Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Study on Re-Identification of Natural Language Data Considering Korean Attributes

Department of Information Security, College of Future Industry Convergence, Seoul Women’s University, Seoul, 01797, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Junhyoung Oh. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 4629-4643. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068221

Received 23 May 2025; Accepted 26 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

This study analyzes the risks of re-identification in Korean text data and proposes a secure, ethical approach to data anonymization. Following the ‘Lee Luda’ AI chatbot incident, concerns over data privacy have increased. The Personal Information Protection Commission of Korea conducted inspections of AI services, uncovering 850 cases of personal information in user input datasets, highlighting the need for pseudonymization standards. While current anonymization techniques remove personal data like names, phone numbers, and addresses, linguistic features such as writing habits and language-specific traits can still identify individuals when combined with other data. To address this, we analyzed 50,000 Korean text samples from the X platform, focusing on language-specific features for authorship attribution. Unlike English, Korean features flexible syntax, honorifics, syllabic and grapheme patterns, and referential terms. These linguistic characteristics were used to enhance re-identification accuracy. Our experiments combined five machine learning models, six stopword processing methods, and four morphological analyzers. By using a tokenizer that captures word frequency and order, and employing the LSTM model, OKT morphological analyzer, and stopword removal, we achieved the maximum authorship attributions accuracy of 90.51%. This demonstrates the significant role of Korean linguistic features in re-identification. The findings emphasize the risk of re-identification through language data and call for a re-evaluation of anonymization methods, urging the consideration of linguistic traits in anonymization beyond simply removing personal information.Keywords

With the rapid advancement of computing technologies and artificial intelligence, the demand for large-scale datasets to support AI training has been steadily increasing. In particular, the field of large language models (LLMs) has emerged as a dominant consumer of massive volumes of textual data, as both model size and performance continue to scale exponentially. Villalobos et al. (2022) warned that, if current data consumption trends persist, the global stock of publicly available human-generated text data could be exhausted between 2026 and 2032 [1]. As the global significance of LLM technology and the utilization of unstructured data continue to expand, this trend has become increasingly evident in South Korea. Domestic efforts to develop Korean-specific LLMs are actively underway, with notable examples including Ko-GPT by Kakao, Clova X by Naver, EXAONE by LG AI Research, and Believe by KT [2].

However, the widespread use of unstructured data in AI technologies has raised serious concerns regarding personal information protection. A representative case is the “Iruda chatbot incident,” where insufficient pseudonymization of unstructured textual data led to the leakage of personally identifiable information (PII) [3]. The dataset in question contained sensitive information such as addresses, bank account numbers, and real names, resulting in a major privacy breach.

Since this incident, the rapid proliferation of LLM technologies has further underscored the necessity of regulating and overseeing data usage. In November 2023, the Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC) of Korea conducted a preemptive audit of several AI services and identified 850 cases of personal information leakage from user-submitted data [4]. In particular, some institutions were found to have stored raw datasets without appropriate safeguards or retained preprocessed training data without implementing adequate protective measures. These findings demonstrate a significant lack of proper personal information protection mechanisms during AI model training.

In response to these issues, the PIPC released new pseudonymization guidelines for unstructured data in February 2024. According to the guidelines, pseudonymization is mandatory when individuals can be identified through recurring vocabulary, grammatical patterns, writing style, or linguistic habits [5]. However, the absence of concrete examples and standardized criteria renders the determination of pseudonymization requirements highly subjective.

This study aims to identify the core linguistic features that enable authorship attribution within Korean textual data and to determine the specific attributes that contribute to such identifiability. Based on these findings, we propose a secure and effective data preprocessing framework. By focusing on linguistic characteristics such as discourse markers, syllable and phoneme counts, syntactic structures, and honorific expressions, this study presents a distinctive approach compared to previous authorship attribution research primarily conducted in English.

Ultimately, the goal of this research is to explore ethical and secure methods for utilizing unstructured data, to contribute to the advancement of Korean natural language processing technologies, and to provide foundational insights for the development of future personal data protection standards.

2.1 De-Identification Techniques for Korean Data

Korean, due to its agglutinative structure and complex conversational characteristics, presents unique challenges for the direct application of existing language-based de-identification techniques. Consequently, the development of de-identification methods specifically tailored to Korean has become increasingly essential. KDPII is a Korean dialogue-based dataset designed to identify PII tokens, such as names and addresses, within real-world conversations [6], while Thunder-DeID is a model demonstrating high de-identification performance on structured Korean court rulings [7]. However, these studies primarily focus on the detection of individual tokens, and their ability to assess re-identification risks arising from context-based authorship attribution is limited.

In this study, we aim to identify the core linguistic features critical for authorship attribution in Korean natural language data and to determine the specific attributes that affect identifiability. Moreover, going beyond mere PII identification, we propose a novel de-identification framework that incorporates authorship attribution within conversational contexts, thereby advancing technologies for Korean data protection.

2.2 Privacy Risks for Natural Language Data

A study analyzing the potential leakage of sensitive information during the increasingly common database linkage processes in the health, social science, government, and business domains has highlighted that, although PPRL techniques are applied in practice, prior research has primarily focused on technical aspects, with discussions on practical information security considerations remaining relatively limited [8]. In contrast, the present study identifies both intentional and unintentional information leakage that may arise during the implementation of such protocols and provides comprehensive security recommendations to mitigate these risks.

Furthermore, research on LLM-based text anonymization has demonstrated that anonymized natural language texts remain vulnerable to re-identification through pattern learning, and it proposes structured frameworks to reduce such re-identification risks while preserving data utility [9]. Building upon these analyses, the present study specifically defines re-identification threats arising from behavioral information within Korean data and proposes a novel framework that addresses both token-level and context-level vulnerabilities, thereby clearly distinguishing it from previous research.

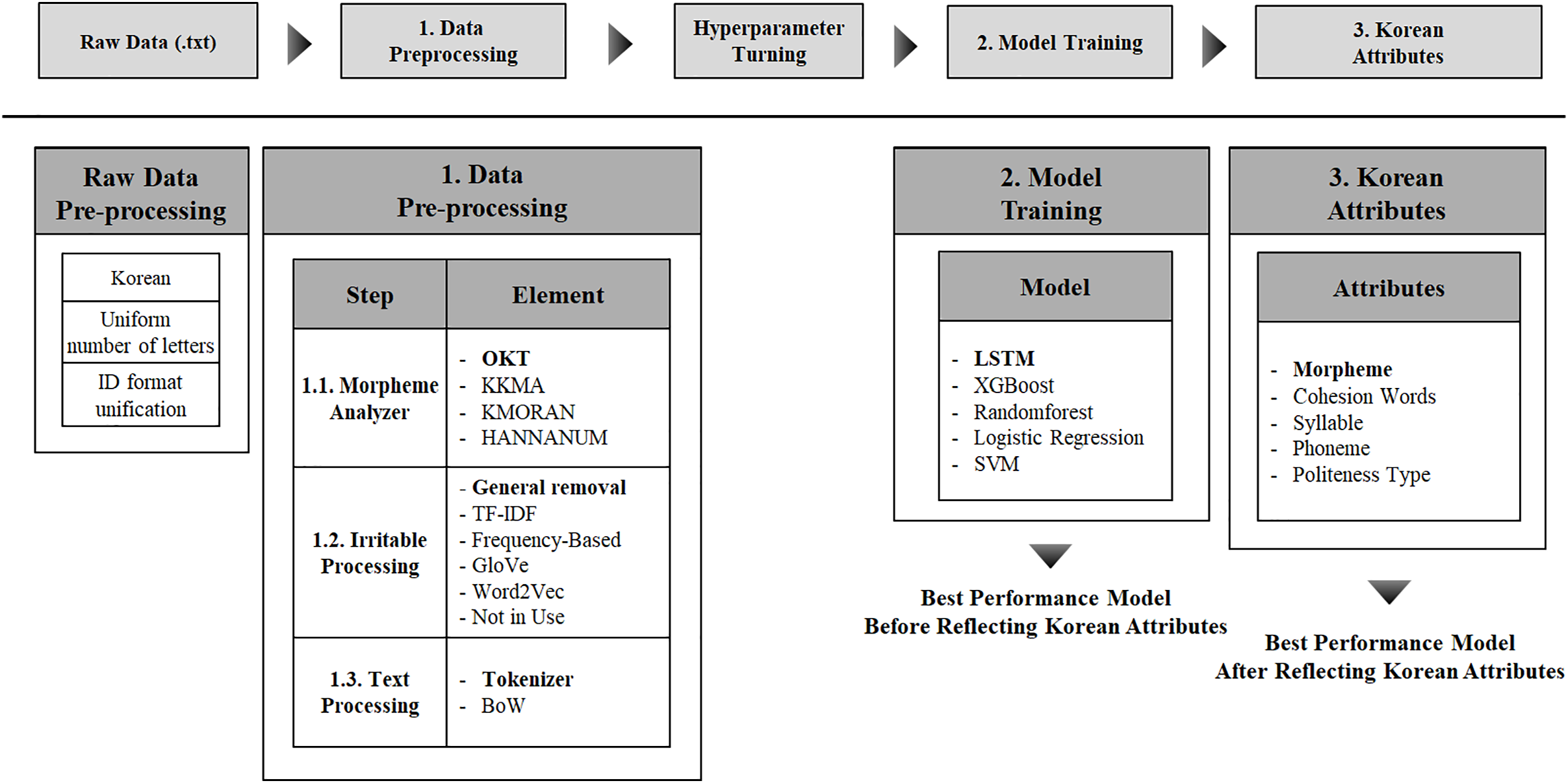

As shown in Fig. 1, the framework of this study efficiently preprocesses and classifies Korean text data. It improves both the accuracy and efficiency of data analysis by integrating the unique linguistic properties and structural complexity of Korean and automating the entire analysis pipeline.

Figure 1: Research framework for the proposed method

The data preprocessing pipeline consists of three sequential stages, namely morphological analysis, stopword filtering, and text normalization. At each stage, diverse Korean-language text processing techniques were systematically evaluated, and the most effective methods were identified through empirical assessment.

A morphological analyzer decomposes sentences into morphemes, the smallest units of meaning, and assigns POS tags to each. As a foundational task in NLP, morphological analysis is essential for converting raw text into a machine-readable format. Its primary functions include segmenting morphemes, assigning POS tags, and differentiating between stems and affixes. Given the flexible word order and rich morphological system of the Korean language, accurate analysis necessitates the comparative evaluation of multiple analyzers.

In this study, we employed KoNLPy [10], a Python library that provides multiple Korean morphological analyzers, and conducted a comparative evaluation of four analyzers: Okt, Komoran, Hannanum, and Kkma. Okt is recognized for its simplicity and user-friendliness, whereas Kkma offers fine-grained syntactic parsing at the expense of processing speed. Komoran is optimized for high-speed, large-scale text analysis, while Hannanum integrates both morphological and syntactic parsing.

Stopword filtering aims to improve model training efficiency by removing contextually insignificant words from the text. In this study, we compared several stopword removal techniques, including standard stopword elimination [11], TF-IDF weighting [12], frequency-based filtering [13], GloVe embeddings [14], Word2Vec embeddings [15], and the Not in Use approach [16]. Standard stopword elimination removes predefined lists of words, although it may inadvertently discard semantically relevant terms. TF-IDF assigns weights to words based on their term frequency and inverse document frequency, capturing their relative importance. Frequency-based filtering reduces noise by excluding extremely common or rare words. GloVe and Word2Vec convert words into vectors and process them based on semantic similarity, enabling more nuanced filtering. The Not in Use method retains all words in the training corpus without applying stopword filtering.

In the text preprocessing stage, we employed the Tokenizer [17] and BoW [18] methods to transform textual data into numerical representations. The Tokenizer segments sentences into tokens while preserving word order, facilitating sequential input to the model. In contrast, BoW encodes text based on word frequency. To assess the impact of word order on the author classification task, we conducted a comparative evaluation of these preprocessing methods and selected the approach demonstrating the highest performance.

In the model training phase, five classification algorithms were employed: LSTM [19], XGBoost [20], Random Forest [21], SVM [22], and Logistic Regression [23]. LSTM is particularly suited for Korean text processing, as it captures contextual dependencies in sequential data, effectively handling word order and context. XGBoost, a decision tree-based ensemble method, provides rapid and accurate classification. Random Forest aggregates multiple decision trees to yield stable predictions while mitigating overfitting. SVM is well-suited for high-dimensional feature spaces and delivers robust classification performance. Logistic Regression, a probability-based binary classifier, is favored for its simplicity and interpretability.

Korean is a language characterized by relatively free word order, extensive use of grammatical particles, and high contextual dependency. These linguistic features exert a significant influence on text analysis and model learning performance. In this study, we focused on five core linguistic attributes of Korean: cohesion words [24], word frequency [25], politeness type [26], syntactic structure [27], and the number of syllables and phonemes. Cohesion words, such as pronouns and conjunctions, function as referential or connective elements that establish logical links between sentences and maintain discourse coherence. Word frequency quantifies the occurrence of specific words or expressions within a text, thereby facilitating the identification of central topics and key terms. Politeness type reflects the author’s social status, age, and level of familiarity, and plays a critical role in interpreting the social context and pragmatic tone of utterances through the use of honorifics or informal language. Syntactic structure analysis entails examining the grammatical arrangements within sentences to elucidate the relationships among lexical items, which is particularly crucial in Korean due to the explicit grammatical roles indicated by particles. The number of syllables and phonemes represents the most fundamental phonological units of a sentence, and these metrics are employed to quantify structural complexity and to analyze linguistic patterns.

Fig. 1 depicts the framework of the present study. For the experiments, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 datasets were randomly selected from a total of 50. The number of training iterations was fixed at 10 for each configuration; however, for the complete set of 50 datasets, only a single iteration was conducted to account for the combinatorial complexity and to mitigate computational overhead. Furthermore, if the average accuracy fell below 5%, the results were deemed statistically insignificant, and the experiment was terminated for the corresponding number of authors. Within each experimental group, only a single configuration parameter was modified, while all other components were held constant according to the settings of the best-performing model.

To further assess the extent to which the observed classification accuracies reflect the underlying population characteristics, 95% confidence intervals [28] were computed for each configuration. This methodology, analogous to approaches employed in privacy-preserving machine learning models, provides a statistically rigorous interpretation of performance variability and uncertainty. Confidence intervals are presented in parentheses alongside accuracy values in the result graphs, facilitating a more transparent and reliable comparison across configurations. The configuration encompassing all 50 datasets was excluded from confidence interval computations due to the absence of repeated trials.

In this study, four criteria were established for dataset construction. First, the data were required to be in Korean text file format. Second, the dataset primarily consisted of SNS data from the 2020s to reflect recent linguistic changes in speech patterns. Third, to ensure sufficient utterance volume per author, more than 1000 sentences were collected for each individual author. Fourth, natural language data satisfying the above conditions were collected from source X, resulting in a dataset comprising 50 authors. The criterion for the number of authors was determined to ensure the validity of the research findings by applying the Central Limit Theorem [29]. Since the Central Limit Theorem can be applied when the sample size is at least 30, a dataset was constructed with data from 50 authors, thereby satisfying the requirement of having more than 30 authors. From the collected text data of each author, 1000 sentences were randomly sampled to standardize the quantity and format of the data during preprocessing. During this process, unique identifiers were assigned to each author to facilitate learning by the artificial intelligence model. These identifiers, in the format “Tn,” were sequentially assigned starting from 1 according to the order of collection. After preprocessing was completed, the assigned identifiers were used as filenames to save the text files. Meanwhile, data bias may negatively impact model training. Therefore, when duplicate sentences existed within a single author’s data, they were removed, and new sentences were randomly added to improve data quality and enhance authorship attribution performance. Additional preprocessing steps applied to the dataset for model input are discussed separately in Section 4.6.

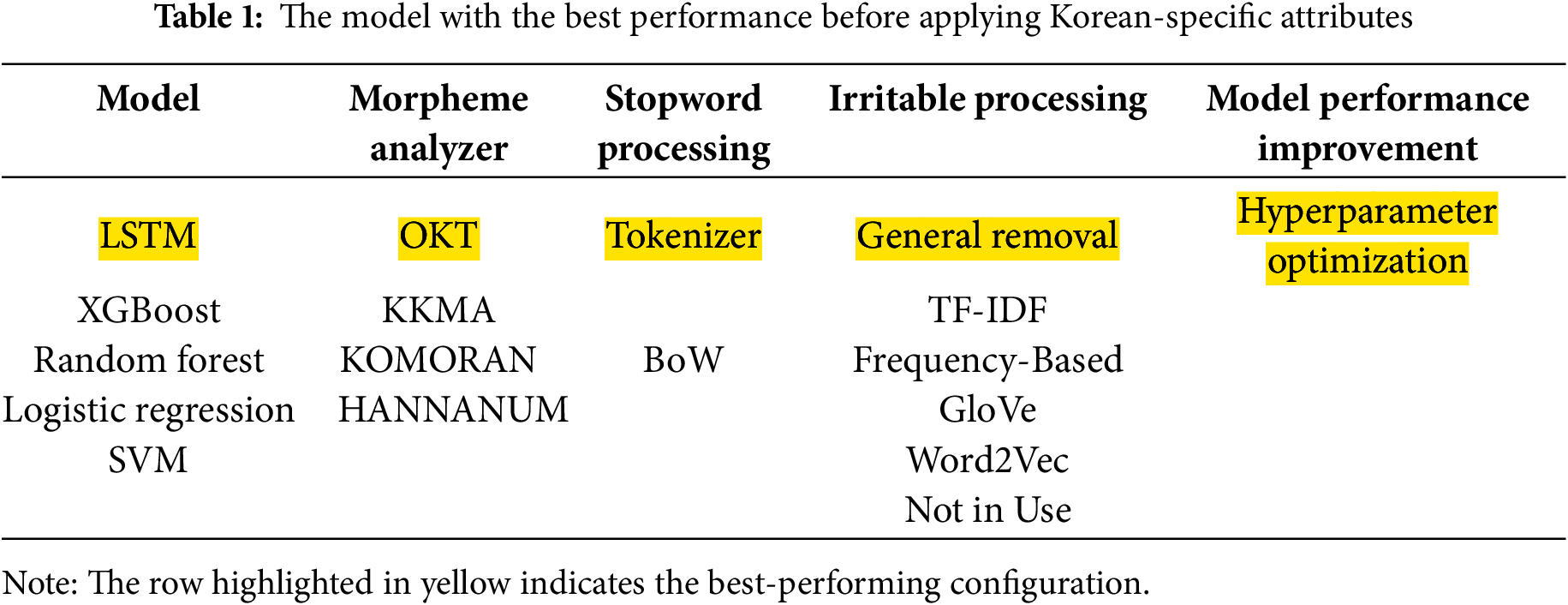

4.2 Best Performance Model before Reflecting Korean Attributes

Table 1 summarizes the results of identifying the optimal performance configuration using various model combinations. The model architecture was composed of an embedding layer to convert words into vector representations, an LSTM layer for sequential information processing, and an output layer with a softmax activation function for author classification. The LSTM network, equipped with a gating mechanism, effectively captures long-term dependencies and sequential patterns, making it especially well suited for Korean text processing where syntactic and semantic context are crucial. The text data were tokenized using the OKT morphological analyzer, which is appropriate for handling the complex lexical structures and diverse inflectional endings found in Korean. This tokenization improves data quality by segmenting sentences into smaller units and removing irrelevant elements. During preprocessing, key stopwords were removed and the data were segmented at the author level. Additionally, a frequency-based filtering method was applied to assign greater weight to important words, thereby enabling the model to focus on salient features and improving training efficiency. To evaluate model performance, a holdout validation approach was adopted. This method clearly separates the training and evaluation phases, allowing the model’s classification accuracy to be assessed without bias.

This combination is expected to achieve high classification accuracy on Korean-language datasets.

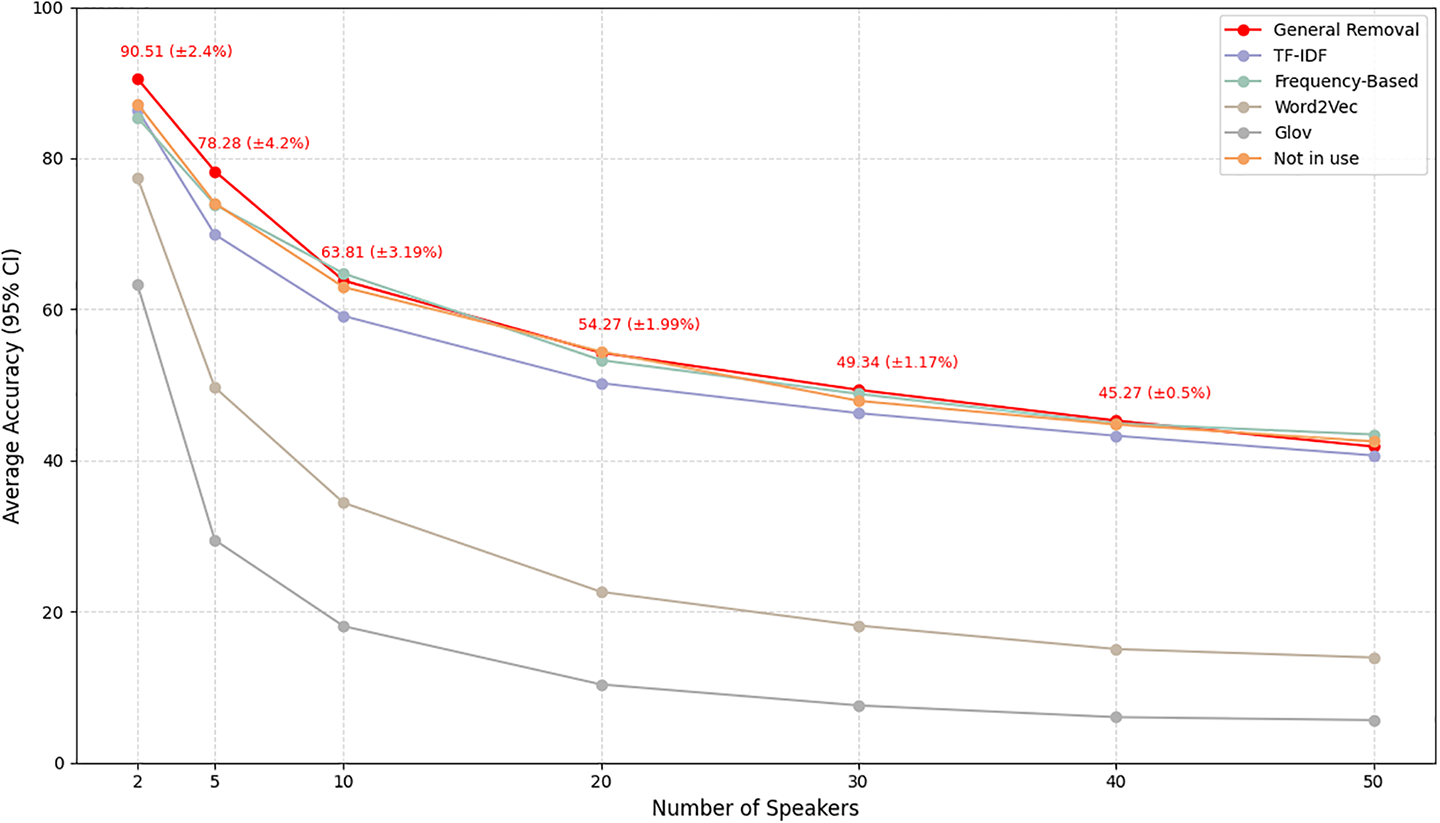

To compare performance with existing models in Korean authorship attribution studies, this research employed the state-of-the-art pretrained language model KLUE-BERT [30]. KLUE-BERT, a BERT-based model trained on large-scale Korean news and knowledge datasets, excels in contextual understanding and capturing relationships between words, and has demonstrated outstanding performance across various Korean natural language processing tasks. Notably, it can effectively represent the complex grammatical structures and subtle semantic nuances of Korean without requiring morphological analysis, making it well suited for distinguishing the unique writing styles of individual authors.

Table 2 presents the results of a comparison of classification accuracy between the LSTM model and the KLUE-BERT model for 20 authors. As shown in the table, although both models achieve similar accuracy, there is a substantial difference in training time, rendering the LSTM model more efficient and advantageous in terms of computational cost.

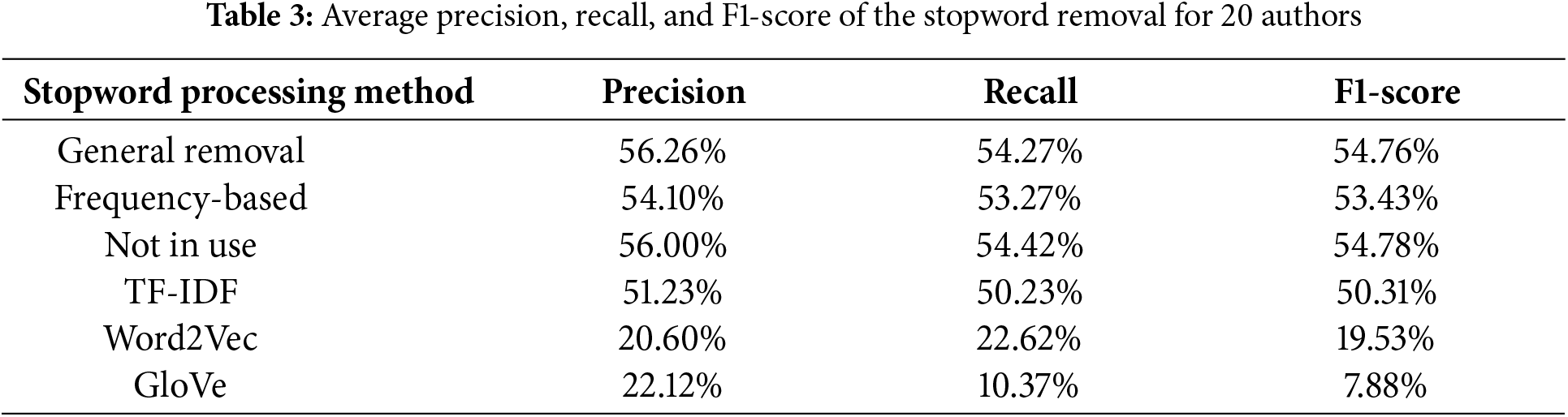

Stopwords refer to words that do not significantly contribute to meaning transmission within a text or appear frequently enough to dilute the informational density. In Korean, typical examples include particles and conjunctive expressions such as “ ” (this), “

” (this), “ ” (that), and “

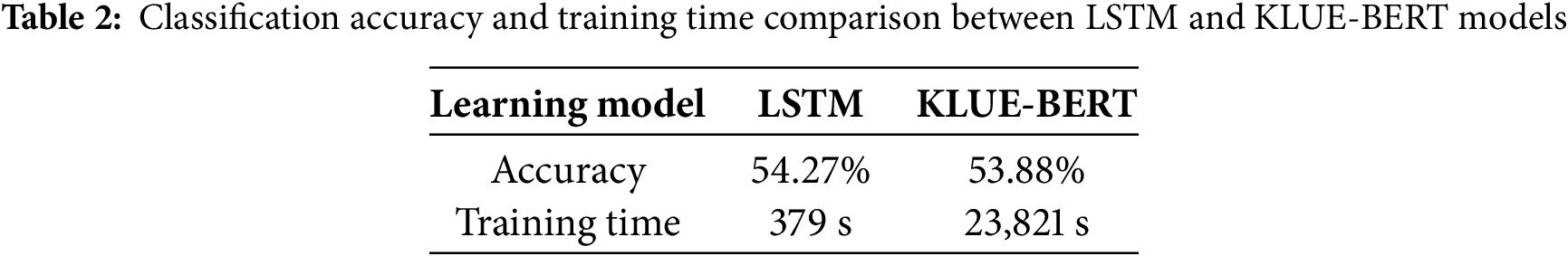

” (that), and “ ” (and). This study evaluates how the removal of stopwords influences preprocessing quality in text analysis by comparing six methods: cohesion word-based removal, general removal, TF-IDF, frequency-based removal, Word2Vec, and GloVe. The experimental results for each stopword are presented in Fig. 2.

” (and). This study evaluates how the removal of stopwords influences preprocessing quality in text analysis by comparing six methods: cohesion word-based removal, general removal, TF-IDF, frequency-based removal, Word2Vec, and GloVe. The experimental results for each stopword are presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Average accuracy of the stopword removal

The Frequency-based stopword removal method, which eliminates unnecessary conjunctives or functional words based on semantic linkage within sentences, demonstrated the highest overall performance among all methods. Specifically, with two authors, this method achieved an F1-score of 90.49% and an accuracy of 90.51%, and it maintained relatively stable performance even as the number of authors increased–recording an F1-score of 42.16% for 50 authors. These results underscore the method’s effectiveness in refining the logical structure of texts, enabling models to more accurately learn from core content. Table 3 summarizes the performance of each method based on the condition of 20 authors.

The general stopword removal method, which excludes commonly used words without relying on a predefined lexicon, achieved the highest accuracy among all methods. For two authors, it yielded an F1-score in the 90s and an accuracy exceeding 90%. These results suggest that removing extraneous content allowed the model to effectively focus on essential information.

However, when the number of authors exceeded 20, the frequency-based removal method produced marginally better accuracy. For instance, at 20 authors, general removal achieved an accuracy of 54.27%, while frequency-based removal reached 54.79%. This indicates that while simplistic, the frequency-based approach is more robust to scaling, maintaining generalization performance as data volume increases. In contrast, the TF-IDF-based method performed relatively well with a small number of authors but showed a steep performance decline as author count increased.

Specifically, general stopword removal is more appropriate for smaller datasets, while frequency-based removal is better suited for larger-scale applications.

4.4 Comparison of Morpheme Analyzers

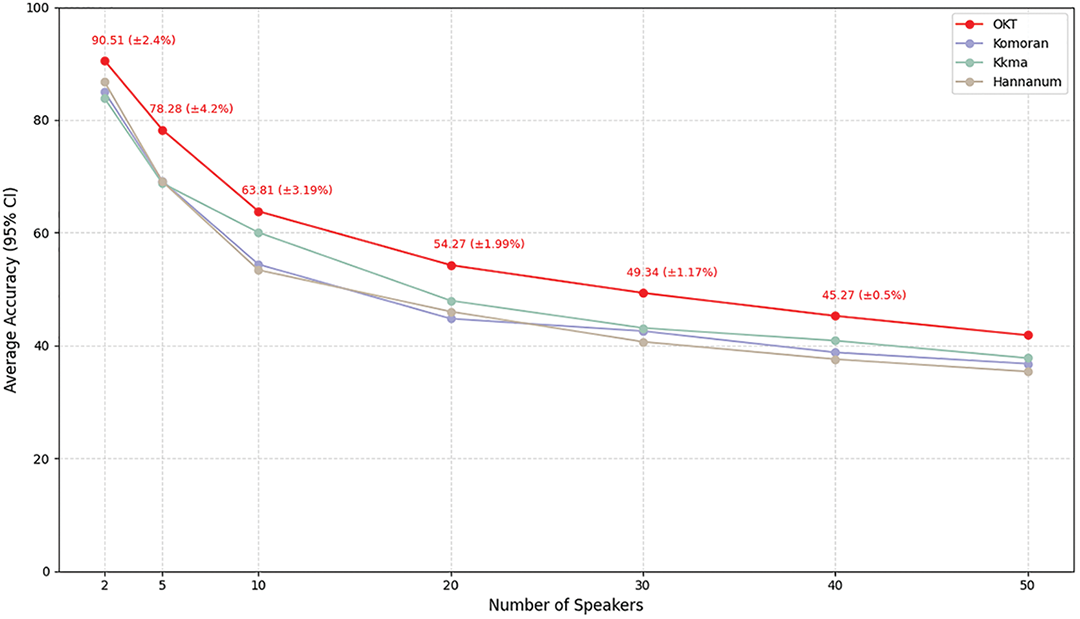

The KoNLPy package encompasses a variety of Korean morphological analyzers, and in this study, experiments were conducted using OKT, Kkma, Komoran, and Hannanum. The Mecab analyzer was excluded as it was developed for Japanese and is unsuitable for this study’s focus on Korean. The experimental results for each analyzer are presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Average accuracy of the morpheme analyzer

As the number of authors increased, the average accuracy of morpheme analyzers including Okt, Kkma, Komoran, and Hannanum gradually declined. Okt initially recorded the highest accuracy at 90.51%, followed by Kkma, Komoran, and Hannanum. Once the number of authors exceeded ten, Okt’s performance advantage became more apparent. Kkma and Komoran showed notable drops in accuracy, falling to the 60%–50% range. In particular, Komoran dropped to 40% when the number of authors reached 50. Although Hannanum started with lower initial accuracy, it exhibited a relatively stable rate of decline as the number of authors increased.

These results suggest that Okt provides relatively robust performance across diverse authorship attribution conditions, suggesting its promising potential for applications involving high authorship attribution variability. On the other hand, Kkma and Komoran appear more sensitive to changes in authorship attribution characteristics, which implies a need for additional training with more diverse authorship attributio ndata or improvements in preprocessing strategies to enhance generalizability.

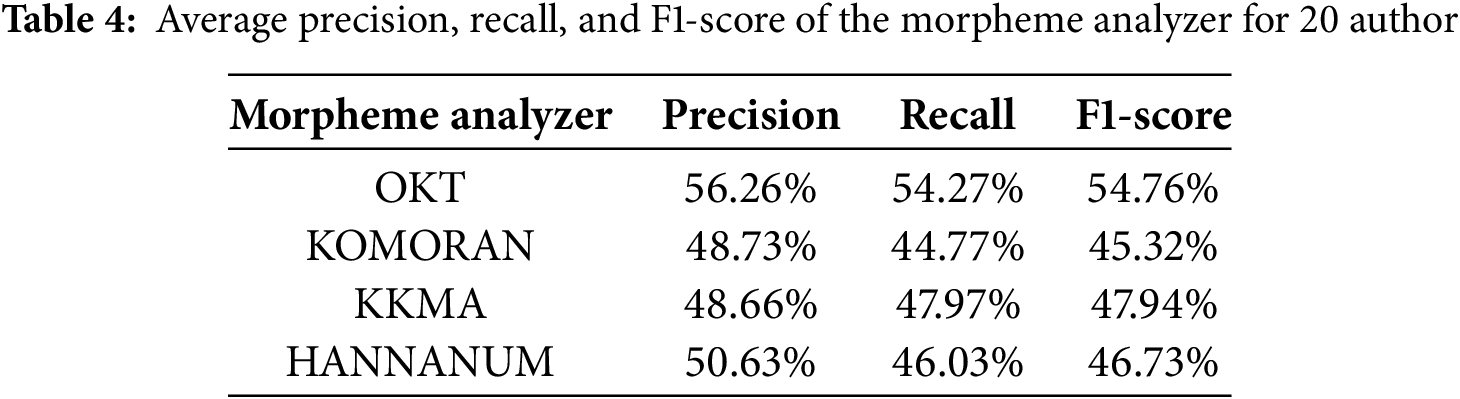

Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of morpheme analyzers based on precision, recall, and F1-score for 20 authors. Okt demonstrated the most consistent and superior performance across all metrics. Kkma and Hannanum exhibited relatively balanced results, whereas Komoran showed the lowest overall performance, particularly in recall and F1-score. These findings highlight the robustness of Okt and indicate its applicability to author-diverse linguistic tasks.

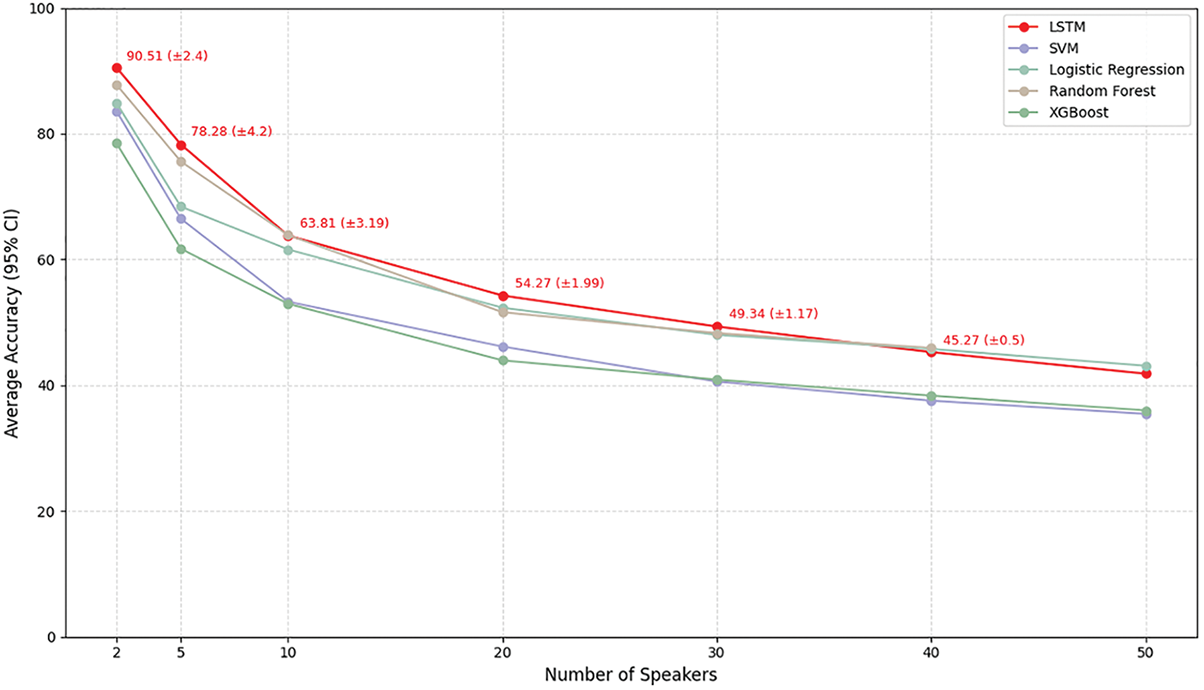

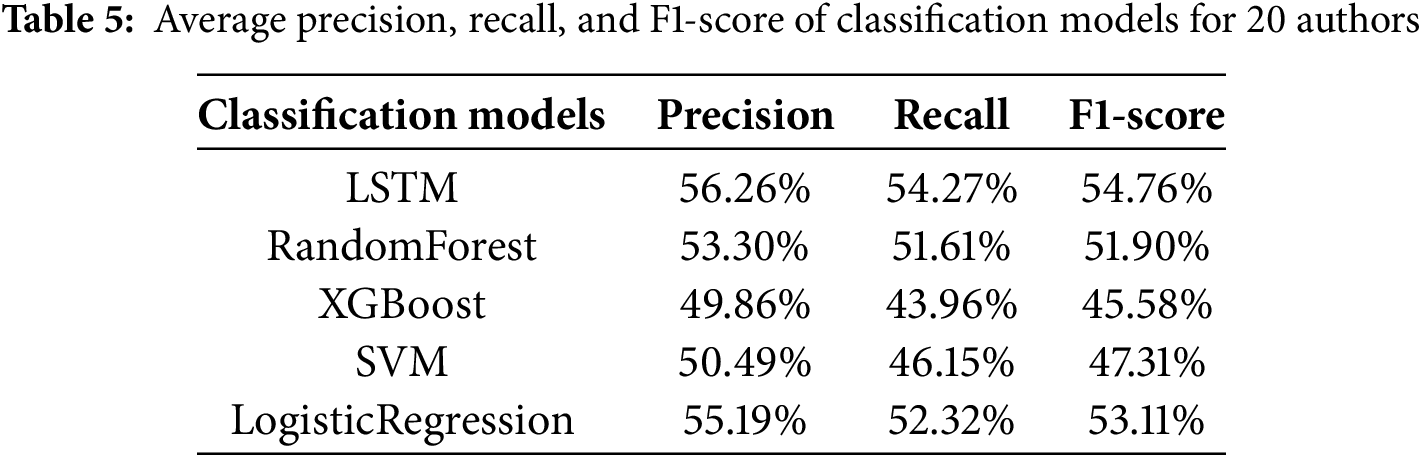

4.5 Comparison of Classification Models

In this study, we conducted experiments using five different classification models to compare their performance in authorship attribution. Fig. 4 presents the results, showing the average accuracy achieved by each model across various authorship settings. The results indicate that the LSTM model consistently achieved the highest average accuracy across most author-count configurations.

Figure 4: Average accuracy of the classification models

LSTM, built upon the RNN architecture, is particularly well-suited for processing sequential data. Its ability to retain or discard past information through specialized gating mechanisms enables the model to effectively capture word order and contextual relationships within text. These characteristics make LSTM highly adept at learning long-term patterns, such as an author’s unique linguistic style, expression patterns, and emotional tone. Consequently, LSTM outperformed other models across most author count configurations. However, as the number of authors increased to 40 and 50, its performance tended to decline. In contrast, Random Forest and Logistic Regression demonstrated superior accuracy in these cases. Random Forest excels at capturing non-linear linguistic patterns and feature interactions through the use of multiple decision trees, maintaining robust classification performance even in large author datasets. Logistic Regression, although a linear model, achieved competitive performance due to the linear separability of linguistic style differences among authors in high-dimensional space. These results suggest that, as the number of authors grows, models that focus on the overall distribution of linguistic features, rather than sequential contextual information, may offer more effective solutions for authorship attribution. Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of classification models based on performance metrics using data from 20 authors.

Excluding accuracy, an analysis of the remaining performance metrics reveals that the LSTM model maintains a well-balanced trade-off between precision and recall, resulting in strong F1-scores. This suggests that LSTM not only accurately identifies the true authors but also minimizes misclassifications, thereby enhancing the overall reliability of its predictions. In contrast, XGBoost displayed a significant discrepancy between precision and recall, indicating a tendency to either over-predict or under-represent certain authors. Similarly, the SVM model struggled to capture contextual nuances, leading to a higher rate of false negatives and, as a result, lower F1-scores. Although Logistic Regression showed relatively stable performance, its inability to capture sequential dependencies contributed to its comparatively lower performance relative to LSTM.

4.6 Tokenizer vs. BoW: The Importance of Word Order in Authorship Attributions

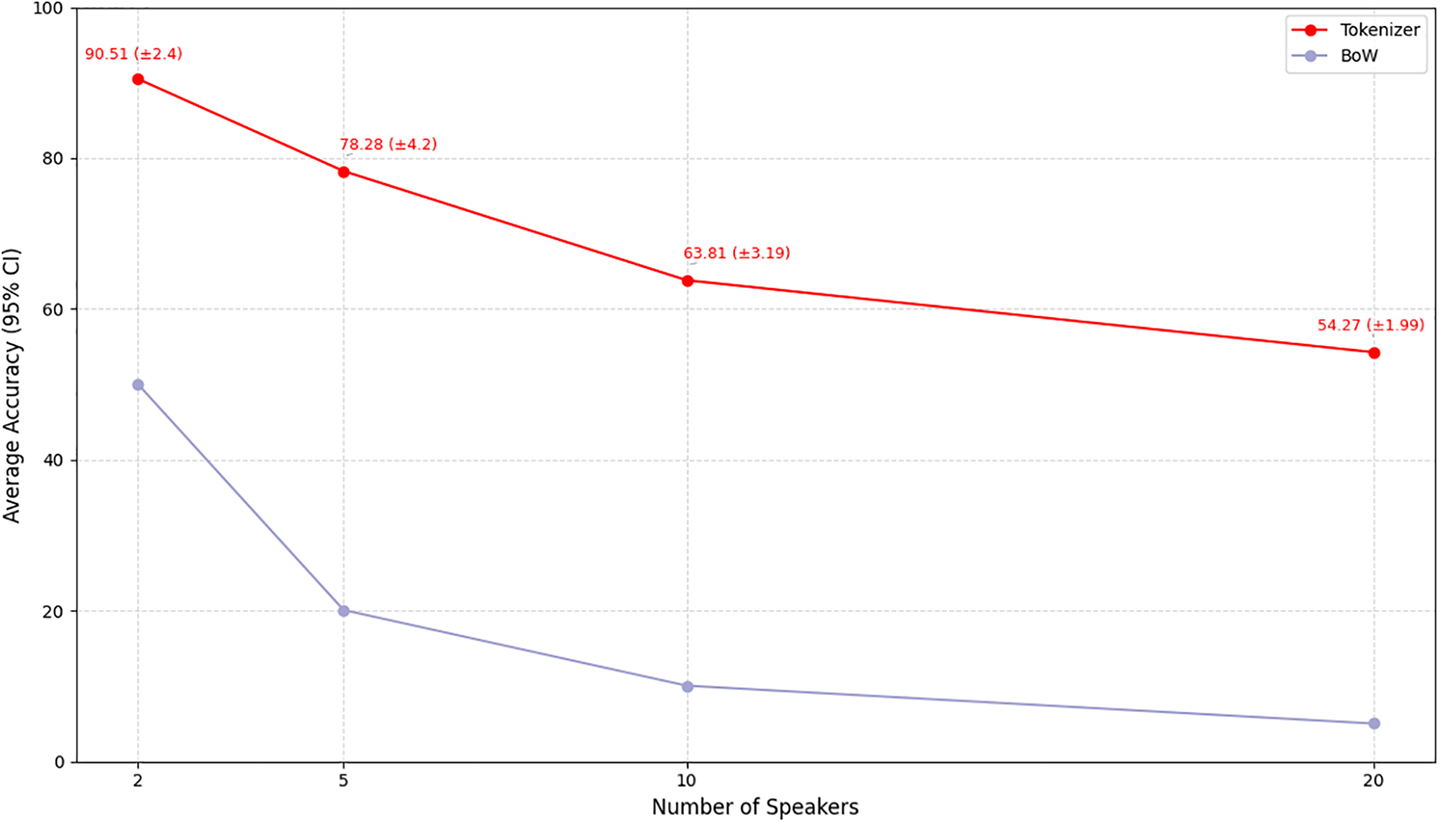

Unlike the BoW approach, which ignores word order and fails to capture contextual information, the Tokenizer preserves the sequence of words and retains contextual semantics. To investigate whether the presence of word order information in particular significantly affects authorship attributions performance, the results presented in Fig. 5 were analyzed.

Figure 5: Average accuracy of the test Processing

BoW-based models exhibited a sharp decline in performance as the number of authors increased. In contrast, although the performance of Tokenizer-based models slightly decreased with the growing number of authors, they maintained relatively stable performance even under high-authorship attribution scenarios. This result can be attributed to the Tokenizer’s ability to preserve word order and contextual meaning, allowing it to effectively capture author-specific utterance patterns. In contrast, the BoW model, which relies solely on word frequency without reflecting contextual features, experienced a steep performance drop as the author count increased. Therefore, it is evident that Tokenizer-based preprocessing, which incorporates contextual information, significantly outperforms BoW in authorship attributions tasks. In this experiment, a comparison between the Tokenizer and BoW methods was conducted using the same text data. Since a significant difference was observed in accuracy, additional performance metrics such as precision, recall, and F1-score were not analyzed. When the overall performance superiority is clear, accuracy alone is sufficient to evaluate the effectiveness of the two preprocessing methods. Therefore, this study proposes the combination of LSTM + OKT + Tokenizer + general stopword removal + hyperparameter tuning as the optimal configuration at the pre-stage, prior to incorporating the unique linguistic characteristics of the Korean language into the authorship attributions task.

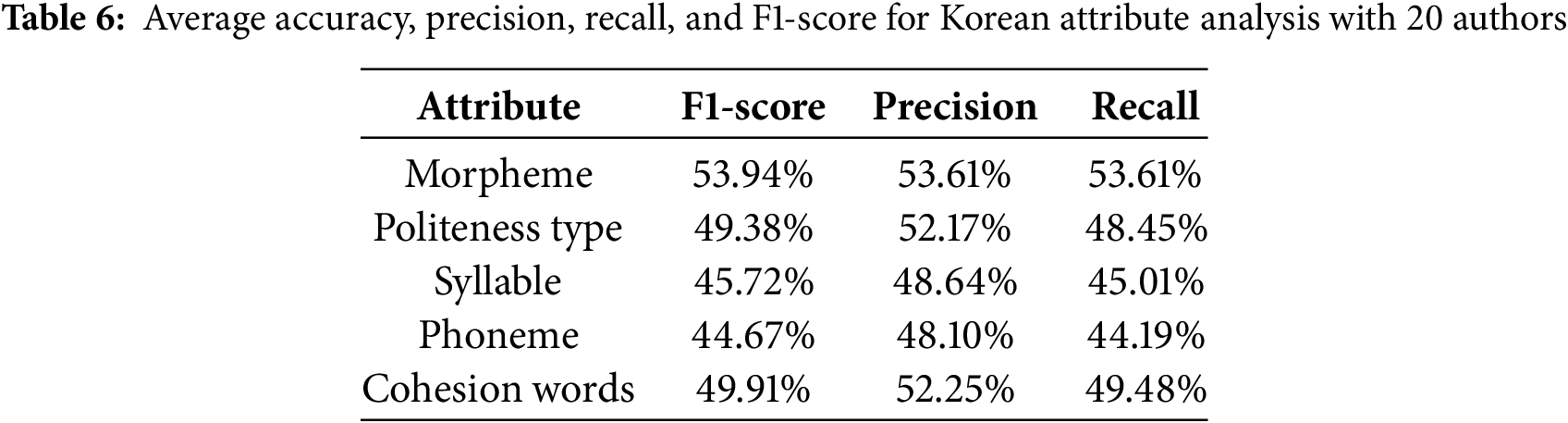

Korean is characterized by its flexible word order, explicit grammatical marking through particles and verb endings, and a rich system of honorifics. Unlike English, where word boundaries are clearly defined, Korean words often combine particles or endings, making morpheme-level segmentation a more natural analytical unit. These features contribute to a high degree of contextual dependency, requiring analytical models to capture both structural and sociolinguistic nuances for tasks like author classification

To address this, we adopted an ablation study framework in which several attribute-based models were constructed to reflect the unique linguistic traits of Korean, enabling us to assess the individual contribution of each attribute to author classification performance. As summarized in Table 6, the morpheme-based model—which leverages Korean morphological segmentation to capture author-specific grammatical and stylistic patterns—achieved the highest classification accuracy and maintained robustness even as the number of authors increased. The politeness expression attribute, while capturing sociolinguistic signals, showed instability due to its sensitivity to relational dynamics. Similarly, syntactic structure attributes and surface-level features like syllable and phoneme counts contributed limited value as sentence variety increased, reflecting more stylistic than semantic elements. The ablation results ultimately demonstrated that morpheme frequency yielded the largest performance drop when removed, underscoring its critical role in capturing author-specific linguistic patterns.

As shown in Fig. 6, as the number of authors increased, overall linguistic diversity and sentence complexity grew, leading to performance degradation in approaches based on simple statistical or low-dimensional linguistic features and a gradual narrowing of performance gaps between attributes. The re-identification risk measured by linkage risk was 27.31% before removing morpheme-based words that had relatively high frequency for each author, and it decreased to 19.53% after removing those words. This significant reduction demonstrates that filtering based on morpheme-level relative word frequency for each author effectively lowers re-identification risk. These findings empirically support the importance of incorporating linguistic features, such as morphological information, to enhance privacy protection in Korean text analysis.

Figure 6: Average accuracy of the Korean Attributes

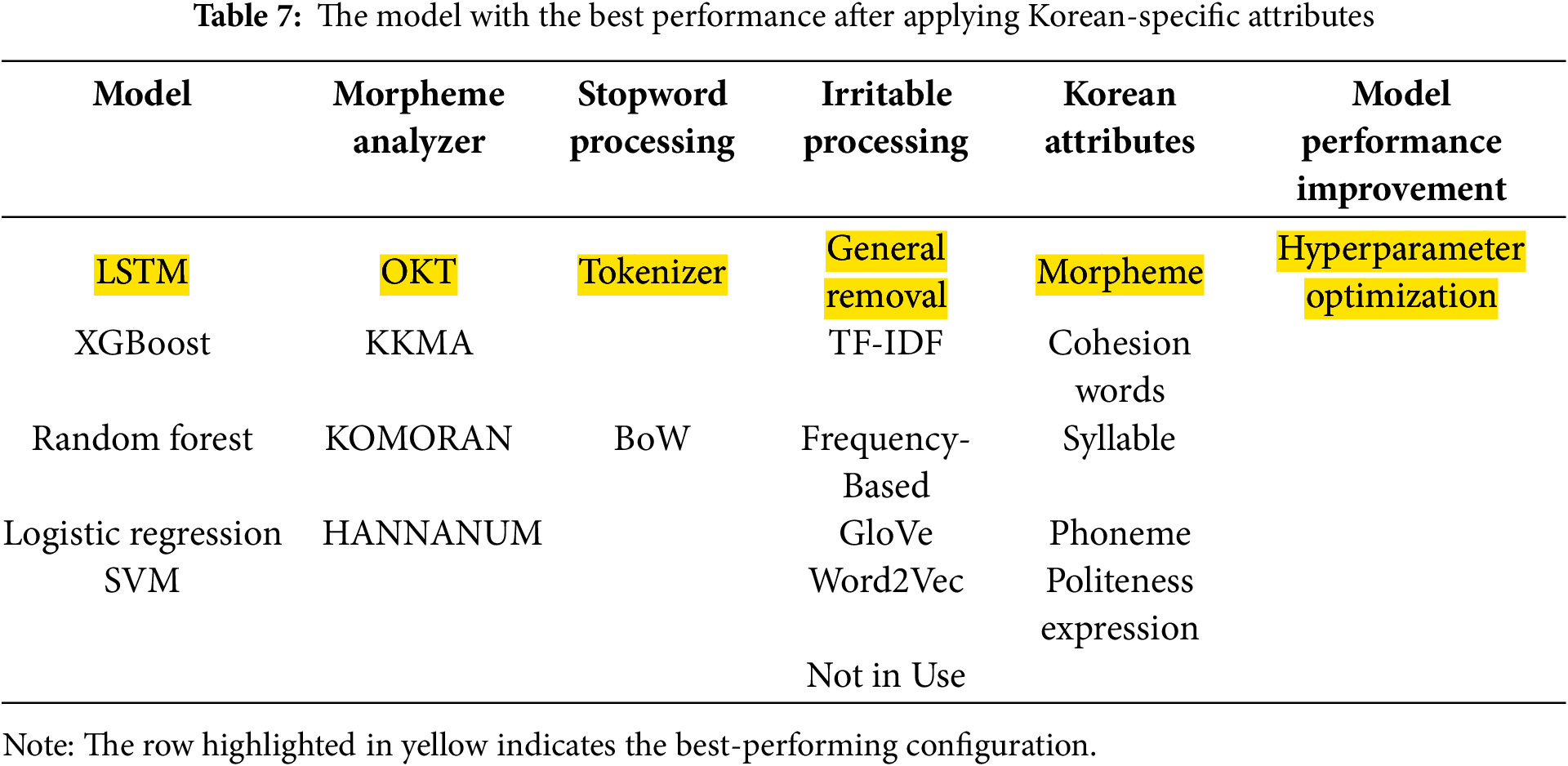

4.8 Best Performance Model after Reflecting Korean Attributes

Building on the findings from the attribute analysis, we identified the most effective model configuration for Korean author classification. Among various approaches, the morpheme-based word frequency model achieved the highest accuracy, highlighting its robustness in capturing lexical patterns across diverse authors. As summarized in Table 7, this model effectively leverages Korean-specific linguistic features such as agglutinative morphology and consistent morpheme use.

Unlike models that rely on cohesive words or key references centered on contextual structures, morpheme frequency-based approaches have performed more reliably amid diversity in syntax and diversity in authors. While cohesive-based models capture sentence-level flow and discourse-level relationships, they were more sensitive to stylistic changes. These findings empirically support the notion that models based on morpheme-level vocabulary signals can be interpreted and generalized across different writing styles, depending on the attributes of Korean authors.

5 Conclusion and Future Directions

This study emphasizes the importance of de-identification in Korean text modeling and demonstrates performance improvements through language-specific preprocessing techniques such as morphological analysis, stopword removal, and hyperparameter tuning. Experimental results confirmed that inadequate preprocessing can expose sensitive linguistic patterns, increasing re-identification risks and providing a practical foundation for privacy-preserving NLP technologies. However, the best-performing model showed a limitation in that training time sharply increased (about 1698 s at 50 authors) and accuracy decreased as the number of authors grew, although the false positive rate improved from 10.93% at 2 authors to 1.2% at 50 authors. These findings highlight a trade-off between accuracy and efficiency, pointing to the need for future work to address this limitation and achieve balanced improvements.

Acknowledgement: This work was grant funded by the Korea government (MOE) (2024 government collaboration type training project [Information security field], No. 2024 personal information protection-002) and Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2023-00238866).

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2023-00238866) and Korea government (MOE) (2024 government collaboration type training project [Information security field], No. 2024 personal information protection-002).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Segyeong Bang, Soeun Kim, Gaeun Ahn and Hyemin Hong; methodology, Segyeong Bang, Soeun Kim, Gaeun Ahn and Hyemin Hong; software, Segyeong Bang, Soeun Kim, Gaeun Ahn and Hyemin Hong; validation, Soeun Kim and Gaeun Ahn; formal analysis, Segyeong Bang, Soeun Kim, Gaeun Ahn and Hyemin Hong; investigation, Segyeong Bang and Hyemin Hong; resources, Segyeong Bang and Hyemin Hong; data curation, Segyeong Bang and Hyemin Hong; writing—original draft preparation, Soeun Kim, Gaeun Ahn and Hyemin Hong; writing—review and editing, Segyeong Bang; visualization, Soeun Kim and Gaeun Ahn; supervision, Junhyoung Oh; project administration, Segyeong Bang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions imposed by Twitter’s terms of service. However, methodological details and data processing procedures are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Villalobos P, Ho A, Sevilla J, Besiroglu T, Heim L, Hobbhahn M. Will we run out of data? Limits of LLM scaling based on human-generated data. arXiv:2211.04325. 2022. [Google Scholar]

2. Chung CM. Large language model and personal data protection: Korean cases and policies. IT Law Res. 2024;28:211–38. (In Korean). doi:10.37877/itnlaw.2024.28.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Shin JH. Regulation on the collection and use of artificial intelligence (AI) training data: focusing on disclosed personal information [Ph.D. thesis]. Seoul, Republic of Korea: Seoul National University; 2024. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

4. Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC). PIPC releases results of preemptive inspection of some artificial intelligence services; 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.pipc.go.kr/eng/user/ltn/new/noticeDetail.do?bbsId=BBSMSTR_000000000001&nttId=2476. [Google Scholar]

5. Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC). Guidelines for pseudonymizing unstructured data; 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.pipc.go.kr/eng/user/lgp/law/ordinancesDetail.do?bbsId=BBSMSTR_000000000005&nttId=2699#none. [Google Scholar]

6. Fei L, Kang Y, Park S, Jang Y, Lee J, Kim H. KDPII: a new Korean dialogic dataset for the deidentification of personally identifiable information. IEEE Access. 2024;12(2):135626–41. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3461804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hahm S, Kim H, Lee G, Park H, Lee J. Thunder-DeID: accurate and efficient de-identification framework for korean court judgments. arXiv:2506.15266. 2025. [Google Scholar]

8. Christen P, Schnell R, Vidanage A. Information leakage in data linkage. arXiv:2505.08596. 2025. [Google Scholar]

9. Yang T, Zhu X, Gurevych I. Robust utility-preserving text anonymization based on large language models. arXiv:2407.11770. 2024. [Google Scholar]

10. Min M, Lee JJ, Lee K. Detecting illegal online gambling (IOG) services in the mobile environment. Secur Commun Netw. 2022;2022(3):3286623. doi:10.1155/2022/3286623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Alshanik F, Apon A, Herzog A, Safro I, Sybrandt J. Accelerating text mining using domain-specific stop word lists. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); 2020 Dec 10–13; Atlanta, GA, USA. p. 2384–91. [Google Scholar]

12. Soufyane A, Abdelhakim BA, Ahmed MB. An intelligent chatbot using NLP and TF-IDF algorithm for text understanding applied to the medical field. In: Emerging Trends in ICT for Sustainable Development: The Proceedings of NICE2020 International Conference. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

13. Kumar GK, Rani DM. Paragraph summarization based on word frequency. AIP Conf Proc. 2021;2317(1):60001. doi:10.1063/5.0037283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Nayak AV, Karthik B, Sudhanva L, Ganger AA, Rekha K, Prakash K. Design of smart glove for sign language interpretation using NLP and RNN. In: Advances in Manufacturing, Automation, Design and Energy Technologies (ICoFT 2020). Singapore: Springer; 2023. p. 345–53. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-1288-9_36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Johnson SJ, Murty MR, Navakanth I. A detailed review on word embedding techniques with emphasis on word2vec. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;38(13):37979. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-17007-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ladani DJ, Desai NP. Stopword identification and removal techniques on tc and ir applications: a survey. In: 2020 6th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS); 2020 Mar 6–7; Coimbatore, India. p. 466–72. [Google Scholar]

17. Park K, Lee J, Jang S, Jung D. An empirical study of tokenization strategies for various Korean NLP tasks. arXiv:2010.02534. 2020. [Google Scholar]

18. Juluru K, Shih HH, Keshava Murthy KN, Elnajjar P. Bag-of-words technique in natural language processing: a primer for radiologists. RadioGraphics. 2021;41(5):1400–16. doi:10.1148/rg.2021210025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Patel R, Choudhary V, Saxena D, Singh AK. LSTM and NLP based forecasting model for stock market analysis. In: 2021 First International Conference on Advances in Computing and Future Communication Technologies (ICACFCT); 2021 Dec 16–17; Meerut, India. p. 52–7. [Google Scholar]

20. Li Z, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Wang S. Social media rumor refuter feature analysis and crowd identification based on XGBoost and NLP. Appl Sci. 2020;10(14):4711. doi:10.3390/app10144711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Shrivash BK, Verma DK, Pandey P. A novel framework for text preprocessing using NLP approaches and classification using random forest grid search technique for sentiment analysis. Econom Comput Econom Cyberne Stud Res. 2025;59(2):91–108. [Google Scholar]

22. Kumar A, Chatterjee JM, Díaz VG. A novel hybrid approach of SVM combined with NLP and probabilistic neural network for email phishing. Int J Elect Comput Eng. 2020;10(1):486. doi:10.11591/ijece.v10i1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Vimal B, Anupama Kumar S. Application of logistic regression in natural language processing. Int J Eng Res Technol (IJERT). 2020;9(6):69–72. [Google Scholar]

24. Kim DH, Ahn S, Lee E, Seo YD. Morpheme-based Korean text cohesion analyzer. SoftwareX. 2024;26(8):101659. doi:10.1016/j.softx.2024.101659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lee S, Lee Y, Lee CH. The influence of the syllable frequency on transposed letter effect of Korean word recognition. Korean J Cog Sci. 2021;32(3):99–115. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

26. Brown L. Politeness as normative, evaluative and discriminatory: the case of verbal hygiene discourses on correct honorifics use in South Korea. J Polite Res. 2022;18(1):63–91. doi:10.1515/pr-2019-0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Martin J, Shin GH. Korean nominal groups: system and structure. WORD. 2021;67(3):387–429. doi:10.1080/00437956.2021.1957549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Covington C, He X, Honaker J, Kamath G. Unbiased statistical estimation and valid confidence intervals under differential privacy. arXiv:2110.14465. 2021. [Google Scholar]

29. Okoro EN, Obike CO, Eze UU. Application of three probability distributions to justify central limit theorem. Af J Math Stat Stud. 2023;6(2):28–45. doi:10.52589/AJMSS-LHCUQZLF. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Park S, Moon J, Kim S, Cho WI, Han J, Park J, et al. KLUE: Korean language understanding evaluation. arXiv:2105.09680. 2021. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools