadcasting, UAVs require global path planning that accounts for terrain obstacles, known threats, and restricted zones, including electronic jamming areas. The fidelity of the 3D environment model directly impacts combat environment realism, UAV performance constraints, and mission requirements. This study employs LiDAR-derived digital elevation models (DEMs) [42], enhanced with combat-relevant hazardous zones requiring avoidance during mission execution. These components collectively form a 3D spatial model (parameters detailed in Table 6). Based on threat density, two baseline scenarios (simple/complex) were established (Fig. 11).

Figure 11: Baseline scenario: (a) simple scenario; (b) complex scenario

5.3 Results and Analysis of Trajectory Planning

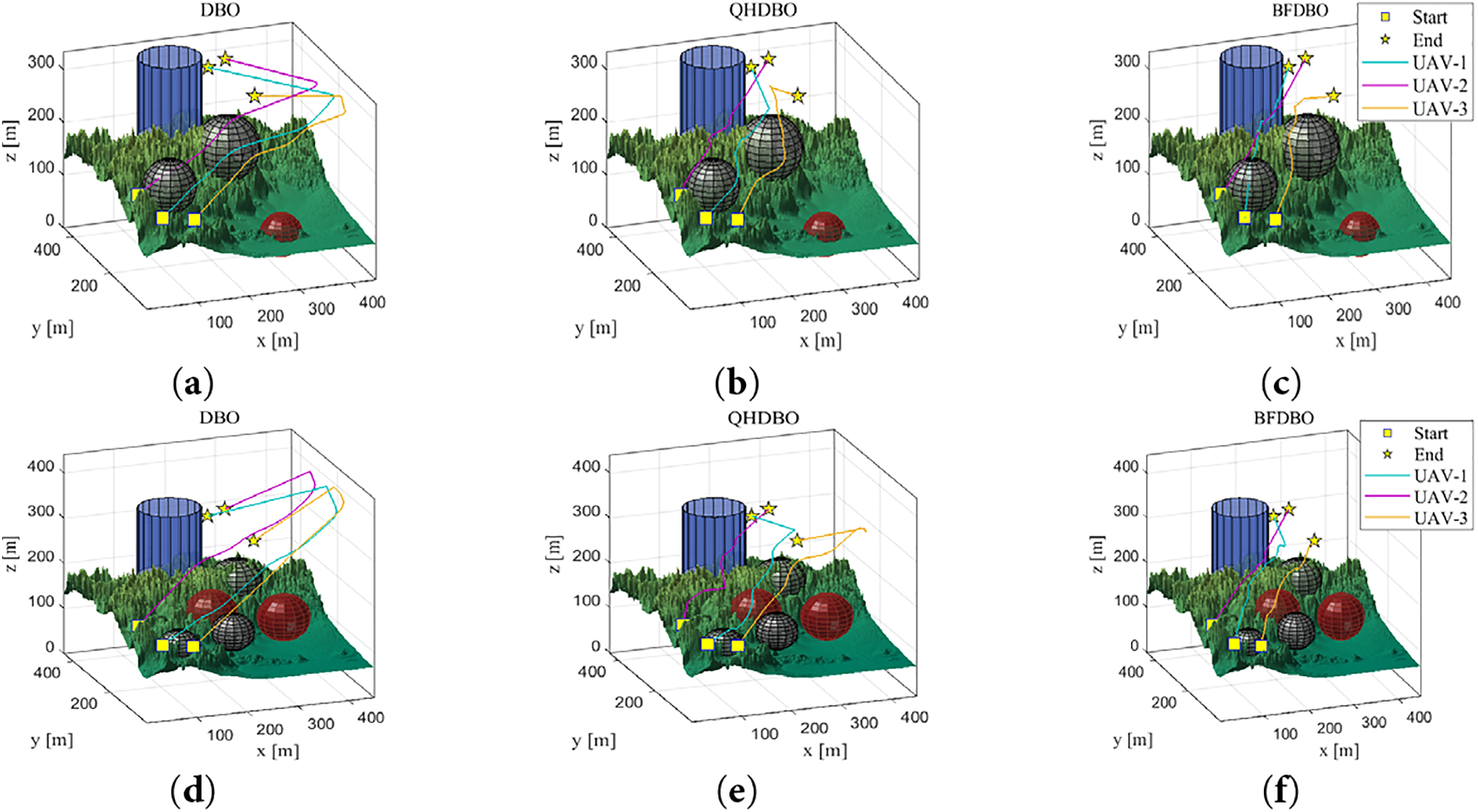

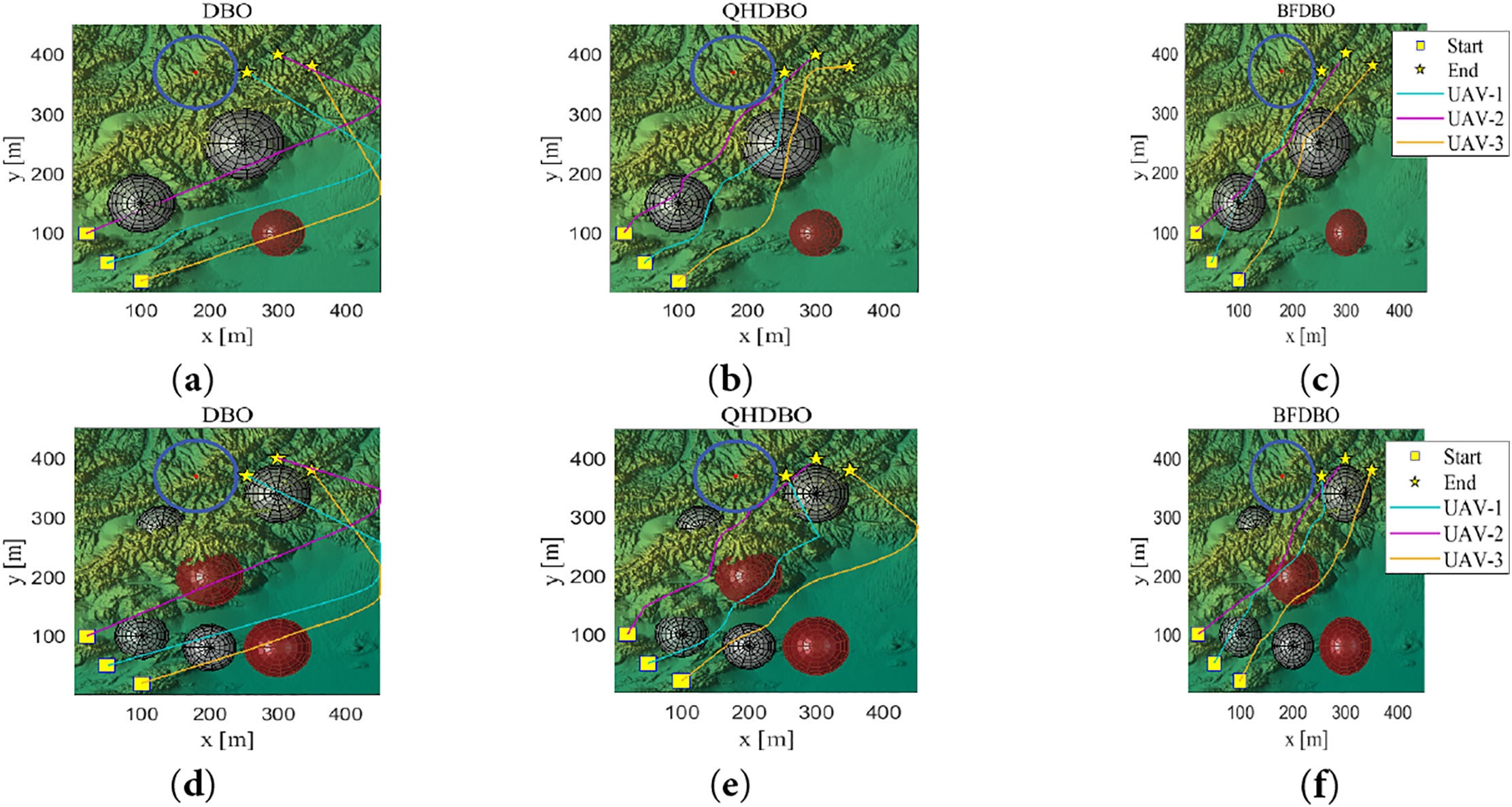

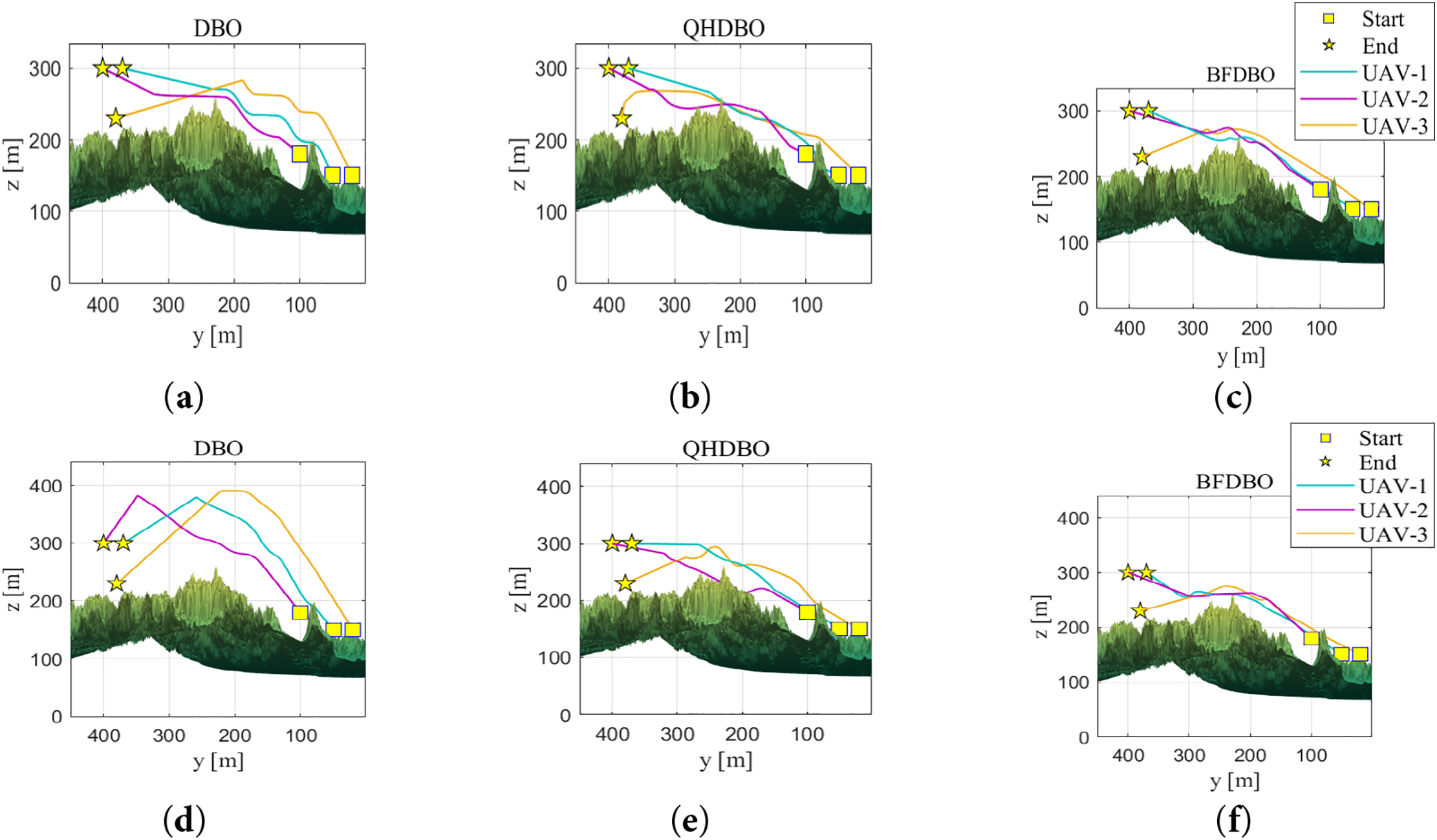

To systematically evaluate collaborative multi-copter trajectory planning, this section analyzes optimal paths across three perspectives: 3D panorama, top-down, and lateral views within two benchmark scenarios (Figs. 12–14). Subfigures (a)–(b) correspond to simplified scenarios, while (d)–(f) represent complex environments. Additionally, each algorithm was independently executed 30 times to statistically evaluate performance metrics [43,44], including average cost, optimal cost, and standard deviation.

Figure 12: 3D flight path: (a) DBO trajectory planning performance in simple scenarios; (b) QHDBO trajectory planning performance in simple scenarios; (c) BFDBO trajectory planning performance in simple scenarios; (d) DBO trajectory planning performance in complex scenarios; (e) QHDBO trajectory planning performance in complex scenarios; (f) BFDBO trajectory planning performance in complex scenarios

Figure 13: Top view: (a) DBO trajectory planning performance in simple scenarios; (b) QHDBO trajectory planning performance in simple scenarios; (c) BFDBO trajectory planning performance in simple scenarios; (d) DBO trajectory planning performance in complex scenarios; (e) QHDBO trajectory planning performance in complex scenarios; (f) BFDBO trajectory planning performance in complex scenarios

Figure 14: Top view: (a) DBO trajectory planning performance in simple scenarios; (b) QHDBO trajectory planning performance in simple scenarios; (c) BFDBO trajectory planning performance in simple scenarios; (d) DBO trajectory planning performance in complex scenarios; (e) QHDBO trajectory planning performance in complex scenarios; (f) BFDBO trajectory planning performance in complex scenarios

Fig. 12 presents the optimal UAV trajectory planning outcomes produced by the three algorithms within a three-dimensional environment. The findings indicate that while all algorithms yield valid trajectory planning results, there are notable differences among them regarding trajectory length, flight altitude, and variations in heading. In comparison to the BFDBO algorithm, both the QHDBO and DBO algorithms tend to generate superfluous localized trajectories, which consequently results in heightened energy consumption during flight. Additionally, these algorithms demonstrate abrupt changes in course direction and exhibit inadequate trajectory smoothing.

Fig. 13 reveals that DBO and QHDBO exhibit diminished global optimization capability, requiring substantial trajectory deviations characterized by pronounced fluctuations in waypoints, and frequent sharp turns with large angles, particularly in complex scenarios. In contrast, BFDBO demonstrates superior performance, with minimal waypoint fluctuations, reduced zigzagging, and smoother curvature in its trajectories. The BFDBO trajectory exhibits minimal fluctuation, reduced tortuosity, and gradual turning angles, achieving the shortest path length among all algorithms. These results confirm BFDBO’s ability to avoid local optima entrapment [45,46] and produce trajectories of superior quality.

Fig. 14 illustrates the trajectories of collaborative planning from a lateral perspective. In straightforward scenarios, the three algorithms demonstrate comparable performance in trajectory planning, with no notable distinctions in their paths. However, in more intricate scenarios, the trajectories produced by DBO and QHDBO reveal considerable fluctuations in height and abrupt alterations in pitch angle. This finding indicates that, as conventional intelligent optimization algorithms, DBO and QHDBO encounter difficulties in escaping local optima, resulting in suboptimal trajectory outcomes. Conversely, the trajectories generated by BFDBO exhibit minimal variations in height and a significant reduction in serpentine motion, thereby aligning more closely with the actual operational requirements of UAV flight.

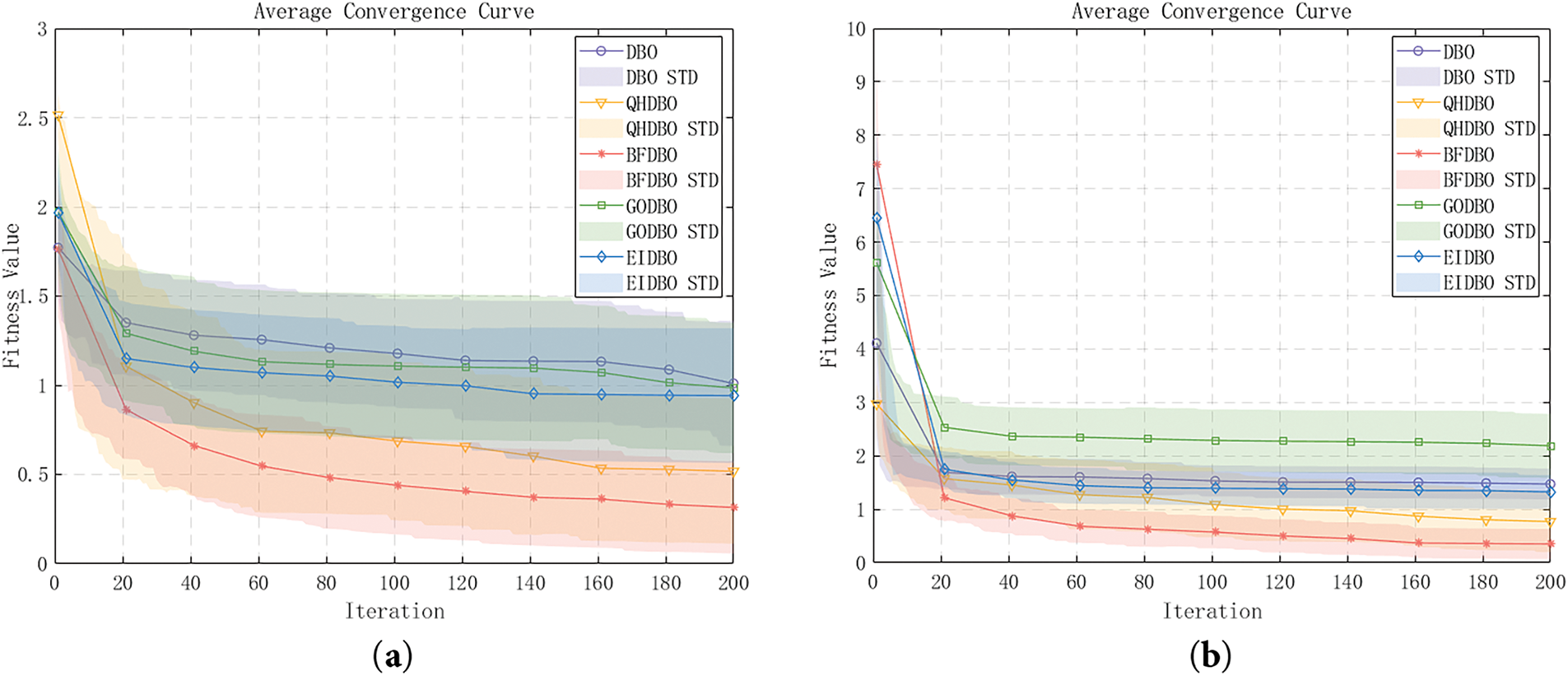

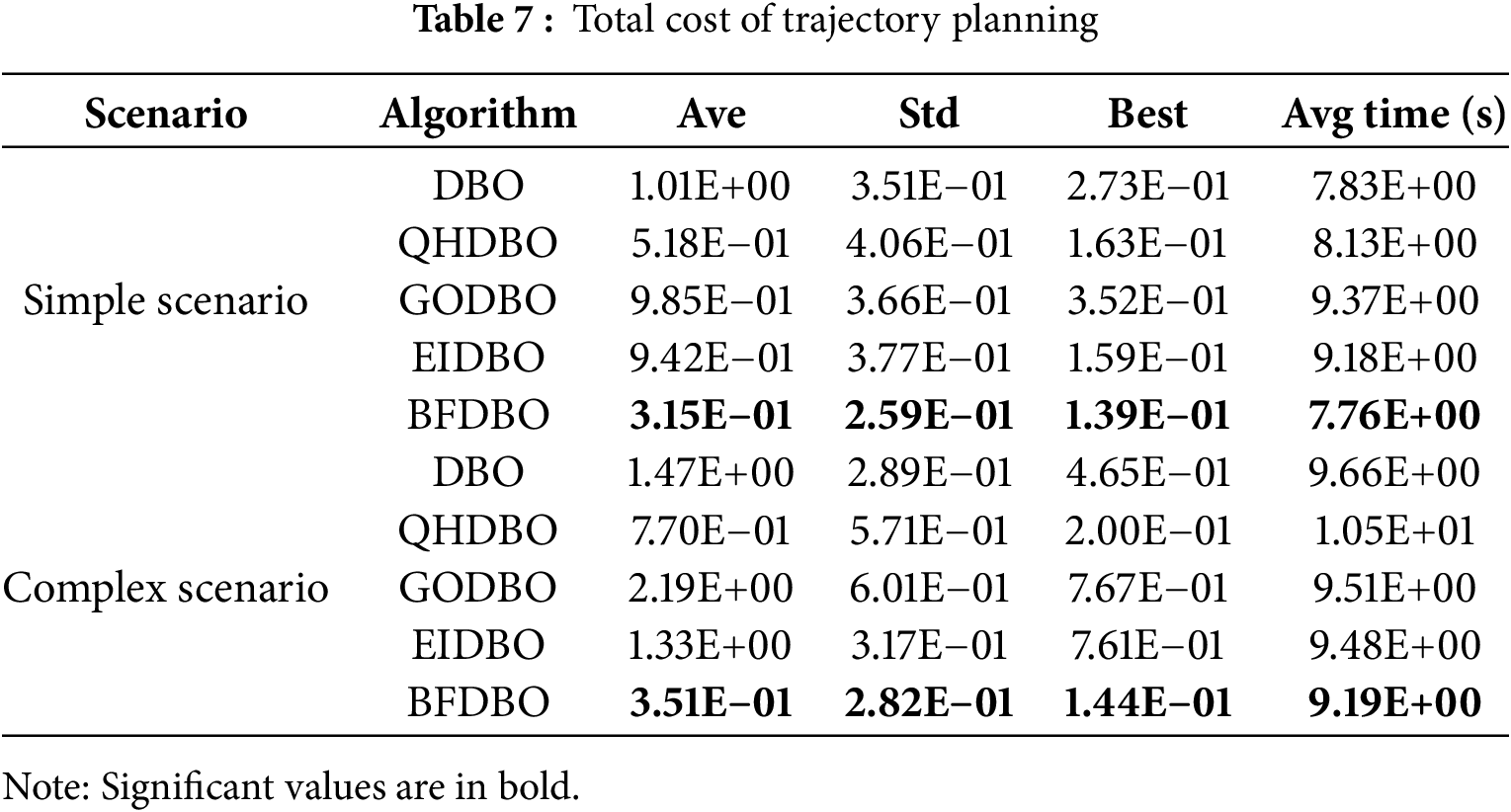

As illustrated in Fig. 15 and Table 7, the trajectory generated by the BFDBO algorithm exhibits a lower total cost and a more rapid convergence rate compared to those produced by alternative algorithms, given identical initial and termination conditions. A statistical analysis encompassing 50 trials—evaluating optimal values, average values, and standard deviations—demonstrates that BFDBO surpasses the baseline DBO algorithm as well as other notable DBO variants in terms of optimality, average performance, and stability. In straightforward scenarios, BFDBO outperforms DBO, QHDBO, GODBO, and EIDBO, achieving reductions in average total cost of 68.81%, 39.19%, 68.02%, and 66.56%, respectively. In more complex scenarios, the algorithm exhibits even greater efficacy, with average total cost reductions of 76.12%, 54.42%, 83.97%, and 73.61%, respectively. In conclusion, BFDBO consistently achieves a minimum reduction of 39% in flight costs relative to other algorithms across various environments, thereby significantly enhancing the efficiency of trajectory planning. Furthermore, BFDBO also demonstrates superior average runtime performance compared to other algorithms, indicating its greater efficiency and suitability for time-sensitive trajectory planning applications.

Figure 15: Average convergence curve: (a) simple scenario; (b) complex scenario

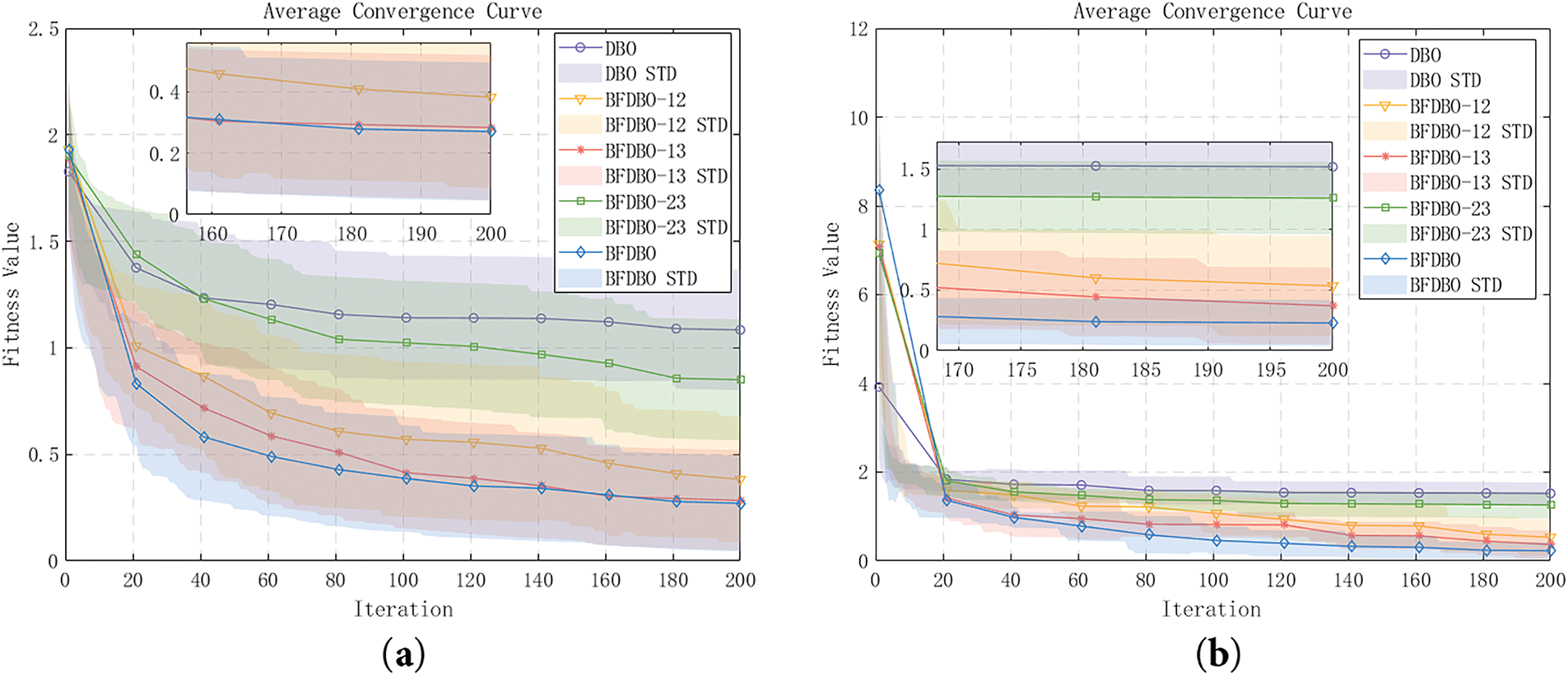

To further investigate the impact of the three enhancement strategies on trajectory planning, ablation experiments were performed utilizing the same parameter configurations as in the preceding experiments, with the findings illustrated in Fig. 16. The results indicate that each enhancement strategy contributes to the overall performance. Notably, the exclusion of improvement strategy 2 from BFDBO-13 leads to convergence speed and accuracy that are comparable to those of the complete BFDBO algorithm in both simple and complex scenarios, suggesting that improvement strategy 2 has a relatively limited impact on the trajectory planning task. Conversely, the removal of improvement strategy 1 from BFDBO-23 resulted in only marginal enhancements in both scenarios, slightly surpassing the baseline algorithm DBO. This finding implies that improvement strategy 1 plays a significant role in the trajectory planning task and can exert a decisive influence. Although variants that incorporate any two of the improvement strategies demonstrate varying levels of enhancement over the original algorithm, the BFDBO that integrates all three strategies remains superior in terms of convergence speed, convergence time, and robustness. This suggests that the synergistic effect of the three strategies is optimal, leading to reduced route costs and promoting more efficient and safer UAV operations.

Figure 16: Average convergence curve: (a) simple scenario; (b) complex scenario

This study proposes an innovative multi-UAV trajectory planning algorithm named BFDBO, which integrates boundary reflection optimization, adaptive hybrid exploration, and dynamic adaptive multi-scale variational strategies based on the DBO algorithm. This integration significantly enhances the algorithm’s obstacle avoidance and swarm coordination capabilities in complex battlefield environments. The carefully designed cost function effectively balances trajectory optimality, safety, and coordination. Comparative and ablation studies conducted using the CEC2022 benchmark dataset demonstrate that BFDBO exhibits robust global optimization capabilities, with the effectiveness of its enhanced strategies validated. Simulations of typical battlefield scenarios show that BFDBO significantly outperforms the original DBO and its three high-performance variants in terms of trajectory quality, a conclusion validated by metrics such as mean, optimal results, and standard deviation, while also demonstrating superior operational efficiency. However, when applied to real military environments, the algorithm faces significant challenges and potential limitations, primarily due to the inherent complexity and uncertainty of battlefield environments. The threat and obstacle models used in the current simulation framework are relatively static and idealized, whereas actual battlefields exhibit dynamic characteristics, including rapidly changing threats, sudden electronic interference, complex weather conditions, and unstructured or unknown terrain. The algorithm’s sensitivity to environmental modelling errors has become a key evaluation metric and requires further study in subsequent phases. Additionally, when deploying the algorithm on resource-constrained embedded airborne platforms, it is essential to develop lightweight, parallel, and potentially distributed computational architectures to support practical applications. Therefore, future research will focus on establishing high-fidelity, adversarial simulation environments to rigorously evaluate BFDBO’s performance in addressing dynamic unknown threats, significant communication interference, and complex electromagnetic conditions, and to conduct empirical validation of BFDBO through deployment on actual unmanned aerial vehicle platforms.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Defense Science and Technology Innovation project, grant number ZZKY20223103; the Basic Frontier Innovation Project at the Engineering University of PAP, grant number WJY202429; the Basic Frontier lnnovation Project at the Engineering University of PAP, grant number WJY202408; the Graduate Student Funding Priority Project, grant number JYWJ2024B006; Key project of National Social Science Foundation, grant number 2023-SKJJ-A-116.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Weicong Tan; data collection: Qiwu Wu; analysis and interpretation of results: Weicong Tan, Lingzhi Jiang; draft manuscript preparation: Weicong Tan, Tao Tong, Yunchen Su. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The readers can access the data used in the study by contacting the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cao H, Li S, Li X, Liu Y. A UAV path-planning approach for urban environmental event monitoring. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(3):5575–93. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.061954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Stodola P, Drozd J, Mazal J, Hodický J, Procházka D. Cooperative unmanned aerial system reconnaissance in a complex urban environment and uneven terrain. Sensors. 2019;19(17):3754. doi:10.3390/s19173754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Tong P, Yang X, Yang Y, Liu W, Wu P. Multi-UAV collaborative absolute vision positioning and navigation: a survey and discussion. Drones. 2023;7(4):261. doi:10.3390/drones7040261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang L, Huang W, Li H, Li W, Chen J, Wu W. A review of collaborative trajectory planning for multiple unmanned aerial vehicles. Processes. 2024;12(6):1272. doi:10.3390/pr12061272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Pishvaee MS, Fazli Khalaf M. Novel robust fuzzy mathematical programming methods. Appl Math Model. 2016;40(1):407–18. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2015.04.054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lieberman ER. Soviet multi-objective mathematical programming methods: an overview. Manag Sci. 1991;37(9):1147–65. doi:10.1287/mnsc.37.9.1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. He Z, Liu C, Chu X, Negenborn RR, Wu Q. Dynamic anti-collision A-star algorithm for multi-ship encounter situations. Appl Ocean Res. 2022;118(1):102995. doi:10.1016/j.apor.2021.102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. AlShawi IS, Yan L, Pan W, Luo B. Lifetime enhancement in wireless sensor networks using fuzzy approach and A-star algorithm. IEEE Sens J. 2012;12(10):3010–8. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2012.2207950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jeong IB, Lee SJ, Kim JH. Quick-RRT*: triangular inequality-based implementation of RRT* with improved initial solution and convergence rate. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;123(2):82–90. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2019.01.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Salzman O, Halperin D. Asymptotically near-optimal RRT for fast, high-quality motion planning. IEEE Trans Robot. 2016;32(3):473–83. doi:10.1109/TRO.2016.2539377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Duhé JF, Victor S, Melchior P. Contributions on artificial potential field method for effective obstacle avoidance. Fract Calc Appl Anal. 2021;24(2):421–46. doi:10.1515/fca-2021-0019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kumar PB, Rawat H, Parhi DR. Path planning of humanoids based on artificial potential field method in unknown environments. Expert Syst. 2019;36(2):e12360. doi:10.1111/exsy.12360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mirjalili S, Mirjalili SM, Lewis A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv Eng Softw. 2014;69:46–61. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2013.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Saremi S, Mirjalili S, Lewis A. Grasshopper optimisation algorithm: theory and application. Adv Eng Softw. 2017;105:30–47. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2017.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chakraborty S, Sharma S, Saha AK, Chakraborty S. SHADE-WOA: a metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization. Appl Soft Comput. 2021;113(3):107866. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Mirjalili S. Genetic algorithm. In: Mirjalili S, editor. Evolutionary algorithms and neural networks: theory and applications. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2019. p. 43–55. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93025-1_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Poli R, Kennedy J, Blackwell T. Particle swarm optimization. Swarm Intell. 2007;1(1):33–57. doi:10.1007/s11721-007-0002-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Katoch S, Chauhan SS, Kumar V. A review on genetic algorithm: past, present, and future. Multimed Tools Appl. 2021;80(5):8091–126. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-10139-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Shao S, Peng Y, He C, Du Y. Efficient path planning for UAV formation via comprehensively improved particle swarm optimization. ISA Trans. 2020;97(1–4):415–30. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2019.08.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Xue J, Shen B. Dung beetle optimizer: a new meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization. J Supercomput. 2023;79(7):7305–36. doi:10.1007/s11227-022-04959-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chen Q, Wang Y, Sun Y. An improved dung beetle optimizer for UAV 3D path planning. J Supercomput. 2024;80(18):26537–67. doi:10.1007/s11227-024-06414-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ye M, Zhou H, Yang H, Hu B, Wang X. Multi-strategy improved dung beetle optimization algorithm and its applications. Biomimetics. 2024;9(5):291. doi:10.3390/biomimetics9050291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zhu F, Li G, Tang H, Li Y, Lv X, Wang X. Dung beetle optimization algorithm based on quantum computing and multi-strategy fusi on for solving engineering problems. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;236(1):121219. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Qiao L, Chen L, Li Y, Hua W, Wang P, Cui Y. Predictions of aeroengines’ infrared radiation characteristics based on HKELM optimized by the improved dung beetle optimizer. Sensors. 2024;24(6):1734. doi:10.3390/s24061734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Hu W, Zhang Q, Ye S. An enhanced dung beetle optimizer with multiple strategies for robot path planning. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):4655. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-88347-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Wu Q, Tan W, Zhan R, Jiang L, Zhu L, Wu H. GLBWOA: a global-local balanced whale optimization algorithm for UAV path planning. Electronics. 2024;13(23):4598. doi:10.3390/electronics13234598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Orozco-Rosas U, Montiel O, Sepúlveda R. Mobile robot path planning using membrane evolutionary artificial potential field. Appl Soft Comput. 2019;77(2):236–51. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2019.01.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liu S, Jin Z, Lin H, Lu H. An improve crested porcupine algorithm for UAV delivery path planning in challenging environments. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):20445. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-71485-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Jorris TR, Cobb RG. Three-dimensional trajectory optimization satisfying waypoint and no-fly zone constraints. J Guid Control Dyn. 2009;32(2):551–72. doi:10.2514/1.37030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kuwata Y, How JP. Cooperative distributed robust trajectory optimization using receding horizon MILP. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2010;19(2):423–31. doi:10.1109/TCST.2010.2045501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Pandit D, Zhang L, Chattopadhyay S, Lim CP, Liu C. A scattering and repulsive swarm intelligence algorithm for solving global optimization problems. Knowl Based Syst. 2018;156(4598):12–42. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2018.05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Arora S, Singh S. Butterfly optimization algorithm: a novel approach for global optimization. Soft Comput. 2019;23(3):715–34. doi:10.1007/s00500-018-3102-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Duan H, Qiao P. Pigeon-inspired optimization: a new swarm intelligence optimizer for air robot path planning. Int J Intell Comput Cybern. 2014;7(1):24–37. doi:10.1108/ijicc-02-2014-0005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhong C, Li G, Meng Z. Beluga whale optimization: a novel nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;251(1):109215. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Jia H, Rao H, Wen C, Mirjalili S. Crayfish optimization algorithm. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(2):1919–79. doi:10.1007/s10462-023-10567-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Dao PB. On Wilcoxon rank sum test for condition monitoring and fault detection of wind turbines. Appl Energy. 2022;318(1):119209. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Murakami H. The power of the modified Wilcoxon rank-sum test for the one-sided alternative. Statistics. 2015;49(4):781–94. doi:10.1080/02331888.2014.913049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chang Z, Luo J. EIDBO-TrICP: a coarse-to-fine algorithm for cross-source point cloud registration in aero-engine blades. Eng Res Express. 2025;7(1):015280. doi:10.1088/2631-8695/adb4bf. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wang Z, Shao P. A multi-strategy dung beetle optimization algorithm for optimizing constrained engineering problems. IEEE Access. 2023;11:98805–17. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3313930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Renner G, Weiß V. Exact and approximate computation of B-spline curves on surfaces. Comput Aided Des. 2004;36(4):351–62. doi:10.1016/S0010-4485(03)00100-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Huo F, Zhu S, Dong H, Ren W. A new approach to smooth path planning of Ackerman mobile robot based on improved ACO algorithm and B-spline curve. Robot Auton Syst. 2024;175(11):104655. doi:10.1016/j.robot.2024.104655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Phung MD, Ha QP. Safety-enhanced UAV path planning with spherical vector-based particle swarm optimization. Appl Soft Comput. 2021;107(2):107376. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kiani F, Nematzadeh S, Anka FA, Findikli MA. Chaotic sand cat swarm optimization. Mathematics. 2023;11(10):2340. doi:10.3390/math11102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Abdollahzadeh B, Khodadadi N, Barshandeh S, Trojovský P, Gharehchopogh FS, El-kenawy EM, et al. Puma optimizer (POa novel metaheuristic optimization algorithm and its application in machine learning. Cluster Comput. 2024;27(4):5235–83. doi:10.1007/s10586-023-04221-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Anka F, Aghayev N. Advances in sand cat swarm optimization: a comprehensive study. Arch Comput Meth Eng. 2025;32(5):2669–712. doi:10.1007/s11831-024-10217-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zhou G, Fang Z, Hu Y, Chen J, Ren J. An adaptive strategy quantum particle swarm optimization method based on intuitionistic fuzzy entropy and evolutionary game theory. Appl Soft Comput. 2025;183:113654. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.113654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools