Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Division in Unity: Towards Efficient and Privacy-Preserving Learning of Healthcare Data

1 College of Computer Science and Technology, National University of Defense Technology, Changsha, 410073, China

2 921 Hospital of Joint Logistics Support Force, People’s Liberation Army of China, Changsha, 410073, China

3 Test Center, National University of Defense Technology, Xi’an, 710018, China

* Corresponding Author: Tongqing Zhou. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2913-2934. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069175

Received 16 June 2025; Accepted 19 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

The isolation of healthcare data among worldwide hospitals and institutes forms barriers for fully realizing the data-hungry artificial intelligence (AI) models promises in renewing medical services. To overcome this, privacy-preserving distributed learning frameworks, represented by swarm learning and federated learning, have been investigated recently with the sensitive healthcare data retaining in its local premises. However, existing frameworks use a one-size-fits-all mode that tunes one model for all healthcare situations, which could hardly fit the usually diverse disease prediction in practice. This work introduces the idea of ensemble learning into privacy-preserving distributed learning and presents the En-split framework, where the predictions of multiple expert models with specialized diagnostic capabilities are jointly explored. Considering the exacerbation of communication and computation burdens with multiple models during learning, model split is used to partition targeted models into two parts, with hospitals focusing on building the feature-enriched shallow layers. Meanwhile, dedicated noises are implemented to the edge layers for differential privacy protection. Experiments on two public datasets demonstrate En-split’s superior performance on accuracy and efficiency, compared with existing distributed learning frameworks.Keywords

Globally, the isolation of healthcare data among hospitals and institutes poses significant barriers to the realization of data-driven advancements in medical services [1]. This data isolation is particularly challenging for data-hungry Artificial Intelligence (AI) models, which depend on large datasets to achieve high accuracy and generalizability [2]. Privacy-preserving distributed learning frameworks, such as swarm learning and federated learning (FL), have emerged as promising solutions by allowing sensitive data to remain localized while still contributing to model training [3–5]. Especially in the medical field, researchers use privacy-preserving distributed learning to improve health care services [6–8]. Given this challenge, we focus on sepsis detection as our primary case study. Sepsis, responsible for approximately 20% of global deaths and affecting over one-third of patients who die in U.S. hospitals, remains a critical focus of medical and healthcare research [9]. However, predictive models developed using data from a single institution may not perform well in other settings due to variations in patient demographics, clinical practices, and data collection methods.

To the best of our knowledge, current research on cross-center sepsis prediction is primarily categorized into two branches: the first focuses on federated learning approaches, which emphasize privacy and collaborative learning without sharing patient data, and the second involves transfer learning approaches, which concentrate on leveraging pretrained models to enhance performance in environments with limited local data.

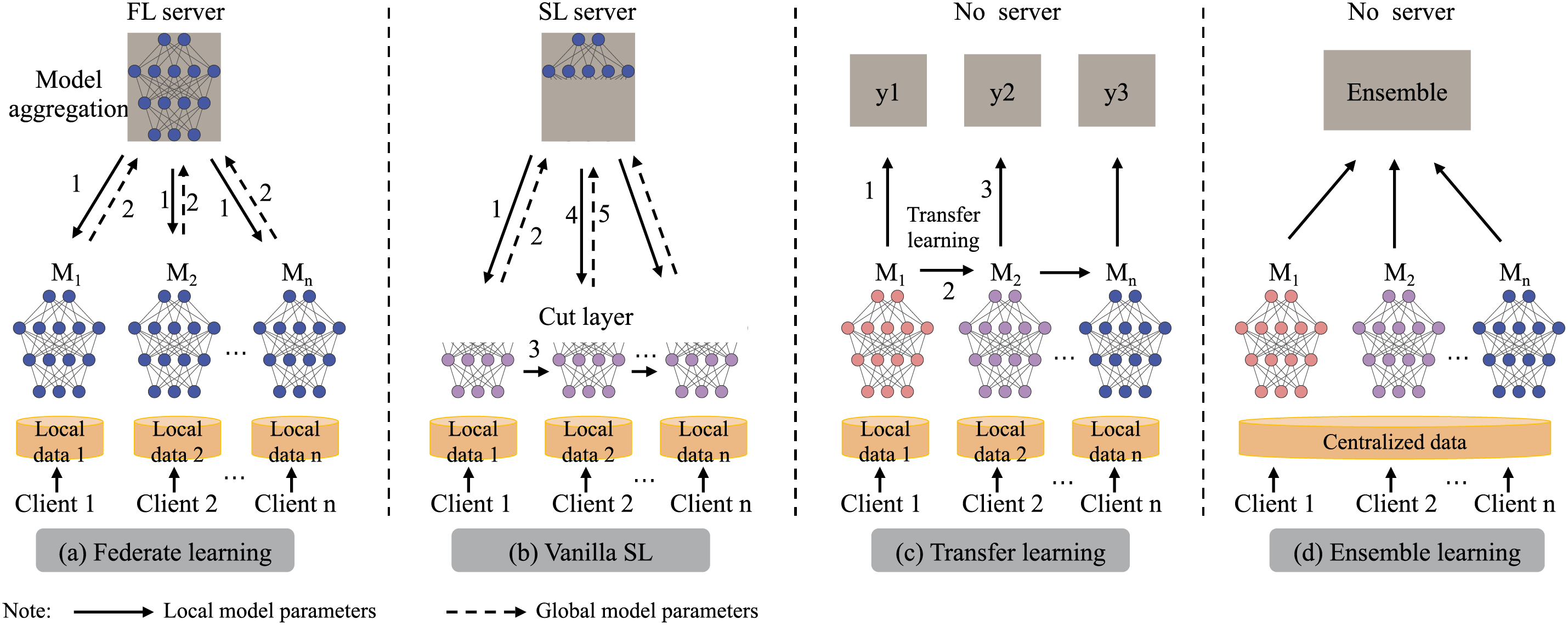

FL (Fig. 1a) enables institutions to collaboratively train models by sharing only weight or gradient updates, keeping raw data local [10,11]. Although FL often outperforms standalone training, data heterogeneity can still degrade its effectiveness, for example, the federated representation and classification learning system algorithm improves sepsis prediction by leveraging superior external classifiers [12]. However, a single global model may miss site-specific patterns and lack diversity. Split Learning (SL) addresses this by partitioning the network between clients and server to reduce client workload without sharing sensitive data [13] (Fig. 1b), but its sequential forward–backward passes incur high latency and even parallel variants struggle with integrating heterogeneous architectures, which limits scalability [14].

Figure 1: Illustration of the learning architectures of FL, vanilla SL, Transfer learning and Common ensemble learning (In order from left to right)

Transfer learning (Fig. 1c) improves generalization across hospitals by adapting a model trained on a well-labeled source domain to a target domain with scarce labels [15]. To predict Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients with sepsis, SofaNet leverages cross-center knowledge sharing and fine-tuning techniques. Moreover, statistical transfer learning has been shown to reduce the data requirements for mortality prediction [16]. However, in highly heterogeneous healthcare settings, transfer methods often need careful feature-space alignment and hyperparameter tuning to fully capture local variability.

Ensemble learning (EL, as shown in Fig. 1d) improves diagnostic accuracy and robustness by combining diverse base models, thereby capturing a broader range of patterns and mitigating correlated errors [17–19]. Aggregation methods—voting [20], averaging [21], or stacking [22]—further improve performance across heterogeneous settings. However, most ensemble work assumes centralized data pools, conflicting with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) privacy rules and complicating the collection of large, varied clinical datasets, especially those with rare subgroups. As a result, data silos and regulatory constraints often prevent traditional ensembles from fully realizing their potential in real-world healthcare.

FL enforces model homogeneity across sites, which limits its ability to handle diverse, site-specific data patterns and can lead to suboptimal performance in heterogeneous healthcare environments. For instance, the reliance on synchronous aggregation often introduces high latency, particularly in scenarios with varying network conditions or computational resources among institutions. Similarly, EL, while effective in combining diverse models, typically assumes centralized data access, which conflicts with privacy regulations and exacerbates latency issues in distributed settings. These limitations highlight the need for frameworks that support model heterogeneity without compromising efficiency.

Existing frameworks usually train a single global model for all sites, which struggles to capture the diverse characteristics of different patient populations and institutions. To solve this, we propose En-split, an integrated Ensemble-Split Learning architecture that combines the privacy of SL with the robustness of EL. In En-split, each hospital trains only its local model fragment—keeping raw data in place—while a central server ensembles their noisy activations into a unified predictor. This design preserves patient privacy through localized data handling, enables heterogeneous models tailored to each institution’s data, and leverages specialized learners to minimize biases and errors, thereby improving early sepsis detection accuracy across varied clinical settings.

In our research, we present three key contributions to sepsis management through our integrated framework.

• We introduce En-split, the first framework that unifies EL with SL to tackle distributed sepsis detection. En-split enhances generalizability via coordinated multi-institutional model fusion and enforces patient privacy by keeping all raw data localized.

• On both Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care III (MIMIC-III) and PhysioNet Computing in Cardiology Challenge 2019 (Challenge) datasets, En-split not only rivals traditional centralized ensembles—delivering an approximate

Through these contributions, the En-split framework provides a new solution in the predictive modeling of sepsis, offering substantial improvements in patient care and operational efficiency within healthcare settings.

The key challenge in managing sepsis is early detection and timely intervention. Research in this field can be categorized into two primary approaches: classical machine learning methods and deep learning models.

Classical Machine Learning Model. Classical machine-learning models have laid the groundwork for sepsis prediction. Decision trees (DT) offer interpretability for exploratory analysis [23,24], while random forests (RF) leverage many DTs—for example, achieving AUC 0.91 on ICU data with 55 features [25]. Logistic regression (LR), when enriched with Electronic Medical Records (EMR), demographic, and history data, also improves early detection up to four hours in advance [26]. Gradient boosting (GB) sequentially corrects weak-learner errors and handles varied clinical inputs effectively. Bayesian networks can flag high-risk septic shock 24 h before onset [27], and K-nearest neighbors (KNN) similarly classify patients using vital signs and labs [28]. However, these methods depend heavily on feature selection, limiting their ability to capture complex data correlations.

Deep Learning Model. The advent of deep learning has led to significant advancements in sepsis prediction. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks excel at processing time-series data, which is essential for tracking changes in patient conditions over time. Strickler et al. [29] introduced a novel global interpretation mechanism to analyze a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model trained on ICU data, identifying 17 key features for sepsis detection. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been adapted for biomedical relation extraction tasks [30], and have also been used to predict the onset of septic shock [31]. Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) are similar to LSTMs but are more efficient computationally, Sakri et al. [32] proposed a hybrid deep learning model combining CNN and BDLSTM, using six observation windows (24 h to 1 h before onset) on the MIMIC-III dataset for early sepsis prediction, achieving an AUROC of 0.9974 and accuracy of 0.9915 at 1 h before onset, outperforming all baseline models.

Split learning (SL) partitions a neural network between clients and a central server, so that each node computes only its local segment and shares intermediate activations instead of raw data. First introduced by Vepakomma et al. in 2018 [13], SL both eliminates global-model privacy risks and cuts communication overhead by transmitting only features, not patient records. In healthcare, Ayad et al. applied a modified SL with semi-supervised learning to electrocardiogram (ECG) classification, achieving high accuracy and efficiency for green-AI internet of things (IoT) devices [33]. Thapa et al. [14] further combined FL and SL in “splitfed learning” boosting privacy and robustness while reducing computation time and network traffic.

Ensemble learning (EL) boosts prediction accuracy and robustness by combining multiple models to mitigate overfitting and capture complex sepsis patterns. Ding et al. proposed self-paced ensemble for Sepsis early detection (SPSSOT), a semi-supervised transfer-ensemble framework, enhances early detection across hospitals with limited labels [8], though it lacks privacy guarantees. Voting ensembles of logistic regression and random forest have also been applied to sepsis screening [34], and deep models trained on multi-national ICU data further improve generalization [35]. Recent privacy-preserving efforts include Secure Multi-Party Computation (MPC) protocols for secure decision-tree ensembles [36] and FedEL’s decentralized ensemble achieving 99% accuracy in transport-mode detection [37]. To date, split learning remains underexplored in medical ensemble contexts despite its natural privacy advantages.

While Federated Learning (FL) and Ensemble Learning (EL) offer valuable approaches, their limitations in handling model heterogeneity and latency warrant further scrutiny. FL’s single global model often fails to accommodate diverse architectures, leading to reduced adaptability in non-IID (independent and identically distributed) healthcare data distributions, as seen in studies on sepsis prediction [10]. EL, on the other hand, incurs high computational overhead due to centralized aggregation, making it impractical for privacy-constrained environments.

In comparison, hybrid privacy-preserving methods such as Homomorphic Encryption (HE) enable computations on encrypted data but introduce significant latency and resource demands, limiting scalability in real-time medical applications. Secure Multi-Party Computation (MPC) provides robust privacy through joint computations without data sharing [36], yet it struggles with efficiency in large-scale, heterogeneous networks. Federated analytics focuses on aggregated statistics rather than full model training, potentially missing nuanced patterns, while MPC-enhanced FL combines these for better security but often at the cost of increased communication overhead. En-split addresses these gaps by integrating SL with EL in a way that enables model diversity—allowing each institution to use heterogeneous architectures tailored to local data—while reducing overhead through efficient activation sharing instead of full model weights. Unlike HE or MPC, which require heavy cryptographic operations, En-split enhances personalized privacy protection via tunable differential privacy on activations, balancing utility and security without excessive latency. This makes En-split particularly suited for distributed sepsis detection, filling the void in scalable, privacy-aware frameworks for heterogeneous healthcare settings. To further clarify the distinctions between these approaches, Table 1 provides a comparative analysis of their key characteristics.

Furthermore, situating En-split within recent advances in secure machine learning for healthcare, we note alignments with studies on IoT and blockchain-based privacy mechanisms. For instance, Qureshi et al. [38] explored dynamic protocols for protecting non-IID data in virtual environments, addressing client heterogeneity through adaptive security. Similarly, Ullah et al. [39] used blockchain for robust auditing and efficient learning across distributed records, emphasizing privacy in heterogeneous settings. These works provide useful comparative perspectives, as they focus on data-level security and heterogeneity, which complement En-split’s emphasis on model training privacy via split learning and differential privacy. By integrating ensemble methods with lower overhead, En-split extends these ideas to collaborative AI tasks, positioning it as a practical bridge between secure data management and efficient distributed model building in healthcare.

In this section, we first define our research problem from the perspective of ensemble learning (EL). Next, we reformulate the problem within the framework of split learning (SL). To enhance the parallelism of SL training, we draw inspiration from the parallel training strategy used in SplitFed [14].

The primary objective of our study is to leverage the clinical data of patients to detect the onset of sepsis. We refer to the “PhysioNet Computing in Cardiology Challenge 20191 ” on the onset of sepsis from clinical data [40]. We first analyze the mainstream sepsis classification scenarios. Consider K hospital, denoted

The

The

We aggregate all clients local models by applying weights to their parameters. Weights of voting

When we try to segment the model for the integrated network, the basic idea is to put different model classifiers in different hospital institutions, which are divided into server side and client side. In other words, we refer to the classic federated learning architecture, but unlike federated learning, which has the same model structure for each client. In our scenario, the server side is the ensemble model, and the client side is different sub-classifier model. For convenience, some key notations are presented in Table 2.

4.1 Ensemble Split Learning Framework

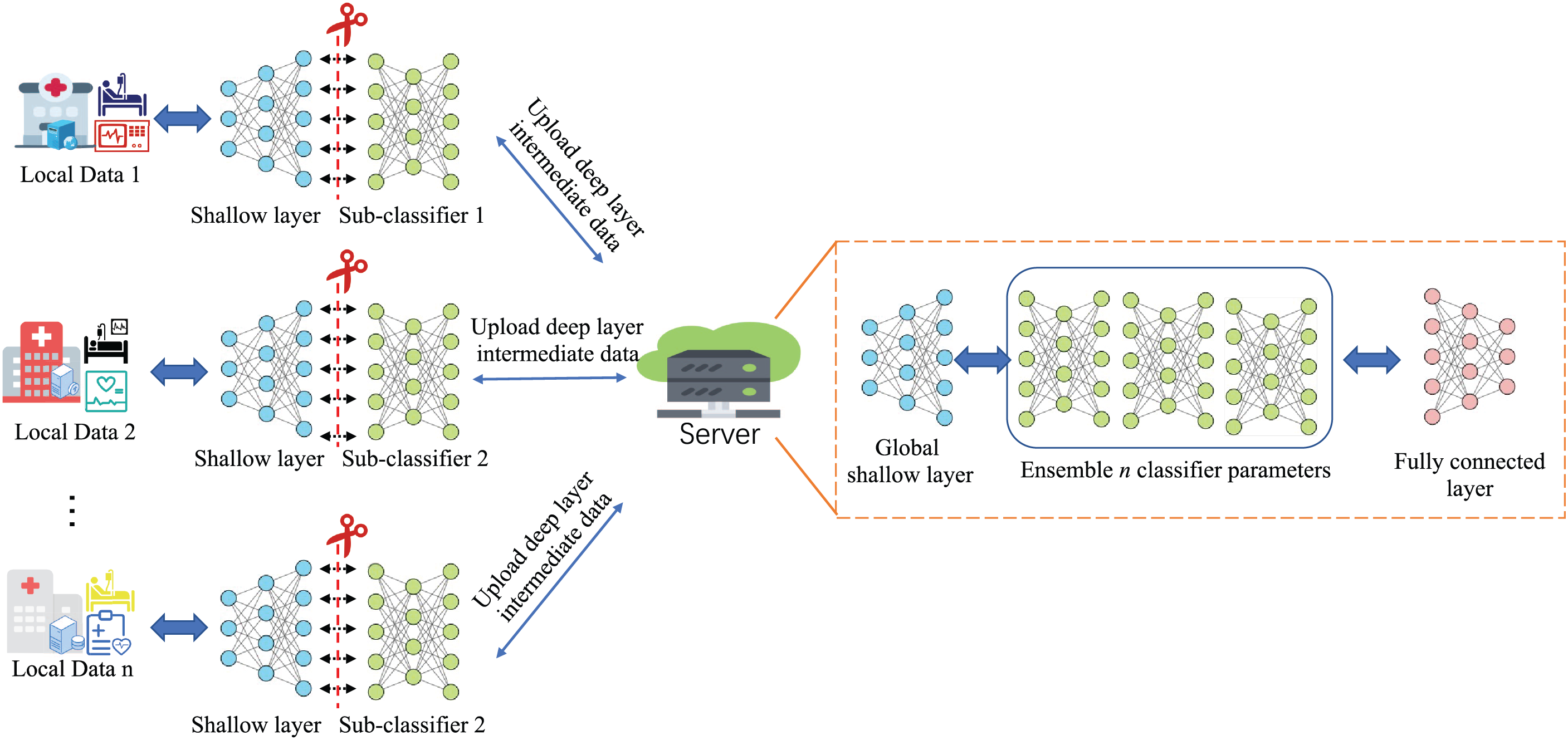

Fig. 2 illustrates the architecture the architecture of the En-split framework. The framework integrates multiple classification algorithms to leverage their joint efforts for sepsis classification. To address data scarcity and imbalance with privacy safeguards, it employs split learning and ensemble neural networks across multiple hospital sites. En-split is structured around a server-client architecture, where the server is typically hosted by a highly trusted institution.

Figure 2: Ensemble split learning (En-split) framework overview

The server mainly acts as a central node in the En-split framework, coordinating the learning process and sending or receiving different models intermediate parameters by different clients. The fundamental procedures of the framework can be outlined as follows:

1. Feature Evaluation and Filtering: The server is responsible for assessing and selecting relevant features from the data. Specifically, let X represent the complete data set features available to all clients. The server defines a feature set

2. Model Initialization and Synchronization: The server initializes the basic parameters of the models for each client, which involves setting up the initial configurations denoted by

3. Intermediate Parameter Integration: After the clients train their models locally, they upload their intermediate model parameters to the server, represented as

To highlight En-split’s advantages over conventional federated learning, we emphasize its support for heterogeneous model architectures across clients. Unlike FL’s strict homogeneity, En-split allows customized neural structures optimized for local data, enabling enhanced personalization, compatibility with diverse distributions, and effective global knowledge aggregation. This produces superior generalization in medical scenarios, from diagnostic tasks to prognostic modeling.

Notably, this architectural divergence facilitates three critical improvements: (1) Enhanced model personalization through domain-specific feature extraction, (2) Improved compatibility with heterogeneous medical data distributions, and (3) More effective knowledge aggregation at the global model level. By allowing localized adaptation of network depth, layer configurations, and attention mechanisms, each client model becomes a specialized feature extractor for its particular clinical context, thereby capturing nuanced pathophysiological patterns that would otherwise be obscured in homogeneous architectures. This heterogeneous ensemble approach ultimately produces a global model with superior generalization capabilities across diverse medical scenarios, ranging from multi-modal diagnostic tasks to population-specific prognostic modeling.

4.2 En-Split Framework Workflow

We first outline the training mechanism for binary classification in sepsis detection using split learning. Each client

where

where

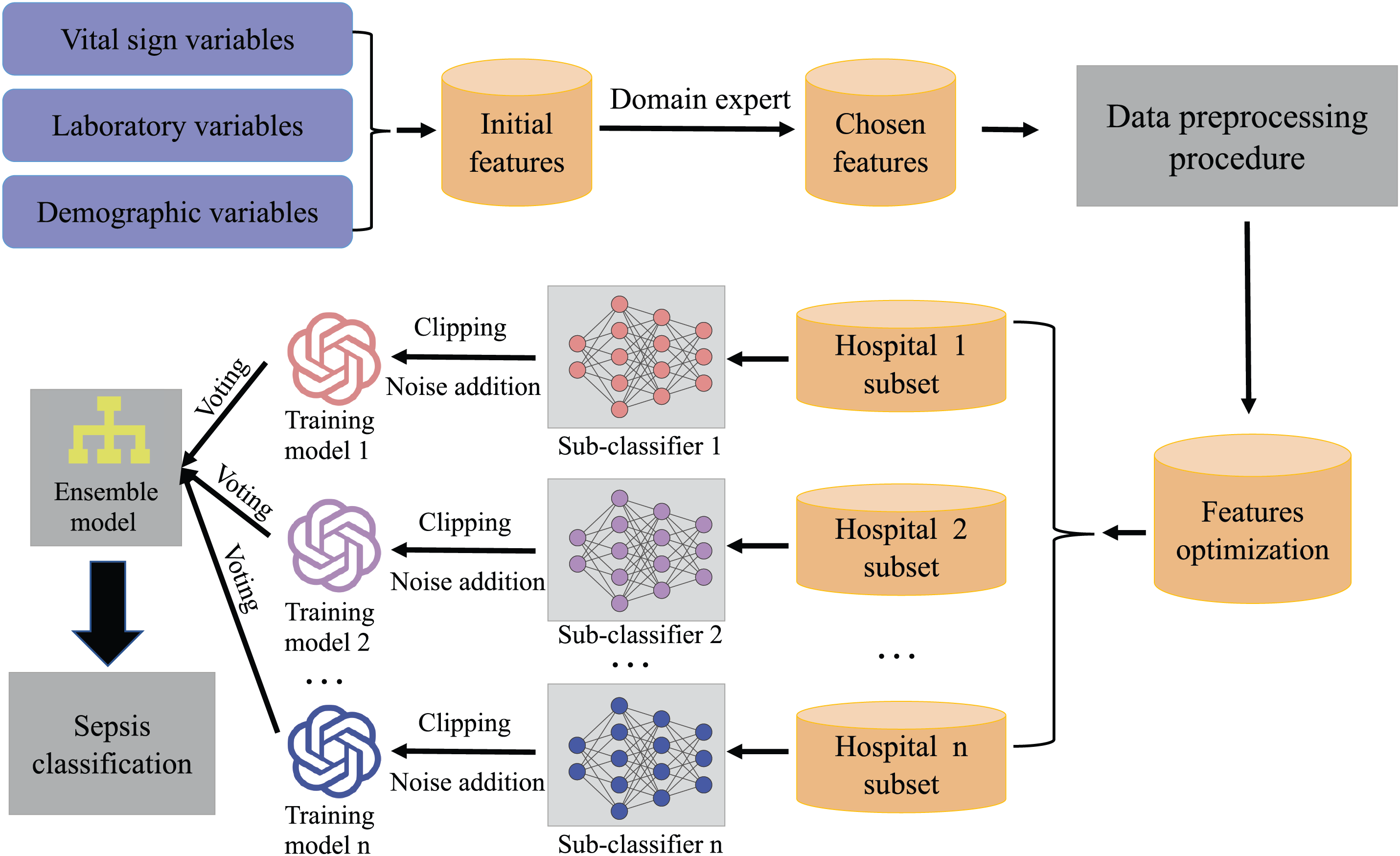

The En-split workflow proceeds as follows, as illustrated in the simplified flow diagram in Fig. 3. The server notifies selected clients to choose consistent models (e.g., random forest, decision tree, and MLP) for sepsis identification. Clients conduct initial local training with global weights, update local parameters, and fit non-neural models before sending them to the server. Predictions from the models are combined via majority voting to produce the final output, where the class with the most votes is selected (e.g., for predictions [1, 1, 0], [1, 0, 0], and [1, 0, 1], the output is determined by index-wise majority).

Figure 3: Simplified flow diagram of En-split workflow

To handle asynchronous or straggler clients, which are common in federated or split learning settings, En-split incorporates a quorum-based aggregation mechanism. The server proceeds with updates after receiving responses from a predefined subset of clients (e.g., a majority quorum) within a time window, mitigating delays from slow or non-responsive participants. This approach ensures training continuity without requiring full synchronization, leveraging the framework’s parallel design (as in the aggregation step of Algorithm 1) to maintain efficiency in variable network conditions.

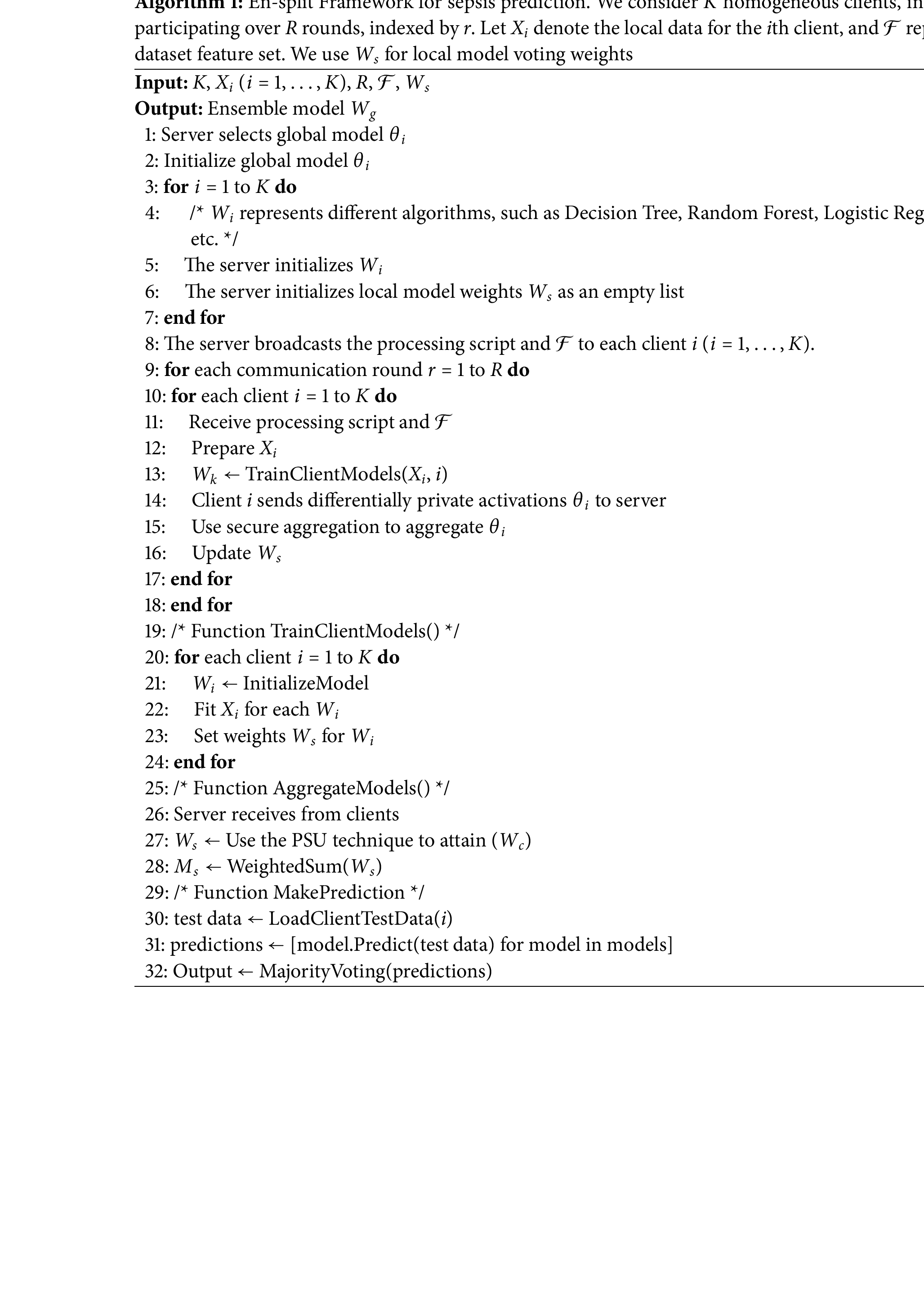

This process is formalized in Algorithm 1 below, which describes the hybrid ensembling combining neural and non-neural networks.

To protect patient information against inversion and membership inference attacks, En-split applies

Here,

In our experiments, we set

This study utilizes two widely recognized, publicly available, de-identified datasets: the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care III (MIMIC-III) and the PhysioNet Computing in Cardiology Challenge 2019. Both datasets contain anonymized patient information, exempting our research from requiring specific institutional review board (IRB) approval or ethics committee oversight, in accordance with standard guidelines for secondary analysis of de-identified data.

MIMIC-III is a comprehensive critical care database containing de-identified health data from over 40,000 ICU patients at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center between 2001 and 2012, including vital signs, medications, and laboratory results. Access to MIMIC-III was obtained after completing the required Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) Program course on data research ethics. The PhysioNet Computing in Cardiology Challenge 2019 dataset focuses specifically on sepsis prediction and includes relevant clinical features essential for our study. These datasets are particularly suitable for validating our proposed framework and evaluating the performance of our differential privacy approaches. Summary statistics of the datasets are provided in Table 3.

In our research, we carefully extracted clinical variables and sepsis indicators from Electronic Medical Records (EMR) to establish the foundation for our feature engineering efforts. The process is visualized in Fig. 4, illustrating our structured stage approach to optimize feature selection for predictive modeling of sepsis.

Figure 4: Flowchart of the processing for dataset MIMIC-III and challenge

Similarly, we start by thoroughly examining relevant datasets and existing research to pinpoint an initial batch of potential features. Through this process, we uncover several key indicators and metrics that are vital for our predictive model. This review brings to light 37 clinical variables (Table 4), which are divided into 6 vital signs, 21 laboratory measures, 4 demographic factors, 4 statistics variables, and 2 other variables (SOFA base and qSOFA (quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment base [42]).

In this study, we evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed algorithm, En-split, compared to three baseline methods: federated learning (FL), vanilla split learning (SL), and conventional ensemble learning (EL). Each of these approaches represents a distinct strategy in handling the complexities of medical data analysis, particularly in the context of leveraging large, diverse datasets like MIMIC-III and the PhysioNet Challenge 2019 dataset.

• Federated Learning: This approach involves training algorithms collaboratively without exchanging the data itself. It is particularly useful in scenarios where data privacy is paramount, allowing multiple institutions to contribute to a model’s learning process without sharing sensitive information.

• Vanilla SL: This variant of supervised learning involves splitting the model training process across multiple parties, where each party computes a portion of the forward pass of the neural network. The intermediate outputs are then transferred to a central server or the next participant for further processing. This method helps in preserving privacy by not requiring the raw data to be shared, and is particularly useful when dealing with sensitive or proprietary datasets. In our experiments, Vanilla SL serves as a baseline to assess the effectiveness of distributed learning techniques in healthcare applications.

• Ensemble Learning with Voting: This approach brings together predictions from several different learning algorithms and then uses a voting system to come up with a final prediction. In our case, we put together a bunch of different classifiers. Each one makes its own prediction on its own, and then we look at all those predictions together. The final answer is whatever the majority of the classifiers decided on. This method makes our predictions more reliable because it cuts down on the chances of making a mistake (that’s the “variance” part) and it also takes advantage of the good points of each model, which helps us get more accurate results overall. In our research, using ensemble learning with voting is kind of like our starting point. It helps us see how well different models can work together to make decisions in complicated healthcare situations.

Similarly, by looking at these different methods side by side, we want to show why En-split is better when it comes to dealing with real-world healthcare data. We’re focusing on how it can keep performing really well while also making sure that data stays private and making the most of the limited labeled data we have.

In this study, we evaluate the effectiveness of the En-split algorithm and compare its performance under proper privacy protection. The models employed include Random Forest, Decision Tree, and Logistic Regression. All experiments were conducted in Python using the PyTorch 1.12 framework. Hyperparameters were tuned via grid search: the Random Forest model used 100 trees, the Gini impurity criterion, and a maximum depth of 20, while Logistic Regression employed default parameters with scale_pos_weight adjusted to address class imbalance. For deep learning components in the federated learning (FL) and split learning (SL) baselines, the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 was used, and each client performed 5 local training epochs per communication round.

Data preprocessing included Min-Max scaling for numerical features, mean imputation for missing values in time-series data, and consistent feature scaling across all clients. Experiments were conducted on a system with an Intel i9-10940X CPU and an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU, and batch sizes for neural network models were set to 32.

For the FL baseline, we adopted the FedAvg algorithm, where the server aggregated client models using a weighted average based on sample sizes. For the SL baseline, a simple multilayer perceptron (MLP) was split after the second fully connected layer. Clients executed forward propagation up to the splitting layer and calculated backward gradients, while the server handled the remaining forward and backward propagation.

To ensure data privacy, a privacy budget of

6.1 Model Convergence Performance

We analyze the performance of our proposed En-split framework compared to federated learning (FL), split learning (SL), and ensemble learning (EL) across different data volume settings. The primary evaluation metric is the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) curve, which assesses the diagnostic ability of the models.

Suppose there are

Figure 5: AUROC curve of SL, FL, EL and En-split under various client data fraction on Challenge datasets

Figure 6: AUROC curve of SL, FL, EL and En-split under various client data fraction on MIMIC datasets

The En-split framework demonstrates an AUROC comparable that of EL. This similar performance is mainly attributed to the robust model aggregation capabilities present in both methods. En-split integrates EL and SL, thereby leveraging the strengths of both. The EL part ensures robust model aggregation, capturing diverse data patterns and enhancing diagnostic accuracy. In contrast, the SL part safeguards data privacy and localization, preventing data breaches and protecting patient information integrity. Together, they effectively address traditional ensemble learning limitations, such as data access problems and model diversity challenges.

EL shows superior performance over FL due to its ability to combine multiple models, enhancing the overall robustness and generalizability of the prediction. EL’s model diversity allows it to capture a broader spectrum of data characteristics, which is particularly beneficial in heterogeneous hospital datasets. However, EL still faces challenges in data sharing and privacy protection, which are less pronounced in federated learning. FL outperforms SL by a noticeable margin. Federated Learning enables multiple institutions to collaboratively train models without sharing raw data, enhancing model generalizability and leveraging diverse patient demographics. However, FL’s reliance on a single global model can limit its ability to capture unique local data characteristics, leading to potential performance degradation. In contrast, SL’s sequential training process and high latency issues hinder its efficiency, making it the least effective among the compared methods.

The En-split framework successfully combines the benefits of ensemble and split learning, enabling it to adapt well to various hospital settings. Regarding the trade-offs between privacy guarantees and model utility, our use of differential privacy (DP) with

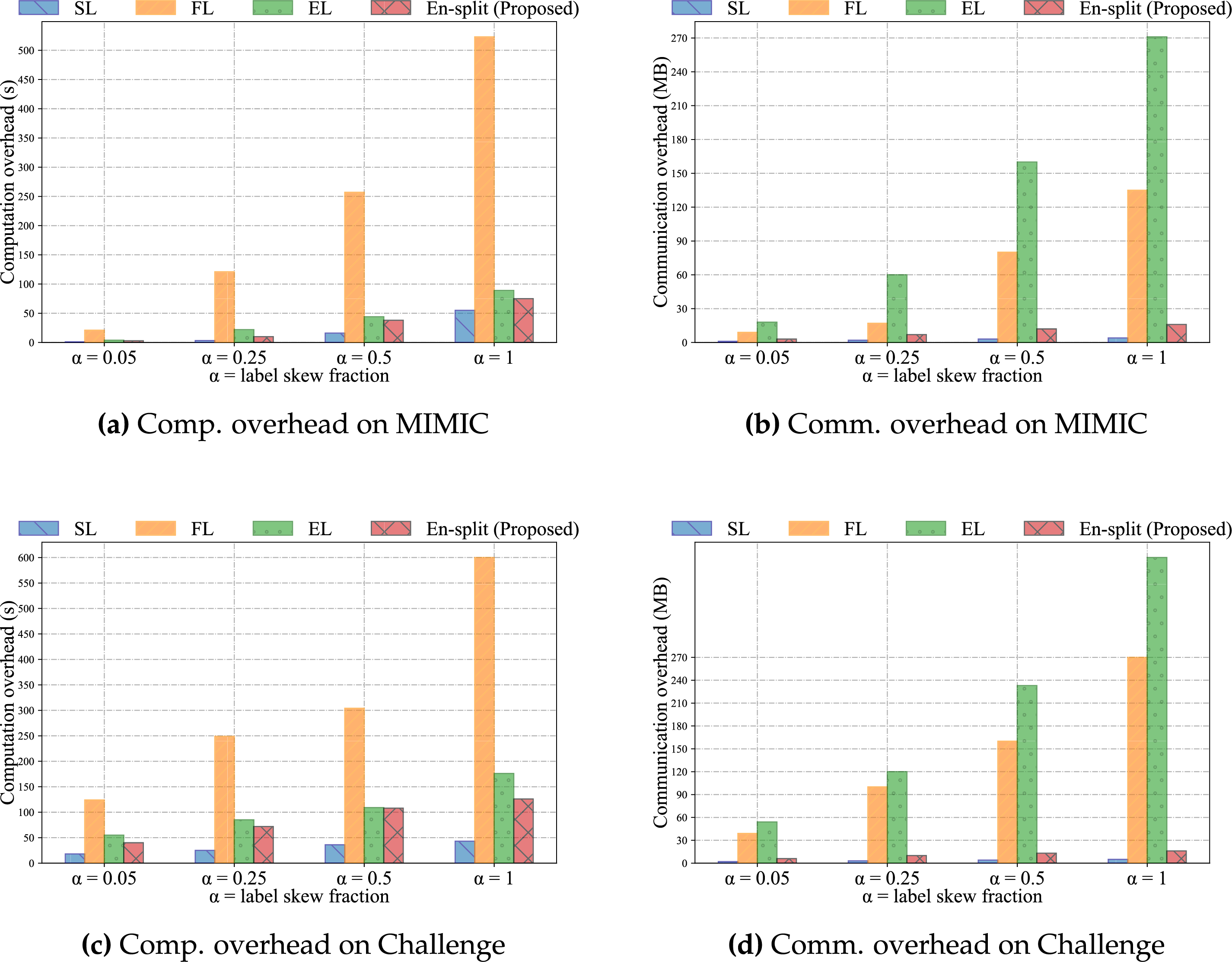

6.2 Comparison of Model Communication Overhead

We evaluated the communication overhead of the En-split framework against SL, FL, and EL by measuring the data transmission between server and clients. As shown in Fig. 7, our results indicate that EL has the highest communication overhead, followed by FL, with En-split significantly reducing the communication overhead compared to FL, and SL having the lowest overhead. EL incurs the highest communication overhead. This is because EL requires transferring multiple model parameters from each participating client to the central server for aggregation. The need to handle multiple models simultaneously results in substantial data transmission, leading to high communication costs. Moreover, the centralized nature of EL necessitates frequent data exchanges to update and maintain the ensemble models, further exacerbating the communication load. FL reduces the communication overhead compared to EL by training a single global model. In FL, clients share model updates (e.g., gradients or model weights) rather than raw data. Although this approach reduces the volume of data transmitted compared to EL, it still involves significant communication, especially with frequent synchronization rounds needed to update the global model across all clients. The transmission of model updates at each round can be substantial, particularly for large and complex models.

Figure 7: Comparison of computation and communication overheads for four methods on the MIMIC dataset and the Challenge dataset

While En-split significantly reduces the computational burden on clients by splitting the model and performing partial local computations, the server does undertake the critical responsibilities of aggregation, ensemble model maintenance, and final voting.

Compared to Federated Learning, where the server must aggregate and update full global model weights, or traditional ensemble learning, which might involve complex model training or distillation processes, these operations in En-split are generally less computationally intensive. Notably, the server processes compressed and typically lower-dimensional intermediate activations, rather than raw data or high-dimensional full model parameters. Consequently, even as the number of clients increases, the growth in server-side computation is relatively manageable. For instance, the computational cost of aggregation scales approximately linearly with the number of clients, but because the volume of transmitted data is significantly reduced, the overall overhead remains far below that of other distributed paradigms. The computational resources required for the final voting mechanism are negligible.

The En-split framework further reduces communication overhead compared to FL. En-split leverages the strengths of SL to split the model training process between the client and the server. By processing part of the model locally on the client side and only sending intermediate activations to the server, En-split significantly cuts down the amount of data transmitted. This method allows En-split to maintain high model performance while minimizing communication costs, making it more efficient and scalable. En-split ensures that essential data characteristics are preserved and transmitted efficiently, optimizing the balance between communication overhead and model accuracy. SL exhibits the lowest communication overhead among the four methods. SL divides the model into two parts, one processed by the client and the other by the server. Only intermediate activations and gradients are exchanged, rather than entire model parameters or raw data. This split reduces the volume of data transmitted significantly. However, the inability of SL to aggregate multiple models, as EL does, limits its performance by reducing its capacity to capture diverse and comprehensive data patterns. Although it has the advantage of low communication costs, this limitation may lead to less robust performance.

Regarding scalability, our results demonstrate that En-split’s communication overhead scales linearly with the number of clients, as evidenced by the trends in Fig. 7. This linear growth is attributable to the framework’s design, which limits transmissions to intermediate activations rather than full model parameters or raw data, making it more efficient than FL or EL for larger networks. The architecture inherently supports parallelism, drawing from SplitFed-inspired methods (as referenced in Section 3), allowing multiple clients to contribute concurrently without exponential increases in latency. This positions En-split as suitable for large-scale hospital networks, where dozens of institutions might participate, though further validation in such scenarios is planned.

6.3 Comparison of Model Computation Overhead

We evaluated the computational overhead of the En-split framework by comparing it with SL, FL, and EL, measuring the computation time on the client side. Among the four approaches, EL exhibits the highest computational overhead. This is primarily because EL requires each client to train multiple models independently. While the server performs model aggregation, the major computational burden remains on the clients, who must conduct extensive training to produce a diverse set of models. Such a high level of client-side computation renders EL less suitable for environments with limited computational resources.

Federated Learning (FL) reduces computational overhead compared to Ensemble Learning (EL) by training a single global model. In FL, clients perform local training on their respective datasets and transmit model updates to a central server. Although this approach alleviates the burden of maintaining multiple models, it still incurs considerable computational costs, particularly during the local training phase. This is especially pronounced when dealing with large datasets or complex model architectures.

The En-split framework further reduces computational overhead relative to FL by partitioning the model training process between the client and the server. Under this framework, clients handle only the initial stages of training, while the server processes the more complex components. This division of labor significantly decreases the computational demands on clients, effectively balancing the overall workload. As a result, En-split is more suitable for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Among the three methods, Split Learning (SL) exhibits the lowest computational overhead. Clients are responsible only for computing the initial layers of the model and then transmitting the intermediate representations to the server. The server subsequently performs the remaining, more computation-intensive operations. This setup substantially reduces client-side computational requirements.

From a scalability perspective, the computational overhead of the En-split framework is designed for efficiency, exhibiting linear scaling with the number of clients as shown in Fig. 7. This is achieved by partitioning the model and offloading computationally intensive operations to the server. While this significantly minimizes the client-side burden, the server’s responsibilities are managed efficiently. Specifically, the primary task of ensemble model maintenance—aggregating intermediate activations from all participants as described in Eq. (4)—has a time complexity of O(K), scaling linearly with the number of clients, K. The final voting step is even more efficient, operating in constant O(1) time. This linear growth is highly manageable because the server processes lightweight intermediate activations rather than high-dimensional model parameters, thereby avoiding the poor scaling of traditional EL and the quadratic overhead found in some advanced secure aggregation methods. Therefore, while our current experiments focus on smaller setups, this architectural design establishes a strong foundation for scalability, making it suitable for deployment in expansive hospital networks and for handling real-time streaming conditions.

In this study, we have developed and validated the En-split framework, a novel integration of Ensemble Neural Networks (ENN) and Split Learning (SL) designed for sepsis prediction across diverse clinical settings. By combining the robustness of ensemble models with the privacy-preserving features of split learning, our framework addresses major challenges, including data privacy and model generalization across patient populations. The En-split framework ensures that sensitive healthcare data remains localized, enhancing patient privacy while allowing institutions to collaborate effectively without sharing raw data. Our empirical evaluations on the MIMIC-III and Sepsis Challenge datasets have shown that the En-split framework not only adheres to privacy regulations but also outperforms existing methods, achieving an approximately 3% improvement in AUROC. These results underscore the potential of our approach to significantly enhance sepsis detection and management, thereby contributing to better healthcare outcomes and bridging the gap in medical services across regions. This work sets a new benchmark in the predictive modeling of sepsis and opens avenues for further research in privacy-conscious, cross-center medical collaborations.

Although En-split reduces computation and communication overhead, it might face scalability challenges when dealing with an extensive number of clients or significantly large datasets. The coordination and synchronization between multiple clients and the server could become complex and resource-intensive, potentially hindering real-time application in large-scale healthcare networks. Future work should explore advanced distributed computing techniques and optimization algorithms to enhance scalability. Efficient load balancing, dynamic resource allocation, and adaptive synchronization mechanisms could help address these challenges. Despite En-split’s enhanced privacy through data localization, there are still potential vulnerabilities related to intermediate data sharing between clients and the server. Advanced privacy-preserving techniques such as differential privacy and homomorphic encryption, commonly used in FL, might need to be integrated to further mitigate these risks.

In summary, while our evaluation highlights En-split’s advantages in accuracy, efficiency, and privacy, future work will explore its scalability in greater depth, including simulations with more than 10 clients and real-time streaming scenarios to fully validate its applicability to large-scale hospital networks. These enhancements will build on the observed linear overhead scaling and parallel architecture to address potential limitations in ultra-distributed settings.

Beyond sepsis detection, En-split’s flexible architecture holds promise for extension to other healthcare prediction tasks. For instance, it could be applied to cancer detection using multi-modal imaging data, where heterogeneous models at different institutions capture site-specific patterns while preserving patient privacy. Similarly, in prognosis prediction for chronic diseases like diabetes or cardiovascular conditions, the framework’s ensemble approach would enhance generalization across diverse patient demographics. A key direction for future research is to empirically validate the benefits of this model heterogeneity. While our current study establishes the framework’s efficacy with homogeneous base models, we plan to conduct experiments in fully heterogeneous settings, where clients can deploy distinct architectures (e.g., CNNs for imaging, GRUs for time-series data) tailored to their local data. This will allow us to quantify the performance gains derived from one of En-split’s core design advantages. Future adaptations might also include infectious disease forecasting, such as COVID-19 outbreak modeling, leveraging distributed data from global health networks. These extensions would build on En-split’s core strengths in privacy-preserving collaboration and model diversity, broadening its impact in data-driven medicine.

Additionally, we plan to extend En-split to better handle asynchronous or straggler clients, which are prevalent in real-world federated and split learning environments. Potential strategies include quorum-based aggregation, where the server advances with updates from a majority of clients within adaptive time windows, and timeout mechanisms to isolate delays while preserving overall model integrity. These enhancements will be evaluated through targeted simulations in large-scale settings, quantifying impacts on key metrics such as AUROC, latency, and convergence speed. This will build on En-split’s current strengths in privacy and efficiency, further validating its robustness for diverse, multi-institutional healthcare applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62172155), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF1203001), the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (Nos. 2022RC3061, 2023RC3027), the Graduate Research Innovation Project of Hunan Province (XJCX2023157), NUDT Scientific Project “Research on Privacy-Enhancing Computing Technologies for Activity Trajectory Data”.

Author Contributions: Panyu Liu: Conceptualization, Methodolgy, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft. Tongqing Zhou: Supervision, Writing—review & editing, Data curation. Guofeng Lu: Supervision, Data curation. Huaizhe Zhou: Supervision, Data curation. Zhiping Cai: Supervision, Writing—review & editing, Data curation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets analyzed during this study are available from publicly accessible sources or upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://physionet.org/content/challenge-2019/1.0.0/ (accessed on 5 May 2024).

References

1. Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27(1):167–94. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Teo ZL, Jin L, Liu N, Li S, Miao D, Zhang X, et al. Federated machine learning in healthcare: a systematic review on clinical applications and technical architecture. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5(2):101256. doi:10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu P, Zhou T, Cai Z, Liu F, Guo Y. Leveraging heuristic client selection for enhanced secure federated submodel learning. Inf Process Manag. 2023;60(3):103211. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2022.103211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Guo Y, Liu F, Zhou T, Cai Z, Xiao N. Seeing is believing: towards interactive visual exploration of data privacy in federated learning. Inf Process Manage. 2023;60(2):103162. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2022.103162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang J, Liu Z, Yang X, Li M, Lyu Z. The Internet of Things under federated learning: a review of the latest advances and applications. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(1):1–39. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.058926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xu Y, Chu X, Yang K, Wang Z, Zou P, Ding H, et al. Seqcare: sequential training with external medical knowledge graph for diagnosis prediction in healthcare data. In: Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023; 2023 Apr 30–May 4; Austin, TX, USA. p. 2819–30. [Google Scholar]

7. Xu Y, Yang K, Zhang C, Zou P, Wang Z, Ding H, et al. VecoCare: visit sequences–clinical notes joint learning for diagnosis prediction in healthcare data. In: IJCAI ’23: Thirty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2023 Aug 19–25; Macao, China. p. 4921–9. [Google Scholar]

8. Ding R, Zhou Y, Xu J, Xie Y, Liang Q, Ren H, et al. Cross-hospital sepsis early detection via semi-supervised optimal transport with self-paced ensemble. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2023;27(6):3049–60. doi:10.1109/jbhi.2023.3253208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–10. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Rajendran S, Xu Z, Pan W, Ghosh A, Wang F. Data heterogeneity in federated learning with Electronic Health Records: case studies of risk prediction for acute kidney injury and sepsis diseases in critical care. PLoS Dig Health. 2023;2(3):e0000117. doi:10.1101/2022.08.30.22279382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yang Z, Liu Y, Feng F, Liu Y, Liu Z. FedCPS: a dual optimization model for federated learning based on clustering and personalization strategy. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(1):357–80. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.060709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Caldas S, Yoon JH, Pinsky MR, Clermont G, Dubrawski A. Understanding clinical collaborations through federated classifier selection. In: Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference; 2021 Aug 6–7; Online. p. 126–45. [Google Scholar]

13. Vepakomma P, Gupta O, Swedish T, Raskar R. Split learning for health: distributed deep learning without sharing raw patient data. arXiv:1812.00564. 2018. [Google Scholar]

14. Thapa C, Arachchige PCM, Camtepe S, Sun L. Splitfed: when federated learning meets split learning. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2022 Feb 22–Mar 1; Online. p. 8485–93. doi:10.1609/aaai.v36i8.20825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Panigrahi S, Nanda A, Swarnkar T. A survey on transfer learning. In: Intelligent and Cloud Computing: Proceedings of ICICC 2019. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 781–9. [Google Scholar]

16. Desautels T, Calvert J, Hoffman J, Mao Q, Jay M, Fletcher G, et al. Using transfer learning for improved mortality prediction in a data-scarce hospital setting. Biomed Inform Insights. 2017;9:1178222617712994. doi:10.1177/1178222617712994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Schamoni S, Hagmann M, Riezler S. Ensembling neural networks for improved prediction and privacy in early diagnosis of sepsis. In: Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference; 2022 Aug 5–6; Online. p. 123–45. [Google Scholar]

18. He Z, Du L, Zhang P, Zhao R, Chen X, Fang Z. Early sepsis prediction using ensemble learning with deep features and artificial features extracted from clinical electronic health records. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(12):e1337–42. doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000004644. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Wickramaratne SD, Mahmud MDS. Bi-directional gated recurrent unit based ensemble model for the early detection of sepsis. In: 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC); 2020 Jul 20–24; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 70–3. [Google Scholar]

20. Zhang X, Huang L, Fu T, Wu Y. Prediction of sepsis mortality risk based on ensemble learning algorithm FBTV. In: International Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computing; 2023 Oct 6–8; Kaohsiung,Taiwan. p. 250–9. [Google Scholar]

21. El-Rashidy N, Abuhmed T, Alarabi L, El-Bakry HM, Abdelrazek S, Ali F, et al. Sepsis prediction in intensive care unit based on genetic feature optimization and stacked deep ensemble learning. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(5):3603–32. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06631-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu X, Niu H, Peng J. Enhancing predictions with a stacking ensemble model for ICU mortality risk in patients with sepsis-associated encephalopathy. J Int Med Res. 2024;52(3):03000605241239013. doi:10.1177/03000605241239013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Yuan KC, Tsai LW, Lee KH, Cheng YW, Hsu SC, Lo YS, et al. The development an artificial intelligence algorithm for early sepsis diagnosis in the intensive care unit. Int J Med Inform. 2020;141:104176. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Gholamzadeh M, Abtahi H, Safdari R. Comparison of different machine learning algorithms to classify patients suspected of having sepsis infection in the intensive care unit. Inform Med Unlocked. 2023;38:101236. doi:10.1016/j.imu.2023.101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang D, Li J, Sun Y, Ding X, Zhang X, Liu S, et al. A machine learning model for accurate prediction of sepsis in ICU patients. Front Public Health. 2021;9:754348. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.754348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Shashikumar SP, Stanley MD, Sadiq I, Li Q, Holder A, Clifford GD, et al. Early sepsis detection in critical care patients using multiscale blood pressure and heart rate dynamics. J Electrocardiol. 2017;50(6):739–43. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2017.08.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Yee CR, Narain NR, Akmaev VR, Vemulapalli V. A data-driven approach to predicting septic shock in the intensive care unit. Biomed Inform Insights. 2019;11:1178222619885147. doi:10.1177/1178222619885147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Alanazi A, Aldakhil L, Aldhoayan M, Aldosari B. Machine learning for early prediction of sepsis in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Patients. Medicina. 2023;59(7):1276. doi:10.3390/medicina59071276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Strickler EA, Thomas J, Thomas JP, Benjamin B, Shamsuddin R. Exploring a global interpretation mechanism for deep learning networks when predicting sepsis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):3067. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-30091-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Liang X, Wang D, Zhong H, Wang Q, Li R, Jia R, et al. Candidate-heuristic in-context learning: a new framework for enhancing medical visual question answering with LLMs. Inf Process Manage. 2024;61(5):103805. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2024.103805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Guo F, Zhu X, Wu Z, Zhu L, Wu J, Zhang F. Clinical applications of machine learning in the survival prediction and classification of sepsis: coagulation and heparin usage matter. J Transl Med. 2022;20(1):265. doi:10.1186/s12967-022-03469-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Sakri S, Basheer S, Zain ZM, Ismail NHA, Nassar DA, Alohali MA, et al. Sepsis prediction using CNNBDLSTM and temporal derivatives feature extraction in the IoT medical environment. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;79(1):1157–84. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.048051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ayad A, Barhoush M, Frei M, Völker B, Schmeink A. An efficient and private ECG classification system using split and semi-supervised learning. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2023;27(9):4261–72. doi:10.1109/jbhi.2023.3281977. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Goh KH, Wang L, Yeow AYK, Poh H, Li K, Yeow JJL, et al. Artificial intelligence in sepsis early prediction and diagnosis using unstructured data in healthcare. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):711. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-20910-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Moor M, Bennet N, Plecko D, Horn M, Rieck B, Meinshausen N, et al. Predicting sepsis in multi-site, multi-national intensive care cohorts using deep learning. arXiv:2107.05230. 2021. [Google Scholar]

36. Adams S, Choudhary C, De Cock M, Dowsley R, Melanson D, Nascimento AC, et al. Privacy-preserving training of tree ensembles over continuous data. arXiv:2106.02769. 2021. [Google Scholar]

37. Alam MM, Ahmed T, Hossain M, Emo MH, Bidhan MKI, Reza MT, et al. Federated ensemble-learning for transport mode detection in vehicular edge network. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2023;149:89–104. doi:10.1016/j.future.2023.07.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Qureshi SS, He J, Zhu N, Nazir A, Fang J, Ma X, et al. Enhancing IoT security and healthcare data protection in the metaverse: a dynamic adaptive security mechanism. Egypt Inform J. 2025;30:100670. doi:10.1016/j.eij.2025.100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ullah F, He J, Zhu N, Wajahat A, Nazir A, Qureshi S, et al. Blockchain-enabled EHR access auditing: enhancing healthcare data security. Heliyon. 2024;10(16):e34407. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Reyna MA, Josef C, Seyedi S, Jeter R, Shashikumar SP, Westover MB, et al. Early prediction of sepsis from clinical data: the PhysioNet/Computing in Cardiology Challenge 2019. In: 2019 Computing in Cardiology (CinC); 2019 Sep 8–11; Singapore. [Google Scholar]

41. Zhou M, Zhao M, Chan TH, Shi E. Advanced composition theorems for differential obliviousness. In: Proceedings of the 15th Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference (ITCS 2024); 2024 Jan 30–Feb 2; Berkeley, CA, USA. p. 103:1–24. doi:10.4230/LIPIcs.ITCS.2024.103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Small RP, Hendry JL, McKay AC, McPhee AS, Jones GE. Is the qSOFA more reliable than SIRS in detecting post-operative PCNL patients requiring escalation of care? J Clin Urol. 2020;13(1):15–8. doi:10.1177/2051415819854889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools