Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Secure and Invisible Dual Watermarking for Digital Content Based on Optimized Octonion Moments and Chaotic Metaheuristics

Laboratory of Engineering, Systems and Applications, National School of Applied Sciences, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, 30000, Morocco

* Corresponding Author: Mhamed Sayyouri. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence Algorithms and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5789-5822. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068885

Received 09 June 2025; Accepted 12 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

In the current digital context, safeguarding copyright is a major issue, particularly for architectural drawings produced by students. These works are frequently the result of innovative academic thinking combining creativity and technical precision. They are particularly vulnerable to the risk of illegal reproduction when disseminated in digital format. This research suggests, for the first time, an innovative approach to copyright protection by embedding a double digital watermark to address this challenge. The solution relies on a synergistic fusion of several sophisticated methods: Krawtchouk Optimized Octonion Moments (OKOM), Quaternion Singular Value Decomposition (QSVD), and Discrete Waveform Transform (DWT). To improve watermark embedding, the biologically inspired algorithm Chaos-White Shark Optimization (CWSO) is used, which allows dynamically adapting essential parameters such as the scaling factor of the insertion. Thus, two watermarks are inserted at the same time: an institutional logo and a student image, encoded in the main image (the architectural plan) through octonionic projections. This allows minimizing the amount of data to be integrated while increasing resistance. The suggested approach guarantees a perfect balance between the discreetness of the watermark (validated by PSNR indices > 47 dB and SSIM > 0.99) and its resistance to different attacks (JPEG compression, noise, rotation, resizing, filtering, etc.), as proven by the normalized correlation values (NC > 0.9) obtained following the extraction. Therefore, this method represents a notable progress for securing academic works in architecture, providing an effective, discreet and reversible digital protection, which does not harm the visual appearance of the original works.Keywords

In the digital era, when it just takes a few clicks to duplicate and distribute works, copyright protection has emerged as a major problem [1,2]. In both the creative and scientific domains, it is essential to guarantee that creators receive credit for their efforts and that their creations are shielded from unapproved duplication. Digital watermarking technologies are proven to be successful ways to preserve the originality of creatives while providing traceability since they allow identifying information to be directly placed into works. In this regard, maintaining the integrity of digital works is increasingly dependent on copyright protection [1,3].

Students’ instruction involves creating architectural sketches, which are distinctive pieces that blend technical accuracy and creativity. These drawings are crucial for learning and presenting architectural concepts, and they frequently reflect creative ideas [3]. However, because they are produced and disseminated digitally, there is a considerable chance that they may be copied or used without authorization. Therefore, in order to ensure that their work is recognized and contributes to the academic community, students must be able to defend it. In order to avoid copyright infringement and to guarantee the traceability of works in the case of litigation, it is imperative that strong measures be put in place to secure these sketches [1,2]. When it comes to copyright protection, especially for scholarly and professional works, architectural drawings must be authenticated. There are a number of techniques available today to ensure the authenticity and integrity of architectural creations. Among these methods, encryption is particularly effective at protecting the confidentiality of data by preventing unauthorized users from accessing it [4]. Conversely, steganography [5–7] makes it possible to covertly secure drawings by hiding information directly within their visual content without changing how they seem [8]. Lastly, one of the most popular techniques for adding a mark of legitimacy to a picture is digital watermarking [9], which involves securely and imperceptibly adding information like logos or personal identification [10–14]. Despite their differences, these methods all work toward protecting authors’ rights and stopping any improper or fraudulent usage of architectural drawings.

In this context, we introduce a novel approach to enhance the protection of digital architectural sketches made in academia. More specifically, we propose a dual watermarking scheme that allows the simultaneous insertion of two visual signatures—an institutional logo and a student’s photograph—within the host image. The specificity of our contribution lies in the synergistic integration of three advanced tools: Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) for efficient frequency localization, Quaternionic Singular Value Decomposition (QSVD) for stable and imperceptible insertion, and Krawtchouk Polynomial-Optimized Octonionic Moments (OKOM) for a compact representation resistant to geometric attacks. This original combination allows both to minimize the amount of inserted information and to optimize the robustness of the watermark without compromising the visual quality of the sketches. Leveraging bio-inspired optimization algorithms, our method dynamically adjusts insertion parameters, ensuring an optimal balance between stealth, traceability, and resilience to malicious manipulation.

The following three points highlight our essential contributions.

1. To enhance search, avoid local minima, and outperform purely random methods, we present the Chaos-White Shark Optimization (CWSO) algorithm, which uses chaotic maps.

2. To improve the accuracy and resilience of our dual watermarking technique, we suggest utilizing OKOM. These moments enable us to introduce less data into the host image while providing increased resilience to geometric alterations.

3. For the first time, we provide a copyright protection technique created especially for architectural sketches created by students.

In this section, we present the main elements of the proposed method, including the wavelet transform (DWT), quaternion singular value decomposition (QSVD), the CWSO optimization algorithm and Krawtchouk optimized octonion moments (OKOM).

2.1 Discrete Wavelet Transform

The Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) is a fundamental method for analyzing the frequency components of an image. This technique is based on a filtering process that divides the image into several distinct sub-bands [15,16]. These sub-bands correspond to key aspects of human visual perception. In addition, DWT allows this decomposition process to be repeated to obtain even more detailed sub-bands, offering even greater flexibility [17]. The use of DWT is crucial to our method as it offers excellent temporal and frequency localization, allowing subtle integration of watermarks into specific sub-bands without compromising visual image quality [18–20].

2.2 Quaternion Singular Value Decomposition

Quaternion singular value decomposition (QSVD) is an extension of classical singular value decomposition (SVD), adapted to quaternion matrices [21]. In addition to providing essential information about matrix structure, QSVD also facilitates applications such as data compression, signal filtering and image reconstruction by exploiting the unique properties of quaternions [22,23]. For our watermarking system, the integration of QSVD is particularly important, as it allows us to exploit the structure of quaternions to insert watermarks in a way that is both imperceptible and robust [24].

2.3 Standard Chaos-White Shark Algorithm

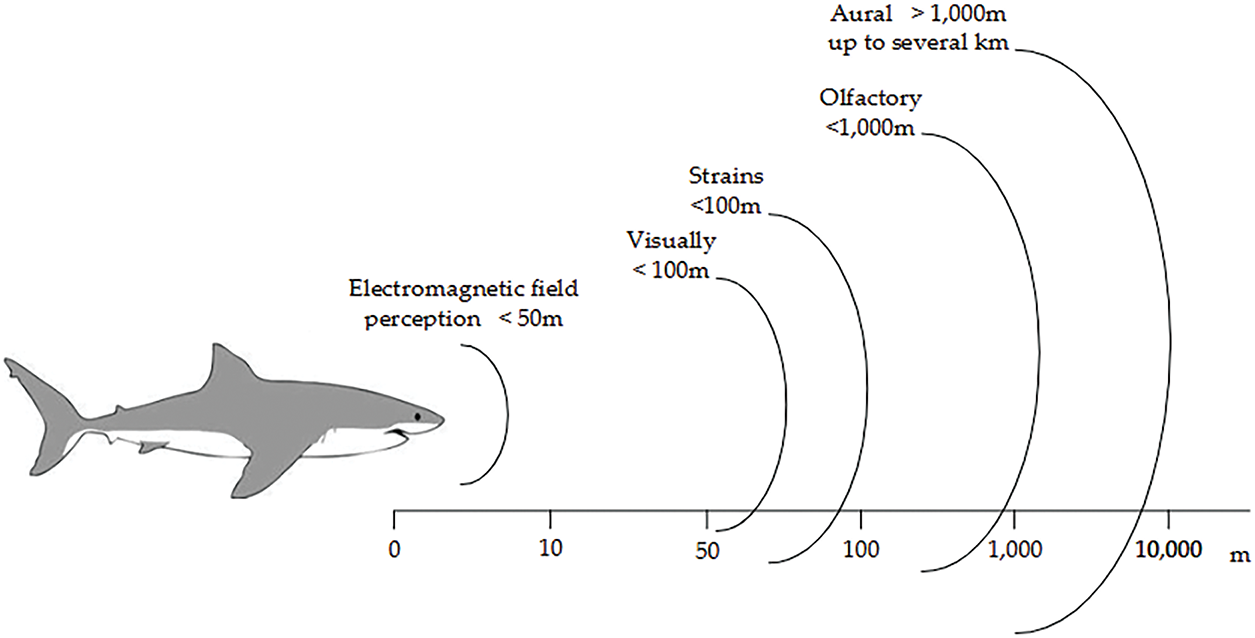

The White Shark Optimization (WSO) algorithm is a new metaheuristic optimization methodology that draws inspiration from great white shark hunting strategies (Fig. 1 [25]). These predators, with their remarkable sense of hearing and smell, serve as a model for this optimization approach. The WSO algorithm balances the exploration and exploitation phases by reproducing three key shark behaviors: moving towards a target, randomly exploring the sea depths, and locating nearby prey. If no prey is detected, shark positions are adjusted according to these behaviors and the best solutions found [26].

Figure 1: Hearing, seeing, and smelling the white shark [25]

The standard WSO algorithm comprises five main phases, explained as follows:

(a) Initialization phase

The WSO algorithm begins the optimization process by generating an initial set of random solutions. The population then evolves in a d-dimensional search space, with each position of a white shark representing a potential solution to the problem under study [26]. This evolution is described by Eq. (1).

(b) Rapid movement towards prey

Great white sharks track and follow their prey by using their exceptional senses of smell, sight, and hearing. Sharks use wave frequency to locate their prey, and they use oscillatory motions to approach their target [26]. Eq. (2) provides a mathematical description of velocity, which facilitates this movement.

The updated current white shark velocities ith at iterations k and k + 1 are represented by variables

(c) Direction phase towards the most promising prey

The great white shark devotes the majority of its time to actively searching for potential prey, irrespective of the prey’s nutritional value or condition. It typically approaches its victim by sensing vibrations from its motions or by smelling it. The prey occasionally moves to avoid the oncoming white shark or to feed. The shark can locate the prey again thanks to the scent it left behind at its previous position. In this way, the white shark searches its surroundings at random for prey, much like a school of fish [26]. Eq. (5), which describes position updating, shows how white sharks move.

The updated location vector of the ith white shark at iteration step (k + 1) is represented by

(d) Direction phase towards the best performing white shark

To stay close to their prey, great white sharks can maintain their position, as expressed in Eq. (11). This positioning strategy gives the algorithm increased realism by mimicking cooperation between sharks to optimize hunting [26].

with

(e) White shark collective behavior phase

To replicate the collective behavior of great white sharks mathematically, the two best solutions were chosen. These ideal places were then used to modify the other sharks’ positions. We came up with a precise formula to explain this phenomenon. Specifically, this formula takes into consideration the two leaders who were shown to have the best answers when determining how each shark in the group modifies its position. This approach allows the model to accurately imitate the aggregate behavior of its components by integrating their interactions and influences. This great white shark behavior is modeled using the following formula (Eq. (13)).

Eventually, great white sharks will make their home in the search area, right next to the prey that is in the ideal position. The way schools of fish behave collectively and how great white sharks migrate heading toward the top white shark found both have an impact on this positioning process. The WSO’s collaborative dynamics enable a broader field of activity, which improves exploration and exploitation skills. Using rand () for random initialization in WSO strongly influences its performance, calling into question the overall efficiency of the algorithm. In light of this, we suggest a major enhancement to this approach that makes use of chaotic systems.

In the following section, we will provide a detailed explanation of the proposed method. This explanation will highlight the mechanisms by which the integration of chaotic systems improves the efficiency of the WSO algorithm, as well as the expected advantages over the traditional approach [26–29].

2.4 The Proposed CWSO Optimization Algorithm

Within this part, we provide Chaos-White Shark (CWSO), an enhanced WSO method that integrates chaotic maps. There are several benefits to using chaotic maps in the WSO algorithm’s search process as opposed to a strictly random one. Specifically, by avoiding local minima, the ergodic characteristics of chaotic maps increase search efficiency.

Chaos theory has proved to be a promising avenue for advanced applications such as data encryption and algorithmic optimization, based on sensitivity to initial conditions and complex dynamic behaviors. More specifically, chaotic maps have proven their effectiveness when integrated into optimization algorithms, enabling them to avoid local bounds and improve the overall quality of solutions. Not only does this increase the resilience of algorithms, it also adds an unpredictable dimension that enriches the search and exploration process. We propose a hybrid method that uses the WSO optimization algorithm in conjunction with one-dimensional chaotic maps. Enhancing the algorithm’s ability to explore the ideal search space is the goal.

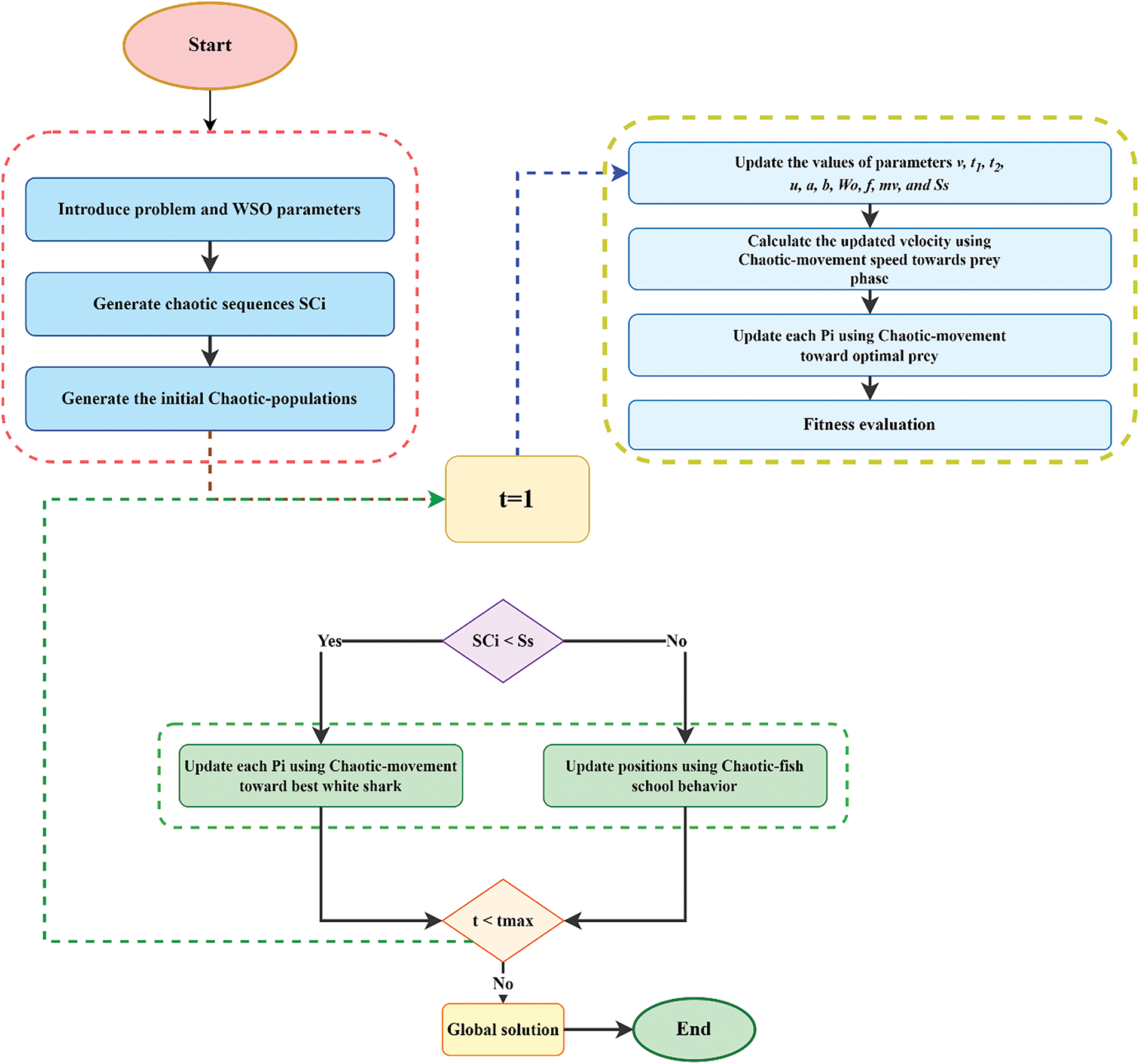

There are generally ten different types of chaotic map used to generate chaotic sequences, which play a role similar to the suggested CWSO algorithm’s random functions. In our approach, we chose to use the logistic map due to its ability to offer unique insights into dynamic complexity and its exceptional accuracy in generating chaotic sequences. By substituting chaotic sequences SCi for WSO’s random sequences in its four essential phases, CWSO enhances search dynamics. Fig. 2 shows an illustrative diagram of the proposed CWSO algorithm, highlighting these modifications and their impact on the overall efficiency of the algorithm.

Figure 2: Flowchart of CWSO algorithm

(a) Utilizing chaotic maps to create a starting population

In contrast to classical WSO, which uses uniformly distributed random numbers to initialize the population, our method uses chaotic maps to produce SCi sequences. The following formula states that these sequences enable a more dynamic initialization of white shark positions:

with

(b) Calculating the speed of movement in the direction of the prey using chaotic maps

Eq. (2) states that the displacement of the shark at iteration k + 1 is modified. Two parameters, c1 and c2, are used in the typical WSO algorithm. They are chosen at random from the interval [0, 1]. Instead of employing random values to determine the optimal positions at each iteration, our suggested approach generates these parameters using chaotic maps. This sophisticated method of using chaotic maps to give values to c1 and c2 presents important opportunities to maximize the search for the best answers. Therefore, the white shark’s position is modified using the following formula at iteration k + 1 and in subsequent iterations:

(c) Implement chaotic maps to modulate the position based on the ideal white shark

The Eq. (11) updates the position of shark i using random parameters r1, r2, and r3 generated in the interval [0, 1]. The proposed CWSO replaces these values with sequences from chaotic maps at each iteration, thus improving the efficiency of the algorithm to achieve a global optimal solution. The new position is calculated according to the following formula.

with

(d) Chaos-driven collective behavior of white sharks

Rand function is used in the particular formula defining white shark behavior to determine how each shark modifies its position with respect to the two leaders who possess the best answers. Rand-based random functions, however, have a variety of drawbacks, including periodicity, correlation between the generated numbers, and long-term predictability. We suggest using chaotic maps in place of rand functions to get around these issues. The modeling of white shark social behavior is enhanced and solution finding is optimized when chaotic maps are incorporated into WSO.

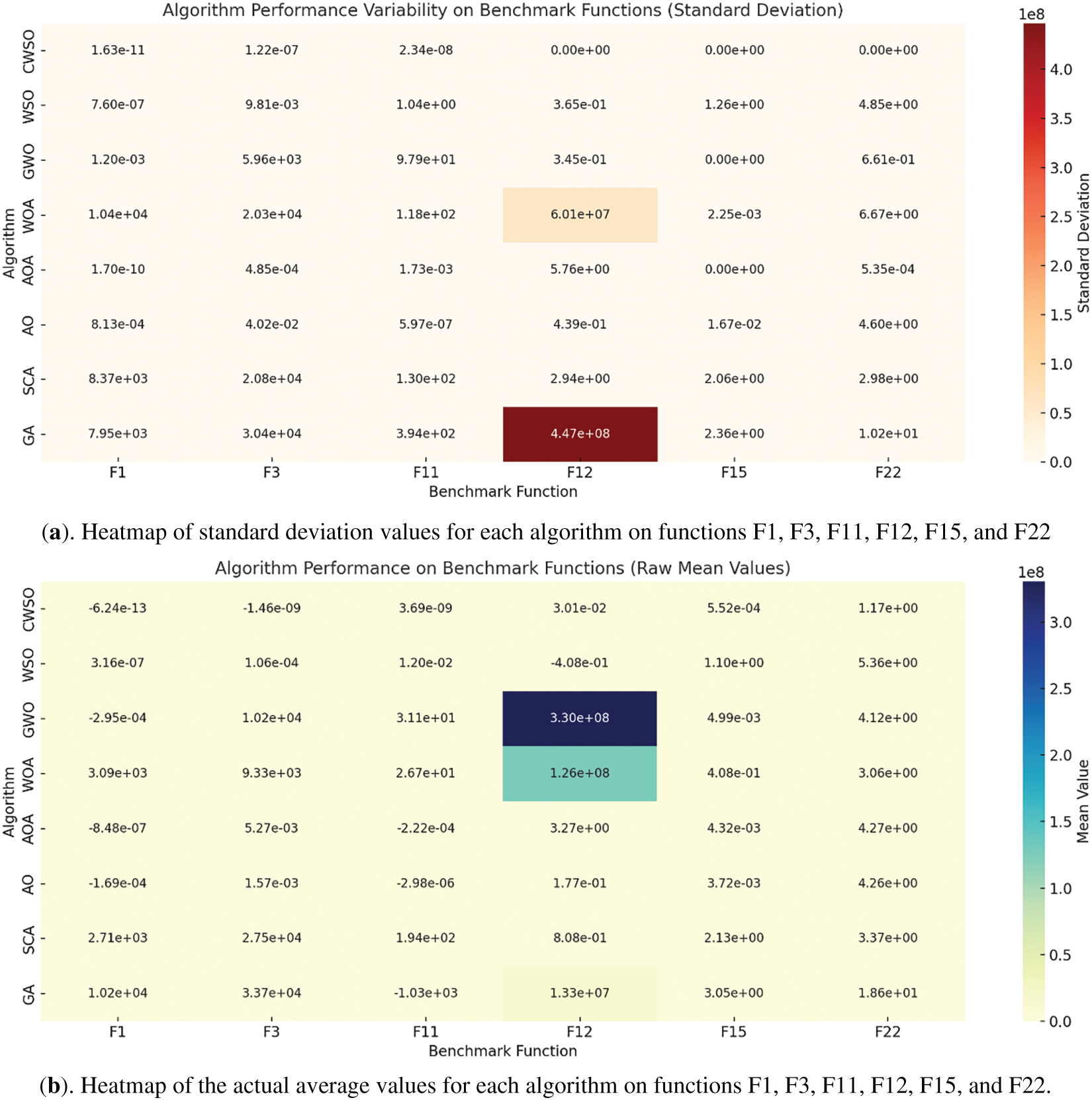

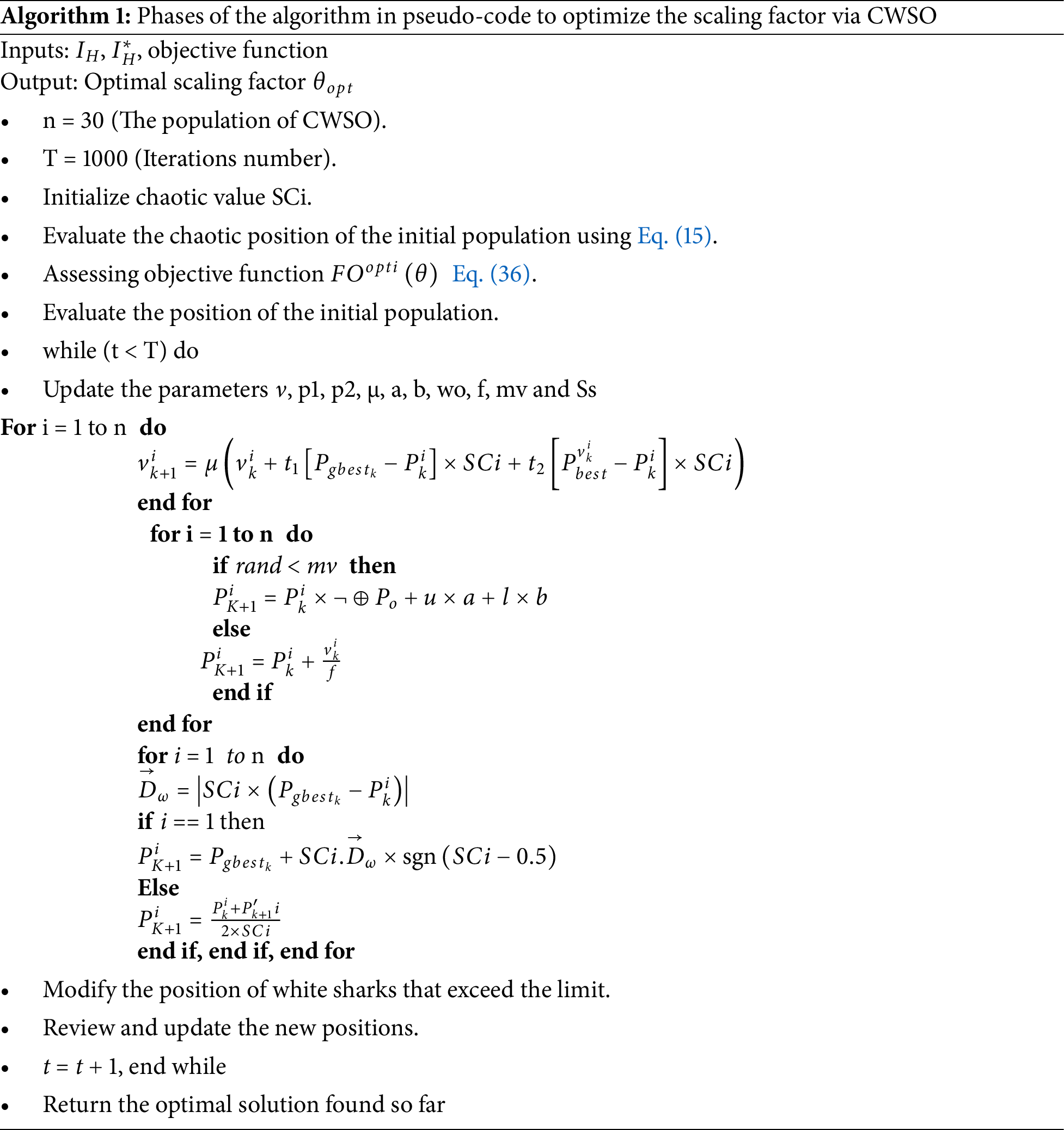

To assess the efficiency of the proposed CWSO, it has been applied to six reference functions (unimodal, multimodal and multimodal fixed dimensions), presented in Table 1. The performance was compared to those of the classic WSO and six well established algorithms: Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA), Genetic Algorithm (GA), Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), Sine Cosine Algorithm (SCA), Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) and Aquila Optimizer (AO) [30,31]. This comparison’s objective is to highlight CWSO-5’s benefits in terms of accuracy and robustness over the standard WSO algorithm and its competitors. To assess the quality of solutions, we used two performance indicators: mean and standard deviation (STD) [31]. In addition, we also carried out a convergence analysis, which is an essential criterion for measuring the effectiveness of algorithms in reaching the global optimum. To ensure fair evaluation under uniform conditions, we carried out 1000 evaluations on a population of 30 individuals. The comparative results, expressed in terms of mean (Fig. 3b) and standard deviation (Fig. 3a). The convergence curves of the test functions are shown in Fig. 3c.

Figure 3: Performance evaluation of optimization algorithms on benchmark functions: (a) heatmap of the standard deviation values showing performance stability, (b) heatmap of the actual mean values representing raw performance, (c) convergence curves illustrating the optimization progress of the compared algorithms

The simulation results show that, for all the functions studied, the CWSO algorithm surpasses the classic WSO as well as the other comparative algorithms, with a faster convergence rate and a more efficient global search capability. These results show the remarkable efficiency of the CWSO algorithm in avoiding local optima, thus favoring the identification of global optimal solutions. Given the remarkable efficiency and flexibility demonstrated by the CWSO algorithm, we had to integrate it into our watermarking scheme. Its capabilities enabled us to precisely optimize the OKOM parameter p and for an optimal selection of scaling factor α in order to achieve the best level of robustness without sacrificing transparency.

2.5 Optimized Krawtchouk Octonion Moments

In this sentence, we highlight the crucial element of our watermarking system, based on the integration of OKOM and the use of its unique features.

(a) General information on the octonion

Octonions are captivating mathematical objects that can be classified as hypercomplex numbers. They extend the concepts of complex numbers and quaternions [32]. The aim of octonions is to extend the concept of complex numbers even further. An octonion consists of a real part and seven distinct imaginary parts:

An octonion

The conjugate

Its modulus

An

Eqs. (26)–(28) highlight some key properties of octonion multiplication, illustrating their unique characteristics. Eq. (26) suggests that octonion multiplication appears to be “associative”. However, unlike other algebraic structures, this property is only apparent, as octonions are not really associative; they are alternative, meaning that any subalgebra formed by two elements remains associative. As for Eq. (27), it shows that the multiplication of octonions is not commutative. In other words, the order of octonions in a multiplication influences the final result. This is a fundamental distinction from other number systems where the order of the factors does not affect the product. Finally, Eq. (28) reveals an interesting property concerning octonion conjugates: the multiplication of two octonion conjugates is commutative. As a reminder, the conjugate of an octonion is obtained by reversing the sign of its imaginary parts, while keeping the real part unchanged. This property is notable for reintroducing a form of symmetry into the structure of octonions, despite their general non-commutative nature.

(b) Optimized Krawtchouk Octonion moments

The process of defining the OKOM in a Cartesian system can be summarized by the following steps:

Step 1: In this first step, building on the octonion definition we presented earlier, we employ a method that allows us to represent the two watermarks in a way that is both integrated and concise. To achieve this, we use the imaginary components of the octonions in a Cartesian coordinate system to encode the six information channels of the two watermarks.

Step 2: In this step, we focus on a key aspect: the computation of Krawchuk moments

Step 3: Since octonion multiplication does not follow the law of commutativity, we need to use specific formulations to define octonion moments (OKMs). In this context,

In this work, we have opted for pure unit octonions, denoted by

Step 4: The stereo image of the F octonion, established in the cartesian frame, can be reconstructed using either the right octonion moment or the left octonion moment.

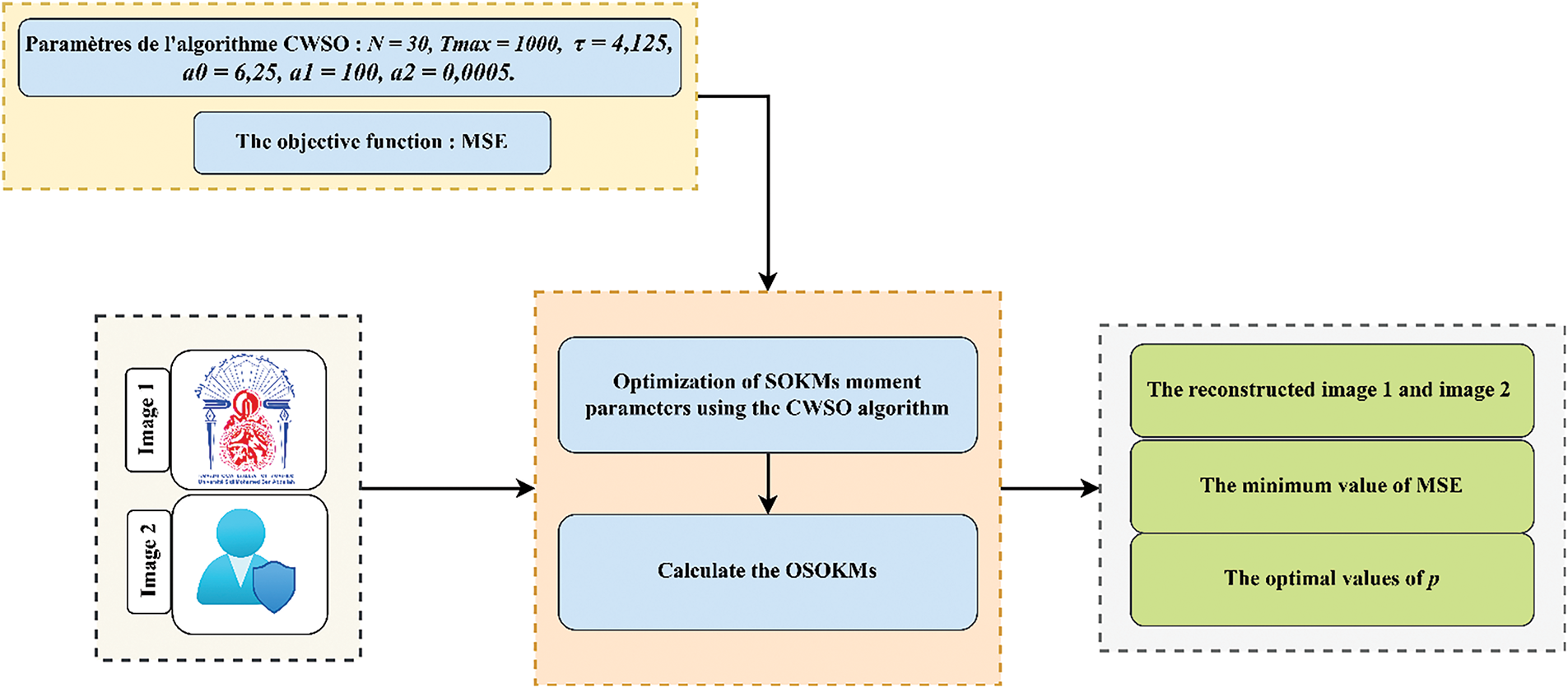

Due to their distinctive properties, OKOM have become valuable tools for image reconstruction tasks, especially in applications where accuracy and quality are crucial. Due to their unique characteristics, OKOMs have become indispensable tools for image reconstruction operations, particularly in areas where precision and quality are essential. However, OKOM results are strongly influenced by a particular control parameter, called p, which has an impact on the sensitivity and adaptability of the reconstruction model. It is therefore crucial to select this parameter optimally in order to maximize reconstruction quality and minimize errors. In order to meet this demand, we suggest employing the CWSO algorithm, which has proven its ability to solve optimization problems in various domains. By enhancing this function with CWSO-5, we have the opportunity to improve OKOM’s behavior, ensuring more accurate and faithful image reconstructions. Fig. 4 shows the image reconstruction steps using OKOM and CWSO. The CWSO-5 algorithm optimizes OKOM parameters for 1024 × 1024 2D images, demonstrating its efficiency in color image reconstruction.

Figure 4: Flowchart of the proposed reconstruction method using OKOM and CWSO

We compared the performance of our algorithm with that of other existing methods in the literature. The results show that the CWSO algorithm is effective in determining the optimal value of parameter (p). As a result (Table 3), image reconstruction is achieved with a significantly low Mean Squared Error (MSE) and high PSNR. These results clearly demonstrate the superiority of our approach, which combines OKOM with the CWSO algorithm, for the reconstruction of high-dimensional color images. The use of these moments in the proposed watermarking algorithm produces remarkable results.

3 Proposed Digital Watermarking Scheme

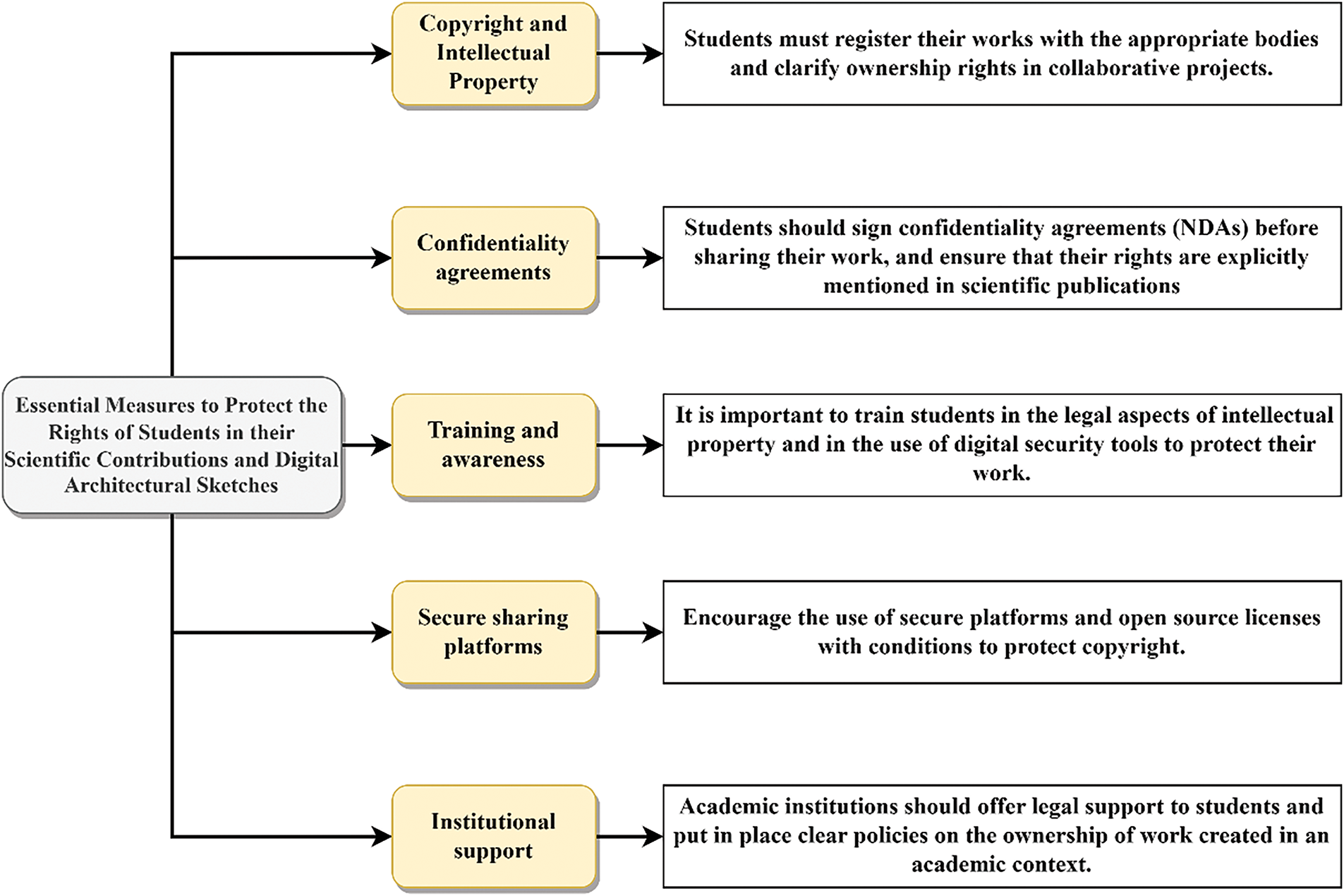

In the field of digital creation, particularly for architectural sketches, copyright protection is crucial. Students, often at the forefront of academic innovation, need to ensure that their work is properly protected against unauthorized copying, and that their contribution is fully recognized [33]. The essential measures for protecting students’ rights in their scientific contributions and digital architectural sketches are summarized in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Essential measures to protect students’ rights in their scientific contributions and digital architectural sketches

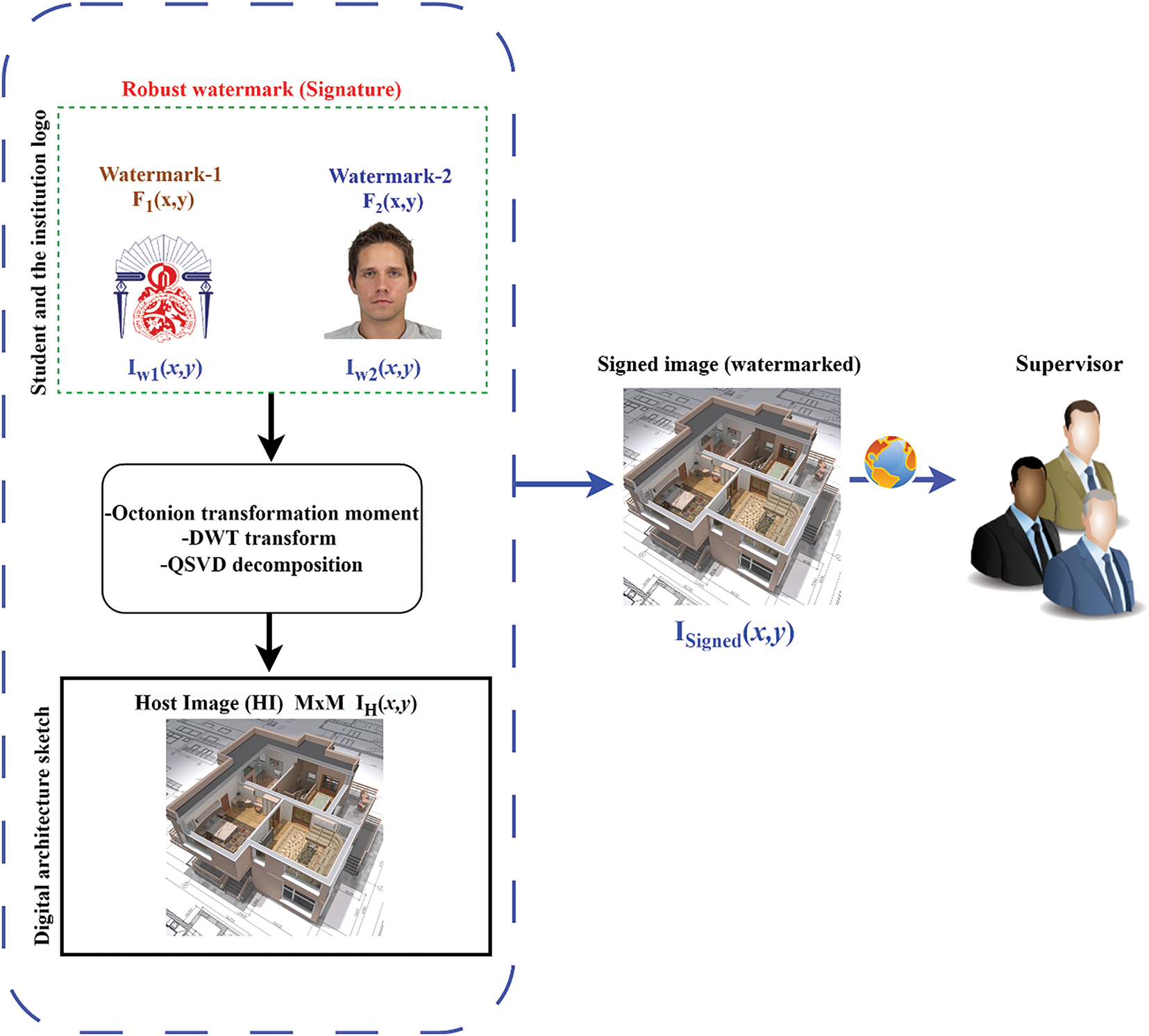

In order to counter this problem, we have proposed an effective method for achieving this objective: the integration of double digital watermarks (watermarking) in sketches. As illustrated in Fig. 6, this process enables essential information, such as institutional logos and the student’s image, to be integrated directly into the Host image (digital architectural sketch). This technique uses advanced tools, such as Krawtchouk’s Octonion moments, Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) and Quaternionic Singular Value Decomposition (QSVD), to create a robust digital watermarking. This watermarking not only deters unauthorized copying, but also enables the origin of the work to be traced in the event of a dispute, thus ensuring the ongoing protection of students’ rights. The proposed watermarking process applied to architectural sketches is:

Figure 6: Flowchart of the proposed scheme for image watermarking

Input: Two watermarks are used: the first (Watermark-1) represents a logo or symbol (perhaps that of an institution or organization), and the second (Watermark-2) is a photo of a student. These watermarks are represented by

Transformation: The

• Optimized Krawtchouk Octonion moments

• The DWT

• The QSVD

Result: The result of this transformation is a signed image

The originality of our approach lies in the integration for the first time of OKOM with QSVD and a CWSO, with the aim of achieving invisible and secure double watermarking. Unlike traditional methods that insert a single watermark or rely on simple transformations, our approach integrates two distinct watermarks (logo and personal image) into a single compact OKOM representation, thus reducing redundancy while maintaining visual quality. In addition, the use of chaotic dynamics during the optimization phase improves robustness by adaptively choosing embedding parameters according to image content.

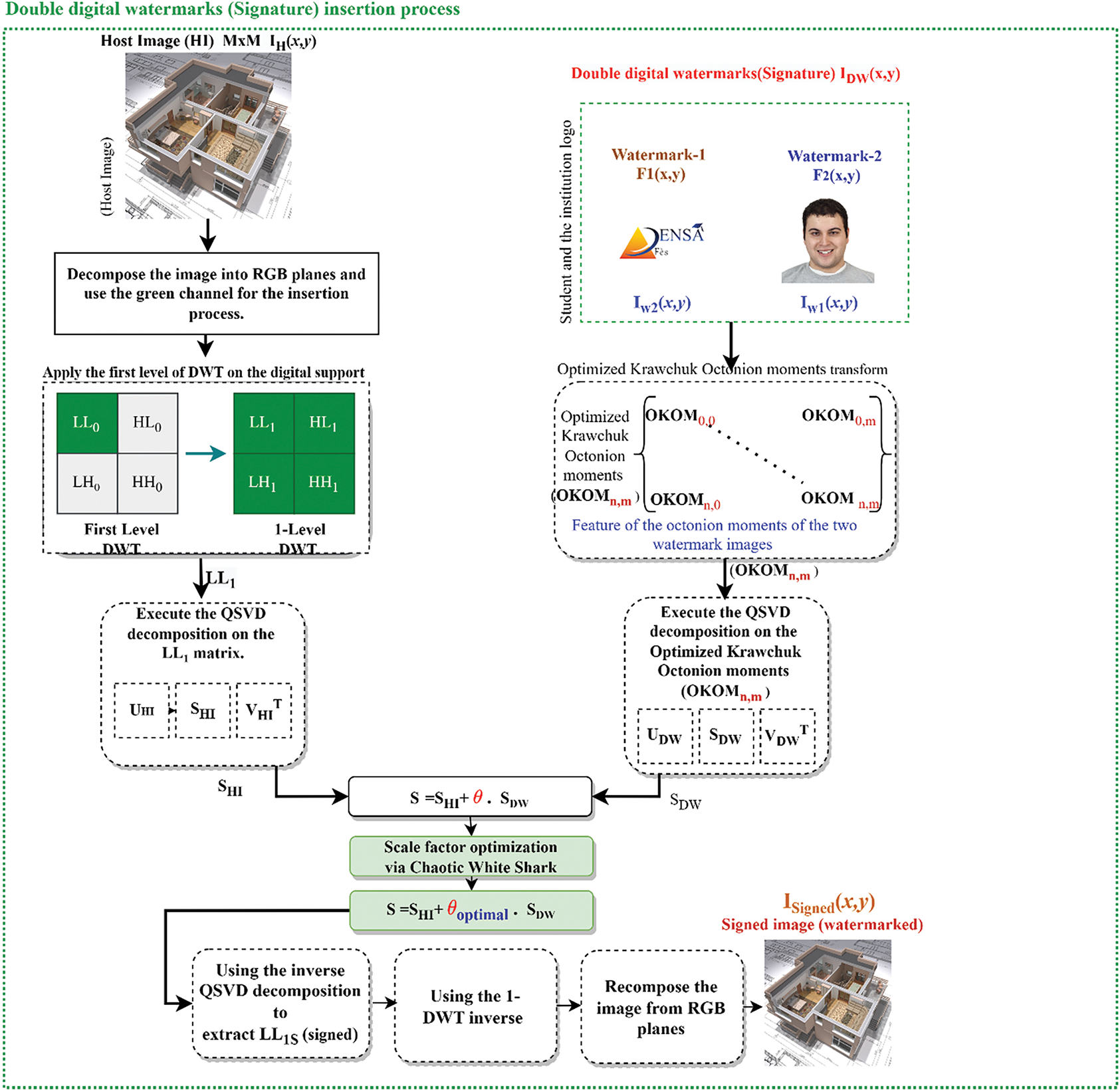

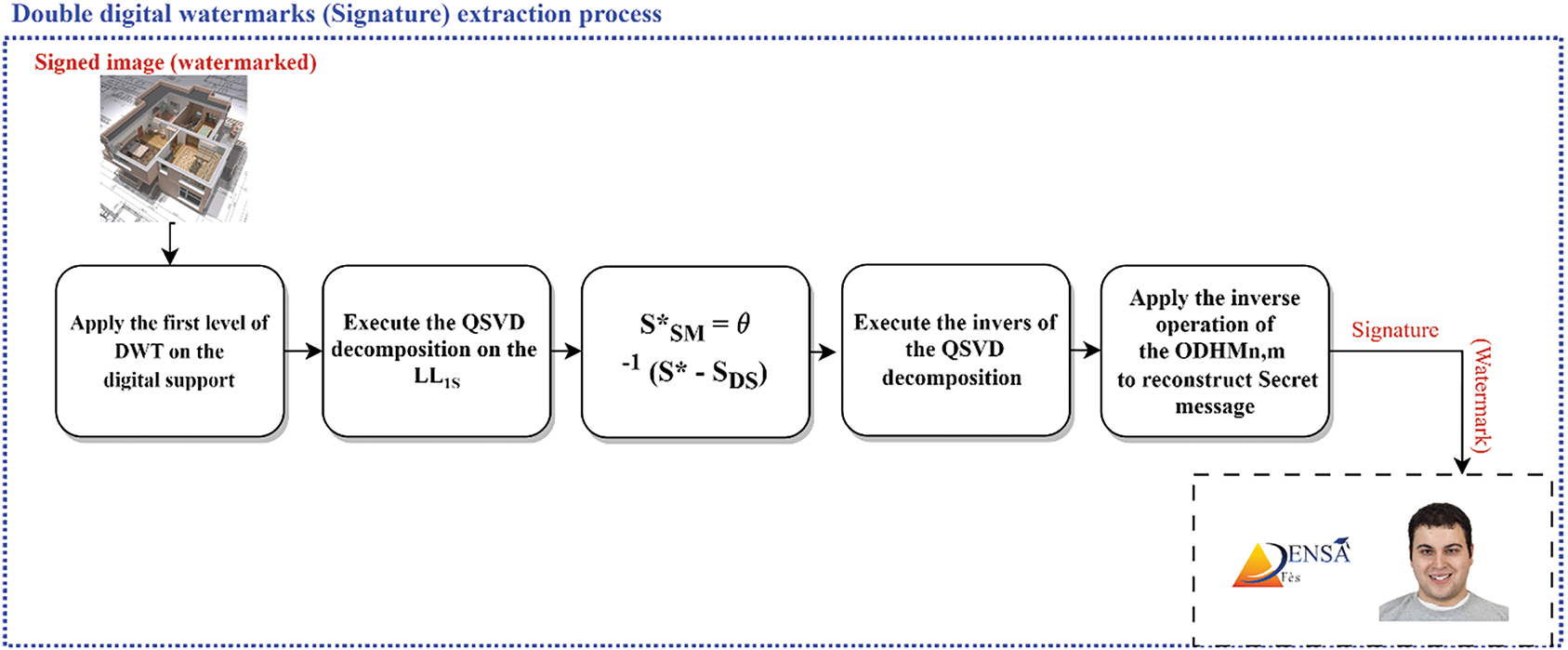

Proposed Double Digital Watermark Insertion Process (Signature)

In this process, two digitals

Figure 7: Digital double watermarking signature insertion and extraction process based on optimized octonion Krawchuk moments and QSVD decomposition

Process 1: For the Host Image (HI)

The host image, noted

• Application of the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT):

The initial step of DWT is performed on the green (G) color channel of the image. DWT divides the image into four sub-bands:

∘

∘

∘

∘

These sub-bands capture different image details. Here, the

• Applying DWT to the next level:

The sub-band

• QSVD decomposition on the sub-band

The QSVD is then applied to the sub-band

with:

∘

∘

∘

This step prepares the sub-band for the insertion of digital watermarks. The singular values in

Process 2: For double digital watermarking (Signature)

This section of the algorithm concerns the insertion of two digital watermarks into a host image. The two watermarks are as follows:

– Watermark-1

– Watermark-2

• Krawchuk’s Optimized Octonion Moment Transformation (OKOM)

The next step is to apply Krawtchouk’s octonion moment transformation to watermarks in order to extract unique and robust features. This step is crucial, as it represents the major contribution of this paper by being the first use of octonion moments in watermarking applications. Importantly, this phase facilitated the integration of all data from the two watermarks into a single matrix, which is essential for watermarking applications. In fact, this reduces the volume of data inserted in the main image, which is a major asset in ensuring the visual quality of the image following the addition of the two watermarks.

To do this, we use the imaginary parts of the octonion representation in the Cartesian coordinate system to encode the six channels of the two watermarks

The

• QSVD decomposition on OKOMs

Once the optimized Krawtchouk moments have been calculated, the next step is the quaternionic singular value decomposition (QSVD) applied to the optimized octonion moments. The OKOM moments are decomposed into

Double digital watermark integration process

• Calculation of the Diagonal Matrix S of the signed image via optimal scaling factor

The diagonal matrix S of the signed image is obtained by:

Next, a chaos-based scaling factor optimization is performed to adjust θ to an optimal value:

In this study, a chaotic variant of the White Shark Optimizer (CWSO) is used to define the optimal scaling factor θ. The inclusion of chaos enhances the optimizer’s exploratory capability and prevents hasty convergence, guaranteeing a better balance between imperceptibility and robustness. The

It’s essential to note that the scale factor θ is influenced by both the host image

• Extraction LL1S (Stego)

Use inverse QSVD decomposition to extract the LL1S (signed) sub-band. This step is crucial for separating the embedded part of the watermark from the signed image.

• Inverse of 1-DWT Transformation

Application of the inverse Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) on the image to reconstruct the original components. This step is necessary to recompose the image in the spatial domain after modifying the coefficients via watermarking.

• Recomposition of images from RGB planes

Finally, the image is recomposed from the RGB planes. The result is an

From a security perspective, each component of the proposed scheme plays a complementary and essential role in the overall robustness of the system. The Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) allows targeted frequency localization, facilitating the insertion of watermarks in perceptually less sensitive sub-bands, which improves stealth while protecting critical areas. The Quaternionic Singular Value Decomposition (QSVD) offers intrinsic stability against tampering, by exploiting the properties of quaternionic matrices, which are particularly resistant to attacks such as compression or noise. As for the Optimized Octonionic Moments (OKOM), they efficiently group the information from the two watermarks into a compact and low-redundant structure, minimizing the visual impact while increasing resilience to geometric manipulations. Finally, the CWSO optimization algorithm dynamically adjusts the insertion parameters (notably the scaling factor), which allows achieving an optimal compromise between invisibility and robustness. The strategic combination of these advanced techniques thus gives the system multi-level security, capable of resisting classic attacks while guaranteeing the traceability and integrity of protected works.

4 Analysis and Experimental Results

4.1 Analysis of OKOM Magnitudes in Attacked Stereo Images

First, we examine OKOM magnitudes in attacked stereo images before confirming our proposed double digital watermarking approach. We employed a collection of nine 256 × 256 pixel color stereo images to carry out these experiments, selected from the Middlebury 2005 stereo datasets (Fig. 8). The aim of this section is to experimentally confirm our OKOM.

Figure 8: Stereo image from the Middlebury 2005 dataset

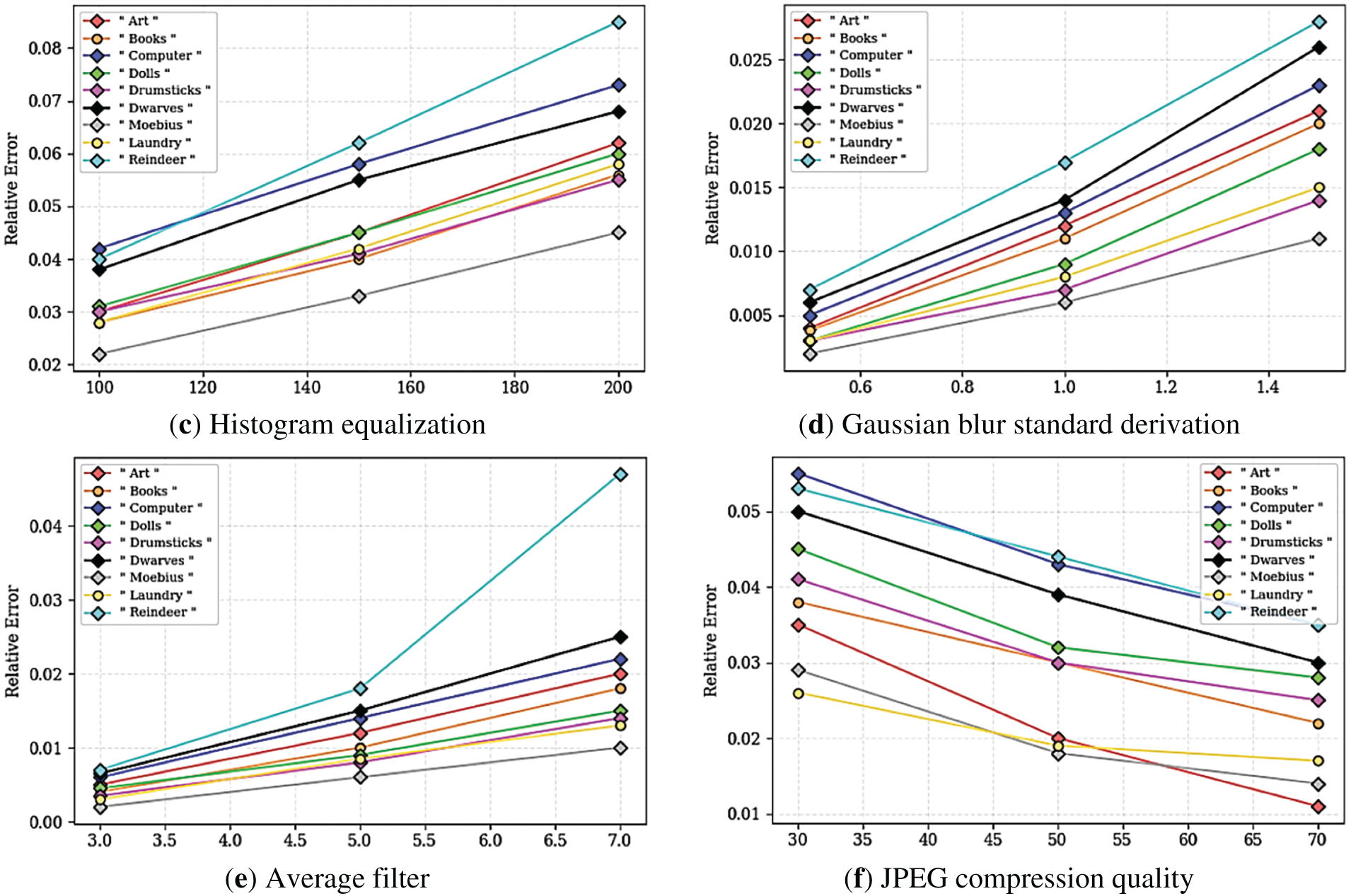

Before confirming the robustness of our dual digital watermarking technique, it is crucial to examine the sensitivity of OKOM magnitudes to various conventional image processing attacks. The analysis is presented in Fig. 9, based on a set of nine color stereo images extracted from the Middlebury 2005 database, each with a dimension of 256 × 256 pixels. This graph is made up of six sub-graphs (a–f), each illustrating the evolution of the relative error of OKOM magnitudes as a function of an attack parameter: (a) Rotation angle: The relative error remains low overall for all image types, indicating good rotation invariance. (b) Pepper noise density: The error increases as noise density increases, highlighting a marked sensitivity to impulsive noise. There is therefore no need for a reinforcement system to improve robustness to this kind of disturbance, as the error remains acceptable. (c) Histogram equalization: A progressive increase in error is observed, indicating that OKOM magnitudes are moderately sensitive to contrast transformations. (d) Gaussian blur (σ): Relative error increases with the standard deviation of Gaussian blur, highlighting increased sensitivity to blur induced by loss of fine detail. (e) Average filter: A similar trend to Gaussian blur is observed, with a linear increase in error depending on the size of the filter kernel. (f) JPEG compression quality: Conversely, error decreases as JPEG quality increases. This indicates sensitivity to the compression ratio, but acceptable resilience at moderate compression levels.

Figure 9: OKOM magnitude analysis under various types of image attacks. (a) Rotation angle; (b) pepper noise density; (c) histogram equalization; (d) Gaussian blur standard deviation; (e) average filter; (f) JPEG compression quality

Overall, these observations demonstrate that OKOM magnitudes are fairly resistant to basic geometric transformations such as rotation. However, they remain vulnerable to noise, blurring and compression attacks. This evaluation is a crucial step before incorporating these elements into our solid, reversible watermarking strategy.

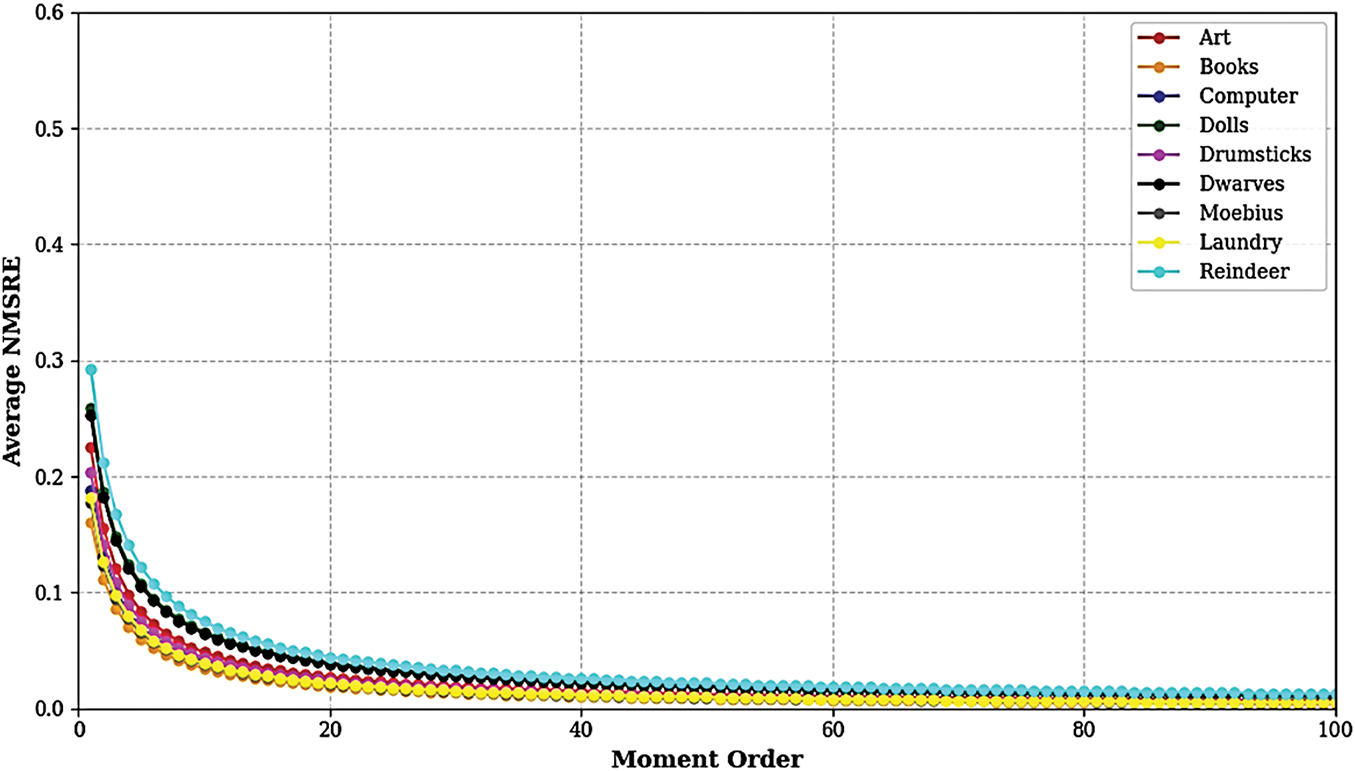

The Fig. 10 shows the change in the normalized mean reconstruction error (NMSRE) of stereo images according to the degree of quaternionic orthogonal moments (OKOMs), for each of the nine stereo images from the Middlebury 2005 dataset which is publicly available at: https://vision.middlebury.edu/stereo/data/scenes2005 (accessed on 01 January 2025). We observe that: (i) Reconstruction error reduces rapidly with increasing moment order, highlighting the superior ability of OKOMs to capture image information as moment order increases. (ii) Above a moment order of 30, error stabilizes around very low values (close to zero), demonstrating that higher moment orders bring little additional improvement. This confirms the rapid convergence of OKOMs. (iii) The differences between the various images (Art, Books, Computer, etc.) are negligible, demonstrating that the suggested reconstruction technique is stable and constant regardless of image content. In short, this illustration confirms the accuracy and efficiency of OKOMs moments in faithfully reconstructing stereo images, a crucial aspect in ensuring reversible, non-invasive tattooing. Computational efficiency is also demonstrated by the low error rate after a certain order, as a minimal number of moments is all that’s needed to achieve a high-quality reconstruction.

Figure 10: Reconstruction error of the nine stereo images using the proposed OKOMs

These experimental results confirm the expected theoretical properties of optimized octonionic moments (OKOMs). Indeed, their mathematical construction confers an invariance capacity to simple geometric transformations such as rotation, which explains the low relative error in this case. However, the moderate sensitivity observed to filters or noise is consistent with the fact that OKOMs are based on projections sensitive to texture and frequency variations. These observations validate that the choice of OKOMs as a signature support is judicious for architectural contents where geometry takes precedence over fine textures. Moreover, the rapid convergence of reconstruction errors from high orders of moments (see Fig. 10) demonstrates the compactness of the encoded information, reducing the need for massive insertion into the host image, which contributes to the discretion of the watermark.

4.2 Experimental Validation of the Proposed Double Digital Watermarking Method

❖ Datasets

In order to avoid any copyright infringement concerning images of building architecture, we opted for image generation using artificial intelligence. The two visuals created, entitled “Architecture-1” and “Architecture-2”, represent original concepts inspired by traditional Moroccan architecture, fused with a modern style. For the 256 × 256 faculty logos, we used those found on the university’s official website, guaranteeing their authenticity and respect for usage rights (Fig. 11). As for student photographs, they come from the Chicago Face Database Version 1.0—September 2014 (https://www.chicagofaces.org), ensuring the use of reliable and legal sources, in compliance with confidentiality rules and image rights. This approach guarantees that all visual resources employed comply with current intellectual property regulations.

Figure 11: Images de test. (a) Architecture-1 de taille 1000 × 1000, (b) Architecture-2 de taille 1000 × 1000, (c) Watermark1 + Watermark2, et (d) Filigrane3 + filigrane4.

❖ Visual testing with the naked eye

The watermark embedded in the main image must be invisible to the unaided eye to ensure data protection. Invisibility is a key requirement when creating a robust watermarking system. Typically, a watermarked image is considered acceptable if it has a PSNR greater than 40 dB. In addition, if the structural similarity index (SSIM) exceeds 0.94, this means that the watermarked image differs only slightly from the source image, thus ensuring visual quality almost identical to that of the original image [35]. These settings ensure image preservation and watermark protection without compromising visual appearance [36–40].

In this work, the test images shown in Fig. 11a,b are used as host images to embed the color double watermark (signature) shown in Fig. 11c,d, respectively. Fig. 12 shows the results after embedding the double watermark (signature) in the host images. It is clear that the watermarked images show no perceptible differences from the original images, demonstrating excellent visual imperceptibility. PSNR and SSIM values are also listed in this figure. The PSNR values obtained exceed 47 dB, well above the acceptable threshold of 37 dB, while the SSIM values are above 0.988, very close to the ideal value of 1. These results show that the watermarked images undergo minimal distortion and retain a high degree of similarity with the host images. As a result, this scheme is particularly well suited to two-color images, offering excellent performance in terms of imperceptibility and visual quality

Figure 12: Imperceptibility analysis

❖ Invisibility and robustness analysis under static attacks

Once imperceptibility is deemed satisfactory, robustness becomes a fundamental criterion for a digital watermarking scheme, highlighting its ability to effectively resist various attacks. In this analysis, system robustness is assessed from two angles: fixed-parameter and dynamic attacks [41]. In general terms, robustness refers to a system’s ability to maintain its performance and cope with changes without requiring adjustments to its initial configuration. It also includes the ability to extract the double watermark (signature) from host images, even after they have been subjected to various forms of attack, thus guaranteeing the integrity and durability of watermarked data in a potentially hostile environment [42].

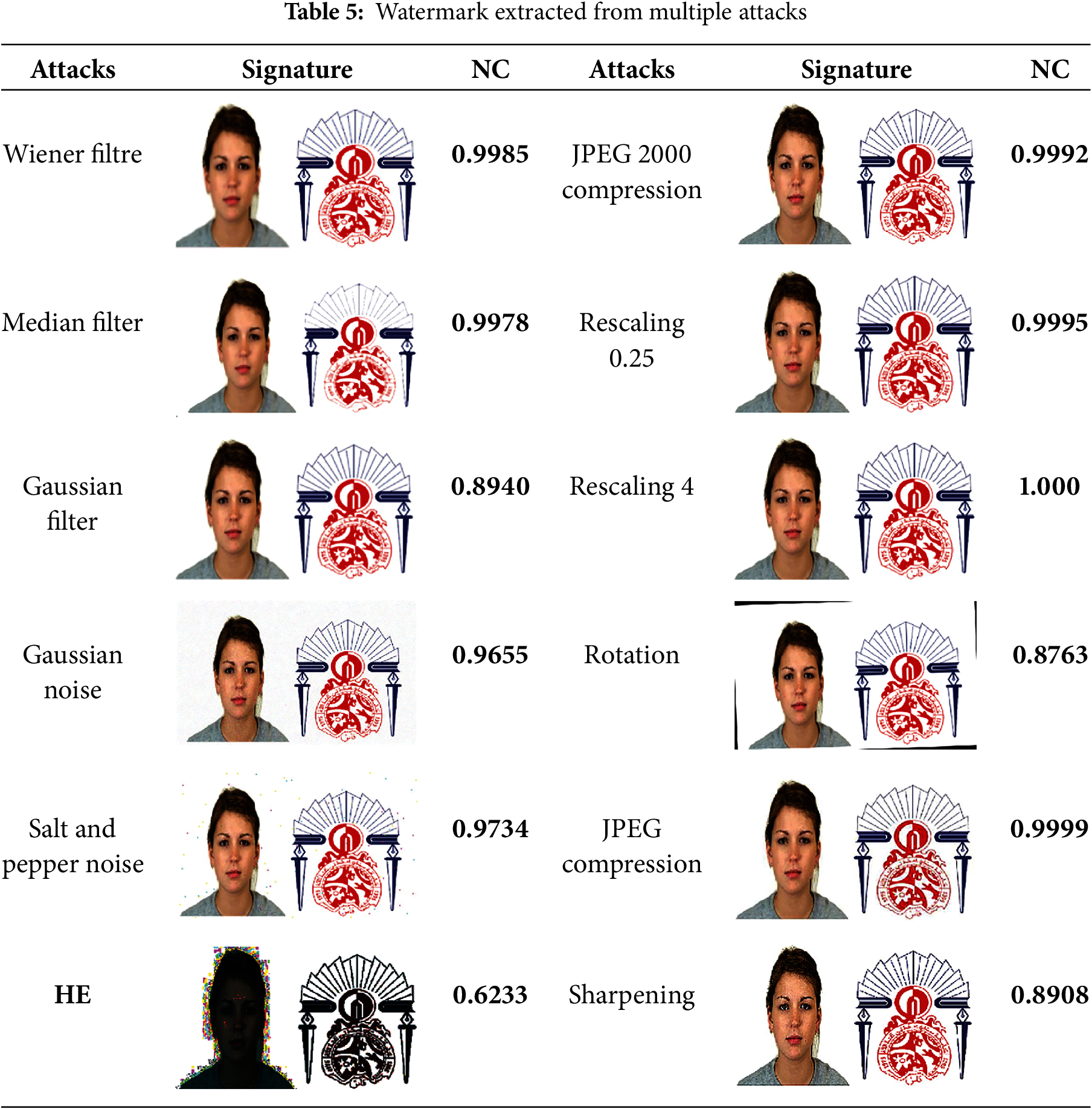

As a detailed example, the “Architecture-1” carrier image was selected for integration of the double watermark (signature). The results after a series of attacks applied to the watermarked image are shown in Table 4. Following these attacks, the watermarks were extracted, and their normalized correlation coefficients (NC) are listed in Table 5. This table shows that the extracted double watermark (signature) remains recognizable, even after several types of attack. As a general rule, a NC is considered acceptable when it reaches a value of 0.9 or more. In our case, all the NCs in Table 5 are above 0.9, underlining the high robustness of the proposed system. It is particularly noteworthy that, without any attack, the NC of the extracted signature is 0.9793, indicating near-perfect quality. This slight decrease is due to the compressive detection applied to the signature before integration, resulting in minimal data loss. Despite this compression, overall performance remains excellent. The proposed scheme demonstrates solid robustness, not only for different types of signature, but also across different carrier images. Overall, the system shows remarkable resilience to a wide range of attacks, confirming its ability to preserve signature integrity while effectively resisting a wide range of external disturbances.

❖ Analysis of invisibility and robustness under dynamic attacks

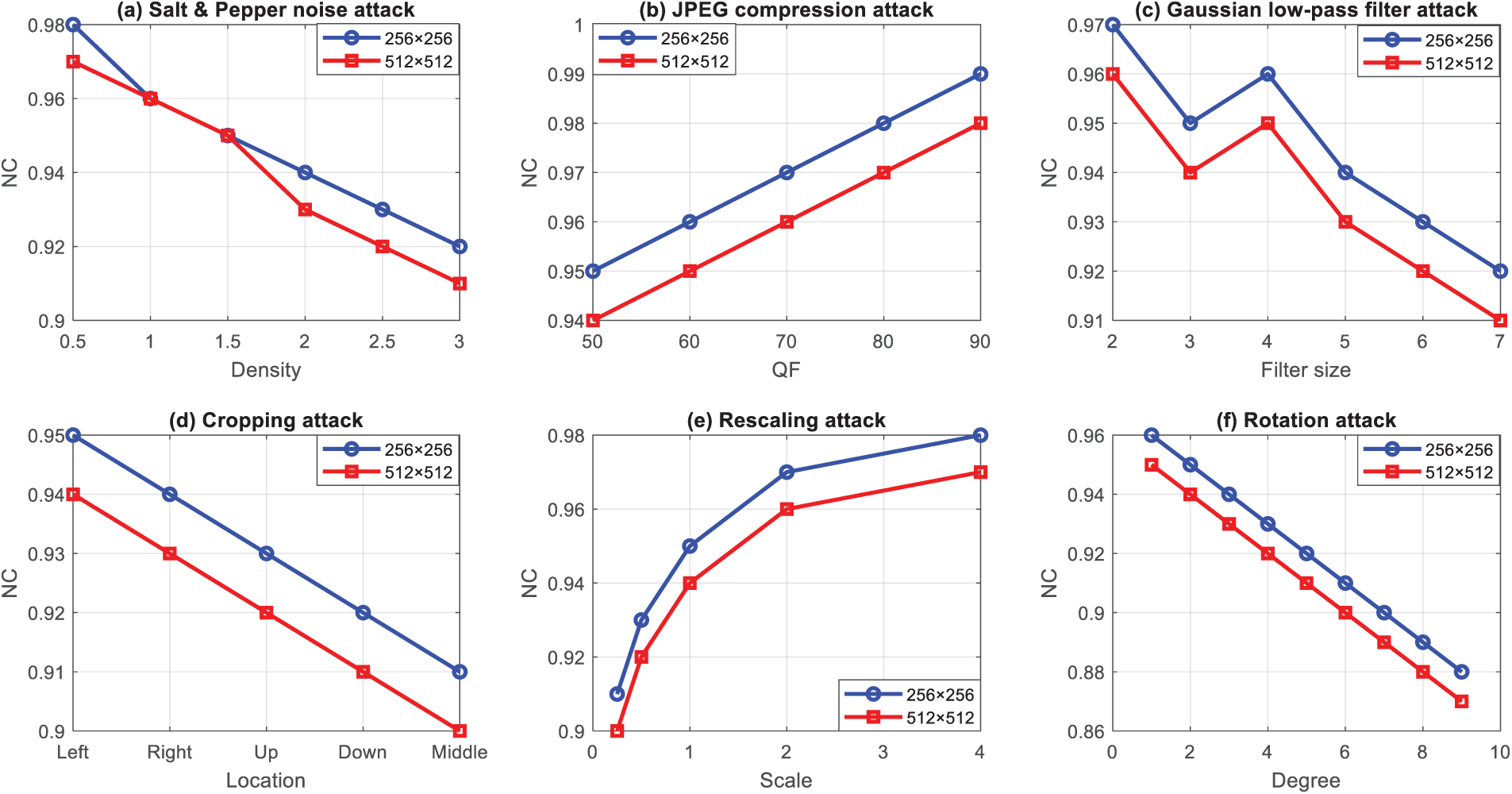

The parameters used in the test attacks mentioned above are static. However, to better represent the impact of parameter choices when applying attacks, it is essential to also consider scenarios with dynamic parameters [33]. This work is undoubtedly part of an advanced approach where robustness performance is rigorously evaluated under various dynamic parameters. The results obtained are summarized in Fig. 10: when transmitting images across a network, interference caused by noise is inevitable, compromising image quality. As a result, the watermarking scheme developed in this study must demonstrate a certain noise resistance. To assess this capability, salt-and-pepper noise is added to the watermarked images, and the test results are shown in Fig. 13a. The density of this noise varies between 0.5% and 3%, with increments of 0.5%. It is observed that, although the increase in noise density leads to a slight reduction in the normalized correlation coefficient (NC), this reduction remains moderate, the lowest NC being around 0.92. In addition to noise interference, image compression plays a crucial role in fast Internet transmission. JPEG compression, a widely used standard, can affect the integrity of the watermark. It is therefore essential that the proposed scheme is resistant to compression attacks. The results obtained for different compression qualities (QF) are shown in Fig. 13b. Interestingly, as QF increases, NC follows an increasing trend. Even when the QF reaches a value as low as 50, the NC remains above 0.94, confirming the watermark’s robustness to compression. The watermark’s robustness was also put to the test against filtering attacks, in particular the Gaussian low-pass filter attack. Tests were carried out using different window sizes, from 2 × 2 to 7 × 7, and the results are shown in Fig. 13c. It is clearly demonstrated that the NCs associated with odd window sizes are higher than those for even windows. Furthermore, progressive increases in window size do not lead to significant variations in NCs, which all remain above 0.91, underlining stable resistance to these types of attack.

Figure 13: NC variation according to different parameters under various attacks. (a) Pepper noise density; (b) JPEG compression quality factor (QF); (c) Gaussian low filter attack; (d) cropping attack; (e) scaling factor; (f) rotation attack

Another decisive criterion for assessing the robustness of a watermarking algorithm is its ability to withstand geometric attacks. Thus, cropping, resizing and rotation attacks were applied to the watermarked images, and their respective effects are illustrated in Fig. 13d–f. Regarding cropping, irrespective of the positions chosen, all the NCs observed are greater than 0.90, as shown in Fig. 10d. As far as resizing attacks are concerned, the testing scales are set at 0.25, 0.5, 2 and 4. It’s important to note that, although the NC under the 0.25 scale is slightly lower (around 0.94), it remains above the acceptable threshold value of 0.75, as illustrated in Fig. 13e. Finally, rotational attacks, carried out with angles ranging from 1 to 9 degrees, reveal a slight drop in NC as the angle increases, but even for a rotation of 9 degrees, NC does not fall below 0.9, as shown in Fig. 13f.

These results confirm the robustness of the proposed scheme. Not only does it effectively resist noise and compression attacks, but it also demonstrates stability in the face of geometric attacks and various types of signal processing. This method therefore proves particularly effective in maintaining the integrity of the signature, even under conditions of varied and intense attacks.

These results confirm the robustness of the proposed scheme. Not only does it effectively resist noise and compression attacks, but it also demonstrates stability in the face of geometric attacks and various types of signal processing. This method therefore proves particularly effective in maintaining the integrity of the signature, even under conditions of varied and intense attacks.

❖ Comparison with similar work

In this section, we conducted an in-depth comparative evaluation using standard evaluation measures to verify the results obtained with our method. We chose these indicators because they provide a comprehensive assessment of signal quality and the resistance of the watermarking system to distortion and manipulation. NC evaluates the correlation between the extracted watermark and the original, while SSIM and PSNR respectively assess the visual quality and fidelity of images after different transformations. Table 6 presents the attack parameters used for the evaluation of PSNR, SSIM, and NC metrics.

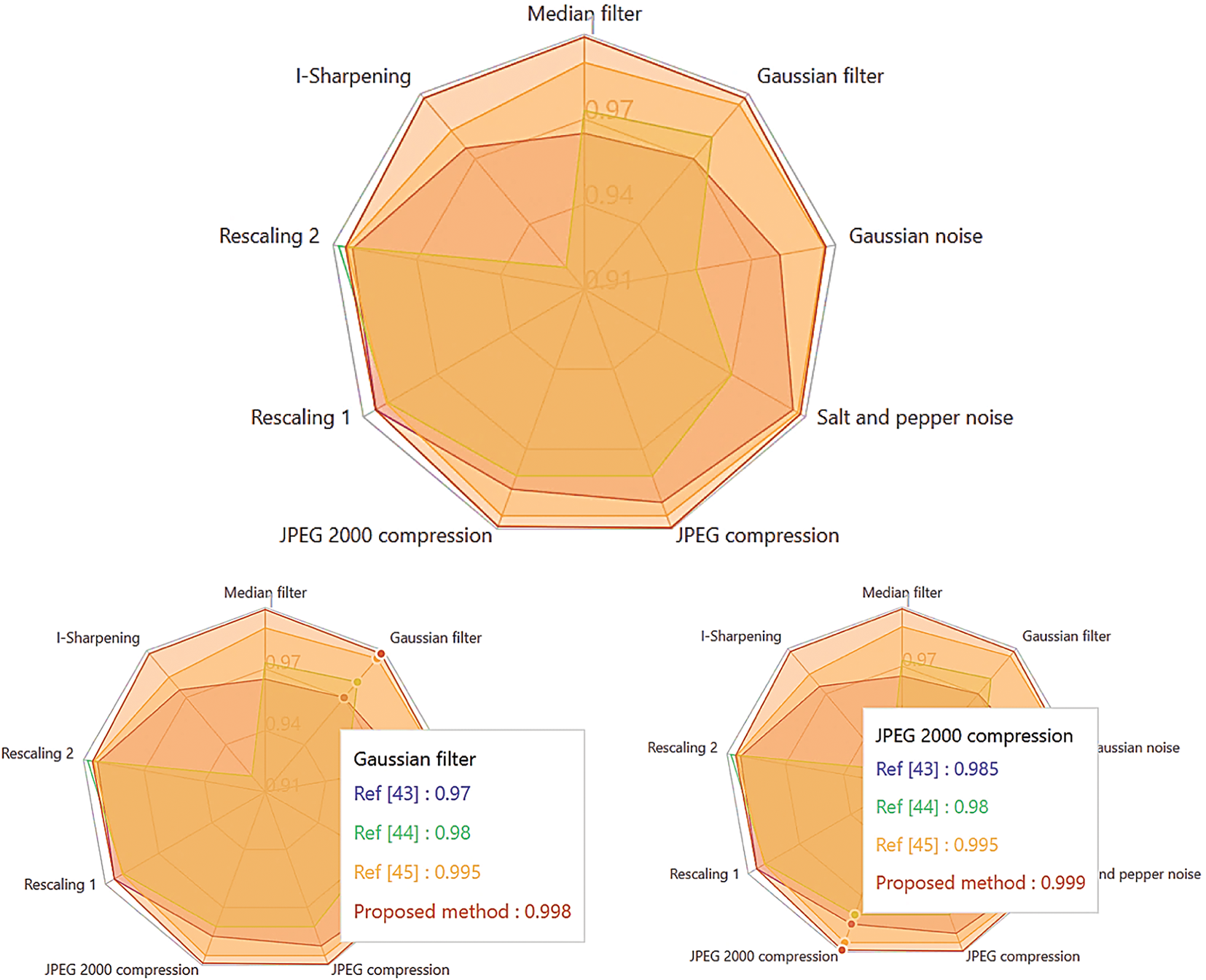

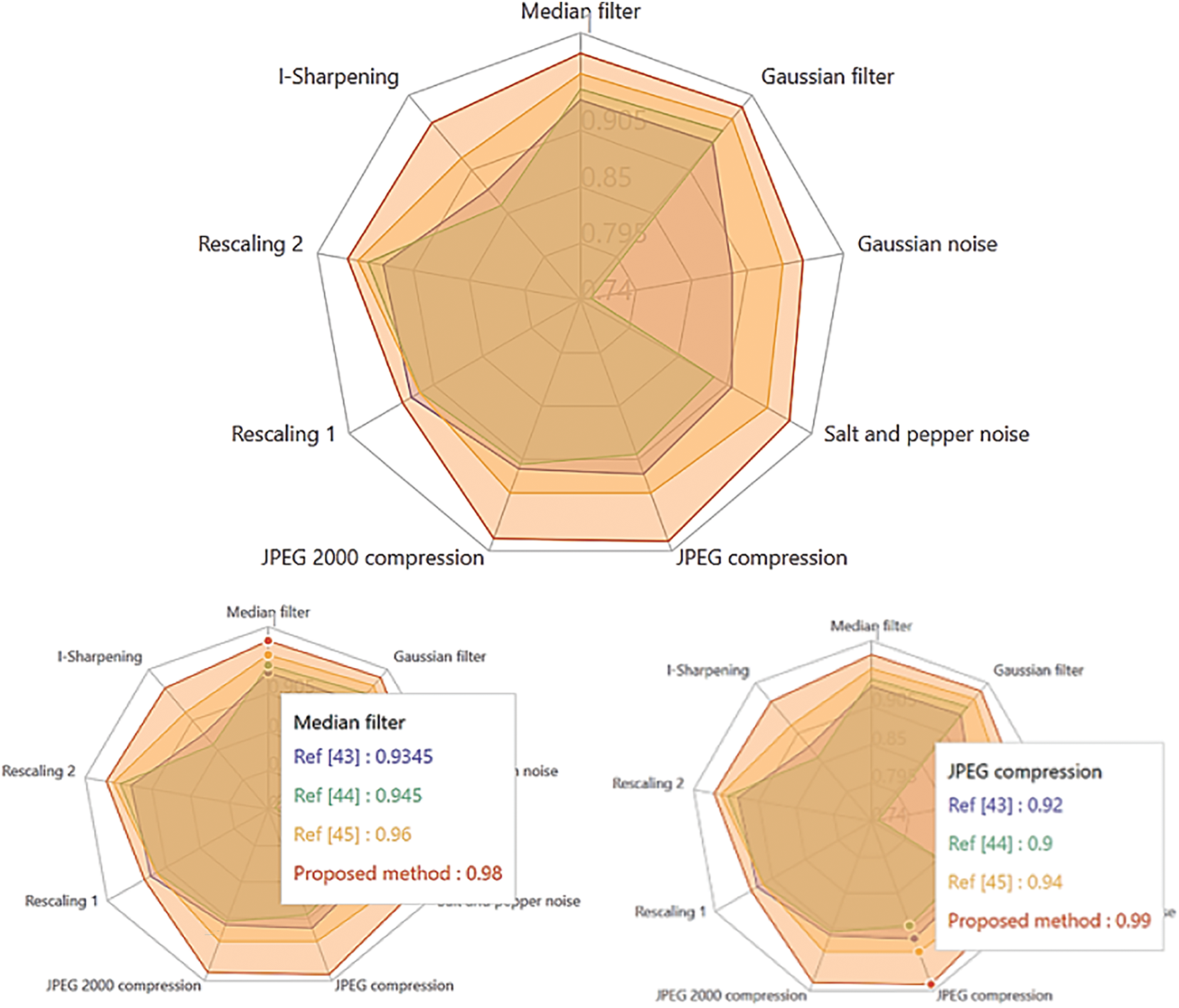

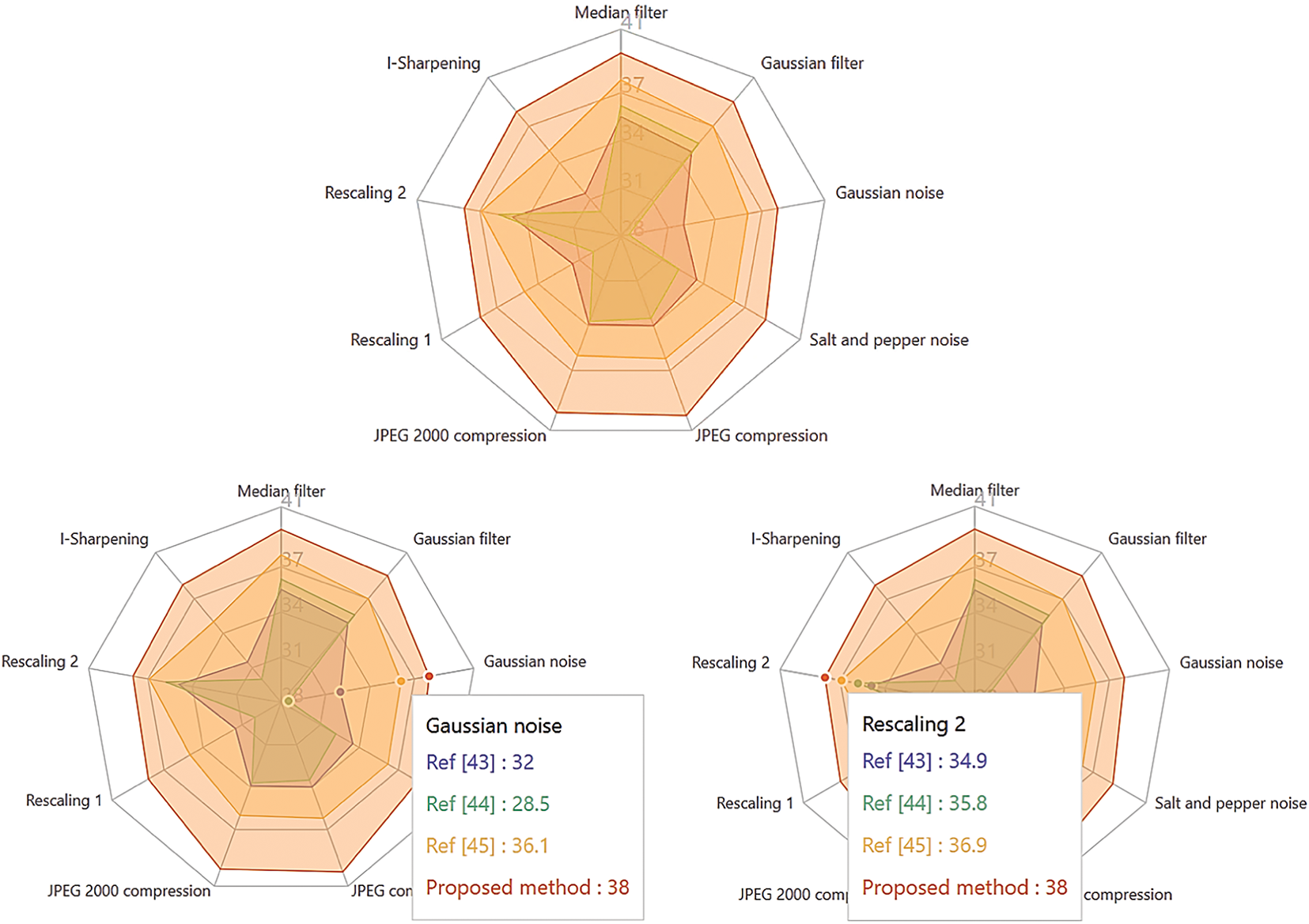

As Figs. 14–16 show, our approach clearly outperforms other methods on several fronts. In particular, the values obtained for NC, SSIM, and PSNR testify to the superiority of the proposed system in terms of watermarked image quality and fidelity, even under disruptive attacks. This enhanced performance can be attributed to the effectiveness of the OKOM by CWSO-5, which offers optimal image representation with very low information redundancy, thus minimizing visible artifacts and improving imperceptibility. In addition, a key element in the robustness of our method lies in the use of the improved CWSO algorithm, which enables the scaling factor to be optimized dynamically and efficiently. Thanks to this optimization, the proposed method guarantees greater robustness while retaining high imperceptibility—an essential balance for practical applications.

Figure 14: Radar comparison of NC performance of the proposed method against state-of-the-art approaches under different attack scenarios [43–45]

Figure 15: Radar comparison of SSIM performance of the proposed method against state-of-the-art approaches under different attack scenarios [43–45]

Figure 16: Radar comparison of PSNR performance of the proposed method against state-of-the-art approaches under different attack scenarios [43–45]

Fig. 14 offers a comparative radar representation of the NC performance of the suggested dual digital watermarking technique, compared to state-of-the-art methods [43–45], in various contexts of standard image processing attacks. The illustration visually and statistically demonstrates that the suggested approach significantly enhances the robustness of digital watermarking without compromising perceived quality, making it an effective option for sensitive uses such as safeguarding digital rights, biometric identification, or medical monitoring.

Fig. 15 shows a radial comparison of the structural similarity indices (SSIM) obtained for the suggested technique and three other competing references [43–45], when exposed to various common image attacks. This graph shows that the suggested technique is not only resistant, but also undetectable, making it specifically suitable for applications requiring excellent image quality after watermarking, such as medical documents, video surveillance or the protection of cultural content.

Fig. 16 shows a radar graphical comparison of the PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) performance achieved by the suggested technique, in contrast to state-of-the-art methods ([43–45]), against different degradation attacks. This graph shows that the suggested technique guarantees excellent visual quality of watermarked images, even after the introduction of common disturbances. It is therefore ideally suited to critical applications where image quality is paramount: visual archives, medical imaging, video surveillance, etc.

After evaluating invisibility and robustness in the event of static and dynamic attacks, the proposed watermarking system demonstrated a satisfactory level of imperceptibility and strong resistance to various distortions. These results confirm that robustness is an essential criterion for digital watermarking and reinforce the system’s ability to withstand various attack scenarios [46–48].

Theoretically, the high robustness observed (NC > 0.9 for most attacks) can be explained by the combined use of QSVD and OKOM: singular values modified in a quaternary space are less sensitive to local transformations, while encoding both watermarks in the moment space reduces information dispersion [49,50]. The use of CWSO allows for dynamic optimization of the scale factor, which maximizes robustness without sacrificing visual quality. Thus, the excellent balance between invisibility (PSNR > 47 dB, SSIM ≈ 1) and resistance to attacks proves that our approach meets the theoretical criteria for an effective digital watermarking system: controlled redundancy, stability under disturbance, and adaptability to the characteristics of the medium [51,52]. This consistency between empirical results and theoretical principles reinforces the scientific validity of the proposed method.

Our approach is deliberately based on the combination of three complementary components: Krawchuk’s Optimized Octonion Moments (OKOM), Quaternionic Singular Value Decomposition (QSVD) and the Chaotic White Shark Optimizer (CWSO). Each of these elements plays a crucial and specific role in the digital watermarking process (Table 7). Furthermore, the experimental evaluation was conducted using the Chicago Face Database, a freely available stimulus set of facial images accompanied by norming data, as described in ‘The Chicago Face Database: A free stimulus set of faces and norming data’, Behavior Research Methods [53,54].

• The OKOM facilitates the extraction of strong, consistent descriptors, taking advantage of the higher-order characteristics of octonions to enhance resistance to geometric and frequency attacks.

• QSVD is implemented to decompose the source image and watermark areas, ensuring that visual quality is preserved, while enabling stable, localized watermarking.

• CWSO, finally, optimizes the scaling factor θ, thus determining the insertion strength. Introducing chaos into the optimization process improves convergence and helps avoid local minima, thus ensuring a better compromise between robustness and imperceptibility.

This study proposes an innovative approach for copyright protection applied to digital architectural sketches made by students. By synergistically combining Krawtchouk octonionic moment optimization via the chaotic CWSO algorithm, quaternionic singular value decomposition (QSVD), and discrete wavelet transform (DWT), our method allows the simultaneous insertion of two watermarks—an institutional logo and a personal image—while preserving the visual quality of the host image. This process ensures multi-level protection: discretion, robustness against attacks, and traceability of academic works. The originality of our contribution lies not only in the combined use of these advanced tools, but also in the adaptive optimization of the insertion parameters, making the watermarking both efficient and imperceptible. This solution stands out for its ability to withstand common manipulations (compression, noise, rotation, etc.), while maintaining high visual fidelity, as demonstrated by the performance achieved (PSNR > 47 dB, SSIM > 0.99, NC > 0.9). In addition to its application to the academic environment, our approach can be generalized to other sensitive fields, such as graphic design, fashion or even the industrial protection of patents and technical diagrams.

Despite the promising results achieved by the proposed double-watermarking scheme, some limitations remain. First, the scheme exhibits moderate sensitivity to certain types of distortions, such as impulsive noise. This is partly due to the reliance on frequency transforms and moment-based representations, which may not fully absorb abrupt or nonlinear pixel intensity perturbations. Moreover, the computational cost associated with the OKOM extraction and optimization process may hinder real-time deployment in resource-constrained environments.

To overcome these constraints, further research could consider the use of lightweight noise reduction filters before watermark detection, or the use of contrast-preserving transformations to reduce sensitivity to histogram changes. Furthermore, applying the suggested model to embedded platforms and Field-Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) systems presents a promising option for real-time and energy-efficient watermarking. By using hardware parallelism and pipelined architectures, the speed of OKOM computation and CWSO optimization could be improved, making their deployment in practical situations such as digital rights management on mobile devices, surveillance systems, or Internet of Things (IoT) based document verification possible.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Ahmed El Maloufy, Mohamed Amine Tahiri, and Ahmed Bencherqui: Conceptualization, Software, Writing—original draft, review & editing. Hicham Karmouni: Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft. Mhamed Sayyouri: Supervision, Writing—original draft, Project administration. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The stereo image dataset used for the OKOM magnitude analysis in Section 4.1 was obtained from the Middlebury 2005 stereo dataset. The dataset is publicly available and can be accessed at: https://vision.middlebury.edu/stereo/data/scenes2005 (accessed on 01 January 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bar-Eli A. Architectural drawings new uses in the architectural design process. Athens J Archit. 2020;6(3):273–92. doi:10.30958/aja.6-3-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gómez-Tone HC, Bustamante Escapa J, Bustamante Escapa P, Martin-Gutierrez J. The drawing and perception of architectural spaces through immersive virtual reality. Sustainability. 2021;13(11):6223. doi:10.3390/su13116223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Martin D, Nettleton S, Buse C. Drawing atmosphere: a case study of architectural design for care in later life. Body Soc. 2020;26(4):62–96. doi:10.1177/1357034x20949934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Tahiri MA, Karmouni H, Bencherqui A, Daoui A, Sayyouri M, Qjidaa H, et al. New color image encryption using hybrid optimization algorithm and Krawtchouk fractional transformations. Vis Comput. 2023;39(12):6395–420. doi:10.1007/s00371-022-02736-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kaushik K, Bhardwaj A. Zero-width text steganography in cybercrime attacks. Comput Fraud Secur. 2021;2021(12):16–9. doi:10.1016/s1361-3723(21)00130-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li Q, Wang X, Ma B, Wang X, Wang C, Xia Z, et al. Image steganography based on style transfer and quaternion exponent moments. Appl Soft Comput. 2021;110(3):107618. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lingamallu NS, Veeramani V. Secure and covert communication using steganography by wavelet transform. Optik. 2021;242(2):167167. doi:10.1016/j.ijleo.2021.167167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Tahiri MA, Bencherqui A, Karmouni H, Amakdouf H, Mirjalili S, Motahhir S, et al. Implementation of a steganography system based on hybrid square quaternion moment compression in IoMT. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2023;35(7):101604. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Meesala P, Roy M, Thounaojam DM. A robust medical image zero-watermarking algorithm using Collatz and Fresnelet transforms. J Inf Secur Appl. 2024;85(1):103855. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2024.103855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Patil AJ, Shelke R. An effective digital audio watermarking using a deep convolutional neural network with a search location optimization algorithm for improvement in robustness and imperceptibility. High Confid Comput. 2023;3(4):100153. doi:10.1016/j.hcc.2023.100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hu Y, Jiang X, Zhu C, Ren N, Guo S, Duan J, et al. A dual watermarking algorithm for trajectory data based on robust watermarking and fragile watermarking. Comput Geosci. 2024;191:105655. doi:10.1016/j.cageo.2024.105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shen Y, Tang C, Fan Z, Wu T, Lei Z. Blind watermarking scheme for medical and non-medical images copyright protection using the QZ algorithm. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;241(5):122547. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Tan T, Zhang L, Zhang M, Wang S, Wang L, Zhang Z, et al. Commutative encryption and watermarking algorithm based on compound chaotic systems and zero-watermarking for vector map. Comput Geosci. 2024;184(8):105530. doi:10.1016/j.cageo.2024.105530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang M, Ding W, Li Y, Sun J, Liu Z. Color image watermarking based on a fast structure-preserving algorithm of quaternion singular value decomposition. Signal Process. 2023;208(2):108971. doi:10.1016/j.sigpro.2023.108971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Bala NV, Shanmughalakshmi DR. High speed VLSI architectures for DWT in biometric image compression: a study. Procedia Comput Sci. 2010;2(4):219–26. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2010.11.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jyotheswar J, Mahapatra S. Efficient FPGA implementation of DWT and modified SPIHT for lossless image compression. J Syst Archit. 2007;53(7):369–78. doi:10.1016/j.sysarc.2006.11.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Oteko Tresor L, Sumbwanyambe M. A selective image encryption scheme based on 2D DWT, henon map and 4D qi hyper-chaos. IEEE Access. 2019;7:103463–72. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2929244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bose A, Maity SP. Secure sparse watermarking on DWT-SVD for digital images. J Inf Secur Appl. 2022;68(14):103255. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2022.103255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ambadekar SP, Jain J, Khanapuri J. Digital image watermarking through encryption and DWT for copyright protection. In: Recent trends in signal and image processing. Singapore: Springer; 2018. p. 187–95. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-8863-6_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Abdulrahman AK, Ozturk S. A novel hybrid DCT and DWT based robust watermarking algorithm for color images. Multimed Tools Appl. 2019;78(12):17027–49. doi:10.1007/s11042-018-7085-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ding W, Li Y, Wang T, Wei M. Dual quaternion singular value decomposition based on bidiagonalization to a dual number matrix using dual quaternion householder transformations. Appl Math Lett. 2024;152(7):109021. doi:10.1016/j.aml.2024.109021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu Y, Wu F, Che M, Li C. Fixed-precision randomized quaternion singular value decomposition algorithm for low-rank quaternion matrix approximations. Neurocomputing. 2024;580(1):127490. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.127490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Huang B, Li W. Neural network models for the quaternion singular value decompositions. Appl Math Model. 2024;129:780–805. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2024.02.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ma Y, Cheng J. A novel joint denoising method for gear fault diagnosis with improved quaternion singular value decomposition. Measurement. 2024;226(2023):114165. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.114165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. You D, Yu J, Jia Z, Zhang Y, Yang Z. Mobile robot path planning based on fused multi-strategy white shark optimisation algorithm. Appl Sci. 2025;15(15):8453. doi:10.3390/app15158453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Braik M, Hammouri A, Atwan J, Al-Betar MA, Awadallah MA. White shark optimizer: a novel bio-inspired meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;243(7):108457. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.108457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Almuqren L, Aljameel SS, Alqahtani H, Alotaibi SS, Hamza MA, Salama AS. A white shark equilibrium optimizer with a hybrid deep-learning-based cybersecurity solution for a smart city environment. Sensors. 2023;23(17):7370. doi:10.3390/s23177370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Braik MS, Awadallah MA, Dorgham O, Al-Hiary H, Al-Betar MA. Applications of dynamic feature selection based on augmented white shark optimizer for medical diagnosis. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;257(14):124973. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Fathy A, Yousri D, Alharbi AG, Ali Abdelkareem M. A new hybrid white shark and whale optimization approach for estimating the Li-ion battery model parameters. Sustainability. 2023;15(7):5667. doi:10.3390/su15075667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Bencherqui A, Tahiri MA, Karmouni H, Alfidi M, El Afou Y, Qjidaa H, et al. Chaos-enhanced archimede algorithm for global optimization of real-world engineering problems and signal feature extraction. Processes. 2024;12(2):406. doi:10.3390/pr12020406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. El Ghouate N, Bencherqui A, Mansouri H, El Maloufy A, Tahiri MA, Karmouni H, et al. Improving the Kepler optimization algorithm with chaotic maps: comprehensive performance evaluation and engineering applications. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(11):313. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10857-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tahiri MA, Boudaaoua B, Karmouni H, Tahiri H, Oufettoul H, Amakdouf H, et al. Octonion-based transform moments for innovative stereo image classification with deep learning. Complex Intell Syst. 2024;10(3):3493–511. doi:10.1007/s40747-023-01337-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Tahiri MA, Karmouni H, Sayyouri M, Qjidaa H, Ahmad M, Hammad M, et al. An improved reversible watermarking scheme using embedding optimization and quaternion moments. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):18485. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-69511-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Karmouni H, Tahiri MA, Dagal I, Amakdouf H, Jamil MO, Qjidaa H, et al. Secure and optimized satellite image sharing based on chaotic eπ map and Racah moments. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;236(4):121247. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Azam NA, Haider T, Hayat U. An optimized watermarking scheme based on genetic algorithm and elliptic curve. Swarm Evol Comput. 2024;91(5):101723. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2024.101723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chekira C, Marzouq M, El Fadili H, Lakhliai Z, da Graça Ruano M. Join security and block watermarking-based evolutionary algorithm and Racah moments for medical imaging. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;96(20):106554. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2024.106554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Guo S, Zhu S, Zhu C, Ren N, Tang W, Xu D. A robust and lossless commutative encryption and watermarking algorithm for vector geographic data. J Inf Secur Appl. 2023;75:103503. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2023.103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Jiang MR, Feng XF, Wang CP, Fan XL, Zhang H. Robust color image watermarking algorithm based on synchronization correction with multi-layer perceptron and Cauchy distribution model. Appl Soft Comput. 2023;140(1):110271. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Li D, Ma C, Gao H, Jin X. LBP feature and hash function based dual watermarking algorithm for database. Data Knowl Eng. 2023;148(3):102228. doi:10.1016/j.datak.2023.102228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Li Q, Wang X, Pei Q, Chen X, Lam KY. Consistency preserving database watermarking algorithm for decision trees. Digit Commun Netw. 2024;10(6):1851–63. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2022.12.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lu Y, Lu X, Yang G, Xiong X. Robust zero-watermarking algorithm for multi-medical images based on FFST-Schur and Tent mapping. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;96(11):106557. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2024.106557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ali Nawaz S, Li J, Bhatti UA, Shoukat MU, Li D, Ahmad Raza M. Hybrid watermarking algorithm for medical images based on digital transformation and MobileNetV2. Inf Sci. 2024;653(1):119810. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.119810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Li M, Yue Y. Security analysis and improvement of dual watermarking framework for multimedia privacy protection and content authentication. Mathematics. 2023;11(7):1689. doi:10.3390/math11071689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Venkateswarlu L, Rao NV, Reddy BE. A robust double watermarking technique for medical images with semi-fragility. In: 2017 International Conference on Recent Advances in Electronics and Communication Technology (ICRAECT); 2017 Mar 16–17; Bangalore, India. p. 126–31. doi:10.1109/icraect.2017.40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Chu SC, Fu L, Pan JS, Xue X, Liu M. Cat swarm algorithm generated based on genetic programming framework applied in digital watermarking. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(2):3135–63. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.062469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ye C, Tan S, Li S, Wang J, Zuo Q, Xiong B. Joint watermarking and encryption for social image sharing. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(2):2927–46. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.062051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Majeed BD, Taherinia AH, Yazdi HS, Harati A. CSRWA: covert and severe attacks resistant watermarking algorithm. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(1):1027–47. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.059789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Liang Y, Niu K, Zhang Y, Meng Y, Hu F. Adaptive video dual domain watermarking scheme based on PHT moment and optimized spread transform dither modulation. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;81(2):2457–92. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.056438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zou JZ, Chen MX, Gong LH. Invisible and robust watermarking model based on hierarchical residual fusion multi-scale convolution. Neurocomputing. 2025;614(1):128834. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Guo Z, Chen SH, Zhou L, Gong LH. Optical image encryption and authentication scheme with computational ghost imaging. Appl Math Model. 2024;131(6):49–66. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2024.04.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Magdy M, Ghali NI, Ghoniemy S, Hosny KM. Multiple zero-watermarking of medical images for Internet of medical things. IEEE Access. 2022;10(2):38821–31. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3165813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Hosny KM, Darwish MM. Invariant image watermarking using accurate polar harmonic transforms. Comput Electr Eng. 2017;62(1):429–47. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2017.05.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Ma DS, Correll J, Wittenbrink B. The Chicago face database: a free stimulus set of faces and norming data. Behav Res Meth. 2015;47(4):1122–35. doi:10.3758/s13428-014-0532-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Ma DS, Kantner J, Wittenbrink B. Chicago face database: multiracial expansion. Behav Res Meth. 2021;53(3):1289–300. doi:10.3758/s13428-020-01482-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools