Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Implementing Convolutional Neural Networks to Detect Dangerous Objects in Video Surveillance Systems

1 Facultad de Ingeniería, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá, 110311-0110, Colombia

2 Department of Computer Science and Technology, Universidad Internacional de La Rioja, Logroño, 26006, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Rubén González-Crespo. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5489-5507. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067394

Received 02 May 2025; Accepted 29 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

The increasing prevalence of violent incidents in public spaces has created an urgent need for intelligent surveillance systems capable of detecting dangerous objects in real time. While traditional video surveillance relies on human monitoring, this approach suffers from limitations such as fatigue and delayed response times. This study addresses these challenges by developing an automated detection system using advanced deep learning techniques to enhance public safety. Our approach leverages state-of-the-art convolutional neural networks (CNNs), specifically You Only Look Once version 4 (YOLOv4) and EfficientDet, for real-time object detection. The system was trained on a comprehensive dataset of over 50,000 images, enhanced through data augmentation techniques to improve robustness across varying lighting conditions and viewing angles. Cloud-based deployment on Amazon Web Services (AWS) ensured scalability and efficient processing. Experimental evaluations demonstrated high performance, with YOLOv4 achieving 92% accuracy and processing images in 0.45 s, while EfficientDet reached 93% accuracy with a slightly longer processing time of 0.55 s per image. Field tests in high-traffic environments such as train stations and shopping malls confirmed the system’s reliability, with a false alarm rate of only 4.5%. The integration of automatic alerts enabled rapid security responses to potential threats. The proposed CNN-based system provides an effective solution for real-time detection of dangerous objects in video surveillance, significantly improving response times and public safety. While YOLOv4 proved more suitable for speed-critical applications, EfficientDet offered marginally better accuracy. Future work will focus on optimizing the system for low-light conditions and further reducing false positives. This research contributes to the advancement of AI-driven surveillance technologies, offering a scalable framework adaptable to various security scenarios.Keywords

Public safety has become a critical concern in urban environments, with video surveillance systems playing an increasingly vital role in crime prevention and security enhancement [1,2]. Traditional surveillance methods rely heavily on human operators, who face challenges such as fatigue, limited attention spans, and subjective interpretation of visual data [3,4]. Recent advances in artificial intelligence, particularly in deep learning and computer vision, have opened new possibilities for automated threat detection [5,6]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have demonstrated remarkable success in object recognition tasks, achieving human-level performance in some applications [7,8]. The development of real-time detection algorithms like YOLO [9] and EfficientDet [5] has further expanded the potential for AI-powered surveillance systems. Several studies have explored weapon detection in controlled environments [10,11], but challenges remain in adapting these systems to real-world surveillance scenarios with variable conditions [12,13]. The integration of cloud computing has emerged as a promising approach to address computational constraints while maintaining real-time performance [14].

Current surveillance systems face three primary limitations that this study addresses: (1) the inability to reliably detect small or partially obscured weapons in crowded scenes [15,16], (2) high false positive rates when distinguishing threats from benign objects [17], and (3) computational constraints that hinder real-time processing on edge devices [18]. These challenges are particularly acute in dynamic public spaces where lighting conditions, camera angles, and object occlusions vary significantly [19].

This paper aims to develop a robust CNN-based system for the real-time detection of dangerous objects in surveillance footage. Specifically, we seek to: (1) optimize detection accuracy for firearms and bladed weapons, (2) minimize false positives through advanced classification techniques, and (3) demonstrate practical deployment through cloud integration.

Our work makes three key contributions. First, we present a comparative analysis of YOLOv4 and EfficientDet architectures for weapon detection, identifying optimal configurations for real-world deployment. Second, we introduce a novel data augmentation strategy that improves the detection of partially obscured weapons. Third, we demonstrate a cloud-based implementation that achieves sub-second processing times while maintaining high accuracy. These advancements bridge the gap between experimental results and operational surveillance systems.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews related work in object detection and surveillance systems. Section 3 details our methodology and system architecture. Sections 4 presents experimental results and discussions. Section 5 concludes with implications and future research directions.

Recent advances in deep learning for object detection have significantly impacted video surveillance systems. This section critically examines relevant approaches, focusing on their methodologies, performance, and limitations.

2.1 Real-Time Object Detection Frameworks

Current research demonstrates that YOLO architectures excel in real-time detection scenarios. Reference [3] implemented an optimized YOLOv4 variant that achieved 92% mean Average Precision (mAP) on weapon detection while processing 45 Frames Per Second (FPS), though performance degraded to 78% recall for small objects (<50 px). Similarly, reference [1] developed a modified Single Shot Multibox Detector (SSD) that maintained 89% accuracy in crowded environments, but required substantial Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) resources. These findings highlight the ongoing trade-off between speed and accuracy in real-time systems.

2.2 Weapon-Specific Detection Systems

Several studies have focused specifically on dangerous object detection. Reference [20] proposed a dual-stream CNN that combined spatial and temporal features, reducing false positives by 32% compared to single-frame approaches. However, their method increased processing latency by 40%, making it unsuitable for strict real-time applications. More recently, reference [21] demonstrated that Pan-Tilt-Zoom (PTZ) camera integration could improve detection rates by 18% through adaptive zooming, though this required specialized hardware configurations.

2.3 Efficient Architectures and Deployment

The pursuit of efficient models has yielded important insights. Reference [5] showed that their EfficientDet architecture could match state-of-the-art accuracy with 40% fewer parameters, enabling deployment on edge devices. Building on this, reference [22] a quantized version that maintained 85% of baseline accuracy while reducing memory requirements by 60%. These advances are particularly relevant for scalable surveillance networks.

2.4 Multi-Modal and Contextual Approaches

Emerging techniques incorporate additional contextual information. Reference [23] combined visual detection with behavioral analysis, improving threat identification by 25% in crowded scenes. Similarly, reference [6] demonstrated that multi-spectral imaging could overcome lighting challenges, though at significant computational cost. These approaches suggest promising directions for complex environments.

2.5 Critical Analysis and Research Gaps

The literature reveals several key insights:

1. Real-time performance often comes at the cost of small object detection accuracy.

2. Architectural efficiency remains crucial for practical deployment.

3. Contextual and multi-modal approaches show promise, but increase complexity.

4. There is a growing need for solutions that balance accuracy, speed, and resource requirements.

Our work addresses these gaps by developing an optimized YOLOv4 implementation that specifically enhances small object detection while maintaining real-time performance. We incorporate efficient feature extraction techniques inspired by [5] while avoiding the hardware dependencies of specialized approaches like that of [10]. The proposed system demonstrates how careful architectural choices can achieve robust performance across diverse surveillance scenarios.

The methodology for advancing this work focuses on the development of a dangerous object detection system using convolutional neural networks. The process includes data collection, image preprocessing, CNN model selection and training, and implementation in the cloud.

3.1 Data Collection and Processing

The dataset used to train the model is composed of more than 50,000 images. These were obtained from public and private sources and include dangerous objects such as knives and firearms. We manually classified these images into two categories: positive (containing dangerous objects) and negative (not containing threats). The proportion of positive images was 60%, as suggested by [4]. Each image included in the dataset must present the object to be detected, which must differ from the environment in a way that allows the neural network to distinguish the object from the background. The object to be detected must be recognizable to be considered a valid image for training the neural network. There are many online sources of free images that can be used for training purposes, such as Google Images, Pixabay, Pexels, and Stokpic; we employed these among many others. To obtain a large training set, synthetic images were generated using data augmentation techniques to improve the system’s ability to detect objects in different lighting conditions and viewing angles. Techniques such as changing the angle or applying a mirror effect to an image provide a greater amount of functional data, as shown in Fig. 1. Video frame extraction can be used to collect a large amount of data, as can be seen in Fig. 2. We created some images for the dataset with a 3D model, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 1: Techniques to obtain additional images from angle changes or mirror effects. Source: author

Figure 2: Images obtained from video sequences. Source: author

Figure 3: Images obtained from 3D modeling, replicas, 3D scanning, and training images. Source: author

Two models were selected for object detection: YOLOv4 and EfficientDet. YOLOv4 has been widely used in real-time detection tasks due to its ability to process images at high speed with high accuracy. EfficientDet, on the other hand, is a more recent model that has shown competitive results in object detection benchmarks thanks to its optimized architecture, which reduces computational complexity without compromising accuracy. The steps used in image categorization are described below.

Image labeling

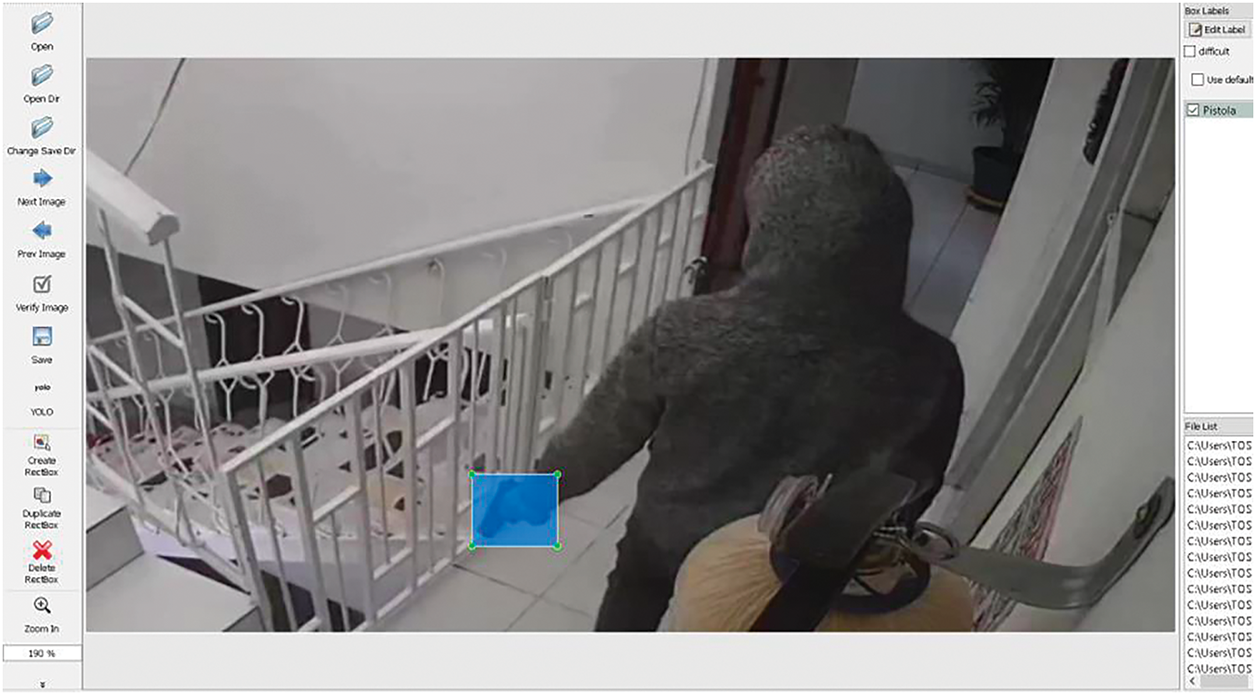

For the selection and use of the images, it is necessary to use labeling software that represents a specific area of an image as a bounding box, which functions as a basis for the recognition of the object to be detected, as shown in Fig. 4. It is also crucial to correctly label the images. Since the analysis and comparison of the images depend on the quality of the neural network training to obtain accurate parameters and make efficient detections, it should be noted that this labeling software must support the neural network in question. For example, LabelImg supports only YOLO and PascalVOC (this is used by several object detection algorithms such as R-CNN, Fast R-CNN, and Faster-CNN). For this project, we used LabelImg for labelling with both neural network models, as shown in Figs. 4 and 5. When a neural network is trained from scratch, the object identification method must be explicitly defined during training.

Figure 4: Object selection by LabelImg, Source: author

Figure 5: The object selected and labeled by LabelImg. Source: author

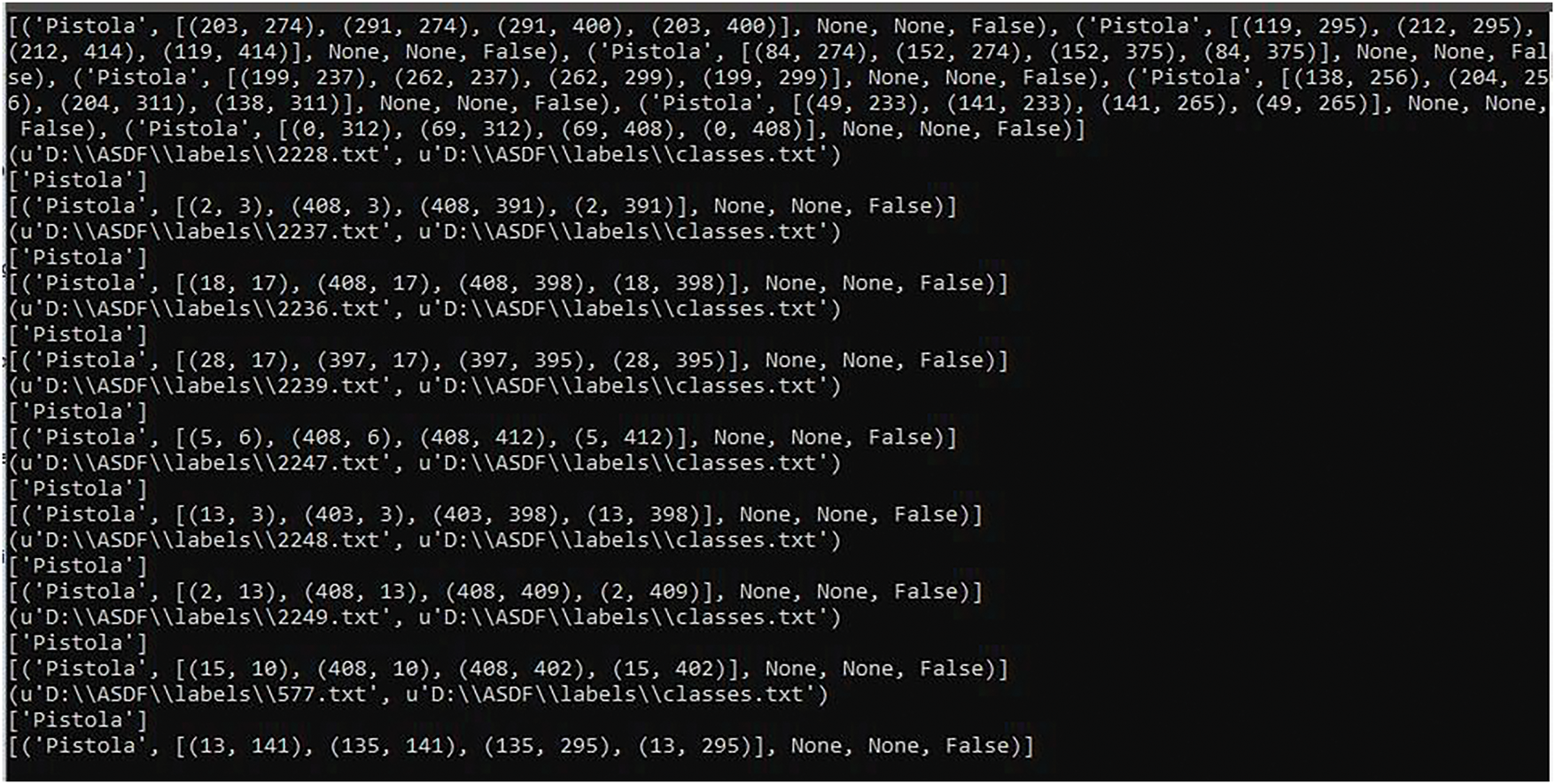

LabelImg runs on the Ubuntu and Windows operating systems, which is a significant advantage, as image categorization, labeling, training, and implementation could be done in either system [24], The parameters stored by the software are the image characteristics, the label name assigned to the object, and the X and Y distances of the object’s dimensions in the image. The destination path hosts the image labels and element information among the set of images for training, as shown in Fig. 6. Unfortunately, this labeling operation consumes a lot of human resources. Since a dataset may have more than 5000 images, labeling each can be a laborious task.

Figure 6: Parameters of each object labeled by the LabelImg tool. Source: author

3.3 Evaluation of Neural Networks and Object Detection Algorithms

Selection of Programming Languages and Environments

A neural network for the detection of objects must go through a training stage. There are several programming languages capable of comparing, selecting, and executing processes on the neural network’s training dataset. To evaluate and select the ideal environment, it is necessary to consider factors such as the selection time, the number of objects that can be trained per stage, and the neural network’s success rates. Several languages have been studied for this role, among which are Java, Matlab, Python, C, and CUDA; reference [18] found Python to be the most suitable.

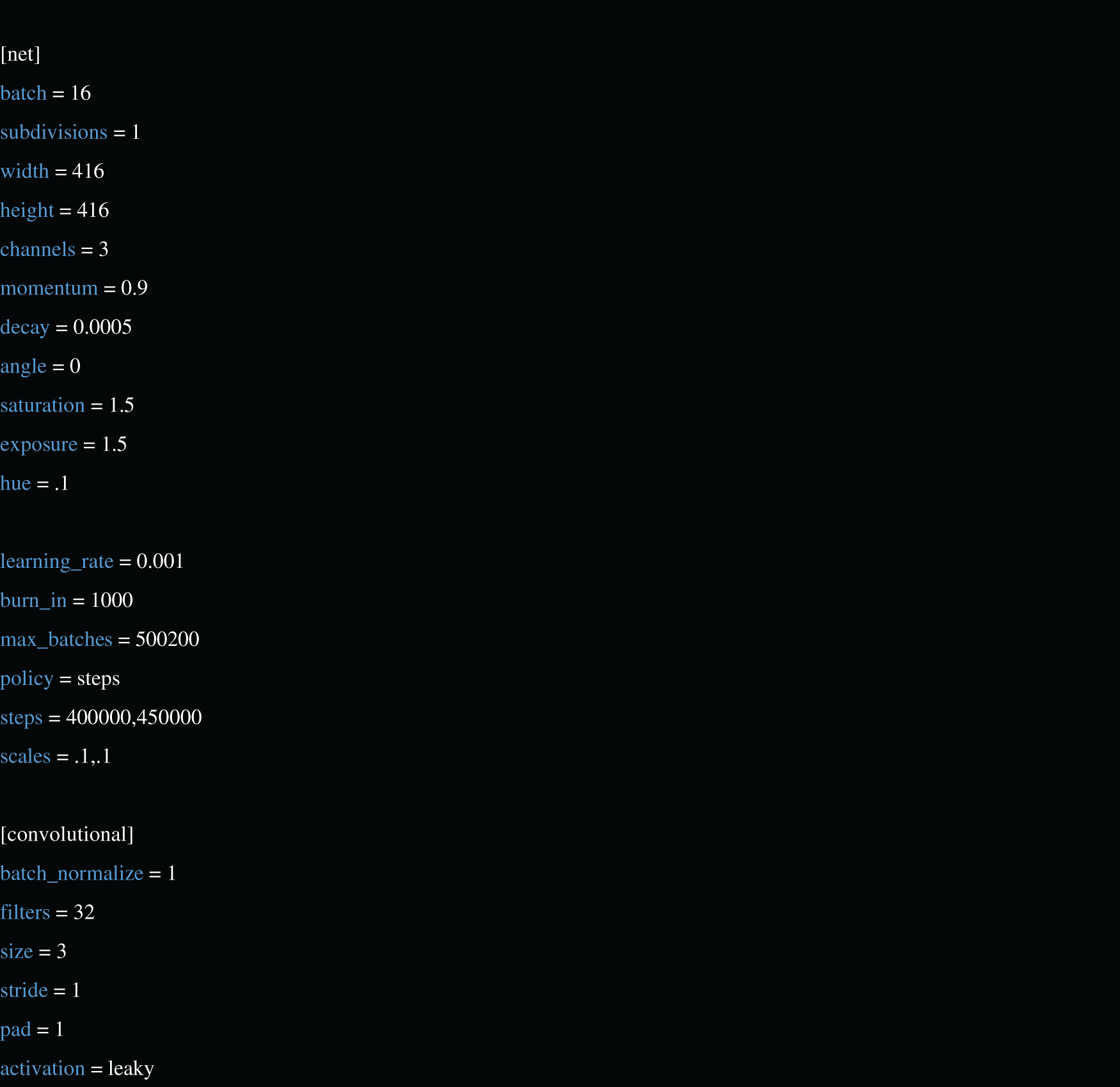

To perform the neural network training, we implemented the system environment, libraries, dataset interpretation, and management codes. We recorded the input and output sources and CPU and GPU machine power to establish a solid base for the analysis of the selected dataset. The implementation code can be found in the repository1. The most relevant configuration hyperparameters are shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Configuration hyperparameters. Source: author

Model training was performed using high-performance GPUs on the AWS platform. A supervised learning approach was used, with optimization using the Adam algorithm. The dataset was split into 80% for training and 20% for validation. During training, hyperparameters such as learning rate, batch size, and number of epochs were adjusted to optimize system accuracy.

Among the libraries and tools required for the Darknet neural network and YOLOv4 algorithm are (all libraries are in the LibreriasRedNeuronal.txt file in the repository (see note 1)):

• Keras

• Pytorch (TorchVision)

• Scipy

• LabelImg

• TensorFlow

• Numpy

• TensorBoard

• Astor

• TerminalTables

Installation from the repository was performed with the command $pip install-r libreriasRedNeuronal.txt. Due to the particularities of the potentially dangerous objects, and since there was no pre-trained network, the network was trained from scratch; therefore, an empty neural network was downloaded.

The file entrenar.py from the repository is used to train the model if it is the first time that it is trained. The path of the DarkNet file with the default weights of the neural network must be specified, as well as the path where the training configuration is located. The number of epochs to be trained (if not specified otherwise) will be 500. Batch size is the number of images that will be sent at the same time to be trained in parallel, and the number of CPU threads to be used during batch generation (if not specified, it is 8). The Darknet model is generated by calling the Darknet class located in the file modelos.py. This class is the default for YOLOv4. The weights of the neural network are also loaded. If the file ends in .pth, it implies that it contains weights generated by training; otherwise, the default DarkNet weights are used. The number of epochs is requested; it is entered in a cycle of the size of the number of epochs. In each iteration, a new save point is generated called punto_guardado%d.pth, where %d is the epoch number. At the end of the training, the files useful for detection are the pre-trained weights of the neural network and the file containing the classes.

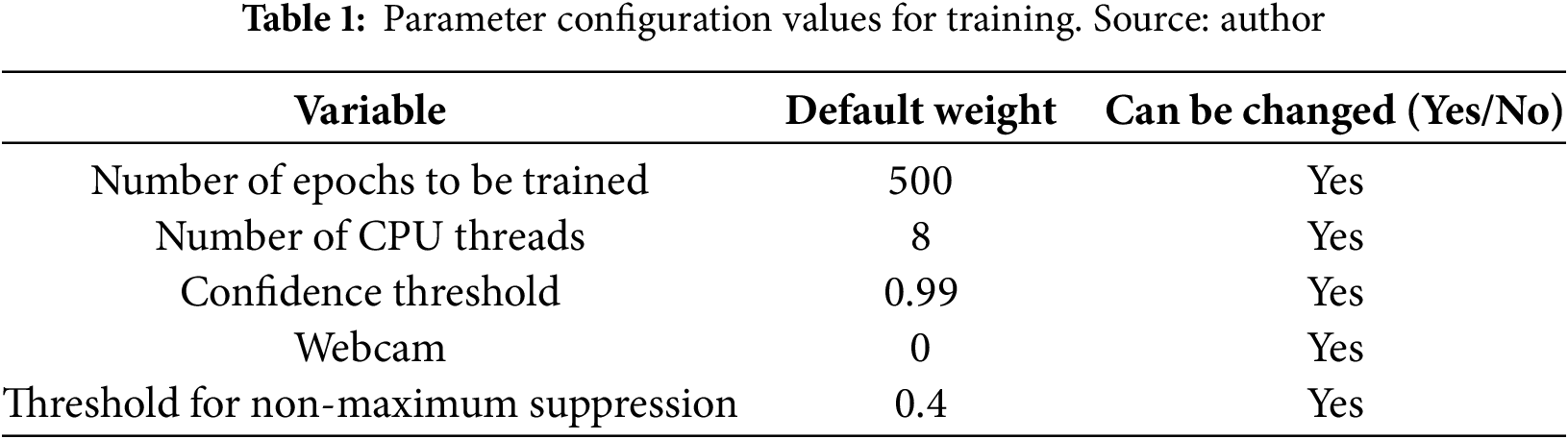

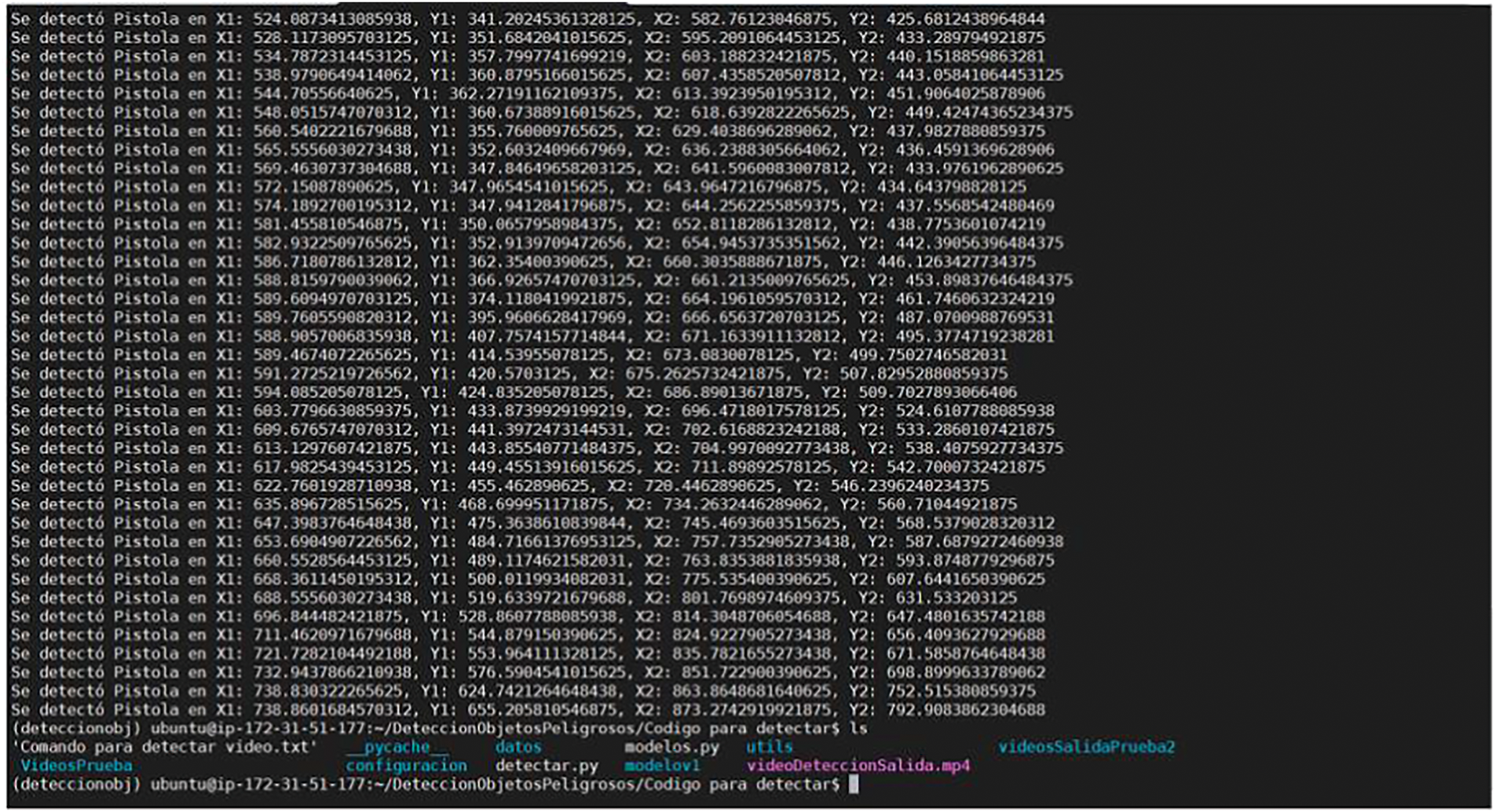

To begin the detection, the necessary libraries are imported; among them is cv2, which is used for video manipulation. This library can be used to load and write the labels (detection boxes) that will be displayed to the user. Torch is used for machine learning and implements the responses of the neural network based on what was achieved in the training. Once the libraries are imported, the system proceeds to request various parameters from the user. These parameters include the model that was generated in the training, the path of the pre-trained weights (punto_guardado_#.pth), the path of the names of the classes, the desired confidence threshold for the detection system (we set this to 0.99 since we wanted to reduce the number of false positives), and whether a webcam is to be used. If a webcam is not employed, this parameter is set to 0, and the user enters the path of the directory where the video to be analyzed is located. Other parameters are a threshold for non-maximum suppression (by default, 0.4) and the size of each image to be launched. A cv2 function is called to process images from the video or webcam, and a video file is created where the detection output will be stored. The manipulation of the webcam video is shown in the file detector.py of the repository. All of these values can be seen in Table 1.

Every time an object is detected, it will be identified by a box drawn in the frame, its location in axes will be printed by the console, and the method that will notify the alert will be called, sending as a parameter the name of the detected class. This can be seen in the file detector.py.

Training algorithm

After downloading the weights and the necessary libraries, the system proceeds to generate the classes that it needs. These classes are the objects that we want the neural network to detect; in this case, the number of required classes is 1. This number can be changed according to the user’s needs.

Next, the images in the dataset are downloaded to an ‘images, and the labels are processed by LabelImg to/Data/labels. Finally, a Python file is run that separates the training images and the images to be validated.

The final step is to train the neural network, which is achieved with the following command: $python entrenar.py –modelo configuracion/yolov4-custom.cfg –configuracion_entrenamiento configuracion/rutas.data –peso_preentrenados pesosDarknet/darknet53.conv.74 –tamanio_lote 1 –epochs 50.

In the command above,

• –modelo selects the model, in this case, Yolov4.

• –configuracion_entrenamiento describes the characteristics of the dataset images, including paths, labels, and custom model data.

• –peso_preentrenados loads the pre-trained Darknet model.

• –tamanio_lote is the number of images that are to be processed at a time. That is to say, if there are 50,000 images and –tamanio_lote is set to 10, there will be 5000 batch processes per epoch.

• –epochs: Is the number of epochs for which the neural network is requested to train. Each time an epoch is performed, a training output file will be generated. This is called (punto_guardado_%d.pth % epoch), which is saved in the generated folder “pesosGenerados.”

Using a CPU for training was not feasible due to the large number of images to be processed; therefore, the training was done with 2 NVIDIA Corporation GK210GL [Tesla K80] graphics cards [10de:102d] (rev a1). The variable used to finalize the training was the loss with each epoch. When the average of this variable was below 0.1, training was stopped, and the trained model was evaluated. Depending on the results, the model continued to be trained, or finally it was terminated. An average loss of 0.001523 was reached in the model that was finally used for the implementation.

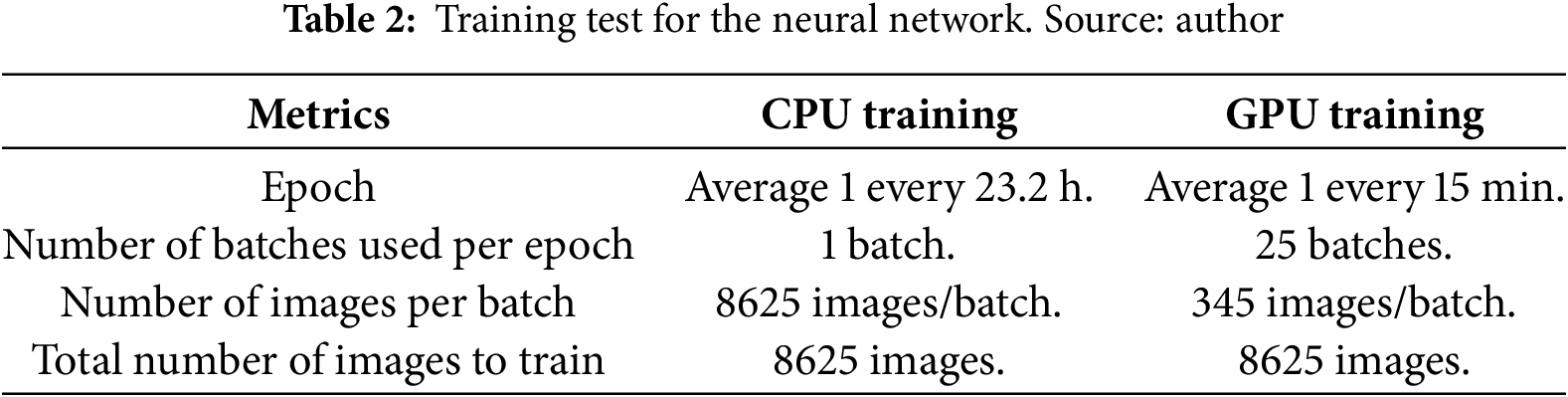

Table 2 presents the data used to compare CPU and GPU training for the neural network in the scenario under study.

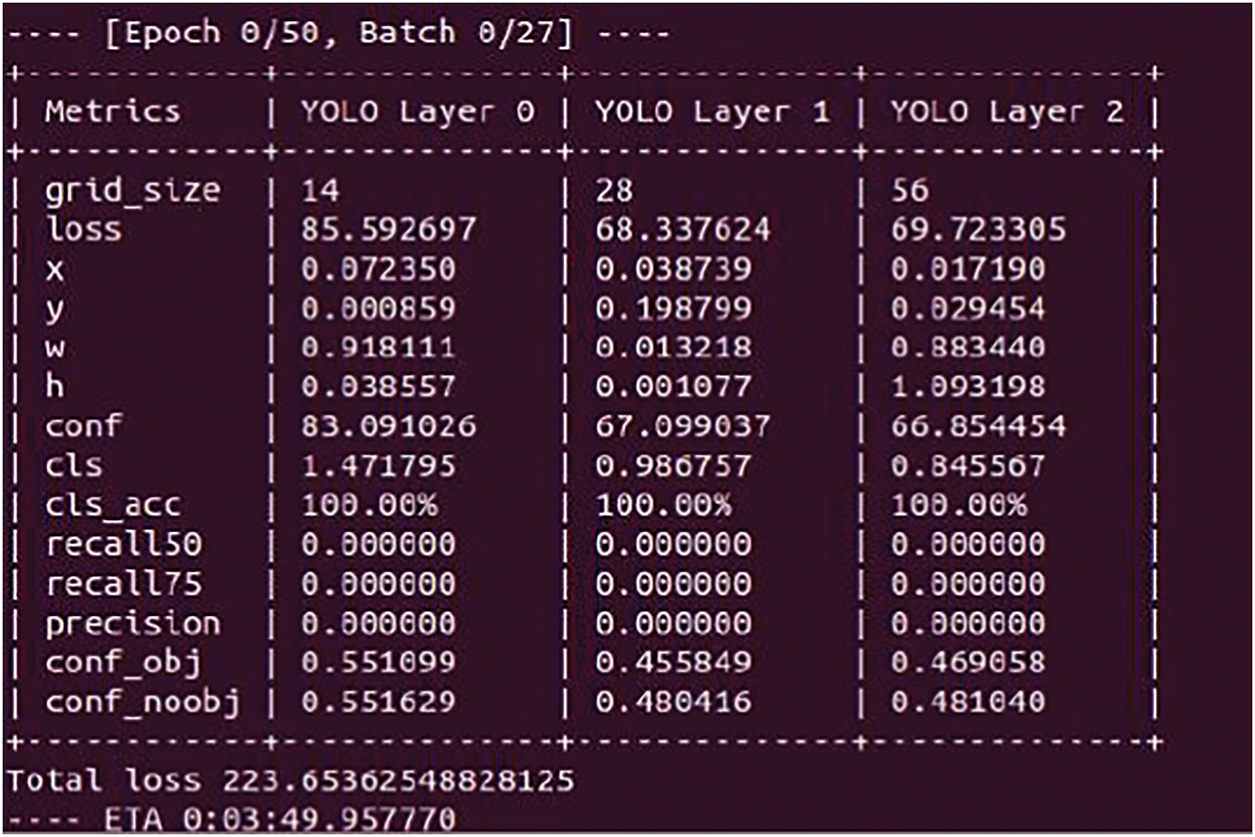

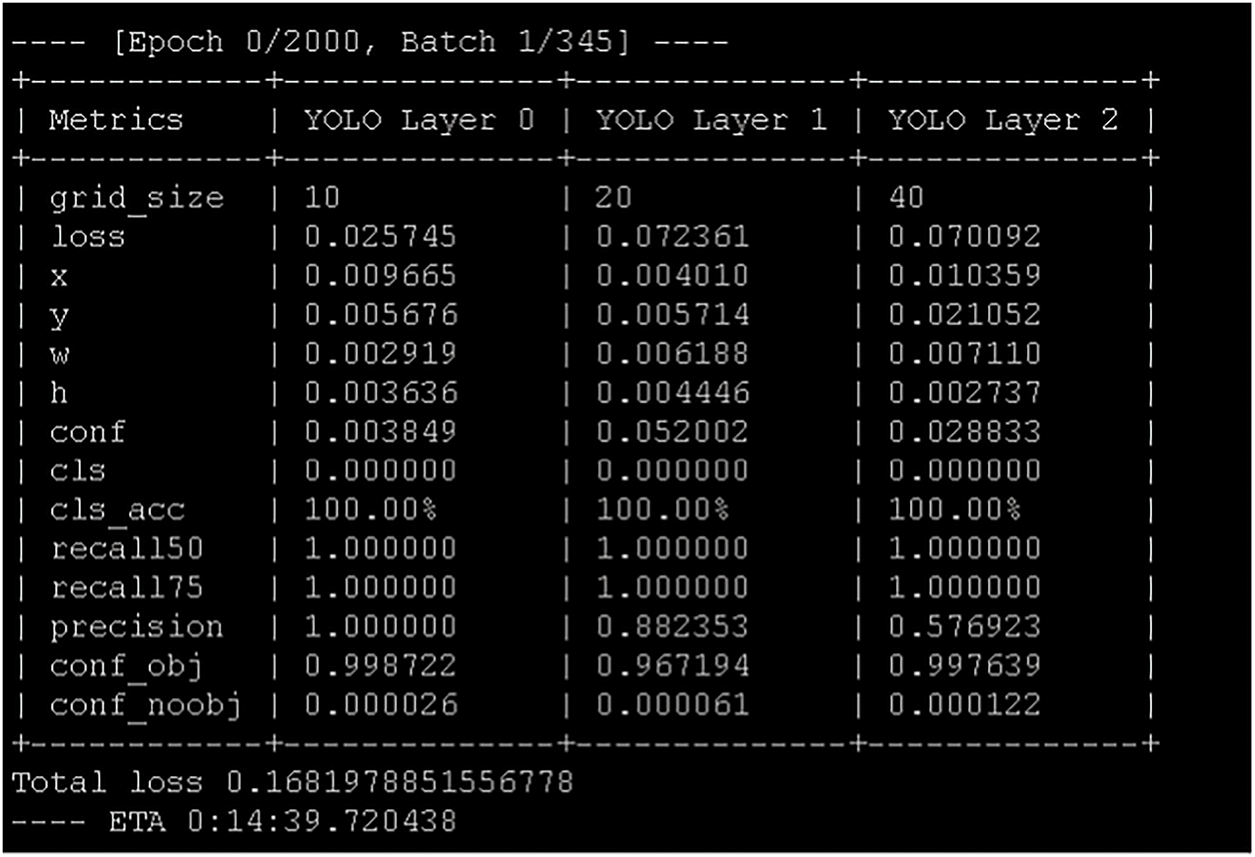

This data was used in two scenarios described below. Fig. 8 shows the training of the neural network on an ordinary desktop CPU for 10 consecutive days to achieve 10 epochs. Fig. 9 shows the same training at the high-performance computing center of the District University (CEDAD). This training involved more than 1150 epochs and more than 8000 training images and lasted approximately 12 days.

Figure 8: Training of the neural network on a desktop CPU for 10 consecutive days to achieve 10 epochs. Source: author

Figure 9: Training of the neural network at the high-performance computing center of the District University (CEDAD) with more than 1150 epochs and more than 8000 training images, lasting approximately 12 days. Source: author

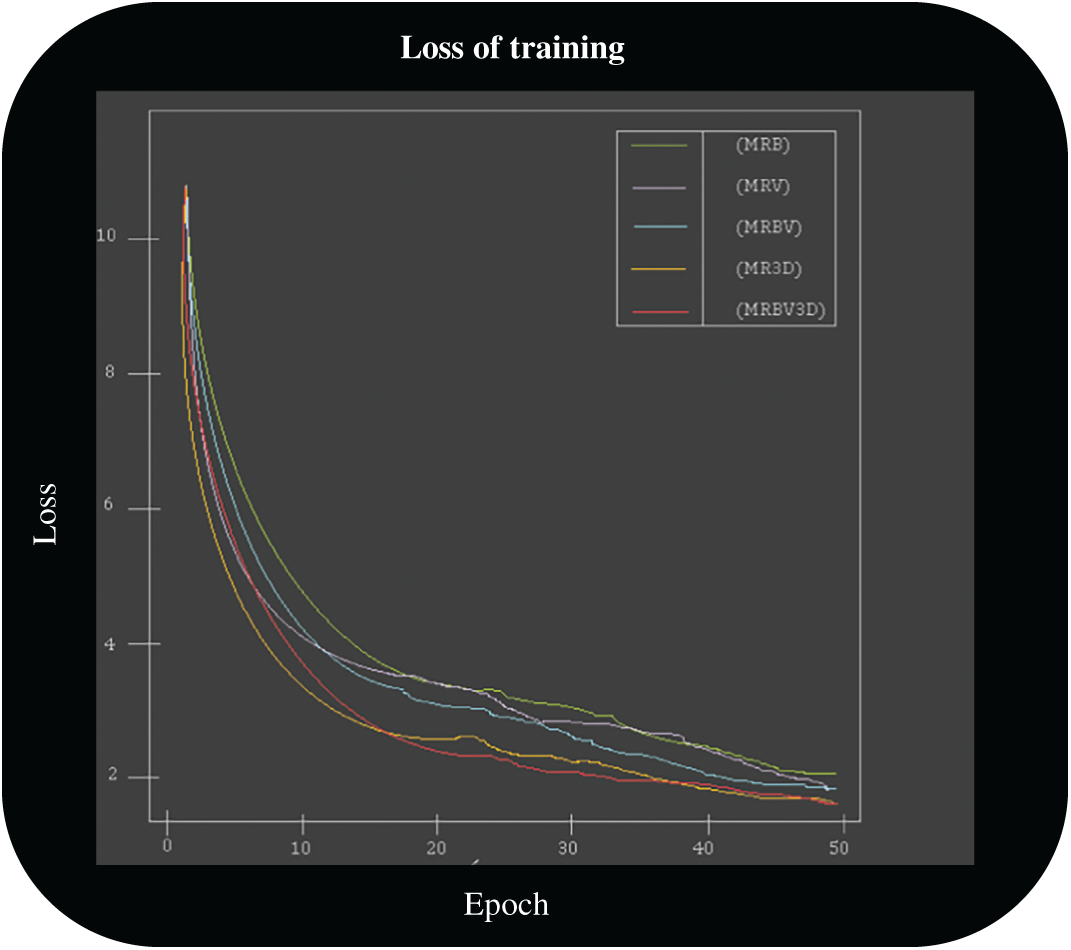

Five training models and combinations thereof were submitted to rigorous testing to calculate which would be the best option for the project’s requirements. These models were:

• A basic model with a dataset of images collected from the Internet (MRB).

• A dataset of images collected from videos (MRV).

• A combined model with a dataset of images collected online and images from videos (MRBV).

• A dataset of images from 3D models (MR3D).

• A combined model with a combination of images collected online and video frames, together with the dataset of images from 3D models (MRBV3D).

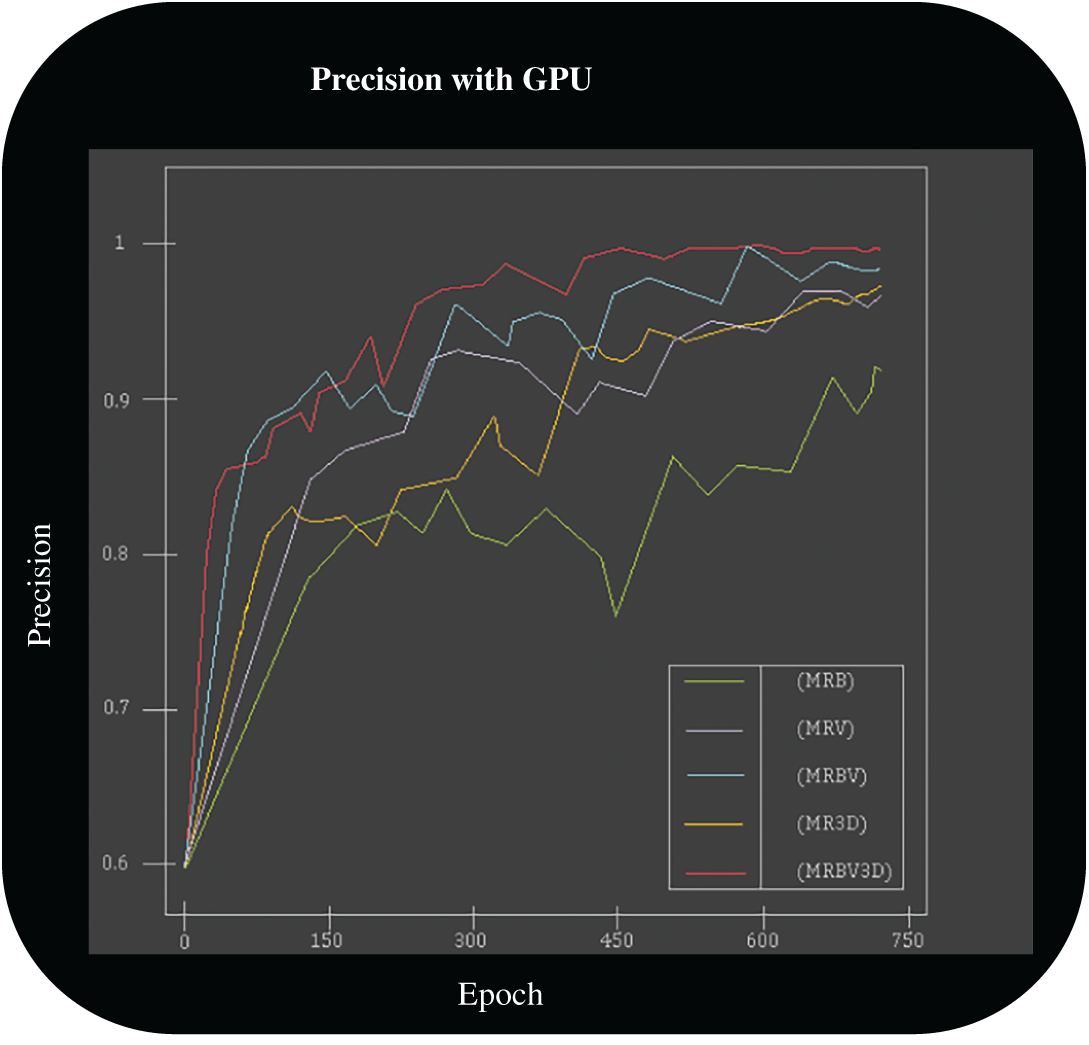

With the MRB, it was difficult to achieve a training loss close to zero since the training images were much more varied than in other models. The MR3D and MRBV3D models were the best in lowering their loss. Having a similar dataset in terms of training objects makes it easier to recognize the object in question. However, the other methods’ loss by epoch curves had similar appearances in the graph, as can be seen in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Training loss using a GPU. Source: author

As shown in Fig. 11, the best accuracy was obtained by the MRBV3D model. Oscillating between 1 and 0.97 after 750 epochs, it also obtained a constant increase in accuracy in a few epochs. However, all models had significant losses of accuracy in specific epochs, with the MRB model having the most losses. Between epoch 352 and epoch 448, the model lost more than 6% accuracy, meaning that it must be trained for more epochs, running the risk of being overtrained.

Figure 11: Precision with a GPU. Source: author

The system was deployed on AWS infrastructure using Amazon EC2 for real-time processing and Amazon S3 for image storage. In addition, Amazon SNS was used for the automatic generation of alerts. These are sent directly to the mobile devices of security personnel when dangerous objects are [14].

This implementation required a camera. The Amazon instance was not so powerful as the high-performance computing center; it was a p2.xlarge, which has a GPU, 4 virtual CPUs, and 61 GiB of RAM.

Once the system was installed on the instance, it was configured following the commands that were in the training section so that it would have the necessary libraries. If the system were to be used with a previously-trained model, this would be possible by cloning the training code folder of the git repository, installing LibreriasRedNeuronal.txt to have the libraries required for the operation of the system, and then adding the training model. The pre-trained weights were generated for classes.name (which contained the names of the classes to be detected).

Once the configuration was completed, the object detection system was tested by executing the following command in the console:

$python detectar.py –ruta_nombre_clases datos/clases.names –ruta_pesos checkpoint.pth –umbral_confianza 0.95 –webcam 0 – directorio_video video.mp4

The parameters in the command have the following roles:

• –ruta_nombre_clases retrieves the data regarding the type of object to be detected.

• –ruta_pesos fetches the checkpoint generated by the training, i.e., the epoch corresponding to the last batch process performed.

• –umbral_confianza is the percentage of tolerance given to the neural network for detection, which ranges from 0 to 1 (1 is 100%).

• –webcam specifies whether the system has a webcam. A value of 1 means a webcam is enabled; this is set to 0 otherwise.

• –directorio_video: If the webcam is disabled, this specifies where the system will find images or video files for analysis.

When an analysis is performed, a visual file of the analysis output is generated. This file is created to evaluate the practical results of the neural network performance and detection.

In Fig. 12 below, the purple letters read “videoDeteccionSalida.mp4,” which is the video generated after the test. This graphically visualizes the moment in which the object was detected and will remain as proof of the alarm.

Figure 12: A dangerous object detection system running on the AWS virtual machine. Source: author

System results were evaluated using standard accuracy, recall, and F1-score metrics. The YOLOv4-based model achieved an accuracy of 92% with a false alarm rate of 4.5%. The average processing time per image was 0.45 s, allowing its use in real-time video surveillance applications. On the other hand, EfficientDet achieved a slightly higher accuracy of 93%, but with a processing time of 0.55 s per image, making it less suitable for speed-critical applications.

Tests in Real Environments

The system was tested in several real environments, such as train stations and shopping malls, where surveillance cameras equipped with the proposed detection system were installed. During these tests, the system was able to detect bladed weapons and firearms in crowded scenarios. The automatic alerts generated enabled security operators to respond quickly to potential threats. Fig. 13 shows the neural network determining the existence or non-existence of dangerous objects under different scenarios, using the same camera.

Figure 13: A neural network determining the existence or non-existence of dangerous objects under different scenarios, using the same camera. Source: author

For the proposed implementation, GPU processing is considered to offer acceptable performance for real-time detection work. With a theoretical hit margin of more than 90% on the trained object, the system can perform valuable support work in the detection of dangerous situations. If a dangerous object is detected by the neural network, it automatically sends information through the cloud and promptly informs security personnel that the object has been detected.

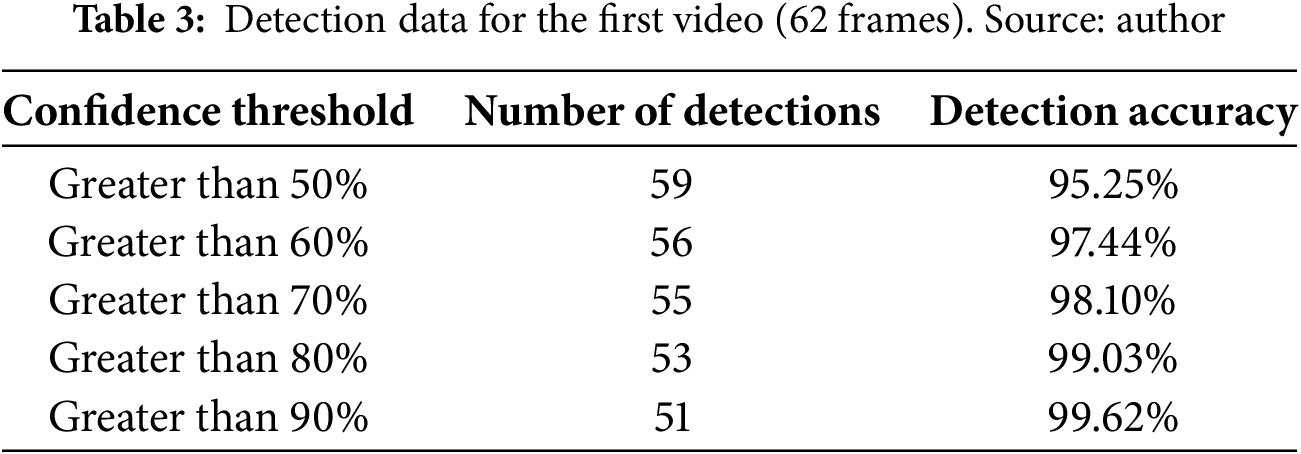

To determine that the neural network correctly detects the object to be evaluated, it is necessary to perform comparison tests on the results, varying the detection’s confidence threshold to analyze the percentage of correct detections. For this purpose, the neural network was tested with different video sequences. The results for one sequence are shown in Table 3 below. “Number of detections” represents the number of frames in which the neural network detected the object.

The video sequence represents 62 frames where the object to be detected is constantly moving. The neural network recognized and detected the object in most of the evaluated frames. However, we observed that by increasing the confidence threshold to 90% or higher, a detection accuracy greater than 99% was obtained.

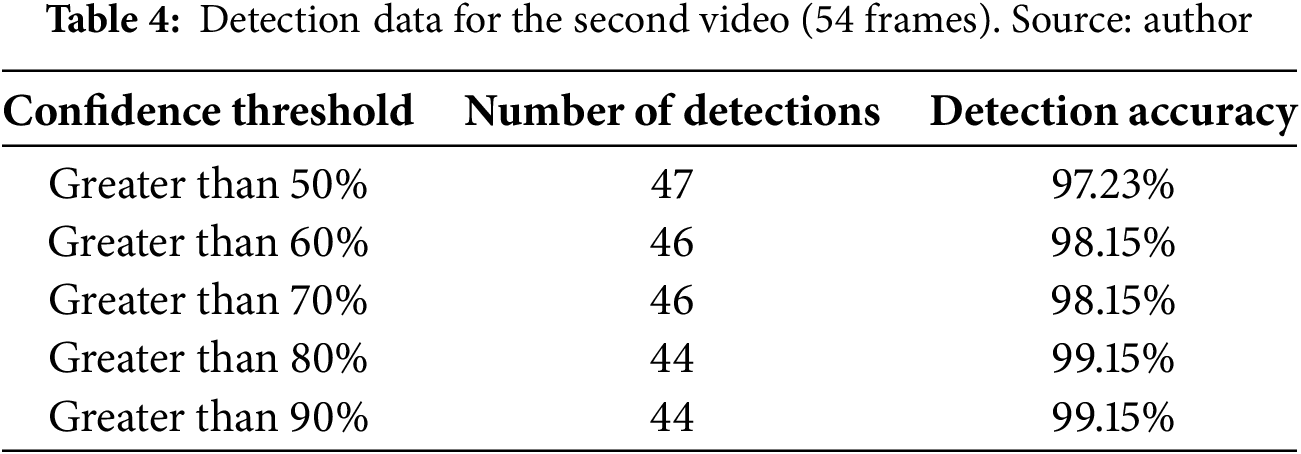

Table 4 shows the results for the evaluation and analysis of the second video. From a sequence of 54 frames, the neural network detects the object of interest in between 47 and 44 frames, depending on the confidence threshold. When the threshold is below 60%, the network detects the object in two frames in which it is blurred by motion (the consequence of a sudden movement), as shown in Figs. 14 and 15.

Figure 14: A blurred object in a frame due to a sudden movement (no detection). Source: author

Figure 15: A blurred object being detected. Source: author

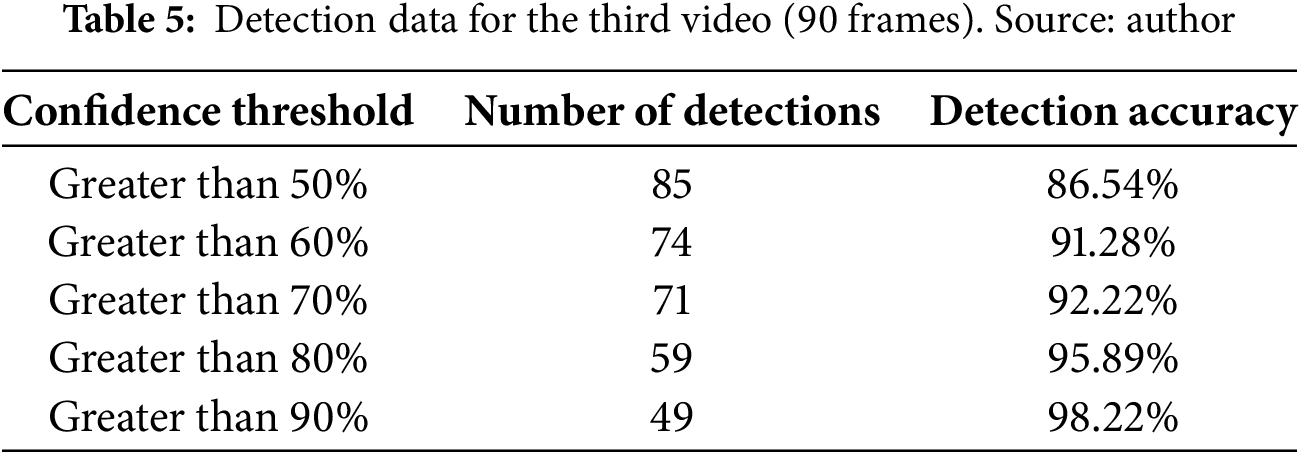

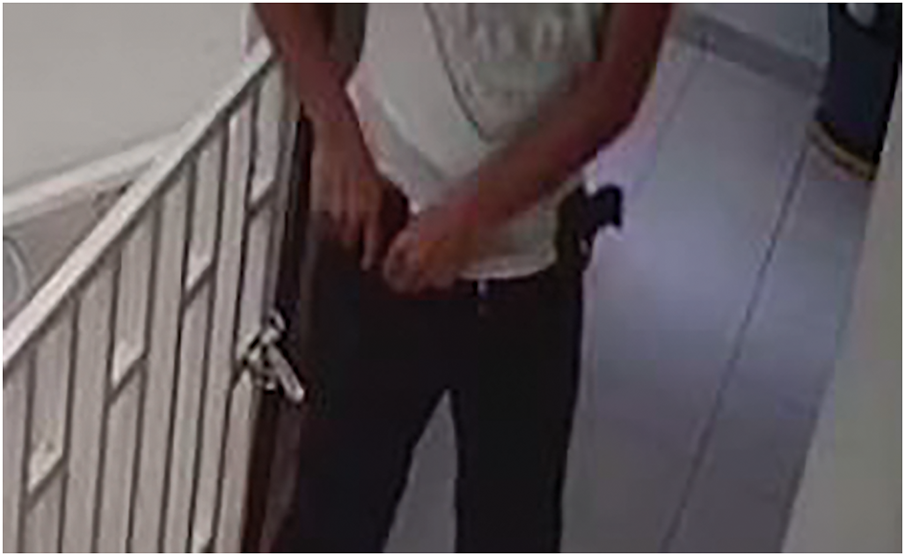

Table 5 shows the results for the third video, which was the longest in the analysis. It corresponds to an object detection sequence of 90 frames in which the object of interest is stored in a person’s pocket and then taken out. When the confidence threshold was lower than 70%, the neural network detected the object while it was almost hidden in the person’s pocket. With a confidence threshold higher than 80%, it only detected the object when it was fully uncovered. Examples of the concealed object are shown in Figs. 16 and 17.

Figure 16: Object being extracted from a pocket (no detection). Source: author

Figure 17: Object detected while being extracted. Source: author

The analysis shows that the higher the detection tolerance margin (that is, the lower the confidence threshold), the greater the number of detections that the neural network will make. However, reducing the confidence threshold reduces the detection accuracy. With a confidence threshold above 90% or even 95%, the neural network continues to perform a large number of detections with a high percentage of success. A high degree of precision is necessary because when objects are moved at speed in a sequence, they tend to become blurry, and the neural network performs detections with less probability of success.

The use of convolutional neural networks for the detection of dangerous objects in video surveillance systems has proven to be highly effective. However, there are significant challenges to consider. The quality of surveillance cameras and lighting conditions can affect system performance, particularly in low-light environments or when low-resolution cameras are used. Additionally, the system’s ability to differentiate between dangerous and non-dangerous objects (e.g., a tool vs a weapon) remains a technical challenge.

Another observed limitation is the system’s dependence on a robust network infrastructure. In environments with limited connectivity, processing times can increase significantly, compromising the system’s ability to generate real-time alerts.

This project’s approach has been to investigate the detection of objects through the support of software tools. This was achieved by means of artificial intelligence and deep learning, and impressive results were obtained. The object detection tool was made with YOLOv4 (an algorithm for object detection) and Darknet (an artificial neural network); these instruments provided a feasible solution and offer adaptability for the development and maintenance of the application. It should be noted that the greatest difficulty encountered in the project was related to the training of the neural network. This task required a great amount of time and effort. It involves the meticulous treatment of the training data, requiring the selection, labeling, and processing of a large number of images for the dataset.

Through the processing of a large dataset of images and extensive training, we have created a neural network that can accurately detect objects that threaten people’s safety. This ability may be particularly useful in environments in which people, under the threat of a weapon, cannot report their predicament to the security forces in charge of protection.

We found that Amazon Web Services’ (AWS) early notification tool is reliable and efficient for sending and processing information. In realizing this project, we concluded that the data transmission had to be through the Internet of Things, since the sending of information must be through interconnection, either by sending information directly to a device or to the cloud. Under such circumstances, transmission times are acceptable.

The comparison between the YOLOv4 and EfficientDet models showed that although both models offer high levels of accuracy, YOLOv4 is more suitable for real-time applications due to its shorter processing time. EfficientDet, however, offers greater robustness in terms of accuracy, making it a good choice for applications where speed is not the most critical factor.

The deployment of AI-powered surveillance systems for dangerous object detection raises critical ethical concerns, including the potential for misuse (e.g., mass surveillance overreach or discriminatory targeting), privacy violations for individuals recorded in public spaces, and algorithmic bias stemming from unrepresentative training data. To address privacy, raw footage should be processed in real-time with anonymization techniques (e.g., blurring non-threat faces) and retained only for forensic review under strict legal safeguards. Mitigating bias requires curated datasets with balanced demographic representation (e.g., diverse skin tones and lighting conditions) and continuous auditing of false positives/negatives to correct disparities. Transparency measures—such as public disclosure of system capabilities, accuracy rates, and oversight protocols—can build trust while preventing misuse. Lastly, adherence to frameworks like GDPR or AI ethics guidelines ensures accountability, with human-in-the-loop reviews to override erroneous alerts. By embedding these safeguards, AI-powered surveillance technology can enhance security without compromising civil liberties.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the High-Performance Computing Center (CEDAD) at the Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas for providing the computational resources necessary to train the neural network models.

Funding Statement: This research has not received any funding other than that provided by the authors.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Carlos Rojas, Cristian Bravo, Carlos Enrique Montenegro-Marín and Rubén González-Crespo; data collection: Carlos Rojas and Cristian Bravo; analysis and interpretation of results: Carlos Rojas, Cristian Bravo, Carlos Enrique Montenegro-Marín and Rubén González-Crespo; draft manuscript preparation: Carlos Enrique Montenegro-Marín and Rubén González-Crespo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The code developed for this project, including scripts for training and detection, is publicly available in the GitHub repository at https://github.com/ingcarlosmontenegro/DangerousObjectsDetection (accessed on 28 August 2025). The dataset used for training, due to its sensitive nature and containing images of weapons, is not publicly available to prevent potential misuse, but may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with appropriate justification for academic research purposes.

Ethics Approval: This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. All image data collected from public sources were used in accordance with their respective licenses and terms of service. For images not openly licensed, permission for use in academic research was obtained where required. Field tests in public spaces were conducted with the full knowledge and cooperation of the site management and security teams. All surveillance footage was processed with a focus on object detection, and no personally identifiable information was stored or used for any purpose beyond the scope of this research.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://github.com/ingcarlosmontenegro/DangerousObjectsDetection (accessed on 28 August 2025)

References

1. Bhatti MT, Khan MG, Aslam M, Fiaz MJ. Weapon detection in real-time CCTV videos using deep learning. IEEE Access. 2021;9:34366–82. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3059170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gawande U, Hajari K, Golhar Y. Real-time deep learning approach for pedestrian detection and suspicious activity recognition. Procedia Comput Sci. 2023;218(4):2438–47. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2023.01.219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang L, Yin S, Alyami H, Ali Laghari A, Rashid M, Almotiri J, et al. A novel deep learning-based single shot multibox detector model for object detection in optical remote sensing images. Geosci Data J. 2024;11(3):237–51. doi:10.1002/gdj3.162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Salido J, Lomas V, Ruiz-Santaquiteria J, Deniz O. Automatic handgun detection with deep learning in video surveillance images. Appl Sci. 2021;11(13):6085. doi:10.3390/app11136085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Tan M, Pang R, Le QV. EfficientDet: scalable and efficient object detection. arXiv:1911.09070. 2019. [Google Scholar]

6. Ramachandra R, Venkatesh S, Damer N, Vetrekar N, Gad R. Multispectral imaging for differential face morphing attack detection: a preliminary study. arXiv:2304.03510. 2023. [Google Scholar]

7. Shen Z, Liu Z, Li J, Jiang YG, Chen Y, Xue X. Object detection from scratch with deep supervision. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;42(2):398–412. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2019.2922181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Liu L, Sun Y, Ge X. A hybrid multi-person fall detection scheme based on optimized YOLO and ST-GCN. Int J Interact Multimed Artif Intell. 2025;9(2):26–38. doi:10.9781/ijimai.2024.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 26]. Available from: http://pjreddie.com/yolo/. [Google Scholar]

10. Muñoz JD, Ruiz-Santaquiteria J, Deniz O, Bueno G. Weapon detection using PTZ cameras. In: Robotics, computer vision and intelligent systems. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 100–14. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-59057-3_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Warsi A, Abdullah M, Husen MN, Yahya M, Khan S, Jawaid N. Gun detection system using Yolov3. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Smart Instrumentation, Measurement and Application (ICSIMA); 2019 Aug 27–29; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/icsima47653.2019.9057329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shah N, Bhagat N, Shah M. Crime forecasting: a machine learning and computer vision approach to crime prediction and prevention. Vis Comput Ind Biomed Art. 2021;4(1):9. doi:10.1186/s42492-021-00075-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Gayathri M. Suspicious activity detection and tracking through unmanned aerial vehicle using deep learning techniques. Int J Adv Trends Comput Sci Eng. 2020;9(3):2812–6. doi:10.30534/ijatcse/2020/51932020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Welcome to AWS documentation [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 26]. Available from: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/. [Google Scholar]

15. Wang L, Hua G, Sukthankar R, Xue J, Niu Z, Zheng N. Video object discovery and co-segmentation with extremely weak supervision. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(10):2074–88. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2612187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Salyut J, Kurnaz C. Profile face recognition using local binary patterns with artificial neural network. In: 2018 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Data Processing (IDAP); 2018 Sep 28–30; Malatya, Turkey. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/IDAP.2018.8620840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Warsi A, Abdullah M, Husen MN, Yahya M. Automatic handgun and knife detection algorithms: a review. In: 2020 14th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication (IMCOM); 2020 Jan 3–5; Taichung, Taiwan. p. 1–9. doi:10.1109/imcom48794.2020.9001725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Santiago C, Moreno R, Bravo CA, Rincon JS, Montenegro-Marín CE, Alonso Gaona-Gracias P. Viabilidad de las redes neuronales en la detección de objetos. Iber J Inf Syst Technol. 2020;E28:981–1000. [Google Scholar]

19. Munoz DJ. Proceso de reconocimiento de objetos, asistido por computador (visión artificialaplicando gases neuronales y técnicas de minería de datos. Sci Technica. 2006;1(30):385–90. [Google Scholar]

20. Li D, Yang L, Zhang H, Wang X, Ma L. Memory-augmented insider threat detection with temporal-spatial fusion. Secur Commun Netw. 2022;2022(2):6418420. doi:10.1155/2022/6418420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Muñoz JD, Ruiz-Santaquiteria J, Deniz O, Bueno G. Concealed weapon detection using thermal cameras. J Imaging. 2025;11(3):72. doi:10.3390/jimaging11030072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhai H, Du J, Ai Y, Hu T. Edge deployment of deep networks for visual detection: a review. IEEE Sens J. 2025;25(11):18662–83. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2024.3502539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Memory A, Goldberg HG, Senator TE. Context-aware insider threat detection; 2013 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 26]. Available from: www.aaai.org. [Google Scholar]

24. Lin T. Label studio [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 26]. Available from: https://github.com/HumanSignal/labelImg. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools