Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Machine Learning-Based Detection of DDoS Attacks in VANETs for Emergency Vehicle Communication

Department of Computer Science, University of Quebec in Outaouais (UQO), 283 Boul. Alexandre-Taché, Gatineau, QC J8X 3X7, Canada

* Corresponding Authors: Bappa Muktar. Email: ,

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Smart Roads, Smarter Cars, Safety and Security: Evolution of Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 4705-4727. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067733

Received 11 May 2025; Accepted 04 September 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks (VANETs) are central to Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), especially for real-time communication involving emergency vehicles. Yet, Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks can disrupt safety-critical channels and undermine reliability. This paper presents a robust, scalable framework for detecting DDoS attacks in highway VANETs. We construct a new dataset with Network Simulator 3 (NS-3) and Simulation of Urban Mobility (SUMO), enriched with real mobility traces from Germany’s A81 highway (OpenStreetMap). Three traffic classes are modeled: DDoS, Voice over IP (VoIP), and Transmission Control Protocol Based (TCP-based) video streaming (VideoTCP). The pipeline includes normalization, feature selection with SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), and class balancing via Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE). Eleven classifiers are benchmarked—including eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Categorical Boosting (CatBoost), Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost), Gradient Boosting (GB), and an Artificial Neural Network (ANN)—using stratified 5-fold cross-validation. XGBoost, GB, CatBoost and ANN achieve the highest performance (weighted F1-score = 97%). To assess robustness under non-ideal conditions, we introduce an adversarial evaluation with packet-loss and traffic-jitter (small-sample deformation); the top models retain strong performance, supporting real-time applicability. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the proposed highway-focused framework is accurate, resilient, and well-suited for deployment in VANET security for emergency communications.Keywords

Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks (VANETs) have emerged as a cornerstone of Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), enabling real-time communication between vehicles and infrastructure to improve traffic efficiency and road safety [1,2]. Unlike general wireless networks, VANETs operate in highly dynamic environments characterized by high node mobility, rapidly changing topologies, and stringent latency requirements. These distinctive features—combined with decentralized architecture and frequent handovers—introduce unique design challenges for communication reliability, scalability, and security. VANETs are particularly vital for emergency response units, which rely on uninterrupted connectivity to minimize response time and save lives. However, their open communication channels, decentralized architecture, and dynamic topology expose them to a wide range of cybersecurity threats [3]. Among the most critical of these threats are Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, which aim to overwhelm network resources and degrade the performance of safety-critical services. Such disruptions can cause severe consequences, including delayed emergency interventions, increased traffic congestion, and potential loss of life [4,5].

In parallel, adjacent research in Wireless Sensor Networks (WSN) has explored multi-pronged defenses that blend detection, trust, and localization. For example, Kaur et al. propose a deep-learning and blockchain approach combined with the Distance Vector-Hop (DV-HOP) algorithm to mitigate DDoS while preserving accurate node localization, further refined via mayfly-based optimization [6]. Their simulations report improvements in localization error and misclassification rates, highlighting the value of combining learning-driven detection with decentralized trust mechanisms. While WSN and highway VANETs differ in link layer, mobility, and traffic models, this line of work underscores the importance of robustness under adversarial conditions and informs our focus on stress-testing detection models in mobile wireless environments.

Despite increasing academic interest in intrusion detection systems for VANETs, many existing studies present notable limitations, such as exclusive reliance on synthetic datasets, lack of reproducibility and an overemphasis on dense urban environments [3,7]. In particular, realistic highway scenarios—where uninterrupted communication for emergency vehicles is equally critical—remain significantly underexplored. Moreover, most prior research depends on a single machine learning classifier, which limits the robustness and generalization capacity of the proposed models.

To bridge these gaps, this paper proposes a comprehensive machine learning-based framework for detecting DDoS attacks in VANETs operating in highway environments.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

• We design and simulate realistic VANET traffic using the Network Simulator 3 (NS-3) and Simulation of Urban Mobility (SUMO) simulators, incorporating real-world vehicle mobility traces from Germany’s A81 highway extracted via OpenStreetMap (OSM).

• We evaluate a wide range of supervised learning algorithms, including eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Categorical Boosting (CatBoost), Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost), Extremely Randomized Trees (Extra Trees), Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB), Support Vector Machine (SVM), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Logistic Regression (LR), Decision Tree (DT), and Artificial Neural Network (ANN).

• We apply SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to assess feature importance, thereby enhancing the interpretability and reliability of the models. The proposed framework achieves excellent predictive performance, with F1-scores reaching up to 96% for XGBoost, GB, CatBoost and ANN classifiers.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review of machine learning-based intrusion detection in VANETs. Section 3 details the methodology, including dataset generation and preprocessing. Section 4 describes the classifiers used and the predictive modeling approach. Section 5 reports and discusses the experimental results. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

Securing VANETs against DDoS attacks has emerged as a critical research area due to the potential disruptions in vital communication channels, especially those involving emergency vehicles. Recent advances have emphasized developing robust, accurate, real-time intrusion detection mechanisms utilizing machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) approaches.

Several researchers have investigated innovative machine learning models tailored explicitly to the unique constraints of VANET environments. For instance, Setia et al. proposed a framework employing machine learning combined with fuzzification methods within cloud-based VANET systems, achieving a remarkable accuracy of 99.59% in proactively detecting DDoS threats [8]. Similarly, Polat, O. et al. introduced a hybrid model blending a one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) with decision trees for real-time detection in Software-Defined Vehicular Ad-Hoc Networks (SD-VANETs), attaining an accuracy close to 90% [4]. Further expanding this direction, Polat et al. presented an advanced deep learning architecture using stacked sparse autoencoders combined with a softmax classifier, significantly improving accuracy to approximately 96.9% in SDN-based VANET scenarios [9].

Addressing not only attack detection but also network congestion, Gopi et al. developed a two-phase Intelligent Denial of Service (DoS) Attack Detection with Congestion Control (IDoS-CC) system. Their methodology combined Teaching and Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO) with a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) deep learning model, demonstrating substantial reductions in network congestion and improved detection accuracy [10]. Kadam and Sekhar also contributed notably by proposing a hybrid classification approach (KSVM) integrating K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and SVM, exhibiting superior sensitivity, recall, and precision compared to traditional classifiers [11].

Achieving data realism and reproducibility remains a key challenge often overlooked in the literature. In response, Alkadiri and Ilyas generated a contemporary dataset leveraging Objective Modular Network Testbed in C++ (OMNeT++), and SUMO simulations, optimized via SMOTE and classified using the XGBoost algorithm, achieving an F1-score of approximately 99% [12]. Similarly, Rashid et al. adopted OMNeT++ and SUMO for a realistic VANET simulation, presenting a real-time adaptive framework with various ML classifiers, yielding accuracies of up to 99% [13]. Oluchi Anyanwu et al. further optimized detection by integrating Radial Basis Function SVM (RBF-SVM) with Grid Search Cross-Validation, showing detection rates of 99.22% on realistic SDN-based VANET datasets [14].

Hybrid optimization and multi-stage detection systems have also been extensively explored. Marwah et al. combined modified SVM enhanced by Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) and Whale-Dragonfly optimization for efficient routing and bandwidth allocation, significantly improving throughput and reducing communication overhead under DDoS conditions [15]. Adhikary et al. developed a hybrid model merging AnovaDot and RBFDot SVM kernels into a chained detection mechanism, achieving improved robustness and detection accuracy compared to single-kernel models [16]. Moreover, Tariq proposed a comprehensive detection framework integrating Autoencoders, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), clustering methods, fog computing, and blockchain technology, offering a low-latency, scalable, and robust solution with a detection rate of approximately 94% [17].

Deep learning-based anomaly detection approaches have recently gained momentum due to their scalability and superior pattern recognition capabilities. Lekshmi et al. leveraged convolutional autoencoders coupled with LSTM networks and self-attention mechanisms, achieving an F1-score of 98.20% in detecting DDoS attacks on realistic VANET data [18]. Similarly, Haydari and Yilmaz introduced a semi-supervised, non-parametric intrusion detection system using roadside units (RSUs), capable of detecting novel attack patterns without prior knowledge, significantly enhancing real-time responsiveness and detection accuracy [19].

Moreover, Gu et al. introduced a DRL-enhanced federated self-supervised learning framework for ISAC-enabled Vehicle Edge Computing, dynamically allocating tasks between vehicle on-board resources and roadside units to minimise energy consumption and accelerate model convergence, thereby reinforcing security in highly dynamic VANET contexts [20].

While extensive progress has been made, gaps remain in terms of evaluating these methodologies in realistic highway scenarios. Most existing works predominantly target dense urban environments or lack reproducible real-world mobility data, limiting the generalizability of results. Additionally, comprehensive comparisons of various machine learning classifiers within a unified, realistic highway scenario remain scarce.

Our study aims to address these critical gaps by evaluating multiple prominent ML classifiers—including XGBoost, CatBoost, AdaBoost, Extremely Randomized Trees (Extra Trees), Random Forest (RF), GB, SVM, KNN, LR, DT, and ANN—in a realistic VANET highway scenario. Leveraging NS-3 and SUMO simulators enriched with real mobility data from the A81 highway in Germany, our approach not only ensures realism but also enables reproducibility. Furthermore, data balancing through SMOTE and rigorous performance evaluation metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score) strengthen our methodological framework, providing a robust and comprehensive assessment of classifier effectiveness.

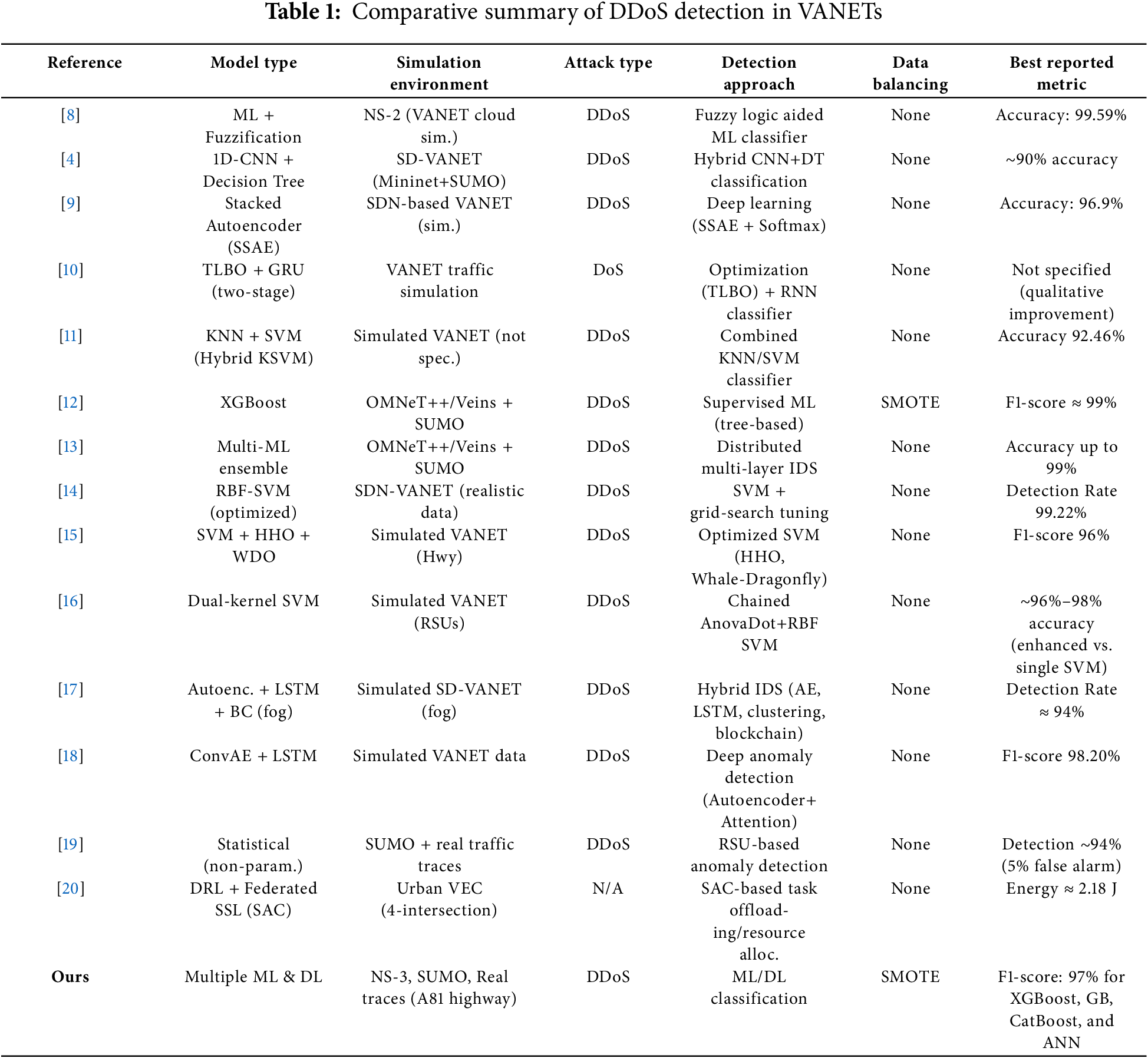

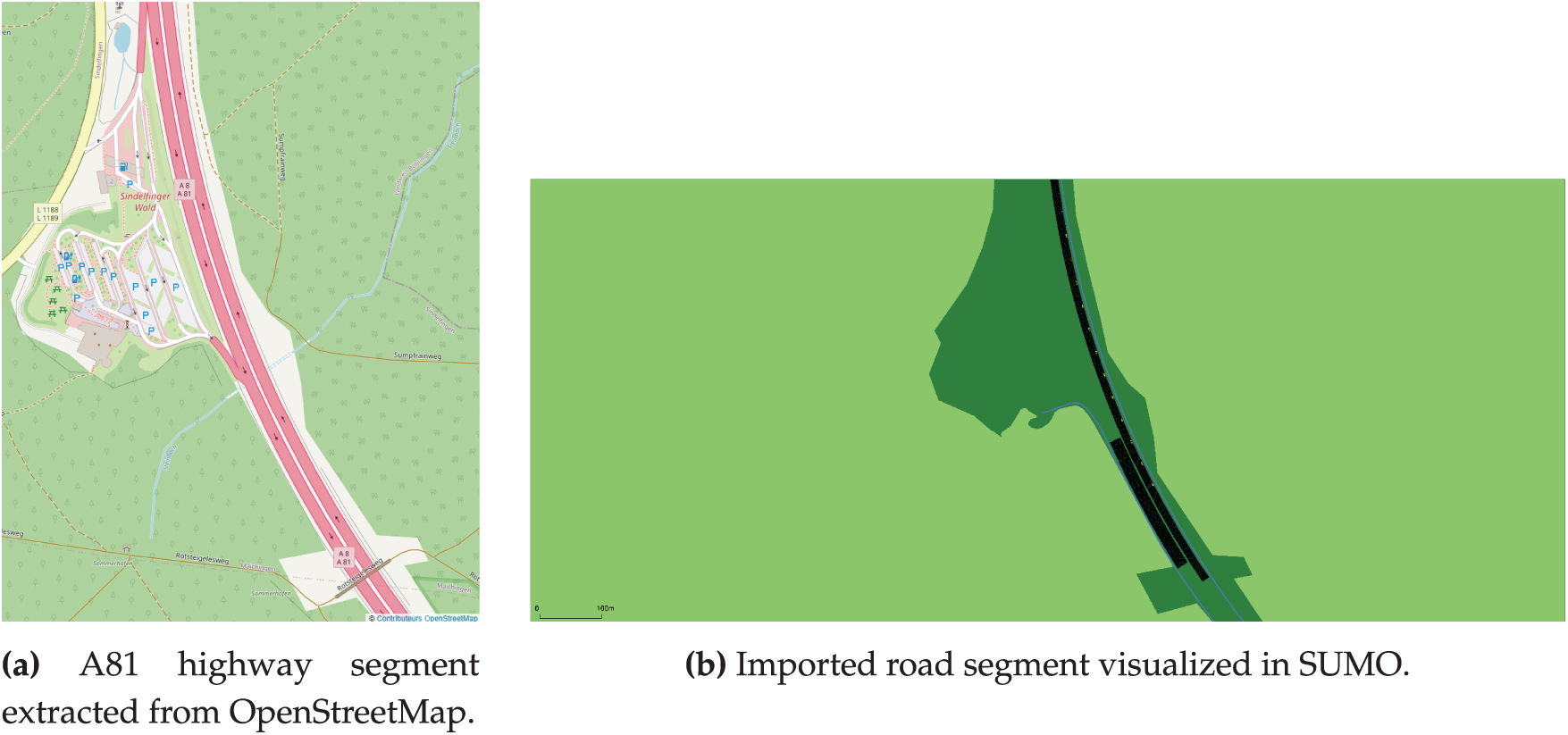

Table 1 below summarizes and positions our work compared to existing state-of-the-art approaches based on several critical criteria.

This comparative analysis underscores the novelty and relevance of our research, emphasizing both methodological rigor and practical applicability, thus effectively filling the identified gaps in the current state of VANET cybersecurity research.

This section outlines the methodological framework for developing a robust classification model for DDoS attacks in a VANET environment, simulating a realistic highway scenario.

This section outlines the architecture and methodology used to simulate a realistic highway-based VANET under coordinated DDoS attacks. It details the scenario design, simulator integration, and incorporation of real mobility traces to ensure data realism and model applicability.

Two simulation scenarios were designed to evaluate the performance and robustness of the proposed detection system.

Baseline DDoS Scenario.

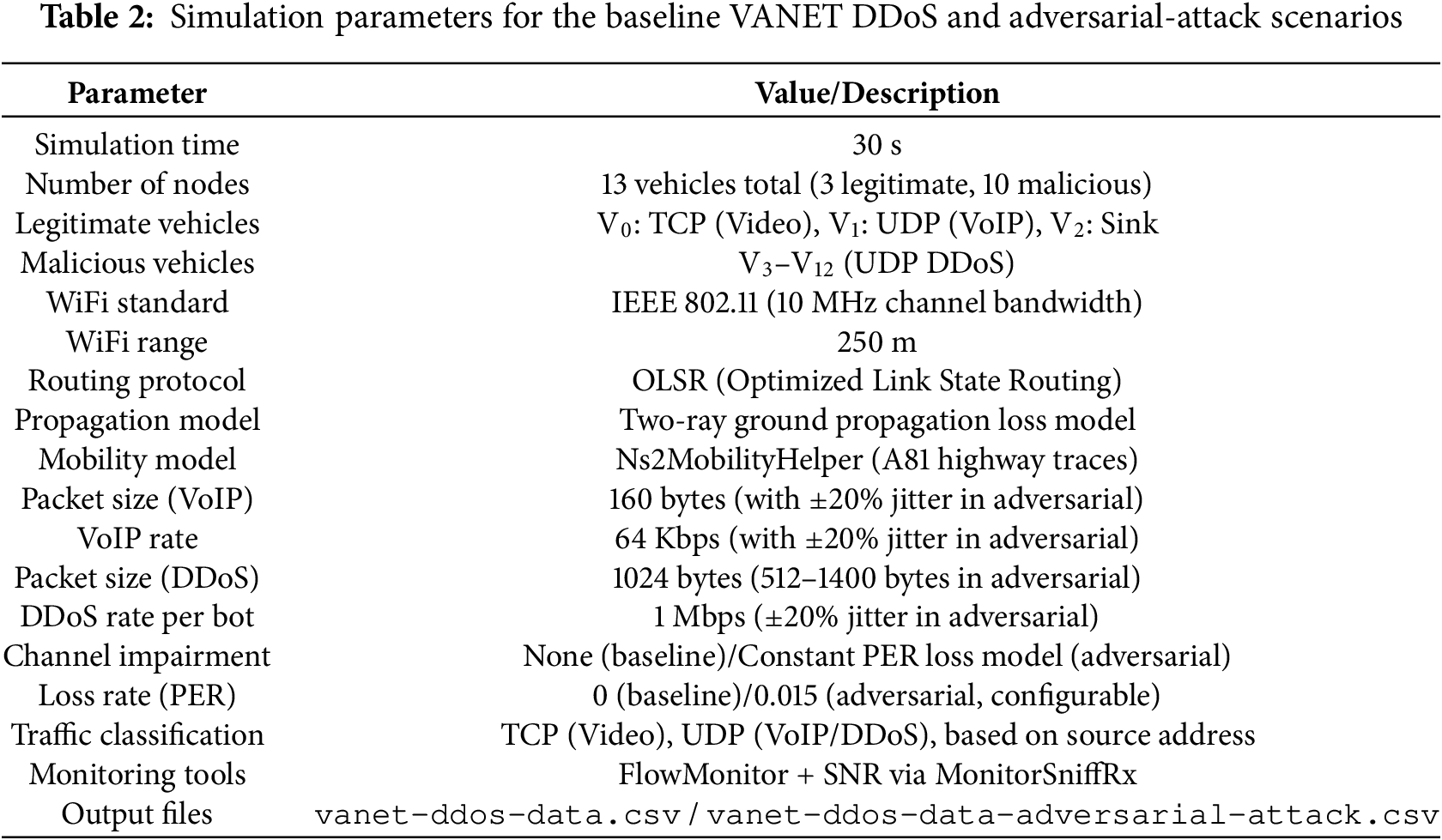

The first scenario (cf. Table 2 and Fig. 1) simulates a VANET highway environment with 13 vehicles (from

Figure 1: Illustration of the VANET highway simulation setup used for both the baseline DDoS and adversarial-attack scenarios

Adversarial-Attack Scenario.

The second scenario (also cf. Table 2) builds upon the baseline DDoS setup but introduces adversarial conditions to test detection robustness in a more realistic, noisy environment. In addition to the 13-vehicle highway topology and identical traffic roles (

• A constant packet error rate (PER) channel model via a custom ConstantErrorRateModel, configured with a configurable LossRate (default: 1% PER), to simulate wireless impairments and random frame losses.

• Traffic deformation, where legitimate and malicious traffic experiences randomized packet sizes and data rate jitter, mimicking real-world variability and evading static detection patterns.

• RNG seed control, ensuring reproducible adversarial noise injection across multiple runs.

These perturbations affect both legitimate and malicious flows, introducing overlap in traffic characteristics and making classification more challenging. Output metrics such as average Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and noise levels are collected alongside standard FlowMonitor statistics to capture the combined effects of network load and channel impairments.

3.1.2 NS-3 and SUMO Integration

The experiment uses NS-3 [21] and SUMO [22] simulators to simulate communication protocols and vehicle dynamics. NS-3 handles network stack, protocol behavior, and traffic generation, while SUMO provides the precise mobility dynamics of the vehicle for realistic traffic scenarios.

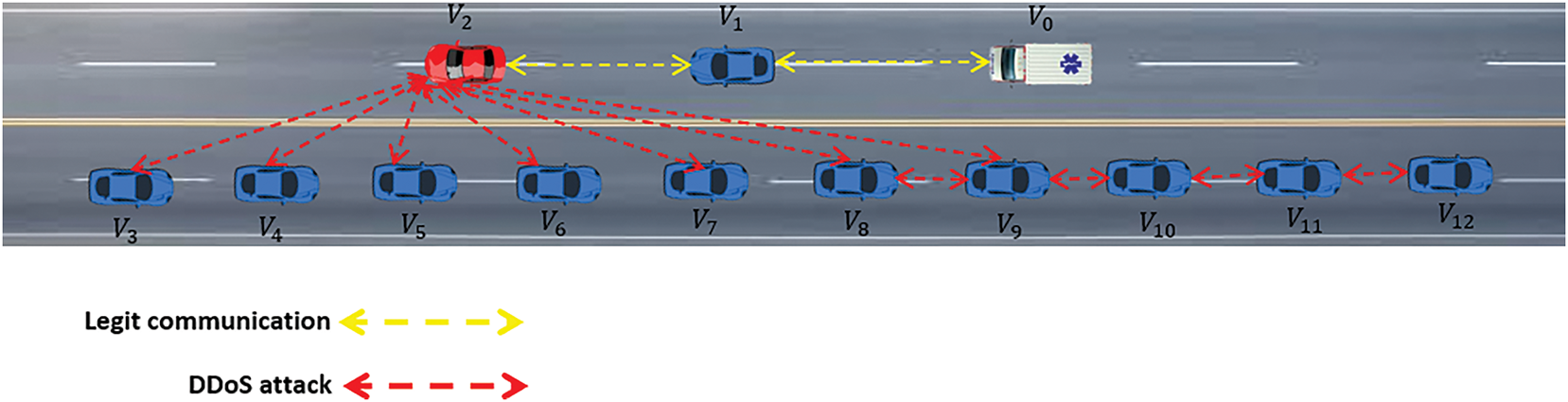

3.1.3 Incorporation of Real Mobility Traces

To further enhance the realism of the simulation, real-world mobility traces from the A81 highway in Germany were integrated into the SUMO simulation and imported into NS-3 using the Ns2MobilityHelper module. This integration ensures that the generated dataset reflects authentic vehicular behavior and spatial-temporal patterns, thus increasing the applicability and reliability of the intrusion detection model trained on this data. Fig. 2 illustrates the A81 highway in OSM and its corresponding import within the SUMO environment.

Figure 2: Visualization of the A81 highway segment used in the simulation. (a) Map segment from OSM. (b) Simulation rendering in SUMO

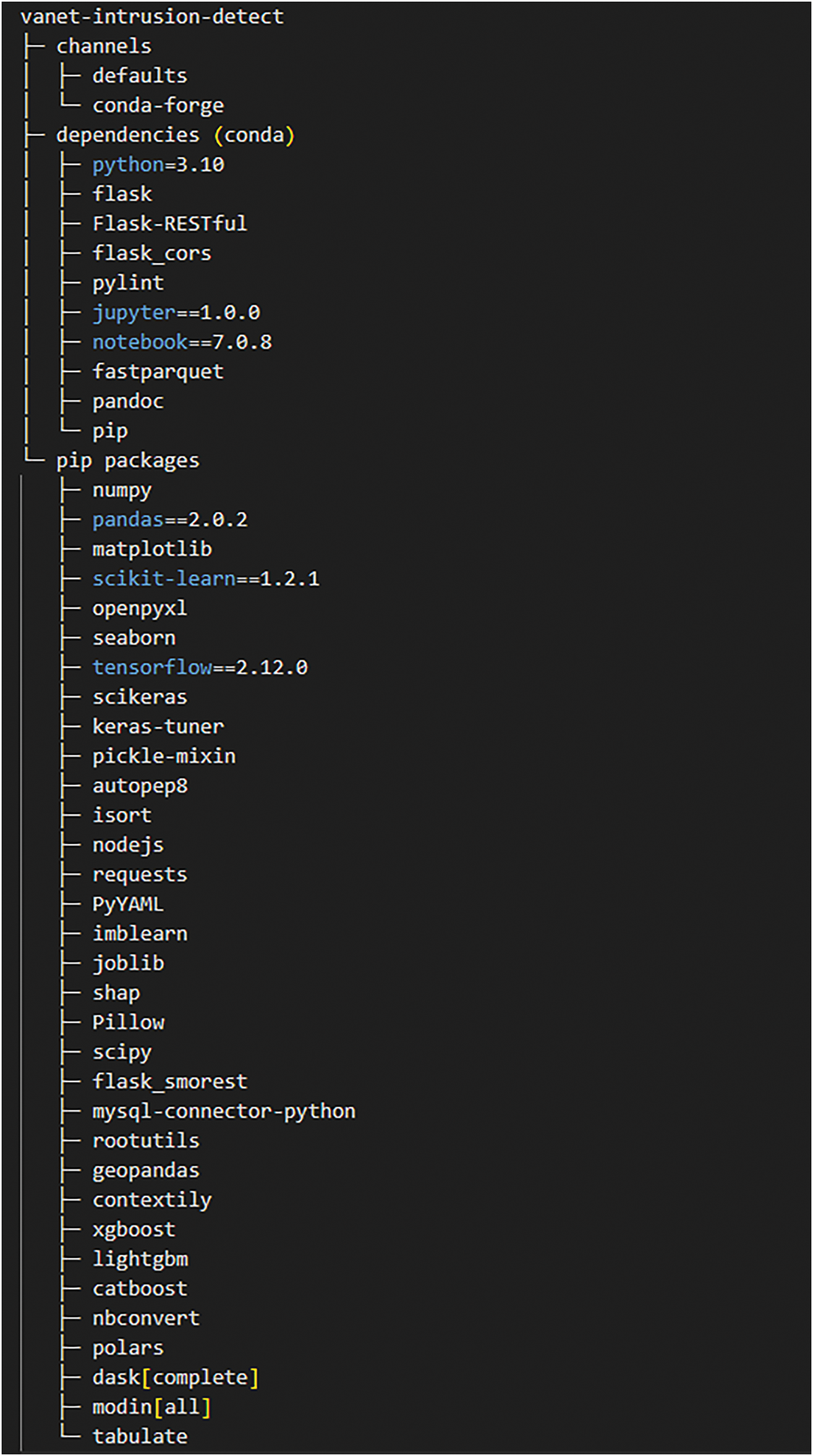

3.1.4 Hardware and Software Environment

All experiments were conducted on a Windows 11 workstation equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1650 GPU, 32 GB RAM, and a 1 TB SSD. The software stack is managed with Conda (channels defaults and conda-forge) and uses Python 3.10. Interactive development employed Jupyter 1.0.0 and notebook 7.0.8.

Core libraries:

• Numerical/data tooling: NumPy, pandas 2.0.2, SciPy, Polars, dask[complete], modin[all].

• Classical ML: scikit-learn 1.2.1, imbalanced-learn, joblib.

• Deep learning: TensorFlow 2.12.0, scikeras, keras-tuner.

• Gradient boosting: xgboost, lightgbm, catboost.

• Visualization: Matplotlib, Seaborn.

• Model interpretation: SHAP.

• I/O and export: fastparquet, openpyxl, nbconvert, tabulate.

• Web/API: Flask, Flask-RESTful, flask_cors, flask_smorest.

• Utilities and geospatial: requests, PyYAML, Pillow, mysql-connector-python, rootutils, geopandas, contextily, nodejs.

• Code quality: pylint, isort, autopep8.

To facilitate reproducibility, a detailed snapshot of the software environment is provided in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Machine Learning environment snapshot for the experimental setup

Note: Only version-pinned packages from the environment file are shown explicitly (e.g., pandas 2.0.2, scikit-learn 1.2.1, TensorFlow 2.12.0, Jupyter 1.0.0, notebook 7.0.8). Other packages follow the latest compatible versions resolved by Conda/Pip at installation time.

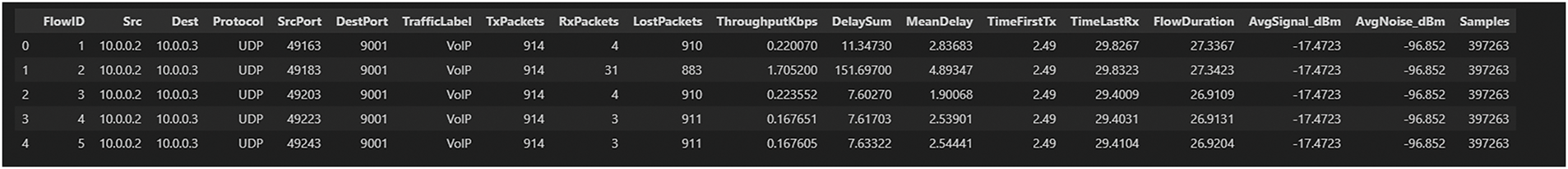

3.2 Data Generation and Labeling

The simulated dataset utilized in this study comprises three distinct classes of network traffic: (DDoS), VoIP, and VideoTCP. Each traffic category was generated using appropriate application models within the NS-3 simulation environment. Specifically, VideoTCP traffic, emulating a real-time video streaming application, was produced using the BulkSendHelper application over a TCP connection directed toward the target vehicle. Concurrently, VoIP traffic was simulated using the OnOffHelper application, configured at a constant data rate of

To characterize the behavior and performance of each network flow, several relevant metrics were collected using the FlowMonitor module in NS-3. Key metrics extracted include the average throughput, measured in kilobits per second (Kbps), computed according to the following equation:

where RxBytes denotes the total number of bytes received and FlowDuration represents the effective duration of the flow in seconds. The mean delay was calculated using:

where

Lastly, each network flow was explicitly labeled according to its traffic class (DDoS, VoIP, or VideoTCP) based on the originating IP address and the employed network protocol. Consequently, TCP-based flows were systematically classified as VideoTCP, UDP-based flows originating from legitimate nodes (IP addresses

Figure 4: Dataset sample

The preprocessing stage is a fundamental step in building an effective intrusion detection model. This process was structured into three main phases: data cleaning and normalization, creation of a derived SNR variable, and class rebalancing through oversampling techniques.

3.3.1 Cleaning and Normalization

The raw dataset initially consisted of 6882 network flows described by 19 features, including identifiers, traffic characteristics, performance metrics, and physical measurements such as average signal and noise power. Several cleaning operations were applied:

• Removal of non-informative or highly correlated features: Columns such as FlowID, Src, Dest, SrcPort, DestPort, and Samples were discarded due to their low predictive value. Similarly, the temporal features TimeFirstTx and TimeLastRx were removed in favor of the derived feature FlowDuration, and DelaySum was excluded in favor of MeanDelay.

• Categorical feature encoding: The categorical variables Protocol and TrafficLabel were converted to numerical representations using LabelEncoder, where DDoS, VoIP, and VideoTCP were encoded as 0, 2, and 1, respectively.

• Duplicate removal: Approximately 7.5% of the data were identified as duplicates and subsequently removed to reduce model bias.

• Normalization: All numerical features were normalized using StandardScaler to enforce zero mean and unit variance—an essential condition for many machine learning algorithms.

Although the dataset initially contained the fields AvgSignal_dBm and AvgNoise_dBm, a new variable representing the average SNR was computed as follows:

where

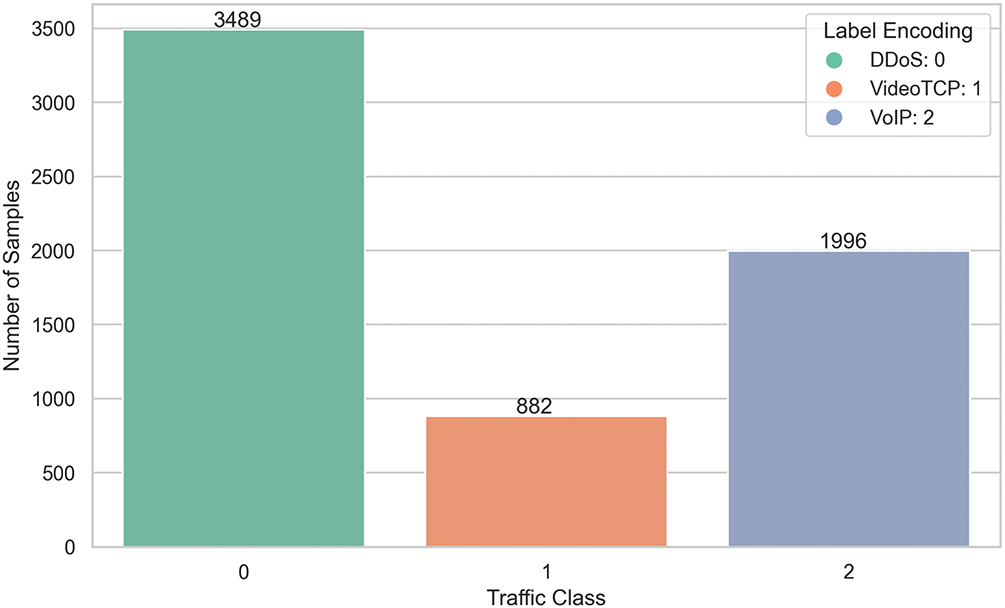

3.3.3 Class Rebalancing Using SMOTE

Fig. 5 shows a significant class imbalance: 3489 DDoS flows, 1996 VoIP flows, and only 882 VideoTCP flows. To address this, we applied the SMOTE [23] to the training data. SMOTE generates synthetic samples for the minority classes, resulting in a balanced training set with 2617 flows per class.

Figure 5: Class distribution of traffic labels before applying SMOTE rebalancing

This rebalancing significantly improved model generalization and reduced bias toward the majority class during training.

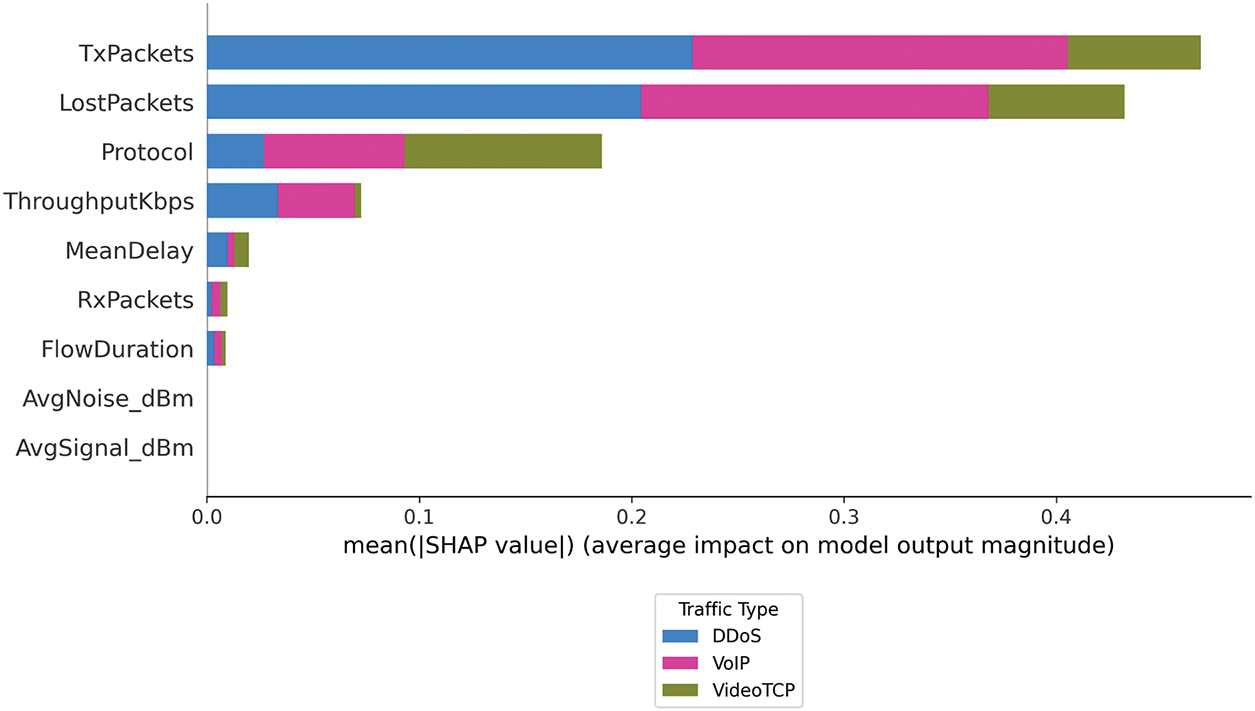

Feature selection plays a pivotal role in the development of any predictive model, particularly in the context of VANETs, where the dataset may include redundant or highly correlated variables. To identify the most relevant attributes for classifying network traffic (DDoS, VoIP, and VideoTCP), we adopted an interpretability-based approach using SHAP values (see Fig. 6). This method quantifies the marginal contribution of each feature to the model’s output while accounting for complex interdependencies among features.

Figure 6: Feature importance based on SHAP values

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the SHAP analysis highlighted TxPackets, LostPackets, and Protocol as the most influential features in predicting the traffic class. Although these features exhibit some degree of correlation, they offer complementary insights into traffic intensity and anomalous behavior, such as packet losses resulting from DDoS attacks.

Nonetheless, TxPackets and LostPackets, despite their high SHAP scores and strong correlation with the target variable, were deliberately excluded from the final feature set to mitigate multicollinearity effects. These variables directly influence several other performance metrics (e.g., ThroughputKbps and MeanDelay), and including them could introduce bias by over-representing certain aspects of the traffic.

The final selection includes the following features:

• Protocol: distinguishes UDP flows (VoIP) from TCP flows (VideoTCP), and supports the identification of traffic patterns typical of DDoS attacks.

• ThroughputKbps: reflects traffic intensity and helps discriminate between high-volume flows such as those generated by VideoTCP and DDoS.

• MeanDelay: captures average packet latency, which is critical for detecting delays caused by attacks or real-time services like VoIP.

• RxPackets: although moderately ranked in SHAP importance, this feature complements flow-level analysis without the redundancy of TxPackets.

• FlowDuration: captures the temporal dynamics of each flow and effectively substitutes highly correlated variables such as TimeFirstTx and TimeLastRx.

This refined feature set was selected based on its discriminative power while minimizing redundancy. It ensures improved robustness and interpretability of the classification model, which is essential for reliable intrusion detection in VANET environments.

This section presents the modeling approach to classify network traffic in a VANET scenario under DDoS conditions.

4.1 Tested Machine Learning Models

To assess the ability to classify network traffic in a VANET environment, several machine learning algorithms were tested, encompassing both traditional methods and more advanced ensemble and boosting techniques.

The traditional models evaluated include:

• RF: An ensemble method based on building multiple decision trees and averaging their predictions to improve generalization.

• Extra Trees: Similar to Random Forest, but introducing greater randomness in the selection of splitting thresholds to enhance diversity.

• DT: A simple hierarchical model based on attribute-based decision rules.

• LR: A linear model adapted for multiclass classification through the softmax activation function.

• SVM: Using an optimized linear kernel to separate network traffic classes effectively.

• KNN: A non-parametric method that classifies each observation based on the majority vote among its

Advanced boosting and ensemble methods were also evaluated:

• XGBoost: A gradient boosting framework optimized for multiclass classification tasks using the multi:softmax objective function.

• CatBoost: Designed to efficiently handle categorical variables and exhibit robustness against class imbalance.

• AdaBoost: An iterative ensemble technique that sequentially improves weak classifiers.

• GB: Builds models sequentially to correct errors made by prior models.

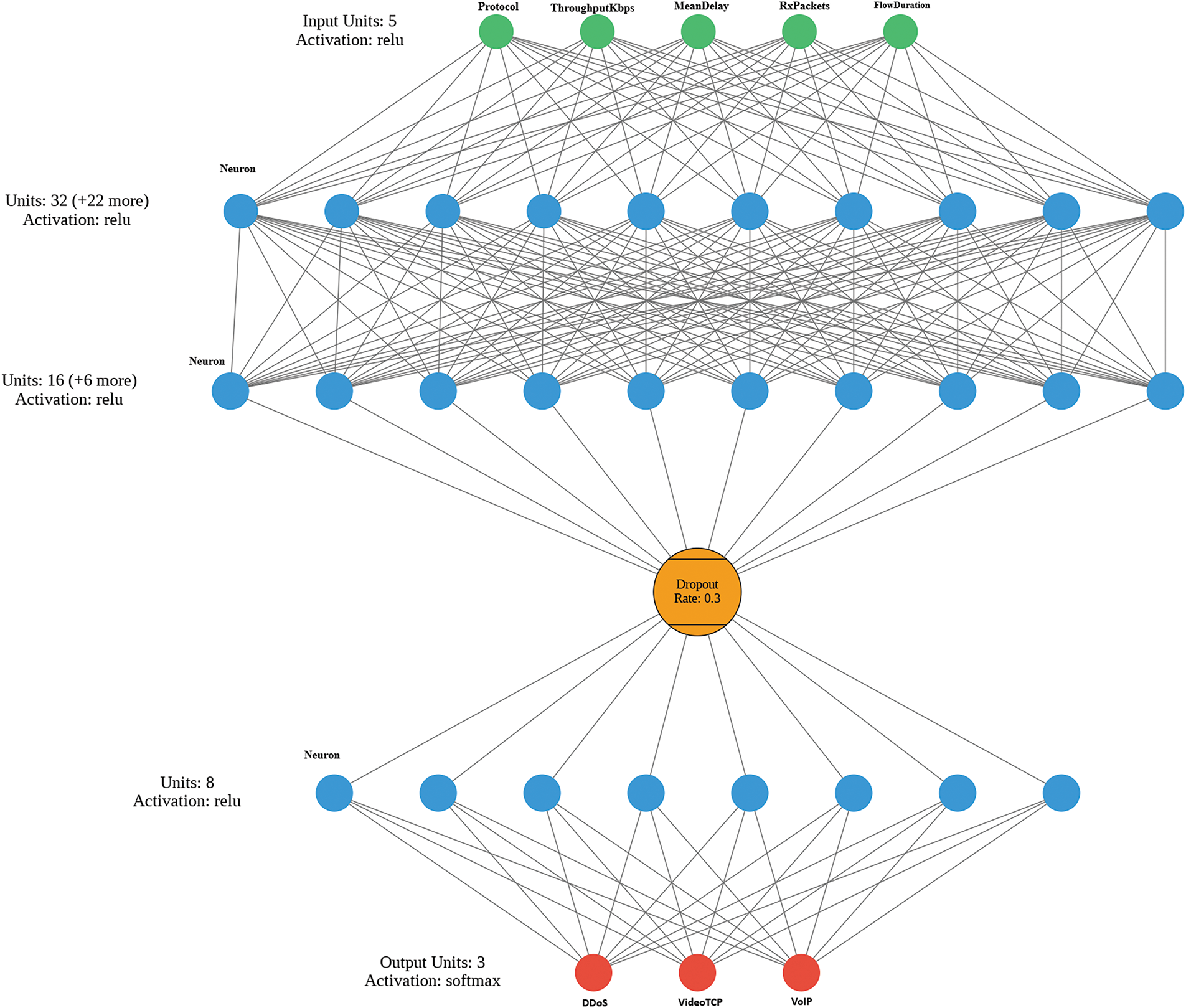

Finally, an ANN was designed and implemented using Keras. The architecture consists of:

• An input layer receiving 5 features (Protocol, ThroughputKbps, MeanDelay, RxPackets, FlowDuration).

• A first dense hidden layer with 32 neurons and a ReLU activation function.

• A second dense hidden layer with 16 neurons, also activated by ReLU.

• A Dropout layer with a rate of

• A third dense hidden layer with 8 neurons and a ReLU activation function.

• An output dense layer with 3 neurons using the Softmax activation function to classify among three classes: DDoS, VoIP, and VideoTCP.

The ReLU activation function was selected for the hidden layers based on empirical testing during preliminary experiments, where it consistently yielded faster convergence. The Softmax activation in the output layer was chosen as it is the standard approach for multi-class classification tasks.

Fig. 7 illustrates the architecture of the designed ANN.

Figure 7: Architecture of the designed ANN

To rigorously assess model generalization and mitigate potential overfitting, a stratified 5-fold cross-validation (CV) methodology was employed for all classifiers, including the ANN implemented with TensorFlow/Keras. The choice of 5-fold was made as it provides an optimal balance between computational efficiency and robust estimation of generalization performance. Lower values (e.g., 3-fold) may yield overly pessimistic estimates, while higher values (e.g., 10-fold) substantially increase computational cost without offering significant performance gains, particularly given the moderate size of our dataset.

During ANN training, dropout and early stopping were maintained to further reduce the risk of overfitting. The CV procedure not only provided statistical robustness to performance estimates but also ensured that the models were consistently evaluated on unseen data in each fold. Mean training and validation accuracy/loss trends from the CV runs, together with the averaged confusion matrix (CM) of the best model, are presented in Section 5.2.2 to visually confirm stable convergence and the absence of over-specialization.

The performance of each classification algorithm was assessed using standard evaluation metrics derived from the confusion matrix, namely Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score. These metrics quantify the models’ ability to correctly classify the network traffic into the three categories: DDoS, VoIP, and VideoTCP. The definitions and formulas are as follows:

• Accuracy (AC): Represents the ratio of correctly predicted instances over the total number of samples. It is computed using:

• Recall (R): Measures the proportion of true positives detected among all actual positive cases. The formula is:

• Precision (P): Indicates the ratio of correctly predicted positive observations to the total predicted positives:

• F1-score: Combines precision and recall into a single metric by calculating their harmonic mean:

To compute these metrics for each algorithm, the confusion matrices were extracted after testing on the evaluation set. These matrices contain the number of true positive (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN), and false negative (FN) predictions for each class. The values were used to assess how each model performed in distinguishing between normal traffic (VoIP, VideoTCP) and malicious traffic (DDoS).

This section outlines the performance outcomes of the machine learning models used in this study and provides a corresponding analysis and interpretation of these findings.

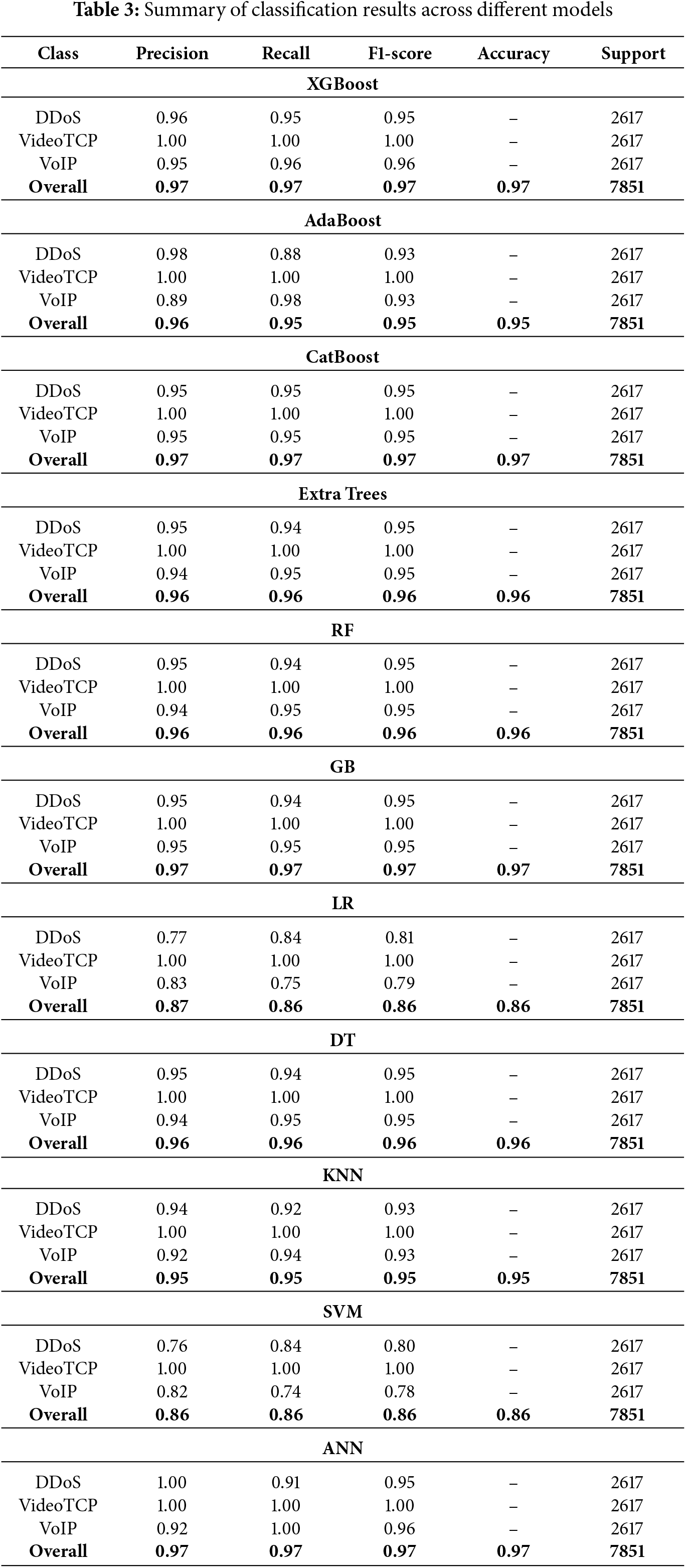

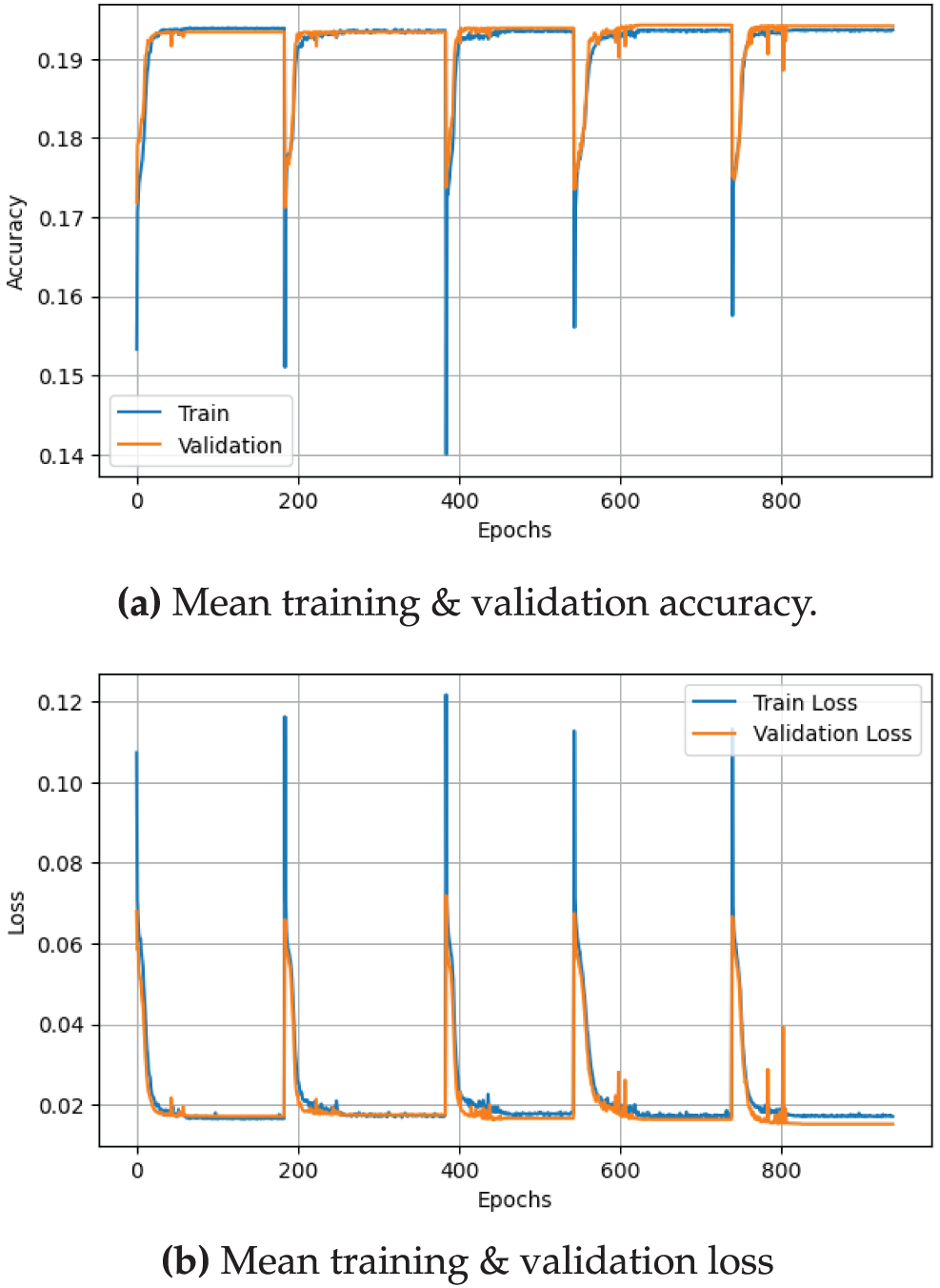

The classification report summary (Table 3), together with the comparative analysis of F1-scores across various algorithms (Fig. 8), offers a thorough evaluation of the predictive capabilities of each model.

Figure 8: F1-score comparison across models

This section analyzes the classification results obtained from various models, focusing on overall performance, robustness to class imbalance, and sources of misclassification. Key insights are drawn from evaluation metrics and confusion matrices to highlight model strengths and areas for improvement.

5.2.1 Performance Interpretation

The classification results in Table 3 and Fig. 8 show that boosted learners and the neural network deliver the strongest performance. In particular, XGBoost, GB, ANN, and CatBoost achieve the highest overall F1-scores of 0.97. Tree-based baselines also perform strongly: Extra Trees, RF, and a single DT reach 0.96. Mid-tier results are obtained by KNN and AdaBoost with overall F1-scores of 0.95. In contrast, linear models—LR and SVM—trail with overall F1-scores of 0.86, indicating limitations in capturing the non-linear interactions present in VANET traffic under DDoS, VoIP, and VideoTCP scenarios.

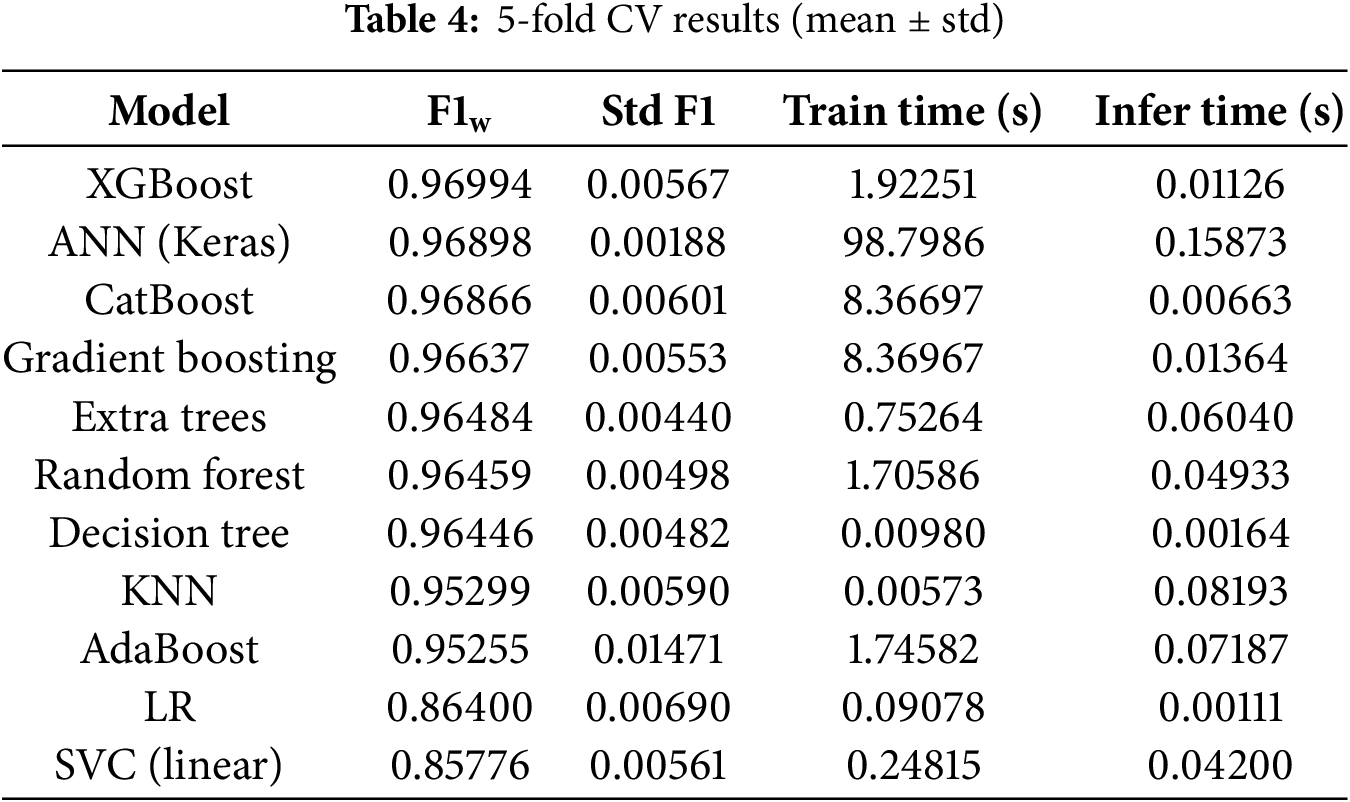

5.2.2 Overfitting & Generalization Analysis

Every classifier was evaluated by stratified 5-fold cross-validation. Table 4 lists the mean weighted F1-score together with the standard deviation, as well as the average training and inference times per fold. The best overall score is obtained by XGBoost (

Fig. 9 shows the fold-averaged learning curves for the ANN. Training and validation trajectories almost coincide and converge rapidly; neither the loss nor the accuracy curves exhibit divergence, providing strong evidence that the dropout regularisation (

Figure 9: Fold-averaged learning curves of the ANN over 5-fold CV. Error bands (barely visible) represent one standard deviation

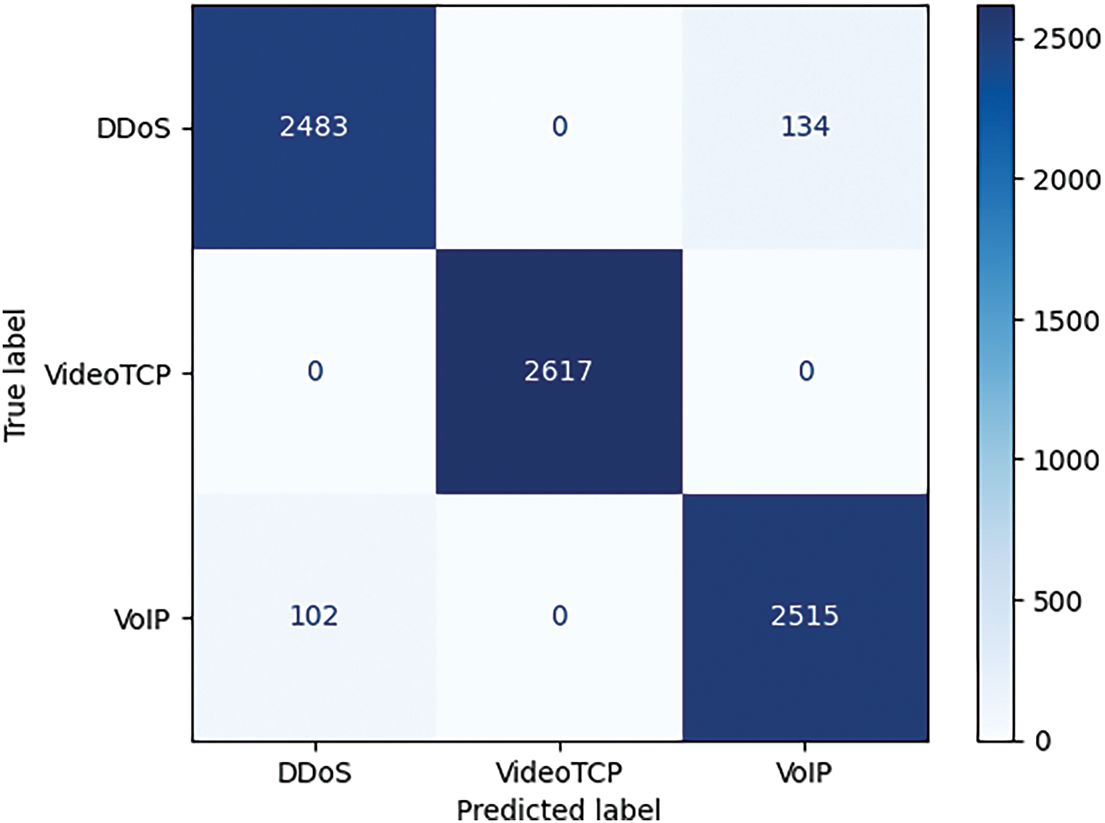

Finally, the confusion matrix averaged over the five folds for the best model (XGBoost, Fig. 10) shows a nearly perfect separation of VideoTCP flows, while the few residual errors are limited to a symmetric confusion between DDoS and VoIP (134 VoIP packets flagged as DDoS and 102 DDoS packets flagged as VoIP). This pattern corroborates the class-similarity analysis reported in Section 5.2.5.

Figure 10: Confusion matrix averaged over the five validation folds for the XGBoost model

5.2.3 Robustness to Class Imbalance

The dataset is inherently imbalanced across DDoS, VoIP, and VideoTCP. After applying SMOTE on the training set, the per-class results in Table 3 show that imbalance no longer dominates performance. VideoTCP is the easiest class: every model attains Precision = Recall = F1-score = 1.00. For DDoS, most models achieve F1 in the

5.2.4 Robustness to Adversarial Traffic

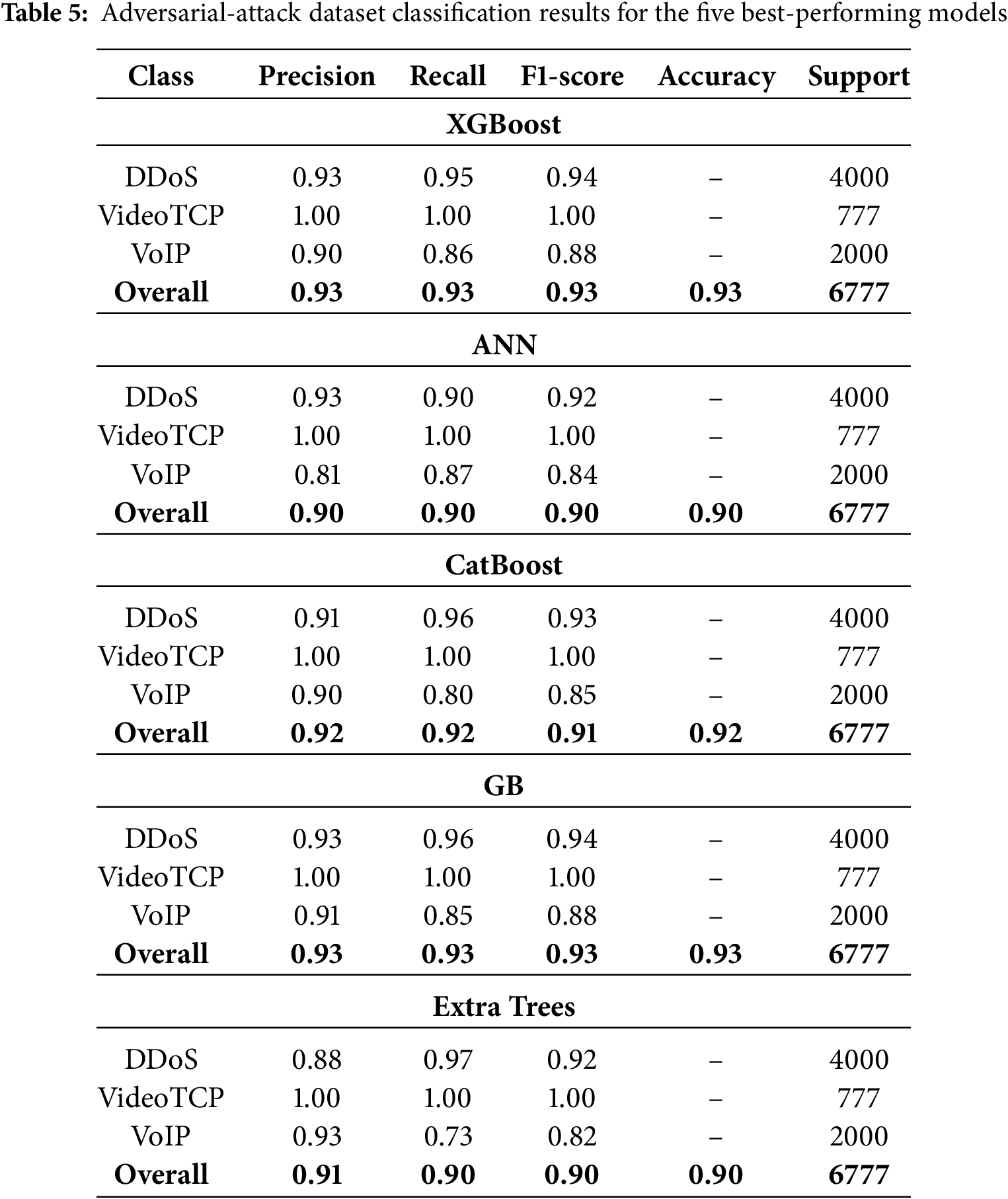

To further assess generalization, we evaluated the five best classifiers—ANN, XGBoost, CatBoost, GB, and ET—on an unseen adversarial-attack dataset (6777 flows: 4000 DDoS, 777 VideoTCP, 2000 VoIP).

As reported in Table 5, overall (weighted) F1-scores remained high under distribution shift, ranging from 0.90 to 0.93. XGBoost and GB achieved the best overall robustness (F1-score = 0.93 each; accuracy = 0.93), CatBoost followed closely (F1-score = 0.91, accuracy = 0.92), while ANN and Extra Trees both reached F1-score = 0.90 (accuracy = 0.90).

Per-class results reveal two consistent patterns. First, VideoTCP was perfectly recognized by all models (precision = recall = F1-score = 1.00). Second, degradation concentrates in the VoIP class: recall spans 0.73–0.87 (Extra Trees: 0.73; CatBoost: 0.80; GB: 0.85; XGBoost: 0.86; ANN: 0.87), with precision between 0.81–0.93. In contrast, DDoS detection remains strong across models (recall 0.90–0.97); Extra Trees attains the highest DDoS recall (0.97) but trades off VoIP recall.

Overall, these results confirm that the top models exhibit robust performance on adversarial traffic: despite targeted distributional shifts, their weighted F1-score and accuracy stay at 0.90–0.93, with errors primarily confined to VoIP under challenging conditions.

5.2.5 Misclassification Analysis

Per-class results in Table 3 show that VideoTCP is almost perfectly identified by all models (precision/recall/F1-score

On the adversarial–attack dataset (Table 5), the same pattern persists and intensifies: overall F1-score for the top models drops to

This paper presented a comprehensive evaluation of multiple machine learning techniques for detecting DDoS attacks in VANETs, specifically targeting emergency vehicle communication scenarios on highways. Leveraging a realistic simulation setup, which integrates the NS-3 network simulator with the SUMO mobility simulator and real-world vehicular mobility traces from Germany’s A81 highway, we generated a robust and reproducible dataset for rigorous evaluation.

The experimental results demonstrated that several machine learning algorithms, notably XGBoost, GB, ANN, and CatBoost, achieved outstanding classification performance, with overall F1-scores reaching up to 0.97. Other models such as Extra Trees, RF, and DT also performed strongly with F1-scores of 0.96, while KNN and AdaBoost followed closely at 0.95. LR and SVM recorded the lowest performances at 0.86. These findings confirm that the adopted data balancing strategy via SMOTE was effective in addressing class imbalance, enabling accurate detection of all traffic types, including the minority VoIP class.

The study offers significant scientific contributions, including the introduction of a reproducible and realistic methodology combining NS-3 and SUMO simulators with authentic mobility data, and a systematic comparison of widely recognized machine learning classifiers in the context of highway VANET scenarios. Furthermore, the detailed SHAP-based feature selection analysis provided valuable insights into the key predictors necessary for accurate intrusion detection.

Despite these contributions, the study has several limitations. Primarily, the results remain constrained by the synthetic nature of the dataset, albeit enhanced by real-world mobility patterns. Moreover, the simulations did not encompass the full complexity of real-world communication scenarios, including dynamic signal propagation, variable network topologies, and real-time adaptive behavior.

Future research should focus on extending the present approach through the following perspectives:

• Conducting experiments in real-world settings by utilizing actual connected vehicles and infrastructure, which would validate and potentially refine the proposed classification models.

• Investigating the feasibility and effectiveness of deploying these detection systems onboard vehicles, thus enabling practical intrusion detection solutions in real-time scenarios.

• Expanding the methodology to detect other prominent cybersecurity threats in VANETs, including spoofing, Sybil, and blackhole attacks, thereby broadening the scope and practical applicability of the developed intrusion detection framework.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Bappa Muktar; Methodology, Bappa Muktar and Vincent Fono; Software, Bappa Muktar; Investigation, Bappa Muktar; Writing—original draft, Bappa Muktar; Writing—review & editing, Vincent Fono and Adama Nouboukpo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, B.M., upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 1D-CNN | One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network |

| AdaBoost | Adaptive Boosting |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| CatBoost | Categorical Boosting |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DDoS | Distributed Denial of Service |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| Extremely Randomized Trees | Extra Trees |

| GB | Gradient Boosting |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| IDoS-CC | Intelligent DoS Attack Detection with Congestion Control |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NS-3 | Network Simulator 3 |

| OMNeT++ | Objective Modular Network Testbed in C++ |

| OSM | OpenStreetMap |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RSU | Roadside Unit |

| SD-VANET | Software-Defined Vehicular Ad Hoc Network |

| SDN | Software Defined Networking |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SUMO | Simulation of Urban MObility |

| TLBO | Teaching and Learning-Based Optimization |

| UDP | User Datagram Protocol |

| VANET | Vehicular Ad Hoc Network |

| VoIP | Voice over IP |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

References

1. Dutta A, Samaniego Campoverde LM, Tropea M, De Rango F. A comprehensive review of recent developments in vanet for traffic, safety & remote monitoring applications. J Netw Syst Manag. 2024;32(4):73. doi:10.1007/s10922-024-09853-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Pawar V, Zade N, Vora D, Khairnar V, Oliveira A, Kotecha K, et al. Intelligent transportation system with 5G vehicle-to-everything (V2Xarchitectures, vehicular use cases, emergency vehicles, current challenges, and future directions. IEEE Access. 2024;12(2):183937–60. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3506815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Al-Mohtaseb A, Hanoon AQ, Samara G, Al Daoud E, Alidmat O, Batyha R, et al. A comprehensive review of VANET attacks: predictive models, vulnerability management, and defense selection. In: 25th International Arab Conference on Information Technology (ACIT); 2024 Dec 10–12; Zarqa, Jordan. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

4. Polat O, Oyucu S, Türkoğlu M, Polat H, Aksoz A, Yardımcı F. Hybrid AI-powered real-time DDoS detection and traffic monitoring for software-defined-based vehicular ad hoc networks: a new paradigm for securing intelligent transportation networks. Appl Sci. 2024;14(22):10501. doi:10.3390/app142210501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ababsa M, Ribouh S, Malki A, Khoukhi L. Deep multimodal learning for real-time DDoS attacks detection in internet of vehicles. arXiv:2501.15252. 2025. [Google Scholar]

6. Kaur B, Prashar D, Mrsic L, Almogren A, Rehman AU, Altameem A, et al. Enhancing the reliability and accuracy of wireless sensor networks using a deep learning and blockchain approach with DV-HOP algorithm for DDoS mitigation and node localization. EURASIP J Wirel Commun Netw. 2025;2025(1):46. doi:10.1186/s13638-025-02465-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Vamshi Krishna K, Ganesh Reddy K. Classification of distributed denial of service attacks in VANET: a survey. Wirel Pers Commun. 2023;132(2):933–64. doi:10.1007/s11277-023-10643-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Setia H, Chhabra A, Singh SK, Kumar S, Sharma S, Arya V, Gupta BB, Wu J. Securing the road ahead: machine learning-driven DDoS attack detection in VANET cloud environments. Cyber Secur Applicat. 2024;2(1):100037. doi:10.1016/j.csa.2024.100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Polat H, Turkoglu M, Polat O. Deep network approach with stacked sparse autoencoders in detection of DDoS attacks on SDN-based VANET. IET Commun. 2020;14(22):4089–100. doi:10.1049/iet-com.2020.0477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Gopi R, Mathapati M, Prasad B, Ahmad S, Al-Wesabi NF, Abdullah Alohali M. Intelligent DoS attack detection with congestion control technique for VANETs. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;72(1):141–56. doi:10.32604/cmc.2022.023306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kadam N, Sekhar KR. Machine learning approach of hybrid KSVN algorithm to detect DDoS attack in VANET. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2021;12(7):82. doi:10.14569/IJACSA.2021.0120782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Alkadiri N, Ilyas M. Machine learning-based architecture for DDoS detection in VANETs system. In: 2022 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence of Things (ICAIoT); 2022 Dec 29–30; Istanbul, Turkey. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

13. Rashid K, Saeed Y, Ali A, Jamil F, Alkanhel R, Muthanna A. An adaptive real-time malicious node detection framework using machine learning in vehicular ad-hoc networks (VANETs). Sensors. 2023;23(5):2594. doi:10.3390/s23052594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Oluchi Anyanwu G, Nwakanma CI, Lee J-M, Kim D-S. Optimization of RBF-SVM kernel using grid search algorithm for DDoS attack detection in SDN-based VANET. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;10(10):8477–90. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2022.3199712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Marwah GPK, Jain A, Malik PK, Singh M, Tanwar S, Safirescu CO, et al. An improved machine learning model with hybrid technique in VANET for robust communication. Mathematics. 2022;10(21):4030. doi:10.3390/math10214030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Adhikary K, Bhushan S, Kumar S, Dutta K. Hybrid algorithm to detect DDoS attacks in VANETs. Wirel Pers Commun. 2020;114(4):3613–34. doi:10.1007/s11277-020-07549-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Tariq U. Optimized feature selection for DDoS attack recognition and mitigation in SD-VANETs. World Elect Veh J. 2024;15(9):395. doi:10.3390/wevj15090395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lekshmi V, Pramila RSuji, Tibbie Pon Symon VA. Defense mechanisms for vehicular networks: deep learning approaches for detecting DDoS attacks. Int J Adv Comput Sci Applicat. 2024;15(7):65. doi:10.14569/IJACSA.2024.0150765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Haydari A, Yilmaz Y. RSU-based online intrusion detection and mitigation for VANET. Sensors. 2022;22(19):7612. doi:10.3390/s22197612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Gu X, Wu Q, Fan P, Cheng N, Chen W, Letaief KB. DRL-based federated self-supervised learning for task offloading and resource allocation in ISAC-enabled vehicle edge computing. Digit Commun Netw. 2024. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2024.12.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Riley GF, Henderson TR. The ns-3 network simulator. In: Wehrle K, Güneş M, Gross J, editors. Modeling and tools for network simulation. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer, Berlin Heidelberg; 2010. p. 15–34. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-12331-3_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Behrisch M, Bieker L, Erdmann J, Krajzewicz D. SUMO–simulation of urban mobility: an overview. In: Proceedings of the SIMUL 2011, The Third International Conference on Advances in System Simulation; 2011 Oct 23–28; Barcelona, Spain. Red Hook, NY, USA: ThinkMind; 2011. [Google Scholar]

23. Chawla NV, Bowyer KW, Hall LO, Kegelmeyer WP. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J Artif Intell Res. 2002;16:321–57. doi:10.1613/jair.953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools