Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

OCR-Assisted Masked BERT for Homoglyph Restoration towards Multiple Phishing Text Downstream Tasks

Department of Artificial Intelligence, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, 06974, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Jaesung Lee. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 4977-4993. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068156

Received 22 May 2025; Accepted 07 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Restoring texts corrupted by visually perturbed homoglyph characters presents significant challenges to conventional Natural Language Processing (NLP) systems, primarily due to ambiguities arising from characters that appear visually similar yet differ semantically. Traditional text restoration methods struggle with these homoglyph perturbations due to limitations such as a lack of contextual understanding and difficulty in handling cases where one character maps to multiple candidates. To address these issues, we propose an Optical Character Recognition (OCR)-assisted masked Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model specifically designed for homoglyph-perturbed text restoration. Our method integrates OCR preprocessing with a character-level BERT architecture, where OCR preprocessing transforms visually perturbed characters into their approximate alphabetic equivalents, significantly reducing multi-correspondence ambiguities. Subsequently, the character-level BERT leverages bidirectional contextual information to accurately resolve remaining ambiguities by predicting intended characters based on surrounding semantic cues. Extensive experiments conducted on realistic phishing email datasets demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms existing restoration techniques, including OCR-based, dictionary-based, and traditional BERT-based approaches, achieving a word-level restoration accuracy of up to 99.59% in fine-tuned settings. Additionally, our approach exhibits robust performance in zero-shot scenarios and maintains effectiveness under low-resource conditions. Further evaluations across multiple downstream tasks, such as part-of-speech tagging, chunking, toxic comment classification, and homoglyph detection under conditions of severe visual perturbation (up to 40%), confirm the method’s generalizability and applicability. Our proposed hybrid approach, combining OCR preprocessing with character-level contextual modeling, represents a scalable and practical solution for mitigating visually adversarial text attacks, thereby enhancing the security and reliability of NLP systems in real-world applications.Keywords

Homoglyph Perturbed Text (HPT) refers to text corrupted by visually similar but semantically different characters, which poses a significant challenge for conventional text-based natural language processing (NLP) systems [1,2]. A primary difficulty stems from homoglyphs, which are characters that share close visual resemblance yet represent distinct semantic units. These perturbations evade detection by standard text processing pipelines and pose a security threat [3].

Optical Character Recognition (OCR) emerges as a promising solution in this context, as it enables recognition based on visual features rather than encoded character identity [4]. However, HPT restoration presents an added complexity: the phenomenon of multi-correspondence, where a single perturbed glyph can map onto multiple potential characters. This ambiguity necessitates context-aware disambiguation, for which Masked Language Models (MLM), such as BERT, offer a viable path by leveraging surrounding semantic cues [5]. Furthermore, robust HPT restoration systems must generalize effectively across diverse downstream tasks and resist novel, previously unseen attack types [6].

Despite recent advances, existing approaches exhibit notable limitations. Some methods [7,8] rely exclusively on visual similarity metrics, leading to substantial errors when resolving multi-correspondence Homoglyph Characters (HC). Others [9] employ word-level spell correction techniques, which often fail to restore out-of-vocabulary or newly coined terms due to limited contextual understanding. Additionally, subword-based models compromise character-level fidelity, impairing precise restoration.

To overcome these challenges, we propose a novel approach that integrates visual and linguistic signals to restore HPT. Our method combines OCR-based visual glyph extraction with a character-level BERT model, enabling fine-grained resolution of HPTs while accounting for contextual dependencies. This hybrid architecture not only addresses multi-correspondence issues but also adapts effectively to unseen HC variants and operates reliably under low-resource conditions. Experimental results demonstrate our method’s superior performance across multiple HPT-affected tasks, affirming its robustness and generalizability.

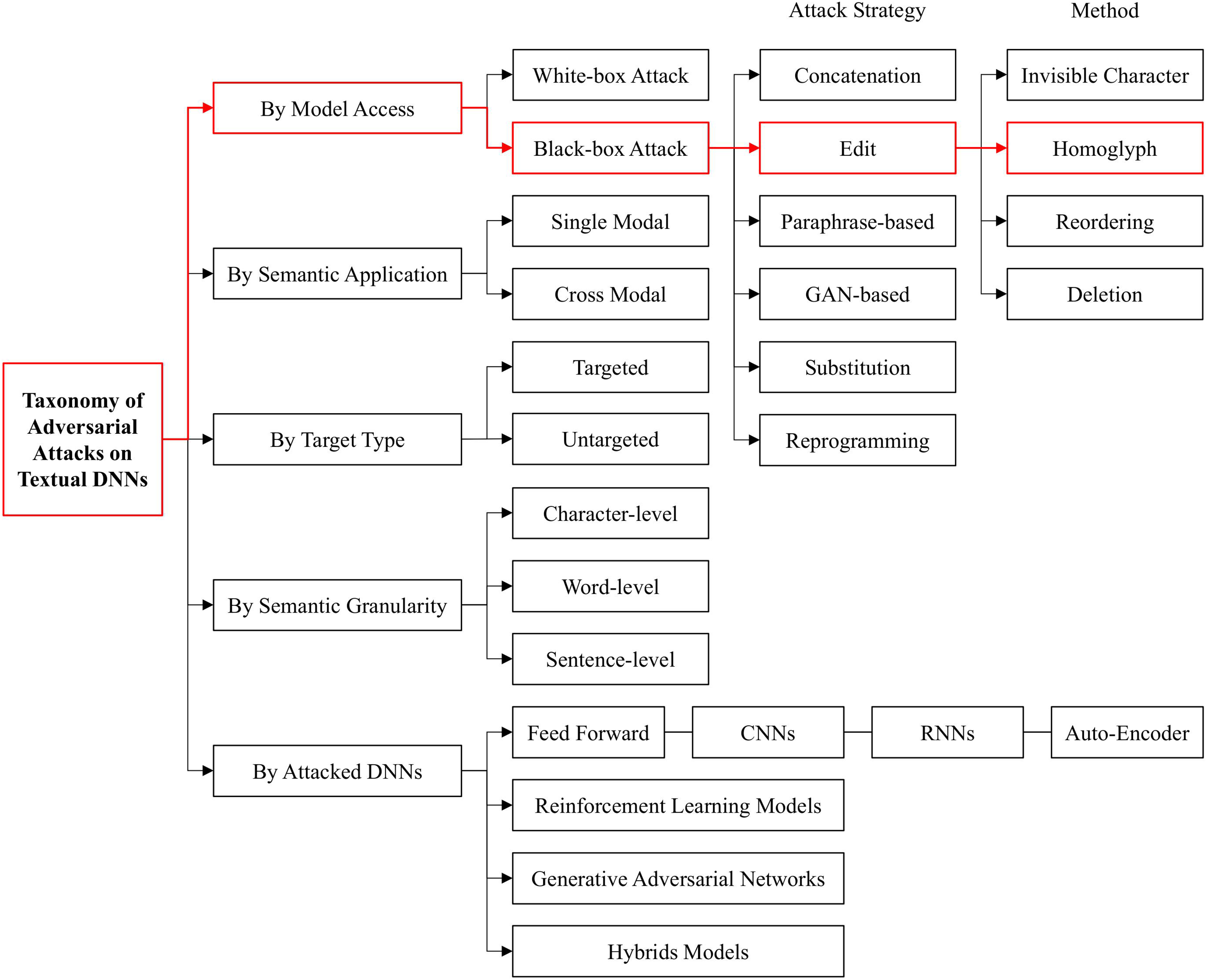

Recent studies on HPT have drawn increasing attention across adversarial NLP, homoglyph detection, restoration techniques, and synthetic dataset generation. Adversarial attacks in NLP are broadly categorized into white-box and black-box attacks, with edit-based strategies—particularly homoglyph perturbations—being representative of black-box settings [1]. Fig. 1 illustrates the taxonomy of adversarial attacks on textual deep neural networks. While early research on homoglyph attacks focused primarily on phishing and Internationalized Domain Name (IDN) spoofing, recent efforts have extended into text-based applications such as spam filtering and adversarial robustness of language models.

Figure 1: Taxonomy of adversarial attacks on textual deep neural networks (adapted from Zhang et al., 2020 [1,2])

Homoglyph detection has been actively explored in IDN security contexts. For instance, Suzuki et al. [7] proposed a SimChar database that maps visually similar character pairs based on pixel-level similarity. Elsayed and Shosha [8], and Woodbridge et al. [10] utilized Siamese neural networks for IDN homoglyph detection, while Yazdani et al. [11] and Almuhaideb et al. [12] presented empirical analyses of homoglyph attack patterns in real-world domains.

Beyond the domain setting, homoglyph perturbations have also been employed in plain-text environments to evade spam filters and toxicity classifiers. Sokolov et al. [2], Julis and Alagesan [13] investigated these attacks in the context of spam email evasion. Similarly, Alvi et al. [14] and Qiu et al. [15] explored detection techniques for homoglyphs in unstructured text.

To mitigate such attacks, various restoration methods have been proposed. OCR-based approaches, such as that by Sawabe et al. [16], convert visually distorted characters into standard forms through image-level processing. Although effective in recognizing HC, these methods are often computationally expensive. Recent approaches like TrOCR [17] extend this idea by integrating Transformer-based architectures with OCR modules, achieving impressive performance in visual text recognition tasks. Although not specifically designed for homoglyph restoration, their methodology highlights the potential of vision-language models in addressing visually perturbed text. Spell-checker-based approaches treat homoglyphs as typographical errors and apply dictionary-based correction, as shown by Imam et al. [9]. However, they struggle with out-of-vocabulary terms and lack contextual reasoning.

Static visual mapping methods such as SimChar [7] provide lightweight alternatives but suffer from ambiguity when a perturbed character maps to multiple plausible candidates. To address the limitations of rule-based techniques, recent studies have employed pre-trained language models. Keller et al. [5] introduced a hybrid architecture combining BERT’s contextual encoding with GPT’s generative capabilities. Additionally, Salesky et al. [18] explored robust open-vocabulary translation using visual text representations, offering valuable insights into bridging vision and language for robust textual modeling under noisy or adversarial conditions. Le et al. [19] further proposed SHIELD, a multi-expert ensemble method to enhance robustness against adversarial perturbations.

In parallel, character-aware language models have demonstrated strong performance in noisy or morphologically complex inputs. CharacterBERT [20] and CharBERT [21] integrate character-level and subword representations to improve resilience against token-level noise, making them well-suited for homoglyph restoration tasks.

Synthetic dataset generation has also played a crucial role in evaluating HPT defenses. TextBugger [22] introduced perturbation strategies for generating adversarial examples through homoglyph substitutions. Viper [23] used embedding-level character replacements at fixed noise ratios, though it has been criticized for unrealistic assumptions. More recently, LEGIT [24] proposed a perceptual model to predict human readability of perturbed text, such as transforming “ergo” into “

Despite these advancements, existing methods still face trade-offs between computational cost, restoration accuracy, and generalizability. To overcome these limitations, our work introduces a character-wise BERT-based restoration framework augmented with OCR-derived visual signals. This hybrid approach effectively captures both the semantic context and visual structure of HC, addressing ambiguity in multi-mapped characters and achieving robust restoration even in low-resource settings.

This section describes a proposed model for effectively restoring HPT caused by HC attacks. The proposed method integrates Optical Character Recognition (OCR) preprocessing with a character-level Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model to enhance accuracy and contextual processing capabilities in text restoration tasks.

HPT is challenging because homoglyph characters intentionally mimic standard characters in appearance while encoding different Unicode symbols [1,2]. Although dictionary-based normalization methods exist, the characteristics of one-to-many mappings in homoglyph attacks (e.g., ‘o’ representing either ‘o’ or ‘0’), which require contextual information for correct restoration, make it even more challenging [7,9]. In addition, they often fail to generalize to unseen substitutions and cannot cover the vast and evolving Unicode space used in HPT attacks [22,24]. As HPT corruption appears across multiple downstream tasks such as phishing detection, toxic comment classification, and document retrieval, restoration models need to generalize effectively without requiring task-specific adjustments [18,25]. Notably, the BitAbuse dataset [25] enables evaluation of homoglyph restoration under real-world phishing scenarios.

Existing works have different limitations regarding the issues mentioned earlier. For example, methods that rely solely on visual similarity to restore homoglyphs often fail when multiple visually similar characters exist, resulting in incorrect or ambiguous mappings [7,16]. Other approaches attempt to apply word-level spell correction techniques, which perform poorly on out-of-vocabulary terms or neologisms that are increasingly common in modern adversarial settings [9,15]. Furthermore, subword-based processing methods, while effective for standard text normalization, struggle to preserve fine-grained character-level distortions introduced by HC, which limits their ability to recover the intended text fully [20,21]. Each of these approaches addresses only a part of the problem—either visual disambiguation or linguistic contextualization—but lacks a comprehensive mechanism to robustly handle both aspects simultaneously across varied application domains.

To address the limitations of conventional methods, we devise an effective restoration method for HPTs in multiple downstream tasks. Specifically, our approach combines vision-based normalization and context-aware disambiguation by integrating OCR-derived shape information with a character-level BERT model. Specifically, the OCR component normalizes visually perturbed glyphs into recognizable alphabetic forms, resulting in a reduced set of target characters to be restored. Next, the character-level BERT captures fine-grained character sequences and leverages surrounding linguistic context to resolve multi-mapping ambiguities. This two-stage mechanism enables robust generalization to novel HC substitutions without relying on exhaustive pre-defined dictionaries. Moreover, by maintaining fine character granularity throughout the restoration process, our method achieves high restoration accuracy and consistent performance across diverse downstream tasks, including phishing detection and adversarial text classification

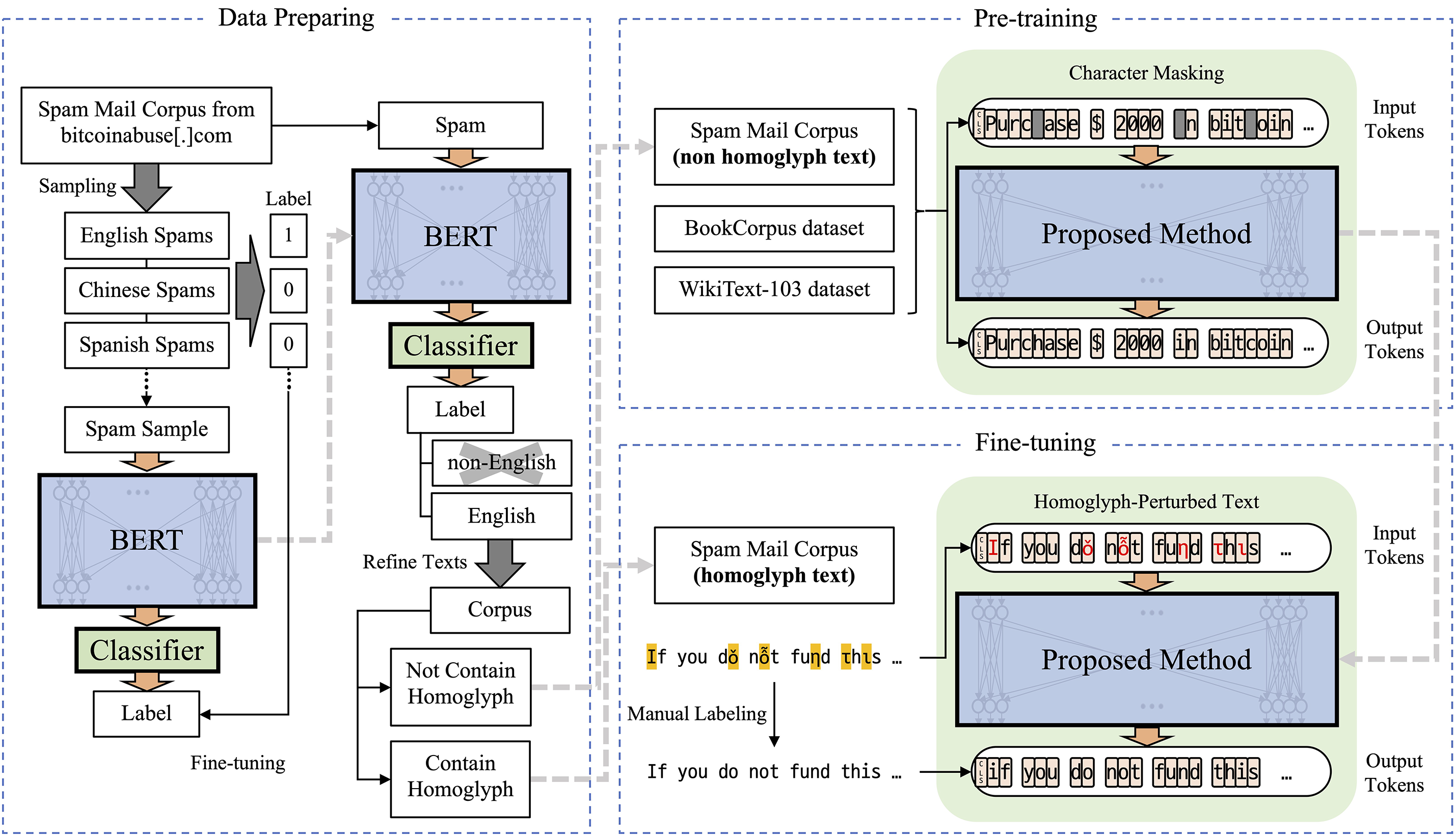

Fig. 2 provides an overview of the proposed HPT restoration framework. Firstly, the OCR preprocessing stage accurately captures the visual characteristics of HC. Although visually similar to legitimate characters, HC differ semantically, creating difficulties in text restoration. OCR preprocessing transforms visually perturbed characters into basic alphabetic characters, significantly reducing ambiguity arising from multi-correspondence and providing clearer input for subsequent restoration processes.

Figure 2: Overview of the proposed HPT restoration framework. The pipeline includes data preparation using multilingual spam filtering, pre-training on clean corpora with character masking, and fine-tuning on manually labeled HPTs. The model leverages OCR-based visual features and contextual cues for accurate character-level restoration

In this work, we employed the open-source Tesseract OCR engine [26] to recognize visually perturbed characters. To optimize recognition accuracy, each homoglyph character was individually rendered using the Noto Sans Runic [27] and GoNotoCurrent [28] fonts, which support a wide range of Unicode symbols. The rendered character images were passed through the OCR engine, and the resulting character pairs (original–recognized) were stored in a JSON file containing a total of 13,488 Unicode alphabet mappings. While most visually similar characters were correctly identified, some recognition errors were observed—e.g., ß misrecognized as K, or ð as A—highlighting the need for contextual modeling in subsequent stages.

After OCR preprocessing, the text is tokenized at the character level to maintain detailed visual and contextual features. Unlike conventional subword or word-level tokenization methods, character-level tokenization allows the model to precisely manage each HC, greatly improving restoration accuracy for individual characters, particularly in context-sensitive scenarios.

The character-level tokenized text processed in this way is then fed into a pre-trained character-wise BERT model. This model leverages bidirectional attention mechanisms at the character level to capture comprehensive contextual information. By effectively utilizing the surrounding context, the character-wise BERT model accurately predicts the original alphabetic characters corresponding to HC perturbations.

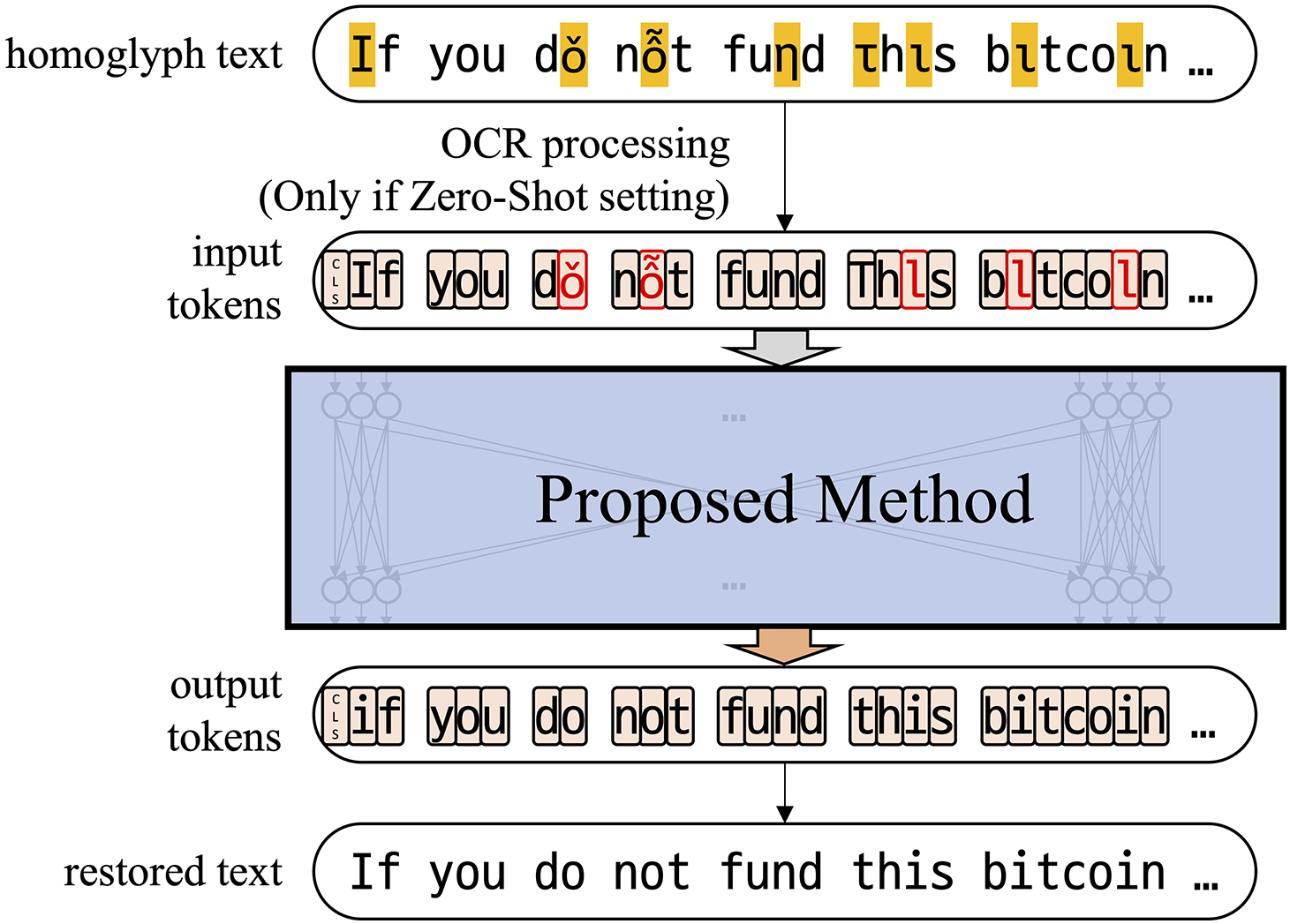

Fig. 3 shows the overview of the proposed model. Our method effectively resolves the multi-correspondence ambiguity inherent in HC attacks, particularly adept at handling one-to-many correspondence scenarios. Moreover, our approach exhibits robust adaptability to previously unseen HC types, maintaining high restoration accuracy even with limited labeled training data. These characteristics make proposed method a highly practical and efficient solution for restoring HPTs.

Figure 3: Overview of the proposed model. The process begins with OCR preprocessing to accurately identify and initially convert visually perturbed characters (highlighted). Subsequently, the character-level tokenized text is fed into a BERT Masked Language Model to restore and predict original alphabetic characters, effectively resolving ambiguities introduced by HC attacks

To construct a realistic and robust dataset for HPT restoration, we designed a multi-stage data preparation pipeline centered on a spam email corpus obtained from bitcoinabuse[.]com [29]. This approach aligns with the BitAbuse dataset by Lee et al. [25], which was also built upon bitcoinabuse.com and enables evaluation on real-world phishing cases. This corpus contains multilingual emails, many of which were authored by real-world attackers leveraging HPTs to evade automated filtering systems. Due to the inherent noise and linguistic variability in the raw data, extensive preprocessing was required to extract meaningful English-language content and to accurately identify HPT instances.

First, to isolate English texts from multilingual content, we trained a supervised BERT-based classifier. Out of 262,268 total samples, 84,214 sentences (approximately 32.1%) were manually annotated with language labels (English or non-English) to construct a labeled subset for training. The annotated data enabled the training of a fully connected classifier built on top of a pre-trained BERT encoder, allowing for accurate and scalable filtering of English-language texts.

Next, we applied regular expressions to remove non-linguistic noise, such as URLs, cryptocurrency wallet addresses, and incoherent character sequences. This step ensured the clarity and consistency of the training data.

To identify and label HPTs, we constructed a dictionary of candidate homoglyph perturbed words by extracting all tokens containing non-ASCII characters. Each entry in this dictionary was manually annotated with its corresponding standard alphabetic form, resulting in a lexicon of over 40,000 labeled instances. While regular expression-based heuristics accelerated this process, many edge cases required manual correction to ensure labeling accuracy. Texts that were semantically incoherent or not written in English were further excluded during this stage.

The BitAbuse dataset includes manually annotated homoglyph-perturbed tokens, where each visually perturbed character is aligned with its intended standard form. Annotation was performed through a semi-automated detection process, followed by manual verification and correction by a single annotator. Although a formal inter-annotator agreement score was not calculated, the entire annotation process was conducted according to a consistent set of guidelines.

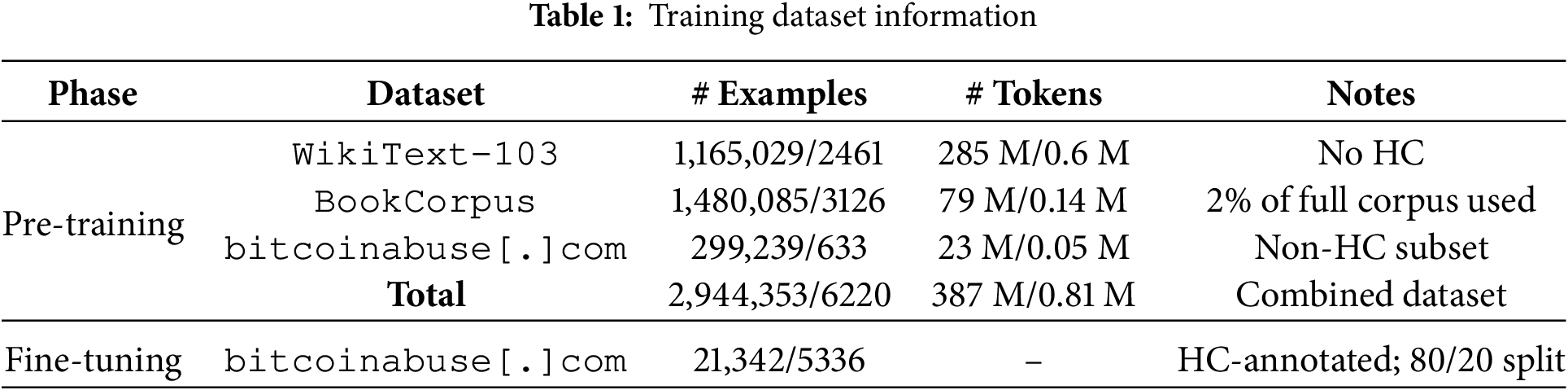

The finalized dataset was divided into two main subsets: (1) clean English spam texts without HPTs, used for pre-training; and (2) HPT-containing texts, used for fine-tuning. This separation allows for the simulation of realistic restoration scenarios and enables the model to learn from both visual and contextual signals for accurate character-level recovery. The statistics of the datasets used for training are shown in Table 1.

The proposed model employs a character-wise BERT architecture trained in two phases: pre-training and fine-tuning. In the pre-training phase, the model is exposed to large-scale unlabeled corpora free of HPTs, enabling it to learn robust character-level language representations and general contextual dependencies.

Three corpora were used for pre-training: a subset of the BookCorpus [30] (approximately 2% of its total size), the WikiText-103 [31] corpus, and a filtered version of the bitcoinabuse[.]com dataset from which all HPTs had been manually removed. The combination of domain-general (BookCorpus and WikiText-103) and domain-specific (spam email) data provided a balanced foundation for learning both syntactic and semantic patterns, as well as domain-relevant structures.

The model was trained using the MLM objective, consistent with the original BERT framework. This objective was chosen because MLM enables the model to learn contextual dependencies at the character level, making it well-suited for recovering visually perturbed characters. By predicting masked tokens based on their surrounding context, the model is encouraged to capture semantic and visual regularities in noisy input text. Specifically, 15% of all character tokens in each input sequence were selected for perturbation: 80% were replaced with a mask token, 10% with a random character, and 10% remained unchanged. The model was then optimized to predict the original characters based on bidirectional context. A character-level tokenizer was used instead of a subword tokenizer to preserve fine-grained character information critical for effective HPT restoration.

Where

The rationale behind utilizing this particular objective remains consistent for both the pre-training and fine-tuning phases of the proposed method.

The homoglyph restoration task is centered around the transformation of non-alphabetic homoglyphs, represented as

In this thesis, a novel method employing a character-wise language model denoted as

For the purpose of learning this probability distribution, the BERT network [33] was opted the choice as the model

This pre-training phase is essential in equipping the model to infer correct alphabetic forms in the presence of visually ambiguous characters. By excluding HPTs during this stage, the model builds a stable internal representation of canonical English character patterns, thereby enabling more accurate restoration when exposed to HPTs during fine-tuning.

Following the pre-training phase, the proposed model is fine-tuned on a supervised dataset comprising HPT, wherein certain characters have been intentionally replaced with HC. The fine-tuning objective is to enable the model to accurately restore the original alphabetic characters from their visually deceptive variants by leveraging contextual representations acquired during the pre-training stage.

The HPT fine-tuning dataset is constructed from a manually annotated subset of the bitcoinabuse[.]com spam email corpus. Instances of HC were meticulously identified and aligned with their correct alphabetic counterparts. To ensure high data quality, non-textual artifacts such as cryptocurrency addresses, URLs, and semantically incoherent character sequences were removed via regular expression filtering. Furthermore, non-English content was excluded to preserve linguistic homogeneity.

The dataset was partitioned into training and validation subsets using an 80:20 random split. Fine-tuning was performed using the same MLM objective employed during pre-training. In this phase, the model was explicitly trained on inputs containing manually labeled HC to strengthen its ability to resolve character-level visual perturbations in context.

The fine-tuning pipeline integrates OCR preprocessing to convert HC into shape-normalized approximations of alphabetic characters, thereby preserving surrounding contextual structure. This step enhances the model’s ability to resolve ambiguities that arise from one-to-many HC mappings, especially when a single perturbed character can correspond to multiple valid candidates depending on context. The use of character-level tokenization further facilitates fine-grained restoration by maintaining strict alignment between tokens and individual HC.

This fine-tuning strategy enables the model to specialize in character-level restoration under realistic HPT conditions, even with limited labeled data. Empirical results validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, demonstrating substantial performance gains over baseline approaches across varying levels of HC density and in both zero-shot and supervised inference settings.

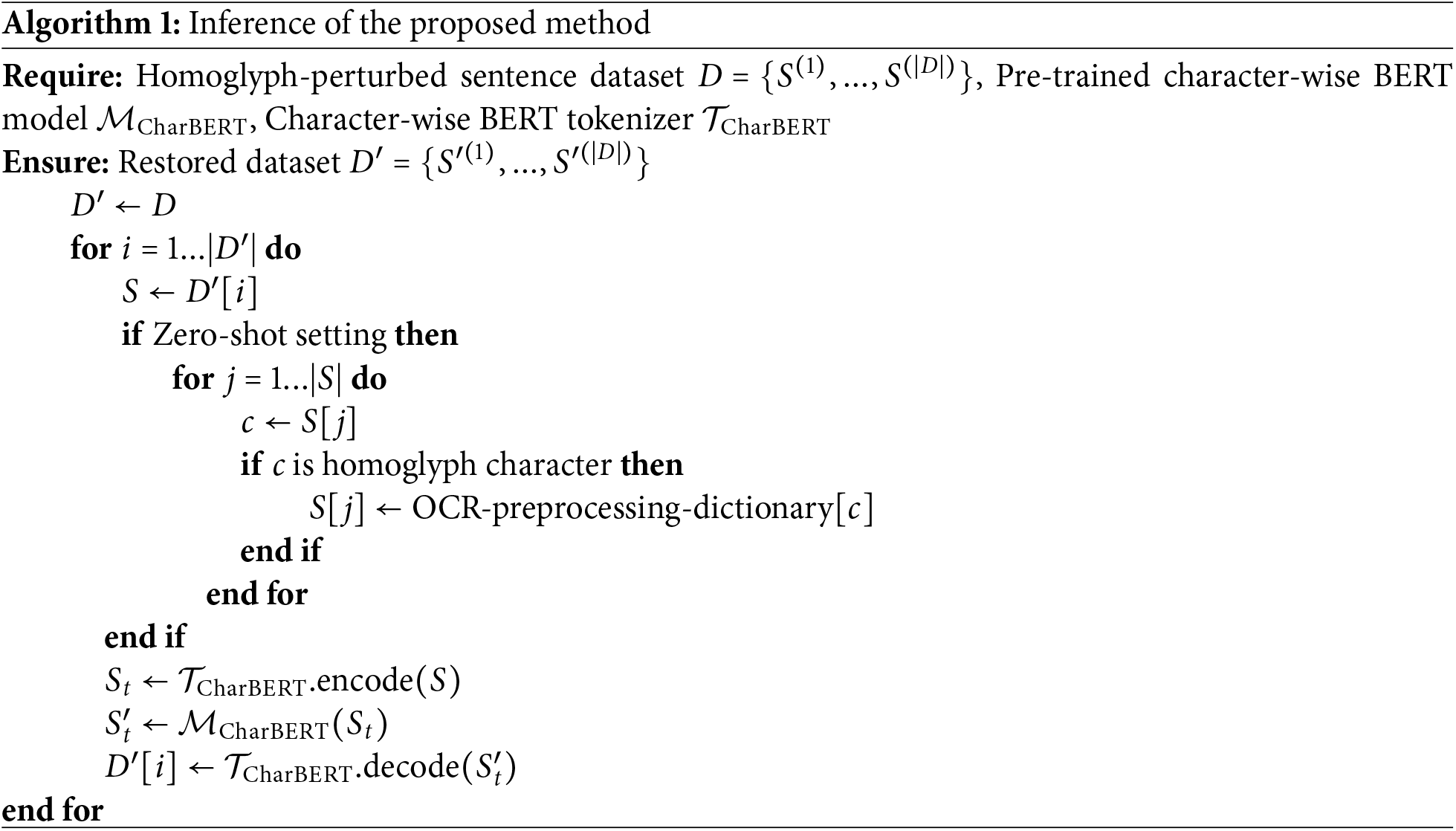

The proposed model leverages OCR at the input stage; however, owing to fine-tuning that enables the restoration of VP text in addition to pretraining, it possesses the advantage of being able to perform inference even in the absence of OCR. Inference procedures, with and without OCR, are described in detail in Algorithm 1.

In this section, we describe the experimental settings for validating the effectiveness of the proposed method and report the comparison results with four existing methods.

To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, we compare it against several existing restoration methods. These include an Optical Character Recognition (OCR)-based method [4], a SimChar database-based method [7], a spell checker-based method [9], and the original BERT model [33]. Among these, the OCR, SimChar DB, and spell checker approaches are deterministic and not trainable. The original BERT model was fine-tuned on corrupted inputs using a subword tokenizer, but due to discrepancies in input token lengths and a lack of character-level alignment, it faced difficulties in learning an effective restoration mapping.

The compared algorithms were configured as follows:

• The OCR and SimChar DB-based methods convert each HC into its alphabetic equivalent.

• The spell checker-based method segments sentences into words using rule-based splitting and corrects them using Levenshtein distance-based spelling correction.

• The original BERT model was used in its standard form as a language model.

The experiment consisted of two stages: pre-training and fine-tuning of the proposed model. The pre-training phase utilized the MLM objective over a corpus free of HC, sourced from WikiText-103 [31], BookCorpus [30], and curated email datasets from bitcoinabuse[.]com [29]. Only 2% of BookCorpus was used due to its large volume.

In the fine-tuning phase, an HPT dataset was constructed with manual annotation and used to optimize the model for restoration performance. Word-level accuracy was employed as the primary evaluation metric. Specifically, let N denote the total number of words in the test set, and let

where

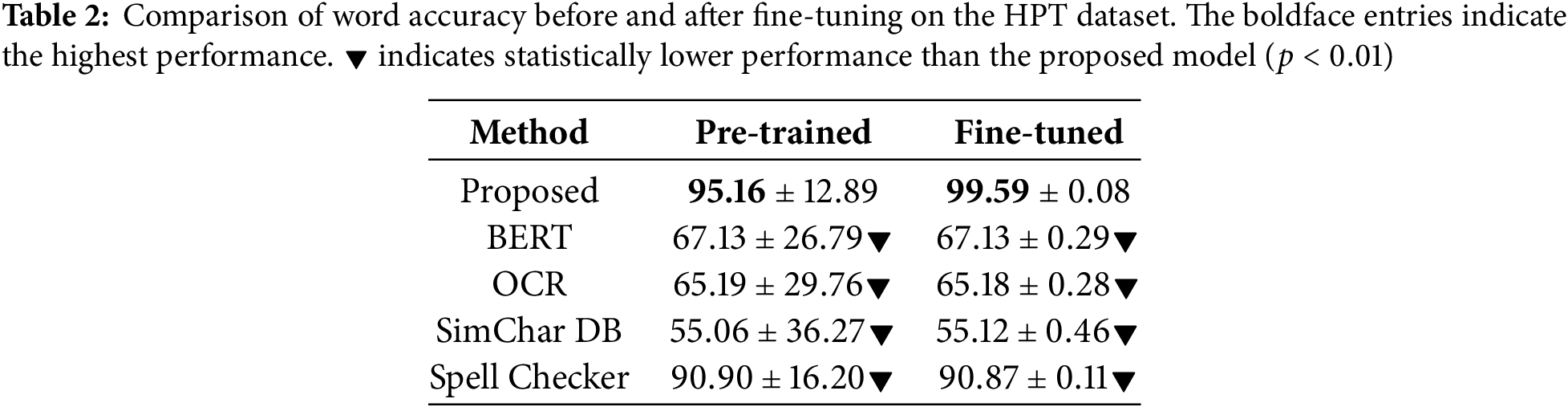

Table 2 shows the performance of the proposed model in both the zero-shot and fine-tuning settings, along with baseline results for comparison. In the zero-shot evaluation, the character-wise BERT model was assessed without any fine-tuning on homoglyph data, using raw homoglyph-injected sentences collected from bitcoinabuse[.]com. This evaluation setup measures the model’s robustness in recovering previously unseen character-level perturbations. The proposed model achieved 95.16% accuracy in this setting, significantly outperforming all baselines. After fine-tuning on 80% of the homoglyph-perturbed corpus and evaluating on the remaining 20% over 50 random splits, the proposed model further improved, achieving 99.59% accuracy. This demonstrates the model’s strong adaptability to real-world homoglyph restoration tasks when exposed to task-specific data.

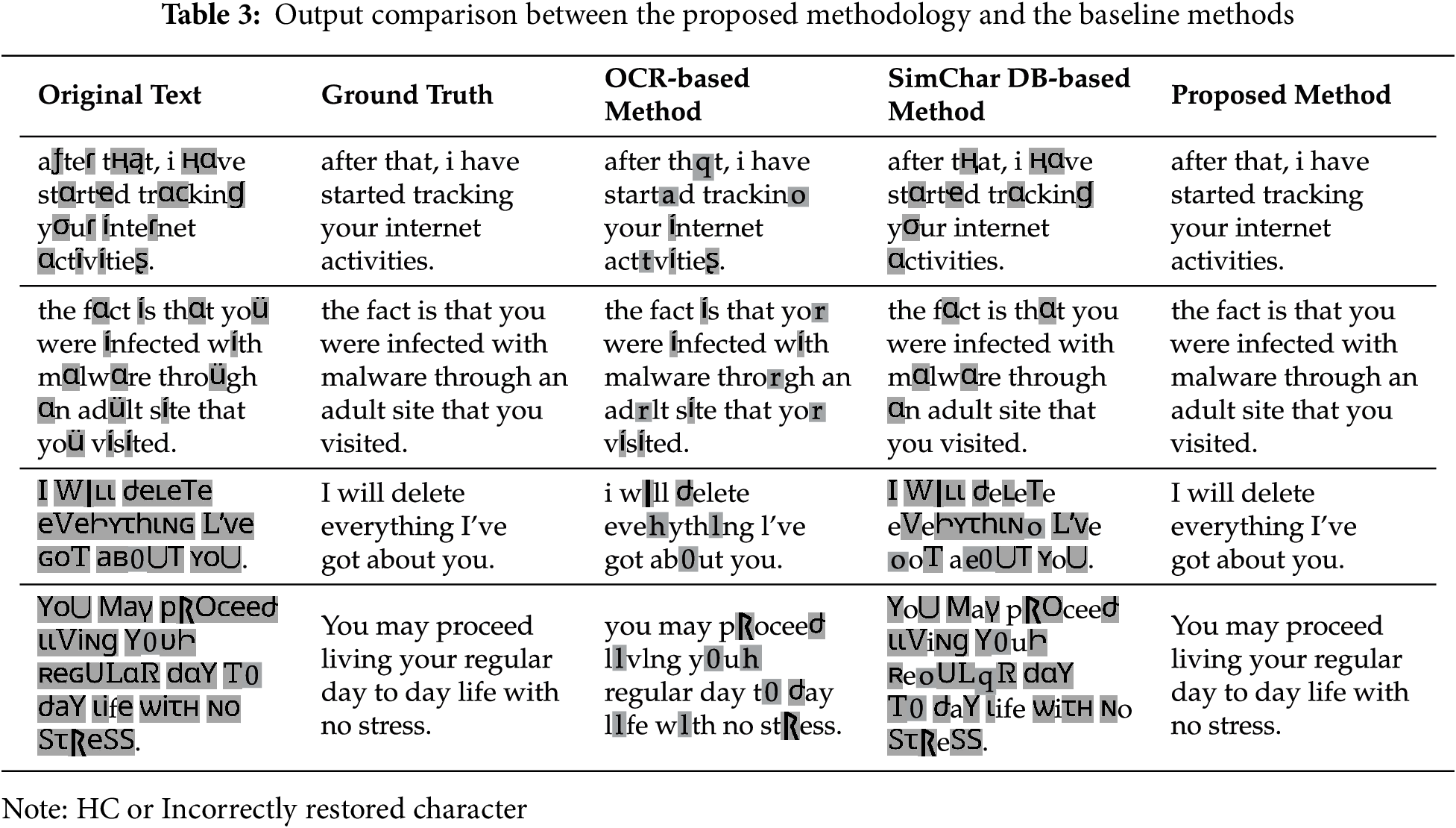

To complement the quantitative evaluation, Table 3 presents several representative examples of HPT restoration across different methods. The proposed model consistently produces outputs that closely match the ground truth, while OCR-based, SimChar DB-based, and spell checker methods exhibit partial or incorrect restorations. These qualitative results highlight the advantage of integrating character-level contextual modeling with OCR preprocessing.

The proposed model substantially outperformed all deterministic baselines. The SimChar DB method showed the weakest performance due to limited coverage and poor similarity metrics. The OCR method struggled with recognizing visually similar characters, and the spell checker was unable to correct words not found in its lexicon.

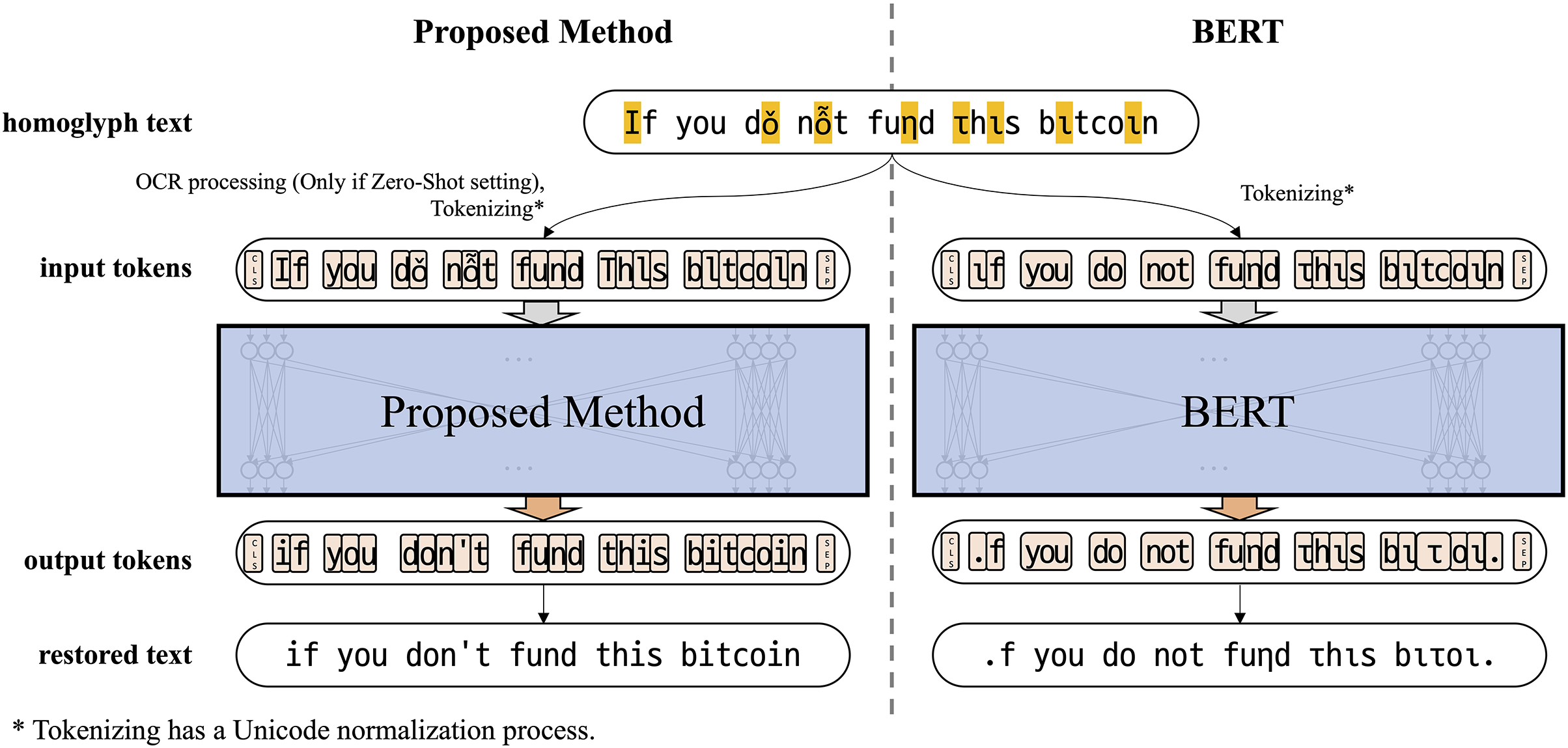

Figure 4: A comparison between the original BERT model and the proposed model

The original BERT model was also unsuitable due to the incompatibility of subword tokenization with character-level tasks. As shown in Fig. 4, inconsistent token lengths led to 334 mismatches between predicted and target sequences.

In contrast, the proposed model’s architecture—based on character-level tokenization and bidirectional masked language modeling—allowed it to achieve high generalization and robustness, even with minimal fine-tuning data.

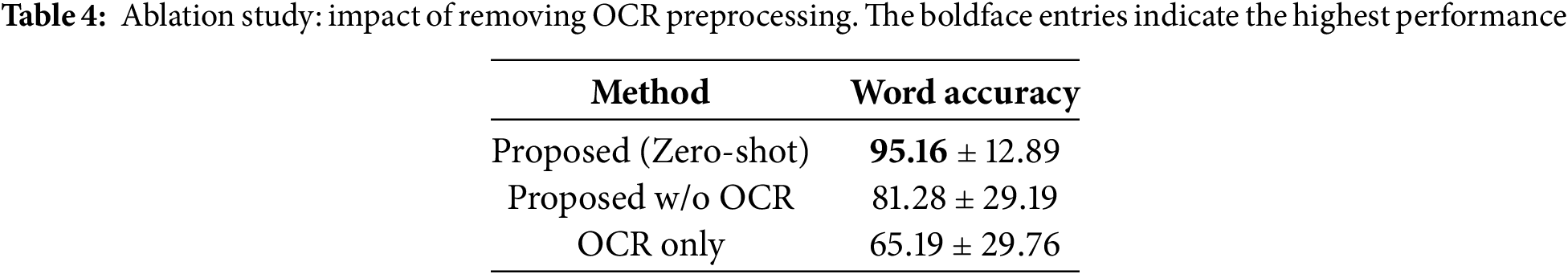

An ablation study further revealed that removing the OCR preprocessing step resulted in a performance drop of approximately 14%, highlighting the synergistic effect of visual normalization and contextual modeling (see Table 4).

To better understand the contribution of each component in the proposed pipeline, we conducted ablation experiments including (1) removing MLM pretraining, which yielded a word accuracy of 0.9974

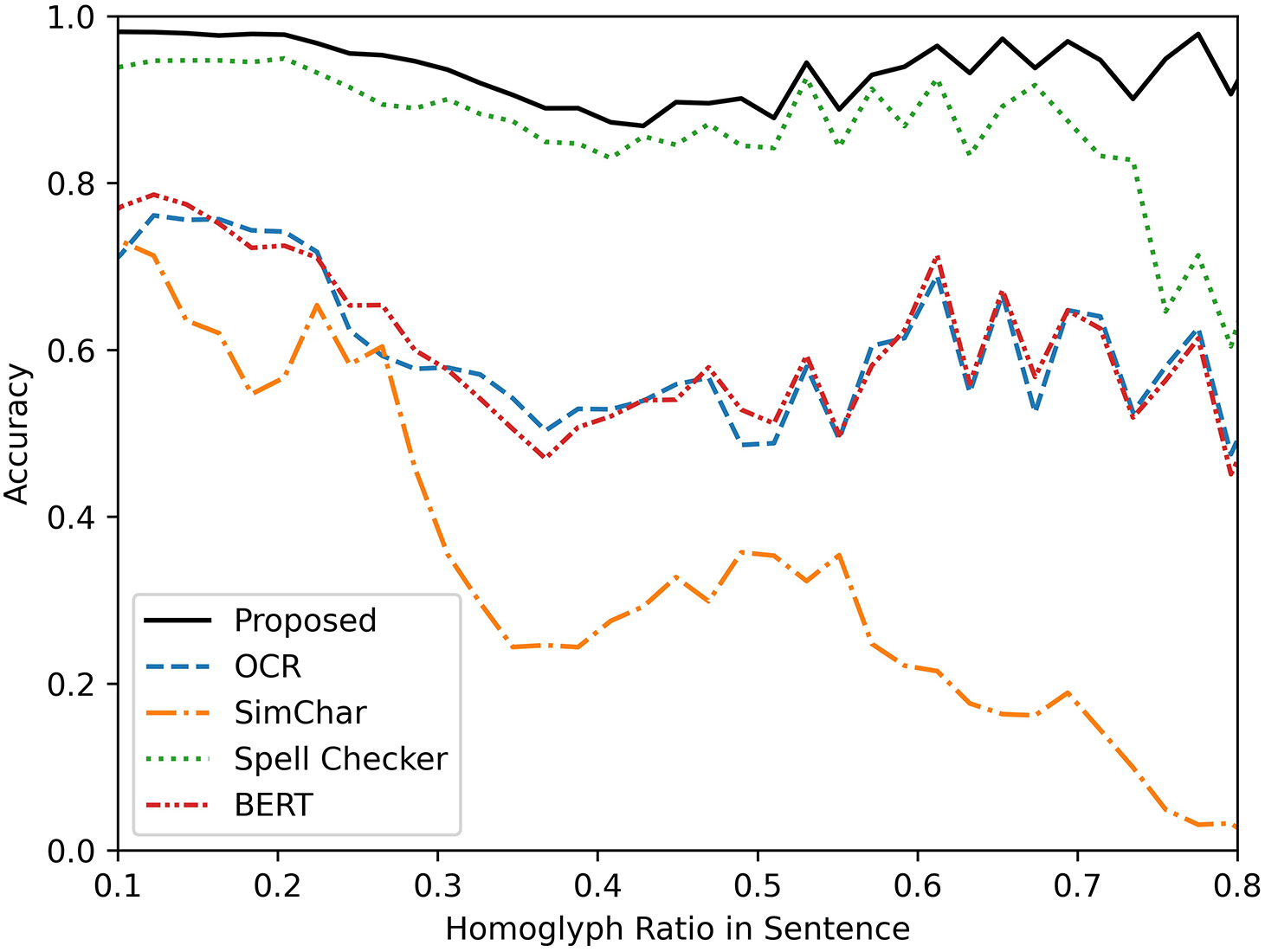

As shown in Fig. 5, the proposed method consistently outperformed the baselines across varying HC perturbation levels. Specifically, as the perturbation ratio increased from 0.2 to 0.6, the accuracy of the model decreased only by about 12%, maintaining the performance above 80%, while the baselines showed a degradation of performance above 30%. This result highlights the robustness of the model in recovering context from visually perturbed characters through effective bidirectional encoding.

Figure 5: Word-level accuracy of the proposed method and baseline approaches across different homoglyph character (HC) ratios. The x-axis denotes the proportion of HC perturbations in each sentence (from 0% to 100%), while the y-axis represents word accuracy

In addition to the quantitative results, qualitative examples demonstrated that the proposed model performed effectively even on visually complex inputs or those challenging for OCR. However, there were also instances where the proposed method failed to fully infer the correct outputs.

Overall, the results validate that character-wise modeling combined with OCR preprocessing provides a scalable and accurate solution for HPT attack restoration. These outcomes highlight the practical potential of our approach for deployment in environments with unpredictable or severe visual noise. Continued advances in character-level modeling and visual preprocessing are likely to further strengthen model resilience in real-world applications.

5.1 Downstream Task Evaluation under VIPER Attacks

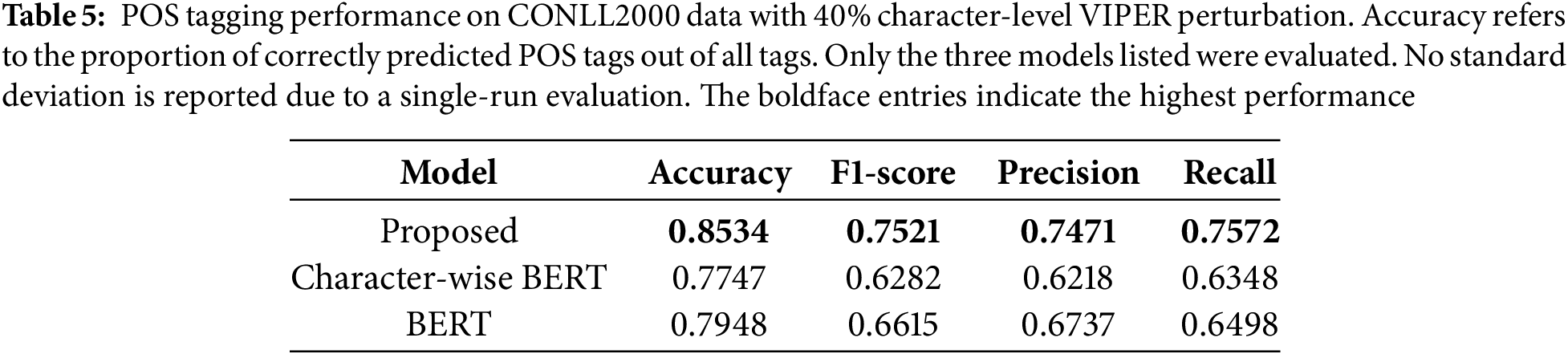

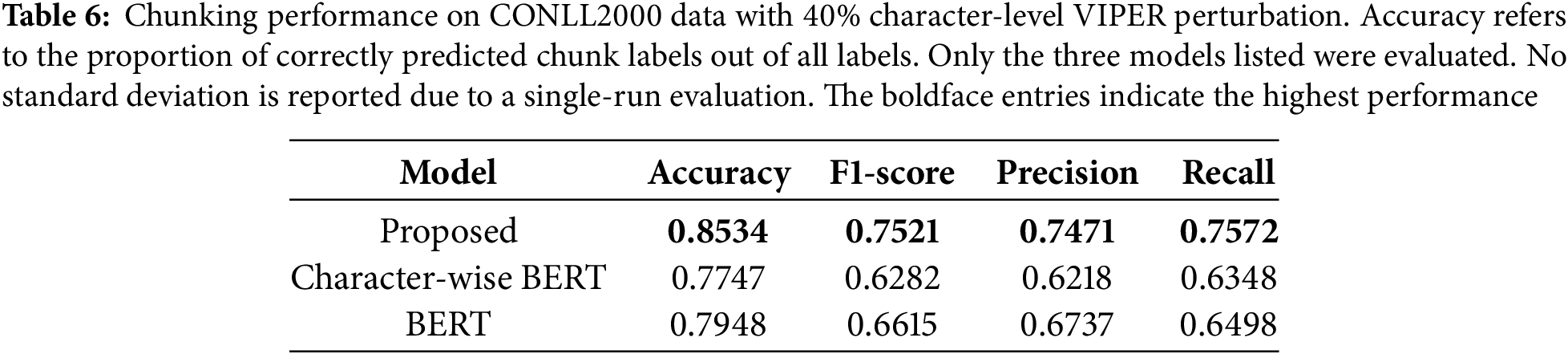

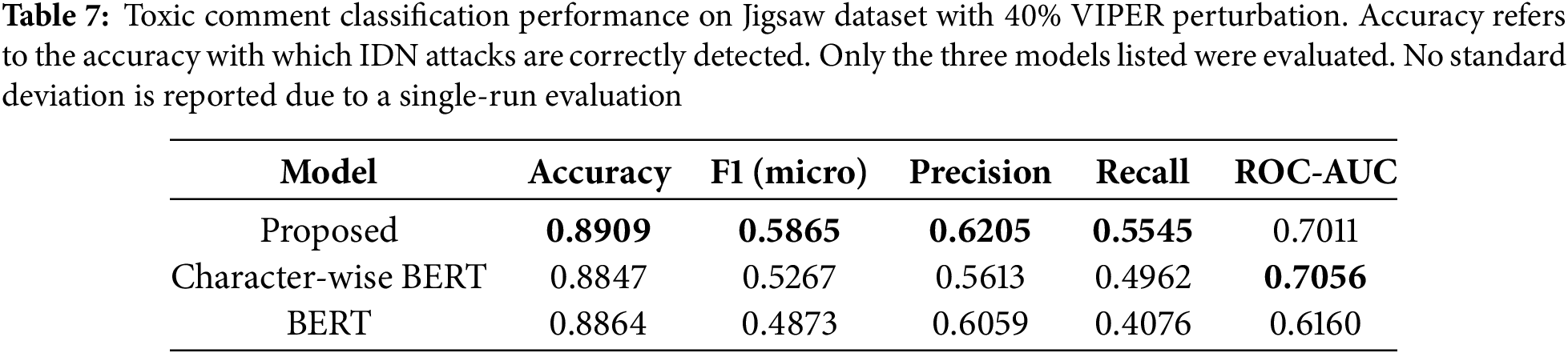

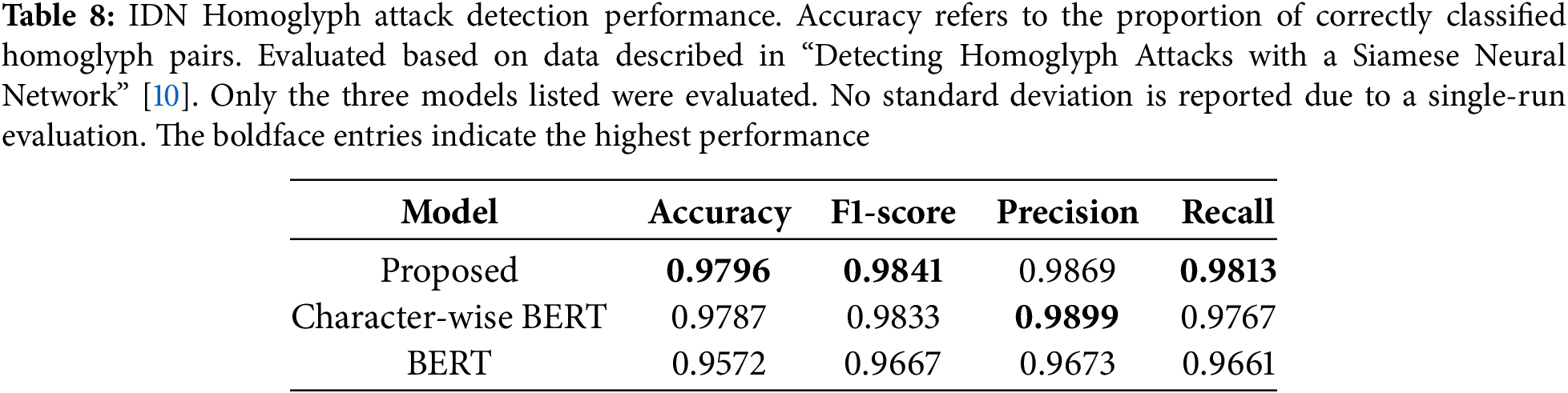

To evaluate the robustness and transferability of the proposed model beyond restoration tasks, we applied it to a diverse set of downstream NLP tasks under visually perturbed input conditions. Tables 5–8 present the results on Part-of-Speech (POS) tagging, chunking, toxic comment classification, and homoglyph attack detection, with 40% of original characters substituted using the VIPER corruption method.

The proposed model consistently outperformed both standard BERT and character-wise BERT across all four tasks. The improvements were especially notable in tasks sensitive to surface forms, such as POS tagging and chunking (Tables 5 and 6), where visual ambiguity severely degrades tokenization and tag prediction. In toxic comment classification (Table 7), the benefit of OCR was also evident despite the task’s semantic complexity. Lastly, in the homoglyph detection benchmark (Table 8), our model outperformed previously reported approaches, such as the Siamese neural network of Woodbridge et al. (2018), achieving near-perfect accuracy and F1-score.

These results demonstrate that our model not only restores perturbed inputs effectively but also enhances downstream task performance under real-world visually adversarial conditions.

These findings further emphasize the value of robust character-level modeling in defending against visual perturbations that can undermine standard NLP pipelines. The model’s improvements were consistent across both syntactic and semantic tasks, indicating its effectiveness in preserving essential linguistic information. This robustness is particularly important for real-world applications where visually corrupted inputs are common. Overall, our results suggest that visually-aware language models can play a key role in ensuring reliable NLP performance in adversarial or noisy environments.

Despite the effectiveness of the proposed OCR-assisted BERT framework for restoring homoglyph-perturbed text, several limitations remain.

First, the model heavily relies on OCR preprocessing. When OCR fails to correctly recognize complex homoglyph characters (e.g., misreading “ß ” as “K”), the subsequent restoration quality deteriorates. While OCR reduces visual ambiguity, robustness under OCR failure or uncommon fonts remains an open challenge.

Second, the computational efficiency of the proposed framework has not been rigorously evaluated. Inference latency, FLOPs, and memory usage were not measured, which limits conclusions about deployment feasibility in resource-constrained settings.

Third, the BitAbuse dataset was annotated manually through semi-automatic methods. Although multiple annotators were involved and guidelines were followed, formal inter-annotator agreement was not calculated, leaving room for annotation bias.

In addition, most downstream task evaluations were conducted on single runs without reporting standard deviations or statistical significance. This limits the strength of our claims regarding generalizability and robustness across tasks. In future work, we aim to include repeated trials with variance reporting and statistical testing (e.g., paired t-tests) to support more rigorous evaluation.

Finally, while the current approach leverages visual preprocessing, it does not fully explore recent advances in multimodal transformers or end-to-end vision-language architectures. Future work may consider incorporating such models to improve restoration performance under severe visual corruption. In particular, multimodal frameworks that jointly model visual glyphs and textual context—such as the zero-shot vehicle classification model by Kerdvibulvech et al. [34]—suggest promising directions for reducing reliance on OCR and enhancing robustness.

HPT attacks pose a serious threat to the robustness and security of NLP systems by exploiting visually similar characters to evade detection mechanisms. While much of the prior research has focused on detecting such attacks, the task of restoring HPT to its original form remains underexplored.

In this study, we proposed a novel character-level language model that combines OCR preprocessing with a character-wise BERT architecture to effectively restore sentences corrupted by HPT attacks. Our model leverages bidirectional contextual information and shows strong generalization, even when a single perturbed character corresponds to multiple possible candidates.

Experimental results show that the proposed model significantly outperforms existing restoration methods, including OCR-based, SimChar DB-based, and spellchecker-based approaches, in both zero-shot and fine-tuned settings. Notably, it maintains robust performance across varying HC ratios, highlighting its effectiveness in real-world scenarios.

Despite these promising results, the proposed model has limitations. Its reliance on OCR for preprocessing introduces potential error propagation, particularly in cases of high HC density or poor OCR accuracy. Furthermore, the encoder-only structure of BERT restricts the model to input-output sequences of equal length, making it less suitable for more complex restoration scenarios.

For future work, we plan to explore decoder-based or encoder-decoder models to accommodate dynamic sequence lengths, enabling more flexible character restoration. Additionally, integrating a trainable visual feature extraction module in place of OCR may improve performance and reduce reliance on external preprocessing tools. Finally, automating the data annotation pipeline—particularly for identifying HC in large corpora—will be essential for scaling this approach to broader applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Chung-Ang University for providing computational resources and administrative support that contributed to this work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) [RS-2021-II211341, Artificial Intelligence Graduate School Program (Chung-Ang University)], and by the Chung-Ang University Graduate Research Scholarship in 2024.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Hanyong Lee; Software, Hanyong Lee; Writing—original draft preparation, Hanyong Lee; Investigation, Ye-Chan Park; Writing—review and editing, Ye-Chan Park; Visualization, Ye-Chan Park; Project administration, Jaesung Lee; Supervision, Jaesung Lee. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in BitAbuse at https://huggingface.co/datasets/AutoML/bitabuse (accessed on 06 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or animals.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhang WE, Sheng QZ, Alhazmi A, Li C. Adversarial attacks on deep-learning models in natural language processing: a survey. ACM Transact Intell Syst Technol (TIST). 2020;11(3):1–41. doi:10.1145/3374217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sokolov M, Olufowobi K, Herndon N. Visual spoofing in content-based spam detection. In: 13th International Conference on Security of Information and Networks (SIN 2020); 2020 Nov 4–7; Merkez, Turkey: East Carolina University. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

3. Boucher N, Shumailov I, Anderson R, Papernot N. Bad characters: imperceptible NLP attacks. In: 2022 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2022 May 22–26; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 1987–2004. [Google Scholar]

4. Sawabe Y, Chiba D, Akiyama M, Goto S. Detection method of homograph internationalized domain names with OCR. J Inform Process. 2019;27(0):536–44. doi:10.2197/ipsjjip.27.536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Keller Y, Mackensen J, Eger S. BERT-Defense: a probabilistic model based on BERT to combat cognitively inspired orthographic adversarial attacks. In: Findings of the association for computational linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. p. 1616–29. [Google Scholar]

6. Goyal S, Doddapaneni S, Khapra MM, Ravindran B. A survey of adversarial defenses and robustness in NLP. ACM Comput Surv. 2023 Jul;55(14s):1–39. doi:10.1145/3593042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Suzuki H, Chiba D, Yoneya Y, Mori T, Goto S. ShamFinder: an automated framework for detecting IDN homographs. In: Proceedings of the Internet Measurement Conference, IMC ’19. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2019. p. 449–62. doi:10.1145/3355369.3355587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Elsayed Y, Shosha A. Large scale detection of IDN domain name masquerading. In: 2018 APWG Symposium on Electronic Crime Research (eCrime); 2018 May 15–17; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

9. Imam NH, Vassilakis VG, Kolovos D. OCR post-correction for detecting adversarial text images. J Inf Secur Appl. 2022;66(11):103170. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2022.103170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Woodbridge J, Anderson HS, Ahuja A, Grant D. Detecting homoglyph attacks with a siamese neural network. In: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security (AISec); 2018 Oct 15–19; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

11. Yazdani R, van der Toorn O, Sperotto A. A case of identity: detection of suspicious IDN homograph domains using active DNS measurements. In: 2020 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW); 2020 Sep 7–11; Genoa, Italy. p. 559–64. [Google Scholar]

12. Almuhaideb AM, Aslam N, Alabdullatif A, Altamimi S, Alothman S, Alhussain A, et al. Homoglyph attack detection model using machine learning and hash function. J Sens Actuator Netw. 2022;11(3):54. doi:10.3390/jsan11030054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Julis MR, Alagesan S. Spam detection in SMS using machine learning through text mining. Int J Scient Technol Res. 2020;9(2):498–502. [Google Scholar]

14. Alvi F, Stevenson M, Clough P. Plagiarism detection in texts obfuscated with homoglyphs. In: Advances in Information Retrieval: 39th European Conference on IR Research, ECIR 2017. Aberdeen, UK: Springer; 2017. p. 669–75. [Google Scholar]

15. Qiu B, Fang N, Wenyin L. Detect visual spoofing in unicode-based text. In: 2010 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition; 2010 Aug 23–26; Istanbul, Turkey. p. 1949–52. [Google Scholar]

16. Sawabe T, Nakamura Y, Sato H. OCR-based detection and correction of homoglyph attacks. In: Proceedings of the 2019 ACM Symposium on Document Engineering. Louvain-la-Neuve. Belgium: ACM; 2019. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

17. Li M, Lv T, Chen J, Cui L, Lu Y, Florencio D, et al. TrOCR: transformer-based optical character recognition with pre-trained models. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Washington, DC, USA: Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI); 2023. p. 13094–102. [Google Scholar]

18. Salesky E, Etter D, Post M. Robust open-vocabulary translation from visual text representations. In: Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). Punta Cana, Dominican Republic: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. p. 7235–52. [Google Scholar]

19. Le T, Park N, Lee D. SHIELD: defending textual neural networks against multiple black-box adversarial attacks with stochastic multi-expert patcher. In: Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022 May 22–27; Dublin, Ireland. p. 6661–74. [Google Scholar]

20. El Boukkouri H, Ferret O, Lavergne T, Noji H, Zweigenbaum P, Tsujii J. CharacterBERT: reconciling ELMo and BERT for word-level open-vocabulary representations from characters. In: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics; 2020 Dec 8–13; Barcelona, Spain. p. 6903–15. [Google Scholar]

21. Ma W, Cui Y, Si C, Wang T, Liu S, Hu G. CharBERT: character-aware pre-trained language model. In: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics; 2020 Dec 8–13; Barcelona, Spain. p. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

22. Li J, Ji S, Du T, Li B, Wang T. TEXTBUGGER: generating adversarial text against real-world applications. In: 26th Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, NDSS 2019. San Diego, CA, USA: The Internet Society; 2019. p. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

23. Eger S, Şahin GG, Rücklé A, Lee JU, Schulz C, Mesgar M, et al. Text processing like humans do: visually attacking and shielding NLP systems. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Minneapolis, MN, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 1634–47. [Google Scholar]

24. Seth A, Kumar R, Singh P. LEGIT: a framework for evaluating the readability of visually perturbed text. J Artif Intelli Res. 2023;76:123–45. [Google Scholar]

25. Lee H, Lee C, Lee Y, Lee J. BitAbuse: a dataset of visually perturbed texts for defending phishing attacks. In: Findings of the association for computational linguistics: NAACL 2025. Albuquerque, New Mexico: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2025. p. 4367–84. [Google Scholar]

26. Lee MA. madmaze/pytesseract; 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://github.com/madmaze/pytesseract. [Google Scholar]

27. Cozens S. Authors TNP, Contributors GF. notofonts/runic. Noto Fonts; 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://github.com/notofonts/runic. [Google Scholar]

28. B S. satbyy/go-noto-universal; 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://github.com/satbyy/go-noto-universal. [Google Scholar]

29. Bitcoin Abuse. Bitcoin Abuse Database; 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.bitcoinabuse.com/. [Google Scholar]

30. Zhu Y, Kiros R, Zemel R, Salakhutdinov R, Urtasun R, Torralba A, et al. Aligning books and movies: towards story-like visual explanations by watching movies and reading books. In: The IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 7–13; Santiago, Chile. p. 13–6. [Google Scholar]

31. Merity S, Xiong C, Bradbury J, Socher R. Pointer sentinel mixture models. In: International Conference on Learning Representations; 2017 Apr 24–26; Toulon, France. p. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

32. Salazar J, Liang D, Nguyen TQ, Kirchhoff K. Masked language model scoring. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020 Jul 5–10; Online. p. 2699–712. [Google Scholar]

33. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Minneapolis, MN, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

34. Kerdvibulvech C. Multimodal AI model for zero-shot vehicle brand identification. Multimed Tools Appl. 2025;84(27):33125–44. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-20559-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools