Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Real-Time Dynamic Multiobjective Path Planning: A Case Study

1 School of Computer, Tonghua Normal University, Tonghua, 134001, China

2 Department of Computer Engineering, Chosun University, Gwangju, 61452, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: SeongKi Kim. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Algorithms for Planning and Scheduling Problems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5571-5594. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067424

Received 03 May 2025; Accepted 04 September 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Path planning is a fundamental component in robotics and game artificial intelligence that considerably influences the motion efficiency of robots and unmanned aerial vehicles, as well as the realism and immersion of virtual environments. However, traditional algorithms are often limited to single-objective optimization and lack real-time adaptability to dynamic environments. This study addresses these limitations through a proposed real-time dynamic multiobjective (RDMO) path-planning algorithm based on an enhanced A* framework. The proposed algorithm employs a queue-based structure and composite multiheuristic functions to dynamically manage game tasks and compute optimal paths under changing-map-connectivity conditions in real time. Simulation experiments are conducted using real-world road network data and benchmarked against mainstream hybrid approaches based on genetic algorithms (GAs) and simulated annealing (SA). The results show that the computational speed of the RDMO algorithm is 88 and 73 times faster than that of the GA- and SA-based solutions, respectively, while the total planned path length is reduced by 58% and 33%, respectively. In addition, the RDMO algorithm also shows excellent responsiveness to dynamic changes in map connectivity and can achieve real-time replanning with a minimal computational overhead. The research results prove that the RDMO algorithm provides a robust and efficient solution for multiobjective path planning in games and robotics applications and has a great application potential in improving system performance and user experience in related fields in the future.Keywords

In the fields of robotics and video games, route planning is one of the key technologies in artificial intelligence (AI) development, playing an indispensable role in guiding the behavior of game characters and the movement and flight of robots and drones [1]. Its importance is mainly reflected in five aspects: behavior guidance, environmental adaptation, interactivity and game experience, efficiency and cost, and multiobjective collaboration.

First, in terms of behavior guidance, path-planning algorithms are the cornerstone of robot behavior guidance for robotics. Robots must be able to efficiently choose the best path to complete specific tasks, such as avoiding obstacles in unknown environments, activating automated operations in factories, or picking up items in warehouses. Good path planning ensures that a robot can perform tasks efficiently and reliably [2,3]. Second, in terms of environmental adaptation, dynamic and unpredictable environments require adaptive algorithms that can respond to changing terrains and obstacle configurations [4,5]. As regards interactivity and game experience, intelligent path planning in video games enhances the realism of nonplayer characters (NPCs), allowing them to perform complex actions and enhance player immersion [6]. In terms of efficiency and cost, optimized path planning minimizes travel time and energy consumption, directly impacting the system performance, especially in energy-constrained platforms like drones [7]. Finally, in relation to multiobjective collaboration, advanced planning must handle multiple goals, such as efficiency, safety, and task priority, simultaneously and balance competing demands in real time [8].

With increasingly complex operational environments, especially in urban infrastructure and smart services, traditional path-planning approaches face growing limitations. In logistics, drones must avoid moving obstacles among high-rise buildings. In healthcare facilities, service robots must simultaneously optimize sterilization efficiency and ensure patient privacy during the disinfection route planning. Meanwhile, in contemporary gaming environments, the growing demand for immersive interactivity, particularly the expectation that NPCs exhibit human-like adaptability during quest execution, has resulted in navigation spaces characterized by dynamically evolving constraints. For example, in open-world Role Playing Games (RPGs) like The Witcher 3, NPCs must optimize multiple objectives—minimizing travel time, avoiding combat zones, and preserving terrain integrity. In such complex scenarios, traditional path-planning algorithms show clear limitations that mainly come from three aspects: single goals, short-sightedness, and behavior predictability.

The first is the problem of single goals. Many traditional algorithms are optimized for only a single goal (e.g., shortest path [9]). This kind of “tunnel vision”-style decision-making is not adaptable in practical applications. The second is the problem of short-sightedness. Traditional algorithms usually only focus on the current optimal solution, thereby neglecting planning to achieve long-term goals. For example, a game AI may only focus on using the shortest path to collect game resources but ignore the goal of collecting more game resources, which affects the overall goal’s chance of success [10]. Finally, there is the problem of behavioral predictability, whereby the robot’s or NPC’s behavior will become predictable and does not change due to a single goal and action [11]. This reduces the game’s challenge and immersion and hinders dynamic responses to environmental changes. These limitations hinder robotic efficiency, drone navigation, and gaming realism [12]. Thus, no matter which field, a real-time, adaptive, multiobjective path-planning algorithm capable of optimization in dynamic, diverse environments is urgently needed [8].

In response to the abovementioned problems, many researchers have proposed their solutions, most of which are based on optimization algorithms and modified (e.g., solutions based on genetic algorithms (GAs) and those based on simulated annealing (SA) algorithms) and thus applied to solve real problems. However, these methods are not originally designed for multiobjective path planning and often suffer from performance and accuracy issues. Please refer to Section 2 for details.

This study proposes a novel real-time dynamically updated multiobjective path-planning algorithm, called the real-time dynamic multiobjective (RDMO) path-planning algorithm, designed to overcome the limitations of existing methods. This algorithm can avoid the problems of poor performance in the robotics field and the rigidity and predictability of game AI in the games field. We prove its effectiveness using games as cases in our study. At the same time, we also selected solutions based on GAs and SA-based algorithms, which are currently widely used in the games field, as comparison objects. A comparative test was designed. The experimental results clearly demonstrate the superiority of RDMO in path quality and execution efficiency.

For the reader to better understand the study content, this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 explains the challenges of multiobjective path planning in current real-time strategy (RTS) games and analyzes the solutions proposed by different researchers; Section 3 mainly introduces the design focus and working principle of the RDMO algorithm; Section 4 conducts comparative experiments based on the single variable control principle and proves the effectiveness of the RDMO algorithm by analyzing the experimental data; and Section 5 summarizes the research results and looks forward to future research directions.

2 Problem Description and Related Work

Path planning is a core technology in drones, robotics, and video games. Classical algorithms like depth-first, breadth-first, Dijkstra, and A* perform well in static, single-objective scenarios. However, real-world and in-game applications are often far more complex, requiring dynamic, real-time responses and multiobjective decision-making.

Whether it is the flight/motion path planning of drones/game NPCs, it must be combined with actual needs. In summary, path planning must be able to solve three key problems: single goal [9], short-sighted [10], and predictable behavior [11]. Moreover, due to constant environmental changes, effective path planning must adapt dynamically and make real-time decisions [13–15]. As demands grow, algorithms have been refined to better meet practical needs.

The main challenges of multiobjective path planning arise from the complexity of the traveling salesman problem (TSP) and the quadratic assignment problem [16]. As early as 1972, Karp proved that the TSP problem is an NP-hard problem [17], a view that was also confirmed in a paper published by Gaery in 1999 [18,19], which substantially limits the classic path-planning algorithm in solving the problem. Through decades of research, scientists have proposed various solutions and algorithms for these problems, such as those based on an ant colony optimization (ACO) algorithm, SA-based algorithms, GAs, and neural network algorithms. Later generations have also been constantly optimizing these algorithms to meet actual usage needs.

Goldberg and Harrelson [20] enhanced Dijkstra’s method with “A* with Landmarks,” improving speed in static and dynamic maps, but it still focused on single-goal optimization and lacked real-time adaptability. Lim et al. [21] proposed a method, called “Evolving Behavior Trees,” which is a GA designed to solve business problems, particularly the multiobjective path-planning problem in the game DEFCON. The algorithm can generate adaptive behaviors based on the game’s dynamic environment and can handle multiple goals. However, its training process may require much time and many resources.

In 2021, Saeed et al. [22] proposed a hybrid method combining GAs, the boundary node method (BNM), and the path enhancement method (PEM) to optimize multi-robot path planning. The solution is to use the GA to optimize the target point sequence and use the BNM to generate an initial collision-free path and finally optimize the initial path through the PEM to reduce the total path length. They demonstrated that the hybrid method can find an optimal and collision-free path in a short time. However, the authors did not test it in large-scale complex scenes, and the premise of their research was that the obstacles in the environment were static, and the environmental information was completely known. This is not always satisfied in practical applications.

In addition to the abovementioned algorithms, reinforcement learning (RL), especially deep reinforcement learning (DRL), has been increasingly used for dynamic path planning in recent years. A recent survey by Zhu et al. highlighted that DRL methods, such as deep Q-networks, proximal policy optimization, and deep deterministic policy gradient, can effectively handle high-dimensional and dynamic environments, providing real-time adaptability and smooth trajectory generation [23]. Huang et al. proposed a multiobjective DRL model for 2.5D off-road terrain planning that balances terrain roughness and energy consumption and is more than 100 times faster than the traditional A* method [24]. However, reinforcement learning-based methods usually require a lot of offline training and are difficult to generalize to new maps or dynamic connection changes.

Similarly, recent studies have proposed several A* extensions, which can natively handle multiobjective or multiheuristic searches, but all show varying degrees of performance loss in the algorithm’s real-time response. For example, Ren et al. proposed EMOA* in 2025, an efficient search-based multiobjective A* framework that can find all unique Pareto optimality paths and analyze runtime complexity with notable performance improvements compared to traditional A* variants [25]. However, they focus on finding the optimal solution in a static graph and cannot handle multiple objectives in real time.

In terms of game frameworks, Santelices and Nussbaum [26] publicly proposed a two-dimensional action video game development framework in 2001, which employs hotspot subsystems and design patterns, such as strategies and template methods, to enhance code reusability and simplify maintenance. The case study showed that the development time of framework-based games was reduced by 70%; however, the approach also incurred a large performance overhead (e.g., frame rate dropped from 14.2 to 8.3 FPS) and lacked adaptability to dynamic content generation, limiting its relevance in game development that requires real-time interaction. Meanwhile, Virtual Reality-Rides (VR-Rides), an immersive VR sports game framework proposed by Wang et al. in 2020 [27], demonstrated its notable advantages in code efficiency and modular design through case studies and code analysis; however, its limitations include limited hardware compatibility and the need to further verify its general applicability to a wider user base.

In addition to classical and hybrid metaheuristics, recent research has focused on energy-constrained and real-time collaborative strategies. Yin and Xiang proposed multistage constrained multiobjective optimization [28], a multiobjective approach addressing energy, safety, and path smoothness constraints in amphibious unmanned surface vehicle operations. Their results confirm the importance of constraint-sensitive heuristics in dynamic marine environments. Their dynamic adaptive priority guidance framework also integrates multi-source fusion and RL for adaptive navigation in perception-limited conditions [29]. These developments reinforce the necessity of real-time, context-aware path planners, aligning with the design goals of our RDMO algorithm.

Based on the abovementioned analysis, the current mainstream algorithms obviously still struggle with real-time processing and dynamic responsiveness. Specifically, current multiobjective path-planning algorithms face the following key challenges:

1. Multiobjective collaboration and tradeoff problem: Existing algorithms have poor processing capabilities for this problem. In finding a balance between multiple objectives, if the balance is appropriate, the planned path can show advantages in multiple aspects (e.g., considering the dual goals of the shortest path and the fewest turns) [30].

2. Dynamic obstacle avoidance problem: Existing algorithms have a good ability of coping with existing obstacles; however, if the obstacles change dynamically, their ability to cope is insufficient. In this case, the algorithms cannot fully ensure that the generated path is safe [7].

3. Computational efficiency problem (real time): The dynamic changes of obstacles are often accompanied by a sharp increase in the amount of calculations. For robotics and games, algorithms must calculate results in real time to avoid catastrophic problems [7].

This study conducts a systematic analysis of the operational constraints in robotic path planning and navigational complexity in gaming environments. Based on the limitations of currently discovered algorithms, we propose the RDMO algorithm, a novel framework enabling a simultaneous optimization of conflicting objectives while maintaining computational efficiency. The RDMO algorithm’s architecture specifically addresses two critical challenges: (1) multiobjective decision-making under dynamic constraints and (2) real-time computational feasibility. The proposed algorithm is rigorously validated using the standard node-link data provided by the Korea National Transport Information Center, OpenStreetMap geospatial data, and a Unity3D simulation environment and is rigorously compared and analyzed with widely employed methods based on GAs and SA-based algorithms. The results comprehensively demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed RDMO algorithm, which addresses a critical gap in the field by successfully balancing real-time performance and adaptability to dynamic environments. Its introduction has notable implications for advancing multiobjective path-planning technologies.

This section introduces a specialized and highly scalable RDMO path-planning algorithm for games.

Herein, we focus on RTS games and analyze the path-planning characteristics involved in gaming, namely, dynamism, real-time, multi-objectives, strategic considerations, and scalability. First, in RTS games, the game map and objectives will change during the game, requiring the algorithm to adaptively recalculate the path [31]. Therefore, dynamism is a major game feature. Second, the game playability requires the algorithm to calculate the optimal path within a strict time limit to avoid game lag [32]. Hence, the game has extremely high requirements for real-time performance. Third, in the game, players must manage multiple units and assign them to different target locations, requiring that effective path planning must simultaneously consider factors like the distance between each target, terrain obstacles, and location of enemy units. Multi-target becomes another major feature. In addition, as an RTS game, the game’s path planning should consider more factors besides the shortest path from point A to B. It must also consider terrain, enemy units, and other strategic factors to select the optimal path. The algorithm should integrate and use this information to make wise decisions [33]. This is considered to be the algorithm’s strategic consideration. Finally, as the scale and complexity of the game increase, path planning must effectively cope with the challenges brought by large-scale maps and numerous units. This requires the algorithm to have a certain degree of scalability and be able to cope with more challenges in the future [34].

Based on the abovementioned characteristics, we first established the core design principles required for game-specific path-planning algorithms. Crucially, the algorithm must support the real-time management of both dynamic movement targets and computational objectives. These two are fundamentally different yet interrelated concepts. The calculating and moving targets are two completely different concepts. To give a simple example, during the calculation process, the path length, the path’s travel time, and the calculation time are all computational goals pursued by the algorithm. During the game object movement, new game missions, game clearance, or target locations and points that change due to player behavior are all moving targets. A good algorithm development must start with a rigorous design. Based on the game analysis, the design criteria for the path-planning process applied to the game must accurately and effectively reflect the abovementioned goals.

Building on the algorithm design guidelines summarized after analyzing the game characteristics, we propose a queue-based composite multiheuristic algorithm that employs a queue structure to dynamically manage the addition and deletion of multiple objectives in real time, perfectly meeting the game’s dynamism and real-time performance requirements. The algorithm incorporates multiple heuristic functions to enhance strategic decision-making and allows for modular scalability to handle increasing game complexity. The algorithm’s design considers specific game features, making it a groundbreaking innovation in multiobjective path planning dedicated to gaming applications.

According to our algorithm design, the multiobjective path-planning process for games can be summarized in the four following steps:

(1) Acquire objectives and generate a target queue.

(2) Path planning for the objectives in the queue:

A. Obtain the position of the nodes in the queue, and calculate the weighted heuristic function

B. Retrieve the node with the minimum heuristic value from the queue as the next target node, and generate the action path to reach that node.

C. Repeat steps A and B to generate a complete multiobjective path for character movement.

(3) Reorganize the target queue upon reaching the target location.

(4) Repeat steps 2 and 3 in real time to generate/update multiobjective movement paths for game player characters and NPCs.

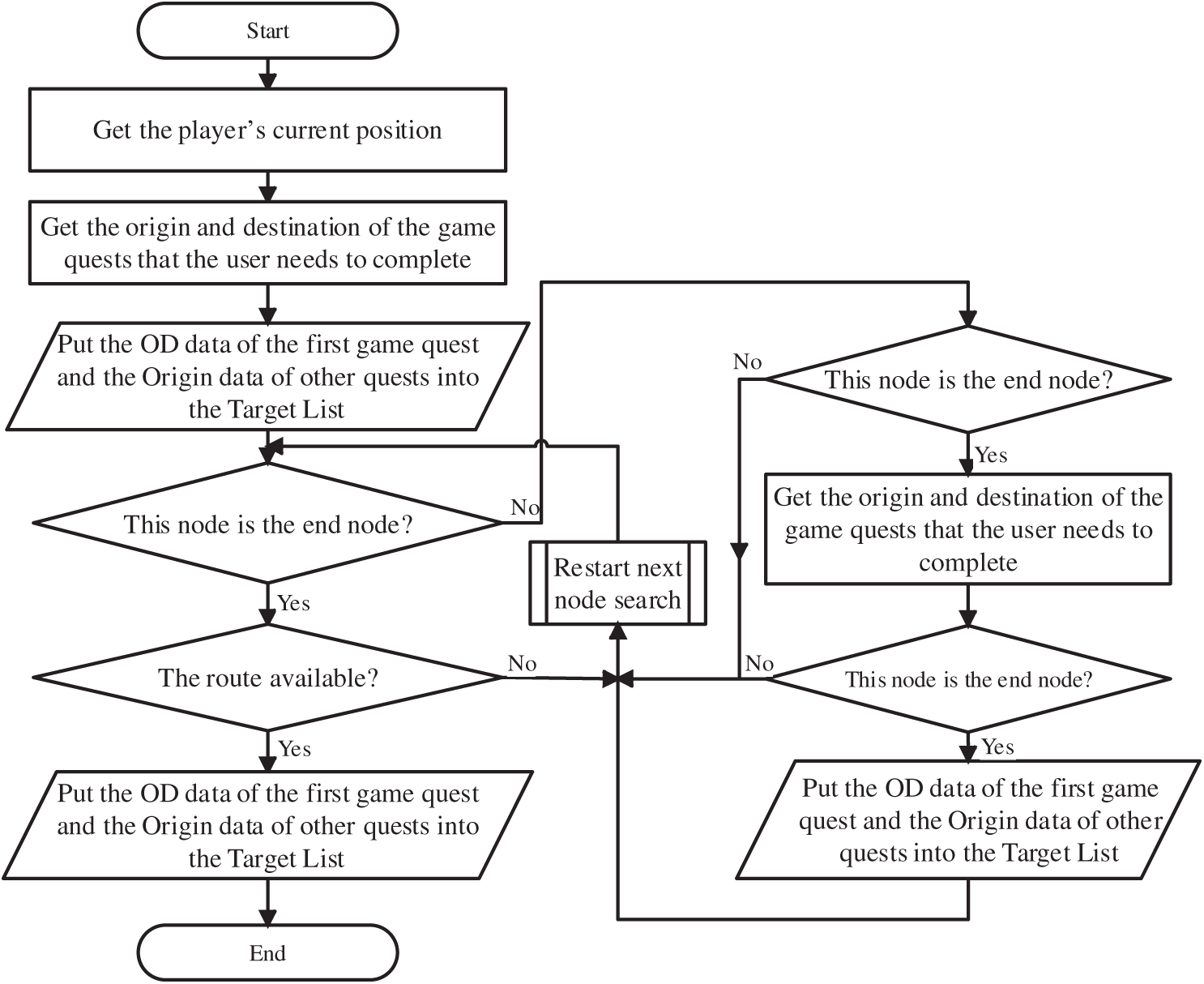

According to the abovementioned processing process, it can be drawn as an algorithm flowchart (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Flowchart of the RDMO algorithm. Note: The flowchart illustrates the iterative process of multiobjective path planning, including target acquisition, heuristic evaluation, queue update, and real-time replanning upon environmental changes

In the steps above, notably, all node processing occurs during the game character movement (players and nonplayers). As the gameplay progresses, the map connectivity and the number of targets for path planning continuously change due to player interactions. Consequently, whenever the user modifies map connectivity or adds/deletes target nodes, the algorithm is triggered in real time to update the paths and ensure that game characters always follow the latest and optimized paths. This handling approach ensures that characters move without crossing through other game units and that their paths remain consistent with the map connectivity, thereby preserving the game’s playability and immersive experience.

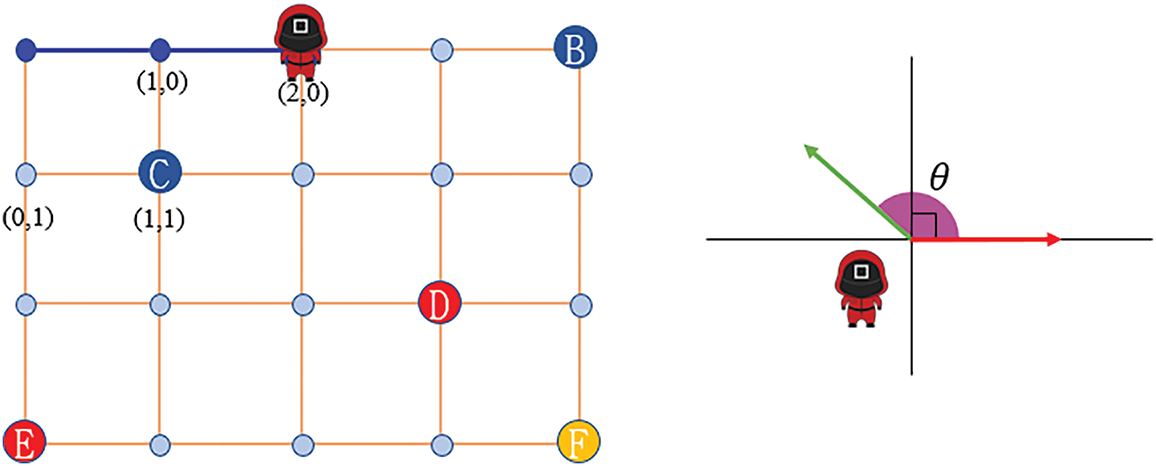

In games, maps are often represented in grid form. These grids typically comprise multiple equal-sized squares or hexagonal “cells,” each representing an area or location on the map [35]. This representation method is highly effective for handling game spatial relations and movement issues. The grid map allows for a clear and intuitive representation of the environment and the object positions. Game characters and other objects are placed in specific cells on this map. Movement is usually represented as transitions from one cell to another. Therefore, when moving on a grid-based game map, a comprehensive understanding of the connectivity between individual grid cells is important. To achieve this, the game program constructs a corresponding map-weighted network before conducting path planning. This network enables a real-time reflection of the connectivity between grid cells in the map.

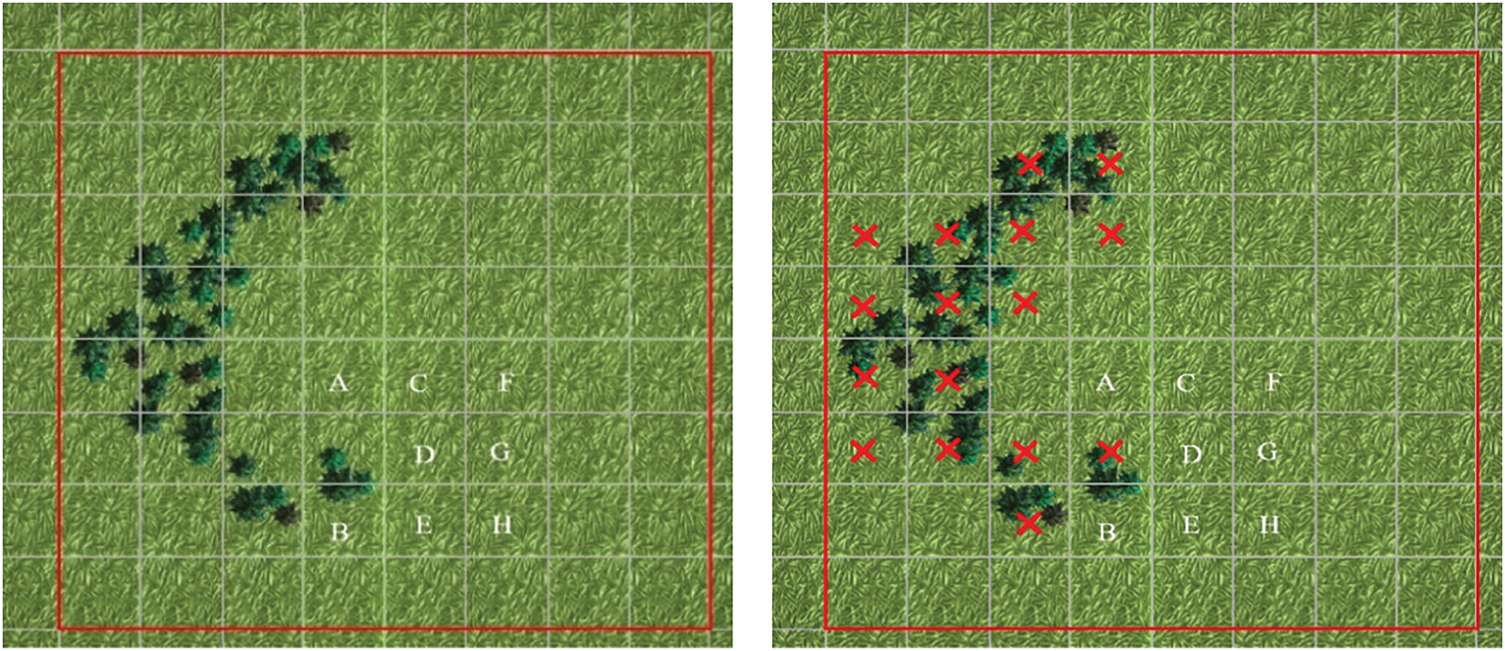

For example, considering the 8 × 8 map in Fig. 2, we use “x” to represent the tree locations in the game. Using

Figure 2: Game map based on square cells

After the mentioned processing steps, a numerical map-weighted network is constructed, with the weight values based on the shortest movement time. This step is the first and crucial part of the RDMO algorithm process, reflecting the real-time connectivity between map grids. From the basic data level, it ensures the accuracy of the path planned by the algorithm in real time. This step is critical to ensure the accuracy of the generated paths.

3.3 Queue-Based Real-Time Processing of Game Quest

In the game, we first define a job that must be completed in the game as a game quest, and a quest contains only one game instruction. Thus, one game quest only represents one movement command. Second, as mentioned, the algorithm comprises two core components: the queue-based design structure and the compound multiheuristic function. These components ensure the algorithm’s dynamic nature, real-time capability, and scalability. To be precise, the queue structure used in this study is not a purely traditional queue.

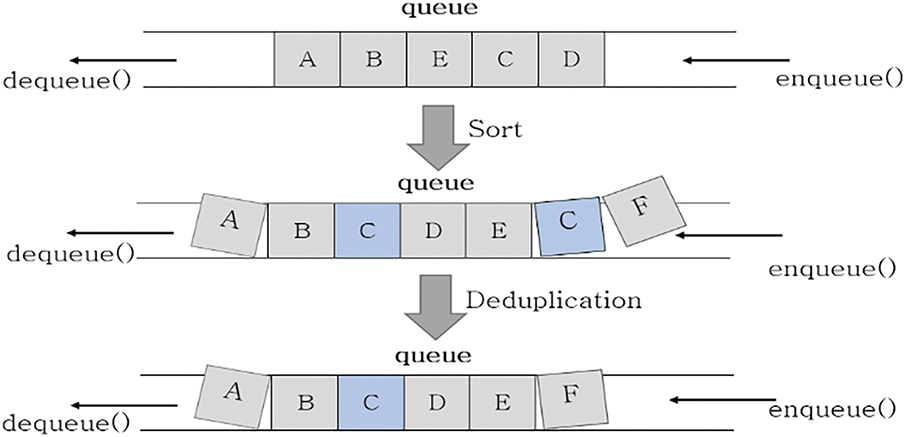

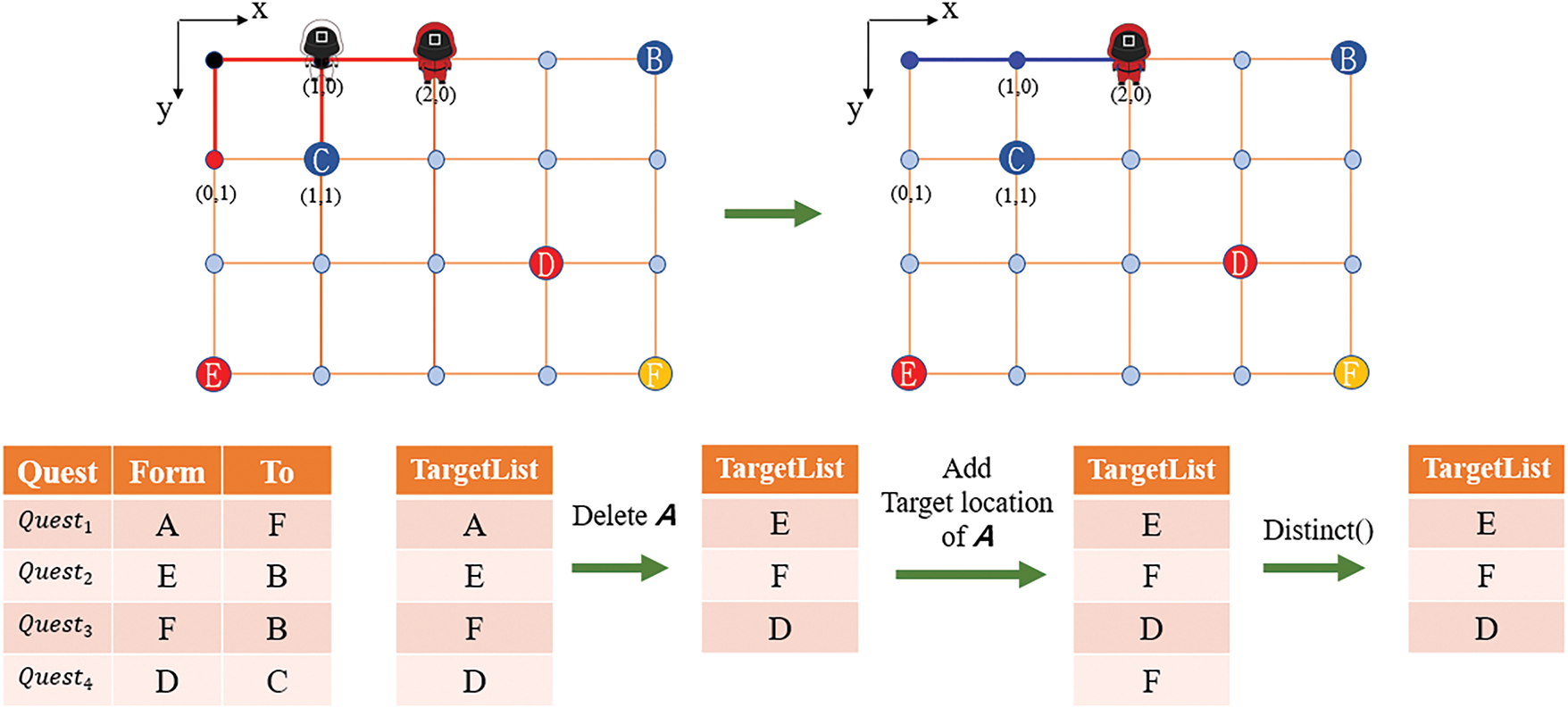

A standard queue is an abstract data type that follows the first-in-first-out (FIFO) principle, allowing insertion at the rear and deletion at the front. However, in our algorithm, as shown in Fig. 3, we adhere to the “FIFO” principle while incorporating the “sort” and “deduplication” functionality within the queue. The sorting process determines the priority of movement between multiple targets. Although the process description may seem simple, it is not a single-step process but rather an important part of the entire path-planning operation.

Figure 3: “Sorting” and “deduplication” processes

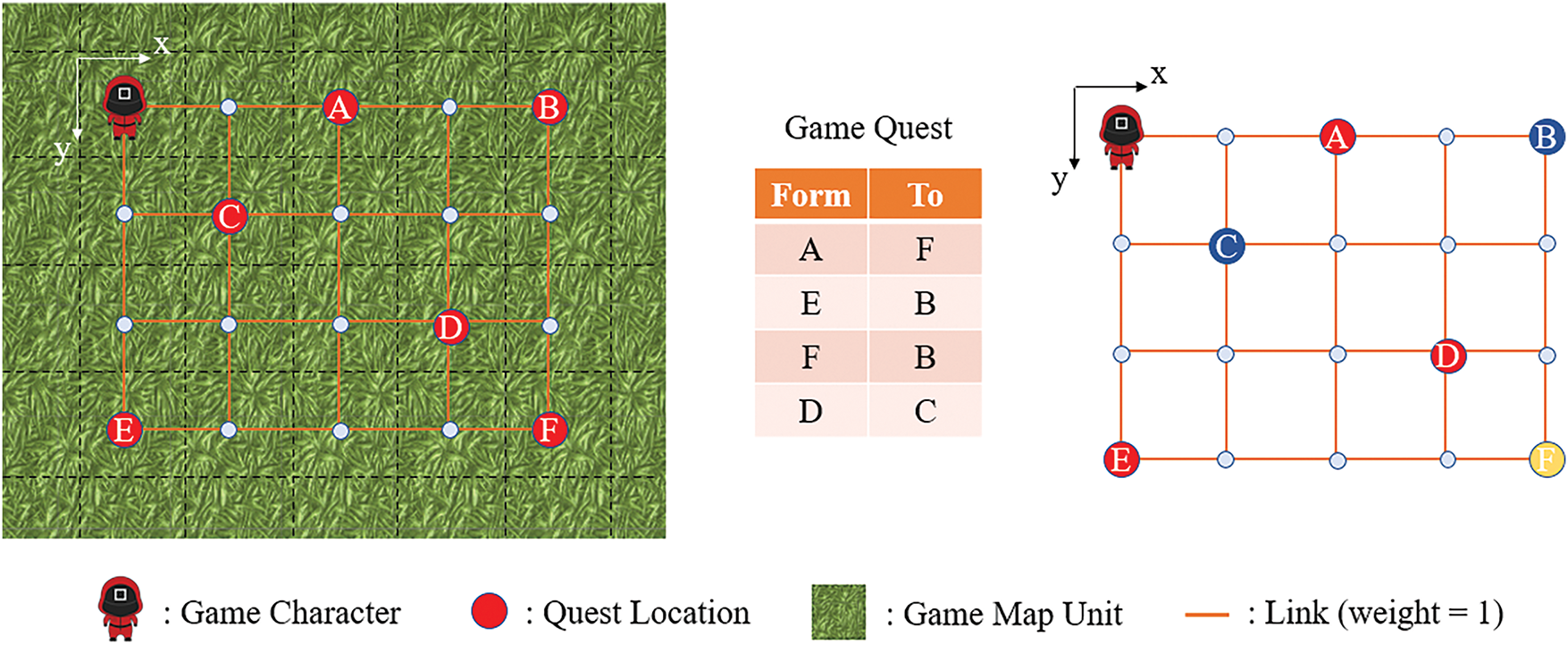

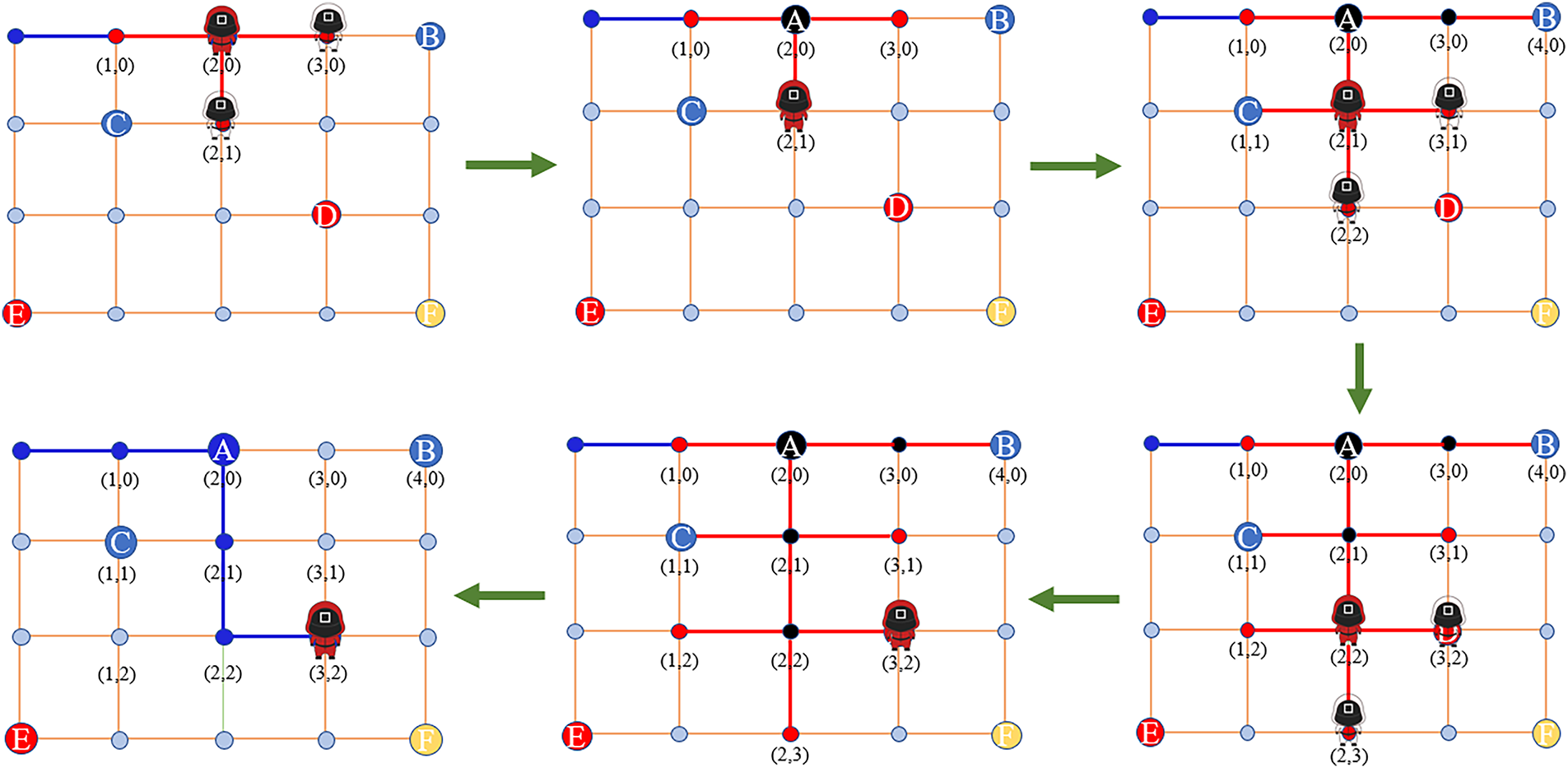

In the queue-based structure design, the “sort” and “deduplication” processes are integral to the second and third steps of the algorithm, respectively. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the game map comprises square map units, with the game characters always positioned at the center of the map units, regardless of their movement. Suppose there are four task sets in the current game, where the game player must move from position

Figure 4: Game quests displayed on the map

During real-time demand processing based on the queue structure, we refer to the target queue as “

1. Add the target position

2. Remove the starting position

3. Perform duplicate removal on the positions saved in

Consequently, after the game character receives “

Figure 5: Queue processing while the algorithm is working

During this process, each time the NPC moves to a node, the algorithm will perform operations on the target positions saved in the

3.4 Multiobjective Heuristic Functions

In path planning, after solving the issue of determining the next target position for the NPC to move to, the algorithm must consider which path to take from the current location to the next node. The proposed RDMO algorithm in this study employs a composite multiheuristic structure to address this requirement.

As known, the A* algorithm is widely used in both real-life and game scenarios, and many A* algorithm variants have been developed to solve specific problems. In practical applications, when multiple conditions must be considered for path planning, the multiheuristic A* algorithm [36] is usually the first choice because it can handle general requirements simply and efficiently. For example, Mi et al. proposed a new multiheuristic A* algorithm in their study, which effectively solved the obstacle avoidance path-planning problem of a manipulator in complex situations [36]. Inspired by the path-planning solutions under multiple conditions, we introduce the multiobjective concept in the RDMO algorithm. Like multiheuristic, the multiobjective approach employs multiple heuristics to balance various conditions from different perspectives to generate a path toward a single target position. However, the critical difference lies in adding multiple objective positions in the heuristic function in the multiobjective concept. Through the heuristic function, the moving nodes are determined to create a complete path for the NPC’s movement. Therefore, based on the multiobjective concept, the function of the proposed RDMO algorithm can be described as follows:

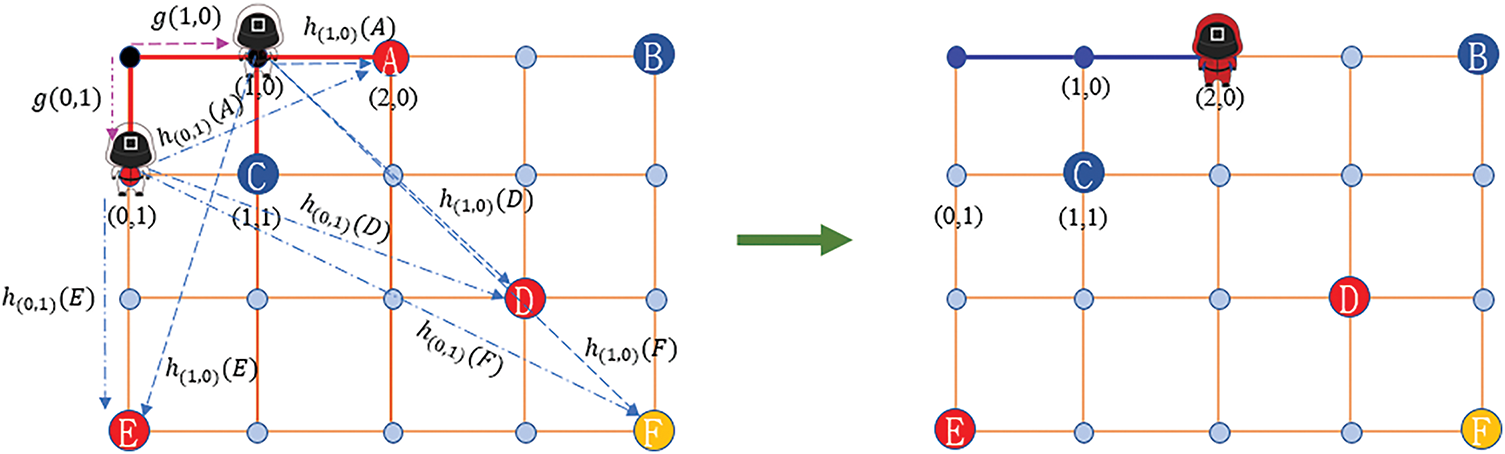

In the moving process shown in Fig. 5, when the NPC moves from the origin to the first target position A, the algorithm determines the final path as (0, 0) -> (1, 0) -> (2, 0). During the calculation of path generation (Fig. 6), since the adjacent and connected nodes to the starting position (0, 0) are (1, 0) and (0, 1), respectively, the algorithm calculates the estimated cost

Figure 6: Multiobjective predictor function as heuristic

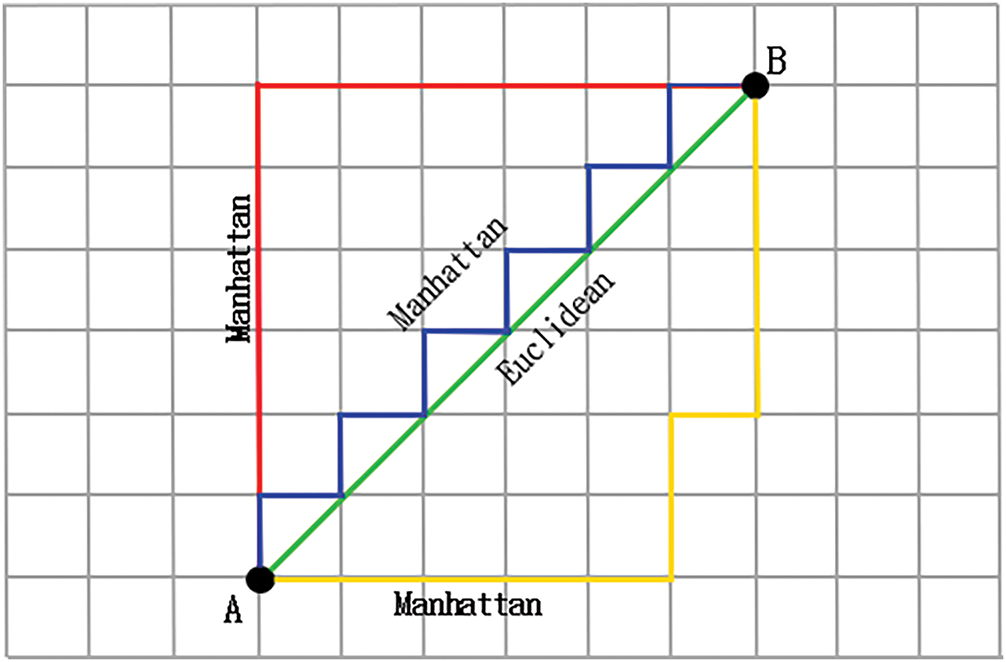

The abovementioned description shows that the estimated cost function

Figure 7: Polymorphic path with the same Manhattan distance. Note: The red path has fewer turns than the yellow and blue ones; thus, it has a lower total cost under the proposed turn-weighted heuristic

Figure 8: Trend graph of the function

In Fig. 9, when the NPC is located at (2, 0) in the figure, it will face three optional situations, that is, (1) toward (3, 0), moving forward horizontally, (2) toward (2, 1) turn downward, and (3) toward (1, 0) turn back. In these three situations requiring turns, the worst-case scenario involves a 180° turn, where the movement direction is opposite (i.e., turning back toward (1, 0)).

Figure 9: Situation faced by the game character when moving to the next map unit. Note: Illustration of possible movement directions for an NPC at position (2, 0). Option 1: forward to (3, 0); option 2: turn downward to (2, 1); and option 3: 180° turn back to (1, 0). Among these, the 180° turn is penalized under the turn-weighted heuristic

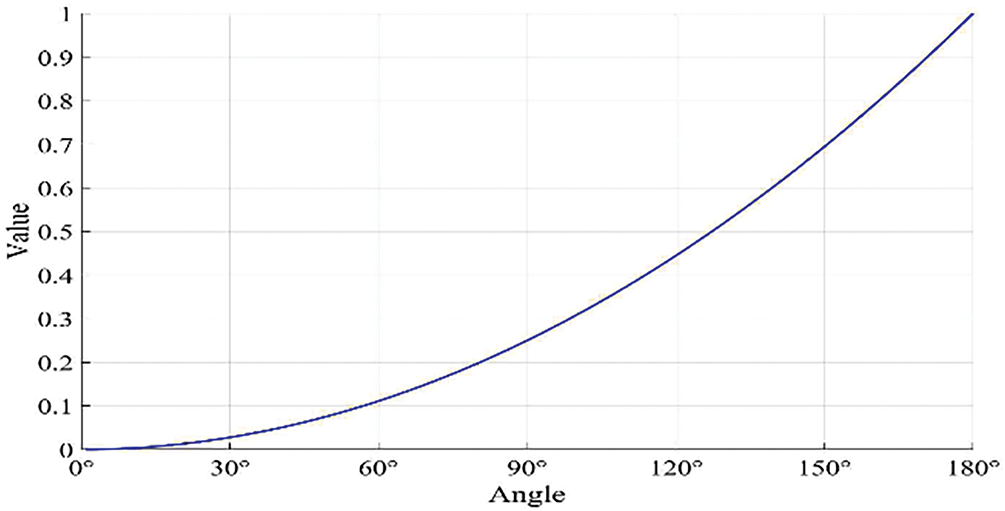

In the mathematical model, as shown in Fig. 8, the parabolic function

The main purpose of using the abovementioned turning weight function is to avoid turns in the path. The reason for selecting function

First is admissibility. The heuristic

Second is consistency. A heuristic is consistent if for every node

Together, these properties ensure the optimality and the correctness of A*-based search under the RDMO framework, even with the inclusion of multiobjective heuristics. The algorithm proposed in this study has a modular structure; therefore, we can add multiple oriented calculation targets to the turning weight function of the algorithm to achieve a tradeoff between multiple moving targets and multiple calculation targets. For example, in the test of this study, we mainly used the path length, calculation time, and the number of turns mentioned as calculation targets, and planned the optimal mobile path in three directions.

In summary, during the path-planning process, in conjunction with the queue-based processing structure and the multiobjective heuristic function, the algorithm searches for the next target position from the origin (target position

Figure 10: Exploratory process for path planning

In addition, notably, in our implementation, the dynamic changes of the environment are modeled by modifying the map connectivity matrix in real time. This includes the addition or removal of links between nodes, simulating dynamic obstacles, such as collapsing structures or temporary barriers. Although moving obstacles (e.g., patrolling NPCs) are not explicitly modeled as mobile agents, the random updates of the connectivity matrix every 2–3 s in simulation approximate the effect of frequent environmental changes. The algorithm immediately reacts upon detecting these changes and updates the path accordingly, preserving real-time responsiveness.

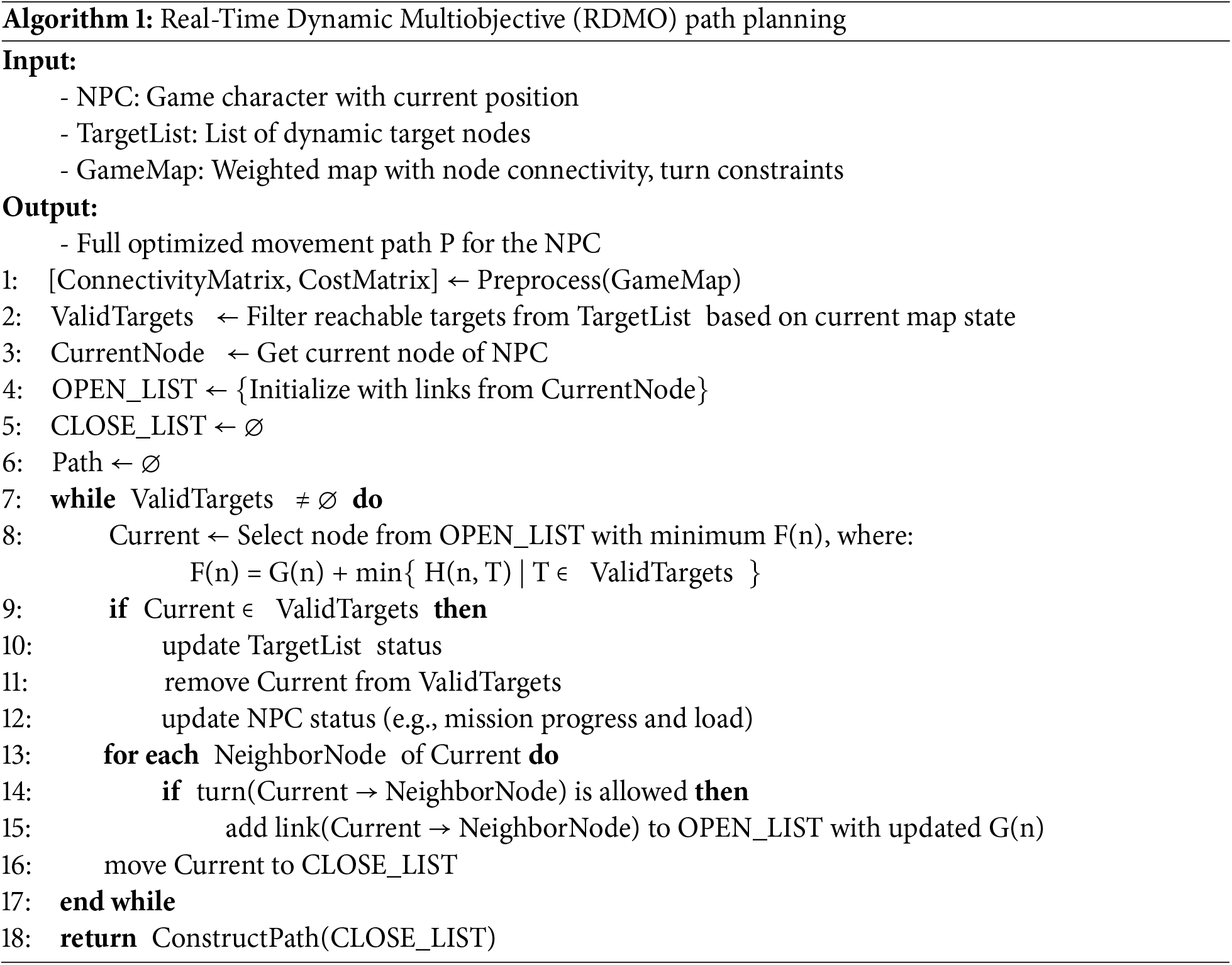

3.5 Pseudocode Implementation of the RDMO Algorithm

We enhance the reproducibility and the clarity of the proposed RDMO algorithm by presenting its core logic in the form of structured pseudocode, as shown in Algorithm 1. This pseudocode describes how the algorithm dynamically manages path planning in a real-time gaming environment, in which player movements, game tasks, and map connectivity may change at any moment.

The main RDMO algorithm procedure starts by initializing a TargetList that includes the player’s start node, destination node, and the start nodes of all current game quests. In each iteration, the algorithm selects the next optimal node to visit by evaluating a multiobjective heuristic function across all candidates in the TargetList. It then generates a sub-path from the current location to the selected node using our proposed multiobjective A* search that incorporates both traditional distance and additional factors, such as turn penalties. After reaching the selected node, the algorithm updates the TargetList, removes completed nodes, and continues this process until the list is exhausted. If new quests appear or the map connectivity changes, the algorithm adapts in real time. The pseudocode is given as Algorithm 1 follows:

To effectively and objectively evaluate the proposed RDMO algorithm in this research and achieve a higher level of realism in the game, we have chosen to test the algorithm in a game environment based on real-world maps. The real-world maps for testing are selected for two main reasons. First, in pursuit of a more immersive gaming experience, many large-scale games nowadays are designed based on real-world maps to enhance player engagement. Second, this RDMO algorithm is explicitly designed for multiobjective path-planning in-game maps comprising simple grid units. However, real-world road networks are often more complex, with intersections and multiple paths converging at a single node. Therefore, testing the algorithm on real-world maps is essential for assessing its robustness and stability when faced with more challenging and realistic road configurations.

We aim to ensure the algorithm’s reliability and stability in various scenarios by conducting simulation testing on real-world maps. This testing approach provides valuable insights into the algorithm’s performance and scalability in handling complex road networks. Additionally, it helps verify the algorithm’s ability to adapt to diverse and dynamic game environments, contributing to its overall effectiveness and practicality for real-time path planning in gaming applications.

While some A* variants can excel in single-objective dynamic environments through heuristic adaptation, they lack the support for multiobjective optimization. Direct extension would require fundamental changes to the problem formulation compared to our Pareto-optimality-based approach. To the best of our knowledge, no established A* variant has yet been specifically designed for true multiobjective optimization in literature.

4.1 Test Data and Evaluation Criteria

In this research, we used standard node-link data provided by the Korea National Transport Information Center to construct a database centered on the road network data of Busan, Korea. This database is a relational database based on MySQL. The region’s map was imported into Unity for testing. The choice of Busan as the test area is twofold. First, Busan has the most complex road network among all regions in Korea [37], making it a representative and challenging area for testing the algorithm’s performance (after importing the standard node-link data into the database, we found that there are 1,318,573 road nodes and 2,714,488 road links in the database). Second, to achieve a more realistic gaming experience, many large-scale games now incorporate real-world maps to enhance player immersion. As such, testing the algorithm on real maps helps validate its effectiveness in handling more complex and realistic road configurations. We ensure the real-time and dynamic adaptability of the algorithm by designing dynamic test sets that invoke the algorithm in real-time scenarios to evaluate its ability to handle a varying map connectivity and perform path planning in real time.

Regarding the selection of comparison algorithms, in most studies focusing on multiobjective path planning, optimization algorithms like ACO, GA, and SA are commonly used in combination with the A* search algorithm to find paths. Therefore, the comparison objects in such studies typically include one or more of these three algorithms. For instance, Anna, Bertha, and Gilang conducted a comparison study of metaheuristic algorithms in their 2017 paper [38]. They compared GA, ACO, PSO, and SA using two different case scenarios to assess their performance. Similarly, Gong and Fu [39] proposed a new solution based on the ant colony optimization algorithm (ABC-ACO) to solve the routing problem of perishable goods vehicles and compared it with the solution based on the traditional ACO algorithm. The results showed that the ACO algorithm increased the speed by >20% and reduced the cost by ~16%, making it a representative successful case. In addition to traditional metaheuristic algorithms, some recent algorithms, such as IMTCMO, emphasize task-constrained collaboration across multiple platform types. Although these methods are very effective in stable environments, they may lack the ability to respond to real-time changes in connections [40]. Meanwhile, Duan et al. proposed improved methods, such as INSGA-II, to balance path length, safety, and energy consumption [41]. However, these algorithms usually focus on offline optimization and also lack the ability to respond in real time; thus, this study also did not use them as comparison objects. Drawing from these previous studies, we selected GAs and SA-based algorithms as the comparison objects for this research.

As for the evaluation criteria, different studies often employ other metrics for assessment. Herein, we evaluated three main aspects: the length of planned paths, the difference between dynamic path variations before and after changes, and the time spent on path planning. These choices are based on three considerations. First, given the real-time and dynamic nature of this research, comparing the differences in path length before and after the changes is essential when game players accept new quests or demands that lead to dynamic changes in requirements. Second, to meet the game’s real-time requirements, the algorithm’s calculation speed must reach a certain standard to keep up with the dynamic environment. Thus, the time spent on path planning is also a critical evaluation metric. Lastly, the selected evaluation criteria are simple yet representative indicators that align with previous research results. For example, in the research by Keiichi et al. [42], the primary evaluation criteria include travel distance and travel time. Meanwhile, Yoon et al. [43] focused on service rate, average travel time, average detour time, average walking time, and computation time. Referring to the research results of other researchers, combining insights from previous studies, this research selected the three abovementioned aspects for evaluating the algorithm’s performance.

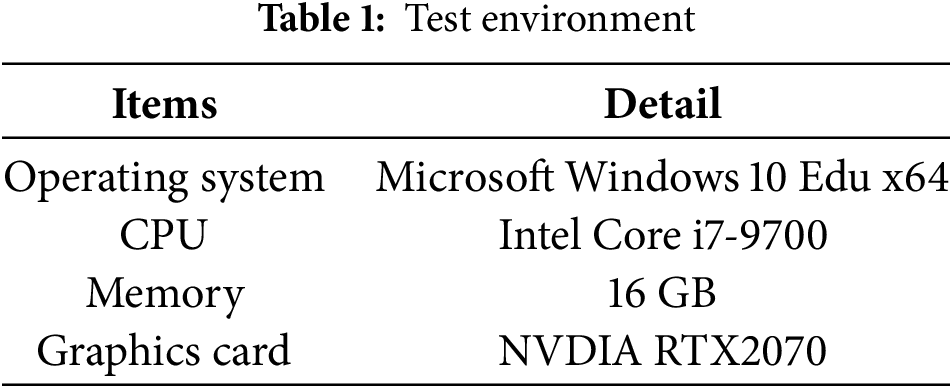

4.2 Test Environment and Parameters

In this study, the simulation testing was conducted on a Windows 10 Education x64 environment with the hardware configuration (Table 1). The input data for testing comprised the road network data of Busan, along with 20 sets of game quests. During the path planning for these 20 game quests, the map’s connectivity was randomly modified to test the algorithm’s robustness.

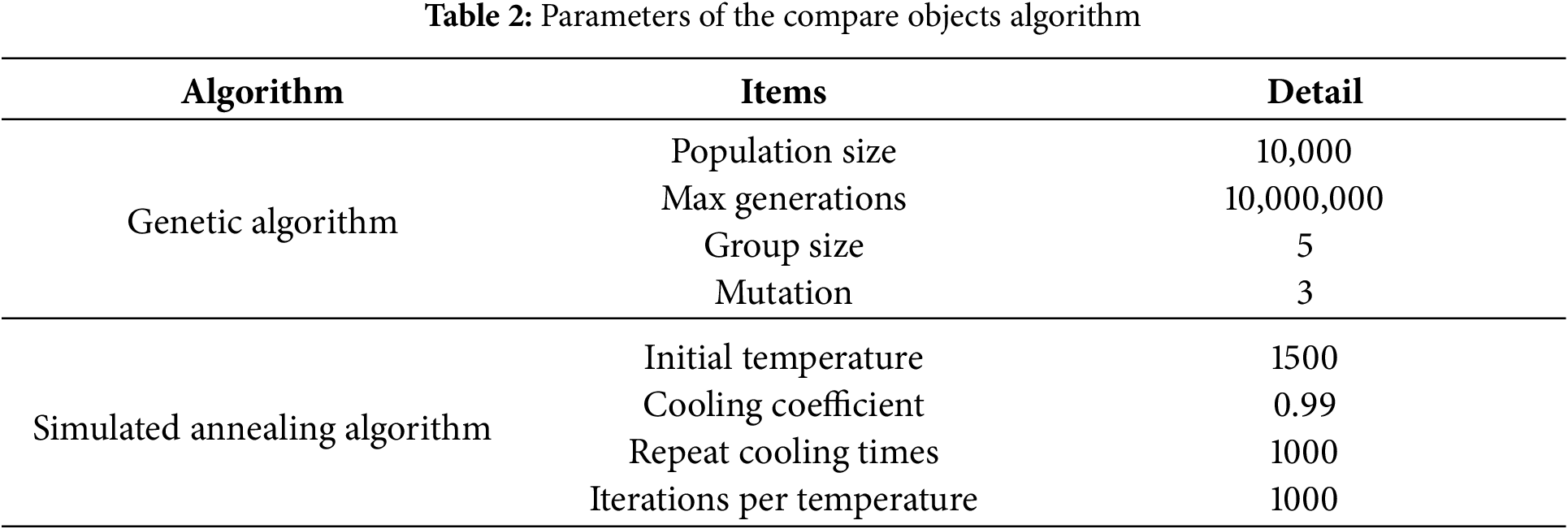

For the selected comparison subjects (GA and SA-based algorithm), we implemented them directly after referring to the work of Anna, Bertha, and Gilang on the metaheuristic algorithm comparison. Regarding the parameter settings, we conducted testing and comparison using the population size, number of generations, crossover rate, and mutation rate (Table 2). The initial temperature, cooling rate, and number of iterations at each temperature for the SA-based algorithm are also found in the same table.

We adopted a grid search strategy during the pre-testing phase to ensure a fair and robust parameter selection for GA and SA. We specifically predefined the candidate ranges for key parameters, such as population size, mutation rate (for GA), and cooling coefficient (for SA), and conducted 10 rounds of pre-tests using the same dataset. Among these test results, some planned paths are too long (237.4% longer than the shortest path), and some calculation speeds are too slow (58.2% slower than the fastest algorithm); however, some results perform well, which can ensure that the length of the planned path is the shortest, and the calculation speed is not too slow (the calculation speed is 1.3% slower than the fastest speed). The algorithm parameters in Table 2 have better results in terms of planned path length and calculation speed. Among 10 tests, the GA has the shortest path length and the second fastest calculation speed. The path length of the SA-based algorithm is similar to the GA, 2 km longer than the path length of the GA. The calculation speed is the fastest among 10 comparisons. Based on this, we finally determined the parameters to be used by the algorithm and tested and compared it with the algorithm proposed in this study.

First and foremost, during the testing process, we found that both GA and SA often require lengthy and iterative computations to plan more optimal paths. However, in the context of real-time path planning in games, generating new paths quickly is a fundamental requirement for game AI. Balancing these conflicting requirements is essential. Thus, in the testing conducted in this study, we primarily evaluated the algorithm’s results within 10 s of the computation time.

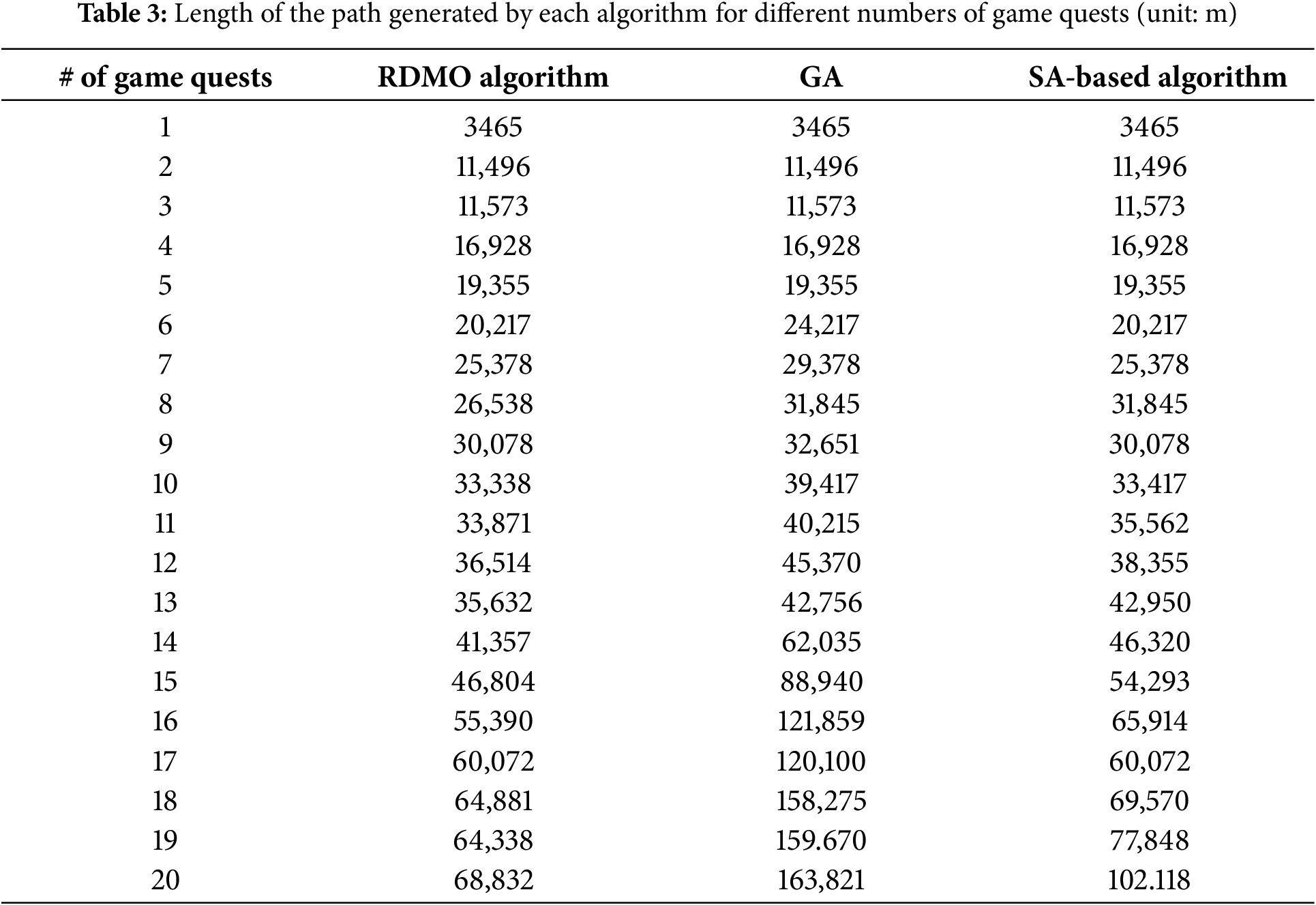

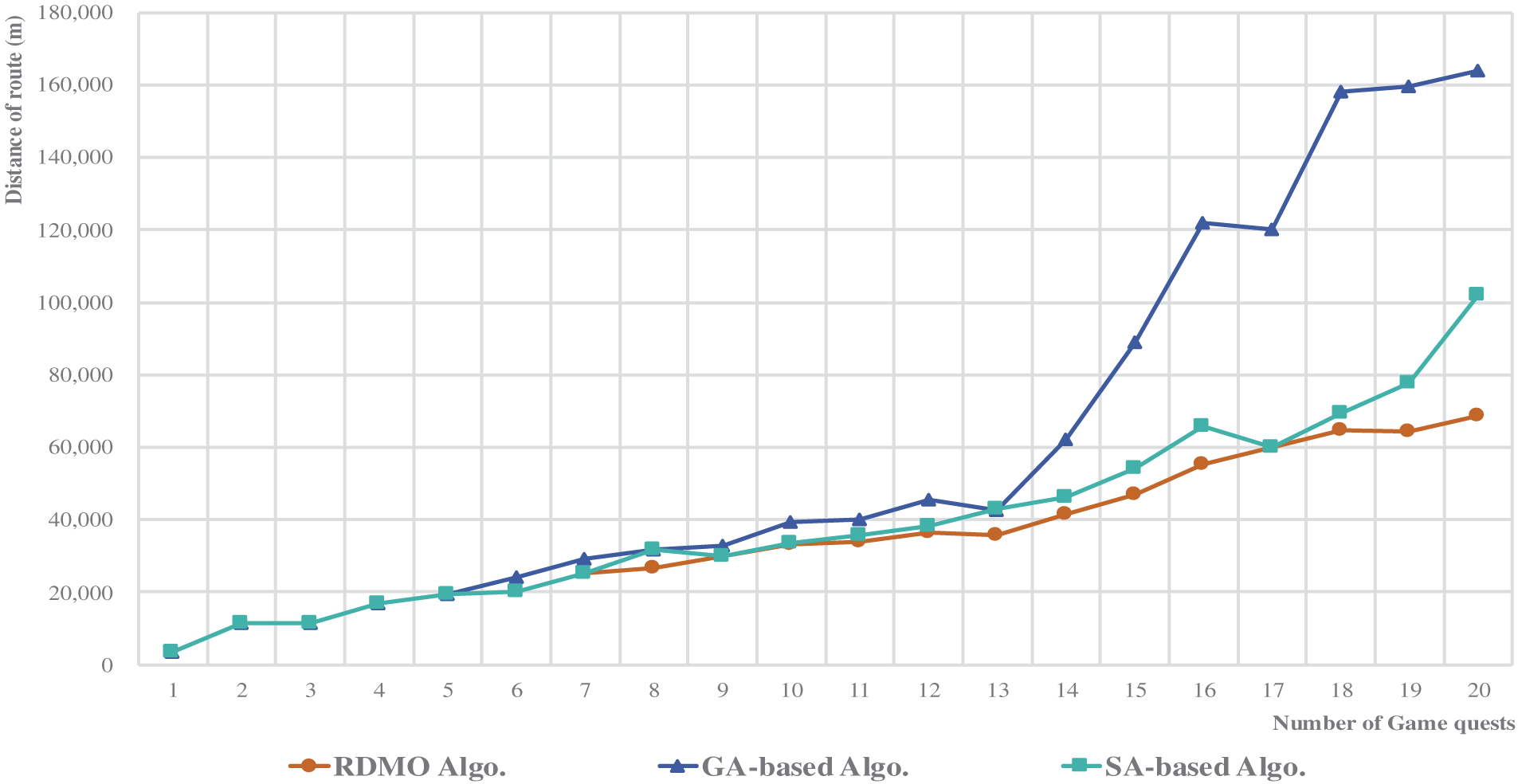

The test results in Table 3 depict that the paths generated by the proposed RDMO algorithm demonstrate an outstanding performance in relation to the path length. The paths generated by this algorithm achieved the optimal results regarding the path length while meeting the game quest requirements, whether for a single game quest or a sequence of 20 game quests. Specifically, when analyzing the paths for 5, 10, 15, and 20 game quests, the algorithm’s planned path length was reduced by 0, 6079, 42,136, and 94,898 m, respectively, compared to paths generated by the GA. Similarly, in comparison with the path lengths generated by the SA-based algorithm, the results almost exactly matched those of the proposed RDMO algorithm, with only a slight difference of 1075 m in the path length when handling the 16th game quest simultaneously.

Looking at specific path examples in Fig. 11, the path results obtained from the GA are remarkably astonishing. Particularly, after the addition of the eighth game quest, the differences between the proposed RDMO algorithm and the paths planned by the SA-based algorithm gradually became evident, and the path length discrepancies continued to widen with the increasing number of game quests. After adding the 20th game quest, the disparity between the RDMO algorithm and GA became substantial, where the RDMO algorithm generated a path length of 68,832 m. In comparison, the GA yielded a path length of 163,821 m, resulting in a 1.38-fold reduction

Figure 11: Relation between the number of game tasks and the generated path length

However, it is imperative to underscore that relying solely on the path length as the sole determinant of algorithm excellence is inadequate. A comprehensive and objective evaluation of the algorithm necessitates the consideration of additional evaluation criteria. In gaming scenarios, victory often hinges on factors beyond the path length, such as accomplishing game quests ahead of opponents or reaching designated locations earlier (e.g., battlefield positions in shooting games). Applying the algorithm to general NPCs would considerably enhance their intelligence and strategic capabilities, consequently heightening the game’s overall difficulty. Players must devise game strategies that outperform NPCs or complete quests faster than NPCs to secure victory. Therefore, the RDMO algorithm introduces an innovative solution to address the predictability drawbacks of game AI to a certain extent.

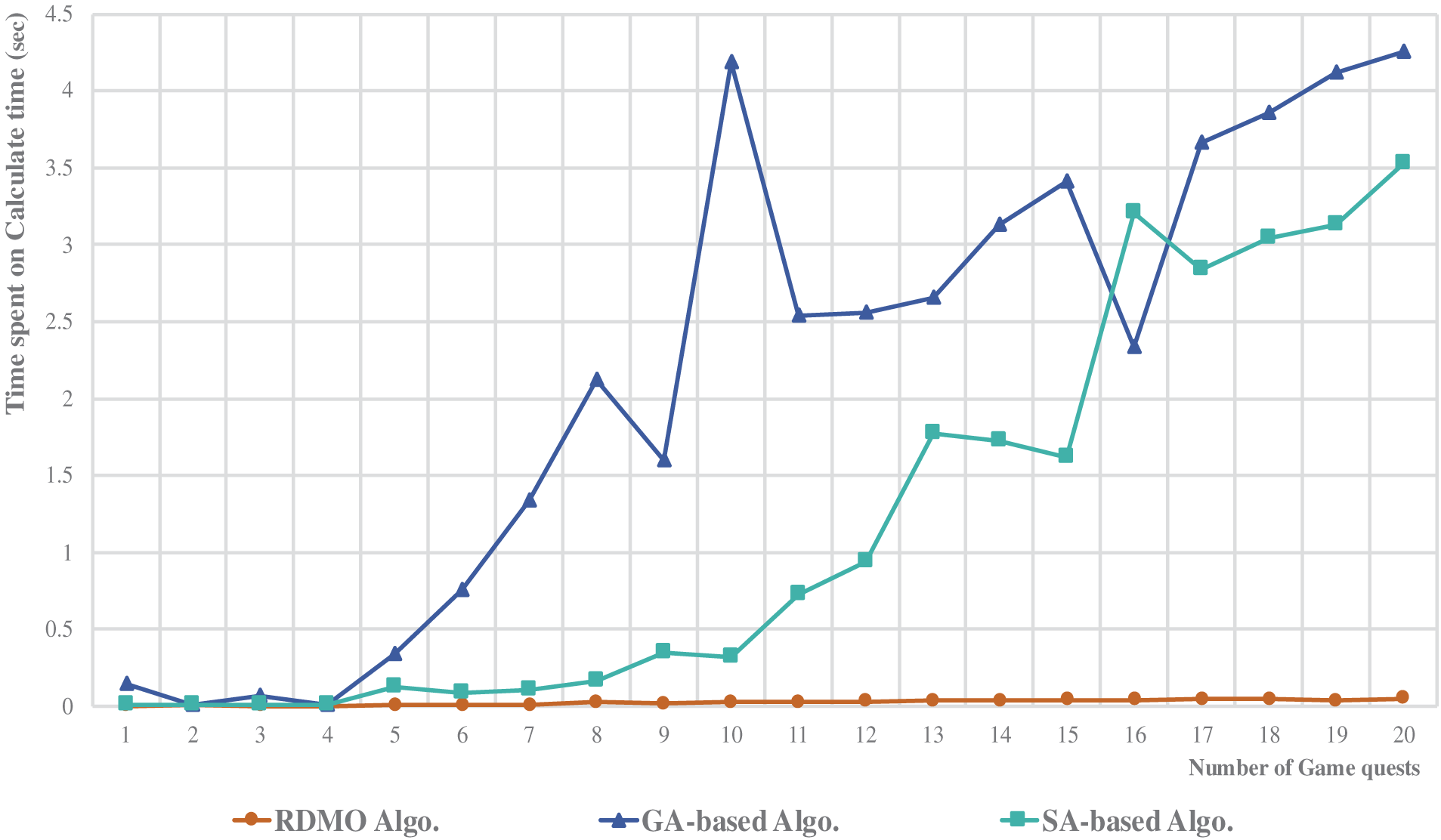

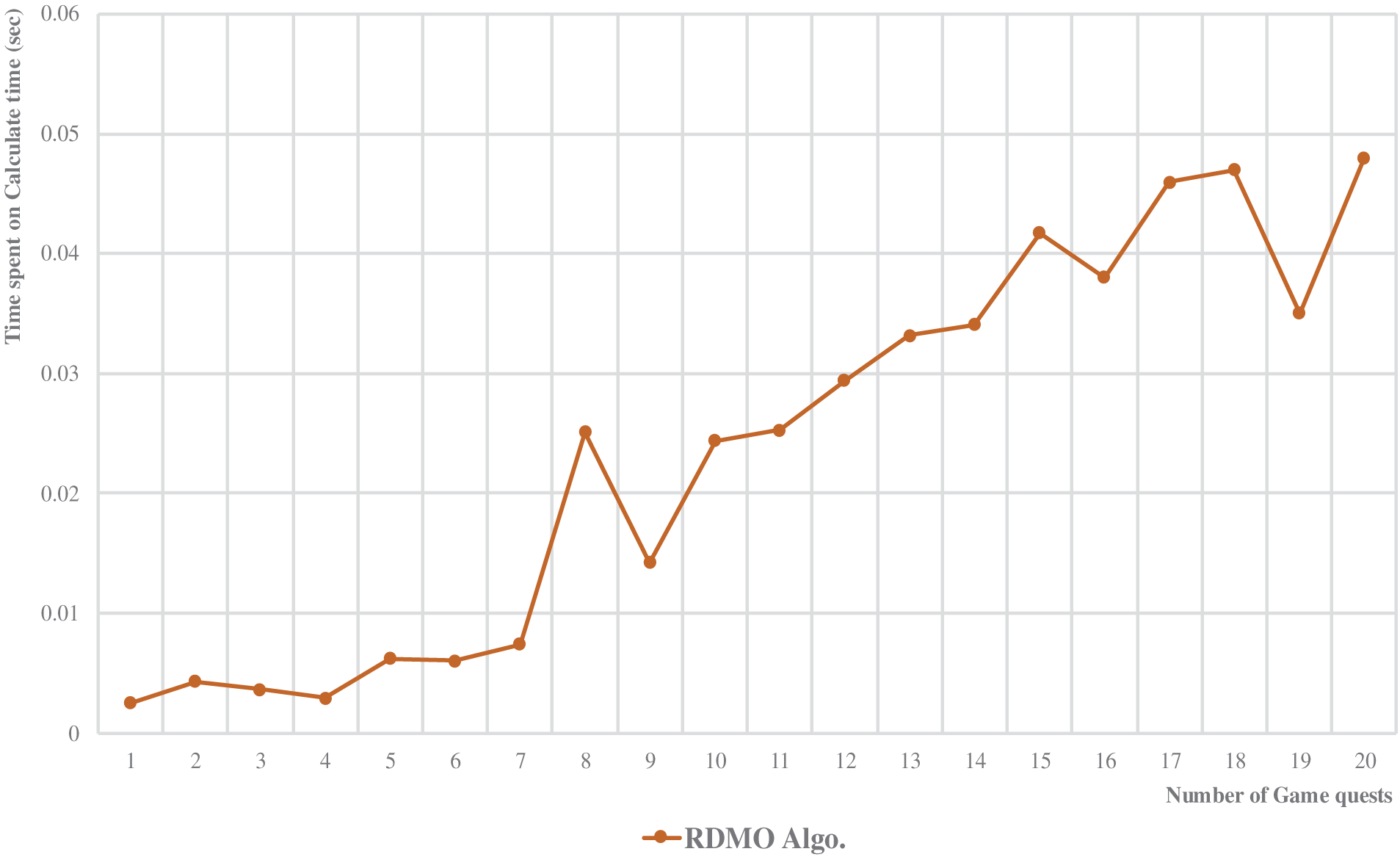

Regarding the time spent on multiobjective path generation, as shown in Figs. 12 and 13, the RDMO algorithm proposed in this study exhibits remarkably short processing times (within 0.05 s), regardless of the number of game quests. Compared with the GA- and SA-based solutions, the RDMO algorithm’s trend in the graph of game quest count vs. path-planning time remains almost entirely horizontal. By contrast, the GA- and SA-based algorithms display fluctuations in their processing times, with the GA approaching the upper limit of computation time during processing (where we set the algorithm’s computation time to be within 10 s, aiming for the optimal value).

Figure 12: Time spent on three algorithm calculations

Figure 13: Time spent on the RDMO algorithm calculation

We know that in both the GA- and SA-based solutions, the time spent on path planning does not linearly increase as the number of game quests increases, as one might expect. Instead, our measurements revealed a pattern of overall growing trends with fluctuations rather than a straightforward linear increment. Analyzing the generated results, we found that this phenomenon is primarily attributed to the nature of GAs and SA-based algorithms.

Both GAs and SA-based algorithms belong to the class of probabilistic optimization algorithms characterized using randomly generated initial values during computation. These algorithms continuously update their results through a predefined number of iterations based on initial values, thereby approaching the optimized solution. The inherent stochastic nature in the initialization process can lead to observed fluctuations in the computational times of both algorithms. Meanwhile, the RDMO algorithm exhibits a more stable and efficient performance. Its unique heuristic function design and queue-based processing structure reduce the computational burden and maintain a consistent processing speed, even with the increasing game quests.

In this process, if the algorithms initially randomly generated starting point is already close to the optimal solution, it only requires a short iterative computation to quickly converge to the global optimal solution, resulting in the most optimized path plan. However, when the initial value falls far from the optimal solution or has notable differences, the algorithm’s convergence process becomes more time-consuming, and the required computational resources increase accordingly, explaining why both GA- and SA-based algorithms demonstrate fluctuating computational times. In the trend graph of the number of game quests vs. the computation time, in some instances, algorithms spend more computation time with fewer game quests compared to when there are more game quests (e.g., in case of GA with 10 and 11 game quests and SA-based algorithm with 14 and 15 game quests).

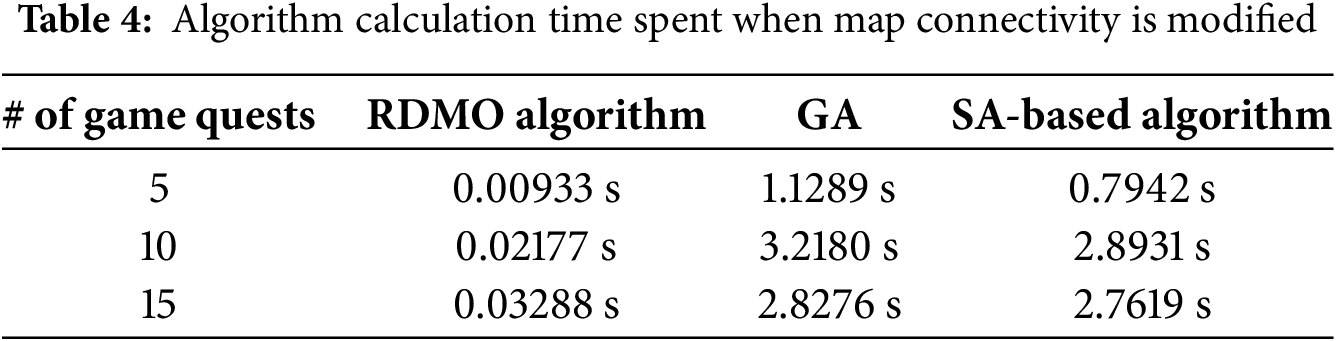

Lastly, when modifying the connectivity of the game map under the same number of game quests, we find noticeable differences in the path outcomes. We conducted 10 iterations of path planning for 20 game quests and calculated the average results to provide a more objective representation of the algorithmic differences. Table 4 shows the average computation times. When modifying the map connectivity, the proposed RDMO algorithm completes the path modification and updates within 0.05 s on average. However, the GA takes an average of 4.385 s to adapt to map connectivity changes, while the SA-based algorithm takes an average of 3.985 s. When simultaneously handling 10 game quests, the differences are smaller but still notable. The GA averages 3.218 s; the SA-based algorithm averages 2.893 s; and the RDMO algorithm only requires 0.02177 s. Compared to the GA- and SA-based algorithms, the RDMO algorithm exhibits 80- and 79-fold speed improvements in handling changes in map connectivity for 20 game quests. When dealing with 10 game quests, the speed improvement is 146- and 131-fold, respectively. The RDMO algorithm truly achieves real-time processing in response to map connectivity changes. While the GA- and SA-based algorithms can also generate new paths to adapt to changes in connectivity within a relatively short time, the 3–5 s of response time is not acceptable for large-scale or RTS games. In such games, victory often hinges on events occurring within seconds. Additionally, although we did not perform full statistical tests due to computational resource limitations, we calculated the standard deviation of the results for the 10 iterations in Table 4. The RDMO algorithm variance was consistently below 3%, while the GA and SA had much larger fluctuations (up to 18%) primarily due to their stochastic nature. These observations support the statistical stability and performance advantages of RDMO in dynamic environments. We acknowledge that future research may incorporate formal hypothesis testing.

In addition, while our experiments were conducted on the Busan map, which is known for its high road network complexity, we acknowledge that only a fixed task distribution was tested. However, the selected 20 game quests involve diverse spatial distributions and include both clustered and dispersed task regions. The random modification of map connectivity across 10 dynamic iterations also introduces varied topological changes, mimicking complex environmental dynamics. Although additional variations in map size and task density are desirable, the current setup captures the key characteristics of real-world large-scale path planning. Future work will extend the framework to multi-scenario benchmarks with varied scales and constraints.

In conclusion, the proposed RDMO algorithm in this study demonstrates excellent results in the aspects of both performance and path lengths. We believe that these outcomes will enhance gameplay enjoyment and immersion while improving the decision-making and predictability issues of game AI. When applied in games, we have strong reasons to believe that they will exhibit an outstanding performance. Furthermore, its exceptional computational speed fully meets the real-time algorithm requirements in games, surpassing the capabilities of probability-based optimization algorithms like GA and SA.

To better understand the computational scalability and the real-time feasibility of the proposed RDMO algorithm, we performed a theoretical runtime complexity analysis and compared it with the GA- and SA-based solutions. In our benchmark comparison implementation, both GA and SA are used in conjunction with the classic A* algorithm to perform path search. That is, the metaheuristic component (GA or SA) is responsible for selecting or optimizing the ordering of game tasks or decision sequences, while the A* algorithm is repeatedly called to compute the actual path between waypoints. This hybrid structure substantially affects the overall complexity.

The proposed RDMO algorithm uses a queue-based structure to dynamically manage multiple objectives and incorporates a composite multiobjective heuristic function within an enhanced A* framework. Suppose the map contains

In contrast, the GA-based hybrid solution works as follows: for each generation, a GA maintains a population of

Similarly, the SA-based hybrid solution generates a single path ordering, applies stochastic local perturbations (e.g., swap, insert), and evaluates the resulting path using A*. Let

Overall, although GAs and SA-based algorithms may offer global search capabilities, their heavy reliance on repeated A* calls for fitness evaluations makes them unsuitable for real-time applications with a critical low latency. In contrast, RDMO’s integrated design allows it to efficiently handle dynamic game quests and connectivity changes with a consistent runtime performance, as shown in the empirical results of Sections 4.2 and 4.3.

These findings confirm that RDMO achieves both lower empirical runtime and favorable theoretical scalability compared to GA/SA-based hybrid solutions.

In the face of complex gaming environments and higher user experience expectations, this study addresses the multiobjective path-planning problem in the gaming domain. By considering the requirements for multiobjective path planning in games, we proposed herein an RDMO path-planning algorithm capable of adapting to changes in the game map. The proposed RDMO algorithm was verified through a comparative evaluation with selected GA- and SA-based solutions and based on the path-planning test results (path lengths, performance, and differences between planned paths).

Regarding the algorithm’s efficiency in multiobjective path planning, the proposed RDMO algorithm can easily handle the joint planning of 20 game quests within 0.05 s, achieving 88-

However, despite the RDMO algorithm’s outstanding performance from various test perspectives, there are still areas for improvement in practical applications. Further testing is required on numerous games, multiple game map types, and real-world maps to assess the algorithm’s stability.

In future research, we plan to gradually enhance the algorithm’s application in the gaming domain and improve its compatibility with different game types, even extending its use to more practical fields, such as transportation and public transportation operations. We hope that the algorithm’s performance can be further improved. We also plan to develop a dedicated multiobjective extension of RTAA* using Pareto dominance principles for systematic comparison. Due to page constraints, we focused this work on comparisons with state-of-the-art multiobjective planners but will include this extended analysis in subsequent publications.

Acknowledgement: We thank the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) for supporting the conduct of this research work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (NRF-2023R1A2C1005950).

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the conceptualization and writing of the paper. Hongle Li led algorithm programming and development as well as was responsible for paper writing. Seongki Kim reviewed this paper, revised it, and funded this work. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The simulated location point data used in the test in this study are primarily based on bus stop location information from the Korean Public Data Portal (https://www.data.go.kr/, accessed on 03 September 2025); part of the data are collected from entrusted third-party companies. All of the involved implementations are available at https://github.com/pipi953/simulationUnity.git (accessed on 03 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This study does not involve any human or animal participants.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rafiq A, Kadir TAA, Ihsan SN. Pathfinding algorithms in game development. IOP Conf Ser: Mater Sci Eng. 2020;769(1):012021. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/769/1/012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Liu L, Wang X, Yang X, Liu H, Li J, Wang P. Path planning techniques for mobile robots: review and prospect. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;227(4):120254. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yang L, Li P, Qian S, Quan H, Miao J, Liu M, et al. Path planning technique for mobile robots: a review. Machines. 2023;11(10):980. doi:10.3390/machines11100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ma Z, Chen J. Adaptive path planning method for UAVs in complex environments. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf. 2022;115(2):103133. doi:10.1016/j.jag.2022.103133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Huang C, Lan Y, Liu Y, Zhou W, Pei H, Yang L, et al. A new dynamic path planning approach for unmanned aerial vehicles. Complexity. 2018;2018(1):e8420294. doi:10.1155/2018/8420294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mehta P, Shah H, Shukla S, Verma S. A review on algorithms for pathfinding in computer games. In: 2015 International Conference on Innovations in Information, Embedded and Communication Systems (ICIIECS); 2015 Mar 19–20; Coimbatore, India. [Google Scholar]

7. Qin H, Shao S, Wang T, Yu X, Jiang Y, Cao Z. Review of autonomous path planning algorithms for mobile robots. Drones. 2023;7(3):211. doi:10.3390/drones7030211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xue Y, Sun J-Q. Solving the path planning problem in mobile robotics with the multi-objective evolutionary algorithm. Appl Sci. 2018;8(9):1425. doi:10.3390/app8091425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Morosan M. Automating Game-design and Game-agent Balancing through Computational Intelligence [dissertation]. Colchester, UK: University of Essex; 2019. [Google Scholar]

10. Ontañón S, Synnaeve G, Uriarte A, Richoux F, Churchill D, Preuss M. A survey of real-time strategy game AI research and competition in starcraft. IEEE Trans Comput Intell AI Games. 2013;5(4):293–311. doi:10.1109/TCIAIG.2013.2286295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Featherstone M, Habgood J. UniCraft: exploring the impact of asynchronous multiplayer game elements in gamification. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2019;127:150–68. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2018.05.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dvořák BJ. AI algorithms for computer games [master’s thesis]. Brno, Czech Republic: Faculty of Informatics, Masaryk University; 2021. [Google Scholar]

13. Sidoti D, Avvari GV, Mishra M, Zhang L, Nadella BK, Peak JE, et al. A multiobjective path-planning algorithm with time windows for asset routing in a dynamic weather-impacted environment. IEEE Trans Syst, Man, Cybern: Syst. 2016;47(12):3256–71. doi:10.1109/TSMC.2016.2573271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Xing B, Yu M, Liu Z, Tan Y, Sun Y, Li B. A review of path planning for unmanned surface vehicles. J Mar Sci Eng. 2023;11(8):1556. doi:10.3390/jmse11081556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tong CK, On CK, Teo J, Mountstephens J. Game AI generation using evolutionary multi-objective optimization. In: 2012 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation; 2012 Jun 10–15; Brisbane, QLD, Australia. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/cec.2012.6256638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Maniezzo V, Colorni A. The ant system applied to the quadratic assignment problem. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 1999;11(5):769–78. doi:10.1109/69.806935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Karp RM. Reducibility among combinatorial problems. In: Complexity of Computer Computations: Proceedings of a symposium on the Complexity of Computer Computations; 1972 Mar 20–22; New York, NY, USA. Boston, MA, USA: Springer; 1972. p. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

18. Arora S. Approximation schemes for NP-hard geometric optimization problems: a survey. Math Program. 2003;97(1):43–69. doi:10.1007/s10107-003-0438-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jiang DL, Yang XL, Du W. Genetic algorithms for vehicle path problems. Syst Eng Theory Practice. 1999;19(6):40–5. [Google Scholar]

20. Goldberg AV, Harrelson C. Computing the shortest path: a search meets graph theory. In: Proceedings of the Sixteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics; 2005. p. 156–65. [Google Scholar]

21. Lim C-U, Baumgarten R, Colton S. Evolving behaviour trees for the commercial game DEFCON. In: Applications of evolutionary computation. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2010. p. 100–10 doi:10.1007/978-3-642-12239-2_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Saeed RA, Reforgiato Recupero D, Remagnino P. The boundary node method for multi-robot multi-goal path planning problems. Expert Syst. 2021;38(6):e12691. doi:10.1111/exsy.12691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhu Y, Wan Hasan WZ, Harun Ramli HR, Norsahperi NMH, Mohd Kassim MS, Yao Y. Deep reinforcement learning of mobile robot navigation in dynamic environment: a review. Sensors. 2025;25(11):3394. doi:10.3390/s25113394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Huang S, Wu X, Huang G. Deep reinforcement learning-based multi-objective path planning on the off-road terrain environment for ground vehicles. arXiv:2305.13783. 2023. [Google Scholar]

25. Ren Z, Hernández C, Likhachev M, Felner A, Koenig S, Salzman O, et al. EMOA*: a framework for search-based multi-objective path planning. Artif Intell. 2025;339:104260. doi:10.1016/j.artint.2024.104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Santelices RA, Nussbaum M. A framework for the development of videogames. Softw Practice Exp. 2001;31(11):1091–107. doi:10.1002/spe.403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wang Y, Ijaz K, Yuan D, Calvo RA. VR-Rides: an object-oriented application framework for immersive virtual reality exergames. Softw: Practice Exp. 2020;50(7):1305–24. doi:10.1002/spe.2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yin S, Xiang Z. Energy-constrained collaborative path planning for heterogeneous amphibious unmanned surface vehicles in obstacle-cluttered environments. Ocean Eng. 2025;330:121241. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2025.121241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yin S, Xiang Z. Adaptive collision avoidance strategy for USVs in perception-limited environments using dynamic priority guidance. Adv Eng Inform. 2025;65:103355. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2025.103355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. von Lücken C, Barán B, Brizuela C. A survey on multi-objective evolutionary algorithms for many-objective problems. Comput Optim Appl. 2014;58(3):707–56. doi:10.1007/s10589-014-9644-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Duc LM, Sidhu AS, Chaudhari NS. Hierarchical pathfinding and AI-based learning approach in strategy game design. Int J Comput Games Technol. 2008;2008(1):e873913. doi:10.1155/2008/873913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Hagelbäck J. Multi-agent potential field based architectures for real-time strategy game bots [dissertation]. Karlskrona, Sweden: School of Computing, Blekinge Institute of Technology; 2012. [Google Scholar]

33. Buro M, Bergsma J, Deutscher D, Furtak T, Sailer F, Tom D, et al. AI system designs for the first RTS-game AI competition. In: GAME-ON North America; 2006 Sep 19–20; Monterey, CA, USA. p. 13–17. [Google Scholar]

34. Cui X, Shi H. A*-based pathfinding in modern computer games. Int J Comput Sci Netw Secur. 2011;11(1):125–30. [Google Scholar]

35. Birch CPD, Oom SP, Beecham JA. Rectangular and hexagonal grids used for observation, experiment and simulation in ecology. Ecol Model. 2007;206(3):347–59. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2007.03.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Mi K, Zheng J, Wang Y, Hu J. A multi-heuristic A* algorithm based on stagnation detection for path planning of manipulators in cluttered environments. IEEE Access. 2019;7:135870–81. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2941537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yang H, Lee H. Smart city and remote services: the case of South Korea’s national pilot smart cities. Telematics Inform. 2023;79(1):101957. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2023.101957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Asih AMS, Sopha BM, Kriptaniadewa G. Comparison study of metaheuristics: empirical application of delivery problems. Int J Eng Bus Manag. 2017;9(8):1847979017743603. doi:10.1177/1847979017743603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Gong W, Fu Z. ABC-ACO for perishable food vehicle routing problem with time windows. In: 2010 International Conference on Computational and Information Sciences; 2010 Dec 17–19; Chengdu, China. p. 1261–4. [Google Scholar]

40. Yin S, Hu J, Xiang Z. Multi-objective collaborative path planning for multiple water-air unmanned vehicles in cramped environments. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;292(2):128625. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.128625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Duan P, Yu Z, Gao K, Meng L, Han Y, Ye F. Solving the multi-objective path planning problem for mobile robot using an improved NSGA-II algorithm. Swarm Evol Comput. 2024;87(2):101576. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2024.101576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Keiichi U, Ryuta W, Takashi S. Real-time scheduling on Dial-a-Ride Vehicle service. Trans Inst Syst, Control Inf Eng. 2002;15(8):413–21. doi:10.5687/iscie.15.413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Yoon G, Chow JYJ, Rath S. A simulation sandbox to compare fixed-route, semi-flexible-transit, and on-demand microtransit system designs. KSCE J Civil Eng. 2022;26(7):3043–62. doi:10.1007/s12205-022-0995-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools