Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Leveraging Federated Learning for Efficient Privacy-Enhancing Violent Activity Recognition from Videos

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Bangladesh University of Business and Technology, Dhaka, 1216, Bangladesh

2 Research Chair of Online Dialogue and Cultural Communication, Department of Computer Science, College of Computer and Information Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, 12372, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Texas A&M University-Kingsville, Kingsville, TX 78363, USA

4 Department of Computer Science, American International University-Bangladesh, Dhaka, 1229, Bangladesh

* Corresponding Author: Mejdl Safran. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5747-5763. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067589

Received 07 May 2025; Accepted 10 September 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Automated recognition of violent activities from videos is vital for public safety, but often raises significant privacy concerns due to the sensitive nature of the footage. Moreover, resource constraints often hinder the deployment of deep learning-based complex video classification models on edge devices. With this motivation, this study aims to investigate an effective violent activity classifier while minimizing computational complexity, attaining competitive performance, and mitigating user data privacy concerns. We present a lightweight deep learning architecture with fewer parameters for efficient violent activity recognition. We utilize a two-stream formation of 3D depthwise separable convolution coupled with a linear self-attention mechanism for effective feature extraction, incorporating federated learning to address data privacy concerns. Experimental findings demonstrate the model’s effectiveness with test accuracies from 96% to above 97% on multiple datasets by incorporating the FedProx aggregation strategy. These findings underscore the potential to develop secure, efficient, and reliable solutions for violent activity recognition in real-world scenarios.Keywords

Human activity recognition (HAR) systems and video surveillance have been significantly enhanced by artificial intelligence (AI), enabling advancements in crowd analysis, behavior monitoring, and public safety [1,2]. These AI-driven developments facilitate the automated recognition of violent activities, which is crucial for maintaining security in public spaces. For instance, recent data indicate that the global video surveillance market is expected to reach $88.71 billion by 2030, with AI integration being the key driver of this growth [3]. However, the integration of AI in surveillance raises critical concerns regarding data security, privacy, and substantial processing demands associated with high-resolution video data [4]. Violence recognition systems often analyze sensitive and identifiable information, thereby increasing the risk of privacy infringement [5]. In response to stringent data protection regulations such as the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), there is a growing imperative for AI systems that not only deliver reliable performance but also provide robust privacy safeguards [6,7].

Addressing these challenges requires innovative approaches to ensure the privacy and efficiency of AI-based automated video surveillance systems. Surveillance videos frequently contain sensitive information, which necessitates stringent privacy measures. In addition, the analysis of large-scale video data poses significant memory and processing challenges, particularly when leveraging cloud-based servers, which can lead to accessibility issues for edge devices [8]. To mitigate these obstacles, researchers have explored privacy-preserving techniques such as secure multiparty computation, federated learning (FL), and differential privacy [5]. Among these, FL has gained prominence for enabling decentralized learning without compromising data privacy. There are several paradigms and variants of FL based on different criteria. For instance, the most common is the horizontal FL, where clients share the same feature space but differ in samples (e.g., surveillance cameras at different locations training on similar video features). In vertical FL, clients share samples but differ in features (e.g., different sensors for the same event), and federated transfer learning combines both horizontal and vertical settings when clients differ in both samples and features [9,10]. Despite these advancements, many existing methods encounter limitations related to real-time scalability, high memory consumption owing to encryption protocols, and excessive computational complexity [11,12]. Furthermore, achieving a balance between high classification accuracy and robust privacy guarantees remains challenging, particularly in resource-constrained environments or scenarios with noisy data [13]. The high memory demands of deep and complex models create barriers to their deployment on resource-constrained edge devices, emphasizing the need for lightweight deep learning (DL) architectures [14].

Motivated by the aforementioned challenges, we investigate an FL-based framework for privacy-enhancing decentralized learning and efficient violence recognition from videos. We incorporate a horizontal FL approach since each surveillance camera or client would hold the same feature space, i.e., video frames with the same modalities but different samples. Our DL classifier emphasizes a lightweight design, recognizing that both FL and on-device deployment shift the computational burden of the entire network to local devices that typically lack high-end processing capabilities. To achieve competitive accuracy, our model employs a two-stream architecture that integrates multiple blocks of 3D depthwise separable convolutions with a linear self-attention mechanism, which enables efficient extraction of spatial and temporal features. In addition, we enforced information fusion between streams through residual connections, thereby enhancing information flow and convergence. The key aspects of this study can be summarized as follows:

• We propose an innovative and effective framework for violent activity recognition integrated with FL to enhance user data privacy through decentralized learning

• Our lightweight model contains only approximately 1.104 million parameters and 4.42 MB in size, significantly fewer than state-of-the-art video classifiers, which typically require approximately 100 times more parameters

• Experiments on multiple datasets demonstrated competitive recognition accuracies attained by the model

• Proposed model outperformed popular models such as ViViT and TimeSformer in a comprehensive performance analysis.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents an overview of past works. Section 3 discusses the methodology in detail. Section 4 summarizes the experiment and findings, followed by a discussion of the overall study in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study.

Recent advancements in violence recognition within surveillance videos have utilized various DL architectures to enhance accuracy and real-time processing. Ullah et al. [15] conducted a comprehensive review of ML and DL methods for violence detection, highlighting existing challenges and future directions focused on surveillance scenarios. Liu et al. [16] proposed a human-centered attention mechanism that can dynamically emphasize the salient regions from videos associated with the action, leading to effective recognition. Aggarwal et al. [17] introduced a system combining MobileNetV2 with a BiLSTM layer, achieving 96% accuracy on CCTV footage. Similarly, Yadav et al. [18] presented a CNN and LSTM framework that achieved up to 98% accuracy and a processing speed of 131 frames/sec. Abbass and Kang [19] enhanced detection by integrating Convolutional Block Attention Modules (CBAM) and using data augmentation and Categorical Focal Loss to address class imbalance. Kumar et al. [20] proposed a lightweight transformer model for indoor violence detection that achieved up to 98% accuracy with occluded subjects. Mohammadi and Nazerfard [21] introduced a semi-supervised hard attention model using reinforcement learning, achieving high accuracies on the RWF and Hockey datasets, although it depends heavily on the quality of the reinforcement learning algorithms and may underperform in less controlled settings. Finally, Vijeikis et al. [22] combined a U-Net-like network with MobileNet V2 and an LSTM module, attaining around 82% accuracy and 81% precision on the RWF-2000 dataset. Many frameworks for protecting sensitive data have also been made available by recent advances in privacy-preserving video analytics. For instance, Frimpong et al. [23] developed Secrets In Motion (SIM), which employs Ciphertext Policy Attribute-Based Encryption (CP-ABE) and Multi-Key Homomorphic Encryption (MKHE) to control access to video content. Although SIM balances privacy with classification accuracy, it may face scalability issues and the computational complexity of its encryption methods, limiting its use in large-scale deployments. Feng et al. [24] introduced X-Stream, a flexible video transformer for privacy-preserving video stream analytics, featuring a declarative query interface for specifying privacy and content exposure preferences, an adaptive mechanism that selects appropriate privacy-preserving techniques at runtime, and an efficient execution engine optimized for multi-task deduplication and inter-frame inference. Gaikwad and Karmakar [25] presented the Privacy-Aware Person Search (PAPS) model for IoT surveillance, which processes data at the edge and fog layers to minimize privacy risks. Mehta et al. [26] introduced SETR-PKD, a seizure detection framework that uses optical flow features to preserve patient confidentiality. However, this method can be less effective in environments with minimal movement or where motion patterns are subtle, reducing its reliability in diverse settings. Singh et al. [27] employed ViViT for violence detection, incorporating data augmentation to enhance performance on smaller datasets. On the other hand, Pajon et al. [28] modified the Flow-Gated model and proposed an innovative approach called “Diff Gated” network, which attained improved results compared to the original model. However, they only experimented with the federated averaging (FedAvg) aggregation strategy, which assumes that data across clients follows a similar distribution, which is often unrealistic in surveillance settings. Similarly, Victor et al. [29] proposed an FL–based violence detection framework that extracts individual frames from the AIRTLab dataset and classifies them using pre-trained CNN backbones. However, their approach is limited to frame-level modeling, thus overlooking critical temporal dynamics, and is evaluated on a single dataset, raising concerns about the generalizability.

Earlier studies have primarily concentrated on enhancing human activity recognition (HAR) methods to improve the efficiency of recognition models. However, these advancements often come with significant computational demands and fail to adequately address crucial factors such as user data privacy, especially when dealing with sensitive footage of daily life or indoor activities. While some studies have explored privacy concerns such as incorporating FL, their approaches are often limited by issues such as a lack of convincing performance, poor generalizability, and high computational complexity that hinders scalability. Additionally, many existing method poses the risk of high false positive rates and inconsistent performance across diverse real-world settings. Therefore, it is essential to develop lightweight architectures that effectively balance accuracy and model complexity. Overcoming these challenges is critical for creating scalable, secure, and efficient solutions for practical applications.

In this section, we first provide an overview of Federated Learning, followed by the introduction of our proposed DL-based architecture for efficient and effective violent activity recognition, leveraging Federated Learning.

Federated Learning, also known as FL, contrasts with traditional centralized learning by enabling multiple entities (known as clients) to train a model collaboratively without sharing private data [30]. Rather, clients only share model updates (e.g., weights or gradients) with the central server. The server aggregates these local updates to construct a global model and distributes the updated global parameters to the entities. The design of FL enhances data privacy and has broad applications across domains such as healthcare, surveillance, and beyond [31,32]. Aggregation strategies vary according to the target application, data distribution, and other factors. An efficient aggregation strategy is one of the popular research domains in FL, and researchers have explored various effective strategies for tackling various challenges while improving performance. In this study, we experimented with two popular strategies that are briefly discussed in the following subsections.

3.1.1 Federated Averaging (FedAvg)

Federated Averaging, widely known as FedAvg, is the most common and intuitive aggregation strategy for FL [30]. It aggregates model updates from multiple clients by simply calculating the weighted average of their locally computed updates, weighted by the size of each client’s dataset. Mathematically,

where,

3.1.2 Federated Proximal (FedProx)

The FedProx algorithm is an extension of FedAvg designed to address the heterogeneity of client data distributions and system constraints in FL [33]. It introduces a proximal term in the loss function that penalizes significant deviations between the local client model parameters and the global model parameters. The proximal term is scaled by the parameter

where,

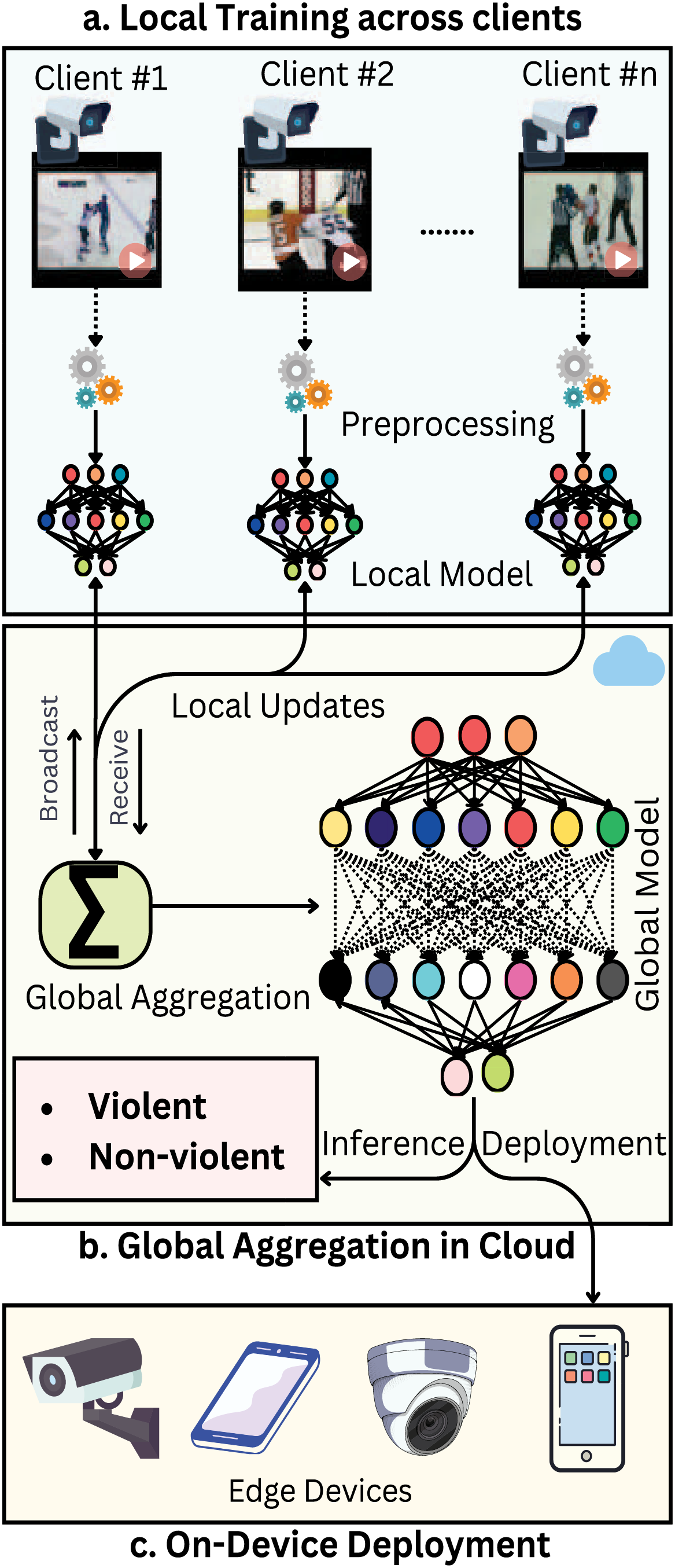

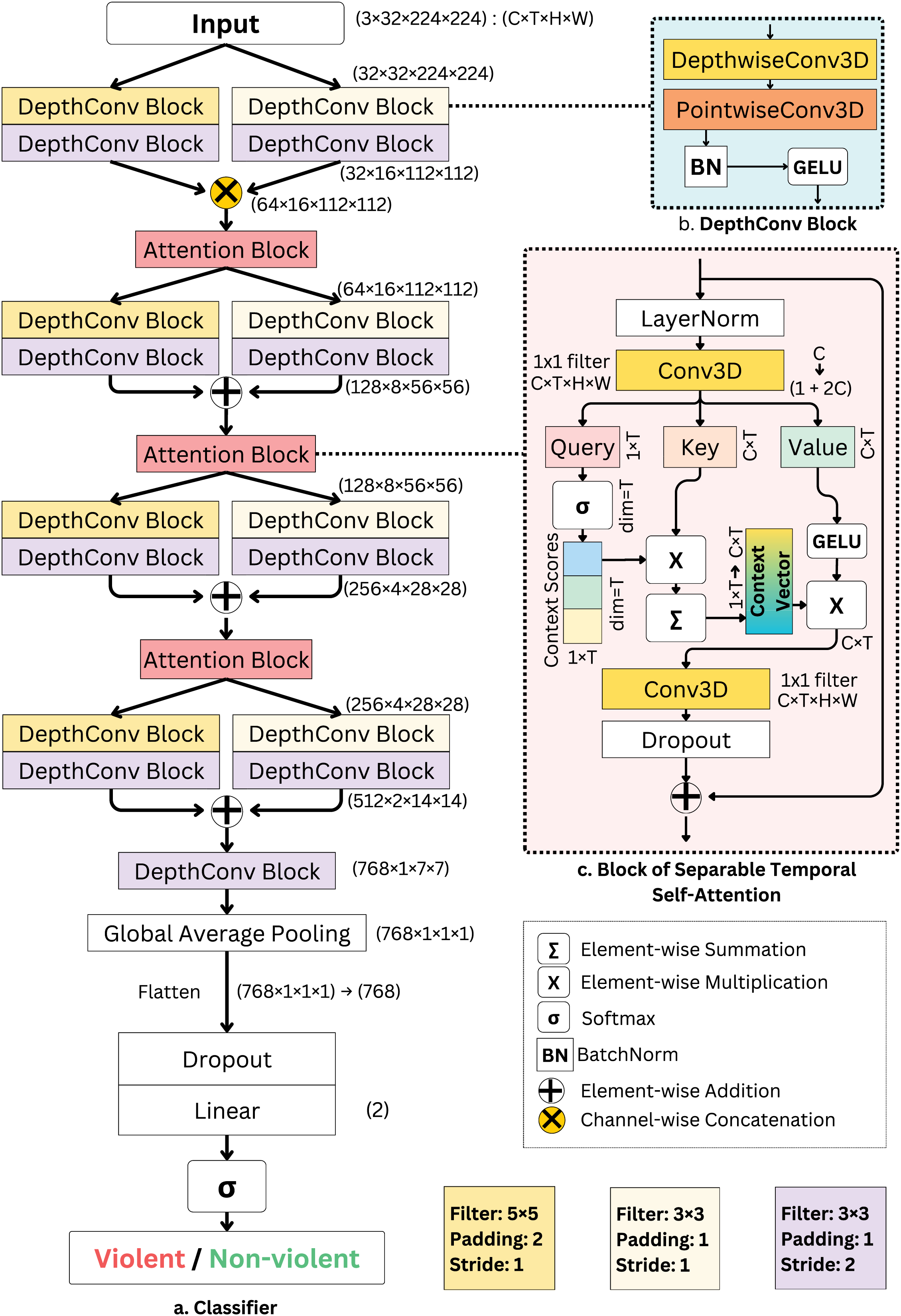

The framework incorporates decentralized training based on FL principles, operating across multiple clients or data sources. As illustrated in Algorithm 1, the process begins with the initialization of the global model

Figure 1: Overview of the FL empowered violent activity recognition

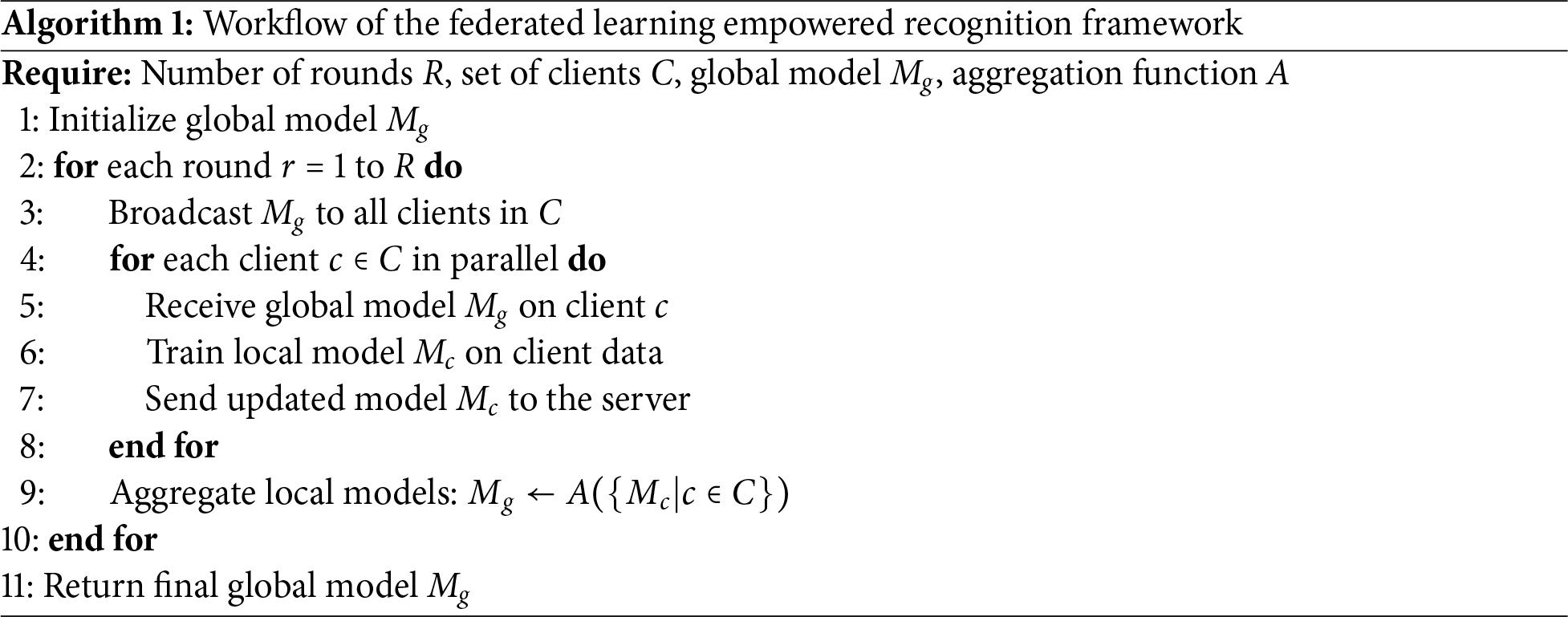

Fig. 2 illustrates the proposed classifier architecture and its key components. Fig. 2a provides an overview of the model, which comprises two-stream feature extraction, where each stream uses different filter sizes during the convolution operation to capture the diverse characteristics of the input frames. Fig. 2b shows the building block of the two-stream formation, the DepthConv block, which employs 3D depthwise separable convolution. In this process, depthwise convolution treats each input channel independently, followed by pointwise convolution to combine the channels. This mechanism efficiently reduces the computational burden while extracting essential features [34]. Mathematically, given an input tensor

where ∗ represents the convolution operation and

where

Figure 2: Outline of employed classifier and its components: (a) the classifier with two-stream feature extraction, (b) DepthConv Block comprising Depthwise Separable 3D Convolution, (c) Attention Block employing Separable Self-Attention over the temporal dimension

Fig. 2c illustrates the attention block, which is a key component of our model that enhances performance while minimizing computational complexity. This block employs a separable temporal self-attention mechanism that is integrated with a residual connection. The MobileViTV2 image classification model inspires the self-attention mechanism [36], which operates with linear complexity, making it well-suited for mobile devices. In our implementation, we adapted the attention mechanism to use 3D convolution and GELU activation instead of the linear operations with ReLU non-linearity for improved performance in video-based tasks. Given an input tensor

where

where

A final

where

In the end, we employed global average pooling to summarize the overall influence of the extracted features for classification. The resulting tensor is flattened and passed through a linear layer with a dropout operation to prevent overfitting. The final classification was achieved using softmax scores.

This section outlines the experimental details and findings of our study, starting with the data preparation and training setup, followed by performance analysis and ablation study, and concluding with the performance comparison with baseline models.

4.1 Experimental Data, and Setup

We conducted experiments using three separate datasets to evaluate the performance of our proposed model, simulating decentralized learning. The first dataset is the Hockey Fight (HF) detection dataset [37], which consists of 1000 clips (500 fight and 500 non-fight) from the National Hockey League (NHL). Each clip contains 50 frames with a resolution of 720

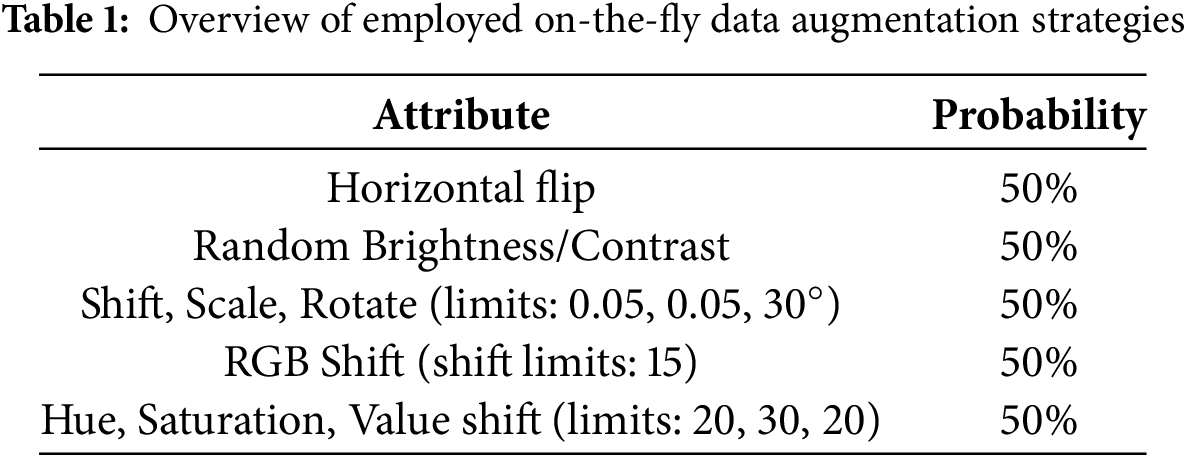

To prepare the datasets for the experiment, we downsampled the resolution of the original clips to 224

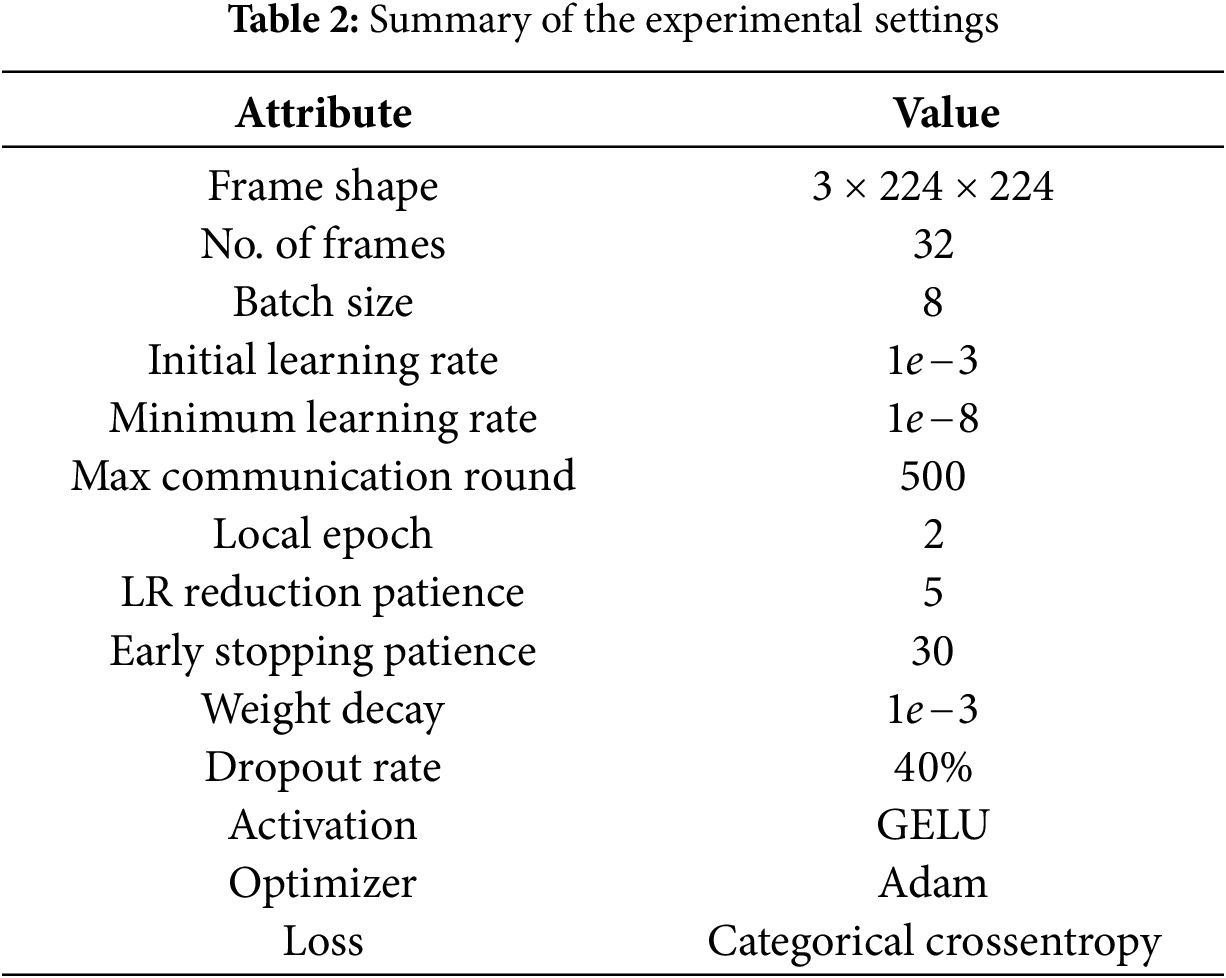

The experimental implementations were carried out using Python and PyTorch to simulate the FL training system. The training data were partitioned into two subsets to simulate two participating local clients, each using their respective local data. Each client was trained on their local data for two consecutive epochs per round. To enhance the training process, we implemented callback strategies, including learning rate reduction and early stopping, based on the validation set performance of the global model after aggregation. If the validation accuracy showed no improvement for five consecutive rounds, the learning rate was reduced by 50% globally. Early stopping was triggered if no improvement in validation accuracy occurred over 30 consecutive rounds. All training and testing experiments were conducted in the Kaggle Notebook environment, utilizing two NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPUs with 29 GB of RAM. A summary of the experimental settings for the proposed model is provided in Table 2.

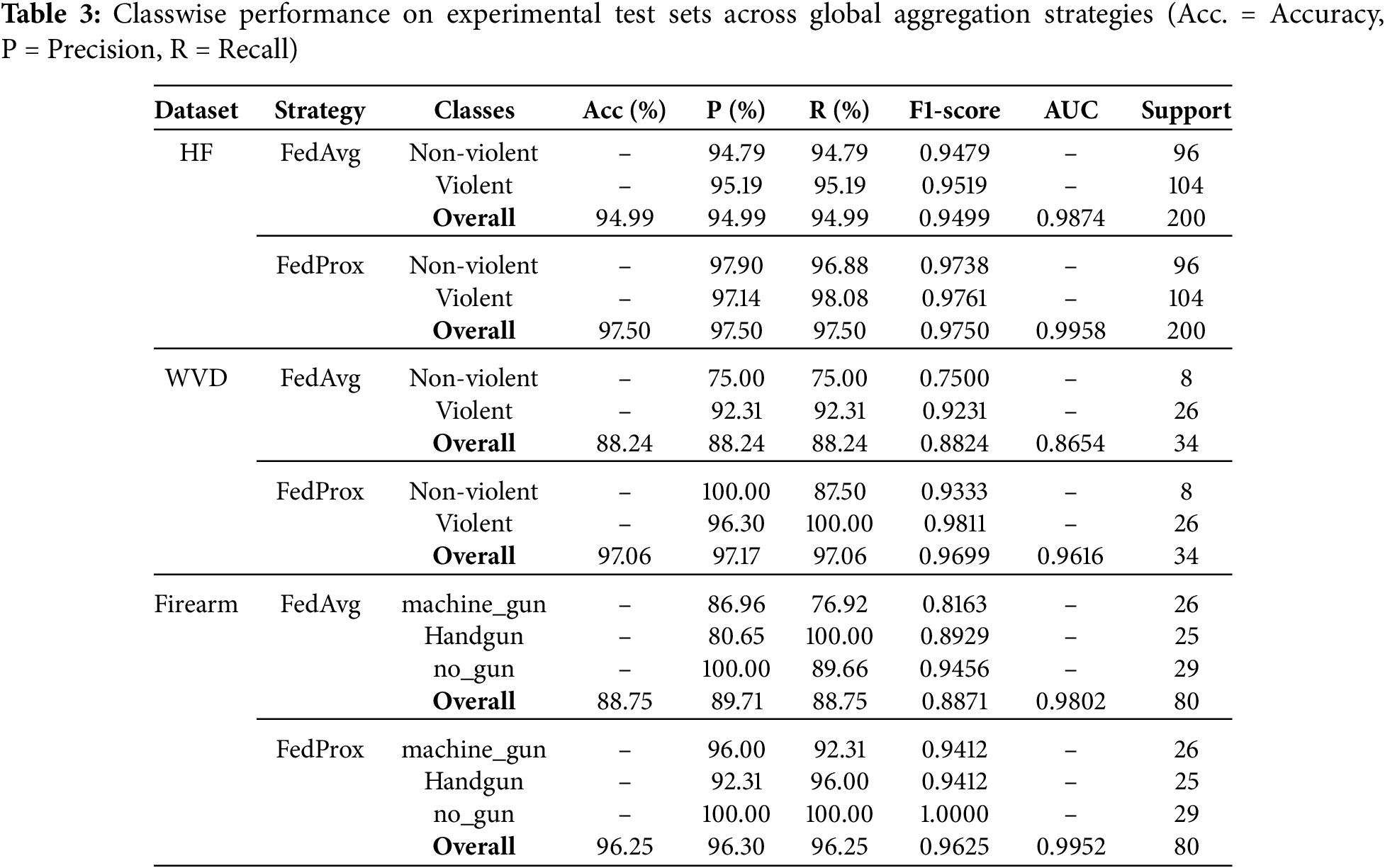

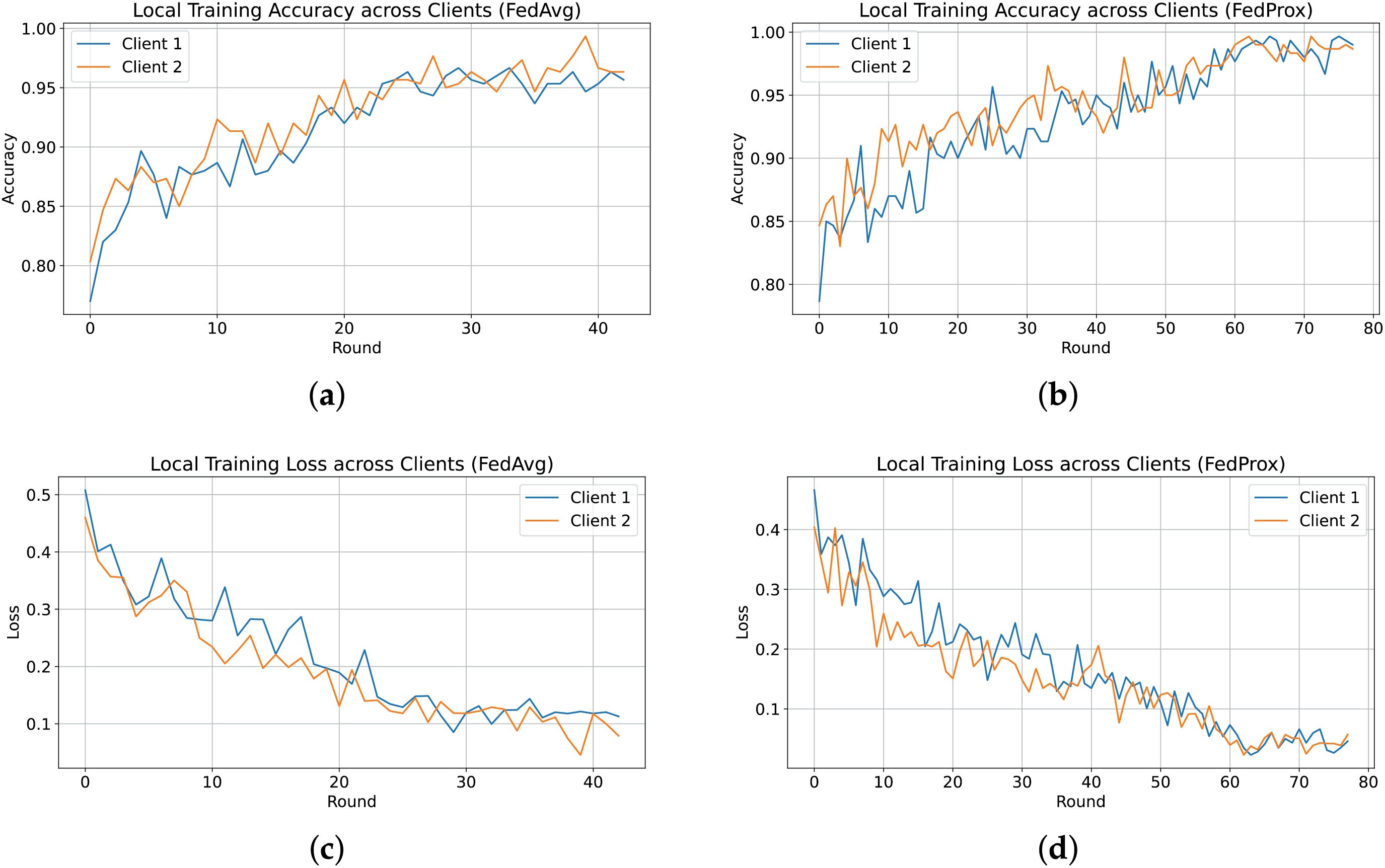

The model consistently outperformed across all datasets when trained with the FedProx strategy compared to FedAvg. As shown in Table 3, FedProx achieved a test accuracy of 97.50% and an AUC of 0.9958 on the HF dataset, whereas FedAvg reached only 94.99%, marking a 2.58% drop in accuracy. A similar trend was observed on the WVD dataset, where FedProx achieved 97.06% accuracy and an AUC of 0.9616—an improvement of nearly 10% over the 88.24% accuracy obtained using FedAvg. On the Firearm dataset, FedProx also led to an 8.46% increase in accuracy compared to FedAvg. It is important to note that the small number of test samples per class had a significant impact on the final accuracy. For example, as illustrated in Fig. 3, a single misclassification out of 34 samples in WVD yielded an accuracy of 97.06%. Similarly, five misclassifications out of 200 samples in HF resulted in 97.50% accuracy, while three misclassified samples out of 80 in the Firearm dataset led to a 96.25% accuracy.

Figure 3: Confusion matrix of the test set evaluation using the FedProx strategy. (a) HF dataset; (b) WVD dataset; (c) Firearm dataset

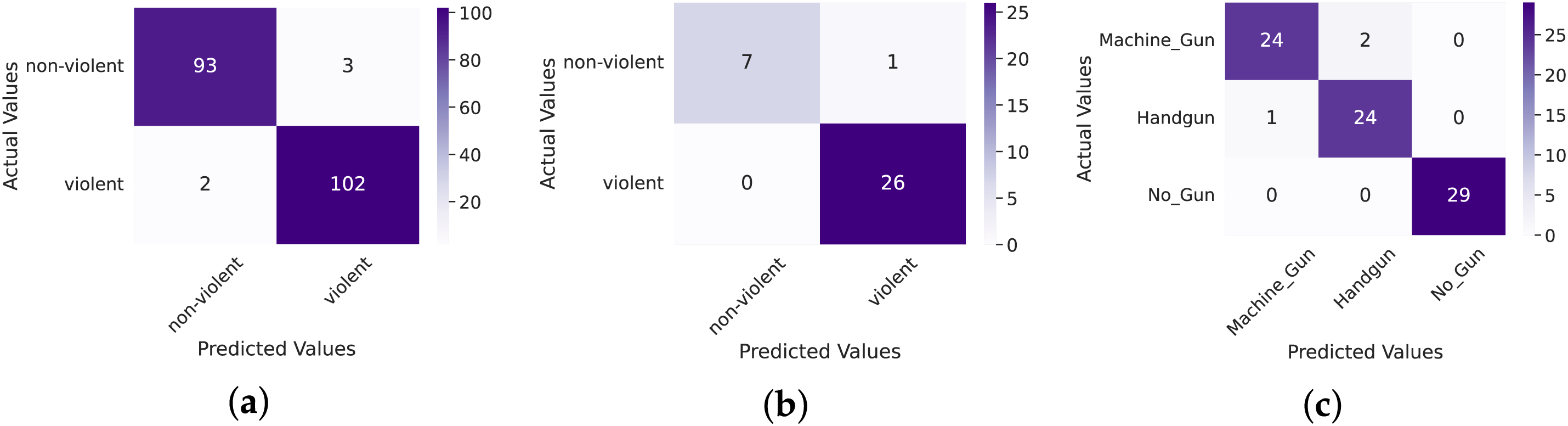

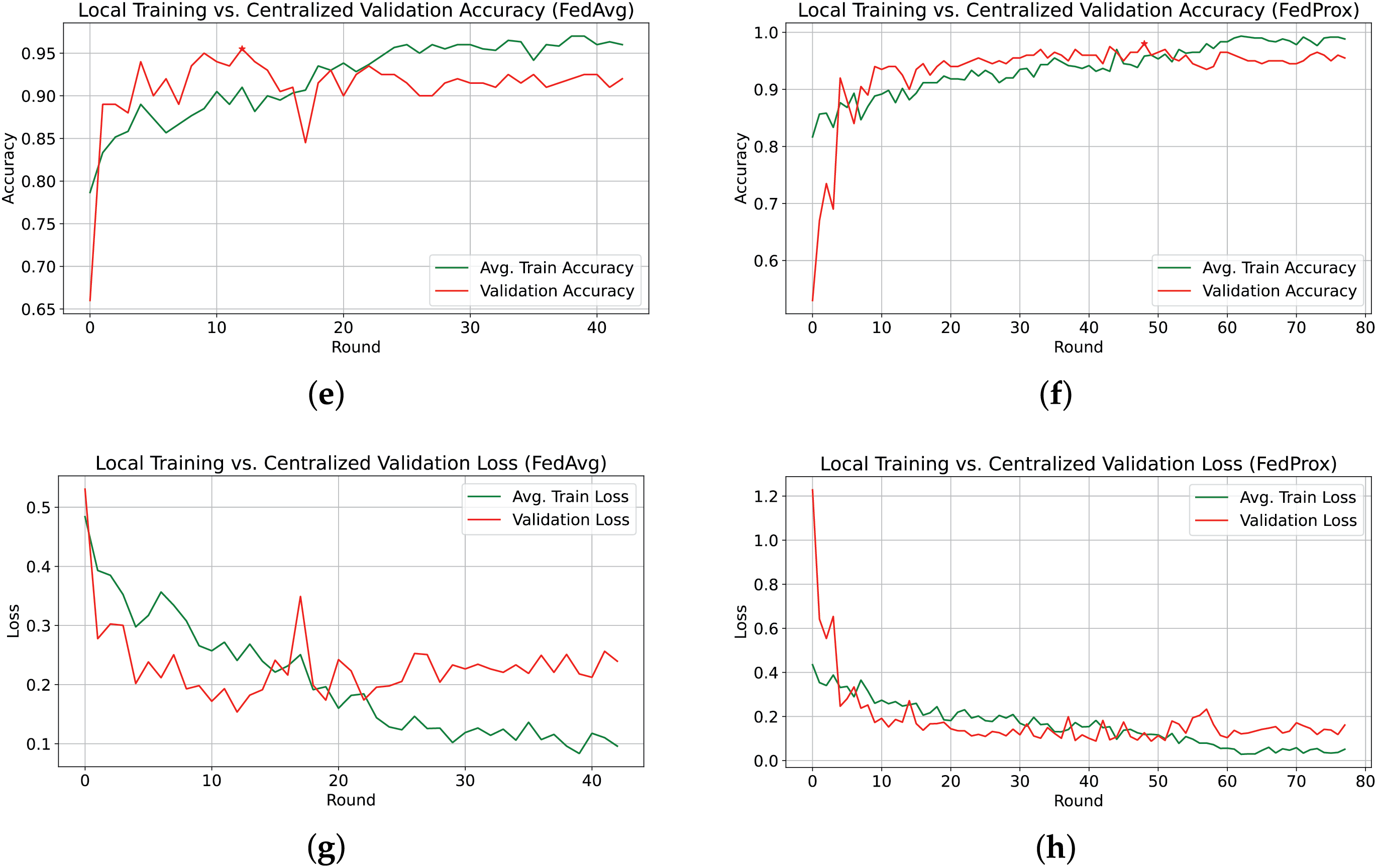

To analyze the impact of FedAvg and FedProx on performance, Fig. 4 illustrates the training accuracy and loss across the communication rounds for each client using the HF dataset. Fig. 4a,c shows that FedAvg completed only 43 rounds before triggering early stopping, while Fig. 4b,d demonstrates that FedProx sustained training for 78 rounds, progressively enhancing robustness, delaying the early stopping threshold, and improving global validation accuracy. Fig. 4 also illustrates the average training accuracy and loss with the global validation performance. Although FedAvg initially achieved a peak validation accuracy of 95.50%, its performance deteriorated in subsequent rounds, as shown in Fig. 4e. In contrast, FedProx exhibited a steady improvement in validation accuracy, aligned with the average training accuracy, ultimately reaching 98.00% validation accuracy, as seen in Fig. 4f. A common trend observed in Fig. 4 is that validation accuracy consistently outperformed training accuracy. This can be attributed to regularization techniques, such as dropout and L2 regularization, applied during training. Furthermore, the validation accuracy reflects the performance of the aggregated model, which is inherently more robust than individual client models, contributing to its superior validation performance.

Figure 4: Overview of local training and centralized validation performance using FedProx and FedAvg aggregation strategies on the HF dataset. (a) Local Train Accuracy with FedAvg; (b) Local Train Accuracy with FedProx; (c) Local Train Loss with FedAvg; (d) Local Train Loss with FedProx; (e) Avg. Train vs. Global Validation Accuracy with FedAvg; (f) Avg. Train vs. Global Validation Accuracy with FedProx; (g) Avg. Train vs. Global Validation Loss with FedAvg; (h) Avg. Train vs. Global Validation Loss with FedProx

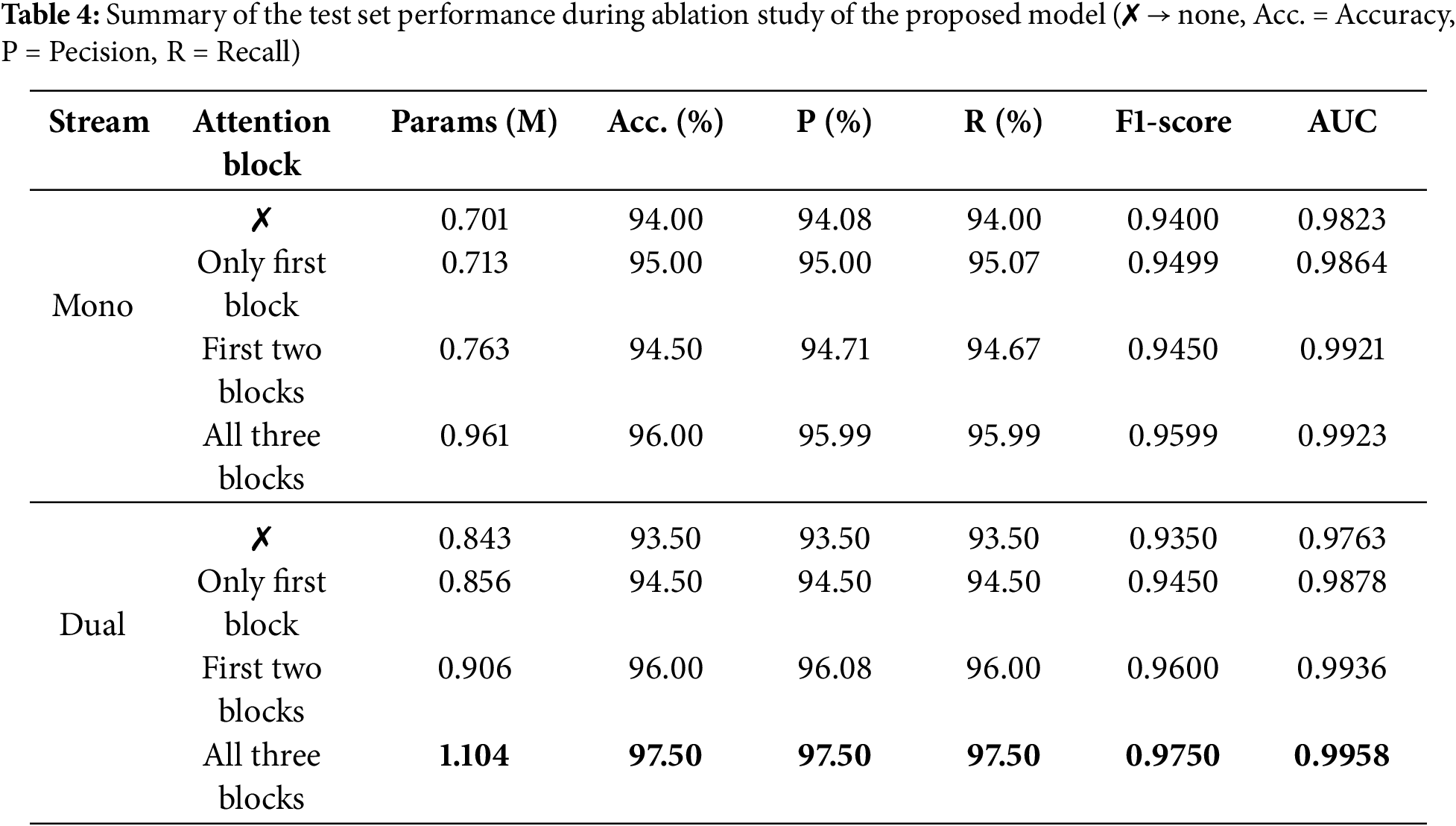

To validate the effectiveness of the model’s architecture, we conducted an ablation study focusing on the dual-stream architecture and the attention block, which are the core components of our proposed model. Table 4 summarizes the results of various configurations evaluated on the test set. The findings show a significant decline in performance across all metrics when attention blocks are excluded or partially included. Without any attention blocks, the model achieved the lowest accuracy of 94.00% with mono-stream and 93.50% with dual-stream. However, the incremental inclusion of attention blocks led to improved performance in both mono- and dual-stream formations. The proposed architecture, incorporating all three attention blocks in the dual-stream formation for effective feature extraction, achieved a test accuracy of 97.50% and an AUC score of 0.9958, underscoring the crucial role of the attention mechanism and the effectiveness of multi-stream feature extraction in enhancing the model’s performance.

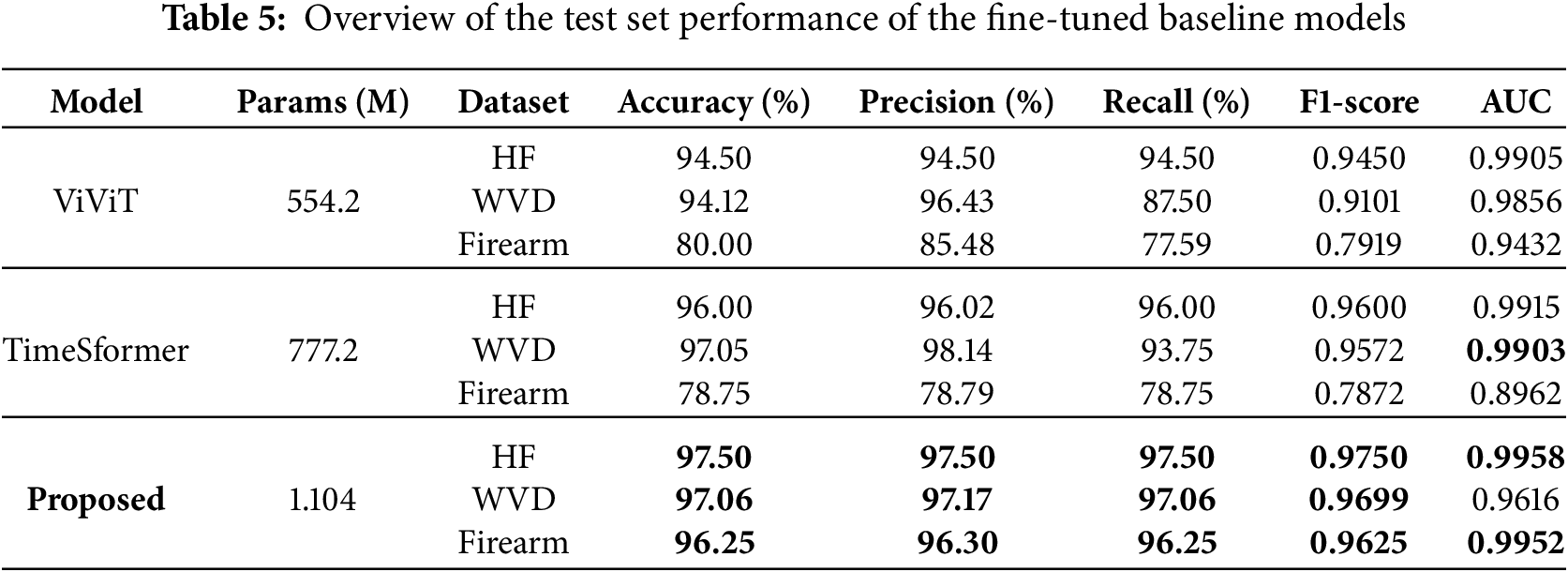

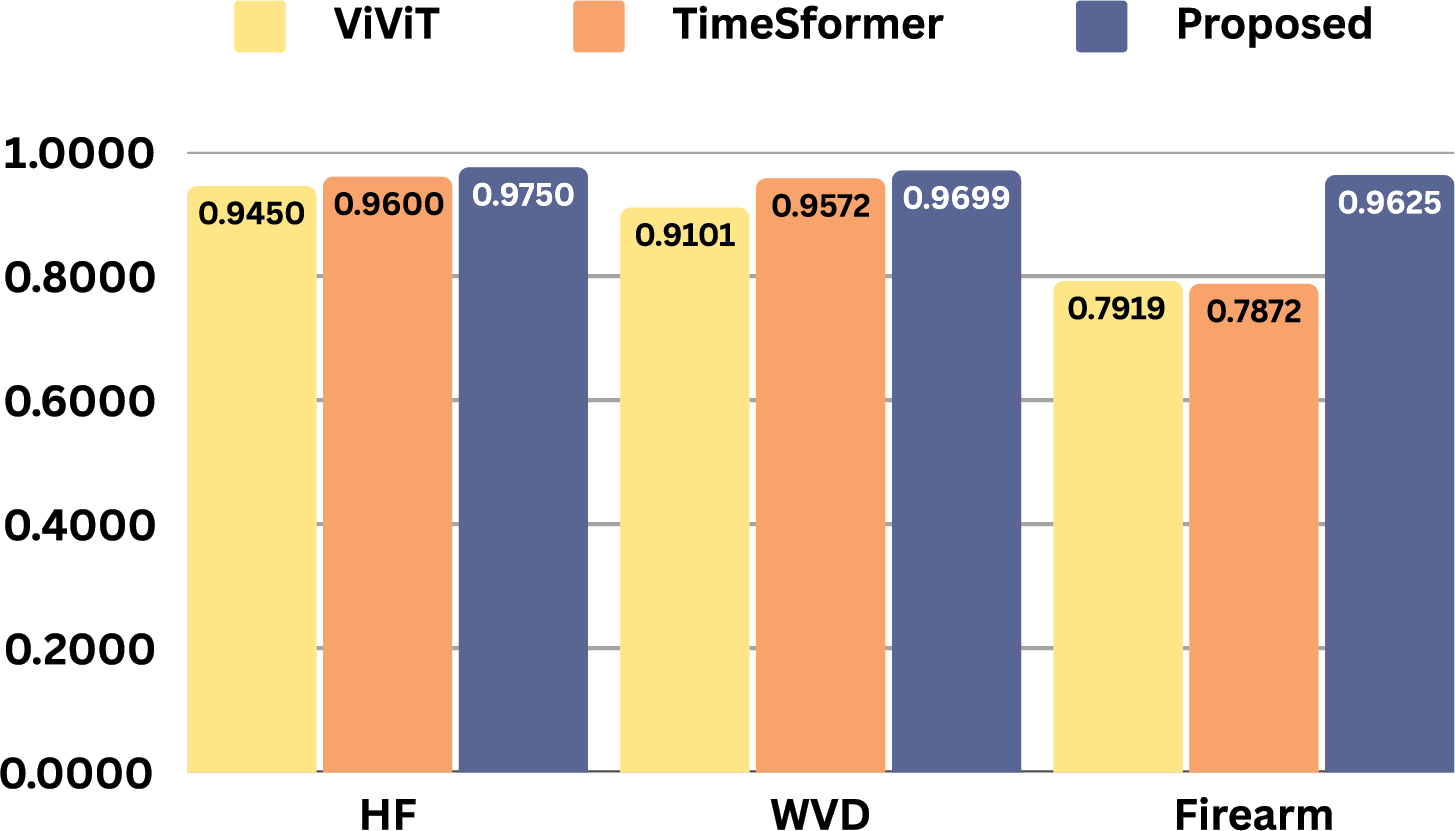

To benchmark the performance of the proposed model against established video classification approaches, we conducted experiments using transfer learning with two widely recognized transformer-based video classifiers: ViViT [41] and TimeSformer [42]. For a fair comparison, both baselines were trained under the same experimental setup (input resolution, frame sampling, preprocessing, splits, and federated configuration) and optimized with the FedProx aggregation strategy, since our proposed model achieved its best performance with FedProx. We employed an additive fine-tuning approach with their pre-trained base architectures. Specifically, we froze the pre-trained layers of each model and appended two trainable dense layers at the end, incorporating a GELU non-linearity between them. This configuration added over one million trainable parameters to each model, enabling task-specific learning while leveraging the representational power of the pre-trained transformers. Table 5 presents the performance metrics obtained from the experiments. Among the baseline models, TimeSformer achieved the highest test accuracy of 96.00% for the HF dataset and 97.05% for the WVD dataset, highlighting its strength in video classification tasks. However, these results slightly lag behind the performance of our proposed model, emphasizing the effectiveness of our approach. Similarly, ViViT recorded the lowest F1-score of 0.945 for HF and 0.9101 for WVD, compared to 0.975 and 0.9699 achieved by our model. Both ViViT and TimeSformer showed significantly poorer results for the Firearm dataset, while our proposed model attained over 96% accuracy. Fig. 5 provides a visual comparison of the F1-scores produced by these models, demonstrating the superior capability of the proposed model in recognizing violent videos.

Figure 5: F1-score visual comparison among baseline models and the proposed one

This study introduces a DL-based method for violent activity recognition that prioritizes user data privacy by employing FL and computational efficiency by incorporating a lightweight design tailored for edge deployment. With only approximately 1.104 million parameters and a model size of 4.42 MB, our model achieves competitive performance, with test set accuracies ranging from 96.25% to 97.50%. This strong performance is a result of our efficient architectural design, which integrates lightweight operations such as depthwise separable 3D convolutions and linear attention mechanisms, and notably the use of the FedProx aggregation method. However,

While our study demonstrates promising results, this study focuses on simulating the feasibility of lightweight models within FL frameworks for violent activity recognition and the key next step is to validate the proposed model on representative edge hardware and quantify practical deployment trade-offs. Future studies with large-scale and more diverse datasets will enhance the statistical reliability and generalizability of our findings. Moreover, although FedProx can effectively handle challenges posed by heterogeneous data distribution via its proximal penalty term, extended experiments with more clients and varying data distributions will better reflect the robustness of our model and FL strategy against the heterogeneity of real-world surveillance systems. In addition, the exploration of the impact of tailored augmentations specific to violent activity characteristics and the role of varying experimental setups (e.g., varying batch sizes) is left for future research. On the other hand, models can sometimes learn spurious or irrelevant patterns while still producing correct predictions; integrating explainable AI (XAI) techniques (e.g., attention-map visualizations, and gradient-based methods) is an important future direction to provide impactful qualitative analyses and to clarify model decision-making, thereby increasing the trustworthiness of HAR applications.

By pursuing these directions, we anticipate establishing a versatile, privacy-preserving and trustworthy activity recognition framework that can adapt to a wide range of applications—from public safety monitoring to assistive care, while maintaining the stringent data-protection guarantees required in sensitive environments.

We propose an effective and efficient DL model for automated violent activity recognition from videos, designed with a focus on real-world, resource-constrained applications. Our approach emphasizes decentralized training, eliminating reliance on cloud servers, and ensuring enhanced user data privacy by keeping data confined to the native device. The proposed lightweight architecture achieved competitive test set accuracies across multiple experimental datasets, outperforming larger pre-trained models that have more than 100 times the number of parameters. These findings not only highlight the model’s effectiveness but also demonstrate its generalization potential across diverse scenarios. Additionally, we found that the FedProx aggregation strategy improves the performance of the employed model over the FedAvg strategy. This study puts a significant step toward developing privacy-enhancing and efficient solutions for violent activity recognition, deployment on edge devices, and beyond, facilitating the broader adoption of secure and effective AI systems in sensitive applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Research Chair of Online Dialogue and Cultural Communication, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia, for funding this research.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Research Chair of Online Dialogue and Cultural Communication, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Moshiur Rahman Tonmoy; methodology, Moshiur Rahman Tonmoy and Md. Mithun Hossain; software, Moshiur Rahman Tonmoy and Md. Mithun Hossain; validation, Mejdl Safran, Sultan Alfarhood and M. F. Mridha; formal analysis, Md. Mithun Hossain; investigation, Moshiur Rahman Tonmoy and Md. Mithun Hossain; resources, Mejdl Safran and M. F. Mridha; data curation, Md. Mithun Hossain; writing—original draft preparation, Moshiur Rahman Tonmoy and Md. Mithun Hossain; writing—review and editing, Mejdl Safran, Dunren Che and M. F. Mridha; visualization, Dunren Che and Sultan Alfarhood; supervision, M. F. Mridha; project administration, M. F. Mridha; funding acquisition, Mejdl Safran and Sultan Alfarhood. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the respective repository as referenced in this study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chaudhary D, Kumar S, Dhaka VS. Video based human crowd analysis using machine learning: a survey. Comput Methods Biomech Biomedical Eng Imag Visual. 2022;10(2):113–31. [Google Scholar]

2. Tripathi G, Singh K, Vishwakarma DK. Convolutional neural networks for crowd behaviour analysis: a survey. Vis Comput. 2019;35(5):753–76. doi:10.1007/s00371-018-1499-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. MarketsandMarkets. Video surveillance industry worth $88.71 billion by 2030; 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 22]. Available from: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/PressReleases/global-video-surveillance-market.asp. [Google Scholar]

4. Badidi E, Moumane K, El Ghazi F. Opportunities, applications, and challenges of edge-ai enabled video analytics in smart cities: a systematic review. IEEE Access. 2023;11:80543–72. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3300658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liu Y, Liu S, Zhu X, Li J, Yang H, Teng L, et al. Privacy-preserving video anomaly detection: a survey. arXiv:2411.14565. 2025. [Google Scholar]

6. ElBaih M. The role of privacy regulations in AI development (A discussion of the ways in which privacy regulations can shape the development of AI). 2023. [cited 2025 Jul 22]. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4589207. [Google Scholar]

7. Gupta R. Safeguarding digital privacy with ai-driven solutions. ESP Int J Adv Comput Technol (ESP-IJACT). 2024;2(1):126–42. [Google Scholar]

8. Do TTT, Huynh QT, Kim K, Nguyen VQ. A survey on video big data analytics: architecture, technologies, and open research challenges. Appl Sci. 2025;15(14):8089. doi:10.3390/app15148089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yang Q, Liu Y, Chen T, Tong Y. Federated machine learning: concept and applications. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol. 2019;10(2):12. doi:10.1145/3298981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Shenaj D, Rizzoli G, Zanuttigh P. Federated learning in computer vision. IEEE Access. 2023;11:94863–84. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3310400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Alsmirat MA, Obaidat I, Jararweh Y, Al-Saleh M. A security framework for cloud-based video surveillance system. Multimedia Tools Appl. 2017;76(21):22787–802. doi:10.1007/s11042-017-4488-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shifa A, Asghar MN, Noor S, Gohar N, Fleury M. Lightweight cipher for H.264 videos in the Internet of multimedia things with encryption space ratio diagnostics. Sensors. 2019;19(5):1228. doi:10.3390/s19051228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Bagdasaryan E, Poursaeed O, Shmatikov V. Differential privacy has disparate impact on model accuracy. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2019;32. [cited 2025 Jul 12]. Available from: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2019/hash/fc0de4e0396fff257ea362983c2dda5a-Abstract.html. [Google Scholar]

14. Tonmoy MR, Rakib AF, Rahman R, Adnan MA, Mridha MF, Huang J, et al. A lightweight visual font style recognition with quantized convolutional autoencoder. IEEE Open J Comput Soc. 2024;5(2):120–30. doi:10.1109/ojcs.2024.3378709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ullah FUM, Obaidat MS, Ullah A, Muhammad K, Hijji M, Baik SW. A comprehensive review on vision-based violence detection in surveillance videos. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;55(10):1–44. doi:10.1145/3561971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Liu S, Li Y, Fu W. Human-centered attention-aware networks for action recognition. Int J Intell Syst. 2022;37(12):10968–87. doi:10.1002/int.23029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Aggarwal S, Ranjan R, Sinha M, Pal V, Kushwaha R. CNN and BiLSTM based framework for real life violence detection from CCTV videos. In: 2024 IEEE Region 10 Symposium (TENSYMP); 2024 Sep 27–29; New Delhi, India. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

18. Yadav V, Kumar S, Goyal A, Bhatla S, Sikka G, Kaur A. Integrated violence and weapon detection using deep learning. In: 2024 First International Conference on Pioneering Developments in Computer Science & Digital Technologies (IC2SDT); 2024 Aug 2–4; Delhi, India. [Google Scholar]

19. Abbass MAB, Kang HS. Violence detection enhancement by involving convolutional block attention modules into various deep learning architectures: comprehensive case study for UBI-fights dataset. IEEE Access. 2023;11:37096–107. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3267409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kumar A, Shetty A, Sagar A, Charushree A, Kanwal P. Indoor violence detection using lightweight transformer model. In: 2023 4th International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET); 2023 May 26–28; Belgaum, India. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

21. Mohammadi H, Nazerfard E. Video violence recognition and localization using a semi-supervised hard attention model. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;212:118791. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Vijeikis R, Raudonis V, Dervinis G. Efficient violence detection in surveillance. Sensors. 2022;22(6):2216. doi:10.3390/s22062216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Frimpong E, Khan T, Michalas A. Secrets in motion: privacy-preserving video classification with built-in access control. In: 2024 9th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech); 2024 Jun 25–28; Bol and Split, Croatia. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

24. Feng D, Wang L, Chen S, Tung L, Liu F. X-stream: a flexible, adaptive video transformer for privacy-preserving video stream analytics. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2024-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2024 May 20–23; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

25. Gaikwad B, Karmakar A. Real-time distributed video analytics for privacy-aware person search. Comput Vis Image Underst. 2023;234(3):103749. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2023.103749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mehta D, Sivathamboo S, Simpson H, Kwan P, O’Brien T, Ge Z. Privacy-preserving early detection of epileptic seizures in videos. In: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2023. p. 210–9. [Google Scholar]

27. Singh S, Dewangan S, Krishna GS, Tyagi V, Reddy S, Medi PR. Video vision transformers for violence detection. arXiv:2209.03561. 2022. [Google Scholar]

28. Pajon Q, Serre S, Wissocq H, Rabaud L, Haidar S, Yaacoub A. Balancing accuracy and training time in federated learning for violence detection in surveillance videos: a study of neural network architectures. J Comput Sci Technol. 2024;39(5):1029–39. doi:10.1007/s11390-024-3702-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Victor EDS, Lacerda TB, Miranda PB, Nascimento AC, Furtado APC. Federated learning for physical violence detection in videos. In: 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2022 Jul 18–23; Padua, Italy. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

30. McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, BAy Arcas. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In: Singh A, Zhu J, editors. Proceedings of the 20th international conference on artificial intelligence and statistics. Vol. 54. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2017. p. 1273–82. [Google Scholar]

31. Guan H, Yap PT, Bozoki A, Liu M. Federated learning for medical image analysis: a survey. Pattern Recognit. 2024;151(3):110424. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2024.110424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Mistry D, Tonmoy MR, Anower MS, Hasan ASMT. Federated transfer learning for vision-based fall detection. In: Arefin MS, Kaiser MS, Bhuiyan T, Dey N, Mahmud M, editors. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference onBig Data, IoT and Machine Learning. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2024. p. 961–75. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-8937-9_64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li T, Sahu AK, Zaheer M, Sanjabi M, Talwalkar A, Smith V. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. In: Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems; 2020 Mar 2–4; Austin, TX, USA. p. 429–50. [Google Scholar]

34. Tonmoy MR, Shams MA, Adnan MA, Mridha MF, Safran M, Alfarhood S, et al. X-Brain: explainable recognition of brain tumors using robust deep attention CNN. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2025;100(18):106988. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2024.106988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hendrycks D, Gimpel K. Gaussian error linear units (GELUs). arXiv:1606.08415. 2023. [Google Scholar]

36. Mehta S, Rastegari M. Separable self-attention for mobile vision transformers. Trans Mach Learn Res. 2023. [cited 2025 Jul 12]. https://openreview.net/forum?id=tBl4yBEjKi. [Google Scholar]

37. Bermejo Nievas E, Deniz Suarez O, Bueno García G, Sukthankar R. Violence detection in video using computer vision techniques. In: Real P, Diaz-Pernil D, Molina-Abril H, Berciano A, Kropatsch W, editors. Computer analysis of images and patterns. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2011. p. 332–9. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-23678-5_39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Nadeem MS, Kurugollu F, Atlam HF, Franqueira VNL. Weapon violence dataset 2.0: a synthetic dataset for violence detection. Data Brief. 2024;54(8):110448. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2024.110448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Ruiz-Santaquiteria J, Muñoz JD, Maigler FJ, Deniz O, Bueno G. Firearm-related action recognition and object detection dataset for video surveillance systems. Data Brief. 2024;52(24):110030. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2024.110030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Buslaev A, Iglovikov VI, Khvedchenya E, Parinov A, Druzhinin M, Kalinin AA. Albumentations: fast and flexible image augmentations. Information. 2020;11(2):125. doi:10.3390/info11020125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Arnab A, Dehghani M, Heigold G, Sun C, Lučić M, Schmid C. ViViT: a video vision transformer. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 6836–46. [Google Scholar]

42. Bertasius G, Wang H, Torresani L. Is space-time attention all you need for video understanding?. In: Meila M, Zhang T, editors. Proceedings of the 38th international conference on machine learning. Vol. 139. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2021. p. 813–24. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools