Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhanced Fire Detection System for Blind and Visually Challenged People Using Artificial Intelligence with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks

1 Department of Computer Science, Applied College at Mahayil, King Khalid University, Abha, 61421, Saudi Arabia

2Applied Collage, Najran University, Najran, 66462, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Information Systems, Faculty of Computer and Information Technology, Sana’a University, Sana’a, P.O. Box 1247, Yemen

4 King Salman Center for Disability Research, Riyadh, 11614, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Computer and Self Development, Preparatory Year Deanship, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, AlKharj, P.O. Box 173, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Fahd N. Al-Wesabi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Computer Vision and Image Processing: Feature Selection, Image Enhancement and Recognition)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5765-5787. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067571

Received 07 May 2025; Accepted 26 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Earlier notification and fire detection methods provide safety information and fire prevention to blind and visually impaired (BVI) individuals in a limited timeframe in the event of emergencies, particularly in enclosed areas. Fire detection becomes crucial as it directly impacts human safety and the environment. While modern technology requires precise techniques for early detection to prevent damage and loss, few research has focused on artificial intelligence (AI)-based early fire alert systems for BVI individuals in indoor settings. To prevent such fire incidents, it is crucial to identify fires accurately and promptly, and alert BVI personnel using a combination of smart glasses, deep learning (DL), and computer vision (CV). The most recent technologies require effective methods to identify fires quickly, preventing damage and physical loss. In this manuscript, an Enhanced Fire Detection System for Blind and Visually Challenged People using Artificial Intelligence with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (EFDBVC-AIDCNN) model is presented. The EFDBVC-AIDCNN model presents an advanced fire detection system that utilizes AI to detect and classify fire hazards for BVI people effectively. Initially, image pre-processing is performed using the Gabor filter (GF) model to improve texture details and patterns specific to flames and smoke. For the feature extractor, the Swin transformer (ST) model captures fine details across multiple scales to represent fire patterns accurately. Furthermore, the Elman neural network (ENN) technique is implemented to detect fire. The improved whale optimization algorithm (IWOA) is used to efficiently tune ENN parameters, improving accuracy and robustness across varying lighting and environmental conditions to optimize performance. An extensive experimental study of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN technique is accomplished under the fire detection dataset. A short comparative analysis of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN approach portrayed a superior accuracy value of 96.60% over existing models.Keywords

Disorders in the visual system are the reason for visual blindness and impairment, which might prevent individuals from carrying out housekeeping in addition to hampering their work, studies, travels, and involvement in sports [1]. Under the WHO, nearly 2.2 billion people are affected by visual blindness or impairment globally, among whom almost 1 billion have a visual impairment that may be unaddressed or has not been tackled [2]. Investigators forecast that the number of people with visual impairment will grow intensely in the following decades owing to the growth of the population and improve life expectancy. BVI people frequently discover day-to-day work and environmental insight (which represents the knowledge of one’s instant environments [3]. Various solutions, namely accessible technologies and software, are being elaborated to tackle these issues. Helpful systems assist BVI people with day-to-day activities like signification for navigation, video media accessibility, differentiating banknotes, image recognizing people, crossing a road, identifying private visual information, clothing, navigating, and selecting outdoors or indoors [4]. For fire safety applications, helpful technology has progressed to rapidly offer safety information and fire prevention to BVI people throughout inside and outside fire emergencies. Nevertheless, this technology suffers from some disadvantages. Early fire recognition is a critical problem that has direct impacts on the environment and the safety of people. Innovative technology requires proper techniques to discover flames as soon as possible to prevent damage to belongings and impairment [5].

Fire control and prevention were frequently problematic tasks for governments throughout the world. All issues that are the reason for domestic fire damages and domestic fires are cooking, smoking materials, purposeful fire starting, electrical distribution, lighting equipment, and heating equipment [6]. Usually, fires are recognized by sensory structures that discover modifications in smoke or temperature inside locations. Most fire-recognition mechanisms have built-in sensors; hence, the system depends on spatial dispersion and sensor dependability [7]. For a higher accuracy fire recognition mechanism, the sensors should be built in a location that can be intended correctly and precisely. Even though various initial warning and recognition devices have been applied to identify particular flames and fire threats in the last few decades, namely sensor-based frameworks, sensing technologies, and fire alarm systems, many issues remain unanswered [8]. The current study has revealed that DL and CV-based models have attained major achievements and play an essential part in fire recognition [9]. AI and CV-based models, like stable and dynamical texture analysis, 360-degree sensors, and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) were generally used in fire detection settings. Furthermore, the predictable inside fire-detection architecture is employed in other dissimilar social and manufacturing fields, namely offices, schools, factories, chemical plants, hospitals, and so on [10]. Numerous publications concentrated on wildfire and outdoor environments for fire recognition, but there was a lack of effort in enclosed areas.

In this manuscript, an Enhanced Fire Detection System for Blind and Visually Challenged People using Artificial Intelligence with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (EFDBVC-AIDCNN) model is presented. The EFDBVC-AIDCNN model presents an advanced fire detection system that utilizes AI to detect and classify fire hazards for BVI people effectively. Initially, image pre-processing is performed using the Gabor filter (GF) model to improve texture details and patterns specific to flames and smoke. For the feature extractor, the Swin transformer (ST) model captures fine details across multiple scales to represent fire patterns accurately. Furthermore, the Elman neural network (ENN) technique is implemented to detect fire. The improved whale optimization algorithm (IWOA) is used to efficiently tune ENN parameters, improving accuracy and robustness across varying lighting and environmental conditions to optimize performance. An extensive experimental study of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN technique is accomplished under the fire detection dataset. The key contribution of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN technique is listed below.

The EFDBVC-AIDCNN model utilizes GF-based image pre-processing to improve texture details and patterns unique to flames and smoke. This refinement allows for distinguishing fire-related features from the background, resulting in more accurate and reliable detection results. Focusing on relevant image characteristics strengthens the model’s capability of detecting fire events effectively.

• The EFDBVC-AIDCNN technique begins with image pre-processing using the GF model, which assists in improving the texture data and emphasizes critical patterns associated with flames and smoke. This pre-processing step enhances the capability of the technique in distinguishing fine visual cues in fire imagery, particularly in low-visibility or cluttered environments.

• The EFDBVC-AIDCNN model handles feature extraction by using ST, which captures detailed spatial and contextual information across multiple scales. The method also exhibits robust representational capacity in enabling the model to recognize complex fire patterns and adapt effectively to diverse environmental conditions, contributing to significantly improved detection accuracy.

• For fire detection, the EFDBVC-AIDCNN technique employs the ENN model, which utilizes its recurrent architecture to model temporal dependencies in sequential image data. This allows the model to track fire progression over time, enhancing performance in real-time fire monitoring and improving reliability under dynamic scenarios.

• To optimize the detection process, the IWOA methodology is integrated with the EFDBVC-AIDCNN method for fine-tuning the parameters of the ENN. This adaptive optimization not only improves classification accuracy and generalization but also mitigates training time and ensures robustness across varying lighting and environmental conditions.

• The integration of GF, ST, ENN, and IWOA presents a novel end-to-end framework that integrates texture enhancement, multi-scale spatial feature extraction, temporal modeling, and parameter optimization. This fusion enables the model to achieve high accuracy and robustness, outperforming conventional fire detection approaches.

• Experimental evaluations confirm the superiority of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN model over existing methods such as YOLOv3, MobileNetV2, Faster R-CNN, and Improved YOLOv4. The model achieves top scores of 96.60% in accuracy, precision, recall, and F-score, illustrating balanced and superior detection capability. Progressive analysis across training epochs exhibits consistent improvement, with optimal performance at 2500 epochs and a peak MCC of 93.20, confirming model stability and low false detection rates.

• In binary classification tasks, the EFDBVC-AIDCNN approach maintains high precision and recall for both fire and non-fire classes, ensuring reliable detection and minimal false alarms. This consistent performance makes it highly appropriate for deployment in real-world fire surveillance and emergency response systems.

Abuelmakarem et al. [11] developed a smart cane with an IoT (SC-IoT) system for BVI people. This device is built by utilizing SolidWorks 3D modelling software. This system uses ultrasonic sensors to assist BVI users in detecting obstacles and is regulated through the Arduino module. The cane alerts BVI users when hurdles are detected. The individual is tracked via a static MCU node that transmits the data to the tracking device on the Blynk application. The scheme is standardized against diverse objects, and the position is transmitted. Marzouk et al. [12] present the sine cosine algorithm model with DL for automatic fire detection (SCADL-AFD) methodology. The input images are initially examined using the EfficientNet method to generate feature vectors. The gated recurrent unit (GRU) method is utilized for detection. Finally, the SCA is implemented to tune the GRU technique. Khan et al. [13] introduce the design of a blind stick to assist blind people. In this, multiple sensors are attached to the individual’s stick. The sensor finds an obstruction, the receiver’s output activates, and the change is detected since the receiver’s outputs are connected to the control unit. This stick detects the impairment in front and vibrates or directs the user. Moreover, a smoke sensor, a fall detection sensor, a heart rate, an SPO2 level sensor, and a temperature sensor are employed for detecting various parameters and not only depict the individual by using the blind stick but also the caregiver through an application associated with the blind stick. Ben Atitallah et al. [14] developed a system that relies on YOLO v5 neural networking, which enhances the network’s speed and detection. This is attained by incorporating the DenseNet model into the backbone of YOLO v5, which affects the usage of features and data transmission with further alterations. The study also employed two compression models: channel pruning and quantization.

AKadhim and KEl Abbadi [15] construct a methodology to improve the agility and liberation of VIB persons by detecting their surroundings and navigation safely. The system integrates AI models and audio and video feedback mechanisms to interpret graphical data. The YOLOv7 model is later implemented for detecting indoor atmospheres and employs triangle similarities for distance assessment and warning, with an approach presented to give instructions throughout navigation. Thi Pham et al. [16] propose a walking stick. An ultrasonic sensor is employed for scanning obstacles via reflected signals, a significant input to the microcontroller, and is late and delayed in determining the distance. Later, it can inform individuals of the distance to the obstacle ahead in meters through voice notifications, accompanied by a vibration alert. A GPS, module card, and an MPU 6050 sensor are also incorporated. Yang et al. [17] introduce a methodology that utilizes a YOLO v5s with a squeeze-and-excitation (SE) technique. Furthermore, internet images are implemented to crawl and annotate to build a dataset. Moreover, the YOLO v5, YOLO v5x, and YOLO v5s approaches are constructed for training and testing the dataset. Malla et al. [18] proposed a tool, namely the smart blind stick (SBS), which is an advanced adaptive tool constructed for addressing navigation threats encountered by VIB persons. The device functions by detecting obstacles and precisely computing the distances by utilizing an incorporated system of a Viola-Jones model, ultrasonic, Arduino UNO controller, and water sensors. The SBS is armed with a camera and sophisticated ultrasonic sensors, integrated with improved coding systems, allowing users to navigate and identify.

While existing systems utilize sensors and AI models like YOLO variants and EfficientNet for obstacle detection and navigation, many encounter limitations such as reliance on static MCU nodes, limited environmental adaptability, and insufficient integration of multi-sensor data for comprehensive user assistance. Some studies lack advanced tuning or optimization for dynamic conditions, as they mainly focus on obstacle detection. Furthermore, several devices do not fully address real-time feedback or multi-parameter monitoring in an integrated manner. There is a clear research gap in developing more agile, robust, and context-aware systems that incorporate effectual model tuning, multi-sensor fusion, and enhanced user interaction to assist VIB users in diverse environments better while addressing these issues.

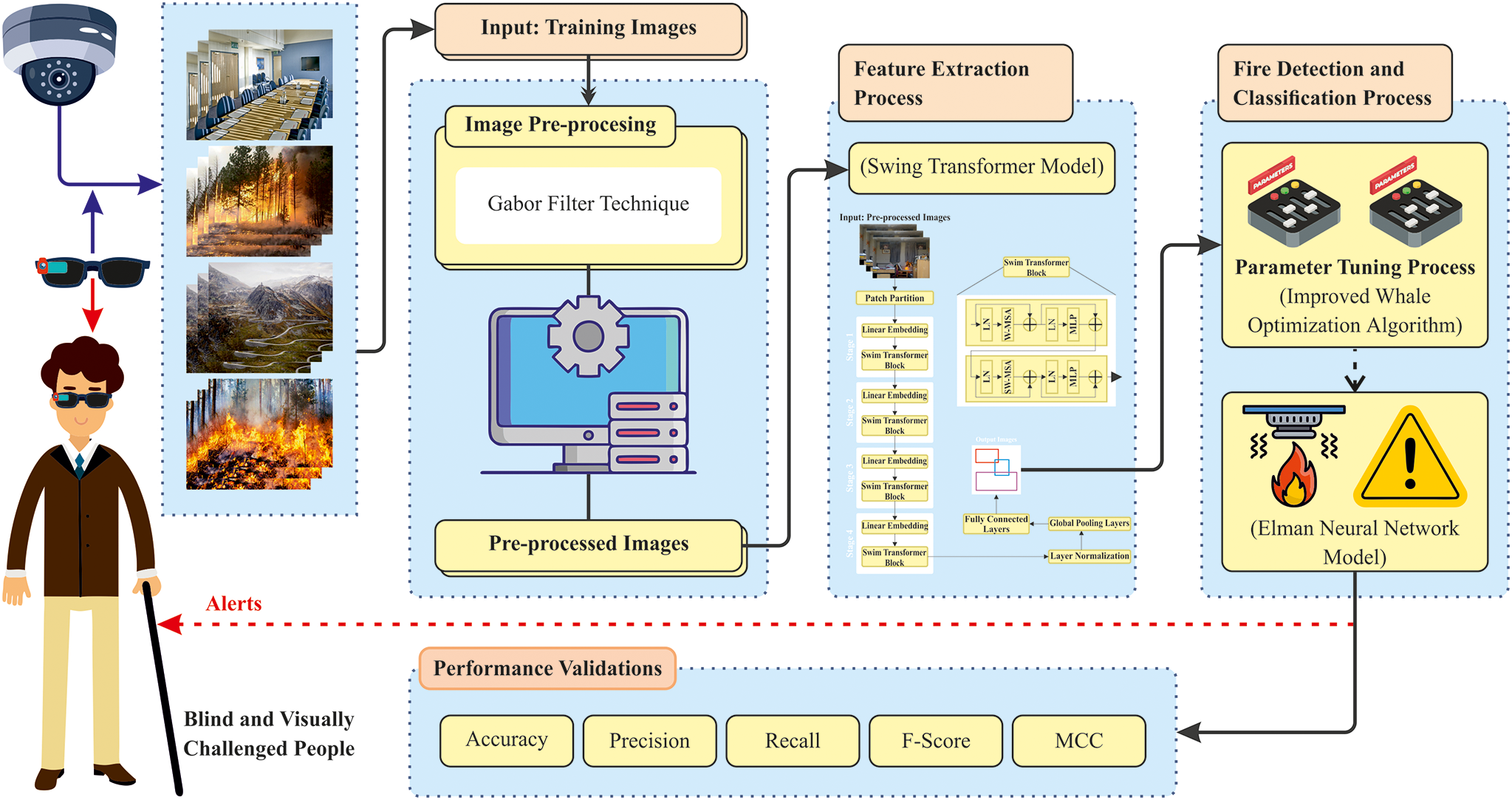

In this manuscript, the EFDBVC-AIDCNN model is proposed. The EFDBVC-AIDCNN model presents an advanced fire detection system that leverages AI to detect and classify fire hazards for BVI people effectively. To obtain that, the EFDBVC-AIDCNN approach has distinct kinds of processes such as image pre-processing, ST-based feature extractor, fire detection using the ENN model, and IWOA-based parameter tuning. Fig. 1 demonstrates the complete workflow of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN approach.

Figure 1: Overall flow of EFDBVC-AIDCNN approach

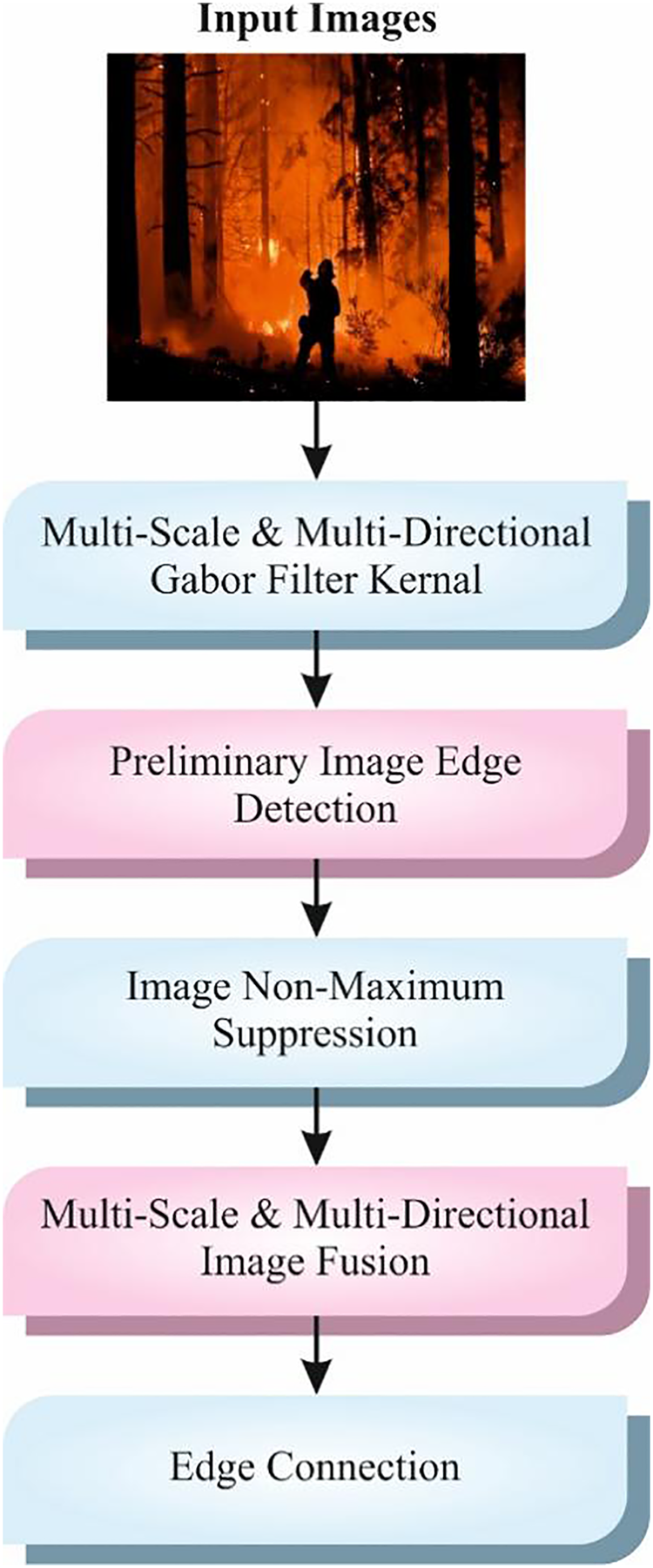

The presented EFDBVC-AIDCNN technique initially applies image pre-processing using the GF model to enhance texture details and patterns specific to flames and smoke [19]. This model is chosen because it can improve texture details and capture edge data, which is significant for detecting patterns like flames and smoke. Unlike conventional filters, GF effectively extracts orientation and frequency-specific features, making it appropriate for intrinsic visual textures. This technique reduces noise while preserving crucial structural data, enhancing the image quality for subsequent analysis. Compared to other methods, GF presents a balanced approach between computational efficiency and feature enhancement, improving detection performance in challenging environments. Its robustness to lighting discrepancies additionally assists its use in diverse real-world conditions. Fig. 2 depicts the workflow of the GF model.

Figure 2: The working flow of the GF method

The GF is a vital image pre-processing device in fire detection methods, mainly designed for improving visual patterns like smoke and flame textures. Using the GF, the system can seize particular frequency and orientation particulars, making distinguishing fire components from background noise easy. This texture improvement considerably increases the model’s accuracy in recognizing fire, even in composite environments. The filter helps consistent fire detection for BVI individuals, permitting the AI method to make precise, timely alerts for better protection.

For the feature extractor, the ST model captures fine details across multiple scales to represent fire patterns accurately [20]. This model is chosen because it captures local and global contextual data through hierarchical representations. Unlike conventional CNNs, ST utilizes shifted window-based self-attention, which enables it to model long-range dependencies effectively while maintaining computational scalability. This architecture adapts well to varying object sizes and complex backgrounds, which is specifically beneficial in fire detection tasks. ST also presents flexibility in integrating multi-scale features, improving the robustness and accuracy of the model. Its proven performance in visual tasks makes it an ideal choice over conventional extractors like ResNet or VGG.

The proposed architecture can remove global context and longer-term dependencies using the ST structure. It is better than conventional CNNs at taking relationships among different image parts, which is significant for precisely identifying. Conventional CNNs mainly concentrate on local spatial features. This framework was built from an essential element count. The patch dimension is a hyperparameter, which is fine-tuned to attack cooperation between the capability to seize spatial information and computation complexity. The following stage embeds every patch with a linear prediction layer into a high-dimensional vector space. This raw data of pixels is transformed through these embedded procedures into a demonstration that is well-matched for the transformer structure. This patch embedding contains the succeeding mathematical model (Eq. (1)):

Whereas, Patch

The hierarchical framework of the ST’s phase transformer blocks creates its basis. In every stage, a feed-forward network follows after many layers of self-attention. This layer defines the attention grades, which discrete every patch in a local window from other patches. This permits the approaches to take related information and longer-term dependency. This score designates how important every patch was concerning the present patches. The mechanism of self-attention is stated as a result:

here, the representations of embedded patches are predicted linearly to give the value, query, and key matrices, correspondingly,

ST’s utilization of the shift window multi-head self-attention (SW-MSA) in the self-attention layer is an important invention. Compared with traditional self-attention, which is limited to a local window, SW-MSA allows the method to concentrate on useful areas that prolong the outer area of the local window. Having this, this technique may slowly take longer-term dependencies during the complete image by regulating the window for every layer inside a phase. This mechanism of SW-MSA was illustrated in the succeeding Eq. (3):

here,

STs are outstanding at learning longer-term dependencies over the mechanism of self-attention. Conversely, CNNs discover it interesting to distinguish relationships among far-off-image areas. Identifying these is especially critical because small changes in the pattern and texture of the radiograph in several regions can specify specific defects. The hierarchical framework of ST blocks allows the approach for learning features at different scales. Subsequent phases can learn the contextual relationships and global features between the local details taken in the first phases. It is a smart option for study due to its scalable stage architecture, flexible patch size, and efficient mechanisms of feature learning.

3.3 Fire Detection System: ENN Classifier

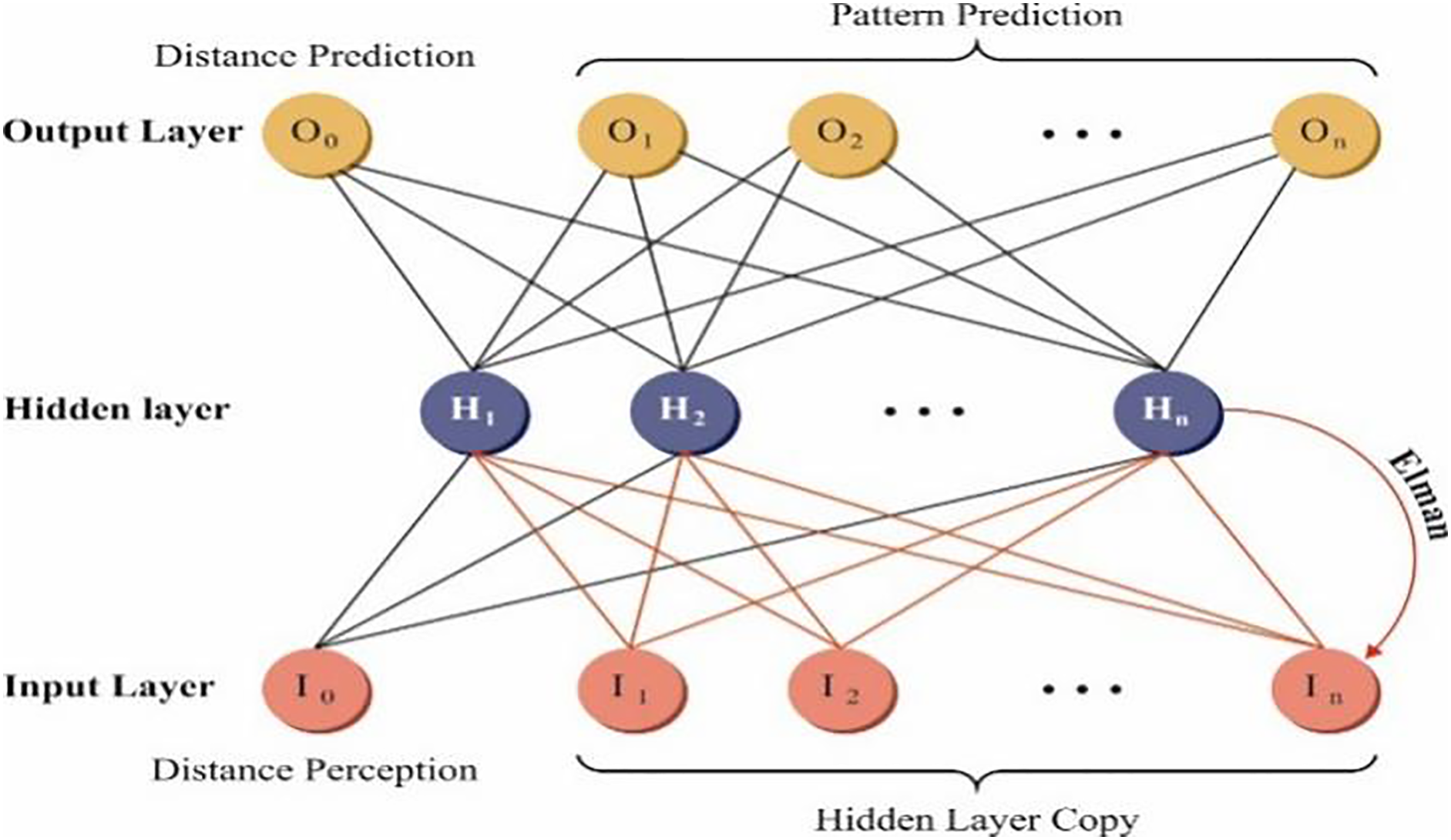

In addition, the ENN technique is employed to detect fire [21]. This technique is chosen because it captures temporal dependencies through its recurrent architecture. This model comprises context units that allow the model to retain and utilize past data, which is significant for detecting dynamic patterns in fire and smoke sequences. This makes the model more effectual in sequential image data than conventional classifiers such as support vector machine (SVM) or standard multi-layer perceptron (MLP). The model’s adaptability to time-varying inputs improves detection accuracy and responsiveness in real-time scenarios. Moreover, ENN’s relatively simple structure allows efficient training and deployment in constrained environments. Fig. 3 signifies the structure of the ENN classifier.

Figure 3: Architecture of ENN

The critical architecture of the ENN includes a hidden layer (HL), input, and output layers, using the recurrent links within the HL as its fundamental function. This recurrent link allows the network to handle present input data; however, it recollects HL from the prior time step, hence utilizing and taking the temporal dependency within the data. This temporary function of memories was essential to predict and understand composite methods that change in time, namely the construction costs. The benefit of choosing the ENN model is its capabilities for modelling dynamic modifications in sequential data, which are mainly significant for the intellectual forecast of construction costs. It is motivated by market modifications and fluctuations in physical costs, which frequently change over time. This ENN, around its interior time-delay component, may successfully take this time-series feature, thus offering detailed and real-world predictions. Also, the ability of the ENN to accomplish extreme efficiency in processing nonlinear and dynamical methods is mainly valued in construction, considering that construction predictions frequently entail composite nonlinear relationships and dynamical modifications.

The HL recurrent networks among neurons permit the system to maintain and use its earlier state and data. This model is expert at propagating and updating information on time. In the time step, this system obtains inputs for the present data and the HL from the preceding time steps and upgrades the HL condition with an activation function. Consequently, these updated HLs are distributed to the following time steps and serve as input toward the output layer. The particular expression from the ENN was offered in Eq. (4).

In Eq. (4),

Now,

The ENN’s training error function

In Eq. (7),

The ENN contains an HL, input, and output layer by its distinct feature of recurrent links within the HL. This connection allows the network to handle present input data by maintaining and using HL from the preceding time step, taking into account the temporal dependency inside the data. The ENN model provides different benefits, mainly its capability for modelling active modifications in sequential data critical for the intellectual prediction of construction cost. Construction costs are subject to various aspects, such as fluctuations and market fluctuations in physical costs, which often differ in time. Over its interior time interval component, the ENN efficiently takes this time series feature, thus allowing accurate and real-world predictions. Additionally, these features create an ENN appropriate for managing nonlinear and dynamical networks, which is highly advantageous in the construction area, where plans frequently include complicated nonlinear relationships and active changes.

3.4 Fine-Tuned Parameter: IWOA Model

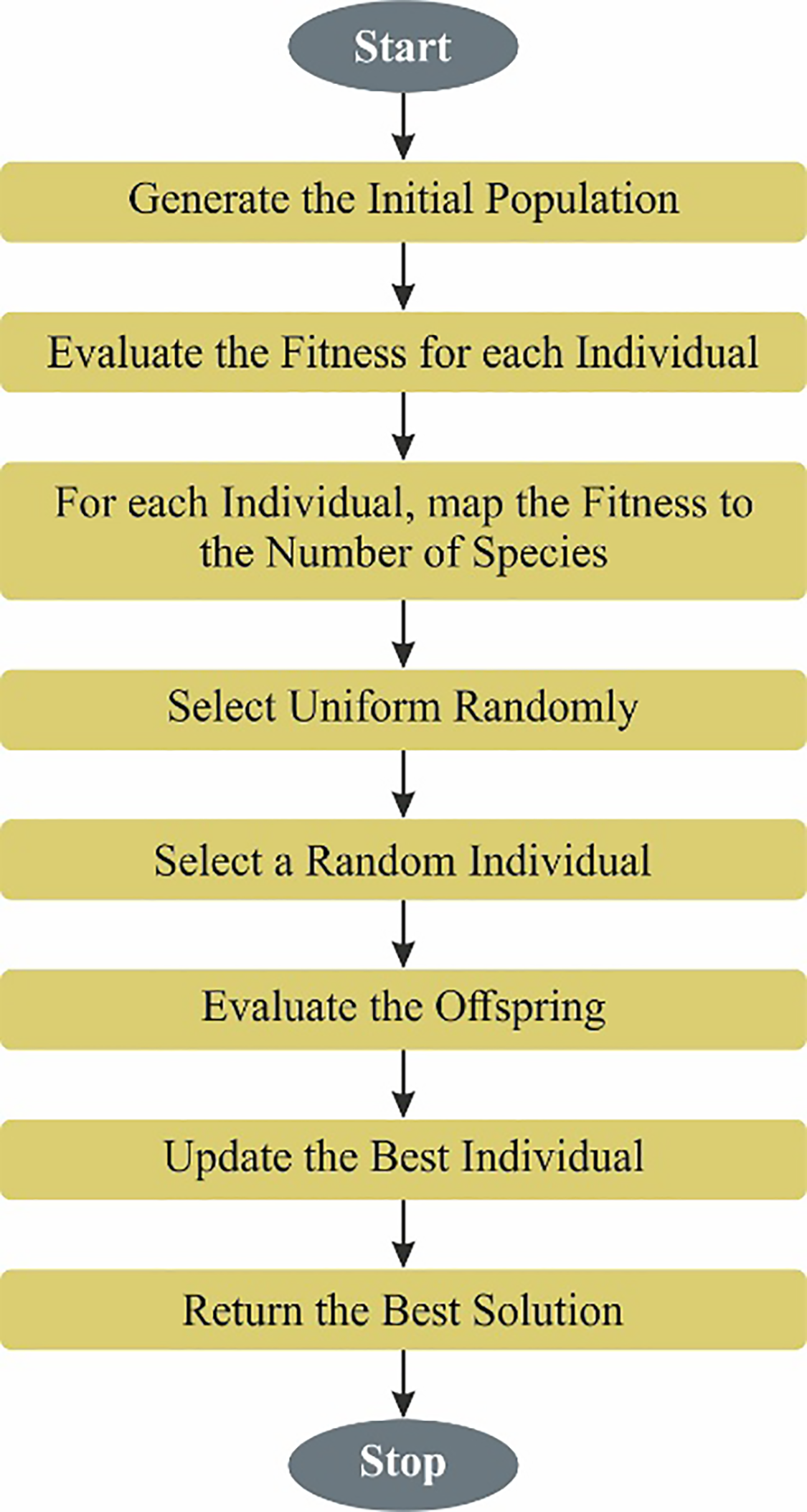

To ensure optimized performance, the IWOA model is integrated to tune the ENN parameters efficiently, enhancing the model’s accuracy and robustness in diverse lighting and environmental conditions [22]. This is an ideal model for fine-tuning neural network parameters, particularly in tasks such as fire detection. This method is constructed from the WOA method by adding features such as adaptive convergence factors and reverse learning strategies. These improvements assist the model in exploring the solution space more effectively and avoiding getting stuck in suboptimal outcomes. The technique also maintains diversity in its search, facilitating an improved balance between global and local searches. This results in more precise and reliable model performance, faster convergence and enhanced generalization compared to conventional optimization methods. WOA classifies sperm whale foraging behaviour into three phases depending on the predatory behaviour of the whale. These phases equal three location-updated models containing prey encircling, random prey search, and spiral bubble net attack. Fig. 4 specifies the working flow of the IWOA methodology.

Figure 4: Flow of the IWOA method

(1) Encircling prey

Whales can identify the position of prey and surround it. Individual whales change their positions with the Eqs. (8) and (9) assume that the target is currently the optimum location in the population.

here,

Now,

Whereas

(2) Bubble net feeding

Using the logarithmic spiral updated location model, it is possible to define a novel location in the bubble net feeding that equals the animal’s spiral movement among the unique locations of whales and the present prey. The next defines its mathematic approach:

here,

The position updated equation of WOA is demonstrated, and the probability

here,

(3) Random search for prey

Individual whales can arbitrarily look for victims to ensure the WOA converges. If

Whereas

Conventional WOA provides many benefits, namely simple theories and dominant global searching abilities. Nevertheless, the arbitrary parameter that defines the WOA location updated method presents randomness and uncertainty in the model, leading to a convergence rate of sluggishness and vulnerability to local bests in the following round. These works recommend two methods for enhancing WOA to encounter these difficulties.

(i) A chaotic mapping with a reverse learning approach

As the WOA initiates population individuals with arbitrary approaches, the initial distribution of the population is unequal, accomplishing it to attain local ideals. To improve the population initialization qualities, this study recommends a model depending on Fuch chaotic mapping and reverse learning, which offers benefits over regular chaotic mappings such as Tent and Logistic, like insensitiveness to primary values, faster convergence, and balanced traversal. The Fuch chaotic mapping contains the subsequent mathematical formulations:

here,

Once the population was initialized with a Fuch chaotic mapping, it was enhanced by reverse learning. These reverse solutions are created depending on the present possible solution, as expressed in Eq. (19). The fitness values of the recent feasible and reverse solutions are calculated, and individuals with fewer fitness values are selected as primary population individuals. The population is updated using Eq. (20).

here, fit

(ii) Hyperbolic tangent function (tanh)

In the WOA stage, individuals modify their positions in connection with the location of the finest individual. Consequently, an inertia weight

Whereas

If inertia weights measured through the

In bubble net feeding, the location updating of the logarithmic spiral equation is as follows:

The IWOA acquires a fitness function (FF) to achieve superior classifier performance. It defines a positive integer to distinguish the enhanced performance of the candidate solutions. In this work, the decrease of the classifier error rate was measured as the FF, as specified in Eq. (25).

4 Experimental Results and Analysis

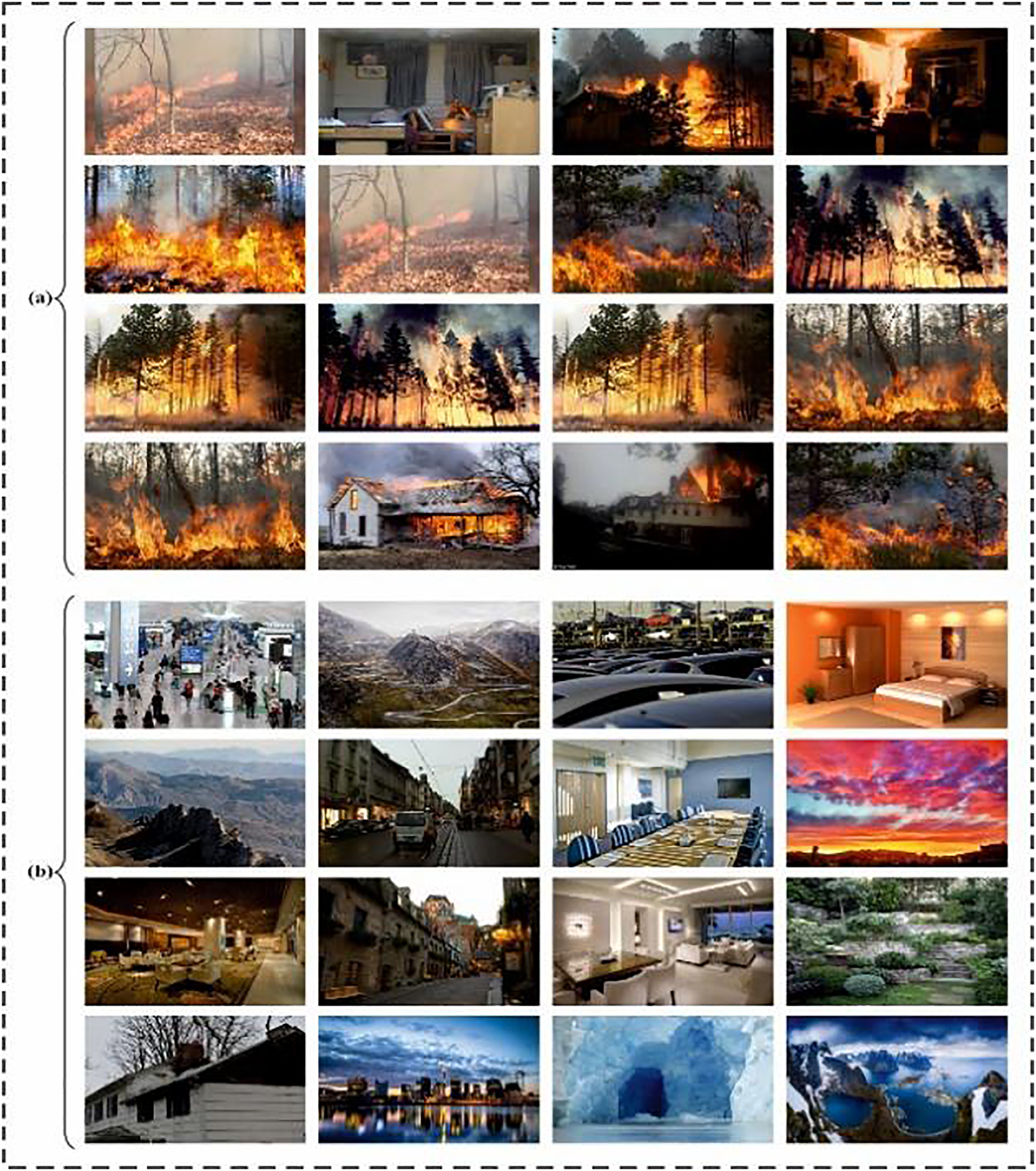

In this section, the performance validation study of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN approach is inspected using a fire detection dataset [23], which contains 1000 samples under two class labels, which are distinct in Table 1. The technique is simulated using Python 3.6.5 on a PC with an i5-8600k, 250 GB SSD, GeForce 1050Ti 4 GB, 16 GB RAM, and 1 TB HDD. Parameters include a learning rate of 0.01, ReLU activation, 50 epochs, 0.5 dropouts, and a batch size of 5. This dataset is applied for image classification tasks with and without fire, and can also be employed to identify fire accidents from a live feed. Fig. 5 signifies the sample images.

Figure 5: Sample images (a) fire (b) non-fire

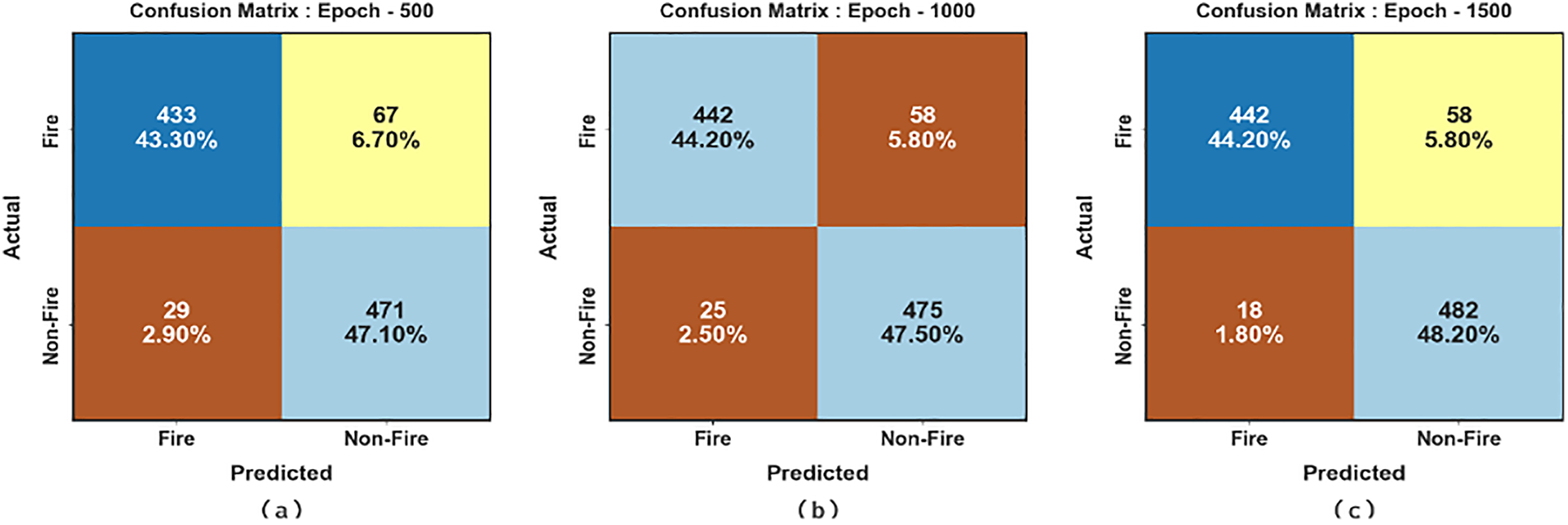

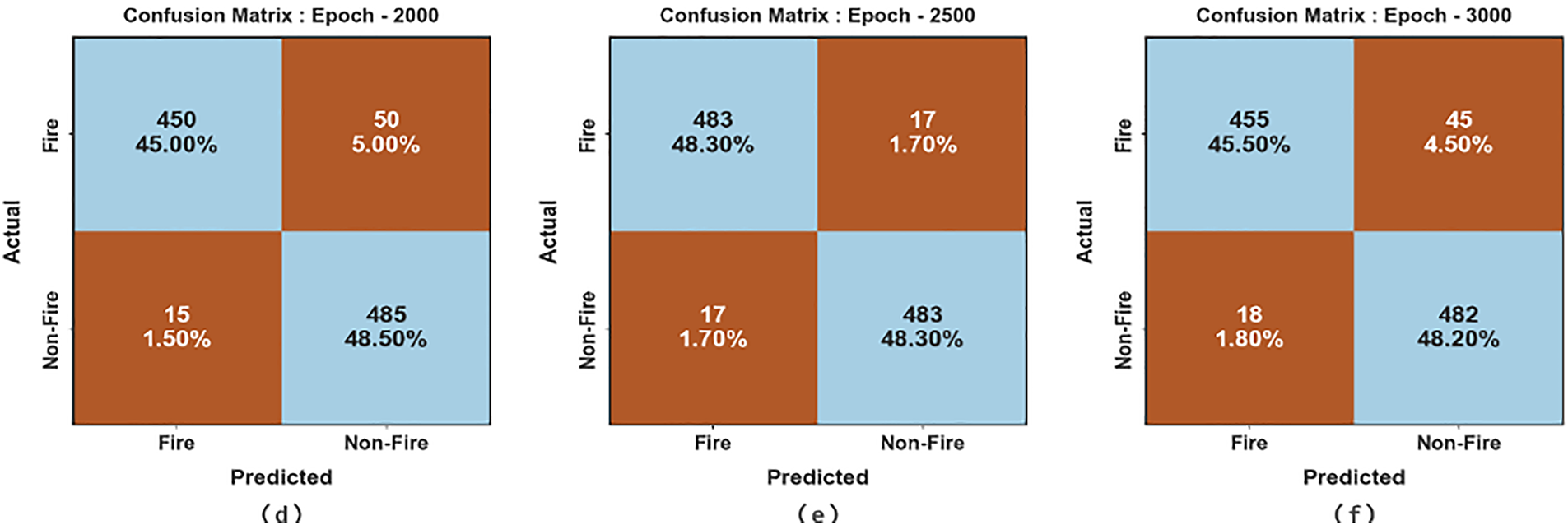

Fig. 6 reports a set of confusion matrices created by the EFDBVC-AIDCNN method on 500–3000 epochs. After 500 epochs, the EFDBVC-AIDCNN method has established 433 samples in the fire and 471 samples in non-fire. After that, on 1000 epochs, the EFDBVC-AIDCNN method recognized 442 samples in fire and 475 samples in non-fire. Similarly, on 1500 epochs, the EFDBVC-AIDCNN methodology recognized 442 samples in fire and 482 samples in non-fire. Besides, in 2000 epochs, the EFDBVC-AIDCNN methodology recognized 450 samples in the fire and 485 samples in non-fire. Lastly, after 3000 epochs, the EFDBVC-AIDCNN methodology recognized 455 samples in the fire and 482 samples in non-fire.

Figure 6: Confusion matrices of EFDBVC-AIDCNN model (a–f) 500–3000 epochs

Table 2 and Fig. 7 illustrate the classification outcomes of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN approach. The outcomes signified that the EFDBVC-AIDCNN approach could find the samples capably. On 500 epochs, the EFDBVC-AIDCNN approach reached an average

Figure 7: Average outcome of EFDBVC-AIDCNN model (a–f) 500–3000 epochs

Fig. 8 depicts the TRA

Figure 8:

Fig. 9 shows the TRA loss (TRALO) and VLA loss (VLALO) analysis of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN method. The loss values are calculated for 0–3000 epochs. The TRALO and VLALO curves exemplify a reducing tendency, which indicates the capacity of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN methodology to balance the trade-off between generality and data fitting. The continuous decline in loss values also promises the maximal performance of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN methodology and the ability to tune the prediction results on time.

Figure 9: Loss graph of EFDBVC-AIDCNN method (a–f) 500–3000 epochs

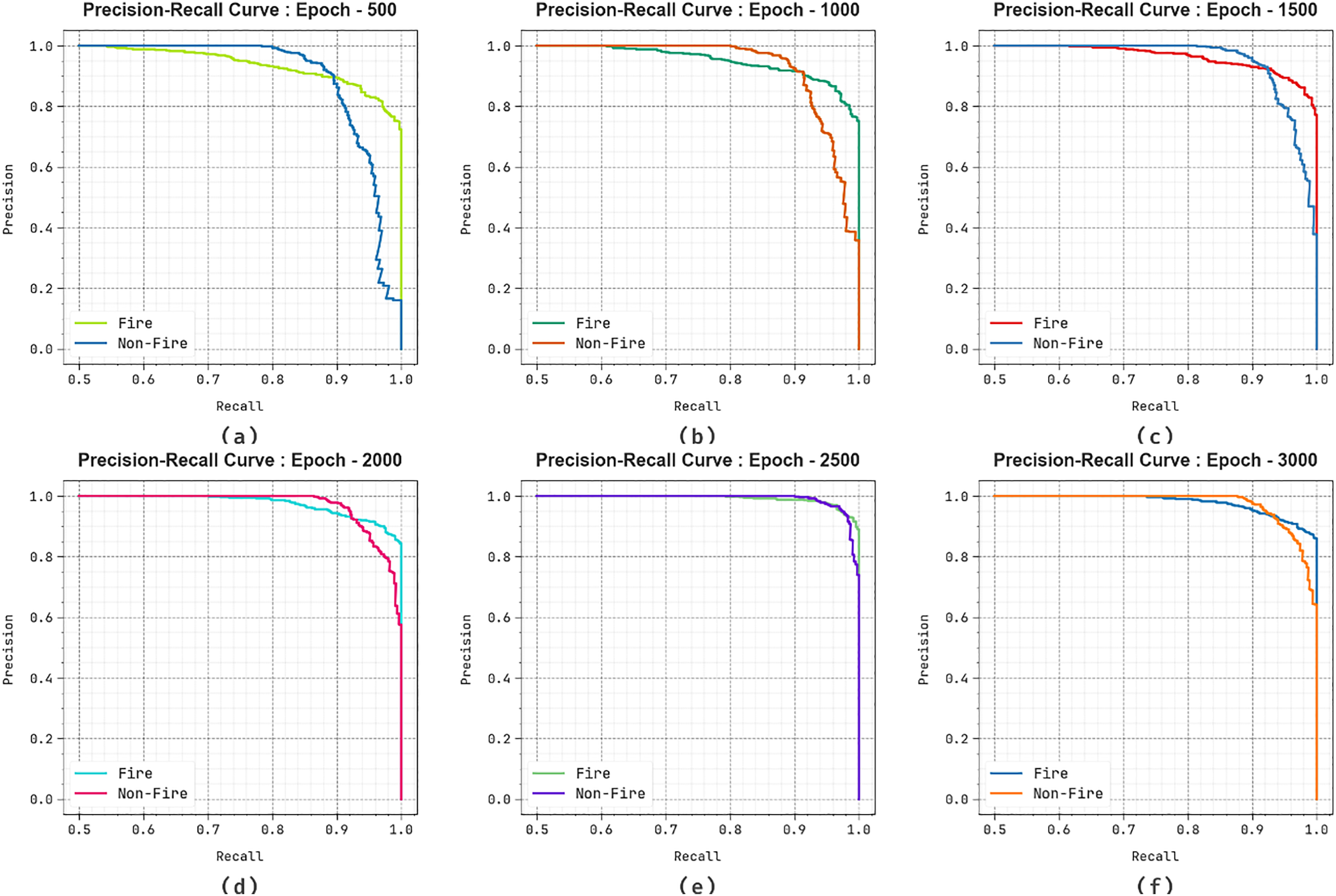

In Fig. 10, the precision-recall (PR) graph result of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN methodology under 500–3000 epochs explains its performance by plotting Precision against Recall for Fire and Non-fire class labels. The figure illustrates that the EFDBVC-AIDCNN methodology continuously accomplishes better PR outcomes across different Fire and Non-fire classes, demonstrating its abilities to sustain a vital part of true positive predictions between every positive prediction (precision) while furthermore capturing a considerable number of definite positives (recall). This steady growth in PR values between the two classes depicts the proficiency of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN model in the classifier process.

Figure 10: PR curve of EFDBVC-AIDCNN model (a–f) 500–3000 epochs

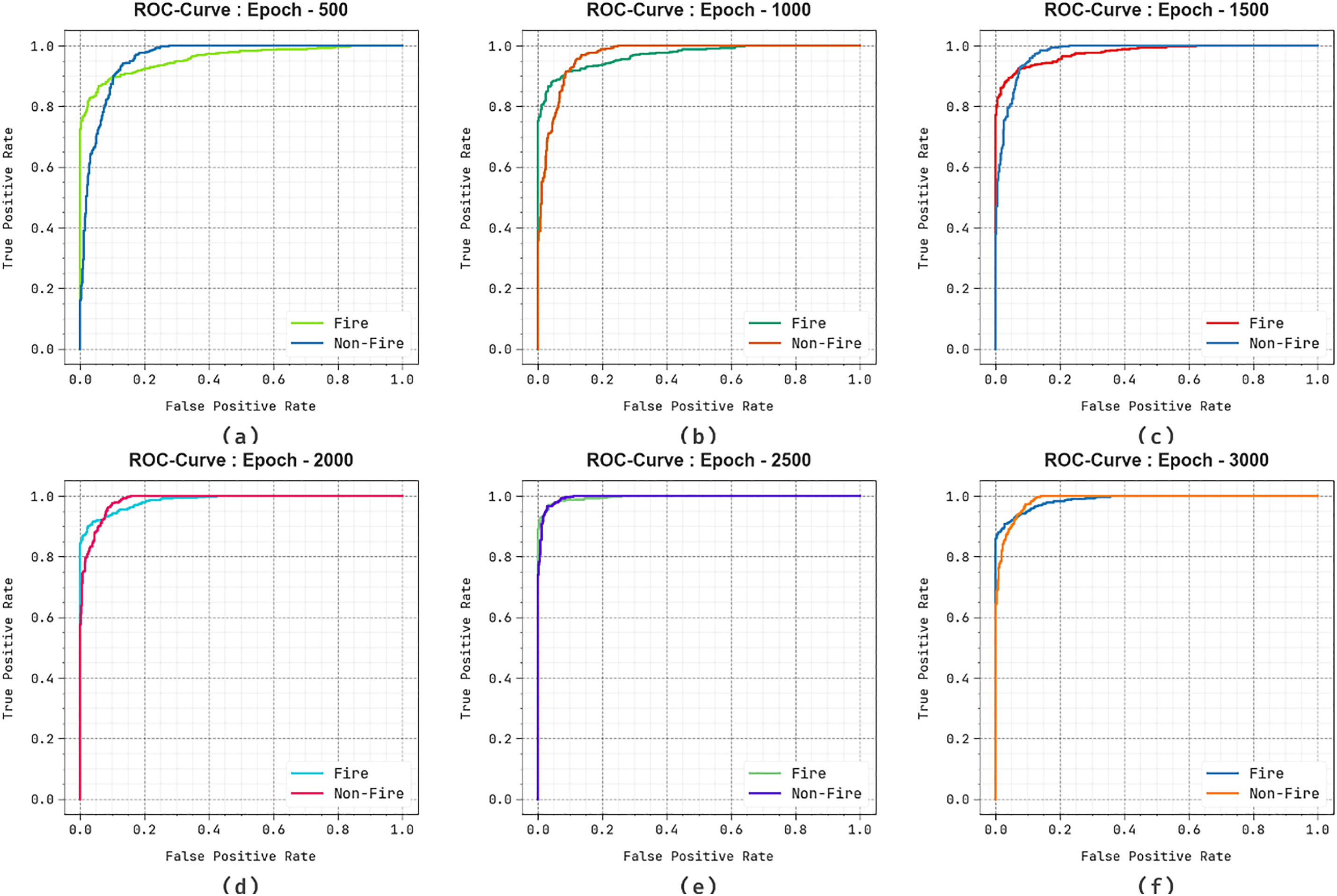

In Fig. 11, the ROC graph of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN model under 500–3000 epochs is considered. The results suggest that the EFDBVC-AIDCNN methodology reaches higher ROC results over each class label, representing critical capabilities to distinguish the class labels. This continual trend of maximum ROC values across several classes means the capable performance of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN methodology in forecasting classes and discovering the robust nature of the classifier process.

Figure 11: ROC curve of EFDBVC-AIDCNN model (a–f) 500–3000 epochs

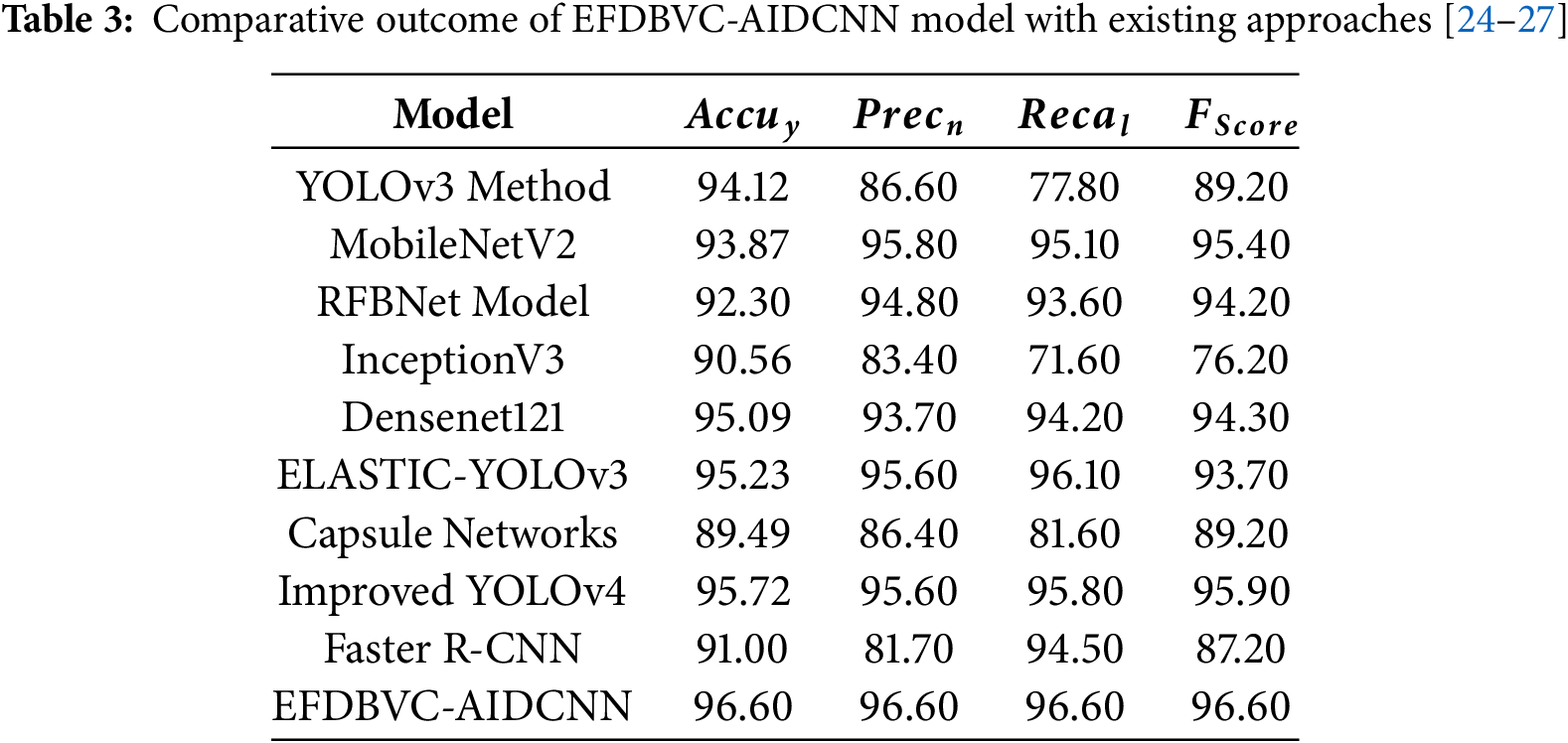

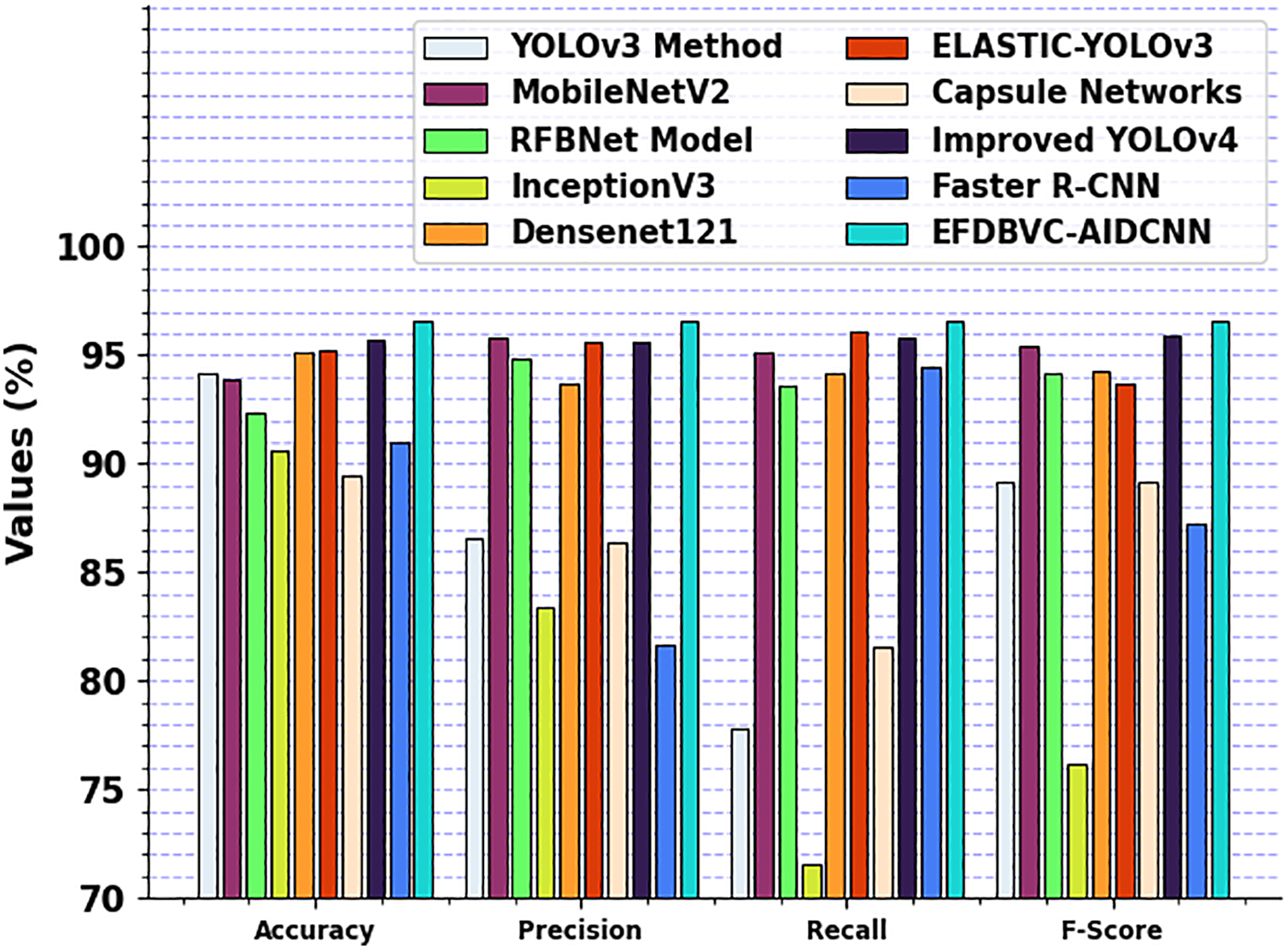

Table 3 and Fig. 12 show the EFDBVC-AIDCNN technique’s experimental outcomes with current methods [24–27]. The results show that the CapsNet method has displayed inferior performance with

Figure 12: Comparative outcome of EFDBVC-AIDCNN model with existing approaches

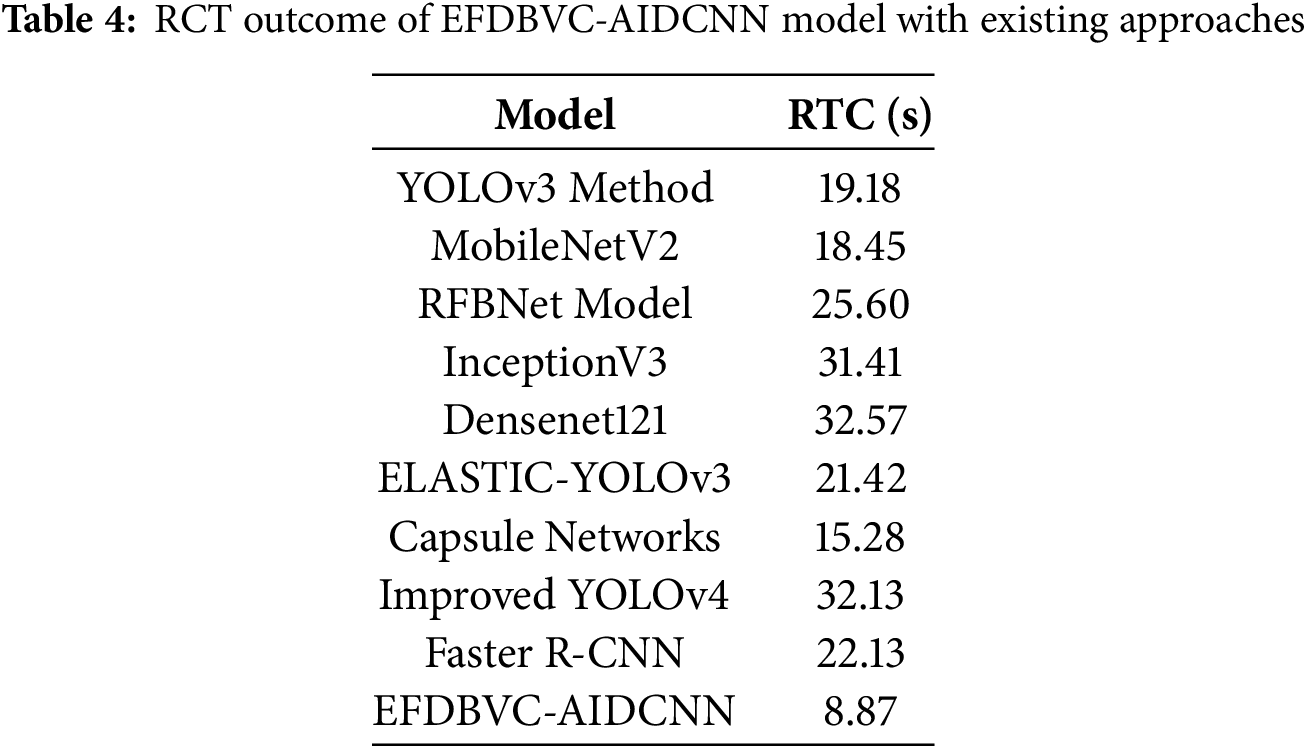

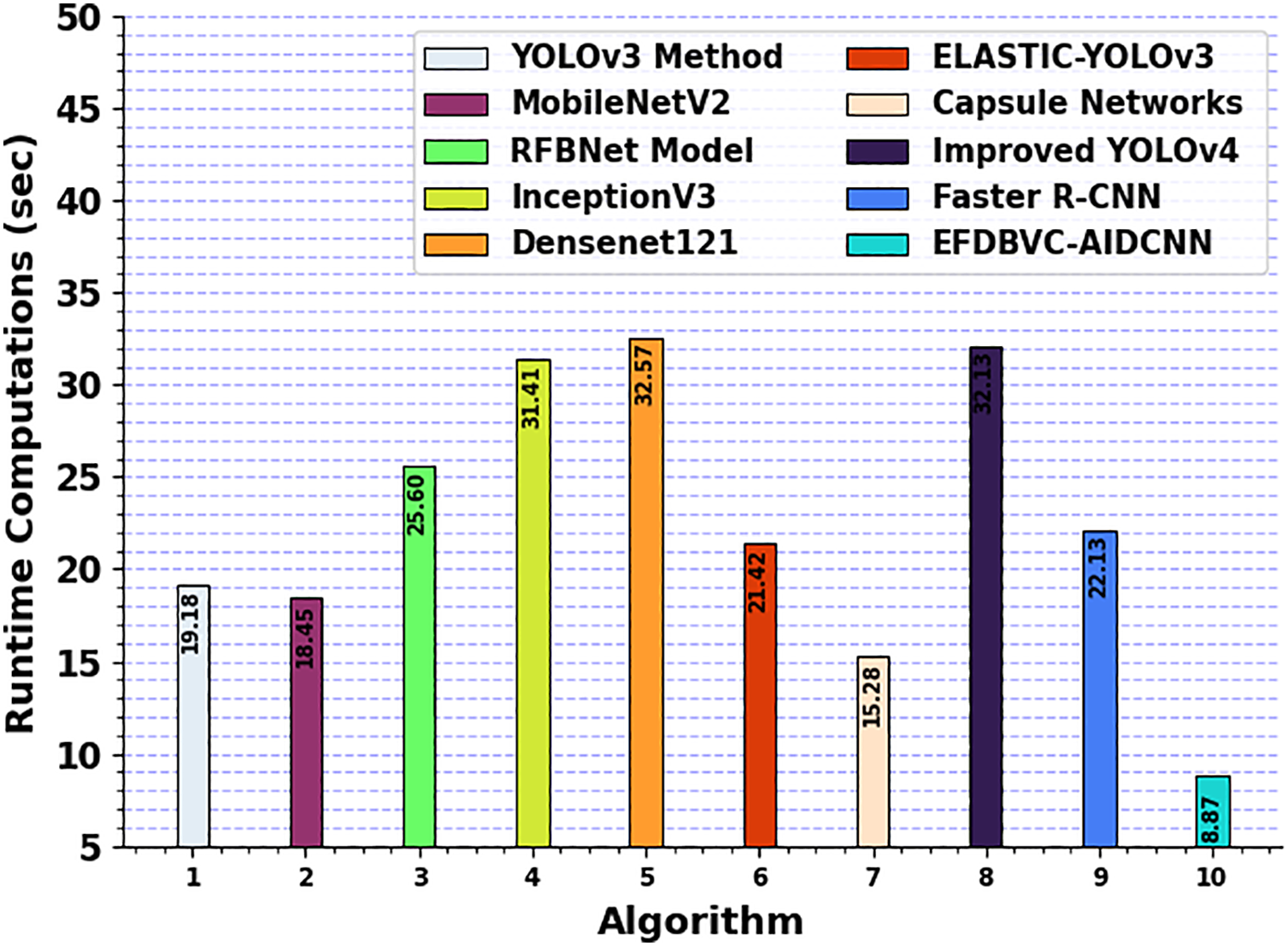

The runtime computation (RTC) of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN model is compared with recent methods in Table 4 and Fig. 13. The outcomes highlight that the Densenet121, Improved YOLOv4, and InceptionV3 methods have gained minimum performance with improved RCT of 32.57, 32.13, and 31.41 s, correspondingly. The RFBNet, Faster R-CNN, and ELASTIC-YOLOv3 methods also attained closer RCT values of 25.60, 22.13, and 21.42 s, respectively. Eventually, the YOLOv3, MobileNetV2, and CapsNet methods have reported substantial RCT values of 19.18, 18.45, and 15.28 s. However, the EFDBVC-AIDCNN technique performed better with an inferior RCT of 8.87 s.

Figure 13: RTC outcome of EFDBVC-AIDCNN model with existing approaches

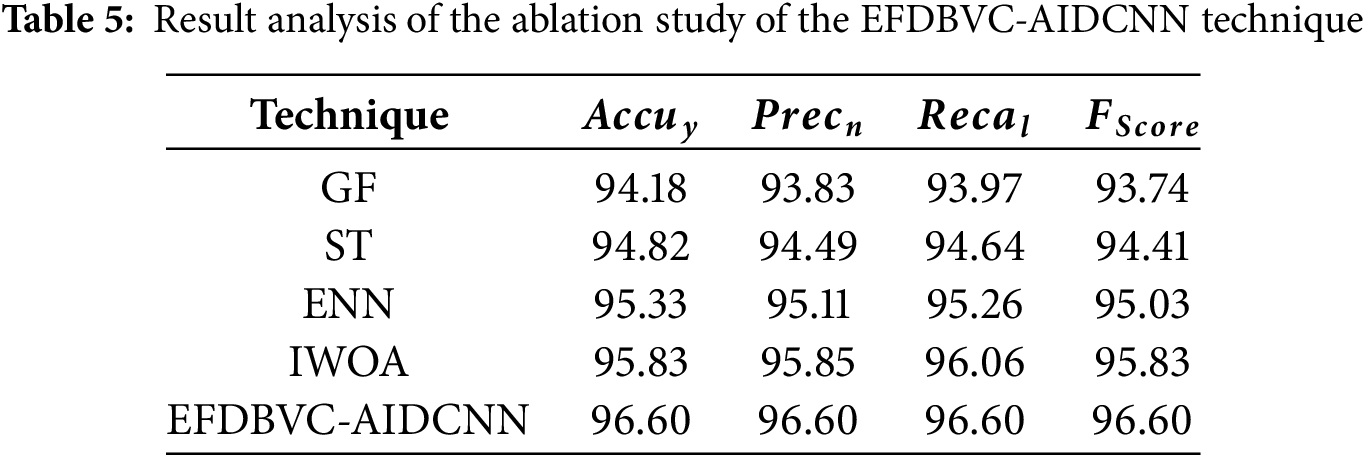

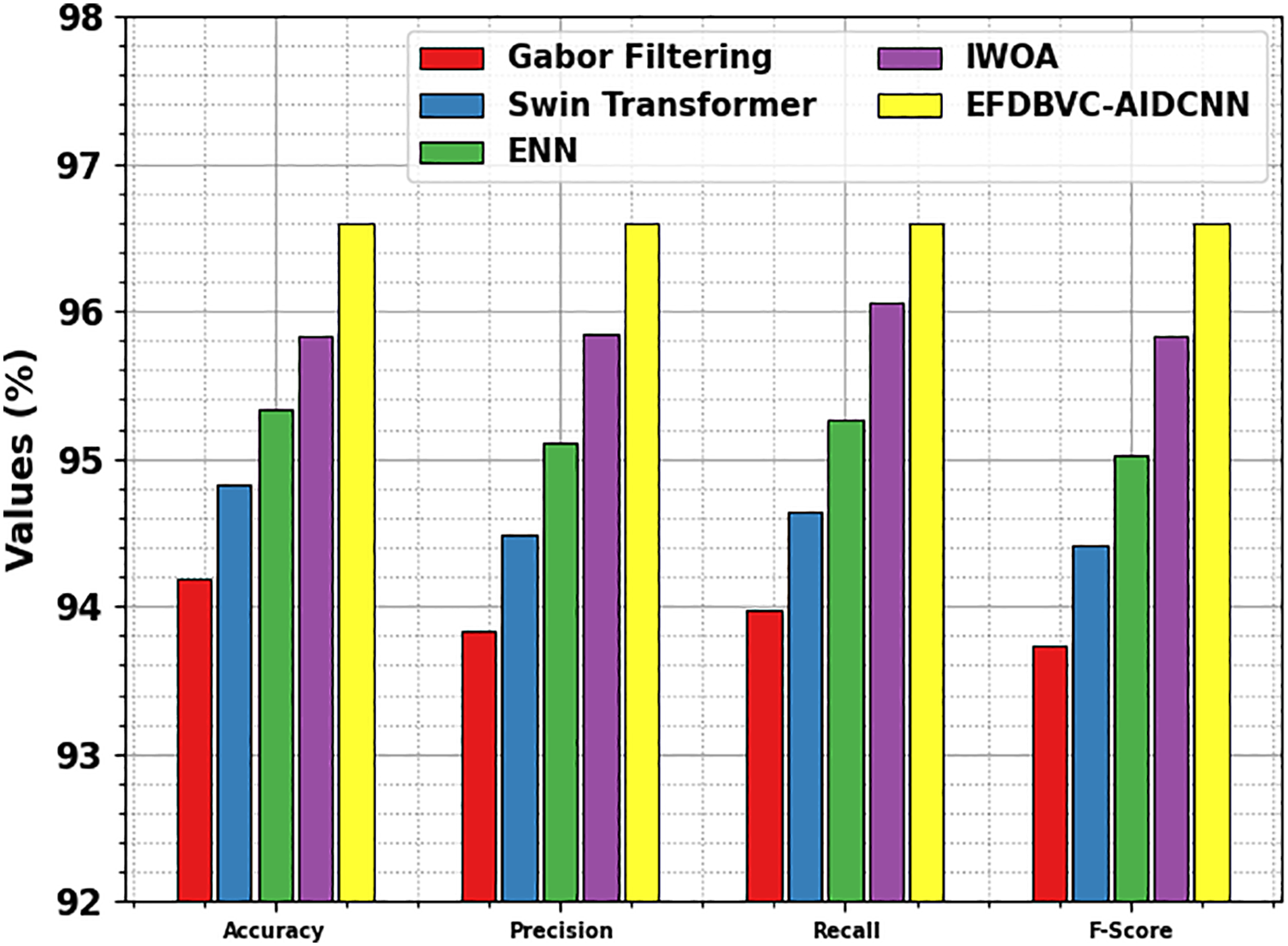

Table 5 and Fig. 14 illustrate the ablation study of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN technique to evaluate the impact of diverse techniques on classification performance using four key metrics. The GF model achieved an

Figure 14: Result analysis of the ablation study of EFDBVC-AIDCNN technique

In this manuscript, the EFDBVC-AIDCNN model is proposed. The EFDBVC-AIDCNN model presents an advanced fire detection system that leverages AI to detect and classify fire hazards for BVI people effectively. The presented EFDBVC-AIDCNN technique initially applies image pre-processing using the GF model to enhance texture details and patterns specific to flames and smoke. For the feature extractor, the ST model captures fine details across multiple scales to represent fire patterns accurately. In addition, the ENN technique is employed for the detection of fire. To ensure optimized performance, the IWOA technique is integrated to tune the ENN parameters efficiently, improving the model’s accuracy and robustness in different lighting and environmental conditions. An extensive experimental study of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN technique is accomplished under the fire detection dataset. A short comparative analysis of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN approach portrayed a superior accuracy value of 96.60% over existing models. The limitations of the EFDBVC-AIDCNN approach comprise its current evaluation being limited to controlled datasets, without real-world deployment or testing on practical edge devices. The performance of the model under highly dynamic or unpredictable environments remains unexplored. Additionally, the system has not yet been evaluated on real devices intended for visually impaired users, which is significant for validating usability, latency, and accessibility in real-time fire detection scenarios. This gap limits the direct applicability of the model in assistive safety technologies. Future work should concentrate on deploying the system in real-world environments, including integration with low-power embedded platforms, and conducting user-centric studies to assess efficiency and responsiveness for visually impaired individuals.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank the King Salman Centre for Disability Research for funding this work.

Funding Statement: The authors thank the King Salman Centre for Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group No. KSRG-2024-068.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design, draft manuscript preparation: Fahd N. Al-Wesabi; data collection: Hamad Almansour; analysis and interpretation of results: Huda G. Iskandar; draft manuscript preparation: Ishfaq Yaseen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting this study’s findings are openly available in the Kaggle repository at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kabilan03/fire-detection-dataset/data (accessed on 01 August 2025), reference number [23].

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Muhammad K, Khan S, Elhoseny M, Hassan Ahmed S, Baik SW. Efficient fire detection for uncertain surveillance environment. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2019;15(5):3113–22. doi:10.1109/TII.2019.2897594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li J, Yan B, Zhang M, Zhang J, Jin B, Wang Y, et al. Long-range Raman distributed fiber temperature sensor with early warning model for fire detection and prevention. IEEE Sens J. 2019;19(10):3711–7. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2019.2895735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Valikhujaev Y, Abdusalomov A, Cho YI. Automatic fire and smoke detection method for surveillance systems based on dilated CNNs. Atmosphere. 2020;11(11):1241. doi:10.3390/atmos11111241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Avazov K, Mukhiddinov M, Makhmudov F, Cho YI. Fire detection method in smart city environments using a deep-learning-based approach. Electronics. 2022;11(1):73. doi:10.3390/electronics11010073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li P, Zhao W. Image fire detection algorithms based on convolutional neural networks. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2020;19:100625. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2020.100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Emmy Prema C, Vinsley SS, Suresh S. Efficient flame detection based on static and dynamic texture analysis in forest fire detection. Fire Technol. 2018;54(1):255–88. doi:10.1007/s10694-017-0683-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kareem FH, Naser MA. Face detection and localization in video using HOG with CNN. Fusion Pract Appl. 2025;17(1):229–29. doi:10.54216/fpa.170117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Huang L, Liu G, Wang Y, Yuan H, Chen T. Fire detection in video surveillances using convolutional neural networks and wavelet transform. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2022;110:104737. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.104737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Xue Z, Lin H, Wang F. A small target forest fire detection model based on YOLOv5 improvement. Forests. 2022;13(8):1332. doi:10.3390/f13081332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sun F, Yang Y, Lin C, Liu Z, Chi L. Forest fire compound feature monitoring technology based on infrared and visible binocular vision. J Phys Conf Ser. 2021;1792(1):012022. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1792/1/012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Abuelmakarem H, Abuelhaag A, Raafat M, Ayman S. An integrated IoT smart cane for the blind and visually impaired individuals. SVU Int J Eng Sci Appl. 2024;5(1):71–8. doi:10.21608/svusrc.2023.222096.1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Marzouk R, Alrowais F, Al-Wesabi FN, Hilal AM. Exploiting deep learning based automated fire-detection model for blind and visually challenged people. J Disabil Res. 2023;2(4):50–7. doi:10.57197/jdr-2023-0054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Khan MA, Qureshi MA, Zahid H, Agha S, Mushtaq T, Nasim S. Innovative blind stick for the visually impaired. Asian Bull Big Data Manag. 2024;4(1):22–32. doi:10.62019/abbdm.v4i1.101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ben Atitallah A, Said Y, Ben Atitallah MA, Albekairi M, Kaaniche K, Alanazi TM, et al. Embedded implementation of an obstacle detection system for blind and visually impaired persons’ assistance navigation. Comput Electr Eng. 2023;108(41):108714. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2023.108714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. AKadhim M, KEl Abbadi N. Enhancing indoor navigation for the visually impaired by objects recognition and obstacle avoidance. Int J Comput Digit Syst. 2024;16(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

16. Thi Pham LT, Phuong LG, Tam Le Q, Thanh Nguyen H. Smart blind stick integrated with ultrasonic sensors and communication technologies for visually impaired people. In: Deep learning and other soft computing techniques. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2023. p. 121–34. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-29447-1_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yang W, Wu Y, Chow SKK. Deep learning method for real-time fire detection system for urban fire monitoring and control. Int J Comput Intell Syst. 2024;17(1):216. doi:10.1007/s44196-024-00592-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Malla S, Sahu PK, Patnaik S, Biswal AK. Obstacle detection and assistance for visually impaired individuals using an IoT-enabled smart blind stick. Rev D’intelligence Artif. 2023;37(3):783–94. doi:10.18280/ria.370327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hammouche R, Attia A, Akhrouf S, Akhtar Z. Gabor filter bank with deep autoencoder based face recognition system. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;197(C):116743. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.116743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Choi S, Song Y, Jung H. Study on improving detection performance of wildfire and non-fire events early using swin transformer. IEEE Access. 2025;13(3):46824–37. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3528983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang Y, Mo H. Intelligent building construction cost optimization and prediction by integrating BIM and Elman neural network. Heliyon. 2024;10(18):e37525. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang T, Zhang W, Meng Z, Li J, Wang M. Research on high-frequency torsional oscillation identification using TSWOA-SVM based on downhole parameters. Processes. 2024;12(10):2153. doi:10.3390/pr12102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Fire detection dataset. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kabilan03/fire-detection-dataset/data. [Google Scholar]

24. Mukhiddinov M, Abdusalomov AB, Cho J. Automatic fire detection and notification system based on improved YOLOv4 for the blind and visually impaired. Sensors. 2022;22(9):3307. doi:10.3390/s22093307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Ali Refaee E, Sheneamer A, Assiri B. A deep-learning-based approach to the classification of fire types. Appl Sci. 2024;14(17):7862. doi:10.3390/app14177862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Abdusalomov AB, Mukhiddinov M, Kutlimuratov A, Whangbo TK. Improved real-time fire warning system based on advanced technologies for visually impaired people. Sensors. 2022;22(19):7305. doi:10.3390/s22197305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Abdusalomov A, Baratov N, Kutlimuratov A, Whangbo TK. An improvement of the fire detection and classification method using YOLOv3 for surveillance systems. Sensors. 2021;21(19):6519. doi:10.3390/s21196519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools