Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Psychological Manipulation of Phishing Emails: A Cognitive Bias Approach

School of Cyberspace Security, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Beijing, 102209, China

* Corresponding Author: Bin Wu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 4753-4776. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065059

Received 02 March 2025; Accepted 28 June 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Cognitive biases are commonly used by attackers to manipulate users’ psychology in phishing emails. This study systematically analyzes the exploitation of cognitive biases in phishing emails and addresses the following questions: (1) Which cognitive biases are frequently exploited in phishing emails? (2) How are cognitive biases exploited in phishing emails? (3) How effective are cognitive bias features in detecting phishing emails? (4) How can the exploitation of cognitive biases in phishing emails be modelled? To address these questions, this study constructed a cognitive processing model that explains how attackers manipulate users by leveraging cognitive biases at different cognitive stages. By annotating 482 phishing emails, this study identified 10 common types of cognitive biases and developed corresponding detection models to evaluate the effectiveness of these bias features in phishing email detection. The results show that models incorporating cognitive bias features significantly outperform baseline models in terms of accuracy, recall, and F1 score. This study provides crucial theoretical support for future anti-phishing methods, as a deeper understanding of cognitive biases offers key insights for designing more effective detection and prevention strategies.Keywords

In today’s society, the widespread adoption of the internet has greatly facilitated information exchange and social development. However, it has also provided attackers with new tools to exploit users through technological means. While email, instant messaging, and social media have brought convenience to daily life, they have also become primary channels for attackers to carry out social engineering attacks [1]. Social engineering attacks exploit vulnerabilities in human psychology rather than weaknesses in technical defence systems. Attackers use psychological profiling techniques, such as social media behaviour analysis and personality trait inference, to precisely identify the cognitive weak points of their targets and design targeted attack strategies [2]. Globally, losses resulting from social engineering attacks exceed $10 billion annually, including financial losses, data breaches, and reputational damage [3]. Moreover, deepfake fraud increased by 3000% in 2023, showing exponential growth. AI-generated false videos or audio recordings significantly enhance the success rate of fraudulent activities [4]. In fact, 77% of cyberattacks are caused by human errors, while only 23% result from technical failures. Therefore, relying solely on technology is insufficient to eradicate phishing attacks, solutions must be explored at the level of human cognitive mechanisms [5].

Phishing emails, as the primary tool of social engineering attacks, owe their success to a large extent to attackers’ precise understanding of victims’ psychology [6]. According to Radicati Group projections, the global number of email users will exceed 4.8 billion by 2027 [7]. The latest report from the Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG) indicates that in 2023, 5 million phishing attack incidents were detected, setting a new record. For attackers, sending what appears to be a harmless email may seem effortless, but for victims, it can lead to severe economic and information security losses.

Current research on phishing emails primarily focuses on detecting them using various technical methods, such as traditional approaches, machine learning, and deep learning algorithms [8–10]. From a client-side perspective, Petelka et al.’s research shows that embedding warnings directly adjacent to suspicious links in emails—especially when combined with forced-attention mechanisms—can significantly reduce the likelihood of users clicking on phishing links [11]. Additionally, Berens et al. found that combining phishing awareness videos with link-centric support tools can synergistically enhance users’ ability to distinguish between phishing and legitimate emails [12]. Additionally, some studies examine the psychological manipulation techniques used in phishing emails, such as persuasion principles [13] or exploring the relationship between phishing emails and the Big Five personality traits [14]. However, existing research has not adequately explored how phishing emails exploit cognitive weaknesses to manipulate victims. Most studies focus on isolated analyses of single biases (e.g., Authority Bias, Urgency Effect) without addressing the synergistic effects of multiple biases or the influence of individual differences. Some focus on how cognitive biases like urgency and authority impact user decisions [15,16], while others examine individual traits such as self-control [17] or the way users perceive suspicious emails [18]. A few studies also analyze attacker strategies or offer theoretical principles to explain victim behaviour [19,20]. According to Kahneman’s dual-system theory, attackers design email content (e.g., urgent deadlines, authoritative institution identifiers) to directly trigger recipients’ intuitive decision-making system (System 1), suppressing their rational analytical abilities (System 2). This amplifies the impact of cognitive biases [21]. However, this critical psychological mechanism’s role in recipients’ judgments and decisions has been overlooked, limiting existing research’s ability to explain why high-accuracy technical defence models fail to curb the increasing prevalence of phishing attacks.

To address this gap, this study provides a new explanatory framework for the underlying principles of phishing emails by integrating perspectives from social sciences and psychology. Cognitive biases refer to the unconscious mental shortcuts individuals use when processing and interpreting decision-related information, which can sometimes lead to decision-making errors [22]. Unlike traditional persuasion principles and the Big Five personality theory, cognitive biases more directly influence individuals’ immediate judgments and decisions [21]. Despite extensive research on phishing email detection and psychological manipulation techniques, studies analyzing how phishing emails exploit human psychological vulnerabilities from a cognitive bias perspective remain relatively scarce.

This study makes the following contributions:

1. Established a cognitive manipulation model for phishing emails based on cognitive biases, systematically revealing the four-stage attack mechanism of attention capture, trust construction, emotion priming, and behaviour elicitation.

2. Conducted precise manual annotation and statistical analysis on 482 phishing emails, identifying and quantifying 10 common cognitive biases along with their synergistic effects.

3. Integrated cognitive bias features into machine learning and deep learning models, significantly enhancing phishing email detection performance and providing solid theoretical and practical support for subsequent defence strategies.

This study begins by discussing traditional countermeasures and detection methods for phishing emails, followed by an exploration of research on persuasion principles in phishing emails. Finally, this study examines studies on the integration of phishing emails with cognitive biases.

2.1 Traditional Phishing Email Detection

Significant progress has been made in phishing email detection research in recent years, with a focus on improving classification accuracy through traditional machine learning and deep learning techniques. Yasin et al. developed an intelligent classification model combining data mining and text processing, achieving a random forest algorithm accuracy of 99.1% through weighted keyword methods [23–25]. Moradpoor et al. utilized neural network models to achieve high accuracy and true positive rates [26]. Gómez et al. introduced a classification method based on content features, enhancing the stability and accuracy of spam and phishing email classification through new statistical feature extraction techniques [27]. Islam et al. designed a multi-layered classification model that reduced false positives by employing weighted feature extraction [28]. While these technical models perform well in laboratory environments, they lack adaptability to the dynamic evolution of attacks. Attackers are increasingly bypassing traditional detection systems by exploiting technical features (e.g., randomizing URLs, obfuscating keywords), compelling researchers to shift focus from “feature recognition” to “psychological defence”.

With the advancement of deep learning, researchers have begun applying more complex neural network models to phishing email detection. For example, graph convolutional networks (GCNs), long short-term memory networks (LSTMs), and hybrid models have shown progress in detecting phishing emails [8,28,29]. These methods enhance detection performance by capturing complex semantic relationships in email text. However, current models still rely on surface-level semantic features (e.g., keywords, grammatical structures) and lack explicit modelling of implicit psychological manipulation strategies (e.g., cognitive bias induction) within the text.

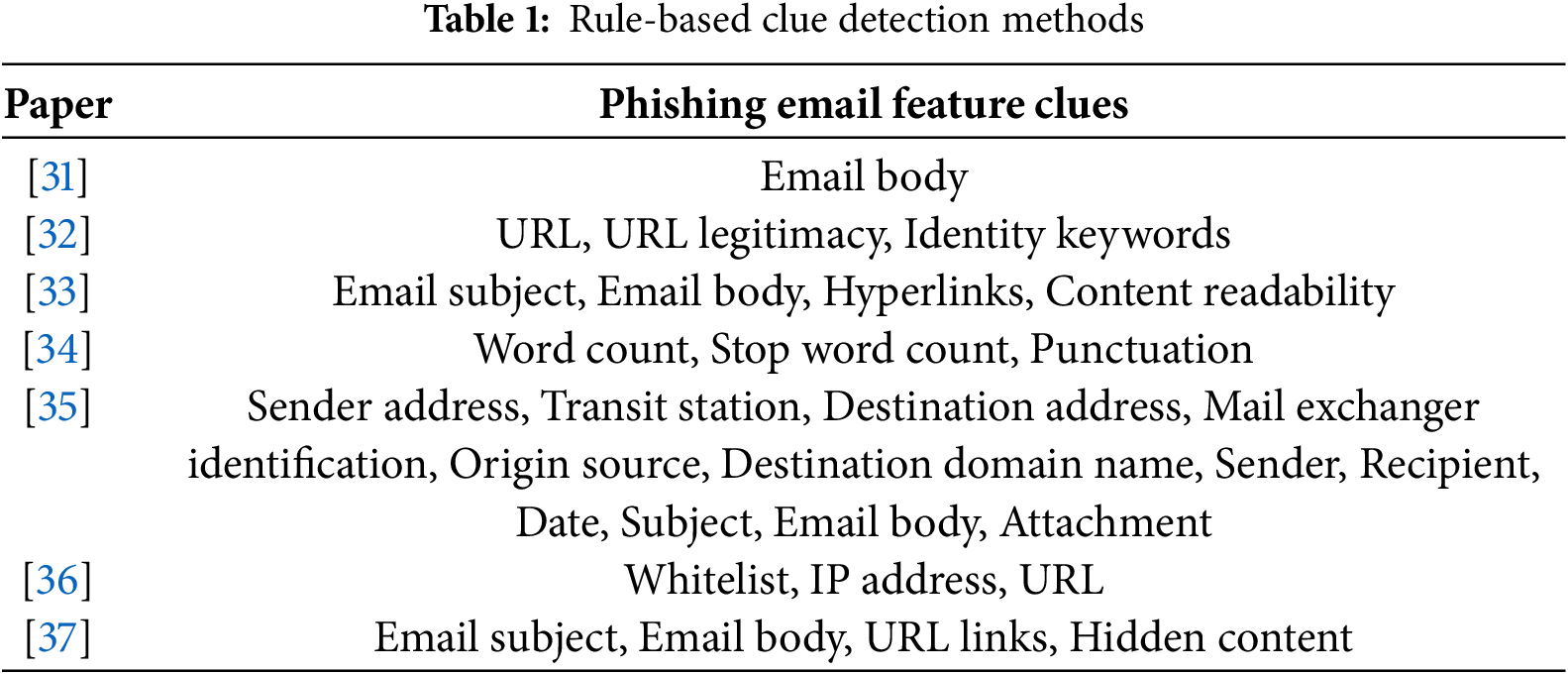

In addition to focusing on the textual content of phishing emails, some studies have started to concentrate on rule-based clue detection methods, such as keyword analysis, syntax checking, sender address verification, and URL identification [30]. Table 1 summarizes the various detection cues examined in prior rule-based research.

Traditional phishing email detection methods primarily rely on data-driven models, which consequently have relatively weaker theoretical explanatory capabilities. Moreover, these techniques depend largely on static, surface-level features (such as keywords, URLs, and syntactic patterns) that attackers can easily manipulate or obfuscate. In addition, there is a notable absence of a unified analysis that addresses the inherent vulnerabilities exploited by phishing schemes—especially those related to the psychological manipulation of victims.

2.2 Persuasion Principles and Phishing Emails

Despite the high accuracy of existing technical methods for phishing email detection—exceeding 95% in some studies—phishing attacks continue to emerge. A key reason is that attackers increasingly exploit human cognitive biases and psychological manipulation strategies to enhance the persuasiveness of phishing emails and design attacks that bypass sophisticated email filtering systems [38,39]. These psychologically based phishing tactics often evade traditional detection models because the latter rely primarily on technical features while neglecting the semantic analysis of persuasive strategies.

According to Cialdini’s research, six fundamental persuasion principles include reciprocity, scarcity, authority, consistency, liking, and consensus [40]. Different persuasion strategies guide users to adopt distinct decision-making criteria, thereby influencing their sensitivity to phishing emails [41]. For example, Valecha et al. analyzed the effectiveness of “gain-loss” persuasion cues in phishing emails using machine learning models. Their results demonstrated that models incorporating these cues significantly outperformed baseline models without them, achieving accuracy improvements of 5% to 20% [42]. From a cognitive bias perspective, “gain-loss” persuasion cues actually reflect framing effects, where users make different decisions based on how information is presented.

Other studies also indicate that commonly used persuasion strategies in phishing emails—such as notifications, authoritative tones, or expressions of shared interests—are more likely to successfully induce user responses [6]. Spelt et al. explored users’ psychological and physiological reactions to messages containing persuasion principles and found that principles such as scarcity, commitment, consensus, and authority significantly influenced users’ attitudes and behaviours [43]. Additionally, Kaptein et al. demonstrated that personalized persuasion profiles could enhance the effectiveness of email reminders [44].

Although current research on persuasion principles in phishing emails has made significant progress, several limitations remain. First, existing work largely relies on surface-level technical features and isolated analyses of individual persuasive cues, lacking a unified and systematic examination of the interplay among various psychological manipulation strategies. Second, these approaches exhibit limited adaptability to the dynamic evolution of attack strategies, making it challenging to counter attackers who continually modify their tactics and presentation styles to bypass detection.

2.3 Cognitive Biases and Phishing Emails

While persuasion principles represent proactive strategies designed by attackers, cognitive biases are unconscious decision-making shortcuts followed by recipients. Although related, the latter are more directly linked to fundamental vulnerabilities in human judgment. According to the dual-system decision theory, attackers manipulate email content (e.g., urgent deadlines, authoritative identifiers) to activate recipients’ intuitive decision-making system (System 1), suppressing their rational analytical abilities (System 2). This amplifies the effects of cognitive biases [21]. For example, urgency strategies create time pressure by setting deadlines, forcing users to rely on intuitive decision-making [45,46]. Under urgent circumstances, users are more likely to adopt heuristic thinking, increasing their risk of falling victim to phishing attacks [14,16–18].

The temptation of benefits and Authority Bias are also common tactics used in phishing emails [13,46]. Research has shown that emails disguised as those from superiors or authoritative institutions can trigger users’ tendency to comply [15,17], while high promises of benefits can induce over-optimism bias [47–49] Other research indicates that overconfidence decreases users’ ability to identify phishing emails, whereas cognitive effort can reduce this bias [50,51]. However, existing studies mostly verify the impact of a single bias through experiments, neglecting the synergistic effect of multiple biases in real attacks. Attackers may simultaneously exploit scarcity and social proof to induce herd behaviour, a complex strategy that has not been systematically studied.

Moreover, the influence of individual differences on cognitive biases has not been fully explored. Different users, due to differences in cultural backgrounds, risk preferences, or cognitive styles, may have opposing reactions to the same phishing email [52,53]. Although individual differences in decision-making have been widely studied in the field of psychology, these findings have not been effectively integrated into phishing email detection models, resulting in existing defence strategies lacking personalized adaptability.

3 The Role Mechanism of Cognitive Biases in Phishing Emails and the Stage Model

3.1 Classification of Cognitive Biases and Mapping to Attack Scenarios

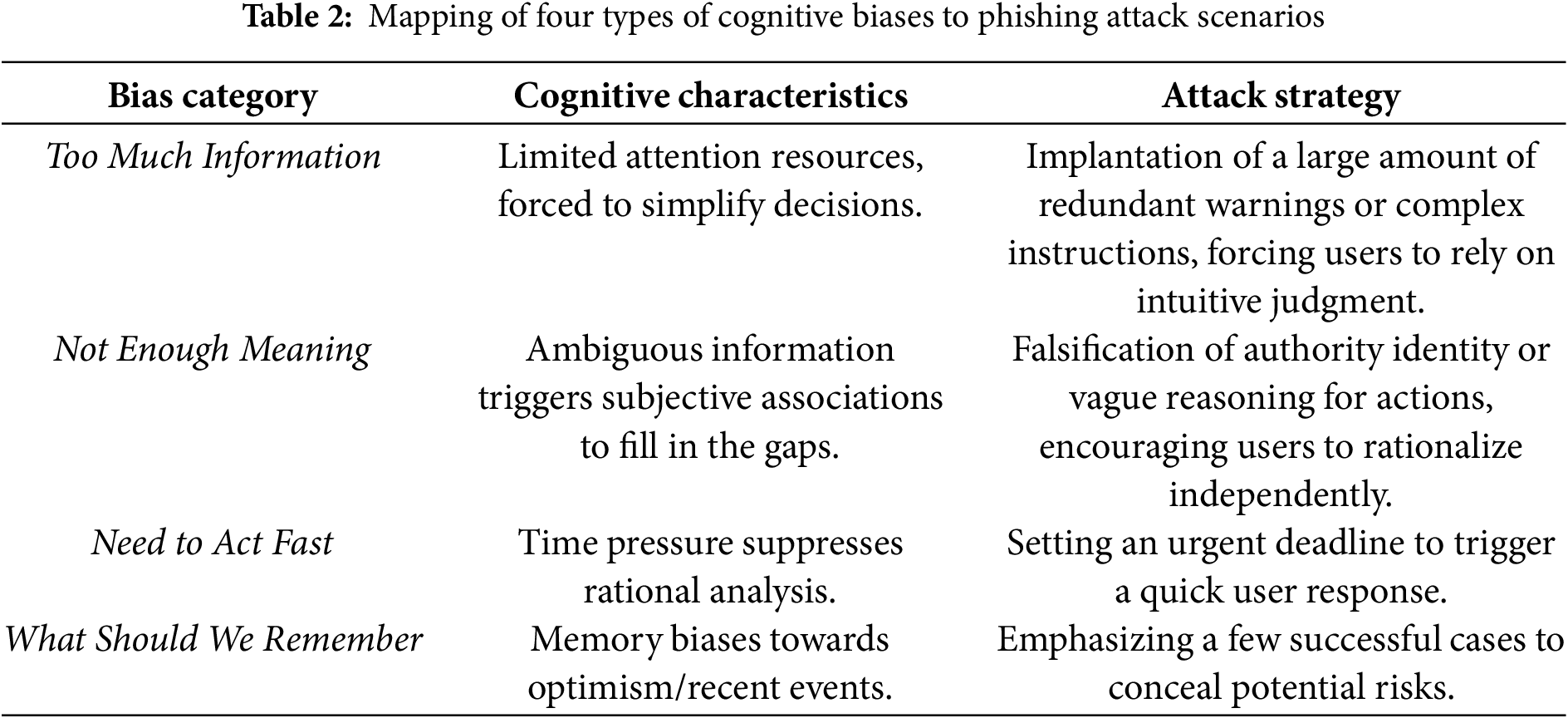

In cognitive science and behavioural economics research, cognitive biases are typically categorized into four major types: Too Much Information, Not Enough Meaning, Need to Act Fast, and What Should We Remember [54]. This classification system achieves a systematic integration of known cognitive biases through dimensional construction, as shown in Table 2. Each category of bias reveals the systematic errors humans may make when facing complex decisions. For instance, the Anchoring Effect in the Too Much Information category reflects the tendency of decision-makers to rely on initial information for simplified judgments, while the Stereotype in the Not Enough Meaning category manifests as filling information gaps using existing cognitive frameworks. Table 2 demonstrates the typical application scenarios of these four types of biases in phishing attacks and the strategies used by attackers.

3.2 A Multi-Stage Attack Model Based on Cognitive Biases

From the perspective of cognitive neuroscience, the effectiveness of phishing emails stems from the systematic exploitation of vulnerabilities in human decision-making systems. Whether by emphasizing authority to induce compliance or leveraging urgency and the “zero risk” perception to prompt users to make quick decisions, these strategies are based on a profound understanding of human psychology. Attackers employ an emotional-cognitive coupling intervention strategy, progressively weakening the victim’s ability for rational evaluation through the synergistic effects of emotional arousal intensity modulation and information ambiguity processing. These biases not only bypass rational analysis but also enhance user compliance and susceptibility by simplifying information and amplifying emotional responses.

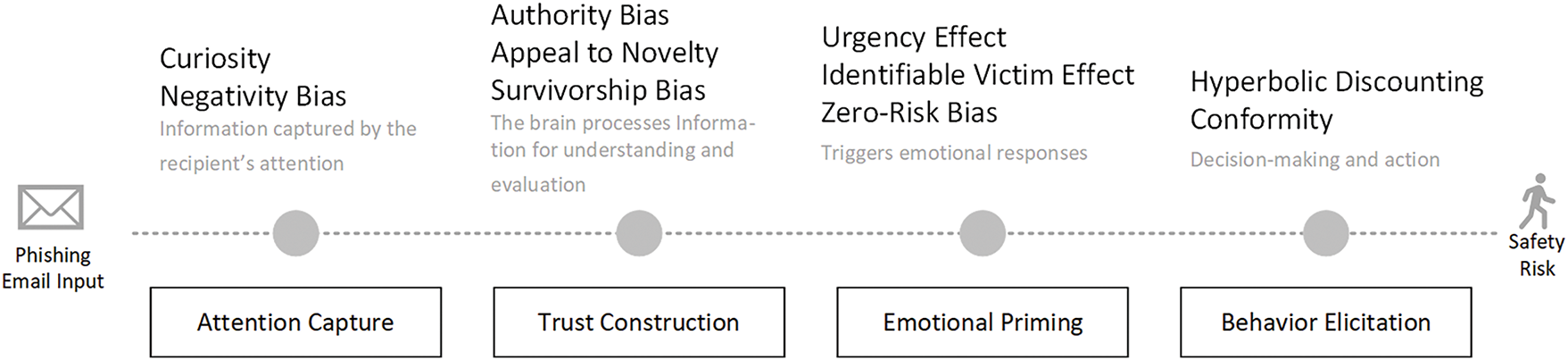

This study systematically analyzes how phishing emails employ cognitive biases to enhance their deceptive effectiveness. To ensure that our selected biases accurately capture the manipulative techniques used in phishing attacks, this study conducted an extensive review of the relevant psychological and cybersecurity literature, coupled with empirical observations of phishing strategies. Based on the prevalence of certain biases in the literature and their strong relevance to observed phishing tactics, this study identified ten cognitive biases that are frequently exploited by attackers.: Curiosity, Negativity Bias, Authority Bias, Appeal to Novelty, Survivorship Bias, Urgency Effect, Identifiable Victim Effect, Zero-Risk Bias, Hyperbolic Discounting, Conformity. Based on this, a stage model is constructed, as shown in Fig. 1. This study proposes a comprehensive cognitive manipulation model for phishing emails, which details a four-stage cognitive hijacking process in social engineering attacks. In the Attention Capture stage, attackers exploit cues like urgency and curiosity to immediately seize the recipient’s focus, predominantly engaging the fast, intuitive System 1. This is followed by the Trust Construction phase, where attackers introduce authority cues and survivorship signals to simulate credibility, thereby reducing scepticism. In the Emotional Priming stage, emotional triggers such as fear and zero-risk assurances heighten the recipient’s arousal, effectively suppressing rational, analytical processing. Finally, in the Behavioural Elicitation stage, these combined effects culminate in an impulsive decision, with the recipient acting against their better judgment. This sequential framework illustrates how attackers break through users’ psychological defences and induce maladaptive decisions. Notably, our model distinguishes the impact on perception from that on decision making in a way that aligns with Kahneman’s dual-system framework. In the first two stages—Attention Capture and Trust Construction—System 1’s fast, automatic processes dominate: attackers manipulate perceptual cues (e.g., urgency signals, credible “from” addresses) to bias the recipient’s intuitive appraisal of the email, making it feel both urgent and trustworthy. This early System 1 activation is critical, because it sets up a biased perceptual lens through which all subsequent information is interpreted. In the latter stages—Emotional Priming and Behavioural Elicitation—there is a transition toward System 2’s deliberative processes, though System 1 remains influential. Here, the initial perceptual distortion (System 1) feeds into an emotionally charged state that prompts System 2 to weigh risks and benefits under a compromised lens. As a result, even when slow, analytic reasoning is available, it often defaults to confirming the biased perception seeded by System 1, leading to impulsive or ill-advised actions (System 2’s execution under System 1’s influence). By explicitly separating these domains—System 1’s perceptual manipulation in stages 1–2 and the subsequent System 2-guided but still partially System 1-driven decision making in stages 3–4—our framework clarifies how initial, fast-paced cognitive bias lays the groundwork for later, more reflective reasoning to go astray.

Figure 1: Cognitive manipulation model for phishing emails

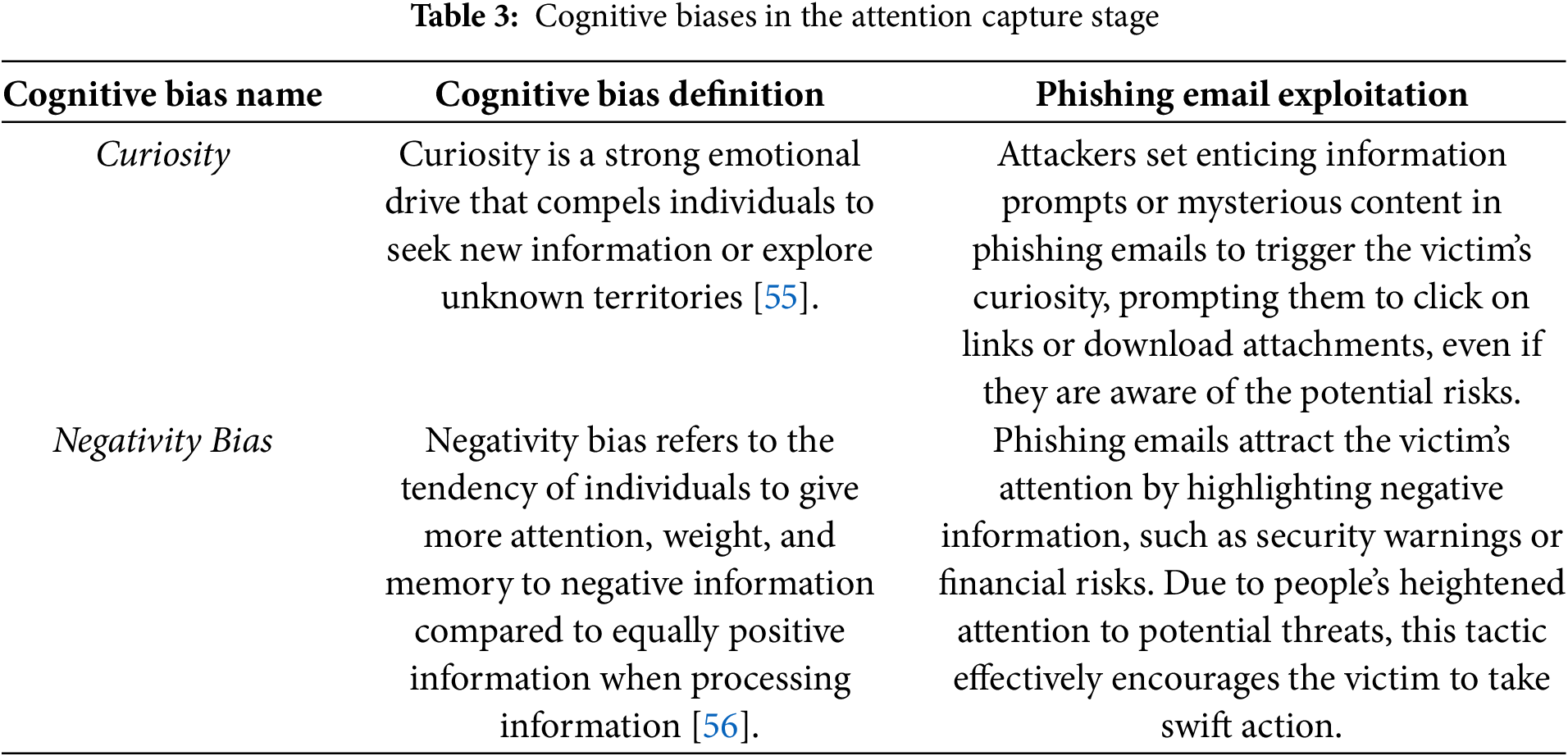

The attention capture stage is the first phase where attackers break through the target’s information filtering mechanism. Attackers use cognitively engineered email subject frameworks, incorporating bias embedding strategies to direct the user’s attention. Since users can only process a limited amount of information in a given time and are instinctively biased toward emotional or high-priority stimuli, attackers often leverage the Curiosity and Negativity Bias to hijack the user’s attention, as shown in Table 3.

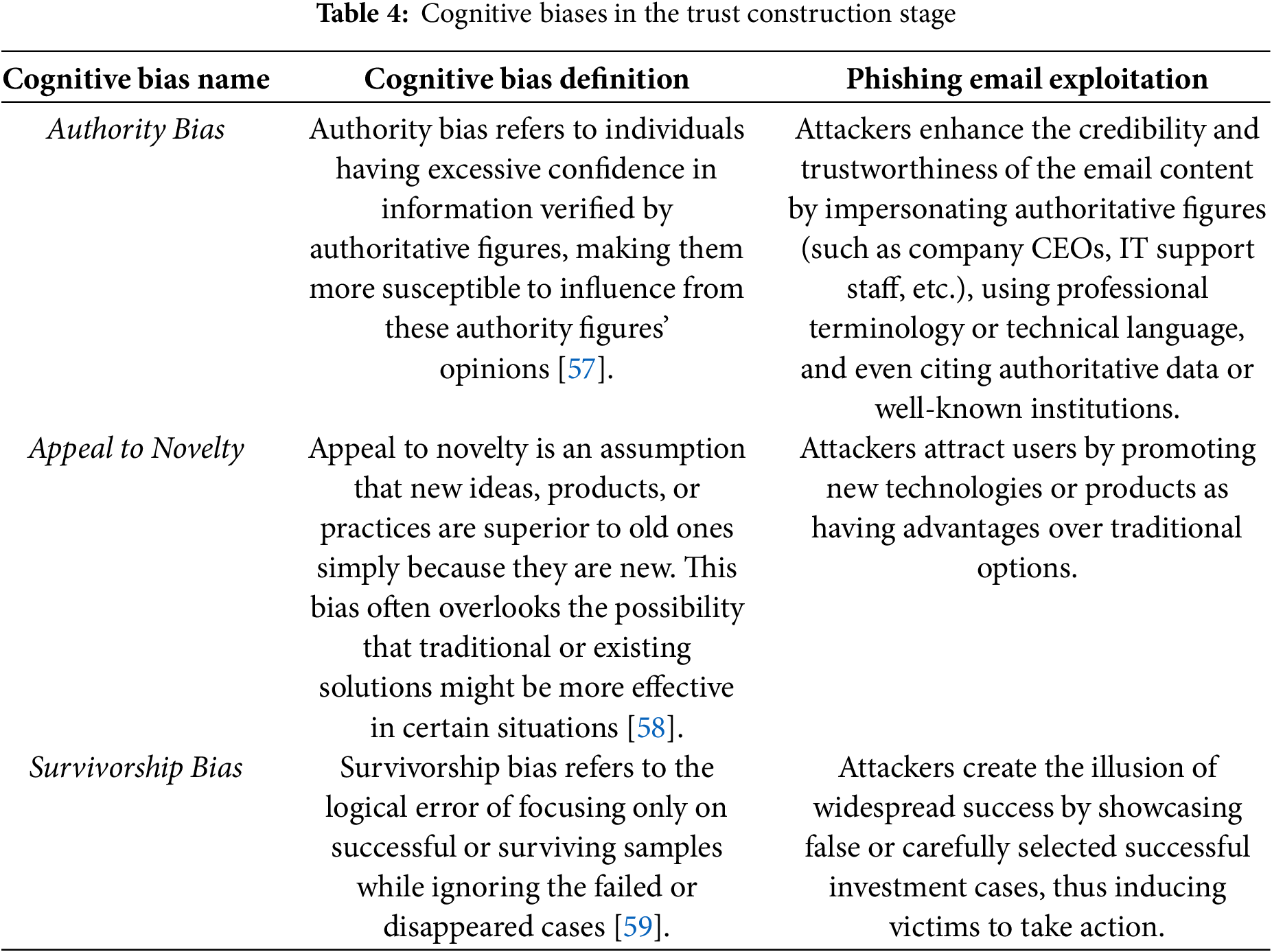

Trust Construction is the process through which attackers, by carefully designing and falsifying information, persuade the victim to believe in the authenticity and credibility of the email content. Attackers leverage the user’s existing knowledge, experience, and beliefs, and enhance the email’s credibility by cleverly simulating real-world scenarios, thereby lowering the victim’s awareness of potential threats. By using intricately crafted email content and fabricated information, attackers gradually convince the victim that the email originates from a trusted source, making it easier for the victim to accept the false information it conveys. The cognitive biases involved in this stage include Authority Bias, Appeal to Novelty, and Survivorship Bias, as shown in Table 4.

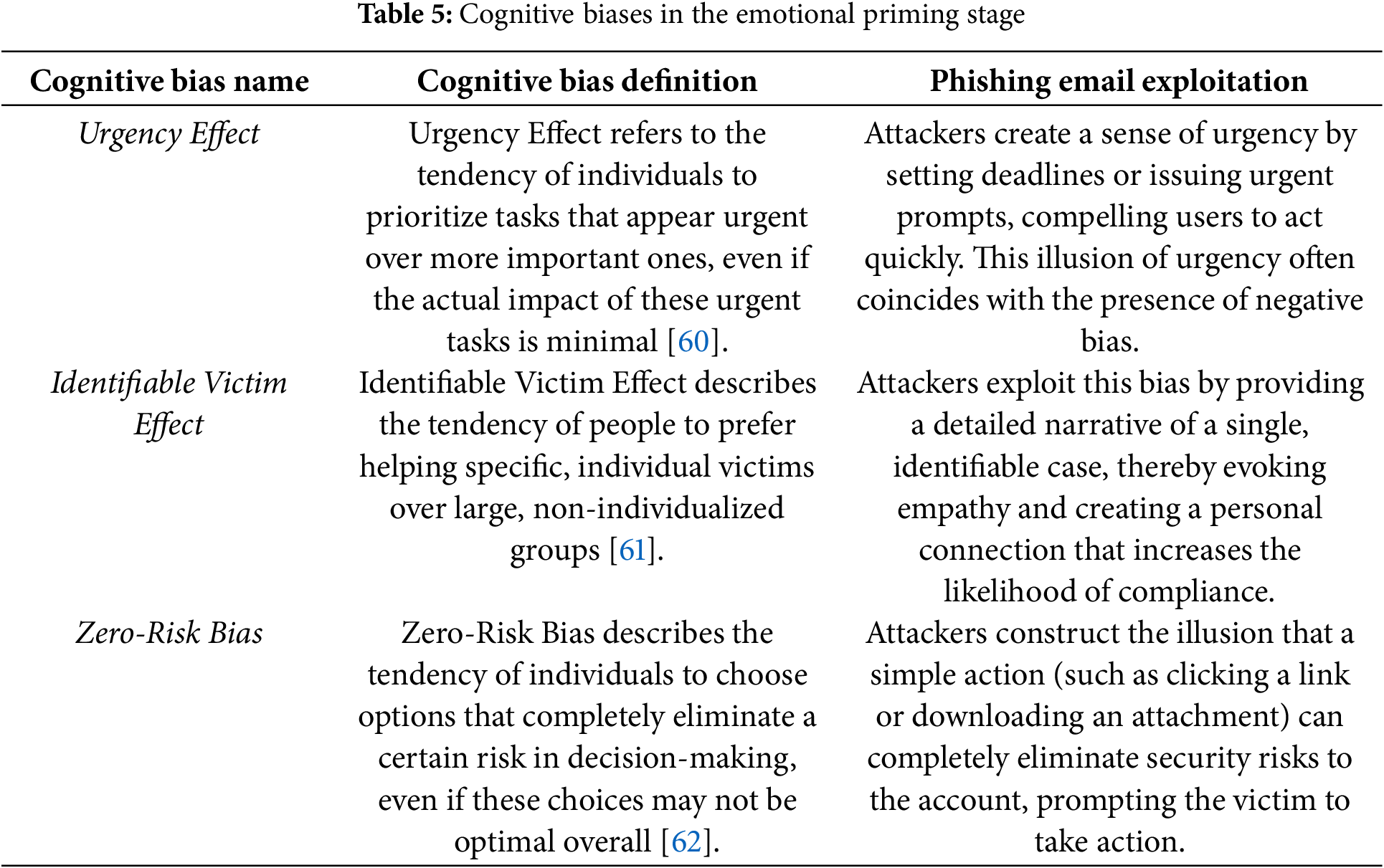

Emotional priming refers to the strategy where attackers trigger emotional reactions in the victim through information delivery, thus intervening in their decision-making process. By systematically eliciting positive or negative emotions, attackers strategically adjust the target’s judgment criteria and behavioural tendencies. Emotions exhibit dual regulatory effects in the cognitive process: positive emotions can enhance trust and compliance, while negative emotions, by activating the stress hormone cortisol, accelerate decision-making speed. The core cognitive biases involved in this process include the Urgency Effect, Identifiable Victim Effect, and Zero-Risk Bias, as shown in Table 5.

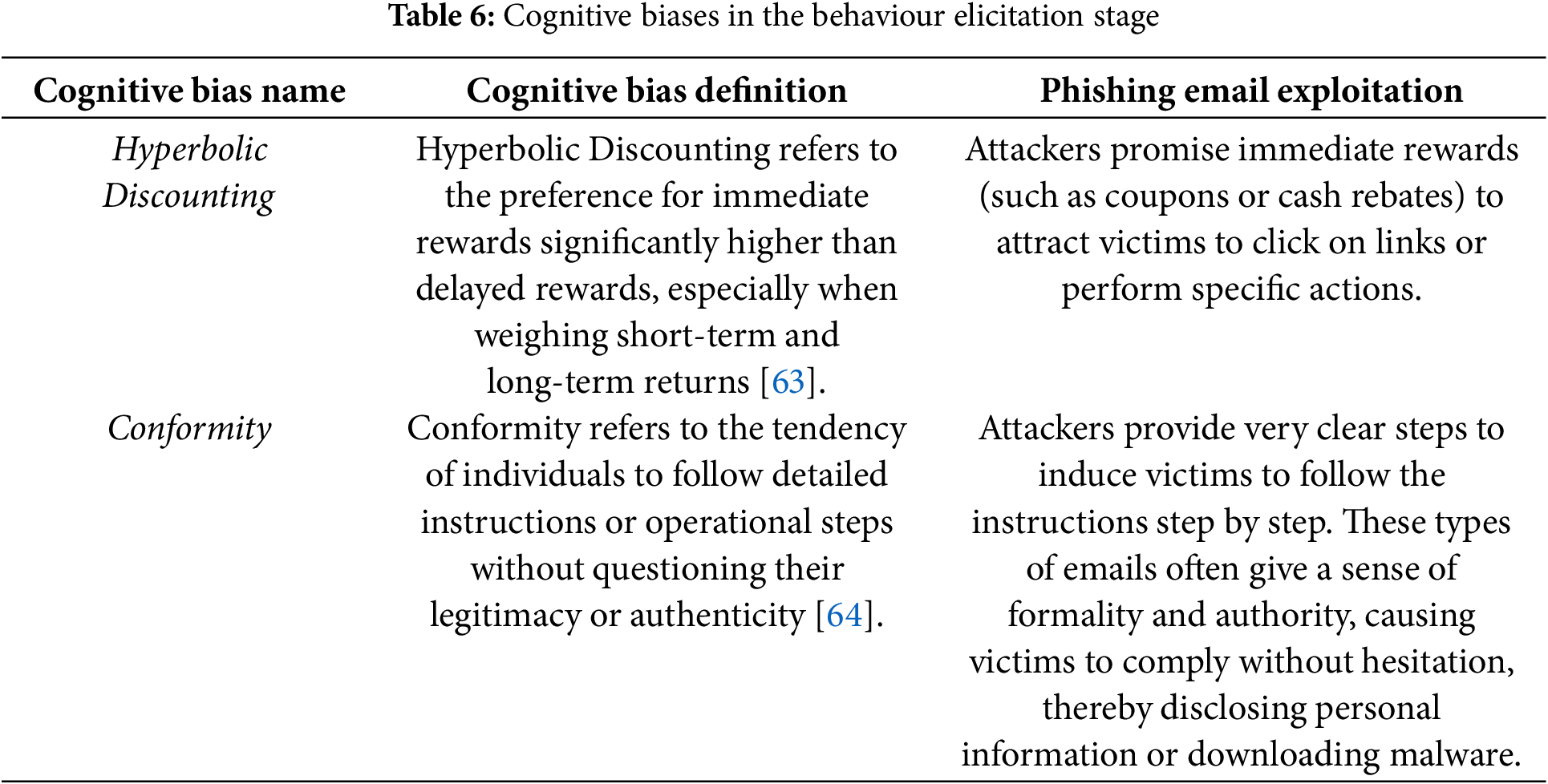

The behaviour elicitation stage is the process in which attackers, by comprehensively utilizing cognitive processing and emotional responses, guide users to make specific behavioural decisions. In this stage, the user’s thoughts and emotions have been carefully manipulated by the attacker, determining whether the user will take action and what action they will take. Attackers further guide the victim to execute their intentions through clear instructions and suggestive wording, ensuring the success of the attack. The core cognitive biases involved in this process include Hyperbolic Discounting and Conformity, as shown in Table 6.

The model system reveals the implementation path of phishing attacks through a four-stage cognitive chain reaction, gradually influencing an individual’s attention, understanding, emotions, and behaviour through specific cognitive biases. Attackers capture attention in the attention capture stage, build trust in the trust construction stage, manipulate emotions in the emotional priming stage, and ultimately guide the victim to take specific actions in the behaviour elicitation stage, effectively achieving their goal.

3.3 Case Analysis of Phishing Emails

This study will analyze several phishing email cases in conjunction with the model proposed in the previous section of this study.

Dear Alice,

I hope this message finds you well. Although this proposal may come as a surprise, please allow me to introduce myself. I am George Osawai, Chairman of NEPA’s Contract Review Committee at the Federal Secretariat of the Nigerian Electricity Board, Ikoyi-Lagos.

After careful consultation with my colleagues, we have chosen to contact you regarding a confidential matter that requires your assistance. We seek your help in facilitating the transfer of $7.1 million and an additional $500,000 (totaling $7.6 million), which are currently held in an offshore payment account at the Central Bank of Nigeria. These funds are an over-invoiced contract amount, presently unclaimed and available for withdrawal to any beneficiary recommended by my committee.

You will be presented as a contractor under the National Environmental Policy Act, who executed the contract but has not yet received payment. The proposed distribution of the funds is as follows:

- 70% to myself and my colleagues

- 20% to you as our representative and partner

- The remaining 10% will cover transaction costs

Due to restrictions on civil servants from operating foreign accounts, we are reaching out to you as a trusted partner for this transaction.

If you agree to proceed, please kindly provide the following information at your earliest convenience:

1. The name you would like listed as the beneficiary of the funds.

2. Your confidential phone and fax numbers.

Once we receive your confirmation, we will provide further details on how the funds will be transferred and discuss how to successfully complete this transaction.

I look forward to your prompt response and our future cooperation.

Best regards,

George Osawai

Chairman of NEPA’s Contract Review Committee

Federal Secretariat of the Nigerian Electricity Board

Ikoyi-Lagos, Nigeria

This Nigerian scam email fully demonstrates the synergistic effects of the four-stage cognitive manipulation: In the attention capture stage, the attacker uses the unusual figure of “71.5 million dollars” and the hint of a “unique opportunity” to direct the victim’s attention through Curiosity. In the trust construction stage, the attacker forges the authority of the “Chairman of the National Power Bureau Contract Review Committee”, leveraging Authority Bias to enhance the credibility of the email. In the emotional priming stage, the attacker applies the Hyperbolic Discounting strategy, promising a 20% immediate return to trigger the victim’s desire for wealth. Finally, in the behaviour elicitation stage, the attacker requests the victim to provide personal information, using Conformity to guide them toward actions that could potentially expose sensitive information.

Dear Alice,

We wanted to inform you that your email account associated with [example@example.com] is nearing its storage limit.

Current Usage: 1989 MB

Maximum Capacity: 2000 MB

Your email storage space is almost full, and you may soon face difficulties receiving new messages. To avoid disruptions in your email service, we strongly recommend upgrading your storage by clicking the link below:

Click here to upgrade your storage

Upgrading is simple and free. Failure to upgrade your mailbox could result in the inability to receive emails, potential account closure, and the deletion of important messages.

Note: Upgrading is completely free.

Please take action now to ensure continuous access to your account.

Best regards,

Mailbox Support Team

In the attention capture stage, the email attracts attention by warning the user that their mailbox capacity is running out, utilizing Negativity Bias. In the trust construction stage, the email is signed as “Mailbox Support Team”, enhancing its credibility through Authority Bias. In the emotional priming stage, the email emphasizes that if the account is not upgraded immediately, it will be closed and important emails will be deleted, leveraging the Urgency Effect to create a sense of urgency. It also claims that the upgrade is free, using Zero-Risk Bias to reduce the user’s defensive mindset. In the behaviour elicitation stage, the email directly instructs the recipient to click a link to upgrade their mailbox, using Conformity to guide them to take potentially risky actions.

Dear Homeowner,

We are pleased to inform you that you have been pre-approved for a $401,000 refinancing loan at a fixed interest rate of 4.51%. This offer is unconditional, and your credit score will not affect your eligibility.

To take advantage of this limited-time opportunity, simply visit our website and complete the 1-minute approval form:

Click here to start your approval process

Act quickly to ensure you secure this offer!

Sincerely,

Maribel Codro

In the attention capture stage, the email offers a high-yield loan with a “4.51% fixed interest rate + $401,000”, attracting the user’s attention through Curiosity. In the emotional priming stage, it emphasizes “unconditional” and “credit is not a factor”, making the user perceive the opportunity as rare, using Hyperbolic Discounting to focus on immediate benefits while ignoring potential risks. In the behaviour elicitation stage, the email asks the user to visit a website and fill out a form, using Conformity to guide them into providing sensitive personal and financial information.

In actual phishing scenarios, the four stages are not strictly linear but may occur in parallel or skip steps. For example, an email with an urgent prompt such as “Account Frozen” in the subject line will simultaneously trigger users’ “attention/perception” and “emotion/motivation”, with the two stages highly overlapping. If an email displays both “preferential temptation” and “authoritative endorsement”, users often switch repeatedly between the motivation-driven stage (Stage 2) and the rational evaluation stage (Stage 3). It can be seen that although the model conceptually presents a dominant sequence of “attention → motivation → reasoning → action”, there is a possibility of parallelism, cycling, or even skipping between stages.

This section aims to explore the utilization of cognitive biases in phishing emails and assess the effectiveness of cognitive bias features in phishing email detection. To achieve this, this study designed a series of experiments, which primarily include the construction of datasets, the establishment of a cognitive bias detection model, the analysis of the Nigerian scam dataset, and the development of a phishing email detection model. The following sections will provide a detailed description of each phase of the experiment.

4.1.1 Data Sources and Sampling Methods

The data for this study was sourced from a phishing email dataset that consolidates seven publicly available repositories [65]. This dataset is widely adopted in phishing research due to its scale and diversity, encompassing diverse attack scenarios such as Nigerian scams, financial lures, institutional impersonation, and urgency-based threats, which cover the 10 cognitive biases identified in this study. This study uniformly sampled emails from these sources and then carefully cleaned and processed the data to remove duplicates and non-relevant entries. This process ensured that a final set of 482 phishing emails was retained, making the subsequent manual annotation work both feasible and reliable.

4.1.2 Data Preprocessing and Labeling

During the data labeling process, this study manually precisely manually annotated the extracted phishing emails using the Doccano tool, targeting the 10 cognitive biases mentioned in Section 3.2. Three domain experts collaborated on this process to ensure high annotation quality and consistency. Three experts first reached consensus on all bias examples, then independently reviewed the emails, clearly marking key sentences or paragraphs with corresponding cognitive bias labels. Any discrepancies or disagreements were resolved through discussions until a consensus was reached via a majority voting process. Specifically, the labeling not only identified the common manipulative language in phishing emails but also detailed the corresponding cognitive bias types.

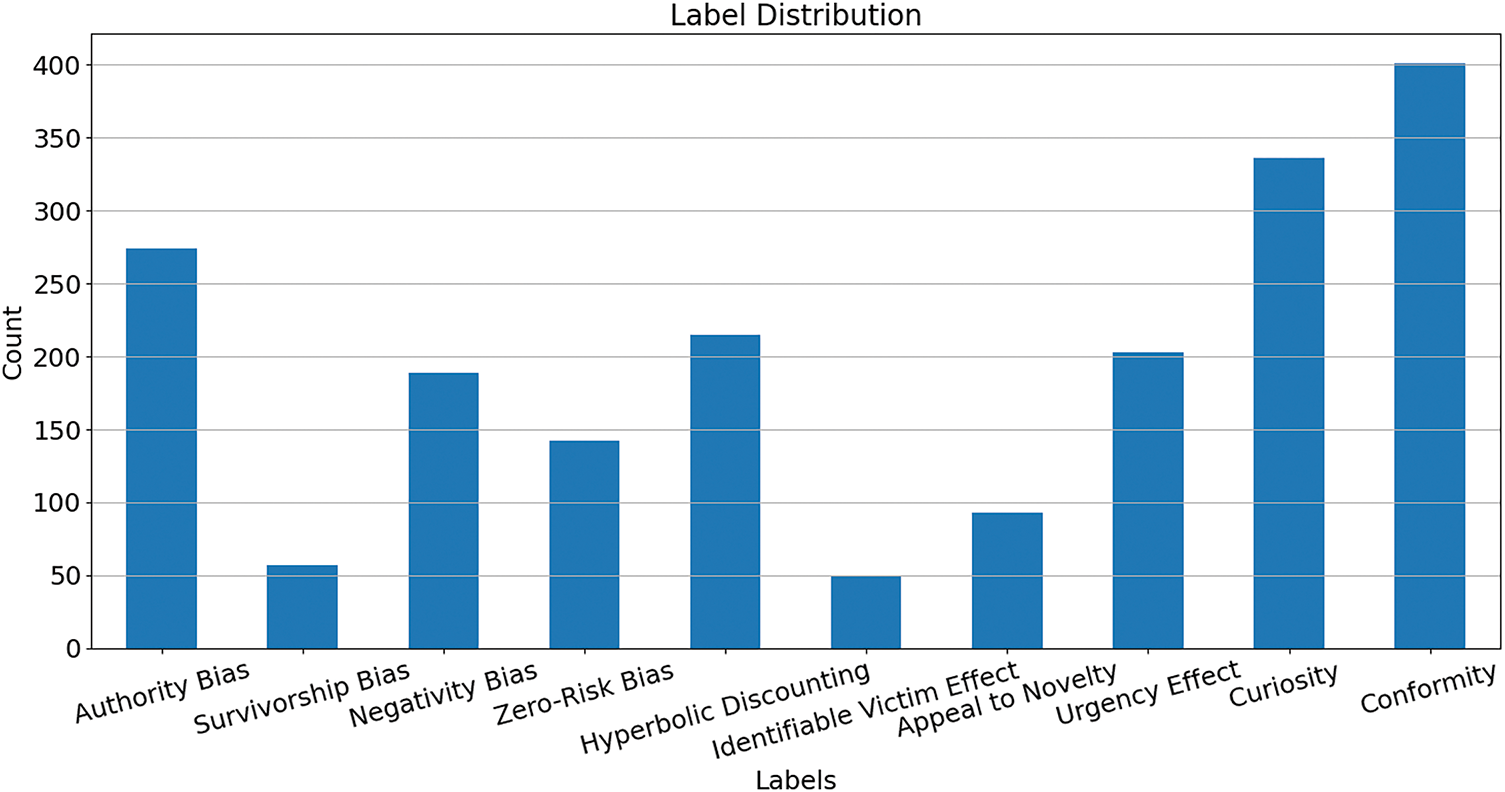

Fig. 2 illustrates the distribution of different cognitive biases in our study dataset. It can be seen that among the 482 phishing emails, there are significant differences in the distribution of various cognitive biases. Specifically, Curiosity and Conformity are the most common in phishing emails, accounting for a large proportion. This indicates that most phishing emails exploit users’ curiosity to motivate them to perform certain actions, while also guiding users to follow instructions by providing clear operational steps.

Figure 2: Dataset distribution chart

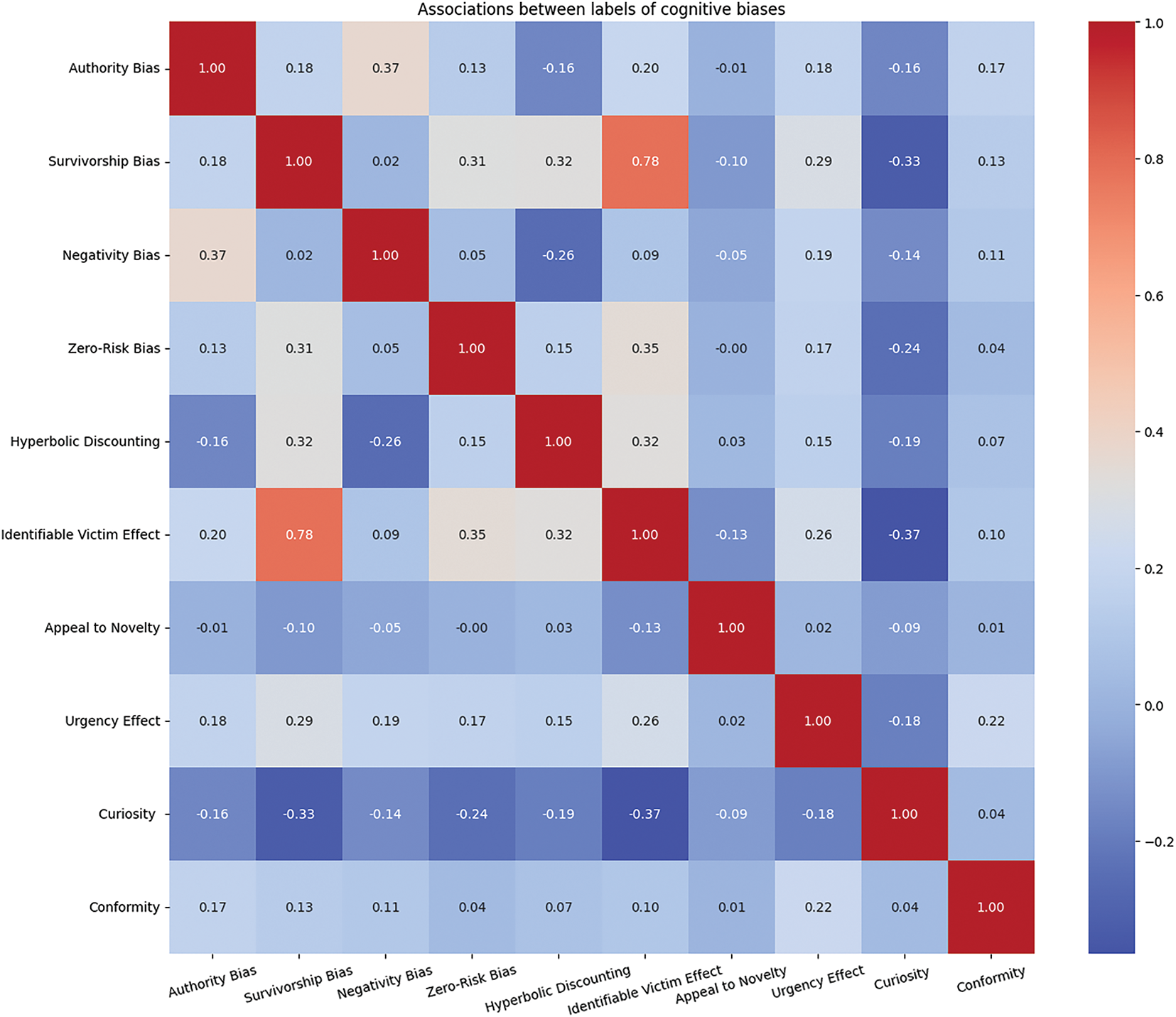

Fig. 3 illustrates the correlations between various cognitive biases in the annotated data. The analysis results indicate that most cognitive biases have low correlations with each other, showing that these biases typically appear independently in phishing emails. However, the correlation between Survivorship Bias and Identifiable Victim Effect reaches 0.78, which is a significant exception. This high correlation mainly arises because these two biases often occur simultaneously in Nigerian scams.

Figure 3: Dataset correlation analysis chart

Specifically, Nigerian scams typically start with a story about an official, utilizing the Identifiable Victim Effect to establish the story’s authenticity and credibility. Subsequently, the email suggests that the recipient is a selected lucky individual with the opportunity to share a substantial fortune, which is a manifestation of Survivorship Bias. This combination is particularly prevalent in Nigerian scams, further explaining the high correlation between these two cognitive biases.

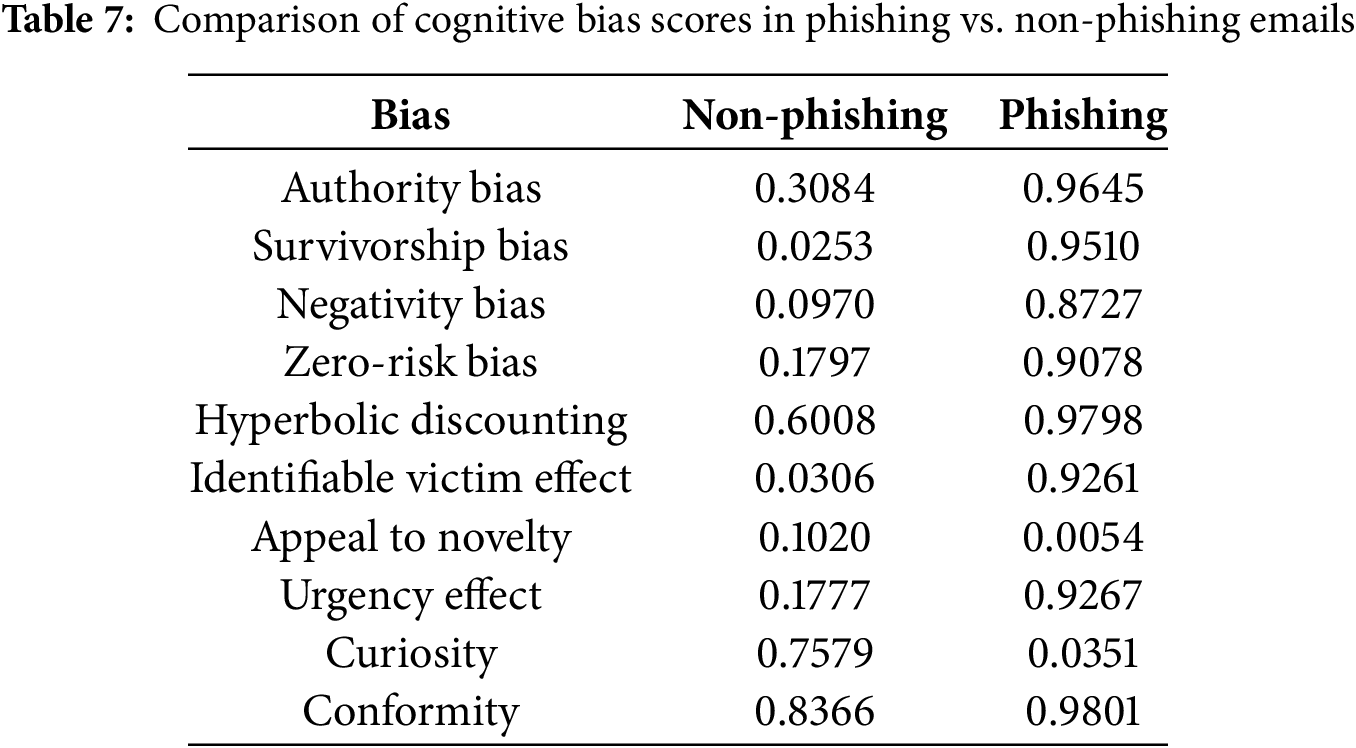

Table 7 compares the cognitive bias scores between non-phishing and phishing emails. The data reveals that most biases—including Authority Bias, Survivorship Bias, Negativity Bias, Zero-Risk Bias, Hyperbolic Discounting, Identifiable Victim Effect, Urgency Effect, and Conformity—are significantly higher in phishing emails (ranging approximately from 0.87 to 0.98), indicating these biases are deliberately exploited in phishing campaigns. In contrast, the biases of Appeal to Novelty and Curiosity show scores of 0.1020 and 0.7579 respectively in non-phishing emails, while their scores are extremely low in phishing emails (0.0054 and 0.0351, respectively). This suggests that these two biases may be more common in legitimate emails or are not effectively employed as deceptive strategies by phishing attackers.

4.2.1 Feature Extraction Methods

To effectively represent the email text and extract useful features, this study employed two feature extraction methods:

1. The term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) method was used for feature extraction on the preprocessed text. This method measures the importance of words in the document and the entire corpus. Specific parameter settings: ngram_range = (1, 1) (considering only unigrams), use_idf = True (using inverse document frequency), norm = ‘l2’ (L2 normalization), smooth_idf = True (IDF smoothing).

2. The pretrained Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach (RoBERTa) model was utilized for deep feature extraction of the email text. Specific parameter settings: using RoBERTa-base version, hidden layer dimension of 768, using RoBERTa’s tokenizer to encode the text, resulting in a 768-dimensional feature vector for each email.

Due to the imbalanced distribution of data across cognitive bias categories, with fewer samples in some biases potentially leading to model training bias towards majority classes, this addressed the data imbalance issue using the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE). This oversampling technique was applied to minority classes to balance the dataset. Specific parameter settings: k_neighbours = 5 (number of nearest neighbours), performing oversampling on minority samples.

4.2.3 Model Selection and Parameter Settings

For traditional machine learning models, this employed six commonly used machine learning algorithms for model training and testing:

1. Logistic Regression (LR): Using L2 regularization, hyperparameter C values in the range [0.01, 0.1, 1, 10], determining the optimal value through cross-validation, using the Liblinear optimizer.

2. Support Vector Machines (SVM): Using a linear kernel.

3. Random Forest (RF): Number of decision trees set to 100, minimum samples per node set to 1.

4. K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN): Number of neighbours set to 5, using Euclidean distance for node distance calculation.

5. Decision Tree (DT): Using information gain as the splitting criterion, with maximum depth determined through cross-validation.

6. Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT): Learning rate set to 0.1, number of weak learners set to 100, maximum depth set to 4.

For comparative experiments, this constructed a neural network model with a specific architecture as detailed in Section 4.3.3. The loss function used was cross-entropy, the optimizer was Adam with both L1 and L2 regularization introduced, learning rate set to 0.001, batch size set to 64, and number of training epochs set to 200.

4.3 Cognitive Bias Detection Models in Phishing Emails

To automatically detect cognitive biases in phishing emails, this study designed and implemented three model methods based on traditional machine learning and deep learning techniques. Below, each method’s implementation process and experimental results are detailed.

4.3.1 Traditional Machine Learning Models Based on TF-IDF Features

In this experiment, this study utilized TF-IDF features combined with traditional machine learning algorithms to detect cognitive biases in phishing emails. Firstly, the TF-IDF method was used to extract features from the preprocessed email texts, capturing important words and phrases to construct a high-dimensional feature space. Subsequently, this study trained the six machine learning models mentioned in Section 4.2.3 on the training set. The performance of the models was evaluated using accuracy metrics, with the results shown in the Table 8.

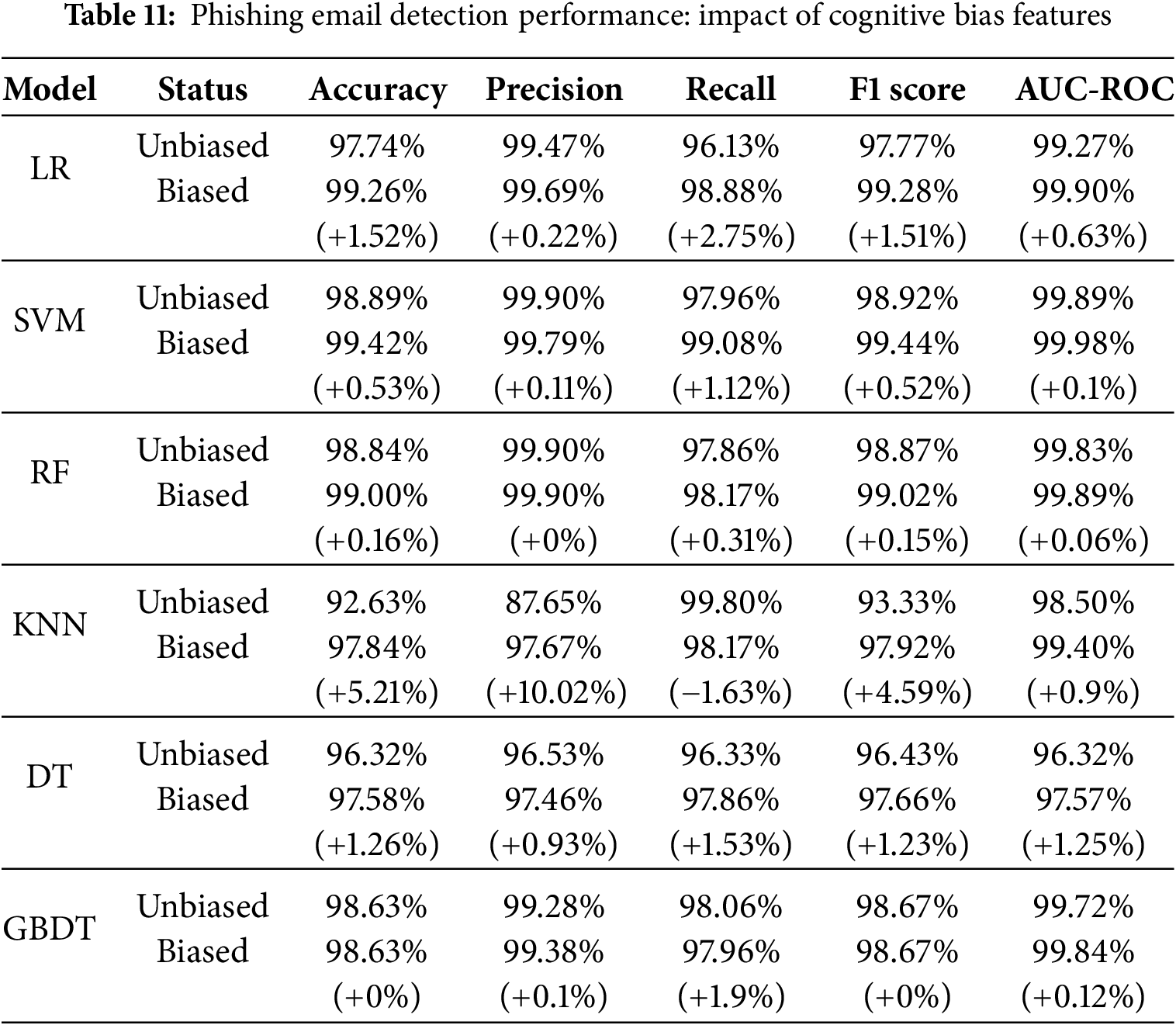

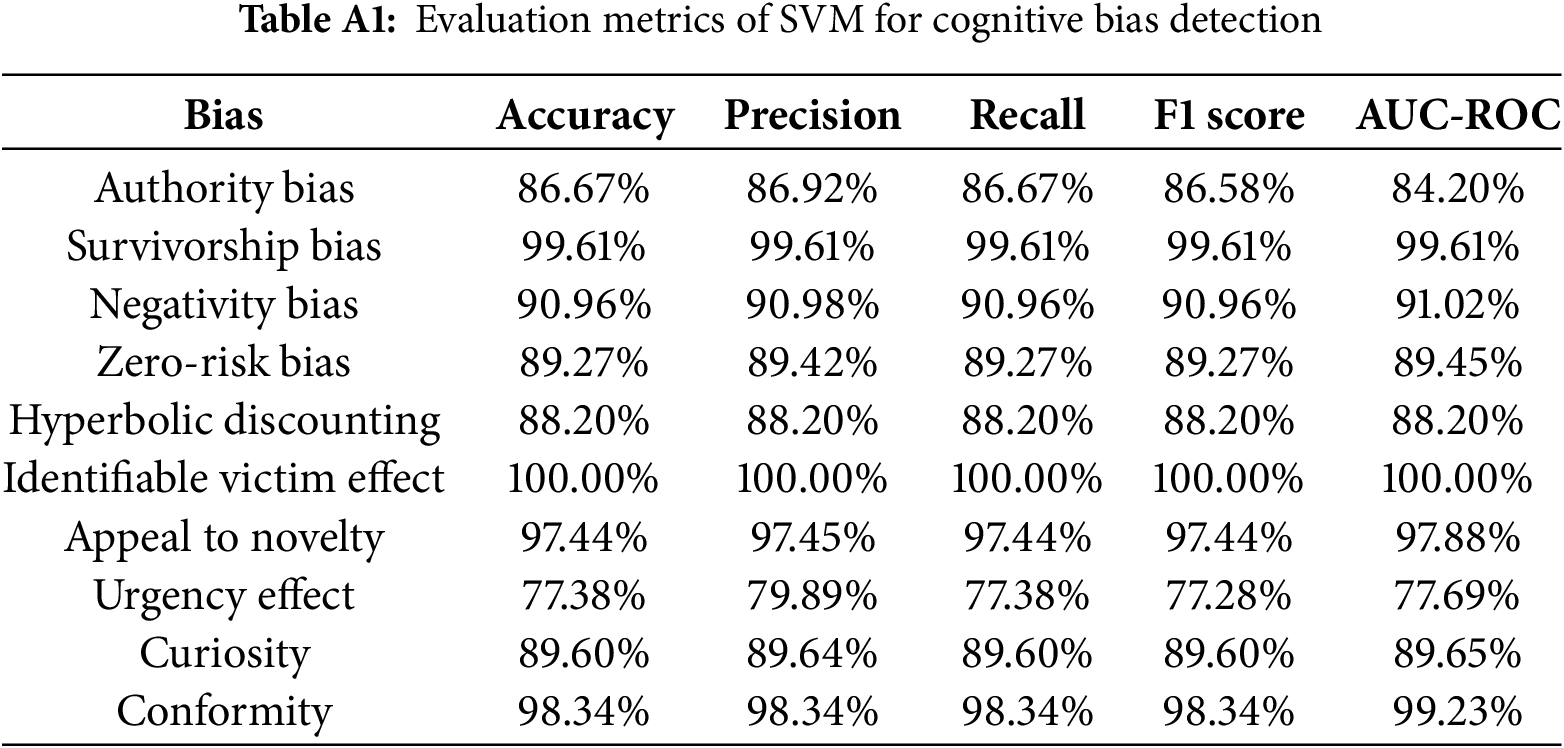

From Table 8, it can be seen that SVM performs the best among all models, with an average accuracy of 91.75%. This indicates that SVM has an advantage in handling high-dimensional sparse feature spaces, effectively capturing the relationship between text features and cognitive biases. In contrast, the KNN model performs the worst, with an accuracy of only 54.2%. This may be because, in high-dimensional spaces, distance metrics between data points become unreliable, making it difficult for the KNN algorithm to correctly classify samples. Other models such as LR, RF, and GBDT also perform relatively well, with accuracies exceeding 84%. Additionally, this study provides further evaluation metrics for each cognitive bias using the SVM model in Table A1 of Appendix A.

4.3.2 Traditional Machine Learning Models Based on RoBERTa Representations

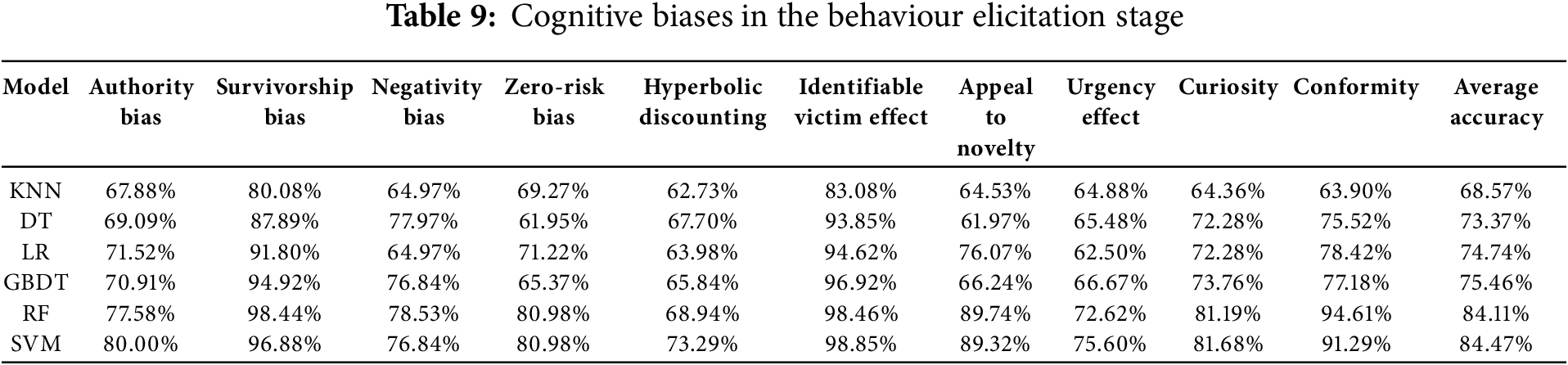

To explore the role of deep semantic features in cognitive bias detection, this study employed the RoBERTa pre-trained model to extract features from email texts in this experiment. RoBERTa is capable of capturing contextual semantic information in the text, generating high-dimensional semantic vectors. After obtaining RoBERTa features, this study used the same traditional machine learning models mentioned in Section 4.2.3 for training and testing. The model performance evaluations are shown in the Table 9.

From the results, it can be seen that except for KNN, the performance of all models has declined. For instance, the accuracy of SVM dropped from 91.75% based on TF-IDF features to 75.46%. The accuracy of KNN slightly improved but still performed poorly.

RoBERTa model is a powerful pre-trained language model capable of capturing complex semantic relationships in the text. However, directly using deep semantic features extracted by RoBERTa in combination with traditional machine learning models did not enhance the performance of cognitive bias detection. This suggests that relying solely on pre-trained semantic features may not sufficiently capture the characteristics of cognitive biases in phishing emails. In contrast, features generated by TF-IDF are relatively simple and direct, allowing traditional machine learning models to handle these features better. Furthermore, RoBERTa-generated features may possess strong non-linear characteristics, posing greater challenges to some linear models (such as Logistic Regression). This non-linearity may make it difficult for models to find suitable classification boundaries, thereby affecting accuracy.

4.3.3 Neural Network-Based Deep Learning Model

Given the limitations of traditional machine learning models in handling deep semantic features, this study further developed a neural network-based deep learning model aimed at more effectively detecting cognitive biases in phishing emails.

Building on the previous experimental results, this study designed a simple neural network model to detect cognitive biases in phishing emails. The architecture of this model is shown in Fig. 4. Firstly, the text data of phishing emails undergoes TF-IDF processing to generate feature vectors. To optimize the model’s computational efficiency and retain the most representative features, this study employed the SelectKBest feature selection method to select the top 5000 most important features. These features are then fed into the neural network.

Figure 4: Model architecture chart

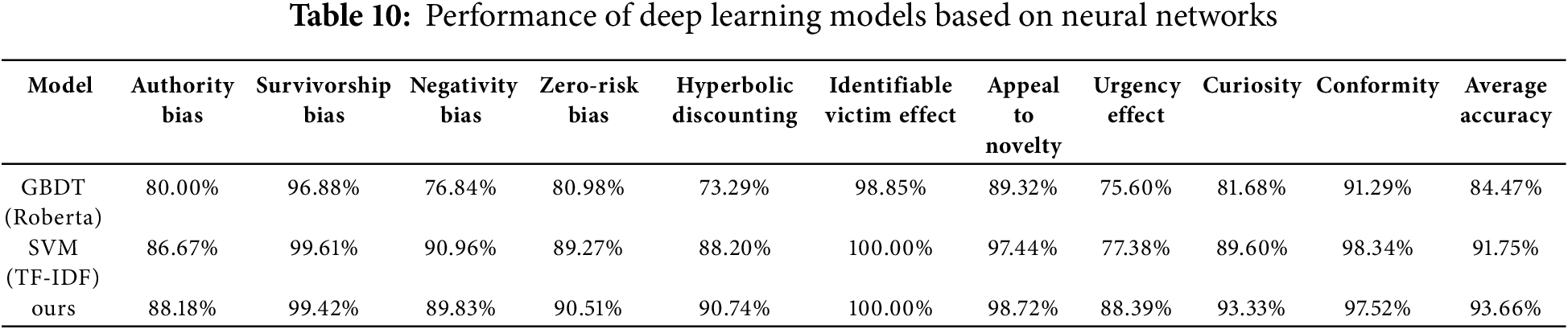

The neural network adopts a shallow structure, consisting of two 1D Convolutional Layers and one Fully Connected Layer. The convolutional layers are responsible for capturing local patterns among the features, enhancing the model’s ability to recognize relevant patterns in the text sequences. Subsequently, the output of the convolutional layers is further processed through the fully connected layer and finally classified through three Linear Layers, outputting predictions for each type of cognitive bias, as shown in the Table 10.

Our neural network model demonstrates excellent performance in the task of detecting cognitive biases in phishing emails. Compared to the previous optimal models based on TF-IDF feature extraction (SVM) and RoBERTa feature extraction, this neural network model achieves superior performance in terms of accuracy, recall, and F1-score. Neural networks can capture complex nonlinear relationships through deep feature extraction, which is crucial for addressing patterns that traditional methods cannot capture. In contrast, traditional models usually rely on manually extracted features and often cannot fully handle the complex relationships and patterns in the data. This indicates that, by combining feature selection with a shallow neural network, the model can better capture the complex patterns present in phishing emails, thereby enhancing classification performance.

4.4 Phishing Email Dataset Cognitive Bias Analysis and Detection

To validate the effectiveness of cognitive bias features in phishing email detection tasks, this study conducted further experiments on the Nigerian scam classification dataset from the repositories described in Section 4.2.1. The experiment comprises two main parts: firstly, automatically annotating cognitive biases in the emails of the dataset and performing correlation analysis; secondly, utilizing these cognitive bias features combined with the six machine learning models previously used to construct phishing email detection models.

4.4.1 Cognitive Bias Annotation and Correlation Analysis

To annotate cognitive biases in all emails within the dataset, this study employed the previously trained neural network-based cognitive bias detection model. The preprocessed email texts were input into the cognitive bias detection model, which outputs the predicted probabilities for each type of cognitive bias in each email. Typically, set a threshold of 0.5; if the predicted probability of a certain bias exceeds the threshold, the email is considered to contain that cognitive bias.

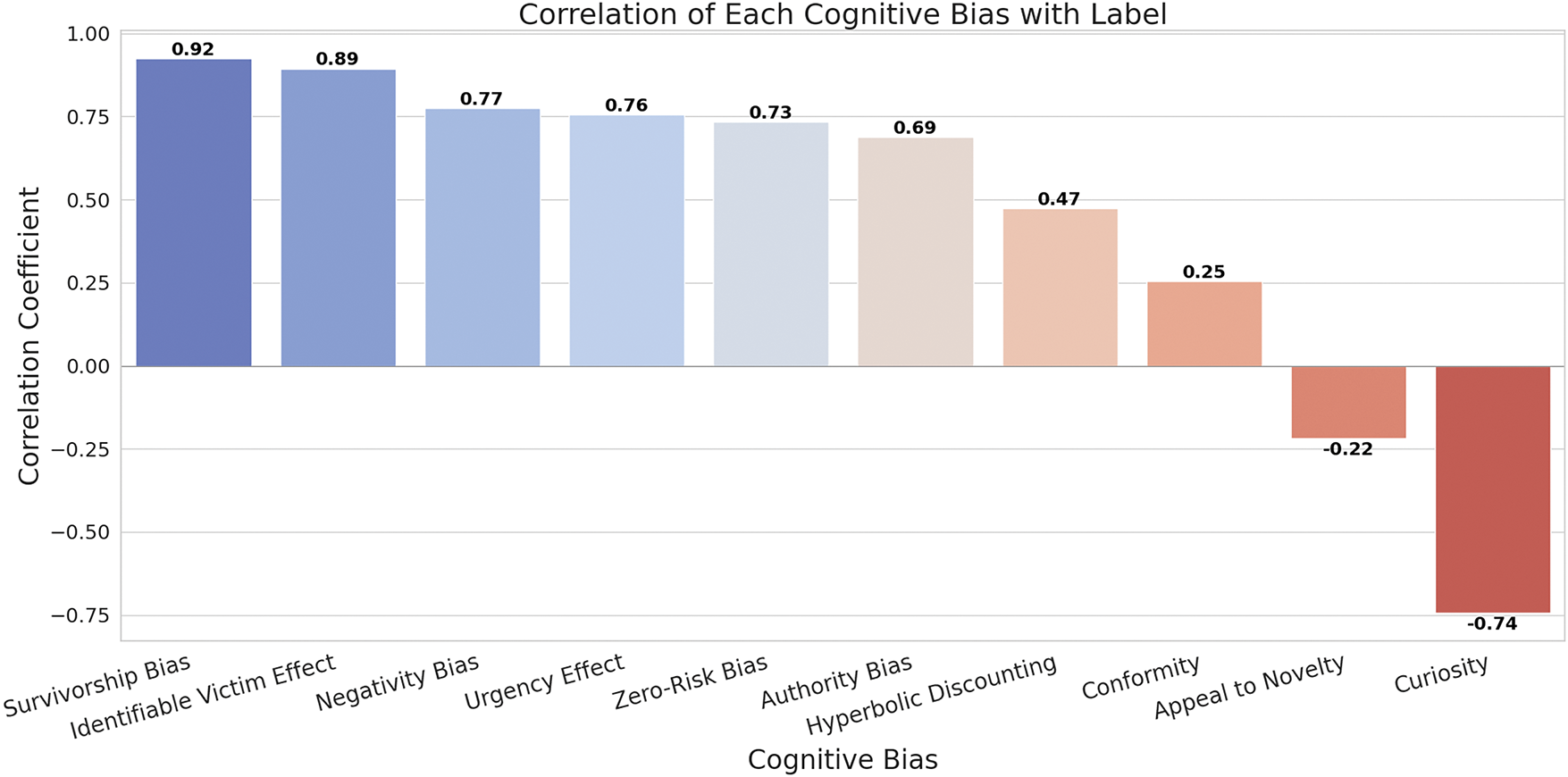

After completing cognitive bias annotation for all emails, this study conducted a correlation analysis between the cognitive biases in the emails and the email labels. The results are shown in Fig. 5. Among them, Survivorship Bias, Identifiable Victim Effect, Negativity Bias, Urgency Effect, Zero-Risk Bias, Authority Bias, Hyperbolic Discounting, and Conformity showed positive correlations. Appeal to Novelty and Curiosity showed negative correlations, indicating that these two biases are more common in non-fraudulent emails, possibly associated with the novelty and interest of legitimate email content.

Figure 5: Correlation of each cognitive biases with label

4.4.2 Phishing Email Detection Based on Cognitive Bias Features

Based on the correlation analysis results above, this study selected seven cognitive biases with a high correlation to email labels: Survivorship Bias, Identifiable Victim Effect, Negativity Bias, Urgency Effect, Zero-Risk Bias, Authority Bias, and Curiosity, as additional features. The experimental results, as shown in Table 11, indicate that most models incorporating cognitive bias features showed performance improvements, especially the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm, which significantly increased its accuracy by approximately 5.21%. This result demonstrates that incorporating cognitive bias features can effectively enhance the recognition capability of phishing email detection models.

Although technical defences have improved significantly, phishing emails continue to succeed by exploiting human psychological vulnerabilities. Therefore, improving user awareness of phishing email characteristics is one of the key strategies to mitigate this issue. Educating users on how to recognize phishing emails, such as spotting urgency cues, unfamiliar sender addresses, and suspicious links, is vital in reducing the impact of phishing attacks. Regular cybersecurity training, simulated phishing campaigns, and scenario-based analyses can enhance users’ vigilance and ability to handle phishing attempts, reducing the risk of incorrect clicks and data breaches at the source.

From a technical perspective, although many defence systems have adopted rule-based and machine learning models to detect phishing emails, attackers continuously evolve their strategies to bypass these defences. In response, beyond refining existing anti-phishing technologies like URL filtering and email content analysis, integrating multiple detection methods and incorporating user behaviour analytics and psychological features into deep learning models can more effectively identify and prevent phishing attacks based on psychological manipulation. Additionally, the use of multi-factor authentication and email encryption can further enhance account security, reducing the losses associated with phishing attacks.

To mitigate ethical risks arising from leveraging cognitive bias features, we first adhere to the principle of data minimization—collecting only the minimum set of features necessary to identify phishing risk and obtaining explicit user consent via a clear, user-friendly disclosure. Next, by integrating explainability modules into the algorithm, users can understand why and how their cognitive traits inform the model’s decision, reducing “black-box” anxiety. Additionally, regular fairness and bias assessments should be conducted, testing separately across diverse cultural, age, and demographic groups to prevent systematic misclassification due to cognitive differences. Finally, combining multi-factor authentication and email encryption as fallback safeguards—requiring additional verification steps when the model flags a high-risk email—ensures that, even in cases of false positives or adversarial exploitation, user account security remains protected.

This study provides an in-depth revelation of how phishing emails exploit cognitive biases to manipulate users’ psychological processes, thereby influencing their decision-making behaviour. By constructing a cognitive processing model, this study thoroughly analyzes how phishing emails cleverly utilize specific cognitive biases in stages such as attention capture, trust construction, and emotional priming to guide users. Additionally, 482 phishing emails were meticulously annotated for cognitive biases, offering an in-depth analysis of the psychological manipulation strategies employed by attackers in these emails.

The experimental results demonstrate that deep learning models based on neural networks perform exceptionally well in detecting cognitive biases in phishing emails. This highlights the significant advantages of deep learning methods in capturing complex psychological manipulation patterns. In the analysis of the Nigerian scam dataset, this study found that Survivorship Bias and Identifiable Victim Effect are highly correlated with fraudulent emails, reflecting how attackers enhance the deception by presenting specific stories and suggesting the victim has been selected. After incorporating these highly correlated cognitive bias features into the phishing email detection model, there was a significant improvement in various performance metrics, especially with the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm, where the accuracy increased by 5.21%.

This study emphasizes the importance of understanding the use of cognitive biases in phishing emails for cybersecurity. Revealing the psychological manipulation tactics used by attackers not only helps improve the performance of phishing email detection models but also provides strong support for user education and the development of prevention strategies. Future research could further explore more psychological features, combine them with advanced deep learning technologies, and continue to optimize phishing email detection and defence methods. Expanding the size and diversity of datasets to verify the model’s applicability in different scenarios is also a direction worth exploring. It is important to note that the current study primarily focuses on Nigerian scam emails, which may not fully represent the variety of phishing strategies found in other types of scams. Therefore, future work should include a broader range of phishing emails to enhance model robustness and generalizability. Furthermore, error analysis and statistical significance testing are equally important, as they help to further elucidate the sources of errors.

While the exploitation of cognitive biases undermines critical thinking, many users also lack the necessary factual knowledge to effectively discern phishing emails. In other words, even if a phishing email does not overtly leverage such biases, users’ inadequate knowledge may still prevent them from correctly identifying a phishing attempt. This observation underscores the multifaceted nature of phishing attacks, which encompass not only psychological manipulation but also deficiencies in user expertise. Although this study primarily focuses on the role of cognitive biases in phishing email detection, we recognize that users’ knowledge gaps significantly contribute to their vulnerability. Consequently, future research should incorporate both psychological insights and knowledge-based training to develop more comprehensive defence strategies.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Yulin Yao, Kangfeng Zheng; data curation/collection: Yulin Yao, Jiaqi Gao, Jvjie Wang, Minjiao Yang; methodology: Yulin Yao, Kangfeng Zheng, Bin Wu, Chunhua Wu; draft manuscript preparation: Yulin Yao; writing—review & editing: Yulin Yao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The code and data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the GitHub repository ‘Cognitive-Bias-Approach’ at https://github.com/kingkongs7/Cognitive-Bias-Approach (accessed on 01 January 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix

References

1. Bera D, Ogbanufe O, Kim DJ. Towards a thematic dimensional framework of online fraud: an exploration of fraudulent email attack tactics and intentions. Decis Support Syst. 2023;171:113977. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2023.113977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mitnick KD, Simon WL. The art of deception: controlling the human element of security. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2003 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://dl.acm.org/doi/book/10.5555/579369. [Google Scholar]

3. Nasdaq V. 2024 global financial crime report 2024 [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://verafin.com/nasdaq-verafin-global-financial-crime-report/. [Google Scholar]

4. Intelligence S. Social engineering in the era of generative AI: predictions for 2024, security Intelligence 2024 [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.securityintelligence.com/articles/social-engineering-generative-ai-2024. [Google Scholar]

5. Coden M, Czumak M. How health care providers can thwart cyber attacks 2021 [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2021/cyber-attack-prevention-for-health-care-providers. [Google Scholar]

6. Rajivan P, Gonzalez C. Creative persuasion: a study on adversarial behaviors and strategies in phishing attacks. Front Psychol. 2018;9:135. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Team R. Email statistics report, 2023–2027 [Online]. Palo Alto, CA, USA: Radicati Group, Inc.; 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.radicati.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Email-Statistics-Report-2023-2027-Executive-Summary.pdf. [Google Scholar]

8. Tang L, Mahmoud QH. A deep learning-based framework for phishing website detection. IEEE Access. 2021;10:1509–21. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3137636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jain AK, Gupta BB. A machine learning based approach for phishing detection using hyperlinks information. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2019;10(5):2015–28. doi:10.1007/s12652-018-0798-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Halgaš L, Agrafiotis I, Nurse JRC. Catching the phish: detecting phishing attacks using recurrent neural networks (RNNs). In: Information Security Applications: 20th International Conference, WISA; 2019 Aug 21–24; Jeju Island, Republic of Korea. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. p. 219–33. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-39303-8_17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Petelka J, Zou Y, Schaub F. Put your warning where your link is: improving and evaluating email phishing warnings. In: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2019 May 4–9; Glasgow, UK. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2019. p. 1–15. doi:10.1145/3290605.3300748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Berens BM, Schaub F, Mossano M, Volkamer M. Better together: the interplay between a phishing awareness video and a link-centric phishing support tool. In: Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2024 May 11–16; Honolulu, HI, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2024. p. 1–60. doi:10.1145/3613904.3642843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cialdini RB, Cialdini RB. Influence: the psychology of persuasion. New York, NY, USA: Collins; 2007. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/works/9GLJxzZ7/. [Google Scholar]

14. Eftimie S, Moinescu R, Răcuciu C. Spear-phishing susceptibility stemming from personality traits. IEEE Access. 2022;10(5):73548–61. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3190009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sharma M, Kumar M, Gonzalez C, Dutt V. How the presence of cognitive biases in phishing emails affects human decision-making? In: International Conference on Neural Information Processing; 2023 Nov 20–23; Changsha, China. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2023. p. 550–60. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-1642-9_47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Cui X, Ge Y, Qu W, Zhang K. Effects of recipient information and urgency cues on phishing detection. In: HCI International 2020: 22nd International Conference, HCII; 2020 Jul 19–24; Copenhagen, Denmark. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. p. 520–5. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-50732-9_67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Modic D. Willing to be scammed: how self-control impacts Internet scam compliance 2012 [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10871/8044/ModicD_fm.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

18. Patel P, Sarno DM, Lewis JE, Shoss M, Neider MB, Bohil CJ. Perceptual representation of spam and phishing emails. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2019;33(6):1296–304. doi:10.1002/acp.3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Stajano F, Wilson P. Understanding scam victims: seven principles for systems security. Commun ACM. 2011;54(3):70–5. doi:10.1145/1897852.1897872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Stojnic T, Vatsalan D, Arachchilage NAG. Phishing email strategies: understanding cybercriminals' strategies of crafting phishing emails. Secur Priv. 2021;4(5):e165. doi:10.1002/spy2.165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kahneman D. Thinking, fast and slow. New York, NY, USA: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2011. doi:10.4324/9781315467498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kahneman D, Frederick S. Representativeness revisited: attribute substitution in intuitive judgment. Heuristics Biases Psychol Intuitive Judgm. 2002;49(49–81):74–81. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511808098.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yasin A, Abuhasan A. An intelligent classification model for phishing email detection. Int J Netw Secur Appl. 2016;8(4):55–72. doi:10.5121/ijnsa.2016.8405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Smadi S, Aslam N, Zhang L, Alasem R, Hossain MA. Detection of phishing emails using data mining algorithms. In: 2015 9th International Conference on Software, Knowledge, Information Management and Applications (SKIMA); 2015 Dec 15–17; Kathmandu, Nepal. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/SKIMA.2015.7399985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mohammed UA, Sanusi M. An optimised phishing email detection and prevention using classification models. Int J Eng Appl Sci Technol. 2023;7(10):9–21. doi:10.33564/ijeast.2023.v07i10.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Moradpoor N, Clavie B, Buchanan B. Employing machine learning techniques for detection and classification of phishing emails. In: 2017 Computing Conference; 2017 Jul 18–20; London, UK. p. 149–56. doi:10.1109/SAI.2017.8252096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Gomez JC, Boiy E, Moens MF. Highly discriminative statistical features for email classification. Knowl Inf Syst. 2012;31(1):23–53. doi:10.1007/s10115-011-0403-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Islam R, Abawajy J. A multi-tier phishing detection and filtering approach. J Netw Comput Appl. 2013;36(1):324–35. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2012.05.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Adebowale MA, Lwin KT, Hossain MA. Intelligent phishing detection scheme using deep learning algorithms. J Enterp Inf Manag. 2023;36(3):747–66. doi:10.1108/jeim-01-2020-0036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Park G, Taylor JM. Using syntactic features for phishing detection. arXiv:1506.00037. 2015. [Google Scholar]

31. Alhogail A, Alsabih A. Applying machine learning and natural language processing to detect phishing email. Comput Secur. 2021;110(8):102414. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2021.102414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tan CL, Chiew KL, Wong K, Sze SN. PhishWHO: phishing webpage detection via identity keywords extraction and target domain name finder. Decis Support Syst. 2016;88(5):18–27. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2016.05.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Sonowal G. Phishing email detection based on binary search feature selection. SN Comput Sci. 2020;1(4):191. doi:10.1007/s42979-020-00194-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Egozi G, Verma R. Phishing email detection using robust NLP techniques. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW); 2018 Nov 17–20; Singapore. p. 7–12. doi:10.1109/ICDMW.2018.00009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Karim A, Azam S, Shanmugam B, Kannoorpatti K, Alazab M. A comprehensive survey for intelligent spam email detection. IEEE Access. 2019;7:168261–95. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2954791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Azeez NA, Misra S, Margaret IA, Fernandez-Sanz L, Abdulhamid SM. Adopting automated whitelist approach for detecting phishing attacks. Comput Secur. 2021;108(2):102328. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2021.102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Bergholz A, De Beer J, Glahn S, Moens MF, Paaß G, Strobel S. New filtering approaches for phishing email. J Comput Secur. 2010;18(1):7–35. doi:10.3233/jcs-2010-0371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Dong X, Clark JA, Jacob JL. Defending the weakest link: phishing websites detection byanalysing user behaviours. Telecommun Syst. 2010;45(2):215–26. doi:10.1007/s11235-009-9247-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Desolda G, Ferro LS, Marrella A, Catarci T, Costabile MF. Human factors in phishing attacks: a systematic literature review. ACM Comput Surv. 2022;54(8):1–35. doi:10.1145/3469886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Cialdini RB. The science of persuasion. Sci Am. 2001;284(2):76–81. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-77600-7_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lawson P, Pearson CJ, Crowson A, Mayhorn CB. Email phishing and signal detection: how persuasion principles and personality influence response patterns and accuracy. Appl Ergon. 2020;86(8):103084. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2020.103084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Valecha R, Mandaokar P, Rao HR. Phishing email detection using persuasion cues. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2022;19(2):747–56. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2021.3118931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Spelt HAA, Westerink JHDM, Ham J, IJsselsteijn WA. Psychophysiological reactions to persuasive messages deploying persuasion principles. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2019;13(1):461–72. doi:10.1109/TAFFC.2019.2931689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kaptein M, van Halteren A. Adaptive persuasive messaging to increase service retention: using persuasion profiles to increase the effectiveness of email reminders. Pers Ubiquitous Comput. 2013;17(6):1173–85. doi:10.1007/s00779-012-0585-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Butavicius M, Taib R, Han SJ. Why people keep falling for phishing scams: the effects of time pressure and deception cues on the detection of phishing emails. Comput Secur. 2022;123(8):102937. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2022.102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Williams EJ, Hinds J, Joinson AN. Exploring susceptibility to phishing in the workplace. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2018;120(3):1–13. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2018.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Vishwanath A, Herath T, Chen R, Wang J, Rao HR. Why do people get phished? Testing individual differences in phishing vulnerability within an integrated, information processing model. Decis Support Syst. 2011;51(3):576–86. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2011.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Parsons K, McCormac A, Pattinson M, Butavicius M, Jerram C. The design of phishing studies: challenges for researchers. Comput Secur. 2015;52(3):194–206. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2015.02.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Akbar N. Analysing persuasion principles in phishing emails 2014 [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://essay.utwente.nl/66177/. [Google Scholar]

50. Wang J, Li Y, College C, Rao HR. Overconfidence in phishing email detection. J Assoc Inf Syst. 2016;17(11):759–83. doi:10.17705/1jais.00442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Cranford EA, Lebiere C, Rajivan P, Aggarwal P, Gonzalez C. Modeling cognitive dynamics in end-user response to phishing emails. Proceedings of the 17th ICCM 2019 [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://iccm-conference.neocities.org/2019/proceedings/papers/ICCM2019_paper_57.pdf. [Google Scholar]

52. Tiwari P. Exploring phishing susceptibility attributable to authority, urgency, risk perception and human factors 2020 [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://hammer.purdue.edu/articles/thesis/EXPLORING_PHISHING_SUSCEPTIBILITY_ATTRIBUTABLE_TO_AUTHORITY_URGENCY_RISK_PERCEPTION_AND_HUMAN_FACTORS/12739592. [Google Scholar]

53. Ferreira A, Teles S. Persuasion: how phishing emails can influence users and bypass security measures. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2019;125:19–31. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2018.12.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Gilligan M. This cognitive bias codex categorizes and defines each cognitive bias 2022 [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://twistedsifter.com/2022/08/this-cognitive-bias-codex-categorizes-and-defines-each-cognitive-bias/. [Google Scholar]

55. Loewenstein G. The psychology of curiosity: a review and reinterpretation. Psychol Bull. 1994;116(1):75–98. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.116.1.75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Rozin P, Royzman EB. Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2001;5(4):296–320. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0504_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Hinnosaar M, Hinnosaar T. Authority bias [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/2108445/Authority. [Google Scholar]

58. Berlyne DE. Novelty, complexity, and hedonic value. Percept Psychophys. 1970;8(5):279–86. doi:10.3758/BF03212593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. The Decision Lab. Survivorship bias 2021 [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/survivorship-bias. [Google Scholar]

60. Kennedy DR, Porter AL. The illusion of urgency. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;86(7):8914. doi:10.5688/ajpe8914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Jenni K, Loewenstein G. Explaining the identifiable victim effect. J Risk Uncertain. 1997;14(3):235–57. doi:10.1016/s0167-6687(97)89155-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Crosby D. The laws of wealth. Mumbai, India: Jaico Publishing House [Internet]; 2021 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.blinkist.com/en/books/the-laws-of-wealth-en. [Google Scholar]

63. Ainslie G. The cardinal anomalies that led to behavioral economics: cognitive or motivational? Manage Decis Econ. 2016;37(4–5):261–73. doi:10.1002/mde.2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Milgram S. Behavioral study of obedience. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1963;67(4):371–8. doi:10.1037/h0040525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Champa AI, Rabbi F, Zibran MF. Why phishing emails escape detection: a closer look at the failure points. In: 2024 12th International Symposium on Digital Forensics and Security (ISDFS); 2024 Apr 29–30; San Antonio, TX, USA. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ISDFS60797.2024.10527344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools