Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Infrared-Visible Image Fusion Network with Channel-Switching for Low-Light Object Detection

Software College, Northeastern University, Shenyang, 110819, China

* Corresponding Author: Jie Song. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2681-2700. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069235

Received 18 June 2025; Accepted 15 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Visible-infrared object detection leverages the day-night stable object perception capability of infrared images to enhance detection robustness in low-light environments by fusing the complementary information of visible and infrared images. However, the inherent differences in the imaging mechanisms of visible and infrared modalities make effective cross-modal fusion challenging. Furthermore, constrained by the physical characteristics of sensors and thermal diffusion effects, infrared images generally suffer from blurred object contours and missing details, making it difficult to extract object features effectively. To address these issues, we propose an infrared-visible image fusion network that realizes multimodal information fusion of infrared and visible images through a carefully designed multi-scale fusion strategy. First, we design an adaptive gray-radiance enhancement (AGRE) module to strengthen the detail representation in infrared images, improving their usability in complex lighting scenarios. Next, we introduce a channel-spatial feature interaction (CSFI) module, which achieves efficient complementarity between the RGB and infrared (IR) modalities via dynamic channel switching and a spatial attention mechanism. Finally, we propose a multi-scale enhanced cross-attention fusion (MSECA) module, which optimizes the fusion of multi-level features through dynamic convolution and gating mechanisms and captures long-range complementary relationships of cross-modal features on a global scale, thereby enhancing the expressiveness of the fused features. Experiments on the KAIST, M3FD, and FLIR datasets demonstrate that our method delivers outstanding performance in daytime and nighttime scenarios. On the KAIST dataset, the miss rate drops to 5.99%, and further to 4.26% in night scenes. On the FLIR and M3FD datasets, it achieves scores of 79.4% and 88.9%, respectively.Keywords

Object detection is crucial in the field of computer vision and serves as a key technology for applications such as autonomous driving and intelligent surveillance [1,2]. However, due to the limitations of visible-light sensors, most object detection methods that rely solely on visible images typically perform poorly. In particular, under low-illumination conditions, visible images suffer from insufficient lighting that leads to a loss of texture information and makes it easy to overlook objects in the dark, thereby limiting model reliability in real-world applications [3,4]. In contrast, infrared sensors are sensitive to temperature variations and capture object contours via thermal radiation. They are unaffected by lighting or smoke and can provide stable visual information in low-light environments where visible-light imaging performs poorly, compensating for the shortcomings of visible imaging. Consequently, image fusion techniques have emerged, integrating complementary information from infrared and visible-light data to overcome the limitations of single-modality recognition, and offering an effective method for all-weather object detection.

Infrared–visible image fusion is an important research direction in multimodal data fusion. As shown in Fig. 1, the RGB modality can capture rich visual details such as texture and color, while the IR modality, independent of ambient lighting due to its thermal radiation characteristics, can effectively detect low-contrast objects. To date, various methods have been proposed to address the infrared–visible fusion problem. Many methods rely solely on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to extract image features and employ manually designed, complex fusion strategies to merge these features at different stages of the network [5]. Although numerous studies have demonstrated the powerful feature-extraction capability of CNNs [6], these methods is limited by the receptive field. Transformer-based methods leverage self-attention to model global features across the entire image, overcoming the receptive-field limitation of CNNs [7]. However, Transformers typically operate on downsampled low-resolution feature maps, which can lead to the loss of fine-grained spatial information and diminish their sensitivity to small objects. In addition, generative adversarial network (GAN)-based methods feed infrared and visible images simultaneously into a generator network to learn modality-conversion patterns and produce fused images, while a discriminator network constrains the distribution of the generated outputs [8]. However, these methods often introduce additional noise and incur high computational costs.

Figure 1: Typical visible–infrared paired examples

Although the above methods have achieved certain progress in feature interaction, visible images captured under nighttime or low-light conditions often have low contrast, loss of detail, and contain noise, making it difficult to effectively compensate for the missing texture and color information in infrared images. At the same time, limited by the characteristics of infrared sensors, infrared images typically have low resolution and blurred object contours, making it hard to distinguish foreground from background accurately. To address this problem, researchers have applied various techniques to enhance infrared image quality, including adaptive filtering, histogram equalization, and deconvolution [9]. However, the infrared preprocessing stage generally relies on fixed-parameter gray-level compression methods, which ignore the dynamic radiance-range variations of infrared sensors and result in the loss of high-radiance object details.

In addition, the fundamental differences in the physical imaging mechanisms of infrared and visible-light images lead to significant heterogeneity in their feature distributions, making effective fusion challenging. To reduce the disparity between the two modalities, mainstream dual-stream network architectures typically employ parallel encoders to process RGB and IR images separately, then fuse the extracted features via fixed-weight 1

To address the above issues, this paper proposes an infrared–visible image fusion network that combines infrared enhancement and image fusion techniques to fully exploit the complementary information of multi-source inputs and improve image quality. The network integrates CNNs and Transformers to leverage their strengths for robust detection in daytime and nighttime scenarios. First, we introduce an adaptive gray-radiance enhancement (AGRE) module that utilizes a parameter-adjustable logarithmic transformation and radiance-enhancement techniques to strengthen the detail representation of infrared images, effectively addressing grayscale information loss caused by dynamic radiometric range variations in infrared sensors. Next, we design a channel-spatial feature interaction (CSFI) module that preserves each modality’s unique features via a dynamic channel-switching mechanism and intelligently selects the most beneficial modality-specific information. Finally, we propose a multi-scale enhanced cross-attention fusion (MSECA) module, which uses dynamic convolution and gating mechanisms to adaptively fuse multi-scale features, addressing the semantic imbalance of multi-scale features inherent in traditional feature pyramid networks (FPNs). It adopts cross-modal self-attention over the global spatial domain to capture long-range dependencies, obtaining high-quality cross-modal fused features. The main contributions of this article are as follows:

1. We propose a dynamic adaptive radiance enhancement method that combines a learnable-parameter logarithmic transformation with radiance correction to improve the feature representation of low-contrast infrared images.

2. We design a dynamic channel-switching fusion mechanism that achieves channel-level information complementarity via dual-modal feature importance estimation, and enhances key regions through multi-scale spatial attention.

3. We construct a multi-scale enhanced cross-attention fusion (MSECA) module that deeply interacts with multi-scale features and employs a global self-attention mechanism to explicitly model cross-modal dependencies across the entire spatial domain, yielding high-quality fused representations.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work. Section 3 introduces the proposed visible–infrared object detection network. Experimental results are presented in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the findings and concludes the paper.

Single-Modal Object Detection Methods. Single-modal detection methods based on visible-light images (e.g., Faster R-CNN [13], the YOLO [14] series) extract texture and color features via convolutional neural networks and perform well in well-lit daytime scenes. However, these methods heavily rely on ambient lighting conditions, and their performance degrades significantly in nighttime or low-light scenarios. In contrast, the methods based on infrared images (e.g., Thermal-YOLO [15]) leverage thermal radiation characteristics for illumination-invariant detection, but they are limited by low contrast and high noise, making it difficult to distinguish objects with similar thermal signatures. Moreover, recent advances in CNNs and transformers have enhanced model performance. Usman et al. [16] introduce the pyramid vision transformer (PVTv2)-assisted trapezoidal attention network (TRSNet) for object detection. They leverage the PVTv2 backbone to efficiently extract multi-level features, achieving an optimal balance between computational cost and detection accuracy. However, the fundamental limitation of single-modal methods is their inability to ensure robustness across complex conditions like day–night transitions and varying illumination. This core issue has driven researchers toward multimodal fusion techniques, which aim to jointly exploit the rich texture detail of the RGB modality and the illumination invariance of the IR modality to achieve high-precision, all-weather object detection.

Multimodal Object Detection Methods. The core of multimodal fusion is effectively integrate the complementary information of the RGB and IR modalities to build more robust feature representations. Multimodal fusion can be realized at different stages. For example, the early fusion strategy directly concatenates RGB and IR images at the input layer and processes the fused data through a single network. Although this is computationally efficient, it ignores inter-modal heterogeneity, leading to feature-space conflicts and especially poor performance on infrared images with large dynamic ranges. Mid-level fusion typically adopts a dual-stream (or multi-stream) architecture to extract features from each modality separately, then fuses them at intermediate (feature) layers. MSDS-Net [17] uses feature concatenation and simple convolution for fusion, but its static strategy cannot adapt to changes in modality importance across scenarios. AFNet [18] introduces a channel-attention mechanism to generate fusion weights but relies solely on global statistics, lacking fine-grained perception of spatial modality complementarity. CMDet [12] fuses multi-scale features via a feature pyramid but employs fixed parameters and structures for heterogeneous features at different levels, resulting in an imbalance between shallow details and deep semantics. The late fusion strategy, represented by ProbEn [19], processes each modality through an independent model and finally fuses results at the decision level (e.g., detection boxes, scores). While late fusion avoids feature conflicts, it loses fine-grained cross-modal interactions.

Furthermore, several common limitations persist in the aforementioned studies. Firstly, infrared preprocessing typically relies on linear normalization or histogram equalization, which cannot fully adapt to dynamic radiometric ranges. Secondly, the ability to perceive spatial positional information during data fusion remains insufficient. For instance, GAFF [20] employs pedestrian masks to guide spatial attention but relies on additional annotations in occlusion scenarios. Thus, this paper introduces a parameterized logarithmic transformation combined with radiometric correction to replace traditional fixed preprocessing, enabling adaptive dynamic radiometric adjustment. Moreover, although CSSA [21] also adopts the idea of channel switching, its channel selection relies on a single global statistical attention, and its spatial attention uses fixed convolution kernels, making it difficult to handle multi-scale objects. Therefore, based on CSSA, we first extract dynamic weights for each channel and then generate gates for dynamic channel switching through a two-layer multi-layer perceptron (MLP). Next, we achieve multi-scale perception in spatial attention by integrating multi-scale depthwise separable convolutions with different dilation rates and learnable fusion weights.

In this section, we propose a novel multimodal nighttime object detection network that can adaptively enhance infrared image quality and, based on channel switching and attention mechanisms, perform cross-modal information interaction and fusion at multiple levels.

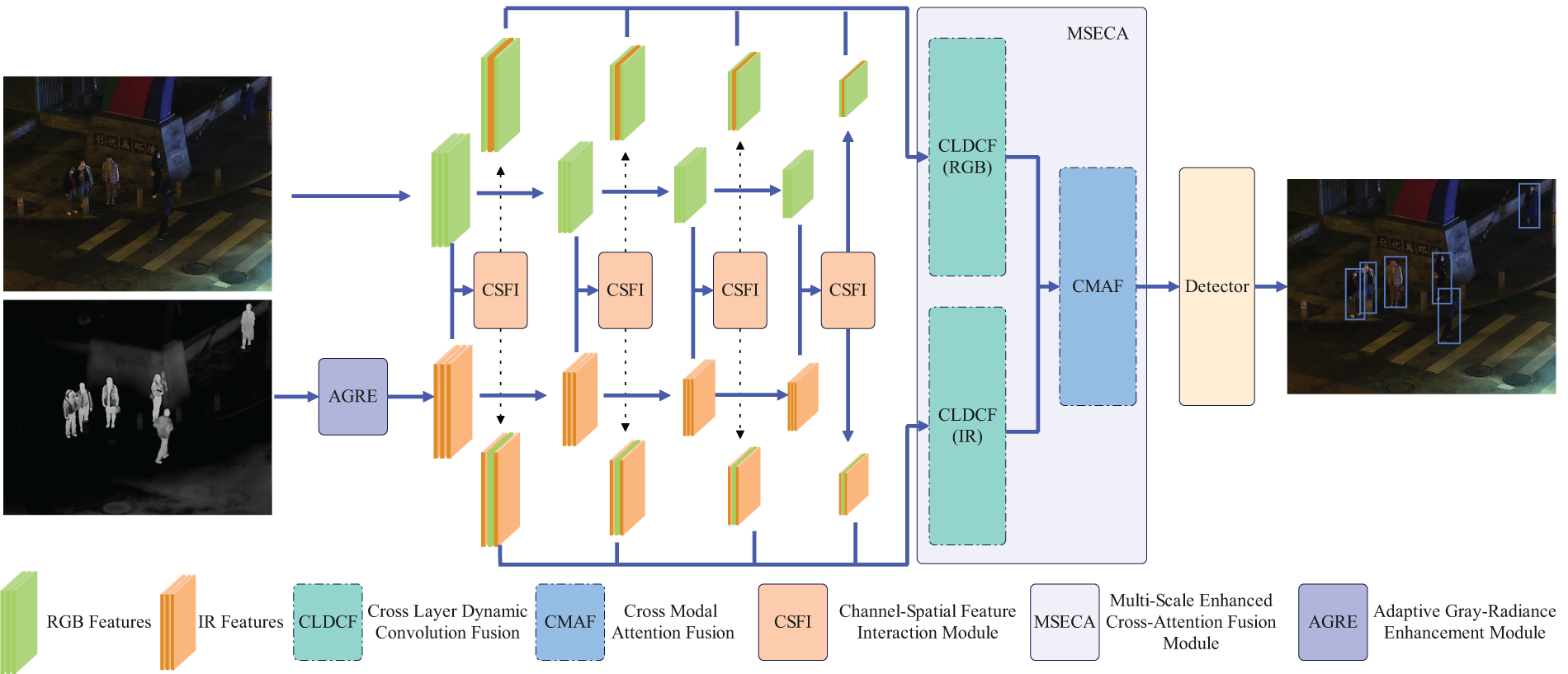

Our method is a multimodal fusion network specifically designed for nighttime object detection. The overall framework is composed of three core modules: dynamic adaptive radiance enhancement (AGREM), channel-spatial feature interaction (CSFI), and multi-scale enhanced cross-attention fusion (MSECA). Fig. 2 illustrates the overall architecture of our method. Among them, the AGREM module enhances infrared image details and contrast through dynamic grayscale compression and radiometric transformation. The CSFI module achieves efficient inter-modal feature complementation using dynamic channel switching and multi-scale spatial attention. The MSECA module optimizes hierarchical fusion of multi-scale features via dynamic convolution and gating mechanisms, while modeling long-range cross-modal dependencies through a global attention mechanism. These modules work collaboratively, ultimately producing object detection results through a standard detection head.

Figure 2: Overall network architecture diagram. Firstly, the RGB image and the grayscale enhanced IR image undergo four feature extraction stages in the backbone network to obtain features of different scales. Afterwards, RGB and IR features of different scales are passed through the CSFI module for channel exchange and obtain feature information exchanged at multiple scales. Finally, the exchanged information from multiple scales is fused through the MSECA module and detected by a detector to obtain the final detection result

3.2 Adaptive Gray-Radiance Enhancement Module

Infrared image feature extraction aims to effectively capture object features from infrared images with low contrast and high noise. However, infrared images generally exhibit a wide dynamic range, causing some detail information to be obscured in the grayscale distribution. Consequently, directly applying traditional feature extraction methods often leads to inaccurate feature representation, thereby impairing object detection performance. Therefore, we first employ a dynamic grayscale compression technique that

where

To further optimize the radiometric characteristics of the image, we introduce radiometric transformation enhancement. Specifically, we apply a nonlinear transformation to the image’s radiometric values to enhance the object’s contrast and distinguishability. The radiometric transformation formula is as follows:

where

Our method improves the detail representation capability of infrared images by combining dynamic grayscale compression and radiometric transformation enhancement. Dynamic grayscale compression addresses the issue of large dynamic range in infrared images, while radiometric transformation enhancement further optimizes the radiometric characteristics of the images.

3.3 Channel-Spatial Feature Interaction Module

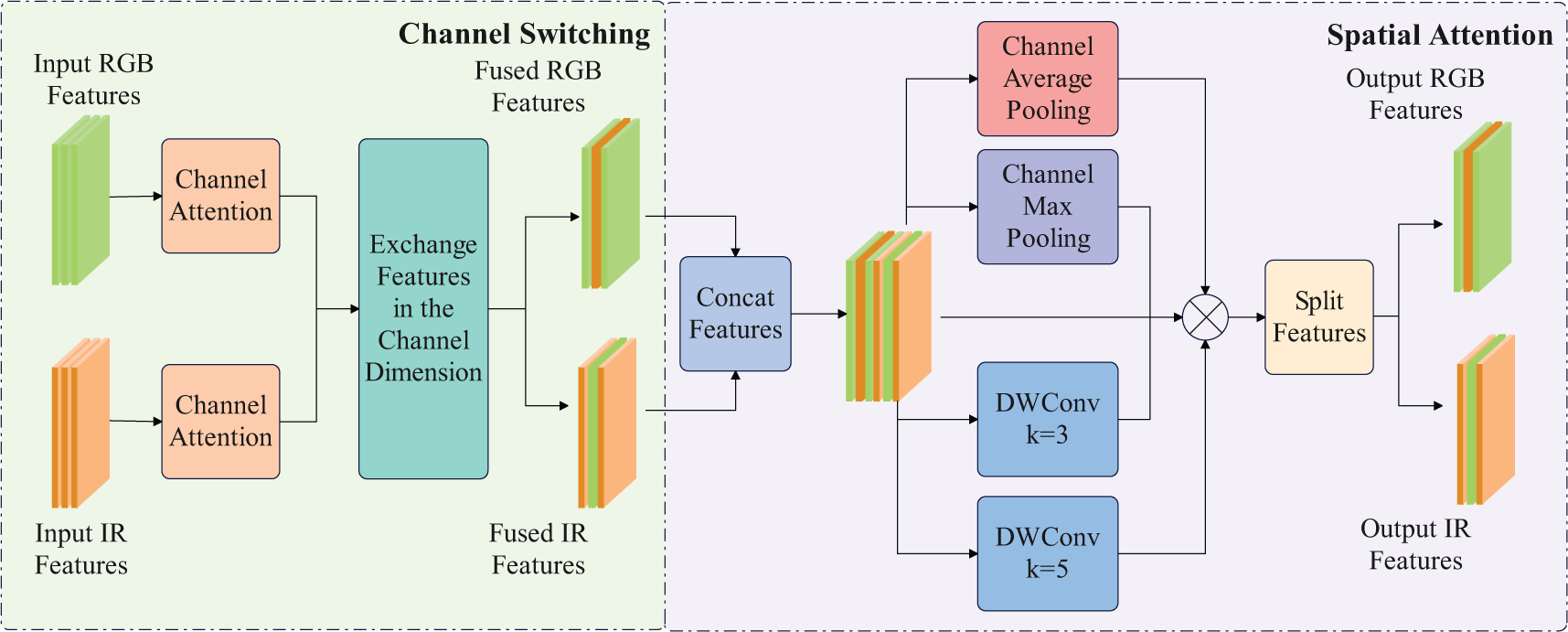

By effectively fusing the complementary information from infrared and visible-light images, the limitations of a single modality in specific environments can be overcome, thereby improving the accuracy and robustness of object detection. Traditional mid-level multimodal fusion strategies often introduce additional backbone networks or complex fusion modules, leading to high computational resource consumption and slow inference speeds. To significantly reduce computation time while maintaining performance, we propose a more efficient CSFI module based on the concept of the CSSA [21] module. Fig. 3 presents the detailed structure of the CSFI module.

Figure 3: CSFI module structure diagram

The CSFI module, as a multimodal feature interaction module, aims to efficiently integrate features from different modalities while incorporating both channel-wise and spatial attention mechanisms. Its core idea is to preserve the unique characteristics of each modality through dynamic channel switching, and to enhance the weights of critical regions using multi-scale spatial attention. This design improves both the accuracy and efficiency of object detection. The CSFI module mainly consists of two processes: dynamic channel switching and multi-scale spatial attention.

The purpose of dynamic channel switching is to evaluate the importance of different channels in the RGB and IR modality feature

where

Finally, for the corresponding channels of different modalities

Here,

The multi-scale spatial attention module assigns spatial weights to key positions in the feature maps

In order for CSFI to capture richer multi-scale perceptual information, we introduce depthwise separable convolutions (DWConv), and use convolutional kernels of different sizes to extract multi-scale spatial features, enhancing CSFI’s perception of objects of various sizes. Specifically, CSFI utilizes both channel average pooling and channel max pooling to extract local features with a

where

3.4 Multi-Scale Enhanced Cross-Attention Fusion

Object detection models typically employ a feature pyramid structure as the neck network to capture multi-scale object details and global context. However, due to significant differences in resolution, semantic representation, and modality fusion between shallow and deep features, simply fusing features from different levels can lead to inaccurate context associations and information loss. This is especially problematic for small object detection and complex scenes such as occlusion and low illumination.

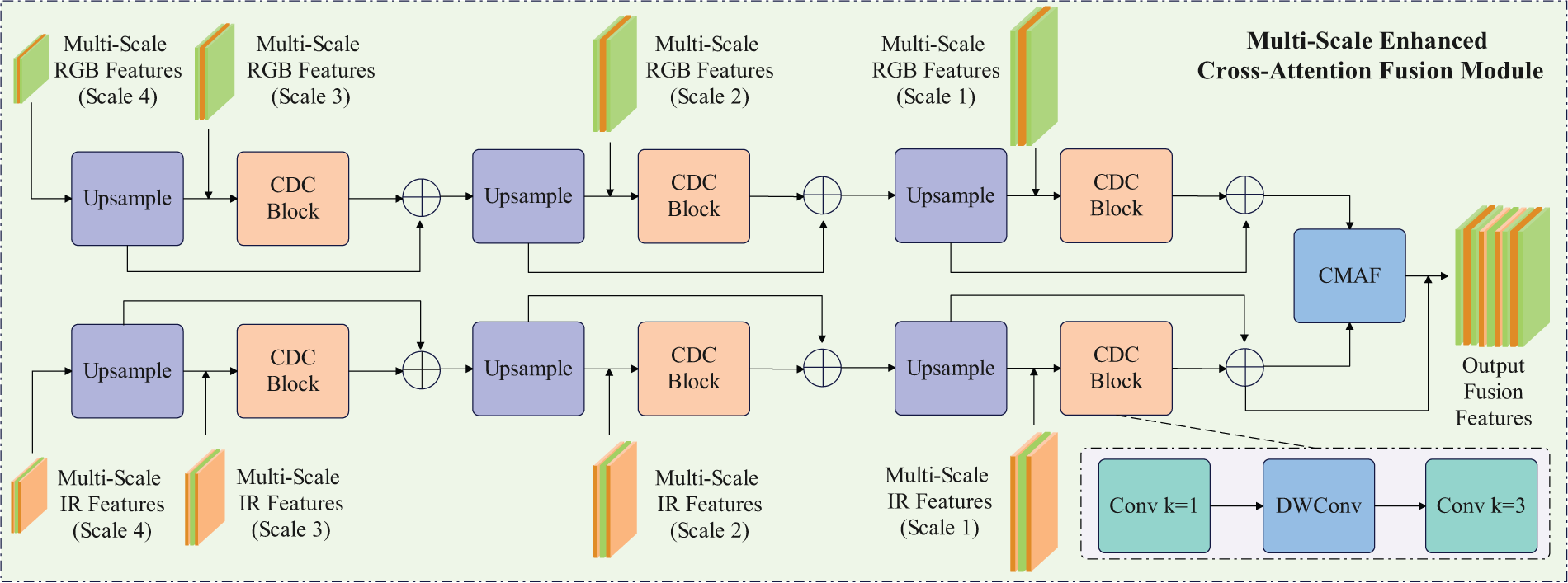

Although CSFI achieves dynamic cross-modal information redistribution along the channel dimension and FPN fuses features at different resolutions within the local spatial scope, both are primarily based on convolution operations with limited receptive fields, making it difficult to capture long-range complementary relationships between RGB and IR features. CSFI channel switching focuses on the weights of channels from different modalities at the same spatial position, but cannot explicitly enhance complementarity between distant pixels. After multi-scale fusion by FPN, multi-level features are combined layer by layer. However, information islands may still form spatially, where key signals in the RGB or IR modalities are locally overwhelmed. To address the core challenges of feature heterogeneity across scales (differences in resolution and semantic representation) and the lack of cross-modal long-range dependencies in multi-scale object detection, we propose the multi-scale enhanced cross-attention Fusion (MSECA) module. Fig. 4 illustrates the specific structure of the MSECA module.

Figure 4: MSECA module structure diagram

The MSECA module mainly consists of two steps: cross-layer dynamic convolutional fusion and cross-modal attention fusion. The cross-layer dynamic convolutional fusion utilizes a lightweight dynamic convolution and gating mechanism to progressively enhance and optimize the interaction between sequentially aligned features from top to bottom and features from the previous layer. Specifically, based on the output features of the CSFI module, we obtain four levels of RGB and IR feature sets

Here,

where

where

Cross-modal attention fusion constructs an explicit global attention mechanism to model cross-modal dependencies within the entire spatial region, enabling the textural cues from RGB and the thermal radiation signals from IR to complement and reinforce each other over long distances. It is based on the multi-head self-attention mechanism in transformers, but only computes cross-modal interactions from RGB to IR to reduce computational cost. Specifically, the 2D features

Then, linear projections are performed on

where

After obtaining the output of each head, the cross-modal attention fusion concatenates the outputs of all heads along the channel dimension. Then, a learnable linear projection matrix

where M is the number of attention heads, and

In summary, the MSECA first utilizes dynamic convolution and gating mechanisms to adaptively fuse multi-scale hierarchical features, addressing the fusion imbalance caused by semantic discrepancies. Subsequently, based on the cross-layer dynamic fusion operation, a global attention mechanism is established to explicitly model cross-modal dependencies of distant high-level features, thereby achieving joint optimization of multi-scale feature fusion and cross-modal global modeling.

In this chapter, we present a series of experiments on the proposed channel-switching infrared–visible image fusion network to verify its effectiveness and superiority. First, we introduce the experimental setup, including the datasets employed, evaluation metrics, and implementation details. Then, we conduct quantitative comparisons on publicly available benchmark datasets against current state-of-the-art visible-light, infrared, and multimodal fusion detection methods. Subsequently, we perform ablation studies to examine the individual contributions of key components such as the channel-switching module and feature fusion strategies. Finally, we provide qualitative results in representative scenarios and discuss the advantages of our method in low-light and complex environments.

4.1 Dataset and Evaluation Metrics

The KAISTT [22] multispectral pedestrian dataset contains 95,328 pairs of fully overlapping RGB thermal infrared images and 103,128 pedestrian bounding boxes. According to the train02 protocol, we sample a total of 25,076 images every 2 frames for training. According to the test20 protocol, we extract 1 frame every 20 frames for a total of 2252 frames (1455 frames during the day and 797 frames at night) for evaluation. The evaluation set is divided into three subsets of driving scenarios: campus, roads, and urban areas. Paired annotations are used during training [23], and purification annotations are used during evaluation [17] to ensure fair comparison with the latest methods.

FLIR1 dataset is one of the most widely used datasets for multimodal object detection tasks. It consists of paired RGB and IR images collected from the perspective of a vehicle driver, including both day and night scenes. This dataset contains 5142 RGB-IR data pairs, with 4129 for training and 1013 for testing. Notably, we removed dog labels from the original dataset, as they do not fit our detection scope.

M3FD [24] dataset was acquired from a ground-level perspective using a dual-spectrum camera, to support our multimodal object detection for unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) obstacle avoidance and trajectory planning. It encompasses challenging weather conditions (e.g., fog, intense glare) and diverse scenes (e.g., forests, urban streets). Visible images are distortion-corrected using the synchronous rig’s intrinsic parameters, while infrared images are rectified via a homogeneous matrix transformation. The collection comprises 4200 image pairs, with 34,407 manually annotated instances across six categories: People, Car, Bus, Motorcycle, Lamp, and Truck. The dataset is split 70%/30%, yielding 2938 pairs for training and 1262 for validation, providing a robust benchmark for multimodal fusion-based detection in complex environments.

As widely used metrics in object detection, we employ different evaluation indicators in our experiments to measure detection performance. For the M3FD and FLIR datasets, we use

The entire model is implemented in PyTorch and trained on an A100 GPU for 40 epochs, with a batch size 8. The optimizer is stochastic gradient descent, with a momentum of 0.9 and a weight decay 0.0005. The initial learning rate is set to 0.005, and a warm-up strategy is adopted. The input image size of the model is 640

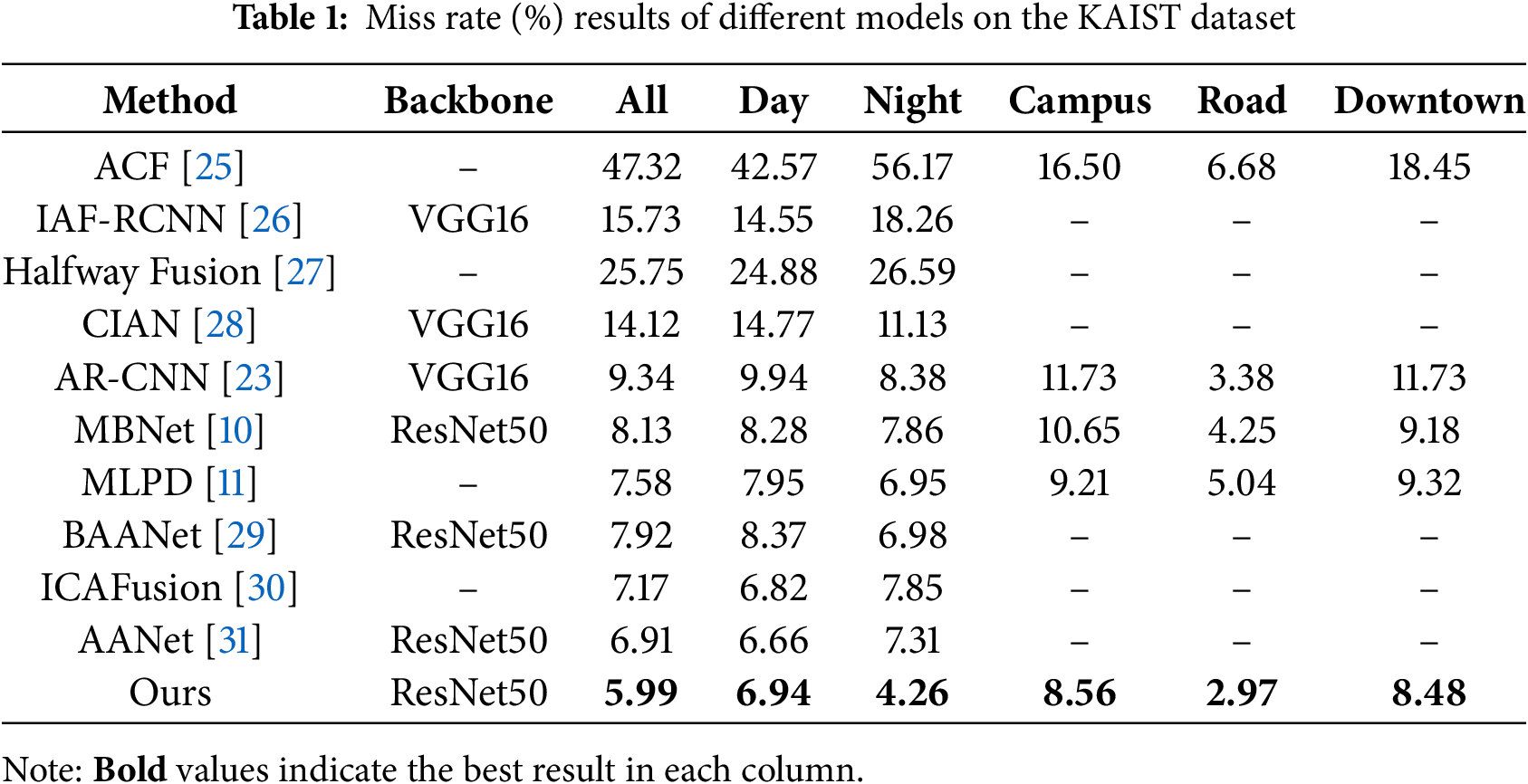

To verify the effectiveness of the method proposed in this paper, we conducted comparative experiments with current mainstream multimodal object detection methods on the KAIST, FLIR, and M3FD datasets. As shown in Table 1. The experimental results show that, for the nighttime detection task on the KAIST dataset, the proposed method achieves a Miss Rate of 4.26% under night scenes, mainly benefiting from the dynamic radiometric enhancement technology of the AGREM module.

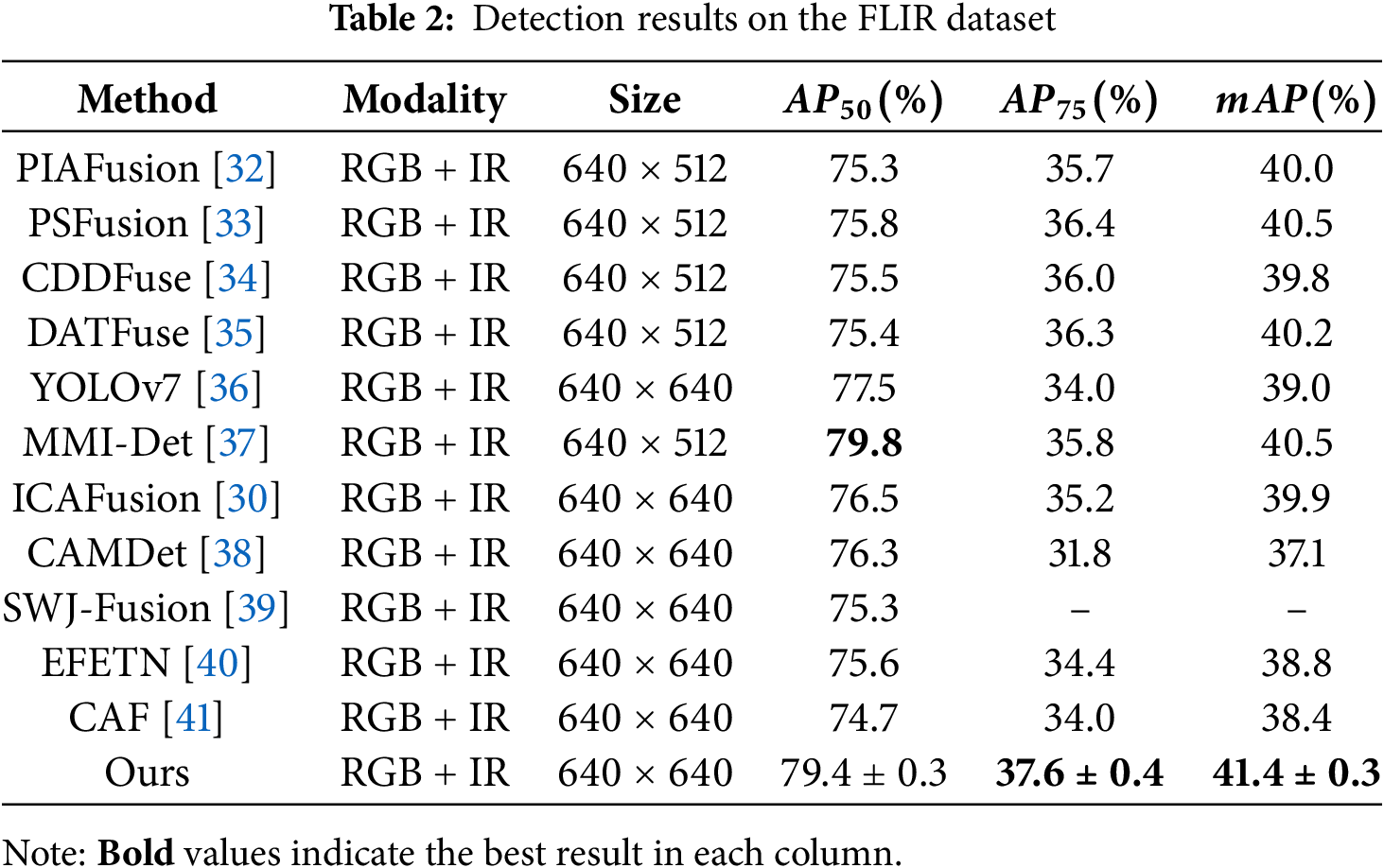

Compared to traditional methods like MLPD, which directly extract features in low-contrast scenes, our approach synergistically applies gray-scale compression and radiometric transformation to enhance the average contrast of pedestrian targets, effectively addressing the detail loss in infrared images. It is worth noting that our method also maintains a competitive Miss Rate of 6.94% under daytime scenes, indicating that the dynamic channel switching mechanism of the CSFI module can adaptively adjust modality weights, thereby avoiding scenario overfitting caused by the dominance of a single modality. We also conducted comparative experiments on the FLIR dataset with results shown in Table 2.

On common

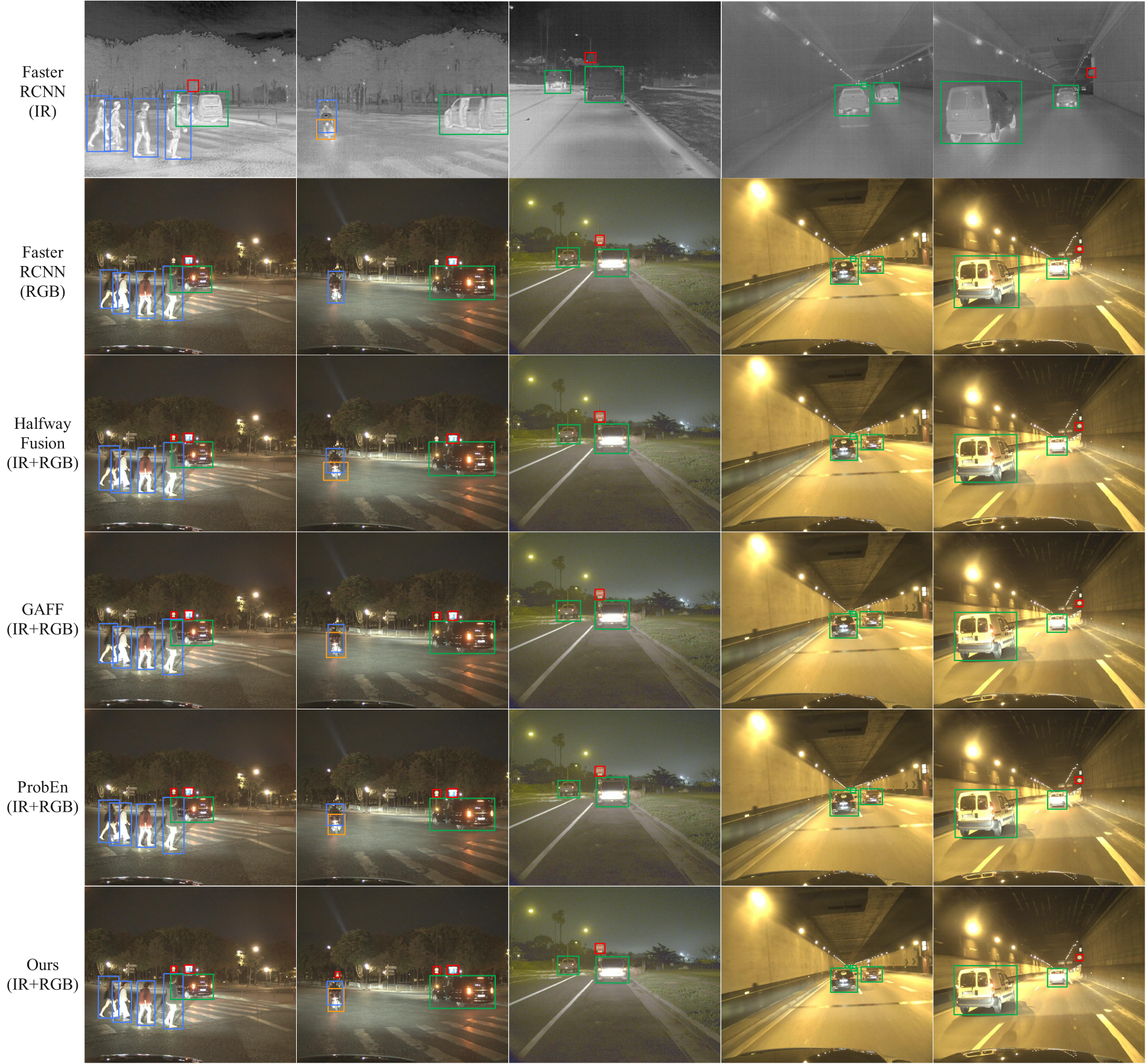

This performance improvement is mainly attributed to our proposed channel switching fusion network. This network dynamically assigns weights to RGB and infrared feature channels under different lighting and scene conditions through learnable gating strategies: in areas with strong light or rich details, priority is given to extracting RGB texture information, In low light or low contrast environments, emphasis is placed on infrared thermal radiation characteristics, thus balancing high recall of large targets and fine positioning of small and edge targets. Experimental results demonstrate that our nighttime object detection model exhibits outstanding performance and achieves excellent results on high-precision metrics, providing stable and efficient detection in complex nighttime environments. Fig. 5 shows the visual effects of our method compared to others.

Figure 5: Qualitative results of different models on the FLIR dataset

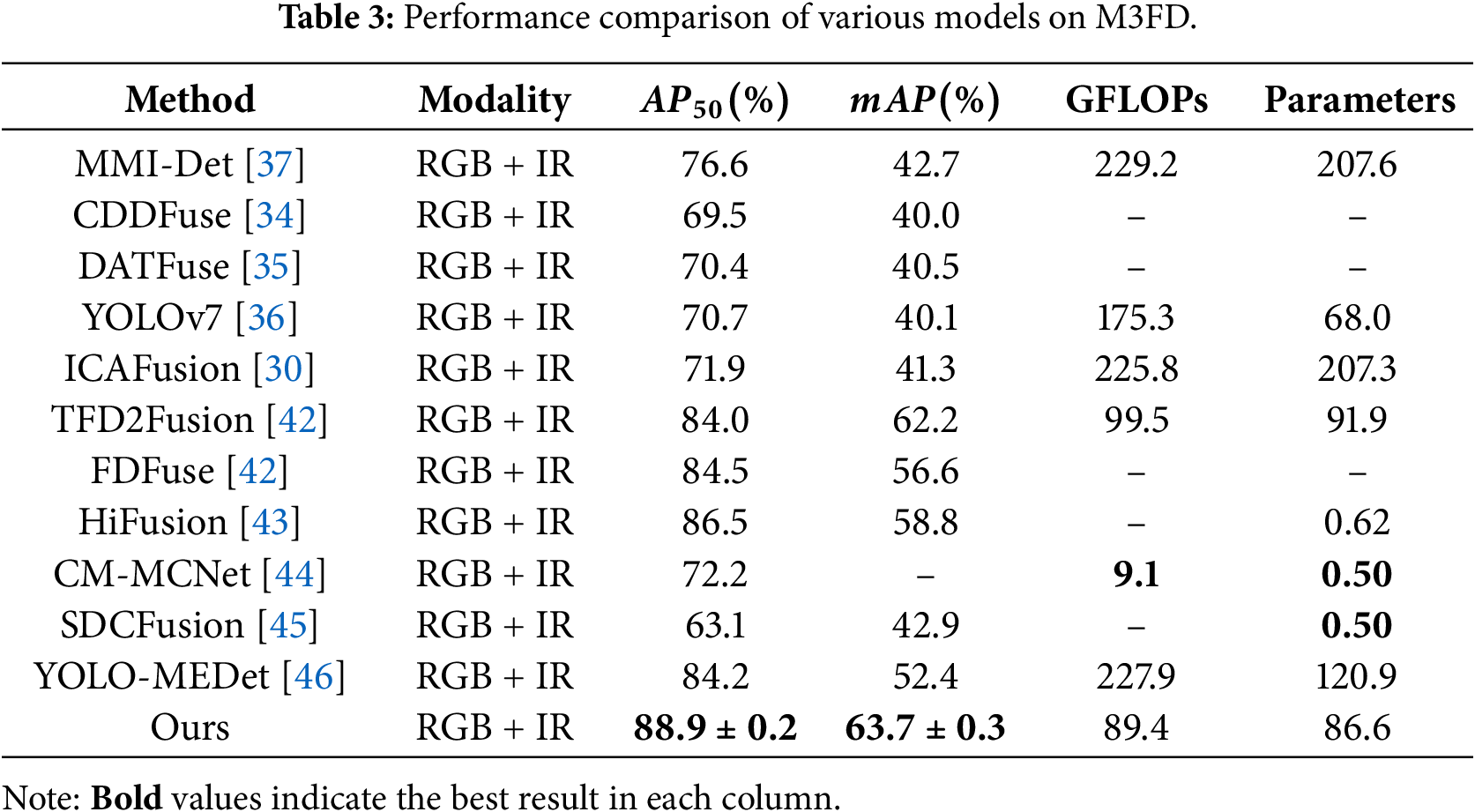

In order to comprehensively compare the differences between our method and existing methods, we also conducted a more comprehensive comparison on the M3FD dataset, and Table 3 shows the specific experimental results.

According to the experimental results, our method achieves the best results of 88.9% and 63.7% in the two key indicators of

To verify the effectiveness of each module in our method, we used a two-stream Faster RCNN combined with a standard FPN as the baseline model on the M3FD dataset. By gradually adding the AGREM, CSFI, and MSECA modules, we quantitatively analyzed their contributions to detection performance. All experiments are conducted using the same training strategy and evaluation protocol, and the results are shown in Table 4.

The baseline model achieved

With CSFI added to AGREM,

Finally, with MSECA incorporated, which combines cross-layer dynamic convolution and cross-modal global self-attention,

To further validate the effects of cross-layer dynamic convolution fusion and cross-modal attention fusion within the MSECA module, we conducted ablation experiments on our method (already integrated with AGREM + CSFI), where these two operations are added individually and jointly. The results of the M3FD dataset are summarized in Table 5.

In the ablation study of the MSECA module, introducing only cross-layer dynamic convolution fusion increased

To verify the performance impact of different operations in the CSFI module, we separately and jointly added different operations on the Cascade FusionNet integrated with AGREM+MSECA. When there is only multi-scale spatial attention, we use features from two branches at the same stage as inputs, simple concatenation, and spatial attention. The results of the M3FD dataset are shown in Table 6.

According to the ablation experiment results, both the dynamic channel switching and the multi-scale spatial attention mechanisms in the CSFI module positively impact model performance. When introducing dynamic channel switching alone, the importance of RGB and IR channels can be adaptively adjusted, effectively mining and integrating the advantageous information of different modalities, thus improving

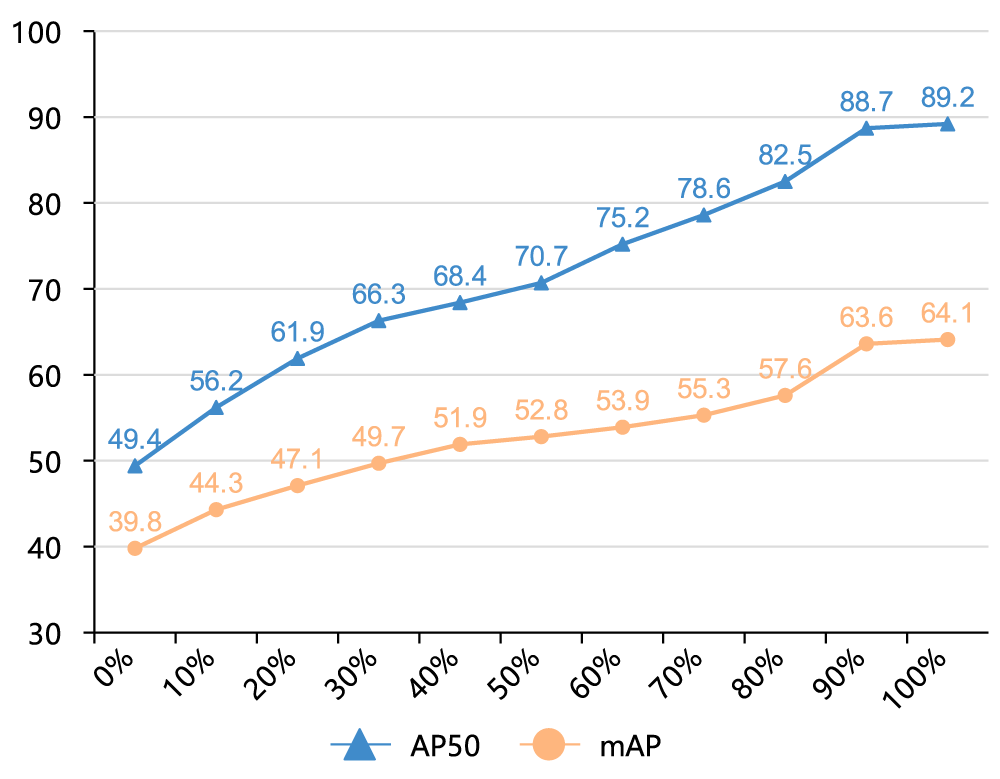

In this experiment, we first pretrained the network extensively on the large-scale infrared visible fusion dataset FLIP (50 rounds, initial learning rate

Figure 6: Model performance results under different proportions of M3FD data conditions

The results indicate that as the proportion of M3FD data increases, the detection performance steadily improves: even in the case of 0% M3FD, the FLIP pretrained model can achieve a baseline

This paper proposes an infrared-visible image fusion network, which addresses the core challenges of multimodal object detection under nighttime and low-light conditions through a multimodal feature optimization framework. Specifically, the AGREM module utilizes adaptive logarithmic transformation and radiometric correction to enhance low-contrast regions in infrared images, enabling deeper network layers to extract richer thermal details. Next, the CSFI module achieves complementary advantages between RGB and IR modalities at the channel level through dynamic channel switching and multi-scale spatial attention. Finally, the MSECA module optimizes the fusion of multi-level features through dynamic convolution and gating mechanisms, while globally capturing long-range complementary relationships between cross-modal features, resulting in high-quality fused features. This effectively enhances the robustness and accuracy of detection under occlusion and low-light conditions. Experimental results demonstrate that our method achieves significant performance improvements on the public KAIST, M3FD, and FLIR datasets: a nighttime miss rate of 4.26%,

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This paper is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62302086), the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (Grant No. 2023-MSBA-070) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. N2317005).

Author Contributions: The contribution of each author is as follows: Study conception and design: Tianzhe Jiao, Jie Song; Algorithm implementation and framework design: Tianzhe Jiao, Yuming Chen; Technical assistance and results analysis: Chaopeng Guo, Xiaoyue Feng; Draft manuscript preparation: Tianzhe Jiao, Yuming Chen; Review and editing: Jie Song. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and materials used in this article are derived from publicly accessible databases and previously published studies cited throughout the text.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://www.flir.cn/oem/adas/adas-dataset-form (accessed on 14 August 2025)

References

1. Fu H, Wang S, Duan P, Xiao C, Dian R, Li S, et al. LRAF-Net: long-range attention fusion network for visible–infrared object detection. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2024;35(10):13232–45. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2023.3266452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Bao W, Huang M, Hu J, Xiang X. Dual-dynamic cross-modal interaction network for multimodal remote sensing object detection. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2025;63:1–13. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2025.3530085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Sun C, Wang X, Fan S, Dai X, Wan Y, Jiang X, et al. NOT-156: night object tracking using low-light and thermal infrared: from multimodal common-aperture camera to benchmark datasets. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2025;63:1–11. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2025.3553695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Khan H, Usman MT, Rida I, Koo J. Attention enhanced machine instinctive vision with human-inspired saliency detection. Image Vis Comput. 2024;152(11):105308. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2024.105308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hu X, Liu Y, Yang F. PFCFuse: a poolformer and CNN fusion network for infrared-visible image fusion. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2024;73:1–14. doi:10.1109/tim.2024.3450061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang R, Luo M, Feng Q, Peng C, He D. Multi-party privacy-preserving faster R-CNN framework for object detection. IEEE Trans Em Top Comp Intell. 2024;8(1):956–67. doi:10.1109/tetci.2023.3296502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Pan C, Jiang Q, Zheng H, Wang P, Jin X, Yao S, et al. DANet: a dual-branch framework with diffusion-integrated autoencoder for infrared–visible image fusion. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2025;74:1–13. doi:10.1109/tim.2025.3548806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yu N, Fu Y, Xie Q, Cheng Q, Hasan MM. Feature extraction and fusion algorithm for infrared visible light images based on residual and generative adversarial network. Image Vis Comput. 2025;154(10):105346. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2024.105346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li Z, Li X, Niu Y, Rong C, Wang Y. Infrared and visible light fusion for object detection with low-light enhancement. In: 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Information Systems and Computer Aided Education (ICISCAE); 2024 Sep 27–29; Dalian, China. p. 120–4. [Google Scholar]

10. Zhou K, Chen L, Cao X. Improving multispectral pedestrian detection by addressing modality imbalance problems. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 787–803. [Google Scholar]

11. Kim J, Kim H, Kim T, Kim N, Choi Y. MLPD: multi-label pedestrian detector in multispectral domain. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2021;6(4):7846–53. doi:10.1109/lra.2021.3099870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xie J, Nie J, Ding B, Yu M, Cao J. Cross-modal local calibration and global context modeling network for RGB–infrared remote-sensing object detection. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2023;16:8933–42. doi:10.1109/jstars.2023.3315544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Girshick R. Fast R-CNN. In: 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 7–13; Santiago, Chile. p. 1440–8. [Google Scholar]

14. Jiang P, Ergu D, Liu F, Cai Y, Ma B. A review of Yolo algorithm developments. Procedia Comput Sci. 2022;199(11):1066–73. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2022.01.135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Farooq MA, Corcoran P, Rotariu C, Shariff W. Object detection in thermal spectrum for advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS). IEEE Access. 2021;9:156465–81. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3129150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Usman MT, Khan H, Rida I, Koo J. Lightweight transformer-driven multi-scale trapezoidal attention network for saliency detection. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;155:110917. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.110917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li C, Song D, Tong R, Tang M. Multispectral pedestrian detection via simultaneous detection and segmentation. arXiv:1808.04818. 2018. [Google Scholar]

18. Xu J, Lu K, Wang H. Attention fusion network for multi-spectral semantic segmentation. Pattern Rec Lett. 2021;146(4):179–84. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2021.03.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chen YT, Shi J, Ye Z, Mertz C, Ramanan D, Kong S. Multimodal object detection via probabilistic ensembling. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 139–58. [Google Scholar]

20. Zhang H, Fromont E, Lefèvre S, Avignon B. Guided attentive feature fusion for multispectral pedestrian detection. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision; 2021 Jan 3−8; Waikoloa, HI, USA. p. 72–80. [Google Scholar]

21. Cao Y, Bin J, Hamari J, Blasch E, Liu Z. Multimodal object detection by channel switching and spatial attention. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2023 Jun 17−24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 403–11. [Google Scholar]

22. Choi Y, Kim N, Hwang S, Park K, Yoon JS, An K, et al. KAIST multi-spectral day/night data set for autonomous and assisted driving. IEEE Trans Intell Trans Syst. 2018;19(3):934–48. doi:10.1109/tits.2018.2791533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang L, Zhu X, Chen X, Yang X, Lei Z, Liu Z. Weakly aligned cross-modal learning for multispectral pedestrian detection. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 5127–37. [Google Scholar]

24. Liu J, Fan X, Huang Z, Wu G, Liu R, Zhong W, et al. Target-aware dual adversarial learning and a multi-scenario multi-modality benchmark to fuse infrared and visible for object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 5802–11. [Google Scholar]

25. Dollár P, Appel R, Belongie S, Perona P. Fast feature pyramids for object detection. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2014;36(8):1532–45. doi:10.1109/tpami.2014.2300479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Li C, Song D, Tong R, Tang M. Illumination-aware faster R-CNN for robust multispectral pedestrian detection. Pattern Rec. 2019;85(4):161–71. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2018.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu J, Zhang S, Wang S, Metaxas DN. Multispectral deep neural networks for pedestrian detection. arXiv:1611.02644. 2016. [Google Scholar]

28. Zhang L, Liu Z, Zhang S, Yang X, Qiao H, Huang K, et al. Cross-modality interactive attention network for multispectral pedestrian detection. Inf Fusion. 2019;50:20–9. [Google Scholar]

29. Yang X, Qian Y, Zhu H, Wang C, Yang M. BAANet: learning bi-directional adaptive attention gates for multispectral pedestrian detection. In: 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2022 May 23−27; Philadelphia, PA, USA. p. 2920–6. [Google Scholar]

30. Shen J, Chen Y, Liu Y, Zuo X, Fan H, Yang W. ICAFusion: iterative cross-attention guided feature fusion for multispectral object detection. Pattern Rec. 2024;145(1):109913. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2023.109913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chen N, Xie J, Nie J, Cao J, Shao Z, Pang Y. Attentive alignment network for multispectral pedestrian detection. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2023 Oct 29−Nov 3; Ottawa, ON, Canada. p. 3787–95. [Google Scholar]

32. Tang L, Yuan J, Zhang H, Jiang X, Ma J. PIAFusion: a progressive infrared and visible image fusion network based on illumination aware. Inf Fusion. 2022;83-84(5):79–92. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2022.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Tang L, Zhang H, Xu H, Ma J. Rethinking the necessity of image fusion in high-level vision tasks: a practical infrared and visible image fusion network based on progressive semantic injection and scene fidelity. Inf Fusion. 2023;99(1):101870. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2023.101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhao Z, Bai H, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Xu S, Lin Z, et al. CDDFuse: correlation-driven dual-branch feature decomposition for multi-modality image fusion. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17−24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 5906–16. [Google Scholar]

35. Tang W, He F, Liu Y, Duan Y, Si T. DATFuse: infrared and visible image fusion via dual attention transformer. IEEE Trans Circ Syst Video Technol. 2023;33(7):3159–72. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2023.3234340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HYM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17−24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 7464–75. [Google Scholar]

37. Zeng Y, Liang T, Jin Y, Li Y. MMI-Det: exploring multi-modal integration for visible and infrared object detection. IEEE Trans Circ Syst Video Technol. 2024;34(11):11198–213. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2024.3418965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Jang J, Lee J, Paik J. CAMDet: condition-adaptive multispectral object detection using a visible-thermal translation model. In: ICASSP 2025−2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2025 Apr 6−11; Hyderabad, India. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

39. Tan MJ, Gao SB, Han SC. Boosting visible-infrared image fusion and target detection performance with sleep-wake joint learning. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2025;74:1–19. doi:10.1109/tim.2025.3554852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhao G, Zhu J, Jiang Q, Feng S, Wang Z. Edge feature enhanced transformer network for RGB and infrared image fusion based object detection. Infrared Phys Technol. 2025;147(2):105824. doi:10.1016/j.infrared.2025.105824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zeng X, Liu G, Chen J, Wu X, Di J, Ren Z, et al. Efficient multimodal object detection via coordinate attention fusion for adverse environmental conditions. Digit Signal Process. 2025;156(6):104873. doi:10.1016/j.dsp.2024.104873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Cheng M, Huang H, Liu X, Mo H, Wu S, Zhao X. FDFuse: infrared and visible image fusion based on feature decomposition. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2025;74:1–13. doi:10.1109/tim.2025.3551460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Xu K, Wei A, Zhang C, Chen Z, Lu K, Hu W, et al. HiFusion: an unsupervised infrared and visible image fusion framework with a hierarchical loss function. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2025;74:1–16. doi:10.1109/tim.2025.3548202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Liu J, Liu S, Huang L, Cen L. CM-MCNet: convolution and multilayer perceptron-integrated multiscale coordinate network for infrared and visible image fusion. Pattern Recognit. 2025;168(5):111843. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2025.111843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Liu X, Huo H, Li J, Pang S, Zheng B. A semantic-driven coupled network for infrared and visible image fusion. Inf Fusion. 2024;108(8):102352. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zhao Y, Gao Y, Yang X, Yang L. Multispectral target detection based on deep feature fusion of visible and infrared modalities. Appl Sci. 2025;15(11):5857. doi:10.3390/app15115857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Lin TY, Maire M, Belongie S, Hays J, Perona P, Ramanan D, et al. Microsoft coco: common objects in context. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2014. p. 740–55. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools