Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Review of the Evolution of Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms

1 Institute for Information Systems, University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland, Olten, 4600, Switzerland

2 Department of Electrical Engineering, Lan.C., Islamic Azad University, Langarud, 4471311127, Iran

* Corresponding Author: Thomas Hanne. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements in Evolutionary Optimization Approaches: Theory and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 4203-4236. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068087

Received 20 May 2025; Accepted 01 September 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms (MOEAs) have significantly advanced the domain of Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO), facilitating solutions for complex problems with multiple conflicting objectives. This review explores the historical development of MOEAs, beginning with foundational concepts in multi-objective optimization, basic types of MOEAs, and the evolution of Pareto-based selection and niching methods. Further advancements, including decom-position-based approaches and hybrid algorithms, are discussed. Applications are analyzed in established domains such as engineering and economics, as well as in emerging fields like advanced analytics and machine learning. The significance of MOEAs in addressing real-world problems is emphasized, highlighting their role in facilitating informed decision-making. Finally, the development trajectory of MOEAs is compared with evolutionary processes, offering insights into their progress and future potential.Keywords

1.1 The Significance of Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO)

Real-world problems rarely involve optimizing a single objective. Zeleny’s statement (1982): “Multiple objectives are all around us” [1] reflects the ubiquity and importance of considering multiple criteria, goals, or objectives in our daily lives. Decision-making often must account for conflicting objectives, necessitating trade-offs. For instance, in automotive design, reducing fuel consumption and emissions often conflicts with cost and performance. Similarly, in supply chain optimization, minimizing costs can conflict with maximizing customer satisfaction. These complexities have led to the emergence of MOO as a crucial area of research. It wasn’t until the early 1970s that formal approaches to considering multiple objectives in decision-making processes were widely studied. A review of the historic development of this field is provided by [2]. Since the 1970s, specific conferences, newsletters, journals, and academic societies have been established for this new research area.

The foundation of MOO is the concept of Pareto-optimality, introduced by Vilfredo Pareto in the early 20th century. A solution is Pareto-optimal if improving one objective necessitates the degradation of at least one other. However, formal methods for MOO gained prominence only in the 1970s with the development of structured approaches to multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) or multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) [1,2]. These methods have since evolved to address diverse applications in engineering, economics, and beyond.

In general, two primary research directions can be identified: The first focuses on determining viable solutions to a MOO problem. This inquiry led to the development of Pareto-optimal solutions (also known as Pareto-efficient or simply efficient) and methods for identifying such solutions across various problem types. Given that there is typically no single, definitive Pareto-optimal solution, a second question emerges: How can we assist a decision-maker in choosing an alternative from those that are mathematically sound (i.e., the Pareto-optimal solutions)? This question spawned numerous approaches that incorporate additional information, particularly regarding a decision maker’s preferences, into the solution process. While this second question involves considering the availability and suitability of relevant information, aspects of rational decision-making, psychological factors, and the user-friendliness of methods, the first question deals with optimization in potentially complex problems. Methods addressing the first question are referred to as type 1 approaches, while those addressing the second are called type 2 approaches. It is also possible to address both questions simultaneously in a single approach that utilizes additional (preference-based) information during the optimization process. This information can be provided beforehand or progressively throughout the optimization process (interactive methods). These combined approaches are classified as type 3 approaches. This typology not only guides algorithm design but also frames how decision-making and optimization are intertwined in practical applications.

Complex optimization problems have found promising solutions in Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs), particularly when conventional optimization and operations research methods fall short due to assumptions about problem properties like linearity, convexity, or differentiability. This makes EAs attractive for tackling intricate MOO challenges as well. However, the widespread exploration of EAs for multi-objective problems didn’t gain traction until the late 1980s. The field’s growth culminated in the organization of specialized conferences, beginning with the in-augural International Conference on Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization in 2001 [3]. This event gave rise to the commonly used acronym for the field, EMO.

1.2 Challenges in Multi-Objective Optimization

Multi-Objective Optimization Problems (MOOPs) present unique challenges compared to single-objective problems. These challenges can be broadly categorized as follows:

• Solution Representation:

⮚ Identifying the Pareto front, a set of Pareto-optimal solutions, is computationally intensive, particularly for high-dimensional problems. Recent advancements, such as the use of deep learning techniques to approximate the Pareto front, have shown promise in alleviating some computational burdens.

⮚ Ensuring diversity in solutions along the Pareto front is critical to provide decision-makers with meaningful trade-offs. To address this, several algorithms and techniques have been developed:

○ Crowding Distance: Used in algorithms like NSGA-II, this technique maintains diversity by measuring the density of solutions around a given solution, helping to ensure that the population covers the Pareto front effectively [4].

○ Fitness Sharing: This approach modifies the fitness of solutions based on their proximity to others in the objective space, encouraging a spread of solutions across different regions of the Pareto front.

○ Multi-Objective Evolutionary Strategies: These strategies often incorporate mechanisms to maintain diversity, such as adaptive mutation rates and selection pressure that favor diverse populations.

• Decision Support [5]:

⮚ Decision-making involves selecting a single solution from the Pareto front based on preferences. This task requires robust frameworks that can accommodate user preferences effectively.

⮚ The implications of user preferences are significant as they can greatly influence the optimization process and the final decision. Preferences can guide the selection of solutions that not only meet technical criteria but also align with the decision-maker’s values and priorities. Incorporating user preferences can be done through various methods, such as a priori, interactive, or a posteriori approaches.

⮚ A priori methods allow users to specify preferences before the optimization process begins, which can streamline the search towards preferred regions of the solution space. Interactive methods enable users to provide feedback during the optimization process, allowing for a more adaptive approach that can adjust based on real-time insights. A posteriori methods involve analyzing the results after the optimization to understand how well the solutions meet user preferences.

⮚ Ultimately, effectively incorporating user preferences enhances satisfaction with the selected solutions and improves the overall decision-making process, ensuring that the results are not only mathematically sound but also contextually relevant.

• Problem Complexity:

⮚ Real-world MOOPs often involve nonlinear, nonconvex, or stochastic systems that are difficult to model using traditional optimization techniques [6].

⮚ The high computational cost of solving such problems limits the scalability of classical methods. Researchers have begun exploring the integration of surrogate models to approximate objective functions, significantly reducing computational load in complex environments. Additionally, adaptive sampling techniques that focus computational resources on promising regions of the solution space have been introduced to improve efficiency [7].

⮚ MOOPs can also involve a large number of objectives (many-objective optimization) and high-dimensional decision spaces, which further increases complexity and computational burden. The challenge of handling high-dimensional search spaces and the sensitivity to parameter settings are also significant limitations [8–10].

⮚ The presence of irregular Pareto fronts (discontinuous, degenerate, or inverted) in real-world MOOPs poses additional challenges for MOEAs, as it makes designing efficient optimization algorithms particularly tricky [11].

⮚ Balancing convergence (finding solutions close to the true Pareto front) and diversity (maintaining a wide spread of solutions along the Pareto front) is a persistent challenge in MOEAs, especially as the number of objectives increases [12].

⮚ The interpretability of MOEA results, particularly for high-dimensional problems, can also be a limitation [7].

⮚ Some MOEAs may suffer from premature convergence and insufficient population diversity, especially in high-dimensional data scenarios [13].

1.3 Multi-Objective vs. Many-Objective Optimization: A Critical Distinction

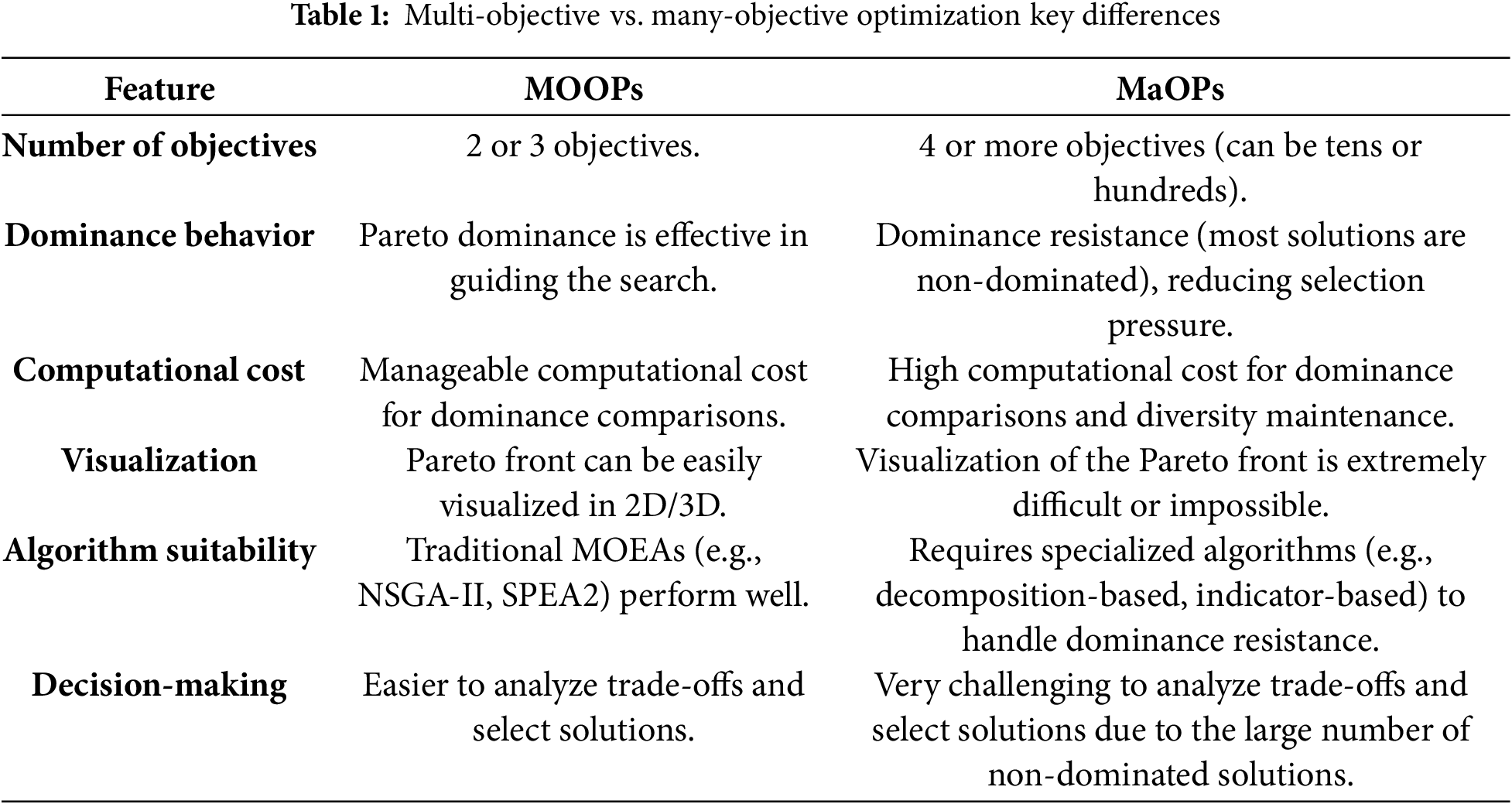

The distinction between “multi-objective” and “many-objective” optimization is primarily a matter of the number of objectives involved, which in turn significantly impacts the complexity of the problem and the effectiveness of traditional Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms (MOEAs).

Multi-objective Optimization (MOOPs) involve optimizing two or three conflicting objectives simultaneously. In this context, the concept of Pareto dominance is well-defined and relatively straightforward to apply. Such problems can be characterized as follows:

• Number of Objectives: Typically, 2 or 3 objectives.

• Pareto Front Visualization: The Pareto front (or Pareto set) can often be visualized and understood relatively easily in 2D or 3D space.

• Algorithm Performance: Many traditional MOEAs, such as NSGA-II and SPEA2, per-form well in this setting, effectively balancing convergence and diversity.

• Decision-Making: Decision-makers can often analyze the trade-offs among a small number of objectives more intuitively.

Many-objective Optimization: Many-objective optimization problems (MaOPs) refer to problems with a large number of objectives, typically four or more, and often extending to tens or even hundreds of objectives. The increase in the number of objectives introduces significant challenges that differentiate MaOPs from traditional MOOPs. MaOPs can be characterized as follows:

• Number of Objectives: Generally, 4 or more objectives, often extending to a much larger number.

• Curse of Dimensionality: As the number of objectives increases, the objective space becomes high-dimensional. This leads to several issues:

⮚ Dominance Resistance: In high-dimensional objective spaces, almost all solutions tend to be non-dominated with respect to each other. This phenomenon, known as “dominance resistance” or “curse of dimensionality in objective space,” makes Pareto dominance-based selection mechanisms less effective in guiding the search towards the true Pareto front. The selection pressure towards the Pareto front diminishes, making it difficult for MOEAs to converge.

⮚ Increased Computational Cost: The computational cost of maintaining diversity and calculating Pareto dominance relationships increases significantly with the number of objectives.

⮚ Visualization Difficulty: Visualizing and understanding the Pareto front becomes extremely challenging, if not impossible, in high-dimensional spaces.

• Algorithm Adaptation: Traditional MOEAs often struggle with MaOPs due to the dominance resistance problem. This has led to the development of new types of algorithms specifically designed for many-objective problems, such as:

⮚ Decomposition-based MOEAs (e.g., MOEA/D): These methods are particularly well-suited for MaOPs as they transform the multi-objective problem into a set of single-objective subproblems, which helps overcome the dominance resistance issue.

⮚ Indicator-based MOEAs: These algorithms use performance indicators (e.g., Hyper-volume, Inverted Generational Distance) to guide the search, providing a scalar measure of solution quality that can maintain selection pressure in high-dimensional spaces.

⮚ Reference-point based MOEAs: These methods incorporate user preferences or reference points to guide the search towards specific regions of interest in the high-dimensional objective space.

• Decision-Making Complexity: Analyzing and selecting a preferred solution from a vast set of non-dominated solutions in a high-dimensional objective space is a significant challenge for decision-makers.

Table 1 summarizes the key differences between multi-objective and many-objective optimization.

In summary, while both multi-objective and many-objective optimization deal with multiple conflicting objectives, the sheer number of objectives in many-objective problems introduces a “curse of dimensionality” that fundamentally changes the behavior of Pareto dominance and necessitates different algorithmic approaches and decision-making strategies.

MOEAs have proven invaluable in diverse domains, including:

• Engineering:

⮚ Structural Design Optimization: MOEAs are employed to optimize designs under multiple constraints. For instance, Reference [14] demonstrated the use of the NSGA-II algorithm for optimizing truss structures, achieving significant improvements in weight reduction while maintaining strength standards. MOEAs are frequently used to optimize designs under multiple constraints like a study by Kalyanmoy Deb and his colleagues that explored various applications of MOEAs in structural optimization, showcasing their effectiveness in minimizing material usage while satisfying performance criteria [15].

⮚ Energy Systems Management: Gong et al. [16] applied MOEAs to optimize the operation of power systems, focusing on minimizing costs while maximizing reliability and sustainability. Their results indicated enhanced performance in managing renewable energy sources. In a study by [17], MOEAs were demonstrated for optimizing smart grid operations, balancing cost, reliability, and environmental impact in energy distribution systems, which is crucial for integrating renewable energy sources.

• Economics:

⮚ Portfolio Optimization: A study by Mohagheghi et al. [18] used MOEAs to develop optimal investment portfolios that balance risk and return, demonstrating how these algorithms can effectively navigate the trade-offs inherent in financial decision-making. Furthermore, a recent study by Bradshaw et al. [19] utilized the MOEA framework to optimize investment portfolios, effectively balancing risk and return in volatile markets, illustrating the robustness of MOEAs in financial decision-making.

⮚ Resource Allocation: MOEAs have been effectively utilized in optimizing resource distribution among competing projects. For instance, a study by Zopounidis and Doumpos [20] illustrated the use of MOEAs in resource allocation, which allowed for more equitable and efficient distribution strategies in various economic scenarios. Recent work by Fernández et al. [21] applied MOEAs for resource allocation across competing projects, demonstrating improved efficiency in distribution strategies.

• Emerging Fields:

⮚ Advanced Analytics and Machine Learning: MOEAs have been successfully applied in hyperparameter tuning for machine learning models. For example, a study by Bader and Zitzler [22] employed MOEAs to optimize model parameters, achieving improved predictive performance in complex datasets. Their work highlighted the synergy between MOEAs and data analytics, demonstrating enhanced decision-making processes in rapidly changing environments. Additionally, a recent study by Rom et al. [23] explored the use of MOEAs for hyperparameter tuning in deep learning models, showcasing how these algorithms can enhance model performance on large datasets.

⮚ Healthcare: A recent application in healthcare optimization used MOEAs to allocate medical resources in emergency departments, balancing patient wait times and resource utilization effectively, showcasing the versatility and adaptability of MOEAs in critical real-world applications. A study by Eriskin et al. [24] highlighted the adaptability of MOEAs in balancing patient care quality and resource management during crisis situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

These specific case studies illustrate the continued relevance and effectiveness of MOEAs in solving complex optimization challenges across diverse fields, underscoring their effectiveness in solving complex optimization problems involving multiple conflicting objectives. They are also reflecting their adaptability to contemporary issues and advancements in technology.

1.5 Historical Milestones of Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms (MOEAs)

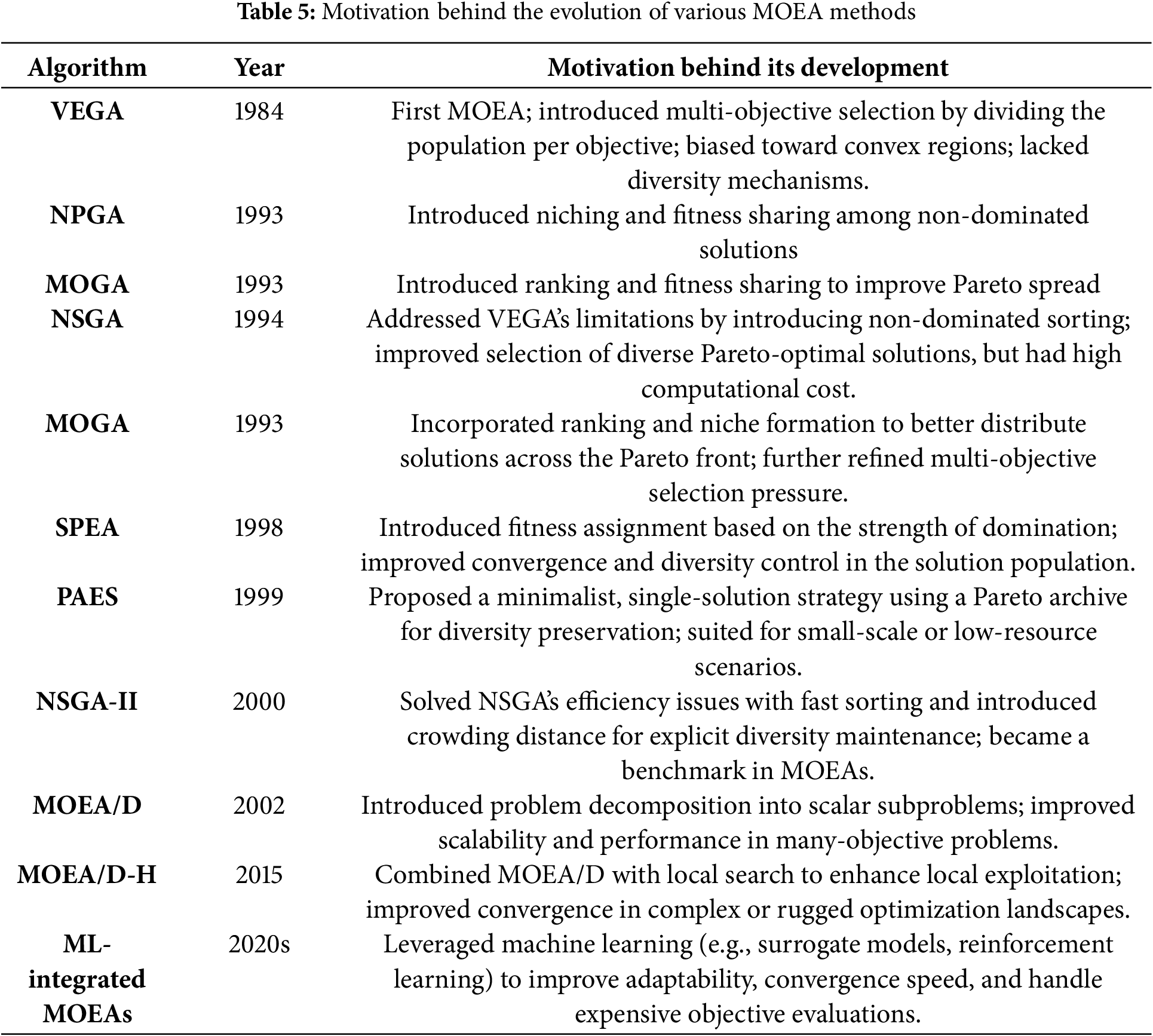

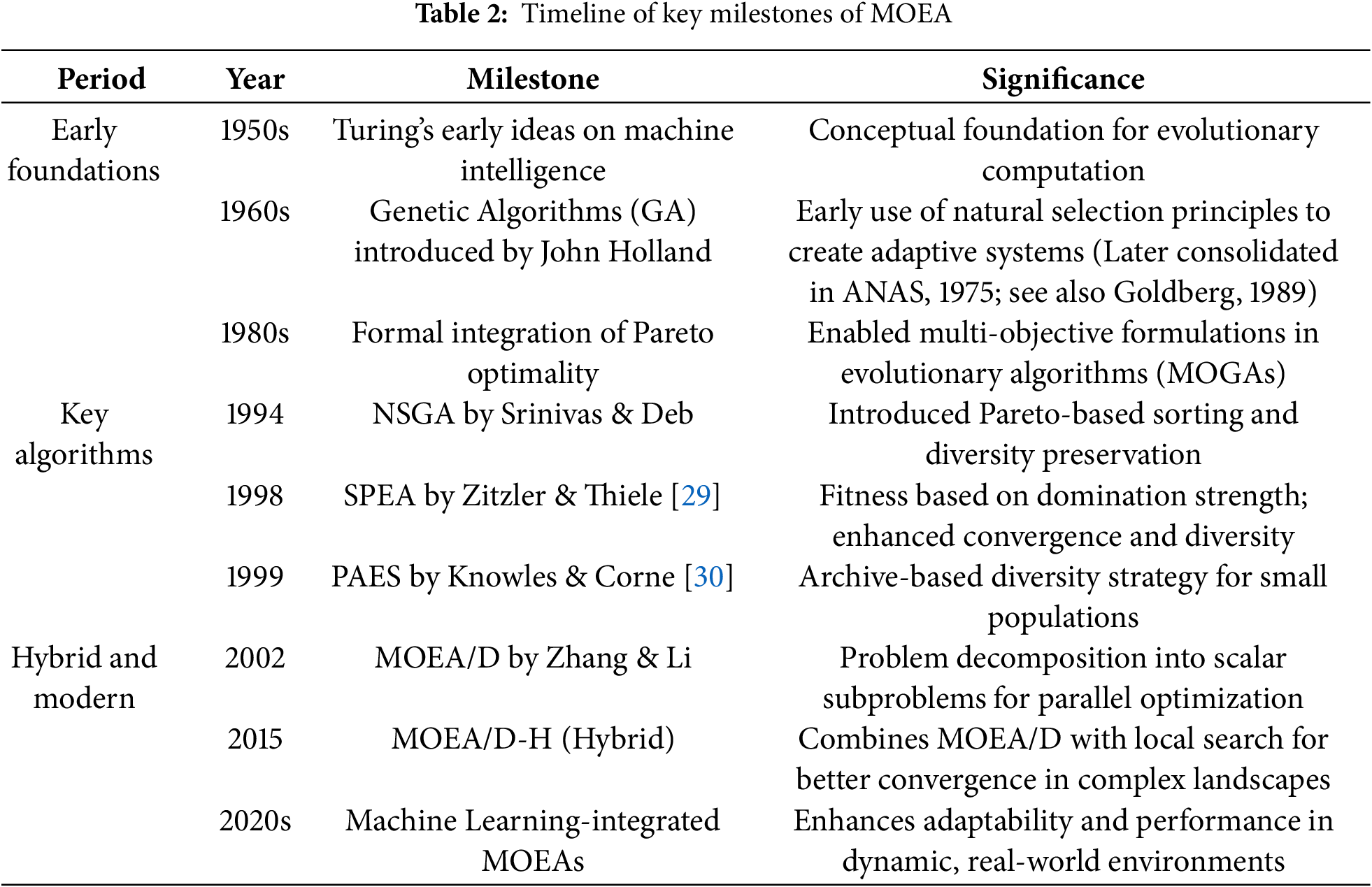

The evolution of MOEAs has been shaped by several landmark contributions, ranging from the conceptual foundation of evolutionary algorithms to the development of sophisticated hybrid techniques. These milestones represent significant progress in algorithmic strategies, problem formulation, and application scope.

Table 2 provides a chronological overview of key milestones in MOEA development. The conceptual groundwork for intelligent behavior in machines can be traced back to Alan Turing’s early ideas in the 1950s, which laid the foundation for machine learning and computational intelligence. Although not directly proposing evolutionary algorithms, Turing’s vision inspired subsequent developments in artificial intelligence. The foundation of genetic algorithms (GAs) was laid in the early 1960s by John Holland, who sought methods to automatically generate adaptive finite-state automata. His initial publications on this concept predate his widely cited book Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems (1975), which formalized and popularized GA methodology. A more comprehensive historical account of GA development can be found in Goldberg’s book Genetic Algorithms in Search, Optimization, and Machine Learning (1989), which outlines the foundational ideas and their early evolution [25]. The first formal evolutionary algorithms, however, were introduced later by Ingo Rechenberg and John Holland in the 1970s [26–28]. Starting from the foundational theories, the field has witnessed the emergence of influential algorithms like NSGA, SPEA, NSGA-II, and MOEA/D. These developments reflect a continuous effort to improve convergence behavior, maintain diversity, and tackle increasingly complex multi-objective problems.

Recent years have seen a shift toward integrating MOEAs with advanced techniques, such as local search, decomposition strategies, and machine learning models. This trend demonstrates the field’s dynamic nature and its responsiveness to the challenges posed by real-world, high-dimensional, and dynamic optimization scenarios.

The historical development of MOEAs is characterized by foundational theories, key algorithmic breakthroughs, and hybrid advancements. Table 2 presents a condensed timeline of these significant milestones, highlighting their contributions to the evolution of the field.

This review aims to:

⮚ Provide a comprehensive historical perspective on the evolution of MOEAs.

⮚ Highlight key methodologies, including Pareto-based, decomposition-based, and hybrid approaches.

⮚ Analyze significant applications and identify gaps in the literature.

⮚ Offer insights into future research directions, emphasizing scalability, real-time performance, and integration with emerging technologies.

By synthesizing these aspects, this article seeks to serve as a resource for researchers and practitioners, advancing both theoretical understanding and practical application of MOEAs.

2 Foundational Concepts and Traditional MOEAs

MOOPs are characterized by the need to optimize two or more conflicting objectives simultaneously. This complexity arises in various fields, including engineering, economics, and environmental management, where decision-makers must balance trade-offs among competing goals. The formulation of an MOOP can be expressed mathematically as follows:

where

The Pareto-optimal set is defined as [28]:

This set represents solutions where no objective can be improved without degrading another, and the corresponding Pareto front is the image of

2.2 Early MOEAs and Selection Mechanisms

In the context of EAs, the multi-objective nature of an optimization problem often appears irrelevant during certain steps. Operations such as random initialization of solutions, mutation, crossover, and recombination generally operate solely within the solution space, without directly considering the objective functions. However, the selection process—a critical step in EAs—explicitly involves the objective function(s) via the fitness function. Frequently, the fitness function mirrors the objective function(s), making selection dependent on relative fitness values.

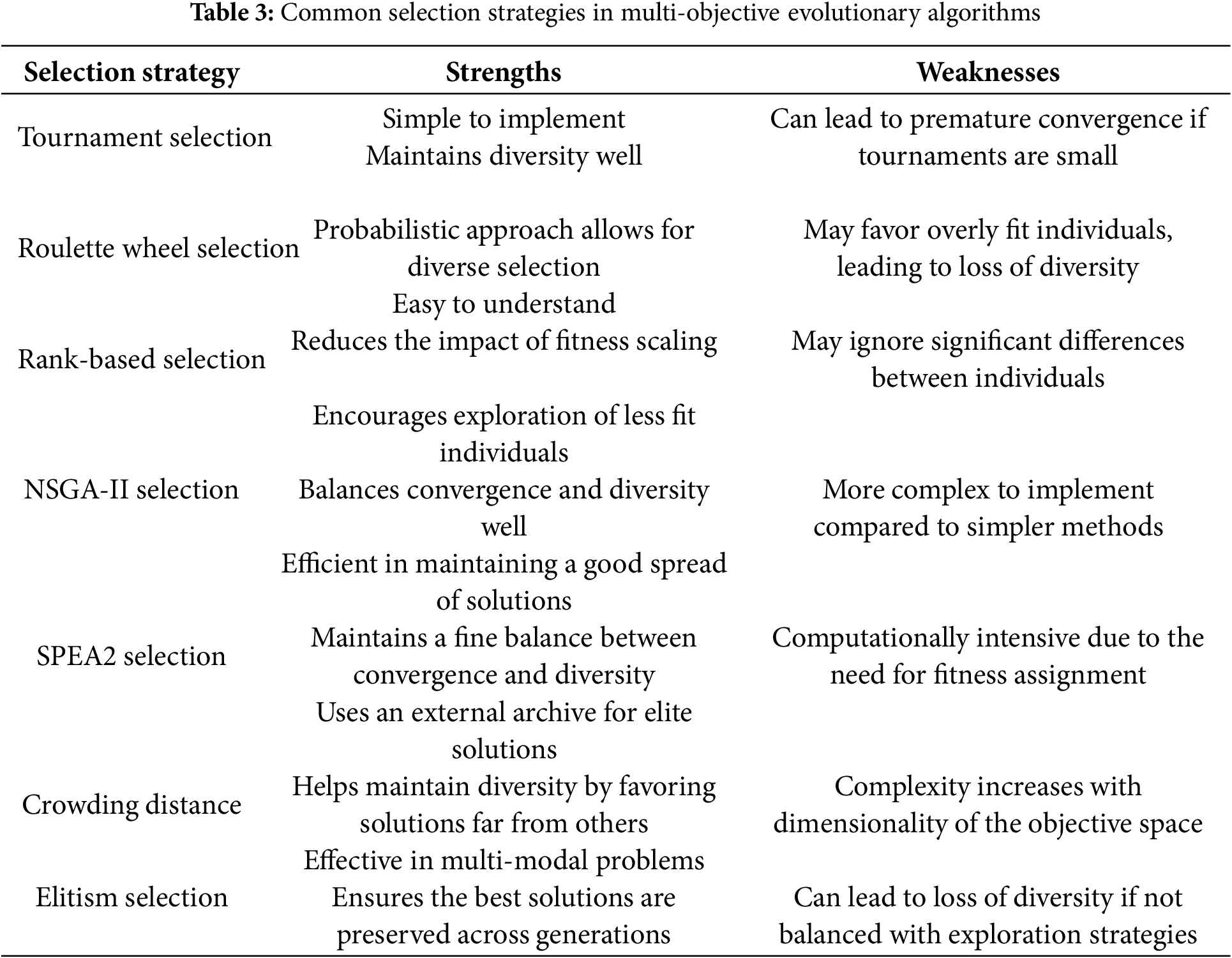

Selection mechanisms play a crucial role in guiding the search process of MOEAs. They determine which individuals from the population are chosen for reproduction based on their fitness relative to multiple objectives. Effective selection strategies not only enhance the convergence towards the Pareto front but also ensure a diverse set of solutions, which is essential for exploring the trade-offs among conflicting objectives. As the field of MOEAs evolves, various innovative selection techniques have emerged, each aiming to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the optimization process [26]. Common selection strategies include:

1) Tournament Selection: Tournament Selection is a popular method in evolutionary algorithms where a subset of individuals is randomly chosen from the population, and the best individual among them is selected for reproduction. This method introduces a competitive aspect to selection, allowing for a balance between exploration and exploitation. The size of the tournament can be adjusted to control selection pressure; larger tournaments favor stronger individuals, while smaller tournaments maintain diversity by giving weaker individuals a chance to be selected [32].

2) Roulette Wheel Selection: Roulette Wheel Selection, also known as fitness proportionate selection, assigns a probability of selection to each individual based on its fitness. It is a method where the probability of selecting an individual for reproduction is directly proportional to its fitness relative to the entire population. This means that individuals with higher fitness values have a greater chance of being selected, akin to a roulette wheel where each individual’s slice of the wheel corresponds to its fitness. Each individual is represented on a wheel, and the wheel is spun to select individuals for reproduction. The main advantage of this method is its simplicity and efficiency; While this method is straightforward and effective, it can lead to issues such as premature convergence, where a few highly fit individuals dominate the selection process, potentially reducing genetic diversity in the population [33,34].

3) Rank-Based Selection: Rank-Based Selection addresses some limitations of fitness proportionate selection by ranking individuals based on their fitness rather than using their absolute fitness values. In this method, individuals are assigned selection probabilities based on their ranks, which helps to maintain diversity in the population and prevents the dominance of highly fit individuals. This approach is particularly useful in MOO, where maintaining a di-verse set of solutions is crucial [6,9].

4) NSGA-II Selection: Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) employs a fast non-dominated sorting approach to rank individuals based on their Pareto dominance. In this method, individuals are sorted into different fronts based on their level of dominance, and a crowding distance metric is used to maintain diversity within each front. This ensures that both convergence towards the Pareto front and diversity in the population are preserved [30].

5) SPEA2 Selection: The Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm 2 (SPEA2) enhances its predecessor by maintaining an external archive of non-dominated solutions. This algorithm uses both the fitness of individuals and a density estimation to select individuals for reproduction, improving the convergence and diversity of solutions in the search space [35].

6) Crowding Distance: Crowding Distance is a technique used in multi-objective optimization to ensure diversity among solutions in the population. It measures how close an individual is to its neighbors in the objective space. By favoring individuals with a larger crowding distance during selection, this method helps maintain a diverse set of solutions and prevents the algorithm from converging prematurely to a small region of the solution space [4,36].

7) Elitist Selection: Elitist Selection is a strategy that ensures that a subset of the best-performing individuals in the population is preserved and carried over to the next generation. This method focuses on retaining high-quality solutions, which can help accelerate convergence towards optimal solutions. By guaranteeing that the best individuals survive, elitist se-lection can improve the overall performance of the evolutionary algorithm. However, it is essential to balance elitism with diversity to avoid premature convergence to suboptimal solutions [33,37].

Table 3 provides a clear overview of different selection strategies used in MOEAs, highlighting their respective strengths and weaknesses. This can help understanding the trade-offs involved in choosing a selection strategy for each specific optimization problem.

EAs adapt well to MOOPs due to their population-based nature, which enables simultaneous exploration of multiple solutions. However, traditional EA selection mechanisms are unsuitable for multi-objective settings, as solutions can be incomparable. These strategies rely on the ability to clearly determine whether one solution is superior to another. In MOO, however, the comparison is complicated by the possibility of incomparability. For two solutions, and the relationship (dominates) or might not hold; instead, and could be incomparable.

To address these challenges, early researchers (e.g., Fonseca and Fleming, 1995) explored scalar-valued fitness functions that allowed standard selection techniques to be applied. Two primary approaches emerged: as discussed in the following.

2.2.1 Aggregation of Objectives (Aggregated Objective Functions)

Aggregation methods combine multiple objectives into a single objective function using additional information, simplifying the optimization process. This approach allows for the application of traditional optimization techniques but may overlook the trade-offs between objectives. The effectiveness of aggregation depends on the choice of weights assigned to each objective, which can significantly influence the results [33]. From objective functions, a single aggregated objective can be derived through:

⮚ Simple Additive Weighting (SAW): Weighted sums of objectives, where the weights reflect the relative importance of each objective.

⮚ Reference-point Approaches: A reference point (e.g., ideal or utopia point) is defined, and the distance to this point is minimized (e.g., goal programming).

⮚ Utility Functions: A utility (or value) function is constructed based on the objectives.

While these methods facilitate the use of traditional EAs, they have significant drawbacks:

✗ Dependence on Decision Maker Input: Requires predefined weights or reference points.

✗ Concentration Bias: Solutions tend to cluster around regions optimal for the aggregated objective, often failing to represent the Pareto set comprehensively.

To address the challenges posed by high-dimensional objective spaces, researchers have explored methods for aggregating groups of objectives. Recent studies have shown that aggregating objectives can effectively reduce the dimensionality of the problem while preserving essential trade-offs among objectives. This approach allows for a more manageable optimization process without sacrificing solution quality [38]. Techniques such as weighted sums, Pareto front approximations, and reference-point methods are notable examples of effective aggregation strategies, which have been successfully applied in various engineering problems [39].

2.2.2 Scalarization without Explicit Input (Population-Based Scalarization)

Population-based scalarization techniques aim to derive a single objective function from a population of solutions without requiring explicit input from the decision-maker. This method allows for a more dynamic adaptation to the search space, facilitating the exploration of diverse solutions while still guiding the search towards the Pareto front. For example:

• Vector Evaluated Genetic Algorithm (VEGA): Proposed by Schaffer and Grefenstette [39], VEGA divides the population into subgroups. Each subgroup is selected based on one of the objectives. The total reproduction probability of a solution is proportional to the weighted sum of its fitness values. This method, however, tends to bias solutions toward convex regions of the Pareto front, making it less effective for detecting solutions in concave regions.

• Objective-based Random Selection: In this method, a single objective is randomly selected during each selection step. Early examples include:

⮚ Fourman (1985) [40]: Tournament selection using randomly selected objectives.

⮚ Kursawe (1991) [41]: Partitioning the population based on randomly chosen objectives within the framework of evolution strategies. Kursawe also introduced a diploid encoding scheme to promote population diversity.

Despite these innovations, these approaches share a tendency to concentrate solutions in specific areas of the Pareto set, limiting their ability to fully explore the objective space. Addressing this challenge remains a key focus in the evolution of multi-objective evolutionary algorithms. While early scalarization methods like VEGA and random objective selection introduced foundational mechanisms for handling multiple objectives, they often struggled with issues such as biased solution distributions and limited diversity across the Pareto front. These limitations highlighted the need for more adaptive, robust, and scalable approaches. In response, modern developments in MOEAs have emerged, offering enhanced strategies to overcome these challenges and better support complex real-world optimization problems.

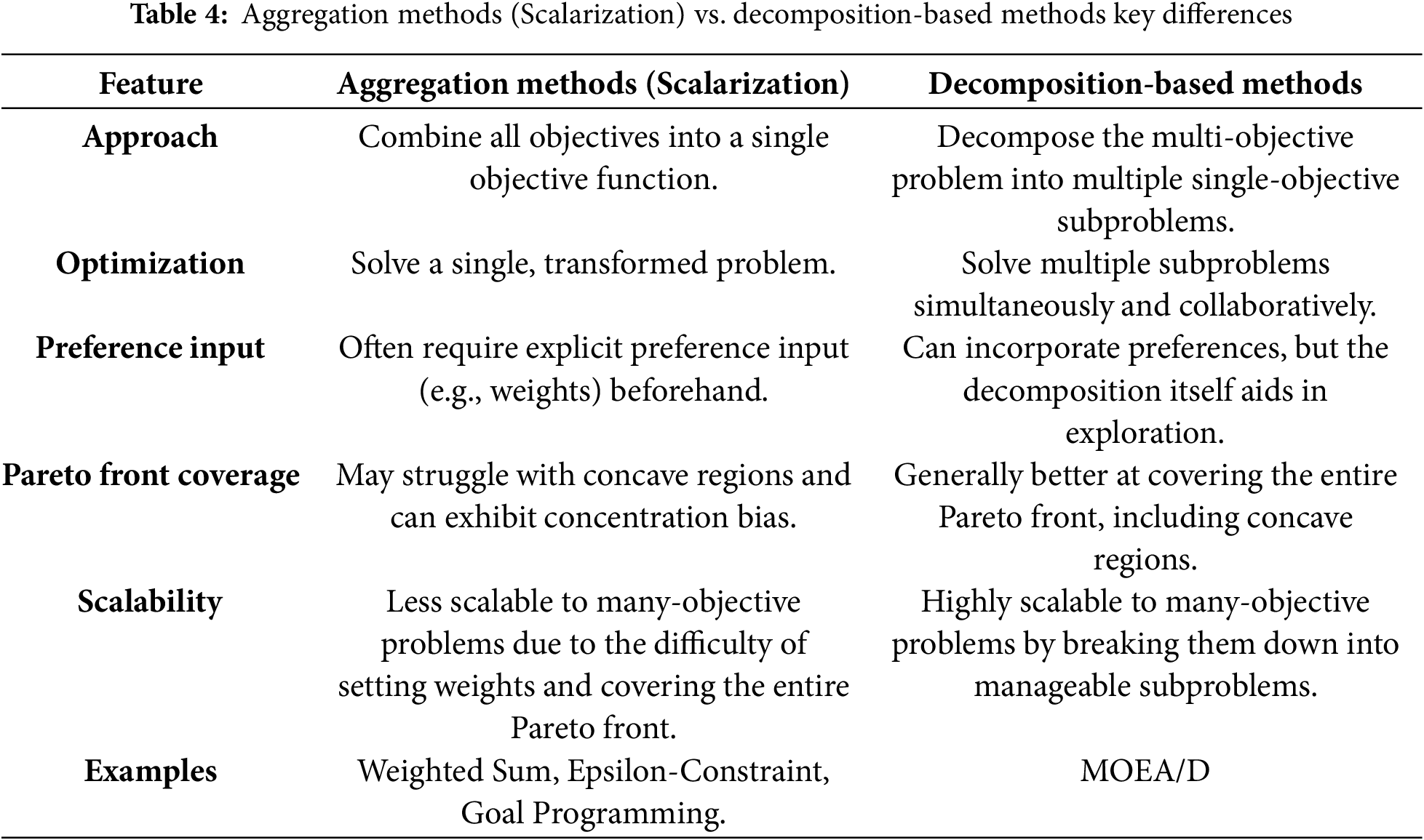

2.3 Strategies for Handling Multiple Objectives: Aggregation vs. Decomposition Developments

Both decomposition-based methods and aggregation methods are strategies used in multi-objective optimization to simplify the problem by transforming multiple objectives into a single, or a set of single, objective problems. However, they differ fundamentally in their approach and how they handle the objectives.

Aggregation Methods (Scalarization): Aggregation methods, also known as scalarization techniques, combine multiple objectives into a single objective function. This is typically achieved by assigning weights to each objective and summing them up, or by using other mathematical formulations. The goal is to transform the multi-objective problem into a single-objective problem that can then be solved using traditional optimization techniques. Basic concept of how they work are as follows:

Simple Additive Weighting (SAW): This is the most common form, where objectives are multiplied by predefined weights and then summed. For example, for objectives

Reference-point Approaches: These methods define a “reference point” (e.g., an ideal or utopia point) and minimize the distance to this point.

Utility Functions: A utility function is constructed to represent the decision-maker’s preferences over different objective values.

Such approaches can be characterized as follows:

Simplicity: They simplify the optimization process by reducing it to a single-objective problem.

Dependence on Decision Maker Input: They often require the decision-maker to specify preferences (e.g., weights or reference points) before the optimization begins.

Concentration Bias: A significant drawback is their tendency to bias solutions towards specific regions of the Pareto front, especially convex ones, and they may fail to find solutions in concave regions of the Pareto front. This means they might not be able to generate a diverse set of Pareto-optimal solutions, potentially limiting the exploration of the entire Pareto front.

Decomposition-based Methods: Decomposition-based methods, exemplified by MOEA/D (Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm based on Decomposition), approach the multi-objective problem by decomposing it into a set of scalar optimization subproblems. These subproblems are then optimized simultaneously and collaboratively. Decomposition-based methods work as follows:

• Subproblem Creation: The multi-objective problem is transformed into a number of single-objective subproblems, often using a set of weight vectors or reference points. Each subproblem is designed to optimize a specific aspect of the overall multi-objective problem.

• Collaborative Optimization: Instead of solving each subproblem independently, decom-position-based methods optimize them in a collaborative manner. Information is shared between neighboring subproblems, allowing for a more efficient exploration of the Pareto front.

• Example MOEA/D: MOEA/D decomposes a multi-objective problem into a number of scalar subproblems using Tchebycheff approach or other aggregation functions. Each sub-problem is associated with a weight vector, and solutions to these subproblems are optimized by leveraging information from their neighbors.

The methods can be characterized as follows:

• Scalability: They are particularly effective in handling many-objective problems (problems with a large number of objectives) because they transform the problem into a set of simpler subproblems, reducing the computational complexity associated with high-dimensional objective spaces.

• Diversity and Convergence: By optimizing multiple subproblems simultaneously and collaboratively, decomposition-based methods can achieve both good convergence towards the Pareto front and maintain diversity among the solutions.

• Less Prone to Concentration Bias: Unlike simple aggregation methods, decomposition-based approaches are generally better at finding solutions across the entire Pareto front, including concave regions, due to their collaborative optimization strategy.

• Adaptability: They can be adapted to various problem types and can incorporate adaptive weight strategies to dynamically adjust to the problem landscape.

Table 4 summarizes the key differences between aggregation methods (scalarization) and de-composition-based methods.

In essence, while both methods aim to simplify multi-objective problems, aggregation methods directly combine objectives into one, often requiring prior knowledge of preferences and potentially limiting the exploration of the Pareto front. Decomposition-based methods, on the other hand, break the problem into smaller, interconnected subproblems, allowing for more effective exploration of the Pareto front, especially in high-dimensional and complex scenarios.

3 Classification of Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms (MOEAs)

Traditional optimization techniques, such as gradient-based methods, rely on assumptions like linearity, convexity, or differentiability, which limit their applicability for complex MOOPs. EAs, by contrast, do not impose such rigid constraints, providing a flexible framework capable of exploring complex solution spaces. EAs inspired by natural selection and biological evolution offer a population-based approach capable of exploring diverse solutions simultaneously, making them particularly well-suited for tackling MOOPs.

The application of EAs to multi-objective problems—known as MOEAs—began in the late 1980s. Initial efforts included approaches like the Vector Evaluated Genetic Algorithm (VEGA) [39]. The earliest attempt to identify Pareto-optimal fronts using evolutionary principles was made by VEGA [39] in 1984. Prior to VEGA, genetic algorithms focused solely on single-objective optimization. VEGA introduced a way to handle multiple objectives by dividing the population into subgroups and selecting individuals based on different objectives. While VEGA introduced the notion of evaluating solutions across multiple objectives, it suffered from poor diversity and biased convergence. However, its tendency to bias solutions toward specific regions of the Pareto front (especially convex ones) revealed the need for more balanced selection strategies. In 1993, the Niched Pareto Genetic Algorithm (NPGA) was proposed by Horn et al. as an early attempt to maintain diversity among non-dominated solutions using a tournament selection mechanism and fitness sharing. NPGA further advanced the application of Pareto dominance in MOEAs and highlighted the importance of maintaining a well-spread Pareto front [42]. The Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm (MOGA) [43] was introduced in 1993, which enhanced the selection mechanism through fitness sharing and ranking, resulting in a better spread of solutions. Building upon these and considering the limitations of VEGA—such as lack of diversity control and inefficiency in identifying well-distributed Pareto fronts—led to the development of NSGA (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm) (1994) [44] which proposed non-dominated sorting and elitism, offering improved convergence toward well-distributed Pareto fronts. This enabled the algorithm to classify and evolve solutions based on Pareto dominance rather than scalarized fitness values. While NSGA improved dominance-based ranking, it still struggled with convergence speed and maintaining diverse solutions. Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm (SPEA) [36] advanced the field by introducing a strength-based fitness assignment where each individual’s fitness is determined by the number of other individuals it dominates. This approach differed from earlier methods (like VEGA, MOGA, and NSGA), which emphasized non-dominated sorting but lacked a quantitative dominance metric for selection pressure. This innovation enabled better selection pressure toward optimal solutions while preserving diversity.

Despite their advancements, early MOEAs had notable limitations. They often struggled to effectively handle large-scale problems due to computational inefficiencies, particularly when the number of objectives increased. Many early algorithms operated under specific assumptions about problem structure, which restricted their applicability to certain problem types. For instance, they frequently relied on a fixed population size and pre-defined selection mechanisms that did not adapt well to the dynamic nature of some optimization landscapes. These limitations called for the development of more sophisticated approaches that could better accommodate the complexities of real-world MOO scenarios.

The field gained formal recognition with the First International Conference on Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization (EMO) in 2001 [3], leading to the establishment of EMO as a distinct research area. Recent advancements in MOEAs have introduced innovative techniques that enhance their performance and applicability. Also, this section explores the modern developments, highlighting how they address the challenges faced in multi-objective optimization. These trends and developments reflect the evolving landscape of MOEAs, showcasing the integration of advanced computational techniques to address increasingly complex optimization challenges across various domains. MOEAs have seen rapid advancements, as discussed in the following subsections.

Pareto-based methods, such as Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA)-II [36,44], are known for their efficiency and widespread application. NSGA, despite its conceptual strengths, suffered from high computational cost due to nested loops in its sorting procedure and lacked an explicit mechanism to maintain diversity. NSGA-II was proposed to address both of these issues: it introduced a fast non-dominated sorting algorithm and the crowding distance concept for diversity preservation, significantly improving scalability and efficiency in practice.

Pareto-based ranking [45,46] is a fundamental concept in MOEAs that prioritizes solutions based on Pareto dominance. Instead of relying solely on fitness values, solutions are ranked according to their ability to dominate others in terms of multiple objectives. This approach promotes a diverse set of solutions that represent different trade-offs among objectives. In multi-objective optimization problems in engineering design, Pareto-based ranking is widely used to identify optimal de-signs that balance performance metrics. For instance, in structural optimization, engineers can use Pareto-based ranking to select designs that minimize weight while maximizing strength.

Decomposition-based methods, such as MOEA/D [47], decompose the multi-objective problem into a series of scalar optimization subproblems, which are then optimized in a collaborative manner. Traditional Pareto-based algorithms like NSGA-II and SPEA rely on dominance comparisons, which become computationally expensive and less effective in many-objective scenarios. MOEA/D was introduced to address this by decomposing a multi-objective problem into a set of scalar subproblems and optimizing them simultaneously. This allowed for better scalability and a structured search, particularly useful in high-dimensional problems. This approach allows for more efficient exploration of the Pareto front and better coverage of the solution space. MOEA/D has been successfully applied in complex engineering problems, such as multi-objective scheduling in manufacturing, where different objectives (e.g., minimizing completion time and maximizing resource utilization) need to be optimized simultaneously [48,49].

Most existing MOEAs used population-based approaches, which could be memory- or computation-intensive. Pareto Archived Evolution Strategy (PAES) provided a minimalist alternative using a single-solution evolution strategy and a Pareto archive to retain diversity. It targeted simplicity and efficiency while still achieving good convergence and coverage in smaller or resource-constrained environments.

3.2.1 Modern Developments Using Diversity Preservation Mechanisms [50,51]

Techniques like crowding distance (in NSGA-II) ensure a well-distributed set of solutions. Diversity preservation mechanisms ensure that the solutions in the population are well-distributed across the objective space. Techniques such as crowding distance, used in NSGA-II, help maintain diversity by favoring solutions that are farther apart in the objective space, thus preventing premature convergence. In environmental management, diversity preservation mechanisms can be employed in land-use optimization problems, where it is essential to maintain a diverse set of land-use options that balance ecological, economic, and social objectives.

3.2.2 Addressing Scalability Challenges in MOEAs Using Decomposition Approaches [48,49]

Decomposition methods have gained traction as effective strategies for tackling many-objective problems. The use of decomposition-based methods in MOEAs continues to evolve, with new algorithms being proposed that leverage reference points and adaptive mechanisms to enhance performance in high-dimensional objective spaces [52]. The MOEA/D framework, proposed by Zhang and Li [47], exemplifies this approach by transforming a multi-objective optimization problem into a set of scalar subproblems. Each subproblem is solved in parallel using different weight vectors, which helps manage complexity and improve coverage of the Pareto front. Re-cent advancements in MOEA/D have included adaptive weight strategies and enhanced neighborhood exploration mechanisms to further improve performance in high-dimensional spaces [53]. Specific examples include adaptive algorithms that dynamically adjust weight vectors based on the current population distribution, as seen in recent studies [54].

Indicator-based methods utilize performance metrics to guide the selection process in MOEAs. Recent works have proposed using indicators such as hypervolume and generational distance to evaluate the quality of the approximated Pareto front. These metrics serve as alternative criteria for selection, enabling algorithms to focus on improving the overall quality of solutions rather than merely exploring the search space [55]. Indicators like the hypervolume indicator have been particularly effective in guiding the optimization process toward better-converged solutions, as demonstrated in recent applications in resource allocation [54].

Recent advancements have integrated performance metrics directly into the selection process of MOEAs. Techniques such as hypervolume maximization and Pareto spread minimization have been employed to enhance the effectiveness of the search process. These methods allow for a more nuanced evaluation of solutions, leading to improved convergence and diversity [56,57]. Practical applications in engineering design often leverage these techniques to achieve optimal trade-offs among competing objectives, showcasing their effectiveness in real-world scenarios [58].

Preference-based evolutionary optimization has emerged as a significant advancement in MOEA research. These methods incorporate user-defined preferences during the optimization process, allowing decision-makers to influence the search towards more desirable solutions. Recent studies have highlighted the potential of artificial preference relations, such as reference directions or preferred areas of solutions, to enhance exploration efficiency and user satisfaction [59]. Examples include applications in resource allocation problems where user preferences significantly impact solution selection, demonstrating the practical utility of these methods [54].

Hybrid methods that combine MOEAs with other optimization techniques, such as swarm intelligence and local search algorithms, are becoming more prevalent. These combinations can enhance the search capabilities of MOEAs, enabling them to tackle more complex and high-dimensional optimization problems effectively [54,60–62]. A recent study proposed a Hybrid Selection based MOEA (HS-MOEA) that combines dominance, decomposition, and indicator-based strategies to enhance the balance between diversity and convergence in multi-objective optimization problems. This approach demonstrated superior performance on various test suites, including DTLZ and WFG [54]. A notable study by Singh & Chaturvedi [60] integrated Particle Swarm Optimization with MOEAs to enhance convergence speed while maintaining solution diversity.

Combining evolutionary methods with machine learning or metaheuristics to enhance performance, improve convergence, and solution quality. For example, combining MOEAs with reinforcement learning has demonstrated promising results in dynamic optimization environments. While MOEA/D offered a powerful decomposition strategy, it lacked fine-tuning capabilities in local regions. MOEA/D-H hybridized MOEA/D with local search methods to combine global exploration with local exploitation. This hybrid approach improved solution quality in complex real-world problems with rugged or discontinuous landscapes. As optimization problems became more dynamic and data-driven, classical MOEAs showed limitations in adaptability and computational efficiency. The integration of machine learning techniques (e.g., neural networks, surrogate models, reinforcement learning) into MOEAs aimed to guide the search process more intelligently, improve convergence in real-time applications, and handle expensive objective evaluations through prediction and adaptation mechanisms.

3.5.1 Modern Developments: Incorporating Machine Learning [63]

Surrogate models and reinforcement learning are now employed to enhance decision-making and exploration in multi-objective optimization. The integration of machine learning techniques, such as surrogate models and reinforcement learning, significantly enhances decision-making and exploration in multi-objective optimization. Surrogate models approximate the objective functions, reducing computation time, while reinforcement learning helps in adaptively selecting solutions. Surrogate-based optimization is widely used in engineering design problems, such as aerodynamic shape optimization, where evaluating the objective functions can be computationally expensive. Machine learning techniques help in efficiently finding optimal designs by predicting performance based on limited evaluations.

3.5.2 Modern Developments: Integration of Deep Learning Techniques [64,65]

Deep learning techniques have been integrated into MOEAs to enhance their ability to model complex relationships between objectives. This integration allows for more effective exploration of the solution space and improved convergence towards optimal solutions. For instance, Li et al. [64] explored the use of deep reinforcement learning to guide the search process in MOEAs, improving convergence speed and solution quality. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of deep learning in recognizing patterns and optimizing search strategies.

3.5.3 Ensemble Methods [66,67]

Ensemble methods combine multiple MOEAs to leverage their strengths and mitigate weaknesses. They are increasingly being applied in MOEAs to enhance solution diversity and robustness. By combining multiple MOEA strategies, researchers have demonstrated improved performance and robustness in complex optimization problems. For example, a study by Chen et al. [49] presented an ensemble approach that integrates different MOEAs, leading to better exploration of the objective space and enhanced Pareto front approximation.

3.5.4 Emerging Trends in Hybrid Approaches

The integration of MOEAs with other optimization techniques, such as metaheuristics and ma-chine learning, is becoming increasingly common. These hybrid approaches aim to balance exploration and exploitation more effectively. Recent applications include multi-agent systems and adaptive control, demonstrating their versatility and effectiveness in complex optimization scenarios [68]. Specific case studies have shown that combining MOEAs with swarm intelligence techniques leads to improved exploration of the solution space, particularly in dynamic environments [58].

Recent developments have also focused on the integration of advanced machine learning paradigms—including neural networks, surrogate models, and large language models (LLMs)—into the design of MOEAs. These integrations aim to improve convergence speed, model expensive objective functions, and enhance decision support in complex, high-dimensional, and dynamic optimization tasks.

A comprehensive and up-to-date account of such developments is presented in the recent book by Saxena et al. (2024), Machine Learning Assisted Evolutionary Multi- and Many-Objective Optimization [69]. The book discusses various ML-assisted strategies such as preference learning, model-based selection, performance prediction, and automated knowledge transfer. Moreover, it addresses the integration of ML in many-objective problems (MaOPs), a growing challenge in the EMO field, and outlines emerging trends such as deep learning and LLM-based hybridizations that guide or accelerate the evolutionary search process.

Table 5 presents the motivation behind the evolution of various MOEA methods.

The landscape of MOEAs is rapidly evolving, with ongoing research addressing the complexities posed by many-objective optimization and high-dimensional spaces. The integration of innovative techniques, such as decomposition methods, preference-based optimization, and hybrid approaches, is paving the way for more effective solutions to diverse and complex real-world problems.

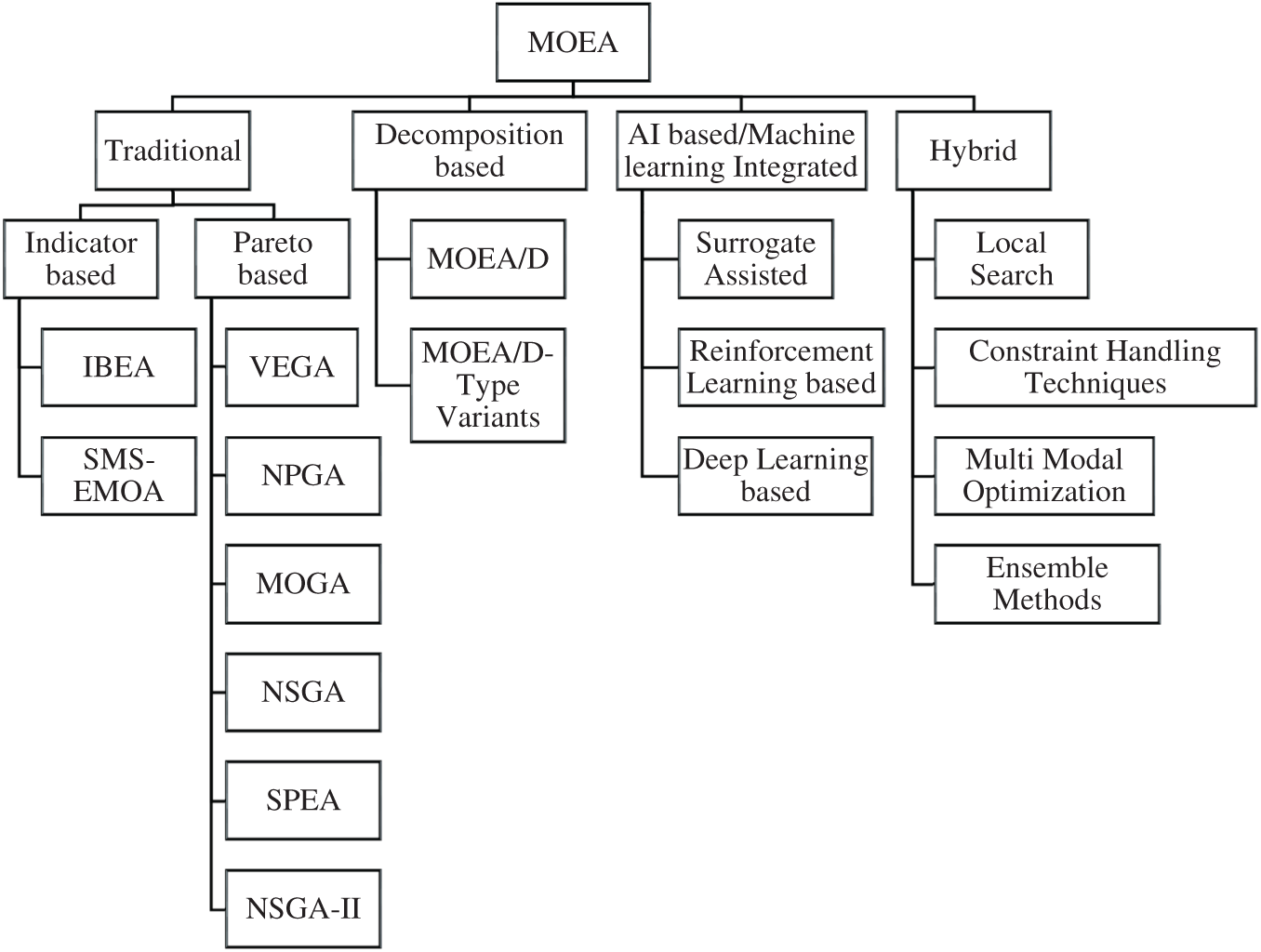

To provide a comprehensive overview of the diverse landscape of MOEAs, Fig. 1 categorizes the main methods and techniques, including traditional, decomposition-based, AI-based, and hybrid approaches.

Figure 1: Classification of MOEAs

4 Advanced Topics and Emerging Trends

4.1 Many-Objective Optimization (MaO)

MOOPS, which involve more than three objectives, introduce significant challenges due to the exponential growth in the number of Pareto-optimal solutions. This phenomenon complicates the search for optimal solutions and necessitates the development of specialized techniques. The term “many-objective optimization” has been introduced to characterize these complex problems, emphasizing the need for innovative approaches to maintain solution diversity and convergence [70,71]. The implications of many-objective optimization extend beyond mere solution count; they affect computational resources and the effectiveness of algorithms in converging to a diverse set of optimal solutions.

As the complexity of real-world problems increases, many applications now involve more than three or four conflicting objectives. This shift has given rise to the field of MaO, typically referring to optimization problems with four or more objectives. The conventional MOEA frameworks, especially Pareto-based methods like NSGA-II and SPEA2, often face scalability issues in such contexts due to challenges like loss of selection pressure, insufficient diversity, and difficulties in Pareto ranking when most solutions tend to become non-dominated.

This has led to the development of EMaO algorithms, which extend MOEAs with specialized techniques for high-dimensional objective spaces. Examples include:

• NSGA-III, which introduces reference points to maintain diversity in many-objective problems.

• MOEA/D with adaptive weights, which improves decomposition-based scalability.

• Objective reduction and dimensionality reduction techniques to mitigate the curse of dimensionality.

• Indicator-based methods, such as hypervolume-based selection or IGD (Inverted Generational Distance), optimized for many-objective landscapes.

Additionally, machine learning techniques and large language models (LLMs) have been recently incorporated into EMaO frameworks to guide the search process intelligently, predict performance, or reduce computational complexity. The growing importance of EMaO is reflected in the increasing number of benchmark suites (e.g., MaF test problems), dedicated workshops, and focused research on real-world, large-scale optimization tasks in fields such as energy systems, supply chains, and bioinformatics.

4.2 Real-Time Decision Support

The application of MOEAs in real-time decision-making scenarios is on the rise. Researchers are exploring how MOEAs can be utilized in systems requiring immediate responses, such as autonomous systems and smart cities. This trend emphasizes the need for algorithms that can deliver quick and reliable solutions in dynamic and uncertain environments [72–74].

Large-Scale Decision Variable Analysis [75,76]: Research on an algorithm denoted as LMEA-DVQA highlights the importance of decision variable analysis in improving the performance of multi-objective evolutionary algorithms. This study compares several algorithms and emphasizes the effectiveness of the proposed method in various test scenarios [20].

Fairness, transparency, and ethical implications in algorithmic decisions are becoming key concerns. With the growing importance of ethical considerations in decision-making, future research may also address the fairness and equity of solutions generated by MOEAs. Future MOEA research will likely incorporate ethical criteria directly into fitness functions or develop mechanisms to ensure equity and sustainability in generated solutions. Ensuring that optimization processes consider social and ethical implications will be vital in areas such as resource allocation and environmental sustainability [73,77–79].

4.4 Parallel and Distributed MOEAs

The utilization of parallel computing resources, including GPUs and distributed architectures, has significantly improved the scalability of MOEAs. Recent advancements emphasize the importance of leveraging parallelization to enhance computational efficiency, particularly in high-dimensional optimization problems [58]. This trend is expected to continue as computational re-sources become more accessible and powerful.

4.5 Integration of Decision-Making in EMO

While Evolutionary Multi-Objective Optimization (EMO) techniques are adept at generating a diverse set of trade-off solutions (Pareto fronts), the ultimate selection of a single solution or a subset of solutions often involves a human decision-maker. This process bridges the gap between optimization and real-world application. As such, the integration of decision-making mechanisms into EMO algorithms has become a key area of interest.

There are three main paradigms for incorporating decision-making in EMO:

• A priori approaches, where decision-makers specify preferences (e.g., weights, aspiration levels) before the optimization begins.

• A posteriori approaches, where the algorithm generates the Pareto front, and the decision-maker selects a preferred solution afterward.

• Interactive approaches, where preferences are iteratively updated during the optimization process, allowing the search to dynamically adjust to evolving decision criteria.

Recent advancements include preference-based EMO algorithms (e.g., reference-point-based NSGA-III) and interactive EMO systems, which employ machine learning or surrogate models to predict and incorporate user preferences on the fly. These approaches enhance the practical usability of EMO methods, especially in domains such as environmental policy planning, engineering design, healthcare, and financial portfolio selection.

Incorporating decision-making into EMO frameworks also facilitates the resolution of many-objective problems, where visualizing or interpreting large Pareto sets becomes increasingly difficult. Decision-making support systems, visualization tools, and dimensionality reduction techniques now play a pivotal role in making EMO results actionable.

5 Bibliometric Analysis and MOEA Visibility

5.1 Bibliometric Analysis and Its Relevance to the Evolution of MOEAs

Bibliometric analysis provides valuable insights into the historical trajectory and scholarly attention surrounding the development of MOEAs. While previous sections have discussed the algorithmic innovations in MOEAs from a technical standpoint, this section complements that perspective by revealing how such developments are reflected in the research landscape through publication trends, journal focus, and geographic distribution.

The annual volume of publications on MOEAs across major academic databases (ScienceDirect, IEEE Xplore, Web of Science) demonstrates a significant growth trend over the past two decades. This increase correlates with key algorithmic breakthroughs such as the introduction of NSGA-II, MOEA/D, and recent hybrid and deep-learning-based MOEAs, showing a tangible link between algorithmic milestones and scholarly output.

Moreover, the distribution of MOEA-related research across journals reveals the interdisciplinary nature of these algorithms. Journals focusing on evolutionary computation, soft computing, applied mathematics, operations research, and domain-specific applications (e.g., energy, healthcare, logistics) have all contributed to shaping the algorithmic evolution of MOEAs. This trend underlines how methodological advancements have been driven both by theoretical interest and practical demand.

Highly cited authors and institutions identified through citation analysis also mirror the timeline of algorithmic development. For instance, the rise in citations of foundational works by Deb (e.g., NSGA-II) and Zhang (e.g., MOEA/D) corresponds to the widespread adoption of these algorithms in subsequent research. Similarly, countries with significant contributions—such as India, China, Germany, and the USA—have played central roles in both theoretical and application-oriented advancements.

Thus, rather than merely presenting descriptive bibliometric statistics, this section contextualizes the scholarly evolution of MOEAs in parallel with their technical advancements. The bibliometric patterns observed serve as a macro-level indicator of how the field has matured, diversified, and responded to new computational and societal challenges.

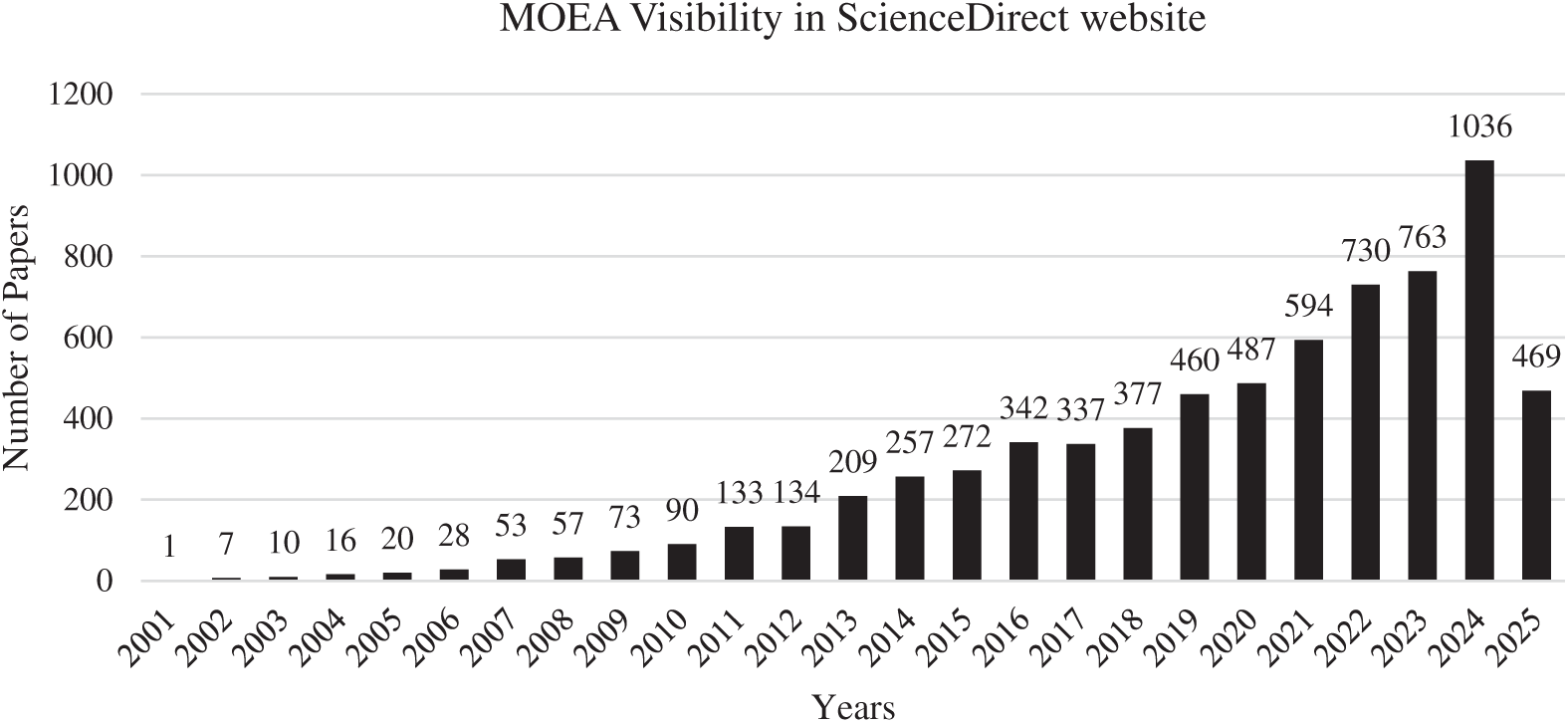

In this section, the visibility of MOEAs in the ScienceDirect website is explored. By the search of (“Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm”) keywords in this science base, the following results were obtained. The number of journal papers in each year is shown in Fig. 2:

Figure 2: Number of MOEA papers in each year in ScienceDirect

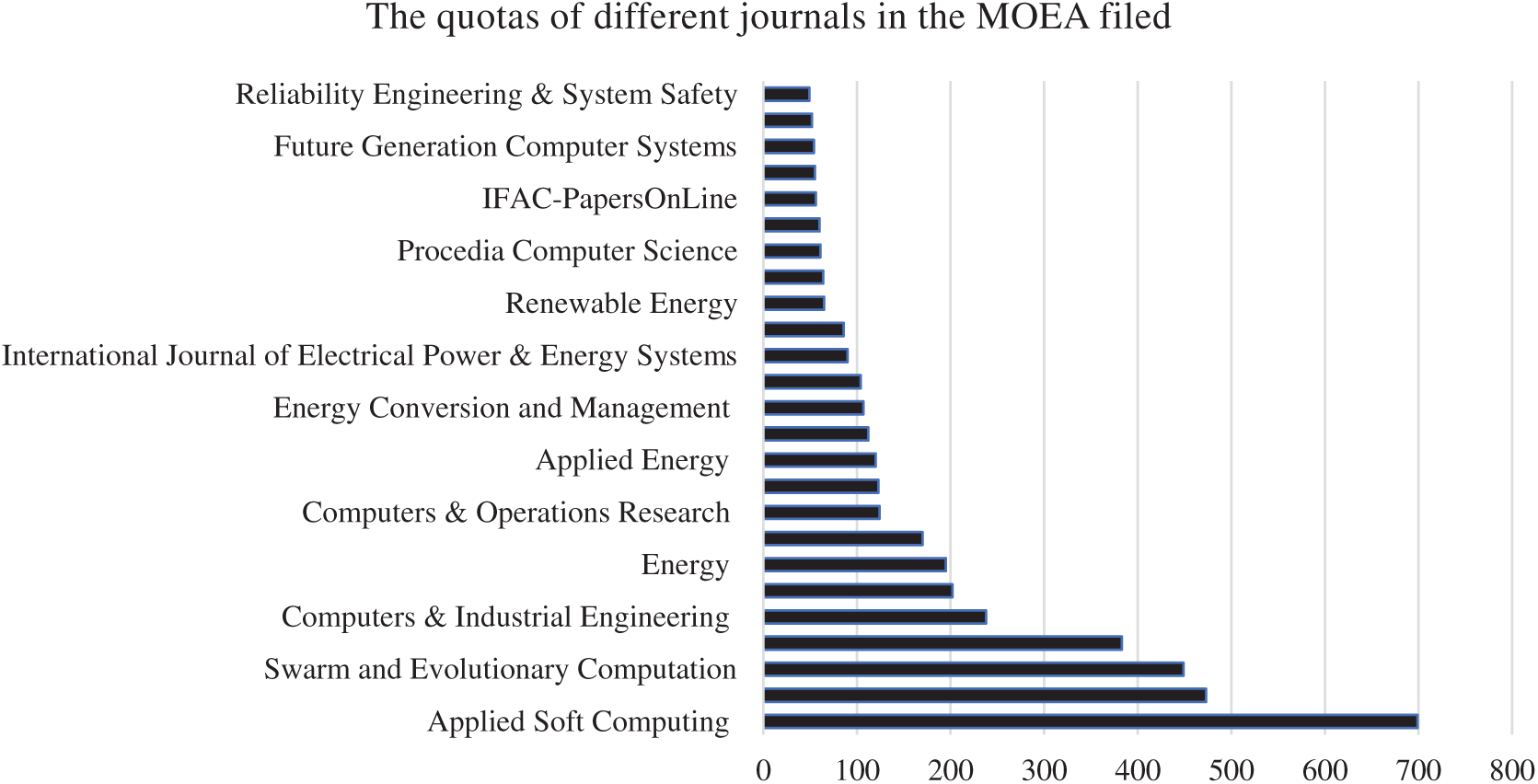

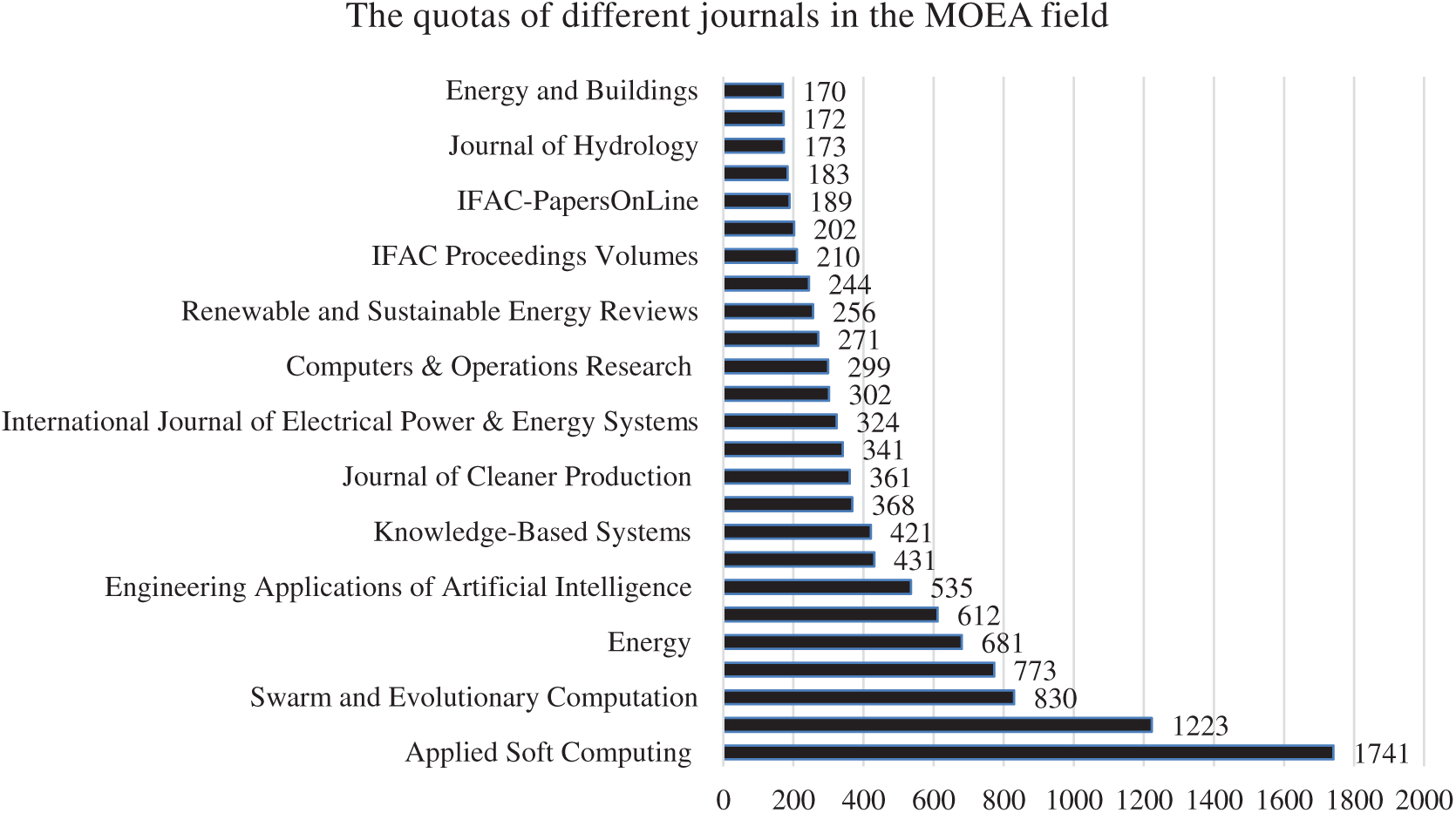

The number of all journal papers in this field has been 6955 papers that quotas of different journals are as follows and illustrated in Fig. 3: Applied Soft Computing (699), Expert Systems with Applications (473), Swarm and Evolutionary Computation (449), Information Sciences (383), Computers & Industrial Engineering (238), Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence (202), Energy (195), Knowledge-Based Systems (170), Computers & Operations Research (124), Neurocomputing (123), Applied Energy (120), Journal of Cleaner Production (112), Energy Conversion and Management (107), Europe-an Journal of Operational Research (104), International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems (90), Journal of Hydrology (86), Renewable Energy (65), Applied Thermal Engineering (64), Procedia Computer Science (61), Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (60), IFAC-Papers On-Line (56), Environmental Modelling & Software (55), Future Generation Computer Systems (54), Ocean Engineering (52), Reliability Engineering & System Safety (49).

Figure 3: The quotas of different journals in ScienceDirect (MOEA)

An increasing number of publications per year are observed that can allow us to say the field of MOEAs has now reached a stage of maturity after the earliest papers published at 2001, and there are also many basic issues yet to be resolved and there is an active and vibrant worldwide community of researchers working on these issues.

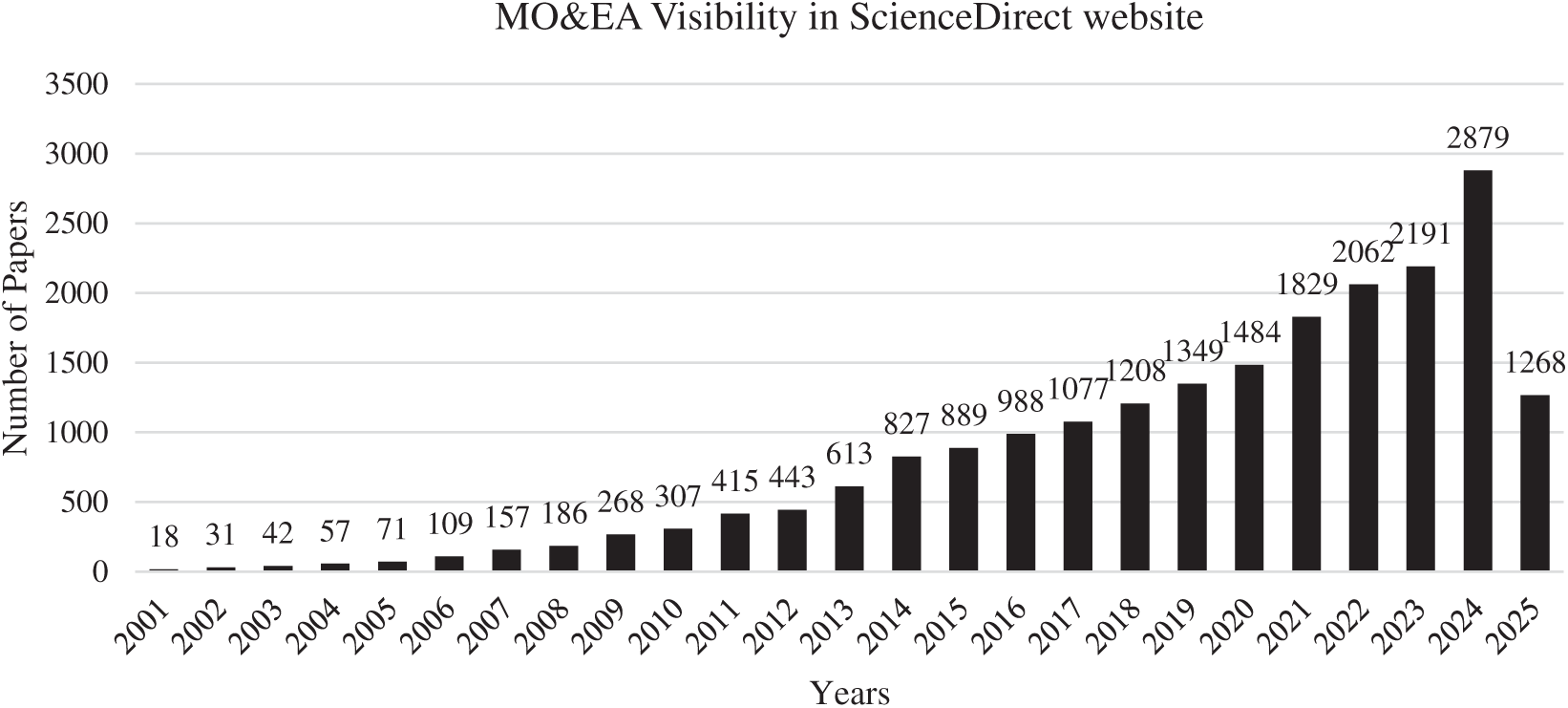

We repeated the search this time with the keywords of (“Multi-objective” and “Evolutionary Algorithm”) keywords in this ScienceDirect website. The number of all journal papers in this field is 20,814 papers and the number of Journal papers in each year is as Fig. 4. In this case, the quotas of different journals are as follows and illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 4: Number of MO&EA papers in each year in ScienceDirect

Figure 5: The quotas of different journals in ScienceDirect (MO&EA)

5.3 MOEAs in IEEE Publications

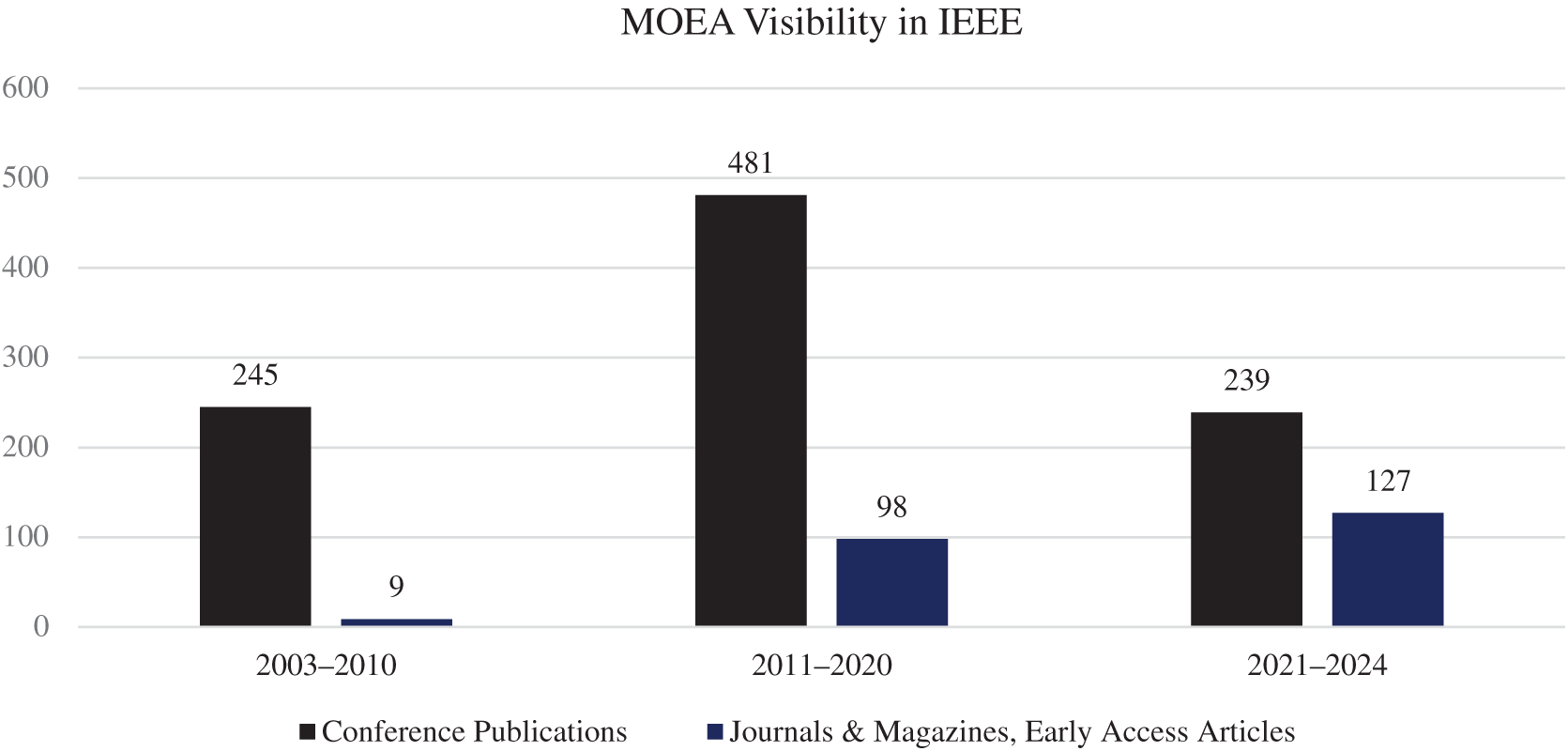

By similar search of (“Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm”) keywords in IEEE website, the following results were obtained. From 2003 up to 2025: Conference Publications (980), Journals & Magazines, Early Access Articles (234). The time extension of publications in IEEE is as follows (Fig. 6):

Figure 6: Number of MOEA papers in each time extension in IEEE publications

2003–2010: Conference Publications (245), Journals & Magazines, Early Access Articles (9).

2011–2020: Conference Publications (481), Journals & Magazines, Early Access Articles (98).

2021–2024: Conference Publications (239), Journals & Magazines, Early Access Articles (127).

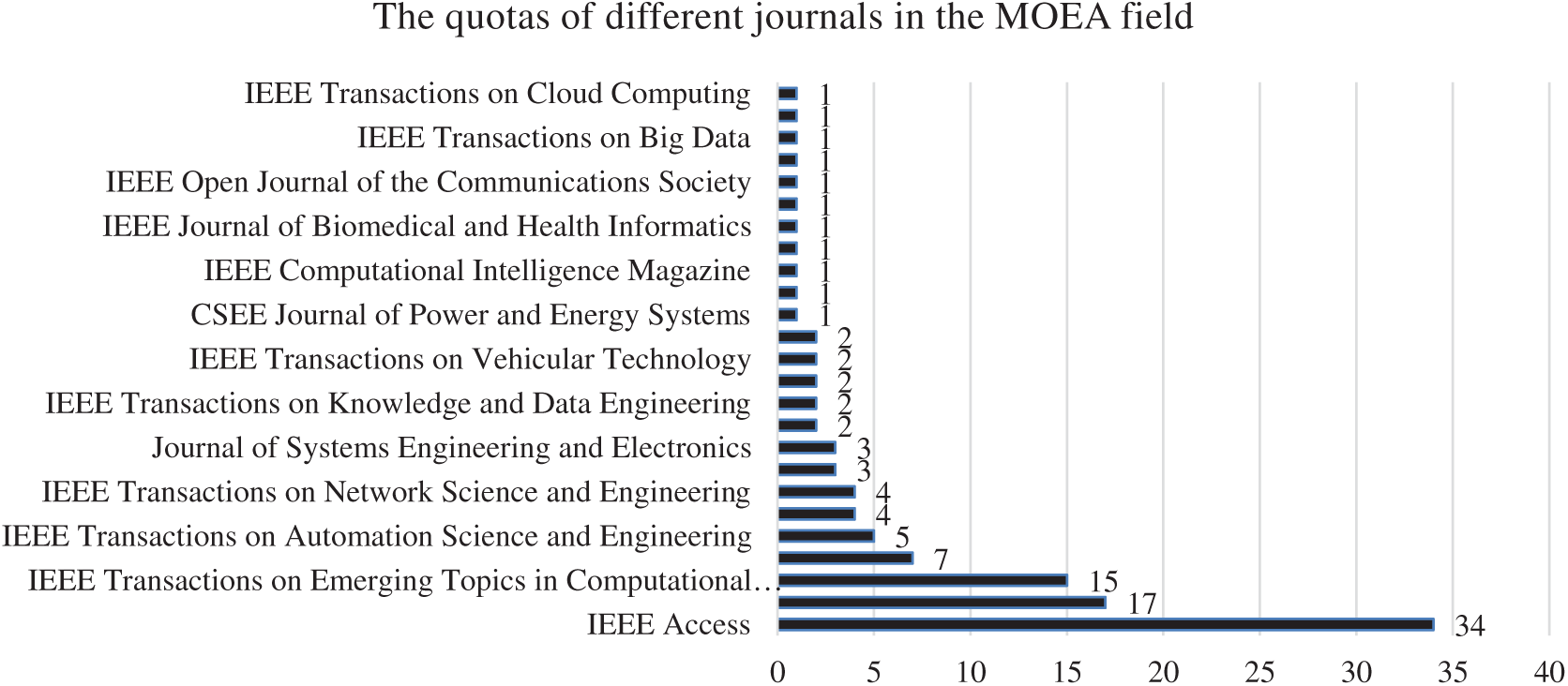

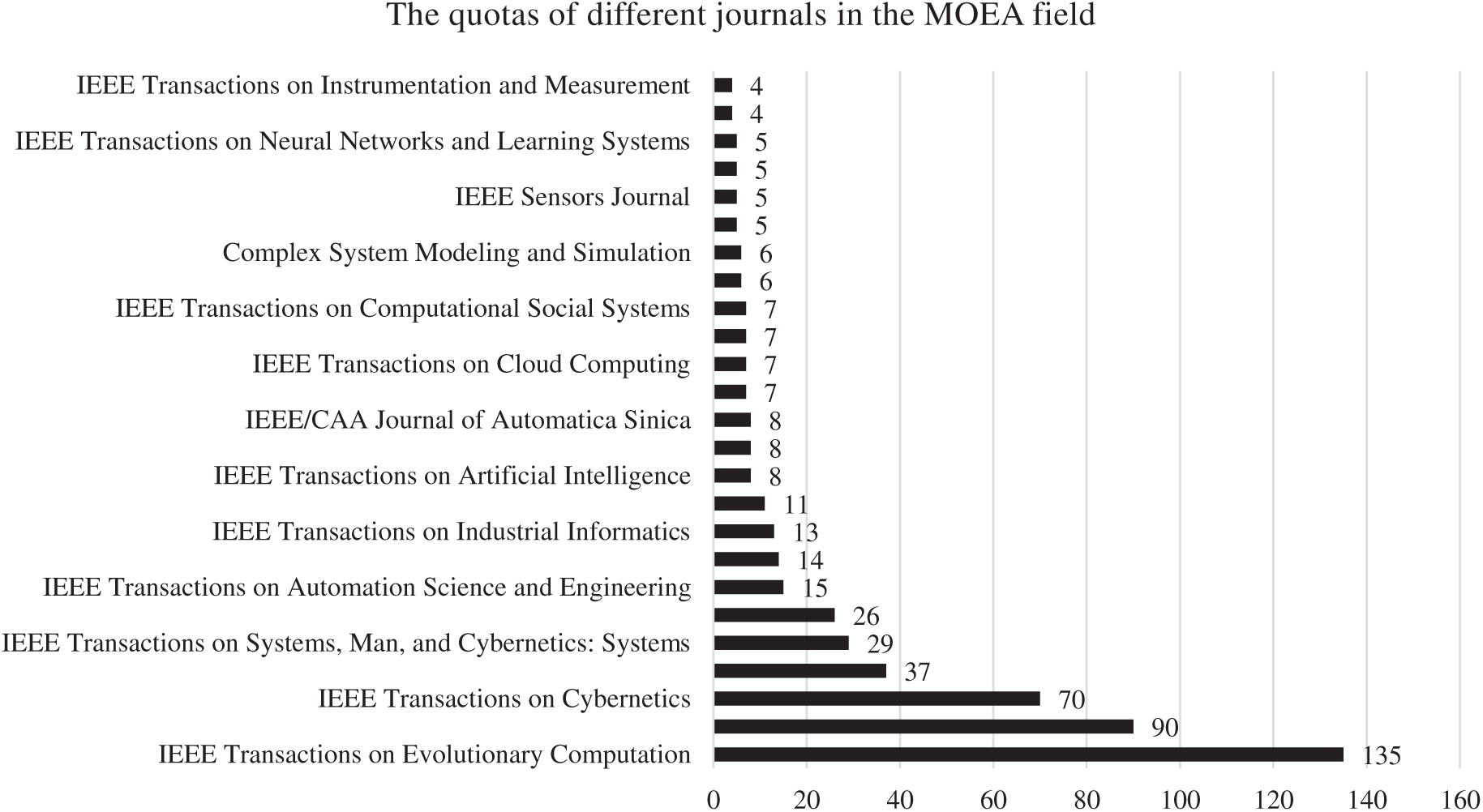

The number of all journal papers in this field has been 234 papers that quotas of different journals are as follows and illustrated in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: The quotas of different journals in IEEE publications (MOEA)

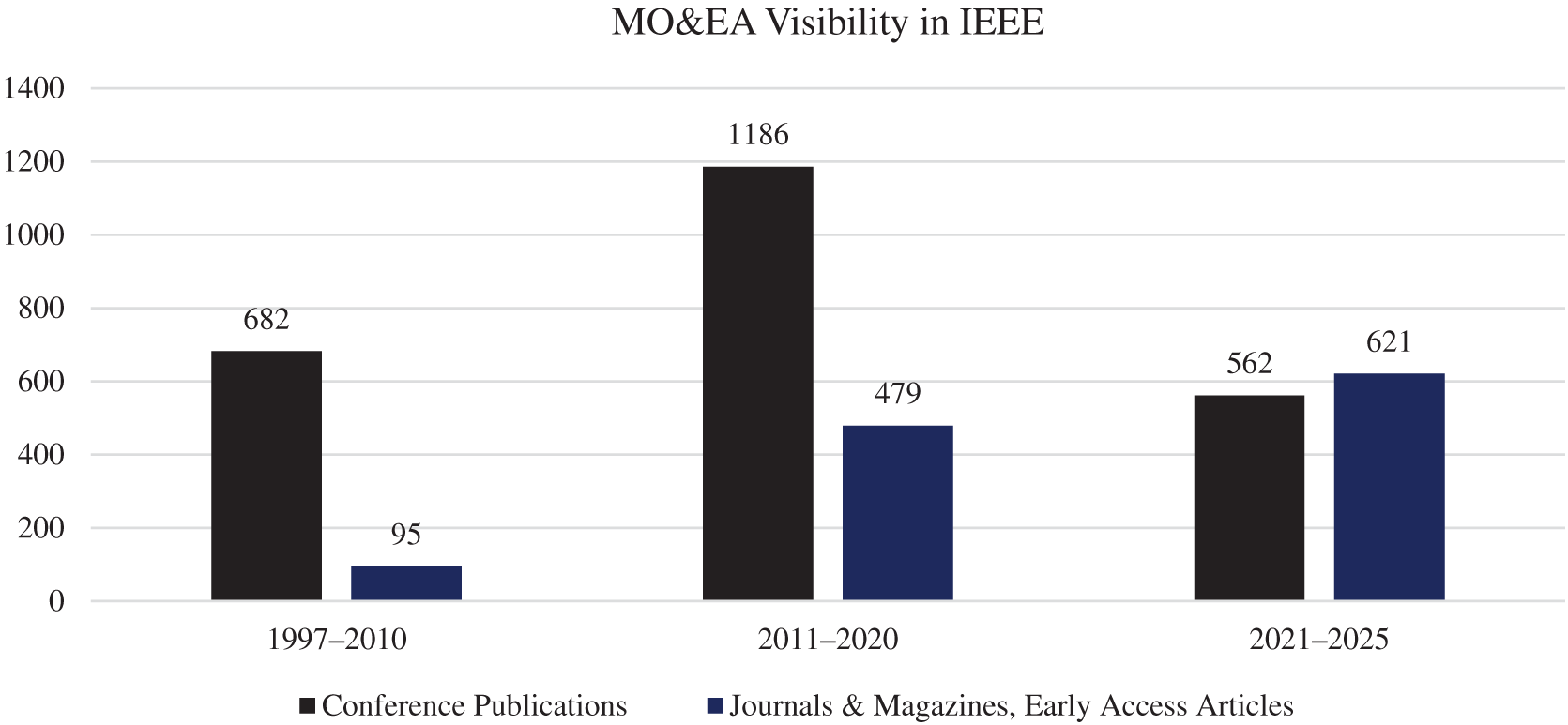

We repeated the search this time with the keywords of (“Multi-objective” and “Evolutionary Algorithm”) keywords in IEEE too. The number of all journal papers in this field has been 1195 papers and the number of Journal papers in each time extension is as Fig. 8. The quotas of different journals in this case are illustrated in Fig. 9.

Figure 8: Number of MO&EA papers in each time extension in IEEE publications

Figure 9: The quotas of different journals in IEEE publications (MO&EA)

As can be seen in Figs. 6 and 8, although the final time extension covers a shorter range (only 2021 to 2025), the number of journal articles in this field has grown compared to previous larger time extensions, indicating the growing attention of the scientific community to this research field.

The authors with the most publication in IEEE, are brought in the following: Yaochu Jin(62), Qingfu Zhang (44), Xingyi Zhang (39), Kay Chen Tan (39), Ye Tian (35), Gary G. Yen (33), Jun Zhang (26), Xin Yao (24), Maoguo Gong (23), Ling Wang (21), Shengxiang Yang (20), Qiuzhen Lin (19), Hisao Ishibuchi (19), Hai-Lin Liu (19), Lei Zhang (19), Dunwei Gong (18), Ran Cheng (17), Yong Wang (16), Aimin Zhou (16), Jing Liu (15), Licheng Jiao (15), Fan Cheng (14), Ke Tang (13), Zexuan Zhu (13), Carlos A. Coello Coello (13).

Also in these years, the number of papers in IEEE conferences with this topic in different countries has been as: China (350), Canada (80), Australia (67), USA (60), Japan (55), Singapore (50), Spain (49), UK (41), New Zealand (38), Mexico (28), Poland (28), Norway (27), Brazil (24).

5.4 MOEAs in the ISI Web of Science (WOS)

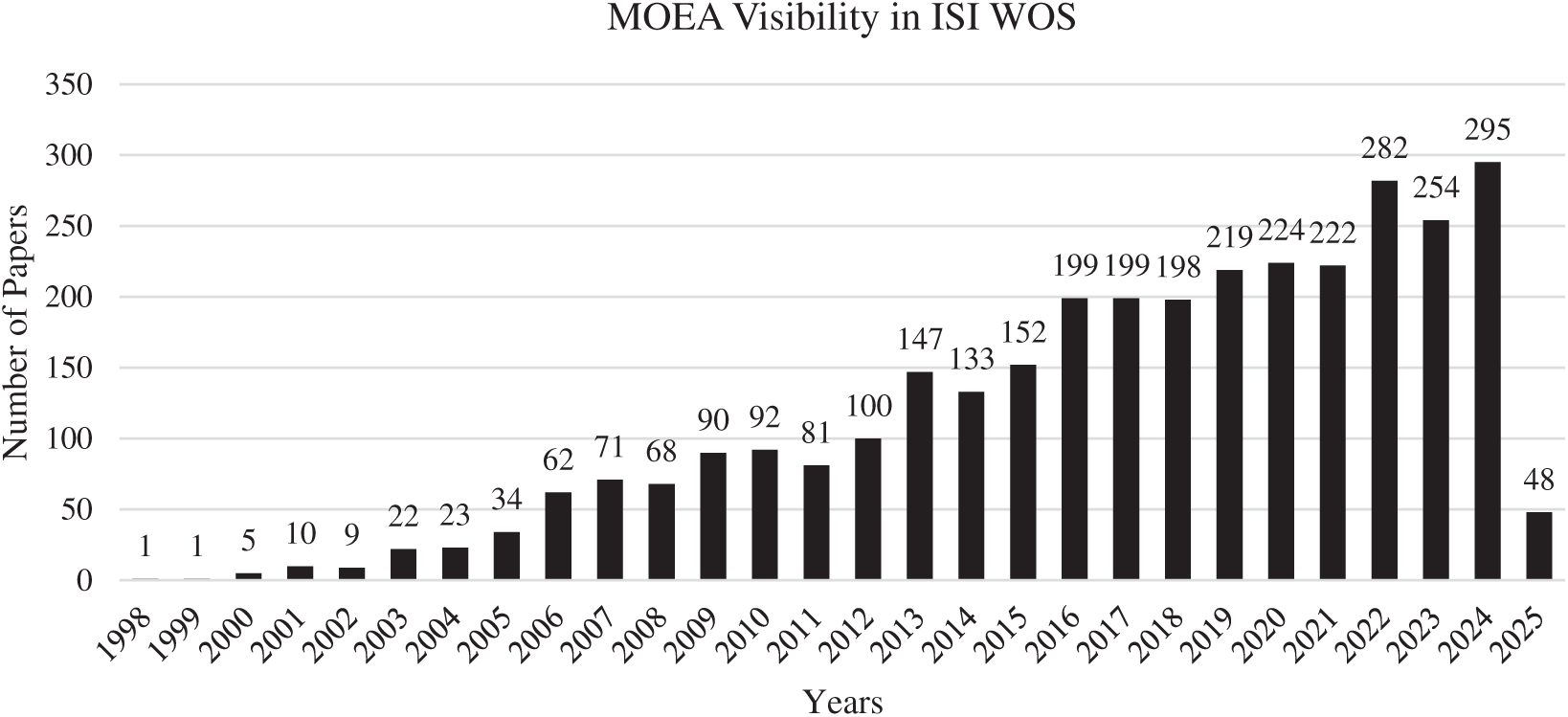

By search of (“Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm”) keywords in ISI WOS, 3241 documents are found which include 2062 Article, 1220 Proceeding Paper, 26 Early Access, 23 Review Article, 7 Book Chapters, 4 Retracted Publication, 2 Editorial Material, 2 Meeting Abstract, 1 Correction, and 1 Letter. Also, the number of published papers in each year in this database is shown in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Number of MOEA papers in each time extension in ISI WOS

In this knowledge database, the authors with the most published papers are: Coello, Carlos A Coello (62), Kim, Kwang-Yong (29), Koziel, Slawomir (23), Tan, Kay Chen (22), GAO, Liang (21), Jin, Yaochu (20), Wang, Ling (19), Bekasiewicz, Adrian (18), London, Joao Bosco Augusto (17), Delbem, Alexandre C B (17), Yao, Xin (17), While, L. (16), Zhang, Hui Jie (16), Jiao, Licheng (16), Rui, Wang (16), Cheng, Fan (15), Husain, Afzal (13), Guo, Xiwang (13), Liu, Jing (13), Konstantinidis, Andreas (13).

5.5 The Most Cited Papers at the ISI WOS

The search on the ISI Web of Science allows us to get the most cited papers that can provide a picture on the important contributions on the topic that are representative approaches of different categorization areas. One notable point about the most cited articles is that 4 of the 6 most cited articles were published in the Journal of Evolutionary Computation.

Regarding the search methodology, let us mention that the citation data reported in this subsection is based on a keyword-specific bibliometric search in the ISI Web of Science database using the exact term “Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm”. This keyword was chosen to ensure consistency and specificity in identifying publications that explicitly fall under the MOEA category. However, it is important to note that some of the most impactful publications in the broader EMO field—such as the NSGA-II paper by Deb et al. (2002)—may not contain this exact phrase in their title or abstract and thus may not appear at the top of this particular search. To address this limitation and better reflect the true academic impact, we have included a dedicated subentry for the NSGA-II paper, which, as of 2024, has accumulated over 33,000 citations, making it the most cited paper in the field of evolutionary computation.

NSGA-II (33,478 Citations) [36]: This seminal paper by Deb et al. (2002) introduced the NSGA-II algorithm, which significantly improved upon earlier multi-objective genetic algorithms in terms of computational efficiency and diversity preservation. Although the paper may not explicitly use the phrase “Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm” in its title or keywords, it is universally recognized as one of the foundational and most impactful works in the EMO domain, and as such, it is included here outside of the strict keyword-based filtering for the sake of completeness and clarity.

HypE: An Algorithm for Fast Hypervolume-Based Many-Objective Optimization (1532 Citations) [45]: This paper addresses the problem of the high computational effort required to calculate Hyper-volume (as the only single set quality measure that is known to be strictly monotonic with regard to Pareto dominance), which has prevented the full exploitation of the potential of this index. It proposes a fast search algorithm that uses Monte Carlo simulation to approximate the exact values of Hypervolume. The main idea is based on the ranking of solutions induced by the Hyper-volume index, rather than the actual values of the indicator. As a result, HypE is presented in detail as an estimation algorithm for MOO that reduces the available computational resources, increases the accuracy of the estimates, and provides a trade-off for the execution times.

Multi-objective grey wolf optimizer: A novel algorithm for multi-criterion optimization (1137 Citations) [80]: In this paper, for the first time, the optimization of MOOP using the Gray Wolf Optimizer (GWO) algorithm is investigated. For this purpose, the Multi-Objective Gray Wolf Optimizer (MOGWO) is introduced by integrating a fixed-size external archive for saving and retrieving Pareto-optimal solutions with GWO. This archive is used to define the GWO optimization parameters such as social hierarchy and simulate the hunting behavior of wolves. It shows improved accuracy compared to some other previous MOEAs.

Borg: An Auto-Adaptive Many-Objective Evolutionary Computing Framework (536 Citations) [81]: This paper introduces a method for many-objective, multimodal optimization by combining epsilon dominance, epsilon-progress as a measure of convergence speed, randomized restarts, and auto-adaptive multi-operator recombination in a unified optimization framework called Borg MOEA. Borg MOEA represents a class of algorithms whose operators are adaptively selected based on the problem and it is not a single algorithm.

MOEA/D with Adaptive Weight Adjustment (523 Citations) [82]: This paper introduces a MOEA based on decomposition (MOEA/D) with Adaptive Weight Vec-tor Adjustment (MOEA/D-AWA) to deal with the complex Pareto front in target MOOP. The considered MOOP is decomposed into a set of scalar subproblems using uniformly distributed aggregation weight vectors. Then, by analyzing the geometric relationship between weight vectors and optimal solutions under the Chebyshev decomposition scheme, a novel weight vector initialization method and an adaptive weight vector adjustment strategy with periodic weight adjustment capability are proposed.

Strategies for finding good local guides in multi-objective particle swarm optimization (MOPSO) (499 Citations) [83]: This paper introduces the Sigma method as a new method for finding the best local guides (global best particle) for each particle in a population of a set of Pareto optimal solutions in Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO). This selection method has a significant impact on the convergence and diversity of solutions, especially when optimizing problems with a large number of objectives.

Evaluating the ε-domination based multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for a quick computation of pareto-optimal solutions (498 Citations) [84]: This paper attempts to present a computational solution for Pareto-optimal solutions to MOOP based on the concept of epsilon dominance, such that offers a good compromise in terms of con-vergence close to the Pareto-optimal front, solution diversity, and computational time. This method allows decision makers to control the achievable accuracy of the obtained Pareto-optimal solutions.

5.6 Notable Researchers and Contributions

While the bibliometric analysis in this section was conducted using the specific keyword “Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm,” we acknowledge that this approach may not have captured all seminal publications and contributors in the broader EMO and MCDM communities. To address this, we highlight below the contributions of several prominent researchers whose work has significantly shaped the field:

• Kalyanmoy Deb: Widely regarded as a foundational figure in EMO, he introduced several key algorithms including NSGA and NSGA-II [36,44], which are central to the evolution of MOEAs. His work is extensively cited and referenced throughout this paper.

• Carlos Fonseca & Peter Fleming: Their work on fitness assignment strategies for multi-objective genetic algorithms (1993, 1995) laid important groundwork for dominance-based approaches and is already referenced in Section 2 and the timeline table.

• Joshua Knowles: Co-developer of the Pareto Archived Evolution Strategy (PAES), he made early contributions to minimalist, archive-based MOEAs, which we discussed in Section 1.4.

• Michael Emmerich: Known for his work on surrogate-assisted and performance indicator-based EMO methods, contributing to methods like SMS-EMOA and hypervolume approximations.

• Kaisa Miettinen: A key contributor to interactive multi-objective optimization and decision-making, particularly within the MCDM community.

• Sanaz Mostaghim: Her research includes swarm intelligence approaches and hybridization strategies in MOEAs, including Particle Swarm and multi-modal optimization.

We recognize that a more comprehensive representation of the field may require extending the keyword strategy to include alternative terms like “evolutionary multi-objective optimization,” “multi-criterion decision-making,” or “interactive EMO.” This limitation is acknowledged and will be addressed in future extensions of this study.

6 Future Directions and Conclusions

As the field of MOEAs continues to evolve, several future directions and research trends are emerging. These directions reflect both ongoing challenges and the expanding potential of MOEAs in diverse applications:

⮚ Hybrid Approaches: There is a growing trend towards hybridizing MOEAs with other optimization techniques, such as machine learning algorithms and swarm intelligence methods. These hybrid approaches aim to enhance the exploration and exploitation capabilities of MOEAs, leading to improved performance in complex optimization landscapes and in uncertain and dynamic environments. Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of combining MOEAs with machine learning techniques to adaptively refine search strategies [61,62,72,84].

⮚ Adaptive Mechanisms [85,86]: The development of adaptive mechanisms within MOEAs is becoming increasingly important. These mechanisms allow algorithms to adjust their parameters dynamically based on the characteristics of the optimization problem at hand. This adaptability allows for more efficient exploration and exploitation of the solution space, leading to improved optimization outcomes. Recent work by Qiao et al. [85] implemented adaptive mutation and crossover rates in MOEAs, resulting in improved performance across various benchmark problems. Research indicates that adaptive MOEAs can significantly enhance convergence rates and solution quality, particularly in dynamic environments where problem characteristics may change over time [64–66,75].

⮚ Many-Objective Optimization: As real-world problems often involve more than three objectives, many-objective optimization is gaining traction. New algorithms are being developed to effectively handle the challenges posed by high-dimensional objective spaces, focusing on maintaining diversity while ensuring convergence to optimal solutions. Recent advancements in many-objective evolutionary algorithms (ManyOEAs) highlight their potential in fields such as drug design and engineering [52].

⮚ Scalability Enhancements: MOEAs must increasingly address high-dimensional and many-objective optimization problems. Research is focusing on scalable designs, such as decomposition-based and surrogate-assisted evolutionary algorithms (SAEAs), which reduce computational burden while maintaining solution quality. Further development of robust surrogate models and adaptive parameter tuning strategies is expected to enhance the scalability and effectiveness of MOEAs in solving complex real-world problems.

⮚ Cross-Disciplinary Applications: The scope of MOEAs is expanding to emerging fields such as personalized medicine, smart cities, autonomous vehicles, and sustainability science. Tailoring algorithms to the complex, data-intensive nature of these domains presents new challenges and opportunities and researchers should focus on tailoring MOEAs to meet these challenges presented by complex, dynamic environments.

⮚ Integration with Machine Learning: The synergy between MOEAs and machine learning techniques is becoming a pivotal research direction. Approaches involving reinforcement learning, neural networks, and ensemble methods are being employed to guide search strategies, adaptively refine solution spaces, and improve convergence behavior. This integration can also lead to intelligent and adaptive MOEAs capable of learning from historical evaluations.