Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Prediction of Water Uptake Percentage of Nanoclay-Modified Glass Fiber/Epoxy Composites Using Artificial Neural Network Modelling

1 Department of Mathematics, Manipal Institute of Technology, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, 576104, Karnataka, India

2 Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Manipal Institute of Technology, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, 576104, Karnataka, India

* Corresponding Author: Manjunath Shettar. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Computational Modeling and Simulations for Engineering Structures and Multifunctional Materials: Bridging Theory and Practice)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2715-2728. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069842

Received 01 July 2025; Accepted 13 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

This research explores the water uptake behavior of glass fiber/epoxy composites filled with nanoclay and establishes an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) to predict water uptake percentage from experimental parameters. Composite laminates are fabricated with varying glass fiber and nanoclay contents. Water absorption is evaluated for 70 days of immersion following ASTM D570-98 standards. The inclusion of nanoclay reduces water uptake by creating a tortuous path for moisture diffusion due to its high aspect ratio and platelet morphology, thereby enhancing the composite’s barrier properties. The ANN model is developed with a 3–4–1 feedforward structure and learned through the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm with soaking time (7 to 70 days), fiber content and nanoclay content as input parameters. The model’s output is the water uptake percentage. The model has high prediction efficiency, with a correlation coefficient of and a mean squared error of . Experimental and predicted values are in excellent agreement, ensuring the reliability of the ANN for the simulation of nonlinear water absorption behavior. The results identify the synergistic capability of nanoclay and fiber concentration to reduce water absorption and prove the feasibility of ANN as a substitute for time-consuming testing in composite durability estimation.Keywords

Fiber reinforced polymer composites (FRPCs) are universally accepted in the automotive industry, marine industry, and civil engineering applications because of their high specific strength, stiffness, corrosion resistance, and light weight [1,2]. Compared to composites reinforced with natural or carbon fibers, glass fiber/epoxy composites provide a more favorable balance between mechanical performance, cost, and environmental durability, making them well-suited for structural applications in the marine and aerospace sectors. Though their short-term performance is satisfactory, long-term performance degrades when subjected to environmental conditions like water, humidity, thermal cycling, and chemical attack. This calls for material modifications and predictive modelling tools to improve performance and predict behavior in service. Water absorption is a critical degradation mechanism in fiber-reinforced polymer composites, leading to plasticization of the matrix, fiber–matrix debonding, and long-term mechanical property deterioration. Even moderate moisture ingress can lead to dimensional instability, reduced load-bearing capacity, and premature failure in marine, civil infrastructure, and transportation sectors. Therefore, quantifying and predicting water uptake behavior is essential for ensuring structural reliability and longevity [3,4].

Over the past few years, advances in nanotechnology have made it possible to utilize nanofillers to design the properties of polymer composites. Among numerous nanofillers, layered silicate-based nanoclay has emerged as a promising nanofiller capable of improving epoxy matrices’ mechanical, thermal, and barrier performances [5–7]. The platelet nature and high aspect ratio of nanoclay help enhance load transfer, decrease moisture permeability, and delay crack propagation [8]. Some studies have shown that adding nanoclay to epoxy/glass fiber composites improves tensile strength, interlaminar shear strength, and hygrothermal aging resistance [9,10]. However, the efficacy of nanoclay reinforcement is influenced significantly by dispersion quality, filler loading, and fiber–matrix interface interaction.

Traditional experimental methods to measure the effect of nanofillers on composite properties are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and material-intensive. In addition, it is challenging for conventional statistical models to predict the nonlinear impact of multiple factors, filler content, environmental exposure, and processing conditions [11,12]. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are powerful tools for modelling complex multivariable systems, especially in material science, where fabrication parameter dependence of performance properties is strongly nonlinear. ANNs are computer models inspired by the brain’s operation that can learn complex input-output mappings without direct physical models [13].

ANNs are successfully employed in composite materials to simulate mechanical strength, water absorption, and wear resistance due to fabrication and material characteristics [14,15]. ANNs are distinct from regression models as they can handle nonlinearities and interactions between multiple variables. They are best-suited for systems with complex input–output behavior, such as nanocomposites.

The study by Yıldırım [16] focuses on using an ANN to accurately predict how the weight of glass fiber-reinforced polymer composites filled with SiC nanoparticles changes during artificial aging. The ANN model is developed using MATLAB with a (2-4-1) architecture and is trained using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. It uses nanoparticle weight percentage and aging time as input parameters. The model achieves high prediction accuracy, with a low mean square error of

Similarly, Capiel et al. [17] design ANN models to predict water absorption in glass fiber-reinforced nanoclay-epoxy composites. Two models are constructed for modified and unmodified bentonite systems. With a three-input (bentonite content, temperature, and immersion time) and one-output (water absorption) architecture with two hidden layers, the networks are trained with the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. With over 4600 experimental data points, both models performed exceptionally well regarding predictive capability, with correlation coefficients

In a related study, Saaidia et al. [18] apply ANN to model water absorption in jute and sisal fiber-reinforced epoxy composites with varying lengths of the fibers (5, 10, and 15 mm). The Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm-trained ANN accurately models the saturation kinetic curve of water absorption. The study emphasizes the capability of ANN in optimizing such critical parameters as immersion time and fiber length with reduced reliance on experimental analysis.

Likewise, Makhlouf et al. [19] use ANN modelling to simulate water absorption in HDPE/jute fiber biocomposites. The model with input parameters of fiber loading and immersion time, and output as water absorption, has an excellent correlation between simulated and experimental data (

While prior studies have implemented ANN for predicting mechanical strength [14], wear resistance [15], and even water absorption [16–19], most models have focused on fixed fiber or filler types and used limited input variables. Yıldırım [16] has used a 2-input ANN model to simulate SiC nanoparticle-filled composites, and Capiel et al. [17] have modeled water uptake in nanoclay-epoxy systems without varying the reinforcement. However, composite water absorption is influenced by complex, nonlinear interactions between fiber content, filler dispersion, and soaking time. This study addresses that gap by developing a multi-input ANN model trained on experimentally validated fiber and nanoclay content combinations across immersion durations, thereby capturing synergistic effects that earlier studies have not explored.

This study’s novelty lies in developing an ANN-based predictive model for water uptake in a hybrid composite system combining varying glass fiber contents with nanoclay-modified epoxy resin. Unlike earlier models that focused solely on natural fibers, single fillers, or fixed reinforcement levels, this work explores the combined influence of fiber loading and nanoclay concentration across multiple immersion durations. Using a tailored feedforward ANN architecture (3-4-1) with input variables of soaking time, glass fiber wt.%, and nanoclay wt.% allows for accurate modelling of the nonlinear moisture absorption behavior. Furthermore, including intermediate confirmation tests not present in the training set demonstrates the model’s strong interpolation capability and generalization strength. This integrated approach offers a cost-effective and accurate alternative to prolonged experimentation, advancing composite design strategies for enhanced hydrothermal durability.

2.1 Materials and Preparation of Composites

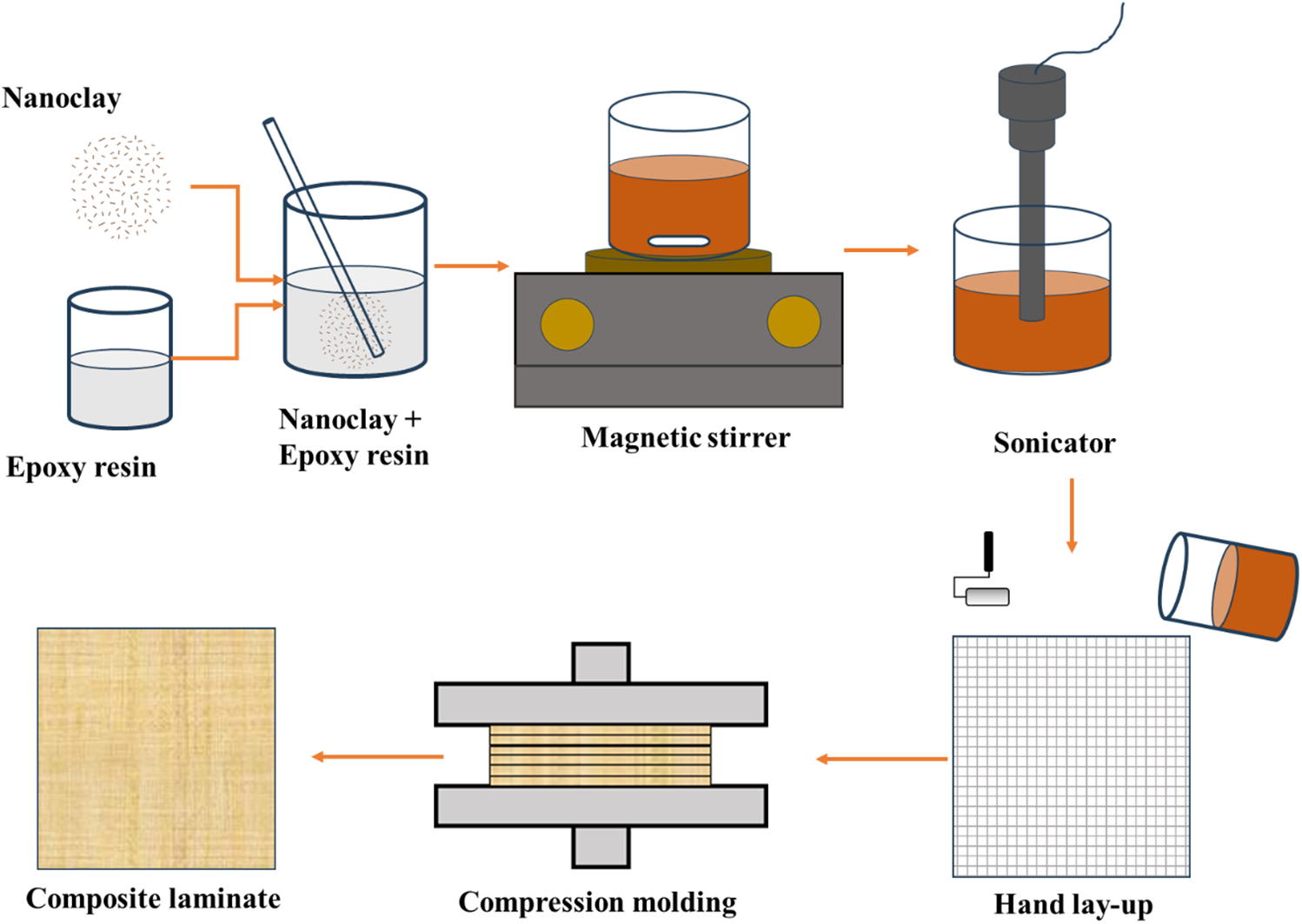

Epoxy resin (L-12) and hardener (K-6) are sourced from Atul Polymers, Gujarat, India, while the bi-directional woven E-glass fabric is obtained from Yuje Enterprises, Bengaluru. The surface-modified nanoclay, containing

Nanoclay is mixed into the epoxy using a magnetic stirrer for

Figure 1: Preparation of composite laminates

Water uptake tests are conducted following ASTM D570-98 standards. Initially, the dry sample weight of each specimen is recorded using a digital weighing machine. The samples are then immersed in tap water at room temperature (

where, Wa—weight of the specimen after absorption, Wd—Weight of the dry specimen

2.3 Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Modelling

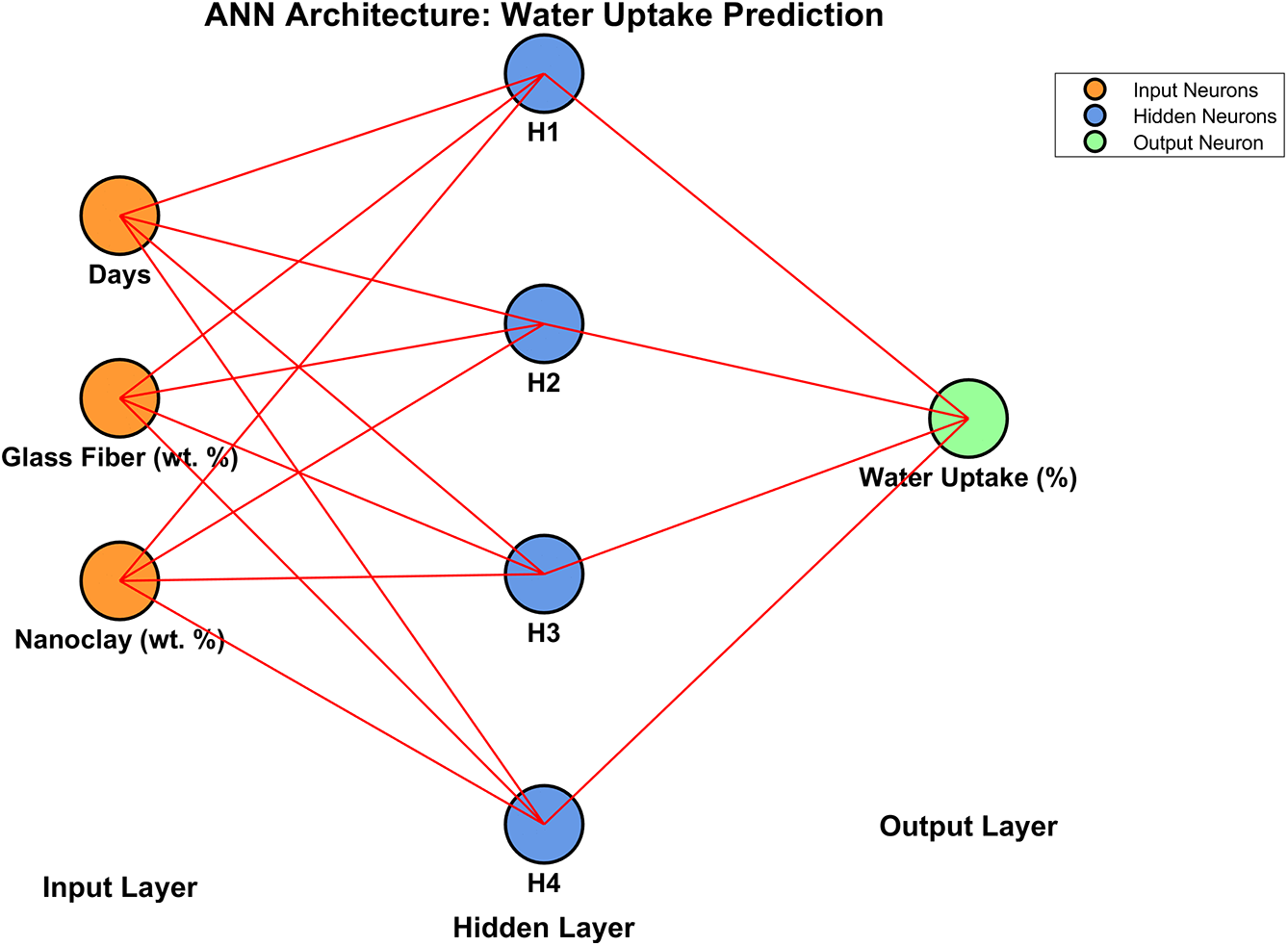

This work develops an ANN-based predictive model to estimate the water uptake percentage of glass fiber/epoxy composites modified with nanoclay under various soaking durations.

The ANN architecture is selected based on preliminary trials to balance model simplicity and prediction accuracy. The optimal structure consists of

a. Three input nodes, corresponding to soaking time (days), glass fiber content (wt.%), and nanoclay content (wt.%).

b. One hidden layer with four neurons, a structure chosen after iterative tuning to avoid underfitting and overfitting. The final ANN architecture (3-4-1) is selected after a manual grid search, trialing different hidden layers (1-3) and neurons (2-6). The (3-4-1) model shows optimal performance in terms of MSE and training stability.

c. One output node, representing the predicted water uptake (%).

2.3.2 Transfer Functions and Learning Algorithm

The hidden layer utilizes a tansig (hyperbolic tangent sigmoid) function, effectively mapping nonlinear relationships between inputs and outputs in the range of

2.3.3 Training Strategy and Data Management

The available data set is partitioned into

2.3.4 Model Evaluation Metrics

The model’s learning performance is assisted through Mean Squared Error (MSE), the Regression coefficient

Figure 2: Architecture of the developed ANN model for water uptake prediction

Table 4 illustrates the water uptake behavior of glass fiber reinforced epoxy composites modified with varying nanoclay content over an immersion period of

A comparison across glass fiber content at constant nanoclay levels reveals that increasing the glass fiber wt.% results in redcution in water uptake percentage. For instance, composites with

Similarly, the incorporation of nanoclay significantly enhances moisture resistance. Increasing the nanoclay loading from

The combined effect of higher glass fiber and nanoclay content is particularly effective. Composites with

Role of Hand Lay-Up and Compression Molding in Controlling Water Uptake (%)

The fabrication process employed in this study involves hand lay-up followed by compression molding at

Though simple and cost-effective, the hand lay-up technique is susceptible to entrapped air and resin-rich zones if not properly managed. To mitigate this, a roller is used to compress the laminate uniformly and expel trapped air, reducing void formation. The presence of voids can significantly enhance water uptake by providing direct capillary pathways for moisture ingress.

Compression molding under

Stronger fiber–matrix adhesion results in fewer interfacial gaps, which are potential moisture ingress sites. Conversely, insufficient pressure or incomplete curing could lead to poor wetting and weak bonding, promoting microcracks and water diffusion. Therefore, the selected processing parameters are critical for mechanical integrity and improving moisture resistance by lowering void content and strengthening the fiber–matrix interface.

The experimental dataset used for training, validation, and testing of the ANN model is derived from the water uptake measurements presented in Table 4, which are obtained from immersion tests on composites with varying soaking time, glass fiber, and nanoclay contents conducted as per ASTM D570-98.

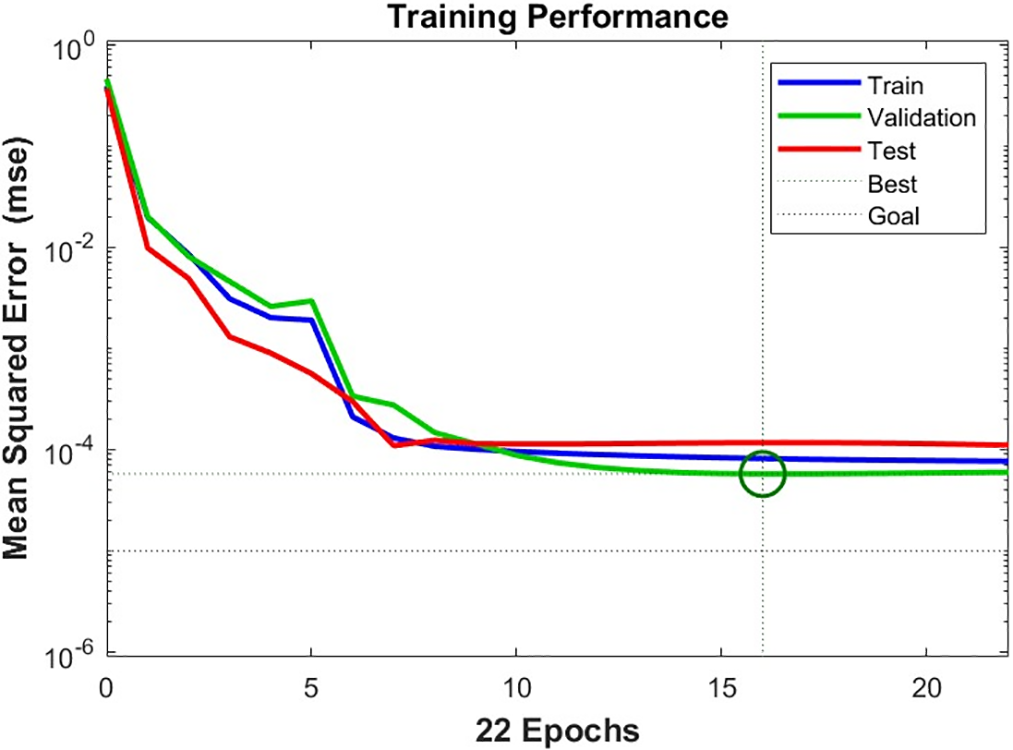

The chosen ANN architecture reflects a balance between model complexity and prediction robustness, avoiding overfitting while capturing nonlinear dependencies between the input variables and moisture absorption behavior. The method exhibits fast convergence within 18 epochs, with the best validation performance achieved early, suggesting effective learning.

The training performance curve in Fig. 3 reveals a steep decline in Mean Squared Error (MSE) within the first

Figure 3: Training performance of ANN

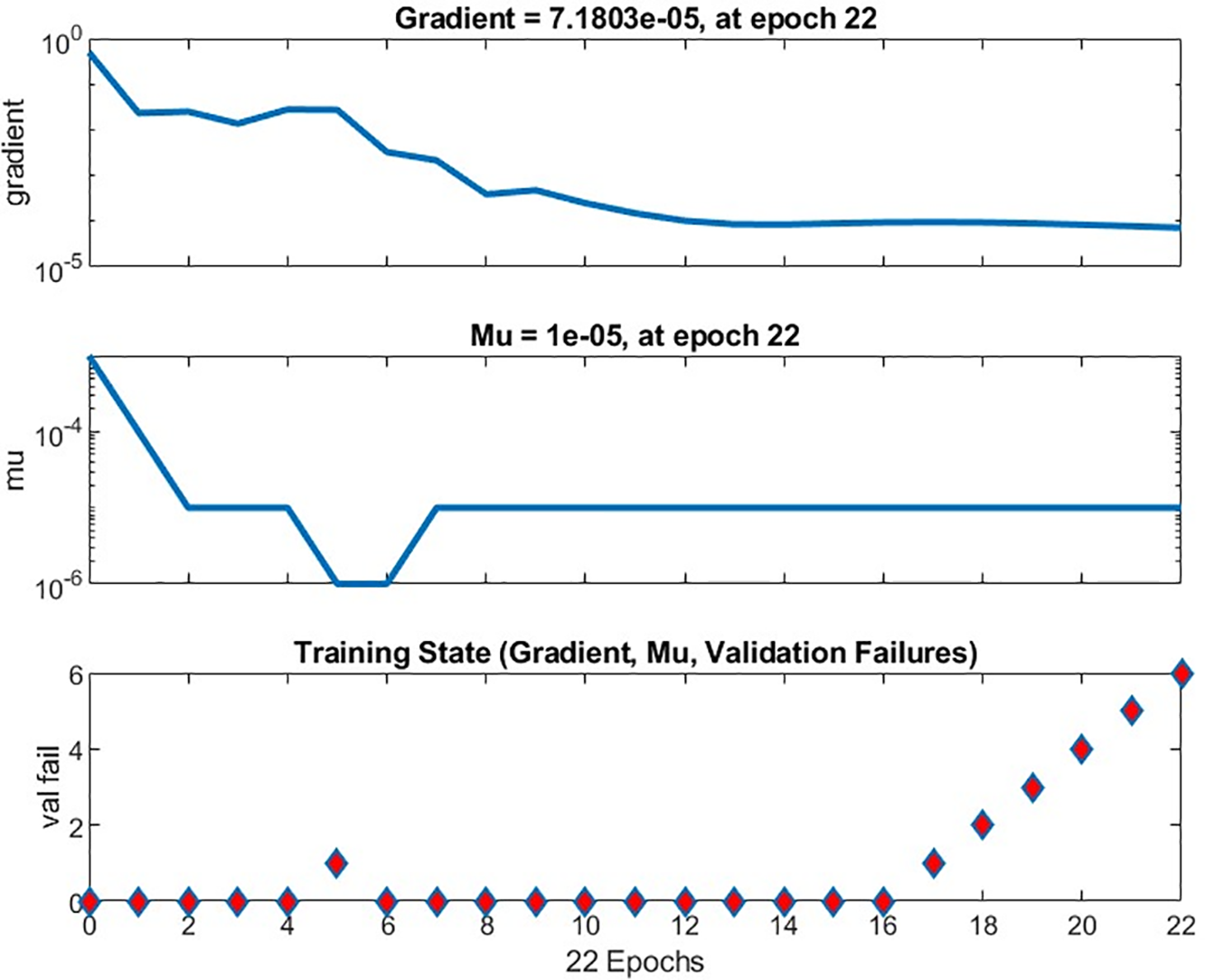

The training state plot in Fig. 4 provides insight into the internal optimization dynamics of the ANN model. The gradient decreases smoothly to

Figure 4: Training state plot—evolution of the gradient, Mu, and validation failure

Each experimental data point represents the mean of five replicate tests. Standard deviation across replicates is consistently below

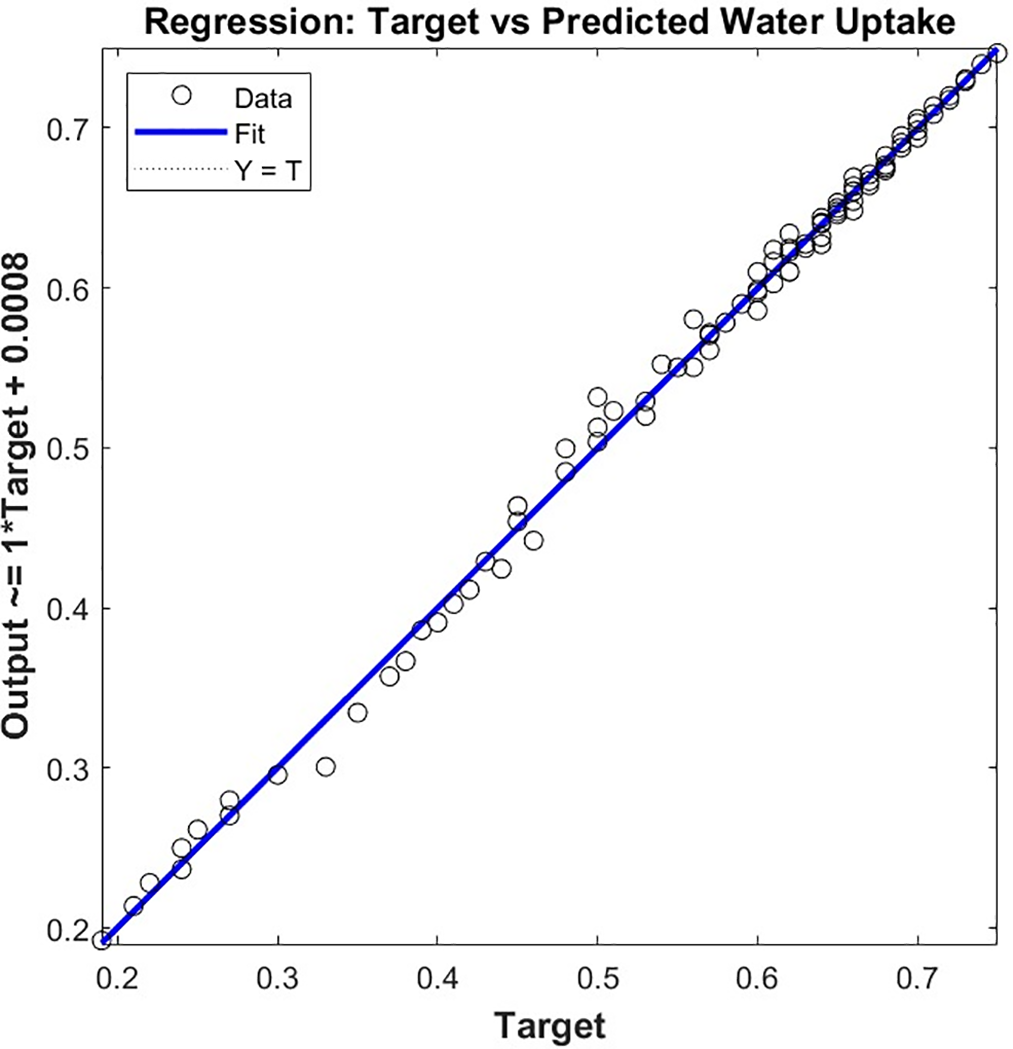

The regression plot in Fig. 5 demonstrates an exceptionally high correlation between the network’s predictions and the experimental targets. The coefficient of determination exceeds

Figure 5: Regression plot for comparing ANN-predicted water uptake values to experimental targets

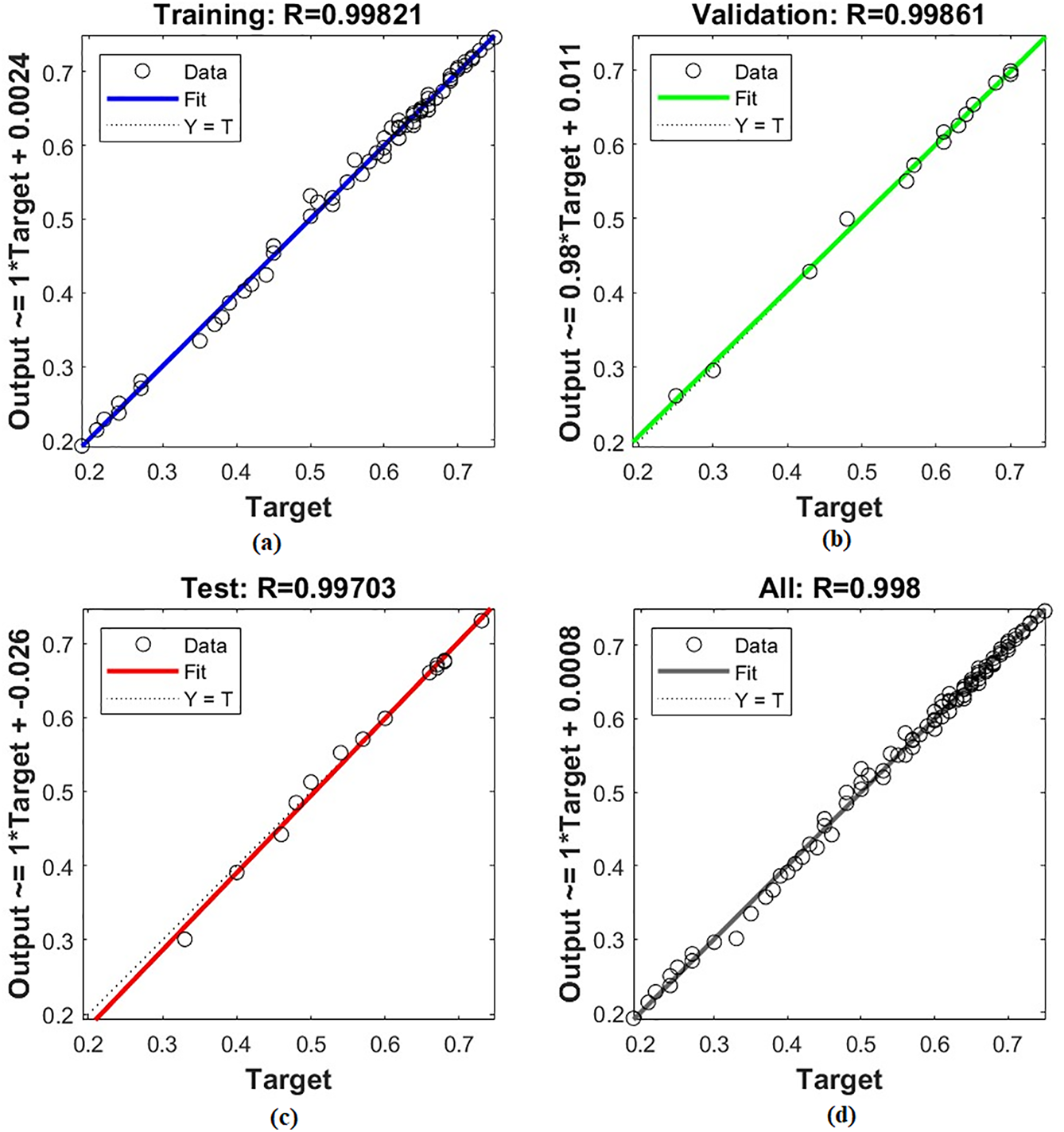

The multi-state regression plot in Fig. 6 extensively evaluates the ANN’s predictive capability across all data splits-training, validation, and testing. All the regression lines are closely aligned with the ideal

Figure 6: Regression plots for ANN model performance across (a) training, (b) validation, (c) testing, and (d) overall data sets

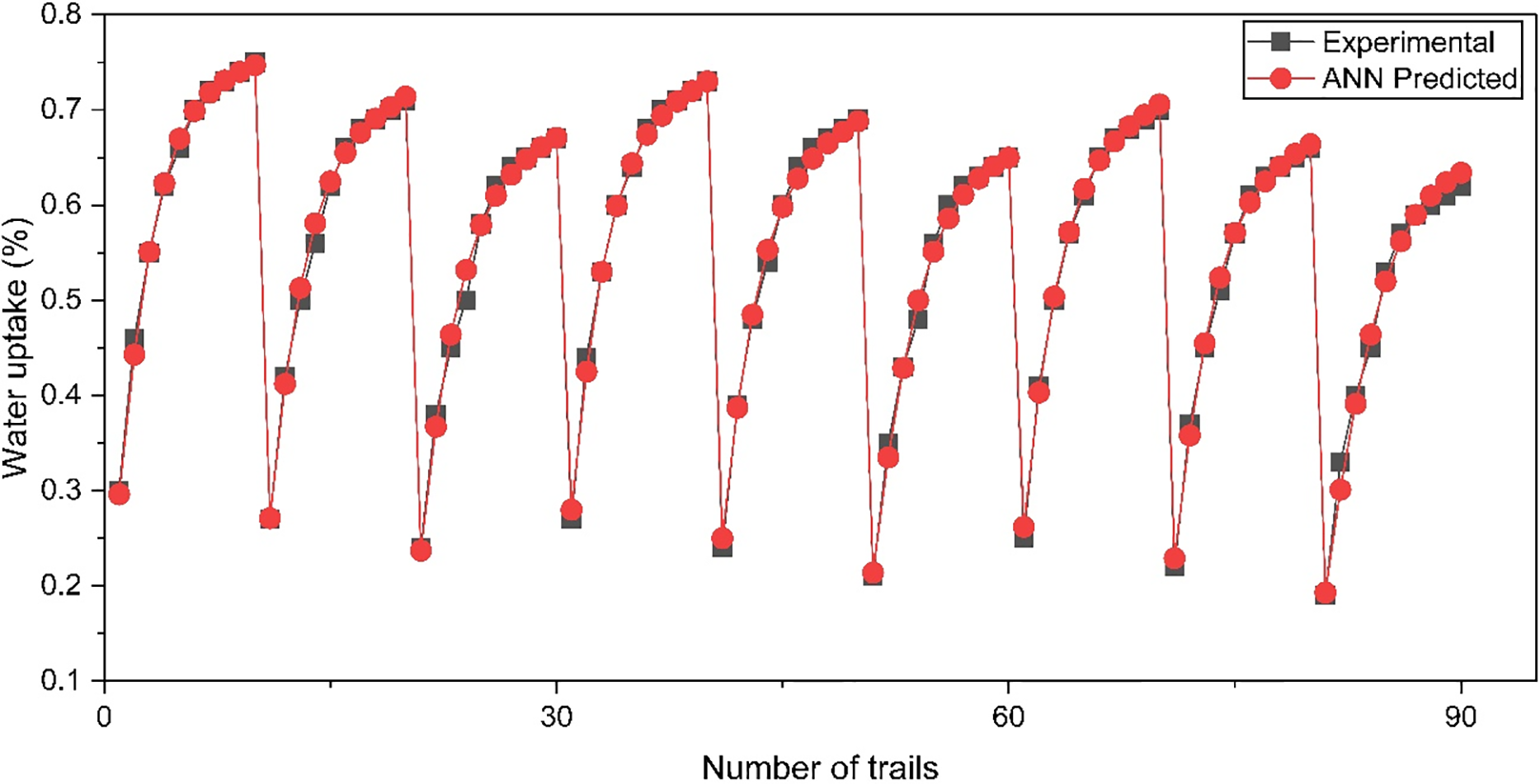

Fig. 7 directly compares the experimental water uptake (%) values and those predicted by the ANN model across all test conditions. The close alignment between both sets of data points validates the robustness and predictive capability of the trained ANN. This figure underscores the model’s ability to generalize across various composite configurations. The minimal deviation between the actual and predicted values reflects a high degree of correlation, which is further supported by regression metrics (with

Figure 7: Comparison of experimental findings and ANN output

Table 5 presents the results of independent confirmation tests conducted at selected intermediate immersion durations

For instance, the water uptake for a composite with

This study focuses on developing an ANN model to predict water uptake behavior in nanoclay-modified glass fiber/epoxy composites subjected to prolonged immersion. Composite laminates are fabricated with varying glass fiber

The developed ANN model accurately predicts water uptake in nanoclay-modified glass fiber/epoxy composites with an

These findings offer practical value for industrial composite design by enabling significant reductions in prototype testing and development time. The validated ANN model provides a fast, cost-effective tool for predicting moisture uptake across various formulations, allowing early-stage screening and optimization without extensive experimental trials. This approach supports accelerated design cycles and efficient material selection for moisture-critical applications.

The current ANN model is trained solely in water immersion data at room temperature

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Ashwini Bhat and Manjunath Shettar; methodology, Ashwini Bhat and Manjunath Shettar; software, Ashwini Bhat; validation, Ashwini Bhat, Nagaraj N. Katagi and M. C. Gowrishankar; formal analysis, Ashwini Bhat; investigation, M. C. Gowrishankar and Manjunath Shettar; resources, M. C. Gowrishankar and Manjunath Shettar; data curation, M. C. Gowrishankar and Manjunath Shettar; writing—original draft preparation, Ashwini Bhat and Nagaraj N. Katagi; writing—review and editing, M. C. Gowrishankar and Manjunath Shettar; visualization, Manjunath Shettar; supervision, Manjunath Shettar; project administration, Manjunath Shettar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Dinită A, Ripeanu RG, Ilincă CN, Cursaru D, Matei D, Naim RI, et al. Advancements in fiber-reinforced polymer composites: a comprehensive analysis. Polymers. 2023;16(1):2. doi:10.3390/polym16010002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Hamzat AK, Murad MS, Adediran IA, Asmatulu E, Asmatulu R. Fiber-reinforced composites for aerospace, energy, and marine applications: an insight into failure mechanisms under chemical, thermal, oxidative, and mechanical load conditions. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2025;8(1):152. doi:10.1007/s42114-024-01192-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Harle SM. Durability and long-term performance of fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) composites: a review. Structures. 2024;60(31):105881. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2024.105881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Idrisi AH, Mourad AHI, Abdel-Magid BM, Shivamurty B. Investigation on the durability of E-glass/epoxy composite exposed to seawater at elevated temperature. Polymers. 2021;13(13):2182. doi:10.3390/polym13132182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Ejeta LO. Nanoclay/organic filler-reinforced polymeric hybrid composites as promising materials for building, automotive, and construction applications—a state-of-the-art review. Compos Interfaces. 2023;30(12):1363–86. doi:10.1080/09276440.2023.2220217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Shelly D, Singhal V, Singh S, Nanda T, Mehta R, Lee SY, et al. Exploring the impact of nanoclay on epoxy nanocomposites: a comprehensive review. J Compos Sci. 2024;8(12):506. doi:10.3390/jcs8120506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Merah N, Ashraf F, Shaukat MM. Mechanical and moisture barrier properties of epoxy-nanoclay and hybrid epoxy-nanoclay glass fibre composites: a review. Polymers. 2022;14(8):1620. doi:10.3390/polym14081620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Uddin MN, Hossain MT, Mahmud N, Alam S, Jobaer M, Mahedi SI, et al. Research and applications of nanoclays: a review. SPE Polym. 2024;5(4):507–35. doi:10.1002/pls2.10146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Örçen G, Bayram D. Effect of nanoclay on the mechanical and thermal properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy composites. J Mater Sci. 2024;59(8):3467–87. doi:10.1007/s10853-024-09387-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Shettar M, Bhat A, Katagi NN, Gowrishankar MC. Experimental investigation on mechanical properties of glass fiber–nanoclay–epoxy composites under water-soaking: a comparative study using RSM and ANN. J Compos Sci. 2025;9(4):195. doi:10.3390/jcs9040195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Champa-Bujaico E, García-Díaz P, Díez-Pascual AM. Machine learning for property prediction and optimization of polymeric nanocomposites: a state-of-the-art. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(18):10712. doi:10.3390/ijms231810712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kumar DS, Sathish T, Rangappa SM, Boonyasopon P, Siengchin S. Mechanical property analysis of nanocarbon particles/glass fiber reinforced hybrid epoxy composites using RSM. Compos Commun. 2022;32(23):101147. doi:10.1016/j.coco.2022.101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Thanikodi S, Rathinasamy S, Solairaju JA. Developing a model to predict and optimize the flexural and impact properties of jute/kenaf fiber nano-composite using response surface methodology. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2025;136(1):195–209. doi:10.1007/s00170-024-13975-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Arunachalam SJ, Saravanan R, Sathish T, Giri J, Kanan M. Mechanical assessment for enhancing hybrid composite performance through silane treatment using RSM and ANN. Results Eng. 2024;24(1):103309. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Arunachalam SJ, Saravanan R, Sathish T, Giri J, Barmavatu P. Optimization of nano-filler and silane treatment on mechanical performance of nanographene hybrid composites using RSM and ANN technique. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2025;39(2):257–80. doi:10.1080/01694243.2024.2403680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yıldırım H. Prediction of weight change of glass fiber reinforced polymer matrix composites with SiC nanoparticles after artificial aging by artificial neural network-based model. J Mater Sci. 2025;60(11):5064–79. doi:10.1007/s10853-025-10747-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Capiel G, Florencia A, Alvarez VA, Montemartini PE, Morán J. An Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model for predicting water absorption of Nanoclay-Epoxy composites. J Mater Sci Chem Eng. 2019;7(8):87–97. doi:10.4236/msce.2019.78010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Saaidia A, Belaadi A, Boumaaza M, Alshahrani H, Bourchak M. Effect of water absorption on the behavior of jute and sisal fiber biocomposites at different lengths: ANN and RSM modeling. J Nat Fibers. 2023;20(1):2140326. doi:10.1080/15440478.2022.2140326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Makhlouf A, Belaadi A, Boumaaza M, Mansouri L, Bourchak M, Jawaid M. Water Absorption behavior of jute fibers reinforced HDPE biocomposites: prediction using RSM and ANN modeling. J Nat Fibers. 2022;19(16):14014–31. doi:10.1080/15440478.2022.2114976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shettar M, Bhat A, Katagi NN. Estimation of mass loss under wear test of nanoclay-epoxy nanocomposite using response surface methodology and artificial neural networks. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):19978. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-05263-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Manaia JP, Manaia A. Interface modification, water absorption behaviour and mechanical properties of injection moulded short hemp fiber-reinforced thermoplastic composites. Polymers. 2021;13(10):1638. doi:10.3390/polym13101638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Borges CSP, Akhavan-Safar A, Marques EAS, Carbas RJC, Ueffing C, Weißgraeber P, et al. Effect of water ingress on the mechanical and chemical properties of polybutylene terephthalate reinforced with glass fibers. Materials. 2021;14(5):1261. doi:10.3390/ma14051261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Cheng W, Cao Y. Strength degradation of GFRP cross-ply laminates in hydrothermal conditions. APL Mater. 2024;12(3):031113. doi:10.1063/5.0201999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Gowrishankar MC, Shettar M, Somdee P, Rangaswamy N, Chate GR. A review on mechanical, water-soaking, thermal, and wear properties of nanoclay-polyester nanocomposites. Discov Mater. 2025;5(1):105. doi:10.1007/s43939-025-00304-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Rafiq A, Merah N. Nanoclay enhancement of flexural properties and water uptake resistance of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy composites at different temperatures. J Compos Mater. 2019;53(2):143–54. doi:10.1177/0021998318781220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools