Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LSAP-IoHT: Lightweight Secure Authentication Protocol for the Internet of Healthcare Things

1 Networks and Systems Laboratory, Department of Computer Science, Badji Mokhtar University, Annaba, 23000, Algeria

2 Institute for Analytics and Data Science, University of Essex, Colchester, CO4 3SQ, UK

3 Department of Computer Science, University of Souk-Ahras, Souk-Ahras, 41000, Algeria

4 Cybersecurity Department, College of Computer Science and Engineering, Taibah University, Medina, 42353, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Insaf Ullah. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5093-5116. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067641

Received 08 May 2025; Accepted 15 July 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

The Internet of Healthcare Things (IoHT) marks a significant breakthrough in modern medicine by enabling a new era of healthcare services. IoHT supports real-time, continuous, and personalized monitoring of patients’ health conditions. However, the security of sensitive data exchanged within IoHT remains a major concern, as the widespread connectivity and wireless nature of these systems expose them to various vulnerabilities. Potential threats include unauthorized access, device compromise, data breaches, and data alteration, all of which may compromise the confidentiality and integrity of patient information. In this paper, we provide an in-depth security analysis of LAP-IoHT, an authentication scheme designed to ensure secure communication in Internet of Healthcare Things environments. This analysis reveals several vulnerabilities in the LAP-IoHT protocol, namely its inability to resist various attacks, including user impersonation and privileged insider threats. To address these issues, we introduce LSAP-IoHT, a secure and lightweight authentication protocol for the Internet of Healthcare Things (IoHT). This protocol leverages Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs), and Three-Factor Authentication (3FA). Its security is validated through both informal analysis and formal verification using the Scyther tool and the Real-Or-Random (ROR) model. The results demonstrate strong resistance against man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks, replay attacks, identity spoofing, stolen smart device attacks, and insider threats, while maintaining low computational and communication costs.Keywords

The Internet of Health Things (IoHT) represents a major innovation that integrates information technologies with medical care, forming an intelligent ecosystem of connected devices dedicated to health monitoring and management [1,2]. It encompasses a broad spectrum of technologies and application domains, ranging from biometric sensors and wearable devices to remote health monitoring platforms and connected medical equipment. IoHT is actively deployed in scenarios such as chronic disease management, emergency response, elderly care, postoperative recovery, and telemedicine. As illustrated in Fig. 1, these systems interact through wireless communication technologies, including Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and cellular networks to collect, transmit, and analyze health data in real time [3,4]. By enabling continuous tracking of vital parameters like heart rate, blood pressure, glucose levels, and respiratory signals, IoHT supports mobile health (mHealth), intelligent drug delivery, and personalized healthcare services.

Figure 1: Internet of health things

However, the sensitive nature of health data, combined with the heterogeneity of interconnected devices, introduces substantial challenges regarding security and privacy [5–7]. Adversaries may exploit vulnerabilities through cyberattacks such as data interception, unauthorized access, and device tampering, all of which pose serious risks. In the absence of robust security mechanisms, sensitive medical information may be exposed to privacy breaches, thereby compromising patient confidentiality. Furthermore, compromised device integrity can result in erroneous diagnoses, inappropriate treatments, or even life threatening outcomes for patients [8,9].

1.1 Motivation and Contribution

With the increasing reliance on Internet of Health Things (IoHT) systems, securing sensitive medical data against cyber threats has become a critical concern, particularly given the potential consequences for patient safety. Although Chen et al. [10] introduced LAT-IoHT, an authentication protocol combining three-factor authentication, asymmetric encryption, and biometric data, our cryptanalysis has revealed significant security flaws. Specifically, LAT-IoHT is vulnerable to smart card theft, privileged insider attacks, and user impersonation.

To address these limitations, we propose LSAP-IoHT, a lightweight and secure authentication protocol tailored for IoHT environments, which offers the following advantages:

• Our scheme combines Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), Three-Factor Authentication (3FA), and hardware-level protection based on Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs), enhancing resistance to duplication and physical attacks.

• Through formal and informal analysis using the Real-Or-Random (ROR) model and the Scyther tool, our scheme is shown to ensure mutual authentication, session key confidentiality, and strong resistance to a wide range of attacks, including stolen smart device attacks, identity spoofing, replay attacks, man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks, and privileged insider threats.

• Our scheme achieves these security properties while maintaining low computational and communication overhead, making it particularly suitable for deployment in resource constrained IoHT environments.

• Comparative evaluation with related authentication protocols confirms that our scheme provides enhanced security guarantees with low computational complexity and communication cost.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses existing authentication mechanisms developed for IoHT, emphasizing their main features and limitations. Section 3 investigates the authentication scheme introduced by Chen et al. [10], highlighting the cryptographic vulnerabilities identified through a detailed security evaluation. Section 5 presents our proposed authentication scheme, referred to as LSAP-IoHT. Section 6 describes the results of the security verification conducted using the Scyther tool and the Real-Or-Random (ROR) model. Section 7 provides a comparative assessment of LSAP-IoHT and other protocols designed for IoHT environments. Finally, Section 8 concludes the paper by summarizing the main contributions.

This section reviews key literature on authentication protocols for the Internet of Health Things (IoHT), focusing on foundational contributions, recent advancements, and emerging trends relevant to this study.

Kumar et al. [11] introduced RAPCHI, a robust protocol for cloud-based connected health infrastructures. By employing digital signatures, it secures authentication and key agreement among patients, cloud servers, and doctors. RAPCHI resists man-in-the-middle and replay attacks, as validated through AVISPA simulation.

Aghili et al. [12] developed an access control and ownership transfer protocol for IoHT, addressing vulnerabilities in the ZZTL protocol [13] related to user traceability, denial-of-service (DoS), insider threats, and desynchronization attacks. Their architecture involves users, medical servers, and patients, ensuring authentication, confidentiality, and seamless privilege transfer. Focusing on lightweight designs for sensor networks,

Soni et al. [14] developed an authentication protocol using smart cards, improving upon the weaknesses identified in Challa et al.’s work [15] by integrating a three-factor approach suited to remote patient monitoring. To accommodate heterogeneous IoHT environments and enhance efficiency, Ullah et al. [16] proposed a certificate-less authentication scheme that employs hyperelliptic curve cryptography (HECC) with 80-bit keys. This construction is particularly appropriate for resource-constrained wireless body area networks (WBANs), offering robust protection against common cyber threats while reducing computational overhead.

Rabie et al. [17] proposed a distributed, privacy-preserving protocol for certificate-less medical sensor networks. Using XOR operations, it aggregates signatures from sensor nodes, thereby reducing centralization. The system includes wearable sensors, zonal nodes, and medical servers, and it prioritizes data privacy during transmission. Xie et al. [18] introduced CasCP, an enhanced certificate-less authentication scheme for WBANs, which addresses weaknesses in Ji et al.’s protocol [19]. It ensures conditional privacy preservation and improves security. Thakur et al. [20] proposed an authentication scheme for WMSN-based medical systems that counters identity spoofing and password guessing attacks. Building on the protocol of Servati and Safkhani [21], it retains a five-phase structure while enhancing security properties. Li et al. [22] developed a three-factor authentication protocol for WMSNs, improving upon the scheme of Amin and Biswas scheme [23] after identifying several vulnerabilities. Based on ECC, the protocol ensures secure transmission of sensitive medical data. Sureshkumar et al. [24] proposed a lightweight ECC-based authentication scheme for WMSNs. Its correctness was formally verified using Burrows-Abadi-Needham (BAN) logic.

In [25], the authors propose a secure communication approach for IoT networks based on key management and authentication. Their method improves data protection, energy efficiency, and overall network performance. In [26], the authors propose an improved lightweight authentication protocol to address security and privacy issues in IoT-based smart healthcare systems. The protocol ensures mutual authentication and secure session key establishment between doctors, gateways, and sensor nodes. Security analysis confirms its efficiency and resistance to various attacks, including identity anonymity and untraceability.

Finally, Chen et al. [10] introduced LAP-IoHT, a three-factor authentication protocol that combines asymmetric encryption and biometric data to ensure confidentiality. It authenticates users and sensors through a gateway, establishes a shared session key, and encrypts biometric features to preserve user anonymity. Its security was analyzed using the Real-or-Random (ROR) model.

Table 1 summarizes the reviewed works by emphasizing their cryptographic features, verification tools, and protocol phases. It also compares them by highlighting their advantages and limitations. In the next section, we detail the workings of LAP-IoHT in particular and reveal its vulnerabilities.

This section provides an overview of the LAP-IoHT protocol and highlights its security weaknesses, despite its original claim of being secure in the study by Chen et al. [10].

The LAP-IoHT protocol [10] is a lightweight authentication scheme designed for the Internet of Health Things (IoHT). It employs three-factor authentication, asymmetric encryption, and biometric verification to secure the transmission of sensitive health information. The protocol is structured into two main phases: the registration phase (covering both user and sensor registration) and the authentication phase. In what follows, we denote the user, gateway, and sensor by

User Registration Phase

If the user

Step 1: The user

Step 2:

Step 3:

Sensor Registration Phase

A sensor must also be registered before it can join the network with

Step 1: The sensor

Step 2:

Step 3:

If

Step 1:

Step 2:

Step 3:

Step 4:

Step 5:

3.2 Security Weaknesses of LAP-IoHT

The attacker A obtains

3.2.2 Privileged Insider Attack

Suppose the attacker A is a privileged insider of the system. The attacker will take

3.2.3 User Identity Impersonation Attack

Fig. 2 illustrates the user impersonation attack where the attacker A seeks to generate a valid Message 1 containing

Figure 2: User identity impersonation attack

4 Preliminaries and System Model

This part presents the necessary background to enhance the clarity of the article.

4.1 Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC)

Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) is a method based on elliptic curves defined over a finite field. Consider two large prime numbers

4.2 Physical Unclonable Function (PUF)

Due to physical variations during chip fabrication, a Physical Unclonable Function (PUF) generates a unique, non-replicable output for each input, following a challenge-response approach. Unlike conventional cryptographic systems that store fixed keys, PUFs dynamically produce device-specific secrets, eliminating the need for key storage. If a device is compromised, the internal structure of the PUF is affected, altering its output and ensuring security without consuming memory. Given a challenge

The proposed health system model is illustrated in Fig. 3. In this paradigm, the workflow of the proposed protocol consists of three main entities: sensors, users, and the gateway.

Figure 3: Proposed health system model

These sensors are placed or implanted in the human body, and their main role is to collect various health-related data, such as ECG, blood pressure, blood glucose, respiratory rate, and body temperature.

In the proposed system model, users are primarily represented as doctors who have authorized access to patients medical data. These doctors use the system to monitor and analyze patients conditions, prescribe treatments, and make informed therapeutic decisions based on the data provided by the sensors.

The gateway acts as a pivot to orchestrate communication between users and sensors, serving as a trusted intermediary that facilitates transparent communication. It constitutes a main unit where information is authenticated and securely linked among the various components of the system.

In Internet of Health Things (IoHT) systems, the Dolev–Yao model [27] is applied to represent hostile network conditions. This framework presumes that an attacker, labeled A, can access all exchanges over unsecured links. Moreover, A is capable of discarding transmissions, changing message content, or introducing counterfeit data into the flow of communication.

5 The Proposed LSAP-IoHT Protocol

To address the security vulnerabilities we identified in LAP-IoHT [10], we propose a new reliable and efficient authentication scheme for the IoHT called: Lightweight Secure Authentication Protocol for the IoHT (LSAP-IoHT). The LSAP-IoHT protocol ensures secure authentication between the user, the gateway, and the sensor. Fig. 4 outlines the message exchanges leading to mutual verification and the establishment of a session key.

Figure 4: Sequence diagram of the authentication steps in the proposed scheme

The improved system incorporates the following four phases:

• Initiation phase

• User registration phase

• Sensor registration phase

• Authentication phase

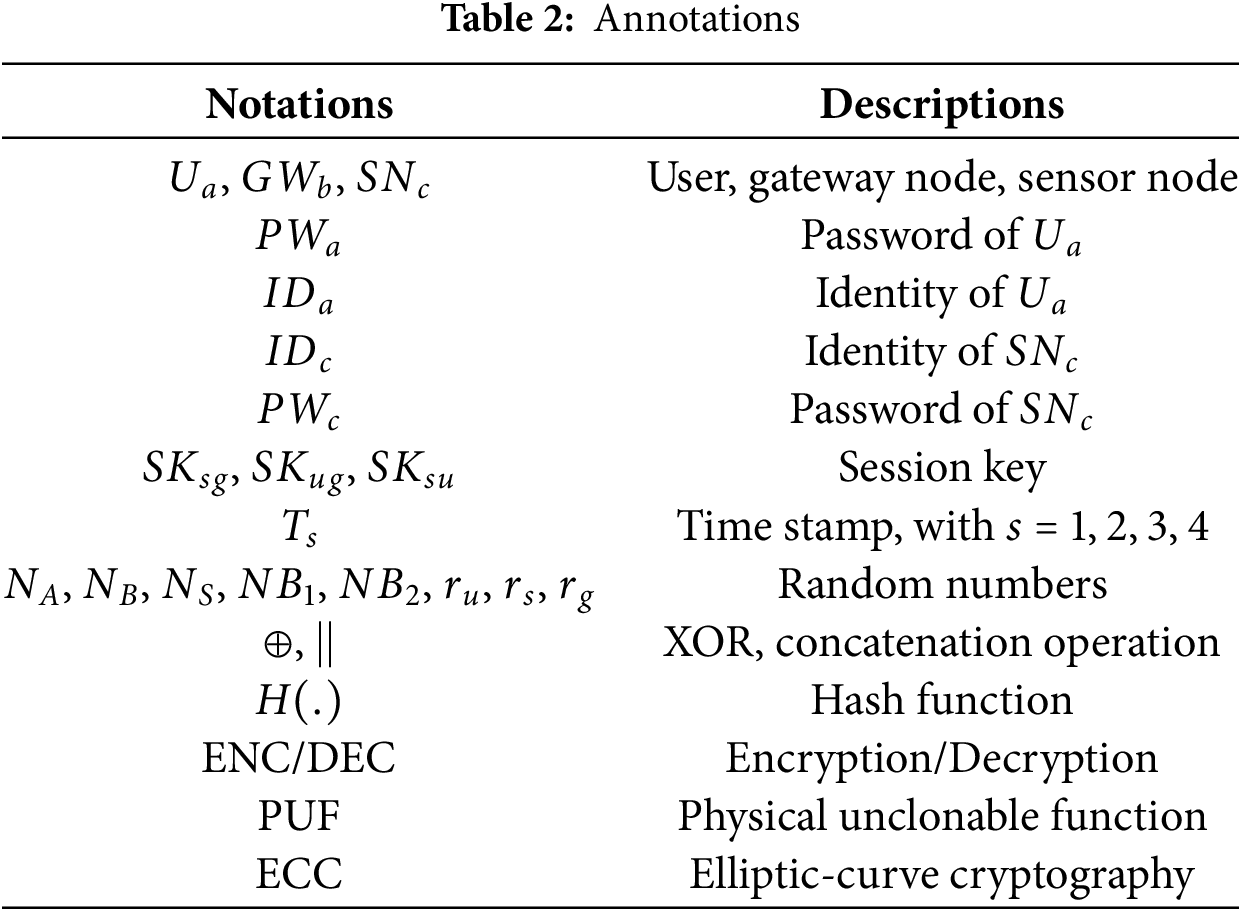

Table 2 summarizes the different annotations used for our protocol.

This phase is considered to be applied before the commencement of the protocol in a secure environment. Each entity gateway, sensor, and user is equipped with PUF (Physical Unclonable Function) technology and has a Challenge-Response based on PUF, referred to as CRP. The gateway has the CRPs of both the sensors and the users (CRPs, CRPa), while both the sensors and users possess the CRP of the gateway (CRPb). This protocol uses a lightweight ECC (Elliptic-Curve Cryptography) system for smart devices as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Initialization phase

For the user

Figure 6: User registration phase

Step 1: The user

Step 2:

Step 3:

Step 4:

Step 5:

5.1.3 Sensor Registration Phase

A portable sensor must also be registered with

Figure 7: Sensor registration phase

Step 1: The sensor

Step 2:

Step 3:

Step 4:

Fig. 8 depicts the steps of the authentication phase. When

Figure 8: Authentication phase

Step 1: Authentication request

Step 2: Verification of authentication parameters and forward the authentication request

Step 3: Verification of the authentication request, authenticity verification response and generate the session key

Step 4: Verification of the authenticity response and forward the authentication response

Step 5: Verification of authentication parameters and generate the session key

This part thoroughly investigates the protection mechanisms embedded in LSAP-IoHT, highlighting its ability to withstand diverse cyber threats. In addition to an intuitive evaluation underscoring the scheme’s strength, we apply structured verification techniques. Leveraging the Real-or-Random model, we perform an in depth theoretical validation of the protocol. Furthermore, we employ Scyther, a widely recognized verification framework, to test the protocol’s resilience through automated analysis.

In this analysis, we prove the LSAP-IoHT protocol resistance to known attacks.

6.1.1 Forward Secrecy Property

If persistent credentials are exposed, earlier session information must remain protected. Within our protocol, secret values such as

In our proposed protocol, transmitted messages include timestamps and random numbers, such as

6.1.3 Identity Spoofing Attack

For each entity in the system, gateway node, sensor node, and user we used double authentication verification for each transmitted message. Additionally, we adopted a three-factor authentication. Each entity is equipped with an identity, password, and a unique Challenge-Response Pair (CRP) from the PUF. This multi-level security approach ensures that even if an attacker tries to infiltrate the system, they will fail to bypass the double authentication verification.

The proposed protocol is secure against insider attacks through the implementation of PUF (Physically Unclonable Functions). Each system entity is authenticated using a unique PUF Challenge-Response Pair (CRP), which cannot be duplicated or predicted. This ensures that even privileged insiders, who might have access to other authentication details, cannot replicate the unique PUF responses of other entities. Even if an attacker obtains some data, they will not be able to find the keys since some of the data used to generate the keys was never transmitted.

The simplicity of IoHT devices makes them highly vulnerable to adversaries. During a physical attack, an attacker may obtain direct access to an IoT device, retrieve its secret keys, and even clone it. The protocol is considered secure against these types of attacks because PUFs and device authentication are implemented on the same chip, ensuring a trusted and secure communication process.

6.1.6 Man-in-the-Middle Attack (MITM)

Our proposed protocol is deemed resistant to MITM attacks because it needs to know specific information to construct valid data and initiate the attack. Discovering all this information is not feasible for an active adversary positioned on the communication line between the three parties involved in the communication.

6.1.7 Stolen Smart Device Attack

The LSAP-IoHT protocol is resilient to stolen device attacks due to its use of physically unclonable functions (PUFs), session dependent secrets, and mutual authentication. Even if an attacker obtains a user’s smart card or a registered sensor, critical values such as session keys, pseudo-identities, and challenge-response pairs remain protected through dynamic nonces and device specific computations. Without knowledge of the user’s password, random nonces, and the unique PUF-based secrets, an adversary cannot impersonate a legitimate entity or reconstruct valid authentication messages.

6.2 Security Evaluation under the ROR Framework

The Real-or-Random approach represents a commonly adopted technique for formally demonstrating the confidentiality of session keys within cryptographic protocols [28]. The LSAP-IoHT protocol involves three main participants:

• Execute (

• Send (

• Corrupt (

• Hash (): Using this function, the adversary is able to compute the digest corresponding to a given input of predetermined size.

• Test (

Theorem 1: In the ROR model [28], we define

•

•

•

•

•

To validate the correctness of the Theorem, the proof proceeds through five game stages, denoted as

Game 0: At this initial game, the adversary attempts to guess a hidden bit

Game 1: The adversary gains access to the Execute oracle, which allows it to passively observe full protocol executions between the user, gateway, and sensor. This includes all exchanged messages such as {

Game 2: In this game, the adversary is allowed to interact with the Hash oracle, attempting to infer internal values involved in session key derivation. For instance, values such as

Game 3: This game models a stronger adversary who can invoke the Corrupt oracle on a participant (e.g., sensor or user), thereby retrieving stored values such as challenge-response pairs, encrypted identities, or PUF-related secrets. However, the session key relies on PUF-derived data, such as

The difference in advantage between this game and the previous one is bounded by:

Game 4: In the final game, the adversary has access to all protocol transcripts and internal values, including those retrieved through Corrupt and Execute queries. The only remaining unknowns are secrets derived through elliptic curve multiplication, such as recovering

After simulating the sequence of games

Based on the individual game transitions Eqs. (1)–(6), we obtain:

We conclude:

In this section, we conduct an in-depth analysis of the proposed protocol, performing formal verification using the SCYTHER tool. This approach aims to assess the robustness and reliability of the protocol in various scenarios and identify potential vulnerabilities. Using SCYTHER allows us to model the protocol in a simulated environment, where we can explore different parameters and configurations to evaluate its performance and security. This methodical approach provides valuable insights into the protocol’s strength, allowing us to take corrective measures if necessary and ensure optimal security for our system. Scyther is a sophisticated verification tool tailored specifically for security protocols, operating under the assumption that all cryptographic functions are flawless [29]. It stands out with its intuitive graphical user interface, making it simple to verify and understand protocols. Whenever an attack is detected concerning a specific claim, Scyther generates corresponding attack graphs, providing a clear visualization of potential vulnerabilities. Furthermore, Scyther can examine all conceivable claims regarding a given protocol. This tool is also valuable in identifying issues arising from protocol design. Additionally, Scyther is capable of generating all possible trace models, allowing for an exhaustive analysis of potential scenarios. The verification can be performed with a limited or unlimited number of sessions, providing optimal flexibility in security assessment [30]. To write protocols in Scyther, we use the SPDL Language(Security Protocol Description Language), which ensures clear syntax and precise protocol representation.

Fig. 9 illustrates an example of SPDL, representing a section of the connection and authentication phase of our proposed protocol. In this excerpt, the three main roles of the system are declared: the “gateway,” the “sensor,” and the “user.” The messages exchanged between these entities are also specified, describing the flow of information during the login and connection phase.

Figure 9: Authentication phase in SPDL

After subjecting our protocol to an in-depth formal analysis using the Scyther tool, which is widely used by researchers to evaluate various security systems in related previous works, we can confirm that our system meets the highest security standards. The results of the analysis conclusively demonstrated that our protocol is robust and resilient against various potential attacks, as shown in Fig. 10. By using Scyther, we were able to model and simulate different situations and interactions, thoroughly verifying every aspect of the protocol and identifying any potential weaknesses.

Figure 10: Result of formal verification

In summary, the formal analysis conducted using the Scyther tool confirms the security and reliability of our protocol, further strengthening our confidence in its ability to protect data and ensure the integrity of communications.

In this section, we compare the security features of similar IoHT authentication protocols and we evaluate the computational and Communication costs of each one. Our analysis focuses on how well these protocols resist various attacks and the efficiency of their operations, highlighting the balance between security and performance.

We compare LSAP-IoHT with several related protocols that follow similar architectures. In the comparison table, a “Y” indicates that the protocol is resistant to a specific attack, while an “X” indicates vulnerability. The attack types considered are as follows:

• R1: replay attack

• R2: impersonation attack

• R3: insider attack

• R4: man-in-the-middle attack

• R5: known session-specific temporary information attack

• R6: stolen smart card attack

• R7: offline password guessing attack

• R8: sensor node capture attack

• R9: de-synchronization attack

• R10: session key disclosure attack

• R11: denial of service (DoS) attack

• R12: message modification attack

The results presented in Table 3, show that many existing protocols are susceptible to these types of attacks. In contrast, LSAP-IoHT demonstrates stronger resistance against these threats, providing enhanced security and robustness for communication sessions in IoHT environments. Our cryptanalysis revealed that LAP-IoHT is vulnerable to a wide range of cyberattacks, including man-in-the-middle attacks, replay attacks, and identity spoofing. Despite their claims of robustness, we identified several critical weaknesses that compromise the integrity and confidentiality of the exchanged data. These vulnerabilities indicate that the protocol fails to provide the level of security required for sensitive healthcare applications, leaving them exposed to significant risks.

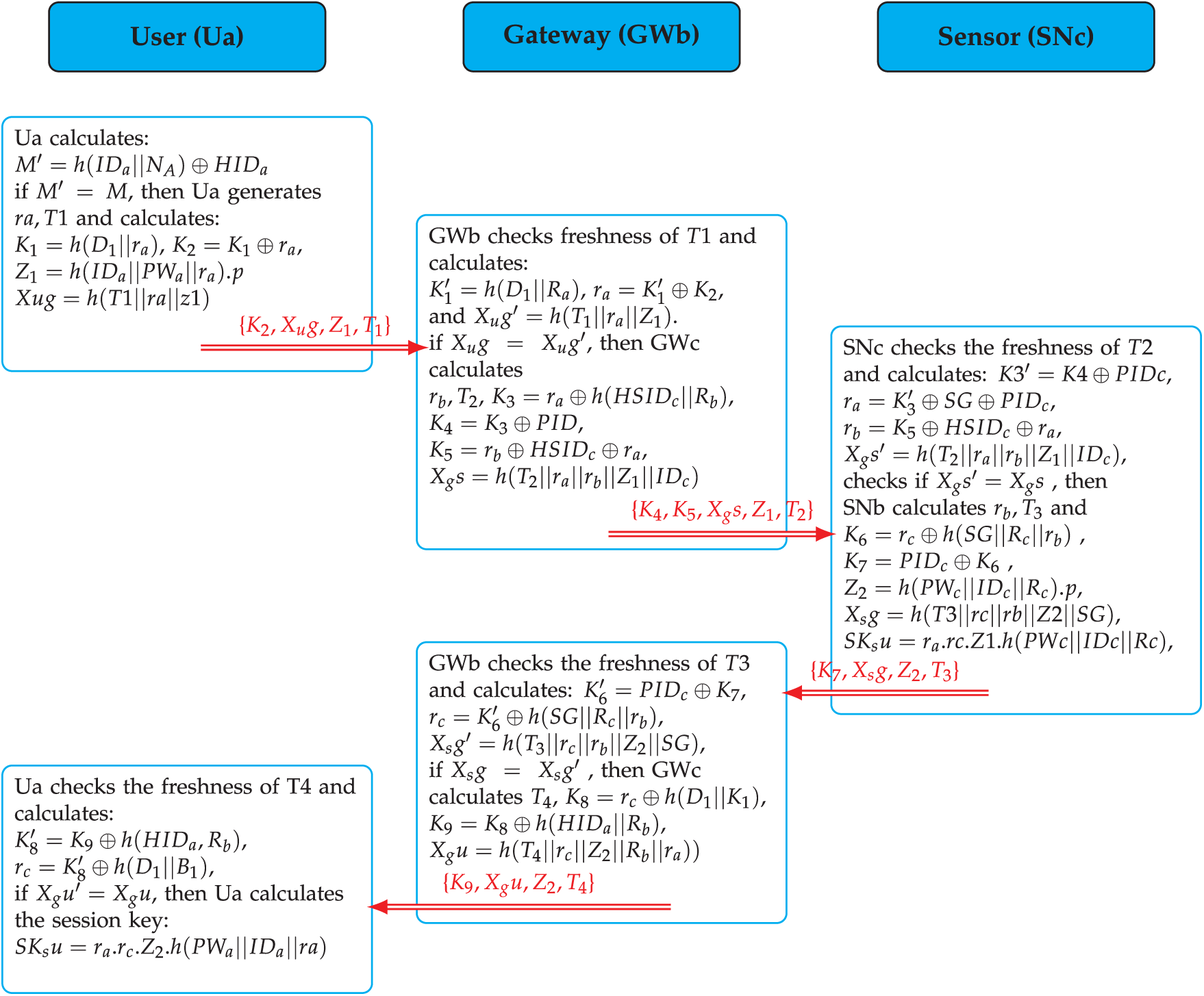

In this section, we evaluate the performance of the LSAP-IoHT protocol by comparing it with other related protocols in terms of computational and communication efficiency. Specifically, in Table 4, we analyze the number of cryptographic operations required, based on the findings in [10]. The time to perform a single hash function operation (HF) is 0.0031 ms for the gateway and 0.0022 ms for the sensor node. For fuzzy extraction operations (FE), it takes 2.2823 ms for the gateway and 1.6197 ms for the sensor node. A single elliptic curve point multiplication (ECCM) requires 16 ms for the gateway and 13 ms for the sensor node, while an elliptic curve point addition (ECCA) takes 0.016 ms for the sensor node and 0.002 ms for the gateway. Additionally, symmetric encryption or decryption operations (AC) require 5.2520 ms for the gateway and 3.7272 ms for the sensor node. We also examine the number of messages exchanged between the user (U), gateway (G), and sensor (S), as well as the total computation time (in milliseconds). According to Table 4, LSAP-IoHT achieves a total computation time of 58.0566 ms, which is lower than [12] (58.5637 ms), [15] (87.0212 ms), [17] (84.9694 ms), and [18] (106.038 ms). This clearly highlights its superior efficiency. Fig. 11 illustrates the computation cost analysis curves.

Figure 11: The result of computational cost between our scheme and other schemes existing in the literature [1,13,14,17,19]

The combined analysis of Tables 3 and 4 highlights the critical importance of LSAP-IoHT in IoHT systems. Although reference [10] achieves better performance in terms of total computational time, it remains vulnerable to several major security threats. In contrast, LSAP-IoHT successfully resists a wide range of attacks while maintaining a lower computational cost compared to references [12,15,17,18]. It is also the only protocol that withstands all evaluated threats, offering stronger security with acceptable performance, making it well-suited for resource constrained healthcare environments.

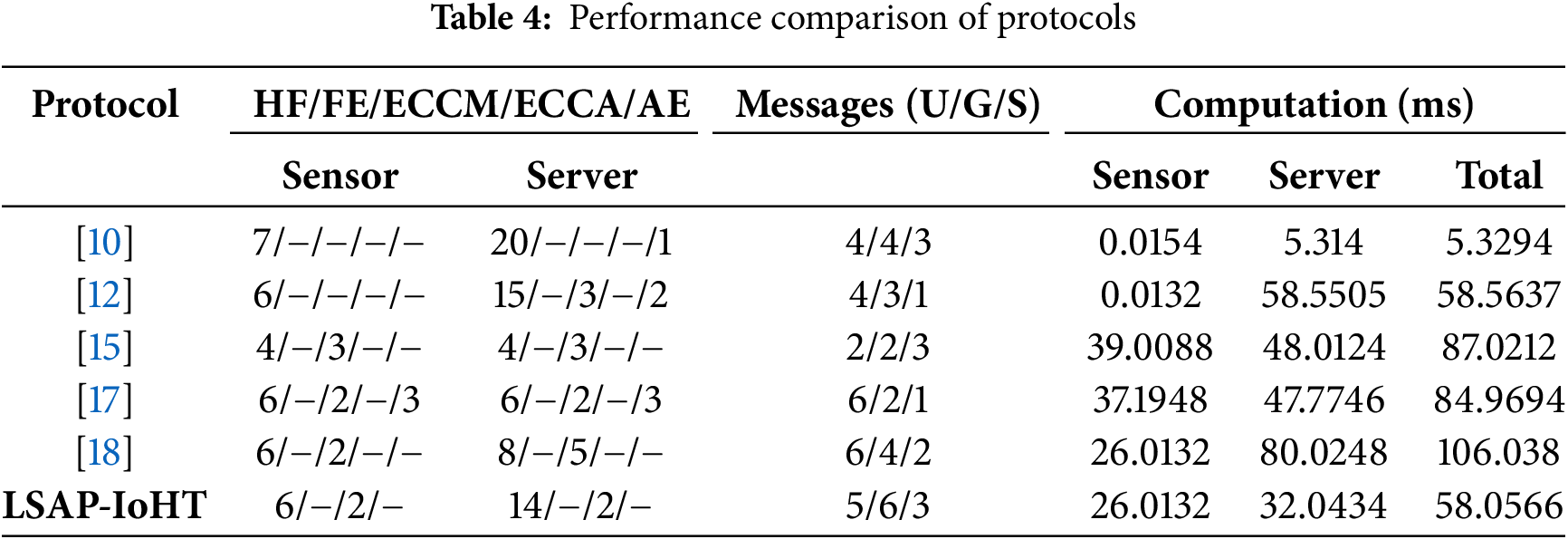

7.3 Communication Cost Analysis

The communication cost of the proposed LSAP-IoHT protocol is compared with existing schemes in terms of bit complexity, as shown in Table 5. The total cost for each protocol is calculated based on the number of times each cryptographic component appears in the protocol messages. Specifically, the following assumptions were used: each identifier (ID) is 160 bits, a nonce is 128 bits, a hash function output is 256 bits, a timestamp is 32 bits, and an ECC public key is 160 bits. By applying these values, we obtain the total communication overhead for each protocol. As shown, LSAP-IoHT achieves a significantly lower communication cost (2560 bits) compared to others, while still incorporating strong security primitives.

In this paper, we provided an in depth analysis of security in IoHT, highlighting the specific challenges and potential risks associated with this emerging technology. We conducted a cryptanalysis of LAP-IoHT, identifying its vulnerabilities and security limitations. Based on this analysis, we proposed a new authentication scheme tailored to the unique needs of IoHT. By employing advanced cryptographic techniques such as Physical Unclonable Functions (PUF), Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), and three-factor authentication (3FA), our protocol offers robust protection against potential threats. Both our formal and informal analyses confirmed the strong security guarantees of the proposed protocol. We first applied the Real-Or-Random (ROR) model to assess the protocol’s resistance to various attack scenarios, demonstrating its theoretical robustness. In addition, we performed a formal verification using the Scyther tool, which allowed us to validate the protocol’s security properties within an automated symbolic analysis framework. The combined results highlight the protocol’s resilience and reliability, making it well-suited for securing communications in Internet of Healthcare Things (IoHT) environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Marwa Ahmim, Nour Ouafi and Ahmed Ahmim; methodology, Insaf Ullah and Reham Almukhlifi; validation, Marwa Ahmim, Djalel Chefrour, Nour Ouafi and Reham Almukhlifi; formal analysis, Ahmed Ahmim, Insaf Ullah and Marwa Ahmim; writing—original draft preparation, Marwa Ahmim, Ahmed Ahmim, Insaf Ullah, Djalel Chefrour and Nour Ouafi; writing—review and editing, Marwa Ahmim, Ahmed Ahmim and Nour Ouafi; visualization, Djalel Chefrour, Insaf Ullah and Reham Almukhlifi; supervision, Ahmed Ahmim, Insaf Ullah and Djalel Chefrour. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Coelho KK, Nogueira M, Marim MC, Silva EF, Vieira AB, Nacif JAM. Lorena: low memory symmetric-key generation method for based on group cryptography protocol applied to the internet of healthcare things. IEEE Access. 2022;10:12564–79. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3143210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Khan MA, Ullah S, Ahmad T, Jawad K, Buriro A. Enhancing security and privacy in healthcare systems using a lightweight RFID protocol. Sensors. 2023;23(12):5518. doi:10.3390/s23125518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Wu TY, Wang L, Chen CM. Enhancing the security: a lightweight authentication and key agreement protocol for smart medical services in the ioht. Mathematics. 2023;11(17):3701. doi:10.3390/math11173701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Khan HU, Ali Y, Khan F. A features-based privacy preserving assessment model for authentication of internet of medical things (IoMT) devices in healthcare. Mathematics. 2023;11(5):1197. doi:10.3390/math11051197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ahmim A, Maazouzi F, Ahmim M, Namane S, Dhaou IB. Distributed denial of service attack detection for the Internet of Things using hybrid deep learning model. IEEE Access. 2023;11:119862–75. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3327620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ahmim I, Ghoualmi-Zine N, Ahmim A, Ahmim M. Security analysis on “three-factor authentication protocol using physical unclonable function for IoV”. Int J Inf Secur. 2022;21(5):1019–26. doi:10.1007/s10207-022-00595-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Sakraoui S, Ahmim A, Derdour M, Ahmim M, Namane S, Dhaou IB. FBMP-IDS: FL-based blockchain-powered lightweight MPC-secured IDS for 6G networks. IEEE Access. 2024;12:105887–905. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3435920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ahmim M, Ahmim A, Ferrag MA, Ghoualmi-Zine N, Maglaras L. ESIKE: an efficient and secure internet key exchange protocol. Wirel Pers Commun. 2023;128(2):1309–24. doi:10.1007/s11277-022-10001-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ahmim I, Ghoualmi-Zine N, Ahmim M, Ahmim A. Lightweight authentication protocols for internet of vehicles: network model, taxonomy and challenges. In: 2022 4th International Conference on Pattern Analysis and Intelligent Systems (PAIS); 2022 Oct 12–13; Oum El Bouaghi, Algeria. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

10. Chen CM, Chen Z, Kumari S, Lin MC. LAP-IoHT: a lightweight authentication protocol for the internet of health things. Sensors. 2022;22(14):5401. doi:10.3390/s22145401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Kumar V, Mahmoud MS, Alkhayyat A, Srinivas J, Ahmad M, Kumari A. RAPCHI: robust authentication protocol for IoMT-based cloud-healthcare infrastructure. J Supercomput. 2022;78(14):16167–96. doi:10.1007/s11227-022-04513-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Aghili SF, Mala H, Shojafar M, Peris-Lopez P. LACO: lightweight three-factor authentication, access control and ownership transfer scheme for e-health systems in IoT. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2019;96(1):410–24. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.02.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang L, Zhang Y, Tang S, Luo H. Privacy protection for e-health systems by means of dynamic authentication and three-factor key agreement. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2018;65(3):2795–805. doi:10.1109/tie.2017.2739683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Soni P, Pal AK, Islam SH. An improved three-factor authentication scheme for patient monitoring using WSN in remote health-care system. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2019;182(1):105054. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Challa S, Das AK, Odelu V, Kumar N, Kumari S, Khan MK, et al. An efficient ECC-based provably secure three-factor user authentication and key agreement protocol for wireless healthcare sensor networks. Comput Electr Eng. 2018;69(6):534–54. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2017.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ullah I, Khan MA, Abdullah AM, Noor F, Innab N, Chen CM. Enabling secure communication in wireless body area networks with heterogeneous authentication scheme. Sensors. 2023;23(3):1121. doi:10.3390/s23031121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Rabie OBJ, Selvarajan S, Hasanin T, Mohammed GB, Alshareef AM, Uddin M. A full privacy-preserving distributed batch-based certificate-less aggregate signature authentication scheme for healthcare wearable wireless medical sensor networks (HWMSNs). Int J Inf Secur. 2024;23(1):51–80. doi:10.1007/s10207-023-00798-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Xie Y, Zhang S, Li X, Li Y, Chai Y. CasCP: efficient and secure certificateless authentication scheme for wireless body area networks with conditional privacy-preserving. Secur Commun Netw. 2019;2019(1):5860286. doi:10.1155/2019/5860286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ji S, Gui Z, Zhou T, Yan H, Shen J. An efficient and certificateless conditional privacy-preserving authentication scheme for wireless body area networks big data services. IEEE Access. 2018;6:69603–11. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2880898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Thakur G, Prajapat S, Kumar P, Das AK, Shetty S. An efficient lightweight provably secure authentication protocol for patient monitoring using wireless medical sensor networks. IEEE Access. 2023;11:114662–79. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3325130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Servati MR, Safkhani M. ECCbAS: an ECC based authentication scheme for healthcare IoT systems. Pervasive Mob Comput. 2023;90(15):101753. doi:10.1016/j.pmcj.2023.101753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li X, Peng J, Obaidat MS, Wu F, Khan MK, Chen C. A secure three-factor user authentication protocol with forward secrecy for wireless medical sensor network systems. IEEE Syst J. 2019;14(1):39–50. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2019.2899580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Amin R, Biswas G. A secure light weight scheme for user authentication and key agreement in multi-gateway based wireless sensor networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2016;36(4):58–80. doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2015.05.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sureshkumar V, Amin R, Vijaykumar V, Sekar SR. Robust secure communication protocol for smart healthcare system with FPGA implementation. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2019;100(4):938–51. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.05.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ataei Nezhad M, Barati H, Barati A. An authentication-based secure data aggregation method in internet of things. J Grid Comput. 2022;20(3):29. doi:10.1007/s10723-022-09619-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Khajehzadeh L, Barati H, Barati A. A lightweight authentication and authorization method in IoT-based medical care. Multimed Tools Appl. 2025;84(12):11137–76. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-19379-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Dolev D, Yao A. On the security of public key protocols. IEEE Trans Inform Theory. 1983;29(2):198–208. doi:10.1109/tit.1983.1056650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ma H, Wang C, Xu G, Cao Q, Xu G, Duan L. Anonymous authentication protocol based on physical unclonable function and elliptic curve cryptography for smart grid. IEEE Syst J. 2023;17(4):6425–36. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2023.3289492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Cremers CJ. The scyther tool: verification, falsification, and analysis of security protocols: tool paper. In: International Conference on Computer Aided Verification. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2008. p. 414–8. [Google Scholar]

30. Cao J, Ma M, Fu Y, Li H, Zhang Y. CPPHA: capability-based privacy-protection handover authentication mechanism for SDN-based 5G HetNets. IEEE Trans Depend Secure Comput. 2019;18(3):1182–95. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2019.2916593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools