Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Comprehensive Review of Dynamic Community Detection: Taxonomy, Challenges, and Future Directions

Department of Computer Science, College of Science, University of Baghdad, Al-Jadriya Area, Baghdad, 10070, Iraq

* Corresponding Author: Amenah Dahim Abbood. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements in Evolutionary Optimization Approaches: Theory and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 4375-4405. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067783

Received 12 May 2025; Accepted 30 July 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

In recent years, the evolution of the community structure in social networks has gained significant attention. Due to the rapid and continuous evolution of real-world networks over time. This makes the process of identifying communities and tracking their topology changes challenging. To tackle these challenges, it is necessary to find efficient methodologies for analyzing the behavior patterns of dynamic communities. Several previous reviews have introduced algorithms and models for community detection. However, these methods have not been very accurate in identifying communities. Moreover, none of the reviewed papers made an apparent effort to link algorithms that can accurately detect dynamic communities. This review aims to present a taxonomy that shows several algorithms and methodologies for detecting dynamic communities. These algorithms are divided into four categories (heuristic- and modularity-based, metaheuristic, deep learning, and hybrid deep learning). It encompasses the past five years and examines the advantages and disadvantages of conventional and recent methods. Currently, many efforts are utilizing deep learning to improve dynamic networks; however, the instability of the network during the training phase affects the model’s accuracy. However, this direction remains unexplored. This study presents a review that aims to tackle this issue. We discuss a research path that explores the integration of deep learning with heuristic, metaheuristic, and hybrid metaheuristic algorithms to facilitate the identification of communities in dynamic networks. This investigation examines how this mixture surpasses the constraints of singular methodologies, resulting in enhanced detection outcomes and enabling researchers to select the most suitable algorithms for their future research.Keywords

In the context of community detection, a complex network is defined as a network with specific structural characteristics that make the identification process challenging. Some of its types include social networks, biological networks, technological networks, etc. The use of complex networks has become critical in the analysis of a large amount of unstructured information within complex systems. In recent years, the goal of detecting the community structure of networks has garnered significant attention from many fields [1]. Community detection is the task of identifying the structures of clusters within a network to capture the nature of these clusters (i.e., nodes and edges), where nodes are more densely connected within clusters than to nodes in other clusters. Many researchers have proposed community detection approaches for static networks where the number of nodes in a particular network remains constant [2–5]. In the real world, network data expands dynamically over time. The total number of nodes and edges within the network changes, resulting in modifications to the community structure. Dynamic networks can be shown as a sequence of snapshots at various time steps. However, temporal changes in structure result in the emergence and evolution of communities, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Linked-In, which have evolved quickly over time [6]. Recently, various algorithms have been developed to identify dynamic communities, which have been increasing in number. Identifying community structures in dynamic networks can provide insight into how communities evolve over time, leading researchers to devote more attention to analyzing this type of network. Additional details about the dynamic network can be obtained in [7–9]. The topology of a dynamic network can suffer significant structural changes as nodes and edges join or leave their communities over time. This is clearly outlined in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Community structures in dynamic networks over three time steps, time step (

A social network is a digital platform that enables connections and interactions between individuals. In terms of social network analysis, many studies have been developed to capture the evolution of community structures [10–12]. A first, official identification of the changes affecting communities was introduced in [13], where six of them were listed (birth, death, growth, contraction, merge, and split). Occasionally, the seventh operation (continue) is added to them. In [14], an eighth operation (resurgence) was presented. These operations are shown in Fig. 2. The three algorithm categories (heuristic, metaheuristic, and hybrid) outlined in this paper are state -of-the-art approaches, which pose numerous challenges. Heuristic algorithms are prone to getting stuck in local minima. Furthermore, these algorithms become inefficient when addressing complex or multilayer networks. Metaheuristic multi-objective optimization algorithms often exhibit longer execution times. The reason is that the topology of dynamic networks changes all the time. In addition, the computational complexity of metaheuristic algorithms arises from their high demand for processing resources. Hybrid metaheuristic algorithms face implementation complications. Although there have been significant improvements made in deep learning for dynamic community detection in recent years, there are several difficulties that require improved solutions and challenges that remain unaddressed [15]. This review concentrates on conventional dynamic community detection algorithms to identify new trends in deep learning for dynamic community detection. Our investigation is divided into five key components:

1- We review dynamic community detection algorithms (heuristic, metaheuristic, and hybrid metaheuristic), explaining their importance and their utilization in detecting dynamic communities.

2- In this paper, we describe the two dynamic approaches that capture the community structure of evolving networks, depending on their nature.

3- We introduce different deep learning methods that operate on temporal graph networks. These methods improve the interactions between nodes and enhance their features in dynamic networks.

4- We discuss the latest advancements in the use of hybrid techniques, combining heuristic algorithms with deep learning categories.

5- We discuss the new direction that integrates deep learning and metaheuristics, as well as hybrid metaheuristic algorithms. We emphasize their importance in capturing evolving networks and propose promising directions for future research.

Figure 2: Community structures in dynamic networks [14]

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the preliminary concepts of dynamic community detection algorithms. Section 3 describes the evaluation measures used to evaluate the algorithms and methods employed for detecting dynamic communities. Section 4 shows a taxonomy of approaches for dynamic community detection. Section 5 presents a taxonomy for community detection algorithms in dynamic networks. Section 6 presents an open research area that discusses the hybridization of (heuristic, metaheuristic, and hybrid metaheuristic) with deep learning. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the conclusion of this paper.

Dynamic community detection is the process of identifying the structure of the community in a dynamically evolving network over time. Dynamic networks typically consist of nodes and edges that change over time. For example, it is feasible to add or remove some nodes and edges from the network. A dynamic network is often represented as a sequence of

Several measures are available to assess the degree of similarity between the network-detected partition and the ground truth partition. These measurements are presented in this section.

A- Normalized Mutual Information score (NMI) introduced by [16], used when the ground truth partition for the network is known. It is a measure employed to examine the performance of community detection algorithms. The NMI was calculated to determine how closely the discovered partition matches the ground truth partition. When two partitions are more similar to each other, the NMI value gradually increases and vice versa.

Here, the number of communities in partitions A and B is denoted by CA and CB. The elements of C in the row

B- Modularity (Q) was introduced by [17,18]. Modularity is frequently used as an internal density metric to assess network partitions when the ground truth partition is unknown. When the modularity values are near 1, they show partitions with a strong community structure, whereas values close to 0 show that the partition does not correspond to a community structure.

Here,

C- Error rate Calculates the difference between the true communities and the detected communities [20,21].

To compute it, we build an

D- F-score represents the weighted harmonic mean of precision and recall. Where weights are equal for both precision and recall [22].

E- Coverage of clustering

4 A Taxonomy of Approaches for Dynamic Community Detection

Researchers employ various approaches based on network features and algorithm objective functions to detect communities and track changes in their structure. Therefore, we suggest a taxonomy of the key approaches to community detection in dynamic networks, as shown in Fig. 3, which categorizes the currently used approaches into two main groups: Snapshot-based (Independent) and continuous community detection.

Figure 3: The proposed taxonomy of approaches for dynamic community detection

4.1 Snapshot-Based (Independent) Community Detection

Strategies of this type separate the network into a series of snapshots. Starting by utilizing a static network algorithm to discover communities on each snapshot separately. Next, a comparison is made between the snapshot in the current time step and the previous one. However, the high complexity and instability of conventional community detection strategies can pose challenges to independently detecting communities [24].

4.2 Continuous Community Detection

Strategies of this type also separate the network into a series of snapshots. The strategies used here are based on previously detected communities to identify communities in the new snapshot. However, the inability to directly use conventional community detection strategies may compromise the approaches used here [24].

5 A Taxonomy for Community Detection Algorithms in Dynamic Networks

Community detection (CD) algorithms in dynamic networks

The dynamic community detection algorithms aim to accurately capture the evolving community structure of a network over time. Fig. 4 illustrates the categorization of community detection algorithms. Through our study, we have divided the algorithms for dynamic networks into three distinct classes.

Figure 4: The taxonomy for community detection algorithms in dynamic networks

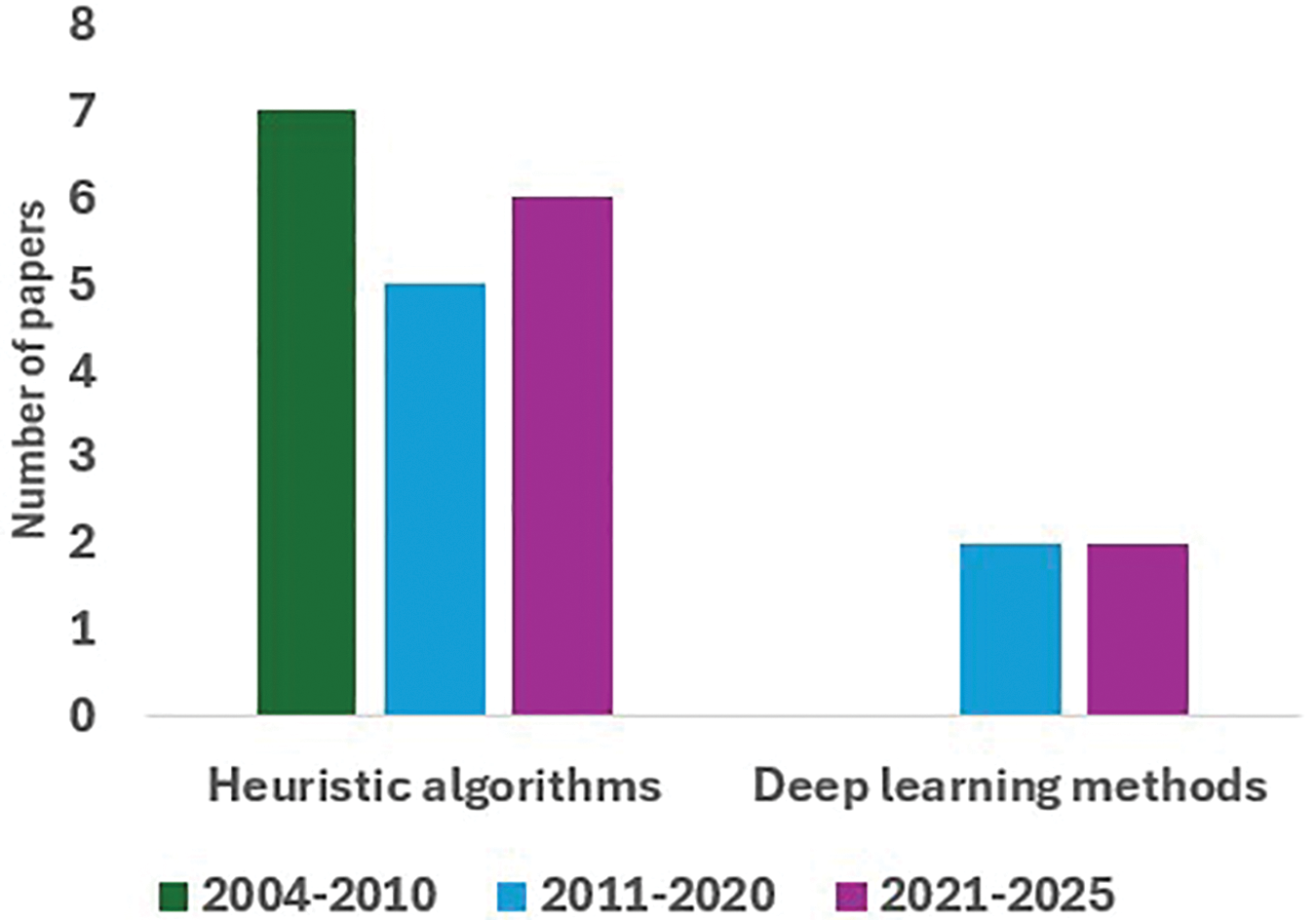

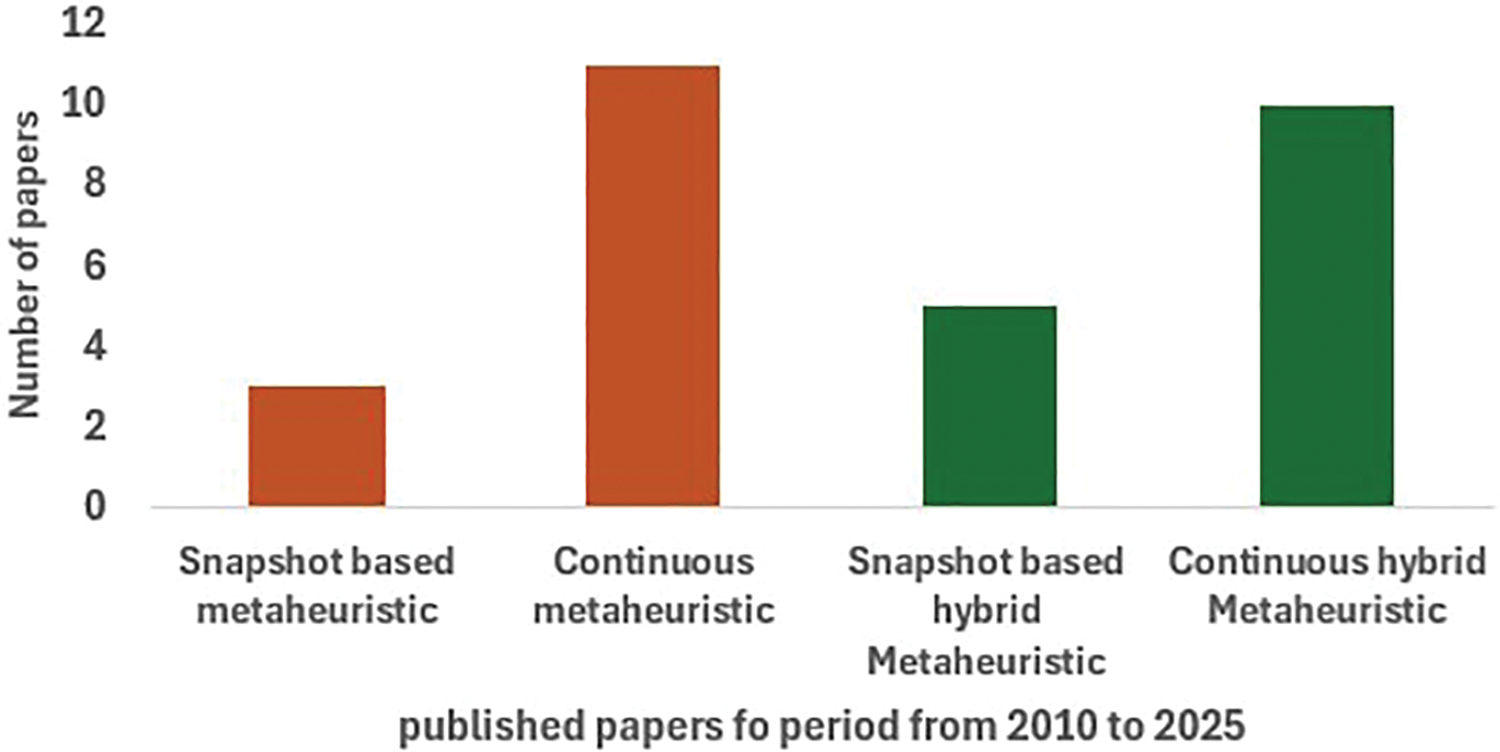

The following taxonomy presents a review of the literature covering research on all classes of dynamic algorithms covered between 2004 and 2025, as shown in Figs. 5 and 6. We annotate this period to provide the reader with a complete understanding of the development and current status of the dynamic community detection field.

Figure 5: The distribution of published papers from 2004 to 2025. This distribution includes: heuristic algorithms and deep learning methods

Figure 6: The distribution of published papers from 2010 to 2025. This distribution includes: metaheuristic algorithms and hybrid-metaheuristic algorithms, which utilize snapshot-based and continuous approaches

The classification of the taxonomy in Fig. 4 depends on the type of basic mathematical methodology adopted by the algorithms (heuristic, metaheuristic, deep learning, or hybrid). This taxonomy considers the level of combination between these methodologies in the case of hybrid algorithms. This classification helps researchers select the most suitable algorithm based on the nature of the network, performance requirements, and available mathematical resources. The systematic algorithm contrast, as demonstrated in the taxonomy classification, helps researchers select and accurately identify the most effective approaches to identify communities in networks based on the characteristics of the data, algorithm type, objective function, and performance criteria. This comparison is necessary to obtain the correct and accurate results in the analysis of complex and dynamic networks.

5.1 Heuristic and Modularity-Based Community Detection (HMCD)

Heuristic-based dynamic community detection is the process of identifying and evaluating communities or clusters within a dynamic network using heuristic algorithms, moreover, referred to non-evolutionary algorithms. Heuristics are a collection of deterministic rule-based algorithms. It finds a locally optimum sub-solution while considering the issue domain. In addition, it repeatedly calculates some regional variance for a particular decision, and the solution determines whether the local solution is appropriate [9,25].

Hopcroft et al. [6] presented one of the first studies on monitoring community changes in static network snapshots. This study used a hierarchical agglomerative clustering algorithm to identify communities. The nodes in the dataset were treated individually as clusters. The algorithm joined the two closest clusters after each iteration until all nodes formed a single cluster. A collection of clustering trees was generated using the clustering algorithm, denoted T, which produced

Kumar et al. [26] proposed an approach to identify communities independently for each snapshot and observe their evolution over time. Chakrabarti et al. [27] used evolutionary clustering to analyze the temporal development of dynamic networks. The researchers observed that noise can cause abrupt changes in node connections, making it crucial to prevent these changes. A temporal smoothness framework meets this need. This framework enabled a smoother evolution for each community over time by avoiding sudden changes in clustering over short periods. A cost function, as shown in Eq. (8), incorporates two sub-costs for smoothing: the Snapshot Cost (SC), which evaluates how a community structure captures the data at time

In this framework, the variable

In PCQ,

Kim and Han [31] suggested an effective density-based clustering technique in Eq. (11) using optimal Q that detected high-precision local clusters.

Here, NC denotes the overall number of clusters, TS denotes the entire degree of similarity between each pair of network nodes,

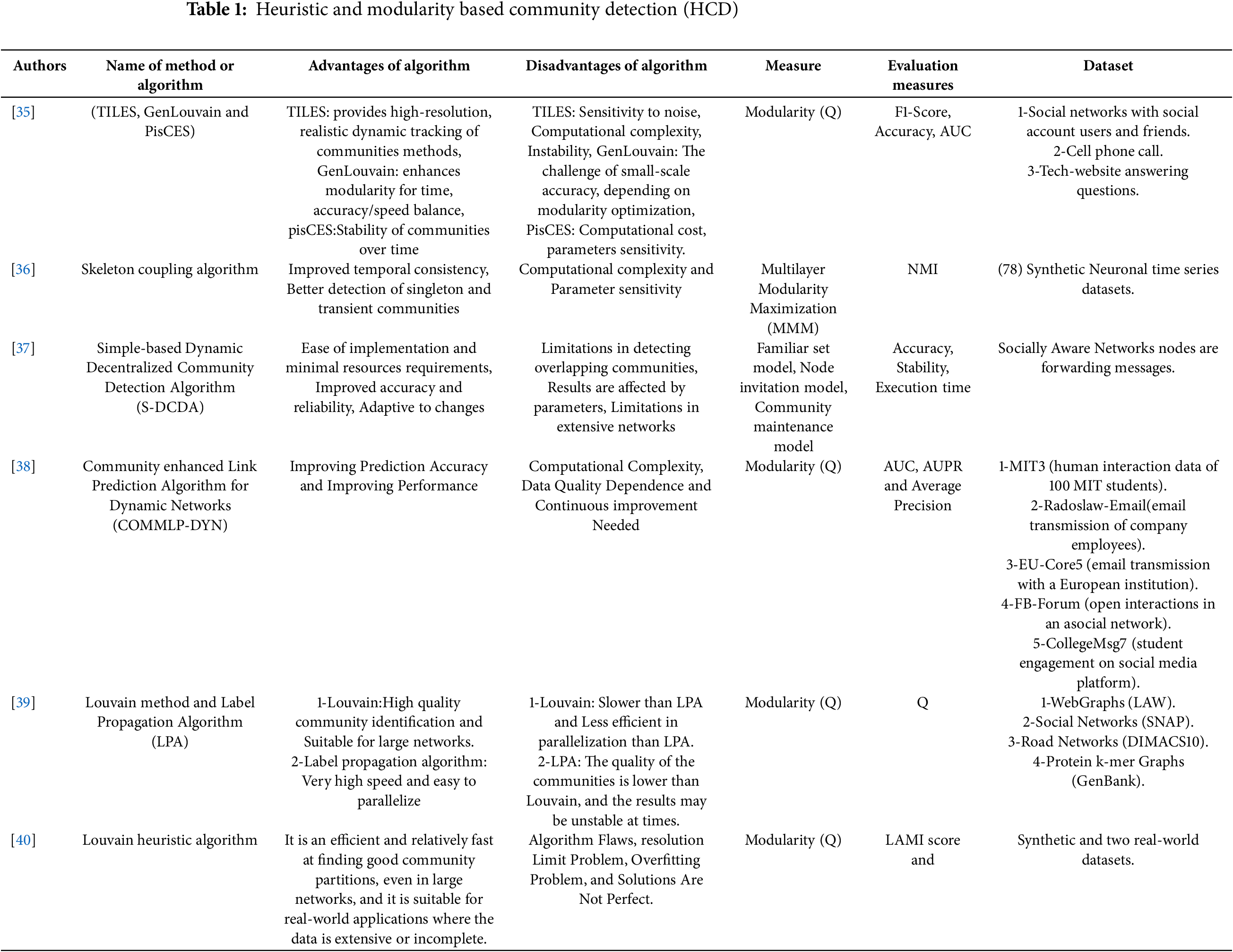

Xu et al. [34] proposed a Density Peak Clustering Algorithm (DPC). This algorithm employed a distance function that relies on shared nodes to manage social networks. Li et al. [35] suggested a framework that combined three methods: TILES, GenLouvain, and PisCES for detecting communities in dynamic networks. TILES used label propagation to influence neighborhood community membership; GenLouvain developed a multi-slice modularity generalization based on the equivalence between the Q quality function and community stability in Laplacian dynamics; and PisCES enhanced spectral clustering for network evolution. Kilic and Muldoon [36] suggested skeleton coupling as a new algorithm for generating inter-layer links in temporal networks. This method was specifically designed to improve connectivity between communities over time. Xiong et al. [37] proposed a Simple-based Dynamic Decentralized Community Detection Algorithm (S-DCDA) to address the challenge of resource consumption in the network and inaccurate community structure identification in standard detection algorithms. This algorithm promoted dynamic decentralization, letting each community node participate in being a community or network core at any point. Kumar et al. [38] presented a Community-enhanced Link Prediction Algorithm for Dynamic Networks (COMMLP-DYN). This algorithm introduced a link prediction approach that uses parameterized influence groups of nodes. Then, unique features were created utilizing local, global, quasi-local, and community information-based similarity functions. Scoring-based was used to optimize this feature set. Finally, four machine learning-based categorization models were used to predict links. Sahu et al. [39] suggested two methods; the first is the Louvain method, which represents a greedy optimization method to maximize modularity. The second method, the Label Propagation Algorithm (LPA), represents a fast heuristic for community assignment. These two methods are implemented in parallel to take advantage of multi-core architectures and gain computational speed. Djurdjevac et al. [40] suggested the Louvain heuristic algorithm to maximize modularity and compared its performance in various scenarios involving missing edges, nodes, or temporal information. The results showed that data insufficiency significantly impacts the quality of the detected communities.

Table 1 summarizes the heuristic algorithms reviewed, detailing their benefits, drawbacks, the measures applied, the evaluation measures used, and the datasets utilized.

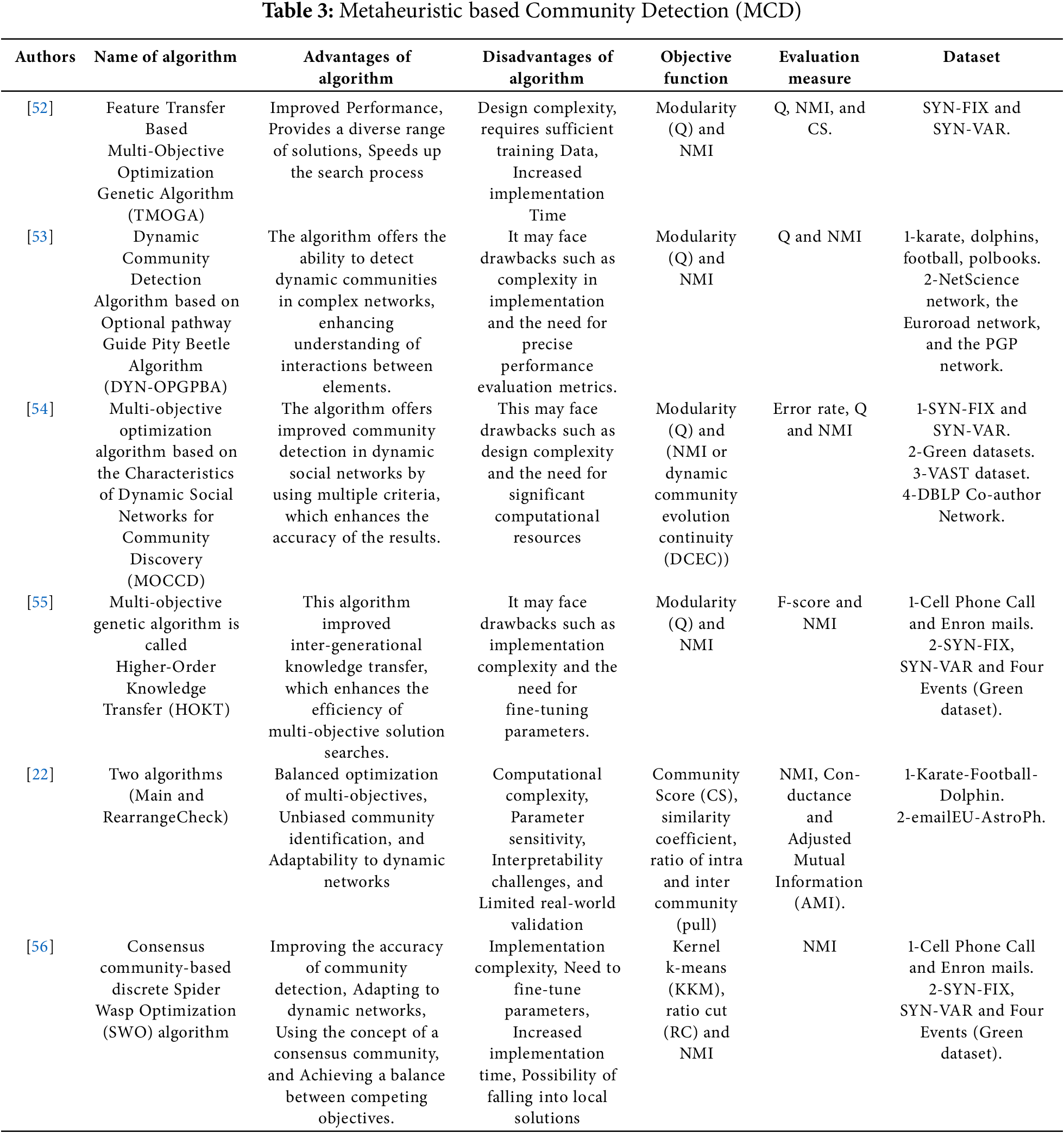

5.2 Metaheuristic Based Community Detection (MCD)

Metaheuristic algorithms, moreover, known as evolutionary algorithms, encouraged researchers to tackle complex global optimization challenges. These algorithms used a fitness function to capture the evolution of the community by evaluating each solution to find optimal or near-optimal solutions, depending on genetic operators [41,42]. The main approaches in Fig. 3 classify dynamic networks in metaheuristic community detection into two groups:

A- Snapshot Based (Independent) Community Detection

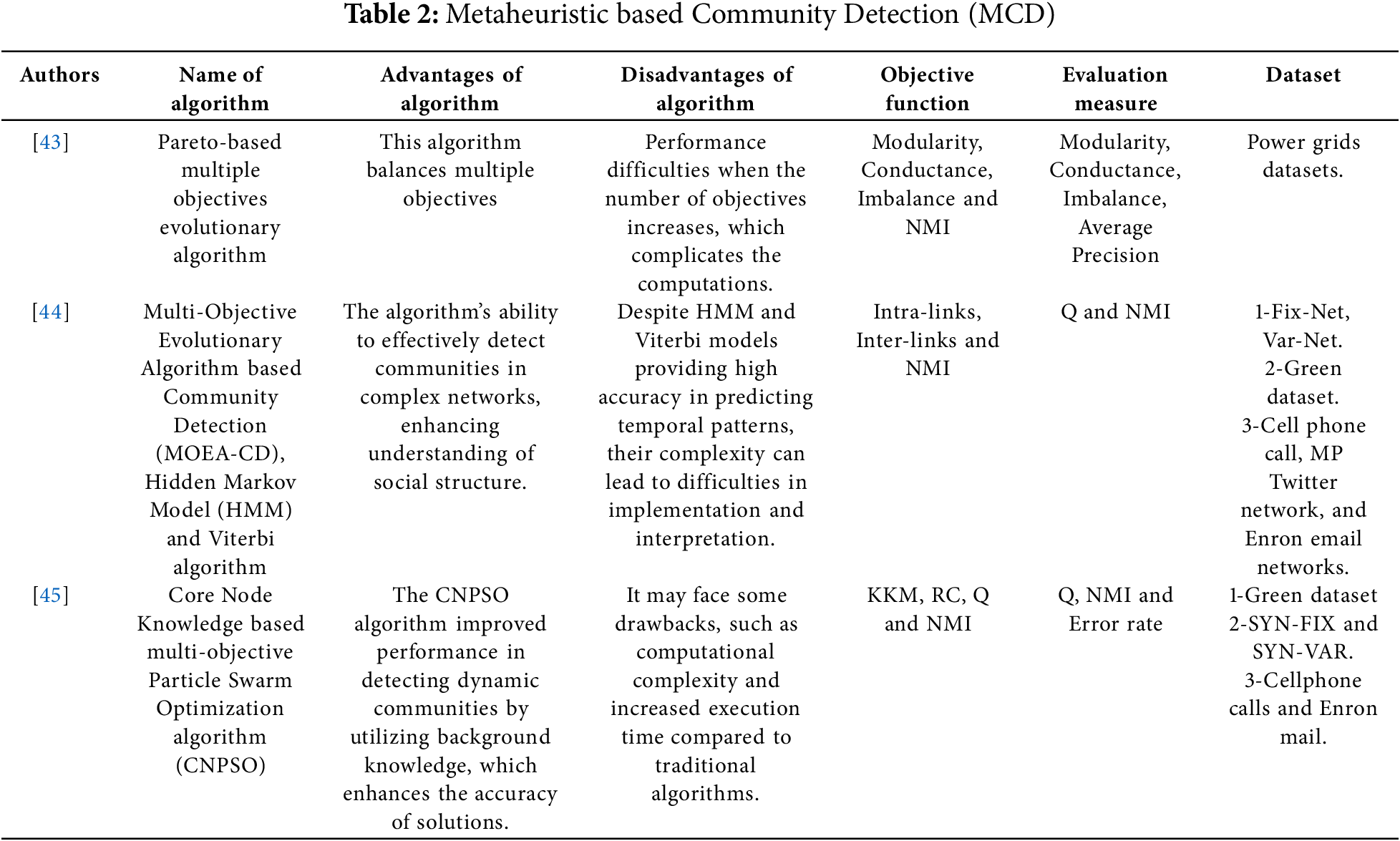

Guerrero et al. [43] proposed a novel Pareto-based multiple-objectives evolutionary algorithm. They employed three objectives, including Q, CO, and the imbalance for clustering nodes into communities.

Here,

where N is the total number of communities,

Let C represents a network partition that is split into K communities, N is the total number of nodes,

The greatest average number of external connections among communities is quantified by the second objective function in Eq. (17). Let

Here, Inter-Score is defined as:

Sun et al. [45] suggested a Core Node Knowledge-based multi-objective Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm (CNPSO) to detect dynamic network community structure. This algorithm minimized two conflicting objective functions: intra (KKM) and inter (RC) to detect community structure at each time step. Assigning weights to KKM and RC for optimization would be difficult. To identify an appropriate solution, the Q metric was introduced to assess the quality of the community structure. To measure the similarity between two successive time steps, NMI was employed for this purpose.

Table 2 summarizes the metaheuristic algorithms reviewed using the independent approach, detailing their benefits, drawbacks, the objective functions applied, the evaluation measures used, and the datasets utilized.

B- Continuous Community Detection

Folino and Pizzuti [46] introduced the concept of a multi-objective optimization problem, which focused on optimizing two objectives. The primary objective was to maximize the CS by maximizing connections within each community and minimizing connections between communities. Second objective, reduce the similarity NMI between the current community structure

where

The second equation represents the number of connections linking the vertices in

where

In the above equations,

Here,

However, concerning the snapshot cost function, several other familiar community detection models have not been studied in our literature review. These include Expansion (EX) and Internal Density (ID) [57,58]. The formulation of EX and ID is restated as follows:

In the above equations,

5.3 Deep Learning Based Community Detection (MCD)

Deep learning can generate more robust representations of node properties and dynamic community structures. Additionally, discover the patterns of nodes, neighbors, and sub-graphs. The deep learning framework generates lower-dimensional vectors from high-dimensional data, which reflect dynamic structural connections within the network [59]. Sankar et al. [60] introduced the Dynamic Self-Attention Network (DySAT), which is an innovative neural architecture that accumulates node representations to capture the evolution of dynamic graph structures. DySAT specifically calculated node representations by combining self-attention across the domains of structural neighborhood and temporal dynamics. Compared to other advanced approaches for simulating graph evolution, dynamic self-attention proved to be economical and consistently delivered higher performance. This study performed link prediction on two types of graphs: communication networks and bipartite rating networks. Rossi et al. [61] introduced Temporal Graph Networks (TGNs), a versatile and practical framework for deep learning on dynamic networks, which are represented as a series of temporal events. TGNs are significantly more effective than older methods because they integrate multiple components (memory modules, memory updater, embedding module, message function) and graph-based operators in a new way, making them more efficient. Additionally, provided an innovative training method that allowed the model to learn from the sequential nature of the input, ensuring effective parallel processing. Costa [62] presented a graph embedding method that used the Node2vec algorithm to transform an adjacency matrix of a dynamic network into a low-dimensional space. Next, they used deep reinforcement learning to improve the density of aggregation in community identification. To capture the structure of communities in dynamic online networks, researchers used an actor-critic reinforcement learning algorithm to maximize the modularity density of the community. This was achieved by combining the efficiency of GNN-based networks, specifically Graph Attention Network (GAT) and Graph Convolution Network (GCN).

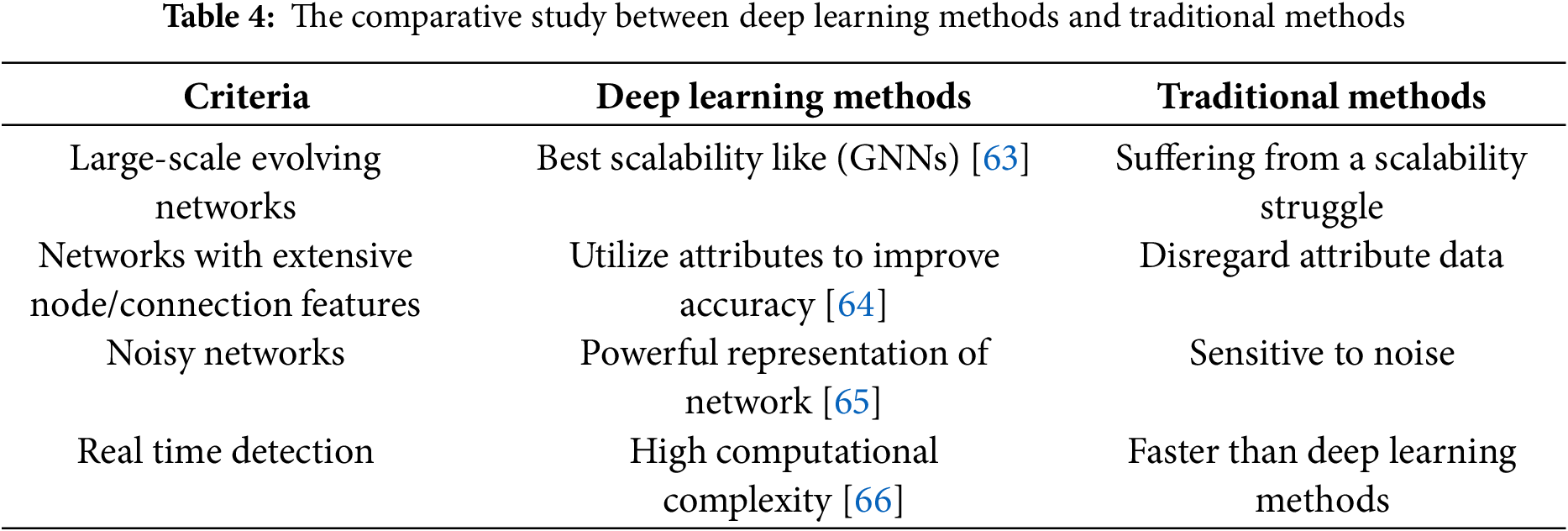

This study presents a comparative table to illustrate why deep learning methods are preferred over traditional methods, as shown in Table 4.

5.4 Hybrid Based Community Detection (HCD)

This section presents a brief description of two types of hybrid metaheuristic-based community detection algorithms.

5.4.1 Hybrid Metaheuristic Based Community Detection (HMCD)

High-level propagated hybrid metaheuristic algorithms (HR-HMDC) are used to identify communities. This type of hybridization displays a clear collaboration between heuristic algorithms (HCD) and metaheuristic algorithms (MCD) [9,67,68]. Mainstream approaches in Fig. 3 classify dynamic networks in the hybrid metaheuristic community detection into two groups:

A- Snapshot Based (Independent) Community Detection

Zeng et al. [69] presented the concept of a consensus cluster, maintaining the stability of these clusters throughout the evolution process. This concept has been previously discussed in several studies by [70,71]. This concept addresses the previous problem of the DYNMOGA algorithm, as presented by [47]. It utilized Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), which combined the CCPSO algorithm to detect communities with the label propagation method for initialization. This algorithm used multiple objectives: KKM, RC, and NMI.

where

B- Continuous Community Detection

Gong et al. [74] proposed a multi-objective immunity algorithm that enhanced precision and efficiency through genetic operators and local search. This algorithm optimized Modularity and NMI simultaneously to enhance community accuracy and stability. Chen et al. [75] proposed a new multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for the identification of dynamic communities. This algorithm is based on the framework of a non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm. The MD function is utilized as a snapshot cost to address the limitations of the Q function. Additionally, NMI was utilized to estimate the temporal cost. Attea and Khoder [8] introduced a new framework for managing the dynamic nature of social networks. This framework integrated the evolutionary algorithm with the migration mutation operator. The algorithm optimized two objective functions: the (intra-neighbor score) in Eq. (32) and the (inter- and intra-temporal cost) in Eq. (34).

Here,

where

where

An

The inverse community score indicates the connectivity of the nodes within a community. Where ms refers to the number of connections in a community S, while ns represents the number of nodes within it.

Here, “Average ODF” measures the number of edges outside a community; C represents the collection of communities encoded by an individual, S represents the community,

Liu et al. [78] presented a framework that combined a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm called “Detecting Evolving Community Structure” (DECS), a label propagation method in initialization, and a migration operator in mutation. This framework employed the temporal smoothness proposed by Chakrabarti et al. [27]. The DECS algorithm maximized Q and NMI simultaneously in every subsequent time step.

At the initial time step, that is,

Besharatnia et al. [79] proposed a new approach (MOGWO-LP) that combines a Multi-Objective Metaheuristic Gray Wolf algorithm with the Label Propagation method to progressively identify communities. This algorithm optimized two objectives: Q and NMI. Yin et al. [80] proposed the Multi-Objective Discrete Particle Swarm Optimization for Dynamic Network algorithm (DYN-MODPSO). Typically, a random walk method was employed to alter the initial snapshot population deviation in an evolving network. The algorithm optimized two objectives: CS and NMI. Cai et al. [81] presented the NOME algorithm, which is based on the combination of multiple objective evolutionary clustering with a node occupancy assignment mutation operator. NOME utilized the MOEA/D framework, which optimized both Q and NMI simultaneously to detect evolving communities. Wang et al. [82] suggested a community identification approach that combines a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm with decomposition and an evolutionary clustering algorithm. This approach used the adaptive mutation evolutionary strategy. This strategy was employed in conjunction with a corresponding change in the number of subproblems in MOEA/D as a means of addressing environmental influences. Furthermore, we dynamically adjust the mutation rate according to population changes. Table 6 summarizes the hybrid metaheuristic algorithms reviewed using the continuous approach, detailing their advantages, drawbacks, the heuristic algorithm employed, the objective functions applied, the evaluation measures used, and the datasets utilized.

The key limitations and future directions of the community detection algorithms in dynamic networks are clarified in Table 7.

5.4.2 Hybrid Deep Learning Based Community Detection (HDLCD)

Heuristic deep learning based community detection(HDLCD): This type of hybridization uses a deep model to show the network in a low-dimensional embedded space, and then a clustering method in the feature space can show how the communities change over time. This hybridization between them offers a robust framework for improving performance and accuracy in the detection of dynamic networks.

Wang et al. [87] employed an evolutionary clustering framework to capture the evolution of the community structure. The sE-Auto-encoder semi-supervised algorithm was suggested to lessen the effect of nonlinear features on the low-dimensional representation. This was achieved by utilizing three overlapping auto-encoders, taking into account time constraints to help maintain relationships between nodes, as well as ensuring temporal smoothness to prevent abrupt changes between time steps. Finally, after obtaining the results from the previous autoencoders, the k-means algorithm was used to divide the results into final communities. Qu et al. [88] proposed a dynamic community detection framework that integrated dynamic community detection based on the evolutionary deep-walk algorithm (DEDW) with the K-means clustering algorithm. The DEDW algorithm integrates the graph embedding algorithm with the deep-walk algorithm. Graph embedding was used to address the issue of data scarcity, transforming the dynamic network into a low-dimensional representation to facilitate enhanced data processing. After that, the Deep Walk static graph embedding algorithm was implemented in the dynamic network to generate node embedding feature vectors derived from the stable characteristics of community structure modifications. Finally, the K-means clustering algorithm was applied to identify the dynamic structure of communities. Zhang et al. [89] suggested a node representation method that combines node influence with a random walk strategy to improve node representation, thus better reflecting the network structure. Subsequently, they employed a dynamic community detection algorithm. This algorithm consisted of two stages: the first stage involved altering the local community structure to maximize modularity. In contrast, the second stage adapted to changes in the number of communities. Pan et al. [86] introduced an innovative dynamic community identification framework that integrated a deep learning model with an evolutionary clustering algorithm (DLEC). Addressing the insufficiency of the adjacency matrix to represent the similarity relationships among nodes suggested a matrix construction technique to produce a similarity matrix that encoded the structure of communities. Subsequently, the deep auto-encoder was used to maximize the quality of community detection at this step. A graph regularization term is incorporated as a temporal smoothness constraint to reduce the evolution of the community. This framework balanced snapshot cost and temporal cost, enhanced accuracy in community detection outcomes across successive time steps, and reduced abrupt modifications in community structures. Ultimately, the K-means clustering method was utilized within the low-dimensional network space to derive the community structure.

Table 8 summarizes the comparative analysis of community detection categories.

The development of network representation learning provides an efficient alternative for mining and analyzing network structures. Network representation learning seeks to derive a low-dimensional representation of the original networks, which can be achieved using deep learning techniques; hence, it facilitates the successful execution of various network research tasks. The importance of deep learning in discovering dynamic communities has emerged due to its high ability to analyze complex patterns of nodes, understand their dynamic interactions, predict the behavior of nodes within communities, and analyze extensive, and complex data. Recently, numerous research studies and review articles have made significant strides in utilizing deep learning methods to effectively address the problem of CD. Although there is a growing interest in this study area, the design of such methods remains open to further development. In general, the utilization of deep learning in the detection of dynamic community structures encounters the following challenges:

1. Deep learning models are dependent on complicated architectural designs, making them challenging to understand and analyze. This complexity affects the evaluation and fixing of errors, thereby affecting the precision of community detection.

2. Instability challenge for dynamic network during deep learning training: In the training of dynamic communities, the problem in learning a constant and steady representation of the network that changes over time is known as network instability. This instability has appeared due to the change of topological dynamics and node interaction in the network; this poses several issues:

A- Temporal variability and non-stationarity: The structure of the network changes over time, resulting in a repeated shift in the distribution of training data. This lack of stationarity is problematic for deep models, as it is hard to converge to a stable representation or community affiliation. Models that are trained on previous images can become inaccurate quickly because new connections or nodes are added or removed.

B- Noise and incomplete data: Dynamic networks often suffer from noise, insufficient communication, or faulty connections. These connections may distort the intended meaning of deep learning during training, leading to the acquisition of poor-quality information.

C- Overfitting to transient patterns: Deep models may be unable to adapt to short- term changes or noise in the network, which would lead to a poor grasp of patterns for the future.

D- Computational complexity and scalability: Training deep models on large-scale graphs that evolve is computationally expensive and may necessitate frequent retraining to adapt to new situations, which is challenging in practice.

E- The absence of real ground and the difficulties of evaluation: Dynamic community detection is often performed without supervision, which makes it difficult to assess the consistency of the model’s stability and performance of the model over time.

To address this challenge, the researchers [86,91–93] have made additional efforts to enhance the stability of communities in dynamic networks.

3. The issue of overfitting has emerged. Models can become overly dependent on training data, resulting in inadequate performance with new or unfamiliar data. This may negatively influence the model’s ability to detect communities effectively.

Consequently, despite the recent adoption of deep learning in the community detection domain, the demand for hybrid deep learning and opportunities for cross-fertilization between deep learning and (heuristic, metaheuristic, and hybrid metaheuristic) algorithms can arise and persistently escalate. The primary motivation stems from the realization that providing comprehensive models, in terms of hybridization, may play an essential role in utilizing the advantages and overcoming the limitations of using a single technique from other classes. The following subsections aim to present researchers with innovative design challenges for hybrid deep learning frameworks, which have still received minimal attention or remain unexplored.

6.1 Heuristic Deep Learning Based Community Detection (HDLCD)

The primary motivation for researchers to employ heuristic deep learning-based community detection (HDLCD) comes from deep learning’s abilities to enhance the representation of dynamic networks and extract hidden data patterns. This procedure enhances the precision of identifying dynamic communities using heuristic algorithms. This integration represents a promising direction. However, this integration faces many challenges:

1. Large amounts of high-quality data are necessary for practical model training, and the complex nature of these models requires significant computational resources.

2. Complex models often store training data rather than extracting general patterns, resulting in poor efficiency when processing novel data.

3. Deep learning algorithms operate as black boxes, making it difficult to comprehend their decision-making processes.

4. Data bias can lead to unfair results, necessitating careful control to ensure the fairness of the models constructed.

However, merging heuristics algorithms with methods based on deep learning provides several benefits:

1- Improved feature extraction: Heuristics enable feasible feature optimization and support heuristic feature extraction within unguided, pre-developed deep network learning.

2- Provide better accuracy: Combining heuristics and deep learning enhances model adaptability to various datasets, thereby improving the classification and prediction performance of the model.

3- Create the model straight: The heuristic helps to make optimal adjustments to the parameters and select how the model should be created, halting extended trial and error.

6.2 Metaheuristic Deep Learning Based Community Detection (MDLCD)

The integration of deep learning with metaheuristic algorithms represents a promising direction in optimizing the efficiency of both. Deep learning can facilitate the collection of significant, high-dimensional representations of nodes and edges within a social network, capturing complex interactions that conventional features may miss. Metaheuristic algorithms can subsequently use the extracted features as input to optimize single or multiple objectives. This combination offers several advantages that can improve the detection of dynamic networks in future research.

1- Improved precision: This integration improves the ability of deep learning to accurately identify complex non-linear patterns. After that, metaheuristic optimization is applied to enhance both the precision and the efficiency of community detection.

2- Enhanced efficiency: Metaheuristic algorithms can optimize the deep learning training process, potentially reducing computational running costs and accelerating convergence rates.

3- Flexibility in objective management: Metaheuristic-based optimization facilitates adaptable objective formulations in deep learning-driven community discovery, therefore enhancing the model’s alignment with specific requirements and limitations.

Despite the advantages mentioned above, this hybridization faces two challenges:

1- Computational complexity: The integration of metaheuristics with deep learning complicates computation due to dynamic inputs. These algorithms frequently deal with dynamic inputs that change throughout the solution process, requiring continuous updates to both the learning model and metaheuristic parameters, which results in added computing costs.

2- Complexity of model tuning: This requires balancing between multi-objective optimization and deep learning parameter optimization, which necessitates complex balancing methodologies in both metaheuristics and deep learning.

However, there are several challenges related to merging metaheuristic algorithms with deep learning methods:

1- Computational Complexity: Metaheuristic algorithms can be very computationally expensive when applied to deep learning on large-scale data.

2- Parameter Setting Difficulty: Setting of parameters for both deep learning and metaheuristics is challenging to achieve for good performance.

3- Issues in Convergence and Stability: There may also be issues with the stability of the training process and convergence to optimal solutions, as metaheuristics are stochastic.

The combination of deep learning with metaheuristic algorithms represents a growing approach that holds significant promise in improving the detection of dynamic networks. As academics continue to explore this field, we can expect creative solutions that enhance the performance of both. In addition, the applicability of these mixtures expanded to encompass more complex networks.

6.3 Hybrid Metaheuristic Deep Learning Based Community Detection (HMDLCD)

This subsection highlights the expected significance of hybrid metaheuristic deep learning-based community detection (HMDLCD) algorithms as a robust framework to understand the interaction between HCD, MCD algorithms, and deep learning. This is achieved by capturing hidden patterns and relationships in complex dynamic networks using different deep learning methods.

On the other hand, deep learning enhances the performance of heuristic and metaheuristic methods. Combining deep learning with hybrid frameworks facilitates enhanced feature extraction from complex networks. This feature enhances the understanding of the underlying, leading to improved data on the hybrid algorithms’ performance in detecting communities over time. We expect that deep learning will have an effective role in improving hybrid algorithms, as shown below:

1- The combination of two heuristic algorithms: Deep learning can enhance heuristic algorithms by producing more efficient features, enabling conventional methods such as K-Means or Louvain to perform effectively on more robust data, resulting in improved community detection and decreased computational complexity.

2- The combination of two metaheuristic algorithms: Combining deep learning with metaheuristic algorithms, such as genetic algorithms or particle swarm optimization, enhances their exploration efficiency. Deep learning methods can facilitate the search process by providing knowledge about the structure of the network, thus improving the convergence rates and the quality of the solutions.

3- Combining heuristic and metaheuristic algorithms: The combination of deep learning with heuristic and metaheuristic approaches has a mutually beneficial effect. Deep learning can preprocess data to identify local structures that are expected, while heuristics effectively improve the speed of metaheuristic algorithms. This blend creates a community that identifies the most comprehensive and efficient solutions within a dynamic network. The collaboration of these three methods will produce robust and scalable solutions that can efficiently tackle the difficulties of detecting the dynamic structure of communities.

This study identifies significant gaps and promising areas for further analysis, synthesizing the limitations of prior approaches with the potential offered by combining hybrid metaheuristics and deep learning. For instance,

1- Dimensionality curse in deep models: The use of metaheuristic dimension reduction methods [94].

2- Design of hybrid frameworks that adapt and combine the strengths of different algorithms.

3- Developing community detection methods that are scalable, interpretable, and robust, and remain dynamic over time and for all community applications.

The community detection problem has been determined to be NP-hard and remains an active research topic. The purpose of this paper is to capture the nature of dynamic communities and assess the effectiveness of algorithms used to detect them. This paper focuses on the current gaps to detecting communities that change over time, its challenges, and provides a comprehensive review of dynamic community detection algorithms by dividing it into four categorize: heuristic, metaheuristic, deep learning and hybrid based community detection to explain the differences between them in the efficiency of understanding and identifying the behavior of the complex networks. This study also highlighted community detection approaches that are divided into two categories according to the kind of dynamic network: (snapshot based (independent) and continuous(dependent)), to provide a critical view about the importance of choosing the suitable approach to specifying the nature of the evolution of communities over time and requirements of these networks to analyze it. In the future, this review paper suggests utilizing deep learning in conjunction with metaheuristic and hybrid metaheuristic algorithms to overcome the main challenges mentioned in this study, thereby enhancing the detection of dynamic communities and providing more accurate solutions.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: No specific funding for this research.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed equally to the conception and writing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ma L, Gong M, Liu J, Cai Q, Jiao L. Multi-level learning based memetic algorithm for community detection. Appl Soft Comput. 2014;19:121–33. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2014.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhao X, Li Y, Qu Z. A density-based clustering model for community detection in complex networks. AIP Conf Proc. 2018;1955(1):040161. doi:10.1063/1.5033825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Pizzuti C. Ga-net: a genetic algorithm for community detection in social networks. In: International Conference on Parallel Problem Solving from Nature; 2008 Sep 13–17; Dortmund, Germany. p. 1081–90. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-87700-4_107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Abdulrahman MM, Abbood AD, Attea BA. The influence of NMI against modularity in community detection problem: a case study for unsigned and signed networks. Iraqi J Sci. 2021;62(6):2064–81. doi:10.24996/ijs.2021.62.6.32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ibraheem SF, Al-Sarray B. A review of community detection based on modularity optimization in complex networks. Iraqi J Sci. 2024;65(5):2775–93. doi:10.24996/ijs.2024.65.5.34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hopcroft J, Khan O, Kulis B, Selman B. Tracking evolving communities in large linked networks. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2004;101(suppl_1):5249–53. doi:10.1073/pnas.0307750100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Khoder HS, Attea BA. Community tracking in time evolving networks: an evolutionary multi-objective approach. Iraqi J Sci. 2016;57(4A):2539–48. [Google Scholar]

8. Attea BA, Khoder HS. A new multi-objective evolutionary framework for community mining in dynamic social networks. Swarm Evol Comput. 2016;31:90–109. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2016.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Attea BA, Abbood AD, Hasan AA, Pizzuti C, Al-Ani M, Özdemir S, et al. A review of heuristics and metaheuristics for community detection in complex networks: current usage, emerging development and future directions. Swarm Evol Comput. 2021;63:100885. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2021.100885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Rossetti G, Cazabet R. Community discovery in dynamic networks: a survey. ACM Comput Surv (CSUR). 2018;51(2):1–37. doi:10.1145/3172867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Dakiche N, Tayeb FB-S, Slimani Y, Benatchba K. Tracking community evolution in social networks: a survey. Inform Process Manage. 2019;56(3):1084–102. [Google Scholar]

12. Amin F, Choi J-G, Choi GS. Advanced community identification model for social networks. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;69:1687–707. [Google Scholar]

13. Palla G, Barabási A-L, Vicsek T. Quantifying social group evolution. Nature. 2007;446(7136):664–7. doi:10.1038/nature05670. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Cazabet R, Rossetti G, Amblard F. Dynamic community detection. In: Encyclopedia of social network analysis and mining. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2017. p. 1–10. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-7163-9_383-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yu G, Ma L, Wang X, Du W, Du W, Jin Y. Towards fairness-aware multi-objective optimization. Complex Intell Syst. 2025;11(1):50. [Google Scholar]

16. Danon L, Diaz-Guilera A, Duch J, Arenas A. Comparing community structure identification. J Stat Mech Theory Exp. 2005;2005(9):P09008. doi:10.1088/1742-5468/2005/09/p09008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Newman MEJ. Fast algorithm for detecting community structure in networks. Phys Rev E. 2004;69(6):066133. doi:10.1103/physreve.69.066133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Newman MEJ, Girvan M. Finding and evaluating community structure in networks. Phys Rev E. 2004;69(2):026113. doi:10.1103/physreve.69.026113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Fortunato S, Barthelemy M. Resolution limit in community detection. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2007;104(1):36–41. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605965104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zhou X, Liu Y, Li B, Li H. A multiobjective discrete cuckoo search algorithm for community detection in dynamic networks. Soft Comput. 2017;21:6641–52. doi:10.1007/s00500-016-2213-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Messaoudi I, Kamel N. A multi-objective bat algorithm for community detection on dynamic social networks. Appl Intell. 2019;49:2119–36. doi:10.1007/s10489-018-1386-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mishra S, Singh SS, Mishra S, Biswas B. Multi-objective based unbiased community identification in dynamic social networks. Comput Commun. 2024;214:18–32. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2023.11.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Brandes U, Gaertler M, Wagner D. Experiments on graph clustering algorithms. In: Algorithms—ESA 2003. ESA 2003. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2003. p. 568–79. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-39658-1_52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Alotaibi N, Rhouma D. A review on community structures detection in time evolving social networks. J King Saud Univ-Comput Inf Sci. 2022;34(8):5646–62. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2021.08.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yang B, Huang T, Li X. A time-series approach to measuring node similarity in networks and its application to community detection. Phys Lett A. 2019;383(30):125870. doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2019.125870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kumar R, Novak J, Tomkins A. Structure and evolution of online social networks. In: Proceedings of the 12th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2006 Aug 20–23; Philadelphia, PA, USA. p. 611–7. [Google Scholar]

27. Chakrabarti D, Kumar R, Tomkins A. Evolutionary clustering. In: Proceedings of the 12th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2006 Aug 20–23; Philadelphia, PA, USA. p. 554–60. [Google Scholar]

28. Chi Y, Song X, Zhou D, Hino K, Tseng BL. Evolutionary spectral clustering by incorporating temporal smoothness. In: Proceedings of the 13th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2007 Aug 12–15; San Jose, CA, USA. p. 153–62. [Google Scholar]

29. Lin Y-R, Chi Y, Zhu S, Sundaram H, Tseng BL. FacetNet: a framework for analyzing communities and their evolutions in dynamic networks. In: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on World Wide Web; 2008 Apr 21–25; Beijing, China. p. 685–94. [Google Scholar]

30. Asur S, Parthasarathy S, Ucar D. An event-based framework for characterizing the evolutionary behavior of interaction graphs. ACM Trans Knowl Discov Data (TKDD). 2009;3(4):1–36. doi:10.1145/1631162.1631164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kim M-S, Han J. A particle-and-density based evolutionary clustering method for dynamic networks. Proc VLDB Endow. 2009;2(1):622–33. doi:10.14778/1687627.1687698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xu KS, Kliger M, Hero III AO. Adaptive evolutionary clustering. Data Min Knowl Discov. 2014;28(2):304–36. doi:10.1007/s10618-012-0302-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Nguyen NP, Dinh TN, Shen Y, Thai MT. Dynamic social community detection and its applications. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e91431. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Xu M, Li Y, Li R, Zou F, Gu X. EADP: an extended adaptive density peaks clustering for overlapping community detection in social networks. Neurocomputing. 2019;337:287–302. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2019.01.074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Li T, Wang W, Wu X, Wu H, Jiao P, Yu Y. Exploring the transition behavior of nodes in temporal networks based on dynamic community detection. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2020;107:458–68. doi:10.1016/j.future.2020.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kilic BU, Muldoon SF. Skeleton coupling: a novel interlayer mapping of community evolution in temporal networks. arXiv:2301.10860. 2023. [Google Scholar]

37. Xiong Z, Zeng M, Xu F, Deng M, Zhang X, Zhou B, et al. Simple-based dynamic decentralized community detection algorithm in socially aware networks. Heliyon. 2024;10(5):e26965. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26965. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Kumar M, Mishra S, Singh SS, Biswas B. Community-enhanced link prediction in dynamic networks. ACM Trans Web. 2024;18(2):1–32. doi:10.1145/3580513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Sahu S, Kothapalli K, Banerjee DS. Parallel multicore algorithms for community detection in dynamic graphs. Int J Netw Comput. 2025;15(1):2–31. doi:10.15803/ijnc.15.1_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Djurdjevac Conrad N, Tonello E, Zonker J, Siebert H. Detection of dynamic communities in temporal networks with sparse data. Appl Netw Sci. 2025;10(1):1. doi:10.1007/s41109-024-00687-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Bartz-Beielstein T, Branke J, Mehnen J, Mersmann O. Evolutionary algorithms. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Data Min Knowl Discov. 2014;4(3):178–95. doi:10.1002/widm.1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Abbood AD, Hasan AA, Bara’a AA. Pearson coefficient matrix for studying the correlation of community detection scores in multi-objective evolutionary algorithm. Periodicals Eng Nat Sci (PEN). 2021;9(3):796–807. doi:10.21533/pen.v9i3.2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Guerrero M, Gil C, Montoya FG, Alcayde A, Banos R. Multi-objective evolutionary algorithms to find community structures in large networks. Mathematics. 2020;8(11):2048. doi:10.3390/math8112048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Abbood AD, Attea BA, Hasan AA, Everson RM, Pizzuti C. Community detection model for dynamic networks based on hidden Markov model and evolutionary algorithm. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56:9665–97. doi:10.1007/s10462-022-10383-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Sun Y, Sun X, Liu Z, Cao Y, Yang J. Core node knowledge based multi-objective particle swarm optimization for dynamic community detection. Comput Ind Eng. 2023;175:108843. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2022.108843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Folino F, Pizzuti C. A multiobjective and evolutionary clustering method for dynamic networks. In: 2010 International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining; 2010 Aug 9–11; Odense, Denmark. p. 256–63. [Google Scholar]

47. Folino F, Pizzuti C. An evolutionary multiobjective approach for community discovery in dynamic networks. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2014;26(8):1838–52. doi:10.1109/tkde.2013.131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Ma J, Liu J, Ma W, Gong M, Jiao L. Decomposition-based multiobjective evolutionary algorithm for community detection in dynamic social networks. Sci World J. 2014;2014:402345. doi:10.1155/2014/402345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Zhang Q, Li H. MOEA/D: a multiobjective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2007;11(6):712–31. doi:10.1109/tevc.2007.892759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Gao C, Chen Z, Li X, Tian Z, Li S, Wang Z. Multiobjective discrete particle swarm optimization for community detection in dynamic networks. Europhys Lett. 2018;122(2):28001. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/122/28001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Wang C, Deng Y, Li X, Chen J, Gao C. Dynamic community detection based on a label-based swarm intelligence. IEEE Access. 2019;7:161641–53. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2951527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zou J, Lin F, Gao S, Deng G, Zeng W, Alterovitz G. Transfer learning based multi-objective genetic algorithm for dynamic community detection. arXiv:2109.15136. 2021. [Google Scholar]

53. Wang Y-J, Song J-X, Sun P. Research on dynamic community detection method based on an improved pity beetle algorithm. IEEE Access. 2022;10:43914–33. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3168714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Li W, Zhou X, Yang C, Fan Y, Wang Z, Liu Y. Multi-objective optimization algorithm based on characteristics fusion of dynamic social networks for community discovery. Inf Fusion. 2022;79:110–23. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2021.10.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Ma H, Wu K, Wang H, Liu J. Higher-order knowledge transfer for dynamic community detection with great changes. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2024;28(1):90–104. doi:10.1109/tevc.2023.3257563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Yu L, Zhao X, Lv M, Zhang J. A consensus community-based spider wasp optimization for dynamic community detection. Mathematics. 2025;13(2):265. doi:10.3390/math13020265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Radicchi F, Castellano C, Cecconi F, Loreto V, Parisi D. Defining and identifying communities in networks. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2004;101(9):2658–63. doi:10.1073/pnas.0400054101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Yang J, Leskovec J. Defining and evaluating network communities based on ground-truth. In: Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD Workshop on Mining Data Semantics; 2012 Aug 12–16; Beijing, China. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

59. Su X, Xue S, Liu F, Wu J, Yang J, Zhou C, et al. A comprehensive survey on community detection with deep learning. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2024;35(4):4682–702. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2021.3137396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Sankar A, Wu Y, Gou L, Zhang W, Yang H. Dysat: deep neural representation learning on dynamic graphs via self-attention networks. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining; 2020 Feb 3–7; Houston, TX, USA. p. 519–527. [Google Scholar]

61. Rossi E, Chamberlain B, Frasca F, Eynard D, Monti F, Bronstein M. Temporal graph networks for deep learning on dynamic graphs. arXiv:2006.10637. 2020. [Google Scholar]

62. Costa AR. Adaptive model to community detection in dynamic social networks. Brasília, Brazil: Universidade de Brasília; 2024. [Google Scholar]

63. La Malfa E, La Malfa G, Nicosia G, Latora V. Characterizing learning dynamics of deep neural networks via complex networks. In: 2021 IEEE 33rd International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI); 2021 Nov 1–3; Washington, DC, USA. p. 344–51. [Google Scholar]

64. Tahabi FM, Luo X. Dynamicg2b: dynamic node classification with layered graph neural networks and BiLSTM. Int FLAIRS Conf Proc. 2023;36(1). [Google Scholar]

65. Zhang S, Xiong Y, Zhang Y, Sun Y, Chen X, Jiao Y, et al. Rdgsl: dynamic graph representation learning with structure learning. In: Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2023 Oct 21–25; Birmingham, UK. p. 3174–83. [Google Scholar]

66. Dumpis M, Navakauskas D. Accuracy vs complexity: a small scale dynamic neural networks case. Baltic J Mod Comput. 2024;12(3):327–48. [Google Scholar]

67. Abdulrahman MM, Abood AD, Attea BA. An enhanced multi-objective evolutionary algorithm with decomposition for signed community detection problem. In: 2020 2nd Annual International Conference on Information and Sciences (AiCIS); 2020 Nov 24–25; Fallujah, Iraq. p. 45–50. [Google Scholar]

68. Saeed HS, Abbood AD. Enhanced evolutionary algorithm for dynamic community detection using a vulnerable node reassignment-based mutation. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2025;18(7):388–411. [Google Scholar]

69. Zeng X, Wang W, Chen C, Yen GG. A consensus community-based particle swarm optimization for dynamic community detection. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2019;50(6):2502–13. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2019.2938895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Lancichinetti A, Fortunato S. Consensus clustering in complex networks. Sci Rep. 2012;2(1):336. doi:10.1038/srep00336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Mandaglio D, Amelio A, Tagarelli A. Consensus community detection in multilayer networks using parameter-free graph pruning. In: Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining: 22nd Pacific-Asia Conference, PAKDD 2018. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 193–205. [Google Scholar]

72. Besharatnia F, Talebpour A, Aliakbary S. An improved grey wolves optimization algorithm for dynamic community detection and data clustering. Appl Artif Intell. 2022;36(1):2012000. doi:10.1080/08839514.2021.2012000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Ranjkesh S, Masoumi B, Hashemi SM. A novel robust memetic algorithm for dynamic community structures detection in complex networks. World Wide Web. 2024;27(1):3. doi:10.1007/s11280-024-01238-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Gong M-G, Zhang L-J, Ma J-J, Jiao L-C. Community detection in dynamic social networks based on multiobjective immune algorithm. J Comput Sci Technol. 2012;27(3):455–67. doi:10.1007/s11390-012-1235-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Chen G, Wang Y, Wei J. A new multiobjective evolutionary algorithm for community detection in dynamic complex networks. Math Problems Eng. 2013;2013:161670. [Google Scholar]

76. Niu X, Si W, Wu CQ. A label-based evolutionary computing approach to dynamic community detection. Comput Commun. 2017;108:110–22. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2017.04.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Panizo-LLedot A, Bello-Orgaz G, Camacho D. A multi-objective genetic algorithm for detecting dynamic communities using a local search driven immigrant’s scheme. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2020;110:960–75. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.10.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Liu F, Wu J, Xue S, Zhou C, Yang J, Sheng Q. Detecting the evolving community structure in dynamic social networks. World Wide Web. 2020;23:715–33. doi:10.1007/s11280-019-00710-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Besharatnia F, Talebpour AR, Aliakbary S. Metaheuristic multi-objective method to detect communities on dynamic social networks. Int J Comput Intell Syst. 2021;14(1):1356–72. [Google Scholar]

80. Yin Y, Zhao Y, Li H, Dong X. Multi-objective evolutionary clustering for large-scale dynamic community detection. Inf Sci. 2021;549:269–87. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2020.11.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Cai L, Zhou J, Wang D. Improving temporal smoothness and snapshot quality in dynamic network community discovery using NOME algorithm. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2023;9:e1477. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.1477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Wang W, Li Q, Wei W. An adaptive dynamic community detection algorithm based on multi-objective evolutionary clustering. Int J Intell Comput Cybern. 2024;17(1):143–60. doi:10.1108/ijicc-07-2023-0188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Lancichinetti A, Fortunato S. Limits of modularity maximization in community detection. Phys Rev E. 2011;84(6):066122. doi:10.1103/physreve.84.066122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Aref S, Mostajabdaveh M, Chheda H. Heuristic modularity maximization algorithms for community detection rarely return an optimal partition or anything similar. In: International Conference on Computational Science. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 612–26. [Google Scholar]

85. Paoletti G, Gioacchini L, Mellia M, Vassio L, Almeida JM. Benchmarking evolutionary community detection algorithms in dynamic networks. arXiv:2312.13784. 2023. [Google Scholar]

86. Pan Y, Liu X, Yao F, Zhang L, Li W, Wang P. Identification of dynamic networks community by fusing deep learning and evolutionary clustering. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):23741. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-4236904/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Wang Z, Wang C, Gao C, Li X, Li X. An evolutionary autoencoder for dynamic community detection. Sci China Inf Sci. 2020;63(11):212205. doi:10.1007/s11432-020-2827-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Qu S, Du Y, Zhu M, Yuan G, Wang J, Zhang Y, et al. Dynamic community detection based on evolutionary DeepWalk. Appl Sci. 2022;12(22):11464. doi:10.3390/app122211464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Zhang B, Mi Y, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Li M, Zhai Q, et al. Dynamic community detection method of a social network based on node embedding representation. Mathematics. 2022;10(24):4738. doi:10.3390/math10244738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Nassef AM, Abdelkareem MA, Maghrabie HM, Baroutaji A. Hybrid metaheuristic algorithms: a recent comprehensive review with bibliometric analysis. Int J Electr Comput Eng (IJECE). 2024;14(6):7022–35. doi:10.11591/ijece.v14i6.pp7022-7035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Liu F, Xue S, Wu J, Zhou C, Hu W, Paris C, et al. Deep learning for community detection: progress, challenges and opportunities. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI 20); 2021 Jan 7–15; Yokohama, Japan. p. 4981–7. [Google Scholar]

92. Morea F, De Stefano D. Enhancing stability and assessing uncertainty in community detection through a consensus-based approach. arXiv:2408.02959. 2024. [Google Scholar]

93. Wang H, Zhang Y, Zhao Z, Cai Z, Xia X, Xu X. Less is more: simple yet effective heuristic community detection with graph convolution network. arXiv:2501.12946. 2025. [Google Scholar]

94. Khosrowshahli, Rahnamayan S, Ombuki-Berman B. Massive dimensions reduction and hybridization with metaheuristics in deep learning. In: 2024 lEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCEcE). Kingston, ON, Canada; 2024. p. 469–75. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools