Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Transfer Learning-Based Approach with an Ensemble Classifier for Detecting Keylogging Attack on the Internet of Things

1 Cybersecurity Research Center (CYRES), Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Penang, 11800, Malaysia

2 Department of Networks and Cybersecurity, Al-Ahliyya Amman University, Amman, 19328, Jordan

3 Computer Department, Applied College, Najran University, Najran, 66462, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Cyber Security, Middle East University, Amman, 11831, Jordan

* Corresponding Author: Selvakumar Manickam. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Towards Privacy-preserving, Secure and Trustworthy AI-enabled Systems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5287-5307. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068257

Received 24 May 2025; Accepted 19 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

The Internet of Things (IoT) is an innovation that combines imagined space with the actual world on a single platform. Because of the recent rapid rise of IoT devices, there has been a lack of standards, leading to a massive increase in unprotected devices connecting to networks. Consequently, cyberattacks on IoT are becoming more common, particularly keylogging attacks, which are often caused by security vulnerabilities on IoT networks. This research focuses on the role of transfer learning and ensemble classifiers in enhancing the detection of keylogging attacks within small, imbalanced IoT datasets. The authors propose a model that combines transfer learning with ensemble classification methods, leading to improved detection accuracy. By leveraging the BoT-IoT and keylogger_detection datasets, they facilitate the transfer of knowledge across various domains. The results reveal that the integration of transfer learning and ensemble classifiers significantly improves detection capabilities, even in scenarios with limited data availability. The proposed TRANS-ENS model showcases exceptional accuracy and a minimal false positive rate, outperforming current deep learning approaches. The primary objectives include: (i) introducing an ensemble feature selection technique to identify common features across models, (ii) creating a pre-trained deep learning model through transfer learning for the detection of keylogging attacks, and (iii) developing a transfer learning-ensemble model dedicated to keylogging detection. Experimental findings indicate that the TRANS-ENS model achieves a detection accuracy of 96.06% and a false alarm rate of 0.12%, surpassing existing models such as CNN, RNN, and LSTM.Keywords

IoT is a rapidly growing technology that is constantly evolving and has a significant impact on society and business infrastructures. It offers a wide range of services and has become an integral part of modern life. The IoT is used to store sensitive data about organizations and individuals, as well as financial transactions and product development data [1,2]. As more and more people conduct important transactions online, the transmission of data between connected devices has created a high demand for security. Cyber dangers and attacks are constantly rising in complexity and frequency. As networks expand, the number of potential attackers increases, and their tactics and tools become more advanced and effective. In order to fully realize the potential of the IoT, it must be protected from threats and attacks. The innovations in the field of technology and smart gadgets, such as hotspots, the Internet, and other IoT have become integrated into every aspect of human life, and their security is essential [3]. While smart technologies have many benefits, they also have significant weaknesses that can lead to cyberattacks that cause harm to people and property. To reduce the danger of hacking or fraud, we use systems with strong security features. Currently, 98% of IoT device traffic is unencrypted, exposing personal and confidential information over the network. In the workplace, IP phones are the most commonly used IoT devices, accounting for 44 percent of enterprise IoT devices, but only 5 percent of security issues compared to other IoT devices. In contrast, cameras, which account for only 5% of IoT usage in organizations, are the leading source of security issues, accounting for 33% of the risk. Introducing IoT-based smart home gadgets into households raises substantial security concerns, as these devices are more vulnerable to assaults than other types of equipment. A smart home gadget can be compromised. The rapid growth in keylogging attacks on IoT networks during the COVID-19 pandemic underscores the urgent need for reliable detection methods. Numerous strategies can be employed to uncover keylogging attacks targeting IoT networks. Detection models often encounter challenges when it comes to analyzing large volumes of data, including traffic and network information, leading to a decrease in their effectiveness. To boost speed, models should prioritize features that enhance attack detection accuracy and minimize false positives, rather than relying on simple heuristics that may fail to detect keylogging attacks on IoT networks.

A keylogging attack is a form of illegal software that is used to steal personal information from users without their consent. It is believed to involve non-privileged software that runs in user space and records all keystrokes, which are then saved in a log file or sent to an FTP server. These types of attacks can be more easily carried out if antivirus and firewall programs are not kept up to date, as per a recent study. Fig. 1 below illustrates statistics on recent cyberattacks as reported by Kaspersky Lab [4].

Figure 1: Kaspersky statistics

Finding exact statistics for keylogging attacks specifically in academic papers can be challenging, but several recent research papers and reports provide insights into trends and data related to keylogging and malware attacks. Here are some studies and reports:

Keylogging attacks on IoT systems are considerably different from those on conventional computing systems since IoT devices take input in different ways and do not have particularly robust security features. Although the general idea of the conventional keylogger looks to intercept keyboard inputs at the operating system level, the IoT keylogger uses other input interfaces like touchscreen, voice, and motion sensors. Because of this, its ability to detect such attacks is further complicated, especially because they are usually carried out at the firmware level or utilize side-channel and network-based methods. Furthermore, a lot of IoT devices lack user interfaces, standard operating systems, or the ability to run antivirus software and other security tools. For example, smart home assistants, wearable gadgets, medical devices, and industrial control panels are all relatively easy to hack because their input channels are not secure and they have constrained resources [5].

The report published by Hitachi Systems Security in 2024 [6] discussed the increasing use of AI in malware, including keyloggers, highlighting cases like the “Black Mamba” malware, which uses AI to evade detection. This report provides an overview of malware trends, including the prevalence of info stealers, which often incorporate keylogging capabilities. It highlights the surge in information stealer activity and its impact on cybersecurity. Moreover, the authors in [7] examine the rise of information stealers, such as REDLINESTEALER, and their role in cybercrime. These information stealers are responsible for capturing sensitive information through keylogging and other methods. Finally, authors in [8] provide statistical data on the frequency and impact of these attacks in recent years. Collectively, these studies have shown the danger of keylogging attacks in the domain of IoT security.

This paper addresses this gap by proposing a hybrid deep learning approach—TRANS-ENS—that combines transfer learning and ensemble feature selection to detect keylogger activity in IoT networks using domain-adapted, packet-level features.

The main contributions of this research are outlined below:

• Ensemble feature selection is suggested as a method to identify shared features between the source and target models.

• The development of Pre-trained deep learning models utilizing transfer learning techniques for the identification of keylogging attacks.

• Building an ensemble transfer learning model (TRANS-ENS) by merging the transfer learning concept with an ensemble classifier for detecting keylogging attacks.

The rest of the research is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of the study’s background. Related literature is discussed in Section 3. Section 4 details the methodology of the proposed model. The results and the discussion of the proposed method are presented in Section 5. Lastly, the conclusion and future work are outlined in Section 6.

This section provides detailed information about the transfer learning concept.

Transfer Learning

Transfer learning, or TL, catalyzes various DL model successes. The models are initially pre-trained on a source dataset and subsequently fine-tuned for the target task, an optimal approach given the insufficient target data [9]. Domain adaptation in transfer learning for small and unbalanced datasets poses significant challenges, including domain shift, class imbalance, and the risk of overfitting [10]. Approaches such as feature alignment, fine-tuning, adversarial learning, and few-shot learning are instrumental in tailoring pre-trained models to the unique attributes of the target domain, particularly in scenarios where data is limited [11]. The main obstacles include feature misalignment, significant variability within small datasets, and the need for specialized metrics to accurately assess performance. By judiciously selecting appropriate domain adaptation strategies, it is possible to effectively modify models to identify infrequent occurrences, such as keylogging attacks. Identifying keylogging attacks through transfer learning presents significant challenges, primarily due to the considerable variability in user behavior, the limited availability of labeled data, and the unique characteristics of keylogging features [5,12]. In contrast to other attack types, such as malware or network intrusion detection, keylogging necessitates the recognition of user-specific patterns, complicating the effective transfer of knowledge across different domains. Addressing these challenges requires the implementation of domain adaptation, meta-learning, and sophisticated feature engineering methodologies [4,13]. Fig. 2 presents intuitive TL examples.

Figure 2: Intuitive TL examples [9]

Keylogging attacks on IoT devices, such as smart locks, pose unique and serious challenges. These systems use unconventional input methods like touchscreens, making traditional detection methods ineffective. Except for PCs, IoT devices often lack operating systems that support antivirus or monitoring tools. Firmware-level keyloggers can remain hidden and persist after reboots. There are usually no user interfaces to alert victims of malicious activity. Insecure update mechanisms make it easier for attackers to inject keyloggers. IoT communication protocols can also mask data exfiltration. Limited memory and processing power restrict security implementations. These factors make detection far more complex than in traditional computing systems. Thus, IoT environments require specialized and proactive keylogging detection approaches.

Traffic classification on TL focuses mainly on ML-centric traffic categorization. In [14], the authors suggested a method for traffic categorization via inductive TL, using TrAdaBoost to migrate many source domain datasets with few destination domain annotation equivalents. The experimental results from the Moore dataset suggested excellent accuracy and precision and reduced computation usage.

Additionally, a transfer learning scheme and an intelligent system were suggested in [15] for a smart building management system. Sophisticated technology can determine how many people are in each residence. The transfer learning method involves utilizing a deep learning model that has previously undergone training on the ImageNet dataset. The model is trained using a dataset acquired explicitly for the human counting scenario to provide the ability for human counting. Their dataset is not large enough to train more advanced networks; however, to create the final classification model.

Additionally, a deep learning approach based on auto encoders was developed in [16] for IoT anomaly detection, transfer learning, and a supervised device-type identification strategy. First, the multiclass classification models of neural networks, along with precise data from intelligent factories, enabled them to effectively distinguish between different types of devices based on their network responses. Then, to put auto encoders in an embedded sensor for anomaly detection for each recognized device type, they first employ them to learn their typical behaviors. Finally, they simulate malicious assaults on genuine equipment in their target factory using auto encoders to distinguish between typical and anomalous behavior based on packet responses. They thus earned an F1 score of 98.36%. Then, with equivalent accuracy, auto encoders detect unexpected traffic on their target site using the reference dataset as a training set. However, they only tested their method on a small selection of device types, and further research is needed to assess how other device kinds and risky IoT activities perform.

An updated deep transfer learning-based intrusion detection system was presented in [17] for IoT, which was developed initially using CNN on the Bot-IoT dataset and updated using a small amount of data from the ToN-IoT dataset. Through several experiments, this system could detect intrusions at a respectable rate. Their research concluded that Transfer Learning would be the best option for making up for the lack of data in certain attack classes and updating IDS systems with the least amount of work and computer resources. First, however, they must deploy their IDS in a natural IoT environment on a portable IoT device and evaluate its effectiveness using IoT network traffic information.

Similarly, the efficacy of transfer-learning-based intrusion detection was investigated in [18] for zero-day attacks, given the scarcity and inequality of datasets available for analysis in IoT environments. They created a sophisticated intrusion detection system that combines knowledge sharing and model enhancement, resulting in exceptional detection accuracy for both established and recently discovered attack types. The researchers utilized the BoT-IoT dataset for both the source and target domains, evaluating their innovative solution on the UNSW-NB15 dataset. Subsequently, in order to analyze the TL-based ID architecture for zero-day attacks, a test dataset was created containing five distinct assaults. They showed that even in asymmetric datasets with enough tagged data to detect zero-day attacks, IDS might be improved by transfer learning and network fine-tuning. Finally, they use experiments to show that the TL-based framework has a low rate of false positives and excellent efficacy. As in previous research, the proposed method must be refined and used with actual data from IoT networks to identify novel zero-day attacks. It must be evaluated using real-world information from IoT networks and low-power IoT gadgets.

In [19], the author tries to combine wireless sensor networks (WSN) with IoT and suggests using machine learning, specifically Support Vector Machines (SVM) with stochastic gradient descent (SGD), to improve intrusion detection. It also recommends incorporating context awareness, which takes into account user preferences and system features, to boost the performance of recommendation systems. Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) are employed to lessen traffic data and distribute the computational workload. The VG-IDS model further classifies network risks. The proposed WSN-DS algorithm showed better performance than other algorithms, achieving an accuracy of 96% and improved recall and F1-measure rates of 98%, 96%, and 97%, respectively, using the WSN-DS dataset. This reflects significant improvements in accuracy and detection capabilities.

Several keylogger detection approaches on IoT devices have been proposed. Machine learning (ML)-based approaches, such as those by [20,21], demonstrate medium to high detection accuracy due to the challenges in learning and adapting to the complex, evolving patterns of keylogging attacks. Detecting keylogging attacks on IoT devices is challenging due to limited datasets that reflect the unique characteristics of these attacks. Deep learning (DL) methods have been applied and trained on insufficient samples or datasets unrelated to keylogging activity, such as in [22]. To address data scarcity, researchers have increasingly turned to transfer learning, such as research works proposed in [23,24], as it enables the adaptation of pre-trained models to new tasks with smaller datasets. However, these approaches often rely solely on a single transfer model, which may limit their effectiveness in capturing the complexity of keylogging patterns. Additionally, the challenge lies in efficiently adapting these models to IoT-specific keylogging detection [25].

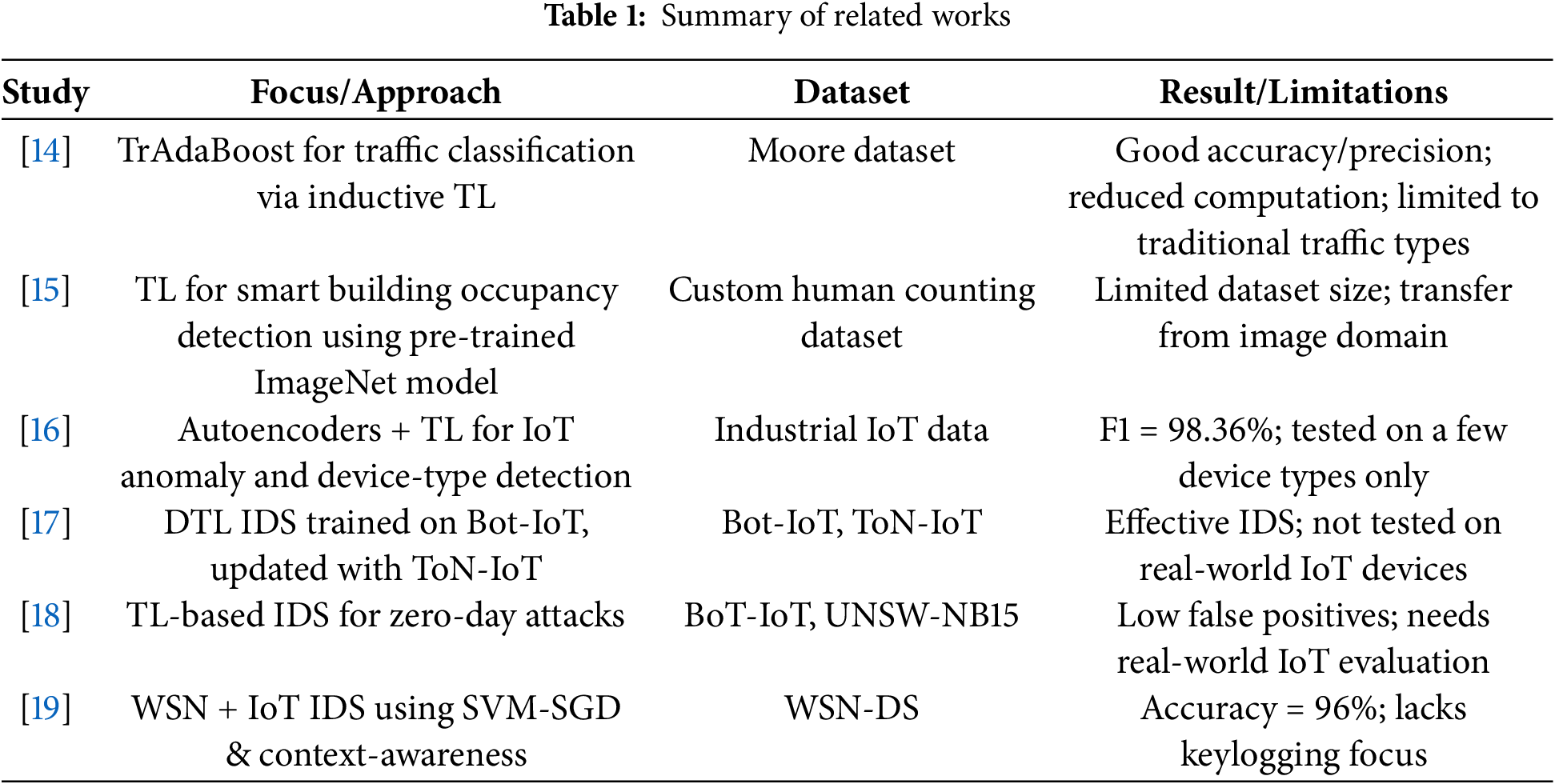

Furthermore, a significant challenge faced by transfer learning based approaches for keylogging detection is the selection of the most relevant features [26]. This selection is essential for enhancing model accuracy. Several existing transfer learning approaches that utilize feature selection techniques, such as those in [18]. Authors in [27] propose to enhance the detection accuracy of keylogging attacks. However, these approaches rely on individual feature selection techniques that encounter issues such as bias, instability, or suboptimal performance, which can vary based on the data distribution and the specific problem being addressed. Table 1 shows a summary of related works.

Although the reviewed studies listed in Table 1 demonstrate the effectiveness of transfer learning and deep learning techniques in IoT-related threat detection, none specifically address the unique characteristics and challenges of detecting keylogging attacks in IoT environments. Most approaches focus on generic anomaly detection, IDS, or traffic classification, often using datasets that are not tailored to keylogging behavior. Furthermore, many rely on single-model transfer learning or feature extraction methods that lack adaptability to evolving keylogging patterns. Several approaches also suffer from limited evaluation across diverse IoT device types, small datasets, or centralized assumptions that may not reflect real-world IoT settings. This highlights a clear gap in the literature: the lack of specialized, efficient, and adaptive models for detecting keylogging attacks in heterogeneous and resource-constrained IoT networks. Our work aims to bridge this gap by proposing a tailored detection approach that leverages hybrid transfer learning and advanced feature selection to improve accuracy, reduce false positives, and adapt to diverse IoT device behaviors.

This section outlines an ensemble transfer methodology designed for the detection of keylogging attacks within IoT networks. The methodology is structured into four distinct stages: The initial stage focuses on the preparation of data for both training and testing purposes. The subsequent stage employs ensemble feature selection to identify shared features. In the third stage, a pre-trained model is generated by training the source model using the dataset from the source domain. The concluding stage, referred to as TRANS-ENS, utilizes CNN, RNN, LSTM, and an ensemble classifier to effectively identify keylogging attacks in the dataset from the target domain. The proposed methodology seeks to enhance the efficacy of intrusion detection systems by emphasizing pertinent and advantageous features while minimizing the necessity to handle extensive volumes of data. The overall structure of the proposed technique is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The overall structure of the proposed technique

The Data Preprocessing Stage encompasses essential procedures necessary for preparing unrefined data before its input into a deep learning model. The objective is to guarantee that the data is cleaned, correctly formatted, and appropriate for the learning process. This stage is critical for enhancing model accuracy and preventing errors during the training of the model. This section explains data cleansing, data normalization, and data transformation, as explained in Sections 4.1.1–4.1.3, respectively.

Removing null records, dropping reserve columns, treating missing values, rectifying junk values or otherwise referred to as outliers, restructuring data to switch it to a lot of clear formats, data cleanup isn’t simply erasing the prevailing data to feature the new data, however rather finding the simplest way to maximize data set’s accuracy while not essentially losing the existing data. Differing kinds of data would require differing kinds of cleanup. However, it is important to consider choosing the right approach as the critical factor.

When the ranges of features in data are completely different, normalization is a technique used during processing to bring the values of numeric columns in a dataset to the same scale. Normalization has numerous advantages, including: Accelerating the improvement technique by preventing weights from erupting all over the place and confining them to a narrow range. Furthermore, reducing the interior covariate shift to improve training, scaling each feature to a comparable range to prevent or reduce bias within the network, and assisting in network regularization to reduce overfitting.

Data transformation refers to the procedure of altering data into a format or structure that is more appropriate for analysis or deep learning. The primary objective of this transformation is to enhance the efficacy of algorithms, improve interpretability, and guarantee that the data aligns with the specifications of the model. This process encompasses various modifications to the data to optimize it for analytical purposes.

4.2 Ensemble Feature Selection Mechanism Stage

The ensemble feature selection mechanism ensures that the selected features generalize well across both the source and target domains. Ensemble mechanisms can be adapted to different types of data distributions and feature spaces, making them more effective in scenarios with significant domain shifts. Combining multiple feature selection mechanisms reduces the risk of overfitting to domain-specific features in the source and target models [28]. The proposed ensemble feature selection mechanism in this stage strategically combines filter and wrapper mechanisms to ensure the selection of efficient features that are common in the source and target domain datasets. The filter selection mechanisms employed in this study are mutual information (MI) and chi-square, where they are chosen due to their efficiency and scalability, though it may not capture complex feature interactions [29]. Meanwhile, the wrapper mechanism employed in this study is recursive feature elimination (RFE) to provide greater accuracy, albeit at a higher computational cost. Furthermore, the untitled features selection (MI, chi square, and RE) is commonly used in existing research, such as in [30–32]. The out-of-feature selection mechanisms are fed to a majority voting ensemble to get common features on both the source and the target domains. Those features that receive votes from the three most feature selection mechanisms are considered common and robust across the source and target domains. By using a voting mechanism, this ensemble mechanism harnesses the strengths of all feature selection mechanisms used in this study to achieve a reliable feature selection process.

The proposed feature ensemble mechanism introduces a well-balanced, accurate, and robust solution. Furthermore, the voting mechanism ensures that selected features are relevant across models, enhancing efficiency and reducing the risk of overfitting—a critical advancement over existing mechanisms. Fig. 4 illustrates the proposed feature selection mechanism.

Figure 4: The proposed ensemble feature selection

It is worth mentioning that the experiments demonstrate that using a high number of feature selection mechanisms can result in computational inefficiency and increase the risk of overfitting, particularly with small datasets. Instead, selecting a few carefully chosen methods can mitigate these issues while still enhancing performance. In many ensemble feature selection mechanisms, using three to five different methods is commonly recommended as it balances robustness with computational cost [33]. Using more than five methods often yields diminishing returns, except for highly complex or large datasets.

The output from the previous stage feeds the transfer learning with common features. The transfer learning stage consists of two main sub-stages, the first sub-stage creates a pre-trained model, and other sub-stage creates transferred CNN, RNN, and LSTM models, namely TRANS-CNN, TRANS-RNN, and TRANS-LSTM, respectively. The BoT_IoT dataset is utilized to train a pre-trained model, and the keylogger_detection dataset is used to train TRANS-CNN, TRANS-RNN, and TRANS-LSTM.

DL models such as two-dimensional CNNs (2D CNNs) have shown their ability to identify complex patterns when large labeled datasets are available for training classification models to detect attacks [34]. However, in IoT environments, there is often a shortage of extensive labeled data, particularly for keylogging attacks. In these networks, acquiring new training data can be costly, time-consuming, or sometimes impossible. As a result, transfer learning is seen as an ideal solution in such situations. The BoT-IoT dataset [35] is utilized as the source dataset because it contains a substantial amount of IoT network traffic data. DDoS attack from BoT_IoT dataset is selected to train the pre-trained model because it has extensive labeled data (33,005,194 instances) and there is a similarity in the behavior of the traffic between DDoS and keylogging attacks, such as source IP address and destination IP address features. However, the BoT-IoT dataset is a tabular dataset, which is not directly compatible with 2D CNNs, as these algorithms are designed to process images. Therefore, in this stage, BoT_IoT is transformed into an image-like format. By transforming the traffic data into an image-like format, it becomes possible to leverage the power of 2D CNNs, which excel at identifying spatial patterns and feature correlations. This approach enables the detection of complex relationships in the data that may not be as apparent with other methods.

The rationale for using a 2D CNN in the source domain to generate the pre-trained model, over other deep learning models like LSTM or RNN, lies in its effectiveness with structured, spatially-oriented data. Since the data is transformed into a structured, image-like format, CNNs—known for their strength in handling spatial patterns—are particularly well-suited.

4.3.2 TRANS-CNN, TRANS-RNN, and TRANS-LSTM Models

In the second sub-stage, TRANS-CNN, TRANS-RNN, and TRANS-LSTM models are created via transferring weights that resulted from the pre-trained model (first sub-stage) for specific detection tasks. The output models—TRANS-RNN, TRANS-CNN, and TRANS-LSTM—are utilized in the next stage (ensemble classifier stage) to build the TRANS-ENS approach. These specialized versions utilize the knowledge gained from the pre-trained model and are specifically optimized to identify keylogging attacks within the target domain when trained on the keylogger detection dataset.

4.4 Ensemble Classifier Stage (TRANS-ENS)

In this stage, the TRANS-CNN, TRANS-RNN, and TRANS-LSTM models are trained on the keylogger_detection dataset within the target domain to detect keylogging attacks. Each model brings unique capabilities to the ensemble classifier, known as TRANS-ENS. TRANS-CNN excels in extracting spatial patterns from static data, while TRANS-RNN and TRANS-LSTM handle sequential and long-term dependencies, making them adept at analyzing temporal data. Combining these models allows the ensemble to effectively capture both spatial and temporal patterns, resulting in improved generalization, enhanced robustness, reduced overfitting, and higher accuracy, particularly for complex datasets requiring multi-dimensional analysis.

The ensemble leverages weighted majority voting and boosting to further enhance its performance. By integrating these techniques, TRANS-ENS compensates for misclassifications made by individual models. For instance, if TRANS-CNN fails to correctly classify an instance due to noisy inputs, TRANS-RNN or TRANS-LSTM can still make an accurate prediction by relying on temporal context. This collaborative approach ensures that the ensemble benefits from the strengths of each model, while boosting iteratively refining their contributions by adjusting weights based on their detection performance. This process improves the ensemble’s adaptability and detection accuracy over successive rounds.

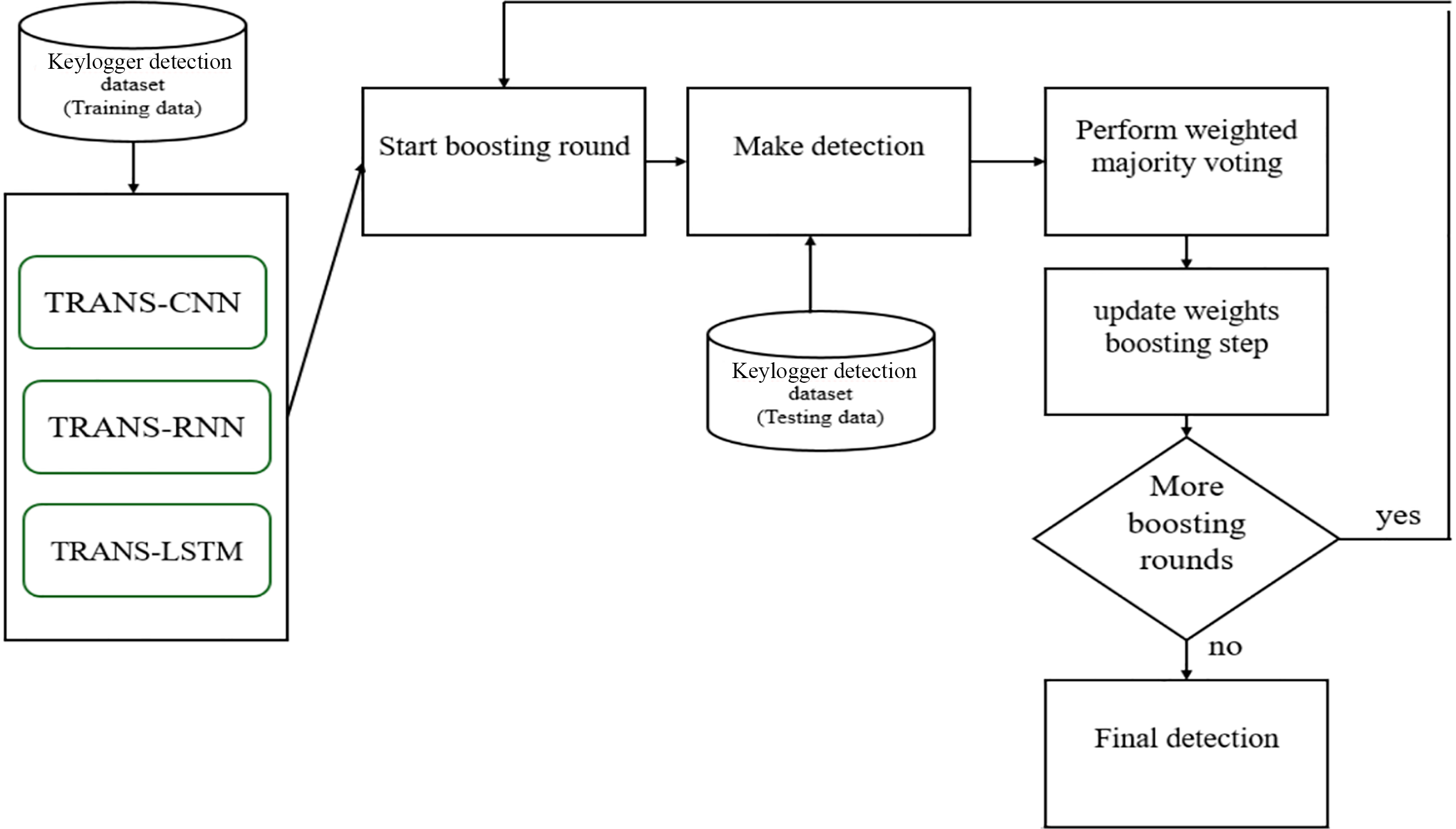

Fig. 5 illustrates the TRANS-ENS structure and workflow. The ensemble begins with initializing the three models with transferred weights and splitting the keylogger_detection dataset into training and testing subsets. After training the models on the training set, their predictions on the test set are combined using weighted majority voting. The boosting mechanism evaluates the accuracy of the combined predictions, adjusting model weights accordingly. If further ensemble is needed, additional boosting rounds are executed until the final ensemble model is ready to make its detection decisions. By integrating spatial and temporal analysis with adaptive voting and boosting, TRANS-ENS provides a robust, accurate, and generalizable solution for detecting keylogging attacks.

Figure 5: The proposed ensemble classifier (TRANS-ENS)

We describe a possible IoT application for the TL-based intrusion detection method in this section. The BoT-IoT dataset was utilized as the source domain in our analysis, which includes a significant amount of typical IoT network activity, and the keylogger_detection dataset [36] for the target domain, which is smaller and more unbalanced and contains keylogger attack traffic in an IoT network, to show the efficacy of this approach.

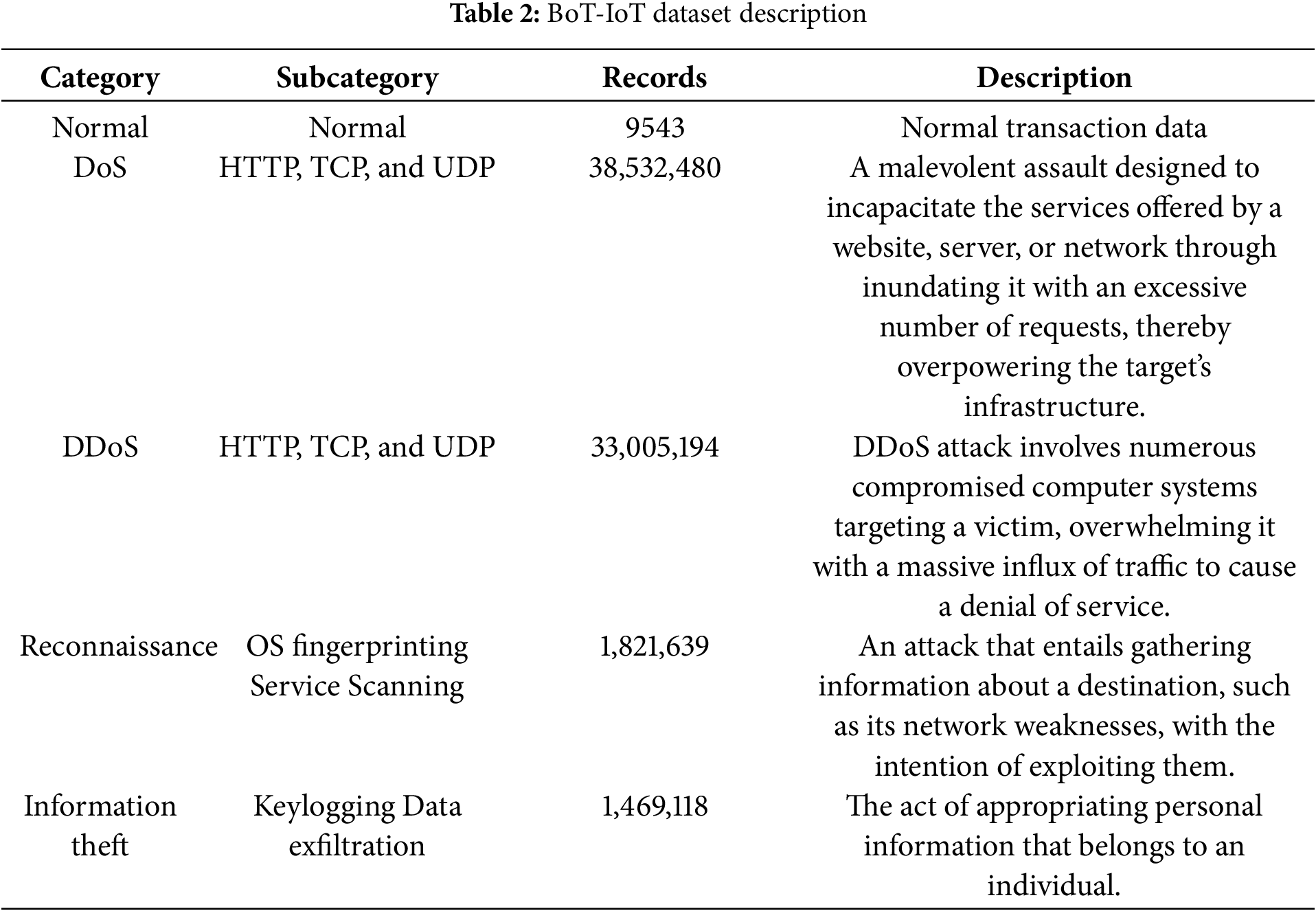

The dataset comprises entries of network operations within a simulated IoT setting, encompassing regular traffic as well as various forms of cyber assaults like denial of service (DoS), distributed DoS (DDoS), reconnaissance, and data theft. The dataset contains 46 characteristics and 5 distinct outcome categories, with one representing regular traffic and four indicating different categories of offensive techniques. The BoT-IoT dataset encompasses more than 73 million entries, yet only a fraction (10%) of the complete dataset is employed in this investigation for simpler management, while preserving the proportional representation of different attack types. Table 2 introduces the description of the BoT-IoT dataset.

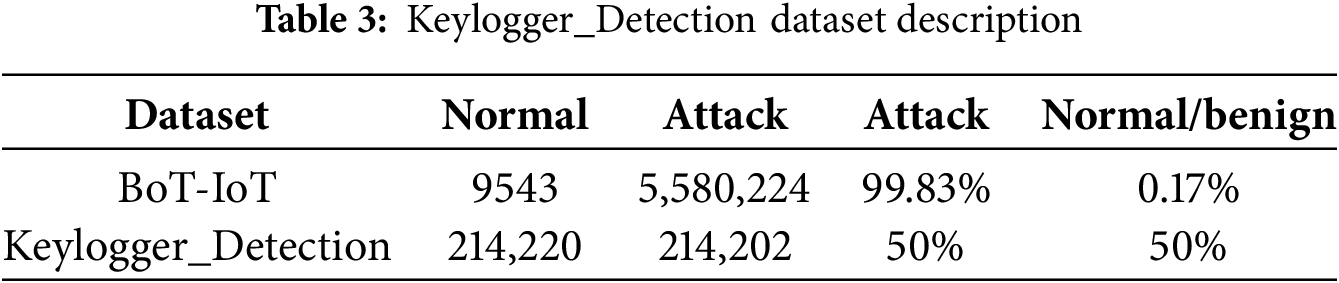

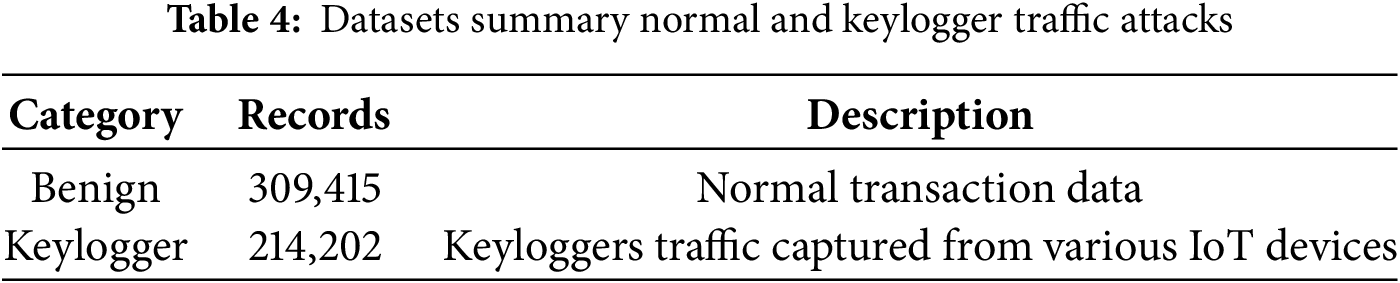

Keyloggers are types of spyware that record the keystrokes made by users and can be used by cybercriminals to steal information from a victim’s computer or other device. There are two main categories of keyloggers: those that are injected into the user’s device to steal information through keystrokes, primarily focusing on stealing login credentials like user IDs and passwords; and those that focus on the user’s behavior to steal sensitive information. The present dataset, which was obtained from the CIC website, contains 523,617 samples of keylogger and benign samples, with 309,415 benign observations and 214,202 keylogger observations. Table 3 presents the description of the Keylogger_Detection dataset. The distribution between normal and keylogger traffic is 59%/41%.

The dataset originating from the source domain underwent a division where 75% was allocated for training and the remaining 25% for testing objectives. Detailed information regarding the datasets, such as the classification of regular and malicious traffic, as well as the distribution of attacks within each category, can be found in Table 4.

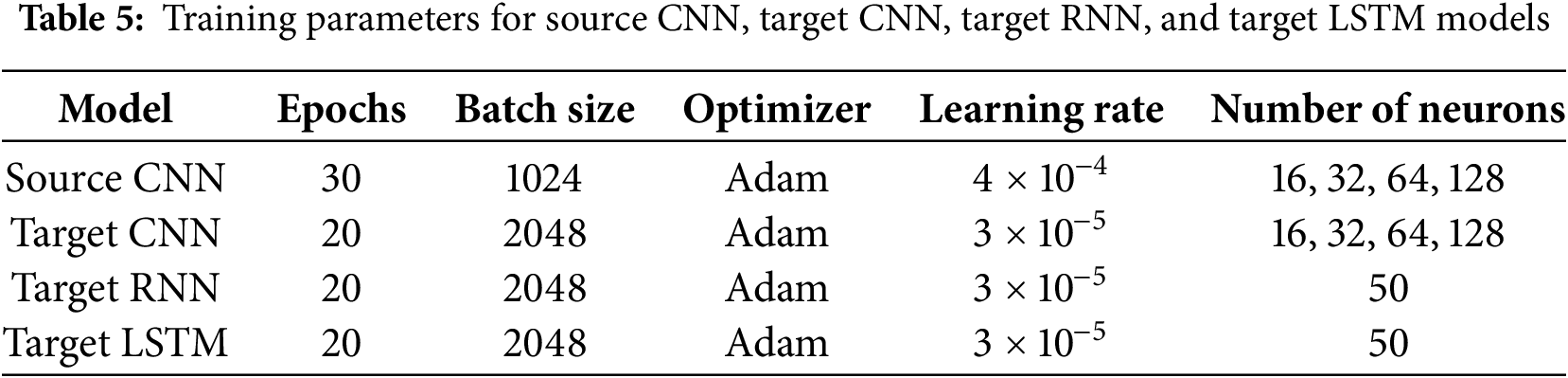

5.3 Deep Learning Model Hyperparameters

The proposed method involved training two datasets: BoT-IoT dataset for the source domain and the keylogger_detection dataset for the target domain. The source CNN model underwent 30 epochs of training using the Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation) optimizer with a learning rate of 4 × 10−4 and a batch size of 1024. Categorical cross-entropy was utilized as the loss function. By setting the number of epochs to 30, it allows the model to see the entire dataset 30 times. This is often enough to learn patterns without the risk of overfitting (learning noise) or underfitting (not learning enough). However, using Adam optimizer gets the benefits of momentum (which helps accelerate the optimizer in the right direction) and adaptive learning rates (which adjust the step size based on past gradients). Adam is often selected for its rapid convergence capabilities. It calculates updates by leveraging exponentially decaying averages of both past gradients and their squares, which aids the model in achieving faster convergence and helps to mitigate oscillations. Furthermore, a learning rate of 4 × 10−4 strikes a balance between learning stability and speed, making it effective for deep models where large learning rates can cause erratic training. Finally, with a large batch size (1024), the model will have faster convergence because the gradients are calculated more accurately, and Adam adapts the learning rate for each parameter. For the target CNN/target RNN/target LSTM models, the Adam optimizer with a small learning rate of 3 × 10−5 and a batch size of 2048 was used during 20 epochs of training. Categorical cross-entropy was also employed as the loss function. The weights transfer from the source model, so the small learning rate of 3 × 10−5 ensures extreme caution to avoid overfitting and aims to enhance the performance of the transfer learning. This setup is highly effective in scenarios like transfer learning, where a pre-trained model is being fine-tuned on a new dataset. The small learning rate and fewer epochs allow the model to adjust its weights slightly while retaining the valuable knowledge from pre-training. The models’ training parameters are presented in Table 5.

To implement the deep learning models, libraries in the Python language are used to write code for the TRANS-ENS model, such as TensorFlow, Keras, sklearn, matplotlib, and pandas.

The keylogger detection dataset was used to evaluate the transfer learning approach, focusing solely on keylogger attacks. The efficiency of the proposed model (TRANS_ENS) is proved by using the following comparisons:

5.4.1 Evaluation of TRANS-ENS with Vanilla CNN, RNN, and LSTM

This section presents the evaluation of TRANS-ENS with vanilla CNN, RNN, and LSTM, using BoT_IoT as a source dataset and Keylogger_Detection as a target dataset.

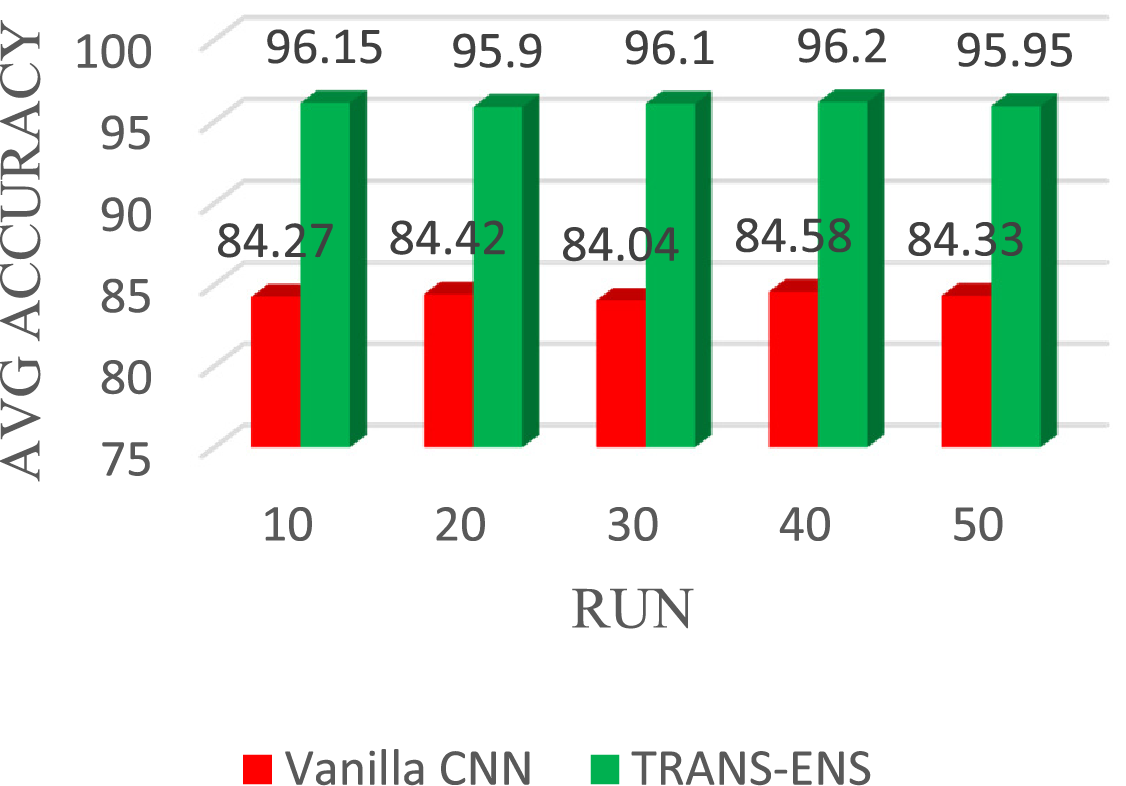

Evaluation of TRANS-ENS with Vanilla CNN

The TRAND-ENS and vanilla CNN classifiers are implemented together in multiple runs (10, 20, 30, 40, and 50) using the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets as source and target datasets, respectively. These runs are conducted to determine the average results and meet the requirements of computer science testing. Regarding average accuracy, the vanilla CNN achieves 84.27%, 84.42%, 84.04%, 84.58%, and 84.33% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the vanilla CNN achieves a detection accuracy of 84.32%. While TRAND-ENS achieves average accuracy of 96.15%, 95.90%, 96.10%, 96.20%, and 95.95% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the TRAND-ENS achieves a detection accuracy of 96.06%. Fig. 6 illustrates the average detection accuracy of the vanilla CNN and TRAND-ENS when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets.

Figure 6: The average detection accuracy of the TRANS-ENS and Vanilla CNN when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets

Furthermore, regarding recall, the vanilla CNN achieves 85.13%, 84.95%, 85.20%, 85.45%, and 85.67% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the vanilla CNN achieves a recall of 85.28%. While TRAND-ENS achieves 95.96%, 95.82%, 96.15%, 95.70%, and 95.96% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the TRAND-ENS achieves a recall of 95.91%. Fig. 7 illustrates the Recall of the vanilla CNN and TRAND-ENS when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets.

Figure 7: The recall of the TRANS-ENS and Vanilla CNN when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets

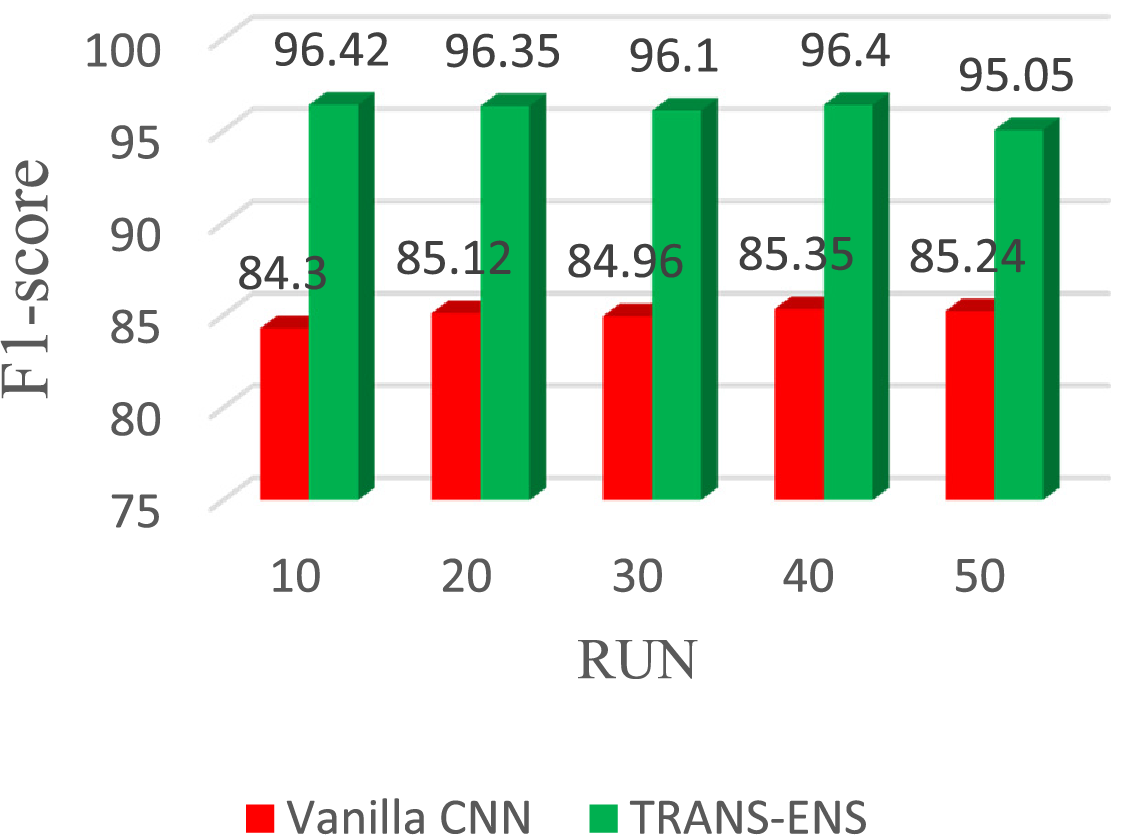

Moreover, regarding F1-score, the vanilla CNN achieves 84.3%, 85.12%, 84.96%, 85.35%, and 85.24% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the vanilla CNN achieves F1-score of 84.99%. While TRAND-ENS achieves 96.42%, 96.35%, 96.1%, 96.4%, and 95.05% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the TRAND-ENS achieves F1-score of 96.06%. Fig. 8 illustrates the F1-score of the vanilla CNN and TRAND-ENS when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets.

Figure 8: F1-score of the TRANS-ENS, and Vanilla CNN when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets

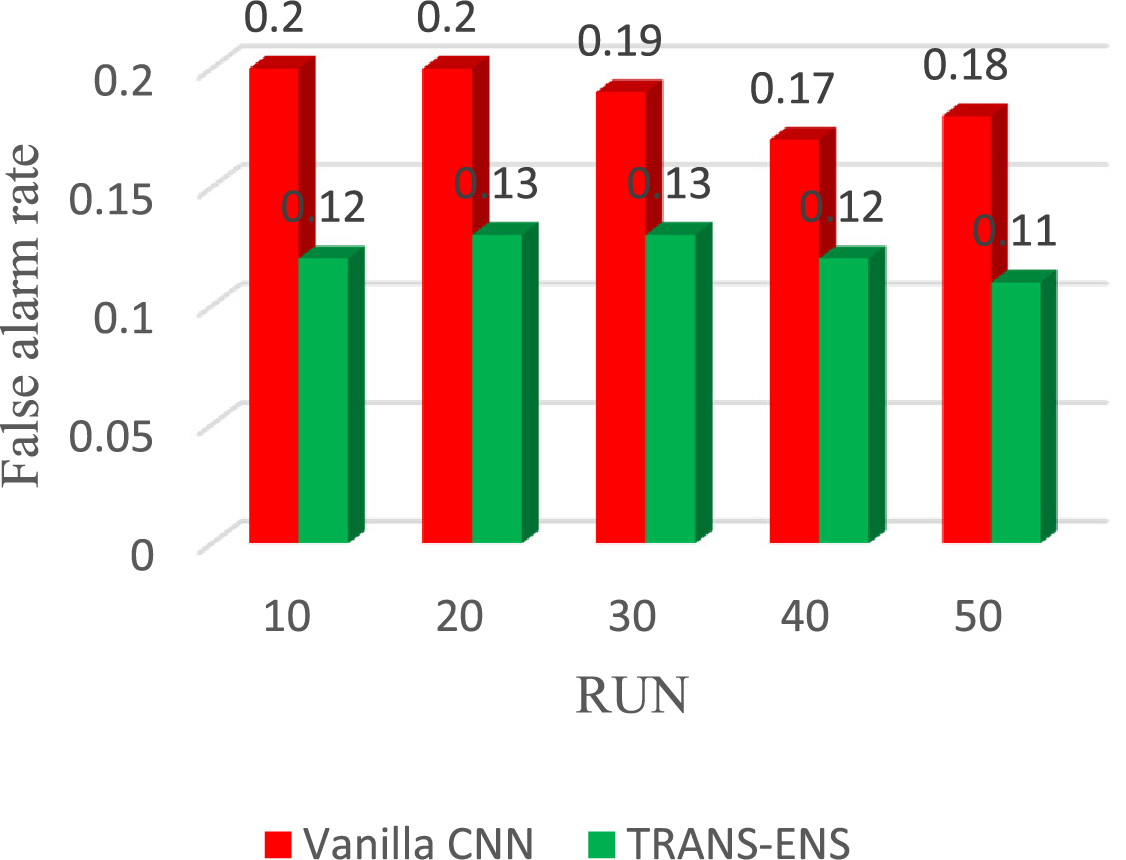

Lastly, the average false alarm rate, the vanilla CNN achieves 0.20%, 0.20%, 0.19%, 0.17%, 0.18% in 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 runs, respectively. On average, the vanilla CNN achieves a 0.19% false alarm rate. While the average false alarm rate, TRANS-ENS achieves 0.12%, 0.13%, 0.12%, 0.11%, 0.10% in 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 runs, respectively. On average, TRANS-ENS achieves a 0.12% false alarm rate. Fig. 9 presents the results of the false alarm rate of the vanilla CNN and TRANS-ENS using the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets.

Figure 9: The results of the false alarm rate of the vanilla CNN, and TRANS-ENS when using the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets

Evaluation of TRANS-ENS with Vanilla RNN

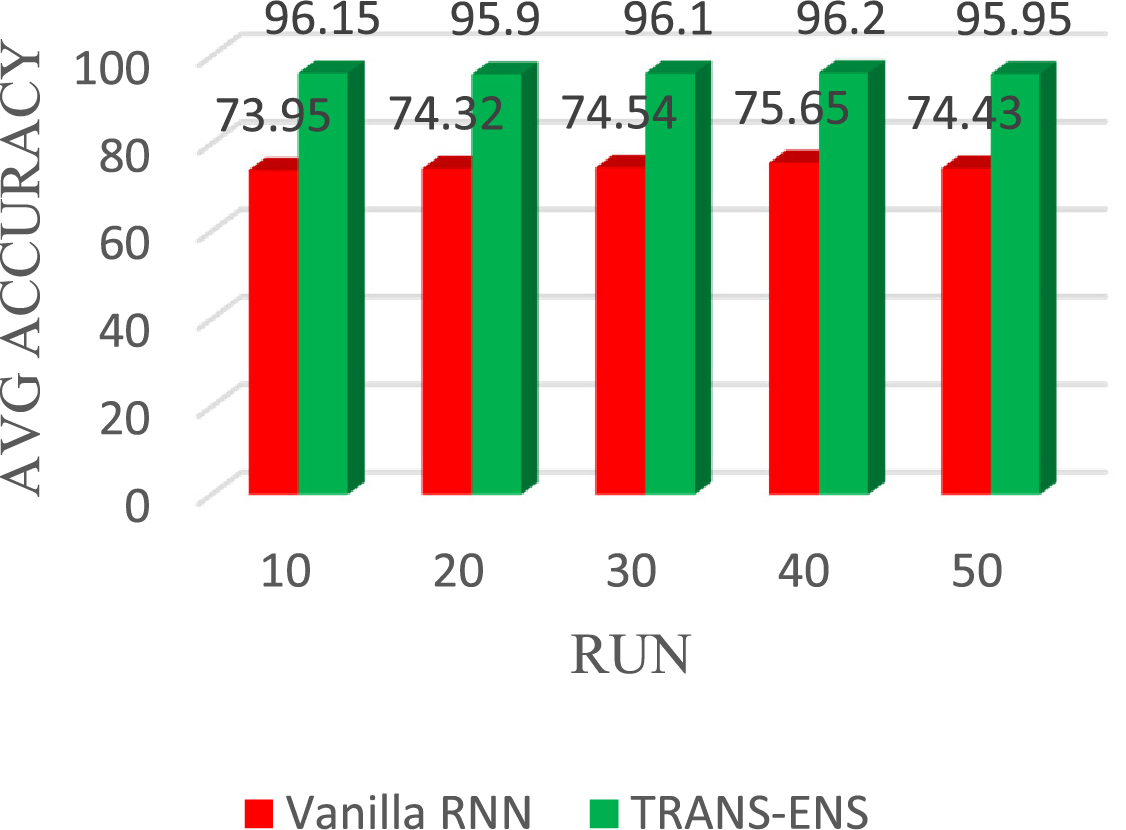

The TRAND-ENS and vanilla RNN classifiers are implemented together in multiple runs (10, 20, 30, 40, and 50) using the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets as source and target datasets, respectively. These runs are conducted to determine the average results and meet the requirements of computer science testing. Regarding average accuracy, the vanilla RNN achieves 73.95%, 74.32%, 74.54%, 75.65%, and 74.43% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the vanilla RNN achieves a detection accuracy of 74.58%. While TRAND-ENS achieves average accuracy of 96.15%, 95.90%, 96.10%, 96.20%, and 95.95% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the TRAND-ENS achieves a detection accuracy of 96.06%. Fig. 10 illustrates the average detection accuracy of the vanilla RNN and TRAND-ENS when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets.

Figure 10: The average detection accuracy of the TRANS-ENS and Vanilla RNN when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets

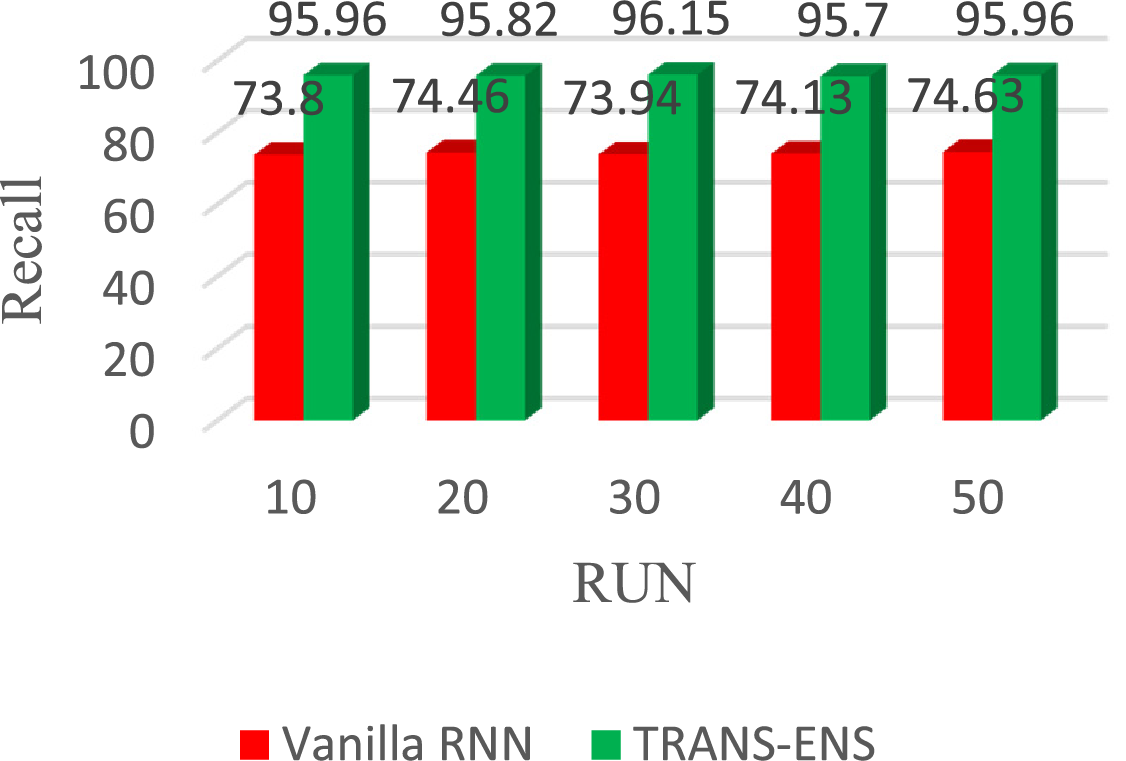

Furthermore, regarding recall, the vanilla RNN achieves 73.80%, 74.46%, 73.94%, 74.13%, and 74.63% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the vanilla RNN achieves a recall of 74.19%. While TRAND-ENS achieves 95.96%, 95.82%, 96.15%, 95.70%, and 95.96% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the TRAND-ENS achieves a recall of 95.91%. Fig. 11 illustrates the Recall of the vanilla RNN and TRAND-ENS when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets.

Figure 11: The Recall of the TRANS-ENS and Vanilla RNN when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets

Moreover, regarding F1-score, the vanilla RNN achieves 74.82%, 74.93%, 74.20%, 75.11%, and 74.98% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the vanilla RNN achieves F1-score of 74.80%. While TRAND-ENS achieves 96.42%, 96.35%, 96.1%, 96.4%, and 95.05% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the TRAND-ENS achieves F1-score of 96.06%. Fig. 12 illustrates the F1-score of the vanilla RNN and TRAND-ENS when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets.

Figure 12: F1-score of the TRANS-ENS and Vanilla RNN when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets

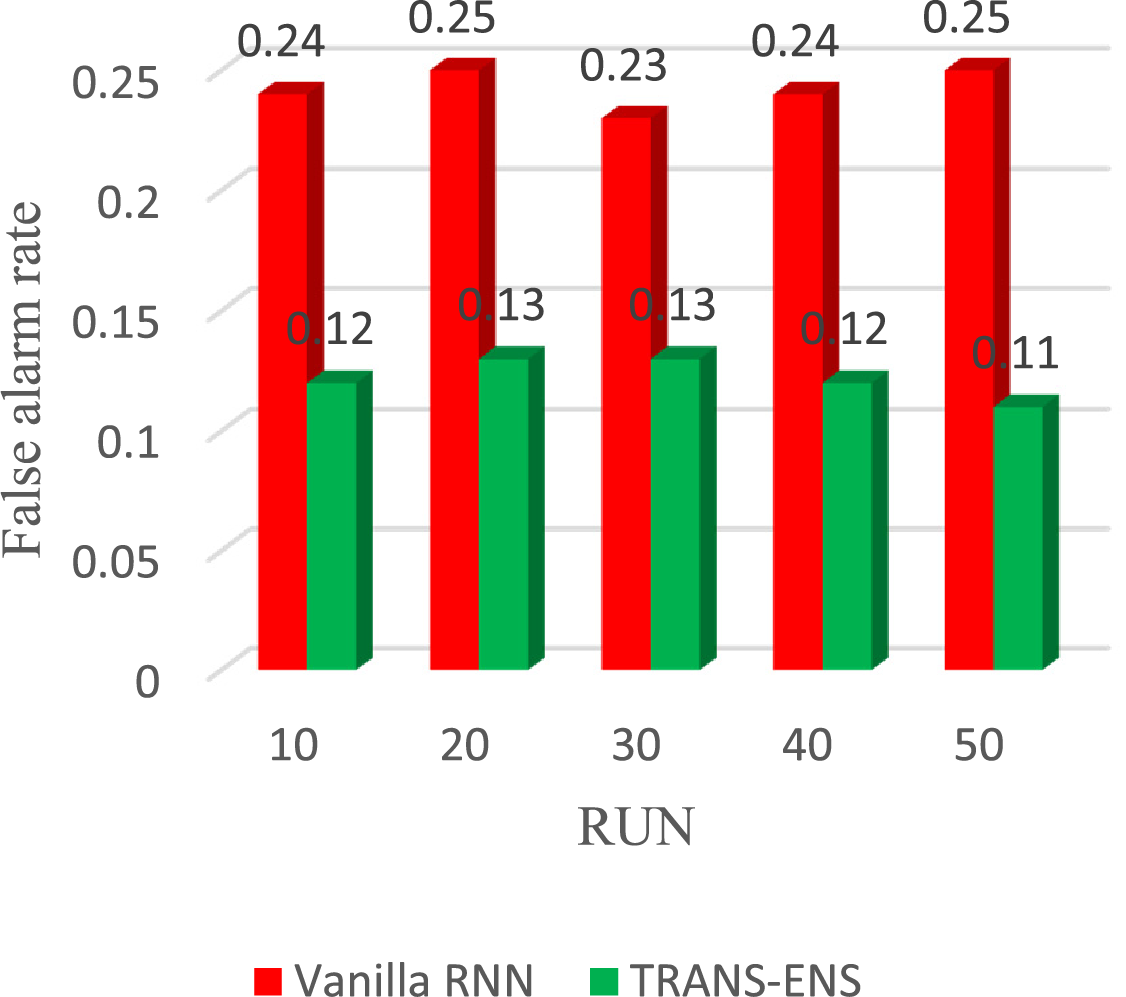

Lastly, the average false alarm rate, the vanilla RNN achieves 0.24%, 0.25%, 0.23%, 0.24%, 0.25% in 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 runs, respectively. On average, the vanilla RNN achieves a 0.24% false alarm rate. While the average false alarm rate, TRANS-ENS achieves 0.12%, 0.13%, 0.12%, 0.11%, 0.10% in 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 runs, respectively. On average, TRANS-ENS achieves a 0.12% false alarm rate. Fig. 13 presents the results of the false alarm rate of the vanilla RNN, and TRANS-ENS using the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets.

Figure 13: The results of false alarm rate of the vanilla RNN, and TRANS-ENS when using the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets

Evaluation of TRANS-ENS with Vanilla LSTM

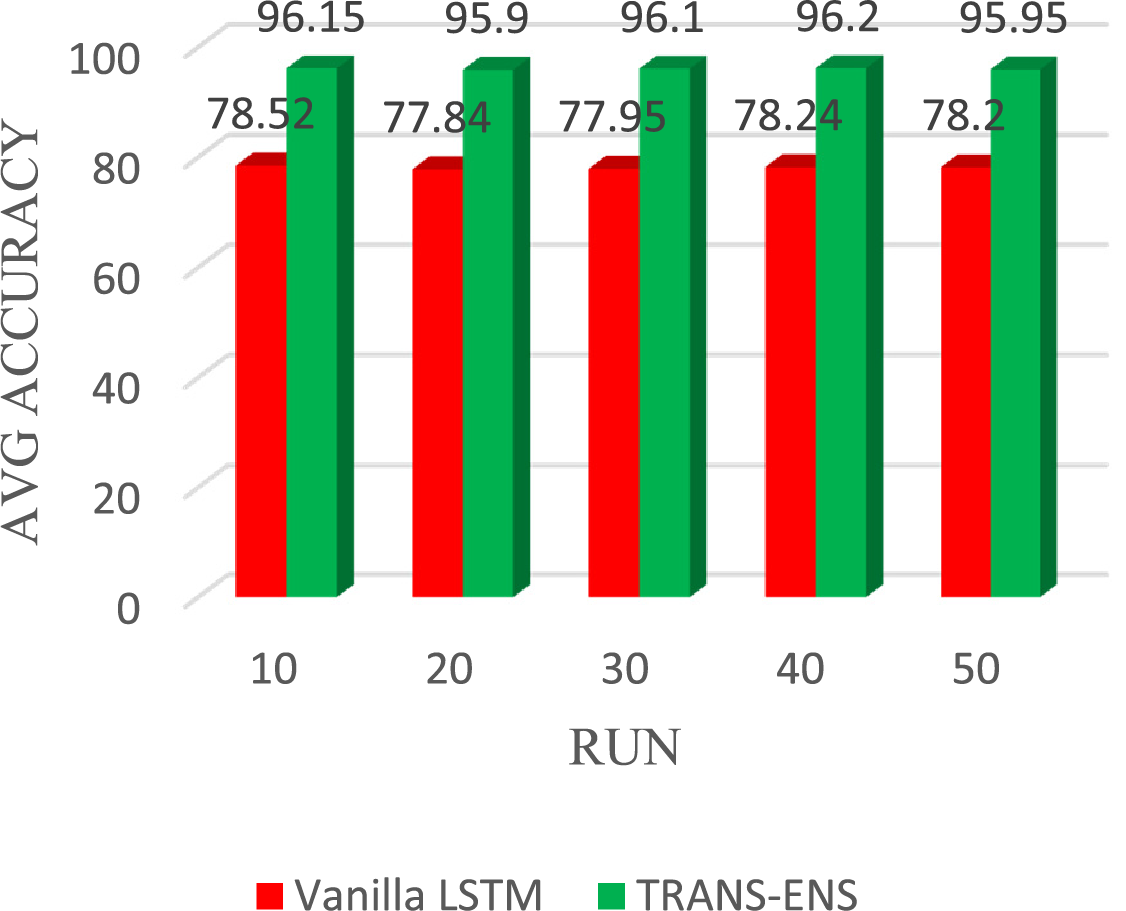

The TRAND-ENS and vanilla LSTM classifiers are implemented together in multiple runs (10, 20, 30, 40, and 50) using the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets as source and target datasets, respectively. These runs are conducted to determine the average results and meet the requirements of computer science testing. Regarding average accuracy, the vanilla LSTM achieves 78.52%, 77.84%, 77.95%, 78.24%, and 78.20% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the vanilla LSTM achieves a detection accuracy of 78.15%. While TRAND-ENS achieves average accuracy 96.15%, 95.90%, 96.10%, 96.20%, and 95.95% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the TRAND-ENS achieves a detection accuracy of 96.06%. Fig. 14 illustrates the average detection accuracy of the vanilla LSTM and TRAND-ENS when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets.

Figure 14: The average detection accuracy of the TRANS-ENS, and Vanilla LSTM when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets

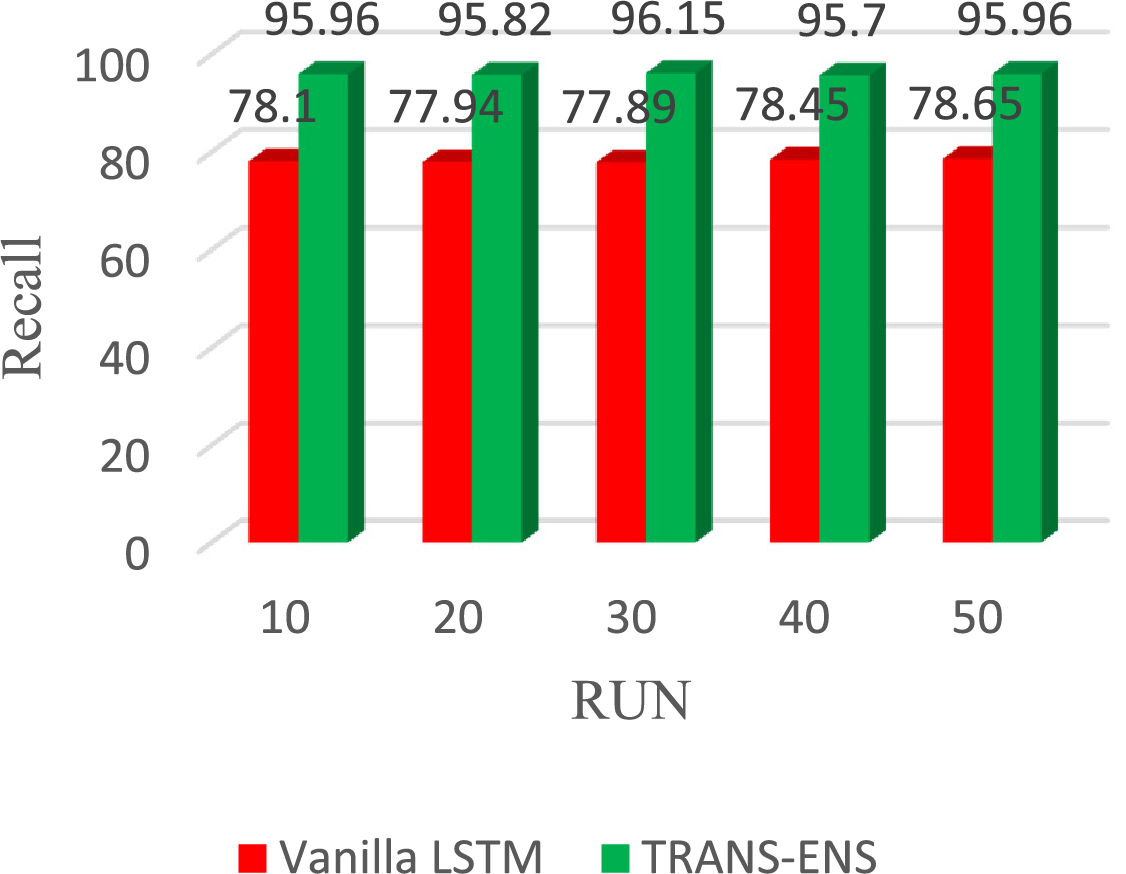

Furthermore, regarding recall, the vanilla LSTM achieves 78.10%, 77.94%, 77.89%, 78.45%, and 78.65% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the vanilla LSTM achieves a recall of 78.20%. While TRAND-ENS achieves 95.96%, 95.82%, 96.15%, 95.70%, and 95.96% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the TRAND-ENS achieves a recall of 95.91%. Fig. 15 illustrates the Recall of the vanilla LSTM and TRAND-ENS when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets.

Figure 15: The recall of the TRANS-ENS and Vanilla LSTM when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets

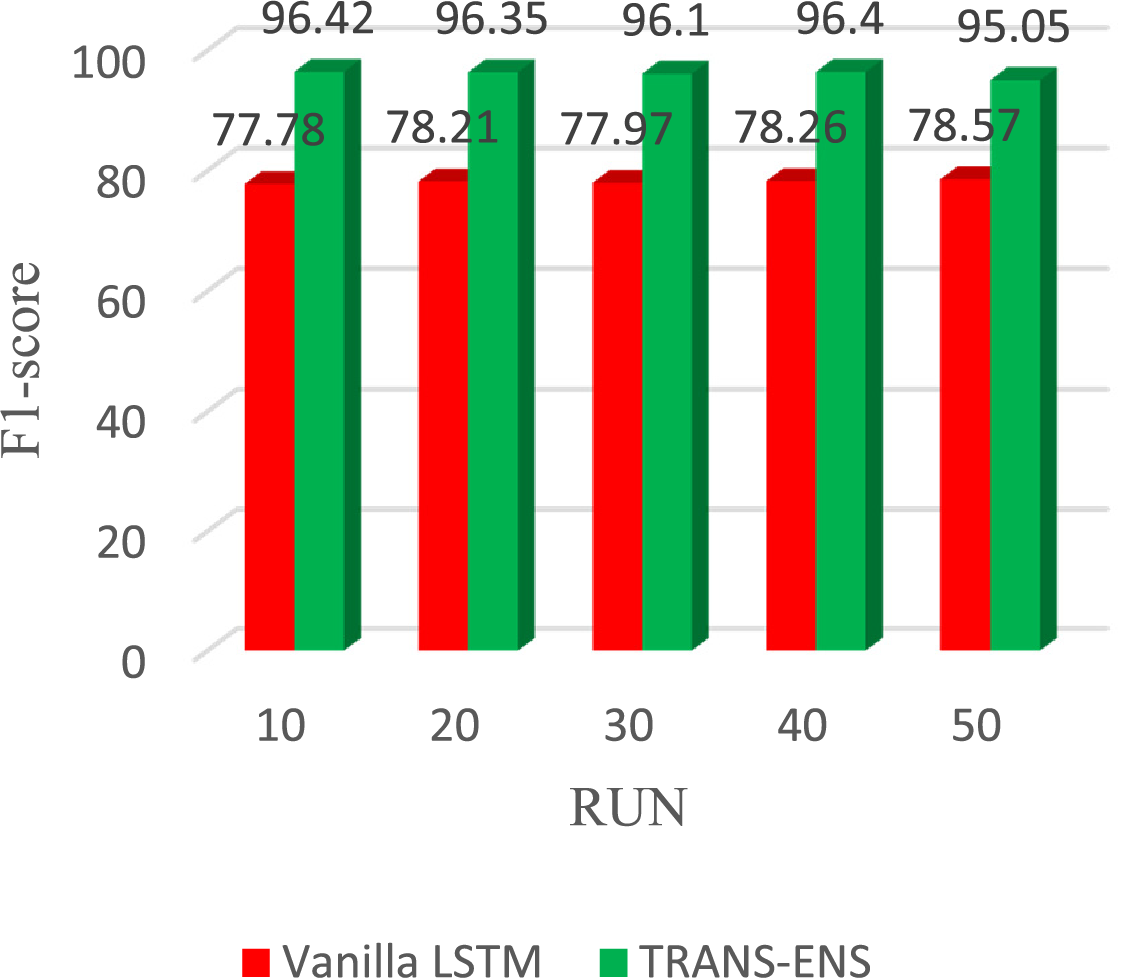

Moreover, regarding F1-score, the vanilla LSTM achieves 77.78%, 78.21%, 77.97%, 78.26%, and 78.57% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the vanilla LSTM achieves F1-score of 78.14%. While TRAND-ENS achieves 96.42%, 96.35%, 96.1%, 96.4%, and 95.05% in the 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 runs, respectively. On average, the TRAND-ENS achieves F1-score of 96.06%. Fig. 16 illustrates the F1-score of the vanilla LSTM and TRAND-ENS when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets.

Figure 16: F1-score of the TRANS-ENS, and Vanilla LSTM when utilizing the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets

Lastly, the average false alarm rate, the vanilla LSTM achieves 0.21%, 0.23%, 0.22%, 0.23%, 0.21% in 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 runs, respectively. On average, the vanilla LSTM achieves a 0.22% false alarm rate. While the average false alarm rate, TRANS-ENS achieves 0.12%, 0.13%, 0.12%, 0.11%, 0.10% in 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 runs, respectively. On average, TRANS-ENS achieves a 0.12% false alarm rate. Fig. 17 presents the results of the false alarm rate of the vanilla LSTM and TRANS-ENS using the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets.

Figure 17: The results of the false alarm rate of the vanilla LSTM, and TRANS-ENS when using the BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection datasets

5.4.2 Comparison with Existing State-of-the-Art Approaches

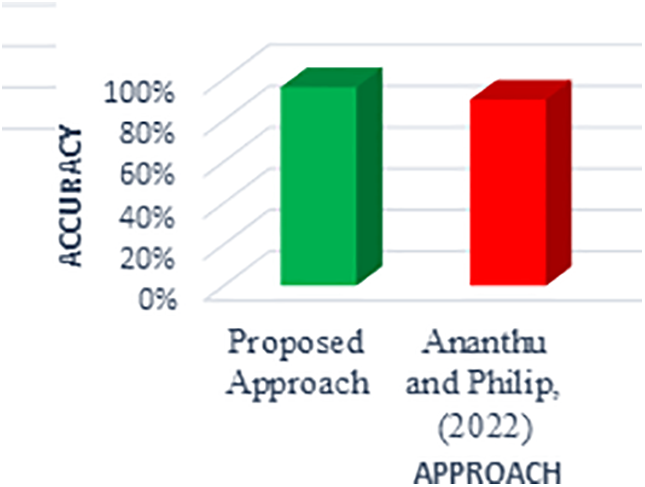

Authors in [5] proposed a model for detecting keylogging attacks that achieved an accuracy of 90%. However, the proposed TRANS-ENS model significantly outperforms it, achieving an average accuracy of 96.06%, alongside a notably lower false alarm rate of 0.12%. This comparison highlights TRANS-ENS as not only more accurate but also more reliable in practical applications due to its enhanced robustness against false positives. These improvements make TRANS-ENS a superior choice for detecting keylogging threats, particularly in scenarios where precision and dependability are critical. Fig. 18 illustrates a Comparison of the proposed work with the existing works.

Figure 18: Comparison of the proposed work with the existing works [5]

This paper analyzes the experimental results of the TRANS-ENS approach using two benchmark datasets: BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection. Multiple runs of the experiments were conducted to ensure accuracy and adherence to computer science testing standards. The results, including accuracy, detection rate, false alarm rate, and F1-score, are evaluated and compared with existing machine learning models such as vanilla CNN, RNN, LSTM. The TRANS-ENS consistently outperforms vanilla models across all metrics in different runs (10, 20, 30, 40, 50). For example, the TRANS-ENS achieved an average accuracy of 96.06%, significantly higher than the vanilla models, which ranged between 74.58% (RNN) and 84.32% (CNN). Similarly, the F1-scores, recall, and false alarm rates showed improvements, indicating the robustness and effectiveness of the TRANS-ENS approach. The false alarm rate of TRANS-ENS remained consistently low at 0.12%, which is an improvement over the vanilla models’ rates, ranging from 0.19% to 0.24%.

The findings and the effectiveness of the proposed model approach were explored, aiming to enhance attack detection efficiency. The accuracy, recall, F1-score, and false alarm rate of the proposed approach were compared with those of existing models. The evaluation of the results was conducted using two datasets: BoT_IoT and Keylogger_Detection. This paper investigates the application of transfer learning and ensemble classifiers to identify keylogging attacks in small and imbalanced datasets specific to IoT. The researchers propose a model that combines TL and ensemble approaches to achieve high accuracy in detecting keylogging attacks. In order to transfer knowledge from a source domain to a target domain, the BoT-IoT dataset is utilized in conjunction with the keylogger_detection dataset. The experimental results highlight the effectiveness of TL and ensemble classifiers in enhancing the model’s performance, even in scenarios with imbalanced datasets and sufficient labeled data for detecting keylogging attacks. The TL-ensemble model (TRANS-ENS) exhibits remarkable accuracy and an exceptionally low false positive rate, demonstrating enhanced detection rates for keylogging attacks compared to previous models based on deep learning. In future endeavors, it is recommended that the proposed model be deployed in real-world environments to detect other types of attacks and be tested on lightweight IoT devices.

As well as the proposed approach can also explore advanced approaches for selecting the most competent base classifiers dynamically during runtime based on the characteristics of the input data.

Acknowledgement: The research team would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Najran University for supporting the research project through the Nama’a program, with the project code NU/GP/SERC/13/712.

Funding Statement: The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Najran University for supporting the research project through the Group Research, with the project code NU/GP/SERC/13/712.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yahya Alhaj Maz, Mohammed Anbar; data collection: Selvakumar Manickam; analysis and interpretation of results: Yahya Alhaj Maz, Mosleh M. Abualhaj, Basim Ahmad Alabsi; draft manuscript preparation: Sultan Ahmed Almalki. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are openly available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/subhajournal/keylogger-detection and https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/bot-iot-dataset (accessed on 01 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ahmad Alabsi B, Anbar M, Rihan SDA. CNN-CNN: dual convolutional neural network approach for feature selection and attack detection on Internet of Things networks. Sensors. 2023;23(14):6507. doi:10.3390/s23146507; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Al-Amiedy TA, Anbar M, Belaton B, Kabla AHH, Hasbullah IH, Alashhab ZR. A systematic literature review on machine and deep learning approaches for detecting attacks in RPL-based 6LoWPAN of Internet of Things. Sensors. 2022;22(9). doi:10.3390/s22093400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Čolaković A, Hadžialić M. Internet of Things (IoTa review of enabling technologies, challenges, and open research issues. Comput Netw. 2018;144:17–39. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2018.07.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wajahat A, Imran A, Latif J, Nazir A, Bilal A. A novel approach of unprivileged keylogger detection. In: 2019 2nd International Conference on Computing, Mathematics and Engineering Technologies (iCoMET); 2019 Jan 30–31; Sukkur, Pakistan. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICOMET.2019.8673404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ananthu Suresh SL, Philip AS. Multiple botnet and keylogger attack detection using CNN in IoT networks. In: 2022 International Conference on Futuristic Technologies (INCOFT); 2022 Nov 25–27; Belgaum, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/INCOFT55651.2022.10094491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hitachi Group. Information security report. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.hitachi.com/sustainability/download/pdf/securityreport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

7. George G, Keith W. Q4 2024 cyber threat landscape: gone phishing. evolving techniques keep organizations on the hook. Cyber threat intelligence reports. New York, NY, USA: Kroll Corporation. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.kroll.com/en/insights/publications/cyber/threat-intelligence-reports. [Google Scholar]

8. Rob S. 157 cybersecurity statistics and trends. New York, NY, USA: Varonis Corporation. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.varonis.com/blog/cybersecurity-statistics. [Google Scholar]

9. Zhuang F, Qi Z, Duan K, Xi D, Zhu Y, Zhu H, et al. A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. Proc IEEE. 2021;109(1):43–76. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2020.3004555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kheddar H, Himeur Y, Awad AI. Deep transfer learning for intrusion detection in industrial control networks: a comprehensive review. J Netw Comput Appl. 2023;220(10):103760. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2023.103760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Iman M, Arabnia HR, Rasheed K. A review of deep transfer learning and recent advancements. Technologies. 2023;11(2):40. doi:10.3390/technologies11020040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tan C, Sun F, Kong T, Zhang W, Yang C, Liu C. A survey on deep transfer learning. In: 27th International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks; 2018 Oct 4–7; Rhodes, Greece. p. 270–9. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01424-7_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sun B, Feng J, Saenko K. Return of frustratingly easy domain adaptation. In: Proceedings of the Thirtieth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2016 Feb 12–17; Phoenix, AZ, USA. p. 2058–65. doi:10.1609/aaai.v30i1.10306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sun G, Liang L, Chen T, Xiao F, Lang F. Network traffic classification based on transfer learning. Comput Electr Eng. 2018;69(4):920–7. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2018.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Pardamean B, Muljo HH, Cenggoro TW, Chandra BJ, Rahutomo R. Using transfer learning for smart building management system. J Big Data. 2019;6(1):110. doi:10.1186/s40537-019-0272-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tien CW, Huang TY, Chen PC, Wang JH. Using autoencoders for anomaly detection and transfer learning in IoT. Computers. 2021;10(7):88. doi:10.3390/computers10070088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Idrissi I, Azizi M, Moussaoui O. Accelerating the update of a DL-based IDS for IoT using deep transfer learning. Indones J Electr Eng Comput Sci. 2021;23(2):1059. doi:10.11591/ijeecs.v23.i2.pp1059-1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Rodríguez E, Valls P, Otero B, Costa JJ, Verdú J, Pajuelo MA, et al. Transfer-learning-based intrusion detection framework in IoT networks. Sensors. 2022;22(15). doi:10.3390/s22155621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ahmed O. Enhancing intrusion detection in wireless sensor networks through machine learning techniques and context awareness integration. Int J Math Stat Comput Sci. 2024;2:244–58. doi:10.59543/ijmscs.v2i.10377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Brown J, Anwar M, Dozier G. An artificial immunity approach to malware detection in a mobile platform. EURASIP J Inf Secur. 2017;2017(1):7. doi:10.1186/s13635-017-0059-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Pillai D, Siddavatam I. A modified framework to detect keyloggers using machine learning algorithm. Int J Inf Technol. 2019;11(4):707–12. doi:10.1007/s41870-018-0237-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ge M, Fu X, Syed N, Baig Z, Teo G, Robles-Kelly A. Deep learning-based intrusion detection for IoT networks. In: 2019 IEEE 24th Pacific Rim International Symposium on Dependable Computing (PRDC); 2019 Dec 1–3; Kyoto, Japan. p. 256–65. doi:10.1109/PRDC47002.2019.00056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yilmaz S, Aydogan E, Sen S. A transfer learning approach for securing resource-constrained IoT devices. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2021;16:4405–18. doi:10.1109/tifs.2021.3096029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mehedi ST, Anwar A, Rahman Z, Ahmed K, Islam R. Dependable intrusion detection system for IoT: a deep transfer learning based approach. IEEE Trans Ind Inf. 2023;19(1):1006–17. doi:10.1109/tii.2022.3164770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Khoa TV, Hoang DT, Trung NL, Nguyen CT, Quynh TTT, Nguyen DN, et al. Deep transfer learning: a novel collaborative learning model for cyberattack detection systems in IoT networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;10(10):8578–89. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3202029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mohammed HA, Husien IM. A deep transfer learning framework for robust IoT attack detection. Informatica. 2024;48(12):55–64. doi:10.31449/inf.v48i12.5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Vu L, Nguyen QU, Nguyen DN, Hoang DT, Dutkiewicz E. Deep transfer learning for IoT attack detection. IEEE Access. 2020;8:107335–44. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3000476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Haq AU, Zhang D, Peng H, Rahman SU. Combining multiple feature-ranking techniques and clustering of variables for feature selection. IEEE Access. 2019;7:151482–92. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2947701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bolón-Canedo V, Alonso-Betanzos A. Ensembles for feature selection: a review and future trends. Inf Fusion. 2019;52(C):1–12. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2018.11.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Thakkar A, Lohiya R. Attack classification using feature selection techniques: a comparative study. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2021;12(1):1249–66. doi:10.1007/s12652-020-02167-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Albaser M, Ali S, Chantar H. Performance analysis of classifying URL phishing using recursive feature elimination. In: Information and communications technologies. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 42–54. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-62624-1_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Alalhareth M, Hong SC. An improved mutual information feature selection technique for intrusion detection systems in the Internet of Medical Things. Sensors. 2023;23(10):4971. doi:10.3390/s23104971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Chen CW, Tsai YH, Chang FR, Lin WC. Ensemble feature selection in medical datasets: combining filter, wrapper, and embedded feature selection results. Expert Syst. 2020;37(5):e12553. doi:10.1111/exsy.12553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Duc-Minh N, Dominic L, Andriy T, Cuong P-Q, Ngoc-Thinh T, Colin CM, et al. Network attack detection on IoT devices using 2D-CNN models, intelligence of things: technologies and applications. In: Lecture notes on data engineering and communications technologies. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023 doi:10.1007/978-3-031-46749-3_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. BoT IoT Dataset. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/bot-iot-dataset. [Google Scholar]

36. Keylogger detection. Dataset. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/subhajournal/keylogger-Detection. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools