Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Federated Learning in Convergence ICT: A Systematic Review on Recent Advancements, Challenges, and Future Directions

1 School of Computing and Information Science, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, CB1 1PT, UK

2 Centre for Machine Vision, Bristol Robotics Laboratory, University of the West of England, Bristol, BS16 1QY, UK

3 Animal and Agriculture Department, Hartpury University, Gloucester, GL19 3BE, UK

4 Department of Embedded Systems Engineering, Incheon National University, Incheon, 22012, Republic of Korea

5 Montis Co., Ltd. Building A, Michuhol Campus, Incheon National University, 12 Gaetbeol-ro, Yeonsu-gu, Incheon, 21999, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Gwanggil Jeon. Email:

#These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in AI Techniques in Convergence ICT)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 4237-4273. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068319

Received 26 May 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

The rapid convergence of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), driven by advancements in 5G/6G networks, cloud computing, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things (IoT), is reshaping modern digital ecosystems. As massive, distributed data streams are generated across edge devices and network layers, there is a growing need for intelligent, privacy-preserving AI solutions that can operate efficiently at the network edge. Federated Learning (FL) enables decentralized model training without transferring sensitive data, addressing key challenges around privacy, bandwidth, and latency. Despite its benefits in enhancing efficiency, real-time analytics, and regulatory compliance, FL adoption faces challenges, including communication overhead, heterogeneity, security vulnerabilities, and limited edge resources. While recent studies have addressed these issues individually, the literature lacks a unified, cross-domain perspective that reflects the architectural complexity and application diversity of Convergence ICT. This systematic review offers a comprehensive, cross-domain examination of FL within converged ICT infrastructures. The central research question guiding this review is: How can FL be effectively integrated into Convergence ICT environments, and what are the main challenges in implementing FL in such environments, along with possible solutions? We begin with a foundational overview of FL concepts and classifications, followed by a detailed taxonomy of FL architectures, learning strategies, and privacy-preserving mechanisms. Through in-depth case studies, we analyse FL’s application across diverse verticals, including smart cities, healthcare, industrial automation, and autonomous systems. We further identify critical challenges—such as system and data heterogeneity, limited edge resources, and security vulnerabilities—and review state-of-the-art mitigation strategies, including edge-aware optimization, secure aggregation, and adaptive model updates. In addition, we explore emerging directions in FL research, such as energy-efficient learning, federated reinforcement learning, and integration with blockchain, quantum computing, and self-adaptive networks. This review not only synthesizes current literature but also proposes a forward-looking road map to support scalable, secure, and sustainable FL deployment in future ICT ecosystems.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material File1.1 Convergence ICT: A New Digital Paradigm

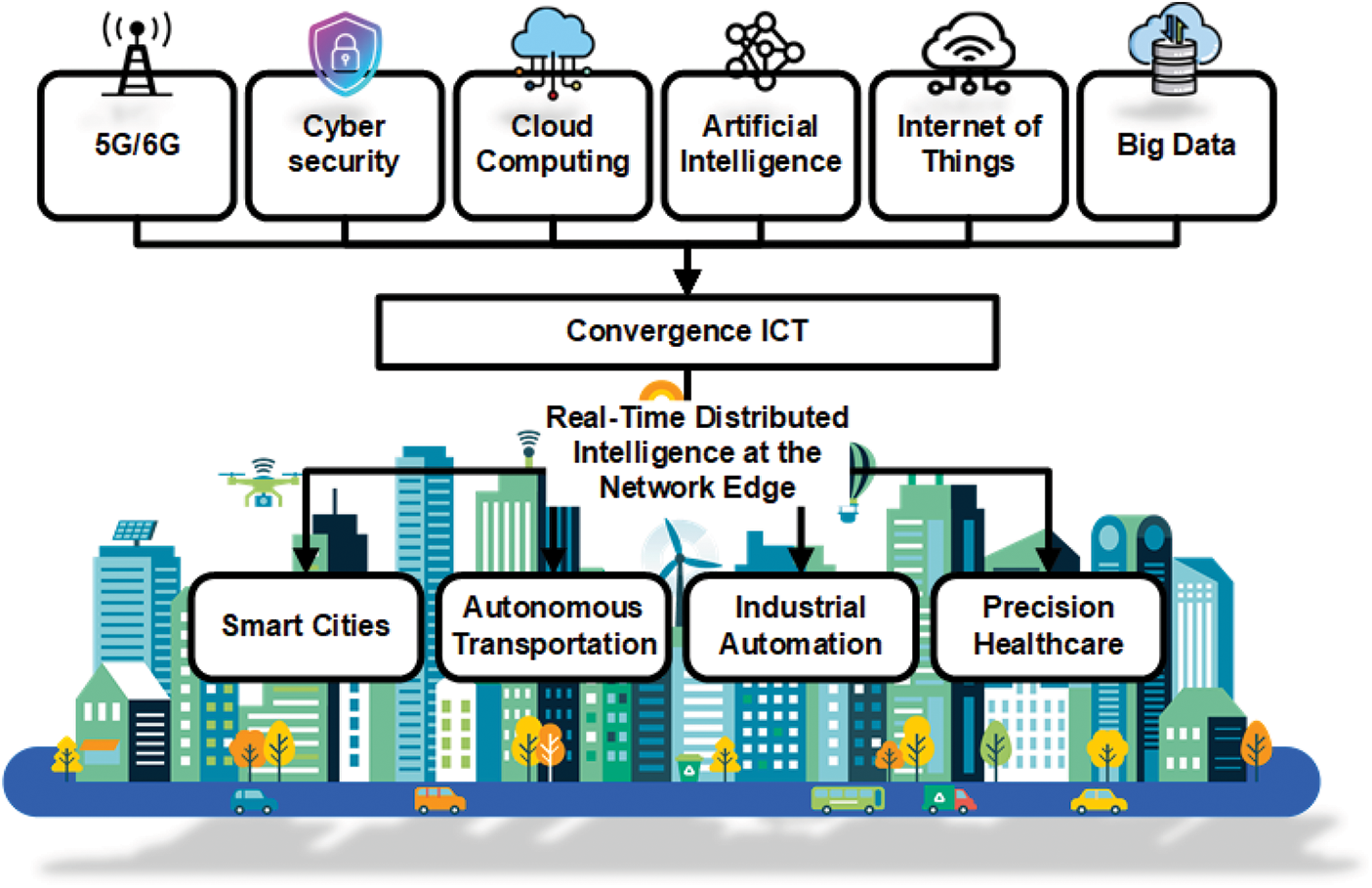

Digital technology landscape is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the rapid evolution of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). Emerging innovations such as 5G/6G networks [1], cloud computing, AI [2], and the Internet of Things (IoT) [2] are converging to create highly interconnected, intelligent environments (Fig. 1). This convergence—commonly referred to as Convergence ICT—signifies more than an expansion of connectivity; it represents a shift toward real-time, distributed intelligence at the network edge, enabling transformative services across smart cities, autonomous transportation, industrial automation, and precision healthcare [3,4]. However, this paradigm introduces significant data-driven challenges. The proliferation of sensors, mobile devices, and edge systems generates massive, heterogeneous, and privacy-sensitive data streams. Traditional centralized machine learning (ML) pipelines, which aggregate raw data on a central server, face several critical limitations: privacy and regulatory constraints such as GDPR and HIPAA restrict large-scale aggregation [5], high communication and bandwidth demands strain networks, and latency impedes real-time decision-making for mission-critical applications like autonomous vehicles and telemedicine.

Figure 1: Convergence of ICT: Integration of 5G/6G, cybersecurity, cloud computing, AI, IoT, and big data enables real-time distributed intelligence at the network edge, powering smart cities, autonomous transportation, industrial automation, and precision healthcare

1.2 Why Federated Learning (FL) Matters in Convergence ICT

Federated Learning, introduced by McMahan et al. in 2016 [6], offers a paradigm shift by enabling decentralized model training, where raw data remains on user devices or edge nodes and only model updates are exchanged. This design mitigates privacy risks, reduces bandwidth consumption, and supports low-latency intelligence, making FL particularly suited for Convergence ICT ecosystems, where billions of distributed devices must collaborate securely and autonomously. This aligns with edge-driven intelligence goals in applications like autonomous systems [7]. Since its introduction, FL has been widely adopted as a privacy-preserving solution in AI research [8], with major technology companies leveraging it to build applications compliant with global data protection laws, including GDPR in Europe [9], the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) in Singapore [10]. The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) in the United States [11]. Non-compliance with these frameworks has led to substantial penalties: Uber paid a $148 million settlement in 2016 for a breach affecting 600,000 drivers [12]; Singapore’s PDPC fined SingHealth and its IT vendor $1 million for PDPA violations in 2019 [13]; and Google, Uber, and TikTok collectively faced over $2 billion in fines between 2019 and 2025 for data protection breaches [14–17]. These cases underscore the growing necessity of privacy-conscious technologies like FL.

1.3 Research Gap and Motivation

Despite its potential, the integration of Federated Learning (FL) into Convergence ICT remains constrained by several unresolved challenges. The central research question of this review is: How can Federated Learning be effectively integrated into Convergence ICT environments, and what are the main challenges in implementing FL in such environments, along with possible solutions? This question will guide our exploration of current FL solutions, identify the major challenges, and highlight emerging trends in the field. These challenges include:

• Communication overhead caused by frequent global model synchronization [18],

• Device and data heterogeneity, stemming from non-IID datasets and diverse hardware capabilities [19],

• Security threats, such as model poisoning and inference attacks [20],

• Resource limitations, including constrained compute, power, and storage on edge devices.

Moreover, while numerous reviews have explored FL within isolated domains—such as mobile edge computing, healthcare, education, or industrial IoT—most of these studies lack a cross-domain perspective and often fail to address the architectural and integration challenges inherent to Convergence ICT. They typically overlook the complexities of multi-domain data fusion, heterogeneous infrastructure, and the need for scalable, secure deployment across the cloud—edge—IoT continuum. Therefore, there is a clear need for a systematic review that unifies architectural insights, cross-sector applications, and emerging research directions to support the advancement of FL within interconnected ICT ecosystems.

1.4 Scope and Contribution of This Review

To address these gaps, this review presents a systematic and cross-domain synthesis of FL in the context of Convergence ICT. Unlike prior studies limited to narrow use cases, this work integrates architectural, technical, and application-level insights into a unified framework. The key contributions are:

• A structured exploration of FL’s foundational concepts, taxonomy, and role within Convergence ICT.

• A cross-domain analysis of real-world FL deployments in smart cities, healthcare, industrial systems, and autonomous applications.

• An evaluation of the primary challenges, including communication bottlenecks, heterogeneity, security threats, and edge resource constraints.

• Insights into emerging research opportunities, including scalable FL architectures, energy-efficient designs, and integration with blockchain, quantum computing, and self-adaptive networks.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 details the research methodology, including data sources, selection criteria, and review strategy. Section 3 presents an overview of FL concepts and taxonomy. Section 4 examines real-world applications of FL in converging ICT environments. This section also discusses major deployment challenges, while Section 5 explores emerging trends and research opportunities. Finally, Section 6 concludes the review with key findings and future outlook.

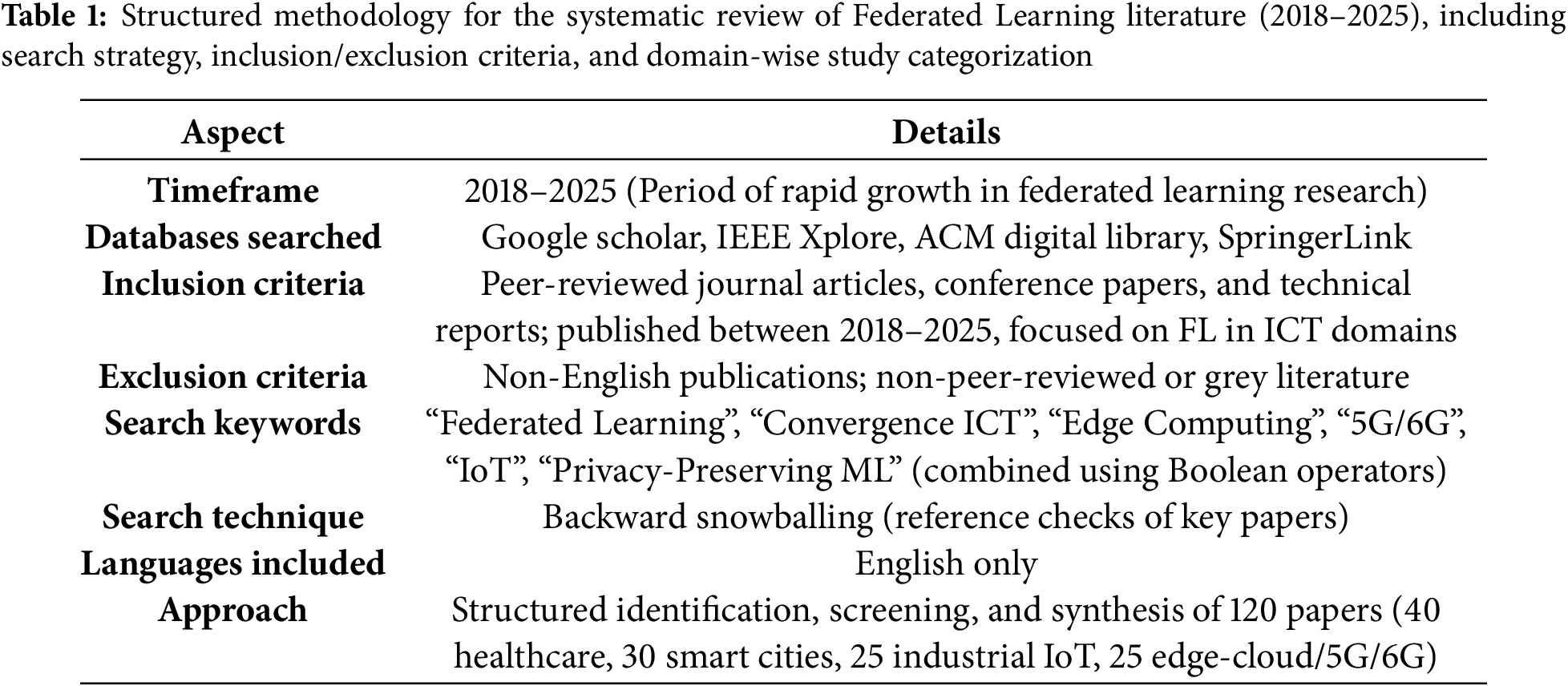

This systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). The review methodology followed the prescribed checklist to ensure transparency and reproducibility. This review is based on a systematic and structured analysis of existing literature on Federated Learning within the context of Convergence ICT. A methodical approach, summarized in Table 1, was employed to identify, collect, analyze, and synthesize relevant studies. This ensures a comprehensive evaluation of the roles, challenges, and future opportunities of Federated Learning in converged ICT ecosystems.

2.1 Data Sources and Search Strategy

The literature was gathered from leading academic databases to ensure the inclusion of high-quality, peer-reviewed research, as shown in the Fig. 2. The primary sources included Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, and SpringerLink. These databases were selected due to their broad coverage of computer science, engineering, and emerging technology fields relevant to FL and ICT. The search focused on publications from 2018 to 2025. This timeframe was chosen to capture the most recent and impactful developments in Federated Learning and its intersection with emerging technologies such as 5G/6G networks, edge-cloud architectures, AI, and the Internet of Things (IoT), which have seen exponential growth in this period. A keyword-driven search strategy was employed using combinations of the following terms: “Federated Learning”, “Convergence ICT”, “Artificial Intelligence”, “Deep Learning”, “Edge Computing”, “5G”, “6G”, “IoT”, “Distributed Learning”, and “Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning”. Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) were used to refine search queries and expand or narrow the scope where appropriate. For example, combinations such as “Federated Learning” AND “Edge Computing” AND “Privacy” and “FL” AND “5G OR 6G” AND “IoT” were utilized to capture domain-specific literature. In addition to database queries, reference lists of selected key papers were manually reviewed using a backward snowballing technique. This iterative method allowed the identification of additional influential studies that may not have appeared in the initial keyword-based searches.

Figure 2: PRISMA flow chart for selecting the relevant papers to be included in this review

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To maintain relevance and academic rigor, the following criteria were applied:

• Inclusion: Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and technical reports published in English between 2018 and 2025, focusing on FL in the context of ICT, including cross-domain applications, challenges, and architecture.

• Exclusion: Non-English publications, duplicate records, editorial notes, short abstracts, preprints without peer review, and studies not directly related to Federated Learning or its application within ICT environments.

2.3 Screening and Selection Process

All identified records were screened by title and abstract, followed by full-text review. Articles were categorized by thematic relevance (FL concepts, ICT convergence, domain-specific applications, challenges, future directions). A total of 120 papers were selected: 40 on healthcare, 30 on smart cities, 25 on industrial IoT, and 25 on edge-cloud/5G/6G architectures. This systematic approach ensured a diverse yet focused selection of literature, forming a strong foundation for the critical analysis presented in subsequent sections of this review.

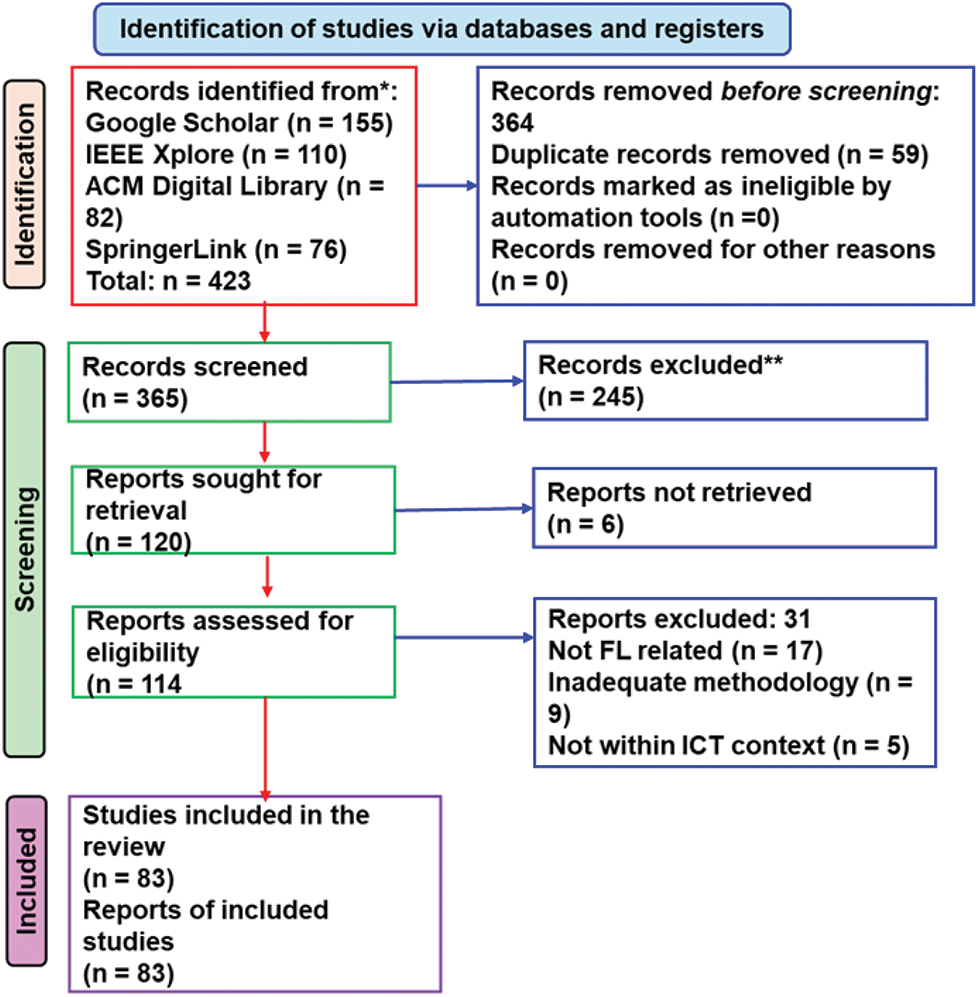

As discussed earlier, FL is a decentralized machine learning paradigm that enables collaborative model training across distributed devices—such as smartphones, IoT sensors, industrial systems, and autonomous vehicles—without transferring raw data. Unlike traditional centralized learning, where all data is collected on a central server, FL transmits only model updates (e.g., gradients or parameters) to a central aggregator, which builds a global model. This approach preserves privacy, reduces bandwidth usage, and supports low-latency, real-time intelligence, making it particularly suited for Convergence ICT ecosystems with geographically dispersed and resource-constrained edge devices.

3.1 Workflow of Federated Learning

FL operates through iterative communication rounds (Fig. 3). In each round, a subset of clients—selected randomly or based on factors such as computational capacity, network availability, or reliability—trains the current global model locally. The resulting updates are aggregated (e.g., via weighted averaging) on a central server to produce a new global model, which is then redistributed. This cycle continues until the model converges, enabling scalable, privacy-preserving intelligence across distributed devices. Each selected client receives the current version of the global model from the central server and performs local training using its private dataset. This localized training allows the model to learn patterns specific to the client’s environment—enabling personalization and context-aware intelligence—without compromising data privacy. Upon completion of local training, clients send their model updates (e.g., weight changes or gradient vectors) back to the central aggregator. These updates do not contain raw data and therefore preserve the confidentiality of locally stored information. The central server then aggregates the received updates using techniques such as weighted averaging (e.g., FedAvg) to produce an improved global model. The updated global model is redistributed to clients for the next round of training. This cyclical process continues iteratively until the model converges or a predefined performance threshold is achieved.

Figure 3: FL workflow: Each client (edge devices and local servers) trains a local model (yellow arrows). The locally trained models are uploaded to the central server (black arrows), where model aggregation is performed (red arrows) to form a new global model. The updated global model is then transmitted back to the clients (blue arrows) for the next communication round, continuing iteratively until convergence”

3.2 Taxonomy of Federated Learning

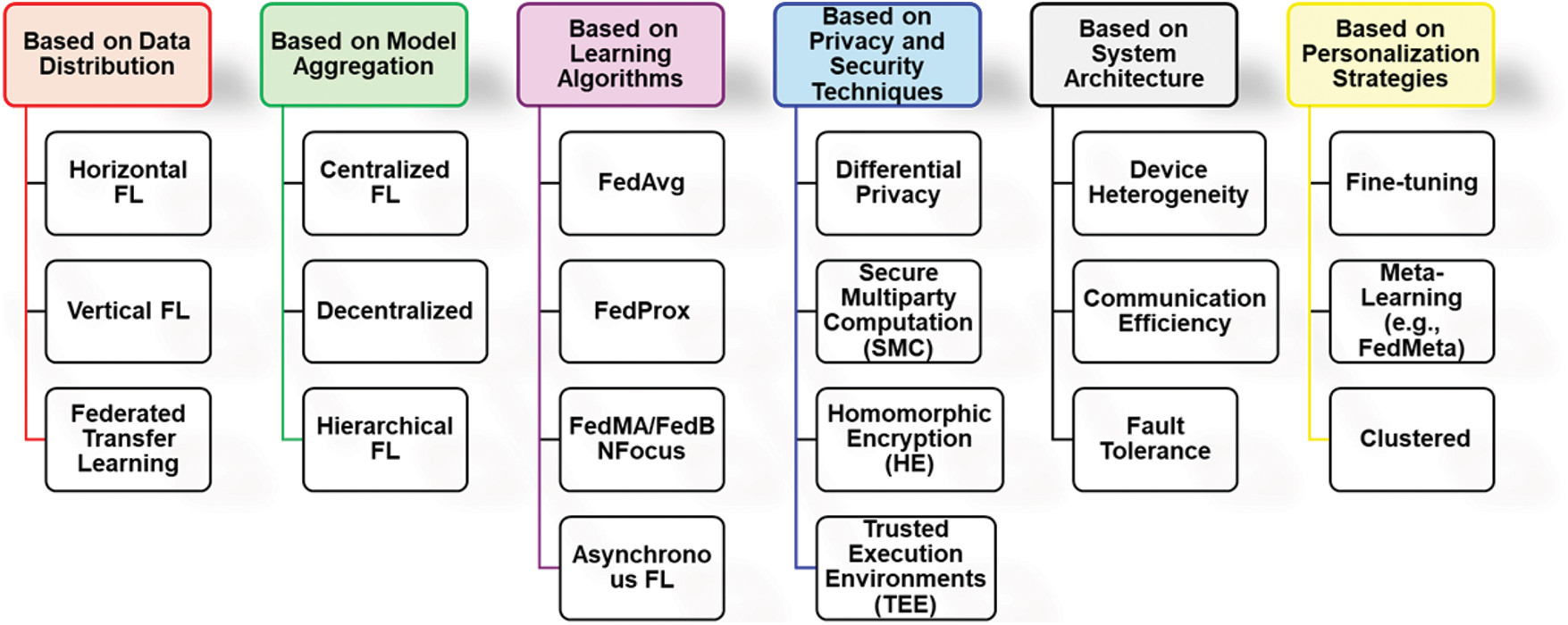

Researchers have proposed multiple taxonomies for FL to classify its diverse methodologies, system architectures, and application domains. This section provides a comprehensive review of both foundational and contemporary literature, organized around a taxonomy that captures the core dimensions of FL. Specifically, we categorize existing approaches based on three primary aspects: data distribution, communication topology, and learning strategies. This taxonomy facilitates a systematic understanding of the underlying design choices and their implications for scalability, privacy, and performance. Fig. 4 illustrates the hierarchical structure of this taxonomy, highlighting the major categories and their interrelationships.

Figure 4: Taxonomy of Federated Learning approaches, categorized by six key dimensions: data distribution, model aggregation, learning algorithms, privacy and security techniques, system architecture, and personalization strategies. This taxonomy highlights the major design considerations and commonly used methods in FL systems

3.3 Classification based on Data Distribution

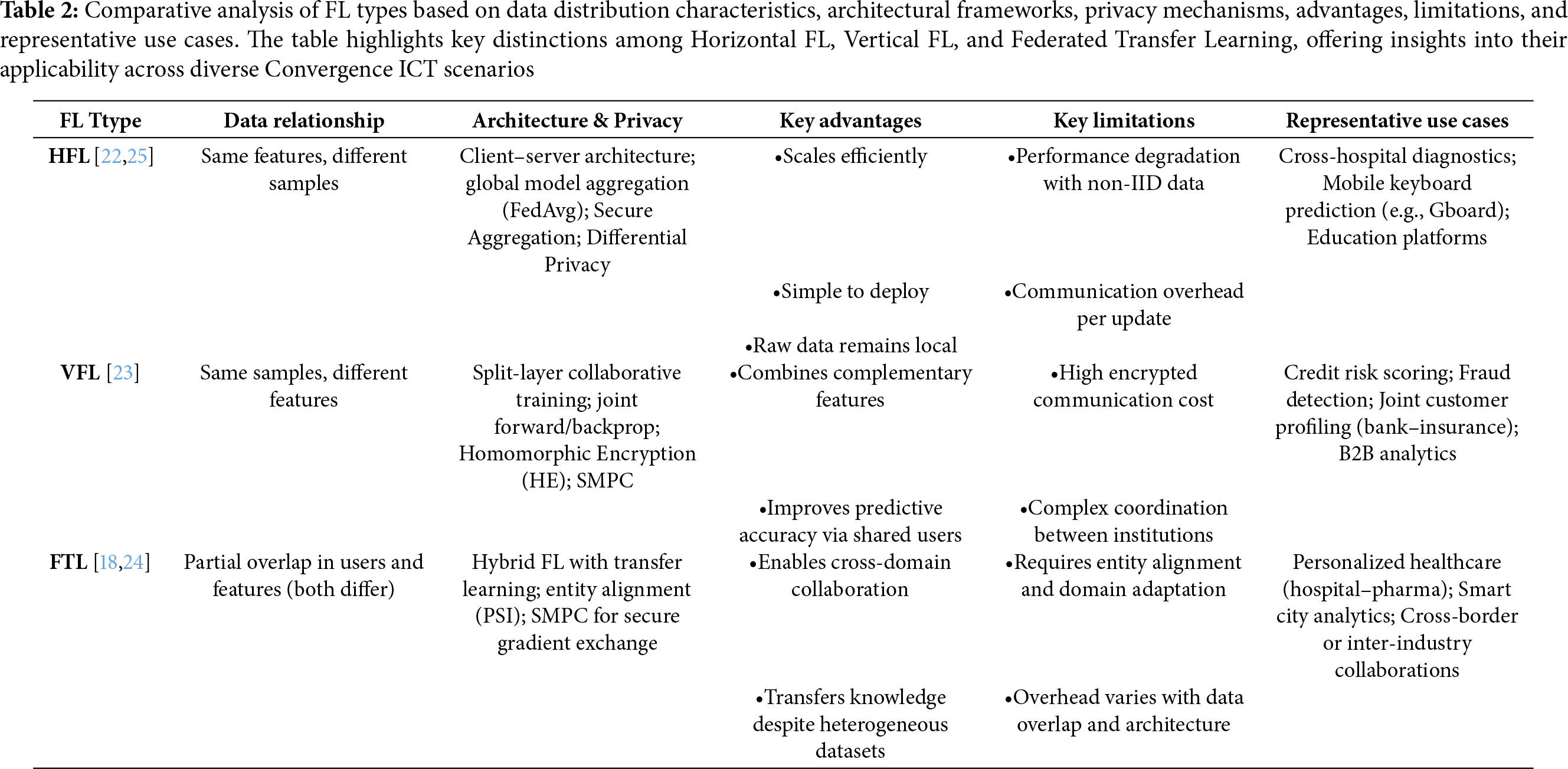

A fundamental way to classify FL is the way in which data is distributed across participants [21]. FL can be categorized into three major types: Horizontal Federated Learning (HFL), Vertical Federated Learning (VFL), and Federated Transfer Learning (FTL).

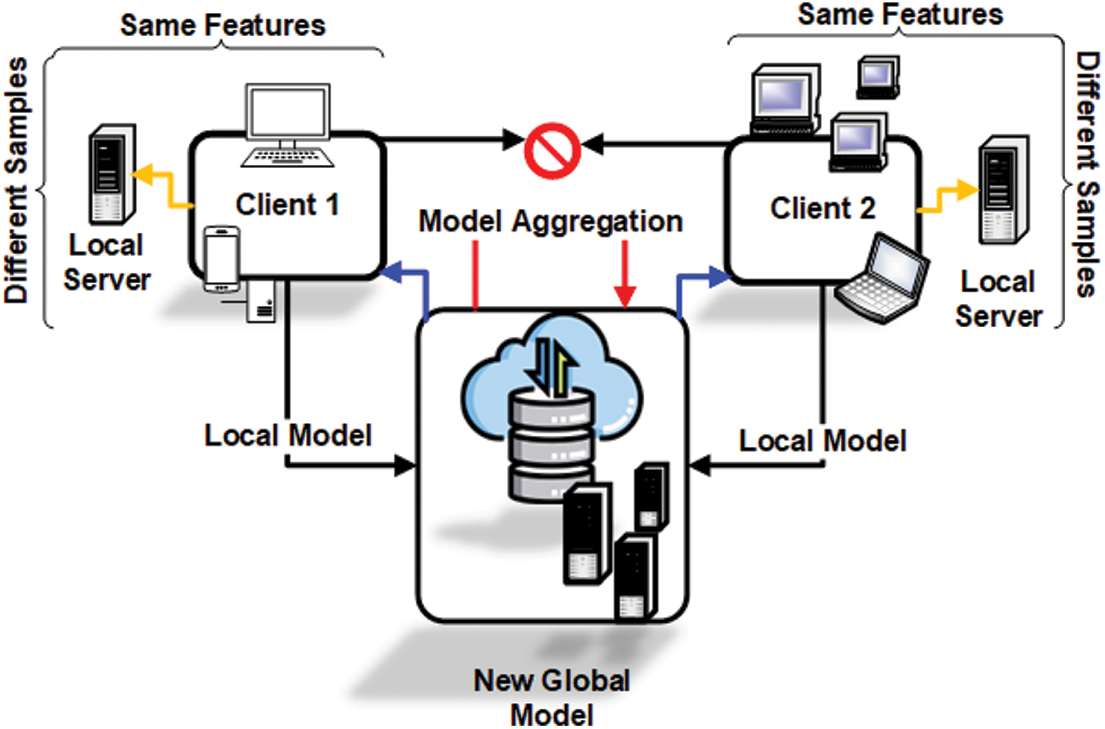

3.3.1 Horizontal Federated Learning

HFL also referred to as sample-based federated learning, is applicable in scenarios where participating clients share an identical feature space but possess non-overlapping data samples. This paradigm is particularly relevant in contexts where homogeneous types of data are independently collected across multiple institutions/clients, yet the individuals represented in each dataset remain different [22]. The general architecture of HFL, as illustrated in Fig. 5, comprises a central coordinating entity (e.g., a cloud server) and multiple distributed clients (e.g., hospitals, smartphones, or IoT devices) that maintain the same set of input features while holding disparate local datasets. The process begins with the server initializing a global model, which is sent to all selected clients. Each client then performs local training using its respective dataset and computes model updates, such as gradients or parameter differentials. These updates are transmitted back to the central aggregator, which employs an aggregation algorithm—commonly Federated Averaging (FedAvg)—to integrate the updates into a refined global model. The updated global model is subsequently redistributed to the clients, initiating the next training iteration. This client–server architecture enables collaborative model development while ensuring that raw data remains localized, thereby preserving data privacy and regulatory compliance. The training process is typically orchestrated in either asynchronous or semi-synchronous modes, contingent upon device availability and network stability.

Figure 5: Architecture of Horizontal Federated Learning (HFL). HFL enables collaborative model training among clients that share the same feature space but hold non-overlapping data samples. Each client trains a local model on its dataset and shares model updates with a central server. These updates are aggregated into a global model, which is redistributed to clients, allowing for privacy-preserving learning without sharing raw data

A practical example of HFL is its use in the healthcare sector, where multiple hospitals across different regions collect patient data with standardized features—such as age, symptoms, and diagnostic results. Each hospital retains its dataset locally due to privacy laws (e.g., HIPAA, GDPR). By employing HFL, these hospitals can collaboratively train a diagnostic model for disease prediction without sharing raw medical records. Instead, each hospital contributes to the global model through encrypted or anonymized parameter updates. This approach not only preserves data privacy but also improves model generalization across geographically and demographically diverse populations.

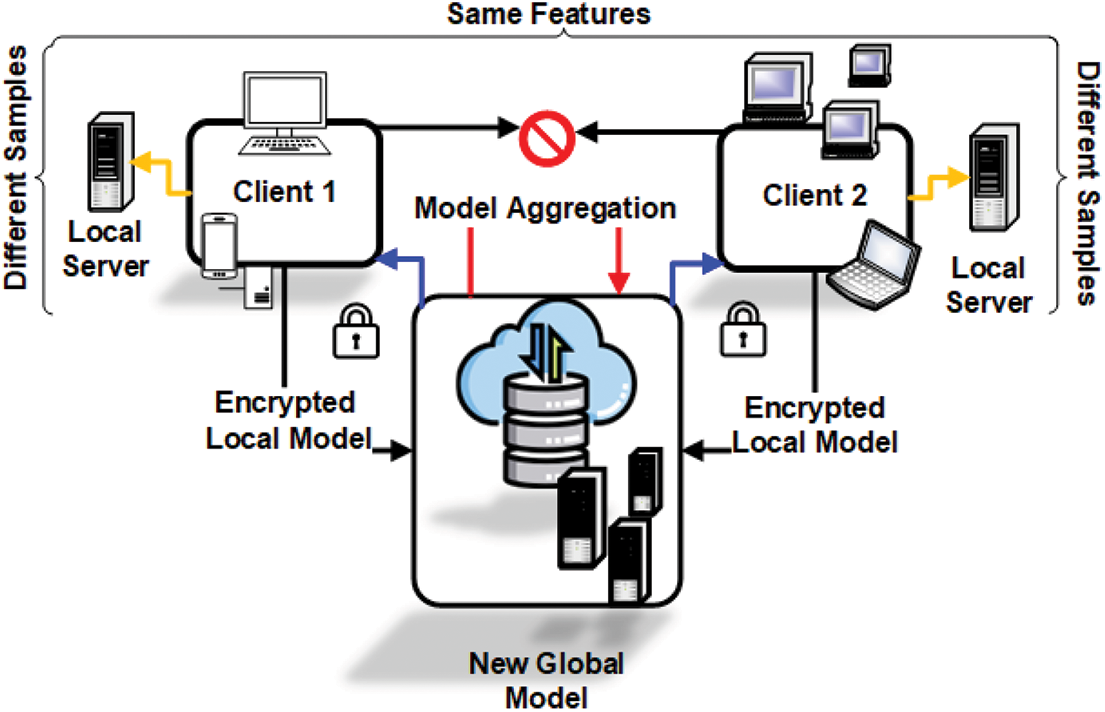

3.3.2 Vertical Federated Learning

VFL is applicable in scenarios where multiple organizations share a common user base but maintain distinct feature spaces for those users. Such situations commonly arise in collaborative ecosystems where each party collects complementary information pertaining to the same individuals, for example, a financial institution and an insurance company [23]. In contrast to HFL, where each client possesses a complete feature set and can independently train a local model, VFL necessitates tightly coordinated training across participating institutions. This requirement stems from the fact that no single party has access to both a full training sample and the complete feature space. As depicted in Fig. 6, the typical VFL architecture consists of multiple data holders and a coordinating server. Each participant performs partial forward and backward propagations based on its locally stored features. During training, only encrypted intermediate outputs—such as feature embeddings or gradients—are exchanged among parties. To safeguard sensitive information and mitigate the risk of data leakage, Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC), Homomorphic Encryption (HE), and Differential Privacy (DP) are commonly employed. The final model predictions or loss calculations are performed collaboratively, with a designated party (often the label holder) supervising the training process. This architecture enables multiple organizations to jointly train machine learning models that leverage their collective data while upholding regulatory compliance and ensuring the confidentiality of proprietary features.

Figure 6: Architecture of Vertical Federated Learning (VFL). VFL facilitates collaborative learning across organizations that share the same user base but maintain distinct feature spaces. Each participant processes its own features, exchanges encrypted intermediate outputs, and contributes to a jointly trained model via a coordinating server. Secure aggregation techniques, such as homomorphic encryption, ensure privacy while enabling model development across complementary datasets

A real-world example of VFL is a partnership between a commercial bank and an insurance company, where both institutions serve the same customers. The bank holds detailed financial transaction records, while the insurance company possesses claim histories and risk assessments. By employing VFL, these two entities can collaboratively train a predictive model for credit risk assessment or insurance fraud detection. Throughout this process, raw data remains securely stored within each organization’s infrastructure, and only encrypted intermediate computations are exchanged. This method allows for the development of a more robust and feature-rich model without breaching user privacy or violating regulatory constraints such as GDPR.

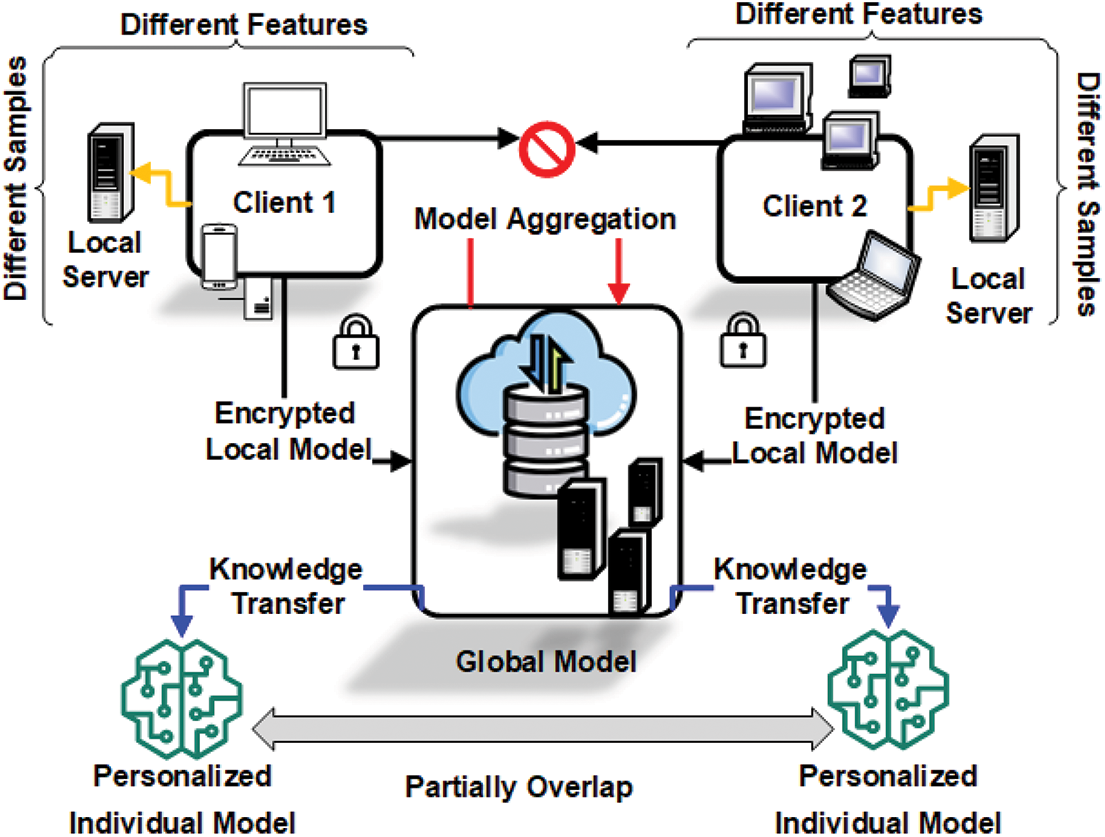

3.3.3 Federated Transfer Learning

Federated Transfer Learning is designed for collaborative learning scenarios in which both the feature space and the sample space differ across participating entities, with only partial overlap in their user bases. This paradigm is particularly relevant in data-scarce environments, where individual organizations hold limited and heterogeneous subsets of data, each covering distinct users and feature dimensions [24]. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the FTL architecture integrates principles from both HFL and VFL while incorporating transfer learning techniques to mitigate gaps in both sample and feature spaces. In a typical FTL workflow, participating parties first perform privacy-preserving entity alignment—commonly using Private Set Intersection (PSI)—to identify shared users. Each institution then trains partial models locally on its proprietary data. Securely encrypted feature representations, gradients, or model updates—protected via homomorphic encryption or (SMPC)—are exchanged to refine a shared model or enhance cross-domain predictions. Transfer learning is a central component of FTL, enabling knowledge acquired in one domain (e.g., drug-response modeling) to be adapted to another (e.g., clinical diagnostics). This approach facilitates robust model training even when local datasets are sparse or exhibit significant heterogeneity.

Figure 7: Architecture of Federated Transfer Learning (FTL). FTL supports collaborative learning where both the feature space and sample space differ across clients, with only partial overlap in their user bases. Each party trains local models using distinct datasets, and encrypted model updates or feature representations are shared with a central server. Through transfer learning, knowledge is exchanged to build personalized models, even in data-scarce and heterogeneous environments, while maintaining privacy

A representative application of FTL involves collaboration between a hospital and a pharmaceutical company. The hospital maintains electronic health records (EHRs), including patient demographics, diagnoses, and treatment histories, while the pharmaceutical company possesses drug interaction logs, clinical trial data, and medication adherence records. Although both organizations serve some of the same patients, their feature spaces are entirely distinct. By jointly leveraging FTL, the two parties can train predictive models for personalized treatment recommendations or adverse drug reaction detection. The hospital contributes clinical insights, while the pharmaceutical company contributes pharmacological expertise. Through the combined use of federated learning and transfer learning, the resulting model can generalize across diverse medical contexts while preserving data privacy and adhering to regulatory constraints.

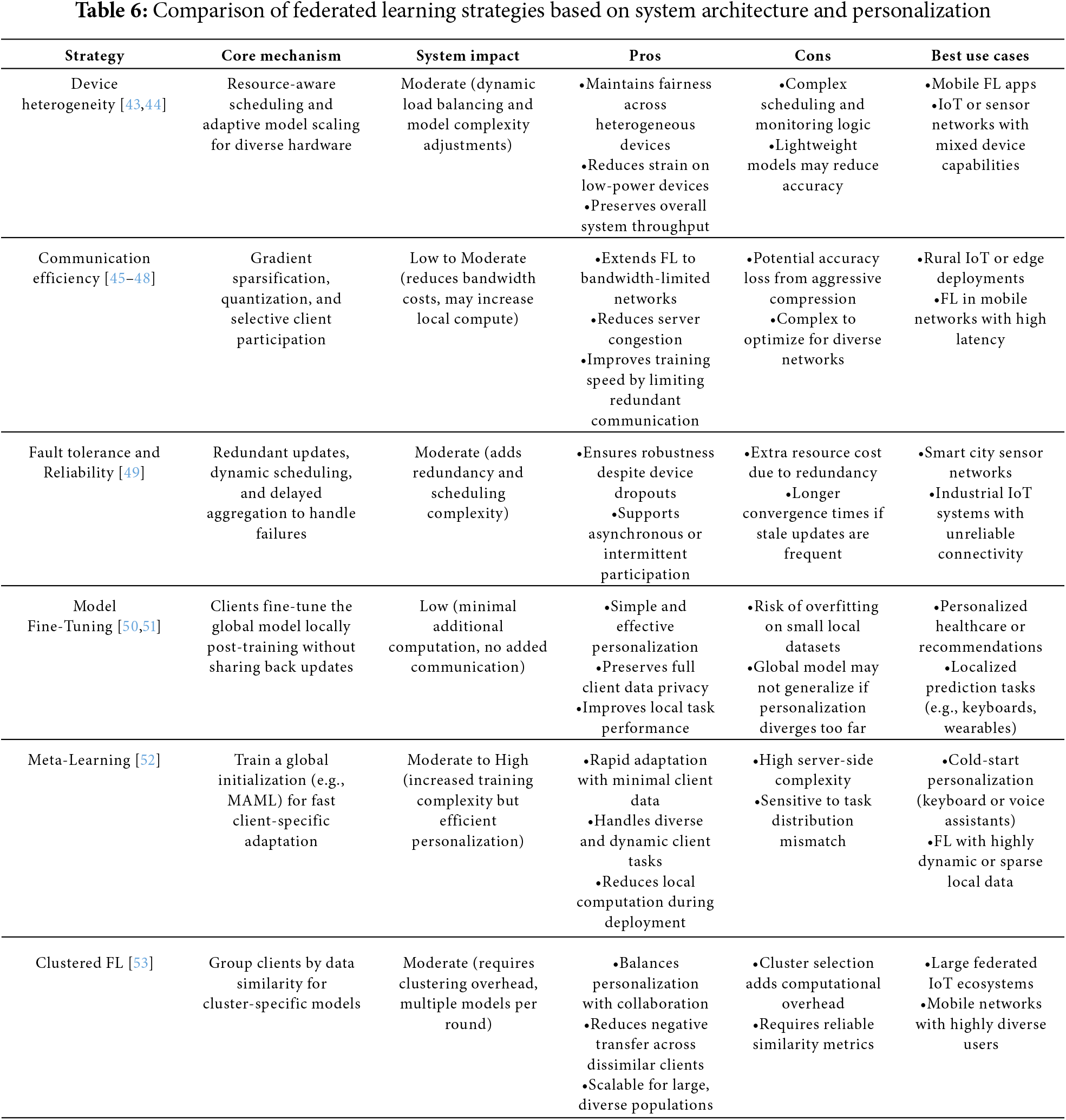

Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of Horizontal, Vertical, and Federated Transfer Learning. It compares their data distribution, architectures, privacy mechanisms, benefits, challenges, and typical applications. This overview highlights how HFL excels in scalable, feature-consistent settings, VFL leverages complementary features across shared users, and FTL enables cross-domain collaboration despite limited data overlap.

3.4 Classification Based on Model Aggregation Architecture

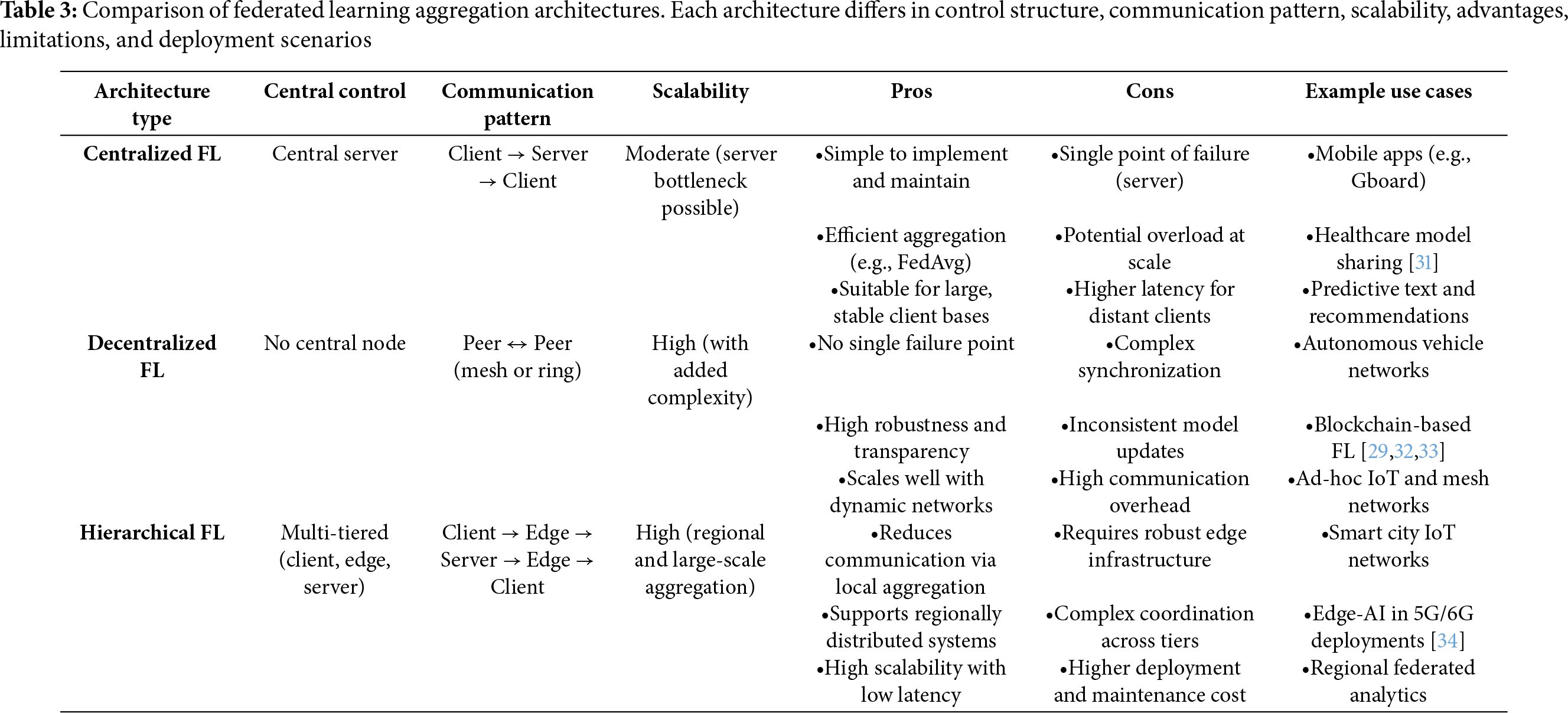

FL systems can be classified according to their model aggregation architecture, which defines how updates from participating clients are combined to train a global model (Fig. 4). The chosen architecture significantly impacts communication efficiency, system scalability, fault tolerance, and overall trustworthiness. This section presents three major aggregation architectures—Centralized FL, Decentralized FL, and Hierarchical FL along with their respective strengths and limitations.

3.4.1 Centralized Federated Learning

Centralized Federated Learning is the most widely adopted architecture. The Fig. 8 illustrates this architecture, which consists of a central server that orchestrates the full training cycle, coordinating multiple clients that train local models on private datasets. After local training, clients send model updates—such as gradients or weights—to the central server, which aggregates them, often using the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) algorithm [26]. This design forms a star topology where clients communicate only with the server, not with each other. A well-known example of this architecture is Google’s Gboard, which leverages FL to enhance word prediction and typing suggestions across Android devices without collecting raw keystroke data [27]. Mobile clients periodically compute local updates and transmit them to Google’s central servers, which then update and redistribute the global model. Centralized FL is relatively easy to deploy and maintain, making it suitable for systems with a large number of clients and stable connectivity. However, the central server represents a single point of failure and can become a communication or computational bottleneck in large-scale deployments.

Figure 8: Centralized Federated Learning architecture. Clients train local models on their private datasets and send updates to a central server, which aggregates them (e.g., using FedAvg) to form a global model that is redistributed back to the clients

3.4.2 Decentralized Federated Learning

Decentralized FL removes the need for a central coordinator. Fig. 9 depicts this architecture. Instead, clients exchange model updates directly with each other through peer-to-peer (P2P) communication, often using structured communication graphs, gossip protocols, or blockchain-based consensus mechanisms [28]. Each client acts as a node in a distributed network, averaging updates with selected peers to collectively converge on a global model. This architecture has been applied to connected autonomous vehicle (CAV) networks, where vehicles collaboratively train object detection models by exchanging updates with nearby peers in real time, avoiding dependence on a roadside server [29]. Decentralized FL enhances fault tolerance and transparency but introduces new challenges, such as ensuring convergence despite asynchronous updates, handling client dropouts, and coping with dynamic network topologies.

Figure 9: Decentralized Federated Learning (DFL) architecture. Clients communicate in a peer-to-peer (P2P) mesh or ring topology, exchanging model updates directly without a central server. Consensus is achieved via gossip-based or neighbor-to-neighbor averaging

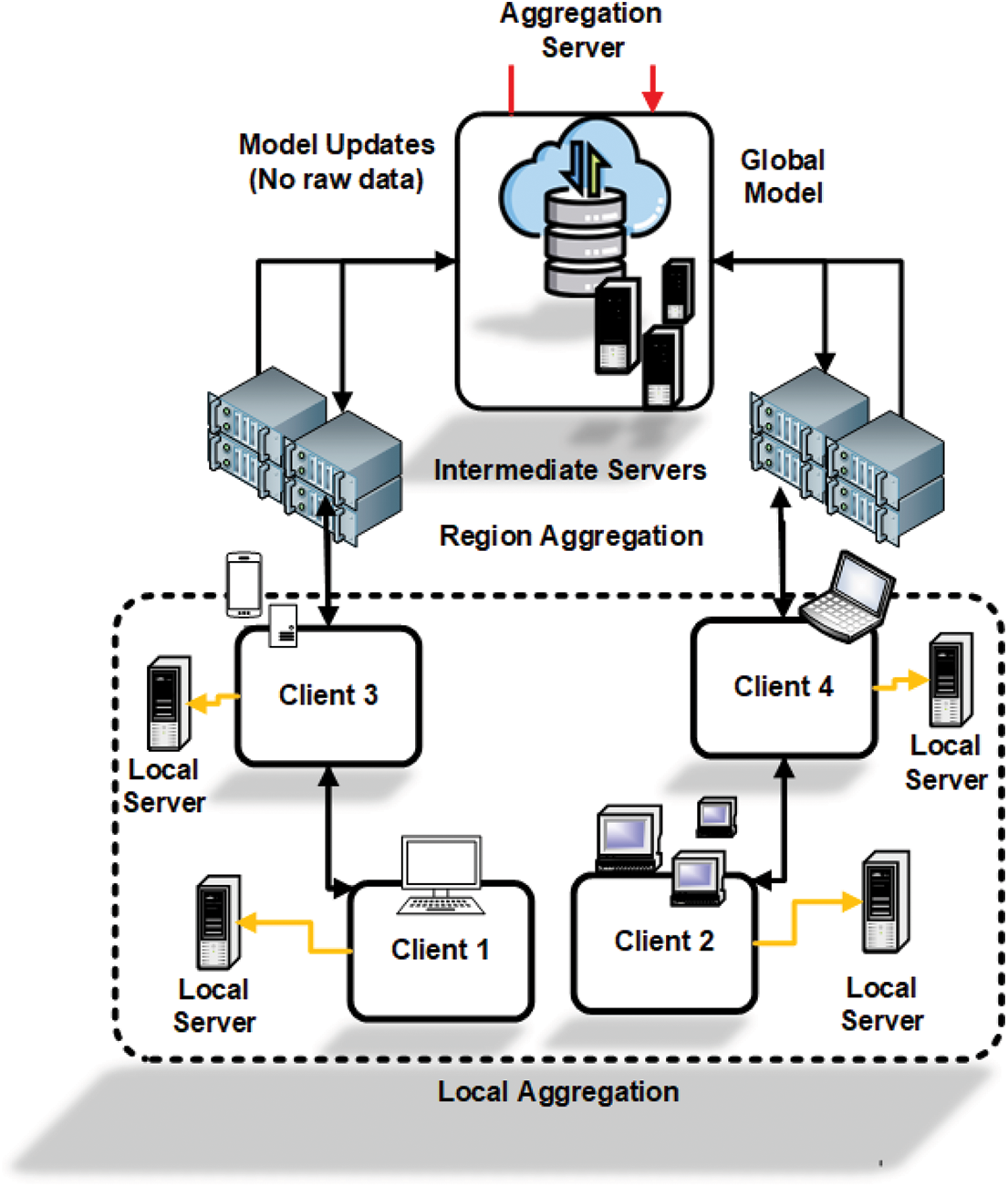

3.4.3 Hierarchical Federated Learning

Hierarchical FL introduces intermediate aggregation nodes—such as edge servers or fog nodes—between clients and a central server, forming a multi-tiered aggregation structure. Fig. 10 shows this architecture. Clients first transmit updates to local edge nodes, which perform partial aggregation. The aggregated results are then forwarded to a central server for final global model computation [30].

Figure 10: Hierarchical Federated Learning (HiFL) architecture. Clients send model updates to local edge servers for partial aggregation. The edge servers forward intermediate results to a global server, which computes the final model, reducing bandwidth costs and improving scalability

This approach is well-suited for geographically distributed and large-scale networks, such as smart city infrastructures. For example, IoT sensors across city regions can send local updates to fog nodes, which aggregate them before forwarding to a central data center for unified traffic prediction. Hierarchical FL improves scalability, reduces communication overhead, and lowers latency in wide-area networks like 5G/6G. However, it requires reliable edge infrastructure and careful coordination across tiers.

Table 3 summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and drawbacks of the three FL aggregation architectures. Each architecture is suitable for specific use cases: centralized FL for consumer applications with stable clients, decentralized FL for dynamic or trustless environments like ad-hoc IoT, and hierarchical FL for large-scale, distributed systems that benefit from edge computing.

3.5 Classification Based on Learning Algorithms

FL comprises a range of optimization algorithms designed to address the practical and theoretical challenges of distributed learning, particularly under constraints such as non-IID data distributions, limited communication bandwidth, and variable device availability. Some of these algorithms are also classified based on personalization. This is essential in FL, as a one-size-fits-all global model may not suit diverse local tasks. These algorithms allow each client to retain personalized components of the model. This section outlines representative algorithms that shape the learning dynamics of FL systems.

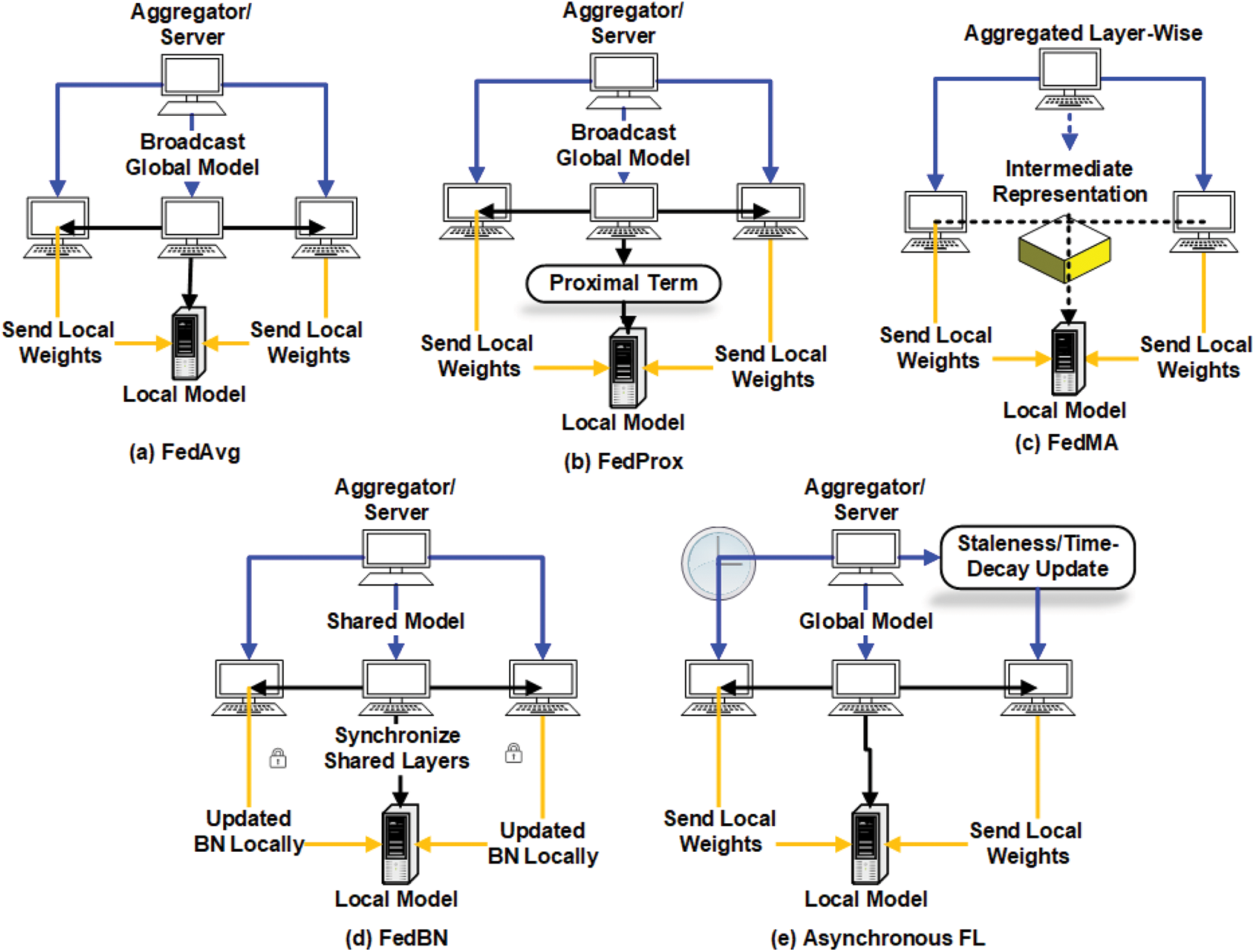

3.5.1 FedAvg (Federated Averaging)

FedAvg [6] is the most foundational and widely adopted learning algorithm in FL as shown in Fig. 11a. It operates by allowing each participating client to perform multiple local training epochs using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) on its private dataset. After local training, each client transmits its updated model weights to a central server, which aggregates them—typically by computing a weighted average—and then broadcasts the updated global model back to the clients. FedAvg follows a synchronous architecture where all selected clients in a training round must complete their local updates before aggregation. This requires uniform participation but is efficient when clients have similar computing capabilities and network conditions. While communication-efficient and straightforward, FedAvg performs poorly on non-IID data distributions where client datasets vary significantly in feature space or label distribution.

Figure 11: Comparison of federated learning algorithms. (a) FedAvg: Clients perform local training and send weights to the server, which aggregates and broadcasts a global model synchronously. (b) FedProx: Extends FedAvg by adding a proximal term to local objectives to handle non-IID data and heterogeneous resources. (c) FedMA: Performs layer-wise aggregation by matching neurons using intermediate representations rather than simple averaging. (d) FedBN: Synchronizes only shared layers while each client updates its batch normalization (BN) layers locally to address distributional shifts. (e) Asynchronous FL: Clients send updates at different times, and the server incorporates them using staleness- or time-decay–aware updates, avoiding strict synchronization

FedProx [35] builds upon FedAvg to improve performance in non-IID and resource-constrained settings. It modifies the local objective function by adding a proximal term that penalizes deviations from the global model as depicted in Fig. 11b. This term encourages clients to make conservative updates, thus reducing divergence in the presence of heterogeneous data or computational capacities. The core communication structure remains similar to FedAvg, but local training objectives are regularized.

The server’s role does not change, making FedProx compatible with existing FL infrastructure.FedProx is ideal for real-world FL scenarios where clients possess vastly different data distributions—e.g., regional hospitals, retail stores, or mobile devices with usage-specific data.

3.5.3 FedMA (Federated Matched Averaging)

FedMA [36] introduces a novel neuron-matching strategy to align model layers across clients (Fig. 11c). It aggregates client models layer by layer, matching corresponding neurons based on activation similarity rather than simple averaging. Clients train their models locally and send intermediate representations to the server. The server performs layer-wise matching and constructs a new global model using aligned weights. FedMA is effective in settings like personalized recommendation or handwriting recognition, where feature representations vary by user.

3.5.4 FedBN (Federated Batch Normalization)

FedBN [37] separates the training of batch normalization (BN) layers from the rest of the model as shown in Fig. 11d. Clients update BN statistics locally while the global model synchronizes only shared layers. Each client maintains its own BN layers, reducing the impact of distributional shift in feature statistics. The shared model is synchronized using FedAvg or similar techniques. FedBN has shown strong results in domain-shifted settings like cross-hospital medical imaging, where batch statistics vary significantly between clients.

3.5.5 Asynchronous Federated Learning

Asynchronous FL [38] is designed for real-world deployments where client availability is unpredictable. Instead of waiting for all clients to report in each round, the server integrates model updates as they arrive. The server maintains a global model and asynchronously incorporates client updates using staleness-aware or time-decay mechanisms to maintain convergence (Fig. 11e). Suitable for edge computing, IoT environments, or mobile networks where connectivity is intermittent or clients have varying computational latency.

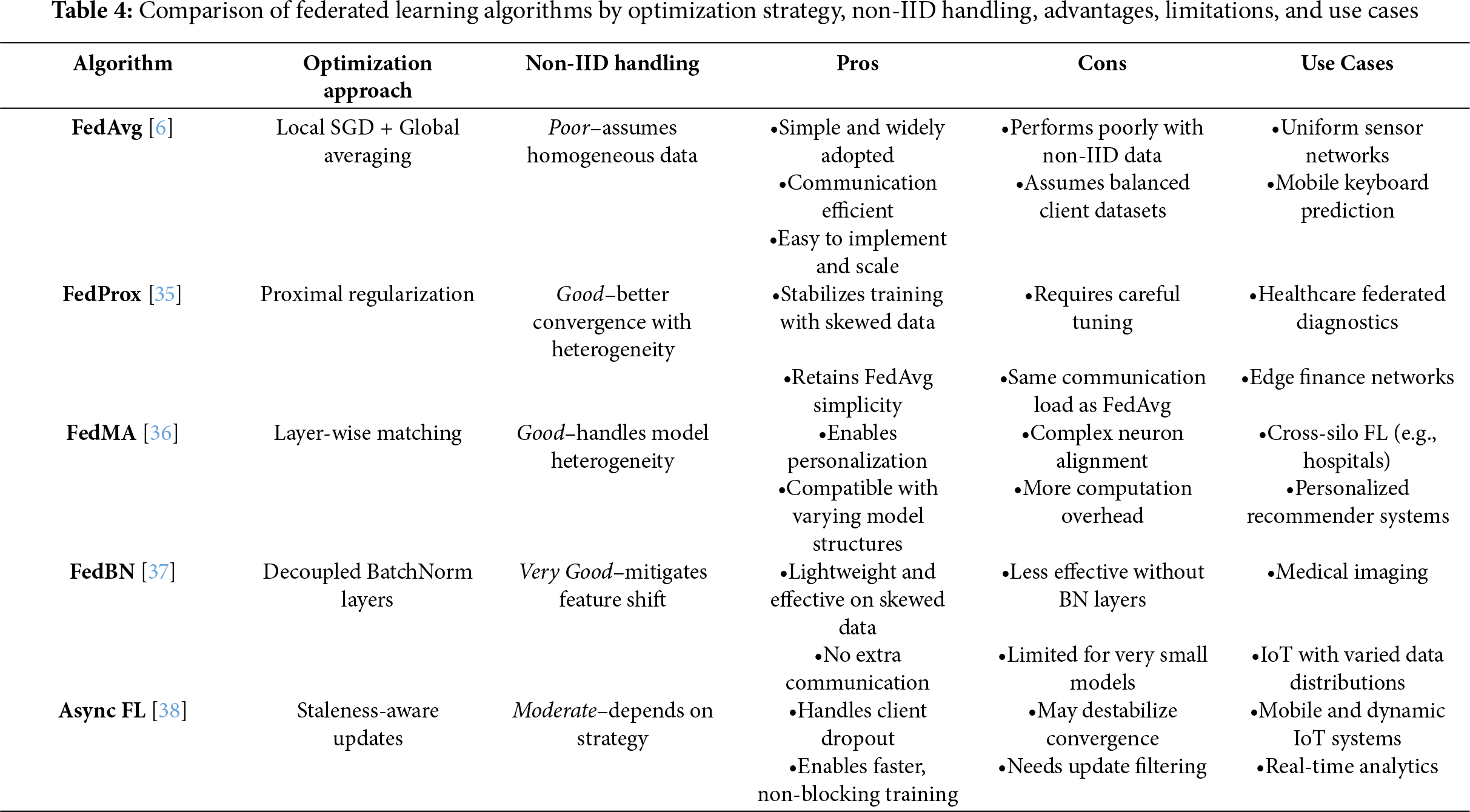

Table 4 summarizes the above key algorithms, highlighting their optimization strategies, ability to handle non-IID client data, and their respective advantages, limitations, and application domains. FedAvg remains the most widely adopted approach due to its simplicity and communication efficiency, though it performs poorly in heterogeneous data settings. FedProx improves convergence under non-IID conditions by introducing a proximal term but requires additional hyperparameter tuning. FedMA supports personalization and diverse model architectures at the cost of higher computational complexity, while FedBN offers lightweight mitigation of feature distribution shifts, making it suitable for domains like medical imaging. Finally, asynchronous FL provides robustness and scalability for large, dynamic networks, though it must manage potential convergence slowdowns due to stale or conflicting updates. Together, these comparisons guide the selection of an appropriate FL strategy based on deployment environment and data characteristics.

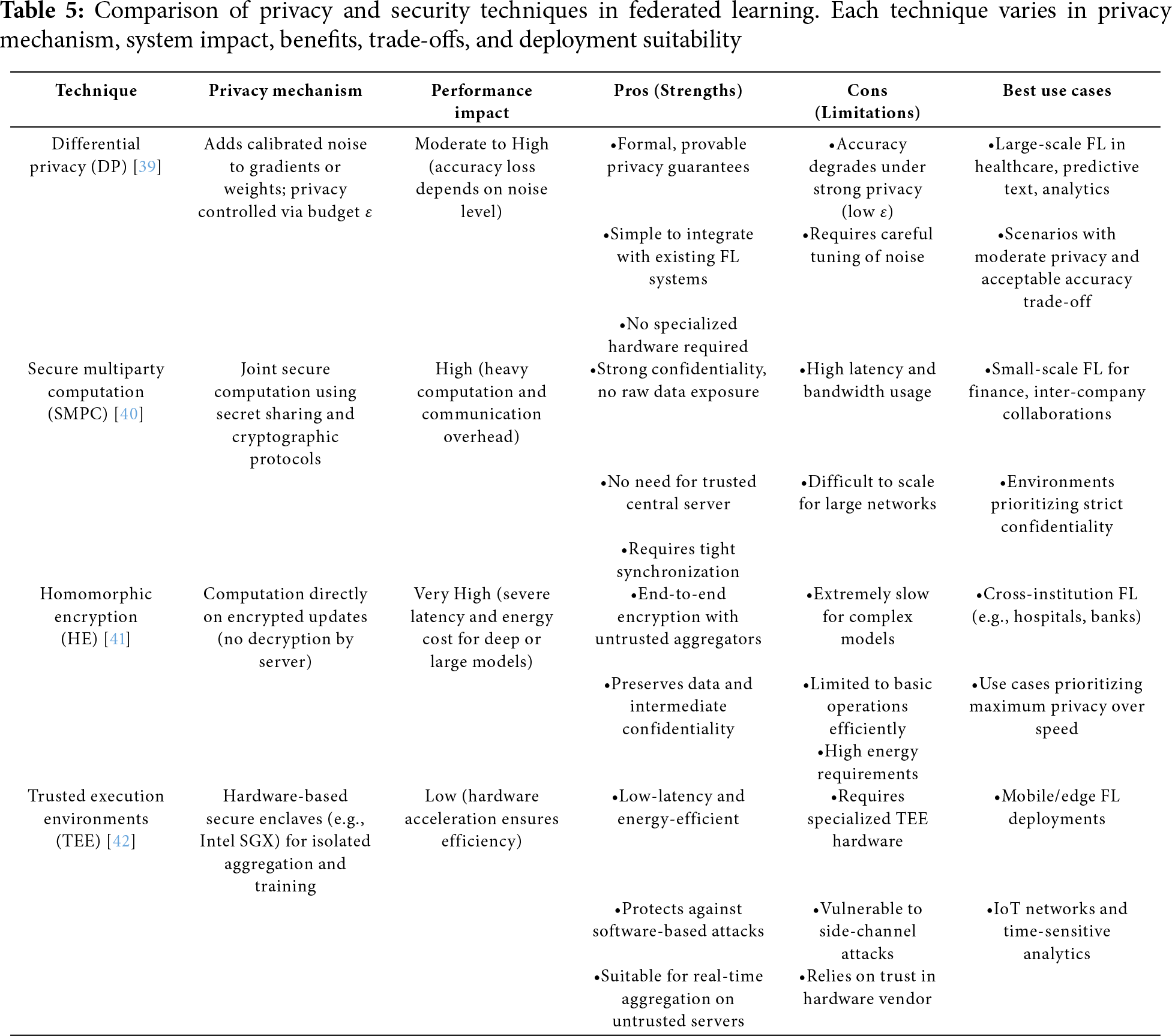

3.6 Classification Based on Privacy and Security Techniques

Privacy preservation is a foundational principle of FL, distinguishing it from centralized machine learning paradigms. In FL, raw data remains on the client device, but model updates and metadata can still reveal sensitive information. Therefore, a range of cryptographic and system-level techniques have been developed to enhance security and mitigate privacy risks during model training and aggregation.

3.6.1 Differential Privacy (DP)

Differential Privacy [39] ensures that the inclusion or exclusion of a single user’s data has a statistically insignificant impact on the overall model output. This is typically achieved by injecting calibrated random noise into model updates before they are transmitted to the server. In a DP-enabled FL system, clients apply noise to gradients or weights locally before communication. The server aggregates noisy updates, ensuring privacy is preserved even if the server is untrusted. DP offers formal, provable privacy guarantees via the

3.6.2 Secure Multiparty Computation (SMPC) and Homomorphic Encryption (HE)

Secure Multiparty Computation [40] and Homomorphic Encryption [41] provide strong cryptographic protection by ensuring computations can be performed without revealing individual inputs.

• SMC: Participating clients collaboratively compute a shared function (e.g., global model aggregation) without revealing their individual updates. Secret sharing and oblivious transfer are common underlying mechanisms.

• HE: Clients encrypt their model updates before sending them to the server. The server performs computations directly on encrypted data and returns encrypted results, which clients decrypt locally.

Both methods offer end-to-end data confidentiality during training. However, they impose significant computational and communication overhead, limiting their practicality in energy-constrained or latency-sensitive environments such as IoT or mobile edge computing.

3.6.3 Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs)

Trusted Execution Environments [42] offer a hardware-based solution to privacy and integrity. TEEs like Intel SGX isolate execution from the host system and ensure secure processing of sensitive tasks. Model updates are sent to a TEE-enabled server or edge node, where aggregation or training is securely conducted inside the enclave. TEEs protect against both software-based attacks and unauthorized access to runtime data. TEEs provide low-latency, energy-efficient protection and are well-suited for scenarios with untrusted servers or mobile environments. However, they require specialized hardware and are susceptible to side-channel attacks, raising concerns about scalability and trust.

Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of key privacy-preserving techniques used in Federated Learning, including DP, SMC, HE, and TEEs. Differential Privacy introduces calibrated noise to model updates, offering formal privacy guarantees with minimal infrastructure, but at the cost of potential accuracy degradation. In contrast, SMC and HE provide strong cryptographic protection by ensuring that raw data is never exposed during computation. However, both approaches incur significant computational and communication overhead, limiting their scalability and practical use in real-time or resource-constrained environments. TEEs address these limitations by using secure hardware enclaves to isolate sensitive operations, offering low-latency and energy-efficient execution. Yet, they depend on specialized hardware and may be susceptible to side-channel attacks. Overall, the table highlights the trade-offs between security strength, performance impact, and deployment feasibility across different FL scenarios.

3.7 Classification Based on System Architecture

The deployment of FL systems in real-world environments faces several system-level challenges, including diverse client hardware, intermittent connectivity, and communication bottlenecks. Effective architecture design is crucial to ensure scalability, robustness, and efficiency across such heterogeneous settings.

Device heterogeneity captures the wide variation in computational power, memory, energy availability, and connectivity across client devices. To address this, FL systems employ resource-aware scheduling, where clients either self-report status or servers track reliability history. Adaptive model scaling (e.g., using compressed CNN architectures on low-power devices) is another approach, enabling lightweight model variants for low-resource devices [43]. In federated mobile applications, devices with limited power or processing capabilities can either train simplified models or participate less frequently, preserving overall system efficiency while maintaining acceptable model quality [44].

3.7.2 Communication Efficiency

Communication overhead between clients and servers is a key bottleneck in FL. Several algorithmic and architectural optimizations mitigate this challenge:

• Gradient Sparsification: Transmit only the top-

• Quantization: Compress gradient values using lower-precision formats (e.g., 8-bit) [46].

• Client Selection: Dynamically choose a subset of clients based on utility and availability to limit redundant communication [47].

Such methods extend FL to bandwidth-constrained environments like rural IoT networks or mobile edge systems [48].

3.7.3 Fault Tolerance and Reliability

FL systems must remain resilient despite device failures and unstable network conditions. To achieve robustness:

• Redundant Training: Replicate model updates across multiple clients to mitigate dropouts.

• Dynamic Scheduling: Replace or reschedule clients in real time upon disconnection.

• Delayed Aggregation: Accept stale updates within a bounded delay window [49].

These mechanisms are especially important in smart city sensor networks or IoT ecosystems, where intermittent connectivity is common.

3.8 Classification Based on Personalization Strategies

Due to the inherently non-IID (non-identically distributed) nature of client data, personalization has become a critical focus in FL. Different clients often exhibit unique data distributions, necessitating approaches that tailor models to individual users while retaining the benefits of global collaboration.

Model fine-tuning is one of the simplest personalization strategies. A global model is collaboratively trained and then fine-tuned locally on each client’s private data without sending updates back to the server. This allows the model to adapt to client-specific patterns while maintaining data sovereignty. Fine-tuning is widely used in applications such as personalized recommendations or healthcare diagnostics, where local adaptation significantly improves task performance [50,51].

Meta-learning, or “learning to learn,” trains a model that can rapidly adapt to new clients using only a few local updates. Algorithms like Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) have been extended to FL by optimizing a global initialization across diverse client tasks. Clients can then quickly fine-tune models with limited local data, making meta-learning particularly effective in scenarios with high task diversity or scarce local samples [52]. Applications include adaptive keyboard prediction or personalized AI assistants that must quickly learn user behavior.

3.8.3 Clustered Federated Learning

Clustered FL groups clients with similar data distributions into clusters, each jointly training a specialized model. Clustering—based on metrics such as model update similarity, statistical properties, or feature distributions—helps balance the benefits of global collaboration and local adaptation. This approach reduces negative transfer between unrelated clients and improves scalability and accuracy. Clustered FL is well-suited for large, diverse networks, such as federated IoT systems or heterogeneous mobile user populations [53].

Table 6 synthesizes key strategies in FL categorized by system architecture and personalization approaches. From the system perspective, techniques such as device-aware scheduling, communication compression, and fault-tolerant aggregation enhance scalability and reliability across heterogeneous and dynamic networks. On the personalization front, methods like local fine-tuning, meta-learning, and clustered FL address the challenges of non-IID data by tailoring models to user-specific distributions. Each strategy offers distinct benefits and trade-offs—such as communication efficiency versus accuracy loss, or personalization depth versus computational cost—making them suitable for different FL scenarios, including IoT ecosystems, smart city infrastructure, and mobile edge environments.

4 Federated Learning in Converged ICT: Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities

Overview of Federated Learning in Converged ICT FL has emerged as a privacy-preserving distributed machine learning paradigm that allows multiple clients to collaboratively train a global model without sharing raw data. In converging ICT infrastructures—where cloud computing, edge AI, IoT, and 5G/6G networks form integrated ecosystems—FL is particularly useful. It reduces bandwidth usage, lowers latency, and supports data sovereignty, making it suitable for domains with sensitive or distributed data. FL improves decision-making in real-time systems while ensuring privacy compliance. Applications range from smart cities and healthcare to industrial automation and autonomous systems. Previous studies focus on FL’s privacy mechanisms, communication efficiency, and optimization strategies. However, its role in fully converged ICT environments—comprising millions of heterogeneous edge nodes—is still an evolving research frontier. Key benefits of FL in such ecosystems include:

• Privacy Preservation: Retains data on-device, minimising risks of breaches and regulatory violations.

• Bandwidth Efficiency: Transmits model updates instead of raw data, reducing communication overhead.

• Scalability: Supports large-scale deployments across heterogeneous networks and devices.

• Low Latency: Leverages edge computation for near real-time decision-making in systems like smart traffic or autonomous vehicles.

4.1 Application Domains of Federated Learning

As digital ecosystems converge, the demand for decentralized learning grows. FL facilitates secure model training across geographically distributed environments. This section explores key application domains of FL in Convergence ICT: Smart Cities, Healthcare, Industrial Automation, and Autonomous Systems.

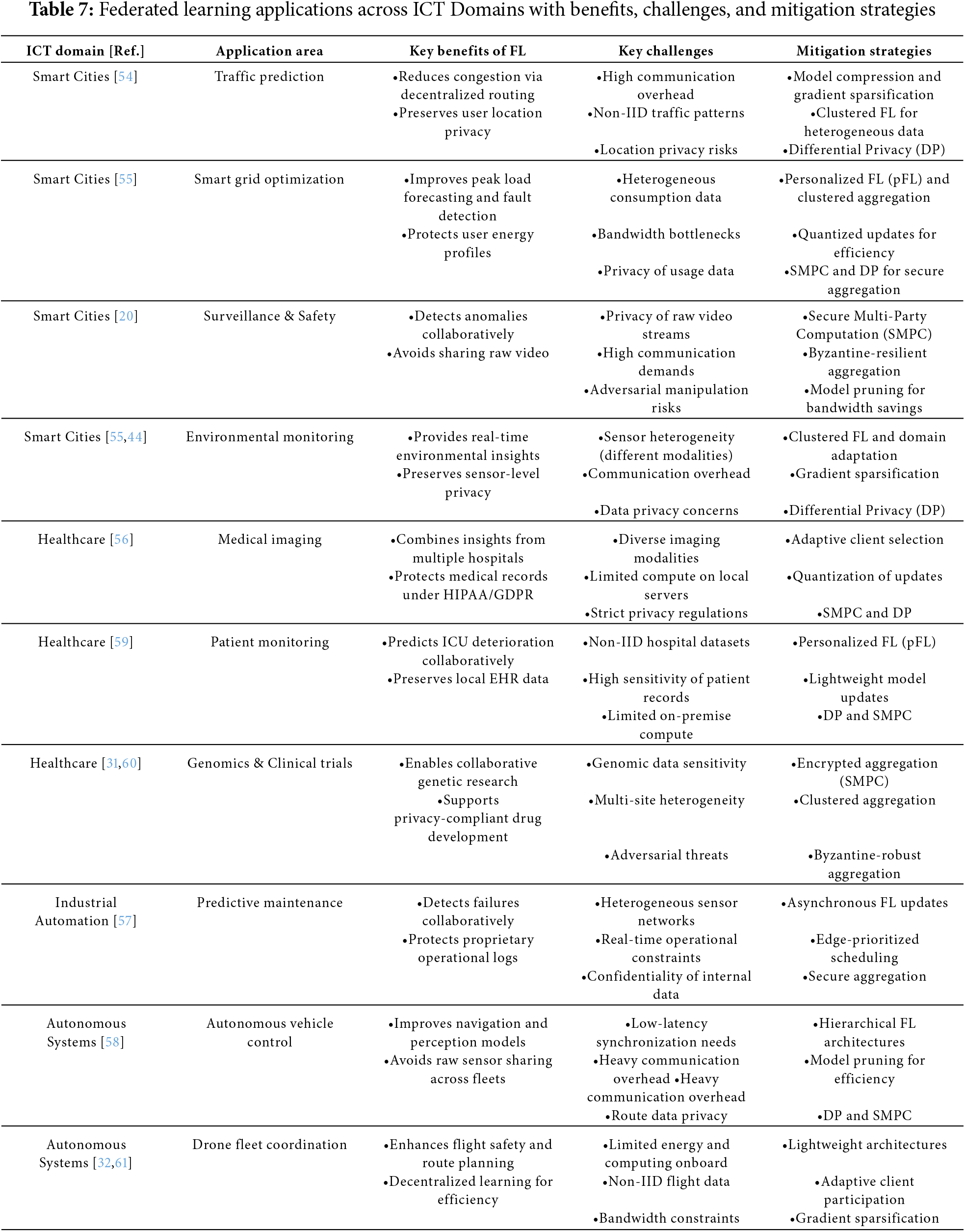

Federated Learning enhances smart city infrastructure by enabling privacy-preserving, decentralized analytics across various urban domains such as traffic management, energy grids, public safety, and environmental monitoring. For instance, Google’s Gboard pioneered large-scale FL by training predictive text models across millions of devices without transmitting raw keystroke data, setting the stage for urban FL applications. In traffic systems, FL supports adaptive signal control by allowing roadside sensors and connected vehicles to collaboratively predict congestion patterns and dynamically adjust traffic lights—without centralizing location-sensitive data [54]. In energy systems, smart grids leverage FL for district-level load forecasting and real-time fault detection, using local consumption data while maintaining user privacy [55]. Surveillance networks deploy FL to detect anomalies in video streams without uploading raw footage, and environmental sensors collaboratively predict air quality and noise patterns to inform city planning.

4.2.1 Challenges and Limitations

Despite its advantages, deploying FL at city scale presents several challenges. Communication overhead becomes significant due to the high volume of model updates exchanged between thousands of distributed edge devices. Non-IID data distributions—caused by differences in sensor types, locations, and usage patterns—undermine model convergence and accuracy. Privacy concerns persist despite data remaining local, especially due to the potential for inference attacks on model updates. Moreover, many edge devices suffer from constrained computational and energy resources, limiting the feasibility of frequent training cycles.

4.2.2 Solutions and Techniques

To address communication inefficiency, techniques such as model compression, gradient sparsification, and hierarchical aggregation are commonly employed to reduce bandwidth consumption. For handling non-IID data, approaches like clustered FL and personalized FL (pFL) help tailor models to specific device or region-level characteristics. Privacy concerns are mitigated using mechanisms such as DP and Secure Multiparty Computation (SMPC), which provide mathematical guarantees against data leakage during aggregation. These strategies are outlined in greater detail in Table 7, along with corresponding use cases and representative references.

Federated Learning is increasingly adopted in healthcare to enable privacy-preserving collaboration among hospitals, research institutions, and pharmaceutical companies, where centralizing data is restricted by strict privacy regulations such as HIPAA and GDPR. By allowing institutions to train models locally and share only model updates, FL supports the development of robust, generalizable AI systems without exposing sensitive patient data. Hospitals leverage FL to jointly train disease detection models for conditions such as cancer and pneumonia using medical images (e.g., MRIs and CT scans) [56]. This collaborative approach improves diagnostic accuracy across diverse populations. Similarly, FL powers early warning systems for sepsis and ICU patient deterioration by enabling predictive models to be trained on local electronic health record (EHR) data before contributing to a global model [56]. Beyond clinical care, institutions use FL to securely analyze distributed genomic datasets, facilitating the discovery of disease-linked biomarkers while maintaining compliance with privacy laws [56]. Pharmaceutical companies also apply FL to aggregate clinical trial outcomes across multiple research sites, enhancing the generalizability of models for evaluating treatment efficacy [56]. Platforms such as NVIDIA Clara exemplify this approach, supporting FL-driven medical imaging analysis by allowing radiology models to be trained across decentralized hospital datasets. This not only accelerates diagnostic model development but also ensures legal and ethical compliance.

4.3.1 Challenges and Limitations

Despite its promise, FL in healthcare faces challenges, including computational constraints on local servers, heterogeneity in imaging modalities and data quality, and stringent security requirements for aggregating model updates. To address these barriers, techniques such as adaptive client selection, model update quantization, and (SMPC) are widely employed. These strategies collectively enhance the scalability, security, and efficiency of FL in medical applications.

4.3.2 Solutions and Techniques

To overcome the limitations associated with applying Federated Learning in healthcare, several mitigation strategies have been developed. Adaptive client selection is commonly employed to prioritize institutions with adequate computational resources and representative datasets, thereby improving model convergence and robustness. Update quantization techniques help reduce communication overhead by compressing model updates, enabling participation from clients with constrained bandwidth or processing capabilities. To safeguard sensitive patient information during aggregation, (SMPC) ensures that intermediate model updates remain encrypted and inaccessible to unauthorized parties. Additionally, DP introduces statistical noise to shared updates, further mitigating the risk of information leakage and enhancing compliance with privacy regulations. Collectively, these techniques strengthen the scalability, security, and effectiveness of FL in medical environments.

Federated Learning is increasingly applied in industrial and manufacturing settings to enable predictive maintenance, process optimization, and operational efficiency without centralizing sensitive operational data. By allowing models to be trained locally on IoT-enabled sensors and production systems, FL facilitates collaboration across industrial sites while protecting proprietary and competitive information. Industrial sites employ FL to forecast equipment failures by analyzing distributed vibration and temperature sensor data, thereby reducing unplanned downtime and optimizing maintenance schedules [57]. Edge devices on production lines also leverage FL to collaboratively optimize production yield and throughput efficiency, training local models that contribute to a global optimization framework [57]. Manufacturing facilities further adopt federated computer vision models for defect detection using localized product images, which improves detection accuracy without compromising competitive secrecy [57]. FL additionally supports real-time demand forecasting and inventory management across geographically distributed warehouses, enabling data-driven logistics coordination while safeguarding sensitive operational data [57]. An example of this in practice is BMW’s adoption of FL across its manufacturing plants, where predictive models for equipment failures are trained collaboratively using distributed sensor data. This approach enhances production efficiency by reducing downtime, while avoiding the risks of centralizing sensitive industrial data.

4.4.1 Challenges and Limitations

Key challenges in deploying FL in industrial environments include balancing computational workloads with real-time production constraints, ensuring security and confidentiality of proprietary datasets, and managing heterogeneity in sensor formats and data distributions. Solutions such as asynchronous FL updates, edge-prioritized scheduling, and secure aggregation are commonly adopted to address these barriers, enabling scalable and secure FL deployment in manufacturing ecosystems.

4.4.2 Solutions and Techniques

To address these barriers, a range of technical solutions have been adopted in industrial FL deployments. Asynchronous FL protocols reduce the need for synchronized communication, allowing edge nodes to contribute updates when computational resources are available. Edge-prioritized scheduling ensures that time-critical processes are not disrupted by learning workloads. Additionally, secure aggregation techniques are applied to protect model updates from reverse-engineering or adversarial inference. These methods collectively enhance the scalability, security, and reliability of FL across manufacturing ecosystems, enabling collaborative intelligence without compromising operational integrity.

Federated Learning is increasingly employed in autonomous systems—including vehicles, drones, and robotics—to enable collaborative intelligence without centralized data aggregation. By training models locally on edge devices and sharing only model updates, FL supports real-time decision-making and adaptability while protecting sensitive sensor and operational data. Autonomous vehicles leverage FL to jointly train navigation, traffic behaviour prediction, and obstacle recognition models, enhancing safety and situational awareness across diverse driving environments without transmitting raw sensor feeds [58]. Distributed drone fleets similarly benefit from FL by collaboratively learning from flight trajectories and object interactions, improving autonomy in logistics and surveillance tasks [58]. Industrial and service robots adopt FL-trained models for coordinated task execution and adaptive interaction with dynamic environments, which enhances efficiency while minimizing operational risks [57]. FL also enables robots and autonomous agents to develop models for navigation within smart buildings and public spaces by utilizing locally gathered environmental data, supporting scalable and privacy-preserving adaptation [58]. Table 7 summarizes these applications. In practice, commercial platforms like Tesla’s Autopilot leverage FL to refine object detection and driving policies across distributed vehicle fleets. By avoiding the centralization of raw sensor data, such systems accelerate collective learning while preserving driver and environmental privacy.

4.5.1 Challenges and Limitations

Despite its advantages, FL deployment in autonomous systems faces significant challenges, including achieving low-latency communication for model updates, safeguarding sensitive route and sensor data, and optimizing resource utilization on mobile platforms with limited computation and energy budgets. To address these issues, strategies such as hierarchical FL architectures, model pruning, and differential privacy techniques are widely adopted, ensuring scalable, efficient, and secure collaborative learning.

4.5.2 Solutions and Techniques

To address these challenges, autonomous FL systems employ several optimization techniques. Hierarchical FL architectures are used to reduce latency by enabling edge-level aggregation before communication with a central server. Model pruning and compression help minimize the size and computational complexity of models, making them suitable for resource-constrained platforms. DP ensures that individual sensor traces or location data cannot be inferred from shared model updates. Together, these techniques enable efficient, scalable, and privacy-preserving FL implementations for autonomous systems, supporting high-stakes decision-making in real-world, time-sensitive environments.

While FL presents a transformative approach for decentralized model training, it faces significant challenges, particularly when applied within Convergence ICT environments. These environments—comprising interconnected smart cities, healthcare networks, industrial IoT, and autonomous systems—introduce complexities that must be effectively managed to realize the full potential of FL. This section provides a detailed exploration of the major challenges in FL, including communication overhead, client heterogeneity, data privacy and security, resource constraints, and security vulnerabilities.

4.7 Communication Overhead in Federated Learning

Communication overhead remains a significant bottleneck in Federated Learning. Unlike traditional centralized machine learning, FL involves frequent communication between edge devices (clients) and the central server for model updates. This repetitive exchange of model parameters, particularly in large-scale networks, can lead to substantial network congestion and latency. Bandwidth consumption during each training round can quickly saturate network capacity, while high latency may severely delay global aggregation, slowing down model convergence. Additionally, synchronization delays caused by variability in client processing speeds can disrupt global updates. To mitigate communication overhead, optimization strategies such as model compression, communication frequency reduction, selective client participation, and asynchronous federated learning are employed. These techniques aim to optimize network usage, reduce data exchange volume, and accelerate global model convergence.

4.8 Client Heterogeneity in Federated Learning

Client heterogeneity in Federated Learning refers to the differences in computational power, network reliability, and data distribution among participating edge devices. In Convergence ICT, edge devices vary widely—from powerful cloud servers to low-power IoT sensors—resulting in disparities in processing capabilities and connectivity. Furthermore, the local data distributions on these devices are often non-IID (Non-Independent and Identically Distributed), reflecting unique behaviors and usage patterns. This heterogeneity can lead to inconsistent update rates, unstable participation, and skewed model learning. Addressing these challenges requires techniques such as FedProx for stabilizing local updates, Asynchronous FL for independent updates, Adaptive Client Selection for prioritizing robust devices, and Gradient Normalization to balance contributions during global aggregation.

4.9 Data Privacy and Security Concerns in Federated Learning

Data privacy is a core motivation for Federated Learning, but maintaining privacy during model updates remains challenging. Although raw data never leaves local devices, model gradients exchanged during training can still reveal sensitive information, making FL vulnerable to gradient leakage and inference attacks. Malicious actors can exploit these updates to infer private attributes or manipulate gradients to poison the model. Moreover, communication interception poses risks if model updates are not securely encrypted. To address these concerns, advanced privacy-preserving techniques such as DP, SMPC, HE, Secure Aggregation Protocols are employed. These mechanisms ensure that sensitive information remains protected while enabling collaborative model training.

4.10 Resource Constraints in Federated Learning

Resource constraints are a critical challenge in Federated Learning, especially given the reliance on edge devices with limited processing power, memory, and battery life. These limitations can hinder local training and model updates, particularly in real-time applications like autonomous driving or smart grid optimization. Computational limitations restrict the ability of low-powered devices to perform complex model training, while memory constraints may prevent the storage of large models. Additionally, repeated training and communication can drain battery life, reducing device availability. To overcome these barriers, strategies such as lightweight model architectures, client selection policies, model distillation, and edge offloading are applied to optimize efficiency and extend device participation.

4.11 Security Vulnerabilities in Federated Learning

Despite its decentralized nature, Federated Learning remains susceptible to various security threats, including poisoning attacks, Sybil attacks, and backdoor attacks. In poisoning attacks, malicious clients inject biased or incorrect updates to degrade the global model’s performance. Sybil attacks involve the creation of multiple fake clients to manipulate global aggregation with malicious data. Backdoor attacks subtly alter the model’s behavior under specific triggers while appearing normal otherwise. Addressing these threats requires robust defense mechanisms, including anomaly detection to identify suspicious updates, robust aggregation techniques to filter out malicious contributions, and client reputation scoring to evaluate the trustworthiness of clients.

5 Emerging Trends in Federated Learning: A Roadmap for Converged, Sustainable, and Secure ICT

FL has established itself as a transformative paradigm for decentralized model training, particularly in Convergence ICT, where data privacy, low latency, and distributed intelligence are crucial. As FL continues to expand across various sectors like smart cities, healthcare, industrial automation, and autonomous systems, emerging challenges demand innovative research directions. This section explores critical advancements and emerging trends poised to redefine FL’s scalability, security, interoperability, and efficiency.

5.1 Foundational Technology Layer: Enabling Trust, Privacy, and Scalability

5.1.1 Quantum Federated Learning (QFL): Redefining Scalability and Security

One of the most disruptive advancements in distributed intelligence is QFL, which integrates quantum computing to address limitations in computational scalability and communication security inherent in classical FL. By leveraging quantum bits (qubits) that represent multiple states simultaneously, QFL enables significant acceleration in tasks such as gradient aggregation and model synchronization across large-scale networks [62]. Quantum-enhanced optimization, combined with Quantum Key Distribution (QKD), ensures secure and efficient exchange of model updates, offering theoretically unbreakable encryption. Foundational architectures for QFL, including hybrid quantum-classical frameworks, are discussed in-depth by Chehimi et al. [63], while Gurung et al. [64] address practical challenges such as device integration and quantum communication overhead. Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) are proposed as core components to support scalable learning in 6G and IoT infrastructures [65]. Qiao et al. [66] provide a comparative survey that highlights QFL’s advantages over classical FL in terms of speed, security, and communication efficiency. Applications span from smart grids [67] to secure IoT ecosystems [68], with extended relevance to Metaverse and blockchain environments, enabling real-time, privacy-preserving interactions [69]. Advanced QFL-based frameworks such as explainable and secure systems (e.g., ESQFL) and quantum-secured Secure Multiparty Computation (SMPC) architectures have been proposed to enhance robustness and privacy [70,71]. Despite its promise, QFL still faces challenges due to current quantum hardware limitations and the complexity of integrating quantum protocols with classical systems. Ongoing research into hybrid architectures aims to bridge this gap, pushing QFL toward practical deployment in next-generation intelligent networks.

5.1.2 Secure Aggregation and Privacy-Preserving Techniques

A core challenge in FL is safeguarding individual client updates during aggregation. Federated Learning with Secure Aggregation addresses this by allowing model updates to be combined without revealing any single client’s data. Techniques such as Secure Multiparty Computation (SMPC) and Homomorphic Encryption enable encrypted computations, preserving privacy throughout the training process. These mechanisms offer several advantages: they enhance data privacy by preventing exposure of sensitive information, protect against adversarial manipulation of model updates, and support regulatory compliance with frameworks such as GDPR and HIPAA. However, secure aggregation introduces computational overhead and latency, especially on resource-constrained devices. As a result, current research is focused on developing lightweight cryptographic protocols and parallelized aggregation methods to ensure both security and efficiency in large-scale FL deployments.

5.1.3 Blockchain-Integrated Federated Learning: Trust and Transparency

To address trust, transparency, and centralization challenges in FL, Blockchain-Integrated Federated Learning (BFL) has emerged as a promising paradigm. Instead of relying on a central server to aggregate model updates, blockchain introduces a decentralized ledger that immutably records each client’s contributions. This mitigates risks of single points of failure and fosters a trustless environment among participating agents. Key benefits include: (i) decentralized trust via distributed consensus, (ii) traceability and auditability of model updates, and (iii) incentive mechanisms enabled by smart contracts to encourage honest participation. Despite these advantages, integrating blockchain into FL introduces significant latency due to consensus protocols and increased energy consumption—issues particularly relevant for low-power edge devices. Current research focuses on optimizing BFL with lightweight consensus mechanisms and scalable architectures tailored for decentralized, resource-constrained environments.

5.2 Application and Intelligence Layer: Decentralized Learning in Action

5.2.1 Federated Reinforcement Learning (FRL): Intelligence for Autonomous Systems

FRL extends classical FL to dynamic environments by enabling multiple agents—such as autonomous vehicles, drones, and industrial robots—to collaboratively learn optimal policies while keeping their local experience data private. Unlike traditional FL, which relies on static datasets, FRL evolves continuously as agents interact with real-time, stochastic environments, making it highly suitable for applications such as traffic control, smart grid optimization, and coordinated robotic operations. FRL combines the decentralized nature of FL with the adaptability of deep reinforcement learning (DRL), making it especially valuable for IoT, cyber-physical systems, and edge intelligence. A comprehensive survey by Qi et al. [72] outlines foundational techniques and key challenges, while Pinto Neto et al. [73] focus on IoT-specific implementations and the need for lightweight protocols. In cyber-physical energy systems, FRL has been applied to connected hybrid electric vehicles (C-HEVs) for efficient energy management [60]. Performance enhancements include phased weight adjustment for faster convergence [74], asynchronous policy gradient methods like AFedPG for communication efficiency [75], and blockchain integration to ensure tamper-proof updates in distributed networks [76]. Further innovations integrate biologically-inspired R-STDP for stable multi-agent learning [61], mobility-aware DRL for vehicular caching [77], adaptive cloud–fog architectures for medical imaging [78], and DDPG-based optimization for heterogeneous edge devices [79]. Despite its promise, FRL faces several challenges. These include synchronizing updates across heterogeneous agents, maintaining policy consistency, and mitigating latency. Current research is increasingly focused on asynchronous communication, decentralized learning, and scalable coordination mechanisms to overcome these hurdles.

5.2.2 Integration with Edge Intelligence: Enabling Real-Time, Localized Learning

The integration of Federated Learning with Edge Intelligence is reshaping real-time, decentralized learning by enabling model training directly at the edge—close to where data is generated. This approach reduces latency, minimizes bandwidth usage, and enhances privacy by keeping sensitive data local. Applications in autonomous vehicles, industrial automation, and smart surveillance systems benefit significantly from this architecture. Key advantages of edge-integrated FL include real-time decision-making, bandwidth efficiency, and enhanced data security. To support these benefits, current research explores collaborative offloading strategies, adaptive model compression, and device-aware training to optimize learning under resource and connectivity constraints.

5.2.3 Cross-Domain Federated Learning: Collaborative Intelligence across Sectors

Cross-Domain Federated Learning (CD-FL) extends the traditional boundaries of FL by enabling collaborative learning across diverse sectors—such as healthcare, finance, and transportation–without compromising data privacy. By leveraging heterogeneous datasets from different domains, CD-FL enhances model generalization, robustness, and adaptability. For instance, a fraud detection model trained in banking can be adapted for anomaly detection in healthcare, benefiting from shared structural patterns without exposing sensitive data. Despite its potential, CD-FL introduces significant challenges, including harmonizing heterogeneous data schemas, aligning disparate feature spaces, and navigating varying privacy regulations across industries. To address these issues, ongoing research is focusing on adaptive FL models and cross-domain transfer learning techniques that enable seamless knowledge sharing while ensuring compliance with sector-specific constraints.

5.3 Sustainability Layer: Energy-Aware, Scalable Federated Learning

As Federated Learning continues to expand across IoT networks and edge devices, addressing its growing energy consumption has become increasingly critical. Sustainable and Green FL focuses on enhancing energy efficiency and reducing the environmental impact of distributed learning, particularly for low-power edge devices such as IoT sensors, wearables, and smartphones. Key strategies include energy-efficient model training through techniques like model compression and gradient sparsification, as well as edge offloading, which transfers heavy computations to nearby servers to alleviate the burden on constrained devices. Additionally, integrating renewable energy sources such as solar or wind into edge infrastructure supports greener deployments. Looking ahead, research is prioritizing dynamic power management, energy-aware client selection, and real-time energy monitoring systems to ensure FL remains scalable, efficient, and environmentally sustainable.

5.4 Unified Vision: Toward Converged and Sustainable ICT with Federated Learning

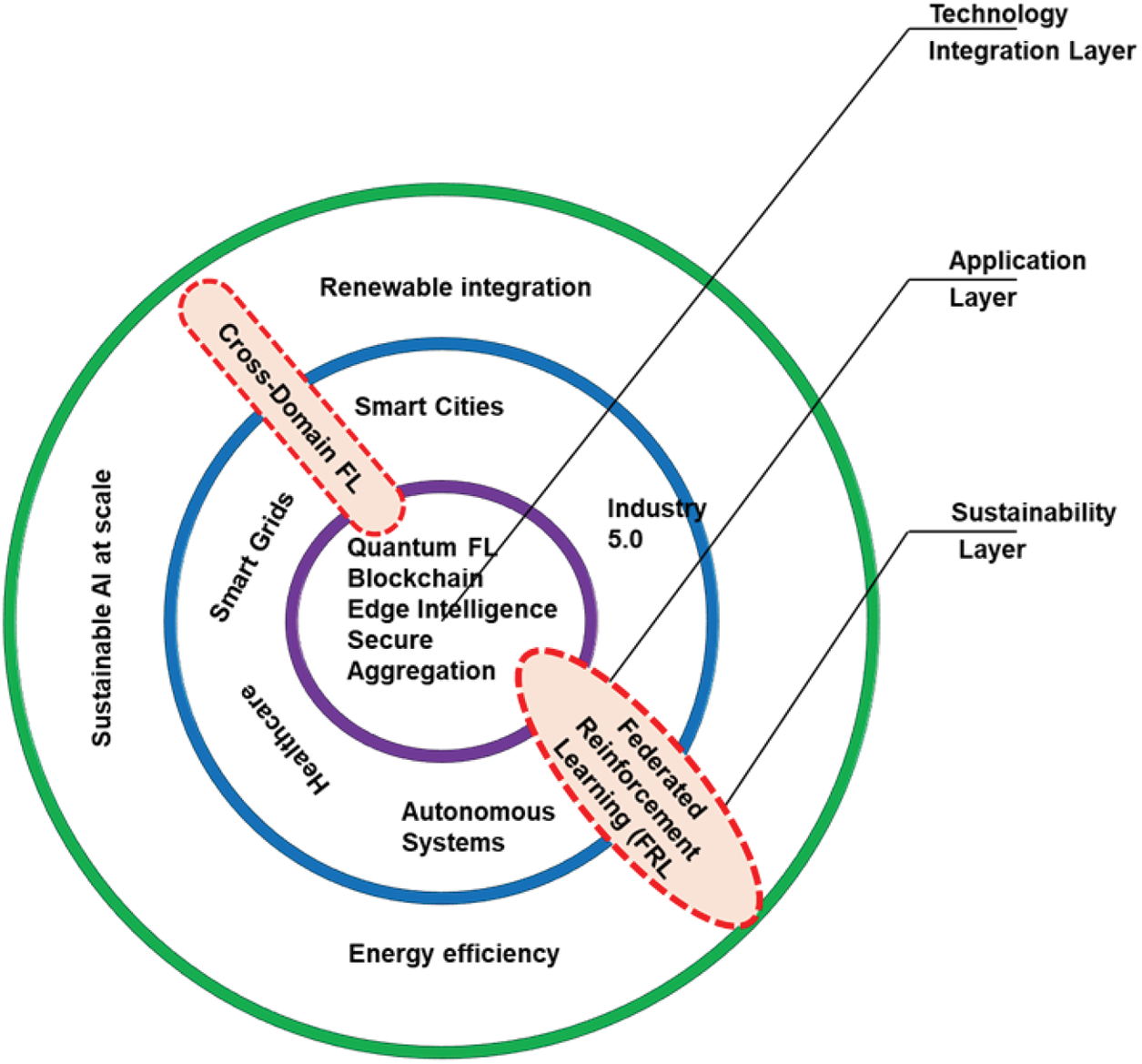

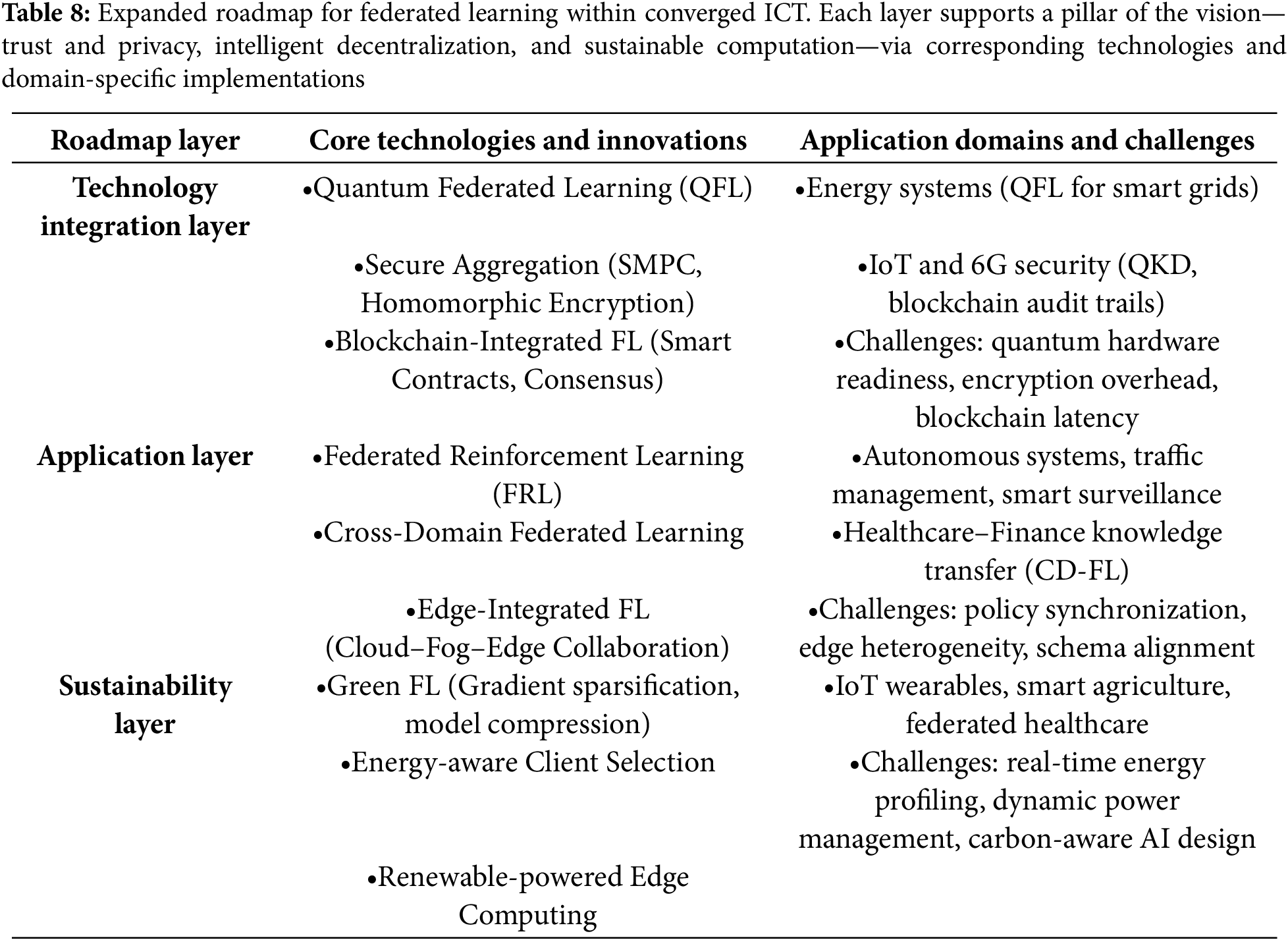

The future revolution of Federated Learning is deeply intertwined with the convergence of next-generation technologies such as quantum computing, blockchain, edge intelligence, and sustainable energy systems. As illustrated in the roadmap Fig. 12, FL acts as the core enabler of secure, decentralised, and intelligent collaboration across diverse application domains–including smart cities, healthcare, autonomous systems, and Industry 5.0. Federated Learning occupies a central role in the convergence of emerging ICT paradigms, bridging foundational technologies with large-scale, sustainable applications. The roadmap outlines three integration layers: a technology integration layer that incorporates secure aggregation, quantum FL, and blockchain; an application layer encompassing smart infrastructure use cases; and a sustainability layer addressing energy efficiency and AI scalability. These layers, as summarized in Table 8, illustrate the alignment between technical innovations, real-world implementations, and ongoing research challenges across sectors. Key trends such as cross-domain FL and Federated Reinforcement Learning (FRL) demonstrate how FL is expanding to meet complex coordination demands across verticals. Ultimately, this roadmap underscores FL’s pivotal role in realising distributed intelligence and sustainability in converged ICT ecosystems.

Figure 12: Federated Learning Roadmap within Converged ICT Ecosystems. The diagram illustrates the core technological enablers (Quantum FL, Blockchain, Edge Intelligence, Secure Aggregation) at the center, surrounded by critical application domains such as Smart Cities, Smart Grids, Healthcare, and Autonomous Systems. The outermost layer highlights sustainability goals including renewable integration, energy efficiency, and scalable AI. Cross-cutting advancements such as Cross-Domain FL and Federated Reinforcement Learning (FRL) point to emerging frontiers that unify these layers into an intelligent, decentralised infrastructure

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of Federated Learning within the rapidly evolving context of Convergence ICT, addressing the central research question: What are the main challenges in implementing Federated Learning (FL) in Convergence ICT environments, and what are the possible solutions? We found that Federated Learning offers a promising solution by decentralizing model training, but faces significant challenges like communication overhead and client heterogeneity, which can be mitigated through techniques like model compression, hierarchical aggregation, and secure aggregation methods. The findings underscore FL’s value as a decentralized, privacy-preserving approach that enables scalable and low-latency intelligence across distributed environments. However, the review also highlights persistent challenges—including communication overhead, client and data heterogeneity, resource constraints, and security vulnerabilities—that hinder the widespread adoption of FL in real-world, heterogeneous systems. A key contribution of this work is the development of a novel FL framework that offers a multi-dimensional taxonomy encompassing data distribution types, aggregation architectures, learning algorithms, personalization strategies, and privacy-preserving mechanisms. Building on this foundation, the review introduces a forward-looking roadmap that situates FL within a layered convergence model. This roadmap spans three core dimensions: (i) foundational technologies such as Quantum FL, blockchain integration, and secure aggregation; (ii) application-driven intelligence through cross-domain FL, federated reinforcement learning, and edge-enabled analytics; and (iii) sustainability initiatives including energy-aware model training, client scheduling, and renewable-powered edge deployments. Together, this framework and roadmap provide a unified vision for designing next-generation FL systems that are not only secure and adaptive but also scalable and sustainable. They offer strategic guidance for researchers, developers, and policymakers aiming to operationalize FL in increasingly complex and interconnected ICT ecosystems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions: Imran Ahmed contributed to the overall conceptualization and initial direction of the research. Misbah Ahmad was responsible for the design of the study, literature review, data analysis, manuscript writing, and editing. Gwanggil Jeon contributed to the conceptual development and manuscript editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: No new datasets were generated or analysed during the current study. All supporting data and materials referenced are publicly available and properly cited within the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: This study did not involve any experiments with human participants or animals. As such, ethics approval was not required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cmc.2025.068319/s1.