Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Data Augmentation: A Multi-Perspective Survey on Data, Methods, and Applications

1 School of Information Science and Technology, Beijing University of Technology, Beijing, 100124, China

2 Department of Automation, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 100084, China

* Corresponding Authors: Junyu Yao. Email: ; Heng Xia. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 4275-4306. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069097

Received 14 June 2025; Accepted 28 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

High-quality data is essential for the success of data-driven learning tasks. The characteristics, precision, and completeness of the datasets critically determine the reliability, interpretability, and effectiveness of subsequent analyzes and applications, such as fault detection, predictive maintenance, and process optimization. However, for many industrial processes, obtaining sufficient high-quality data remains a significant challenge due to high costs, safety concerns, and practical constraints. To overcome these challenges, data augmentation has emerged as a rapidly growing research area, attracting considerable attention across both academia and industry. By expanding datasets, data augmentation techniques improve greater generalization and more robust performance in actual applications. This paper provides a comprehensive, multi-perspective review of data augmentation methods for industrial processes. For clarity and organization, existing studies are systematically grouped into four categories: small sample with low dimension, small sample with high dimension, large sample with low dimension, and large sample with high dimension. Within this framework, the review examines current research from both methodological and application-oriented perspectives, highlighting main methods, advantages, and limitations. By synthesizing these findings, this review offers a structured overview for scholars and practitioners, serving as a valuable reference for newcomers and experienced researchers seeking to explore and advance data augmentation techniques in industrial processes.Keywords

Data-driven modeling aims to uncover latent patterns within the data, enabling reliable decision support for industrial operations [1]. The development of accurate and robust models depends on high-quality data. In most cases, industrial systems operate safely and stably under normal conditions, whereas abnormal or fault conditions occur infrequently [2]. This results in a long-tailed data distribution, which can bias the models toward majority classes and increase the risk of overfitting [3,4]. Furthermore, due to technological and cost constraints, certain critical parameters are difficult to measure online, leading to a limited number of labeled samples for model training [5]. As a result, data-driven modeling for industrial processes often contends with the challenge of ‘big data, small sample’.

Data augmentation offers a promising strategy for expanding datasets and improving modeling performance. A keyword search for ‘industrial’ and ‘data augmentation’ in the Web of Science (WoS) database reveals the number of related publications and citations, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The upward trend in both metrics reflects a growing scholarly interest in this field. In particular, the application of data augmentation in industrial processes has increased significantly between 2019 and 2024.

Figure 1: Development trends of data augmentation for industrial processes (2006–2025)

Data augmentation aims to approximate the true data distribution by generating virtual samples. Over the past decade, numerous review articles have examined various data augmentation techniques. For example, reference [6] surveyed several data augmentation methods for text classification across data and feature spaces. Reference [7] provided a comprehensive analysis of data augmentation techniques in medical imaging. Reference [8] systematically reviewed mix-based data augmentation methods, focusing on multi-modal data such as images, text, and video. In the context of mechanical equipment, references [9] and [10] synthesized state-of-the-art data augmentation strategies for fault diagnosis and predictive maintenance. However, there remains a lack of comprehensive reviews that specifically address the unique challenges and applications of data augmentation in industrial processes. To fill this gap, this survey offers an in-depth review of data augmentation techniques, with a particular emphasis on their applications in industrial processes. The main contributions are as follows: 1) It highlights the impact of data characteristics on modeling performance and introduces a framework based on sample size and feature dimensionality. 2) It categorizes and analyzes recent studies, summarizing targeted solutions to key challenges. 3) It reviews the application of data augmentation methods in representative industrial domains, providing insight and guidance to researchers and engineers.

For this survey review, a thematic approach was employed, which is defined by four data topics (details are provided in Section 2). Our objective was to cover both classical foundations and emerging trends in data augmentation strategies by utilizing the four data characteristics outlined in the survey. The review process involved a structured literature search in major academic databases, including WoS, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and ScienceDirect. We identified relevant literature using keyword combinations such as ‘small sample learning’, ‘industrial process’, and ‘data augmentation’. Subsequently, each paper was tagged according to a four-quadrant framework based on its sample size and feature dimensionality, and then classified by methodological category. The final step was to synthesize key themes and practical industrial applications, providing readers with both breadth and depth of understanding.

This survey is organized as follows. Section 2 defines the data characteristics and analyzes existing challenges from the perspective of sample size and feature dimensionality. Section 3 reviews recent studies on data augmentation and evaluates the strengths and limitations of various methods. Section 4 explores industrial applications of these techniques and compares their characteristics across different domains. Section 5 discusses current challenges and proposes potential directions for future research. Finally, Section 6 concludes the survey.

2 Data Characteristics and Problem Formulation

A typical dataset is denoted as

Figure 2: Diagram of the process data

Remark: Determining the appropriate sample size and feature dimensionality is critical before starting modeling tasks [11]. Reference [12] introduced the probably approximately correct theory, which estimates the sample size required to ensure optimal model performance. This theory emphasizes that sufficient samples are an essential prerequisite for data-driven models. However, collecting sufficient samples in actual industrial processes is often challenging, particularly in a setting with small sample sizes and high-dimensional data [13]. For the small sample, reference [14] defined a training set with fewer than 100 samples as a small sample case. In [15–17], the small sample problem was characterized by sample sizes smaller than 50 in engineering applications and smaller than 30 in academic research. In this survey, a sample size of

Without loss of generality, data can be classified into four categories based on sample size and feature dimensionality: small sample with low dimensionality (SSLD), small sample with high dimensionality (SSHD), large sample with low dimensionality (LSLD), and large sample with high dimensionality (LSHD), as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Coordinate diagram of data characteristics

Case 1: Large sample with low dimension (LSLD)

In Case 1, the large sample size and low-dimensional datasets are defined below:

where

LSLD data are commonly encountered in the monitoring of industrial equipment, particularly rotating machinery. Abnormal or fault conditions typically occur infrequently and have a short duration, resulting in a low proportion of fault samples. As a result, the numerous redundant normal data and the scarcity of fault data hinder the development of accurate detection models. This imbalance often leads to class distribution problems [19]. A representative example is shown in Fig. 4, where minority fault classes introduce challenges such as decision boundary overlap and outliers.

Figure 4: Diagram of the class imbalance for LSLD

Case 2: Small sample with high dimension (SSHD)

In Case 2, the small sample size and high-dimensional datasets are defined below:

This scenario introduces the curse of dimensionality (CoD) [20], resulting in a sparse sample space, as illustrated in Fig. 5. As dimensionality increases, sample sparsity grows exponentially. Moreover, high dimensionality often causes multicollinearity, further complicating model training. Therefore, SSHD modeling is highly susceptible to overfitting, making it difficult to achieve strong generalization performance.

Figure 5: The sample space is sparse due to the increase in dimension

Case 3: Small sample with low dimension (SSLD)

In Case 3, the small sample size and low-dimensional datasets are defined below:

SSLD modeling is highly susceptible to noise interference, especially due to sensor drift. The statistical confidence of the process data is low, and the available information is insufficient to support reliable real-time decision-making. SSLD data commonly occurs during early-stage device monitoring, such as in the initial phase of a process or during the debugging stage of new equipment, when the sample size and feature dimensionality are typically limited. This scenario often causes overfitting during the modeling process, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Diagram of the overfitting problem

Case 4: Large sample with high dimension (LSHD)

In Case 4, the large sample size and high-dimensional datasets are defined below:

LSHD modeling not only inherits the challenges present in SSLD, SSHD, and LSLD cases, but also imposes higher demands on data analysis and mining. LSHD data are commonly encountered in plant-level monitoring and multi-plant federated learning tasks. Industrial systems often integrate multi-source data, such as sensor readings, production logs, image inspections, and maintenance records, resulting in a high-dimensional, heterogeneous feature space. This complexity gives rise to challenges such as long-tailed data distributions in intelligent monitoring and maintenance, as illustrated in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Diagram of the class imbalance distribution problem

Existing data augmentation methods can be classified into five categories based on their generation mechanisms, as illustrated in Fig. 8: transform-based, statistical-based, deep generative-based, transfer learning-based, and physical model-based methods. Statistical methods were first introduced in 2008. With the rise of deep learning, deep generative models became a key focus in data augmentation from 2018 onward. In 2019, transform-based methods emerged to address the small sample problem in time series datasets. Physical model-based approaches began to appear in 2021. Since 2022, transfer learning has been employed to extract domain knowledge and augment minority classes. Based on four data characteristics, the existing data augmentation techniques are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 8: Classification of data augmentation methods

3.1 Data Augmentation for LSLD

LSLD datasets often exhibit significant class imbalance, with minority class samples representing only a small portion of the overall dataset. This imbalance leads to models biased toward the majority class, whereas overlooking the minority class. To address this problem, various data augmentation methods have been proposed, which can be categorized into transform-based, deep generative model-based, transfer learning-based, and physical model-based approaches.

(a) LSLD based on transform techniques

1) The noise injection method enhances data generalization by superimposing random noise on the original data. The core idea is to simulate the uncertainty inherent in actual scenarios. The noise injection process is described as follows:

where

where

2) The geometric scaling method generates new samples by adjusting the amplitude or time scale of the original data. This method aims to simulate variations in equipment operating conditions through techniques such as amplitude scaling and time scaling.

• The amplitude scaling is defined as follows:

where

• The time scaling is defined as follows:

where

3) The zero-masking method generates new samples by randomly setting continuous segments of the original data to zero, thereby simulating sensor failures or communication interruptions [21,22,26–29]. The process is defined as follows:

where

4) The time-shift method generates new samples by shifting the original time series data to the left or right, thus simulating different time delays [21,24–26,30]. Given an original sample

where

5) The flip method reverses the order of the time series data to improve the model’s generalization capability [26,27]. Given an original sample

Transform-based data augmentation methods apply various transformation strategies within the bounds of physical constraints to generate new samples and expand the dataset. Although these techniques improve the diversity of the time series data, their applicability is typically limited to specific scenarios. Therefore, it remains challenging to establish a unified framework for their general application.

(b) LSLD based on deep generative models

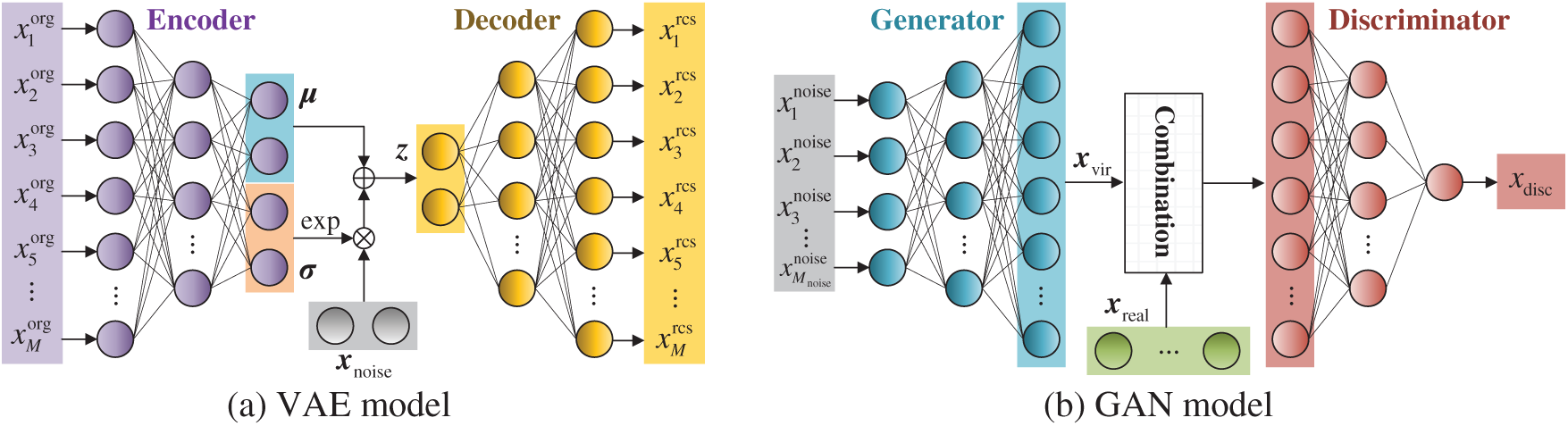

Deep generative models based on neural networks have emerged as a prominent direction in data augmentation research [105]. These methods aim to learn the latent data distribution using neural architectures, generating new samples through sampling from them. Among the various models, the variational autoencoder (VAE) and the generative adversarial network (GAN) are two representative and widely used methods, as illustrated in Fig. 9. Moreover, several studies [106] have transformed one-dimensional (1-D) signals into two-dimensional (2-D) images using techniques such as the fast Fourier transform [107], the continuous wavelet transform [108,109], and the Gramian angular field [110]. These transformations enable diffusion models, originally developed for image data, to be applied to LSLD scenarios. The details of three deep generative models are presented in Table 2.

Figure 9: Diagram of the typical deep generative models

1) VAEs can learn the original data distribution and generate new samples by sampling the latent space [31]. To improve the performance of VAEs for industrial data, existing studies have primarily focused on optimizing the objective function and network architectures.

• In terms of objective functions, Dixit et al. [32] proposed a fault diagnosis framework based on a modified conditional VAE with centroid loss, which effectively enhances the generation of virtual samples. Zhao et al. [33] developed a modified Wasserstein autoencoder that integrates a squeeze-and-excitation attention mechanism and utilizes the sliced Wasserstein distance along with a gradient penalty to improve sample similarity. In another study, Zhao et al. [34] further improved the representational capacity of VAEs by introducing a Gaussian mixture prior and optimizing it via the expectation-maximization algorithm.

• In terms of network architectures, Karamti et al. [35] introduced a stacked VAE framework for multi-fault machinery identification, in which a VAE is used for data augmentation and two sparse autoencoders are used for feature extraction. Han et al. [114] proposed a VAE incorporating long short-term memory units to capture temporal dependencies and generate realistic virtual samples. To address the limitations of non-Gaussian signals and sparse fault data, Luo et al. [115] developed a mixture network VAE by integrating Gaussian mixture models and Weibull distributions. Wang et al. [116] combined the noise robustness of VAE with the expressive capacity of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to enhance diagnostic precision and robustness. Zhang et al. [117] proposed a multi-scale dilated variational convolutional autoencoder, which integrates a multi-scale dilated convolutional attention mechanism and a graph convolution module to capture both hierarchical features and inter-sensor dependencies. For CNN structure, Zeng et al. [118] introduced an attention-guided hierarchical wavelet CNN that integrates multi-layer wavelet decomposition, a time-frequency attention module, and gradient-weight fusion to simultaneously suppress noise and highlight fault-relevant frequency bands.

2) The training process of GANs is formulated as a minimax game between two neural networks: the generator and the discriminator. The overall performance of GANs is influenced by the structures of both components. Moreover, the stability and convergence of the training process depend on the design of loss functions. Consequently, existing studies have focused on three aspects: objective functions, generator structures, and discriminator structures. The development trend of these studies is summarized in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Development trend of GANs for LSLD scenarios [52–64]

• Regarding objective functions, the Wasserstein distance has been used as a replacement for the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, effectively alleviating problems such as gradient vanishing and mode collapse [36]. Based on this advancement, [37] integrated the Wasserstein distance with a hierarchical feature matching loss to constrain local category similarity, thus improving the quality and validity of generated samples. Subsequently, reference [38] introduced a gradient penalty term to further stabilize the training process and reduce the risk of mode collapse. Moreover, studies such as [39,40] incorporated the Wasserstein distance and the gradient penalty into the time series GAN and the auxiliary classifier GAN, respectively, resulting in improved model convergence.

• Regarding generator structures, Pan et al. [119] enhanced the generator by incorporating an additional sequence into the condition, allowing the generation of more abundant samples. Zareapoor et al. [120] proposed a minority oversampling GAN, where the generator learns a mixture data distribution to generate samples from the minority class. Zhang et al. [121] introduced an adaptive decoupling strategy in the generator, which adjusts each intermediate output using labels to prevent mode collapse and improve sample diversity. Xu et al. [122] employed multiple generators to generate virtual samples from the real data distribution, thus increasing sample variety and reducing the risk of mode collapse. Ren et al. [123] improved the generator through pre-training based on the majority classes, followed by fine-tuning with anchor samples. This approach preserves the learned distribution from pre-training while ensuring that the generated samples remain close to real ones. Huo et al. [124] incorporated a residual mixed self-attention module into the generator to effectively extract time- and frequency-domain features. Chen et al. [125] utilized a serial CNN-Transformer architecture as the foundation of the generator to capture long-range dependencies and improve understanding of local features.

• Regarding discriminator structures, Wang et al. [126] proposed a GAN framework where the generator generates new samples to expend the dataset, and a stacked denoising autoencoder serves as the discriminator to extract robust fault-related features, thereby enhancing the model’s fault classification capability. Ding et al. [127] introduced a multi-discriminator structure designed to learn data distributions associated with different health states, improving performance through a semi-supervised learning strategy.

3) The denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) is a representative diffusion-based generative model widely applied in data augmentation, as illustrated in Fig. 11. Reference [41] integrated a classifier-free denoising diffusion implicit model with multiclass contrastive learning to tackle challenges posed by limited fault samples and variable operating conditions. Reference [42] combined DDPM with a physical simulation model to generate diverse fault samples. In addition, reference [43] proposed a DDPM-based method that generates high-fidelity images, effectively enhancing the diversity of feature representations. Reference [44] introduced a lightweight DDPM variant that incorporates multi-dconv head transposed attention, reducing computational complexity while improving the model’s ability to capture fine local details.

Figure 11: Diagram of the DDPM

(c) LSLD based on transfer learning

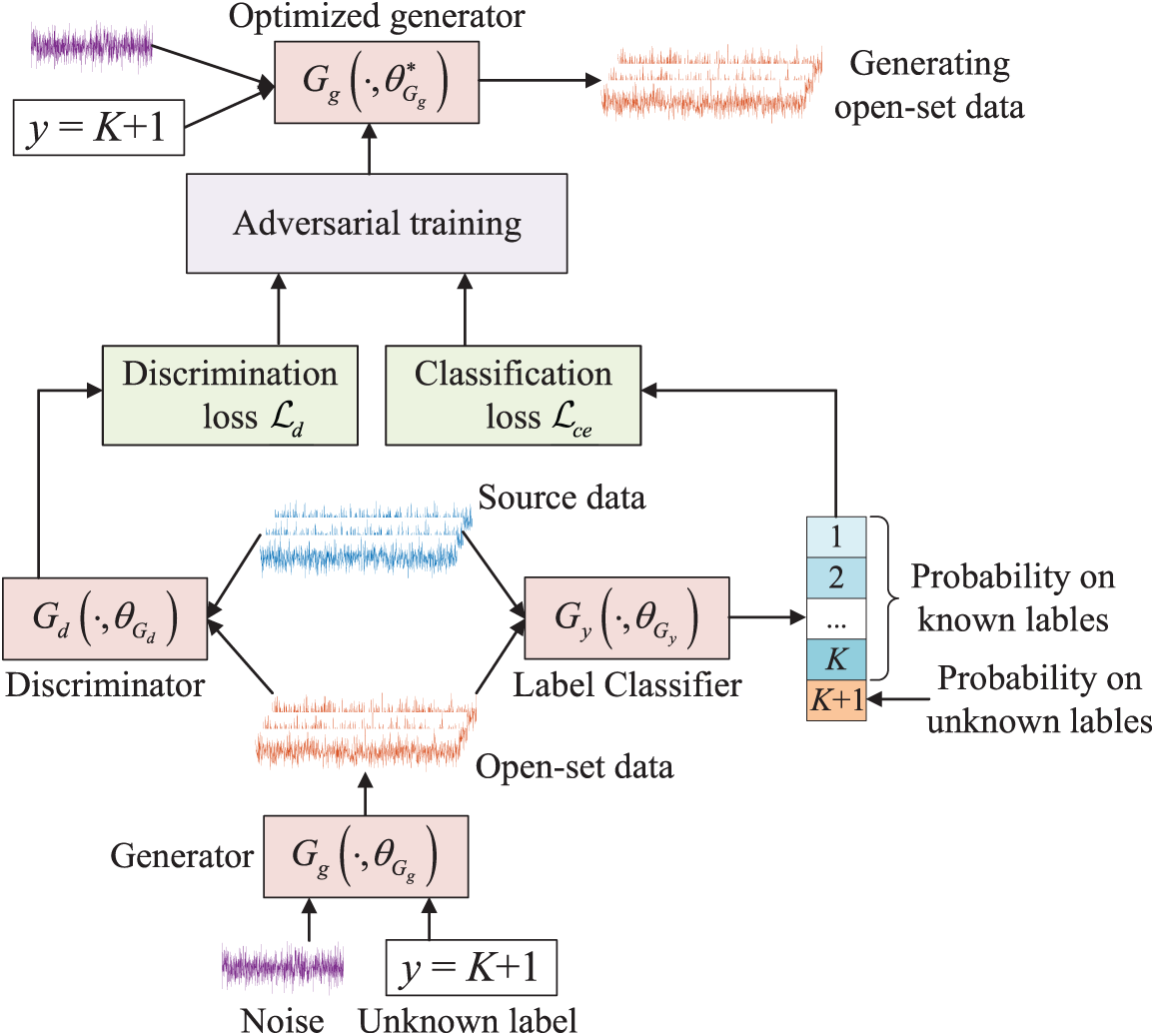

Transfer learning-based methods generate target domain data through cross-domain knowledge transfer. These methods utilize the distribution and feature relationships of the source domain to generate new samples in the target domain that conform to actual operating conditions. Recently, Li et al. [128] proposed a cross-domain augmentation method, which employs convex combinations of data and feature-label pairs to create an augmented domain. He et al. [45] introduced an attention-based cross-domain adaptive GAN that applies attention mechanisms for adaptive feature selection and incorporates correlation alignment regularization to enable transferable data augmentation between varying machining parameters. Ge et al. [46] developed a transfer learning method based on multiple mixed augmentations, which combines auto-augment-driven dynamic strategies with multi-stage data mixing. This method enhances cross-condition fault diagnosis by adaptively extracting transferable features from limited vibration data. Jian et al. [47] proposed an auxiliary classifier GAN (ACGAN) to generate open-set samples. This method used the multi-domain mixup to expand fault representation diversity across operating conditions, while ACGAN generates targeted open-set data, as illustrated in Fig. 12. Mu et al. [48] proposed a task-oriented meta-learning network based on the Theil index, incorporating a gradient calibration strategy to address the challenge of cross-domain fault diagnosis in rotating machinery under extremely limited sample conditions. This method integrates a fine-grained feature learner, a task-specific Theil index, and a gradient calibration mechanism to enhance model generalization and stability across diverse industrial scenarios. Wang et al. [49] proposed a dynamic collaborative adversarial domain adaptation network that adaptively adjusts the generator and adversarial components to enable unsupervised fault diagnosis of rotating machinery across multiple source domains, without requiring labeled data from the target domain.

Figure 12: Diagram of generating open-set data using the ACGAN

(d) LSLD Data augmentation methods based on physical models

Physical model-based methods simulate the behavior of actual systems by establishing mathematical models. These methods are generally divided into two categories: numerical simulations and digital twins. Numerical simulations reproduce the dynamic behavior of physical systems through mathematical equations and computational techniques, while digital twins create real-time, dynamic digital representations of physical entities via virtual-real mapping, as illustrated in Fig. 13. Current research primarily focuses on developing physical models for rotating machinery, such as gears, bearings, and rotors, due to their well-defined physical characteristics and mechanical principles, which facilitate the construction of numerical simulations and digital twin models [129,130].

Figure 13: Diagram of the digital twin model

1) Regarding numerical simulations, references [50,51] developed simulation models of rotors and propellers to generate virtual fault samples, thus alleviating data imbalance problems in neural network-based fault diagnosis.

2) Regarding digital twins, Cai et al. [52] developed a digital twin model of a triplex pump to generate diverse fault data. Qin et al. [53] proposed a data augmentation method based on digital twin for rolling bearings to address class imbalance in fault diagnosis. Zhang et al. [54] constructed a digital twin-based rolling bearing model that integrates virtual modeling with transformer-based discrepancy learning and multi-loss alignment. Ming et al. [55] introduced a virtual-physical component fusion method that incorporates frequency-adaptive filtering and a feature fusion self-attention network to align subdomain features and effectively alleviate distribution discrepancies in imbalanced bearing fault diagnosis.

In this context, various data augmentation methods have been developed to address the challenges of LSLD data. Transform technique-based methods quickly generate new samples through simple signal transformations, offering high computational efficiency and strong interpretability. However, they often lack data diversity and struggle to provide a unified, generalizable framework. Deep generative model-based methods learn the data distribution to generate complex virtual samples, improving model generalization. Despite these benefits, such methods have high training complexity and unstable generation quality. Transfer learning-based methods use cross-domain knowledge transfer to alleviate data scarcity, enhancing adaptability under different operational conditions. However, their effectiveness is sensitive to domain discrepancies and feature alignment. Physical model-based methods expand datasets with strong physical interpretability and high fidelity but involve high modeling costs and offer limited adaptability.

3.2 Data Augmentation for SSHD

The sparsity introduced by the CoD often causes overfitting in data-driven models. Therefore, data augmentation methods for SSHD data need to address the challenges associated with high dimensionality during sample generation processes. In this regard, statistical technique-based, deep generative model-based, and transfer learning-based approaches have been developed to effectively augment SSHD data and improve model generalization.

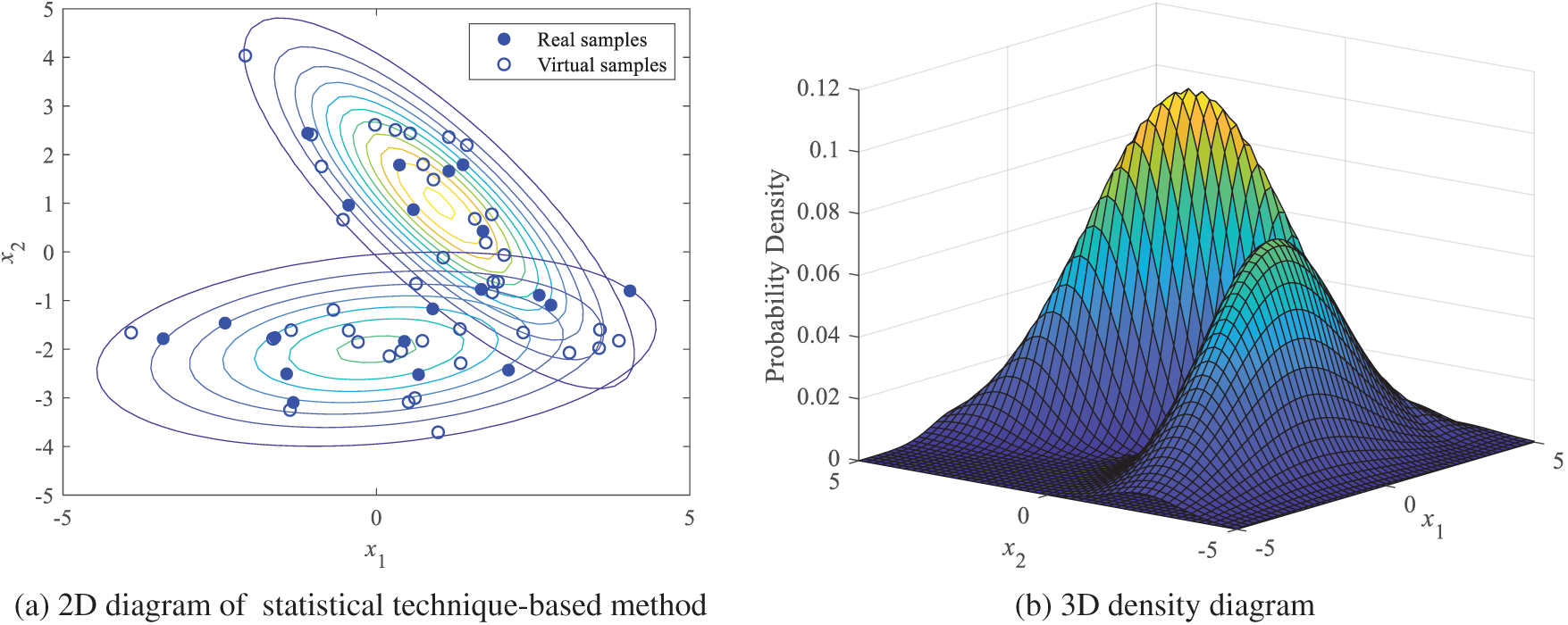

(a) SSHD based on statistical techniques

Statistical technique-based methods aim to learn the latent distribution of the original dataset and generate new samples, using statistical models in sparse areas, as illustrated in Fig. 14. However, directly applying traditional statistical methods to high-dimensional data poses significant challenges due to CoD. Feature engineering serves as an effective solution to alleviate these limitations by reducing dimensionality and highlighting relevant features.

Figure 14: Diagram of the data augmentation based on statistical techniques

Feature selection methods aim to obtain a subset of features that are most relevant to the target variables [56–58]. In contrast, feature extraction methods transform the original high-dimensional data into a low-dimensional space to capture essential patterns and reduce redundancy [59]. These techniques are effective in capturing nonlinear characteristics and enhancing low-dimensional representations. For example, reference [60] employed locally linear embedding to map high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space, which facilitated the identification of sparse areas for virtual sample generation (VSG). Similarly, reference [17] applied Isomap to embed data in a two-dimensional space, enabling a sparse area detection and interpolation-based augmentation. In [61], t-SNE was used for feature extraction and then virtual samples were generated by interpolation in the reduced space. In addition, reference [62] used discriminant locality preserving projection to handle high-dimensional data and introduced Monte Carlo sampling for VSG. Reference [63] proposed detecting sparse regions based on projection point spacing and then generated new samples based on midpoint and radial basis function interpolation. Finally, reference [131] utilized singular value decomposition to extract principal features, thus effectively addressing the challenge of high dimensionality.

In addition, multi-model methods have been explored to address the complexities associated with SSHD data. For example, reference [64] proposed a co-training strategy that detects sparse areas and fills them through interpolation. This method dynamically selects virtual samples based on model performance, improving the quality and relevance of the generated data. In another study, reference [65] introduced an adaptive data augmentation approach using generalized correntropy, which effectively utilizes

(b) SSHD based on deep generative models

High-dimensional process data exhibit more complex and diverse characteristics compared to low-dimensional data, which presents significant challenges for training deep generative models. Therefore, the development and training of such models for SSHD data should be designed for specific tasks.

1) VAEs learn the low-dimensional latent distribution of the original data and generate new samples accordingly. To address information loss during layer-wise pretraining, Yuan et al. [66] generated virtual samples at each layer through linear interpolation between adjacent samples, thereby improving the training of stacked autoencoders. Jiang et al. [67] introduced a causality-informed VAE to alleviate data sparsity and high dimensionality in just-in-time learning for soft sensor applications. Tian et al. [4] developed an adaptive loss function and utilized kernel mean matching to assign weights to virtual samples, thus improving data quality and learning performance. Moreover, Xu et al. [68,69] integrated VAE with SMOTE and Glow models to stabilize the training process and enhance sample generation.

2) Training GANs with SSHD data often faces significant challenges, such as gradient vanishing and mode collapse. To address them, references [70,71] introduced a gradient penalty into the Wasserstein GAN (WGAN-GP), which stabilizes the training process and enhances the quality of generated samples. Based on this foundation, reference [72] incorporated a deep neural network regressor into a conditional WGAN-GP framework to address the small sample problem in soft sensor. Subsequently, Jiang et al. [73] extended this architecture to a multi-generator setting, enabling more effective handling of complex data imbalances. To address the any-shot learning problem in industrial fault diagnosis, Zhuo et al. [74] proposed a data augmentation method that integrates auxiliary fault attribute information with GANs. Moreover, Cui et al. [132] introduced fuzzy set theory into the GAN framework, which effectively alleviates uncertainty and high-dimensional challenges in data augmentation. Liu et al. [133] developed a robust VAE to constrain the generator’s sampling space, while density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise clustering was introduced to guide the generation process. Finally, Zhang et al. [134] incorporated regression loss assistance into a conditional StyleGAN to generate high-quality virtual samples.

(c) SSHD based on transfer learning

Recently, transfer learning has gained attention as a promising solution for SSHD data. Ren et al. [75] proposed a low-rank joint domain adaptation network, which enhances the effectiveness of industrial small-sample datasets by extracting discriminative features and aligning cross-domain sample distributions. Furthermore, Zhu et al. [76] introduced a data self-generating transfer learning framework designed for chemical process fault diagnosis under limited sample conditions. Li et al. [77] developed the dual adversarial and contrastive network, a data augmentation method that combines adversarial and contrastive learning. It is designed to generate virtual samples while simultaneously extracting domain-invariant feature representations from single-modality data.

In this context, various data augmentation methods have been developed to address the challenges associated with SSHD data. Statistical technique-based methods typically perform dimensionality reduction before VSG and employ interpolation in reduced spaces. These methods are valued for their simplicity and interpretability but struggle to capture the characteristics inherent in high-dimensional data. Deep generative model-based methods, on the other hand, utilize neural networks to extract features and learn latent distributions to generate virtual samples. Transfer learning-based methods address domain discrepancies by transferring knowledge from source to target domains, incorporating adversarial or contrastive learning mechanisms to generate domain-invariant features and samples. In summary, these methods alleviate overfitting risks and improve model robustness in SSHD scenarios.

3.3 Data Augmentation for SSLD

SSLD data present challenges due to their limited latent information, which causes underfitting and hinders model performance. Data augmentation methods based on statistical techniques and deep generative models have been introduced to address the above problems and expand the size of the dataset.

(a) SSLD based on statistical techniques

In statistical techniques, data augmentation methods are generally classified into distributional assumption-based and interpolation-based approaches, depending on their generative principles. These studies are summarized in Table 3.

1) Distributional assumption-based methods fit a probability distribution to existing data and then generate new samples by sampling from the fitted distribution. The low dimensionality of SSLD data facilitates the modeling of their distributional characteristics. For example, in [78], the generalized internalized kernel density estimation was used to incorporate time-dependent data properties and address the challenges of knowledge acquisition in early-stage manufacturing systems. Reference [79] introduced a maximal p-value method based on the two-parameter Weibull distribution to generate virtual samples and evaluate product lifetime performance in scenarios with limited datasets. In [80], the small Johnson data transformation was proposed to normalize small datasets for effective VSG.

Information diffusion theory [136], which integrates distributional assumptions with fuzzy set theory, has been applied to estimate feature expansion ranges. Based on this, the mega-trend diffusion (MTD) method introduces an asymmetric diffusion mechanism to generate virtual samples [135], as illustrated in Fig. 15a. Liu et al. [81] further improved the MTD method by integrating PSO, allowing an accurate prediction of forming forces in single-point incremental forming processes under the conditions of limited data. To address challenges in supervised and unsupervised learning with small samples, Sivakumar et al. [82] proposed a modified version of MTD, termed k-Nearest Neighbor MTD.

Figure 15: Diagram of typical statistical technique-based methods

2) Interpolation-based methods represent another prominent direction in data augmentation research. These techniques generate new samples based on relationships between existing data points, using linear or nonlinear interpolation.

• A representative linear approach is the synthetic minority over-sampling technique (SMOTE) [137], which interpolates between samples from minority class, as illustrated in Fig. 15b. To address limitations of standard SMOTE, Mathew et al. [83] proposed weighted kernel-based SMOTE, which performs oversampling in the feature space of support vector machines to better preserve minority class characteristics. Soltanzadeh et al. [84] introduced range-controlled SMOTE to alleviate class overlap near decision boundaries. Li et al. [85] proposed multi-vector stochastic exploration oversampling, which generates diverse virtual samples through randomized direction and scaling vectors. Khan [138] proposed a balanced weighted extreme learning machine (WELM) that integrates k-fold sampling strategies, such as SMOTE and TomekLinks, with a cost-sensitive WELM framework to reduce data complexity and improve minority class classification in imbalanced datasets.

• For nonlinear interpolation, He et al. [16] developed the nonlinear interpolation VSG method, integrated with neural networks to improve the accuracy of energy prediction. In another study, Zhu et al. [86] utilized a distance-based criterion to detect sparse data regions and employed Kriging interpolation to generate virtual samples. Similarly, Song et al. [87] proposed data augmentation with weighted interpolation for the VSG method, which improves sample quality for soft sensing models.

(b) SSLD based on deep generative models

For classification tasks, deep generative models play a crucial role in expanding minority class datasets to alleviate class imbalance and improve model performance. In [88], an augmented generator was introduced to produce high-quality virtual samples representing abnormal states. This approach incorporated augmented filter layers and batching techniques to enhance the diversity and reliability of the generated data. Then, reference [89] integrated a multi-head attention mechanism into a GAN framework, effectively improving the sample quality and modeling performance. Furthermore, reference [90] proposed two augmentation strategies, individual-based and concatenation-based, which enhanced the representation of minority classes and effectively balanced the dataset.

For regression tasks, deep generative models must generate virtual input-output pairs that maintain their mapping relationship. In [91], Gaussian noise was injected into the features extracted by a target-relevant autoencoder to generate informative input-output sample pairs. In [92], labels were incorporated as conditional information in a GAN framework, allowing the generation of labeled samples specifically designed to populate the sparse regions of the feature space. Then, reference [93] integrated GAN with vine copula regression to address the challenge of limited labeled data in complex chemical processes. In [94], a supervised variational autoencoder and a WGAN-GP were combined to generate high-quality labeled samples, thus improving the accuracy and robustness of soft sensor models. In [95], the TimeCVAE model incorporated time-dependent features and conditional information into the virtual sample generation process, improving the performance of time series prediction.

In this context, various data augmentation methods have been proposed for SSLD data. Statistical technique-based methods emphasize simplicity and computational efficiency. These methods are well-suited to low-dimensional data, where they can effectively infer latent information. However, they often face limitations when modeling complex, high-dimensional relationships. In contrast, deep generative model-based methods aim to learn latent data distributions through neural networks. Although these models are highly expressive and capable of capturing complex patterns, they require careful hyperparameter tuning to ensure training stability. Consequently, statistical methods provide greater interpretability and reliability in low-dimensional scenarios, whereas deep generative models demonstrate superior adaptability and performance.

3.4 Data Augmentation for LSHD

High dimensionality in industrial datasets often results from multi-source data fusion across different processes, causing massive and complex datasets. However, these high-dimensional datasets contain substantial noise and redundant features. As a result, the research focus should shift from achieving ‘sufficient data size’ to ensuring ‘sufficient data quality and scenario coverage’. In this context, deep generative model-based and physical model-based data augmentation methods have been developed to address these challenges.

(a) LSHD based on deep generative models

For LSHD data, developing effective deep generative models remains a challenging task due to data sparsity and variability. Recent studies have addressed these limitations through task-specific model designs. For example, reference [96] proposed three data-level augmentation strategies:

• a VAE-based augmentation approach that reconstructs virtual samples by learning latent feature distributions;

• a CVAE-based balancing approach that employs label-guided generation to expand minority class;

• a hybrid CVAE approach combined with random undersampling, which reduces the dominance of majority classes while retaining essential information.

In [97], a complementary classifier was incorporated into a basic GAN framework to augment minority class and improve classification accuracy through collaborative adversarial training. Then, reference [98] proposed a data augmentation framework that integrates cooperative and competitive strategies. The cooperative strategy utilizes cross-training and parallel training among multiple GANs to improve diversity and efficiency. In contrast, the competitive strategy introduces a filtering mechanism to retain only high-quality generated samples. Zaman et al. [99] developed a comprehensive framework combining preprocessing, GAN-based augmentation, automated feature selection, and predictive modeling to alleviate class imbalance and enhance generalization to unseen data. To support privacy-preserving learning, Feng et al. [100] integrated CVAE and GAN to generate balanced virtual samples in federated learning environments and used geometric median aggregation to ensure privacy preservation. Furthermore, Zhang et al. [101] employed Isomap for dimensionality reduction while preserving critical data structures and used CGAN to generate additional fault samples.

Furthermore, for high-precision quality prediction tasks, the availability of sufficient training samples is critical. To address this, reference [139] proposed a two-phase framework that first introduced TimeGAN to generate temporally consistent data to impute missing values and then used minimal gated unit to enable efficient quality prediction with reduced computational complexity.

(b) LSHD based on physical models

Huang et al. [102] proposed an edge-intelligent digital twin framework that utilizes edge-cloud collaboration and real-time data processing to identify early-stage faults in automation systems. In another study, Krespach et al. [103] introduced a hybrid data augmentation method that combines historical data with virtual data generated from a digital twin. This method addresses the limitations of traditional data-driven predictive control by generating virtual samples that cover previously unexplored operational conditions.

In this context, data augmentation methods for LSHD data have been preliminarily explored. Among them, deep generative model-based methods effectively address the challenges of high-dimensional complexity and class imbalance by learning latent data distributions. However, these methods often involve complex training procedures, high computational costs, and risks of pattern collapse. In contrast, physical model-based methods generate high-quality samples grounded in physical mechanisms, enabling the capture of complex dynamic behaviors and improving prediction reliability. However, their applicability to unseen operating conditions remains limited due to strict model structures and high modeling overhead.

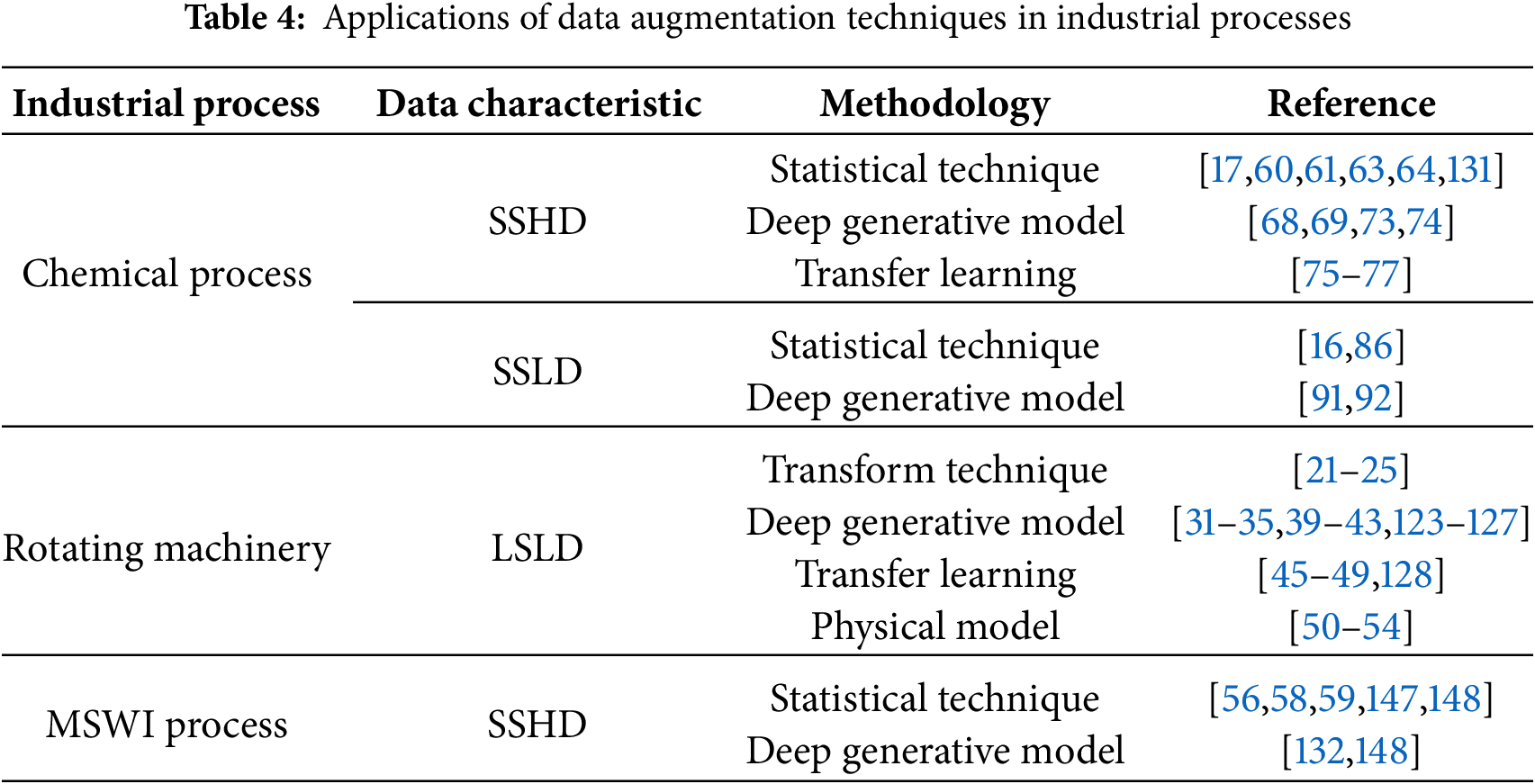

4 Application of Data Augmentation

This section summarizes current advances in data augmentation methods across three critical industrial domains: chemical processes, rotating machinery, and municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI). In addition, it highlights emerging research trends within each domain, aiming to offer valuable insights and practical references for researchers and engineers working in related fields.

The chemical process involves the transformation of raw materials into final products through chemical and physical operations. It is a critical industry where accurate process monitoring and key performance index prediction are essential. Numerous studies have focused on these tasks using simulated and actual datasets. A typical benchmark is the Tennessee Eastman (TE) platform, a simulation system modeled on an actual chemical reaction process [140,141], as shown in Fig. 16. The TE dataset includes 11 manipulated and 41 measured variables across various operating conditions, as it is suitable for evaluating data augmentation methods. Beyond simulations, researchers have also investigated actual industrial scenarios, such as purified terephthalic acid and ethylene production processes, to assess the practical effectiveness of proposed data augmentation methods.

Figure 16: Diagram of the TE process

1) To alleviate the class imbalance in TE datasets, various data augmentation methods have been proposed. For example, Jiang et al. [73] developed a multi-generator framework to overcome the limitations of single-generator models in handling complex imbalance scenarios. Zhuo et al. [74] introduced auxiliary fault attributes into a GAN framework, enabling VSG for rare and unseen faults, thus supporting zero-shot and few-shot fault diagnosis. Furthermore, Xu et al. [68] proposed a deep encoder-decoder network integrated with SMOTE to balance data distribution, complemented by an ensemble classifier to improve diagnostic accuracy. Transfer learning has also gained advances in augmented TE datasets. Ren et al. [75] extracted simplified and accurate fault features from multiple conditions to augment data under the current condition. Similarly, Zhu et al. [76] utilized adversarial learning to transfer features of real samples for VSG, paired with a model-based transfer learning approach to improve robustness against low-quality generated samples. In addition, Li et al. [77] addressed single-source domain generalization by generating virtual samples and learning domain-invariant feature representations, thereby enabling cross-mode fault diagnosis.

2) In purified terephthalic acid (PTA) processes, the conductivity of the solvent dehydration tower is a key quality index, so the development of accurate soft sensors is important. However, due to the SSHD characteristics of the PTA data, multiple learning techniques such as locally linear embedding [60], Isomap [17], and t-SNE [61] have been widely employed to reduce dimensionality and identify sparse areas to generate samples based on interpolation. For example, reference [63] utilized projection point spacing in the low-dimensional feature space to detect sparsity and then generated virtual samples using midpoint and radial basis function interpolation. Similarly, reference [131] applied the singular value decomposition to extract the principal features and expand datasets and generated the corresponding output values using the gradient boosting decision tree. In another study, reference [64] generated virtual samples through interpolation and used co-trained KNN regressors to generate the associated outputs. Furthermore, Xu et al. [69] proposed a Gaussian VAE-based VSG method, which employs improved least squares regression to generate high-quality virtual outputs.

3) In ethylene production processes, accurate energy analysis is vital to optimize industrial operations. However, the limited data on energy consumption pose significant challenges. To address this, data augmentation techniques have been widely utilized. For example, reference [16] applied interpolation within the hidden layers of neural networks to generate virtual input samples, while employing the Moore-Penrose generalized inverse to estimate the corresponding output values. Similarly, reference [86] utilized dimension-wise interpolation via Kriging to create feasible virtual samples in sparse regions, thus improving the prediction accuracy of soft sensors. In addition, several studies have focused on deep generative models to further improve the quality of generated samples. Reference [91] introduced Gaussian noise into latent features extracted from a target-relevant VAE, generating informative input-output pairs. Meanwhile, in [92], a combination of local outlier factor and K-means clustering was used to identify sparse regions for input generation, and a CGAN was used to generate the corresponding output values. These approaches significantly improved the performance of data-driven soft sensor models under limited data.

Rotating machinery includes mechanical systems that perform energy conversion or transmission through rotational motion. As essential components in modern industrial systems, their health monitoring and fault diagnosis are crucial to ensuring operational safety and reliability [142,143]. To facilitate theoretical research and validation of diagnostic methods, several benchmark datasets have been developed. Among them, the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) bearing dataset is one of the most widely utilized in the diagnosis of rotating machinery faults [144], as illustrated in Fig. 17. This dataset includes signals collected under normal conditions as well as various fault scenarios, such as 12k and 48k drive-end bearing faults and fan-end bearing faults. Similarly, the University of Connecticut (UoC) gearbox dataset provides experimental data from a two-stage gearbox system equipped with interchangeable gears [145]. It involves a series of conditions, including healthy operation, missing teeth, root cracks, spalling, and chipped teeth. Due to the limited availability of fault data, numerous data augmentation methods have been proposed to expand datasets and enhance robustness and generalization.

Figure 17: Diagram of the CWRU motor experimental platform

The data augmentation methods based on transform technique generate new samples by applying various transformations to original vibration signals. Common techniques include noise injection, geometric scaling, zero-masking, time-shifting, and signal flipping [21–30,104]. In recent years, deep generative models have become a major focus in machine fault diagnosis. Among these, VAEs employ an encoder to extract distributional representations and a decoder to reconstruct low-dimensional latent variables [31–35,114–117]. GANs use adversarial learning between a generator and a discriminator to generate high-quality virtual samples [36–40,119–127]. Based on these, the conversion of 1-D vibration signals into two-dimensional 2-D images has enabled the use of more advanced deep learning algorithms. Recently, diffusion models based on Markov chain processes have emerged as an effective generative framework that offers stable training and high-quality image generation [41–44]. Meanwhile, transfer learning techniques use data and knowledge from a source domain to generate more diverse and informative samples for a target domain [45–49,128]. Finally, several studies have introduced numerical simulations [50,51] and digital twin models [52–55], which are based on physical laws and mechanistic knowledge, to expand datasets and improve model generalization capabilities.

4.3 Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Process (MSWI)

The MSWI process has emerged as the primary approach to managing MSW, due to its advantages in innocuity, reduction, and reuse. The MSWI process comprises several stages: feeding, combustion, heat exchange, gas cleaning, and emissions [5,146], as illustrated in Fig. 18. Among emission by-products, dioxins (DXNs) represent a critical environmental pollutant because of their high toxicity and persistence. However, DXNs are difficult to detect online, resulting in a limited number of effective samples with true values [5]. Moreover, since DXN emissions are influenced by the whole MSWI process, the DXN data are high-dimensional. Therefore, data augmentation methods have become essential for enabling data-driven modeling of DXN emissions.

Figure 18: Diagram of the MSWI process

For high-dimensional DXN data, dimensionality reduction is a critical preprocessing step. In [56,58,147,148], features were selected based on domain knowledge and expert experience to reduce data complexity. In [132], the random forest algorithm was introduced to achieve a subset of features relevant to DXN emissions by modifying the model performance. In [59], the principal component analysis was applied to extract low-dimensional features that capture the dominant variance in the data.

Based on this basic, reference [56] improved the MTD method by expanding the range of input features and employing equal-interval interpolation to generate virtual input-output pairs. Similarly, reference [58] used MTD and interpolation techniques to generate virtual samples and further enhanced the PSO algorithm to select high-quality samples. Then, reference [147] used a multi-objective PSO approach to identify optimal virtual samples for soft sensor modeling, balancing model accuracy with minimal sample selection. Reference [59] generated virtual samples along independent principal components using kernel density estimation and obtained virtual outputs through mapping models. Furthermore, reference [148] integrated the active learning mechanism with GAN to generate virtual samples, building an accurate and robust DXN warning model. In reference [132], fuzzy set theory was incorporated into the GAN framework to address uncertainty and facilitate the generation of high-quality samples.

Building on this foundation, the applications of data augmentation techniques in representative industrial processes are summarized in Table 4. From a managerial perspective, practitioners can make informed decisions regarding model deployment by applying data augmentation techniques to specific data regimes and industrial conditions, as well as guiding data acquisition planning and digital strategies. This survey is intended to serve as a comprehensive reference for mapping data-related challenges to suitable data augmentation strategies within a range of industrial constraints.

This review has examined four categories of data characteristics—SSLD, SSHD, LSLD, and LSHD—along with their corresponding data augmentation strategies. Despite notable advancements, several critical limitations remain in existing approaches. Drawing on these insights, we propose four key directions for future research:

(1) Data Augmentation for Few-Shot Scenarios: In actual industrial scenarios, safety constraints often restrict data collection under extreme or failure conditions, resulting in long-tailed distributions and limited model generalization. Traditional generative models struggle to capture these rare dynamics, particularly in systems characterized by nonlinear and multi-physics behaviors. Future research should focus on developing knowledge-guided or physics-informed augmentation strategies capable of simulating rare events with greater fidelity, while ensuring physical plausibility and adherence to safety constraints.

(2) Cooperative Multi-Modal Data Augmentation: The heterogeneity and inconsistency inherent in multi-modal data (e.g., sensor signals, images, and logs) pose significant challenges. Existing augmentation techniques often overlook cross-modal dependencies, increasing the risk of semantic misalignment. Advancing cooperative augmentation methods that align representations across modalities while preserving domain-specific semantics remains a critical need, particularly for robust modeling in data-scarce scenarios.

(3) Evaluation and Closed-Loop Optimization of Generated Samples: The absence of rigorous evaluation criteria undermines confidence in generated virtual samples. Furthermore, few existing methods incorporate feedback loops for iterative refinement of data augmentation. There is a critical need for closed-loop frameworks that integrate expert constraints, dynamic evaluation metrics, and system feedback to continuously validate and enhance generated data, particularly in safety-critical applications.

(4) ChatGPT to Data Conversion Augmentation: Recent advances in large language models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, have enabled the transformation of unstructured expert knowledge into structured data, opening new avenues for data augmentation. However, significant challenges persist in semantic grounding, domain adaptation, and reliability of LLM-generated data. Future research should investigate hybrid frameworks that integrate LLM-based generation with domain-specific rules to enhance interpretability and facilitate knowledge integration in data-driven modeling.

Current data augmentation techniques still face challenges in generalizing to operating conditions, handling data heterogeneity, and maintaining interpretability. To fill these gaps, future research should pursue hybrid, domain-informed, and feedback-integrated frameworks that leverage both data-driven and knowledge-based approaches.

Data augmentation plays a vital role in improving the performance and robustness of artificial intelligence (AI) models in industrial applications, particularly under conditions of data scarcity and imbalance. This survey reviews data augmentation techniques on four representative data characteristics and five methodological categories, emphasizing their applications and limitations. Despite recent advancements, significant challenges remain in cross-domain generalization, multi-modal data fusion, evaluation of generated data, and the integration of domain knowledge. Future research should prioritize the development of hybrid augmentation frameworks, the enforcement of cross-modal consistency, feedback-driven validation mechanisms, and the application of LLM to integrate expert knowledge with data-driven modeling. Addressing these challenges is essential for the advancement of reliable and adaptable industrial AI systems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program (Grade B) of China (GZB20250435) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62403270).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Canlin Cui, Heng Xia; Literature collection and analysis: Canlin Cui; Draft manuscript preparation: Canlin Cui, Junyu Yao, Heng Xia; Funding acquisition and supervision: Heng Xia, Junyu Yao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jiang X, Kong X, Ge Z. Augmented industrial data-driven modeling under the curse of dimensionality. IEEE/CAA J Automat Sinica. 2023;10(6):1445–61. doi:10.1109/jas.2023.123396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yang HJ, Li CI. Nonparametric control limits incorporating exceedance probability criterion for statistical process monitoring with commonly employed small to moderate sample sizes. Quality Eng. 2025;37(1):145–61. doi:10.1080/08982112.2024.2363828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Peng P, Lu J, Tao S, Ma K, Zhang Y, Wang H, et al. Progressively balanced supervised contrastive representation learning for long-tailed fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2022;71(1):3506112. doi:10.1109/tim.2022.3151946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Tian J, Jiang Y, Zhang J, Luo H, Yin S. A novel data augmentation approach to fault diagnosis with class-imbalance problem. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2024;243:109832. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2023.109832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Xia H, Tang J, Aljerf L, Cui C, Gao B, Ukaogo PO. Dioxin emission modeling using feature selection and simplified DFR with residual error fitting for the grate-based MSWI process. Waste Manage. 2023;168(4):256–71. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2023.05.056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Bayer M, Kaufhold MA, Reuter C. A survey on data augmentation for text classification. ACM Comput Surv. 2022;55(7):1–39. doi:10.1145/3544558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Garcea F, Serra A, Lamberti F, Morra L. Data augmentation for medical imaging: a systematic literature review. Comput Biol Med. 2023;152(1):106391. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Cao C, Zhou F, Dai Y, Wang J, Zhang K. A survey of mix-based data augmentation: taxonomy, methods, applications, and explainability. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;57(2):1–38. doi:10.1145/3696206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ju Z, Chen Y, Qiang Y, Chen X, Ju C, Yang J. A systematic review of data augmentation methods for intelligent fault diagnosis of rotating machinery under limited data conditions. Meas Sci Technol. 2024;35(12):122004. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ad7a97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Schwarz A, Rahal JR, Sahelices B, Barroso-García V, Weis R, Duque Antón S. Data augmentation in predictive maintenance applicable to hydrogen combustion engines: a review. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(1):1–24. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-11021-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Raudys SJ, Jain AK. Small sample size effects in statistical pattern recognition: recommendations for practitioners. IEEE Transact Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 1991;13(3):252–64. doi:10.1109/34.75512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shawe-Taylor J, Anthony M, Biggs N. Bounding sample size with the Vapnik-Chervonenkis dimension. Discrete Appl Mathem. 1993;42(1):65–73. doi:10.1016/0166-218x(93)90179-r. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yu W, Lu Y, Wang J. Application of small sample virtual expansion and spherical mapping model in wind turbine fault diagnosis. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;183(14):115397. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.115397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yuan JL, Fine TL. Neural-network design for small training sets of high dimension. IEEE Transact Neu Netw. 1998;9(2):266–80. doi:10.1109/72.661122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Chen Z, Zhu B, He Y, Yu L. A PSO based virtual sample generation method for small sample sets: applications to regression datasets. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2017;59:236–43. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2016.12.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. He Y, Wang P, Zhang M, Zhu Q, Xu Y. A novel and effective nonlinear interpolation virtual sample generation method for enhancing energy prediction and analysis on small data problem: a case study of Ethylene industry. Energy. 2018;147(1):418–27. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2018.01.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang X, Xu Y, He Y, Zhu Q. Novel manifold learning based virtual sample generation for optimizing soft sensor with small data. ISA Trans. 2021;109(5):229–41. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2020.10.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Tang J, Jia M, Liu Z, Chai T, Yu W. Modeling high dimensional frequency spectral data based on virtual sample generation technique. In: 2015 IEEE International Conference on Information and Automation; 2015 Aug 8–10; Lijiang, China. p. 1090–5. [Google Scholar]

19. Wang Y, Chung SH, Khan WA, Wang T, Xu DJ. ALADA: a lite automatic data augmentation framework for industrial defect detection. Adv Eng Inform. 2023;58(2):102205. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2023.102205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Altman N, Krzywinski M. The curse(s) of dimensionality. Nat Methods. 2018;15(6):399–400. doi:10.1038/s41592-018-0019-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Li X, Zhang W, Ding Q, Sun J. Intelligent rotating machinery fault diagnosis based on deep learning using data augmentation. J Intell Manufact. 2020;31(2):433–52. doi:10.1007/s10845-018-1456-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Peng T, Shen C, Sun S, Wang D. Fault feature extractor based on bootstrap your own latent and data augmentation algorithm for unlabeled vibration signals. IEEE Transact Indust Elect. 2022;69(9):9547–55. doi:10.1109/tie.2021.3111567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Abeysinghe A, Tohmuang S, Davy JL, Fard M. Data augmentation on convolutional neural networks to classify mechanical noise. Appl Acoust. 2023;203(16):109209. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2023.109209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Nematirad R, Behrang M, Pahwa A. Acoustic-based online monitoring of cooling fan malfunction in air-forced transformers using learning techniques. IEEE Access. 2024;12:26384–400. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3366807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Alharbi F, Luo S, Zhao S, Yang G, Wheeler C, Chen Z. Belt conveyor idlers fault detection using acoustic analysis and deep learning algorithm with the YAMNet pretrained network. IEEE Sens J. 2024;24(19):31379–94. doi:10.1109/jsen.2024.3439509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wan W, Chen J, Zhou Z, Shi Z. Self-supervised simple siamese framework for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery with unlabeled samples. IEEE Transact Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2024;35(5):6380–92. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2022.3209332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Russell M, Wang P, Liu S, Jawahir I. Mixed-up experience replay for adaptive online condition monitoring. IEEE Transact Indust Elect. 2024;71(2):1979–86. doi:10.1109/tie.2023.3260351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yao Y, Feng J, Liu Y. Domain knowledge-guided contrastive learning framework based on complementary views for fault diagnosis with limited labeled data. IEEE Transact Indust Inform. 2024;20(5):8055–63. doi:10.1109/tii.2024.3369704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wu J, Cabrera D, Cerrada M, Sánchez RV, Sancho F, Estupinan E. Fault diagnosis generalization improvement through contrastive learning for a multistage centrifugal pump. IEEE Transact Reliab. 2025;74(7):2373–81. doi:10.1109/tr.2024.3381014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chen H, Hu N, Cheng Z, Zhang L, Zhang Y. A deep convolutional neural network based fusion method of two-direction vibration signal data for health state identification of planetary gearboxes. Measurement. 2019;146(7553):268–78. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2019.04.093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhao D, Liu S, Gu D, Sun X, Wang L, Wei Y, et al. Enhanced data-driven fault diagnosis for machines with small and unbalanced data based on variational auto-encoder. Meas Sci Technol. 2020;31(3):035004. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ab55f8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Dixit S, Verma NK. Intelligent condition-based monitoring of rotary machines with few samples. IEEE Sens J. 2020;20(23):14337–46. doi:10.1109/jsen.2020.3008177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhao K, Jiang H, Liu C, Wang Y, Zhu K. A new data generation approach with modified Wasserstein auto-encoder for rotating machinery fault diagnosis with limited fault data. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;238(1):107892. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2021.107892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhao Z, Xu Y, Zhang J, Zhao R, Chen Z, Jiao Y. A semi-supervised Gaussian mixture variational autoencoder method for few-shot fine-grained fault diagnosis. Neural Netw. 2024;178(8):106482. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2024.106482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Karamti H, Lashin MM, Alrowais FM, Mahmoud AM. A new deep stacked architecture for multi-fault machinery identification with imbalanced samples. IEEE Access. 2021;9:58838–51. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3071796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yin H, Li Z, Zuo J, Liu H, Yang K, Li F. Wasserstein generative adversarial network and convolutional neural network (WG-CNN) for bearing fault diagnosis. Math Probl Eng. 2020;2020(1):2604191. doi:10.1155/2020/2604191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Peng Y, Wang Y, Shao Y. A novel bearing imbalance Fault-diagnosis method based on a Wasserstein conditional generative adversarial network. Measurement. 2022;192(6):110924. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2022.110924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Jalayer M, Kaboli A, Orsenigo C, Vercellis C. Fault detection and diagnosis with imbalanced and noisy data: a hybrid framework for rotating machinery. Machines. 2022;10(4):237. doi:10.3390/machines10040237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Shi Y, Li J, Li H, Yang B. An imbalanced data augmentation and assessment method for industrial process fault classification with application in air compressors. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2023;72:3521510. doi:10.1109/tim.2023.3288257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Li X, Yue C, Liu X, Zhou J, Wang L. ACWGAN-GP for milling tool breakage monitoring with imbalanced data. Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 2024;85:102624. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2023.102624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Liu J, Xiao J, Ma T, Cen L, Shao H, Liu Y. Small-sample-oriented multi-condition fault diagnosis framework based on classifier-free denoising diffusion implicit model with multi-class contrastive learning. IEEE Sens J. 2024;24(24):41635–46. doi:10.1109/jsen.2024.3487209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Yang X, Ye T, Yuan X, Zhu W, Mei X, Zhou F. A novel data augmentation method based on denoising diffusion probabilistic model for fault diagnosis under imbalanced data. IEEE Transact Indust Inform. 2024;20(5):7820–31. doi:10.1109/tii.2024.3366991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Zhao P, Zhang W, Cao X, Li X. Denoising diffusion probabilistic model-enabled data augmentation method for intelligent machine fault diagnosis. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;139(4):109520. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.109520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Fan C, Zhang Y, Ma H, Yu K, Ma Z. A novel lightweight DDPM-based data augmentation method for rotating machinery fault diagnosis with small sample. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2025;232:112741. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2025.112741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. He J, Xu Y, Pan Y, Wang Y. Adaptive weighted generative adversarial network with attention mechanism: a transfer data augmentation method for tool wear prediction. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2024;212(3–4):111288. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2024.111288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ge H, Shen C, Lin X, Wang D, Shi J, Huang W, et al. A new multiple mixed augmentation-based transfer learning method for machinery fault diagnosis. Meas Sci Technol. 2024;35(8):086141. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ad4d15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Jian C, Peng Y, Mo G, Chen H. Open-set domain generalization for fault diagnosis through data augmentation and a dual-level weighted mechanism. Adv Eng Inform. 2024;62:102703. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2024.102703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Mu M, Jiang H, Wang X, Dong Y. A task-oriented theil index-based meta-learning network with gradient calibration strategy for rotating machinery fault diagnosis with limited samples. Adv Eng Inform. 2024;62(10):102870. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2024.102870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Wang X, Jiang H, Mu M, Dong Y. A dynamic collaborative adversarial domain adaptation network for unsupervised rotating machinery fault diagnosis. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2025;255:110662. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2024.110662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Lim D, Jung W, Bae J, Park Y. Utilization of high-fidelity simulation data for data augmentation of artificial neural net-based rotor faults diagnosis. In: Active and passive smart structures and integrated systems XVI. Vol. 12043. Bellingham, WA, USA: SPIE; 2022. p. 441–7. [Google Scholar]

51. Feng Y, Chen W, Fu H, Wang H, Gao C, Sun X, et al. Fault diagnosis of controllable pitch propeller as few-shot classification with mechanism simulation data augmentation. In: 2023 IEEE 2nd Industrial Electronics Society Annual On-Line Conference (ONCON); 2023 Dec 8–10; SC, USA. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

52. Cai W, Zhang Q, Cui J. A novel fault diagnosis method for denoising autoencoder assisted by digital twin. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022;2022(1):5077134. doi:10.1155/2022/5077134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Qin Y, Liu H, Mao Y. Faulty rolling bearing digital twin model and its application in fault diagnosis with imbalanced samples. Adv Eng Inform. 2024;61(6):102513. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2024.102513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Zhang Y, Zhou X, Gao C, Lin J, Ren Z, Feng K. Contrastive learning-enabled digital twin framework for fault diagnosis of rolling bearing. Meas Sci Technol. 2024;36(1):015026. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ad8f52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Ming Z, Tang B, Deng L, Yang Q, Li Q. Digital twin-assisted fault diagnosis framework for rolling bearings under imbalanced data. Appl Soft Comput. 2025;168:112528. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.112528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Qiao J, Guo Z, Tang J. Virtual sample generation method based on improved megatrend diffusion and hidden layer interpolation with its application. CIESC J. 2020;71(12):5681–95. [Google Scholar]

57. Li L, Damarla SK, Wang Y, Huang B. A Gaussian mixture model based virtual sample generation approach for small datasets in industrial processes. Inform Sci. 2021;581(4):262–77. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2021.09.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Tang J, Wang D, Guo Z, Qiao J. Prediction of dioxin emission concentration in the municipal solid waste incineration process based on optimal selection of virtual samples. J Beijing Univ Technol. 2021;47(5):431–43. doi:10.1109/ccdc52312.2021.9601628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Tang J, Cui C, Wang D, Qiao J. Virtual sample generation method using reduced feature probability density distribution. Control Theory Appl. 2024;41(11):2165–73. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

60. Zhu Q, Zhang X, He Y. Novel virtual sample generation based on locally linear embedding for optimizing the small sample problem: case of soft sensor applications. Indus Eng Chem Res. 2020;59(40):17977–86. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.0c01942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. He Y, Hua Q, Zhu Q, Lu S. Enhanced virtual sample generation based on manifold features: applications to developing soft sensor using small data. ISA Transact. 2022;126(4):398–406. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2021.07.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. He Y, Li K, Liang L, Xu Y, Zhu Q. Novel discriminant locality preserving projection integrated with Monte Carlo sampling for fault diagnosis. IEEE Transact Reliab. 2021;72(1):166–76. doi:10.1109/tr.2021.3115108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Zhu Q, Liu D, Xu Y, He Y. Novel space projection interpolation based virtual sample generation for solving the small data problem in developing soft sensor. Chemometr Intell Lab Syst. 2021;217(35):104425. doi:10.1016/j.chemolab.2021.104425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Zhu Q, Zhang H, Tian Y, Zhang N, Xu Y, He Y. Co-training based virtual sample generation for solving the small sample size problem in process industry. ISA Transact. 2023;134(C):290–301. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2022.08.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Quan T, Yuan Y, Luo Y, Song Y, Zhou T, Wang J. From regression to classification: fuzzy multikernel subspace learning for robust prediction and drug screening. IEEE Transact Indust Inform. 2024;20(3):4137–48. doi:10.1109/tii.2023.3321332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Yuan X, Ou C, Wang Y, Yang C, Gui W. A layer-wise data augmentation strategy for deep learning networks and its soft sensor application in an industrial hydrocracking process. IEEE Transact Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2021;32(8):3296–305. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2019.2951708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Jiang X, Ge Z. Improving the performance of just-in-time learning-based soft sensor through data augmentation. IEEE Transact Indust Elect. 2022;69(12):13716–26. doi:10.1109/tie.2021.3139194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Xu Y, Fan R, He Y, Zhu Q, Zhang Y, Zhang M. DeepSMOTE with Laplacian matrix decomposition for imbalance instance fault diagnosis. Chemometr Intell Lab Syst. 2025;259(3):105338. doi:10.1016/j.chemolab.2025.105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Xu Y, Zhu Q, Ke W, He Y, Zhang M, Xu Y. Virtual sample generation for soft-sensing in small sample scenarios using glow-embedded variational autoencoder. Comput Chem Eng. 2025;193(1):108925. doi:10.1016/j.compchemeng.2024.108925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Gao X, Deng F, Yue X. Data augmentation in fault diagnosis based on the Wasserstein generative adversarial network with gradient penalty. Neurocomputing. 2020;396(99):487–94. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2018.10.109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Jiang X, Ge Z. Augmented multidimensional convolutional neural network for industrial soft sensing. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2021;70:2508410. doi:10.1109/tim.2021.3075515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. He Y, Li X, Ma J, Lu S, Zhu Q. A novel virtual sample generation method based on a modified conditional Wasserstein GAN to address the small sample size problem in soft sensing. J Process Cont. 2022;113(4):18–28. doi:10.1016/j.jprocont.2022.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Jiang X, Ge Z. Data augmentation classifier for imbalanced fault classification. IEEE Transact Automat Sci Eng. 2021;18(3):1206–17. doi:10.1109/tase.2020.2998467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Zhuo Y, Ge Z. Auxiliary information-guided industrial data augmentation for any-shot fault learning and diagnosis. IEEE Transact Indust Inform. 2021;17(11):7535–45. doi:10.1109/tii.2021.3053106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Ren Y, Liu J, Chen Y, Wang W. LJDA-net: a low-rank joint domain adaptation network for industrial sample enhancement. IEEE Sens J. 2022;22(12):11881–91. doi:10.1109/jsen.2022.3170085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Zhu J, Wang B, Wang X. A model transfer learning based fault diagnosis method for chemical processes with small samples. Int J Control Autom Syst. 2023;21(12):4080–7. doi:10.1007/s12555-022-0798-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Li G, Atoui MA, Li X. Dual adversarial and contrastive network for single-source domain generalization in fault diagnosis. Adv Eng Inform. 2025;65(3):103140. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2025.103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Li DC, Lin YS. Learning management knowledge for manufacturing systems in the early stages using time series data. European J Operat Res. 2008;184(1):169–84. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2006.10.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Li DC, Lin LS. A new approach to assess product lifetime performance for small data sets. European J Operat Res. 2013;230(2):290–8. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2013.04.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Li DC, Wen IH, Chen WC. A novel data transformation model for small data-set learning. Int J Product Res. 2016;54(24):7453–63. doi:10.1080/00207543.2016.1192301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]