Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Modified Watermarking Scheme Using Informed Embedding and Fuzzy c-Means–Based Informed Coding

1 Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, National Chin-Yi University of Technology, Taichung, 41170, Taiwan

2 Department of Electronic Engineering, National Chin-Yi University of Technology, Taichung, 41170, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Chi-Chun Chen. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5595-5624. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066160

Received 31 March 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Digital watermarking must balance imperceptibility, robustness, complexity, and security. To address the challenge of computational efficiency in trellis-based informed embedding, we propose a modified watermarking framework that integrates fuzzy c-means (FCM) clustering into the generation off block codewords for labeling trellis arcs. The system incorporates a parallel trellis structure, controllable embedding parameters, and a novel informed embedding algorithm with reduced complexity. Two types of embedding schemes—memoryless and memory-based—are designed to flexibly trade-off between imperceptibility and robustness. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms existing approaches in bit error rate (BER) and computational complexity under various attacks, including additive noise, filtering, JPEG compression, cropping, and rotation. The integration of FCM enhances robustness by increasing the codeword distance, while preserving perceptual quality. Overall, the proposed framework is suitable for real-time and secure watermarking applications.Keywords

The rapid expansion of the Internet and other public communication networks has significantly increased interest in data hiding, a key component of multimedia technology [1]. Watermarking codes embed data into host signals (e.g., images, audio, video, text) with two primary goals: imperceptibility, ensuring minimal degradation, and robustness, maintaining integrity against distortions. This study focuses on digital watermarking, with an emphasis on analyzing the aforementioned trade-offs—robustness, imperceptibility, payload, and complexity—as well as the development of practical algorithms. In recent years, deep learning–based image watermarking approaches have attracted increasing attention for their potential to enable adaptive embedding strategies. However, many existing methods fall short of fully leveraging deep learning’s capacity to learn and automate both embedding and extraction processes [2–4]. Moreover, existing methods often struggle to simultaneously achieve key requirements such as robustness and blind detection. The issue of copyright protection for medical images has garnered considerable attention, positioning digital watermarking as a prominent research focus. Unlike traditional approaches that embed a single watermark directly into a cover image, leveraging deep neural networks to embed multiple watermarks provides enhanced capabilities for image authentication and ownership verification—features particularly valuable in healthcare applications [5–8]. In [9], a novel Residual Chaotic System (RCS) was proposed to generate more complex, unpredictable, and ergodic chaotic sequences, thereby enhancing security. Chaotic systems are widely employed to generate highly random and unpredictable sequences, which serve as the foundation for data encoding, information hiding, and authentication [10]. To improve the imperceptibility and security of the watermark, chaotic sequences are used to encrypt and perturb the watermark information. During the embedding phase, a chaotic map is employed to further encrypt and scramble the watermark, thereby enhancing its robustness and unpredictability [11,12].

The objective of informed coding is to select the most suitable message codeword from a set of candidates that best represents the watermark while introducing minimal perceptual distortion to the host signal. Within this framework, binning schemes are employed to achieve information-theoretic capacity [13]. Theoretical bounds and practical watermarking schemes have been developed based on Costa’s seminal result. Costa demonstrated that random dirty paper codes can be constructed using appropriate random coding techniques; however, his approach did not adequately address issues of practical efficiency.

Implementing such watermarking algorithms is particularly challenging due to the exhaustive search required to identify random dirty paper codes. To enhance practical applicability, structured codes are preferred in watermarking systems, as they allow for the efficient construction of watermarked signals. Miller et al. [14] introduced a dirty-paper trellis framework in which multiple candidate codewords may correspond to the same message. They proposed a suboptimal trellis-based embedding algorithm that starts with the host signal and iteratively refines the watermarked signal, guiding it toward the interior of the Voronoi region associated with the target message codeword. Although the trellis-based approach in [14] achieves a favorable trade-off between imperceptibility and robustness in watermarked images, it remains computationally intensive and difficult to implement in practice.

Miller et al. [14] and Wang et al. [15,16] proposed a robust informed embedding algorithm that utilizes codewords derived from convolutional codes, linear codes, and random codes. In these approaches, each arc in the trellis is labeled with a block codeword corresponding to each trellis section. The embedding algorithm iteratively constructs a watermarked signal by moving it toward the interior of the Voronoi region associated with the message codeword. In the present study, we extend the methods proposed by Miller [14] and Wang [15,16] by modifying their trellis structures. Instead of using randomly generated reference vectors or random codewords as arc labels [14–16], our algorithm employs codewords from linear block codes generated via the fuzzy c-means (FCM) algorithm. FCM, a widely adopted fuzzy clustering method, was originally introduced in [17]. Block codes generated using FCM improve the imperceptibility of watermarked images across various embedding scenarios. Due to its flexibility and robustness in handling uncertainty, FCM has been successfully applied in numerous domains [18–20]. In our approach, the arc labels of block codes are refined by clustering codewords using the FCM algorithm. Refining a linear code while maintaining its linearity can potentially increase its minimum distance, thereby enhancing robustness. FCM exhibits rich structural properties and has been extensively explored in mathematical and theoretical studies. A key feature of emerging clustering methods [20] is the ability for a data sample to belong to multiple clusters, rather than being limited to a single one. To further improve time complexity, Ref. [21] introduced a method for reducing large datasets into smaller, weighted representations. The extended FCM (E-FCM) algorithm, proposed in [22], enhances the clustering process by merging highly similar clusters during each iteration until convergence of the objective function is achieved. In our watermarking system, we apply an informed embedding algorithm to modify the host signal, achieving a balance between the original host and the encoded watermark signal. This algorithm features a parallel arc structure, which connects the current state to the next in each trellis section. By leveraging the characteristics of linear block codes and applying them to trellis partitioning, the system simplifies the process of tuning imperceptibility and robustness. Building on this foundation, we propose an informed embedding algorithm that employs linear block codes based on the FCM algorithm, such as simplex codes and Walsh–Hadamard codes. The embedding process proceeds iteratively, section by section. The algorithm’s parallel structure not only reduces computational complexity but also achieves satisfactory error rate performance, contributing to an improved trellis design. In the informed coding stage, the system selects the message codeword that causes minimal perceptual distortion to the host signal from a parallel set of candidate codewords, thereby defining the watermarked path. Unlike the accumulative nature of the Viterbi algorithm, our method uses the extraction vector solely to identify the closest message codeword within the parallel arc structure. This approach substantially reduces the computational complexity of the encoding process compared to that in [14–16]. The integration of informed embedding and coding in our proposed method further enhances the performance of the informed watermarking system. Our approach is designed to maintain a balance between imperceptibility and robustness, optimizing the trade-off between these two critical aspects in watermarked images [14,23,24]. Moreover, the proposed algorithms are easier to implement and less computationally intensive than other informed watermarking methods. We evaluated the performance of our algorithm in comparison with those presented in [14,15]. First, we assessed embedding distortion by simulating its effect on watermarked image quality. Second, we evaluated robustness against common signal distortions, including Gaussian noise, low-pass filtering, and JPEG compression. Finally, we summarized the complexity comparison in tabular form. We have also summarized the main contributions of this paper as follows: (1) This study employs the FCM technique to select good codewords as labels in the trellis structure, unlike reference [14], which uses random codes as labels. (2) The algorithm proposed in this study can effectively achieve a trade-off between robustness and time complexity. In contrast, the method in Reference [14] has higher time complexity as well as greater computational complexity than our approach. (3) Compared with Reference [15,16], this paper integrates two embedding coding methods, informed embedding and informed coding, for information embedding.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the trellis-based informed watermarking system proposed in [14] and introduces our proposed watermarking framework. Section 3 details the core contributions of this study, including the modified informed embedding and coding algorithms. Section 4 presents the experimental results along with a constructive discussion. Finally, conclusions are provided in Section 5.

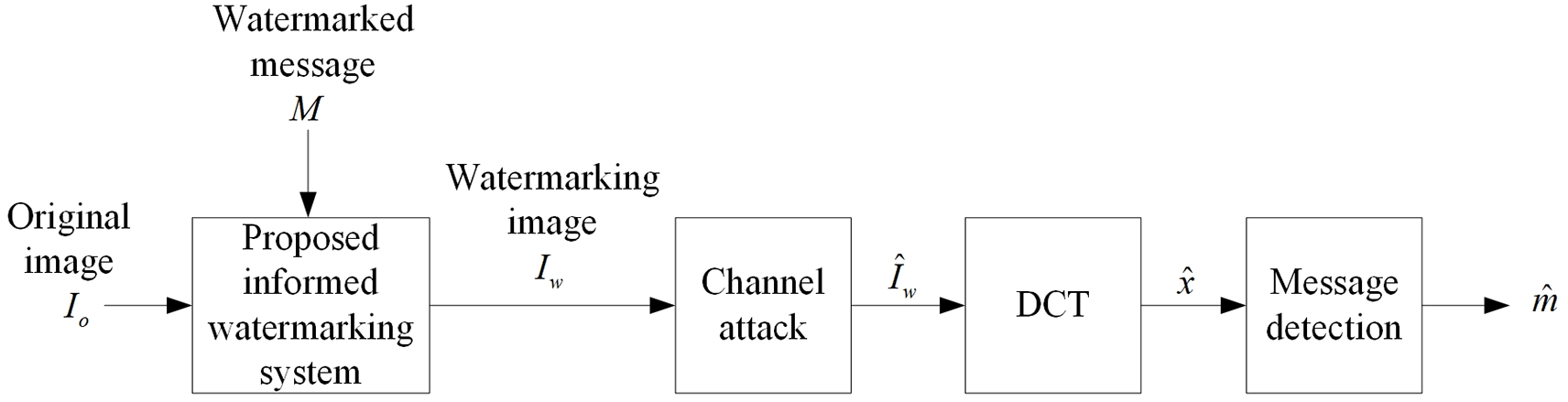

This paper proposes a trellis-based informed watermarking system with controllable parameters. The proposed system enhances the approach introduced in [14,15] by modifying the arc labels within the trellis structure. Fig. 1 illustrates the fundamental block diagram of the proposed watermarking system, which consists of three primary components: the informed watermarking module, the channel attack process, and the message detection unit.

Figure 1: Watermarking system model

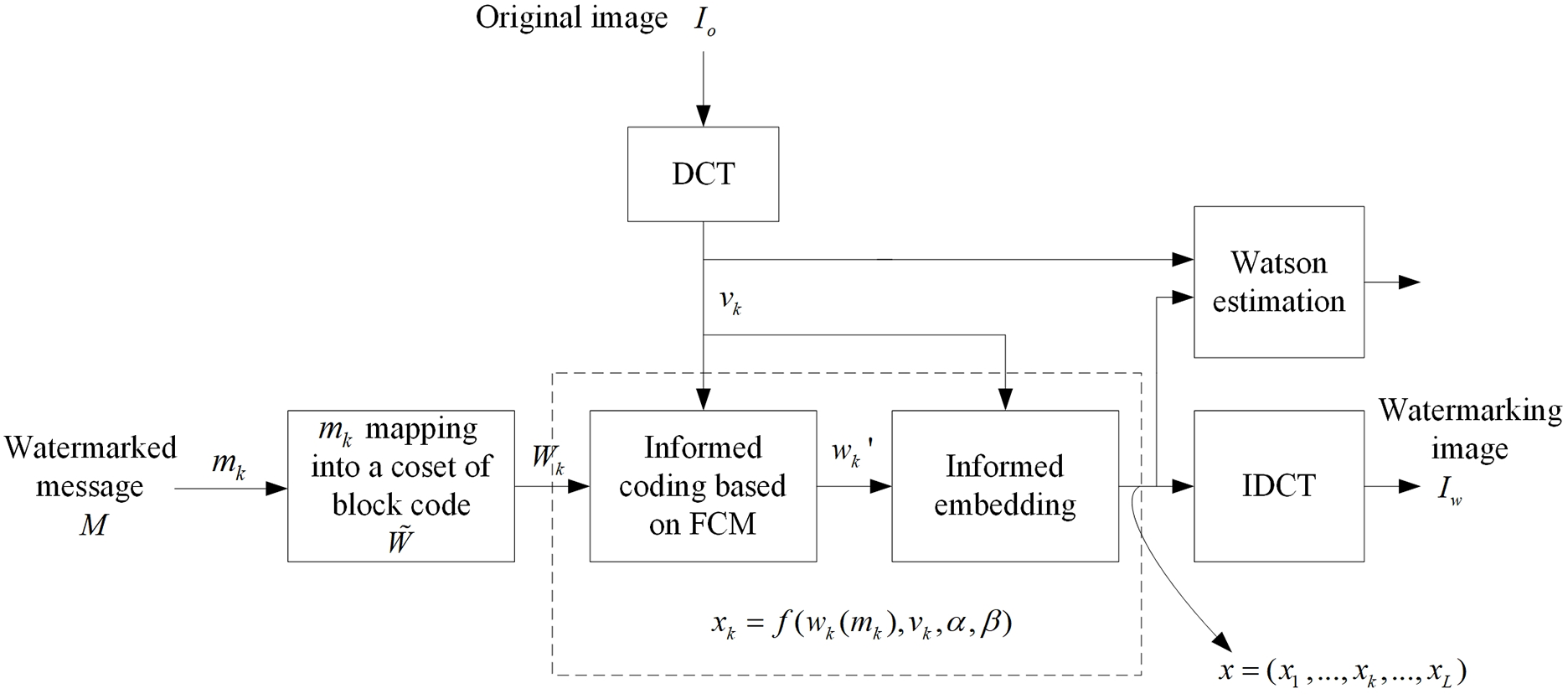

In the first component, detailed in Fig. 2, the watermarked message

Figure 2: Proposed informed watermarking system

The output of the embedder, which transforms the watermarked sequence

where

As demonstrated in [14,15], the watermark is embedded in the frequency domain of the host signal rather than directly on the host image. First, various host images are simulated. Each host signal, Io, with

3 Proposed Informed Watermarking Scheme Based on Fuzzy c-Means Algorithm

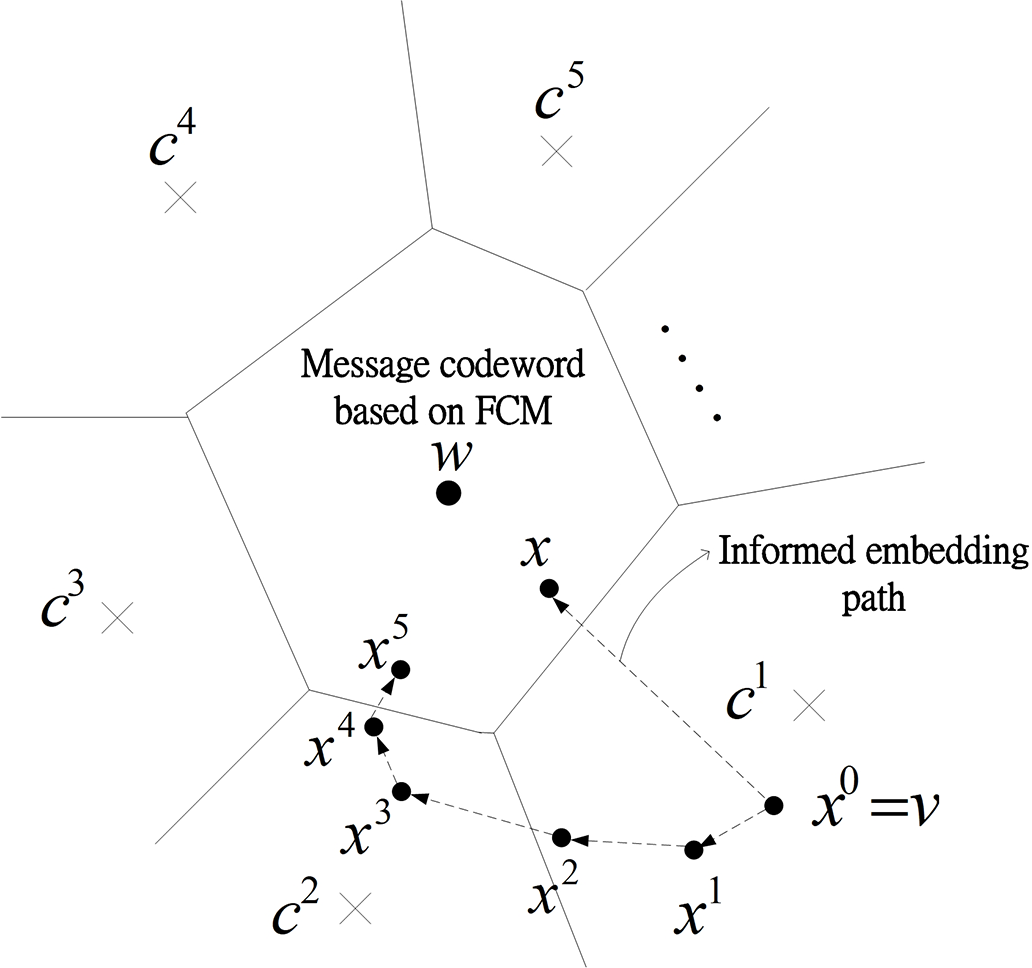

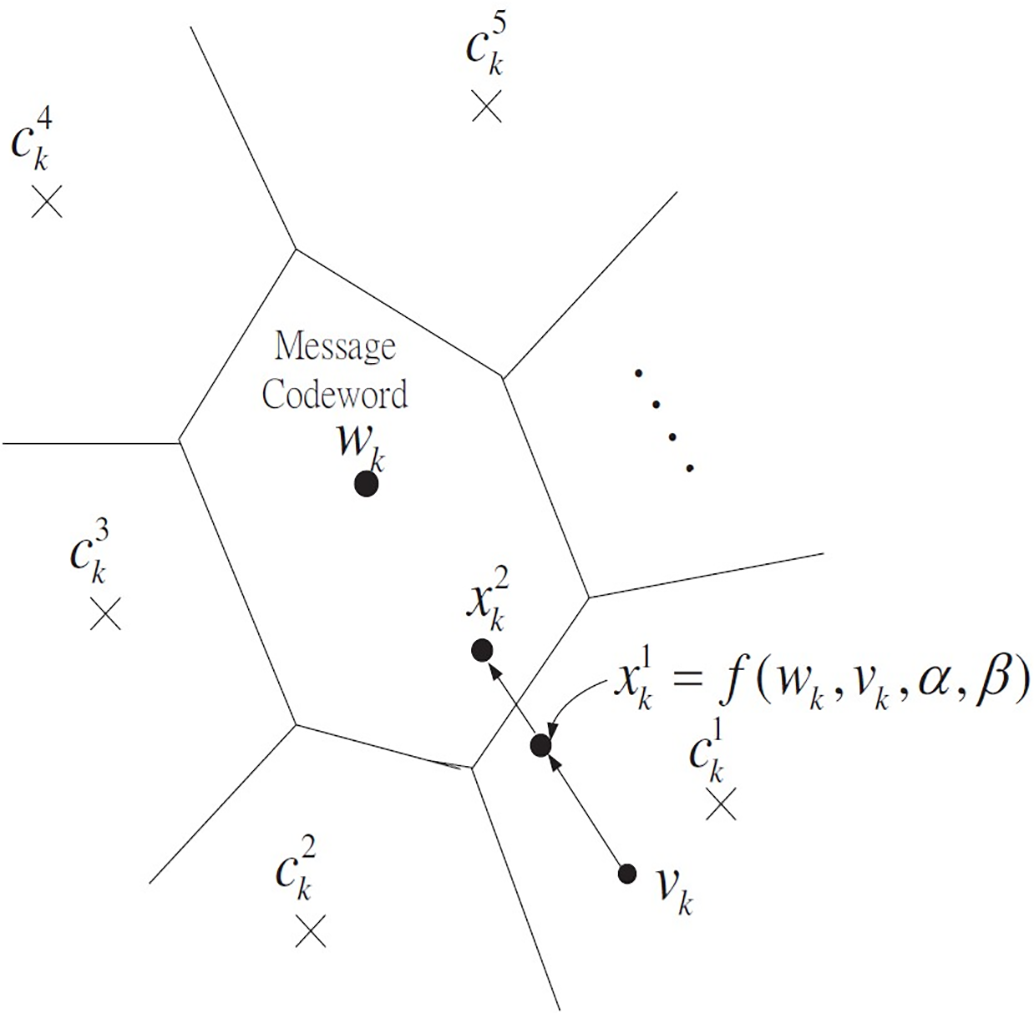

The efficiency of embedding in informed watermarking is influenced by factors such as the design of the trellis structure, the labeled codeword in the arcs, the informed watermarking algorithm, and the codeword length. On the basis of the design of the trellis structure and the informed watermarking algorithm, Miller et al. [14] and Wang et al. [15,16] proposed a suboptimal algorithm for generating a watermarked image. In their study, an iterative algorithm for informed watermarking was proposed. In informed embedding, the watermarked image is designed to fall within the decoding region of the message codeword and to incur minimal perceptual distortion from the host signal. Identifying the optimal watermarked image is generally challenging. However, several approaches have been developed for identifying suboptimal watermarked images, including the trellis-based informed embedding described in [14–16]. In this approach, it is assumed that every path through the trellis corresponds to a watermark message codeword. Using a Viterbi decoder, the trellis-based informed embedding in [14–16] is used to identify a suitable watermarked image. The watermarked signal is iteratively updated in the geometric interpretation of the suboptimal embedding algorithm, as illustrated in Fig. 3. In this process, the Viterbi decoder is used in the first iteration to identify the codeword vector,

Figure 3: Trellis-based informed embedding [14,15]

Using vectors

3.1 Informed Embedding Using an Iterative Algorithm with Controllable Parameters

This subsection introduces an iterative informed embedding (IE) algorithm that incorporates tunable parameters to balance computational complexity and embedding effectiveness. Unlike Miller’s approach, which utilizes randomized arc labels in the trellis, our method employs structured codewords derived from linear block codes to enhance efficiency and consistency during encoding. Among these codes, simplex codes with parameters

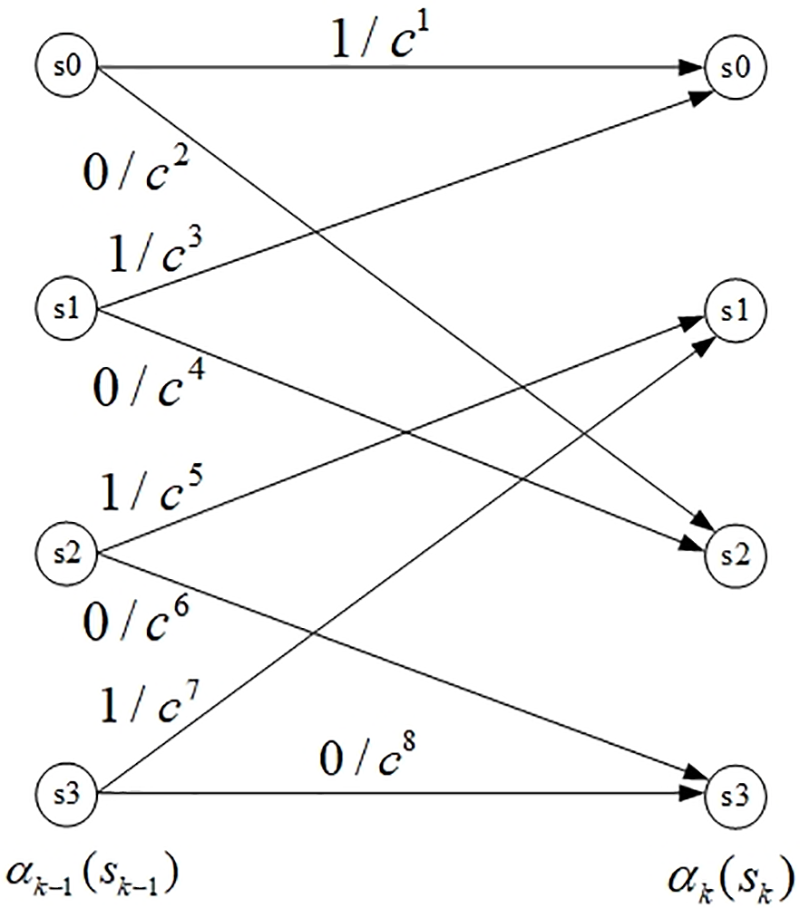

To enhance robustness in the watermarking process, our approach incorporates linear block codewords as arc identifiers within the trellis-based embedding framework. The underlying trellis is constructed using a convolutional encoder defined by parameters

The design allows for flexibility in adjusting performance characteristics: increasing

Figure 4: Trellis with eight arcs labeled by a (7, 3, 4) simplex code [15,16]

The proposed informed embedding algorithm is based on trellis partitioning, where at each trellis section

where

(1) Memoryless informed embedding, type-1: Define

Figure 5: Geometrical view of the informed embedding at trellis section k

The detailed procedure for identifying such an

where

We construct the

Essentially, we shift

1. Let

2. If the current

3. Update the

4. If

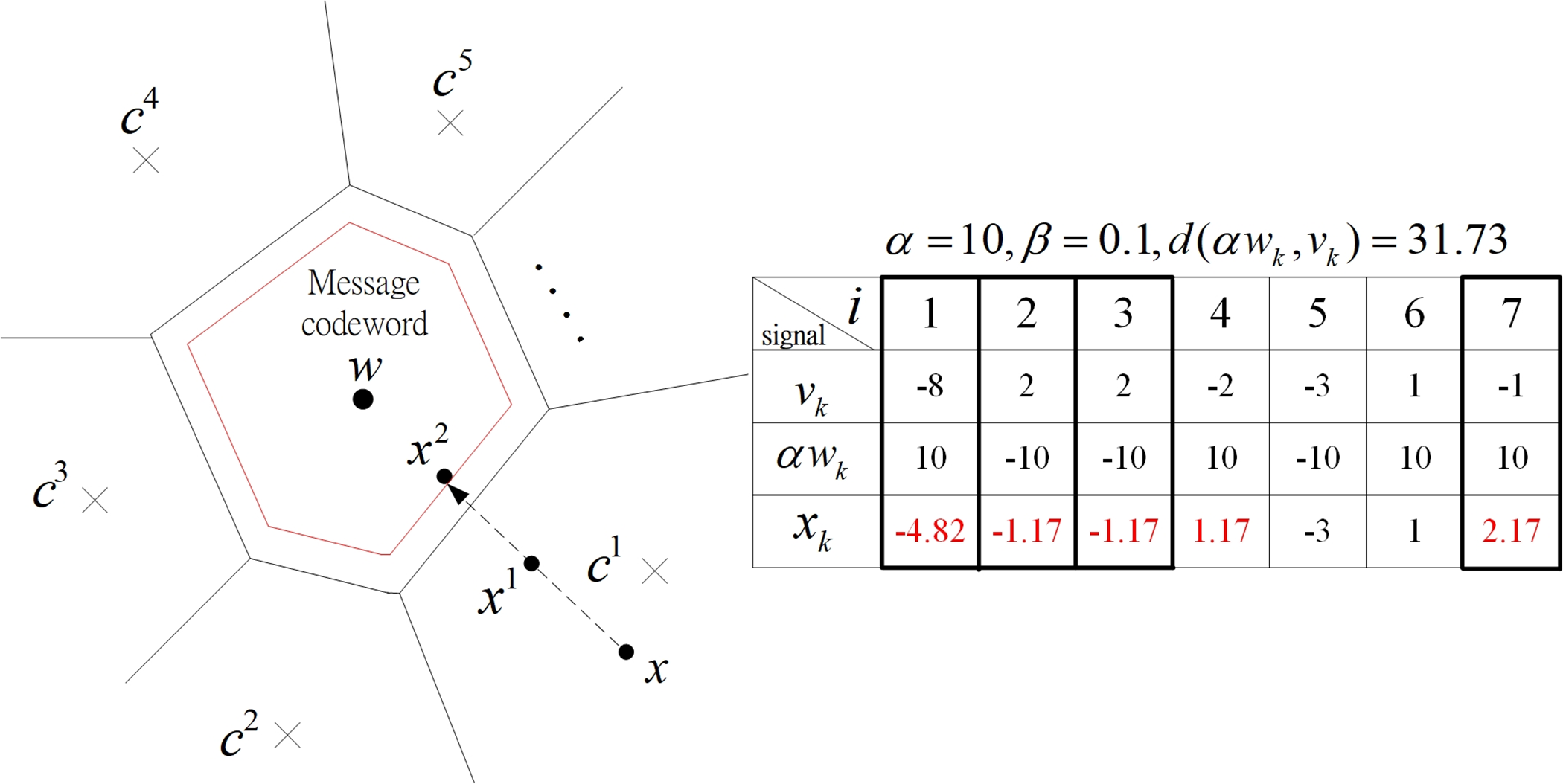

Illustrated in Fig. 6 is the type-1 informed embedding approach employing a (7, 3, 4) simplex code with parameters

Figure 6: Type-1 informed embedding using a (7, 3, 4) simplex code with

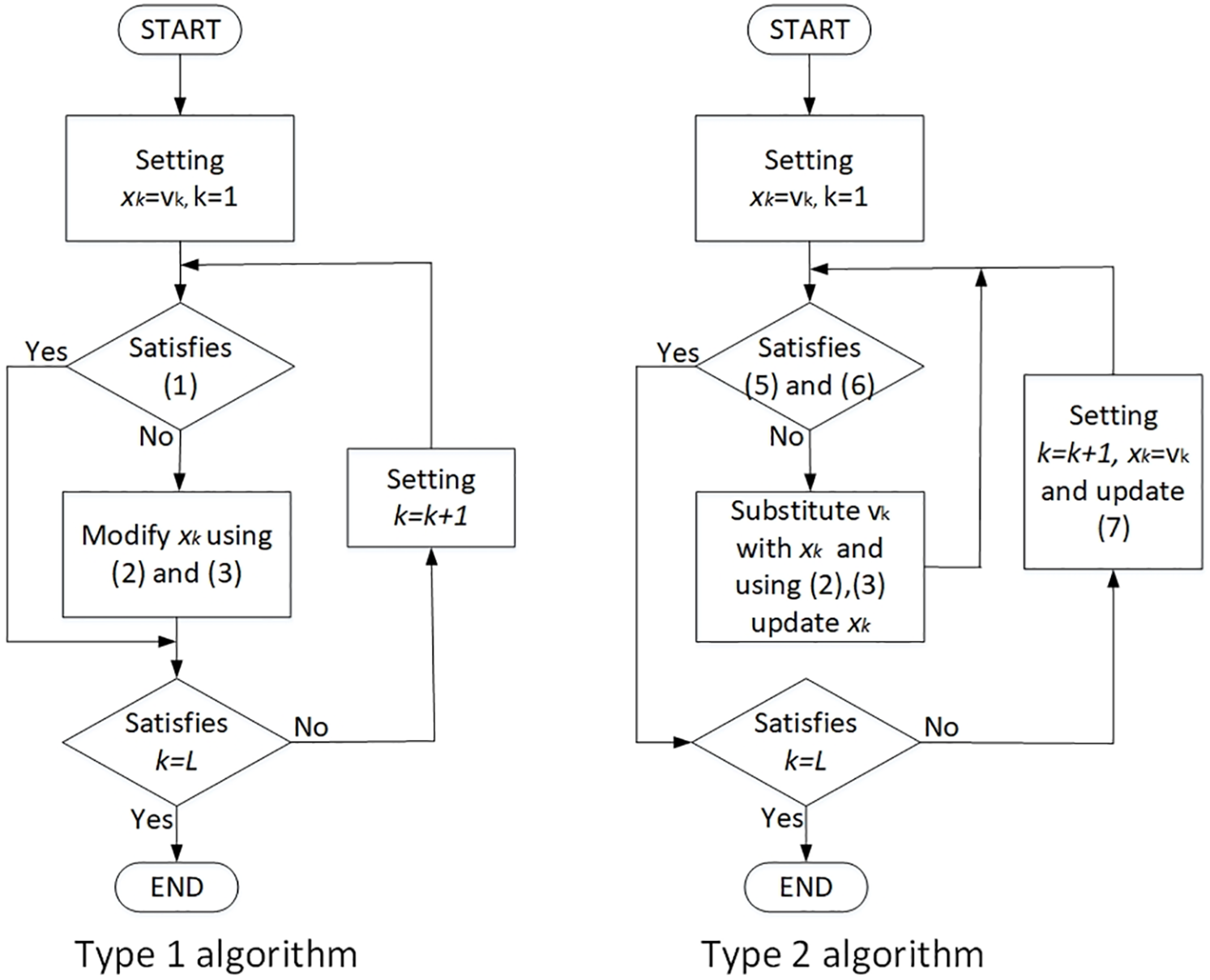

Because the embedding algorithm operates independently in each section, the type-1 algorithm exhibits high robustness. Although it performs well in terms of robustness, the type-1 algorithm requires an increasing number of iterations. To mitigate the complexity caused by these iterative procedures, a memory-augmented version of the type-1 algorithm is proposed.

(2) Memory-based informed embedding, type-2: The reduced complexity of the algorithm in Section 3.1 arises from its section-wise update of

where

Eq. (5) indicates that

where the maximum is taken over those

The algorithm proposed in this section embeds information using the procedure outlined previously. It achieves a low level of distortion through hard decoding at the receiver. The reduced embedding complexity compared with that of those discussed in the previous section. This informed embedding algorithm, which accumulates distortion, is summarized as follows:

1. Let

2. If the current

3. Update the

4. If

Finally, the proposed type-1 and type-2 algorithms are illustrated as block diagrams in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Block diagrams of the proposed type-1 and type-2 algorithms

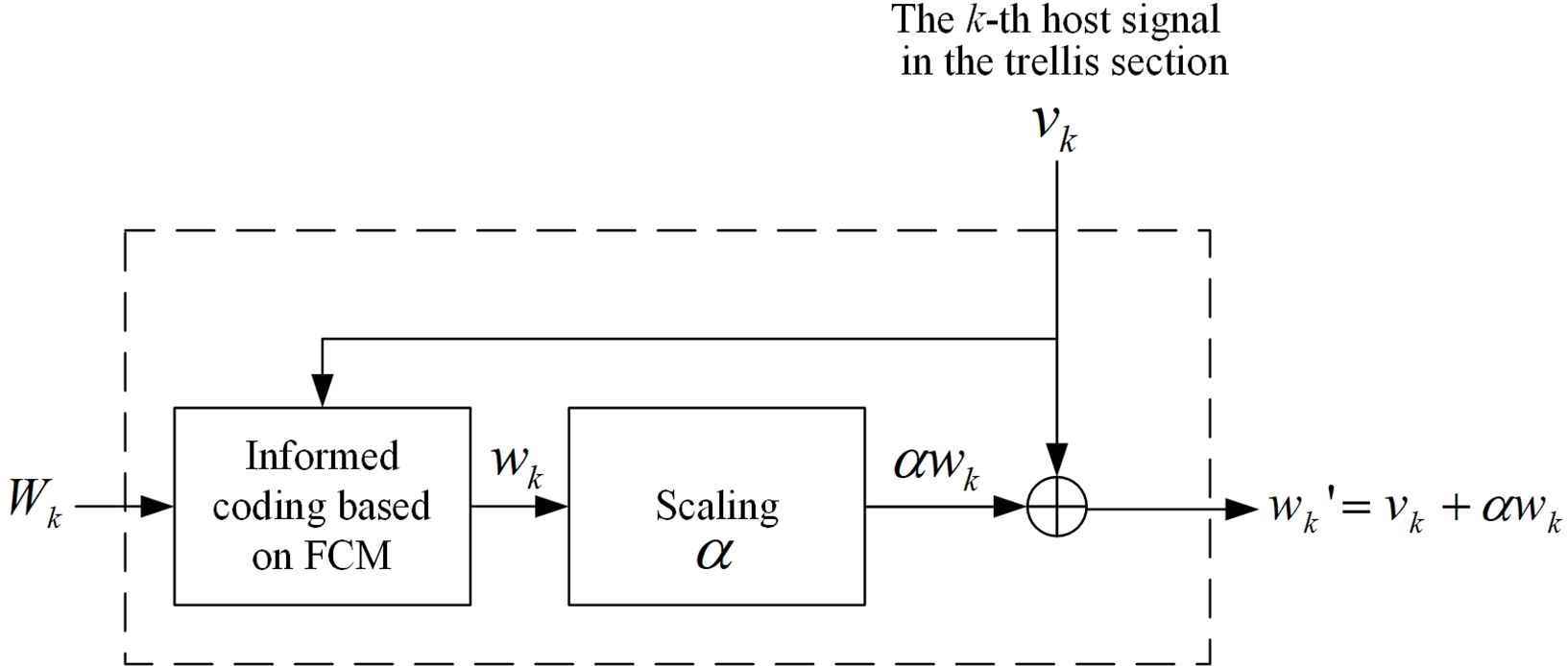

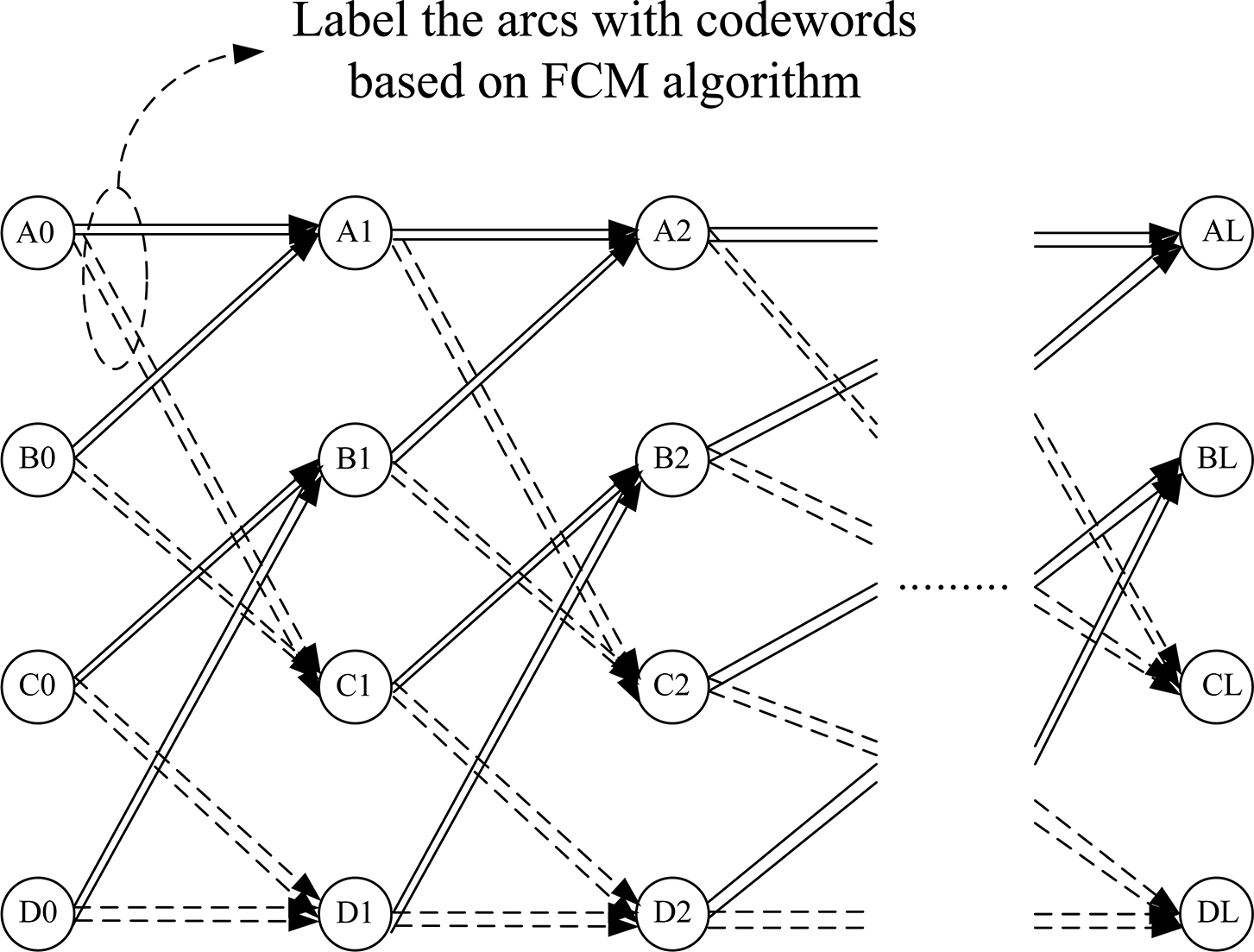

3.2 Informed Coding with Codewords Based on FCM Algorithm for Parallel Branch Trellis Structure

To improve the distance property, in informed coding (IC), the FCM algorithm is used to construct a codeword space with a large minimum distance. This approach, known as expurgating informed coding based on the FCM algorithm, is used to select codewords for the arc labels in the trellis structure from a subset of all codewords of a block code. It generates new center codewords with a large minimum distance by using the FCM algorithm. The modified informed coding scheme proposed in this study is described as follows: Assume that each block codeword,

where

The FCM algorithm for linear block codes can provide the codeword space with a large minimum distance. The basic concept underlying watermarking is hiding information into the host signal in such a way that the perceptual imperceptibility of the host signal is minimally affected. Perceptual imperceptibility efficiency can be achieved using informed coding in addition to informed embedding. Informed coding is a structured design of the trellis. We divide the informed coding technique into parallel and scatter structures for trellis architecture. The parallel structure uses a configuration in which the current state connects to the next identical state through multiple arcs, allowing for the selection of various codewords. By contrast, the scatter structure is designed such that the current state connects to a different state and the arcs do not have a parallel configuration. The informed coding with a scatter structure requires the use of the Viterbi algorithm to embed messages. For the informed coding with a parallel structure, the message is embedded without performing the Viterbi algorithm; instead, the closest codeword in the parallel arcs is identified. Thus, the computational complexity when a parallel structure is used is lower than that when a scatter structure is used in the design of informed coding.

Fig. 8 illustrates the concept of the informed coding system. The purpose of the informed coding system is to select a codeword close to the host

where

Figure 8: Informed coding system

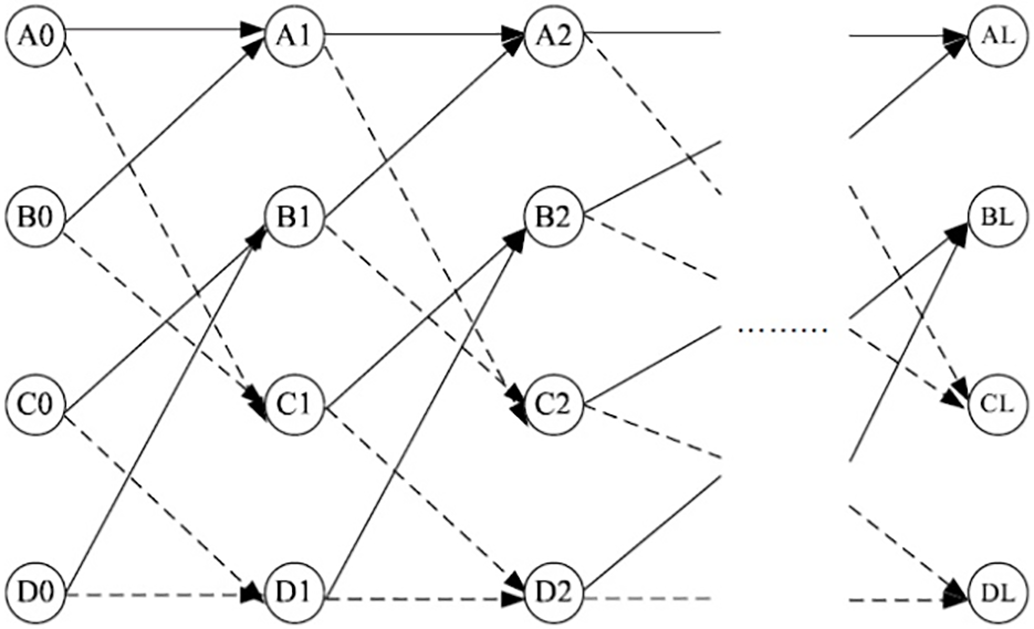

Figure 9: Blind coding: Four-state, eight-arc trellis

As indicated in Fig. 9, each current state node is connected to next state node by two arcs; for example, A0 connects to A1 and C1. A “section” of the trellis comprises current state nodes and their subsequent state node. Transitions from current to next state nodes are represented by arcs. The dotted arc corresponds to the message bit“1”, whereas the solid arc corresponds to message bit“0”. Thus, any arbitrary sequence of

The key distinction between blind coding and informed coding lies in the selection of candidate codewords on the basis of perceptual distance. In Fig. 10, the informed coding trellis structure includes four arcs for each state node. The informed coding process can be divided into two steps. First, one of the candidate paths through the trellis is selected. For example, if the message bit is “1”, the dotted arcs in the trellis are disregarded. Subsequently, the Viterbi algorithm [25] is employed to determine the codeword path based on host imperceptibility.

Figure 10: Informed coding: Four-state, sixteen-arc trellis

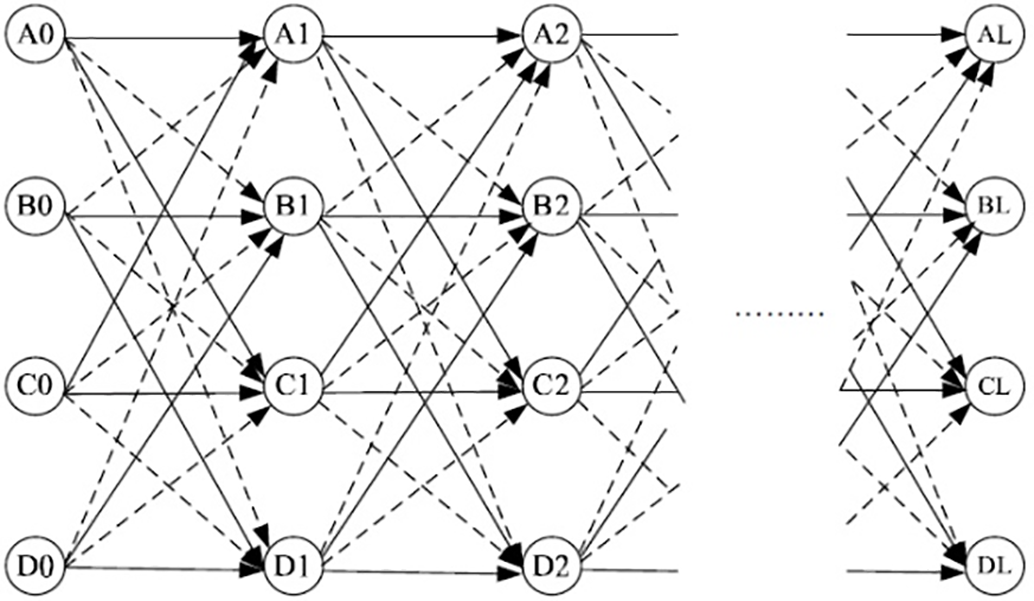

In modifying the trellis structure depicted in Fig. 10, we introduce a parallel arc configuration, as illustrated in Fig. 11. In this modified trellis, the connection of each state node is similar to that in blind coding but with two arcs (codewords) based on the FCM algorithm leading from one state node to the same state node in the next stage. Essentially, this trellis is similar to the one used in blind coding but includes twice as many arcs. During encoding, the informed coding with a parallel structure selects the candidate arcs that are closest to the host signal according to the encoded message

Figure 11: Modified informed coding: Four-state, sixteen-arc trellis

3.3 Combining Informed Embedding with Informed Coding

Regarding robustness, the proposed informed watermarking system primarily benefits from the informed embedding (IE) approach. The type-1 IE is implemented as a section-based, memoryless method that enhances robustness by making the watermarked signal as close as possible to the message codeword while maintaining acceptable imperceptibility. However, achieving the optimal watermarked signal remains challenging. Therefore, we adopt a section-based strategy to generate a robust watermarked signal, which is more practical than optimizing over the entire trellis. The type-1 embedding algorithm adjusts robustness section by section by aligning the watermarked signal with the target message codeword. Although this method achieves high robustness, it incurs considerable iterative complexity and may compromise imperceptibility. To address these issues, we propose the type-2 embedding algorithm, which generates a watermarked signal that better balances robustness and complexity. To further enhance robustness, this approach employs linear block codes instead of random codewords or Miller’s arc labels. The objective of the informed watermarking system is to identify an efficient algorithm that achieves both optimal robustness (i.e., low error rate) and low complexity. Informed coding (IC) selects a target message codeword close to the host signal before applying the embedding algorithm. As discussed in the preceding section, the modified IC scheme with a parallel structure further reduces the encoding complexity. The proposed informed embedding combines a section-based algorithm to improve robustness with reduced computational complexity. The integration of the proposed IE and IC constitutes the informed-coding-embedding (ICE) algorithm.

As done in [14,15], four standard grayscale images (‘House’, ‘Baboon’, ‘Jet’, and ‘Scene’, each of

where MSE represents the mean square error between the original JPEG image and the decoded image over a slow-fading channel with AWGN. MSE is calculated using

where

where

(1) Imperceptibility experiments

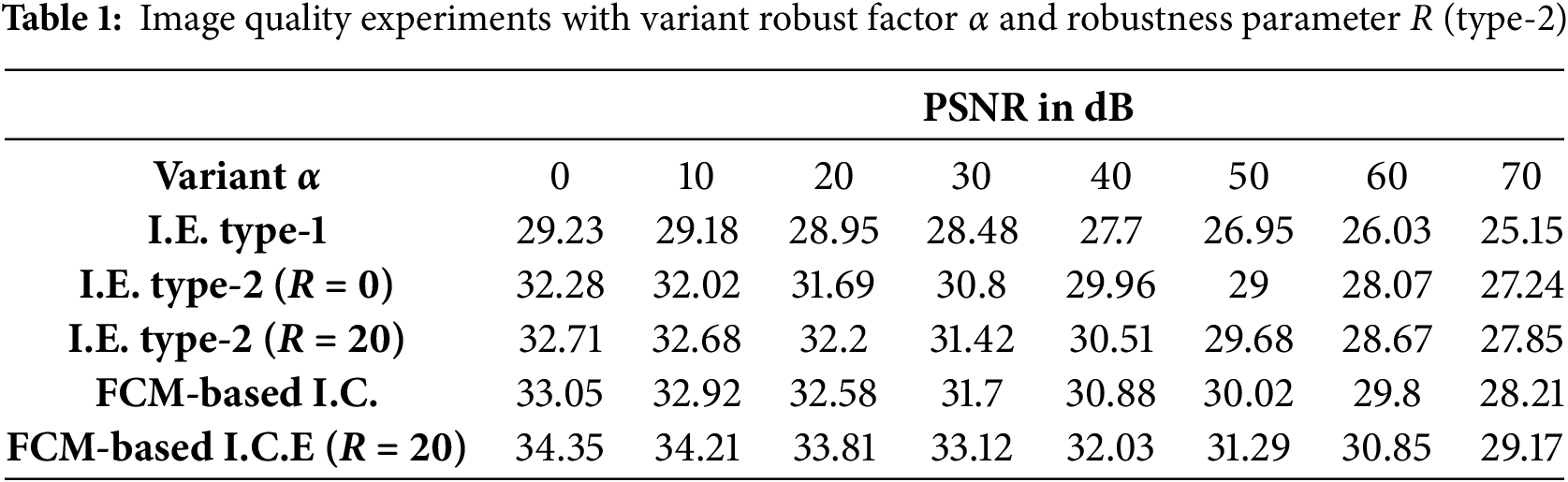

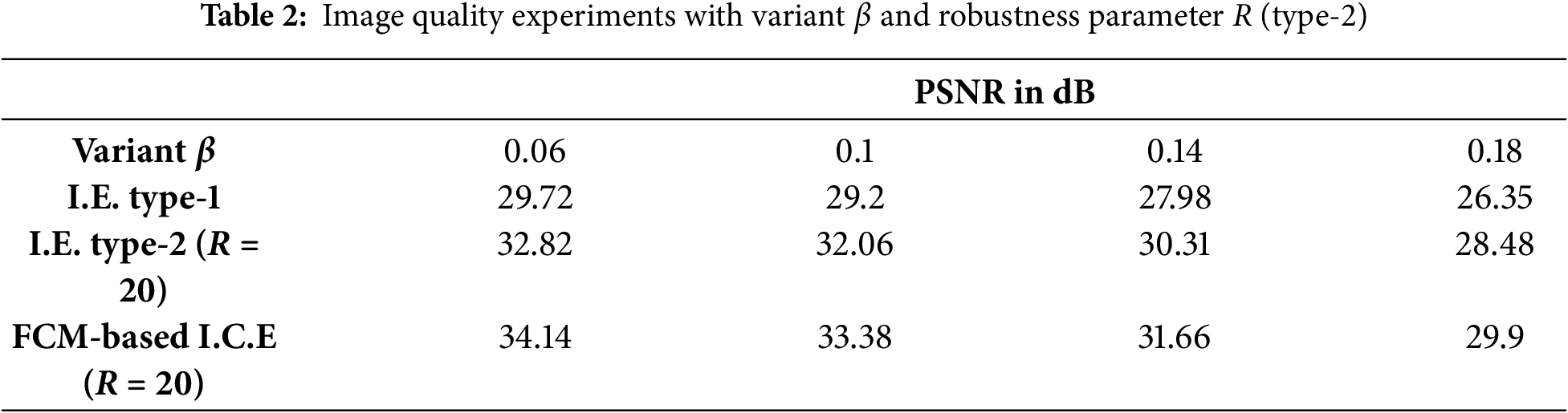

Parameters

Figure 12: Imperceptibility experiments with variant α and robustness parameter R

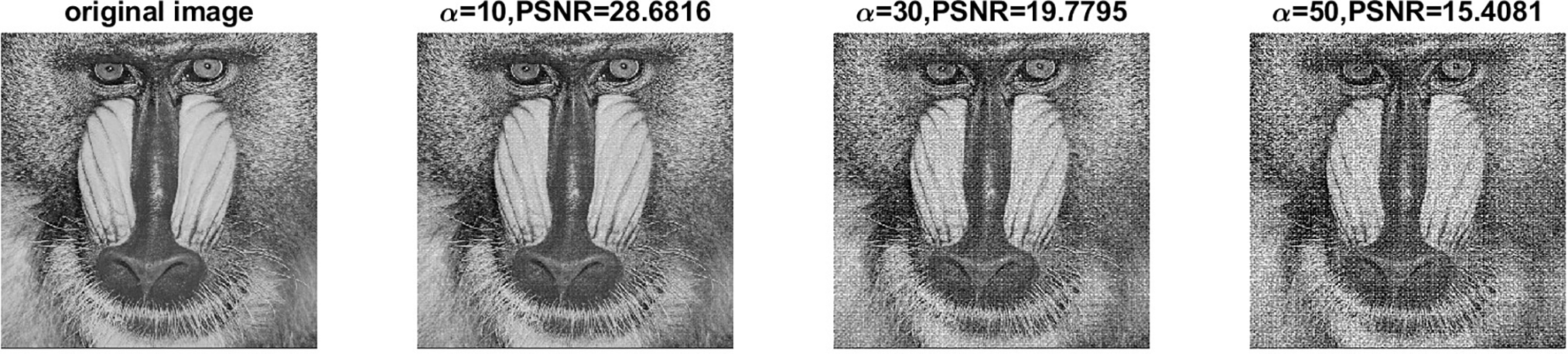

The imperceptibility of the watermarked images was evaluated by varying

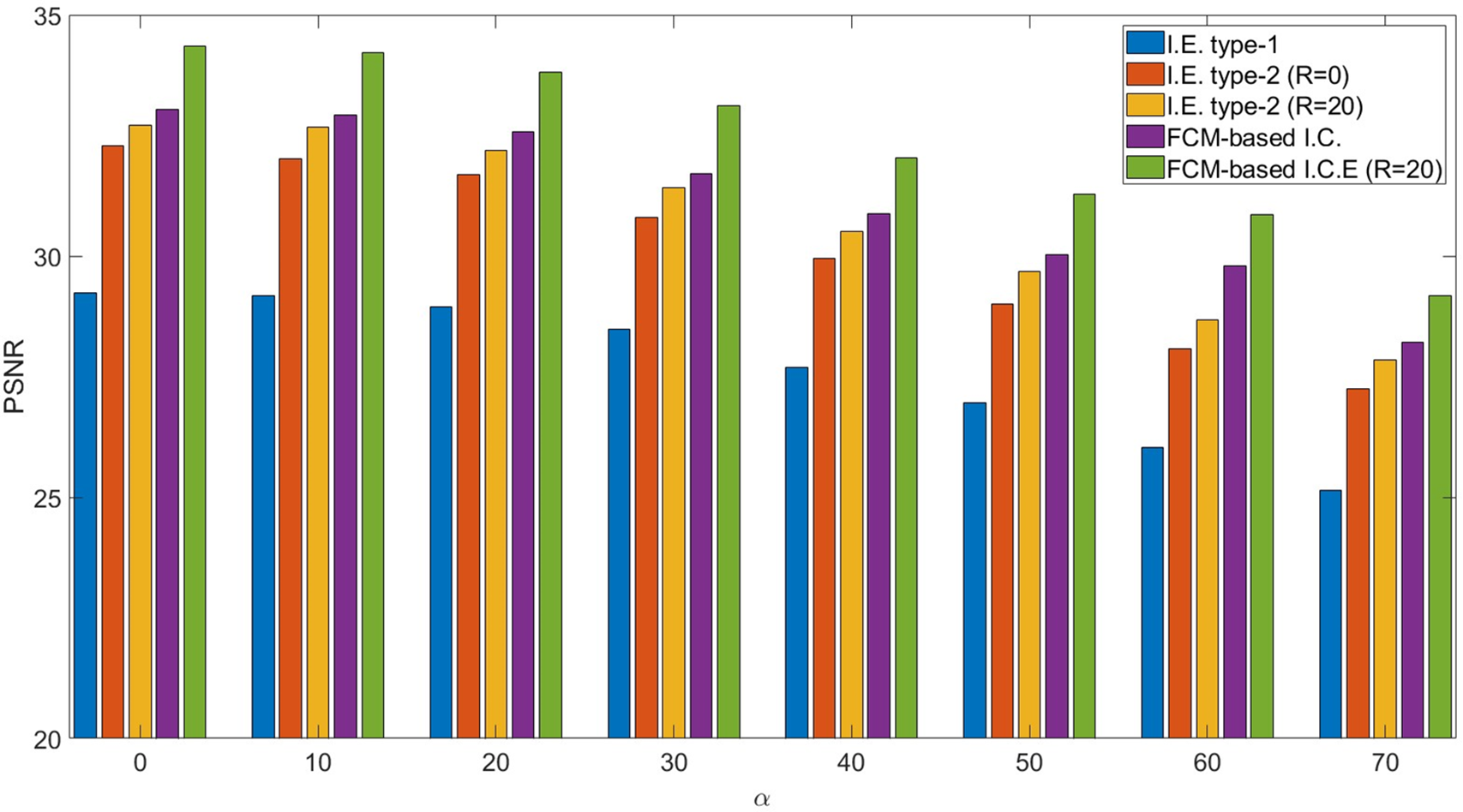

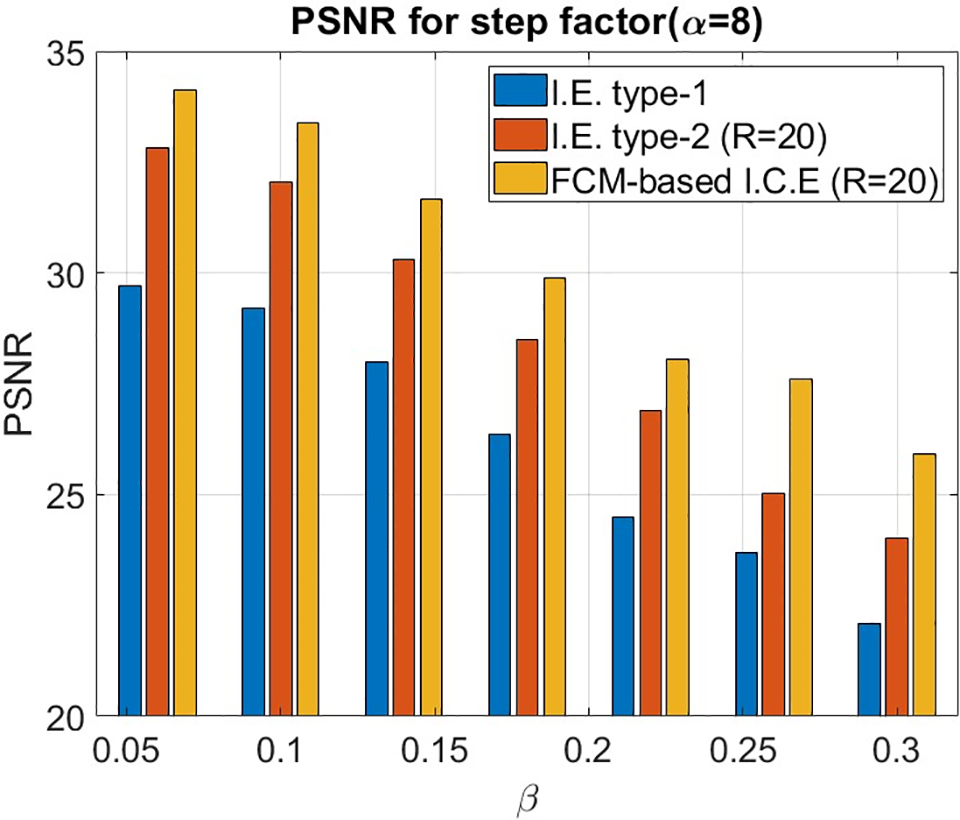

Furthermore, the data presented in Tables 1 and 2 are illustrated using the bar charts shown below.

Fig. 13 illustrates the relationship between PSNR and the parameter

Figure 13: PSNR experiments with variant

Figure 14: PSNR experiments with variant

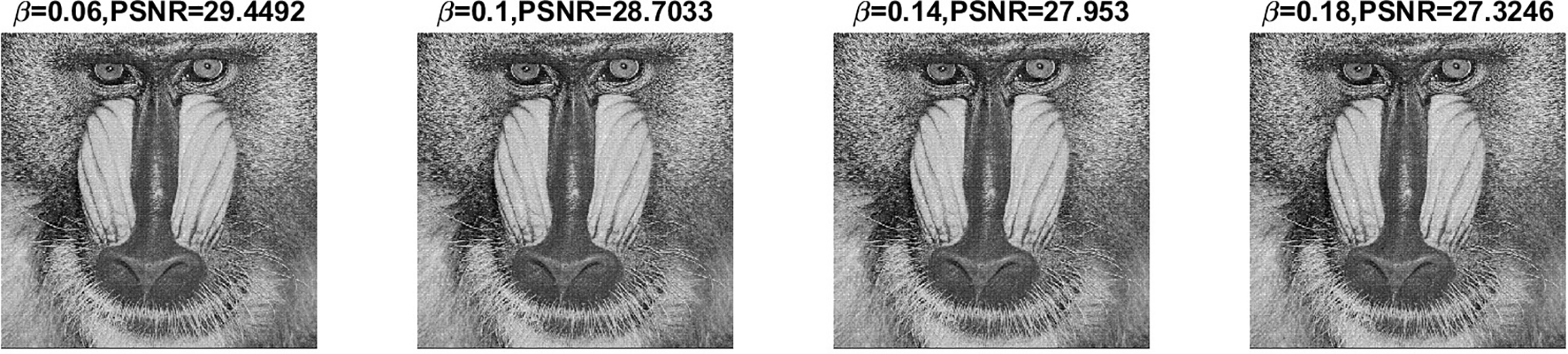

Fig. 14 illustrates that as the step factor

Figure 15: Images at different

Fig. 16 illustrates the changes in image quality resulting from variations in the

Figure 16: Images at different

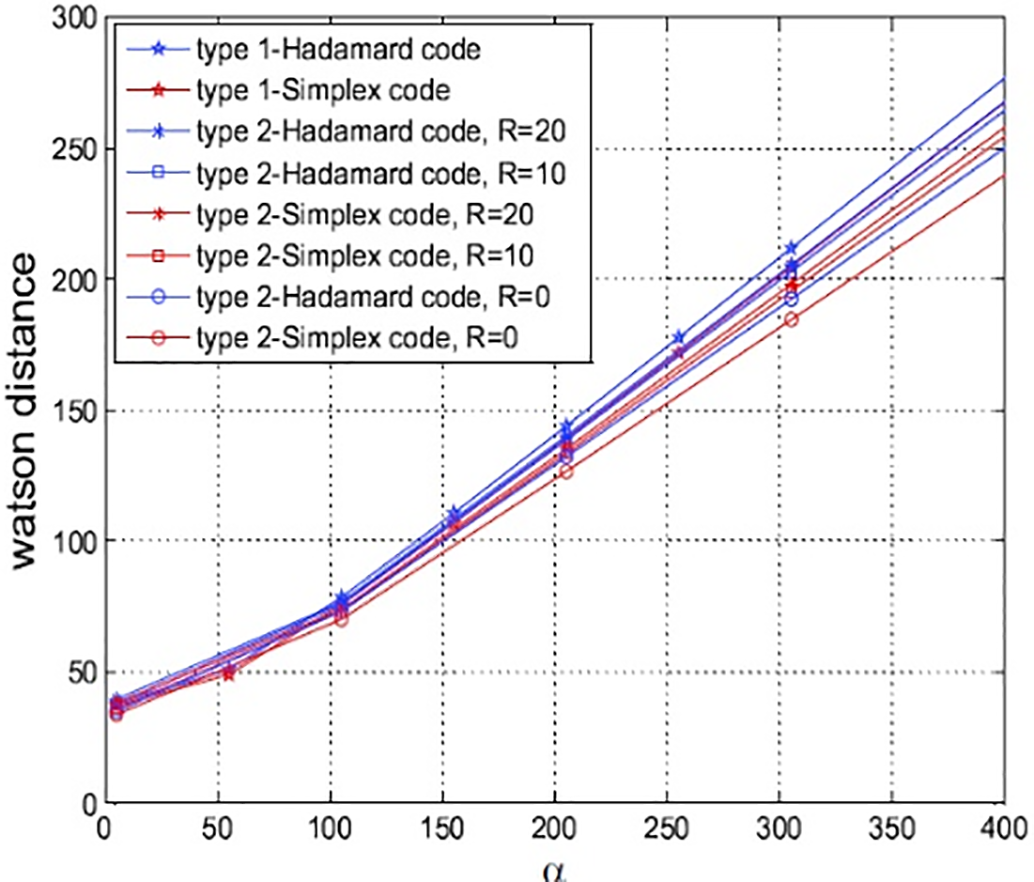

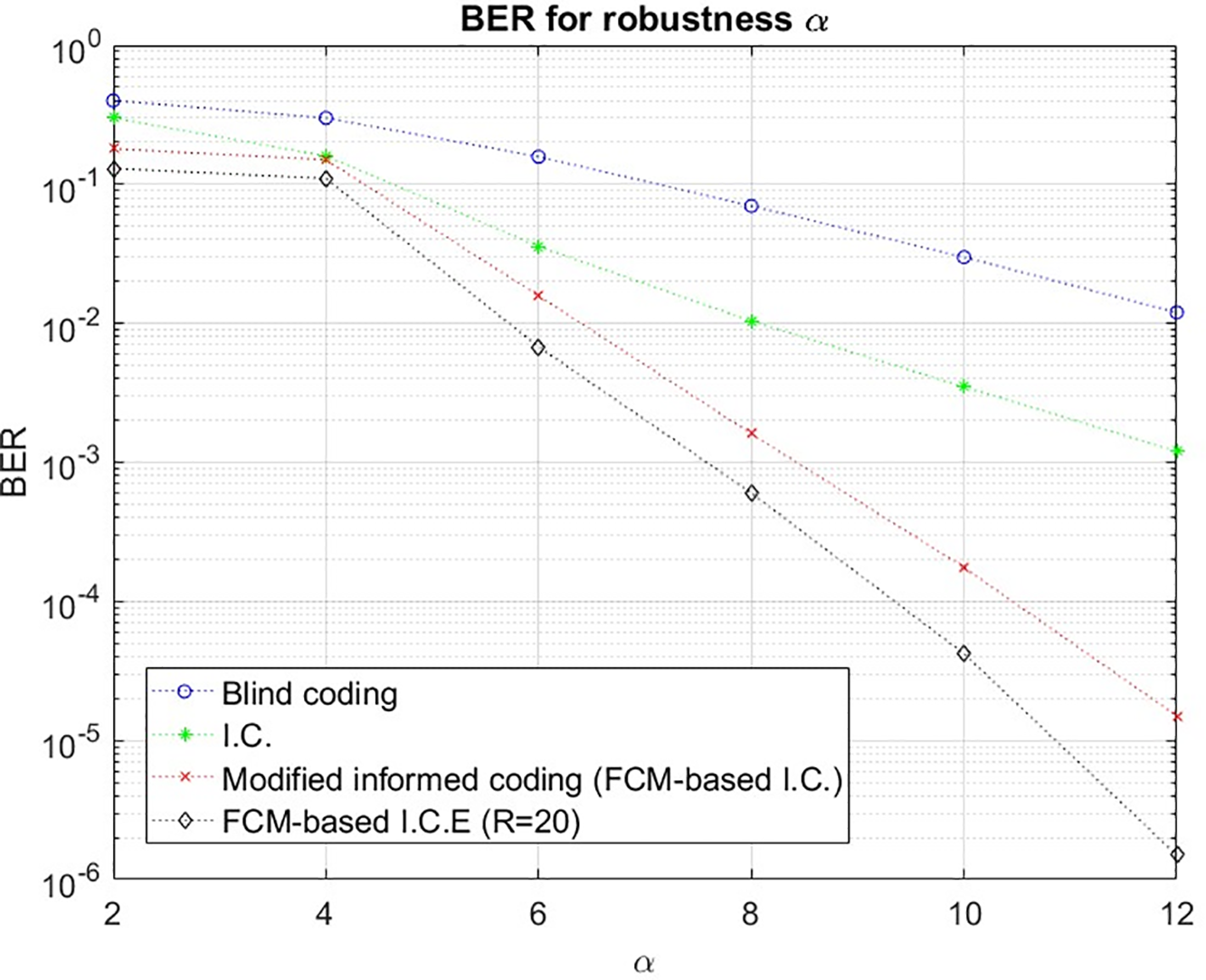

Performance of proposed informed coding: As indicated in Fig. 17, as

Figure 17: BER for robustness α

The figure illustrates the BER performance of different algorithms as the parameter

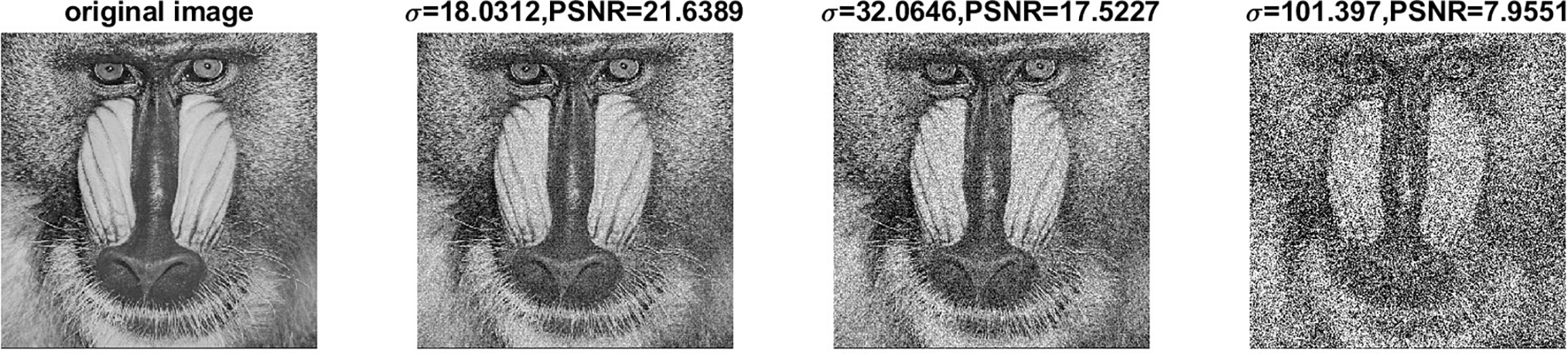

Figure 18: Images under various noise power levels

(1) Attack channel experiments

(a) AWGN

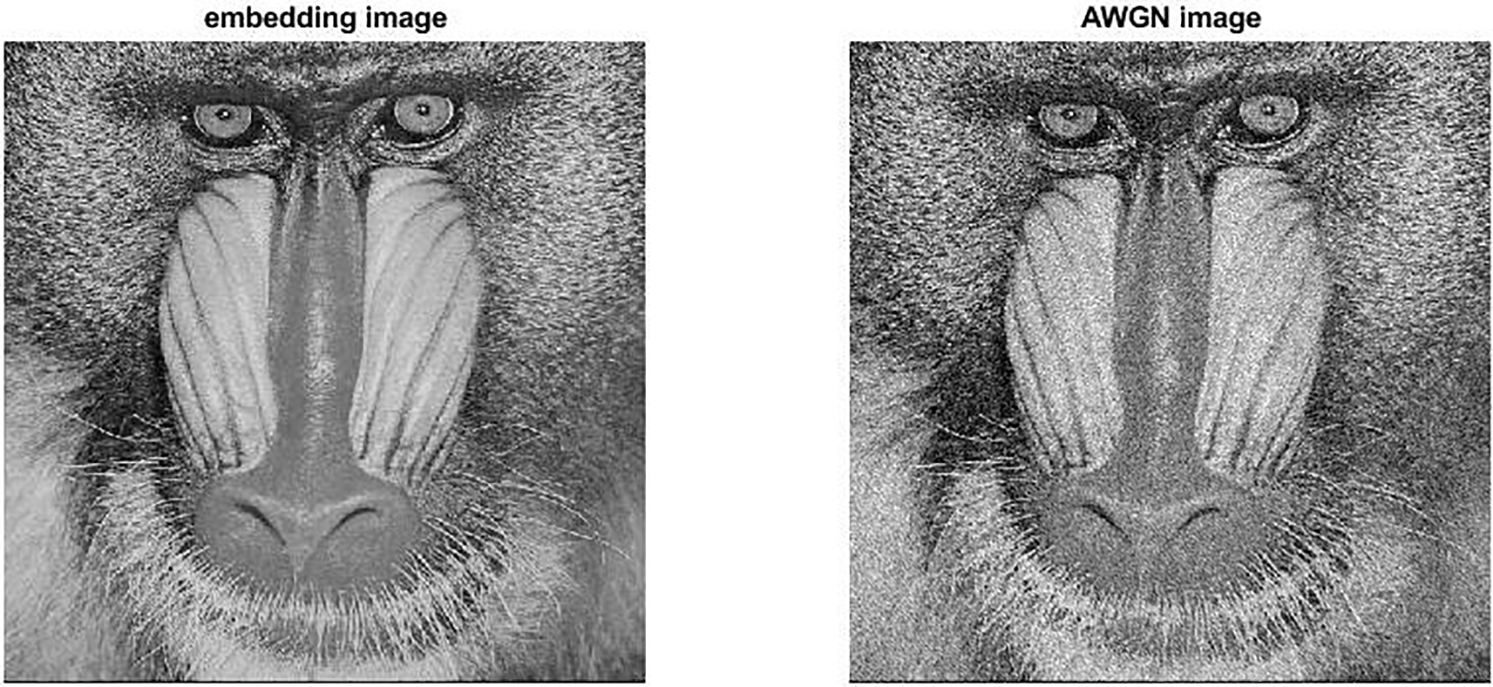

Considering out of additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) channel is expressed by

Figure 19: Watermark robustness against AWGN

Figure 20: Watermarked image with AWGN and variance = 400

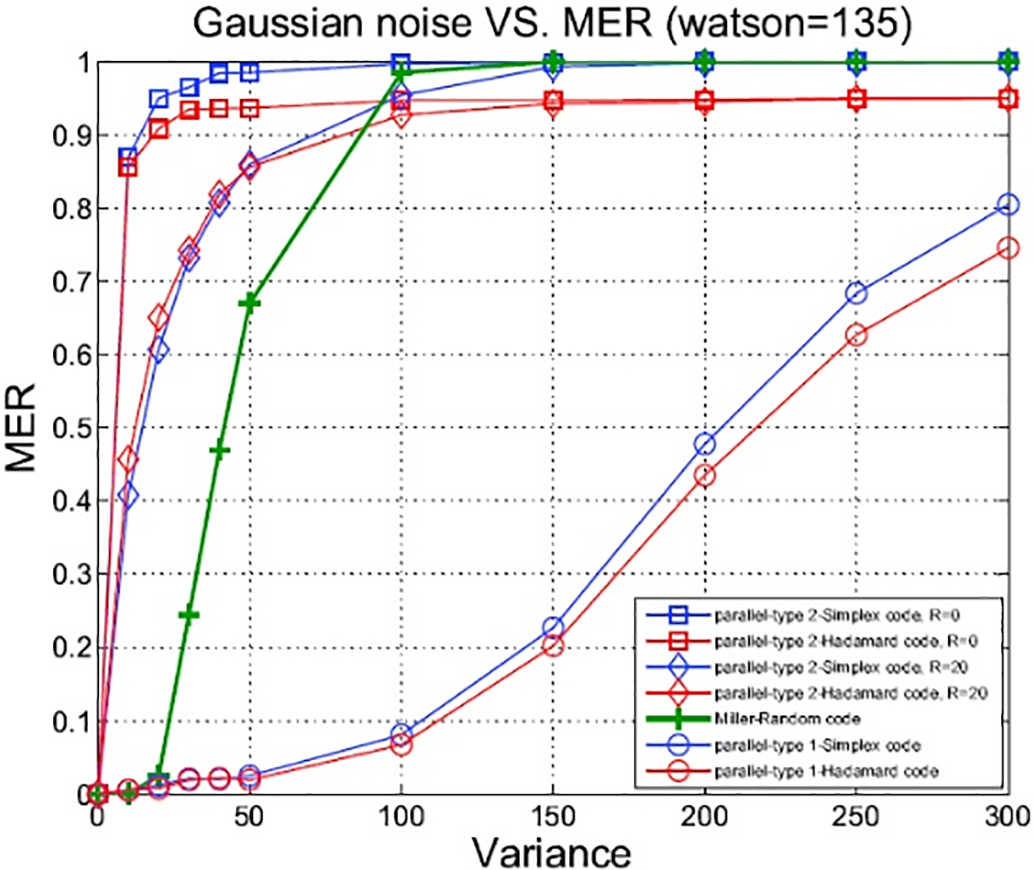

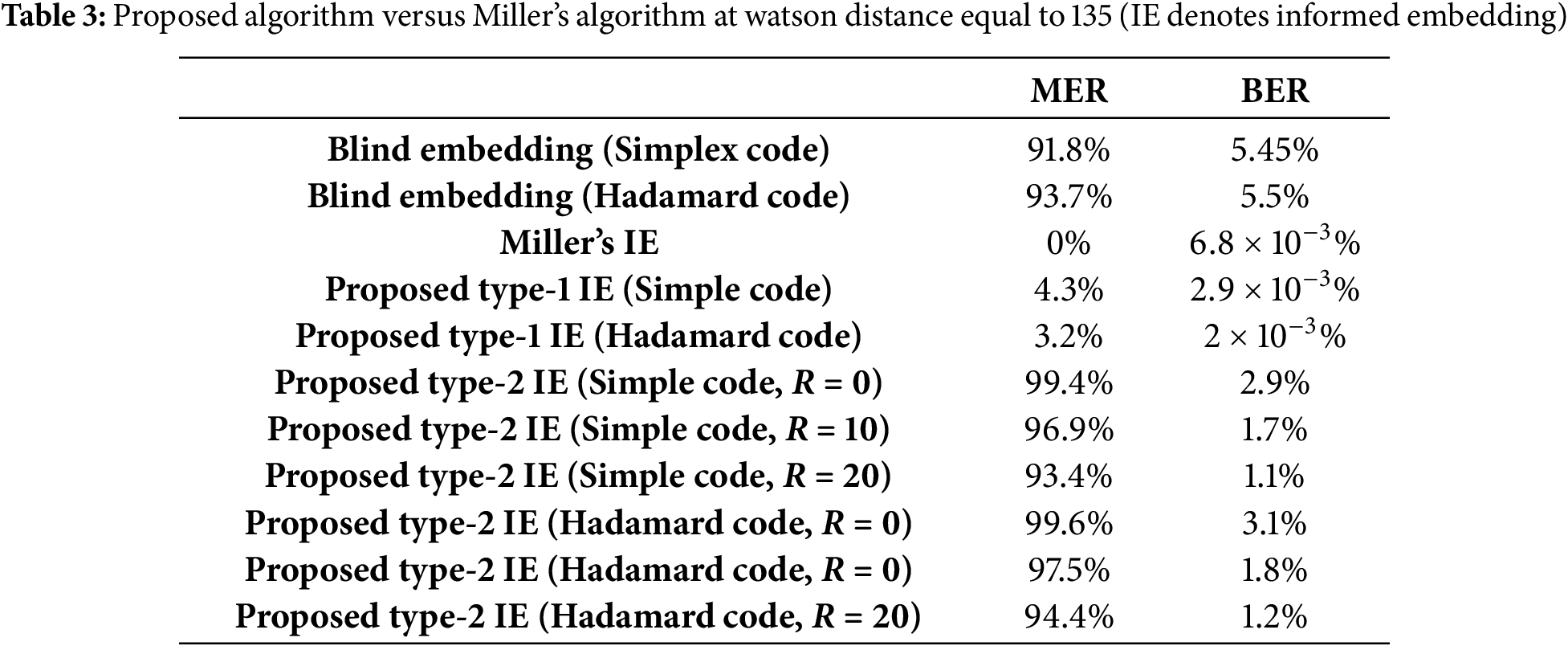

Furthermore, simulation results of the proposed algorithm over the AWGN channel have been carried out. The robustness results of informed embedding for multiple algorithms, subjected to Gaussian noise, are reported in Table 3. For fixed image quality with a Watson distance of 135, the error rate of the type-1 algorithm is comparable to that of Miller’s in terms of robustness. Although the error rate of the type-2 informed embedding algorithm is higher than that of the type-1 and Miller’s algorithm, the complexity of the type-2 algorithm is substantially lower than that of the others.

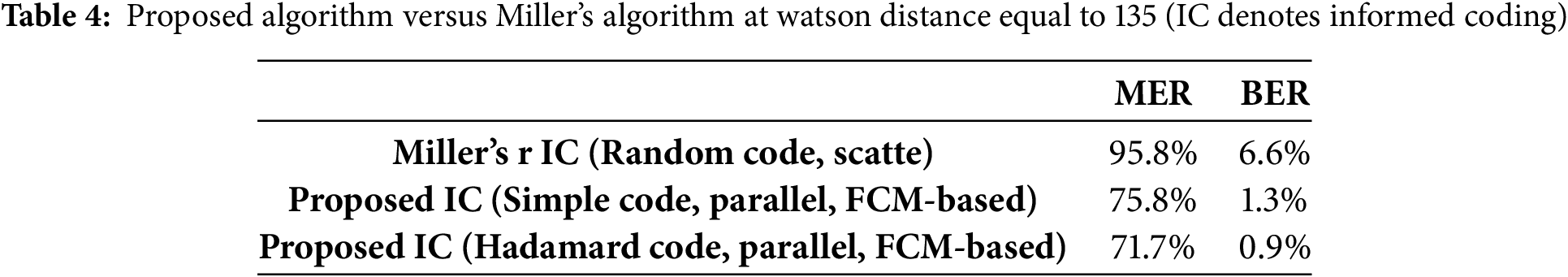

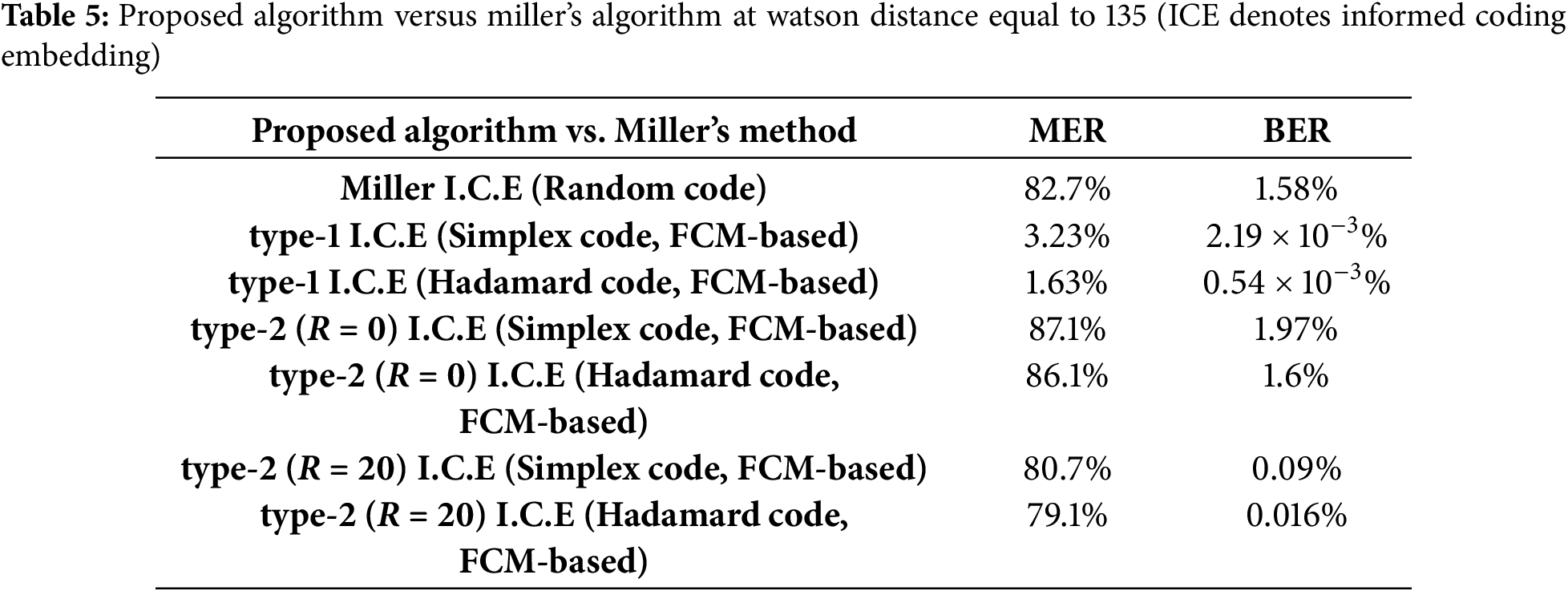

Regarding robustness, particularly in the context of Gaussian noise addition, we discuss the error ratio performance for different trellis structures, including the scatter and parallel configurations, as illustrated in Table 4. The data presented in Table 4 indicates that the informed coding using the codewords of linear block codes as arc labels achieves a superior error rate to that achieved using random codes as arc labels in Miller’s approach.

Experimental results are presented in Tables 5 and 6 to facilitate comparison of the robustness and computational complexity among various algorithms. The results in Table 5 demonstrate that the type-1 ICE algorithm exhibits superior robustness compared to other algorithms, owing to the trellis structure design and the use of codewords as arc labels. Furthermore, the proposed algorithm achieves significantly lower overall computational complexity.

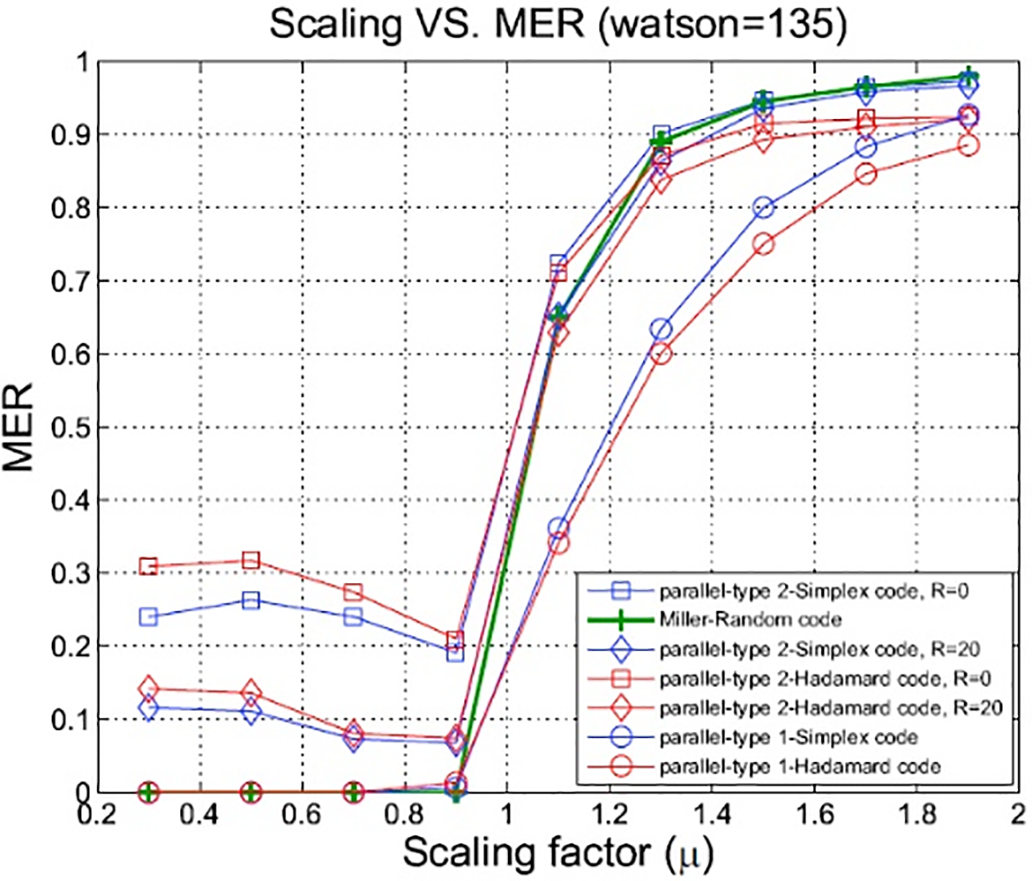

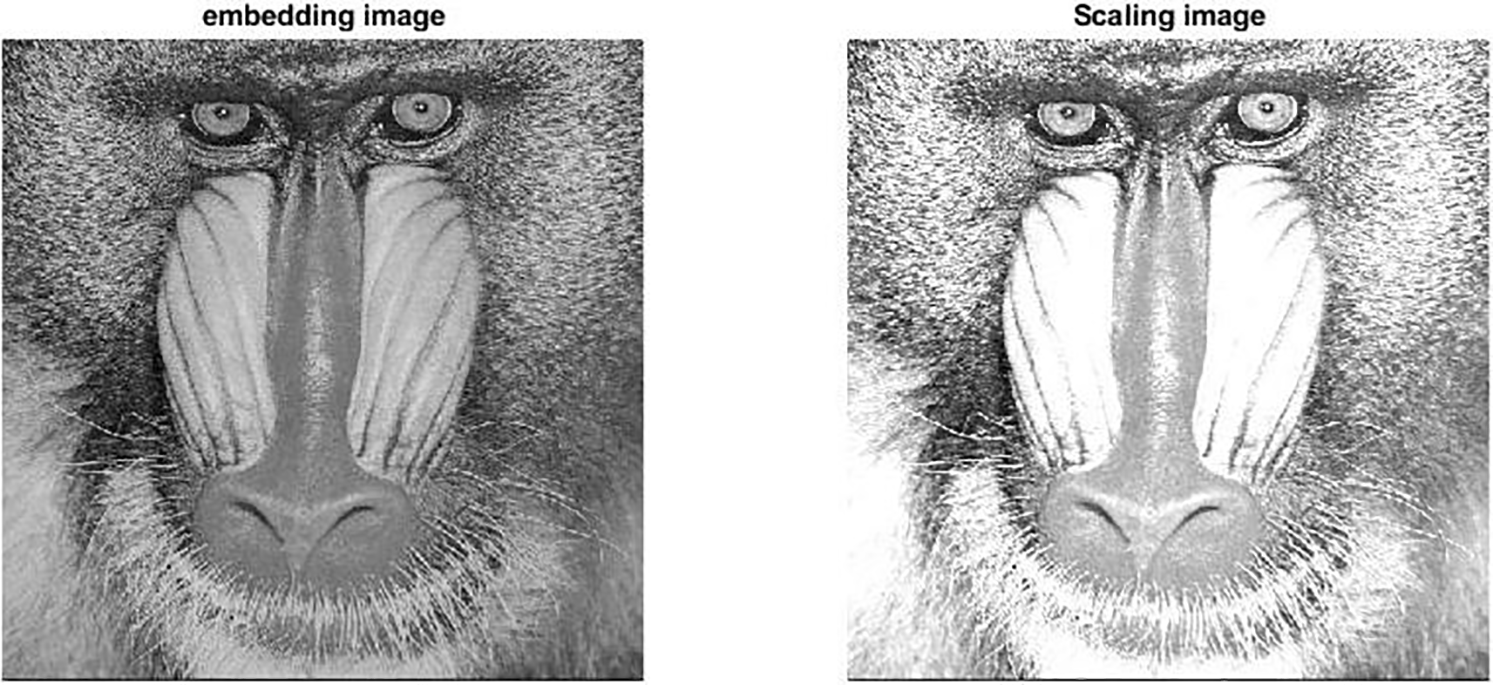

(b) Scaling

Image scaling, a notable form of distortion, involves scaling in amplitude and is herein represented as follows:

where

Figure 21: Robustness to the scaling factor

Figure 22: Watermarked image with

(c) Low pass filter

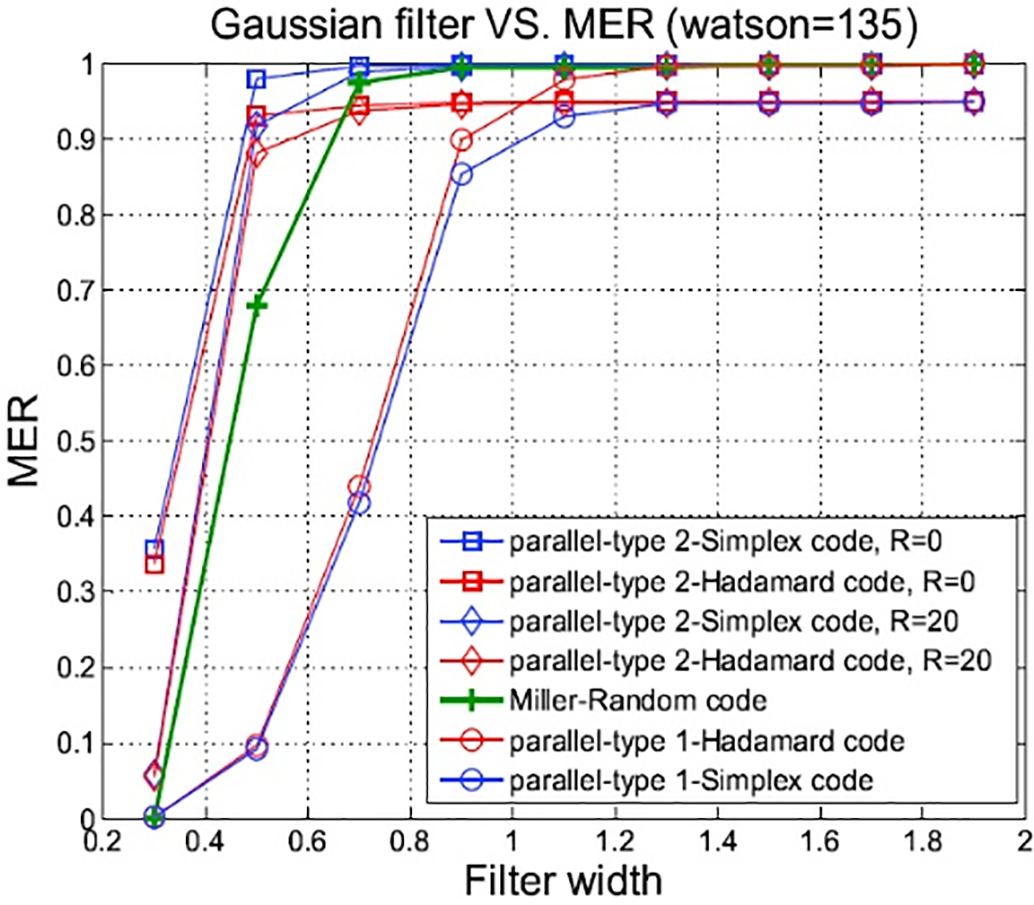

Image processing frequently utilizes low-pass filters, such as the running average or Gaussian filter. The Gaussian filter was chosen for use in our simulations in this study. Under the low-pass filter attack, Fig. 23 presents the BER results of four algorithms, including the algorithm optimized by parameters

Figure 23: Robustness against low-pass filtering attacks

Figure 24: Watermarked image subjected to [7,7] Gaussian filter

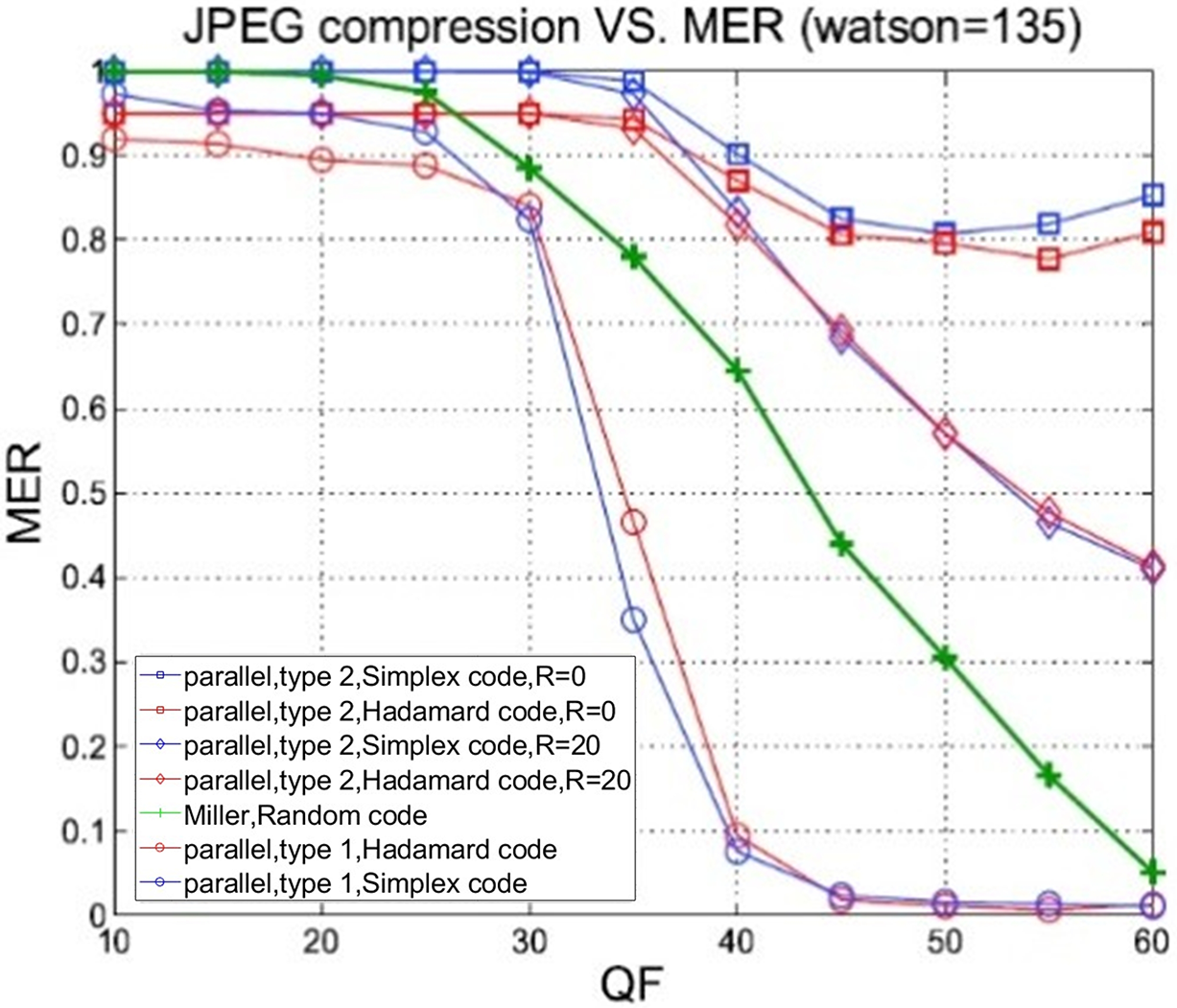

(d) JPEG

Lossy compression is a widely used technique, making watermark robustness against such compression highly desirable. Hence, we performed experiments to assess the impact of JPEG compression. The bit error rates were analyzed under varying degrees of JPEG compression. These levels specify DCT coefficient quantization values through multiplication by a quantization matrix:

where

The comparison of BERs was conducted over JPEG compression quality factors (QF) ranging between 20 and 80. The BER comparison between the proposed algorithm and the method in [14] is presented in Fig. 25. Using the informed embedding with memory algorithm, the BER quickly drops as QF rises, especially when QF is less than 25. These findings highlight the outstanding robustness of the informed embedding with memory algorithm against watermark degradation when JPEG compression quality is low. The watermarked image subjected to JPEG compression at QF = 20 is illustrated in Fig. 26.

Figure 25: Robustness to JPEG compression at different

Figure 26: Watermarked image with

(e) Image quality (PSNR) under different attack channels

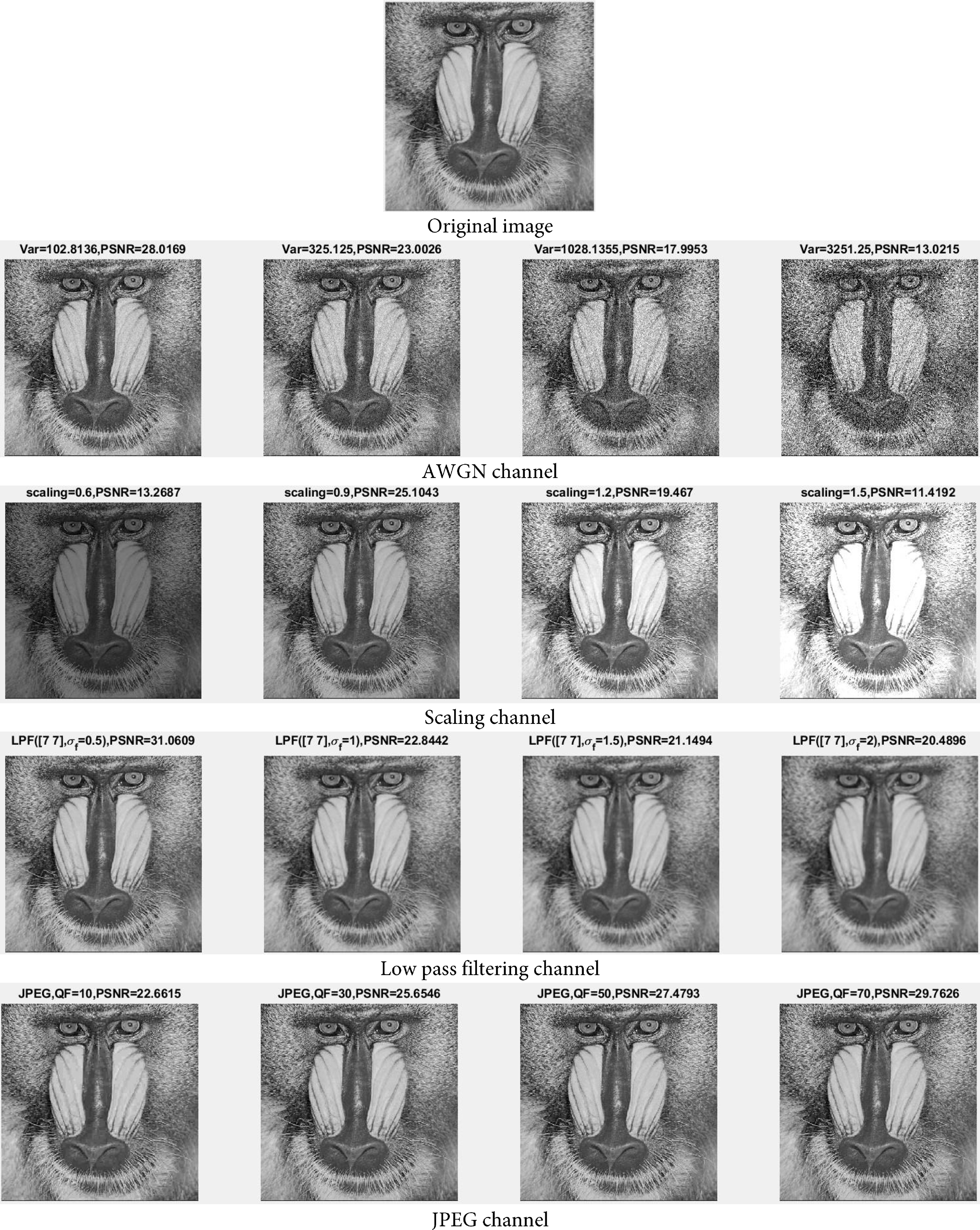

Finally, the proposed optimal method was employed to evaluate image quality under attack channels. The type 2 algorithm based on Hadamard code is used to simulate under various attack channels. Fig. 27 summarizes the image quality degradation caused by four different channels—AWGN, scaling, low-pass filtering (LPF), and JPEG—under varying attack strengths.

Figure 27: The image quality of watermarked image under different attack channels

(2) Computational complexity

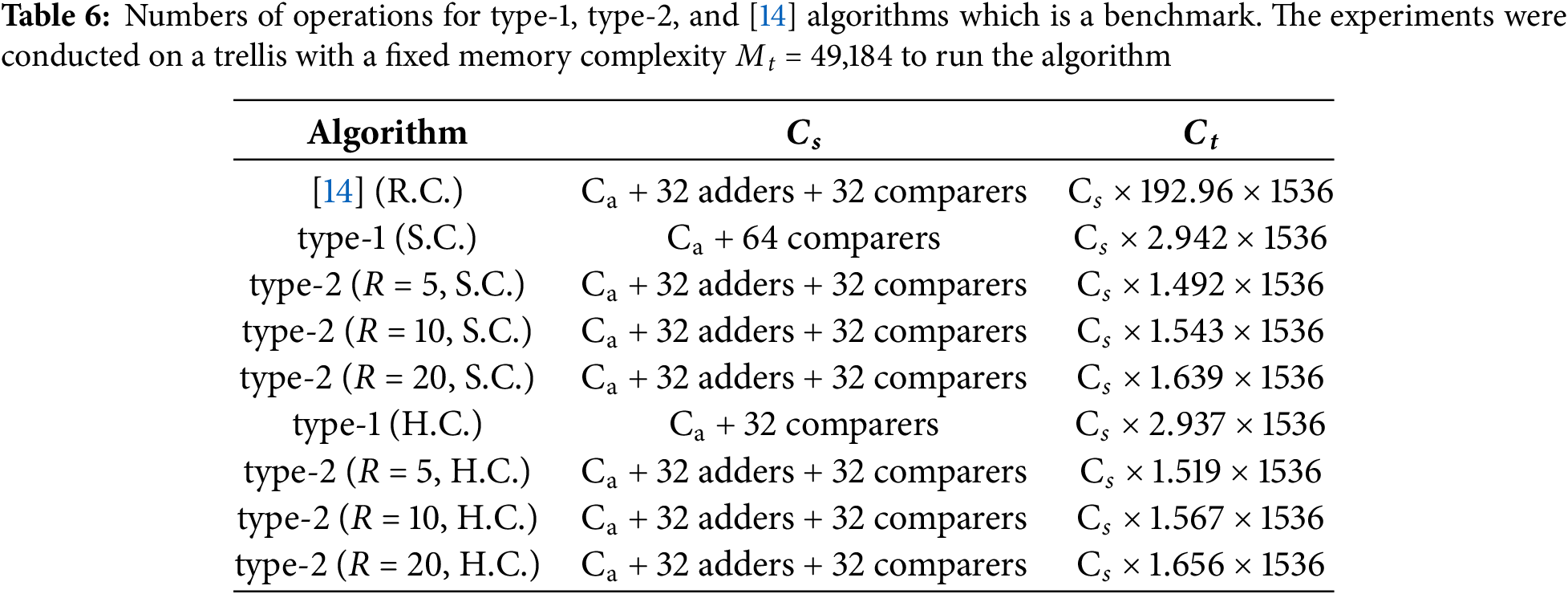

In this section, we compare the algorithmic complexity of the approach outlined in [14] with that of the approach proposed in this study. The proposed ICE watermarking system performs informed coding followed by informed embedding. The complexity of the ICE system primarily arises from the informed coding and embedding algorithms. In the case of informed coding, the computational complexity involves identifying the codeword closest to the object message among parallel candidate arcs on a section-by-section basis. This process contrasts with the approach used in [14] because the accumulation operation in the Viterbi algorithm, which is a key component affecting their complexity, is not required in our informed coding scheme.

In addition to employing informed coding, the proposed informed embedding algorithm is section-based and does not require iterative processing of the overall codeword, as is the case in the algorithm of [14]. Informed coding with a parallel structure exhibits lower computational complexity than informed coding with a scatter structure. Here, we briefly compare the informed embedding algorithms. Complexity assessment for both the proposed method and that of [14] counts each arc in each trellis section as a unit. This metric represents the total computations performed per arc following the completion of embedding. The add-compare-select (ACS) operations performed in each trellis section of memory-based or accumulated Viterbi algorithms result in higher computational complexity than those of memoryless embedding structures. In this study, the operational counts for the proposed algorithm and that of [14] are tabulated and compared. Additionally, three complexity parameters relevant to the trellis structure are defined as follows:

where

where

where

The computational cost of the four algorithms and [14] is presented in Table 6, with the results revealing the processing requirements of each arc and the ACS operations. The total operational complexity,

Miller’s method > type-1 > type-2 (R = 20) > type-2 (R = 10) > type-2 (R = 5)

This ranking indicates that despite the proposed algorithms exhibiting lower complexity, they maintain the same level of robustness as the other algorithms. The simulation results reveal that the type-1 algorithm demonstrates high robustness against certain attacks and has low operation complexity.

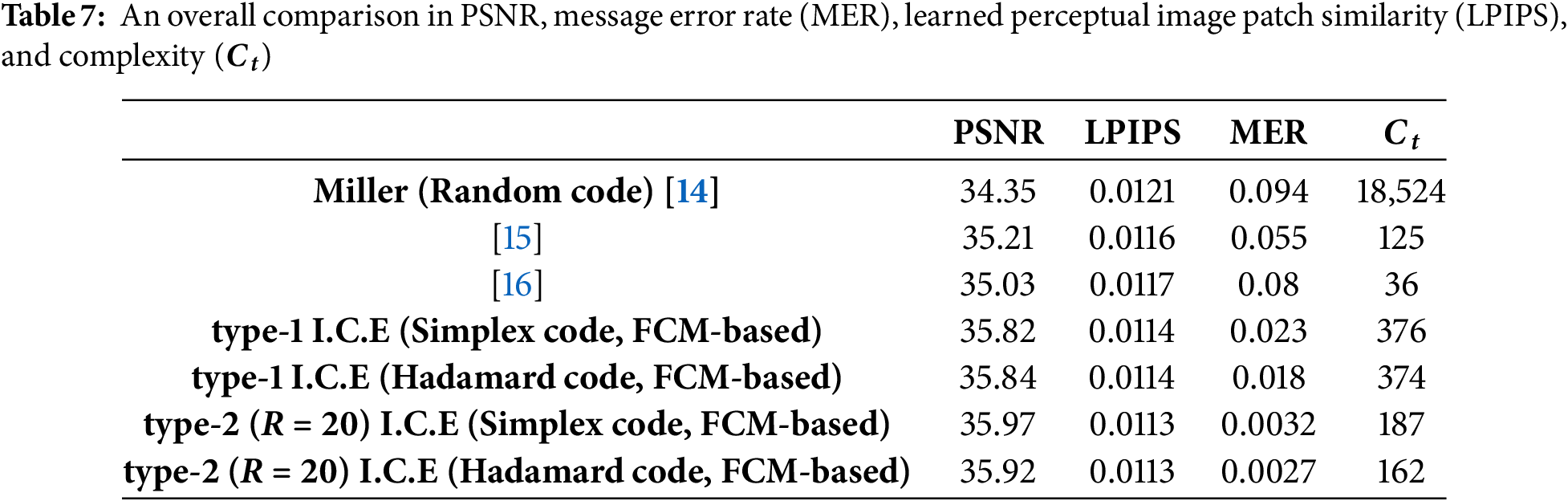

To more clearly illustrate the advantages and differences of the proposed algorithm, an overall comparison is necessary. Finally, we compared with [14] and tabulated as Table 7. The simulation environment is based on a Gaussian channel with a variance of 25. We evaluated image quality using three metrics: PSNR, and LPIPS, and assessed robustness and complexity through MER and computational complexity

In this paper, we presented three informed embedding algorithms for watermarking systems. These algorithms employ codewords derived from the FCM algorithm applied to linear block codes for labeling arcs in the trellis. They then adjust the imperceptibility and robustness of watermarked images using controllable parameters. The proposed informed coding and embedding algorithms exhibit three key properties: (1) control through parameters; (2) employment of parallel arcs in informed coding; and (3) execution of an iterative algorithm, segment by segment. The trellis is constructed to resist channel attacks while maintaining a predetermined level of imperceptibility. These methods reduce the operational complexity of achieving high-quality watermarked images and provide better BER performance compared with Miller’s informed embedding. Furthermore, the generated watermarked images were subjected to a variety of attacks, and the experimental results demonstrate their performance in terms of the BER and message error rate. Moreover, this study utilizes the FCM algorithm to generate codewords serving as arc labels in each trellis structure. For future research, replacing the FCM algorithm with deep learning–based approaches may be considered, as these methods are expected to provide enhanced encoding performance. This study primarily focuses on embedding binary data into grayscale images. Although other image formats are not explicitly discussed, the proposed algorithm can be extended to any carrier format that represents image content as a data sequence. For instance, a color image can be separated into three channels (R, G, and B), and the proposed method can be applied to embed data into each channel individually. Moreover, the proposed algorithms are mainly designed to withstand non-geometric attacks such as Gaussian noise, compression, and filtering, and they demonstrate strong robustness in these scenarios. However, this study does not comprehensively address geometric channel attacks, which is a limitation of the current work. Future research should therefore prioritize the extension of the algorithm to enhance its robustness against geometric distortions. Especially, we will extend this work by investigating techniques such as synchronization templates, feature points/regions, transform-domain methods, geometric-invariant wavelets/moments, and blind synchronization.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, under grant number NSTC 114-2221-E-167-005-MY3, and NSTC 113-2221-E-167-006-.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jyun-Jie Wang, Yin-Chen Lin, Chi-Chun Chen; data collection: Jyun-Jie Wang, Yin-Chen Lin; analysis and interpretation of results: Jyun-Jie Wang, Chi-Chun Chen; draft manuscript preparation: Jyun-Jie Wang, Chi-Chun Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Symbols and Specific Notation

| FCM | Fuzzy c-means |

| BER | Bit error rate |

| MER | Message error rate |

| JPEG | Joint photographic experts group |

| DCT | Discrete cosine transform |

| IC | Informed coding |

| IE | Informed embedding |

| ICE | Informed coding and embedding |

| AC | Alternating cofficient |

| AWGNA | Additive white Gaussian noise |

| PSNR | Peak signal-to-noise ratio |

| QF | Quality factors |

| ACS | Add-compare-select |

| Original image | |

| Watermarking image | |

| Watermarking image after attack channels | |

| Watermarked message | |

| Message sequence | |

| Message extraction | |

| The | |

| The | |

| A set of all | |

| A message codeword in the | |

| Codeword vector in the | |

| The | |

| The detection of | |

| The | |

| A set of all | |

| The | |

| The | |

| The state sequence of in an L-section trellis | |

| The bit length for | |

| The image dimension | |

| The length of | |

| The robust factor | |

| The step factor | |

| The memory number for a convolutional code | |

| Γ | The codeword set of a linear block code |

| The | |

| The | |

| The previously stored state metric in the | |

| The robustness parameter in the | |

| the fuzzy membership of the | |

| The objective function of FCM |

References

1. Moulin P, Koetter R. Data-hiding codes. Proc IEEE. 2005;93(12):2083–126. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2005.859599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tian C, Zheng M, Li B, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Zhang D. Perceptive self-supervised learning network for noisy image watermark removal. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2024;34(8):7069–79. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2024.3349678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wen S, Zhang Q, Hu T, Li J. Robust audio watermarking against manipulation attacks based on deep learning. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2024;32:126–30. doi:10.1109/LSP.2024.3501285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhong X, Huang PC, Mastorakis S, Shih FY. An automated and robust image watermarking scheme based on deep neural networks. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2020;23:1951–61. doi:10.1109/TMM.2020.3006415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Amrit P, Baranwal N, Singh KN, Singh AK. ConvNet-HIDE: deep-learning-based dual watermarking for health-care images. IEEE Multimed. 2024;31(3):78–87. doi:10.1109/MMUL.2024.3423370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Han B, Jhaveri RH, Wang H, Qiao D, Du J. Application of robust zero-watermarking scheme based on federated learning for securing the healthcare data. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2023;27(2):804–13. doi:10.1109/jbhi.2021.3123936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Anand A, Singh AK. Health record security through multiple watermarking on fused medical images. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2022;9(6):1594–603. doi:10.1109/TCSS.2021.3126628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chen L, Bai W, Yao Z. A secure and privacy-preserving watermark based medical image sharing method. Chin J Electron. 2020;29(5):819–25. doi:10.1049/cje.2020.07.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tong G, Liang Z, Xiao F, Xiong N. A residual chaotic system for image security and digital video watermarking. IEEE Access. 2021;9:121154–66. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3108196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bordel B, Alcarria R, Robles T, Iglesias MS. Data authentication and anonymization in IoT scenarios and future 5G networks using chaotic digital watermarking. IEEE Access. 2021;9:22378–98. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3055771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang ZX, Sha KY, Gao XL. Digital watermarking technology based on LDPC code and chaotic sequence. IEEE Access. 2022;10(2):38785–92. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3166475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Singh HK, Singh AK. Using deep learning to embed dual marks with encryption through 3-D chaotic map. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(1):3056–63. doi:10.1109/TCE.2023.3286487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wainwright MJ. Sparse graph codes for side information and binning. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2007;24(5):47–57. doi:10.1109/MSP.2007.904816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Miller ML, Doërr GJ, Cox IJ. Applying informed coding and embedding to design a robust high-capacity watermark. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2004;13(6):792–807. doi:10.1109/tip.2003.821551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wang JJ, Chen H, Lin CY. A robust informed embedding with low complexity of digital watermarking. Int J Innov Comput Inf Control. 2012;8(10A):6849–68. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang JJ, Chen H, Liang H. A trellis-based informed embedding with linear codes for digital watermarking. In: 2011 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Consumer Electronics (ISCE); 2011 Jun 14–17; Singapore. doi:10.1109/ISCE.2011.5973782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bezdek JC, Hathaway RJ, Sabin MJ, Tucker WT. Convergence theory for fuzzy c-means: counterexamples and repairs. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1987;17(5):873–7. doi:10.1109/TSMC.1987.6499296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bezdek JC. Pattern recognition with fuzzy objective function algorithms. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2013, 10.1007/978-1-4757-0450-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jain AK. Data clustering: 50 years beyond K-means. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2010;31(8):651–66. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2009.09.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Döring C, Lesot MJ, Kruse R. Data analysis with fuzzy clustering methods. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2006;51(1):192–214. doi:10.1016/j.csda.2006.04.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hathaway RJ, Hu Y. Density-weighted fuzzy c-means clustering. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2009;17(1):243–52. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2008.2009458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kaymak U, Setnes M. Fuzzy clustering with volume prototypes and adaptive cluster merging. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2002;10(6):705–12. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2002.805901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Desset C, Macq B, Vandendorpe L. Block error-correcting codes for systems with a very high BER: theoretical analysis and application to the protection of watermarks. Signal Process Image Commun. 2002;17(5):409–21. doi:10.1016/S0923-5965(02)00010-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lin L, Doerr G, Cox IJ, Miller ML. An efficient algorithm for informed embedding of dirty-paper trellis codes for watermarking. In: IEEE International Conference on Image Processing 2005; 2005 Sep 14; Genova, Italy. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2005.1529846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Forney GD. The viterbi algorithm. Proc IEEE. 1973;61(3):268–78. doi:10.1109/PROC.1973.9030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools